信用评级机构外文翻译

盈余质量分析的评价指标体系外文翻译

原文:Analysis of earnings quality evaluation index system Earnings quality is an important aspect of evaluating an entity's financial health, yet investors, creditors, and other financial statement users often overlook it. Earnings quality refers to the ability of reported earnings to reflect the company's true earnings, as well as the usefulness of reported earnings to predict future earnings. Earnings quality also refers to the stability, persistence, and lack of variability in reported earnings. The evaluation of earnings is often difficult, because companies highlight a variety of earnings figures: revenues, operating earnings, net income, and pro forma earnings. In addition, companies often calculate these figures differently. The income statement alone is not useful in predicting future earnings.The SEC and the investing public are demanding greater assurance about the quality of earnings. Analysts need a more suitable basis for earnings estimates. Credit rating agencies are under increased scrutiny of their ratings by the SEC. Such comfort level and information is not provided in the audit report or the financial statements. Only 27% of finance executives recently surveyed by CFO “feel 'very confident' about the quality and completeness of information available about public companies” [“It's Better (and Worse) Than You Think,” by D. Dupree May 3, 2004].There are a variety of definitions and models for assessing earnings quality. The authors have proposed a uniform, independent definition of quality of earnings that allows for the development of an Earnings Quality Assessment (EQA) model. The proposed EQA model evaluates the degree to which a company's income statement reports its true earnings and the extent to which it can predict and anticipate future earnings.Earnings Quality DefinedA variety of earnings-quality definitions exist. Teats [“Quality of Earnings: An Introduction to the Issues in Accounting Education,” Issues in Accounting Education, 17 (4), 2002] states that “some consider quality of earnings to encompass the underlying economic performance of a firm, as well as the accounting standards that report on that underlying phenomenon; others consider quality of earnings to refer only to how well accounting earnings convey information about the underlying phenomenon.” Pratt defines earnings quality as “the extent to which net income reported on the income statement differs from true earnings” [in F. Hodge, “Investors'Perceptions of Earnings Quality, Auditor Independence, and the Usefulness of Audited Financial Information,” Accounting Horizons 17 (Supplement), 2003]. Penman [“The Quality of Financial Statements: Perspectives from the Recent Stock Market Bubble,” Accounting Horizons 17 (Supplement), 2003] indicates that quality of earnings is based on the quality of forward earnings as well as current reported earnings. Shipper and Vincent [“Earnings Quality,” Accounting Horizons 17 (Supplement), 2003] define earnings quality as “the extent to which reported earnings faithfully represent Hicks Ian income,” which includes “the change in net economic assets other than from transactions with owners.”Using various definitions of earnings quality, researchers and analysts have developed several models. The Sidebar summarizes eight models for measuring earnings quality. The models are used for very narrow, specific purposes. While the criteria used in these definitions and models overlap, none provide a comprehensive view of earnings quality. For example, the primary purpose of the Center for Financial Research and Analysis (CRFA)'s model is to uncover methods of earnings manipulation. Of the eight models discussed, only the Lev-Thiagarajan and Empirical Research Partners models have been empirically tested for evidence of usefulness related to quality of earnings. Lev and Thiagarajan's findings confirm that their fundamental (earnings) quality score correlates to earnings persistence and growth, and that subsequent growth is higher in high quality–scoring groups. Empirical Research Partners' model is based in part on methodology developed and tested by Potosi, whose findings indicate a positive relationship between scores based on the model and future profitability.The following summarizes the criteria considered in each of the eight models for measuring earnings quality.Center for Financial Research and Analysis: Four criteria to uncover methods used to manipulate earnings. Report includes financial summary, accounting policy analysis, discussion of areas of concernEmpirical Research Partners: Three components: net working-capital growth rate, net concurrent assets, deferred taxes; incremental earnings and free cash flow production relative to each new dollar of revenue or book value; and nine financial indicators, put together for a single gauge of fundamentals. Items viewed favorably:positive return on assets and operating cash flow; increases in return on assets, current ratio, gross margin, asset turnover; operating cash flow that exceeds net income.Items viewed unfavorably: increases in long-term debt-to-assets; presence of equity offerings. Each indicator given a 1 if favorable, an O if not; scores aggregated on an O to 9 scales.Ford Equity Research: Earnings variability is minimum standard error of earnings for past eight years, fitted to an exponential curve. Growth persistence considers earnings growth consistency over 10 years; projected earnings growth rate is applied to normal earnings to derive long-term value. Operating earnings calculated by excluding unusual items, such as restructuring charges and asset write-downs; earnings trend analysis done on this adjusted figure. Repurchases of an entity's own shares are analyzed to determine if results are favorable.Lev-Thiagarajan: Each fundamental is assigned a value of 1 for positive signal, O for negative signal. Each of 12 factors is equally weighted to develop aggregate fundamental score. Negative signals include: decrease in gross margins disproportionate to sales; disproportionate (versus industry) decreases in capital expenditures and R&D; increases in S&A expenses disproportionate to sales; and unusual decreases in effective tax rate. Inventory and accounts receivable signals measure percent change in each (individually) minus percent change in sales; inventory increases exceeding cost of sales increases and disproportionate increases in receivables to sales are considered negative. Unusual changes in percent change of provision for doubtful receivables, relative to percent change in gross receivables, are also viewed negatively. Percent change in sales minus percent change in order backlog is considered an indication of future performance.Merrill Lynch (David Hawkins) (see earnings quality: the establishment of a real 360 View, 2002). Higher total capital ratio (pre-tax operating return on total capital) returns a higher quality of earnings equivalent. Liquidity ratio above 1.0 (net income figure how close it is to achieve positive cash) that the higher quality of earnings. Re-investment in productive assets ratio above 1.0 (committed to maintaining the fixed asset investment) that a higher quality of earnings. The ratio ofeffective tax rate for all companies meet or exceed the average level (dependence on low-tax report) that the higher quality of earnings. Model also believes that long-term credit rating and Standard & Poor's S & P earnings and dividend growth and stability of rank-based, over the past 10 years.Raymond James & Partners (Michael Krensavage) (also see the earnings quality monitoring, 2003.) 1 (worst) to 10 (best) rating as a benchmark of 10 exclusive distributions; weighted average rating in the combined to determine the earnings quality scores. Low earnings quality indicators: increase in receivables; earnings growth due to reduced tax rates, interest capitalization, high frequency / time scale of the project. In a recent major acquisition made during the punishment. Practice of conservative pension fund management and improve the R & D budget faster than revenue in return. Cash flow growth and the related net income and gross margin of profit a positive impact on quality improvement.Standard & Poor's core earnings (see also the technical core earnings Bulletin, October 2002). Attempts to give a more accurate performance of the existing business of the real. Core benefits include: Employee stock option expenses; restructuring charges from ongoing operations; offset the depreciation of business assets or deferred pension costs; purchased research and development costs; merger / acquisition costs; and unrealized gains and losses on hedging. Excluded items: Goodwill impairment charges, pension income; litigation or insurance settlements, from the sale of assets (loss) and the provisions of the previous year's expenses and the reversal.UBS (David Bianca) (also see S & P 500 accounting information quality control, 2003.) Comparison of GAAP operating income; the difference between the net one time standard. Employee stock option expenses charged to operating profit. Assuming the market value of return on pension assets to adjust interest rates or the discount rate times. Health care costs adjusted for inflation, if the report is 300 basis points more than the S & P 500 companies are expected weighted average. Joint Oil Data Initiative is AUTHOR_AFFILIATION Bell ovary, CPA, is a Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Don E. Incoming, CPA, graduate students, professors, and Donald E &Beverly Flynn is Chairman of the holder at Marquette University. Michael D • Akers, CPA, CMA, CFE, CIA, CBM, is a Professor and Head of the Department.Of the 51 criteria/measurements used in the eight models, only eight (acquisitions; cash flow from operations/net income; employee stock options; operating earnings; pension fund expenses; R&D spending; share buyback/issuance; and tax-rate percentage) are common to two models, and only two (gross margin and one-time items) overlap in three models.The first step, then, is to develop a standard definition of earnings quality. One of the objectives of Fast’s Conceptual Framework is to assist investors in making investment decisions, which includes predicting future earnings. The Conceptual Framework refers not only to the reliability (or truthfulness) of financial statements, but also to the relevance and predictive ability of information presented in financial statements. The authors' definition of quality of earnings draws from Pratt's and Penman's definitions. The authors define earnings quality as the ability of reported earnings to reflect the company's true earnings and to help predict future earnings. They consider earnings stability, persistence, and lack of variability to be key. As Beaver indicates: “current earnings are useful for predicting future earnings … [and] future earnings are an indicator of future dividend-paying ability” (in M. Bauman, “A Review of Fundamental Analysis Research in Accounting,” Journal of Accounting Literature 15, 1996).Earnings Quality Assessment (EQA)The authors propose an Earnings Quality Assessment (EQA) that provides an independent measure of the quality of a company's reported earnings. The EQA consists of a model that uses 20 criteria that impact earnings quality (see Exhibit 2 ), applied as a “rolling evaluation” of all p eriods presented in the financial statements. The EQA is more comprehensive than the eight models presented, considering revenue and expense items, as well as one-time items, accounting changes, acquisitions, and discontinued operations. The model also assesses the stability, or lack thereof, of a company, which leads to a more complete understanding of its future earnings potential.The criteria were drawn from the eight models discussed, including the 10 criteria overlapping two or more models. The EQA evaluator assigns a point value ranging from 1 to 5 for each of the 20 criteria, with a possible total of 100 points. Ascore of 1 indicates a negative effect on earnings quality, and a score of 5 indicates a very positive effect on earnings quality. EQA scores, then, can range from 20 to 100. Similar to the grading methods for bond ratings, grades are assigned based on the following scale: 85–100 points = A, 69–84 points = AB, 53–68 points = B, 35–51 points = BC and 20–34 points = C. While the EQA evaluator needs to use professional judgment in assigning scores to each of the criteria, the guidelines in Exhibit 2 are recommended.The Application of EQATo illustrate the process of applying the EQA, the authors chose two large pharmaceutical companies, Merck and with. Each of the authors independently applied the EQA to Merck's and Width’s 2003 financial statements, and then met to discuss their results. Based upon each individual assessment and the subsequent discussion, they reached an agreed-upon score, presented in Exhibit 3 .This process is similar to what an engagement team would go through. Each member would complete the EQA independently, and then the group would meet as a whole to discuss the assessment and reach a conclusion. This process allows for varying levels of experience, and takes into account each team member's perspective based on exposure to various areas of the company. The audit team's discussion is also helpful when one member finds an item that another might not have, which may explain variances in the scores assigned by each individual.For the illustration, the EQA was based solely on data provided in the financial statements. The authors found a high level of agreement on the quality of earnings measures, and there was little variation in the scores for both companies. One would expect even less variation when a group more intimately exposed to an organization, such as the audit engagement team, completes the EQA. The consistency provided by use of the EQA model would enhance the comfort level of users of the financial statements and the EQA.Need for Further DevelopmentThere is significant need for the development of a uniform definition and a consistent model to measure earnings quality. This article provides such a definition, positing that the quality of earnings includes the ability of reported earnings to reflect the company's true earnings, as well as the usefulness of reported earnings to predict future earnings. The authors propose an Earnings Quality Assessment (EQA) model that is consistent with this definition. The EQA recognizes many of the fragilities ofGAAP, and takes into account factors that are expected to affect future earnings but that are not explicitly disclosed in the financial statements.The authors propose that auditors conduct the EQA and issue a public report. Auditors' EQA reports will provide higher-quality information to financial statement users and meet the SEC's demand for greater assurance about the reliability of earnings figures.Source: MichaelD.Akers, 2005. “Analysis of earnings quality evaluation index system” the CPA journal. November.pp.199.译文:盈余质量分析的评价指标体系盈余质量是债权人评价一个实体的财务状况的重要方面,但投资者和其他财务报表使用者往往忽略它。

camels评价体系

CAMELS评级体系一种国际通行的商业银行主管部门评判银行运营质量的评级体系。

CAMELS这6个英文大写字母分别代表6项标准,C是资本充足率、A是资产质量、M 是管理质量、E是盈利、L是流动性,S是对市场风险的敏感性。

该体系评分由1(最好)到5(最差),如果银行综合评分在2以下,说明该银行运营质量极佳,如果大于3,就需要主管部门警惕。

银行股投资者不仅可以根据CAMELS评级分数来直接了解银行质地的优劣,也可以按照这一框架来对商业银行进行具体分析。

CAMELS Rating System CAMELS评级制度国际通用银行评级制度,银行监察机构根据六个因素评定金融机构的登记。

CAMELS代表六个评级因素,包括资本充足(capital adequacy)、资产质量(asset quality)、管理质量(management quality)、盈利(earnings)、流动资金(liquidity)、对市场风险的敏感度(sensitivity to market risk) 駱駝信用評級指標體系出自MBA智库百科(/)(重定向自CAMELS Rating System)駱駝信用評級指標體系(CAMELS Rating System/CAMEL Rating System)目錄[隱藏]∙ 1 什麼是駱駝信用評級指標體系∙ 2 “駱駝”評級體系的內容∙ 3 “駱駝”評級體系的指標與考評標準∙ 4 “駱駝”評級體系的特點∙ 5 駱駝評級體系的具體內容、指標與方法∙ 6 駱駝體系的綜合評級與評估報告∙7 駱駝體系的修訂[編輯]什麼是駱駝信用評級指標體系“駱駝”評級體系是目前美國金融管理當局對商業銀行及其他金融機構的業務經營、信用狀況等進行的一整套規範化、制度化和指標化的綜合等級評定製度。

因其五項考核指標,即資本充足性(Capital Adequacy)、資產質量(Asset Quality)、管理水平(Management)、盈利水平(Earnings)和流動性(Liquidity),其英文第一個字母組合在一起為“CAMEL”,正好與“駱駝”的英文名字相同而得名。

信用评级机构[文献翻译]

![信用评级机构[文献翻译]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/7077db4fc281e53a5802ff7c.png)

一、外文原文The Credit Rating Agencies: How Did We Get Here? Where Should We Go?Lawrence J. White*"…an insured state savings association…may not acquire or retain any corporate debt securities not of investment grade." 12 Code of Federal Regulations § 362.11 " …any user of the information contained herein should not rely on any credit rating or other opinion contained herein in making any investment decision." The usual disclaimer that is printed at the bottom of Standard & Poor’s credit ratings The U.S. subprime residential mortgage debacle of 2007-2008, and the world financial crisis that has followed, will surely be seen as a defining event for the U.S. economy -- and for much of the world economy as well -- for many decades in the future. Among the central players in that debacle were the three large U.S.-based credit rating agencies: Moody's, Standard & Poor's (S&P), and Fitch.These three agencies' initially favorable ratings were crucial for the successful sale of the bonds that were securitized from subprime residential mortgages and other debt obligations. The sale of these bonds, in turn, were an important underpinning for the U.S. housing boom of 1998-2006 -- with a self-reinforcing price-rise bubble. When house prices ceased rising in mid 2006 and then began to decline, the default rates on the mortgages underlying these bonds rose sharply, and those initial ratings proved to be excessively optimistic -- especially for the bonds that were based on mortgages that were originated in 2005 and 2006. The mortgage bonds collapsed, bringing down the U.S. financial system and many other countries’ financial systems as well.The role of the major rating agencies has received a considerable amount of attention in Congressional hearings and in the media. Less attention has been paid to the specifics of the financial regulatory structure that propelled these companies to the center of the U.S. bond markets –and that thereby virtually guaranteed that when they did make mistakes, those mistakes would have serious consequences for the financial sector. But an understanding of that structure is essential for any reasoned debate about the future course of public policy with respect to the rating agencies.This paper will begin by reviewing the role that credit rating agencies play in the bond markets. We then review the relevant history of the industry, including the crucial role that the regulation of other financial institutions has played in promoting the centrality of the major credit rating agencies with respect to bond information. In the discussion of this history, distinctions among types of financial regulation –especially between the prudential regulation of financial institutions (which, as we will see, required them to use the specific bond creditworthiness information that was provided by the major rating agencies) and the regulation of the rating agencies themselves –are important.We next offer an assessment of the role that regulation played in enhancing the importance of the three major rating agencies and their role in the subprime debacle. We then consider the possible prospective routes for public policy with respect to the creditrating industry. One route that has been widely discussed –and that is embodied in legislation that the Obama Administration proposed in July 2009 –would tighten the regulation of the rating agencies, in efforts to prevent the reoccurrence of those disastrous judgmental errors. A second route would reduce the required centrality of the rating agencies and thereby open up the bond information process in way that has not been possible since the 1930s.Why Credit Rating Agencies?A central concern of any lender -- including the lender/investors in bonds -- is whether a potential or actual borrower is likely to repay the loan. This is, of course, a standard problem of asymmetric information: The borrower is likely to know more about its repaying proclivities than is the lender. There are also standard solutions to the problem: Lenders usually spend considerable amounts of time and effort in gathering information about the likely creditworthiness of prospective borrowers (including their history of loan repayments and their current and prospective financial capabilities) and also in gathering information about the actions of borrowers after loans have been made.The credit rating agencies (arguably) help pierce the fog of asymmetric information by offering judgments -- they prefer the word "opinions"-- about the credit quality of bonds that are issued by corporations, governments (including U.S. state and local governments, as well as "sovereign" issuers abroad), and (most recently) mortgage securitizers. These judgments come in the form of “ratings”, which are usually a letter grade. The best known scale is that used by S&P and some other rating agencies: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, etc., with pluses and minuses as well.4Credit rating agencies are thus one potential source of such information for bond investors; but they are far from the only potential source. There are smaller financial services firms that offer advice to bond investors. Some bond mutual funds do their own research, as do some hedge funds. There are “fixed income analysts” at many financial services firms who offer recommendations to those firms’ clients with respect to bondinvestments.Although there appear to be well over 100 credit rating agencies worldwide,6 the three major U.S.-based agencies are clearly the dominant entities. All three operate on a worldwide basis, with offices on all six continents; each has ratings outstanding on tens of trillions of dollars of securities. Only Moody’s is a free-standing company, so the most information is known about Moody’s: Its 2008 annual report listed the company’s total revenues at $1.8 billion, its net revenues at $458 million, and its total assets at year-end at $1.8 billion.7 Slightly more than half (52%) of its total revenue came from the U.S.; as recently as 2006 that fraction was two-thirds. Over two-thirds (69%) of the company’s revenues comes from ratings; the rest comes from related services. At year-end 2008 the company had approximately 3,900 employees, with slightly more than half located in the U.S.Because S&P’s and Fitch’s ratings operations are components of larger enterprises (that report on a consolidated basis), comparable revenue and asset figures are not possible. But S&P is roughly the same size as Moody’s, while Fitch is somewhat smaller. Table 1 provides a set of roughly comparable data on each company’s analytical employees and numbers of issues rated. As can be seen, all three companies employ about the same numbers of analysts; however, Moody’s and S&P rate appreciably morecorporate and asset-backed securities than does Fitch.The history of the credit rating agencies and their interactions with financial regulators is crucial for an understanding of how the agencies attained their current central position in the market for bond information. It is to that history that we now turn. What Is to Be Done?In response to the growing criticism (in the media and in Congressional hearings) of the three large bond raters' errors in their initial, excessively optimistic ratings of the complex mortgage-related securities (especially for the securities that were issued and rated in 2005 and 2006) and their subsequent tardiness in downgrading those securities, the SEC in December 2008 promulgated NRSRO regulations that placed mild restrictions on the conflicts of interest that can arise under the rating agencies' "issuer pays" business model (e.g., requiring that the agencies not rate debt issues that they have helped structure, not allowing analysts to be involved in fee negotiations, etc.) and that required greater transparency (e.g., requiring that the rating agencies reveal details on their methodologies and assumptions and track records) in the construction of ratings.Political pressures to do more -- possibly even to ban legislatively the "issuer pays" model –have remained strong. In July 2009 the Obama Administration, as part of its larger package of proposed financial reforms, offered legislation that would require further, more stringent efforts on the part of the rating agencies to deal with the conflicts and enhance transparency.This regulatory response –the credit rating agencies made mist akes; let’s try to make sure that they don’t make such mistakes in the future –is understandable. But it ignores the history of the other kind of financial regulation – the prudential regulation of banks and other financial institutions -- that pushed the rating agencies into the center of the bond information process and that thereby greatly exacerbated the consequences for the bond markets when the rating agencies did make those mistakes. It also overlooks the stultifying consequences for innovation in the development and assessment ofinformation for judging the creditworthiness of bonds.Regulatory efforts to fix problems, by prescribing specified structures and processes, unavoidably restrict flexibility, raise costs, and discourage entry. Further, although efforts to increase transparency may help reduce problems of asymmetric information, they also have the potential for eroding a rating firm’s intellectual property and, over the longer run, discouraging the creation of future intellectual property.There is another, quite different direction in which public policy might proceed in the wake of the credit rating agencies’ mistakes. Rather than trying to fix them through regulation, it would provide a more markets-oriented approach that would likely reduce the importance of the incumbent rating agencies and thus reduce the importance (and consequences) of any future mistakes that they might make. This approach would call for the withdrawal of all of those delegations of safety judgments by financial regulators to the rating agencies. The rating agencies’ judgments would no longer have the force of law. Those financial regulators should persist in their goals of having safe bonds in the portfolios of their regulated institutions (or that, as in the case of insurance companies and broker-dealers, an institution's capital requirement would be geared to the risk ness of the bonds that it held); but those safety judgments should remain the responsibility of theregulated institutions themselves, with oversight by regulators.Under this alternative public policy approach, banks (and insurance companies, etc.) would have a far wider choice as to where and from whom they could seek advice as to the safety of bonds that they might hold in their portfolios. Some institutions might choose to do the necessary research on bonds themselves, or rely primarily on the information yielded by the credit default swap (CDS) market. Or they might turn to outside advisors that they considered to be reliable -- based on the track record of the advisor, the business model of the advisor (including the possibilities of conflicts of interest), the other activities of the advisor (which might pose potential conflicts), and anything else that the institution considered relevant. Such advisors might include the incumbent credit rating agencies. But the category of advisors might also expand to include the fixed income analysts at investment banks (if they could erect credible "Chinese walls") or industry analysts or upstart advisory firms that are currently unknown.The end-result -- the safety of the institution's bond portfolio -- would continue to be subject to review by the institution's regulator.That review might also include a review of the institution's choice of bond-information advisor (or the choice to do the research in-house) -- although that choice is (at best) a secondary matter, since the safety of the bond portfolio itself (regardless of where the information comes from) is the primary goal of the regulator. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that the bond information market would be opened to new ideas -- about ratings business models, methodologies, and technologies -- and to new entry in ways that have not actually been possible since the 1930s.It is also worth asking whether, under this approach, the "issuer pays" business model could survive. The answer rests on whether bond buyers are able to ascertain which advisors do provide reliable advice (as does any model short of relying on government regulation to ensure accurate ratings). If the bond buyers can so ascertain,then they would be willing to pay higher prices (and thus accept lower interest yields) on the bonds of any given underlying quality that are "rated" by these reliable advisors. In turn, issuers -- even in an "issuer pays" framework -- would seek to hire these recognized-to-be-reliable advisers, since the issuers would thereby be able to pay lower interest rates on the bonds that they issue.That the "issuer pays" business model could survive in this counter-factual world is no guarantee that it would survive. That outcome would be determined by the competitive process.ConclusionWhither the credit rating industry and its regulation? The central role -- forced by seven decades of financial regulation -- that the three major credit rating agencies played in the subprime debacle has brought extensive public attention to the industry and its practices. The Securities and Exchange Commission has recently (in December 2008) taken modest steps to expand its regulation of the industry. The Obama Administration has proposed further efforts.There is, however, another direction in which public policy could proceed: Financial regulators could withdraw their delegation of safety judgments to the credit ratingagencies. The policy goal of safe bond portfolios for regulated financial institutions would remain. But the financial institutions would bear the burden of justifying the safety of their bond portfolios to their regulators. The bond information market would be opened to new ideas about rating methodologies, technologies, and business models and to new entry in ways that have not been possible since the 1930s.Those who are interested in this public policy debate should ask themselves the following questions: Is a regulatory system that delegates important safety judgments about bonds to third parties in the best interests of the regulated financial institutions and of the bond markets more generally? Will more extensive regulation of the rating agencies actually succeed in forcing the rating agencies to make better judgments in the future? Would such regulation have consequences for flexibility, innovation, and entry in the bond information market? Or instead, could the financial institutions be trusted to seek their own sources of information about the creditworthiness of bonds, so long as financial regulators oversee the safety of those bond portfolios?二、翻译文章信用评级机构:我们怎么会在这里?我们到哪去?劳伦斯 J 怀特美国联邦法规法典第362章11节12条指出:“…任何已投保的国家储蓄机构…不得取得或者保留任何公司债券投资级别的债券。

The US and EU credit rating agency reforms(美国和欧盟信用评级机构改革)

2

Institute of Law

FOCOFIMA lecture

The Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs)

Private entities assessing the creditworthiness of borrowers and the risks associated with the full and timely payment of debt securities Issuing credit ratings: Corporate ratings Sovereign ratings Structured finance ratings Assessing credit risk – Components of credit risk: Probability of default Recovery in the case of default Correlation of defaults (for investments with multiple assets)

Investment grade

BB

B CCC CC C D

Non-investment grade – Speculative

Highly speculative Extremely speculative In default with little prospect for recovery In default with little prospect for recovery In default Non-investment – Speculative grade

Introduction

各国信用评级列表2012

阿布扎比酋长国AA 稳2011年11月[4][5]阿尔巴尼亚B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]安道尔 A 降2011年11月[4][5]安哥拉BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]阿根廷 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]阿鲁巴A- 稳2011年11月[4][5]澳大利亚AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]奥地利AA+ 降2012年1月[4][5]阿塞拜疆BB+ 升2011年11月[4][5]巴哈马BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]巴林BBB 降2011年11月[4][5]孟加拉国BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]巴巴多斯BBB- 降2011年11月[4][5]白俄罗斯 B 降2011年11月[4][5]比利时AA 降2011年11月[4][5]伯利兹B- 降2011年11月[4][5]贝宁 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]百慕大AA 稳2011年11月[4][5]玻利维亚B+ 升2011年11月[4][5]波斯尼亚和黑塞哥维那B+ 降2011年11月[4][5]博茨瓦纳A- 稳2011年11月[4][5]巴西BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]保加利亚BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]布基纳法索 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]柬埔寨 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]喀麦隆 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]加拿大AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]佛得角B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]智利A+ 升2011年11月[4][5]中国AA- 稳2011年11月[4][5]哥伦比亚BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]库克群岛BB- 降2011年11月[4][5]哥斯达黎加BB 稳2011年11月[4][5]克罗地亚BBB- 降2011年11月[4][5]库拉索A- 稳2011年11月[4][5]塞浦路斯BB+ 降2012年1月[4][5]捷克AA- 稳2011年11月[4][5]丹麦AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]多米尼加共和国B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]厄瓜多尔B- 升2011年11月[4][5]埃及B+ 降2011年11月[4][5]萨尔瓦多BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]拉斯海玛 A 稳2011年11月[4][5]爱沙尼亚AA- 降2012年1月[4][5]斐济 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]芬兰AAA 降2012年1月[4][5]法国AA+ 降2012年1月[4][5]加蓬BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]格鲁吉亚BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]德国AAA 稳2012年1月[4][5]加纳 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]希腊CC 降2011年11月[4][5]格林纳达B- 稳2011年11月[4][5]危地马拉BB 降2011年11月[4][5]根西岛AA+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]洪都拉斯 B 升2011年11月[4][5]香港AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]匈牙利BB+ 降2011年12月[4][5]冰岛BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]印度BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]印尼BB+ 升2011年11月[4][5]爱尔兰BBB+ 降2012年1月[4][5]马恩岛AA+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]以色列A+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]意大利BBB+ 降2012年1月[4][5]牙买加B- 降2011年11月[4][5]日本AA- 降2011年11月[4][5]约旦BB 降2011年11月[4][5]哈萨克BBB+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]肯尼亚B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]韩国 A 稳2011年11月[4][5]科威特AA 稳2011年11月[4][5]拉脱维亚BB+ 升2011年11月[4][5]黎巴嫩 B 稳2011年11月[4][5]列支敦士登AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]立陶宛BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]卢森堡AAA 降2012年1月[4][5]马其顿共和国BB 稳2011年11月[4][5]马来西亚A- 稳2011年11月[4][5]马耳他A- 降2012年1月[4][5]墨西哥BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]蒙古国BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]黑山BB 降2011年11月[4][5]蒙特塞拉特岛BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]摩洛哥BBB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]莫桑比克B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]荷兰AAA 降2012年1月[4][5]新西兰AA 稳2011年11月[4][5]尼日利亚B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]挪威AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]阿曼 A 降2011年11月[4][5]巴基斯坦B- 稳2011年11月[4][5]巴拿马BBB- 升2011年11月[4][5]巴布亚新几内亚B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]巴拉圭BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]秘鲁BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]菲律宾BB 稳2011年11月[4][5]波兰A- 稳2011年11月[4][5]葡萄牙BB 降2012年1月[4][5]波多黎各BBB 稳2011年3月[6]卡塔尔AA 稳2011年11月[4][5]罗马尼亚BB+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]俄罗斯BBB 稳2011年11月[4][5]沙特阿拉伯AA- 稳2011年11月[4][5]塞内加尔B+ 降2011年11月[4][5]塞尔维亚BB 稳2011年11月[4][5]新加坡AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]斯洛伐克 A 稳2012年1月[4][5]斯洛文尼亚A+ 降2012年1月[4][5]南非BBB+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]西班牙 A 降2012年1月[4][5]斯里兰卡B+ 升2011年11月[4][5]苏里南BB- 稳2011年11月[4][5]瑞典AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]瑞士AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]中华民国AA- 稳2011年11月[4][5]泰国BBB+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]特立尼达和多巴哥 A 稳2011年11月[4][5]突尼斯BBB- 降2011年11月[4][5]土耳其BBB- 升2011年11月[4][5]乌干达B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]乌克兰B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]英国AAA 稳2011年11月[4][5]美国AA+ 降2011年11月[7][8]乌拉圭BB+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]委内瑞拉B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]越南BB- 降2011年11月[4][5]赞比亚B+ 稳2011年11月[4][5]阿布达比酋长国AA 稳2007年7月[10]安哥拉BB- 稳2011年5月[10]阿根廷 B 稳2010年7月[10]亚美尼亚BB- 稳2009年8月[10]阿鲁巴BBB 稳2006年6月[10]澳大利亚AAA 稳2003年2月[10]奥地利AAA 稳2000年9月[10]阿塞拜疆BBB- 升2011年5月[10]巴林BBB+ 目前降2011年3月[10]比利时AA+ 降2011年5月[10]贝宁 B 稳2004年9月[10]百慕大AAA 稳2006年8月[10]玻利维亚B+ 稳2010年10月[10]巴西BBB 稳2011年4月[10]保加利亚BBB 升2011年5月[10]喀麦隆B- 稳2007年3月[10]加拿大AAA 稳2004年8月[10]佛得角BB- 稳2009年6月[10]智利AA- 稳2011年2月[10]中国AA- 降2011年4月[10]哥伦比亚BBB- 升2011年6月[10]哥斯达黎加BB+ 稳2011年3月[10]克罗地亚BBB 降2009年5月[10]塞浦路斯A- 降2011年5月[10]捷克A+ 升2010年6月[10]丹麦AAA 稳2003年11月[10]多米尼加共和国B 升2011年2月[10]厄瓜多尔B- 稳2010年11月[10]埃及BB+ 目前降2011年2月[10]萨尔瓦多BB 降2009年6月[10]爱沙尼亚A+ 稳2011年7月[10]芬兰AAA 稳2000年9月[10]法国AAA 稳2000年9月[10]加蓬BB- 稳2007年10月[10]格鲁吉亚B+ 升2011年3月[10]德国AAA 稳2000年9月[10]加纳B+ 稳2010年9月[10]希腊 C 目前降2012年2月[10]危地马拉BB+ 稳2006年2月[10]香港AA+ 稳2010年11月[10]匈牙利BBB 降2010年12月[10]冰岛BBB+ 稳2011年5月[10]印度BBB- 稳2010年6月[10]印尼BB+ 升2011年2月[10]爱尔兰共和国BBB+ 降2011年4月[10]以色列A+ 稳2008年2月[10]意大利AA- 稳2006年10月[10]牙买加B- 稳2010年2月[10]日本AA- 降2011年5月[10]哈萨克BBB 升2010年12月[10]肯尼亚BB- 稳2009年1月[10]韩国AA 稳2009年9月[10]科威特AA 稳2008年9月[10]拉脱维亚BBB 升2011年3月[10]黎巴嫩 B 稳2010年3月[10]莱索托BB 降2011年5月[10]立陶宛BBB+ 升2011年5月[10]卢森堡AAA 稳2000年9月[10]马其顿共和国BB+ 稳2010年10月[10]马来西亚 A 稳2009年6月[10]马耳他A+ 稳2007年7月[10]墨西哥BBB+ 稳2009年11月[10]蒙古国B+ 稳2010年11月[10]摩洛哥BBB 稳2007年4月[10]莫桑比克B+ 稳2003年7月[10]纳米比亚BBB 升2010年12月[10]荷兰AAA 稳2011年7月[10]新西兰AA 稳2011年9月[10]尼日利亚BB 降2010年10月[10]挪威AAA 稳2000年9月[10]巴拿马BBB- 升2010年3月[10]秘鲁BBB 升2010年6月[10]菲律宾BB+ 稳2006年2月[10]波兰 A 稳2007年1月[10]葡萄牙BB+ 目前降2011年11月[10]拉斯海玛 A 稳2008年1月[10]罗马尼亚BBB- 稳2011年7月[10]俄罗斯BBB 升2010年9月[10]卢旺达 B 稳2010年8月[10]圣马利诺 A 降2009年10月[10]沙特阿拉伯AA- 稳2008年7月[10]塞尔维亚BB- 稳2010年11月[10]塞舌尔B+ 稳2011年2月[10]新加坡AAA 稳2003年5月[10]斯洛伐克A+ 稳2008年7月[10]斯洛文尼亚AA 稳2006年7月[10]南非 A 稳2011年1月[10]西班牙AA+ 降2011年3月[10]斯里兰卡BB- 稳2011年7月[10]苏里南B+ 稳2009年10月[10]瑞典AAA 稳2004年3月[10]瑞士AAA 稳2000年9月[10]中华民国A+ 稳2012年1月[10]泰国A- 稳2011年5月[10]突尼斯BBB 降2011年3月[10]土耳其BB+ 升2010年11月[10]乌干达 B 升2009年8月[10]乌克兰 B 升2011年7月[10]英国AAA 稳2000年9月[10]美国AAA 稳2000年9月[10]乌拉圭BB+ 升2010年7月[10]委内瑞拉B+ 稳2008年12月[10]越南B+ 稳2010年7月[10]赞比亚B+ 稳2011年3月[10]阿尔巴尼亚B1 稳2011年7月[12]安哥拉Ba3 稳2011年7月[12]阿根廷B3 稳2011年7月[12]亚美尼亚Ba2 稳2011年7月[12]澳大利亚Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]奥地利Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]阿塞拜疆Ba1 升2011年7月[12]巴哈马A3 稳2011年7月[12]巴林Baa1 降2011年7月[12]孟加拉国Ba3 稳2011年7月[12]巴巴多斯Baa3 降2011年7月[12]白俄罗斯B3 目前降2011年7月[12]比利时Aa1 稳2011年7月[12]伯利兹B3 稳2011年7月[12]百慕大Aa2 稳2011年7月[12]玻利维亚B1 升2011年7月[12]波斯尼亚和黑塞哥维那B2 降2011年7月[12]博茨瓦纳A2 降2011年7月[12]巴西Baa2 升2011年7月[12]保加利亚Baa2 稳2011年7月[12]柬埔寨B2 稳2011年7月[12]加拿大Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]开曼群岛Aa3 稳2011年7月[12]智利Aa3 稳2011年7月[12]中国Aa3 升2011年7月[12]哥伦比亚Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]哥斯达黎加Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]克罗地亚Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]古巴Caa1 稳2011年7月[12]塞浦路斯Baa1 降2011年7月[13]捷克A1 稳2011年7月[12]丹麦Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]多米尼加共和国B1 稳2011年7月[12]厄瓜多尔Caa2 稳2011年7月[12]埃及Ba3 降2011年7月[12]萨尔瓦多Ba2 稳2011年7月[12]爱沙尼亚A1 稳2011年7月[12]斐济B1 降2011年7月[12]芬兰Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]法国Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]格鲁吉亚Ba3 稳2011年7月[12]德国Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]希腊Ca 降2011年7月[14]危地马拉Ba1 稳2011年7月[12]洪都拉斯B2 稳2011年7月[12]香港Aa1 升2011年7月[12]匈牙利Ba1 降2011年11月[12]冰岛Baa3 降2011年7月[12]印度Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]印尼Ba1 稳2011年7月[12]爱尔兰Ba1 降2011年7月[12]马恩岛Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]以色列A1 稳2011年7月[12]意大利Aa2 目前降2011年7月[12]牙买加B3 稳2011年7月[12]日本Aa3 稳2011年8月[12]约旦Ba2 降2011年7月[12]哈萨克Baa2 稳2011年7月[12]韩国A1 稳2011年7月[12]科威特Aa2 稳2011年7月[12]拉脱维亚Baa3 升2011年7月[12]黎巴嫩B1 稳2011年7月[12]立陶宛Baa1 稳2011年7月[12]卢森堡Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]澳门Aa3 稳2011年7月[12]马来西亚A3 稳2011年7月[12]马耳他A1 稳2011年7月[12]毛里求斯Baa2 稳2011年7月[12]墨西哥Baa1 稳2011年7月[12]摩尔多瓦B3 稳2011年7月[12]蒙古国B1 稳2011年7月[12]黑山Ba3 稳2011年7月[12]摩洛哥Ba1 稳2011年7月[12]荷兰Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]新西兰Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]尼加拉瓜B3 稳2011年7月[12]挪威Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]阿曼A1 稳2011年7月[12]巴基斯坦B3 稳2011年7月[12]巴拿马Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]巴布亚新几内亚B1 稳2011年7月[12]巴拉圭B1 稳2011年7月[12]秘鲁Baa3 升2011年7月[12]菲律宾Ba2 稳2011年7月[12]波兰A2 稳2011年7月[12]葡萄牙Ba2 降2011年7月[12]波多黎各A3 降2011年5月[15]卡塔尔Aa2 稳2011年7月[12]罗马尼亚Baa3 稳2011年7月[12]俄罗斯Baa1 稳2011年7月[12]沙特阿拉伯Aa3 稳2011年7月[12]塞内加尔B1 稳2011年7月[12]新加坡Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]斯洛伐克A1 稳2011年7月[12]斯洛文尼亚Aa2 稳2011年7月[12]南非A3 稳2011年7月[12]西班牙A1 降2011年10月[12]斯里兰卡B1 升2011年7月[12]圣文森特和格林纳丁斯B1 稳2011年7月[12]苏里南B1 稳2011年7月[12]瑞典Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]瑞士Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]中华民国Aa3 稳2011年7月[12]泰国Baa1 稳2011年7月[12]特立尼达和多巴哥Baa1 稳2011年7月[12]突尼斯Baa3 降2011年7月[12]土耳其Ba2 升2011年7月[12]乌克兰B2 稳2011年7月[12]阿拉伯联合酋长国Aa2 稳2011年7月[12]英国Aaa 稳2011年7月[12]美国Aaa 降[16]2011年8月[12]乌拉圭Ba1 稳2011年7月[12]委内瑞拉B2 稳2011年7月[12]越南B1 降2011年7月[12]阿根廷 B Stable 2010-07-11 [18]澳大利亚AAA Stable 2010-07-11 [18]奥地利AA+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]比利时A+ Negative 2010-07-11 [19]巴西A- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]加拿大AA+ Stable 2010-07-11 [18]智利AA- Stable 2011-05-31 [18]中国AAA Stable 2010-07-11 [18]丹麦AA+ Stable 2011-11-01 [18]厄瓜多尔CCC Stable 2010-07-11 [18]埃及BB- Negative 2011-11-22 [18]爱沙尼亚 A Stable 2010-07-11 [18]芬兰AAA Negative 2010-12-06 [18]法国AA- Negative 2011-06-02 [18]德国AA+ Stable 2011-07-01 [18]希腊 C Negative 2011-11-22 [18]香港AAA Stable 2010-10-20 [18]匈牙利BBB- Negative 2011-03-11 [18]冰岛BB- Negative 2010-07-11 [18]印度BBB Stable 2010-07-11 [18]印尼BBB- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]爱尔兰BBB Stable 2010-12-06 [18]以色列A- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]意大利A- Negative 2010-07-11 [18]日本AA- Stable 2011-06-02 [18]哈萨克BBB- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]肯尼亚 B Stable 2010-12-06 [18]韩国AA- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]拉脱维亚BB Stable 2010-10-20 [18]立陶宛BBB- Stable 2011-03-16 [18]卢森堡AAA Stable 2011-07-11 [18]澳门AA+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]马达加斯加CCC Stable 2011-03-16 [18]马来西亚A+ Stable 2011-06-21 [18]墨西哥BBB Stable 2010-07-11 [18]蒙古国B+ Stable 2011-06-28 [18]摩洛哥BBB+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]荷兰AA+ Stable 2011-06-02 [18]新西兰AA+ Stable 2010-07-11 [18]尼日利亚BB+ Stable 2010-07-11 [18]挪威AAA Stable 2010-07-11 [18]巴基斯坦B- Negative 2010-07-11 [18]秘鲁BBB+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]菲律宾B+ Stable 2010-07-11 [18]波兰A- Negative 2011-08-03 [20]葡萄牙BB+ Negative 2011-11-24 [18]罗马尼亚BB Negative 2010-07-11 [18]俄罗斯 A Stable 2010-07-11 [18]沙特阿拉伯AA Stable 2011-07-01 [18]新加坡AAA Stable 2010-07-11 [18]南非 A Stable 2010-07-11 [18]西班牙 A Negative 2011-06-21 [18]斯里兰卡B+ Stable 2011-03-16 [18]苏丹 C Stable 2010-12-06 [18]瑞典AA+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]瑞士AAA Stable 2010-07-11 [18]中华民国AA- Stable 2010-10-20 [18]泰国BBB Stable 2010-07-11 [18]突尼斯BBB+ Stable 2010-10-20 [18]土耳其BB- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]英国A+ Negative 2011-05-27 [18]美国 A Negative 2011-08-03 [21]乌克兰B- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]阿拉伯联合酋长国BBB Negative 2010-07-11 [18]乌拉圭BB+ Positive 2010-12-06 [18]委内瑞拉BB+ Stable 2010-07-11 [18]越南BB- Stable 2010-07-11 [18]阿富汗阿尔及利亚安提瓜和巴布达不丹文莱布隆迪中非共和国乍得科摩罗刚果共和国刚果民主共和国科特迪瓦吉布提多米尼克赤道几内亚厄立特里亚埃塞俄比亚冈比亚其唯一的可交易国际债券失效后,惠誉国际中止评级。

信用评级机构的作用为投资者提供信心保证

信用评级机构的作用为投资者提供信心保证信用评级机构(Credit Rating Agency,CRA)是一种独立的金融机构,通过对债务人或发行人的信用风险进行评估和评级,为投资者提供信心保证。

在现代金融体系中,信用评级机构扮演着极为重要的角色,它们的评级结果直接影响着公司债券、国家债券以及其他金融产品等的流通和交易。

首先,信用评级机构的主要作用之一是评估债务人的信用风险。

债务人指的是政府、公司或个人借债的实体。

评级机构通过对这些实体的财务状况、市场前景以及宏观经济环境等因素进行分析和研究,给予其一个相应的信用评级。

评级结果通常以字母或符号表示,如AAA、AA、A、BBB等,不同等级代表着不同的信用风险水平。

投资者可以依据这些评级结果来判断债务人的还款能力和信誉状况,从而决定是否进行投资。

其次,信用评级机构为投资者提供了一个客观的信息来源。

在金融市场中,信息不对称是一种常见的问题,投资者常常面临着信息获取的困难。

信用评级机构的存在弥补了这一缺陷。

评级机构以专业的角度和严谨的方法对实体进行评级,给出客观的评价结果。

投资者可以通过评级机构发布的报告和评级结果,获取到可信、权威的信息,为自己的投资决策提供参考依据。

此外,信用评级机构还可以提高债务人的透明度和公信力。

一个好的信用评级结果可以为债务人带来更低的融资成本,因为投资者对于信用评级较高的债券更为信任,愿意以较低的利率购买。

债务人可以通过提高自身的信用评级,降低融资成本,增加债务的可持续性。

同时,评级机构的评级结果也可以促使债务人更加规范和透明地运营,以增强投资者对其的信心和信任。

然而,需要注意的是,信用评级机构也存在一些局限性和问题。

首先,评级结果有时会受到评级机构的误差和偏见的影响,存在一定的主观性。

其次,过度依赖评级结果可能会使投资者忽视其他重要的风险提示。

最后,评级机构在金融危机中的失职行为也曾引发公众对其业务模式和独立性的质疑。

为了改善和规范信用评级机构的工作,监管机构采取了一系列措施。

信用评级(英文版ppt)

27% banks 8% corporations

Five National Rating Angencies

(Full licences conferred by government departments)

Dagong Global Credit Rating Co. LTD Golden Credit Rating Co. LTD

Comparison with Factor Analysis ——

Character

Capacity

Capital

Collateral

Condition

Comparison with Factor Analysis ——

Personal

Purpose

Payment

Protection

Perspective

Liquidity

The Past & Now

Traditional credit rating:

Modern credit rating:

Comparison with Comprehensive Analysis——

Observe the different status of the specific indicators in the Disadvantages: -cannot distinguish different natures of index Advantage: -unable to dynamically easy corporation's to calculate reflect development -ignore the interval specified of weight functions overall goal of the rating

信用评级机构

CRA business models

• By contrast, most large and medium-sized CRAs (including Moody's, S&P, Fitch, Japan Credit Ratings, R&I, A.M. Best and others) today rely on an "issuer-pays" business model in which most of the CRA's revenue comes from fees paid by the issuers themselves. Under this business model, while subscribers to the CRA's services are still provided with more detailed reports analyzing an issuer, these services are a minor source of income and most ratings are provided to the public for free. Proponents of this model argue that if the CRA relied only on subscriptions for income, the vast majority of bonds would go unrated since subscriber interest is low for all but the largest issuances. These proponents also argue that while they face a clear conflict of interest vis-a-vis the issuers they rate (as described above), the subscriber-based model also presents conflicts of interest, since a single subscriber may provide a large portion of a CRA's revenue and the CRA may feel obligated to publish ratings that support that subscriber's investment decisions.

信用评级机构的角色与责任

信用评级机构的角色与责任信用评级机构(Credit Rating Agencies, CRA)在金融市场中扮演着至关重要的角色。

它们主要负责对各类债券、公司和国家进行信用评估,为投资者提供信用评级和风险评估的参考依据。

然而,近年来,信用评级机构因其评级行为和相关责任问题备受争议。

本文将探讨信用评级机构的角色与责任,并分析其对金融市场的影响。

一、信用评级机构的角色1. 评估信用风险:信用评级机构的首要职责是评估发行债券的实体(公司、机构或国家)的信用风险。

评级结果通过信用评级等级来表示,如AAA、AA+、BBB-等。

这些评级信息被广泛应用于债券市场,并对投资者的决策起着重要作用。

2. 提供市场透明度:信用评级机构通过对债券发行主体的评级,为市场参与者提供了信息透明度。

投资者可以根据这些评级判断债券的信用风险,从而更好地进行投资决策。

此外,信用评级还能够提高市场效率,减少信息不对称的情况发生。

3. 保护投资者权益:信用评级机构扮演着保护投资者权益的角色。

通过对债券发行实体进行独立评估,投资者能够更好地了解债券的风险和回报特征,降低投资风险。

这种独立的第三方评估有助于避免信息不对称和潜在的欺诈行为。

二、信用评级机构的责任1. 独立与公正性:信用评级机构应当保持独立和公正的评估态度。

他们的评级应基于客观的标准和准则,避免受到任何利益相关方的影响。

评级机构应该建立和维护有效的内部控制机制,确保评级结果的准确性和可靠性。

2. 透明与可追溯性:信用评级机构需要对其评级结果和方法进行透明披露。

这包括评级标准、评估方法和相关数据的公开,以便投资者和其他市场参与者了解评级的依据和过程。

评级机构还应当建立评级结果的可追溯性,使投资者能够了解评级变动的原因和影响。

3. 持续监测与更新:信用评级机构应当对其评级结果进行持续监测和更新。

债券发行实体的信用风险是动态变化的,评级机构应及时调整评级结果以反映最新情况。

这有助于保持评级的准确性,并减少投资者因过时评级而受到损失的风险。

国际三大评级机构(详细版)讲解

•

现在,标准普尔是麦格劳-希尔集团的子公司,专为全球资本市场提供独立信用评级、指 数服务、风险评估、投资研究和数据服务, 标准普尔在业内一向处于领先地位。标准普 尔是全球金融基础建构的重要一员,在150年来一直发挥着领导者的角色,为投资者提供 独立的参考指针,作为投资和财务决策的信心保证。

麦格劳-希尔集团

•

•

标准普尔全球1200种股价指数的采样范围,除了美国、日本、英国与加拿大外,还包 括欧洲、亚太以及拉丁美洲等地区,采样企业的市值共计20万亿美元,占全球股市总 市值的七成。标准普尔未来还会根据标准普尔全球1200种股价指数或其他地区成份股 ,推出期货基金、共同基金以及外汇基金等衍生性投资工具。

资料来源:MBA智库

•

穆迪长期债务评级(到期日一年或以上)

投资级别

Aaa级

评 定

优等

说明

信用质量最高,信用风险最低。利息支付有充足保证,本金安全。为还本 付息提供保证的因素即使变化,也是可预见的。发行地位稳固。 信用质量很高,有较低的信用风险。本金利息安全。但利润保证不如Aaa 级债券充足,为还本付息提供保证的因素波动比Aaa级债券大。 投资品质优良。本金利息安全,但有可能在未来某个时候还本付息的能力 会下降。 保证程度一般。利息支付和本金安全现在有保证,但在相当长远的一些时 间内具有不可靠性。缺乏优良的投资品质。

标准普尔全球1200指数(S&P Global 1200 Index)

• S&P全球1200指数是第一个实时计算的全球指数,它旨在为投资者提供可投资的全球投资组合, 该指数涵盖了31个国家,由6个地区指数组成:S&P500指数(美国)、S&P多伦多60指数、S&P拉丁 美洲40指数、S&P东京150指数、S&P亚太100指数和S&P欧洲350指数。每个地区基准指数均采用 与S&P500类似的方法构建,采用经可投资权重因子调整的市值加权。 该指数以1997年12月31日为基期,基点为1000。成分股选择标准主要为规模、流动性(交易额) 和地区范围内的行业代表性,同时在国家和地区行业比例上进行平衡。

金融业中英文对照表

金融业中英文对照表第一篇:金融业中英文对照表2M method 2M法 3M method 3M法A scores A值Accounting convention 会计惯例Accounting for acquisitions 购并的会计处理Accounting for debtors 应收账款核算 Accounting for depreciation 折旧核算Accounting for foreign currencies 外汇核算Accounting for goodwill 商誉核算Accounting for stocks 存货核算Accounting policies 会计政策Accounting standards 会计准则Accruals concept 权责发生原则Achieving credit control 实现信用控制Acid test ratio 酸性测试比率 Actual cash flow 实际现金流量Adjusting company profits 企业利润调整Advance payment guarantee 提前偿还保金Adverse trading 不利交易Advertising budget 广告预算Advising bank 通告银行Age analysis 账龄分析Aged debtors analysis 逾期账款分析Aged debtors'exception report 逾期应收款的特殊报告Aged debtors'exception report 逾期账款特别报告Aged debtors'report 逾期应收款报告 Aged debtors'report 逾期账款报告All—monies clause 全额支付条款 Amortization 摊销Analytical questionnaire 调查表分析 Analytical skills 分析技巧Analyzing financial risk 财务风险分析Analyzing financial statements 财务报表分析Analyzing liquidity 流动性分析Analyzing profitability 盈利能力分析Analyzing workingcapital 营运资本分析 Annual expenditure 年度支出Anticipating future income 预估未来收入Areas of financial ratios 财务比率分析的对象 Articles of incorporation 合并条款Asian crisis 亚洲(金融)危机Assessing companies 企业评估Assessing country risk 国家风险评估 Assessing credit risks 信用风险评估 Assessing strategic power 战略地位评估 Assessment of banks 银行的评估Asset conversion lending 资产转换贷款Asset protection lending 资产担保贷款Asset sale 资产出售Asset turnover 资产周转率Assets 资产Association of British Factors and Discounters 英国代理人与贴现商协会Auditor's report 审计报告 Aval 物权担保 Bad debt 坏账Bad debt level 坏账等级 Bad debt risk 坏账风险Bad debts performance 坏账发生情况 Bad loans 坏账Balance sheet 资产负债表Balance sheet structure 资产负债表结构Bank credit 银行信贷Bank failures 银行破产Bank loans.availability 银行贷款的可获得性Bank status reports 银行状况报告 Bankruptcy 破产Bankruptcy code 破产法Bankruptcy petition 破产申请书Basle agreement 塞尔协议Basle Agreement 《巴塞尔协议》 Behavorial scoring 行为评分Bill of exchange 汇票 Bill of lading 提单 BIS 国际清算银行BIS agreement 国际清算银行协定Blue chip 蓝筹股 Bonds 债券Book receivables 账面应收账款 Borrowing money 借人资金Borrowing proposition 借款申请 Breakthrough products 创新产品Budgets 预算Building company profiles 勾画企业轮廓Bureaux(信用咨询)公司Business development loan 商业开发贷款 Business failure 破产Business plan 经营计划 Business risk 经营风险 Buyer credits 买方信贷 Buyer power 购买方力量Buyer risks 买方风险CAMPARI 优质贷款原则Canons of lending 贷款原则 Capex 资本支出Capital adequacy 资本充足性Capital adequacy rules 资本充足性原则 Capital commitments 资本承付款项 Capital expenditure 资本支出 Capital funding 资本融资 Capital investment 资本投资 Capital strength 资本实力 Capital structure 资本结构Capitalization of interest 利息资本化Capitalizing development costs 研发费用资本化Capitalizing development expenditures 研发费用资本化Capitalizing interest costs 利息成本资本化 Cascade effect 瀑布效应Cash assets 现金资产Cash collection targets 现金托收目标 Cash cycle 现金循环周期Cash cycle ratios 现金循环周期比率Cash cycle times 现金循环周期时间 Cash deposit 现金储蓄Cash flow adjustments 现金流调整 Cash flow analysis 现金流量分析 Cash flow crisis 现金流危机 Cash flow cycle 现金流量周期Cash flow forecasts 现金流量预测 Cash flow lending 现金流贷出 Cash flow profile 现金流概况 Cash flow projections 现金流预测Cash flow statements 现金流量表Cash flows 现金流量Cash position 现金头寸Cash positive JE现金流量Cash rich companies 现金充足的企业Cash surplus 现金盈余Cash tank 现金水槽Cash-in-advance 预付现金Categorized cash flow 现金流量分类CE 优质贷款原则CEO 首席执行官Chairman 董事长,总裁 Chapter 11 rules 第十一章条款 Charge 抵押Charged assets 抵押资产Chief executive officer 首席执行官 Collateral security 抵押证券Collecting payments 收取付款Collection activitv 收款活动Collection cycle 收款环节Collection procedures 收款程序Collective credit risks 集合信用风险Comfortable liquidity positi9n 适当的流动性水平Commercial mortgage 商业抵押 Commercial paper 商业票据 Commission 佣金Commitment fees 承诺费 Common stock 普通股Common stockholders 普通股股东Company and its industry 企业与所处行业 Company assets 企业资产 Company liabilities 企业负债 Company loans 企业借款Competitive advantage 竞争优势Competitive forces 竞争力Competitive products 竞争产品 Complaint procedures 申诉程序Computerized credit information 计算机化信用信息Computerized diaries 计算机化日志 Confirmed letter of credit 承兑信用证Confirmed letters of credit 保兑信用证 Confirming bank 确认银行 Conservatism concept 谨慎原则 Consistency concept 一贯性原则 Consolidated accounts 合并报表Consolidated balance sheets 合并资产负债表Contingent liabilities 或有负债Continuing security clause 连续抵押条款Contractual payments 合同规定支出 Control limits 控制限度Control of credit activities 信用活动控制 Controlling credit 控制信贷Controlling credit risk 控制信用风险 Corporate credit analysis 企业信用分析Corporate credit controller 企业信用控制人员Corporate credit risk analysis 企业信用风险分析 Corporate customer 企业客户Corporate failure prediction models 企业破产预测模型Corporate lending 企业贷款Cost leadership 成本领先型Cost of sales 销售成本 Costs 成本Country limit 国家限额Country risk 国家风险Court judgments 法院判决 Covenant 贷款保证契约 Covenants 保证契约Creative accounting 寻机性会计 Credit analysis 信用分析Credit analysis of customers 客户信用分析Credit analysis of suppliers 供应商的信用分析Credit analysis on banks 银行信用分析 Credit analysts 信用分析 Credit assessment 信用评估Credit bureau reports 信用咨询公司报告 Credit bureaux 信用机构 Credit control 信贷控制Credit control activities 信贷控制活动Credit control performance reports 信贷控制绩效报告 Credit controllers 信贷控制人员Credit cycle 信用循环Credit decisions 信贷决策Creditdeterioration 信用恶化 Credit exposure 信用敞口Credit granting process 授信程序 Credit information 信用信息Credit information agency 信用信息机构 Credit insurance 信贷保险Credit insurance advantages 信贷保险的优势 Credit insurance brokers 信贷保险经纪人 Credit insurance limitations 信贷保险的局限Credit limits 信贷限额Credit limits for currency blocs 货币集团国家信贷限额 Credit limits for individual countries 国家信贷限额 Credit management 信贷管理 Credit managers 信贷经理Credit monitoring 信贷监控Credit notes 欠款单据 Credit period 信用期 Credit planning 信用计划 Credit policy 信用政策Credit policy issues 信用政策发布 Credit proposals 信用申请Credit protection 信贷保护Credit quality 信贷质量Credit rating 信用评级Credit rating agencies 信用评级机构 Credit rating process 信用评级程序Credit rating system 信用评级系统 Credit reference 信用咨询Credit reference agencies 信用评级机构 Credit risk 信用风险Credit risk assessment 信用风险评估 Credit risk exposure 信用风险敞口 Credit risk insurance 信用风险保险Credit risk.individual customers 个体信用风险Credit risk:bank credit 信用风险:银行信用 Credit risk:trade credit 信用风险:商业信用 Credit scoring 信用风险评分Credit scoring model 信用评分模型 Credit scoring system 信用评分系统Credit squeeze 信贷压缩Credit taken ratio 受信比率Credit terms 信贷条款Credit utilization reports 信贷利用报告 Credit vetting 信用审查Credit watch 信用观察 Credit worthiness 信誉Creditor days 应付账款天数Cross-default clause 交叉违约条款Currency risk 货币风险 Current assets 流动资产 Current debts 流动负债Current ratio requirement 流动比率要求Current ratios 流动比率 Customer care 客户关注Customer credit ratings 客户信用评级Customer liaison 客户联络Customer risks 客户风险Cut-off scores 及格线Cycle of credit monitoring 信用监督循环Cyclical business 周期性行业 Daily operating expenses 经营费用Day’s sales outstanding 收回应收账款的平均天数 Debentures 债券 Debt capital 债务资本Debt collection agency 债务托收机构Debt issuer 债券发行人Debt protection levels 债券保护级别Debt ratio 负债比率 Debt securities 债券Debt service ratio 还债率 Debtor days 应收账款天数 Debtor's assets 债权人的资产Default 违约Deferred payments 延期付款Definition of leverage 财务杠杆率定义 Deposit limits 储蓄限额Depositing money 储蓄资金Depreciation 折旧Depreciation policies 折旧政策Development budget 研发预算 Differentiation 差别化 Direct loss 直接损失Directors salaries 董事薪酬Discretionary cash flows 自决性现金流量Discretionary outflows 自决性现金流出 Distribution costs 分销成本Dividend cover 股息保障倍数Dividend payout ratio 股息支付率Dividends 股利Documentary credit 跟单信用证DSO 应收账款的平均回收期Duration of credit risk 信用风险期 Eastern bloc countries 东方集团国家EBITDA 扣除利息、税收、折旧和摊销之前的收益ECGD 出口信贷担保局Economic conditions 经济环境Economic cycles 经济周期Economic depression 经济萧条Economic growth 经济增长Economic risk 经济风险Electronic data interchange(EDI)电子数据交换 Environmental factors 环境因素Equity capital 权益资本 Equity finance 权益融资Equity stake 股权EU countries 欧盟国家 EU directives 欧盟法规 EUlaw 欧盟法律Eurobonds 欧洲债券European parliament 欧洲议会European Union 欧盟Evergreen loan 常年贷款Exceptional item 例外项目Excessive capital commitments 过多的资本承付款项Exchange controls 外汇管制Exchange-control regulations 外汇管制条例Exhaust method 排空法Existing competitors 现有竞争对手 Existing debt 未清偿债务Export credit agencies 出口信贷代理机构Export credit insurance 出口信贷保险 Export factoring 出口代理Export sales 出口额Exports Credit Guarantee Department 出口信贷担保局Extending credit 信贷展期 External agency 外部机构External assessment methods 外部评估方式External assessments 外部评估External information sources 外部信息来源Extraordinary items 非经常性项目Extras 附加条件 Facility account 便利账户 Factoring 代理Factoring debts 代理收账Factoring discounting 代理折扣Factors Chain International 国际代理连锁Failure prediction scores 财务恶化预测分值FASB(美国)财务会计准则委员会 Faulty credit analysis 破产信用分析 Fees 费用Finance,new business ventures 为新兴业务融资Finance,repay existing debt 为偿还现有债务融资Finance,working capital 为营运资金融资Financial assessment 财务评估Financial cash flows 融资性现金流量Financial collapse 财务危机Financial flexibility 财务弹性Financial forecast 财务预测Financial instability 财务的不稳定性Financial rating analysis 财务评级分析 Financial ratios 财务比率 Financial risk 财务风险Financial risk ratios 财务风险比率 Fitch IBCA 惠誉评级Fitch IBCA ratings 惠誉评级Fixed assets 固定资产Fixed charge 固定费用Fixed charge cover 固定费用保障倍数Fixed costs 固定成本Floating assets 浮动资产 Floating charge 浮动抵押 Floor planning 底价协议 Focus 聚焦Forced sale risk 强制出售风险Foreign exchange markets 外汇市场 Forfaiting 福费廷Formal credit rating 正式信用评级 Forward rate agreements 远期利率协议 FRAs 远期利率协议 Fund managers 基金经理FX transaction 外汇交易GAAP 公认会计准则 Gearing 财务杠杆率Geographical spread of markets 市场的地理扩展Global target 全球目标Going concern concept 持续经营原则Good lending 优质贷款Good times 良好时期Government agencies 政府机构 Government interference 政府干预 Gross income 总收入Guarantee of payment 支付担保Guaranteed loans 担保贷款Guarantees 担保High credit quality 高信贷质量High credit risks 高信贷风险High default risk 高违约风险 High interest rates 高利率High risk regions 高风险区域Highly speculative 高度投机High-risk loan 高风险贷款High-value loan 高价值贷款Historical accounting 历史会计处理Historical cost 历史成本 IAS 国际会计准则IASC 国际会计准则委员会IBTT 息税前利润ICE 优质贷款原则Idealliquidity ratios 理想的流动性比率Implied debt rating 隐含债务评级Importance of credit control 信贷控制的重要性Improved products 改进的产品I Improving reported asset values 改善资产账面价值In house assessment 内部评估In house credit analysis 内部信用分析In house credit assessments 内部信用评估In house credit ratings 内部信用评级Income bonds 收入债券 Income statement 损益表Increasing profits 提高利润Increasing reported profits 提高账面利润Indemnity clause 赔偿条款Indicators of credit deterioration 信用恶化征兆 Indirect loss 间接损失Individual credit transactions 个人信用交易 Individual rating 个体评级Industrial reports 行业报告Industrial unrest 行业动荡Industry limit 行业限额 Industry risk 行业风险Industry risk analysis 行业风险分析 Inflow 现金流入Information in financial statements 财务报表中的信息In-house credit ratings 内部信用评级 Initial payment 初始支付Insolvencies 破产Institutional investors 机构投资者Insured debt 投保债务Intangible fixed asset 无形固定资产Inter-company comparisons 企业间比较 Inter-company loans 企业间借款 Interest 利息Interest cost 利息成本Interest cover ratio 利息保障倍数Interest cover test 利息保障倍数测试 Interest holiday 免息期Interest payments 利息支付 Interest rates 利率Interim statements 中报(中期报表)Internal assessment methods 内部评估方法 Internal financing ratio 内部融资率Internal Revenue Service 美国国税局International Accounting Standards Committee 国际会计准则委员会International Accounting Standards(IAS)国际会计准则International Chamber of Commerce 国际商会 International credit ratings 国际信用评级International Factoring Association 国际代理商协会International settlements 国际结算 Inventory 存货Inverse of current ratio 反转流动比率Investment analysts 投资分析人员 Investment policy 投资政策Investment risk 投资风险Investment spending 投资支出Invoice discounting 发票贴现 Issue of bonds 债券的发行Issued debt capital 发行债务资本 Junk bond status 垃圾债券状况Just-in-time system(JIT)适时系统Key cash flow ratios 主要现金流量指标Labor unrest 劳动力市场动荡Large.scale borrower 大额借贷者 Legal guarantee 法律担保Legal insolvency 法律破产Lending agreements 贷款合约 Lending covenants 贷款保证契约Lending decisions 贷款决策Lending proposals 贷款申请Lending proposition 贷款申请Lending transactions 贷款交易Letters of credit 信用证Leverage 财务杠杆率LIBOR 伦敦同业拆借利率 Lien 留置Liquid assets 速动资产 Liquidation 清算Liquidation expenses 清算费 Liquidity 流动性Liquidity and working capital 流动性与营运资金Liquidity ratios 流动比率 Liquidity run 流动性危机Liquidity shortage 流动性短缺 Loan covenants 贷款合约 Loan guarantees 贷款担保 Loan principal 贷款本金Loan principal repayments 贷款本金偿还 Loan review 贷款审查London Inter-bank Offered Rate 伦敦同业拆借利率Long’term debt 长期负债 Long-term funding 长期融资Long-term risk 长期风险Management 管理层Marginal lending 边际贷款Marginal trade credit 边际交易信贷 Market surveys 市场调查Marketing 市场营销 Markets 市场Matching concept 配比原则Material adverse-change clause 重大不利变动条款 Maximum leverage level 最高财务杠杆率限制 Measurement and judgment 计量与判断 Measuring risk 风险计量 Medium-term loan 中期贷款Microcomputer modelling 计算机建模Minimum current ratio requirement 最低流动比率要求Minimum leverage ratio 最低举债比率 Minimum net worth 最低净值Minimum net-worth requirement 最低净值要求 Minimum risk asset ratio 最低风险资产比率Monitoring activity 监管活动Monitoring credit 信用监控Monitoring customer credit limits 监管客户信贷限额Monitoring risks 监管风险Monitoring total credit limits 监管全部信贷限额Monthly reports 月报Moody's debt rating 穆迪债券评级 Mortgage 抵押mpr’oving balance she et 改善资产负债表Multiple discriminate analysis 多元分析National debt 国家债务 NCI 无信贷间隔天数Near-cash assets近似于现金的资产 Negative cash flow 负现金流量Negative net cash flow 负净现金流量Negative operational cash flows 负的经营性现金流量Negative pledge 限制抵押Net book value 净账面价值Net cash flow 净现金流量Net worth test 净值测试New entrants 新的市场进人者 No credit interval 无信贷间隔天数 Non-cash items 非现金项目 Non-core business 非核心业务Non-operational items 非经营性项目Obtaining payment 获得支付One-man rule 一人原则Open account terms 无担保条款Operating leases 经营租赁 Operating profit 营业利润Operational cash flow 营性现金流量 Operational flexibility ~营弹性 Optimal credit 最佳信贷 Order cycle 订货环节Ordinary dividend payments 普通股股利支付 Organization of credit activities 信贷活动的组织 Overdue payments 逾期支付 Over-trading 过度交易Overview of accounts 财务报表概览·Parent company 母公司PAT 税后利润Payment in advance 提前付款 Payment obligations 付款义务Payment records 付款记录 Payment score 还款评分 PBIT 息税前利润 PBT 息后税前利润Percentage change 百分比变动 Performance bonds 履约保证Personal guarantees 个人担保Planning systems 计划系统Pledge 典押Points-scoring system 评分系统 Policy setting 政策制定Political risk 政治风险Potential bad debt 潜在坏账Potential credit risk 潜在信用风险 Potential value 潜在价值Predicting corporate failures 企业破产预测Preference dividends 优先股股息Preferred stockholders 优先股股东Preliminary assessment 预备评估 Premiums 溢价Primary ratios 基础比率Prior charge capital 优先偿付资本 Priority cash flows 优先性现金流量 Priority for creditors 债权人的清偿顺序 Priority payments 优先支付Product life cycle 产品生命周期Product market analysis 产品市场分析 Product range 产品范围Products 产品 Professional fees 专业费用 Profit 利润Profit and loss account 损益账户Profit margin 利润率Profitability 盈利能力Profitability management 盈利能力管理 Profitability ratios 盈利能力比率 Promissory notes 本票Property values 所有权价值Providers of credit 授信者Provision accounting 准备金会计处理 Prudence concept 谨慎原则 Public information 公共信息 Public relations 公共关系Purpose of credit ratings 信用评级的目的 Purpose of ratios 计算比率的目的 Qualitative covenants 定性条款Quantitative covenants 定量条款Query control 质疑控制Quick ratio 速动比率Rating exercise 评级实践 Rating process for a company 企业评级程序 Ratio analysis 比率分析Ratio analyst weaknesses ~L率分析的缺陷 Real insolvency 真实破产Real sales growth 实际销售收入增长率 Realization concept 实现原则 Receivables 应收账款 Recession 衰退Reducing debtors 冲减应收账款 Reducing profits 冲减利润Reducing provisions 冲减准备金Reducing reported profits 冲减账面利润 Reducing stocks 减少存货Registrar of Companies 企业监管局 Regulatory risk 监管风险Releasing provisions 冲回准备金 Relocation expenses 费用再分配 Reminder letters 催缴单Repayment on demand clause 即期偿还条款Replacement of principal 偿还本金 Report of chairman 总裁/董事长报告 Reserve accounting 准备金核算 Residual cash flows 剩余现金流量 Restricting bad debts 限制坏账 Restrictions on secured borrowing 担保借款限制 Retention-of-title clauses 所有权保留条款Revenues 总收入Risk analysis reports 风险分析报告 Risk and banks 风险与银行Risk and companies 风险与企业 Risk and Return 风险与回报 Risk capital 风险资本Risk-reward 风险回报Risk-weighted assets 风险加权资产 ROCE 资本收益率Romapla clauses “一手交钱一手交货”条款Sales 销售额Secondary ratios 分解比率Secure methods of payment 付款的担保方式Secured assets 担保资产Secured creditors 有担保债权人 Secured loans 担保贷款Securities and Exchange Commission(美国)证券交易委员会Security guarantees 抵押担保Security of payment 付款担保Security general principles 担保的一般原则 Segmentation 细分Setting and policing credit limits 信用限额的设定与政策制定Settlement discount(提前)结算折扣Settlement terms 结算条款Share price 股价Short-term borrowing 短期借款Short-term creditors 短期负债 Short-term liabilities 短期债务Short-termism 短期化 SIC 常务诠释委员会Significance of working capital 营运资金的重要性 Single credit customer 单一信用客户Single ratio analysis 单一比率分析 Size of credit risk 信用风险的大小Slow stock turnover 较低的存货周转率Sources of assessments 评估信息来源Sources of credit information 信用信息来源 Sources of risk 风险来源Sovereign rating 主权评级Specialist agencies 专业机构Specific debt issue 特别债券发行 Speculative 投机性Speculative grades 投机性评级 Split rating 分割评级Spot rate 现价(即期比率)Spreadsheets 电子数据表Staff redundancies 员工遣散费Standard and Poor 标准普尔Standard security clauses 标准担保条款Standard&Poor's 标准普尔 Standby credits 备用信用证Standing Interpretations Committee 证券交易委员会Standing starting credit limits 持续更新信用限额Statistical analysis 统计分析Statistical techniques 统计技巧Status reports(企业)状况报告Stock valuations 存货核算Stocks 股票Straight line depreciation method 直线折旧法Strategic positioning 战略定位Suplus assets 盈余资产 Suplus rating 盈余评级Supplier power 供应商的力量Supply chain 供应链Support rating 支持评级 Swap agreement 换合约Swaps 互换SWOT analysis SWOT分析Symptoms of failure questionnaires 企业破产征兆调查表Takeovers 收购Tax payments 税务支付Technical insolvency 技术破产Technology and change 技术进步Term loan 定期贷款Term of borrowing 借款期限Third party guarantees 第三方担保Tier 1 capital 一类资本 Tier 2 capital 二类资本Total credit limit 整体信用限额 T otal current assets 流动资产总额Trade companies 贸易企业 Trade credit 商业信用Trade creditors 应付账款Trade cycle 商业循环Trade cycle times 商业循环周期Trade debt 应收账款Trade debtors 贸易债权人Trade Indemnity 贸易赔偿Trade references 贸易参考 Trade-off 协定Trading outlook 交易概况 Trading profit 营业利润Traditional cash flow 传统现金流量Triple A 三AUCP 跟单信用证统一惯例Uncovered dividend 未保障的股利Uniform Customs&Practice 跟单信用证统一惯例Unpaid invoices 未付款发票Unsecured creditors 未担保的债权人Usefulness of liquidity ratios 流动性比率的作用Uses of cash 现金的使用Using bank risk information 使用银行风险信息 Using financialassessments 使用财务评估 Using ratios 财务比率的运用Using retention-of-title clauses 使用所有权保留条款Value chain 价值链 Value of Z scores Z值模型的价值Variable costs 变动成本 Variable interest 可变利息Variety of financial ratios 财务比率的种类Vetting procedures 审查程序Volatitle revenue dynamic 收益波动Volume of sales 销售量Warning signs of credit risk 信用风险的警示 Working assets 营运资产 working capital 营运资本Working capital changes 营运资本变化额Working capital management 营运资本管理 working capitalratios 营运资本比率Write-downs 资产减值Write-offs 勾销Z score assessments Z值评估 z score models z值模型Z scores z值Z scoring Z值评分系统第二篇:乐器中英文对照表Woodwinds: 木管乐器Brass:铜管乐器 1.Piccolo 短笛 2.Flute 长笛3.Soprano Recorder 高音竖笛4.Oboe 双簧管5.English Horn 英国管6.Bassoon 大管7.Contrabassoon 低音巴松8.Clarinet in Eb 降E调单簧管(小黑管)9.Clarinet in A A调单簧管10.Clarinet in Bb 降B调单簧管11.Bass Clarinet 低音单簧管12.Soprano Saxophone 高音萨克斯 13.ALto Saxophone 中音萨克斯 14.Tenor Saxophone 次中音萨克斯 15.Baritone Saxophone 上低音萨克斯 16.Alto Flute 中音长笛* 17.Bass Flute 低音长笛 18.Oboe d' Amore 双簧管的一种 19.Piccolo Clarinet 高音单簧管*20.Alto Clarinet 中音单簧管(Eb调的,属于低音单簧管)21.Contrabass Clarinet 倍低音单簧管 22.Descant Recorder 高音竖笛23.Alto Recorder 中音竖笛24.Tenor Recorder 次中音竖笛25.Bass Recorder 低音竖笛 26.Bagpipes 风笛27.Basset Horn 巴赛管(单簧管)28.Panpipes 排萧Organ(风琴)Church Organ 教堂管风琴Draw Organ 拉杆式舌风琴Percussion Organ 敲击试管风琴Pipe Organ 管风琴Reed Organ 簧风琴Rock Organ 摇滚管风琴1.Cornet 短号2.Trumpet in Bb 降B调小号3.Trumpet in C C调小号4.Flugelhorn 夫吕号(行进乐队常用)5.Horn in F F调圆号6.Trombone 长号7.Tenor Trombone 次中音长号8.Bass Tromone 低音长号9.Baritone(T.C.)次中音号 10.Baritone 次中音 11.Euphonium 小低音号 12.Tuba 大号13.Bass Tuba 低音大号 14.Piccolo Cornet 高音短号15.Piccolo Trumpet in A A调高音小号 16.Bass Trumpet in C C 调低音小号 17.Alto Trombone 中音长号 18.Contrabass Trombone 倍低音长号Drums: 鼓 1.Drum Set 架子鼓2.Bongo Drums 邦加鼓(用手指敲的小鼓,夹在两腿间)3.Timbales 蒂姆巴尔鼓4.Conga Drums 康加鼓(橄榄型)5.Snare Drum 小军鼓6.Quad Toms 4组鼓筒鼓7.Quint T oms 五组筒鼓8.Tenor Drum 次高音鼓9.T om Toms 筒鼓 10.Roto T oms 轮鼓 11.Bass Drum 低音鼓12.Aerial Tom-T oms 悬空通通鼓13.Floor Tom-T om/Tom-T om/T enor Drum 落地通通鼓/中鼓14.Hi-Hat Cymbal 脚钹 15.Side Cymbal 小钹 16.Top Cymbal 大钹 17.Side Drum 击边Ethnic and Other Instrument 民族乐器Accordion 手风琴Agogo bell 阿哥哥铃Alpine Herd Cowbell牧牛铃Angklung 摇竹Appalachian Dulcimer 阿帕拉契扬琴(美国的民族乐器)Autoharp ***齐特琴Bagpipe 风笛(苏格兰民俗乐器)Balalaika 巴拉拉卡琴(俄国的弦乐器之一,琴身呈三角形)Bamboo chime 竹风铃Bandurria 墨西哥传统吉他Banjo 班左琴/五弦琴(相传源起於西非,以手指奏鸣的五弦或六弦的乐器)Bell plate 铁片Bell tree 树铃Bongos 邦哥小对鼓/曼波鼓(拉丁音乐)Boobam 火箭筒鼓Bouzouki 布祖基琴(一种形状似曼陀林的希腊弦乐器)Cabasa 椰予沙铃/卡巴沙铃/串珠沙铃Castanets 响板(常用於西班牙佛们哥舞曲)Caxixi 编织摇铃Charango 夏朗哥吉他/小型八弦(盛行於中南美)Chinese hand drum 手摇鼓Chinese temple bell 中国钵Citterns 西特恩(类似吉他的梨形古乐器,流行於十五至十八世纪) Concertina 六角形手风琴(用於阿根廷探戈曲)Conga 康加鼓/细长型大手鼓/墨西哥鼓(拉丁音乐)Cowbell 牛铃Crumhorn 克鲁姆管/钩形管/J形管(流行於15世纪末叶)Cuica 锯加鼓Darabucca 土耳其手鼓Didgeridoo 澳洲土著的吹管乐器Djembe 非洲鼓(源起於非洲之肯亚部落,属於原住民型之乐器) Domra 苏俄传统乐器(状似吉他,三或四弦)Fiddle 古提琴Fife 横笛Flageolet 六孔的竖笛Flexatone 弹音器Frame drum 手鼓Gadulka 一种保加利亚传统的弦乐器Gaida 风笛(保加利亚的传统乐器)Gamelan 木琴(印尼的一种竹制打击乐器)Glass chime 玻璃风铃Guiro 葫芦锯琴/刮胡/刮葫(拉丁音乐)Gusli 古斯里琴(一种俄国古代的弦乐器)Harmonica/Mouth-Organ 口琴Hurdy-Gurdy 绞弦琴/手摇风琴(18世纪流行於法国社交界)Japanese temple bell 日本钵Jew’s Harp 口拨琴/单簧口琴Kalimba 卡林巴琴Kantele 齐特琴(芬兰)Kaval 长笛/牧羊人的笛子(保加利亚的传统乐器)Kazoo 卡祖笛(一种木制或金属制玩具笛子)Kokiriko 鼓牌板Koto 科多琴Lithophone 石板琴Lute 诗琴/鲁特琴(最古老的乐器之一)Lyre 七弦竖琴(古希腊)Mark tree / Wind chime 风铃Mirliton 膜笛Nefer 古埃及吉他Ocarina 亚卡利那笛/陶制甘薯形笛/小鹅笛(17世纪后半源於义大利)Ocean drum 波浪鼓Panpipe 排笛/牧神笛Pifano 印地安鼓Quena 八孔木笛(安第斯山脉民族的乐器,声音浑厚)Ratchet 辣齿/嘎嘎器Roarer/Barker 吼声器Saltepry 萨泰里琴(上古及中古的乐器,可能源自伊朗、印度)Shaker 金属沙铃Shamisen 三弦琴(日本)Shanai 山奈琴Sistrum 叉铃/ㄙㄙ铃(古埃及)Sitar 锡他琴/西塔琴/西他琴(形似吉他的北印度民族弦乐器)Slit drum 非洲裂缝鼓Steel Drum 钢鼓(来自於加勒比海的千里达)Surdo 印地安笛Symphonle 三弦共鸣弦乐器(约十三世纪前出现)Tablas 塔布拉鼓/印度鼓(印度的一种手敲小鼓)TaikoDrum/Kodo 太鼓(日本)Talking drum 讯息鼓Tambura 冬不拉(保加利亚的民俗弦乐器)Thunder sheet 雷板Timbales 天巴鼓/廷巴鼓Tin Whistle / Penny Whistle 六孔小笛/锡笛(镀锡铁皮所制造的玩具笛)Tub Fiddle 金盆琴Tupan 牛皮鼓Ukulele/Ukelele 尤库里里琴(源於葡萄牙,形如小吉他的弦乐器) Vibra-slap 震荡器/震音板Vihuela 古吉他(源起於墨西哥)Viola da Gamba 古大提琴Waterphone 水琴Whistle 哨子Wind machine 风声器Zither 齐特琴(欧洲的一种扁形弦乐琴)Dulcimer 扬琴Crotales/Antique cymbal 古钹 Temple block 西洋木鱼Electric Instrument 电子乐器Clavinova 数位钢琴/数位化电子琴Double-Neck Guitar 双颈吉他Electone 电子琴Electric Guitar 电吉他Electric Organ 电子琴Electric Piano 电钢琴Electronic Piano 电子钢琴Pedal Steel Guitar/Hawaiian Guitar 立式电吉他/夏威夷式电吉他Portatone keyboards 手提电子琴Synthesizer 电子合成器Percussion: 小打击乐器1.Percussion 小打击乐器组2.Wind Chimes3.Bell Tree 音树 4.Triangle 三角铁 5.Crotales 响板6.Finger Cymbals 手指小镲7.Sleigh Bells 马铃8.Cymbals 大镲9.Cowbell 牛铃10.Agogo Bells(由两个锥型铁筒组成,比牛玲音高)11.Flexatone12.Musical Saw 乐锯 13.Brake Drum 闸鼓 14.Tam Tam 大锣15.Gong 锣16.Claves 响棒17.Slapstick 击板18.VibraSlap19.Sand Block 沙轮20.Ratchet 齿轮剐响器21.Guiro (木制,用铁棍剐)22.Cuica(发出的声音象狗叫的拉丁乐器)23.Maracas 沙槌24.Castanets 响板25.Wood Blocks 盒棒26.Temple Blocks 木鱼27.Log Drum 木鼓 28.Tambourine 铃鼓 29.Whistle 哨 30.Siren 汽笛 31.Jawbone32.Anvil 乐钻 33.Bar Chimes 风铃 34.Crash cymbal 双面钹 35.Finger Cymbal 手指钹 36.Gong 锣37.Jingle-ring 铃环38.Maracas 响葫芦/沙球/沙铃39.Rotary Tom 轮旋鼓 40.Sleighbells 雪铃 41.Suspended Cymbal 吊钹Plucked Strings: 弹拨乐 1.Harp 竖琴 2.Guitar 吉他 3.Scoustic Guitar4.electric Guitar 电吉他 5.Banjo 班卓6.Bass 贝司7.Acoustic Bass 非电贝斯 8.Electric Bass 电贝司 9.String Bass 弦贝司 10.Mandolin 曼陀林 11.Lute 琉特琴ulele 夏威夷四弦琴 13.Zither 齐特尔琴 14.Sitar 锡塔尔琴Keybords: 键盘 1.Piano 钢琴 an 管风琴 3.Harpsichord 大键琴4.Celesta 钢片琴5.Accordion 手风琴6.Clavichord 古钢琴7.Harmonium 脚踏式风琴 8.Synthesizer 电子合成器Chorus: 合唱 1.Soprano 女高2.Soprano Ⅰ 女高1 3.Soprano Ⅱ 女高2 4.Mezzo-Soprano 女次高5.Contralto 女低6.Alto 女低7.Counter-Tenor8.T enor 男高9.Tenor Ⅰ 男高1 10.Tenor Ⅱ 男高2 11.Baritone 男中 12.Bass 男低13.Bass Ⅰ 男低1 14.Bass Ⅱ 男低2 15.Voice 人声 16.Vocals 元音Strings: 弦乐 1.Violin 小提琴2.Violin Ⅰ 小提琴1 3.Violin Ⅱ 小提琴2 4.Viola 中提琴 5.Cello 大提琴6.Violoncello 低音提琴7.Contrabass 低音提琴8.Double Bass 倍低音提琴9.Solo Violin 独奏小提琴10.Solo VIola 独奏中提琴11.Solo Cello 独奏大提琴12.Solo Bass 独奏低音提琴13.Viola d' AmoreHandbells: 手铃 1.Handbells 手铃2.Handbells(T.C)手铃(中音)钢琴0 Acoustic Grand Piano 大钢琴(声学钢琴)1 Bright Acoustic Piano 明亮的钢琴2 Electric Grand Piano 电钢琴3 Honky-tonk Piano 酒吧钢琴4 Rhodes Piano 柔和的电钢琴5 Chorused Piano 加合唱效果的电钢琴 6 Harpsichord 羽管键琴(拨弦古钢琴)7 Clavichord 科拉维科特琴(击弦古钢琴)色彩打击乐器8 Celesta 钢片琴9 Glockenspiel 钟琴10 Music box 八音盒11 Vibraphone 颤音琴12 Marimba 马林巴13 Xylophone 木琴14 Tubular Bells 管钟15 Dulcimer 大扬琴风琴Hammond Organ 击杆风琴17 Percussive Organ 打击式风琴18 Rock Organ 摇滚风琴19 Church Organ 教堂风琴20 Reed Organ 簧管风琴21 Accordian 手风琴22 Harmonica 口琴Tango Accordian 探戈手风琴吉他Acoustic Guitar(nylon)尼龙弦吉他25 Acoustic Guitar(steel)钢弦吉他26 Electric Guitar(jazz)爵士电吉他27 Electric Guitar(clean)清音电吉他28 Electric Guitar(muted)闷音电吉他29 Overdriven Guitar 加驱动效果的电吉他30 Distortion。

NRSROs制度分析及我国信用评级业发展政策建议

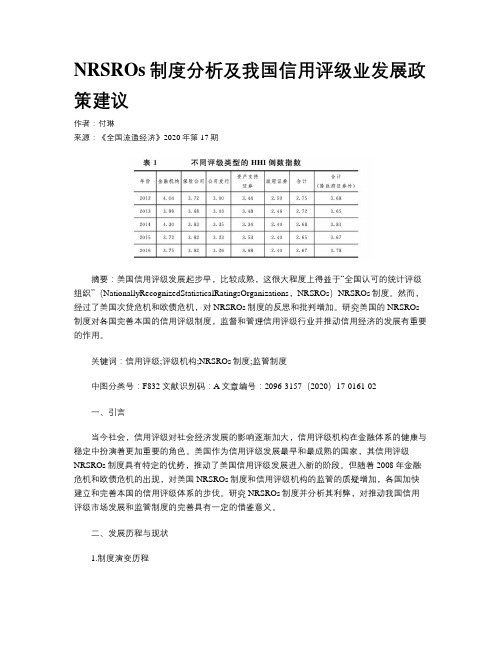

NRSROs制度分析及我国信用评级业发展政策建议作者:付琳来源:《全国流通经济》2020年第17期摘要:美国信用评级发展起步早,比较成熟,这很大程度上得益于“全国认可的统计评级组织”(NationallyRecognizedStatisticalRatingsOrganizations,NRSROs)NRSROs制度。

然而,经过了美国次贷危机和欧债危机,对NRSROs制度的反思和批判增加。

研究美国的NRSROs 制度对各国完善本国的信用评级制度,监督和管理信用评级行业并推动信用经济的发展有重要的作用。

关键词:信用评级;评级机构;NRSROs制度;监管制度中图分类号:F832文献识别码:A文章编号:2096-3157(2020)17-0161-02一、引言当今社会,信用评级对社会经济发展的影响逐渐加大,信用评级机构在金融体系的健康与稳定中扮演着更加重要的角色。

美国作为信用评级发展最早和最成熟的国家,其信用评级NRSROs制度具有特定的优势,推动了美国信用评级发展进入新的阶段。

但随着2008年金融危机和欧债危机的出现,对美国NRSROs制度和信用评级机构的监管的质疑增加,各国加快建立和完善本国的信用评级体系的步伐。

研究NRSROs制度并分析其利弊,对推动我国信用评级市场发展和监管制度的完善具有一定的借鉴意义。

二、发展历程与现状1.制度演变历程(1)准备阶段:20世纪30年代,第一次世界经济大危机爆发,因公司破产导致债券倒债增加,但评级较高的债券违约较少使得监管部门、投资者逐渐认可评级机构观点并将其作为决策依据。

1931年,美国货币监理署明确规定银行持有债券按照面值入账需经过至少一家评级机构评级,1936年,美国货币监理署和美联储规定银行持有的债券均需经过至少两家评级机构公开评级,但此时并没有对评级机构实施严格监管。

(2)产生:1974年,美国发生了自20世纪30年代以来最为严重的经济衰退,市场上集聚的信用风险再一次爆发。

信用评分卡英文文献

信用评分卡英文文献Credit scoring is a crucial tool in the financial industry, especially when it comes to assessing the creditworthiness of individuals or businesses. It's like a report card for your financial habits, telling lenders how likely you are to repay a loan on time.Scoring models are built using historical data and advanced analytics to predict the risk of default. Think of it as a magic formula that helps banks and other lenders make informed decisions. The higher your score, the more trustworthy you seem to them.But credit scoring isn't just about numbers and algorithms. It's also about understanding people'sfinancial situations and behaviors. For instance, a missed payment might not always mean someone's a bad borrower. It could be a one-time thing due to a job loss or a medical emergency.That's why lenders need to look at the whole picture, not just the score. They consider factors like income, employment history, and even things like your credit history with other lenders. It's a bit like a puzzle, and the credit score is just one piece of it.On the flip side, having a good credit score can open up a world of opportunities. You might get lower.。

盈余质量分析的评价指标体系外文翻译