Anemia and iron deficiency in heart failure

婴幼儿缺铁性贫血患病情况及相关因素分析

56智慧健康Smart Healthcare2020年11月第6卷第31期No.6 roll up No. 31 Issue, November, 2020健康科学_临床医学工程DOI:10.19335/ki.2096-1219.2020.31.022婴幼儿缺铁性贫血患病情况及相关因素分析刘蕊,张慧,郭志强,白桦*(内蒙古自治区妇幼保健院,内蒙古 呼和浩特 010020)摘 要:目的分析婴幼儿缺铁性贫血患病的情况及原因。

方法选取2019年1月至2019年12月在我院儿童保健门诊定期体检的6~24个月龄婴幼儿为研究对象,回顾性分析其相关资料,分析其患病情况及原因。

结果患儿和正常儿童在家庭经济、家长对贫血知晓情况、母体孕期患有贫血,早产儿等状况都存在明显的差异(P<0.05);患儿病情情况分析:对婴幼儿体检资料进行回顾性分析,发现484例患儿中,6~12个月龄患儿334例(69.0%),13~24个月患儿150例(31.0%),两者之间在患病人数上存在明显的差异(c2=23.395,P=0.001);母乳喂养为主208例(43.0%),配方奶粉为主149例(30.8%),肉量少为主127例(26.2%),三组存在明显差异(c2=1.341,P=0.001)。

结论营养性缺铁性贫血和患儿的年龄、家庭经济情况、喂养方式、母孕期患病、家长对贫血知识的了解等都存在相关性,改善婴幼儿营养性缺铁性贫血情况需从这些方面着手。

关键词:婴幼儿;缺铁性贫血;原因;分析本文引用格式:刘蕊,张慧,郭志强,等.婴幼儿缺铁性贫血患病情况及相关因素分析[J].智慧健康,2020,6(31):56-58.Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Infants and its Related FactorsLIU Rui, ZHANG Hui, GUO Zhi-qiang, BAI Hua*(Inner Mongolia Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia 010020) ABSTRACT: Objective To analyze the prevalence and causes of iron deficiency anemia in infants. Methods The infants aged from 6 months to 24 months who received regular physical examination in the outpatient department of child health care of our hospital from January to December 2019 were selected as the research objects. The relevant data were analyzed retrospectively, and the disease status and causes were analyzed. Results There were significant differences between children and normal children in terms of family economy, parents’ awareness of anemia, maternal anemia during pregnancy, and premature infants (P<0.05). Analysis of the condition of the children: Retrospective analysis of the physical examination data of 484 children, 334 (69.0%) from 6 months to 12 months, 150 (31.0%) from 13 to 24 months, there was a significant difference in the number of patients (c2=23.395, P=0.001). 208 cases (43.0%) were mainly breast-fed, 149 cases (30.8%) were mainly mixed with rice milk powder, there were 127 cases (26.2%) with less meat. There was significant difference among the three groups (c2=1.341, P=0.001). Conclusion Nutritive iron deficiency anemia is related to the age, family economic situation, feeding mode, maternal disease during pregnancy, and parents’ understanding of anemia, etc. These aspects should be addressed to improve infant nutritional iron deficiency anemia.KEY WORDS: Infants; Iron deficiency anemia; Reason; Analysis0 引言缺铁性贫血(Iron Deficiency Anemia, IDA)是儿保门诊中常见的营养不良性疾病,具有显著的年龄分布特征,以6个月至2岁的儿童为主要发病人群,该年龄段儿童患有此疾病的发病率在发展中国家高达31.3%[1],主要是因食物中铁的摄入不足,体内储存铁缺乏导致机体血红蛋白合成减少而引发。

ANEMIA,ANDIRONDEFICIENCYANEMIA

ANEMIA,IRON DEFICIENCY ,AND IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIAA nemia is one of the most widespread public healthproblems, especially in developing countries, and has important health and welfare, social, and economic consequences. These include impaired cognitive development, reduced physical work capacity, and in severe cases increased risk of mortality, particularly during the perinatal period. There is also evidence that anemia may result in reduced growth and increased morbidity. Given the magnitude of the problem, greater efforts are needed todevelop and implement programs both to prevent and to control anemia. In program development, it is essential to understand the differences between anemia, iron deficiency,and iron deficiency anemia, and to recognize that anemia can result both from nutrition-related causes and from inflammatory/infectious disease, as well as from blood loss.Anemia can resultfrom nutrition-related causes, inparticular irondeficiency, frominflammatory/infectious disease,and from blood loss.This statement wasprepared by Dr. PenelopeNestel and Dr. LenaDavidsson. It wasreviewed by the INACGSteering Committee.What is anemia?Anemia is defined as a hemoglobin concentration lower than the established cutoff defined by the World Health Organization. This cutoff figure ranges from 110 g/L for pregnant women and for children 6 months–5 years of age, to 120 g/L for nonpregnant women, to 130 g/L for men.1 In addition to sex, age, and pregnancy status, other factors influence the cutoff values for hemoglobin concentration. These include altitude, race, and whether the indi-vidual smokes.1 Anemia can be diagnosed by analyzing the hemoglo-bin concentration in blood or by measuring the proportion of red blood cells in whole blood (hematocrit).Hemoglobin is an iron-containing protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to cells throughout the body. Without sufficient oxygen the physical capacity of individuals is reduced. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemiaWith adequate nutrition, a reserve of iron is stored in tissues and is used when insufficient iron is absorbed, for example, when dietary intakes are inadequate or bioavailability is low.* The size of the body’s iron reserve, mostly in the liver, is therefore an index of iron nutritional status. Iron deficiency occurs in three sequentially developing stages.The first stage is depleted iron stores. This occurs when the body no longer has any stored iron but the hemoglobin concentration remains above the established cutoff levels. A depleted iron store is defined by a low serum ferritin concentration (<12 µg/L). It is important to note that because ferritin is an acute-phase reactant, its concentration in the blood increases in the presence of subclini-cal and clinical inflammatory/infectious diseases; thus, it cannot be used to accurately assess depleted iron stores in settings where poor health is common.The second stage is known as iron-deficient erythropoiesis. Developing red blood cells have the greatest need for iron, and inthis stage the reduced transport of iron is associated with the development of iron-deficient erythropoiesis. However, the hemoglo-*Bioavailability refers to the degree to which iron is available for absorption in the gut and utilized for normal metabolic functions.bin concentration remains above the established cut off levels. This condition is characterized by an increase in the transferrin recep-tor concentration and increased free protoporphyrin in red blood cells.The third and most severe form of iron deficiency is iron deficiency anemia (IDA). IDA develops when the iron supply is inadequate for hemoglobin synthesis, resulting in hemoglobin concentrationsbelow the established cutoff levels. To diagnose IDA, measurements of iron deficiency as well as hemoglobin concentration are needed.For practical purposes, the first and second stages are often re-ferred to collectively as iron deficiency.Other causes of anemiaOther nutrient deficiencies have been associated with anemia.These include deficiencies of vitamins A, B-6, and B-12, riboflavin,and folic acid,2 although not all of the causal pathways have been clearly established.Besides specific nutrient deficiencies, general infections and chronic diseases including HIV/AIDS, as well as blood loss, can cause anemia. For example, the risk of anemia increases when individuals are exposed to malaria and helminth infections. There are also many other, rarer causes of anemia, the most common being genetic disorders such as the thalassemias.Malaria, especially from the protozoan Plasmodium falciparum ,causes anemia by rupturing red blood cells and by suppressing the production of new red blood cells. Malaria does not, however, cause iron deficiency, because much of the iron in hemoglobin released from the ruptured cells stays in the body.Helminths such as hookworms and flukes such as schistosomes can cause blood loss and therefore iron loss. Adult hookworms attach themselves to the gut wall, where the mature larvae and adult worms ingest both the gut wall and blood. Hookworms changefeeding sites every 4–6 hours and during feeding secrete anticoagu-lant, resulting in secondary blood loss from the damaged gut wall after the worms have stopped feeding. The number of adult hook-worms and the fecal egg count, which is an indirect estimate of the number of worms, are strongly correlated with the amount of blood lost, which if chronic can result in iron deficiency anemia.The nematode Trichuris trichiura can cause anemia when the worm burden is heavy. Heavy infections also cause inflammation and dysentery, which in turn can cause further blood loss.The trematode Schistosoma haematobium can cause significant urinary blood loss in severe infection. The effect of this blood loss can be significant even in moderate infections if the person isyoung and already anemic. The eggs are wedged into capillaries by female worms when they are laid, and the mechanical movements of the body push them into the bladder wall. The emerging eggs rupture the bladder wall, causing blood to leak into the bladder. With Schistosoma mansoni, emerging eggs rupture the intestinal lining, resulting in the leakage of blood and other fluids and nutri-ents into the lumen.Anemia from iron deficiency versus other causesIn developed countries iron deficiency is generally the major cause of anemia. Data from the United States3 showed that for each case of anemia, there were 2.5 cases of iron deficiency. There are, how-ever, no data to show that this ratio applies to other parts of the world where iron deficiency is not always the only or primary cause of anemia.Studies in Côte d’Ivoire4 and Benin5 estimated that iron deficiency anemia accounted for about 50% of the anemia observed. In theCôte d’Ivoire study, the proportion of anemic individuals with iron deficiency varied by age and sex. About 80% of the anemic pre-school-age children had iron deficiency anemia, compared with 50% of the school-age children and women and 20% of the men. Malaria and other infections or inflammatory disorders contributed significantly to the high prevalence of anemia, particularly in young children, but these infections and/or disorders and iron deficiency could not explain all of the anemia cases.Two studies used a technique called attributable risk analysis to estimate the proportion of anemia cases in the study population that can be attributed to hookworm and malaria. In the first study, carried out on the Kenyan coast,6 76% of the preschool-age chil-dren were anemic (Hb<110 g/L) and 3% severely so (Hb<50 g/L). Only 4%, 3%, and 7% of the anemia in the study population—irrespective of whether the subjects had hookworm or not—were attributed to, respectively, hookworm infection, heavy hook-worm infection, and malaria. Among the children infected with hookworm in the study, however, 14%, 28%, and 18% of the anemia cases could be explained by, respectively, hookworm infec-tion, heavy hookworm infection, and malaria infection. Thus, in areas where the attributable risk of malaria or helminth infection to anemia is high, it is important to identify and treat these infections, especially in the most vulnerable segments of the population. The authors of the above study note that the low percentages attribut-able to malaria could be partially explained by the marked annual and seasonal variation in prevalence, which makes it difficult to capture the dynamic association between malaria and anemia. The same complexities apply in determining attributable proportions for helminth parasitemia and anemia.In the second study involving attributable risk analysis, among Zanzibari schoolchildren,7 62% of the children were anemic, 3%were severely anemic, and 51% were iron-deficient anemic. The authors estimated that if hookworm infection could be eradicated,the prevalence of anemia could be reduced by as much as 25%,iron deficiency anemia by 35%, and severe anemia (Hb<70 g/L) by 73%. Ten percent or less of anemia and iron deficiency anemia was attributable to malaria, infection with the nematode Ascarislumbricoides , or stunting (a proxy indicator for a chronically poor diet).A review of studies conducted between 1985 and 2000 among pregnant women in areas with Plasmodium falciparum malaria 8estimated that the population-attributable risk range for this type of malaria in pregnant women was 2–15% for moderate (Hb<100–110g/L) and severe (Hb<70–80 g/L) anemia.Distinguishing between attributable risk for the entire population—whether or not infection is present—and attributable risk forinfected individuals can be important for evaluating program effec-tiveness. For example, if iron-fortified wheat flour is introduced in a hookworm- or malaria-endemic area where no control programs are in place, the prevalence of anemia might not be reduced signifi-cantly at the population level, so the program would be deemed unsuccessful. However, among those who are iron-deficient anemic but not infected, the program could be effective.SummaryAnemia can be caused by iron deficiency or by other nutritional and health factors. The distinction between causes is important for two reasons:•Hemoglobin measurements are important in diagnosing ane-mia, but they are neither sensitive to nor specific to iron defi-ciency.•The success of any intervention to correct and control anemiadepends on whether the intervention deals with the underlying causes. In many developing countries, it is unlikely that all anemia results from iron deficiency, because other nutritional deficiencies as well as malaria, heavy loads of some helminths,and other inflammatory/infectious diseases also cause anemia.Knowing the underlying causes of anemia will enable programmanagers to identify which interventions need to be implemented to reduce the unacceptably high prevalence of anemia in many coun-tries. Where most of the anemia is not the result of iron deficiency,iron supplementation or the fortification of food with iron will be inadequate by themselves to prevent and control anemia.References1World Health Organization/United Nations University/UNICEF. Iron deficiency anaemia, assessment, prevention and control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: WHO, 2001.2Van den Broek NR, Letsky EA. Etiology of anemia in pregnancy in south Malawi. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72(suppl):247S–256S.3Dallman PR, Yip R, Johnson C. Prevalence and causes of anemia in the Unites States, 1976 to 1980. Am J Clin Nutr 1984;39:437–445.4Staubli Asobayire F, Adou P, Davidsson L, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency, with and without concurrent anemia, in population groups withhigh prevalence of malaria and other infections: a study in Côte d’Ivoire.Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74 776–782.5Hercberg S, Chaulica M, Galan P, et al. Prevalence of iron deficiency andiron deficiency anemia in Benin. Public Health 1988;102:73–83.6Brooker S, Peshu N, Warn PA, et al. The epidemiology of hookworminfection and its contribution to anemia among preschool children on the Kenyan Coast. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1999;93:240–246.7Stoltzfus R, Chwaya HM, Tielsch JM, et al. Epidemiology of iron deficiency anemia among Zanzibari schoolchildren: the importance of hookworms. AmJ Clin Nutr 1997;65:153–159.8Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. The burden of malariain pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;61(suppl1–2):28–35.About INACGThe International Nutritional Anemia Consultative Group (INACG) is dedicated to reducing the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia and other nutritionally preventable anemias worldwide. It sponsors international meetings and scientific reviews and convenes task forces to analyze issues related to etiology, treatment, and prevention of nutritional ane-mias. Examination of these issues is important to the establishment of public policy and action programs.INACG Steering CommitteeDr. John Beard Pennsylvania State University, USADr. Frances R. Davidson, Secretary U.S. Agency for International Development, USADr. Lena Davidsson, Chair Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Switzerland Dr. Eva Hertrampf Micronutrients Lab, INTA, ChileDr. Marian Jacobs University of Cape Town, South AfricaDr. Sean Lynch Eastern Virginia Medical School, USADr. Rebecca J. Stoltzfus The Johns Hopkins University, USADr. Olivia Yambi UNICEF- ESARO, KenyaINACG Secretariat StaffSuzanne S. Harris, Ph.D.Veronica I. Triana, MPHThis publication is made possible by support from Micronutrient Global Leadership, a project of the Office of Health, Infectious Disease and Nutrition, Bureau for Global Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, under Cooperative Agreement Number HRN-A-00-98-00027-00.March 2002Printed in the United States of AmericaAdditional copies of this and other INACG publications are available free of charge to developing countries and for US $3.50 to developed countries. Copies can be ordered from the INACG Secretariat:INACG Secretariat Tel:(202) 659-9024ILSI Human Nutrition Institute Fax:(202) 659-3617One Thomas Circle, NW Email:************Ninth Floor Internet:Washington, DC 20005 USAThe ILSI Research Foundation’s Human Nutrition Institute serves as the INACG Secretariat.。

常见病痛的英文说法

cough 咳嗽asthma 哮喘pneumonia 肺炎heart disease 心脏arrhythmia 心律不齐indigestion 消化不良gastritis 胃炎appendicitis 盲肠炎hepatitis 肝炎dermatitis皮炎freckle/ephelis 痣,雀斑acne 粉刺flu 流感diarrhoea 痢疾quarantine 检疫vaccinate 打疫苗endemic 水土不服relapse 复发症casualty急症stupor 昏迷sprain 扭伤scaldinggraze 擦伤scratch 搔挠trauma 外伤bruise 淤伤fracture骨折dislocation 脱臼tinnitus 耳鸣trachoma 沙眼colour blindness 色盲nearsightedness/myopia近视astigmatism 散光gingivitis 牙龈炎cavity 龋齿fever 发烧discomfort/disorder 不适malnutrition 营养不良incubation 潜伏期asthenia 虚弱poisoning 中毒fatigue 疲劳heat stroke 中暑itching 发痒ache/pain 痛tetanus 破伤风night sweat 盗汗chill 打冷颤pale 脸色发白shuddering 发抖inflammation 炎症acute 急症chronic 慢性病congenital 先天性病nausea恶心vomit 呕吐哮喘asthma扁桃体tonsil扁桃体炎tonsillitis糖尿病diabetes头痛headache感冒cold咳嗽cough肺炎pneumonia肝炎hepatitis脑膜炎brain fever/meningitis膀胱炎cystitis急性胃炎acute gastritis胃炎gastritis气管炎trachitis支气管炎bronchitis阑尾炎appendicitis胃肠炎gastroenteritis乳腺炎mastitis肿瘤tumor癌症cancer禽流感bird flu/avian influenza非典SARS(Severe Acute Respiratary Syndrome)疯牛病mad cow disease黑死病black death白血病leukemia爱滋病AIDS(Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) 流感influenza白内障cataract狂犬病rabies中风stroke冠心病coronary heart disease糖尿病diabetes肺癌lung cancer肝癌liver cancer肺结核pulmonary tuberculosis肝硬化hepatocirrhosis慢性病chronic肺气肿emphysema胃癌cancer of stomach胃病stomach trouble心脏病heart disease发烧fever心脏病heart disease糖尿病sugar diabetes心脑血管疾病cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease 小儿麻痹症infantile paralysis癌症cancer狂犬病hydrophobia肺结核pulmonary tuberculosis艾滋病AIDS=Acquired Immure Deficiency Syndrome乙型肝炎hepatitis B白内障cataractInternal Medicine 内科Acidosis 酸中毒Adams-Stokes syndrome 亚-斯氏综合症alcoholism, alcoholic intoxication 酒精中毒alkalosis 碱中毒anaphylaxis 过敏症anemia 贫血iron deficiency anemia 缺铁性贫血megaloblastic anemia 巨幼红细胞性贫血aplastic anemia 再生障碍性贫血angiitis 脉管炎angina pectoris 心绞痛arteriosclerosis 动脉硬化apoplexy 中风auricular fibrillation 心房纤颤auriculo-ventricular block 房室传导阻滞bronchial asthma 支气管哮喘bronchitis 支气管炎bronchiectasis 支气管扩张bronchopneumonia 支气管肺炎carcinoma 癌cardiac arrhythmia 心律紊乱cardiac failure 心力衰竭cardiomyopathy 心肌病cirrhosis 肝硬化coronary arteriosclerotic heart disease 冠状动脉硬化性心脏病Crohn disease 克罗恩病Cushing's syndrome 库欣综合症diabetes 糖尿病diffuse intravascular coagulation 弥散性血管凝血dysentery 痢疾enteritis 肠炎gastric ulcer 胃溃疡gastritis 胃炎gout 痛风hepatitis 肝炎Hodgkin's disease 霍奇金病hyperlipemia 高脂血症,血脂过多hyperparathyroidism 甲状旁腺功能亢进hypersplenism 脾功能亢进hypertension 高血压hyperthyroidism 甲状腺功能亢进hypoglycemia 低血糖hypothyroidism 甲状腺功能减退infective endocarditis 感染性心内膜炎influenza 流感leukemia 白血病lobar pneumonia 大叶性肺炎lymphadenitis 淋巴结炎lymphoma 淋巴瘤malaria 疟疾malnutrition 营养不良measles 麻疹myeloma 骨髓瘤myocardial infarction 心肌梗死myocarditis 心肌炎nephritis 肾炎nephritic syndrome 肾综合症obstructive pulmonary emphysema 阻塞性肺气肿pancreatitis 胰腺炎peptic ulcer 消化性溃疡peritonitis 腹膜炎pleuritis 胸膜炎pneumonia 肺炎pneumothorax 气胸purpura 紫癜allergic purpura 过敏性紫癜thrombocytolytic purpura 血小板减少性紫癜pyelonephritis 肾盂肾炎renal failure 肾功能衰竭rheumatic fever 风湿病rheumatoid arthritis 类风湿性关节炎scarlet fever 猩红热septicemia 败血症syphilis 梅毒tachycardia 心动过速tumour 肿瘤typhoid 伤寒ulcerative colitis 溃疡性结肠炎upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage 上消化道血Neurology 神经科brain abscess 脑脓肿cerebral embolism 脑栓塞cerebral infarction 脑梗死cerebral thrombosis 脑血栓cerebral hemorrhage 脑出血concussion of brain 脑震荡craniocerebral injury 颅脑损伤epilepsy 癫痫intracranial tumour 颅内肿瘤intracranial hematoma 颅内血肿meningitis 脑膜炎migraine 偏头痛neurasthenia 神经衰弱neurosis 神经官能症paranoid psychosis 偏执性精神病Parkinson's disease 帕金森综合症psychosis 精神病schizophrenia 精神分裂症Surgery 外科abdominal external hernia 腹外疝acute diffuse peritonitis 急性弥漫性腹膜炎acute mastitis 急性乳腺炎acute pancreatitis 急性胰腺炎acute perforation of gastro-duodenal ulcer急性胃十二指肠溃疡穿孔acute pyelonephritis 急性肾盂肾炎anal fissure 肛裂anal fistula 肛瘘anesthesia 麻醉angioma 血管瘤appendicitis 阑尾炎bleeding of gastro-duodenal ulcer 胃十二指肠溃疡出血bone tumour 骨肿瘤breast adenoma 乳房腺瘤burn 烧伤cancer of breast 乳腺癌carbuncle 痈carcinoma of colon 结肠炎carcinoma of esophagus 食管癌carcinoma of gallbladder 胆囊癌carcinoma of rectum 直肠癌carcinoma of stomach 胃癌cholecystitis 胆囊炎cervical spondylosis 颈椎病choledochitis 胆管炎cholelithiasis 胆石症chondroma 软骨瘤dislocation of joint 关节脱位erysipelas 丹毒fracture 骨折furuncle 疖hemorrhoid 痔hemothorax 血胸hypertrophy of prostate 前列腺肥大intestinal obstruction 肠梗阻intestinal tuberculosis 肠结核lipoma 脂肪瘤lithangiuria 尿路结石liver abscess 肝脓肿melanoma 黑色素瘤osseous tuberculosis 骨结核osteoclastoma 骨巨细胞瘤osteoporosis 骨质疏松症osteosarcoma 骨质疏松症osteosarcoma 骨肉瘤Paget's disease 佩吉特病perianorecrtal abscess 肛管直肠周围脓肿phlegmon 蜂窝织炎portal hypertension 门静脉高压prostatitis 前列腺炎protrusion of intervertebral disc 椎间盘突出purulent arthritis 化脓性关节炎pyogenic ostcomyclitis 化脓性骨髓炎pyothorax 脓胸rectal polyp 直肠息肉rheumatoid arthritis 类风湿性关节炎rupture of spleen 脾破裂scapulohumeral periarthritis 肩周炎tenosynovitis 腱鞘炎tetanus 破伤风thromboangiitis 血栓性脉管炎thyroid adenocarcinoma 甲状腺腺癌thyroid adenoma 甲状腺腺瘤trauma 创伤urinary infection 泌尿系感染varicose vein of lower limb 下肢静脉曲张Paediatrics 儿科acute military tuberculosis of the lung 急性粟粒性肺结核acute necrotic enteritis 急性坏死性结肠炎anaphylactic purpura 过敏性紫癜ancylostomiasis 钩虫病ascariasis 蛔虫病asphyxia of the newborn 新生儿窒息atrial septal defect 房间隔缺损birth injury 产伤cephalhematoma 头颅血肿cerebral palsy 脑性瘫痪congenital torticollis 先天性斜颈convulsion 惊厥Down's syndrome 唐氏综合症glomerulonephritis 肾小球肾炎hemophilia 血友病infantile diarrhea 婴儿腹泻intracranial hemorrhage of the newborn 新生儿颅内出血intussusception 肠套叠necrotic enterocolitis of newborn 新生儿坏死性小肠结膜炎neonatal jaundice 新生儿黄疸nutritional iron deficiency anemia 营养性缺铁性贫血nutritional megaloblastic anemia 营养性巨幼细胞性贫血patent ductus arteriosis 动脉导管未闭poliomyelitis 骨髓灰质炎premature infant 早产儿primary tuberculosis 原发性肺结核progressive muscular dystrophy 进行性肌肉营养不良pulmonary stenosis 肺动脉狭窄purulent meningitis 化脓性脑膜炎rickets 佝偻病sepsis of the newborn 新生儿败血症tetanus of the newborn 新生儿破伤风tetralogy of Fallot 法洛四联症thrush 鹅口疮,真菌性口炎varicella 水痘ventricular septal defect 室间隔缺损viral encephalitis 病毒性脑炎viral myocarditis 病毒性心肌炎Gynecology and Obstetrics 妇,产科abortion 流产adenomyosis 子宫内膜异位症amniotic fluid embolism 羊水栓塞Bartholin's cyst 巴氏腺囊肿carcinoma of cervix 子宫颈癌carcinoma of endometrium 子宫内膜癌carcinoma of ovary 卵巢癌cervicitis 宫颈炎chorio-epithelioma 绒毛膜上皮癌corpora luteum cyst 黄体囊肿dystocia 难产eclampsia 子痫edema-proteinuria-hypertension syndrome水肿蛋白尿高血压综合征(妊娠高血压综合征)endometriosis 子宫内膜异位症extrauterine pregnancy 子宫外孕hydatidiform mole 葡萄胎hyperemesis gravidarum 妊娠剧吐infertility 不育症irregular menstruation 月经失调lochia 恶露monilial vaginitis 念珠菌性阴道炎multiple pregnancy 多胎妊娠myoma of uterus 子宫肿瘤oligohydramnios 羊水过少ovarian tumour 卵巢肿瘤pelvic inflammatory disease 盆腔炎placenta previa 前置胎盘placental abruption 胎盘早期剥离pregnancy-hypertension syndrome 妊娠高血压综合症premature birth 早产premature rupture of membrane 胎膜早破postpartum hemorrhage 产后出血puerperal infection 产褥感染rupture of uterus 子宫破裂trichomonas vaginitis 滴虫性阴道炎uteroplacental apoplexy 子宫胎盘卒中vulvitis 外阴炎Ophthalmology and Otorhinolaryngology 五官科amblyopia 弱视amygdalitis, tonsillitis 扁桃体炎astigmatism 散光carcinoma of nasopharynx鼻咽癌carcinoma of larynx 喉癌cataract 白内障tinnitus 耳鸣chalazion 霰粒肿,脸板腺囊肿colour blindness 色盲deflection of nasal septum 鼻中隔偏曲deafness 聋furuncle of nasalvestibule 鼻前庭疖glaucoma 青光眼heterotropia 斜视hyperopia 远视injury of cornea 角膜损伤ceruminal impaction 耵聍嵌塞iritis 虹膜炎keratitis 角膜炎labyrinthitis 迷路炎,内耳炎laryngitis 喉炎mastoiditis 乳突炎myopia 近视nasal sinusitis 鼻窦炎otitis media 中耳炎obstruction of larynx 喉梗阻peritonsillar abscess 扁桃体中脓肿pharyngitis 咽炎rhinitis 鼻炎Dermatoloty 皮科acne 痤疮carcinoma of skin 皮肤癌bed sore 褥疮decubitus ulcer 褥疮性溃疡drug eruption 药皮疹eczema 湿疹herpes simplex 单纯疱疹herpes zoster 带状疱疹lupus erythematosis 红斑狼疮psoriasis 牛皮癣urticaria 荨麻疹wart 疣neuralgia 神经痛neurasthenia 神经衰弱paralysis 麻痹peritonitis 腹膜炎pharyngitis 咽炎phtisis 痨病,肺结核pneumonia 肺炎poliomyelitis 脊髓灰质炎rabies 狂犬病rheumatism 风湿病rickets, rachitis 佝偻病scabies, itch 疥疮scarlet fever 猩红热sciatica 坐骨神经痛sclerosis 硬化septicemia, septicaemia 败血病sinusitis 窦炎smallpox 天花anemia, anaemia 贫血angina pectoris 心绞痛appendicitis 阑尾炎arthritis 关节炎bronchitis 支气管炎cancer 癌catarrh 卡他,粘膜炎chicken pox, varicella 水痘cholera 霍乱cold 感冒,伤风,着凉(head) cold 患感冒diabetes 糖尿病diphtheria 白喉eczema 湿疹epilepsy 癫痫erysipelas 丹毒gangrene 坏疽German measles, rubella 风疹gout 痛风headache 头痛hemiplegy, hemiplegia 偏瘫,半身不遂interus, jaundice 黄疸indigestion 消化不良influenza, flu 流感insanity 精神病leukemia 白血病malaria 疟疾malnutrition 营养不良Malta fever 马耳他热,波状热measles 麻疹migraine, splitting headache 偏头痛miocardial infarction 心肌梗塞mumps 流行性腮腺炎swamp fever 沼地热syncope 晕厥syphilis 梅毒tetanus 破伤风thrombosis 血栓形成torticollis, stiff neck 斜颈tuberculosis 结核病tumour 瘤(美作:tumor)typhus 斑疹伤寒urticaria, hives 荨麻疹whooping cough 百日咳yellow fever 黄热病zona, shingles 带状疮疹cough 咳嗽asthma 哮喘pneumonia 肺炎heart disease 心脏病arrhythmia 心律不齐indigestion 消化不良gastritis 胃炎appendicitis 盲肠炎hepatitis 肝炎dermatitis皮炎freckle/ephelis 痣,雀斑acne 粉刺flu 流感diarrhoea 痢疾quarantine 检疫vaccinate 打疫苗endemic 水土不服relapse 复发症casualty急症stupor 昏迷sprain 扭伤scalding烫伤graze 擦伤scratch 搔挠trauma 外伤bruise 淤伤fracture骨折dislocation 脱臼tinnitus 耳鸣trachoma 沙眼colour blindness 色盲nearsightedness/myopia 近视astigmatism 散光gingivitis 牙龈炎cavity 龋齿fever 发烧discomfort/disorder 不适malnutrition 营养不良incubation 潜伏期asthenia 虚弱poisoning 中毒fatigue 疲劳heat stroke 中暑itching 发痒ache/pain 痛tetanus 破伤风night sweat 盗汗chill 打冷颤pale 脸色发白shuddering 发抖inflammation 炎症acute 急症chronic 慢性病congenital 先天性病nausea恶心vomit 呕吐。

琥珀酸亚铁和右旋糖酐铁治疗缺铁性贫血的疗效对比分析

贫血指人体外周血红细胞容量减少至正常范围下线的一种临床症状,依据病因及临床特点不同可分为多种类型。

缺铁性贫血是由于体内贮存铁缺乏使血红蛋白合成减少所引起的一种小细胞低色素性贫血[1],是临床常见贫血类型,可引起头晕头痛、耳鸣眼花、心悸气短、乏力困倦等症状,以及口腔、毛发、指(趾)甲等组织病理改变[2]。

铁剂是临床治疗缺铁性贫血的首选药物,文章现以2013年1月—2017年10月该院192例患者为例,对琥珀酸亚铁、右旋糖酐铁两种铁剂治疗缺铁性贫血的疗效与安全性进行分析和探讨,现报道如下。

1资料与方法1.1一般资料方便选取该院血液科收治的192例缺铁性贫血患者为研究对象,依据治疗方法分为两组。

右旋糖苷铁组(96例):男21例,女75例;年龄16~87岁,平均(48.6±12.7)岁;病程(按出现症状统计)最短2周,最长2年余。

病情分级(按血红蛋白浓度统计):轻度贫血59例,中度贫血37例。

病因:营养不良36例,月经量过多32例,出血性疾病19例,其他9例。

琥珀酸亚铁(96例):男20例,女76例;年龄16~85岁,平均(49.1±12.4)岁;病程最短3周,最长2年余。

病情分级:轻度贫血61例,中度贫血35例。

病因:营养不良35例,月经量过多DOI:10.16662/ki.1674-0742.2018.11.124琥珀酸亚铁和右旋糖酐铁治疗缺铁性贫血的疗效对比分析曹莉江苏省新沂市人民医院血液科,江苏新沂221400[摘要]目的探讨琥珀酸亚铁和右旋糖酐铁治疗缺铁性贫血的疗效与安全性。

方法方便选取2013年1月—2017年10月该院血液科收治的192例缺铁性贫血患者为研究对象,依据治疗方法分为右旋糖苷铁组(96例)和琥珀酸亚铁(96例),对比观察患者不同用药时期血红蛋白水平恢复情况,评价两组疗效,统计并发症。

结果右旋糖苷铁组治疗总有效率(92.71%)与琥珀酸亚铁组(90.63%)比较差异无统计学意义(χ2=1.06,P>0.05);右旋糖苷铁组用药不良反应发生率(11.46%)与琥珀酸亚铁组(19.79%)比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=3.97,P<0.05)。

右旋糖酐铁联合五维赖氨酸治疗婴儿营养性缺铁性贫血的综合疗效

现代医学Modern Medical Journal2020,Aug ;48(8):1020-1024[收稿日期]2019-02-22[修回日期]2020-07-28[作者简介]陈杰超(1986-),女,山东临沂人,主治医师。

E -mail :zzzzqu@163.com[引文格式]陈杰超,赵忠全,邢德强,等.右旋糖酐铁联合五维赖氨酸治疗婴儿营养性缺铁性贫血的综合疗效[J ].现代医学,2020,48(8):1020-1024.·论著·右旋糖酐铁联合五维赖氨酸治疗婴儿营养性缺铁性贫血的综合疗效陈杰超1,赵忠全2,邢德强1,蒋妍1,杜瑞1(1.聊城市东昌府区妇幼保健院儿保科,山东聊城252000;2.聊城市第三人民医院骨科,山东聊城252000)[摘要]目的:研究右旋糖酐铁联合五维赖氨酸颗粒对婴儿营养性缺铁性贫血的血红蛋白水平以及发育商的影响。

方法:124例门诊患儿随机分为研究组(63例)和对照组(61例),对照组给予右旋糖酐铁口服液配合口服维生素C 片辅助治疗,研究组在此基础上加用五维赖氨酸颗粒,统一治疗8周。

比较两组间血红蛋白水平和发育商数值的变化。

结果:研究组患儿Hb 增长幅度明显大于对照组(P <0.01);研究组的DQ 数值增幅明显高于对照组(P <0.01);研究组的总有效率(95.24%)大于对照组的总有效率(81.97%),P <0.05;研究组的不良反应率(4.76%)小于对照组的不良反应率(16.39%),P <0.05。

结论:与单用铁剂相比较,右旋糖酐铁联合五维赖氨酸颗粒治疗婴儿营养性缺铁性贫血,能较快提升血红蛋白水平以及发育商数值,可进一步提高疗效。

[关键词]营养性缺铁性贫血;五维赖氨酸颗粒;血红蛋白;发育商[中图分类号]R556.3[文献标识码]A[文章编号]1671-7562(2020)08-1020-05doi :10.3969/j.issn.1671-7562.2020.08.016Comprehensive efficacy of nutritional iron deficiency anemia in infants treated with iron dextran and five -dimensional lysineCHEN Jiechao 1,ZHAO Zhongquan 2,XING Deqiang 1,JIANG Yan 1,DU Rui 1(1.Department of Child Protection ,Maternal and Child Health Hospital ,Dongchangfu District ,Liaocheng 252000,China ;2.Department of Orthopedics ,Liaocheng Third People 's Hospital ,Liaocheng 252000,China )[Abstract ]Objective :To investigate the effects of iron dextran and five -dimensional lysine granules on hemoglo-bin levels and developmental quotients in infants with nutritional iron deficiency anemia.Methods :124outpatients were randomly divided into study group (63cases )and control group (61cases ).The control group was given iron dextran oral solution combined with oral vitamin C tablets for adjuvant treatment ,on top of which ,the study group-was given five -dimensional lysine granules for 8weeks.The changes in hemoglobin levels and developmental quo-tient values were compared between the two groups.Results :The growth rate of Hb in the study group was signifi-cantly higher than that in the control group (P <0.01).The DQ value of the study group was significantly higher than that of the control group (P <0.01).The total effective rate of the study group (95.24%)was greater than the total effective rate of the control group (81.97%),P <0.05.The adverse reaction rate of the study group (4.76%)was lower than that of the control group (16.39%),P <0.05.Conclusion :Compared with iron alone ,iron dextran combined with five -dimensional lysine granules can improve hemoglobin levels and developmen-·0201·tal quotient values in infants with nutritional iron deficiency anemia.At the same time,this method can further im-prove the curative effect.[Key words]nutritional iron deficiency anemia;five-dimensional lysine granules;hemoglobin;development quo-tient营养性缺铁性贫血(nutritional iron deficiency anemia,NIDA)是常见的贫血类型,发病率最高的群体是6个月 1岁的婴幼儿,具有极大危害。

我国抗生素滥用现状_原因及对策综述_廖全山

世界最新医学信息文摘 2016年 第16卷 第57期41·综述·我国抗生素滥用现状、原因及对策综述廖全山(广西柳州钢铁集团公司医院,广西 柳州 545001)摘 要:抗生素是目前临床常用抗感染药物,应用范围广泛,关系着人类健康。

近年来,抗生素的不断应用,逐渐出现药物滥用情况,使临床抗生素耐药性和不良反应不断增加,影响患者疾病恢复。

本文对我国抗生素滥用现状和原因进行简单综述,并提出一定的解决对策,以此提高抗生素应用效果。

关键词:抗生素;现状;原因;对策中图分类号:R978.1 文献标识码:A DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-3141.2016.57.0260 引言 抗生素在临床应用范围广泛,自1928年青霉素的问世及应用,抗生素直到现在一直被广泛应用,并不断发展,层出不穷,为人类疾病的预防和治疗作出了杰出贡献[1]。

但抗生素的广泛应用,所存在的问题也逐渐显露出来,对人类健康产生一定危害。

尤其是近年来,我国部分医院存在抗生素滥用情况,药物耐药性及不良反应发生率明显增加,影响药物应用效果。

本次研究对我国抗生素滥用现状、原因和解决措施进行简单综述,为我国医院抗生素的应用提供必要参考依据。

1 我国抗生素滥用现状分析1.1 不合理的临床使用。

临床抗生素使用时,多数医师根据经验用药,患者病原学送检率不高;或受利益驱使,选择价格昂贵的抗生素和新药、进口药,未正确选择抗生素。

抗生素使用时,未准确给药、疗程和配伍不合理、联合用药不当等。

相关调查研究[2]显示,97.3%儿童输液含有抗生素,抗生素联合用药超过30%。

抗生素使用期间,预防控药不严,尤其围术期抗生素使用率为100%,成为手术必须使用预防性药物。

1.2 患者不合理使用。

患者是抗生素使用的主体,也是造成抗生素滥用的主要因素。

患者对医学知识的缺乏,自行购买或随意使用抗生素,依从性差,未谨遵医嘱用药,均会导致抗生素的不合理使用。

anemia

anemiaAnemia: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and TreatmentIntroduction:Anemia is a medical condition characterized by a decrease in the number of red blood cells or a decrease in the amount of hemoglobin in the blood. Hemoglobin is the protein responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body. Anemia can affect people of all ages, but women and individuals with certain chronic conditions are more susceptible.Causes of Anemia:There are several possible causes of anemia, including:1. Iron deficiency: This is the most common cause of anemia worldwide. Iron is essential for the production of hemoglobin, so a lack of iron can lead to a decrease in red blood cells. Iron deficiency is more prevalent in menstruating women, pregnant women, and individuals with poor diets.2. Vitamin deficiency: Lack of vitamins like vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin C can also result in anemia. Vitamin B12 and folate are necessary for the production of red blood cells, while vitamin C helps in the absorption of iron. Vegetarians and vegans, as well as individuals with malabsorption disorders, are at a higher risk of developing vitamin deficiencies.3. Chronic diseases: Some chronic conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, kidney disease, and cancer, can lead to anemia. These diseases can disrupt the production of red blood cells or cause blood loss, resulting in anemia.Symptoms of Anemia:The symptoms of anemia can vary depending on the severity and underlying cause but may include:1. Fatigue and weakness: One of the common symptoms of anemia is feeling tired and weak, even after getting enough rest.2. Pale skin and nails: Anemia can cause a decrease in oxygen-carrying red blood cells, resulting in paleness of the skin and nails.3. Shortness of breath: Due to the reduced oxygen supply, individuals with anemia may experience difficulty breathing, especially during physical exertion.4. Rapid heartbeat: Anemia can cause the heart to pump faster in an attempt to compensate for the decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.Diagnosis of Anemia:To diagnose anemia, a healthcare professional may perform several tests, including:1. Complete blood count (CBC): This test measures the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets present in the blood. It also provides information on the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.2. Blood iron level: A blood test can determine the level of iron in the blood. Low iron levels may indicate iron deficiency anemia.3. Vitamin deficiency test: A blood test can be conducted to measure the levels of vitamins B12, folate, and C in the body.4. Bone marrow biopsy: In certain cases, a small sample of bone marrow may be removed and examined to determine the cause of anemia.Treatment of Anemia:The treatment of anemia depends on its underlying cause. Some common treatment options include:1. Iron supplementation: In cases of iron deficiency anemia, iron supplements or dietary changes may be recommended to increase iron levels in the body.2. Vitamin supplementation: If anemia is caused by a vitamin deficiency, supplements or dietary modifications can help restore the levels of vitamins B12, folate, or C.3. Blood transfusion: In severe cases of anemia, a blood transfusion may be necessary to immediately increase the number of red blood cells.4. Medications: In certain types of anemia, medications may be prescribed to stimulate the production of red blood cells.Prevention of Anemia:While not all forms of anemia can be prevented, there are steps individuals can take to reduce their risk. These include:1. Ensuring a balanced diet: Consuming a diet rich in iron, vitamins, and minerals can help prevent anemia caused by deficiencies.2. Regular health check-ups: Regular visits to a healthcare professional can help in early detection and treatment of anemia.3. Managing chronic conditions: Proper management of underlying chronic diseases can help prevent anemia associated with these conditions.Conclusion:Anemia is a common medical condition that can have a significant impact on a person's overall health and well-being. Understanding the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of anemia is essential for timely intervention and management. By identifying and addressing the underlying cause of anemia, individuals can improve their quality of life and reduce the risk of complications associated with this condition.。

Iron Deficiency Anemia

– Usually normocytic (MCV 80-100 fl) or microcytic (MCV < 80)

• Nuclear division/maturation

– Usually macrocytic (MCV > 100 fl)

ANEMIA

Causes - Cytoplasmic Protein Production

• Decreased hemoglobin synthesis

– Disorders of globin synthesis – Disorders of heme synthesis

• Heme synthesis

– Decreased Iron – Iron not in utilizable form – Decreased heme synthesis

IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Prevalence

Country S. India N. India Latin America Israel Poland Sweden USA Men (%) Women (%) 6 4 14 35 64 17 29 7 13 Pregnant Women (%) 56 80 38 47 22

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe Fe

益气维血胶囊治疗妊娠期缺铁性贫血的效果及对铁代谢、妊娠结局的影响

益气维血胶囊治疗妊娠期缺铁性贫血的效果及对铁代谢、妊娠结局的影响盛杰① 【摘要】 目的:探究与分析益气维血胶囊治疗妊娠期缺铁性贫血的效果及对铁代谢、妊娠结局的影响。

方法:采取随机数字表法将桓台县人民医院门诊2021年5月-2022年5月收治的妊娠期缺铁性贫血患者90例进行分组,每组45例,对照组给予右旋糖酐铁口服溶液与维生素C联合治疗,观察组在对照组基础上增加益气维血胶囊治疗,治疗12周。

对比两组临床疗效、治疗前后血常规指标、铁代谢指标变化,同时对患者的妊娠结局及不良反应进行观察。

结果:观察组临床总有效率高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

观察组治疗后血红蛋白(Hb)、平均红细胞体积(MCV)、血清铁(SI)、可溶性转铁蛋白受体(TSAT)、血清铁蛋白(SF)均高于对照组,可溶性转铁蛋白受体(STFR)低于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

两组不良妊娠结局与不良反应相比,差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

结论:益气维血胶囊联合右旋糖酐铁口服溶液与维生素C治疗妊娠期缺铁性贫血患者可获得更高的临床总有效率,血常规及铁代谢指标得到有效改善,但通过采用益气维血胶囊治疗未能在妊娠结局上体现出更高的优势,同时也未增加不良反应,安全性有保障。

【关键词】 益气维血胶囊 妊娠期缺铁性贫血 铁代谢 妊娠结局 Efficacy of Yiqi Weixue Capsules in the Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy and Its Effect on Iron Metabolism and Pregnancy Outcome/SHENG Jie. //Medical Innovation of China, 2023, 20(16): 119-122 [Abstract] Objective: To explore and analyze the efficacy of Yiqi Weixue Capsules in the treatment of patients with iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy and its effect on iron metabolism and pregnancy outcome. Method: A total of 90 patients with iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy were admitted to the Outpatient Department of People's Hospital of Huantai County from May 2021 to May 2022 were divided into two groups by random number table method, there were 45 cases in each group, and the control group was given Iron Dextran Oral Solution and Vitamin C combined treatment, the observation group was additionally treated with Yiqi Weixue Capsules on the basis of the control group, treatment for 12 weeks. The clinical efficacy, changes of blood routine indexes and iron metabolism indexes before and after treatment were compared between the two groups, and the pregnancy outcomes and adverse reactions of the patients were also observed. Result: Compared with the control group, the total clinical effective rate of the observation group was higher, and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). Compared with the control group after treatment, Hb, MCV, SI, TSAT, SF in the observation group were higher, and STFR in the observation group was lower, the differences were statistically significant (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes and adverse reactions between the two groups (P>0.05). Conclusion: Yiqi Weixue Capsules combined with Iron Dextran Oral Solution and Vitamin C in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy can obtain higher clinical total effective rate. The results showed higher advantages, and at the same time, there were no adverse reactions, and the safety was guaranteed. [Key words] Yiqi Weixue Capsules Iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy Iron metabolism Pregnancy outcome First-author's address: People's Hospital of Huantai County, Shandong Province, Huantai 256400, China doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2023.16.029①山东省桓台县人民医院 山东 桓台 256400通信作者:盛杰 缺铁性贫血作为一种妊娠期女性常见病,在疾病进展期间不仅对母体的健康造成了较大的影响,也对胎儿的生长发育过程造成了威胁,需要及时地提供铁剂补给,以达到良好的治疗目的[1]。

内分泌课件缺铁性贫血英文课件Iron Deficiency Anemia

Definition

Iron deficiency: the content of iron in the body is less than normal.

Iron depletion: the earliest stage of iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency erythropoiesis: a more advanced stage of iron deficiency, characterized by decreased or absent storage iron, usually low serum iron concentration and transferrin saturation, but without frank anemia.

ID IDE IDA

Lack of iron

Low serum iron Low t.s.

Low hemoglobin

Epidemiology

The prevalence of IDA varies between age, sexes, economic groups et al

population Shanghai

IDA: the most advanced stage of iron deficiency, characterized by decreased or absent iron stores, low serum iron concentration, low transferrin saturation, and low blood hemoglobin concentration.

Age group

infants F (12-49)

铁元素在维持人体健康中的作用和重要性,一篇600字文章

铁元素在维持人体健康中的作用和重要性,一篇600字文章English Answer:Iron is an essential mineral for the human body and plays a crucial role in maintaining overall health. It is an integral component of hemoglobin, which is responsible for transporting oxygen to all cells in the body. Iron also plays a key role in energy production and the functioning of the immune system.Iron deficiency can lead to anemia, a condition characterized by fatigue, weakness, and a weakened immune system. On the other hand, excessive iron intake can be harmful and may lead to a condition called iron overload, which can damage organs such as the liver and heart.To maintain a healthy iron balance, it is important to consume foods rich in iron, such as red meat, poultry, fish, legumes, and leafy green vegetables. It is also essential to consume vitamin C-rich foods, as vitamin C enhances iron absorption. However, it is important to note that iron absorption can be affected by certain factors, such as the presence of other minerals and medications.Regular blood tests can help monitor iron levels in the body and detect any deficiencies or excesses. In cases of iron deficiency, iron supplements may be recommended by a healthcare professional.In conclusion, iron is vital for maintaining good health. It is important to consume a balanced diet that includes iron-rich foods and to monitor iron levels regularly to ensure a healthy iron balance in the body.中文回答:铁是人体必需的矿物质,对维持整体健康起着重要作用。

Iron deficiency anemia缺铁性贫血-英文

Tests---morphology---bone marrow

Tests---iron metabolism

• Serum iron • Total iron binding capacity,TIBC • Transferrin satuation • Serum ferritin

Causes

Blood loss

Increase of needs

gastrointestinal

pregnancy

ulcer baby

cancer

hookworm disease

haemorrhoids

menstruation

hemolysis

MANIFESTATIONS

MANIFESTATIONS

Iron deficiency is the leading cause of anmeia worldwide.

oglobin

heme

globin

Fe++

protoporph yrin

Serum iron

Decrease of intake Dietary deficiency Gastric disease

DIFFERENTIAL

• 1,thalassemia • 2,anemia of chronic disease

serum iron ,serum ferritin, • TIBC normal,ringed sideroblast • 3,ringed siderblast anemia • ringed sideroblast,>15%

treatment

常见病痛的英文说法

cough 咳嗽asthma 哮喘pneumonia 肺炎heart disease 心脏arrhythmia 心律不齐indigestion 消化不良gastritis 胃炎appendicitis 盲肠炎hepatitis 肝炎dermatitis皮炎freckle/ephelis 痣,雀斑acne 粉刺flu 流感diarrhoea 痢疾quarantine 检疫vaccinate 打疫苗endemic 水土不服relapse 复发症casualty急症stupor 昏迷sprain 扭伤scaldinggraze 擦伤scratch 搔挠trauma 外伤bruise 淤伤fracture骨折dislocation 脱臼tinnitus 耳鸣trachoma 沙眼colour blindness 色盲nearsightedness/myopia近视astigmatism 散光gingivitis 牙龈炎cavity 龋齿fever 发烧discomfort/disorder 不适malnutrition 营养不良incubation 潜伏期asthenia 虚弱poisoning 中毒fatigue 疲劳heat stroke 中暑itching 发痒ache/pain 痛tetanus 破伤风night sweat 盗汗chill 打冷颤pale 脸色发白shuddering 发抖inflammation 炎症acute 急症chronic 慢性病congenital 先天性病nausea恶心vomit 呕吐哮喘asthma扁桃体tonsil扁桃体炎tonsillitis糖尿病diabetes头痛headache感冒cold咳嗽cough肺炎pneumonia肝炎hepatitis脑膜炎brain fever/meningitis膀胱炎cystitis急性胃炎acute gastritis胃炎gastritis气管炎trachitis支气管炎bronchitis阑尾炎appendicitis胃肠炎gastroenteritis乳腺炎mastitis肿瘤tumor癌症cancer禽流感bird flu/avian influenza非典SARS(Severe Acute Respiratary Syndrome)疯牛病mad cow disease黑死病black death白血病leukemia爱滋病AIDS(Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) 流感influenza白内障cataract狂犬病rabies中风stroke冠心病coronary heart disease糖尿病diabetes肺癌lung cancer肝癌liver cancer肺结核pulmonary tuberculosis肝硬化hepatocirrhosis慢性病chronic肺气肿emphysema胃癌cancer of stomach胃病stomach trouble心脏病heart disease发烧fever心脏病heart disease糖尿病sugar diabetes心脑血管疾病cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease 小儿麻痹症infantile paralysis癌症cancer狂犬病hydrophobia肺结核pulmonary tuberculosis艾滋病AIDS=Acquired Immure Deficiency Syndrome乙型肝炎hepatitis B白内障cataractInternal Medicine 内科Acidosis 酸中毒Adams-Stokes syndrome 亚-斯氏综合症alcoholism, alcoholic intoxication 酒精中毒alkalosis 碱中毒anaphylaxis 过敏症anemia 贫血iron deficiency anemia 缺铁性贫血megaloblastic anemia 巨幼红细胞性贫血aplastic anemia 再生障碍性贫血angiitis 脉管炎angina pectoris 心绞痛arteriosclerosis 动脉硬化apoplexy 中风auricular fibrillation 心房纤颤auriculo-ventricular block 房室传导阻滞bronchial asthma 支气管哮喘bronchitis 支气管炎bronchiectasis 支气管扩张bronchopneumonia 支气管肺炎carcinoma 癌cardiac arrhythmia 心律紊乱cardiac failure 心力衰竭cardiomyopathy 心肌病cirrhosis 肝硬化coronary arteriosclerotic heart disease 冠状动脉硬化性心脏病Crohn disease 克罗恩病Cushing's syndrome 库欣综合症diabetes 糖尿病diffuse intravascular coagulation 弥散性血管凝血dysentery 痢疾enteritis 肠炎gastric ulcer 胃溃疡gastritis 胃炎gout 痛风hepatitis 肝炎Hodgkin's disease 霍奇金病hyperlipemia 高脂血症,血脂过多hyperparathyroidism 甲状旁腺功能亢进hypersplenism 脾功能亢进hypertension 高血压hyperthyroidism 甲状腺功能亢进hypoglycemia 低血糖hypothyroidism 甲状腺功能减退infective endocarditis 感染性心内膜炎influenza 流感leukemia 白血病lobar pneumonia 大叶性肺炎lymphadenitis 淋巴结炎lymphoma 淋巴瘤malaria 疟疾malnutrition 营养不良measles 麻疹myeloma 骨髓瘤myocardial infarction 心肌梗死myocarditis 心肌炎nephritis 肾炎nephritic syndrome 肾综合症obstructive pulmonary emphysema 阻塞性肺气肿pancreatitis 胰腺炎peptic ulcer 消化性溃疡peritonitis 腹膜炎pleuritis 胸膜炎pneumonia 肺炎pneumothorax 气胸purpura 紫癜allergic purpura 过敏性紫癜thrombocytolytic purpura 血小板减少性紫癜pyelonephritis 肾盂肾炎renal failure 肾功能衰竭rheumatic fever 风湿病rheumatoid arthritis 类风湿性关节炎scarlet fever 猩红热septicemia 败血症syphilis 梅毒tachycardia 心动过速tumour 肿瘤typhoid 伤寒ulcerative colitis 溃疡性结肠炎upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage 上消化道血Neurology 神经科brain abscess 脑脓肿cerebral embolism 脑栓塞cerebral infarction 脑梗死cerebral thrombosis 脑血栓cerebral hemorrhage 脑出血concussion of brain 脑震荡craniocerebral injury 颅脑损伤epilepsy 癫痫intracranial tumour 颅内肿瘤intracranial hematoma 颅内血肿meningitis 脑膜炎migraine 偏头痛neurasthenia 神经衰弱neurosis 神经官能症paranoid psychosis 偏执性精神病Parkinson's disease 帕金森综合症psychosis 精神病schizophrenia 精神分裂症Surgery 外科abdominal external hernia 腹外疝acute diffuse peritonitis 急性弥漫性腹膜炎acute mastitis 急性乳腺炎acute pancreatitis 急性胰腺炎acute perforation of gastro-duodenal ulcer急性胃十二指肠溃疡穿孔acute pyelonephritis 急性肾盂肾炎anal fissure 肛裂anal fistula 肛瘘anesthesia 麻醉angioma 血管瘤appendicitis 阑尾炎bleeding of gastro-duodenal ulcer 胃十二指肠溃疡出血bone tumour 骨肿瘤breast adenoma 乳房腺瘤burn 烧伤cancer of breast 乳腺癌carbuncle 痈carcinoma of colon 结肠炎carcinoma of esophagus 食管癌carcinoma of gallbladder 胆囊癌carcinoma of rectum 直肠癌carcinoma of stomach 胃癌cholecystitis 胆囊炎cervical spondylosis 颈椎病choledochitis 胆管炎cholelithiasis 胆石症chondroma 软骨瘤dislocation of joint 关节脱位erysipelas 丹毒fracture 骨折furuncle 疖hemorrhoid 痔hemothorax 血胸hypertrophy of prostate 前列腺肥大intestinal obstruction 肠梗阻intestinal tuberculosis 肠结核lipoma 脂肪瘤lithangiuria 尿路结石liver abscess 肝脓肿melanoma 黑色素瘤osseous tuberculosis 骨结核osteoclastoma 骨巨细胞瘤osteoporosis 骨质疏松症osteosarcoma 骨质疏松症osteosarcoma 骨肉瘤Paget's disease 佩吉特病perianorecrtal abscess 肛管直肠周围脓肿phlegmon 蜂窝织炎portal hypertension 门静脉高压prostatitis 前列腺炎protrusion of intervertebral disc 椎间盘突出purulent arthritis 化脓性关节炎pyogenic ostcomyclitis 化脓性骨髓炎pyothorax 脓胸rectal polyp 直肠息肉rheumatoid arthritis 类风湿性关节炎rupture of spleen 脾破裂scapulohumeral periarthritis 肩周炎tenosynovitis 腱鞘炎tetanus 破伤风thromboangiitis 血栓性脉管炎thyroid adenocarcinoma 甲状腺腺癌thyroid adenoma 甲状腺腺瘤trauma 创伤urinary infection 泌尿系感染varicose vein of lower limb 下肢静脉曲张Paediatrics 儿科acute military tuberculosis of the lung 急性粟粒性肺结核acute necrotic enteritis 急性坏死性结肠炎anaphylactic purpura 过敏性紫癜ancylostomiasis 钩虫病ascariasis 蛔虫病asphyxia of the newborn 新生儿窒息atrial septal defect 房间隔缺损birth injury 产伤cephalhematoma 头颅血肿cerebral palsy 脑性瘫痪congenital torticollis 先天性斜颈convulsion 惊厥Down's syndrome 唐氏综合症glomerulonephritis 肾小球肾炎hemophilia 血友病infantile diarrhea 婴儿腹泻intracranial hemorrhage of the newborn 新生儿颅内出血intussusception 肠套叠necrotic enterocolitis of newborn 新生儿坏死性小肠结膜炎neonatal jaundice 新生儿黄疸nutritional iron deficiency anemia 营养性缺铁性贫血nutritional megaloblastic anemia 营养性巨幼细胞性贫血patent ductus arteriosis 动脉导管未闭poliomyelitis 骨髓灰质炎premature infant 早产儿primary tuberculosis 原发性肺结核progressive muscular dystrophy 进行性肌肉营养不良pulmonary stenosis 肺动脉狭窄purulent meningitis 化脓性脑膜炎rickets 佝偻病sepsis of the newborn 新生儿败血症tetanus of the newborn 新生儿破伤风tetralogy of Fallot 法洛四联症thrush 鹅口疮,真菌性口炎varicella 水痘ventricular septal defect 室间隔缺损viral encephalitis 病毒性脑炎viral myocarditis 病毒性心肌炎Gynecology and Obstetrics 妇,产科abortion 流产adenomyosis 子宫内膜异位症amniotic fluid embolism 羊水栓塞Bartholin's cyst 巴氏腺囊肿carcinoma of cervix 子宫颈癌carcinoma of endometrium 子宫内膜癌carcinoma of ovary 卵巢癌cervicitis 宫颈炎chorio-epithelioma 绒毛膜上皮癌corpora luteum cyst 黄体囊肿dystocia 难产eclampsia 子痫edema-proteinuria-hypertension syndrome水肿蛋白尿高血压综合征(妊娠高血压综合征)endometriosis 子宫内膜异位症extrauterine pregnancy 子宫外孕hydatidiform mole 葡萄胎hyperemesis gravidarum 妊娠剧吐infertility 不育症irregular menstruation 月经失调lochia 恶露monilial vaginitis 念珠菌性阴道炎multiple pregnancy 多胎妊娠myoma of uterus 子宫肿瘤oligohydramnios 羊水过少ovarian tumour 卵巢肿瘤pelvic inflammatory disease 盆腔炎placenta previa 前置胎盘placental abruption 胎盘早期剥离pregnancy-hypertension syndrome 妊娠高血压综合症premature birth 早产premature rupture of membrane 胎膜早破postpartum hemorrhage 产后出血puerperal infection 产褥感染rupture of uterus 子宫破裂trichomonas vaginitis 滴虫性阴道炎uteroplacental apoplexy 子宫胎盘卒中vulvitis 外阴炎Ophthalmology and Otorhinolaryngology 五官科amblyopia 弱视amygdalitis, tonsillitis 扁桃体炎astigmatism 散光carcinoma of nasopharynx鼻咽癌carcinoma of larynx 喉癌cataract 白内障tinnitus 耳鸣chalazion 霰粒肿,脸板腺囊肿colour blindness 色盲deflection of nasal septum 鼻中隔偏曲deafness 聋furuncle of nasalvestibule 鼻前庭疖glaucoma 青光眼heterotropia 斜视hyperopia 远视injury of cornea 角膜损伤ceruminal impaction 耵聍嵌塞iritis 虹膜炎keratitis 角膜炎labyrinthitis 迷路炎,内耳炎laryngitis 喉炎mastoiditis 乳突炎myopia 近视nasal sinusitis 鼻窦炎otitis media 中耳炎obstruction of larynx 喉梗阻peritonsillar abscess 扁桃体中脓肿pharyngitis 咽炎rhinitis 鼻炎Dermatoloty 皮科acne 痤疮carcinoma of skin 皮肤癌bed sore 褥疮decubitus ulcer 褥疮性溃疡drug eruption 药皮疹eczema 湿疹herpes simplex 单纯疱疹herpes zoster 带状疱疹lupus erythematosis 红斑狼疮psoriasis 牛皮癣urticaria 荨麻疹wart 疣neuralgia 神经痛neurasthenia 神经衰弱paralysis 麻痹peritonitis 腹膜炎pharyngitis 咽炎phtisis 痨病,肺结核pneumonia 肺炎poliomyelitis 脊髓灰质炎rabies 狂犬病rheumatism 风湿病rickets, rachitis 佝偻病scabies, itch 疥疮scarlet fever 猩红热sciatica 坐骨神经痛sclerosis 硬化septicemia, septicaemia 败血病sinusitis 窦炎smallpox 天花anemia, anaemia 贫血angina pectoris 心绞痛appendicitis 阑尾炎arthritis 关节炎bronchitis 支气管炎cancer 癌catarrh 卡他,粘膜炎chicken pox, varicella 水痘cholera 霍乱cold 感冒,伤风,着凉(head) cold 患感冒diabetes 糖尿病diphtheria 白喉eczema 湿疹epilepsy 癫痫erysipelas 丹毒gangrene 坏疽German measles, rubella 风疹gout 痛风headache 头痛hemiplegy, hemiplegia 偏瘫,半身不遂interus, jaundice 黄疸indigestion 消化不良influenza, flu 流感insanity 精神病leukemia 白血病malaria 疟疾malnutrition 营养不良Malta fever 马耳他热,波状热measles 麻疹migraine, splitting headache 偏头痛miocardial infarction 心肌梗塞mumps 流行性腮腺炎swamp fever 沼地热syncope 晕厥syphilis 梅毒tetanus 破伤风thrombosis 血栓形成torticollis, stiff neck 斜颈tuberculosis 结核病tumour 瘤(美作:tumor)typhus 斑疹伤寒urticaria, hives 荨麻疹whooping cough 百日咳yellow fever 黄热病zona, shingles 带状疮疹cough 咳嗽asthma 哮喘pneumonia 肺炎heart disease 心脏病arrhythmia 心律不齐indigestion 消化不良gastritis 胃炎appendicitis 盲肠炎hepatitis 肝炎dermatitis皮炎freckle/ephelis 痣,雀斑acne 粉刺flu 流感diarrhoea 痢疾quarantine 检疫vaccinate 打疫苗endemic 水土不服relapse 复发症casualty急症stupor 昏迷sprain 扭伤scalding烫伤graze 擦伤scratch 搔挠trauma 外伤bruise 淤伤fracture骨折dislocation 脱臼tinnitus 耳鸣trachoma 沙眼colour blindness 色盲nearsightedness/myopia 近视astigmatism 散光gingivitis 牙龈炎cavity 龋齿fever 发烧discomfort/disorder 不适malnutrition 营养不良incubation 潜伏期asthenia 虚弱poisoning 中毒fatigue 疲劳heat stroke 中暑itching 发痒ache/pain 痛tetanus 破伤风night sweat 盗汗chill 打冷颤pale 脸色发白shuddering 发抖inflammation 炎症acute 急症chronic 慢性病congenital 先天性病nausea恶心vomit 呕吐。

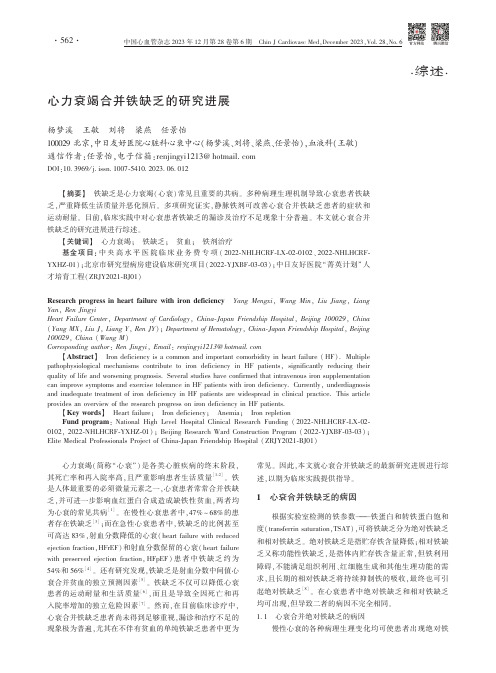

心力衰竭合并铁缺乏的研究进展

㊃综述㊃心力衰竭合并铁缺乏的研究进展杨梦溪㊀王敏㊀刘将㊀梁燕㊀任景怡100029北京,中日友好医院心脏科心衰中心(杨梦溪㊁刘将㊁梁燕㊁任景怡),血液科(王敏)通信作者:任景怡,电子信箱:renjingyi1213@DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2023.06.012㊀㊀ʌ摘要ɔ㊀铁缺乏是心力衰竭(心衰)常见且重要的共病㊂多种病理生理机制导致心衰患者铁缺乏,严重降低生活质量并恶化预后㊂多项研究证实,静脉铁剂可改善心衰合并铁缺乏患者的症状和运动耐量㊂目前,临床实践中对心衰患者铁缺乏的漏诊及治疗不足现象十分普遍㊂本文就心衰合并铁缺乏的研究进展进行综述㊂ʌ关键词ɔ㊀心力衰竭;㊀铁缺乏;㊀贫血;㊀铁剂治疗基金项目:中央高水平医院临床业务费专项(2022-NHLHCRF-LX-02-0102㊁2022-NHLHCRF-YXHZ-01);北京市研究型病房建设临床研究项目(2022-YJXBF-03-03);中日友好医院 菁英计划 人才培育工程(ZRJY2021-BJ01)Research progress in heart failure with iron deficiency㊀Yang Mengxi,Wang Min,Liu Jiang,LiangYan,Ren JingyiHeart Failure Center,Department of Cardiology,China-Japan Friendship Hospital,Beijing100029,China(Yang MX,Liu J,Liang Y,Ren JY);Department of Hematology,China-Japan Friendship Hospital,Beijing 100029,China(Wang M)Corresponding author:Ren Jingyi,Email:renjingyi1213@ʌAbstractɔ㊀Iron deficiency is a common and important comorbidity in heart failure(HF).Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to iron deficiency in HF patients,significantly reducing theirquality of life and worsening prognosis.Several studies have confirmed that intravenous iron supplementationcan improve symptoms and exercise tolerance in HF patients with iron deficiency.Currently,underdiagnosisand inadequate treatment of iron deficiency in HF patients are widespread in clinical practice.This articleprovides an overview of the research progress on iron deficiency in HF patients.ʌKey wordsɔ㊀Heart failure;㊀Iron deficiency;㊀Anemia;㊀Iron repletionFund program:National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding(2022-NHLHCRF-LX-02-0102,2022-NHLHCRF-YXHZ-01);Beijing Research Ward Construction Program(2022-YJXBF-03-03);Elite Medical Professionals Project of China-Japan Friendship Hospital(ZRJY2021-BJ01)㊀㊀心力衰竭(简称 心衰 )是各类心脏疾病的终末阶段,其死亡率和再入院率高,且严重影响患者生活质量[1-2]㊂铁是人体最重要的必须微量元素之一,心衰患者常常合并铁缺乏,并可进一步影响血红蛋白合成造成缺铁性贫血,两者均为心衰的常见共病[1]㊂在慢性心衰患者中,47%~68%的患者存在铁缺乏[3];而在急性心衰患者中,铁缺乏的比例甚至可高达83%,射血分数降低的心衰(heart failure with reduced ejection fraction,HFrEF)和射血分数保留的心衰(heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,HFpEF)患者中铁缺乏约为54%和56%[4]㊂还有研究发现,铁缺乏是射血分数中间值心衰合并贫血的独立预测因素[5]㊂铁缺乏不仅可以降低心衰患者的运动耐量和生活质量[6],而且是导致全因死亡和再入院率增加的独立危险因素[7]㊂然而,在目前临床诊疗中,心衰合并铁缺乏患者尚未得到足够重视,漏诊和治疗不足的现象极为普遍,尤其在不伴有贫血的单纯铁缺乏患者中更为常见㊂因此,本文就心衰合并铁缺乏的最新研究进展进行综述,以期为临床实践提供指导㊂1㊀心衰合并铁缺乏的病因根据实验室检测的铁参数 铁蛋白和转铁蛋白饱和度(transferrin saturation,TSAT),可将铁缺乏分为绝对铁缺乏和相对铁缺乏㊂绝对铁缺乏是指贮存铁含量降低;相对铁缺乏又称功能性铁缺乏,是指体内贮存铁含量正常,但铁利用障碍,不能满足组织利用㊁红细胞生成和其他生理功能的需求,且长期的相对铁缺乏将持续抑制铁的吸收,最终也可引起绝对铁缺乏[8]㊂在心衰患者中绝对铁缺乏和相对铁缺乏均可出现,但导致二者的病因不完全相同㊂1.1㊀心衰合并绝对铁缺乏的病因慢性心衰的各种病理生理变化均可使患者出现绝对铁㊃265㊃中国心血管杂志2023年12月第28卷第6期㊀Chin J Cardiovasc Med,December2023,Vol.28,No.6缺乏,其原因主要包括铁的摄入不足㊁吸收障碍以及丢失过多[1,9-10]㊂在铁摄入方面,心衰患者常因纳差㊁营养不良引起铁摄入不足,也可因合并肾脏疾病的低蛋白饮食导致铁摄入减少㊂Hughes等[11]研究发现,心衰患者每天的铁摄入量明显低于正常健康者,在严重心衰的患者(NYHA心功能分级Ⅲ级和Ⅳ级)中更为显著㊂在铁吸收方面,心衰患者常存在胃肠道黏膜淤血水肿,可明显降低铁的吸收㊂此外,心衰患者应用抗血小板或抗凝药物时可诱发消化道溃疡或出血,亦可引起铁丢失过多㊂1.2㊀心衰合并相对铁缺乏的病因心衰系统性炎症状态是引起相对铁缺乏的主要原因,其机制主要是影响调节铁稳态的重要因子 铁调素(hepcidin)的水平㊂铁调素是肝脏合成并分泌的富含半胱氨酸的多肽,在机体内铁平衡的维持中起到负反馈调节作用,其在炎症过程铁代谢中发挥了重要作用[12]㊂铁调素与细胞表面的膜铁转运蛋白结合,促进其内化㊁降解,抑制细胞内的铁转运至循环中,导致储存铁释放减少㊂在炎症状态下,铁调素表达增加,不仅可以抑制十二指肠对铁的吸收,还可抑制肝脏及巨噬细胞内贮存铁的释放,进而减少循环铁并降低铁的生物利用度,导致相对铁缺乏㊂2㊀心衰合并铁缺乏的病理生理学机制心衰导致铁缺乏的病理生理学机制仍不完全清楚,目前认为与全身系统性炎症和神经内分泌系统异常激活等有关㊂心衰患者的白细胞介素1㊁白细胞介素6和肿瘤坏死因子α等炎症因子表达增加,这些促炎因子可引起铁调素水平升高;同时由于心衰患者的肌酐清除率通常减低,可进一步升高体内铁调素水平,进而导致铁利用障碍[9]㊂升高的铁调素通过与十二指肠上皮细胞和脾脏巨噬细胞膜上的铁蛋白结合,使得细胞内向循环释放铁减少与膳食铁吸收障碍,最终导致患者出现相对铁缺乏㊂心衰患者神经内分泌系统持续激活,包括交感神经系统活性增强和肾素-血管紧张素-醛固酮系统激活等㊂去甲肾上腺素和醛固酮分泌增多,通过氧化应激下调铁调蛋白表达,导致与转铁蛋白结合的铁减少,引起各组织器官铁利用障碍㊂在血管紧张素Ⅱ的刺激下,调控细胞内外铁分布的膜铁转运蛋白及其mRNA表达降低,抑制了细胞内铁的释放[13],导致患者出现铁缺乏㊂心衰本身不仅可诱发铁缺乏,更为重要的是,铁缺乏本身也会损害氧化代谢㊁细胞能量和免疫机制,一旦出现铁缺乏会引起心肌细胞线粒体功能障碍及能量代谢异常,进一步加速心衰进展㊂因此,心衰与铁缺乏相互影响,形成恶性循环[14]㊂3㊀铁缺乏降低心衰患者运动耐量并增加死亡率多项研究表明,铁缺乏与心衰患者运动耐量下降和生活质量降低独立相关,而与是否合并贫血或左心室射血分数(left ventricular ejection fraction,LVEF)无关㊂Martens等[15]研究发现,在慢性心衰患者中,无论LVEF是否降低,铁缺乏均普遍存在且显著降低患者峰值耗氧量,证实合并铁缺乏后心衰患者活动耐力明显下降㊂进一步的回归分析证实,铁缺乏而非贫血是降低心衰患者生活质量的独立危险因素㊂总的来说,在心衰合并铁缺乏中,以患者为导向的结局包括峰值耗氧量降低,6min步行距离更短,健康相关生活质量恶化等[16-17]㊂此外,铁缺乏还可导致患者预后不良㊂已有观察性研究提示,心衰患者一旦出现铁缺乏,无论其是否存在贫血,死亡率均显著升高㊂但如果铁缺乏同时合并贫血,则患者的预后更差㊂一项评估铁缺乏对慢性心衰患者预后影响的研究发现,在578例HFrEF患者中,47%的患者存在绝对或相对铁缺乏,铁缺乏显著增加心衰患者全因死亡及再入院风险[18]㊂为进一步评估铁缺乏与贫血预测心衰患者预后的能力,一项纳入4个队列研究㊁共1506例慢性心衰患者㊁中位随访1.92年的汇总分析发现,铁缺乏与心衰患者疾病严重程度相关,无论是否合并贫血,铁缺乏均是心衰患者死亡的独立预测因素,并且其预测能力高于贫血㊂值得注意的是,在随访至6个月时,合并铁缺乏的患者死亡率已显著高于不合并铁缺乏的患者(8.7%比3.6%,P<0.001),且该差异在近2年的随访期间持续存在[19]㊂上述研究均提示无论是否合并贫血,铁缺乏是心衰患者预后恶化的独立危险因素㊂4㊀心衰合并铁缺乏的诊断由于体内贮存铁含量无法直接测量,临床上应用铁蛋白和TSAT来间接反映体内铁贮存和利用的情况㊂在一般人群中,铁缺乏的诊断为铁蛋白<30μg/L和TSAT<16%㊂但在心衰患者中,由于存在明显的炎症状态,可导致铁蛋白非特异性升高㊂因此,铁蛋白的诊断阈值应高于一般人群,以提高铁缺乏诊断的特异性㊂依据2018年‘中国心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南“㊁2021年‘欧洲心脏病学会急慢性心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南“以及最新的2022年‘美国心力衰竭管理指南“的建议,在慢性心衰中,绝对铁缺乏定义为铁蛋白< 100μg/L,相对铁缺乏定义为铁蛋白100~299μg/L且TSAT<20%[20-22]㊂此外,有研究提出可溶性转铁蛋白受体(soluble transferrin receptor,sTfR)和铁调素也可用于铁缺乏的诊断并且可以协助鉴别绝对或相对铁缺乏㊂sTfR是转铁蛋白受体在蛋白水解酶的降解作用下产生的,与体内转铁蛋白受体正相关,能准确反映转铁蛋白受体数量,因此,sTfR可间接反映体内贮存铁含量㊂铁缺乏时sTfR水平升高且不受炎症㊁感染影响,而且因sTfR主要由骨髓产生,即使在营养不良㊁低白蛋白血症的患者中,sTfR仍可升高[23]㊂铁调素水平与储存铁含量密切相关,铁缺乏可抑制肝细胞中铁调素的产生和释放,使循环中铁调素明显降低,反映了储存铁的耗尽;而炎症则可刺激铁调素的产生,在心衰全身炎症状态时,尽管存在铁缺乏,铁调素水平反而升高,提示相对铁缺乏㊂因此铁调素可用于诊断㊁鉴别绝对或相对铁缺乏㊂然而,目前sTfR和铁调素的检测尚无标准化阈值,不同检测手段结果㊃365㊃中国心血管杂志2023年12月第28卷第6期㊀Chin J Cardiovasc Med,December2023,Vol.28,No.6差异较大,临床应用较为困难㊂除检测循环中铁代谢的生物标志物外,骨髓中的铁含量不会受到炎症的影响,是确诊铁缺乏的金标准[24]㊂一项针对37例终末期心衰合并贫血患者的研究发现,尽管患者的血清铁㊁铁蛋白均在正常范围,但通过骨髓穿刺进行骨髓铁检测,高达73%的患者骨髓铁含量明显降低,提示骨髓铁检测对存在明显炎症状态的终末期心衰患者可显著提高铁缺乏诊断的敏感性[25]㊂然而,测定骨髓铁需进行有创的骨髓穿刺操作,因此临床实践中较难广泛开展应用㊂5 心衰合并铁缺乏的治疗心衰合并铁缺乏的治疗目前虽无有效的手段,但此类患者如及时发现并进行有效干预,可改善患者生活质量及预后㊂最常用的治疗药物为口服和静脉铁剂,目前已有6项大规模的临床随机对照研究完成了心衰合并铁缺乏患者应用铁剂治疗有效性的评估(表1)㊂5.1㊀口服铁剂口服铁剂应用方便,然而由于生物利用度不高,且常有胃肠道不良反应,导致治疗效果不佳㊂评估口服铁剂能否改善心衰合并铁缺乏患者活动耐力和生活质量的IRONOUT-HF(口服补铁对心衰患者峰值耗氧量的影响)试验[26]发现,随机给予225例心衰合并铁缺乏患者多糖铁复合物或安慰剂治疗16周,尽管口服铁剂增加了心衰患者的血清铁水平,但并不能改善其活动耐力和生活质量,其原因可能与心衰患者中高铁调素水平抑制铁的吸收有关㊂一项纳入5项随机对照研究共590例心衰合并铁缺乏患者的荟萃分析显示,口服铁剂不能改善患者的生活质量和活动耐力,对全因死亡风险无影响[27]㊂但另一项荟萃分析显示,尽管口服铁剂不能改善心衰患者的活动耐力和生活质量,但可降低心衰再入院及全因死亡风险[28]㊂目前,国内外指南均未推荐口服铁剂用于治疗心衰合并铁缺乏患者㊂因此,未来需要更多的临床试验评估口服铁剂在心衰合并铁缺乏患者中的有效性及安全性㊂5.2㊀静脉铁剂5.2.1㊀静脉铁剂对心衰患者生活质量的影响㊀静脉铁剂生物利用度高,是目前唯一证实在慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者中有效的补铁方式㊂最为常用的静脉铁剂为羧基麦芽糖铁(ferric carboxymaltose,FCM)和异麦芽糖酐铁(iron isomaltoside,IIM),以及蔗糖铁㊁右旋糖酐铁㊁葡萄糖酸铁和纳米氧化铁㊂尽管静脉铁剂在输注过程中存在过敏的风险,但在医院进行皮试后罕见过敏性休克,具有较好的安全性㊂多项临床随机对照试验及荟萃分析均提示,应用静脉铁剂可改善心衰合并铁缺乏患者的运动耐量㊁生活质量和临床预后㊂最早评估FCM能否改善慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者症状的FAIR-HF(在慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者中评估FCM的作用)试验[29]共纳入459例慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者,随机给予FCM或安慰剂治疗24周,发现无论是否存在贫血,与安慰剂组相比,FCM组患者自我评估㊁6min步行试验㊁NYHA 心功能分级和生活质量均有所改善,药物的不良反应主要有注射部位疼痛/皮肤异常(1.3%)㊁神经系统紊乱(1%)㊁血管疾病(1%)和胃肠道反应(0.7%)等,与对照组相比无统计学差异,不良反应在可接受范围内㊂随后为了评估更长时间静脉应用FCM对心衰合并铁缺乏患者的获益与安全性,CONFIRM-HF(FCM在慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者中的效果)试验[30]纳入了304例慢性HFrEF 合并铁缺乏患者,随机给予FCM或安慰剂治疗1年,结果证实心衰合并铁缺乏且有临床症状的患者经过长期FCM治疗,可持续改善其运动耐量和生活质量,并降低心衰患者的住院风险㊂且与安慰剂相比,长期静脉应用FCM并不增加呼吸系统㊁神经系统的不良事件发生率㊂由于生活质量㊁6min步行试验等指标存在患者主观影响偏倚,需进一步通过客观指标来明确静脉补铁对心衰合并铁缺乏患者的获益㊂EFFECT-HF(FCM对慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者运动能力的影响)试验[31]则纳入172例心衰合并铁缺乏患者,随机给予FCM或安慰剂治疗24周,通过峰值耗氧量变化这一客观评估运动耐量的指标,再次证实了FCM可提高心衰合并铁缺乏患者的运动能力㊂因此,对于心衰合并铁缺乏患者,通过补充静脉铁可有效改善患者的生活质量和活动耐力,且未增加不良事件㊂5.2.2㊀静脉铁剂对心衰患者预后的影响㊀既往研究表明,应用静脉铁剂在短期内对心衰患者生活质量及活动耐力带来益处㊂为了进一步明确静脉铁剂对HFrEF合并铁缺乏患者的长期疗效和安全性,近期公布的IRONMAN研究[32],共纳入1137例HFrEF合并铁缺乏患者,根据患者体重和血红蛋白给予不同剂量IIM或安慰剂,中位随访2.7年㊂结果显示,IIM组主要终点事件(心衰再入院和心血管死亡)发生率低于常规治疗组,但未达到统计学差异㊂但通过预先设定的敏感性分析发现,IIM组主要终点发生率进一步降低(P= 0.047)㊂IRONMAN研究为心衰患者静脉使用IIM提供了重要数据,进一步表明对于HFrEF合并铁缺乏的患者静脉应用IIM与较低的心衰再住院及心血管死亡风险相关㊂除上述针对慢性心衰患者的静脉铁剂研究外,新近发表在The Lancet杂志上的AFFIRM-AHF(FCM对急性心衰合并铁缺乏的住院患者死亡率及再入院率的影响)试验[33]探讨了应用静脉铁剂对急性心衰患者预后的影响㊂该研究共纳入1110例急性心衰合并铁缺乏患者,在出院前㊁出院后6周㊁12周及24周,根据患者体重和血红蛋白给予不同剂量静脉注射FCM或安慰剂,随访52周㊂结果发现,与安慰剂组相比,接受静脉FCM治疗患者的主要终点事件(心衰再入院和心血管死亡事件复合终点)有下降趋势,但未达到统计学差异(RR=0.79,95%CI:0.62~1.01,P=0.059)㊂一项荟萃分析探讨了静脉铁剂对心衰合并铁缺乏患者预后的影响,共纳入839例心衰合并铁缺乏患者,约90%的患者来自FAIR-HF和CONFIRM-HF研究,其主要发现是, FCM治疗降低心血管再入院和心血管死亡风险(RR=0.59, 95%CI:0.40~0.88,P=0.009),降低心衰再入院和心血管死㊃465㊃中国心血管杂志2023年12月第28卷第6期㊀Chin J Cardiovasc Med,December2023,Vol.28,No.6表1㊀补铁治疗临床试验总结临床研究(注册号)试验设计试验组/对照组(例)主要纳入标准补铁方式随访时间试验结果不良反应I R O N O U T -H F ㊀(N C T 02188784)随机㊁双盲㊁安慰剂对照111/114N Y H A Ⅱ~Ⅳ级,L V E F ɤ40%,㊀9g /d l ɤH b ɤ13.5g /d l ,铁蛋白<100μg /L 或铁蛋白在100~299μg /L 且T S A T <20%口服多糖铁复合物150m g ,2次/d16周p V O 2基本不变,6M W T 距离及㊀K C C Q 评分无统计学差异恶心㊁呕吐㊁黑便F A I R -H F ㊀(N C T 00520780)多中心㊁随机㊁双盲㊁安慰剂对照304/155N Y H A Ⅱ级且L V E F ɤ40%或㊀N Y H A Ⅲ级且L V E F ɤ45%,9g /d l ɤH b ɤ13.5g /d l ,铁蛋白<100μg /L 或铁蛋白在100~299μg /L 且T S A T <20%分为纠正期和维持期㊂在纠正期,每周给予患者F C M 200m g ,直至患者铁缺乏纠正;随后在维持期,每4周给予患者F C M 200m g ,直至24周研究结束24周P G A 改善及N Y H A 级别改善㊀(P <0.001),6M W T 距离增加(P <0.001),K C C Q 评分改善(P <0.001)注射部位疼痛/皮肤异常㊁神经系统紊乱㊁血管疾病㊁胃肠道反应㊁感染C O N F I R M -H F㊀(N C T 01453608)多中心㊁随机㊁双盲㊁安慰剂对照150/151N Y H A Ⅱ~Ⅲ级,L V E F ɤ45%,㊀铁蛋白<100μg /L 或铁蛋白在100~299μg /L 且T S A T<20%分为纠正期和维持期㊂在纠正期,依据H b 水平(<10g /d l ㊁10~14g /d l 或>14g /d l )㊁体重(<70k g 或ȡ70k g ),分别在第0周和第6周给予F C M 500或1000m g ;在维持期,第12㊁24和36周时进行检测,若有铁缺乏,则给予F C M 500m g /次52周6M W T 距离增加(P =0.002),㊀N Y H A 级别改善(P <0.001)㊁P G A 改善(P =0.001)及Q o L 改善(P <0.05)注射部位疼痛/皮肤异常㊁神经系统紊乱㊁胃肠道反应㊁血管疾病E F F E C T -H F㊀(N C T 01394562)多中心㊁随机㊁双盲㊁安慰剂对照86/86N Y H A Ⅱ~Ⅲ级,L V E F ɤ45%,㊀N T -p r o B N P >400p g /m l ,铁蛋白<100μg /L 或铁蛋白在100~299μg /L 且T S A T <20%,p V O 210~20m l ㊃k g -1㊃m i n -1第0周依据H b (<14g /d l 或ȡ14g /d l )和第6周根据体重(<70k g 或>70k g )及H b 水平(<14g /d l 或ȡ14g /d l )分别给予F C M 500或1000m g ;第12周时,若患者存在铁缺乏,予F C M 500m g24周p V O 2基本维持不变(P =0.02),㊀血清铁蛋白和T S A T 水平升高(P <0.05)A F F I R M -A H F㊀(N C T 02937454)多中心㊁随机㊁双盲㊁安慰剂对照535/524急性心衰,L V E F ɤ45%,铁蛋白<100μg /L 或铁蛋白在100~299μg /L 且T S A T <20%急性心衰稳定后,依据H b (<14g /d l 或ȡ14g /d l )予F C M 500或1000m g ;出院后第6周根据体重(<70k g 或>70k g )和H b 水平(<10g /d l ㊁10~14g /d l或>14g /d l )给予F C M 500~1000m g ;在第12周和(或)第24周,若患者铁缺乏持续存在,继续予F C M500m g 52周因心衰再入院和心血管死亡事件复合终点无改善(P =0.059),因心衰再入院的风险降低(P =0.013)I R O N M A N㊀(N C T 02642562)前瞻性㊁多中心㊁随机㊁开放标签㊁盲法终点569/568年龄ȡ18岁㊁有症状的心衰患者,过去24个月内L V E F ɤ45%,且合并铁缺乏(血清铁蛋白<100μg /L ,或T S A T<20%)体重<50k g ,无论H b 如何,静脉注射铁剂20m g /k g ;体重50~70k g ,如果H b ȡ10g /d l ,则静脉注射铁剂1000m g ,如果H b <10g /d l ,则为20m g /k g ;体重ȡ70k g ,静脉注射铁剂20m g /k g ,其中H b ȡ10g /d l 者,最多可至1500m g ,H b <10g /d l 者,最多可至2000m g ㊂第1次随访为第4周,以后每4个月随访1次㊂如果铁蛋白<100μg /L 或T S A T <25%,则在第4周㊁第4个月和之后的每4个月重新给药㊂对照组为常规治疗2.7年I I M 组心衰再入院和心血管死亡发生率低于常规治疗组,但未达到统计学差异(P =0.070);通过预先指定的敏感性分析,I I M 组主要终点发生率进一步降低(P =0.047)㊀㊀注:N Y H A :纽约心脏病协会;L V E F :左心室射血分数;H b :血红蛋白;T S A T :转铁蛋白饱和度;p V O 2:峰值耗氧量;6M W T :6m i n 步行试验;K C C Q :堪萨斯城心肌病问卷;F C M :羧基麦芽糖铁;P G A :患者总体评估;Q o L :生活质量;N T -p r o B N P :N 末端B 型利钠肽原;I I M :异麦芽糖酐铁㊃565㊃中国心血管杂志2023年12月第28卷第6期㊀Chin J Cardiovasc Med,December 2023,Vol.28,No.6亡风险(RR=0.53,95%CI:0.33~0.86,P=0.011),降低心血管再入院和全因死亡风险(RR=0.60,95%CI:0.41~0.88, P=0.009),且静脉铁剂与不良事件风险增加无关[34]㊂另一项网状荟萃分析纳入16项随机对照研究共5205例心衰合并铁缺乏患者,发现使用静脉铁剂可减少心衰再入院(RR= 0.52,95%CI:0.37~0.73,P<0.001),改善生活质量及活动耐力,但未降低全因死亡率[28]㊂最近的一项荟萃分析纳入了10项临床试验,涉及3373例心衰合并铁缺乏患者,其中静脉铁剂组1759例㊂结果显示,静脉铁剂降低了心衰再入院和心血管死亡风险(RR=0.75,95%CI:0.61~0.93,P< 0.01),也减少了首次心衰再入院或心血管死亡的复合终点(OR=0.72,95%CI:0.53~0.99,P=0.04),而对心血管死亡(OR=0.86,95%CI:0.70~1.05,P=0.14)和全因死亡率(OR=0.93,95%CI:0.78~1.12,P=0.47)的影响尚无定论[35]㊂尽管已有的针对慢性心衰患者的临床随机对照研究评估了应用静脉铁剂的有效性,但仍需要更多静脉铁剂对慢性心衰合并铁缺乏患者硬终点改善的研究,目前正在进行的2项大型随机对照试验[FAIR-HF2(NCT03036462)㊁HEART-FID(NCT03037931)]均计划纳入超过1000例慢性心衰合并铁缺乏的患者,评估应用静脉铁剂对其死亡率和再入院率的影响㊂此外,对于HFpEF,静脉铁剂是否同样有效仍不清楚,正在进行的2项大规模临床研究,FAIR-HFpEF (NCT03074591)和IRONMET-HFpEF(NCT04945707),将对此类患者给出更为明确的指导㊂因此,结合现有关于静脉铁剂在心衰合并铁缺乏患者中的临床试验研究结果来看,静脉铁剂可改善患者的预后,且未增加不良事件㊂5.3㊀静脉铁剂引起的铁超载尽管指南推荐心衰合并铁缺乏患者应用静脉铁剂,但在临床实际应用时需注意铁超载问题㊂生理情况下,机体可通过抑制膳食铁在十二指肠的吸收防止铁超载㊂然而,应用静脉铁剂可越过胃肠道抑制铁吸收这一保护机制引起铁超载,使体内铁元素成为非转铁蛋白结合铁,其中一部分为不稳定的血清铁或细胞铁,可催化氧自由基的形成,破坏线粒体㊁脂质㊁蛋白质和核酸;活性氧的形成还将加重心衰和心肌疾病及增加菌血症的风险[36]㊂因此,在应用静脉铁剂纠正心衰患者铁缺乏时,需定期监测患者各项铁参数水平,当患者TSAT水平超过70%~85%时应警惕铁超载㊂5.4㊀指南推荐及静脉铁剂治疗方案基于上述临床循证证据,2018年‘中国心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南“[20]认为静脉补充铁剂有助于改善HFrEF合并铁缺乏患者活动耐力和生活质量(Ⅱb,B)㊂2021年‘欧洲心脏病学会急慢性心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南“[21]建议对所有心衰患者定期筛查全血细胞计数㊁血清铁蛋白浓度和TSAT,以判断是否存在贫血或铁缺乏(Ⅰ,C),对于LVEF<45%且铁缺乏有症状的心衰患者,应静脉补充FCM,以缓解心衰症状,提高运动能力和生活质量(Ⅱa,A)㊂对于近期因心衰住院㊁LVEF<50%且铁缺乏的患者,应考虑静脉补充FCM,以降低心衰住院的风险(Ⅱa,B)㊂2022年‘美国心力衰竭管理指南“[22]认为对于伴或不伴贫血的HFrEF合并铁缺乏患者,应用静脉铁剂可改善患者运动耐量和生活质量(Ⅱa,B),口服铁剂的证据尚不确定㊂尽管国内外指南推荐了静脉铁剂应用于心衰患者的治疗,但指南中并未明确给出标准的治疗方案㊂在已完成的临床随机对照研究(FAIR-HF㊁CONFIRM-HF㊁EFFECT-HF㊁AFFIRM-AHF和IRONMAN)中,由于随访时间不同,应用静脉铁剂次数不同,补铁方案亦不尽相同,但通常可分为纠正期和维持期,最常选用的静脉铁剂为FCM㊂常根据Ganzoni 公式计算铁缺乏量,即铁缺乏量(mg)=体重(kg)ˑ(15-实际血红蛋白浓度)(g/dl)ˑ2.4+500㊂在纠正期,主要依据体重(<70kg或ȡ70kg)及血红蛋白水平(<14g/dl或ȡ14g/dl),分别在第0周和第6周给予FCM500mg或1000mg;在维持期,从第12周起,每隔12周评估有无铁缺乏直至研究结束,若存在铁缺乏则给予FCM500mg/次㊂在静脉铁剂治疗过程中,定期监测铁代谢参数的变化,警惕铁超载,同时也应监测肝肾功能,警惕不良反应㊂6 展望综上所述,临床中心衰患者合并铁缺乏十分常见,显著影响患者预后㊂迄今为止,静脉铁剂是治疗心衰合并铁缺乏的有效方法,可改善患者心衰症状㊁运动耐量和生活质量,该治疗方法亦得到国内外指南的共同推荐,准确评估并及时治疗心衰患者的铁缺乏尤为重要㊂然而,目前在心衰合并铁缺乏的发病机制和临床治疗上仍面临较多挑战,包括静脉铁剂对终末期心衰和HFpEF患者的获益尚不清楚;对血红蛋白> 15g/dl的患者的疗效及安全性,以及在更长随访时间(>1年)内重复使用静脉铁剂的剂量仍有待研究㊂此外,现有研究尚未评估应用静脉铁剂后进行生物标志物监测的频率,且现有结果仍不足以评估应用静脉铁剂是否能够降低慢性心衰患者的死亡率㊂未来仍需更多证据对心衰合并铁缺乏的患者给予更为个体化的指导,要积极研发新型治疗靶点(如铁调素)的相关干预措施以进一步改善患者预后㊂利益冲突:无参㊀考㊀文㊀献[1]von Haehling S,Ebner N,Evertz R,et al.Iron Deficiency inHeart Failure:An Overview[J].JACC Heart Fail,2019,7(1):36-46.DOI:10.1016/j.jchf.2018.07.015.[2]Virani SS,Alonso A,Aparicio HJ,et al.Heart Disease andStroke Statistics-2021Update:A Report From the AmericanHeart Association[J].Circulation,2021,143(8):e254-e743.DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950.[3]Masini G,Graham FJ,Pellicori P,et al.Criteria for IronDeficiency in Patients With Heart Failure[J].J Am CollCardiol,2022,79(4):341-351.DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.039.[4]Beale A,Carballo D,Stirnemann J,et al.Iron Deficiency inAcute Decompensated Heart Failure[J].J Clin Med,2019,8(10):1569.DOI:10.3390/jcm8101569.[5]王震,苏康康,杨晓月,等.不同射血分数心力衰竭患者贫血发生率的相关因素分析[J].中国心血管杂志,2022,27(6):525-530.DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2022.06.004.㊀Wang Z,Su KK,Yang XY,et al.Analysis of related factors ofanemia in patients with heart failure of different ejection fractions[J].Chin J Cardiovasc Med,2022,27(6):525-530.DOI:㊃665㊃中国心血管杂志2023年12月第28卷第6期㊀Chin J Cardiovasc Med,December2023,Vol.28,No.6。

血清HMGB1_与COPD_急性加重期患者炎性指标肺功能参数之间的相关性

管病研究,2022,20(6):481-485.[2]㊀中国心血管健康与疾病报告编写组.中国心血管健康与疾病报告2021概要[J].中国循环杂志,2022,37(6):553-578.[3]㊀魏峰,张松林,张玉顺,等.心力衰竭生物学标志物的临床意义及研究进展[J].重庆医科大学学报,2018,43(3): 311-315.[4]㊀Werhahn SM,Becker C,Mende M,et al.NT-proBNP as amarker for atrial fibrillation and heart failure in four observa-tional outpatient trials[J].ESC Heart Fail,2022,9(1):100-109.[5]㊀Givertz MM,Postmus D,Hillege HL,et al.Renal functiontrajectories and clinical outcomes in acute heart failure[J].Circ Heart Fail,2014,7(1):59-67.[6]㊀Anand IS,Gupta P.Anemia and iron deficiency in heart fail-ure:current concepts and emerging therapies[J].Circula-tion,2018,138(1):80-98.[7]㊀中华医学会心血管病学分会,心力衰竭学组,中国医师学会心力衰竭委员会,等.中国心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南2018[J].中华心血管病杂志,2018,46(10):760-789.[8]㊀Almeida AG.NT-proBNP and myocardial fibrosis:the invisi-ble link between health and disease[J].Am Coll Cardiol, 2017,70(25):3110-3112.[9]㊀国家心血管病医疗质量控制中心专家委员会心力衰竭专家工作组.2020中国心力衰竭医疗质量控制报告[J].中国循环杂志,2021,36(3):221-237.[10]㊀于舟淇,杨巍.心肾综合征病理生理机制及治疗研究的进展[J].心血管康复医学杂志,2021,30(5):606-609.[11]㊀李榕,王亮,钱豪英,等.肌酐作为生物标志物在疾病诊断及药物评价方面的研究进展[J].药物评价研究,2021,44(9):2007-2012.[12]㊀曲巍,付强.贫血对老年慢性心力衰竭患者预后的影响[J].武警后勤学院学报(医学版),2015,24(1):31-33.[13]㊀Senni M,Lopez-Sendon J,Cohen-Solal A,et al.Vericiguatand NT-proBNP in patients with heart failure with reducedejection fraction:analyses from the VICTORIA trial[J].ESC Heart Fail,2022,9(6):3791-3803. [14]㊀An Y,Wang Q,Wang H,et al.Clinical significance ofsFRP5,RBP-4and NT-proBNP in patients with chronicheart failure[J].Am Transl Res,2021,13(6):6305-6311.[15]㊀Losito A,Nunzi E,Pittavini L,et al.Cardiovascular morbid-ity and long term mortality associated with in hospital smallincreases of serum creatinine[J].Nephrol,2018,31(1):71-77.[16]㊀梁德贤,李庆军,陈康荣.慢性充血性心力衰竭患者贫血患病率与心功能的关系及血红蛋白对预后的影响[J].黑龙江医学,2015,39(7):739-741.[17]㊀Oremus M,Don-Wauchope A,McKelvie R,et al.BNP andNT-proBNP as prognostic markers in persons with chronicstable heart failure[J].Heart Fail Rev,2014,19(4):471-505.[18]㊀Zhang S,Hu Y,Zhou L,et al.Correlations between serumintact parathyroid hormone(PTH)and N-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels in elderly patients with chro-nic heart failure(CHF)[J].Arch Gerontol Geriatr,2015,60(2):359-365.ʌ文章编号ɔ1006-6233(2023)10-1649-06血清HMGB1与COPD急性加重期患者炎性指标肺功能参数之间的相关性唐文君1,㊀曾㊀珠1,㊀杨㊀帆2,㊀肖㊀玮1(1.成都中医药大学附属医院呼吸内科,㊀四川㊀成都㊀6100722.成都医学院第一附属医院呼吸与危重医学科,㊀四川㊀成都㊀610500)ʌ摘㊀要ɔ目的:分析血清高迁移率族蛋白1(HMGB1)与急性加重期慢性阻塞性肺疾病(AECOPD)患者炎性指标㊁肺功能参数之间的相关性㊂方法:从2020年1月至2022年6月到我院就诊的AECOPD 患者中选取104例纳入AECOPD组;从就诊的稳定期慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)患者中选取104例纳入COPD组;从同期健康体检者中选取104例那纳入健康对照组㊂比较各组入院时的外周血相关指标[HMGB1㊁缺氧诱导因子1α(HIF-1α)㊁白细胞计数(WBC)]水平㊁血清炎性因子[白细胞介素-6(IL-6)㊁C反应蛋白(CRP)㊁降钙素原(PCT)]水平及肺功能参数[6min步行距离(6MWD)㊁肺动脉压㊁二氧化碳分压(PaCO2)㊁氧分压(PaO2)];分析血清HMGB1与上述炎性指标及肺功能参数的关系㊂结果:三组入院时的血清HMGB1㊁HIF-1α㊁IL-6㊁CRP㊁PCT水平及WBC均表现为AECOPD组>COPD组>健康㊃9461㊃ʌ基金项目ɔ四川省科学技术厅项目,(编号:2022YFS0423);成都市科学技术局项目,(编号:2021-YF05-02035-SN)对照组,组间比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)㊂三组入院时的6MWD值及PaO2水平均表现为AECO-PD组<COPD组<健康对照组,组间比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)㊂三组入院时的肺动脉压㊁PaCO2水平均表现为AECOPD组>COPD组>健康对照组,组间比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)㊂Pearson相关性分析显示,AECOPD患者入院时的血清HMGB1水平与IL-6㊁CRP㊁肺动脉压水平呈正相关(r分别=0.566㊁0.287㊁0.230,P均<0.05),与PaO2水平呈负相关(r=-0.212,P<0.05)㊂结论:与稳定期COPD及健康体检者相较,AECOPD患者的血清HMGB1水平异常升高,且与IL-6㊁CRP㊁肺动脉压㊁PaO2水平密切相关㊂ʌ关键词ɔ㊀慢性阻塞性肺疾病;㊀急性加重期;㊀血清高迁移率族蛋白1;㊀肺功能;㊀相关性ʌ文献标识码ɔ㊀A㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀ʌdoiɔ10.3969/j.issn.1006-6233.2023.10.012Correlation between Serum HMGB1and Inflammatory Indicators and Lung Function Parameters in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of COPDTANG Wenjun,ZENG Zhu,et al(The Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine,Sichuan Chengdu610072,China)ʌAbstractɔObjective:To analyze the correlation of serum high mobility group protein1(HMGB1)with inflammatory indicators and pulmonary function parameters in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic ob-structive pulmonary disease(AECOPD).Methods:A total of104patients with AECOPD who were treated in the hospital from January2020to June2022were selected and included in AECOPD group,and another104 patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD)were enrolled as COPD group.104health-y subjects with physical examination during the same time period were included in healthy control group.The levels of peripheral blood related indicators[HMGB1,hypoxia-inducible factor-1α(HIF-1α),white blood cell count(WBC)]and serum inflammatory factors[interleukin-6(IL-6),C-reactive protein(CRP), procalcitonin(PCT)]and pulmonary function parameters[6-minute walk distance(6MWD),pulmonary ar-tery pressure,partial pressure of carbon dioxide(PaCO2),partial pressure of oxygen(PaO2)]were com-pared among the groups at admission.The relationship between serum HMGB1and the above inflammatory in-dicators and pulmonary function parameters was analyzed.Results:The levels of serum HMGB1,HIF-1α, IL-6,CRP,PCT and WBC in the three groups at admission were manifested as AECOPD group>COPD group >healthy control group(P<0.05).The6MWD and PaO2at admission were shown as AECOPD group<COPD group<healthy control group(P<0.05).The pulmonary artery pressure and PaCO2of the three groups at ad-mission showed AECOPD group>COPD group>healthy control group(P<0.05).Pearson correlation analysis showed that serum HMGB1level at admission was positively correlated with IL-6,CRP and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with AECOPD(r=0.566,0.287,0.230,all P<0.05),and was negatively correlated with PaO2(r=-0.212,P<0.05).Conclusion:Compared with patients with stable COPD and healthy sub-jects,serum HMGB1level in patients with AECOPD is abnormally increased,and serum HMGB1is closely related to IL-6,CRP,pulmonary artery pressure and PaO2.ʌKey wordsɔ㊀Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;㊀Acute exacerbation;㊀Serum high mobility group protein1;㊀Pulmonary function;㊀Correlation㊀㊀慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,COPD)是一种不可逆的肺功能损伤,患者以呼吸气流受限为特征,主要表现为胸闷㊁气短㊁咳痰等症状㊂抽烟㊁职业性粉尘接触㊁感染等均是引发COPD的相关因素㊂近年来随着空气污染的加重,COPD的发病率呈升高趋势㊂调查显示,COPD及相关疾病已成为世界第3大死因,至2060年可造成超540万人次死亡[1]㊂急性加重期COPD(acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,AECOPD)指呼吸道症状急性加重超过日常变异水平且需改变治疗方案,该病㊃0561㊃可诱发心血管疾病及呼吸衰竭等并发症,导致死亡㊂因此,探究AECOPD的致病机制,监测疾病进展,是改善患者预后的重要环节㊂血清高迁移率族蛋白1(highmobility group protein1,HMGB1)是与损伤相关的高度保守核蛋白,在多种肺泡细胞中表达,参与细胞的分化㊁转移㊁免疫应答等过程,其血清水平升高可能与肺部感染加重密切相关[2],但关于其与白细胞介素-6 (interleukin-6,IL-6)㊁C反应蛋白(C-reactive protein, CRP)等炎性因子水平及肺功能参数的关系还需更多临床支持㊂本研究选取同期到我院就诊的AECOPD㊁COPD患者及健康体检者为受试对象,获得如下报道㊂1㊀资料与方法1.1㊀临床资料:从2020年1月至2022年6月到我院就诊的AECOPD患者中选取104例纳入AECOPD组;从就诊的稳定期COPD患者中选取104例纳入COPD 组;从同期健康体检者中选取104例纳入健康对照组㊂AECOPD组患者中男61例,女43例;年龄50~81岁,平均(65.52ʃ8.21)岁㊂COPD组患者中男68例,女36例;年龄52~80岁,平均(66.10ʃ9.33)岁㊂健康对照组受试者中男59例,女45例;年龄49~78岁,平均(64.85ʃ8.24)岁㊂比较三组间一般资料比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)㊂纳入标准:①AECOPD组㊁COPD组患者经临床诊疗确诊符合‘慢性阻塞性肺疾病基层诊疗指南(2018年)“[3]中相关诊断标准: COPD诊断:慢性咳嗽㊁咳痰㊁呼吸困难;有危险因素暴露史;肺功能检查吸入支气管扩张剂后第1秒用力呼气容积(forced expiratory volume in one second,FEV1)/用力肺活量(forced vital capacit,FVC)<0.7,排除其他疾病㊂AECOPD诊断:COPD患者出现气促加重㊁痰量增加㊁痰变脓性中2项即可确诊㊂②所有受试者入组前3个月未服用过免疫抑制剂㊁激素等影响本研究检测指标水平的药物;③所有受试者自愿参加本研究,签署知情同意书㊂排除标准:①需行机械通气或于重症监护室治疗者;②合并严重感染㊁血液系统疾病㊁自身免疫病㊁恶性肿瘤者;③心㊁肝㊁肾功能不全者;④近半年内重大外科手术史者;⑤患有先天性肺病㊁支气管扩张等其他肺部疾病者;⑥肢体运动功能障碍,无法完成6min步行距离(6-minute walk distance,6MWD)测定者㊂健康对照组均为本院健康体检者,且排除AECO-PD㊁COPD及其他呼吸系统疾病诊断,其余排除标准同AECOPD组㊁COPD组㊂本研究符合赫尔辛基人体试验标准,经医院伦理委员会批准㊂1.2㊀方㊀法1.2.1㊀血液生化指标检测:采患者入院24h清晨空腹静脉血4mL,采用Eppendorf5425离心机以3500r/ min,室温下离心10min,离心半径6cm,收集上清液于-80ħ冰箱保存备用㊂采用全自动生化分析仪(日立7600)及ELISA法测定血清HMGB1㊁IL-6㊁CRP㊁降钙素原(procalcitonin,PCT)水平;采用放射免疫法测定血清缺氧诱导因子1α(hypoxia-inducible factor-1α,HIF -1α)水平;相关试剂盒购自上海科艾博生物技术有限公司,所有操作均由专业检验科人员严格按照试剂盒说明进行㊂血常规检查测定白细胞计数(white blood cell count,WBC)㊂1.2.2㊀肺功能参数测定:采用6MWD测定患者活动量,患者测定前休息30min,而后在标有长度的医院走廊内行走,记录其6min步行距离,中途允许停歇㊂留取患者入院24h内的桡/股动脉血,采用全自动血气分析仪(罗氏cobas-b-123)测定二氧化碳分压(partial pressure of carbon dioxide,PaCO2)㊁氧分压(partial pres-sure of oxygen,PaO2)水平㊂采用彩色多普勒超声心动图(GE Vivid7-BT06)测定收缩期肺动脉压力㊂1.3㊀统计学方法:采用SPSS22.0进行数据处理分析,血清HMGB1㊁IL-6水平等计量资料以均数ʃ标准差( x ʃs)表示,三组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较LSD-t检验;性别等计数资料以n(%)表示,采用χ2检验;采用Pearson相关分析血清HMGB1水平与炎性指标及肺功能参数的关系;以P<0.05表示差异或相关性有统计学意义㊂2㊀结㊀果2.1㊀三组入院时的外周血相关指标水平比较:三组入院时的血清HMGB1㊁HIF-1α水平及WBC差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),且AECOPD组>COPD组>健康对照组(P<0.05),见表1㊂表1㊀三组入院时的外周血相关指标水平比较( xʃs)组别例数HMGB1(μg/L)HIF-1α(ng/L)WBC(ˑ109L-1) AECOPD组104135.72ʃ26.37∗#202.30ʃ16.25∗#9.63ʃ0.58∗# COPD组104105.46ʃ20.15∗168.37ʃ13.62∗7.82ʃ0.61∗㊃1561㊃健康对照组10468.14ʃ10.3272.58ʃ12.41 6.94ʃ0.63F 295.9902339.429530.942P<0.001<0.001<0.001㊀㊀注:与健康对照组比较,∗P<0.017;与COPD 组比较,#P<0.0172.2㊀三组入院时的血清炎性因子水平比较:三组血清IL -6㊁CRP ㊁PCT 水平差异有统计学意义(P <0.05),且AECOPD 组>COPD 组>健康对照组(P<0.05),见表2㊂表2㊀三组入院时的血清炎性因子水平比较( xʃs)组别例数IL -6(pg /mL )CRP (mg /L )PCT (ng /mL )AECOPD 组10476.25ʃ6.04∗#32.35ʃ4.02∗#9.54ʃ1.20∗#COPD 组10451.38ʃ5.63∗25.17ʃ3.58∗7.61ʃ1.15∗健康对照组1045.78ʃ0.89 1.65ʃ0.390.85ʃ0.10F 5778.1532762.0722343.303P<0.001<0.001<0.001㊀㊀注:与健康对照组比较,∗P<0.017;与COPD 组比较,#P<0.0172.3㊀三组入院时的肺功能参数比较:三组入院时的6MWD 值及PaO 2水平差异有统计学意义(P <0.05),且AECOPD 组<COPD 组<健康对照组(P <0.05)㊂三组入院时的肺动脉压㊁PaCO 2水平差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),且AECOPD 组>COPD 组>健康对照组(P <0.05),见表3㊂表3㊀三组入院时的肺功能参数比较( xʃs)组别例数6MWD (m )肺动脉压(mmHg )PaCO 2(mmHg )PaO 2(mmHg )AECOPD 组104242.39ʃ22.62∗#50.20ʃ9.41∗#65.03ʃ6.42∗#69.50ʃ7.25∗#COPD 组104314.58ʃ26.73∗32.58ʃ8.29∗59.51ʃ6.53∗82.37ʃ6.46∗健康对照组104397.30ʃ35.899.92ʃ0.5333.12ʃ3.4597.32ʃ1.01F 745.613807.434947.661634.541P<0.001<0.001<0.001<0.001㊀㊀注:与健康对照组比较,∗P<0.017;与COPD 组比较,#P<0.0172.4㊀AECOPD 患者入院时血清HMGB1水平与炎性因子㊁肺功能参数等指标的相关性:Pearson 相关分析显示,AECOPD 患者入院时的血清HMGB1水平与IL -6㊁CRP ㊁肺动脉压水平呈正相关(P <0.05),与PaO 2水平呈负相关(P<0.05),见表4㊂表4㊀血清HMGB1水平与炎性因子肺功能参数等指标的相关性指标统计值HIF -1αWBC IL -6CRP PCT 6MWD 肺动脉压PaCO 2PaO 2HMGB1r0.1210.1860.5660.2870.132-0.1240.2300.131-0.212P 0.2220.059<0.0010.0030.1820.2100.0190.1840.0273㊀讨㊀论COPD 目前已成为全球公共卫生问题,其炎细胞㊃2561㊃浸润可累及内分泌系统㊁骨骼系统等多种组织,若不及时治疗病情加重,则诱发AECOPD㊂AECOPD患者短期内可出现呼吸困难加重,痰量增多,咳嗽加剧等症状,临床死亡率高㊂目前AECOPD的致病机制尚未完全明确,但关于机体炎性因子过度分泌对肺组织结构的破坏作用已形成共识㊂HMGB1主要来源有2种,一种由单核巨噬细胞㊁单核细胞等炎性细胞主动分泌,另一种由坏死细胞被动分泌,可扩大组织炎症级联反应,在多种疾病进展中发挥作用㊂此前Pouwels等经小鼠实验表明HMGB1与白细胞介素-37(IL-37)激活可诱导急性肺损伤,抑制肺泡上皮修复[4]㊂本研究显示AECOPD患者的血清HMGB1水平较COPD患者及健康受试者异常升高,且与IL-6㊁CRP㊁肺动脉压㊁PaO2水平显著相关,这为呼吸系统疾病的临床诊疗提供新方向㊂本研究中三组血清HMGB1㊁HIF-1α㊁IL-6㊁CRP㊁PCT及外周血WBC水平,AECOPD组>COPD组>健康对照组㊂说明上述炎性指标在COPD患者病情严重程度评估方面具有一定指导意义㊂IL-6作为一种多功能细胞因子,主要由单核巨噬细胞㊁T淋巴细胞合成释放,参与机体免疫调节,加剧炎性损伤㊂有报道称血清IL-6水平升高是COPD急性加重的预测指标,AECO-PD组患者的IL-6水平高于COPD稳定期及健康对照组㊂PCT主要由肺组织神经内分泌细胞及甲状腺髓质C细胞分泌,通常状态下血浆水平稳定,当机体出现细菌㊁真菌等感染时水平明显升高[5]㊂CRP是机体较为敏感的急性期时项蛋白,可激活补体,增强吞噬作用,以清除病原微生物㊂一项回顾性分析显示血清PCT㊁CRP可辅助诊断COPD合并Ⅱ型呼吸衰竭患者预后,与肺部CT联合诊断的效能为0.835[6]㊂Francis等[7]证明给予AECOPD住院患者CRP水平监测指导可有效反映患者病情状况,降低治疗过程中的抗生素用量㊂核蛋白HIF-1α普遍存在于哺乳动物细胞,缺氧状态下其降解作用得到抑制,与β亚基结合形成HIF,参与细胞核内基因转录[8]㊂贺孟君等[9]报道AECOPD患者血清HIF-1α高于正常水平,与肺功能密切相关,这为本研究提供理论支持㊂比较各组肺功能参数,结果显示三组6MWD值及PaO2水平:AECOPD组<COPD组<健康对照组,三组肺动脉压㊁PaCO2水平:AECOPD组>COPD组>健康对照组㊂肺动脉压升高可提示肺部炎症损伤,肺部血管平滑肌细胞增殖,血管内皮损伤均可提高血管阻力,形成肺动脉高压㊂Kovacs等[10]回顾性分析142例COPD 患者的临床资料,发现肺动脉高压严重程度是影响患者预后的相关因素㊂血氧PaCO2㊁PaO2水平是反映肺通气功能的重要指标㊂相关研究显示COPD合并呼吸衰竭患者的PaO2水平较低,PaCO2水平较高,且与细胞因子水平密切相关[11]㊂进一步分析血清HMGB1水平与炎性指标及肺功能参数的关系,显示HMGB1与IL-6㊁CRP㊁肺动脉压呈正相关,与PaO2水平呈负相关㊂表明HMGB1水平是评估COPD发生发展重要指标㊂近期一项非随机队列研究发现COPD患者HMGB1㊁IL-6㊁肿瘤坏死因子α(tumor necrosis fctor-alpha,TNF-α)及HIF-1α与肺动脉压呈正相关,与FEV1/FVC呈负相关㊂还有研究显示COPD患者痰液中HMGB1㊁IL-37㊁热应激蛋白(Heatstressproteins,HSP70)水平与S100A8蛋白浓度呈负相关[12]㊂综上所述,AECOPD患者的血清HMGB1水平异常升高,与IL-6㊁CRP㊁肺动脉压呈正相关,与PaO2水平呈负相关,这为AECOPD的临床诊断及预后评估提供新思路㊂ʌ参考文献ɔ[1]㊀中华医学会呼吸病学分会慢性阻塞性肺疾病学组,中国医师协会呼吸医师分会慢性阻塞性肺疾病工作委员会.慢性阻塞性肺疾病诊治指南(2021年修订版)[J].中华结核和呼吸杂志,2021,44(3):170-205.[2]㊀Yang K,Fan M,Wang X,et ctate promotes macrophageHMGB1lactylation,acetylation,and exosomal release inpolymicrobial sepsis[J].Cell Death Differ,2022,29(1):133 -146.[3]㊀中华医学会,中华医学会杂志社,中华医学会全科医学分会,等.慢性阻塞性肺疾病基层诊疗指南(2018年)[J].中华全科医师杂志,2018,17(11):15.[4]㊀Pouwels SD,Hesse L,Wu X,et al.LL-37and HMGB1in-duce alveolar damage and reduce lung tissue regeneration viaRAGE[J].Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol,2021,321(4):641-652.[5]㊀Lin SH,He YP,Lian JJ,et al.Procalcitonin kinetics to guidesequential invasive-noninvasive mechanical ventilation wea-ning in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructivepulmonary disease and respiratory failure:procalcitonin's ad-junct role[J].Libyan Med,2021,16(1):1961382. [6]㊀邓爱兵,宋健,王静,等.肺CT联合降钙素原㊁C反应蛋白检测对COPDⅡ型呼吸衰竭疗效㊁预后评估的临床价值[J].临床和实验医学杂志,2021,20(2):161-165. [7]㊀Francis NA,Gillespie D,White P,et al.C-reactive proteinpoint-of-care testing for safely reducing antibiotics for acuteexacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:thePACE RCT[J].Health Technol Assess,2020,24(15):1-㊃3561㊃108.[8]㊀Shukla SD,Walters EH,Simpson JL,et al.Hypoxia-induc-ible factor and bacterial infections in chronic obstructive pul-monary disease[J].Respirology,2020,25(1):53-63. [9]㊀贺孟君,张家艳,李燕舞,等.血清SDC-1㊁HIF-1α㊁PGRN与AECOPD患者肺功能及预后恢复的相关性分析[J].标记免疫分析与临床,2021,28(6):977-982. [10]㊀Kovacs G,Avian A,Bachmaier G,et al.Severe pulmonaryhypertension in COPD:impact on survival and diagnosticapproach[J].Chest,2022,162(1):202-212.[11]㊀傅正,苏晋豫,白志余.PaO2㊁PaCO2㊁SaO2对呼吸衰竭病人病情发生发展的影响[J].内蒙古医科大学学报,2020,42(6):623-625.[12]㊀Huang X,Tan X,Liang Y,et al.Differential DAMP releasewas observed in the sputum of COPD,asthma and asthma-COPD overlap(ACO)patients[J].Sci Rep,2019,9(1):19241.ʌ文章编号ɔ1006-6233(2023)10-1654-06CT引导下经皮穿刺肺活检诊断非小细胞肺癌准确率及其影响因素分析刘㊀阳,㊀岳孟超(四川省巴中市中心医院放射科,㊀四川㊀巴中㊀636000)ʌ摘㊀要ɔ目的:探讨CT引导下经皮穿刺肺活检(PTNB)诊断非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)准确率及其影响因素㊂方法:选取2020年5月至2022年5月在本院就诊的98例NSCLC患者为研究对象,均行PT-NB并以术后病理检查结果为金标准,统计PTNB诊断NSCLC结果,分析PTNB诊断NSCLC准确率的影响因素㊂结果:PTNB诊断NSCLC准确率为87.76(86/98),其中,诊断腺癌㊁鳞癌㊁大细胞癌㊁腺鳞癌的准确率分别为91.53%(54/59)㊁93.94(31/33)㊁0.00%(0/2)㊁25.00%(1/4)㊂单因素分析结果显示,诊断准确组和诊断不准确组在性别㊁年龄㊁是否合并钙化㊁穿刺活检组织大小㊁穿刺次数比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);在病灶位置㊁病灶长径㊁病灶与胸壁的距离㊁是否合并坏死㊁穿刺深度比较,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);多因素分析结果显示,病灶位置为下叶㊁病灶长径<2cm㊁病灶与胸壁的距离<2cm㊁合并坏死是影响PTNB诊断NSCLC准确率的独立危险因素㊂结论:PTNB应用于NSCLC,诊断腺癌和鳞癌的价值较高,诊断大细胞癌和腺鳞癌准确率偏低,影响PTNB诊断NSCLC准确率的独立危险因素有病灶位置为下叶㊁病灶长径<2cm㊁病灶与胸壁的距离<2cm㊁合并坏死,针对性采取措施,有利于提高诊断准确率㊂ʌ关键词ɔ㊀CT引导下经皮穿刺肺活检;㊀非小细胞肺癌;㊀准确率;㊀影响因素ʌ文献标识码ɔ㊀A㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀ʌdoiɔ10.3969/j.issn.1006-6233.2023.10.013Diagnostic Accuracy of CT-Guided Percutaneous Transthoracic NeedleBiopsy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Influencing FactorsLIU Yang,YUE Mengchao(Bazhong Central Hospital,Sichuan Bazhong636000,China)ʌAbstractɔObjective:To explore the diagnostic accuracy of CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic nee-dle biopsy(PTNB)for non-small cell lung cancer(NSCLC)and its influencing factors.Methods:A total of 98patients with NSCLC treated in the hospital were enrolled as the research subjects between May2020and May2022.All underwent PTNB.Taking the results of postoperative pathological examination as the golden standard,diagnostic results of PTNB for NSCLC were statistically analyzed,and the influencing factors of di-agnostic accuracy were analyzed.Results:The diagnostic accuracy of PTNB for NSCLC was87.76%(86/ 98),and the accuracy rates of adenocarcinoma,squamous cell carcinoma,large cell carcinoma and adeno-squamous carcinoma were91.53%(54/59),93.94%(31/33),0.00%(0/2)and25.00%(1/4),re-㊃4561㊃ʌ基金项目ɔ四川省医学科研青年创新课题,(编号:Q15010)。

常见病痛的英文说法