英语亚历山大体诗歌

英国文学诗歌术语解释

英国⽂学诗歌术语解释A Glossary of Poetic TermsAccent(重⾳)Another word for stress. The emphasis placed on a syllable. Accent is frequently used to denote stress in describing verse.Aestheticism(唯美主义)A literary movement in the 19th century of those who believed in “art for art?s sake” in opposition to the utilitarian doctrine that everything must be morally or practically useful. Key figures of the aesthetic movement were Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.Alexandrine(亚历⼭⼤诗体)The most common meter in French poetry since the 16th century: a line of twelve syllables. The nearest English equivalent is iambic hexameter. The Alexandrine being a long line, it is often divided in the middle by a pause or caesura into two symmetrical halves called hemistiches. Alexander Pope?s “Essay on Criticism” offers a typical example.Allegory(讽喻)A pattern of reference in the work which evokes a parallel action of abstract ideas. Usually allegory uses recognizable types, symbols and narrative patterns to indicate that the meaning of the text is to be found not in the represented work but in a body of traditional thought, or in an extra-literary context.Rrepresentative works are Edmund Spenser?s The Faerie Queene, John Bunyan?s The Pilgrim’s Progress.Alliteration(头韵) A rhyme-pattern produced inside the poetic line by repeating consonantal sounds at the beginning of words. It is also called initial rhyme.Allusion(引喻) A passing reference in a work of literature to something outside itself. A writer may allude to legends, historical facts or personages, to other works of literature, or even to autobiographical details. Literary allusion requires special explanation. Some writers include in their own works passages from other writers in order to introduce implicit contrasts or comparisons. T.S. Eliot?s The Waste Land is of this kind.Analogy(类⽐)The invocation of a similar but different instance to that which is being represented, in order to bring out its salient features through the comparison.Anapest(抑抑扬格) A trisyllabic metrical foot consisting of two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable.Apostrophe(顿呼) A rhetorical term for a speech addressed to a person, idea or thing with an intense emotion that can no longer be held back, often placed at the beginning of a poem or essay, but also acting as a digression or pause in an ongoing argument.Arcadia(阿卡狄亚)A mountainous region of Greece which was represented as the blissful home of happy shepherds. During the Renaissance Arcadia became the typical name for an idealized rural society where the harmonious Golden Age still flourished. Sir Philip Sidney?s prose romance is entitled Arcadia.Assonance(半谐⾳)The repetition of accented vowel sounds followed by different consonant sounds.Aubade(晨曲) A song or salute at dawn, usually by a lover lamenting parting at daybreak, for example, J ohn Donne?s “The Sun Rising”.Augustan Age: may refer to 1) The period in Roman history when Caesar Augustus was the first emperor; 2) The period in the history of the Latin language when Caesar Augustus was emperor and Golden-age Latin was in use; 3) Augustan literature and Augustan poetry, the early 18th century in British literature and poetry, where the authors highly admired and emulated the original Augustan Age.Avant-garde (先锋派) A military expression used in literature refers to a group of modern artists and writers. Their main concern is deliberate and self-conscious experimentation in writing to discover new forms, techniques and subject matter in the arts.Ballad(民谣)A narrative poem which was originally sung to tell a story in simple colloquial language.Ballad metre (民谣格律)A quatrain of alternate four-stress and three-stress lines, usually roughly iambic.Ballad stanza(民谣体诗节) A quatrain that alternates tetrameter with trimeter lines, and usually rhymes a b c b.Blank verse(⽆韵诗)Verse in iambic pentameter without rhyme scheme, often used in verse drama in the sixteenth century and later used for poetry.Burlesque(诙谐作品)An imitation of a literary style, or of human action, that aims to ridicule by incongruity style and subject. High burlesque involves a high style for a low subject, for instance, Alexander Pope?s The Rape of the Lock. Byronic hero(拜伦式英雄)A character type portrayed by George Lord Gordon Byron in many of his early narrative poems, especially Child Harold’s Pilgrimage. The Byronic hero is a brooding solitary, who seeks exotic travel and wild nature to reflect his superhuman passions. He is capable of great suffering and guilty of some terrible, unspecified crime, but bears this guilt with pride, as it sets him apart from society, revealing the meaninglessness of ordinary moral values. He is misanthropic, defiant, rebellious, nihilistic and hypnotically fascinating to others.Canto(诗章)A division of a long poem, especially an epic. Dante?s Divine Comedy, Byron?s Don Juan and Ezra Pound?s The Cantos are all divided into these chapter-length sections.Carpe Diem(及时⾏乐)A poem advising someone to “seize the day” or “seize the hour”. Usually the genre is addressed by a man to a young woman who is urged to stop prevaricating in sexual or emotional matters.Cavalier poets(骑⼠诗⼈)English lyric poets during the reign of Charles I. Richard Lovelace, Sir John Suckling, Thomas Carew, EdmundWaller and Robert Herrick are the representatives of this group. Cavalier poetry is mostly concerned with love, and employs a variety of lyric forms.Cockney school of poetry (伦敦佬诗派) A derisive term for certain London-based writers, including Leigh Hunt, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Hazlitt and John Keats. This term was invented by the Scottish journalist John Gibson Lockhart in an anonymous series of article on The Cockney School of Poetry, in which he mocked the supposed stylistic vulgarity of these writers.Complaint (怨诗) A poetic genre in which the poet complains, often about his beloved. Geoffery Chaucer?s “Complaint to His Purse”, Edward Young?s “The Complaint”, or “Night Thoughts”are examples.Conceit(奇思妙喻)Originally it meant simply a thought or an opinion. The term came to be used in a derogatory way to describe a particular kind of far-fetched metaphorical association. It has now lost this pejorative overtone and simply denotes a special sort of figurative device. The distinguishing quality of a conceit is that it should forge an unexpected comparison between two apparently dissimilar things or ideas. The classic example is John Donne?s The Flea and A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.Didactic poetry(说教诗)Poetry designed to teach or preach as a primary purpose.Dirge (挽歌)Any song of mourning, shorter and less formal than an elegy. Shakespeare?s Full Fathom Five in The Tempest is a famous example..Dithyramb(酒神颂歌)A Greek choric hymn in honour of Dionysus. In general “dithyrambic” is applied to a wildly enthusiastic song or chant.Eclogue (牧歌)A pastoral poem, especially a pastoral dialogue, usually indebted to the Virgillian tradition.Elegy(挽诗)A poem of lamentation, concentrating on the death of a single person, like Alfred Tennyson?s “In Memoriam”, Thomas Gray?s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”, or W. B. Yeats?s “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory”.Epic(史诗) A long narrative poem in elevated style, about the adventures of a hero whose exploits are important to the history of a nation. The more famous epics in western literature are Homer?s Iliad, Virgil?s Aeneid, Dante?s Divine Comedy and John Milton?s Paradise Lost.Epigram(警句诗) A polished, terse and witty remark that packs generalized knowledge into short compass.Epigraph(铭⽂)A short quotation cited at the start of a book or chapter to point up its theme and associate its content with learning. Also an inscription on a monument or building explaining its purpose.Epitaph(墓志铭)An inscription on a tomb or a piece of writing suitable for that purpose, generally summing up someone?s life, sometimes in praise, sometimes in satire. John Keats wrote an Epitaph for himself. It says, “Here lies one whose name is writ in water.”Epithet(表述词语)From Latin epitheton, from Greek epitithenai meaning “to add”, an adjective or adjective cluster that is associated with a particular person or thing and that usually seems to capture their prominent characteristics. For example,“Ethelred the unready”, or “fleet-footed Achilles” in Alexander Pope?s version of The Iliad.Folk ballad(民间歌谣) A narrative poem designed to be sung, composed by an anonymous author, and transmitted orally for years or generations before being written down. It has usually undergone modification through the process of oral transmission.Foot(⾳步)a unit of measure consisting of stressed and unstressed syllables.Free verse(⾃由诗)Verse released from the convention of meter, with its regular pattern of stresses and line length.Georgian Poetry:the title of a series of anthologies showcasing the work of a school of English poetry that established itself during the early years of the reign of King George V of the United Kingdom. Edward Marsh was the general editor of the series and the centre of the circle of Georgian poets, which included Rupert Brooke. It has been suggested that Brooke himself took a hand in some of the editorial choices.Graveyard poets(墓园诗⼈)Several 18th century poets wrote mournfully pensive poems on the nature of death, which were set in graveyards or inspired by gloomy nocturnal meditations. Examples of this minor but popular genre are Thomas Parnell?s “Night-Piece on Death”, Edward Young?s “Night Thoughts” and Robert Blair?s “The Grave”. Thomas Gray?s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” owes something to this vogue.Haiku(俳句)A Japanese lyric form dating from the 13th century which consists of seventeen syllables used in three lines: 5/7/5. Several 20th century English and American poets have experimented with the form, including Ezra Pound.Heroic couplet(英雄双韵体) Lines of iambic pentameter rhymed in pairs. Alexander Pope brought the meter to a peak of polish and wit, using it in satire. Because this practice was especially popular in the Neoclassic Period between 1660 and 1790, the heroic couplet is often called the “neoclassic couplet” if the poem originates during this time period.Heroic quatrain(英雄四⾏诗)Lines of iambic pentameter rhymed abab, cdcd, and so on. Thomas Gray?s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” is a notable example.Hexameter(六⾳步) In English versification, a line of six feet. A line of iambic hexameter is called an Alexanderine.Iamb(抑扬格)The commonest metrical foot in English verse, consisting of a weak stress followed by a strong stress.Iambic-anapestic meter(抑扬抑抑扬格) A meter which freely mixes iambs and anapests, and in which it might be difficult to determine which foot prevails without actually counting.Iambic hexameter(六⾳步抑扬格)A line of six iambic feet.Iambic pentameter(五⾳步抑扬格)A line of five iambic feet. It is the most pervasive metrical pattern found in verse in English.Iambic tetrameter(四⾳步抑扬格)A line of four iambic feet.Idyll(⽥园诗)A poem which represents the pleasures of rural life.Image, imagery(意象) A critical word with several different applications. In its narrowest sense an …image? is a word-picture, a description of some visible scene or object. More commonly, however, …imagery? refers to figurative language in a piece of literature; or all the words which refer to objects and qualities which appeal to the senses and feelings.Imagism(意象派)A self-conscious movement in poetry in England and America initiated by Ezra Pound and T.E. Hulme in about 1912. Pound described the aims of Imagism in his essay “A Petrospect”as follows:1) Direct treatment of the …thing? whether subjective or objective.2) To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.3) As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of a metronome. Pound defined an …Image? as …that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time?. His haiku-like two-line poem In a Station of the Metro is often quoted as the quintessence of Imagism.Irony(反讽)The expression of a discrepancy between what is said and what is meant.Lake poets(湖畔派诗⼈) The three early 19th century romantic poets, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey, who lived in the Lake District of Cumbria in northern England. This term was often applied in a derogatory way, suggesting the provincialism of their themes and interests.Lyric(抒情诗) A poem, usually short, expressing in a personal manner the feelings and thoughts of an individual speaker. The typical lyric subject matter is love, for a lover or deity, and the mood of the speaker in relation to this love.Metaphysical poets (⽞学派诗⼈) Metaphysics is the philosophy of being and knowing, but this term was originally applied to a group of 17th century poets in a derogatory manner. The representatives are John Donne, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan and Richard Crashaw and John Cleveland, Andrew Marvell and Abraham Cowley. The features of metaphysical poetry are arresting and original images and conceits, wit, ingenuity, dexterous use of colloquial speech, considerable flexibility of rhythm and meter, complex themes, a liking for paradox and dialecticalargument, a direct manner, a caustic humor, a keenly felt awareness of mortality, and a distinguished capacity for elliptical thought and tersely compact expression. But for all their intellectual robustness the metaphysical poets are also capable of refined delicacy, gracefulness and deep feeling, passion as well as wit. They had a profound influence on the course of English poetry in the 20th century.Meter(格律)The regular pattern of accented and unaccented syllables. The line is divided into a number of feet. According to their stress pattern the feet are classed as iambic, trochaic, anapestic, dactylic, spondaic or pyrrhic.Metonymy(借代)A figure of speech: the substitution of the name of a thing by the name of an attribute of it, or something closely associated with it.Monometer(单⾳步诗⾏)A metrical line containing one foot.Monologue(独⽩) A single person speaking, with or without an audience, is uttering a monologue. The dramatic monologue is the name given to a specific kind of poem in which a single person, not the poet, is speaking.Dramatic Monologue(戏剧独⽩) A poem in which a poetic speaker addresses either the reader or an internal listener at length. It is similar to the soliloquy in theater, in that both a dramatic monologue and a soliloquy often involve the revelation of the innermost thoughts andfeelings of the speaker. Two famous examples are Browning?s “My Last Duchess”.Interior Monologue:A type of stream of consciousness in which the author depicts the interior thoughts of a single individual in the same order these thoughts occur inside that character's head. The author does not attempt to provide (or provides minimally) any commentary, description, or guiding discussion to help the reader untangle the complex web of thoughts, nor does the writer clean up the vague surge of thoughts into grammatically correct sentences or a logical order. Indeed, it is as if the authorial voice ceases to exis t, and the reader directly “overhears” the thought pouring forth randomly from a character?s mind. An example of an interior monologue can be found in James Joyce?s Ulysses. Here, Leopold Bloom wanders past a candy shop in Dublin, and his thoughts wander back and forth.The Movement:A term coined by J. D. Scott, literary editor of The Spectator, in 1954 to describe a group of writers including Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Donald Davie, D.J. Enright, John Wain, Elizabeth Jennings, Thom Gunn, and Robert Conquest. The Movement was essentially English in character; poets in Scotland and Wales were not generally included. The Movement poets were considered anti-Romantic, but we find many Romantic elements in Larkin and Hughes. We may call The Movement the revival of the importance of form. To these poets, good poetry meant simple, sensous content, and traditional, conventional and dignified form.Neoclassicism(新古典主义)This word refers to the fact that some writers, particularly in the 18th century, modeled their own writing on classical, especially Roman literature. Neoclassicism is applied to a period of English literature lasting from 1660, the Restoration of Charles II, until about 1800. The following major writers flourished then, in poetry, John Dryden, Alexander Pope and Oliver Goldsmith; in prose, Jonathan Swift, Addition, Samuel Johnson. Neoclassical writers did not value creativity or originality highly. They valued the various genres, such as epic, tragedy, pastoral, comedy. The meter for most of Neoclassic writings was the heroic couplet.Octameter(⼋⾳步诗⾏)A metrical line containing eight feet; only occasionally attempted in English verse.Octave(⼋⾏体)An eight-line stanza or the first eight lines of a sonnet, especially one structured in the manner of an Italian sonnet.Ode(颂歌)A form of lyric poem, characterized by its length, intricate stanza forms, grandeur of style and seriousness of purpose, with a venerable history in Classical and post-Renaissance poetry.Onomatopoeia(拟声词)The use of words that resemble the sounds they denote, for example, …hiss?, …bang?, …pop? or …smack?.Oxford Movement: A movement of High Church Anglicans, eventually developing into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, the members of which were often associated with the University of Oxford, argued for the reinstatement of lost Christian traditions of faith and their inclusion intoAnglican liturgy and theology. They conceived of the Anglican Church as one of three branches of the Catholic Church.Oxymoron(逆喻)A figure of speech in which contradictory terms are brought together in what is at first sight an impossible combination. It is a special variety of the paradox.Paradox(悖论)An apparently self-contradictory statement, or one that seems in conflict with all logic and opinion; yet lying behind the superficial absurdity is a meaning or truth. It is common in metaphysical poetry.Parody(嘲仿)An imitation of a specific work of literature or style devised so as to ridicule its characteristic features. Exaggeration, or the application of a serious tone to an absurd subject, are typical methods. Henry Fielding?s Shamela,Samuel Richardson?s Pamela,and Lewis Carroll?s version of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow?s Hiawatha are examples.Pastoral(⽥园诗)An artistic composition dealing with the life of shepherds or with a simple, rural existence. It usually idealizes shepherds? lives in order to create an image of peaceful and uncorrupted existence. More generally, pastoral describes the simplicity, charm, and serenity attributed to country life, or any literary convention that places kindly, rural people in nature-centered activities. The pastoral is found in poetry, drama, and fiction. Many subjects, such as love, death, religion, and politics, have been presented in pastoral settings.Pattern poetry(拟形诗)The name for verse which is written in a stanza form that creates a picture or pattern on the page. It is a precursor of concrete poetry. George Herbert?s “Easter Wings” is a typical example.Pentameter(五⾳步诗⾏)A poetic line of five feet and the most common poetic line in English.Personification(拟⼈) A figure of speech in which things or ideas are treated as if they were human beings, with human attributes and feeling.Poem(诗)An individual composition, usually in some kind of verse or meter, but also perhaps in heightened language which has been given some sense of pattern or organization to do with the sound of its words, its imagery, syntax, or any available linguistic element.Poet (诗⼈)Originally from the Greek poiein, a person who …makes?.Poet laureate (桂冠诗⼈) A laurel crown is the traditional prize for poets, based on the myth in which Apollo turns Daphne into a laurel tree. Poet laureates have been officially named by the British monarch since John Dryden?s appointment in 1668 by Charles II. T hey are supposed to stand as the figurehead of British poetry, but in the two centuries after John Dryden, with the exceptions of William Wordsworth and Alfred Tennyson, most were minor poets. Some indeed were poets of no significance whatever. The poets laureate in the 20th century have been less negligible. Ted Hughes is the present incumbent.Poetic licence(诗的破格)The necessary liberty given to poets, allowing them to manipulate language according to their needs, distorting syntax, using odd archaic words and constructions, etc. It can also refer to the manner in which poets, sometimes through ignorance, or deliberately, make mistaken assumptions about the world they describe.Pre-Raphaelites(前拉斐尔学派)Originally a group of artists (including John Millais, Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti) who organized the …Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood? in 1848. Their aim was a return to the …truthfulness? and simplicity of medieval art. The representatives include Christina Rossetti, Algernon Swinburne and William Morris. The typical aspects of their poetry are medievalism, archaism and lush sensuousness combined with religious feeling.Prosody(韵律学)The technical study of versification, including meter, rhyme, sound effects and stanza patterns.Psalm(赞美诗)A sacred song or hymn, especially one from the Book of Psalms in the Bible.Pun(双关语)A figure of speech in which a word is used ambiguously, thus, invoking two or more of its meanings, often for comic effect.Pyrrhic(抑抑格) A metrical foot consisting of two short or unstressed syllables. As with the spondee, from a linguistic point of view it is doubtful if the pyrrhic is necessary in English scansion, as two successive syllables are unlikely to bear exactly similar levels of stress.Quatrian(四⾏诗节) A stanza of four lines. A very common form in English, used with various meters and rhyme schemes..Refrain(叠句)Words or lines repeated in the course of a poem, recurring at intervals, sometimes with slight variation, usually at the end of a stanza. Refrains are especially common in songs and ballads.Rhyme(诗韵)The pattern of sound that established unity in verse forms. Rhyme at the end of lines is …end rhyme?; inside a line it is …internal rhyme?. End rhyme is clearly the most emphatic and usually relies on homophony between final syllables.Rhyme scheme(韵式)The pattern of rhymes in a stanza or section of verse, usually expressed by an alphabetical code.Rhythm(韵律)Rhythm refers to any steady pattern of repetition, particularly that of a regular recurrence of accented or unaccented syllables at equal intervals.Romance(传奇故事)Primarily medieval fiction in verse or prose dealing with adventures of chivalry and love. Notable English romances include Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Thomas Malory?s Le Morte d’Arthur.Romanticism(浪漫主义)A word used in an appallingly large number of different ways in different contexts.(1) Romantic in popular sense means idealized and facile love. (2) The Romantic Period.A term used to refer to the period dating from 1789 to about 1830 in English literature.Novelists of the period include Sir Walter Scott and Jane Austen; essayists such as Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt and Thomas De Quincey are notable for their contributions to the fast-developing literary magazines. There were two generations of Romantic poets: the first included William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southy; the second were George Gordon Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats. (3) Romanticism. It was in contrast to neoclassical literature. Writers showed their concern for feeling and emotion rather than the human capacity to reason. William Wordsworth?s The Prelude is the foremost text of Romanticism. The romantic poets were interested in nature. They saw nature as a way of coming to understand the self and made use of their imagination to create harmony. They also showed their disapproval toward neoclassical rules of poetry.Scansion(韵律分析)Scansion is the process of measuring the stresses in a line of verse in order to determine the metrical pattern of the line. It starts with identifying the standard of its prevailing meter and rhythm.Sestet(六⾏诗)The last six lines of a Petrarchan sonnet which should be separated by rhyme and argument from the preceding eight lines, called the octave.Sestina(六节诗)A rare and elaborate verse form, consisting of six stanzas, each consisting of six lines of pentameter, plus a three-line envoi. The end words for each stanza are the same, but in a different order from stanza to stanza. An example is Ezra Pound?s Sestina, Altaforte.Song(歌) A short lyric poem intended to be set to music, though often such poems have no musical setting.Sonnet(⼗四⾏诗) A lyric poem of fixed form: fourteen lines of iambic pentameter rhymed and organized according to several intricate schemes. Three patterns predominate: (1) The Petrarchan or Italian sonnet is divided into an octave which rhymes abba abba, and a sestet usually rhymes cde cde, or cdc dcd. The sestet usually replies to the argument of the octave.(2) Spenserian sonnet is a nine-line stanza of iambics rhymed abab bcbc cdc dee. The first eight lines are pentameters; the final line is a hexameter; (3) Shakespearean sonnet has three quatrains and a final couplet which usually provides an epigrammatic statement of the theme. The rhyme scheme is abab cdcd efef gg.Spenserian Stanza(斯宾塞诗节)A nine-line stanza rhyming in an ababbcbcc pattern in which the first eight lines are iambic pentameter and the last line is an iambic hexameter line. The name Spenserian comes from the form?s most famous user, Spenser, who used it in The Fairie Queene. Other examples include Keat?s “Eve of Saint Agnes” and Shelley?s “Adonais.” The Spenserian stanza is probably the longest and most intricate stanza generally employed in narrative poetry.Spondee(扬扬格)A metrical foot consisting of two long syllables or two strong stresses, giving weight to a line.Stanza(诗节)A unit of several lines of verse. Much verse is split up into regular stanzas of three, four, five or more lines each. Examples of。

英语诗TheDaffodils赏析

英语诗TheDaffodils赏析赏析意思是欣赏并分析(诗文等),通过鉴赏与分析得出理性的认识,既受到艺术作品的形象、内容的制约,又根据自己的思想感情、生活经验、艺术观点和艺术兴趣对形象加以补充和完善。

下面是店铺为大家整理的英语诗The Daffodils赏析,仅供参考,大家一起来看看吧。

The DaffodilsWilliam WordsworthI wander’d lonely as a cloudThat floats on high o’er vales and hills,When all at once I saw a crowd,A host , of golden daffodils;Beside the lake, beneath the trees,Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.Continuous as the stars that shineAnd twinkle on the Milky way,They stretch’d in never-ending lineAlong the margin of a bay:Ten thousand saw I at a glance,Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.The waves beside them danced, but theyOut-did the sparkling waves in glee:A poet could not but be gayIn such a jocund company!E gaze ?and gazed ?but little thoughtWhat wealth the show to me had brought:For oft, when on my couch I lieIn vacant or in pensive mood,They flash upon that inward eyeWhich is the bliss of solitude;And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils.扩展:译文心中的水仙花作者:威廉·华兹华斯象孤云独去一样我的心和我流浪在山间在不经意的`一切之中我邂逅了水仙花的芳艳金灿灿的水仙啊在湖畔的树下连成一片逸动的身姿迎风翩跹魅力的光无法收敛见过夜晚的银河吗闪烁的星星在那里倾泻、绵延顷刻沿着湖湾边缘一线九千九百九十九朵水仙花映入我猝不及防的眼帘花随风舞轻快的节奏舞动着美艳河里的波涛也来伴舞映衬水仙花自由摇摆的欢畅此情此景,我心激扬我久久地凝视,但一时无法解读美丽的鲜花如何拥有那超越财富的力量因为,后来每当我孑然独处,或陷入沉思之际,它们的身影总会在我的脑海闪现;---- 黯黯的孤寂忽现一道来自天堂的瑞光 ---- 于是,美就在心中流淌心就随着那摇曳着欢愉的水仙花激荡,激荡【英语诗The Daffodils赏析】。

十四行诗欣赏

十四行诗Sonnet,又译为商籁体,这是欧洲抒情诗中占首席地位的一种诗体。

自13世纪产生于意大利之后,在以后的岁月里传遍了世界各国:15世纪流传到了西班牙,16世纪流传到了英、法;17世纪传到德、美;19世纪传到俄国;20世纪初又传入我国……影响深远。

总的说来,十四行诗有两种基本的体式:意大利体(或彼特拉克体)和英国体(或莎士比亚体)。

彼特拉克体彼特拉克(1304——1374),文艺复兴时期的第一个人文主义学者,被誉为“人文主义之父”,其代表作《歌集》对欧洲诗歌产生了巨大影响,是当时整个欧洲的桂冠诗人。

学者们一般认为,十四行诗源自13世纪的意大利,但彼特拉克并不是这种诗体的创立者,也不是其最早的使用者(例如,但丁);但是因彼特拉克几近完美的创作使得这种诗体成为欧洲最重要的诗体。

于是它便被冠上了“彼特拉克体”的名称。

具体说来,它可分为两部分:前面是一个“八行组”(八行体);后面是一个“六行组”(六行体)。

一般说来,前面的“八行组”用于展现主题或提出疑问;后面的“六行组”是解决问题或作出结论。

从韵式上看,前八行又包括两个“四行组”,使用抱韵,韵式固定:abba abba;后六行则又包括两个“三行组”,韵式则多变,常见的有:cde cde; cdc dcd等。

这样全诗就形成了“4 4 3 3”结构,寓变化于整齐之中,富有结构美,韵律美。

爱的矛盾我结束了战争,却找不到和平,我发烧又发冷,希望混合着恐怖,我乘风飞翔,又离不开泥土,我占有整个世界,却两手空空;我并无绳索缠身枷锁套颈,我却仍是个无法脱逃的囚徒,我既无生之路,也无死之途,即便我自寻,也仍求死不能;我不用眼而看,不用舌头而抱怨,我愿灭亡,但我仍要求康健,我爱一个人,却又把自己怨恨;我在悲哀中食,我在痛苦中笑,不论生和死都一样叫我苦恼,我的欢乐啊,正是愁苦的原因。

我形单影只我形单影只,思绪万千,在最荒凉的野地漫步徘徊,我满怀戒备,小心避开一切印有人的足迹的地点。

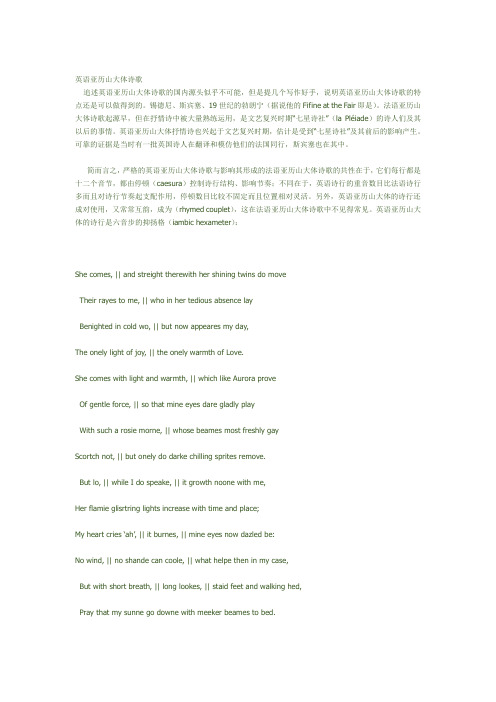

英语亚历山大体诗歌

英语亚历山大体诗歌追述英语亚历山大体诗歌的国内源头似乎不可能,但是提几个写作好手,说明英语亚历山大体诗歌的特点还是可以做得到的。

锡德尼、斯宾塞、19世纪的勃朗宁(据说他的Fifine at the Fair即是)。

法语亚历山大体诗歌起源早,但在抒情诗中被大量熟练运用,是文艺复兴时期“七星诗社”(la Pléiade)的诗人们及其以后的事情。

英语亚历山大体抒情诗也兴起于文艺复兴时期,估计是受到“七星诗社”及其前后的影响产生。

可靠的证据是当时有一批英国诗人在翻译和模仿他们的法国同行,斯宾塞也在其中。

简而言之,严格的英语亚历山大体诗歌与影响其形成的法语亚历山大体诗歌的共性在于,它们每行都是十二个音节,都由停顿(caesura)控制诗行结构、影响节奏;不同在于,英语诗行的重音数目比法语诗行多而且对诗行节奏起支配作用,停顿数目比较不固定而且位置相对灵活。

另外,英语亚历山大体的诗行还成对使用,又常常互韵,成为(rhymed couplet),这在法语亚历山大体诗歌中不见得常见。

英语亚历山大体的诗行是六音步的抑扬格(iambic hexameter):She comes, || and streight therewith her shining twins do moveTheir rayes to me, || who in her tedious absence layBenighted in cold wo, || but now appeares my day,The onely light of joy, || the onely warmth of Love.She comes with light and warmth, || which like Aurora proveOf gentle force, || so that mine eyes dare gladly playWith such a rosie morne, || whose beames most freshly gayScortch not, || but onely do darke chilling sprites remove.But lo, || while I do speake, || it growth noone wi t h me,Her flamie glisrtring lights increase wi t h time and place;My heart cries …ah‟, || i t burnes, || mine eyes now dazled be:No wind, || no shande can coole, || what helpe then in my case,But with short breath, || long lookes, || staid feet and walking hed,Pray that my sunne go downe with meeker beames to bed.每行六个重音,比法语诗行多两个。

斯宾塞的长诗《仙后》

斯宾塞的长诗《仙后》卷一,第一章一位高贵的骑士策马在平原上奔驰。

他身披坚厚的甲胄,手持盾牌,上边有累累伤痕,那是血腥的战场上留下的“残酷的痕迹(cruell markes)。

尽管身披战甲,这位骑士从未亲临战场挥舞过兵刃,他跨下的骏马愤怒的咆哮着,口吐白沫,虽套着嚼子,但似乎并不愿对骑士惟命是从。

因为这位英勇的骑士端庄的坐于马上,但已做好了与敌相遇拚杀一场恶战到底的准备。

这位骑士胸前佩带着一个血红的十字架,那是对上帝缅怀的表示;之所以佩带这个饰物(badge),就是为了这种表示。

而且,不论生死,他都对上帝顶礼膜拜。

他的盾牌上边也同样有一个十字架,那标志着他在上帝帮助下可以获得至高无上的希望。

因此,不论是行动上还是表达上,他都是一样忠诚真挚。

不过,他此时神情(cheere=expression)十分凝重,尽管他无所畏惧,别人对他十分敬畏。

他将出发进行一次伟大的冒险,这是仙国最为伟大的高尚的女王格劳瑞安娜(Gloriana)命他做的,既可以使他赢得荣誉,又可以使他得到仙后的恩宠,而这是所有的人世中的东西中他最为渴望得到的。

他越是骑马前行,越是渴望在战场上无畏的证明他压倒对手的力量,体验他学得的新的竞技手段,那是制服他的对手、可怕而又严酷的“恶龙”的手段。

那是一位骑着比雪还白的驴子的娇美女士。

这位女士尽管更为雪白纯洁,但她的面部却遮掩在面纱之下,而且有许多皱褶,压的很低;她整个身体批裹着黑色长袍(stole),就象是一个悲痛欲绝的人。

她坐在低矮的驴子上,面带悲伤,心情沉重,缓缓向前行进,似乎心中隐藏着什么焦虑。

她旁边是一只奶白色的羊羔,她用一条皮带牵着。

她纯洁天真、如同那只羊羔(耶稣),她的祖先是古代的国王王后,所以属贵族血统。

而在古代,她祖先的权力范围从东岸延伸到西岸,整个世界都处于他们统治之下,俯首听命(subjection),直到那个凶残的恶魔(infernall feend=infernal fiend)以邪恶肮脏的暴乱(foule uprore)摧毁了他们的王国,并将他们驱逐。

波德莱尔诗作《L'Albatros》中诗歌符号的象征意义

课程名称:符号学与文学专业:法语语言文学姓名:周春悦学号:MG0809065指导老师:张新木此生难料,心在天山,身老沧州——析波德莱尔诗作《信天翁》中诗歌符号的象征意义摘要:《信天翁》(L’Albatros)选自诗集《恶之花》,是波德莱尔旅行时,在南方海域所见的印象。

原诗是一首每行有12个音节的亚历山大体诗,由四个四行诗组成,诗歌文体遵守古典规则,阴韵和阳韵交错出现,押交错韵,即abab格式。

全诗充满托物言志的气氛,也表现出诗人或天才十分苦涩的自嘲。

这首诗象征意义明显,借信天翁的形象引寓诗人自己,抒发不被世人所理解的诗人的孤独感。

该诗象征意味浓重,本文将通过信天翁的形象、外部世界、从高空坠落人间的动作这三个角度的切入,着重分析散落于文字和意境间的种种诗歌象征符号。

关键词:信天翁,恶之花,象征性,诗歌符号《信天翁》出自法国现代派大诗人、象征派诗歌先驱夏尔·波德莱尔(1821——1867)的代表作品《恶之花》的第二部分《忧郁和理想》(《Spleen et idéal》)。

该诗是诗人根据1841年前往毛里求斯岛的海上所见、所感而作。

这首极具象征意义的诗歌借“信天翁”的形象来比喻在对高尚的向往和不可阻挡的堕落趋势之间痛苦挣扎的人,而这种痛苦正是源自所谓的一种“忧郁”(spleen)的欲望,它与人类自身的境遇息息相关,密不可分,并最终在人内心和精神的斗争中取得胜利。

“信天翁”的形象被波德莱尔用于表达渴望与众不同的希翼。

借助这一象征色彩浓烈的形象,诗人想要描绘的是他在一个对他完全漠视的社会中的自身处境。

被捕获的“信天翁”的形象即相当于一个与周围世界彻底决裂的人。

波德莱尔是“被诅咒的诗人”(les poètes maudits)中最耀眼的代表,这也注定了他在短短一生之中无法被同时代人所理解。

诗歌的前三节讲述了“信天翁”的悲惨经历,最后一节则献给诗人自己。

原诗和参考翻译如下:L'ALBATROS①Souvent, pour s'amuser, les hommes d'équipage Prennent des albatros, vastes oiseaux des mers, Qui suivent, indolents compagnons de voyage,Le navire glissant sur les gouffres amers.A peine les ont-ils déposés sur les planches,Que ces rois de l'azur, maladroits et honteux, Laissent piteusement leurs grandes ailes blanches Comme des avirons traîner à côté d'eux.Ce voyageur ailé, comme il est gauche et veule! Lui, naguère si beau, qu'il est comique et laid!L'un agace son bec avec un brûle-gueule,L'autre mime, en boitant, l'infirme qui volait!Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuéesQui hante la tempête et se rit de l'archer;Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,Ses ailes de géant l'empêchent de marcher.信天翁②常常,为了消遣,航船上的海员捕捉些信天翁,这种巨大的海禽,它们,这些懒洋洋的航海旅伴,跟在飘过苦海的航船后面飞行。

十四行诗

•

• •

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

• • •

by: William Shakespeare LOOK in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest Now is the time that face should form another,

•

• •

Whose fresh repair if now thou renewest,

• 彼得拉克的十四行诗形式整齐,音韵优美, 以歌颂爱情,表现人文主义思想为主要内 容。他的诗作在内容和形式方面,都为欧 洲资产阶级抒情诗的发展开拓了新路。同 时代的意大利诗人和后来其他国家的一些 诗人,都曾把彼得拉克的诗作,视为十四 行诗的典范,竞相仿效。每首分成两部分: 前一部分由两段四行诗组成,后一部分由 两段三行诗组成,即按四、四、三、三编 排。因此,人们又称它为彼得拉克诗体。

• • •

爱的忠诚 Set me whereas the sun doth parch the green置我于太阳炙烤的绿茵,

•

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

Or where his beams do not dissolve the ice或阳光难以消融的寒冰,

In temperate heat, where he is felt and seen或人们感觉温暖的环境, In presence prest of people mad or wise受压众生或愚昧或聪明。 Set me in high, or yet in low degree即便我显达,抑或是微贱, In longest night, or in the shortest day白天短暂还是长夜漫漫, In clearest sky. or where clouds thickest be乌云密布或是气清天蓝, In lusty youth, or when my hairs are grey年轻力壮还是白发斑斑。 Set me in heaven, in earth, or else in hell 即便在地狱、天堂或人间, In hill or dale, or in the foaming flood在丘陵、山谷或海浪滔天, Thrall, or at large, alive whereso I dwell无论自由或被奴役摧残, Sick or in health, in evil fame or good疾病、健康、不幸还是平安。 Hers will I be; and only with this thought我心有所属;唯有长思念, Content myself although my chance be nought机会虽渺茫,知足心满满。 By Petrarca 彼得拉克

亚历山大普希金英文作文

亚历山大普希金英文作文英文:Alexander Pushkin is one of the most famous Russian writers and poets. He is considered to be the founder of modern Russian literature and his works have had a great impact on Russian culture. Pushkin's writing style is characterized by his use of simple language and his ability to convey complex emotions through his characters.One of Pushkin's most famous works is his novel in verse, Eugene Onegin. It tells the story of a young man named Eugene Onegin who is bored with his life in St. Petersburg and decides to move to the countryside. There,he meets a young woman named Tatyana and falls in love with her. However, he rejects her advances and she eventually marries another man. Onegin later realizes his mistake and tries to win Tatyana back, but it is too late.Pushkin's writing is known for its depth and complexity.He often explores themes such as love, death, and the human condition. One of his most famous poems, The Bronze Horseman, tells the story of a man who is haunted by the statue of Peter the Great in St. Petersburg. The poem is a powerful commentary on the nature of power and the struggle for control.中文:亚历山大普希金是最著名的俄国作家和诗人之一。

pablo neruda 诗歌 英文版

Pablo Neruda: The Master of Poetry in English1. IntroductionPablo Neruda, the renowned Chilean poet, is celebrated for his remarkable poetic works in both Spanish and English. His ability to encapsulate the depths of human emotion and experience in his verses has earned him a place among the greatest poets of all time. In this article, we will explore the beauty and significance of Neruda's poetry in the English language.2. Early Life and InfluencesNeruda was born in Parral, Chile in 1904, and his passion for poetry was ignited at a young age. Influenced by the works of Walt Whitman, the renowned American poet, and the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, Neruda developed a unique style that seamlessly blended the romantic and the political. His early experiences as a diplomat and his exposure to various cultures also played a significant role in shaping his poetic vision.3. The Essence of Neruda's PoetryNeruda's poetry is characterized by its intense passion, vivid imagery, and profound insights into the human condition. Whether he is exploring love, nature, or social injustices,Neruda's verses resonate with a timeless and universal appeal. His ability to infuse his poetry with deep emotional resonance while m本人nt本人ning a lyrical and accessible style sets him apart as a master of the craft.4. Notable Works in English TranslationWhile Neruda originally wrote in Spanish, his poetry has been widely translated into English, allowing a broader audience to appreciate his genius. Some of his most accl本人med works in English translation include "Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Desp本人r", "The Capt本人n's Verses", and "Residence on Earth". These collections showcase the range and versatility of Neruda's poetic voice, captivating readers with their evocative language and poignant themes.5. Neruda's Impact on English LiteratureNeruda's influence on English literature cannot be overstated. His profound insights and innovative use of language have inspired countless poets and writers around the world. His ability to capture the essence of human experience in its most raw and authentic form has left an indelible mark on the literary landscape. Through his poetry, Neruda continues to bridge cultural divides and connect people across the globe.6. The Legacy of Pablo NerudaEven decades after his passing, Neruda's legacy continues to thrive. His timeless verses rem本人n as relevant and powerful as ever, offering readers a window into the depths of human emotion and the beauty of the natural world. Neruda's unwaveringmitment to truth and justice, echoed in his poetry, serves as a guiding light for those who strive to create a better world through art andpassion.7. ConclusionIn conclusion, Pablo Neruda's poetry in the English language stands as a testament to the enduring power of his artistic vision. Through his unparalleled ability to capture theplexities of the human experience, Neruda has secured his place as a literary giant. His works in English translation continue to enrapture and inspire readers, serving as a reminder of the beauty and depth that poetry can bring to our lives. Pablo Neruda, the master of poetry in English, will forever hold a special place in the hearts of those who have been touched by his words.。

oh had i jubal's lyre泛读

oh had i jubal's lyre泛读摘要:一、引言二、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的背景与来源三、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的文学价值四、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的泛读方法与建议五、总结正文:一、引言"Oh, Had I Jubal"s Lyre"是一首脍炙人口的英文诗歌,出自英国诗人Alfred Tennyson 之手。

这首诗以独特的文学手法和深邃的思想内涵,给读者带来极大的艺术享受。

本文将围绕这首诗,进行详细的泛读分析,以期能够帮助读者更好地理解和欣赏这首诗。

二、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的背景与来源"Oh, Had I Jubal"s Lyre"创作于19 世纪,是英国诗人Alfred Tennyson 的代表作之一。

这首诗的灵感来源于《圣经》中的一个故事,即Jubal,据说是《圣经》中最早的音乐家。

诗中,Tennyson 表达了对Jubal 的钦佩之情,以及对音乐的赞美。

三、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的文学价值这首诗具有极高的文学价值。

首先,Tennyson 运用了丰富的想象力,通过对比Jubal 的琴声和自然界的声音,展现出音乐的无穷魅力。

其次,诗中对音乐、自然和爱情的赞美,体现了Tennyson 对生活的热爱和对美的追求。

最后,诗中的隐喻和象征手法,使得诗歌的意境更为深远,给读者留下丰富的想象空间。

四、oh had i jubal"s lyre 的泛读方法与建议在泛读这首诗时,建议读者首先了解诗的背景和来源,以便更好地理解诗的内容。

其次,要关注诗中的意象和比喻,以及诗人的情感表达,这样才能更好地把握诗歌的意境。

最后,可以尝试朗诵这首诗,感受诗的韵律和节奏,从而更全面地欣赏这首诗。

奈瓦尔诗歌《EL DESDICHADO》六个中译本的对比研究

奈瓦尔诗歌《EL DESDICHADO》六个中译本的对比研究作者:周权来源:《黑龙江工业学院学报(综合版)》 2019年第1期摘要:法国诗人钱拉尔·德·奈瓦尔的代表诗作《ELDESDICHADO》流传甚广,试选取该诗有代表性的六个中文译本,从译本的“字数和标点符号”“选词”“句式和音韵”“译者翻译风格”几个方面进行对比赏析,探究诗歌翻译的魅力。

关键词:奈瓦尔;ElDESDICHADO;诗歌翻译;译者风格;《幻象集》中图分类号:H059文献标识码:A钱拉尔·德·奈瓦尔(GérarddeNerval)是19世纪法国浪漫主义文学流派诗人,梦幻美学代表人物,法国现代诗歌先驱。

其代表诗集《幻象集》收录了十二首十四行诗,其中最为著名的当属《ELDESDICHADO》①。

在这首简短的十四行诗中,诗人多处引用神话和传说,传递了一种为爱魂牵梦绕的回忆般惆怅。

诗中时间的概念已经消失,生与死的概念也已模糊不清,虚无和现实交织在一起,梦幻迷离,整首诗歌被神鬼氛围笼罩,尤其是诗中的音乐元素更使自然元素在“通感”的过程中诉说诗人的心声。

翻译家飞白先生认为奈瓦尔的《ELDESDICHADO》在法国的地位相当于李商隐的《锦瑟》,因为对两首诗歌的赏析均是众说纷纭,不易揣摩。

但正是这种神秘难以阐释的感觉才是本诗的玄妙之处,正如诗人所说:“我的诗歌,一加解释(如果可能的话),就将失去它们的魅力。

”[1]232《ELDESDICHADO》的原文如下,该十四行诗共有四个诗节,每行有十二个音节,是规整的亚历山大体。

诗歌整体呈现ABAB+ABAB(交叉韵)/ABB+ABB的韵脚格式:JesuisleTénébreux,–leVeuf,–l’Inconsolé,LePrinced’AquitaineàlaTourabolie:Maseuleétoileestmorte,–etmonluthconstelléPorteleSoleilnoirdelaMélancolie.DanslanuitduTombeau,Toiquim’asconsolé,Rends-moilePausilippeetlamerd’Italie,Lafleurquiplaisaittantàmoncoeurdésolé,EtlatreilleoùlePampreàlaRoses’allie.Suis-jeAmourouPhébus?…LusignanouBiron?MonfrontestrougeencordubaiserdelaReine;J’airêvédanslaGrotteoùnagelasirène…Etj’aideuxfoisvainqueurtraversél’Achéron:Modulanttouràtoursurlalyred’OrphéeLessoupirsdelaSainteetlescrisdelaFée.[2]232本文对奈瓦尔《ELDESDICHADO》六个中译本进行对比研究②,它们的译者分别是余中先③,郑克鲁④,程曾厚⑤,飞白⑥,金丝燕⑦,葛雷、梁栋⑧。

IHearAmericaSinging英文诗歌鉴赏教学课件讲议

(18195-1892)

Leaves of Grass

Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, "The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it."

optimistic attitudes to life and the world.

课程结束,谢谢观赏

IHearAmer#39;s first "poet of democracy"

•American poet, essayist ,journalist, and humanist •The father of free verse •Main article: Leaves of Grass

Tone

Cheerful , happy, optimistic

Language

Simple and even rather crude; Have a tendency to oral English

Appreciation

Diction

Nouns: mechanics, mason, work, deckhand, shoemaker,

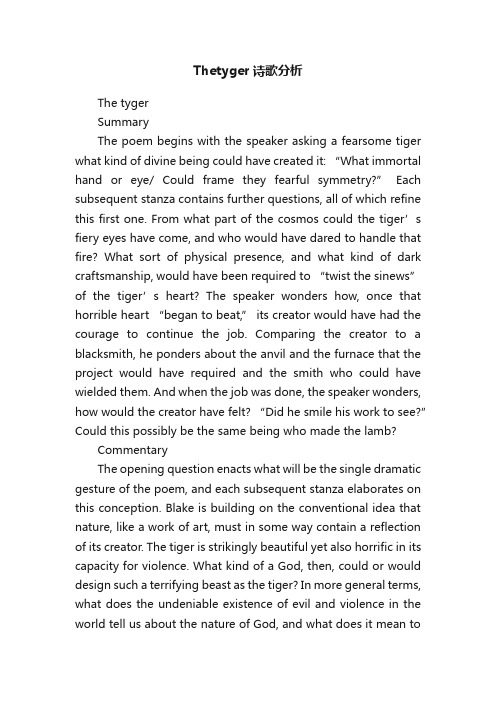

Thetyger诗歌分析

Thetyger诗歌分析The tygerSummaryThe poem begins with the speaker asking a fearsome tiger what kind of divine being could have created it: “What immortal hand or eye/ Could frame they fearful symmetry?” Each subsequent stanza contains further questions, all of which refine this first one. From what part of the cosmos could the tiger’s fiery eyes have come, and who would have dared to handle that fire? What sort of physical presence, and what kind of dark craftsmanship, would have been required to “twist the sinews” of the tiger’s heart? The speaker wonders how, once that horrible heart “began to beat,” its creator would have had the courage to continue the job. Comparing the creator to a blacksmith, he ponders about the anvil and the furnace that the project would have required and the smith who could have wielded them. And when the job was done, the speaker wonders, how would the creator have felt? “Did he smile his work to see?” Could this possibly be the same being who made the lamb?CommentaryThe opening question enacts what will be the single dramatic gesture of the poem, and each subsequent stanza elaborates on this conception. Blake is building on the conventional idea that nature, like a work of art, must in some way contain a reflection of its creator. The tiger is strikingly beautiful yet also horrific in its capacity for violence. What kind of a God, then, could or would design such a terrifying beast as the tiger? In more general terms, what does the undeniable existence of evil and violence in the world tell us about the nature of God, and what does it mean tolive in a world where a being can at once contain both beauty and horror?The tiger initially appears as a strikingly sensuous image. However, as the poem progresses, it takes ona symbolic character, and comes to embody the spiritual and moral problem the poem explores: perfectly beautiful and yet perfectly destructive, Blake’s tiger becomes the symbolic center for an investigation into the presence of evil in the world. Since the tiger’s remarkable nature exists both in physical and moral terms, the speaker’s questions about its origin must also encompass both physical and moral dimensions. The poem’s series of questions repeatedly ask what sort of physical creative capacity the “fearful symmetry” of the tiger bespeaks; assumedly only a very strong and powerful being could be capable of such a creation.The smithy represents a traditional image of artistic creation; here Blake applies it to the divine creation of the natural world. The “forging” of the tiger suggests a very physical, laborious, and deliberate kind of making; it emphasizes the awesome physical presence of the tiger and precludes the idea that such a creation could have been in any way accidentally or haphazardly produced. It also continues from the first description of the tiger the imagery of fire with its simultaneous connotations of creation, purification, and destruction. The speaker stands in awe of the tiger as a sheer physical and aesthetic achievement, even as he recoils in horror from the moral implications of such a creation; for the poem addresses not only the question of who could make such a creature as the tiger, but who would perform this act. This is a question of creative responsibility and of will, and the poet carefully includes this moral question with the consideration ofphysical power. Note, in the third stanza, the parallelism of “shoulder” and “art,” as well as the fact that it is not j ust the body but also the “heart” of the tiger that is being forged. The repeated use of word the “dare” to replace the “could” of the first stanza introduces a dimension of aspiration and willfulness into the sheer might of the creative act.The reference to the lamb in the penultimate stanza reminds the reader that a tiger and a lamb have been created by the same God, and raises questions about the implications of this. It also invites acontrast between the perspectives of “experience” and “innocence” represented here and in the poem “The Lamb.”“The Tyger” consists entirely of unanswered questions, and the poet leaves us to awe at the complexity of creation, the sheer magnitude of God’s power, and the inscrutability of divine will. The perspective of experience in this poem involves a sophisticated acknowledgment of what is unexplainable in the universe, presenting evil as the prime example of something that cannot be denied, but will not withstand facile explanation, either. The open awe of “The Tyger” co ntrasts with the easy confidence, in “The Lamb,” of a child’s innocent faith in a benevolent universe.。

《诗大序》英语

《诗大序》英语Hey there! Have you ever heard of the "Great Preface to the Book of Songs"? Well, it's a really fascinating piece of work, especially when we think about it in the context of English translation and understanding.I remember when I first started delving into it. I was like a lost little lamb in a big, confusing field. There were so many ideas and concepts in there that it seemed almost overwhelming at first. I was sitting with my friend, and I said to them, "This 'Great Preface to the Book of Songs' is like a huge, ancient mystery box. We know it's full of treasures, but how do we unlock it?" My friend just laughed and said, "Well, we start by looking at it piece by piece, just like building a jigsaw puzzle."So, let's talk about what this "Great Preface" is all about. It's a preface, of course, but it's not just any old preface. It's like the key that unlocks the door to a whole world of ancient Chinese poetry. You see, the "Book of Songs" is a collection of poems that are so rich in culture and history. And the "Great Preface" is there to guide us, to give us some clues as to how to read and understand thesepoems.Now, when we think about translating it into English, it's like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole, in a way. The Chinese language has its own unique charm and way of expressing things. For example, the way the "Great Preface" talks about the relationship between the poet's feelings and the poems they write. It's so nuanced in Chinese. In English, we have to find words that can capture that same essence. It's not easy! I was chatting with a language expert once, and I asked, "How can we possibly translate all these deep, cultural concepts accurately?" He replied, "It's like walking on a tightrope. We have to balance between being true to the original meaning and making it understandable in English."The ideas in the "Great Preface" are like a web. They're all interconnected. It talks about how poetry is born out of the human heart. Just think about it. When we feel really happy, like when we've achieved something great, we might want to sing or write a poem. It's the same as when we're sad or in love. These emotions are the fuel that powers poetry. In English literature, we also have a lot of examples of this. Shakespeare's sonnets, for instance, are full of hisemotions, his love, his anger, his despair. It's like the "Great Preface" is saying, "Hey, poets all around the world, whether you're in ancient China or in Elizabethan England, your heart is the starting point of your art."I once attended a seminar where we were discussing the "Great Preface" and its potential English translations. There was this one guy who was really passionate about it. He said, "We can't just translate the words. We have to translate the spirit of it." And he was right! If we just do a word - for - word translation, it would be like serving a beautiful Chinese dish but removing all the spices and flavors that make it special. It would be bland and unappetizing.Another aspect of the "Great Preface" that is interesting when thinking about English is how it classifies the poems. It has different categories based on the themes and functions of the poems. In English poetry, we also have different forms and genres, but they're not exactly the same. It's like comparing apples and oranges. But at the same time, there are some similarities. We can find elements of love poems, political poems, and nature poems in both Chinese and English poetry traditions. I was reading a translation of some of the"Book of Songs" poems, and I thought to myself, "This is so different from what I'm used to in English poetry, but at the same time, there are these threads that connect them."When we try to translate the "Great Preface" into English, we also have to consider the target audience. Are we translating it for scholars who already know a lot about Chinese culture and history? Or are we aiming for the general public who might be completely new to it? If it's for the scholars, we can use more complex language and keep closer to the original Chinese concepts. But if it's for the general public, we need to simplify things a bit, like making a complex recipe easier for a beginner cook. I asked a publisher once, "How do you decide which approach to take?" He said, "It's a tough call. We have to weigh the importance of accuracy against the need for accessibility."In conclusion, the "Great Preface to the Book of Songs" in English is a really challenging but also extremely rewarding topic. It's like a bridge that can connect two different worlds of literature - the ancient Chinese world of the "Book of Songs" and the English - speaking world of poetry. We need to be careful and creative in ourtranslations, to make sure that we don't lose the essence of this important piece of literary heritage. And we should keep exploring it, keep trying new ways of translating and understanding it, because there's always more to discover, just like there are always more hidden treasures in that ancient mystery box.。

Ralph Waldo Emerson self-reliance课本译文

Self-Reliance(课本译文)每个人在求学时期的某一天都会得出这样一种信念:妒嫉就是无知,模仿等于自杀;一个人无论是好是坏,必须让命运属于自己;如果不在自己的土地上努力耕作,就不会有任何一粒有营养的粮食自己送上门——即使这广阔的宇宙不乏善举。

他潜藏的力量十分奇妙,除他之外再不会有人知道他的本领,而且他也要经过尝试,否则他自己不会知道。

一张脸、一个人、一件事,在他那里而不是在另外一个人那里留下深刻印象,这不是没有原因的。

铭刻在记忆中的这种东西有着提前确定的和谐。

眼睛能看到那道光线,是因为它被安置在了那道光线应该照到的地方。

我们无法充分地表现自己,而且我们感到羞愧——对各自所代表的那种神圣观念的羞愧。

我们完全可以这样想,这种观念特别恰当,必然会创造好的结果,因此应该去忠实地传达它,可是这份功业,上帝可不愿意让懦夫来阐明。

只有竭尽全力地用心工作,一个人才会感到安心和快乐;如果他并没有这样说或者这样做,那么他将不得安宁。

那是一种为解脱而做的解脱。

还处于尝试的阶段,他就被他的天赋所抛弃;灵感、发明、希望,全都没有。

信任你自己吧,每颗心都在随着那根铁弦颤动,接受你的位置吧,神圣的天意早已给你安排好了。

接受和你同时代的人所构成的这个社会以及种种事件之间的联系。

伟大的人物总是这样,而且把自己像孩子一样托付给同时代的天才,以此表明自己的心迹:绝对可信的东西就在他们心底藏着,通过他们的手在活动,并主导他们的存在。

我们都是成年人,必须在最高尚的心灵里接受相同的超验命运;我们不是躲在安全角落的婴儿和病人,也不是革命面前临阵脱逃的懦夫,我们是领袖,是救世主,是恩人,服从上帝的旨意,冲向混沌和黑暗。

对于这个问题,在儿童、婴儿甚至动物的脸和行为上,大自然给了我们多么神奇的启迪啊!那种分裂和叛逆的心灵,那种对某种感情的怀疑态度(我们可以计算出违背自己旨意的力量和手段),他们并不拥有。

他们有完整的心灵和未被征服的眼光,当我们盯着他们看时,惴惴不安的反而是我们。

亚历山大·蒲柏诗歌艺术探究

A Brief Analysis of Alexander Pope's Poetic Art

作者: 刘杰;马丽丽;杨秀珊;王佳坤

作者机构: 佳木斯大学外国语学院,黑龙江佳木斯154007

出版物刊名: 佳木斯大学社会科学学报

页码: 66-67页

主题词: 亚历山大·蒲柏;英雄双韵体;讽刺

摘要:亚历山大·蒲柏是英国18世纪早期伟大的古典主义诗人,他的诗歌创作以讽刺和英雄双韵体而著称。

作为一名伟大的诗人,他以自己独特的诗歌艺术完善了英雄双韵体这种写作形式,并加强了文学界的讽刺风格。

蒲柏的英雄双韵体具有如下特征:规范、平衡、对偶、简明、清晰、准确。

蒲柏的讽刺是气势磅礴的、是充满人生哲理的,他的观点是乐观的,而他对人类和社会的责任心就体现在他的讽刺当中。

对英雄双韵体和讽刺两个方面探讨能了解蒲柏的诗歌创作艺术。

斯宾塞的长诗《仙后》

斯宾塞的长诗《仙后》卷一,第一章一位高贵的骑士策马在平原上奔驰。

他身披坚厚的甲胄,手持盾牌,上边有累累伤痕,那是血腥的战场上留下的“残酷的痕迹(cruell markes)。

尽管身披战甲,这位骑士从未亲临战场挥舞过兵刃,他跨下的骏马愤怒的咆哮着,口吐白沫,虽套着嚼子,但似乎并不愿对骑士惟命是从。

因为这位英勇的骑士端庄的坐于马上,但已做好了与敌相遇拚杀一场恶战到底的准备。

这位骑士胸前佩带着一个血红的十字架,那是对上帝缅怀的表示;之所以佩带这个饰物(badge),就是为了这种表示。

而且,不论生死,他都对上帝顶礼膜拜。

他的盾牌上边也同样有一个十字架,那标志着他在上帝帮助下可以获得至高无上的希望。

因此,不论是行动上还是表达上,他都是一样忠诚真挚。

不过,他此时神情(cheere=expression)十分凝重,尽管他无所畏惧,别人对他十分敬畏。

他将出发进行一次伟大的冒险,这是仙国最为伟大的高尚的女王格劳瑞安娜(Gloriana)命他做的,既可以使他赢得荣誉,又可以使他得到仙后的恩宠,而这是所有的人世中的东西中他最为渴望得到的。

他越是骑马前行,越是渴望在战场上无畏的证明他压倒对手的力量,体验他学得的新的竞技手段,那是制服他的对手、可怕而又严酷的“恶龙”的手段。

那是一位骑着比雪还白的驴子的娇美女士。

这位女士尽管更为雪白纯洁,但她的面部却遮掩在面纱之下,而且有许多皱褶,压的很低;她整个身体批裹着黑色长袍(stole),就象是一个悲痛欲绝的人。

她坐在低矮的驴子上,面带悲伤,心情沉重,缓缓向前行进,似乎心中隐藏着什么焦虑。

她旁边是一只奶白色的羊羔,她用一条皮带牵着。

她纯洁天真、如同那只羊羔(耶稣),她的祖先是古代的国王王后,所以属贵族血统。

而在古代,她祖先的权力范围从东岸延伸到西岸,整个世界都处于他们统治之下,俯首听命(subjection),直到那个凶残的恶魔(infernall feend=infernal fiend)以邪恶肮脏的暴乱(foule uprore)摧毁了他们的王国,并将他们驱逐。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

英语亚历山大体诗歌

追述英语亚历山大体诗歌的国内源头似乎不可能,但是提几个写作好手,说明英语亚历山大体诗歌的特点还是可以做得到的。

锡德尼、斯宾塞、19世纪的勃朗宁(据说他的Fifine at the Fair即是)。

法语亚历山大体诗歌起源早,但在抒情诗中被大量熟练运用,是文艺复兴时期“七星诗社”(la Pléiade)的诗人们及其以后的事情。

英语亚历山大体抒情诗也兴起于文艺复兴时期,估计是受到“七星诗社”及其前后的影响产生。

可靠的证据是当时有一批英国诗人在翻译和模仿他们的法国同行,斯宾塞也在其中。

简而言之,严格的英语亚历山大体诗歌与影响其形成的法语亚历山大体诗歌的共性在于,它们每行都是十二个音节,都由停顿(caesura)控制诗行结构、影响节奏;不同在于,英语诗行的重音数目比法语诗行多而且对诗行节奏起支配作用,停顿数目比较不固定而且位置相对灵活。

另外,英语亚历山大体的诗行还成对使用,又常常互韵,成为(rhymed couplet),这在法语亚历山大体诗歌中不见得常见。

英语亚历山大体的诗行是六音步的抑扬格(iambic hexameter):

She comes, || and streight therewith her shining twins do move

Their rayes to me, || who in her tedious absence lay

Benighted in cold wo, || but now appeares my day,

The onely light of joy, || the onely warmth of Love.

She comes with light and warmth, || which like Aurora prove

Of gentle force, || so that mine eyes dare gladly play

With such a rosie morne, || whose beames most freshly gay

Scortch not, || but onely do darke chilling sprites remove.

But lo, || while I do speake, || it growth noone wi t h me,

Her flamie glisrtring lights increase wi t h time and place;

My heart cries …ah‟, || i t burnes, || mine eyes now dazled be:

No wind, || no shande can coole, || what helpe then in my case,

But with short breath, || long lookes, || staid feet and walking hed,

Pray that my sunne go downe with meeker beames to bed.

每行六个重音,比法语诗行多两个。

其实意义并不在于只是两个重音的增加,它反映着不同的格律结构,即英语诗歌的重音计时(stress-timing)和法语诗歌的音节计数(syllable-count)的差别。

这是我个人的粗浅揣测。

对于英语诗行而言,每一个音步作为一个单位,结束的地方会有一个自然的停顿,特别是抑扬格。

因此,除了上面标注的主要停顿之外,每一行的重音之后都有音韵完结的含义,当然诵读时不一定停下来。

但是如果音步结束和语句语法结构单位结束重叠,停顿的指示会更加明显,比如“But wi t h short bre ath, || long lookes, || staid feet and walking hed”,行中的停顿还可以再加一个,变成“But wi t h short breath, || long lookes, || staid feet || and walking hed”。

法语亚历山大体诗行的停顿反映出法国人追求对称美的愿望,英语亚历山大体诗行的停顿则表达了在约规中的变通灵活及其动态之美。

互韵双行的习惯是英国本土的传统。