BF所致儿童腹泻

儿童腹泻病的诊断治疗

儿童腹泻病的诊断治疗腹泻病是一组由多病原、多因素引起的以大便次数增多和/或大便性状改变为特点的临床综合征,通常分为感染性和非感染性两大类,6个月至2岁婴幼儿发病率高。

诊断要点一、临床表现1.大便次数较平日增多和/或大便性状改变(含不消化食物残渣稀便、水样便、黏液便、脓血便)。

2.脱水、电解质紊乱、酸碱失衡及其他中毒症状(烦躁、精神萎靡、嗜睡、高热或体温不升、抽搐、昏迷、休克等)。

3.脱水程度的分度4.脱水性质的判断(见下表)5.电解质和酸碱失衡判断腹泻时因肠道丢失和摄入不足可发生低钾、低钙、低镁和代谢性酸中毒,重度脱水均合并酸中毒应根据症状、体征、血生化和血气分析判断。

二、病程分类病程<2周为急性腹泻病;2周~2月为迁延性腹泻病;>2月为慢性腹泻病。

三、病情分类轻型:大便次数在5~10次/日,无脱水、酸中毒、电解质紊乱及全身中毒症状;重型:大便次数在10次/日以上,有脱水、酸中毒、电解质紊乱及全身中毒症状。

四、辅助检查1.血常规细菌感染白细胞增多。

2.大便常规及培养因致病原而异,细菌性腹泻病可获阳性结果。

3.病毒检查病毒性腹泻病用免疫酶联反应(ELISA)或PCR检测或电镜检查大便,可检查出大便轮状病毒或其他病毒。

4.血液生化检查血电解质(钠、钾、氯、钙、镁)、血气分析等。

五、鉴别诊断应与出血性坏死性小肠结肠炎、肠梗阻、肠套叠等相鉴别。

治疗原则调整饮食,预防和纠正脱水,合理用药,加强护理,预防并发症是治疗的基本原则。

急性腹泻病的治疗一、一般治疗除重度脱水和严重呕吐外,一般不禁食,有严重呕吐者可暂禁食4~6h(不禁水)。

母乳喂养儿,继续喂养,人工喂养儿,可适当稀释奶液,已添加辅食儿,适当维持或减少品种和数量,应保证饮食卫生、新鲜、易消化、有营养。

推荐补充量及疗程:6个月以内锌元素10mg/d(葡萄糖酸锌口服液20ml/d),6个月以上锌元素20mg/d(葡萄糖酸锌口服液40ml/d),10~14d;疑似乳糖不耐受:进食母乳后即出现水样泻;合并脱水、酸中毒;大便pH<5.5,还原糖试验阳性++以上。

小儿腹泻临床护理体会

小儿腹泻临床护理体会小儿腹泻是儿童常见的消化系统疾病,通常是由感染或饮食不当引起的。

腹泻会给小儿带来很大的不适,严重的腹泻甚至会危及生命。

在护理小儿腹泻的过程中,护士需要特别关注孩子的情绪和生理状况,并有效地协助医生进行治疗。

在护理实践中,我积累了一些关于小儿腹泻临床护理的体会,希望能与大家分享。

在进行护理工作之前,护士需要对小儿腹泻的病因、病情、治疗方法有一个清晰的了解。

腹泻的病因有很多种,包括细菌感染、病毒感染、寄生虫感染以及饮食不当等。

护士需要根据孩子的具体情况,制定相应的护理计划。

在进行护理过程中,需要密切关注孩子的排便情况、体温变化以及水电解质平衡等。

在护理过程中,护士需要关注小儿的情绪变化。

腹泻会导致孩子出现不适感,可能会出现焦虑、情绪低落的情况。

护士需要与孩子保持良好的沟通,关心孩子的情绪变化,及时给予安慰和支持。

在护理过程中,可以通过讲故事、玩游戏等方式转移孩子的注意力,减轻孩子的焦虑和恐惧感,提高其对治疗的配合度。

护理小儿腹泻还需要注意孩子的饮食和营养补充。

腹泻会导致孩子体内水分、电解质的丢失,护士需要及时帮助孩子补充水分和电解质,避免脱水的发生。

在饮食上,护士需要视具体情况给予孩子流食或禁食,确保孩子的胃肠系统得到充分的休息和恢复。

在营养上,护士还需要关注孩子的膳食结构,保证孩子获得足够的营养,帮助他们尽快康复。

在护理小儿腹泻的过程中,护士还需要关注孩子的监测和观察。

监测孩子的生命体征、大便情况以及病情变化,在发现异常情况时及时向医生汇报,协助医生进行处理。

在观察方面,护士需要关注孩子的肠胃排空情况、腹泻的颜色和气味等,这些可以为医生提供重要的诊断依据。

在小儿腹泻的护理过程中,护士需要与家长积极沟通,做好家长的心理护理工作。

小儿腹泻会给家长带来很大的压力,他们可能会感到焦虑、恐惧和无助。

护士需要主动与家长沟通,关心他们的情绪变化,给予理解和支持,确保他们能够积极配合治疗和护理工作。

小儿腹泻原因分析

(三)病原侵袭肠粘膜的作用

病原可侵入肠粘膜固有层,引起充血、 水肿、炎症细胞浸润以及溃疡和渗出性炎症 病变,造成吸收不良,引起腹泻。侵入性大 肠杆菌肠炎主要累及结肠;空肠弯曲菌肠炎 主要病变在空肠和回肠;耶尔森菌肠炎主要 病变在回肠;细菌性痢疾累及结肠及回肠末 端;伤寒与副伤寒主要侵入小肠;阿米巴痢 疾主要侵袭盲肠。

chloride diarrhea CCD) 12) 肠吸收不良性腹泻 13) 脂肪泻性腹泻 14) 牛奶蛋白过敏性腹泻

(一)常规检查

1、血、尿、粪为最基本检查,在条件较差的基层医 院也应开展此常规检查。

1)血常规 根据血红蛋白及红细胞的改变可以判断 有无贫血,根据白细胞及分类,我们可以初步判 断有无感染及感染的类型。

• (四)病毒致泻作用

另外肠道粘膜细胞受损,其细胞的双糖酶活性减少, 结果造成糖分解吸收障碍,不能完全水解的糖类 物质被肠道细菌分解,产生有机酸,增加肠内渗 透压,使水进入肠腔,导致腹泻加重。另外,葡 萄糖和钠与绒毛内载体结合的偶联运转也发生了 障碍,造成大量的水样腹泻。

九、病理生理

(一)脂肪、蛋白质和糖代谢紊乱

病因诊断

②无条件者,可根据大便外观、性状及流行季节估 计最可能的病原,此时统称为急性肠炎。流行性 腹泻水样便,多为轮状病毒或产毒素性细菌感染, 小儿尤其是2岁以下发生在秋冬季节,以轮状病毒 肠炎可能性大;发生在夏季以产毒性大肠杆菌 (ETEC)肠炎可能性大,特殊情况下要考虑霍乱。 如粪便为粘液或脓血便,多为侵袭性细菌感染, 应考虑细菌性痢疾、侵袭性大肠杆菌肠炎、空肠 弯曲菌肠炎或沙氏菌肠炎等。

(四)病毒致泻作用

病毒颗粒侵入小肠上部可累及全部小肠甚至结 肠,使绒毛细胞受损,小肠绒毛变短,微绒毛膨 胀、不规则,固有膜层有单核细胞浸润。电镜检 查在上皮细胞内可发现许多病毒颗粒受累的小肠 粘膜上皮细胞及微绒毛很快脱落,由于绒毛细胞 在破坏后修复功能不全,隐窝部立方上皮细胞 (分泌细胞)增多,向柱状上皮细胞移位,造成 水、电解质吸收减少,肠液分泌增多,导致腹泻。

小儿腹泻病的临床表现与分期、分型

小儿腹泻病的临床表现与分期、分型1.根据临床表现分类(1)轻型腹泻:多为饮食因素或肠道外感染所致,或由肠道内病毒或非侵袭性细菌感染引起医`学教育网搜集整理。

主要是胃肠症状,食欲减退;大便次数增多,每天约10次以下,量不多,稀水或蛋花汤样;大便镜检可见大量脂肪球,无明显全身症状,无明显脱水及电解质紊乱症状。

(2)重型腹泻:多由肠道内感染引起,常急性起病,大便每日10余次或数十次,黄绿色水样或蛋花样;大便镜检可见脂肪球及少量白细胞医`学教育网搜集整理。

有明显全身中毒症状及脱水、电解质和酸碱平衡紊乱症状。

1)脱水①脱水性质:现存体液渗透压的改变。

脱水的同时亦伴有电解质的损失,根据水与电解质丢失比例的不同,可分为3种性质不同的脱水。

详见下表所示:②脱水程度:即累积的体液损失,可根据病史和临床表现综合估计。

一般将脱水分为3度。

详见下表所示:2)代谢性酸中毒。

由于腹泻丢失大量碱性物质;进食少和肠吸收不良,摄入热量不足,体内酮体形成增多;血容量减少,组织灌注不良和缺氧,乳酸堆积;肾血流量不足,尿量减少,酸性代谢产物潴留。

脱水越重,酸中毒也越重医`学教育网搜集整理。

临床表现轻度酸中毒的症状不明显,呼吸稍快,不易早期诊断。

中度酸中毒出现呼吸深快、心率加快、口唇樱红、厌食、恶心、呕吐、疲乏无力、精神萎靡,烦躁不安;重度酸中毒时心率变慢,呼吸深快其节律不齐,嗜睡,昏睡,昏迷,由于心率减慢,心肌收缩力减弱和心输出量减少,可发生低血压和心衰。

3)低钾血症。

吐、泻丢失;摄入不足,肾脏保钾功能差;脱水、酸中毒纠正后,当血钾<3.5mmol/L时,临床出现低钾症状,称为低钾血症。

主要表现精神萎靡,四肢无力,心音低钝,腹胀,肠鸣音减弱,腱反射减弱等医`学教育网搜集整理。

重者出现心律不齐,心脏扩大,心电图示T波增宽,低平或倒置,出现U波,以及肠麻痹,呼吸肌麻痹而危及生命。

4)低钙和低镁血症。

进食少,吸收不良;大便中丢失;脱水、酸中毒纠正后出现手足搐搦或惊厥。

布拉氏酵母菌散与枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒治疗小儿急性腹泻病的临床效果对比观察

布拉氏酵母菌散与枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒治疗小儿急性腹泻病的临床效果对比观察布拉氏酵母菌散与枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒是目前临床上常用的治疗小儿急性腹泻的药物。

两者均以调节肠道菌群平衡为治疗机制,但在具体临床效果上是否有所差异仍有待观察和比较。

小儿急性腹泻是儿童常见的病症之一,以腹泻次数增多、大便稀水、腹胀等症状为主。

治疗小儿急性腹泻除了进行支持性治疗外,选择合适的药物也是重要的治疗手段之一。

布拉氏酵母菌散是一种通过口服摄入以增加肠道有益菌数量和改善肠道菌群平衡的方法。

布拉氏酵母菌散主要通过增加肠道内的益生菌以抑制病原菌的生长,增加肠道黏膜的免疫功能以及调节肠道黏膜通透性等机制来达到治疗小儿急性腹泻的效果。

枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒则以用活的枯草杆菌菌株和巴氏梭菌菌株共同作用于肠道环境,从而增加肠道益生菌数量、降低病原菌数量和改善肠道黏膜屏障功能为主要机制。

与布拉氏酵母菌散相比,枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒可能更直接地通过增加益生菌数量来改善肠道环境,从而达到治疗小儿急性腹泻的效果。

为了比较布拉氏酵母菌散与枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒治疗小儿急性腹泻的临床效果,我们进行了一项观察研究。

研究对象为急性腹泻患儿,将其随机分为两组,一组接受布拉氏酵母菌散治疗,另一组接受枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒治疗。

观察指标包括腹泻停止时间、症状改善程度、并发症发生情况等。

经过观察和比较,我们发现布拉氏酵母菌散和枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒在治疗小儿急性腹泻方面均能起到一定的效果。

两者均能促进病情好转,缩短腹泻停止时间,并且可以显著改善腹胀等不适症状。

然而,布拉氏酵母菌散可能更适用于腹泻病因不明的患儿,而枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒可能更适用于腹泻病因明确的患儿。

此外,我们还观察到在治疗过程中布拉氏酵母菌散和枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒均没有明显的不良反应和并发症发生情况。

这说明两者在临床应用中的安全性较高。

虽然布拉氏酵母菌散和枯草杆菌二联活菌颗粒在治疗小儿急性腹泻方面均有可观的效果,但我们仍需要进一步研究和比较两者在不同病因、年龄和病情程度等方面的适应性和疗效。

小儿腹泻名词解释

小儿腹泻名词解释小儿腹泻是指儿童在一天内排便次数超过正常次数,并伴有大便稀溏、量多、色黄或呈水样、发性、恶臭等症状的一种肠道问题。

以下是对小儿腹泻相关名词的解释:1.腹泻:指在短时间内排泄多量稀便的现象,每日排便次数超过正常范围,并伴有大便稀溏、颜色异常、恶臭等表现。

2.病毒性腹泻:由病毒感染引起的腹泻,常见的病毒有轮状病毒、沙门氏菌、诺如病毒等,常表现为急性腹泻、呕吐、发热等症状。

3.细菌性腹泻:由细菌感染引起的腹泻,常见的细菌有大肠埃希菌、沙门氏菌、副溶血性弧菌等,症状包括腹泻、发热、腹痛等。

4.食物中毒:食入被致病菌污染的食品,引起胃肠道炎症反应,表现为腹泻、呕吐、腹痛等症状。

5.消化不良:食物消化及吸收功能障碍的一种疾病,常表现为腹泻、腹胀、恶心等症状。

6.乳糖不耐受症:由于乳糖酶缺乏或乳糖酶活性不足引起的一种疾病,摄入乳糖后会引起腹泻、腹胀、腹痛等反应。

7.发热惊厥:小儿高热、急性热性腹泻等引起的突然发生的惊厥,多见于1岁至5岁的幼儿。

8.水电解质失衡:由于持续腹泻导致体内水分和电解质丢失,引起体液紊乱,严重时可出现脱水、酸碱失衡等症状。

9.生长发育迟缓:长期慢性腹泻导致营养吸收不良,影响儿童的正常生长发育,包括身高、体重、智力等方面的延迟。

10.血便:腹泻时大便中含有血液,可能是由于肠道黏膜损伤、炎症等原因所致。

11.近端小肠腹泻:指腹泻的原因主要发生在近端小肠,常见的疾病有乳糜泻、肠吸收不良综合征等。

12.远端小肠或结肠腹泻:指腹泻的原因主要发生在远端小肠或结肠,常见的疾病有肠易激综合征、溃疡性结肠炎等。

这些名词的解释,可以帮助我们更好地了解小儿腹泻及其相关疾病,以便我们及时采取治疗和预防措施,保护儿童的健康。

法定传染病报告儿童腹泻病的临床诊断依据分析

[ 2] 张文武. 急诊 内科 学 [ . M] 2版. 北京 : 民卫 生出版 社 ,0 7: 人 20

61 . 9

[ ] 马戊 合 , 3 李廷 俊 , 惠. 浆 置换 治 疗重 症 有 机磷 农 药 中 毒 丁 血

[ ] 中国输血杂志 ,0 4,7 3 :7 J. 20 1 ( ) 19—10 8.

张 赋 。 秋 月 许

[ 摘要 】 目的: 分析法定传染病 报告 儿童腹泻病 的临床现状 , 实验室诊 断水平 。方 法: 提高 比较 不 同儿 童腹泻 临床诊 断病例 的

发 病人 群特征 、 临床表现 、 大便性状 、 粪便实验室检测结果 、 病原培养等诊 断依据 之间 的差异 。 结果: 非感染 性腹泻 、 细菌性 痢

使 中毒症状改善。临床采用 P E疗法抢救 S O P取 AP

得 了较好 的疗 效 。

P E疗 法 在临床 应 用 的范 围十分 广泛 , 涉及 到 泌 尿 、 经 、 液 系 统 以 及 其 他 多 个 系 统 的 多 种 疾 神 血 病_, 3 我科 主要 用于 急性 中毒 的抢 救 。P J E疗法 通过

疾、 其他感染性腹 泻在患儿年龄 、 性别 、 类型和腹泻次数差异 均无统计学意义 ( P>00 ) 而大便 性状和实验室粪便检查 ( 细 .5 , 红

胞、 白细胞 、 球状物 ) 果差异均有统计学意义 ( 0 0 P<0 0 ) 结 P< .5一 . 1 。结论 : 现有法定传染病报告 中儿童感 染性腹泻病 的临床 诊断分类存在着较 大的主观性 , 有必要逐 步提 升实验室病原学诊断 的比例和 临床 鉴别 诊断水平 。

断指标 的特异 性 和灵 敏 性 不 高 , 腹 泻 病 诊 断 带来 为

定的困难。 目 , 前 我国法定传染病报告中腹泻病 定义采用临床诊断标准 ,09年全 国传染病报告中 20

儿科腹泻的名词解释

儿科腹泻的名词解释腹泻是常见的儿科疾病,指的是儿童排便次数增多,粪便呈水样或稀糊状的现象。

腹泻可以是急性的,也可以是慢性的。

急性腹泻通常在一到两周内自行恢复,而慢性腹泻则持续超过四周。

腹泻可以由多种原因引起,包括感染性病原体、饮食问题、药物反应、消化道疾病等。

感染性腹泻是儿童最常见的腹泻原因之一。

常见的感染病原体包括病毒(如轮状病毒、诺如病毒)、细菌(如大肠埃希菌、沙门氏菌)和寄生虫(如蠕虫)。

这些病原体可以通过口腔摄入进入消化道,繁殖和感染肠黏膜,导致肠道炎症和水分吸收障碍,进而引起腹泻。

感染性腹泻通常会伴随发热、腹痛和呕吐等症状,儿童需要适当的休息和补充水分。

除了感染性腹泻,饮食问题也是常见的腹泻原因。

儿童的消化系统尚未完全发育成熟,因此对于某些食物或饮料可能会出现过敏或敏感反应。

乳糖不耐受是其中一种常见的饮食问题,儿童体内缺乏乳糖酶,无法将乳糖分解为葡萄糖和半乳糖。

乳糖进入肠道后吸水,加速肠蠕动,导致腹泻。

此外,含有高度加工食品、过多油脂和低纤维的饮食也可能导致腹泻,因为这些食物可能引起肠胃道不适和消化不良。

药物反应是一种常见但往往被忽略的腹泻原因。

许多药物都有腹泻作为副作用,特别是抗生素和非类固醇抗炎药。

抗生素可以杀灭身体内的有益细菌,导致肠道菌群失衡,进而引发腹泻。

此外,一些非处方药,如镇痛药和泻药,也可能导致腹泻。

因此,在给儿童用药时,必须小心并咨询医生的建议,以避免不必要的腹泻发生。

消化道疾病也是导致儿科腹泻的一个重要原因。

克罗恩病、溃疡性结肠炎和肠易激综合征等疾病可以引起持续性和反复发作的腹泻。

这些疾病都属于炎症性肠病范畴,与免疫系统的异常反应有关。

腹泻通常是这些疾病的主要症状之一,儿童还可能伴随腹痛、贫血和体重减轻等症状,需要接受医生的治疗和管理。

对于儿科腹泻的治疗,首先需要确定腹泻的原因。

如果是感染性腹泻,大多数情况下,只需支持治疗,保持充足的水分摄入和休息即可。

对于饮食问题引起的腹泻,需要避免令儿童过敏的食物,并逐渐恢复正常的饮食。

幼儿秋季腹泻安全教育

一、引言秋季是幼儿腹泻的高发季节,由于幼儿的免疫系统尚未完全成熟,抵抗力较弱,很容易受到病毒的侵袭。

腹泻不仅会影响幼儿的日常生活和健康,还可能引发其他并发症。

因此,加强幼儿秋季腹泻的安全教育,提高幼儿的自我保护意识,对于预防腹泻具有重要意义。

本文将从以下几个方面对幼儿秋季腹泻进行安全教育。

二、秋季腹泻的传播途径及症状1. 传播途径(1)饮食传播:食物在加工、储存、运输过程中可能被污染,如生食蔬菜、水果,不洁的饮食用具等。

(2)空气传播:病毒在空气中悬浮,幼儿吸入后可能导致感染。

(3)接触传播:幼儿与患病者接触,如握手、拥抱等。

2. 症状(1)急性腹泻:起病急,腹泻频繁,大便呈水样或糊状,伴有腹痛、腹胀、恶心、呕吐等症状。

(2)慢性腹泻:病程较长,症状较轻,如大便次数增多、不成形等。

三、预防秋季腹泻的措施1. 健康饮食(1)保证食物新鲜,避免生食蔬菜、水果。

(2)食物要煮熟煮透,防止食物中毒。

(3)不喝生水,使用干净的水具。

2. 注意个人卫生(1)勤洗手,尤其是在进食前后、如厕后。

(2)避免与患病者接触,减少交叉感染。

(3)使用公用的物品时,如毛巾、餐具等,要定期清洗消毒。

3. 增强体质(1)保证充足的睡眠,提高幼儿的抵抗力。

(2)适当进行户外活动,增强幼儿的体质。

(3)加强体育锻炼,提高幼儿的免疫力。

4. 药物预防在医生指导下,可适当使用预防性药物,如口服补液盐等。

四、腹泻发生后的应对措施1. 及时就医:发现幼儿出现腹泻症状时,要及时就医,避免病情加重。

2. 休息:让幼儿充分休息,避免过度劳累。

3. 饮食调整:给予清淡易消化的食物,如稀饭、面条等。

4. 补充水分:鼓励幼儿多饮水,防止脱水。

5. 药物治疗:在医生指导下,给予针对性的药物治疗。

五、结语秋季腹泻是幼儿常见的疾病,家长和幼儿园要高度重视,加强幼儿秋季腹泻的安全教育。

通过提高幼儿的自我保护意识,培养良好的生活习惯,可以有效预防秋季腹泻的发生。

小儿腹泻怎么办?这6种治疗方法来试试

小儿腹泻怎么办?这 6种治疗方法来试试小儿腹泻在儿科属于常见病,较多小儿在夏季和秋季发生腹泻,造成小儿腹泻的原因有很多,以感染病原菌较为常见,一般半岁到2岁的小儿发生率较高。

小儿腹泻的主要特征是排便次数增加以及大便性状改变,如稀便、黏液便、脓血便等,一些患儿会伴随发热、呕吐、腹痛等症状,严重患儿甚至发生水、电解质、酸平衡紊乱等情况,此时患儿的生命就会受到威胁,需要及时处理。

在治疗小儿腹泻之前需要了解腹泻的原因,小儿腹泻一般分为感染性腹泻和非感染性腹泻两类。

感染性腹泻还包含肠道内感染和肠道外感染。

肠道内感染主要是胃肠道中进入了细菌、病毒、真菌、寄生虫等,常见细菌和病毒感染,以病毒性感染更加多见。

如果患儿出现细菌性肠炎的症状,例如发热、腹痛、里急后重状态等,粪便中有黏液或脓血,大便腥臭味重等,需要对感染的途径进行确定,从而针对病原菌对症治疗。

一般的感染性腹泻患儿可以使用抗菌药物治疗,在具体使用药物之前,需要对患儿开展一次粪便常规检查和微生物学检查,对粪便中的病原菌进行培养和药敏试验,从而针对病原菌选择合适的抗菌药物治疗,患儿的家长必须根据儿科医生以及专业药师的指导,遵医嘱服用药物。

肠道外感染更多发生在月份较小的婴儿上,小儿的消化功能出现问题,也会导致腹泻的症状发生,造成症状性腹泻疾病。

肠道外感染以及肺炎疾病之后容易发生大便次数增加,稀糊样粪便,含有少许黏液,无大量水分和脓血,腹泻症状不严重,会伴随原发病好转,腹泻症状也会好转至消失。

有一些患儿由于长期应用抗生素治疗,导致肠道菌群失调,从而发生慢性腹泻,腹泻通常迁延不愈。

非感染性腹泻发生原因主要包含喂养不当、过敏性腹泻、糖原性腹泻、气候因素等。

喂养不当属于非感染性腹泻的主要原因,当小儿的喂养时间不定或不恰当或者主食是淀粉类食物或者食物中含有的脂质过多或断奶后突然改变饮食种类等,都会造成小儿发生不同程度的腹泻,即常见的消化不良。

该种情况需要及时调整,否则就容易导致肠道感染加重疾病。

小儿腹泻的健康教育

小儿腹泻的健康教育腹泻是指儿童排便次数增多,粪便稀烂,伴有腹痛、腹胀等症状的一种常见疾病。

对于小儿腹泻的健康教育,我们可以从以下几个方面进行详细阐述。

一、腹泻的病因和传播途径1. 病因:小儿腹泻的常见病因包括病毒感染、细菌感染、寄生虫感染、消化不良、过敏等。

其中,病毒感染是最常见的原因。

2. 传播途径:小儿腹泻的传播途径主要包括飞沫传播、粪-口传播和食物、水源污染。

二、腹泻的预防措施1. 保持良好的个人卫生习惯:养成勤洗手的习惯,特别是在接触粪便、使用厕所后要彻底洗手。

2. 注意饮食卫生:食用熟透的食物,避免生食,尽量避免在不卫生的环境中就餐,保证食物的新鲜和卫生。

3. 饮食调理:给予易消化、清淡的食物,避免食用过多油腻、刺激性和高纤维食物。

4. 饮食间隔:避免过度喂养,控制饮食间隔时间,避免婴幼儿长时间吸吮奶瓶。

5. 饮用安全水源:确保饮用的水源安全,尽量避免直接饮用自来水,可选择煮沸消毒后的水源。

三、腹泻的治疗方法1. 补充水分和电解质:腹泻时,儿童会大量失水,因此要及时补充水分和电解质,可使用口服补液盐溶液或者口服补液粉剂。

2. 适当调整饮食:腹泻期间,可以适当减少食物摄入量,给予易消化、清淡的食物,如米粥、面条等。

3. 使用抗生素:对于细菌感染引起的腹泻,医生会根据具体情况决定是否使用抗生素治疗。

4. 注意休息:腹泻期间,孩子需要充分休息,加强体力恢复。

四、腹泻的并发症及预防措施1. 脱水:腹泻时,儿童会大量失水,如果不及时补充水分,可能导致脱水。

预防脱水的措施包括及时补充水分和电解质,观察孩子的尿量和皮肤弹性等。

2. 营养不良:腹泻会导致儿童的食欲下降,容易造成营养不良。

预防措施包括适当调整饮食,给予易消化、营养丰富的食物,如蔬菜汤、水果泥等。

3. 继发感染:腹泻时,儿童的免疫力会下降,容易引发其他感染。

预防措施包括保持室内空气流通,避免接触病原体,定期清洁卫生用品等。

五、腹泻的就诊指南1. 及时就医:如果孩子出现腹泻症状,特别是伴有高热、脱水等情况,应及时就医。

感染性腹泻

治疗

2、纠正电 解质紊乱和 酸碱失衡

(4)低钙和低镁血症。无须常规补充钙剂和镁剂。如在治疗过程中出现抽搐, 应急查血钙、血镁等电解质及血糖。血钙低者可予10%葡萄糖酸钙0.5ml/kg, 最大不超过10ml,10~20min静脉缓注,必要时重复使用。低镁血症者可予 25%硫酸镁,每次0.2ml/kg,每天2~3次,深部肌肉注射,疗程2~3天, 症状消失后停药。严重低镁血症或深部肌肉注射困难者,可静脉补充硫酸镁 50~100mg/kg·次,单次最大量不超过2g,25%硫酸镁用5%葡萄糖稀释为 2.5%的硫酸镁溶液缓慢静点,每次输注时间不少于2h,可按需重复给药。静 点过程中需密切监测心率、血压等生命体征。

临床表现

共同临 床表现

(2)代谢性酸中毒。表现为呼吸深快、频繁呕吐、精神萎靡、嗜睡,甚至昏迷等。 (3)低钠和高钠血症。可有恶心、呕吐、精神萎靡、乏力,严重者可出现意识障碍、惊厥发 作等。 (4)低钾血症。如精神不振、无力、腹胀、心律紊乱等。 (5)低钙血症和低镁血症。主要表现为手足搐搦和惊厥,营养不良患儿更易发生。脱水、酸 中毒纠正过程中或纠正后出现上述表现时,应考虑低钙血症可能。补钙治疗无效时应考虑低 镁血症。

星状病毒

志贺菌 小肠结肠炎耶尔森菌

艰难梭菌 金黄色葡萄球菌 副溶血性弧菌

肠道病毒 冠状病毒 札如病毒属

寄生虫

隐孢子虫

蓝氏贾第鞭毛虫 溶组织内阿米巴

人芽囊原虫

表1 急性感染性腹泻常见病原体

真菌

念珠菌Hale Waihona Puke 毛霉菌 曲霉菌临床表现

临床表现

共同临 床表现

1.消化道症状。大便性状改变,如稀糊便、水样便、黏液便、脓血便;大便次数增多,

治疗

1、补液 治疗

中国儿童急性感染性腹泻病临床实践指南

一、前言感染性腹泻病是全球发病率高和流行广泛的传染病,对人类尤其是儿童的健康危害严重。

在我国,根据一些省份的入户调查资料,全人口的腹泻病发病率为0.17~0.70次/人年,5岁以下儿童则为2.50~3.38次/人年[1]。

儿童急性感染性腹泻通常由胃肠道病毒和细菌感染所致,临床上常伴或不伴呕吐、恶心、发热、腹痛等症状。

儿童急性感染性腹泻的病因多为病毒感染,以轮状病毒、诺如病毒最为常见,细菌病原包括大肠埃希菌属、弯曲菌属、沙门菌属以及志贺菌属等。

我国小儿腹泻病调查结果显示,每年有2个发病季节高峰,一个高峰为6至8月,主要病原为致泻性大肠埃希菌和痢疾杆菌,另一高峰为10至12月,主要病原为轮状病毒。

无论何种病因所致的急性感染性腹泻,治疗方法主要为补液治疗[口服补液盐(ORS)、静脉补液]以预防和治疗水电解质紊乱及酸碱失衡、饮食治疗、药物治疗。

为了规范腹泻病的诊治,2009年中华医学会儿科学分会消化学组、感染学组及《中华儿科杂志》编辑委员会,参照世界卫生组织(WHO)和联合国儿童基金会(UNICEF)2005年联合发表的腹泻管理推荐指南,制定了“儿童腹泻病诊断治疗原则的专家共识”[2],强调腹泻病管理中脱水征的识别、口服补液、继续喂养,提倡母乳喂养,推荐使用低渗ORS和补锌治疗。

“专家共识”的推行和实施,在规范腹泻病治疗、早期应用ORS预防和纠正脱水、减少静脉补液、减少抗生素滥用方面起到了积极的作用,取得了一些效果。

但是上述治疗方法以及众多药物的疗效、安全性和经济学指标如何,是广大儿科医务工作者所关注的。

为了更好地帮助临床医生恰当地管理急性感染性腹泻患儿,中华医学会儿科学分会消化学组及《中华儿科杂志》编辑部委员会再次组织儿科消化病、感染病以及流行病学专家组成的专家工作组,在原有的“专家共识”基础上,参考WHO及UNICEF的“腹泻病临床管理指南”以及美国、英国等有关腹泻病的指南,根据循证医学原则分析国内外截至2013年6月的临床研究资料,制定“中国儿童急性感染性腹泻病临床实践指南”,以便给儿科医生在临床实践时参考。

小儿腹泻病因

小儿腹泻病因小儿腹泻是由于感染性腹泻病原微生物多随污染的食物或饮水进入消化道或由饮食不当引起的。

主要是由于细菌或病毒感染引起突发的严重腹泻。

小儿腹泻病因详细解析病因机理:细菌或病毒感染可引起突发的严重腹泻,感染常常是小婴儿急性腹泻最常见的病因。

持续数周或数月的轻度腹泻,常怀疑以下几种情况:粥样泻(肠吸收不良综合征)、囊性纤维病、糖吸收不良综合征和过敏性疾病。

婴幼儿时期容易发生腹泻病主要与下列因素有关:1.消化系统发育尚未成熟表现为胃酸和消化酶分泌较少,消化酶活力低下,对食物的耐受力较差,不能适应食物质和量的较大变化。

2.生长发育快所需营养物质相对较多,且婴儿食物以液体为主,进入量较多,胃肠道负担重,加之婴儿时期神经调节功能差,容易发生肠道功能紊乱。

3.机体防御功能较差①婴儿胃酸偏低(乳汁尤其是生乳可中和胃酸,使酸度更为降低)胃排空较快,对进入胃内的细菌杀灭能力减弱;②血液中免疫球蛋白(尤其是IgM、IgA)和胃肠道SlgA均较低,对感染的防御能力较差。

4.肠道菌群失调:正常肠道菌群对入侵的致病微生物有拮抗作用,新生儿生后尚未建立正常肠道菌群或由于滥用抗生素等,均可使肠道正常菌群的平衡失调,易患肠道感染。

5.人工喂养母乳中含有大量体液因子(SlgA、乳铁蛋白等)、巨噬细胞和粒细胞、溶菌酶、溶酶体,此类活性物质有很强的抗肠道感染作用。

家畜乳中虽有某些上述成分,但在加热过程中被破坏,而且人工喂养的食物和食具极易受污染,故人工喂养儿肠道感染发生率明显高于母乳喂养儿。

小儿腹泻病因:1.感染因素肠道内感染可由病毒、细菌、真菌、寄生虫引起,前两者多见,尤其是病毒。

(1)病毒感染①轮状病毒(rotavirus,RV):是婴幼儿秋冬季腹泻最常见的病原,发达国家和发展中国家20%~70%5岁以下的婴幼儿都感染过轮状病毒,发展中国家每年大约有800000名患儿死于轮状病毒腹泻。

轮状病毒属呼肠病毒科RV属,常温下存活7个月,耐酸故不能被胃酸破坏。

脆弱类杆菌

BFT编码基因(bft)位于细菌染色体上一个长约6kb的致病岛小于常规致病岛,只包含bft和编码另一种金属 蛋白酶的基因,称作为mp II,缺乏编码将毒素运送支靶细胞的分泌系统的基因。部分ETBF可存在双拷贝致病岛 基因。Bft有3种等位基因。即bft-1,bft-2和bft-3,分别编码BFT-1、BFT-2和BFT-3。Bft-1,bft-2碱基序列 相符率为93%,bft-3与bft-1,bft-2具有高度同源性,枋苷酸序列相符率为89%~94%,与bft-2关系更加密切。 1999年Franco等发现除致病岛外,ETBF还具有一个长度为3kb的致病岛侧翼区(flanking region)。通过将致 病岛克隆到II型NTBF(不含致病岛及侧翼区)和III型NTBF(不含致病岛但含有侧翼区)后观察ETBF合成能力的 研究发现,致病岛和其上游的700bpDNA片段对BFT合成和分泌具有重要的作用。2000年Grosso等利用限制性片段 长度多态性分析、基因测序及等位基因特异性PCR等技术检测66例来自不同类型酝酿的ETBF产肠毒素基因,结果 显示bft-1是最常见的等位基因。约占分离ETBF菌株的65%,在来自成人粪便的ETBF菌株中更常见,而bft-2主要 存在儿童粪便的ETBF菌株。该研究还发现携带bft-1或bft-2基因的ETBF产生的具有生物活性的毒素最远多于携 带bft-3基因的ETBF。

PCR以BFT为检测目标,1997年Pantosti等采用HT-29/C1细胞培养和PCR同时检测113株来自培养物和粪便标 本的BFT,结果表明两者的实验结果完全吻合,并且PCR的灵敏达105~104CFU/g粪便标本。Kato等用HT-29/C1细 胞培养和PCR方法检测188株从肠道外标本分离的Bf,结果发现35株Bf两种方法均为阳性,而细胞培养法阴性,两 者的相符率达99%以上。Shetab等报道套用式PCR可将灵敏度进一步提高到103~102CFU/g粪便标本。由于粪便中 存在的抑制物可降低PCR的敏感性。为了排除PCR抑制物的干扰,Weintraub等采用特异性单抗包被的磁球捕获、 分离细胞与PCR相结合的IMS-PCR方法直接检测粪便是的ETBF,将灵敏度提高至0~50CPU/g粪便标本。PCR方法存 在的主要问题:粪便及其他肠外标本均含有PCR抑制物,易导致PCR敏感性降低,造成假阴性结果;PCR以bft为检 测目标,如果存在基因不表达或死亡细菌残骸,则易导致假阴性;PCR方法费用较高。

儿童腹泻病诊断治疗原则的专家共识

一、“低渗”ORS配方

• 近年腹泻病治疗的两项重要成果是:

• 1、低渗ORS配方(hypoosmolarity ORS):将钠浓 度降到75mmol/L、葡萄糖浓度降低到75mmol/L、总渗 透压降低到245mmol/L。防止脱水与标准ORS同样有效, 且有助于缩短腹泻持续时间,减少粪便排出量以及减少静 脉补液使用率。

七、腹泻病的预防

• 1、注意饮食卫生、环境卫生,养成良好的 卫生习惯; • 2、提倡母乳喂养; • 3、积极防治营养不良; • 4、合理应用抗生素和肾上腺皮质激素; • 5、接种疫苗:目前认为可能有效的为轮状 病毒疫苗。

The end

Thank you

• 2、补锌:

“低渗”ORS配方

• “低渗”ORS配方有助于缩短腹泻持续时间,减少大便的量 以及减少静脉补液,新ORS配方(低渗ORS)将取代以前 的ORS配方。

• 表 新ORS配方的组成

配方 氯化钠 无水葡萄糖 氯化钾 柠檬酸钠 g/L 2.6 13.5 1.5 2.9 组分 钠 氯 葡萄糖 钾 柠檬酸 mmol/L 75 65 75 20 10

腹泻患儿补锌的意义

• • • 1、锌是体内200余种金属酶的必要组成成分,参与调节DNA的 复制和核酸合成,影响细胞分化与复制; 2、对免疫系统发育和功能的维持、调节起重要作用; 3、能有效改善机体中各种抗氧化物之间的协同关系,从而提高 其总体抗氧化损伤能力; 4、对儿童肠结构与功能起着重要作用,缺锌可导致肠绒毛萎缩、 肠道双糖酶活性下降,补锌能加速肠粘膜再生,增加刷状缘酶水平。 腹泻时补锌,是考虑到锌在细胞生长和免疫功能方面起着核心作 用。 儿童是缺锌的高危人群。据报道,在世界范围内大约有三分之一 的儿童缺锌,发展中国家儿童缺锌较为普遍。腹泻时锌大量丢失,加 剧了已经存在的锌缺乏。腹泻导致血锌浓度的降低与腹泻的持续时间 有关,腹泻和锌缺乏之间形成了恶性循环。

医学院-新华-儿童-儿童医学中心-儿科学-之-小儿急性腹泻

3. 渗透性腹泻 双糖酶先天性或继发性缺乏、某些高渗药物的影 响。

4. 病毒作用 轮状病毒侵犯小肠上皮细胞,破坏微绒毛、双糖酶缺 乏。

第九页,编辑于星期一:点 分。

轻

< 5% < 3% + 轻度减少 正常或稍陷 正常 稍干 稍增快 正常 正常 温暖 正常

中

5% ~ 9% 3% ~ 6% ++ 明显减少 下陷 差 干燥 增快 正常或稍降 2秒左右 稍凉 萎靡、嗜睡

重

10% ~ 15% 7% ~ 9 % +++ 无尿 明显下陷 明显差 明显干燥 明显增快,弱 降低 > 3秒 凉、湿 嗜睡 ~ 昏迷

第三十八页,编辑于星期一:点 分。

累积损失的补充

补充液体的张度及速度:等渗脱水按1/2张 ~ 2/3张液补充,低渗性脱水按2/3 ~ 等张液 补充,高渗性脱水按1/3 ~ 1/2张液补充。等 渗及低渗性脱水累积损失宜在8 ~ 12小时内 补足。高渗性脱水血钠下降速度每小时不超 过1 ~ 2mmol/L,每天不超过10 ~ 15 mmol/L,防止发生急性脑水肿。

第十六页,编辑于星期一:点 分。

O157:H7

临床表现:三大特征:特发性、痉挛性腹痛; 血性粪便;低热或不发热。

预后:自限性疾病,自然病程5~7天。 溶血尿毒综合征:三大症状:急性肾衰、血

小板减少、溶血性贫血。

第十七页,编辑于星期一:点 分。

O157:H7

血栓性血小板减少性紫癜:五联症:发热明 显、血小板减少、溶血性贫血、肾功能异常、 神经系统症状。

感染性腹泻诊断标准(WS271-2007)

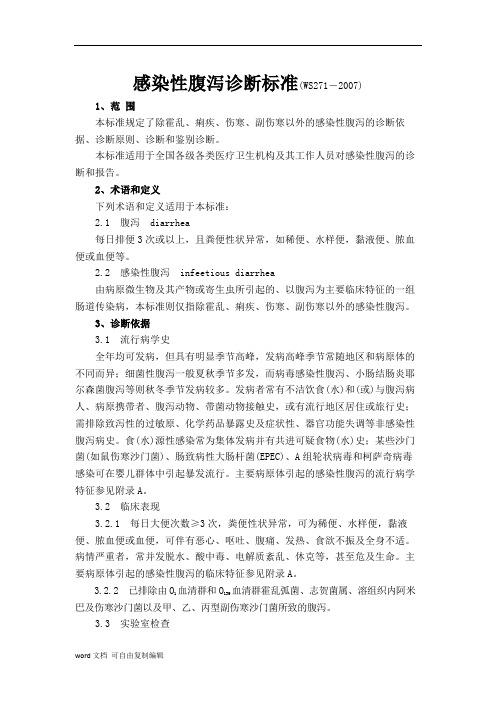

感染性腹泻诊断标准(WS271-2007)1、范围本标准规定了除霍乱、痢疾、伤寒、副伤寒以外的感染性腹泻的诊断依据、诊断原则、诊断和鉴别诊断。

本标准适用于全国各级各类医疗卫生机构及其工作人员对感染性腹泻的诊断和报告。

2、术语和定义下列术语和定义适用于本标准:2.1 腹泻diarrhea每日排便3次或以上,且粪便性状异常,如稀便、水样便,黏液便、脓血便或血便等。

2.2 感染性腹泻infeetious diarrhea由病原微生物及其产物或寄生虫所引起的、以腹泻为主要临床特征的一组肠道传染病,本标准则仅指除霍乱、痢疾、伤寒、副伤寒以外的感染性腹泻。

3、诊断依据3.1 流行病学史全年均可发病,但具有明显季节高峰,发病高峰季节常随地区和病原体的不同而异;细菌性腹泻一般夏秋季节多发,而病毒感染性腹泻、小肠结肠炎耶尔森菌腹泻等则秋冬季节发病较多。

发病者常有不洁饮食(水)和(或)与腹泻病人、病原携带者、腹泻动物、带菌动物接触史,或有流行地区居住或旅行史;需排除致泻性的过敏原、化学药品暴露史及症状性、器官功能失调等非感染性腹泻病史。

食(水)源性感染常为集体发病并有共进可疑食物(水)史;某些沙门菌(如鼠伤寒沙门菌)、肠致病性大肠杆菌(EPEC)、A组轮状病毒和柯萨奇病毒感染可在婴儿群体中引起暴发流行。

主要病原体引起的感染性腹泻的流行病学特征参见附录A。

3.2 临床表现3.2.1 每日大便次数≥3次,粪便性状异常,可为稀便、水样便,黏液便、脓血便或血便,可伴有恶心、呕吐、腹痛、发热、食欲不振及全身不适。

病情严重者,常并发脱水、酸中毒、电解质紊乱、休克等,甚至危及生命。

主要病原体引起的感染性腹泻的临床特征参见附录A。

3.2.2 已排除由O1血清群和O139血清群霍乱弧菌、志贺菌属、溶组织内阿米巴及伤寒沙门菌以及甲、乙、丙型副伤寒沙门菌所致的腹泻。

3.3 实验室检查3.3.1 粪便常规检查粪便有性状改变,常为黏液便、脓血便或血便、稀便、水样便。

胜利油区134例儿童抗生素相关性腹泻病因分析

菌具有抗毒素作用 , 能够分 泌某种 蛋 白酶 , 接水解 难辨 梭 直 状芽孢杆菌分泌的毒素 , 激肠道 免疫系统 活性 , 别是 非 刺 特

现继发性腹泻 3 ( 7o ) 两组 比较有统计学意义 ( = 7例 3 .% , 4 1 , 00 ) .6 P< .5 。预防组治疗 后显效 1 , 8例 有效 7例 , 无效

素的患儿 出现抗生 素相 关性 腹泻 ( A 的病 因进行 分 析 , A D)

临床资料 : 院住 院使 用抗 生素 的患儿 共 1 5 我 3例 , 2 出

现 A D 14例 (0 6 % ) A 3 1 .9 。其 中男 7 0例 、 6 女 4例 。新 生儿 l 7例 , 婴儿 7 7例 , 幼儿 2 6例 , 儿童 l 4例 ; 用 1种抗 素 4 使 6

性 腹 泻 后 再 加 用 布 拉 酵 母 菌 。两 组 治 疗 前 后 均 检 查 肝 肾 功

被 胃酸灭活 , 迅速在肠 道 内达 到有效浓 度 , 药期 间在 肠道 服

保持恒定 水平 , 但停药 2~ 5d粪便 中找不到该菌 , 提示布拉 酵母 菌不 会在肠 道 内永 久定 植 , 十分 安全 的微 生 态 调节 是

特异性免疫功 能 , 加肠道 内 sg 增 IA含量 。同时 布拉 酵母 菌

含有多胺 , 能提供肠黏 膜营养 , 著增加肠 上皮 细胞 刷状 缘 显

2例 , 总有效率 9 .9 ; 2 5 % 对照 组分 别为 1 、 、O例 , 有效 98 1 总 率 7 .7 ; 2 9 % 两组 比较有 统计 学 差异 ( 2 . 4 P<0 0 ) =3 9 , .5 。

儿童腹泻怎样止住宝宝的泻肚子

儿童腹泻怎样止住宝宝的泻肚子腹泻是儿童常见的消化系统疾病之一,给家长和孩子带来了很多困扰。

宝宝的泻肚子不仅会带来身体不适,还容易导致脱水和营养不良等问题,因此及时采取合理的措施来止住宝宝的泻肚子至关重要。

本文将介绍一些有效的方法来帮助宝宝缓解腹泻症状。

1. 注意饮食调理饮食是调理宝宝泻肚子的关键。

宝宝腹泻期间,应忌食刺激性食物,如辛辣食物、油炸食物、酸、甜等。

可以选择清淡易消化的食物,如稀粥、面条、蒸蛋等。

此外,宝宝应保持充足的水分摄入,以防脱水。

可以给宝宝喝些温开水、果汁或椰子水等。

2. 给宝宝适量使用益生菌益生菌是一种可以帮助恢复消化道菌群平衡的微生物制剂,对腹泻有一定的辅助治疗作用。

可以咨询医生,选择适合宝宝年龄的益生菌产品,并按照说明适量使用。

3. 注意保持宝宝的休息腹泻期间容易导致宝宝脱水和疲劳,因此宝宝需要适当的休息来恢复体力。

可以让宝宝多躺在床上或沙发上休息,鼓励宝宝多睡觉以加快康复。

4. 坚持正确的手卫生习惯腹泻是由病毒、细菌等传染引起的,因此在处理宝宝的大小便以及喂食前后要注意洗手,确保手卫生。

此外,还要保持宝宝的居住环境清洁卫生,定期清洗宝宝的衣物、床上用品等。

5. 遵循医生的建议用药对于宝宝的腹泻症状,如果病情较为严重,建议及时就医并遵循医生的建议用药。

一些抗生素和止泻药可以帮助控制腹泻症状,但注意不要滥用药物,并遵循医生的用药指导。

总结起来,宝宝的腹泻虽然常见,但家长们仍然需要重视起来。

通过注意饮食调理、适量使用益生菌、保持休息、正确的手卫生习惯以及遵循医生的建议用药,可以帮助宝宝有效地缓解腹泻症状,促进康复。

但是在处理宝宝的腹泻情况时,如果症状持续严重或出现其他并发症,一定要及时就医,以获得专业的医学建议和治疗。

希望宝宝们能够早日康复,恢复健康。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis–Associated Diarrhea in Children0–2Y ears of Agein Rural BangladeshPreeti Pathela,1K.Zahid Hasan,3Eliza Roy,3Korshed Alam,3Fazlul Huq,3A.Kasem Siddique,3and R.Bradley Sack2 Departments of1Epidemiology and2International Health,Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health,Baltimore,Maryland;3International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research,Bangladesh,Dhaka,BangladeshThe burden of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis(ETBF)–related diarrhea was determined in a birth cohort of252children in rural Bangladesh.Isolation rates of ETBF in stool and risk factors for acquisition of ETBF and disease were established.Of382B.fragilis–positive specimens,14.4%of the strains found in them produced enterotoxin,as determined by a tissue-culture assay.The overall isolation rate of ETBF was2.3%(40/1750) from diarrheal specimens and0.3%(15/5679)from nondiarrheal specimens collected throughout the2years of the study().ETBF was isolated from20.3%(40/197)of the B.fragilis–positive diarrheal specimens P!.001and from8.1%(15/185)of the B.fragilis–positive nondiarrheal specimens()and was significantlyP!.001associated with acute diarrheal disease in childrenу1year of age().The diarrheal illness was mildP p.0001in nature.In conditional multivariate analyses that examined environmental and host risk factors,the presence of livestock in the household area was linked to the acquisition of ETBF(chickens,;cows,).P!.05P p.06 ETBF was found to be a small but significant contributor to diarrheal disease in this rural community.Improved management of livestock may be useful for the prevention of ETBF infection.Acute diarrheal disease remains a problem for millions of children worldwide.In developing countries,it is1 of the2main causes of death and contributes greatly to the severity of malnutrition[1].In the preceding2 decades,significant advances have been made in the identification of enteropathogens and in the under-standing of pathogenic mechanisms.Yet,some acute diarrheal illnesses still have unknown etiologies.Iden-tifying new enteropathogens and establishing the path-ogenicity of recently recognized ones remain important goals for understanding childhood diarrhea. Bacteroides fragilis(BF)bacteria are gram-negative,Received12July2004;accepted19November2004;electronically published 14March2005.Presented in part:The analysis and manuscript were completed as a part of a doctoral thesis project(P.P.).Financial support:US Agency for International Development(grant HRN-A-00-96-90005-02).Reprints or correspondence:Dr.R.Bradley Sack,Dept.of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health,615N.Wolfe St.,Rm.5035, Baltimore,MD21205(rsack@).The Journal of Infectious Diseases2005;191:1245–52ᮊ2005by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.All rights reserved. 0022-1899/2005/19108-0008$15.00anaerobic rods that are normal inhabitants of the largebowel of mammals.A subgroup of this species has beenfound to produce an enterotoxin.Enterotoxigenic BF(ETBF)secretes an extracellular20-kDa metallopro-tease toxin(termed BF toxin[BFT])that causes swellingof human colonic epithelial cells without cell injury andalters the distribution of actinfilaments in intestinalepithelial cells.BFT acts by causing a“leaky epithelium”and stimulating active chloride secretion by cells,whichmay contribute to the pathogenesis of diarrhea in hu-mans[2].ETBF strains werefirst described in1984,when My-ers et al.[3]found that they produced a secretory re-sponse in ligated ileal loops of calves and lambs.Shortly thereafter,this novel enteropathogen was proven to beassociated with diarrheal disease in a variety of youngdomestic animals[4–6].In1987,isolation of ETBF from human adults andchildren with acute and chronic diarrhea was described[7].Thefirst controlled study of ETBF disease in Apachechildren with and without diarrhea who were attendingan Arizona clinic found a strong association betweenacute diarrhea and ETBF in children11year of ageETBF-Associated Diarrhea in Infants•JID2005:191(15April)•1245[8].To assess the significance of ETBF infections in the de-veloping world,a subsequent controlled study[9]of children !5years of age who were admitted to the hospital of the In-ternational Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research,Bangladesh (ICDDR,B)in Dhaka was performed.Again,ETBF was sig-nificantly associated with diarrhea in children11year of age. To our knowledge,to date,no community surveillance stud-ies of ETBF infections have been reported.The present study was conducted to describe the prevalence of ETBF organisms and the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of ETBF infections in children!2years of age in rural Bangladesh.SUBJECTS,MATERIALS,AND METHODSStudy population.A household surveillance study was carried out in Mirzapur,Bangladesh,from1993to1996.Thefield team was composed of12trained female community health workers (CHWs)and a physician.From July to August1993,CHWs conducted a door-to-door census in10villages,identified preg-nant and married women of childbearing age,and invited them to participate in the study.From August1993to October1994, 288newborns were enrolled into the study.A household baseline survey that collected socioeconomic and environmental information on families of enrolled newborns was conducted.Two hundredfifty-two children were followed for diarrheal morbidity from birth until2years of age.CHWs visited the participants’homes twice weekly to record occurrences of diarrhea and respiratory tract infections and clinical features of illnesses.Stool specimens or rectal swabs were collected from children when they had diarrhea,as well as on a monthly basis. Diarrhea was defined asу3loose stools,or any number of stools containing blood,within a24-h period.Diarrheal episodes were separated by at least3diarrhea-free days.Informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardi-an for inclusion of each child in the study.During the study, children were provided with health care by a pediatrician in the home or at Kumudini Hospital,located4–9km from each study village.If a child had diarrheal illness,oral rehydration therapy was provided,and the physician administered antibi-otics if indicated.The protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of ICDDR,B,and the analysis plan was ap-proved by the Committee on Human Research of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Microbiological assessment.Stool specimens and rectal swabs were collected in the morning,kept in an ice cooler,and trans-ported to the laboratory for processing that afternoon.The specimens were tested for recognized bacterial,viral,and par-asitic enteropathogens—such as Escherichia coli,Campylobacter jejuni,Shigella species,Salmonella species,Vibrio cholerae,Cryp-tosporidium species,Entamoeba histolytica,rotavirus,and as-trovirus—using methods that are routine at ICDDR,B[10].Isolation of BF and assays for toxin production.All stool specimens were tested for the presence of BF.Although earlier investigations of ETBF used PINN medium,which contains polymyxin B,irgasan,nalidixic acid,and novobiocin[8,9,11], it has been reported to be less than satisfactory for growing BF [9].Thus,alternative media were used.Specimens collected between1October1993and31March1995were cultured for BF by streaking them onto Bacteroides bile esculin(BBE)agar for colony isolation.This medium allows the growth of several species of Bacteroides and has been shown to have the selectiv-ity necessary for the isolation of BF[12].Because information suggested that another medium was superior to BBE for grow-ing BF,from1April1995to the end of the study(30September 1996),colonies were grown on Reuben BF media(RBF),which was specifically formulated for the primary isolation of BF from stool specimens.The novel medium consisted of3.7%Difco brain-heart infusion base,1%yeast extract,1%casamino acids, vitamin K,hemin additives,∼20%ox bile,4m g/mL gentamicin, 1m g/mL pefloxacin,and100m g/mL kanamycin.When enriched with5%lysed sheep blood,this medium provided good growth of isolates while inhibiting normalflora in stool[13].Colonies were subcultured on blood agar,and BF colonies were identi-fied by their characteristic mottled appearance.In all instances, plates were incubated anaerobically for48h at37ЊC.Specimens were stored in chopped meat medium.When diarrheal specimens tested positive for BF,colonies were tested for enterotoxin production.Additionally,1of every 5of the monthly stool specimens was tested for bo-ratory workers were not aware of the source of the BF cultures. The cultures were coded only with numbers,handled in the order in which they were received,and decoded later.A tissue-culture assay using the cloned human colonic-epithelial-cellline HT29/C1was used to detect ETBF in BF-positive specimens. HT29/C1cells that are treated with the supernatants of ETBF strains develop morphological changes,including loss of cell-to-cell attachments,rounding,and swelling within as little as 1h after treatment.Morphological changes progress over at least thefirst24h after treatment with supernatants of ETBF strains.This assay was proven to be89%sensitive and100% specific in detecting ETBF strains as defined by the previously used lamb–ligated-intestinal-loop assay[14].Statistical analyses.T o assess the pathogenicity of ETBF, children with ETBF-positive diarrheal specimens were compared with children with ETBF-positive nondiarrheal specimens.A sim-ilar comparison was done for children with BF-positive speci-mens.x2and Fisher exact tests were used to compare differences between groups.To determine if household and biological factors were as-sociated with acquisition of ETBF,a nested matched case-con-trol study was conducted.Case patients were defined as all ETBF-positive children,and control subjects were defined as ETBF-negative children matched to case patients by age(within1246•JID2005:191(15April)•Pathela et al.Table1.Isolation rates of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis(ETBF),distributed by age group.Age groupDiarrheal specimens a Nondiarrheal specimens bOR(95%CI)P BFpositiveETBFpositive Rate,%BFpositiveETBFpositive Rate,%0–5months18316.7251 4.0 4.80(0.34–262.2).29 6–11months49510.23837.9 1.33(0.24–9.10).71 12–17months571628.144715.9 2.06(0.70–6.58).15 18–23months731621.9784 5.1 5.19(1.55–22.28).003 Total1974020.3185158.1 2.89(1.49–5.84)!.001NOTE.CI,confidence interval;OR,odds ratio.a89.1%(197/221)of BF organisms isolated from diarrheal specimens were tested for enterotoxin production.b21.5%(185/862)of BF organisms isolated from nondiarrheal specimens were tested for enterotoxin production.3months)and season of specimen collection.A second analysis to determine risk factors for diarrhea-associated ETBF infection was performed.ETBF-positive children with diarrheal speci-mens were matched by age and season of specimen collection to ETBF-negative children with nondiarrheal specimens.In-dependent variables in the regression models included factors recorded during household surveys(i.e.,water sources,pres-ence of livestock in the household area,sex,birth weight,and duration of exclusive breast-feeding).Indicators of nutritional status(normal versus low z scores of weight-for-age,height-for-age,and weight-for-height)were also studied in this analy-sis.Significant variables in the univariate analyses(at an a level of0.05)and potential confounders were included in conditional multivariate logistic regression models.Statistical analyses were performed using Stata(version7.0;StataCorp).RESULTSA total of7429specimens(1750diarrheal and5679nondi-arrheal)were collected from the252children included in the present study.The overall isolation rate of BF,which included ETBF and non-ETBF strains,was14.6%(1083/7429specimens). From October1993to March1995,a total of3740specimens were tested for BF using BBE medium,and from April1995 to September1996,a total of3689specimens were tested for BF using RBF medium.The overall distributions of diarrheal and nondiarrheal specimens were similar for the2culturing periods.From October1993through March1995,there were 786(21.0%)diarrheal specimens and2954(79.0%)nondiar-rheal specimens.From April1995through September1996, there were964(26.1%)diarrheal specimens and2725(73.9%) nondiarrheal specimens.The isolation rate for BF when BBE medium was used was11.1%(417/3740),which was signifi-cantly less than the18.1%(666/3689)isolation rate when RBF medium was used().P!.001BF was not isolated more frequently in children with diar-rhea;actually,the reverse was true.BF was isolated in221 (12.6%)of1750diarrheal specimens and in862(15.2%)of 5679nondiarrheal specimens().P p.008A total of382BF-positive specimens were tested for entero-toxin production.These were composed of89.1%of the BF isolates from the diarrheal specimens(some cultures were lost in storage)and a random sample of21.5%of the BF isolates from the nondiarrheal specimens.The overall isolation rate of ETBF was2.3%(40/1750)from diarrheal specimens and0.3% (15/5679)from nondiarrheal specimens().P!.001Table1shows the isolation rates of ETBF in the382BF-positive specimens.A total of14.4%(55/382)of the BF isolates were enterotoxin producers.ETBF was identified in40(20.3%) of197BF-positive diarrheal specimens and in15(8.1%)of 185BF-positive nondiarrheal specimens().ETBF wasP!.001isolated more frequently from the stool specimens of children у1year of age than from the stool specimens of children in other age groups.The difference between the isolation rates of ETBF in BF-positive children attained statistical significance in the oldest age group(18–23months).The numbers of ETBF-positive specimens in the younger age groups were low.The data,analyzed according to whether the specimens were from children!1year of age orу1year of age,showed that isolation rates of ETBF in diarrheal specimens versus those in nondi-arrheal specimens for those!1year of age were not statistically significantly different(11.9%vs.6.4%;odds ratio[OR],2.00; 95%confidence interval[CI],0.50–9.53),but were statistically significantly different for childrenу1year of age(24.6%vs.9.0%;OR,2.73;95%CI,1.51–7.62).Both non-ETBF strains and ETBF were isolated in diarrheal and nondiarrheal specimens throughout the year.In Bangla-desh,the dry,hot spring occurs from March to May;the wet, hot summer occurs from June to October;and the winter oc-curs from November to February.BF was significantly more prevalent in nondiarrheal specimens than in diarrheal speci-mens during all seasons(data not shown).The seasonal dis-tribution of isolation of ETBF(figure1)was also examined. When the isolation rates of ETBF in BF-positive nondiarrheal specimens were compared with those in diarrheal specimens, the diarrheal specimens had higher isolation rates of ETBF dur-ing each season,but they were statistically significantly higherETBF-Associated Diarrhea in Infants•JID2005:191(15April)•12471248•JID 2005:191(15April)•Pathela etal.Figure 1.Seasonal isolation rates of enterotoxigenic Bacteroidesfragilis(ETBF)in diarrheal specimens (D;black bars )and in nondiarrheal specimens(ND;gray bars ).a,,comparing isolation rates of ETBF in diarrhealP p .03specimens taken during March–May and November–February with isolationrates of ETBF in diarrheal specimens taken during June–October.b,P p,comparing isolation rates of ETBF in diarrheal specimens and non-.001diarrheal specimens taken during June–October.Table 2.Clinical profile of 18diarrheal episodes in which en-terotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF)was isolated.Characteristic No.Loose stool episodes 15Mucoid stool episodes 9Bloody stool episodes 4Vomiting episodes 1Fever episodes 1Dehydration episodes 1Maximum stools passed per day,median (range)5(3–20)Duration (in days)of ETBF episode,median (range)6(2–39)NOTE.The 18diarrheal episodes were in 15children.At the time of the isolation of ETBF ,2children were 0–5months of age,3children were 6–11months of age,8children were 12–17months of age,and 5children were18–23months of age.during the summer (30.8%in diarrheal specimens vs.8.6%innondiarrheal specimens)().In the nondiarrheal spec-P p .001imens,the isolation rates of ETBF did not change significantlyfrom season to season.In the diarrheal specimens only,the peakin the isolation rate of ETBF (30.8%)in the summer differedsignificantly ()from the isolation rates of ETBF in di-P p .03arrheal specimens in the spring and winter (15.1%and 15.3%,respectively).Of the 55specimens from which ETBF was isolated,14spec-imens were from children who already had tested positive forETBF;therefore,41children (16.3%of all study children)hadat least 1ETBF-positive specimen.Repeat isolations of ETBFfrom diarrheal specimens came from separate diarrheal episodes,which indicates that these were sequential infections rather thanpersistent ETBF-related symptoms.The children who tested pos-itive for ETBF more than once during the study had 2–4ETBFepisodes each.The repeat isolations of ETBF were separated bydiarrheal episodes that were caused by other pathogens.The data were further examined to determine whether spec-imens harboring ETBF had other enteropathogens.Fifteen of55ETBF isolates were not accompanied by diarrheal symptoms.There were a total of 40ETBF-positive diarrheal episodes in33children.Of these 40episodes,22(55%)were accompaniedby other bacterial and/or parasitic agents (data not shown).The clinical data were analyzed after exclusion of the ETBF-positive diarrheal episodes in which multiple enteropathogenswere identified,which left for analysis 18separate diarrheal ep-isodes in 15children.As is shown in table 2,there was a strikingdifference in ETBF-positive case patients by sex.With the ex-ception of 4diarrheal episodes that were accompanied by bloodin the stool and 3episodes that were persistent (lasting у14days),the illnesses were generally found to be mild and secre-tory in nature.Case-control studies.A nested case-control study of 40ETBF-positive children and 78matched ETBF-negative control subjects was performed to assess the association of risk factors with the acquisition of ETBF.For 1ETBF-positive child,a matched control subject was not identified.The household and host characteristics,as well as distributions of other entero-pathogens,were similar in case patients and control subjects.In the analysis to determine risk factors for diarrhea-associated ETBF infections,32of 33children who had diarrhea-associated ETBF-positive episodes were matched by age and season of spec-imen collection to 55ETBF-negative control subjects who had nondiarrheal specimens.One ETBF-positive child was not in-cluded in this analysis because a matched control subject was not identified.There were no significant differences between case patients and control subjects with regard to household charac-teristics,nutritional indicators,and other enteropathogens.Univariate conditional logistic regressions for both case-con-trol analyses are shown in table 3.No potential risk factors showed a significant association with ETBF-positive diarrheal specimens,but the presence of chickens or cows in the house-hold area was statistically significantly associated with the ac-quisition of ETBF.As is shown in table 4,only the adjusted OR for the presence of chickens in the household area remained significantly associated with the acquisition of ETBF.The pres-ence of cows in the household area had an association that approached statistical significance ().P p .06DISCUSSION Although numerous enteropathogens are known to cause di-arrheal infections,the etiologies of a substantial number of cases of diarrhea remain unrecognized,and this suggests that addi-tional,unidentified pathogens may be responsible for disease.Our results confirm that the isolation of ETBF is low but isTable3.Crude odds ratios(95%confidence intervals)for acquisition of en-terotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis(ETBF)and disease,by variable.Variable Acquisition of ETBF a ETBF-associated disease bSexMale 1.00 1.00Female0.80(0.39–1.64)0.47(0.17–1.28) Exclusive breast-feedingу3months 1.00 1.00!3months0.72(0.29–1.79)0.82(0.32–2.11) First born in familyY es 1.00 1.00No0.48(0.20–1.16)0.31(0.10–0.99)c Low birth weightY es0.62(0.26–1.46)0.36(0.09–1.37)No 1.00 1.00Mother’s education15years of schooling 1.00 1.00р5years of schooling 1.09(0.41–2.88)0.89(0.34–2.28) Father’s education15years of schooling 1.00 1.00р5years of schooling0.71(0.31–1.61)0.33(0.10–1.06) Household monthly salaryу3000Taka 1.00 1.00!3000Taka0.79(0.38–1.65) 1.53(0.61–3.81) Family sizeр6members 1.00 1.0016members 1.40(0.66–2.98) 1.23(0.54–2.81) Source of drinking waterTube well 1.00 1.00Surface 1.41(0.08–23.57)0.78(0.07–8.88) Source of washing waterTube well 1.00 1.00Surface0.78(0.19–3.22)0.20(0.02–1.79) Type of latrine used by motherSanitary 1.00 1.00Open 2.28(0.65–8.04) 1.76(0.53–5.83) Type of latrine used by childSanitary 1.00 1.00Open 1.00(0.23–4.35) 1.28(0.23–7.14) Chickens in household areaY es 5.89(1.31–26.49)d 3.36(0.71–15.77) No 1.00 1.00Cows in household areaY es 2.17(1.02–4.62)d 1.32(0.56–3.08)No 1.00 1.00Site of cookingDry seasonInside house 1.00 1.00Outside house 1.37(0.63–2.99)0.79(0.32–1.92) Wet seasonInside house 1.00 1.00Outside house 1.10(0.39–3.06)0.70(0.18–2.65) Own tube wellY es 1.00 1.00No0.95(0.44–2.06) 1.16(0.38–3.38) Store waterY es0.97(0.40–2.33) 1.00(0.32–3.13)No 1.00 1.00a For the analysis,40ETBF-positive children were matched to78ETBF-negative control subjects.For1ETBF-positive child,a suitable control subject was not identified.b For the analysis,32ETBF-positive children with diarrheal specimens were matched to55 ETBF-negative control subjects.c.P p.05d.P!.05Table4.Adjusted odds ratios(95%confidenceintervals)for the acquisition of enterotoxigenicBacteroides fragilis(ETBF),by selected variables.Variable Acquisition of ETBFSexMale 1.00Female0.62(0.28–1.37)Chickens in household areaY es 5.41(1.09–26.91)aNo 1.00Cows in household areaY es 2.30(0.97–5.44)No 1.00NOTE.For the analysis,40ETBF-positive childrenwere matched to78ETBF-negative control subjects.For1ETBF-positive child,a suitable control subject was notidentified.a.P!.05significantly associated with acute diarrheal disease in children у1year of age in rural Bangladesh.The disease is relatively mild and is readily treated with oral rehydration therapy.The present study—which is,to our knowledge,thefirst longitu-dinal study to be conducted at the household level on rural children of a developing country—found that16.3%of all children were infected with ETBF during thefirst2years of life.To our knowledge,this study is also the second one[15] to indicate a seasonal pattern of ETBF infection and may be thefirst to demonstrate that ETBF infection is associated with environmental and household factors.An interestingfinding was that RBF medium was more sen-sitive in identifying BF organisms than was the traditional BBE medium.The isolation rate when RBF medium was used was about twice the rate seen when BBE medium was used(18.1% vs.11.1%)().In the future,studies of BF should benefit P!.001from the use of RBF medium.In the present study,BF of any type was isolated from12.6% of diarrheal specimens and from15.2%of nondiarrheal spec-imens.Thus,unlike thefinding from an Oklahoma hospital study by San Joaquin et al.[15],but in accordance with the finding from a study of Apache children by Sack et al.[8], there was no significant association between the presence of any BF and diarrhea in Mirzapur.That BF was consistently more often isolated from nondiarrheal specimens supports the idea that,like E.coli,it is a normal inhabitant of the colon. Approximately14%of BF isolates tested were enterotoxin producers.Similarly,San Joaquin et al.[15]discovered that,in Oklahoma,∼15%of BF in stool specimens(regardless of di-arrheal status,age,and season)were enterotoxin producers. After enumeration of the organisms in municipal sewage in Montana,it was found that9.3%of BF was ETBF[16].ETBF may make up a considerable portion of the BFflora of the intestinal tract,and,like diarrheogenic E.coli,BF may have additional virulence factors that are important in the patho-genesis of diarrheal disease.Recently,in epidemiological studies conducted throughout the world[8,9,15,17–21],ETBF has been explored as a human diarrheal pathogen in persons presenting at clinics or hospitals. Seven of these studies have focused on the association between ETBF and childhood diarrhea[8,9,15,17–20].A1997study by Pantosti et al.[18]in Italy showed that the rate of ETBF carriage was high and was not significantly different between children with diarrhea(17%)and healthy control subjects(12%) 1month–9years of age.A Bangladeshi hospital–based study [9]found ETBF rates in children!5years of age to be lower (6.1%of case patients and1.2%of control subjects)than those in the Italian study.The rates at this Bangladeshi hospital are therefore similar to the childhood rates found in the Oklahoma study(4.4%of case patients and3.1%of control subjects)and in the study of Apache children(12%of patients and6%of control subjects).In all3studies,differences in isolation rates of ETBF in case patients and control subjects attained statistical significance only for children11year of age.In the present study,overall isolation rates of ETBF from BF-positive diarrheal and nondiarrheal specimens were high(20.3%from diarrheal specimens and8.1%from nondiarrheal specimens).Similar to the isolation rates in the3previous studies mentioned,the isolation rates for the2groups in the present study were sig-nificantly different only for those specimens taken from chil-drenу1year of age,in which the isolation rates of ETBF rose to24.6%in diarrheal specimens but remained virtually con-stant in nondiarrheal specimens.Our isolation rates of ETBF from diarrheal specimens and from nondiarrheal specimens(2.3%and0.3%,respectively)were close to those seen for a number of other organisms detected in this cohort:Shigellaflexneri(5.4%in diarrheal specimens and 0.02%in nondiarrheal specimens),Salmonella species(1.83% in diarrheal specimens and0.2%in nondiarrheal specimens), V.cholerae O1Ogawa(0.2%in diarrheal specimens and0.0% in nondiarrheal specimens),and Cryptosporidium species(0.6% in diarrheal specimens and0.2%in nondiarrheal specimens). The burden of ETBF in our study may have even been un-derestimated because of the medium initially used to detect BF, as was indicated above.To our knowledge,this is the second study to report a sea-sonal pattern in ETBF infections.San Joaquin et al.[15]found no appreciable differences in isolation rates of ETBF from sea-son to season in Oklahoma in43case patients and18control subjects.In contrast to those results,we found a peak in di-arrhea-associated ETBF during the summer,compared with the rates in spring and winter.Isolation rates of ETBF in non-diarrheal specimens did not change seasonally.This seasonal difference suggests some as-yet-unspecified property of the di-1250•JID2005:191(15April)•Pathela et al.arrhea-associated ETBF that is lacking in those strains not as-sociated with diarrhea.In the crude analysis of risk factors for acquisition of ETBF, the presence of cows and chickens in the household area showed statistically significant,positive associations with the acquisition of ETBF.After controlling for cows in the household and sex of the child,there was still a5-fold increase in the odds of ac-quiring ETBF for children who had any chickens in the house-hold area,compared with the odds for children who had no chickens.Although it has been determined that different do-mestic animals,including lambs and calves,can have ETBF-associated diarrhea[3,11],to our knowledge there has not been a report of ETBF being isolated from the feces of chickens. It is possible that feces from chickens could yield ETBF,as has been seen in the case of Campylobacter[22].The results of the present study suggest that both cows and chickens could be sources of human infection or vehicles for the transmission of ETBF.Thisfinding points to areas of future investigation.Further surveillance studies could include col-lection of specimens from livestock with diarrhea,particularly when a case of ETBF is discovered in humans.ETBF-positive stool specimens from livestock and ill children within the same time frame would give strength to the epidemiological asso-ciation we found.Because a large proportion of families in Mirzapur keep livestock in the household area(i.e.,50%of families keep13chickens),the discovery of a definitive animal-to-human transmission of ETBF infection would have impli-cations for the prevention of this infection in this community and in comparable populations.No significant associations between ETBF-associated diar-rhea and environmental or biological risk factors could be dem-onstrated.The inhabitants of Mirzapur are a largely homo-geneous population;few disparities in living conditions and behaviors exist.Because they have access to the same water sources and exposure to the same unsanitary conditions,the children of these families had high levels of illness.For example, in this cohort,the incidence of infant diarrhea was4.25episodes per child per year(P.P.,K.Z.H.,E.R.,F.H.,A.K.S.,and R.B.S., unpublished data).Thus,because almost all children in this cohort are exposed to the same potential disease-causing con-ditions,it is difficult to determine which ones specifically are linked with diarrheal disease.Additionally,the use of ETBF-associated diarrhea as the outcome of a study could be prob-lematic,given that there is a high prevalence of mixed infections in this population and that ETBF-positive diarrheal specimens were also often found to be positive for other enteropathogens. To be able to attribute diarrhea solely to ETBF would have required omitting children who had additional enteropathogens from the study,which would have greatly reduced the numbers studied and the statistical power of the analysis.In summary,ETBF has been shown to be a small but im-portant contributor to disease burden in young children living in rural Bangladesh.Approximately16%of all children!2years of age were infected with ETBF at some time.This community study had the advantage of detecting illnesses of a mild nature; most children with ETBF-associated diarrhea would probably not be seen at a treatment center.Approximately22%of ETBF-positive diarrheal episodes were associated with bloody stool; similarfindings have been reported elsewhere[7],and,in the present study,these episodes may have been the result of un-recognized coinfections.Prevention of ETBF infection through the improved management of livestock,as well as adequate treatment of the infection with oral rehydration therapy,would help to lessen the impact of diarrheal diseases,which are a persistent problem in this part of the world. AcknowledgmentsWe thank B.P.Pati of Mirzapur Hospital,for providing medical services to the study population,and to the hospital staff,thefield staff,and the people of Mirzapur,for their cooperation in the study.The researchers affiliated with the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh(Dakha)acknowledge with gratitude the commitment of the Department for International Development,United Kingdom,and the Ford Foundation to the center’s research efforts.We thank Cynthia Sears(Johns Hopkins School of Medicine,Baltimore,MD),for her valuable comments on the manuscript.References1.Rice AL,Sacco L,Hyder A,Black RE.Malnutrition as an underlyingcause of childhood deaths associated with infectious diseases in de-veloping countries.Bull World Health Organ2000;78:1207–21.2.Sears CL.The toxins of Bacteroides fragilis.Toxicon2001;39:1737–46.3.Myers LL,Firehammer BD,Shoop DS,Border MM.Bacteroides fragilis:a possible cause of acute diarrheal disease in newborn lambs.InfectImmun1984;44:241–4.4.Myers LL,Shoop DS,Byars TD.Diarrhea associated with enterotox-igenic Bacteroides fragilis in foals.Am J Vet Res1987;48:1565–7.5.Myers LL,Shoop DS.Association of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragiliswith diarrheal disease in young pigs.Am J Vet Res1987;48:774–5.6.Myers LL,Shoop DS,Collins JE,Bradbury WC.Diarrheal diseasecaused by enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in infant rabbits.J Clin Microbiol1989;27:2025–30.7.Myers LL,Shoop DS,Stackhouse LL,et al.Isolation of enterotoxigenicBacteroides fragilis from humans with diarrhea.J Clin Microbiol1987;25:2330–3.8.Sack RB,Myers LL,Almeido-Hill J,et al.Enterotoxigenic Bacteroidesfragilis:epidemiologic studies of its role as a human diarrhoeal path-ogen.J Diarrhoeal Dis Res1992;10:4–9.9.Sack RB,Albert MJ,Alam K,Neogi PKB,Akbar MS.Isolation ofenterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis from Bangladeshi children with di-arrhea:a controlled study.J Clin Microbiol1994;32:960–3.10.Albert MJ,Faruque ASG,Faruque SM,Sack RB,Mahalanabis D.Case-control study of enteropathogens associated with childhood diarrhea in Dhaka,Bangladesh.J Clin Microbiol1999;37:3458–64.11.Border M,Firehammer BD,Shoop DS,Myers LL.Isolation of Bac-teroides fragilis from the feces of diarrheic calves and lambs.J Clin Microbiol1985;21:472–3.12.Livingston SJ,Kominos SD,Yee RB.New medium for selection andpresumptive identification of the Bacteroides fragilis group.J Clin Mi-crobiol1978;7:448–53.ETBF-Associated Diarrhea in Infants•JID2005:191(15April)•1251。