The functions of past tenses Greek, Latin, Italian, French

探索英语学科的奥秘随笔作文

探索英语学科的奥秘随笔作文The Mysterious Journey of English: Unlocking theSecrets of the Language.English, a language that has traversed the globe, becoming a universal language of communication, holdswithin it an infinite array of mysteries and wonders. Its origins trace back to the ancient Anglo-Saxons, but its influence and reach have far exceeded the boundaries of its homeland. As I delve into the depths of this fascinating subject, I find myself captivated by the intricate web ofits vocabulary, grammar, and cultural influence.The vocabulary of English is a testament to its rich history and diverse influences. Words borrowed from Latin, Greek, French, and even Native American languages, among others, have enriched its lexicon. Each word carries a unique story, a snippet of history, or a cultural reference. For instance, the word "jazz," which originated in the United States, has come to represent a genre of music thatis not just American but also global. Similarly, words like "tea" and "silk," which entered the English vocabulary from China, tell tales of ancient trade routes and cultural exchanges.The grammar of English, often perceived as complex and challenging, is actually a testament to its adaptabilityand evolution. The language's grammar has been shaped by centuries of usage and borrowing, resulting in a systemthat is both robust and flexible. The use of tenses, modals, and clauses allows English speakers to convey a vast arrayof ideas and emotions. The intricacies of grammar alsoreflect the language's literary heritage, with writers like Shakespeare and Austen mastering its nuances to craft timeless works of literature.Beyond its linguistic complexity, English is a language that has shaped global culture and thought. It has been the medium of scientific discovery, the language of diplomacy, and the voice of revolutionaries. The works of Shakespeare, Emerson, and Orwell have influenced generations of thinkers and writers, while the music, films, and literature of theEnglish-speaking world have captivated audiences worldwide. English has become a bridge between cultures, a common ground for people to connect and communicate.Moreover, English is a language that is constantly evolving. It is a living language that breathes and grows with each new generation. The emergence of new words and phrases, the reinterpretation of old ones, and theborrowing of terms from other languages all contribute toits rich tapestry. The internet has further acceleratedthis evolution, with new words and abbreviations emergingto reflect the changing landscape of technology and society.In conclusion, the exploration of English is a journey that is both exciting and rewarding. It is a language thatis both ancient and modern, rooted in history but always looking towards the future. Its mysteries and wonders lienot just in its vocabulary and grammar but also in itsability to connect people, shape culture, and inspire creativity. As I continue to delve into the depths of this fascinating subject, I find myself not just learning alanguage but also embarking on a journey of discovery and understanding.。

英国文学中古时期到17世纪 (含答案)

英国文学中古时期到17世纪I. 选择题1. Generally speaking, it is in _____ that the English literary history starts.A. 6th C (BC.)B. 5th C (BC.) C. 6th C. (AD.) D. 5th C. (AD.)2. ______ is a pagan poem which portraits a panoramic picture of the tribal society in British Island.A. The Legend of King ArthurB. BeowulfC. The Tall TalesD. The Canterbury Tales3. In English poetry, a quatrain is _____.A. a four-line stanzaB. a coupletC. a fourteen-line stanzaD. a terza rima4. Anglo-Saxon literature is almost exclusively a verse literature in _____. It was passed down by words of mouth from generation to generation.A. Realistic formB. lyrical formC. oral formD. no form5. The _____ is an important form of British literature in the 15th century.A. epicB. popular balladC. sonnetD. quatrain6. _____ period extended from the invasion of the Celtic England by German tribes in the first half of the 5th century to the conquer of England in 1066 by the Norman French under the leadership of William the Conqueror.A. The Anglo-NormanB. The Middle EnglishC. The Chaucerian EnglishD. The Old English7. The hero in Romance is usually the _____.A. kingB. knightC. ChristD. churchman8. Geoffrey Chaucer, regarded as the first famous English poet in the history of English literature, wrote the following except ______.A. The Canterbury TalesB. The House of FameC. The Parliament of FowlsD. Boethius9. Geoffrey Chaucer planned originally to have each of the pilgrims tell _____ stories on the way to Canterbury and the same number of stories on the way back in his famous The Canterbury Tales.A. 1B. 2C. 3D. 410. Geoffrey Chaucer’s contribution to English poetry lies chiefly in the fact that he introduced from France the rhymed stanzas of various types, especially what was later to be called _____. A. the alliterative verse B. the balladC. the heroic coupletD. the blank verse11. The English Renaissance Period was an age of _____.A. ballads and songsB. poetry and dramaC. essays and journalD. prose and novel12. The well-known soliloquy by Hamlet “To be ,or not to be...And lose the name of action.” shows his_____.A. hatred for his uncleB. love for lifeC. resolution of revengeD. inner contradiction13. The first poet to introduce the sonnet into English literature is_____.A. William ShakespeareB. Thomas WyattC. Francis BaconD. Thomas More14. It was _____who made blank verse the principal vehicle of expression in drama.A. Thomas MoreB. Christopher MarloweC. Francis BaconD. William Shakespeare15 Choose the one author who does not belong to the group of “University Wits” from the following playwrights.A. John LylyB. Robert GreeneC. William ShakespeareD. Christopher Marlowe16 Whom does the poet praise in the Sonnet 18 and Sonnet 29? The person is_____.A. a young beautiful ladyB. a dark ladyC. a handsome young manD. the poet's girl friend17. Paradise Lost is not _____.A. Milton's masterpieceB. a great epic in 12 booksC. written in blank verseD. Metaphysical poetry18. Milton has the following titles, except one. Which one?A. a great revolutionary poet of the 17th centuryB.an outstanding political pamphleteerC. foremost critic of his ageD. a great master of blank verse19. The stories of Paradise Lost were taken from _____.A. Greek mythologyB. the Old TestamentC. the New TestamentD. Chinese ancient tales20. John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim's Progress in the form of _____.A. religious instructionB. clear, and simple expressionC. allegory and dreamD. conceit and satireII. 判断题1.Beowulf is the national epic of England.2.The earliest poem in English literature is Beowulf, which belongs to lyric poetry.3.Beowulf is a folk legend brought to England by Anglo-Saxons from their continental homes.4.“King Arthur and His Round Table” was popular at medieval period. One of the knownromance is The Robin Hood Ballads.5.The Canterbury Tales is written for the greater part in heroic couplets.6.William Langland, known as the father of English literature, is widely considered thegreatest poet of the Middle Ages.7.Geoffrey Chaucer is regarded as the first realist in English Literature because he gives us theordinary daily life of the 14th century.8.Chaucer made the dialect of London the foundation for modern English language.9.Thomas More wrote his famous prose work Essays.10.Thomas More’s Utopia is the first example of that genre in English literature, which has beenrecognized as an important landmark in the development of English prose11.In Elizabethan Period, Francis Bacon wrote more than fifty excellent essays, which made himone of the best essayists in English literature.12.Shakespeare’s four great tragedies generally refer to Hamlet, Prince of Denmark; Othello, theMoore of V enice; King Lear; and Romeo and Juliet.13.Two features are striking of this Renaissance movement. The one is a thirsting curiosity forclassical literature. Another feature of the Renaissance is the keen interest in life and human activities.14.Spenser’s fame in English literature is chiefly based upon his masterpiece The Faerie Queene,which was dedicated to Queen Mary.15.1649, Charles I was tried and beheaded. The civil war ended and England was declared acommonwealth.16.In 1660, the son of the beheaded king was welcomed back as King Charles II until 1688,which has been known as the period of the Commonwealth.\17.John Bunyan is a great stylist. His poetry has a grand style.18.The most remarkable feature in The Flea is its use of conceit.III.连线题1.the first and greatest English epic Utopia2.Thomas Malory The Pilgrim’s Progress3.William Langland Piers the Plowman4.Geoffrey Chaucer Essays5.Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene6.Christopher Marlowe The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus7.Thomas More Beowulf8.Francis Bacon The Canterbury Tales9.John Milton Paradise Lost10.John Bunyan The Death of King Arthur11.William Shakespeare A Midsummer Night’s DreamIV. 赏析题1.Studies serve for delight, for ornament, and for ability. Their chief use for delight is in privateness and retiring; for ornament, is in discourse; and for ability, is in the judgment and disposition of business. For expert men can execute, and perhaps judge of particulars, one by one; but the general counsels, and the plots and marshalling of affairs, come best from those that are learned. To spend too much time in studies is sloth; to use them too much for ornament is affectation; to make judgment wholly by their rules is the humour of a scholar. They perfect nature, and are perfected by experience: for natural abilities are like natural plants, that need pruning by study; and studies themselves do give forth directions too much at large, except they be bounded in by experience. Crafty men contemn studies, simple men admire them, and wise men use them, forthey teach not their own use; but that is a wisdom without them, and above them, won by observation. Read not to contradict and confute, nor to believe and take for granted, nor to find talk and discourse, but to weigh and consider.Q1:What’s the title of this essay from which it is taken? And who is the author?Q2: Please give a simple analysis of the literature style of this essay.Q3: What are “three abuses of studies”?Q4: What’s the theme of this essay?2.As soon as April pierces to the rootThe drought of March, and bathes each bud and shootThrough every vein of sap with gentle showersFrom whose engendering liquor spring the flowers;When Zephyrus have breathed softly all aboutInspiring every wood and field to sprout,And in the zodiac the youthful sunHis journey halfway through the Ram has run;When little birds are busy with their songWho sleep with open eyes the whole night longLife stirs their hearts and tingles in them so,Then off as pilgrims people long to go,And palmers to set out for distant strandsAnd foreign shrines renowned in many lands.And specially in England people rideTo Canterbury from every countrysideTo visit there the blessed martyred saintWho gave them strength when they were sick and faint.Q1: What’s the title of this literary work from which it is taken? And who is the author?Q2: What’s the metrical scheme of this poem?Q3: What’s the theme of this literary work?V. 论述题1. What are the artistic features of The Canterbury Tales?2. What are the writing Features of Shakespeare?英国文学中古时期到17世纪I. 选择题1-5: DBACB 6-10: DBDBC 11-15: BDBBC 16-20:CDCBCII. 判断题1-5: TFTFT 6-10: FTTFF 11-15:TFTFT 16-18:FFTIII. 连线题12.the first and greatest English epic —— Beowulf13.Thomas Malory——The Death of King Arthur14.William Langland——Piers the Plowman15.Geoffrey Chaucer——The Canterbury Tales16.Edmund Spenser——The Faerie Queene17.Christopher Marlowe——The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus18.Thomas More——Utopia19.Francis Bacon——Essays20.John Milton——Paradise Lost21.John Bunyan——The Pilgrim’s Progress22.William Shakespeare——A Midsummer Night’s DreamIV. 赏析题1.Q1:What’s the title of this essay from which it is taken? And who is the author?A1: Of Studies; Francis BaconQ2: Please give a simple analysis of the literature style of this essay.A2: simple, precise, compact, aphoristic(格言式的), gravity, eleganceQ3: What are “three abuses of studies”?A3: Read to contradict and confute, to believe and take for granted, to find talk and discourse.Q4: What’s the theme of this essay?A4: Different ways of studies may exert different influences over human characters.2.Q1: What’s the title of this literary work from which it is taken? And who is the author?A1: General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales; Geoffrey Chaucer.Q2: What’s the metrical scheme of this poem?A2: The heroic couplet.Q3: What’s the theme of this literary work?A3: Chaucer affirmed man’s right to pursue earthly happiness and opposed asceticism, praised man's energy, intellect, and love of life. Meanwhile, he also exposed and satirized the social evils, especially the religious abuses.V. 论述题1. What are the artistic features of The Canterbury Tales?1) Realistic Presentation of Characters and Contemporary LifeNot only the characters represent the classes they come from, but each also possesses an individual personality. The characters are as important a part of the poem as the tales told by them.The poet tries to give a comprehensive picture of the English society of his time and arranges to present a colorful gallery of pilgrims that covers a great range of social life.2) Chaucer’s HumorHe is well-skilled in mild and subtle irony to create humorous effects. He was a broad-minded humanist and had sympathy for people at large. He treats his characters kindly on the whole, using gentle satire and irony to criticize vanity, ill-manners, deceptive tricks and all sorts of follies and human weaknesses.3) Unity Trough a Framed StoryAlthough the story-tellers are very different and the stories are diverse, a unity is achieved through the device of the framed story that is Chaucer’s invention of a pilgrimage as the occasion of all the story-telling and thus makes it realistic. The pilgrimage frame offers the possibility for comparison and contrast of characters and their interplay.4) Metrical SchemeThe metrical scheme of The Canterbury Tales is Chaucer’s chief contribution to English poetry. He is the poet who introduced to England the rhymed stanzas of many kinds from French poetry, especially the heroic couplet.2. What are the writing Features of Shakespeare?1) Shakespeare is one of the founders of realism in world literature. He faithfully and vividly reflects the major social contradictions of his time.2) The method of adoption from the plots of Greek legends, Roman history and Italian stories, etc.3) Elastic dramas: action develops freely, without the three unities of time, place and action. And there are many themes in one play.4) Poetic forms: the song, the sonnet, the couplet and the dramatic blank verse.5) Shakespeare was a great master of the English language: large vocabulary.。

the greeks assumed that the structure of language

The Greeks Assumed That the Structure of LanguageIntroductionLanguage is a fundamental aspect of human communication and plays a significant role in shaping our thoughts and ideas. The Greeks, renowned for their contributions to philosophy and literature, also pondered over the nature and structure of language. This article aims to delve intothe Greek assumptions regarding the structure of language, exploringtheir theories and implications.Origins of Greek Linguistic ThoughtThe Greek fascination with language can be traced back to prominent philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. Plato believed that language was not a mere tool for communication but a reflection of the ultimate reality. According to him, words and their meanings were not arbitrarybut had a deeper connection to the essence of objects or concepts. Aristotle, on the other hand, studied language from a more empirical perspective, focusing on its function and structure.Greek Assumptions about Language StructureThe Greeks made several assumptions about the structure of language,which had a profound impact on subsequent linguistic thought. These assumptions include:1. Words Reflect RealityThe Greeks assumed that words had an inherent connection to the objectsor concepts they represented. They believed that through language, individuals could access and understand the true nature of reality. This assumption laid the foundation for the philosophical concept of “logos,” which refers to the relationship between words and reality.2. Language Is Composed of Basic ElementsThe Greeks recognized that language could be broken down into smaller units with distinctive meanings. They postulated that these basic elements, known as morphemes, combined to form words. This assumption paved the way for the development of morphological analysis in linguistics, which studies the internal structure of words.3. Syntax and Grammar Govern LanguageAncient Greek philosophers acknowledged the importance of syntax and grammar in organizing and conveying meaning. They recognized that language followed specific rules and structures that determined the relationships between words in a sentence. This assumption laid the groundwork for syntactical analysis, which explores the arrangement of words and phrases in a sentence.4. Language Is InnateThe Greeks assumed that the ability to acquire and understand language was innate to humans. They believed that language proficiency stemmed from natural predispositions rather than external influences. This assumption aligns with modern theories of language acquisition, such as Noam Chomsk y’s concept of a Universal Grammar.Implications of Greek Linguistic ThoughtThe Greek assumptions about language structure had far-reaching implications for various disciplines, including linguistics, philosophy, and literature. Some of these implications are:1. Language as a Mirror of RealityThe concept of language reflecting reality influenced subsequent philosophical and metaphysical thought. It prompted thinkers to explore the relationship between language, perception, and knowledge. This exploration ultimately shaped diverse philosophical schools, such as phenomenology and hermeneutics.2. Development of Linguistic AnalysisThe Greek assumptions regarding the composition of language elements and the importance of syntax and grammar laid the groundwork for linguistic analysis. These assumptions influenced the development of structural linguistics, generative grammar, and other linguistic theories that investigate the form and function of language.3. Influence on Literary StylesGreek linguistic thought permeated literary works, influencing writing styles and literary devices. Writers began incorporating rhetorical techniques, such as metaphors and analogies, to convey deeper meanings and evoke emotional responses. These techniques shaped the foundations of poetry, prose, and dramatic literature.4. Evolution of Language EducationThe Greek assumptions about language being innate and governed by rules contributed to the development of language education methodologies. They inspired instructional approaches that emphasize the systematic teaching of grammar, syntax, and vocabulary. These approaches continue to influence language teaching methodologies worldwide.ConclusionThe Greeks’ assumptions about the structure of language have left an indelible mark on human understanding and exploration of linguistic phenomena. Their belief that language reflects reality, the recognition of basic language elements, the importance of syntax and grammar, and the innate nature of language have shaped various disciplines. From philosophy to linguistics, and literature to education, the Greek assumptions continue to shape our understanding and appreciation of language.。

拉丁语五格

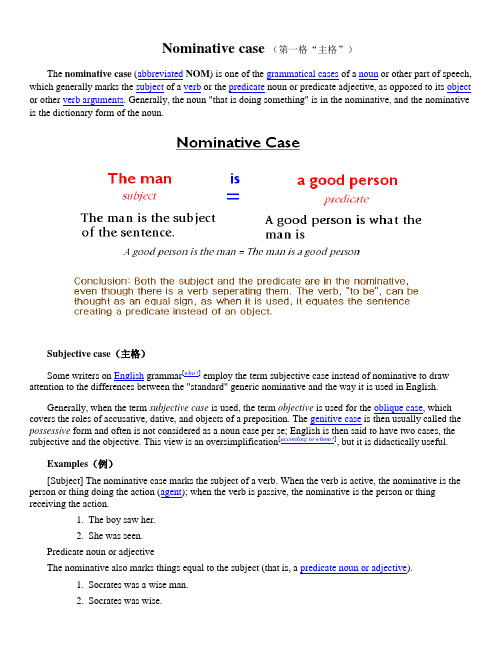

Nominative case(第一格“主格”)The nominative case (abbreviated NOM) is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb or the predicate noun or predicate adjective, as opposed to its object or other verb arguments. Generally, the noun "that is doing something" is in the nominative, and the nominative is the dictionary form of the noun.Subjective case(主格)Some writers on English grammar[who?] employ the term subjective case instead of nominative to draw attention to the differences between the "standard" generic nominative and the way it is used in English.Generally, when the term subjective case is used, the term objective is used for the oblique case, which covers the roles of accusative, dative, and objects of a preposition. The genitive case is then usually called the possessive form and often is not considered as a noun case per se; English is then said to have two cases, the subjective and the objective. This view is an oversimplification[according to whom?], but it is didactically useful.Examples(例)[Subject] The nominative case marks the subject of a verb. When the verb is active, the nominative is the person or thing doing the action (agent); when the verb is passive, the nominative is the person or thing receiving the action.1.The boy saw her.2.She was seen.Predicate noun or adjectiveThe nominative also marks things equal to the subject (that is, a predicate noun or adjective).1.Socrates was a wise man.2.Socrates was wise.Genitive case(第二格“属格”)In grammar, genitive (abbreviated GEN;[1] also called the possessive case or second case) is the grammatical case that marks a noun as modifying another noun. It often marks a noun as being the possessor of another noun;[2] however, it can also indicate various other relationships than possession: certain verbs may take arguments in the genitive case, and it may have adverbial uses (see Adverbial genitive).Placing the modifying noun in the genitive case is one way to indicate that two nouns are related in a genitive construction. Modern English typically does not morphologically mark nouns for a genitive case in order to indicate a genitive construction; instead, it uses either the 's clitic or a preposition (usually of). However, the personal pronouns do have distinct possessive forms. There are various other ways to indicate a genitive construction, as well. For example, many Afroasiatic languages place the head noun (rather than the modifying noun) in the construct state.Depending on the language, specific varieties of genitive-noun–main-noun relationships may include: ∙possession (see possessive case, possessed case):o inalienable possession ("Janet’s height", "Janet’s existence", "Janet’s long fingers")o alienable possession ("Janet’s jacket", "Janet’s drink")o relationship indicated by the noun being modified ("Janet’s husband")∙composition (see Partitive):o substance ("a wheel of cheese")o elements ("a group of men")o source ("a portion of the food")∙participation in an action:o as an agent ("She benefited from her father's love") – this is called the subjective genitive (Compare "Her father loved her", where Her father is the subject.)o as a patient ("the love of music") – this is called the objective genitive (Compare "She loves music", where music is the object.)∙origin ("men of Rome")∙reference ("the capital of the Republic" or "the Republic's capital")∙description ("man of honour", "day of reckoning")∙compounds ("dooms day" ("doom's day"), Scottish Gaelic "ball coise" = "football", where "coise"= gen. of "cas", "foot")∙apposition (Japaneseふじの山 (Fuji no Yama), "Mount Fuji"; Latin urbs Romae ("city of Rome"))Depending on the language, some of the relationships mentioned above have their own distinct cases different from the genitive.Possessive pronouns are distinct pronouns, found in Indo-European languages such as English, that function like pronouns inflected in the genitive. They are considered separate pronouns if contrasting to languages where pronouns are regularly inflected in the genitive. For example, English my is either a separate possessive adjective or an irregular genitive of I, while in Finnish, for example, minun is regularly agglutinated from minu- "I" and -n (genitive).In some languages, nouns in the genitive case also agree in case with the nouns they modify (that is, it is marked for two cases). This phenomenon is called suffixaufnahme.In some languages, nouns in the genitive case may be found in inclusio–that is, between the main noun’s article and the noun itself.Many languages have a genitive case, including Albanian, Arabic, Armenian, Basque, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, Georgian, German, Greek, Icelandic, Irish, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Romanian, Sanskrit, Scottish Gaelic, Turkish and all Slavic languages except Bulgarian and Macedonian. English does not have a proper genitive case, but a possessive ending, -’s, although some pronouns have irregular possessive forms which may more commonly be described as genitives; see English possessive.【Latin】The genitive is one of the cases of nouns and pronouns in Latin. Latin genitives still have certain modern scientific uses:∙Scientific names of living things sometimes contain genitives, as in the plant name Buddleja davidii, meaning "David's buddleia". Here Davidii is the genitive of Davidius, a Latinized version of the English name. It is not capitalized because it is the second part of a binomial name.∙Names of astronomical constellations are Latin, and the genitives of their names are used in naming objects in those constellations, as in the Bayer designation of stars. For example, the brightest star in theconstellation Virgo is called Alpha Virginis, which is to say "Alpha of Virgo", as virginis is the genitive of virgō.∙Modus operandi, which can be translated to English as "mode of operation", in which operandi is a singular genitive gerund (i.e. "of operation"), not a plural of operandus as is sometimes mistakenly assumed.The dative case (abbreviated DAT, or sometimes D when it is a core argument) is a grammatical case generally used to indicate the noun to which something is given, as in "Maria gave Jakob a drink". Here, Jakob is an indirect dative.In general, the dative marks the indirect object of a verb, although in some instances, the dative is used for the direct object of a verb pertaining directly to an act of giving something. This may be a tangible object (e.g., "a book" or "a tapestry"), or an intangible abstraction (e.g., "an answer" or "help").Sometimes the dative has functions unrelated to giving. In Scottish Gaelic and Irish, the term dative case is misleadingly used in traditional grammars to refer to the prepositional case-marking of nouns following simple prepositions and the definite article. In Georgian, the dative case also marks the subject of the sentence with some verbs and some tenses. This is called the dative construction.The dative was common among early Indo-European languages and has survived to the present in the Balto-Slavic branch and the Germanic branch, among others. It also exists in similar forms in several non-Indo-European languages, such as the Uralic family of languages, and Altaic languages. In some languages, the dative case has assimilated the functions of other now-extinct cases. In Ancient Greek, the dative has the functions of the Proto-Indo-European locative and instrumental as well as those of the original dative.Under the influence of English, which uses the preposition "to" for both indirect objects (give to) and directions of movement (go to), the term "dative" has sometimes been used to describe cases that in other languages would more appropriately be called lative.【Latin】Except the main case (Dativus), there are several other kinds:∙Dativus finalis (dative of purpose), e.g., non scholae sed vitae– "we learn for life, not for school", auxilio vocare - "to call for help", venio auxilio - "I'm coming for help", accipio dono - "I receive this as a gift" or puellaeornamento est - "this serves for the girl's decoration";∙Dativus commŏdi (incommodi), which means action for (or against) somebody, e.g., Graecis agros colere - "to till fields for Greeks"; Combination of Dativus commodi and finalis (double dative): tibi laetitiae "to you for joy"∙Dativus possessivus (possessive dative) which means possession, e.g., angelis alae sunt - literally "to (or for) the angels are wings", this is typically found with a copula and translated as "the angels have wings".∙Dativus ethicus (ethic dative) indicates that the person in the dative is or should be especially concerned about the action, e.g., Quid mihi Celsus agit? "What is Celsus doing?" (expressing the speaker being especiallyinterested in what Celsus is doing for him or her);[4] or Cui prodest? "Whose interest does this serve?" (literally "To whom does this do good?")∙Dativus auctoris, meaning; 'in the eyes of', e.g., 'vir bonus mihi videtur' 'the man seems good to me'.∙The dative is also used to express agency with the gerundive, a future passive participle that, along with the verb to be, expresses obligation or necessity of the action being performed on the noun with which it agrees, e.g., 'haec nobis agenda sunt,' 'these things must be done by us'The accusative case (abbreviated ACC) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb. The same case is used in many languages for the objects of (some or all) prepositions. It is a noun that is having something done to it, usually joined[clarification needed] (such as in Latin) with the nominative case. The syntactic functions of the accusative consist of designating the immediate object of an action, the intended result, the goal of a motion, and the extent of an action.[1]The accusative case existed in Proto-Indo-European and is present in some Indo-European languages (including Latin, Sanskrit, Greek, German, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian), in the Uralic languages, in Altaic languages, and in Semitic languages (such as Hebrew and Classical Arabic). Finnic languages, such as Finnish and Estonian, have two cases to mark objects, the accusative and the partitive case. In morphosyntactic alignment terms, both perform the accusative function, but the accusative object is telic, while the partitive is not.Modern English, which almost entirely lacks declension in its nouns, does not have an explicitly marked accusative case even in the pronouns. Such forms as whom, them, and her derive rather from the old Germanic dative forms, of which the -m and -r endings are characteristic. This conflation of the old accusative, dative, instrumental, and (after prepositions) genitive cases is the oblique case. Most modern English grammarians no longer use the Latin accusative/dative model, though they tend to use the terms objective for oblique, subjective for nominative, and possessive for genitive (see Declension in English).Hine, a true accusative masculine third person singular pronoun, is attested in some northern English dialects as late as the 19th century.[2]【Latin】In Latin, nouns, adjectives, or pronouns in the accusative case (accusativus) can be used ∙as direct object.∙to indicate duration of time. E.g., multos annos, "for many years"; ducentos annos, "for 200 years." This is known as the accusative of duration of time.∙to indicate direction towards which. E.g. domum, "homewards"; Romam, "to Rome" with no preposition needed. This is known as the accusative of place to which, and is equivalent to the lative case found in some other languages.∙as the subject of an indirect statement (e.g. Dixit me fuisse saevum, "He said that I had been cruel;" in later Latin works, such as the Vulgate, such a construction is replaced by quod and a regularly structured sentence, having the subject in the nominative: e.g., Dixit quod ego fueram saevus).∙with case-specific prepositions such as "per" (through), "ad" (to/toward), and "trans" (across).∙in exclamations, such as me miseram, "wretched me" (spoken by Circe to Ulysses in Ovid's Remedium Amoris;note that this is feminine: the masculine form would be me miserum).Ablative case(第五格“离格”或“夺格”)In grammar, ablative case (abbreviated ABL) is a grammatical case (a type of noun inflection) in various languages that is used generally to express motion away from something, although the precise meaning may vary by language. The name "ablative" derives from the Latin ablatus, the (irregular) perfect passive participle of auferre "to carry away".[1] There is no ablative case in modern Germanic languages, such as English.【Latin】Main article: Ablative (Latin)The ablative case in Latin ([casus] ablativus) has various uses, including following various prepositions, in an ablative absolute clause, and adverbially. The ablative case was derived from three Proto-Indo-European cases: ablative (from), instrumental (with), and locative (in/at).。

George Lakoff

George LakoffFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaProfessor George LakoffBorn May 24, 1941 (1941-05-24) (age 68)Residence Berkeley, California, USANationality United StatesFields Cognitive linguisticsCognitive scienceInstitutions University of California, BerkeleyAlma mater Indiana UniversityKnown for Conceptual metaphor theoryEmbodied cognitionGeorge P. Lakoff (pronounced /ˈleɪkɒf/, born May 24, 1941) is an American cognitive linguist and professor of linguistics at the University of California, Berkeley, where he has taught since 1972. Although some of his research involves questions traditionally pursued by linguists, such as the conditions under which a certain linguistic construction is grammatically viable, he is most famous for his ideas about the centrality of metaphor to human thinking, political behavior and society. He is particularly famous for his concept of the "embodied mind", which he has written about in relation to mathematics. In recent years he has applied his work to the realm of politics, exploring this in his books. He was the founder of the now defunct progressive think tank the Rockridge Institute.[1][2]Reappraisal of metaphor:Lakoff began his career as a student and later a teacher of the theory of transformational grammar developed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Noam Chomsky. In the late 1960s, however, he joined with others to promote generative semantics as an alternative to Chomsky's generative syntax. In an interview he stated:During that period, I was attempting to unify Chomsky's transformational grammar with formal logic. I had helped work out a lot of the early details of Chomsky's theory of grammar. Noam claimed then —and still does, so far as I can tell —that syntax is independent of meaning, context, background knowledge, memory, cognitive processing, communicative intent, and every aspect of the body...In working through the details of his early theory, I found quite a few cases where semantics, context, and other such factors entered into rules governing the syntactic occurrences of phrases and morphemes. I came up with the beginnings of an alternative theory in 1963 and, along with wonderful collaborators like Haj Ross and Jim McCawley, developed it through the sixties.[1]Lakoff's claim that Chomsky claims independence between syntax and semantics has beenrejected by Chomsky and he has given examples from within his work where he talks about the relationship between his semantics and syntax. Chomsky goes further and claims that Lakoff has "virtually no comprehension of the work he is discussing" (the work in question being Chomsky's) [3]. His differences with Chomsky contributed to fierce, acrimonious debates among linguists that have come to be known as the "linguistics wars".Lakoff's original thesis on conceptual metaphor was expressed in his book with Mark Johnson entitled Metaphors We Live By in 1980.Metaphor has been seen within the Western scientific tradition as purely a linguistic construction. The essential thrust of Lakoff's work has been the argument that metaphors are primarily a conceptual construction, and indeed are central to the development of thought. He says, "Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature." Non-metaphorical thought is for Lakoff only possible when we talk about purely physical reality. For Lakoff the greater the level of abstraction the more layers of metaphor are required to express it. People do not notice these metaphors for various reasons. One reason is that some metaphors become 'dead' and we no longer recognize their origin. Another reason is that we just don't "see" what is "going on".For instance, in intellectual debate the underlying metaphor is usually that argument is war (later revised as "argument is struggle"):He won the argument.Your claims are indefensible.He shot down all my arguments.His criticisms were right on target.If you use that strategy, he'll wipe you out.For Lakoff, the development of thought has been the process of developing better metaphors. The application of one domain of knowledge to another domain of knowledge offers new perceptions and understandings.Lakoff's theory has applications throughout all academic disciplines and much of human social interaction. Lakoff has explored some of the implications of the embodied mind thesis in a number of books, most written with coauthors.Embodied mind:Further information: Embodied philosophyWhen Lakoff claims the mind is "embodied", he is arguing that almost all of human cognition, up through the most abstract reasoning, depends on and makes use of such concrete and "low-level" facilities as the sensorimotor system and the emotions. Therefore embodiment is a rejection not only of dualism vis-a-vis mind and matter, but also of claims that human reason can be basically understood without reference to the underlying "implementation details".Lakoff offers three complementary but distinct sorts of arguments in favor of embodiment. First,using evidence from neuroscience and neural network simulations, he argues that certain concepts, such as color and spatial relation concepts (e.g. "red" or "over"; see also qualia), can be almost entirely understood through the examination of how processes of perception or motor control work.Second, based on cognitive linguistics' analysis of figurative language, he argues that the reasoning we use for such abstract topics as warfare, economics, or morality is somehow rooted in the reasoning we use for such mundane topics as spatial relationships. (See conceptual metaphor.)Finally, based on research in cognitive psychology and some investigations in the philosophy of language, he argues that very few of the categories used by humans are actually of the black-and-white type amenable to analysis in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. On the contrary, most categories are supposed to be much more complicated and messy, just like our bodies."We are neural beings," Lakoff states, "Our brains take their input from the rest of our bodies. What our bodies are like and how they function in the world thus structures the very concepts we can use to think. We cannot think just anything — only what our embodied brains permit."[2]Many scientists share the belief that there are problems with falsifiability and foundation ontologies purporting to describe "what exists", to a sufficient degree of rigor to establish a reasonable method of empirical validation. But Lakoff takes this further to explain why hypotheses built with complex metaphors cannot be directly falsified. Instead, they can only be rejected based on interpretations of empirical observations guided by other complex metaphors. This is what he means when he says, in "The Embodied Mind", that falsifiability itself can never be established by any reasonable method that would not rely ultimately on a shared human bias. The bias he's referring to is the set of conceptual metaphors governing how people interpret observations.Lakoff is, with coauthors Mark Johnson and Rafael E. Núñez, one of the primary proponents of the embodied mind thesis. Others who have written about the embodied mind include philosopher Andy Clark (See his Being There), philosopher and neurobiologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela and his student Evan Thompson (See Varela, Thompson & Rosch's "The Embodied Mind"), roboticists such as Rodney Brooks, Rolf Pfeifer and Tom Ziemke, the physicist David Bohm (see his Thought As A System), Ray Gibbs (see his "Embodiment and Cognitive Science"), John Grinder and Richard Bandler in their neuro-linguistic programming, and Julian Jaynes. All of these writers can be traced back to earlier philosophical writings, most notably in the phenomenological tradition, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger.Mathematics:According to Lakoff, even mathematics itself is subjective to the human species and its cultures: thus "any question of math's being inherent in physical reality is moot, since there is no way to know whether or not it is." By this, he is saying that there is nothing outside of the thought structures we derive from our embodied minds that we can use to "prove" that mathematics issomehow beyond biology. Lakoff and Rafael E. Núñez (2000) argue at length that mathematical and philosophical ideas are best understood in light of the embodied mind. The philosophy of mathematics ought therefore to look to the current scientific understanding of the human body as a foundation ontology, and abandon self-referential attempts to ground the operational components of mathematics in anything other than "meat".Mathematical reviewers have generally been critical of Lakoff and Núñez, pointing to mathematical errors. (Lakoff claims that these errors have been corrected in subsequent printings.) Their book has yet to elicit much of a reaction from philosophers of mathematics, although the book can be read as making strong claims about how that philosophy should proceed. The small community specializing in the psychology of mathematical learning, to which Núñez belongs, is paying attention.Lakoff has also claimed that we should remain agnostic about whether math is somehow wrapped up with the very nature of the universe. Early in 2001 Lakoff told the AAAS: "Mathematics may or may not be out there in the world, but there's no way that we scientifically could possibly tell." This is because the structures of scientific knowledge are not "out there" but rather in our brains, based on the details of our anatomy. Therefore, we cannot "tell" that mathematics is "out there" without relying on conceptual metaphors rooted in our biology. This claim bothers those who believe that there really is a way we could "tell". The falsifiability of this claim is perhaps the central problem in the cognitive science of mathematics, a field that attempts to establish a foundation ontology based on the human cognitive and scientific process.Political significance and involvement:Lakoff's application of cognitive linguistics to politics, literature, philosophy and mathematics has led him into territory normally considered basic to political science.Lakoff has publicly expressed both ideas about the conceptual structures that he views as central to understanding the political process, and some of his particular political views. He almost always discusses the latter in terms of the former.Moral Politics gives book-length consideration to the conceptual metaphors that Lakoff sees as present in the minds of American "liberals" and "conservatives". The book is a blend of cognitive science and political analysis. Lakoff makes an attempt to keep his personal views confined to the last third of the book, where he explicitly argues for the superiority of the liberal vision.[2]Lakoff argues that the differences in opinions between liberals and conservatives follow from the fact that they subscribe with different strength to two different metaphors about the relationship of the state to its citizens. Both, he claims, see governance through metaphors of the family. Conservatives would subscribe more strongly and more often to a model that he calls the "strict father model" and has a family structured around a strong, dominant "father" (government), and assumes that the "children" (citizens) need to be disciplined to be made into responsible "adults" (morality, self-financing). Once the "children" are "adults", though, the "father" should not interfere with their lives: the government should stay out of the business of those in society whohave proved their responsibility. In contrast, Lakoff argues that liberals place more support in a model of the family, which he calls the "nurturant parent model", based on "nurturant values", where both "mothers" and "fathers" work to keep the essentially good "children" away from "corrupting influences" (pollution, social injustice, poverty, etc.). Lakoff says that most people have a blend of both metaphors applied at different times, and that political speech works primarily by invoking these metaphors and urging the subscription of one over the other.[4]Lakoff further argues that one of the reasons liberals have had difficulty since the 1980s is that they have not been as aware of their own guiding metaphors, and have too often accepted conservative terminology framed in a way to promote the strict father metaphor. Lakoff insists that liberals must cease using terms like partial birth abortion and tax relief because they are manufactured specifically to allow the possibilities of only certain types of opinions. Tax relief for example, implies explicitly that taxes are an affliction, something someone would want "relief" from. To use the terms of another metaphoric worldview, Lakoff insists, is to unconsciously support it. Liberals must support linguistic think tanks in the same way that conservatives do if they are going to succeed in appealing to those in the country who share their metaphors.[5]Lakoff has distributed some much briefer political analyses via the Internet. One article distributed this way is "Metaphor and War: The Metaphor System Used to Justify War in the Gulf", in which Lakoff argues that the particular conceptual metaphors used by the first Bush administration to justify American involvement in the Gulf ended up either obscuring reality, or putting a spin on the facts that was accommodating to the administration's case for military action.In recent years, Lakoff has become involved with a progressive think tank, the Rockridge Institute, an involvement that follows in part from his recommendations in Moral Politics. Among his activities with the Institute, which concentrates in part on helping liberal candidates and politicians with re-framing political metaphors, Lakoff has given numerous public lectures and written accounts of his message from Moral Politics. In 2008, Lakoff joined Fenton Communications, the nation's largest public interest communications firm, as a Senior Consultant.One of his political works, Don't Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, self-labeled as "the Essential Guide for Progressives", was published in September 2004 and features a foreword by former Democratic presidential candidate Howard Dean.Debate with Steven Pinker:In 2006 Steven Pinker wrote an unfavourable review [3] of Lakoff's book Whose Freedom? The Battle Over America's Most Important Idea. Pinker's review was published in The New Republic magazine. Pinker argued that Lakoff's propositions are unsupported and his prescriptions a recipe for electoral failure. He writes that Lakoff is condescending and deplores Lakoff's "shameless caricaturing of beliefs" and his "faith in the power of euphemism". Pinker portrays Lakoff's arguments as "cognitive relativism, in which mathematics, science, and philosophy are beauty contests between rival frames rather than attempts to characterize the nature of reality". Lakoff wrote a rebuttal to the review [4] stating that his position on many matters is the exact reverse of what Pinker attributes to him and explicitly rejecting for example the cognitive relativism andfaith in euphemism as described above.Geoffrey Nunberg, linguist, UC Berkeley professor and author of Talking Right, weighed in on Lakoff vs Pinker in a post on The New Republic's web site.[5]Selected bibliography:2003 (1980) with Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press. 2003 edition contains an 'Afterword'.1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46804-6.1989 with Mark Turner. More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. University of Chicago Press.1996. Moral politics : What Conservatives Know that Liberals Don't, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-022*******2001 Edition. Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-022*******1999 (with Mark Johnson). Philosophy In The Flesh: the Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books.2000 (with Rafael Núñez). Where Mathematics Comes From: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics into Being. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03771-2.2004. Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-19314987152005, "A Cognitive Scientist Looks at Daubert", American Journal of Public Health. 95, no. 1: S114.2006. Whose Freedom? : The Battle over America's Most Important Idea. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-15828-62008. The Political Mind : Why You Can't Understand 21st-Century American Politics with an 18th-Century Brain, ISBN 978-0670019274Videos:How Democrats and Progressives Can Win: Solutions from George Lakoff DVD formatC-Span program online, The Political Mind: Why You Can't Understand 21st-Century American Politics with an 18th Century BrainBooks that discuss Lakoff:Harris, Randy Allen (1995). The Linguistics Wars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509834-X. (Focuses on the disputes Lakoff and others have had with Chomsky.)Haser, Verena (2005). Metaphor, Metonymy, and Experientialist Philosophy: Challenging Cognitive Semantics (Topics in English Linguistics), Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110182835 (A critical look at the ideas behind embodiment and conceptual metaphor.)Kelleher, William J. (2005). Progressive Logic: Framing A Unified Field Theory of Values For Progressives. La CaCañada Flintridge, CA: The Empathic Science Institute. ISBN 0-9773717-1-9. McGlone, M. S. (2001). "Concepts as Metaphors" in Sam Glucksberg, Understanding Figurative Language: From Metaphors to Idioms. Oxford Psychology Series 36. Oxford University Press,90–107. ISBN 0195111095.O'Reilly, Bill (2006). Culture Warrior. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-2092-9. (Calls Lakoff the guiding philosopher behind the "secular progressive movement".)Renkema, Jan (2004). Introduction to Discourse Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 1588115291.Richardt, Susanne (2005). Metaphor in Languages for Special Purposes: The Function of Conceptual Metaphor in Written Expert Language and Expert-Lay Communication in the Domains of Economics, Medicine and Computing. European University Studies: Series XIV, Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature, 413. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 0820473812. Soros, George (2006). The Age of Fallibility: Consequences of the War on Terror. ISBN 1586483595. (discusses Lakoff in regard to the application of his theories on the work of Frank Luntz and with respect to his own theory about perception and reality)Winter, Steven L. (2003). A Clearing in the Forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-90222-6. (Applies Lakoff's work in cognitive science and metaphor to the field of law and legal reasoning.)Dean, John W. (2006), Conservatives without Conscience, Viking Penguin ISBN 0-670-03774-5.。

Grammatical tense

Grammatical tenseIn grammar, tense is a category that locates a situation in time, to indicate when the situation takes place. Tense is the grammaticalisation of time reference, and in general is understood to have the three delimitations of "before now", i.e. the past; "now", i.e. the present; and "after now", i.e. the future. The "unmarked" reference for tense is the temporal distance from the time of utterance, the "here-and-now", this being absolute-tense. Relative-tense indicates temporal distance from a point of time established in the discourse that is not the present, i.e. reference to a point in the past or future, such as the future-in-future, or the future of the future (at some time in the future after the reference point, which is in the future) and future-in-past or future of the past (at some time after a point in the past, with the reference point being a point in the past).Not all languages grammaticalise tense, and those that do differ in their grammaticalisation thereof. Not all grammaticalise the three-way system of past–present–future. For example,two-tense languages such as English and Japanese express past and non-past, this latter covering both present and future in one verb form. Four-tense languages make finer distinctions either in the past (e.g. remote vs recent past), or the future (e.g. near vs remote future). The six-tense language Kalaw Lagaw Ya of Australia has the remote past, the recent past, the today past, the present, the today/near future and the remote future. The differences between such finer distinctions are the distance on the timeline between the temporal reference points from the present.Tense comes from Old French tens "time" (now spelled temps through deliberate archaisation),Tense is normally indicated by a verb form, either on the main verb or on an auxiliary verb. The tense markers are normally affixes, but also stem modification such as ablaut or reduplication can express tense reference, and in some languages tense can be shown by clitics. Often combinations of these can interact, such as in Irish, where there is a proclitic past tense marker do (various surface forms) used in conjunction with the affixed or ablaut-modified pastexpress time reference through adverbials, time phrases, and so on.Other uses of the term "Tense" : Tense, aspect, and moodIn many language descriptions, particularly those of traditional European linguistics, theterm tense is erroneously used to refer to categories that do not have time reference as their prototypical use, but rather are grammaticalisations of mood/modality (e.g. uncertainty, possibility, evidentiality) or aspect(e.g. frequency, completion, duration). Tense differsfrom aspect in showing the time reference, while aspect shows how the action/state is "envisaged" or "seen" as happening/occurring. The most common aspectual distinction inlanguages of the world is that between perfective (complete, permanent, simple, etc.)and imperfective (incomplete, temporary, continuous, etc.).The term tense is therefore at times used in language descriptions to represent any combination of tense proper, aspect, and mood, as many languages include more than one such reference in portmanteau TAM (tense–aspect–mood) affixes or verb forms. Conversely, languages that grammaticalise aspect can have tense as a secondary use of an aspect. In many languages, such as the Latin, Celtic and Slavic languages, a verb may be inflected for both tense and aspect together, as in the passé composé/passé simple (historique) and imparfait of French. Verbs can also be marked for both mood and tense together, such as the present subjunctive (So be it) and the past subjuncitve (Were it so), or all three, such as the past perfect subjunctive (Had it been so).Latin and Ancient GreekThe word tempus was used in the grammar of Latin to describe the six "tenses" of Latin. Four are absolute tenses, of which two are combined tense–aspect categories, marking aspect in the past, while two are relative tenses, in showing time reference to another point of time:▪Praesens (= present)▪Praeteritum imperfectum (= imperfective past, i.e. a combined tense–aspect)▪Praeteritum perfectum (= perfective past, i.e. a combined tense–aspect)▪Futurus (= future)▪Plus quam perfectum (= relative past, i.e. a past that refers to the past of a reference in the past)▪Anterior Futurus (= relative future, i.e. a past that refers to the past of a future point) The tenses of Ancient Greek are similar, though having a three-way aspect contrast in the past, the aorist, the perfect and the imperfect. The aorist was the simple past which contrasted with the imperfective (uncompleted action in the past) and the perfect, the past form that had relevance to the present.The study of modern languages has been greatly influenced by the grammar of these languages, seeing that the early grammarians, often monks, had no other reference point to describe their language. Latin terminology is often used to describe modern languages, at times erroneously, as in the application of the term "pluperfect" to the English "past perfect", the application of "perfect" to what in English more often than not is not "perfective", or where the German simple and perfect pasts are called respectively "Imperfektum" and "Perfektum", despite the fact that neither has any real relationship to the aspects implied by the use of the Latin terms.EnglishSee also: English verbs and English clause syntaxEnglish, like the other Germanic languages, Japanese, Persian, and so on, has only two morphological tenses, past and non-past (alt. present–future). These are distinguished by verb form, by either ablaut or suffix (sings ~ sang, walks ~ walked). The non-past may be used to reference the future ("The bus leaves tomorrow").Tense and aspect in EnglishTense Simple Perfect Continuous/Progressivenonpast past -Ø/-s-ed, -t, ablaut, etc.has/have -en, -ed, ablaut, etc.had -en, -ed, ablaut, etc.am/is/are -ingwas/were -ingnonpast past go, goeswenthave/has gonehad goneam/is/are goingwas/were goingOther languagesIn general Indo-European languages have either two-tense systems like English (e.g. the German languages, Persian, etc.) or three-tense systems of past–present–future (e.g. the Latin and Celtic languages), with finer categorisations made by the use of "compound tenses" using auxiliary verbs, as with English be going to, French venir de, and so on. Such compound tenses often have a combined aspectual or modal meaning, as in be going to, which focuses on the modalilty of intended/obvious future based on present evidence.Other tensed languages of the world are similar, or mark tense in a variety of ways, often with TAM affixes where tense, aspect and mood are expressed by portmanteau affixes - as is often the case also in Indo-European languages.Many languages, such as Irish, also mark person and number as part of the TAM suffix, such as the first, second and third person singular marking of Munster Irish. Examples of tense systems in languages of the world are the following:Germanic Languages:German: Past – Non-Past : In many dialects the former perfect form has replaced the preterite as the marker of the past tense, except for "fossilised forms".Dutch: Past – Non-PastDanish: Past – Non-PastCeltic Languages:Irish: Past – Present – FutureThe past contrasts perfective and imperfective aspect, and some verbs retain aperfective-imperfective contrast in the present. In Classical Irish/Gaelic, a three-way aspectual contrast of simple-perfective-imperfective in the past and present existed.Latin Languages:Italian: Past – Present – FutureThe present covers definite non-past, while the Future covers the probable non-past.Indo-Iranian Languages:Persian: imperfective vs perfective past - non-pastSome verbs retain the imperfective-perfective contrast in the non-past.Slavic Languages:Bulgarian: perfective vs imperfective past – perfective vs imperfective present – future Macedonian: perfective vs imperfective past – present – futureUralic Languages:Finnish: past – non-pastHungarian: past – present – futureTurkic Languages:Turkish: pluperfect – perfective vs imperfective past – present – futurePapuan Languages:Meriam Mìr: remote past – recent past – present – near future – remote futureAll tenses contrast imperfective and perfective aspect.Pama-Nyungan Languages:Kalaw Lagaw Ya: remote past – recent past – today past – present – near future – remote future; one dialect also has a "last night" tenseAll tenses contrast imperfective and perfective aspect.Many languages do not grammaticalize all three categories. For instance, English has pastand non-past ("present"); other languages may have future and non-future. In some languages, there is not a single past or future tense, but finer divisions of time, such as proximal vs. distant future, experienced vs. ancestral past, or past and present today vs. before and after today. Some attested tenses:Future tenses.Immediate future: right nowNear future: soonHodiernal future: later todayVespertine future: this evening[citation needed]Post-hodiernal: after todayCrastinal: tomorrowRemote future, distant futurePosterior tense (relative future tense)Nonfuture tense: refers to either the present or the past, but does not clearly specify which. Contrasts with future.Present tenseStill tense: indicates a situation held to be the case, at or immediately before the utteranceNonpast tense: refers to either the present or the future, but does not clearly specify which. Contrasts with past.Past tenses. Some languages have different past tenses to indicate how far into the past we are talking about.Immediate past: very recent past, just nowRecent past: in the last few days/weeks/months (conception varies)Nonrecent past: contrasts with recent pastHodiernal past: earlier todayMatutinal past: this morningPrehodiernal: before todayHesternal: yesterday or early, but not remotePrehesternal: before yesterdayRemote past: more than a few days/weeks/months ago (conception varies)Nonremote past: contrasts with remote pastHistorical Past: shows that the action/state was part of an event in the pastAncestral past, legendary pastGeneral past: the entire past conceived as a wholeAnterior tense (relative past tense)。

英语是令我头疼的一门学科英语作文

英语是令我头疼的一门学科英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1English is a Subject that Gives Me a Headache (An Essay from a Student's Perspective)English, the language that has become a global lingua franca, is a subject that has been a constant source of frustration and headaches for me throughout my academic journey. As a student, I have grappled with the intricacies of this language, often feeling like I'm trapped in a maze of grammar rules, vocabulary, and pronunciation nuances.One of the biggest challenges I face with English is its grammar. The seemingly endless list of tenses, conjugations, and sentence structures can be overwhelming. Just when I think I have a firm grasp on the present perfect tense, I'm introduced to the past perfect continuous, and my brain short-circuits. It's as if English grammar is a sadistic puzzle designed to confuse and torment students like me.Then there's the vocabulary. English has an insatiable appetite for words, borrowing from numerous languages andconstantly expanding its lexicon. Just when I feel confident with a set of vocabulary, a new batch of words emerges, leaving me scrambling to keep up. It's like playing a never-ending game of word catch-up, and I'm always a few steps behind.Pronunciation is another hurdle that consistently trips me up. English has a knack for defying logical phonetic patterns, with words like "tough," "cough," and "rough" pronounced in completely different ways. It's as if the language is mocking my futile attempts to master its sounds. I often find myself questioning the sanity of the individuals who established these pronunciation rules.But perhaps the most frustrating aspect of English is its abundance of idiomatic expressions and figurative language. Phrases like "raining cats and dogs" or "let the cat out of the bag" leave me utterly perplexed. How am I supposed to decipher these cryptic metaphors when they seem to defy all logic? It's as if English delights in confounding non-native speakers with its linguistic riddles.Despite these challenges, I can't deny the importance of mastering English in today's globalized world. It's the language of international business, academia, and pop culture. However,my struggles with this subject often leave me feeling inadequate and discouraged.I vividly remember the countless times I've stared blankly at an English essay prompt, my mind a whirlwind of half-formed thoughts and jumbled grammar rules. Or the moments when I've been called upon in class to read aloud, only to stumble over words and mispronounce them, my face flushing with embarrassment.Yet, through all these trials and tribulations, I remain determined to conquer English. I remind myself that every stumble is an opportunity to learn, and every headache is a testament to my perseverance. I seek solace in the fact that even native speakers sometimes struggle with the complexities of their own language.As I continue my academic journey, I hold onto the hope that one day, English will no longer be a source of frustration but rather a tool for self-expression and communication. Until then, I'll keep pushing through the headaches, armed with a dictionary, a grammar guide, and an unwavering determination to master this linguistic labyrinth.篇2English: The Subject That Gives Me a HeadacheAs a student, there are few things more dreadful than the words "English class." Just the thought of it makes my head start pounding. You'd think that since it's my native language, English would be one of my strongest subjects. But for some reason, it's always been my academic kryptonite - my greatest weakness and source of frustration.I can still vividly remember struggling through grammar lessons in elementary school, trying in vain to memorize the countless rules about when to use "its" versus "it's", or how to properly structure a complex sentence. My teacher would drone on about subjects, predicates, and modifying phrases, and I'd just stare blankly, feeling like she was speaking ancient Greek rather than English.Even when we moved on to reading classic novels and analyzing poetry, I found little joy in it. Dissecting metaphors and discussing symbolism just felt like a colossal waste of time to me.I wanted to shout "Who cares if the white whale represents man's struggle against nature? It's a dumb book about a grumpy sea captain obsessed with killing an overgrown fish!"Writing assignments were perhaps my biggest source of anguish. The five-paragraph essay structure was my personalninth circle of hell. Having to methodically plan an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion felt more like a form of cruel and unusual punishment than an exercise in composition. And don't even get me started on MLA or APA formatting rules - I've had nightmares about endnotes and hanging indentations.Despite my passionate disdain for the subject, English was a required class every single year from kindergarten through 12th grade. I took it begrudgingly, always counting down the days until I could take my last final exam and be done with it forever. Alas, those hopes were dashed when I got to college and realized I needed two English courses for my general education requirements. Are you kidding me?!So there I was, stuck in English Composition 101, writing essay after torturous essay, consulting cherished grammar guides like Old Faithful to avoid potentially embarrassing myself. The feelings of resentment and inadequacy came flooding back as I watched classmates debate the finer points of MLA styling with eagerness. Me? I just wanted it to be over.I have to admit, a small part of me envied those students who seemed to have a natural flair for English. The ones who could artillery historical context and analyze text like it was second nature. How I longed for even an ounce of that ability!But alas, it was not meant to be. I am simply linguistically challenged when it comes to my native tongue.Even today, years after suffering through my last English course, I still feel a tinge of anxiety anytime I have to compose an important email or document. I carefully construct each sentence, read and re-read for errors, and send it off with a silent prayer that I didn't egregiously violate some commonly grammar rule. I use tools like Grammarly as a safety net, hoping against hope that the little green squiggles under my words will miraculously disappear.Maybe I'm being overly dramatic about my English language woes. It's quite possible that I'm the only one who has noticed or cared about my occasional slip-ups over the years. But I can't shake the feeling that I'm an utter failure when it comes to what should be the most natural form of communication for me.If I'm being honest with myself, a part of the struggle has been a self-fulfilling cycle of negativity and expecting failure. From those earliest memories of grammar-induced headaches, I started telling myself "I'm just not good at this subject." That mentality became a safe little shelter to which I could attribute my struggles. If I'm "just not good at English," then there's no point in putting in the hard work to get better, right?In recent years, I've come to realize how flawed andself-defeating that mindset truly is. Just because a subject doesn't come naturally to me doesn't give me an excuse to resign myself to perpetual mediocrity. We all have strengths and weaknesses, subjects that click and those that don't. The key is putting in the effort in those areas of weakness, powered by discipline rather than perceived innate ability.So here I am, in my late 20s, stubbornly refusing to let English remain the bane of my academic existence. I'vere-committed myself to reading more, exposing myself to quality writing and allowing some of those skills to sublime themselves into my own work. I purchased the grammar books that once induced cold sweats and have been methodically working through them. And I've tried to embrace writing as a process, an art that requires practice, iteration and perseverance.Is it working?It's hard to say for certain. Old habits and that little voice of self-doubt are hard to quiet sometimes. But I'd like to think I'm making progress, slowly chipping away at those mental blocks I've allowed to hold me back for far too long. Perhaps one day, years of persistent effort will transform English from one of my biggest areas of weakness into a hard-earned strength.Because in the end, that's the harsh reality - few things in life worth achieving can be attained without dedication and struggle. If I want to improve my English skills, there are no shortcuts; no magic pills orLife hacks that can supplement good old-fashioned work. It will be a long, arduous journey of re-learning fundamentals and changing the deeply-ingrained habits of a lifetime.But I'll keep chipping away, re-writing that flawed narrative I've been telling myself for decades. One day, I hope to be able to say that English is no longer the subject that gives me a headache - but one that I've finally mastered through perseverance. Maybe then I'll be able to look back with a sense of pride, grateful for the important life lesson that challenges need not result in resignation. With focus and effort, they can become emblematic of our ability to grow.篇3English: The Bane of My Academic ExistenceIf you ask any student what their least favorite subject is, I can almost guarantee that English will be high on the list for many. As someone who has struggled with this language and its bizarre rules from a young age, I can attest to the fact thatEnglish is the bane of my academic existence – a never-ending source of frustration, confusion, and metaphorical headaches.From the moment we start learning to read and write, English throws curveball after curveball our way. The spelling rules make no sense – for every "tough" there's a "though", for every "weight" there's a "height". How are we supposed to keep track? And don't even get me started on homophones like "their", "there", and "they're" – a single misplaced apostrophe and the entire meaning changes. It's maddening!Then we get to grammar, where the rules are even more confounding. Subject-verb agreement seems simple in theory until you encounter collective nouns, which can be either singular or plural depending on the context. Split infinitives are taboo unless they're not. And let's not forget about the dreadfully confusing cases where "fewer" is correct instead of "less", or vice versa. By the time you've muddled through all the nitpicky grammar guidelines, your head is spinning.But the true headache inducer has to be vocabulary. English proudly flaunts its trove of obscure, ludicrously complicated words that serve no purpose other than to confuse and intimidate. "Antidisestablishmentarianism" – a 28-letter monster that basically means "the opposition to disestablishing theChurch of England". Tell me, in what conceivable situation would the average person need to utter that ungodly word? And that's just one egregious example out of many. The English vocabulary is a labyrinth with no exit in sight.Even simple conversations can turn into linguistic nightmares thanks to English's extensive collection of idioms and figurative phrases. "Pulling someone's leg", "raining cats and dogs", "kicking the bucket" – how is a non-native speaker supposed to decipher these bizarre sayings that make no logical sense when taken literally? Talk about a recipe for confusion and embarrassment.Don't even get me started on trying to learn English as a second language. As a native speaker, I still struggle daily with the convolutions of this crazy tongue. I can only imagine the migraines that those striving to learn it as an additional language must endure. The poor grammar structure, bizarre spelling rules, and trap-laden vocabulary must make English feel like a daunting, insurmountable mountain at times.And this isn't even touching on the different accents, dialects, and colloquialisms that pop up across regions – turning one "English" into a hundred different, barely recognizable variations. How's a student supposed to keep up?At the end of the day, English is my mother tongue, the language I've grown up speaking and writing in. And yet, it remains an endless source of frustration - a beast I can never fully tame no matter how hard I try. Its rules are a paradox, its vocabulary is absurd, and its very existence seems determined to induce metalinguistic headaches galore.From daunting dissertations to simple spelling drills, English is there, lurking ominously and ready to strike at a moment's notice. If this rant has proven anything, it's that even native speakers aren't immune to the maddening quirks and confusing nuances of the English language. We're all in this crazy, headache-inducing journey together, for better or worse.So to all my fellow English students out there, I feel your pain. I, too, lie awake at night pondering the "i before e except after c" rule and its millions of ridiculous exceptions. Like you, I've banged my head against the wall trying to figure out where to properly place a modifier or how to correctly conjugate an irregular verb.We're all in the same boat, constantly trying – and often failing – to master what might be the most maddeningly inconsistent yet unavoidable language on the planet. All we can do is persevere, take some Tylenol for our English-inducedmigraines, and look on the bright side: at least we're not alone in our struggles against this linguistic behemoth.。

外研社剑桥六年级下册英语课堂笔记