Degradation of Methylparathion in Aqueous Solution by Electrochemical Oxidation

卤代对羟基苯甲酸酯 英语

卤代对羟基苯甲酸酯英语Halogenated Hydroxybenzoic Acid Esters.Halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters, commonly known as halogenated parabens, are a class of chemical compounds that are widely used as preservatives in cosmetics, personal care products, and food items. These esters are derived from hydroxybenzoic acid, which is naturally found in plants, and are halogenated, typically with chlorine or bromine, to enhance their antimicrobial properties.Applications and Uses.Halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters are primarily used as preservatives due to their ability to inhibit the growth of bacteria, fungi, and mold. They are commonly found in products such as lotions, creams, shampoos, conditioners, makeup, and other personal care items. Additionally, they are also used in food processing to preserve the freshness and shelf life of various foodproducts.Properties and Characteristics.The halogenation of hydroxybenzoic acid esters confers upon them several unique properties. Chlorine and bromine are highly reactive halogens that can easily replace the hydrogen atoms on the hydroxybenzoic acid esters, creating stable and water-soluble compounds. These halogenated esters are typically colorless or slightly yellow liquids with low volatility.The antimicrobial activity of halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters is attributed to their ability to disrupt the cellular membranes of microorganisms. The halogen atoms interact with the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane, causing it to become more permeable, which leads to the leakage of cellular contents and ultimately cell death.Types of Halogenated Hydroxybenzoic Acid Esters.There are several types of halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters, each with its own unique properties and applications. Some common examples include:1. Chloroparabens: Chlorinated derivatives of hydroxybenzoic acid esters are known as chloroparabens. These compounds are widely used as preservatives in cosmetics and personal care products due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Common chloroparabens include methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.2. Bromoparabens: Brominated derivatives of hydroxybenzoic acid esters are known as bromoparabens. These compounds are less common than chloroparabens but are also used as preservatives in some products due to their antimicrobial properties. Bromoparabens such as bromomethylparaben and bromopropylparaben are used in specific applications where additional antimicrobial activity is desired.Safety and Regulations.The use of halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters in cosmetics and personal care products is generally considered safe. However, there has been some concern regarding their potential impact on human health and the environment. Some studies have suggested that parabens may act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with the normal function of hormones in the body. However, these findings are still controversial, and more research is needed to confirm their potential health effects.In response to these concerns, some countries and regions have implemented regulations limiting the use of parabens in cosmetics and personal care products. Additionally, some consumers may choose to avoid products containing parabens due to their personal preferences or concerns about their potential health effects.Conclusion.Halogenated hydroxybenzoic acid esters, particularly chloroparabens, are widely used as preservatives incosmetics, personal care products, and food items due to their antimicrobial properties. While they are generally considered safe for use in these applications, there are concerns regarding their potential impact on human health and the environment. Ongoing research and regulatory efforts aim to ensure the safety of these compounds while also addressing consumer preferences and concerns.。

甲基环己烷

有害燃烧产物:一氧化碳、二氧化碳。 灭火方法:喷水冷却容器,可能的话将容器从火场移至空旷处。处在火场中的容器若已变

甲基环己烷

品名:(中文) 甲基环己烷

(英文)methylcyclohexane

化学式:C7 H14 分子量:98.18

别名:(中文) 六氢(化)甲苯;环己基甲烷

(英文)

CAS No.:108-87-2

理化特性 (1)成分/组成信息:

(2)外观与性状:无色液体 (3)熔点(℃):-126.4℃ (4)沸点(℃):100.3℃ (5)相对密度(水=1):0.79 (6)溶解性:不溶环境污染 ,溶于乙醇、乙醚、丙酮、苯、石油醚、四氯化碳等

意外预防措施:

(1)急救措施 皮肤接触:立即脱去被污染的衣着,用肥皂水和清水彻底冲洗皮肤。 眼睛接触:提起眼睑,用流动清水或生理盐水冲洗。就医。 吸入:迅速脱离现场至空气新鲜处。保持呼吸道通畅。如呼吸困难,给输氧。如呼吸停止,

立即进行人工呼吸。就医。

食入:饮足量温水,催吐,就医。 (2)消防措施

危险特性:其蒸气与空气可形成爆炸性混合物。遇热源和明火有燃烧爆炸的危险。与氧化

管理操作及储藏:

操作注意事项: 储存注意事项:

废品处理及销毁:

(1)废弃物性质: (2)废弃处置方法: (3)废弃注意事项:

色或从安全泄压装置中产生声音,必须马上撤离。灭火剂:泡沫、干粉、二氧化碳、砂土。用水灭火无效。

(3)溅散及泄漏: 迅速撤离泄漏污染区人员至安全区,并进行隔离,严格限制出入。切断火源。

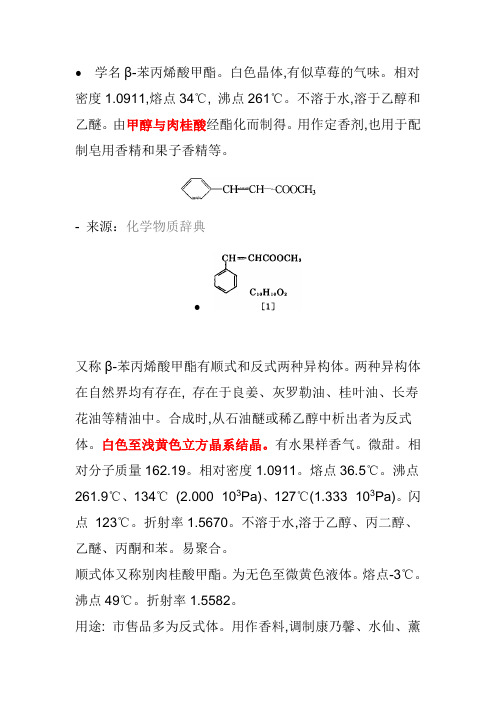

肉桂酸甲酯

∙学名β-苯丙烯酸甲酯。

白色晶体,有似草莓的气味。

相对密度1.0911,熔点34℃, 沸点261℃。

不溶于水,溶于乙醇和乙醚。

由甲醇与肉桂酸经酯化而制得。

用作定香剂,也用于配制皂用香精和果子香精等。

- 来源:化学物质辞典∙又称β-苯丙烯酸甲酯有顺式和反式两种异构体。

两种异构体在自然界均有存在, 存在于良姜、灰罗勒油、桂叶油、长寿花油等精油中。

合成时,从石油醚或稀乙醇中析出者为反式体。

白色至浅黄色立方晶系结晶。

有水果样香气。

微甜。

相对分子质量162.19。

相对密度1.0911。

熔点36.5℃。

沸点261.9℃、134℃(2.000×103Pa)、127℃(1.333×103Pa)。

闪点123℃。

折射率1.5670。

不溶于水,溶于乙醇、丙二醇、乙醚、丙酮和苯。

易聚合。

顺式体又称别肉桂酸甲酯。

为无色至微黄色液体。

熔点-3℃。

沸点49℃。

折射率1.5582。

用途: 市售品多为反式体。

用作香料,调制康乃馨、水仙、薰衣草、东方香型等香型香精,用于化妆品、洗涤剂、香皂、室内清新剂;也用作定香剂;调制草莓、葡萄和樱桃等果香型香精用于食品,我国GB2760—1996规定为暂时允许使用的食用香料。

制法: ①以肉桂酸和甲醇为原料,在无机酸(盐酸或硫酸)作用下,加热酯化,可得粗制[1],取出有机相,用稀氢氧化钠溶液中和,分出有机相,用水洗涤至中性,浓缩,析出结晶,过滤,在乙醇中重结晶,可得精制[1]。

②以苯乙烯为原料,在催化剂作用下,在乙二醇溶液中,与甲醇、二氧化碳和氧进行氧化反应,可制得[1]。

- 来源:实用精细化工辞典∙别名3—苯基丙烯酸甲酯;桂皮酸甲酯分子式C10H10O2分子量162.18结构式性状白色至微黄色结晶固体,其顺式是液体,市售商品不是......- 来源:合成香料产品技术手册阅读全文>>∙分子式C10H10O2。

分子量162.19。

结晶状物质。

熔点36.5℃,沸点261.9℃(101.325kPa ),相对密度1.0911,折光率1.5766。

有色可溶性有机物在线荧光技术在水质监测中的应用

关键词: 有色可溶性有机物ꎻ 水质参数ꎻ 荧光探头ꎻ 千岛湖ꎻ 水质监测

中图分类号: X853 文章编号: 1001 ̄6929(2020)03 ̄0608 ̄09

文献标志码: A

DOI: 10 13198∕j issn 1001 ̄6929 2019 07 16

段崇森1

1.聊城大学环境与规划学院ꎬ 山东 聊城 252059

2.中国科学院南京地理与湖泊研究所ꎬ 湖泊与环境国家重点实验室ꎬ 江苏 南京 210008

3.杭州市环境保护科学研究院ꎬ 浙江 杭州 310014

4.中国科学院大学ꎬ 北京 100049

摘要: FDOM ( 荧光有机物) 在线荧光探头是采用激发波长 370 nm 和发射波长 460 nm 下荧光强度来计算水体 CDOM ( 有色可溶

460 nm of has broad application prospects in monitoring the water quality of drinking water lakes.

Keywords: chromophoric dissolved organic matter ( CDOM) ꎻ water quality parametersꎻ fluorescence sensorꎻ Lake Qiandaoꎻ water quality

0 91ꎬ P<0 01) and a(350) ( R2 = 0 90ꎬ P<0 01) . This indicated that the fluorescence intensity of FDOM could be a useful tracer for

四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸在水中溶解度曲线

四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸(THCA)是一种重要的有机化合物,具有广泛的应用价值。

其在水中的溶解度是一个非常重要的物理化学性质,不仅与其在实际应用中的溶解行为相关,也与环境污染和生物活性等方面有着密切的通联。

研究四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸在水中的溶解度曲线对于深入了解其性质和应用具有重要意义。

1. THCA在水中的溶解度四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸是一种有机酸,其溶解度受温度、压力、溶剂性质等因素的影响,因此在不同条件下其溶解度表现也会有所不同。

研究显示,THCA在水中的溶解度随着温度的升高而增加,而受压力变化的影响相对较小。

溶剂的性质也会对其溶解度产生一定的影响,如加入其他溶剂或溶剂混合物时,其溶解度也会发生变化。

2. 溶解度曲线的绘制为了更加直观地了解THCA在水中的溶解度变化规律,可以通过实验手段绘制出溶解度曲线。

在实验中,可以控制温度、压力等条件,逐渐增加固体THCA的质量,记录溶解后溶液的浓度随固体质量增加的变化规律,从而绘制出溶解度曲线。

通过实验数据的处理和分析,可以得到THCA在水中的溶解度随温度变化的曲线图,从而揭示其溶解度与温度的定量关系。

3. 应用前景深入研究四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸在水中的溶解度曲线,有助于预测其在实际应用中的溶解行为,为工业生产、应用技术提供重要参考。

另外,对其溶解度的深入了解还有助于分析其在环境中的迁移、转化规律,从而对其环境行为和生物活性进行更全面的评估。

该研究具有广泛的应用前景和重要的科学意义。

通过对四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸在水中的溶解度曲线进行深入研究,不仅有助于加深对该有机化合物性质的认识,也为其在实际应用和环境行为等方面的研究提供了重要的基础数据。

希望在未来能够有更多的科研人员投入到该领域的研究中,共同推动该领域的发展和进步。

深入研究有机化合物在水中的溶解度曲线,对于理解其物理化学特性,预测其在实际应用中的溶解行为以及分析其在环境中的行为和生物活性具有重要意义。

在探讨四氢甲基嘧啶羧酸(THCA)在水中的溶解度曲线的基础上,我们还可以从以下几个方面对其进行进一步的研究:1. 溶解度与结晶形态有机化合物的溶解度与其固体的结晶形态密切相关。

布地奈德雾化吸入治疗小儿急性喉炎的临床效果

小儿急性喉炎是一种常见的呼吸道感染性疾病,多发生于2~6岁的儿童,以冬春季为高发期[1]。

其主要病原体为病毒,如腺病毒、流感病毒、副流感病毒等,也可由细菌或真菌引起。

其临床特点为突发的犬吠样咳嗽、声音嘶哑、吸气性喉鸣、发热等,严重者可出现喉梗阻,危及患儿生命。

目前,小儿急性喉炎的治疗主要包括吸氧、抗感染、止咳、雾化吸入等,其中雾化吸入是一种有效的治疗手段,能够直接作用于呼吸道黏膜,减轻炎症,扩张气道,缓解症状[2]。

常用的雾化药物有布地奈德,布地奈德是一种吸入性糖皮质激素,具有强效的抗炎作用,能够抑制炎症细胞的浸润和活化,降低炎症因子的释放,减少黏液的分泌,改善气道的通畅性。

布地奈德的亲脂性强,能够促进呼吸道黏膜内脂肪酸的结合,使其慢慢分解,用游离的状态进入组织,保持药物浓度。

布地奈德的【摘要】 目的 探讨布地奈德雾化吸入对小儿急性喉炎的治疗效果及安全性。

方法 选取2022年1月- 2023年10月医院收治的小儿急性喉炎患者120例作为研究对象,根据组间基线资料均衡可比原则,采用随机数字表法分为对照组和观察组,每组各60例。

两组患儿均给予常规治疗,对照组在此基础上加用地塞米松静脉注射,观察组加用布地奈德雾化吸入。

比较两组患儿的临床症状改善时间、治疗效果及不良反应发生情况。

结果 采用布地奈德雾化吸入治疗方法的观察组患儿咳嗽、喉鸣、呼吸困难、喉梗阻等症状的改善时间均显著短于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

观察组患儿的治疗总有效率为96.67%,高于对照组的81.67%,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

两组患儿均未发生咽喉部不适、血糖升高、免疫功能抑制等严重不良反应,观察组患儿不良反应总发生率为5.00%,虽然低于对照组的10.00%,但差异无统计学意义(P >0.05)。

结论 布地奈德雾化吸入对小儿急性喉炎有良好的治疗效果,能有效缓解症状,缩短病程,提高疗效,且安全性较高。

胺基保护——邻苯二甲酰亚胺脱保护

New1H-Pyrazole-Containing Polyamine Receptors Able ToComplex L-Glutamate in Water at Physiological pH ValuesCarlos Miranda,†Francisco Escartı´,‡Laurent Lamarque,†Marı´a J.R.Yunta,§Pilar Navarro,*,†Enrique Garcı´a-Espan˜a,*,‡and M.Luisa Jimeno†Contribution from the Instituto de Quı´mica Me´dica,Centro de Quı´mica Orga´nica Manuel Lora Tamayo,CSIC,C/Juan de la Cier V a3,28006Madrid,Spain,Departamento de Quı´mica Inorga´nica,Facultad de Quı´mica,Uni V ersidad de Valencia,c/Doctor Moliner50, 46100Burjassot(Valencia),Spain,and Departamento de Quı´mica Orga´nica,Facultad deQuı´mica,Uni V ersidad Complutense de Madrid,A V plutense s/n,28040Madrid,SpainReceived April16,2003;E-mail:enrique.garcia-es@uv.esAbstract:The interaction of the pyrazole-containing macrocyclic receptors3,6,9,12,13,16,19,22,25,26-decaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetraene1[L1],13,26-dibenzyl-3,6,9,12,13,16,-19,22,25,26-decaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetraene2[L2],3,9,12,13,16,22,-25,26-octaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetraene3[L3],6,19-dibenzyl-3,6,9,12,13,-16,19,22,25,26-decaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetraene4[L4],6,19-diphenethyl-3,6,9,12,13,16,19,22,25,26-decaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetraene5[L5],and 6,19-dioctyl-3,6,9,12,13,16,19,22,25,26-decaazatricyclo-[22.2.1.111,14]-octacosa-1(27),11,14(28),24-tetra-ene6[L6]with L-glutamate in aqueous solution has been studied by potentiometric techniques.The synthesis of receptors3-6[L3-L6]is described for the first time.The potentiometric results show that4[L4]containing benzyl groups in the central nitrogens of the polyamine side chains is the receptor displaying the larger interaction at pH7.4(K eff)2.04×104).The presence of phenethyl5[L5]or octyl groups6[L6]instead of benzyl groups4[L4]in the central nitrogens of the chains produces a drastic decrease in the stability[K eff )3.51×102(5),K eff)3.64×102(6)].The studies show the relevance of the central polyaminic nitrogen in the interaction with glutamate.1[L1]and2[L2]with secondary nitrogens in this position present significantly larger interactions than3[L3],which lacks an amino group in the center of the chains.The NMR and modeling studies suggest the important contribution of hydrogen bonding andπ-cation interaction to adduct formation.IntroductionThe search for the L-glutamate receptor field has been andcontinues to be in a state of almost explosive development.1 L-Glutamate(Glu)is thought to be the predominant excitatory transmitter in the central nervous system(CNS)acting at a rangeof excitatory amino acid receptors.It is well-known that it playsa vital role mediating a great part of the synaptic transmission.2However,there is an increasing amount of experimentalevidence that metabolic defects and glutamatergic abnormalitiescan exacerbate or induce glutamate-mediated excitotoxic damageand consequently neurological disorders.3,4Overactivation ofionotropic(NMDA,AMPA,and Kainate)receptors(iGluRs)by Glu yields an excessive Ca2+influx that produces irreversible loss of neurons of specific areas of the brain.5There is much evidence that these processes induce,at least in part,neuro-degenerative illnesses such as Parkinson,Alzheimer,Huntington, AIDS,dementia,and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis(ALS).6In particular,ALS is one of the neurodegenerative disorders for which there is more evidence that excitotoxicity due to an increase in Glu concentration may contribute to the pathology of the disease.7Memantine,a drug able to antagonize the pathological effects of sustained,but relatively small,increases in extracellular glutamate concentration,has been recently received for the treatment of Alzheimer disease.8However,there is not an effective treatment for ALS.Therefore,the preparation of adequately functionalized synthetic receptors for L-glutamate seems to be an important target in finding new routes for controlling abnormal excitatory processes.However,effective recognition in water of aminocarboxylic acids is not an easy task due to its zwitterionic character at physiological pH values and to the strong competition that it finds in its own solvent.9†Centro de Quı´mica Orga´nica Manuel Lora Tamayo.‡Universidad de Valencia.§Universidad Complutense de Madrid.(1)Jane,D.E.In Medicinal Chemistry into the Millenium;Campbell,M.M.,Blagbrough,I.S.,Eds.;Royal Society of Chemistry:Cambridge,2001;pp67-84.(2)(a)Standaert,D.G.;Young,A.B.In The Pharmacological Basis ofTherapeutics;Hardman,J.G.,Goodman Gilman,A.,Limbird,L.E.,Eds.;McGraw-Hill:New York,1996;Chapter22,p503.(b)Fletcher,E.J.;Loge,D.In An Introduction to Neurotransmission in Health and Disease;Riederer,P.,Kopp,N.,Pearson,J.,Eds.;Oxford University Press:New York,1990;Chapter7,p79.(3)Michaelis,E.K.Prog.Neurobiol.1998,54,369-415.(4)Olney,J.W.Science1969,164,719-721.(5)Green,J.G.;Greenamyre,J.T.Prog.Neurobiol.1996,48,613-63.(6)Bra¨un-Osborne,H.;Egebjerg,J.;Nielsen,E.O.;Madsen,U.;Krogsgaard-Larsen,P.J.Med.Chem.2000,43,2609-2645and references therein.(7)(a)Shaw,P.J.;Ince,P.G.J.Neurol.1997,244(Suppl2),S3-S14.(b)Plaitakis,A.;Fesdjian,C.O.;Shashidharan,S Drugs1996,5,437-456.(8)Frantz,A.;Smith,A.Nat.Re V.Drug Dico V ery2003,2,9.Published on Web12/30/200310.1021/ja035671m CCC:$27.50©2004American Chemical Society J.AM.CHEM.SOC.2004,126,823-8339823There are many types of receptors able to interact with carboxylic acids and amino acids in organic solvents,10-13yielding selective complexation in some instances.However,the number of reported receptors of glutamate in aqueous solution is very scarce.In this sense,one of the few reports concerns an optical sensor based on a Zn(II)complex of a 2,2′:6′,2′′-terpyridine derivative in which L -aspartate and L -glutamate were efficiently bound as axial ligands (K s )104-105M -1)in 50/50water/methanol mixtures.14Among the receptors employed for carboxylic acid recogni-tion,the polyamine macrocycles I -IV in Chart 1are of particular relevance to this work.In a seminal paper,Lehn et al.15showed that saturated polyamines I and II could exert chain-length discrimination between different R ,ω-dicarboxylic acids as a function of the number of methylene groups between the two triamine units of the receptor.Such compounds were also able to interact with a glutamic acid derivative which has the ammonium group protected with an acyl moiety.15,16Compounds III and IV reported by Gotor and Lehn interact in their protonated forms in aqueous solution with protected N -acetyl-L -glutamate and N -acetyl-D -glutamate,showing a higher stability for the interaction with the D -isomer.17In both reports,the interaction with protected N -acetyl-L -glutamate at physiological pH yields constants of ca.3logarithmic units.Recently,we have shown that 1H -pyrazole-containing mac-rocycles present desirable properties for the binding of dopam-ine.18These polyaza macrocycles,apart from having a highpositive charge at neutral pH values,can form hydrogen bonds not only through the ammonium or amine groups but also through the pyrazole nitrogens that can behave as hydrogen bond donors or acceptors.In fact,Elguero et al.19have recently shown the ability of the pyrazole rings to form hydrogen bonds with carboxylic and carboxylate functions.These features can be used to recognize the functionalities of glutamic acid,the carboxylic and/or carboxylate functions and the ammonium group.Apart from this,the introduction of aromatic donor groups appropriately arranged within the macrocyclic framework or appended to it through arms of adequate length may contribute to the recognition event through π-cation interactions with the ammonium group of L -glutamate.π-Cation interactions are a key feature in many enzymatic centers,a classical example being acetylcholine esterase.20The role of such an interaction in abiotic systems was very well illustrated several years ago in a seminal work carried out by Dougherty and Stauffer.21Since then,many other examples have been reported both in biotic and in abiotic systems.22Taking into account all of these considerations,here we report on the ability of receptors 1[L 1]-6[L 6](Chart 2)to interact with L -glutamic acid.These receptors display structures which differ from one another in only one feature,which helps to obtain clear-cut relations between structure and interaction(9)Rebek,J.,Jr.;Askew,B.;Nemeth,D.;Parris,K.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1987,109,2432-2434.(10)Seel,C.;de Mendoza,J.In Comprehensi V e Supramolecular Chemistry ;Vogtle,F.,Ed.;Elsevier Science:New York,1996;Vol.2,p 519.(11)(a)Sessler,J.L.;Sanson,P.I.;Andrievesky,A.;Kral,V.In SupramolecularChemistry of Anions ;Bianchi,A.,Bowman-James,K.,Garcı´a-Espan ˜a,E.,Eds.;John Wiley &Sons:New York,1997;Chapter 10,pp 369-375.(b)Sessler,J.L.;Andrievsky,A.;Kra ´l,V.;Lynch,V.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1997,119,9385-9392.(12)Fitzmaurice,R.J.;Kyne,G.M.;Douheret,D.;Kilburn,J.D.J.Chem.Soc.,Perkin Trans.12002,7,841-864and references therein.(13)Rossi,S.;Kyne,G.M.;Turner,D.L.;Wells,N.J.;Kilburn,J.D.Angew.Chem.,Int.Ed.2002,41,4233-4236.(14)Aı¨t-Haddou,H.;Wiskur,S.L.;Lynch,V.M.;Anslyn,E.V.J.Am.Chem.Soc.2001,123,11296-11297.(15)Hosseini,M.W.;Lehn,J.-M.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1982,104,3525-3527.(16)(a)Hosseini,M.W.;Lehn,J.-M.Hel V .Chim.Acta 1986,69,587-603.(b)Heyer,D.;Lehn,J.-M.Tetrahedron Lett.1986,27,5869-5872.(17)(a)Alfonso,I.;Dietrich,B.;Rebolledo,F.;Gotor,V.;Lehn,J.-M.Hel V .Chim.Acta 2001,84,280-295.(b)Alfonso,I.;Rebolledo,F.;Gotor,V.Chem.-Eur.J.2000,6,3331-3338.(18)Lamarque,L.;Navarro,P.;Miranda,C.;Ara ´n,V.J.;Ochoa,C.;Escartı´,F.;Garcı´a-Espan ˜a,E.;Latorre,J.;Luis,S.V.;Miravet,J.F.J.Am.Chem.Soc .2001,123,10560-10570.(19)Foces-Foces,C.;Echevarria,A.;Jagerovic,N.;Alkorta,I.;Elguero,J.;Langer,U.;Klein,O.;Minguet-Bonvehı´,H.-H.J.Am.Chem.Soc.2001,123,7898-7906.(20)Sussman,J.L.;Harel,M.;Frolow,F.;Oefner,C.;Goldman,A.;Toker,L.;Silman,I.Science 1991,253,872-879.(21)Dougherty,D.A.;Stauffer,D.A.Science 1990,250,1558-1560.(22)(a)Sutcliffe,M.J.;Smeeton,A.H.;Wo,Z.G.;Oswald,R.E.FaradayDiscuss.1998,111,259-272.(b)Kearney,P.C.;Mizoue,L.S.;Kumpf,R.A.;Forman,J.E.;McCurdy,A.;Dougherty,D.A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1993,115,9907-9919.(c)Bra ¨uner-Osborne,H.;Egebjerg,J.;Nielsen,E.;Madsen,U.;Krogsgaard-Larsen,P.J.Med.Chem.2000,43,2609-2645.(d)Zacharias,N.;Dougherty,D.A.Trends Pharmacol.Sci.2002,23,281-287.(e)Hu,J.;Barbour,L.J.;Gokel,G.W.J.Am.Chem.Soc.2002,124,10940-10941.Chart 1.Some Receptors Employed for Dicarboxylic Acid and N -AcetylglutamateRecognitionChart 2.New 1H -Pyrazole-Containing Polyamine Receptors Able To Complex L -Glutamate inWaterA R T I C L E SMiranda et al.824J.AM.CHEM.SOC.9VOL.126,NO.3,2004strengths.1[L1]and2[L2]differ in the N-benzylation of the pyrazole moiety,and1[L1]and3[L3]differ in the presence in the center of the polyamine side chains of an amino group or of a methylene group.The receptors4[L4]and5[L5]present the central nitrogens of the chain N-functionalized with benzyl or phenethyl groups,and6[L6]has large hydrophobic octyl groups.Results and DiscussionSynthesis of3-6.Macrocycles3-6have been obtained following the procedure previously reported for the preparation of1and2.23The method includes a first dipodal(2+2) condensation of the1H-pyrazol-3,5-dicarbaldehyde7with the corresponding R,ω-diamine,followed by hydrogenation of the resulting Schiff base imine bonds.In the case of receptor3,the Schiff base formed by condensation with1,5-pentanediamine is a stable solid(8,mp208-210°C)which precipitated in68% yield from the reaction mixture.Further reduction with NaBH4 in absolute ethanol gave the expected tetraazamacrocycle3, which after crystallization from toluene was isolated as a pure compound(mp184-186°C).In the cases of receptors4-6, the precursor R,ω-diamines(11a-11c)(Scheme1B)were obtained,by using a procedure previously described for11a.24 This procedure is based on the previous protection of the primary amino groups of1,5-diamino-3-azapentane by treatment with phthalic anhydride,followed by alkylation of the secondary amino group of1,5-diphthalimido-3-azapentane9with benzyl, phenethyl,or octyl bromide.Finally,the phthalimido groups of the N-alkyl substituted intermediates10a-10c were removed by treatment with hydrazine to afford the desired amines11a-11c,which were obtained in moderate yield(54-63%).In contrast with the behavior previously observed in the synthesis of3,in the(2+2)dipodal condensations of7with 3-benzyl-,3-phenethyl-,and3-octyl-substituted3-aza-1,5-pentanediamine11a,11b,and11c,respectively,there was not precipitation of the expected Schiff bases(Scheme1A). Consequently,the reaction mixtures were directly reduced in situ with NaBH4to obtain the desired hexaamines4-6,which after being carefully purified by chromatography afforded purecolorless oils in51%,63%,and31%yield,respectively.The structures of all of these new cyclic polyamines have been established from the analytical and spectroscopic data(MS(ES+), 1H and13C NMR)of both the free ligands3-6and their corresponding hydrochloride salts[3‚4HCl,4‚6HCl,5‚6HCl, and6‚6HCl],which were obtained as stable solids following the same procedure previously reported18for1‚6HCl and2‚6HCl.As usually occurs for3,5-disubstituted1H-pyrazole deriva-tives,either the free ligands3-6or their hydrochlorides show very simple1H and13C NMR spectra,in which signals indicate that,because of the prototropic equilibrium of the pyrazole ring, all of these compounds present average4-fold symmetry on the NMR scale.The quaternary C3and C5carbons appear together,and the pairs of methylene carbons C6,C7,and C8are magnetically equivalent(see Experimental Section).In the13C NMR spectra registered in CDCl3solution, significant differences can be observed between ligand3,without an amino group in the center of the side chain,and the N-substituted ligands4-6.In3,the C3,5signal appears as a broad singlet.However,in4-6,it almost disappears within the baseline of the spectra,and the methylene carbon atoms C6and C8experience a significant broadening.Additionally,a remark-able line-broadening is also observed in the C1′carbon signals belonging to the phenethyl and octyl groups of L5and L6, respectively.All of these data suggest that as the N-substituents located in the middle of the side chains of4-6are larger,the dynamic exchange rate of the pyrazole prototropic equilibrium is gradually lower,probably due to a relation between proto-tropic and conformational equilibria.Acid-Base Behavior.To follow the complexation of L-glutamate(hereafter abbreviated as Glu2-)and its protonated forms(HGlu-,H2Glu,and H3Glu+)by the receptors L1-L6, the acid-base behavior of L-glutamate has to be revisited under the experimental conditions of this work,298K and0.15mol dm-3.The protonation constants obtained,included in the first column of Table1,agree with the literature25and show that the zwitterionic HGlu-species is the only species present in aqueous solution at physiological pH values(Scheme2and Figure S1of Supporting Information).Therefore,receptors for(23)Ara´n,V.J.;Kumar,M.;Molina,J.;Lamarque,L.;Navarro,P.;Garcı´a-Espan˜a,E.;Ramı´rez,J.A.;Luis,S.V.;Escuder,.Chem.1999, 64,6137-6146.(24)(a)Yuen Ng,C.;Motekaitis,R.J.;Martell,A.E.Inorg.Chem.1979,18,2982-2986.(b)Anelli,P.L.;Lunazzi,L.;Montanari,F.;Quici,.Chem.1984,49,4197-4203.Scheme1.Synthesis of the Pyrazole-Containing MacrocyclicReceptorsNew1H-Pyrazole-Containing Polyamine Receptors A R T I C L E SJ.AM.CHEM.SOC.9VOL.126,NO.3,2004825glutamate recognition able to address both the negative charges of the carboxylate groups and the positive charge of ammonium are highly relevant.The protonation constants of L 3-L 6are included in Table 1,together with those we have previously reported for receptors L 1and L 2.23A comparison of the constants of L 4-L 6with those of the nonfunctionalized receptor L 1shows a reduced basicity of the receptors L 4-L 6with tertiary nitrogens at the middle of the polyamine bridges.Such a reduction in basicity prevented the potentiometric detection of the last protonation for these ligands in aqueous solution.A similar reduction in basicity was previously reported for the macrocycle with the N -benzylated pyrazole spacers (L 2).23These diminished basicities are related to the lower probability of the tertiary nitrogens for stabilizing the positive charges through hydrogen bond formation either with adjacent nonprotonated amino groups of the molecule or with water molecules.Also,the increase in the hydrophobicity of these molecules will contribute to their lower basicity.The stepwise basicity constants are relatively high for the first four protonation steps,which is attributable to the fact that these protons can bind to the nitrogen atoms adjacent to the pyrazole groups leaving the central nitrogen free,the electrostatic repulsions between them being therefore of little significance.The remaining protonation steps will occur in the central nitrogen atom,which will produce an important increase in the electrostatic repulsion in the molecule and therefore a reduction in basicity.As stated above,the tertiary nitrogen atoms present in L 4-L 6will also contribute to this diminished basicity.To analyze the interaction with glutamic acid,it is important to know the protonation degree of the ligands at physiological pH values.In Table 2,we have calculated the percentages ofthe different protonated species existing in solution at pH 7.4for receptors L 1-L 6.As can be seen,except for the receptor with the pentamethylenic chains L 3in which the tetraprotonated species prevails,all of the other systems show that the di-and triprotonated species prevail,although to different extents.Interaction with Glutamate.The stepwise constants for the interaction of the receptors L 1-L 6with glutamate are shown in Table 3,and selected distribution diagrams are plotted in Figure 1A -C.All of the studied receptors interact with glutamate forming adduct species with protonation degrees (j )which vary between 8and 0depending on the system (see Table 3).The stepwise constants have been derived from the overall association constants (L +Glu 2-+j H +)H j LGlu (j -2)+,log j )provided by the fitting of the pH-metric titration curves.This takes into account the basicities of the receptors and glutamate (vide supra)and the pH range in which a given species prevails in solution.In this respect,except below pH ca.4and above pH 9,HGlu -can be chosen as the protonated form of glutamate involved in the formation of the different adducts.Below pH 4,the participation of H 2Glu in the equilibria has also to be considered (entries 9and 10in Table 3).For instance,the formation of the H 6LGlu 4+species can proceed through the equilibria HGlu -+H 5L 5+)H 6LGlu 4+(entry 8,Table 3),and H 2Glu +H 4L 4+)H 6LGlu 4(entry 9Table 3),with percentages of participation that depend on pH.One of the effects of the interaction is to render somewhat more basic the receptor,and somewhat more acidic glutamic acid,facilitating the attraction between op-positely charged partners.A first inspection of Table 3and of the diagrams A,B,and C in Figure 1shows that the interaction strengths differ markedly from one system to another depending on the structural features of the receptors involved.L 4is the receptor that presents the highest capacity for interacting with glutamate throughout all of the pH range explored.It must also be remarked that there are not clear-cut trends in the values of the stepwise constants as a function of the protonation degree of the receptors.This suggests that charge -charge attractions do not play the most(25)(a)Martell,E.;Smith,R.M.Critical Stability Constants ;Plenum:NewYork,1975.(b)Motekaitis,R.J.NIST Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes Database ;NIST Standard Reference Database,version 4,1997.Table 1.Protonation Constants of Glutamic Acid and Receptors L 1-L 6Determined in NaCl 0.15mol dm -3at 298.1KreactionGluL 1aL 2aL 3bL 4L 5L 6L +H )L H c 9.574(2)d 9.74(2)8.90(3)9.56(1)9.25(3)9.49(4)9.34(5)L H +H )L H 2 4.165(3)8.86(2)8.27(2)8.939(7)8.38(3)8.11(5)8.13(5)L H 2+H )L H 3 2.18(2)7.96(2) 6.62(3)8.02(1) 6.89(5)7.17(6)7.46(7)L H 3+H )L H 4 6.83(2) 5.85(4)7.63(1) 6.32(5) 6.35(6) 5.97(8)L H 4+H )L H 5 4.57(3) 3.37(4) 2.72(8) 2.84(9) 3.23(9)L H 5+H )L H 6 3.18(3) 2.27(6)∑log K H n L41.135.334.233.634.034.1aTaken from ref 23.b These data were previously cited in a short communication (ref 26).c Charges omitted for clarity.d Values in parentheses are the standard deviations in the last significant figure.Scheme 2.L -Glutamate Acid -BaseBehaviorTable 2.Percentages of the Different Protonated Species at pH 7.4H 1L aH 2LH 3LH 4LL 11186417L 21077130L 3083458L 4083458L 51154323L 6842482aCharges omitted for clarity.A R T I C L E SMiranda et al.826J.AM.CHEM.SOC.9VOL.126,NO.3,2004outstanding role and that other forces contribute very importantly to these processes.26However,in systems such as these,which present overlapping equilibria,it is convenient to use conditional constants because they provide a clearer picture of the selectivity trends.27These constants are defined as the quotient between the overall amounts of complexed species and those of free receptor and substrate at a given pH[eq1].In Figure2are presented the logarithms of the effective constants versus pH for all of the studied systems.Receptors L1and L2with a nonfunctionalized secondary amino group in the side chains display opposite trend from all other receptors. While the stability of the L1and L2adducts tends to increase with pH,the other ligands show a decreasing interaction. Additionally,L1and L2present a close interaction over the entire pH range under study.The tetraaminic macrocycle L3is a better(26)Escartı´,F.;Miranda,C.;Lamarque,L.;Latorre,J.;Garcı´a-Espan˜a,E.;Kumar,M.;Ara´n,V.J.;Navarro,mun.2002,9,936-937.(27)(a)Bianchi,A.;Garcı´a-Espan˜a,c.1999,12,1725-1732.(b)Aguilar,J.A.;Celda,B.;Garcı´a-Espan˜a,E.;Luis,S.V.;Martı´nez,M.;Ramı´rez,J.A.;Soriano,C.;Tejero,B.J.Chem.Soc.,Perkin Trans.22000, 7,1323-1328.Table3.Stability Constants for the Interaction of L1-L6with the Different Protonated Forms of Glutamate(Glu) entry reaction a L1L2L3L4L5L6 1Glu+L)Glu L 3.30(2)b 4.11(1)2HGlu+L)HGlu L 3.65(2) 4.11(1) 3.68(2) 3.38(4) 3Glu+H L)HGlu L 3.89(2) 4.48(1) 3.96(2) 3.57(4) 4HGlu+H L)H2Glu L 3.49(2) 3.89(1) 2.37(4) 3.71(2)5HGlu+H2L)H3Glu L 3.44(2) 3.73(1) 2.34(3) 4.14(2) 2.46(4) 2.61(7) 6HGlu+H3L)H4Glu L 3.33(2) 3.56(2) 2.66(3) 4.65(2) 2.74(3) 2.55(7) 7HGlu+H4L)H5Glu L 3.02(2) 3.26(2) 2.58(3) 4.77(2) 2.87(3) 2.91(5) 8HGlu+H5L)H6Glu L 3.11(3) 3.54(2) 6.76(3) 4.96(3) 4.47(3) 9H2Glu+H4L)H6Glu L 2.54(3) 3.05(2) 3.88(2) 5.35(3) 3.66(4) 3.56(3) 10H2Glu+H5L)H7Glu L 2.61(6) 2.73(4) 5.51(3) 3.57(4) 3.22(8) 11H3Glu+H4L)H7Glu L 4.82(2) 4.12(9)a Charges omitted for clarity.b Values in parentheses are standard deviations in the last significantfigure.Figure1.Distribution diagrams for the systems(A)L1-glutamic acid, (B)L4-glutamic acid,and(C)L5-glutamicacid.Figure2.Representation of the variation of K cond(M-1)for the interaction of glutamic acid with(A)L1and L3,(B)L2,L4,L5,and L6.Initial concentrations of glutamate and receptors are10-3mol dm-3.Kcond)∑[(H i L)‚(H j Glu)]/{∑[H i L]∑[H j Glu]}(1)New1H-Pyrazole-Containing Polyamine Receptors A R T I C L E SJ.AM.CHEM.SOC.9VOL.126,NO.3,2004827receptor at acidic pH,but its interaction markedly decreases on raising the pH.These results strongly suggest the implication of the central nitrogens of the lateral polyamine chains in the stabilization of the adducts.Among the N-functionalized receptors,L4presents the largest interaction with glutamate.Interestingly enough,L5,which differs from L4only in having a phenethyl group instead of a benzyl one,presents much lower stability of its adducts.Since the basicity and thereby the protonation states that L4and L5 present with pH are very close,the reason for the larger stability of the L4adducts could reside on a better spatial disposition for formingπ-cation interactions with the ammonium group of the amino acid.In addition,as already pointed out,L4presents the highest affinity for glutamic acid in a wide pH range,being overcome only by L1and L2at pH values over9.This observation again supports the contribution ofπ-cation inter-actions in the system L4-glutamic because at these pH values the ammonium functionality will start to deprotonate(see Scheme2and Figure1B).Table4gathers the percentages of the species existing in equilibria at pH7.4together with the values of the conditional constant at this pH.In correspondence with Figure1A,1C and Figure S2(Supporting Information),it can be seen that for L1, L2,L5,and L6the prevailing species are[H2L‚HGlu]+and[H3L‚HGlu]2+(protonation degrees3and4,respectively),while for L3the main species are[H3L‚HGlu]+and[H4L‚HGlu]2+ (protonation degrees4and5,respectively).The most effective receptor at this pH would be L4which joins hydrogen bonding, charge-charge,andπ-cation contributions for the stabilization of the adducts.To check the selectivity of this receptor,we have also studied its interaction with L-aspartate,which is a competitor of L-glutamate in the biologic receptors.The conditional constant at pH7.4has a value of3.1logarithmic units for the system Asp-L4.Therefore,the selectivity of L4 for glutamate over aspartate(K cond(L4-glu)/K cond(L4-asp))will be of ca.15.It is interesting to remark that the affinity of L4 for zwiterionic L-glutamate at pH7.4is even larger than that displayed by receptors III and IV(Chart1)with the protected dianion N-acetyl-L-glutamate lacking the zwitterionic charac-teristics.Applying eq1and the stability constants reported in ref17,conditional constants at pH7.4of 3.24and 2.96 logarithmic units can be derived for the systems III-L-Glu and IV-L-Glu,respectively.Molecular Modeling Studies.Molecular mechanics-based methods involving docking studies have been used to study the binding orientations and affinities for the complexation of glutamate by L1-L6receptors.The quality of a computer simulation depends on two factors:accuracy of the force field that describes intra-and intermolecular interactions,and an adequate sampling of the conformational and configuration space of the system.28The additive AMBER force field is appropriate for describing the complexation processes of our compounds,as it is one of the best methods29in reproducing H-bonding and stacking stabiliza-tion energies.The experimental data show that at pH7.4,L1-L6exist in different protonation states.So,a theoretical study of the protonation of these ligands was done,including all of the species shown in5%or more abundance in the potentiometric measurements(Table4).In each case,the more favored positions of protons were calculated for mono-,di-,tri-,and tetraprotonated species.Molecular dynamics studies were performed to find the minimum energy conformations with simulated solvent effects.Molecular modeling studies were carried out using the AMBER30method implemented in the Hyperchem6.0pack-age,31modified by the inclusion of appropriate parameters. Where available,the parameters came from analogous ones used in the literature.32All others were developed following Koll-man33and Hopfinger34procedures.The equilibrium bond length and angle values came from experimental values of reasonable reference compounds.All of the compounds were constructed using standard geometry and standard bond lengths.To develop suitable parameters for NH‚‚‚N hydrogen bonding,ab initio calculations at the STO-3G level35were used to calculate atomic charges compatible with the AMBER force field charges,as they gave excellent results,and,at the same time,this method allows the study of aryl-amine interactions.In all cases,full geometry optimizations with the Polak-Ribiere algorithm were carried out,with no restraints.Ions are separated far away and well solvated in water due to the fact that water has a high dielectric constant and hydrogen bond network.Consequently,there is no need to use counteri-ons36in the modelization studies.In the absence of explicit solvent molecules,a distance-dependent dielectric factor quali-tatively simulates the presence of water,as it takes into account the fact that the intermolecular electrostatic interactions should vanish more rapidly with distance than in the gas phase.The same results can be obtained using a constant dielectric factor greater than1.We have chosen to use a distance-dependent dielectric constant( )4R ij)as this was the method used by Weiner et al.37to develop the AMBER force field.Table8 shows the theoretical differences in protonation energy(∆E p) of mono-,bi-,and triprotonated hexaamine ligands,for the (28)Urban,J.J.;Cronin,C.W.;Roberts,R.R.;Famini,G.R.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1997,119,12292-12299.(29)Hobza,P.;Kabelac,M.;Sponer,J.;Mejzlik,P.;Vondrasek,put.Chem.1997,18,1136-1150.(30)Cornell,W.D.;Cieplak,P.;Bayly,C.I.;Gould,I.R.;Merz,K.M.,Jr.;Ferguson,D.M.;Spelmeyer,D.C.;Fox,T.;Caldwell,J.W.;Kollman,P.A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1995,117,5179-5197.(31)Hyperchem6.0(Hypercube Inc.).(32)(a)Fox,T.;Scanlan,T.S.;Kollman,P.A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1997,119,11571-11577.(b)Grootenhuis,P.D.;Kollman,P.A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1989,111,2152-2158.(c)Moyna,G.;Hernandez,G.;Williams,H.J.;Nachman,R.J.;Scott,put.Sci.1997,37,951-956.(d)Boden,C.D.J.;Patenden,put.-Aided Mol.Des.1999, 13,153-166.(33)/amber.(34)Hopfinger,A.J.;Pearlstein,put.Chem.1984,5,486-499.(35)Glennon,T.M.;Zheng,Y.-J.;Le Grand,S.M.;Shutzberg,B.A.;Merz,K.M.,put.Chem.1994,15,1019-1040.(36)Wang,J.;Kollman,P.A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1998,120,11106-11114.Table4.Percentages of the Different Protonated Adducts[HGlu‚H j L](j-1)+,Overall Percentages of Complexation,andConditional Constants(K Cond)at pH7.4for the Interaction ofGlutamate(HGlu-)with Receptors L1-L6at Physiological pH[H n L‚HGlu]an)1n)2n)3n)4∑{[H n L‚HGlu]}K cond(M-1)L13272353 2.44×103L2947763 4.12×103L31101324 3.99×102L423737581 2.04×104L51010222 3.51×102L6121224 3.64×102a Charges omitted for clarity.A R T I C L E S Miranda et al. 828J.AM.CHEM.SOC.9VOL.126,NO.3,2004。

羟基自由基测定

Quantitation of hydroxyl radical during Fenton oxidationfollowing a single addition of iron and peroxideMichele E.Lindsey,Matthew A.Tarr*Department of Chemistry,University of New Orleans,New Orleans,LA 70148,USAReceived 2October 1998;accepted 15July 1999AbstractChemical probes were used to study the formation of hydroxyl radical in aqueous iron±hydrogen peroxide reaction.Hydroxyl radical formation rate and time dependent concentration were determined in pure water,in aqueous fulvic acid (FA)and humic acid (HA)solutions,and in natural surface waters.Indirect determinations of hydroxyl radical were made by quantitating hydroxyl radical reactions with probe compounds under controlled conditions.High probe concentrations were used to determine radical formation rates and low probe concentrations were used to determine time dependent radical concentration.Two independent probes were used for intercomparison:benzoic acid and 1-propanol.Good agreement between the two probes was observed.Natural water matrices resulted in lower radical formation rates and lower hydroxyl radical concentrations,with observed formation rate and yield in natural waters up to four times lower than in pure water.HA and FA also reduced hydroxyl radical formation under most conditions,although increased radical formation was observed with FA at certain pH values.Hydroxyl radical formation increased linearly with hydrogen peroxide concentration.Ó2000Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.Keywords:Fenton oxidation;Hydroxyl radical;Degradation;Iron;Hydrogen peroxide;Natural water1.IntroductionNumerous studies have investigated the use of Fen-ton chemistry for pollutant degradation or remediation (Graf et al.,1984;Puppo,1992;Yoshimura et al.,1992;Zepp et al.,1992).In these applications,hydrogen per-oxide is converted to hydroxyl radical in a catalytic cycle with cationic iron acting as catalyst.The high reactivity of hydroxyl radical is advantageous since it readily de-grades a wide array of pollutants (reaction with alkanes,k 107±109M À1s À1;reaction with alkenes and aro-matics,k 109±1010M À1s À1).Unfortunately this ad-vantage is also an important drawback since the hydroxyl radical often reacts with non-pollutant species present at higher concentration.Furthermore,the cata-lytic cycle is in¯uenced by pH,iron complexation,iron solubility,and iron redox cycling between the +2and +3states.In order to better understand the use of Fenton chemistry for pollutant degradation in waste streams or contaminated sites,a better understanding of matrix e ects is needed.This report focuses on the e ects of natural water matrices on hydroxyl radical formation and scavenging.Iron/peroxide systems have been used to degrade a number of contaminants,mostly in the aqueous phase.Degradation of the herbicides 2,4-D,2,4,5-T,and atr-azine in aqueous solution by Fe (II)/H 2O 2or Fe (III)/H 2O 2has been reported (Pignatello,1992).Reactions were pH sensitive,and acidic conditions were necessary for iron solubility.Vella and Munder (1993)used Fe (II)/H 2O 2for the degradation of phenolic compounds in water.Again,acidic conditions (pH 4)were used.Although complete elimination of the parent compound could be achieved for chlorinated and otherphenols,Chemosphere 41(2000)409±417*Corresponding author.Fax:+1-504-280-6860.E-mail address:mtarr@ (M.A.Tarr).0045-6535/00/$-see front matter Ó2000Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.PII:S 0045-6535(99)00296-9the presence of phosphate signi®cantly hindered degradation.To allow reaction at near neutral pH,researchers have utilized iron chelating agents(Sun and Pignatello, 1992,1993).Several iron chelates were found to be ac-tive in Fenton oxidation although the chelator was also degraded at a slower rate(Sun and Pignatello,1992). Naturally occurring compounds can act as metal che-lators.For example,inorganic salts,humic acids(HAs), fulvic acids(FAs),and organic colloids have been shown to exhibit signi®cant metal complexation(Pettersson et al.,1997;Ganguly et al.,1998;Klein and Niessner, 1998;Rose et al.,1998;Roux et al.,1998).Commercial applications of Fenton chemistry to remediation of contaminated soil are currently in use. These methods add both iron and peroxide to the sat-urated zone,and utilize iron chelators and peroxide stabilizers(Watts and Dilly,1996;Greenburg et al., 1997).Such applications have been successful in reme-diating the saturated zone after petroleum leakage from an underground storage tank.However,conditions for such remediation have typically been developed from empirical observations of degradation e ciency rather than from a fundamental understanding of the HOádynamics.Furthermore,a large excess of peroxide is often used.Fenton reagents have also been used for degradation of bio-recalcitrant perchloroethylene(PCE)and poly-chlorinated biphenyls(PCBs)adsorbed on sand(Sato et al.,1993).Treatment required adjustment of the pH to3with degradation severely limited at pH7.Even at optimum pH,PCB treatment still yielded chlorinated degradation products,indicating incomplete degrada-tion.Further studies on degradation of PCBs indicated that dissolved PCBs are much more readily degraded by hydroxyl radical than are PCBs sorbed to sand(Sedlak and Andren,1994).Some studies involving soil/water systems have re-lied on naturally occurring iron in soils to react with added H2O2(Croft et al.,1992;Watts et al.,1993). However,water insoluble pollutants adsorb to the surface of soil particles thus impeding degradation.Due to the di culty of oxidation across the liquid±solid boundary,high stoichiometric amounts of H2O2were required to achieve complete degradation of the pol-lutants in these environments(Watts et al.,1993). Again,a lack of understanding of the HOáand pollu-tant degradation dynamics was overcome in these sys-tems simply by using an excess of peroxide,rather than adjusting other parameters to optimize the degradation e ciency.The e ciency of hydroxyl radical production from peroxide is a ected by a number of factors,including pH,iron oxidation state,and iron chelation.Phosphate has been reported to inhibit hydroxyl radical production (Vella and Munder,1993),and additional reports indi-cate either inhibition(Croft et al.,1992)or acceleration (Puppo,1992)of HOáproduction in the presence of various ligands.Once formed,hydroxyl radicals may be lost through reaction with matrix mon matrices include FA and HA in natural freshwaters,as well as inorganic species in brackish waters.Due to the relatively high concentration of matrix species,generally only a small fraction of the radicals formed can react with the pol-lutant.This process is a major limitation of Fenton chemistry for degradation of pollutants in the presence of matrix constituents,and results in increased peroxide demand and higher costs.Although signi®cant research has focused on Fenton systems and quantitation of hydroxyl radical concen-tration,several important issues have not yet been ad-dressed.Some researches(Ravikumar and Gurol,1994; Lin and Gurol,1998)have measured loss of hydrogen peroxide as an indicator for hydroxyl radical formation. This approach is not entirely su cient because not all peroxide degraded is converted to hydroxyl radical,and hence measurement of peroxide loss does not allow di-rect determination of[HOá].Other researchers have measured hydroxyl radical concentration under steady state[HOá]conditions,primarily in photochemical sys-tems(Haag and Hoign e,1985;Zhou and Mopper, 1990).While this approach is applicable to photo-chemical systems,it is not representative of common Fenton systems in which peroxide is added in a single dose,resulting in non-steady state[HOá].Additional studies have attempted to quantitate hydroxyl radical under non-steady state conditions(Tomita et al.,1994; Mizuta et al.,1997);however,due to a number of fac-tors,these reports did not provide conclusive hydroxyl radical information.In this study,chemical probes were used to measure both hydroxyl radical formation rate and time depen-dent hydroxyl radical concentration under non-steady state conditions.Methods were developed that allow these determinations in pure water and natural waters, allowing assessment of the role of natural matrices on Fenton oxidations.2.ExperimentalMaterials.Puri®ed water was obtained by further puri®cation of distilled water with a NanopureUV (Barnstead)water treatment system.Natural water samples were collected from sites in Southeast Louisiana at Crawford Landing(CL)on the West Pearl River and from a small water body connecting Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Maurepas(LM).The LM water contained a higher concentration of dissolved organic carbon and inorganic species than the CL water.All natural water samples were®ltered using pre-combusted0.5l m glass410M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr/Chemosphere41(2000)409±417®ber®lters(Machery±Nagel,Rund®lter MN,Alberta, Canada)and were stored in the dark at4°C.Natural water samples were used directly or were diluted with pure water.Suwannee River FA and HA standard ma-terials were purchased from the International Humic Substances Society.FA and HA concentrations are reported as mg FA lÀ1and mg HA lÀ1.The carbon content of these materials are52.44%and52.55%by weight,respectively.Hydrogen peroxide(EM science,$30%)was stan-dardized using iodometric titration(Christian,1994). Iron(II)perchlorate(99+%)was purchased from Alfa. Benzoic acid(BA)(99.5+%),p-hydroxybenzoic acid (99+%),and2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine(DNPH)(70%) were purchased from Aldrich.Propionaldehyde(98%) was purchased from Fluka,and1-propanol(PrOH) (99+%)was purchased from Mallinkrodt.Dimethyl sulfoxide(certi®ed ACS)and acetonitrile(HPLC grade) were obtained from Fisher.All reagents were used as received.Hydroxyl radical trapping.Both benzoic acid and n-propanol were used as probes for hydroxyl radical. Benzoic acid has a known reaction rate constant of 4.2´109MÀ1sÀ1with hydroxyl radical in aqueous media(Buxton et al.,1988).This reaction produces p-hydroxybenzoic acid(p-HBA)as well as o-HBA, m-HBA,and other products.The fraction of p-HBA produced per reaction was taken from(Zhou and Mopper,1990),who reported5X87Æ0X18moles HOáreacted per mole p-HBA produced.1-Propanol reacts with hydroxyl radical in aqueous media at a rate of 2.8´109MÀ1sÀ1to form propionaldehyde in46%yield (Buxton et al.,1988).BA or PrOH solutions of various concentrations were prepared in pure and natural water.At time zero, a single dose of hydrogen peroxide and a single dose of Fe(II)were added with vigorous mixing.These additions resulted in time zero concentrations of 0.2±1.0mM H2O2and0.2±0.53mM Fe(II).Reactions were stirred,kept in the dark,and maintained at20°C. After a given time interval,reactions were quenched by addition of a su cient amount of a quencher that e ectively outcompeted the probe molecule for reaction with hydroxyl radical.For benzoic acid probe studies, 0.5ml of PrOH was added per10ml of reaction solution.For PrOH probe studies,4ml of dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO)containing5mM DNPH were added per10ml of reaction solution.These amounts of added quencher had rates of reaction with hydroxyl radical of 50±5600times greater than the probe;therefore,it was assumed that upon addition of quencher,no signi®cant reaction of probe with hydroxyl radical occurred.The resulting products of probe-hydroxyl radical reaction were then analyzed as described below.Each of these experiments produced a single time point.Repetition of the experiment for di erent times then enabled recon-struction of time dependent data from the individual experiments.Quantitation of products.Reaction products were quantitated by high performance liquid chromatography using a Hewlett-Packard1090liquid chromatograph.A Spherisorb ODS-2column(5l m particle size,25cm length´4.6mm id)was used for all separations.Benzoic acid and hydroxybenzoic acids were sepa-rated using the following procedure(Zhou and Mopper, 1990).Samples were brought to pH2±3using HCl then loaded onto a1.5ml loop.After injection,the analytes were pre-concentrated on-column during the initial 3min,then were eluted by increasing the solvent strength.The elution gradient was:water at pH$2.5(A) and acetonitrile(B);0±3min15%B,3±13min linear to 75%B,13±15min linear to100%B.The¯ow rate was 1.0ml minÀ1.Analytes were detected by absorbance at 254nm.For natural water samples it was necessary to ®lter the samples before injection to remove particulates. This was accomplished by raising the pH to P8using NaOH then passing the sample through a0.2l m nylon ®lter(Cole Parmer).The pH adjustment eliminated loss of benzoic acid and hydroxybenzoic acids on the®lters by forming the more soluble ionized species.After®l-tration,the pH was re-adjusted to2±3using HCl and the sample was analyzed as above.Both benzoic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid were stable under these condi-tions over the time required for analysis.Propionaldehyde,the product of1-propanol reac-tion with hydroxyl radical,was quantitated following derivitization with DNPH(Coutrim et al.,1993).The derivitization was carried out by adding5mM DNPH in DMSO and allowing12h for the derivitization to occur.Extended time periods(up to48h)did not a ect the concentration of propionaldehyde detected. The derivitized product was injected using a50l l loop.The elution gradient was:water(A)and aceto-nitrile(B);0±2min50%B,2±16min linear to100% B.The analytes were detected by absorbance at 254nm.Hydrogen peroxide determination.Hydrogen peroxide was determined by titration(Christian,1994).In this method,excess IÀplus a catalyst was added to the hy-drogen peroxide solution to form IÀ3.The IÀ3was then titrated with thiosulfate.Hydrogen peroxide was quantitated at di erent times after addition of Fe2 ,and it was assumed that any further Fenton reaction was quenched upon the addition of excess IÀ.3.Results and DiscussionHydroxyl radical quantitation.In a system with both sources and sinks for hydroxyl radical,the change in [HOá]with respect to time is described by Zhou and Mopper(1990):M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr/Chemosphere41(2000)409±417411d HO áa d t F Àk p HO áP Àk S i HO á S iÀk HO HO á 21where F is the formation rate of hydroxyl radical,and the remaining negative terms are loss due to reaction with probe (P),with scavengers (S),and self reaction,respectively.This equation does not represent steady state conditions,but rather the rate of change in hy-droxyl radical concentration with respect to time.Therefore,this equation is applicable under non-steady state conditions.As [P]increases,the term Àk p HO á P will dominate the loss terms.Under these conditions,the total moles of P reacted will be stoichiometrically related to the total moles of HO áformed (Blough,1988),provided that the reaction product does not react signi®cantly with hy-droxyl radical.Since in this study product concentration was always considerably lower than the probe concen-tration,we assumed no signi®cant loss of product due to hydroxyl radical reaction.In the case of low probe concentrations,if [P]is small enough so that k p HO á P ( S i HO áS i k HO HO á 2,then d HO á a d t will be relatively una ected by the probe.In such cases,the concentration of hydroxyl radical in the absence of the probe can be calculated from the second order rate law R p k p HO á P 2 HO á R p a f k p P g 3 HO á avg R p a f k p P avg g4where R p is the rate of probe reaction,k p is the second order rate constant,and avg indicates time averaged values.Over short time intervals,the value for R p was calculated from the linear change in the concentration of the product resulting from probe-HO áreaction.This approach is valid when [HO á]and [P]do not change signi®cantly in the time interval.Validation of experimental approach .In order to con®rm that the approach used here is valid,several experiments were undertaken.The ®rst set of experi-ments involved measurement of product yield as a function of probe concentration.These experiments al-lowed de®nition of high probe concentrations (useful for determination of total HO áformation)and low probe concentration (useful for determination of HO ácon-centration with minimal perturbation by the probe).Product formation was quantitated as a function of re-action time for several probe concentrations.Data for benzoic acid experiments in several matrices are pre-sented in Fig.1.In all matrices,as the benzoic acid concentration increased,the amount of product in-creased,indicating that higher concentrations of benzoic acid were better able to outcomplete the naturalscavengers for reaction with HO á.At su ciently high benzoic acid concentrations,further increases in con-centration resulted in little increase in product yield,as seen by a plateau in the curves in Fig.1at higher [BA].Such behavior has been observed previously (Tomita et al.,1994).These data indicate that no additional trapping of HO ácould be achieved by increasing [BA],and therefore at these concentrations the benzoic acid must be trapping essentially all of the HO á.Under these conditions,the total moles of product obtained is directly proportional to the total moles HO áproduced (for benzoic acid,the proportionality factor is 5.9(Zhou and Mopper,1990)).Increased content of LM water resulted in a lower total amount of HO átrapped in the plateau region (above 5mM BA).This result is most likely due to a decrease in the e ciency of radical production in the presence of the natural water matrix.This result was also evident in time dependent measurements of total HO áproduced,as will be discussed below.As the benzoic acid concentration was lowered,the yield of product decreased.In order to determine hy-droxyl radical concentration in the absence of the added probe,it was necessary that the probe had a negligible e ect on hydroxyl radical concentration.We used the ratio of product yield at low [BA]to product yield at the high [BA]plateau to determine the extent of perturba-tion caused by the addition of benzoic acid.For exam-ple,in a 50/50mixture of pure water with LM water,0.5mM BA has a product yield of only 4%of the yield for P 5mM BA.In contrast,the product yield for 0.5mM BA in pure water was 40%of the yield at 5mM BA.Based on these results,we selected benzoic acid concentrations for use in further experiments to deter-mine HO áproduction and HO áconcentration.For HO áproduction,we used benzoic acid concentrations intheFig.1.Moles of hydroxyl radical trapped as a function of probe concentration (benzoic acid)in pure water and several dilutions of LM water.All data were acquired 10min after the addition of iron (II)perchlorate and H 2O 2at time zero concentrations of 0.2and 0.5mM,respectively.412M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr /Chemosphere 41(2000)409±417plateau region(typically9mM),and for[HOá]mea-surements we used benzoic acid concentrations that had product yields of less than10%of the maximum yield on the plateau(typically0.2mM).Also illustrated in Fig.1is the e ect of increased matrix components on HOáscavenging.As the per-centage of natural water increased,higher concentra-tions of benzoic acid were required to reach the plateau region.These results indicate the higher level of scav-engers in the natural water,therefore requiring a higher benzoic acid concentration to trap all of the hydroxyl radical formed.The presence of these scavengers also minimized the perturbation at low benzoic acid concentrations.Similar studies using propanol as probe were also conducted,and the results are presented in Fig.2.For pure water,complete trapping could be achieved above 100mM PrOH.In contrast to the benzoic acid probe, propanol did not signi®cantly perturb the[HOá]with propanol concentrations below$2mM.For LM water, the PrOH product yield did not plateau as was observed for benzoic acid.Even with propanol concentrations as high as1M,the product yield did not plateau.Therefore PrOH was not used to determine formation rate of HOáin natural waters.However,measurement of[HOá]in natural water was deemed feasible at propanol concen-trations below$10mM.The use of higher concentra-tions of PrOH as compared to benzoic acid is likely a result of the lower rate constant for propanol reaction with hydroxyl radical.Propanol and benzoic acid are distinct probes with di erent mechanisms of reaction with hydroxyl radical. We used such distinct probes to eliminate any possible bias of a single parison of the BA and PrOH results under the same conditions showed good agree-ment.These results can be seen in Fig.3,and are dis-cussed further below.The strong agreement between data from these distinct probes indicate that the probes introduced little or no bias into these measurements.For example,complexation of iron by benzoic acid was de-termined to be insigni®cant,as any such interaction would have resulted in divergent results for the two probes.Measurement of HOáProduction.Hydroxyl radical production was measured in pure water,CL water,LM water,and aqueous solutions of Suwannee River HA and FA.For these experiments,benzoic acid was used as probe at a concentration of9mM(pH$3).The total moles of HOáproduced was measured as a function of time after a single addition of Fe(II)and H2O2.A comparison of moles HOáproduced as a function of time for pure water and the two natural waters is pre-sented in Fig.4.The CL water matrix showed slightly lower HOáproduction than pure water,and the LM water matrix showed dramatically lower production than pure water.After20min,the reaction in pure water had produced$3X5Â10À6mol of HOá,while in CL water only$3Â10À6mol HOáwere produced,and in LM water only$0X8Â10À6moles HOáwere produced. These data indicate that the natural water matrices used here resulted in a lower e ciency of hydroxyl radical formation compared to pure water.Observed rates of formation of hydroxyl radical were also lower in the natural waters than in pure water.We measured the initial rates of hydroxyl radical formation from the ini-tial slopes of the curves in Fig.4,and the resulting values are presented in Table1.Suwannee River HA and FA also showed decreased hydroxyl radical formation.Fig.5illustrates the for-mation of HOávs time for various concentrations of HA and FA.HA caused a more dramatic decrease inradicalFig.2.Moles of hydroxyl radical trapped as a function ofprobe concentration(PrOH)in pure water and dilutions of LMwater.All data were acquired10min after the addition of iron(II)perchlorate and H2O2at time zero concentrations of0.2and0.5mM,respectively.The x-axis is presented with a loga-rithmic scale due to the large range of propanol concentrationsused.Fig.3.Measured time dependent hydroxyl radical concentra-tion(symbols)based on reaction with benzoic acid(0.2mM,pH 4.3)or PrOH(1mM,pH 6).Curves are polynomial®tsto the data points.Matrix is CL water.M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr/Chemosphere41(2000)409±417413production than FA.The initial rate of hydroxyl radical production was decreased by 11%in the presence of 30mg l À1FA and by 27%in the presence of 30mg l À1HA.For HA,the initial hydroxyl radical production rate showed a linear decrease over the range of HA concentrations studied,as illustrated in Fig.6.Since the FA and HA solutions (with 9mM BA)were very close in pH to pure water (with 9mM BA),and since no additional inorganic species were present,these data indicate that dissolved natural organic matter can have a dramatic e ect on hydroxyl radical formation as well as scavenging.Hydroxyl radical formation was assessed as a func-tion of pH with and without added FA.The total moles of HO áformed was measured at 20and 300s after mixing Fe 2 and peroxide.Fig.7represents total moles of HO áformed in a 300s time interval as a function of pH and FA content.The highest yield of hydroxyl radical was observed at pH 3.1,which is in good agreement with previous studies (Pignatello,1992).At this pH,addition of FA resulted in a slight decrease in radical production.However,as the pH was increased,the FA had the opposite e ect,with increased radical production at increased [FA].Furthermore,the e ect of pH was minimized at the highest FA concentration.The data for a 20s time interval showed similar results.The distribution of Fe 2 and Fe 3 is sensitive to pH,with the Fe 2 state becoming less stable with increasing pH,and the formation of oxides and hydroxides also increases with increasing pH.It is therefore reasonable to expect,as has been previously observed (Pignatello,1992),that Fenton production of hydroxylradicalFig.6.Initial rate of hydroxyl radical formation as a function of HA concentration.Benzoic acid used as probe at 9mM,(pH $3).Fig.5.Total moles of HO áformed as a function of time for aqueous FA (a)and HA (b)solutions.Benzoic acid used as probe at 9mM (pH $3).Fig.4.Total moles of HO áformed as a function of time for pure water (pH 3.1),CL water (pH 3.3),and LM water (pH 3.6).Benzoic acid used as probe at 9mM.Table 1Observed initial rate for hydroxyl radical formation in pure water and natural waters Water Initial rate (M s À1)DOC a (mg C l À1)Puri®ed 1.2´10À6<0.003CL 1.0´10À629.9LM0.3´10À6123aDissolved organic carbon.414M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr /Chemosphere 41(2000)409±417becomes less e cient at higher pH.Also previously observed is that iron chelation minimizes these pH ef-fects by stabilizing the chelated Fe 2 ion (Sun and Pig-natello,1993).Our results provide evidence that iron chelation by FA results in stabilization of Fe 2 with respect to pH.At low pH,Fe 2 stability is high,and any chelation of iron by FA has only a small e ect on HO áformation.At higher pH,chelation by FA likely results in increased Fe 2 stability,resulting in a marked increase in Fenton reaction yield upon addition of FA.Previous reports have indicated pseudo ®rst order loss of H 2O 2in the presence of Fe (II)(Walling,1975),Fe (III)+light (Pignatello,1992),and iron oxides (Lin and Gurol,1998).Our peroxide data also indicate ®rst order behavior,although the kinetic behavior did not stabilize until 30±60s after the addition of peroxide.An illustration of this behavior is given in Fig.8.Previous studies did not monitor kinetics at such short times.Our observations were consistent over a wide range of per-oxide concentrations (5±100mM).A possible explana-tion is that initially all of the iron is present as Fe 2 ,which can react with H 2O 2to form HO á.As this reaction proceeds,the concentration of Fe 2 declines,and con-sequently the rate of H 2O 2consumption and HO áfor-mation decline.The loss of Fe 2 is eventually balanced by formation of Fe 2 through reduction of Fe 3 by re-action with peroxide or hydroperoxyl radical,and a steady state Fe 2 concentration is reached.At this point (>60s),pseudo ®rst order loss of H 2O 2is observed.This explanation is also supported by evidence that the HO áformation rate is signi®cantly higher in the ®rst 60s.The in¯uence of hydrogen peroxide concentration on hydroxyl radical production was also assessed.The moles of HO áformed increased linearly with increasing [H 2O 2].The hydroxyl radical formation was measured at20s and 300s intervals after mixing Fe 2 and H 2O 2.The data are presented in Fig.9.The slope of the line was greater at 300s than at 20s,indicating that increasing H 2O 2concentration will result in more signi®cant in-creases in hydroxyl radical over longer time periods.The above observations could be used in evaluating the e ciency of Fenton oxidation in a given matrix.Three possible explanations exist for the observed dif-ferences in the natural water matrices:(1)the rate of peroxide reaction with iron may be altered by iron complexation (Croft et al.,1992;Puppo,1992)with matrix components,(2)Fe (II)/Fe (III)redox cycling may be altered by complexation (Croft et al.,1992)or by the presence of oxidants /reductants in the matrix,or (3)peroxide may be consumed by reaction with matrix components.This method provides a basic understand-ing of the time dependent radical formation rate and allows direct assessment of matrix e ects onradicalFig.8.Plot of ln[H 2O 2]vs time after addition of peroxide to solution of 0.5mM Fe 2 (aq).Line is linear regression to the data points for t P 60s.Fig.9.Total moles of HO áformed as a function of hydrogen peroxide concentration.Benzoic acid used as probe at 9mM (pH 3.1).Measurements made 20and 300s after mixing Fe 2 and H 2O 2in purewater.Fig.7.Total moles of HO áformed as a function of pH for pure water and aqueous FA.Benzoic acid used as probe at 9mM.Lower pH was achieved by addition of perchloric acid,and higher pH was achieved by addition of NaOH.Measurements made 300s after mixing Fe 2 and H 2O 2.M.E.Lindsey,M.A.Tarr /Chemosphere 41(2000)409±417415。

三苯甲烷类染料的氧化降解反应研究及其应用

作者签名: 导师签名: 2014 年 月 日

67

万方数据

目 录

中 文 摘 要 .....................................................................................................................I Abstract ......................................................................................................................... III 第一章 绪论 .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 三苯甲烷染料概述 ............................................................................................ 1 1.1.1 三苯甲烷染料结构分类及其性质 ............................................................ 1 1.1.2 三苯甲烷类染料的应用 ........................................................................... 2 1.2 三苯甲烷类染料废水处理方法研究进展 ......................................................... 4 1.2.1 物理方法................................................................................................... 4 1.2.2 化学方法................................................................................................... 5 1.2.3 生物方法................................................................................................... 7 1.3 三苯甲烷类染料的降解机理研究进展 .............................................................. 7 1.3.1 化学氧化法的降解机理 ............................................................................ 7 1.3.2 生物降解法的降解机理 ......................................................................... 10 1.4 本论文研究意义及内容 .................................................................................. 11 1.4.1 研究意义................................................................................................. 11 1.4.2 研究内容................................................................................................. 12 参考文献........................................................................................................................ 12 第二章 过碳酸钠对四种三苯甲烷染料的降解研究 .................................................... 19 2.1 引言 ................................................................................................................. 19 2.2 实验部分 ......................................................................................................... 20 2.2.1 仪器 ........................................................................................................ 20 2.2.2 试剂 ........................................................................................................ 20 2.2.3 实验步骤................................................................................................. 21 2.3 结果与讨论 ..................................................................................................... 23 2.3.1 过碳酸钠对不同染料的褪色作用 .......................................................... 23 2.3.2 四种模型染料的紫外可见光谱 .............................................................. 25 2.3.3 pH 对降解率的影响 ................................................................................ 25 2.3.4 过碳酸钠用量和反应时间对降解率的影响 ........................................... 26 2.3.5 反应温度对降解率的影响...................................................................... 27

氨基甲基苯甲酸的规格

氨基甲基苯甲酸的规格The specification of aminomethylbenzoic acid, also known as AMBA, is a crucial aspect to consider in various industries such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and research. The specification of AMBA typically includes information regarding its physical and chemical properties, purity, and potential impurities. This information is essential for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of products in which AMBA is used.First and foremost, the physical properties of AMBA are an important part of its specification. This includesdetails such as its appearance, color, odor, and solubility. For example, knowing that AMBA is a white crystalline powder with a slight characteristic odor, and is soluble in water, can provide valuable insights for formulating pharmaceutical or cosmetic products. These physical properties can also impact the handling and storage of AMBA, making it essential to include in its specification.In addition to physical properties, the chemical properties of AMBA are also a key component of its specification. This includes information about its chemical structure, molecular weight, and potential reactivity. Understanding the chemical properties of AMBA is crucialfor assessing its compatibility with other ingredients in a formulation and predicting its behavior under various conditions. For instance, knowing that AMBA is a derivative of benzoic acid with a molecular weight of 153.17 g/mol can aid in the development of analytical methods for its quantification and identification.Furthermore, the specification of AMBA includes details about its purity and potential impurities. Purity is a critical aspect, especially in pharmaceutical and research applications, as it directly impacts the safety andefficacy of the final product. The presence of impurities can affect the stability and performance of AMBA, making it essential to establish strict limits for impurities in its specification. This often involves using analytical techniques such as HPLC or GC to quantify impurities and ensure that they are within acceptable levels.Moreover, the specification of AMBA may also encompass information regarding its manufacturing process and quality control measures. This can include details about the synthesis of AMBA, starting materials used, and anyspecific quality attributes that need to be monitoredduring production. For example, the specification mayoutline the acceptable limits for residual solvents or by-products to ensure the purity of the final product. Additionally, quality control measures such as in-process testing and stability studies may be included to guarantee the consistency and reliability of AMBA.In conclusion, the specification of AMBA is a comprehensive document that encompasses its physical and chemical properties, purity, potential impurities, manufacturing process, and quality control measures. This information is vital for various industries that rely on AMBA for the development of high-quality products. By providing a detailed and accurate specification, manufacturers and suppliers can ensure the safety, efficacy,and reliability of AMBA, ultimately contributing to the overall success of the products in which it is used.。

甲基四氢邻苯二甲酸酐酸值英文

甲基四氢邻苯二甲酸酐酸值英文Alright, here's a casual and conversational way to talk about the acid value of methyl tetrahydrophthalic anhydride in English:Hey, so you wanna know about the acid value of methyl tetrahydrophthalic anhydride, huh? Well, let's just sayit's a pretty important measurement when dealing with this kind of chemical. It gives us a clue about how reactive it is, and that's crucial for a lot of applications.You know, when we talk about acid value, we're really just referring to how much of a certain chemical is present that can react with a base. And in the case of methyl tetrahydrophthalic anhydride, it's pretty significant. So, if you're using it for something specific, knowing that acid value can make a big difference.So, why is it important? Well, let's just say you're making a polymer or something that requires precise controlover reactions. Knowing the acid value can help you dial in those reactions just right. It's like having a recipe and knowing exactly how much of each ingredient to use.And don't forget, it's not just about the number itself. It's also about how that number changes over time or under different conditions. So, keeping an.。

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法是一种常用的分析方法,它可以用于分离和检测氨甲基膦酸类化合物。

本文将介绍氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法的原理、步骤和应用。

氨甲基膦酸类化合物是一类重要的有机磷农药,它们广泛应用于农业生产中。

然而,由于其结构中含有酸性氢原子,导致它们在常规气相色谱分析中无法直接检测。

为了克服这个问题,人们发展了氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法。

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法的原理是通过在样品中加入合适的衍生剂,使氨甲基膦酸类化合物发生衍生反应生成易于分析的衍生物。

衍生反应通常是在碱性条件下进行的,常用的衍生剂有乙酰胺、乙酰氯等。

衍生反应的产物通常是酰胺类化合物。

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法的步骤主要包括样品制备、衍生反应和色谱分析。

首先,将待分析的样品经过适当的前处理,如提取、浓缩等,得到纯净的样品溶液。

然后,向样品溶液中加入适量的衍生剂,并在碱性条件下进行衍生反应。

衍生反应一般在室温下进行,反应时间通常为10-30分钟。

衍生反应完成后,将反应溶液进行适当的处理,如稀释、过滤等,得到最终的分析样品溶液。

分析样品溶液可以通过气相色谱或液相色谱进行分析。

在气相色谱分析中,通常采用毛细管柱或色谱柱进行分离。

气相色谱条件的选择应根据具体的衍生物性质和分析要求进行优化。

在液相色谱分析中,常用的分离柱包括反相柱、离子交换柱等。

分析条件的选择应根据具体的衍生物性质和溶剂体系进行优化。

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法在农药残留、环境监测、食品安全等领域具有重要的应用价值。

它可以用于分析各种氨甲基膦酸类化合物,如氨甲基膦酸、甲胺膦、丙胺膦等。

该方法具有灵敏度高、选择性强、重复性好等优点。

同时,氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法还可以与质谱联用,进一步提高分析的灵敏度和准确性。

氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法是一种有效的分析方法,可以用于分离和检测氨甲基膦酸类化合物。

它在农药残留、环境监测、食品安全等领域具有广泛的应用前景。

随着分析技术的不断发展,相信氨甲基膦酸类柱前衍生法将在未来得到更广泛的应用。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。