“Mr.Wu Mi-A Scholar and A Gentlemen”文学鉴赏

霉霉纽约大学英语演讲稿

Ladies and Gentlemen,Good evening. It is an immense honor to stand before you today at the New York University, a place that has been a beacon of knowledge, creativity, and intellectual curiosity for over 175 years. I am thrilled to be a part of this vibrant community, and I am excited to share with you my passion for literature and its transformative power.Let me begin by thanking you for inviting me to speak here today. New York University is not just a university; it is a melting pot of cultures, ideas, and dreams. It is a place where the boundaries between disciplines blur, and where the pursuit of knowledge knows no limits. As a writer and a speaker, I find myself deeply inspired by such an environment, and I am eager to explore with you the world of literature that awaits us.Literature, my friends, is not just a collection of words on a page; it is a mirror that reflects the human condition, a lamp that illuminates the path to understanding, and a vessel that carries the hopes and fears of generations. It is through the power of literature that we come to understand ourselves and others, and it is through literature that we can transform the world.At NYU, we are fortunate to be surrounded by an abundance of resources that allow us to delve into the depths of literature. From the majestic libraries that house countless volumes to the diverse range of courses that cater to every taste, NYU is a haven for those who seek to explore the world of books. Today, I would like to take you on a journey through some of the great works of literature that have shaped my life and my understanding of the world.Let us start with Shakespeare, the Bard of Avon, whose plays have captivated audiences for centuries. In "Hamlet," we find a profound exploration of themes such as revenge, betrayal, and the nature of madness. Through the character of Hamlet, Shakespeare challenges us to question the very essence of our humanity and to consider the consequences of our actions. As we read these words, we are remindedthat literature has the power to provoke deep introspection and to make us question our own beliefs and values.Moving forward in time, we come across the works of Jane Austen, a master of social commentary. In "Pride and Prejudice," Austen crafts a story that is both a romantic comedy and a biting critique of theBritish class system. Through the characters of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy, we learn about the importance of self-awareness, the dangers of pride, and the joy of finding true love. Austen's wit and wisdom continue to resonate with readers today, reminding us that literature has the power to entertain and to educate.As we traverse the annals of time, we cannot overlook the works of Franz Kafka, a writer whose works are often described as existentialist and surreal. In "The Trial," Kafka presents us with a man who is trapped in a Kafkaesque world where absurdity and injustice reign supreme. Through this story, Kafka challenges us to confront the absurdity of our own lives and to seek meaning in a world that often seems senseless. Kafka's work serves as a reminder that literature can be a catalyst for profound self-reflection and personal growth.In the 20th century, we find ourselves in the midst of a literary explosion, with authors from around the world contributing their voices to the global conversation. One such voice is that of Gabriel GarcíaMárquez, the Colombian author whose "One Hundred Years of Solitude" is a masterful exploration of the Latin American experience. Through the magical realism of his narrative, Márquez invites us to consider the complexities of history, the interconnectedness of lives, and the power of love. Márquez's work teaches us that literature can be a bridge between cultures, fostering empathy and understanding.As we continue our journey through literature, we cannot forget the American author Harper Lee, whose "To Kill a Mockingbird" is a timeless classic that tackles the issue of racial injustice. Through the eyes of Scout Finch, we witness the trials and tribulations of a young girl growing up in the racially charged atmosphere of the American South.Lee's novel serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of moral courage, the need for empathy, and the unyielding quest for justice.Now, let us take a moment to reflect on the contemporary landscape of literature. Today, we are witness to a literary renaissance, with authors from diverse backgrounds and cultures contributing their unique perspectives to the global discourse. Whether it is the dystopian worlds of Neil Gaiman or the raw, emotional storytelling of Elena Ferrante, contemporary literature continues to push the boundaries of what we consider possible, challenging us to think critically and to embrace the complexity of our world.As we delve into the pages of these works, we must remember that literature is not just a source of entertainment or enlightenment; it is a powerful tool for social change. It is through literature that we can foster empathy, challenge our preconceptions, and inspire action. The words we read have the power to ignite a spark within us, to motivate us to stand up for what is right, and to fight against injustice.Here at NYU, we are part of a community that values the power of words. We are a community that recognizes the transformative potential of literature, and we are committed to nurturing that potential within ourselves and within others. As you continue your academic journey, I urge you to embrace the beauty and complexity of literature. Let it be your companion on the road to self-discovery, let it be your guide on the path to understanding, and let it be your inspiration to make a difference in the world.In closing, I would like to leave you with a quote from C.S. Lewis, a20th-century writer and scholar: "We read to know we are not alone." As you engage with literature, remember that you are part of a grand conversation that spans centuries and cultures. Your voice, your thoughts, and your experiences are invaluable contributions to this conversation. Embrace the power of words, and let them carry you to new heights of understanding and creativity.Thank you for listening, and may your journey through literature be as enriching and transformative as mine has been.Godspeed.[Applause]。

罗密欧与朱丽叶 英文版介绍

All‘s Well That Ends Well 皆大欢喜 As You Like It 如愿 Comedy of Errors 错中错 Love‘s Labour’s Lost 空爱一场 The Merchant of Venice威尼斯商人 Measure for Measure 一报还一报 The Merry Wives of Windsor 温莎的风流夫人 Much Ado About Nothing 无事生非 A Midsummer Night‘s Dream 仲夏夜之梦 The Taming of the Shrew 驯悍记 The Tempest 暴风雨 Twelfth Night 第十二夜 Two Gentlemen of Verona 维洛那二绅士 The Winter‘s Tale 冬天的故事

House of Montague

• Montague is the patriarch of the house of

• • Montague. Lady Montague is the matriarch of the house of Montague. Romeo is the son of Montague, and the play's male protagonist. Benvolio is Romeo's cousin and best friend. Abram and Balthasar are servants of the Montague household

Shakespeare & Romeo and Juliet

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) is considered to be the greatest writer in the history of English literature. From 1590 to 1613, he totally wrote 38 plays. Along with Shakespeare’ plays, his 154 sonnets and several lyrical poems have been translate into over 80 different languages throughout the world.

名词解释

英美文学重要作家作品英汉对照

英国作家作品

Edmund Spencer (1552-1599) 埃德蒙·斯宾塞

Henry Fielding (1707-1754) 亨利·菲尔丁

The Coffee-House Politician 咖啡屋政客

Pasquin 讽刺诗文

The Historical Register for the Year 1736 一七三六年历史记事

Joseph Andrews 约瑟夫·安德鲁斯

The Elegies and Satires 挽歌与讽刺诗

The Songs and Sonnets 歌曲与十四行诗

The Sun Rising 日出

Death,Be Not Proud 死神莫骄傲

John Milton (1608-1674) 约翰·弥尔顿

Lycidas 列西达斯

Areopagitica 论出版自由

Othello 奥赛罗

King Lear 李尔王

Macbeth 麦克佩斯

Cymbeline 辛白林

The Tempest 暴风雨

The Two Gentlemen of Verona 维罗娜二绅士

Timon of Athens 雅典的泰门

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) 弗朗西斯·培根

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) 丹尼尔·笛福

Robinson Crusoe 鲁宾逊漂流记

英美文学选读作者和作品对照

Areopagitica论出版自由

Chapter 2新古典主义时期

I.John Bunyan

The Pilgrim’s Progress天路历程

Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners罪人头目的赫免

The Life and Death of Mr. Badman拜德门先生生死录

Cavalry Crossing a Ford

Song of Myself

草叶集

名主展望

有个天天向前走的孩子

骑兵过河

自我之歌

Herman Melville

赫尔曼.麦尔维尔

Bartleby, The Scrivner

The Confidence Man

Billy Budd

Moby Dick

巴特尔比

自信者

The Merry Wise of Windsor温莎的风流娘儿们

Two Tragedies:

Romeo and Juliet罗米欧与朱丽叶

Julius Caesar凯撒

Hamlet

Othello

King Lear

Macbeth

Antony and Cleopatra安东尼与克里佩特拉

Troilus and Cressida, and Coriolanus特洛伊勒斯与克利西达

比利.巴德

莫比.迪克

Mark Twain

马克.吐温

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

The_American_Scholar

The American Scholar,国外论知识和做学问写的最好的文章Emerson:The American Scholar1837年8月31日,爱默生在美国大学生联谊会上以《论美国学者》为题发表演讲,抨击美国社会中灵魂从属于金钱的拜金主义和资本主义的劳动分工使人异化为物的现象,强调人的价值;他提出学者的任务是自由而勇敢地从表相中揭示真实,以鼓舞人、提高人和引导人;他号召发扬民族自尊心,反对一味追随外国学说。

这一演讲轰动一时,对美国民族文化的兴起产生了巨大影响,被誉为是美国“思想上的独立宣言”。

这是Bantom classic 的版本,也可以算国外论知识和做学问写的最好的文章-----------------------------------------------------------------------------Mr. President and Gentlemen,I greet you on the re-commencement of our literary year. Our anniversary is one of hope, and, perhaps, not enough of labor. We do not meet for games of strength or skill, for the recitation of histories, tragedies, and odes, like the ancient Greeks; for parliaments of love and poesy, like the Troubadours; nor for the advancement of science, like our contemporaries in the British and European capitals. Thus far, our holiday has been simply a friendly sign of the survival of the love of letters amongst a people too busy to give to letters any more. As such, it is precious as the sign of an indestructible instinct. Perhaps the time is already come, when it ought to be, and will be, something else; when the sluggard intellect of this continent will look from under its iron lids, and fill the postponed expectation of the world with something better than the exertions of mechanical skill. Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close.The millions, that around us are rushing into life, cannot always be fed on the sere remains of foreign harvests. Events, actions arise, that must be sung, that will sing themselves. Who can doubt, that poetry will revive and lead in a new age, as the star in the constellation Harp, which now flames in our zenith, astronomers announce, shall one day be the pole-star for a thousand years?In this hope, I accept the topic which not only usage, but the nature of our association, seem to prescribe to this day,--the AMERICAN SCHOLAR. Year by year, we come up hither to read one more chapter of his biography. Let us inquire what light new days and events have thrown on his character, and his hopes.It is one of those fables, which, out of an unknown antiquity, convey an unlooked-for wisdom, that the gods, in the beginning, divided Man into men, that he might be more helpful to himself; just as the hand was divided into fingers, the better to answer its end.The old fable covers a doctrine ever new and sublime; that there is One Man,--present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man. Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state, these functions are parceled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his. The fable implies, that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the other laborers. But unfortunately, this original unit, this fountain of power, has been so distributed to multitudes, has been so minutely subdivided and peddled out, that it is spilled into drops, and cannot be gathered. The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters,--a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.Man is thus metamorphosed into a thing, into many things. The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney, a statute-book; the mechanic, a machine; the sailor, a rope of a ship.In this distribution of functions, the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state, he is, Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society, he tends to become a mere thinker,or, still worse, the parrot of other men's thinking.In this view of him, as Man Thinking, the theory of his office is contained. Him nature solicits with all her placid, all her monitory pictures; him the past instructs; him the future invites.Is not, indeed, every man a student, and do not all things exist for the student's behoof? And, finally, is not the true scholar the only true master? But the old oracle said, `All things have two handles: beware of the wrong one.' In life, too often, the scholar errs with mankind and forfeits his privilege. Let us see him in his school, and consider him in reference to the main influences he receives.I. The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of nature. Every day, the sun; and, after sunset, night and her stars. Ever the winds blow; ever the grass grows. Every day, men and women, conversing, beholding and beholden. The scholar is he of all men whom this spectacle most engages. He must settle its value in his mind. What is nature to him? There is never a beginning, there is never an end, to the inexplicable continuity of this web of God, but always circular power returning into itself. Therein it resembles his own spirit, whose beginning, whose ending, he never can find,--so entire, so boundless. Far, too, as her splendors shine, system on system shooting like rays, upward, downward, without centre, without circumference,--in the mass and in the particle, nature hastens to render account of herself to the mind. Classification begins. To the young mind, every thing is individual, stands by itself. By and by, it finds how to join two things, and see in them one nature; then three, then three thousand; and so, tyrannized over by its own unifying instinct, it goes on tying things together, diminishing anomalies, discovering roots running under ground, whereby contrary and remote things cohere, and flower out from one stem. It presently learns, that, since the dawn of history, there has been a constant accumulation and classifying of facts. But what is classification but the perceiving that these objects are not chaotic, and are not foreign, but have a law which is also a law of the human mind? The astronomer discovers that geometry, a pure abstraction of the human mind, is the measure of planetary motion. The chemist finds proportions and intelligible method throughout matter; and science is nothing but the finding of analogy, identity, in the most remoteparts. The ambitious soul sits down before each refractory fact; one after another, reduces all strange constitutions, all new powers, to their class and their law, and goes on for ever to animate the last fibre of organization, the outskirts of nature, by insight.Thus to him, to this school-boy under the bending dome of day, is suggested, that he and it proceed from one root; one is leaf and one is flower; relation, sympathy, stirring in every vein. And what is that Root? Is not that the soul of his soul?--A thought too bold,--a dream too wild. Yet when this spiritual light shall have revealed the law of more earthly natures,--when he has learned to worship the soul, and to see that the natural philosophy that now is, is only the first gropings of its gigantic hand, he shall look forward to an ever expanding knowledge as to a becoming creator. He shall see, that nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal, and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments. So much of nature as he is ignorant of, so much of his own mind does he not yet possess. And, in fine, the ancient precept, "Know thyself," and the modern precept, "Study nature," become at last one maxim.II. The next great influence into the spirit of the scholar, is, the mind of the Past,--in whatever form, whether of literature, of art, of institutions, that mind is inscribed. Books are the best type of the influence of the past, and perhaps we shall get at the truth,--learn the amount of this influence more conveniently,--by considering their value alone.The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him, life; it went out from him, truth. It came to him, short-lived actions; it went out from him, immortal thoughts. It came to him, business; it went from him, poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.Or, I might say, it depends on how far the process had gone, of transmuting life into truth. In proportion to the completeness of the distillation, so will the purity and imperishableness of theproduct be. But none is quite perfect. As no air-pump can by any means make a perfect vacuum, so neither can any artist entirely exclude the conventional, the local, the perishable from his book, or write a book of pure thought, that shall be as efficient, in all respects, to a remote posterity, as to contemporaries, or rather to the second age. Each age, it is found, must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding. The books of an older period will not fit this.Yet hence arises a grave mischief. The sacredness which attaches to the act of creation,--the actof thought,--is transferred to the record. The poet chanting, was felt to be a divine man: henceforth the chant is divine also. The writer was a just and wise spirit: henceforward it is settled, the book is perfect; as love of the hero corrupts into worship of his statue. Instantly, the book becomes noxious: the guide is a tyrant. The sluggish and perverted mind of the multitude, slow to open to the incursions of Reason, having once so opened, having once received this book, stands upon it, and makes an outcry, if it is disparaged. Colleges are built on it. Books are written on it by thinkers, not by Man Thinking; by men of talent, that is, who start wrong, who set out from accepted dogmas, not from their own sight of principles. Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views, which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries, when they wrote these books.Hence, instead of Man Thinking, we have the bookworm. Hence, the book-learned class, who value books, as such; not as related to nature and the human constitution, but as making a sort of Third Estate with the world and the soul. Hence, the restorers of readings, the emendators, the bibliomaniacs of all degrees.Books are the best of things, well used; abused, among the worst. What is the right use? What is the one end, which all means go to effect? They are for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book, than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul. This every man is entitled to; this every man contains within him, although, in almost all men, obstructed, and as yet unborn. The soul active sees absolute truth; and utters truth, or creates. In this action, it is genius;not the privilege of here and there a favorite, but the sound estate of every man. In its essence, it is progressive. The book, the college, the school of art, the institution of any kind, stop with some past utterance of genius. This is good, say they,--let us hold by this. They pin me down. They look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his hindhead: man hopes: genius creates. Whatever talents may be, if the man create not, the pure efflux of the Deity is not his;--cinders and smoke there may be, but not yet flame. There are creative manners, there are creative actions, and creative words; manners, actions, words, that is, indicative of no custom or authority, but springing spontaneous from the mind's own sense of good and fair.On the other part, instead of being its own seer, let it receive from another mind its truth, though it were in torrents of light, without periods of solitude, inquest, and self-recovery, and a fatal disservice is done. Genius is always sufficiently the enemy of genius by over influence. The literature of every nation bear me witness. The English dramatic poets have Shakspearized nowfor two hundred years.Undoubtedly there is a right way of reading, so it be sternly subordinated. Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar's idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men's transcripts of their readings. But when the intervals of darkness come, as come they must,--when the sun is hid, and the stars withdraw their shining, --we repair to the lamps which were kindled by their ray, to guide our steps to the East again, where the dawn is. We hear, that we may speak. The Arabian proverb says, "A fig tree, looking on a fig tree, becometh fruitful."It is remarkable, the character of the pleasure we derive from the best books. They impress us with the conviction, that one nature wrote and the same reads. We read the verses of one of the great English poets, of Chaucer, of Marvell, of Dryden, with the most modern joy,--with a pleasure, I mean, which is in great part caused by the abstraction of all time from their verses. There is some awe mixed with the joy of our surprise, when this poet, who lived in some past world, twoor three hundred years ago, says that which lies close to my own soul, that which I also hadwellnigh thought and said. But for the evidence thence afforded to the philosophical doctrine of the identity of all minds, we should suppose some preestablished harmony, some foresight of souls that were to be, and some preparation of stores for their future wants, like the fact observed in insects, who lay up food before death for the young grub they shall never see.I would not be hurried by any love of system, by any exaggeration of instincts, to underrate the Book. We all know, that, as the human body can be nourished on any food, though it were boiled grass and the broth of shoes, so the human mind can be fed by any knowledge. And great and heroic men have existed, who had almost no other information than by the printed page. I only would say, that it needs a strong head to bear that diet. One must be an inventor to read well. As the proverb says, "He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry out the wealth of the Indies." There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world. We then see, what is always true, that, as the seer's hour of vision is short and rare among heavy days and months, so is its record, perchance, the least part of his volume. The discerning will read, in his Plato or Shakespeare, only that least part,--only the authentic utterances of the oracle;-- all the rest he rejects, were it never so many times Plato's and Shakespeare's.Of course, there is a portion of reading quite indispensable to a wise man. History and exact science he must learn by laborious reading. Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office,--to teach elements. But they can only highly serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and, by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns, and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.III. There goes in the world a notion, that the scholar should be a recluse, a valetudinarian,--as unfit for any handiwork or public labor, as a penknife for an axe. The so-called 'practical men'sneer at speculative men, as if, because they speculate or see, they could do nothing. I have heard it said that the clergy,--who are always, more universally than any other class, the scholars of their day,--are addressed as women; that the rough, spontaneous conversation of men they do not hear, but only a mincing and diluted speech. They are often virtually disfranchised; and, indeed, there are advocates for their celibacy. As far as this is true of the studious classes, it is not just and wise. Action is with the scholar subordinate, but it is essential. Without it, he is not yet man. Without it, thought can never ripen into truth. Whilst the world hangs before the eye as a cloud of beauty, we cannot even see its beauty. Inaction is cowardice, but there can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action. Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not.The world,--this shadow of the soul, or other me, lies wide around. Its attractions are the keys which unlock my thoughts and make me acquainted with myself. I run eagerly into this resounding tumult. I grasp the hands of those next me, and take my place in the ring to suffer and to work, taught by an instinct, that so shall the dumb abyss be vocal with speech. I pierce its order; I dissipate its fear; I dispose of it within the circuit of my expanding life. So much only of life as I know by experience, so much of the wilderness have I vanquished and planted, or so far have I extended my being, my dominion. I do not see how any man can afford, for the sake of his nerves and his nap, to spare any action in which he can partake. It is pearls and rubies to his discourse. Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructors in eloquence and wisdom. The true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power.It is the raw material out of which the intellect moulds her splendid products. A strange process too, this, by which experience is converted into thought, as a mulberry leaf is converted into satin. The manufacture goes forward at all hours.The actions and events of our childhood and youth, are now matters of calmest observation. They lie like fair pictures in the air. Not so with our recent actions,--with the business which we now have in hand. On this we are quite unable to speculate. Our affections as yet circulate through it.We no more feel or know it, than we feel the feet, or the hand, or the brain of our body. The new deed is yet a part of life,--remains for a time immersed in our unconscious life. In some contemplative hour, it detaches itself from the life like a ripe fruit, to become a thought of the mind. Instantly, it is raised, transfigured; the corruptible has put on incorruption. Henceforth it is an object of beauty, however base its origin and neighborhood. Observe, too, the impossibility of antedating this act. In its grub state, it cannot fly, it cannot shine, it is a dull grub. But suddenly, without observation, the selfsame thing unfurls beautiful wings, and is an angel of wisdom.So is there no fact, no event, in our private history, which shall not, sooner or later, lose its adhesive, inert form, and astonish us by soaring from our body into the empyrean. Cradle and infancy, school and playground, the fear of boys, and dogs, and ferules, the love of little maids and berries, and many another fact that once filled the whole sky, are gone already; friend and relative profession and party, town and country, nation and world, must also soar and sing.Of course, he who has put forth his total strength in fit actions, has the richest return of wisdom. I will not shut myself out of this globe of action, and transplant an oak into a flower-pot, there to hunger and pine; nor trust the revenue of some single faculty, and exhaust one vein of thought, much like those Savoyards, who, getting their livelihood by carving shepherds, shepherdesses, and smoking Dutchmen, for all Europe, went out one day to the mountain to find stock, and discovered that they had whittled up the last of their pine-trees. Authors we have, in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers, to replenish their merchantable stock. If it were only for a vocabulary, the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary. Years are well spent in country labors; in town,--in the insight into trades and manufactures; in frank intercourse with many men and women; in science; in art; to the one end of mastering in all their facts a language by which to illustrate and embody our perceptions. I learn immediately from any speaker how much he has already lived, through the poverty or the splendor of his speech. Life lies behind us as the quarry from whence we get tiles and copestones for the masonry of to-day. This is the way to learn grammar. Colleges and books only copy the language which the field and the work-yard made.But the final value of action, like that of books, and better than books, is, that it is a resource. That great principle of Undulation in nature, that shows itself in the inspiring and expiring of the breath; in desire and satiety; in the ebb and flow of the sea; in day and night; in heat and cold; and as yet more deeply ingrained in every atom and every fluid, is known to us under the name of Polarity,--these "fits of easy transmission and reflection," as Newton called them, are the law of nature because they are the law of spirit.The mind now thinks; now acts; and each fit reproduces the other. When the artist has exhausted his materials, when the fancy no longer paints, when thoughts are no longer apprehended, and books are a weariness,--he has always the resource to live. Character is higher than intellect. Thinking is the function. Living is the functionary. The stream retreats to its source. A great soul will be strong to live, as well as strong to think. Does he lack organ or medium to impart his truths? He can still fall back on this elemental force of living them. This is a total act. Thinking is a partial act. Let the grandeur of justice shine in his affairs. Let the beauty of affection cheer his lowly roof. Those 'far from fame,' who dwell and act with him, will feel the force of his constitution in the doings and passages of the day better than it can be measured by any public and designed display. Time shall teach him, that the scholar loses no hour which the man lives. Herein he unfolds the sacred germ of his instinct, screened from influence. What is lost in seemliness is gained in strength. Not out of those, on whom systems of education have exhausted their culture, comesthe helpful giant to destroy the old or to build the new, but out of unhandselled savage nature,out of terrible Druids and Berserkirs, come at last Alfred and Shakespeare.I hear therefore with joy whatever is beginning to be said of the dignity and necessity of labor to every citizen. There is virtue yet in the hoe and the spade, for learned as well as for unlearned hands. And labor is everywhere welcome; always we are invited to work; only be this limitation observed, that a man shall not for the sake of wider activity sacrifice any opinion to the popular judgments and modes of action.I have now spoken of the education of the scholar by nature, by books, and by action. It remainsto say somewhat of his duties. They are such as become Man Thinking. They may all be comprised in self-trust. The office of the scholar is to cheer, to raise, and to guide men by showing them facts amidst appearances. He plies the slow, unhonored, and unpaid task of observation. Flamsteed and Herschel, in their glazed observatories, may catalogue the stars with the praise of all men, and, the results being splendid and useful, honor is sure. But he, in his private observatory, cataloguing obscure and nebulous stars of the human mind, which as yet no man has thought of as such, --watching days and months, sometimes, for a few facts; correcting still his old records;--must relinquish display and immediate fame. In the long period of his preparation, he must betray often an ignorance and shiftlessness in popular arts, incurring the disdain of the able who shoulder him aside. Long he must stammer in his speech; often forego the living for the dead. Worse yet, he must accept,--how often! poverty and solitude. For the ease and pleasure of treading the old road, accepting the fashions, the education, the religion of society, he takes the cross of making his own, and, of course, the self-accusation, the faint heart, the frequent uncertainty and loss of time, which are the nettles and tangling vines in the way of the self-relying and self-directed; and the state of virtual hostility in which he seems to stand to society, and especially to educated society. For all this loss and scorn, what offset? He is to find consolation in exercising the highest functions of human nature. He is one, who raises himself from private considerations, and breathes and lives on public and illustrious thoughts. He is the world's eye.He is the world's heart. He is to resist the vulgar prosperity that retrogrades ever to barbarism, by preserving and communicating heroic sentiments, noble biographies, melodious verse, and the conclusions of history. Whatsoever oracles the human heart, in all emergencies, in all solemn hours, has uttered as its commentary on the world of actions,--these he shall receive and impart. And whatsoever new verdict Reason from her inviolable seat pronounces on the passing men and events of to-day,--this he shall hear and promulgate.These being his functions, it becomes him to feel all confidence in himself, and to defer never to the popular cry. He and he only knows the world. The world of any moment is the merest appearance. Some great decorum, some fetish of a government, some ephemeral trade, or war, or man, is cried up by half mankind and cried down by the other half, as if all depended on thisparticular up or down. The odds are that the whole question is not worth the poorest thought which the scholar has lost in listening to the controversy. Let him not quit his belief that a popgun is a popgun, though the ancient and honorable of the earth affirm it to be the crack of doom. In silence, in steadiness, in severe abstraction, let him hold by himself; add observation to observation, patient of neglect, patient of reproach; and bide his own time,--happy enough, if he can satisfy himself alone, that this day he has seen something truly. Success treads on every right step. For the instinct is sure, that prompts him to tell his brother what he thinks. He then learns, that in going down into the secrets of his own mind, he has descended into the secrets of all minds. He learns that he who has mastered any law in his private thoughts, is master to that extent of all men whose language he speaks, and of all into whose language his own can be translated. The poet, in utter solitude remembering his spontaneous thoughts and recording them, is found to have recorded that, which men in crowded cities find true for them also. The orator distrusts at first the fitness of his frank confessions, --his want of knowledge of the persons he addresses,--until he finds that he is the complement of his hearers;--that they drink his words because he fulfill for them their own nature; the deeper he dives into his privatest, secretest presentiment, to his wonder he finds, this is the most acceptable, most public, and universally true. The people delight in it; the better part of every man feels, This is my music; this is myself.In self-trust, all the virtues are comprehended. Free should the scholar be,--free and brave. Free even to the definition of freedom, "without any hindrance that does not arise out of his own constitution." Brave; for fear is a thing, which a scholar by his very function puts behind him. Fear always springs from ignorance. It is a shame to him if his tranquility, amid dangerous times, arise from the presumption, that, like children and women, his is a protected class; or if he seek a temporary peace by the diversion of his thoughts from politics or vexed questions, hiding his head like an ostrich in the flowering bushes, peeping into microscopes, and turning rhymes, as a boy whistles to keep his courage up. So is the danger a danger still; so is the fear worse. Manlike let him turn and face it. Let him look into its eye and search its nature, inspect its origin,--see the whelping of this lion,--which lies no great way back; he will then find in himself a perfect comprehension of its nature and extent; he will have made his hands meet on the other side, and can henceforth defy it, and pass on superior. The world is his, who can see through its pretension.。

黄世坦译文《吴宓先生其人 -- 一位学者和博雅之士》鉴赏

六、添加形容词或副词,增加修辞效果

例如:(1)All this set on a neck too long by half. 译文:所有这一切都安放在一个加倍地过长的脖颈上。 评析:例(1)中,增译了副词“加倍地”,更显示出脖子比一般人的长, 将这脖颈长一特点鲜明突出。

8

例如:(2)Punctual as his lectures. 译文:他像钟表一样守时,像奴隶船上的一名划船苦工那样辛苦地备课。 评析:译文中增译了形容词“奴隶船上的”以及副词“辛苦地”。使译文更加 通顺。不会生硬拗口。

英译汉中的增词技巧 ——黄世坦

译文《吴宓先生其人 -- 一位学者和博雅之士》 鉴赏

前言

◆ 英汉两种语言由于词法结构、语法结构和修辞手段的差异, 在翻译过程中,往往出现词的添加现象。翻译时常常有必 要在译文的词量上作适当的增加,使译文既能忠实地传达 原文的内容和风格,又能符合译入语的表达习惯。翻译时 增词是由于意义、语法、修辞或逻辑上的需要,也是翻译 中必不可少的技巧。 ◆ 黄世坦在翻译<Mr.Wu Mi-A Scholar and a Gentleman>时, 多处使用该方法,以达到译文准确,清晰,且符合原文意 思。

例如:(2)Their faces are so ordinary:no mannerisms,no "anything",just plain Jack,Tom and Harry. 译文:他们的面孔太一般化了:没有丝毫个性,简直“一无所有”,仅 仅是一位平平常常的张三,李四或王五而已。 评析:例(1)中,“独一”与“无二”意同,但为了符合汉语习惯, 增译了“无二”。同样的例(2)中,增译了“丝毫”“常常”。

二、增译量词,使译文增加修辞效果

外研版英语选修八 MODULE 5 课文原文

【MODULE 5】The Conquest of the Universe【READING AND VOCABULARY】Space: the Final Frontier[Part 1]Ever since Neil Armstrong first set foot on the Moon back on 21st July, 1969, people have become accustomed to the idea of space travel. Millions of people watched that first moon landing on television, their hearts in their mouths, aware of how difficult and dangerous an adventure it was, and whatrisks had to be taken. With Armstrong`s now famous words:“That`s onesmall step for man, one giant leap for mankind”, a dream was achieved. All three astronauts made it safely back to Earth, using a spaceship computer that was much less powerful than the ones used by the average school students today.There were several more journeys into space over the next few years but the single spaceships were very expensive as they could not take off more than once. People were no longer so enthusiastic about a peace travel programme that was costing the United States $10 million a day. That was until the arrival of the space shuttle——a spacecraft that could be used for severaljourneys. The first shuttle fight into space was the Columbia——launched from the Kennedy Space Centre on 12th April, 1981,. The aim of this flight was to test the new shuttle system, to go safely up into orbit and to return to the Earth for a safe landing. It was a success and a little more than a decade after Apollo 11`s historic voyage, the Columbia made a safe, controlled, aeroplane-style landing in California. This was the start of a new age of space travel.By the time the Challenger took off in 1986, the world seemed to have lost its fear and wonder at the amazing achievement of people going to be a special flight and so millions of people turned in to witness the take-off on TV. An ordinary teacher, Christa McAuliffe, 37, who was married with two children, was to be the first civilian in space. She was going to give two fifteen-minute lessons from space. The first was to show the controls of the spacecraft and explain how gravity worked. The second was to describe theaim of the Challenger space programme. Christa hoped to communicate a sense of excitement and create new interest in the space programme. Sadly, she never came back to her classroom again, as the shuttle exploded just over a minute after taking off in Florida and all seven astronauts were killed.The world was in shock——maybe they assumed this space flight would be no more dangerous than getting on an aeroplane. But how wrong they were——in one moment excitement and success turned into fear and disaster. It was the worst space accident ever. As one Russian said at the time,“When something like this happens we are neither Russians nor Americans. We are just human being who have the same feelings.”[Part 2]I can remember that day so clearly, watching the take-off on TV at school. There was an ordinary teacher on the Challenger, and we were all very excited. We didn`t have much patience waiting for the launch. We had seen the smiling faces of the astronauts waving to the world as they stepped into the shuttle. Then, little more than a minute after take-off, we saw a strange red and orange light in the sky, followed by a cloud of white smoke. The Challenger had exploded in mid-air and we all started screaming.It happened so quickly and everyone was schoolboy I had thought that going into space as an astronaut must be the best job in the world. When I heard, a few weeks later, that the bodies of the astronaut and even the teacher`s lesson plans had been found at the bottom of the ocean, I was not so sure it was worth it at all. In spite of all our advanced technology, the world is still only at the very beginning of its voyage into space.【READINH AND VOCABULARY】Secrets of the Gas GiantThe Cassini-Huygens space probe, which reached Saturn last week, has sent bank amazing photographs of the planet`s famous rings viewed in ultraviolet light. The pictures show them in shades of blue, green and red. The different colours shoe exactly what the rings are made of: the red means the ring contains tiny pieces of rock and the blue and green is likely to be a mixture of water and frozen gases. Saturn itself is made of gases. It is so light and it could float on water——if a big enough ocean could be found!The probe is an international project to explore the planet and its rings and moons. It was launched in 1997 and its mission was to explore the “gas giant” planet which is the furthest planet to be seen from the Earth without a telescope.Scientist says the spacecraft`s four-year tour of Saturn may tell them how the rings are formed. It will also study the planet`s atmosphere and magnetic field.The porbe has sent back pictures of some of Saturn`s moon, including tiny Phoebe, which has a strange shape——unlike other planets and their moons, it is not perfectly round——and Saturn`s biggest moon, Titan, which is believed to be the only body in the solar system other than the Earth with liquid on the surface.The images of Titan and Phoebe look strangely like photos of Earth and our own Moon, taken decades ago by the earliest space missions. They are so clear that it is easy to forget they ear coming from a distance fone-and-a-half-billion kilometers.【READING PRACTICE】May the Force Be with YouStar Wars is a series of science fantasy films. The six-film series began in 1977, and has a world-wide audience, with films, books, video games, television series and toys. It is now acknowledged by the movie industry as the most successful film series ever.The films were made in random order, and move backwards and forwards through two hundred years. They describe the deeds of Anakin Skywalker, a noble Jedi knight, while Darth Vader, under orders from Lord Sith, creates tension then conflict between various autonomous republics and movements. This results in the defeat of the Jedi.Then Anakin`s son, Luke Skywalker, joins the Rebel Alliance to attack the authority of the new evil Empire. He accuses Darth Vader of killing his father, so he trains to become a Jedi knight and swears to avenge his loss. But to his sorrow, he learns that his father is actually Darth Vader himself. Luke escapes the latter`s grasp, as well as the Emperor`s attempt to turn him to the Dark Side. Instead, to his great relief, he achieves glory by turning his father back to the light side, while the divisions of the Rebel Alliance fleet flights the battle for the airspace over the motherland, and wins the war. Star Wars reflects many abstract concepts in Greek, Roman and Chinesefolk stories, such as an ability to foresee the future and the impossibility of controlling one`s destiny. For example, Anakin Skywalker cause the deathof his wife coming to her aid. Luke is like the hero lf a wuxia film, with his intention of avenging the death of his father, to become the most powerful Master of his art.The broad theme of Star Wars` philosophy is the Force, and in every movie someone says “May the Force be with you.” Star Wars stresses the dangers of fear, anger, and hate, as well as putting aside one`s sympathy for certain people. For example, Luke Skywalker is ever told that his training rather than rescue his friends.This is consistent with many religious faiths, which stress rational thought, personal dignity and a devotion to praying for holy understanding, as opposed to the “Dark Side”, of violent passion and acute emotion.However, the strongest influence is Taoist philosophy. The Force is similar to Qi, a stable balance of the Yin and Yang forces to human beings and the environment. Many true Taoist masters eventually become supreme beings, similar to Obi-Wan and Yoda who Luke, as their scholar, consults for their teaching and advice.Even the language and clothing convey the philosophy of the Force——the Dark Force soldiers speak with British accents and wear black uniforms whilst most of the Rebels speaker American English and wear light colours.【CULTURAL CORNER】The War of the WorldsIn 1898, the English writer H.G. Wells wrote what is arguably the most important novel in the history of science fiction The War of the Worlds. It is a dramatic story about an invasion of the Earth by aliens from Mars, a subject that has fascinated science fiction writers and film-makers ever since. But when, in 1938, the American actor and director, Orson Welles set a radio drama of The War of the Worlds in real life New Jersey town of Grover`s Mill, little did he know what people turned on their radios and heard the Mercury Theatre Company broadcast, it was so realistic that they believed every word:Ladies and gentlemen, I have a grave announcement to make. Incredible as it may seen, both the observations of science and the evidence of our eyes lead to the inescapable assumption that those strange beings who landed in the New Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars.Orson Welles had managed to set in motion a panic across America. When people heard that an invasion by aliens from Mars was underway, there was a wave of mass hysteria. Hundreds of people left their homes in panic, there were traffic jams all over the state and the police received thousands of telephone calls from terrified listeners who believed that Martians were attacking.The sleepy town of Grover`s Mill for an hour became the centre of the universe.One 13-year-old boy was doing his homework when he hears the first newsflash of the invasion. Taking the radio into the cafédownstairs where his mother worked, he and a dozen or so customers listened with mounting fear to the broadcast, until the men jumped up and announced they were going to get their guns and join in the defence at Grover`s Mill.Did Orson Welles deliberately set out to terrify the nation? Or was it simply a masterpiece of realistic theatre? Either way, The War of the Worlds will be remembered as a piece of broadcasting history.。

“前景化”理论下赏析《孔乙己》两个英译本[权威资料]

![“前景化”理论下赏析《孔乙己》两个英译本[权威资料]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/b66e65e4f80f76c66137ee06eff9aef8941e4883.png)

“前景化”理论下赏析《孔乙己》两个英译本本文档格式为WORD,感谢你的阅读。

摘要:《孔乙己》作为鲁迅的短篇小说名篇,具有很高的文学价值和历史意义,其中文章塑造的“孔乙己”这个人物,与阿Q一道成为鲁迅笔下最具民族代表性的典型形象。

因此,在英译《孔乙己》一文时,应当注意对文章中人物以及具有文学、艺术价值的东西前景化、突出化。

本文将按照文体学中的“前景化”概念,比较赏析杨宪益、戴乃迭和威廉・莱尔两个译本的《孔乙己》,并从中探究高质量的译本应该在文学翻译时注意的前景化处理方式。

关键词:前景化;小说翻译;文体学;译本比较;假象等值I206.6 A 1006-026X(2014)01-0000-02一、《孔乙己》简介《孔乙己》是鲁迅先生在1919年创作的一篇白话文小说佳作,原文最初登载于《新青年》杂志,后收入《呐喊》一书,成为鲁迅白话文小说中的经典之作。

全书以“我”――酒店小伙计的视角出发,通过“我”对酒客孔乙己的大量动作、语言描写以及“我”自身的心理活动描写,呈现了孔乙己――一个深受封建文化毒害的读书人的短暂而又不幸的一生,表现了旧中国的穷困潦倒的读书人的悲惨命运,而他的遭遇表现的则是是当时整个社会的病态。

这篇小说的艺术价值在于:叙述角度独特,全文出自“我”这个酒店小伙计之口;典型人物自身矛盾纠葛,生活状态食不果腹却依旧不屑于与短衣主顾为伍,深受封建思想熏陶毒害;语言文字老辣深刻,文笔冷硬但充满批判性。

因此,在翻译这篇小说时,应把握以上特点,努力做到把作者着力传达的信息突出放大,达到同等的艺术效果。

二、前景化理论作为文体学的一个重要术语,“前景化”概念的发展先后经历了俄国的形式主义、布拉格学派和英国文体学家等的理论创造和规范而形成完整的理论系统。

雅各布森认为前景化就是把“文学性”是文学研究的对象。

韩礼德把前景化称作“有动因的突出”,利奇则认为“前景化就是一种对艺术的偏离”。

各位学者对于前景化的表述不同,但该概念的内涵却很明确。

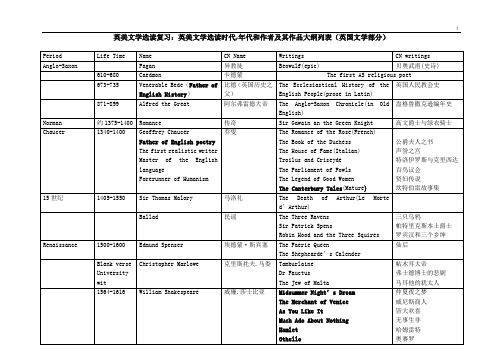

英美文学选读复习资料(时期作家作品)

福赛特世家

有产业的人

骑虎

出租

现代喜剧

William Butler Yeats

威廉.伯特勒.业芝

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

The Man Who Dreamed of Fairyland

Easter Rising of 1916

Sailing to Byzantian

Leda and The Swan

华特.斯哥特

Waverley

Ivanhoe

威弗利

艾凡赫

Victorian

1870-1914

Charles Dickens

查尔斯.狄更斯

Oliver Twist

The

雾都孤儿

The Bronte Sister

夏治特.布郎帝

Jane Eyre

Wuthering Heights

简爱

呼啸山庄

Alfred Tennyson

Nathaniel Hawthorne

纳萨尼尔.霍桑

The Scarlet Letter

The House of the Seven Gables

Young Goodman Brown

红字

七个尖角阁的房子

Macbeth

Romeo and Juliet

JuliusCaesar

The Winter’s Tale

The Tempest

ASonnet(154)

Henry Ⅳ、Ⅴ

Venus and Adonis

The Rape of Lucrece

Richard III

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

Isabella

把目光投向中国(英文翻译稿)

把目光投向中国Turning Your Eyes to China校长先生,女士们,先生们:Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen,衷心感谢萨莫斯校长的盛情邀请。

I would like to begin by sincerely thanking President Summers for his kind invitation.哈佛是世界著名的高等学府,精英荟萃,人才辈出。

建校367年来,曾出过7位总统,40多位诺贝尔奖获得者。

这是你们的光荣。

Harvard is a world-famous institution of higher learning, attracting the best minds and bringing them up generation after generation. In its 367 years of history, Harvard has produced seven American presidents and more than 40 Nobel laureates. You have reason to be proud of your school.今天,我很高兴站在哈佛讲台上同你们面对面交流。

我是一个普通的中国人。

我出生在一个教师家庭,有过苦难的童年,曾长期工作在中国艰苦地区。

中国有2500个县(区),我去过1800个。

我深爱着我的祖国和人民。

It is my great pleasure today to stand on your rostrum and have this face-to-face exchange with you. I am an ordinary Chinese, the son of a school teacher. I experienced hardships in my childhood and for long years worked in areas under harsh conditions in China. I have been to 1,800 Chinese counties out of a total of 2,500. I deeply love my country and my people.我今天演讲的题目是——把目光投向中国。

重要英美作家作品英汉对照

重要英美作家作品英汉对照英国作家作品Edmund Spenser (1552-1599) 埃德蒙·斯宾塞The Shepherds Calendar《牧人日历》The Faerie Queen 《仙后》Christopher Marlow (1564-1593) 克里斯托弗·马洛Tamburlaine, Parts I &II 《铁木耳大帝,第一部和第二部》The Tragical History of Dr.Faustus《浮士德博士的悲剧》The Jew of Malta《马尔他的犹太人》Edward II《爱德华二世》“The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”《多情的牧羊人致情人歌》William Shakespeare (1564-1616) 威廉·莎士比亚Henry VI《亨利六世》Richard III《查理三世》Henry IV《亨利四世》A Midsummer Night’s Dream《仲夏夜之梦》As You Like It《皆大欢喜》The Merchant of Venice《威尼斯商人》Twelfth Night《第十二夜》Romeo and Juliet《洛密欧与朱丽叶》Hamlet《哈姆雷特》Othello《奥赛罗》King Lear《李尔王》Macbeth《麦克佩斯》Cymbeline《辛白林》The Tempest《暴风雨》The Two Gentlemen of Verona《维洛那二绅士》Timon of Athens《雅典的泰门》Francis Bacon (1561-1626) 弗兰西斯·培根The Advancement of Learning《学术的进展》Novum Orgaum《新工具》History Of the Reign of King Henry VII《亨利七世王朝史》The New Atlantis《新大西岛》Essays《论说文集》“Of Studies”《论读书》John Donne (1572-1631) 约翰·邓恩The Elegies and Satires《挽歌与讽刺诗》The Songs and Sonnets《歌曲与十四行诗》“The Sun Rising”《日出》:Death, Be Not Proud”《死神莫骄傲》John Milton (1608-1674) 约翰·米尔顿Lycidas《列西达斯》Areopagitica《论出版自由》Paradise Lost《失乐园》Paradise Regained《复乐园》Samson Agonistes《力士参孙》John Bunyan (1628-1688) 约翰·班杨Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners《功德无量》The Pilgrim’s Progress《天路历程》The Life and Death of Mr.Badman《培德曼先生传》The Holy War《圣战》Alexander Pope (1688-1744)亚历山大·蒲柏Pastorals《田园诗集》The Rape of the Lock《卷发遭劫记》The Dunciad《愚人志》An Essay on Criticism《批评论》Essay on Man《人论》Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) 丹尼尔·迪福Robinson Crusoe《鲁宾逊漂流记》Captain Singleton《辛格顿船长》Moll Flanders《摩尔·弗兰德斯》Colonel Jack《杰克上校》Roxana《洛珊娜传》A Journal of the Plague Year《大疫年记》Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) 乔纳森·斯威夫特The Battle of the Books《书的战争》A Tale of a Tub《一个木桶的故事》The Drapier’s Letters《布商的书信》A Modest Proposal《一个温和的建议》Gulliver’s Travels《格列佛游记》Henry Fielding (1707-1754)亨利·菲尔丁The Coffee-House Politician《咖啡屋政客》Pasquin《讽刺诗文》The Historical Register for the Year 1736《一七三六年历史纪事》Joseph Andrews 《约瑟夫·安德鲁斯》The Life of Mr. Jonathan Wild the Great《大伟人乔纳森·威尔德传》The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling《弃儿,汤姆·琼斯传》Amelia《阿米丽亚》Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)塞缪尔·约翰逊A Dictionary of the English Language《英语词典》Lives of the Poets《诗人传》London《伦敦》The Vanity of Human Wishes《人类欲望之虚幻》The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia《阿比西尼亚王子拉塞拉斯》“To the Right Honorable the Eael of Chesterfield”《致切斯特菲尔德书》Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) 查理德·布林斯利·谢立丹The Rivals《情敌》The School fro Scandal《造谣学校》St. Patrick’s Day《圣·帕特立克节》The Duenna《杜埃娜》The Critic《批评家》Thomas Gray (1716-1771)托马斯·格雷“An Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”《墓园挽歌》“Ode on the Spring”《春天颂》“Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College”《伊顿学院的遥远前景颂》“Ode on the Death of a Favorite Cat”《爱猫之死颂》“Hymn to Adversity”《逆境赞》William Blake (1757-1827)威廉·布莱克Poetical Sketches《素描诗集》Songs of Innocence《天真之歌》Songs of Experience《经验之歌》The Marriage of Heaven and Hell《天堂与地域的婚姻》The Book of Urizen《尤里真之书》“The Chimney Sweeper”《扫烟窗的孩子》“The Tyger”《老虎》The Book of Los《洛斯之书》The Four Zoas《四个佐亚》Milton《米尔顿》William Wordsworth (1770-1850) 威廉·华兹华斯The Prelude《序曲》An Evening Walk 《黄昏散步》Lyrical Ballads《抒情歌谣集》Ode: Intimations of Immortality《不朽颂》The Excursion《远足》“I Wondered Lonely as a Cloud”《我好似一朵孤独的流云》“Composed upon Westminster Bridge”《西敏寺桥上》“She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways”《她住在人迹罕见的路边》“The Solitary Reaper”《孤独的割麦女》Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) 塞缪尔·泰勒·柯尔勒治Remorse 《懊悔》Biographia Literaria《文学传记》“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”《老船夫》“Kubla Khan”《忽必烈汗》“Frost at MIdnight”《午夜寒降》George Gordon Byron (1788-1824)乔治·戈登·拜伦Hours of Idleness《懒散时光》English Bards and Scotch Reviewers《英格兰诗人与苏格兰评论家》Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage《恰尔德·哈罗德游记》The Prisoner of Chillon《奇伦的囚犯》Manfred 《曼弗雷德》Cain《该隐》The Island《岛》Don Juan《唐璜》“Song for the Luddites”《献给路德派的歌》“The Isles of Greece”《哀希腊》Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)波西·比希·雪莱The Necessity of Atheism《无神论的必然性》Queen Mab《麦布女王》Alstor《阿拉斯特》Julian and Maddalo《朱利安和马达洛》The Revolt of Islam《伊斯兰的反抗》The Cenci《钦契》Prometheus Unbound《解放了得普罗米修斯》Adonais《安东尼斯》A Defence of Poetry《诗辩》“Ode to a Skylark”《云雀颂》“A Song: Men of England”《给英格兰人的歌》“Ode to the West Wind”《西风颂》John Keats (1795-1821) 约翰·济慈Endymion《恩狄弥翁》Lamia《拉米娅》Isabella《伊莎贝拉》The Eve of Saint Agnes《圣爱尼节前夜》“Ode on a Grecian Urn”《希腊古瓷颂》“Ode to a Nightingale”《夜莺颂》“Ode to Psyche”《普塞克颂》“To Autumn”《秋颂》“Ode on Melancholy”《忧郁颂》Jane Austen (1775-1817) 简·奥斯汀Sense and Sensibility《理智与情感》Pride and Prejudice《傲慢与偏见》Persuasion《劝告》The Watsons《沃森一家》Northanger Abbey《诺桑觉寺》Emma《爱玛》Mansfield Park《曼斯菲尔德公园》Charles Dickens (1812-1870) 查尔斯·狄更斯Sketches by Boz《博兹素描》The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club《匹克威克外传》Oliver Twist《雾都孤儿》David Copperfield《大卫·科波菲尔》Martin Chuzzlewit《马丁·朱述尔维特》Dombey and Son《董贝父子》A Tale of Two Cities《双城记》Bleak House《荒凉山庄》Little Dorrit《小多利特》Hard Times《艰难时世》Great Expectations《远大前程》Our Mutual Friend《我们共同的朋友》The Old Curiosity Shop《老古玩店》Charlotte Bronte (1816-1855) 夏洛特·布朗蒂Jane Eyre《简·爱》Shirley《雪莉》The Professor《教授》Emily Bronte (1818-1848) 埃米莉·布朗蒂Wuthering Heights《呼啸山庄》Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) 阿尔弗雷德·丁尼生Poems by Two Bothers《两兄弟诗集》In Memoriam《悼念》Maud《毛黛》Idylls of the King《国王之歌》Enoch Arden《伊诺克·阿登》“Break, Break, Break”《碎了,碎了,碎了》“Crossing the Bar”《过沙洲》“Ulysses”《尤利西斯》Robert Browning (1812-1889) 罗伯特·布朗宁Pauline《波琳》Sordello《索德罗》Dramatic Lyrics《戏剧抒情传》Dramatic Romances and Lyrics《戏剧传奇与抒情诗》Bell and Pomegranates《铃与石榴》Men and Women《男男女女》Dramatic Personae《登场人物》Ring and Book《戒指与书》“My Last Duchess”《我已故的公爵夫人》“Meeting at Night”《夜会》“Parting at Moring”《晨别》George Eliot (1819-1880)乔治·艾略特Adam Bede《亚当·德比》The Mill on the Floss《弗洛斯河上的磨坊》Silas Marner《织工马南传》Middlemarch《米德尔马契》Daniel Deronda《丹尼尔·德伦达》Thomas Hardy托马斯·哈代Desperate Remedies《孤注一掷的措施》Under the Green Tree《绿荫下》Far from the Madding Crowd《远离尘嚣》Tess of the D’urbervilles《德伯家的苔丝》Jude The Obscure《无名的裘德》The Dynastes《统治者》The Trumpet Major《喇叭上校》The Mayor of Casterbridge《卡斯特桥市长》The Woodlanders《林中居民》George Berard Shaw (1856-1950) 乔治·萧伯纳Cashel Byron’s Profession《卡希尔·拜伦的职业》Widower’s Houses《鳏夫的房产》Candida《堪迪达》Mrs. Warren’s Profession《华伦夫人的职业》Caesar and Cleopatra《凯撒与克利奥佩特拉》St. Joan《圣女贞德》Pygmalion《皮格马利翁》The Apple Cart《苹果车》Too True To Be Good《真相毕露》John Galsworthy (1867-1933)约翰·高尔斯华绥From the Four Winds《八面来风》The Man of Property《有产业的人》The Silver Box《银匣》The Forsyte Saga《福尔赛世家》In Chancery《骑虎》To Let《出租》William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) 威廉·巴特勒·叶芝The Countess Cathleen《伯爵夫人凯思琳》Cathleen in Houlihan《凯思琳在毫里汗》The Land of Heart’s Desire《理想的国土》Purgatory《炼狱》“The Lake Isle of Innisfree”《茵纳斯弗利岛》“Down by the Salley Gardens”《走过黄柳园》T.S.Eliot (1888-1965) T.S.艾略特“The love Song of J.Alfred Prufrock”《普鲁弗洛克的情歌》The Waste Land《荒原》The Hollow Man《空心人》Ash Wednesday《灰星期三》Four Qurtets《四个四重奏》Murder in the Cathedral《大教堂里的谋杀》The Family Reunion《家庭团圆》The Cocktail Party《鸡尾酒会》Confidential Clerk《心腹职员》The Elder Statesman《资深政治家》D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) 戴维·赫伯特·劳伦斯Sons and Lovers《儿子与情人》The White Peacock《白孔雀》The Trespasser《侵犯者》The Rainbow《虹》Women in Love《恋爱中的女人》Aaron’s Rod《阿伦之杖》Kangaroo《袋鼠》The Plumed Serpent《羽蛭》Chatterley’s Lover《查特莱夫人的情人》Lady St. Mawr《烈马圣莫尔》The Daughter of the Vicar《牧师的女儿》The Horse Dealer’s Daughter《马贩子的女儿》The Captain’s Doll《上尉的偶像》James Joyce (1882-1941) 詹姆斯·乔伊斯Dubliners《都柏林人》A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man《青年艺术家的画像》Ulysses《尤利西斯》“Araby”《阿拉比》美国作家作品Washington Irving (1783-1859) 华盛顿·欧文A History of New York《纽约外史》The Sketch Book《见闻札记》Tales Of a Traveler《旅行者的故事》“Rip Van Winkle”《瑞普·凡·温克尔》Bracebridge Hall《布雷斯布里奇田庄》“The Legend of Sleep Hollow”《睡谷的传说》Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) 拉尔夫·瓦尔多·爱默生Nature《论自然》The American《美国学者》Self-Reliance《论自立》The Over-soul《论超灵》The American Scholar《论美国学者》Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) 纳撒尼尔·霍桑Twice-Told Tales《众人皆知的故事》Mosses from Old Manse《古屋青苔》The Snow-Image and Other Twice-Told Tale雪的形象及其他尽人皆知的故事》The Scarlet letter《红字》The Home of the Seven Gables《有七个尖角阁的房子》The Blithedale Romance《福谷传奇》The Marble Faun《玉石雕像》“Young Goodman Brown”《年轻的古德曼·布朗》Walt Whitman (1819-1892) 华尔特·惠特曼Leaves of Grass《草叶集》“Song of Myself”《自我之歌》“There Was a Child Went Forth”《有个天天向前走的孩子》“Cavalry Crossing a Ford”《骑兵过河》Herman Melville (1819-!891) 赫尔曼·麦尔维尔Moby-Dick《白鲸》Billy Budd《比利·巴德》Typee《泰比》Omoo《奥穆》Mardi《玛地》Redburn《雷得本》White Jacket《白外衣》Pierre《皮埃尔》Mark Twain (1835-1910) 马克·吐温Adventures of Huckleberry Finn《哈克贝利·费恩历险记》Life on the Mississippi《密西西比河上的生活》Innocents Abroad《傻子出国记》Roughing It《含辛茹苦》The Adventures of Tom Sawyer《汤姆·索亚历险记》The Gilded Age《镀金时代》A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court《亚瑟王宫廷上的康涅狄格州美国人》The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson《傻瓜威尔逊》Henry James (1843-1916) 亨利·詹姆斯The American《美国人》Daisy Miller《黛西·米勒》The Europeans《欧洲人》The Portrait of A Lady《贵妇人的画像》The Bostonians《波士顿人》The Princess of Casamassima《卡撒玛西玛公主》The Private Life《私生活》The Death of a Lion《狮之死》The Turn of the Screw《螺丝在拧紧》The Beast in the Jungl e《丛林猛兽》The Wing of the Dove《鸽翼》The Ambasssadors《大使》The Golden Bowl《金碗》Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) 艾米利·狄金森The Poems of Emily Dickinson 《艾米利·狄金森诗集》“This is my letter to the world”《这是我写给世界的信》“I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died”《当我死的时候,我听到苍蝇嗡嗡叫》“I like to see it lap the Miles”《我爱看它舔食一哩又一哩》“Because I could not stop to death”《因为我不能停步等候死神》Theodore Dreiser (1875-1945) 西奥多·德莱塞Sister Carrie《嘉利妹妹》Jennie Gerhardt《珍妮姑娘》Trilogy of Desire《欲望三部曲》The Financier《金融家》An American Tragedy《美国的悲剧》Ezra Pound (1885-1975) 埃兹拉·庞德The Cantos《诗章》The Pisan Cantos《比萨诗章》Personae《人物》Huge Selwyn MAuberly《休·塞尔温》“In a Station of the Metro”《在地铁站》“The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter”《河商的妻子》Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) 罗伯特·李·弗洛斯特A Boy’s Will《一个男孩的志向》North of Boston《波士顿以北》Mountain Interval《山间低地》New Hampshire《新罕普什尔》West-Running Brook《西去的河流》A Witness Tree《见证树》“After Apple-Picking”《摘苹果之后》“The Road Not Taken”《没有走的路》“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”《雪夜林边驻脚》Eugene O’Neil (1874-1940)尤金·奥尼尔Beyond the Horizon《天外边》The Straw《草》Anna Christie《安娜。

the Renaissance Period 思维导图英美文学选读

the Renaissance period•time:between the 14th and mid-17th centuries.•it first started in Italy. painting,sculpture and culture.•marks a transition from the medieval to the modern world.•is a movement stimulated by a series of historical events.o the rediscovery of ancient Roman and Greek culture.o the new discoveries in geography and astrology.o the religious reformation and the economic expansion.•in essence,is a historical period in which the European humanist thinkers and scholars made attempts to get rid of those old feudalist ideas in medieval Europe,to introdue new ideas that expressed the interests of the rising bourgeoisie,and to recover the purity of the early church from the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church.•the Renaissance was slow in reaching Englando England's separation from the Continento its domestic unrest.•show its effect in Englando it was not until the reign of Henry VIII(from 1509 to 1547)▪The Oxford reformers,scholars and humanists introduced classicalliterature to England.▪religious reformation from the Continent.▪Martin Luther(1483-1546)a German Protestant,who initiatedthe Reformantion.who believed that every true Christian washis own priest and was entitled to interpret the Bible forhimself.▪the colorful and dramatic ritual of the CatholicChurch was simplified.Indulgences,pilgrimages andother practices were condemned.▪in the early stage of the continental Reformantion,he was regardedas a faithful son of the Catholic Church and named "Defender of theFaith",by the pope.▪his need for a legitimate male heir,and hence a new wife,led him tocut ties with Rome.the common english people had long beendissatisfied with the corruption of the church and inspired by thereformers'ideas from the Continent.▪1534,he was the Supreme Head of the Church of England,▪Bible in English was placed in every church andservices were held in English instead of Latin.so thatpeople could understand.▪Edward VI,Henry's son, the reform of the church's doctrine andteaching was carried out▪After Mary ascended the throne ,there was a violent swing toCatholicism▪by the middle of Elizabeth's reign,Protestantism had been firmlyestablished,with a certain extent of compromise between Catholicismand Protestantism.•had no sharp break with the past,Attitudes and feelings which had been characteristic of the 14th and 15th centuries persisted well down into the era of Humanism and Reformation.•Humanism is the essence of the Renaissance.o it sprang from the endeavor to restore a medieval reverence for the antique authors and is frequently taken as the beginning of the Renaissance on itsconscious,intellectual side,for the Greek and Roman civilization was based onsuch a conception that "man is the measure of all things"o Renaissance humanists found in the classics a justification to exalt human nature and came to see that human beings were glorious creatures capableof individual development in the direction of perfection,and that the worldthey inhabited was theirs not to despise but to question,explore,andenjoy.Thus ,by emphasizing the dignity of human beings and the importanceof the present life,they voiced their beliefs that man did not only have theright to enjoy the beauty of this life,but had the ability to perfect himself andto perform wonders.o Humanism began to take hold in England when the Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus(1466-1536) came to teach the classical learning,first at Oxford andthen at Cambridge.o Thomas More,Christopher Marlowe,William Shakespeare are the best representatives of the English humanists.•Strong national feeling in the time of the Tudors gave a great incentive to the cultural development in England.o English schools and universities were established in place of the old monasteries.with classical culture and the Italian humanistic ideas coming intoEngland,the English Renaissance began flourishing.o William Caxton,for he was the first person who introduced printing into England.▪printed Chaucer's "The Canterbury Tales" and Malory's "Morte Darthur".▪with the introduction of printing, an age of translation came into being.▪Plutarch's"Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans" wastranslated by North.▪Ovid's"Metamorphoses" by Golding▪Homer's "The Iliad" by Chapman▪Montaigne's"Essays" by Florio.•The first period of the English Renaissanc was one of imitation and assimilation.o Academies after the Italian type were founded.o Petrarch was regarded as the fountainhead of literature by the English writers.▪he and his successors who established the language of love and sharply distinguished the love poetry of the Renaissance from itscounterparts in the ancient world.▪Wyatt and Surrey began engraving the forms and graces of Italian poetry upon the native stock.▪Wyatt introduced the Petrarchan sonnet into England.▪Surrey brought in blank verse.▪Sidney followed with the sestina and terza rima and withvarious experiments in classic meters.▪Marlowe gave new vigor to the blank verse with his "mightylines"▪"The Passionate Shepherd to His Love", innocent.o Spenser's "The Shepheardes Calender" pastoral.•in the early stage of the Renaissance,poetry and poetic drama were the most outstanding literary forms.o they were carried on especially by Shakespeare and Ben Jonson.o The Elizabethan drama is the real mainstream of the English Renaissance.▪Lively,vivid native English material was put into the regular form of the Latin comedies of Plautus and Terence,Tragedies were in the styleof Seneca.▪the most famous dramatists in the Renaissance England are Christopher Marlowe,William Shakespeare,and Ben Jonson. •Francis Bacon(1561-1626) the first important English essayist,he was also the founder of modern science in England.•VIP Writerso William Shakespeare(1564-1616)▪playwright and poet.with his 38 plays,154 sonnets and 2 long poems.▪born into a merchant's family in Stratford-on-Avon.his father,John Shakespeare,his wife Anne Hathaway gave birth to threechildren:Susanna,and the twins,Judith and Hamnet.1586 or 1587 heleave home to London.▪he worked as actor and playwright in King's Men,Robert Greene,"University Wits" declared him to be" an upstart crow"▪ 2 long narrative poems,"Venus and Adonis" and "The Rape of Lucrece",they were dedicated to the Earl of Southampton.(1593-1594) ▪his dramatic career is divided into four periods.▪the first period- one of apprenticeship.▪five history plays:"Henry VI,Parts I,II,and III" "RichardIII" and "Titus Andronicus"; four comedies:"TheComedy of Errors" "The Two Gentlemen of Verona""Taming of the Shrew" "Love's Labour's Lost"(5,4,0)▪second period-style and approach became highlyindividualized.▪five histories: "Richard II" "King John" "Henry IV,PartsI and II" "Henry V"; six comedies:"A MidsummerNight's Dream" "The Merchant of Venice" "Much AdoAbout Nothing" "As You Like It" "Twelfth Night" "TheMerry Wives of Windsor"; two tragedies:"Romeo andJuliet" "Julius Caesar"(5,6,2)▪third period-greatest tragedies and his so-called dark comedies.▪two comedies:"All's Well That Ends Well" "Measurefor Measure": seven tragedies:"Hamlet" "Othello""Macbeth" "King Lear" "Antony and Cleopatra""Troilus and Cressida" "Coriolanus"(0,2,7)▪last period-romantic tragicomedies and two final plays.▪four romantic tragicomedies:"Pericles" "Cymbeline""The Winter's Tale" "The Tempest"; two finalplays:"Henry VIII" "The Two Noble Kinsmen".▪prevalent Christian teaching ofatonement.he seems to have entered animagined pastoral world.he could achievewhat he failed to in the real world.▪"The Tempest",the characters areallegorical and the subject full ofsuggestion.the humanly impossibleevents can be seen occurringeverywhere in the play. the wildstrom becomes magic,answeringProspero's every signal.,it is a typicalexample of his pessimistic viewtowards human life and society in hislate years.▪154 sonnets▪1-126 are addressed to a young man,beloved of the poet,of superior beauty and rank but of somewhat questionablemorals and constancy.▪127-152,they involve a mistress of the poet, a mysterious "Dark Lady",who is sensual,promiscuous,and irresistible.▪153-154,they are translations or adaptations of some version of a Greek epigram,and they evidently refer to the hot springsat Bath.▪99,126,154,three exceptions,▪history plays▪mainly written under the principle that national unity under a mighty and just sovereign is a necessity.▪romantic comedies▪an optimistic attitude toward love and youth.▪"The Merchant of Venice" ,praise the friendship between Antonio and Bassanio.to idealize Portia as a heroine of greatbeauty,wit,and loyalty.and to expose the insatiable greed andbrutality of the Jew.▪after centuries' abusing of the Jews,especially theholocaust committed by the Nazi Germany duringthe Second World War,it is very difficult to seeShylock as a conventional evil figure.and manypeople today tend to regard the play as a satire ofthe Christians' hypocrisy and their false standards offriendship and love,their cunning ways of pursuingworldliness and their unreasoning prejudice againstJews.▪romantic tragedy▪"Romeo and Juliet",which eulogizes the faithfulness of love and the spirit of pursuing happiness.though a tragedy,ispermeated with optimistic spirit.▪great tragedies▪each portrays some noble hero,who faces the injustice of human life and is caught in a difficult situation and whosefate is closely connected with the fate of the whole nation.each hero has his weakness of nature.▪"Hamlet",the melancholic scholar-prince,faces thedilemma between action and mind,▪base on northernEurope,Denmark,Claudius,his father'sbrother,who murdered his father,taken bothhis father's throne and widow.By revealingthe power-seeking,the jostling for place,thehidden motives.the courteous superficialitiesthat veil lust and guilt,Shakespearecondemns the hypocrisy and treachery andgeneral corruption at royal court.▪"Othello",his inner weakness is made use of by theoutside evil force.▪"King Lear",who is unwilling to totally give up hispower makes himself suffer from treachery andinfidelity;▪he has shown to us the two-foldeffects,exerted by the feudalist corruptionand the bourgeois egoism,which havegradually corroded the ordered society.▪"Macbeth" ,his lust for power stirs up his ambitionand leads him to incessant crimes.▪selected reading▪sonnet 18▪is one of the most beautiful sonnets written byShakespeare,in which he has a profound meditationon the destructive power of time and he eternalbeauty brought forth by poetry to the one he loves.Anice summer's day is usually transient,but the beautyin poetry can last for ever.Thus Shakespeare has afaith in the permanence of poetry.▪"The Merchant of Venice"▪An impoverished young Venetian,Bassanio,asks hisfriend, Antonio,for a loan so that he might gain inmarriage the hand of Portia,a rich and beautifulheiress of Belmont.Antonio's money is all invested inmercantile expeditions;in order to help Bassanio hehas to borrow from Shylock,the Jewishusurer.Shylock has made a strange bond thatrequires Antonio to surrender a pound of his flesh ifhe fails to repay him within a certain period of time.▪"Hamlet"▪to live on in this world or to die;to suffer or to takeaction.o John Milton(1608-1674)▪born in London,his father was both a scholar and a cated at St.Paul's School and Cambridge.1638 travelon the Continent.▪he once had an ambition to write an epic which England would "not willingly let die",but the English Revolution broke out his dream.hewas entirely occupied with the thoughts of fighting for humanfreedom.1649,he was appointed Latin Secretary to Cromwell'sCouncil of State. 1652,blind because strains.after the restoration ofCharles II,he was imprisoned for a short time and then retired toprivate life.▪"Paradise Lost" was finished in 1665,after 7 years' labor in darkness.▪"Paradise Regained",1666 started,▪"Samson Agonistes",1671,last important work.the most powerful dramatic poem on the Greek model.▪three groups▪the early poetic works▪"Lycidas"(1637),composed for a collection of elegiesdedicated to Edward King,a fellow undergraduate ofMilton's at Cambridge,who was drowned in the IrishSea.▪the middle prose pamphlets▪"Areopagitica"(1644) is probably his mostmemorable prose work.it is a great plea for freedomof the press.rather smooth and calm.▪the last great poems▪after the Restoration in 1660,when he was blind and suffering,and when he was poor and lonely,Miltonwrote his three major poetical works:▪"Paradise Lost",the only generallyacknowledged epic in English literature since"Beowulf"▪divided into 12 books.taken fromGenesis 3:1-24 of the Bible.thetheme is the "Fall of Man".the poemgoes on to tell how Satan tookrevenge by tempting Adam andEve,the first human beings createdby God,to eat fruit from the tree ofknowledge against God'sinstructions.Eden.intending toexpose the ways of Satan andto"justify the ways of God tomen"and then the tragedy was re-enacted,but with a difference-"Manshall find grace",but he must lay holdof it by an act of free will.thefreedom of the will is the keystone ofMilton's creed.▪"Paradise Regained"▪show how mankind,in the person ofChrist,withstands the tempter and isestablished once more in the divinefavor.▪"Samson Agonistes",is the most perfectexample of verse drama after the Greek stylein English.▪Milton again borrows his story fromthe Bible.but this time he turns to amore vital and personal theme.thewhole poem strongly suggestsMilton's passionate longing that hetoo could bring destruction downupon the enemy at the cost of hisown life.in this sense,Samson isMilton.in his life,Milton showshimself a real revolutionary, a masterpoet and a great prose writer,Hefought for freedom in all aspects asa Christian humanist,while hisachievements in literature make himtower over all the other Englishwriters of his time and exert a greatinfluence over later ones.▪selected reading▪"Paradise Lost"▪the story is taken from the Old Testament.Satan andother angels rebel against God,but they are defeatedand driven from Heaven into Hell.。

英国文学史笔记