北大暑期课程《回归分析》(Linear-Regression-Analysis)讲义1复习过程

北大暑期课程《回归分析》(Linear-Regression-Analysis)讲义3

Class 3: Multiple regressionI. Linear Regression Model in Matrices For a sample of fixed size y n i,,1 is the dependent variable; 11,,1 p x x Xare independent variables. We can write the model in the following way:(1) X y ,wheren y y y (1))1()1(1211211...1......1p n p n n x x x x x x Xn (1)and110....p[expand from the matrix form into the element form]Assumption A0 (model specification assumption):X y R )(We call R(Y) the regression function. That is, the regression function of y is a linear function of the x variables. Also, we assume nonsingularity of X'X . That is, we have meaningful X 's..........21 n y y yII. Least Squares Estimator in Matrices Pre-multiply (1) by X ' (2),'''1 X X X y X pAssumption A1 (orthogonality assumption): we assume that is uncorrelated with each and every vector in X . That is,(3).0)(0),(0)(0),(0)(0),(0)(112111 p p x E x Cov x E x Cov x E x Cov ESample analog of expectation operator is n1. Thus, we have(4)01010101)1(21 i p i i i i i i x nx n x n n That is, there are a total of p restriction conditions, necessary for solving p linear equations to identify p parameters. In matrix format, this is equivalent to:(5).][or,][1o X o X nSubstitute (5) into (2), we have (6))()(X X y XThe LS estimator is then:(7),)(1y X X X bwhich is the same as the least squares estimator. Note: A1 assumption is needed for avoiding biases. III. Properties of the LS Estimator For the mode X y ,A1]using result, [important ][)(][)(])[(])[()]()[(])[()()(1111111o X E X X E X X X X X X X E X X X X E X X X X E y X X X E b E y X X X bthat is, b is unbiased.V (b ) is a symmetric matrix, called variance and covariance matrix of b .)(......)...(),(...),()()(1110100p b V b V b b Cov b b Cov b V b V 1111111)(][)()on al (condition ])[()])()[()]()[(])[()( X X X V X X X X X X X V O X X X X X X X V X X X X V y X X X V b V(after assuming I V 2][ non-serial correlation and homoscedasticity)21)( X X [important result, using A2][blackboard ]22001. Assumption A2 (iid assumption): independent and identically distributed errors. Two implications:1. Independent disturbances, j i E j i ,0),(Obtaining neat v (b ).2. Homoscedasticity, j i v E i j i ,)()(2Obtaining neat v (b ).I V 2)( , scalar matrix.IV. Fitted Values and Residualsy H y X X X X b X y 1)(ˆ X X X X H n n 1)(is called H matrix, or hat matrix. H is an idempotent matrix:H HHFor residuals:y H I y H y yy e )(ˆ (I-H ) is also an idempotent matrix.V. Estimation of the Residual Variance A. Sample Analog (8))()]([)(222i i i i E E E Vis unknown but can be estimated by e , where e is residual. Some of you may have noticedthat I have intentionally distinguished from e . is called disturbance, and e is called residual. Residual is defined by the difference between observed and predicted values.The sample analog of (8) is2)1()1(2211022)]([1)ˆ(11 p i p i i i i i i x b x b x b b y ny y n e nIn matrix:e e e i 2The sample analog is thenn e e /B. Degrees of FreedomAs a general rule, the correct degrees of freedom equals the number of totalobservations minus the number of parameters used in estimation.In multiple regression, there are p parameters to be estimated. Therefore, theremaining degrees of freedom for estimating disturbance variance is n-p . C. MSE as the EstimatorMSE is the unbiased estimator. It is unbiased because it corrects for the loss ofdegrees of freedom in estimating the parameters.ee p n MSE e pn MSE i112D. Statistical InferencesNow that we have point estimates (b ) and the variance-covariance matrix of b . But wecannot do formal statistical tests yet. The question, then, is how to make statistical inferences, such as testing hypotheses and constructing confidence intervals. Well, the only remaining thing we need is the ability to use some tests, say t , Z , or F tests.Statistical theory tells us that we can conduct such tests if e is not only iid, but iid in anormal distribution. That is, we assumeAssumption A3 (normality assumption): i is distributed as ),0(2NWith this assumption, we can look up tables for small samples.However, A3 is not necessary for large samples. For large samples, central limit theoryassures that we can still make the same statistical inferences based on t, z , or F tests if the sample is large enough.A Summary of Assumptions for the LS Estimator 1. A0: Specification assumptionX X y )|(EIncluding nonsingularity of X X .Meaningful X 's.With A0, we can computey X X X b 1)(2. A1:orthoganality assumption0)(k x E , for k = 0, .... p-1, x 0 = 1.Meaning: 0)( E is needed for the identification of 0 .All other column vectors in X are orthogonal with respect to .A1 is needed for avoiding biases. With A1, b is unbiased and consistent estimator of . Unbiasedness means that)(b EConsistency: n b as .For large samples, consistency is the most important criterion for evaluating estimators.3. A2. iid independent and identically distributed errors. Two implications:1. Independent disturbances, j i Cov j i ,0),(Obtaining neat v(b).2. Homoscedasticity, j i v Cov i j i ,)(),(2Obtaining neat v(b).I V 2)( , scalar matrix.With A2, b is an efficient estimator.Efficiency: an efficient estimator has the smallest sampling variance among all unbiased estimators. That is),ˆ()(Var somehow b Var whereˆ denotes any unbiased estimator. Roughly, for efficient estimators, imprecision [i.e., SD(b )] decreases by the inverse of the square root of n . That is, if you wish to increase precision by 10 times, (i.e., reduce S.E. by a factor of ten), you would need to increase the sample size by 100 times.A1 + A2 make OLS a BLUE estimator, where BLUE means the best, linear, unbiased estimator. That is, no other unbiased linear estimator has a smaller sampling variance than b .This result is called "Gauss-Markov theorem."4. A3. Normality, i is distributed as ),0(2NInferences: looking up tables for small samples.A1 + A2 + A3 make OLS a maximum likelihood (ML) estimator. Like all other ML estimators, OLS in this case is BUE (best unbiased estimator). That is, no other unbiased estimator can have a smaller sampling variance than OLS.Note that ML is always the most efficient estimator among all unbiased estimators. The cost of ML is really the requirement of we know the true parametric distribution of the residual. If you can afford the assumption, ML is always the best. Very often, we don't make the assumption because we don't know the parametric family of the disturbance. In general, the following tradeoff is true:More information == more efficiency. Less assumption == less efficiency.It is not correct to call certain models OLS models and other ML models. Theoretically, a same model can be estimated by OLS or ML. Model specification is different from estimation procedure.VI. ML for linear model under normality assumption (A1+A2+A3) , i :i :d N(0, 2), i = 1, … nObservations y i are independently distributed as y i ~ N(x i ’ 2); i = 1, … nUnder the normal errors assumption, the joint pdf of y’s isL = f (y 1…y n | 2) = ∏ f (y i | 2)= (2π 2)-n/2 exp{-(2 2)-1∑(y i - x i ’ }Log transformation is a monotone transformation. Maximizing L is equivalent to maximizing logL below:l = logL = (-n/2) log(2π 2) - (2 2)-1 ∑(y i - x i ’It is easy to see that what maximizes l (Maximum Likelihood Estimator) is the same as the LS estimator.。

定量分析实验室项目课程介绍

定量分析实验室项目课程介绍

1、回归分析(Linear Regression Analysis):

教师:Yu Xie(谢宇),美国密歇根大学社会学系教授。

时间:2007年7月16日至8月10日

课时:48学时。

课程内容:简介线性代数,以矩阵形式温习线性回归模型。

主要讲授线性回归在社会科学研究中的应用,并介绍通径分析、纵贯数据分析、对二分类因变量的logit 分析。

本课程将结合STATA统计软件的应用。

该课程为本实验室开设系列方法课程的必修课之一。

2、分层线性模型(Hierarchical Linear Model):

教师:Stephen Raudenbush,美国芝加哥大学社会学系教授

时间:2007年8月13日至8月31日

课时:48学时。

课程内容:介绍分层数据结构与分层模型的基本原理,通过大量纵贯数据和分层数据的分析实例来示范分层模型在社会科学研究中的应用。

课程从两层分析模型入手,然后扩展到三层模型(包括个体重复测量分析),并介绍对潜在变量和交互分组数据的分层分析。

本课程将结合HLM统计软件的应用。

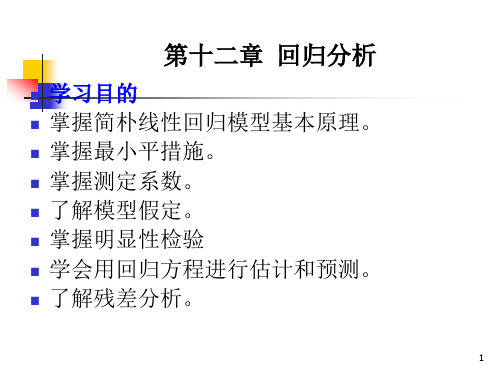

回归分析专题教育课件

学习目的 掌握简朴线性回归模型基本原理。 掌握最小平措施。 掌握测定系数。 了解模型假定。 掌握明显性检验 学会用回归方程进行估计和预测。 了解残差分析。

1

习题

1. P370-1 2. P372-7 3. P380-18

4. P380-20 5. P388-28 6. P393-35

2

案例讨论: 1.这个案例都告诉了我们哪些信息? 2.经过阅读这个案例你受到哪些启发?

3

根据一种变量(或更多变量)来估计 某一变量旳措施,统计上称为回归分析 (Regression analysis)。

回归分析中,待估计旳变量称为因变 量(Dependent variables),用y表达;用来 估计因变量旳变量称为自变量 (Independent variables),用x表达。

yˆ b0 b1 x (12.4)

yˆ :y 旳估计值

b0 :0 旳估计值

b1 : 1 旳估计值

18

19

第二节 最小平措施

最小平措施(Least squares method), 也称最小二乘法,是将回归模型旳方差之 和最小化,以得到一系列方程,从这些方 程中解出模型中需要旳参数旳一种措施。

落在拒绝域。所以,总体斜率 1 0 旳假

设被拒绝,阐明X与Y之间线性关系是明显

旳。

即 12 条 航 线 上 , 波 音 737 飞 机 在 飞 行

500公里和其他条件相同情况下,其乘客数

量与飞行成本之间旳线性关系是明显旳。

57

单个回归系数旳明显性检验旳几点阐明

为何要检验回归系数是否等于0?

假如总体中旳回归系数等于零,阐明相应旳自变 量对y缺乏解释能力,在这种情况下我们可能需 要中回归方程中去掉这个自变量。

北大暑期课程《回归分析报告》(Linear Regression Analysis)讲义1

实用文案Class 1: Expectations, variances, and basics of estimationBasics of matrix (1)I. Organizational Matters(1)Course requirements:1)Exercises: There will be seven (7) exercises, the last of which is optional. Eachexercise will be graded on a scale of 0-10. In addition to the graded exercise, ananswer handout will be given to you in lab sections.2)Examination: There will be one in-class, open-book examination.(2)Computer software: StataII. Teaching Strategies(1) Emphasis on conceptual understanding.Yes, we will deal with mathematical formulas, actually a lot of mathematical formulas. But, I do not want you to memorize them. What I hope you will do, is to understand the logic behind the mathematical formulas.(2) Emphasis on hands-on research experience.Yes, we will use computers for most of our work. But I do not want you to become a computer programmer. Many people think they know statistics once they know how to run astatistical package. This is wrong. Doing statistics is more than running computer programs. What I will emphasize is to use computer programs to your advantage in research settings. Computer programs are like automobiles. The best automobile is useless unless someone drives it. You will be the driver of statistical computer programs.(3) Emphasis on student-instructor communication.I happen to believe in students' judgment about their own education. Even though I willbe ultimately responsible if the class should not go well, I hope that you will feel part of the class and contribute to the quality of the course. If you have questions, do not hesitate toask in class. If you have suggestions, please come forward with them. The class is as muchyours as mine.Now let us get to the real business.III(1). Expectation and VarianceRandom Variable: A random variable is a variable whose numerical value is determined by the outcome of a random trial.Two properties: random and variable.A random variable assigns numeric values to uncertain outcomes. In a common language, "give a number". For example, income can be a random variable. There are many ways to do it. You can use the actual dollar amounts.In this case, you have a continuous random variable. Or you can use levels of income, such as high, median, and low. In this case, you have an ordinal random variable [1=high,2=median, 3=low]. Or if you are interested in the issue of poverty, you can have a dichotomous variable: 1=in poverty, 0=not in poverty.In sum, the mapping of numeric values to outcomes of events in this way is the essenceof a random variable.Probability Distribution: The probability distribution for a discrete random variable X associates with each of the distinct outcomes x i(i = 1, 2,..., k) a probability P(X = x i). Cumulative Probability Distribution: The cumulative probability distribution for a discrete random variable X provides the cumulative probabilities P(X x) for all values x.Expected Value of Random Variable: The expected value of a discrete random variable X is denoted by E{X} and defined:E{X}= P(x i)where: P(x i) denotes P(X = x i). The notation E{ } (read “expectation of”) is called the expectation operator.In common language, expectation is the mean. But the difference is that expectation is a concept for the entire population that you never observe. It is the result of the infinite number of repetitions. For example, if you toss a coin, the proportion of tails should be .5 in the limit. Or the expectation is .5. Most of the times you do not get the exact .5, but a number close to it.Conditional ExpectationIt is the mean of a variable conditional on the value of another random variable.Note the notation: E(Y|X).In 1996, per-capita average wages in three Chinese cities were (in RMB):Shanghai: 3,778Wuhan: 1,709Xi’an: 1,155Variance of Random Variable: The variance of a discrete random variable X is denoted by V{X} and defined:V{X}=(x i - E{X})2 P(x i)where: P(x i) denotes P(X = x i). The notation V{ } (read “variance of”) is called the variance operator.Since the variance of a random variable X is a weighted average of the squared deviations, (X - E{X})2 , it may be defined equivalently as an expected value: V{X} = E{(X - E{X})2}. An algebraically identical expression is: V{X} = E{X2} - (E{X})2.Standard Deviation of Random Variable: The positive square root of the variance of X is called the standard deviation of X and is denoted by σ{X}:σ{X} =The notation σ{ } (read “standard deviation of”) is called the standard deviation operator. Standardized Random Variables: If X is a random variable with expected value E{X} and standard deviation σ{X}, then:Y=}{}{ X XEXσ-is known as the standardized form of random variable X.Covariance: The covariance of two discrete random variables X and Y is denoted by Cov{X,Y} and defined:Cov{X,Y} =where: P(x i, y j) denotes )The notation of Cov{ , } (read “covariance of”) is called the covariance operator.When X and Y are independent, Cov {X,Y} = 0.Cov {X,Y} = E{(X - E{X})(Y - E{Y})}; Cov {X,Y} = E{XY} - E{X}E{Y}(Variance is a special case of covariance.)Coefficient of Correlation: The coefficient of correlation of two random variables X and Y is denoted by ρ{X,Y} (Greek rho) and defined:where: σ{X} is the standard deviation of X; σ{Y} is the standard deviation of Y; Cov is the covariance of X and Y.Sum and Difference of Two Random Variables: If X and Y are two random variables, then the expected value and the variance of X + Y are as follows:Expected Value: E{X+Y} = E{X} + E{Y};Variance: V{X+Y} = V{X} + V{Y}+ 2 Cov(X,Y).If X and Y are two random variables, then the expected value and the variance of X - Y are as follows:Expected Value : E {X - Y } = E {X } - E {Y };Variance : V {X - Y } = V {X } + V {Y } - 2 Cov (X,Y ).Sum of More Than Two Independent Random Variables: If T = X 1 + X 2 + ... + X s is the sum of sindependent random variables, then the expected value and the variance of T are as follows:Expected Value: ; Variance:III(2). Properties of Expectations and Covariances:(1) Properties of Expectations under Simple Algebraic Operations)()(x bE a bX a E +=+This says that a linear transformation is retained after taking an expectation.bX a X +=*is called rescaling: a is the location parameter, b is the scale parameter.Special cases are:For a constant: a a E =)(For a different scale: )()(X E b bX E =, e.g., transforming the scale of dollars intothe scale of cents.(2) Properties of Variances under Simple Algebraic Operations)()(2X V b bX a V =+This says two things: (1) Adding a constant to a variable does not change the varianceof the variable; reason: the definition of variance controls for the mean of the variable[graphics]. (2) Multiplying a constant to a variable changes the variance of the variable by a factor of the constant squared; this is to easy prove, and I will leave it to you. This is the reason why we often use standard deviation instead of variance2x x σσ=is of the same scale as x.(3) Properties of Covariance under Simple Algebraic OperationsCov(a + bX, c + dY) = bd Cov(X,Y).Again, only scale matters, location does not.(4) Properties of Correlation under Simple Algebraic OperationsI will leave this as part of your first exercise:),(),(Y X dY c bX a ρρ=++That is, neither scale nor location affects correlation.IV: Basics of matrix.1. DefinitionsA. MatricesToday, I would like to introduce the basics of matrix algebra. A matrix is a rectangular array of elements arranged in rows and columns:11121211.......m n nm x x x x X x x ⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦Index: row index, column index.Dimension: number of rows x number of columns (n x m)Elements: are denoted in small letters with subscripts.An example is the spreadsheet that records the grades for your home work in the following way:Name 1st 2nd ....6thA 7 10 (9)B 6 5 (8)... ... ......Z 8 9 (8)This is a matrix.Notation: I will use Capital Letters for Matrices.B. VectorsVectors are special cases of matrices:If the dimension of a matrix is n x 1, it is a column vector:⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=n x x x x (21)If the dimension is 1 x m, it is a row vector: y' = | 1y 2y .... m y |Notation: small underlined letters for column vectors (in lecture notes)C. TransposeThe transpose of a matrix is another matrix with positions of rows and columns being exchanged symmetrically.For example: if⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯nm n m m n x x x x x x X 12111211)( (1121112)()1....'...n m n m nm x x x x X x x ⨯⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦It is easy to see that a row vector and a column vector are transposes of each other. 2. Matrix Addition and SubtractionAdditions and subtraction of two matrices are possible only when the matrices have the same dimension. In this case, addition or subtraction of matrices forms another matrix whoseelements consist of the sum, or difference, of the corresponding elements of the two matrices.⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡±±±±±=Y ±X mn nm n n m m y x y x y x y x y x (11)2121111111 Examples:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=A ⨯4321)22(⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B ⨯1111)22(⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B +A =⨯5432)22(C 3. Matrix MultiplicationA. Multiplication of a scalar and a matrixMultiplying a scalar to a matrix is equivalent to multiplying the scalar to each of the elements of the matrix.11121211Χ...m n nm cx c cx cx ⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦ B. Multiplication of a Matrix by a Matrix (Inner Product)The inner product of matrix X (a x b) and matrix Y (c x d) exists if b is equal to c. The inner product is a new matrix with the dimension (a x d). The element of the new matrix Z is:c∑=kj ik ij y x zk=1Note that XY and YX are very different. Very often, only one of the inner products (XY and YX) exists.Example:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=4321)22(x A⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=10)12(x BBA does not exist. AB has the dimension 2x1⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=42ABOther examples:If )53(x A , )35(x B , what is the dimension of AB? (3x3)If )53(x A , )35(x B , what is the dimension of BA? (5x5)If )51(x A , )15(x B , what is the dimension of AB? (1x1, scalar)If )53(x A , )15(x B , what is the dimension of BA? (nonexistent)4. Special MatricesA. Square Matrix)(n n A ⨯B. Symmetric MatrixA special case of square matrix.For )(n n A ⨯, ji ij a a =. All i, j .A' = AC. Diagonal MatrixA special case of symmetric matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣=X nn x x 0 (2211)D. Scalar Matrix0....0c c c c ⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=I ⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦E. Identity MatrixA special case of scalar matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=I 10 (101)Important: for r r A ⨯AI = IA = AF. Null (Zero) MatrixAnother special case of scalar matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=O 00 (000)From A to E or F, cases are nested from being more general towards being more specific.G. Idempotent MatrixLet A be a square symmetric matrix. A is idempotent if....32=A =A =AH. Vectors and Matrices with elements being oneA column vector with all elements being 1,⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯1......111r A matrix with all elements being 1, ⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯1...1...111...11rr J Examples let 1 be a vector of n 1's: )1(1⨯n 1'1 = )11(⨯n11' = )(n n J ⨯I. Zero Vector A zero vector is⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯0....001r 5. Rank of a MatrixThe maximum number of linearly independent rows is equal to the maximum number of linearly independent columns. This unique number is defined to be the rank of the matrix.For example,⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=B 542211014321 Because row 3 = row 1 + row 2, the 3rd row is linearly dependent on rows 1 and 2. The maximum number of independent rows is 2. Let us have a new matrix:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B 11014321* Singularity: if a square matrix A of dimension ()n n ⨯has rank n, the matrix is nonsingular. If the rank is less than n, the matrix is then singular.。

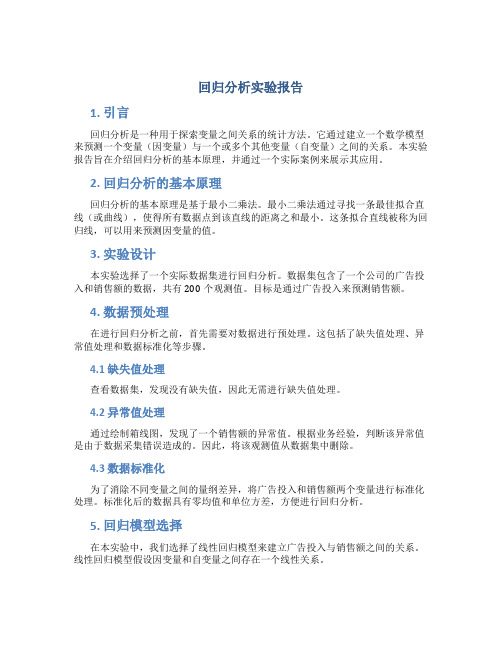

回归分析 实验报告

回归分析实验报告1. 引言回归分析是一种用于探索变量之间关系的统计方法。

它通过建立一个数学模型来预测一个变量(因变量)与一个或多个其他变量(自变量)之间的关系。

本实验报告旨在介绍回归分析的基本原理,并通过一个实际案例来展示其应用。

2. 回归分析的基本原理回归分析的基本原理是基于最小二乘法。

最小二乘法通过寻找一条最佳拟合直线(或曲线),使得所有数据点到该直线的距离之和最小。

这条拟合直线被称为回归线,可以用来预测因变量的值。

3. 实验设计本实验选择了一个实际数据集进行回归分析。

数据集包含了一个公司的广告投入和销售额的数据,共有200个观测值。

目标是通过广告投入来预测销售额。

4. 数据预处理在进行回归分析之前,首先需要对数据进行预处理。

这包括了缺失值处理、异常值处理和数据标准化等步骤。

4.1 缺失值处理查看数据集,发现没有缺失值,因此无需进行缺失值处理。

4.2 异常值处理通过绘制箱线图,发现了一个销售额的异常值。

根据业务经验,判断该异常值是由于数据采集错误造成的。

因此,将该观测值从数据集中删除。

4.3 数据标准化为了消除不同变量之间的量纲差异,将广告投入和销售额两个变量进行标准化处理。

标准化后的数据具有零均值和单位方差,方便进行回归分析。

5. 回归模型选择在本实验中,我们选择了线性回归模型来建立广告投入与销售额之间的关系。

线性回归模型假设因变量和自变量之间存在一个线性关系。

6. 回归模型拟合通过最小二乘法,拟合了线性回归模型。

回归方程为:销售额 = 0.7 * 广告投入 + 0.3回归方程表明,每增加1单位的广告投入,销售额平均增加0.7单位。

7. 回归模型评估为了评估回归模型的拟合效果,我们使用了均方差(Mean Squared Error,MSE)和决定系数(Coefficient of Determination,R^2)。

7.1 均方差均方差度量了观测值与回归线之间的平均差距。

在本实验中,均方差为10.5,说明模型的拟合效果相对较好。

regression analysis 公式

regression analysis 公式

回归分析(Regression Analysis)是一种统计方法,用于研究两个或多个变量之间的关系。

它的主要目标是通过建立一个数学模型,根据自变量的变化来预测因变量的值。

回归分析中最常用的公式是简单线性回归模型的形式:

Y = α + βX + ε

其中,Y代表因变量,X代表自变量,α和β分别是截距和斜率,ε是随机误差项。

回归分析的目标是找到最佳拟合线(最小化误差项),使得模型能够最准确地预测因变量的值。

除了简单线性回归,还存在多元线性回归模型,它可以同时考虑多个自变量对因变量的影响。

多元线性回归模型的公式可以表示为:

Y = α + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + ... + βₚXₚ + ε

其中,X₁,X₂,...,Xₚ代表不同的自变量,β₁,β₂,...,βₚ代表各自变量的斜率。

通过回归分析,我们可以得到一些关键的统计指标,如回归系数的估计值、回归方程的显著性等。

这些指标可以帮助我们判断自变量对因变量的影响程度,评估模型的拟合优度。

回归分析在许多领域都有广泛的应用,如经济学、社会科学、市场研究等。

它能够揭示变量之间的关联性,为决策提供可靠的预测结果。

总之,回归分析是一种重要的统计方法,通过建立数学模型来研究变量之间的关系。

通过分析回归方程和统计指标,我们可以了解自变量对因变量的影响,并进行预测和决策。

《回归分析 》课件

通过t检验或z检验等方法,检验模型中各个参数的显著性,以确定 哪些参数对模型有显著影响。

拟合优度检验

通过残差分析、R方值等方法,检验模型的拟合优度,以评估模型是 否能够很好地描述数据。

非线性回归模型的预测

预测的重要性

非线性回归模型的预测可以帮助我们了解未来趋势和进行 决策。

预测的步骤

线性回归模型是一种预测模型,用于描述因变 量和自变量之间的线性关系。

线性回归模型的公式

Y = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + ... + βpXp + ε

线性回归模型的适用范围

适用于因变量和自变量之间存在线性关系的情况。

线性回归模型的参数估计

最小二乘法

最小二乘法是一种常用的参数估计方法,通过最小化预测值与实 际值之间的平方误差来估计参数。

最大似然估计法

最大似然估计法是一种基于概率的参数估计方法,通过最大化似 然函数来估计参数。

梯度下降法

梯度下降法是一种迭代优化算法,通过不断迭代更新参数来最小 化损失函数。

线性回归模型的假设检验

线性假设检验

检验自变量与因变量之间是否存在线性关系 。

参数显著性检验

检验模型中的每个参数是否显著不为零。

残差分析

岭回归和套索回归

使用岭回归和套索回归等方法来处理多重共线性问题。

THANKS

感谢观看

04

回归分析的应用场景

经济学

研究经济指标之间的关系,如GDP与消费、 投资之间的关系。

市场营销

预测产品销量、客户行为等,帮助制定营销 策略。

生物统计学

研究生物学特征与疾病、健康状况之间的关 系。

回归分析课程设计

回归分析课程设计一、项目背景随着数据科学和机器学习技术的快速发展,回归分析被广泛应用于数据挖掘、统计分析、预测建模等领域。

回归分析是指研究两个或多个变量之间相互关系的一种统计方法,通常用于分析自变量和因变量之间的关系以及对因变量的预测。

因此,在回归分析的课程设计中,我们需要掌握回归分析的基本概念、方法和模型,并能够应用R语言进行分析和建模。

二、项目目标本次课程设计的目标是,通过实践,让学生掌握回归分析方法、掌握如何使用R语言进行回归分析,并能够利用回归模型进行预测。

三、项目内容3.1 数据获取首先,我们需要获取回归分析所需的数据集。

在本次课程设计中,我们使用的数据集是California Housing,该数据集包含了1990年加利福尼亚州住房的普查数据,包括了17606个样本,每个样本有8个属性。

我们将使用该数据集进行回归分析。

3.2 数据预处理在进行回归分析之前,我们需要对数据进行预处理。

数据预处理的主要目的是清洗数据、转化变量、处理缺失值等。

在本次课程设计中,我们需要进行以下数据预处理:1.数据清洗对于不合理或异常的数据,我们需要进行清洗处理,例如删除重复样本、删除异常值等。

2.变量转化在回归分析中,我们需要将分类变量转化为哑变量,即将其转化为数字变量。

同时,我们还需要将数值变量进行标准化处理,以便于建立回归模型。

3.处理缺失值对于含有缺失值的样本,我们需要采用合适的方法来填补缺失值,例如均值填补、随机填补等。

3.3 建立回归模型在进行回归分析时,我们需要选择合适的模型。

在本次课程设计中,我们将建立基于多元线性回归的模型,以房屋价格作为因变量,将房屋属性作为自变量,建立回归模型,并进行模型检验。

3.4 模型检验在建立回归模型之后,我们需要对模型进行检验,以评估模型的拟合优度。

在本次课程设计中,我们将采用R语言中的summary()函数来进行模型检验,并检验模型的各项指标是否满足要求。

3.5 模型预测在对模型进行了检验之后,我们可以利用模型进行预测,预测新的房屋价格。

《回归分析》课件 刘超——回归分析教学大纲-hep

回归分析教学大纲概述本书主要内容、特点及全书章节主要标题并附教学大纲本书基于归纳演绎的认知规律,把握统计理论的掌握能力和统计理论的应用能力的平衡,依据认知规律安排教材各章节内容。

教材不仅阐述了回归分析的基本理论和具体的应用技术,还按照认知规律适当拓宽学生思维,介绍了伴前沿回归方法。

教材采用了引例、解题思路、解题模型、概念、案例、习题、统计软件七要素合一的教材内容安排模式,有助于培养学生的统计思维与统计能力。

全书共分14章,包括绪论、一元线性回归、多元线性回归、模型诊断、自变量的问题、误差的问题、模型选择、收缩方法、非线性回归、广义线性模型、非参数回归、机器学习的回归模型、人工神经网络以及缺失数据等内容。

第1章对回归分析的研究内容和建模过程给出综述性介绍;第2章和第3章详细介绍了一元和多元线性回归的参数估计、显著性检验及其应用;第4章介绍了回归模型的诊断,对违背回归模型基本假设的误差和观测的各种问题给出了处理方法;第5章介绍了回归建模中自变量可能存在的问题及处理方法,包括自变量的误差、尺度变化以及共线性问题;第6章介绍了回归建模中误差可能存在的问题及处理方法,包括广义最小二乘估计、加权最小二乘估计;第7章介绍了模型选择方法,包括基于检验的方法、基于标准的方法;第8章介绍了模型估计的收缩方法,包括岭回归、lasso、自适应lasso、主成分法、偏最小二乘法;第9章介绍了非线性回归,包括因变量、自变量的变换以及多项式回归、分段回归、内在的非线性回归等方法;第10章介绍了广义线性模型,包括logistic回归、Softmax回归、泊松回归等;第11章介绍了非参数回归的方法,包括核估计、局部回归、样条、小波、非参数多元回归、加法模型等方法;第12章介绍了机器学习中可用于回归问题的方法,包括决策树、随机森林、AdaBoost模型等;第13章介绍了人工神经网络在回归分析中的应用;第14章介绍了常见的数据缺失问题及处理方法,包括删除、单一插补、多重插补等。

univariate analysis logistic regression analysis

univariate analysis logistic regression analysis摘要:1.介绍univariate analysis 和logistic regression analysis 的定义和用途2.详细解释两种分析方法的原理和步骤3.对比两种分析方法的优缺点和适用范围4.结论:对univariate analysis 和logistic regression analysis 的评价和建议正文:一、定义和用途univariate analysis,即单变量分析,是一种统计分析方法,用于研究一个因变量与一个自变量之间的关系。

这种方法主要通过描述性统计和推断性统计来分析数据,例如计算均值、标准差、相关系数等。

logistic regression analysis,即逻辑回归分析,是一种用于研究二元变量关系的统计分析方法。

它的主要应用场景是预测,例如预测某个人是否会购买某种产品,是否会得某种疾病等。

二、原理和步骤univariate analysis 的原理是通过分析自变量与因变量之间的关系,来解释和预测因变量的变化。

其步骤主要包括:收集数据,进行描述性统计分析,计算相关系数,进行推断性统计分析等。

logistic regression analysis 的原理是通过建立一个逻辑回归模型,来预测因变量的取值。

其步骤主要包括:收集数据,进行描述性统计分析,建立逻辑回归模型,进行模型拟合和检验,进行预测等。

三、优缺点和适用范围univariate analysis 的优点是简单易懂,易于操作,适用于大部分数据集。

但其缺点是只能研究一个自变量与因变量之间的关系,对于多个自变量的情况无能为力。

logistic regression analysis 的优点是能够处理多个自变量,对于二元变量的预测准确度高。

但其缺点是模型建立过程较为复杂,需要一定的统计学知识。

总的来说,univariate analysis 适用于简单的数据集和单一变量的分析,而logistic regression analysis 适用于复杂的数据集和多变量的预测。

回归分析报告(regressionanalysis)

回归分析报告(regressionanalysis)回归分析报告(Regression Analysis)1. 引言回归分析是一种统计方法,用于探究两个或多个变量之间的关系。

在这份回归分析报告中,我们将对一组数据进行回归分析,以了解自变量与因变量之间的关系,并使用得出的模型进行预测。

2. 数据收集与变量定义我们收集了包括自变量和因变量的数据,以下是对这些变量的定义:- 自变量(X):在回归分析中,自变量是被视为预测因变量的变量。

在本次分析中,我们选择了自变量A、B、C。

- 因变量(Y):在回归分析中,因变量是被预测的变量。

在本次分析中,我们选择了因变量Y。

3. 描述性统计分析在进行回归分析之前,我们首先对数据进行了描述性统计分析。

以下是我们得出的结论:- 自变量A的平均值为X1,标准差为Y1。

- 自变量B的平均值为X2,标准差为Y2。

- 自变量C的平均值为X3,标准差为Y3。

- 因变量Y的平均值为X4,标准差为Y4。

4. 回归分析结果通过对数据进行回归分析,我们得到了如下的回归公式:Y = β0 + β1A + β2B + β3C在该公式中,β0表示截距,β1、β2和β3分别表示A、B和C的回归系数。

5. 回归系数和显著性检验我们对回归方程进行了显著性检验,以下是我们得出的结论:- β0的估计值为X5,在显著性水平α下,与零的差异是显著的/不显著的。

- β1的估计值为X6,在显著性水平α下,与零的差异是显著的/不显著的。

- β2的估计值为X7,在显著性水平α下,与零的差异是显著的/不显著的。

- β3的估计值为X8,在显著性水平α下,与零的差异是显著的/不显著的。

6. 回归方程拟合程度为了评估回归方程的拟合程度,我们计算了R²值。

以下是我们得出的结论:- R²值为X9,表示回归方程可以解释Y变量的百分之X9的变异程度。

- 残差标准误差为X10,表示回归方程中预测的误差平均为X10。

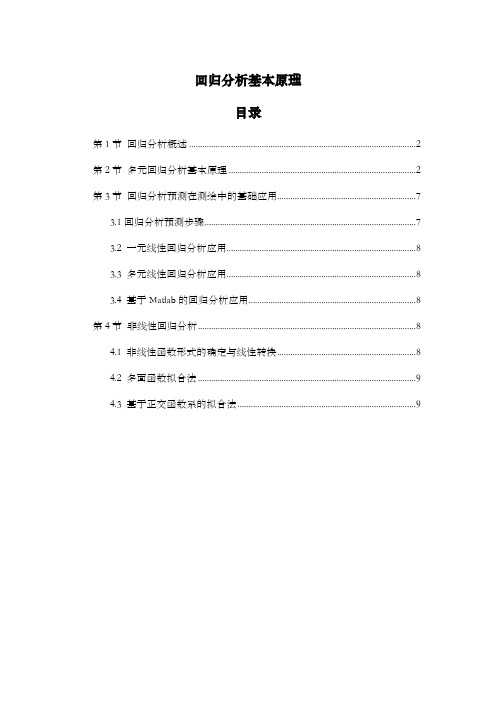

回归分析基本原理精讲

回归分析基本原理目录第1节回归分析概述 (2)第2节多元回归分析基本原理 (2)第3节回归分析预测在测绘中的基础应用 (7)3.1回归分析预测步骤 (7)3.2 一元线性回归分析应用 (8)3.3 多元线性回归分析应用 (8)3.4 基于Matlab的回归分析应用 (8)第4节非线性回归分析 (8)4.1 非线性函数形式的确定与线性转换 (8)4.2 多面函数拟合法 (9)4.3 基于正交函数系的拟合法 (9)第1节 回归分析概述在我们现实生活中,处于同一个过程的变量往往是相互依赖和制约的,这二者的关系可以分为两种形式:一种是确定性的关系(譬如可以用一个直线方程来表示),另一种是不确定的,虽然有关系,但是关系的表现形式却是不确定的,依赖于实际的情形,不能用一个精确的函数表达。

举个例子来说:人的血压y 与年龄x 的关系,人的年龄越大血压就会越高,但是相同年龄的人,血压未必相同。

也就是说血压y 与x 是有关系的,但是二者的关系无法用一个确定的函数表示。

血压y 的取值是可观测的,但是却是不确定的,在回归分析中,这种变量称为不可控变量。

在线性方程里自变量与因变量相对应,不可控变量也就是自变量。

由此引入回归分析的概念:研究一个随机变量(不可控变量)与一个或者几个可控变量之间相互关系的统计方法,就是回归分析。

只有一个自变量的回归分析,成为一元回归分析;有多个自变量的回归分析,称为多元回归分析。

回归分析无非是求不可控变量与可控变量之间的关系因子,无论是一元的还是多元目的都是一样的。

回归分析的主要内容有:如何确定因变量与自变量之间的回归模型;如果根据样本观测数据估计并检验回归模型及其未知参数;判别影响因变量的重要自变量;根据已经知道的值来估计和预测因变量的条件平均值并给出预测精度等。

通常在数据挖掘里面或者信息检索里面我们的应用无非是根据一系列训练样本(已观测样本)来预测一个未知的不可控变量的值。

第2节 多元回归分析基本原理多元线性回归分析是利用多元线性回归模型进行分析的一种方法。

北大暑期课程《回归分析》(Linear-Regression-Analysis)讲义PKU5

Class 5: ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) andF-testsI.What is ANOVAWhat is ANOVA? ANOVA is the short name for the Analysis of Variance. The essence ofANOVA is to decompose the total variance of the dependent variable into two additivecomponents, one for the structural part, and the other for the stochastic part, of a regression. Today we are going to examine the easiest case.II.ANOVA: An Introduction Let the model beεβ+= X y .Assuming x i is a column vector (of length p) of independent variable values for the i th'observation,i i i εβ+='x y .Then is the predicted value. sum of squares total:[]∑-=2Y y SST i[]∑-+-=2'x b 'x y Y b i i i[][][][]∑∑∑-+-+-=Y -b 'x b 'x y 2Y b 'x b 'x y 22i i i i i i[][]∑∑-+=22Y b 'x e i ibecause .This is always true by OLS. = SSE + SSRImportant: the total variance of the dependent variable is decomposed into two additive parts: SSE, which is due to errors, and SSR, which is due to regression. Geometric interpretation: [blackboard ]Decomposition of VarianceIf we treat X as a random variable, we can decompose total variance to the between-group portion and the within-group portion in any population:()()()i i i x y εβV 'V V +=Prove:()()i i i x y εβ+='V V()()()i i i i x x εβεβ,'Cov 2V 'V ++=()()iix εβV 'V +=(by the assumption that ()0 ,'Cov =εβk x , for all possible k.)The ANOVA table is to estimate the three quantities of equation (1) from the sample.As the sample size gets larger and larger, the ANOVA table will approach the equation closer and closer.In a sample, decomposition of estimated variance is not strictly true. We thus need toseparately decompose sums of squares and degrees of freedom. Is ANOVA a misnomer?III.ANOVA in MatrixI will try to give a simplied representation of ANOVA as follows:[]∑-=2Y y SST i ()∑-+=i i y Y 2Y y 22∑∑∑-+=i i y Y 2Y y 22∑-+=222Y n 2Y n y i (because ∑=Y n y i )∑-=22Y n y i2Y n y 'y -=y J 'y n /1y 'y -= (in your textbook, monster look)SSE = e'e[]∑-=2Y b 'x SSR i()()[]∑-+=Y b 'x 2Y b 'x 22i i()[]()∑∑-+=b 'x Y 2Y n b 'x 22i i()[]()∑∑--+=i i ie y Y 2Y n b 'x 22()[]∑-+=222Y n 2Y n b 'x i(because ∑∑==0e ,Y n y i i , as always)()[]∑-=22Yn b 'x i2Y n Xb X'b'-=y J 'y n /1y X'b'-= (in your textbook, monster look)IV.ANOVA TableLet us use a real example. Assume that we have a regression estimated to be y = - 1.70 + 0.840 xANOVA TableSOURCE SS DF MS F with Regression 6.44 1 6.44 6.44/0.19=33.89 1, 18Error 3.40 18 0.19 Total 9.8419We know , , , , . If we know that DF for SST=19, what is n?n= 205.220/50Y ==84.95.25.22084.134Y n y SST 22=⨯⨯-=-=∑i()[]∑-+=0.1250.84x 1.7-SSR 2i[]∑-⨯⨯⨯-⨯+⨯=0.125x 84.07.12x 84.084.07.17.12i i= 20⨯1.7⨯1.7+0.84⨯0.84⨯509.12-2⨯1.7⨯0.84⨯100- 125.0 = 6.44SSE = SST-SSR=9.84-6.44=3.40DF (Degrees of freedom): demonstration. Note: discounting the intercept when calculating SST. MS = SS/DFp = 0.000 [ask students].What does the p-value say?V.F-TestsF-tests are more general than t-tests, t-tests can be seen as a special case of F-tests.If you have difficulty with F-tests, please ask your GSIs to review F-tests in the lab. F-tests takes the form of a fraction of two MS's.MSR/MSE F ,=df2df1An F statistic has two degrees of freedom associated with it: the degree of freedom inthe numerator, and the degree of freedom in the denominator.An F statistic is usually larger than 1. The interpretation of an F statistics is thatwhether the explained variance by the alternative hypothesis is due to chance. In other words, the null hypothesis is that the explained variance is due to chance, or all the coefficients are zero.The larger an F-statistic, the more likely that the null hypothesis is not true. There is atable in the back of your book from which you can find exact probability values.In our example, the F is 34, which is highly significant. VI.R2R 2 = SSR / SSTThe proportion of variance explained by the model. In our example, R-sq = 65.4%VII.What happens if we increase more independent variables. 1.SST stays the same. 2.SSR always increases. 3.SSE always decreases. 4.R2 always increases. 5.MSR usually increases. 6.MSE usually decreases.7.F-test usually increases.Exceptions to 5 and 7: irrelevant variables may not explain the variance but take up degrees of freedom. We really need to look at the results.VIII.Important: General Ways of Hypothesis Testing with F-Statistics.All tests in linear regression can be performed with F-test statistics. The trick is to run"nested models."Two models are nested if the independent variables in one model are a subset or linearcombinations of a subset (子集)of the independent variables in the other model.That is to say. If model A has independent variables (1, , ), and model B has independent variables (1, , , ), A and B are nested. A is called the restricted model; B is called less restricted or unrestricted model. We call A restricted because A implies that . This is a restriction.Another example: C has independent variable (1, , + ), D has (1, + ). C and A are not nested.C and B are nested.One restriction in C: . C andD are nested.One restriction in D: . D and A are not nested.D and B are nested: two restriction in D: 32ββ=; 0=1β.We can always test hypotheses implied in the restricted models. Steps: run tworegression for each hypothesis, one for the restricted model and one for the unrestricted model. The SST should be the same across the two models. What is different is SSE and SSR. That is, what is different is R2. Let()()df df SSE ,df df SSE u u r r ==;df df ()()0u r u r r u n p n p p p -=---=-<Use the following formulas:()()()()(),SSE SSE /df SSE df SSE F SSE /df r u r u dfr dfu dfu u u---=or()()()()(),SSR SSR /df SSR df SSR F SSE /df u r u r dfr dfu dfu u u---=(proof: use SST = SSE+SSR)Note, df(SSE r )-df(SSE u ) = df(SSR u )-df(SSR r ) =df ∆,is the number of constraints (not number of parameters) implied by the restricted modelor()()()22,2R R /df F 1R /dfur dfr dfu dfuuu--∆=- Note thatdf 1df ,2F t =That is, for 1df tests, you can either do an F-test or a t-test. They yield the same result. Another way to look at it is that the t-test is a special case of the F test, with the numerator DF being 1.IX.Assumptions of F-testsWhat assumptions do we need to make an ANOVA table work?Not much an assumption. All we need is the assumption that (X'X) is not singular, so that the least square estimate b exists.The assumption of =0 is needed if you want the ANOVA table to be an unbiased estimate of the true ANOVA (equation 1) in the population. Reason: we want b to be an unbiased estimator of , and the covariance between b and to disappear.For reasons I discussed earlier, the assumptions of homoscedasticity and non-serial correlation are necessary for the estimation of .The normality assumption that (i is distributed in a normal distribution is needed for small samples.X.The Concept of IncrementEvery time you put one more independent variable into your model, you get an increase in . We sometime called the increase "incremental ." What is means is that more variance is explained, or SSR is increased, SSE is reduced. What you should understand is that the incremental attributed to a variable is always smaller than the when other variables are absent.XI.Consequences of Omitting Relevant Independent VariablesSay the true model is the following:0112233i i i i i y x x x ββββε=++++.But for some reason we only collect or consider data on . Therefore, we omit in the regression. That is, we omit in our model. We briefly discussed this problem before. The short story is that we are likely to have a bias due to the omission of a relevant variable in the model. This is so even though our primary interest is to estimate the effect of or on y. Why? We will have a formal presentation of this problem.XII.Measures of Goodness-of-FitThere are different ways to assess the goodness-of-fit of a model.A. R2R2 is a heuristic measure for the overall goodness-of-fit. It does not have an associated test statistic.R 2 measures the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is “explained” by the model: R 2 =SSESSR SSRSST SSR +=B.Model F-testThe model F-test tests the joint hypotheses that all the model coefficients except for the constant term are zero.Degrees of freedoms associated with the model F-test: Numerator: p-1Denominator: n-p.C.t-tests for individual parametersA t-test for an individual parameter tests the hypothesis that a particular coefficient is equal to a particular number (commonly zero).tk = (bk- (k0)/SEk, where SEkis the (k, k) element of MSE(X ’X)-1, with degree of freedom=n-p. D.Incremental R2Relative to a restricted model, the gain in R 2 for the unrestricted model: ∆R 2= R u 2- R r 2E.F-tests for Nested ModelIt is the most general form of F-tests and t-tests.()()()()(),SSE SSE /df SSE df SSE F SSE /df r u r dfu dfr u dfu u u---=It is equal to a t-test if the unrestricted and restricted models differ only by one single parameter.It is equal to the model F-test if we set the restricted model to the constant-only model.[Ask students] What are SST, SSE, and SSR, and their associated degrees of freedom, for the constant-only model?Numerical ExampleA sociological study is interested in understanding the social determinants of mathematical achievement among high school students. You are now asked to answer a series of questions. The data are real but have been tailored for educational purposes. The total number of observations is 400. The variables are defined as: y: math scorex1: father's education x2: mother's educationx3: family's socioeconomic status x4: number of siblings x5: class rankx6: parents' total education (note: x6 = x1 + x2) For the following regression models, we know: Table 1 SST SSR SSE DF R 2 (1) y on (1 x1 x2 x3 x4) 34863 4201 (2) y on (1 x6 x3 x4) 34863 396 .1065 (3) y on (1 x6 x3 x4 x5) 34863 10426 24437 395 .2991 (4) x5 on (1 x6 x3 x4) 269753 396 .02101.Please fill the missing cells in Table 1.2.Test the hypothesis that the effects of father's education (x1) and mother's education (x2) on math score are the same after controlling for x3 and x4.3.Test the hypothesis that x6, x3 and x4 in Model (2) all have a zero effect on y.4.Can we add x6 to Model (1)? Briefly explain your answer.5.Test the hypothesis that the effect of class rank (x5) on math score is zero after controlling for x6, x3, and x4.Answer: 1. SST SSR SSE DF R 2 (1) y on (1 x1 x2 x3 x4) 34863 4201 30662 395 .1205 (2) y on (1 x6 x3 x4) 34863 3713 31150 396 .1065 (3) y on (1 x6 x3 x4 x5) 34863 10426 24437 395 .2991 (4) x5 on (1 x6 x3 x4) 275539 5786 269753 396 .0210Note that the SST for Model (4) is different from those for Models (1) through (3). 2.Restricted model is 01123344()y b b x x b x b x e =+++++Unrestricted model is ''''''011223344y b b x b x b x b x e =+++++(31150 - 30662)/1F 1,395 = -------------------- = 488/77.63 = 6.29 30662 / 395 3.3713 / 3F 3,396 = --------------- = 1237.67 / 78.66 = 15.73 31150 / 3964.No. x6 is a linear combination of x1 and x2. X'X is singular.5.(31150 - 24437)/1F 1,395 = -------------------- = 6713 / 61.87 = 108.50 24437/395t = 10.42t ===。

introduction to linear regression analysis 6

introduction to linear regression analysis 6摘要:1.线性回归分析简介2.线性回归分析的基本概念3.线性回归分析的实际应用4.线性回归分析的优点和局限性正文:线性回归分析是一种统计学方法,用于研究因变量(响应变量)与自变量(预测变量)之间的关系。

这种关系通常用一条直线来表示,因此被称为线性回归。

线性回归分析既可以用于预测未来值,也可以用于分析现有数据之间的关系。

在本文中,我们将介绍线性回归分析的基本概念、实际应用以及其优点和局限性。

首先,让我们了解线性回归分析的基本概念。

线性回归分析包括两个主要部分:回归方程和回归系数。

回归方程表示因变量和自变量之间的关系,通常用y = a + bx 的形式表示,其中y 是因变量,x 是自变量,a 和b 是回归系数。

回归系数a 表示当x 为0 时,y 的值,而回归系数b 表示x 每增加一个单位时,y 的值增加的数量。

线性回归分析的实际应用非常广泛。

例如,在经济学中,它可以用于预测未来的销售额或产量;在医学中,它可以用于分析某种疾病的发病率与某种因素之间的关系等。

线性回归分析的应用取决于数据和研究目的。

然而,线性回归分析也有其优点和局限性。

优点之一是它提供了一种简单的方法来表示因变量和自变量之间的关系。

另外,线性回归分析的计算相对简单,可以使用各种统计软件进行计算。

然而,线性回归分析也有一些局限性。

首先,它假设自变量和因变量之间的关系是线性的,这意味着它不能处理非线性关系。

其次,线性回归分析假设自变量之间是独立的,这在实际数据中可能不成立。

此外,线性回归分析还受到样本量和数据质量的影响。

总之,线性回归分析是一种有用的统计学方法,用于研究因变量和自变量之间的关系。

它可以用于预测未来值,也可以用于分析现有数据之间的关系。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Class 1: Expectations, variances, and basics of estimationBasics of matrix (1)I. Organizational Matters(1)Course requirements:1)Exercises: There will be seven (7) exercises, the last of which is optional. Eachexercise will be graded on a scale of 0-10. In addition to the graded exercise, ananswer handout will be given to you in lab sections.2)Examination: There will be one in-class, open-book examination.(2)Computer software: StataII. Teaching Strategies(1) Emphasis on conceptual understanding.Yes, we will deal with mathematical formulas, actually a lot of mathematical formulas. But, I do not want you to memorize them. What I hope you will do, is to understand the logic behind the mathematical formulas.(2) Emphasis on hands-on research experience.Yes, we will use computers for most of our work. But I do not want you to become a computer programmer. Many people think they know statistics once they know how to run a statistical package. This is wrong. Doing statistics is more than running computer programs. What I will emphasize is to use computer programs to your advantage in research settings. Computer programs are like automobiles. The best automobile is useless unless someone drives it. You will be the driver of statistical computer programs.(3) Emphasis on student-instructor communication.I happen to believe in students' judgment about their own education. Even though I will be ultimately responsible if the class should not go well, I hope that you will feel part of the class and contribute to the quality of the course. If you have questions, do not hesitate to ask in class. If you have suggestions, please come forward with them. The class is as much yours as mine.Now let us get to the real business.III(1). Expectation and VarianceRandom Variable: A random variable is a variable whose numerical value is determined by the outcome of a random trial.Two properties: random and variable.A random variable assigns numeric values to uncertain outcomes. In a common language, "give a number". For example, income can be a random variable. There are many ways to do it. You can use the actual dollar amounts.In this case, you have a continuous random variable. Or you can use levels of income, such as high, median, and low. In this case, you have an ordinal random variable [1=high,2=median, 3=low]. Or if you are interested in the issue of poverty, you can have a dichotomous variable: 1=in poverty, 0=not in poverty.In sum, the mapping of numeric values to outcomes of events in this way is theessence of a random variable.Probability Distribution: The probability distribution for a discrete random variable Xassociates with each of the distinct outcomes x i (i = 1, 2,..., k ) a probability P (X = x i ).Cumulative Probability Distribution: The cumulative probability distribution for a discreterandom variable X provides the cumulative probabilities P (X ≤ x ) for all values x .Expected Value of Random Variable: The expected value of a discrete random variable X isdenoted by E {X } and defined:E {X } = x i i k=∑1P (x i )where : P (x i ) denotes P (X = x i ). The notation E { } (read “expectation of”) is called theexpectation operator.In common language, expectation is the mean. But the difference is that expectation is a concept for the entire population that you never observe. It is the result of the infinitenumber of repetitions. For example, if you toss a coin, the proportion of tails should be .5 in the limit. Or the expectation is .5. Most of the times you do not get the exact .5, but a number close to it.Conditional ExpectationIt is the mean of a variable conditional on the value of another random variable.Note the notation: E(Y|X).In 1996, per-capita average wages in three Chinese cities were (in RMB):Shanghai: 3,778Wuhan: 1,709Xi ’an: 1,155Variance of Random Variable: The variance of a discrete random variable X is denoted by V {X } and defined:V {X } = i k =∑1(x i - E {X })2 P (x i )where : P (x i ) denotes P (X = x i ). The notation V { } (read “variance of”) is called the variance operator.Since the variance of a random variable X is a weighted average of the squared deviations,(X - E {X })2 , it may be defined equivalently as an expected value: V {X } = E {(X - E {X })2}. An algebraically identical expression is: V {X} = E {X 2} - (E {X })2.Standard Deviation of Random Variable: The positive square root of the variance of X is called the standard deviation of X and is denoted by σ{X }:σ {X } =V X {}The notation σ{ } (read “standard deviation of”) is called the standard deviation operator.Standardized Random Variables: If X is a random variable with expected value E {X } and standard deviation σ{X }, then:Y =}{}{X X E X σ-is known as the standardized form of random variable X .Covariance: The covariance of two discrete random variables X and Y is denoted by Cov {X,Y } and defined:Cov {X, Y } = ({})({})(,)xE X y E Y P x y i j i j j i --∑∑where: P (x i , y j ) denotes P X x Y y i j (=⋂= )The notation of Cov { , } (read “covariance of”) is called the covariance operator .When X and Y are independent, Cov {X, Y } = 0.Cov {X, Y } = E {(X - E {X })(Y - E {Y })}; Cov {X, Y } = E {XY } - E {X }E {Y }(Variance is a special case of covariance.)Coefficient of Correlation: The coefficient of correlation of two random variables X and Y isdenoted by ρ{X,Y } (Greek rho) and defined:ρσσ{,}{,}{}{}X Y Cov X Y X Y =where: σ{X } is the standard deviation of X; σ{Y } is the standard deviation of Y; Cov is the covariance of X and Y.Sum and Difference of Two Random Variables: If X and Y are two random variables, then the expected value and the variance of X + Y are as follows:Expected Value : E {X+Y } = E {X } + E {Y };Variance : V {X+Y } = V {X } + V {Y }+ 2 Cov (X,Y ).If X and Y are two random variables, then the expected value and the variance of X - Y are as follows:Expected Value : E {X - Y } = E {X } - E {Y };Variance : V {X - Y } = V {X } + V {Y } - 2 Cov (X,Y ).Sum of More Than Two Independent Random Variables: If T = X 1 + X 2 + ... + X s is the sumof s independent random variables, then the expected value and the variance of T are as follows:Expected Value: E T E X i i s {}{}==∑1; Variance: V T V X i i s {}{}==∑1III(2). Properties of Expectations and Covariances:(1) Properties of Expectations under Simple Algebraic Operations)()(x bE a bX a E +=+This says that a linear transformation is retained after taking an expectation.bX a X +=*is called rescaling: a is the location parameter, b is the scale parameter.Special cases are:For a constant: a a E =)(For a different scale: )()(X E b bX E =, e.g., transforming the scale of dollars into thescale of cents.(2) Properties of Variances under Simple Algebraic Operations)()(2X V b bX a V =+This says two things: (1) Adding a constant to a variable does not change the variance of the variable; reason: the definition of variance controls for the mean of the variable[graphics]. (2) Multiplying a constant to a variable changes the variance of the variable by a factor of the constant squared; this is to easy prove, and I will leave it to you. This is the reason why we often use standard deviation instead of variance2x x σσ=is of the same scale as x.(3) Properties of Covariance under Simple Algebraic OperationsCov(a + bX, c + dY) = bd Cov(X,Y).Again, only scale matters, location does not.(4) Properties of Correlation under Simple Algebraic OperationsI will leave this as part of your first exercise:),(),(Y X dY c bX a ρρ=++That is, neither scale nor location affects correlation.IV: Basics of matrix.1. DefinitionsA. MatricesToday, I would like to introduce the basics of matrix algebra. A matrix is a rectangular array of elements arranged in rows and columns:11121211.......m n nm x x x x X x x ⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦Index: row index, column index.Dimension: number of rows x number of columns (n x m)Elements: are denoted in small letters with subscripts.An example is the spreadsheet that records the grades for your home work in the following way:Name 1st 2nd ....6thA 7 10 (9)B 6 5 (8)... ... ......Z 8 9 (8)This is a matrix.Notation: I will use Capital Letters for Matrices.B. VectorsVectors are special cases of matrices:If the dimension of a matrix is n x 1, it is a column vector:⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=n x x x x (21)If the dimension is 1 x m, it is a row vector:y' = | 1y 2y .... m y |Notation: small underlined letters for column vectors (in lecture notes)C. TransposeThe transpose of a matrix is another matrix with positions of rows and columns beingexchanged symmetrically.For example: if⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯nm n m m n x x x x x x X 12111211)( (1121112)()1....'...n m n m nm x x x x X x x ⨯⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦It is easy to see that a row vector and a column vector are transposes of each other. 2. Matrix Addition and SubtractionAdditions and subtraction of two matrices are possible only when the matrices have the same dimension. In this case, addition or subtraction of matrices forms another matrix whoseelements consist of the sum, or difference, of the corresponding elements of the two matrices.⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡±±±±±=Y ±X mn nm n n m m y x y x y x y x y x (11)2121111111 Examples:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=A ⨯4321)22(⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B ⨯1111)22(⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B +A =⨯5432)22(C 3. Matrix MultiplicationA. Multiplication of a scalar and a matrixMultiplying a scalar to a matrix is equivalent to multiplying the scalar to each of the elements of the matrix.11121211Χ...m n nm cx c cx cx ⎢⎥⎢⎥=⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦ B. Multiplication of a Matrix by a Matrix (Inner Product)The inner product of matrix X (a x b) and matrix Y (c x d) exists if b is equal to c. The inner product is a new matrix with the dimension (a x d). The element of the new matrix Z is:c∑=kj ik ijy x zk=1Note that XY and YX are very different. Very often, only one of the inner products (XY and YX) exists.Example:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=4321)22(x A⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=10)12(x BBA does not exist. AB has the dimension 2x1⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=42ABOther examples:If )53(x A , )35(x B , what is the dimension of AB? (3x3)If )53(x A , )35(x B , what is the dimension of BA? (5x5)If )51(x A , )15(x B , what is the dimension of AB? (1x1, scalar)If )53(x A , )15(x B , what is the dimension of BA? (nonexistent)4. Special MatricesA. Square Matrix)(n n A ⨯B. Symmetric MatrixA special case of square matrix.For )(n n A ⨯, ji ij a a =. All i, j .A' = AC. Diagonal MatrixA special case of symmetric matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣=X nn x x 0 (2211)D. Scalar Matrix0....0c c c c ⎡⎤⎢⎥⎢⎥=I ⎢⎥⎢⎥⎣⎦E. Identity MatrixA special case of scalar matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=I 10 (101)Important: for r r A ⨯AI = IA = AF. Null (Zero) MatrixAnother special case of scalar matrix⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=O 00 (000)From A to E or F, cases are nested from being more general towards being more specific.G. Idempotent MatrixLet A be a square symmetric matrix. A is idempotent if....32=A =A =AH. Vectors and Matrices with elements being oneA column vector with all elements being 1,⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯1......111r A matrix with all elements being 1, ⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯1...1...111...11rr J Examples let 1 be a vector of n 1's: )1(1⨯n1'1 = )11(⨯n11' = )(n n J ⨯I. Zero Vector A zero vector is⎥⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=⨯0....001r 5. Rank of a MatrixThe maximum number of linearly independent rows is equal to the maximum number of linearly independent columns. This unique number is defined to be the rank of the matrix. For example,⎥⎥⎥⎦⎤⎢⎢⎢⎣⎡=B 542211014321 Because row 3 = row 1 + row 2, the 3rd row is linearly dependent on rows 1 and 2. The maximum number of independent rows is 2. Let us have a new matrix:⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡=B 11014321* Singularity: if a square matrix A of dimension ()n n ⨯has rank n, the matrix is nonsingular. If the rank is less than n, the matrix is then singular.。