presentation on microglia

微观形貌观察英文作文高中

微观形貌观察英文作文高中英文:Microscopic observation is an essential part of scientific research in various fields, including biology, chemistry, and material science. In my opinion, it is fascinating to observe the microscopic morphology of different objects and materials, as it reveals the hidden structure and properties that cannot be seen by the naked eye.For instance, when I observed the surface of a butterfly wing under a scanning electron microscope, I was amazed by the intricate patterns and textures that were invisible to the human eye. The wing surface was covered with tiny scales, which were arranged in a precise and orderly manner, creating a beautiful and unique pattern. The microscopic observation of the butterfly wing not only revealed its aesthetic value but also provided insights into its functional properties, such as water repellencyand light reflection.Similarly, when I examined the surface of a metal alloy using transmission electron microscopy, I was able to see the crystal structure and defects at the atomic level. This allowed me to understand the mechanical properties and deformation behavior of the material, which is crucial for designing and optimizing its performance in various applications.Overall, microscopic observation is a powerful tool for scientific research, enabling us to explore and understand the hidden world of microstructures and properties. It is a fascinating and rewarding experience that requires patience, skill, and curiosity.中文:微观形貌观察是各个领域科学研究中不可或缺的一部分,包括生物学、化学和材料科学等。

仿生科技演讲稿英语范文

仿生科技演讲稿英语范文Bionics, as an emerging interdisciplinary field, has been making significant strides in recent years. It integrates biology and engineering to develop innovative technologies that mimic natural systems. Today, I am honored to speak to you about the exciting advancements in bionic technology and its potential impact on the future.First and foremost, bionic technology has revolutionized the medical field. Prosthetic limbs, for example, have become more advanced and functional, allowing amputees to regain mobility and independence. The development of bionic organs and tissues also holds great promise for the treatment of various medical conditions. By replicating the structure and function of natural biological systems, bionic technology has the potential to improve the quality of life for countless individuals.In addition to its medical applications, bionic technology has also made significant contributions to the field of robotics. By drawing inspiration from nature, engineers have been able to design robots with enhanced agility, dexterity, and adaptability. These bio-inspired robots are capable of navigating complex environments, performing delicate tasks, and even interacting with humans in more natural ways. As a result, bionic technology is reshaping the landscape of automation and has the potential to revolutionize industries such as manufacturing, healthcare, and agriculture.Furthermore, bionic technology has paved the way for the development of innovative materials and structures. By studying natural biological systems, researchers have been able to create materials that are stronger, more flexible, and more durable than traditional synthetic materials. These biomimetic materials have the potential to transform various industries, from construction and aerospace to fashion and consumer goods. Additionally, the integration of bionic principles into architecture and design has led to the creation of more sustainable and environmentally friendly solutions.Looking ahead, the future of bionic technology is filled with endless possibilities. As our understanding of biology and engineering continues to advance, we can expect to see even more groundbreaking innovations in the field of bionics. From the development ofadvanced neural interfaces to the creation of fully autonomous bio-inspired systems, the potential applications of bionic technology are truly limitless.In conclusion, bionic technology represents a convergence of biology and engineering that has the power to transform the world as we know it. From its impact on healthcare and robotics to its influence on materials and design, bionic technology is reshaping the way we approach innovation and problem-solving. As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible, the future of bionics holds tremendous promise for improving the human experience and advancing society as a whole. Thank you.。

脸上的微生物英文演讲稿

脸上的微生物英文演讲稿以下是一篇关于“脸上的微生物”的英文演讲稿,供您参考:Ladies and gentlemen,Today, I am going to talk about the microorganisms on our faces. Our faces are constantly covered by a variety of microorganisms, some of which are beneficial while others may cause harm. Understanding the composition and function of these microorganisms is crucial for maintaining our health and skin well-being.Firstly, let’s take a look at the types of microorganisms found on our faces. There are over 100 species of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that call our faces their home. The distribution of these microorganisms varies from person to person and depends on a range of factors such as genetics, environment, and personal hygiene habits.One of the most common types of bacteria found on the face is Propionibacterium acnes. This bacteria is known to play a role in the development of acne vulgaris, commonly known as “acne”. However, Propionibacterium acnes is not the only bacteria that can cause acne. Other species such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes can also be involved in the development of this skin condition.On the other hand, there are also beneficial microorganisms on our faces. One example is the yeast strain known as Malassezia globosa. This yeast is believed to have anti-inflammatory properties and can help protect the skin from harmful microorganisms.Now that we have a better understanding of the types of microorganisms on our faces, let’s move on to discuss their function and how they impact our health. Microorganisms on our faces can influence our skin in a number of ways. For example, some bacteria can help to protect our skin from harmful external factors such as UV rays and environmental toxins. In addition, some species can also help to maintain the acidity of the skin surface, which helps to keep the skin healthy and hydrated.Moreover, the presence of certain microorganisms can also trigger an immune response in our bodies, helping us to fight off harmful invaders. However, if the balance of these microorganisms is disturbed, it can lead to various skin problems such as acne, rosacea, or psoriasis.To maintain a healthy balance of microorganisms on our faces, it is important to practice good hygiene habits. Regularly washing your face with warm water and mild soap can help to remove excess oil, dirt, and dead skin cells that can clog pores and lead to the development of acne.In conclusion, our faces are home to a diverse community of microorganisms that play both harmful and beneficial roles in our health. Understanding the types and functions of these microorganisms is crucial for maintaining a healthy complexion. By practicing good hygiene habits and adopting an anti-inflammatory diet, we can help to support the balance of microorganisms on our faces and promote healthy, glowing skin. Thank!。

micro-ch17-presentation

OLIGOPOLY

2

Concentration Ratios in Selected U.S. Industries

Industry Video game consoles Tennis balls Credit cards Batteries Soft drinks Web search engines Breakfast cereal Cigarettes Greeting cards Beer Cell phone service Autos Concentration ratio 100% 100% 99% 94% 93% 92% 92% 89% 88% 85% 82% 79%

CHAPTER

17

Oligopoly

Microeonomics

N. Gregory Mankiw

Premium PowerPoint Slides by Ron Cronovich

2009 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning, all rights reserved

OLIGOPOLY

EXAMPLE: Cell Phone Duopoly in Smalltown

P $0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 Q 140 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 50

5

Smalltown has 140 residents The “good”: cell phone service with unlimited anytime minutes and free phone Smalltown’s demand schedule Two firms: T-Mobile, Verizon (duopoly: an oligopoly with two firms) Each firm’s costs: FC = $0, MC = $10

presentation部分的作用和如何实现这部分的教学

presentation部分的作用和如何实现这部分的教学一、引言在当今的教育环境中,Presentation已经成为一项重要的学习技能。

它不仅是传达信息的一种方式,更是培养学生沟通、协作和公众演讲能力的手段。

因此,了解Presentation的作用并掌握其实现方法,对于提高学生的综合素质具有重要意义。

二、Presentation的作用1. 信息共享:Presentation为学生提供了一个平台,让他们可以与他人分享自己的研究、理解和发现。

通过有效的口头表达,学生能够更好地组织并传达自己的思想。

2. 沟通能力:一个成功的Presentation需要良好的沟通技巧。

学生需要理解观众的需求,清晰地表达自己的观点,并回答可能的问题。

这有助于提高学生的沟通技巧。

3. 自信心建立:公众演讲往往让人感到紧张,但通过练习和经验积累,学生可以克服这种紧张感,增强自信心。

4. 团队协作:在小组项目中,学生需要与队友协作,分配任务,这有助于培养学生的团队协作能力。

三、如何实现Presentation的教学1. 明确教学目标:教师需明确Presentation的教学目标,是提高学生的沟通能力、公众演讲技巧还是信息组织能力。

2. 制定教学计划:根据教学目标,制定详细的教学计划,包括教学内容、教学方法和评估标准。

3. 激活学生的前知:了解学生已有的知识和经验,以便更好地引导他们进行Presentation。

4. 教学策略选择:选择适合的教学策略,如小组讨论、案例分析或角色扮演等。

5. 练习与反馈:为学生提供充足的练习机会,并给予及时反馈,帮助他们改进。

6. 评估与反思:制定评估标准,对学生的Presentation进行评估,并反思教学方法,以便进一步提高教学效果。

四、结论Presentation在教育中的作用不容忽视。

它不仅能够提高学生的沟通能力、自信心和团队协作能力,还有助于培养学生的综合素质。

为了实现良好的Presentation教学效果,教师需要明确教学目标、制定教学计划、选择合适的教学策略、提供充足的练习机会和及时的反馈,以及进行有效的评估和反思。

显微镜的英语作文

显微镜的英语作文Microscopes have been a cornerstone of scientific discovery since their invention. They have allowed us to explore the microscopic world that is invisible to the naked eye. In this essay, we will delve into the history of microscopy, its various types, and the impact it has had on our understanding of the natural world.The first microscopes were simple, with limited magnification power. However, they laid the groundwork for the sophisticated instruments we have today. As technology advanced, so did the complexity and magnificationcapabilities of microscopes. The electron microscope, for example, can magnify objects up to two million times their original size, revealing atomic and molecular structures.There are several types of microscopes, each serving a specific purpose. The compound light microscope is the most common and uses visible light to magnify samples. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) uses electron beams to create detailed images of surfaces, while the transmission electron microscope (TEM) is used to study thin samples at an atomic level.Microscopes have revolutionized fields such as biology, medicine, and materials science. In biology, they have enabled us to study cells and microorganisms, leading to breakthroughs in understanding life processes. In medicine,they have been instrumental in the diagnosis of diseases by allowing doctors to observe pathogens and cellular changes. Materials science has also benefited from microscopy, as it allows for the examination of material structures and defects at a microscopic level.Moreover, the use of microscopes extends beyond the laboratory. They are used in forensic science to analyze evidence, in environmental science to study microorganisms and their impact on ecosystems, and in education to teach students about the unseen world.In conclusion, microscopes are not just scientific tools; they are windows into a world that is as complex and diverse as the macroscopic world we inhabit. They have expanded our knowledge and continue to be essential in the quest for understanding the intricate details of life and matter. As technology progresses, we can expect microscopes to become even more powerful, unveiling even more secrets of the microscopic universe.。

Microbial Biofilm Sample

Microbial Biofilm SampleMicrobial biofilms are complex communities of microorganisms that grow on surfaces and are embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix. These biofilms play a crucial role in various fields such as medicine, industry, and environmental engineering. However, they also pose a significant challenge to human health, as they can cause chronic infections that are difficult to treat. In this essay, I will discuss the importance ofstudying microbial biofilms, their impact on human health, and potential strategies to prevent and control their growth.Microbial biofilms are important to study because they are ubiquitous in nature and have a significant impact on various ecosystems. They can be found in aquatic environments, soil, and on the surfaces of plants and animals. Biofilms also play a crucial role in biogeochemical cycles, suchas the nitrogen and carbon cycles. Therefore, understanding the structure, function, and dynamics of biofilms is essential to gain insights into the ecological processes that drive microbial communities.However, biofilms can also have detrimental effects on human health. They are responsible for a wide range of infections, including chronic wound infections, dental plaque, and infections associated with medical devices. Biofilms are particularly difficult to treat because the extracellular matrix provides protection against antibiotics and the immune system. Moreover, biofilms can act as a reservoir for antibiotic-resistant bacteria, making infections even harder to treat.To prevent and control biofilm growth, various strategies have been developed. One approach is to use antimicrobial agents that target the biofilm matrix. For example, enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix have been shown to disrupt biofilm formation and enhance the efficacy of antibiotics. Another strategy is to use physical methods, such asultrasound or photodynamic therapy, to disrupt biofilms. These approacheshave shown promising results in laboratory studies, but their effectiveness in clinical settings needs further investigation.Additionally, understanding the mechanisms that drive biofilm formation and persistence is crucial for developing new strategies to prevent and control biofilms. For example, quorum sensing, a mechanism by which bacteria communicate with each other, plays a critical role in biofilm formation. Targeting quorum sensing pathways has been proposed as a potential strategy to prevent biofilm formation. Moreover, understanding the interactions between different microbial species within biofilms can provide insights into the dynamics of microbial communities and their impact on human health. In conclusion, microbial biofilms are complex communities of microorganisms that play a crucial role in various ecosystems, but also pose a significant challenge to human health. Studying biofilms is essential to gain insights into the ecological processes that drive microbial communities and to develop strategies to prevent and control their growth. While various approaches have been developed to prevent and control biofilms, further research is needed to understand the mechanisms that drive biofilm formation and persistence and to develop new strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections.。

Microglia express distinct M1 and M2 phenotypic markers in nervous system in mice

Microglia Express Distinct M1and M2Phenotypic Markers in the Postnatal and Adult Central Nervous System in Male and Female MiceJessica M.Crain,1,2Maria Nikodemova,3*and Jyoti J.Watters 1,2,31Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology,University of Wisconsin,Madison,Wisconsin 2Center for Women’s Health Research,University of Wisconsin,Madison,Wisconsin 3Department of Comparative Biosciences,University of Wisconsin,Madison,WisconsinAlthough microglial activation is associated with all CNS disorders,many of which are sexually dimorphic or age-dependent,little is known about whether microglial basal gene expression is altered with age in the healthy CNS or whether it is sex dependent.Analysis of microglia from the brains of 3-day (P3)-to 12-month-old male and female C57Bl/6mice revealed distinct gene expression profiles during postnatal development that differ signifi-cantly from those in adulthood.Microglia at P3are char-acterized by relatively high iNOS,TNF a and arginase-I mRNA levels,whereas P21microglia have increased expression of CD11b,TLR4,and FcR g I.Adult microglia (2–4months)are characterized by low proinflammatory cytokine expression,which increases by 12months of age.Age-dependent differences in gene expression sug-gest that microglia likely undergo phenotypic changes during ontogenesis,although in the healthy brain they did not express exclusively either M1or M2phenotypic markers at any time.Interestingly,microglia were sexually dimorphic only at P3,when females had higher expres-sion of inflammatory cytokines than males,although there were no sex differences in estrogen receptor expression at this or any other time evaluated pared with microglia in vivo ,primary microglia prepared from P3mice had considerably altered gene expression,with higher levels of TNF a ,CD11b,arginase-I,and VEGF ,sug-gesting that culturing may significantly alter microglial properties.In conclusion,age-and sex-specific variances in basal gene expression may allow differential microglial responses to the same stimulus at different ages,perhaps contributing to altered CNS vulnerabilities and/or diseasecourses.VC 2013Wiley Periodicals,Inc.Key words:microglia;development;aging;sexualdimorphism;M1/M2phenotypeMicroglia,the resident innate immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS),are associated with the pathogenesis of virtually all CNS disorders or injuries.One important characteristic of these cells is high morpho-logical and functional plasticity.They acquire an activated,amoeboid morphology in response to invading pathogens and/or CNS damage.At the same time,they increase their production of a wide array of chemokines,cytokines,ni-tric oxide,and reactive oxygen species that mediate neu-roinflammation (Hoek et al.,2000;Streit et al.,2005;Graeber et al.,2011).In contrast,microglia in the healthy adult CNS are characterized by a quiescent morphology with numerous thin,ramified processes.Although com-monly considered “resting,”emerging evidence suggests that quiescent microglia are highly motile and are actively involved in many physiological processes that include making dynamic contacts with neurons (Wake et al.,2009;Graeber,2010;Parkhurst and Gan,2010;Ketten-mann et al.,2011;Paolicelli et al.,2011;Tremblay and Majewska,2011;Tremblay et al.,2011).However,the gene expression profiles of “resting”microglia in the healthy CNS are not well characterized,and even less is known about whether microglia undergo changes in gene expression that accompany their functional alterations from postnatal development to aging.In the postnatal brain,microglia are important for synaptic pruning (Paoli-celli et al.,2011),and they have an activated,amoeboid morphology with high phagocytic activity (Schwarz et al.,2012).Microglial changes toward an amoeboid morphol-ogy are also associated with aging (Conde and Streit,2006;von Bernhardi et al.,2010),suggesting that their gene expression profiles may also be altered at these times.Therefore,for the present study,we hypothesized that,in the normal CNS,microglia undergo age-dependent geneJ.M.Crain and M.Nikodemova contributed equally to this work.Contract grant sponsor:NINDS;Contract grant number:R01NS049033;Contract grant sponsor:NIH;Contract grant number:R25GM083252(to J.M.C.)*Correspondence to:Maria Nikodemova,PhD,Department of Compar-ative Biosciences,University of Wisconsin,2015Linden Drive,Madison,WI 53706.E-mail:nikodemova@Received 2January 2013;Revised 20February 2013;Accepted 29March 2013Published online 17May 2013in Wiley Online Library().DOI:10.1002/jnr.23242VC 2013Wiley Periodicals,Inc.Journal of Neuroscience Research 91:1143–1151(2013)expression changes that reflect the morphologic and func-tional plasticity that they exhibit during development and aging.We focused on key genes associated with the classi-cal proinflammatory(M1)and alternative anti-inflamma-tory(M2)phenotypes,hypothesizing that microglia will express more M1markers in the postnatal and aging CNS when they display an activated morphology,whereas,in the young adult CNS,microglia will be polarized toward the M2phenotype.Another aspect of microglial biology that is rarely studied is whether microglial gene expression is sex de-pendent(Sierra et al.,2007).Many neurodegenerative diseases characterized by neuroinflammation are sexually dimorphic.For example,women are at higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis, whereas men are more likely to develop amyotrophic lat-eral sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease(Payami et al.,1996; Logroscino et al.,2010;Wirdefeldt et al.,2011;Voskuhl and Gold,2012).Although the causes of these sex differ-ences remain poorly understood,potential sexual dimor-phisms in microglia may play a role.Estrogen receptors (ER)in the CNS mediate the effects of estrogens in females as well as the effects of testosterone in males, which is converted in the brain to estrogen by aromatase (Balthazart and Ball,1998).ERs underlie sex-dependent differences in neurons(Bloch et al.,1992;Simerly et al., 1997;Shughrue et al.,2002;Flores et al.,2003)and sup-press inflammatory responses of microglia and macro-phages(Vegeto et al.,2006;Smith et al.,2011;Arevalo et al.,2012).Therefore,we hypothesized that microglial inflammatory gene expression would be sex dependent and that alterations in ER expression would accompany these changes.A major goal of this study was to deter-mine the age at which potential sexual dimorphisms in microglial gene expression would be evident.To address our hypotheses,we evaluated ER and M1 and M2marker gene expression in microglia from healthy C57Bl/6male and female mice ranging in age from3days to12months.Primary microglial cultures derived from neonatal animals are an invaluable tool to study many aspects of microglial activities.Therefore,we also com-pared their gene expression profiles with those of microglia in vivo from neonates of the same age,to determine whether and how in vitro culturing alters their properties.MATERIALS AND METHODSAnimalsC57Bl/6mice were purchased from Charles River.All animals were maintained in an AALAC-accredited animal facil-ity with a12-hr light/dark cycle regime and access to food and water ad libitum.The7–8-week-old and4-month-old females were virgins.The12-month-old mice were retired breeders, with females not having borne a litter for at least2months prior to their use to minimize the possibility that hormones associated with pregnancy/lactation would interfere with microglial activ-ities.All experiments were approved by the University of Wis-consin Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.We examined microglial gene expression at different ages,selected based on important developmental milestones. Postnatal day3(P3)is a time following the testosterone surge in males(that occurs on the day of birth)that is responsible for masculinization of the still developing CNS.In addition,pri-mary microglial cultures are usually prepared from mice of this age.P21is a time proximal to weaning and represents an im-portant transition before the onset of puberty that begins during the fourth week of age in this mouse strain(Witham et al., 2012).Seven-to eight-week-old mice are young adults that have acquired full reproductive capacity,and4-month-old mice represent sexually mature adults.These adult ages are also the most commonly used ages in most studies.Finally,12-month-old mice represent older animals at a time when both male and female reproductive potential and gonadal hormone levels are beginning to decline.C57Bl/6mice usually do not produce litters after1year of age(Liu et al.,2013).CD11b1Cell IsolationCD11b1cells were isolated as previously described (Crain et al.,2009;Nikodemova and Watters,2012). Briefly,mice were euthanized and perfused with cold phos-phate-buffered saline(PBS).Whole brains(including cere-bellum and brainstem)were dissected and dissociated into a single-cell suspension using the Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit containing papain(Miltenyi Biotec,Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).Myelin was removed by centrifugation in0.9M sucrose in Hank’s buffered salt solution.Cells were stained with phycoerythrin(PE)-conjugated anti-CD11b antibodies, followed by magnetic bead-conjugated secondary antibodies against PE.Magnetically tagged CD11b1cells were then separated using MS columns according to the manufacturer’s protocol(Miltenyi Biotec).Reagents were used at4 C,and the cells were kept on ice during the isolation process.The average purity of isolated cells having the characteristics of microglia was>97%as determined byflow cytometry for CD11b/CD45staining(Crain et al.,2009;Nikodemova and Watters,2012).We recently showed that the isolation efficiencies of microglia expressing low and high CD11b levels were equal;therefore,microglial isolation is not expected to be affected by variations in CD11b expression at different time points(Nikodemova and Watters,2012). GenotypingThe sex of the3-day-old mice was verified by genotyp-ing for the sex-determining region Y(SRY)gene,which is located on the Y chromosome,as previously described(Crain et al.,2009).Genomic DNA was isolated by digestion of a small section of tail and then used in PCR for SRY.Primary Microglial CulturesPrimary neonatal microglial cultures were prepared as previously described,from approximately50%female and50% male litters(Nikodemova et al.,2007).Briefly,3-day-old C57Bl/6mice were euthanized,and brains were dissected and cleaned of meninges and visible blood vessels and then dissoci-ated by incubation in0.25%trypsin and DNase I,followed by1144Crain et al.Journal of Neuroscience Researchtrituration with a Pasteur pipette.Cells were plated in T75flasks containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supple-mented with10%fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomy-cin.Microglia were harvested by shaking10–14days later and cultured for2days in the medium described above.The purity of microglial cultures was>96%as assessed by CD11b1stain-ing,as described previously(Nikodemova et al.,2007).RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCRRNA was extracted from either primary microglial cul-tures or freshly isolated microglia using Tri reagent(Sigma-Aldrich,St.Louis,MO).cDNA was synthesized from1l g total RNA and MMLV reverse transcriptase(Invitrogen,Carlsbad, CA)as previously described(Crain et al.,2009).Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI7300system using Power SYBR green(Applied Biosystems,Carlsbad,CA).The primer sequences are given in Table I and were designed to span introns whenever possible.Primer efficiency was tested by serial dilu-tion.ER b expression was tested by using three independent primer sets whose efficiency was verified with cDNA from ovary as a positive control.The Ct values for ER b were 20in the ovaries(highly expressed),26in whole brain tissue homoge-nates,and>33in isolated microglia(defined as undetectable).Ct values from duplicate measurements of each sample were averaged,and relative expression levels were determined by the DD Ct method.The expression of each gene was nor-malized to the levels of18s and/or b-actin within each sample as previously described(Crain et al.,2009).Statistical AnalysisData are expressed as mean6SEM of n58–14mice in each group.Results for primary microglial cultures are from three independent culture preparations.Statistical analyses were performed in Sigma Stat3.1software.One-way ANOVA was used to determine statistically significant differences in gene expression over time in the same sex,and two-way ANOVA followed by the Holm-Sidak test was used to determine differ-ences in age-dependent gene expression between females and males.Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.Levels of gene expression are displayed relative to3-day-old males,which allowed comparison over time and between sexes.In some cases,a Student’s t-test was used to determine differences between primary cultures and P3microglia or differences in expression between males and females at the same time point, as indicated in Results.Gene expression in microglial cultures was compared with both P3male and female microglia.RESULTSAge-and Sex-Dependent M1Gene Expression We examined basal expression levels of key proin-flammatory genes typically associated with the M1pheno-type:iNOS,TNF a,IL-1b,and IL-6in na€ıve mice at P3, P21,7–8weeks,4months,and12months of age.Nota-bly,the expression of each gene displayed a unique time course,suggesting their independent regulation with age. The levels of mRNA for each gene are expressed relative to3-day-old males.iNOS mRNA levels were highest at P3,followed by a significant70%downregulation by P21(Fig.1A).In adult mice,iNOS expression was only10–20%of that seen at P3(two-way ANOVA,P<0.001).We did not detect any sex differences in the expression of iNOS at any age.TNF a was highly expressed at P3,but it was signifi-cantly lower between P21and4months of age(Fig.1B).A second peak of TNF a mRNA levels occurred at12months in both sexes.A two-way ANOVA revealed significant age-dependent changes in TNF a expression(P<0.001), without significant interaction with sex(P<0.2).Although a two-way ANOVA analysis did not reveal significant sex-dependent TNF a expression,females had60%higher TNF a mRNA levels at P3than males,a difference that was statistically significant by Student’s t-test(P<0.007).In males,there were no significant age-dependent changes in the expression of IL-1b(Fig.1C),and,in females,IL-1b decreased by50%at7weeks of age com-pared with P3.By12months,IL1-b appeared to be up-regulated in both sexes,but this increase did not reach statistical significance as determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA.A sex difference was observed in IL-1bTABLE I.Primer Sequences Used for qPCRGene Forward primer Reverse primerVEGF TTGAGACCCTGGTGGACATCT CACACAGGACGGCTTGAAGA ER a TGCGCAAGTGTTACGAAGTGG TCATGTCTCCTGAAGCACCCA ER b GCTGGCTGACAAGGAACTGGT CGAGGTCTGGAGCAAAGATGA Arginase-I AGCCAATGAAGAGCTGGCTGGT AACTGCCAGACTGTGGTCTCCA IL-10GCCTTATCGGAAATGATCCA TCTCACCCAGGGAATTCAAA iNOS TGACGCTCGGAACTGTAGCAC TGATGGCCGACCTGATGTT TNF a TGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGCAA AGGTACAACCCATCGGCTGG IL-6ACTTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTC GTCTCCTCTCCGGACTTGTG IL-1b TGTGCAAGTGTCTGAAGCAGC TGGAAGCAGCCCTTCATCTT TLR4GAGGCAGCAGGTGGAATTGTAT TTCGAGGCTTTTCCATCCAA TLR2CGAGTGGTGCAAGTACGAACTG TGGTGTTCATTATCTTGCGCAG FcR g I TGCTACTTTGGGTTCCAGTCGGT TACTGACCCATGGAGGCTGCA CD11b AAGGATTCAGCAAGCCAGAA GGAGGGATGAGAGTCCACAT 18S CGGGTGCTCTTAGCTGAGTGTCCCG CTCGGGCCTGCTTTGAACAC b-Atin ACCCTAAGGCCAACCGTGAA AGAGCATAGCCCTCGTAGATGGMicroglial Gene Expression in Healthy Brain1145 Journal of Neuroscience ResearchmRNA levels at P3,when expression was significantly higher in females than in males (t -test,P <0.001).Contrary to other proinflammatory genes that have high expression levels at P3,IL-6expression was lowest at P3compared with adult animals,which had three to four times greater IL-6mRNA levels (two-way ANOVA,P <0.002).Interestingly,whereas females had higher IL-6mRNA levels at P3(t -test,P <0.001),this sexual dimorphism did not persist in adulthood (Fig.1D).Age-and Sex-Dependent M2Gene ExpressionWe investigated the expression of genes often used to indicate the M2phenotype:the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10,arginase-I,and the growth factor VEGF.We detected no significant age-dependent changes in the expression of IL-10in males (one-way ANOVA,P 50.12;Fig.2A);however,females showed decreased expression at 7weeks of age (one-way ANOVA,P <0.04).Females alsohad almost twofold higher levels of IL-10mRNA at P3than males (two-way ANOVA,P <0.03).The time course of arginase-I was very similar to that of iNOS.The highest expression was observed at P3,followed by downregulation by P21to 30%of P3levels (Fig.2B).In adulthood,the levels of arginase-I mRNA were <10%of P3expression (two-way ANOVA,P <0.001).No differences were observed between males and females.The expression of VEGF,a growth factor that supports neuronal survival,was unchanged at all time points evaluated (Fig.2C),and no differences between males and females were observed.Age-and Sex-Dependent Expression of Membrane ProteinsToll-like receptors (TLRs)play an important role in the activation of innate immune cells,including microglia.We analyzed the expression of TLR4and TLR2becauseFig.1.Basal expression of proinflammatory genes in microglia.The expression of iNOS (A )and TNF a (B ),but not of IL-1b (C ),was significantly higher in microglia isolated from whole brains of 3-day-old mice.On the contrary,IL-6(D )expression was lowest at P3compared with other ages.Females had higher expression of TNF a ,IL-1b ,and IL-6than males at P3.Gene expression in primary micro-glia was significantly affected by culturing in vitro .Gene expressiondata are expressed as fold change relative to 3-day-old males.+Signifi-cant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old males.*Significant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old females.#Significant differences between males and females of the same age.“a”indicates significant difference in gene expression in primary microglia vs.3-day-old males.One symbol,P <0.05;two symbols,P <0.01;three symbols,P <0.001;N.D.,not determined.1146Crain et al.Journal of Neuroscience Researchthey are associated with CNS disorders such as ischemia,infections,multiple sclerosis,and others,and males and females are differentially predisposed to these disorders.The highest expression of TLR4was observed at P21in both sexes (Fig.3A;two-way ANOVA,P <0.02).TLR2expression also exhibited age-dependent changes (two-way ANOVA,P <0.016),the lowest mRNA levels being observed at 7weeks of age (Fig.3B).There were no statis-tically significant sex-dependent differences in the expres-sion of TLR2or TLR4.Fc receptors mediate antibody-dependent phagocy-tosis,and morphological studies indicate differences in the prevalence of amoeboid microglia in postnatal males and females (Schwarz et al.,2012).We evaluated the expres-sion of FcR g I that binds IgG,the most common class of antibodies (Fig.3C).FcR g I mRNA levels were signifi-cantly upregulated at P21compared with all other ages (two-way ANOVA,P <0.002),but there were no differ-ences between males and females.Finally,we examined the expression of CD11b,an integrin involved in cell adhesion,phagocytosis,chemo-taxis,and inflammation.CD11b is often upregulated upon microglial activation.CD11b mRNA levels were lowest at P3,followed by the highest expression levels at P21(one-way ANOVA,P <0.001,for males;P <0.01,for females;Fig.3D).Although CD11b expression was downregulated after P21,it still remained higher than at P3.We found no significant differences in CD11b expression between males and females at any age.Age-and Sex-Dependent Expression of ERsWe also evaluated ER a and ER b expression in microglia,given the sexual dimorphisms in several neuro-logic disorders.ER a mRNA expression was very low at P3but increased at P21.Its expression further increased by 7–8weeks of age,after which time its levels remained constant until 12months of age in both sexes (Fig.4).Compared with P3,ER a mRNA levels were approxi-mately fourfold higher at 21days and six-to sevenfold higher at the other time points.Importantly,no differen-ces were observed in microglial ER a expression between males and females at any age.ER b mRNA expression was not detectable at any age evaluated,in either male or female mice,suggesting that this gene is not expressed in microglia from healthy animals.Basal Gene Expression in Primary MicrogliaBecause mixed-sex primary microglial cultures are commonly used to study microglia in vitro ,we compared gene expression in cultured cells to that of microglia freshly isolated from animals of the same age (P3)from which the primary cultures had been prepared.We found that gene expression in primary microglia was significantly different from that of male and female P3microglia in vivo .Moreover,primary microglial gene profiles did not match the profile of microglia at any age evaluated here.TNF a mRNA levels were highly upregulated in neonatal microglial cultures compared with male butnotFig.2.Basal expression of anti-inflammatory and trophic factor genes in microglia.P3females had higher microglial expression of IL-10(A )than males.Arginase-I (B )expression was highest at P3both in males and in females compared with other ages.There were no sex-or age-dependent changes in VEGF (C )expression.Primary microglia cultures had signifi-cantly lower expression of IL-10compared with males or females in vivo ,whereas VEGF was significantly upregulated compared with any age or sex in vivo .Gene expression data are expressed as fold change relative to 3-day-old males.+Significant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old males.*Sig-nificant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old females.#Significant differ-ences between males and females of the same age.“a”indicates significant difference in gene expression in primary microglia vs.3-day-old males.One symbol,P <0.05;two symbols,P <0.01;three symbols,P <0.001.Microglial Gene Expression in Healthy Brain 1147Journal of Neuroscience Researchfemale P3microglia (Fig.1B),whereas iNOS expression was significantly downregulated,with levels comparable to those observed in male and female adult microglia (Fig.1A).IL-10mRNA levels were also significantly lower in primary cultures compared with male and female micro-glia of any age (Fig.2A).Arginase-I mRNA showed lev-els comparable to levels in male and female P3microglia (Fig.2B).Interestingly,the expression of VEGF was increased by sevenfold in primary cultures compared with freshly isolated male and female microglia from mice of any age.CD11b mRNA levels in primary cultures were 16–18times higher than at P3in males and females (Fig.3),whereas the expression of TLR2,TLR4,and FcR g I was comparable to that of P3mice.Finally,ER a mRNA levels in primary microglial cells were significantly down-regulated compared with male and female microglia in vivo from any age,whereas ER b mRNA levels remained undetectable (Fig.4).DISCUSSIONMicroglia possess great morphological and functional plas-ticity that allow their rapid response to specific physiolog-ical or pathological signals.However,it is not known whether microglial properties differ in the healthy CNS of postnatal,adult,and aged mice,since no studies have systematically evaluated microglia over time.Our data demonstrate that basal microglial gene expression significantly varies in the postnatal and the adult brain,perhaps allowing microglial acquisition of specific age-dependent phenotypes.Interestingly,however,microglia in the healthy CNS are not fully committed to either an inflammatory or an anti-inflammatory phenotype at any age but rather display some M1and M2markers with variable age-dependent expression levels.At P3,microglia were characterized by high expres-sion of iNOS,TNF a ,and arginase-I mRNAlevelsFig. 3.Basal expression of membrane proteins in microglia.P21microglia were characterized by elevated expression of TLR4(A ),FcR g I (C ),and CD11b (D ),but not of TLR2(B ),compared with other ages.Interestingly,primary microglial cells had elevated CD11b levels compared with male or female P3pups in vivo .Gene expression data are expressed as fold change relative to 3-day-old males.+Significant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old males.*Signifi-cant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old females.#Significant differences between males and females of the same age.“a”indicates significant difference in gene expression in primary microglia vs.3-day-old males.One symbol,P <0.05;two symbols,P <0.01;three symbols,P <0.001.1148Crain et al.Journal of Neuroscience Researchrelative to other ages.Thus,during the early postnatal pe-riod,microglia express concomitant M1(iNOS,TNF a )and M2(arginase-I)markers,suggesting either that they acquire a unique phenotype related to specific develop-mental needs at this age or that there are several microglial subpopulations that may be region specific.The latter is supported by the presence of at least three different microglial morphologies found in many CNS regions at this age,with the amoeboid morphology being the most prevalent (Schwarz et al.,2012).Both TNF a and nitric oxide (produced by iNOS)exert pleiotropic effects.In addition to their well-known role in inflammation,both are involved in neuronal apoptosis and synaptic plasticity and pruning,frequent processes during early CNS devel-opment in which microglia are actively involved (McCoy and Tansey,2008;Zhou and Zhu,2009).The signifi-cance of arginase-I expression at this age is not yet clear.Both iNOS and arginase-I use arginine as a substrate for their enzymatic activities,thus competing for arginine availability.Some studies suggest that arginase-I may function as a modulator of iNOS activity to prevent over-production of nitric oxide in immune cells (Chang et al.,1998;Mori,2007).On the other hand,in macrophages,arginase-I activity is important for extracellular matrix production,facilitating wound healing (Bansal and Ochoa,2003).At P3the brain is still developing and growing,so it is possible that microglia participate in extracellular matrix building through arginase-I activities.At P21,iNOS,TNF a ,and arginase-I are downre-gulated,whereas IL-6,CD11b,TLR4,and FcR g ImRNAs are significantly increased,suggesting that micro-glia at P21are phenotypically and functionally distinct from both P3and adult microglia.The functional signifi-cance of elevated CD11b and TLR4expression at P21is not yet clear and warrants further study.Fc receptors mediate antibody-dependent phagocytosis and are impor-tant modulators of microglial activities.Although increased IgG and Fc receptor levels are evident in the aged CNS and during neurodegenerative disease in ani-mal models and humans (Lira et al.,2011;Lunnon et al.,2011;Cribbs et al.,2012),the role of microglial Fc recep-tors during CNS development is unknown.Our data sug-gest that they may play a role in the postnatal period,when increased phagocytosis may be necessary for clear-ing debris from neuronal remodeling processes.Between 2and 4months of age,microglia express low levels of the M1markers iNOS and TNF a mRNA.IL-10and arginase-I expressions,markers of two different M2subtypes,are also low,suggesting that microglia in the healthy adult brain are not polarized to either the M1or M2phenotype.However,by 12months of age,microglial TNF a mRNA had increased to the levels found during early postnatal development.IL-1b mRNA was also increased at 12months,although not significantly.Similar results have been reported from other studies (Godbout et al.,2005;Sierra et al.,2007)and suggest that,at this older age,microglia may be polarizing toward the M1phenotype.The only significant sexual dimorphisms we observed in microglial gene expression were in the early postnatal period (P3).Microglia from female mice had higher mRNA levels for TNF a ,IL-1b ,IL-6,and IL-10than those from males.The testosterone surge occurring in male mice shortly after birth may underlie this sex-related differences,as androgens reportedly reduce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages (Brown et al.,2007;Vignozzi et al.,2012),and they are converted to estrogens in the CNS which also exert anti-inflammatory effects.ER a levels were lowest at P3rela-tive to other ages,and no differences between males and females were found at this age or at any other tested.In addition,we did not detect ER b mRNA in microglia at all,consistent with a report by Sierra et al.(2008).Previ-ous studies have shown effects of ER b in activated micro-glial cell lines and primary cultures and in ischemically injured nonhuman primates (Mor et al.,1999;Baker et al.,2004;Takahashi et al.,2004;Lewis et al.,2008),but no reports to our knowledge have demonstrated effects of ER b activation on inflammatory gene expres-sion in quiescent microglia.Together these data suggest that ER b is not expressed in microglia in the healthy CNS and that neither ER a nor ER b underlies the sexual dimor-phisms observed in early postnatal microglial gene expres-sion.However,a recent study by Sato et al.(2004)showed that some effects of male sex hormones in the CNS are mediated via androgen receptors,so they may be responsi-ble for some sex-dependent differences in microglial gene expression,although androgen receptors have not been detected in microglia (Sierra et al.,2008).Regardless,theFig.4.Basal expression of estrogen receptors in microglia.The expres-sion levels of ER a and ER b were evaluated by qRT-PCR and are expressed as fold change relative to 3-day-old males.P3male and female microglia had the lowest expression of ER a compared with other ages.No sex-dependent differences were detected in ER a expression at any age.Primary microglia had downregulated ER a levels compared with P3male and female microglia in vivo .ER b was unde-tectable in all ages.+Significant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old males.*Significant age-dependent differences vs.3-day-old females.#Significant differences between males and females of the same age.“a”indicates significant difference in gene expression in primary microglia vs.3-day-old males.Two symbols,P <0.01;three symbols,P <0.001.Microglial Gene Expression in Healthy Brain 1149Journal of Neuroscience Research。

The function of microglia

Associate editor:M.EndohThe function of microglia through purinergic receptors:Neuropathic pain and cytokine releaseKazuhide Inoue *Department of Molecular and System Pharmacology,Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences,Kyushu University,Maidashi 3-1-1,Higashi-ku,Fukuoka 812-8582,JapanAbstractMicroglia play an important role as immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS).Microglia are activated in threatened physiological homeostasis,including CNS trauma,apoptosis,ischemia,inflammation,and infection.Activated microglia show a stereotypic,progressive series of changes in morphology,gene expression,function,and number and produce and release various chemical mediators,including proinflammatory cytokines that can produce immunological actions and can also act on neurons to alter their function.Recently,a great deal of attention is focusing on the relation between activated microglia through adenosine 5V -triphosphate (ATP)receptors and neuropathic pain.Neuropathic pain is often a consequence of nerve injury through surgery,bone compression,diabetes,or infection.This type of pain can be so severe that even light touching can be intensely painful and it is generally resistant to currently available treatments.There is abundant evidence that extracellular ATP and microglia have an important role in neuropathic pain.The expression of P2X4receptor,a subtype of ATP receptors,is enhanced in spinal microglia after peripheral nerve injury model,and blocking pharmacologically and suppressing molecularly P2X4receptors produce a reduction of the neuropathic pain.Several cytokines such as interleukin-1h (IL-1h ),interleukin-6(IL-6),and tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a )in the dorsal horn are increased after nerve lesion and have been implicated in contributing to nerve-injury pain,presumably by altering synaptic transmission in the CNS,including the spinal cord.Nerve injury also leads to persistent activation of p38mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)in microglia.An inhibitor of this enzyme reverses mechanical allodynia following spinal nerve ligation (SNL).ATP is able to activate MAPK,leading to the release of bioactive substances,including cytokines,from microglia.Thus,diffusible factors released from activated microglia by the stimulation of purinergic receptors may have an important role in the development of neuropathic pain.Understanding the key roles of ATP receptors,including P2X4receptors,in the microglia may lead to new strategies for the management of neuropathic pain.D 2005Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.Keywords:ATP;P2X4;Microglia;Neuropathic pain;Allodynia;Spinal cord;p38Abbreviations:ADP,adenosine 5V -diphosphate;ATP,adenosine 5V -triphosphate;ATP g S,adenosine 5V -O -(3-thiotriphosphate);BDNF,brain-derived neurotrophic factor;BzATP,2V -and 3V -O -(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5V -triphosphate;[Ca 2+]i,intracellular Ca 2+concentration;CD11b,clusterdeterminant 11b;CNS,central nervous system;CR3,complement receptor 3;ERK,extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase;Iba1,ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1;ICE,IL-1h -converting enzyme;IL-1h ,interleukin-1h ;IL-6,interleukin-6;iNOS,inducible nitric oxide synthase;InsP3,inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate;JNK,c-Jun N-terminal kinase;LPS,lipopolysaccharide;MAPK,mitogen-activated protein kinase;MEK,mitogenactivated protein kinase kinase;MHC,histocompatibility complex;oATP,oxidized ATP;PK11195,[1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N -methyl-N -(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolineisoquinoline carboxamide];PKC,protein kinase C;PLC,phospholipase C;PPADS,pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2V ,4V -disulphonic acid;PTK,protein tyrosine kinase;PTX,pertussis toxin;SB203580,4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)I H -imidazole;SOC,store-operated Ca 2+entry;SP600125,anthra[1,9-cd]pyrazol-6(2H )-one;TNF-a ,tumor necrosis factor-a ;TNP-ATP,2V ,3V -O -(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)adenosine 5V -triphosphate;U0126,1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis [2-amino-phenylthio]butadiene;UTP,uridine 5V -triphosphate.0163-7258/$-see front matter D 2005Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.001*Tel./fax:+81926424729.E-mail address:inoue@phar.kyushu-u.ac.jp.Pharmacology &Therapeutics 109(2006)210–226/locate/pharmtheraContents1.Introduction (211)2.Purinergic receptors expressing in microglia (212)3.Activated microglia in neuropathic pain (213)3.1.Microglia activation in patients bearing a kind of neuropathic pain (213)3.2.Microglia activation in neuropathic pain model rats (213)3.3.High expression of P2X4in spinal microglia in neuropathic pain model (213)3.4.P2X4stimulation causes and maintains allodynia (214)4.Microglia activation through purinergic receptors (215)4.1.Chemotaxis following membrane ruffling (215)4.2.Function and release of plasminogen (215)4.3.Function and the release of tumor necrosis factor-a (217)4.4.Function and the release of interleukin-6 (218)4.5.Function and the release of interleukin-1h (219)4.6.Function and the release of ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule1/microglialresponse factor-1/allograft inflammatory factor-1 (220)5.Conclusion and consideration (221)References (222)1.IntroductionMicroglia are often considered to be resident macro-phages and to play an important role as immune cells in the central nervous system(CNS;Kreutzberg,1996;Stoll &Jander,1999;Nakajima&Kohsaka,2001).In adults, microglia are distributed throughout CNS and represent5–10%of glia.They have a small soma bearing thin and branched processes under normal conditions.Such micro-glia are said to be F resting_,but acting as sensors for a range of stimuli that threaten physiological homeostasis, that is,CNS trauma,apoptosis,ischemia,inflammation, and infection.Once activated by these stimuli,that is, bioactive substances,cytokines and neurotransmitters, including adenosine5V-triphosphate(ATP),microglia show a stereotypic,progressive series of changes in morphology, gene expression,function,and number(Perry,1994; Kreutzberg,1996;Stoll&Jander,1999;Streit et al., 1999;Nakajima&Kohsaka,2001).Activated microglia change their morphology from a resting,ramified shape into an active,amoeboid shape(Perry,1994;Kreutzberg, 1996;Stoll&Jander,1999;Streit et al.,1999;Nakajima& Kohsaka,2001).They up-regulate expression of a variety of cell-surface molecules,including the complement receptor3(CR3;also known as clusterdeterminant[CD] 11b(integrin a M)/CD18(integrin h2),or as Mac-1; Kreutzberg,1996;Stoll&Jander,1999;Ehlers,2000; Nakajima&Kohsaka,2001),which is recognized by the antibody OX-42(Robinson et al.,1986).Activated micro-glia also express immunomolecules such as major histo-compatibility complex(MHC)class I and II(Kreutzberg, 1996;Stoll&Jander,1999;Streit et al.,1999),which have a role in antigen presentation to T lymphocytes.Activated microglia produce and release various chemical mediators, including proinflammatory cytokines that can produce immunological actions and can also act on neurons to alter their function(Kreutzberg,1996;Stoll&Jander, 1999;Nakajima&Kohsaka,2001;Hanisch,2002). Recently,a great deal of attention has been focused on the relation between neuropathic pain and microglia activated through ATP receptors(Tsuda et al.,2005).ATP is released from damaged cells as a result of ischemia or inflammation and serves as a cell-to-cell mediator through cell surface P2receptors,which are widely distributed throughout the nervous system,including microglia(Inoue, 2002).P2receptors are divided into2subtypes:P2X and P2Y(Abbracchio&Burnstock,1994;Fig.1).P2X receptors (P2X1–P2X7)are coupled to nonselective cation channels, allowing the influx of Na+and Ca2+(North,2002),whereas Fig.1.P2receptors.P2receptors are divided into2subtypes:P2X and P2Y. P2X receptor subtypes(P2X1–P2X7)are40–50%identical in amino acid sequence.Each subtype has2transmembrane domains.Nonselective cation channels form as multimers(presumably3multimers)of several subunits. Homomeric P2X1,P2X2,P2X3,P2X4,P2X5,and P2X7channels and heteromeric P2X2/3and P2X1/5channels have been most fully charac-terized following heterologous expression.P2Y receptors(P2Y1,P2Y2, P2Y4,P2Y6,P2Y11,P2Y12,P2Y13,and P2Y14)are G-protein coupled, and their activation leads to inositol lipid hydrolysis,intracellular Ca2+ mobilization,or modulation of adenylate cyclase activation,through G q/11 (P2Y1,P2Y2,P2Y4,P2Y6),G s(P2Y6)and G i/o(P2Y11,P2Y12,P2Y13, and P2Y14),respectively.K.Inoue/Pharmacology&Therapeutics109(2006)210–226211P2Y receptors (P2Y1,P2Y2,P2Y4,P2Y6,P2Y11,P2Y12,P2Y13,and P2Y14)are G-protein coupled,and their activation leads to inositol lipid hydrolysis,intracellular Ca 2+mobilization,or modulation of adenylate cyclase activation (Inoue,2002).ATP strongly activates microglial to show chemotaxis via the Gi-and Go-coupled P2Y12receptor (Honda et al.,2001)and stimulates the release of plasminogen,interleukin (IL)-6,tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a ),and IL-1h (Ferrari et al.,1997a,1997b;Inoue et al.,1998;Hide et al.,2000;Shigemoto-Mogami et al.,2001;Inoue,2002;Suzuki et al.,2004)by means of different types of P2receptor and intracellular signals.Neuropathic pain is a type of pathological pain that often develops when nerves are damaged through surgery,bone compression,diabetes or infection,also which does not resolve even when the overt tissue damage has healed (Aldskogius &Kozlova,1998;Carson,2002;Eikelen-boom et al.,2002).Neuropathic pain can be so severe that even light contact with clothing can be intensely painful (tactile allodynia:an abnormal hypersensitivity to innocuous stimuli)and is often resistant to most current treatments,including a narcotic analgesia,although a number of drugs produce some relief.Accumulating evidence concerning how peripheral nerve injury creates neuropathic pain has suggested that molecular and cellular alterations in primary sensory neurons and in the spinal dorsal horn after nerve injury have an important role in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain (Aldskogius &Kozlova,1998;Carson,2002;Eikelenboom et al.,2002).While there is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that P2X3Rs,a subtype of ionotropic ATP receptors,in primary sensory neurons have a role in neuropathic pain (Colburn et al.,1999;Banati,2002;Garden,2002),other P2XR and P2YR subtypes of ATPreceptors are also beginning to be investigated in terms of their changes in expression using cDNA microarray (Visentin et al.,1999;Inoue,2002;Suzuki et al.,2004).Recently,it was reported that astrocyte and microglia are activated strongly in neuropathic model animals,suggest-ing the role of glial cells in the pain sensation (Watkins et al.,2001).However,there was no direct evidence supporting this suggestion.More recently,we have revealed that the P2X4R subtype in the activated spinal microglia is required for the expression of neuropathic pain after nerve injury (Tsuda et al.,2003).This review shows the progress in the current understanding of how the ATP receptor participates in the activation of microglia leading into neuropathic pain.2.Purinergic receptors expressing in microglia ATP evokes currents in rat microglia (No ¨renberg et al.,1994;Illes et al.,1996)and increases in intracellular calcium ([Ca 2+]i)in mouse and human microglia (Walz et al.,1993;Toescu et al.,1998;Moller et al.,2000).ATP induces the release of IL-1h (Ferrari et al.,1996,1997b )and IL-6(Shigemoto-Mogami et al.,2001)from mice microglia.ATP causes chemotaxis (Honda et al.,2001)and the release of plasminogen (Inoue et al.,1998)and TNF-a (Hide et al.,2000;Morigiwa et al.,2000)from rat microglia.ATP activates nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT;Ferrari et al.,1999),which modulates the early inflammatory gene expression and transcriptional activator NF-n B,which controls cytokine expression and apoptosis (Ferrari et al.,1997a ).ATP also stimulates the phosphor-ylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK;Hide et al.,2000;Honda et al.,2001;Shigemoto-Mogami et al.,P2XP2YM X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X 6 X7M X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X 6 X7M Y1 Y2 Y4 Y6 Y12M Y1 Y2 Y4 Y6 Y12-RT-RT200015001000700500400300200200015001000700500400300200Fig.2.mRNA expression of P2purinoceptors receptors in primary culture microglia from rat brain.Upper :Electrophoresis photograph after a quantitative RT-PCR using specific primers for P2X1,P2X2,P2X3,P2X4,P2X5,P2X6,and P2X7.Clear bands were detected in the P2X4and P2X7lanes.Lower :Electrophoresis photograph after a quantitative RT-PCR using specific primers for P2Y1,P2Y2,P2Y4,P2Y6,and P2Y12receptors.Clear bands were detected in the P2Y2,P2Y6,and P2Y12lanes.K.Inoue /Pharmacology &Therapeutics 109(2006)210–2262122001).These data suggest that microglia possess functional receptors for purines and pyrimidines,that is,P2X receptors,ligand-gated ion-channels(Cook et al.,1998; Li et al.,1999;Ueno et al.,1999;Tsuda et al.,2000;Chizh &Illes,2001;Dunn et al.,2001),and P2Y receptors,G protein-coupled receptors(Svichar et al.,1997;Koizumi et al.,2001;Tominaga et al.,2001;Molliver et al.,2002; Sanada et al.,2002;Moriyama et al.,2003).There, however,are very few reports available indicating the mRNA expression of P2receptor subtypes in microglia. We examined using a quantitative RT-PCR method and found that microglia in a primary culture from rat brain express mainly mRNAs of P2X4and P2X7,and P2Y2, P2Y6,and P2Y12(Shigemoto-Mogami et al.,personal communication),as shown in Fig.2.3.Activated microglia in neuropathic pain3.1.Microglia activation inpatients bearing a kind of neuropathic painSince the peripheral benzodiazepine binding site practi-cally absent in the normal brain parenchyma is strongly and preferentially expressed by activated microglia around the soma of the injured neuron,[1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinoline isoquinoline carboxa-mide](PK11195),a ligand for the peripheral benzodiazepine binding site,binds with relative cellular selectivity to activated microglia,not to residential microglia.Thus,(R)-PK11195labeled with carbon-11and positron emission tomography(PET)have been used for the study of inflammatory and neurodegenerative brain disease in vivo, even in human.This technology is highly useful to reveal the retrograde and anterograde projection areas(Banati et al., 1997,2000).For example,increased microglial(R)-PK11195 binding is seen in the motor facial nucleus after peripheral facial nerve transection(Banati et al.,1997),in the gracile nucleus after sciatic nerve lesion(Banati et al.,1997),in the ipsilateral thalamus after cerebral cortical ischemic stroke (Pappata et al.,2000),and in the lateral geniculate bodies in multiple sclerosis patients with optic neuritis(Banati et al., 2000).The potentially useful clinical application of the specific ligand PK11195is based on3observations(Banati et al.,2001):(1)normal brain shows only minimal binding of PK11195;(2)in CNS pathology,in vivo PK11195binding is predominantly found on activated microglia;and(3)when labeled with carbon-11,PK11195can be used as a ligand for PET(Benavides et al.,1988;Junck et al.,1989;Myers et al., 1991a,1991b,1999;Cremer et al.,1992;Ramsay et al.,1992; Sette et al.,1993;Banati et al.,1999).The cortical plasticity developed after the amputation of a limb may be associated with the development of abnormal sensations,such as phantom pain,a kind of neuropathic pain, and referred cutaneous sensations(Banati et al.,2001).It was reported that cortical reorganization may be the consequence of a reorganization of the thalamus following changes of afferent inputs from the amputated limb(Jones,2000).The cause of the sustained representational plasticity in the thalamus has recently been suggested to be transneuronal atrophy in the thalamus that,in turn,would mediate cortical plasticity(Woods et al.,2000).Acute or chronic neuronal injury after the amputation of a limb evokes a rapid,transient and localized activation of microglia(Kreutzberg,1996). Banati et al.(2001)reported that limb amputation induces a trans-synaptic increase in[11C](R)-PK11195binding in the human thalamus but not somatosensory cortex,suggesting the activation of microglia in the thalamus of a patient with phantom pain.The increased thalamic signal is detectable many years after nerve injury,and this means persistent reorganization of the thalamus.The microglial activation, beyond the first-order projection area of the injured neurons, may reflect continually altered afferent activity.The activa-tion of microglia can therefore be used as a sensor of neuronal injury.3.2.Microglia activation in neuropathic pain model ratsClinical evidence that neuropathic pain results from damage to peripheral nerves in humans led to the develop-ment of a variety of models for studying neuropathic pain in laboratory animals.Evidence from studies using such models has revealed that peripheral nerve injury leads to a dramatic change in microglia within the spinal dorsal horn(Eriksson et al.,1993;Colburn et al.,1997,1999;Coyle,1998;Stuesse et al.,2000).Spinal microglia become hypertrophic in their short and thick processes within24hr after peripheral nerve injury(Eriksson et al.,1993;Tsuda et al.,2003).This is followed by a burst proliferation of microglia with a peak at around2–3days after the nerve injury(Gehrmann&Banati, 1995).Activated microglia exhibit up-regulated OX42label-ing(Eriksson et al.,1993;Liu et al.,1995;Coyle,1998; Colburn et al.,1999;Stuesse et al.,2000;Tsuda et al.,2003), which starts to increase as early as1day after nerve injury and peaks at around14days(Coyle,1998).The temporal pattern of OX42up-regulation in the dorsal horn correlated with that of the development of tactile allodynia(Coyle,1998), suggesting the role of microglia in neuropathic pain. Although there have been many studies showing that the activation of microglia in the dorsal horn is correlated with the development of pain hypersensitivity in a wide variety of nerve injury models(Eriksson et al.,1993;Liu et al.,1995; Coyle,1998;Colburn et al.,1999;Stuesse et al.,2000; Watkins et al.,2001),it remained an open question whether spinal microglia play a causal role in neuropathic pain until the report by Tsuda et al.(2003).3.3.High expression of P2X4inspinal microglia in neuropathic pain modelA clue to identifying P2X4Rs in the spinal microglia required for neuropathic pain first came from pharmaco-K.Inoue/Pharmacology&Therapeutics109(2006)210–226213logical investigations of pain behaviour after nerve injury using the P2XR antagonists 2V ,3V -O -(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)a-denosine 5V -triphosphate (TNP-ATP)and pyridoxalphos-phate-6-azophenyl-2V ,4V -disulphonic acid (PPADS;Tsuda et al.,2003).It was found that the marked tactile allodynia that develops following the injury of a spinal nerve is reversed by acutely administering TNP-ATP intrathecally but is unaffected by administering PPADS (Fig.3A).TNP-ATP has no effect on acute pain behaviour in the uninjured state nor on motor behaviour.TNP-ATP at high concentration shows the antagonistic effect on P2X1,P2X2,P2X3,P2X4,P2X5,and P2X7.PPADS inhibits the action of all these subtypes,excluding P2X4.From these pharmacological profiles of TNP-ATP and PPADS,it was inferred that tactile allodynia depends upon P2X4Rs in the spinal cord.The expression of P2X4R protein,normally low in the naivespinal cord,progressively increases in the days following nerve injury with a time-course parallel to that of the development of tactile allodynia (Fig.3B and C).Immuno-histochemical analysis demonstrated that many small cells in the dorsal horn on the side of the nerve injury are intensely positive for P2X4R protein.These cells are identified as microglia rather than neurons or astrocytes by double immunolablelling using cell-specific markers (Fig.5A).The cells expressing P2X4R in the nerve-injured side of the dorsal horn are more numerous than under control conditions and showed high levels of OX42labeling and morphological hypertrophy,all of which are character-istic markers of activated microglia.Moreover,intrathecal administration with antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (AS)targeting P2X4R reduces the up-regulation of P2X4R protein in spinal microglia (Fig.4A)and prevents the development of the nerve injury-induced tactile allodynia (Fig.4B).The treatment with a mismatch ODN (MM)as a control does not reduce the expression of P2X4nor prevent the tactile allodynia (Fig.4A and B).The evidence implies that P2X4R’s activation is necessary for pain hypersensi-tivity following nerve injury,and that microglia are required for this hypersensitivity since the expression of these receptors in the dorsal horn is restricted to this type of cell.3.4.P2X4stimulation causes and maintains allodyniaTo demonstrate the sufficiency of P2X4R activation in microglia for the development of allodynia,Tsuda et al.(2003)performed the intrathecal administration of primary cultured microglia a stimulated in vitro by ATP.In normal rats,intrathecal administration of cultured microglia that were preincubated with ATP to activate P2X4Rs on microglia produces tactile allodynia progressively over the 3–5hr following the administration.In contrast,intrathecal administration of unstimulated microglia does not cause allodynia,nor does administering vehicle or ATP alone.Microglia also express another subtype of P2XR,P2X7R,but this receptor subtype appears not to be involved because the activation of P2X7Rs typically requires a higher concentration (more than 1mM)of ATP (Surprenant et al.,1996;Khakh et al.,2001).Moreover,in the tactile allodynia caused by the admin-istration of ATP-stimulated microglia,this allodynia is reversed by administering TNP-ATP (Tsuda et al.,2003).Thus,the stimulation of P2X4Rs is required in the tactile allodynia caused by ATP-stimulated microglia,and this tactile allodynia therefore resembles that caused by nerve injury.These findings indicate that P2X4R stimulation of microglia is not only necessary for tactile allodynia,but is also sufficient to cause the allodynia.Furthermore,this finding makes a strong case that microglia activation is not simply correlated with neuropathic pain behaviour.Rather,microglia within the dorsal horn play an active and ongoing role in the tactile allodynia produced by injury to peripheral nerves.For revealing the exact mechanism ofPost i.th. injection (min)P W T (g r a m )Day 0(Naive)Post-operation Post operation (day)P W T(g r a m )Neuropathic Pain after Nerve Injury11015ABCDay 3Day 14Day 1Day 7Fig.3.Effect of TNP-ATP on tactile allodynia and expression of P2X4R in the dorsal horn after nerve injury.(A )Tactile allodynia that develops following the injury of a spinal nerve was reversed by acutely administering TNP-ATP intrathecally but was unaffected by administering PPADS.TNP-ATP had no effect on acute pain behaviour in the uninjured state or on motor behaviour.(B ,C )The expression of P2X4R protein and the development of tactile allodynia after nerve injury.The expression of P2X4R protein progressively increased in the days following nerve injury with a time course parallel to that of the development of tactile allodynia.K.Inoue /Pharmacology &Therapeutics 109(2006)210–226214the P2X4-microglia-involving neuropathic pain,more deep research efforts should be endeavored.4.Microglia activation through purinergic receptorsThe variety of biological effects produced by ATP in microglia may provide hints towards clarifying the mech-anisms of neuropathic pain.4.1.Chemotaxis following membrane rufflingThe initial microglial responses that occur after brain injury and in various neurological diseases are characterized by microglial accumulation in the affected sites of the brain, which results from the migration and proliferation of these cells.The early-phase signal responsible for this accumu-lation is likely to be transduced by rapidly diffusible factors. Honda et al.(2001)examined the possibility that ATP released from injured neurons and nerve terminals affects the cell motility in rat primary cultured microglia.They found that extracellular ATP and adenosine5V-diphosphate (ADP)induces membrane ruffling and markedly enhances chemokinesis in a Boyden chamber assay.Further analyses using the Dunn chemotaxis chamber assay,which allows direct observation of the cell movement,revealed that both ATP and ADP induce chemotaxis of microglia.The elimination of extracellular calcium or treatment with PPADS or suramin does not inhibit ATP-or ADP-induced membrane ruffling,whereas AR-C69931MX,a P2Y12and P2Y13receptor blocker(Hollopeter et al.,2001;Fumagalli et al.,2004),or pertussis toxin(PTX)treatments clearly inhibit the ruffling.As an intracellular signaling moleculeunderlying these phenomena,the small G-protein Rac is activated by ATP and ADP stimulation,and its activation is also inhibited by pretreatment with PTX.These findings suggested that the membrane ruffling and chemotaxis of microglia induced by ATP or ADP are mediated by G(i/o)-coupled P2Y receptors(P2Y12and/or P2Y13).4.2.Function and release of plasminogenIt was shown that ATP stimulates the release of plasminogen from primary cultured rat microglia in a concentration-dependent manner from10to100A M,with a peak response at5–10min after the stimulation(Inoue et al.,1998).A1-hr pretreatment with BAPTA-AM com-pletely inhibits the plasminogen release evoked by ATP.The Ca2+ionophore A23187induces plasminogen release in a concentration-dependent manner(0.3to10A M).ATP induces a transient increase in the[Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner,which is very similar to the ATP-evoked plasminogen release.A second application of ATP(100A M) stimulates an increase in[Ca2+]i similar to that of the first application(21out of21cells).The ATP-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i is totally dependent on extracellular Ca2+.2-Methylthio ATP is effective(7out of7cells),but a,h-methylene ATP was ineffective(7out of7cells)at inducing an increase in[Ca2+]i.Suramin(100A M)is shown not to inhibit the ATP-evoked increase in[Ca2+]i(20out of20 cells).2V-and3V-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine5V-triphosphate(BzATP)evokes a long-lasting increase in [Ca2+]i,even at1A M,a concentration at which ATP does not evoke the increase.One hour pretreatment with oxidized ATP(oATP;100A M),a selective antagonist of P2X7 receptors,blocks the increase in[Ca2+]i induced by ATP(10 and100A M).These data suggest that ATP may transit information from neurones to microglia,resulting in an increase in[Ca2+]i via the ionotropic P2X7receptor which stimulates the release of plasminogen from the microglia. However,the possible involvement of P2X4in this release cannot be excluded because BzATP can affect on P2X4.It has been found that uridine5V-triphosphate(UTP)also stimulates plasminogen release from a subpopulation of microglia(about20%of total cells),presumably through store-operated Ca2+entry(SOC)activated by ATP stim-ulation of G protein-coupled receptors,since the release evoked by UTP is also dependent on extracellular Ca2+ (Inoue et al.,unpublished data).ASMMP2X4RASMM***B LNerve injury51015PWT(gram)##ABFig.4.Effects of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide(AS)targeting P2X4R on the expression of P2X4protein and the development of tactile allodynia after nerve injury.(A)Western blotting analysis of the expression of P2X4receptor protein in the spinal dorsal horn7days after nerve injury.The animals were treated with intrathecal administration of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (AS)targeting P2X4R for7days,beginning on the day of the nerve lesion. Intrathecal administration of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide(AS)targeting P2X4R reduced the up-regulation of P2X4R protein in spinal microglia.The treatment with a mismatch ODN(MM)as a control did not reduce the expression of P2X4.(B)AS treatment prevented the development of the nerve injury-induced tactile allodynia.The paw withdrawal threshold in animals treated with MM was not different from that of untreated controls, suggesting that MM did not prevent the tactile allodynia.K.Inoue/Pharmacology&Therapeutics109(2006)210–226215。

presentation5分钟范文(合集10篇)

presentation5分钟范文(合集10篇)(经典版)编制人:__________________审核人:__________________审批人:__________________编制单位:__________________编制时间:____年____月____日序言下载提示:该文档是本店铺精心编制而成的,希望大家下载后,能够帮助大家解决实际问题。

文档下载后可定制修改,请根据实际需要进行调整和使用,谢谢!并且,本店铺为大家提供各种类型的经典范文,如工作总结、工作计划、合同协议、条据文书、策划方案、句子大全、作文大全、诗词歌赋、教案资料、其他范文等等,想了解不同范文格式和写法,敬请关注!Download tips: This document is carefully compiled by this editor. I hope that after you download it, it can help you solve practical problems. The document can be customized and modified after downloading, please adjust and use it according to actual needs, thank you!Moreover, our store provides various types of classic sample essays for everyone, such as work summaries, work plans, contract agreements, doctrinal documents, planning plans, complete sentences, complete compositions, poems, songs, teaching materials, and other sample essays. If you want to learn about different sample formats and writing methods, please stay tuned!presentation5分钟范文(合集10篇)presentation5分钟范文第1篇如何做好企业Presentation现在,在企业里做Presentation是比较常见的。

01 How to Make a Mini Presentation in English 怎样做英语迷你演讲?

3. Persuasive Presentation 说服型演讲

Objectives目的:

1)Change views 改变听众观念 2)Call for actions 号召听众采取行动

说服型演讲“四要诀”

1. 论点鲜明 —— 忌模糊不清 2. 论据给力 —— 忌不确凿不充分 3. 论证合理 —— 忌不条理不简洁 4. 结论可靠 —— 忌不可靠不可信

2. 准确 —— 忌模糊不清 3. 科学 —— 忌杂乱无章

信息型演讲用途

1. 发布信息 e.g. Weather forecast Stock exchange prices 获取信息,掌握先机。 2. 传播知识 e.g. Lectures in school 获取知识,增强力量。

信息型演讲组织方法

信息型演讲与说服型演讲的关系

1. 信息是说服的基础; 说服是信息的归宿。

2.

陈述事实要像科学家; 说服劝导要像政治家。

3 Levels of Oral Presentation

1. Speak correctly -- pronunciation, grammar 2. Speak clearly -- structure, content 3. Speak convincingly -- proposition, evidence

How to Make a Mini Presentation in English 怎样做迷你英语演讲?

Hu Yinping The College of Foreign Languages, USST huyinping66@ Aug. 31, 2012

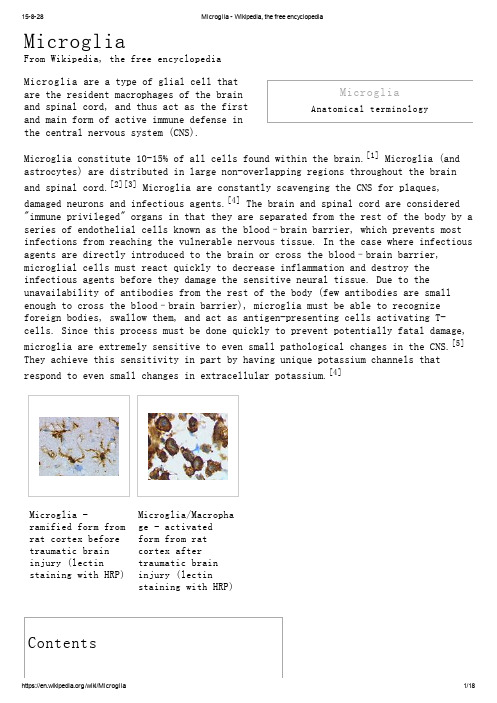

Microglia - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia