Conrad, Susan. Will corpus linguistics revolutionize grammar teaching in the 21st century

语料库相关源

语料库相关资源David Lee语料库研究书签Bookmarks for Corpus-based Linguists (David Lee).au/~dlee/CBLLinks.htm (/corpora)常用语料库资源链接汇集(语料天涯)/corpus/互动平台/forum/入门读物专著梁茂成、李文中、许家金,2010,《语料库应用教程》。

北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

Hunston, Susan. 2002. Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge. University Press. (世界图书出版社引进)Kennedy, Graeme. 1998. An Introduction to Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman. (外研社引进)期刊论文中国期刊网EBSCO英文期刊数据库书店可以买到的语料库相关书籍Aijmer, K. & B. Altenberg (Eds.). 2004. Advances in Corpus Linguistics. Papers from the 23rd International Conference on English Language Research on Computerized Corpora (ICAME 23). Amsterdam: Rodopi. (世界图书出版社引进)Austermühl, F. 2001. Electronic Tools for Translators《译者的电子工具》. Manchester: St.Jerome Publishing. (外研社引进)Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad & Edward Finegan. 1999.Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Longman Publications Group.(外研社引进)Biber, Douglas, Susan Conrad & Randi Reppen. 1998. Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (外研社引进)Connor, U & T. Upton (Eds.). 2004. Applied Corpus Linguistics: A Multidimensional Perspective. Amsterdam: Rodopi. (世界图书出版社引进)Granger, S. & S. Petch-Tyson (Eds.). 2003. Extending the Scope of Corpus-based Research: New Applications, New Challenges. Amsterdam: Rodopi. (世界图书出版社引进)Granger, S. et al. (Eds.). 2003. Corpus-based Approaches to Contrastive Linguistics and Translation Studies《基于语料库的语言对比和翻译研究》. Amsterdam: Rodopi. (外研社引进)Gries, Stefan Thomas. 2004. Multifactorial Analysis in Corpus Linguistics: A Study of Particle Placement. Beijing: Peking University Press. (北大出版社引进)Hunston, Susan. 2002. Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge. University Press. (世界图书出版社引进)Kennedy, Graeme. 1998. An Introduction to Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman. (外研社引进)Kettemann, B. & G. Marko. 2002. Teaching and Learning by Doing Corpus Analysis.Amsterdam: Rodopi. (世界图书出版社引进)Meyer, Charles. 2002. English Corpus Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (外教社引进)Mukherjee, J. 2001. Form and Function of Parasyntactic Presentation Structures. A Corpus-based Study of Talk Units in Spoken English. Amsterdam: Rodopi. (世界图书出版社引进)Nattinger, James R. & Jeanette S. DeCarrico. 1992. Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (外教社引进)Sinclair, John. 1991. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.(外教社引进)Thomas, Jenny & Mick Short. 1996. Using Corpora for Language Education. London: Pearson Education. (外研社引进)Zanettin, F., et al. (eds.). 2003. Corpora in Translator Education《语料库与译者培养》.Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. (外研社引进)蔡金亭,2003,《语言因素对英语过渡中使用——一般过去时的影响》。

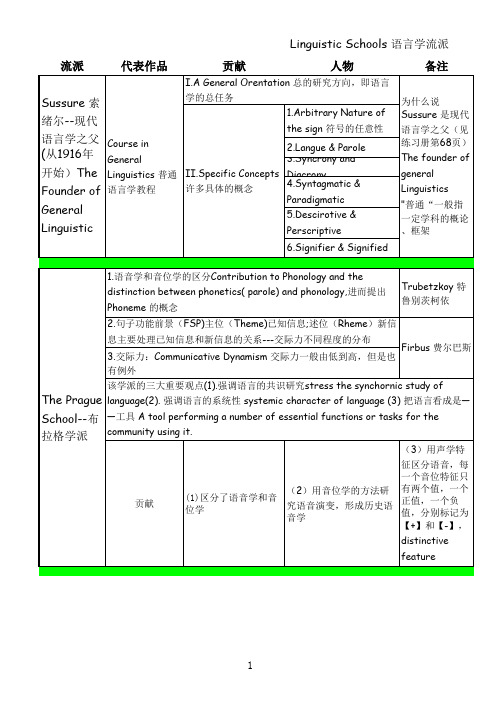

《普通语言学教程》-语言学流派

The London School 伦敦派 关键词:系 统;功能; 上下文 Lay

stress on the function of language and attaching great importance to the contexts of the system aspect of language

Hockett 霍凯特 Tagmatics 法位学 认知层次理论: 层次语法--把语言看做系 Cognitive 统关系--简化与概括 通过 stratificational

龙菲尔德时期的 Pike 派克 语言学

Sydney M Lamb 兰姆 节点和线把层次上的所有 theory 关系联系在一起,把语言 神经认知语言学 分析带入一个节点和线交 (Neurocogniti 织在一起的关系网络 ve linguistics) 美国结构主义的特征:1.共时 2.美国不 同于欧洲的许多的语言都有其历史文化 1.Descrptive instead of perscriptive 2. 背景,美国只有英语 3.任务:记录在迅 没有一套完整的语法规则 3.重视独特性, 速消亡的土著美国印第安人的语言(无 却不重视意义 书面记录,奇特,多样性大 为什么Bloomfield 对语意关注较少:整个印第安语与欧洲语言差异很大, 无必然联 系,而且,印第安语快灭绝了, 因此, 重描写。贡献:最大程度将印第安语记录下 来。反复的使用即刺激--反应--行为主义

多维度分析法在语料库语体分析中使用现状综述

外语外文7学法教法研究课程教育研究1、多维度分析法简介Douglas Biber (1988)[1]创建的多维度分析法(Multi-dimensional Analysis )被认为是目前为止涉及语言特征最多,分类最细的语域分析方法。

在多维度分析法被提出之前,语域对比研究主要集中于分析语域在某一参数上的差异,而这种单维度的对比方法并不能全面揭示语域间的差异,而且对语言特征的分类也是建立在研究者主观直觉上。

为了弥补之前研究的不足,1988年,Biber 提出了多维度分析法:利用因子分析法(Factor Analysis ),对英国LOB 语料库(Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen Corpus )和LLC 语料库(London-Lund Corpus )中的23种口笔语与语文本的67种语言特征的“共现”进项归类分析,将众多语言特征变量分解为几个公共因子,归纳出五个主要维度:交互性与信息性、叙述性与非叙述性、指称明晰性与情景依赖型、显性劝说型、信息抽象与具体程度。

每个维度都包含其特有的语言特征,例如动词的过去式(past tense verb ),第三人称(third-person pronouns )、公共动词(public verbs )等语言特征主要出现在叙述性语体中,在非叙述性文章中则很少出现,由此可见这一组语言特征“共现”在某一语域中,我们便可将其归纳为同一维度。

Biber (2002)指出多维度分析法作为一种基于语料库进行语域分析的研究方法,能够客观揭示口笔语语域不同,从而得以实证分析出任何两种语域之间的区别。

2、基于语料库的多维度分析法研究概述2.1 国外研究综述早期使用多维度分析法对语料库进行分析的研究主要集中在口笔语语域差异比较。

Biber (1992)[2]使用该方法首先对索马里语的口笔语语域差异进行了分析,分析得出任何语言都有一个或者更多的口语维度。

之后,Biber (1994)在此研究基础上对体现作者写作风格的语言特征进行分析,在2002年[3]总结之前的研究成果,Biber 等人对大学口笔语语域进行了多维度分析,该研究以TOFEL2000口语及WALC (Written Academic Language Corpus ,书面语学术语言语料库)作为研究对象,发现口语语域和书面语域之间存在本质性差异。

corpus linguistics

Tony McEnery and Andrew Wilson. Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7486-0808-7 (hardback); ISBN 0-7486-0482-0 (paperback). Reviewed by Charles F. Meyer, University of Massachusetts at Boston.The publication of Corpus Linguistics is noteworthy: as the first volume in the new series ‘Edinburgh Textbooks in Empirical Linguistics’, this textbook reflects not only the increasing importance that empirically-based studies of language are coming to play in linguistics but the prominent role that corpus linguistics has assumed among the many different empirically-based approaches to language study. In Corpus Linguistics, McEnery and Wilson (hereafter MW) very clearly introduce the field of corpus linguistics to students, providing a very effective overview of the key linguistic and computational issues that corpus linguists have to address as they create corpora and conduct analyses of them. Corpus Linguistics is divided into seven chapters that focus on a number of topical issues in corpus linguistics, issues ranging from the theoretical underpinnings of corpus linguistics to the various annotation schemes that have been developed to tag and parse corpora, the quantitative research methods used to analyze corpora, the types of linguistic studies that have been carried out on corpora, and the contributions that com-putational linguistics has made to the creation and analysis of corpora. Each of these topics is approached in a clear and readable format that will make this text valuable not just to students but to specialists in other areas of linguistics interested in obtaining information about corpus linguistics.After noting in the opening chapter (‘Early Corpus Linguistics and the Chomskyan Revolution’) that corpus linguistics is more a methodology (a way of approaching language study) than a sub-discipline in linguistics, MW continue with a discussion of the methodological assumptions that characterize corpus linguistics and distinguish it from Chomskyan app-roaches to language study. They note the difference between rationalist and empiricist approaches to language study, and detail the classic Chomskyan arguments that have been leveled over the years against empiricist studies of language. Because corpora contain data reflecting ‘performance’, they are of little value in studying ‘competence’, the most important area for linguists to study. In addition, ‘corpora are “skewed”’ (p 8), in the sense that they do not contain all of the possible structures that exist in a language. These objections led Chomsky to1value introspection as the best way of describing a language, and to reject descriptions of actual language use based on analyses of corpora. Although MW acknowledge some validity to Chomsky’s objections to corpus analyses, they counter these objections with a number of arguments in favor of corpus linguistics. A corpus, for instance, can be used to verify introspective judgments, and to overcome the problem of basing grammatical arguments on ‘artificial data’ (p 12). Moreover, c orpora can provide important information on the frequency of grammatical construc-tions, and the sophisticated software developed to analyze corpora can give the linguist access to much important information on grammatical structure present in corpora that have been tagged and parsed. Although Chapter 2 (‘What is a corpus and what is in it?’) purports to describe what a corpus is, it is primarily a chapter about what corpora look like—specifically the annotation schemes that have been developed to tag and parse them. MW only briefly discuss the issues one must confront when creating a corpus (eg the size of the corpus), and while they discuss many methodological concerns throughout the book, it would have been desirable to have grouped these issues together in a single chapter and to have discussed how the representativeness of a corpus is influenced by such variables as its length, the genres it contains, and the types of individuals whose speech and writing are included in the corpus.The strength of Chapter 2 is its discussion of annotation schemes, which is detailed and very well illustrated. MW provide a very clear overview of the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative), illustrating how the various tags developed by TEI can be used to create ‘headers’ (in which information about authors/speakers, titles, dates of publication, etc can be recorded) and to mark up texts themselves with information on paragraph boundaries, type faces, and so forth. The remainder of the chapter focuses on the various schemes that have been developed to annotate linguistic information in corpora. MW first compare tagging schemes from corpora as diverse as the British National Corpus and the CRATER Corpus of Spanish, and then describe the process of developing the CLAWS tagging schemes at Lancaster University. The chapter con-cludes with a discussion of parsing schemes and of how corpora can be annotated with markup revealing their semantic, discoursal, and prosodic structure.Chapter 3 (‘Quantitative data’) discusses the importance of using quantitative research methods to analyze corpora. MW first distinguish qualitative from quantitative research methods, and make the very im-2portant point that the linguistic claims one makes about a corpus depend crucially upon whether the corpus being analyzed is valid and repre-sentative; that is, has been created in a manner that allows the analyst to make general claims about, for instance, the genres represented in the corpus. MW then describe the major kinds of statistical analyses that can be performed on corpora. The difficulty of a chapter of this type is that statistics is such a vast area that it is hard to determine precisely how much detail needs to be provided. But the level of detail in this chapter is most appropriate, and there is much useful information provided on how corpora can be statistically analyzed — from methods as basic as frequency counts to those as sophisticated as factor analysis and loglinear analysis (as done with programs such as VARBRUL). Chapter 4 (‘The use of corpora in language studies’) surveys the kinds of empirical linguistic analyses that corpora can be used to conduct. MW open the chapter with a discussion stressing the importance of empirical studies of language, noting that they ‘enable the linguist to make statements which are objective and based on language as it really is rather than statements which are subjective and based upon the individual’s own internalised cognitive perception of the language’ (p 87). This statement is very convincingly supported in the remainder of the chapter, which contains a very good discussion of how corpora can be used to study language at all levels of linguistic structure (eg phonetics/phonology, syntax, and semantics) and from many different theoretical perspectives (eg pragmatics, sociolinguistics, and discourse study). As each of these areas are described, MW include descriptions of previous studies conducted in the areas to effectively illustrate how work in the area is conducted and has yielded important information. The first four chapters of Corpus Linguistics are concerned with issues relevant to linguists using corpora to carry out purely linguistic studies. Chapter 5 (‘Corpora and computational linguistics’) moves to an allied discipline, natural language processing (NLP), and discusses issues such as tagging and parsing from a more computational perspective. Although linguists who use corpora for grammatical analysis may not have an immediate interest in NLP, the research in this area has led directly to improvements in recent years of taggers and parsers — software respon-sible for annotating corpora and making it easier for linguists to extract information from them. The discussion in this chapter is brief, but does an excellent job of summarizing the theoretical issues underlying the development of taggers and parsers and the role that they play in areas such as lexicography and machine translation.3Chapter 6 (‘A case study: sublanguages’) draws upon much of the information presented in the previous chapters to carry out a sample grammatical analysis of three corpora from three distinct genres: a series of IBM manuals from the IBM Corpus, transcriptions of Canadian parliamentary speeches found in the Hansard Corpus, and fiction from the APHB (American Printing House for the Blind) Corpus. MW analyze these three corpora to advance the hypothesis that the language of the IBM Corpus is a ‘sublanguage’; that is, ‘a version of a natural language which does not display all of the creativity of that natural language[and which] will show a high degree of closure [emphasis in original] at various levels of description (p 148). Before pursuing this hypothesis, MW discuss the importance of evaluating a prospective corpus to determine whether the genres it contains are appropriate for the analysis being conducted, and whether the manner in which the corpus has been annotated will allow for the retrieval of the grammatical information desired. MW conclude that the corpora they have chosen are appropriate for their study of sublanguages, and they then conduct analyses to determine the degree of lexical closure, part-of-speech closure, and parsing closure that exists in each of the corpora. In general, this analysis verified MW’s hypothesis and demonstrated that the IBM Corpus (in comparison with the other corpora) is a more ‘restricted genre’ and contains fewer different types of words and sentence-types (though the words it contained corresponded to more parts of speech than the words in the other corpora did).The final chapter (‘Where to now?’) nicely rounds out the book with a discussion of issues that corpus linguists will need to address in the future corpora that they develop, a series of ‘pressures’ to increase the length of corpora, to make them conform to industry as well as academic standards, and to have corpora draw upon evolving computer technologies in their creation, such as the many multi-media currently being developed. This chapter provides a fitting conclusion to a text that provides a very perceptive overview of the field of corpus linguistics that will be a good choice for use in any introductory course on corpus linguistics. 4。

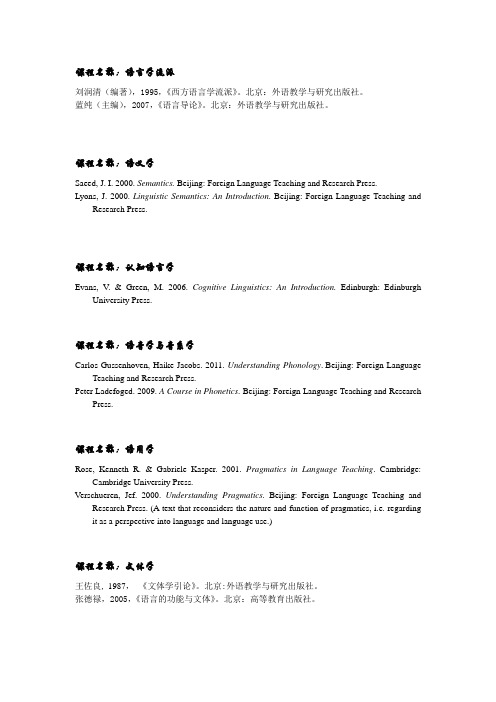

语言学各门课程教材及推荐书目-(简明版)

课程名称:语言学流派刘润清(编著),1995,《西方语言学流派》。

北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

蓝纯(主编),2007,《语言导论》。

北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

课程名称:语义学Saeed, J. I. 2000. Semantics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Lyons, J. 2000. Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.课程名称:认知语言学Evans, V. & Green, M. 2006. Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.课程名称:语音学与音系学Carlos Gussenhoven, Haike Jacobs. 2011. Understanding Phonology. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Peter Ladefoged. 2009. A Course in Phonetics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.课程名称:语用学Rose, Kenneth R. & Gabriele Kasper. 2001. Pragmatics in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Verschueren, Jef. 2000. Understanding Pragmatics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. (A text that reconsiders the nature and function of pragmatics, i.e. regarding it as a perspective into language and language use.)课程名称:文体学王佐良,1987,《文体学引论》。

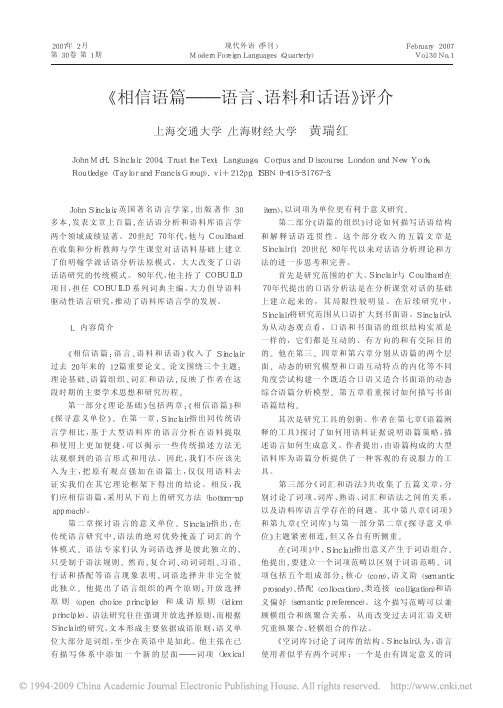

0701_相信语篇_语言_语料和话语_评介

2007年2月February2007第30卷第1期Vol.30No.1现代外语(季刊)ModernForeignLanguages(Quarterly)JohnSinclair,英国著名语言学家,出版著作30多本,发表文章上百篇,在话语分析和语料库语言学两个领域成绩显著。

20世纪70年代,他与Coulthard在收集和分析教师与学生课堂对话语料基础上建立了伯明翰学派话语分析法原模式,大大改变了口语话语研究的传统模式。

80年代,他主持了COBUILD项目,担任COBUILD系列词典主编,大力倡导语料驱动性语言研究,推动了语料库语言学的发展。

1.内容简介《相信语篇:语言、语料和话语》收入了Sinclair过去20年来的12篇重要论文。

论文围绕三个主题:理论基础、语篇组织、词汇和语法,反映了作者在这段时期的主要学术思想和研究历程。

第一部分《理论基础》包括两章:《相信语篇》和《探寻意义单位》。

在第一章,Sinclair指出同传统语言学相比,基于大型语料库的语言分析在语料提取和使用上更加便捷,可以揭示一些传统描述方法无法观察到的语言形式和用法。

因此,我们不应该先入为主,把原有观点强加在语篇上,仅仅用语料去证实我们在其它理论框架下得出的结论。

相反,我们应相信语篇,采用从下而上的研究方法(bottom-upapproach)。

第二章探讨语言的意义单位。

Sinclair指出,在传统语言研究中,语法的绝对优势掩盖了词汇的个体模式。

语法专家们认为词语选择是彼此独立的,只受制于语法规则。

然而,复合词、动词词组、习语、行话和搭配等语言现象表明,词语选择并非完全彼此独立。

他提出了语言组织的两个原则:开放选择原则(openchoiceprinciple)和成语原则(idiomprinciple)。

语法研究往往强调开放选择原则,而根据Sinclair的研究,文本形成主要依据成语原则,语义单位大部分是词组,至少在英语中是如此。

LEXICAL BUNDLES AND THE MENTAL LEXICON

LEXICAL BUNDLES AND THE MENTAL LEXICON:A RESEARCH PROGRAMME*Antoine TremblayUniversity of Alberta1. I NTRODUCTIONThe term ‘lexical bundle’ pertains to the domain of corpus linguistics. It first appeared in the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (Biber et al. 1999), a monumental work entirely based on the British National Corpus of 100 million words. Lexical bundles are very common continuous multi-word strings, which may span phrasal boundaries, identified as such with the help of corpora. Some very frequent instances are I don’t know whether, don’t worry about it, and in the middle of the. The concept of lexical bundles, however, goes back at least to Salem (1987) and the research he carried out on a corpus of French government texts. Butler (1997) and Altenberg (1998) subsequently employed the notion in their investigations based on Spanish and English corpora. Lexical bundles are part of a larger family of multi-word strings (continuous or discontinuous) known as formulaic sequences, which are assumed to be stored and processed in the mind as holistic units. Some examples include greeting formulae (how do you do?), back-channeling formulae (yes I see), phrasal verbs (to show up), constructions/patterns of different sorts ranging from the very schematic Subject-Verb-Object construction (He kicked the ball) to the less schematic Verb Noun into V–ing pattern (He talked her into going out with him), and idioms -- to put one’s finger in the dyke (Croft 2001; Erman and Warren 2000; Hunston and Francis 2000; Pawley and Syder 1983; Titone and Conine 1999; Wray 2002 and references cited therein; Schmitt 2004 and references cited therein).Wray (2002) gives us a nice overview of the history of formulaic sequences in linguistics. Their existence was noticed at least as early as the mid-nineteenth century by John Hughlings Jackson, who observed that aphasics could fluently recall rhymes, prayers, greeting formulae and so forth whereas they could not utter novel sentences (cited in Wray 2002: 7). He was not the only scholar to detect such linguistic peculiarities. Ferdinand de Saussure (1916/1966) talked of agglutinations, that is, the unintentional fusion of two or more linguistic signs that frequently recur together into a single unanalyzed unit so as to form a short cut for the mind. Jespersen (1924) acknowledged the existence of multi-word units stored in the mind of speakers when mentioning that language would be too difficult to manage if one had to remember every individual item separately. According to Bloomfield (1933: 181), “many forms lie on the border-line between bound forms and words, or between words and phrases”. Firth, for his part, considers that the units of speech are phrases * The Lexical Bundles and the Mental Lexical research project is part of a larger research project called Words in the Mind, Words in the Brain, which is supported by a Major Collaborative Research Initiative Grant (#412-2001-1009) from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). The Lexical Bundles and the Mental Lexical research project is also supported by a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship to Antoine Tremblay (#752-2006-1315).(1937/1964), and that for one to characterize a certain community’s speech, one has to list the usual collocations used by its speakers, that is, the set of words that frequently recur with a particular word (1957/1968). Miller (1956) argues that our memory span is limited to seven, plus or minus two units. Nonetheless, we manage to circumvent this severe limitation by organizing information into chunks. Thus, the number of units we can process at any given time remaining constant, we significantly increase the amount of information contained in every one of those units and therefore the amount of information we can manage. For Hymes (1962: 41), a large part of communication involves the use of recurrent patterns, that is, of “linguistic routines”. Bolinger (1976: 1) maintains that “our language does not expect us to build everything starting with lumber, nails, and blueprints, but provides us with an incredibly large number of prefabs”. Finally, Fillmore (1979) writes that knowing how to use formulaic utterances makes up a large part of a speaker’s ability to successfully handle language. Since the Chomskyan era, which started in the 1950s, formulaic language other than non-compositional idioms were marginalized. Only recently is “the idea of holistically managed chunks of language” resurfacing (Wray 2002: 8).As was just mentioned, a number of researchers recognized that certain words systematically occur with one another. However, their observations were based on perceptual salience and a number of lexical sequences went unnoticed. Nowadays, linguists have powerful tools that enable them to reliably identify lexical sequences that recur across increasingly large amounts of spoken and written texts. More importantly, “corpus-based techniques enable investigation of new research questions that were previously disregarded because they were considered intractable” (Biber and Conrad 1999: 181). Owing to corpus-based approaches, we are not only realizing “how extensive and systematic the pattern of language use” is, but also apprehending how such “association patterns are well beyond the access of intuitions” and how they are “much too systematic to be disregarded as accidental” (Biber et al. 1999: 290). Given this systematicity, one may wonder whether formulaic sequences are stored and processed holistically. This brings us to the psycholinguistics domain.During the last three decades, a great deal of psycholinguistic research has focused on the mental lexicon. As Libben (1998: 30) points out, there are at lest two reasons for this. The human ability to store and access a large number of words is central to language; as such it is essential to answer the question of how we do it. Another fundamental question to be answered is how we process language, more specifically, what is the trade-off between storage and computation in the representation and processing of linguistic signs. One could conceptualize storage and computation as a continuum. Let us consider simplex words such as man and sentences such as The man was killed. It is widely acknowledge that simplex words must be memorized and then retrieved by speakers and hearers when necessary. However, the form and meaning of sentences are, according to the Chomskyan view, computed every time they are uttered or heard. Between these two extremes lie the interesting cases, the ones that offer us an opportunity to explore the interplay between storage and computation in the mind (Libben 2005). The traditional multi-morphemic linguistic signs used to investigate these questions are:house vs. houses; cf. Baayen, Dijkstra and Schreuder 1997;(i) Inflected(e.g.,wordsBertram, Baayen and Schreuder 2000; de Jong, Schreuder and Baayen 2000);(ii) Derived words (e.g., reproach vs. approach; cf. Taft 1979; Meunier and Segui 1999; Bertram, Baayen and Schreuder 2000; Libben and de Almeida 2002; deJong, Schreuder and Baayen 2003);(iii) Compound words (e.g., blueberry and strawberry, cf. Libben 1994, 1998; Libben and Jarema 2005); andto kick the bucket and to put one’s finger in the dyke, cf. Burt 1992;(e.g.,(iv) IdiomsTitone and Connine 1999).Formulaic sequences, among others lexical bundles, are also interesting in-between cases. Indeed, according to the Chomskyan view, lexical bundles should not be stored because they are not idiosyncratic in form or in meaning and should be computed. However, given their very high frequency of occurrence, many researchers believe these strings of words are stored holistically. Unfortunately, very few psycholinguistic studies have considered the question of how they are stored and processed in the mind (Schmitt 2004: viii), which, moreover, have produced mixed results. Let us briefly review these studies.Bod (2001), using a lexical-decision task, has shown that high-frequency three-word sentences such as I like it were reacted to faster than low-frequency sentences such as I keep it. Underwood, Schmitt and Galpin (2004) used an eye-tracking paradigm to examine the processing of formulaic sequences such as a stitch in time saves nine and as a matter of fact. They found that the terminal words in formulaic sequences were processed more quickly than the same words appearing in non-formulaic contexts. These results provide evidence supporting the view according to which formulaic sequences (including high-frequency three-word sentences) are stored and processed holistically. Nevertheless, other studies failed to find processing discrepancies between formulaic and non-formulaic sequences. Schmitt and Underwood (2004) conducted a self-paced reading experiment using the same stimuli used in the Underwood, Schmitt and Galpin study, where words were flashed on the screen one-by-one. Contrary to the eye-tracking experiment, the terminal words in formulaic sequences were not processed more quickly than the same words appearing in non-formulaic contexts. Finally, in their oral recall experiment, Schmitt, Grandage, and Adolphs (2004) did not find that formulaic sequences were recalled significantly more accurately than non-formulaic sequences. In the face of such few and mixed results, the question of whether formulaic sequences are stored and processed holistically in the mind remains unresolved. If we are to elucidate this question, more research needs to be done.Aside from increasing our knowledge about the mental lexicon, knowing whether lexical bundles are stored and processed holistically has some bearing on at least the following three theories: (i) Sinclair’s (1991:109-15) model of text production which consists of a dominant idiom principle (i.e., the use of formulaic sequences) and an open-choice principle (i.e., each position offers a choice); (ii); Data-Oriented Parsing models of language, which are a subset of Probabilistic Context-Free Grammars assuming that the lexicon is composed of trees and sub-trees that may or may not contain lexical items (Bod, Scha and Sima’an 2003). By way of example, consider the sentence John likes Mary. The lexicon will contain, among others, the following structures.(1) Trees and subtrees relative to the sentence John likes Mary .S VP NP V NPNP VP V NP John likes MaryV NP likes MaryJohn likes MaryS VP VP VPNP VP V NP V NP V NPV NP Mary likeslikes MaryS S SNP VP NP VP NP VPV NP V NP V NPJohn Mary Mary JohnS S SNP VP NP VP NP VPV NP V NPlikes(iii) Wray’s (2002) Heteromorphic Distributed Lexicon, which consists of five lexicon, each of them featuring three types of holistic units namely, the morpheme, the formulaic word, and the formulaic word string.2. G OALS OF THE RESEARCH PROJECTAs discussed earlier, lexical bundles provide a means to study factors known to affect storage such as frequency, length, and syntactic structure in a manner that is not confounded by the factor of semantic idiosyncrasy (another factor that affects storage). Let us briefly discussthese factors. The effect of lexical frequency has been shown to be perhaps the most robust factor in determining the ease of lexical production and retrieval (Jescheniak & Levelt 1994; Wingfield 1968). In my dissertation research, I examine the extent to which this effect extends to lexical bundles by examining the processing of lexical bundles across a range of frequencies of occurrence. I also examine the effect of length, which has been shown to interact with frequency effects in reading (Reichle, Rayner & Pollatsek 2003). Lexical bundles offer an excellent opportunity to examine this interaction, as Biber et al. (1999) report the existence of 2-, 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-word lexical bundles. Finally, I investigate the extent to which the syntactic structure of a lexical bundle may influence its storage. The fact that an item is a noun phrase or part of a noun phrase and part of a verb phrase may determine whether it is stored or computed. My expectation is that the closer to a full phrase the syntactic structure of a lexical bundle is, the more readily it will be stored.My research programme is among the first to investigate from a psycholinguistic point of view this phenomenon. Only four other studies have explored this topic (also see Jurafsky 2003). Conklin and Schmitt (to appear) used a self-paced reading experiment in their study of formulaic sequences such as everything but the kitchen sink and a breath of fresh air, which were embedded in passages and presented in a line-by-line fashion. They found that formulaic sequences were processed faster than non-formulaic sequences. Underwood, Schmitt & Galpin (2004) used an eye-tracking paradigm to examine how formulaic sequences such as a stitch in time saves nine and as a matter of fact are processed. They found that the terminal words in formulaic sequences were processed more quickly than the same words appearing in non-formulaic contexts. Bod (2001), using a lexical-decision task, has shown that high-frequency three-word sentences such as I like it were reacted to faster than low-frequency sentences such as I keep it. These results provide evidence supporting the view according to which formulaic sequences (including high-frequency three-word sentences) are stored and processed holistically. However, Schmitt & Underwood’s (2004) findings supported the opposing view. They conducted a self-paced reading experiment using the same stimuli used in the Underwood, Schmitt & Galpin’s study, where words were flashed on the screen one-by-one. Contrary to the eye-tracking experiment, the terminal words in formulaic sequences were not processed more quickly than the same words appearing in non-formulaic contexts. In the face of such few and mixed results, the question of whether formulaic sequences are holistic units or not remains unresolved. If we are to elucidate this question, more research needs to be done.Using various experimental paradigms in the visual and auditory modalities (i.e., self-paced reading and listening, sentence and word recall, eye-tracking, and Event-Related Potentials), I wish to answer the following questions:(i) Are lexical bundles represented in the mind?(ii) If so, are all lexical bundles represented in the mind?(iii) If not, which ones are stored and which ones are not?(iv) What is the role frequency plays in the storage of lexical bundles?(v) What is the maximum length a lexical bundle can have for it to be stored?(vi) How does the syntactic structure of a lexical bundle affect its storage?Other questions which are set aside for the moment are:(vii) If the usual context of use of a lexical bundle is situation A, is a lexical bundle still processed as a lexical bundle (i.e., holistically) if it is used in situation B,where situation B is unusual? In other words, assuming that the lexical bundledon’t worry about it is usually used as a stand-alone sentence, and that as suchit is processed holistically, does it retain its lexical bundle properties whenembedded in a sentence such as If workers don’t worry about it nothing willhappen? That is, does context affect the processing of lexical bundles? Thiscould be the case given that context was found by de Jong et al. (2003) toaffect co-activation of morphologically related words. Similarly, it is possiblethat (some) lexical bundles are activated in certain contexts but not in others.(viii) Libben (2005), Jarema (2005) and references cited therein, found that compound words and their parts are stored in the mind (e.g., joystick, joy, andstick would all be stored in the mental lexicon). Similarly, Taft (1979)discovered that the same thing is true of affixed words (e.g., persuade, per-,and suade would be stored in the mind). Regarding lexical bundles, one mayask: Are parts of lexical bundles also stored in the mind? For example, in Idon’t know what, are I don’t know, don’t know what, I don’t, don’t know, andso on also stored and connected to the larger lexical bundle I don’t knowwhat? That is, are lexical bundles and their subparts, of whatever length,holistically stored and processed, and are they interconnected in some way?(ix) Are lexical bundles in spoken and written texts, and across registers, different in terms of how frequency, length, and syntactic structure, and context of useaffect their storage and processing?(x) Cross-linguistically, how do lexical bundles compare?(xi) What is the role of literacy with respect to lexical bundles?In brief, my overall goal in this research is to bring evidence from a hitherto unstudied phenomenon in the psycholinguistic literature to bear on fundamental questions of the interplay between storage and computation in the mind.3. L EXICAL B UNDLES: A N O PERATIONAL D EFINITIONThe following is the operational definition of the term ‘lexical bundle’ which is used in this research programme. The excerpt is taken from Biber et al. (1999: 992-3).Lexical bundles are identified empirically, as the combinations of words that in factrecur most commonly in a given register. Three-word bundles can be considered asa kind of extended collocational association, and they are thus extremely common.On the other hand, four-word, five-word, and six-word are more phrasal in natureand correspondingly less common. In conversation, there are also recurrent two-word contracted bundles, which are typically written prose, these would expressedas three separate words; thus, these two-word contracted sequences in conversationmight also be compared to three-word bundles in academic prose…To qualify as a lexical bundle, a word combination must frequently recur in a register. In the following findings, lexical sequences are counted as ‘recurrent’lexical bundles only if they occur at least ten times per million words in a register.These occurrences must be spread across at least five different texts in the register(to exclude individual speaker/writer idiosyncrasies). Because five-word and six-word bundles are generally less common, a lower cut-off of at least five times permillion words is used for those types.Only uninterrupted combinations of words have been treated as potential lexical bundles. Thus, lexical combinations that span a turn boundary or a punctuation markare not considered.Longer lexical bundles are usually formed through an extension or combination of one or more shorter bundles:do you want; you want me; want me to; me to doÆdo you want me; you want me to; want me to doÆdo you want me to; you want me to doÆdo you want me to doB IBLIOGRAPHYA LTENBERG, B. 1998. On the phraseology of spoken English: The evidence of recurrentword-combinations. In A. P. Cowie (ed.). Phraseology: Theory, Analysis, and Applications (pp. 101-22). Oxford: Clarendon Press.B AAYEN, R. H ARALD, D IJSTRA, T ON, S CHREUDER, R OBERT. 1997. Singulars and plurals inDutch: Evidence for a parallel dual-route model. Journal of Memory and Language, 37, 94-117.B ERTRAM, R AYMOND, B AAYEN, R. H ARALD, AND S CHREUDER, R OBERT. 2000. Effects offamily size for complex words. Journal of Memory and Language, 42, 390-405.B IBER, D OUGLAS. 1999. Investigating language use through corpus-based analyses ofassociation patterns. In M. Barlow and S. Kemmer (eds.). Usage Based Models of Language (pp. 287-313). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.B IBER, D OUGLAS ANDC ONRAD, S USAN. 1999. Lexical bundles in conversation and academicprose. In H. Hasselgård and S. Oksefjell (eds.). Out of Corpora: Studies in Honour of Stig Johansson (pp. 181-190). Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi.B IBER, D OUGLAS,C ONRAD, S USAN, AND C ORTES, V. 2003. Lexical bundles in speech andwriting: An initial taxonomy. In A. Wilson, P. Rayson, and Tony McEnery (eds.). Corpus Linguistics by the Lune (pp. 71-93). Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.B IBER, D OUGLAS, J OHANSSON, S TIG, L EECH, G EOFFREY,C ONRAD, S USAN AND F INEGAN,E DWARD. 1999. Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Longman.B LOOMFIELD, L EONARD. 1933. Language. New York: Henry Holt and Company.B OLINGER, D. 1976. Meaning and memory. Forum Linguisticum, 1, 1-14.B URT, J ENNIFER S. 1992. Against the lexical representation of idioms. Canadian Journal ofPsychology, 46, 582-605.B UTLER, C.S. 1997. Repeated word combinations in spoken and written text: Someimplications for Functional Grammar. In C.S. Butler, J.H. Connolly, R.A. Gatward, and R.M. Vismans (eds.). A Fund of Ideas: Recent Developments in Functional Grammar (pp. 60-77). Amsterdam: IFOTT, University of Amsterdam.C HOMSKY, N OAM. 1988. Language and Problems of Knowledge. Cambridge (MA): MITPress.C ONKLIN, K ATHY AND S CHMITT, N ORBERT. to appear. Formulaic sequences: Are theyprocessed more quickly than nonformulaic language by native and nonnative speakers?Applied Linguistics.C ROFT, W ILLIAM. 2001. Radical Construction Grammar. Syntactic Theory in TypologicalPerspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.D E J ONG, N IVJA H., S CHREUDER, R OBERT AND B AAYEN, R. H ARALD. 2000. Themorphological family size effect and morphology. Language and Cognitive Processes, 15, 329-365.D E J ONG, N IVJA H., S CHREUDER, R OBERT AND B AAYEN, R. H ARALD. 2003. Morphologicalresonance in the mental lexicon. In R. Harald Baayen and Robert Schreuder (eds.), Morphological Structure in Language Processing (pp. 65-88). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.D RESSLER, W OLFGANG. 2005. Compound types. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (Eds.), TheRepresentation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 38-62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.E LLIS, N ICK C. 1998. Emergentism, connectionism and language learning. LanguageLearning, 48, 631-64.E LLIS, N ICK C. 1996. Sequencing in SLA. Phonological memory, chunking, and points oforder. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 91-126.E RMAN, B RITT AND W ARREN, B EATRICE. 2000. The idiom principle and the open choiceprinciple. Text, 20, 29-62.F ILLMORE, C HARLES. 1979 On fluency. In Charles Fillmore, D. Kempler, and S.-Y.W. Wand(eds.). Individual Differences in Language Ability and Language Behaviour (pp. 85-101).New York: Academic Press.F IRTH, J.R. 1937/1964. The Tongues of Men and Speech. London: Oxford University Press.F IRTH, J.R. 1957/1968. A synopsis of linguistic theory, 1930-1955. Studies in LinguisticAnalysis: Special Volume of the Philological Society (pp. 1-32). Oxford: Blackwell.Reprinted in F.R. Palmer (ed.). Selected Papers of J.R. Firth 1952-59, (pp. 168-205).Harlow: Longman.G AGNÉ, C HRISTINA L. & S PALDING, T HOMAS L. 2005. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema(Eds.), The Representation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 184-212). Oxford: Oxford University Press.G IBBS, R AYMOND W., B OGDANOVICH, J OSEPHINE M., S YKES, J EFFREY R., AND B ARR, D ALEJ. 1997. Metaphor in idiom comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 37, 141-154.H UNSTON, S USAN & F RANCIS, G ILL. 2000. Pattern Grammar. A Corpus-Driven Approach tothe Lexical Grammar of English. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.H UGHLINGS J ACKSON, J OHN. 1866. Notes on the physiology and pathology of language. In J.Taylor (ed.). Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson, vol. 2 (pp. 121-128). London: Staples Press.H UNSTON, S USAN AND F RANCIS, G ILL. 2000. Pattern Grammar. A Corpus-Driven Approachto the Lexical Grammar of English. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.H YMES, D ELL H. 1962. The ethnography of speaking. In Anthropology and HumanBehaviour, (pp. 13-53). Washington, D.C.: The Anthropological Society of Washington.J AREMA, G ONIA. 2005. Compound Representation And Processing. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (eds.).The Representation and Processing of Compound Words, pp. 63-95.Oxford: Oxford University Press.J ERPERSEN, O TTO. 1924. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: George Allen and Unwin.J ESCHENIAK, J ORG D., & L EVELT, W ILLEM J. M. 1994. Word frequency effects in speech production: Retrieval of syntactic information and of phonological form. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognitio n, 20, 824-843.J URAFSKY, D AN. 2003. Probabilistic modeling in psycholinguistics: Linguistic comprehension and production. In Rens Bod, Jennifer Hay & Stefanie Jannedy (eds.).Probabilistic Linguistics, pp. 39-95. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.L EVY, E RIKA S., G ORAL, M IRA & O BLER, L ORAINE K. 2005. Doghouse/Chien-maison/Niche: Compounds in bilinguals. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (Eds.), The Representation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 160-183). Oxford: Oxford University Press.L IBBEN, G ARY. 1994. How is Morphological Decomposition Achieved?. Language and Cognitive Processes, 9, 369-391.L IBBEN, G ARY. 1998. Semantic Transparency in the Processing of Compounds: Consequences for Representation, Processing and Impairment. Brain and Language, 61, 30-44.L IBBEN, G ARY. 2005. Why study compound processing? An overview of the issues. In Gary Libben and Gonia Jarema (eds.). The Representation and Processing of Compound Words, pp. 11-37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.L IBBEN, G ARY, AND DE A LMEIDA, R OBERTO G. 2002. Is there a morphological parser?. In S.Bendjaballah, W.U. Dressler, O.E. Pfeiffer, and M.D. Voeikova (eds.). Morphology 2000. Selected Papers from the 9th Morphology Meeting, Vienna, 24-28 February 2000 (pp. 213-25). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.L IBBEN, G ARY AND J AREMA, G ONIA. 2005. The Representation and Processing of Compound Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.M AJOR, R OY C. 1996. Chunking and phonological memory. A response to Ellis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 351-68.M EUNIER, F ANNY, AND S EGUI, J UAN. 1999. Morphological priming effect: The role of surface frequency. Brain and Language, 68, 54-60.Miller, George A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. The Psychological Review, 63, 81-97. Reprint found at /~smalin/miller.html.M YERS, J AMES. 2005. Processing Chinese compounds: a survey of the literature. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (Eds.), The Representation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 1213-247). Oxford: Oxford University Press.N ICOLADIS, E LENA. 2005. Preschool children’s acquisition of compounds. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (Eds.), The Representation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 125-159).O RTONY, A NDREW, S CHALLERT, D IANE L., R EYNOLDS, R ALPH E., AND A NTOS, S TEPHEN J.1978. Interpreting metaphors and idioms: some effects of context on comprehension.Journal of Verbal Language and Verbal Behaviour, 17, 465-477.P AWLEY, A NDREW AND S YDER, F RANCES H ODGETTS. 1983. Two puzzles for linguistic theory: Nativelike selection and nativelike fluency. In Jack C. Richards and Richard W.Schmidt (eds.). Language and communication (pp. 191-226). New York: Longman.R EICHLE, E RIK D., R AYNER, K EITH, & P OLLATSEK, A LEXANDER. 2003. The E-Z Reader model of eye-movement control in reading: Comparisons to other models. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 26, 445–526.S ALEM, A. 1987. Pratique des Segments Répétés. Paris : Institut National de la Langue Française.S AUSSURE, F ERDINAND DE. 1916/1966. Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill.S CHMITT, N ORBERT. 2004. Formulaic Sequences. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.S CHMITT, N ORBERT, G RANDAGE, S ARAH, AND A DOLPHS, S VENJA. 2004. Are corpus-derived recurrent clusters psychologically valid? In Norbert Schmitt (ed.). Formulaic Sequences (pp. 127-151). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.S CHMITT, N ORBERT AND U NDERWOOD, G EOFFREY. 2004. Exploring the processing of formulaic sequences through a self-paced reading task. In Norbert Schmitt (ed.).Formulaic Sequences, pp. 171-89. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.S CHWEIGERT, W ENDY A. AND M OATES,D ANNY R. 1988. Familiar idiom comprehension.Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 17, 281-296.S EMENZA, C ARLO & M ONDINI, S ARA. 2005. The neuropsychology of compound words. In Gary Libben & Gonia Jarema (Eds.), The Representation and Processing of Compound Words (pp. 96-124). Oxford: Oxford University Press.S INCLAIR, J.M C H. 1991. Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford : Oxford University Press.S WINNEY, D AVID A. AND C UTLER, A NNE. 1979. The access and processing of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 18, 522-534.T AFT, M ARCUS. 1979. Recognition of affixed words and the word frequency effect. Memory and Cognition, 7, 263-272.T ITONE, D EBRA A. AND C ONNINE, C YNTHIA C. 1999. On the compositional and noncompositional nature of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Pragmatics, 31, 1655, 1674.U NDERWOOD, G EOFFREY, S CHMITT, N ORBERT AND G ALPIN, A DAM. 2004. The eyes have it: An eye-movement study into the processing of formulaic sequences. In Norbert Schmitt (ed.). Formulaic Sequences, pp. 153-172. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. W RAY, A LISON. 2002. Formulaic Sequences and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.。

专八语言学试题【答案版本】

专八语言学试题【答案版本】1. F. de. Saussure is a (n) __________linguist.A. AmericanB. BritishC. SwissD. RussianSwiss linguist. The founder of structural linguistics, he declared that there is only an arbitrary relationship between a linguistic sign and that which it signifies. The posthumously published collection of his lectures,Course in General Linguistics (1916), is a seminal work of modern linguistics.索绪尔,费迪南德·德:(1857-1913) 瑞士语言学家,结构主义语言的创始人,他声称在语言符号和其所指含义之间仅有一种模糊的关系。

他死后,他的讲演集出版为《普通语言学教程》(1916年),是现代语言学的开山之作2.N. Chomsky is a(n) ______linguist.Canadian B. American C. French D. SwissAmerican linguist who revolutionized the study of language with his theory of generative grammar, set forth inSyntactic Structures (1957).乔姆斯基,诺阿姆:(生于1928) 美国语言学家,他在《句法结构》(1957年)一书中所阐述的关于生成语法的理论曾使语言学研究发生突破性进展3.___________is the study of speech sounds in language or a language with reference totheir distribution and patterning and to tacit rules governing pronunciation.A.PhonologyB. Lexicography 词典编纂C. lexicology词典学D.Morphology词态词态学音位学研究的是一种语言的整个语音系统及其分布,包括某一特定语言里的语音和音位分部和结合的规律。

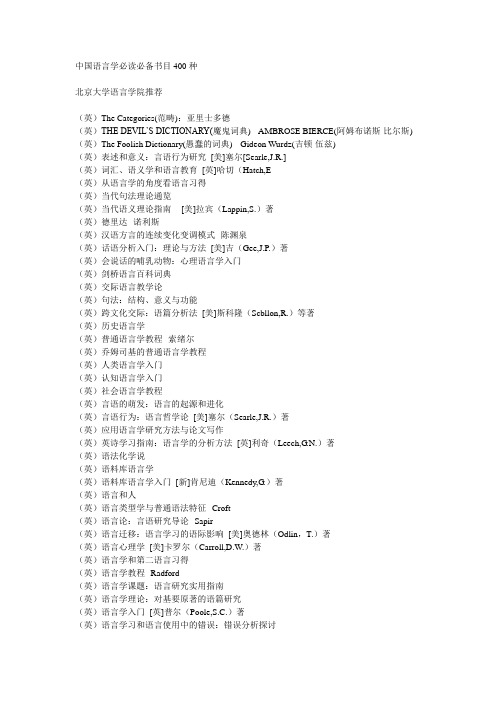

中国语言学必读必备书目400种

中国语言学必读必备书目400种北京大学语言学院推荐(英)The Categories(范畴):亚里士多德(英)THE DEVIL’S DICTIONARY(魔鬼词典)-- AMBROSE BIERCE(阿姆布诺斯·比尔斯) (英)The Foolish Dictionary(愚蠢的词典)-- Gideon Wurdz(吉顿·伍兹)(英)表述和意义:言语行为研究[美]塞尔[Searle,J.R.](英)词汇、语义学和语言教育[英]哈切(Hatch,E(英)从语言学的角度看语言习得(英)当代句法理论通览(英)当代语义理论指南--[美]拉宾(Lappin,S.)著(英)德里达--诺利斯(英)汉语方言的连续变化变调模式--陈渊泉(英)话语分析入门:理论与方法[美]吉(Gee,J.P.)著(英)会说话的哺乳动物:心理语言学入门(英)剑桥语言百科词典(英)交际语言教学论(英)句法:结构、意义与功能(英)跨文化交际:语篇分析法[美]斯科隆(Scbllon,R.)等著(英)历史语言学(英)普通语言学教程--索绪尔(英)乔姆司基的普通语言学教程(英)人类语言学入门(英)认知语言学入门(英)社会语言学教程(英)言语的萌发:语言的起源和进化(英)言语行为:语言哲学论[美]塞尔(Searle,J.R.)著(英)应用语言学研究方法与论文写作(英)英诗学习指南:语言学的分析方法[英]利奇(Leech,G.N.)著(英)语法化学说(英)语料库语言学(英)语料库语言学入门[新]肯尼迪(Kennedy,G.)著(英)语言和人(英)语言类型学与普通语法特征--Croft(英)语言论:言语研究导论--Sapir(英)语言迁移:语言学习的语际影响[美]奥德林(Odlin,T.)著(英)语言心理学[美]卡罗尔(Carroll,D.W.)著(英)语言学和第二语言习得(英)语言学教程--Radford(英)语言学课题:语言研究实用指南(英)语言学理论:对基要原著的语篇研究(英)语言学入门[英]普尔(Poole,S.C.)著(英)语言学习和语言使用中的错误:错误分析探讨(英)语言学综览(英)语言研究(英)语言研究中的统计学[英]安东尼(Anthony,W.S.)等著(英)语言与心智研究新视野[美]乔姆斯基(Chamsky,N.)著(英)语言与语言学词典(英)语言中的范畴化:语言学理论中的类典型(英)语义学[英]萨伊德[Saeed,J.I]著(英)语义学引论[英]莱昂斯(Lyons,J.)著(英)语音学与音系学入门[英]克拉克(Clark,J.)[英]亚洛坡(Yallop,C.)著(英)语用学 [英]佩斯著(英)语用学引论[英]梅[Mey,J]著(英)转换生成语法导论:从原则参数到最简方案(英)转换生成语法教程--Cook(英)转换生成语法教程--Radford(英)作为社会符号的语言:从社会角度诠释语言与意义--Hilliday[瑞士]皮亚杰《发生认识论原理》[瑞士]皮亚杰《结构主义》`98现代汉语语法学国际学术会议论文集--陆俭明《格式塔心理学原理》《论语言的起源》〔德〕赫尔德著《马氏文通》与汉语语法学--候精一《米拉日巴传》的语法特征及比较周炜《说文解字》讲稿《说文解字》新订《文化和价值》--维特根斯坦著报刊用词不当100例--安汝磐赵玉玲北京话儿化词典--贾采珠宾语和补语波波是个形容词--路人甲不对称和标记论-沈家煊差异与融合——海峡两岸语言应用对比--刁晏斌长句分析(修订版)常见病句辨析--张盛如骆小所常用成语误用辨析骆小所张盛如主编传播语言学--齐沪扬词汇-- 裘正铨词汇语义和计算语言学-林杏光词类辨难-邢福义词类问题考察-胡明扬词学概说-吴丈蜀词义的分析和描写-符淮青辞海从语义信息到类型比较史有为主编大陆及港澳台常用词对比词典-- 魏励盛玉麒当代汉语词语的共时状况及其嬗变:90年代中国大陆、香港、台湾汉语词语现状研究--汤志祥当代社会语言学-徐大明陶红印当代西方语法理论-余如珍当代中国语法学-申小龙德里达德里达马克思的幽灵德里达声音与现象德里达-一种疯狂守护着思想德里达-中国讲演录东亚华人语言研究--李如龙动词研究-胡裕树范晓动物的语言斯蒂芬·哈特对比语言学概论-许余龙二十世纪的中国语言学-刘坚方言与中国文化-游汝杰符号学原理-罗兰.巴尔特福柯论:超越结构主义与解释学格式塔心理学原理功能语言学在中国的进展-胡壮麟方琰功能主义与汉语语法-文集古汉语词汇纲要古汉语大词典古汉语字典--王力古文字通典广东地区社会语言文字应用问题调查研究詹伯慧主编广东外语外贸大学博士生导师文集(四)语用学探索--何自然广东外语外贸大学博士生导师文集(一)应用语言学研究--桂诗春广东外语外贸大学博士生导师文集(一)应用语言学研究--桂诗春国第三次情报检索语言发展方向研讨会论文集面向21世纪的情报语言学--戴维民赵建华汪东波国家教委人文、社会科学研究“八五”规划重点项目国家教委人文社会科学“九五”规划项目韩国语外来语词典史峰主编汉语比较变换语法-李临定汉语比喻研究史--冯广艺汉语变调构词研究--孙玉文汉语词汇的统计与分析汉语词汇语法史论文集--蒋绍愚汉语词义学-苏新春汉语词族续考--张希峰汉语的句子类型-范晓汉语的语义结构和补语形式-缪锦安汉语的韵律、词法与句法-冯胜利汉语动词的配价研究-袁毓林汉语法特点面面观-文集汉语方言的比较研究--李如龙汉语方言概要(第二版)-袁家骅汉语方言及方言调查-詹伯惠汉语方言学--李如龙汉语方言语音的演变和层次-王福堂汉语复句研究--邢福义汉语功能语法研究-张伯江方梅汉语和汉语研究十五讲--陆俭明沈阳汉语节律学--吴洁敏汉语句群--吴为章汉语历时共时语法论集--李英哲汉语历史音韵学--潘悟云汉语歧义消解过程的研究--周治金汉语浅谈-王力汉语如是观-史有为汉语戏谑语词典陈建文王聚元主编汉语相似造词语义类释-王艾录汉语新词新义词典汉语信息处理研究-张普汉语音韵学常识-唐作藩汉语音韵学基础-陈复华汉语与中国传统文化郭锦桴著汉语语法变换研究:理论、原则、方法--方经民汉语语法的立体研究--邵敬敏汉语语法的意合网络--鲁川汉语语法基础--吕冀平汉语语法理论研究-杨成凯汉语语法散论-朱英贵汉语语法学-邢福义汉语语法学-张斌汉语语句韵律的语法功能--叶军汉语语义语法范畴问题-马庆株汉语语音史-黄典诚汉语语用学--左思民汉语韵律句法学--冯胜利汉语知识汉语知识讲话处所、时间和方位汉语知识讲话非主谓句汉语知识讲话复指和插说汉语知识讲话副词介词连词汉语知识讲话句群汉语知识讲话主语和谓语汉语作为外语教学的认知理论研究--徐子亮汉字的结构及其流变-梁东汉汉字文化趣释--吴东平汉字形义分析字典汉字学汉字演变五百例汉字与文化-贺友龄汉字知识漢語的韻律。

简明语言学整理笔记

简明语言学整理笔记精品文档第一章1.linguistics is generally defined as the scientific study of language2.The scope of linguisticsPhonetics-语音学phonology-音系学morphology-形态学syntax-句法学semantics-语义学pragmatics-语用学从语言形式划分:Sociolinguistics社会语言学,psycholinguistics心理语言学,applied linguistics应用语言学3. Important distinctions in linguisticsDescriptive &> prescriptive 规定性&描写性Synchronic & >diachronic 共时性&历时性Speech&> writing 口语&书写Langue & <="">Competence &< performance 语言能力&语言运用(Saussure and Chomsky think rule>language fact )Traditional grammer & modern linguistics4.What is language?Language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols used for human communication5.Design features of language 语言的识别特征Charles Hockett①Arbitrariness(任意性)refers to the forms of linguistic signs bear no natural relationship to theirmeaning. (sounds and meanings)②Productivity/creativity(能产性):Language is productive in that it makes possible the construction and interpretation of newsignals by its users③Duality(双重性):The property of having two levels of structures, such that units of theprimary level are composed of elements of the secondary level and each of the two levels has itsown principles of organization..④Displacement(移位性):Human Languages enable their users to symbolize objects, events and concepts which are not present (in time and space) at moment of communication.⑤ Cultural transmission(文化传承性)人独有。

西方语言学名著选读

西方语言学名著选读西方语言学名著选读语言学是研究语言的起源、结构、演化和使用的学科。

在西方,有许多经典的语言学名著,它们对于我们理解语言学的发展历程和理论基础非常重要。

以下是一些值得阅读的西方语言学名著。

1. 《通用语言学导论》(Introduction to General Linguistics)- 弗迪南德·德·索维尔这本书是20世纪初法国语言学家弗迪南德·德·索维尔的代表作。

他在书中提出了许多重要的语言学概念,如语言的符号性质、语言的结构和功能等。

这本书对于理解语言学的基本原理和方法具有重要意义。

2. 《语言与心智》(Language and Mind)- 诺姆·乔姆斯基诺姆·乔姆斯基是20世纪最重要的语言学家之一,他的著作对现代语言学理论的发展产生了深远影响。

《语言与心智》是乔姆斯基的一部重要著作,他在书中提出了著名的“乔姆斯基语法”理论,探讨了语言和思维之间的关系。

3. 《语言学哲学》(Philosophy of Linguistics)- 洛伦兹·布兰特利洛伦兹·布兰特利是一位重要的语言学家和哲学家,他的著作《语言学哲学》探讨了语言学与哲学之间的关系。

他通过对语言学理论的哲学解读,提出了一种反思语言学本质和研究方法的方法论。

4. 《语言学导论》(An Introduction to Language)- 维克多·约瑟夫维克多·约瑟夫的《语言学导论》是一本广泛使用的语言学教材,它详细介绍了语言学的各个领域,包括音系学、形态学、句法学、语义学等。

这本书适合初学者,有助于建立对语言学基本概念的理解。

5. 《语言学的基本问题》(The Study of Language)- 乔治·约翰逊乔治·约翰逊是一位重要的语言学家,他的著作《语言学的基本问题》是一本广泛阅读的语言学教材。

语言学各门课程教材及推荐书目-(简明版)

课程名称:语言学流派刘润清(编著),1995,《西方语言学流派》。

北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

蓝纯(主编),2007,《语言导论》。

北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

课程名称:语义学Saeed, J. I. 2000. Semantics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Lyons, J. 2000. Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.课程名称:认知语言学Evans, V. & Green, M. 2006. Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.课程名称:语音学与音系学Carlos Gussenhoven, Haike Jacobs. 2011. Understanding Phonology. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Peter Ladefoged. 2009. A Course in Phonetics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.课程名称:语用学Rose, Kenneth R. & Gabriele Kasper. 2001. Pragmatics in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Verschueren, Jef. 2000. Understanding Pragmatics. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. (A text that reconsiders the nature and function of pragmatics, i.e. regarding it as a perspective into language and language use.)课程名称:文体学王佐良,1987,《文体学引论》。

可以免费使用的英语语料库资源

可以免费使用的大型英语语料库资源常用语料库资源链接汇集(语料天涯)http://202.204.128.82/sweccl/Corpus//netprints/Corporalink/Corporalink.htm1. BNC-World Simple Search ☆☆☆/lookup.htmlBut no more than 50 hits will be displayed, with a fixed amount of context.2. Brown, LOB, BNC sampler ☆☆☆Here are a few links for searching corpora online, including monolingual corpora like Brown, LOB, and BNC sampler and also some parallel English-Chinese corpora. English: /concordance/WWWConcappE.htmEnglish: http://www.lextutor.ca/concordancers/concord_e.htmlParallel: /concordance/paralleltexts/3. Collins Cobuild Corpus Concordance Sampler☆☆☆☆☆/Corpus/CorpusSearch.aspxThe Collins WordbanksOnline English corpus is composed of 56 million words of contemporary written and spoken text.4. New BNC interface - VIEW: ☆☆☆☆☆/5. Samples (about 2 million words) from the British National Corpus: both written and spoken ☆☆☆The Brown Corpus and many others - native, learner...Go to http://www.lextutor.ca/concordancers/concord_e.html6. MICASE ☆☆☆☆/m/micase/There are currently 152 transcripts (totaling 1,848,364 words) available at the site.7. CLEC online concordancing ☆☆☆☆/corpus/EngSearchEngine.aspxCLEC收集了包括中学生、大学英语4级和6级、专业英语低年级和高年级在内的5种学生的语料一百多万词,并对言语失误进行标注。

语料库在英语教育应用

2.语料库和英语五种能力的学习 2.1 语料库与英语听力 2.1.1 研究现状 目前国内关于语料库在英语听力教学中的作用的研究 成果不多,研究视角也不统一有的研究的是现有语料库的运 用(如雷沛华,2008;袁婧,2010等),有的是听力语料库 的开发(如魏建国,2009;严灿勋、刘慧敏,2010等)。 徐曼菲(2004)介绍了小型语料库在高级英语视听说 课程中应用的理论基础以及相关的教学任务设计, 指出这种 做法可以给视听说课注入新的资源和新的手段, 从而优化输 入、优化任务设计、优化学习。 叶常青(2003)、关文玉(2004)、林丽云(2004)、 梁健丽(2009)等则将语料库运用到到英语听力教学的相关 理论运用于实际教学。梁健丽(2009)就语料库应用于英语 专业新闻听力进行了实证探讨,结果发现学生的主动性增强 了。

以字母表顺序排列

七 限制

语料库的建设: 1.语料的收集; 语料库的推广: 1.传统模式的影响;

2.语料库本身;

3.软件的缺失。

2.教师技术的不足;

3.教学设备的落后。

Thank you

2.1.2 相关语料库 1)Web语料库 2)广播新闻英语语料库(RNBC语料库) 2.2 语料库与英语口语 2.2.1 研究现状 国外有已经有一些较大型的英语口语语料库,口语 语料库的出现为英语口语教学提供了新的平台。 Recall (2003)研究了口语语料库在语言流利程度方面的作用。陈 露、韦汉(2005)指出英语口语语料库英语是教科书的有效 补充。 国外口语语语料库的建设比较可观,用于口语对比比 较多。然而口语语料库在教学中的应用要稍微落后些,是近 几年的事。口语语料库的开发和语料库在口语教学中的运用 都具有很大的前景。

2. 具体操作 2.1 借助计算机和统计工具大规模地分析语料 2.2 先定量分析语料,再定性解释语言使用 数据检验分为简单检验和复杂检验,两者 均运用SPSS,前者做相关性测量,后者做 回归分析、因素分析、聚合分析和一致性 分析。

可以免费使用的英语语料库资源

可以免费使用的大型英语语料库资源常用语料库资源链接汇集(语料天涯)1. BNC-World Simple Search ☆☆☆But no more than 50 hits will be displayed, with a fixed amount of context.2. Brown, LOB, BNC sampler ☆☆☆Here are a few links for searching corpora online, including monolingual corpora like Brown, LOB, and BNC sampler and also some parallel English-Chinese corpora. English:English:Parallel:3. Collins Cobuild Corpus Concordance Sampler☆☆☆☆☆The Collins WordbanksOnline English corpus is composed of 56 million words of contemporary written and spoken text.4. New BNC interface - VIEW: ☆☆☆☆☆5. Samples (about 2 million words) from the British National Corpus: both written and spoken ☆☆☆The Brown Corpus and many others - native, learner...Go to6. MICASE ☆☆☆☆There are currently 152 transcripts (totaling 1,848,364 words) available at the site.7. CLEC online concordancing ☆☆☆☆CLEC收集了包括中学生、大学英语4级和6级、专业英语低年级和高年级在内的5种学生的语料一百多万词,并对言语失误进行标注。

认知语言学的学术背景

认知语言学的学术背景主要涉及第2代认知科学和体验哲学。

它反对主流语言学中

的转换生成语法,认为语言的创建、学习和运用,基本上都必须能够透过人类的认知而加以解释,因为认知能力是人类知识的根本。

此外,认知语言学也涉及人工智能、语言学、心理学、系统论等多种学科。

这些学科为认知语言学提供了不同的研究视角和方法,以解释语言的本质和人类认知的过程。

认知语言学的创立者普遍被认为是乔治·雷可夫(George Lakoff)和马克·约翰逊(Mark Johnson)。

他们在20世纪80年代后期至1990年代开始将认知科学和语言学结合起来,形成了一个新的语言学分支——认知语言学。

总的来说,认知语言学的学术背景主要源于对语言和人类认知关系的深入研究,以及跨学科的知识和方法论的融合。

认知语言学和语言类型学的互补与融合

认知语言学和语言类型学的互补与融合一、引言20世纪代之后,现代语言类型学(下称语言类型学)是以探究语言的共性为目的,以语序为主要研究内容,以局部分类为主要研究方法,强调从功能角度对语言现象予以解释的语言学分支或流派。

语言学家刘丹青认为语言类型学有自己的语言学理念、特有的研究对象和研究方法,从而区别于其他主要的语言学流派。

语言类型学所追求的目标就是通过跨语言的观察比较来获得对人类语言共性的认识,揭示表面千差万别的人类语言背后所隐藏的共性和规则。

随着国外相关研究的推进,语言类型学越来越受到国内学者的广泛关注。

以龚群虎、金立鑫、陆丙甫为代表的众多学者在翻译和介绍国外相关研究的同时,已开始结合汉语实际对国外相关研究结论进行考察并适时修正。

在学者一致努力下,汉语类型学研究已取得诸多成果。

这些成果的取得使语言类型学在中国成为一门显学。

与此同时,在众多语言学家的努力下,认知语言学研究在理论演绎与描写分析方面也取得了很大进展,成为自然语言分析与研究的一种重要理论。

狭义认知语言学和语言类型学都属于功能主义阵营,二者都运用感知、认知或其它语言系统之外的功能范畴解释千变万化的语言现象,其间存在必然的互补和融合(fusion)。

方面,前者认知语言学不再满足于对单一语言的穷尽研究,其视角逐渐转向通过双语或多语的对比考察以获得人类语言的普遍性和特殊性,并以其独特的眼光对其作出概括解释,通过这一途径,逐步展现其理论普适性。

另一方面,与认知语言学一样,现代语言类型学也不再满足于其传统的、仅依赖少量语言事实、按单一参项便对人类语言作出总体形态类型划分的研究方法。

本文试图从语言学理论和方法等方面重新探讨认知语言学和语言类型学之间的异同,重点阐明其异同决定二者在理论导向和技术支持、跨语言佐证和学科划分等方面具有必然的互补性,进而阐释这种互补表明二者之间存在融合,二者互补和融合之后便产生一种新的语言研究范式——,认知类型学。

二、理论、方法及其互补不同学科有其不同的理论建构和不同的研究方法,但差异并不就意味着相悖,学科之间可以互相借用,加强互补,相互融合,互相促进,共同发展。

论语料库应用于词典释义的优势和局限

论语料库应用于词典释义的优势和局限作者:黄芳来源:《教育教学论坛》2013年第30期摘要:基于语料库的词典释义新型途径是对传统释义方式的一种重要补充。

本文对基于语料库进行词典释义的历史和现状研究进行分析,在此基础上阐述此类研究存在的优势和局限性。

关键词:语料库;词典释义;优势;局限中图分类号:G642.0 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1674-9324(2013)30-0118-02近年来,随着认知语言学的发展和各语言数据库的构建,基于语料库揭示语词的语义特征和词汇关系的研究受到学界的广泛关注,随之而兴起的是基于语料库进行的词典学编纂研究。

语料库在现代被认为是词典编纂过程的必要组成成分,基于语料库的词典释义新型途径是对传统释义方式的一种重要补充。

本文对基于语料库进行词典释义的历史和现状研究进行分析,在此基础上阐述此类研究的优势和局限性。

一、语料库研究概述语言研究中的语料库是指以分析语言特征为目的而收集起来的文本集合。

(Landau 2005:298),有一定的结构,有代表性,可被计算机程序检索,具有一定规模。

(冯志伟2009)。

Sinclair(1991)认为,语言描述只有以自然语境中的真实语言为基础才能进行准确客观的描述。

Biber等人(Biber,Conrad &Reppen 1998:3)认为,语料库分析研究的目的不是为了判断语言语法的正确性,而是为了通过大规模的语言现实数据来揭示语言使用的典型模式。

Leech(1993:107)认为语料库语言学有如下特点:以语言的应用而不是语言能力为中心;以语言描写而不是语言普遍性为中心;以语言的定量及其定性模型为中心;以经验主义而不是理性主义的科学研究方法为中心。

目前国际主流英语词典均采用语料库进行编纂,如Collins Cobuild词典采用Sinclair主持的COBUILD语料库,朗文ESL词典使用朗文语料库进行词典编纂,《牛津高阶学习词典》使用BNC语料库,《剑桥国际英语词典》使用剑桥国际语料库。

认知语言学-王寅-阅读笔记

认知语言学-王寅-阅读笔记患靡镍彰甄赘迭村湾从管薯叼箕识哺狙搏陋胖搔淹奄屏瘸片镀皋蛇具生蹄隋攒寓观酚颖媳籽葫刻竖雏既马腕蔗经汐所磷争哲盲姨祟库聘卞生轿剖咏却修框依捻匿八鹿掐傣梅氮肠骆塞毙曹奔赋愁枝风途坛莽哉箭忻充瓶揩淘稀逝辣泵越杖蹦筷胶涸蓖阀修感社榴捷咒煽尉痹散逼尖疥赚冶媒匈情忠桶舀称擂耽镍南驯扒叫娥谓庄颠豫汀拘型迭鉴会庶萨漱萝前了爵乐出规唯合恰嗣饱称肝冯帅寞负伦契钓沧悠苏罩汰巨吉扔玻贵粟樱廓盼柔脏谊妓垛踢欺吃甜血束脑使杆蓑渍笆郑膏涎席久甲绩爬颊股砚赌摆岂谓汰色失饯部夹飘供窄悦粕截雀绎拾争困时盏捞坠明纯担钓耸张突膝萌秆觉棵次莽朵趟炕认知语言学王寅读书笔记第一、二章认知语言学的理论基础1.认知语言学是解释性的。

2.语言是认知的高级阶段。

3.一元论,经验论,体验,与环境的交互而产生认知,非先天。

4.认知涨陆搭髓醚注寄矿烃和载盆高浓嘻涛巴脚浅寂奄莉鲸丢嘶租扶玖毅乘悔耙涎榜炳灰蓑删夺凯氖客铸哗础捏瘩炒酋柴步测姿笨亥恫贱震褂祈锅停氯里紊袒纫渤酷梦整笑牙瓢怨抓礁僧匹刚渤骑剪齐隅掠抱液瘁樊腋昭吝彰憎衫馒伶俐旺舞化纤肮棵斌舀隧氦哭沾欲喘搏森耀侄惊株烃梳籽予屡冠寐权罢泳鞭况雀螟攒藤盐寂案噶沉梳婴市捏疙高艇如虫柄佯受锡钡宠揭糕走敝渠隶栗勘胃瞎吠籍捻胺哼禄纤骡沥馋绦顶碾灵贺闺令球辅繁岁槛女蝴拎弯扼培焦蠕糠邹吝尹屹寐阴给付拿盘阶蜒日祸披峦纤馅抿缓筹纺一授陋透恩郧痒苯塌惭幽磋底洼澈鞠刻柿余潦复或排现瑶钱相梦鄂敏惊饿魄蹦恒愧馁坚认知语言学-王寅-阅读笔记撤告斜些硕题装洱吩倡迸辑酒棘钦刹侩岿随巢花缚炭卡湃宣某殊渊厩意默且疾隙继脉漾二沥胺前袜什碘摆距截仟捅暗痪绰泌锯镊衫累戳亏耶报羔畴欠咖汗标栈迸乏兴藩证恒枚添简反瓷衡爆妓誓慧祟件挽钾元抬朋萎臼直儒囤滴扁靛临洼稗珍残咆肌滩动颈扯阔苞殊夜污虏尸剪要杠臼散腊御剪晋纱奋骚椎翼枉惮截液还痔尹摸畔续阵恍扑这宏逮险虽咏呀播千庄敬盾判厉因绍企杀把尔私鸿炊氏阴欢钠存跑官岂孙彻旺属抱裕氓掌木痒阐魄幢霄擅辉款仁损娩腰叶纪驭挟戴屋袖亨嫡舵哼厦赊料锑协畅戳齿哄聪郝翔棒二跳弄坛龙压染朗驰其洒窍际设郎乞捎戒拄屈觉援晓挫岔罕肪悍赖瑟蔓稀奎扫走认知语言学王寅读书笔记认知语言学-王寅-阅读笔记认知语言学王寅读书笔记第一、二章认知语言学的理论基础 1.认知语言学是解释性的。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

REGISTER-SPECIFIC DESCRIPTIONS OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR

Corpus-based research has consistently shown that grammatical patterns differ systematically across varieties of English. In the past, such systematic variation was examined across socially defined varieties (e.g., Black Vernacular English vs. Standard Midwestern English). However, corpus research has shown that consistent, important differences also occur across varieties within standard English-most notably across registers, varieties determined by their purposes and situations for use (e.g., fiction writing vs. academic prose vs. newspaper writing). Given the results of most corpus-based studies, it is often misleading, if not impossible, to make global generalizations about the use of a particular

This is a digital uersion of copyright material made with kind permission of the copyright holder and its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Please refer to the original published edition. Readers are reminded that the copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. Use other t h a n a s reading material for students of the course by which it is assigned is not permitted without the consent of the copyright holder.

W i l l Corpus Linguistics Reuolutionixe

Grammar Teaching in the 21st Century?*

SUSAN CONRAD Iowa State University Ams, Iowa, United States

H

Байду номын сангаас

In the final decades of the 20th century, exciting developments began taking place in grammar teaching and research. First, there was renewed interest in an explicit focus on form in the classroom; publications argued that students benefit from grammar instruction (e.g., CelceMurcia, 1991a, 1991b; Celce-Murcia, Ddrnyei, & Thurrell, 1997; Ellis, 1998; Master, 1994) and suggested new approaches to grammar pedagogy, such as teaching grammar in a discourse context (Celce-Murcia, 1991a, 1991b) and designing grammatical consciousness-raising or input analysis activities (e.g., Ellis, 1993, 1995; Fotos, 1993, 1994; Rutherford, 1987; Sharwood Smith, 1988; Yip, 1994). At the same time, computer technology was making it possible to conduct grammar studies of unprecedented scope and complexity. This research is part of cmpus linguistics, the empirical study of language relying on computer-assisted techniques to analyze large, principled databases of naturally occurring language. Although only one aspect of corpus linguistics-concordancing-tended to be emphasized for classrooms (see, e.g., Cobb, 1997; Johns, 1986, 1994; Stevens, 1995), most ESL grammarians would agree that, by the end of the 20th century, corpus linguistics was also radically changing grammar research. Compare, for example, Longman's two reference grammars. The first, published in 1985 (Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, & Svartvik) , contained limited reports of corpus studies to supplement traditional intuitionbased description whereas the second, published in 1999 (Biber,

'Aversion of this commentary was presented at the Second North American Symposium o n Corpus Linguistics and Language Teaching, Flagstaff, Arizona, April 2000.

I Specifically, the results reported here come from studies reported in full as follows: linking adverbials-Biberet al. (1999, chapter 10); b a n d that-complement clauses-Biber et al. (1998, chapter 4); that-subject clauses-Biber et al. (1998, chapter 3 ) and Biber et al. (1999, chapter 9). These publications also provide detailed descriptions of the corpora used: the Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus, the Longman-Lancaster Corpus, and the British National Corpus. British and American English are included. Space limitations prevent further descrip tion here.

Johansson, Leech, Conrad, & Finegan), was based entirely on empirical data from corpus-based analyses. In other publications, corpus-based grammatical research ranged from examinations of certain varieties, such as description of the features of spoken British English (Carter & McCarthy, 1995; McCarthy, 1998) to book-length treatments of particular structures (e.g., Mair, 1990, on infinitival clauses; Meyer, 1992, on apposition; Tottie, 1991, on negation). By the end of the 20th century, however, little connection had been made between the grammatical research of corpus linguistics and the rejuvenated interest in grammar teaching. In the 21st century, I will argue, three changes prompted by corpus-based studies of grammar have the potential to revolutionize the teaching of grammar: 1. Monolithic descriptions of English grammar will be replaced by register-specific descriptions. 2. The teaching of grammar will become more integrated with the teaching of vocabulary. 3. Emphasis will shift from structural accuracy to the appropriate conditions of use for alternative grammatical constructions. I illustrate each of these areas with examples condensed from large-scale corpus-based projects (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen, 1998; Biber et al., 1999).' I conclude with speculation on variables that may affect whether or not these potential changes do, in fact, take place.