Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period

second language acquisition简介

★1. SLA (Second language acquisition) is the process by which a language other than the mother tongue is learnt in a natural setting or in a classroom.★2. Acquisition vs. Learning (Krashen1982)Acquisition refers to the learning of a language unconsciously under natural settings where learners pay attention only to the meanings or contents rather than forms or grammars.Learning refers to the learning of a language consciously under educational settings where learners mainly pay attention to forms or grammars.3. The study of second language acquisition is a branch of applied linguistics.It mainly deals with how the second language is acquired. The process not only involves linguistics but also a great many subjects including linguistic physiology, psychology, psycholinguistics, cognitive science and so on.4. Factors affecting SLASocial factors (external factors)Learner factors (internal factors)Social factors (external factors)Social contextLanguage policy and the attitude of the public sector;Social demandWith the trend of globalization of the world economy , it is widely accepted among educators and national leaders that proficiency in another language is an indispensable quality of educated peopleLearner factors (internal factors)MotivationAgeLearning strategy5. Through observations and experiments they have found that children all undergo certain stages of language development.Babbling stage (articulating certain speech sounds)(6 -12)One word or Holophrastic stage (using single words to represent various meanings)(12-18 months)Two –word stage (18-20 months)Telegraphic speech stage (using phrase and sentences composed of only content words.)(2-3 years )。

Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis

Second Language Acquisition and the Critical PeriodHypothesisBirdsong, David (Ed.) (1999)Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum AssociatesIs there a single key issue in the field of second language acquisition / learning, an as yet unresolved matter on which all else depends? A good case could be made for the question of whether or not there is a critical period for second language learning being just such a key issue. In other words, does the nature of second language acquisition change if the first exposure to the new language comes after a certain age? This question is closely linked to the question of whether first language (L1) acquisition and second language (L2) acquisition are essentially the same process, or very similar processes, and if so whether this is the case for some learners, or for all. In practical terms, it could be central not only to such issues as the optimal age at which children should start learning foreign languages, but also to the best teaching/learning approach for adults. Krashen's Input Hypothesis (Krashen, 1985) is totally undermined if a critical period does indeed exist, since the hypothesis assumes not only that L2 acquisition is similar in nature to L1 acquisition, but also that this is the case for learners of any age. Alhough many would claim that Krashen's theoriesare seriously flawed in any case, their influence in the field of second language teaching can hardly be denied. Issues such as the relative importance of lexis and syntax in teaching materials must ultimately link back to the way in which second language knowledge is organised in the brain. If that organisation is different in learners who have first been exposed to L2 after a certain age, then this has a bearing on choice of teaching approach. Yes, I believe there is a strong prima facie case for regarding the debate over the Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH) as a central issue.The concept of a critical period is well known in nature. One example is imprinting in ducks and geese, where it is claimed that ducklings and goslings can be induced to adopt chickens, people, or even mechanical objects as their mothers if they encounter them within a certain short period after hatching. (Note, however, that the exact nature of even this apparently well-documented instance of a critical period is now coming under fire; see Hoffmann, 1996). In humans, on the basis of extant evidence, it seems that there is a critical period for first language acquisition; those unfortunate persons who are not exposed to any language before puberty seem unable to properly acquire the syntax of their first language later in life. (Inevitably, our knowledge in this area is sketchy and unreliable, being based solely on a very few cases, of whichthat of "Genie" is the most celebrated and best known; see Eubank and Gregg's article in Birdsong for a discussion.) [-1-]Provided that a person learns a first language in the way, the question is then whether there is a certain biologically-determined critical period during which that person can acquire further languages using one mental mechanism, probably resulting in a high level of achievement if learning continues, and after which the learning process for new languages changes, so that the learning outcome will not be as good. Note that we are not talking here about the commonly-observed and widely-accepted generalisation that learning gets harder as one gets older; nor is the question one of whether changes in attitudes or situation alter the learning process as one gets older. The issue is whether a fundamental change in the learning process and thus in potential learning outcomes related to second languages occurs in the brain at a fairly fixed age, closing a biological "window of opportunity" (although as Birdsong points out in his introduction to this book, there is no single formulation of the Critical Period Hypothesis, but a number of different versions of the theory).This book contributes to the debate by juxtaposing a number of papers which consider the CPH from a variety of points of view, and which arrive at a variety of conclusions. Most of the papers in the book are based on talks given at an AILA symposium on the CPH which tookplace in Finland in 1996. It must have been quite a conference; the names of the contributors to this book make up a Who's Who of researchers in fields related to the CPH issue, and the diversity of the opinions held by the contributors must have made for some sharp exchanges. The book contains research papers by both proponents and opponents of a CPH for SLA, thus drawing the reader into the controversy.What you get in the book is what you might expect from the above description. First, it must be said that it is a fairly tough read. Some of the writers are easier to follow than others, but these are research papers, and anyone unfamiliar with the fields covered--and there is a considerable range of fields--is likely to have to work quite hard at some of the texts at least. Second, there is no overall conclusion, even though the editor does have his own clearly-expressed view. This is not because of differences in the interpretation of data; it is because the various writers operate in different areas of research, each casting a different light on the central issue. These varied areas of research produce conclusions which point in different directions, and because of the lack of common ground on which to debate, the differences cannot easily be resolved. Third, there is an unevenness about the book. Some writers report on tentative conclusions from ongoing research; others simply reproduce material on completed projects which can be found in almost identical form elsewhere. The relevance of the research presented to the central issue also varies. Thesepoints might be regarded as drawbacks. But the compensation comes in having so much relevant and fairly up-to-date material on the issue collected together in one volume, providing insights into current knowledge and thinking from a variety of angles.In his introduction, Birdsong briefly surveys the background to the debate, outlining some of the arguments previously advanced for and against the existence of a critical period. He is particularly well suited to this task, having "changed sides" on the issue in the early 1990s. After the background section, Birdsong goes on to present a careful summary of each of the chapters in the book. While admitting his adherence to the "anti-CPH" camp, he makes no attempt to resolve the evidence presented in the various chapters, and concludes that in total the contributions to the book demonstrate "the richness, depth and breadth of the critical period enquiry" and that they "testify to the unmistakable centrality of the CPH in L2A research" (p. 18). The introduction is clearly written, and since it contains so much summarising material it can stand as a valuable survey of the field in itself. However, some of the chapters in the book do not lend themselves to brief summaries (the chapter by Eubank and Gregg, for example, is far too broad in scope) and thus reading the introduction is no substitute for reading the entire book. [-2-]There are three chapters providing evidence for the existence of an SLA critical period. First, Weber-Fox and Neville take a frontal approach to the issue with an investigation of neural activity while performing L2 tasks in subjects whose first exposure to L2 was at different ages. Their paper has the rather daunting title of "Functional Neural Subsystems Are Differentially Affected by Delays in Second Language Immersion: ERP and Behavioural Evidence in Bilinguals." The findings do not point to the existence of a single critica l period; the patterns of change vary for different language tasks. The authors claim, fairly circumspectly, that "our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the development of at least some neural subsystems for language processing is constrained by maturational changes, even in early childhood. Additionally, our results are compatible, at least in part, with aspects of Lenneberg's . . . original hypothesis that puberty may mark a significant point in language learning capacity and neural reorganization capabilities" (pp. 35-36). Eubank and Gregg, in a wide-ranging paper entitled "Critical Periods and (Second) Language Acquisition: Divide et Impera," recognise the importance of neurological investigation in their consideration of whether second language learners retain access to Universal Grammar, and find Weber-Fox and Neville's line of research a promising one. Sandwiched between these two chapters comes a paper by Hurford and Kirby which takes a very different approach to the problem. The writers' argument isan evolutionary one; they produce computer models to suggest that a critical period for language acquisition finishing at puberty inevitably evolves in order to produce maximum language learning by the time a reproductive age is reached. However, their argument appears predicated on the assumption that the level of an individual's language knowledge governs the likelihood of his or her being able to reproduce. Alas, it has never been my personal experience that linguistic ability provides a crucial advantage in the competition for sexual partners, and I do not find myself convinced in any great measure by this application of the currently fashionable evolutionary approach to exploring the nature of the human mind.Then come three chapters arguing against the existence of a critical period. James Flege provides research evidence to show that level of achievement in pronunciation is closely related to age of first exposure to the second language. He claims that, even for children, the later in life the first exposure to L2, the greater the degree of foreign accent, with no sudden discontinuity in the figures at a certain age to suggest that a critical [-3-] period has ended, a window of opportunity suddenly closed. Other hypotheses, he claims, can be advanced to explain the linear nature of the relationship between age of first exposure and L2 pronunciation, notably that pronunciation of L2 varies as a function of how well one pronounces L1. Theo Bongaerts takes a very different approach in hispaper, which again focusses on pronunciation; his view is that people who begin learning L2 later in life can sometimes achieve native-like pronunciation. If such learners do indeed exist, and Bongaerts presents evidence to suggest that they do, then there can be no biological window of learning opportunity that closes at a fixed age; instead, there must be other explanations for the lack of success.。

二语习得SecondLanguageAcquisition资料讲解

eg. watashiwa Nihonjin desu

第二语言习得的调查以参数的重新设定为主。例如说日语的人学英语就得重新设 定’中心参数’,使之从‘中心词为后’,调整至’中心词为先’。 79xx

Second Language Acquisition

UG principle The principle of structure-dependency(结构依存关系)which states

Second Language Acquisition

Implicit learning is coming to learn the underlying structure of a complex stimulus environment by a process which takes place naturally, simply and without conscious operations. Explicit learning is a more conscious operation where the individual makes and tests hypotheses.

二语习得Second Language Acquisition教学内容

explicit knowledge

L2 Input

noticed input

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

comprehended input

intake

implicit knowledge

L2 output

Second Language Acquisition

Noticing In order for some feature of language to be acquired, it is

Second Language Acquisition

Implicit learning is coming to learn the underlying structure of a complex stimulus environment by a process which takes place naturally, simply and without conscious operations. Explicit learning is a more conscious operation where the individual makes and tests hypotheses.

《英语语言学导论》(第四版Chapter11 Second Language Acquisition

11.2.2 Learner’s factors

• Learner’s factors mainly cover the following aspects:

• Motivation • Language aptitude • Age • Learning strategy

11.2.1 Social factors

Discussing Task

Group work: Have a discussion on the following questions.

1. How does (second) language acquisition take place?

2. How is foreign language learning different from second language acquisition?

The Symbolic Function of Words

Teaching Aims

1. To know what SLA is, and how the theories account for SLA. 2. To understand different factors affecting SLA 3. To know how learner’s language is analyzed 4. To cultivate students’ research awareness and innovative spirit in discovering and solving problems by analyzing the different kinds of errors and individual differeneces in SLA.

最新二语习得Second Language Acquisition教学提纲

Theoretical i of

how language is represented in the mind and whether there

is a difference between the way language is acquired and

75

Second Language Acquisition

1. The Grammar-Translation Method (structuralism) 2. The Audio-Lingual Method (听说法) (structuralism, behaviorism s-r) 3. Communicative Language Teaching (交际法语言教学) (cognitive science, linguistic competent, communicative competent) 4. Content-based, Task-based Approaches (学科性方法)

Second Language Acquisition

Implicit learning is coming to learn the underlying structure of a complex stimulus environment by a process which takes place naturally, simply and without conscious operations. Explicit learning is a more conscious operation where the individual makes and tests hypotheses.

英语语言学名词解释补充

Chapter 11 : Second Language Acquisition1. second language acquisition:It refers to the systematic study of how one person acquires a second language subsequent to his native language.2. target language: The language to be acquired by the second language learner.3. second language:A second language is a language which is not a native language in a country but which is widely used as a medium of communication and which is usually used alongside another language or languages.4. foreign language:A foreign language is a language which is taught asa school subject but which is not used as a medium of instruction in schools nor as a language of communication within a country.5. interlanguage: A type of language produced by second and foreign language learners, who are in the process of learning a language, and this type of language usually contains wrong expressions.6. fossilization: In second or foreign language learning, there is a process which sometimes occurs in which incorrect linguistic features become a permanent part of the way a person speaks or writes a language.7. contrastive analysis: a method of analyzing languages for instructional purposes whereby a native language and target language are compared with a view to establishing points of difference likely to cause difficulties for learners.8. contrastive analysis hypothesis: A hypothesis in second language acquisition. It predicts that where there are similarities between the first and second languages, the learner will acquire second language structure with ease, where there are differences, the learner will have difficulty.9. positive transfer:It refers to the transfer that occur when both the native language and the target language have the same form, thus making learning easier. (06F)10. negative transfer:the mistaken transfer of features of one’s native language into a second language.11. error analysis: the study and analysis of errors made by second and foreign language learners in order to identify causes of errors or common difficulties in language learning.12. interlingual error:errors, which mainly result from cross-linguistic interference at different levels such as phonological, lexical, grammatical etc.13. intralingual error:Errors, which mainly result from faulty or partial learning of the target language, independent of the native language. The typical examples are overgeneralization and cross-association.14. overgeneralization:The use of previously available strategies in new situations, in which they are unacceptable.15. cross-association: some words are similar in meaning as well as spelling and pronunciation. This internal interference is called cross-association.16. error: the production of incorrect forms in speech or writing by a non-native speaker of a second language, due to his incomplete knowledge of the rules of that target language.17. mistake:mistakes, defined as either intentionally or unintentionally deviant forms and self-corrigible, suggest failure in performance.18. input: language which a learner hears or receives and from which he or she can learn.19. intake: the input which is actually helpful for the learner.20. Input Hypothesis:A hypothesis proposed by Krashen , which states that in second language learning, it’s necessary for the learner to understand input language which contains linguistic items that are slightly beyond the learner’s present linguistic competence. Eventually the ability to produce language is said to emerge naturally without being taught directly.21. acquisition: Acquisition is a process similar to the way children acquire their first language. It is a subconscious process without minute learning of grammatical rules. Learners are hardly aware of their learning but they are using language to communicate. It is also called implicit learning, informal learning or natural learning.22. learning: learning is a conscious learning of second languageknowledge by learning the rules and talking about the rules.23. comprehensible input:Input language which contains linguistic itemsthat are slightly beyond the learner’s present linguistic competence.(06F)24. language aptitude: the natural ability to learn a language, notincluding intelligence, motivation, interest, etc.25. motivation:motivation is defined as the learner’s attitudes andaffective state or learning drive.26. instrumental motivation: the motivation that people learn a foreignlanguage for instrumental goals such as passing exams, or furthering acareer etc. (06C)27. integrative motivation:the drive that people learn a foreign languagebecause of the wish to identify with the target culture. (06C/ 05)28. resultative motivation: the drive that learners learn a secondlanguage for external purposes. (06F)29. intrinsic motivation: the drive that learners learn the secondlanguage for enjoyment or pleasure from learning.30. learning strategies:learning strategies are learners’ consciousgoal-oriented and problem-solving based efforts to achieve learningefficiency.31. cognitive strategies: strategies involved in analyzing, synthesis,and internalizing what has been learned. (07C/ 06F)32. metacognitive strategies:the techniques in planning, monitoring andev aluating one’s learning.33. affect/ social strategies: the strategies dealing with the wayslearners interact or communicate with other speakers, native ornon-native.Chapter 12 : Language And Brain1. neurolinguistics: It is the study of relationship between brain andlanguage. It includes research into how the structure of the braininfluences language learning, how and in which parts of the brain language is stored, and how damage to the brain affects the ability to use language.2. psycholinguistics: the study of language processing. It is concerned with the processes of language acqisition, comprehension and production.3. brain lateralization: The localization of cognitive and perceptive functions in a particular hemisphere of the brain.4. dichotic listening:A technique in which stimuli either linguistic or non-linguistic are presented through headphones to the left and right ear to determine the lateralization of cognitive function.5. right ear advantage: The phenomenon that the right ear shows an advantage for the perception of linguistic signals id known as the right ear advantage.6. split brain studies: The experiments that investigate the effects of surgically severing the corpus callosum on cognition are called as split brain studies.7. aphasia: It refers to a number of acquired language disorders due to the cerebral lesions caused by a tumor, an accident and so on.8. non-fluent aphasia:Damage to parts of the brain in front of the central sulcus is called non-fluent aphasia.9. fluent aphasia: Damage to parts of the left cortex behind the central sulcus results in a type of aphasia called fluent aphasia.10. Acquired dyslexia: Damage in and around the angular gyrus of the parietal lobe often causes the impairment of reading and writing ability, which is referred to as acquired dyslexia.11. phonological dyslexia:it is a type of acquired dyslexia in which the patient seems to have lost the ability to use spelling-to-sound rules.12. surface dyslexia: it is a type of acquired dyslexia in which the patient seems unable to recognize words as whole but must process all words through a set of spelling-to-sound rules.13. spoonerism:a slip of tongue in which the position of sounds, syllables, or words is reversed, for example, Let’s have chish and fips instend of Let’s have fish and chips.14. priming: the process that before the participants make a decision whether the string of letters is a word or not, they are presented with an activated word.15. frequency effect: Subjects take less time to make judgement on frequently used words than to judge less commonly used words . This phenomenon is called frequency effect.16. lexical decision: an experiment that let participants judge whethera string of letter is a word or not at a certain time.17. the priming experiment:An experiment that let subjects judge whethera string of letters is a word or not after showed with a stimulus word, called prime.18. priming effect:Since the mental representation is activated through the prime, when the target is presented, response time is shorter that it otherwise would have been. This is called the priming effect. (06F)19. bottom-up processing: an approach that makes use principally of information which is already present in the data.20. top-down processing:an approach that makes use of previous knowledge and experience of the readers in analyzing and processing information which is received.21. garden path sentences: a sentence in which the comprehender assumesa particular meaning of a word or phrase but discovers later that the assumption was incorrect, forcing the comprehender to backtrack and reinterpret the sentence.22. slip of the tongue:mistakes in speech which provide psycholinguistic evidence for the way we formulate words and phrases.(注:可编辑下载,若有不当之处,请指正,谢谢!)。

Main Theories of Second Language Acquisition and Their Implications

Main Theories of Second Language Acquisition and TheirImplicationsAbstract: Language learning and language teaching are vital to everyone’s daily life.What is the best way to learn a second language? D. Brown’s Principles of Language Learning and Teaching is one of books to work on it. This paper tries to review the main theories of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and to explore their implications for us. Key Words: Second Language Acquisition; Theory; Implication1. IntroductionLanguage is the center of human life. It is one of the most important ways of expressing our love or our hatred to people; it is vital to achieve many of our goals and our careers; it is a source of artistic satisfaction or simple pleasure. Some people are able to use more than one language. Knowing another language may mean: getting a job, a chance to get educated, the expression of one’s opinion and affective gains. It affects people’s careers and possible future and their lives. In a word, with the globalization of the world, language learning and language teaching are vital to everyone’s daily life.What is the best way to learn a second language? This question arouses many a study in the field of English Curriculum and Instruction research. Many books, articles experiments and theories have been spawned from it, D. Brown’s Principles of Language Learning and Teaching is one ofthem.Although there seem to be some neatly-packaged programs in society which claim to help anyone learn English quickly, effectively and with little work, there are no quick and easy ways. Because learning a new language is complex and multifaceted, the process is equally fascinating and miraculous .This paper tries to review the main theories of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and to explore their implications for us.2. The Nature and Goal of SLASLA research began to be recognized as an independent disciple during the 1970s, SLA studies how a second language is learned and used. It is a scientific discipline that tries co describe how people learn and use another language. Therefore, SLA is a study of second and foreign language learning in natural and classroom settings, with a focus on the underlying competence of second language knowledge through their performances that show their knowledge of L2 rules.SLA is a multidisciplinary field of study. Second language learning process is cognitive, social, psychological as well as linguistic. As Brown put it, “ Second language learning is not a set of easy steps that can be programmed in a quick do-it-yourself kit”. The complexity of second language learning is partially due to the multidisciplinary nature of SLA. It draws theories and ideas from related disciplines for its own construct,such as linguistics, psychology, sociology and even neurolinguistics. SLA aims to describe and explain what happens when someone learns and uses a second language. It constitutes the how and why about second language learning. The goal of SLA can be simply and clearly stated as the description and explanation of L2 learning. It describes what L2 learner language looks like. Also, it explains how the language development is brought about and how the internal and external factors contribute to the mastery of a second language.SLA helps teachers understand the learning process better. SLA, with the description and explanation of L2 learning directly serves the teaching practice. It provides learners’perspectives on, and insight into, the processes of teaching and learning a second language. It enables teachers to reflect critically on the methodological procedures, adjust to the learners' condition and subsequently, create and construct a facilitative classroom atmosphere to promote SLA. Though the knowledge of SLA cannot give you a definite warrant for teaching success, the fruitful teaching practice comes about only when it is in harmony with the integrated understanding of the learning process and learner.3. Models of SLA3.1 An Innatist Model: Krashen’s Input HypothesisIn recent years the “Input Hypothesis”has come to identify what is really a set of five interrelated hypotheses. These fivehypotheses are summarized below.The Acquisition-learning Hypothesis. Krashen claimed thatadult second language learners have two means for internalizing the target language.The first is “acquisition”, a subconscious and intuitive process of constructing the system of a language, not unlike the process used by a child to “pick up” a language. The second means is a conscious “leaming” process in which learners attend to form, figure out rules, and are generally aware of their own process. According to Krashen, “fluency in second language performance is due to what we have acquired, not what we have learned”. Adults should, therefore, do as much acquiring as possible in order to achieve communicative fluency; otherwise, they will get bogged down in rule learning and too much conscious attention to the forms of language and to watching their own progress.The Monitor Hypothesis. The “monitor” is involved in learning, not in acquisition. It is a device for “watchdogging” one’s output, for editing and making alterations or corrections as they are consciously perceived. Only once fluency is established should an optimal amount of monitoring,or editing, be employed by the learner.The Natural Order Hypothesis. Krashen has claimed that we acquire language rules in a predictable or “natural” order.The Input Hypothesis. The Input Hypothesis claims that animportant “condition for language acquisition to occur is that the acquirer understand input language that contains structure “a bit beyond”his current level of competence.... If an acquirer is at stage or level i, the input he or she understands should contain i +1”.The Affective Filter Hypothesis. Krashen has further claimed that the best acquisition will occur in environments where anxiety is low and defensiveness absent, or, in Krashen's terms, in contexts where the “affective filter” is low.3.2 Cognitive Models3.2.1 McLaughlin’s Attention-processing ModelMcLaughlin’s Attention-processing Model juxtaposes processing mechanisms and categories of attention to form four cells.Controlled processes are “capacity limited and temporary”, and automatic processes are a relatively permanent. We can think of controlled processing as typical of anyone leaming a brand new skill in which only a very few elements of the skill can be retained.Automatic processes, on the other hand, refer to processing in a more accomplished skill, where the “hard drive”of your brain can manage hundreds and thousands of bits of information simultaneously The automatizing of this multiplicity of data isaccomplished by a process of restructuring in which “the components of a task are coordinated, integrated, or reorganized into new units, therebyallowing the ... Old components to be replaced by a more efficient procedure”.Both ends of this continuum of processing can occur with either focal or peripheral attention to the task at hand; that is, focusing attention either centrally or simply on the periphery. It is easy to fall into the temptation of thinking of focal attention as “conscious” attention, but such a pit-fall must be avoided. Both focal and peripheral attention to some task may be quite conscious. When you are driving a car, for example, your focal attention may center on cars directly in front of you as you move forward; but your peripheral attention to cars beside you and behind you, to potential hazards, and of course to the other thoughts “running through your mind”, is all very much within your conscious awareness.3.2.2 Implicit and Explicit ModelsIn the explicit category are the facts that a person knows about language and the ability to articulate those facts in some way. Explicit processing differs from McLaughlin’s focal attention in that explicit signals one’s knowledge about language. Implicit knowledge is information that is automatically and spontaneously used in language tasks. Children implicitly learn phonological, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic rules for language, but do not have access to an explanation, explicitly, of those rules. Implicit processes enable a learner to perform language but not necessarily to cite rules governing the performance.3.3 A Social Constructivist Model: Long’s Interaction HypothesisOne of the most widely discussed social constructivist positions in the field emerged from the work of Michael Long. Taking up where in a sense Krashen left off, Long posits, in what has come to be called the interaction hypothesis, that comprehensible input is the result of modified interaction. The latter is defined as the various modifications hat native speakers and other interlocutors create in order to render their input comprehensible to learners.In Long’s view, interaction and input are two major players in the process of acquisition. In a radical departure from an old paradigm in which second language classrooms might have been seen as contexts for “practicing”grammatical structures and other language forms, conversation and other interactive communication are, according to Long, the basis for the development of linguistic rules.Long’s Interaction Hypothesis has pushed pedagogical research on SIA into a new frontier. It centers us on the language classroom not just as a place where learners of varying abilities and styles and backgrounds mingle, but as a place where the contexts for interaction are carefully designed. It focuses materials and curriculum developers on creating the optimal environments and tasks for input and interaction such that the learner will be stimulated to create his or her own learner language in a socially constructed process. Further , it reminds us that the manyvariables at work in an interactive classroom should prime teachers to expect the unexpected and to anticipate the novel creations of learners engaged in the process of discovery.4. Implication of SLA’s TheorySLA theories are developed on the basis of the study of the processes and rules SLA. Although they cannot be applied directly to solve the problems of foreign language teaching and learning, they provide insight and guidance for English teaching.According to Krashen's SLA theory, comprehensible input is the key to language acquisition. That is to say, during the course of second language or foreign language learning, a learner develops from his present level i to “i +W by means of understanding an input of “i十l” which is a little bit beyond his level. Therefore how to provide the learner with comprehensible language input is a vital problem of foreign language teaching. Considering the present English language teaching in China, we should make great effort on the quantity of comprehensible language input in order to improve the efficiency of foreign language learning. English is taught as a foreign language in our country. In most cases, learners have very little opportunity to acquire English. They learn English mainly in class, therefore classroom instruction is a very important channel to provide students with comprehensible language input. In traditional English classes with the teacher as the center,intensive reading is much more stressed than extensive reading. The teacher greatly emphasizes the explanation, understanding and practice of language rules but neglects students’reception and usage of language rules, which has resulted in the fact that students have little comprehensible input in class. This kind of classroom instruction hinders the improvement of students’language competence. In order to let the students receive more comprehensible language input, we must create as many chances as possible for them to use English in real communication, such as teaching in English, i.e. Using English to explain language rules and teaching materials and organize class activities; let students communicate with each other in English.Taking part in English activities after class is also an applicable means of receiving comprehensible input that should not be neglected in foreign language teaching and leaming. Students may talk in English in “English Corners”, visit foreign teachers and talk with them, or see English films. Thus they can receive more comprehensible language input and improve their language acquisition.However, traditional language classes over-emphasize the role of teacher’s instruction, and consider foreign language leaming as obtaining “knowledge” instead of acquiring a “skill”. Teachers do most of the job in classes, giving students little opportunity to practice. As a result, after learning English for several years, students still can not make effectivecommunication in English, though they may have learned a lot of linguistic knowledge. Practice has proved that this kind of classroom environment is very unfavorable to the cultivation and development of learners’ competence of using English in communication.According to SLA theories, an ideal classroom environment should be like this: it provides students with more conditions and chances to use the target language directly; it “immerses” students in the environment of the target language, and stimulates students to take part in the communicative activities where they solve problems and fulfill tasks.5.Conclusion:We can’t deny that something about SLA’s theories are not suitable for our teachers and students, but we must admit that they contribute greatly to English Teaching and Learning in our country. However, we still have a long road to progress.Reference:[1] Brown,H,Douglas. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching[M].London: Person Education Company.[2] 姜玫. Krashen二语习得理论带给英语教学的启示与思考[J]. 外语教学与研究,2009(23):71.[3] 王慧颖. 外语教学法与二语习得理论的互动关系[J].贵州师范学院学报,2010(4):55.。

Secondlanguageacquisition

Second language acquisitionSecond language acquisition or second language learning is the process by which people learn a . Second language acquisition (often capitalized as Second Language Acquisition or abbreviated to SLA) is also the name of the scientific discipline devoted to studying that process. Second language refers to any language learned in addition to a person's ; although the concept is named second language acquisition, it can also incorporate the learning of third, fourth or subsequent languages. Second language acquisition refers to what learners do; it does notrefer to practices in .The academic discipline of second language acquisition is a sub-discipline of . It is broad-based and relatively new. As well as the various branches of , second language acquisition is also closelyrelated to , , and . To separate the academic discipline from the learning process itself, the terms second language acquisition research, second language studies, and second language acquisition studies are also used. SLA research began as an field, and because of this it is difficult to identify a precise starting date. However, it does appear to have developed a great deal since the mid-1960s. The term acquisition was originally used to emphasize the subconscious nature of the learning process, but in recent years learning and acquisition have becomelargely synonymous.Second language acquisition can incorporate , but it does not usually incorporate . Most SLA researchers see bilingualism as being the end result of learning a language, not the process itself, and see the termas referring to native-like fluency. Writers in fields such as education and psychology, however, often use bilingualism loosely to refer to all forms of . Second language acquisition is also not to be contrasted with the acquisition of a ; rather, the learning of second languages and the learning of foreign languages involve the same fundamental processes in different situations.Comparisons with first language acquisitionPeople who learn a second language differ from children in a number of ways. Perhaps the most striking of these is that very few adult second language learners reach the same competence as native speakers of that language. Children learning a second language are more likely to achieve native-like fluency than adults, but in general it is very rare for someone speaking a second language to pass completely for a native speaker. When a learner's speech plateaus in this way it is known as .In addition, some errors that second language learners make in their speech originate in their first language. For example, speakers learning may say "Is raining" rather than "It is raining", leaving out the of the sentence. speakers learning English, however, do not usually make the same mistake. This is because sentence subjects can be left out in Spanish, but not in French. This influence of the first language on the second is known as .Also, when people learn a second language, the way they speak theirfirst language changes in subtle ways. These changes can be with any aspect of language, from pronunciation and syntax to gestures the learner makes and the things they tend to notice. For example, Frenchspeakers who spoke English as a second language pronounced the /t/ sound in French differently from monolingual French speakers. When shown afish tank, Chinese speakers of English tend to remember more fish and fewer plants than Chinese monolinguals. This effect of the second language on the first led to propose the idea of , which sees the different languages a person speaks not as separate systems, but as related systems in their mind.Learner languageLearner language is the written or spoken language produced by a learner. It is also the main type of data used in second language acquisition research. Much research in second language acquisition is concerned with the internal representations of a language in the mind of the learner, and in how those representations change over time. It is not yetpossible to inspect these representations directly with brain scans or similar techniques, so SLA researchers are forced to make inferences about these rules from learners' speech or writing.Item and system learningThere are two types of learning that second language learners engage in. The first is , or the learning of formulaic chunks of language. These chunks can be individual words, set phrases, or formulas like Can I have a ___? The second kind of learning is , or the learning of systematic rules.InterlanguageOriginally attempts to describe learner language were based on and on . However, these approaches weren't able to predict all the errors that learners made when in the process of learning a second language. For example, Serbo-Croat speakers learning English may say "What does Pat doing now?", although this is not a valid sentence in either language.To explain these kind of systematic errors, the idea of the interlanguage was developed. An interlanguage is an emerging language system in the mind of a second language learner. A learner's interlanguage is not a deficient version of the language being learned filled with random errors, nor is it a language purely based on errors introduced from the learner's first language. Rather, it is a languagein its own right, with its own systematic rules. It is possible to view most aspects of language from an interlanguage perspective,including , , , and .There are three different processes that influence the creation of interlanguages:. Learners fall back on their mother tongue to help create theirlanguage system. This is now recognized not as a mistake, but as a process that all learners go through.Overgeneralization. Learners use rules from the second language ina way that native speakers would not. For example, a learner maysay "I goed home", overgeneralizing the English rule of adding -ed to create past tense verb forms.Simplification. Learners use a highly simplified form of language, similar to speech by children or in . This may be related to .The concept of interlanguage has become very widespread in SLA research, and is often a basic assumption made by researchers.Sequences of acquisitionIn the 1970s there were several studies that investigated the order in which learners acquired different grammatical structures. These studies showed that there was little change in this order among learners withdifferent first languages. Furthermore, it showed that the order was the same for adults as well as children, and that it did not even change if the learner had language lessons. This proved that there were factors other than language transfer involved in learning second languages, and was a strong confirmation of the concept of interlanguage.However, the studies did not find that the orders were exactly the same. Although there were remarkable similarities in the order in which all learners learned second language grammar, there were still some differences among individuals and among learners with different first languages. It is also difficult to tell when exactly a grammatical structure has been learned, as learners may use structures correctly in some situations but not in others. Thus it is more accurate to speak of sequences of acquisition, where particular grammatical features in a language have a fixed sequence of development, but the overall order of acquisition is less rigid.Process of acquisitionThere has been much debate about exactly how language is learned, and many issues are still unresolved. There have been many theories of second language acquisition that have been proposed, but none has been accepted as an overarching theory by all SLA researchers. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the field of second language acquisition, this is not expected to happen in the foreseeable future. However, there are various principles of second language acquisition that are agreed on by most researchers.Input, output, and interactionThe primary factor affecting language acquisition appears to be the input that the learner receives. took a very strong position on the importance of input, asserting that is all that is necessary for second language acquisition. Krashen pointed to studies showing that the length of time a person stays in a foreign country is closely linked with his level of language acquisition. Further evidence for input comes from studies on reading: large amounts of free voluntary reading have a significant positive effect on learners' vocabulary, grammar, and writing. Input is also the mechanism by which people learn languages according to the model.The type of input may also be important. One tenet of Krashen's theoryis that input should not be grammatically sequenced. He claims that such sequencing, as found in language classrooms where lessons involve practicing a "structure of the day", is not necessary, and may even be harmful.While input is of vital importance, Krashen's assertion that only input matters in second language acquisition has been contradicted by more recent research. For example, students enrolled in programs in still produced non-native-like grammar when they spoke, even though they had years of meaning-focused lessons and their listening skills were statistically native-level. Output appears to play an important role, and among other things, can help provide learners with feedback, make them concentrate on the form of what they are saying, and help them to automatize their language knowledge. These processes have been codified in the theory of .Researchers have also pointed to interaction in the second language as being important for acquisition. According to Long's the conditions for acquisition are especially good when interacting in the second language; specifically, conditions are good when a breakdown in communication occurs and learners must negotiate for meaning. The modifications to speech arising from interactions like this help make input more comprehensible, provide feedback to the learner, and push learners to modify their speech.Form and meaningThe meaning of things being communicated is more important for second language acquisition than their form. There is a general agreement among researchers that learners must be engaged in decoding and encoding messages in the second language for the conditions to be right for second language learning. Learners must also be engaged in creating pragmatic meaning in order to develop fluency.Some sort of does appear to be necessary for second language acquisition, however. Some advanced language structures may not be fully acquired without the opportunity for repeated practice. Schmidt's states that conscious attention to specific language forms is necessary for a learner's interlanguage to develop. This attention does not have to be in the form of conscious grammar rules, however; the attention is on how each specific form affects the meaning of what is being said.Conscious and subconscious knowledgeDeveloping subconscious knowledge of the second language is more important than developing conscious knowledge. While conscious language knowledge is important for many aspects of second language acquisition, developing subconscious knowledge is vital for fluency. The knowledgethat people use when they are speaking a language is mostly subconscious. It appears that learners can use conscious knowledge in speech if they have time and they are focused on form, but if these conditions are not met then they will fall back on subconscious knowledge. However, if learners have time to plan their speech, grammatical accuracy can improve.It is not certain exactly how subconscious language knowledge is developed in the mind. According to , subconscious language knowledge is gained by practicing language until it becomes automatic. However, according to emergentist theories subconscious knowledge develops naturally from input and communication. The nature of the between conscious and subconscious language knowledge in the brain is also not clear; that is, it is not clear how conscious knowledge can develop into subconscious knowledge. It appears that conscious knowledge and subconscious knowledge are not completely separate, and practice at various aspects of language can lead to language knowledge becoming subconscious. However, studies have found that the two types of knowledge are stored differently in the brain, and this has led to the idea that conscious knowledge merely primes language acquisition processes rather than being directly involved. Both of these issues are still under debate.Language processingThe way learners process sentences in their second language is also important for language acquisition. According to MacWhinney's , learners can only concentrate on so many things at a time, and so they mustfilter out some aspects of language when they listen to a second language. Learning a language is seen as finding the right weighting for each of the different factors that learners can process.Similarly, according to , the sequence of acquisition can be explained by learners getting better at processing sentences in the second language. As learners increase their mental capacity to process sentences, mental resources are freed up. Learners can use these newly freed-up resources to concentrate on more advanced features of the input they receive. One such feature is the movement of words. For example, in English, questions are formed by moving the or the question word to the start of the sentence (John is nice becomes Is John nice?) This kind of movement is too brain-intensive for beginners to process; learners must automatize their processing of static language structures before they can process movementIndividual variationThere is considerable variation in the rate at which people learn second languages, and in the language level that they ultimately reach. Some learners learn quickly and reach a near-native level of competence, but others learn slowly and at relatively early stages of acquisition, despite living in the country where the language is spoken for several years. The reason for this disparity was first addressed with the study of in the 1950s, and later with the in the 1970s. More recentlyresearch has focused on a number of different factors that affect individuals' language learning, in particular strategy use, social and societal influences, personality, motivation, and anxiety. The relationship between age and the ability to learn languages has also been a subject of long-standing debate.The issue of age was first addressed with the . The strict version ofthis hypothesis states that there is a cut-off age at about 12, after which learners lose the ability to fully learn a language. This strict version has since been rejected for second language acquisition, asadult learners have been observed who reach native-like levels of pronunciation and general fluency. However, in general, adult learnersof a second language rarely achieve the native-like fluency thatchildren display, despite often progressing faster in the initial stages. This has led to speculation that age is indirectly related to other, more central factors that affect language learning.There has been considerable attention paid to the strategies which learners use when learning a second language. Strategies have been found to be of critical importance, so much so that strategic competence has been suggested as a major component of . Strategies are commonly divided into and , although there are other ways of categorizing them. Learning strategies are techniques used to improve learning, such as or using a . Communicative strategies are strategies a learner uses to convey meaning even when she doesn't have access to the correct form, such as usinglike thing, or using non-verbal means such as .Affective factorsThe learner's attitude to the learning process has also been identified as being critically important to second language acquisition. Anxiety in language-learning situations has been almost unanimously shown to be detrimental to successful learning. A related factor, personality, has also received attention, with studies showing that are better language learners than .Social attitudes such as gender roles and community views toward language learning have also proven critical. Language learning can be severely hampered by cultural attitudes, with a frequently cited example being the difficulty of children in learning English. Also, the of the individual learner is of vital importance to the success of language learning. Studies have consistently shown that intrinsic motivation, or a genuine interest in the language itself, is more effective over the long-term than extrinsic motivation, as in learning a language for a reward such as high grades or praise.In the classroomWhile the majority of SLA research has been devoted to language learning in a natural setting, there have also been efforts made to investigate second language acquisition in the classroom. This kind of research has a significant overlap with , but it is always , based on and , and it is mainly concerned with the effect that instruction has on the learner, rather than what the teacher does.The research has been wide-ranging. There have been attempts made to systematically measure the effectiveness of language teaching practices for every level of language, from phonetics to pragmatics, and foralmost every current teaching methodology. This research has indicated that many traditional language-teaching techniques are extremely inefficient. It is generally agreed that pedagogy restricted to teaching grammar rules and vocabulary lists does not give students the ability to use the L2 with accuracy and fluency. Rather, to become proficient in the second language, the learner must be given opportunities to use it for communicative purposes.Another area of research has been on the effects of corrective feedback in assisting has been shown to vary depending on the technique used to make the correction, and the overall focus of the classroom, whether on formal accuracy or on communication of meaningful content. There is also considerable interest in supplementing published research with approaches that engage language teachers in action research on learner language in their own classrooms. As teachers become aware of the features of learner language produced by their students, they can refine their pedagogical intervention to maximize interlanguage development。

the second language acqusition第二语言习得复习资料

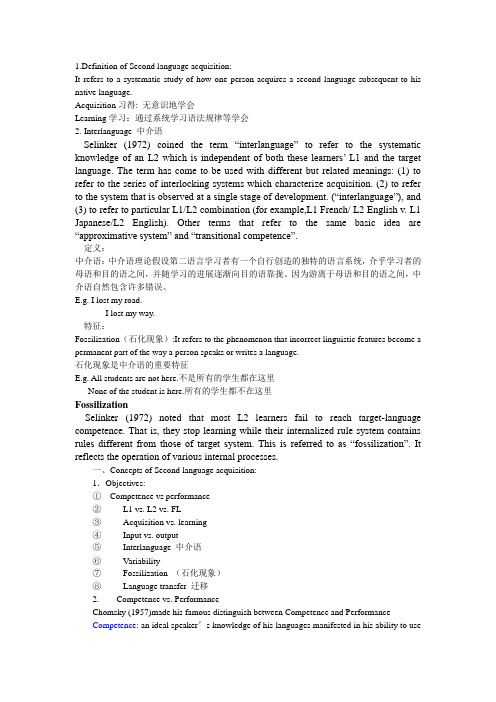

1.Definition of Second language acquisition:It refers to a systematic study of how one person acquires a second language subsequent to his native language.Acquisition习得: 无意识地学会Learning学习:通过系统学习语法规律等学会2.Interlanguage 中介语Selinker (1972) coined the term “interlanguage” to refer to the systematic knowledge of an L2 which is independent of both these learners’ L1 and the target language. The term has come to be used with different but related meanings: (1) to refer to the series of interlocking systems which characterize acquisition. (2) to refer to the system that is observed at a single stage of development. (“interlanguage”), and (3) to refer to particular L1/L2 combination (for example,L1 French/ L2 English v. L1 Japanese/L2 English). Other terms that refer to the same basic idea are “approximative system” and “transitional competence”.定义:中介语:中介语理论假设第二语言学习者有一个自行创造的独特的语言系统,介乎学习者的母语和目的语之间,并随学习的进展逐渐向目的语靠拢。

Second Language Acquisition

Conclusion

It is already clear that decontextualized pronunciation instroduction is not enough and that a combination of instruction, exposure, experience, and motivation is required if learners are to change their way of speaking.

Questions for reflection

What aspects of learners' interlanguage are

most likely to affect their ability to use language effectively outside the classroom?

Second Language Acquisition

• •

Vocabulary Pragmatics

•

phonology

Vocabulary

Introduction

In 1980, Paul Meara characterized vocabulary learning

as a 'neglected aspect of language learning'. Researchers in

learn them after a single exposure. Such as 'nation' and 'dictionary', are cognates.(words that come from the same

二语习得Second Language Acquisition资料

86xx p15

Second Language Acquisition

Noticing is of considerable theoretical importance because it accounts for which features in the input are attended to and so become intake. For noticed input to become intake, learners have to carry out a comparison of what they have observed in the input and what they themselves are typically producing on the basis of their current interlanguage system. This is a conscious process, referred to as ‘noticing the gap’.

is a difference between the way language is acquired and

nds of information are

acquired and processed.

74

Second Language Acquisition

(任务性方法)

(cognitive science, functional view of language, comprehensible input, output, motivation…)

75+1

Second Language Acquisition

Gass 's framework for investigating L2 acquisition

——Second Language Acquisition全书