继续解读:观察性研究报告规范STROBE声明

临床研究的 trial profiles, study profiles

临床研究中的Trial Profiles和Study Profiles是描述和概述临床试验关键信息的文档或格式,它们对于透明化研究设计、执行和结果至关重要。

以下是对这两个术语的解释:

1. Trial Profiles:

Trial Profile通常提供了一个临床试验的概览,包括试验的设计、目标、参与者资格、干预措施、主要和次要结局、样本量计算、随机化方法、盲法(如果适用)、数据收集和分析计划等。

这些信息有助于研究人员、伦理审查委员会、监管机构以及公众理解试验的目的、方法和预期结果。

一些临床试验注册平台,如,要求在注册试验时提交Trial Profile。

2. Study Profiles:

Study Profile有时可以与Trial Profile互换使用,但也可以更广泛地指代对一项研究的详细描述,包括其背景、理论基础、研究问题、研究设计、数据来源、数据分析方法和预期贡献等。

Study Profile可能包含比Trial Profile更深入的科学和方法学细节,特别是对于观察性研究或非干预性研究。

Study Profiles常用于学术出版物、研究提案、研究机构的数据库和在线平台上,以促进研究的可发现性和再现性。

无论是Trial Profile还是Study Profile,其目标都是提高临床研究的透明度、可重复性和科学研究的质量。

这些资料的准确和全面对于确保研究的可信度和公正性非常重要。

在撰写这些文档时,应遵循相关的报告标准和指南,如

CONSORT声明(对照试验的报告)或STROBE声明(观察性研究的报告)。

(STROBE)声明 - 山东大学课程中心

Exposure Occurred (smoking)

相对危险度(Relative risk,RR)---前瞻性研究:队列研究

Risk in exposed (Re) = a/(a+b)=26/(26+74) = 26/100 = 0.26 Risk in unexposed (Ru) = c/(c+d) =4/(4+96) = 4/100 = 0.04 RR = Re/Ru= 0.26/0.04 = 6.5 暴露组某事件发生率是对照组的多少倍

暴露 非暴露 暴露 对照 非暴露

观 察 方 向

病例

总体

病例对照研究( Case-Control Studies)

优势:

• 病例对照研究属于回顾性研究。快捷,只需了解病史

• 无须特殊的研究方法,对照设置简单易行 • 新的临床假设常可以来自病例对照研究或病例分析研究 ,一般此类假设必须经过随机对照研究的证实。 弱点:

Erik von Elm, Douglas G Altman, Matthias Egger, for the STROBE initiative 世界临床医学.2008,2(1):78-82 LANCET.2007:370:1453-57

20

队列设计、病例-对照设计和横断面设计 22个条目的清单 其中18个条目适用于所有三种主要的观察性研究设计, 其余4个条目则专门用于队列、病例-对照或横断面设计。

Step3: critical appraisal of evidence

Critical appraisal of a case-control/cohort study

王克芳 山东大学护理学院

病例对照研究( Case-Control Studies)

Meta分析系列之四观察性研究的质量评价工具

Meta分析系列之四观察性研究的质量评价工具一、本文概述本文旨在探讨观察性研究的质量评价工具,为研究者提供一套系统、全面的评价框架,以提高观察性研究的可靠性和有效性。

观察性研究作为医学和社会科学领域重要的研究方法,其质量直接影响到研究结果的准确性和可信度。

因此,开发和应用质量评价工具对于提升观察性研究的质量至关重要。

本文将介绍几种常用的观察性研究质量评价工具,包括其评价原理、应用场景、优缺点等方面,并结合实际案例进行分析和讨论。

通过本文的阐述,读者将能够更好地理解和应用这些质量评价工具,以提高观察性研究的水平和质量。

二、观察性研究的基本概念与特点观察性研究,又称为非实验性研究或自然研究,是医学研究中常用的一种方法。

与实验性研究不同,观察性研究不人为地改变研究对象的状态或干预其进程,而是通过观察自然状态下的现象,收集相关数据,以揭示变量之间的关系和规律。

这种方法强调在自然环境中收集数据,减少了对研究对象的干扰,因此其结果往往更加接近真实情况。

自然性:观察性研究在自然环境下进行,研究对象处于自然状态,不受人为干预的影响。

这有助于获得更真实、更贴近实际的数据。

灵活性:观察性研究可以根据研究目的和问题的不同,选择不同的研究对象、观察指标和数据收集方法。

这种灵活性使得观察性研究能够适应各种复杂的研究场景。

广泛性:观察性研究可以涵盖大量的研究对象和多种不同的观察指标,从而提供丰富的数据支持。

这种广泛性有助于揭示变量之间的复杂关系,为深入研究奠定基础。

实时性:观察性研究能够实时跟踪研究对象的变化,及时捕捉各种现象和事件。

这种实时性有助于获取最新的研究数据,为决策提供有力支持。

然而,观察性研究也存在一些局限性。

由于缺乏对研究对象的干预和控制,观察性研究可能受到多种未知因素的影响,导致结果产生偏差。

观察性研究通常需要较长的时间来收集数据,因此耗时较长。

对于某些特定的问题或疾病,观察性研究可能难以获得足够数量和质量的数据支持。

医学研究报告规范——CONSORT声明

方法(Methods)

➢ 3a :描述试验设计 ➢ 3b:描述试验开始后对方法重要改变(包括入排标准),及理

由

精品课件

方法(Methods)

➢ 4a:入选标准 ➢ 4b:搜集数据资料的场所

➢ 5:详细描述每组的干预措施,包括如何及何时进行干预。

精品课件

方法(Methods)

➢ 6a:包括主要和次要结局测量指标,包括如何及何时进行评估 ➢ 6b:试验开始后,任何针对试验结局测量进行的改变,及理由

精品课件

方法(Methods)

➢ 8a 随机分组序列的产生方式 ➢ 8b 随机化的方式;任何限制性详细情况(如分层和区组大小) ➢ 9 如何来完成随机系列分配,如用数字产生器还是中心电话数字,数字

安排是否随机隐藏,干预分配方案是否隐藏。 ➢ 10 谁产生随机分配实验,谁登记参与者,谁分配参与者接受干预 ➢ 11a 干预分配后谁是对分配情况不知道的(如参加者、护理者、结局评

精品课件

www.consort-statement.or

CONSORT 2010 Checklist

精品课件

CONSORT 2010 Checklist

精品课件

题目和摘要 (Title and Abstract)

➢ 1a: 题目中说明随机分配方式 要点:试验设计、受试对象、干预措施

精品课件

题目和摘要 (Title and Abstract)

精品课件

方法(Methods)

➢ 7a:样本大小是如何确定的

精品课件

示例要点: 主要终点指标、 预期差异、 I类错误α值、 单侧/双侧假设、 power值、 脱落率

方法(Methods)

➢ 7b:如有,需解释中间分析和停止原则 Many trials recruit participants over a long period. If an intervention is working particularly well or badly, the study may need to be ended early for ethical reasons. This concern can be addressed by examining results as the data accumulate, preferably by an independent data monitoring committee.

RCT和观察性研究的报告规范-2011博士(精)

结局指标

样本量 随机化 盲法 统计学方 法

a.受试者的纳入排除标准;b.数据收集的环境及地点 详述每组干预的细节(以便其它研究者的复制)及实际实施 5 情况,包括了实施时间和实施方式 a. 明确定义预先指定的首要和次要结局变量,包括了如何和 6 何时进行评价; b. 如果在试验开始后对结局变量进行修改, 必须说明原因 7 a.如何确定样本量;b.必要时,解释期中分析及试验终止原则 8-10 序列产生;分配遮蔽;实施 a. 若使用了盲法,需指明谁是干预的被盲者(例如受试者、 11 干预给予者、结果评价者)以及如何设盲; b. 如若涉及,描 述每组干预的相似性 a.用于比较组间主要和次要结局的统计学方法; 12 b.附加分析的统计学方法,比如亚组分析和校正分析

6

主要内容

一

RCT研究的报告规范 ——CONSORT

二

观察性研究的报告规范 ——STROBE

7

主要内容

一

RCT研究的报告规范 ——CONSORT

二

观察性研究的报告规范 ——STROBE

8

PubMed中RCT研究的报告情况

很多综述都报道了临床试验报告中的缺陷。

2000年与2006年PubMed中有缺陷临床试验文章的百分比(%) 2000年 2006年 报告缺陷 (n=519) (n=616) 79 未报告分配受试者的方法 66 55 47 未报告主要结局指标 73 55 未报告样本量的计算

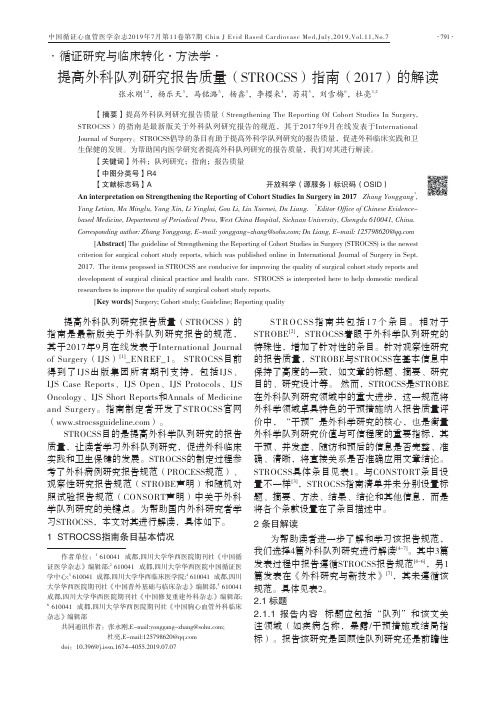

提高外科队列研究报告质量(STROCSS)指南(2017)的解读

•循证研究与临床转化·方法学 •提高外科队列研究报告质量(STROCSS)指南(2017)的解读张永刚1,2,杨乐天3,马铭潞3,杨鑫3,李樱来4,苟莉5,刘雪梅6,杜亮1,2作者单位:1 610041 成都,四川大学华西医院期刊社《中国循证医学杂志》编辑部;2 610041 成都,四川大学华西医院中国循证医学中心;3 610041 成都,四川大学华西临床医学院;4 610041 成都,四川大学华西医院期刊社《中国普外基础与临床杂志》编辑部,5 610041 成都,四川大学华西医院期刊社《中国修复重建外科杂志》编辑部; 6610041 成都,四川大学华西医院期刊社《中国胸心血管外科临床杂志》编辑部共同通讯作者:张永刚,E-mail:yonggang-zhang@; 杜亮,E-mail:125798620@ doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2019.07.07【摘要】提高外科队列研究报告质量(Strengthening The Reporting Of Cohort Studies In Surgery, STROCSS)的指南是最新版关于外科队列研究报告的规范,其于2017年9月在线发表于International Journal of Surgery。

STROCSS倡导的条目有助于提高外科学队列研究的报告质量,促进外科临床实践和卫生保健的发展。

为帮助国内医学研究者提高外科队列研究的报告质量,我们对其进行解读。

【关键词】外科;队列研究;指南;报告质量【中图分类号】R4【文献标志码】A 开放科学(源服务)标识码(OSID)An interpretation on Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies In Surgery in 2017 Zhang Yonggang *, Yang Letian, Ma Minglu, Yang Xin, Li Yinglai, Gou Li, Liu Xuemei, Du Liang. *Editor Office of Chinese Evidence-based Medicine, Department of Periodical Press, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China. Corresponding author: Zhang Yonggang, E-mail: yonggang-zhang@; Du Liang, E-mail: 125798620@[Abstract ] The guideline of Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) is the newest criterion for surgical cohort study reports, which was published online in International Journal of Surgery in Sept. 2017. The items proposed in STROCSS are conducive for improving the quality of surgical cohort study reports and development of surgical clinical practice and health care. STROCSS is interpreted here to help domestic medical researchers to improve the quality of surgical cohort study reports.[Key words ] Surgery; Cohort study; Guideline; Reporting quality提高外科队列研究报告质量(STROCSS)的指南是最新版关于外科队列研究报告的规范,其于2017年9月在线发表于International Journal of Surgery(IJS)[1]_ENREF_1。

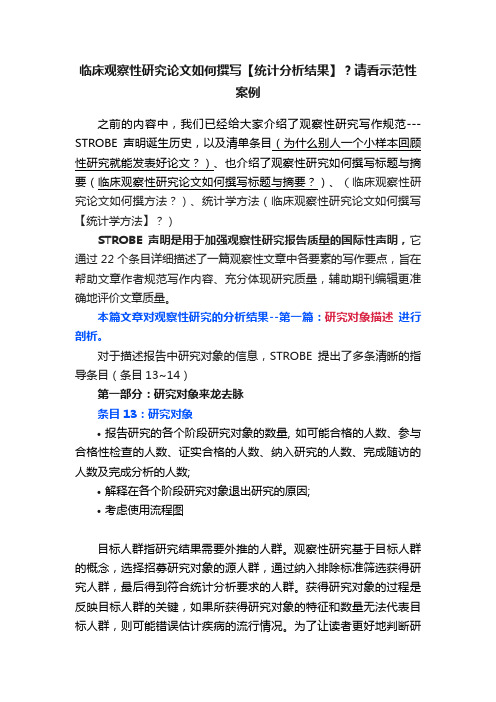

临床观察性研究论文如何撰写【统计分析结果】?请看示范性案例

临床观察性研究论文如何撰写【统计分析结果】?请看示范性案例之前的内容中,我们已经给大家介绍了观察性研究写作规范---STROBE声明诞生历史,以及清单条目(为什么别人一个小样本回顾性研究就能发表好论文?)、也介绍了观察性研究如何撰写标题与摘要(临床观察性研究论文如何撰写标题与摘要?)、(临床观察性研究论文如何撰方法?)、统计学方法(临床观察性研究论文如何撰写【统计学方法】?)STROBE声明是用于加强观察性研究报告质量的国际性声明,它通过22个条目详细描述了一篇观察性文章中各要素的写作要点,旨在帮助文章作者规范写作内容、充分体现研究质量,辅助期刊编辑更准确地评价文章质量。

本篇文章对观察性研究的分析结果--第一篇:研究对象描述进行剖析。

对于描述报告中研究对象的信息,STROBE提出了多条清晰的指导条目(条目13~14)第一部分:研究对象来龙去脉条目13:研究对象•报告研究的各个阶段研究对象的数量, 如可能合格的人数、参与合格性检查的人数、证实合格的人数、纳入研究的人数、完成随访的人数及完成分析的人数;•解释在各个阶段研究对象退出研究的原因;•考虑使用流程图目标人群指研究结果需要外推的人群。

观察性研究基于目标人群的概念,选择招募研究对象的源人群,通过纳入排除标准筛选获得研究人群,最后得到符合统计分析要求的人群。

获得研究对象的过程是反映目标人群的关键,如果所获得研究对象的特征和数量无法代表目标人群,则可能错误估计疾病的流行情况。

为了让读者更好地判断研究设计的合理性以及实施过程的严谨性,STROBE声明建议研究者应在结果的第一段中给出从源人群到最后纳入统计分析人群过程中每个招募阶段的参与者数量,并描述每个阶段的排除原因和人数。

案例一:From May 11, 2020, to Nov 2, 2020, 3249 (70%) of 4657 elig ible participants were enrolled in CHARM. After excluding 28 pa rticipants who were SARS-CoV-2 PCR positive at baseline and 53 who lacked baseline serology results, 3168 (98%) underwent a s upervised 2-week quarantine. 45 participants who were SARS-C oV-2 PCR positive on at least one of two PCR tests performed d uring quarantine, and 47 who were lost to follow-up, were furth er excluded from the study prior to the prospective study period (figure 1)[1].如案例一,作为结果的第一段内容。

继续解读:观察性研究报告规范STROBE声明

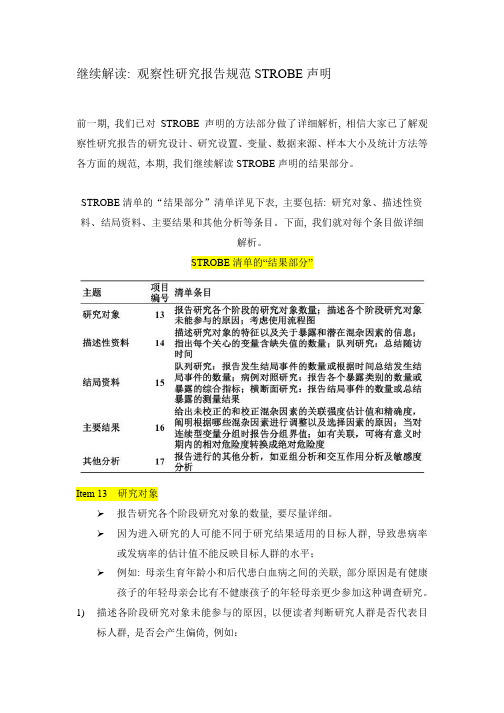

继续解读: 观察性研究报告规范STROBE声明前一期, 我们已对STROBE声明的方法部分做了详细解析, 相信大家已了解观察性研究报告的研究设计、研究设置、变量、数据来源、样本大小及统计方法等各方面的规范, 本期, 我们继续解读STROBE声明的结果部分。

STROBE清单的“结果部分”清单详见下表, 主要包括: 研究对象、描述性资料、结局资料、主要结果和其他分析等条目。

下面, 我们就对每个条目做详细解析。

STROBE清单的“结果部分”Item 13 研究对象➢报告研究各个阶段研究对象的数量, 要尽量详细。

➢因为进入研究的人可能不同于研究结果适用的目标人群, 导致患病率或发病率的估计值不能反映目标人群的水平;➢例如: 母亲生育年龄小和后代患白血病之间的关联, 部分原因是有健康孩子的年轻母亲会比有不健康孩子的年轻母亲更少参加这种调查研究。

1)描述各阶段研究对象未能参与的原因, 以便读者判断研究人群是否代表目标人群, 是否会产生偏倚, 例如:2)横断面调查中, 所选对象由于与健康无关的原因而不参加研究(如征集信函由于错误的地址而没有邮寄到)会影响估计的精度, 但却可能不会产生偏倚。

建议使用流程图, 例如:Item 14 描述性资料➢描述研究对象的特征(如人口学、临床和社会特征)以及关于暴露和潜在混杂因素的信息以及关于暴露和潜在混杂因子的信息;指出每个关心的变量有缺失值的研究对象数目、暴露、潜在混杂因子和患者的其他重要特征, 不同程度和原因的失访;队列研究总结随访时间, 报告随访期限的最大值和最小值或总体分布的百分位数, 总随访人年, 所获得潜在数据的一些比例指标。

Item 15 结局资料1)报告发生结局事件(队列研究、横断面研究)或暴露类别(病例-对照研究)的数量;2)或根据时间总结发生结局事件的数量。

Item 16 主要结果1)给出未校正的和校正的混杂因素的关联强度估计值、精确度(如95%CI);➢阐明根据哪些混杂因素进行了调整以及选择这些因素的原因;当对连续性变量分组时, 报告分组界值;如有关联, 可将有意义时期内的相对危险度转化成绝对危险度。

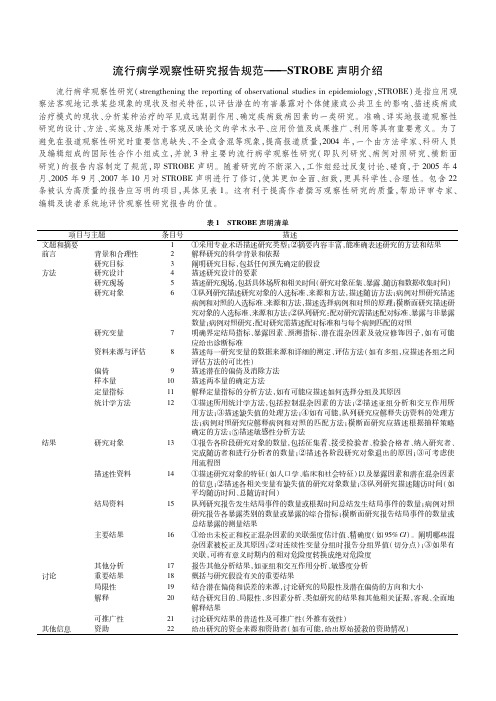

流行病学观察性研究报告规范――strobe声明介绍

流行病学观察性研究报告规范———STROBE声明介绍 流行病学观察性研究(strengtheningthereportingofobservationalstudiesinepidemiology,STROBE)是指应用观察法客观地记录某些现象的现状及相关特征,以评估潜在的有害暴露对个体健康或公共卫生的影响、描述疾病或治疗模式的现状、分析某种治疗的罕见或远期副作用、确定疾病致病因素的一类研究。

准确、详实地报道观察性研究的设计、方法、实施及结果对于客观反映论文的学术水平、应用价值及成果推广、利用等具有重要意义。

为了避免在报道观察性研究时重要信息缺失、不全或含混等现象,提高报道质量,2004年,一个由方法学家、科研人员及编辑组成的国际性合作小组成立,并就3种主要的流行病学观察性研究(即队列研究、病例对照研究、横断面研究)的报告内容制定了规范,即STROBE声明。

随着研究的不断深入,工作组经过反复讨论、磋商,于2005年4月、2005年9月、2007年10月对STROBE声明进行了修订,使其更加全面、细致,更具科学性、合理性。

包含22条被认为高质量的报告应写明的项目,具体见表1。

这有利于提高作者撰写观察性研究的质量,帮助评审专家、编辑及读者系统地评价观察性研究报告的价值。

表1 STROBE声明清单条目号描述 项目与主题 文题和摘要1①采用专业术语描述研究类型;②摘要内容丰富,能准确表述研究的方法和结果前言背景和合理性2解释研究的科学背景和依据研究目标3阐明研究目标,包括任何预先确定的假设方法研究设计4描述研究设计的要素研究现场5描述研究现场,包括具体场所和相关时间(研究对象征集、暴露、随访和数据收集时间)研究对象6①队列研究描述研究对象的入选标准、来源和方法,描述随访方法;病例对照研究描述病例和对照的入选标准、来源和方法,描述选择病例和对照的原理;横断面研究描述研究对象的入选标准、来源和方法;②队列研究:配对研究需描述配对标准、暴露与非暴露数量;病例对照研究:配对研究需描述配对标准和与每个病例匹配的对照研究变量7明确界定结局指标、暴露因素、预测指标、潜在混杂因素及效应修饰因子,如有可能应给出诊断标准资料来源与评估8描述每一研究变量的数据来源和详细的测定、评估方法(如有多组,应描述各组之间评估方法的可比性)偏倚9描述潜在的偏倚及消除方法样本量10描述两本量的确定方法定量指标11解释定量指标的分析方法,如有可能应描述如何选择分组及其原因统计学方法12①描述所用统计学方法,包括控制混杂因素的方法;②描述亚组分析和交互作用所用方法;③描述缺失值的处理方法;④如有可能,队列研究应解释失访资料的处理方法;病例对照研究应解释病例和对照的匹配方法;横断面研究应描述根据抽样策略确定的方法;⑤描述敏感性分析方法结果研究对象13①报告各阶段研究对象的数量,包括征集着、接受检验者、检验合格者、纳入研究者、完成随访者和进行分析者的数量;②描述各阶段研究对象退出的原因;③可考虑使用流程图描述性资料14①描述研究对象的特征(如人口学、临床和社会特征)以及暴露因素和潜在混杂因素的信息;②描述各相关变量有缺失值的研究对象数量;③队列研究描述随访时间(如平均随访时间、总随访时间)结局资料15队列研究报告发生结局事件的数量或根据时间总结发生结局事件的数量;病例对照研究报告各暴露类别的数量或暴露的综合指标;横断面研究报告结局事件的数量或总结暴露的测量结果主要结果16①给出未校正和校正混杂因素的关联强度估计值、精确度(如95%CI)。

观察性研究报告规范

报告规范—结果

其他 (a)报告任何其他分析,包括亚组分析和敏感性分析

报告规范—讨论

总结: (a) 根据研究目的讨论关键关键结果 (b) 局限性(偏倚,样本量,研究对象)

(c) 谨慎的解释和总结我们的结果

(d) 意义

报告规范—其他

Funding Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based

Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or

summary measures 对于队列或者横断面研究: 发生某个结局的数目(分类变量)

,或者每个暴露组的某指标(连续变量)总的测量结果(平均数)。

对于病例对照组: 病例和对照组中暴露于某个因素(分类变量)

,暴露时间)

报告规范--方法

方法中各类观察性研究的共同规范 Variables : clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give

diagnostic criteria, if applicable

Байду номын сангаас

rationale for the investigation being reported.

(b) Objectives: state specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses. 总结:前言应该包括背景介绍,研究的理由,研究的目的

观察性研究的报告规范

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studiesErik von Elm, Douglas G Altman, Matthias Egger, Stuart J Pocock, Peter C Gøtzsche, Jan P Vandenbroucke, for the STROBE initiativeMuch biomedical research is observational. The reporting of such research is often inadequate, which hampers the assessment of its strengths and weaknesses and of a study’s generalisability. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative developed recommendations on what should be included in an accurate and complete report of an observational study. We defi ned the scope of the recommendations to cover thre e main study de signs: cohort, case-control, and cross-se ctional studie s. We conve ne d a 2-day workshop in September, 2004, with methodologists, researchers, and journal editors to draft a checklist of items. This list was subsequently revised during several meetings of the coordinating group and in e-mail discussions with the larger group of STROBE contributors, taking into account e mpirical e vide nce and me thodological conside rations. The workshop and the subsequent iterative process of consultation and revision resulted in a checklist of 22 items (the STROBE statement) that relate to the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections of articles.18 items are common to all three study designs and four are specifi c for cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies.A detailed explanation and elaboration document is published separately and is freely available on the websites of PLoS Medicine, Annals of Internal Medicine, and Epidemiology. We hope that the STROBE statement will contribute to improving the quality of reporting of observational studies.IntroductionMany questions in medical research are investigated in observational studies.1Much of the research into the cause of diseases relies on cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies. Observational studies also have a role in research into the benefits and harms of medical interventions.2 Randomised trials cannot answer all important questions about a given intervention. For example, observational studies are more suitable to detect rare or late adverse eff ects of treatments, and are more likely to provide an indication of what is achieved in daily medical practice.3 Research should be reported transparently so that readers can follow what was planned, what was done, what was found, and what conclusions were drawn. The credibility of research depends on a critical assessment by others of the strengths and weaknesses in study design, conduct, and analysis. Transparent reporting is also needed to judge whether and how results can be included in systematic reviews.4,5 However, in published observational research important information is often missing or unclear. An analysis of epidemiological studies published in general medical and specialist journals found that the rationale behind the choice of potential confounding variables was often not reported.6 Only a few reports of case-control studies in psychiatry explained the methods used to identify cases and controls.7 In a survey of longitudinal studies in stroke research, 17 of 49 articles (35%) did not specify the eligibility criteria.8 Others have argued that without sufficient clarity of reporting, the benefi ts of research might be achieved more slowly,9 and that there is a need for guidance in reporting observational studies.10,11 Recommendations on the reporting of research can improve reporting quality. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement was devel-oped in 1996 and revised 5 years later.12 Many medicaljournals supported this initiative,13 which has helped toimprove the quality of reports of randomised trials.14,15Similar initiatives have followed for other researchareas—eg, for the reporting of meta-analyses ofrandomised trials16 or diagnostic studies.17 We estab-lished a network of methodologists, researchers, andjournal editors to develop recommendations for thereporting of observational research: the Strengtheningthe Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology(STROBE) statement.Aims and use of the STROBE statementThe STROBE statement is a checklist of items that shouldbe addressed in articles reporting on the three main studydesigns of analytical epidemiology: cohort, case-control,and cross-sectional studies. The intention is solely toprovide guidance on how to report observational researchwell: these recommendations are not prescriptions fordesigning or conducting studies. Also, while clarity ofreporting is a prerequisite to evaluation, the checklist is notan instrument to evaluate the quality of observationalresearch.Here we present the STROBE statement and explainhow it was developed. In a detailed companion paper, theexplanation and elaboration article,18–20 we justify theinclusion of the different checklist items and givemethodological background and published examples ofwhat we consider transparent reporting. We stronglyrecommend using the STROBE checklist in conjunctionwith the explanatory article, which is available freely on thewebsites of PLoS Medicine (), Annalsof Internal Medicine (), and Epidemiology().Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–57Institute of Social andPreventive Medicine (ISPM),University of Bern, Bern,Switzerland (E von Elm MD,Prof M Egger MD);Centre forStatistics in Medicine,University of Oxford, Oxford,UK (Prof D G Altman DSc);Department of Social Medicine,University of Bristol, Bristol,UK (M Egger);London School ofHygiene and Tropical Medicine,University of London, London,UK (Prof S J Pocock PhD);NordicCochrane Centre, Copenhagen,Denmark (P C Gøtzsche MD);and Department of ClinicalEpidemiology, LeidenUniversity Hospital,Leiden, Netherlands(Prof J P Vandenbroucke MD)Correspondence to:Dr Erik von Elm, Institute ofSocial and Preventive Medicine(ISPM), University of Bern,Finkenhubelweg 11, CH-3012Bern, Switzerlandstrobe@ispm.unibe.chSTROBE StatementSTROBE StatementSTROBE StatementDevelopment of the STROBE statementWe established the STROBE initiative in 2004, obtained funding for a workshop, and set up a website (). We searched textbooks,bibliographic databases, reference lists, and personal fi les for relevant material, including previous recommendations, empirical studies of reporting, and articles describing relevant methodological research. Because observational research makes use of many diff erent study designs, we felt that the scope of STROBE had to be clearly defi ned early on. We decided to focus on the three study designs that are used most widely in analytical observational research: cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies.We organised a 2-day workshop in Bristol, UK , in September, 2004. 23 individuals attended this meeting, including editorial staff from Annals of Internal Medicine , BMJ , Bulletin of the World Health Organization , Inter-national Journal of Epidemiology , JAMA , Prev e ntive Medicine , and The Lancet , as well as epidemiologists, methodologists, statisticians, and practitioners from Europe and North America. Written contributions were sought from ten other individuals who declared an interest in contributing to STROBE, but could not attend. Three working groups identifi ed items deemed to be important to include in checklists for each type of study. A provisional list of items prepared in advance (available from our website) was used to facilitate discussions. The three draft checklists were then discussed by all participants and, where possible, items were revised to make them applicable to all three study designs. In a fi nal plenary session, the group decided on the strategy for fi nalising and disseminating the STROBE statement.After the workshop we drafted a combined checklist including all three designs and made it available on our website. We invited participants and additional scientists and editors to comment on this draft checklist. We subsequently published three revisions on the website, and two summaries of comments received and changes made. During this process the coordinating group (ie, the authors of the present paper) met on eight occasions for 1 or 2 days and held several telephone conferences to revise the checklist and to prepare the present paper and the explanation and elaboration paper.18–20 The coordinating group invited three additional co-authors with method o logical and editorial expertise to help write the explanation and elaboration paper, and sought feedback from more than 30 people, who are listed at the end of this paper. We allowed several weeks for comments on subsequent drafts of the paper and reminded collaborators about deadlines by e-mail.STROBE componentsThe STROBE statement is a checklist of 22 items that we consider essential for good reporting of observational studies (table). These items relate to the article’s title and abstract (item 1), the introduction (items 2 and 3), methods (items 4–12), results (items 13–17), anddiscussion sections (items 18–21), and other information(item 22 on funding). 18 items are common to all three designs, while four (items 6, 12, 14, and 15) are design-specific, with diff erent versions for all or part of the item. For some items (indicated by asterisks), information should be given separately for cases and controls in case-control studies, or exposed and unexposed groups in cohort and cross-sectional studies. Although presented here as a single checklist, separate checklists are available for each of the three study designs on the STROBE website.Implications and limitationsThe STROBE statement was developed to assist authors when writing up analytical observational studies, to support editors and reviewers when considering such articles for publication, and to help readers when critically appraising published articles. We developed the checklist through an open process, taking into account the experience gained with previous initiatives, in particular CONSORT . We reviewed the relevant empirical evidence as well as methodological work, and subjected consec-utive drafts to an extensive iterative process of consultation. The checklist presented here is thus based on input from a large number of individuals with diverse back-grounds and perspectives. The comprehensive explana t oryarticle,18–20which is intended for use alongside the check-list, also benefi ted greatly from this consultation process.Observational studies serve a wide range of purposes, on a continuum from the discovery of new fi ndings to the confi rmation or refutation of previous fi ndings.18–20 Some studies are essentially exploratory and raise interesting hypotheses. Others pursue clearly defi ned hypotheses in available data. In yet another type of studies, the collection of new data is planned carefully on the basis of an existing hypothesis. We believe the present checklist can be useful for all these studies, since the readers always need to know what was planned (and what was not), what was done, what was found, and what the results mean. We acknowledge that STROBE is currently limited to three main observational study designs. We would welcome extensions that adapt the checklist to other designs—eg, case-crossover studies or ecologicalstudies—and also to specific topic areas. Four extensions are now available for the CONSORT statement.21–24 A fi rst extension to STROBE is underway for gene-disease association studies: the STROBE Extension to Genetic Association studies (STREGA) initiative.25 We ask those who aim to develop extensions of the STROBE statement to contact the coordinating group fi rst to avoid duplicationof eff ort.The STROBE statement should not be interpreted as an attempt to prescribe the reporting of observational research in a rigid format. The checklist items should be addressedin sufficient detail and with clarity somewhere in an article, but the order and format for presenting informationFor more on theSTROBE initiative see STROBE Statementdepends on author preferences, journal style, and the traditions of the research fi eld. For instance, we discuss the reporting of results under a number of separate items, while recognising that authors might address several items within a single section of text or in a table. Also, item 22, on the source of funding and the role of funders, could be addressed in an appendix or in the methods section of the article. We do not aim at standardising reporting. Authors of randomised clinical trials were asked by an editor of a specialist medical journal to “CONSORT” their manuscripts on submission.26 We believe that manuscripts should not be “STROBEd”, in the sense of regulating style or terminology. We encourage authors to use narrative elements, including the description of illustrative cases, to complement the essential information about their study, and to make their articles an interesting read.27We emphasise that the STROBE statement was not developed as a tool for assessing the quality of published observational research. Such instruments have been developed by other groups and were the subject of a recent systematic review.28 In the explanation and elaboration paper, we used several examples of good reporting from studies whose results were not confi rmed in further research—the important feature was the good reporting, not whether the research was of good quality. However, if STROBE is adopted by authors and journals, issues such as confounding, bias, and generalisability could become more transparent, which might help temper the over-enthusiastic reporting of new fi ndings in the scientific community and popular media,29 and improve the methodology of studies in the long term. Better reporting may also help to have more informed decisions about when new studies are needed, and what they should address.We did not undertake a comprehensive systematic review for each of the checklist items and subitems, or do our own research to fi ll gaps in the evidence base. Further, although no one was excluded from the process, the composition of the group of contributors was infl uenced by existing networks and was not representative in terms of geography (it was dominated by contributors from Europe and North America) and probably was not representative in terms of research interests and disciplines. We stress that STROBE and other recommendations on the reporting of research should be seen as evolving documents that require continual assessment, refinement, and, if necessary, change. We welcome suggestions for the further dissemination of STROBE—eg, by re-publication of the present article in specialist journals and in journals published in other languages. Groups or individuals who intend to translate the checklist to other languages should consult the coordinating group beforehand. We will revise the checklist in the future, taking into account comments, criticism, new evidence, and experience from its use. We invite readers to submit their comments via the STROBE website.ContributorsThe following individuals have contributed to the content and elaboration of the STROBE statement: Douglas G Altman,Maria Blettner, Paolo Boff etta, Hermann Brenner, Geneviève Chêne, Cyrus Cooper, George Davey-Smith, Erik von Elm, Matthias Egger, France Gagnon, Peter C Gøtzsche, Philip Greenland, Sander Greenland, Claire Infante-Rivard, John Ioannidis, Astrid James, Giselle Jones, Bruno Ledergerber, Julian Little, Margaret May, David Moher,Hooman Momen, Alfredo Morabia, Hal Morgenstern,Cynthia D Mulrow, Fred Paccaud, Stuart J Pocock, Charles Poole, Martin Röösli, Dietrich Rothenbacher, Kenneth Rothman,Caroline Sabin, Willi Sauerbrei, Lale Say, James J Schlesselman, Jonathan Sterne, Holly Syddall, Jan P Vandenbroucke, Ian White, Susan Wieland, Hywel Williams, Guang Yong Zou.Confl ict of interest statementWe declare that we have no confl ict of interest.AcknowledgmentsThe workshop was funded by the European Science Foundation (ESF). Additional funding was received from the Medical Research Council Health Services Research Collaboration, and the National Health Services Research and Development Methodology Programme. We are grateful to Gerd Antes, Kay Dickersin, Shah Ebrahim, andRichard Lilford for supporting the STROBE initiative. We are grateful to the following institutions that have hosted working meetings of the coordinating group: Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark; and Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Oxford, UK. We are grateful to six reviewers who provided helpful comments on a previous draft of this paper.References1 Glasziou P, Vandenbroucke JP, Chalmers I. Assessing the quality ofresearch. BMJ 2004; 328: 39–41.2 Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate theeff ectiveness of health care. BMJ 1996; 312: 1215–18.3 Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, Ioannidis JP. Comparison ofevidence on harms of medical interventions in randomized andnonrandomized studies. CMAJ 2006; 174: 635–41.4 Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care:assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001; 323:42–46.5 Egger M, Schneider M, Davey Smith G. Spurious precision?Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 1998; 316: 140–44.6 Pocock SJ, Collier TJ, Dandreo KJ, et al. Issues in the reporting ofepidemiological studies: a survey of recent practice. BMJ 2004; 329: 883.7 Lee W, Bindman J, Ford T, et al. Bias in psychiatric case-controlstudies: literature survey. Br J Psychiatry 2007; 190: 204–09.8 Tooth L, Ware R, Bain C, Purdie DM, Dobson A. Quality ofreporting of observational longitudinal research. Am J Epidemiol2005; 161: 280–88.9 Bogardus ST Jr, Concato J, Feinstein AR. Clinical epidemiologicalquality in molecular genetic research: the need for methodological standards. JAMA 1999; 281: 1919–26.10 Anon. Guidelines for documentation of epidemiologic studies.Epidemiology Work Group of the Interagency Regulatory LiaisonGroup. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 114: 609–13.11 Rennie D. CONSORT revised – improving the reporting ofrandomized trials. JAMA 2001; 285: 2006–07.12 Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement:revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports ofparallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001; 357: 1191–94.13 Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Elbourne DR. Opportunities andchallenges for improving the quality of reporting clinical research: CONSORT and beyond. CMAJ 2004; 171: 349–50.14 Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, et al. Does the CONSORT checklistimprove the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? Asystematic review. Med J Aust 2006; 185: 263–67.15 Egger M, Jüni P, Bartlett C. Value of fl ow diagrams in reports ofrandomized controlled trials. JAMA 2001; 285: 1996–99.STROBE Statement16 Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF.Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomisedcontrolled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet 1999; 354: 1896–900.17 Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete andaccurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARDInitiative. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138: 40–44.18 Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al, for the STROBEinitiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med2007; 4: e297.19 Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al, for the STROBEinitiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med (in press).20 Vandenbroucke JP von Elm E, Altman DG, et al, for the STROBEinitiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology (in press).21 Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, et al. Better reporting ofharms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORTstatement. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141: 781–88.22 Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement:extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004; 328: 702–08.23 Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ.Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006; 295: 1152–60. 24 Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, Moher D, Barnes J, Bombardier C.Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 364–67.25 Ioannidis JP, Gwinn M, Little J, et al. A road map for effi cient andreliable human genome epidemiology. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 3–5.26 Ormerod AD. CONSORT your submissions: an update for authors.Br J Dermatol 2001; 145: 378–79.27 Schriger DL. Suggestions for improving the reporting of clinicalresearch: the role of narrative. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45: 437–43.28 Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality andsusceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: asystematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36: 666–76.29 Bartlett C, Sterne J, Egger M. What is newsworthy? Longitudinalstudy of the reporting of medical research in two Britishnewspapers. BMJ 2002; 325: 81–84.© 2007 The Authors。

4横断面研究与STROBE声明

虚假联系 间接联系 因果联系

1.1 疾病与因素的两类3种关系

并存无因果,时间差可能有因果,因素与结局的时间关系有两类3种:

因素在前 结局在后

1.从结局出发,回顾以前某因素--病例对照研究 2.从某因素出发,随访至部分对象出现结局--队列研究

3. 因素与结局并存同一时间--现况研究

例1、己烯雌酚与青年妇女阴道腺癌(1971年); 例2、吸烟与肺癌; 例3、不同民族(性别、血型)食管癌的患病率;

研究这种分类,能找出存在于患者中而区别于健 康人的特征。

13

1.3.1 时间分布

例 2019年,4月1日至5月28日期间,美国某县共报告传染性肝炎63例。

其中60例发生时间在4月26日至5月20日(下图)。

14

12

病 例 数

10 8 6

4

2

0

2

6 10 14 18 22 26 30 4

4月

8 12 16 20 24 28 2 日期

表1 某县4月28日至5月26日传染性肝炎的年龄和性别罹患率

人口

病例数

男

女

合计

罹患率(‰)

男

女

1740

0

0

0

0.0

0.0

1000

2

2

4

3.7

4.5

989

12

6

18

22.2

13.4

868

16

7

23

35.9

16.6

494

1Leabharlann 344.2

11.8

455

0

1

1

0.0

4.6

435

3

0

医学研究报告规范——CONSORT声明 ppt课件

PPT课件

11

题目和摘要 (Title and Abstract)

要点:

4. 结果:每组受试者数目、募集状态、进入分析集的每组受试者数目、主要

结局、不良事件

5. 结论

6. 基金

PPT课件

12

题目和摘要 (Title and Abstract)

结构式摘要: Objectives, Design, Setting, Participants, Intervention, Main

医学研究报告规范 ——CONSORT声明

PPT课件

1

Why

文章发表障碍: Poor research Poor trial design Poor reporting of research

——An editor of the Lancet Oncol

PPT课件

2

Why

循证证据金字塔

Excluded (n= ) ¨ Not meeting inclusion criteria (n= ) ¨ Declined to participate (n= ) ¨ Other reasons (n= )

Randomized (n= )

Allocated to intervention (n= )

PPT课件

14

方法(Methods)

3a :描述试验设计 3b:描述试验开始后对方法重要改变(包括入排标准),及理由

PPT课件

15

方法(Methods)

4a:入选标准 4b:搜集数据资料的场所

5:详细描述每组的干预措施,包括如何及何时进行干预。

PPT课件

16

方法(Methods)

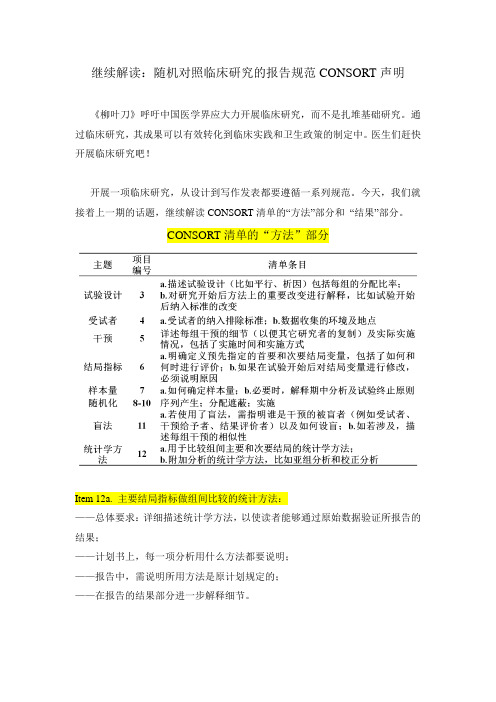

继续解读:随机对照临床研究的报告规范CONSORT声明

继续解读:随机对照临床研究的报告规范CONSORT声明《柳叶刀》呼吁中国医学界应大力开展临床研究,而不是扎堆基础研究。

通过临床研究,其成果可以有效转化到临床实践和卫生政策的制定中。

医生们赶快开展临床研究吧!开展一项临床研究,从设计到写作发表都要遵循一系列规范。

今天,我们就接着上一期的话题,继续解读CONSORT清单的“方法”部分和“结果”部分。

CONSORT清单的“方法”部分Item 12a. 主要结局指标做组间比较的统计方法:——总体要求:详细描述统计学方法,以使读者能够通过原始数据验证所报告的结果;——计划书上,每一项分析用什么方法都要说明;——报告中,需说明所用方法是原计划规定的;——在报告的结果部分进一步解释细节。

Item 12b. 附加分析的方法,比如亚组分析和校正分析:——不鼓励亚组分析,因为假阳性率常常很高,容易出虚假结果。

事后的亚组间比较(Post hoc subgroup comparisons)是看到数据之后才想起来做的分析,往往不能被进一步研究所确认,这类分析不可信。

——校正分析必须事先在研究计划里规定,并说明理由。

例如,(1)关于分层变量的校正。

(item 8b 随机化中采用的分层变量)必须说明选择被校正的变量是计划规定的还是事后根据数据提议的。

(2)关于baseline的校正。

(item 16)如果事先没有规定,事后发现baseline有统计学差异,才来决定校正,不能算是正式结果,只能算是探索性分析。

CONSORT清单的“结果”部分Item 13. 受试者流程图:——分组后排除受试者并不随机;如:有些受试者因为急性恶化或出现副作用而失访,如果这类受试者在两组间的排除不均衡,就会导致错误结论。

——了解多少人没有按分配接受干预或没有完成治疗有助于读者判断多大程度低估或高估了疗效;——为了详细报告受试者流程图及相关信息,研究者须:(1)事先周密计划随访事宜;(2)实施过程中,由专人负责随访;详细记录随机化分组之后每一位病人的信息(case report form)。

如何提高临床观察调研报告的可靠性

如何提高临床观察调研报告的可靠性临床观察调研报告在医学研究和医疗实践中具有重要的意义,它为医疗决策提供了依据,有助于推动医学的发展和进步。

然而,要确保临床观察调研报告的可靠性并非易事,需要从多个方面入手,采取一系列有效的措施。

首先,研究设计的合理性是提高临床观察调研报告可靠性的基础。

在设计阶段,研究者应明确研究的目的和问题,选择合适的研究对象和研究方法。

例如,如果研究某种药物的疗效,应确保研究对象的纳入和排除标准明确且合理,以保证研究群体的同质性。

同时,要根据研究目的选择恰当的研究方法,如随机对照试验、队列研究、病例对照研究等。

此外,样本量的计算也至关重要。

样本量过小可能导致结果的偶然性,无法反映真实情况;样本量过大则会增加研究成本和时间。

因此,需要通过科学的方法计算出既能满足研究目的又具有可行性的样本量。

数据的准确性和完整性是决定临床观察调研报告可靠性的关键因素。

在数据收集过程中,应采用标准化的测量工具和方法,确保数据的一致性和可比性。

对于主观的数据,如患者的症状和生活质量评估,应进行严格的培训,使评估者之间具有良好的一致性。

同时,要建立完善的数据管理系统,及时记录和存储数据,避免数据的丢失和错误。

在数据录入时,应进行双人核对,以确保数据的准确性。

另外,对于缺失的数据,要分析其原因,并采取合理的方法进行处理,如多重插补法等。

研究者的专业素养和严谨态度对于提高临床观察调研报告的可靠性起着重要作用。

研究者应具备扎实的医学知识和研究方法学的技能,熟悉相关的伦理和法律规范。

在研究过程中,要严格遵守伦理原则,保护研究对象的权益和隐私。

同时,要保持严谨的科学态度,避免主观偏见和先入为主的观念。

对于研究结果,要进行客观、公正的分析和解释,不夸大或缩小研究的效果。

统计分析方法的正确选择和应用也是确保临床观察调研报告可靠性的重要环节。

应根据数据的类型和研究目的选择合适的统计方法。

例如,对于连续型变量,可以采用 t 检验、方差分析等方法;对于分类变量,可以采用卡方检验等方法。

中国HIV阴性梅毒血清固定患者中无症状神经梅毒流行率

中国HIV阴性梅毒血清固定患者中无症状神经梅毒流行率Meta分析方案Meta-analysis protocol for the prevalence of asymptomaticneurosyphilis among HIV-negative serofast patients in China一、目的1、通过meta分析,得到中国HIV阴性的血清固定梅毒患者中无症状神经梅毒的流行情况。

2、为指导医生对血清固定的梅毒患者的临床管理提供信息。

3、了解神经梅毒与血清固定状态的关系。

二、研究对象接受了脑脊液检测的HIV阴性的血清固定梅毒患者。

1、血清固定定义:是指梅毒患者接受初次治疗之后非梅毒螺旋体血清学试验的血清滴度下降4倍及以上,随访1年及以上血清滴度仍保持低水平,未转阴。

2、无症状神经梅毒定义:分为确诊病例和疑似病例。

确诊病例的定义是无神经梅毒的临床症状,脑脊液VDRL检测结果阳性。

疑似病例的定义是无神经梅毒的临床症状,但脑脊液蛋白升高(>50mg/dL2)或白细胞计数(>5wbc/mm3),且没有其他已知原因导致这些异常。

三、文献检索1、检索文献数据库:英文数据库:PubMed、Embase、Medline、the Cochrane library中文数据库:中国知网、维普、万方、中国生物医学文献数据库2、检索关键词英文关键词:Serofast; Seroresistance; neurosyphilis; cerebrospinal fluid; China中文关键词:神经梅毒;脑脊液;血清固定;血清抵抗四、文献纳入与排除标准1、纳入标准:(1)研究报告了血清固定患者中神经梅毒患者的比例,或血清固定患者的脑脊液检测结果。

(2)所有血清固定患者均至少接受过一次治疗,无神经系统相关症状或体征,均接受腰椎穿刺获得了脑脊液的检测结果。

(3)研究纳入的血清固定患者的数量≥20人。

(4)研究范围限定在中国大陆。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

继续解读:观察性研究报告规范STROBE声明

前一期,我们已对STROBE声明的方法部分做了详细解析,相信大家已了解观察性研究报告的研究设计、研究设置、变量、数据来源、样本大小及统计方法等各方面的规范,本期,我们继续解读STROBE声明的结果部分。

STROBE清单的“结果部分”清单详见下表,主要包括:研究对象、描述性资料、结局资料、主要结果和其他分析等条目。

下面,我们就对每个条目做详细解析。

STROBE清单的“结果部分”

Item 13研究对象

1)报告研究各个阶段研究对象的数量,要尽量详细。

因为进入研究的人可能不同于研究结果适用的目标人群,导致患病率或发病率的估计值不能反映目标人群的水平;

例如:母亲生育年龄小和后代患白血病之间的关联,部分原因是有健康孩子的年轻母亲会比有不健康孩子的年轻母亲更少参加这种调查研究。

2)描述各阶段研究对象未能参与的原因,以便读者判断研究人群是否代表目标

人群,是否会产生偏倚,例如:

横断面调查中,所选对象由于与健康无关的原因而不参加研究(如征集

信函由于错误的地址而没有邮寄到)会影响估计的精度,但却可能不会

产生偏倚。

3)建议使用流程图,例如:

Item 14描述性资料

描述研究对象的特征(如人口学、临床和社会特征)以及关于暴露和潜在混杂因素的信息以及关于暴露和潜在混杂因子的信息;

指出每个关心的变量有缺失值的研究对象数目、暴露、潜在混杂因子和患者的其他重要特征,不同程度和原因的失访;

队列研究总结随访时间,报告随访期限的最大值和最小值或总体分布的百分位数,总随访人年,所获得潜在数据的一些比例指标。

Item 15结局资料

1)报告发生结局事件(队列研究、横断面研究)或暴露类别(病例-对照研究)

的数量;

2)或根据时间总结发生结局事件的数量。

Item 16 主要结果

1)给出未校正的和校正的混杂因素的关联强度估计值、精确度(如95%CI);

阐明根据哪些混杂因素进行了调整以及选择这些因素的原因;

2)当对连续性变量分组时,报告分组界值;

3)如有关联,可将有意义时期内的相对危险度转化成绝对危险度。

Item 17 其他分析

1)亚组分析:

分辨几个合适分类的亚组分别分析的关联与总体关联是否一致;

介绍在数据分析过程中出现的感兴趣的亚组,需报告准备进行哪些分析,没有准备的哪些分析;

2)交互作用分析:

应同时报告每种暴露各自的效果和他们之间的联合作用及置信区间;3)敏感性分析:

有助于估计在缺失数据或可能的偏倚下得到的研究结果是否可靠;

如果所分析的问题很受关注,或者效应估计值变化很大时需要详细说明。