How to Do Case Study Research

大学生怎么写案例研究? How to write a case study 英语论文写作技巧

大学生怎么写案例研究?学习技巧介绍How to write a case study Tips and Techniques for aBeginnerHello people! I hope you all are well. Today I am going to take a topic which troubles almost every student. “How to write a case study,” every student wonders this at some time in their lives. In a layman’s terms, case study involves in-depth and detailed research of the case of study. It also involves research of its related conditions. It requires thorough study and analysis of the case. Keep reading this article till the end forideas on how to write a case study? This article will provide nitty-gritty on how to write a case study.Writing an excellent case study can be a challenging task. However, if you keep some essential points in mind, then the job will become easy for you. I am going to talk about everything related to how to write a case study?In this article, I am going to discuss the following important points:Steps to write a case study?Types of case studiesTypes of subjects of case studiesSteps to write a case study?The first thing you have to choose while wondering “how to write a case study?” is your case. A case is different for the different case studies. However, there are few things which are common to every case studies. There are other factors followed by recognition of a case. I am providing step by step guide on how to write a case study:1. Identifying the caseIdentifying a case for research involves more than choosing a research problem. Cases are often those topics that are already probed. This is because such cases can provide better and new ways of knowing a research problem. A thorough analysis of a case can be based on thehypothesis. Hypothesis could be that this new case study will reveal valuable insights and issues. Especially, those insights which have not been published in previous research. There are many assumptions which are based on previous research. However, with time those assumptions, sometimes become obsolete. Make sure you select a case through which you can gather crucial evidence. Evidence which challenges prevailing assumptions.While selecting a case, you should consider how the study and research on this particular case may reveal ways to solve present-day problems. Time and access to information are the critical factors while choosing your case. Many research and studies are based on the time at which they have been formulated. Your caseshould challenge already formulated studies and should answer present-day problems.A case can be used when there are fewer studies to a particular problem. A case can be used as a tool which offers a new direction to establish a clear understanding of how to address a specific issue.2. Structure and Writing StyleThe purpose of writing a case study is to investigate a particular case thoroughly. The thorough study includes revealing a new awareness of research problem. In doing so, contributing new knowledge to what is already know. Following are the essential elements to structure and writing a case study:IntroductionThe introduction should reveal the scope and purpose of your research. It should not only describe the problem, but it should also explain why this case is being used and how it helps in solving the issue.Describe your research problem and the method of analysis which would address the problem. In an introduction, you can explain how the above-said elements are linked together.The second thing which you can explain in an introduction is the significance of your case. You can tell how your chosen case is suitable for solving problems.The third thing could be the background of a case study. With new insights, you can also explain the history of initial findings.Explain how your case study will help in expanding knowledge and understanding of a specific problem.Literature Review-This is about exploring books, scholarly articles, and any other sources of a specific area. In doing so, provides a description and summary of those works in relation to current problem.In the literature review, you can highlight relevant works and their contribution. This could include highlighting studies that have included a similar case to investigate the research problem. You can also explain why using the same case is essential (e.g. earlier studies were long ago developed).A particular case may have a no. of previous studies. There could be many unresolved issues that need to be addressed. Your present case study should help in resolving the existing conflicts. This, in turn, will assist in forming fresh insights.Summarize how your present case study helps to find new ways to understanding the research problem. It includes identifying the loopholes in earlier studies. It also, includes how the current study helps in removing those loopholes.Method-A method is an integral part of how to write a case study? In this, you will explain the reason behind choosing a particular case to study. Also, you can highlight the strategy you have used to identify and decide that your case is appropriate in addressing the researchproblem. The way you describe your method depends upon the type of subject of analysis. Case studies use different kind of subjects. I have explained them below.When Subject is an incident or event: The subject of analysis could be a rare or critical event, or it can be a regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event could be thinking about broader research problem or testing a hypothesis. You can explain the reason for choosing this particular subject.When your subject of analysis is a person: You can explain why you selected this specific person to be studied. You can also describe the experience this person is having which can advance understanding about the researchproblem. Consider what experience they have that make them worthy of this study.When your subject is a place: When a subject of case study is place, it must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem (i.e., physical, social, cultural, economic, political, etc.) but also highlight the method which will illuminate new understanding about the research problem.When your subject is a phenomenon: A phenomenon is anything which manifests itself. It also referred to a fact or occurrence that can be studied or observed. There are many phenomena which are not clearly understood. You can choose such case which provides insightful understanding of a particular phenomenon.3. DiscussionThe key elements of discussion revolve around interpreting and drawing a conclusion about the key findings. It will be a good idea to link description of findings with the discussion about their implications. You should briefly explain your research problem, and then you can demonstrate the outcomes of your study. In the discussion, you can also define the meaning of your findings. Highlight your points which shows the significance of your results. It rarely happens that your subject has not been studied previously. Try to find similar studies and try to form a link between your and earlier studies on same issue.In discussion part, it is essential to make highlight the limitations of your study. Even afteryou have studied your subject thoroughly, there may still be many things which are left. Acknowledge those limitations and highlight question which your research could not answer.4. ConclusionThe conclusion is significant part of any case study. Summarize your conclusion in a simple language. Also, you can explain how your case study is different from previous studies. In conclusions, you will mention the most significant points of your research. The conclusion should briefly explain your research and findings of the case study. I have discussed in detail about how to write a case study. Even after this, if you stuck anywhere in your case study, I would suggest you to try assignment help online. They have many professionalexperts who can guide you to achieve the best results.Types of case studiesTill now, you have understood how to write a case study. Now I am going to talk about various kinds of case studies. Following are different types of case studies.Explanatory Case studyThis mainly focuses on an explanation for a specific question or phenomenon. A case study which has person or group of a person as their subjects would not be explanatory, as with humans, there will always be variables.Exploratory Case studyThese are case studies performed before implementing a large-scale study. The objective of this type of study is that further research is needed. Psychology and social sciences are the two subjects which use exploratory case studies highly. Psychologists always keen to find better ways to treat their subjects. This type of case study helps them to research the new ideas or theories.Multiple-Case StudiesMultiple or collective studies use information from different studies. This, in turn, helps to formulate a new case. Sometimes, a researcher has to spend time and money on additional studies. However, by using past studies allow additional information, which then prevents extra time and money.Intrinsic Case studyAn intrinsic case study is the study of a case (e.g., person, group, company) where the case itself is of primary interest in the exploration.Instrumental Case studyAn instrumental case study is the study of the case (i.e., person, group, department, company). This type of case study helps to gain new insights into specific topics, redraw generalizations, or build theory.Types of subjects of case studiesThere are typically five types of subjects. Whether it is an instrumental or intrinsic casestudy, each kind of case study uses subjects. I am going to mention different subjects below:PersonThis type of case studies focuses on a specific person. The best example of person case would be “Genie” case. Genie was only 13 years old when she was discovered in Los Angeles in 1970. Her father believed her to be mentally retarded and locked her in an empty room without any sort of stimulation. When she was discovered, psychologist wanted to know everything about her physical, emotional and mental health. They were interested in knowing her language skills. But when she was found, she had no form of language. A study was conducted on her. The objective was to see whether she was able to acquire language skillsat the age of 13. After that, she was placed in a hospital under the observation. This case study is still one of the most valuable.GroupThis type of study focuses on a group of people. Group can be family, company or even colleagues. An example of such kind of case study would be tribes living in African forests. These tribes have never had any modern contact. Therefore, many researchers take a deep interest in studying them.LocationThis type of study focuses on a place and the manner in which this place is related to people. For example, many studies have focused onSiberia, and people who live there. Siberia is very cold and barren place in Russia. Also, it is considered one of the most challenging place to live. Studying such area, and its climate can help people learn how to cope up with extreme weather and conditions.OrganizationThis sort of study focuses on a business or an organization. This could also include people working on the organization, or an event occurred at the organization. There are many studies which provide insights into a collapse of an organization. Such studies are essential as they help other companies to sustain and flourish.EventThis type of studies focuses on an event and how it affects the people. One of the significant studies which covered an event was of September 11th. The event in itself was very popular. Many studies were conducted on it. It was important to know what elements initiated such event and how to control such activities from happening in future. Related studies are not only important for US government but also other nations who want to prevent terrorism.Final wordsThis article tried to shed light on the information about the case study. From how to write a case study to types of case studies, this article everything about the case study. Case studies are considered useful in research as they provide insightful information about a particularcase (subject). Case studies from various disciplines and domains are widely published. Thanks for reading.。

如何做研究 how to do research

∙麻省理工学院人工智能实验室AI Working Paper 316 1988年10月来自MIT人工智能实验室:如何做研究?作者:人工智能实验室全体研究生编辑:David Chapman版本:1.3时间:1988年9月译者:柳泉波北京师范大学信息学院2000级博士生摘要本文的主旨是解释如何做研究。

我们提供的这些建议,对做研究本身(阅读、写作和程序设计),理解研究过程以及开始热爱研究(方法论、选题、选导师和情感因素),都是极具价值的。

Copyright 1987, 1988 作者版权所有备注:人工智能实验室的Working Papers用于内部交流,包含的信息由于过于初步或者过于详细而无法发表。

不像正式论文那样,会列出所有的参考文献。

1. 简介这是什么?并没有什么神丹妙药可以保证在研究中取得成功,本文只是列举了一些可能会有所帮助的非正式意见。

目标读者是谁?本文档主要是为MIT人工智能实验室新入学的研究生而写,但对于其他机构的人工智能研究者也很有价值。

即使不是人工智能领域的研究者,也可以从中发现对自己有价值的部分。

如何使用?要精读完本文,太长了一些,最好是采用浏览的方式。

很多人觉得下面的方法很有效:先快速通读一遍,然后选取其中与自己当前研究项目有关的部分仔细研究。

本文档被粗略地分为两部分。

第一部分涉及研究者所需具备的各种技能:阅读,写作和程序设计,等等。

第二部分讨论研究过程本身:研究究竟是怎么回事,如何做研究,如何选题和选导师,如何考虑研究中的情感因素。

很多读者反映,从长远看,第二部分比第一部分更有价值,也更让人感兴趣。

? 小节2 如何通过阅读打好AI研究的基础。

列举了重要的AI期刊,并给出了一些阅读的诀窍。

? 小节3 如何成为AI研究领域的一员:与相关人员保持联系,他们可以使你保持对研究前沿的跟踪,知道应该读什么材料。

? 小节4 学习AI相关领域的知识。

对几个领域都有基本的理解,对于一个或者两个领域要精通。

How to do research

ASK THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

• All data is equal unless you discriminate among it with questions • Cannot find an answer without a question • Asking the right question is critical to doing good research • Need to refine the relevant questions and focus on the most important one(s) • The question is the focus of research

DECIDING ON A PURPOSE

• What do I intend to do in this paper?

– Describe and analyze how something is done? – Discover what happened at a particular time and place? – Understand and explain a concept? – Marshall evidence to persuade others on a particular point of view?

TURN YOUR RESEARCH NOTES INTO PRECISE QUESTIONS

• What do you need to know? • What specific questions must be answered to write this paper? • What--specifically--do you need to find out to do this? Where can you find it? • If you don’t need it for the paper, don’t use it in the paper!

case study 的指南

case study 的指南Case Study的指南导言:Case Study(案例研究)是一种常见的研究方法,用于深入了解特定情境、问题或组织,并提供解决方案。

本文将为您提供一份Case Study的指南,帮助您撰写一篇符合要求的案例研究报告。

一、引言在引言部分,您需要简要介绍案例研究的背景和目的。

明确阐述研究的目标,解释为什么选择该案例,并简要描述研究方法。

二、案例背景在案例背景部分,您需要详细描述研究的案例。

包括案例所在的行业、公司或组织的背景信息,如公司规模、产品或服务等。

同时,提供案例中的具体问题或挑战。

三、问题分析在问题分析部分,您需要对案例中的问题进行分析。

通过收集和整理相关数据和信息,对问题进行梳理和分类,并分析问题的原因和影响。

四、解决方案在解决方案部分,您需要提出解决问题的方法和策略。

确保您的解决方案与案例的背景和问题相符,并基于相关理论或实践经验进行支持。

在描述解决方案时,可以使用实例或案例来说明。

五、实施和结果在实施和结果部分,您需要详细描述实施解决方案的过程和取得的结果。

说明实施的步骤、时间和资源投入,并提供可量化的结果和效益。

六、讨论和总结在讨论和总结部分,您需要对解决方案的有效性和可行性进行讨论。

分析解决方案的优点和局限性,并提出改进和发展的建议。

最后,总结案例研究的主要发现和结论。

七、结论在结论部分,简洁明了地总结整个案例研究的内容和结果。

强调解决方案的重要性和价值,并提出进一步研究的方向。

八、参考文献在参考文献部分,列出您在案例研究中使用的参考资料。

确保引用格式正确,并按字母顺序排列。

九、附录在附录部分,可以提供一些案例研究中使用的补充材料,如调查问卷、访谈记录等。

确保附录内容与案例研究的主要内容相关。

总结:本文为您提供了一份Case Study的指南,帮助您撰写一篇符合要求的案例研究报告。

通过按照指南的结构和要点进行撰写,您可以清晰地描述案例背景、问题分析、解决方案、实施和结果等关键内容,使读者能够全面了解您的研究成果。

【海归招聘会】咨询公司面试的Case Study,这样做准能过

【海归招聘会】咨询公司面试的Case Study,这样做准能过●●●想从100个candidate中,脱颖而出?那么,你必须知道如何搞定面试的案例分析环节(Case Study)。

咨询公司和投资银行的申请人背景大同小异,真正起到筛选作用的是面试中案例分析环节。

过去三年,我曾在三家咨询公司干过,目前我们正在招收管培生项目。

这里是一些关于面试的建议。

●●●勤能补拙,请多加练习!事实上,没人有这方面的天资。

这是一门需要后天练习的学问。

一旦进入到分析员的角色里,公司会提供资源对这部分员工进行培训,让他们适应公司的研究方法论。

所以,在面试阶段,候选人必须展示对案例分析的基本认识和日后的发展潜力。

面试官希望看到你能够通过逻辑缜密和高效的方法解决问题。

面试之前,你必须熟谙申请公司官网的客户及其信息,竞品的信息也必须同时关注。

所有成功的候选人在之前都有练习,正是不断的练习让他们在面试中胸有成竹。

其实,最好的练习就是参与面试。

在面试中,无论是面试官的明示或是暗示,你都可以得到反馈和指导。

如果你得到了这样的讯号,那么就坦然地接受并作出改变,或者你也可以说明你的方法为什么更好。

你对问题的反应能力也是面试官考核的一个方面。

●●●建模是开始面试之前,你必须学习掌握所有分析问题的模板。

举个简单的例子,你必须知道怎样将成本拆分成可变成本和不可变成本,或是把收入拆解成定价和数量。

然后再尝试通过更加具体的方式,比如市场营销的4P模式来解决问题。

面试官希望你知道一些方法论或是商业模式,因为咨询公司天天都在使用它们。

这些方法论或是模式让你的思考更加有结构,帮助你更快的得到几个“相互独立,完全穷尽”(MECE)的选择来解决问题。

然而,面试过程中,千万别做以下两件事。

一,千万别解释你的模板或是使用的原因。

模板只是为了建构你的答案,毕竟客户只关注如何解决问题而不是解决问题所采用的模板。

所以把面试官当成你的客户吧!二、跳出惯性思维的圈子。

运用已知的模板解决未知的问题,这正是一流咨询公司引以为傲之处。

案例研究设计与方法Case Study Research Design and Methods

案例研究设计与方法Case Study Research Design andMethodsCase Study Research. Design and Methods (1994, Second edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage)By Robert K. YinSummaryGeneral characteristics, When to use case study method?1) The type of research question: typically to answer questions like “how”or “why”2) Extent of control over behavioural events: when investigator hasalittle/no possibility to control the events3) General circumstances of the phenomenon to be studied: contemporaryphenomenon in a real-life context, Case study is an empirical inquiry, in which:-Focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context &boundaries between phenomenon and its context are not clearly evident, Suitable for studying complex social phenomena-Procedural characteristics in the situation include: Many variables ofinterest; multiple sources of evidence; theoretical propositions to guide thecollection and analysis of data-Types of case studies might be: explanatory; exploratory; descriptive-Designs can be single- or multiple-case studies-Used methods can be qualitative, quantitative, or both, Typical criticisms towards case studies & correcting answers: -Lack of systematic handling of data -> Systematic reporting of all evidence-No basis for scientific generalization -> Purpose is to generalize to theoreticalpropositions, not to population as in statistical research-Take too long, end up with unreadable documents -> Time limits & writingformula depend on the choices of investigatorsCase study research design, Central components of a case study design & their functions:1) A study’s questions –“how”, “why”2) Study’s (theoretical) propositions – pointing attention, limiting scope,suggesting possible links between phenomena3) Study’s units of analysis – main units must be at the samelevel as thestudy questions & typically comparable to those previously studied4) Logic linking the data to the propositions – matching pieces ofinformation to rival patterns that can be derived from the propositions5) Criteria for interpreting the findings – iteration between propositionsand data, matching sufficiently contrasting rival patterns to data; thereis no precise way of setting the criteria1Research design links the data to be collected and conclusions to be drawn to theinitial questions of the study – it provides a conceptual framework & an action planfor getting from questions to set of conclusions., Preliminary theory & blueprint of the study: having solved thefive stepsmentioned above leads to the formation of a loose theory & a blueprint relatedto the topic of study-Initial theory & understanding of what is being studied is necessarybefore any field contacts; the complete research design embodies a “theory”of what is being studied, Deciding between explanatory, exploratory and descriptive designs: -Depends on the richness of the rival propositions in theoriesrelated to thetopic of the study; richest theories allow explanatory designs-> Search for theoretical propositions that can be elaborated to cover studyquestions, propositions, units of analysis, data-proposition links & criteria ofinterpretation-> Reviewing literature, discussing with investigators, asking challengingquestions, thinking what is to be learned from the study-> Being aware of the range of theories & selecting the requiredlevel(individual, organization, societal)-> Construction of the design / conceptual framework takes time &can bedifficult, but is a crucial step for the success of the study, Selection of the cases:-Cases should be selected in the same way as the topic of an experiment isselected-> Developed preliminary theory is used as a template with which to comparethe characteristics & empirical findings from the case(s)-> Selected cases should reflect characteristics & problems identified in theunderlying theoretical propositions / conceptual framework, The level of generalization of the study results = appropriately developedpreliminary theory / study design-Mode of generalization = theory-related analytic generalization, notstatistical-Analytic generalization possible from one or more casesHOW MANY OF CASES & UNITS OF ANALYSIS?1) Case – represents somehow the interesting topic of the study empirically (e.g.the role of the United States in the world economy) 2) Unit of analysis – is the actual source of information: individual, organizational document, artifact, for example (e.g. the capital flow betweencountries, an economic policy)1) Cases:A) Single cases – if case seems to represent a critical test to existing theory;rare or unique events -> Important to select case & unit of analysis properly2B) Multiple cases –if a “replication logic” is supposed to reveal support for theoreticallyi. Similar resultsii. Contrasting results for predictable reasons-> Theoretical framework must identify clearly the conditions, when aparticular phenomenon is likely to be found (i.) and when it is not likely (ii.)-> Theoretical framework is the vehicle for generalizing to new cases; ifempirical cases do not work as predicted, modifications must be made to thetheory-> Number of case replications depends upon the certainty wanted to achieve& richness of the underlying theoretical propositions2) Units of analysis:A) Holistic designs – include a single unit of analysis; if aim is to study the global nature of the phenomenon; when no logical sub-units can be pointed ->danger of abstractnessB) Embedded designs – include multiple units of analysis; study may includemain & smaller units on different levels -> looking for consistent patterns ofevidence across units, but within a case, Note: The flexibility of case study design is in selecting cases different fromthose initially identified, not in changing the purpose or objectives of thestudy to suit the casesConducting case studies, Desired skills of the investigator:-Good knowledge of the phenomenon (->collection procedures are not routinized)-Sensitivity for novel & unexpected issues in data collection-Asking good questions-Being a good “listener” -Adaptiveness & flexibility, A case study protocol should be essential part of every case study project - A protocol contains the instrument for the research, but also the proceduresand general rules that shoud be followed using the instrument:- Overview of the study project (objectives, issues, readings,literature & research)- Field procedures (access to field sites, sources of information) - Case study questions posed to INVESTIGATORS; keyclassifications; suggestions for likely sources of evidence (not the literal questions to be asked)- A guide for the case study report- Note: Case study protocol should be co-authored by all study investigators, Important to identify different levels of questions:A) Single case -level1. Questions asked of specific interviewees32. Questions asked of the individual caseB) More general levels1. Findings across multiple cases2. Findings across an entire study (including reviewed literature)3. Normative questions about policy recommendations & conclusions, Sometimes a pilot study may provide useful helpCollecting the evidence, Six sources of evidence:1) Documents (letters, agendas, progress reports)2) Archival records (Service records, organizational charts, budgets etc.)3) Interviews (typically open-ended, but also focused, structured &surveys are possible)4) Direct observations (formal or casual; useful to have multipleobservers)5) Participant observation (assuming a role in the situation &getting aninside view of the events)6) Physical artefacts, Three principles of data collection:1) Use multiple sources of evidence-Triangulation = searching converging findings from differentsources ->increases construct validity2) Create a case study database-A database separate from the final report to be written, containing - Case study notes (clear & available for later use)- Case study documents- Tabular materials (collected & created)- Narratives (initial open-ended answers to the study questionssuggested by investigators)3) Maintain a chain of evidence-> The link between initial study questions and case study procedureshould be pointed out in the case study protocol, as also the circumstancesof the evidence to be collected-> Putting the data collection to practice on the basis of the protocol-> Actual evidence storage in the database for later checks (specificcollection circumstances indicated)-> Sufficient citing of the case study data base & evidence in the finalreport and conclusions to be drawnAnalysing the evidenceAnalysis of evidence is one the least developed and most difficult aspects of doingcase studies. Most important is to have a general analytic strategy, which helps tochoose among different techniques. In absence preliminarytechniques – matrixes,4tabulation of frequencies, temporal schemes etc. – can be tried out to get the analysisstarted., Two general analytic strategies:1) Relying on theoretical propositions: theoretical orientation guidingthe analysis; following theoretical propositions that have formed thedesign of the case study -> helps to focus attention on certain data &to ignore other data2) Developing a case description: a descriptive framework fororganizing the case study; analysis organized on the basis ofdescription of the general characteristics and relations of the phenomenon in question, Analytic techniques to be used as part of the general strategy:1) Pattern matching (explanatory / descriptive)-Comparing empirically based patterns with predicted one(s)a) Expected outcomes as a pattern: comparing if theinitially predicted results have been found andalternative patterns are absentb) Rival explanations as patterns: searching if some of thetheoretically salient explaining conditions might bearticulated in empirical findings; then the presence ofcertain explanation should exclude the presence ofothersc) Simpler patterns: pattern matching is possible also withonly few variables, if the derived patterns are predictedto have enough clear differences2) Explanation-building (mainly explanatory)-Analyzing case study data by building an explanation about the case & identifying a set of causal links-Explanation is a result of series of iterations:Initial theoretical statement -> Comparing findings of an initial case ->revising statement -> Comparing details of the case -> Revising -> Comparing to other additional cases-Note: Danger of drifting away from original topic of interest3) Time-series analysis-“How”- and “why”- questions about relationships & changes of events over time-Identifying theoretically proposed sequences of an event that are expected to lead to a certain outcome; identification of events must bedone before the onset of the investigation->Comparing this trend with the trend of empirical data points -> Comparing with some rival trend to rule alternatives out, Analysis should show that:It relied on all the relevant evidence; all major rival interpretations are dealt;most significant issue of the study is addressed; prior expert knowledge isbrought to the study 5。

how to Design Case Studies(中英文版)

结构有效性 Construct Validity

建立起正确的操作方法

Establishing correct operational measures for the concepts being studied

案例研究受到质疑的地方是,数据收集过 程中充满主观判断

Case studies are often criticized that subjective judgement is used collecting data.

假设Propositions

Directs attentions on what to examine in the study

比问题更加具体More concrete than questions 强迫研究处在一种正确的方向Forces the study in the ―right‖ direction 在探索性研究中,也可以没有假设In exploratory studies - no propositions

调查真实情境下的当代现象

Investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context 现象与环境之间并不非常清晰的边界 the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not cleraly evident

关于案例研究

About Case Studies

什么时候使用案例研究法

When to use a CS? 回答“怎么样” 和“为什么” In answering ‖how‖ and ‖why‖ questions 存在多种信息来源 Relies of multiple sources of evidence 基于先前的理论假设,指导数据收集和分析 Benefits from prior theoretic propositions, guiding data collection and analysis

How to write Case Study 如何写好案例分析

How to Write a Case StudyWhat Is a Case Study?A case study is a puzzle that has to be solved. The first thing to remember about writing a case study is that the case should have a problem for the readers to solve. The case should have enough information in it that readers can understand what the problem is and, after thinking about it and analyzing the information, the readers should be able to come up with a proposed solution. Writing an interesting case study is a bit like writing a detective story. You want to keep your readers very interested in the situation. A good case is more than just a description. It is information arranged in such a way that the reader is put in the same position as the case writer was at the beginning when he or she was faced with a new situation and asked to figure out what was going on. A description, on the other hand, arranges all the information, comes to conclusions, tells the reader everything, and the reader really doesn't have to work very hard.When you write a case, here are some hints on how to do it so that your readers will be challenged, will "experience" the same things you did when you started your investigation, and will have enough information to come to some answers.There are three basic steps in case writing: research, analysis, and the actual writing. You start with research, but even when you reach the writing stage you may find you need to go back and research even more information.The Research Phase:1. Library and Internet research. Find out what has been written before, and read the important articles about your case site. When you do this, you may find there is an existing problem that needs solving, or you may find that you have to come up an interesting idea that might or might not work at your case site. For example, your case study might be on a national park where there have been so many visitors that the park's eco-system is in danger. Then the case problem would be to figure out how to solve this so the park is protected, but tourists can still come. Or, you might find that your selected site doesn't have many tourists, and one reason is that there are no facilities. Then the case problem might be how to attract the right kind of businesses to come and build a restaurant or even a hotel -- all without ruining the park.Or your case study might be on historic sites that would interest tourists–IF the tourists knew where the sites were or how to get to them. Or maybe your case study is about how to interest people in coming to your country so they can trace their family’s historic roots (origins).Once you have decided on the situation or issue you would like to cover in your case study (and you might have several issues, not just one), then you need to go to the site and talk to experts.2. Interview people who know the place or the situation. Find knowledgeable people to interview -- they may be at the site itself or they work in a government office or company that deals with the historic preservation. In addition to people who work in the site, talk to visitors. When you are interviewing people, , ask them questions that will help you understand their opinions, questions like the following:"What is your impression of the site (maybe it’s an old fort, or a burial site, or an excavation of historic interest)?""How do you feel about the situation?""What can you tell me about how the site (or the situation) developed?""What do you think should be different, if anything?You also need to ask questions that will give you facts that might not be available from an article, questions like:"Would you tell me what happens here in a typical day?""What kind of statistics do you keep? May I have a copy?"How many businesses are involved here?"When you ask a question that doesn't let someone answer with a "yes" or a "no" you usually get more information. What you are trying to do is get the person to tell you whatever it is that he or she knows and thinks -- even though you don't always know just what that is going to be before you ask thequestion. Then you can add these facts to your case. Remember, your readers can't go to your site, so you have to "bring it to them."The Analysis Phase:1. Put all the information in one place. Now you have collected a lot of information from people, from articles and books. You can't include it all. So, you need to think about how to sort through it, take out the excess, and arrange it so that the situation at the case site will be understandable to your readers. Before you can do this, you have to put all the information together where you can see it and analyze what is going on.2. Assign sections of material to different people. Each person or group should try to figure out what is really important, what is happening, and what a case reader would need to know in order to understand the situation. It may be useful, for example, to put all the information about visitors on one chart, or on a chart that shows visitors to two different sites throughout a year.3. Try to formulate the case problem in a few sentences. When you do this, you may find that you need more information. Once you are satisfied with the way you have defined the problem you want your readers to think about, break the problem down into all its parts. Each one represents a piece of the puzzle that needs to be understood before the problem can be solved. Then spend some time discussing these with the others in your group.For example, suppose:a. Your heritage site doesn't have many visitors, but many people say they would like to visit if it had servicesb. There is unemployment in the village around the site,c. The town is big enough to be able to accommodate many more visitors, andd. The surrounding environment (animals, trees and plants) need to be protected from too many visitorse. The town is far away, but there are no places to eat or sleep around theref. The government owns the location, but the government does not want to own and operate either a restaurant or a hotel Ask yourselves: “How much information do people who will read your case study need to have in order to be able to discuss items a through f?One answer to "a." is that they need to know data about past numbers of visitors, and they need to know what evidence exists that more people want to visit but are discouraged from going there. Your evidence will come from the articles and statistics you have gathered, and from the interviews you have completed.Once you have broken down the problem into pieces, you can analyze the information you now have and see if you can think about possible answers to each of the pieces. If you have enough information, then you can think about how to write the case study itself.There are usually eight sections in a case study:Synopsis/Executive Summary• Outline the purpose of the case study• Describe the field of research – this is usually an overview of the company• Outline the issues and findings of the case study without the specific details• Identify the theory that will be used.• Here, the reader should be able to get a clear picture of the essential contents of the study.• Note any assumptions made (you may not have all the information you’d like so some assumptions may be necessary eg: “It has been assumed that...”, “Assuming that it takes half an hour to read one document...”)Findings• Identify the problems found in the case. Each analysis of a problem should be supported by facts given in the case together with the relevant theory and course concepts. Here, it is important to searchfor the underlying problems for example: cross-cultural conflict may be only a symptom of the underlying problem of inadequate policies and practices within the company.• This section is often divided into sub-sections, one for each problem.Discussion• Summarise the major problem/s• Identify alternative solutions to this/these major problem/s (there is likely to be more than one solution per problem)• Briefly outline each alternative solution and then evaluate it in terms of its advantages and disadvantages• No need to refer to theory or coursework here.Conclusion• Sum up the main points from the findings and discussionRecommendations• Choose which of the alternative solutions should be adopted• Briefly justify your choice explaining how it will solve the major problem/s• This should be written in a forceful style as this section is intended to be persuasive• Here integration of theory and coursework is appropriateImplementation• Explain what should be done, by whom and by when• If appropriate include a rough estimate of costs (both financial and time).References• Make sure all references are sited correctlyAppendices (if any)• Note any original data that relates to the study but which would have interrupted the flow of the main body.。

case studies 和case study

案例研究(Case Studies)是一种深入研究特定主题的方法,它通常包括对特定个体、组织或事件的详细调查和分析。

案例研究的目的是通过对具体案例的深入研究,去揭示某一问题或现象的本质和特点。

案例研究方法被广泛应用于各个领域,包括商业、管理、心理学、教育及社会科学等。

在实际应用中,案例研究往往被视为一种重要的调查方法,能够帮助研究人员深入了解和分析研究对象的具体情况,从而得出更加客观和全面的结论。

一、案例研究的特点1.案例研究的独特性案例研究通常涉及对具体个体、组织或事件的深入分析,因此每个案例都具有独特性。

研究人员通过对特定案例的全面观察和分析,可以揭示出该案例的特殊特点和规律,从而更好地理解研究对象及其背后的原因和影响。

2.案例研究的全面性案例研究方法可以提供对研究对象的全面了解,包括其历史、背景、发展过程、问题及影响等方面。

通过对案例的全面观察和分析,研究人员可以更好地把握研究对象的整体情况,从而得出更加全面和客观的结论。

3.案例研究的综合性案例研究方法通常需要跨学科的知识和方法,因为对特定案例的深入分析涉及多个领域的知识和技能。

研究人员需要结合多种研究方法和工具,如定性分析、定量分析、文献调研、专家访谈等,来从不同角度深入研究案例,从而得出更加全面和准确的结论。

二、案例研究的应用1.商业管理领域在商业管理领域,案例研究常常被用于分析市场营销策略、管理决策、组织变革等方面。

通过对成功或失败案例的深入分析,管理者可以从中汲取经验教训,为自己的决策提供参考和借鉴。

2.心理学领域在心理学领域,案例研究通常被用于临床实践和心理疾病研究等方面。

通过对个体或裙体的案例深入观察和分析,心理学家可以更好地理解心理问题的本质和规律,为临床实践提供指导。

3.教育领域在教育领域,案例研究被广泛应用于教学实践和教育改革等方面。

通过对学生、教师、学校及政策的案例进行深入分析,教育研究者可以更好地了解教育问题的本质和特点,为教学实践和政策制定提供依据。

如何撰写案例分析(CaseStudy)的内容

如何撰写案例分析(CaseStudy)的内容下面是在写案例分析时,给读者思考问题的空间,同时又能很好地了解你所描述的问题,并且提供足够信息推导出结论的一些建议:在写作时有三个基本步骤:前期调研、整理分析和实际写作。

写作要从研究调查开始入手,但即使正式进入了写作阶段,我们也需要回过头去进行调研工作。

前期调研1.图书馆和互联网调研。

找出以前别人写过的文章,并着重阅读与你的研究内容相关的重点部分。

在阅读的同时,我们会发现一些有待提出解决方案的问题,又或者我们可能会得出一些与自己主题相关或无关,但却很有趣地思路。

举个例子,假如我们想针对一个国家公园的游客过多以至于该公园得生态系统受到了威胁写案例分析,那么下一步我们面临的问题就是:如何在不影响游客数量的情况下保护该公园的生态系统。

也有可能,我们发现在选择的案例中,这个公园的游客并不多,导致游客匮乏的原因之一是该公园的基础设施建设不够完善。

因此,这时这个案例分析应该研究的问题就是:如何在不破坏公园生态系统的情况下吸引合适的投资方来开设一家餐厅甚至建设一幢酒店。

再比如,我们案例可能是一处历史遗迹,问题是如何提高自己的知名度。

首先我们要让游客知道遗迹在哪,还有如何去,以此来吸引游客参观。

又或者,我们研究课题可能是如何吸引游人来一些村庄探寻家族的历史。

一旦我们决定了研究方向或者在案例分析中包含的问题(可能不只是一个,而是有好几个问题),那么我们需要就研究目标与专家交流。

常用问题如下:“你对这里的印象如何?”“你怎么看待这种情况?”“你能告诉我这里需要如何发展?”“你觉得这里有什么需要改进?”你也需要提出一些不能从文章中知道的问题,如:“你能和我讲讲这里的日常吗?”“你有关于什么的统计数据?可以给我一份吗?”“这里有多少企业?”这里有个小技巧:提出那些不能简单地用“是”或“不是”来回答的问题,也就是尽量使自己的问题具有开放性,这样会让回答问题的人给我们提供更多的信息。

how to research 如何做研究

Open University Press Buckingham .PhiladelphiaHOW TO RESEARCH SECOND EDITION Loraine Blaxter,Christina Hughes andMalcolm TightOpen University PressCeltic Court22 BallmoorBuckinghamMK18 1XWemail: enquiries@world wide web: and325 Chestnut StreetPhiladelphia, PA 19106, USAFirst Published 2001Copyright © Loraine Blaxter, Christina Hughes and Malcolm Tight, 2001All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Copyright Licensing Agency Limited. Details of such licences (for reprographic reproduction) may be obtained from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd of 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, W1P 0LP.A catalogue record of this book is available from the British LibraryISBN0 335 20903 3 (pb)0 335 21121 6 (hb)Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataBlaxter, Loraine, 1945–How to research / by Loraine Blaxter, Christina Hughes, and MalcolmTight. – 2nd ed.p.cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0–335–20903–3 (pbk.)1.Research—Methodology.I.Hughes, Christina, 1952–II.Tight, Malcolm. III.Title.Q180.55.M4 B592001001.4′2–dc2100-068920 Typeset by Graphicraft Limited, Hong KongPrinted in Great Britain by Biddles Limited, Guildford and King’s LynnCONTENTSList of exercises viii List of boxes x Acknowledgements xiv 1Thinking about research1 Introduction1 What is research?2 Why research?9 What is original?13 Truth, power and values14 How to use this book16 What is different about this edition?19 Summary19 Further reading19 2Getting started21 Introduction21 Choosing a topic22 What to do if you can’t think of a topic30 Focusing34 Finding and choosing your supervisor43 Individual and group research46 Keeping your research diary48 Summary51 Further reading513Thinking about methods 53Introduction53Everyday research skills 54Which method is best?59Families, approaches and techniques 62Action research 67Case studies 71Experiments 74Surveys77Which methods suit?79Deciding about methods 85Summary86Further reading874Reading for research 97Introduction 97Why read?98Coping with the research literature 98Basic reading strategies 100Using libraries 104Using the Internet 107Good enough reading111Reading about method as well as subject 117Recording your reading 119The literature review 120Issues in reading 123Summary127Further reading1285Managing your project 130Introduction 130Managing time131Mapping your project 133Piloting135Dealing with key figures and institutions 137Sharing responsibility142Using wordprocessors and computers145Managing not to get demoralized when things do not go as planned148Summary150Further reading1516Collecting data 153Introduction153Access and ethical issues 154Sampling and selection161Applying techniques to data collection 164Documents167vi Contents 士气低落Interviews 171Observations 176Questionnaires179Recording your progress182The ups and downs of data collection 185Summary188Further reading 1887Analysing data192Introduction192The shape of your data 193The nature of data 196Managing your data 202Computer-based analysis 203The process of analysis 205Analysing documents 207Analysing interviews 210Analysing observations 212Analysing questionnaires 215Interpretation 218Summary222Further reading2228Writing up227Introduction227Drafting and redrafting 228How to argue 234How to criticize238Whom am I writing for?240Grammar, punctuation and spelling246Using tables, diagrams and other illustrations 247Panics 247Summary250Further reading 2519Finishing off253Introduction253Planning to finish?254The penultimate and final drafts 255Added extras 258The process of assessment 261What do I do now?267Summary269Further reading270References 277Index284Contentsvii 倒数第二1THINKING ABOUTRESEARCHIntroductionThis book is about the practice and experience of doing research. It is aimed at those, particularly the less experienced, who are involved in small-scale research projects. It is intended to be useful to both those doing research, whether for academic credit or not, and those responsible for teaching, supervising or man-aging new researchers.The book is written in an accessible and jargon-free style, using a variety of different forms of presentation. The text has been divided into relatively small, linked sections. It is supplemented by a series of exercises, designed to help you progress your research thinking. It has been illustrated by the inclu-sion of a range of examples, lists, diagrams and tables in ‘boxes’, as well as through the inclusion of hints and relevant quotations from researchers in the text.Suggestions for further reading are listed at the end of each chapter, with an indication of their contents. A list of the references used in the text is provided at the end of the book.The book focuses on process rather than just methods, though these are also considered. It aims to demystify research, recognizing the everyday skills and techniques involved. It presents research as a series of stages, but without sug-gesting that the research process is either simple or linear.The book is multidisciplinary in scope. It is designed to be suitable for those undertaking research in the social sciences, as well as in related subjects such as education, business studies and health and social care.荣誉写作目的易懂的建议非神秘化2Thinking about researchThe purpose of this opening chapter is to explore the nature of the research process in the social sciences, to outline the contents of this book and to suggest how you might make use of them. The chapter is organized into the following sections:•What is research? Different understandings of the nature of research, and of who can do it.•Why research? Your motivations for undertaking research.•What is original? Debunking the idea of originality.•Truth, power and values. The context for your research.•How to use this book. What you will find in it, and how to make your way through it.•What is different about this edition? What has changed, and what has been added, since the first edition.The chapter ends with a summary.What is research?The nature of researchWe see and hear headlines and stories like those reproduced in Box 1 every day.Research and its results are indeed familiar to us.You will have had research findings presented to you many times – through books, newspapers and television programmes – in the form of theories, articles or reports. Thus we learn, for example, that the United Kingdom has the highest divorce rate in Europe, or that the price of cars and petrol is also relatively high here. If you are, or have been, a student, you may have written many essays or assignments which ‘compare and contrast ’ or ‘critically analyse ’ the research of others.We are also continually in contact with research as workers and citizens.Changes in our working practices are justi fied by the reports of in-house re-search teams, or those of external consultants. Outside of work, you may havetaken part in research through a consumer survey held in a shopping precinct on a Saturday afternoon. You will probably have taken part, whether directly or indirectly, in one of the most extensive research surveys conducted: the national census.So we may say to you that you are already an expert when it comes to being a recipient of research. You will certainly have opinions. You don ’t think so?Try Exercise 1: try yourself out!Now compare your answer to some of the common understandings of re-search listed in Box 2. Did your view match any of those we selected? If it did,we told you that you were already an expert! If you had a different view, well done!Do you think ‘I could never do research ’? Do you feel even the slightest sense of self-identity with this view? If so, read on. Our intention in this book is to区What is research?3Box 1:Research in the headlinesgive you the skills and the con fidence that you will require to take you success-fully from the initial idea to a completed piece of research.Let us continue by opening up your mind to some of the realities of doing research. In Box 3 you will find a list of some of the things about research whichExercise 1:Your own understanding of researchHow do you view research? Complete the following sentence in no more than 20 words to convey your view of research.Research is ...4Thinking about researchBox 2:Ten views of research 1Research is about proving your pet theory.2Research is something done by academics or experts.3Research is about establishing the facts.4Research is objective.5Research is about justifying what your funder wants to do.6Research can prove anything you want.7Research is time-consuming.8Research is scientific.9Research is removed from reality.10Research cannot change anything.Note :None of these views is necessarily endorsed by the authors.Box 3:Ten things you didn’t know about research 1Research is very time-consuming.2Research is subjective.3Research is often boring, but can also be fun.4Research can take over your life.5Research can be much more interesting than its results.6Research is about being nosey.7Research can be done in many ways.8Research uses everyday skills.9Research gets into your dreams.10Research can lead you in unexpected directions.your previous experience may not have told you. You may find it interesting to compare these with the views already listed in Box 2.Yes, you can do research! Many of the skills you need are commonplace and everyday. They include the ability to ask questions, to listen, to make notes and to think.Yet for many, students and non-students alike, there is no doubt that the very word ‘research ’ can be awe-inspiring. This may be particularly so for the new researcher, who can feel that to conduct and complete even a small-scale re-search study is well beyond their capabilities.爱追问的令人惊叹What is research?5Let us repeat: you can do research! The main lesson to learn is that you need to practice your skills, read and think about research, and to build up your con fidence. This book aims to help you in these processes.Types of researchPoint 7 in Box 3 states that research can be done in many ways. Even a brief review of writings on research will uncover a lengthy and potentially baf flinglist of types of research. These include, for example:•pure, applied and strategic research;•descriptive, explanatory and evaluation research;•market and academic research;•exploratory, testing-out and problem-solving research;•covert, adversarial and collaborative research;•basic, applied, instrumental, participatory and action research.The basic characteristics shared by all of these different kinds or views of research are that they are, or aim to be, planned, cautious, systematic and reli-able ways of finding out or deepening understanding.To illustrate further this variety of approach and interest, Box 4 describes a number of examples of research projects in the social sciences. Do any of these have similarities with the research which you are undertaking, or planning to undertake?令人困惑的Representations of the research processJust as there are a wide variety of views as to what research consists of, and great differences in actual practices as to what people research and how, so there are alternative perspectives of what the process of undertaking research should look like. A number of diagrammatic representations of the research process have been collected together in Box 5.What is research?78Thinking about researchSources:(a)Burgess (1993: 1).(b)Kane (1985: 13).(c)Rudestam and Newton (1992: 5).(d)Miles and Huberman (1994: 308).Why research?9 Clearly, all of these diagrams are both simplifications and idealizations of the research process. Real research is inevitably going to be a rather messier process. Nevertheless, Box 5 does suggest at least four common viewpoints:•Research is often presented as a fixed, linear series of stages, with a clear start and end. You may think, at first glance, that this book is also organized in a linear fashion. Take a closer look! You will find extensive cross-referencing, and different kinds of text and presentation. The book has been designed to make the reader’s use of it anything but linear.•There are also somewhat more complicated presentations of this linear view, which allow for slightly different routes to be taken through the process at particular stages.•Another common representation portrays research as a circular process,analogous to the more general process of learning. Much the same set of stages is included, and in much the same order, but there is an implication both that the process might be entered at a number of points, and that the experience of later stages might lead to a reinterpretation or revisiting of earlier stages.•There are also variants to this approach, often associated with action research, which see the research process as cyclical or iterative. Here, the process is shown as going through a number of cycles, the effects of each one impacting upon the way in which successive cycles are approached.Our preferred view builds on these representations, seeing the research process as a spiral (see Box 6). Seen from this perspective, research:•is cyclical;•can be entered at almost any point;•is a never-ending process;•will cause you to reconsider your practice;•will return you to a different starting place.The nature of the cycle varies between research designs. For example, in most quantitative research, decisions about analysis have to be taken before any fieldwork or data collection is undertaken. This is because the types of statistical techniques that are possible vary with the types of data collected. In the case of qualitative research, by contrast, data collection, sorting, analysis and reading can take place simultaneously.Why research?Understanding your motivation and selfSo why are you undertaking, or interested in undertaking, research? Think about your reasons and try to complete Exercise 2.Did you manage to think of six reasons? Did you think of more and run out of space? In our experience, people have at least three reasons for being10Thinking about researchBox 6:The research spiralinvolved in research; so, if you could only manage one or two, perhaps you might think again.Now compare the reasons which you identi fied with those expressed by experi-enced researchers. A selection of these is included in Box 7.Exercise 2:Reasons for undertaking researchList your reasons for your current or anticipated involvement in research. List as many as you can think of.123456Why research?11Box 7:Reasons for researching1Many of us study aspects of our autobiographies partially disguised as a ‘detached’ choice of an interesting problem.(Acker 1981: 96) 2Edwards quotes Acker and offers herself as an example. Her study of mature women students was not ‘motivated by academic concernalone...While to some extent they statistically noted the stresses thatI, along with others, had undergone, they told me nothing satisfactoryabout what had been going on in my life.’(Edwards 1993: 12)3 A few years ago I had some time off work to become a parent.Following this experience of leaving – and returning – I became excitedabout researching women’s experiences of leaving management jobs. Iwanted to tell the women’s stories from their perspectives...Thisseemed like research I personally had to do.(Marshall 1995: 23) 4My interest in the topic of on-the-job training (OJT) stems from my personal experience. When I worked on vocational training for peoplefrom developing countries, and dealt with the comments andrequirements from them, one of the most significant points wasthat there might be a difference between their and our (Japanese)concept of OJT.(Suzuki 1995: 1) 5Before university, and some of the way through it, I entertained grand but vague ideas about my future career all in the realm of changing theworld dramatically! However, I gradually became reconciled to anacademic future. The reconciliation was, of course, accompanied by abloated sense of the potential for social change of the right kind ofresearch, and in particular of my research project.(Hammersley 1984: 42) 6The research project had as its inception my own passage through that decade [the 1980s], and my own despair over the confused mess thatwhite feminist women’s response to charges of racism had collectivelybecome by 1983–84...as a white feminist, I knew that I had notpreviously known I was ‘being racist’ and that I had never set out to‘be racist’.(Frankenberg 1993: 2–3)As a researcher, you will find it useful to understand why you are involved in research. This will affect how you go about your research, and what you get out of it. If you are in doubt about your motivation, you might ask yourself the following questions:12Thinking about research•Where are you coming from?•Whose side are you on?•And where are you intending to get to?•Do you want to change the world, or to change your world?•Are you a pragmatist or an idealist?You may see yourself as a detached researcher, separate from the subjects of your research, an objective bystander who is there to chronicle what happens,find the solutions and make appropriate recommendations. Or you might see yourself as totally enmeshed in the subject of your research, an active partici-pant, committed to improving the circumstances of yourself and your colleagues through your work.In practice, you are unlikely to be at either of these extremes, but they are useful stereotypes. They suggest the extent to which your motivation may affect your openness to certain approaches to research, and perhaps even influence the kinds of findings you come up with. It is important to you, as a researcher, to be aware of these possible influences. To other people, including those who read and judge the results of your research, these influences may be far more obvious. Of course, it is possible that you could give no answer to Exercise 2. You may think of yourself as having no particular motivation for undertaking research. Perhaps you are doing it because your boss requires you to, or because it is an essential (but unwanted) part of a course you have signed up for. But even this suggests some motivation, if only to keep your boss happy or to try to get a particular qualification.But what might you do if you really feel you have no motivation? After all, if you aren’t motivated, or are not motivated very strongly, this will affect your drive to finish the research project successfully. The obvious answer to the researcher with no motivation is to get some quickly, or do something else! If the latter is not possible, you might seek motivation in one of the following ways:•by changing your research project to something you are more interested in;•by focusing on the skills you will develop through undertaking the research, rather than the output;•by incorporating within the research some knowledge acquisition of relevance to you;•by seeing the research project as part of a larger activity, which will have knock-on benefits for your work, your career, your social life or your life in general;•by finding someone who will support you and push you through until you finish;•by promising yourself a reward when it is successfully completed.What is original?13Exercise 3:Originality in researchComplete the following sentence in no more than 20 words:My research is original in...What is original?For many research projects, particularly those carried out for a university degree, there is often a need for some kind or level of originality. This will typically be expressed in regulations or guidance in very general terms: ‘an original project’,‘an original contribution’, ‘evidence of original thinking’.But what is originality? And where can you get some? If you are unsure, and it matters to you in your research, try Exercise 3.Were you able to answer the question in a way which you found satisfactory? In Box 8 you will find 15 definitions of originality, collected together by another author. Have a look at them, and see how they compare with your own answer.Box 8:Fifteen definitions of originalityHere are 15 definitions of originality, as put together by Phillips and Pugh. The first six are derived from a previous author, Francis, while the other nine derive from interviews with Australian students, supervisors and examiners.1Setting down a major piece of new information in writing for the first time.2Continuing a previously original piece of work.3Carrying out original work designed by the supervisor.4Providing a single original technique, observation or result in an otherwiseunoriginal but competent piece of research.5Having many original ideas, methods and interpretations all performed byothers under the direction of the postgraduate.6Showing originality in testing someone else’s idea.7Carrying out empirical work that hasn’t been done before.8Making a synthesis that hasn’t been made before.9Using already known material but with a new interpretation.10Trying out something in this country that has previously only been done in other countries.11Taking a particular technique and applying it in a new area.12Bringing new evidence to bear on an old issue.13Being cross-disciplinary and using different methodologies.14Looking at areas that people in the discipline haven’t looked at before.15Adding to knowledge in a way that hasn’t previously been done before.Source: Phillips and Pugh (2000: 63–4); partly after Francis (1976).14Thinking about researchAs the definitions quoted indicate, it is possible to be original in terms of topic, approach or presentation. The element of originality in your own research is, realistically, likely to very small. Highly original research is very unusual, and you are probably setting your sights far too high if you try aiming for it. The corollary of this is that your research is almost certainly original in some way, always providing, that is, that you are not slavishly copying someone else’s earlier research. So be reassured. But if you are in doubt, check it out with those who will judge the originality of your research as early as possible. This advice also applies if you fear that you may be being too original for comfort. If you want to complete a useful piece of research in a particular context, it would not be sensible to, for example, present it in a way which is unacceptable.Truth, power and valuesThe dominant tradition of the research-policy relationship in Britain sees research as providing objective, factual information which is handed over to policy-makers for their use...This approach therefore embodies a clear distinction between facts and values, and sees ‘fact-finding’ and ‘making value judgements’ as two separate activities which are pursued sequentially.(Finch 1986: 195) The meaning of subjectivity has had distinct power implications in the sense that it has been capable of dismissing many sorts of action and account which are not based on rationality, logic and objective procedure. These forms of action and account are...most likely to characterise the ‘others’ produced as different from white middle-class men: black and Third World people, working-class people and women.(Hollway 1989: 133) One memory that I would have sworn was ‘the truth and nothing but the truth’concerned a wagon that my brother and I shared as a child. I remembered that we played with this toy only at my grandfather’s house, that we shared it, that I would ride it and my brother would push me. Yet one facet of the memory was puzzling, I remembered always returning home with bruises or scratches from this toy. When I called my mother, she said there had never been any wagon, that we had shared a red wheelbarrow, that it had always been at my grandfather’s house because there were sidewalks on that part of town.(hooks 1989: 157) Many people coming to research for the first time have a tendency to think that they are in the business of establishing ‘the truth’ about a particular issue orTruth, power and values15Exercise 4:The context for your researchImagine you are doing research on experiences of training at work, whether within your own company or another.Would your findings be different if you approached your interviewees through:•the managing director?•the personnel manager?•the shop stewards’ committee?•the unemployed centre?How might they differ? How might this affect your conclusions? What if you had to write a report of your conclusions for each of these audiences?You can think about this as an exercise in finding out what is safe and what is risky in terms of expectations, theory, styles of writing etc.subject. They want to find out ‘the facts’, or want to ‘prove’ (or perhaps disprove) a particular argument. They believe that they can be ‘objective’ in their research, and that others will sit up and take notice when they present their findings. But research is not a wholly objective activity carried out by detached sci-entists. It is, as we have suggested, a social activity powerfully affected by the researcher’s own motivations and values. It also takes place within a broader social context, within which politics and power relations influence what research is undertaken, how it is carried out and whether and how it is reported and acted upon. If you don’t believe this, try Exercise 4.As Exercise 4 suggests, politics, power and values may be important con-siderations for your research as well, especially if you carry it out within your own or another organization. Your contacts will affect your access to the sub-jects of your research, may require you to submit your research proposals for scrutiny, and to revise them, and may exercise some veto over what you can actually write up or publish. If you are unlucky, misread the organizational politics or irritate the researched, you may find cooperation withdrawn part way through your project.So it is important to understand not just where you are coming from, but also where those you are seeking to research are coming from. Preparatory time spent in learning about this is almost always well spent, as well as being valuable contextual research in its own right.Rather than expecting to ‘find the truth’, it is probably better to think of research work in terms of words like rigour, reliability, professionalism and honesty. No one research project can realistically aspire to do more than advance our understanding in some way. Most researchers have to compromise their practices to fit into the time and other resources available for their studies. Doing research is, therefore, about producing something which is ‘good enough’. This does not mean, of course, that such research cannot be pursued with drive, passion and commitment; though it might also be pursued in a more detached。

case study 思路

case study 思路在解决问题的过程中,Case Study 是一个非常有效的工具。

其目的是通过分析某个特定案例的解决方案,来发现适用于类似问题的最佳实践。

下面就为大家介绍一下 Case Study 思路的步骤。

第一步:确定问题首先需要明确解决什么问题。

要想获得成功的答案,需要非常清楚地了解问题的性质与范围。

建议可以通过设定关键性问题并进行原因分析的方式来帮助梳理重点。

第二步:寻找合适的案例选择一个恰当的案例对解决这个问题是非常关键的。

应该选择那些在业务上或是功能上与问题相关的案例。

最好能选择那些成功解决了此问题的案例,以便于找到关键成功要素并进行借鉴。

第三步:收集信息这个阶段是收集资料的关键时期。

流程包括从多种途径搜集数据,并进行分析、调查、研究来获得尽可能清晰真实的数据。

可以使用多种方式,如:问卷调查、访谈/采访、现有文献、报告等。

第四步:记录与分析根据获得的资料进行分析并进行记录。

这个阶段有助于将获得的信息转换成有价值的见解。

建议在此阶段将记录的信息与企业自己的理念、价值观等进行对比,确保数据的完整性与可靠性。

第五步:提出解决方案将所有数据、信息、见解进行汇总,并提出解决方案。

应该将方案分解成容易跟踪的小步骤,并快速执行所提出的解决方案。

第六步:检验解决方案检验方案是否实施成功,需要在一定的期限内跟踪解决方案的实施情况,获得可操作的信息,并继续提出建议。

如果必要的话,可以修改和改进解决方案。

关键是了解解决方案的进展情况,以便取得实质性成果。

以上就是 Case Study 思路的相关步骤。

先要清晰的定义问题,然后根据确定的问题寻找合适的案例,并对案例进行资料的搜集和分析。

之后根据分析的结果提出解决方案,并进行实施及跟踪检验。

这种方法可以有效解决业务、管理以及产品上一系列的问题。

什么是案例研究 What is a Case study 英语作文论文写作技巧

什么是案例研究What is a Case studyThings you should knowabout itIn today’s education system, the whole academic process basically asks for creativity and productivity from the students. Our complete coursework involves assignment writing, dissertation writing and other stuff which demands hard research work from the students. The main purpose of these activities is to bring out the research skills and draw their interest in their course. Many new students who are clueless or lack research skills take help fromthe assignment help online services. These services make their work easier while saving a lot of their time. However, a student can show up their interest by adopting different research methods in their assignment or dissertation writing. One of them is- the Case study. But many of us might wonder, what is a case study? It is the best research method to demonstrate the efficiency in your research work. But very few of us knows about its importance.Hence in this article, I am hereby introducing you all with the necessary things about the Case study, such as:What is a Case studyImportance of Case study researchTypes of case studyHow to write a case studyWhat is a Case Study?Once Charles Horton Cooley in his research paper “The life-study method as applied to rural social research” defined the Case study method as:“Case study depends on our perception and gives clear insight into life directory.”A case study is a research methodology in which the researcher aims at the intensive study of a group or unit to draw a general conclusion out of it. It is also known as“research strategy,” a specific inquiry of a phenomenon in real- life context. This research method was first introduced in 1829 by an French sociologist-Frederic Le Play. The popularity of case study format has increased in the recent decades. As the word says, the research focuses on a real-life case, describes its problems, and gives a detailed analysis of how the problem is being solved in a sequential process.Case study method is a descriptive analysis of people, group, event or policies that are studied by using one or more processes. In this method, the researcher takes up an incident from real life context and goes for an in-depth investigation to find out the possible solution to the problem highlighted in the case study example. Theresearcher focuses on a single case to make detailed observations over a longer period. This is not possible with larger samples without investing lots of money. However, the case study seems quite economical comparatively.Importance of Case study ResearchBe it any subject like- Law, Medicine, Business, or Science; case study research plays a vital role in presenting best assignment or thesis to your professor. In online assignment help services, the writing experts use case studies to present the research work in an impressive way.Learning from real-life scenariosCase studies presents examples from real life scenarios. Hence it gives a realistic and complexfeeling to the readers. This real-life situation helps the readers to connect themselves with the situation and inspires to find out a solution in their real-life situations.As the case is discussed in the classroom, it gives an opportunity to the student to evoke their problem-solving technique to find out different solutions for that particular problem.It focuses on the customersCase studies are meant to do in-depth research to gather information about a specific group, unit or person specific. Hence, with case study examples customers or readers can get detailed information about the particular subject or topic.It demonstrates successin the case study, the researcher gives explicitly detail about everything. He/she goes forward to highlight the problem in a specific case and then describes each step to solve it. Hence it gives a chance to demonstrate success in stressful situations.It is comprehensiveUnlike the other research methods, Case study research gives an opportunity to the researcher to use various tools and techniques to get a solution to the problem discussed in the case. Hence this gives time and space to the researcher to think on the topic from every aspect.Hence, until now you got to know what is a case study and its importance. Let’s read further to know about its types.Types of Case studyA case study is quite useful for the researcher in their early stage, as it gives them an opportunity to explore different ideas, methods, and instruments, and to prepare for a more extensive study. In modern times, case study research is popular not only in the field of sociology, but also in the fields of psychology, education, political science, anthropology, and clinical science.However, different fields opt for different types of case study. Majorly there are four types of case studies, which as follows:Illustrative Case studiesThis type of case study is mainly descriptive in nature. In this method, the researcher takes up one or two instances from an event to show the set of circumstances and processes that are possible in similar kind of situations. This Case study method is used to make people aware of any situation, which is not well known to them.Exploratory (or pilot) Case studiesThe Exploratory case study primarily focuses on identifying the questions and helps the researcher to choose the method that would be useful, prior to the initial investigation. This method is useful in implementing on a large scale investigation.This type of case study is commonly preferred in Psychology and Social science. The psychologists try to innovate new methods to help their patients, and hence prefer exploratory case study to find out new theories and ideas.Cumulative Case studiesThis type of case study collects the information from different sources to formulate the case for a new study. The main purpose of this study is that the past studies allow them additional information for their new case without spending much time, efficiency and money on the additional study.For instance, suppose a researcher wants to work on the topic- “what type of behaviour makes animals comfortable with a veterinarian?”In order to draw a conclusion or sketch out the perfect answer for the question, the researcher would take up some 4-5 real cases. These cases would describe how a vet behaved with their patient. Hence the researcher can easily find out the possible answer for his/her research question. Eventually, this type of research can uncover the differences as well.Critical Instance Case studiesThis Case study method is used when the researcher wants to challenge a commonly set up assumption which can be wrong but cannot get proved due to the lack of critical understanding. It is used to examine the problems that accumulate into larger issues. This method is also useful if there is somespecial or unique event which got a special interest of the researcher.Before selecting the type of case study for your research work, it is essential to identify your purpose, goal, and approach to conduct sound and successful research. However, this sometimes may feel difficult for you. Hence, it is advisable to seek help from online websites who offer the best case study service to the folks. The writing experts are proficient in selecting the best suitable case study research method for your topic.How to write a case studyThere are few questions which are quite common among the new researchers. They find it difficult to find out general things about thecase study. I have tried to clear a few things about what is a case study and case study template. Now in this section, I am going to discuss how to write a case study. Here are few steps which you need to follow while writing a case study:1. Determine the case study typeAs we discussed in the above section, you are now acquainted with the different types of case studies. Every other field requires a different type of case study research. Hence you must determine the type of research work you are going to take. Before deciding the type of case study you want to demonstrate, it is essential for you to know what is a case study and what type of case study is suitable for your research work.2. Determine the topic for your case studyNow as you have chosen the type of case study, you should further move to decide your topic. Make sure that the topic is relatable to your subject, and you can find enough sources to help yourself in your research work.3. Follow the case study templateOnce you determine the topic for your case study, you need to follow the following case study format:Title pageThis section contains the title of your work, the name of the author and institution. In general, itlet the readers acknowledge your name and the topic of your research.AbstractThere are two types of abstract- narrative and structured.Thenarrative abstract is the summary of the whole research work. It is presented to give an idea about the content of the research work to the readers.Thestructured abstract is used in scientific studies.IntroductionThis is the first section. Hence the section provides an idea about the topic that is going to be discussed in the research work. It gives a clue in such an interesting way that it tempts the reader to go through the whole work. You can start with introducing the topic. Suppose you are writing on “Different types of ca se in Social sciences.” You can open the research work with a question such as- what is a case study? This will bring the curiosity in the minds of the readers and they will further go through your research work.PresentationHere the researcher presents the raw information he/she has collected during the case study.OutcomesHere the researcher comes up with a plan on how the problem discussed in the topic should be treated.ConclusionsIt is the last section, where the researcher gives his/her own thoughts about the problem discussed and his perception towards it.ReferencesThis section includes the name of the sources which helped you out during the case study method.Hence in this article, we discussed several basic things about the case study, beginning from what is a case study to its importance and types of the case study. I hope this will help you with your research work. Case study format could be a better option for those who can easily process information and can analyze the case study format to understand how it works. It will take less time and efforts for a researcher to complete the assignment quickly. There are several websites which provide service to new researchers to let them complete their case study research. However, if you want to write a case study on your own, you must go through the tips and techniques that are necessary for it.。

case study写法

case study写法

案例研究(Case Study)是一种研究方法,通过对一个或多个特定情境进行深入、全面的分析,以了解该情境中的问题和挑战,并探讨可能的解决方案。

以下是撰写案例研究的一般步骤:

1.确定研究问题:首先需要确定一个具体的研究问题,这

个问题应该是具有现实意义和实用价值的,并且可以通过案例

研究的方法得到解决。

2.选择案例:根据研究问题,选择一个或多个适合的案例。

案例应该是具有代表性的,能够反映研究问题的普遍性,并且

能够提供充分的资料和数据。

3.收集数据:通过各种方式收集与案例相关的数据和资料,

包括文献资料、访谈、观察、问卷调查等。

收集的数据应该能

够支持研究问题和案例选择。

4.分析数据:对收集到的数据进行深入的分析,以了解案

例中的问题和挑战。

分析应该包括对数据的描述性统计、推断

性统计和定性分析等方面。

5.得出结论:根据数据分析的结果,得出结论。

结论应该

能够回答研究问题,并且提供对实践的启示和建议。

6.撰写报告:将研究结果整理成书面报告,报告应该清晰、

简洁、有逻辑性,并且符合学术规范和格式要求。

在撰写案例研究时,需要注意以下几点:

•突出案例的独特性和代表性,说明为什么选择这个案例进行研究。

•保持研究的客观性和中立性,避免主观臆断和偏见。

•注意数据的准确性和可靠性,避免数据错误和误差。

•在分析数据时,可以采用多种方法和技术,以得出全面、深入的研究结果。

•结论应该具有实用性和可操作性,能够对实践提供有价值的启示和建议。

How to Research如何开展研究工作共68页文档

Purpose

➢ To gather information, e.g., comments or opinions on the service or products of a company.

Title Help readers see what the

questionnaires are about.

➢ Questionnaires on the TV Show ➢ Survey on Hotel Service QualityInFra bibliotekroduction

Show the reason to fill in the questionnaire.

Rate of successful campus love that results in marriage

Qualities of a most attractive college student

……

Off-campus topics

Demand for English tutors in society

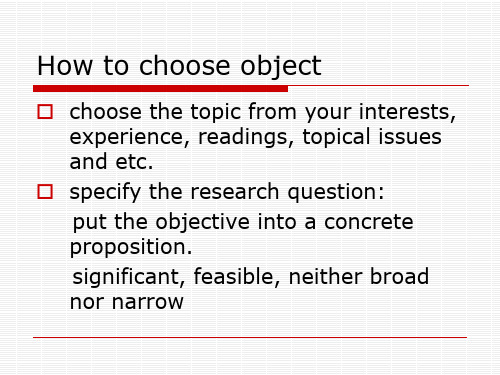

How to choose object

choose the topic from your interests, experience, readings, topical issues and etc.

specify the research question: put the objective into a concrete proposition. significant, feasible, neither broad nor narrow

HowtoResearch如何开展研究工作

Avoid loaded questions, e.g., “Why do people think that this brand is popular?”

Avoid potentially biased questions, e.g., “Don’t you think…?”

Formulate questions whose answers can be readily computed

2. Open format questions require more thought and time on the part of the respondent.