CashFlowEstimationandRiskAnalysis

财务管理英文第十三版

Corporate Capital Gains / Losses

Currently, capital gains are taxed at ordinary income tax rates for corporations, or a maximum 35%.

The Capital Budgeting Process

Generate investment proposals consistent with the firm’s strategic objectives.

Estimate after-tax incremental operating cash flows for the investment projects.

c) - (+) Taxes (tax savings) due to asset sale or disposal of “new” assets

d) + (-) Decreased (increased) level of “net” working capital

e) = Terminal year incremental net cash flow

Depreciation and the MACRS Method

Everything else equal, the greater the depreciation charges, the lower the taxes paid by the firm.

基于现金流量的公司价值分析 外文原文 精品

Free Cash Flow, Enterprise Value, and Investor CautionHarlan PlattCollege of Business AdministrationNortheastern UniversitySebahattin DemirkanSchool of ManagementSUNY Binghamton UniversityMarjorie PlattCollege of Business AdministrationNortheastern UniversityAbstract:By analyzing actual cash flows in comparison with enterprise values (market capitalization plus debt minus cash) we document that the market dramaticall undervalues firms. The findings suggest that the equity market appears to have an extraordinarily high discount rate which negates future earnings in the calculus of firm value. That is, the discount rate is so high that the vast majority of future cash flows are virtually ignored.Our research finds that stock prices do not reflect future corporate earnings. This finding contrasts with the well known statement in finance textbooks that “the value of a firm equals the present discounted value of future cash flows.” In fact, we find that enterprise values are substantially less than the present discounted value of future cash flows. A one-dollar increase in future cash flows produces only a 75 cent increase in a firm’s enterprise value.The implication of our work is clear: companies are worth far more than the market believes. This provides strong support to the idea behind the private equity industry. We realize that of late private equity firms have overpaid for acquisitions and may lose their entire investment during the current phase of deleveraging. Yet, if private equity firms acquire companies at reasonable prices using less debt, they are likely to create substantial value as a consequence of the fact that companies are so undervalued by the market relative to their cash flows.There are no previous research efforts following our methodological design based on actual cash flows. Rather, .prior research studies have focused on the relationship between forecasted cash flows (by market analysts) and enterprise value. Our approach focuses on a different question – the relationship between discounted future cash flows and the current market value as posited by financial theory.Keywords: Enterprise Value, Actual Cash Flow, Cash Flow, Valuation1.IntroductionThe common explanation provided in finance textbooks for the value of the firm is that it equals the present discounted value of future free cash flows (FCF). Few analysts or market observers disagree with this statement. Despite its universal acceptance, there are few studies of the basic FCF proposition and the theory that underlies the science of valuation. In this paper, we explore the question of whether the value of the firm is related to its future cash flows. Existent literature on this subject includes a few studies conceptually similar to ours and a large body of work on questions peripheral to the basic issue addressed in this paper. Those related works use the FCF valuation theory to address issues of market efficiency. Our work is directed at valuation and not the market efficiency question.Obviously actual future cash flows are unknown when analysts estimate value. Lacking actual future cash flow data, analysts create careful projections of annual cash flows for several years, usually less than 10, and then estimate cash flows in additional years with a terminal value. Public companies have value forecasts prepared for them by many unrelated individuals and organizations. Some forecasts are too optimistic while others are too pessimistic. Presumably optimistic forecasters are buyers of securities while pessimistic forecasters are sellers. A secu rity’s market price would then be the share value that clears the market of optimists and pessimists.The specific projections of all individual forecasters are unavailable. What is known, at a point in time, is the actual market capitalization and enterprise value (EV) that results from the interactions of these many forecasts. Some researchers have tested the relationship between the value of the firm and cash flow forecasts by obtaining a sample of analyst’s forecasts or forecasts from other published so urces. We instead substitute actual cash flows for forecasted cash flows. Our null hypothesis assumes that the market-clearing forecast of future free cash flows is correct for every company. In that case, actual cash flows can be substituted for cash flow forecasts. If the market clearing forecast is too optimistic (pessimistic) then the observed EV exceeds (is less than) the present discounted value of actual free cash flows. Our first empirical test examines how closely EV compare with the present discounted value of actual subsequent cash flows. Finding the theory to be less than complete, our second empirical exercise considers additional explanatory factors to explain EV. This portion of the paper tests whether the accepted FCF theory fully explains EVs.2.LITERATURE REVIEWThe earliest written discussion of the idea that the value of something is related to its future cash flows comes from Johan de Witt (1671); though the basic idea traces back to the early Greeks1. In modern times, the idea that corporate value is related to 1See Daniel Rubinstein, Great Moments in Financial Economics, Journal of Investment Management (Winter 2003).future dividends was first described by John Williams (1938)2. Durand (1957) observed what later became known as the Gordon growth model, that a dividend growing at a constant rate forever can be capitalized to estimate a firm’s va lue.The literature that tests the FCF theory examines a variety of valuation methods. All of these tests rely on forecasts of cash flows or earnings made contemporaneously with the valuation estimate. That is, starting in a given year, they compare actual EV against forecasts, made that year, for the same company. For example, Francis, Olsson, and Oswald (2000) compared three theoretical valuation models-- discounted dividends (DD), discounted FCF, and discounted abnormal earnings (AE)3– by analyzing Value Line annual forecasts for the period 1989 – 1993 for a sample of2,907 firm years that ranges between 554 and 607 firms per year. They found that the AE model had a 27% lower absolute prediction error than the FCF model and a 57% lower absolute prediction error than the DD model.Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) also consider three multiperiod accounting based valuation methods: an earnings capitalization model (similar to FCF), residual income (a version of AE) without a terminal value, and residual income with a terminal value4. They put analyst’s earnings forecasts into the three theoretical models and find overall that they provide greater insight than merely relying on current earnings, book values or dividends. Their sample covered 36,532 firm years over the period 1981 – 1998 of which 22,705 consisted of one year forecasts, 9,420 of two year forecasts, 1,279 of three year forecasts, and 3,128 of four year forecasts. They found that the AE model with a terminal value most accurately predicted current equity values in 48% of cases, the FCF model was most accurate in 18% of cases, and the AE without a terminal value was most accurate in 13% of cases. Current income and book values provided the best forecasts for the remaining 21% of the sample.Liu, Nissim and Thomas (LNT) (2002) in an article similar to Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) found that multiples based on analyst’s forward earnings projections (made in the same year) explain stock prices within 15% of their actual value while historical earnings, cash flow measures, book value, and sales were not nearly as insightful. LNT argue that multiples value future profits and risk better than present value forecasts. Their multiples are derived based on current earnings and stock prices.Gentry, Whitford, Sougiannis, and Aoki (2001) took a different theoretical and empirical approach comparing an accounting method which looked at the discounted value of future net income to a finance method that looked at the discounted value of FCFs to equity. Their analysis tested the closeness with which each model predicted capital gains. The sample included both US (1981 – 1998) and Japanese companies (1985– 1998). Each year had between 881 and 1034 US companies and 166 to 3652See, Aswath Damodaran, “Valuation Approaches and Metrics: A Survey of the Theory,” Stern School of Business Working Paper, November 2006. Damodaran notes that Ben Graham saw the connection between value and dividends but not with a discounted valuation model.3Abnormal earnings as discussed by Ohlson (1995) assume that the value of equity equals the sum ofbook value plus abnormal earnings.4They also report that a 4% constant growth rate provides the best terminal value, even better than onesbased on individual firm growth forecasts.Japanese companies. They found that the FCFs to equity method were not closely related to capital gains rates of return for either US or Japanese companies. In the US they found a strong relationship between cash flows associated with operations, interest, and financing (the accounting method) to capital gains; no similar relationship was found in Japan.Finally, Dontoh, Radhakrishnan, and Ronen (2007) compared the association between stock prices and accounting figures. They found that the association between stock prices and accounting numbers has been declining over time. They suggest that this may be due to increased noise in stock prices resulting from higher trading volume driven by non-information based trading.A further related literature examines the relationship between valuation and changes in dividends . These studies are concerned with market efficiency. Dividends are a straightforward concept: they are the payments made to equity holders by a company. Dividends may also be thought to include all cash payouts to equity including share repurchases, share liquidations, and cash dividends. Several studies have examined whether changes in dividends relate to changes in equity values; among these are Shiller (1981), LeRoy and Porter (1981), and Campbell and Shiller (1987). These tests generally find that stock market volatility can not be explained by subsequent changes in dividends. Larrain and Yogo (2008) take a slightly different look at equity volatility. Using a more aggregate sample they find that the majority of the change in asset prices (88%) is explained by cash flow growth while the remaining 12% is explained by changes in asset returns. They conclude that stock prices are not explained by dividend changes.The residual income method is conceptually more similar to FCF than to dividends. Residual income at its most basic equals the firm’s net income minus the cost of its capital. In the accounting literature, Ohlson’s (1991, 1995) formulation of a residual income model (RIM) is widely accepted and has been subjected to numerous tests. RIM begins with an accounting identity; namely that the change in book value equals the difference between net income and dividends. Ohlson then defines AE as the difference between net income and lagged book value. It is then a small step to observe that the present discounted value of expected future abnormal earnings plus the book value of equity equals stock price5. Jiang and Lee (2005) test both the RIM and the dividend discount model. Their test of equity volatility finds that RIM provides more and better information than dividends.3.METHODOLOGYUnlike previous studies, we rely on actual subsequent cash flows over a period of time rather than forecasts of cash flow made contemporaneously with EV. Previous researchers can be thought of as studying the consistency between contemporaneous EV determined in the market and forecasts of future cash flows. Our study does not have that focus. We instead are interested in the actual accuracy of market determined EVs. We compare EVs at a point in time to subsequent cash flows. The closer these values are the more accurate is the market in valuing companies based on their future 5See Jiang and Lee (2005), page 1466.cash flows.In order to estimate corporate value with FCFs, annual costs of capital must be estimated for each company. An alternative is to determine value using the capital cash flow (CCF) method. CCF yields the same present value as FCF6but only requires a single cost of capital estimate for each firm. This is the approach we follow.CCF is determined following Arzac (2005) as follows:CCF = net income + depreciation - capital expenditures –Δ working capital +Δ deferred taxes + net interestEstimated enterprise value (EEV) is calculated with the CCF estimates as follows:EEV =Σ(CCFi,j ) /(1+ kj )t TVj /(1+ kj )y , (i=1….y)where k is cost of capital, TV is terminal value, i is year, y is the final year with cash flow data and j represents firm. Terminal value is estimated according to the Gordon growth model. EEV estimates are compared with EV, the firm’s actual va lue as of the last trading day of the year. EV is calculated following Arzac (2005) as follows;EV = MarketCap + Debt −CashThe comparison between EV and EEV is a test of the accuracy of the market’s valuation process. Cases where EV exceeds (is less than) EEV are ones of overly optimistic (pessimistic) market valuation.4.DataWe begin with all firms with fiscal year end for which there is data for:• cash and short-term investments (data1),• total assets (data6),• current assets (data4),• current liabilities (data5),• short-term debt (data44),• long-term debt (data9),• notes payable (data206), and• deferred taxes (data74),• capital expenditures (data128)• sales (data12),• net income (data172)• depreciation (data14)• interest expense (data15)• interest income (data62)• common shares outstanding (data25),• year-end stock price (data199).This results in an initial sample of 131,518 firm-year observations. All firms are classified into their respective industries using historical SIC codes (data324).For each firm-year in the initial sample, we compute the following variables;EV = Market Cap (data199*data25) + Debt (data9 + data44 + data206)6See Arzac (2005) or Platt (2008).- Cash (data1)WC= Net current assets (data4 - data5) – cash (data1) + notes (data206)D= Long term (data9) + short term (data44 + data206)E= Share price (data199) * Number of shares (data25)(where EV is enterprise value, WC is working capital, D is debt, and E is equity) In addition we also compute lagged values for WC and deferred taxes (data74).Next, we obtain betas for firm-years from Compustat’s Research Insight. Betas are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to account for extreme outliers in the data.Interest rates based on the 10-year constant maturity series (I10YR) are obtain from the Federal Reserve Bank’s website. After merging with the interest rate data and the betas, the sample size reduces to 69,643 firm-year observations. The loss in observations is largely due to missing data on the betas or deletions due tonon-availability of lagged firm-year data.With the merged dataset, we compute the following variables, where LWC represents the lagged value of WC and Ldata74 is the lagged value for data74: CCF = net income (data172) + depreciation (data14) - capital expenditures(data128) + WC - LWC + deferred taxes (data74) - Ldata74 +interest paid (data15) –interest received (data62);βA = (1 / (1 + D/E))*βKU1 = I10YR + βA *ERP1KU2 = I10YR + βA *ERP2KU3 = I10YR + βA *ERP3;(where CCF is capital cash flow, βA is the asset beta, ERP is the equity risk premium, and KU1, KU2 and KU3 are estimates of the unlevered cost of capital for three different ERPs (ERP1 = 0.03;ERP2 = 0.05;ERP3 = 0.07)Results were essential identical regardless of the choice of ERP and so we report on those for ERP3. We then drop all observations with fiscal year greater than 2000 to allow a sufficient numbers of years of actual cash flow data to be in the dataset.From the summary files of the Institutional Brokers Estimate System (IBES) database, we extract median values of long-term growth in sales forecasts for all firms. The median value is based on all analyst estimates of long-term (5 to 10 years) growth forecasts made for each firm. Prior studies use this as a measure of the estimated growth rate for a firm’s cash flow. Many of the growth rate forecasts were extraordinarily large, and so we followed Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) by using the growth rate in GDP instead of the IBES values.The final dataset consists of 27,027 firm-year observations with complete data on all variables of interest. Of this 2,820 firm-years are data for companies with five or more years of information. Firm’s whose last year of data had negative FCF were dropped from the sample since terminal value could not be calculated for them. This left us with 1,821 firms.Some companies in our sample have only five years of actual cash flow data; others have as many as 12 years of data. Recently it has been argued that the terminal value estimate dominates estimates of present value, see Platt and Demirkan (2008).To insure that EEV estimates are not unduly influenced by estimates of terminal value, EEV is calculated repeatedly for each company starting with using five years of data and then using more years,12 years, depending on how much data the company has available.5.CONCLUSIONWe began this paper saying that the most common explanation in finance textbooks for the value of the firm was that it equaled the present discounted value of future cash flows. Our results suggest that a better description for textbooks is that the value of the firm is related to but unequal to the present discounted value of future cash flows. In conjunction with Platt and Demirkan (2008) which finds that the TV is the principle part of EEV (i.e., approximately 92.3%) it would seem that the market values firms based on their near term (perhaps five years or fewer) subsequent cash flows. In fact, one dollar increase in future cash flows produces far less of an increase in a firm’s EV. Theoretically this conforms to a version of the Gordon (1962)two-stage growth model with a WACC based discount rate during the early period and a very high discount rate during the future period).Supporting evidence to our surprising finding appear in everyday stock market tables. For example, the following quote from of December 8, 2008 speaks precisely to our findings.“Cheapest Stocks Since 1995 Show Cash Exceeds Market(By Michael Tsang and Alexis Xydias)Dec. 8 (Bloomberg) –“Stocks have fallen so far that 2,267companies around the globe are offering profits to investors for free. That’s eight times as many as at t he end of the last bear market, when the shares rose 115 percent over the next year.Bank of New York Mellon Corp. in New York, Danieli SpA in Buttrio, Italy and Seoul-based Namyang Dairy Products Co. Hold more cash than the value of their stock and debt as the slowing world economy wiped out $32 trillion in capitalization this year.”The Bank of New York Mellon, for example, on that day had a market capitalization of $31.71 billion, debt of $35.83 billion, and cash of $75.50 billion. In this case, the market has an infinite discount rate on any and all cash flows.A possible explanation for our higher EEV estimate than actual EV is that our unlevered cost of capital (KU) estimate is too low and therefore associated with a too high TV estimate. However, we calculated three KU estimates, based on generally accepted equity risk premium (ERP) levels and then used the highest KU. It is true however, that there is a KU which equilibrates EV with our EEV.Another possible explanation is that forecasts relied upon the valuation process are inaccurate and that future cash flows far exceed what analysts had expected. We find this to be the least satisfactory explanation.REFERENCESArzac, Enrique, 2005, Valuation For Mergers, Buyouts, and Restructuring, John Wiley & Sons.Campbell, J., and Shiller, R., 1987, Cointegration and Tests of Present Value Models, Journal of Political Economy, 95(5):1062-88.Daines, R, 2001, Does Delaware law improve firm value?, Journal of Financial Economics, 62: 525-558Damodaran, A., 2006, Valuation Approaches and Metrics: A Survey of the Theory, Working Paper, Stern School of Business..Dontoh, A., Radhakrishnan, S., and Ronen, J., 2007, Is Stock Price a Good Measure for Assessing Value-Relevance of Earnings? An Empirical Test, Review of Managerial Science, 1(1):3-45.Fama Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French, 1992, The Cross- Section of Expected Stock Returns, The Journal of Finance,47: 427-465.Fama Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French., "Size and Book-to-Market Factors in Earnings and Returns", The Journal of Finance, 1995, No. 50. -pp. 131-155. Francis, J., Olsson, P., and Oswald, D, 2000, Comparing the Accuracy and Explainability of Dividend, Free Cash Flow, and Abnormal Earnings Equity Value Estimates, Journal of Accounting Research, 38(1).Gentry, J. Whitford, D., Sougiannis, T., and Aoki S., 2001, Do Accounting Earnings or Free Cash Flows Provide a Better Estimate of Capital Gain Rates of Return on Stocks?, Security Analysts Journal, 39(5):66-78.Hovakimian, A., T. Opler, and S. Titman, 2001, The debt-equity choice, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 36(1):1–24.Larrain, B. and Yogo, M., 2008, Does firm value move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in cash flow, Journal of Financial Economics, 87(1):200-26. LeRoy, S. F. and Porter, R. D., 1981, The Present-Value Relation: Tests Based on Implied Variance Bounds, Econometrica, 49(3):555-574.20Jiang, X. and Lee B., 2005, An Empirical Test of the Accounting-Based Residual Income Model and the Traditional Dividend Discount Model, Journal of Business, 78(4):1465–1504.Larrain, B., Yogo, M., 2008. Does Firm Value Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Cash Flow?, Journal of Financial Economics, 87 (1),200–226.Liu, J., Nissim, D., and Thomas, J., 2002, Equity Valuation using Multiples, Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1): 135- 172.Myers, S. C., 1977, Determinants of corporate borrowing, Journal of Financial Economics, 5:147-175.Ohlson, J., 1991, The theory of value and earnings, an introduction to the Ball-Brown analysis, Contemporary Accounting Research, 8:1-19.Ohlson, J., 1995, Earnings, book values, and dividends in security valuation, Contemporary Accounting Research, 11: 661-87.Polk, C., Thompson, S. and Vuolteenaho, T., 2006, Cross-sectional forecasts of the equity premium, Journal of Financial Economics, 1:101-141.Platt, H, 2008, Cash Flow Contradistinctions, Commercial Lending Review, 23 (2):19-24Platt, H. and Demirkan, S., 2008, Perilous Forecasts: Implications of Reliance onTerminal Value, Working Paper, Northeastern University.Shiller, R.J., 1981, Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent movements in dividends?, American Economic Review,71 (3): 421-36. Sougiannis, T., and Yaekura, T.,2001, The Accuracy and Bias of Equity Values Inferred from Analysts Earnings Forecasts, The Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, 16(4):331–362.Rubinstein D.,2003, Great Moments in Financial Economics: II. Modigliani-Miller Theorem, Journal of Investment Management. 1(2).Tsang M. and Xydias A., 2008 Cheapest Stocks Since 1995 Show CashExceeds Market, , December 8, 2008.。

金融风险管理中的定量分析方法

金融风险管理中的定量分析方法金融行业涉及大量的投资和贷款等活动,存在着各种风险。

为了避免风险造成的损失和影响,金融机构需要采用有效的风险管理措施,并运用定量分析方法来评估和控制风险。

下面将介绍金融风险管理中常用的定量分析方法。

一、价值-at-风险(VaR)测度价值-at-风险(VaR)是金融风险管理中经常使用的一种量化方法,用于测量风险敞口的最大潜在损失。

VaR 将风险与收益之间的关系相结合,确定一个具有特定置信度的最大可能损失值。

VaR 的目标是确保风险承担者在特定置信水平下(通常为95%或99%)不会损失超过某个限度的财富,保护金融机构不会遭受巨大的损失。

VaR 的计算方法包括历史模拟法、蒙特卡洛模拟法、参数化模型法等。

其中,历史模拟法是最常用的方法之一,它基于过去的市场数据来计算风险价值。

蒙特卡洛模拟法则是以预测未来市场价格波动的随机性以及各种风险因素的不确定性为基础来计算风险价值。

参数化模型法则使用模型来估计价格波动和各种风险因素之间的关系,以便更准确地计算风险价值。

二、方差-协方差(VaC)方法方差-协方差方法是一种基于风险收益关系的定量分析方法,可用于计算投资组合的风险。

通过分析资产的历史价格和收益率,可以确定不同资产之间的相关性以及整个投资组合的风险敞口。

考虑到各种风险因素的相互作用,方差-协方差方法可以提供一种覆盖各种情况的综合风险分析方法。

通过使用此方法,金融机构可以根据其特定风险偏好和预期收益率,选择最合适的投资组合。

VaC 方法的主要优点是使用简单、易于理解和计算成本较低。

但该方法主要的缺点是它不考虑非线性的风险和控制风险的其他方法,如对冲和多项式规则。

三、条件风险测度(CVar)方法条件风险测度方法是另一种测量风险敞口的方法,它基于 VaR 方法,但是更注重风险的杠杆效应和暴露度。

除了计算最大可能损失,CVar 还可以确定在损失事件发生后,风险负担者暴露于风险程度。

CVar 可以提供一种综合性的风险分析,可用于评估不同投资组合和交易的风险。

Intermediate Financial Management

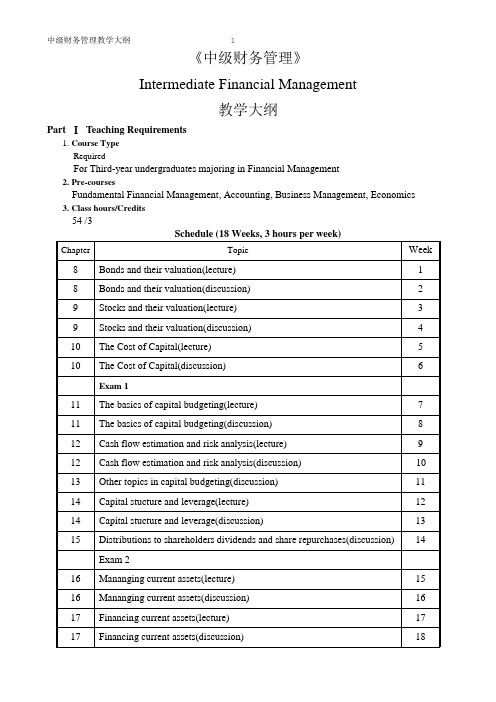

《中级财务管理》Intermediate Financial Management教学大纲Part ⅠTeaching Requirements1. Course TypeRequiredFor Third-year undergraduates majoring in Financial Management2. Pre-coursesFundamental Financial Management, Accounting, Business Management, Economics3. Class hours/Credits54 /3Part Ⅱ: Course ContentsCourse OverviewThis course is continued with fundamental financial management. Ihe same textbook are used in this semester. The course covers four parts of textbook. Part Ⅲcovers the valuation of stocks and bonds. Part IV applies the concepts covered in earlier chapters to decisions related to fixed asset investments. Part Ⅴdiscusses how firms should finance their long-term assets. In part Ⅵ, the focus shifts from long-term, strategic decisions to short-term, day-to-day operating decisions. Specific contentsⅠ. Financial AssetsThis part covers the valuation of stocks and bonds. Chapter 8 focuses on bonds, and Chapter 9 considers stocks. Both chapters describe the relevant institutional details, then explain how risk and time value jointly determine stock and bond prices.Chapter 8 Bonds and their valuationThis chapter is to describe the different types of bonds governments and corporations issue, explain how bond prices are established, and to discuss how investors estimate the rates of return they can expect to earn. We will also discuss the various types of risks that investors face when they buy bonds.Contents:1.Who issues bonds?2.Key characteristics of bonds3.Bond valuation4.Bond yields5.Bonds with semiannual coupons6.Assessing the riskiness of bond7.Default risk8.Bond marketsChapter 9 Stocks and their valuationThis chapter shows how stock value are determined, and also how investors go about estimating the rates of return they expect to earn.Contents:1.Legal rights and privileges of common stockholders2.Types of common stock3.The market for common stockmon stock valuation5.Constant growth stocks6.Expected rate of return on a constant growth stock7.Valuing stocks that have a nonconstant growth rate8.Valuate the entire corporation9.Stock market equilibrium10.Actual stock prices and returns11.Preferred stockⅡ. Investing in Long-Term AssetsChapter 10 The Cost of CapitalChapter 10 uses the rate of return concepts covered in previous chapters, along with the concept of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), to develop a corporate cost of capital for use in capital budgeting.Contents:1. E xplain what is meant by a firm’s weighted average cost of capital.2. Define and calculate the component costs of debt and preferred stock.3. Explain why retained earnings are not free and use three approaches to estimate the component cost of retained earnings.4. Briefly explain why the cost of new common equity is higher than the cost of retained earnings, calculate the cost of new common equity, and calculate the retained earnings breakpoint--which is the point where new common equity would have to be issued.5. Briefly explain the two alternative approaches that can be used to account for flotation costs.6. Calculate the firm’s composite, or weighted average, cost of capital.7. Identify some of the factors that affect the overall, composite cost of capital.8. Briefly explain how firms should evaluate projects with different risks, and the problems encountered when divisions within the same firm all use the firm’s composite WACC when considering capital budgeting projects.9. List and briefly explain the three separate and distinct types of risk that can be identified, and explain the procedure many firms use when developing subjective risk-adjusted costs of capital.10. List some problem areas in estimating the cost of capital.Chapter 11 The basics of capital budgetingContents:1. Discuss difficulties and relevant considerations in estimating net cash flows, and explain the four major ways that project cash flow differs from accounting income.2. Define the following terms: relevant cash flow, incremental cash flow, sunk cost, opportunity cost, externalities, and cannibalization.3. Identify the three categories to which incremental cash flows can be classified.4. Analyze an expansion project and make a decision whether the project should be accepted on the basis of standard capital budgeting techniques.5. Explain three reasons why corporate risk is important even if a firm’s stockholders are well diversified.6. Identify two reasons why stand-alone risk is important.7. Demonstrate sensitivity and scenario analyses and explain Monte Carlo simulation.8. Discuss the two methods used to incorporate risk into capital budgeting decisions.Chapter 12 Cash flow estimation and risk analysisContents:1. Use the replacement chain method to compare projects with unequal lives.2. Explain why conventional NPV analysis may not capture a project’s impact on the firm’s opportunities.3. Define the term option value, and identify four different types of embedded real options.4. Explain what an abandonment option is, and give an example of a project that includes one.5. Explain what a decision tree is and provide an example of one.6. Explain what an investment timing option is, and give an example of a project that includes one.7. Explain what a growth option is, and give an example of a project that includes one.8. Explain what a flexibility option is, and give an example of a project that includes one.9. List the steps a firm goes through when establishing its optimal capital budget in practice.Chapter 13 Other topics in capital budgetingContents:1. Explain why capital structure policy involves a trade-off between risk and return, and list the four primary factors that influence capital structure decisions.2. Distinguish between a firm’s business risk and its financial risk.3. Explain how operating leverage contributes to a firm’s business risk and conduct a breakeven analysis, complete with a breakeven chart.4. Define financial leverage and explain its effect on expected ROE, expected EPS, and the risk borne by stockholders.5. Briefly explain what is meant by a firm’s optimal capital structure.6. Specify the effect of financial leverage on beta using the Hamada equation, and transform this equation to calculate a firm’s unlevered beta, bU.7. Illustrate through a graph the premiums for financial risk and business risk at diffe rent debt levels.8. List the assumptions under which Modigliani and Miller proved that a firm’s value is unaffected by its capital structure, then explain trade-off theory, signaling theory, and the effect of taxes and bankruptcy costs on capital structure.9. List a number of factors or practical considerations firms generally consider when making capital structure decisions.10. Briefly explain the extent that capital structure varies across industries, individual firms in each industry, and different countries.Ⅲ. CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND DIVIDEND POLICYChapter 14 Capital stucture and leverageContents:1. Define target payout ratio and optimal dividend policy.2. Discuss the three theories of investors’ dividend preference: (1) the dividend irrelevan ce theory, (2) the “bird-in-the-hand” theory, and (3) the tax preference theory; and whether empirical evidence has determined which theory is best.3. Explain the information content, or signaling, hypothesis and the clientele effect.4. Identify the two components of dividend stability, and briefly explain what a “stable dividend policy” means.5. Explain the logic of the residual dividend policy, and state why firms are more likely to use this policy in setting a long-run target than as a strict determination of dividends in a given year.6. Explain the use of dividend reinvestment plans, distinguish between the two types of plans, and discuss why the plans are popular with certain investors.7. List a number of factors that influence dividend policy in practice.8. Discuss why the dividend decision is made jointly with capital structure and capital budgeting decisions.9. Specify why a firm might split its stock or pay a stock dividend.10. Discuss stock repurchases, including advantages and disadvantages, and effects on EPS, stock price, and the firm’s capital structure.Chapter 15 Distributions to shareholders dividends and share repurchasesContents:1. Define basic working capital terminology.2. Calculate the inventory conversion period, the receivables collection period, and the payables deferral period to determine the cash conversion cycle.3. Briefly explain the basic idea of zero working capital.4. Briefly explain how a negative cash conversion cycle works.5. Distinguish among relaxed, restricted, and moderate current asset investment policies, and explain the effect of each on risk and expected return.6. Explain how EVA methodology provides a useful way of thinking about working capital.7. List the reasons for holding cash.8. Construct a cash budget, and explain its purpose.9. Briefly explain useful tools and procedures for effectively managing cash inflows and outflows.10. Explain why firms are likely to hold marketable securities.11. State the goal of inventory management and identify the three categories of inventory costs.12. Identify and briefly explain the use of several inventory control systems.13. Monitor a firm’s receivables position by calculating its DSO and reviewing aging schedules.14. List and explain the four elements o f a firm’s credit policy, and identify other factors influencing credit policy.ⅣWORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENTChapter 16 Mananging current assetsContents:1. Identify and distinguish among the three different current asset financing policies.2. Briefly explain the advantages and disadvantages of short-term financing.3. List the four major types of short-term funds.4. Distinguish between free and costly trade credit, calculate both the nominal and effective annual percentage costs of not taking discounts, given specific credit terms, and explain what stretching accounts payable is and how it reduces the cost of trade credit.5. Describe the importance of short-term bank loans as a source of short-term financing and discuss some of the key features of bank loans.6. Calculate the effective interest rate for (1) simple interest, (2) discount interest, (3) add-on interest loans; and explain the effect of compensating balances on the effective cost of a loan.7. List some factors that should be considered when choosing a bank.8. Explain why large, financially strong corporations issue commercial paper, and why this source of short-term credit is typically less reliable than bank loans if the firm gets into financial difficulties.9. Define what a “secured” loan is and what type of collateral can be used to secure a loan.Chapter 17 Financing current assetsContents:1. Briefly explain the following terms: mission statement, corporate scope, corporate purpose, corporate objectives, and corporate strategies.2. Briefly explain what operating plans are.3. Identify the six steps in the financial planning process.4. List the advantages of computerized financial planning models over “pencil-and-paper” calculations.5. Discuss the importance of sales forecasts in the financial planning process, and why managers construct pro forma financial statements.6. Briefly explain the steps involved in the percent of sales method.7. Calculate additional funds needed (AFN), using both the projected financial statement approach and the formula method.8. Identify other techniques for forecasting financial statements discussed in the text and explain when they should be used.Part Ⅲ:Teaching MethodBased on the integrative problems of each chapter to lecture and discussPart ⅣGradingHomework assignments are due at the beginning of class following the class in which they are assigned, unless otherwise indicated. There will be a final exam and a project due at the end of the course. Class participation is expected and students will be called upon in class. Final grades are determined by the following formula:Grade =0.10(attendance)+0.10(homework) +0.10(quizzes) + 0.70(final)Part ⅤTextbook and Reference BooksTextbookEugene F. Brigham, and Joel F. Houston, Fundamentals of financial management9th edition by CITIC Publishing HouseReference BooksKeown, Martin, Petty, and Scott, Financial Management: Principles and Applications, Ninth Edition, Pearson Education, Inc., 2002Stephen A. Ross, Randolph W. Westerfield, and Bradford D. Jordan, Fundamentals of corporate finance (six edition) 2002 by China Machine Press.《公司理财精要》,斯蒂芬·罗斯等著,张建平译,人民邮电出版社,2003年1月《财务管理原理》,(英)理查德·布雷利(Richard A·Brealey)(美)斯图尔特·C·迈尔斯(Stewart C·Myers)机械工业出版社英文版原书第6版。

金融风险管理的定量分析方法

金融风险管理的定量分析方法金融市场的不确定性使得金融机构面临着各种风险,如信用风险、市场风险和操作风险等。

为了更好地管理这些风险,金融机构必须采用定量分析方法来评估和控制风险。

本文将介绍金融风险管理中常用的定量分析方法,并探讨其优缺点以及应用。

一、历史模拟法历史模拟法是金融风险管理中最常用的一种方法。

它基于历史数据来预测未来的风险水平。

具体而言,该方法通过收集历史数据,计算金融资产或投资组合的风险指标,如价值变动的标准差或风险价值(VaR),从而评估未来可能出现的风险水平。

优点:历史模拟法简单易懂,容易实施,可以基于真实数据进行分析和预测,能够捕捉到市场波动的历史趋势。

缺点:历史模拟法忽略了金融市场的非线性特征和复杂性,假设未来的市场行为与历史行为相似,但实际市场可能会发生结构性变化。

此外,历史模拟法依赖于历史数据,无法准确预测未来的风险。

二、蒙特卡洛模拟法蒙特卡洛模拟法是一种基于随机性的模拟方法,用于评估金融风险。

它通过生成大量的随机样本,模拟金融市场的潜在走势,从而计算投资组合的风险度量值,如VaR或条件VaR。

优点:蒙特卡洛模拟法可以考虑多种市场场景和可能性,能够更准确地评估风险。

它不仅可以估计风险水平,还可以提供概率分布信息,有助于决策者更好地理解风险。

缺点:蒙特卡洛模拟法计算复杂度高,需要生成大量的随机样本,消耗计算资源。

此外,模型的准确性依赖于输入变量的选择和分布假设,结果可能受到这些假设的影响。

三、基于统计方法的风险模型除了历史模拟法和蒙特卡洛模拟法外,还有许多基于统计方法的风险模型被广泛应用于金融风险管理中,如GARCH模型和ARIMA模型。

这些模型利用时间序列数据,通过建立数学模型来分析金融市场的波动性和风险传导机制。

优点:基于统计方法的风险模型可以更好地理解金融市场的动态特征,通过建立数学模型,能够更准确地预测和度量风险。

缺点:基于统计方法的风险模型需要对金融市场的数据进行假设和建模,假设可能会导致模型的不准确性。

Cash-Flow-Analysis

2024/2/9

9

w Analysis

Growth Consumes Ca$h!

• Increasing revenue with controlled expenses will result in increased profits

• Revenue increases also drive increases in operating assets

Sheets

2024/2/9

3

w Analysis

Business Challenges

• Earn Profits

• Convert Profits to Cash as Fast as Possible

2024/2/9

4

Cash Flow

• From Operating Activities

2024/2/9

Cash Flow Analysis

2

w Analysis

In case you missed the last session…….

We covered ………. • I&E • Balance Sheets • The linkages between I&E and Balance

Cash +Accounts Receivable +Inventory +Prepaid Expenses +Property, Plant & Equipment +Accumulated Depreciation = Total Assets

Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable + Accrued Operating Expenses + Accrued Interest Payable + Income Tax Payable + Notes Payable + Capital stock + Retained Earnings = Total Liability & Equity 2024/2/9

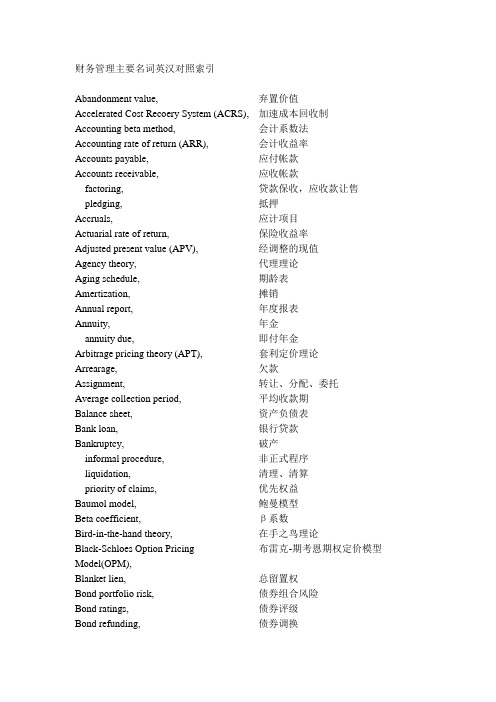

财务管理主要名词英汉对照索引

财务管理主要名词英汉对照索引Abandonment value, 弃置价值Accelerated Cost Recoery System (ACRS), 加速成本回收制Accounting beta method, 会计系数法Accounting rate of return (ARR), 会计收益率Accounts payable, 应付帐款Accounts receivable, 应收帐款factoring, 贷款保收,应收款让售pledging, 抵押Accruals, 应计项目Actuarial rate of return, 保险收益率Adjusted present value (APV), 经调整的现值Agency theory, 代理理论Aging schedule, 期龄表Amertization, 摊销Annual report, 年度报表Annuity, 年金annuity due, 即付年金Arbitrage pricing theory (APT), 套利定价理论Arrearage, 欠款Assignment, 转让、分配、委托Average collection period, 平均收款期Balance sheet, 资产负债表Bank loan, 银行贷款Bankruptcy, 破产informal procedure, 非正式程序liquidation, 清理、清算priority of claims, 优先权益Baumol model, 鲍曼模型Beta coefficient, β系数Bird-in-the-hand theory, 在手之鸟理论布雷克-期考恩期权定价模型Black-Schloes Option PricingModel(OPM),Blanket lien, 总留置权Bond portfolio risk, 债券组合风险Bond ratings, 债券评级Bond refunding, 债券调换Bond valuation, 债券评价Bond yield to call, 债券赎回收益Bond yield to maturity 债券到期收益Bonds, 债券call provision, 回购条款debenture, 信用债券floation rates, 浮动利率floation cost, 发行成本income, 收入indenture, 契约indexed, 指数化junk, 垃圾债券mortgage, 抵押redeemable at par, 可按票面值偿还restrictive covenants, 约束性条款sinking fund, 偿债基金subordinated debenture, 次级信用债券zero coupon, 零息票Breakeven analysis, 盈亏临界点或平衡点分析business risk, 商业或营业风险Call premium, 赎回溢价,买入溢价Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), 资本资产定价模型capital market line, 资本市场线market risk primium, 市场风险报酬riskless rate, 无风险利率security market line, 证券市场线Capital budgeting, 资本预算beta risk, β风险capital rationing, 资本合理分配(配置)cash flow estimation, 现金流量估计certainty equivalents, 确定等值equity residual method, 股本剩余法inflation adjustments, 通货膨胀调整internal rate of return(IRR) 内部收益率market risk, 市场风险Monet Carlo simulation, 蒙特卡罗模拟分析multiple IRRs, 多元内部收益率net present value(NPV) 净现值nonconstant capital costs, 非固定资本成本NPV profiles, NPV曲线optimal capital budget, 最优资本预算payback, 回收期profitablity index, 获利能力指数reinvestment assumtion, 再投资率假设replacement decision, 更新决策risk-adjusted discount rates, 风险调整折现率risk analysis, 风险分析scenario analysis, 方案分析sensitivity analysis 敏感度分析unequal lives, 不等年限Capital components, 资本要素Capital intensity, 资本密度Capital market line, 资本市场线Capital structure, 资本结构agency costs, 代理成本asymmertric information theory, 不对称消息理论finacial distress costs, 财务拮据成本Miller model 米勒模型Modigliani-Miller model, 莫迪格莱尼-米勒模型net income theory, 净收入理论net operating income theory, 净经营收入理论tradeoff model, 权衡模型traditional theory, 传统理论Cash flow cycle, 现金流量周期Cash management, 现金管理cash budget, 现金预算computer simulation, 计算机模拟concentration banking, 现金银行集中管理disbursement control, 现金支付控制lockboxes, 销箱法matching cost and benefit, 成本和收益配比Miller-Orr model, 米勒-奥罗模型pre-authorized debit, 事先核定记帐法target cash balance, 目标现金金额Characteristic line, 特征线Clientele effect, 股本构成效应Coefficient of variation, 变动系数Commercial bank loan, 商业银行信贷Commercial paper, 商业票据Common life, or replacement chain, 共同年限,或更新系列Common size analysis, 同型(百分率)分析Common stock, 普通股going public, 股份公众化listing, 挂牌,上市preemptive right, 优先认购权primary market, 一级市场rights offerings, 发行认股权secondary market, 二级市场Company-specific risk, 公司特定风险Compensating balances, 补偿性余额Compensating plans, 补偿计划Constant growth model, 固定增长模型Constant growth stock, 固定增长股票Continuous compouding and discountiing, 连续复利和贴现Continuous distribution, 连续分布Convertibles, 可转换证券Correlation coefficicent, 相关系数Cost of capital, 资本成本bond yield plus risk premium, 债券收益风险报酬capital components, 资本要素CAPM approach, CAPM方法debt, 债务、负债deferred taxes, 递延税depreciation-generated funds, 折旧基金equity, 股本、企业自有资本、股本权益investment opportunity schedule, 投资机会表marginal cost of capital schedule, 资本边际成本表preferred stock, 优先股加权平均资本成本weighted average cost ofcapital(WACC),Covariance, 协方差Coverage ratio, 偿债能力比率Credit instruments, 信用工具banker’s acceptance, 银行承兑commercial draft, 商业汇票conditional sales contract, 附条件的售货合同open account, 贸易帐户、往来帐户promissory note, 本票、期票sight draft, 即期汇票time draft, 远期汇票Credit plicy, 信用政策Credit reporting agencies, 信用报告代理人Credit scoring system, 信用评分制Current ratio, 流动比率Days sales outstanding, 销售未收款期Decision tree analysis, 决策树风析Default risk, 拖欠或违约风险Depreciable basis, 应计折旧基础Discounted cash flow analysis, 现金流量折现分析Discriminant function, 判别函数Diversifiable risk, 可分散、可消除风险Divestitures, 分离Divident policy, 股利政策constant payout ratio, 固定股利发放率constant, or steadily increasing divident, 固定或稳定增长的股利declaration date, 公告日期ex-divident date, 除息日holder - of - record date, 股票持有人登记日信息内涵(或信号)假设information content(or signaling)hypothesis,irrelevance theory, 无关理论low regular divident plus extra, 固定低股利加额外分红payment date, 发放日redidual policy, 剩余股利政策tax differential theory, 税差理论Divident reinvestment plans, 股利再投资计划Du Pont system of financial analysis, 杜邦财务分析体系Earning per share (EPS), 每股收益full diluted 完全权益稀释primary, 每股基本收益simple, 每股单纯收益Ecomomic ordering quantity (EPQ) 经济订货批量Effective annual rate, 实际年利率Efficient frontier, 有效边界Efficient Market Hypothesis, 有效市场假设Efficient portfolio, 有效投资组合Employee purchase plans, 雇员购股计划Equity multiplier, 权益乘数Equity portfolio risk, 股本组合风险Equity residual method, 股本剩余理论Equivalent annual annuity method, 等值年金法Eurobond, 欧洲债券Exchange rate. 汇率Exercise price, 行使价Expected rate of return, 期望收益率Financial forcasting, 财务预测percentage of sales method, 销售百分率法Financial lease, 财务租赁Financial leverage, 财务杠杆Financial statement, 财务报表Financial policies, 财务政策aggressive approach, 激进方法conservative approach, 保守方法maturity matching, 到期配合Future value, 将来值Futures, 期货commodity, 商品contract, 合同、合约hedging, 套期Global market portfolio, 全球市场投资组合Gordon model, 戈登模型Holding company, 控股公司Hostile takeover, 恶意兼并Immunization, 免除风险duration, 持续期Rebalanced bond portfolios, 重新平衡后的债券组合Income statement, 收益表Incremental analysis, 增量分析Indifference curve, 无差异曲线Interest rates, 利息率pure rate, 纯利率real rate, 实际利率Inventory, 存货carrying costs, 库存成本FIFO 先进先出法LIFO 后进先出法ordering costs, 订货成本order point, 订货点quantity discount, 数量折扣safety stock, 安全存货specific identification, 个别鉴定法Investment banking, 投资银行competitive bid, 竞争性投标negotiated deal, 协商交易offering price, 开盘价,要价selling group, 推销集团underwriting syndicate, 联合认购unsyndicated stock offering, 非联合股票发行Investment tax credit (ITC), 投资税减免Joint venture, 合资Lease financing, 租赁筹资financial (or capital) leases, 财务(或资本性)租赁leasee, 承租人leasor, 出租人leveraged lease, 杠杆式租赁operating lease, 经营租赁Leverage buyout, 举债(杠杆式)收购Line of credit, 信贷限额Liquidity, 流动性Liquidation, 清算Long-term debt, 长期负债amortization, 摊销floating rate bond, 浮动利率债券income bond, 收益债券mortgage bond, 抵押债券secured, 有担保的term loan, 银行贷款warrants, 认购权Marketable security, 有价证券Mean-variance paradox, 均值-方差悖论Mergers, 兼并accounting treatment, 会计处理congeneric, 同属兼并conglomerate, 综合性企业集团diversification, 多样化经营horizontal, 横向兼并synergy, 协同效应tender offer, 股权收购vertical, 纵向兼并Multiple discriminant anslysis, 多元判断分析Net working capital, 净营运资本Norminal yield, 名义收益Nondiversifiable risk, 不可分散风险Nonnormal capital priojects, 非正常资本项目Operating leverage, 经营杠杆Opportunity cost principle, 机会成本原理Optimal capital budget, 最优资本预算Options, 选择权、期权call, 买权put, 卖权Payment pattern approach, 支付方式法Pension plan management, 退休金计划管理actuarial rate of return, 保险收益率defined benefit plan, 确定退休金计划defined contribution plan, 确定退休金拨付计划performance measurement, 经营成果衡量portability, 可携性profit sharing plan, 分红制退休金tapping assets, 退休金资产开发vesting, 既得、归属Performance shares, 绩优股Positive concept, 实证概念Preemptive rate, 优先认购权Prime rate, 靠优惠利率,基本利率Private placement, 私幕,私下包销Probability, 概率discrete distribution, 散点分布normal distribution, 正态分布triangular distribution, 三角分布uniform distribution, 均匀分布Proxy fight, 代理权Public offering, 公开发价Pourchasing power risk, 购买力风险Pure play method, 单一经营法Ratio analysis, 比率分析Redeemable bonds, 可偿还债券Rights, 股权ex rights, 除权offering, 发价Risk/return trade-off, 风险/收益权衡Stockholder wealth maximization, 股东价值最大化Standard deviation, 标准离差Stated yield, 报告收益Specific item forcasting, 具体项目预测Stock splits, 股份分割Striking price, 协定价Sunk costs, 沉没成本Systematic risk, 系统风险Time-interest-earned (TIE) ratio, 已获利息倍数,利息保障倍数Time value of money, 货币的时间价值Total risk, 总风险Trade credit, 商业信用Trustee, 受托管理人Unsecured bond, 无担保债券Z score, Z评分法。

分析师现金流预测、盈余预测准确度与估值效应

05

结论与建议

对分析师的结论与建议

建议

关注行业动态和市场走势,及时 调整预测模型和参数。

结论:分析师在进行现金流预测 和盈余预测时,应充分考虑企业 的经营状况、行业趋势和市场环 境,以提高预测的准确度。

深入研究企业财务报表和相关公 告,了解企业财务状况和经营成 果。

加强与企业管理层的沟通,了解 企业未来发展战略和计划。

结论:企业应重视分析师的现金 流预测和盈余预测,并根据预测 结果及时调整经营策略和管理措 施。

加强企业财务管理和信息披露, 提高财务报表透明度。

关注市场反馈和投资者需求,及 时调整业务结构和经营模式。

加强与分析师的沟通合作,共同 推动企业价值的合理评估。

THANKS

谢谢您的观看

分析师现金流预测、盈余预 测准确度与估值效应

汇报人: 2023-12-30

目录

• 引言 • 分析师现金流预测准确度 • 盈余预测准确度 • 现金流预测、盈余预测准确度

与估背景

1

现金流预测和盈余预测是投资者进行投资决策的 重要依据。

2

分析师的预测准确度对于投资者来说具有重要意 义。

03

盈余预测准确度

盈余预测方法

基础分析法

基于公司财务报表和公开信息,通过财务比率、趋势分析等手段 预测未来盈余。

收益模型法

利用统计学和计量经济学模型,通过历史数据预测未来盈余。

专家预测法

依靠行业专家或资深分析师的经验和判断预测未来盈余。

盈余预测准确度的影响因素

信息披露质量

公司财务报表和公开信息的质量直接影响分 析师预测的准确性。

盈余预测的持续性对估值效应的影响

持续的盈余预测能够增强投资者对公司的信心,从而提高公司估值。

cashflows 估值计算方法

cashflows 估值计算方法现金流量估值计算方法估值是金融领域中非常重要的概念,它用于确定某个资产或企业的价值。

现金流量估值是一种常见的计算方法,它通过对未来现金流量进行预测和折现,来确定资产或企业的价值。

本文将介绍现金流量估值的基本概念和具体计算方法。

一、现金流量估值的基本概念现金流量估值是一种将未来现金流量进行预测和折现的方法,通过计算资产或企业未来一段时间内的现金流量,然后将这些现金流量按照适当的折现率进行折现,最终确定资产或企业的价值。

现金流量估值的基本概念包括未来现金流量、折现和计算期限。

1. 未来现金流量未来现金流量是指企业在未来一段时间内所预计产生的现金流入和现金流出。

通常,未来现金流量可以分为两类:现金流入和现金流出。

现金流入包括企业未来的收入、资本回收和收回投资等。

现金流出包括企业未来的成本、支出和投资等。

准确预测未来现金流量是现金流量估值的核心。

2. 折现折现是将未来的现金流量按照适当的折现率进行调整,得到可比较的现值。

折现的目的是考虑时间价值的影响,因为未来的现金流量具有不确定性,而现金流量的价值在经济上是与时间相关的。

折现率通常由风险和收益要求来确定,折现率越高,资产或企业的价值越低。

3. 计算期限计算期限是指在估值计算中所考虑的时间范围。

计算期限可以是短期、中期或长期,具体取决于估值的目的和需要。

通常,短期的估值主要考虑近期的现金流量,中长期的估值则需要考虑未来几年的现金流量,特别是对于企业估值来说。

二、现金流量估值的计算方法现金流量估值的计算方法包括净现值法、内部收益率法和收益倍数法。

这些方法在实际应用中可以相互结合,根据具体情况选择适合的计算方法。

1. 净现值法净现值法是一种常用的现金流量估值方法,它通过计算未来现金流量的现值减去投资的成本,来确定资产或企业的净现值。

具体计算公式如下:净现值= Σ(未来现金流量/(1+折现率)^n) - 投资成本其中,Σ表示求和,n表示未来现金流量发生的期数。

评价财务风险的方法

评价财务风险的方法财务风险评价的方法1、单变量判定模型。

这种方法用单一的财务比率来评价企业财务风险,依据是:企业出现财务困境时,其财务比率和正常企业的财务比率有显著差别。

一般认为,比较重要的财务比率是:现金流量/负债总额、资产收益率、资产负债率。

单变量模型将财务指标用于风险评价是一大进步,指标单一,简单易行,但是不可避免会出现评价的片面性。

这种方法在人们开始认识财务风险时采用,但随着经营环境的日益复杂、多变,单一的指标已不能全面反映企业的综合财务状况。

2、多元线性评价模型。

它的形式是:Z=1.2x1+1.4x2+3.3x3+0.6x4+0.999x5.Z:判别函数值;x1:营运资金/资产总额;x2:留存收益/资产总额;x3:息税前利润/资产总额;x4:普通股和优先股市场价值总额/负债账面价值总额;x5:销售收入/资产总额。

Z值应在1.81~2.99之间,Z=2.675时居中。

Z>2。

675时,企业财务状况良好;Z<1.81时,企业存在很大的破产风险;Z值处于1.81~2.99之间,称为“灰色地带”,这个区间的企业财务极不稳定。

多元线性模型在单一式的基础上趋向综合,且把财务风险概括在某一范围内,这是它的突破,但仍没有考虑企业的成长能力,同时它的假设条件是变量服从多元正态分布,没有解决变量之间的相关性问题。

这种方法在现实中比较常见。

3、综合评价法。

这种方法认为,企业财务风险评价的内容主要是盈利能力,其次是偿债能力,此外还有成长能力,它们之间大致按5∶3∶2来分配。

盈利能力的主要指标是资产净利率、销售净利率、净值报酬率,按2∶2∶1安排分值;偿债能力有4个常用指标:自有资金比率、流动比率、应收账款周转率、存货周转率,分值比为1;成长能力有3个指标:销售增长率、净利增长率、人均净利增长率,分值比为1,总分为100分。

这里的关键是确定标准评分值和标准比率,需要经过长时间实践,主观性比较强。

这种方法以及下面的概率模型在应用中很普遍。

财务风险评估的方法与工具

财务风险评估的方法与工具财务风险评估是企业在资金运作过程中不可忽视的重要环节之一,它可以帮助企业及时发现并有效应对潜在的财务风险,确保企业稳健运行。

在这篇文章中,我们将探讨财务风险评估的方法与工具。

一、财务风险评估的方法1. 定性分析法定性分析法通过主观判断和经验总结对企业财务风险进行评估。

评估者需要结合企业的财务报表、市场情况、行业发展趋势等因素,综合考虑经营环境、管理层能力、行业竞争等因素,评估企业面临的财务风险程度。

这种方法的优势在于能够充分考虑企业的具体情况,但在客观性和准确性上可能存在一定的不足。

2. 定量分析法定量分析法通过数据分析和统计模型对企业的财务风险进行量化评估。

常用的定量分析方法包括财务比率分析、财务模型建立、风险值计算等。

这种方法的优势在于能够提供定量的风险评估结果,减少主观因素的干扰,但也需要充分的数据支持和准确的模型建立。

3. 综合分析法综合分析法是将定性分析法和定量分析法相结合,综合考虑各种因素对于财务风险的影响。

评估者可以先进行定性分析,然后再运用定量方法进行数据分析和模型建立,最后进行综合评估。

这种方法可以充分利用定性和定量分析的优势,提高评估的准确性和可靠性。

二、财务风险评估的工具1. 财务比率分析财务比率分析是最常用的财务风险评估工具之一,通过分析企业的财务指标,如偿债能力、盈利能力、营运能力等,评估企业的财务状况和财务风险。

常用的财务比率包括流动比率、速动比率、负债比率、资产收益率等。

2. 敏感性分析敏感性分析是通过对影响企业财务风险的关键因素进行变动,评估这些变动对于企业经营业绩和财务状况的影响程度。

通过敏感性分析,企业可以了解各种因素对于风险程度的敏感性,以及对应的风险应对策略。

3. 财务模型建立财务模型可以帮助企业模拟和预测不同的财务风险情景,并评估企业在这些情景下的风险承受能力。

常用的财务模型包括财务风险价值计算模型、盈利风险模型、行业发展模型等。

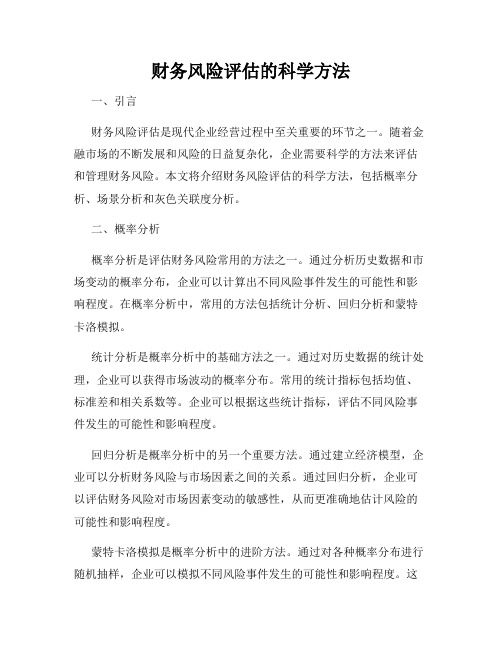

财务风险评估的科学方法

财务风险评估的科学方法一、引言财务风险评估是现代企业经营过程中至关重要的环节之一。

随着金融市场的不断发展和风险的日益复杂化,企业需要科学的方法来评估和管理财务风险。

本文将介绍财务风险评估的科学方法,包括概率分析、场景分析和灰色关联度分析。

二、概率分析概率分析是评估财务风险常用的方法之一。

通过分析历史数据和市场变动的概率分布,企业可以计算出不同风险事件发生的可能性和影响程度。

在概率分析中,常用的方法包括统计分析、回归分析和蒙特卡洛模拟。

统计分析是概率分析中的基础方法之一。

通过对历史数据的统计处理,企业可以获得市场波动的概率分布。

常用的统计指标包括均值、标准差和相关系数等。

企业可以根据这些统计指标,评估不同风险事件发生的可能性和影响程度。

回归分析是概率分析中的另一个重要方法。

通过建立经济模型,企业可以分析财务风险与市场因素之间的关系。

通过回归分析,企业可以评估财务风险对市场因素变动的敏感性,从而更准确地估计风险的可能性和影响程度。

蒙特卡洛模拟是概率分析中的进阶方法。

通过对各种概率分布进行随机抽样,企业可以模拟不同风险事件发生的可能性和影响程度。

这种方法能够更全面地考虑各种不确定性因素,提供更准确的风险评估结果。

三、场景分析场景分析是另一种常用的财务风险评估方法。

与概率分析不同,场景分析通过制定不同的情景来评估财务风险。

企业可以根据不同的市场变动、政策变化或竞争态势等因素,构建不同的场景,模拟风险事件对企业的影响。

在进行场景分析时,企业需要考虑到各种可能的情景,并评估每个情景发生的可能性和影响程度。

通过对不同情景的分析,企业可以更全面地了解各种风险的可能性和潜在影响,制定相应的风险管理措施,提高企业对财务风险的抵御能力。

四、灰色关联度分析灰色关联度分析是一种综合评估方法,可以帮助企业评估不同因素对财务风险的影响程度。

该方法通过计算不同因素之间的相关性,确定对财务风险影响最大的因素。

在进行灰色关联度分析时,企业首先需要确定相关因素和评估指标。

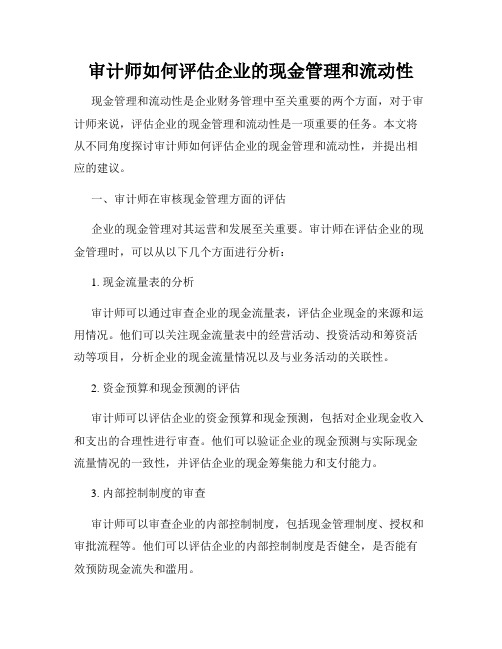

审计师如何评估企业的现金管理和流动性

审计师如何评估企业的现金管理和流动性现金管理和流动性是企业财务管理中至关重要的两个方面,对于审计师来说,评估企业的现金管理和流动性是一项重要的任务。

本文将从不同角度探讨审计师如何评估企业的现金管理和流动性,并提出相应的建议。

一、审计师在审核现金管理方面的评估企业的现金管理对其运营和发展至关重要。

审计师在评估企业的现金管理时,可以从以下几个方面进行分析:1. 现金流量表的分析审计师可以通过审查企业的现金流量表,评估企业现金的来源和运用情况。

他们可以关注现金流量表中的经营活动、投资活动和筹资活动等项目,分析企业的现金流量情况以及与业务活动的关联性。

2. 资金预算和现金预测的评估审计师可以评估企业的资金预算和现金预测,包括对企业现金收入和支出的合理性进行审查。

他们可以验证企业的现金预测与实际现金流量情况的一致性,并评估企业的现金筹集能力和支付能力。

3. 内部控制制度的审查审计师可以审查企业的内部控制制度,包括现金管理制度、授权和审批流程等。

他们可以评估企业的内部控制制度是否健全,是否能有效预防现金流失和滥用。

二、审计师在评估企业流动性方面的考虑企业的流动性是指企业能够满足其短期债务和经营需求的能力。

审计师在评估企业的流动性时,可以从以下几个方面进行考虑:1. 资产负债表的分析审计师可以通过审查企业的资产负债表,评估企业的流动性状况。

他们可以关注企业的流动资产和流动负债,计算和比较各项比率指标,如流动比率、速动比率等,以评估企业的流动性水平。

2. 应收账款和应付账款的审计审计师可以审计企业的应收账款和应付账款,评估企业的应收账款回收和应付账款支付的情况。

他们可以验证账款的真实性和准确性,评估企业的客户信用风险和供应链风险。

3. 银行贷款和信用额度的审查审计师可以审查企业的银行贷款和信用额度,评估企业的借款能力和信用状况。

他们可以验证企业的贷款协议和合同,并评估企业的还款能力和担保能力。

三、审计师评估现金管理和流动性时的建议在审计师评估企业的现金管理和流动性时,可以考虑以下建议:1. 深入了解企业的业务模式和运营情况,把握企业的现金流量特点和规律。

国外财务风险与对策的主要研究方法

国外财务风险与对策的主要研究方法

国外财务风险是指企业在海外经营过程中所面临的各种可能对其财务状况产生不利影响的不确定性因素。

为了有效应对和管理这些风险,研究人员一直在努力探索相应的研究方法。

以下是国外财务风险与对策研究的主要方法:

1. 文献综述:这是一种通过研究相关领域的文献来了解国外财务风险与对策的主要方法。

通过对已有研究的回顾和综合分析,可以了解已有研究的主要结论和方法,从而为新的研究提供启示和指导。

2. 实证研究:这种研究方法通过采集实际数据,运用统计分析等方法来验证或推翻已有理论假设,从而获得与国外财务风险与对策相关的实证研究结论。

实证研究方法可以进一步增进我们对国外财务风险及其对策的理解。

3. 案例研究:这种研究方法通过深入研究具体企业或国家的财务风险问题,了解其所面临的风险因素、应对策略和效果。

案例研究方法可以提供实践中的经验教训,并为其他企业或国家的决策者提供借鉴。

4. 资料分析:这是一种通过收集和分析相关的统计数据、报告和财务报表等材料来研究国外财务风险与对策的方法。

通过对这些资料的梳理和分析,可以揭示不同国家或地区的财务风险因素和对策特点。

5. 模型建立:这种研究方法通过构建数学模型来模拟和研究国外财务风险与对策。

这些模型可以通过假设和参数的设定,模拟实际情况中可能发生的风险,并研究不同对策的效果。

模型建立方法可以帮助我们更好地理解国外财务风险的本质和影响因素。

综上所述,国外财务风险与对策的研究方法涵盖文献综述、实证研究、案例研究、资料分析和模型建立等多种途径。

这些方法互相补充和交叉验证,可以帮助我们更加全面地了解和应对国外财务风险。

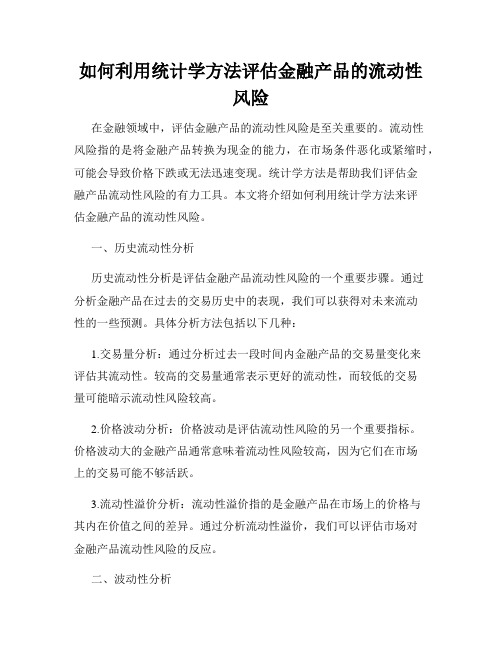

如何利用统计学方法评估金融产品的流动性风险

如何利用统计学方法评估金融产品的流动性风险在金融领域中,评估金融产品的流动性风险是至关重要的。

流动性风险指的是将金融产品转换为现金的能力,在市场条件恶化或紧缩时,可能会导致价格下跌或无法迅速变现。

统计学方法是帮助我们评估金融产品流动性风险的有力工具。

本文将介绍如何利用统计学方法来评估金融产品的流动性风险。

一、历史流动性分析历史流动性分析是评估金融产品流动性风险的一个重要步骤。

通过分析金融产品在过去的交易历史中的表现,我们可以获得对未来流动性的一些预测。

具体分析方法包括以下几种:1.交易量分析:通过分析过去一段时间内金融产品的交易量变化来评估其流动性。

较高的交易量通常表示更好的流动性,而较低的交易量可能暗示流动性风险较高。

2.价格波动分析:价格波动是评估流动性风险的另一个重要指标。

价格波动大的金融产品通常意味着流动性风险较高,因为它们在市场上的交易可能不够活跃。

3.流动性溢价分析:流动性溢价指的是金融产品在市场上的价格与其内在价值之间的差异。

通过分析流动性溢价,我们可以评估市场对金融产品流动性风险的反应。

二、波动性分析波动性是评估金融产品流动性风险的另一个重要方面。

波动性是指金融产品价格的变动幅度。

波动性分析可以帮助我们判断金融产品的流动性风险以及在不同市场条件下的表现。

1.历史波动率分析:历史波动率是通过分析金融产品价格的历史数据计算得出的。

较高的历史波动率通常意味着流动性风险较高。

2.隐含波动率分析:隐含波动率是根据市场上的期权价格计算得出的。

通过分析隐含波动率,我们可以了解市场对金融产品未来波动性的预期。

三、回归分析回归分析是一种常用的统计学方法,可以帮助我们了解流动性风险与其他因素之间的关系。

通过回归分析,我们可以找到对金融产品流动性风险有显著影响的变量,并作出相应的预测。

1.多元回归分析:多元回归分析可以帮助我们确定多个变量对金融产品流动性风险的影响。

通过多元回归分析,我们可以建立一个模型来预测金融产品的流动性风险,并进行风险控制。

公司财务风险评估的关键指标与模型

公司财务风险评估的关键指标与模型一、引言公司财务风险评估是在企业经营过程中非常重要的一项工作。

对于企业而言,财务风险可能涉及到盈利能力、偿债能力、流动性、市场竞争力等多个方面。

本文将介绍公司财务风险评估的关键指标与模型,帮助企业提前预警、规避风险。

二、关键指标1.资产负债率资产负债率是衡量企业财务风险的重要指标之一。

它反映了企业自有资本与债务的比例,即企业的债务风险。

较高的资产负债率可能会导致企业偿债困难,增加财务风险。

2.流动比率流动比率是企业流动性的度量指标,它计算了企业短期偿债能力。

较高的流动比率代表企业有更大的偿债能力,减少了短期偿债风险。

3.盈利能力指标盈利能力是企业财务状况的一个重要方面。

净利润率、毛利润率和营业利润率是评估企业盈利能力的关键指标。

较低的盈利能力可能表明企业存在经营不善或市场竞争压力较大的风险。

4.现金流量指标现金流量是核心财务指标之一,它可以反映企业现金的流入和流出情况。

企业若面临现金流量短缺的风险,则可能会导致偿债困难、无法支付员工和供应商等问题。

5.股东权益比率股东权益比率是衡量企业财务稳定性的指标之一,它反映了企业自有资本与总资产的比例。

较高的股东权益比率代表企业财务状况相对稳定,降低了财务风险。

三、评估模型1.Altman Z-Score模型Altman Z-Score模型是一种常用的评估企业破产风险的模型。

它通过将企业的财务指标进行加权计算,得出一个综合的评分,根据评分来判断企业是否面临破产风险。

Altman Z-Score模型被广泛应用于企业财务风险评估中。

2.巴舍克模型巴舍克模型是一种用于评估企业财务风险的定量模型。

它通过考虑企业的财务状况、市场竞争力和盈利能力等因素,综合计算出一个风险指数,用于衡量企业的财务风险水平。

巴舍克模型的使用可以更全面地评估企业的财务风险。

3.违约概率模型违约概率模型是一种常用的评估企业违约风险的模型。

它通过分析企业财务数据、行业情况和宏观经济环境等因素,计算出企业的违约概率。

经济风险的定量分析方法

经济风险的定量分析方法经济风险是企业和个人在经济活动中不可避免的问题,为了更好地应对和规避经济风险,定量分析方法是不可或缺的,本文将从以下几个方面展开讨论经济风险的定量分析方法。

一、风险的概念与分类首先,我们需要了解风险的概念和分类。

风险是指在预测未来的活动中出现可能的损失或不确定性的可能性,而风险可以分为市场风险、信用风险、操作风险、流动性风险等多种不同的类型。

对于不同类型的风险,我们需要选择不同的定量分析方法。

二、正态分布法正态分布法是一种经典的定量分析方法,常用于市场风险和信用风险的分析。

该方法基于正态分布函数(即高斯函数),通过对历史数据的分析来预测未来可能出现的损失或收益。

该方法在数据分布近似正态时效果较好,但在极端事件等非正态分布情况下不适用。

三、蒙特卡洛模拟法蒙特卡洛模拟法是一种计算机模拟方法,可以用于各种形式的风险分析,如市场风险、操作风险等。

该方法基于随机数生成和数学模型,通过模拟多次随机事件的结果来预测未来的风险和利润。

由于蒙特卡洛模拟法可以模拟各种不同的风险情况,因此在应对复杂的风险问题时较适用。

四、价值-at-风险(VaR)方法VaR方法是一种较新的定量风险分析方法,用来度量投资组合或企业在一定置信水平下可能遭受的最大损失。

该方法基于统计学方法和数据挖掘技术,可以在较短的时间内进行快速筛选和分析。

然而,VaR方法的缺陷是无法提供有关风险事件的概率分布等更细致的信息,因此在风险多样化与风险分散程度较高的投资组合或企业较适用。

五、格雷方法格雷方法是一种全新的定量风险分析方法,是一种基于智能算法的综合性方法。

它定义了一系列权重和关系模型,利用数学、经济等多个领域的知识进行风险度量、风险预测等分析。

格雷方法由于其灵活性和适应性,逐渐成为了应对市场风险和信用风险等复杂风险问题的理想方式。

综上所述,定量风险分析方法是企业和个人应对经济风险不可或缺的手段。

不同的风险种类适用的定量分析方法也各不相同。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

3

$200 -120 -36

44 18 26 36 62

4

$200 -120 -17

63 25 38 17 55

Net Terminal CF at t = 4:

Recovery of NOWC $20

Salvage Value

25

Tax on SV (40%)

-10

Net termination CF $35

Yes. The effect on other projects’ CFs is an “externality.”

Net CF loss per year on other lines would be a cost to this project.

Externalities can be positive or negative, i.e., complements or substitutes.

Inventories will rise by $25,000 and payables by $5,000.

Economic life = 4 years. Salvage value = $25,000. MACRS 3-year class.

Sales: 100,000 units/year @ $2. Variable cost = 60% of sales. Tax rate = 40%. WACC = 10%.

Q. Always a tax on SV? Ever a positive tax number?

Q. How is NOWC recovered?

Should CFs include interest expense? Dividends?

No. The cost of capital is accounted for by discounting at the 10% WACC, so deducting interest and dividends would be “double counting” financing costs.

Operating cash flows:

1

Revenues

$200

Op. Cost, 60% -120 Depreciation -79

Oper. inc. (BT) 1

Tax, 40%

--

Oper. inc. (AT) 1

Add. Depr’n 79

Op. CF

80

2

$200 -120 -108 -28 -11 -17 108

Equipment

-$200

Installation & Shipping Increase in inventories Increase in A/P

Net CF0

-40 -25

5 -$260

DNOWC = $25 – $5 = $20.

What’s the annual depreciation?

Here are all the project’s net CFs (in thousands) on a time line:

0

1

2

k = 10%

3

4

-260 79.7 91.2

62.4

54.7

Terminal CF

35.0

89.7

Enter CFs in CF register, and I = 10%.

Suppose the plant could be leased out for $25,000 a year. Would this affect the analysis?

Yes. Accepting the project means foregoing the $25,000. This is an opportunity cost, and it should be charged to the project.

Set up, without numbers, a time line for the project’s cash flows.

0

Initial Costs (CF0)

1 OCF1

2 OCF2

NCF0

NCF1

NCF2

3

4

OCF3 NCF3

OCF4

+ Terminal

CF

NCF4

Investment at t = 0:

NPV = -$4.03 IRR = 9.3%

What’s the project’s MIRR?

0

1

2

3

4

-260 -260

79.7

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

91.2

62.4

Suppose $50,000 had been spent last year to improve the building. Should this cost be included in the analysis?

No. This is a sunk cost. Analyze incremental investment.

CHAPTER 12

Cash Flow Estimation and Risk Analysis

Relevant cash flows Incorporating inflation Types of risk

Proposed Project

Cost: $200,000 + $10,000 shipping + $30,000 installation. Depreciable cost: $240,000.

A.T. opportunity cost = $25,000(1 – T) = $25,000(0.6) = $15,000 annual cost.

If the new product line would decrease sales of the firm’s other lines, would this affect the analysis?

Year Rate x Basis Depreciation

1 0.33 2 0.45 3 0.15 4 0.07

1.00

$240 240 240 240

$ 79 108 36 17

$240

Due to 1/2-year convention, a 3-year asset is depreciated over 4 years.