OECD-WTODatabaseonTradeinValueadded:oecd-wto数据库贸易增加值

国际贸易的分析指标

• 5、 市场结构(地理方向或分布) • (1)对外贸易地理方向:某国对外贸易总值、

出口值、进口值的地区分布和国别分布情况

• (2)国际贸易地区分布:世界各洲、各国或各 经济集团通过其对外贸易额所显示的在国际贸 易中所处的地位和作用

不同点

• 更困难 • 更复杂 • 风险大

更困难

• 语言 • 法律.风俗习惯 • 贸易障碍:关税和非关税壁垒 • 市场调查 • 交易接洽、技术困难多,贸易纠纷不易解决

更复杂

• 各国的货币与度量衡差别大 • 商业习惯复杂 • 海关制度及其他贸易法规的不同 • 国际汇兑复杂 • 货物的运输与保险

风险大

(2)对外贸易可以促进技术进步

• • 对外贸易是一国技术进步所需技术的主要供给渠 道

• • 对外贸易具有重要的“技术外溢效应” (Technology spillovers)和“边干边学效应” (Learning by doing)

• • 对外贸易为技术进步提供强大的动力

(3)对外贸易促进制度创新

1、对外贸易可以带来静态利益:在资源总 量不变的条件下增加该国的经济福利

▲从交换中可以获得利益。即通过对外贸易活动 可以获得本国不能生产或国内生产成本太高的 产品,使消费者得到更高水平的满足

• ▲从专业化分工中可以获得利益。即通过参与 国际分工专门生产本国具有比较优势的产品, 可以提高本国的资源利用效率

• 6、 • 也叫对外贸易系数,是一国对外贸易额在该国国

民生产总值(或国内生产总值)中所占的比例。它反 映的是一国国民生产总值中有多大比例是通过国际市 场实现的

WTO规则中英文教程第七章 服务贸易

(To be continued) 2.A Member may meet the requirement of paragraph 1 by according to services and service suppliers of any other Member, either formally identical treatment or formally different treatment to that it accords to its own like services and service suppliers.

• (3)对外国服务提供者实施差别 待遇。如给本国投资者补贴、对 外国服务提供者征收歧视性的国 内税费、限制外国服务提供者的 经营范围、要求外国服务提供者 履行比本国服务商更繁杂的义务 或手续,以此达到削弱或抵消外 国服务提供者竞争优势的目的。

• (4)对国外颁发的教育证书、技术资格证 书、执业许可证等不予承认。此类规定 的目的在于禁止或限制外国服务人员提 供服务。 • (5)制定各种国内规章。限制人员、资金、 技术、信息的国际流动。如限制本国居 民出境旅游以此节省外汇支出;规定只 有具备最低资格或条件的人员才能入境; 资金汇出到达一定标准必须经国家特定 批准等。

第七章 WTO服务贸易规则

WTO Rules of Trade in Service

一、概述

1、国际服务贸易壁垒 由于国际服务贸易的壁垒并非海关措施或关税,而 是各成员方的国内法规(政策、法令、行规)对服务要 素(机构、资金、人员)作跨国流动的限制。与货物贸 易相比,国际服务贸易壁垒种类繁多。 (1)严格限制开业权。如禁止外国服务提供商进入 某些行业或地区设立机构和提供服务,或对某些行业 实行政府垄断。 (2)数量限制。限制外国服务提供者的数量、限制 服务交易量的数量、限制雇佣自然人的数量、限制外 商投资的股权比例和提供服务的实体形式等。

全球服务贸易壁垒:主要手段、行业特点与国家分布——基于OECD服

全球服务贸易壁垒:主要手段、行业特点与国家分布——基于OECD服务贸易限制指数的分析作者:赵瑾来源:《国际贸易》 2017年第2期一、引言近年来,随着信息技术的发展、国际分工的深化,以及全球价值链的形成,人们对服务业与服务贸易在经济增长和就业中的作用有了新的认识。

数据显示,在OECD国家中,服务业占就业的80%和GDP的75%。

在新兴市场国家中,服务业在就业和GDP中占40%~70%。

2010年服务业出口在全球贸易总出口中占22%,不足制造业出口的三分之一(占比为71%),但按照新的增值贸易统计方法,根据OECD-WTO TiVA-GVC数据,在总出口中服务业增加值的占比(46%)超过制造业(43%),几乎占出口增加值的一半。

因此,为促进全球经济增长和就业,OECD开始度量服务贸易限制措施,推动全球服务贸易自由化。

与此同时,美国、欧盟和澳大利亚正主导诸边服务贸易谈判( TISA),推动全球服务贸易市场开放,以此带动本国优势产业发展,促进经济增长和就业。

由于服务贸易的无形性、异质性和多样性,长期以来服务贸易壁垒难以像货物贸易一样量化。

近十年学术界为量化服务贸易壁垒,研究了几种不同的方法,如频度衡量、限制度指数、价格影响和数量影响、引力模型,以及基于财务的测量等。

在此基础上,OECD建立了衡量各国服务贸易壁垒的服务贸易限制指数( Service Trade Restric-tiveness Index,STRI)。

STRI数据建立在目前已经实行的监管措施基础上。

其数据库涵盖的部门包括:计算机服务、建筑服务、专业服务(法律、会计、工程和设计)、电信服务、分销服务、视听服务(广播、电影、音像)、运输服务(空运、海运、铁路运输、公路运输)、快递服务、金融服务(商业银行、保险)、物流服务(货物装卸、仓储、货运代理、报关服务)。

本文基于OECD数据库重点分析42个国家(包括OECD全部35个成员国和巴西、中国、哥伦比亚、印度、印度尼西亚、俄罗斯、南非7个非OECD国)18个部门服务贸易限制指数,研究当代全球服务贸易壁垒的主要手段、行业特点与国家分布,对于我国精准了解不同服务行业限制的手段和特点,有效推进服务业对外开放,并根据不同国家、不同服务业市场开放状况开展精准的国际投资,具有重要的现实意义。

第4章当代国际贸易理论双学位

M·Casson 拉格曼 A·M·Rugman

27

基本概念

市场内部化 Internal Market:将市场建立在企业内部的过 程

市场失效 Market failure:是指出于市场不完全,以至于 企业在让渡其中间产品时难以保障其权益,也不能通过市 场来合理配置其资源而难以保证企业最大经济效益的情形。

10

4、对产业内贸易的理论解释

假设: 规模经济和不完全竞争 理论上的解释

产品的差异性:垂直和水平差异

不同国家需求结构的多样性与相似性 垄断竞争 企业内部规模收益递增 国际市场的开放和一体化

11

Consumer preferences with a demand for different varieties of similar products;

decline

Maximize market share

Maximize profit while defending market share

Reduce expenditure and milk the brand

22

数量

创新国出口

t0

t1

t2

创新国进口

创新国消费 创新国生产

模仿国生产

模仿国进口

yield a particular pattern of tastes. --these tastes of ‘representative consumers’ will

in turn yield demands for products.-----a production response by firms; --trade between countries with similar per capita income levels.

《全球价值链与我国贸易增加值合算报告》解读

我国的进口也给贸易伙伴带来了大量的就业岗位。研究表明,我国单位进口对印度的就业拉动作用最大,其他依次是韩国、欧盟和日本,美国最低。从拉动的进口来源地就业总量看,2012年我国从印度、欧盟、韩国、日本和美国进口对这些国家/经济体拉动的就业岗位分别达到497万个、241.2万个、163.7万个、114.4万个和66.5万个。

五、如何评价我国全球价值链参与与攀升的过程?

答:三十多年改革开放的进程就是我国主动融入全球价值链的过程。伴随着我国对外开放的扩大,参与全球价值链水平也得到稳步提高,前期货物贸易和吸收外资是主渠道,后期“走出去”、服务贸易逐步发力,对于我国全方位参与全球价值链并向全球价值链高端攀升的推动作用日益凸现,潜力巨大。过去三十多年通过扩大开放,我国对全球价值链的参与有效推动了经济增长、就业、税收、结构升级、效率提升、技术进步和自主创新,这些也反过来进一步提升了我国在全球价值链上的位置。

ﻫ 四、与货物贸易出口相比,服务出口增加值有多大?ﻫ

答:服务贸易在全球价值链中发挥着重要的作用。单位服务出口拉动的增加值远高于货物出口。以2012年为例,我国每1000美元服务出口拉动的国内增加值为848美元。从服务贸易分项目看,高附加值服务项目为通信服务、保险和金融服务、计算机和信息服务;建筑服务和特许权使用和许可费用相对较低。

从商品类别来看,农业、纺织服装、食品、家具制造等传统劳动密集型产业单位出口(以1000美元计)的国内增加值含量较高(800-900美元之间);机械制造产品、电子类产品等技术密集型产品以及石油化工产品单位出口的国内增加值含量较低(400-700美元之间)。ﻫﻫ 此外,2012年单位加工贸易出口增加值(385美元左右)不及一般贸易出口(780美元左右)的一半。需要指出的是,虽然加工贸易出口的增加值率偏低,但加工贸易对我国经济发展产生的作用是多个层面的,它对我国嵌入全球价值链发挥了并且还将继续发挥重要的作用。ﻫ

不完全替代和贸易成本与技术性贸易壁垒的关税等值外文翻译(可编辑)

不完全替代和贸易成本与技术性贸易壁垒的关税等值外文翻译外文翻译原文Tariff Equivalent of Technical Barriers to Trade with Imperfect Substitution and Trade CostsMaterial Source: American Journal of Agricultural EconomicsAuthor: CHENGYAN YUE, JOHN BEGHIN, AND HELEN H. JENSENArticle 20 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade GATT permits governments to set their own standards and regulations on trade in order to protect human, animal, or plant life or health, provided they do not discriminate among countries or use this motive as concealed protectionism. In addition, two specific World Trade Organization WTO agreements deal with food safety and animal and plant health, and with product standards: the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Agreement SPSA and the Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement TBTA. The SPSA allows countries to set their own standards, but it requires that the standards should not arbitrarily discriminate between countries with similar conditions. The TBTA was generated to minimize unnecessary obstacles in regulations, standards, and testing and certification procedures. Inpractice, however, some governments use stricter health and safety regulations than necessary to isolate domestic producers from international competition. The stricter regulations may lead to questionable impediments to imports that compete with domestic products in addition to the existing tariff barriers. When the possibility of a disease or pest transmission is very low or threat to food safety is small, these trade impediments often cause welfare losses for importing countries and mercantilist losses for exporting countries due to reduced exports These issues have of course attracted the attention of economists Anderson, McRae, and Wilson 2001; Bureau, Marette, and Schiavina 1998; Josling, Roberts, and Orden 2004; Roberts and Krissoff 2003. The growing literature on sanitary and phytosanitary SPS regulations and other technical barriers to trade TBT often uses a price-wedge approach1 to quantify the impact of a barrier on market equilibrium and trade, e.g., Calvin and Krissoff 1998; Campbell and Gossette 1994. Although not unique or sophisticated, the method has been legitimized in the economics literature with some prescriptions and qualifiers to account for transportation cost and quality differences Baldwin 1991; Deardorff and Stern 1998. The use of a price-wedge approach often abstracts from quality differences or simply addresses the difference by choosing “close” substitutes. Transportation costs may be reduced to the differential between cost-insurance-freight andfree-onboard CIF-FOB prices and abstract from the internal transportation cost once imports are landed. All price-wedge estimates of which we are aware rely on the assumption of homogeneous commodities and a price arbitrage condition. By assuming that domestic and imported goods are perfect substitutes, the gap between their prices reflects trade impediments from various policies and natural protection. Border tariffs and transportation and transaction costs prevent full arbitrage between the two prices Head and Mayer2002. Hence, in principle, the price gap can yield an estimate of the tariff equivalent of the TBT once transportation and trade costs and other impediments have been taken into account.In this article we derive a revamped tariff equivalent estimate of a TBT. We extend the price-wedge framework by first relaxing the homogeneous commodity assumption, straightforward but instrumental step overlooked in the literature on TBT measurement. We account explicitly for commodity heterogeneity and perceived quality of substitutes. Next, we incorporate recent developments and findings on large and costly border effects arising from transportation, linguistic differences, and poor infrastructure and law enforcement Anderson and van Wincoop 2004; Head and Mayer 2002; Hummels and Skiba 2004. Two major findings of this new literature are particularly relevant to our work. First, trading costs are very large and often greater than policy impediments, and cannot be ignored. While CIF-FOB ratios have fallen over time, other transportationand trade costs have remained high and have been underestimated. Second, these costs are structured on a per-unit basis rather than following the so-called iceberg method;2 they act as a specific tariff rather than an ad valorem tax Hummels and Skiba 2004. These per-unit costs shift supply in a parallel manner rather than proportionally, which influences the estimate of the TBT. We provide a consistent approach to apportion the internal-border price difference between potential sources of the difference quality and heterogeneity of goods, border tariff, TBT, transportation and other transaction costs. This approach allows us to elucidate the respective role of each source leading to a credible estimate of the tariff equivalent of the TBT.We systematically explore the robustness of the tariff-equivalent estimate to underlying assumptions on commodity heterogeneity, home-good preference, trading costs, and the chosen reference data. We show the importance of selecting best values of these key determinants substitution elasticity, home-good preference, and trade cost on which the policy analysis can be centered. We then analyze the sensitivity of the TBT estimate around these central values of the determinants and associated welfare implications. The analysis shows the value of narrowing the set of possible estimates of the TBT using available dataand knowledge on the quality and heterogeneity of the domestic and competing imported goods.Our article bridges two methods often used to estimate the trade effects of TBTs: the tariff-equivalent?price-wedge approach mentioned previously and the gravity-equation approach.3 Recent conceptual developments have provided theoretical foundations to the gravity-equation approach and account explicitly for relative prices of traded and domestic substitutes and for trading costs. In addition, they attempt to better measure and decompose “border effects” of trade barriers and transportation costs between trade partners. These new approaches have been applied to aggregate trade data but not to individual commodities Anderson and vanWincoop2004; Head and Mayer 2002.Calvin and Krissoff 1998 provide a tariff equivalent of phytosanitary barriers in the Japanese apple market regarding the risk of contamination by fire blight that has been the origin of a long WTO dispute between United States and Japan WTO 2002, 2003a?e, 2004a?d, 2005. The dispute has attracted much attention. Calvin and Krissoff 1998 use the law of one price under a homogeneous commodity assumption arbitrage condition to calculate the tariff equivalent of SPS barriers affecting apple imports in Japan to avoid damages from fire blight. By assuming that Japan’s dom estic and imported apples are perfect substitutes, the gap between the prices of domestic and imported apples accounts for the bordertariff and other trade impediments that prevent full arbitrage. The latter authors also abstract from other border effects internal transportation and transaction costs, leading to a likely overstatement of the cost of a TBT barrier, other things being equal. They rely on several reference years to mitigate annual variations in the reference data used to calibrate the tariff equivalent to the TBTs. Using recent data and the proposed revamped approach. We provide a new investigation of the Japan?U.S. apple dispute. We compute the tariff equivalent of Japanese TBT regulations affecting apple trade and quantify the impact of removing these policies on welfare and apple trade flows. We also draw policy implications. The apple dispute offers an opportunity to validate our contention that departures from perfect substitution and significant trade costs have a substantial impact on the estimate of SPS/TBT regulation and hence on welfare and policy implications derived from this estimate.The high technical barriers to importing apples into Japan have brought repeated complaints from several exporting countries and have led to a thirty-year dispute Elms 2004. The latest episode of this dispute has taken place within the WTO. Japan-Measures Affecting the Importation of Apples WTO 2002, 2003a?e, 2004a?d, 2005 relates to the United States’ complaint about the Japanese requirements imposed on apples imported from the United States and their inconsistency with WTO principles. Theprohibitions and requirements included, for example, the prohibition of imported apples from states other than designated areas in Oregon and Washington; the prohibition of imported apples from any orchard whether it is free of fire blight or not if fire blight was detected within a 500-meter buffer zone surrounding such orchard; the requirement that export orchards be inspected three times a year at blossom, fruitlet, and harvest stages to check if fire blight is present in order to apply the afore-mentioned prohibitions; the requirement that at the post-harvest stage, apples for export to Japan be separated from fruits for export to other markets; and chlorination of apples for export to Japan. In 1997, the United States requested that Japan modify its import restrictions on apples based on published scientific evidence that mature, symptomless apples are not carriers of fire blight. In 2000, the United States agreed to carry out joint research proposed by Japan to confirm the results of those earlier studies. The USDA’s Agricultural Research Service ARS and Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries MAFF conducted the joint research. The research results confirmed that mature, symptomless apples are not carriers of fire blight. This finding provided additional scientific support for the U.S. position. Because the results of this research were released in February 2001, the U.S. government has repeatedly pressured Japan to modify its import restrictions. After extensive bilateral discussions with USDA scientists, Japan refused tomodify its import restrictions in October 2001.In March 2002, the United States requested WTO consultations concerning Jap an’s import restrictions on the U.S. apples. Consultations in April 2002 failed to settle the dispute. In May 2002, the United States requested that the WTO establish a panel to consider the Japanese restrictions. In June 2002, a panel was established by the Dispute Settlement Body DSB of the WTO to consider this issue. Before the Panel, the United States claimed that Japan was acting inconsistently with some articles of the SPSA, certain articles of the Agreement on Agriculture, and the so-called “GATT1994.” In July 2003, the Panel found that Japan’s phytosanitary measures were maintained without sufficient scientific evidence and inconsistent with Japan’s obligation, did not qualify as a provisional measure, and were not based on a risk assessment. In September 2003, Japan appealed the WTO Panel ruling. In addition to Japan’s appeal, the United States cross-appealed the Panel Report. At the same time, third participants, such as Australia, Brazil, the European Union, and New Zealand, filed their submissions. After more investigations, in November 2003, the DSB upheld the findings of July 2003. Therefore, the Appellate Body recommended that the DSB request that Japan bring its inconsistent measures into conformity with SPSA.Half a year later, in July 2004, the United States held that Japan failed to comply with the recommendations and rulings of the DSB by theend of the reasonable period of time. Therefore, the United States requested that the DSB establish a panel and simultaneously requested authorization on suspension of concessions and other obligations in one or more of the following: tariff concessions and related obligations under the GATT 1994 on a list of products; and concessions and other obligations under the SPS Agreement and the Agreement on Agriculture. Because Japan objected to the United States’ suspension request, this matter has been referred to arbitration. The arbitration Panel’s report of June 2005 mostly sided with the U.S. arguments. In August 2005, Japan issued a protocol agreeable to the United States, which removed measures that had been deemed inconsistent with WTO principles WTO 2005.译文不完全替代和贸易成本与技术性贸易壁垒的关税等值资料来源: 美国农业经济学杂志作者:CHENGYAN YUE, JOHN BEGHIN, AND HELEN H. JENSEN《关税及贸易总协定总协议》第20条允许各国政府来制定自己的标准和贸易法规以保护人类、动物或植物的生命或健康,只要他们不歧视国家之间或不使用此动机为贸易隐蔽的保护主义。

英国早在14世纪末就首先采取步骤管制海上交通

案例1. 英国早在14世纪末就首先采取步骤管制海上交通,并随着它的殖民体系的扩大,实施了越来越多的排他性控制措施,但直到两个半世纪后1651年和1660年,才通过著名的航海法来加强和巩固这些措施。

促成这些法律通过的动机,是荷兰人趁英国于1642~1646年忙于内战期间,使英国的运输贸易受到严重损失。

这些法令的目的和影响,是要尽可能无例外地保障英国(包括殖民地)船只运输货物,往返于英国与殖民地的各个港口。

航海法成功地把外国船排挤出英国的沿海贸易,排挤出英国与其殖民地的贸易,并排挤出亚洲、非洲或美洲运送进口货到英国及其殖民地的业务。

此外,英国船还必须由英国建造,并由四分之三的英国人操纵。

但是人们认为,不让外国人把英国的出口商品运往非殖民地的目的地,是不明智的,因为这可能意味着更大量的出口,这是一个至少同垄断海运贸易一样重要的目标。

但如果让外国船只进入英国港口,就得允许它们把货物带进来。

因此,从大陆向不列颠各岛进口货物是允许的,虽然它们在抵港后必须加倍付税。

英国在确立了一系列“列举的”商品后,加强了对殖民地贸易的垄断,这些商品包括殖民地只能向其他英属殖民地出口的最重要的殖民地产品。

这份商品目录最初仅限于包括糖、烟草和棉花在内的6种商品,后来扩大到20种商品,1776年则扩大为殖民地的所有出口商品。

西班牙和法国也曾竭力垄断同各自殖民地之间的贸易,但它们的政策不如英国那么严厉,也不如英国那么成功。

请谈一谈英国在上述时期执行的是什么贸易政策?这种贸易政策的主要观点是什么?2. 下表给出了1988-1991年及1996-2000年间工业国家在制成品方面发生的产业内贸易的份额。

该表显示1996-2000年间,法国的产业内贸易比例最高(77.5%),其次是加拿大(76.5%)和奥地利(74.2%)。

在其他七国集团的国家中,英国的比例为73.7%,德国为72.0%,美国为68.5%,意大利为64.7%,日本为47.6%。

WTO规则中英文教程第十七章 WTO原产地规则_OK

顾名思义,WTO原产地规则主要用 于确定产品的原产地(国)。WTO有关原产地 的规则体现于WTO《原产地规则协定》 (Agreement on Rules of Origin)[1]中。制定这一 规则目的在于促进各成员国原产地制度的协 调,使其原产地制度本身不致于成为不必要 的贸易障碍(unnecessary obstacles to trade)。

HS其全称为“商品的品名与编码协调 制”(Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System, HS),是国际公认的统一的海关“语言”。一般说来,产 品经加工后,在HS中四位数字级(章、目)发生改变,即证

明已发生了实质性改变。

2021/6/30

7

• 2. ad valorem percentages criterion

优惠的原产地规则适用于自由贸易区及其他经济一体化组织内部贸易产品原产地的确定是wto一般最惠国待遇原则的例二原产地的认定规则establishingrulesorigin一原产地的认定标准及相应要求determiningcriteriacorrespondingrequirement在原产地的认定时涉及两类产品一类是完全原产whollyobtained的产品另一类是发生实质性改变substantialtransformation的产品

• 3、制造或加工工序标准

• 要求:应准确说明授予有关货物原产地的工序。

制造或加工工序标准规定,只要在产品的 生产过程中有几个特定的生产阶段或生产工序 是在一个WTO成员内进行的,则这种产品即以 该成员为原产地。

2021/6/30

9

小结

OECD绿色增长战略阶段性报告2010英文版

Box 1. Contribution of the Green Growth Strategy ................................. 14 Box 2. Progress on key environmental challenges.................................. 16 Box 3. Environmental externalities and market failures ....................... 19 Box 4. Key pillars for pro-poor Green Growth ......................................... 25 Box 5. Employment potential of green components of stimulus packages – some examples ........................................................................ 27 Box 6. The scope for moving forward public infrastructure investment .................................................................................................... 29 Box 7. Car-scrapping schemes and green growth................................... 30 Box 8. Agricultural subsidies and green growth ..................................... 35 Box 9. Examples of renewed interest in CO2-related taxes.................... 38 Box 10. Proceeds from auctioned emissions trading permits: some examples ....................................................................................................... 40 Box 11. Addressing carbon leakage and competitiveness impacts of climate policies............................................................................................. 41 Box 12. Patents and international technology transfer.......................... 47 Box 13. Transport – a growing source of CO2 emissions1 ....................... 52 Box 14. An extension of the OECD ENV-Linkages model....................... 56 Box 15. Regional and local implications of a transition towards a low-carbon economy and green growth .................................................. 58 Box 16. Key principles in selecting indicators to monitor progress with green growth........................................................................................ 62 Box II.1. The role of regulatory policy and reform .................................. 77 Box II.2. Markets and competition............................................................. 79 Box II.3. Consumer policy ........................................................................... 80 Box II.4. Responsible business conduct in support of a low carbon economy ........................................................................................................ 81 Box II.5. Taxation, innovation and the environment ............................. 82 Box II.6. “Smart” ICT applications enabling green growth .................... 84 Box II.7. Regional innovation systems for eco-innovation .................... 85 Box II.8. New models for international co-operation on ecoinnovation ..................................................................................................... 86 Box II.9. Enhancing the cost-effectiveness of biodiversity policies...... 87 Box II.10. Outcome of the February 2010 OECD Agriculture Ministerial Meeting ...................................................................................... 88 Box II.11. Relevant work for green growth measurements ................... 89

数字贸易壁垒与数字化转型的政策走势——基于欧洲和OECD数字贸易限制指数的分析

数字贸易壁垒与数字化转型的政策走势——基于欧洲和OECD数字贸易限制指数的分析赵瑾内容摘要:文章基于欧洲“数字贸易限制指数”(DTRI)和OECD数字服务贸易限制指数(数字STRI)研究发现,目前影响数字贸易发展的壁垒主要是关税壁垒、非关税壁垒和数据限制。

其中,非关税壁垒包括贸易限制、投资限制、财政限制、自然人流动限制和知识产权等。

数据限制包括数据政策、平台责任、内容访问等。

近五年数字贸易壁垒有强化的趋势,且发展中国家普遍高于发达国家。

推动数字贸易发展的关键是制定国家数字发展战略和综合政策,加快数字化转型。

实现数字化转型的有效路径是扩大数字市场开放,防范数字安全风险、加强技能培训、实行技术创新,强化战略协调和国际合作。

关键词:数字贸易壁垒数字贸易限制指数数字化转型综合政策框架随着数字技术的发展,数字化生产、数字化消费、数字化创新推动世界经济进入数字全球化发展新阶段。

数字技术跨越时空,将不可贸易的服务可贸易化,改变了商业模式,扩大了国际贸易的规模、范围和速度,有利于培育经济发展新动能,实现经济可持续增长。

但目前国际社会普遍认为,各国对数字跨境传输等限制措施阻碍了数字贸易、数字化转型与数字经济发展。

研究数字贸易壁垒的表现形式和特点,把握推动数字化转型的政策走势,对“十四五”时期加快产业数字化和数字产业化发展,发挥数字贸易在经济增长与可持续发展中的作用具有重要意义。

一、数字贸易框架、数字贸易壁垒与数字贸易限制指数对于什么是数字贸易,长期以来国际社会没有标准的答案。

2020年经合组织、世界贸易组织和国际货币基金组织共同发布的《数字贸易测度手册》界定了数字贸易,并构筑了数字贸易的基本框架(见图1)。

数字贸易是指通过计算机网络,以数字订购和/或数字交付方式进行商品或服务的国际交易。

数字贸易基本框架由交易主体、交易客体、交易方式组成,系统回答了谁在交易(买方与卖方),在哪儿交易,交易什么(产品类型),如何交易的问题。

《区域全面经济伙伴关系协定》原产地累积规则辨析

品的材料,如最终产

制成品或材料进行加工或 2. 每一缔约方应规定,如一个或多 品 的 中 国 - 东 盟 自 由

处理的缔约方。

个缔约方的原产货物或材料在另一缔 贸 易 区 累 计 成 分 ( 即

二、缔约方应当自本协定 约方领土内用于生产另一个货物,则 所 有 成 员 方 成 分 的 完

对所有签署国生效之日起 该货物或材料应被视为原产于该另一 全累计)不低于40%,

RCEP第四条累积

CPTPP第3.10条累积规则

CAFTA规则五累计 原产地规则

一 、 除 本 协 定 另 有 规 定 1. 每一缔约方应规定,如一货物在一 除 另 有 规 定 的 以 外 ,

外 , 符 合 第 三 章 第 二 条 个或多个缔约方内由一个或多个生产 符 合 规 则 二 原 产 地 要

世界海关组织使用了一个务实的办法加以区分,即看相关累积规则的累积地域范 围和累积客体范围。首先,累积的地域范围。按累积的地域范围划分要看哪些国家和 地区可以纳入累积,这个地域范围可以是一个自贸协定的部分国家和地区,也可以是 全部国家和地区,还可以是自贸协定外的第三国和地区。一个自贸协定外的第三方如 果和进口国有自贸安排或者优惠安排,是有可能纳入累积范围的。其次,累积的客体 范围。按照累积的客体范围划分,累积可以分为货物(材料)累积①和生产累积。货 物(材料)累积要求中间品出口国的货物(材料)具有原产资格以后可以被进口国累 积,视为原产于进口国。而生产累积则不要求中间品具有中间品出口国原产资格,其 在出口国的生产和增值可以被统一累积到进口国。

(二)原产地累积规则的分类

自贸协定优惠原产地累积规则最常见的分类方法是分为三类,包括双边累积、对 角累积和完全累积(中国贸促会广东分会优惠原产地课题组,2014)。除此之外,还 有单边累积、地区累积的说法(孟国碧,2008)。不过,对于这些概念,文献中的 定义并不一致。这使得人们对一些自贸协定中的原产地累积规则到底属于何种类型, 看法并不一致。例如,对于CAFTA中的累积规则属于何种类型,存在多种不同的说 法。各种自贸协定的文本一般不会直接将自己的累积规则界定为某种类型。

外文翻译--关于技术性贸易壁垒的世界贸易组织协定

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:The WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade出处:CONSUMER POLICY REVIEW作者:Dr James Mathis原文:As one of the Mulitlateral Agreements on Trade in Goods, the Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement is subscribed to by all World Trade Organization members. The Agreement's provisions apply to the technical regulations and standards of the characteristics of products. This article looks at the implications of this Agreement and the development of a set of international standards for standards bodies, how they can govern themselves and the possible implications for consumersEfforts by General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)-47 Contracting Parties to harmonize product regulations and standards and address more subtle forms of ‘nontariff’barriers, led to the conclusion of the original GATT Tokyo Round Standards Code (1980). This plurilateral (limited membership) agreement was updated and concluded in the course of the Uruguay Round as the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement).As one of the Multilateral Agreements on Trade in Goods, the TBT is subscribed to by all WTO members and fully subject to the provisions of the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU). The DSU allows for panel and Appellate Body (AB) reviews for any dispute between WTO Members.The TBT Agreement applies to all products including industrial and agriculture products, but not for government purchasing requirements and sanitary and phytosanitary measures designed to protect food, plant and animal health, covered by the The WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement). Its provisions apply to product technical regulations (mandatory) and product standards (non-mandatory) for requirements that deal with the characteristics of products, including their contents, appearance and labelling. The prevailing view appears to be that the agreement does not cover standards describing product processes that are not directly incorporated or related to the end product, except possibly for product labels that designate production processes.The original Standards Code extended the reach of GATT law in two ways, both of which continue on as part of the WTO single undertaking:Firstly, it established a new legal theory for complaints based on unnecessary obstacle to trade' which focuses on the inherent trade restrictiveness of a regulation. (This is not the same as GATT national treatment that requires nondiscrimination between domestic and imported like products.)Secondly, it obliged signatories to use applicable and relevant internationalstandards as a basis for their own domestic product regulations.The first standard above has yet to be examined in a WTO case. The second has received treatment in the European Commission (EC) Sardines case.In a more procedural sense, the WTO TBT Agreement encourages WTO members to:• participate in international standard setting;• ensure their conformity systems are open to the products of all Members on an equal basis; and• ensure the transparency of technical regulations.It also requires members to notify their technical regulations to the TBT Committee: if they have a significant effect on trade; if no international standard exists; and when a domestic a domestic regulation is not 'in accordance' with an existing international standard. This notification process allows for other member review and consultation. There is no obligation for any country to establish any national product requirements but when regulating, countries are encouraged to adopt an international standard. This is done by the 'safe harbour' provision found in TBT Article 2.5. Members are presumed to not be creating unnecessary obstacles to trade when they enact their domestic regulations in accordance with an existing international standard. This only available for the national objectives of: ensuring the quality of exports; the protection of human, animal or plant life or health; protection of the environment; or for the prevention of deceptive practices. WTO cases have ruled that 'in accordance' means conformity with the international standard.EC SardinesThe EC Sardines case concerned a claim by Peru that the EC failed to apply a Codex standard for its labelling regulation. The European regulation only permitted pilchards to carry the name 'sardines' on the label. The Codex standard allows other varieties to also be labelled called sardines if they also state the variety or a geographical designation (for example, 'Peruvian Sardines', 'Eastern Pacific Sardines', and so on). The case provides a first substantive ruling on a TBT case and also the first ruling on the stated requirement for Members to use international standards as a basis for their own domestic regulations. Although much commentary on the TBT Agreement tends to emphasise the TBT provisions that 'encourage' the use of international standards, like the safe harbour provision noted above, this ruling is far more direct in applying the rather unambiguous and obligatory text of Article 2.4 of the TBT Agreement in order to resolve the dispute. This subparagraph reads:'Where technical regulations are required and relevant international standards exist or their completion is imminent. Members shall use them, or the relevant parts of them, as a basis for their technical regulations except when such international standards or relevant parts would be an ineffective or inappropriate means for the fulfilment of the legitimate objectives pursued, for instance because of fundamental climatic or geographical factors or fundamental technological problems.Not all implications are negative for international standards. This case is notable for the value added contributed by a consumer organization letter attached to the Perusubmission. The organization argued strongly against the value of the EC regulation and the panel used this resource to assess whether or not the EC's deviation from the international Codex standard served any legitimate objective in protecting consumer interest. In this case, the international standard and the WTO rule obliging its use as a 'basis' would have to be said to be within the European consumer interest overall.Since standards generated by international bodies have an otherwise non-binding legal character, the TBT provisions, as interpreted by the panel and the Appellate Body, generate implications for global governance issues.^ While participation legitimacy in rule making should be of interest to States and standard bodies, it is of particular importance to the ultimate consumers of products and to the organisations that seek to secure their interests before domestic and international rule-making bodies.International standardsDevelopment of international standardsThe term 'international standard' is a WTO creation for the purpose of the TBT Agreement, Since legal obligations flow from the term, there has to he some sort of criteria to determine what qualifies as an international standard. For the SPS Agreement, international bodies are designated. The TBT Agreement only has a single provision that defines an international body or system as one 'whose membership is open to the relevant bodies of at least all Members’.The clear emphasis throughout is to ensure that all WTO members have rights of participation in those bodies, and to raise the participation of developing members in particular. Given the focus on 'WTO members' in the TBT definition, one would not expect to see any particular accommodation in the decision for non-state actors and there is nothing in the decision that can be read to suggest that an international body should elevate the participation of a consumer organisation (or any other non-governmental actor). Since this document controls the definitional gateway of what may or may not qualify as an international standard, what is not considered in the recommendations raises as many questions as what has been included. Similar, the committee process of consultation and from whom it did or did not receive comment, also raises process considerations for what is an example of WTO committee rulemaking. These are governance issues.The value of the Committee decision as a source of law for interpretation in a dispute settlement case is recognised even though the language of the decision uses the term 'should' rather than 'shall'. The issue of whether a standard qualifies as an international standard can definitely be raised in a case and the Committee decision would be used to assess whether a standard meets the enunciated criteria. The EC referred to the decision in the Sardines case for its (unsuccessful) argument that a consensus was required in the standard body process in order to qualify as an international standard.'^Unfortunately, the decision does not require that the members actually solicit and receive comments from interested parties, just that they be given time to do so. This is a significant deference to sovereignty, especially as it is combined with an obligationon draft standards to give notice to members only. Receiving input from interested parties is completely the choice of a member and any requirements for members to take up comments remains a matter between the members and the standard bodies. One single point of reference in the Triennial Report does however refer to the larger community of interest, here in the context of developing countries.Even though this democracy issue has not fallen within the field of interest of the TBT Committee, the manner by which states and international bodies respond to the gap will have an impact on the longer term credibility of the TBT Agreement's obligation to use international standards irrespective of the decision. This suggests that further enhancements and evolution in the criteria are possible and perhaps likely. Governance and consumer implicationsThe implications for consumers and consumer organisations are complex and in some cases appear contradictory. Where international standards facilitate trade, consumers are offered some consistency in information and the benefits of lower prices generated by competitive imports. At the same time, where consumers of the importing country support a variation from international standard, as their national choice, the benefits of diversity may be at risk. Given the obligation to review and amend national requirements, the entire field of existing technical regulations is open for consideration. This presents a myriad of challenges and opportunities for consumers seeking to affect the outcome of national regulations.States have their own systems for passing laws and regulation and vary in the degree of democratic participation and procedural due process they adopt. These domestic procedures are probably eroded, even where participation guarantees are given, when a binding rule is established by a body beyond a state's domestic rule making system.To the extent that the TBT Agreement has upgraded international standards to obligations, it is also apparent that this has raised the profile of trade interests in standard setting processes. If standards are designed to reflect only trade interests then the objectives of health and safety are challenged. There is a need, therefore, for consumers to be engaged at the institutional level of standard bodies to ensure diversity of representation and ensure that objectives remain balanced.States are aware that WTO claims can be filed against non-conforming regulations and many will seek to avoid even minor non-conformities if there is a chance that they will be accused of barriers to trade. The tendency would be to ensure that their own trade interests are reflected in standard body delegations. While the legitimate objectives incorporated in standard body preambles remain in place, the constitutional realities on the ground suggest a more trade-oriented disposition in the process and probably more trade-sensitive substantive outcomes as well.If consumer organisations want to have more input into this process and a seat at the table when international standards are being set, then they have to be able to understand these governance issues and coordinate their focus at their national levels, at the international standard bodies ... and at the WTO.译文:关于技术性贸易壁垒的世界贸易组织协定作为在货物贸易多方协定之一,技术性贸易壁垒协定被所有世贸组织成员签署并高度关注。

数字贸易标准化国内外情况

数字贸易标准化国内外情况英文回答:International Standards for Digital Trade.Digital trade is becoming increasingly important in today's global economy. It is estimated that cross-border digital trade will reach $4.9 trillion by 2025. However, there are a number of challenges to the growth of digital trade, including a lack of standardization.Standards are essential for facilitating digital trade. They ensure that goods and services can be exchanged electronically in a secure and reliable manner. Standards also help to reduce costs and increase efficiency.There are a number of international organizations that are working to develop standards for digital trade. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has established a working group on e-commerce. The International Organization forStandardization (ISO) has developed a number of standards for digital trade, including the ISO 27001 standard for information security.In addition to these international organizations, there are a number of regional and national organizations that are working to develop standards for digital trade. For example, the European Union has developed a number of directives on e-commerce. The United States has developed a number of standards for digital trade, including the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.The development of standards for digital trade is a complex and challenging process. However, it is essential for the growth of digital trade. Standards help to ensure that goods and services can be exchanged electronically in a secure and reliable manner. Standards also help to reduce costs and increase efficiency.Domestic Standards for Digital Trade.In addition to international standards, there are alsoa number of domestic standards that have been developed for digital trade. These standards are typically developed by national governments or industry associations.Domestic standards for digital trade can vary significantly from country to country. However, there are a number of common elements that are found in many domestic standards. These elements include:Security: Domestic standards typically include requirements for data security. These requirements may include encryption, access controls, and incident response plans.Privacy: Domestic standards typically include requirements for data privacy. These requirements may include notice and consent requirements, and data breach notification requirements.Interoperability: Domestic standards typically include requirements for interoperability. These requirements may include the use of common data formats and protocols.Domestic standards for digital trade can play an important role in promoting the growth of digital trade. These standards can help to ensure that goods and services can be exchanged electronically in a secure and reliable manner. Standards can also help to reduce costs andincrease efficiency.中文回答:数字贸易的国际标准。

UN_Comtrade数据库使用指南课件

学习交流PPT

13

选择商品、报告 国家、交易国家、 年份、其他进一 步筛选查询

选择交易方向

可根据交易量 对结果进行筛 选

是否累加检索单元 内各记录的数值

其他检索选项

选择商品分类

选择结果排序方式

学习交流PPT

14

检索/查询

除平台首页的快速检索框外,Data Query下拉菜单提供 四种检索方式: 快速检索 Shortcut Query 基本检索 Basic Selection 浏览器检索 Comtrade Explorer w/Map 浏览选择 Express Selection

学习交流PPT

30

按年份、时间 段依次排列, 根据商品分类 和国家浏览相 应时间段的商 品数据

年份浏览

选择不同时间段

国家列表,鼠标滑 过显示对应数据记 录数

查看该年份商品交 易情况概述

学习交流PPT

31

根据商品分类、 报告国家、年 份、上传时段 浏览数据上传 信息

上传日期浏览

商品分类、 报告国家、 年份、上传 时段选择

动态信息

学习交流PPT

5

检索/查询

除平台首页的快速检索框外,Data Query下拉菜单提供 四种检索方式: 快速检索 Shortcut Query 基本检索 Basic Selection 浏览器检索 Comtrade Explorer w/Map 浏览选择 Express Selection

学习交流PPT

12

选择商品、报告 国家、交易国家、 年份、其他进一 步筛选查询

选择年份来源, 全部/用户设置 的年份

年份列表浏览, 点击Add,确 认选择

按年份检索

选择商品分类

Why and how we measure trade in value-added terms part2_e

Why and how we measure trade in value-added terms

3 Estimating trade in value-added:

why and how?

Nadim Ahmad

3.1. Introduction

Global value chains (GVCs) have become a dominant feature of today’s global economy. This growing process of international fragmentation of production, driven by technological progress, cost, access to resources and markets and trade policy reforms has challenged our conventional wisdom on how we look at and interpret trade and, in particular, the policies that we develop around it. Indeed, traditional measures of trade that record gross flows of goods and services each and every time they cross borders, alone, may lead to misguided decisions being taken. In practice, two main approaches (micro and macro) have been used to shed light on this issue. The former is perhaps best characterized by the well known Apple iPod example (Dedrick et al., 2010), which showed that of the US$ 144 (Chinese) factorygate price of an iPod, less than ten per cent contributed to Chinese value-added, with the bulk of the components (about US$ 100) being imported from Japan and much of the rest coming from the United States and the Republic of Korea. This stylized approach, however, can generally only be conducted for specific products and, even then, only reveals part of the story related to who benefits from trade and how global value chains work as it is typically unable to reveal how the intermediate parts are created. For example, the message would be significantly different if, for sake of argument, the imported parts from Japan used to make the iPod required significant Chinese content. To deal with the bigger picture and also to capture all of the upstream effects, a number of studies have adopted a macro approach based on the construction of inter-country or world input-output (I-O) tables (Hummels et al., 2001; Daudin et al., 2006; 2009), Johnson and Noguera, 2011 and Koopman et al., 2011). A number of pioneering initiatives, such as those of GTAP, the WTO with IDE-JETRO and the WIOD (World Input-Output Database),

世界贸易数据库WorldTradeDatabase

EPS数据库介绍一、访问地址:二、内容简介:1.世界贸易数据库(World Trade Database)世界贸易数据库,数据来源于联合国统计司(署)、中国海关,是用于进行国际贸易分析的必不可少的数据库。

此数据库提供了国际海关组织的多种商品分类标准数据查询,包括HS1992、HS1996、HS2002、HS2007、HS2012多个子库,已经覆盖250多个国家、地区和经济体,6000多种HS2、HS4、HS6位编码商品的年度进出口数据。

主要数据指标有:进口、出口、进出口、贸易差额、贸易总额等。

数据起始于1992年,年度更新。

2. 世界能源数据库(World Energy Database)世界能源数据库,数据来源于世界能源组织、英国BP,是用于分析全球能源生产、消费状况和研究新能源必不可少的数据库。

此数据库提供了世界主要能源生产国和能源消费国的能源生产、消费、库存、价格、能源国际贸易等方面数据,并对石油、天然气、煤炭、电力以及可再生能源等的生产、消费、贸易、价格、及能源环保的数据都分别进行统计,同时可以进行分类对比分析。

主要指标涵盖:能源、石油、天然气、煤、核能、水电、一次能源、地热、太阳能、风能、乙醇燃料、生物燃料、其它可再生能源。

数据起始于1965年,年度更新。

3. 世界宏观经济数据库(Worl d Macro Economy Database)世界宏观经济数据库,数据来源于国际货币基金组织,是用于评估国家总体经济发展水平和经济状况的基础数据库。

此数据库提供了世界各国的宏观经济,人均经济指标,国际收支,货币供应,财政收支结构,政府债务状况等方面数据。

主要数据指标有:经常项目余额、政府收支余额、国内生产总值、国民储蓄总额、通胀、负债、就业人数、失业率、政府负债总额等。

数据起始于1980年,年度更新。

4. 世界经济发展数据库(Worl d Economy Development Database)世界经济发展数据库,数据来源于是世界银行,是用于对比分析世界各国经济状况的综合数据库。

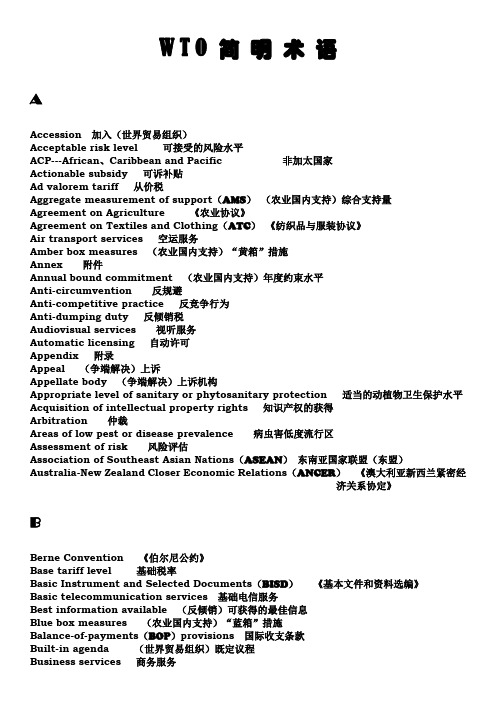

WTO简明术语

W T O简明术语AAccession 加入(世界贸易组织)Acceptable risk level 可接受的风险水平ACP---African、Caribbean and Pacific 非加太国家Actionable subsidy 可诉补贴Ad valorem tariff 从价税Aggregate measurement of support(AMS)(农业国内支持)综合支持量Agreement on Agriculture 《农业协议》Agreement on Textiles and Clothing(ATC)《纺织品与服装协议》Air transport services 空运服务Amber box measures (农业国内支持)“黄箱”措施Annex 附件Annual bound commitment(农业国内支持)年度约束水平Anti-circumvention 反规避Anti-competitive practice 反竞争行为Anti-dumping duty 反倾销税Audiovisual services 视听服务Automatic licensing 自动许可Appendix 附录Appeal (争端解决)上诉Appellate body (争端解决)上诉机构Appropriate level of sanitary or phytosanitary protection 适当的动植物卫生保护水平Acquisition of intellectual property rights 知识产权的获得Arbitration 仲裁Areas of low pest or disease prevalence 病虫害低度流行区Assessment of risk 风险评估Association of Southeast Asian Nations(ASEAN)东南亚国家联盟(东盟)Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations(ANCER)《澳大利亚新西兰紧密经济关系协定》BBerne Convention 《伯尔尼公约》Base tariff level 基础税率Basic Instrument and Selected Documents(BISD)《基本文件和资料选编》Basic telecommunication services 基础电信服务Best information available (反倾销)可获得的最佳信息Blue box measures (农业国内支持)“蓝箱”措施Balance-of-payments(BOP)provisions 国际收支条款Built-in agenda (世界贸易组织)既定议程Business services 商务服务Bound level 约束水平Bretton Woods Conference 布雷顿森林会议CCairns Group 凯恩斯集团Causal link 因果联系Ceiling bindings (关税)上限约束Central Product Classification(CPC)《(联合国)中心产品分类》Challenge Procedures (政府采购)质疑程序Clean report of findings 检验结果清洁报告书Codex Alimentarius Commission(CAC)食品法典委员会Common Agriculture Policy(CAP)(欧洲共同体)共同农业政策Communication services 通信服务Conciliation 调解Confidential information 机密信息Conformity assessment procedures 合格评定程序Circumvention 规避Combined tariff 复合税Commercial presence (服务贸易)商业存在Committee on Trade and Development(CTD)贸易与发展委员会Committee on Trade and Environment(CTE)贸易与环境委员会Compensation 补偿Competition policy 竞争政策Complaining party (争端解决)申诉方Computed value 计算价格Consensus 协商一致Constructed value (反倾销)结构价格Consultation 磋商Consumption abroad (服务贸易)境外消费Copyright 版权Council for Trade in Goods(CTG)货物贸易理事会Counterfeit trademark goods 冒牌货Counter-notification 反向通知Countervailing duty 反补贴税Contraction parties 关税与贸易总协定缔约方Cross border supply (服务贸易)跨境交付Cross retaliation 交叉报复Currency retention scheme 货币留成制度Current market access(CMA)现行市场准入Current total AMS (农业国内支持)现行综合支持量Customs duty 关税Customs tariff 海关税率,海关税则Customs value 海关完税价值Customs valuation 海关估价Customs union 关税同盟DDeveloped member 发达成员Developing member 发展中成员Direct payment (农业国内支持)直接支付Distribution services 分销服务Domestic industry 国内产业Domestic production 国内生产Domestic sales requirement 国内销售要求Domestic subsidy 国内补贴Domestic support (农业)国内支持Dispute Settlement Body 争端解决机构Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes(DSU)《关于争端解决规则与程序的谅解》Due restraint (对农产品反补贴)适当克制Dumping 倾销Dumping margin 倾销幅度EEconomies in transition 转型经济体Enabling clause 授权条款Enforcement of intellectual property rights 知识产权法Equivalence (检验检疫标准)等效性European Communities(EC)欧洲共同体European Free Trade Association (EFTA)欧洲自由贸易联盟Electronic commerce 电子商务Enquiry point 咨询点European Union 欧洲联盟Exhaustion of intellectual property rights 知识产权权利用尽Existing subject matter (知识产权)现有客体Ex officio 依职权Export credit 出口信贷Export credit guarantee 出口信贷担保Export subsidy 出口补贴FFall-back method (海关估价)“回顾”方法Findings 争端解决调查结果First-come first served 先来先得Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO)联合国粮农组织Food security 粮食安全Foreign direct investment(FDI)外国直接投资Foreign exchange balancing requirement 外汇平衡要求Free-rider 搭便车(指根据最惠国待遇享受其他成员贸易减让而不进行相应减让的成员)Free trade area 自由贸易区GGATT 1947 《1947年关税与贸易总协定》GATT 1994 《1994年关税与贸易总协定》General Agreement on Trade in Service(GATS)《服务贸易总协定》General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT)《关税与贸易总协定》General Council 总理事会General exceptions 一般例外Geographical indications (知识产权)地理标识Genetically Modified Organisms(GMO)转基因生物Good offices 斡旋Government procurement 政府采购Green box measures (农业国内支持)“绿箱”措施Grey area measures 灰色区域措施General Preferential System(GPS)普惠制HHarmonized Commodity Description and Coding System(HS)《商品名称及编码协调制度》Havana Charter 哈瓦那宪章Horizontal commitments (服务贸易)水平承诺IIdentical product 相同产品Illustrative list 例示清单Import deposits 进口押金Import licensing 进口许可Import substitution 进口替代Import surcharge 进口附加税Import variable duties 进口差价税Industrial designs 工业设计Infant industry 幼稚产业Information Technology Agreement(ITA)《信息技术协议》Injunctions 禁令Initial negotiating rights (INRs)最初谈判权(初谈权)Integration process 一体化进程Intellectual property rights(IPRs)知识产权Internal taxes 国内税International Labor Organization (ILO ) 国际劳工组织International Monetary Fund (IMF)国际货币基金组织International Organization for Standardization (ISO)国际标准化组织International Plant Protection Convention 《国际植物保护公约》International Textile and Clothing Bureau (ITCB)国际纺织品与服装局International Trade Organization (ITO)国际贸易组织International Trade Center (ITC)国际贸易中心International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 国际复兴开发银行JJudicial review 司法审议Judicial person (服务贸易)法人KLLayout-designs(Topographies)of integrated circuits 集成电路外观设计(拓扑图)Least-developed countries (LDCs)最不发达国家License fee (知识产权)许可费Like product 同类产品Limited tendering (政府采购)有限招标Local content requirement 当地含量要求Local equity requirement 当地股份要求MMad-cow disease 疯牛病Maintenance of intellectual property rights 知识产权的维护Maritime transport services 海运服务Market access 市场准入Market boards 市场营销机构Market price support 市场价格支持Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization 《建立世界贸易组织马拉喀什协定》Marrakesh protocol 《马拉喀什协定书》Material injury 实质损害Medication 调停Minimum market access (MMA)最低市场准入Minimum values (海关估价)最低限价Most-favored-nation treatment (MFN)最惠国待遇MFN exemptions (服务贸易)最惠国待遇例外Ministerial conference 部长级会议Modalities 模式Modulation of quota clause (保障措施)配额调整条款Movement of natural persons 自然人流动Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA)《多种纤维协定》Multilateral trade negotiations (MTNs)多边贸易谈判Mutual recognition agreement 相互承认协议NNational treatment 国民待遇Natural person 自然人Negative standard (原产地)否定标准Neighboring rights (版权)邻接权New issues (世界贸易组织)新议题Non-actionable subsidy 不可诉补贴Non-automatic licensing 非自动许可Non-discrimination 非歧视Non-violation complaints 非违规之诉North American Free Trade Agreement(NAFTA)《北美自由贸易协定》Notification obligation 通知义务Non-tariff measures(NTMs)非关税措施Non-trade concern 非贸易关切Nullification or impairment (利益)丧失或减损oOffer (谈判)出价Open tendering (政府采购)公开招标Orderly marketing arrangement (OMA)有序销售安排Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development(OEDC)经济合作与发展组织Original member (世界贸易组织)创始成员PPanel 争端解决专家组Paris convention 《巴黎公约》Patents 专利Peace clause 关于农产品反补贴的和平条款Pest or disease-free area 病虫害非疫区Pirated copyright goods 盗版货Plurilateral agreement 诸边协议Positive standard (原产地)肯定标准Presence of natural person 自然人存在Preshipment inspection 装运前检验Price verification (装运前检验)价格核实Price undertaking (反倾销)价格承诺Principal supplying interest 主要供应利益Product mandating requirement 产品授权要求Product-to-product method 产品对产品(谈判)方法Production subsidy 生产补贴Professional services 专业服务Prohibited subsidy 被禁止的补贴Protocol accession 加入议定书Protocol of Provisional Application of GATT 关贸总协定临时适用协议书Provisional application 临时适用Prudential measures 审慎措施QQuads 四方集团(至美国、欧盟、日本和加拿大)Quantitative restrictions 数量限制Quantity trigger level (农业特殊保障措施)数量触发水平RReciprocity 对等Recommendations (争端解决)建议Reference years 参照年Regional trade agreements 区域贸易协议Request (谈判)要价Responding Party (争端解决)应诉方Restrictive business practices 限制性商业惯例Risk analysis 风险分析Risk assessment 风险评估Roll-back 逐步退回Rome convention 《罗马公约》Round (知识产权)使用费Rules of origin 原产地规则SSafeguards 保障措施Sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS)measures 卫生与植物措施Schedule of commitments (服务贸易)承诺表Schedule of concessions (货物贸易)减让表Sectoral negotiations 部门谈判Security exceptions 安全例外Selective tendering (政府采购)选择性招标Separate customs territory 单独关税区Serious injury 严重损害Serious prejudice 严重侵害Simple average tariff 简单平均关税Similar product 类似产品Special and differential(S&D)treatment provisions 特殊与差别待遇条款Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)(国际货币基金组织)特别提款权Special safeguard(SSG)measures (农产品)特殊保障措施Specific tariff 从量税Specificity (补贴)专项性Standardizing bodies 标准化机构Standards 标准Standstill 维持现状State trading enterprises (STEs)国营贸易企业Subsidy 补贴Subsidies in general 一般补贴Substantial supplying interest 实质供应利益Substantial transformation (产品)实质改变Suspend concessions 暂停减让TTariffs 关税Tariff bindings 关税约束Tariff classification 税则归类Tariff concessions 关税减让Tariff equivalent 关税等值Tariff escalation 关税升级Tariff headings 税目Tariffication 关税化Tariff line 税号Tariff peaks 关税高峰Tariff rate quotas/ Tariff quotas (TRQ)关税配额Technical assistance 技术援助Technical barriers to trade(TBT)技术性贸易壁垒Technical regulationsTelecommunication services 电信服务Terms of reference (TOR)(争端解决专家组)职责范围Textile Monitoring Body (TMB)(关税与贸易总协定)纺织品监督机构Textile Surveillance Body (TSB) (关税与贸易总协定)纺织品监督机构Tokyo Round Codes 东京回合守则Total AMS (农业国内支持)综合支持总量Trade-balancing requirement 贸易平衡要求Trade facilitation 贸易便利化Trade in civil aircraft 民用航空器贸易Trade in goods 货物贸易Trade in services 服务贸易Trademark(TM)商标Trade Policy Review Body (TPRB)贸易政策审议机构Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM)贸易政策审议机制Trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPs)与贸易有关的知识产权Trade-related investment measures (TRIMs)Trade remedies 贸易救济(措施)Trade-weighted average tariff 贸易加权平均关税Transaction Value 成交价格Transition economies 转型经济体Transitional safeguard measures (纺织品)过渡性保障措施Transparency 透明度Transport services 运输服务Trigger prices (农产品特殊保障措施)触发价格UUndisclosed information (知识产权)未公开信息United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 联合国贸易与发展会议Uruguay Round 乌拉圭回合VVariable duties 差价税Value-added telecommunication services 增值电信服务Voluntary export restraints (VERs)自愿出口限制WWaiver (义务)豁免Washington Treaty 《华盛顿条约》Withdraw concessions 撤回减让World Customs Organization(WCO)世界海关组织World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)世界知识产权组织World Trade Organization(WTO)世界贸易组织WTO Members 世界贸易组织全体成员WTO Secretariat 世界贸易组织秘书处。