Effects of Ionic Concentrations on Survival and Growth in Polyculture of Litopenaeus vannamei wi

壳聚糖溶液行为研究-温度、分子量、浓度、酸浓度依赖性

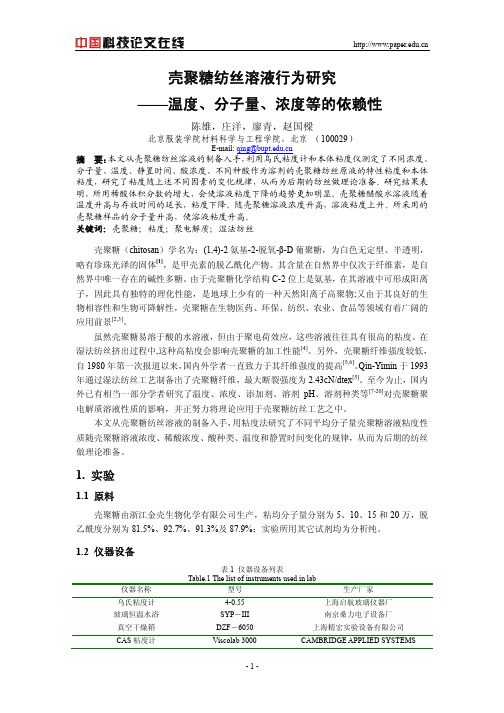

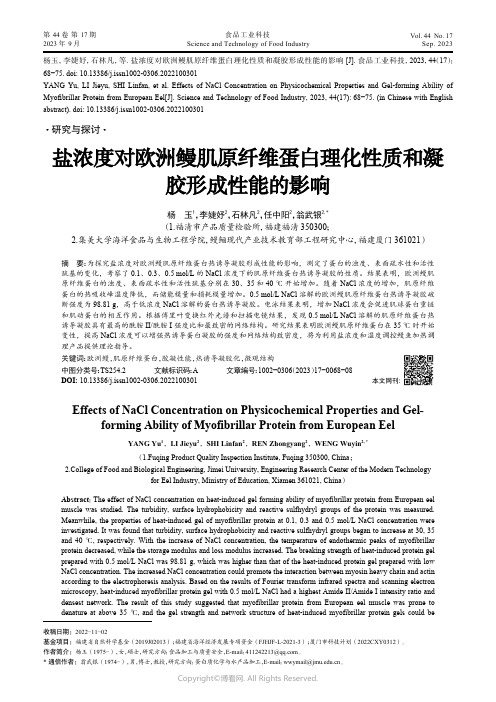

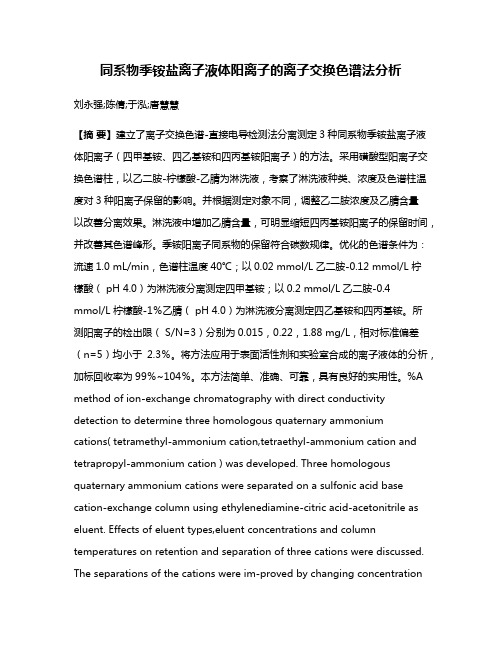

壳聚糖纺丝溶液行为研究 ——温度、分子量、浓度等的依赖性陈雄,庄洋,廖青,赵国樑北京服装学院材料科学与工程学院,北京 (100029)E-mail: qing@摘 要: 本文从壳聚糖纺丝溶液的制备入手, 利用乌氏粘度计和本体粘度仪测定了不同浓度、 分子量、温度、静置时间、酸浓度、不同种酸作为溶剂的壳聚糖纺丝原液的特性粘度和本体 粘度,研究了粘度随上述不同因素的变化规律,从而为后期的纺丝做理论准备。

研究结果表 明,所用稀酸体积分数的增大,会使溶液粘度下降的趋势更加明显。

壳聚糖醋酸水溶液随着 温度升高与存放时间的延长,粘度下降。

随壳聚糖溶液浓度升高,溶液粘度上升。

所采用的 壳聚糖样品的分子量升高,使溶液粘度升高。

关键词:壳聚糖;粘度;聚电解质;湿法纺丝 壳聚糖(chitosan)学名为:(1,4)-2 氨基-2-脱氧-β-D 葡聚糖,为白色无定型、半透明, 略有珍珠光泽的固体[1],是甲壳素的脱乙酰化产物。

其含量在自然界中仅次于纤维素,是自 然界中唯一存在的碱性多糖。

由于壳聚糖化学结构 C-2 位上是氨基, 在其溶液中可形成阳离 子,因此具有独特的理化性能,是地球上少有的一种天然阳离子高聚物;又由于其良好的生 物相容性和生物可降解性,壳聚糖在生物医药、环保、纺织、农业、食品等领域有着广阔的 应用前景[2,3]。

虽然壳聚糖易溶于酸的水溶液,但由于聚电荷效应,这些溶液往往具有很高的粘度。

在 湿法纺丝挤出过程中,这种高粘度会影响壳聚糖的加工性能[4]。

另外,壳聚糖纤维强度较低, 自 1980 年第一次报道以来, 国内外学者一直致力于其纤维强度的提高[5,6]。

Qin-Yimin 于 1993 年通过湿法纺丝工艺制备出了壳聚糖纤维,最大断裂强度为 2.43cN/dtex[5]。

至今为止,国内 外已有相当一部分学者研究了温度、浓度、添加剂、溶剂 pH、溶剂种类等[7-20]对壳聚糖聚 电解质溶液性质的影响,并正努力将理论应用于壳聚糖纺丝工艺之中。

介绍冷凝现象英语作文

介绍冷凝现象英语作文English Response:Understanding Condensation.Condensation is a fascinating phenomenon that occurs when a gas transforms into a liquid. It's a common sight in our daily lives, whether it's seeing droplets form on a cold drink or watching mist appear on a mirror after a hot shower.What Causes Condensation?Condensation happens due to a decrease in temperature. When warm, moisture-laden air comes into contact with a colder surface, it loses heat energy. As a result, the air cools down, causing the water vapor within it to lose energy as well. This loss of energy leads to the water vapor changing its state from gas to liquid, forming droplets.Real-Life Examples.Imagine you're sipping a refreshing drink on a warm summer day. The cold surface of the glass cools down the surrounding air. As a result, the water vapor in the air condenses on the outside of the glass, forming dropletsthat trickle down its surface. This is a classic example of condensation in action.Another example is when you take a hot shower. The steam generated from the hot water fills the bathroom with moisture-laden air. When this warm air comes into contact with the cooler surface of a mirror, condensation occurs, fogging up the mirror's surface.Importance of Condensation.Condensation plays a crucial role in various natural processes and human activities. In the atmosphere, condensation is responsible for the formation of clouds and precipitation, which are essential for the water cycle andsustaining life on Earth. In industrial settings, condensation is utilized in processes like distillation and refrigeration.Preventing Condensation.While condensation is a natural occurrence, excessive condensation can lead to issues such as mold growth and water damage. To prevent these problems, proper ventilation and insulation are key. By controlling indoor humidity levels and ensuring adequate airflow, you can minimize the risk of condensation forming on surfaces within your home or workplace.Conclusion.In summary, condensation is a fascinating natural phenomenon driven by temperature differences. Whether it's observing droplets form on a cold surface or witnessing clouds form in the sky, condensation surrounds us in various forms. Understanding the causes and effects of condensation not only deepens our appreciation for theworld around us but also helps us manage its impact on our daily lives.---。

金在氰化物中的溶解与活化动力学和机理研究,英文文献

www.elsevier.nlrlocaterhydromet

Gold dissolution and activation in cyanide solution: kinetics and mechanism

M.E. Wadsworth), X. Z Pereira

Keywords: Cyanide; Gold; Dissolution kinetics

1. Introduction

The widespread use of cyanide in the leaching of gold and other precious metals has been a driving force for research on gold dissolution. The linear, two-coordinate AuŽI. complex, wAuŽCN.2 xy, is produced during the treatment of gold with cyanide

The mechanism of gold dissolution has been widely discussed. It has been suggested that the rate of gold dissolution is controlled by aqueous bound-

0169-4332r00r$ - see front matter q 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 3 0 4 - 3 8 6 X Ž 0 0 . 0 0 0 8 4 - 0

The Effects of Nanoparticles on the Environment

The Effects of Nanoparticles on theEnvironmentNanoparticles are tiny particles that range in size from 1 to 100 nanometers. They are often used in consumer and industrial products, such as cosmetics, sunscreens, and electronics. While nanoparticles have revolutionized many industries, their impact on the environment is only beginning to be understood.One of the most significant effects of nanoparticles on the environment is their ability to enter the ecosystem and harm both plants and animals. Once released into the environment, nanoparticles can travel long distances and can accumulate in various organisms and even in the soil and water. They can damage plants by interfering with their normal growth and photosynthesis process, reducing crop yields and even leading to plant death.Likewise, nanoparticles can cause harm to animals by interfering with their metabolism, growth, and reproduction. Studies have shown that nanoparticles can enter the bloodstream of animals and accumulate in their organs, leading to inflammation and oxidative stress. Furthermore, nanoparticles can be ingested by small aquatic invertebrates, which can in turn be consumed by larger animals, including fish and mammals, resulting in a buildup of these particles in the food chain.Another impact of nanoparticles on the environment is their ability to alter the microorganism community in the soil or water. When nanoparticles are introduced into the soil, they can inhibit the growth and activity of soil microorganisms, reducing soil fertility and impacting the nutrient cycle. In water, nanoparticles can change the composition of microorganisms, leading to the disappearance of certain species and the proliferation of others. This can, in turn, disrupt aquatic ecosystems and harm aquatic life.Finally, nanoparticles can also affect the air quality, particularly in industrial areas where nanoparticles are produced or used. Nanoparticles from industrial exhaust gases can enter the atmosphere, eventually depositing on the ground or in the water.Nanoparticles that enter the lungs can cause respiratory problems, including inflammation, allergy, and increased risk of lung diseases, such as asthma.In conclusion, the impact of nanoparticles on the environment is complex and multifaceted. While they have contributed to various technological advancements, their effects on the environment is a growing concern. Understanding how nanoparticles interact with the environment is important for developing sustainable practices and mitigating the negative impact of nanoparticle exposure on both humans and the ecosystem.。

离子强度 英文

离子强度英文Ionic strength is a crucial parameter in various scientific fields, including chemistry, biochemistry, and environmental science. It refers to the concentration of ions in a solution, which can significantly impact the behavior of substances dissolved in that solution. The ionic strength of a solution is determined by the types and concentrations of ions present, as well as their respective charges.离子强度是化学、生物化学和环境科学等各种科学领域中的一个关键参数。

它指的是溶液中离子的浓度,这可以显著影响溶解在该溶液中的物质的行为。

溶液的离子强度由存在的离子的类型、浓度以及它们的电荷共同决定。

In chemistry, ionic strength plays a vital role in determining the stability of chemical reactions and the solubility of compounds. Higher ionic strength can promote the dissociation of ionic compounds into their constituent ions, while lower ionic strength may lead to precipitation or the formation of complexes. Understanding the ionic strength of a solution is essential fordesigning effective chemical processes and controlling reaction outcomes.在化学中,离子强度在决定化学反应的稳定性和化合物的溶解度方面起着至关重要的作用。

沙子吸附铅

Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395Removal of copper(II)and lead(II)from aqueoussolution by manganese oxide coated sand I.Characterization and kinetic studyRunping Han a ,∗,Weihua Zou a ,Zongpei Zhang a ,Jie Shi a ,Jiujun Yang baDepartment of Chemistry,Zhengzhou University,No.75of Daxue North Road,Zhengzhou 450052,PR ChinabCollege of Material Science and Engineering,Zhengzhou University,No.75of Daxue North Road,Zhengzhou 450052,PR ChinaReceived 8November 2005;received in revised form 25December 2005;accepted 13February 2006Available online 28February 2006AbstractThe preparation,characterization,and sorption properties for Cu(II)and Pb(II)of manganese oxide coated sand (MOCS)were investigated.A scanning electron microscope (SEM),X-ray diffraction spectrum (XRD)and BET analyses were used to observe the surface properties of the coated layer.An energy dispersive analysis of X-ray (EDAX)and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)were used for characterizing metal adsorption sites on the surface of MOCS.The quantity of manganese on MOCS was determined by means of acid digestion analysis.The adsorption experiments were carried out as a function of solution pH,adsorbent dose,ionic strength,contact time and temperature.Binding of Cu(II)and Pb(II)ions with MOCS was highly pH dependent with an increase in the extent of adsorption with the pH of the media inves-tigated.After the Cu(II)and Pb(II)adsorption by MOCS,the pH in solution was decreased.Cu(II)and Pb(II)uptake were found to increase with the temperature.Further,the removal efficiency of Cu(II)and Pb(II)increased with increasing adsorbent dose and decreased with ionic strength.The pseudo-first-order kinetic model,pseudo-second-order kinetic model,intraparticle diffusion model and Elovich equation model were used to describe the kinetic data and the data constants were evaluated.The pseudo-second-order model was the best choice among all the kinetic models to describe the adsorption behavior of Cu(II)and Pb(II)onto MOCS,suggesting that the adsorption mechanism might be a chemisorption process.The activation energy of adsorption (E a )was determined as Cu(II)4.98kJ mol −1and Pb(II)2.10kJ mol −1,respectively.The low value of E a shows that Cu(II)and Pb(II)adsorption process by MOCS may involve a non-activated chemical adsorption and a physical sorption.©2006Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.Keywords:Manganese oxide coated sand (MOCS);Cu(II);Pb(II);Adsorption kinetic1.IntroductionThe presence ofheavy metals in the aquatic environment is a major concern due to their extreme toxicity towards aquatic life,human beings,and the environment.Heavy metal ions from wastewaters are commonly removed by chemical precipitation,ion-exchange,reverse osmosis processes,and adsorption by activated carbon.Over the last few decades,adsorption has gained importance as an effective purification and separation technique used in wastewater treatment,and the removal of heavy metals from metal-laden tap or wastewater∗Corresponding author.Tel.:+8637167763707;fax:+8637167763220.E-mail address:rphan67@ (R.Han).is considered an important application of adsorption processes using a suitable adsorbent [1,2].In recent years,many researchers have applied metal oxides to adsorption of heavy metals from metal-laden tap or wastewa-ter [3].Adsorption can remove metals over a wider pH range and lower concentrations than precipitation [4].Iron,aluminum,and manganese oxides are typically thought to be the most important scavengers of heavy metals in aqueous solution or wastewater due to their relatively high surface area,microporous structure,and possess OH functional groups capable of reacting with met-als,phosphate and other specifically sorbing ions [5].However,most metal oxides are available only as fine powders or are gener-ated in aqueous suspension as hydroxide floc or gel.Under such conditions,solid/liquid separation is fairly difficult.In addition,metal oxides along are not suitable as a filter medium because of0304-3894/$–see front matter ©2006Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.02.021R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395385their low hydraulic conductivity.Recently,several researchers have developed techniques for coating metal oxides onto the surface of sand to overcome the problem of using metal oxides powers in water treatment.Many reports have shown the impor-tance of these surface coatings in controlling metal distribution in soils and sediments[3,6,7].In recent years,coated minerals have been studied because of their potential application as effective sorbents[3,8,9].Iron oxide coated meterials for heavy metal removal have been proved successful for the enhancement of treatment capacity and efficiency when compared with uncoatedfilter media,such as sil-ica sand[10–14],granular activated carbon[15]and polymeric media[16,17].For example,Edwards and Benjamin[7]found that coated media have similar properties to unattached coating materials in removing metals over a wide pH range,and that Fe oxide coated sand was more effective than uncoated sand.Bai-ley et al.[18]used iron oxide coated sand to remove hexavalent chromium from a synthetic waste stream.The influent contained 20mg l−1Cr(VI)and better than99%removal was achieved. Satpathi and Chaudhuri[19]and Viraraghavan et al.[20]have recently reported on the ability of this medium to adsorb metals from electroplating rinse waters and arsenic from drinking water sources,respectively.Green-Pedersen and Pind reported that a ferrihydrite-coated montmorillonite surface had a larger specific surface area and an increased sorption capacity for Ni(II)com-pared to the pure systems[21].Meng and Letterman[22]found that the adsorption properties of oxide mixtures are determined by the relative amount of the components.They also found that ion adsorption on aluminum oxide-coated silica was better mod-eled assuming uniform coverage of the oxide rather than using two distinct surfaces[23].Lo and Chen[8]determined the effect of Al oxide mineralogy,amount of oxide coating,and acid-and alkali-resistance on the removal of selenium from water.Bran-dao and Galembecket reported that the impregnation of cellulose acetates with manganese dioxide resulted in high removal effi-cient of Cu(II),Pb(II),and Zn(II)from aqueous solutions[24]. Al-Degs and Khraisheh[25]also reported that diatomite and manganese oxide modified diatomite are effective adsorbents for removing Pb2+,Cu2+,and Cd2+ions.The sorption capac-ity of Mn-diatomite was considerably increased compared to the original material for removing the studied metals.Filtration quality of diatomite is significantly increased after modification with Mn-oxides.Merkle et al.[26–28]reported that manganese dioxide coated sand was effective for removal of arsenic from ground water in column experiments.Merkle et al.developed a manganese oxide coating method on anthracite to improve the removal of Mn2+from drinking water and hazardous waste effluent.They generated afilter media with an increased surface area after coating with manganese oxides and found manganese oxide coated media have the ability to adsorb and coprecipi-tate a variety of inorganic species.Stahl and James[29]found their manganese oxide coated sands generated a larger surface area and increased adsorption capability with increasing pH as compared to uncoated silica sand.Additional researchers have been investigated to evalu-ate coating characteristics.X-ray diffraction(XRD),X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy(XPS),Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy(FTIR),transmission electron microscopy(TEM), and scanning electron microscopy(SEM)have been used as well to identify components,distribution,and structure of surface oxide coating[7,9,30,31].An energy dispersive X-ray (EDAX)technique of analysis has been used to characterize metal adsorption sites on the sorbent surface.Typically,oxide was non-uniform over the surface as both the oxide and substratum had been observed[7].The research described here was designed to investigate characteristics of manganese oxide coated sand(MOCS)and test the properties of MOCS as an adsorbent for removing copper(II)and lead(II)from synthetic solutions in batch system.SEM/EDAX,XRD,XPS and BET analysis were employed to examine the properties of adsorption reactions for Cu(II)and Pb(II)ions on MOCS in water.The system variables studied include pH,MOCS dose,ionic strength,contact time and temperature.The kinetic parameters,such as E a,k1,k2, have been calculated to determine rate constants and adsorption mechanism.1.1.Kinetic parameters of adsorptionThe models of adsorption kinetics were correlated with the solution uptake rate,hence these models are important in water treatment process design.In order to analyze the adsorption kinetics of MOCS,four kinetic models including the pseudo-first-order equation[32],the pseudo-second-order equation[33], Elovich equation[34],and intraparticle diffusion model[35] were applied to experimental data obtained from batch metal removal experiments.A pseudo-first-order kinetic model of Lagergen is given as log(q e−q t)=log q e−K1t2.303(1)A pseudo-second-order kinetic model istq t=1(K2q2e)+tq e(2) andh=K2q2e(3) an intraparticle diffusion model isq t=K t t1/2+C(4) and an Elovich equation model is shown asq t=ln(αβ)β+ln tβ(5) where q e and q t are the amount of solute adsorbed per unit adsorbent at equilibrium and any time,respectively(mmol g−1), k1the pseudo-first-order rate constant for the adsorption process (min−1),k2the rate constant of pseudo-second-order adsorption (g mmol−1min−1),K t the intraparticle diffusion rate constant (mmol g−1min−1),h the initial sorption rate of pseudo-second-order adsorption(mmol g−1min−1),C the intercept,αthe initial sorption rate of Elovich equation(mmol g−1min−1),and386R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395the parameter βis related to the extent of surface coverage and activation energy for chemisorption (g mmol −1).A straight line of log(q e −q t )versus t ,t /q t versus t ,q t versus ln t ,or q t versus t 1/2suggests the applicability of this kinetic model and kinetic parameters can be determined from the slope and intercept of the plot.1.2.Determination of thermodynamic parametersThe activation energy for metal ions adsorption was calcu-lated by the Arrhenius equation [36]:k =k 0exp −E aRT (6)where k 0is the temperature independent factor ing mmol −1min −1,E a the activation energy of the reaction of adsorption in kJ mol −1,R the gas constant (8.314J mol −1K −1)and T is the adsorption absolute temperature (K).The linear form is:ln k =−E aRT+ln k 0(7)when ln k is plotted versus 1/T ,a straight line with slope –E a /R is obtained.2.Materials and methods 2.1.AdsorbentThe quartz sand was provided from Zhengzhou’s Company of tap water in China.The diameter of the sand was ranged in size from 0.99to 0.67mm.The sand was soaked in 0.1mol l −1hydrochloric acid solution for 24h,rinsed with distilled water and dried at 373K in the oven in preparation for surface coating.Manganese oxide coated sand was accomplished by utilizing a reductive procedure modified to precipitate colloids of man-ganese oxide on the media surface.A boiling solution containing potassium permanganate was poured over dried sand placed in a beaker,and hydrochloric acid (37.5%,W HCl /W H 2O )solution was added dropwise into the solution.After stirring for 1h,the media was filtered,washed to pH 7.0using distilled water,dried at room temperature,and stored in polypropylene bottle for future use.2.2.Metal solutionsAll chemicals and reagents used for experiments and anal-yses were of analytical grade.Stock solutions of 2000mg l −1Pb(II)and Cu(II)were prepared from Cu(NO 3)2and Pb(NO 3)2in distilled,deionized water containing a few drops of concen-trated HNO 3to prevent the precipitation of Cu(II)and Pb(II)by hydrolysis.The initial pH of the working solution was adjusted by addition of HNO 3or NaOH solution.2.3.Mineral identificationThe mineralogy of the sample was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD)(Tokyo Shibaura Model ADG-01E).Pho-tomicrography of the exterior surface of uncoated sand and man-ganese oxide coated sand was obtained by SEM (JEOL6335F-SEM,Japan).The distribution of elemental concentrations for the solid sample can be analyzed using the mapping analysis of SEM/EDAX (JEOL SEM (JSM-6301)/OXFORD EDX,Japan).The existence of Cu(II)and Pb(II)ions on the surface of manganese oxide coated sand was also confirmed by using EDAX.Samples for EDAX analysis were coated with thin carbon film in order to avoid the influence of any charge effect during the SEM operation.The samples of MOCS and MOCS adsorbed with copper/lead ions were also analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)(ESCA3600Shimduz).2.4.Specific surface area and pore size distribution analysesAnalyses of physical characteristics of MOCS included spe-cific surface area,and pore size distributions.The specific sur-face area of MOCS and pore volumes were test using the nitrogen adsorption method with NOV A 1000High-Speed,Automated Surface Area and Pore Size Analyer (Quantachrome Corpora-tion,America)at 77K,and the BET adsorption model was used in the calculation.Calculation of pore size followed the method of BJH according to implemented software routines.2.5.Methods of adsorption studiesBatch adsorption studies were conducted by shaking the flasks at 120rpm for a period of time using a water bath cum mechanical shaker.Following a systematic work on the sorp-tion uptake capacity of Cu(II)and Pb(II)in batch systems were studied in the present work.The experimental process was as following:put a certain quantity of MOCS into conical flasks,then,added the solute of metals of copper or lead in single component system,vibrated sometime at a constant speed of 120rpm in a shaking water bath,when reached the sorption equilibrium after 180min,took out the conical flasks,filtrated to separate MOCS and the solution.No other solutions were provided for additional ionic strength expect for the effect of ionic strength.The concentration of the free metal ions in the filtrate was analyzed using flame atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS)(Aanalyst 300,Perkin Elmer).The uptake of the metal ions was calculated by the difference in their initial and final concentrations.Effect of pH (1.4–6.5),quantity of MOCS,contact time,temperature (288–318K)was studied.The pH of the solutions at the beginning and end of experiments was measured.Each experiment was repeated three times and the results given were the average values.2.5.1.Effect of contact time and temperature on Cu(II)and Pb(II)adsorptionA 2.0g l −1sample of MOCS was added to each 20ml of Cu(II)or Pb(II)solutions with initial concentration of Cu(II)0.315mmol l −1and Pb(II)0.579mmol l −1,respectively.The temperature was controlled with a water bath at the temperature ranged from 294to 318K for the studies.Adsorbent of MOCS and metal solution were separated at pre-determined time inter-R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395387 vals,filtered and analyzed for residual Cu(II)and Pb(II)ionconcentrations.2.5.2.Effect of pH on the sorption of Cu(II)and Pb(II)byMOCSThe effect of pH on the adsorption capacity of MOCSwas investigated using solutions of0.157mmol l−1Cu(II)and0.393mmol l−1Pb(II)for a pH range of1.4–6.5at293K.A20g l−1of MOCS was added to20ml of Cu(II)and Pb(II)solu-tions.Experiments could not be performed at higher pH valuesdue to low solubility of metal ions.2.5.3.Effect of MOCS doseIt was tested by the addition of sodium nitrate and calciumnitrate to the solution of Cu(II)and Pb(II),respectively.The doseof adsorbents were varied from10to80g l−1keeping initial con-centration of copper0.157mmol l−1and lead0.393mmol l−1,respectively,and contact time was180min at the temperature of293K.2.5.4.Effect of ionic strength on Cu(II)and Pb(II)adsorptionThe concentration of NaNO3and Ca(NO3)2used rangedfrom0to0.2mol l−1.The dose of adsorbents were20g l−1,the initial concentration of copper0.157mmol l−1and lead0.393mmol l−1,respectively,and contact time was180min atthe temperature of293K.The data obtained in batch model studies was used to calculatethe equilibrium metal uptake capacity.It was calculated for eachsample of copper by using the following expression:q t=v(C0−C t)m(8)where q t is the amount of metal ions adsorbed on the MOCS at time t(mmol g−1),C0and C t the initial and liquid-phase concentrations of metal ions at time t(mmol l−1),v the volume of the aqueous phase(l)and m is the dry weight of the adsorbent(g).3.Results and discussion3.1.Mineralogy of manganese oxide coated sandThe samples of sand coated with manganese oxide were dark colored(brown–black)precipitates,indicating the presence of manganese in the form of insoluble oxides.The X-ray diffrac-tion spectrum(XRD)of the samples(data not shown)revealed that the manganese oxide were totally amorphous,as there was not any peak detected,indicative of a specific crystalline phase. SEM photographs in Fig.1were taken at10,000×magnifi-cations to observe the surface morphology of uncoated sand and manganese oxide coated sand,respectively.SEM images of acid-washed uncoated quartz sand in Fig.1(a)showed very ordered silica crystals at the surface.The virgin sand had a rela-tively uniform and smooth surface and small cracks,micropores or light roughness could be found on the sand -paring the images of virgin(Fig.1(a))and manganeseoxide Fig.1.SEM micrograph of sample:(a)sand;(b)manganese oxide coated sand. coated sand(Fig.1(b)),MOCS had a significantly rougher sur-face than plain sand and the coated sand surfaces were apparently occupied by newborn manganese oxides,which were formed during the coating process.Fig.1(b)also showed manganese oxides,formed in clusters,apparently on occupied surfaces.At the micron scale,the synthetic coating was composed of small particles on top of a more consolidated coating.In most regions individual particles of manganese oxide(diameter=2–3m) appeared to be growing in clumps in surface depressions and coating cracks.The amount of manganese on the surface of the MOCS,measured through acid digestion analysis,was approx-imately5.46mg Mn/g-sand.3.2.SEM/EDAX analysisThe elements indicated as being associated with manganese oxide coated were detected by the energy dispersive X-ray spec-trometer system(EDAX)using a standardless qualitative EDAX analytical technique.The peak heights in the EDAX spectra are proportional to the metallic elements concentration.The quali-tative EDAX spectra for MOCS(Fig.2(a))indicated that Mn,O,388R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395Fig.2.EDAX spectrum of MOCS under:(a)adsorbed without copper and lead ion;(b)adsorbed copper ions;(c)adsorbed lead ions.Si,and K are the main constituents.These had been known as the principal elements of MOCS.EDAX analysis yielded indirect evidence for the mechanism of manganese oxide on the surface of MOCS.The peak of Si occurred in EDAX showed that man-ganese oxides do not covered a full surface of the MOCS.If the solid sample of MOCS caused a change of elemental con-stitution through adsorption reaction,it could be inferred that manganese oxide has already brought about chemical interac-tion with adsorbate.The EDAX spectrum for copper and lead system was illustrated in Fig.2(b and c).It could be seen that copper and lead ion became one element of solid sample in this spectrum.The reason was that copper and lead ions were chemisorbed on the surface of MOCS.Dot mapping can provide an indication of the qualitative abundance of mapping elements.The elemental distribution mapping of EDAX for the sample of MOCS and MOCS adsorbed copper or lead ions is illustrated in Fig.3.The bright points represented the single of the element from the solid sam-ple.A laryer of manganese oxide coating is clearly shown in the dot map for Mn in Fig.3(a),and a high density of white dots indicates manganese is the most abundant element.Results indicated that manganese oxide was spread over the surface of MOCS,and was a constituent part of the solid sample.The ele-ment distribution mapping of EDAX for the sample ofMOCS Fig.3.EDAX results of MOCS(white images in mapping represent the cor-responding element):(a)adsorbed without copper and lead ion;(b)adsorbed copper ions;(c)adsorbed lead ions.R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395389Fig.4.XPS wide scan of the manganese oxide coated sand. reacting with copper and lead ions is illustrated in Fig.3(b and c).Copper or lead ions were spread over the surfaces of MOCS. Results indicated that manganese oxide produces chemical bond with copper or lead ions.Thus,copper or lead element was a constituent part of the solid sample.3.3.Surface characterization using the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy(XPS)XPS analyses were performed on samples of MOCS alone and reacting with copper or lead ions.The wide scan of MOCS is presented in Fig.4.It can be noticed that the major elements constituent are manganese,oxygen,and silicon.Detailed spectra of the peaks are shown in Fig.5.Manganese oxides are generally expressed with the chemical formula of MnO x,due to the multiple valence states exhibited by Mn.Therefore,it is reasonable to measure the average oxidation state for a manganese mineral[37].The observation of the Mn 2p3/2peak at641.9eV and the separation between this and the Mn2p1/2peak of11.4eV indicates the manganese exhibited oxidation between Mn3+and Mn4+as shown from the auger plot,but it can be seen to show Mn4+predominantly from the Mn2p3/2peaks[38].The large peak in Fig.5(b)is a sum of the two peaks at 529.3and533.1eV,which can be assigned to O1s;a low bind-ing energy at529.7eV,which is generally accepted as lattice oxygen in the form of O2−(metal oxygen bond).This peak is characteristic of the oxygen in manganese oxides.The second peak at533.4eV can be assigned to surface adsorbed oxygen in the form of OH−[38].As seen the XPS spectra of the sample of MOCS reacting with copper,Fig.6(a)shows the binding energies of the observed photoelectron peaks of Cu2p3/2,2p1/2.The binding energy of the Cu2p3/2peak at a value of933.9eV shows the presence of copper(+2).The XPS spectra obtained after Pb(II)adsorption on MOCS is presented in Fig.6(b).Fig.6(b)shows that doublets charac-teristic of lead appear,respectively,at138.3eV(assigned to Pb 4f7/2)and at143.8eV(assigned to Pb4f5/2)after loadingMOCSFig.5.XPS detailed spectra of MOCS:(a)Mn2p3/2;(b)O1s.with Pb(II)solution.The peak observed at138.3eV agrees with the138.0eV value reported for PbO[39].This shows afixation of lead onto MOCS during the process.3.4.Specific surface area and pore size distribution analysesThe specific surface areas for sand and MOCS under un/adsorbed Pb(II)ions are summarized in Table1.Plain uncoated sand had a surface area of0.674m2g−1.A surface coating of manganese oxide increased the surface area of sand to0.712m2g−1,while average pore diameter decreased from 51.42to42.77˚A.This may be caused by the increase in both Table1Specific surface areas and average pore diameters for sand and various MOCSSurface area(m2g−1)Average pore diameter(˚A) Sand0.67451.42Unadsorbed a0.71242.77Adsorbed b0.55239.64Desorbed c0.70142.71a Without reacting with Pb(II)ions.b After reacting with Pb(II)ions.c After soaking with0.5mol l−1acid solution.390R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395Fig.6.XPS detailed spectra of MOCS reacting with(a)copper;(b)lead. inner and surface porosity after adding the manganese oxides admixture.After reacting with Pb(II)ions,the pore size distribu-tion of MOCS had been changed,and parts of pores disappeared through the adsorption process.The results indicated the parts of pores were occupied with Pb(II)ions and average pore diameters decreased simultaneously,compared with unadsorbed MOCS, the surface area value of adsorbed MOCS is decreased,varying from of0.712to0.552m2g−1.Besides,pore size distribution of desorbed MOCS was similar to that of unadsorbed MOCS. The surface area of desorbed MOCS increased and average pore diameter also increased after regeneration with acid solution. The results indicated Pb(II)ions could be desorbed from the surface site of micropore and mesopores.3.5.Effect of contact time and temperature on Cu(II)andPb(II)adsorptionEffect of contact time and temperature on the adsorption of the copper(II)and lead(II)on MOCS was illustrated in Fig.7(a and b).The uptake equilibrium of Cu(II)and Pb(II) were achieved after180min and no remarkable changes were observed for higher reaction times(not shown in Fig.7).The shapes of the curves representing metal uptake versus time suggest that a two-step mechanism occurs.Thefirstportion Fig.7.Effect of contact time on Cu(II)and Pb(II)ions adsorption at pH4and various temperatures:(a)adsorption capacity vs.time;(b)adsorption percent vs.time(C0(Cu)=0.315mmol l−1,C0(Pb)=0.579mmol l−1).indicates that a rapid adsorption occurs during thefirst30min after which equilibrium is slowly achieved.Almost80%of total removal for both Cu(II)and Pb(II)occurred within60min.The equilibrium time required for maximum removal of Cu(II)and Pb(II)were90and120min at all the experimental temperatures, respectively.As a consequence,180min was chosen as the reac-tion time required to reaching pseudo-equilibrium in the present “equilibrium”adsorption experiments.Higher removal for cop-per and lead ions was also observed in the higher temperature range.This was due to the increasing tendency of adsorbate ions to adsorb from the interface to the solution with increasing temperature and it is suggested that the sorption of Cu(II)and Pb(II)by MOCS may involve not only physical but also chem-ical sorption.The metal uptake versus time curves at different temperatures are single,smooth and continuous leading to sat-uration,suggesting possible monolayer coverage of Cu(II)and Pb(II)on the surface of MOCS[40].3.6.Effect of pH on the sorption of Cu(II)and Pb(II)by MOCSIt is well known that the pH of the system is an important vari-able in the adsorption process.The charge of the adsorbate and the adsorbent often depends on the pH of the solution.The man-R.Han et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials B137(2006)384–395391 ganese oxide surface charge is also dependent on the solution pHdue to exchange of H+ions.The surface groups of manganeseoxide are amphoteric and can function as an acid or a base[41].The oxide surface can undergo protonation and deprotonationin response to changes in solution pH.As shown in Fig.8,the uptake of free ionic copper and leaddepends on pH,increasing with pH from1.4to5.1for Cu(II)and1.4to4.3for Pb(II).Above these pH levels,the adsorptioncurves increased very slightly or tended to level out.At low pH,Cu(II)and Pb(II)removal were inhibited possibly as result ofa competition between hydrogen and metal ions on the sorp-tion sites,with an apparent preponderance of hydrogen ions.Asthe pH increased,the negative charge density on MOCS sur-face increases due to deprotonation of the metal binding sitesand thus the adsorption of metal ions increased.The increase inadsorption with the decrease in H+ion concentration(high pH)indicates that ion exchange is one of major adsorption process.Above pH6.0,insoluble copper or lead hydroxide starts precip-itating from the solution,making true sorption studies impossi-ble.Therefore,at these pH values,both adsorption and precipita-tion are the effective mechanisms to remove the Cu(II)and Pb(II)in aqueous solution.At higher pH values,Cu(II)and Pb(II)inaqueous solution convert to different hydrolysis products.In order to understand the adsorption mechanism,the varia-tion of pH in a solution and the metal ions adsorbed on MOCSduring adsorption were measured,and the results are shown inFig.8.The pH of the solution at the end of experiments wasobserved to be decreased after adsorption by MOCS.Theseresults indicated that the mechanism by means of which Cu(II)and Pb(II)ion was adsorbed onto MOCS perhaps involved anexchange reaction of Cu2+or Pb2+with H+on the surface andsurface complex formation.According to the principle of ion-exchange,the more metalions that is adsorbed onto MOCS,the more hydrogen ions arereleased,thus the pH value was decreased.The complex reac-tions of Cu2+and Pb2+with manganese oxide may be writtenas follows(X=Cu,Pb and Y=Pb)[42]:MnOH+X2+ MnO−X2++H+(9)MnO−+X2+ MnO−X2+(10)Fig.8.Effect of pH on adsorption of Cu(II)and Pb(II)by MOCS.2(MnOH)+X2+ (MnO−)2X2++2H+(11)2(MnO−)+X2+ (MnO−)2X2+(12)MnOH+X2++H2O MnOXOH+2H+(13)MnOH+2Y2++H2O MnOY2OH2++2H+(14)Eqs.(9)–(14)showed the hydrogen ion concentration increasedwith an increasing amount of Cu(II)or Pb(II)ion adsorbed onthe MOCS surface.3.7.Effect of MOCS doseFig.9shows the adsorption of Cu(II)and Pb(II)as a functionof adsorbent dosage.It was observed that percent adsorptionof Cu(II)and Pb(II)increased from29to99%and19to99%with increasing adsorbent load from10to80g l−1,respectively.This was because of the availability of more and more bindingsites for complexation of Cu(II)ions.On the other hand,theplot of adsorption per unit of adsorbent versus adsorbent doserevealed that the unit adsorption capacity was high at low dosesand reduced at high dose.There are many factors,which can con-tribute to this adsorbent concentration effect.The most importantfactor is that adsorption sites remain unsaturated during theadsorption reaction.This is due to the fact that as the dosageof adsorbent is increased,there is less commensurate increasein adsorption resulting from the lower adsorptive capacity uti-lization of the adsorbent.It is readily understood that the numberof available adsorption sites increases by increasing the adsor-bent dose and it,therefore,results in the increase of the amountof adsorbed metal ions.The decrease in equilibrium uptake withincrease in the adsorbent dose is mainly because of unsaturationof adsorption sites through the adsorption process.The corre-sponding linear plots of the values of percentage removal(Γ)against dose(m s)were regressed to obtain expressions for thesevalues in terms of the m s parameters.This relationship is asfollows:for Cu(II):Γ=m s0.221+6.61×10−3m s(15)Fig.9.Effect of dosage of MOCS on Cu(II)and Pb(II)removal.。

Correlation effects in ionic crystals I. The cohesive energy of MgO

a rXiv:c ond-ma t/956009v12J un1995Correlation effects in ionic crystals:I.The cohesive energy of MgO Klaus Doll,Michael Dolg,Peter Fulde Max-Planck-Institut f¨u r Physik komplexer Systeme D-01187Dresden,Germany Hermann Stoll Institut f¨u r Theoretische Chemie Universit¨a t Stuttgart D-70550Stuttgart,Germany February 1,2008Abstract High-level quantum-chemical calculations,using the coupled-cluster approach and extended one-particle basis sets,have been performed for (Mg 2+)n (O 2−)m clusters embedded in a Madelung potential.The results of these calculations are used for setting up an incremental ex-pansion for the correlation energy of bulk MgO.This way,∼96%of the experimental cohesive energy of the MgO crystal is recovered.It is shown that only ∼60%of the correlation contribution to the cohesiveenergy is of intra-ionic origin,the remaining part being caused by van der Waals-like inter-ionic excitations.accepted by Phys.Rev.B1IntroductionWhile the density-functional(DFT)method,with its long tradition in solid-state physics,is getting wide acceptance in thefield of quantum chemistry nowadays,there are also attempts to the reverse,i.e.,making use of the tra-ditional quantum-chemical Hartree-Fock(HF)and configuration-interaction (CI)methods not only for molecular but also for solid-state applications. The Torino group of Pisani and co-workers,e.g.,devised an ab-initio HF scheme for solids[1],which has successfully been applied to a broad range of(mostly)covalently bonded and ionic solids,within the pastfive years.A main asset of the HF scheme is the availability of a well-defined wave-function,which may not only be used for extracting properties but also as a starting-point for systematically including electron-correlation effects.Such effects,which are only implicitly accounted for in density-functional meth-ods,often have a strong influence on physical observables,in molecules as well as in solids.Several suggestions have been made how to explicitly in-clude electron correlation in solids,among them the Quantum Monte-Carlo (QMC)approach[2],the Local Ansatz(LA)[3],and the method of local increments[4](which may be considered as a variant of the LA);in QMC the HF wavefunction is globally corrected for electron-correlation effects by multiplying it with a factor containing inter-electronic coordinates(Jastrow factor);the latter two methods rely on applying selected local excitation operators to the HF wavefunction and thus have a rather close connection to traditional quantum-chemical post-HF methods.The number of test examples is still rather limited with all three solid-state correlation schemes,and is mainly restricted to semiconductors so far. For ionic insulators where quantum-chemical methods would seem to be most suitable and easily advocated,much work indeed has been devoted to correlation effects on band structures(cf.e.g.[5a,b]),but only few stud-ies refer to cohesive energies(cf.e.g.[5c]),and only a single application of the post-HF schemes mentioned in the last paragraph exists to our knowl-edge(NiO with QMC[5d]).This does not mean that such applications to ground-state correlation effects are without challenge.For MgO,the system to be dealt with in this paper,HF calculations[6]yield a lattice constant which is in agreement with experiment to∼0.01˚A,but the correlation con-tribution to the cohesive energy is significant(∼3eV,nearly half as large as the HF value).The local-density approximation(LDA)of DFT does not a good job here either:an overbinding results which is more than two times as large as the correlation contribution to the lattice energy[7],and1invocation of gradient-corrected functionals is indispensable for obtaining reasonable results[6b],cf.Sect.3.5below.The situation would not seem too complicated,nevertheless,if the effect could be explained just by adding correlation contributions of individual ions;in fact,such a suggestion has repeatedly been made in literature,cf.Refs.[6a,17c].However,the O2−ion, one of the building blocks of the MgO crystal,is not stable as a free entity, and an accurate determination of the correlation energy of this highlyfluc-tuating and easily polarizable ion in its crystal surroundings is not expected to be an easy task;the more so,since already for the determination of the electron affinity of the free O atom high-level quantum-chemical correlation methods are required[8].Moreover,as we shall show below,intra-ionic in-teractions contribute only with∼60%to the total correlation effect on the bulk cohesive energy,and van der Waals-like inter-ionic excitations play an important role here.This paper is thefirst in a series devoted to the application of the method of local increments to ionic solids;it shows,at the example of MgO,how to set up an incremental expansion of the bulk correlation energy using in-formation from quantum-chemical calculations onfinite clusters only.The organization of the paper is as follows:in Section2,computational de-tails are given for the applied quantum-chemical methods,and test calcula-tions are performed for thefirst two ionization potentials of the Mg atom, for the electron affinity of the O atom,and for spectroscopic properties of the MgO molecule.The method of local increments is briefly described in Section3;correlation-energy increments are evaluated from calculations on (Mg2+)n(O2−)m clusters,and the incremental expansion for the total cor-relation energy of bulk MgO is discussed.Conclusions follow in Section 4.2Test calculationsOurfirst test concerns the electron affinity,EA,of the oxygen atom.We performed separate calculations for the ground states of O and O−,respec-tively,using various single-and multi-reference quantum-chemical config-uration interaction methods for treating many-body correlation effects[9]. The one-particle basis sets employed have been taken from the series of correlation-consistent(augmented)polarized Gaussian basis sets of Dun-ning and co-workers[10,8a].The ab-initio program package MOLPRO[11] has been used in these and all of the following calculations of the present2paper.The results for EA(O)are collected in Table1.It is seen that the best single-and multi-reference methods(coupled-cluster with single and double excitations and perturbative inclusion of triples(CCSD(T))and2s-2p active space;multi-reference averaged coupled pair functional with single and double excitations(MR-ACPF)and2s-3p active space)yield quite similar results(1.40eV),which differ from the experimental value by only 0.06eV.Effects of the one-particle basis set are significant,even at the stage of including g functions,and probably are responsible for the major part of the remaining deviation from experiment.In the(Mg2+)n(O2−)m cluster calculations to be described in Sect.3,we could only afford the valence triple-zeta[5s4p3d2f]basis set,at the single-reference level;the concomi-tant differential errors can be estimated to about0.1eV per O atom and (added)electron.The next test deals with the ionization potentials,IP,of the magnesium atom(Mg→Mg+,Mg+→Mg2+).A difficulty is encountered here,since not only the correlation energy of the valence(3s2)electron pair has to be accounted for but also core-valence correlation effects are non-negligible: the latter contribute with0.3eV to the Mg+→Mg2+IP,e.g..For ac-curately describing these effects explicitly,a high computational effort is needed in quantum-chemical ab-initio calculations.In(all-electron)calcu-lations with a basis set of medium quality((12s9p1d)/[5s4p1d][12])errors of0.12and0.21eV remain for the two IPs,and even a very large uncon-tracted(20s15p6d3f)basis[13]still yields deviations from experiment of 0.03and0.04eV in CCSD(T)calculations.Without loss of accuracy,how-ever,the computational effort can be effectively reduced[14,15]by simulat-ing the Mg2+core by a pseudopotential(PP)which describes core-valence interaction at the HF level,in conjunction with a core-polarization poten-tial(CPP)which accounts for core-valence correlation effing these methods,very good agreement with experiment is obtained,at the corre-lated level,cf.the results of Table2.(Only ACPF data are given,in the Table,since for a two-electron system all the correlation methods of Table 1(CI,ACPF,CCSD)coincide.)For the cluster calculations of Sect.3,we adopt the PP+CPP description,together with the energy-optimized(4s4p) valence basis set;the concomitant differential errors can be estimated to about0.02eV per Mg atom and(removed)electron.The last test of our quantum-chemical arsenal of methods was performed for the MgO molecule.The basis sets applied here are the same as those used in the next section for(Mg2+)n(O2−)m clusters.The results for bond length,dissociation energy and vibrational frequency are compiled in Table33.It is seen that excellent agreement with experiment(to0.02˚A,0.1eV, 10cm−1(1%))is obtained at the(single-reference)CCSD(T)level.At the multi-reference level(without triples),the agreement is slightly less good, but this could certainly be improved upon by enlarging the2-configuration reference space which was chosen in our calculations.3Local increments3.1Methodological aspectsThe main idea to be discussed here is the possibility to extract informa-tion from calculations onfinite clusters and to transfer it to the infinite crystal.Such a transfer would certainly not be a good idea for global clus-ter properties(cohesive energy,ionization potential,etc.)–it only makes sense for local quantities.Now,localized orbitals are entities which can be defined within ionic crystals as well as within clusters of these materials. Moreover,electron correlation in or between such orbitals is a local effect. Therefore,if we prepare localized orbitals in the interior of a cluster(in a sufficiently solid-like environment)and if we calculate correlation energies involving these orbitals,we can hope to obtain transferable quantities.Of course,there is no reason to expect that these quantities would be additive in the solid.If we separately calculate,e.g.,the pieces of correlation energy due to orbitals localized at ionic positions A,B,C,...ǫ(A),ǫ(B),ǫ(C), (1)the correlation energy of the common orbital system of AB(or AC,BC, ...)will deviate in general from the sum of constituents,due to inter-ionic interactions,and we can define non-additivity corrections such as∆ǫ(AB)=ǫ(AB)−ǫ(A)−ǫ(B).(2)Again,the next larger systems of three ions,ABC,...,will have correlation energies slightly different from the sum of the constituents plus the two-body non-additivity corrections,and this gives rise to three-body increments∆ǫ(ABC)=ǫ(ABC)−[ǫ(A)+ǫ(B)+ǫ(C)]−[∆ǫ(AB)+∆ǫ(AC)+∆ǫ(BC)].(3)Similar definitions apply,in principle,to higher-body increments.4If we now make use of all these quantities,i.e.,the intra-ionic correlation energies and the various inter-ionic correction terms,and multiply them with weight factors appropriate for the solid,we can hope to get a meaningful incremental expansion of the correlation energy per unit cell of the infinite crystal:ǫbulk= Aǫ(A)+13! A,B,C∆ǫ(ABC)+ (4)In Ref.[4d]we have shown that this equation can be formally derived,under appropriate approximations,from an expression for the correlation energy of an infinite system.Let us discuss now the assumptions implicit in this approach more closely for the case of the MgO crystal.MgO is generally considered as a nearly perfect ionic crystal consisting of Mg2+and O2−ions[17];the question of a quantitative measure for the ionicity of MgO has been addressed only recently by Bagus and co-workers[17c,d],and in careful studies using various criteria the ionic charges have been shown to deviate from±2by<0.1only. Thus,the attribution of localized orbitals to ionic positions made above seems to be a valid assumption.But even if there were some degree of covalency and/or some tendency for delocalization in MgO,this would not invalidate our approach.In fact,thefirst applications of the method of local increments were made for covalently bonded crystals(diamond,silicon [4a,b]),and even for theπ-system of graphite which according to usual classifications is considered as completely delocalized the method has been shown to yield meaningful results[4c].Secondly,the determination of increments for non-additive inter-ionic correlation contributions in Eqs.2and3makes sense only,if the number of non-negligible increments is small,i.e.,if the∆ǫ(AB)rapidly decrease with increasing distance of the ions and if the three-body terms∆ǫ(ABC) are significantly smaller than the two-body ones making the use of four-body contributions obsolete.A necessary pre-requisite for satisfying these conditions is the use of a size-extensive correlation method for calculating the increments.This excludes,for instance,the(variational)configuration-interaction method with single and double excitations(CISD),since it does not scale linearly with n for a system of non-interacting atoms A n.On the other hand,correlation methods of the coupled-cluster variety such as those discussed in the last section(ACPF,CCSD,CCSD(T))do have this property.(These are benchmark methods of increasing complexity widely5used in quantum chemistry;we display results derived from all of them in the following Tables,in order to monitor convergence with respect to the many-particle basis set used.)When applying such a method,∆ǫ(AB) should indeed rapidly decrease with increasing AB distance,since for non-overlapping pairs of ions only van der Waals-like correlation effects(∼1/r6) become effective.Furthermore,three-body terms can be expected to be significantly smaller than two-body terms,since two-electron excitations, involving a pair of orbitals at most,are known to dominate correlation effects.Afinal assumption underlying our approach is that of the transferability of localized orbitals from clusters to the bulk which was mentioned right at the beginning of this subsection.Its fulfillment depends,of course,on the preparation of the clusters.A free O2−ion,e.g.,would be unstable,and it is essential,therefore,to put this ion in a cage of Mg2+ions in order to stabilize it,and to simulate the Madelung potential of the surrounding ions in order to provide the correctfield near the O nucleus.More details on cluster preparation and transferability tests will be given in the following subsections,where the determination of individual increments is discussed.3.2Intra-ionic correlationThefirst increment to be calculated is the correlation energy which can be locally attributed to an O2−ion in crystal surroundings of Mg2+and other O2−ions.As already mentioned,a realistic modelling of the crystal sur-roundings is essential,since otherwise the O2−ion would not be stable at all.Fortunately,stabilization can be achieved in a both very simple and effi-cient way,by simulating the Pauli repulsion of the6nearest-neighbour Mg2+ ions by means of pseudopotentials;we used the same energy-consistent pseu-dopotentials here as were used for the treatment of the Mg atom in the calcu-lations of Sect.2.For representing the crystal environment of the resulting 7-atom cluster,a Madelung approximation was made:336ions surrounding this cluster in a cube of7x7x7ions were simulated by point charges±2 (with charges at the surface planes/edges/corners reduced by factors2/4/8, respectively).Here and in the following,the experimental bulk lattice con-stant(r MgO=2.105˚A)was adopted.Employing the[5s4p3d2f]basis set, which was already used for O and O−,for the description of the O2−orbitals, too,we obtain the differential correlation-energy contributions,∆ǫ(O2−)=ǫ(O2−)-ǫ(O),to the affinity of the extra electrons in crystal O2−which are listed in Table4.6Afirst point to make is that at all levels of approximation∆ǫ(O2−)comes out considerably smaller than one would expect from a simple linear scaling of∆ǫ(O−)values(2.77vs.1.86eV,at the CCSD(T)level,cf.Table1);such a linear scaling,which approximately works for the iso-electronic systems,∆ǫ(Ne)and∆ǫ(Ne−),[18]probably fails for O2−due to the increased spac-ing of excited-state levels,when compressing the O2−charge density in the (Mg2+)6cage.When comparing individual∆ǫ(O2−)values in Table4,we observe that in our single-reference calculations(active space2s-2p),the effect of single and double excitations is quite similar for ACPF and CCSD, while the inclusion of triples in CCSD(T)yields an increase by another5%. Thus,the effect of triples is of less(relative)importance than in free O−but is still non-negligible.As in the case of O−,we checked that enlarging the ac-tive space(to2s-3p)in the ACPF calculations(MRACPF)leads to a result numerically nearly identical to CCSD(T).Moreover,we tested the influence of an increase of the basis set([5s4p3d2f]→[6s5p4d3f2g],cf.Table1);at the CCSD(T)level,the correlation-energy increment changes by-0.008a.u. (-0.2eV),in line with our estimate given in Sect.2.We also tried increasing the[5s4p3d2f]basis set by adding off-center functions(the(4s4p)sets of Sect.2at the positions of the Mg2+ions);the correlation-energy change of-0.005a.u.is somewhat smaller here because not all components of the higher polarization functions(f,g)at the oxygen site cannot be simulated this way.A last test concerns the influence of the Madelungfield.Leaving out all of the point-charges and performing the calculation with the bare (O2−)(Mg2+)6cluster leads to quite negligible correlation-energy changes of ≤4·10−5a.u.only,at all theoretical levels;this underlines the notion of electron correlation being a local effect.Summarizing,lack of completeness of the one-particle basis set seems to be the largest source of error in the O2−results listed in Table4,and the order of magnitude of the resulting error for the MgO cohesive energy per unit cell(with respect to separated neutral atoms)can be assessed to0.2...0.3eV.Let us next consider the Mg→Mg2+correlation-energy increment.This increment can directly be evaluated using the atomic calculations described in Sect.2.This is so,since the Madelung effect identically vanishes here, when Mg2+is described by a bare pseudopotential.We checked this point by performing all-electron calculations for Mg2+with and without Madelung field:the non-frozen-core effect obtained thereby is of the order of1·10−6 a.u.with our largest basis set.Thus,the pseudopotential approximation is certainly valid here.Adding the Mg2+and O2−correlation-energy increments of Table4,we7get,at the highest theoretical level(CCSD(T)),a correlation contribution of0.0547a.u.to the bulk cohesive energy,E coh,per(primitive)unit cell of the MgO crystal.The experimental cohesive energy corrected for zero-point energy is known to be0.3841a.u.[19];the most recent(and probably best)HF value is0.2762a.u.[6c].This yields an’experimental’correlation contribution to E coh of0.108a.u.which is just about the double of the intra-ionic value calculated so far.Thus,it is clear that inter-ionic contributions to be dealt with in the next subsection play an important role.3.3Two-Body CorrectionsIn this subsection,non-additivity corrections are determined,which arise when simultaneously correlating two ions in a cluster.Let usfirst consider here the interaction of ions with charges of opposite sign,i.e.Mg2+and O2−,which are next neighbours in the ing the same cluster as in the previous subsection when determining the intra-ionic correlation energy of O2−(O2−plus6surrounding Mg2+plus336 point charges)and adding a core-polarization potential at one of the Mg2+ neighbours of the central O2−ion,we obtain an inter-ionic core-valence cor-relation contribution(cf.Table5)which is due to the dynamic polarization of the Mg2+core by the O2−valence electrons and which was clearly absent in the free Mg2+ion.Although the resulting value for the increment turns out to be considerably smaller than the intra-ionic correlation contributions of Table4,its effect on the cohesive energy of MgO is by no means negligible, due to the large weight factor.In order to study the convergence of the correlation-energy increments with increasing distance of the ions,we replaced,in the cluster described above,one of the Madelung charges(at positions of Mg2+ions successively more distant from the central O2−ion)by a pseudopotential and evaluated the influence of core-polarization.A rapid decrease with r MgO is observed, with the fourth-nearest neighbour MgO increment already approaching the numerical noise in our calculations.Turning now to the increments related to pairs of ions of the same kind, we can safely neglect Mg2+-Mg2+interactions.The correlation-energy con-tributions are exactly zero,at the pseudopotential plus core-polarization level.All-electron test calculations yield very small values around∼2·10−5 a.u.for a nearest-neighbour pair of Mg2+ions in the crystal.Far more important are interactions between O2−ions with their diffuse,fluctuating charge distributions.For the increment between nearest neigh-8bouring O2−ions,we used a cluster with448ions,where two central O2−ions were treated explicitly,while the10next Mg2+neighbours of these ions were simulated by pseudopotentials and the remaining ions were represented by point charges.The non-additivity correction with respect to two single O2−ions(cf.Table5)turns out to be of the same order of magnitude as the MgO increment.The greater strength of interaction in the O-O case compared to the Mg-O one(larger polarizability of O2−compared to Mg2+) is effectively compensated by the enhanced ion distance.Results for O2−-O2−increments between2nd through5th neighbours are also given in Table5.The decrease with increasing ion distance is not quite as rapid as that for the Mg-O increments.By multiplying the O-O increments with r−6,one can easily check that a van der Waals-like behaviour is approached for large r,and one can use the resulting van der Waals constant to obtain an estimate of the neglected increments beyond 5th neighbours;this estimate which is∼3·10−4a.u.(including appropriate weight factors)should be considered as an error bar for the truncation of the incremental expansion of the MgO cohesive energy in our calculations.Adding up all the two-body increments which have been determined in this work,wefind(st row in Table5)that the inter-ionic two-body correlation contribution to the cohesive energy of MgO is of comparable magnitude as the intra-ionic one.Thus,the important conclusion may be drawn that even in a(nearly purely)ionic crystal a mean-field description of inter-ionic interactions(electrostatic attraction,closed-shell repulsion)is not sufficient.3.4Three-Body CorrectionsLet us complete now the information necessary for setting up the incremen-tal expansion of the correlation energy of bulk MgO,by evaluating the most important non-additivity corrections involving three ions.These corrections are obtained for triples with at least two pairs of ions being nearest neigh-bours of their respective species,using Eq.3(cf.Sect.3.1).The numerical results are listed in Table6.It is seen that the largest3-body corrections are smaller by nearly two orders of magnitude compared to the leading two-body ones,thus indicating a rapid convergency of the many-body expansion with respect to the number of atoms included;the total three-body contri-bution to the correlation piece of the bulk cohesive energy,E coh is∼2%of the two-body part and of opposite sign.93.5Incremental ExpansionIn Table7,the sum of local correlation-energy increments to the cohesive-energy,E coh,of MgO(with respect to separated neutral atoms)is compared to the difference of experimental and HF values for E coh.Our calculated values amount to between∼80and∼85%,depending on the correlation method applied,of the experimental value.The inclusion of triple excita-tions in the correlation method seems to be significant for describing the largefluctuating O2−ions.A major part of the remaining discrepancy to experiment is probably due to deficiencies of the one-particle basis set:as discussed in Sect.3.2,extension of the O2−basis set to include g functions, for the evaluation of the intra-ionic contribution,already reduces the error by a factor of2.A comparison to related theoretical results is possible at the density-functional level.A correlation-energy functional including gradient correc-tions(Perdew91)yields a∆E coh value of0.087a.u.[6b],only slightly inferior to our CCSD(T)one.Further density-functional results for lattice energies have been reported in Ref.[7];these results have been determined forfixed HF densities,and the reference of the lattice energies is to Mg2++O−+ e−.As already mentioned in Sect.1,the LDA value is much too high(by 0.069a.u.);the results with the Perdew-91correlation-energy functional on top of the HF exchange is much better(error0.014a.u.),and the same may be said for a xc-DFT treatment with the Becke and Perdew-91gradient cor-rections for exchange and correlation,respectively(error0.011a.u.).Using the Mg2+and O−data of Tables1and2,our present calculations lead,at the CCSD(T)level,to a value of0.071a.u.for the correlation contribution to the lattice energy;adding this value to the HF result of Ref.[7],a de-viation from experiment of0.009a.u.is obtained,which is similar to that of the gradient-corrected DFT ones.Note,however,that this comparison must be taken with a grain of salt:the HF calculation of Ref.[7]is certainly not too accurate,since a relatively small basis set was used.Otherwise it would be difficult to explain why our correlation contribution to the lattice energy should be too large,although all possible sources of errors(discussed in Sects.3.2and3.3)point to the opposite direction.4ConclusionThe correlation energy of the MgO crystal can be cast into a rapidly con-vergent expansion in terms of local increments which may be derived from10finite-cluster calculations.One-particle basis sets of triple-zeta quality with up to f functions at the positions of the O atoms and high-level quantum-chemical correlation methods(CCSD(T))are necessary for obtaining∼85% of the correlation contribution to the bulk cohesive energy.About one half of this contribution can be attributed to intra-ionic interactions,the rest is due–to about equal parts–to dynamic polarization of the Mg2+cores by the O2−ions and to van der Waals-like O2−-O2−interactions.Although numerical results from quantum-chemical calculations of this type are not necessarily superior to DFT ones,they provide additional physical insight into the sources of correlation contributions to solid-state properties. AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful to Prof.H.-J.Werner(Stuttgart)for providing the program package MOLPRO.11References1.R.Dovesi,C.Pisani,and C.Roetti,Int.J.Quantum Chem.17,517(1980); C.Pisani,R.Dovesi,and C.Roetti,Lecture Notes in Chemistry,vol.48(Springer,Berlin,1988)2.S.Fahy,X.W.Wang,and S.G.Louie,Phys.Rev.B42,3503(1990);X.P.Li,D.M.Ceperley,and R.M.Martin,Phys.Rev.B44,10929 (1991)3.G.Stollhoffand P.Fulde,J.Chem.Phys.73,4548(1980);P.Fulde inElectron Correlations in Molecules and Solids,Springer Series in Solid State Sciences,vol.100(Springer,Berlin,1993)4.H.Stoll,Chem.Phys.Lett.191,548(1992);H.Stoll,Phys.Rev.B46,6700(1992);H.Stoll,J.Chem.Phys.97,8449(1992);B.Paulus, P.Fulde,and H.Stoll,Phys.Rev.B(accepted)5.R.Pandey,J.E.Jaffe,and A.B.Kunz,Phys.Rev.B43,9228(1991);B.H.Brandow,Adv.Phys.26,651(1977);J.M.Recio,R.Pandey,A.Ayuela,and A.B.Kunz,J.Chem.Phys.98,4783(1993);S.Tanaka, J.Phys.Soc.Jpn.62,2112(1993)6.M.Caus`a,R.Dovesi,C.Pisani,and C.Roetti,Phys.Rev.B33,1308(1986);R.Dovesi,C.Roetti,C.Freyria-Fava,E.Apr`a,V.R.Saunders, and N.M.Harrison,Philos.Trans.R.Soc.London Ser.A341,203 (1992);M.Catti,G.Valerio,R.Dovesi,and M.Caus`a,Phys.Rev.B 49,14179(1994)7.M.Caus`a and A.Zupan,Chem.Phys.Lett.220,145(1994)8.R.A.Kendall,T.H.Dunning,Jr.,and R.J.Harrison,J.Chem.Phys.96,6796(1992);D.L.Strout and G.E.Scuseria,J.Chem.Phys.96, 9025(1992)9.For a survey of quantum-chemical ab-initio methods,cf.e.g.R.J.Bartlett and J.F.Stanton in Reviews in Computational Chemistry, vol.5,edited by K.B.Lipkowitz and D.B.Boyd(VCH,New York, 1994)10.T.H.Dunning,Jr.,J.Chem.Phys.90,1007(1989)12。

定量分析10电解质对化学平衡的影响EFFECT OF ELECTROLYTES ON CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIA

aX =x[X] where, aX is the activity nd x is a dimensionless quantity called the activity coefficient.

…continued…

sulfate, or sodium perchlorate, is added to this solution,

the color of the triiodide ion becomes less intense. This

decrease in color intensity indicates that the concentration of I3- has decreased and that the equilibrium has been shifted to the left by the added

4. At any given ionic strength, the activity coefficients of ions of the same charge are approximately equal. The small variations that do exist can be correlated with the effective diameter of the hydrated ions.

不同浓度阴离子瓜尔胶溶液的流变特性

Effects of concentrations of aqueous anionic guar solutions on their rheological properties

ZHU Hui, WU Wei-du*, WANG Ya-qiong, LI Yan-jun, SHI Wen-rong

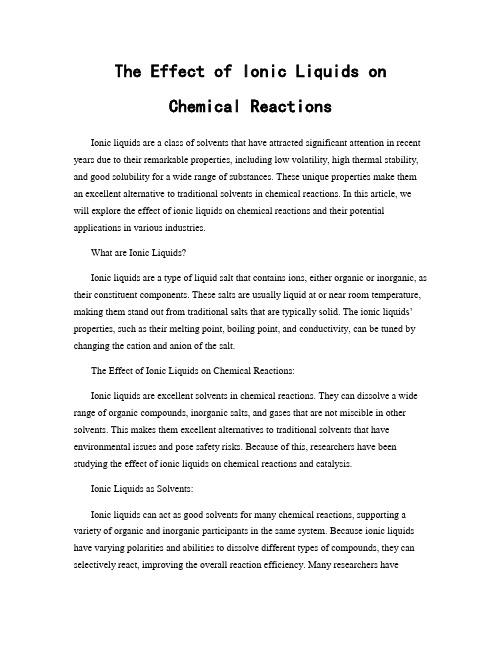

瓜尔胶 η0/ 浓度/% (Pa·s) 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.0087 0.0079 0.06154 0.05817 0.3001 0.304 1.195 1.187 3.736 3.648 6.813 6.917 16.66 17.9 27.92 28.25 44.1 0.9 44.58 45.63 1.0 70.36 71.98 71.17 44.77 η0均值 /(Pa·s) 0.0083 0.060 0.302 1.191 3.692 6.865 17.28 28.09

食品科技

FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 2012年 第 37卷 第 9期

mm平行板;稳态流动:间距750 μm;温度:25 ℃;100 s-1预剪切3 min;剪切后平衡15 min;扫描 范围:0.001~100 s-1;应变扫描:间距500 μm; 温度:25 ℃;上样后平衡5 min;频率:1 Hz; 扫描范围:0.1%~1000%;频率扫描:间距500 μm;温度:25 ℃;上样后平衡5 min;应变: 10%;扫描范围:0.1~10 Hz;动态黏弹性温度扫 描:间距1000 μm;上样后平衡5 min;应变: 10%;频率:1 Hz;扫描速率:2 ℃/min。 2 结果与分析 2.1 稳态流动实验 本文应用Cross方程对稳态流动曲线有效区 间进行拟合,得到零剪切黏度与剪切稀化指数, 另外,选取剪切速率10 s-1时的黏度测试值作为黏 度值(η),对于黏度衰减,则通过63 s -1时的黏度 值与6.3 s -1时的黏度值之间的比值来表达。对于 0.1%~1.0%各浓度下的瓜尔胶溶液分别进行稳态流 动实验,并相应进行重复性试验,其结果如表1。

翻译 Effects of Film Thickness on

薄膜厚度对含银纳米颗粒聚噻吩–富勒烯薄膜光电流产生的影响我们研究了入射光子-电流转换效率(IPCE)的薄膜的聚(3 -己基噻吩)(P3HT)和[6,6] -苯基C61丁酸甲酯(PCBM)作为薄膜厚度的函数,在存在或不存在的银纳米粒子(AGPS)薄膜的铟锡氧化物和–(ITO)电极之间。

该膜的厚度通过原子力显微镜评价。

测量研究的P3HT厚度的影响,薄膜的光电流作用光谱的吸收:PCBM薄膜。

结果表明,在较薄的薄膜光电转换效率急剧增加的厚度的最佳范围:PCBM P3HT薄膜为50–120 nm。

在这个最佳的范围内,1.5的ipces–1.8倍大的AGPS的存在。

1.景区简介有机薄膜太阳能电池作为下一代太阳能电池已经吸引了越来越多的关注,因为其廉价和简单的制造过程,和灵活性等。

特别是,聚(3 -己基噻吩)(P3HT)组合(电子供体:D)和[6,6] - phenyl-c61-butylic酸甲基酯(PCBM)(电子受体:一)已被通常使用的本体异质结(BHJ)光伏薄膜太阳能电池局域表面等离子体共振(LSPR)是在纳米水平的贵金属如金和银的一个独特的现象。

LSPR提供独特的光学性质,如增强的吸收特定波长的增加电领域在指定的表面。

4)最近,已经有越来越多的研究中使用的银或金的纳米粒子或纳米结构的LSPR提高光电转换效率。

5–10)之前,我们发现,银纳米粒子(AGPS)可以提高P3HT光发电效率:三电极的光电化学电池的PCBM薄膜。

11)不同,AGPS,激发分子的淬火,由于重原子效应,应在金纳米颗粒的情况下考虑(AUPS)。

例如,愤怒等。

12)报道,当荧光分子之间的距离和AUP(直径80 nm,在40 nm),样品的发射率实际上是相等的荧光分子的发射率。

因此,AGPs用于分子激发的增强是可取的。

然而,即使在AGPS的情况下,光活性分子和AGPS之间的空间距离是很重要的。

事实上,Tanaka等人。

13)报道,用荧光分子层和AGP膜之间的距离的增加,分子的荧光增强下降13)。

Influence of non-ionic surfactants on surface activity of