debate team联系方式

首届北京国际大学生英语辩论大赛

首届北京国际大学生英语辩论大赛2006年11月9日至11月13日活动简介:北京外国语大学与国际辩论教育协会将于2006年11月9日至11月13日在北京外国语大学举行首届北京国际大学生辩论大赛。

本次大赛旨在提高非英语国家大学生英语水平,促进各国大学生之间的交流,培养全体参赛成员的思辨能力及积极参与探讨全球热点问题的意识。

本次大赛采取英国议会制辩论形式,比赛前设有对该形式辩论选手及评委的专业培训,赛后设有大赛感想交流。

参加本次大赛的评委将会获得国际辩论教育协会颁发的专业评委证书,辩手们也将得到不同形式的奖励。

另外,外语教学与研究出版社将赞助优胜辩手的图书奖品,主办方将根据比赛时间组织辩手们外出游览北京名胜。

活动费用:本次大赛无需报名费用,比赛期间,北京外国语大学将安排住宿房间及就餐地点,所有参赛学生和老师只需负担食宿费。

校内单人房间费用每晚100元左右,每顿正餐10元左右。

具体安排:11月9日至11月10日上午,英国议会制辩论培训(辩手及指导教师分别进行);11月10日下午至11月11日上午,五轮循环预赛;11月10日晚,欢迎晚宴暨开幕式;11月11日下午,四分之一决赛;11月12日上午,半决赛;11月12日下午,总决赛;11月12日晚,颁奖典礼暨闭幕式。

11月13日上午,大赛感想及经验技巧总结。

北京名胜游览时间将根据大赛期间情况确定。

报名方式:本次大赛采用网上报名形式,请各位学生与老师登录以下网址注册报名/events/index.php?event_id=76每位学生既可以一个人为单位参赛(主办方负责为个人辩手组队参赛),也可以组队参赛(每队两人)。

同一大学参赛队伍不可超过四组,每两组学生需要一位老师带队,如任何一学校有多于八位选手报名,主办方将视最后参赛人数另行处理。

如有任何疑问,请发电子邮件咨询国际辩论教育协会,Jeanne Chen jellybeanne@北京外国语大学英语学院,梁泓magliangcn@培训专家简介:莎伦·波特在美国路易斯安那州巴吞鲁日市路易斯安那州立大学获得博士学位。

英国议会制辩论赛规则(BP-Debate)

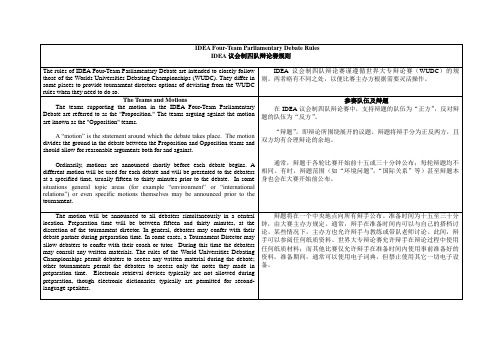

IDEA议会制四队辩论赛规则

The rules of IDEA Four-Team Parliamentary Debate are intended to closely follow those of the Worlds Universities Debating Championships (WUDC). They differ in some places to provide tournament directors options of deviating from the WUDC rules when they need to do so.

7分钟

反方一队,一辩

反对党领袖"Leader of the Opposition"

7分钟

正方一队,二辩

副首相"Deputy Prime Minister"

7分钟

反方一队,二辩

反对党副领袖"Deputy Leader of the Opposition"

7分钟

正方二队,一辩

内阁成员"Member for the Government"

A “motion” is the statement around which the debate takes place. The motion divides the ground in the debate between the Proposition and Opposition teams and should allow for reasonable arguments both for and against.

赢得他人的一次尊重的经历的英语作文

赢得他人的一次尊重的经历的英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Earning Respect: My Moment of PrideAs students, we often find ourselves in situations where we must prove our worth and capabilities to those around us. Whether it's in the classroom, on the sports field, or in extracurricular activities, the opportunity to earn respect from our peers, teachers, and mentors is a constant challenge. For me, this moment of earning respect came during my time as a member of the school's debate team.I still vividly remember the day I decided to join the debate team. It was during my sophomore year of high school, and I had always been intrigued by the art of public speaking and the exchange of ideas. However, despite my interest, I was plagued by a crippling fear of speaking in front of others. The mere thought of standing on a stage, facing a crowd of critical eyes and ears, sent shivers down my spine.Nevertheless, I knew that joining the debate team would be a crucial step in overcoming this fear and developing a skill thatwould serve me well in life. With a mixture of trepidation and determination, I attended the first meeting and found myself surrounded by a group of confident and articulate individuals who seemed to possess a natural talent for public speaking.In the beginning, I struggled to keep up with the pace and complexity of the debates. I would stumble over my words, lose my train of thought, and often find myself at a loss for a counterargument. The more experienced debaters would effortlessly dismantle my arguments, leaving me feeling discouraged and questioning my decision to join the team.However, I refused to give up. I spent countless hours researching topics, practicing my delivery, and honing my critical thinking skills. Slowly but surely, I began to improve, and my confidence grew with each passing debate.The turning point came during a pivotal debate tournament against a highly regarded team from a neighboring school. The topic was one that I had extensively researched and felt passionately about – the importance of environmental sustainability. As I stood on the podium, facing the opposing team and a panel of judges, I could feel the weight of expectation resting on my shoulders.With a deep breath, I launched into my opening statement, articulating my arguments with clarity and conviction. I could sense the shift in the room as the judges and audience members leaned in, captivated by my words. As the debate progressed, I deftly countered the opposition's points, drawing upon my research and employing logical reasoning to reinforce my stance.It was during the final rebuttal that I truly shone. With unwavering conviction, I delivered a powerful closing statement that encapsulated the essence of my arguments and left a lasting impression on all those present. As I stepped down from the podium, the room erupted in thunderous applause, and I could see the looks of awe and respect on the faces of my teammates and coaches.In that moment, I realized that I had not only earned the respect of my peers but also of the judges and the opposing team. The journey had been arduous, but the sense of accomplishment and validation was overwhelming.After the tournament, my coach pulled me aside and commended me on my performance. He acknowledged the remarkable progress I had made and how I had truly embodied the spirit of debate – the ability to articulate complex ideas with poise and persuasion.From that day forward, I carried myself with a newfound sense of confidence and pride. The respect I had earned from my teammates, coaches, and opponents was a testament to the power of perseverance and hard work. It taught me that with dedication and a willingness to learn, any obstacle can be overcome, and any goal can be achieved.The lessons I learned through my experience on the debate team have stayed with me long after I graduated from high school. The ability to effectively communicate my ideas, think critically, and present myself with confidence has proven invaluable in my academic and professional pursuits.Looking back, I can say with certainty that joining the debate team was one of the most transformative decisions of my life. It not only helped me conquer my fear of public speaking but also instilled in me a sense of self-belief and a drive to continually challenge myself.The moment when I earned the respect of those around me through my performance in that pivotal debate will forever be etched in my memory as a defining moment of personal growth and achievement. It serves as a reminder that with determination and a willingness to learn, we can overcome our limitations and exceed even our own expectations.篇2Earning Respect: My Journey to Being HeardAs a young student, I often felt like my voice didn't carry much weight. Adults seemed to brush off my opinions as just the naive ramblings of a kid who didn't really understand how the world worked yet. Even among my peers, I struggled to get people to take me seriously sometimes. I was the quiet kid who kept to myself a lot, and that made it easy for the louder, more boisterous students to drown me out.It wasn't that I lacked confidence exactly. I knew my own worth and I stood up for myself when it really mattered. But I also didn't want to come across as arrogant or like I thought I was better than everyone else. So I tended to hang back and only speak up when I felt I had something meaningful to contribute.That all changed during my junior year of high school when I got involved with the school's debate team. At first, I'll admit I was a bit intimidated by the prospect. After all, debating meant really putting yourself out there and fighting tenaciously for your side with facts, logic and skilled rhetoric. It was the total opposite of my usual quiet, reserved demeanor.But I was drawn to it because I loved researching different topics and looking at issues from multiple angles. Debate seemed like it could be an ideal fit for my particular set of strengths. And I was definitely intrigued by the idea of learning how to formulate persuasive arguments and articulate my perspectives more forcefully.So I went for it, and from those first few debate team meetings and practice rounds, I was hooked. I loved theback-and-forth nature of it, the way you had to really listen and then rapidly counter with a composed but fervent rebuttal. It challenged me in exhilarating new ways that I hadn't quite experienced before.Of course, it was tough at first and I definitely took some lumps early on. The other students had more experience and could run circles around me with their smooth cadences and confidence. A few times I even got flustered and choked up in the middle of a practice debate. But I persevered and was determined to get better.Slowly but surely, I started improving through many hours of practice, research, and a lot of help from my coaches and teammates. While I would never be the showiest or mostflamboyant debater, I developed a very precise and methodical style that turned out to be highly effective.I learned to marshall airtight logical arguments and back them up with cold, hard facts that were tough to refute. I became a master at poking holes in my opponent's reasoning and exposing any flaws or inconsistencies in their arguments. And I cultivated an unflappable presence and calm demeanor so that I could never be thrown off my game or rattled by opponents' attempts to provoke me.My skills were really put to the test at a major regional debate tournament during my senior year. We had made it all the way to the finals after beating out dozens of other schools in the preceding rounds. My opponent was a master orator and had a way of using flowery language to make even flimsily arguments sound profound and persuasive.When it was my turn for my opening statements, I'll admit I was more nervous than I had been in a long time. Here was the biggest stage I had debated on so far, with coaches, judges, and crowds of people watching and evaluating my every word. It would have been easy to get flustered or psyche myself out.But as soon as I started speaking, I felt an incredible calm and sense of determination wash over me. All those hours andhours of practicing, of sharpening my skills at cutting through distractions and superficial rhetoric to get at the core of an issue, gave me a laserlike focus and confidence. I wasn't going to be swayed by my opponent's linguistic pyrotechnics.Slowly and systematically, I dismantled his main arguments one by one, countering his charisma and flourishes with a steady barrage of well-researched facts and airtight logic. On the rare occasions when he did briefly put me on the defensive, I deftly deflected and quickly turned it back around on him, never losing my cool.By the time I delivered my closing statements, reiterating the key reasons why my position was ultimately the stronger and more defensible one, I could sense that I had won over the judges and spectators. There was a palpable shift in the atmosphere of the room. What had started as mild bemusement towards the shrinking violet facing off against the silver-tongued orator had turned into genuine respect and admiration for my mastery of the substance behind the rhetoric.When it was all over and I was declared the winner, it was one of the most profoundly gratifying moments of my life. Not because I cared about winning some trophy, but because I had finally commanded the respect and attention of an audience thathad initially dismissed me. Through deliberate preparation, steely self-discipline, and sheer force of skilled argumentation, I had proven that I didn't need to be some showboating loudmouth to have real substance and gravitas.From that point on, I carried myself with a new sense of self-assurance and poise. I knew that if I researched diligently and marshaled airtight logic, I would be able to hold my own and even dominate a reasoned debate against anyone, no matter how much more naturally gifted they may have been as a speaker.That experience gave me something invaluable that extended far beyond the debate arena – the ability to make myself heard and be taken seriously. No matter what setting I found myself in during college or later in my career, I always had the skills and confidence to articulately present even highly complex subjects in a way that earned the respect and consideration of my audience.Whether I was giving reports and presentations, speaking up in meetings, or simply opining in more casual discussions, I never had to worry about being dismissed or overlooked. People knew from experience that if I felt strongly enough to throw my hatinto a conversation, I would make arguments rooted in facts and reasoning rather than dazzle with superficial showmanship.In an age when it can feel like rhetorical bombast and emotive appeals often carry more sway than logical arguments, having that ability tocut through the noise has been invaluable. Being the calm voice of reasoned analysis has allowed me to earn a reputation for credibility in all kinds of different circles.Of course, that big regional debate tournament was just one early milestone in what has been a lifelong journey of constantly working to improve my communication skills, strengthen my ability to understand different perspectives, and substantiate my own views through diligent research and ahh logic.But looking back, it is clearly the defining moment when I went from being just another not-so-confident kid whose voice could be easily dismissed or ignored to someone who could truly command a room. Earning that respect through skilled argumentation and proving my substance gave me an empowering belief in myself that persists to this day.篇3Earning Respect: A Lesson in PerseveranceAs students, we often find ourselves in situations where we have to prove our worth, whether it's to our teachers, our peers, or even ourselves. One such experience that stands out in my mind is the time I had to earn the respect of a particularly demanding professor, Dr. Williams.Dr. Williams was known for being a tough grader, with high expectations and little patience for mediocrity. He taught a course on advanced literary analysis, which was a requirement for my English major. From the first day of class, it was clear that he was not going to go easy on us.During the first few weeks, I struggled to keep up with the workload and comprehend the complex theories we were studying. My papers were constantly returned with scathing feedback and low grades, leaving me feeling discouraged and questioning my abilities.One day, after receiving yet another disappointing grade, I decided to approach Dr. Williams during his office hours. I was nervous, but I knew I had to do something to turn things around."Dr. Williams," I began, trying to keep my voice steady. "I'm having a hard time with this course, and I was hoping you could give me some guidance."He looked at me over the rim of his glasses, his expression impassive. "What seems to be the problem, Mr. Johnson?" he asked.I took a deep breath and explained how I felt like I was constantly missing the mark with my analyses, despite putting in countless hours of effort. I expressed my frustration and my desire to improve.To my surprise, Dr. Williams didn't immediately dismiss my concerns. Instead, he listened intently, nodding as I spoke. When I finished, he leaned back in his chair and regarded me for a moment."Mr. Johnson," he said finally, "the problem isn't your effort or your intelligence. The problem is your approach."He then proceeded to explain that my analyses were too surface-level, and that I needed to dig deeper into the texts, exploring the symbolism, the subtext, and the broader cultural and historical contexts. He gave me specific examples of how to do this, and even recommended a few additional resources to help me develop my skills.I left his office feeling invigorated and determined. From that point on, I approached each assignment with a renewed sense ofpurpose, applying the techniques Dr. Williams had taught me and constantly seeking feedback to improve.Slowly but surely, my grades began to improve. More importantly, I found myself genuinely enjoying the process of literary analysis, relishing the opportunity to uncover the deeper meanings and nuances within the texts we studied.As the semester progressed, Dr. Williams seemed to take notice of my progress. He would occasionally offer a nod of approval or a rare compliment on a particularly insightful analysis. And while he never went easy on me, his feedback became more constructive and less critical.The turning point came with our final paper, a comprehensive analysis of a novel of our choice. I poured countless hours into researching, analyzing, and crafting my argument, determined to produce a piece of work that would truly showcase my growth and understanding.When I received my grade, I was elated to see an 'A' at the top of the page, accompanied by a brief note from Dr. Williams: "Excellent work, Mr. Johnson. You've come a long way this semester."Those few words meant more to me than any grade ever could. I had not only earned Dr. Williams' respect, but I had also gained a newfound respect for myself and my abilities as a student of literature.In the end, my experience with Dr. Williams taught me a valuable lesson about perseverance and the importance of being open to feedback and criticism. It's easy to get discouraged when faced with challenges, but true growth and respect come from embracing those challenges and working tirelessly to overcome them.As I reflect on that semester, I'm filled with gratitude for Dr. Williams' unwavering standards and his willingness to push me beyond my perceived limits. It was a humbling experience, but one that has undoubtedly made me a better student, a more critical thinker, and a more resilient individual.To this day, whenever I face a daunting task or encounter someone who doubts my abilities, I remember the journey I took in Dr. Williams' class – a journey that taught me that respect is not something that is given freely, but something that must be earned through hard work, dedication, and a willingness to learn and grow.。

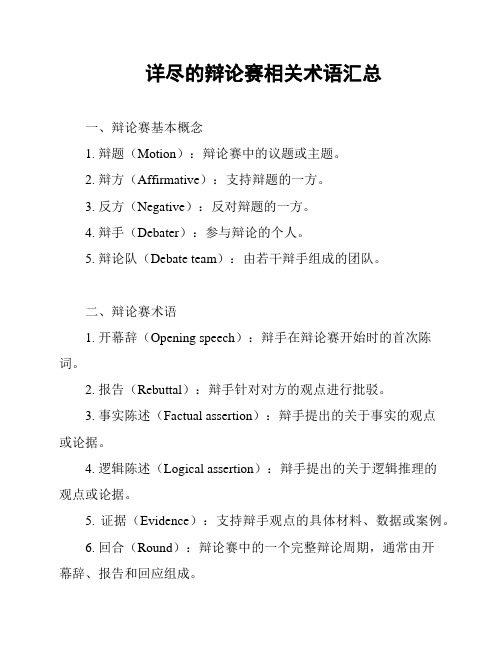

详尽的辩论赛相关术语汇总

详尽的辩论赛相关术语汇总一、辩论赛基本概念1. 辩题(Motion):辩论赛中的议题或主题。

2. 辩方(Affirmative):支持辩题的一方。

3. 反方(Negative):反对辩题的一方。

4. 辩手(Debater):参与辩论的个人。

5. 辩论队(Debate team):由若干辩手组成的团队。

二、辩论赛术语1. 开幕辞(Opening speech):辩手在辩论赛开始时的首次陈词。

2. 报告(Rebuttal):辩手针对对方的观点进行批驳。

3. 事实陈述(Factual assertion):辩手提出的关于事实的观点或论据。

4. 逻辑陈述(Logical assertion):辩手提出的关于逻辑推理的观点或论据。

5. 证据(Evidence):支持辩手观点的具体材料、数据或案例。

6. 回合(Round):辩论赛中的一个完整辩论周期,通常由开幕辞、报告和回应组成。

8. 陈词(Presentation):辩手陈述自己的观点和论据的过程。

9. 交叉质询(Cross-examination):辩手之间进行的互相质询和回答问题的环节。

10. 辩论技巧(Debate techniques):辩手使用的各种策略和方法,如逻辑推理、反驳、陈述等。

11. 辩论评分(Debate scoring):评判辩论赛胜负的标准和方法。

12. 辩论规则(Debate rules):辩论赛中参赛者必须遵守的规定和约定。

三、辩论赛类型1. 英国议会辩论(British Parliamentary Debate):四人辩论,分为两队,每队有两名辩手,其中一名为首辩,另一名为次辩。

2. 单辩(One-on-One Debate):两人辩论,一方为辩方,另一方为反方。

3. 小组辩论(Group Debate):多人辩论,由若干辩手组成若干小组,各小组之间进行辩论。

四、辩论赛策略1. 引言(Introduction):开场陈词的第一部分,用于吸引听众注意和引起兴趣。

Debate_Judges_Manual

Table of ContentsIntroduction………………………………………………………………...pg. 3 Policy Debate (Team or CX )………………..……………………pg. 6Glossary of Terms for Policy Debate……….…………………..pg. 7Lincoln-Douglas Debate….………………………………………pg. 12Glossary of Terms for Lincoln-Douglas Debate……………..pg. 13© Richard Herder, 2001Naples, FL(941)-417-4500rahfl@I offer my sincere gratitude to the following people who provided assistance in editing andimproving this manual:Dr. Rich Edwards of Baylor University: Policy Debate Dr. Jackson Mumey of Celebration High School in Orlando: Policy Debate and LD Debate Michael Menelli co-captain of LHS Debate for 200 2001: Policy DebateThomas McMullin, LHS debate officer, 2001-2002: LD DebateIntroductionIf you are a volunteer judge—We offer our sincere gratitude. This wonderful activity would not be possible without your help. Thank you!If you are a novice volunteer judge—This manual is intended to make your job easier. The students are used to speaking before lay judges. No one expects perfection. All we ask is that you make a sincere effort to listen to the students carefully and to write thoughtful, constructive ballots.Purpose of this manual: the information in this manual is intended to be supplemental. Please refer to the official National Forensic League (NFL) and National Catholic Forensic League (NCFL) materials for the complete rules. NCFL prints the complete rules for individual events categories on the ballots.Essential Information for all eventsREAD THIS!Timing—You may have to time the round. If you don’t have a stopwatch, a regular watch or a clock in the room will suffice. Ask the students if they have any special preferences (i.e. time signals for the last two or three minutes). If there are no time cards available, you should hold up fingers to indicate the number of minutes left. Signal 30 seconds remaining by holding your fingers at a 90 degrees angle. When time has expired, hold up a clenched fist. Do not say anything. Make sure that all time signals are clearly visible. Do not penalize students for going over time unless you are 100% sure you have timed correctly. In policy debate students often provide a brief “road map” before speaking. This is to assist you and the other debaters in flowing the debate. Start the watch when they begin the actual speech.Writing a ballot—Write a few constructive comments explaining what you liked about the student’s performance, the arguments you accepeted or rejected, and the reason for your decision. If you are a novice judge, relax. All that coaches and students ask is that you make an honest effort. Students are discouraged by blank ballots. Your ballot will be used by students and their coaches to improve future performances.Oral Critiques—Some tournaments encourage oral critiques in policy debate. Oral critiques are not as common in Lincoln – Douglas debate. If you are a novice judge, the best policy is: Do not tell students anything about their debate beyond, perhaps, “good round”.Policy Debate (Also Called Team Debate or CX Debate)Speaker Order and TimesFirst Affirmative Constructive Speech (1AC) 8 minutes3minutesNC21ACexaminedcrossbyFirst Negative Constructive Speech (1NC) 8 minutes1ACby3minutes 1NCcrossexaminedSecond Affirmative Constructive Speech (2AC) 8 minutes1NC3byminutes 2ACcrossexaminedSecond Negative Constructive Speech (2NC) 8 minutes2AC3minutesexaminedby2NCcross(1NR)minutes5RebuttalNegativeFirst5(1AR)minutesRebuttalFirstAffirmativeSecond Negative Rebuttal (2NR) 5 minutes(2AR) 5minutes AffirmativeRebuttalSecondperteamminutesPrepTime*5(some tournaments allow 8 minutes)*Prep time refers to the amount of time each team may use between speeches. Eachteam has 5 minutes TOTAL for the debate. For example, if the First Negative Constructive speaker takes 4 minutes of preparation time before his/her speech, the negative team will have only 1 minute remaining for the whole rest of the debate.Between speeches, preparation time is charged to the team speaking next; sometimesthis means that a team is charged prep time because they are not ready to begin crossexamination. Ask each team if they would like for you to call out the prep time.Sometimes teams will have their own stopwatch and will keep their own time. Othertimes, teams will ask you to call out the preparation time used. Most teams will ask youto announce the time in thirty-second intervals. Once the debater is ready to speak, writedown the remaining prep time so that you can pick up his/her prep time from where itstopped.Description--Students debate one resolution per school year. There will be two teams of two debaters. The affirmative team advocates the resolution. The negative team opposes the resolution. Refer to NCFL or NFL materials for complete rules.Priority Concerns:1.Evidence, evidence, evidence!--All claims must be backed up by “evidence.” This usually means quotations from experts on the issue as found in current periodicals, on the Internet, etc. Currency of the information, credibility of the source, and credentials of the writer may become important issues in the debate.2.State your concerns, prejudices, and paradigms—Some debaters, for example, speak very quickly (called “spreading”). If you prefer that students speak at a more normal speed, tell them this before the round begins, and they should adjust. This also applies to any special judging theories or paradigms. Be sure to keep these announcements short and to the point, and be sure both teams are present to hear your preferences.3.Be objective—You must do your best to set aside any preconceived ideas you may have regarding the topic. Judge the round on who has done the best job of presenting persuasive, well-documented arguments. Ignore external factors such as the number of boxes available or “name dropping” concerning debate camps, tournaments, awards, etc.4.Take notes—If you are not an experienced judge, you will not be expected to write a complete “flow sheet” for the round. However, it is still a good idea to write down what you perceive to be the most important arguments. You can write this down on the ballot or on your own paper.5.Timing—Fortunately, many debaters time speeches for their own partners; this leaves you time to concentrate on your ballot. If the teams wish to do their own timing, let them do it. If you are doing the timing, try to announce the prep time used in 30 second intervals. Be sure the debaters know whether you are telling them how much time has been used or how much time remains.Glossary of Terms for Team DebateAbuse/abusive—a strategy or argument which, although it may technically be within the rules, places the other team at an unfair disadvantage. Introducing major new arguments in the last minute of the second affirmative or negative constructive speech could be considered abusive. Making derogatory remarks about a person’s gender, race, or culture would be abusive.Advantages—the advantages the affirmative claims will result if the plan is adopted. Advantages are a voting issue. Typically, the affirmative team must show that the advantages of adopting their plan outweigh any disadvantages presented by the negative team.Affirmative—The team which proposes a change to the status quo. The affirmative team advocates the resolution and will offer a specific plan.A priori—a question of theory which must be considered before other issues. A negative team may argue that topicality arguments are a priori.Block—a fully developed, pre-written argument.Brink—an argument employed by the negative as part of a disadvantage. The negative argues that the status quo is facing some sort of crucial decision or eminent danger. The affirmative plan, if adopted, will “tip the scales” and lead to the impact of the disadvantage.Burden of Proof—The affirmative is required to prove the inadequacies of the status quo, the viability of the affirmative plan, and the advantages that will accrue from the plan. The negative is required to prove the validity of off case arguments.Card—a piece of evidence used in support of an argument.Case—the content of the first affirmative speech. Typically, this includes harms, inherency, the plan, and solvency. The speech may also include advantages.Case Arguments—arguments in which a debater directly attacks or defends the affirmative case.Clash—vigorous argumentation that directly answers the arguments of the other team. Clash is good. Losing one’s composure is not.Competition—This is the key question determining the legitimacy of a negative counterplan (see counterplan). The negative team must show why the counterplan competes with the affirmative plan; if it is possible to do both the plan and the counterplan, then the counterplan gives no justification for rejecting the plan. The two normal standards for competition are (1) mutual exclusivity: a claim that it is logically impossible to do both the plan and the counterplan, and (2) net benefits: a claim that adopting the counterplan alone would be more advantageous than adopting both the plan and the counterplan. Competition answers the question for the judge,“Why can’t I do both the plan and the counterplan?” Mutual exclusivity says one can not do both the plan and the counterplan; net benefits says one should not do both the plan and the counterplan.Constructive Speeches—the first four speeches of the debate. Typically, the entire affirmative case will be introduced in the first affirmative constructive speech. The primary negative arguments are usually introduced in the first negative constructive speech. New arguments are permitted in the second affirmative and second negative constructive speeches, but this is not customary.Counterplan—an alternative plan proposed by the negative team.Cross Examination—(Cross-Ex of CX)—the question and answer period which follows each constructive speech. In traditional cross-examination, two debaters stand side by side facing the judge. The debaters who remain seated do not ask or answer questions. If the judge allows “open cross examination,” the students’ partners may ask or answer questions in a tag team format. Only one person should be talking at any given time, however.Disadvantage—(Disad)—a block argument in which the negative maintains that a significant problem will occur if the affirmative plan is adopted. Disadvantages are usually divided into three parts: uniqueness,link, and impact.Documentation—the author, name of a source, date, etc., for a piece of evidence (card).Effects topicality—see mixing burdensEvidence—see card.Fiat—in Latin, this word means “Let it be done.” The affirmative has the power of fiat when proposing a plan. In other words, they can assume that the plan would be adopted by the status quo. Therefore, the negative cannot simply argue that the plan would be unpopular and would be unlikely to be adopted.Flow—the mapping of arguments in a debate.Flow Chart (flow sheet)—a sheet or sheets of paper, divided into seven columns, on which debaters and judges map arguments in the debate. Typically, one piece of paper is used for each major argument. Affirmative arguments are written in black ink and negative in red.Generic Disadvantage—a disadvantage which can be used against almost any plan.Impact—a serious problem that will occur if the affirmative plan is enacted. It is the last argument of a disadvantage.Inherency—an affirmative argument showing that the harm is deeply rooted in the present system (that the harm will continue absent the adoption of the affirmative plan). The negative team will try to show that the status quo can and will solve the problem even without adopting the affirmative plan.Kritik—(kri –teek) is a philosophical argument. A kritik argument can be introduced by either the affirmative or negative team, though it is more commonly a negative argument. There are many types of kritik arguments, however, topics such as justice, Marxism, and language theory are common. If you are confused by kritik arguments and you do not wish to hear more about them, you may, before the round begins, request that the debaters not use kritik arguments.A kritik is part of a negative strategy that makes global observations in which the affirmative plan should be evaluated. They are sophisticated arguments that question fundamental issues of the world in which the affirmative plan exists. A kritik argument is similar to a DA in that there must be a clear link to the affirmative plan. One distinction is that the DA concludes with an impact whereas a kritik concludes with one or more implications. Implications are the logical end-result of the kritik. If a judge accepts the kritik, she/he is accepting that there is sufficient warrant for the implications. This may include a fundamental shift in the manner in which issues of policy are perceived. Procedurally, a kritik is usually evaluated after topicality and before policy issues.Lexis-Nexis—an advanced, fee-based online service that offers full-text access to many newspapers, magazines, law reviews, and government documents.Link—the specific connection between the plan and a disadvantage argument. An internal link is the specific connection between two ideas within the disadvantage argument.Mixing Burdens—a topicality argument which claims that “topicality by effects” is illegitimate. Some affirmative plans will claim to be topical even thought the plan (on its face) fails toimplement the resolution, but the plan would lead to something topical. The negative team often answers that “topicality by effects” is illegitimate because it mixes the burdens of topicality and solvency. In this case, one does not know whether the plan is topical until after the affirmative solvency evidence is evaluated. Since topicality is supposed to be an a priori issue, it is not appropriate to be forced to evaluate solvency before one can know whether the case is topical.Multiple Actor Fiat—when a plan or counterplan mandates simultaneous action by several “actors” it strains the bounds of credulity or normality. An example would be a counterplan proposing that all fifty states simultaneously adopt the affirmative plan. Against such a counterplan, an affirmative team might argue that it is abusive to fiat by multiple actors.Mutual Exclusivity—one of the methods for establishing the competitiveness of a counterplan; see competition.Need—(also called harm)—the problems in the status quo which demonstrate the need for the affirmative plan. Need is a voting issue.Negative—the team which opposes the resolution. Typically, the negative will defend the status quo. Some negative teams, however, choose to defend a counterplan as an alternative to the status quo.Net Benefits—one of the methods for establishing the competitiveness of a counterplan; see competition.Non-unique—an affirmative answer to a disadvantage claiming that the disadvantage will happen regardless of whether the plan is adopted. Consider, for example, a budget disadvantage claiming that any new federal spending will destroy the budget consensus in Congress. The affirmative team could read evidence that Congress has just adopted some new spending program. Given this action, the disadvantage should happen with or without the adoption of the plan. Since the disadvantage will happen in any event, it gives no reason to reject the affirmative plan.Observation—a term used to label arguments.Off Case Argument—negative arguments which are not direct attacks on the affirmative case. Disadvantages, counterplans, topicality, and the kritik are all examples of off case arguments.Open Cross Examination—see cross examination.Permutation—a test of counterplan competition . Negative counterplans are relevant ONLY if they offer some reason to reject the affirmative plan. The negative team must show that the counterplan is competitive: that the adoption of the counterplan ALONE is more desirable than the plan plus the counterplan. The affirmative team will often describe a particular way that the plan and counterplan could be beneficially adopted at the same time: such descriptions are called permuations.Plan—the affirmative team’s proposal for changing the status quo. The plan will be presented in the first affirmative speech. The plan is a voting issue.Plan Meet Need—(PMN, also called solvency) the plan must solve some or all of the problems which the affirmative case says are inherent in the present system. The affirmative does not need to prove 100% solvency in order to win.Policy – (also policy issues) Matters of political and/ or governmental policy related to the resolution.Prima Facie—a Latin phrase which means “on first view.” In debate, the term means that the affirmative team has the responsibility in the first affirmative speech to offer a case which establishes the essential stock issues of (1) significance of harm, (2) inherency, and (3) solvency.Rebuttal Speech—the last four speeches in the debate. No new arguments may be presented in rebuttals, but new evidence may be presented in defense of existing arguments.Resolution—the debate topic for the year written out in sentence form.Significance—(also significance of harm) a voting issue; the affirmative team must prove that a serious problem exists in the present system.Sign Posting – listing of arguments in outline form. Some debaters use sign posting; some do not. Sign posting can be helpful, but is not a requirement.Solvency—the plan must solve for the problems the affirmative team claims are inherent in the status quo. Solvency is a voting issue.Spread—to speak rapidly in order to introduce more evidence and more arguments. The opposing team is forced to “spread” itself thin because it must respond to more arguments and evidence.Status Quo—the current situation regarding the topic.Topicality—(sometimes just called “T”) an argument used by the negative in which they claim that the plan proposed by the affirmative team is outside the bounds of the topic of the resolution. The negative team should win if the judge agrees that the plan is non-topical since topicality is an apriori issue.Turn—an argument usually made by an affirmative team against a disadvantage. The “turn” or “turnaround” can take one of two forms: (1) “Link turns” claim that the plan, far from causing the disadvantage, would actually prevent the disadvantage from happening; (2) “Impact turns” claim that if the plan did cause the disadvantage, it would actually be a good thing rather than a bad thing. One of the worst mistakes debaters can make is to turn BOTH the links and the impacts, creating a “double turn”, and thus reinforcing their opponents’ case.Uniqueness—the first argument in most disadvantage arguments…Voting Issue(voter)—the key issues of the debate. The primary issues which the judge must consider in rendering his/her decision. The traditional voting issues are (1) topicality,(2) significance of harm, (3) inherency, (4) solvency, and (5) advantage over disadvantage. If the negative team wins any one of these issues, they should win the debate. A team can, however, lose a minor argument and still win the voting issue overall.Lincoln-Douglas DebateSpeaking Order and TimesAffirmative6minutesConstructiveCross examination by the negative speaker 3 minutesminutes7NegativeConstructive*Cross examination by the affirmative speaker 3 minutesminutesRebuttal 4FirstAffirmativeminutesRebuttal 6Negativeminutes3SecondAffirmativeRebuttalPreparation time 3 minutes for each speaker*The negative constructive speech will consist of a negative case and a rebuttal of the affirmative caseDescription- Students debate a proposition of value one on one. The affirmative debater advocates the resolution. The negative debater negates the resolution. Refer to NFL or NCFL materials for complete rules.Priority concerns:1. Be objective- You must do your best to set your personal opinions or expectations regardingthe topic. Judge the round based on effective use of logic, on communication skills, and on persuasive advocacy of a relevant value. Ignore external factors such as the presence of a “cheering section” or name dropping regarding debate camps, tournaments, awards, etc.2. Weigh the value- Each debater will propose a value which is closely related to theresolution. He/she may also propose criteria by which the value is to be measured. Under most circumstances, the debater who persuades you that he/she is advocating a higher value should win the round. The emphasis is on fair issues of persuasion. Evidence, though it may be used to illustrate a point, is not required. Excellent Lincoln Douglasdebaters will demonstrate a mature grasp of rhetorical terminology and a soundunderstanding of the works of relevant philosophers.3. Expect clash – Excellent debaters will also be able to clash strongly with their opponentswithout losing composure.4. Listen for dropped points – If a debater drops an important point, this could become animportant issue in the debate. However, dropped points should only be an issue when the opposing debater brings it to your attention in a speech. Also, Lincoln-Douglasdebaters are not necessarily required to respond to every argument. A debater may choose to group arguments or to disregard unimportant arguments.5. Disregard new arguments in the rebuttals - No new arguments are allowed in the rebuttalspeeches. If, in your opinion, a debater does this, note it on the ballot, and disregard this argument in making your decision.6. Take notes – If you are not an experienced judge, you will not be expected to write acomplete “flow sheet” for the round. However, it is still a good idea to write down what you percieve to be the most important arguments. You can write this on the ballot or on your own piece of paper.Glossary of Terms for Lincoln-Douglas DebateAffirmative – the debater who speaks first and advocates the resolutionCase – the content of the affirmative constructive speech and the portion of the negative constructive speech in which he/she advocates a value and negates the resolution.Case Arguments – arguments in which a debater directly attacks or defends the affirmative or negative case.Categorical Imperative – an ethical concept proposed by the philosopher Immanuel Kant. He wrote, “Act only according to a maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become universal law.” An example would be, “One should not commit murder, because if all people behaved in the same manner we all would perish.”Flow – the mapping of arguments in a debate.Flow Chart – a sheet of paper, divided into columns, on which the debaters, and the judge map arguments in a debate.Hierarchy of Needs – a concept proposed by the psychologist Abraham Maslow. The hierarchy of needs is written out as a pyramid. Man’s basic needs such as food and shelter are at the bottom of the pyramid. At the top of the pyramid, Maslow placed what he perceived to be man’s most noble need: self-actualization.Market Place of Ideas - the idea that the economic concept of free enterprise is applicable to the interchange of ideas in society. the concept was first advocated by the philosopher John Stuart Mill.Means/Ends Argument – the abuse of individuals in order to achieve a desired end.Positive Obligation – an obligation to take a positive action. Generally a positive obligation is more highly valued than a negative obligation.Rebuttal Speech – the last speech delivered be each debater. No new arguments may be introduced in a rebuttal speech.Resolution – the current debate topic written out in sentence form.Sign Posting – listing of arguments in outline form. Some debaters use sign posting; some do not. Sign posting can be helpful, but is not a requirement.Social Contract -– the theory that society is held together by a common agreement or contract. There are several versions of the social contract theory, but generally they include the idea that individuals agree to a limitation of rights in order to live in a civilized society. Well known proponents of the social contract theory include Thomas Hobbes, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke.State of Nature— in social contract theory, the conditions under which men lived before they entered into the social contract.Utilitarianism – the theory that societies ought to take those actions which provide the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people.Value— a universally held principle which the debater advocates in order to affirm or negate the resolution. Common values include justice, progress, morality, individual dignity, etc.Vacuum Values Debate – according to this theory, decisions should be based on values and logic alone – without real world examples. However, both the NFL and the NCFL allow evidence for purposes of illustration.。

Asian debate(上课用)

•Inappropriateness [,ɪnə'proprɪɪtnɪs] a •governmental

a. relating to a particular government, or to the practice of governing a country. b. Having to do sth or accept it, because it is the law or because someone in a position of authority says you must. c. say sth again in words or writing, usually in a slightly different way. (FORMAL) d. give reasons why a charge or criticism made against you is untrue or unacceptable. (FORMAL) e. a statement which gives reasons why an accusation against you is untrue. (FORMAL) f. Not being useful or suitable for a particular situation or purpose. g. a Member of Parliament who is an expert on the rules and procedures of Parliament and takes an active part in debates.

The Debate Judging

•

Structure

– Room Setup – Speaking Order – Timing – Rules

高二英语英语辩论技巧练习题30题

高二英语英语辩论技巧练习题30题1<背景文章>Debate is an essential activity for high school students. It not only helps improve language skills but also enhances critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. In an English debate, students are required to express their opinions clearly and persuasively, using proper language and logical reasoning.English debate promotes the development of various thinking skills. Firstly, it encourages students to analyze different viewpoints and arguments. By researching and understanding various positions on a topic, students learn to think critically and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different ideas. Secondly, debate helps improve students' logical thinking. They need to organize their thoughts in a logical way and present their arguments in a coherent manner. This requires them to use deductive and inductive reasoning to support their claims. Thirdly, debate enhances creativity. Students are challenged to come up with unique and innovative arguments to support their positions. This helps them develop their creative thinking skills and think outside the box.Moreover, English debate also improves language proficiency. Students need to use accurate and appropriate language to express theirideas. They learn new vocabulary, improve their grammar and pronunciation, and develop their speaking and listening skills. Through debate, students become more confident in using English and are better able to communicate their thoughts and opinions.In conclusion, English debate is of great importance for high school students. It helps develop thinking skills and improve language proficiency, preparing students for future challenges.1. What is one of the benefits of English debate mentioned in the passage?A. Improving math skills.B. Enhancing critical thinking.C. Increasing physical strength.D. Promoting artistic talent.答案:B。

WHAT IS DEBATE

WHAT IS DEBATE?Debate is about change. We are constantly engaged in a struggle to make our lives, our community, our country, our world, our future, a better one. We should never be satisfied with the way things are now - surely there is something in our lives that could be improved.Debate is that process which determines how change should come about. Debate attempts to justify changing the way we think and live. In the real world, debate occurs everyday on the floor of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. Debate occurs at the United Nations, the faculty meetings at your school, and at your dinner table. The procedures for these debates may differ, but the process is the same - discussion that resolves an issue which will determine whether change is good or bad. The United Nations debated whether or not the Iraq invasion of Kuwait was good or bad; the faculty meetings debate school policies; you may recently have debated with your parents after dinner about the size of your allowance or when you can begin to drive your own car.In the classroom, we will attempt to"formalize"this debate process.1 . You will work with a partner. You and your partner form a"debate team". Sometimesyou will have to be for the issue (the affirmative) and sometimes you will have to beagainst the issue (negative). In any instance, you will have plenty of time to get ready for the debate.2. You will deliver speeches in a format that is unique to debate. The speeches are calledconstructives and rebuttals. Each person on each team will speak twice. There areaffirmative constructives and negative constructives. There are affirmative rebuttals andnegative rebuttals.3.You will learn rules and techniques that will seem strange to you. The way we learn howto debate may at first seem difficult. But once you take on the challenge, you will begin to understand its relationship to debating. The most difficult part of debate is the first fewweeks, after that it gets easier and easier once you have learned the rules.4.We will debate only one resolution. Most of our emphasis will be on competitive ortournament debating. In order to compete at tournaments and to give the debaters sufficient time to prepare, a standard topic or resolution is used all year. Thousands of high schools at this very minute are researching and debating the very same issues and ideas that you will be. The resolution determines the debate area. From this area there can be thousands of issues so that all of the debates are never the same and are always changing.5.Those students who want to be challenged can participate in debate tournaments againstother high schools during the school year.Developing and Implementing a Debate Activity1.The faculty member introduces the topic or problem.2.Teams are formed (usually 2-3 per team); each team commits to defending or arguing forone side or the other.3.Teams prepare a defense or argument for their position – ideally, this is done based oninformation from the literature. Debate preparation requires students to be able to articulate their position, and argue against the opposing position – thus students must be well prepared on both sides of the argument. The amount of time for preparation should depend on the type of problem posed. Preparation is often done as an out of class assignment for the following class period.4.The debate occurs after the teams have had preparation time. The debate process includesopening arguments, presentation of viewpoints, rebuttal, and summary.Discussion after the debate may be done to explore how the debate process changed the thinking of the students involved.Brief DescriptionTry the standard debate format. Includes adaptations of the format plus ten more strategies for engaging students!Keywordsdebate, role play, Lincoln, constructive, constructor, affirmative, negative, cross-examine, summary, summarize, think-pair-share, inner circle, graphic organizerMaterials Needed•copy of rules of debate (provided)•debate rubric for grading their own and/or peers' debate performances (provided)Lesson PlanThis lesson presents several basic debate formats, including the popular Lincoln-Douglas format. In addition, it provides adaptation suggestions for using debates with whole classes and small groups. Plus, it offers ten strategies teachers can use to make the debate process more interesting to students.In 1859, Senator Stephen A. Douglas was up for re-election to his Illinois Senate seat. His opponent was Abraham Lincoln. During the campaign, the two men faced off in a TheLincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858, a series of seven debates on the issue of slavery. On Election Day, Douglas was re-elected, but Lincoln's position on the issue and his inspiring eloquence had earned him wide recognition that would aid his eventual bid for the presidency in the Presidential Elections of 1860.The basic format of the Lincoln-Douglas debates has long been used as a debate format in competition and in classrooms. The Lincoln-Douglas Debate format is a one-to-one debate, in which two sides of an issue are debated. It starts with a statement of purpose/policy. (For example, School uniforms should be required in all schools.) The debater who agrees with the statement (the Affirmative) begins the debate, which is structured in this way:•Affirmative position debater presents constructive debate points. (6minutes)•Negative position debater cross-examines affirmative points. (3 minutes)•Negative position presents constructive debate points. (7 minutes)•Affirmative position cross-examines negative points. (3 minutes)•Affirmative position offers first rebuttal (4 minutes)•Negative position offers first rebuttal (6 minutes)•Affirmative position offers second rebuttal (3 minutes)Generally speaking, in a Lincoln-Douglas competitive debate, debaters do not know the statement of purpose/policy in advance. The purpose is proposed, and each presenter is given 3 minutes to prepare for the face-off.In the classroom, however, the Lincoln-Douglas debate format is adapted in a wide variety of ways. Following are some of the ways that procedure might be adapted in a classroom setting to involve small groups or an entire class.Adapt the Lincoln-Douglas Format for Classroom or Small Group UseArrange the class into groups of six. Each group will represent one side -- the affirmative or negative -- of a debatable question or statement. In order to involve all six individuals, each member of the team will have a specific responsibility based on the Lincoln-Douglas debate format detailed above. Each team will include students who assume the following roles:•Moderator -- calls the debate to order, poses the debatable point/question, and introduces the debaters and their roles.•Lead Debater/Constructor -- presents the main points/arguments for his or her team's stand on the topic of the debate.•Questioner/Cross-Examiner -- poses questions about the opposing team's arguments to its Question Responder.•Question Responder -- takes over the role of the Lead Debater/Constructor as he or she responds to questions posed by the opposing team's Questioner/Cross-Examiner.•Rebutter -- responds on behalf of his or her team to as many of the questions raised in the cross-examination as possible.•Summarizer -- closes the debate by summarizing the main points of his or her team's arguments, especially attempts by the opposition to shoot holes in their arguments.Note: In the standard Lincoln-Douglas debate format, the negative position isgiven a lengthy rebuttal time in which to refute the affirmative rebuttal and makea final summary argument for the position. Then the affirmative position has abrief opportunity to rebut the rebuttal (offer a closing argument, if you will) --and the debate is over. In this format, adapted for the classroom, both teams offera closing summary/argument after the rebuttals.The six-student team format enables you to arrange a class of 24 students into four equal teams.•If your class is smaller than 24 students, you might adapt the format described above by having the teacher serve as moderator.•If your class is larger than 24 students, you might arrange students into more and/or smaller groups and combine some roles (for example, Moderator and Summarizer or Moderator and Questioner/Cross-Examiner).You can apply the Lincoln-Douglas classroom debate adaptations above by having pairs of teams debate the same or different issues. If this is your first experiment with debate in the classroom, it would probably be wise to have both teams debating the same issue, or you can use your most confident students to model good debate form by using the fishbowl strategy described in theAdditional Strategies section below.Additional StrategiesThe following strategies can be used to extend the Lincoln-Douglas debate structure by involving the entire class in different ways:•Three-Card strategy --This technique can be used as a pre-debate strategy to help students gather information about topics they might not know a lot about. It also can be used after students observe two groups in a debate, when the debatable question is put up for full classroom discussion. This strategy provides opportunities for all students to participate in discussions that might otherwise be monopolized by students who are frequent participators. In this strategy, the teacher provides each student with two or three cards on which are printed the words "Comment or Question." When a student wishes to make a point as part of the discussion, the student raises a card; after making a comment or asking a question pertinent to the discussion, the student turns in the card. This strategy encourages participants to think before jumping in; those who are usually frequent participants in classroom discussions must weigh whether the point they wish to make is valuable enough to turn in a card. When a student has used all the cards, he or she cannot participate in the discussion again until all students have used all their cards.•Participation Countdown strategy --Similar to the above technique, the countdown strategy helps students monitor their participation, so they do not monopolize the discussion. In this strategy, students raise a hand when they have something to say. The second time they have something to say, they must raise their hand with one finger pointing up (to indicate they have already participated once). When they raise their hand a third time, they do so with two fingers pointing up (to indicate they have participated twice before). After a student has participated three times, he or she cannot share again as long as any other student has something to add to the discussion.•Tag Team Debate strategy -- This strategy can be used to help students learn about a topic before a debate, but it is probably better used when opening up discussion after a formal debate or as an alternative to the Lincoln-Douglas format. In a tag team debate, each team of five members represents one side of a debatable question. Each team has a set amount of time (say, 5 minutes) to present its point of view. When it's time for the team to state its point of view, one speaker from the team takes the floor. That speaker can speak for no more than 1 minute, and must "tag" another member of the team to pick up the argument before the minute is up. Team members who are eager to pick up on or add to the team's argument, can put out a hand to be tagged. That way, the current speaker knows who might be ready to pick up the argument. No member of the team can be tagged twice until all members have been tagged once.•Role Play Debate strategy --In the Lincoln-Douglas debate format, students play the roles of Constructor, Cross-Examiner, and so on. But many debate topics lend themselves to a different form of debate -- the role play debate.In a role play debate, students examine different points of view or perspectives related to an issue. See a sample lesson: Role Play Debate.•Fishbowl strategy -- This strategy helps focus the attention of students not immediately involved in the debate; or it can be used to put your most skilled and confident debaters center stage as they model proper debate form and etiquette. As the debaters sit center-stage (in the "fishbowl"), other students observe the action from outside the fishbowl. To actively involve observers, appoint them to judge the debate; have each observer keep a running tally of new points introduced by each side as the debate progresses. Note: If you plan to use debates in the future, it might be a good idea to videotape the final student debates your current students present. Those videos can be used to help this year's students evaluate their participation, and students in the videos can serve as the "fishbowl" group when you introduce the debate structure to future students.Another alternative: Watch one of the Online Debate Videos from Debate Central. •Inner Circle/Outer Circle strategy -- This strategy, billed as a pre-writing strategy for editorial opinion pieces, helps students gather facts and ideas about an issue up for debate.It focuses students on listening carefully to their classmates. The strategy can be used as an information-gathering session prior to a debate or as the structure for the actual debate.See a sample lesson: Inner Circle/Outer Circle Debate.•Think-Pair-Share Debate strategy --This strategy can be used during the information-gathering part of a debate or as a stand-alone strategy. Students start the activity by gathering information on their own. Give students about 10 minutes to think and make notes about their thoughts. Next, pair each student with another student; give them about 10 minutes to share their ideas, combine their notes, and think more deeply about the topic. Then pair each student pair with another pair; give them about 10 minutes to share their thoughts and gather more notes?Eventually, the entire class will come together to share information they have gathered about the topic. Then students will be ready to knowledgably debate the issue at hand. See the Think-Pair-Share strategy in action in an Education World article, Discussion Webs in the Classroom.•Four Corners Debate strategy -- In this active debate strategy, students take one of four positions on an issue. They either strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree.See a sample lesson: Four Corners Debate.•Graphic Organizer strategy -- A simple graphic organizer enables students to compare and contrast, to visualize, and to construct their position on any debatable question. See a sample lesson using a simple two-column comparison graphic organizer in the Education World article Discussion Webs in the Classroom.•Focus Discussions strategy -- The standard rules for a Lincoln-Douglas style debate allow students 3 minutes to prepare their arguments. The debatable question is not introduced prior to that time. If your students might benefit from some research and/or discussion before the debate, you might pose the question and then have students spend one class period (or less or more) gathering information about the issue's affirmative arguments (no negative arguments allowed) and the same amount of time on the negative arguments (no affirmative arguments allowed). See a sample lesson: Human Nature: Good or Evil?.。

BPdebate

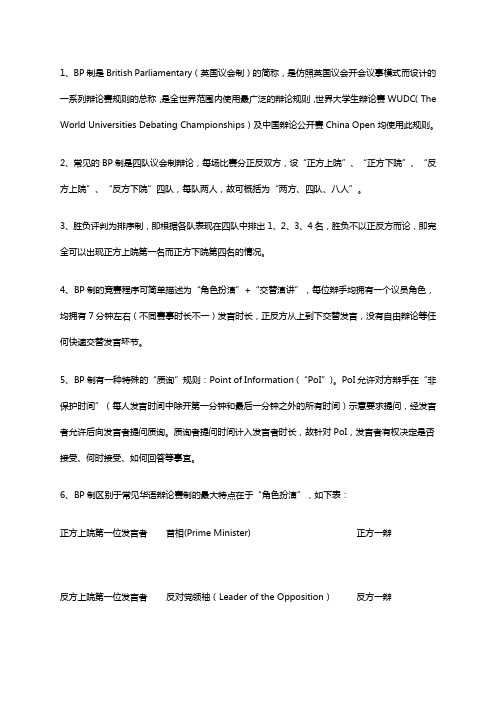

1、BP制是British Parliamentary(英国议会制)的简称,是仿照英国议会开会议事模式而设计的一系列辩论赛规则的总称,是全世界范围内使用最广泛的辩论规则,世界大学生辩论赛WUDC(The World Universities Debating Championships)及中国辩论公开赛China Open均使用此规则。

2、常见的BP制是四队议会制辩论,每场比赛分正反双方,设“正方上院”、“正方下院”、“反方上院”、“反方下院”四队,每队两人,故可概括为“两方、四队、八人”。

3、胜负评判为排序制,即根据各队表现在四队中排出1、2、3、4名,胜负不以正反方而论,即完全可以出现正方上院第一名而正方下院第四名的情况。

4、BP制的竞赛程序可简单描述为“角色扮演”+“交替演讲”,每位辩手均拥有一个议员角色,均拥有7分钟左右(不同赛事时长不一)发言时长,正反方从上到下交替发言,没有自由辩论等任何快速交替发言环节。

5、BP制有一种特殊的“质询”规则:Point of Information (“PoI”)。

PoI允许对方辩手在“非保护时间”(每人发言时间中除开第一分钟和最后一分钟之外的所有时间)示意要求提问,经发言者允许后向发言者提问质询。

质询者提问时间计入发言者时长,故针对PoI,发言者有权决定是否接受、何时接受、如何回答等事宜。

6、BP制区别于常见华语辩论赛制的最大特点在于“角色扮演”,如下表:正方上院第一位发言者首相(Prime Minister)正方一辩反方上院第一位发言者反对党领袖(Leader of the Opposition)反方一辩正方上院第二位发言者副首相(Deputy Prime Minister)正方二辩反对党副领袖(Deputy Leader of the反方上院第二位发言者反方二辩Opposition)正方下院第一位发言者政府阁员(Member of Government)正方三辩反方下院第一位发言者反对党阁员(Member of the Opposition)反方三辩正方下院第二位发言者政府党鞭(Government Whip)正方四辩反方下院第二位发言者反对党党鞭(Opposition Whip)反方四辩7、除一般的“立我方、批对方”的发言责任外,BP制中每个角色还有其独特的角色责任,对该责任的实现程度构成胜负评判的最大因素。

debate

3. Delivery

To bring the topic alive, you need to consider your delivery. Here are some tips and pointers.

i. Cue cards

Do not write out your speech on cue cards. Debating is an exercise in lively interaction between two teams and the audience. Use cue cards the same way you would use a prompt(台词提示) in a play. They are there for reference if you lose your spot.

Supporting materials can be examples. An example is a fact or piece of evidence, which supports an argument. Your arguments can also be backed up with other supporting materials, like reasons, statistics, and even with anecdotes, idioms, proverbs , quotations and analogies.

1. Language

Language is important, of course, since contestants must be understood. Judges look for accurate pronunciation, and articulation as well as the ability to vary the pace and pitch of the voice when speaking. This often requires speakers to slow their speech more than they would for everyday language.

public-speaking-and-Debate-英语公共演讲与辩论

by computer.

• Compare your reason with another pair of students.

Resolution: the opinion about which two teams argue.

Affirmative team: agrees with the resolution.

Negative team: disagrees with the resolution.

Argument: supports your position on the resolution. (add this to your handout)

clearly • it is convincing to a majority of people

weak or strong?

Smoking should be banned in public places because:

• it is bad. • it gives people bad breath and makes

Impromptu speeches Business Class 1

127 Kenson

111 Mathias

121 Bennie

Does an all-star cast enhance or distract a film’s message?

Universities should cut off electricity in dormitories at night.

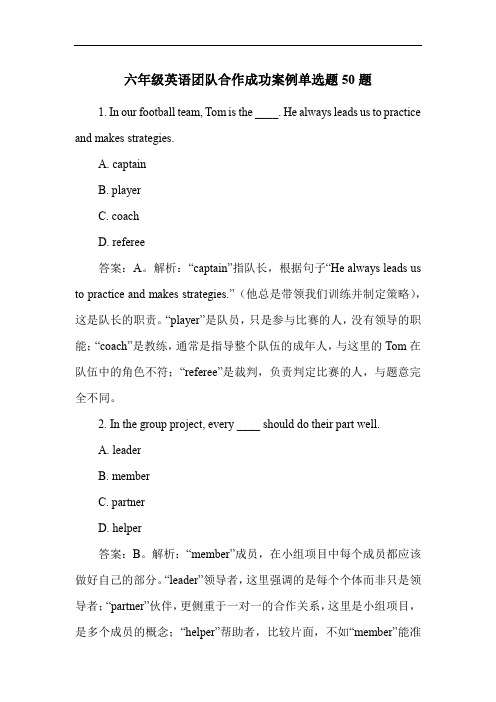

六年级英语团队合作成功案例单选题50题

六年级英语团队合作成功案例单选题50题1. In our football team, Tom is the ____. He always leads us to practice and makes strategies.A. captainB. playerC. coachD. referee答案:A。

解析:“captain”指队长,根据句子“He always leads us to practice and makes strategies.”(他总是带领我们训练并制定策略),这是队长的职责。

“player”是队员,只是参与比赛的人,没有领导的职能;“coach”是教练,通常是指导整个队伍的成年人,与这里的Tom在队伍中的角色不符;“referee”是裁判,负责判定比赛的人,与题意完全不同。

2. In the group project, every ____ should do their part well.A. leaderB. memberC. partnerD. helper答案:B。

解析:“member”成员,在小组项目中每个成员都应该做好自己的部分。

“leader”领导者,这里强调的是每个个体而非只是领导者;“partner”伙伴,更侧重于一对一的合作关系,这里是小组项目,是多个成员的概念;“helper”帮助者,比较片面,不如“member”能准确表达小组中的个体。

3. Our school basketball team has a very strict ____. He makes us train hard every day.A. teammateB. captainC. trainerD. fan答案:C。

解析:“trainer”训练者,根据“He makes us train hard every day.”((他让我们每天刻苦训练)可知是训练者的角色。

“teammate”队友,主要是一起比赛的伙伴,不是负责训练的;“captain”队长主要是领导队伍比赛等,不一定是训练的主导者;“fan”粉丝,和让队员训练没有关系。

辩论赛规则及流程详细英文介绍

辩论赛规则及流程详细英文介绍Debate Competition Rules and Detailed Process.Introduction.Debate competitions are a vibrant and intellectualforum where participants engage in lively discussions, arguing for or against a particular motion or resolution. These competitions test the analytical, argumentative, and persuasive skills of the debaters. They also fostercritical thinking, improve public speaking abilities, and enhance understanding of diverse perspectives.Rules of the Debate Competition.1. Team Composition: Debates are typically conducted by two teams, each representing a different side of the motion. Each team consists of two or more debaters, often referredto as speakers.2. Motion or Resolution: The debate revolves around a central motion or resolution, which is the topic to be debated. The motion is typically proposed by the organizing committee.3. Opening Statements: Each team begins with an opening statement, outlining their position on the motion and previewing their main arguments.4. Main Speeches: Following the opening statements, debaters present their arguments in favor of or against the motion. These speeches are structured and typically include the introduction of evidence, analysis of the topic, and conclusion.5. Rebuttal Speeches: After the main speeches, there is usually a round of rebuttals where debaters respond to the arguments presented by the opposing team.6. Closing Arguments: Both teams present closing arguments, summing up their positions and attempting to persuade the judges or audience of their viewpoint.7. Judging Criteria: Debates are judged based on various criteria such as content, clarity, logic, and delivery. Judges evaluate the debaters' ability to present coherent arguments, respond effectively to their opponents, and persuade the audience.8. Decision and Awards: At the end of the debate, judges deliberate and announce a decision, determining the winning team. Awards are typically given to outstanding debaters or teams.Detailed Process of the Debate Competition.1. Preparation: Debaters need to thoroughly research the motion or resolution, collect evidence, and develop their arguments. They also practice their speeches and learn to effectively present their case.2. Registration and Team Formation: Debaters register for the competition and form teams. Teams are typically assigned randomly or by mutual agreement between theparticipants.3. Competition Venue Setup: The competition venue is set up with a stage for the debaters, a judging panel, and seating for the audience. The debate motion or resolution is displayed prominently for all participants and audience members.4. Opening Ceremony: The competition begins with an opening ceremony, introducing the judges, debaters, and the topic of debate. The organizing committee may also provide an overview of the rules and procedures.5. Opening Statements: Each team takes turns presenting their opening statements, outlining their positions and previewing their arguments. This is an opportunity for the debaters to set the tone for the debate and introduce their main themes.6. Main Speeches: Debaters present their main arguments in favor of or against the motion. They must ensure that their speeches are well-structured, coherent, and supportedby evidence. Debaters also need to be responsive to their opponents' arguments and counter-arguments.7. Rebuttal Speeches: After the main speeches, there is usually a round of rebuttals where debaters have the opportunity to respond directly to their opponents' arguments. This is a crucial part of the debate as it allows debaters to clarify misunderstandings, correct factual errors, and strengthen their own positions.8. Closing Arguments: Following the rebuttals, both teams present closing arguments, summing up their positions and attempting to persuade the judges or audience of their viewpoint. These arguments should be concise and powerful, leaving a lasting impression on the listeners.9. Judging and Deliberation: After the closing arguments, the judges deliberate to determine the winning team. They consider various criteria such as content, clarity, logic, and delivery in making their decision.10. Announcement and Awards: The judges announce theirdecision and award the winning team. Additional awards may also be given to outstanding debaters or teams. This concludes the debate competition, and participants depart, often with newfound respect for their opponents and a deeper understanding of the topic debated.Conclusion.Debate competitions are an excellent platform for developing critical thinking, public speaking, and persuasive skills. They foster respectful and intellectual discussions, encouraging participants to consider diverse perspectives and argue effectively for their positions. The rules and process of a debate competition ensure fairness, structure, and order, allowing for a competitive and enjoyable experience for all participants.。

我的对手很友好英语作文

In the tapestry of life, we all encounter various individuals who play different roles. Some are mentors, some are friends, and others are adversaries. However, its not every day that you find an opponent who is also a friend. My story is about such an individual, who, despite being my competitor, became a beacon of friendship and mutual respect.It all began during my sophomore year in high school when I joined the schools debate team. The team was a melting pot of diverse personalities, each with their unique strengths. Among them was Emily, a girl with a sharp mind and an uncanny ability to articulate her thoughts with eloquence. She was my opponent in more ways than one.Our first encounter was during a practice debate. The topic was The impact of social media on society, and we were pitted against each other. I was nervous, not just because it was my first debate, but also because I was going up against Emily. She was known for her quick wit and persuasive arguments. As the debate commenced, I could feel the tension in the air. Emily opened with a strong argument, and I countered with my own. Back and forth we went, each trying to outdo the other. It was intense, but it was also exhilarating.Despite our competitive nature, there was a certain level of respect between us. We both admired each others skills and intellect. After the debate, instead of walking away, Emily approached me. She complimented my arguments and suggested ways I could improve. I was taken aback by her gesture. It was unexpected, but it also felt genuine. From that moment on, we started to develop a friendship.Over time, our friendship grew stronger. We would spend hours discussing various topics, from politics to philosophy. We challenged each other, pushed each others boundaries, and helped each other grow. Our debates became less about winning and more about learning. We were no longer just opponents we were partners in intellectual growth.Emilys friendly nature extended beyond our debates. She was always there to lend a helping hand or a listening ear. When I was struggling with a difficult assignment, she would offer her assistance. When I was feeling down, she would provide words of encouragement. She was not just a friendly opponent she was a true friend.Our friendship was put to the test during the state debate competition. We were both selected to represent our school, and once again, we found ourselves on opposing teams. The stakes were higher, and the pressure was immense. However, our friendship remained unshaken. We knew that regardless of the outcome, our bond would remain strong.The competition was fierce, and both of us gave it our all. In the end, Emilys team emerged as the winner. While I was disappointed, I was also genuinely happy for her. She had worked hard, and she deserved the victory. When she came over to congratulate me, I could see the sincerity in her eyes. There was no gloating, just mutual respect and admiration.Our friendship continued to flourish even after high school. We went to different colleges, but we stayed in touch. We would call each other duringexams, share our achievements, and discuss our future plans. Our debates had turned into conversations, and our competition had turned into collaboration.In conclusion, having a friendly opponent like Emily has been a blessing in disguise. She taught me the importance of respect, humility, and the value of a genuine friendship. She showed me that its possible to be competitive and kind at the same time. Our journey together has been filled with challenges, growth, and unforgettable memories. Its a testament to the fact that even in the face of competition, we can find friendship and mutual respect. And that, in my opinion, is the true essence of life.。

Critisim

Dear xiao Li,I know you has no idea what to do when you get so much criticism. What I want to emphasize is that it is no use feeling embarrssed and awkward. Instead, you should be brave and need to find out why you are confronted with so much criticism. Also, it is helpful to think of some good ideas to solve the problem.From my perspective, there are two reasons for the situation. It is possible that in US culture, Americans place great emphasize on democracy. But you promised Hugo a place on the debate-team by yourself. Although you are an advisor of the debate team, it is not up to you. You can’t ignore your fellow advisors’and others’ideas. Everyone plays a role in the debate-team. They maybe think that you disrespect their rights. Another possibility is that Americans also attach great importance to the cooperation. As you know, the debate-team have taken four-week training while Hugo hasn’t taken any training. It is not strange that others will not believe Hugo. They don’t know anything about Hugo. They will be sure to doubt whether Hugo have the ability to debate and join them to do good teamwork.Then what you need to do is to think of some helpful ideas that make it easy for others to accept Hugo. You can restore trust from your teammates and reduce the bad impression at first. You can ask them to have a coffee and so on. Then you can try to talk with them heart-to-heart. Don’t talk about Hugo at first and it is good to talk about it next time because people always need time to think of something new. The best way to make them to accept Hugo is to hold a debate and ask Hugo to take part in. So it is easy for others to check up whether Hugo have the ability to fit the place onthe debate-team.People can make their mind by themself. Whatever the result will be, it is okay for everyone accept.You just need to face up to the criticism. Don’t wear a upset expression. Everything will be ok if you try to find some ideas to solve the problem.Yours,Auter Counts:385。

推荐参加过的社团活动英语作文初中