Using Cost-Benefit Analysis to Review Regulation

成本效益分析法的重要意义(英文)

Importance of Cost - Benefit Analysis成本效益法的重要意义Cost - benefit analysis is usually a decision-making method used by some enterprises in economic management. This method, we can also easily know from the literal, is mainly aimed at the correlation between Chen Ben and benefits, and then analysis can be made to obtain some effective evaluation of the implementation value of related projects. In some enterprises, for the implementation of a project, relevant benefit analysis methods should be carried out for analysis and research so as to use the minimum investment as far as possible to achieve the maximum benefit. Therefore, we can often see the application of this method in some public utilities. For example, public hospitals, which have been fully illustrated by the addition of the word " public" in front of them, are very necessary to analyze the social benefits and Chen Ben of some large public hospitals. In the process of economic management of public hospitals, the first thing relevant departments do is to calculate and analyze the costs, and then they can work out a set of reasonable and scientific plans to control the changes in Chen Ben. The ultimate goal is to reduce the costs of public hospitals, on the premise of ensuring certain medical quality. In the process of cost analysis, the role of cost-benefit analysis is to give a comprehensive, true and accurate feedback on the cost of a public hospital through the analysis and summary of relevant data, so as to help formulate relevant plans.When cost-benefit analysis is implemented in financial management, it is usually divided into five steps. In the first step, we must first clarify the cost of the project. The second step is to analyze and estimate the additional income of the project. The third step is to carefully analyze the whole project implementation process, find out where the cost can be saved, and determine how much can be saved by relevant data. The fourth step is to sort out the data of expected input cost and income benefit. The hospital sorts out the data of all economic activities, collects and distributes the different costs according to the accounting objects, and then makes a reasonable and scientific comparison table. The fifth and final step is to carefully compare and analyze the cost and benefit, and then obtain the whole evaluation result and carry out relevant quantitative work. Cost - benefit analysis is basically carried out according to these five steps.As the hospital's economic management personnel, sorting out and analyzing the data of thehospital's economic activities is the main content of their work. Through the statistical work of specific data on the revenue and expenditure of each department, and then the next analysis of these data, some feasible policy suggestions are finally obtained, which are very necessary for hospital managers to make decisions. Hospital managers can only improve their economic management level if they have sufficient data and analysis. The application of Chen Ben's benefit analysis method is precisely through the analysis of the hospital's economic activities, and then to control the medical cost of public hospitals from the root. As for controlling the economy of public hospitals, cost-benefit analysis plays a very important role. In the economic management of public hospitals, this method not only improves the overall level of economic management, but also effectively controls the cost and optimizes the allocation of hospital resources. In the process of using the economic benefit analysis method, the hospital manager can know the development status of each specialty of the hospital in detail through the data, so as to master the detailed situation of the whole hospital, and can adopt some corresponding supporting policies to support those departments that need to be supported, so as to promote their development. In addition, the cost-benefit analysis method provides an effective basis for the future development direction of the hospital, which is conducive to the adjustment of relevant incentive measures for public hospital leaders.。

成本效益分析 Cost Benefit Analysis 专业技巧

成本效益分析Cost Benefit AnalysisYour path towards SuccessHey guys. So, in this article, I will talk about Cost benefit analysis(CBA). Let me start with a simple example, and then I will move into details.Example: Say suppose, there is a person named A. So, now, A wants to start a business of selling Rugs. Now, when this person starts his business, he will need to invest some amount which is his investment amount. He spent 1000$ on starting his business. Now, no one will just want to invest money, without knowing the benefits he will get in the future.So, now comes the benefits analysis of our cost, i.e., the money which we are investing in the initial cost. The role of cost benefit analysis is that you will get an appropriate idea of your future benefits. The analysis will bring out ways to seek benefits in the future.If A invested 1000$, then he must have analyzed at first hand, that what benefits he will get in future and how? If one rug he bought at 50$, then he might sell that at 60$ or even more, according to the plan made after cost benefit analyses. So, this is what the cost benefit analysis does. Hope this example worked.So, now let’s move on the details. Following are the points which I will cover in this article:What is Cost Benefit Analysis?Process of doing a Cost Benefit Analysis EvaluationHistory of CBA in USlimitations of Cost Benefit AnalysisConclusionSo, here it goes. Let’s begin.What is Cost Benefit Analysis?Cost benefit analysis(CBA) also known as, benefit-cost analysis(BCA), is an organized manner to calculate the strengths and weaknesses of different transactions, project investments, etc. It is used to identify options which provide the best approach, to gainbenefits and at the same time, preserve savings. CBA is also described as an organized process for calculating and comparing benefits and costs of a decision, project or policy.A cost benefit analysis is a way to analyze business decisions. You understand it in this way that the benefits from a particular business are calculated, and then the costs related to it are subtracted.CBA(Cost Benefit Analysis) main purposes:To identify, whether the investment decision is correct or not. To justify and to check its feasibility. CBA checks whether the benefits will be more than the initial invested cost or not and by how much?To compare the projects initial cost with the future benefits. It includes expected cost and expected benefits.CBA aims to provide a correct decision with proper information, to lead a beneficial path.To make quick and simple financial decisions.To bring perfection in social welfare and economic efficiency. CBA talks in monetary terms. It keeps a check that the flow of benefits and flow of project costs over time is maintained on a regular basis. There may be some similarities informal techniques of CBA with some other analytical terms which include: Cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, risk-benefit analysis, social return on investment(SROI)analysis, etc. All these termsare nearly related to cost, and it’s benefits analysis in one or another way.If you are a decision maker, then CBA is very useful for you as it:provides you with both quantitative and qualitative information about the effects of regulation.surveys the effect of regulatory proposals in a standard manner. This promotes comparability, helps in the assessment of relative priority and encourages ethical decision making.encourages you to take charge of all the positive and negative effects of the proposed regulation. It also discourages you to make decisions basedonly on the impacts, on a single group within the community.look at different linkages between the regulatory proposal and other sectors of the economy. It also helps you maximise net benefits to society.helps you in finding out cost-effective solutions to various problems by identifying and measuring all costs.help you in making precise and transparent assumptions and judgments, even when it is difficult to calculate some costs or benefits.provides perfection in terms of economic efficiency. Provides well educated estimate of the best alternative.Process of doing a Cost benefit analysisCost benefit analysis is a simple way of weighing up project costs and its benefits. It is to determine whether to go ahead with a particular project or not?CBA can be performed regarding many different situations like:If you want to add on a new department, which also requires hiring of new employees.To determine the practicality of a capital purchase.Look upon a new project or a big change.Steps to do a Cost Benefit Analysis(CBA)<figure aria-describedby="caption-attachment-2716" class="wp-caption aligncenter" id="attachment_2716" style="width: 638px"><figcaption class="wp-caption-text" id="caption-attachment-2716">Image: SourceSo, let’s move on to the details. These steps will surely help you with your cost benefit analysis.Step 1: Analyse Costs and BenefitsThe first step is to analyze all the costs related to your project. Make a list of all those costs.Then, analyze all the profits which are associated with your projectIt happens, that there may be some unexpected costs or benefits that you might not have predicted earlier. So, when you sit to calculatethe costs and benefits, then think about the lifetime of those costs and benefits. You should know how these costs and benefits may change with time?Step 2: Give a monetary value to the costsCosts includes: Cost of required physical resources and the cost of the human effort included in all phases of a project.Run your mind and think of as many costs as you can. Example: For a Rugs shop to run, you need to purchase rugs, hire people to work at your shop and then there are costs regarding their work at the shop and many such other present and future costs too.Remember, not to forget any cost. Think of long life of your project and then work accordingly. You might have to add more people to your team or bring some new technology into your business with time. So, you need to be prepared earlier only regarding the costs.Step 3: Give a monetary value to the benefitsSo, it becomes a bit difficult to calculate the value of the benefits you may gain regarding your business.Things which you predict and the benefits which you calculate are soft benefits as predictions may change with near-future changes. This might include: what is the impact on the environment? Employee satisfaction or evenhealth and safety issues. What is the monetary value of these impacts?Example: What is the safe and stress free, travel cost of your employees? This may change accordingly. Here, you need to consult with other stakeholders and then decide how you will handle these changing items. Keep yourself updated all the time.Step 4: Compare your Costs and BenefitsThis is the final step. Contrast the value of your costs to the value of your benefits and then decide, what actions you need to take.Calculate both values of costs and benefits separately and then check whether the value of benefits is greater than that of costs or notAnalyse and calculate the approximate time that your benefits will take, to repay you the initial cost back. The simple way is to just divide the total cost value by the total benefit value. This will give you the length of the payback period or time.So, these were the steps to calculate your Cost benefit analysis. I hope you are now much more clear about the importance of CBA. Let’s now move towards evaluation.EvaluationCBA tries to measure all the positive and negative consequences of a project, that includes:Effects on the people dealing with it.Effects on the people who are not directly involved with it.Outside effects.Option value or other social gains.There can be a diverse no. of Costs and benefits. Financial costs are represented briefly in cost benefit analyses. It is due to larger market data. The net benefits may include cost savings or public willingness to pay compensation or willingness to accept it. It is for the welfare changes from the policy.The principal which guides you here is, to list all the categories of parties affected by an external mean and then add the positive or negative value. Surveys or market behavior are often used to calculate the compensation associatedwith a policy. People make market choices among few items that have different aspects related to the environment. They, then reveal the value they keep on these environmental factors.One controversy which occurs is, valuing a human life. For example, when recognizing road safety measures or life safety measures. However, this situation sometimes gets avoided with cost-utility analysis. Again, for example, road safety gets measured regarding cost per life saved, without just formally placing a financial value on the life.Another controversy is to value the environment which in today’s date means valuing ecosystem services. This includes air and water quality and pollution. Monetary values may also be given toother changing effects like business reputation, market penetration, etc.History of CBA in USIn the 1980’s, some academic and insti tutional critiques of CBA started to emerge. The main three critiques were:CBA could be used for political goals. Discussions can be used on the merits of cost and benefit, to step aside political or philosophical goals, rules and regulations.CBA is anti-regulatory, therefore it’s not a neutral analysis tool.The time which is necessary to complete CBA, can create some delays, which can hinder policyregulations.These critiques continued through 1990’s. Then they got reduced slowly. The main argument was that CBA should play no part in the regulatory process. But, the use of CBA continued after that too. It was due to the debate over its practicality and objective values. Some analysts still oppose the use of CBA in policy making, but most of them are in favour of its use.Limitations of Cost Benefit AnalysisFor projects that have small to mid-level capital and are running short of time, then CBA will be sufficient enough to make a detailed decision. But, for a very large project with a longer time period, CBA fails to see into important financial concerns. It includes interest rates, varying cash flows, inflation and the present value of money.ConclusionCost benefit analysis(CBA) is a straightforward tool to decide whether you should pursue a project or not.First, list down all the costs related to the project and then calculate the benefits that you will receive from it.Work on the time in which the benefits will repay you your initial cost.You can carry out a whole analysis by only using financial costs and benefits. You may also include items which change over time.So, guys, this was all about Cost benefit analysis.。

成本-效益与成本-效果分析

• 目的:消除货币时间价值的影响

Bt Ct NPV t (1 i ) t 0

n

• Bt:在第t年发生的效益;Ct:在第t年发生的成本;i:贴

现率;n:今后方案实施的年限。

• 基准点选择:通常把计划方案的第1年年初作 为计算现值的时间基准点。不同方案的时间 基准点应该是同一年份。

延期变动成本

• 当工作量超过预定服务量时,对卫生或医 务人员支付加班费、津贴等,这种成本称 为延期变动成本

机会成本(opportunity cost)

• 定义:就是将同一卫生资源用于另一最佳 替代方案的净效益。

• 机会成本可以看作是作出一种选择而放弃 另一选择的代价。 • 作用:机会成本不是实际的支出,只是在 评价和决策时作为一个现实的因素加以认 真考虑。

成本相同比较效果的大小

• 方案成本总额相同,比较效果。 • 效果越好,方案越易被采纳,投资效果较 好。

效果相同比较成本的大小

• 方案的效果相同,比较其成本。 • 在效果相同的情况下,成本低的方案是较 好的方案。

比较增量成本和增量效果的比率

• 当卫生计划方案的投资不受预算约束的情 况下,成本可多可少,效果也随之变化, 这时对卫生计划方案的评价可采用增量成 本与增量效果的比率指标。

无形成本(invisible cost)

• 定义:因疾病引起的疼痛;精神上的痛苦、 紧张和不安;生活与行动的某些不便,或诊 断治过程中的担忧、痛苦等。

• 特点和作用:也是付出的代价,但是很难定 量计算,也无法用货币来表示。作为一种客 观的实际存在应该予以考虑,对这方面的描 述将会使我们对方案的评价和决策更为完善

执业药师继续教育考试试题及答案

1、灰婴综合症是因为早产儿或重生儿使用了()选A2、对于透皮汲取的表达,错误的选项是()A.早产儿、重生儿和婴少儿皮肤角化层薄,药物穿透性高选B3、他克莫司和氨氯地平合用后,他克莫司血药浓度高升的主要原由是()选C4、以下期间,体内脂肪含量比率最低的是()选A5、以下药物与血浆蛋白联合率高且竞争力最强的是()C. 吲哚美辛选C重生儿期胆红素与白蛋白联合不坚固,某些血浆蛋白联合率高且竞争力强的药物可争夺白蛋白,使游离胆红素增高,即便在血清总胆红素水平不太高的状况下也极易发生高胆红素血症甚至核黄疸(胆红素脑病)。

竞争力最强的有重生霉素、吲哚美辛、水溶性维生素K、毛花苷丙、地西泮等;竞争力较强的有磺胺类药物、水杨酸盐、安钠咖等;竞争力较弱的有红霉素、卡那霉素、氯丙嗪、肾上腺素等。

以上药物在重生儿有黄疸时应慎用或禁用。

6、完美中药材流通行业规范。

健全()种常用中药材商品规格等级,成立包装、仓储、保养、运输行业标准。

选D7、成立覆盖主要中药材品种的全过程追忆系统。

成立中药材从()使用全过程追忆系统,实现根源可查、去处可追、责任可究。

推进中药生产公司使用源泉明确的中药材原料。

A.栽种、养殖、炮制、收买、储藏、运输、销售B.栽种、养殖、加工、收买、储藏、运输、销售C.栽种、养殖、加工、提取、收买、储藏、运输、销售D.栽种、养殖、加工、收买、储藏、运输、销售、研发选B成立中药材从栽种养殖、加工、收买、储藏、运输、销售到使用全过程追忆系统,实现根源可查、去处可追、责任可究。

推进中药生产公司使用源泉明确的中药材原料。

8、良种繁育是运用遗传育种的理论与技术,在保持其实不停提升良各种性、良种的()的前提下快速扩大良种数目的一套完好的种苗生产技术。

选D在保持其实不停提升良各种性、良种纯度与生活力的前提下快速扩大良种数目的一套完好的种苗生产技术。

9、中药材供给保障。

提升国家()能力,成立100种常用中药材的国家贮备。

选A10、推进完美中药材有关法律法例,增强濒危野生中药材资源管理,规范栽种养殖中药材的生产和使用。

经济学原理(曼昆)第十一章答案英文版

SOLUTIONS TO TEXT PROBLEMS:Quick Quizzes1. Public goods are goods that are neither excludable nor rival. Examples include national defense,knowledge, and uncongested nontoll roads. Common resources are goods that are rival but not excludable. Examples include fish in the ocean, the environment, and congested nontoll roads. 2. The free-rider problem occurs when people receive the benefits of a good but avoid paying for it.The free-rider problem induces the government to provide public goods because if the government uses tax revenue to provide the good, everyone pays for it and everyone enjoys its benefits. The government should decide whether to provide a public good by comparing the good’s costs to its benefits; if the benefits exceed the costs, society is better off.3. Governments try to limit the use of common resources because one person’s use of the resourcediminishes others’ use of it, so there is a negative externality which leads people to use common resources excessively.Questions for Review1. An excludable good is one that people can be prevented from using. A rival good is one for whichone person's use of it diminishes another person's enjoyment of it. Pizza is both excludable, sincea pizza producer can prevent someone from ea ting it who doesn't pay for it, and rival, since whenone person eats it, no one else can eat it.2. A public good is a good that is neither excludable nor rival. An example is national defense, whichprotects the entire nation. No one can be prevented from enjoying the benefits of it, so it is not excludable, and an additional person who benefits from it does not diminish the value of it to others, so it is not rival. The private market will not supply the good, since no one would pay for itbecause they cannot be excluded from enjoying it if they don't pay for it.3. Cost-benefit analysis is a study that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a publicgood. It is important because the government needs to know which public goods people value most highly and which have benefits that exceed the costs of supplying them. It is hard to dobecause quantifying the benefits is difficult to do from a questionnaire and because respondents have little incentive to tell the truth.4. A common resource is a good that is rival but not excludable. An example is fish in the ocean. Ifsomeone catches a fish, that leaves fewer fish for everyone else, so it's a rival good. But theocean is so vast, you cannot charge people for the right to fish, or prevent them from fishing, so it is not excludable. Thus, without government intervention, people will use the good too much,since they don't account for the costs they impose on others when they use the good.Problems and Applicat ions1. a. The externalities associated with public goods are positive. Since the benefits from thepublic good received by one person don't reduce the benefits received by anyone else, thesocial value of public goods is substantially greater than the private value. Examplesinclude national defense, knowledge, uncongested non-toll roads, and uncongested parks.Since public goods aren't excludable, the free-market quantity is zero, so it is less than the215efficient quantity.b. The externalities associated with common resources are generally negative. Sincecommon resources are rival but not excludable (so not priced) the use of the commonresources by one person reduces the amount available for others. Since commonresources are not priced, people tend to overuse them their private cost of using theresources is less than the social cost. Examples include fish in the ocean, theenvironment, congested non-toll roads, the Town Commons, and congested parks.2. a. (1) Police protection is a natural monopoly, since it is excludable (the police may ignoresome neighborhoods) and not rival (unless the police force is overworked, they're availablewhenever a crime arises). You could make an argument that police protection is rival, ifthe police are too busy to respond to all crimes, so that one person's use of the policereduces the amount available for others; in that case, police protection is a private good.(2) Snow plowing is most likely a common resource. Once a street is plowed, it isn'texcludable. But it is rival, especially right after a big snowfall, since plowing one streetmeans not plowing another street.(3) Education is a private good (with a positive externality). It is excludable, sincesomeone who doesn't pay can be prevented from taking classes. It is rival, since thepresence of an additional student in a class reduces the benefits to others.(4) Rural roads are public goods. They aren't excludable and they aren't rival sincethey're uncongested.(5) City streets are common resources when congested. They aren't excludable, sinceanyone can drive on them. But they are rival, since congestion means every additionaldriver slows down the progress of other drivers. When they aren't congested, city streetsare public goods, since they're no longer rival.b. The government may provide goods that aren't public goods, such as education, becauseof the externalities associated with them.3. a. Charlie is a free rider.b. The government could solve the problem by sponsoring the show and paying for it with taxrevenue collected from everyone.c. The private market could also solve the problem by making people watch commercials thatare incorporated into the program. The existence of cable TV makes the good excludable,so it would no longer be a public good.4. a. Since knowledge is a public good, the benefits of basic scientific research are available tomany people. The private firm doesn't take this into account when choosing how muchresearch to undertake; it only takes into account what it will earn.b. The United States has tried to give private firms incentives to provide basic research bysubsidizing it through organizations like the National Institute of Health and the NationalScience Foundation.c. If it's basic research that adds to knowledge, it isn't excludable at all, unless people in othercountries can be prevented somehow from sharing that knowledge. So perhaps U.S.firms get a slight advantage because they hear about technological advances first, butknowledge tends to diffuse rapidly.5. When a person litters along a highway, others bear the negative externality, so the private costsare low. Littering in your own yard imposes costs on you, so it has a higher private cost and is thus rare.6. When the system is congested, each additional rider imposes costs on other riders. For example,when all seats are taken, some people must stand. Or if there isn't any room to stand, somepeople must wait for a train that isn't as crowded. Increasing the fare during rush hourinternalizes this externality.7. On privately owned land, the amount of logging is likely to be efficient. Loggers have incentives todo the right amount of logging, since they care that the trees replenish themselves and the forest can be logged in the future. Publicly owned land, however, is a common resource, and is likely to be overlogged, since loggers won't worry about the future value of the land.Since public lands tend to be overlogged, the government can improve things by restricting thequantity of logging to its efficient level. Selling permits to log, or taxing logging, could be used to reach the appropriate quantity by internalizing the externality. Such restrictions are unnecessary on privately owned lands, since there is no externality.8. a. Overfishing is rational for fishermen since they're using a common resource. They don'tbear the costs of reducing the number of fish available to others, so it's rational for them tooverfish. The free-market quantity of fishing exceeds the efficient amount.b. A solution to the problem could come from regulating the amount of fishing, taxing fishingto internalize the externality, or auctioning off fishing permits. But these solutionswouldn't be easy to implement, since many nations have access to ocea ns, so internationalcooperation would be necessary, and enforcement would be difficult, because the sea is solarge that it is hard to police.c. By giving property rights to countries, the scope of the problem is reduced, since eachcountry has a greater incentive to find a solution. Each country can impose a tax or issuepermits, and monitor a smaller area for compliance.d. Since government agencies (like the Coast Guard in the United States) protect fishermenand rescue them when they need help, the fishermen aren't bearing the full costs of theirfishing. Thus they fish more than they should.e. The statement, "Only when fishermen believe they are assured a long-term and exclusiveright to a fishery are they likely to manage it in the same far-sighted way as good farmersmanage they land," is sensible. If fishermen owned the fishery, they would be sure not tooverfish, because they would bear the costs of overfishing. This is a case in whichproperty rights help prevent the overuse of a common resource.f. Alternatives include regulating the amount of fishing, taxing fishermen, auctioning offfishing permits, or taxing fish sold in stores. All would tend to reduce the amount offishing from the free-market amount toward the efficient amount.9. The private market provides information about the quality or function of goods and services inseveral different ways. First, producers advertise, providing people information about the product and its quality. Second, private firms provide information to consumers with independent reportson quality; an example is the magazine Consumer Reports. The government plays a role as well, by regulating advertising, thus preventing firms from exaggerating claims about their products,regulating certain goods like gasoline and food to be sure they are measured properly and provided without disease, and not allowing dangerous products on the market.10. To be a public good, a good must be neither rival nor excludable. When the Internet isn’tcongested, it is n ot rival, since one person’s use of it does not affect anyone else. However, at times traffic on the Internet is so great that everything slows down at such times, the Internet is rival. Is the Internet excludable? Since anyone operating a Web site can charge a customer for visiting the site by requiring a password, the Internet is excludable. Thus the Internet is notstrictly a public good. Since the Internet is usually not rival, it is more like a natural monopolythan a public good. However, since most people’s Web sites contain information and exclude no one, the majority of the Internet is a public good (when it is not congested).11. Recognizing that there are opportunity costs that are relevant for cost-benefit analysis is the key toanswering this question. A richer community can afford to place a higher value on life and safety.So the richer community is willing to pay more for a traffic light, and that should be considered in cost-benefit analysis.。

工程解决方案英文

工程解决方案英文IntroductionEngineering problem solving is an essential aspect of the engineering process, and it requires a systematic approach to ensure that the solutions are effective and efficient. Engineers are faced with a wide range of problems, from simple technical issues to complex and multifaceted challenges. In this paper, we will discuss the various steps in the engineering problem-solving process and present a comprehensive approach to solving engineering problems.Identify the ProblemThe first step in the engineering problem-solving process is to identify the problem. This may seem obvious, but it is essential to clearly define the problem and understand its scope and complexities. It is important to ask the right questions and collect relevant data to gain a thorough understanding of the problem. In many cases, the problem may not be well defined, and it is crucial to work with stakeholders to identify the problem accurately. Once the problem is clearly articulated, the next step is to analyze it, gather data, and define the criteria for a good solution.Analyze the ProblemAfter the problem has been clearly identified, the next step is to analyze it. This involves understanding the underlying causes of the problem, identifying the constraints, and evaluating the possible solutions. Engineers need to use various analytical tools and techniques to break down the problem into its component parts and understand the interrelationships between them. This may involve using mathematical models, simulations, and other analytical methods to gain insights into the problem. It is also important to consider the potential impacts of the problem on various stakeholders and assess the risks associated with different solutions.Generate Possible SolutionsOnce the problem has been thoroughly analyzed, the next step is to generate possible solutions. This stage involves brainstorming and coming up with creative and innovative ideas to address the problem. Engineers should be open to new ideas and think outside the box to explore all potential solutions. It is important to involve a diverse group of stakeholders in this process to ensure that a wide range of perspectives are considered. Engineers should also consider the ethical and sustainability implications of the solutions to ensure that they align with the organization's values and long-term goals.Evaluate and Select the Best SolutionAfter generating a range of possible solutions, the next step is to evaluate and select the best solution. This involves comparing the solutions against the criteria defined earlier andassessing their feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and impact. Engineers should also consider the potential risks and trade-offs associated with each solution and conduct a thorough analysis to determine the best course of action. It may be necessary to use decision-making tools, such as decision matrices or cost-benefit analysis, to assess the solutions objectively and make an informed decision.Implement the SolutionOnce the best solution has been selected, the next step is to implement it. This may involve developing a detailed plan, allocating resources, and coordinating with various stakeholders to ensure that the solution is implemented effectively. Engineers need to consider the potential barriers to implementation and develop strategies to overcome them. It is important to communicate the plan to all relevant stakeholders and ensure that everyone is aligned and committed to the solution. Engineers should also monitor and evaluate the implementation process to identify any issues and make adjustments as necessary.Review and Learn from the ExperienceThe final step in the engineering problem-solving process is to review and learn from the experience. This involves assessing the outcomes of the solution and identifying lessons learned. Engineers should evaluate the effectiveness of the solution and identify any areas for improvement. It is important to document the entire problem-solving process and share the findings with the broader engineering community to contribute to the collective knowledge base. By reflecting on the experience, engineers can improve their problem-solving skills and enhance their ability to tackle future challenges.Case Study: A Comprehensive Approach to Solving an Engineering ProblemTo illustrate the comprehensive approach to solving engineering problems, let us consider a case study involving the design and implementation of a sustainable energy solution for a manufacturing facility. The facility is currently reliant on non-renewable energy sources and is facing increasing pressure to reduce its carbon footprint and operating costs. The management has tasked a team of engineers to develop a sustainable energy solution that meets the facility's energy needs while minimizing its environmental impact.Step 1: Identify the ProblemThe first step is to clearly identify the problem. The team works with key stakeholders to understand the facility's energy needs, current energy consumption, and environmental impact. They also consult with energy experts to gain a thorough understanding of sustainable energy options and regulatory requirements. Through this process, the team defines the problem as the need to develop a sustainable energy solution that reduces the facility's dependence on non-renewable energy sources and lowers its carbon emissions. Step 2: Analyze the ProblemOnce the problem has been defined, the team conducts a comprehensive analysis to understand the underlying causes and constraints. They evaluate the facility's energy consumption patterns, identify the potential sustainable energy sources, and assess the technical and economic feasibility of different solutions. The team uses mathematical models and simulations to analyze the energy requirements and the potential impact of different energy sources on the facility's operations.Step 3: Generate Possible SolutionsThe team then engages in a brainstorming process to generate possible solutions. They consider a wide range of sustainable energy options, including solar, wind, and biomass energy, and explore innovative technologies, such as energy storage and energy efficiency measures. The team also considers the potential partnerships with external energy providers and government incentives to support the adoption of sustainable energy solutions.Step 4: Evaluate and Select the Best SolutionAfter generating a range of possible solutions, the team evaluates and selects the best solution. They assess the feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact of each solution and consider the potential risks and trade-offs. The team uses a decision matrix to compare the solutions and ultimately selects a combination of solar and wind energy, supported by energy storage and energy efficiency measures, as the best solution.Step 5: Implement the SolutionWith the solution selected, the team develops a detailed implementation plan and allocates the necessary resources. They collaborate with external energy providers and government agencies to secure the required permits and funding. The team also coordinates with the facility's management and staff to ensure a smooth transition to the new sustainable energy solution. Throughout the implementation process, the team monitors the progress and addresses any issues that may arise.Step 6: Review and Learn from the ExperienceFinally, the team reviews the outcomes of the solution and identifies lessons learned. They evaluate the performance of the sustainable energy solution and its impact on the facility's operations, costs, and environmental footprint. The team documents the entire problem-solving process and shares the findings with the broader engineering community to contribute to the collective knowledge base. They also identify opportunities for continuous improvement and explore ways to further enhance the facility's sustainability efforts.ConclusionThe comprehensive approach to solving engineering problems involves a systematic and collaborative process that encompasses identifying, analyzing, generating, evaluating, and implementing solutions. By following this approach, engineers can effectively tacklecomplex challenges and develop innovative solutions that meet the needs of various stakeholders. Case studies, such as the one presented above, illustrate how this approach can be applied in real-world engineering scenarios to deliver practical and sustainable solutions. As engineers continue to face evolving challenges, the comprehensive approach to problem-solving will remain a critical skill for driving innovation and advancing the field of engineering.。

Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-Benefit Analysis and Regulatory Reform: An Assessment of the Science and the ArtRaymond J. Kopp, Alan J. Krupnick,and Michael TomanDiscussion Paper 97-19January 1997Resources for the Future1616 P Street, NWWashington, DC 20036Telephone 202-328-5000Fax 202-939-3460© 1997 Resources for the Future. All rights reserved.No portion of this paper may be reproduced without permission of the authors.Discussion papers are research materials circulated by their authors for purposes of information and discussion. They have not undergone formal peer review or the editorial treatment accorded RFF books and other publications.Cost-Benefit Analysis and Regulatory Reform:An Assessment of the Science and the ArtRaymond J. Kopp, Alan J. Krupnick,and Michael TomanAbstractThe continuing efforts in the 104th Congress to legislate requirements for cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and the revised Office of Management and Budget guidelines for the conduct of such assessments during a regulatory rulemaking process highlight the need for a comprehensive examination of the role that CBA can play in agency decision-making. This paper summarizes the state of knowledge regarding CBA and offers suggestions for improvement in its use, especially in the context of environmental regulations.Key Words: cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, risk management, regulatory reformJEL Classification Nos.: D6, L5Table of ContentsList of Tables (iv)Executive Summary .................................................................................................................ES-10.Purpose and Objectives (1)1.Background on Cost-Benefit and Cost-Effectiveness (1)1.A Introduction to Cost-Benefit Analysis (1)1.B Social Welfare (2)1.C Individual Preferences (4)1.D Economic Value (4)1.E Aggregation from the Individual to Society (6)1.F Summary (6)2.Conceptual Strengths and Limitations of Cost-Benefit Analysis (6)2.A Introduction (6)2.B Strengths (7)2.B.1Transparency (7)2.B.2Ignorance Revelation (7)2.B.3Comparability (7)2.C Limitations (7)2.C.1Trumping Preference Satisfaction (8)2.C.2Equity Considerations (8)2.C.3Preference Satisfaction (9)2.C.4Elements of the Individual Social-Welfare Index (11)2.C.5Economic Value Is Not a Measure of Preference Satisfaction (12)2.C.6The Economic Value of Some Things Cannot Be Measured (12)2.C.7The Well-Being of Society Is Not Necessarily an Aggregation ofIndividual Well-Being (13)3.Measuring Benefits and Costs (14)3.A Benefits (14)3.A.1State of the Science (16)3.A.2Detail on Benefit-Estimation Approaches (19)3.A.2.a Health Valuation (19)Mortality (20)Morbidity Valuation: Acute (22)Morbidity Valuation: Chronic Effects (22)3.A.2.b Ecosystem Valuation (23)3.B Costs (24)3.B.1Monetary Measures of Reduced Well-Being (25)3.B.2Cost as Opportunities Forgone (26)3.B.3General Equilibrium Effects (27)3.B.4Dynamics (28)3.B.5Incentive-Based Policies (30)3.B.6Conclusion (31)3.C Addressing Uncertainties (31)4.Improving Methods for Regulatory Analysis (32)4.A Guidance on Risk Assessment for CBA (32)4.A.1Match Risk Characterization End Points with Valuation Start-Points (33)4.A.2Risk Targets vs. Dose-Response Relationships (33)4.A.3Estimate Population Risk, Not Individual Risk (34)4.A.4Worst-Case vs. Measures of Central Tendency and Other Measures (35)4.A.5Expert vs. Lay Risks (35)4.A.6Baselines (36)4.A.7Substitution Risks (36)4.B Guidance on CBA Methods (37)4.B.1OMB Guidance (37)4.B.2What is the Market Failure? Where are the Response Options? (38)4.B.3What is the Baseline for Assessing the Effects of Regulation? (38)4.B.4How Should the Analysis Address Risk and Uncertainty? (39)4.B.5What Costs and Benefits Should Be Considered? (40)4.B.6How Should Key Market Failures (or Nonmarket Goods) Be Assessed? (40)4.B.7How Should Benefits and Costs Be Compared Over Time? (41)4.B.8How Should Agencies Gauge the Appropriate Level of Effort for Assessingthe Economic Effects of Regulation? (42)4.B.9Interpretation of Statutory Requirements (42)4.B.10Damage versus Benefit (43)4.B.11Marginal versus Average Damages (43)4.B.12Issues in Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (44)4.B.13Application of General-Equilibrium Methods (44)5.Overarching Issues (44)5.A Decision Rules (44)5.B What Has Standing in a CBA? (46)5.B.1Nonquantifiable Elements (46)5.B.2Quantifiable Elements (47)5.C Uncertainty and Decision Rules (48)5.D Justification, Transparency, and Peer Review (48)5.E Treatment of Specific Regulatory Effects (49)5.E.1Nonuse Values (49)5.E.2Unemployment and Competitiveness (50)5.F Integrated Assessment (51)5.G Use of CBA in Legislative Design (51)5.H Interagency Consistency in Methods (51)5.H.1Reporting (52)5.H.2Methods (52)6.Concluding Remarks (53)References (57)List of TablesTable 3A-1.Benefit Categories and Estimation Approaches (15)Table 3B-1.Annual Estimates of Monetary Changes in Well-Being and EPA Estimates of Compliance Cost for the Clean Air and Water Acts (25)Table 3B-2.Percent Change in Selected Macro Variables Between Base and Scenario (29)Cost-Benefit Analysis and Regulatory Reform:An Assessment of the Science and the ArtRaymond J. Kopp, Alan J. Krupnick, and Michael TomanSenior Fellows, Resources for the FutureExecutive SummaryThe continuing efforts in the 104th Congress to legislate requirements for cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and the revised Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines for the conduct of such assessments during a regulatory rulemaking process highlight the need for a comprehensive examination of the role that CBA can play in agency decision-making. This paper summarizes the state of knowledge regarding CBA and offers suggestions for improvement in its use, especially in the context of environmental regulations. Its scope is not confined to assessments of cancer risks or other toxic-substance concerns; rather, it addresses the entire range of environmental policy issues.CBA is a technique intended to improve the quality of public policy decisions, using as a metric a monetary measure of the aggregate change in individual well-being resulting from a policy decision. Individual welfare is assumed to depend on the satisfaction of individual preferences, and monetary measures of welfare change are derived by observing how much individuals are willing to pay, i.e., willing to give up in terms of other consumption opportunities. This approach can be applied to nonmarket "public goods" like environmental quality or environmental risk reduction as well as to market goods and services, although the measurement of nonmarket values is more challenging. Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is a subset of CBA in which a policy outcome (e.g., a specified reduction in ambient pollution concentration) is taken as given and the analysis seeks to identify the least-cost means for achieving the goal (taking into account any ancillary benefits of alternative actions).To its adherents, the advantages of CBA (and CEA) include transparency and the resulting potential for engendering accountability; the provision of a framework for consistent data collection and identification of gaps and uncertainty in knowledge; and, with the use of a money metric, the ability to aggregate dissimilar effects (such as those on health, visibility, and crops) into one measure of net benefits.Criticisms of CBA hinge on questions about the assumption that individual well-being can be characterized in terms of preference satisfaction, the assumption that aggregate social well-being can be expressed as an aggregation (usually just a simple summation) of individual social welfare, and the empirical problems encountered in quantifying economic value and aggregating measures of individual welfare. We take the first as axiomatic, noting that because CEA is a subset of CBA, philosophical objections to the use of a preference-based approach to individual welfare measurement apply equally to both. As to the second, we agree that CBAdoes not incorporate all factors that can and should influence judgments on the social worth of a policy and that individual preference satisfaction is not the only factor; nevertheless, we assert that CBA must be included as a key factor. The problems referred to in the third criticism are measurement problems--how choices based on preferences permit one to infer economic values in practice.The state of the science of measuring such economic values is exceedingly active. Estimates of the willingness to pay for reductions in mortality and morbidity risks, for avoiding environmental damage to recreation opportunities, and for avoiding visibility degradation constitute the busiest and most-successful activities in the field of valuation. Issues of a higher order stalk the estimation of nonuse values, and a variety of mostly empirical concerns have left material damage poorly understood. Estimation of the costs of reducing environmental effects, generally thought to be relatively straightforward, is at least as challenging as estimation of the benefits, although there are easy-to-estimate, but perhaps poor, proxies for the loss of social well-being that such costs represent.This paper offers a number of suggestions to regulatory agencies in conducting CBA, drawing on the "best practices" identified in new guidelines recently issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). These include the use of clear and consistent baseline assumptions; the evaluation of an appropriately broad range of policy alternatives, including alternatives to new regulation; appropriate treatment of discounting future benefits and costs and accounting for the cost of risk-bearing; the use of probabilistic analyses and other methods to explore the robustness of conclusions; the identification of nonmonetizable or nonquantifiable aspects of a policy and the potential incidence of all effects; and the use of benefit and cost measures that are grounded in economic theory (measures of willingness to pay and opportunity cost).We also argue that from an economic perspective, risk assessment is a subset of benefits analysis in that quantitative relationships between pollution exposure and some human or ecological response are needed to estimate the effects and therefore the marginal change in welfare that results from a policy. That the culture of risk assessment is not generally oriented toward this role implies that risk assessments do not always provide the necessary input to an economic benefits analysis. Suggested changes in risk-assessment practices include estimating population risks, not just individual risks; providing information on the entire distribution of risks, including central tendencies, rather than just upper-end risk measures based on conservative assumptions about the potential threat; providing as much information as is practicable about how risks vary with exposure, rather than just identifying "safe" or "acceptable" thresholds of exposure; and considering substitution risks as being as important as direct risk reductions. Economists and risk assessors together must also address how to give appropriate attention to both lay perceptions and expert assessments of risks.The improvements in the methods for estimating the costs and benefits of regulatory activities discussed above are necessary but not sufficient for substantially improvingregulatory decisions. Several more overarching issues involving the role of CBA in public decision-making must also be debated and resolved. These include the following:• Decision rules and CBA. Although decisions should not be based solely on a simple cost-benefit test, a CBA should be one of the important factors in the decision. This approach is consistent with Executive Order 12866. A rule with negative measured net benefits could still be promulgated with this approach if it could be shown that other factors (such as an improvement in the equity of the income distribution or an enhancement of environmental justice) justified the action. A discussion providing the justification would help to ensure accountability.• Quantifiable benefits and costs. CBA needs to have standing as a part of all major regulatory and legislative decisions. In particular, CBA must have standing to implement the decision approach outlined above. Administrative reforms could accomplish much, but legislative changes will be needed to implement this suggestion where the use of CBA currently is precluded.• Nonquantifiable elements and CBA. A value of information approach should be used. This involves estimating the net benefits for the quantifiable elements and asking how large the nonquantifiable elements would have to be to reverse the conclusion of the analysis or, as a broader measure, the regulatory decision. This provides information about nonquantifiables (beyond their enumeration and description) in a useful format for the decision-maker.• Goals and standards--marrying efficiency and equity. CBA can be given appropriate standing and be introduced systematically into goal-setting without compromising other social concerns by first developing regulatory goals or aspirations, ideally expressed as ranges of acceptable risk and based on health or other criteria that reflect equity or fairness concerns. CBA, defined broadly, would then be used to justify where the standard would be set within this range or, to the extent that the range expressed aspirations versus more concrete requirements, how far toward the stated goal the regulation should go. An example of this approach can be seen in recent Congressional actions to reauthorize the Safe Drinking Water Act.• Insuring credibility of analysis. Agencies need to be clear about their justification for proceeding with a regulatory action, especially when the regulation fails an implicit or explicit cost-benefit test. They should have the scientific and economic assessments underlying major rules peer-reviewed, and both the analysis and the peer review should be done early enough to influence the outcome, not as a rubber stamp on decisions made on other grounds. Peer review can be performed inside the agency (although the Environmental Protection Agency has recently dismantled this function), can be part of an interagency process, can be part of an expanded role for OMB, or can even be privatized. The combination of expanded peer review and timely completion of analysis would greatly support and enhance, respectively, the performance and perceived credibility of the existing Executive Branch regulatory review process managed by OMB.Cost-Benefit Analysis and Regulatory Reform:An Assessment of the Science and the ArtRaymond J. Kopp, Alan J. Krupnick, and Michael Toman∗For the Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management0.PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVESThe need for improvement in the content and process of regulation has been a consistent theme of policy leaders over the last 3 years. During this time, President Clinton has promulgated a major new executive order on regulatory planning and review, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has issued revised guidelines for economic assessments of regulations. Of greater political salience, however, have been the efforts in the 104th Congress (building on similar but less sweeping efforts in the 103d Congress) to legislate requirementsfor cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and risk assessments. Whether one sees these efforts as attempts to make regulation and regulators more accountable or as attempts to subvert the achievement of important goals, the efforts have increased interest in the strengths and limitation of CBA as a tool for regulatory assessment.This paper provides a summary of the state of knowledge regarding CBA of environmental regulations, an assessment of its capabilities, and some suggestions for improving both the state of knowledge and the state of the art in agency applications of CBA techniques. The first section of the paper provides an overview of this technique, the assumptions on which it rests, and critiques of those assumptions. Section 2 is a more detailed examination of the philosophic debates about CBA. Section 3 is a review of the state of knowledge regarding techniques for estimating the benefits and costs of regulations to protect the environment. Section 4 is a discussion of specific issues that arise in implementation of CBA. Section 5 considers some larger issues surrounding the application of CBA (such as the role of CBA as a decision rule and the treatment of nonquantifiables).1.BACKGROUND ON COST-BENEFIT AND COST-EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS1.A Introduction to Cost-Benefit AnalysisThis paper addresses the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), a special case of CBA, in public decision-making. Although CBA and CEA are used in a wide range of public decision-making settings, we focus our attention here on their use in decisions concerning environment, health, and safety. Unlike the Commission's main report, we do not restrict our primary attention to regulations that affect toxic substances.∗ Raymond J. Kopp, Senior Fellow and Division Director, Quality of the Environment Division, Resources for the Future; Alan J. Krupnick, Senior Fellow, Quality of the Environment Division, Resources for the Future; Michael Toman, Senior Fellow, Energy and Natural Resources Division, Resources for the Future.CBA and CEA are economic techniques that produce information intended to improve the quality of public policies. In this context, quality refers to a measure of the social well-being that a policy conveys to society. Policies that reduce well-being are a priori inferior to those that improve well-being, and policies that improve well-being a great deal are superior to those which improve it only marginally. Conceptually, then, CBA could be used to rank policies on the basis of their improvements or reductions in well-being. For example, on the basis of such improvements, one could rank three air-quality policies that are related to urban ozone and that offer various ambient ozone standards to be attained, various reductions in illnesses related to ozone exposure, and various costs of attaining those standards.CEA is a particular form of CBA. In the example of air quality above, one would use CEA if it is determined that the standard-setting portion of the air-policy decision has already been made (e.g., to tighten the current ambient ozone standard to 0.10 ppm) and the decision-maker must choose among options all of which attain the 0.10-ppm standard but through different approaches that give rise to different costs. CEA does not imply choosing the policy with the smallest dollar price tag (although many people believe that it does). Strictly speaking, CEA chooses the policy that achieves the specified goal with the smallest loss in social well-being. The smallest welfare loss might not be associated with the smallest dollar cost.The remainder of this section introduces terms and concepts that will be used throughout the paper. It draws on the language of welfare economics, the subdiscipline of economics that gives CBA and CEA their intellectual foundation. Many of the terms that will be used, like economic value, have specific definitions in economics.1.B Social WelfareWe have used social well-being as an indicator of social quality--in the abstract, the combination of all the things that members of a society see as contributing to the quality of their lives, individually and collectively--without enumerating what those factors might be. However, to develop empirical measures of well-being in CBA, we need a concrete definition of well-being. To avoid confusing the abstract notion of well-being with its operational counterpart, we will hereafter term the latter social welfare. Unlike the components of well-being which are left vague and open to interpretation, the components of social welfare included in CBA must be clearly delineated and therefore will give rise to disagreements about what is included and what is excluded.Social welfare is meant to be a yardstick that permits us to look at our society in alternative states of the world and choose the state in which we are best off. Because the well being of a society is based on so many things, reducing it to a single measure might on its face seem ridiculous. Politicians, and the general public for that matter, routinely compare countries on the basis of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and often evaluate our own economy and society on the basis of household disposable income and the distribution of that income. However, many of the important aspects of well-being are left out by suchsimplifications. Nevertheless, such a simplification can contribute to understanding important public policy issues.The concept of social welfare is meant to offer a single measure that captures as manyas possible of the important features of well-being that might be affected by a policy. For example, if a range of policies under consideration affected only GDP per capita and we could state that, all other things being equal, higher GDP per capita led to greater well-being, thenwe could base our measure of social welfare simply on GDP per capita. In fact, economists have long recognized that GDP per capita is not a reliable measure of either individual or social well-being, because market values do not encompass all the important economic values (suchas environmental protection) and because market values that do exist might suffer from distortions that mask underlying economic values (as in the exercise of market power by a monopoly). More generally, it is clear that many important aspects of well-being could be left out by a simple measure of welfare. However, a measure of social welfare need not capture all aspects of well-being to be useful for decision-making.If one accepts for the sake of argument that a measure of social welfare is a reasonably good approximation by which to evaluate the well-being of a society, then CBA can be simply described as a study to determine what effect a proposed policy would have on the value of this social-welfare metric.1 Other things being the same, policies that would increase welfare as indicated by the metric would be preferred to policies that would reduce welfare, and policies that would increase welfare more would be preferred to policies that would increase welfare less.CEA analysis is a study of two or more policies with the same or very similar types of desired outcomes to determine which policy leads to the least net detriment in social welfare. CEA thus ranks the policies on the basis of the detrimental effect that the costs will have on social welfare. One way CEA can treat differences in ancillary benefits is as negative costs inthe policy comparisons.Constructing the measure of social welfare used in CBA can in principle be broken into two steps. In the first step, one attempts to develop measures of well-being for individual people in a society. In the second step, one aggregates the measures of individual welfare to form a measure of aggregate social welfare. The individual measures are subject to two critical concerns: the appropriateness of the single measure chosen as a valid measure of anindividual's well-being and the problems that one faces when attempting to quantify the components of the measure. The appropriateness of the aggregate measure depends on boththe appropriateness of the individual measures and their aggregation.1 Formally, the measure of social welfare used in CBA is an index. That is, it is a mathematical aggregation of numerous components to form a single numeric value.To find CBA or CEA useful and appropriate for public decision-making, one must find that the index of social welfare used in the CBA or CEA studies is a reasonably good metric by which to measure the well-being of a society. It is safe to say that much of the criticism of CBA starts and ends with a rejection of this view. These critiques are discussed in Section 2. CEA is a special case of CBA, so the concerns expressed above are as relevant to CEA as they are to CBA. Therefore, we focus our attention on CBA with the recognition that the same reasoning holds for CEA (unless explicitly noted otherwise).1.C Individual PreferencesIndividual measures of well-being are premised on a fundamental economic assumption: that the satisfaction of individual preferences gives rise to individual well-being. Economists take this assumption as a matter of faith, and it underlies most if not all of economic theory. Others reject the assumption outright. At its base, the assumption is that individuals know what is good for them (what will enhance their well-being), their preferences for actions and outcomes reflect this knowledge, and they act in a manner consistent with these preferences in a desire to increase their well-being. The validity of the "preference satisfaction" assumption has been debated since Bentham and will continue to be debated. There is nothing we can add to the debate but to note simply the crucial importance of the assumption to the intellectual foundation of CBA.2If we accept the preference satisfaction assumption, we can look to people's actions as guides to their well-being. For example, if we see a person exchanging $3 for a six-pack of beer, we can state that the exchange made the person better off (increased the person's well-being) on the grounds that actions are motivated by a desire to satisfy preferences. But how much better off? The answer to that question brings us to the concept of economic value.1.D Economic ValueTo economists, the term value has a specific meaning that we hereafter refer to in this paper as economic value.3 The most important, but often overlooked, features of economic value are that it is a theoretical construct and that monetary measures of it are inferred by analysts from the actions that people make in accordance with their preferences. Economic2 If one wishes to delve into the debate regarding preference satisfaction one can begin with the exchange between Sagoff (1993) and Kopp (1993). More strictly philosophical discussions can be found in Williams (1985) and Scanlon (1991).3 The term value as used by economists causes a great deal of confusion. For example, if one asked you what are your "values" you probably would not respond by saying $2.00 for a Big Mac or $30 for a round of golf at a public course. Rather, when asked about your values, you might say things like honesty or hard work. Similarly, if one asked you what value do you place on the environment, you might say the need to preserve it for future generations, or you might mention your commitment to environmental stewardship and conservation. You would probably not say, $32 per day to view Bald Eagles along the California Coast.value cannot be independent of an action, in particular, a type of action that requires a personto make a choice whereby something is given up and something gained.For economists, the study of choice allows economic values to be defined and quantified.4 Choice implies that a person is confronted with a selection of alternatives and that the consideration of the alternatives defines a tradeoff. The economic theory of individual behavior, based on the assumption of preference satisfaction, suggests that when a person is confronted by choices, the alternative that is chosen must be at least as desirable, from the perspective of that person, as the alternatives that were not chosen. The theory implies thatthe alternative chosen is at least as good or as valuable as the alternatives that were not chosen; the value of the alternative chosen is thus defined in terms of the alternatives foregone. For example, if a person chooses to relinquish three apples to gain a peach, an analyst can state that under the circumstances of the choice (perhaps known in their entirety only to the person), the economic value of the peach to the person is at least three apples. If the choice were to giveup $1 for the peach and the person chose the peach, the analyst would conclude that the value of the peach to that person was at least $1.5Now that we have defined economic value, we can return to the problems of measuring changes in individual well-being. Suppose that a policy is being considered that would lower the price of peaches by 25% and have no other consequences. From the perspective of the person who is willing to pay at least a dollar for a peach, the policy enables him or her to pay only $0.75. The difference between the amount given up and the economic value of the peach is a monetary measure of the increase of the person's well-being--in this case $0.25.64 One could say that the analyst "constructs" the economic value rather than estimating them. The verb constructs underscores the notion that economic value does not exist in a free standing fashion amenable to empirical measurement. Rather, economic value can only be measured with reference to a choice, and the characteristics of that choice largely determine the measured value.5 To monetize economic value, the foregone alternative (defined by an individual's choice within a specified trade-off) must be expressed in dollars. Unfortunately, this monetization has sometimes created misconceptions. For example, it has been suggested that economic values are confined to prices observed in markets. These misconceptions arise because many people commonly think of the monetary measure of economic value as a price; if a widget sells for $6 in a market, then $6 must be its value. This view is misleading, however. When a person buys a widget the analyst only learns that it is worth at least $6 to the buyer. He or she might be willing to pay much more than $6 if necessary to get the widget. Markets do offer opportunities for people to make choices, but it is these choices and the circumstances relevant to them that permit construction of the underlying economic values, not the existence of markets and market prices per se.6 Policies rarely affect only one good or one price. Most often they affect many goods and many prices. But if we knew the economic value of all the goods affected by the policy and the effects on those goods of the policy, we could aggregate the monetary measures of well-being gains or losses across all the affected goods to capture the full impact of the policy on individual well-being.。

经济评审英语

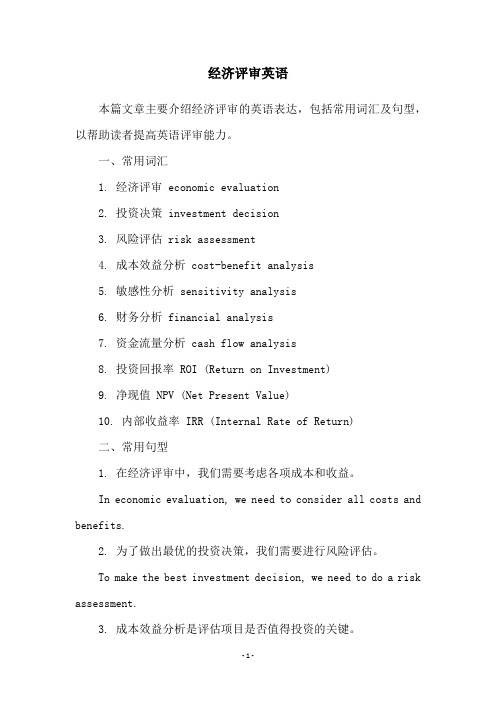

经济评审英语本篇文章主要介绍经济评审的英语表达,包括常用词汇及句型,以帮助读者提高英语评审能力。

一、常用词汇1. 经济评审 economic evaluation2. 投资决策 investment decision3. 风险评估 risk assessment4. 成本效益分析 cost-benefit analysis5. 敏感性分析 sensitivity analysis6. 财务分析 financial analysis7. 资金流量分析 cash flow analysis8. 投资回报率 ROI (Return on Investment)9. 净现值 NPV (Net Present Value)10. 内部收益率 IRR (Internal Rate of Return)二、常用句型1. 在经济评审中,我们需要考虑各项成本和收益。

In economic evaluation, we need to consider all costs and benefits.2. 为了做出最优的投资决策,我们需要进行风险评估。

To make the best investment decision, we need to do a risk assessment.3. 成本效益分析是评估项目是否值得投资的关键。

Cost-benefit analysis is the key to evaluating whether a project is worth investing in.4. 敏感性分析可以帮助我们确定项目对不确定性因素的敏感程度。

Sensitivity analysis can help us determine how sensitivea project is to uncertain factors.5. 财务分析可以更全面地评估项目的财务状况。

Financial analysis can more comprehensively evaluate the financial situation of a project.6. 资金流量分析可以帮助我们预测未来的现金流量。

成本效益分析(英文版精品)Cost-Benefit Analysis

Private Sector Project Evaluation

• Suppose there are two projects, X and Y • Each entails certain benefits and costs,

denoted as BX, CX, BY, and CY. • Need to ask:

– $376,889 if r=.05 – $148,644 if r=.10

10

Present Value: Inflation

• Nominal amounts are valued according to the level of prices in the year the return occurs.

– A project is admissible only if its present value is positive

– When two projects are mutually exclusive, the preferred project is the one with the highest present value.

9

Present Value: Future Dollars into the Present

• Present value is an enormously important concept

• A $1,000,000 payment 20 years from now is only worth today:

22

Discount rate for government projects

• Less consensus on appropriate discount rate in public sector. One possibility are rates based on returns in private sector.

英语作文-员工项目立项审批

英语作文-员工项目立项审批As the company continues to grow and expand, it is essential to carefully consider and approve the projects proposed by our employees. Project approval is a critical step in ensuring that the company's resources are allocated efficiently and effectively. In this document, we will outline the process for employee project proposal and approval, as well as the criteria that will be used to evaluate the proposed projects.First and foremost, it is important for employees to clearly articulate the purpose and objectives of their proposed project. This should include a detailed description of the project, its goals, and the expected outcomes. Additionally, employees should provide a comprehensive analysis of the potential benefits and risks associated with the project, as well as a realistic timeline for completion.Furthermore, employees should outline the resources that will be required to execute the project, including budgetary considerations, human resources, and any other necessary support. It is crucial for employees to demonstrate a clear understanding of the resource requirements and to provide a detailed plan for how these resources will be utilized.In addition to the project proposal itself, employees should also provide an analysis of the potential impact of the project on the company as a whole. This should include an assessment of how the project aligns with the company's strategic objectives, as well as any potential implications for other areas of the business.Once the project proposal has been submitted, it will undergo a thorough review process. This will involve a cross-functional team of reviewers who will carefully evaluate the proposal based on the following criteria:1. Alignment with company strategy: Does the project align with the company's overall strategic objectives? Will it contribute to the long-term success of the business?2. Feasibility: Is the project feasible given the resources that are available? Are the proposed timelines realistic? Are there any potential roadblocks or challenges that need to be addressed?3. Potential impact: What is the potential impact of the project on the company and its stakeholders? Will it create value for the business? Are there any potential risks that need to be mitigated?4. Cost-benefit analysis: What are the potential costs associated with the project, and what are the expected benefits? Is the project financially viable, and will it provide a positive return on investment?Based on the evaluation of these criteria, the review team will make a recommendation regarding the approval of the project. This recommendation will then be presented to the appropriate decision-makers within the company for final approval.It is important to note that the project approval process is intended to be thorough and rigorous, in order to ensure that the company's resources are allocated to the most valuable and impactful projects. By carefully evaluating and approving employee project proposals, we can continue to drive innovation and growth within the company, while also maximizing the return on investment for our stakeholders.In conclusion, the approval of employee project proposals is a critical process that requires careful consideration and evaluation. By following the outlined process and criteria, we can ensure that the projects approved are aligned with the company's strategic objectives, feasible, impactful, and financially viable. This will ultimately contribute to the long-term success and sustainability of the company.。

should-cost analysis -回复

should-cost analysis -回复"Should-cost analysis"指的是企业或个人在决策过程中,通过评估成本,推断对于特定产品或服务应当具有的合理成本。

这种分析方法可以帮助企业或个人更好地管理成本,提升效率,并做出更具竞争力的商业决策。

一. 什么是Should-cost Analysis?Should-cost analysis是一个系统性的方法,通过对特定产品或服务的成本进行评估,预测其应当具有的合理成本水平。

这种分析方法通过对供应链的各个环节进行细致的评估,包括原材料成本、工艺流程、人力资源和外部环境等,从而推断出可接受的成本范围。

二. Should-cost Analysis的重要性1. 管理成本:通过should-cost analysis,企业可以更好地管理成本,了解产品或服务的实际成本,并达到合理的成本节约目标。

2. 提升效率:should-cost analysis帮助企业识别和消除非必要的成本,优化供应链,提高生产效率和产品质量。

3. 可持续竞争力:通过深入了解产品或服务的合理成本范围,企业可以制定竞争性价格策略,提高市场竞争力。

三. Should-cost Analysis的步骤1. 识别目标产品或服务:确定需要进行should-cost analysis的目标产品或服务,明确评估范围和目标。

2. 收集数据:收集相关数据,包括原材料成本、劳动力成本、运输成本和其他相关费用。

这些数据可以通过对供应商的沟通和文件记录进行收集。

3. 评估供应链:评估供应链的各个环节,包括供应商选择、生产工艺和最终产品交付等,以确定其中的成本。

4. 制定成本模型:根据收集到的数据和对供应链的评估,建立一个成本模型,模拟产品或服务的成本结构。

5. 进行成本分析:通过对成本模型的运行,进行成本分析。

识别出哪些成本是合理的,哪些是可以优化的。

6. 制定节约措施:根据成本分析的结果,制定节约成本的具体措施,包括降低原材料成本、优化生产工艺、提高效率等。

基础科研业务费绩效评估

基础科研业务费绩效评估英文回答:Performance Assessment of Basic Research Overhead.Basic research overhead costs are essential for supporting the infrastructure and activities necessary for conducting fundamental scientific research. These costs cover a wide range of expenses, including lab equipment, supplies, personnel, and administrative support. Accurately assessing the performance of basic research overhead is crucial to ensure that these funds are being used effectively and efficiently.Key Considerations for Performance Assessment.Alignment with Research Objectives: Overhead costs should directly support the research goals and objectives of the institution.Efficiency and Effectiveness: Overhead costs should be used in a manner that maximizes research output and impact.Transparency and Accountability: The allocation and use of overhead costs should be transparent and accountable to funding agencies and other stakeholders.Benchmarking and Comparison: Performance should be assessed against benchmarks and compared to similar institutions.Continuous Improvement: There should be a mechanismfor ongoing monitoring and evaluation to identify areas for improvement.Methods for Performance Assessment.Activity-Based Costing: This method allocates overhead costs based on the specific activities conducted by researchers.Cost-Benefit Analysis: This approach compares thebenefits of research overhead to the costs incurred.Return on Investment: This measure evaluates the value generated by research overhead in relation to the initial investment.Peer Review: External эксперты can provide valuable insights on the efficiency and effectiveness of overhead use.Internal Audits: Regular internal audits can assess compliance with policies and procedures.Reporting and Communication.The results of performance assessments should be communicated effectively to funding agencies, university administrators, and researchers. This transparency promotes accountability and enables informed decision-making. Reporting should include:Assessment Findings: A summary of the key findingsfrom the performance assessment.Recommendations: Specific recommendations for improvement based on the assessment results.Action Plan: A plan for implementing the recommendations and monitoring progress.Conclusion.Regular and rigorous performance assessment is essential for ensuring the effective and efficient use of basic research overhead costs. By implementing robust assessment methods and fostering a culture of transparency and accountability, institutions can optimize the allocation of these funds to support cutting-edge research and maximize its impact.中文回答:基础科研业务费绩效评估。

the cost-effective analysis -回复

the cost-effective analysis -回复什么是成本效益分析?成本效益分析(Cost-Effectiveness Analysis)是一种经济学工具,用于评估不同政策、项目或决策的成本和效果之间的关系。

它是一种经济评估方法,旨在确定资源的最佳分配方式,以使得所获得的效果达到最大化。

成本效益分析在公共政策制定、医疗保健领域、环境保护、能源等领域中得到广泛应用。

成本效益分析的步骤步骤1:确定目标和问题表述成本效益分析的第一步是明确研究的目标和问题。

这涉及到确定评估的政策、项目或决策,以及建立明确的问题陈述。

问题陈述应该清楚描述研究的目标,例如“评估投资imm项目的成本效益”。

步骤2:确定和比较替代方案在这一步中,需要确定存在的替代方案,并确保它们是可比较的。

这些替代方案可能包括不同的政策措施、不同的投资选项或不同的决策路径。

确定的替代方案应该能够有效实施,并具有一定的可比性。

步骤3:明确目标和效果的测量在成本效益分析中,目标通常是衡量效果的指标。

这些效果指标可能是生命质量调整年(QALYs)、生产力提高或环境污染减少等等。

确定和测量这些效果指标是决策分析的关键步骤之一。

需要确保效果的测量是客观准确的,并能够反映出替代方案的差异。

步骤4:收集和估计成本数据成本效益分析的另一个重要方面是收集和估计成本数据。

这些数据应包括所有与替代方案相关的成本,如直接成本、间接成本、机会成本等。

成本数据的收集通常需要通过文献研究、问卷调查、采访等多种方法获取。

估计成本数据时,需要考虑到通货膨胀率和时间价值的影响。

步骤5:使用成本效益比进行评估一旦目标和效果的测量以及成本数据的收集和估计完成,就可以使用成本效益比对替代方案进行评估。

成本效益比是用来衡量每个单位效果(如每生命质量调整年)所需的成本。

根据成本效益比的比较,可以确定哪个替代方案是最优的选择。

步骤6:敏感性分析敏感性分析是成本效益分析中的一个重要步骤。

【参考文档】成本效益分析(Cost-Benefit Analysis)-范文word版 (1页)

【参考文档】成本效益分析(Cost-Benefit Analysis)-范文word版本文部分内容来自网络整理,本司不为其真实性负责,如有异议或侵权请及时联系,本司将立即删除!== 本文为word格式,下载后可方便编辑和修改! ==成本效益分析(Cost-Benefit Analysis)during the six - hour flight to new york , i did a cost -benefit analysis . i asked myself : what was the cost of just listening when lyda called out the warning ? zero . i then reasoned : what was the potential benefit ? what could have been saved ? several potential benefits came to mind , including her life , my life , the lives of our children , and the lives of other people .when someone gives us something that has a huge potentialbenefit and costs us absolutely nothing what should we say to such a fine person ? thank you ! i landed in new york feeling lonely ,guilty , and ashamed of myself . i immediately called lyda and told her my cost - benefit story . i assured her : the next time you help me with my driving , i am just going to say , thank you . sure you will , she said with a laugh . for some reason , she seemed to doubt that i had undergone a true religious conversion . just you wait . i am going to do better . i continued . we ll see . she replied .。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。