Advisors Dr. Aaron Bobick and Dr. Irfan Essa Thesis Example-based Rendering of Textural Phe

Global venture capital insights and trends report 2010

Global venture capital landscape . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Perspective from the United States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Interview with Dr. Kai-Fu Lee, Innovation Works, and Peter Liu, WI Harper Group

Perspective from China . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Interview with Denis Lucquin, SoÕnnova Partners

What makes a country attractive to VC investors? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

by Alexander P. Groh, en Lieser and Heinrich Liechtenstein

Innovation and venture investment trends in China . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

高考冲刺2024年高考英语真题重组卷01(考试版)

冲刺2024年高考英语真题重组卷(上海专用)真题重组卷01I.Listening prehension (第110题, 每题1分;第1120题,每题1.5分;共25分)Section ADirections: In Section A, you will hear ten short conversations between two speakers. At the end of each conversation, a question will be asked about what was said. The conversations and the questions will be spoken only once. After you hear a conversation and the question about it, read the four possible answers on your paper, and decide which one is the best answer to the question you have heard.1. A By the shuttle bus B. By a friend's private carC By the subway D. By a shared bike.2、A. Academic problems. B. The man's university tourC. A Weekend travel planD. The man's tour to a lake3. A. The lady will go hiking next weekB. The lady took her kitten to the clinic last weekC. The man cares about the woman.D. The man didn't go hiking last week.4. A. He wants to travel to Shanghai.B. He has found a suitable job.C. He graduated last month.D. His hometown may be Nantong5. A. Silent B.Crazy C.Relieved. D. Depressed6. A. He wants the house to have a garage and a garden.B.He just wants a space to sunbathe in his house.C.He wants to buy a villa.D.He likes European style decoration7. A. He is crazy about readingB. He likes the decoration style of the libraryC. He is a knowledgeable college studentD. He is a librarian8. A. She likes similar car models.B. She promised a refund within a weekC. She encouraged the man to buy the model carD She has sold a lot of cars9. A.He wants to leave the panyB. He is the project leader of the panyC. He thinks their hard work will be wastedD.He will announce the progress of the project10. A. His child came home late and had no foodB. He has spared some food for his child.C.The whole family waited the child came back for dinnerD. He was very angry with his child's behavior.Section BDirections: In Section B, you will hear two passages and passage or conversation, you will be asked several questions will be read twice, but the question will be spoken only one the four possible answers on your paper and decide which o you have heard.Questions 11 through 13 are based on the following passage11.A. Negative effects of eating too many snacksB. The differences between snacks and meals.C. Strategies of avoiding eating too many snacks before meals.D. Healthy ways of having meals.12. A Avoid eating things between meals.B. Eat as much fruit as possible.C. Eat food like toast shortly before dinner to help with digestion.D. Have a cup of yogurt in the afternoon.13.A. To control the amount of snacks you eatB. To make it healthier.C. To help you focus on the main eventD. To help you know what exactly you are eatingQuestions 14 through 16 are based on the following passage.14. A. 3,000 billion trees. B. 400 billion trees.C.50 million trees.D. 15 billion trees.15.A.Russia has always ranked first in the number of trees.B.Trees would be gone in the future at current removal rate.C.People will plant trees on the cultivated land.D.It is impossible to calculate the total number of trees16. A. To stop people from building houses endlessly.B.To draw people's attention to the importance of trees.C.To call on people to protect the homes of wild animals.D.To attract people to study the growth environment of treesQuestions 17 through 20 are based on the following conversation.17. A. Personal travel plan. B. TravelC. Party dress.D. Organization of work18. A. Jerry will travel by highspeed railB. Jerry is Helen's cousin.C. Jerry's parents live in NanjingD. Jerry is resting in his apartment now19. A. She knows the boss thereB. She booked the table a month earlier.C. Her friend works in this restaurantD. She has a noble status.20. A. Going for a picnic in the forest park.B. Resting in the apartment.C. Going to the Domingo restaurant for dinner.D. Going to Shanghai MuseumII.Grammar and Vocabulary (每题1分;共20分)Section ADirections: After reading the passage below, fill in the blanks to make the passage coherent and grammaticallycorrect. For the blanks with a given word, fill in each blank with the proper form of the given word; for the other blanks, use one word that best fits each blank.(2023年1月上海春季高考)Young EnterpriseYoung Enterprise is an organization that makes serious efforts to teach all types of young people the general principles of running a business(21) __________( originate ) in the United States of America, the idea of Young Enterprise was introduced into Britain by a successful banker.(22)__________ it developed slowly in its early years, the organization grew rapidly later. Young Enterprise is now backed by industry and merce, so that today young people throughout the United Kingdom can participate.A participant in Young Enterprise is known as an Achiever. Young Enterprise primarily meets the needs of young people ( 23 )__________ are still at school, giving them an understanding of industry and the opportunities it may offer them in the future. But it is usually possible (24 )__________ ( include ) young people in the same age group who have left school but have not yet started work.An Adviser is a practicing business executive (管理人员) with an expert knowledge of his own field who volunteers to keep a Young Enterprise pany during its trading year.(25)__________counts for Advisers is an ability to get on with young people and to put across the subject. As the name(26)__________ (imply), Advisers are there to advise: they do not run the panies.Normally, three Advisersone on accountancy, one on production and one on marketing,(27)__________ ( be ) available to each pany. Young Enterprise makes (28)__________ a rule that the Advisers must e from a variety of business occupations.A Sponsor,(29)__________ (reward) only by the success of the enterprise of "its" Achievers, is an organization which participates in Young Enterprise and,(30 )__________ its own expense, provides facilities by making available munications,advice and encouragement.Section B(2021年上海春季高考)Directions: Fill in each blank with a proper word chosen from the box. Each word can be used only once. Note that there is one word more than you need.The nature is part of us. Therefore , it holds a mysterious ( 31 )__________for me. In my memory , the valley was quiet and calm, only to see the wheat all over the mountains waving together in rhythm when the wind blew through, like a ballet troupe. The sun rose every morning as usual, sweeping across the valley and ultimately falling behind the peaks. The snow that falls in winter always melts in spring, bringing new hope to this nature where everything was pleasant and beautiful.Led by fate , I have became an environmentalist and had the honor of being invited to address students about my green lifestyle for a long time. The students were surprised at my lifestyle and maybe they thought my lifestyle was no longer suitable for modern life.Fortunately , they were still listened to whole lecture , saluting or ( 32 )_________ meto some extent the applause implied their encouragement to me. s I began to interact with them under the stage, I was (33 )__________by kids' lack of knowledge of nature so that they had little knowledge of protecting environment.After the address, I put up a stand in the ( 34 )__________offering green food , hoping them interested in it to get the ( 35 )____________experiencing a firsthand feeling of the green lifestyle no one shows any interest in. So I decided to team up with the concert (36)__________to run a campaign: “anyone who can answer a( n)(37)__________ environmental question is qualified to attend the concert. Soon the music can(38 )___________them ing here”.Since then , I have been considering why kids today do not have the same deep appreciation for nature that I do. One of the significant factors may be that the former rural civilization has been replaced by the urban civilization. In the past, the poor played the ( 39 )_________role in the nature , so they cleared the wasteland, planted crops and reproduced civilization. With the massive invasion of industrialization and urbanization, people were forced to move away from nature. The struggle between tradition and modernity , the confrontation between humans and nature has led people to believe that they are the masters of the universe. Is this really the case? It is time to think about who ( 40 )_________ us to destroy nature.III.Reading prehension (共45分。

比较研究方法_戴维_科利尔

比较研究方法①[美]戴维·科利尔著章远译戴维·科利尔(David Collier)生于1942年,是比较政治学以及方法论等研究领域的知名美国学者。

本篇《比较研究方法》原收录于埃达·W.费尼弗特(Ada W.Finifter)主编的《政治科学:学科的现状(二)》文集之中,全文是在早前收录于《比较政治的动力:全球研究视角》(1991年出版)文集中同名文章的修正和补充。

在本文中,戴维·科利尔综述了20世纪60年代晚期到90年代初期比较研究方法的不同观点。

科利尔认为标准的“比较研究方法”指的是针对小规模样本、或者说少量案例的研究方法,这种研究方法显然适用632①In Ada W.Finifter,ed.,Political Science:The State of the Discipline II(Washington D.C.:American Political Science Association,1993).本文是早先发表的Dankwart A.Rustow and Kenneth Paul Erickson,eds.,Comparative Political Dynamics:Global Research Perspective(New York:Harper Collins,1991)的修正版本。

利帕特引发的经典争论:比较研究方法于缺少大规模案例的政治现象研究。

因此在政治学学科领域,科利尔肯定比较研究方法才是分析工具中的最基本选项。

科利尔以阿伦·利帕特(Arend Lijphart)发表于1971年的《比较政治学和比较研究方法》为分析起点。

从文中的图1中可以明晰地看出,利帕特对比较研究和个案研究、实验研究以及统计研究三种研究方法进行了优劣评估。

利帕特的评估标准有两个,分别是判定竞争性的对立假说,也即涉及能否对样本进行控制;另一个标准是获得有关数据的难易程度。

私募股权投资者:萨姆·泽尔人物简介

房地产投资

• 投资了大量的房地产资产,如写字楼、购物中心等

• 通过房地产投资实现资产价值的最大化

私募股权投资

• 投资了许多知名企业和初创公司

• 通过私募股权投资实现企业价值的提升和收益最大化

其他投资

• 投资于股票、债券等其他金融产品

• 实现投资组合的多元化和风险分散

⌛️

萨姆·泽尔的经典投资案例

• 捐赠了大量的资金和物资,支持教育、医疗等领域的发

展

CREATE TOGETHER

谢谢观看

THANK YOU FOR WATCHING

DOCS

• 投资回报高达10倍

萨姆·泽尔的投资组合回报与影响

投资组合回报

• 萨姆·泽尔的投资组合实现了持续的高回报

• 长期投资回报远高于行业平均水平

行业影响

• 萨姆·泽尔的投资策略和方法对私募股权行业产生了深远影响

• 许多投资者效仿萨姆·泽尔的投资策略,取得了成功

04

萨姆·泽尔对私募股权行业的贡献

萨姆·泽尔对行业投资策略的启示

CREATE TOGETHER

DOCS SMART CREATE

私募股权投资者:萨姆·泽尔人物简介

DOCS

01

萨姆·泽尔的职业生涯与成就

萨姆·泽尔的早期经历与教育背景

出生于美国纽约市

• 1944年出生,成长于一个犹太家庭

• 父母都是普通的工薪阶层,家庭环境并不富裕

教育背景

• 1966年毕业于哥伦比亚大学,获得经济学学士学位

• 在行业内享有很高的声誉和尊敬

05

萨姆·泽尔的个人品质与领导力

萨姆·泽尔的职业精神与诚信原则

职业精神

诚信原则

社会交换理论约翰蒂博哈罗德凯利

客的忠诚度和品牌价值

社会交换理论约翰·蒂博&哈罗德·凯利

总之,社会交换理论是一个具有重要价值的理论,它为我们理解人类之间的互动关系提供 了重要的框架和指导。通过进一步的研究和实践应用,我们可以不断完善和发展这个理论 ,以更好地适应人类社会的复杂性和变化性 除了上述提到的观点,社会交换理论还有一些其他重要方面

社会交换理论约翰·蒂博&哈罗德·凯利

社会交换与文化因素

社会交换理论可以用来解释文化因素对人类互动的影响。不同文化背景下,社会交换的规则、方式和

1 价值观可能存在差异。例如,一些文化可能更加强调个人主义和竞争,而另一些文化可能更加强调集

体主义和合作。通过研究不同文化背景下的社会交换,我们可以更好地理解文化对人类互动的影响和

作用

社会交换与网络结构

2 社会交换理论可以与网络结构理论相结合,解释社会网络中的资源交换和权力关系。在社会网络中,

个体之间会形成复杂的交换关系,这些关系可以是直接的联系,也可以是间接的影响。通过研究网络

结构中的社会交换,我们可以更好地理解社会网络对个体和群体行为的影响和作用

社会交换与心理健康

3 社会交换理论还可以用来解释心理健康问题中的社会支持和社会关系。在心理健康领域,社会支持和

的利益

社会交换的情感因素:社会交换

4 不仅仅是物质上的交换,还包括

情感上的交换。参与者之间通过 情感上的交流和互动来增进彼此

之间的信任和依赖

3

社会交换的依赖性:社会交换的 参与者之间是相互依赖的,他们 需要对方的资源和支持来获得自 己所需的利益。这种依赖性可以 促进交换关系的建立和维持

Rough Approximation of a perference Relation by Dominance Relations

文献导读

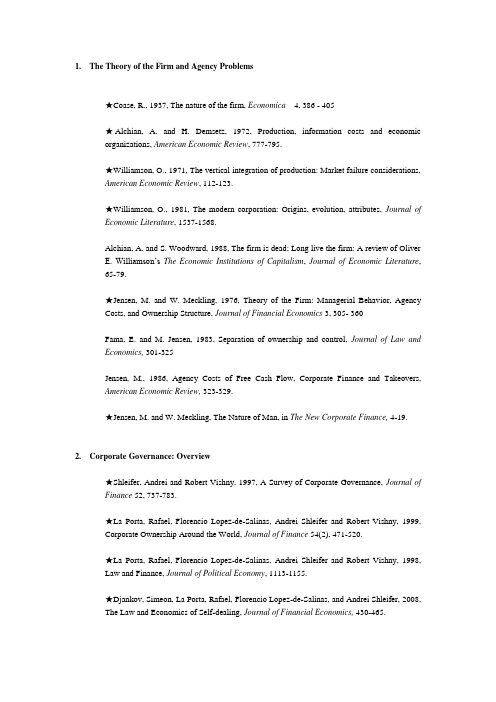

1. The Theory of the Firm and Agency Problems★Coase, R., 1937, The nature of the firm, Economica4, 386 - 405★Alchian, A. and H. Demsetz, 1972, Production, information costs and economic organizations, American Economic Review, 777-795.★Williamson, O., 1971, The vertical integration of production: Market failure considerations, American Economic Review, 112-123.★Williamson, O., 1981, The modern corporation: Origins, evolution, attributes, Journal of Economic Literature, 1537-1568.Alchian, A. and S. Woodward, 1988, The firm is dead; Long live the firm: A review of OliverE. Williamson’s The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, Journal of Economic Literature,65-79.★Jensen, M. and W. Meckling, 1976, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305- 360Fama, E. and M. Jensen, 1983, Separation of ownership and control, Journal of Law and Economics, 301-325Jensen, M., 1986, Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and Takeovers, American Economic Review, 323-329.★Jensen, M. and W. Meckling, The Nature of Man, in The New Corporate Finance, 4-19. 2. Corporate Governance: Overview★Shleifer, Andrei and Robert Vishny, 1997, A Survey of Corporate Governance, Journal of Finance 52, 737-783.★La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Salinas, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, 1999, Corporate Ownership Around the World, Journal of Finance 54(2), 471-520.★La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Salinas, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, 1998, Law and Finance, Journal of Political Economy, 1113-1155.★Djankov, Simeon, La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Salinas, and Andrei Shleifer, 2008, The Law and Economics of Self-dealing, Journal of Financial Economics, 430-465.★Bebchuk, Lucian and Assaf Hamdani, 2009, The Elusive Quest for Global Governance Standards, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, forthcoming.3. Corporate Governance and Capital MarketsShleifer, Andrei and Robert Vishny. 2000, Investor protection and corporate governance, Journal of Financial Economics 58, 3-27★Morck, Randall, Bernard Yeung, and Wayne Yu, 2000, The information content of stock markets: Why do emerging markets have synchronous stock price movements? Journal of Financial Economics 58, 215-260Jin, Li and Stewart Myers, 2006, R2 around the world: New theory and new tests, Journal of Financial Economics 79, 257 - 292.La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Salinas, and Andrei Shleifer, 2006, What works in securities laws? Journal of Finance, 1-32.4. Corporate Governance and Firm Value★La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Salinas, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, 2002, Investor protection and corporate valuation, Journal of Finance, 1147-1170.★Gompers, P., J. Ishii, and A. Metrick, 2003, Corporate governance and equity prices, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107 – 155.★Core, J., W. Guay, and T. Rusticus, 2006, Does weak governance cause weak stock returns?An examination of firm operating performance and investors’ expectations, Journal of Finance, 655 – 687.★Morck, Randall, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, 1988, Management Ownership and Market Valuation: An Empirical Analysis, Journal of Financial Economics 20, 293-315.★McConnell, J. and H. Servas, 1990, Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value, Journal of Financial Economics 27, 595-613.★Cho, M.H., 1998, Ownership structure, investment, and corporate value: An empirical analaysis, Journal of Financial Economics 47, 103-121.Baek, J., J. Kang, and K. S. Park, 2004, Corporate governance and firm value: evidence from the Korean financial crisis, Journal of Financial Economics 71, 265-313.Doidge, C., G.A. Karolyi, and R. M. Stulz, 2004, Why are foreign firms listed in the U.S.worth more? Journal of Financial Economics 71, 205-238.Mitton, T., 2002, A cross-firm analysis of the impact of corporate governance on the East Asian financial crisis, Journal of Financial Economics 64, 215-241.Friedman, E., S. Johnson, and T. Mitton, 2003, Propping and tunneling, Journal of Comparative Economics 31, 732-750.Bae, K., J. Kang, and J. Kim, 2002, Tunneling or valued-added? Evidence from mergers by Korean business groups, Journal of Finance 57, 2695-2740.5. Asymmetric information and Capital market☆ Alchian, A., 1950, Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory, The Journal of Political Economy, 58 (3): 211-221.☆ Black, Fischer, 1986,Noise, The Journal of Finance, 41 (3): 529-543.☆Dequech, D. 1999, Expectations and Confidence under Uncertainty, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 21 (3): 415-430.○Chan, K., A.J. menkvel and Z. Yang, 2008, Information Asymmetry and Asset prices: Evidence from the China Foreign Share Discount, Journal of Finance.☆ Healy, Paul M., Krishna G. Palepu, 2001, Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure,and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature, Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 405-440.★ Francis, J., R. LaFond, P. Olsson and K. Schipper, 2003, Accounting Anomalies andInformation Uncertainty, Working paper.★ Attig, N., W. Fong, Y. Gadhoum and L. Lang, 2004, Effects of Large Shareholding onInformation Asymmetry and Stock Liquidity, Working paper.6. Information disclosure and corporate governance★ Botosan, Christine A., 1997, Disclosure Level and the Cost of Equity Capital, TheAccounting Review Vol72 (3): 323-349.★Botosan, C. A. And M. A. Plumlee, 2002, A Re-examination of disclosure Level and theExpected Cost of Equity Capital, Journal of Accounting Research vol. 40 (1).☆ Song, F. and A. V. Thakor, 2006, Information Control, Career Concerns, and CorporateGovernance, Journal of Finance (4).○ Gul F. and H. Qiu, Legal Protection, Corporate Governance and Information Asymmetryin Emerging Financial Markets, Working paper.☆ Bebchuk, L. 2002, Asymmetric information and the choice of corporate governancearrangements, Working paper.☆ Bushman, R.M. and A.J. Smith, 2003, Transparency, Financial Accounting Informationand Corporate Governance, FRBNY Economic Policy Review, 65-87.7. Large Shareholder, Liquidity and Stock Market☆ Bolton, P. and E. Thadden, 1998, Blocks, Liquidity, and Corporate Control, The Journal of Finance 53 (1): 1-25.☆ Demsetz, H. 1983, The structure of Ownership and the Theory of the Firm, Journal ofLaw and Economics, 26 (2): 375-390.☆ Shleifer A. and R.W. Vishny, 1986, Large Shareholders and Corporate Control, Journal of Political Economy, 94: 461-488.☆ Maug, E., 1998, Large Shareholders as Monitors: Is There a trade-Off Between Liquidityand Control? The Journal of Finance, Vol LIII: 65-98.★Parigi, B.M. and L. Pelizzon, 2007, Diversification and ownership concentration, Journal of Banking & Finance 32: 1743-1753.★ Maury, B. and A. pajuste, 2005, Multiple large shareholders and firm value, Journal ofBanking & Finance 29: 1813-1834.○Lemmon, M. and K. V. Lins, 2003, Ownership Structure, Corporate Governance, andFirm Value: Evidence from the East Asian Financial Crisis, The Journal of Finance, Vol.LVIII: 1145-1168.8. Political Connection, Regulations and Firm Value☆ Stigler, "What Can Regulators Regulate? The case of electricity", 1962, Journal of Law and Economics★ Stigler, George, “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics, I(Spring1971), 3-21.★ Blanchard, Olivier, and Shleifer, Andrei, “Federalism with and withoutPoliticalCentralization: China versus Russia,” manuscript, MIT and HarvardUniversity,February 2000.☆ Faccio, Mara, “Politically-Connected Firms: Can They Squeeze the State,” manuscript,University of Notre Dame, March 2002.★ Shleifer, Andrei and Robert Vishny, "Politicians and Firms," Quarterly Journal ofEconomics (109) 1994, 995-1025.☆ Bhattacharya, Utpal., Hazem Daouk, 2009, “When no law is better than a good law”,Working Paper.○Mingyi Hung TJ Wong and Tianyu Zhang, “Political Relations and Overseas StockExchange Listing: Evidence from Chinese State-owned Enterprises”, working paper.★ Fan, Wong and Zhang, 2007, Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance,andPost-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms, Journal of FinancialEconomics, 84, 330-357.9. Behavior Finance★ Nicholas Baeberis, and Richard Thaler, 2002. Survey of Behavioral Finance.○Graham, J.F., Harvey, C.R., 2001. The theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics 60, 187-243.★ Alti, A., 2006. How persistent is the impact of market timing on capital structure? Journal of Finance 61, 1681-1710.○ Baker, M., Wurgler, J., 2002. Market Timing and capital structure. Journal of Finance 57,1-32.○Kayhan, A., Titman, S., 2007. Firms’ histories and their capital structures. Journal ofFinancial Economics 83, 1-32.★ Fama, E.F., French, K.R., 2001. Disappearing dividends: changing firm characteristics or lower propensity to pay? Journal of Financial Economics 60, 3-43.○ DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., Skinner, D.J., 2004. Are dividends disappearing? Dividendconcentration and the consolidation of earnings? Journal of Financial Economics 72, 425-456.★ Billett, M., Qian, Y., 2006. Are overconfident CEOs born or make? Evidence ofself-attribution bias from frequent acquirers. Unpublished working paper, Henry B, TippieCollege of Business, University of Iowa.○ Doukas, J., Petmezas, D., 2006. Acquisitions, overconfident managers and self-attributionbias.Unpublished working paper, Department of Finance, Graduate School of Business, OldDominion University.○ Malmendier, U., Tate, G., 2005. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. Journal ofFinance 60, 2661-2700.10. The Board of DirectorsWeisbach, M., 1988, Outsider directors and CEO turnovers, Journal of Financial Economics 20, 431-460.Yermack, D., 1996, Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors, Journal of Financial Economics 40, 185-211.Rosenstein, S. and J. Wyatt, 1997, Inside Directors, Board Effectiveness, and Shareholder Wealth, Journal of Financial Economics 44, 229-250.Hermalin, B. and M. Weisbach, 1988, The determinants of board composition, Rand Journal of Economics 19, 589-606.Warner, J., R. Watts, and K. Wruck, 1988, Stock prices and top management changes, Journal of Financial Economics 20, 461-492.Johnson, Bruce, Robert Magee, Nandu Nagarajan and Henry Newman, 1985, An Analysis of the Stock Price Reaction to Sudden Executive Deaths: Implications for the Management Labor Model, Journal of Accounting and Economics 7, 151-174.11. Talent, Incentives, and Executive CompensationsBaumol, W., 1990, Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive, Journal of Political Economy 98, 893-921.Murphy, K., A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny, 1991, The allocation of talent: Implications for growth, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 503-530.Jensen, Michael, and Kevin Murphy, 1990, Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives, Journal of Political Economy 98, 225-264.Core, John, Robert Holthausen and David Larcker, 1999, Corporate Governance, Chief Executive Officer Compensation, and Firm Performance, Journal of Financial Economics 51, 371-406.Rose, Nancy, and Andrea Shepard, 1997, Firm Diversification and CEO Compensation: Managerial Ability or Executive Entrenchment? RAND Journal of Economics 28, 489-514. 12. Corporate RestructuringDesai, H. and P. Jain, 1999, Firm performance and focus: Long-run stock market performance following spinoffs, Journal of Financial Economics 54, 75-101.Daley, L., V. Mehrotra and R. Sivakumar, 1997, Corporate focus and value creation: Evidence from spinoffs, Journal of Financial Economics 45, 257-281.Chen, P., V. Mehrotra, R. Sivakumar, and W. Yu, 2001, Layoffs, shareholders’ wealth, and corporate performance, Journal of Empirical Finance 8, 171-199.Servaes, H., 1996, The Value of Diversification During the Conglomerate Merger Wave, Journal of Finance 51, 1201-1225.Berger, P. and E. Ofek, 1996, Bustup Takeovers of Value-Destroying Diversified Firms,Journal of Finance 51, 1175-1200.Lamont, O. A. and C. Polk, 2002, Does diversification destroy value? Evidence from the industry shocks, Journal of Financial Economics 63, 51-77.Gillian, S., J. Kensinger, and J. Martin, 2000, Value creation and corporate diversification: the case of Sears, Roebuck & Co., Journal of Financial Economics 55, 103-137.Cusatis, P., J. Miles and J. Woolridge, Some new evidence that spinoffs create value, in NCF, 592-599.Mansi, S and D. M. Reeb, 2002 Corporate diversification: What gets discounted, Journal of Finance, 2167-2183Graham J. R., M. L. Lemmon and J. G. Wolf, 2002, Does corporate diversification destroy value? Journal of Finance , LVII, 695-720.Schoar, A, 2002, Effects of corporate diversification on productivity, Journal of Finance, LVII, 2379-2403.Campa, J. M. and S. Kedia, 2002, Explaining the diversification discount, Journal of Finance, 1731-1762.Aggarwal, R. and A. A. Samwick, 2003, Why do managers diversify their firms? Agency reconsidered. Journal of Finance, LVIII, 71-118.13. Risk ManagementGuay, W.R., 1999, The impact of derivatives on Þrm risk: An empirical examination of new derivative, Journal of Accounting and Economics 26 , 319-351Allayannis, G., and Weston, J.P., 2001, The use of foreign currency derivatives and firm market value, The Review of Financial Studies 14, 243-276.Guaya, W., and Kothari, S.P., 2003, How much do firms hedge with derivatives? Journal of Financial Economics 70, 423–461.Tufano, P., 1996, Who manage risks: An empirical examination of risk manage practices in gold mining industry, The Journal of Finance, 1097-1137.。

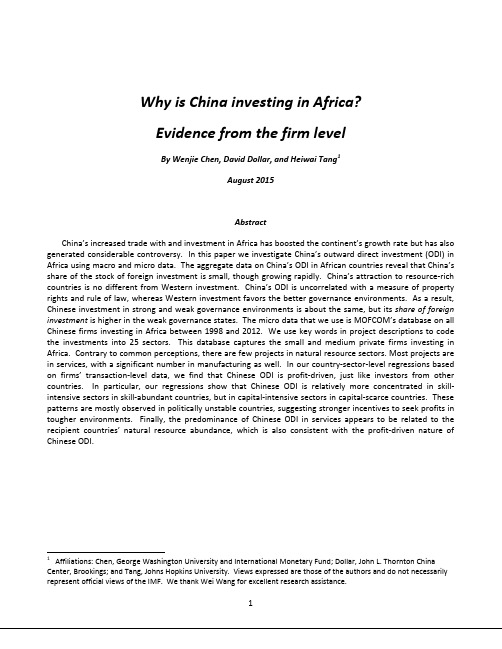

Why is China investing in Africa

Why is China investing in Africa?Evidence from the firm levelBy Wenjie Chen, David Dollar, and Heiwai Tang1August 2015AbstractChina’s increased trade with and investment in Africa has boosted the continent’s growth rate but has also generated considerable controversy. In this paper we investigate China’s outward direct investment (ODI) in Africa using macro and micro data. The aggregate data on China’s ODI in African countries reveal that China’s share of the stock of foreign investment is small, though growing rapidly. China’s attraction to resource-rich countries is no different from Western investment. China’s ODI is uncorrelated with a measure of property rights and rule of law, whereas Western investment favors the better governance environments. As a result, Chinese investment in strong and weak governance environments is about the same, but its share of foreign investment is higher in the weak governance states. The micro data that we use is MOFCOM’s database on all Chinese firms investing in Africa between 1998 and 2012. We use key words in project descriptions to code the investments into 25 sectors. This database captures the small and medium private firms investing in Africa. Contrary to common perceptions, there are few projects in natural resource sectors. Most projects are in services, with a significant number in manufacturing as well. In our country-sector-level regressions based on firms’ transaction-level data, we find that Chinese ODI is profit-driven, just like investors from other countries. In particular, our regressions show that Chinese ODI is relatively more concentrated in skill-intensive sectors in skill-abundant countries, but in capital-intensive sectors in capital-scarce countries. These patterns are mostly observed in politically unstable countries, suggesting stronger incentives to seek profits in tougher environments. Finally, the predominance of Chinese ODI in services appears to be related to the recipient countries’ natural resource abundance, which is also consistent with the profit-driven nature of Chinese ODI.1 Affiliations: Chen, George Washington University and International Monetary Fund; Dollar, John L. Thornton China Center, Brookings; and Tang, Johns Hopkins University. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the IMF. We thank Wei Wang for excellent research assistance.1.IntroductionSince 2000 China has emerged as Africa’s largest trading partner. Chinese direct investment in and lending to African countries has grown rapidly as well. This Chinese engagement in Africa has no doubt led to faster growth and poverty reduction on the continent. Per capita growth rate of the average African economy surged from 0.6% per annum in the 1990s to 2.8% in the 2000s. African countries have strengthened their institutions and macroeconomic policies, and that is one factor in the growth acceleration. But demand from China for the continents’ main exports – oil, iron, copper, zinc, and other primary products – led to better terms of trade and higher export volumes, other important factors in the growth accelerations.In the Pew Global Attitudes survey for 2015, African respondents had a significantly more positive view of China (70% with a favorable view) than respondents in other regions such as Europe (41%), Asia (57%), or Latin America (57%). This likely reflects the positive impact of China’s engagement on African growth. At the same time, China’s involvement in Africa is not without controversy, as conveyed by some typical headlines from the Western press: “Into Africa: China’s Wild Rush”: “China in Africa: Investment or Exploitation?”; “Clinton warns against ‘new colonialism’ in Africa.” The criticism comes not just from Western voices. In an op-ed essay last year in The Financial Times, Lamido Sanusi, who was recently suspended as Nigeria’s central bank governor, wrote: “In much of Africa, they have set up huge mining operations. They have also built infrastructure. But, with exceptions, they have done so using equipment and labor imported from home, without transferring skills to local communities. So China takes our primary goods and sells us manufactured ones. This was also the essence of colonialism.”In this paper we investigate one aspect of China’s engagement in Africa, its outward direct investment (ODI). We start, in Section 2, by examining the allocation of Chinese investment across 49African countries and by comparing it to the continent’s total foreign direct investment (FDI). A first important point is that at end-2012 China’s share of the stock of FDI in Africa was on the order of 3%. While its investment may be growing rapidly, it is still a small player, and the vast majority of FDI in Africa comes from Western sources. In this section we show that Chinese investment and Western investment are similar in that they are attracted to larger markets and to countries with natural resource wealth. Controlling for those factors, Western investment tends to stay away from countries with poor governance in terms of property rights and rule of law. Chinese investment, on the other hand, is indifferent to those governance measures, with the result that the countries where China’s investment share is large tend to be ones with weak governance.China’s investment in Africa includes some large deals that have been highly publicized. In DR Congo, for example, the Sicomines iron mine involves the Chinese state-owned enterprises China Railway Engineering Corporation and Sinohydro and the private company Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, in partnership with Congolese state-owned companies. Other high-profile deals include CNPC’s gas investment in Mozambique, Chinalco’s mining investment in Guinea, and Sinopec’s oil and gas acquisition in Angola. In the data on the stock of Chinese investment in different African countries, these large state-to-state deals no doubt play an important role.In Section 3 we turn to a different kind of data source. All Chinese enterprises making direct investments abroad have to register with the Ministry of Commerce. The resulting database provides the investing company’s location in China and line of business. It also includes the country to which the investment is flowing, and a description in Chinese of the investment project. However, it does not include the amount of investment. The investment to Africa over the period 1998 – 2012 includes about 2000 Chinese firms investing in 49 African countries. We think of the typical entry as a private firm that is much smaller than the big state-owned enterprises involved in the mega-deals. Thesedata provide insight into what the Chinese private sector is doing in Africa. Section 3 introduces this firm-level database. Based on the descriptions of the overseas investment, we categorize the projects into 25 industries covering all sectors of the economy (primary, secondary, and tertiary). The allocation of the projects across countries and across sectors provides a snapshot of Chinese private investment in Africa.Section 4 then investigates the allocation of projects more rigorously. In particular we ask whether factor endowments and other country characteristics influence the number and types of investment projects from Chinese investors. If Chinese investment is similar to other profit-oriented investment, then the number and nature of projects should be related to the factor endowments and other characteristics of the recipient countries. Indeed, we find that while Chinese ODI is less prevalent in skill-intensive sectors in Africa, it is more prevalent in the more skill-abundant countries, suggesting that Chinese investors aim to exploit the local comparative advantage. We also find that Chinese ODI is more concentrated in capital-intensive sectors in the more capital-scarce countries, suggesting its importance as a source of external financing to the continent. These patterns are mostly observed in politically unstable countries, implying firms’ stronger incentives to seek profits in tougher environments. We also find that the prevalence of Chinese ODI in services is positively related to the recipient countries’ natural resource abundance.Our paper is related to various strands of literature. First, it relates to the classical theory of multinational enterprises (MNEs) about how firms use their capabilities and resources to generate competitive advantage over indigenous firms in host countries (Caves 1971, Hymer 1976, Kindleberger 1969 and 1970). More recent studies show that in addition to facilitating foreign sales, firms undertake ODI to acquire resources, assets and technology to develop their competitiveadvantage (Child and Rodrigues 2005, Makino et al. 2002, Mathews 2006).2 Second, our paper contributes to the growing literature on Chinese ODI. Most of the earlier studies were descriptive in nature, sometimes relying on case studies (e.g., Deng 2003 and 2004, Wu and Chen 2001). Cai (1999) proposes that Chinese firms invest overseas mainly to seek markets, natural resources, technology, managerial skills, and financial capital.3 More recent studies focus on the empirical examination of the determinants of Chinese ODI (e.g., Buckley et al. 2007), but most of these studies rely on aggregate data for analysis. There are a few notable exceptions that use micro-level data. For instance, Luo et al. (2011) show empirically that ODI by private Chinese firms had been prompted to exploit firm-specific advantages as well as to tackle market imperfection due to underdevelopment of China’s domestic institutions. Other studies on Chinese overseas M&As support the resource-seeking and technology-seeking motives (Antkiewicz and Whalley 2007, Rui and Yip 2008). Using aggregate data, Cheng and Ma (2007) and Cheung and Qian (2007) show that China’s investment was motivated by both market seeking and resource seeking.Our paper contributes to this literature by showing that the African investment by private sector firms that predominate in the MOFCOM database is driven by the profit-oriented motivations that drive outward investment from other countries.2.Allocation of Chinese ODI and total FDI across African countriesChina’s official statistics on the country’s overseas direct investment (ODI) in Africa reveal a number of paradoxes. Simply put, China’s investment in Africa is both big and small. It is small in the2 Here, technology is broadly defined to include production technology, management skills, and brand names.3 Deng (2004) identifies two additional motives: strategic assets (e.g., brands, marketing networks) and diversification. The focus of our paper focuses on the non-financial type of OFDI. Clearly, because the PRC was itself a low-cost production base, cost minimization was not a major motivation of Chinese ODI.sense that China is a latecomer to Africa and accounts for only a very small share of the total stock of foreign investment on the continent. At end-2011, that total stock was $629 billion, of which the Chinese share was 3.2%. China’s investment in Africa has been growing rapidly and its share will rise over time, but slowly, starting from a low base. China’s investment in Africa is big in a relative sense, however. The world as a whole has six times as much direct investment in the U.S. as in Africa, reflecting the fact that most FDI goes to advanced economies. China’s pattern of investment is different, however. As of end-2013, China had more ODI in Africa ($26 billion) than in the U.S. ($22 billion). So, China’s relative focus on Africa is large, though it is still a small player in investment overall.What about the allocation of China’s investment among African countries? Is it similar to or different from the pattern seen from existing, mostly Western investors? To answer this question we use the data on the stock of Chinese ODI in 49 African countries at end-2012 from the Ministry of Commerce.4 A useful point of departure is the allocation of the overall stock of FDI among those 49 countries. Those data are available at end-2011.5 Globally, the allocation of FDI can be explained quite well by a parsimonious set of variables that measure (1) market size (total PPP GDP); (2) natural resource rents as a share of the economy; and (3) governance. For governance we consider two distinct measures, from the World Governance Indicators:Rule of law “captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence”;4 Ministry of Commerce of China, 2012 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.5 The stocks of FDI end-2011 are from the updated online database originally published as Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2007).Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism “measures perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including politically-motivated violence and terrorism.”Regression 1 in Table 1 shows that the allocation of FDI across 49 African countries follows the global pattern. FDI is attracted to larger markets with an elasticity of 0.74. Other things equal, resource rich countries receive more FDI. The standard deviation across African countries of the resource rents variable is 17.6, so that the coefficient indicates that one standard deviation richer in resource wealth attracts 49% more FDI. Finally, FDI prefers an environment of good property rights and rule of law. Across African countries the standard deviation of the rule of law index is 0.49, so one standard deviation better on rule of law attracts 31% more investment. Figure 1, a partial scatter plot of the log of total FDI and the rule of law index, shows this strong relationship.How does the allocation of Chinese ODI compare? Specification 2 in Table 1 shows that Chinese ODI is positively correlated with market size and natural resource wealth, with coefficients similar to those in the equation for overall FDI. However, Chinese ODI has a modest, negative correlation with the Rule of Law index (specification 3). While property rights/rule of law may not matter, Chinese ODI is positively correlated with the index of political stability (specification 4). Also, population seems to matter as a measure of economic size, not just total GDP (specification 5). Comparing the FDI equation in specification 1 and the Chinese ODI allocation in specification 5: China has a modestly stronger attraction to natural resources and in terms of governance favors political stability over property rights/rule of law. The partial scatter of the log of Chinese ODI and the political stability index is shown in Figure 2. This relationship makes sense given that some significant part of the volume of Chinese investment in Africa is tied up in state-to-state resource deals. China is more concerned with thepolitical stability of the government than with the environment of rule of law in the domestic economy. Political stability and rule of law are fairly highly correlated (0.59 across African countries). Still, there are countries that are rated to be significantly better on political stability than on rule of law. Some examples are Angola, Eritrea, Madagascar, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – all of which have significant Chinese investment relative to their total FDI. Dollar (2015) finds that these relationships exist globally: total FDI is strongly attracted to good property rights and rule of law, whereas Chinese ODI is attracted to politically stable environments, without reference to the rule of law. So, the relationship is not special to Africa but says something about Chinese ODI in general.Since Chinese investment is indifferent to the property rights/rule of law environment, there are similar amounts of Chinese investment in good governance countries and poor governance countries. For example, if we divide the 49 African countries into three groups based on the Rule of Law index in 2012, the stock of Chinese ODI is nearly the same in the good governance countries, as in the poor governance ones (Figure 3). For the stock of FDI, on the other hand, nearly 60% is in the good governance environments, compared to 25% in the poor governance environments (Figure 4). These patterns together mean that the countries in which China’s share of inward investment is large tend to be ones with poor governance. Still, note that it is only a minority of Chinese investment that is in those environments.3.Data on Chinese Outward Direct InvestmentThe data on Chinese ODI transactions was obtained from the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and includes deals that were approved by the ministry between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2012. For each ODI deal, the data set reports the name of the investing firm, the firm's sector of business, the province of origin, and the recipient country of the ODI flow. There is, however, noinformation on the amount of the deal or the name of the target for mergers and acquisitions. The raw data contains 2,005 deals at the firm level, covering 49 countries on the African continent.6 The top five destination countries for Chinese ODI are: Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, Ethiopia, and Egypt, with Nigeria taking the clear lead, representing 12% of all deals. Figure 5 depicts the geographical distribution of the number of deals by country. Deals tend be more concentrated in the East and South African regions, whereas Central and West Africa, with the exception of Nigeria, have relatively fewer deals. In East Africa, countries such as Ethiopia, and to some extent Kenya and Tanzania are relatively resource poor compared to some of the Southern African countries such as Zambia, Angola, and South Africa. Some of the reasons why East Africa stands out as a popular destination for these private Chinese investments are its relatively more developed infrastructure, including ports, and its relative closeness to China. The East Africa Community (EAC), in particular, forms a customs and single market trading union that has invested heavily in infrastructure investments, mostly with loans from the Chinese government, such as the Standard Gauge Rail project originating in Kenya as well as the Karuma Hydroelectric power project in Uganda. These projects will enhance the connectivity between these countries and supply reliable energy in the future years to come, thus, making the region an attractive destination.Within each transaction, we categorize the types of projects the Chinese investing firm is conducting in the destination countries. By using key words in the deal descriptions provided in the data, we categorize projects into different industries. Since most of the deals involve multiple projects, sometimes in different industries, we obtain a sample of 3,989 projects. For the remainder of the analysis, we use the project-based sample that we categorize into different industries based on the United Nations 34 sector industry classification, which we then further condense into 176 Chen and Tang (2014) provide a detailed description of the distribution of Chinese ODI outside Africa, and study the causes and consequences of ODI at the firm level.manufacturing sectors, 7 service sectors, and 1 mining sector. Table 2 presents the country breakdown in terms of number of Chinese investing firms and the number of projects that we identified based on the firm-level deals. Table 3 presents the sectoral distribution in terms of number of projects.We find that about 60 percent of the projects are in service sectors, with the remaining portion almost evenly split between manufacturing and natural resources. The two sectors that received the most Chinese ODI in terms of the number of deals are business service (1053 deals) and import and export (539 deals). Thus, against popular perception, most of the Chinese ODI deals are not engaging in raw material related projects, but rather, are involved in service sectors. For instance, in oil-rich Nigeria, about two-thirds of the projects are actually in service sectors. In Figure 6, we divide the countries in terms of the resource intensities of their exports. Following the IMF’s categorization for oil exporters, non-oil resource intensive countries, and the rest of African economies, we can see that regardless of the degree of raw material export intensity of the country, the majority of Chinese ODI projects tend to be in the service sector.4.Sectoral Distribution of Chinese Investments in AfricaNext we exploit the transaction-level data to study the distribution of Chinese ODI in Africa. Specifically, we examine whether the distribution of Chinese ODI across countries and sectors is related to various country and sector characteristics. For the country characteristics, we focus on the levels of factor endowment and institutional development. We measure a country’s capital abundance as the (log) capital endowment per worker, using data from the Penn World Tables. We measure a country’s human capital abundance as the fraction of high-school graduates in the workforce, using data from Barro and Lee (2014). Countries’ levels of institutional development are measured by rule of law and political stability, as discussed in Section 2 above.For the sector characteristics, we explore the varying factor intensity of production across sectors. We measure labor intensity of a sector as the ratio of total wage bill to value added of all firms in the sector, following Romalis (2004). Capital intensity is defined as one minus labor intensity. Skill intensity is defined as the share of non-production workers in the employment of the sector, multiplied by its labor intensity. To construct these measures, we use industry-level data from the database put together jointly by the National Bureau of Economic Research and the U.S. Census Bureau's Center for Economic Studies (CES).7 Because of the lack of the required data to construct factor intensity measures for service sectors, we exclude them in the baseline analysis, and include them only at the later part of the analysis when we examine the determinants of Chinese ODI specialization in services.8 As such, our baseline analysis focuses on explaining the distribution of Chinese manufacturing ODI in Africa. Despite the prevalence of Chinese ODI projects in services in the continent, such analysis is still important as it can shed light on the low level of industrialization in the continent.Without information on the value of each ODI deal, we explore the determinants of the investment pattern by using two dependent variables in the following regression analyses: (1) a dummy variable to indicate whether there was any ODI within a sector-country during the sample period (the extensive margin); and (2) the (log) number of ODI deals at the sector-country level (the intensive margin). In Table 4, we regress either of these two variables on country fixed effects and the interaction between a country’s capital (human capital) endowment and a sector’s capital (skill) intensity. In columns (1)-(3), we use the ODI dummy as the dependent variable and estimate the specification using a Probit model. We find a negative and significant coefficient on the stand-alone7 The idea of using the same measures of factor intensity based on U.S. firms for other countries is originally proposed by Rajan and Zingales (1998).8 Even if we have the same set of data for service firms in the U.S., it is not clear whether we can apply the Cobb-Douglas production functional form to measure factor intensity of a sector.term of the sector’s skill intensity, but a positive and significant coefficient on the interaction between a country’s skill endowment and a sector’s skill intensity. These results suggest that while Chinese firms are less likely to invest in skill-intensive sectors in Africa on average, they are more likely to do so in the relatively more skill-abundant countries. In other words, African nations that are relatively more successful in investing in human capital tend to attract more Chinese ODI in the skill-intensive sectors. We also find a negative coefficient on the interaction between a country’s capital endowment and a sector’s capital intensity, but it is not statistically significant.In columns (4) to (6), we use the (log) number of ODI deals at the sector-country level as the dependent variable. We add 1 to the number of deals in order to include sector-countries with zero ODI deals in the regression sample. To tackle the resulting estimation bias due to sample censoring at zero, we estimate the specification using a Tobit model. We find a positive and significant coefficient on the interaction between a country’s skill endowment and a sector’s skill intensity, after controlling for country fixed effects. These results suggest that while Chinese ODI tends to be concentrated in low-skill intensive sectors in Africa on average, it is biased toward the more skill-intensive sectors in skill-abundant countries. Together with the results about the extensive margin of Chinese ODI, this finding suggests that Chinese firms tend to exploit the local comparative advantage of the host country when investing abroad.Interestingly, we find that Chinese firms are less likely to invest in capital-intensive sectors in the more capital-abundant host countries. While this result appears to contradict the predictions based on the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, it is consistent with the idea that Chinese ODI serves as a source of external financing to the continent, especially in the capital-scarce host countries. To the extent that capital is more mobile than labor, the opposing signs on the two interaction terms actually offer a coherent portrait of the main hypothesis of this paper -- Chinese investors are largely profit-driven and are responsive to market conditions, just like investors from other countries.We have shown in Table 1 that Chinese ODI is attracted to African countries that are politically stable. What extra lessons can we learn from a sector-level analysis? To this end, we split our sample into two subsamples based on whether a country has rule of law that is above or below the continent’s median. Similarly, we also split the sample into two based on whether a country is above or below the median value of political stability. We then use the two subsamples to repeat the analysis of Table 4.Table 5 reports the regression results. In columns (1)-(4), we examine the probability of Chinese ODI across sectors and countries. Supporting the conclusions of the cross-country analysis, we find that host countries’ levels of rule of law do not seem to matter for Chinese firms’ investments in Africa; however, political stability is crucial. In particular, we find that the results reported in the previous table about how Chinese firms respond to market conditions are mostly observed for the group of politically unstable nations (column (3)). A potential explanation is that in politically unstable business environments, investment is risky but the expected return could be high. Facing a risky investment environment, investors need to be more cautious when choosing projects to invest. Such investment incentives imply that investors will be more motivated to exploit the host country’s comparative advantage. The finding that Chinese ODI deals are more concentrated in skill-intensive sectors in the more skill-abundant countries, especially in politically unstable countries, confirms this hypothesis. For the same reason, investors should be driven to seek projects that promise a higher return in a riskier environment. Such hypothesis is confirmed by the positive coefficient on the interaction between a country’s capital abundance and a sector’s capital intensity, as reported in column (3), when the sample of below-median rule-of-law countries is used. In other words, Chinese ODI is concentrated in the more capital-intensive sectors in countries that are both politically unstable and scarce in capital. No such pattern is found for the more politically stable countries.。

身份经济学

[美]乔治·阿克洛夫 瑞秋·克兰顿 著颜超凡 汪潇潇 译中信出版社第一篇 经济学与身份第一章 引论第二章 身份经济学第三章 效用论中的身份和准则第三章后记 罗塞塔石碑第四章 身份经济学在当代经济学中的位置第二篇 工作和学习第五章 身份与组织经济学第六章 身份与教育经济学第三篇 性别与种族第七章 性别与工作第八章 种族与少数族裔贫困问题第四篇 展望未来第九章 身份经济学与经济学方法论第十章 结论以及身份改变经济学的五个方面致谢版权页一位西点军校新学员(左)正在向系红色腰带的队友老学员敬礼。

在接待日,新学员开始了成为美国陆军军官的进程。

他们要经历行政管理程序,穿上首次发给他们的军装,剔掉头发,并在行军、军事礼仪及纪律方面开始他们的第一课。

()1978年安娜·霍普金斯女士受雇于普华永道的政府事务办公室,无论从哪方面来说,她都尽职尽责、工作勤勉。

她曾经从一份被遗弃的提交给美国国务院的项目建议书中,挖掘出了价值约2500万美元的合同,这也是普华永道有史以来最大的一单生意。

[1] 1982年,她作为88名候选人中唯一的女性被提名为事务所合伙人[2],但最终落选了。

她落选的原因是什么?她的工作表现究竟有何失误呢?我们听到了来自她同事及下属对她待人接物、举止态度方面的抱怨。

在她晋升的书面意见中,高级合伙人读到了这样的评价:“在魅力方面需要加强学习”、“像个男人”、“需要努力学习如何做一个女人”。

大力推举她的老板告诫她:“如果你仍然希望成为合伙人,那么你在走路、与人交谈、着装方面,就需要女性化一些,除了精心打扮、佩戴首饰,还得好好做做头发。

”[3]霍普金斯女士依据《民权法》(Civil Rights Act)第七条下的性别歧视条款,起诉普华永道公司。

几轮上诉之后,美国联邦最高法院于1988年受理了此案。

大部分人认为公司采取了双重标准,最高法院指出:“雇主反对女性在工作上积极进取,但女性的职位又要求她们必须积极进取,这样一来,雇主就使女性陷入了左右为难的困境:如果工作积极就会失业,而工作不积极也会失业。

Initial Public Offerings, An Analysis of Theory and Practice