Structural and Electrical Properties of Metal Silicide Precipitates in Silicon

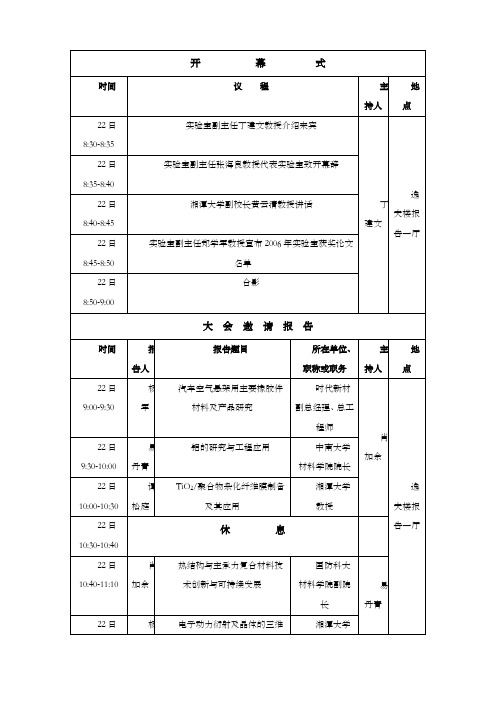

“第17届凝聚态理论与统计物理学术会议”日程(初稿)

吴超(西安交通大学) 题目: The influence of local arrangements of oxygen adatoms on the energetics of O2 dissociation over Pt(111) 赵明文(山东大学) 题目: 新型碳材料结构设计和性能调控的理 论模型 李希茂(北京宏剑公司)(12:10-12:25) 题目: 第一原理计算材料的缺陷和掺杂特性

李文飞(南京大学) 题目: 蛋白质分子体系多尺度理论模拟

孙久勋(电子科技大学) 题目: Improvement of unified mobility model and electrical properties for organic diodes under dc and ac conditions

关丽(河北大学):Structural stability and electronic properties of two nonstoichiometric SrTiO3 phases

休息

报告厅 3(主题: 冷原子物理) 分会报告 ST3.3 主席:成 泽 教授(华中科技大学) (邀请报告) 周琦(香港中文大学) 题目:自旋轨道耦合下波色凝聚体的命运

主席:金国钧 教授(南京大学)

(邀请报告) 杨义峰(中国科学院物理研究所) (邀请报告) 孟胜(中国科学院物理研究所)

题目:重费米子物理中的演生现象

题目:Energy Conversion At Nanoscale

张胜利-TheHGI-南京理工大学

张胜利邮箱:zhangslvip@通讯地址:南京市玄武区孝陵卫200号材料科学与工程学院,邮编:210094主要研究方向:1.二维半导体精细结构的XAFS实验和模拟相结合的研究;2.新型光电信息功能材料的设计和电子结构性质研究;3.低维纳米材料结构与物理化学性质的第一性原理研究。

主持科研项目:1. 国家自然科学青年基金项目,过渡金属二硫属化物范德华异质结的组装、能带调控和光学性质研究,2015.1-2017.12,主持(在研)。

2. 江苏省科技计划项目-青年项目,类石墨烯TMDCs范德华异质结能带调控和光学性质研究,2014.7-2017.6,主持(在研)。

3. 中国博士后科研资助计划项目(2014M551594),过渡金属二硫属化物范德华异质结的理论设计与物性调控,2014.9-2016.9,主持(在研)。

4. 江苏省博士后科研资助计划项目(1402154C),新型二维VIB族硫属化合物层状复合材料的设计和性能调控,2014.11-2016.11,主持(在研)。

研究工作经历:2013/7-至今,南京理工大学,材料科学与工程学院,讲师;2008/09 – 2013/06 北京化工大学,计算材料方向, 博士。

教学工作:《新材料技术概论》,《纳米CMOS集成电路设计与加工》和《半导体器件TCAD设计》代表性学术论文:2014Antimonene: Semimetal-semiconductor and Indirect-direct Band Gap Transitions, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2014, Accepted. (IF=11.336)phase transition between metallic and semiconducting single-layer MoS2 and WS2 through size effects, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2014, On-line, DOI: 10.1039/c4cp04775c. (IF=4.198)storage for B/n-codoped graphyne, RSC Advances, 4, 54879, 2014. (IF=3.708)24. Yousheng Zou, Haipeng Wang, Shengli Zhang, Dong Lou, Yuhui Dong, Xiufeng Song, Haibo Zeng. Structural, electrical and optical properties of Mg-doped CuAlO 2 films by pulsed laser deposition. RSC Advances, 4, 41294, 2014. (IF=3.708)23. Xiaoming Li, Shengli Zhang, Sergei A Kulinich, Yanli Liu, Haibo Zeng. Engineering surface states ofcarbon dots to achieve controllable luminescence for solid-luminescent composites and sensitiveBe2+ detection. Scientific Reports, 4, 4976-4983, 2014. (IF=5.078)22. Lihong Zhang, Shengli Zhang, Peng Wang, Chuan Liu, Shiping Huang, Huiping Tian. The effect of electric field on Ti-decorated graphyne for hydrogen storage. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry, 1035, 68-75, 2014. (IF=1.368)21. Xiaoli Du, Chuan Liu, Shengli Zhang, Peng Wang, Shiping Huang, Huiping Tian. Structural, magnetic and electronic properties of FenPt13-n clusters with n=0-13: A first-principle study. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 369, 27-33, 2014. (IF=2.002)201320. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. First-principles study of cubane-type ZnO: Another ZnO polymorph. Chemical Physics Letters, 556, 102-105, 2013.(IF=1.991)19. Shengli Zha ng, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang and Huiping Tian. Mechanistic investigations on the adsorption of thiophene over cubane–type Zn3NiO4 bimetallic oxide. Applied Surface Science, 258, 10148-10153, 2013. (IF=2.538)18. Chuan Liu, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Structure, electronic characteristic and thermodynamic properties of K2ZnH4 hydride crystal: A first–principles study.Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 549, 30-37, 2013. (IF=2.726)17. Jia Li, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Structural, electronic and thermodynamic properties of R3ZnH5(R=K, Rb, Cs): A first–Principle calculation. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 198, 433-439, 2013. (IF=2.200)16. Zheng Wu, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Shengli Zhang. The structural and electronic properties of assembled CdTe Multi–cage nanochains. Computational Materials Science, 68, 238-244, 2013. (IF=1.879)15. Peng Wang, Mingxia Yang, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang, Huiping Tian. Density functional theory study of the electronic and magnetic properties of Mn–doped (MgO)n (n=2–10) clusters. Chinese Journal Chemical Physics, 1, 35-42, 2013. (IF=0.720)14. Jiali Jiang, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Density functional theory studies of Yb-, Ca- and Sr-substituted Mg2NiH4 hydrides. Computational Materials Science, 7, 55-64, 2013. (IF=1.879)13. Ping Cheng, Shengli Zhang, Peng Wang, Shiping Huang, Huiping Tian. First-principles investigation of thiophene adsorption on Ni13 and Zn@Ni12 putational and Theoretical Chemistry, 1020, 136-142, 2013. (IF=1.368)12. Chuan Liu, Shengli Zha ng, Peng Wang, Shiping Huang, Huiping Tian. Confinement effects on structural, electronic properties and dehydrogenation thermodynamics of LiBH4. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 20, 8367-8375, 2013. (IF=2.930)11. Yonghong Zhang, Hui Ding, Chuan Liu, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang. Significant effects of graphite fragments on hydrogen storage performances of LiBH4: A first-principlesapproach. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 38, 13717-13727, 2013. (IF=2.930)201210. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Chunru Wang, Theoretical investigationsof sp–sp2 hybridized zero–dimensional fullerenynes. Nanoscale,4, 2839-2842, 2012. (IF=6.739)9. Hui Ding, Sh engli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Effects of nonmetal element (B, C and Si) additives in Mg2Ni hydrogen storage alloy.International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37, 6700-6713, 2012. (IF=2.930)8. Yonghong Zhang, Xiaozhen Zheng, Shengli Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Bare and Ni decorated Al12N12cage as materials for hydrogen storage: Density functionalcalculation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 37, 12411-12419, 2012. (IF=2.930)20117. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Liang Qiao, Shansheng Yu, Weitao Zheng, Field emission mechanism of island−shape Graphene–BN nanocomposite. Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 115, 9471-9476, 2011. (IF=4.835)6. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Hui Liu, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian.Theoretical investigation of growth, stability, and electronic properties of beaded ZnO nanoclusters. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 21, 16905-16910, 2011. (IF=6.626)5. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Hui Liu, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Theoretical investigation of electronic structure and field emission properties of ZnO–CNT nanocontacts. Carbon, 49, 3835-3841, 2011. (IF=6.160)4. Rui Jin, Shengli Zhang,Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian. Theoretical investigation of adsorption and dissociation of H2 on (ZrO2)n (n=1–6) clusters. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 36, 9069-9078, 2011. (IF=2.930)20103. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Hui Liu, Peng Wang, Huiping Tian, First–principles study of field emission properties of Graphene–ZnO nanocomposite. Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 114, 19284-19288, 2010. (IF=4.835)2. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Hui Liu, Huiping Tian, First-principles study of structural, electronic and vibrational properties of aluminum-doped silica nanotubes. Chemical Physics Letters, 498, 172-177, 2010. (IF=1.991)1. Shengli Zhang, Yonghong Zhang, Shiping Huang, Peng Wang and Huiping Tian. Molecular dynamics simulations of silica nanotube: structural and vibrational properties under differenttemperatures. Chinese Journal of Chemical Physics, 23, 497-503, 2010. (IF=0.720)。

三元材料英文缩写

三元材料英文缩写三元材料英文缩写为TMCs (Ternary Metal Carbides). TMCs are a class of materials that consist of three elements, typically a transition metal, carbon, and a third element. They are known for their unique structural and electrical properties, making them attractive for a wide range of applications such as catalysts, energy storage devices, and electronic devices.The structural properties of TMCs are determined by the combination and arrangement of the three elements. The transition metal provides the metallic properties, carbon provides the hardness and stability, while the third element can vary and influence the properties of the material. The crystal structures of TMCs can be varied, including cubic, hexagonal, or layered arrangements.TMCs have been extensively studied for their catalytic activities. Due to their unique chemical and electronic properties, they can act as efficient catalysts for various chemical reactions. For example, TMCs have shown promising catalytic activities for hydrogen evolution reactions in water splitting, which is a key process in renewable energy production. The presence of carbon in TMCs can enhance the catalytic performance by increasing the surface area and providing active sites for the reaction.In addition to catalytic applications, TMCs have also been explored for energy storage devices such as batteries and supercapacitors. TMCs can be used as electrode materials in these devices due to their excellent electrical conductivity and high surface area. For example, certain TMCs have been investigated asanode materials for lithium-ion batteries, exhibiting high energy density and long cycling stability. The third element in TMCs can also influence the electrochemical performance, and researchers are actively studying different compositions to optimize the properties.Furthermore, TMCs have shown potential in electronic devices such as field-effect transistors and photodetectors. The unique combination of metallic and semiconducting properties in TMCs makes them attractive for electronic applications. For instance, certain TMCs have demonstrated high carrier mobility and on/off ratios, making them suitable for transistor applications. The role of the third element in these devices is crucial, as it can modulate the electronic properties and bandgap of the material.In conclusion, TMCs (Ternary Metal Carbides) are a class of materials consisting of three elements, including a transition metal, carbon, and a third element. They exhibit unique structural and electrical properties, making them suitable for various applications such as catalysts, energy storage devices, and electronic devices. Further research and development of TMCs can lead to advancements in renewable energy, energy storage, and electronics.。

电气控制英文参考文献(精选120个最新)

改革开放以来,随着我国工业的迅速发展和科学技术的进步,电气控制技术在工业上的运用也越来越广泛,对于一个国家的科技水平高低来说,电气控制技术水平是一项重要的衡量因素.电气控制技术主要以电动机作为注重的对象,通过一系列的电气控制技术,买现生产或者监控的自动化.下面是搜索整理的电气控制英文参考文献,欢迎借鉴参考。

电气控制英文参考文献一: [1]Laiqing Xie,Yugong Luo,Donghao Zhang,Rui Chen,Keqiang Li. Intelligent energy-saving control strategy for electric vehicle based on preceding vehicle movement[J]. Mechanical Systems andSignal Processing,2019,130. [2]F.N. Tan,Q.Y. Wong,W.L. Gan,S.H. Li,H.X. Liu,F. Poh,W.S. Lew. Electric field control for energy efficient domain wallinjection[J]. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials,2019,485. [3]N. Nursultanov,W.J.B. Heffernan,M.J.W.M.R. van Herel,J.J. Nijdam. Computational calculation of temperature and electrical resistance to control Joule heating of green Pinus radiata logs[J]. Applied Thermal Engineering,2019,159. [4]Min Cheng,Junhui Zhang,Bing Xu,Ruqi Ding,Geng Yang. Anti-windup scheme of the electronic load sensing pump via switchedflow/power control[J]. Mechatronics,2019,61. [5]Miles L. Morgan,Dan J. Curtis,Davide Deganello. Control of morphological and electrical properties of flexographic printed electronics through tailored ink rheology[J]. OrganicElectronics,2019,73. [6]Maciej ?awryńczuk,Pawe?Oc?oń. Model Predictive Control and energy optimisation in residential building with electric underfloor heating system[J]. Energy,2019,182. [7]Lorenzo Niccolai,Alessandro Anderlini,GiovanniMengali,Alessandro A. Quarta. Electric sail displaced orbit control with solar wind uncertainties[J]. Acta Astronautica,2019,162. [8]Patrik Beňo,Matej Kubi?. Control and stabilization of single-wheeled electric vehicle with BLDC engine[J]. Transportation Research Procedia,2019,40. [9]André Murilo,Rafael Rodrigues,Evandro Leonardo SilvaTeixeira,Max Mauro Dias Santos. Design of a Parameterized Model Predictive Control for Electric Power Assisted Steering[J]. Control Engineering Practice,2019,90. [10]Kazusa Yamamoto,Olivier Sename,Damien Koenig,Pascal Moulaire. Design and experimentation of an LPV extended state feedback control on Electric Power Steering systems[J]. Control EngineeringPractice,2019,90. [11]Pedro de A. Delou,Julia P.A. de Azevedo,Dinesh Krishnamoorthy,Maurício B. de Souza,Argimiro R. Secchi. Model Predictive Control with Adaptive Strategy Applied to an Electric Submersible Pump in a Subsea Environment[J]. IFACPapersOnLine,2019,52(1). [12]Unal Yilmaz,Omer Turksoy,Ahmet Teke. Intelligent control of high energy efficient two-stage battery charger topology forelectric vehicles[J]. Energy,2019,186. [13]Qiuyi Guo,Zhiguo Zhao,Peihong Shen,Xiaowen Zhan,Jingwei Li. Adaptive optimal control based on driving style recognition forplug-in hybrid electric vehicle[J]. Energy,2019,186. [14]Leonid Lobanov,Nikolai Pashсhin. Electrodynamic treatment by electric current pulses as effective method of control of stress-strain states and improvement of life of welded structures[J]. Procedia Structural Integrity,2019,16. [15]Evangelos Pournaras,Seoho Jung,Srivatsan Yadhunathan,Huiting Zhang,Xingliang Fang. Socio-technical smart grid optimization via decentralized charge control of electric vehicles[J]. Applied Soft Computing Journal,2019,82. [16]Guoming Huang,Xiaofang Yuan,Ke Shi,Xiru Wu. A BP-PID controller-based multi-model control system for lateral stability of distributed drive electric vehicle[J]. Journal of the Franklin Institute,2019,356(13). [17]Ioannis Kalogeropoulos,Haralambos Sarimveis. Predictive control algorithms for congestion management in electric power distribution grids[J]. Applied Mathematical Modelling,2020,77. [18]Junjun Zhu,Zhenpo Wang,Lei Zhang,David G. Dorrell.Braking/steering coordination control for in-wheel motor drive electric vehicles based on nonlinear model predictive control[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory,2019,142. [19]Jiechen Wu,Junjie Hu,Xin Ai,Zhan Zhang,Huanyu Hu. Multi-time scale energy management of electric vehicle model-based prosumers by using virtual battery model[J]. Applied Energy,2019,251. [20]G. Coorey,D. Peiris,T. Usherwood,L. Neubeck,J. Mulley,J. Redfern. An Internet-Based Intervention Integrated with the Primary Care Electronic Health Record to Improve Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor Control: a Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Acceptability, Usage Trends and Persuasive Design Characteristics[J]. Heart, Lung and Circulation,2019,28. [21]Félice Lê-Scherban,Lance Ballester,Juan C. Castro,Suzanne Cohen,Steven Melly,Kari Moore,James W. Buehler. Identifying neighborhood characteristics associated with diabetes and hypertension control in an urban African-American population usinggeo-linked electronic health records[J]. Preventive Medicine Reports,2019,15. [22]Yuekuan Zhou,Sunliang Cao. Energy flexibility investigation of advanced grid-responsive energy control strategies with thestatic battery and electric vehicles: A case study of a high-rise office building in Hong Kong[J]. Energy Conversion and Management,2019,199. [23]D. Aravindh,R. Sakthivel,B. Kaviarasan,S. MarshalAnthoni,Faris Alzahrani. Design of observer-based non-fragile load frequency control for power systems with electric vehicles[J]. ISA Transactions,2019,91. [24]Augusto Matheus dos Santos Alonso,Danilo IglesiasBrandao,Tommaso Caldognetto,Fernando Pinhabel Maraf?o,Paolo Mattavelli. A selective harmonic compensation and power control approach exploiting distributed electronic converters inmicrogrids[J]. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems,2020,115. [25]Hay Wong,Derek Neary,Eric Jones,Peter Fox,Chris Sutcliffe. Benchmarking spatial resolution in electronic imaging for potential in-situ Electron Beam Melting monitoring[J]. Additive Manufacturing,2019,29. [26]Yunfei Bai,Hongwen He,Jianwei Li,Shuangqi Li,Ya-xiong Wang,Qingqing Yang. Battery anti-aging control for a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle with a hierarchical optimization energy management strategy[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production,2019,237. [27]N. Samartin-Veiga,A.J. González-Villar,M.T. Carrillo-de-la-Pe?a. Neural correlates of cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia patients: Reduced brain electrical activity during the execution ofa cognitive control task[J]. NeuroImage: Clinical,2019,23. [28]Masato Nakaya,Shinta Watanabe,Jun Onoe. Control of electric, optical, thermal properties of C 60 films by electron-beam irradiation[J]. Carbon,2019,152. [29]R. Saadi,M.Y. Hammoudi,O. Kraa,M.Y. Ayad,M. Bahri. A robust control of a 4-leg floating interleaved boost converter for fuel cell electric vehicle application[J]. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation,2019. [30]Frederik Banis,Daniela Guericke,Henrik Madsen,Niels Kj?lstad Poulsen. Supporting power balance in Microgrids with Uncertain Production using Electric Vehicles and Indirect Control ? ? This work has been supported by ENERGINET.DK under the project microgrid positioning - uGrip and the CITIES project.[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(4). 电气控制英文参考文献二: [31]Huijuan Luo,Jinpeng Yu,Chong Lin,Zhanjie Liu,Lin Zhao,Yumei Ma. Finite-time dynamic surface control for induction motors with input saturation in electric vehicle drive systems[J]. Neurocomputing,2019. [32]Peter K. Joseph,D. Elangovan,G. Arunkumar. Linear control of wireless charging for electric bicycles[J]. Applied Energy,2019,255. [33]Yu Congyang,Zhu Dequan,Wang Chaoxian,Zhu Lin,Chu Tingting,Jen Tien-Chien,Liao Juan. Optimizing Electric Adjustment Mechanism Using the Combination of Multi-body Dynamics and Control[J]. Procedia Manufacturing,2019,35. [34]Hussein Termous,Xavier Moreau,Clovis Francis,Hassan Shraim. Effect of fractional order damping control on braking performancefor electric vehicles ? ? This work was supported by the Lebanese research program and the AUF-CNRSL-UL program.[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [35]Manuel Schwartz,Florian Siebenrock,S?ren Hohmann. Model Predictive Control Allocation of an Over-actuated Electric Vehicle with Single Wheel Actuators[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(8). [36]Di Wu,Nikitha Radhakrishnan,Sen Huang. A hierarchical charging control of plug-in electric vehicles with simpleflexibility model[J]. Applied Energy,2019,253. [37]Abhishek Nayak,Rubi Rana,Sukumar Mishra. Frequency Regulation by Electric Vehicle during Grid Restoration using Adaptive Optimal Control[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(4). [38]Nicolò Robuschi,Mauro Salazar,Pol Duhr,FrancescoBraghin,Christopher H. Onder. Minimum-fuel Engine On/Off Control for the Energy Management of a Hybrid Electric Vehicle via Iterative Linear Programming ? ? We thank Ferrari S.p.A. for supporting this project.[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [39]Anas A. Ahmed,M.R. Hashim,Marzaini Rashid. Control of the structural, electrical and optical properties of spin coated NiO films by varying precursor molarity[J]. Thin Solid Films,2019,690. [40]Wilco van Harselaar,Niels Schreuders,Theo Hofman,Stephan Rinderknecht. Improved Implementation of Dynamic Programming on the Example of Hybrid Electric Vehicle Control[J]. IFACPapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [41]Jose A. Matute,Mauricio Marcano,Sergio Diaz,Joshue Perez. Experimental Validation of a Kinematic Bicycle Model Predictive Control with Lateral Acceleration Consideration ? ? This project has received funding from the Electronic Component Systems for European Leadership Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No 737469 (AutoDrive Project). This Joint Undertaking receives support fromthe European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programmeand Germany, Austria, Spain, Italy, Latvia, Belgium, Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Romania,[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(8). [42]Vladislav S. Gromov,Oleg I. Borisov,Sergey S. Shavetov,AntonA. Pyrkin,FatimatB. Karashaeva. Modeling and Control of Robotic Systems Course: from Fundamentals to Applications ? ? The work was written with the support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, project unique identifier RFMEFI57818X0271 “Adaptive Sensorless Control for Synchronous Electric Drives in Intelligent Robotics and Transport Systems”.[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(9). [43]H. Mbarak,A.K. Kodeary,S.M. Hamidi,E. Mohajarani,Y. Zaatar. Control of nonlinear refractive index of AuNPs doped with nematic liquid crystal under external electric field[J]. Optik,2019,198. [44]Yanzhao Jia,Rabee Jibrin,Yutaro Itoh,Daniel G?rges. Energy-Optimal Adaptive Cruise Control for Electric Vehicles in Both Time and Space Domain based on Model Predictive Control[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [45]Lukas Engbroks,Daniel G?rke,Stefan Schmiedler,TobiasG?decke,Bastian Beyfuss,Bernhard Geringer. Combined energy and thermal management for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles -analyses based on optimal control theory ? ? This work has been performed within the Daimler AG in Stuttgart, Germany in cooperation with the Institute for Powertrains and Automotive Technology at Vienna University of Technology, Austria.[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [46]Jean Kuchly,Dominique Nelson-Gruel,Alain Charlet,Yann Chamaillard,Cédric Nouillant. Projected Gradient and ModelPredictive Control : Optimal Energy and Pollutants Management for Hybrid Electric Vehicle[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [47]Pier Giuseppe Anselma,Yi Huo,Joel Roeleveld,Giovanni Belingardi,Ali Emadi. From Off-line to On-line Control of a Multimode Power Split Hybrid Electric Vehicle Powertrain[J]. IFAC PapersOnLine,2019,52(5). [48]Xiaoyong Zhu,Deyang Fan,Zixuan Xiang,Li Quan,Wei Hua,Ming Cheng. Systematic multi-level optimization design and dynamiccontrol of less-rare-earth hybrid permanent magnet motor for all-climatic electric vehicles[J]. Applied Energy,2019,253. [49]. Engineering - Industrial Engineering; Findings from Southwest Jiaotong University Provides New Data about Industrial Engineering (Optimal Energy Management and Control In Multimode Equivalent Energy Consumption of Fuel Cell/supercapacitor of Hybrid Electric Tram)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [50]. SK Planet Co. Ltd.; Patent Issued for Electronic Stamp System For Security Intensification, Control Method Thereof, And Non-Transitory Computer Readable Storage Medium Having ComputerProgram Recorded Thereon (USPTO 10,361,857)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [51]. Energy - Electric Power; Study Data from National Institute of Technology Calicut Update Understanding of Electric Power (Modified switching scheme-based explicit torque control of brush-less direct current motor drive)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [52]. Energy; Findings from School of Mechanical Engineering Reveals New Findings on Energy (Deep Reinforcement Learning of Energy Management With Continuous Control Strategy and Traffic Information for a Series-parallel Plug-in Hybrid Electric Bus)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [53]. Energy - Electric Power; Reports Outline Electric Power Study Results from Dalian Maritime University (Direct VoltageControl of Stand-alone Dfig Under Asymmetric Loads Based On Non-singular Terminal Sliding Mode Control and Improved Extended State Observer)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [54]. Energy - Electric Power; Studies from Xi'an Jiao Tong University Add New Findings in the Area of Electric Power (A model predictive control approach for matching uncertain wind generation with PEV charging demand in a microgrid)[J]. Energy WeeklyNews,2019. [55]. Energy - Electric Power; Researchers from Northwestern Polytechnical University Discuss Findings in Electric Power (Decoupling Start Control Method for Aircraft Wound-rotor Synchronous Starter-generator Based On Main Field Current Estimation)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [56]. Energy - Electric Power; Wuhan University Reports Findings in Electric Power (Adjustable virtual inertia control of supercapacitors in PV-based AC microgrid cluster)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [57]. Lg Electronic Inc.; Researchers Submit Patent Application, "Method And Apparatus For Monitoring Control Channel In Unlicensed Band", for Approval (USPTO 20190229825)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [58]. Special Conditions: Pilatus Aircraft Ltd., Model PC-12/47E Airplanes; Electronic Engine Control System Installation[J]. The Federal Register / FIND,2019,84(158). [59]. Apple Inc.; Patent Issued for Offset Control For Assembling An Electronic Device Housing (USPTO 10,368,457)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [60]. Mitsubishi Electric Corporation; Researchers Submit Patent Application, "Synchronization Control System And Control Device",for Approval (USPTO 20190238071)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. 电气控制英文参考文献三: [61]. Technology - Cybernetics; Findings from North ChinaElectric Power University Provides New Data about Cybernetics (Hierarchical Distributed Model Predictive Control of Standalone Wind/solar/battery Power System)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [62]. Nidec Corporation; "Motor Control System And Electric Power Steering System" in Patent Application Approval Process (USPTO 20190233002)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [63]. Mobvoi Information Technology Co. LTD.; Researchers Submit Patent Application, "Display Device, Electronic Device And Display Control Method For Screen", for Approval (USPTO 20190235540)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [64]. Engineering - Power Delivery; Studies from North China Electric Power University Have Provided New Data on Power Delivery (Fault Tripping Criteria In Stability Control Device Adapting ToHalf-wavelength Ac Transmission Line)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [65]. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd.; "Electronic Device For Sensing Biometric Information And Control Method Thereof" in Patent Application Approval Process (USPTO 20190231235)[J]. Medical Patent Business Week,2019. [66]Asiabar Aria Noori,Kazemi Reza. A direct yaw momentcontroller for a four in-wheel motor drive electric vehicle using adaptive sliding mode control[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(3). [67]. Energy - Electrical Energy Systems; New Electrical Energy Systems Findings Has Been Reported by Investigators at University of Sfax (Constrained design and control of trapezoidal waves-forms hybrid excitation synchronous motor increasing energy accumulator lifetime)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [68]. Energy; Findings from School of Mechanical Engineering Has Provided New Data on Energy (Considering Well-to-Wheels Analysis in Control Design: Regenerative Suspension Helps to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Battery Electric Vehicles)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [69]. Mitsubishi Electric Corporation; Patent Application Titled "Electric-Power Control Device, Electric Motor, Air-Conditioning Apparatus, And Method For Manufacturing Electric Motor" Published Online (USPTO 20190242594)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [70]. Energy; Reports Summarize Energy Study Results from Warsaw University of Technology (Model Predictive Control and energy optimisation in residential building with electric underfloorheating system)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [71]. Energy - Nuclear Power; Researchers from Korea Electric Power Corporation Report New Studies and Findings in the Area of Nuclear Power (Development of Anti-windup Pi Control and Bumpless Control Transfer Methodology for Feedwater Control System)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [72]. Energy - Electric Power; Data on Electric Power Discussed by Researchers at School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering (Analysis of the Performance Characteristics and Arm Current Control for Modular Multilevel Converter With Asymmetric Arm Parameters)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [73]. Energy - Electric Power; Study Findings on Electric Power Are Outlined in Reports from University of Technology (Direct power control for VSC-HVDC systems: An application of the global tracking passivity-based PI approach)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [74]Allous Manel,Mrabet Kais,Zanzouri Nadia. Fast fault-tolerant control of electric power steering systems in the presence of actuator fault[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(12). [75]. Energy - Electric Power; Researchers from College of Engineering Detail New Studies and Findings in the Area of Electric Power (Power Control Strategy of Photovoltaic Plants for Frequency Regulation In a Hybrid Power System)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [76]. Energy - Electric Power; Researchers at Shiv Nadar University Report New Data on Electric Power (Methods for overcoming misalignment effects and charging control of a dynamic wireless electric vehicle charging system)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [77]Zhang Bing,Zong Changfu,Chen Guoying,Li Guiyuan. An adaptive-prediction-horizon model prediction control for path tracking in a four-wheel independent control electric vehicle[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(12). [78]Ren Yue,Zheng Ling,Yang Wei,Li Yinong. Potential field–based hierarchical adaptive cruise control for semi-autonomous electric vehicle[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of MechanicalEngineers,2019,233(10). [79]. Energy - Electric Power; Data from University of the Basque Country Advance Knowledge in Electric Power (Sliding Mode Control of an Active Power Filter With Photovoltaic Maximum Power Tracking)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [80]Izadbakhsh Alireza,Kheirkhahan Payam. Adaptive fractional-order control of electrical flexible-joint robots: Theory and experiment[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(9). [81]Yang Weiwei,Liang Jiejunyi,Yang Jue,Zhang Nong. Optimal control of a novel uninterrupted multi-speed transmission for hybrid electric mining trucks[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(12). [82]Guercioni Guido Ricardo,Vigliani Alessandro. Gearshiftcontrol strategies for hybrid electric vehicles: A comparison of powertrains equipped with automated manual transmissions and dual-clutch transmissions[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(11). [83]. Energy - Electric Power; Findings from PontificalUniversity Provides New Data on Electric Power (A Communication-free Reactive-power Control Strategy In Vsc-hvdc Multi-terminal Systems To Improve Transient Stability)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [84]. Energy - Electric Power; Findings from Yazd University in the Area of Electric Power Reported (An adaptive time-graded control method for VSC-MTDC networks)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [85]Liu Hui,Li Xunming,Wang Weida,Han Lijin,Xin Huibin,Xiang Changle. Adaptive equivalent consumption minimisation strategy and dynamic control allocation-based optimal power management strategy for four-wheel drive hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(12). [86]. Networks - Neural Networks; Findings on Neural Networks Reported by Investigators at School of Electrical Engineering and Automation (Stability Analysis of Fractional Order Hopfield Neural Networks With Optimal Discontinuous Control)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [87]. Energy - Electric Power; Researchers from NanjingUniversity of Aeronautics and Astronautics Describe Findings in Electric Power (Synchronous Vibration Control for a Class of Cross-coupled Antisymmetric Msr Systems)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [88]. Energy - Electric Power; Investigators at Chung Ang University Detail Findings in Electric Power (Flexible Risk Control Strategy Based On Multi-stage Corrective Action With Energy Storage System)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [89]. Energy - Electric Power; Findings in Electric Power Reported from National Institute of Technology (An adaptive PI control scheme to balance the neutral-point voltage in a solar PV fed grid connected neutral point clamped inverter)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [90]Najjari Behrouz,Mirzaei Mehdi,Tahouni Amin. Constrained stability control with optimal power management strategy for in-wheel electric vehicles[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,2019,233(4). 电气控制英文参考文献四: [91]. Energy - Wind Farms; Investigators at School of Electrical Power Detail Findings in Wind Farms (Theoretical Study On Control Strategy of Grid-connected High Voltage Ride Through In Doubly-fed Wind Farm)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [92]. Kia Motors Corporation; Patent Issued for Wireless Charging Control Apparatus And Method For Optimal Charging By Adjusting The Inclination Of The Electric Vehicle Being Charged (USPTO10,399,449)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [93]. Energy; New Data from Institute of Electrical Engineering Illuminate Findings in Energy (Charging-Discharging Control Strategy for a Flywheel Array Energy Storage System Based on the Equal Incremental Principle)[J]. Energy Weekly News,2019. [94]. Science - Applied Sciences; Findings from North China Electric Power University Broaden Understanding of Applied Sciences (Coordinated Frequency Control Strategy with the Virtual Battery Model of Inverter Air Conditionings)[J]. Science Letter,2019. [95]. Science - Materials Science; Studies from Tsinghua University in the Area of Materials Science Described (ElectricField Control of Neel Spin-orbit Torque In an Antiferromagnet)[J]. Science Letter,2019. [96]. Electronics - Power Electronics; Studies from Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics Have Provided New Data on Power Electronics (Wireless battery charging control for electric vehicles: a user-involved approach)[J]. Computers, Networks & Communications,2019. [97]Kivanc,Ustun. Dynamic control of electronic differential in the field weakening region[J]. International Journal ofElectronics,2019,106(10). [98]Mohit Batra,John McPhee,Nasser L. Azad. Real-time model predictive control of connected electric vehicles[J]. Vehicle System Dynamics,2019,57(11). [99]Kim Daihyun,Echelmeier Austin,Cruz Villarreal Jorvani,Gandhi Sahir,Quintana Sebastian,Egatz-Gomez Ana,Ros Alexandra. Electric Triggering for Enhanced Control of Droplet Generation.[J].Analytical chemistry,2019,91(15). [100]Kurien Caneon,Srivastava Ajay Kumar. Impact of Electric Vehicles on Indirect Carbon Emissions and Role of Engine Post-Treatment Emission Control Strategies.[J]. Integrated environmental assessment and management,2019. [101]Aravindh D,Sakthivel R,Kaviarasan B,Anthoni SMarshal,Alzahrani Faris. Design of observer-based non-fragile loadfrequency control for power systems with electric vehicles.[J]. ISA transactions,2019,91. [102]Chen Xianzhe,Zhou Xiaofeng,Cheng Ran,Song Cheng,Zhang Jia,Wu Yichuan,Ba You,Li Haobo,Sun Yiming,You Yunfeng,Zhao Yonggang,Pan Feng. Electric field control of Néel spin-orbit torque in an antiferromagnet.[J]. Nature materials,2019,18(9). [103]Lê-Scherban Félice,Ballester Lance,Castro Juan C,Cohen Suzanne,Melly Steven,Moore Kari,Buehler James W. Identifying neighborhood characteristics associated with diabetes and hypertension control in an urban African-American population using geo-linked electronic health records.[J]. Preventive medicine reports,2019,15. [104]Samartin-Veiga N,González-Villar A J,Carrillo-de-la-Pe?a M T. Neural correlates of cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia patients: Reduced brain electrical activity during the execution of a cognitive control task.[J]. NeuroImage. Clinical,2019,23. [105]Leibel Sydney,Weber Rachel. Utilizing a PhysicianNotification System in the EPIC Electronic Medical Record to Improve Pediatric Asthma Control: A Quality Improvement Project.[J].Clinical pediatrics,2019,58(11-12). [106]Bernacka-Wojcik Iwona,Huerta Miriam,Tybrandt Klas,Karady Michal,Mulla Mohammad Yusuf,Poxson David J,Gabrielsson Erik O,Ljung Karin,Simon Daniel T,Berggren Magnus,Stavrinidou Eleni. Implantable Organic Electronic Ion Pump Enables ABA Hormone Delivery for Control of Stomata in an Intact Tobacco Plant.[J]. Small (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany),2019. [107]Stoynova Nevena,Laske Christoph,Plewnia Christian. Combining electrical stimulation and cognitive control training to reduce concerns about subjective cognitive decline.[J]. Brainstimulation,2019,12(4). [108]Bettano Amy,Land Thomas,Byrd Alice,Svencer Susan,Nasuti Laura. Using Electronic Referrals to Address Health Disparities and Improve Blood Pressure Control.[J]. Preventing chronicdisease,2019,16. [109]Xu Meng,Yan Jian-Min,Guo Lei,Wang Hui,Xu Zhi-Xue,Yan Ming-Yuan,Lu Yun-Long,Gao Guan-Yin,Li Xiao-Guang,Luo Hao-Su,ChaiYang,Zheng Ren-Kui. Nonvolatile Control of the Electronic Properties of In<sub>2- x </sub>Cr<sub> x </sub>O<sub>3</sub> Semiconductor Films by Ferroelectric Polarization Charge.[J]. ACS appliedmaterials & interfaces,2019,11(35). [110]Gao Tao,Mirzadeh Mohammad,Bai Peng,Conforti Kameron M,Bazant Martin Z. Active control of viscous fingering using electricfields.[J]. Nature communications,2019,10(1). [111]Chaux Robin,Treussier Isabelle,Audeh Bissan,Pereira Suzanne,Hengoat Thierry,Paviot Béatrice Trombert,Bousquet Cedric. Automated Control of Codes Accuracy in Case-Mix Databases by Evaluating Coherence with Available Information in the Electronic Health Record.[J]. Studies in health technology andinformatics,2019,264. [112]Bolat Mustafa Suat,Cinar Onder,Asci Ramazan,Buyukalpelli Recep. A novel method for pain control: infiltration free local anesthesia technique (INFLATE) for transrectal prostatic biopsy using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).[J]. International urology and nephrology,2019. [113]Cruz Chad D,Yuan Jennifer,Climent Clàudia,Tierce NathanT,Christensen Peter R,Chronister Eric L,Casanova David,Wolf Michael O,Bardeen Christopher J. Using sulfur bridge oxidation to control electronic coupling and photochemistry in covalent anthracene dimers.[J]. Chemical science,2019,10(32). [114]Zhou Canliang,Sun Linfeng,Zhang Fengquan,Gu Chenjie,Zeng Shuwen,Jiang Tao,Shen Xiang,Ang Diing Shenp,Zhou Jun. Electrical Tuning of the SERS Enhancement by Precise Defect DensityControl.[J]. ACS applied materials & interfaces,2019,11(37). [115]Taeho Park,Hyeongcheol Lee. Optimal Supervisory Control Strategy for a Transmission-Mounted Electric Drive Hybrid Electric Vehicle[J]. International Journal of AutomotiveTechnology,2019,20(4). [116]Zoé Magalh?es,André Murilo,Renato V. Lopes. Development and evaluation with MIL and HIL simulations of a LQR-based upper-level electronic stability control[J]. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering,2019,41(8). [117]Justin Roger Mboupda Pone,Victor Kamdoum Tamba,Guillaume Honore Kom,Mathieu Jean Pierre Pesdjock,Alain Tiedeu,Martin Kom. Numerical, electronic simulations and experimental analysis of a no-equilibrium point chaotic circuit with offset boosting and partial amplitude control[J]. SN Applied Sciences,2019,1(8). [118]Alberto Cavallo,Antonio Russo,Giacomo Canciello.Hierarchical control for generator and battery in the more electric aircraft[J]. Science China Information Sciences,2019,62(9). [119]Ying Liu,Kai Cao,Jingjun Liu,Zhengping Zhang,Jing Ji,Feng Wang,Zhilin Li. Electrodeposition of copper-doped SnS thin films and their electric transmission properties control for thermoelectric enhancement[J]. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics,2019,30(17). [120]Feng Tian,Liqi Sui,Yuanfan Zeng,Bo Li,Xingyue Zhou,Lijun Wang,Hongxu Chen. Hardware Design and Test of a Gear-ShiftingControl System of a Multi-gear Transmission for ElectricVehicles[J]. Automotive Innovation,2019,2(3).。

Characterizing the properties of carbon nanotubes

Characterizing the properties ofcarbon nanotubesCarbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been the subject of extensive research due to their unique structural, electronic, mechanical, and thermal properties. CNTs are cylindrical tubes of carbon atoms, having a diameter of a few nanometers and a length of several micrometers. The walls of CNTs are made of graphene sheets that are rolled up into cylinders, resulting in a seamless tube with a hollow core. The properties of CNTs depend on their diameter, length, chirality, and defects, which can be controlled during the synthesis process.One of the most important properties of CNTs is their high aspect ratio, which is the ratio of their length to diameter. CNTs can have aspect ratios of up to 100,000, which makes them the strongest known materials, with tensile strengths up to 63 GPa. The strength of CNTs comes from their sp2 hybridized carbon bonds, which make the tubes extremely stiff and resilient. CNTs are also highly flexible, and can bend and twist without breaking, enabling them to be used in a wide range of applications.Another important property of CNTs is their electrical conductivity. CNTs are excellent conductors of electricity, with an electrical conductivity of up to 1x107 S/m, which is higher than that of copper. The conductivity of CNTs is dependent on their diameter and chirality, with smaller diameter tubes being more conductive than larger diameter tubes. The high conductivity of CNTs makes them a promising material for electronic and optoelectronic applications, such as transistors, sensors, and solar cells.CNTs also possess exceptional thermal conductivity, which is the ability to conduct heat. CNTs have an extremely high thermal conductivity of up to 3500 W/mK, which is higher than that of any other known material. The high thermal conductivity of CNTs makes them ideal for use in thermal management applications, such as heat sinks and nanocomposites.Furthermore, CNTs are highly hydrophobic, meaning that they repel water. This property makes them useful in applications where water resistance is required, such as in coatings and membranes. CNTs are also resistant to chemical corrosion and oxidation, which makes them highly durable and long-lasting.However, CNTs also have some limitations that need to be addressed. One of the major challenges is their toxicity. While CNTs have shown great promise in medical applications, such as drug delivery and cancer therapy, their potential toxicity to cells and tissues is a cause of concern. Studies have shown that CNTs can cause lung damage and inflammation in rodents, raising questions about their safety for human use. Therefore, it is important to thoroughly evaluate the toxicity of CNTs before using them in biomedical applications.In conclusion, CNTs are a remarkable material with unique and exceptional properties that make them suitable for a wide range of applications. Their high strength, electrical and thermal conductivity, hydrophobicity, and chemical stability make them a promising material in the fields of electronics, energy, and healthcare. However, their potential toxicity needs to be addressed before they can be widely used in biomedical applications. Understanding the properties of CNTs is essential for developing new applications that can exploit their exceptional properties while minimizing their drawbacks.。

氧化铋

Structural and multiferroic properties of La-modified Bi Fe O 3 ceramicsS. R. Das, R. N. P. Choudhary, P. Bhattacharya, R. S. Katiyar, P. Dutta, A. Manivannan, and M. S. SeehraCitation: Journal of Applied Physics 101, 034104 (2007); doi: 10.1063/1.2432869View online: /10.1063/1.2432869View Table of Contents: /content/aip/journal/jap/101/3?ver=pdfcovPublished by the AIP PublishingArticles you may be interested inEffect of Pr- and Nd- doping on structural, dielectric, and magnetic properties of multiferroicBi0.8La0.2Fe0.9Mn0.1O3J. Appl. Phys. 115, 134102 (2014); 10.1063/1.4870454Improved dielectric and magnetic properties of Ti modified BiCaFeO3 multiferroic ceramicsJ. Appl. Phys. 113, 023908 (2013); 10.1063/1.4774283Structural, magnetic, and optical properties of Pr and Zr codoped BiFeO3 multiferroic ceramicsJ. Appl. Phys. 112, 094102 (2012); 10.1063/1.4761968Structure and properties of La-modified Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 at ambient and elevated temperaturesJ. Appl. Phys. 112, 054111 (2012); 10.1063/1.4751357Structural and physical properties of room temperature stable multiferroic properties of single-phase ( Bi 0.9 La 0.1 ) FeO 3 – Pb ( Fe 0.5 Nb 0.5 ) O 3 solid solution systemsJ. Appl. Phys. 105, 07D919 (2009); 10.1063/1.3072034Structural and multiferroic properties of La-modified BiFeO3ceramics S.R.Das,R.N.P.Choudhary,P.Bhattacharya,and R.S.Katiyar a͒Department of Physics,University of Puerto Rico,San Juan,PR-00931,Puerto RicoP.Dutta,A.Manivannan,and M.S.SeehraDepartment of Physics,West Virginia University,Morgantown,West Virginia26506͑Received4May2006;accepted23November2006;published online6February2007͒The coexistence of the magnetic and the electrical properties in lanthanum͑La͒-modified bismuthferrite͑Bi1−x La x FeO3,x=0.05,0.1,0.15,and0.2͒ceramics was studied and compared with those ofbismuth ferrite͑BiFeO3͒.The presence of a small secondary phase of BiFeO3͑arises due to excessBi2O3͒was removed on La substitution at the Bi site,as observed in x-ray diffraction͑XRD͒.Theeffect of La substitution on dielectric constant,loss tangent,and remnant polarization of the sampleswas studied in a wide range of temperature͑77–400K͒and frequency͑1kHz–1MHz͒.Thevariation of magnetization,coercivefield,and exchange bias with temperature͑2–300K͒and Laconcentration were investigated.These changes in the magnetic parameters with La doping alongwith those of the electron magnetic resonance parameters measured at300K and9.28GHz areunderstood in terms of increase in the magnetic anisotropy and magnetization.These results alsoshow that stabilization of crystal structure and nonuniformity in spin cycloid structure by Lasubstitution enhances the multiferroic properties of BiFeO3.©2007American Institute of Physics.͓DOI:10.1063/1.2432869͔I.INTRODUCTIONBismuth ferrite͑BiFeO3͒has recently gained consider-able importance both technologically and scientifically be-cause of the existence of both ferroelectrics and͑anti͒ferro-magnetic ordering in the same phase in the material,and also magnetoelectric coupling between the two respective order parameters͑spin and charge͒.Unfortunately,spontaneous polarization and magnetization of the material at room tem-perature are small due to large leakage current and loss tan-gent,and hence it is difficult to study the dielectric properties in the low frequency range.1,2Therefore,Krainik et al.3mea-sured the temperature dependence of dielectric constant of bismuth ferrite͑BFO͒at microwave frequencies.The low value of polarization is attributed to the presence of second-ary phases and low resistivity of BiFeO3ceramics whereas the high leakage current is attributed to the presence of Fe2+ ions.4,5In order to increase the dielectric constant,reduce the leakage current,and hence to improve the ferroelectric po-larization in BFO,some attempts have been made including a small doping at the Bi/Fe sites.There are also several reports on the synthesis of solid solution of BiFeO3with other perovskite structures͑with different concentrations͒, which has improved electrical properties of BFO.Fedulov et al.6studied the BiFeO3–PbTiO3solid solutions,and re-ported that up to78mole%of BiFeO3the structure remains rhombohedral,after which it becomes tetragonal.Ismailzade et al.7showed that in BiFeO3–BaTiO3solid solution,the structure remains rhombohedral for67mole%of BiFeO3, from67toϳ6mole%it is cubic,and below6mole%,the structure of solid solution transforms to tetragonal.There are also some reports on the ferroelectric and ferromagnetic properties of cationic substituted BiFeO3.8–10Palkar et al.9,10 reported the ferroelectric and ferromagnetic properties of La and Tb at the Bi site,and La at the Bi site and Mn at the Fe site substituted BiFeO3.Though they did not observed any improvement in the ferroelectric properties in La/Mn-substituted BiFeO3,a small enhancement of mag-netic properties was clearly observed.The͑La,Tb͒substi-tuted at the Bi site in BiFeO3ceramic showed high values of dielectric constant and magnetoelectric coupling at room temperature.Recently,Wang et al.8observed an improve-ment in the dielectric properties of BiFeO3on substituting La at the Bi site and Ga at the Fe site,and making its composite with43mole%of PbTiO3.The room temperature dielectric constant was found to be1800with low loss tangent of0.024,and T c shifted toϳ500from1103K͑BiFeO3͒.Also,a larger induced magnetization͑compared to single crystal BiFeO3͒was obtained at room temperature at much lower magneticfield,and the magnetization value increased at5K.BiFeO3has a ferroelectric Curie temperature T c Ϸ1103K and antiferromagnetic͑AF͒Neel temperature T N Ϸ643K.11Since T c and T N are significantly different,it may be argued that spin and polarization ordering must be un-coupled and driven by different modes.The AF ordering is not completely compensated because of observed weak magnetism.12Neutron diffraction studies13have shown an incommensurately modulated cycloidal spin structure with a long wavelengthϷ600Å.In electron magnetic resonance ͑EMR͒studies,a low-field mode with paramagnetic-resonance-like linear relationship between energy andfield ͑h=gB H͒is observed for TϽT N with gϷ2.0͑for low La concentration͒,in addition to the highfield antiferromagnetic resonance͑AFMR͒modes,with criticalfield͑spinflip͒Ϸ18kOe.11In thinfilms of BiFeO3,the enhanced polariza-tion and magnetization have been interpreted due to epitaxiala͒Author to whom correspondence should be addressed;FAX:ϩ1-787-764-2571;electronic mail:rkatiyar@JOURNAL OF APPLIED PHYSICS101,034104͑2007͒0021-8979/2007/101͑3͒/034104/7/$23.00©2007American Institute of Physics101,034104-1constraint destroying the cycloidal ordering.14,15Magneto-electric properties of epitaxially grown La-modified BiFeO 3thin films have recently been reported by Lee et al.16and showed enhancement in the polarization and magnetization.In this paper,we report the effect of La substitution ͑5–20mole %at the Bi site ͒on structural,electrical,and magnetic properties of BiFeO 3ceramics ͓i.e.,Bi 1−x La x FeO 3͑BFOL ͔͒.II.EXPERIMENTThe high purity ͑99.9%,Alfa Aesar ͒bismuth oxide ͑Bi 2O 3͒,iron oxide ͑Fe 2O 3͒,and lanthanum oxide ͑La 2O 3͒were mixed ͑stoichiometry ͒in an agate mortar and pestle in wet medium ͑alcohol ͒to prepare BiFeO 3͑BFO ͒and Bi 1−x La x FeO 3͓x =0.05͑BFOL5͒,x =0.10͑BFOL10͒,x =0.15͑BFOL15͒,and x =0.20͑BFOL20͔͒ceramics.The slurries of the above mixtures were dried overnight in anoven at 50°C.The homogeneous mixed powders were cal-cined at different temperatures for different duration.BFO powder was calcined in two different steps;͑a ͒500°C.for 1h and ͑b ͒850°C.for 2h.The calcination temperatures/time for BFOL5/BFOL10and BFOL15/BFOL20were found to be 870°C/2h and 890°C/2h,respectively.The fine calcined powders of BFO and BFOL were used to make circular pellets of 7mm diameter and 1–2mm thickness.All the pellets were sintered at 890°C.for 4h for densifi-cation.In order to study phase formation and to carry out pre-liminary structural analysis of BFO and BFOL,x-ray diffrac-tion pattern were taken using Cu K ␣radiation ͑=1.5405Å͒of a Seimens D5000powder diffractometer.Dif-ferential thermal analysis of all the samples were carried out to study the phase transition behavior,using Shimatzu differ-ential thermal analyses ͑DTA ͒thermal analyser.The scan-ning electron micrographs ͑SEM ͒of the pellet samples were taken to study the grain size and size distributions.The di-electric constant and loss tangent were measured using an impedance analyzer ͑HP4294A ͒and temperature controller ͑M/s MMR Technology,Inc.͒in a wide range of frequencies ͑1kHz–1MHz ͒and temperatures ͑77–500K ͒.Ferroelec-tric polarizations were measured on poled samples using a hysteresis loop tracer ͑M/s Radiant Technology Inc.͒.The magnetization M as a function of applied field H at different temperatures ͑2–300K ͒was measured using a supercon-ducting quantum interference device ͑SQUID ͒magnetome-ter.The EMR studies of all the samples were carried out at 300K using an X -band spectrometer operating at 9.28GHz.TABLE parison of lattice parameters,and tolerance factors of ͑Bi 1−x La x ͒FeO 3ceramics.The estimated standard deviations are in the positiona ͑Å͒c ͑Å͒V ͑Å͒3t x =0.0 5.6206͑20͒13.6924͑20͒374.570.915x =0.05 5.6011͑80͒13.6472͑80͒371.010.916x =0.10 5.6019͑70͒13.6429͑70͒370.770.917x =0.15 5.5942͑48͒13.6386͑48͒369.640.919x =0.205.5879͑48͒13.6066͑48͒367.940.920FIG.1.X-ray diffraction patterns of BiFeO 3and Bi 1−x La x FeO 3͑0.05ഛx ഛ0.2͒polycrystalline ceramics.FIG.2.Differential thermal analyses ͑DTA ͒of BiFeO 3and Bi 1−x La x FeO 3͑0.05ഛx ഛ0.2͒.FIG.3.Scanning electron micrographs ͑SEM ͒of BFO,BFOL5,BFOL10,and BFOL20ceramics.III.RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONFigure 1shows the XRD pattern of BFO and BFOL ceramics.All the diffraction peaks of BFO were indexed and lattice parameters were determined in a hexagonal unit cell using a powder diffraction refinement computer program.17The La-modified BiFeO 3was also fitted with the same crys-tal structure.Though all the diffraction peaks were well iden-tified,few low intensity peaks were observed at 2ϳ27°–28°in case of BiFeO 3ceramic.Upon La substitution at the Bi site,the impurity phase was eliminated.The impu-rity peaks were identified,probably because of the addition of 10%extra Bi 2O 3.Peak shifts were calculated using peak fit software.Table I compares the refined least squares lattice constants of BFO and BFOL with their estimated standard deviations in parenthesis.Figure 2shows the thermograms of BFO and BFOL powders in the temperature range of 0–1200°C.Three dis-tinct features were observed ͑based on change of slopes of all the curves ͒:͑a ͒ϳ300–350°C corresponds to Neel tempera-tures of magnetic phase transition,͑b ͒800–900°C corre-sponds to the ferroelectrics Curie temperatures/phase transi-tion,and ͑c ͒950–1150°C corresponds to the heat loss at the melting points of BFO and BFOL ceramics.These observa-tions suggest that the lanthanum substitution lowered the ferroelectric phase transition temperature but increases the melting point of BFO.Figure 3shows the scanning electron micrographs of BFO and BFOL ceramics.The average grain size of all the samples is very much similar,and in the range of 2–3m.However,it can be noticed that with a small lanthanum con-centration ͑5–10mole %͒,the density of sample ͑i.e.,lessvoids ͒increases.In the BFOL20sample,small grains coa-lesce to form large grains,and hence different microstruc-tures of large grain size are obtained.The microstructures and absence of secondary phases on La substitution in BFO are some of the main reasons for enhanced electrical and magnetic properties of BFOL.Figures 4͑a ͒and 4͑b ͒show the variation of dielectric constant of BFOL with frequency at 300and 630K,respec-tively.It is observed that at higher temperature ͑630K ͒,the dielectric constant of the ceramic samples increases by an order of magnitude ͑with minimal changes in BFOL10and BFOL15͒.This increase is considered as due to the magnetic phase transition around that temperature.This is more evi-dent from the Fig.5.At 300K,no frequency dispersion was observed in the material ͑with an exception of BFOL5͒.However,at 630K most of the ceramic samples exhibited frequency dispersion at lower frequencies.Figures 5͑a ͒and 5͑b ͒show the temperature variation of dielectric constant at two different frequencies 100kHz and 1MHz,respectively.Because of temperature limitation of our sample holder ͑i.e.,maximum temperature=700K ͒,we could not obtain ferroelectric phase transition temperature of BFO and BFOL ͑as observed from DTA results ͒.However,a sharp increase in dielectric constant started from 500K for all the ceramics.Figures 6͑a ͒and 6͑b ͒show variation of loss tangent with temperature at 100kHz and 1MHz,respectively.At the lower frequency,the loss tangent is higher,and it decreases as a function of the frequency ͑lower frequency data are not shown here ͒.Around room temperature ͑ϳ300K ͒loss tan-gent peaks were observed for all the samples.AsevidentFIG.4.͓͑a ͒and ͑b ͔͒.Dielectric con-stant vs frequency ͑100kHz–1MHz ͒of BFO and BFOL ceramics at 300and 630K.FIG.5.͓͑a ͒and ͑b ͔͒.Dielectric con-stant vs temperature of BFO and BFOL ceramics at 100kHz and 1MHz.from our dielectric measurements,dielectric anomaly of BFOL corresponds to the magnetic phase transition tempera-tures.Both the dielectric constant and the loss tangent of all the ceramics have a signature of attaining local maxima,a characteristic for multiferroics.Figure 7shows the ferroelectric hysteresis loops mea-sured on poled samples of BFO,BFOL5,and BFOL20at 300K and at different applied fields.BFO did not give a perfect ferroelectric loop.However,on La substitution,the loop gradually changes to that of ferroelectric nature reduc-ing the leakage.Still the samples are not totally leakage free.The ferroelectric polarization of x =0.05sample,which has a better microstructure and higher dielectric constant is shown for comparison.The remnant polarization of BFOL20ce-ramic was found to be 2P r Ϸ13C/cm 2at an applied field of 20kV/cm.These suggest the improvement of electrical and ferroelectric properties upon lanthanum substitutions at the Bi site in BFO ceramics.Figure 8shows the magnetization M versus applied field H of BFO and BFOL at room temperature ͑BFOL5data not shown in the figure ͒.Asymmetric hysteresis loops at 300and2K were obtained from which we measured the coercivity H c ,the exchange bias H e ,the average remanence magnetiza-tion M r =͑M r ++M r −͒/2and the magnetization at 55kOe ͑de-fined as M H ͒.In Table II ,we have compared the value of these quantities for all the BFO and BFOL samples.All the samples have negative H e ͑i.e.,their loops are shifted to the negative side by exchange bias ͒.At T =2K the magnitudes of the loop parameters ͑H c ,H e ,M H ,and M r ͒increase on increasing La concentration.The enhancement of the mag-netic parameters,perhaps due to increased magnetoelectric coupling 8,18on La-modified BFO are observed here.The hysteresis loops parameters ͑at 300K ͒for the samples of BFO ͑Table II ͒are presented graphically in Fig.8͑inset ͒.The M vs H curves are nearly linear,and hence M does not have any tendency to saturate even at 55kOe.Consequently the saturation magnetization cannot be determined and only the magnetization at 55kOe,viz.,M H is listed in Table II .For 20%La in BFO,a typical loop in the low field region was observed.Similar sets of data were obtained at 2K,except the magnitudes of H e ,H c ,and M H aredifferent.FIG.6.͓͑a ͒and ͑b ͔͒.Loss tangent vs temperature of BFO and BFOL ceram-ics at 100kHz and 1MHz.FIG.7.Ferroelectric hysteresis of BFO,BFOL5,and BFOL20ceramics at different applied fields.In Fig.9͑a ͒,we plot the magnitude of the negative ex-change bias,viz.,H e of BFOL both at T =2and 300K.A similar plot for the coercivity H c and the average remanence M r is shown in Figs.9͑b ͒and 9͑c ͒,respectively,where a systematic increase in their magnitudes with La doping is observed,especially at 2K.We also measured temperature dependence of H c ,H e ,and M H ͑Fig.10͒of BFO,where H c increases with increase in temperature and H e goes through a maximum near 100K.The presence of exchange bias H e in all our samples here is most intriguing since H e usually signifies the presence of a ferromagnet/antiferromagnet ͑F/AF ͒interface in a system.19–21In the weak ferromagnet ␣-Fe 2O 3,in which Dzyloshisky-Moriya ͑DM ͒antisymmetric exchange interac-tion is considered as the source of weak ferromagnetism,we did not observe exchange bias in a separate experiment not reported here.In BFO,the conventional DM interaction is zero.11A magnetoelectric interaction ͑such as DM interac-tion ͒,which couples both to the polarization and magnetiza-tion,has been introduced to explain the cycloidal spin struc-ture and its transformation to a homogeneous AF state under an applied magnetic field.11–16,18–22Whether the observed ex-change bias can be theoretically explained by this DM inter-action still needs to be understood.The temperature dependence of the low-field ͑H =200Oe ͒susceptibility for all the samples is shown in Fig.11.The temperature dependence of is quite subtle except for the pure BFO sample,which obeys Curie law at lower temperatures,perhaps due to an otherwise undetected para-magnetic impurity.Also,in the 20%La doped sample,is considerably lower which may be due to the different shape of its hysteresis loop ͑Fig.8͒.Figure 12shows the room temperature EMR studies of all the samples at 9.28GHz suggesting an EMR line near g Ϸ2.0for BFO,BFOL5,and BFOL10samples,which is in good agreement with the observations of Ruette et al.11The samples with 15%and 20%La doping have higher gvalues.FIG.8.Magnetic hysteresis loops of BFO and BFOL samples.The insets show the details of the loops for lower fields.TABLE II.Magnetic parameters of ͑Bi x La x ͒FeO 3͑x =0.0,0.05,0.10,0.15,and 0.20͒at room temperature.Composition H c ͑Oe ͒H e ͑Oe ͒M r ͑emu/g ͒M H ͑emu/g ͒at 55kOe⌬H ͑Oe ͒g value ͑⌬H ͒2ᐉ͑104͒/mg x =0620−3500.00380.35335 2.04 3.16x =0.05478−1800.00320.35900 2.0314.3x =0.101045−3600.00770.401050 2.0517.5x =0.152840−3250.02150.401480 2.1655.4x =0.20840−3300.07360.5518602.52304The peak-to-peak linewidth ⌬H and the line intensity I =͑⌬H ͒2ᐉ͑ᐉ=peak-to-peak height ͒of this line also increase with increase in La doping.These observed changes in the EMR and magnetic parameters with increase in La doping ͑Table II ͒are mutually consistent in the following way.The increase in H c implies increase in magnetic anisotropy,which in turn increases the EMR linewidth ⌬H and gvalues.23Since the EMR line intensity is proportional to ͑⌬H ͒2as noted above,the line intensity also increases with increase in La doping.In the doped samples,a second over-lapping line begins to emerge and shifts to lower fields with increasing La doping.Since exchange bias H e is also ob-served in the undoped BFO,it is unlikely that the source of this line is related to the presence of the exchange bias.The EMR parameters ͑Table II ͒represent values for the compos-ite line observed here since it is difficult to completely re-solve the two lines.The second line could result from any nonuniformity in the spatial magnetization of the samples such as from magnetic domains.Because of the increase of the EMR linewidth and H c with increase in La doping,both signifying increase in anisotropy,domains are more likely to be present for the larger Ladopings.FIG.9.Effect of La doping on ͑a ͒exchange bias ͑−H e ͒,͑b ͒coercivity H c ,and ͑c ͒average magnetization M r at 2and 300K.Lines joining the points are for visualaid.FIG.10.Temperature dependence of exchange bias ͑−H e ͒,coercivity ͑H c ͒,and magnetization M H at 55kOe for the BFO.Lines joining the points are for visualclarity.FIG.11.Temperature dependence of the low-field susceptibility measured at H =200Oe for BFO and BFOLceramics.FIG.12.Room temperature EMR spectra of the BFO and BFOL samples measured at f =9.28GHz.The vertical line marks the calculated position for g =2.0.IV.CONCLUSIONSPure and La substituted BiFeO3ceramics were synthe-sized using solid-state reaction substitution at Bisite eliminated the small impurity phase of BiFeO3and sta-bilized the crystal structure into hexagonal symmetry.Though the dielectric properties were not enhanced by Lasubstitution,systematic increase in both the ferroelectric andferromagnetic properties were achieved.The observed in-creases in the magnetic parameters͑H c,H e,and M r͒and EMR parameters͑⌬H,g,intensity I͒with increase in Ladoping reflect corresponding increases in the magnetic aniso-tropy and magnetization.However,the observation of ex-change bias H e in this ferromagnetic-ferroelectric system ismost intriguing and requires theoretical interpretation.It ishoped that these studies will stimulate such an investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTThis research was supported in part by NSF͑DMR0305588͒and DOD͑W911NF-06-1-0030͒grants.1Yu.E.Roginskaya,Yu.Ya.Tomashpol’ski,Yu.N.Venevtsev,V.M. Petrov,and G.S.Zhdanov,Sov.Phys.JETP23,490͑1966͒.2I.R.Teague,R.Gerson,and W.J.James,Solid State Commun.8,1073͑1970͒.3N.N.Krainik,N.P.Khuchua,V.V.Zhdanova,and V.A.Evseev,Fiz. Tverd.Tela͑S.-Peterburg͒8,816͑1966͒.4S.T.Zhang,M.H.Lu,D.Wu,Y.F.Chen,and N.B.Ming,Appl.Phys. Lett.87,262907͑2005͒.5C.Ederer and N.A.Spaldin,Phys.Rev.B71,224103͑2005͒.6S.A.Fedulov,dyzhinskii,I.L.Pyatigorskaya,and Yu.N.Venevt-sev,Sov.Phys.Solid State6,375͑1964͒.7I.H.Ismailzade,R.M.Ismailov,A.I.Alekberov,and F.M.Salaev,Phys. Status Solidi A68,K81͑1981͒.8N.Wang,J.Cheng,A.Pyatakov,A.K.Zvezdin,J.F.Li,L.E.Cross,and D.Viehland,Phys.Rev.B72,104434͑2005͒.9V.R.Palkar,D.C.Kundaliya,and S.K.Malik,J.Appl.Phys.93,4337͑2003͒.10V.R.Palkar,D.C.Kundaliya,S.K.Malik,and S.Bhattacharya,Phys. Rev.B69,212102͑2004͒.11B.Ruette,S.Zvyagin,A.P.Pyatakov,A.Bush,J.F.Li,V.I.Belotelov,A. K.Zvezdin,and D.Viehland,Phys.Rev.B69,064114͑2004͒.12G.A.Smolenskii and I.Chupis,p.25,475͑1982͒.13I.Sosnowka,M.Loewenhaupt,W.I.F.David,and R.M.Ibberson, Physica B180–181,117͑1992͒.14F.Bai et al.,Appl.Phys.Lett.86,032511͑2005͒.15J.Li et al.,Appl.Phys.Lett.84,5261͑2004͒.16D.Lee,M.G.Kim,S.Ryu,H.M.Jang,and S.G.Lee,Appl.Phys.Lett. 86,222903͑2005͒.17E.Wu,computer code POWD,an interactive powder diffraction data inter-pretation and indexing program,Ver.2.1,School of Physical Sciences, Flinder University of South Australia,Bedford Park,SA5042,Australia. 18J.Hemberge,P.Lunkenheimer,R.Fichtl,H.-A.Knug V on Nidda,V.Tsur-kan,and A.Loidt,Nature͑London͒434,364͑2005͒.19W.H.Meiklejohn and C.P.Bean,Phys.Rev.102,1413͑1956͒;J.Appl. Phys.33,1328͑1962͒.20J.Nogues and I.K.Schullar,J.Magn.Magn.Mater.192,203͑1999͒. 21A.Punnoose,E.H.Morales,Y.Wang,D.Lederman,and M.S.Seehra,J. Appl.Phys.93,771͑2003͒.22I.Sosnowska and A.Zvezdin,J.Magn.Magn.Mater.140–144,167͑1995͒.23T.G.Castner and M.S.Seehra,Phys.Rev.B4,38͑1971͒.。

英汉互译

一、英译汉

Title: Aerogels with 3D Ordered Nanofiber Skeletons of

Liquid-Crystalline Nanocellulose Derivatives as Tough and Transparent Insulators

Abstract:

Aerogels of high porosity and with a large internal surface area exhibit outstanding performances as thermal, acoustic, or electrical insulators【1】. However, most aerogels are mechanically brittle and optically opaque, and the structural and physical properties of aerogels strongly depend on their densities. The unfavorable characteristics of aerogels are intrinsic to their skeletal structures consisting of randomly interconnected spherical nanoparticles【2】. A structurally new type of aerogel with a three-dimensionally ordered nanofiber skeleton of liquidcrystalline nanocellulose (LC-NCell) is now reported. This LCNCell material is composed of mechanically strong, surfacecarboxylated cellulose nanofibers dispersed in a nematic LC order. The LC-NCell aerogels are transparent and combine mechanical toughness and good insulation properties. These properties of the LC-NCell aerogels could also be readily controlled.

工艺参数对CrNx涂层性能的影响

工艺参数对CrNx涂层性能的影响宋慧瑾;鄢强;李玫;董志红;冯威;朱晓东;孙艳【摘要】采用直流磁控溅射技术制备了氮化铬(CrNx)涂层,研究了制备CrNx涂层的工艺参数对所制备的CrNx涂层的膜基结合力及力学性能的影响.研究结果表明:工艺参数对CrNx涂层性能的影响不成各向同性关系;在较低的N2含量、较高的脉冲偏压、约100V的直流偏压、较高的真空度、较高的沉积温度和较高的靶功率下制备的CrNx涂层的硬度较高,而在较低的N2含量、恰当的脉冲偏压和占空比配对、较高的直流偏压、较高的真空度、较高的沉积温度和较高的靶功率下制备的CrNx涂层的表面形貌较好.【期刊名称】《高技术通讯》【年(卷),期】2015(025)003【总页数】7页(P300-306)【关键词】氮化铬(CrNx);涂层;工艺参数;直流磁控溅射【作者】宋慧瑾;鄢强;李玫;董志红;冯威;朱晓东;孙艳【作者单位】成都大学工业制造学院成都610106;成都大学工业制造学院成都610106;西南石油大学机电工程学院成都610500;成都大学城乡建设学院成都610106;成都大学工业制造学院成都610106;成都大学工业制造学院成都610106;成都大学工业制造学院成都610106;成都大学工业制造学院成都610106【正文语种】中文氮化铬(CrNx)涂层硬度高、耐磨性好、摩擦系数低,具有高温抗氧化性和耐腐蚀性能,并且对有色金属及其合金化学惰性好,是加工铝合金、黄铜和镍合金等的理想涂层材料。

氮化铬涂层已经广泛应用在很多领域,近年来越来越受到人们的关注和重视[1-4]。

在机械制造和加工领域,氮化铬涂层的硬度较高,摩擦系数较低,与钢摩擦时,摩擦系数比钢-钢摩擦小20%~30%,比氮化钛-钢摩擦小10%~20%,因为使用中表面容易形成一层稳定致密、硬度高并且结合紧密的氧化层,所以氮化铬涂层作为耐磨涂层已广泛用于一些机械零部件、模具和切削工具的表面强化以增长使用寿命。

万青个人简历

6. C. C. Li, Z. F. Du, L. M. Li, H. C. Yu, Q. Wan, and T. H. Wang, "Surface-depletion controlled gas sensing of ZnO nanorods grown at room temperature", Applied Physics Letters. 91, 032101 (2007).

19. Q.Wan, K.Yu, T.H.Wang, C.L.Lin, "Low-field electron emission from tetrapod-like ZnO nanostructures synthesized by rapid evaporation", Applied Physics Letters, 83, 2253 (2003).

21. Q.Wan, T.H.Wang M.Zhu,and C.L.Lin,"Resonant tunneling of Si nanocrystals embedded in Al2O3 matrix prepared by electron-beam co-evaporation",Applied Physics Letters, 81, 538 (2002)

在研课题

2007年,湖南省杰出青年基金项目,负责人(30万)

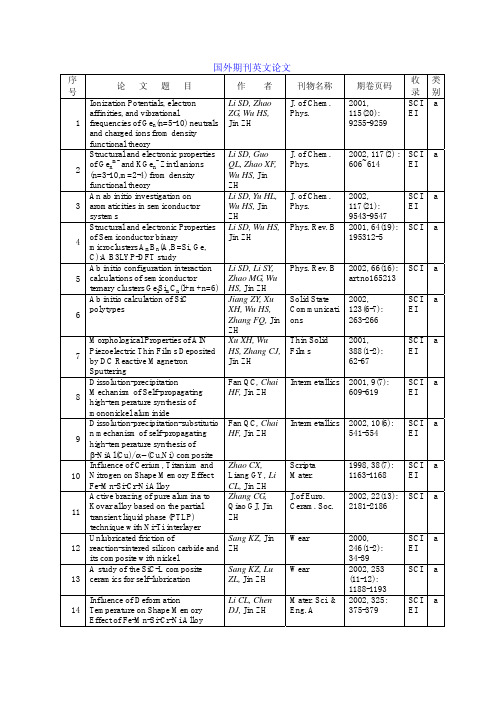

国外期刊英文论文

Influence of Deformation

Li CL, Chen Mater. Sci. & 2002, 325: SCI a

14 Temperature on Shape Memory

DJ, Jin ZH Eng. A

375-379

EI

Effect of Fe-Mn-Si-Cr-Ni Alloy

Wang TJ

Comparison between fatigue

Qiao GJ,

Int. J. Fatigue 2002, 24(5): SCI a

17

behavior of some ceramics: a new concept of intrinsic stress-corrosion

Wang HJ, Jin ZH

Ding HF, Jin

258-264

EI

ZH

The interfacial stability of the

Tang WM,

Mater. Chem. 2002, 77:

SCI a

21 coated-SiC/Fe couple

Zheng ZX,

Phys.

Ding HF, Jin

236-241

EI

ZH

31

Unlubricated wear of Si/SiC and its composite with nickel Si/SiC-Ni

Sang KZ, Jin ZH

Tribology Int.

2001, 34(5): SCI a

315 -319

EI

Effects of crystalline morphology Xu T, Yu J, Jin Mater.

Influence_of_Composite_Non_Magnetic_Ions_(Cd-Ti)_D