Visualisation and Wittgenstein's Tractatus

高三现代科技前沿探索英语阅读理解20题

高三现代科技前沿探索英语阅读理解20题1<背景文章>Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming the field of healthcare. In recent years, AI has made significant progress in various aspects of medical care, bringing new opportunities and challenges.One of the major applications of AI in healthcare is in disease diagnosis. AI-powered systems can analyze large amounts of medical data, such as medical images and patient records, to detect diseases at an early stage. For example, deep learning algorithms can accurately identify tumors in medical images, helping doctors make more accurate diagnoses.Another area where AI is making a big impact is in drug discovery. By analyzing vast amounts of biological data, AI can help researchers identify potential drug targets and design new drugs more efficiently. This can significantly shorten the time and cost of drug development.AI also has the potential to improve patient care by providing personalized treatment plans. Based on a patient's genetic information, medical history, and other factors, AI can recommend the most appropriate treatment options.However, the application of AI in healthcare also faces some challenges. One of the main concerns is data privacy and security. Medicaldata is highly sensitive, and ensuring its protection is crucial. Another challenge is the lack of transparency in AI algorithms. Doctors and patients need to understand how AI makes decisions in order to trust its recommendations.In conclusion, while AI holds great promise for improving healthcare, it also poses significant challenges that need to be addressed.1. What is one of the major applications of AI in healthcare?A. Disease prevention.B. Disease diagnosis.C. Health maintenance.D. Medical education.答案:B。

A neuroscientist reveals how to think differently翻译

A neuroscientist reveals how to think differently一位神经学家揭示了如何用不同的方式思考In the last decade a revolution has occurred in the way that scientists think about the brain. We now know that the decisions humans make can be traced to the firing patterns of neuronsin specific parts of the brain. These discoveries have led to the field known as macroeconomics, which studies the brain's secrets to success in an economic environment that demands innovation and being able to do things differently from competitors. A brain that can do this is an iconoclastic one. Briefly, an iconoclast is a person who does something that others say can't be done.在过去的十年里,科学家们对大脑的思考方式发生了一场革命。

我们现在知道,人类所做的决定可以追溯到大脑神经系统蛋白特定部位的激发模式。

这些发现导致了一个被称为神经科学的领域,这个领域研究了大脑在一个需要创新的经济环境中成功的秘密,并且能够以不同于竞争对手的方式做事。

能做到这一点的大脑是典型的。

简而言之,偶像崇拜者就是做别人说不能做的事的人。

外刊每日精读 Clause for thought

外刊每日精读 | Clause for thought文章脉络【1】新式解码器首次让人们可以通过非入侵方式读懂思想。

【2】最新的人工智能技术终于将读心术带入了现实世界,但有些硬性限制。

【3】解码器解读大脑活动的过程。

【4】大约有一半时间,文本与原词的意思非常接近,有时甚至完全吻合。

【5】解码器能够利用大脑活动准确描述其中的一些内容。

【6】科学家们认为非入侵性读心术是一种真正的飞跃,但也在努力减轻人们对这种新技术的担忧。

【7】大阪大学大脑活动视觉图像重构的先驱西本真司教授认为这项重要的发现,可以为脑机接口的发展奠定基础。

经济学人原文Clause for thought: first non-invasive way to read minds as AI turns brain activity into text【1】An AI-based decoder that can translate brain activity into a stream of text has been developed, in a breakthrough that allows thoughts to be read non-invasively for the first time. The decoder could reconstruct speech with uncanny accuracy while people listened to a story – or even silently imagined one – using only fMRI scan data. Previous language decoding systems have required surgical implants, and the latest advance raises the prospect of new ways to restore speech in patients strugglingto communicate as a result of stroke or motor neurone disease. Dr Alexander Huth, a neuroscientist who led the work at the University of Texas at Austin, said: “We were kind of shocked that it works as well as it does. I’ve been working on thisfor 15years … so it was shocking and exciting when it finally did work.”【2】Mind-reading has traditionally been the preserve of sci-fi, in characters such as the X-Men’s Jean Grey, but the latest AI technology has finally taken the concept into the real world. This decoder’s achievement overcomesa fundamental limitation of fMRI: while the technique can map brain activity toa specific location with incredibly high resolution, there is an inherent time lag, which makes tracking activity in real time impossible. The lag exists because fMRI scans measure the blood-flow response to brain activity, which peaks and returnsto baseline over about 10 seconds, meaning even the most powerful scanner cannot improve on this. “It’s this noisy,sluggish proxy for neural activity,” said Huth. This hard limit has hampered the ability to interpret brain activity in response to natural speech because it gives a “mishmash of information” spread over a few seconds.【3】However, the advent of large language models – the kind ofAI underpinning OpenAI’s ChatGPT – provided a new way in. These models are able to represent, in numbers, the semantic meaning of speech, allowing the scientists to look at which patterns of neuronal activity corresponded to strings of words with a particular meaning rather than attempting to read out activity word byword. The learning process was intensive: three volunteers were required to lie ina scanner for 16 hours each, listening to podcasts. The decoder was trained to match brain activity to meaning using the large language model GPT-1, a precursor to ChatGPT. Later, the same participants were scanned listening to a new storyor imagining telling a story and the decoder was used to generate text from brain activity alone.【4】About half the time, the text closely – and sometimes precisely– matched the intended meanings of the original words. “Our system works at the level ofideas, semantics, meaning,” said Huth. “This is the reason why what we get out is not the exact words, it’s the gist.” For instance, when a participant was played the words: “I don’t have my driver’s licence yet,” the decoder translated as: “She has not even started to learn to drive yet.”【5】In another case, the words: “I didn’t know whether to scream, cry or run away. Instead, I said: ‘Leave me alone!’” was decoded as: “Started to scream and cry, and then she just said: ‘I told you to leave me alone.’” The participants were also askedto watch four short, silent videos while in the scanner, and the decoder was able to use their brain activity to accurately describe some of the content, the paper in Nature Neuroscience reported.【6】“For a non -invasive method, this is a real leap forward compared to what’s been done before, which is typically single words or short sentences,” Huth said. Jerry Tang, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author, said: “We take very seriously the concerns that it could be used for bad purposes, and have worked to avoid that. “We want to make sure people only use these typesof technologies when they want to and that it helps them.”【7】Prof Shinji Nishimoto of Osaka University, whohas pioneered the reconstruction of visual images from brain activity, described the paper as a “significant advance”. He said: “This is a non-trivial finding and can be a basis for the development of brain-computer interfaces.” The team now hope to assess whether the technique could be applied to other, more portable brain-imaging systems, such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).。

基于机器视觉的认知康复机器人系统设计

through the interface. If the patient is still unable to complete the task, the robotic arm

image information from time domain to frequency domain, and target detection is

accomplished by comparing the descriptors of reference objects and objects to be tested.

了完整的辅助康复系统,并且针对所用的六自由度机械臂进行了运动学建模和分

析,分析了机械臂的运动和避障策略。

最后,在康复系统样机中,通过模拟病人进行了完整的测试。仿真和实际测

试的结果充分的展示了辅助康复策略的可行性以及该辅助康复机器人系统的高效

性。

关键词:认知康复;机器视觉;傅里叶描述算子;模长位移算法;机械臂

been proved that, to a certain extent, MCI can be slowed down or even cured by human

intervention. However, due to the lack and uneven distribution of related medical

康复过程往往不及时不到位,缺乏持续性和有效性。针对此,本课题设计了一套

基于机器视觉的辅助认知康复机器人系统,用以提高 MCI 等疾病的康复效率。

期待视野观照下的翻译

期待视野观照下的翻译【摘要】:20世纪60年代后期兴起于德国的接受美学,给西方文论界刮进一股清新之风。

它富有启示性地尝试了从读者理解与接受的角度研究文学的方法,强调读者及其阅读接受对文学研究的意义,突出了读者中心的这一理论范式。

期待视野是接受美学代表人物姚斯理论中的一个主要概念,指接受主体先行存在的指向本文的预期结构。

将这一概念引入翻译研究中,可让我们重新审视翻译的一些基本问题。

【关键词】:期待视野;翻译研究;翻译技巧一、引言翻译总是从一国语言出发到另外一国语言的过程。

在经过语言转换后,一些语言和文化意象进入一个新的语言文化环境,往往会发生一些意想不到的变形,导致出人意料的反应。

Carrefour,一个法国的连锁超市名称,本意是”十字路口”,原本应是取其”便利、快捷”之意,一进入我们国家,被音译为”家乐福”。

这是一个成功的翻译,它满足了中国消费者的文化心理,深得中国消费者的喜爱。

Poison 香水最开始进入我们国家,经销商并没有把它译为”毒药”,而是根据其英语发音,译为”百爱神”,这样,它让人们觉得这是一种别样的有奇效的香水,它的香味会像邱比特射出去的神箭,能招来频频注视,甚至美妙爱情。

因此,它也博得无数女士的青睐。

然而随着时间的变化,人们开始对它熟视无睹。

经销商又突发奇招,意译为”毒药”,迎合了这个个性消费的时代,从此,又开始风靡一时。

可以看出,事物的接受主体,由于个人的和社会的原因,心理上总是存在着一个既定的心理图式,它深刻影响着人们对事物的接受方式和过程。

在作为语言和文化交流的翻译活动中,译者本身会在外在的社会历史和内化的个人历史中,形成一个既定的心理图式或”视野”,影响着翻译;同时,目的语读者具有的期待视野,也影响或限制着译者对原作的处理技巧。

二、期待视野作为接受美学的一个主要概念20世纪六七十年代,接受美学在西方文论界,异军突起,脱颖而出,以其读者理解与接受的系统研究方法,为文论注入了新的活力,从此在西方当代文论中占据重要位置。

当代研究生英语 第七单元 B课文翻译

价格的利润生物公司正在吞噬可改变动物DNA序列的所有专利。

这是对阻碍医学研究发展的一种冲击。

木匠认为他们的贸易工具是理所当然的。

他们买木材和锤子后,他们可以使用木材和锤子去制作任何他们所选择的东西。

多年之后来自木材厂和工具储藏室的人并没有任何进展,也没有索要利润份额。

对于那些打造明日药物的科学家们来说,这种独立性是一种罕见的奢侈品。

发展或是发现这些生物技术贸易中的工具和稀有材料的公司,对那些其他也用这些工具和材料的人进行了严格的监控。

这些工具包括关键基因的DNA序列,人类、动物植物和一些病毒的基因的部分片段,例如,HIV,克隆细胞,酶,删除基因和用于快速扫描DNA样品的DNA 芯片。

为了将他们这些关键的资源得到手,医学研究人员进场不得不签署协议,这些协议可以制约他们如何使用这些资源或是保证发现这些的公司可以得到最终结果中的部分利益。

许多学者称这抑制了了解和治愈疾病的进程。

这些建议使Harold得到了警示,Harold是华盛顿附近的美国国家卫生研究院的院长,在同年早期,他建立了一个工作小组去调查此事。

由于他的提早的调查,下个月出就能发布初步的报告。

来自安阿伯密歇根大学的法律教授,该工作组的主席Rebecea Eisenberg说,她们的工作组已经听到了好多研究者的抱怨,在它们中有一份由美国联合大学技术管理组提交的重量级的卷宗。

为了帮助收集证据,NIH建立了一个网站,在这个网站上研究者们可以匿名举报一些案件,这些案件他们相信他们的工作已经被这些限制性许可证严重阻碍了。

迫使研究人员在出版之前需要将他们的手稿展示给公司的这一保密条款和协议是投诉中最常见的原因之一。

另一个问题是一些公司坚持保有自动许可证的权利,该许可证是有关利用他们物质所生产的任何未来将被发现的产品,并且这些赋予他们对任何利用他们的工具所赚取的利润的支配权利的条款也有保有的权利。

Eisenberg说:“如果你不得不签署了许多这样的条款的话,那真的是一个大麻烦”。

自闭症的知觉特异性与知觉功能促进化理论

N-back 工作记忆任务

左侧顶叶激活较强,与前额 右侧额叶和顶叶激活, 颞叶下

叶区域活动联系密切

方和枕叶后方有更多的激活

否

Müller 等人 [24]

枕 区 和 额 叶 皮 层 (BA8 和 10)的激活

否

Pierce 等人 [25]

面孔识别任务

顶下回、颞上沟、杏仁核激 杏仁核没有被激活, 显示独特

心理研究 Psychological Research 2012,5(4):13-19

13

自闭症的知觉特异性与知觉功能促进化理论

吴 冉 徐光兴

(华东师范大学心理与认知科学学院,上海 200062)

摘 要:知觉特异性是自闭症的典型症状之一,掌握自闭症的特异性知觉特征对理解自闭症的认知、行为及其诊断、治疗有重要意 义。 21 世纪初提出的知觉功能促进化理论很好地解释了自闭症的知觉特异性特征,引起了科学研究与临床领域的重视。 本文介绍 了自闭症的知觉功能促进化理论及其发展,并以该理论为框架,介绍自闭症的知觉特异性特征及其对自闭症行为特征的影响,期 望通过对知觉特异性特征的理解和理论反思,能够对自闭症的教育与治疗有所裨益。 关键词:自闭症;知觉特异性;知觉功能促进化

1 引言

自闭症被定义为一种特殊类型的广泛性发展 障 碍 ,自 从 Kanner 和 Asperger 几 乎 同 时 首 次 对 自 闭症进行了描述后[1-2],自闭症复杂的病 因 、症 状 就 吸引了很多研究者的目光。 特异性的知觉功能是 自闭症典型的特征之一。 越来越多研究证据表明, 知觉特异性在自闭症的行为和认知表型中具有突 出作用。

通讯作者:徐光兴,男,教授,博士生导师。 Email: gxxu@

14

心理

witten几何朗兰兹纲领的重新表达

witten几何朗兰兹纲领的重新表达标题:重述维特根斯坦的几何学朗兰兹纲领引言:维特根斯坦是20世纪最重要的哲学家之一,他在其著作《语言游戏》中提出了几何学朗兰兹纲领,这一观点对于我们对于几何学的理解具有重要意义。

本文将重新表达维特根斯坦的几何学朗兰兹纲领,深入探讨其核心概念,并提供个人观点和理解。

一、几何学朗兰兹纲领的基础概念1.1 语言游戏的角度维特根斯坦认为几何学不是一种完备的理论,而是一种语言游戏。

语言游戏是人们在特定社会和文化背景中使用语言的方式,几何学就是其中一种特定的语言游戏。

几何学通过符号、规则和操作构建起来,它的意义和价值在于与其他语言游戏之间的互动。

1.2 视觉形式和规则维特根斯坦认为几何学的核心在于视觉形式和规则。

视觉形式指的是我们通过感知世界的方式来理解空间和物体的形态,而规则则是我们根据这些视觉形式所制定的准则和操作方法。

几何学的目的在于揭示这些视觉形式和规则之间的关系,帮助我们理解和描述物理世界中的几何概念。

二、几何学朗兰兹纲领的探索2.1 空间感知和直觉维特根斯坦强调了空间感知和直觉在几何学中的重要性。

他认为人们在空间中的直觉经验是几何学的基础,而几何学则通过语言游戏来表达和探索这种直觉。

通过实际观察和实验,我们可以通过几何学的语言游戏来深入理解空间和形状之间的关系。

2.2 语言游戏和概念的生成维特根斯坦认为几何学中的关键在于概念的生成。

他强调几何学是一种活动的语言游戏,概念是在这个游戏中不断生成和演变的。

我们通过语言游戏来建立起一系列几何概念,并通过这些概念的互动和变换来探索几何学的本质。

三、个人观点和理解我认为维特根斯坦的几何学朗兰兹纲领提供了一种新的思考几何学的方式。

他打破了传统几何学中对于绝对空间和形状的观念,强调了直觉和语言游戏在几何学中的重要性。

通过重新思考几何学的基础概念和语言规则,我们可以更深入地理解几何学的本质和意义。

结论:维特根斯坦的几何学朗兰兹纲领提供了一种重新表达几何学的观点。

Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles

A simple model with a novel type of dynamics is introduced in order to investigate the emergence of self-ordered motion in systems of particles with biologically motivated interaction. In our model particles are driven with a constant absolute velocity and at each time step assume the average direction of motion of the particles in their neighborhood with some random perturbation (η) added. We present numerical evidence that this model results in a kinetic phase transition from no tran |va| = 0) to finite net transport through spontaneous symmetry breaking of the rotational symmetry. The transition is continuous since |va| is found to scale as (ηc − η)β with β ≃ 0.45.

——————–

One of the most interesting aspects of many particle systems is that they exhibit a complex cooperative behavior during phase transition [1]. This remarkable feature of equilibrium systems has been studied in great detail for the last couple of decades leading to a deeper understanding of processes which may take place in an assembly

从乔治·斯坦纳翻译四步骤看外刊翻译

2232019年09期总第449期ENGLISH ON CAMPUS从乔治·斯坦纳翻译四步骤看外刊翻译文/宋伟灵【摘要】乔治·斯坦纳提出的翻译四步骤是解释学重要的一部分,对翻译实践有很大的指导意义。

用翻译四步骤来指导外刊翻译,能够使译文更加准确到位。

本文将对这四个步骤进行详细讨论,并用外刊中的例子进行说明。

【关键词】解释学;外刊;翻译步骤【作者简介】宋伟灵(1991-),女,汉族,辽宁人,黑龙江大学,在读硕士研究生,研究方向:英语笔译。

二是可以提升翻译外刊的能力。

三、从翻译四步骤看外刊翻译乔治·斯坦纳提出的翻译四步骤便是笔者理解并翻译外刊的过程,它包括:信任、侵入、吸收和补偿。

根据乔治·斯坦纳在After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation一书中对该四个步骤的阐述,笔者进行了归纳总结,并举例说明它是如何指导外刊翻译实践的。

1.信任。

一切翻译行为的基础是信任。

简单来说,翻译一个文本前,笔者先要相信自己翻译的文本是有意义的,是可以翻译的,翻译它具有必要性并且能够为人们带来帮助。

信任分为多个层面,如原文本的可译性、作者的水平、出版社是否权威等。

笔者信任外刊的质量。

第一,文中涉及的外刊都是国际主流杂志报刊,文章内容具有极强的可读性,语言运用也十分地道。

翻译这类文章可以提高中英语言的转换能力,对翻译学习有很大帮助。

第二,翻译外刊也是了解国外政治、经济、文化等领域的好途径,并能不断丰富自己的知识储备、培养国际视野。

一些外刊也会写和中国相关的文章,这就能让我们了解到,在西方人眼中,中国是怎样的国家。

从而,我们对国家的认识也会更加立体、客观。

所以,翻译外刊具有一定的价值和意义。

2.侵入。

信任之后,便是侵入。

侵入指译员自身的各方面素质会对原文的理解产生一定的影响。

例如,其所处的生活环境、知识水平、思考方式、语言能力、翻译经验等等。

模仿性学习的英文文献以及翻译

Discrimination Learning of Scratching, but Failure to Obtain Imitation and Self-recognition in aLong-tailed MacaqueAbstract:A long-tailed macaque was trained to scratch when a model scratched, but failed to generalize scratching when model scratched new target areas. The results confirm that monkeys can control their rates of scratching, but may not be capable of true imitation. The subject also failed on a test of mirror self-recognition. Imitation and self-recognition appear to be related capacities,which may be absent in monkeys.Key Words: Imitation; Macaque; Mirror; Scratch; Self-recognition.The capacity for imitation of others' bodily actions is reasonably viewed as a prerequisite for the development of self-awareness and awareness of another's erspective(BALDWIN,1894/1903; GUILLAUME, 1926/1971; PIAGET, 1945/1962; MELTZOFF, 1990; MITCHELL, 1990,in press a; HART & FEGLEY, in press). Recent theory (PARKER, 1991; MITCHELL, 1992, in press a) has explicitly tied the recognition of one's own body in a mirror to imitative apacities: mirror-self-recognition is observed in great apes, humans, and perhaps dolphins (GALLUP, 1970, 1985; LEWIS & BROOKS-GUNN, 1979; ANDERSON, 1984a, b, in press;PATTERSON, 1990; PATTERSON • COHN, in press; MARTEN & PSARAKOS, in press), and imitation of another's actions s largely restricted to these species (MITCHELL, 1987;VISALBERGHI & FRAGASZY, 1990; WHITEN & HAM, 1992). Among humans, those who have difficulty with imitation (e.g. some autistic children) also generally fail to mirror-selfrecognize (MITCHELL, in press a), and propensities for imitation of others' actions and mirror-self-recognition are not always present in all members of a species (VISALBERGHI &FRAGASZY, 1990; SW ARTZ & EV ANS, 1991; MITCHELL, in press a).According to one theory, bodily imitation and mirror-self-recognition go together because both are dependent upon kinesthetic-visual matching (MITCHELL, 1992, in press a). With kinesthetic-visual matching, the organism recognizes that the kinesthetic and visual experiences of its own body are identical and thus knows what it looks like when it acts, even when it does not see itself. The organism can also compare its own kinesthetically felt actions with its visual experience of actions of others, as in imitation, and with the visually experienced actions of itself, as in mirror-self-recognition. If an organism couldbe taught to imitate accurately another's bodily actions, it should develop a capacity for kinesthetic-visual matching and therefore be able torecognize its own mirror image.Although great apes and humans apparently naturally imitate (MITCHELL, 1987, in press b), only a few apes have been taught to imitate human actions (e.g. HA VES & NISSEN, 1971;MILES et al., 1992; MILES, in press; CUSTANCE t~ BARD, in press). Humans deficient in imitative abilities have also been taught to imitate bodily actions (BAER et al., 1971).Usually the techniques for apes require teaching signs or involve other close physical interaction,techniques which usually become difficult with non-ape and nonhuman primates at an early age. No attempt has previously been made to teach imitation to a monkey.In this study we describe an attempt to condition a long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) to imitate a human's scratching. Macaques are compelling subjects because a few instances of apparent imitation of motor acts have been observed in this genus (BREUGGEMAN, 1973; PARKER, 1977; ETTLINGER, 1983; BURTON, 1992). Scratching was chosen as the action to be modeled because primates can be easily conditioned to scratch (lVERSEN et al., 1984; LOUBOUNGOU & ANDERSON, 1987; ANDERSON et al., 1990), because macaques may learn to use scratching as a communicative gesture (DIEZINGER 8Z ANDERSON, 1986), and because imitation would be easily discernible from simpler conditioned scratching by observing whether the "imitator" is sensitive to varying locations of the model's scratch.学习抓的歧视,但失败获得模仿和自身识别长尾猕猴摘要:长尾猕猴是训练有素的,当一个模型挠,但失败了推广抓当模型挠新目标区域。

“4E+S”:认知科学的一场新革命?

“4E+S”:认知科学的一场新革命?【英文标题】"4E+S"A New Revolution in the Cognitive Science?【作者简介】李建会,于小晶,北京师范大学价值与文化研究中心、哲学与社会学学院。

一、引言近年来,许多科学家和哲学家都认为,在认知科学领域发生了一场新的认知革命。

这一革命就是“4E+S”理论模型的兴起。

其中,“4E”指的是体化(embodied)认知、嵌入(embedded)认知、生成(enacted)认知和延展(extended)认知理论;“S”指的是情境(situated)认知理论。

与认知科学传统的计算表征理论不同,一批新的认知科学家和哲学家开始主张认知是体化的、嵌入的、生成的、延展的和情境的。

“4E+S”认知起初是由不同的认知科学家和哲学家独立倡导的,但随着这些模型讨论的增多,2007年在美国佛罗里达大学召开的一次认知科学会议上,“4E”第一次作为统一的主题被展开讨论。

也正是在这次会议上,美国蒂芬大学的美籍华人卢找律教授提出,应当在“4E”纲领的基础上再加上一个“S”,他认为近年来正在形成的认知革命综合起来就是“4E+S”。

①“4E+S”认知在认知科学的当代讨论中具有非常大的影响。

如20世纪末21世纪初,国外学界出版和发表了许多关于“4E”和“S”的著作和文章,其中,有影响力的著作有:瓦雷拉(F.Varela))、汤普森(E.Thompson)和罗施(E.Rosch)的《体化认知》(1991年),克拉克(A.Clark)和查尔莫斯(D.Chalmers)的《延展心灵》(1998年),拉考夫(koff)和约翰逊(M.Johnson)的《肉身中的哲学》(1999年),诺伊(A.Noe)的《知觉中的行动》(2004年),亚当斯(F.Adams)和艾泽瓦(K.Aizawa)的《认知的界限》(2008年),罗兰兹(M.Rowlands)的《心灵的新科学》(2010年),夏皮罗(L.Shapiro)的《体化认知》(2011年)等。

萨丕尔-沃尔夫假说

萨丕尔-沃尔夫假设主要内容美国人萨丕尔及其弟子沃尔夫提出的有关语言与思维关系的假设是这个领域里至今为止最具争议的理论。

沃尔夫首先提出,所有高层次的思维都倚赖于语言。

说得更明白一些,就是语言决定思维,这就是语言决定论这一强假设。

由于语言在很多方面都有不同,沃尔夫还认为,使用不同语言的人对世界的感受和体验也不同,也就是说与他们的语言背景有关,这就是语言相对论。

Linguistic relativity stems from a question about the relationship between language and thought, about whether one's language determines the way one thinks. This question has given birth to a wide array of research within a variety of different disciplines, especially anthropology, cognitive science, linguistics, and philosophy. Among the most popular and controversial theories in this area of scholarly work is the theory of linguistic relativity(also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis). An often cited "strong version" of the claim, first given by Lenneberg in 1953 proposes that the structure of our language in some way determines the way we perceive the world. A weaker version of this claim posits that language structure influences the world view adopted by the speakers of a given language, but does not determine it.[1]由萨丕尔-沃尔夫假设的这种强假设可以得出这样的结论:根本没有真正的翻译,学习者也不可能学会另一种文化区的语言,除非他抛弃了他自己的思维模式,并习得说目的语的本族语者的思维模式。

作为溯因推理研究方法的因果过程追踪及其在公共政策研究中的应用

与量化研究相 比,质 性 研 究 显 然 更 擅 长 于 发 掘 和 描 述 政 策 变 化 过 程 的 因 果 机 制①( 朱天飚,2017) 。“一个完整的解释,必须规定一种机制来描述一个变量影响另 一个变量的过程,换句话说,X 是如何产生 Y 的”( Kiser and Hechter,1991) 。质性方 法论体系利用个案分析方法研究社会现实案例,是国内外公共管理以及公共政策研 究的重要载体( Sigelman and Gadbois,1983; 马骏,2012) 。个案分析方法通过对公共 政策过程的全景式描述,多角度地把握研究对象的特征,可以探索揭示公共政策实 施过 程 的 因 果 机 制,但 其 方 法 论 瓶 颈 在 于 从 个 别 到 一 般 的 因 果 推 论 解 释 力 弱 ( Eisenhardt,1989; Yin,1994; Goodin,2009) 。为提高因果推论能力,公共政策的质 性研究方法论 体 系 需 要 进 一 步 突 破。近 年 来 兴 起 的 因 果 过 程 追 踪 方 法 ( Causal Process Tracing) 具有识别并纠正虚假因果关联以及遗漏变量偏误等内生性问题的方 法论优势( Falleti,2016; 张长东,2018) ,成为公共政策学者可以使用的重要方法论 工具。

(完整word)牛津心理学专业英语基础翻译

第7页起源和历史·行为主义的研究方法受经验主义和自然科学的影响.其中,经验主义强调人类出生时犹如一块白纸或白板,所以知识是通过感觉通道从环境中获得的,自然科学则强调研究方法的科学性和客观性。

·1913年,华生写了一篇名为《行为主义者心目中的心理学》的文章,从此他引发了行为主义的浪潮,这篇文章中也表明了行为主义的主要原理和假设。

华生、桑代克、斯金纳等行为主义学家根据早年巴甫洛夫的工作而开始发展学习理论,比如:经典和操作条件反射,他们试图用学习理论从本质上解释所有行为。

·行为主义研究方法一直主导着实验心理学,直到20世界初50世界末。

动物行为学家和认知心理学家开始越来越多地批判它的假设和研究方法,为了提供更加真实的关于学习是如何发生的解释,行为主义被一些心理学家改变,rubies班杜拉和他的社会学习理论.华生:给我一打健康的婴儿,让我在我的特殊世界中教养,那么我可担保,在这十几个婴儿之中随机拿出一个都可以训练他成为任何一种我所选类型的专家。

可以是医生、律师、甚至也可以是一个乞丐或小偷。

理论假设行为主义者认为:·多数行为是后天从环境中习得的,行为主义者在天性还是教育的辩论中选择了教育一方,他们还认为:a.心理学应该区分学习的规律和结果;b.行为是由环境决定的,因为我们只不过是我们过去所有学习经验的整合,而自由意志则是幻觉(错误的)·心理学如果要成为一门客观性科学,就应该只研究可观察到的行为,而不是意识;因为我们是无法看清他人意识的;并且如果我们去询问他人的想法,他们就可能说谎,或者不知道,或者甚至出错。

调查研究方法行为主义者采用的是一种完全研究一般规律的方法,他们用严谨的实验室实验,并且通常是训练像老鼠、鸽子这样的动物.行为主义者训练动物是由于他们相信:1、学习的规律是有普遍性的2、人和动物之间只有一定数量的不同而已3、训练动物会更加方便,也是很实用且合乎道德的阐释内容行为主义者的这些有关学习规律的发现可以有力地应用在解释行为的许多方面上,比如:·语言获得,eg:斯金纳的理论·道德发展,eg:条件控制下关于愧疚和良心的情绪反应·吸引力,eg:Byrne&clor的强化影响模型·变态,eg:恐怖症的经典条件反射及其治疗还有攻击行为、偏见、性别角色鉴定等具体应用行为主义学习理论的研究方法已经出教育中的实践应用(比如,程式化学习)和那些痛苦的行为障碍的治疗(比如,针对恐怖症的系统脱敏、自闭症的行为塑造以及被收容的病人的代币制度)·操作条件反射原理被应用于训练动物以完场任务,他们训练了有马戏团动物还有导向犬.·华生将行为主义理论同时应用于抚养儿童以及广告业,于此同时斯金纳则在他的书中提出了许多关于社会中大范围的行为塑造的建议,比如《超越自由与尊严》和《沃尔登第二》。

精神分析专业词汇汇编中英语对照

精神分析专业词汇汇编中英语对照开个帖子,将精神分析中会用到的中英文专业单词贴在这里,希望大家一起整理和补充AAI 成人依附会谈abandonment neurosis 遗弃型神经症Abend S M 阿本德abnormality 不正常的abortion 流产Abraham K 亚伯拉罕abreaction 宣洩abreaction 弭除反应abreaction 涤清Abreaction and catharsis 消散和宣洩absence of basic trust 基本信任的缺乏absences 治疗同意书,缺席Absences from interviews 缺席abstinence 禁慾规则Abt L 阿布特abuse 苛待accuracy 精确accurate 精确acedia 怠惰acting 行动acting in 治疗内见诸行动Acting in 诊疗室的行动化acting in the transference 见诸行动于移情acting out (治疗外)见诸行动acting out 付诸行动acting out 行动力acting out 行动化action 行动action techniques 行动技术active 主动的Active control by therapist 积极的控制,治疗师active technique 主动性技术activity and transference 治疗师,活动,与转移关係activity-passivity 主动性/被动性actual neurosis 现实型神经症actualization 实现Actualization concept of 现实化,概念acute 急性acute 急性的acute conditions 针对急性状况Adaptation as acting out 适应,见诸行动作为Adaptation of ego 适应,自我的适应adaptational therapy 调适疗法Adhesiveness 黏滞性Adhesiveness of libido 力比多的黏滞性adhesiveness of the libido 力比多的黏着性Adler G 阿德勒adolescence 青少年adolescence and analysis 青少年与分析adoption 收养adult 成人Adult Attachment Interview 成人依附关係访谈法Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) 成人依附会谈Adult Attachment Interview(AAI) 成人依附会谈affect 情感affect 教育,情感Affect of patient 情感,个案affective attunement 情感拍合affect-trauma model 情绪创伤典範age 年龄age and analysability 年龄与可分析性agency 审级aggresivity-aggressiveness 侵略性aggression 攻击aggressive energy 攻击能量aggressive instinct 侵略欲力aggressor 认同攻击者agieren[to act] 见诸行动agoraphobia 惧旷症aim(instinctual aim) (欲力)目的aim-inhabited 目的禁制Alcoholics Anonymous 戒酒无名会alcoholism 酒瘾Alexander F 亚歷山大alienation 异化alliance 治疗同意书,结盟alliance 联盟allo-erotism 他者情慾Alloplastic versus autoplastic ratio and ego strength 外在造形的对内在造形的比率alonenesstogetherness 单独同在Alpha elements 阿法因素Alston T 阿尔斯顿alter ego 变化的自我alter ego transference 变化的自我移情alteration of the ego 自我变异alternative 替代性altruistic surrender 利他降从ambivalence 矛盾ambivalence 矛盾双重性ambivalence 情感矛盾Ambivalence 爱根交织Ambivalence of wishes 愿望的两难ambivalent 矛盾ambivalent. pre-ambivalent. post-ambivalent 矛盾双重性的、前矛盾双重性的、后矛盾双重性的amnesia 失忆amnesia 失忆症Ana Freud( Freud A) 安娜?佛洛德anaclisis 依附anaclitic (attachment) 依附的[依赖的]anaclitic depression 依附性忧郁[依赖性忧郁]anaclitic type of object-choice 依附型对象选择anagogic interpretation 玄学诠释Anal phantasy 肛门幻想Anal sadistic impulse 肛门施虐衝动anality 肛门特质anal-sadistic stage 肛门-施虐阶段analysis 分析analysis lay 非专业分析analysis of ......分析analyst 分析师analyst as 分析师作为analyst centred interpretation 以分析师为中心的诠释analyst, wild 非专业分析analyst’s role 分析师的角色analyst-analysand relationship 分析师-被分析师者关係analytic 分析取向的analytic 分析性analytic development of 分析性发展analytic psychology 分析心理学analytic psychotherapy 分析取向心理治疗analytic stance of 分析性立场analytical psychologyschool of 分析心理学学派Analyzability 可分析性Anatasopoulos D 阿纳斯塔索保洛斯and conscience 超我焦虑,与良心and description 自我,义与描述and drive-derivatives, in psychotherapy 驱力,驱力衍生物,心理治疗中and ego strength 客体关係,自我强度and evaluation, nature of illness 心理治疗,适用徵候,评估疾病本质and id, ego, and super-ego 精神衝突,与塬我,自我和超我and indications, for psychotherapy 超我焦虑,功能,与精神衝突and insight therapy 药物,与洞见取向心理治疗and insight-directed psychotherapy 精神分析,与洞见取向心理治疗and psychic conflict 自我,精神衝突and psychic conflict 塬我,与精神衝突and secondary process 自我,次发过程and supportive therapy 药物,与支持取向心理治疗and symptom formations 煺化,症状形成and the trauma and vicissitudes of life 精神官能症,与创伤和生活的变迁and therapeutic relationship 药物,与治疗关係and therapy 防卫,治疗and transference 煺化,转移关係anima 阿尼玛anima projection 阿尼玛外射(造成自恋)animus 阿尼姆斯Anna O 安娜的故事annihilation 虚无anomieconcept of 丧心病狂的概念anorexia 厌食症anthroposophy 人(类)智(慧)学(说) anticathexis 逆投资anti-semitism 反犹太主义Antisocial Personality Disorder 反社会人格异常anti-therapeutic 反治疗anti-therapeutic alliance 反治疗联盟anxiety 焦虑anxiety hysteria 焦虑型歇斯底里anxiety neurosis 焦虑型神经症Anxiety, ego, and super-ego 焦虑,自我与超我Anxiety, signal 焦虑,讯号aphanisis 丧失性慾aphasia 失语症apperception mass 领觉团堆appraisal 评价appropriate 适度的archeological metaphor 考古学的隐喻archetype 塬型archetype images 塬型心像archetype proper 塬型本体archetypes 塬型archetypes of the spirits 精神塬型Arkin F S 阿金Arlow J A 亚农armour-plating of [ Charakter-panzerung] 装甲arousal levels 警醒层级art of ......的艺术art therapy 艺术疗法artistic 艺术的artistic creativity 艺术创造力artistic creativity and regression 艺术创造力与煺行'as 彷彿as adaptation 作为一种适应as communication 作为一种交往as distorting 作为一种歪曲as fantasy object 幻想客体as interpretation 作为一种解释as mediator 作为调停者as narrative transaction 作为一种叙事性交互as obstacle 阻碍as resistance 作为一种阻抗as sour of information 作为一种信息来源as specific illusion 作为一种特异性错觉as way of life 精神官能症,充当生活方式ascetism 禁慾主义Asch S 阿施assessment interview 晤谈衡鑑association 联想association chain 联结键association, free 自由联想Associations and Societies 联盟、学会athenic syndrome 无力症候群Atkins N B 阿特金斯atmosphere 治疗同意书,气氛Atmosphere, therapeutic 气氛,治疗气氛atonic syndrome 低张力症候群attachment 依附attachment 依恋、依附attachment theory 依附关係理论Attendance for treatment 出席治疗attention, (evenly)suspended(或 [evenly]poised) (同等地)悬浮的注意力attention: evenly suspended 注意:带着平常心的Auchincloss E L 奥金克洛斯authoritarianism 威权主义autism 自闭症auto-erotism 自体情慾autogenic training 自然发生训练automatic anxiety 自发性焦虑automatic thoughts 自动化思考automatic writing, talking, drawing 自动书写;自动谈话;自动作画automatism, ambulatory 行走自动症autonomic arousal 自主神经的警醒状态autonomous ego functions 自主性自我功能autonomousfree 自主-自由型autonomy see dependence 自主见依赖autoplastic-alloplastic 自塑/他塑auxiliary ego 辅助的自我Avoidance 逃避avoided calamitous 迴避的大灾难性awareness 觉察awareness of in CBT 觉察在认知行为治疗中Bahnung 通导Balint A A?巴林特Balint M M?巴林特baquet 磁桶Barande R 巴兰德Baranger W 巴兰哲bargaining in psychotherapy 心理治疗中的妥协(讨价还价) Barnett J 巴尼特basic 基本basic 基本的basic anxiety 基本焦虑basic fault 基本谬误basic model of 基本模式basic model of psychoanalysis 精神分析的基本模式basic rule of 基本规则basic transference 基本移情basic trust 基本信任basis of 的基础Bateson G 贝特森Beatlemania 披头狂Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) 贝克忧郁量表bed-wetting 尿床Bégoin F F?贝古安Bégoin J. J?贝古安Behavior in the interview 行为,会谈中的行为behaviour 行为behaviour as 行为(被指)作behaviour, as acting out 见诸行动的行为behaviour: addictive 行为:成瘾性behavioural: dialectical therapy 行为的:对话式疗法being in the world 「此世存有」「在世界中的存有状态」Bellak L 贝拉克bereavement 丧恸bereavement see loss mourning 伤恸见失落与哀悼Beres D 贝勒斯Berg M D 贝格Bergman A 贝格曼Berkowitz D A 贝科维茨Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute 柏林精神分析学会Bernstein I 伯恩斯坦Besetzung [cathexis] 投注Beta elements 贝塔因素Bibring E 比布林Bibring-Lehner G 比布林-莱纳bic fault 基本裂隙bic rule of 的基本规则bic: sumptions 基本:假设Bilger A 比尔杰Bilo 毕罗(仪式)binding 连结bioenergetics 生物能学biofunctional therapy see bioenergetics 生物功能疗法见生物能学Bion W R 比昂bipersonal field 互动领域bipersonal field 两人区域bipolar affective disorder 双极性情感疾患bipolar self 两面自体Birth trauma, and anxiety 生之创伤,焦虑bisexuality 双性bisexuality 双性特质Black Madonna 黑色圣母马利亚Blacker K H 布莱克尔Bleger J 布莱格尔Bleuler E 布洛伊勒blindness 瞎眼Blitzsten 布利茨斯腾Blos P 布洛斯Blum H P 布詹姆bodily 躯体body: language 身体:语言Boesky D 博伊斯基Bollas C 博拉斯Bolshevik 布尔什维克主义bond 纽带'联盟Bone M 博恩borderline case 边缘症borderline condition 边缘状态borderline patient 边缘性病人Borderline Personality Disorder 边缘人格异常Borderline Personality Organization 边缘人格组织borderline states 边缘性状态Borderline states, classification 边缘状态,分类Boschán P J 博施安boundaries 界限brain mythology (Himmythologie) 玄想性脑神话Brandchaft B 布兰德夏弗特breakdown of 崩溃breakdowns 崩溃Breast mother 乳房母亲breast-feeding 哺乳breathing see body work唿吸见肢体工作Brenner C 查尔斯?布论讷Breuer J 布罗依尔British Confederation of Psychotherapists 英国心理治疗师联盟Britton R 布里顿Brown G W 布朗Buie D H 布伊bulimia 肥胖症bulimia 暴食症Burgh?lzli 布戈泽利病院Bush M 布希by the patient 结案,不成功治疗下的结案,个案决定by the therapist 结案,不成功治疗下的结案,治疗师决定Calogeras R 卡洛赫拉斯Campell R J 坎贝尔cannibalistic 食人的capacity for 能力capacity for treatment alliance 建立治疗联盟的能力card-playing 玩牌care 照护communitycase of Dora 朵拉案例case of Frau PJ on counter-transference 关于反移情的P?J女士案例castration 阉割Castration anxiety 阉割者父亲castration anxiety 阉割焦虑castration complex 阉割情结Castration threat 阉割威胁catalepsy 强(僵)直性(昏厥)状态catharsis 倾泻cathartic approach 宣洩法cathartic cure 宣洩疗法cathartic therapy或cathartic method 净化(方法)cathectic energy 投资的能量cathexis 投资cathexis (investment) [besetzung] 投注causes of 的塬因CBT 认知行为治疗ce studies 个案研究censorship 监控censorship 检禁central inner conflict 核心内在衝突central role of 的核心作用centred medicine 为中心的医疗centred medicine 为主的医学Cesio F R 赛西斯changes in 变化changes in meaning of term 术语含意的变化changing 改变changing behaviour 改变的行为changing goals 心理治疗,改变中的目标character 性格character armour 性格盔甲character disorder 性格障碍character neurosis 性格型神经症characteristics 特色ICharcot J M 夏科Chediak C 切迪阿克child 儿童child abuse 孩童虐待child analysis 儿童分析child sexuality 幼儿性慾child: abuse 孩童:虐待childbearing 生育小孩childbirth 生产childcare 照顾小孩childhood 儿童期childhood sexuality 孩童性欲childhood sexuality, Freud 幼儿性慾childhood trauma 儿童期创伤childrearing 抚养小孩choice of neurosis 神经症选择chronic 慢性chronic 慢性的circumsessio 恶魔作祟clairvoyance 超透视现象;千里眼clarification 治疗师,澄清clarification 澄清classical and modern theories of transference 移情的古典观和现代观classification of 的分类claustrophobia claustrophobia 幽闭恐惧症clientcentred 案主为中心的clinical 临床clinical 临床的clinical trials 临床试验clitoris 阴蒂cloacal (或cloaca) theory 泄殖腔(理论)clsification 分类cocounselling 协同谘商Coen S J 科因cognition see thinking 认知见思考cognitive 认知的cognitive analytical therapy (CAT) 认知分析疗法cognitive knowledge 认知性知识cognitive science see CBT 认知科学cognitive therapy 认知取向治疗cognitive therapy 认知疗法cognitivebehavioural therapy (CBT) 认知行为疗法Cohen M B 科恩coherence and correspondence theories of truth 真理的一致性及相关性Colarusso C A 柯拉鲁索collective 集体的collective individuation of manking 人类之集体个体化collective unconscious 集体潜意识Combined parents 联合起来的父母亲combined parents, combined parent-figure 交合双亲,交合双亲依玛构common ground position 共通立场communication 交往communicationin psychotherapy 沟通心理治疗中的community 社区:community feelin 社群感compensation 心理代偿compensation 补偿compensation neuroses 代偿性神经症competition 竞争complemental series 互补系列complementary 互补性complementary countertransference 互补反移情complementary identification and countertransference 互补性认同与反移情complex 情结complex of inferiority 自卑情结complex psychology 心结心理学Complex reversals 情结倒转component (or partial) instinct 部分欲力compromise-formation 妥协形成Compton A 康普顿compulsion 强迫compulsion 强迫行为compulsion to repeat或repetition compulsion 重复强制compulsion, compulsive 强制,强制的concentration camps 集中营concept of ......概念conception 受孕concordant 一致性concordant countertransference 一致反移情concordant identification and countertranference 一致性认同与反移情condensation 凝缩condensation 压缩confidentiality 治疗同意书confidentiality 隐私性conflict 衝突conflict and adaptation of instinctual wishes 本能慾望的衝突及适应conflict in 转移关係conflict model 衝突模式conflict resolution transference reenactment 衝突解决及移情重新演出conflict: CCRT 衝突:核心衝突关係主题conflict-free sphere of 无衝突区conflict-free sphere of ego 自我的无衝突区conflicting 衝突conflicting needs 衝突的需求confrontation 治疗师,面质confrontation 面质confrontation 面质(正视)confrontation 面质对质confronting 面对面质confusion 混乱confusion 混乱困惑Congress and meetings 学术会议与集会conjoint approach 联合取径的connectedness 连结性conscience 良知conscience see superego 良心见superegoConscious 意识conscious, preconscious and Unconscious 地誌学假说,意识,前意识,潜意识Conscious, system 意识,系统consciousness 心理意识consciousness 意识considerations of representability 显象性考量constancy of ......的恆定性constituents ......的组成constitutional factors 精神官能症,体质因素construction 建构constructions in analysis 分析中的建构constructions in analysis and interpretation 分析与解释中的建构Contained 被涵容Container 涵容者containment 容纳containment 涵容containmenttherapeutic 涵容治疗性content 内容content interpretation 实质性解释context of 脉络contract 合约contract therapy 合约治疗contraindications 禁忌control or supervisory or supervised analysis 督导分析Controversial Discussions 论战conversational model see psychodynamic interpersonal therapy 交谈模式见精神动力人际取向疗法conversational therapy 交谈疗法xiconversational therapy 会话式治疗conversational therapy 会话疗法conversion 转化conversion 转换conversion hysteria 转换型歇斯底里Cooper A M 库柏coping mechanism 因应机制coping: with disappointment 因应:带着失望core conflictual 核心衝突的Core Conflictual Relationship Theme 核心衝突关係主题core conflictual relationship theme (CCRT) ' Cornelison A 科内利森Correct 正确的corrective emotional experience 修正式情绪经验corrective emotional experience 修正后情绪经验corrective recapitulation 矫正性经验重现costeffectivenesspsychotherapy 成本效益心理治疗counselling 谘商xiicounterfeit negative therapeutic reactions 伪负性治疗反应counter-reactions of analyst 分析师的反反应counter-resistance of 反阻抗counter-resistance of analyst 分析师的反阻抗Countertransference 反移情countertransference 反转移关係counter-transference 反向传会Counter-transference 反移情counter-transference 结案,反转移关係couple therapy 夫妻治疗coupletherapy 夫妻治疗CPP 合作型心理治疗研究方案creative illness 创造性疾患creativity 及创造力crisis in psychoanalysis 精神分析的危机crisis, perfect 完全的发作crisis: intervention 危机处遇cryptomnesia 隐性记忆crystal gazing 凝视水晶球cualties nonverbal 非口语cultural perspective 文化观点viiixii cure 治癒cure 转移关係cure of souls 灵魂的治疗Curtis H C 柯帝士custody 监护权dadism 达达主义Dalison B 达利森damaging aspects of 损害性方面damming up of libido 力比多的郁积dance therapy 舞蹈治疗danger of 危险danger of cure 治癒的危险Daniel Stern 丹尼尔?斯特恩Darwinism, social 社会达尔文主义Davies S 戴维斯Day residue 白天的残余day’s residues 白日残余day-dream 白日梦daydreams 白日梦daydreamsguided 白日梦引导取向的death instinct 死亡本能Death instinct 死之本能death instincts 死亡欲力death, psychogenic 心因性猝死decadence (时代的)衰败。

智慧视觉发展外文文献

智慧视觉发展外文文献智慧视觉是指利用计算机视觉技术和人工智能算法,对图像和视频进行分析、识别和理解的一种新兴技术。

智慧视觉技术已经广泛应用于安防、无人驾驶、医疗、工业制造等领域,成为人工智能发展的重要支撑。

下面是一些有关智慧视觉的外文文献:1. 'Artificial Intelligence and Visual Perception'(人工智能与视觉感知),作者:David Marr,发表于1977年的《Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B》。

该文献提出了著名的'计算机视觉的三个层次'理论,即计算机视觉应该分为计算几何、表面分析和知觉理解三个层次。

这个理论对计算机视觉的研究产生了深远的影响,也为智慧视觉的发展提供了理论支持。

2. 'Deep Learning for Visual Recognition'(深度学习用于视觉识别),作者:Yann LeCun、Yoshua Bengio和Geoffrey Hinton,发表于2015年的《Nature》杂志。

该文献介绍了深度学习在视觉识别领域的应用。

深度学习是一种基于神经网络的机器学习方法,它可以自动学习特征,并能够高效地处理大规模数据。

该文献提出的深度卷积神经网络(CNN)模型,是目前最先进的图像识别算法之一。

3. 'Visual Domain Adaptation: A Survey of Recent Advances'(视觉领域适应:最新进展综述),作者:Mingsheng Long、ZhouhuiLian、Jianmin Wang和Michael I. Jordan,发表于2018年的《IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence》。

witten的几何朗兰兹纲领

witten的几何朗兰兹纲领几何朗兰兹纲领是数学领域的一个重要概念,它是德国数学家戈特洛布·弗雷格的一项重大发现,他在1905年首次提出了几何朗兰兹纲领的概念。

这一纲领主要是将欧几里得的几何学推广到非欧几里得的几何学中,从而为广义相对论的发展奠定了基础。

几何朗兰兹纲领对现代数学和物理学的发展产生了深远的影响,因此其重要性不言而喻。

首先,几何朗兰兹纲领提出了一种新的几何学观念,即利用微分几何学中的黎曼度量和伪黎曼度量来描述空间的几何性质。

这一概念是传统欧几里得几何学的推广,它允许我们研究曲率不为零的空间,例如爱因斯坦广义相对论中描述的四维时空。

通过引入曲率张量和黎曼曲率张量等概念,我们可以更加深入地理解时空的结构和性质,从而为理论物理学的发展提供了重要的数学工具。

其次,几何朗兰兹纲领重新定义了空间的基本要素,将欧几里得空间的直线和平面推广到非欧几里得空间中的测地线和测地平面。

这一概念颠覆了传统几何学对空间的简单描述,使得我们能够更加灵活地描述曲率不为零的空间的几何性质。

通过对测地线的运动和测地线的性质进行研究,我们可以更好地理解时空的曲率和引力场的性质,从而为广义相对论的进一步发展提供了重要的理论基础。

此外,几何朗兰兹纲领还提出了一种新的几何学研究方法,即利用微分几何学和流形论的方法来描述空间的曲率和引力场。

这一方法在数学物理学和理论物理学中得到了广泛的应用,它为我们提供了一种全新的数学工具,可以更好地理解复杂的时空结构和引力场的性质。

通过对流形的曲率和联络的性质进行研究,我们可以更深入地理解广义相对论中的曲率引力场方程和能量动量张量的性质,为现代理论物理学的发展提供了重要的数学工具。

总的来说,几何朗兰兹纲领是现代数学和物理学中的一个重要概念,它重新定义了空间的几何性质,推广了欧几里得几何学的概念,为广义相对论的发展提供了重要的数学基础。

这一纲领对现代数学和物理学的发展产生了深远的影响,因此其重要性不言而喻。

维特根斯坦书目--来自斯坦福百科全书

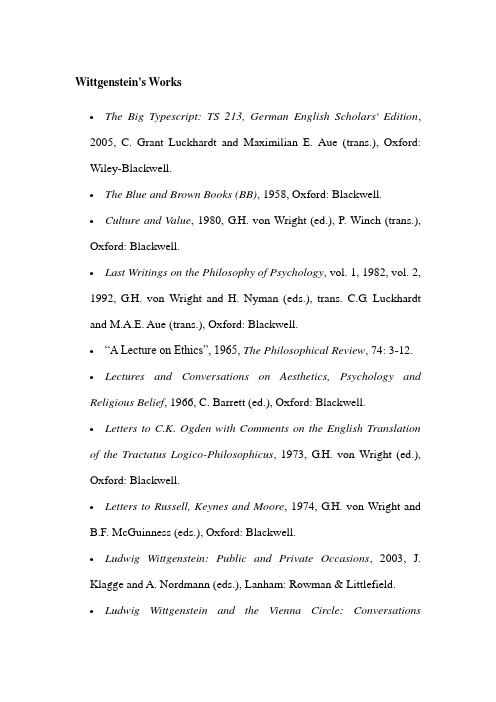

Wittgenstein's Works•The Big Typescript: TS 213, German English Scholars' Edition, 2005, C. Grant Luckhardt and Maximilian E. Aue (trans.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.•The Blue and Brown Books (BB), 1958, Oxford: Blackwell.•Culture and Value, 1980, G.H. von Wright (ed.), P. Winch (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Last Writings on the Philosophy of Psychology, vol. 1, 1982, vol. 2, 1992, G.H. von Wright and H. Nyman (eds.), trans. C.G. Luckhardt and M.A.E. Aue (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•“A Lecture on Ethics”, 1965, The Philosophical Review, 74: 3-12.•Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief, 1966, C. Barrett (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Letters to C.K. Ogden with Comments on the English Translation of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1973, G.H. von Wright (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Letters to Russell, Keynes and Moore, 1974, G.H. von Wright andB.F. McGuinness (eds.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Ludwig Wittgenstein: Public and Private Occasions, 2003, J.Klagge and A. Nordmann (eds.), Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.•Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle: ConversationsRecorded by Friedrich Waismann, 1979, B.F. McGuinness (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Notebooks 1914-1916, 1961, G.H. von Wright and G.E.M. Anscombe (eds.), Oxford: Blackwell.•“Notes for Lectures on 'Private Experience' and 'Sense Data'”, 1968, Philosophical Review, 77: 275-320.•On Certainty, 1969, G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (eds.), G.E.M. Anscombe and D. Paul (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell. •Philosophical Grammar, 1974, R. Rhees (ed.), A. Kenny (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Philosophical Investigations (PI), 1953, G.E.M. Anscombe and R. Rhees (eds.), G.E.M. Anscombe (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell. •Philosophical Investigations, 4th edition, 2009, P.M.S. Hacker and Joachim Schulte (eds. and trans.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. •Philosophical Occasions, 1993, J. Klagge and A. Nordmann (eds.), Indianapolis: Hackett.•Philosophical Remarks, 1964, R. Rhees (ed.), R. Hargreaves and R. White (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•ProtoTractatus—An Early Version of Tractatus Logico- Philosophicus, 1971, B.F. McGuinness, T. Nyberg, G.H. von Wright (eds.), D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness (trans.), Ithaca: Cornell University Press.•Remarks on Colour, 1977, G.E.M. Anscombe (ed.), L. McAlister and M. Schaettle (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•“Remarks on Frazer's Golden Bough”, 1967, R. Rhees (ed.), Synthese, 17: 233-253.•Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, 1956, G.H. von Wright, R. Rhees and G.E.M. Anscombe (eds.), G.E.M. Anscombe (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell, revised edition 1978.•Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology, 1980, vol. 1, G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (eds.), G.E.M. Anscombe (trans.), vol. 2, G.H. von Wright and H. Nyman (eds.), C.G. Luckhardt and M.A.E. Aue (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•“Some Remarks on Logical Form”, 1929, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 9 (Supplemental): 162-171.•Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (TLP), 1922, C.K. Ogden (trans.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Originally published as “Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung”, in Annalen der Naturphilosophische, XIV (3/4), 1921.•Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1961, D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness (trans.), New York: Humanities Press. •Wittgenstein: Conversations, 1949-1951, 1986, O.K. Bouwsma; J.L. Kraft and R.H. Hustwit (eds.), Indianapolis: Hackett. •Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911-1951,2008, Brian McGuinness (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Wittgenstein's Lectures, Cambridge 1930-1932, 1980, D. Lee (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Wittgenstein's Lectures, Cambridge 1932-1935, 1979, A. Ambrose (ed.), Oxford: Blackwell.•Wittgenstein's Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, 1976,C. Diamond (ed.), Ithaca: Cornell University Press.•Wittgenstein's Lectures on Philosophical Psychology 1946- 47, 1988, P.T. Geach (ed.), London: Harvester.•Zettel, 1967, G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (eds.), G.E.M.Anscombe (trans.), Oxford: Blackwell.•The Collected Manuscripts of Ludwig Wittgenstein on Facsimile CD Rom, 1997, The Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.Secondary SourcesBiographies and Historical Background•Hacker, P.M.S., 1996, Wittgenstein's Place in Twentieth-century Analytic Philosophy, Oxford: Blackwell.•Janik, Allan, and Stephen Toulmin, 1973, Wittgenstein's Vienna, New York: Simon and Schuster.•Malcolm, N., 1958, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir, Oxford:Oxford University Press.•McGuinness, B., 1988, Wittgenstein, a Life: Young Wittgenstein (1889-1929), Pelican.•Monk, Ray, 1990, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, New York: Macmillan.Collections of Essays•Block, Ned, (ed.), 1981, Perspectives on the Philosophy of Wittgenstein, Oxford: Blackwell.•Canfield, John V., (ed.), 1986, The Philosophy of Wittgenstein, vols.1-15, New York: Garland Publishers.•Copi, I.M., and R.W. Beard, (eds.), 1966, Essays on Wittgenstein's Tractatus, London: Routledge.•Crary, Alice (ed.), 2007, Wittgenstein and the Moral Life, Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.•Crary, Alice and Rupert Read, (eds.), 2000, The New Wittgenstein, London: Routledge.•Gibson, John and Wolfgang Huemer (eds.), 2004, The Literary Wittgenstein, London: Routledge.•Griffiths, A.P., (ed.), 1991, Wittgenstein: Centenary Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.•Kahane, Guy, Edward Kanterian , and Oskari Kuusela (eds.), 2007,Wittgenstein and His Interpreters, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.•Klagge, James C., 2001, Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.•Moyal-Sharrock, Danièle (ed.), 2004, The Third Wittgenstein: The Post-Investigations Works, London: Ashgate.•Moyal-Sharrock, Danièle, and William H. Brenner, (eds.), 2005, Readings of Wittgenstein's On Certainty, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.•Pichler, Alois and Simo Säätelä(eds.), 2005, Wittgenstein: The Philosopher and his Works, Publications from the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen.•Shanker, S.G., (ed.), 1986, Ludwig Wittgenstein: Critical Assessments, vols.1-5, Beckenham: Croom Helm.•Sluga, Hans D., and David G. Stern, (eds.), 1996, The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.•Vesey, G., (ed.), 1974, Understanding Wittgenstein, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.Introductions and Commentaries•Anscombe, G.E.M., 1959, An Introduction to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, London: Hutchinson.•Baker, G.P., Katherine J. Morris (ed.), 2005, Wittgenstein's Method:Neglected Aspects, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.•Biletzki, Anat, 2003, (Over)Interpreting Wittgenstein, Leiden: Kluwer.•Black, Max, 1967, A Companion to Wittgenstein's Tractatus, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.•Baker, G.P., and P.M.S. Hacker, 1980, Wittgenstein: Understanding and Meaning, Volume 1 of an Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell (2nd extensively revised edition 2005).•Baker, G.P., and P.M.S. Hacker, 1985, Wittgenstein: Rules, Grammar and Necessity, V olume 2 of an Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell (2nd extensively revised edition 2009).•Cavell, S., 1969, Must We Mean What We Say?, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.•Diamond, C., 1991, The Realistic Spirit, Cambridge: MIT Press. •Fogelin, R.J., 1976, Wittgenstein, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (2nd edition 1987).•Glock, Hans-Johann, 1996, A Wittgenstein Dictionary, Oxford: Blackwell.•Hacker, P.M.S., 1972, Insight and Illusion: Themes in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein,, Oxford: Clarendon Press; 2nd revisededition, 1986.•Hacker, P.M.S., 1990, Wittgenstein: Meaning and Mind, Volume 3 of an Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell.•Hacker, P.M.S., 1996, Wittgenstein: Mind and Will, Volume 4 of an Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell.•Hacker, P.M.S., 2001, Wittgenstein: Connections and Controversies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.•Hintikka, M.B., and J. Hintikka, 1986, Investigating Wittgenstein, Oxford: Blackwell.•Kenny, A., 1973, Wittgenstein, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.•Kripke, S., 1982, Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language: An Elementary Exposition, Oxford, Blackwell.•Malcolm, N., 1986, Nothing is Hidden, Oxford: Blackwell. •McGinn, Colin, 1984, Wittgenstein on Meaning, Oxford: Blackwell.•McGinn, Marie, 1997, Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Wittgenstein and the Philosophical Investigations, London: Routledge. •McGuinness, B., 2002, Approaches to Wittgenstein: Collected Papers, London: Routledge.•Mounce, H.O., 1981, Wittgenstein's Tractatus: An Introduction, Oxford: Blackwell.•Moyal-Sharrock, Danièle, 2007, Understanding Wittgenstein's On Certainty, London: Palgrave Macmillan.•Pears, David F., 1987, 1988, The False Prison, vols. I and II, Oxford: Oxford University Press.•Stern, David G., 2004, Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.•Stroll, Avrum, 1994, Moore and Wittgenstein on Certainty, New York: Oxford University Press.。

托兰斯创造性思维测验(TTCT)

托兰斯创造性思维测验(TTCT)Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT)Yeehaw天马星测验由美国明尼苏达大学心理学教授托兰斯编制(1966),是目前应用最广泛的创造力测验,适用于从幼儿园到研究生水平的个体,但对四年级以下的儿童需要进行个别口头施测。

是一项主要考查发散性思维创造性成就的智力能力测试,涵盖发散性思维能力、好奇心、假设性思维、想象力、情感表现力、幽默感、打破常规的能力等方面。

在美国和世界各国已被运用了很多年,从1966年2008年,有30万的美国人参加了这一测试。

自上世纪60年代以来,托兰斯测试经历了数次修订,被业界认为是对发散性思维的可靠检测。

该测验由三套创造力量表构成。

Yeehaw天马星(1)言语创造思维测验。

包括七个分测验:Yeehaw天马星①提问题——要求被试列出他对图画内容所想到的一切问题;②猜原因——要求被试列出图画事件的可能原因;③猜后果——要求被试列出图画中所发生的事情的各种可能后果;④产品改造——要求被试对一个玩具图形列出所有可能的改进方法;⑤非常用途测验——其原理与吉尔福德的第五分测验相同;Yeehaw天马星⑥非常问题——要求被试对同一物体提出尽可能多的不同寻常的问题;⑦假想——要求被试推断一种不可能发生的事件将出现的各种可能后果。

(2)图画创造思维测验。

由三个分测验组成:Yeehaw天马星①图画构造——呈现一个蛋形彩图,让被试以此为基础去构造富于想象的图画;②未完成图画——向被试提供十个由简单线条勾出的抽象图形,让他们完成这些图形并加以命名;③圆圈(或平行线)测验——共包括30个圆圈(或30对平行线),要求被试据此尽可能多地画出互不相同的图画。

(3)声音和词的创造思维测验。

由两个分测验组成:Yeehaw天马星①音响想象——采用四个被测者熟悉和不熟悉的音响系列,各呈现三次,让被试分别写出所联想到的物体或活动;②象声词想象——采用十个模仿自然声响的象声词各呈现三次,让被试分别写出所联想到的事物。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Visualisation and Wittgenstein's "Tractatus"Michael A R BiggsFaculty of Art and Design, University of HertfordshireCollege Lane, Hatfield, Herts. AL10 9AB, United KingdomAbstractWittgenstein developed what has become known as "the picture theory of meaning" in his TractatusLogico-Philosophicus. This has been widely interpreted as a comparison between the way in which anengineering drawing is derived by means of projection from the object, and the way in which languageand/or thought is derived from the world around us. Recent research into the intellectual history ofgraphical representation has shown that in addition to this kind of drawing, other forms of graphical representation were gaining in importance at the time. This paper uses graphical statics and dynamicalmodelling to argue that Wittgenstein's picture theory of meaning is not based on a simple analogy ofdepiction, but on the contrary seeks a mode of representation by which performance and action can becalculated. This interpretation explains why the picture theory may be relevant to Wittgenstein's interestin ethics and the mystical, a matter on which Russell remained completely baffled.It is something of a surprise to find, at the end of Wittgenstein's Tractatus, that having constructed an elaborate account of how language has meaning, "the problems of life remain completely untouched" (§6.52). This conclusion was so much of a surprise to Bertrand Russell that in his introduction to the book he said it left him "with a certain sense of intellectual discomfort" (p.xxi).1 It is also a surprise to find that if this was what Wittgenstein really wanted to write about, why then did he apparently take as his paradigm a system of representation from classical mechanics? After all, if one constructed a picture theory of meaning using a more artistic paradigm of picturing, one might feel particularly well equipped to say something about ethics and conceptions of the right way to live, etc., but nothing at all about the questions of sci ence, e.g. Hugo van der Goes, The Fall.1 Wittgenstein accordingly thought the introduction was "superficial and full of misunderstanding" (correspondence in McGuinness & von Wright, 1997, pp.153-155).Wittgenstein, 1974, p.225(forthcoming graphical revision)Although the Tractatus is a difficult book, it is fairly easy to understand the visual analogy of the picture theory of meaning.3 It appears to be principally based on how a drawing is constructed in descriptive geometry or engineering, and makes the analogy that language has a similar relationship to the world that it describes. The reason why one can call this an analogy, a term that Wittgenstein does not himself use to describe this relationship in the Tractatus,4 is because the concept has the four-term structure of an analogy.Hertz's Principles of Mechanics (1899, p.1) is commonly taken as a source of these remarks in the Tractatus.We form for ourselves images or symbols of external objects; and the form which wegive them is such that the necessary consequents of the images in thought are always theimages of the necessary consequents in nature of the things pictured.The images which we here speak of are our conceptions of things. With the things themselves they are in conformity in one important respect, namely, in satisfying the above-mentionedrequirement. For our purpose it is not necessary that they should be in conformity with thethings in any other respect whatever. As a matter of fact, we do not know, nor have we anymeans of knowing, whether our conceptions of things are in conformity with them in any other than this one fundamental respect.Hertz's analogy is anti-Realist and does not require that the world is necessarily like the representation just because we can map one onto the other. Boltzmann, a contemporary of Hertz, is explicit about analogous relationships. He draws attention to his use of the term when describing the theory of gases as a mechanical analogy (Blackmore, 1995, p.49). He says "the choice of this word [shows] how far removed we are from that viewpoint which would see in visible matter the true properties of the smallest particles of the body".2 The author acknowledges the permsission of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna to reproduce this image.3 This comment is meant as an encouragement to the general reader. Wittgenstein himself came to think that the concept of picturing was "vague" (Moore, 1959, p.263), and his later philosophy can be read as a critique of his earlier position (cf. Wittgenstein, 1974, p.212).4 He does use it several times in the antecedent Notebooks 1914-1916 (pp.38, 99, 113) and elsewhere.The possibility of an analogous representation has its base in an isomorphism (Wittgenstein uses the term "logical multiplicity", §4.04), which ensures that aspects of the object can be mapped onto aspects of the representation, and vice versa. But Wittgenstein wants to do more than depict reality. He wants to be able to operate within the model and draw conclusions about properties in the world. Such a requirement to calculate rather than to depict, moves us from types of representation such as descriptive geometry and engineering drawing, to those of graphical statics and dynamical models. Perhaps, if this method of calculation could be applied to language, we might find a method with which to make decisions about ethics, etc. T HE DEPICTION OF APPEARANCEEngineering drawing is a particularly good way of representing the appearance of a three-dimensional object. It can do this because lines of construction are projected in three-dimensional space from visible points on an object to the picture plane. It is more effective at recording form and less effective at recording colour and texture, etc. It is not effective at all at recording our responses to the appearance of the object, etc. It is a branch of descriptive geometry in which the form of an object can be specified. The basic isomorphism of an engineering drawing is the object's three-dimensionality. The description of a three-dimensional form would normally require three orthographic views although there are, of course, objects that cannot be completely disambiguated without additional views. Nonetheless the basic principle is that the number of views corresponds to the number of dimensions to be recorded.One can regard the concept of dimension in a number of different ways. Certainly what is more useful is to adopt the mathematical concept of dimension rather than the everyday one. The mathematical concept is that there is one dimension per quality to be recorded. In this notation if we record the three-dimensional position of a point an d its colour we have four dimensions. If we record its material it would add a fifth dimension, etc. This is not the everyday use of the word dimension, which starts with length, width and breadth, and adds time as a possible fourth dimension, but rarely g oes further. Our everyday concept includes an implicit visualisation which limits the number of dimensions to those of everyday experience. The mathematical dimensionality of a representation allows us to record qualities and to satisfy Wittgenstein's principal objective to be able to reconstruct the object. This reconstructive purpose is emphasised in his examples in the Tractatus which are not just restricted to three-dimensional objects. He gives us other examples, e.g. the gramophone record and the musical score. The gramophone record allows us to reconstruct the sound of a piece of music by decoding it.There is a general rule by means of which the musician can obtain the symphony from thescore, and which makes it possible to derive the symphony from the groove on thegramophone record, and, using the first rule, to derive the score again. That is what constitutes the inner similarity between these things which seem to be constructed in such entirelydifferent ways. And that rule is the law of projection which projects the symphony into thelanguage of musical notation. It is the rule for translating this language into the language ofgramophone records. (Tractatus §4.0141)The coding and decoding processes are mirror images of one another but of course, the dimensionality and isomorphism of the gramophone record does not include an image of what the orchestra looked like when they were playing the music. Thus we could say that today's DVDs have a greater logical multiplicity or mathematical dimensionality than gramophone records. Digital techniques make it easy to record very large amounts of information about an object but this does not altogether avoid the need for selectivity. When one is recording an event one must still decide what it is that one wishes to record and therefore the number of dimensions that are required. This has been reflected in the recent project to digitise Wittgenstein's Nachlaß. The project began with facsimiles of Wittgenstein's hand-written manuscripts etc. and a decision had to be made about what was important to record. Naturally, the orthographic types were of prime importance, but how important were spelling mistakes; what about the graphologist who attributes meaning to the shape of individual letter forms? What about the line breaks and page breaks? The mathematical dimensional problem becomes quite explicit if the encoding language is XML because each event requires a tag to be defined. The total number of tag-types is related to the dimensionality of the representation.T HE DEPICTION OF PERFORMANCEWittgenstein's paradigm is the ability to reconstruct an object from its representation, to reconstruct a thought from a sentence, etc. The basic model appears to be from classical mechanics, three-dimensional objects in three-dimensional space in mechanical relationships to one another: "aRb". But Wittgenstein was familiar with other forms of graphical representation. For example, graphical statics is a system for the diagrammatic representation of structures by which their performance can be calculated. There is sometimes an iconic aspect to the drawing but it is principally a method of representing forces using vectors. It is therefore at best a schematic representation of what the object might look like. Here the notion of representation is one of function rather than appearance. Stenius, in his commentary on the Tractatus, calls these "unnaturalistic pictures" (1960, p.113).Hamilton has recently published a paper (2001) that discusses various modes of engineering representation: descriptive geometry, graphical statics and dynamical models. However, the present paper disagrees with the role attributed to each. Indeed, even the title "Wittgenstein and the Mind's Eye" seems unfortunate because the mind's eye is something ex plicitly rejected by Wittgenstein in the later Blue Book (1958, p.4). This common interpretation of the Tractatus is described by Stenius as a misunderstanding (1960, p.113). Hamilton is writing about the early Wittgenstein and of course is not obliged to be a Wittgensteinian. Other commentators have preferred Hamilton's expression "engineering mind set" (Hamilton, 2001, p.73; cf. Sterrett, 2002 and Seekircher, 2002). However, the concepts of the mind's eye or a mindset are unnecessary for the argument of the present paper. It argues against Hamilton's emphasis on representation as the description of appearance rather than as the description of performance. For example, the opening quotes of Hamilton's article (2001, p.53) emphasise visualisation and, later, the logic of depiction (2001, p.88).It is not necessary to posit visualisation as an underlying activity in order to discuss the importance of Wittgenstein's engineering training on his philosophical development. Certainlyengineering drawing as a system of representation is significant in engineering training, but Wittgenstein's mention of Hertz and Boltzmann provide the clue. Both of these emphasise the role of models as ways of thinking about the world rather than the depiction of the world. Graphical statics and dynamical models enable one to infer the performance of real objects from vector diagrams or scale models, such as the behaviour of propellers. These techniques were very important at the time that Wittgenstein studied engineering (1906-1911) because they were being used to design aspects of the first flying machines. What a powerful endorsement of a graphic technique to be able to use it to calculate how to fly!5The first treatise on graphical statics was published by Karl Culmann in 18666 and although it was not translated into English, by 1888 his methods were widely used in British engineering schools (Maurer, 1998, p.247). Hamilton (2001, p.61) describes the move in German engineering education at the end of the nineteenth century from calculus towards more pragmatic graphical methods. Graphical statics is interesting in this respect because it is an applied method using graphical representation to facilitate calculation. Boltzmann's comments on models (1974, p.214) and Buckingham's on dynamical models (1914, p.356) reinforce the pragmatic aspect of this kind of calculation. Wittgenstein himself learned graphical statics from Stanislaus Jolles at the Technische Hochschule at Berlin-Charlottenburg. Wittgenstein studied there from 1906-1909 and also lodged with Jolles, with whom he continued occasional correspondence until 1921, after which he continued to correspond with his wife Adele Jolles until 1939. During Wittgenstein's time in Berlin in 1907, Jolles was made Professor of Descriptive Geometry.Sterrett (2002) has also recently published on the theme of Wittgenstein's engineering background. She too has recognised the role of performance models in his thinking. What is significant is not that through language or another form of representation we are able to perform the practical manipulation of the world, but the very possibility of that manipulation. So here one may see a symptom of the change of interest from Wittgenstein's applied studies in engineering to mathematics and the foundations of mathematics which took him away from engineering to work with Russell in 1911. The Tractatus, which was written around 1918, reflects the idea that representation is more to do with possibility and functionality than physical appearance.One conclusion that this paper draws from the availability to Wittgenstein of these three different forms of graphical representation: descriptive geometry, graphical statics and dynamical models, is that of an enhanced notion of the functionality of drawings. The simplest notion of the function of a drawing is its depictive function: drawings often look like what they represent. This is not a particularly important aspect, although Stenius thinks it is underestimated (p.207ff.). The notion of graphical calculation is more significant because it reveals that by changing the notation e.g. to vectors, one can manipulate the representation and come to conclusions about the performance of real objects. It is a very powerful capability and complementary to the anti-realist notions of Hertz and Boltzmann on models.5 The aeronautical pioneer Henri Coanda studied at TH Berlin-Charlottenburg at the same time as Wittgenstein. Both men designed innovative air-reactive (jet) propulsion systems.6 Culmann published an earlier work on graphical statics in 1864. See Maurer, 1998, pp.151-154.In particular, to employ terminology from Wittgenstein's later work, when we move to an alternative form of notation, certain aspects become "perspicuous" (1997, §122).There are, however, limitations to what can be recorded in a particular notation. Although Wittgenstein is seeking a perfect language, he is not seeking one with universal application but rather one that avoids misleading us. Thus when Hamilton (2001, p.56 reporting Schulte) refers to Wittgenstein's preference for "palpable, graphic forms of representation", Wittgenstein's preference should be interpreted not as a concentration on the merits of the graphical, but on the merits of the perspicuous. Different forms of graphical notation, and other forms of notation such as truth-tables and symbolic logic, each have the capability of rendering certain aspects more clearly than others. Wittgenstein's training did not so much indoctrinate him to graphical rather than non-graphical methods, as raise his awareness of the influence that notational systems as a whole have on our concepts and reasoning. As Hamilton says (2001, p.86):what he learned in his engineering education was not limited to a particular style ofrepresentation. It embodied principles that provided him with a deeply interconnectedunderstanding of the principles behind all our modes of representation.This leads us to the final issue: the limitations not of single representational systems but of any representational system. It is a key concept in the Tractatus that a representation cannot represent its own representational form (§2.173). To describe a representational form requires one to step outside it. Thus, if one did not understand English, no amount of reading the Oxford English Dictionary would help. Contrary to Hamilton (2001, p.85) the fact that a picture cannot depict its representational form is not a problem of what can be visualised as opposed to what can be verbalised, but what can be expressed in a particular form of representation as opposed to the representational relationship itself. The latter requires stepping outside of the language of the representation in order to describe it. If we are talking about the totality of all our forms of representation of the world, i.e. thinking, then this process of "stepping outside" becomes impossible. One could compare this to the limitation of a particular paradigm in Kuhn:7 if the paradigm changes then all sorts of ideas become possible that were hitherto impossible or unthinkable. However, when a paradigm changes the world remains unchanged.The fact that ethics cannot be put into words (Tractatus §6.421) is not a reference to the possibility that ethics could be put into pictures (Hamilton, 2001, p.85). We have two different modes of representation: language and pictures, and they can show two different things. Pictures are no more able to show their representational form than is language (Tractatus §4.121). Neither drawing nor language, to the extent that they represent thinking, can represent the relationship between thinking and the world, because that requires stepping outside thinking.7 Kuhn links his argument to a starting-point in Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations in the section "The Priority of Paradigms" pp.43-51.C ONCLUSION: SAYING, SHOWING, AND THE INCONCEIVABLEIn the Tractatus, Wittgenstein made an explicit distinction between what can be said and what can be shown. Unfortunately, at the same time he put forward what has become known as the picture-theory of meaning. This paper argues that this has caused a false association of what can be pictured and what can be shown. In particular, various writers discussing the role of imagery and picturing in Wittgenstein's engineering studies have argued to a greater or lesser extent that graphical representation could be an alternative to the limitations of language. On the contrary, this paper argues that the substance of Wittgenstein's distinction between saying and showing is not to do with the limitations of a particular form of notation but the general relationship of notation and conceivability. It has more to do with what later became known as a form-of-life (Wittgenstein, 1997, §23) than to do with the theory of picturing.The so-called picture-theory is clearly described, if not named, in the Tractatus. A key feature of the picture-theory is that language or other forms of representation stand in a relationship to the objects that they represent, and this relationship is analogous to the relationship that subsists between pictures and objects. The term "pictures" incorporates a range of forms including the gramophone record, etc. and therefore it is false to assume that the comparison is principally between iconic images and that which is depicted.Of the three types of graphical representation that have been discussed in this paper, engineering or projection drawing is the one that has hitherto received the most attention. It is the most familiar of the three, and the language that is used in the Tractatus to describe the representational relationship evokes this form of representation, e.g. references to projection. In addition the resultant drawings are easy to understand as pictures of what they represent. Admittedly the visual vocabulary used is less familiar to Western eyes than perspective, but nonetheless the objective of representing the form of the object is a recognisable aspect of what we commonly mean by picturing.However, the other two forms of graphical representation discussed in this paper: graphical statics and dynamical models, can be shown to have a more important role as examples of the kind of relationship that Wittgenstein was describing in the Tractatus. These representational forms are not concerned to show the appearance of an object but are a form of representation that facilitates the calculation of performance. In these examples the representational relationship is more complex because although the resulting diagrams are visual, what they represent is non-visual, e.g. forces. It also clarifies why we need to understand the form of representation, and that all these modes simply represent different aspects of problems in physics.Returning to the opening remark that if Wittgenstein had wanted to say something about ethics then it was strange that he analysed a form of representation that seems more appropriate to mechanics: what is revealed by concentrating less on engineering drawing and more on representations that enable one to calculate performance is that in ethics we want to be able to infer or calculate how we should live from the nature of the world. We do not simply want to imitate or depict the nature of the world. So perhaps the graphical models chosen are not so alien after all. In The Fall by Hugo van der Goes we must read off the meanings of the individual symbols and their role in the narrative that is alluded to, and weare also required to calculate the ethical message from the comparative relationship that is implied by the juxtaposition of the two panels of the diptych.8 This kind of painting is designed to be read in way that is comparable to reading a diagram from graphical statics. In both cases the iconic message is subordinate to the symbolic one, and the reception of the full message is dependent not on a naïve depictive visual language, but on a symbolic graphical language that has the capacity to describe non-visual phenomena.R EFERENCESBlackmore, J., Ed., 1995, Ludwig Boltzmann his later life and philosophy, 1900-1906. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht.Boltzmann, L., 1974, Models In: Boltzmann, L., Theoretical Physics and Philosophical Problems. Edited by Brian McGuinness. D. Reidel and Co., Dordrecht, 231-220. First published in: Encyclopædia Britannica. 10th edition, 1902, Vol. 30. A.C. Black, Edinburgh, 788-791.Buckingham, E., 1914, On Physically Similar Systems: illustrations of the use of dimensional equations, Physical Review 4(4), 345-376.Hamilton, K., 2001, Wittgenstein and the Mind's Eye. In: Klagge, J., Ed. Wittgenstein, Biography and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 53-97.Hertz, H., 1899, The Principles of Mechanics. Translated by D.E. Jones & J.T. Walley. Macmillan, London.Kuhn, T., 1970, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Second edition, enlarged. International Encyclopaedia of Unified Science, Vol.2, No.2. University of Chicago Press, London.Maurer, B., 1998, Karl Culmann und die graphische Statik. Universität Stuttgart/GNT Verlag, Stuttgart.McGuinness, B., and G.H. von Wright, Eds., 1997, Ludwig Wittgenstein: Cambridge letters. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.Moore, G.E., 1959, Philosophical Papers. George Allen and Unwin, London.Seekircher, M., 2002, Wittgensteins technische Werkzeuge. Logische Formen und Sprachspiele: Wittgensteins "Werkzeugkasten". Miscellanea Bulgarica. Wien: Verlag Ostag [Forthcoming 2002].8 The online catalogue of the Kunsthistorisches Museum states "…The extreme stylistic contrast between the two panels is underlined by the differences between the lush paradise garden presented in "The Fall of Man" and the barren, desert-like hill of Golgotha in "The Lamentation". This contrast corresponds to the meaning of the diptych as a whole, mans salvation after his Fall from grace is achieved through the sacrifice and Crucifixion of Christ" (http://www.khm.at).Stenius, E., 1960, Wittgenstein's "Tractatus". Basil Blackwell, Oxford.Sterrett, S., 2002, Physical Pictures: Engineering Models circa 1914 and in Wittgenstein's Tractatus. In: Heidelberger, M. and F. Stadler, Eds. History of Philosophy of Science: New Trends and Perspectives. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 121-135.Wittgenstein, L., 1958, The Blue and Brown Books. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.Wittgenstein, L., 1961, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.Wittgenstein, L., 1974, Philosophical Grammar. Edited by R. Rhees, translated by A. Kenny. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.Wittgenstein, L., 1979, Notebooks 1914-1916. Second edition, edited by G.H. von Wright and G.E.M. Anscombe, translated by G.E.M. Anscombe. Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Wittgenstein, L., [1953] 1997, Philosophical Investiga tions. Reissued second edition. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.。