Pragmatic Analysis of Irony:An Adaptation approach

修辞格Irony

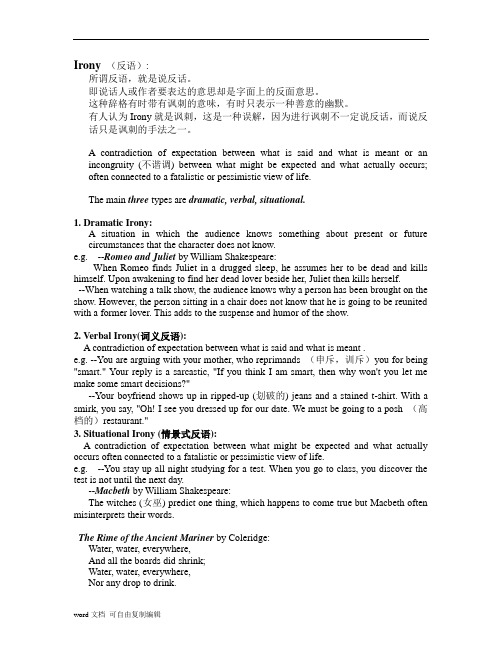

Irony (反语):所谓反语,就是说反话。

即说话人或作者要表达的意思却是字面上的反面意思。

这种辞格有时带有讽刺的意味,有时只表示一种善意的幽默。

有人认为Irony就是讽刺,这是一种误解,因为进行讽刺不一定说反话,而说反话只是讽刺的手法之一。

A contradiction of expectation between what is said and what is meant or anincongruity (不谐调) between what might be expected and what actually occurs;often connected to a fatalistic or pessimistic view of life.The main three types are dramatic, verbal, situational.1. Dramatic Irony:A situation in which the audience knows something about present or futurecircumstances that the character does not know.e.g. --Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare:When Romeo finds Juliet in a drugged sleep, he assumes her to be dead and kills himself. Upon awakening to find her dead lover beside her, Juliet then kills herself.--When watching a talk show, the audience knows why a person has been brought on the show. However, the person sitting in a chair does not know that he is going to be reunited with a former lover. This adds to the suspense and humor of the show.2. Verbal Irony(词义反语):A contradiction of expectation between what is said and what is meant .e.g. --You are arguing with your mother, who reprimands (申斥,训斥)you for being "smart." Your reply is a sarcastic, "If you think I am smart, then why won't you let me make some smart decisions?"--Your boyfriend shows up in ripped-up (划破的) jeans and a stained t-shirt. With a smirk, you say, "Oh! I see you dressed up for our date. We must be going to a posh (高档的)restaurant."3. Situational Irony (情景式反语):A contradiction of expectation between what might be expected and what actually occurs often connected to a fatalistic or pessimistic view of life.e.g. --You stay up all night studying for a test. When you go to class, you discover the test is not until the next day.--Macbeth by William Shakespeare:The witches (女巫) predict one thing, which happens to come true but Macbeth often misinterprets their words.The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge:Water, water, everywhere,And all the boards did shrink;Water, water, everywhere,Nor any drop to drink.(In this example it is ironic that water is everywhere but none of it can be drunk.) Sarcasm (讽刺,挖苦):指用尖酸刻薄的讽刺话,既可用反语、比喻,也可用直叙法对个人的缺点、过失或社会上的丑恶现象及黑暗而进行讽刺、挖苦,常是有意伤害他人的感情,所以它常含有相当强的贬义。

Pragmatic Functions of Irony 反语的作用

Pragmatic Functions of Irony1.AbstractIrony is a common linguistic phenomenon in verbal communication. Recent years have seen a mushroom growth of distinctly angled theorizations in this orientation, which nevertheless exhibit strong complementarity. Traditionally, irony is treated as a figure of speech whose intended meaning is the opposite of that expressed by the words uttered.In this paper, focus will be laid upon what is irony , what are the Pragmatic functions of irony in English culture and in Chinese culture .and what is the comparison between English irony and Chinese irony.2. What is ironyIt is difficult to define the word of “irony” which could be understood in various ways. The expansion of its research area may be the direct cause of the diversity of the definition of irony. The following are some definitions of irony from dictionaries.2.1 Dictionary definitions of irony1) Expression of one‟s meaning by saying the direct opposite of one‟s thoughts in order to be emphatic, amusing, sarcastic, etc. [2]Oxford Advanced Learner’s English-Chinese Dictionary2) Use of words which are clearly opposite to one‟s meaning, usually either in order to be amusing or to show annoyance (e.g. by saying …What charming behavior‟ when someone has been rude.) [3]Longman Dictionary of English Language &Culture (English-Chinese) 3) Irony is a literary technique that achieves the effect of saying one thing and meaning another through the use of humor or mild sarcasm. [4]Webster’s New World Encyclopedia4) The use of words to express something other than and especially the opposite of the literal meaning. [5]Webster English Dictionary5) Irony is a figure of speech that achieves emphasis by saying the opposite of what is meant, the intended meaning of the words being the opposite of their usual sense. This form of irony is called verbal irony, and differs from the stylistic device of dramatic irony. [6]English Rhetorical Options6) Definition of irony from Grolier International Dictionary:a). An expression or utterance marked by such a deliberate contrast between apparent and intended meaning, for humorous or rhetorical effect.b). Incongruity between what might be expected and what occurs. [7]The above definitions, although explained by different experts from different angles, roughly display the nature of irony from both the form and function. Among these definitions, the basic meaning of irony could be found as “saying one thing but meaning another.” The best description of irony, say, the Grolier International Dictionary, takes both the form and function of irony into consideration and gives us a better picture. However, all of these definitions have some shortcomings. First, none of them provides an effective way to identify irony from non-irony. Second, they basically regard irony as a trope or a figure of speech whose literal and connotative meanings are mutually opposed to each other. This traditional understanding has been under challenges by modern research.3. Pragmatic functions of ironyIn the former parts of this paper, we have already discussed about the relation between irony and CP, the association between irony and IP, and the connection between irony and verbal humor. Though irony seems to take flouting CP as its own duty, it acts as an assistant of IP actively. As a type of verbal humor, irony devotes itself to produ ce humor in people‟s communications. However, what are the pragmatic functions of irony? In this section, the key to this question will be presented mainly from two major aspects: pragmatic functions of English irony and pragmatic functions of Chinese irony.3.1 Pragmatic functions of English ironyPragmatic functions of English irony can be stated in various ways, similar to theclassification of it. In the following passage, the effort will be concentrated on the major functions of irony. Firstly, while using irony people tend to use affirmative to express critique or discontent. Secondly, irony is always used as a means to satirize. Thirdly, irony is used as an approach to be polite. Last but not the least, irony is used as an approach to be humorous.3.1.1 Used as an affirmative to express critique or discontentIn English, irony is often used to state one‟s negative attitude to something. For example:(1) I just adore mosquitoes. (郑国龙,2003,P28)(2) You are a big help! (邱政政,2005,P2)(3) You are telling stories! (邱政政,2005,P2)In example (1), “adore” actually tells us the displeasure of the speaker. It can be learned from the meaning between the lines that the speaker hates mosquitoes in fact. The sentence of example (2) is not really used to praise the “help” but to indicate, “You only do nothing to help.” The speaker of example (3) applies irony to make a mockery.In everyday life, people tend to use irony in their speech though sometimes they may not be conscious of it. The following is another instance:(4) This morning, I was late for work; at noon, I had my bike stolen; on the way home this afternoon, I slipped down in the street. So today, I am certainly enjoying myself. (郑国龙,2003,P28)Obviously, the narrator did not enjoy himself indeed this day. With the strong discontent of the terrible experience, he expressed his displeasure by using the opposite word “enjoy”.3.1.2 Used as a means to satirizeIrony is used to veil feelings in a subtle way. Words of praise are often found where condemnation is meant. Below are some examples:(1) Like all the other officers at Group Headquarters except Major Danby, Colonel Cathcart was infused with the democratic spirit: he believed that all men outside Group equal, and he therefore spurned all men outside Group Headquarters with equalfervor. (冯翠华,1995,P214)(This passage implies that Colonel Cathcart was not democratic at all: his democratic spirit extended only to his own group; all others he treated with scorn and highhandedness.)(2) …a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a mo st delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout. (郑国龙,2002,P28)The author here proposed the measure to solve the problem of starvation and overpopulation by eating or selling children from poor families. However, his real purpose was to rip off the hypocritical mask of hypocrites. Used as a means to satirize, irony helped to disclose the serious problem of the society in above example.3.1.3Used as an approach to be politeIn daily conversation, people are apt to be polite. As an indirect expression, irony is widely applied. For example:(1) “Have a drink?”“All right, but not up at the bar. We will take a table.”“The perfect father.” (薛利芳,2004,P65)(2) “The boy has broken another glass,” said the mother.“A fine thing!” the father replied. (冯庆华,2001,P160)In example (1), the son chose the polite way of using “the perfect father” which actually referred to one who was stingy about money matter. If he complained directly to his father that “A stingy father”, the impoliteness would break the relationship between the father and son more or less. Conversely, the father in example (2) criticized the fault of his son in a n indirect way. “A fine thing!” could be treated as a criticism out of goodwill.3.1.4 Used as an approach to be humorousIn Section 5.2 of this paper, we have learned that verbal irony serves as an approach of verbal humor. Therefore, the humorous function of irony can be easily revealed. Below are some more examples for further acknowledging.(1) Polite horseThe Bach sees Ball walking lamely, asks him: “ What‟s happened?” Ball says: “ I went to the forest park to ride the horse on Sunday.” “ I‟m sure th at it was an unruly,or the horse did not allow to ride?” “Both are not. Just the horse was very polite --- when it ran to a stockade at a full gallop, it stopped all of a sudden and made me leap over first.” Says Ball. (艾临,2005,P170)(2) Taken in Twice“What‟s the matter with your hands?”“They were bitten by the serpent.”“How can it happen?”“I went to the forest the day before yesterday. Seeing there is a snake around the tree, I picked up a stick to beat.”“Missed the target.”“No, what is twisted around the tree was a rope, while what I picked up was just a snake.” (艾临,2005,P2)A new conception of what a polite horse is shows forth in example (1). Humor occurred when Ball understated his displeasing experience by using irony. Similarly, the embarrassment of the narrator in example (2) is well veiled in the ironic statement, which brings humor to good effect.3.2 Pragmatic functions of Chinese irony3.2.1 Chinese ironyChinese irony, to some extent, is equal to the type of English irony, namely verbal irony. Generally speaking, it can be classified as five types: irony for commendation and derogation,irony for satire,irony for fun, irony for affection and irony for emphasis. The classification is basically in the light of the pragmatic functions of irony. The detailed demonstration of them will be continued in the following parts.3.2.2 Pragmatic functions of Chinese irony(i) Irony for praise and denigrationIrony for praise and denigration is to use praise instead of derogatory term, or vice versa. It is an indirect utterance that can avoid making comments in direct way. Ithas nothing to do with sarcasm. For instance:凤姐道:“我那里管得这些事来?见识又浅,口角又笨,心肠又直率,人家给个棒槌我就认作针,脸皮又软,搁不住人家两句好话,心里就慈悲了。

_傲慢与偏见_中的反语研究

《齐齐哈尔大学学报》(哲学社会科学版)2010年1月Journal of Qiqihar University (Phi&Soc Sci )January 2010[收稿日期]2009-09-30[作者简介]陈慧(1970-)女,绥化学院外语系助教。

研究方向:应用语言学。

《傲慢与偏见》中的反语研究陈慧(绥化学院外语系,黑龙江绥化152061)[关键词]关联理论;反语回应论;傲慢与偏见[摘要]本文通过对《傲慢与偏见》中言语反讽例证分析来阐述如何在关联理论框架下理解反语,证明关联理论反语观合理性、可行性以及对反语的强大阐释力。

通过论证得出,关联理论框架下的反语回应论不仅对反语有强大的阐释力,还可以帮助我们更好的理解文学作品。

[中图分类号]I106.6[文献标识码]A[文章编号]1008-2638(2010)01-0040-03A Study of Irony in Pride and PrejudiceCHEN Hui(Foreign Language Department ,Suihui University ,Suihua 152061,China )Key words :the relevance theory ;the echoic mention theory of verbal irony ;Pride and PrejudicAbstract :The thesis aims at testing the rationality and feasibility of the echoic mention theory of irony proposed by Sperber and Wilson as well as its explanatory power to the interpretation of irony by analyzing the examples in Pride and Prejudice to elaborate how to interpret the verbal irony within the framework of the relevance theory.Through investigation we can reach a conclusion that the echo-ic mention theory of verbal irony within the framework of the relevance theory can not only have a great explanatory power to the inter-pretation of irony ,but also help us have a better understanding of literature.《傲慢与偏见》是英国19世纪著名女作家简·奥斯丁的代表作之一。

irony

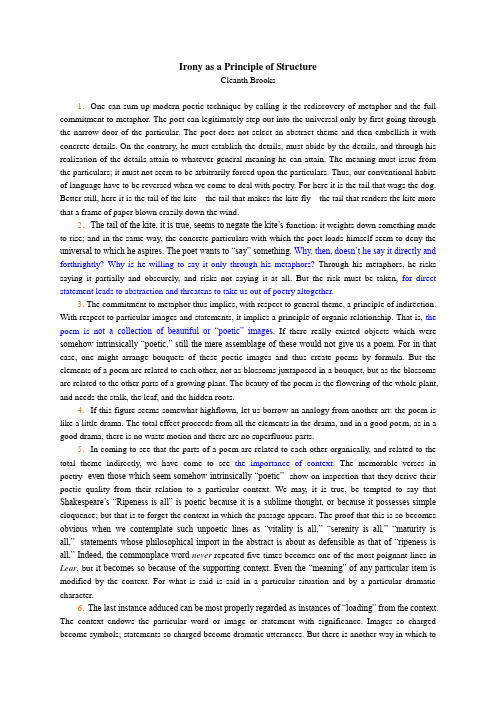

Irony as a Principle of StructureCleanth Brooks1.One can sum up modern poetic technique by calling it the rediscovery of metaphor and the full commitment to metaphor. The poet can legitimately step out into the universal only by first going through the narrow door of the particular. The poet does not select an abstract theme and then embellish it with concrete details. On the contrary, he must establish the details, must abide by the details, and through his realization of the details attain to whatever general meaning he can attain. The meaning must issue from the particulars; it must not seem to be arbitrarily forced upon the particulars. Thus, our conventional habits of language have to be reversed when we come to deal with poetry. For here it is the tail that wags the dog. Better still, here it is the tail of the kite---the tail that makes the kite fly---the tail that renders the kite more that a frame of paper blown crazily down the wind.2.The tail of the kite, it is true, seems to negate the kite’s function: it weights down something made to rise; and in the same way, the concrete particulars with which the poet loads himself seem to deny the universal to which he aspires. The poet wants to “say” something. Why, then, doesn’t he say it directly and forthrightly? Why is he willing to say it only through his metaphors?Through his metaphors, he risks saying it partially and obscurely, and risks not saying it at all. But the risk must be taken, for direct statement leads to abstraction and threatens to take us out of poetry altogether.3.The commitment to metaphor thus implies, with respect to general theme, a principle of indirection. With respect to particular images and statements, it implies a principle of organic relationship. That is, the poem is n ot a collection of beautiful or “poetic” images. If there really existed objects which were somehow intrinsically “poetic,” still the mere assemblage of these would not give us a poem. For in that case, one might arrange bouquets of these poetic images and thus create poems by formula. But the elements of a poem are related to each other, not as blossoms juxtaposed in a bouquet, but as the blossoms are related to the other parts of a growing plant. The beauty of the poem is the flowering of the whole plant, and needs the stalk, the leaf, and the hidden roots.4.If this figure seems somewhat highflown, let us borrow an analogy from another art: the poem is like a little drama. The total effect proceeds from all the elements in the drama, and in a good poem, as in a good drama, there is no waste motion and there are no superfluous parts.5.In coming to see that the parts of a poem are related to each other organically, and related to the total theme indirectly, we have come to see the importance of context.The memorable verses in poetry--even those which seem somehow intrinsically “poetic”--show on inspection that they derive their poetic quality from their relation to a particular context. We may, it is true, be tempted to say that Shakespeare’s “Ripeness is all” is poetic because it is a sublime thought, or because it possesses simple eloquence; but that is to forget the context in which the passage appears. The proof that this is so becomes obvious when we contemplate such unpoetic lines as “vitality is all,” “serenity is all,” “maturity is all,”--statements whose philosophical import in the abstract is about as defensible as that of “ripeness is all.” Indeed, the commonplace word never repeated five times becomes one of the most poignant lines in Lear, but i t becomes so because of the supporting context. Even the “meaning” of any particular item is modified by the context. For what is said is said in a particular situation and by a particular dramatic character.6.The last instance adduced can be most properly regarded as instances of “loading” from the context. The context endows the particular word or image or statement with significance. Images so charged become symbols; statements so charged become dramatic utterances. But there is another way in which tolook at the impact of the context upon the part. The part is modified by the pressure of the context.7.Now the obvious warping of a statement by the context we characterize as “ironical.” To take the simplest instance, we say “this is a fine state of affairs,” and in certain contexts the statement means quite the opposite of what it purports to say literally. This is sarcasm, the most obvious kind of irony. Here a complete reversal of meaning is effected: effected by the context, and pointed, probably, by the tone of voice. But the modification can be most important even though it falls far short of sarcastic reversal, and it need not be underlined by the tone of voice at all. The tone of irony can be effected by the skillful disposition of the context. Gray’s Elegy will furnish an obvious example.Can storied urn or animated bustBack to its mansion call the fleeting breath?Can Honor’s voice provoke the silent dust,Or Flatt’ry soothe the dull cold ear of deat h?8.In its context, the question is obviously rhetorical. The answer has been implied in the characterization of the breath as fleeting and of the ear of death as dull and cold. The form is that of a question, but the manner in which the question has been asked shows that it is no true question at all.9.These are obvious instances of irony, and even on this level, much more poetry is ironical than the reader may be disposed to think. Many of Hardy’s poems and nearly all of Housman’s, for example, reveal irony quite as definite and overt as this. Lest these examples, however, seem to specialize irony in the direction of the sardonic, the reader ought to be reminded that irony, even in its obvious and conventionally recognized forms, comprises a wide variety of modes: tragic irony, self-irony, playful, arch, mocking, or gentle irony, etc. The body of poetry which may be said to contain irony in the ordinary senses of the term stretches from Lear, on the one hand, to Cupid and Campaspe Played, on the other.10.What indeed would be a statement wholly devoid of an ironic potential--- a statement that did not show any qualification of the context? One is forced to offer statements like “Two plus two equals four,” or “The square on the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the two sides.” The meaning of these statements is unqualified by any context; if they are true, they are equally true in any possible context. These statements are properly abstract, and their terms are pure denotat ions. (If “two” or “four” actually happened to have connotations for the fancifully minded, the connotations would be quite irrelevant: they do not participate in the meaningful structure of the statement.)11.But connotations are important in poetry and do enter significantly into the structure of meaning which is the poem. Moreover, I should claim also---as a corollary of the foregoing proposition--- that poems never contain abstract statements. That is, any “statement” made in the poem bears the pressure of the context and has its meaning modified by the context. In other words, the statements made---including those which appear to be philosophical generalizations---are to be read as if they were speeches in a drama. Their relevance, their propriety, their rhetorical force, even their meaning, cannot be divorced from the context in which they are imbedded.12.The principle I state may seem a very obvious one, but I think that it is nonetheless very important. It may throw some light upon the importance of the term irony in modern criticism. As one who has certainly tended to overuse the term irony and perhaps, on occasion, has abused the term, I am closely concerned here. But I want to make quite clear what that concern is: it is not to justify the term irony as such, but rather to indicate why modern critics are so often tempted to use it. We have doubtless stretched the term too much, but it has been almost the only term available by which to point to a general andimportant aspect of poetry.13.Consider this example: The speaker in Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach states that the world, “which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams…hath really neither joy nor love nor light…” For some readers the statement will seem an obvious truism. (The hero of a typical Hemingway short story or novel, for example, will say this, though of course in a rather different idiom.) For other readers, however, the statement will seem false, or at least highly questionable. In any case, if we try to “prove” the prop osition, we shall raise some very perplexing metaphysical questions, and in doing so, we shall certainly also move away from the problems of the poem and, finally, from a justification of the poem. For the lines are to be justified in the poem in terms of the context: the speaker is standing beside his loved one, looking out of the window on the calm sea, listening to the long withdrawing roar of the ebbing tide, and aware of the beautiful delusion of moonlight which “blanches” the whole scene. The “truth” of the statement, and of the poem itself, in which it is imbedded, will be validated, not by a majority report of the association of sociologists, or a committee of physical scientists, or of a congress of metaphysicians who are willing to stamp the statement as proved. How is the statement to be validated? We shall probably not be able to do better than to apply T. S. Eliot’s test: does the statement seem to be that which the mind of the reader can accept as coherent, mature, and founded on the facts of experience? But when we raise such a question, we are driven to consider the poem as drama. We raise such further questions as these: Does the speaker seem carried away with his own emotions? Does he seem to oversimplify the situation? Or does he, on the other hand, seem to have won to a kind of detachment and objectivity? In other words, we are forced to raise the question as to whether the statement flows properly out of a context; whether it acknowledges the pressures of the context; whether it is “ironical”---or merely callow, glib, and sentimental.14.I have suggested elsewhere that the poem which meets Eliot’s test comes to the same thing as I. A. Richards’ “poetry of synthesis”---that is, a poetry which does not leave out what is apparently hostile to its dominant tone, and which, because it is able to fuse the irrelevant and discordant, has come to terms with itself and is invulnerable to irony. Irony, then, in this further sense, is not only an acknowledgment of the pressures of a context. Invulnerability to irony is the stability of a context in which the internal pressures balance and mutually support each other. The stability is like that of the arch: the very forces which are calculated to drag the stones to the ground actually provide the principle of support---a principle in which thrust and counterthrust become the means of stability.。

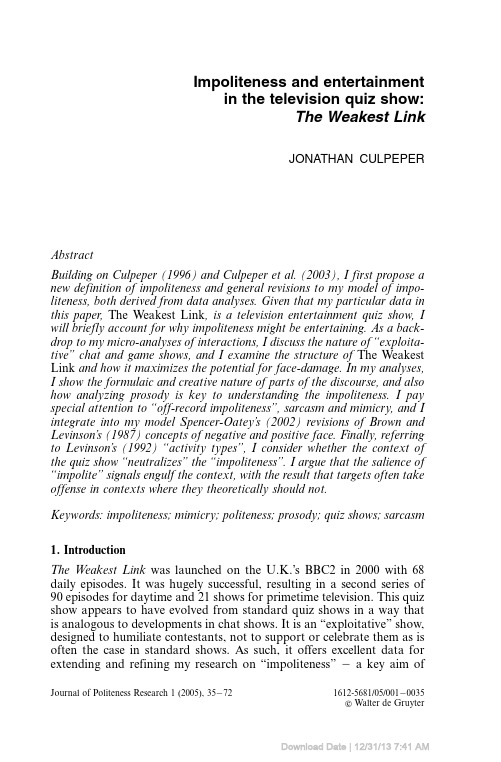

Impoliteness and entertainment in the television quiz show-The Weakest Link

Impoliteness and entertainmentin the television quiz show:The Weakest LinkJONATHAN CULPEPERAbstractBuilding on Culpeper(1996)and Culpeper et al.(2003),I first propose a new definition of impoliteness and general revisions to my model of impo-liteness,both derived from data analyses.Given that my particular data in this paper,The Weakest Link,is a television entertainment quiz show,I will briefly account for why impoliteness might be entertaining.As a back-drop to my micro-analyses of interactions,I discuss the nature of“exploita-tive”chat and game shows,and I examine the structure of The Weakest Link and how it maximizes the potential for face-damage.In my analyses, I show the formulaic and creative nature of parts of the discourse,and also how analyzing prosody is key to understanding the impoliteness.I pay special attention to“off-record impoliteness”,sarcasm and mimicry,and I integrate into my model Spencer-Oatey’s(2002)revisions of Brown and Levinson’s(1987)concepts of negative and positive face.Finally,referring to Levinson’s(1992)“activity types”,I consider whether the context of the quiz show“neutralizes”the“impoliteness”.I argue that the salience of “impolite”signals engulf the context,with the result that targets often take offense in contexts where they theoretically should not.Keywords:impoliteness;mimicry;politeness;prosody;quiz shows;sarcasm1.IntroductionThe Weakest Link was launched on the U.K.’s BBC2in2000with68 daily episodes.It was hugely successful,resulting in a second series of 90episodes for daytime and21shows for primetime television.This quiz show appears to have evolved from standard quiz shows in a way that is analogous to developments in chat shows.It is an“exploitative”show, designed to humiliate contestants,not to support or celebrate them as is often the case in standard shows.As such,it offers excellent data for extending and refining my research on“impoliteness”Ϫa key aim of Journal of Politeness Research1(2005),35Ϫ721612-5681/05/001Ϫ0035ąWalter de Gruyter36Jonathan Culpeperthis paper.The first section of this paper clarifies what is meant by impo-liteness,proposing a new definition,and the second section introduces my model of impoliteness,examining further the notion of sarcasm and proposing a new category of“off-record impoliteness”.I also suggest that Spencer-Oatey’s(2002)refinement of Brown and Levinson’s notions of positive and negative face should be adopted.These revisions are all data-driven:as I will show,they are needed in order to offer an adequate but parsimonious account of my data.The fact that The Weakest Link is clearly an entertainment showϪa media constructϪis significant.Amongst other things,I will need to explain why impoliteness might be entertaining,something which I have already undertaken for another genre,the fictional film(Culpeper1998). Some of my previous publications in the area of impoliteness did not pay adequate attention to the context.Consequently,before my micro-analyses of interactions in The Weakest Link,I will elaborate on the nature of“exploitative”chat and game shows;the structure of The Weakest Link and how it maximizes the potential for face-damage;and, briefly,the persona which the host,Anne Robinson,has created for the show.I will focus again on context at the end of the paper,in order to address the issue of whether the context of the quiz show“sanctions”or “neutralizes”the“impoliteness”.The heart of this paper contains micro-analyses of interactions within The Weakest Link.The first analyses,in particular,show the formulaic and creative nature of parts of the dis-course.The remaining analyses pay special attention to prosody,some-thing which other researchers typically overlook.They give truth to the frequent observation made by people who have been offended that it was not what was said but how it was said.2.The notion of impolitenessThe phenomenon of impoliteness is to do with how offense is communi-cated and taken.My first task in this section will be to delimit and define impoliteness more precisely,and my second will be to point out a number of areas where further research is needed.I begin by proposing four things which impoliteness is not:(1)Impoliteness is not incidental face-threat.As Goffman(1967:14)puts it,“[t]here are incidental offences;these arise as an unplanned but sometimes anticipated by-product of actionϪaction the of-fender performs in spite of its offensive consequences,though not out of spite”1.The key point here is that they are not performed “out of spite”.Tutors,for example,regularly give students critical comments which may have potentially offensive consequences,butImpoliteness and The Weakest Link37 this is a by-product of helping the students to improve,not the pri-mary goal.The tutor is not(usually!)seeking to offend the student.Incidental face-threat is at the heart of politeness theories.Tutors typically do politeness work,in order to counter those potential of-fensive consequences.(2)Impoliteness is not unintentional.Again,this can be related to Goff-man(1967:14),when he points out that the offending person“may appear to have acted innocently;his[sic]offence seems to be unin-tended and unwitting[…].In our society one calls such threats to face faux pas,gaffes,boners or bricks”.A sub-type here is“failed politeness”.For example,an interactant might misjudge how much politeness work is required in a particular situation and thus cause offense(e.g.,not appreciating the extraordinary lengths somebody went to in procuring a particular gift,and thereby giving insufficient thanks from the giver’s point of view).(3)Impoliteness is not banter.Drawing upon Leech(1983),I suggestedin my earlier paper(1996)that we should distinguish“mock impo-liteness”from“genuine impoliteness”.Banter or mock impoliteness remains on the surface,because it is understood in particular contexts not to be true.Ritualized banter(or“sounding”,“playing the dozens”)has,of course,been the subject of some of Labov’s (1972)famous work.(4)Impoliteness is not bald on record(BOR)politeness.As elaboratedin Culpeper et al.(2003),Brown and Levinson’s(1987:69)definition of BOR politeness states that it is direct(complies with Grice)and occurs in specific contexts:emergency situations,when the face-threat is very small,and when the speaker has great power.However, the vast majority of instances of what I would call“impoliteness”fail to fit the definition of BOR.As an example of BOR politeness, Thomas(1995:171)cites Tam Dalyell’s reference to Margaret Thatcher(then Prime Minister)in the British House of Commons:“I say that she is a bounder,a liar,a deceiver,a crook”.The repeti-tion clearly flouts the maxim of manner,whereby Dalyell implicates the impolite belief that Thatcher is extremely dishonest.Thus,it nei-ther complies with Grice(1975)nor fits the specific contexts for BOR.So what is impoliteness?In my most recent work on impoliteness(2003), a collaboration with Derek Bousfield and Anne Wichmann,attention was drawn to a number of deficits in the original politeness model I proposed in1996.We emphasized the need to go beyond the single speaker’s utterance,lexically and grammatically defined.However,my original definition of impoliteness was not revised,simply restated in a38Jonathan Culpeperslightly more succinct form as:“communicative strategies designed to attack face,and thereby cause social conflict and disharmony”(Culpeper et al.2003:1546.Reference was also made to similar definitions in the literature:Kienpointner1997:259Ϫ260;Beebe,1995:159).One problem with this original definition is the assumption that face-attack will“cause social conflict and disharmony”.This element of the definition had evolved by way of contrast to how researchers had defined politeness, for example:[The role of the Politeness Principle is]“to maintain the social equilibrium and the friendly relations which enable us to assume that our interlocutors are being cooperative in the first place”(Leech 1983:82).But there are two problems here:it is not clear what this social conflict and disharmony consists of,and it is not a necessary condition of impoliteness having taken place.In fact,looking ahead to our discus-sion of The Weakest Link,it is not at all clear in what sense there is social conflict and disharmony here.Moreover,the definition fails to take adequately into account what the hearer is doing.This speaker bias is another legacy from politeness work,particularly that of Brown and Levinson(1987).A better definition is proposed by Tracy and Tracy:“we define face-attacks as communicative acts perceived by members of a social com-munity(and often intended by speakers)to be purposefully offensive”(1998:227).Like me,the authors also refer to Goffman(1967),who relates such face-threat to cases where“the offending person may appear to have acted maliciously and spitefully,with the intention of causing open insult”(Goffman,1967:14).However,their definition still needs some unpacking(e.g.,in what ways might these attacks be unintended?), and the roles of the speaker and hearer are not very transparent.I thus propose a revised definition:Impoliteness comes about when:(1)the speaker communicates face-attack intentionally,or(2)the hearer perceives and/or constructs be-havior as intentionally face-attacking,or a combination of(1)and(2). The key aspect of this definition is that it makes clear that impoliteness, as indeed politeness,is constructed in the interaction between speaker and hearer.Perhaps the prototypical instance of impoliteness involves both(1)and(2),the speaker communicating face-attack intentionally and the hearer perceiving/constructing it as such.For example,a poten-tially impolite act such as an interruption may seem just to involve activ-ity on the part of the speaker,but,as Bilmes(1997)convincingly argues, interruptions are a reciprocal activity,involving both“doing interrupt-ing”and“doing being interrupted”(1997:514Ϫ550).“Doing being in-terrupted”involves the communication of disruptive intents to the in-Impoliteness and The Weakest Link39 terrupter through overt protests,ignoring or“interruption displays”Ϫ“a show of insistence and/or annoyance”by“facial expressions,gestures, grammatical devices,repetition,and raised voice”(1997:518Ϫ520). However,other permutations of(1)and(2)are possible.Face-attack may be intentionally communicated but fail to find its mark in any way, or,conversely,the hearer may perceive or construct intentional face-attack on the part of the speaker,when none was intended.Consider this example of the latter:[Context:An extended family is eating a meal at a Pizza Hut.There is a tense relationship between participants A and B.]A:Pass me a piece of garlic bread,will you?B:That’ll be50p[A opens purse and proceeds to give B50p]In this context,B’s request for payment was intended as a jokeϪas banter.A,however,reconstructs it as a genuinely impolite act,thereby, attacking B herself by constructing him as mean.This particular strategy is,in fact,one that occurs elsewhere in my data collection.Two other aspects of my definition are noteworthy.Firstly,the notion of intention is of central importance,and it will be clear from my discus-sion of what impoliteness is not and also my references to Goffman why this is so(i.e.,it helps us exclude by-product,accidental and mock types of face-threat).This can be related to Grice’s distinction between“natu-ral meaning”and“non-natural meaning”:for an utterance to have non-natural meaning it must not merely have been uttered“with the intention of inducing a certain belief but also the utterer must have intended the “audience”to recognize the intention behind the utterance”(Grice[1957] 1989:217).Impoliteness,then,has two layers:the offensive information being expressed by the utterance and the information that that informa-tion is being expressed intentionally2.Of course,recognizing intentions is highly problematic:they have to be inferred in communication.A corollary of this is that recognizing categories like“by-product”,“acci-dental”and“mock”is a matter of inferencing not just signaling.Sec-ondly,it will be clear that I am not abandoning the concept of“face”, despite criticisms in the literature,particularly with regard to Brown and Levinson’s notion of negative face having a“Western”bias in focusing on individual autonomy(e.g.,Matsumoto1988;Gu1990;for a more general critique of“face”,see Bargiela-Chiappini2003).Impoliteness concerns offense,and face,in my view,still represents the best way of understanding offense.Of course,face should be more adequately con-ceptualized and contextually sensitive.Helen Spencer-Oatey(e.g.,2002) is one of the few researchers to get out of the armchair and propose40Jonathan CulpeperTable1.Revising the notion of face:Components of“rapport management”(Spencer-Oatey2002:540Ϫ2)3.Face Quality face:“We have a fundamental de-(defined with reference to Goffman sire for people to evaluate us positively in (1972:5):“the positive social value in terms of our personal qualities,e.g.,our a person effectively claims for himself confidence,abilities,appearance etc.”[sic]by the line others assume he hasSocial identity face:“We have a fundamen-taken during a particular contact”tal desire for people to acknowledge and up-[Spencer-Oatey’s emphasis])hold our social identities or roles,e.g.,asgroup leader,valued customer,closefriend.”Sociality rights Equity rights:“We have a fundamental be-(defined as“fundamental personal/so-lief that we are entitled to personal con-cial entitlements that a person effec-sideration from others,so that we are tively claims for him/herself in his/her treated fairly,that we are not unduly im-interactions with others”[Spencer-posed upon or unfairly ordered about,that Oatey’s emphasis])we are not taken advantage of or exploited,and that we receive the benefits to which weare entitled.”Association rights:“We have a fundamentalbelief that we are entitled to associationwith others that is in keeping with the typeof relationship that we have with them.”definitions based on solid empirical work.Space precludes a full outline of her proposals,but I offer a brief summary in Table1.The notion of face is split into two components.Quality face is clearly present in Brown and Levinson’s(1987)notion of positive face,and there are hints of social identity face.Spencer-Oatey explicitly splits two very different components:the former being an individual or personal aspect,and the latter being a matter of one’s identity in the group.Al-ready,one can see how we are moving away from Brown and Levinson’s (1987)emphasis on individual autonomy.Interestingly,“sociality rights”are not considered face issues,“in that an infringement of sociality rights may simply lead to annoyance or irritation,rather than to a sense of face-threat or loss(although it is possible,of course,that both will oc-cur)”(Spencer-Oatey2002:541).Brown and Levinson’s(1987)notion of negative face overlaps primarily with the notion of equity rights,in as far as they relate to matters of imposition and costs/benefits,but it also overlaps to a degree with association rights.I will refer to all these com-ponents in my analyses of impoliteness in The Weakest Link,but the most relevant components are Quality face(e.g.,attacks on the inad-equacy of the contestant in answering the questions)and Social Identity face(e.g.,attacks on the contestant’s regional accent and job).Impoliteness and The Weakest Link41 3.A model of impolitenessIn my work,I refrain from referring to an impoliteness“theory”.In so far as theories have predictive power,the model of impoliteness I have been developing is not yet a theory.Two areas in particular need atten-tion.Firstly,impoliteness is not inherent in particular linguistic and non-linguistic signals.The same argument for politeness is made repeatedly by Watts(2003).This is not to refute the fact that some linguistic items are very heavily biased towards an impolite interpretation(one has to work quite hard to imagine contexts in which“you fucking cunt”would not be considered impolite).Nevertheless,this instability means that im-politeness comes about in the interaction between linguistic and non-linguistic signals and the context,and so context must be fully factored in.Some work on the co-text was undertaken in Culpeper et al.(2003), but we still know little about the effect of particular social relations(e.g., power)and of the activity type in which the impoliteness takes place. This paper has as one of its aims an examination of a particular genre or activity type.Secondly,descriptions of politeness and impoliteness tend to over-emphasize lexical and grammatical resources,and hence they have a limited view of the communicative signal.Work on prosody undertaken in Culpeper et al.(2003)by Anne Wichmann made a start in improving this situation.A particular aim of the present study is to emphasize the importance of prosody in descriptions of impoliteness, and in The Weakest Link in particular.It is appropriate at this point to re-state my impoliteness model in brief,because I will refer to it in this paper and because I wish to develop it further.Bald on record impoliteness:the FTA is performed in a direct,clear, unambiguous and concise way in circumstances where face is not irrel-evant or minimized.Positive impoliteness:the use of strategies designed to damage the ad-dressee’s positive face wants,e.g.,ignore the other,exclude the other from an activity,be disinterested,unconcerned,unsympathetic,use inappropriate identity markers,use obscure or secretive language,seek disagreement,use taboo words,call the other names.Negative impoliteness:the use of strategies designed to damage the addressee’s negative face wants,e.g.,frighten,condescend,scorn or ridicule,be contemptuous,do not treat the other seriously,belittle the other,invade the other’s space(literally or metaphorically),explicitly associate the other with a negative aspect(personalize,use the pro-nouns“I”and“Y ou”),put the other’s indebtedness on record.42Jonathan CulpeperSarcasm or mock politeness:the FTA is performed with the use of politeness strategies that are obviously insincere,and thus remain sur-face realisations.Withhold politeness:the absence of politeness work where it would be expected.For example,failing to thank somebody for a present may be taken as deliberate impoliteness.(summarized from Culpeper1996:356Ϫ7) One conclusion of Culpeper et al.(2003)is that these“super strategies”rarely occur singularly but are more often mixed(contrary to what Brown and Levinson claim for politeness).Moreover,it is often the case that orientation to one kind of face may have implications for another. Thus,an interruption may,in specific contexts,attack negative face by impeding someone,but it may also imply that the interuptee’s opinion was not valuedϪa positive face issue4.Thus,there can be primary effects for one type of face and secondary for another.Moreover,as I suggested in the last section,the superstrategies of positive and negative impoliteness should be revised to fit Spencer-Oatey’s categorization of face or“rapport management”,giving Quality Face impoliteness,Social Identity Face impoliteness,Equity Rights impoliteness and Association Rights impoliteness.It is to these categories that I will refer in my up-coming analyses.Each of the super strategies was originally modeled on a politeness counterpart in Brown and Levinson’s(1987)politeness framework,with one apparent exceptionϪ“sarcasm or mock politeness”Ϫwhich is not clearly the counterpart of off-record politeness.Sarcasm,inspired by Leech’s(1983)conception of irony,is unlike the others in the sense that it is a meta-strategy,using politeness for impoliteness.An illustration from Leech is“DO`help yourse`lf(won’t you?)”,said to someone who is greedily helping him/herself already.The polite assumption that the ad-dressee is holding back from the feast until invited to tuck in is obviously untrue,and so an opposite impolite assumption is implicated.Thus,po-liteness is used for impoliteness.As Leech(1983:142)points out,irony is a“second-order principle”.But is there any sense in which sarcasm might be the opposite of Brown and Levinson’s“off-record politeness”? Let us start from another of Leech’s(1983:80)examples,one showing how Grice’s(1975)cooperative principle might be sacrificed in order to uphold politeness:A:We’ll all miss Bill and Agatha,won’t we?B:Well,we’ll all miss BI˘LL.B’s response fails to observe the maxim of quantity,suggesting the“im-polite”implicature that Agatha will not be missed.Leech(1983:81)Impoliteness and The Weakest Link43 remarks that this could have been made more cooperative(in Grice’s sense)with the addition of“but not Agatha”,but that this would have had consequence of making it more“impolite”.Such an example,of course,fits Brown and Levinson’s(1987)understanding of off-record politeness,since the“impolite”belief is conveyed indirectly by an impli-cature and could be cancelled(e.g.,denied).However,Leech(1983:82) later adds that examples such as this“can easily tip over into an ironic interpretation”,and states that“[i]rony typically takes the form of being too obviously polite for the occasion.This can happen if s overvalues the PP[Politeness Principle]by blatantly breaking a maxim of the CP in order to uphold the PP”.The maxim of quantity is fairly obviously flouted in the above example.To further clarify the argument,consider this example:[Context:From the television program Pop Idol,hosted by Ant and Dec.The aim of the show is to select the best contestant from numer-ous would-be pop stars.This extract occurs in one of the later pro-grams in a series,when the number of contestants is down to10.It occurs at the beginning of the program.The judges sit in front of the studio audience and can hear all that is said.]Ant:Our judges have been accused of being ill-informed,opinion-ated and rude.Dec:We’d like to set the record straight:our judges are not ill-in-formed.In some ways,this appears to fit the notion of off-record politeness.As with the Bill and Agatha example,an“impolite”belief that they are “opinionated and rude”is not statedϪan ostensibly polite maneuver. Moreover,setting“the record straight”raises expectations of a polite defense.However,they very obviously fail to set the whole record straight,thus flouting the maxim of quantity and generating the strong implicature that the accusation that the judges are“opinionated and rude”is true.The blatant way in which this happens would make it very difficult for Ant and Dec to deny the implicature.In sum,what we have here is insincere off-record politeness:it is not a genuine attempt to avoid causing offense.As such,it falls within my category of sarcasm. However,there is a further kind of off-recordness or indirectness that is not covered by any of my categories.Consider the following example, specifically,the emboldened part5:[Context:From the film Scent of a Woman.Charlie(CH)is a student at a prestigious private school,but he is not rich and is supported by student aid.In order to make ends meet,rather than go home for44Jonathan CulpeperThanksgiving,he responds to an advertisement asking for somebody to act as a carer for a blind relativeϪthe Colonel(COL).The dia-logue below occurs a few turns into their first encounter.]COL:Simms Charles,senior.Y ou on student aid,Simms?CH:Ah,yes I am.COL:For student aid read crook.Y our father peddles car telephones at a300%mark-up;your mother works on heavy commissionin a camera store,graduated to it from expresso machines.Ha,ha!What are you...dying of some wasting disease? CH:No...I’m right here.This is not at all cooperative in Grice’s(1975)sense,and,as with off-record politeness,the“impolite”belief is conveyed by implication.It is a rhetorical question that implicates,via the maxim of quality,the impo-lite belief that there is evidence that Charlie is dying of a wasting disease. However,this is not like the sarcasm examples that have as one of their defining features some claim,no matter how superficial,to be polite. The Colonel’s utterance has no such claim.What we have here is the off-record(in the sense that it flouts a maxim)expression of impoliteness.I thus propose an additional category for my impoliteness model:Off-record impoliteness:the FTA is performed by means of an implica-ture but in such a way that one attributable intention clearly out-weighs any others.In the outline of the model above,this can take the place of sarcasm, which can be separated out as distinct from the others,given its“meta-strategic”nature.It is not to be forgotten that these more indirect forms of impoliteness,such as off-record impoliteness,should not be consid-ered any less impolite than more direct forms.In fact,I argued in Cul-peper et al.(2003),with reference to Leech(1983:171),that there are theoretical grounds for believing it to work in the opposite direction, namely,that more indirect forms of impoliteness are more offensive.I shall illustrate off-record impoliteness further in my analyses of The Weakest Link,particularly in section5.2.4.Impoliteness as entertainmentThe Weakest Link,in common with all the television data that I have collected for my impoliteness research,is designed for entertainment. Even the“documentaries”(e.g.,Red Caps,Clampers,Ramsey’s Boiling Point),for example,do not present the latest scientific discovery,butheated confrontational interactions for entertainment.This begs the question as to whether there is a link between impolite interactions and entertainment.I would argue that this is indeed the case,and posit four generic factors:1.Intrinsic pleasure.As Myers puts it,discussing chat shows,“[s]ome-thing is engaging about argument for its own sake.”(Myers2001: 174).Importantly,he adds“[…]the thrill is in the potential for vio-lence”(Myers2001:183).In other words,we don’t need actual fisti-cuffs:the mere suggestion of fisticuffs can cause the thrill.2.Voyeuristic pleasure.Again in relation to chat shows,researchers haveidentified a voyeuristic aspect in the entertainment:“Daytime talk shows now resemble stunt wrestling,stock car racing,or video games.Colourful confrontationalism and quick,bruising skirmishes are the rule.”(Paglia1995,in Richardson and Meinhof1999:128);“[…] these shows trade in the exploitation of human weakness for the sake of voyeuristic pleasure.”(Richardson and Meinhof1999:132).3.The audience is superior.“Superiority theories”(e.g.,Bergson[1900]1911),developed within humor theory,articulate the idea that there is self-reflexive pleasure in observing someone in a worse state than oneself.Although foreshadowed in Plato and Aristotle,most theorists refer to Hobbes’Leviathan([1651]1946:Part I,chapter6): Sudden glory,is a passion which maketh those grimaces called LAUGHTER;and is caused either by some sudden act of their own,that pleaseth them;or by the apprehension of some deformed thing in another,by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves.Superiority theories have been used to explain the“butts”of jokes.There is a sense in which“exploitative”chat or quiz shows create “butts”out of the contestants for the audience’s amusement.4.The audience is safe.This factor can be seen as a sub-category of theprevious.Lucretius(De Rerum Natura,Book II,1Ϫ4)states it thus: It is pleasant,when on the great sea the winds are agitating the waters,to look from the land on another’s great struggle;not because it is a delectable joy that anyone be distressed,but because it is pleasant to see what ills you yourself are free from6.Compare,for example,witnessing an actual fight in a pub,in which case you might feel insecure and wish to make hasty exit,with a pub fight presented in a film.。

irony(2)

Secondly,whereas sarcasm typically operates by

heaping crude—and unfelt—praise on the individual, irony often employs blame. Irony must also be distinguished from satire, which ridicules human weaknesses in an effort to spur reform. The satirist derides humanity primarily in an effort to better it. Satire may involve irony, but irony typically lacks satire’s ameliorative (改善 的)intent.

• It saves a lot of trouble if, instead of having to earn money and save it, you can just go and borrow it. (假如你干脆可以去借 钱,以此代替赚钱与省钱,那会省掉许多 麻烦)。 • Yes,she is so beautiful that even the pockmarks(麻子) on her face are shining brightly.What is ugly about her is the countless wealth.(Irony:beautiful,ugly)

f Irony

• Irony is a figure of speech that achieves emphasis by saying the opposite of what is meant, the intended meaning of the words being the opposite of their usual sense.

修辞-Irony

这是证明他那可爱的国家的仁慈法律 的一个多么漂亮的例证!— 他们允许 穷人睡觉!

(This passage implies that Colonel Cathcart was not democratic at all: his democratic spirit extended only to his own group; all others he treated with scorn and highhandedness)

Heavy Irony:

A famous example of heavy irony is Mark Antony’s speech at the burial ceremony of Caesar in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

“Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them, The good is oft interred with their bones; So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus Hath told you Caesar was ambitious. If it were so, it was a grievous fault; And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it. Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest— For Brutus is an honorable man;

Satire与Irony差异浅析

Definition of Irony 具有讽刺意味的的定义

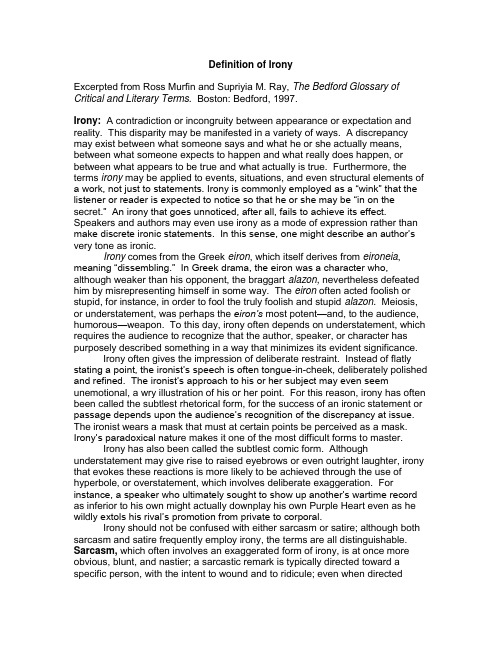

Definition of IronyExcerpted from Ross Murfin and Supriyia M. Ray, The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. Boston: Bedford, 1997.Irony: A contradiction or incongruity between appearance or expectation and reality. This disparity may be manifested in a variety of ways. A discrepancy may exist between what someone says and what he or she actually means, between what someone expects to happen and what really does happen, or between what appears to be true and what actually is true. Furthermore, the terms irony may be applied to events, situations, and even structural elements of a work, not just to statements. Irony is commonly employed as a “wink” that the listener or reader is expected to notice so that he or she may be “in on the secret.” An irony that goes unnoticed, after all, fails to achieve its effect. Speakers and authors may even use irony as a mode of expression rather than make discrete ironic statements. In this sense, one might describe an author’s very tone as ironic.Irony comes from the Greek eiron, which itself derives from eironeia, meaning “dissembling.” In Greek drama, the eiron was a character who, although weaker than his opponent, the braggart alazon, nevertheless defeated him by misrepresenting himself in some way. The eiron often acted foolish or stupid, for instance, in order to fool the truly foolish and stupid alazon. Meiosis, or understatement, was perhaps the eiron’s most potent—and, to the audience, humorous—weapon. To this day, irony often depends on understatement, which requires the audience to recognize that the author, speaker, or character has purposely described something in a way that minimizes its evident significance.Irony often gives the impression of deliberate restraint. Instead of flatly stating a point, the ironist’s speech is often tongue-in-cheek, deliberately polished and refined. The ironist’s approach to his or her subject may even seem unemotional, a wry illustration of his or her point. For this reason, irony has often been called the subtlest rhetorical form, for the success of an ironic statement or passage depends upon the audience’s recognition of the discrepancy at issue. The ironist wears a mask that must at certain points be perceived as a mask. Irony’s paradoxical natur e makes it one of the most difficult forms to master.Irony has also been called the subtlest comic form. Although understatement may give rise to raised eyebrows or even outright laughter, irony that evokes these reactions is more likely to be achieved through the use of hyperbole, or overstatement, which involves deliberate exaggeration. For instance, a speaker who ultimately sought to show up another’s wartime record as inferior to his own might actually downplay his own Purple Heart even as he wild ly extols his rival’s promotion from private to corporal.Irony should not be confused with either sarcasm or satire; although both sarcasm and satire frequently employ irony, the terms are all distinguishable. Sarcasm, which often involves an exaggerated form of irony, is at once more obvious, blunt, and nastier; a sarcastic remark is typically directed toward a specific person, with the intent to wound and to ridicule; even when directedtoward a person, irony generally lacks a hurtful aim. Furthermore, whereas sarcasm typically operates by heaping crude—and unfelt—praise on the individual, irony often employs blame. Irony must also be distinguished from satire, which ridicules human weaknesses in an effort to spur reform. Thesatirist derides humanity primarily in an effort to better it. Satire may involve irony, but irony typically lacks satire’s ameliorative intent.Several types of irony exist, all of which may be classified under one of three broad headings: verbal irony, situational irony, and structural irony.Verbal irony, also called rhetorical irony, is the most common kind of irony. Verbal irony is characterized by a discrepancy between what a speaker or writer says and what he or she believes to be true. More specifically, a speakeror writer using verbal irony will say the opposite of what he or she actually means. For instance, imagine that you have come home after a day on which you failed a test, wrecked your car, and had a fight with your best friend. If your roommate were to as k you how your day went and you replied, “Great day. Best ever,” you would be using verbal irony. Usually, however, the clues are not quite so obvious, as when the narrator of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837) says that “the parish authorities magnan imously and humanely resolved that Oliver should be ‘farmed,’ or, in other words, dispatched to a branch workhouse some three miles off.”Verbal irony is sometimes viewed as one of the tropes, which are figuresof speech, since it is a rhetorical device that involves saying one thing but meaning the opposite. Verbal irony can be the most difficult rhetorical device to master, since successful usage requires recognition by the reader or audience, even as it may demand authorial subtlety. Missing a verbal irony may lead the reader or audience to adopt a belief opposite to the one intended by the author. Tone probably keys the listener in to the irony more than any other element, but knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the statement may also spurrec ognition of the speaker’s true meaning. The roommate from the aforementioned example might, for instance, pick up on the irony either via the speaker’s tone or because he or she knew that the speaker had suffered one or more calamities that day. Since readers do not have the benefit of hearing a particular speaker’s tone, knowledge and the general tone of the work play a greater role in accurately identifying ironic statements.Situational irony, also called irony of situation, derives primarily from events or situations themselves, as opposed to statements made by any individual, whether or not that individual understands the situation as ironic. It typically involves a discrepancy between expectation and reality. For instance, situational irony existed when college-bound men in the Vietnam War era celebrated their avoidance of the draft, unaware that their exemption as college students was about to be revoked by Congress. Situational irony continued to exist even after the men learned about the revocation, provided that their college applications had been motivated solely by a desire to avoid the draft, the exemption was revoked after they went through the trouble of applying, and they actually got drafted. The scenarios described by Alanis Morrisette in her song “Ironic” (1995) also exemplify situational irony: dying the day after you win thelottery; working up the courage to take your first airplane flight and then crashing; finding the man of your dreams only to discover that he has a beautiful wife; and so forth.Literary examples of situational irony include O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi” and the mythic story of King Midas. In “Gift of the Magi,” both husband and wife give up their most prized possessions in order to give something to complem ent the other’s most prized possession. The woman sells her beautiful long hair to buy a platinum fob chain for the man’s watch; the man sells his watch to buy the woman tortoiseshell combs to hold up her hair. In the story of King Midas, Bacchus grants the king’s wish that everything he touch be turned to gold; much to his chagrin, the king finds that this power does anything but enhance his true wealth when he hugs his beloved daughter, thereby (inadvertently) turning her to gold as well. A poetric example of situation irony is Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” (1818), in which “a traveller from an ancient land” tells of coming upon a ruined state, the pedestal of which reads “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings, Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and des pair!”Three types of irony—dramatic irony, tragic irony, and Socratic irony—can be classified as situational irony. The term dramatic irony may be used to refer to a situation in which the character’s own words come back to haunt him or her. However, i t usually involves a discrepancy between a character’s perception and what the reader or audience knows to be true. The reader or audience possesses some material information that the character lacks, and it is the character’s imperfect information that m otivates or explains his or her discordant response. The character may respond to a statement or situation in three ways: by making a statement; forming an expectation; or taking some action. A verbal response involves dramatic irony when a character fails to recognize the true import of his or her words; characters with partial information may thus assign meanings to their words that differ from the meanings assigned by the reader or audience. Expectation and action involve dramatic irony when they are inappropriate under the circumstances that actually exist. Characters may even accurately assess a situation without realizing it, attributing to someone or something a truth that they do not recognize as such.Dramatic irony has often been used synonymously with tragic irony, but this usage is incorrect. Dramatic irony occurs in a wide variety of works, ranging from the comic to the tragic. Tragic irony is a type of dramatic irony marked by a sense of foreboding. As with all dramatic irony, tragic irony involves imperfect information, but the consequences of this ignorance are catastrophic, leading to the character’s tragic downfall. The reader or audience experiences a sense of foreboding while anticipating this downfall. In Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (430B.C.E.), for instance, Oedipus, the King of Thebes, vows to find the murderer of the prior king, only to find out something the audience knew all along: that Oedipus himself is the guilty party. Incidentally, neither dramatic nor tragic irony is limited to plays; both types of irony may appear in novels, movies and other literary forms.Socratic irony, also called dialectical irony, is, loosely speaking, situational in nature. The term stems from Plato’s depiction of Socrates. In his early fourthcentury B.C.E.dialogues, Plato recounts Socrates’s habitual practice of acting foolish or naïve when questioning his fellow citizens. Having assumed the role of the eiron, Socrates successfully forced his “opponents” to recognize the irrationality or preposterous implications of their positions by using their own responses against them. For instance, when Euthyphro, a citizen of Athens who is about to turn his father in for murder, says that this is obviously the right thingto do, Socrates pretends to b e really impressed by Euthyphro’s moral certainty. He subsequently asks naive-seeming questions demonstrating not that Euthyphro is wrong to turn his father in, but rather that his grounds for doing so are irrational and self-contradictory.The third major category of irony is structural irony. Works that exhibit structural irony contain an internal feature that creates or promotes a discrepancy that typically operates throughout the entire work. Some element of the work’s structure (or perhaps even its form), unrelated to the plot per se, invites the audience or reader to probe beneath surface statement or appearances. Authors most commonly use narration to tip off the reader or audience. For instance, the author may employ a naïve or otherwise unreliable narrator whose flaw the audience or reader readily recognizes. A naïve narrator means what he or she says, but having recognized the narrator’s flaw, the audience or reader mistrusts that narrator’s perceptions or version of events. The reader or au dience thus searches for and derives a different meaning that reflects the author’s intention. For instance, the reader of Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” (1729) quickly recognizes that its narrator—an economist who advocates cannibalism, specificall y, selling poor Irish infants to the wealthier English to solve Ireland’s perpetual, cyclic problems of poverty, overpopulation, and starvation—is fallible. Since no reasonable reader would take this work at face value, discovering Swift’s true view and purpose in using a fallible narrator becomes the reader’s task. Swift’s title is itself ironic, though this can be viewed as irony of a verbal rather than situational nature; calling such a proposal “modest” involves understatement, to say the least.Structural irony should not be confused with situational irony. The former involves some sustained feature that makes up part of the very frame of the work, whereas the latter involves an event or comment keyed to the plot rather than to the work’s structure. Granted, this difference sometimes seems more one of degree than an absolute difference, as in the case where a plot element underlines the entire work. In Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), a misunderstanding about identity serves as the basis of the comic plot and pervades the work. Similarly, in Oedipus Rex, Oedipus’s ignorance that a man he murdered in the past was the prior king of Thebes underlies the plot and leads to his tragic fall from grace. Although both of these works are based on their protagonists’ lack of crucial knowledge, both involve situational rather than structural irony, for the ironic discrepancies arise from the story line rather than the structure or form of the work itself.Two types of irony—cosmic irony and romantic irony—can be classified as structural irony. Cosmic irony, also called irony of fate, arises from the disparity between a character’s (incorrect) belief in his or her ability to shape his or herdestiny and the audience’s recognition that an external, supernatural force has the power to manipulate or even control that character’s fate. Just as the unreliable narrator serves as a structural device giving rise to structural irony, so the supernatural force of cosmic irony makes the irony structural rather than situational in nature. The use of cosmic irony is more than a matter of plot.Cosmic irony is characterized by four elements. First, it typically involves some powerful deity (or, sometimes, fate itself) with the ability and the desire to manipulate or even control events in a character’s life. Second, the character subject to this irony believes—erroneously—in free will. Whether or not the character acknowledges the deity’s existence, he or she persists in attempting to control or at least affect events. Third, the deity toys with the character much as a cat might with a mouse; the outcome is clear to the disinterested observer, but the mouse hopes desperately for escape. The deity may permit—or even encourage—the character to believe in self-determination, thereby raising false hopes that the audience knows or at least suspects will be dashed. Fourth, cosmic irony inevitably involves a tragic outcome. Ultimately, the character’s struggle against destiny will be for naught; he or she will have to succumb to forces larger than him- or herself. Cosmic irony is notably apparent in Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), the last chapter of which contains the statement “the President of the Immortals…had ended his sport with Tess.”Romantic irony, as defined by nineteenth-century German philosopher Friedrich Schlegel, is present in poems and prose works whose authors or speakers at some point reveal their narration to be the capricious fabrication of an idiosyncratic and highly self-conscious creator. Romantic ironists typically “give up the game” only after they have carefully constructed some vision of “reality”, however. They may reveal their narrator to be a liar, for instance, or they may speak directly to the reader as an author. As a result, they wreak havoc with the reader’s or audience’s usual suspension of disbelief, debunking as illusion the normal operating assumption that the narration is a believable representation of reality. Romantic ironists want their readers or audienc es to “see through” them, i.e., to appreciate the manipulative nature of their art and the slightly comic quality of even their most serious artistic endeavors. Authors as different as Geoffrey Chaucer, Miguel de Cervantes, George Gordon, Lord Byron, Luigi Pirandello, and Vladimir Nabokov have been called romantic ironists. A modern example of romantic irony is Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1961), a novel thinly disguised as a nine hundred and ninety-nine-line poem composed by a fictional poet named John Francis Shade, with a foreword, two hundred page commentary, and index by an equally fictional friend named Charles Kinbote. (“Kinbote” gives away Nabokov’s game in the foreword, where he writes that although his commentary and index, “in conformity with custom, come after the poem, the reader is advised to consult them first”, since “without my notes Shade’s text simply has no human reality at all.”) Referring to Pale Fire in a review, novelist Mary McCarthy wrote: “Pretending to be a curio, it cannot disguise the f act that it is one of the very great works of art of this century, the modern novel that everyone thought dead and that was only playing possum.”More recent examples of romantic irony include Steven Millhouser’s Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer, 1943-1954, by Jeffrey Cartwright (1972)—the fictional biography of a cartoon-crazy preadolescent supposedly written by his best friend—and David Leavitt’s The Term Paper Artist (1997) , a novella that disguises fiction as autobiography insofar as its protagonist is the author of books bearing the same titles as Leavitt’s own works.FURTHER EXAMPLES: Sometimes several types of irony come into play at once. The following passage from Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis (c. 405 B.C.E.) illustrates both dramatic irony and rhetorical irony. Agamemnon has brought his daughter Iphigenia to Aulis to be sacrificed to the gods: Iphegenia thinks a marriage has been arranged for her at Aulis with Achilles. Agamemnon’s comments exemplify rhetorical irony: there is a discrepancy between his literal words and what he really means—and this discrepancy is readily perceived by the audience. Dramatic irony is exemplified by Iphigenia’s failure to understand the true import of her words:Ighigenia: It’s a long journey then, and you’re leaving me behind!Agamemnon: Yours is a long journey too, like mine.Ighigenia: We could travel together then. You could arrange it.Agamemnon: No, your journey is different. You must remember me.Iphigenia: Will my mother sail with me? Or must I travel alone?Agamemnon: You’ll sail alone…without father or mother.Iphigenia: Have you found me a new home, Father? Where is it?Agamemnon: That’s enough…There are some things young girls shouldn’t know.Iphigenia: Sort of Phrygians out quickly, Daddy, and come back to me.Agamemnon: I must perform a sacrifice, before I go.Iphigenia: Of course you must! The right sacred rituals.Agamemnon: You’ll be there too. By the holy waterIphigenia: Shall I be part of the ceremonies at the altar?In Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), cosmic and situational irony coexist in the scene in which Angel Clare confesses to his new bride Tess that he once "lunged into eight-and-forty hours dissipation with a stranger." This confession prompts Tess, who incorrectly believes that Angel knows about her own past from a letter she slipped under his door (but which he did not receive because that letter also slid under his rug), to allude reassuringly to the child she had out of wedlock. Upon hearing about Tess’s past for the first time, Angel subsequently announces that he cannot possibly live with her because “the woman I have been loving is not you.” We can say that both cosmic and situational irony operate in this scene because, although the newlyweds’ conversation grows out of the tragic situation created when a letter slipped under a rug as well as a door, the situation somehow seems fated. Hardy’s novel, after all, describes earth as a “blighted star” (Phase the First), Tess as being “doomed to receive” a dark stain for reasons unintelligible to “analytical philosophy” or our “sense of order” (Phase the Second), and “The President of the Immortals” as “sport[ing] with Tess” (Phase the Seventh).。

irony英美文学名词解释

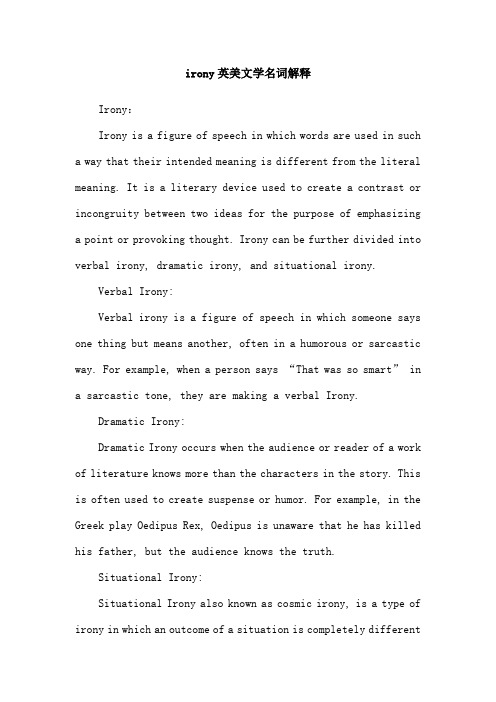

irony英美文学名词解释Irony:Irony is a figure of speech in which words are used in such a way that their intended meaning is different from the literal meaning. It is a literary device used to create a contrast or incongruity between two ideas for the purpose of emphasizing a point or provoking thought. Irony can be further divided into verbal irony, dramatic irony, and situational irony.Verbal Irony:Verbal irony is a figure of speech in which someone says one thing but means another, often in a humorous or sarcastic way. For example, when a person says “That was so smart” in a sarcastic tone, they are making a verbal Irony.Dramatic Irony:Dramatic Irony occurs when the audience or reader of a work of literature knows more than the characters in the story. This is often used to create suspense or humor. For example, in the Greek play Oedipus Rex, Oedipus is unaware that he has killed his father, but the audience knows the truth.Situational Irony:Situational Irony also known as cosmic irony, is a type of irony in which an outcome of a situation is completely differentfrom what would be expected. For example, if a fireman’s house is on fire, it is ironic because the fireman is expected to put out fires, not have his own home on fire.。

Analysisofrepresentationsfordomainadaptation