2009-wear-Slurry and cavitation erosion resistance of thermal spray coatings!

A Vision for Carbon Fiber in the Automotive Market,2009

The composites industry is markedly lagging the metals industry in terms of fast fabrication technology, e.g., there is no composite processing alternative, to date, to high-speed metal stamping. A consortium of industries needs to come Easy repair technology and bonding solutions are just starting to be introtogether and attack the problem from all duced for structural composites. One angles, which include improvements in dispensing technologies, curing chem- problem with permanent bonding technology is disassembly, which is not a istries and the energy sources that drive concern for metals. Using conventional cure. The most talked-about effort within metal fastening technology for composthe automotive composites sector is that of a Japanese consortium lead by Nissan, ites usually leads to disasters, due to crack initiation and propagation from the which has reduced cycle time from 160 high stress concentration regions. But to 10 minutes for resin transfer molding (RTM] simple flat panels with carbon fi- clever assembly designs that circumvent ber/epoxy. The fact that this is newswor- such situations are few and far between. Engineering knowledge for designing thy clearly indicates that the challenge is parts with composites, although growformidable; Composites musí increase manuing, is still limited. While universities are facturing speed f}y almost an order of magnitude teaching courses on this topic, the emlo become competitive. phasis is still on metals. When students In the realm of reinforcements, comface real-world situations, they soon realposites will require carbon fiber if they ize that there would have to be a huge change in how cars are put together before they could take full advantage Current carbon fiber of composites. One-to-one replacetechnology is hostage to ment of a metal part is often the best way to prove the deficiency of a comexcessive cost. posite solution. Conversely, the biggest advantage is realized only by comare to replace metals in high-perfor- bining various functionalities in one part. mance applications- Carbon fiber perIn my opinion, multifunctional carbon formance and cost are important parts composites could become commonplace of the equation when considering com- in mainstream automobiles by 2030 if posites for an automotive application. several factors fall into place: the price of Aerospace-grade carbon fibers of 600 to carbon fiber comes down; designers be1,000 ksi tensile strength and 40 msi to come more comfortable designing cars 60 msi modulus are in the range of Si 5/ with monocoque and/or highly integrated, Ib to $50/lb ( USD). While standard-grade multifunctional structures; and fabricacarbon fibers of 550 to 650 ksi tensile tors reach a part cycle time on the order strength and 32 to 37 msi modulus are two to four minutes. Is it possible? Peravai lable at S7 to S14/lb, the need is great haps. But it will be a long process that will for higher performance at lower cost. require several breakthroughs, including Current carbon fiber technology is hos- a willingness on the part of automotive OEMs to invest in the technology. • tage to the excessive cost of either the precursor or the conversion technology.

米兰设计周

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 2009

My Bauhaus Is Better Than Yours 45 Kilo's "Hallo Lamp" sits on a beautiful conical concrete base and has simple yet exciting details like a wire handle on the lamp head and a leather loop height adjustment.

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 2009

Fiam At the fairgrounds Fiam displayed a series of glass furniture, and table ornaments.

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 2009

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 2009

Campeggi At the Campeggi both, everything was not only what it seemed, but transformed into much more. Check out the Tent Sofa Video Drive-by for an example

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 2009

Hale Waihona Puke ecal Alejandro Bona's playful 813m woven blue rope furniture was one of many woven pieces this year in Milan but stood out because of its intense color and excellent craftsmanship. I almost thought the lamp was going to walk away as I approached it as if I had stumbled across some unknown alien creature.

可食用涂膜材料对白芦笋品质的影响

Impact of edible coatings and packaging on quality of white asparagus (Asparagus officinalis ,L.)during cold storageMaria V.Tzoumaki a ,Costas G.Biliaderis a,*,Miltiadis Vasilakakis ba Laboratory of Food Chemistry and Biochemistry,Department of Food Science and Technology,School of Agriculture,Aristotle University,GR-54124Thessaloniki,Greece bLaboratory of Pomology,Department of Horticulture,School of Agriculture,Aristotle University,GR-54124Thessaloniki,Greecea r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 18December 2008Received in revised form 14February 2009Accepted 19March 2009Keywords:White asparagus spears quality Edible coatings TextureAnthocyanins Lignificationa b s t r a c tThe effects of edible coatings and plastic packaging on quality aspects of refrigerated white asparagus spears were studied using two different experimental protocols.The first included four coating formula-tions based on carboxymethyl-cellulose and sucrose fatty acid esters,whey protein isolate alone and in combination with stearic acid,and pullulan and sucrose fatty acid esters,and an uncoated sample serving as a control.The second set consisted of four treatments;uncoated asparagus spears (control),coated with a carboxymethyl-cellulose formulation,packaged in plastic packaging and combination of coated and packaged asparagus spears.All products were stored at 4°C and the quality parameters such as weight loss,texture,visual appearance,lignin and anthocyanins concentration,and colour were evalu-ated during their storage.Edible coatings exhibited a beneficial impact on the quality of asparagus by retarding moisture loss,reducing hardening in their basal part and slowing down the purple colour devel-opment.The plastic packaging had a remarkable influence in reducing weight loss and retarding harden-ing but its impact to the rest of the quality parameters was similar to that of the edible coatings.The combination of packaging and edible coating did not seem to offer any additional advantage on asparagus spears apart from the fact that the product had a brighter appearance at the middle part of the stem com-pared to the packaged spears alone.Ó2009Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionAsparagus (Asparagus officinalis ,L.)has very short shelf life due to its high respiration rate,which continues after harvesting.White asparagus undergoes a sequence of considerable physiological and biochemical changes which quickly influence its chemical compo-sition and lead to quality loss,mainly due to an increase of hard-ness,water loss and the synthesis of anthocyanins (Chang,1987).Therefore,ensuring an extended shelf-life by adequate post-har-vest conservation appears to be very challenging for commerciali-zation of this highly valued vegetable (Villanueva,Tenorio,Sagardoy,Redondo,&Saco,2005).Postharvest treatments to in-crease storage and shelf life included storage in modified atmo-sphere packaging (MAP)(Siomos,Sfakiotakis,&Dogras,2000)and prestorage hot water treatments (Siomos,Gerasopoulos,&Tsouvaltzis,2005).The role of packaging on vegetable conservation,distribution and marketing is also quite popular and is frequently used in com-bination with other conservation methods,an approach called hur-dle technology (Hoover,1997).However,the final disposal of the packaging materials leads to ecological problems and additionalrecycling costs (Viña et al.,2007).On the other hand,the applica-tion of edible coatings appears to be one of the most innovative ap-proaches to extend the commercial shelf life of fruits and vegetables by,among other mechanisms,acting as a barrier against gas transport and showing similar effects to storage under con-trolled atmospheres (Park,1999).Indeed,over the last two decades the development and use of bio-based packaging materials to pro-long the shelf-life and improve the quality of fresh products has been receiving increased attention.The reasons for such an interest are mainly related to environmental issues due to disposal of con-ventional synthetic food-packaging materials.However,in order such edible films and coatings to be used at a commercial level in food products they must fulfill some basic requirements:accept-able sensorial characteristics,appropriate barrier properties,good mechanical strength,reasonable microbial,biochemical and phys-icochemical stability,safety,low cost and simple technology for their production (Diab,Biliaderis,Gerasopoulos,&Sfakiotakis,2001).The effectiveness of edible coatings for protection of fruits and vegetables also depends on controlling the wettability of the coating solutions,which affects the coating thickness (Park,1999).Thus,edible coating formulations must wet and spread uni-formly on the vegetable’s surface and,after drying,a coating that has adequate adhesion,cohesion and durability to function prop-erly must be formed (Ribeiro,Vicente,Teixeira,&Miranda,2007).0308-8146/$-see front matter Ó2009Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.03.076*Corresponding author.Tel./fax:+302310991797.E-mail address:biliader@agro.auth.gr (C.G.Biliaderis).Food Chemistry 117(2009)55–63Contents lists available at ScienceDirectFood Chemistryj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :/locate/foodchemEdiblefilms and coatings are generally based on biological materials such as proteins,lipids and polysaccharides.The main polysaccharides that can be included in edible coating formula-tions are starch and starch derivatives,cellulose derivatives,chito-san,pectin,alginate and other gums.Carboxymethyl-cellulose is a cellulose derivative that has received considerable attention with several examples of applications in many fruits and vegetables.A commercial edible coating formulation based on carboxymethyl-cellulose and sucrose fatty acid esters,named Semperfresh TM,has been applied to pears(Zhou et al.,2008),cherries(Yaman&Bayo-indirli,2002)and many other fruits.Pullulan,an extracellular poly-saccharide produced by Aureobasidium pullullans,also is capable of forming ediblefilms but has not been largely exploited as a coating material in fruits and vegetables,presumably because of its high water solubility.One example of pullulan used as a coating hydro-colloid was for strawberries and kiwifruit(Diab et al.,2001).Pro-teins that can also be used in formulations of edible coatings for fruits and vegetables include those derived from animal sources, such as casein and whey proteins,or obtained from plant sources, like corn zein,wheat gluten and soy protein(Vargas,Pastor,Chir-alt,McClements,&Gonzalez-Martinez,2008).Whey protein based coatings have been extensively used to extend the shelf life of fruits and vegetables(Cisneros-Zevallos&Krochta,2003;Ler-dthanangkul&Krochta,1996).To the best of our knowledge there are no available data regard-ing the effect of edible coatings on postharvest quality aspects of white asparagus spears.Therefore,the aims of the present work were to evaluate the effect of different edible coating formulations on quality parameters of white asparagus spears during refriger-ated storage,to compare the impact of one of these edible coatings with that of a plastic packaging on the extension of asparagus post-harvest life,and to explore if there is any additional beneficial ef-fect of a combined treatment using edible coating and packaging with the syntheticfilm.2.Materials and methods2.1.Plant materialWhite asparagus(Asparagus officinalis,L.)spears were harvested from commercial farms in the regions of Imathia and Pella,Greece. The spears were hydrocooled and transported to the laboratory within3h after harvest,under refrigerated conditions.Straight, undamaged samples,around18–22mm in diameter,with closed bracts were carefully selected and cut at18cm from the tip.2.2.Coating solutions preparation and applicationSodium carboxymethyl-cellulose(CMC2500F Tic Gums,USA), whey protein isolate(WPI)(Bi-ProÒ,Davisco Foods International, USA)and pullulan(Hyashibara Biochem Laboratory Inc.,Okayama, Japan)were used as biopolymer matrices in the coating formula-tions.Other substances used were sucrose fatty acid ester F-50 with an HLB value of six(Dai Ichi Kogyo Seyaku Co.,Ltd.,Tokyo,Ja-pan),polyethylenoglycol PEG400(Merck,Darmstadt,Germany), sorbitol and stearic acid(Sigma–Aldrich GmbH,Steinheim,Ger-many).Ethyl alcohol was reagent grade and water used in all experiments was distilled.The carboxymethyl-cellulose based coating(CMC)was pre-pared byfirstly dissolving the CMC(0.2%w/w)in a water–ethanol mixture(4:1v/v)under magnetic stirring at60°C and then adding the plasticizer PEG(0.1%w/w)and the sucrose fatty acid ester F-50 (0.8%w/w),followed by stirring for1h.Two different coatings using the whey protein isolate were prepared;WPI1and WPI2, which included4%w/w WPI and1%w/w sorbitol as a plasticizer, both dissolved in distilled water.The solutions were denatured for30min in a90°C water bath under continuous shaking and then were rapidly cooled in an ice bath,in order to stop further protein denaturation,andfinally equilibrated to room tempera-ture.WPI2also included1%w/w stearic acid as a lipid constituent, which was incorporated to the coating solution just after the dena-turation step by homogenization at19,000rpm for4min using an UltraTurrax T25homogenizer(IKA Labortechnik,Staufen,Ger-many).The pullulan based coating solution(P)was obtained by dissolving pullulan(5%w/w)in distilled water under magnetic stirring at60°C with subsequent addition of sorbitol(1%w/w) and a sucrose fatty acid ester F-50(1%w/w),followed by stirring for1h.All the coating solutions were left overnight at4°C in order to eliminate air bubbles.The composition of the coatings used in this work was selected among a large number of other coatings examined in preliminary trials.Coating was carried out at room temperature by dipping the asparagus spears for30s in the formulated suspensions and then slow drying at ambient conditions,by turning them from time to time,for about2h.After the coating treatment the samples were placed in plastic trays and subjected to cold storage.2.3.Coating characterizationThe surface tension of each suspension was measured by the Ring Method using a Kruss tensiometer at20°C.Rheological char-acterization of the coating formulations was conducted by a rota-tional Physica MCR300rheometer(Physica Massterchnic GmbH, Stuttgart,Germany)using a double gap cylindrical geometry;tem-perature was regulated by a Paar Physica circulating bath and a controlled peltier system(TEZ150P/MCR)with an accuracy of ±1°C.The data of the rheological measurements were analyzed with the supporting software US200V2.21.Flow curves were per-formed by measuring steady shear viscosity(g)over a range of shear rates between0.1and1200sÀ1at25°C.The contact angles at the asparagus surface were measured following the Choi and Han procedure(Choi&Han,2002),using a digital microscope(Intel QX3,Mattel Inc.,El Segundo,CA).All the liquid drops used for the measurements were axecimetric.The estimation of the critical surface tension(c C)of the white asparagus surface was obtained by extrapolation from the Zisman plot(Zisman,1964),which was developed using water(HPLC grade),glycerol,ethylene glycol and dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO) (Sigma–Aldrich GmbH,Steiheim,Germany),as reference liquids. Their surface tensions are72.8,63.4,48.0and44.0mN/m2,respec-tively.To avoid changes on the asparagus surface,the measure-ments took place in less than30s.Ten replicates of contact angle measurements were obtained at20(±1)°C.2.4.Sample treatmentsTwo different experimental sets were adopted.Thefirst(set A) included application of four different coatings,CMC,WPI1,WPI2 and P on white asparagus spears and uncoated spears served as control(C).The samples were placed in a cold room at4°C and 95%RH for11days and the quality parameters were evaluated on days6and11after harvest.In the second experimental set (set B),four different treatments were employed:(a)uncoated samples(control–C),(b)CMC coated spears,(c)packaged aspara-gus in plastic trays wrapped with a16l m stretchfilm(Fabri Arti Grafiche S.R.L.-Vignola,Modena,Italy).The syntheticfilm had O2 and CO2transmission rates of583and1750ml mÀ2hÀ1atmÀ1, respectively,and a moisture vapor transmission rate of 14.6g mÀ2hÀ1atmÀ1at39°C and90%RH(film permeabilities were measured by the manufacturer)(Pack).The fourth treatment (d)involved a combination of CMC coating and the above packag-ing(Pack+CMC),in order to investigate if there is any additional56M.V.Tzoumaki et al./Food Chemistry117(2009)55–63effect when combining edible coating and synthetic film packag-ing.All trays were placed in cold storage at 4°C and 95%RH for 17days.The determination of asparagus quality was held at the day of harvest (day 0)and at days 11and 17.Each sample,contain-ing five lots (6–7spears/lot),was included for each experimental set,storage condition and sampling time.2.5.Weight lossWeight loss was measured periodically by weighting five trays containing 6–7spears,for each treatment.The results were ex-pressed as the percentage loss of initial weight.2.6.Texture determinationThe asparagus spears,18cm in length,were marked at 6-cm intervals from the tip and then sectioned at the ink markings into three cylindrical portions;apical,middle and basal,since it is known that there is evidence for significant differences in texture over the different parts of white asparagus (Rodríguez et al.,2004).The texture was measured at the middle of each of the three sections of each spear by applying the cutting test using a Texture Analyzer (NF -{N 2i,Stable Microsystems).Values were expressed as maximum force (kg),using a Warner–Blatzler cell with a blade (0.3cm width)that cut the spears at a speed of 5mm/s (average of 20replicates).2.7.Visual evaluation of appearanceThe general appearance of the products was assessed by at least 10trained panelists.Samples were evaluated using the following hedonic scale:1=bad,2=fairly good,3=good,4=very good and 5=excellent.A value of three was considered as the commercial acceptability threshold.2.8.Colour measurementsColour readings of the spears were performed with a chroma-tometer (Minolta CR-400/410,Minolta,Osaka,Japan),equipped with an 8-mm measuring head.The meter was calibrated using the manufacturer’s standard white plate.Colour changes were quantified in the L *,a *,b *colour space.Chroma value ðChroma ¼ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffia Ã2þb Ã2q Þwas also calculated in order to compare changes among treatments.On each spear two readings in two different areas were taken;the first at 2cm from the tip,in order to study if there is a violet colour development,and the second at 10cm,so as to explore if there is any ‘greying’appearance on the spear surface.The colour was also assessed visually by a 10-member trained panel using the following hedonic scale:5=total white,4=violet colour development at 2cm from the tip,3=violet colour at 3cm,2=violet colour at 4cm,1=violet colour at 5cm and 0=vio-let colour development over longer distance.2.9.Lignin determinationThe lignin content of the different parts of the asparagus spears (apical,middle,and basal)was determined with the thioacidoglyc-olysis method,as described by Bruce and West (1989).About 150g of tissue was homogenised with 95%ethanol for 5min.The mix-ture was vacuum filtered,the residue was washed with 100ml of ethanol and then dried at 50°C for 24h.About 0.25g of the above dry residue was mixed with 7.5ml of 2N HCl and 0.5ml of thiogly-colic acid which was then boiled with occasional shaking for 4h and centrifuged at 7500g for 15min.The residue (lignin thioglyco-late)was washed with 10ml of water,suspended again in 10ml of 0.5N NaOH with occasional shaking for 18h at room temperature and centrifuged;2ml of concentrated HCl was added to the super-natant liquid.The lignin thioglycolic acid complex was precipitated at 4°C for 4h,centrifuged (7500g ,15min)and the residue was dis-solved in 10ml of 0.5N NaOH.After the appropriate dilutions,the absorbance was read at 280nm,using a Metertech UV/vis SP8001(Taipei,Taiwan)spectrophotometer.Quantification was carried out using a standard lignin curve.The lignin standard was pur-chased from Sigma–Aldrich GmbH (Steinheim,Germany).2.10.Anthocyanin determinationThe anthocyanin content was determined on the peel of aspar-agus,which was obtained by a sharp razor from 1cm from the tip until 6cm from the tip;this region is where most of the colour development occurs.The method of Fuleki and Francis (1968)was employed for the determination of anthocyanins with a few changes which were proposed by Flores,Oosterhaven,Martínez-Madrid,and Romojaro (2005).The plant tissue was chopped in a mortar,and 2g were extracted with 5ml of extractant solution;the latter was 100%ethanol/0.5N HCl (85:15v/v),and was kept in agitation with the tissue for 1min.The resulting homogenate was incubated for 4h in darkness.Every step was carried out in an ice bath in order to keep the temperature at 4°C.The homoge-nate was then centrifuged at 7500g for 15min and the supernatant was used to perform the spectrophotometric measurement at 533nm,using the extraction medium as blank.The extinction coefficient of anthocyanins,984(g/100ml)À1cm À1,was used for calculation of the anthocyanin content in the peel of white aspar-agus (Fuleki &Francis,1968).The results were expressed as mg anthocyanins per g FW of peel.2.11.Statistical analysisAll results are means ±s.e.,and the data were statistically eval-uated by ANOVA with mean differentiation by the Duncan’s multi-ple range test (a =0.05).The statistical software used was the SPSS,version 15.0.3.Results and discussion 3.1.Coating characterizationFor coating solutions,Cisneros-Zevallos and Krochta (2003)have found that the average liquid film thickness on coated apples is a function of viscosity,draining time,density of the biopolymer solutions,surface tension of the fruit,surface tension of the liquid,and the surface roughness.Since the film thickness can greatly af-fect the gas and water barrier properties of the coatings,it was con-sidered important to study the asparagus surface properties and the surface tension and rheological properties of the coating solutions.The critical surface tension of the white asparagus peel,derived from the Zisman plot,was 26.7mN/m.This indicates that the asparagus peel is a solid surface with low surface energy.Several authors have reported the values of critical surface tension ob-tained from a Zisman plot for various fruits and vegetables like gar-lic peel with a value of 18.3mN/m (Hershko &Nussinovitch,1998),strawberry with a value of 18.8mN/m (Ribeiro et al.,2007),and to-mato and carrot with values of 17.4and 24.1mN/m,respectively (Casariego et al.,2008).The peel or surface of many fruits and veg-etables has low surface tension for protection purposes;however,this natural advantage is a shortcoming for application of aqueous coatings on plant tissues (Viña et al.,2007).M.V.Tzoumaki et al./Food Chemistry 117(2009)55–6357The surface tension of a coating suspension is an essential factor for determining coating success.Table1shows the surface tensions of the four different coatings applied on white asparagus spears.The coatings CMC and P had a surface tension of37.0and 38.3mN/m,respectively.These values were significantly lower than those of coatings based on whey protein isolate;the WPI1 and WPI2had values of50.0and49.0mN/m,respectively,typical for protein solutions.Thefirst two coatings,CMC and P,had a low surface tension due to the sucrose fatty acid ester which was in-cluded in their formulation as a surface active ingredient.Another reason for the low surface tension of the CMC coating may be the fact that the diluent was a water–ethanol mixture4:1.These re-sults show that the CMC and P coatings were more prone to spreading on white asparagus peel since their surface tension val-ues were closer to the critical surface tension of the asparagus peel obtained from the Zisman’s plot,compared to the respective values of WPI1and WPI2.Theflow properties of afilm forming liquid greatly affect its coating quality in the solid state.Moreover,the smoothness of the surface to be coated has a strong influence on the coating appearance.Levelling of the coating surface takes place after appli-cation of the liquid and during drying,due to solvent evaporation and is a crucial part of the coating process.The levelling of irregu-larities in liquid coating depends on the rheological properties and surface tension of the liquid,the effects of gravity and the charac-teristics of the surface to coat.A positive characteristic of coatings in the liquid state is the presence of a yield stress or a viscosity(g0) high enough to prevent gravity effects(sagging and dripping),but sufficiently small to allow capillarity-driven levelling(Peressini,Bravin,Lapasin,Rizzotti,&Sensidoni,2003).In Table1,the apparent viscosities at100sÀ1of the four differ-ent coatings applied on white asparagus are given.The CMC coat-ing exhibited a pseudoplastic behavior(flow curves not shown)as the viscosity decreased with the increase of shear rate and it showed the highest apparent viscosity at100sÀ1(52.9mPa s), compared to the rest of the coating solutions.The pullulan-based (P)coating showed Newtonian behavior with an apparent viscosity of19.6mPa s.The whey protein isolate coating solutions,WPI1 and WPI2,also showed Newtonian-like behavior and their appar-ent viscosities were lower than the others,with values of2.8and 3.5mPa s,respectively.The addition of stearic acid in the whey protein solution did not seem to alter the apparent viscosity to a great extent.In a previous study,starch-based coatings exhibited a pseudoplastic behavior and the most viscous formulation(med-ium amylose content starch-based with20g lÀ1of glycerol) showed an apparent viscosity of22.6mPa s at512sÀ1(Garcìa, Martino,&Zaritzky,1998).3.2.Weight lossThis quality parameter is quite crucial,since every loss in weight is translated into an economic loss.Additionally,the weight loss has a strong impact on the spear appearance,due to shrinkage, and an8%weight loss makes asparagus spears unsaleable(Siomos, 2003).Fig.1shows the weight loss of the asparagus spears for both experimental sets A and B.The weight loss increased progressively upon storage,and is mainly attributed to the water loss by transpi-ration due to differences in the water vapour pressure of water be-tween the atmosphere and the asparagus surface(Park,Chinnan,& Shewfelt,1994).After11days of storage(set A),the weight losses of the control and the coated samples were7.3%and$5.0%,respec-tively.The edible coatings applied on white asparagus spears sig-nificantly reduced the weight loss,probably due to the hydrophobic ingredients they contained,such as the sucrose fatty acid ester,and stearic acid,which may had decreased the water va-pour permeability of the surface.However,the WPI1coating, without including any of these substances,also acted as a water vapour barrier,presumably due to denaturation of its protein com-ponents.Among all the coatings employed,there were no major differences,in spite of the variation in the solids content,biopoly-mer type and other substances used.Several studies had dealt with the effect of various coatings based on polysaccharides in controlling the weight loss of several fruits and vegetables.Many of them referred to the application of commercial formulations that contained carboxymethyl cellulose and sucrose fatty acid esters,e.g.,Semperfresh TM and TAL Pro-long, exerting a better weight loss control of many products such as cherries(Yaman&Bayoindirli,2002).Pullulan coatings applied on strawberries and kiwifruit also exhibited a positive impact by extending their shelf life(Diab et al.,2001).Furthermore,the prop-erties of protein basedfilms have been extensively studied in applications of fruits and vegetables.More specifically,whey pro-tein ediblefilms attracted much of attention as it was found thatTable1Characterization of the coating formulations.Coating formulation Surface tension(mN/m)Apparent viscosityat100sÀ1,g ap(mPa s)CMC37.1±1.052.9 WPI150.0±1.0 2.8 WPI249.2±1.0 3.5 P38.3±0.619.658M.V.Tzoumaki et al./Food Chemistry117(2009)55–63they can afford moderate potential as moisture barriers for food systems.The reduction in water vapour permeability of WPI based films could be further enhanced through the addition of lipids (McHugh&Krochta,1994).Placing the asparagus spears in plastic packaging significantly reduced their weight loss,as shown in Fig.1for set B,whereas the combination of coating with packaging offered no additional protection to weight loss,compared to the packaging alone.The prevention of weight loss due to the mainte-nance of a high relative humidity environment is a major advan-tage of vegetable packaging;the beneficial effect of this approach in asparagus spears,as evidenced by the presentfindings is in agreement with thefindings of Siomos et al.(2000).In another work,the effects of starch-based coatings and combination treat-ments of plasticfilm packaging with the coatings on weight loss of Brussels sprouts were studied(Viña et al.,2007);the coatings did not seem to reduce the weight loss during storage,whereas the plastic packaging substantially reduced the weight loss below the maximum admissible level in coated or uncoated sprouts.3.3.Visual evaluation of appearanceAfter six days of refrigerated storage(set A)the appearance of the coated samples was rated as‘‘excellent”or‘‘very good”,in con-trast to the uncoated control C which fell into the‘‘good”category. The uncoated asparagus spears exhibited a more dehydrated sur-face than the coated spears.The differences among the four differ-ent coating treatments were significant,with the WPI1and P giving the highest rating values in the appearance,probably be-cause of the glossiness that these coating formulations imparted to the surface of the plant tissue.Samples coated with WPI2had the lowest score,possibly due to the incorporation of stearic acid which can lead to an undesirable opaque appearance after drying. After11days of storage the uncoated samples showed a strongly dehydrated surface,especially at the basal part of the spears,thus leading to quality ratings well below the acceptability threshold. Instead,all the asparagus spears treated with the CMC,WPI1, WPI2and P coatings maintained their quality above the accep-tance threshold level(see Fig.2).With respect to experimental set B,after11days of refrigerated storage,the uncoated product exhibited significantly lower quality levels compared to the other treatments and far below the accep-tance level.In contrast,the treatments with CMC,Pack and the combination Pack+CMC did not differ significantly in their quality ratings.At day17,the asparagus spears that were not packaged showed significantly lower quality ratings,compared to the treat-ments of Pack and Pack+CMC which were ranked under the‘‘very good”category.No differences were observed among the last two treatments(Pack,Pack+CMC),probably because the packaging in a plastic container has a stronger impact on quality preservation than the edible coating alone.3.4.TextureThe texture of asparagus has been related tofibrousness and the process of hardening that occurs after harvesting;the latter is accompanied by the lignification of the pericyclic(schlerenchyma)fibres(Rodríguez et al.,2004).Additionally,changes in texture may also reflect losses of tissue water and increases in other phenolic compounds apart from lignin.Several methods have been devel-oped to determine textural changes along with thefibre content and the degree of lignification.Currently,textural measurements involve shearing through the asparagus spears by using the War-ner–Blatzler geometry(Rodríguez et al.,2004).Fig.3represents the texture of the three distinct asparagus parts for the different treatments of set B samples,measured as maxi-mum cutting force F max.Regarding the apical part of asparagus spears all the samples(C,CMC,Pack and Pack+CMC)exhibited sig-nificantly increasedfirmness values during storage,compared to the day of harvest(day0).On the other hand,thefirmness values in the middle part of samples Pack and Pack+CMC were main-tained to similar levels with the fresh asparagus(day0),while the uncoated(C)and the coated with CMC spears showed signifi-cantly increased values compared to the day of harvest(day0).Sim-ilarly,the basal parts of the packaged samples(Pack and Pack+CMC)retained their texture values during storage at levels similar to the fresh asparagus.The basal part of CMC coated aspar-agus seemed to maintain its texture to initialfirmness levels after 11days of storage,but after17days thefirmness value significantly increased.The CMC coating used is expected to modify the internal gas composition of white asparagus,especially by reducing oxygen and elevating carbon dioxide concentration,thus retarding the bio-chemical reactions that lead to hardening;the latter might explain the slower textural changes observed for the basal part of the coated spears.Additionally,the packaging helped maintain the tex-ture of asparagus spears.In a previous work it was found that the use of Modified Atmosphere Packaging in green asparagus exhib-ited a beneficial effect in retarding the hardening process,especially of the basal part of the stalks(Villanueva et al.,2005).Finally,the uncoated spears exhibited significantly higherfirmness value in the basal part during storage compared to the day of harvest.3.5.Lignin contentLignin is the cell wall component frequently associated with tissue hardening.The lignification in asparagus is controlled by Set BC CMC Pack Pack+CMCbaa acbaaSet A611Time (days)C CMC WPI1WPI2dbc aaaabbcaM.V.Tzoumaki et al./Food Chemistry117(2009)55–6359。

土木专业英语词汇统计

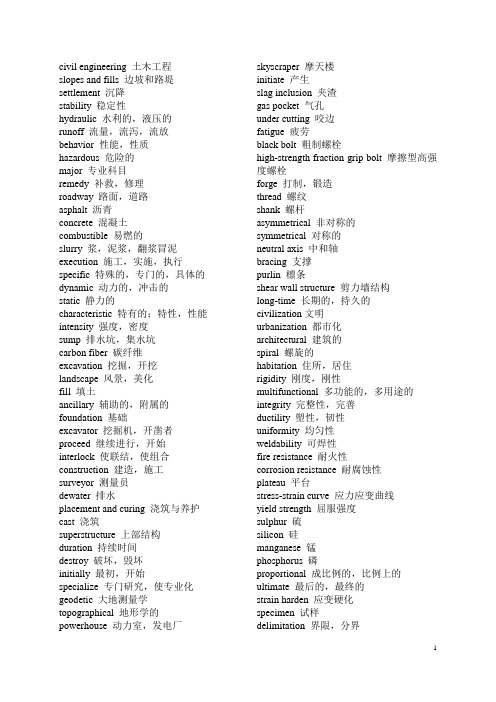

civil engineering 土木工程slopes and fills 边坡和路堤settlement 沉降stability 稳定性hydraulic 水利的,液压的runoff 流量,流泻,流放behavior 性能,性质hazardous 危险的major 专业科目remedy 补救,修理roadway 路面,道路asphalt 沥青concrete 混凝土combustible 易燃的slurry 浆,泥浆,翻浆冒泥execution 施工,实施,执行specific 特殊的,专门的,具体的dynamic 动力的,冲击的static 静力的characteristic 特有的;特性,性能intensity 强度,密度sump 排水坑,集水坑carbon fiber 碳纤维excavation 挖掘,开挖landscape 风景,美化fill 填土ancillary 辅助的,附属的foundation 基础excavator 挖掘机,开凿者proceed 继续进行,开始interlock 使联结,使组合construction 建造,施工surveyor 测量员dewater 排水placement and curing 浇筑与养护cast 浇筑superstructure 上部结构duration 持续时间destroy 破坏,毁坏initially 最初,开始specialize 专门研究,使专业化geodetic 大地测量学topographical 地形学的powerhouse 动力室,发电厂skyscraper 摩天楼initiate 产生slag inclusion 夹渣gas pocket 气孔under cutting 咬边fatigue 疲劳black bolt 粗制螺栓high-strength fraction grip bolt 摩擦型高强度螺栓forge 打制,锻造thread 螺纹shank 螺杆asymmetrical 非对称的symmetrical 对称的neutral axis 中和轴bracing 支撑purlin 檩条shear wall structure 剪力墙结构long-time 长期的,持久的civilization文明urbanization 都市化architectural 建筑的spiral 螺旋的habitation 住所,居住rigidity 刚度,刚性multifunctional 多功能的,多用途的integrity 完整性,完善ductility 塑性,韧性uniformity 均匀性weldability 可焊性fire resistance 耐火性corrosion resistance 耐腐蚀性plateau 平台stress-strain curve 应力应变曲线yield strength 屈服强度sulphur 硫silicon 硅manganese 锰phosphorus 磷proportional 成比例的,比例上的ultimate 最后的,最终的strain harden 应变硬化specimen 试样delimitation 界限,分界periodically 定期地,周期地Poisson ratio 泊松比modulus 模量coefficient 系数distortion 扭曲,变形cement 水泥bituminous 沥青eco-materials 生态材料calcareous 石灰质的,钙质的argillaceous 黏土质的,黏土的calcined 焙烧的,煅烧的clinker 水泥熟料,熟料gypsum 石膏pulverize 粉碎set 凝固,安置,调节,硬化Portland cement 波特兰水泥,硅酸盐水泥rapid hardening cement 快硬性水泥formwork 模板工程,模板Portland pozzolana cement 火山灰质硅酸盐水泥air-entraining cement 引气水泥fineness 细度,纯度prestressed concrete 预应力混凝土mould 塑造,模具,模型shell structure 壳体结构paneling 嵌板,格子,镶板falsework 脚手架,临时支撑glued-laminated 胶合叠层metallic luster 金属光泽load bearing capacity 承载能力modulus of elasticity 弹性模量yield stress 屈服应力elongation 伸长率,伸长度waterproof 防水,抗水,防水的,耐水的,不透水的emulsion 乳液,乳化剂,乳胶capillary 毛细,毛细管polymer 聚合物,高分子,高分子聚合物crack 开裂,裂纹,裂缝pour 浇注,倾倒pump 抽吸,泵送spray 喷涂reinforcing steel=reinforcing bar 钢筋longitudinal 长度的,纵向的,轴向的shear force 剪力multistory building 多层建筑rate of contraction 收缩率rate of expansion 膨胀率embed 放入,埋入,埋置,嵌入reinforced concrete 钢筋混凝土adhesion 附着力,黏合力bond 结合力,黏合力,黏结,握裹hot-rolled reinforcing bar 热轧钢筋rib-shaped surface 肋形表面alkaline 碱性的,碱性corrosion 腐蚀,侵蚀,锈spalling 剥落,层裂galvanized 镀锌的epoxy-coated 环氧涂层的rigid 刚性的frame 框架anchorage 锚固,锚具curtain wall 幕墙bearing wall 承重墙durability 耐久性deterioration 恶化,损坏,退化chloride 氯化物,漂白剂sulphate 硫酸盐alkali 碱absorption 吸收性,吸收permeability 渗透性,渗透率homogeneous 同类的,均质的,均相的disruptive 破坏性的thaw 解冻,融化reservoir 水库,蓄水池compatible 相容的,能共处的workability 和易性,可用性deicing 去冰,除冰leaching 浸析,浸出carbonation 碳化cement paste 水泥浆cavitation 气蚀,气穴,凹穴abrasive 磨蚀的,磨平的attrition 磨损,磨耗erosion 腐蚀,侵蚀fly ash 粉煤灰silica fume 硅粉mineral admixture 矿物掺合料calcium hydroxide 氢氧化钙porosity 孔隙率,多孔性segregation 离析,分离deformable 可变形的axially 轴向地torsion 扭转,扭力shell 壳体distortion 扭转,扭曲,翘曲,变形formula 公式,方程式,方案strain 应变deflection 挠度,挠曲,偏离,偏差角failure 失效,失败,破裂,故障criterion 准则,判据,标准criteria (复数)准则,判据,标准factor of safety 安全系数fracture 破裂,破碎,折断,断裂collapse 坍塌,破坏,倒塌,陷落,倒闭static 静的,静力的,静电的code 规范,标准linear elastic range 线弹性范围allowable stress 允许应力mild steel 低碳钢ultimate stress 极限应力margin 边缘部分,栏外,页面的空白intensity强度,密度carbon fiber 碳纤维novel 新的,异常的bracing 支撑immense 无限的,广大的placement and curing 浇筑和养护shrinkage收缩,缩减dimension 大小,尺寸,维数,量纲equilibrium condition 平衡条件boom 悬臂,吊杆dragline 拉牵,导索,拉铲挖土机impair 损害,损伤,断裂diagram 图表,图解,立体图cross-sectional横截面的linear 线性的,线的negligible 可不计的,可忽视的gray cast iron 灰口铸铁curvature 弧度,曲率,弯曲Y oung’s modulus 杨氏模量proportional 成比例的plastic deformation 塑性变形slip 滑动,滑移creep 徐变,蠕变ductile 延性的,可延展的,可塑的,柔软的neck down 颈缩concentric 同心(轴)的(with),集中的eccentric 离心的,偏心的midspan 跨中pre-tensioned method 先张法post-tensioned method 后张法grout 灰浆mortar 砂浆,灰浆,水泥浆,用灰浆涂抹net tensile stress 纯拉应力pretension 张拉indeterminancy 不确定性eccentricity 偏心,偏心距,离心率flexural member 受弯构件segmental 分节的,分段的versatility 多方面适用性,多用性,多功能性principle 原理capacity 承载力yield stress 屈服应力ultimate strength 极限强度plastic design 塑性设计margin 安全系数,边界fraction 零头,小部分,系数nominal 标定的,名义上的Allowable Stress Design 容许应力设计法Load and Resistance Factor Design 荷载与抗力系数设计法client 顾客,委托人,业主joint 接合,连接处systematically 系统地inertia 惯性,惯量sincere 实在的,真诚的preliminary 初步的,预备的specification 说明书,规范code 章程,法规elasticity 弹性plastic hinge 塑性铰connection 连接,联系coefficient of thermal expansion热膨胀系数shell structure 壳结构structural engineering 结构工程geotechnical engineering 岩土工程transportation engineering 交通运输工程fluid mechanics 流体力学position 定位expand 膨胀contract 收缩installation 安装criteria 准则,尺度,标准tension 拉力,张力compression 压力,压缩bending moment 弯矩shear 剪力torsion扭转; 扭力; 扭曲excessive 过量的,大量的sway 摇摆,摇动lateral 横向的longitudinal 纵向的vertical 竖向的horizontal 水平的external force 外力internal force 内力blast 爆破proceed继续进行, 开始, 着手process 过程procedure 程序,规程,手续probability 概率instruction 指示,指令expansion膨胀, 扩展, 扩充defect 缺陷brittle fracture 脆性破坏ductile fracture 延性破坏distortion 变形,扭曲,曲解stiffness 刚性attribute 性能,属性,特性slender细长的, 苗条的, 微薄的, 少量的uncertainty 不确定性simplify 简化assumption 假定,设想timber木材, 木料aggregate 骨料,集料temporary structure 临时结构permanent structure永久结构fatigue 疲劳impact 冲击wear磨损, 穿戴abrasion擦伤, 磨损, 磨损处crack 破裂,裂开impermeability不渗透性permeability渗透; 可透性; 渗透性; 导磁性compact 压紧,紧密的restraint 约束expansion 膨胀contraction 收缩absorption 吸收性assembly集合, 装配, 集会, 集结manipulate操纵, 操作, 利用fatigue failure 疲劳破坏allowable stress 允许应力undergo 承受,经历particle 粒子,散体,颗粒deflection 挠曲,挠度rupture破裂, 裂开, 断裂resultant load 合力eliminate除去, 剔除, 排除,消除utilize 利用,发展impose 施加,强加,利用anchor 锚固anchorage 锚固,锚具component 构件,杆件validity合法性, 有效性, 正确性rib-shaped surface肋形表面interlock相互咬合alkaline碱性的corrosion腐蚀erosion 腐蚀etching腐蚀,蚀刻load bearing capacity承载能力earthquake 地震factor 因素,系数panic 恐慌,惊慌vibratory 振动的,震荡的tsunami 海啸,地震海浪sizable 相当大的,广大的slippage 滑移,滑动propagation 传递,传导,传播partitioning wall 隔墙cladding wall 填充墙rectangular coordinate 直角坐标beam 梁column 柱deflect 挠曲,下垂statically indeterminate structure 超静定结构static determinacy 静定appreciation 评价,鉴赏the law of equilibrium 平衡原理suspension bridge 悬索桥geometry 几何形状,几何学buckling 弯曲,屈曲,翘曲bracing 撑杆,支撑drastically 彻底地,激烈地resultant 合成的,总的mixer 搅拌机,搅拌器cobble 鹅卵石,中砾,圆石coarse aggregate 粗集料,粗骨料homogeneous 同种的,同类的,均一的,均匀的unduly 不适当地,过度地agitator 搅拌器,搅拌机chute 斜槽,滑槽insert 插入,插入物systematically 系统地,有组织地,有条理地segregation 隔离,分离,离析stratification 层化,成层,分层preliminary 初步的,预备的,在前的optimum 最优的,最适宜的glisten 闪亮,闪耀,闪光cement paste 水泥浆bleeding 泛油,泛浆laitance 水泥翻沫,浮浆皮,浮浆joint 接合,粘接处,铰接,接缝,接头construction joint 施工缝curing compound 养护剂membrane 膜,隔膜,表层discoloration 变(脱,褪)色,漂白,污点shutdown period 停工期hoist 绞车hoisting 起重,提升excavating 挖掘,挖取hauling 搬运,运输grading 等级,分阶段,坡度缓和paving 铺面,铺砌drilling 演练,钻孔configuration 结构,布局,形态sound attenuation 消音,消声,声衰减tractor 拖拉机heavy-duty tractor 重型拖拉机endless 无止境的,没完没了的track 小路,跑道,轨道,惯例,常规bulldozer 推土机debris 碎片,残骸boulder 大圆石scraper 铲运机grader 平地机finishing equipment 精整设备backhoe 反向铲scoop 铲子,舀取front-end 前端dragline 拉索shovel 铲bucket 水桶derrick 动臂起重机cableway 空中索道conveyor 输送机monorail 单轨铁路sheaves 滑轮pulley 滑车winch 卷扬机blocks 吊链,滑轮组grooved 开槽的eye 吊环trolley 缆车jib crane 回转起重机,臂架起重机overhead-traveling crane 桥式起重机gantry crane 龙门起重机scaffolding脚手架framework 结构,构架,框架gin wheel 起重滑轮sheeting 薄片(薄膜,挡板,护墙板)guard rail 护栏seasoned 经验丰富的norm 标准,规范jack 插座,千斤顶,抬起stage 台架,脚手架anchorage 下锚,停泊所,停泊税transom 横档,横楣,横梁tubular 管状的unit 7。

Agricultural Water Management

Application of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)to predict the impact of alternative management practices on water quality and quantityAntje Ullrich *,Martin VolkHelmholtz Centre for Environmental Research –UFZ,Department of Computational Landscape Ecology,Permoserstr.15,D-04318Leipzig,Germany1.IntroductionDue to insufficient water quality of European streams environmental programs such as the European Water Framework Directive (WFD)were implemented to achieve good ecological and chemical conditions of water quality of groundwater and surface water bodies (EC,2000;Rekolainen et al.,2003).Main nutrient input comes from nonpoint source pollution,mainly forced by intensive agricultural activities (Behrendt et al.,1999).Therefore,alternative land management practices are increasingly used to reduce nonpoint source pollution.Reduction of soil tillage intensity positively affects numerous soil properties,such as aggregate stability,macroporosity,and saturated hydraulic con-ductivity and consequently increases infiltration rates and reduces surface runoff,nutrient loss,and soil erosion (Jones et al.,1969;Pitka¨nen and Nuutinen,1998;Schmidt et al.,2001;Kirsch et al.,2002;Pandey et al.,2005;Tripathi et al.,2005).Alternative land management practices may include reduced tillage such asconservation tillage (e.g.without deep ploughing,field preparation just before planting)or no-tillage (direct drilling)(Sullivan,2003;LfULG,2006).In Germany the implementation of alternative tillage systems is increasingly supported by agro-environmental pro-grams.In the German State of Saxony,for instance,conservation tillage and mulch seeding on arable land has increased from <1%to about 27%during 1994–2004with support from the Saxonian Program for Environmental Agriculture (LfL,2006).A number of field studies have illustrated the positive effects of conservation tillage and no-tillage practices on water and material fluxes at the field local level (e.g.Sloot et al.,1994;King et al.,1996;Schmidt et al.,2001),but this effect needs to be assessed on the watershed level to guide river basin management programs as WFD claimed (Kirsch et al.,2002;Chaplot et al.,2004;Pandey et al.,2005;Behera and Panda,2006;Bracmort et al.,2006).Therefore,watershed models are useful tools and have been used for decades to evaluate nonpoint source pollution and the short-and long-term impacts of alternative management practices.In order to fulfill the objectives of the WFD,we have chosen the semi-distributed river basin model,Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)2005(Neitsch et al.,2002;Arnold and Fohrer,2005)to examine the impact of alternative management practices on waterAgricultural Water Management 96(2009)1207–1217A R T I C L E I N F O Article history:Received 3September 2008Accepted 6March 2009Keywords:SWATTillage management practice Conservation tillage Water balance Nutrient ModellingA B S T R A C TAlternative land management practices such as conservation or no-tillage,contour farming,terraces,and buffer strips are increasingly used to reduce nonpoint source and water pollution resulting from agricultural activities.Models are useful tools to investigate effects of such management practice alternatives on the watershed level.However,there is a lack of knowledge about the sensitivity of such models to parameters used to represent these conservation practices.Knowledge about the sensitivity to these parameters would help models better simulate the effects of land management.Hence,this paper presents in the first step a sensitivity analysis for conservation management parameters (specifically tillage depth,mechanical soil mixing efficiency,biological soil mixing efficiency,curve number,Manning’s roughness coefficient for overland flow,USLE support practice factor,and filter strip width)in the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT).With this analysis we aimed to improve model parameterisation and calibration efficiency.In contrast to less sensitive parameters such as tillage depth and mixing efficiency we parameterised sensitive parameters such as curve number values in detail.In the second step the analysis consisted of varying management practices (conventional tillage,conservation tillage,and no-tillage)for different crops (spring barley,winter barley,and sugar beet)and varying operation dates.Results showed that the model is very sensitive to applied crop rotations and in some cases even to small variations of management practices.But the different settings do not have the same sensitivity.Duration of vegetation period and soil cover over time was most sensitive followed by soil cover characteristics of applied crops.ß2009Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.*Corresponding author.Tel.:+493454722602;fax:+493412351939.E-mail address:antje.ullrich@ (A.Ullrich).Contents lists available at ScienceDirectAgricultural Water Managementj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /a g w a t0378-3774/$–see front matter ß2009Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2009.03.010quantity and quality.Gassman et al.(2007)point out that‘‘a key strength of SWAT is aflexible framework that allows the simulation of a wide variety of conservation practices and other BMP,such as fertiliser and manure application rate and timing, cover crops(perennial grasses),filter strips,conservation tillage, irrigation management,flood prevention structures,grassed waterways,and wetlands.The majority of conservation practices can be simulated in SWAT with straightforward parameter changes’’.Many studies have used SWAT(Saleh et al.,2000; Shanti et al.,2001;Vache et al.,2002;Shanti et al.,2003;Chaplot et al.,2004;Pandey et al.,2005;Tripathi et al.,2005;Arabi et al., 2006;Behera and Panda,2006;Rode et al.,2008;Volk et al.,2009) and EPIC(Sloot et al.,1994;King et al.,1996)to evaluate the effects of land use scenarios and management practices.Several studies have analysed the long-term effects of structural Best Management Practices(BMP)on water quality(e.g.Kirsch et al.,2002;Chaplot et al.,2004;Tripathi et al.,2005;Pandey et al.,2005or Behera and Panda,2006;Bracmort et al.,2006).Arabi et al.(2007)investigated the impact of modelling uncertainty on evaluation of management practices using a Monte Carlo-based probabilistic approach.The SWAT model was developed for application to large complex watersheds over long periods of time(Neitsch et al., 2002).Working on the watershed-scale means that required input data are often aggregated in terms of temporal scale(e.g.daily climate data).In contrast,land management parameters(tillage, fertilisation,crop rotation,etc.)can be included in high resolution and detail,due to its modular structure and its historical development based on the EPIC(Erosion Productivity Impact Calculator)model(Benson et al.,1988;Neitsch et al.,2002;Arnold and Fohrer,2005;Gassman et al.,2007).Furthermore,modelling evaluations of conservation management effects at the watershed-scale are limited by the lack of management operation data.Thus, knowledge is needed of the sensitivity of such models to conservation management parameters and practice to improve the efficiency of model parameterisation and the quality of model calibration.Furthermore,potential simulation uncertainties based on ranges of realistic parameter values and on influences of scale need to be understood because simulated effects often drive financial and political decisions(Onatski and Williams,2003).As a result,the main objective of this study is to analyse the sensitivity of the SWAT model to selected conservation manage-ment parameters and practices to improve model parameterisa-tion and calibration.To the best of our knowledge,a sensitivity analysis of the model to conservation management parameters and practices has not yet been conducted.But in our opinion this is essential for a more efficient use of models for the implementation of land management practices as tools to improve water quantity and quality.We used a so-called semi-virtual watershed for which we combined topography and climate information of an existing watershed(Parthe watershed,Saxony,Germany)but with homo-geneous land use and soil information.Homogeneous land use and soil information were utilised because the resulting data sets are concise and manageable and calculation time is reduced. Recommendations are given for the parameterisation of tillage operations under certain conditions.2.Materials and methods2.1.Model descriptionThe SWAT model is considered as one of the most suitable models for predicting long-term impacts of land management measures on water,sediment,and agricultural chemical yield (nutrient loss)in large complex watersheds with varying soils,land use,and management conditions(Arnold and Fohrer,2005;Behera and Panda,2006;Gassman et al.,2007).The model has been gained international acceptance as a robust interdisciplinary watershed modelling tool(Gassman et al.,2007).SWAT is a physically based, conceptual,continuous-time river basin model with spatial distributed parameters operating on a daily time step.It is not designed to simulate detailed,single-eventflood routing(Neitsch et al.,2002).The relationship between input and output variables is described by regression equations.The SWAT model integrates all relevant eco-hydrological processes including waterflow, nutrient transport and turn-over,vegetation growth,and land use and water management at the subbasin scale.Consequently, the watershed is subdivided into subbasins based on the number of tributaries.Size and number of subbasins is variable,depending on stream network and size of the entire watershed.Subbasins are further disaggregated into classes of Hydrological Response Units (HRU),whereby each unique combination of the underlying geographical maps(soils,land use,etc.)forms one class.HRU are the spatial unit where the verticalflows of water and nutrients are calculated,which are then aggregated and summed for each subbasin.Water and material from HRU in sub-watersheds are routed to the sub-watershed outlet.The HRU in SWAT are spatially implicit,their exact position in the landscape is unknown,and it might be that the same HRU covers different locations in a subbasin(Neitsch et al.,2002;Di Luzio et al.,2005).The water balance for each HRU is represented by the four storages snow,soil profile,shallow aquifer and deep aquifer.The soil profile can be subdivided in up to ten soil layers.Soil water processes include evaporation,surface runoff,infiltration,plant uptake,lateralflow and percolation to lower layers(Arnold and Allen,1996;Neitsch et al.,2002).The surface runoff from daily rainfall is estimated with a modification of the SCS curve number method from United States Department of Agriculture-Soil Conservation Service(USDA SCS) (Arnold and Allen,1996;Neitsch et al.,2002).Nitrogen movement and transformation are simulated as a function of the nitrogen cycle(Neitsch et al.,2002;Jha et al.,2004). The SWAT model monitorsfive different pools of nitrogen in the soils:two inorganic(ammonium(NH4+)and nitrate(NO3À))and three organic(fresh organic nitrogen(associated with crop residue and microbial biomass)and active and stable organic nitrogen (associated with the soil humus)).Nitrogen is added to the soil by fertiliser,manure or residue application,fixation by bacteria,and rain(Neitsch et al.,2002).Nitrogen losses occur by plant uptake, surface runoff in the solution and the eroded sediment(Neitsch et al.,2002;Jha et al.,2004).Background for the crop growth and the management practices is the EPIC crop growth model,which is a comprehensivefield scale model.EPIC was originally developed to simulate the impact of erosion on crop productivity and has now evolved into a comprehensive agricultural management,field scale,nonpoint source loading model(Benson et al.,1988;King et al.,1996; Neitsch et al.,2002).The management practices are defined by specific management operations(e.g.the beginning and end of growing season,timing of tillage operations as well as timing and amount of fertiliser,pesticide,and irrigation application).These management operations take place in every HRU.The operations in turn are defined by specific management parameters(e.g. tillage depth,biological soil mixing efficiency,etc.)(Neitsch et al., 2002).2.2.Input dataWe used a semi-virtual watershed.Therefore we combined topography and climate information of an existing watershed with virtual land use and soil information.The Parthe watershed was chosen as study area.It is located in the State of Saxony in Central Germany and drains an area of about315km2(Fig.1).It is aA.Ullrich,M.Volk/Agricultural Water Management96(2009)1207–1217 1208subbasin of the Weiße Elster catchment in the Elbe River system. The topography of the area isflat with altitudes between106and 230m above sea level.The mean annual precipitation is about 570mm.The model input data are shown in Table1.For the sensitivity analysis,we assumed‘‘arable land’’to be homogeneous land use without any further differentiation.A typical soil profile was used from a soil map(1:25,000)of the Parthe watershed.The use of homogeneous land use and soil(semi-virtual catchment)is advantageous because the resulting data sets are concise and manageable and calculation time is reduced.Daily precipitation data and other climate data are from one weather station in the watershed.This station is part of the environmental monitoring network of the Environmental Operation Agency of the Saxon State Agency for the Environment,Agriculture and Geology.2.3.Sensitivity analysisModel sensitivity analysis regarding selected management practices was donefirstly by varying the most important tillage and management parameters:tillage depth,mechanical mixing efficiency,biological mixing efficiency,curve number,and Man-ning’s roughness coefficient for overlandflow,USLE support practice factor,andfilter strip width.Secondly,management practices were parameterised and varied for different crops and dates of operation. Subsequently,the influence of varying these practices on water balance components and nutrients was evaluated.2.4.Management parametersThe applied tillage operation(plough,stubble cultivation, harrow,etc.)is defined by the parameters tillage depth(DEPTIL) and mechanical soil mixing efficiency(EFFMIX).These parameters also define the fraction of crop residue,nutrients,pesticides,and bacteria for each soil horizon,which are redistributed within the mixed soil depth(Neitsch et al.,2002).The biological soil mixing efficiency(BIOMIX)defines the activity of soil organisms,such as earthworms as representatives of macrofauna,which influence soil porosity and waterfluxes by their grubbing activity(Kladivoka, 2001;Neitsch et al.,2002).The biological soil mixing efficiency can be defined for each HRU.The SCS curve number(CN)defines soil permeability based on soil characteristics and land cover(land use).This parameter routes the process of infiltration and generation of surface runoff.The parameter CN can generally be defined on the HRU level and more detailed based on tillage operations data(Neitsch et al.,2002).The Manning’s roughness coefficient for overlandflow(OV_N)is a parameter toestimateFig.1.Location of the study area in Germany.Table1Input data.Topography Land use Soil WeatherDEM Homogeneous Homogeneous Daily values-Area:315km2-Arable land-Cambisol-Precipitation[mm]-Grid cell size:30m-Mean wind speed(recorded in2.5m height)[m/s]-Max.and min.air temperature[8C]-total solar radiation(calculated using global radiation)[MJ/m2]-Mean relative humidity(recorded in0.5and2m height)[%]A.Ullrich,M.Volk/Agricultural Water Management96(2009)1207–12171209overlandflow velocity,which depends on characteristics of the land surface.This parameter can be defined for each HRU(Neitsch et al.,2002).The management parameter USLE support practice factor(USLE_P)defines the ratio of soil loss with a specific support practice(such as contour tillage,strip cropping,and terraces)to the corresponding loss with up-and-down the cultivation.The parameter USLE_P can also be defined on the HRU level(Neitsch et al.,2002).The width of edge offieldfilter strip(FILTERW)defines filter strips with a specific width in meters.Thefilter strips are not differentiated any further.Sediment and nutrient loads in surface runoff and subsurfaceflow are reduced as it passes through the strip.Filter strips can be defined for each HRU(Neitsch et al.,2002).For each simulation only one parameter was varied within a realistic range(see Table2).The value ranges defined for each model parameter are based on literature studies(Neitsch et al., 2002).SWAT also supplies the user with default parameters values. For the basic settings we used these default values,as we are not working with real conditions where these values would have to be adjusted to.The advantage of this method is that the effect on model output is related to the variability of only the selected parameter,but it does not consider the dependency on settings chosen for the other parameters(Arabi et al.,2007).For sensitivity analysis a basic management scenario was used. This is a generalised Agricultural Land Close Grown(AGRC) scenario,which uses values for winter wheat.One fertiliser application(70kg N/ha)just after seeding,and one tillage operation(deep ploughing)just after harvesting,was implemen-ted.This basic scenario was not changed during sensitivity analysis of management parameters.The model output parameters investigated are surface runoff,baseflow,total water yield,total sediment loading,organic nitrogen,organic phosphorus,nitrate in surface runoff,nitrate,and phosphorus leached.The results(see Fig.2)indicate SCS curve number as a very sensitive parameter for water balance components and nutrient and sediment load.This observation is confirmed by Neitsch et al. (2002)as well as by other studies,such as Sloot et al.(1994), Heuvelmans et al.(2004),Bracmort et al.(2006),and Arabi et al. (2007).The CN is most sensitive for values above65.For example surface runoff increased from almost zero up to more than100mm between CN65to95.At the same time,corresponding surface runoff organic nitrogen,organic phosphate,nitrate in surface runoff and total sediment loading increased.In contrast,based on the decrease of baseflow,nitrate and phosphate leached decreased.Biological soil mixing efficiency and Manning’s roughness coefficient for overlandflow do only moderately affect water balance components.The values vary less than5mm for applied parameter ranges.For the value range of biological soil mixing efficiency(0–1)the results for organic nitrogen(simulated range between0.225kg/ha and0.55kg/ha),organic phosphate(0.034–0.069kg/ha),and total sediment loading(0.057–0.318t/ha)increased while phosphate leached(0.318–0.145kg/ha)decreased. For the watershed area(315km2)this represents load values for organic nitrogen between7.1t and17.3t,organic phosphate between1.1t and2.2t,phosphate leached between10t and4.6t, and total sediment loading between1795t and10,017t.Based on these results we assume biological mixing efficiency to be a sensitive parameter regarding the above described nutrient components.Manning’s roughness coefficient for overlandflow affected organic nitrogen(simulated range between0.248kg/ha and 0.135kg/ha;7.8–4.3t for watershed area)followed by sediment loading(0.088–0.048t/ha; 2.8–1.5t for watershed area)and organic phosphorus(0.038–0.02kg/ha; 1.2–0.6t for watershed area).Therefore,we assume this parameter to be sensitive with respect to the described nutrients and sediment load.Both the USLE support practice factor and the width of edge of fieldfilter strip do not influence water balance components.But USLE support practice factor is very sensitive to total sediment loading(simulated range between0.007t/ha and0.067t/ha;220–2110t for watershed area),organic nitrogen(0.019–0.187kg/ha, 0.6–5.9t for watershed area),and organic phosphorus(0.003–0.027kg/ha;0.09–0.9t for watershed area)while the width of edge offieldfilter strip affected organic nitrogen and decreased from 0.187kg/ha to0.076kg/ha(see Fig.3).This means that with an extension of thefilter strip width from0.5m to5m the organic nitrogen loss related to the watershed area decreased about50% (from5.9t to2.4t).Furthermore,with increasing width of edge of fieldfilter strip organic phosphate(simulated values:0.027kg/ha and0.011kg/ha;0.85t and0.35t),nitrate load in surface runoff (0.047–0.019kg/ha;1.5–0.6t)and total sediment loading0.067–0.027t/ha;2110–850t)decreased.In this study the variation of tillage depth and mechanical soil mixing efficiency did not influence neither water cycle components nor nutrient and sediment cycle components.2.5.Management practicesWith respect to the management parameters’sensitivity,the tillage operations subject to management practices(conventional (CVT),conservation(CST)and no-tillage(NOT))were parameterised exemplary(see Table3).Here,conventional tillage primarily is distinguished dependent on tillage practices applied after harvest-ing including deep ploughing,previous stubble cultivation and following harrow operation before seeding/planting.For conserva-tion management a multiplicity of measures can be taken.For tillage practice we chose altogether three variations:(a)deep ploughing operation is replaced by a less intensive operation(CST_A),(b)deep ploughing operation is left out and not replaced(CST_B)and(c) harrow operation is applied only(CST_C).Parameters were set as follows.Differentiated by applied tillage operation,we parameterised curve number(CN)values in detail. The curve number adjustment is strongly linked to the soil dependent basic curve number identified within calibration process,planted crop(grain and root crop),applied tillage operation,and residue coverage(defined by applied management practice).The allocation of the SCS curve number is based on the parameterisations suggested by Neitsch et al.(2002)and continuative on the comments of Rawls and Richardson(1983). Rawls and Richardson(1983)recommend lowering the SCS curve number by2%for soils with poor hydrological conditions when applying conservation tillage(compared to conventional tillage). Forfields with good hydrological conditions,the SCS curve number should be lowered by4%compared to conventional tillage.King et al.(1996)applied EPIC using curve number values of87and82 for conventional tillage and for no-tillage practices respectively representing the soil hydrological group D(clay soil).Sloot et al. (1994)used the initial curve numbers:A value of84forTable2Basic parameter settings and variation ranges.Parameter Basic setting Parameter rangeSCS curve number(CN)7535–95 Biological soil mixingefficiency(BIOMIX)0.20–1.0Manning’s roughnesscoefficient for overlandflow(OV_N)0.140.01–0.5Tillage depth(DEPTIL)[cm]300–95 Mechanical soil mixingefficiency(EFFMIX)0.50–1.0USLE support practicefactor(USLE_P)1.00.1–1.0Width of edge offieldfilter strip(FILTERW)[m]0.00–5.0A.Ullrich,M.Volk/Agricultural Water Management96(2009)1207–12171210conventional tillage,83for minimum tillage(conservation tillage) and82for no-tillage.Here,the initial CN representing the soil hydrological group A(for soils with good hydrological conditions) was used.Biological soil mixing efficiency is a sensitive parameter and was parameterised in detail depending on the intensity of the applied management practice.As a result,the biological mixing activity decreases with increasing tillage intensity.Theparameter Fig.2.Sensitivity of SWAT model to tillage parameters:CN,BIOMIX andOV_N.Fig.3.Sensitivity of SWAT model to management practice parameters USLE_P and FILTERW.A.Ullrich,M.Volk/Agricultural Water Management96(2009)1207–12171211values for biological soil mixing efficiency used in this study were discussed with local farmers.Manning’s roughness coefficient for overland flow was defined subject to management practise and changing residue cover (Sloot et al.,1994;Neitsch et al.,2002).The parameter increases with increasing soil coverage according to decreasing tillage intensity.We defined only one tillage depth and mixing efficiencies for one main tillage operation (as applied crop-dependent on the field in reality;Abraham et al.,2004).The timing of tillage operations affects soil coverage (residue decomposition).For example,fall tillage operation reduces residue over the winter and spring period.The timing of tillage and theTable 3Parameterisation of tillage operations within management practices.ScenarioTillage operationDEPTIL a (cm)EFFMIX bBIOMIX cOV_N dCN*e GrainsRow cropsConventional tillage (CVT)CVT Cultivation stubble120.450.10.0976Plough (bare soil)250.8577Harrow 70.3Plant 6367Harvest 74Conservation tillage (CST)CST_A Cultivation stubble120.450.20.1376Harrow 70.3Plant 6266Harvest74CST_B 0.30.19CST_C Harrow70.30.40.374Plant 6165Harvest 73No-tillage (NOT)Plant 0.40.36064Harvest73a Abraham et al.(2004)—based on practical experience.b Neitsch et al.(2002).c Discussed with local farmers.d Neitsch et al.(2002).eNeitsch et al.(2002)–CN is exemplarily used representatively for soil hydrological group A –soil with good hydrological conditions.Table 4Tillage scenarios based on tillage practices;(P)plough,(St)stubble cultivation,(H)harrow,(S)seed (dates by Abraham et al.,2004).Dates of operation Fall tillageSpring tillage Spring barley 03.August 10.October 01.March 05.March 10.March15.MarchWinter barley 12.August 20.August 01.September 05.September Sugar beet08.October 11.October 26.March 01.April 05.April 10.April Conventional tillage CVTSt P ––H S CVT_1St P –––S CVT_2–P ––H S CVT_3–P –––S CVT_4St ––P H S CVT_5St ––P –S CVT_6––St P H S CVT_7––St P –S Conservation tillage CST_A St St ––H S CST_A1St St –––S CST_A2St ––St H S CST_A3St ––St –S CST_A4––St St H S CST_A5––St St –S CST_B St –––H S CST_B1St ––––S CST_B2–St ––H S CST_B3–St –––S CST_B4–––St H S CST_B5–––St –S CST_B6––St –H S CST_B7––St ––S CST_C ––––H S No-tillage NOT–––––SA.Ullrich,M.Volk /Agricultural Water Management 96(2009)1207–12171212choice of tillage operation depend on the crop being planted and the chosen management practice (Kirsch et al.,2002).Therefore differences between spring and winter crops as well as between grains and root crops are expected.Hence we applied commonly planted crops:spring barley (Hordeum vulgare )—representative for grains planted in early spring;winter barley (Hordeum vulgare var.a genuinum )—representative for grains planted in early fall and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris )—representative for root crops planted in early spring.For each crop depending on management practice basic scenarios were defined (see Table 4).Conventional and conservation tillage are primarily distinguished by tillage practices applied directly after harvesting (deep ploughing,previous stubble cultivation).The harrow operation is applied for all scenarios just before seeding/planting.Following sub-scenarios for conventional and conservation tillage (CVT_1,CVT_2,etc.)we defined where,e.g.tillage operations,were applied at different dates (for springplanted crops spring tillage instead of autumn tillage)to identify the sensitivity of SWAT model to the timing of the tillage operations.Management practices related tillage operations are chronolo-gical (e.g.conventional tillage:stubble cultivation/deep ploughing/harrowing).Thus,the harrow operation is least intensive operation.In the following,varying tillage operation combinations were applied to find out if it is necessary to parameterise a less intensive operation which follows a more intensive operation (e.g.harrowing after ploughing).If the effect on model output parameters is only marginal the less intensive operation could be left out.Additionally,the conservation management practice contour-ing and implementation of filter strips was applied to the base tillage scenarios of conservation tillage CST_A and CST_B (e.g.CST_Aa)and no-tillage practise (see Table 5).Finally,a catch crop (red clover)scenario was implemented (CST_CC)for green manuring (only applied for conservation tillage basic scenario with sugar beet).3.Results and discussionGenerally,our results confirm the outcome of studies under-taken by Kirsch et al.(2002),Chaplot et al.(2004),Pandey et al.(2005),Tripathi et al.(2005),and Behera and Panda (2006)that conventional tillage practices need to be replaced by less intensiveTable 5Parameter settings for contouring and filter stripes.ScenarioParameter USLE_PFILTERW (m)_a 0.60_b 1.02_c0.62Fig.4.Percentage deviation of modelling results regarding to application of basic management scenarios with a)sugar beet,b)spring barley and c)winter barley on water balance components,nutrients and sediment loading.A.Ullrich,M.Volk /Agricultural Water Management 96(2009)1207–12171213。

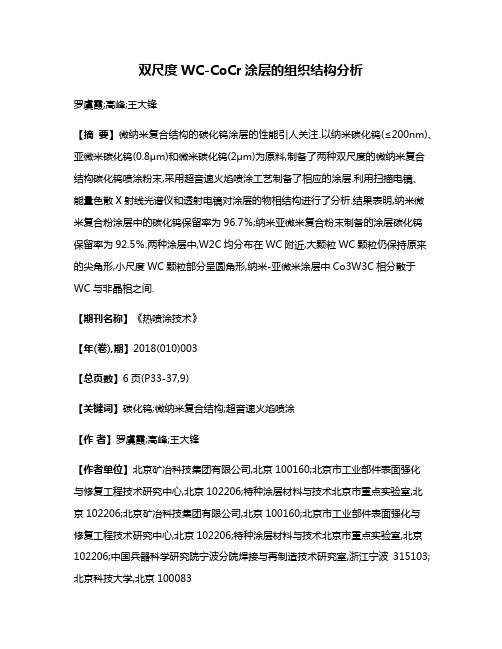

双尺度WC-CoCr涂层的组织结构分析

双尺度WC-CoCr涂层的组织结构分析罗虞霞;高峰;王大锋【摘要】微纳米复合结构的碳化钨涂层的性能引人关注.以纳米碳化钨(≤200nm)、亚微米碳化钨(0.8μm)和微米碳化钨(2μm)为原料,制备了两种双尺度的微纳米复合结构碳化钨喷涂粉末,采用超音速火焰喷涂工艺制备了相应的涂层.利用扫描电镜、能量色散X射线光谱仪和透射电镜对涂层的物相结构进行了分析.结果表明,纳米微米复合粉涂层中的碳化钨保留率为96.7%;纳米亚微米复合粉末制备的涂层碳化钨保留率为92.5%.两种涂层中,W2C均分布在WC附近,大颗粒WC颗粒仍保持原来的尖角形,小尺度WC颗粒部分呈圆角形,纳米-亚微米涂层中Co3W3C相分散于WC与非晶相之间.【期刊名称】《热喷涂技术》【年(卷),期】2018(010)003【总页数】6页(P33-37,9)【关键词】碳化钨;微纳米复合结构;超音速火焰喷涂【作者】罗虞霞;高峰;王大锋【作者单位】北京矿冶科技集团有限公司,北京100160;北京市工业部件表面强化与修复工程技术研究中心,北京102206;特种涂层材料与技术北京市重点实验室,北京102206;北京矿冶科技集团有限公司,北京100160;北京市工业部件表面强化与修复工程技术研究中心,北京102206;特种涂层材料与技术北京市重点实验室,北京102206;中国兵器科学研究院宁波分院焊接与再制造技术研究室,浙江宁波315103;北京科技大学,北京100083【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TG174.40 引言热喷涂WC-CoCr涂层具有优异的耐磨耐蚀性能,广泛地应用于冶金、石油化工、航空航天等领域[1,2]。

WC-CoCr涂层的力学性能取决于涂层的物相结构、粒子间的结合情况等显微组织结构。

研究表明,在一定喷涂工艺范围内,碳化钨颗粒的尺寸是影响涂层性能的主要因素[3]。

不同研究者制备的纳米碳化钨性能差异较大[4-7]。

因此纳米碳化钨的使用并不广泛,而微纳米复合结构的碳化钨性能较优,并获得了较多的应用。

CAV2009-final13