Simplified design of common-mode chokes for reduction of motor ground currents in inverter drives

仪表放大器输入RFI保护

G1

G2

B See for manufactures of x2y capacitors

图4:X2Y®电容静电模型

G1和G2引脚在器件内部相连。X2Y电容的内部板结构形成一种集成电路,具有一些有趣 的特性。从静电角度来看,三个电节点构成两个电容,这两个电容共享G1和G2引脚。制 造工艺会自动严格匹配这两个电容。此外,X2Y结构包含有效的自动变压器/共模扼流圈。 因此,当共模滤波器使用这类器件时,与类似RC滤波器相比,高于滤波器转折频率的共 模信号衰减幅度更大。因此,通常无需电容C3,进而节省了成本和电路板空间。 图5A所示为传统的RC共模滤波器,而图5B所示为采用X2Y器件的共模滤波器电路。图6比 较了这两种滤波器的RF衰减性能。

C1·C2 C1 + C2 + C3

图1:代码跃迁噪声(折合到输入端噪声)及其对ADC传递函数的影响

假设C3 >> C1,由此得到CM滤波器带宽为1/2πR1⋅C1,而DM滤波器带宽则大约为1/4πR1⋅C3。 总体DM滤波器带宽应至少为输入信号带宽的100倍。滤波器元件应对称安装在具有较大面 积接地层的电路板上,并且应该靠近仪表放大器的输入端,以便获得最佳性能。 图2显示了一系列适合各种不同仪表放大器的此类滤波器。RC元件应根据不同仪表放大器 进行定制,具体如表中所示。选择这些滤波器元件是为了实现低EMI/RFI灵敏度和低噪声 增长的合理平衡(与无滤波器的相应仪表放大器相比)。 要测试配置的EMI/RFI灵敏度,可以向输入电阻施加1 V p-p CM信号,如上所述。当 AD620等常用仪表放大器在增益为1000下工作时,20 MHz范围内观测到的最大RTI输入失 调电压漂移为1.5 V。在AD620滤波器示例中,差分带宽约为400 Hz。

英语作文-揭秘集成电路设计中的设计规则与布局约束

英语作文-揭秘集成电路设计中的设计规则与布局约束Integrated circuit (IC) design is a complex process that involves various design rules and layout constraints. In this article, we will delve into the secrets of IC design and explore the key considerations in designing and laying out integrated circuits.To begin with, one of the fundamental design rules in IC design is the minimum feature size. This refers to the smallest dimension that can be reliably manufactured on a chip. As technology advances, the minimum feature size decreases, allowing for more transistors to be packed onto a single chip. Designers must adhere to these rules to ensure the manufacturability and functionality of the IC.Another important design rule is the spacing between different components on the chip. This is known as the minimum spacing rule and ensures that there is sufficient isolation between adjacent components. Violating this rule can lead to interference and crosstalk, which can severely impact the performance of the IC. Designers must carefully consider the spacing requirements and optimize the layout to minimize any potential issues.Furthermore, the design of power distribution networks is crucial in IC design. Efficient power delivery is essential to ensure the proper functioning of the circuitry. Designers must consider factors such as voltage drop, current density, and thermal management when designing the power distribution network. By carefully analyzing and optimizing the power delivery system, designers can enhance the overall performance and reliability of the IC.In addition to design rules, layout constraints play a vital role in IC design. One such constraint is the placement of components on the chip. Proper component placement is essential to minimize signal delays and optimize the overall performance of the IC. Designers must consider factors such as signal integrity, power consumption, and thermal considerations when determining the optimal component placement.Another important layout constraint is the routing of interconnects. Interconnect routing refers to the process of connecting different components on the chip using metal traces. Designers must carefully plan and optimize the routing to minimize signal delays, reduce power consumption, and ensure proper signal integrity. Advanced routing algorithms and techniques are employed to achieve efficient and reliable interconnects.Moreover, the consideration of design for manufacturing (DFM) rules is crucial in IC design. DFM rules ensure that the design can be manufactured with high yield and reliability. Designers must consider factors such as lithography constraints, process variations, and mask alignment accuracy when designing the IC. By incorporating DFM rules into the design process, designers can minimize manufacturing issues and improve the overall yield of the IC.In conclusion, the design rules and layout constraints in integrated circuit design are essential for ensuring the manufacturability, functionality, and performance of the IC. Designers must carefully adhere to these rules and constraints while considering factors such as minimum feature size, component spacing, power distribution, component placement, interconnect routing, and design for manufacturing. By following these guidelines, designers can create efficient, reliable, and high-performance integrated circuits.。

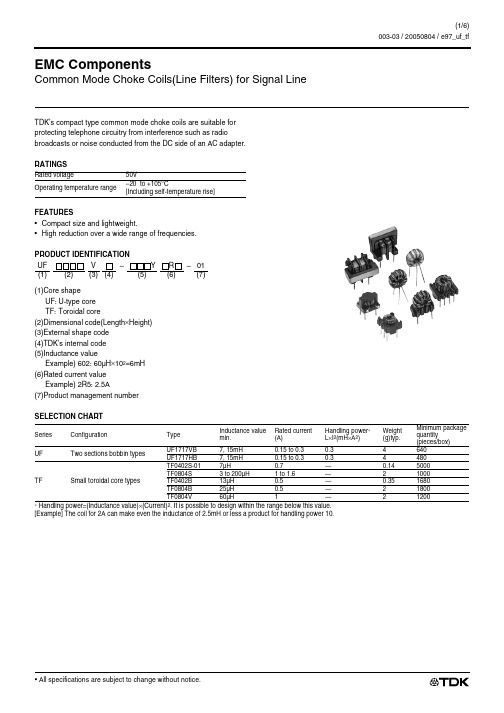

共模扼流圈的参数及选型

共模扼流圈的参数及选型Common mode chokes are essential components in electronic circuits to reduce electromagnetic interference. 共模抑制器是电子电路中必不可少的元件,用于减少电磁干扰。

They are designed to suppress common mode noise by providing a high impedance path for common mode currents while allowing differential mode signals to pass through unaffected. 它们的设计是为了通过为共模电流提供高阻抗路径来抑制共模噪声,同时允许差分模信号无受影响地通过。

Common mode chokes consist of two windings wound on a ferromagnetic core, which can be customized based on the specific requirements of the application. 共模抑制器由绕在铁磁芯上的两个绕组组成,可以根据应用的具体要求进行定制。

The parameters and selection of common mode chokes are crucial in ensuring optimal performance and noise suppression in electronic circuits. 共模抑制器的参数和选择对于确保电子电路的最佳性能和噪声抑制至关重要。

When selecting common mode chokes, it is important to consider factors such as impedance, current rating, frequency range, and temperature stability. 在选择共模抑制器时,需要考虑阻抗、电流额定值、频率范围和温度稳定性等因素。

Silicon Laboratories 微控制器低功耗选择指南说明书

How to Pick the Right Microcontroller Based on Low-PowerSpecificationsIntroductionChoosing the right ultra-low-power microcontroller (MCU) for your next embedded design can be a confusing task when you compare claimed current consumption specifications in a myriad of data sheets provided by MCU vendors. In many cases, developers initially scan the first page of a data sheet as a reference point to gain basic information about an MCU, including peripherals, operating speed, package information, number of GPIOs and power characteristics. This approach works well to assess an MCU’s overall functionality, but it is not particularly useful when trying to gauge low-power characteristics.To get a broader view of an M CU’s true low-power operation, developers must take into consideration current consumption, state retention, wake-up time, wake-up sources and peripherals that are capable of operating while in low-power mode. Developers must compare a common operating mode to gain a balanced, apples-to-apples comparison among competing low-power MCUs. It is also important to take into consideration any additional functionality or peripherals that can reduce total system power and available evaluation tools that can make an engineer’s job easier.Microcontroller vendors will usually list the lowest power achievable on the first page of the data sheet. Although the device may be capable of achieving the specification in the data sheet, the actual operating mode may not be practical and useful in a real-world application. Some of the non-advertised features of the lowest power mode may include a very slow wake time, no state or RAM retention, or a reduced operating voltage range.To get around the variety of low-power specifications, developers must identify a common operating mode consisting of two sections: electrical specifications and low-power functionality.Comparing Electrical Specifications of MicrocontrollersThe electrical specifications are available in the data sheet, but determining which specifications are relevant may require some digging. Usually the electrical specifications are organized by vendor-specific power mode. This makes assessment slightly more difficult, as it requires knowledge and familiarity with the functionality of each power mode.In general, it is beneficial to define a set of operating conditions and then map them to a power mode. For example, the developer might define the following set of operating conditions:∙Sleep mode current consumption with state and RAM retentiono All other peripherals disabled∙Sleep mode current consumption with RTC running with state and RAM retentiono RTC enabled and running all other peripherals disabled.∙Wake time∙Supply voltage rangeOnce the operating conditions are clearly defined, it should be easy to determine the applicable vendor-specific power mode.Additional Low-Power FunctionalityThe second section, low-power functionality, is not as easy to locate in the vendor’s documentation and may be spread across the data sheet and reference manual. Examples of low-power functionality include: ∙Available wake sources∙How code resumes execution∙Peripherals capable of operating in sleep mode.Once the common operating mode has been clearly defined, developers can begin to examine the documentation in more detail.While going through this exercise of compiling data, keep in mind that there may be some MCU-specific features that can further optimize an application for ultra-low power. Optimizations may reduce bill of material (BOM) costs, provide longer product life or provide greater design flexibility. For example, an on-chip dc-dc converter can efficiently provide power to the system and decrease power consumption. This can enable the use of smaller batteries, which will decrease the overall BOM costs, or provide power budget flexibility. A variety of wake sources can provide design flexibility and allow the microcontroller to stay in the lowest power mode as long as possible, further reducing the average current consumption of the application.Allowing firmware to scale the internal supply voltage is another optimization knob available to the developer. If an MCU is operating at a slow frequency, it may be possible to decrease the supply voltage and save power. Selective clock gating allows hardware blocks to be disconnected from the active circuits, preventing inactive peripherals from consuming power. These types of features are not comprehended by supply current specifications that are commonly used to rank low-power MCUs, but are critical to achieving the lowest overall system power consumption.Reducing Complexity Using ToolsAs MCUs become more and more configurable to achieve the lowest power consumption, they also can become more complex. To cope with this increased complexity, developers should take a close look at the evaluation platforms available for an MCU and the overall ease of implementing a solution. For example, the development board and software tools used to program the MCU should be intuitive and easy-to-use. Hardware that is difficult to understand or use is not likely to lead to an easy firmware development process. From a firmware perspective, MCU vendors should supply firmware examples that can recreate specifications from the data sheet. If advertised current consumption specifications cannot be recreated on an evaluation platform, it is likely that it will be just as difficult (if not impossible) to configure the MCU to achieve these numbers on custom hardware. Giving customers a variety of code examples that can be used as a starting point for their code development can reduce time-to-market and help engineers learn to use a device.Graphical configuration tools can aid in development and help the developer gain a deeper understanding of an MCU. When developing low-power applications, it is helpful to know where the total consumed power is going. This information is useful because it highlights what aspect of a design needs to be further optimized and can also help the developer understand the overall architecture of the device. Ideally, low-power configuration tools could give tips on further reducing power as well as highlight any configuration errors that were detected throughout the configuration process. For example, the Power Estimator utility within Silicon Labs’ AppBuilder graphical configuration tool provides Power Tips that give configuration guidance and a power-budget pie chart showing how much power is consumed and which peripherals are consuming the power. As configuration changes are made, the pie chart automatically updates.Figure 1. Power Estimator Enables Developers to Optimize for Lowest Current Consumption To facilitate the microcontroller comparison process, the following table provides a list of common operating modes, as well as system-level optimizations and development tools available for Silicon Labs’32-bit SiM3L1xx MCUs based on the ARM® Cortex™-M3 core.SummaryEvaluating and selecting a microcontroller for a low-power application requires more than a quick scan of the first page of the data sheet. Determining which MCU provides the lowest overall system power requires developers to know the device’s supply current specifications, as well as any system-level optimizations that can reduce the overall supply current.Unfortunately, each MCU vendor specifies operating conditions differently and in some cases advertises a low-power number that is available in an unusable mode. Using a common operating mode to compare MCUs will prevent developers from being misled by vendor claims of ultra-low-power operation.Once the electrical characteristics of a device are understood and quantified, developers should take a look at the evaluation platform and software tools available. These considerations are crucial in getting an engineering team up and running quickly and should be included in the final microcontroller selection process. Find out more about Silicon Labs’ microcontrollers, including 8-bit and 32-bit MCUs at/mcu.# # #Silicon Labs invests in research and development to help our customers differentiate in the market with innovative low-power, small size, analog intensive, mixed-signal solutions. Silicon Labs' extensive patent portfolio is a testament to our unique approach and world-class engineering team. Patent: /patent-notice© 2013, Silicon Laboratories Inc. ClockBuilder, DSPLL, Ember, EZMac, EZRadio, EZRadioPRO, EZLink, ISOmodem, Precision32, ProSLIC, QuickSense, Silicon Laboratories and the Silicon Labs logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Silicon Laboratories Inc. ARM and Cortex-M3 are trademarks or registered trademarks of ARM Holdings. ZigBee is a registered trademark of ZigBee Alliance, Inc. All other product or service names are the property of their respective owners.。

反激式开关电源外文翻译

Measurement of the Source Impedance of Conducted Emission Using Mode Separable LISN: Conducted Emission of a Switching Power SupplyJUNICHI MIY ASHITA,1 MASAYUKI MITSUZAW A,1 TOSHIYUKI KARUBE,1KIYOHITO Y AMASAW A,2 and TOSHIRO SA TO21Precision Technology Research Institute of Nagano Prefecture, Japan2Shinshu University, JapanSUMMARYIn the procedure for reducing conducted emissions, it is helpful to know the noise source impedance. This paper presents a method of measuring noise source complex impedances of common and differential mode separately. We propose a line impedance stabilization network (LISN) to measure common and differential mode noise separately without changing LISN impedances of each mode. With this LISN, conducted emissions of each mode are measured inserting appropriate impedances at the equipment under test (EUT) terminal of the LISN. Noise source complex impedances of switching power supply are well calculated from measured results. © 2002 Scripta Technica, Electr Eng Jpn, 139(2): 72 78, 2002; DOI 10.1002/eej.1154Key words:Conducted emission; noise terminal voltage; noise source impedance; line impedance stabiliza-tion network (LISN); EMI.1. IntroductionSwitching power supplies are employed widely in various devices. High-speed on/off operation is accompa-nied by harmonic noise that may cause electromagnetic interference (EMI) with communication devices and other equipment. To prevent the interference, methods of meas-urement and limit values have been set for conducted noise (~30 MHz) and radiated noise (30 to 1000 MHz). Much time and effort are required to contain the noise within the limit values; hence, the efficiency of noise removal tech-niques is an urgent social problem. Understanding of the mechanism behind noise generation and propagation is necessary in order to develop efficient measures. In particu-lar, the propagation of conducted noise must be investi-gated.Modeling and analysis of equivalent circuits have been carried out in order to investigate conducted noise caused by switching [1, 2]. However, the stray capacitance and other circuit parameters of each device must be known in order to develop an equivalent circuit, which is not practicable in the field of noise removal. On the other hand, noise filters and other noise-removal devices do not actually provide the expected effect [3, 4], which is explained by the difference between the static characteristics measured at an impedance of 50 Ω, and the actual impedance. Thus, it is necessary to know the noise source impedance in order to analyze the conducted noise.Regulations on the measurement of noise terminal voltage [5] suggest using LISN; in particular, the vector sum (absolute voltage) of two propagation modes, namely, common mode and differential mode, is measured in terms of the frequency spectrum. Such a measurement, however, does not provide phase data, and propagation modes cannot be separated; therefore, the noise source impedance cannot be derived easily. There are publications dealing with the calculation of the noise source impedance; for example, common mode is only considered as the principal mode, and the absolute value of the noise source impedance for the common mode is found from the ground wire current and ungrounded voltage [6], or mode-separated measure-ment is performed by discrimination between grounded and ungrounded devices [7]. However, measurement of the ground wire current is impossible in the case of domestic single-phase two-line devices. The complex impedance can be found using an impedance analyzer in the nonoperating state, but its value may be different for the operating state. Thus, there is no simple and accurate method of measuring source noise impedance as a complex impedance.© 2002 Scripta TechnicaElectrical Engineering in Japan, V ol. 139, No. 2, 2002Translated from Denki Gakkai Ronbunshi, V ol. 120-D, No. 11, November 2000, pp. 1376 1381The authors assumed that the noise source impedance could be found easily using only a spectrum analyzer, provided that the noise could be measured separately for each mode, and the LISN impedance could be varied. For this purpose, a LISN with a balun transformer was devel-oped to ensure noise measurement, with the common mode and differential mode strictly separated. An appropriate known impedance is inserted at the EUT (equipment under test) terminals, and the noise source impedance is found from the variation of the noise level. This method was used to measure the conducted noise of a switching power sup-ply, and it was confirmed that the noise source impedance could be measured as a complex impedance independently for each mode. Thus, significant information for noiseremoval and propagation mode analysis was acquired.This paper presents a new method of measuring the noise source impedance of conducted emission using mode-separable LISN.2. Separate Measurement for Common Mode andDifferential ModeThe conventional single-phase LISN circuit for measurement of the noise terminal voltage is shown in Fig.1. The power supply is provided with high impedance by a 50-µH reactor, and a meter with an input impedance of 50Ω is connected between one line and the ground via a high-pass capacitor, and another line is terminated by 50 Ω. Thus, the LISN impedance as seen at the EUT is 100 Ω in the differential mode, and 25 Ω in the common mode. The measured value is the vector sum of both modes, and the noise must be found separately in order to find the noise source impedance for each mode. There is LISN with Y-to-delta switching to provide mode separation [8], but its impedance is 150 Ω, giving rise to a problem of data compatibility with 50-Ω LISN. Thus, a new mode-separa-ble LISN was developed as shown in Fig.2. The circuit is identical to that in Fig. 1 from the power supply through the high-pass capacitor. Switching of the connection pattern ensures measurement with one line of the balun transformer terminated by 50 Ω, and another line connected to the meter.In Fig. 2, the secondary side of the 2:1 balun trans-former is terminated by 50 Ω, while the primary side has 200 Ω; in the differential mode, the impedance (line-to-line) is 100 Ω since 200 Ω at the high-pass capacitor is connected in parallel. With the switch set at D, the meter is connected to the secondary side of the balun transformer. The voltage is one-half that of the line-to-line voltage, and measurement is performed in the standard way.The common mode current flows from both sides of the balun transformer via the middle tap to the 50-Ω termi-nal. The currents in the windings are antiphase, and no voltage is generated at the secondary side. Therefore, the impedance of the primary side is the terminal resistance of the tap. Since this impedance is connected in parallel to 50Ω (two 100 Ω in parallel) at the high-pass capacitor, the impedance between the common line and ground is 25 Ω. With the switch set at C, the meter is connected to the middle tap of the balun transformer, and the common-mode voltage is the line-to-ground voltage.3. Measurement of Noise Source Impedance3.1 Measurement circuit and calculationThough the propagation routes are different in the two modes, propagation from the noise source to the LISN can be represented in a simplified way as shown in Fig. 3. In the initial measurement, the load impedance Z L is the LISN impedance. Z L can be varied by inserting a knownimpedance at the EUT terminals. Consider three load im-Fig. 1. Standard 50-Ω/50-µH LISN.Fig. 2.Mode-separable LISN.Fig. 3. Schematic circuit of noise propagation.pedances, namely, LISN only and LISN with two different impedances inserted, Z L 1(R 1 + jX 1), Z L 2(R 2 + jX 2), andZ L 3(R 3+ jX 3). Using the values I 1, I 2, I 3 (scalars) measured in the three cases, Z 0(R 0 + jX 0) is found. Since V 0 = |Z L | × I ,the following expressions can be derived:From the above,Here a , b , and c are as follows:Substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1), the following quadratic equation for R 0 is obtained:Thus, R 0 and X 0 have two solutions each. The series of frequency points with positive R 0 is taken as the noise source impedance.3.2 Method of measurementAn impedance is inserted at the EUT terminals in order to measure the noise source impedance in the LISN as seen at the EUT. As shown in Fig. 4, the impedance is inserted so as to vary only the impedance in the mode under consideration, thus preventing an influence on the imped-ance in the other mode. In the diagram, V m is the voltage at the meter connected to the LISN, while the input impedance of the meter (50 Ω) is represented by the parallel resistance.Since parameters of both the LISN and the inserted imped-ance are known, the noise current I can be calculated from V m . Now Z 0 is calculated for each mode from the measured data obtained while varying Z L , by using Eqs. (2) and (3).With the differential mode shown in Fig. 4(a), CR is inserted between the two lines, thus varying the load im-pedance Z L . In the differential mode, Z 0 is assumed to be a low impedance, and hence the inserted impedance exerts a significant effect on the measured value. For this reason, 1Ω/0.47 µF and 0 Ω/0.1 µF were inserted, which are rather small compared to the LISN impedance.The measurement of the common mode shown in Fig.4(b) employs common-mode chokes that basically have no impedance in the differential mode. The common-mode chokes are provided with a secondary winding (ratio 1:1),so that the impedance at the secondary side can be varied.In the common mode, Z 0 is assumed to have a particularly high impedance in the low-frequency band. For this reason,5.1 k Ω and 100 pF were used as the secondary load for the common-mode choke to obtain a high inserted impedance.The measured data for the inserted impedance in the case of resistive and capacitive loads are presented in Fig. 5. The impedance of the common-mode choke includes its own inductance and the secondary load. In the case of a capaci-tive load, the resonance point is around 200 kHz; at higher frequencies, the impedance becomes capacitive.A single-phase two-line switching power supply (an ac adapter for a PC with an input of ac 100 V , a rated power of 45 W, and PWM switching at 73 kHz) was used as the EUT, and the rated load resistance was connected at the dcside. Filters were used for both the common and differential(1)modes, except for the case in which one common-mode choke was removed, in order to obtain the high noise level required for analysis. Both the EUT and the loads had conventional commercial ratings, and were placed 40 cm above a metal ground plate; the power cord was fixed.4. Measurement Results and Discussion The results of conventional measurement as well as common-mode and differential-mode measurement for the LISN without inserted impedance are shown in Fig. 6. The measurements were performed in the range of 150 kHz through 30 MHz, divided into three bands, using a spectrum analyzer with frequency linear sweep. Time-variable data were measured at their highest levels using the Max Hold function of the spectrum analyzer, and only the peak values were employed for calculation of Z 0. For this purpose, the values measured in every frequency band were subjected to the FFT, and all harmonics higher than the fundamental frequency were removed. The data were smoothed, and about 10 peak points were detected in every frequency band. In addition, only those peaks that were stronger than the meter s background noise by at least 6 dB were consid-ered.The results in Figs. 6(b) and 6(c) pertain to the LISN only; the level would vary with inserted impedance. The noise source impedance for both modes calculated from the measured data (using triple measurement) is given in Figs.7 and 9, respectively. The bold and dashed lines pertain to data acquired with the impedance analyzer at the EUT power plug, with the EUT not in operation. With the differ-ential mode, there were no high-frequency components, as shown in Fig. 6(b), and hence the impedance is calculated only for significant low-frequency peaks.The noise source impedance in differential mode can be represented schematically as in Fig. 8. The noise sourceimpedance is equal to the impedance between the LISNFig. 5.Inserted impedance in common mode.Fig. 6. Measured results of standard, differential-mode,and common-mode.Fig. 7. Noise source impedance for differential mode.terminals when the noise source is short-circuited. With switching power supplies, filtering is usually performed by a capacitor of 0.1 to 1 µF inserted between the lines. Since the impedance of the power cord is small in the measured frequency range, one may assume that the impedance as seen at the LISN is low, and that the phase changes from capacitive toward inductive as with the measured static characteristics. However, in the case of the given EUT, a nonlinear resistor was inserted between the power cord and the filter as shown in Fig. 8, and hence the impedance is rather high in the nonoperating state. In addition, there are rectifying diodes on the propagation route, but they do not conduct at the measurement voltage of the impedance ana-lyzer. The noise levels show considerable variation at 120Hz, which corresponds to the on/off frequency of the recti-fying diodes; however, only the peak values are measured and then used for calculation, and hence the impedance obtained by the proposed method is considered to pertain to the conductive state. For this reason, the results do not agree well with static characteristics. Thus, the impedance in the operating state cannot be measured in the differential mode.On the other hand, the measured data for |Z 0| in common mode agree well with the static characteristics, as shown in Fig. 9. The phase, too, exhibits a similar variation,although the scatter is rather large. The resistive part of three load impedances and Z 0 may be presented in a simplified way as in Fig. 10. From Eq. (1), the following is true for R 2,R 3, and Z 0:The distance ratio from Z 0 to R 3 and R 2 on the R X plane that satisfies this equation is I 2:I 3, which corresponds to a circle with radius r as in Eq. (4), with the center lying on the line R 3R 2:Similar circles for R 1 and R 2 are also shown in the diagram.When Z 0 and the load impedances lie on one line, the twocircles have a common point. Equation (4) indicates that if I 3 increases slightly, the outer circle becomes bigger, and the two circles do not adjoin. On the other hand, when the outer circle becomes smaller, the two circles intersect at two points, and X 0 varies more strongly than R 0. In practice, the difference in noise level due to the inserted impedance may drop below 1 dB at some frequencies, so that the solution for Z 0 becomes unavailable because of the scatter, or the phase scatters too much. The measurement accuracy is governed by the difference in noise level, and thus the inserted impedance should have a large enough variation compared to the measurement scatter; in addition, there should be a phase difference so that the two circles are not aligned, as in Fig. 10.Figures 7 and 9 pertain to one of the solutions of Eq.(3) with larger R 0. Here R 0 is not necessarily positive and the other solution is not necessarily negative. The two solutions may be basically discriminated from the fre-quency response and other characteristics, but other inser-tion data are employed for the sake of accuracy.Fig. 8. Equivalent circuit of differential-mode noisesource impedance.(4)Fig. 9.Noise source impedance for common mode.Fig. 10. Load impedances and Z 0 on R X plane.Figure 11 compares the measured data and calculated data for the variation of noise level due to insertion of a commercially available common-mode choke, with the cal-culation based on the results of Fig. 9 and the impedance of the common-mode choke. As is evident, the calculation agrees well with the measured values. On the other hand, a considerable discrepancy was confirmed for the other solu-tion. The noise source impedance found as explained above is accurate enough to predict the filtering effect.The noise source resistance in the common mode can be represented as in Fig. 12. Here Z 1 is the stray capacitance between the internal circuit and the case, and Z 2 is the stray capacitance between the case and the ground plate (or in the case of the ground wire, the impedance of the wire). The common-mode noise source impedance for a single-phase two-line EUT is primarily Z 2, becoming capacitive at low frequencies. Since the EUT is equipped with a filter, the influence of the primary rectifying diodes is not related to common-mode, and hence the data measured by the pro-posed method are very close to the static characteristics.However, this is not necessarily true in the case of a grounded line (Z 2 short-circuited) with no filter installed.In addition, here the full impedance as seen at the LISN is found; in practice, however, a filter or Z 1 is employed to suppress noise. Therefore, the impedance of the power cord is required as well as Z 1 and Z 2 in order to analyze the filtering effect. The impedance of the power cord or grounded wire can be easily determined by measurement or calculation. In our experiments without ground, the impedance is very close to Z 2; on the other hand, Z 1 might be measured by grounding the case and removing the filter (Fig. 12), and then used to analyze the filtering effect between the case and the lines. However, noise propagation in the inner circuit must be further investigated in order to estimate the noise-suppressing efficiency of Z 1.5. ConclusionsA new mode-separable LISN is proposed that sup-ports noise measurement without changing the impedance depending on the mode. The proposed LISN ensures accu-rate measurement for each mode, thus supporting imped-ance analysis.With the proposed LISN, an appropriate impedance is inserted at the EUT terminals, and the noise impedance can be found as a complex impedance, just as simply as with conventional measurement of the noise terminal voltage.The value of the inserted impedance must be chosen prop-erly in order to determine the phase accurately. The pro-posed method ensures sufficient accuracy not only to investigate noise propagation and design efficient counter-measures, but also to predict the filtering effect. The pro-posed technique can supply important data for future analysis of noise generation and propagation in switching power supplies.REFERENCES1.Matsuda H et al. Analysis of common-mode noise in switching power supplies. NEC Tech Rep 1998;51:60 65.2.Ogasawara S et al. Modeling and analysis of high-frequency leak currents generated by voltage-fed PWM inverter. Trans IEE Japan 1995;115-D:77 83.3.Iwasaki M, Ikeda T. Evaluation of noise filters for power supply. Tech Rep IEICE EMCJ 1999;90:1 6.4.Kamita M, Toyama K. A study on attenuation char-acteristics of power filters. Tech Rep IEICE EMCJ 1996;96:45 50.rmation technology equipment Radio distur-bance characteristics Limits and method of meas-urement. CISPR 22, 1997.Fig. 11. V ariation of noise level due to insertion ofanother impedance (measured and calculated data).Fig. 12. Equivalent circuit of common-mode noisesource impedance.6.K amita M, Oka N. Calculation of common-mode noise output impedance during operation. Tech Rep IEICE EMCJ 1998;98:59 65.7.Ran L, Clare C, Bradley K J, Chriistoopoulos C.Measurement of conducted electromagnetic emis-sions in PWM motor drive without the need for an LISN. IEEE Trans EMC 1999;41:50 55.8.Specification for radio disturbance and immunity measuring apparatus and method Part 1: Radio dis-turbance and immunity measuring apparatus. CISPR 16-1, 1993.AUTHORS (from left to right)Junichi Miyashita (member) graduated from Tohoku University in 1981 and joined the Precision Technology Research Institute of Nagano Prefecture. His research interests are EMC measurement and prevention. He is a member of IEICE.Masayuki Mitsuzawa (nonmember) graduated from Nagoya University in 1984 and joined the Precision Technology Research Institute of Nagano Prefecture. His research interests are EMC measurement and prevention. He is a member of JIEP .Toshiyuki Karube (nonmember) graduated from Waseda University in 1991 and joined the Precision Technology Research Institute of Nagano Prefecture. His research interests are EMC measurement and prevention. He is a member of IEICE and JIEP .Kiyohito Yamasawa (member) completed the M.E. program at Tohoku University in 1970. He has been a professor at Shinshu University since 1993. His research interests are magnetic device integration, microswitching power units, and microwave sensors. He holds a D.Eng. degree and is a member of IEICE, SICE, the Magnetics Society of Japan, the Japan AEM Society, and IEEE.Toshiro Sato (member) completed his doctorate at Chiba University in 1989 and joined Toshiba Research Institute. He has been an associate professor at Shinshu University since 1996. His research interests are magnetic thin-film devices. He received a 1994 IEE Japan Paper Award and a 1999 Japan Society of Applied Magnetism Paper Award. He holds a D.Sc. degree,and is a member of IEE Japan, IEICE, and the Magnetics Society of Japan.。

multisim 共模扼流圈

multisim 共模扼流圈英文版Multisim Common-Mode ChokeIn the realm of electronics, Multisim stands as a powerful tool for simulating circuits and electronic systems. Among the various components that can be simulated in Multisim, the common-mode choke, or common-mode inductor, plays a crucial role in filtering and suppressing unwanted noise and interference.A common-mode choke is a type of inductor designed to block or reduce common-mode currents, which are currents that flow in the same direction in two conductors. These currents are often caused by electromagnetic interference (EMI) or electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) issues. By effectively blocking these currents, common-mode chokes improve the overall performance and reliability of electronic systems.In Multisim, simulating a common-mode choke allows engineers and hobbyists to analyze its impact on a circuit's behavior. By inserting a common-mode choke into a simulated circuit, it's possible to observe how it affects the flow of currents and how it mitigates EMI or EMC issues. This simulation capability is invaluable in the design and optimization of electronic systems.Moreover, Multisim's simulation of common-mode chokes enables users to experiment with different configurations and parameters, such as inductance values and circuit arrangements. This flexibility allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how common-mode chokes work and how they can be optimized for specific applications.In conclusion, Multisim's simulation of common-mode chokes is a powerful tool for electronic design and analysis. It enables users to gain valuable insights into the behavior of these components and how they can be effectively used to improve the performance and reliability of electronic systems.中文版Multisim共模扼流圈在电子领域,Multisim是一款强大的电路和电子系统仿真工具。

共模扼流圈滤波器计算公式

共模扼流圈滤波器计算公式英文回答:Common Mode Choke Filter Design.Common mode choke (CMC) filters are used to suppress common mode noise, which is noise that appears on both conductors of a differential signal. CMC filters are typically used in conjunction with differential mode filters to provide a comprehensive noise suppression solution.The design of a CMC filter involves the selection of the following parameters:Inductance (L)。

Core material.Number of turns (N)。

Cross-sectional area of the core (A)。

Air gap length (g)。

The inductance of the CMC filter is determined by the following formula:L = (N^2 A) / (g l)。

where:L is the inductance in henrys.N is the number of turns.A is the cross-sectional area of the core in square meters.g is the air gap length in meters.l is the magnetic path length in meters.The core material for the CMC filter is typically a ferrite material, such as MnZn or NiZn. The choice of core material depends on the desired inductance and frequency response of the filter.The number of turns for the CMC filter is determined by the following formula:N = (L g l) / (A)。

共模扼流圈在can电路中的趋势

共模扼流圈在can电路中的趋势1.共模扼流圈在can电路中起着重要作用。

The common mode choke plays an important role in the CAN circuit.2.它能够有效抑制干扰信号的影响。

It can effectively suppress the influence of interference signals.3.通过对信号进行滤波处理,可以保证数据传输的稳定性。

By filtering the signals, the stability of data transmission can be ensured.4.在can总线上,共模扼流圈具有良好的抗干扰能力。

On the CAN bus, the common mode choke has good anti-interference ability.5.它可以提供可靠的信号传输环境。

It can provide a reliable signal transmission environment.6.通过合理设计电路结构,可以最大限度地减小共模干扰。

By designing the circuit structure reasonably, common mode interference can be minimized as much as possible.7.共模扼流圈的使用可以提高信号传输的质量。

The use of common mode chokes can improve the quality of signal transmission.8.在can通信中,共模噪声往往是影响通信质量的重要因素之一。

In CAN communication, common mode noise is often one ofthe important factors affecting communication quality.9.共模扼流圈能够有效地减少这种噪声的影响。

X电容与Y电容容量的计算

120

PI-1622-111695

120

AN-15

Safety is a vital issue which determines EMI filter component selection, the transformer reinforced insulation system, and PC board primary to secondary spacing. In fact, safety is an integral part of the power supply/EMI filter design and is difficult to discuss as a separate issue. Throughout this application note, design guidance will also be presented for meeting safety requirements in TOPSwitch power supplies.

MITAC 3.5” SBC M B PD10AS 产品手册说明书

MITAC 3.5” SBC M/B PD10AS Product GuideDesktop Board FeaturesThis chapter briefly describes the features of 3.5” SBC M/B PD10AS.Below to summarizes the major features of the3.5” SBC M/B. Feature SummaryT ABLE: M I TAC 3.5”SBC M/B PD10AS F EATURESDesktop Board ComponentsFigure shows the approximate location of the major components on the top side of MiTAC3.5” SBC M/B PD10ASFigure: MiTAC 3.5” SBC M/B PD10AS Components (Top)ProcessorMITAC 3.5” SBC M/B PD10AS includes a passively-cooled, Intel Apollo Lake N3350/N4200 processor with integrated graphics and memory controller. The processor is solderedto the 3.5” SBC M/B and is not customer upgradeable.NOTEThe board is designed to be passively cooled in a properly ventilated chassis.Chassis venting locations are recommended above the processor heatsink area for maximumheat dissipation effectiveness.System MemoryNOTETo be fully compliant with all applicable SDRAM memory specifications,theboard should be populated with DIMMs that support the Serial Presence Detect(SPD)data structure.If your memory modules do not support SPD,you will see anotification to this effect on the screen at power up.The BIOS will attempt toconfigure the memory controller for normal operation.The Desktop Board has two204-pin DDR3L SO-DIMM sockets with gold-plated contacts.These sockets support:●Support for DDR3L SO-DIMMs●Serial Presence Detect(SPD)memory only●Non-ECC memory●Up to8GB of memoryHDMI feature: High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI*)∙HD – HDMI1.4 flush mount graphics connector: backpanel video∙∙The High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI*) is provided for transmitting uncompressed digital audio and video signals from DVD players, set-top boxes, and other audio-visual sources totelevision sets, projectors, and other video displays. It can carry high-quality multi-channel audiodata and all standard and high-definition consumer electronics video formats. The HDMI displayinterface connecting the processor and display devices uses transition minimized differentialsignaling (TMDS) to carry audiovisual information through the same HDMI cable.∙∙HDMI includes three separate communications channels: TMDS, DDC, and the optional CEC (consumer electronics control). CEC is not supported on the processor. As shown in the followingfigure, the HDMI cable carries four differential pairs that make up the TMDS data and clockchannels. These channels are used to carry video, audio, and auxiliary data. In addition, HDMIcarries a VESA DDC. The DDC is used by an HDMI Source to determine the capabilities andcharacteristics of the Sink.∙∙Audio, video, and auxiliary (control/status) data is transmitted across the three TMDS data channels. The video pixel clock is transmitted on the TMDS clock channel and is used by thereceiver for data recovery on the three data channels. The digital display data signals drivennatively through the PCH are AC coupled and needs level shifting to convert the AC coupledsignals to the HDMI compliant digital signals.∙∙The processor HDMI interface is designed in accordance with the High-Definition Multimedia Interface.VGA feature: High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI*) HD – HDMI1.4 flush mount graphics connector: backpanel videoThe CH7517 can support analog RGB output up to 1920x1200@60Hz or2048x1152@60Hz with reduced blanking through triple video DACs, and the DACsupports pixel rate up to 200MHz. The de-serialized data from the DisplayPortReceiver, after proper decoding and image enhancement process, are transported to the video DACs. This operating mode uses 8-bits of the DAC’s 9-bit range, andprovides a nominal signal swing of 0.7V(depending on DAC Gain setting in controlregisters) when driving a 75Ω doubly terminated load. No scaling, scan conversion or flicker filtering is applied.TF-CON;LVDS,SBU,INTEL,15Pin*2,1.0mm,MA,ST,Gold Flash,WHITE (ACES ELECTRONIC: 87216-3016-06)LVDS feature:Table 1: LVDS 15Px2 panel main header signalsTF-CON;LVDS,SBU,40Pin,0.5mm,FM,R/A,Gold Flash,BLACK (ACES ELECTRONIC: 50203-04001-001)eDP feature:Additional requirements for eDP panel interface:40-pin eDP connector must be right-angled, single-row shrouded colored black, as shown in Figure 2 (part number reference: ACES 50203-04001-001). Connector must support four lanes of eDP traffic, AUX channel, panel logic power as well as backlight power and control signals, compliant with the VESA Embedded DisplayPort TM (eDP TM) Standard for 40-pin eDP pin assignment, Connector must be located on the backside of the board, preferably under the LVDS connector.Figure 2: Panel 40-pin eDP connectorTable 2: 40-pin eDP connector pin-out∙ Interface must be fully validated with WUXGA/1920x1200@60Hz 24bpp eDP panel connected by 2-lane link at 2.7Gbps as well as four-lane link at 1.62Gbps.3V, 5V and 12V as well as for backlight inverter power at 5V and 12V.∙ Output voltage for LCD panel at eDP connector pins 18-21 must be selectable between 3.3V (default), 5V and 12V by a 2x3, 2.54mm pitch header capable of 3A per pin and colored red with black jumper, as defined in Figure 4 and Table 3.Figure 3: Panel LCD voltage selection headerTable 3-1: Panel LCD voltage selection header pin-out (R0C)Table 3-2: Panel LCD voltage selection header pin-out (R01)Figure 4: Backlight inverter voltage selection headerTable 4: Backlight inverter voltage selection header pin-out Shared requirements for LVDS and eDP interfaces:Board must provide separate backlight inverter connectivity via an “FPD Brightness” connector. 8-pin FPD brightness connector must be 1x8 shrouded, 2.00mm pitch with 2A rating per pin and colored red, as shown in Figure 5 (part number reference: Foxconn HF5508). Connector must provide backlight inverter control signals (same as routed to LVDS and eDP connectors, for customer convenience) as well as panel brightness control signals, as defined in Table 5.Figure 5: 8-pin FPD power connectorTable 5: 8-pin FPD power connector pin-out∙ Brightness control signals must be GPIO inputs; specific GPIO addresses must be determined by ODM.∙ Backlight brightness must be dynamically controlled via discrete panel brightness buttons (on the front panel bezel) enabling tactile interface for end-user screen brightness adjustments.-pin FPD power connector must be validated to support maximum power delivery at all voltage levels, as wellas to correctly support backlight control signals.and control features.ed by BIOS setting at boot time.1.1.3A udioImplemented using the nuvoTon NAU88L25YGBBoard must support 3-channel audio output from the rear analog ports, with jack detection as indicated. An additional 2-channel analog port is required for front panel audio, with jack detection and independent multi-streaming support for separate front vs back panel audio streams (i.e. simultaneous VoIP and 8.1/10 audio streams).Front panel audio header must be 2x5, 2.54mm pitch, colored yellow (Pantone color code 123C) and keyed at pin 8, as shown in Figure .Figure 6: HD Front panel audio headerTable 6: HD headphone/mic front panel audio port pin assignments1.1.42ea LAN portBoard must implement a LAN solution supporting 10/100/1000 Mb/s with the following features:Onboard RJ45 connectors must have integrated magnetics and support dual status LEDs per port, as shown in Table 2.Table 7: RJ45 LED behaviorNote: LAN subsystem must be tested for IEEE802.3 conformance on each port.1.1.5S ATASATA PORT0: This is optional port from mini PCI-E and SATA0 ConnectorBoard must also support the following Serial ATA Gen 3 compliant ports∙One fully-shrouded right angle internal SATA gen 3 ports (colored GREY)SATA PORT1Board must also support the following Serial ATA Gen 3 compliant∙one fully-shrouded right angle internal SATA gen 3 ports (colored BLACK)∙Note: All SATA must be compliant with the Serial ATA Revision 3.0 Specification, as noted in the Reference Documentation section.1.1.6S uper I/OBoard must support the following features through a SuperIO controller device:∙SMBUS/SMLink support for SOC temp∙Support for as one fan headers as required in section 1.4.2 - Fan Header Requirements∙Support minimum of 2 temperature inputs per PWM Controller for duty cycle determination∙Support for non-ACPI based fan control (thermal responsiveness independent of system software) ∙Support 4ea serial port: 3ea RS232, 1ea RS485/RS422/RS232∙Legacy I/O (for applicable ports)1.2Expansion I/O1.2.1B ack Panel I/OBackpanel must be designed with horizontal keepout space between ports exceeding specifications for ease of cable connectivity/removal. A minimum of 2 mm between cable connectors is required when all ports are being used with commonly available “off-the-shelf” cables.Board must have a back panel layout similar to Figure , 5:Figure 7: Back panel layout1.2.2U SBBoard must support the following Universal Serial Bus ports:Port Summary∙ 2 total USB2.0 Ports (2 internal)∙ 1 total USB2.0 Ports (m2 key-E Connector)∙ 1 total USB2.0 Ports (Mini PCIE Connector)∙ 4 total USB 3.0 Ports (2 back-panel with standard USB3.0 I/O port)Front panel USB2.0 headers must be 2x5, 2.0mm pitch, colored black and keyed at pin 9, as defined in Figure and Table . Follow the Intel Front Panel I/O Connectivity Design Guide for front panel USB solutions.(SUPERIOR TECH : PHDD-SS010G1ABONE-N088)Figure 8: Front panel USB header pin-outTable 8: Front panel USB header signalsNotes: Front panel USB headers must be placed within a keep-out-zone no smaller than 1 inch (half-inch to the left and half-inch to the right of the header) so as to support commonly available USBconnectors.Thermistor protection is required for all back panel and front panel USB ports.ESD protection is required for all D+ and D- signals. Signal routing/layout for all front panel andbackpanel ports must include pads for ESD protection; protection components must be stuffed.ESD protection circuitry must meet respective signal qualification, functionality and performance.Common mode choke footprint must be routed for all back panel and front panel USB ports (to bestuffed on back panel ports shall EMI test fail with less than 4dB margin).Rear USB3.0 I/O portTable 9: Rear USB3.0 I/O signals1.2.3S PI Programing Header – None1.2.4P CI Express Expansion SlotsBoard’s PCI Express slot(s) must be PCI Express Specification v2.0 compliant and compatible with PCI Express v2.0 and v1.1 add-in cards.PCI Express x16 slot must be compatible with x16/x8/x4/x1 PCI Express add-on cards. PCIe x16 slot’s reten tion mechanism must be consistent across Intel desktop boards.PCI Express x4 slot(s) must be compatible with PCI Express x4 and x1 add-on cards. Slot power capability must comply with 25W requirement as defined in the PCI Express Card Electromechanical 3.0 Specification.PCI Express x1 slot(s) must be compatible with x1 PCI Express add-on cards.Route WAKE# to support ACPI wake events.Design must provide SMBus routed to all PCI Express slots, with individual/per slot de-stuffing option via strapping resistor (strapping resistor must be stuffed by default).Follow the ATX specification and Industrial DFA (Design for Assembly) standard requirements for connector placement and spacing.Keep-out zone of PCI Express v3.0 x16 slot must allow use of double-width and long graphics cards without blocking access to any connectors (i.e. SATA ports, DIMM connector tabs, front panel audio header, …).1.2.5E xpansion Slot LayoutBoard must have the following expansion slot layout:●M.2 Suport key-E 3 Type2230 for WLAN/USB2.0 feature●Mini PCIE for mSATA feature support SATA SSD or PCIE SSD module1.3Additional Headers1.3.1F ront PanelThe front panel main header must be shrouded 2x5, 2.54mm pitch, multi-colored, keyed at pin 10 and with silkscreen text as defined in Figure 8 and Table 4. Polarity markings on pins 1 & 2 and color-coding on all pins are required. Refer to Intel PN 2100C888-121 and other Intel® Desktop Boards for front panel header connectivity references.Figure 9: Front panel main header pin-outTable 10: Front panel main header signals1.3.2C hassis Intrusion Detection-NONe1.3.3M iAPI featureThe MiAPI port header must be 2x10, 1.mm pitch, colored black and keyed at pin 20 Dual COM port header: Molex 5011902017_sd1.3.4S erial PortThe serial port header must be 2x5, 2.00mm pitch, colored green and keyed at pin 10, as defined in Figure 10Table 13: RS232/RS422/RS485 Serial port header signals Internal I/O header: Standard 9 pin RS232 or RS485, RS422 portCOM port 2 header : J_RS232_P2 is RS232 feature only(SUPERIOR TECH : PHDD-SS010G1AGONX-N092)COM port 4 header: RS485/RS422/RS232 feature(SUPERIOR TECH : PHDD-SS010G1ABONE-N092)Figure 10: RS232, RS485, RS232 Serial port header pin-out Internal I/O header: 10Px2, 1.0mm, ST: dual RS232 portDual COM port header: Molex 5011902017_sdCOM port #1,#3 header: RS485/RS422/RS232 featureSerial Port #1, #3: RS232_P1P3 pin defintionTable 14: Dual Serial port header signals1.3.5A T/ATX, CMOS , mSATA header in silkscreen / featureJUMPERJ_AT_CMOS1(1-2)Clear CMOS(1-3)Normal(4-6)ATX(8-6)AT(5-7)PCIE(5-7) NA mSATAmSATA detection function:Base on some PCIE/USB 3G module pin51 suport PCM_SYNC Base on old SATA module pin43 can ’t meet datasheet NC pin1.3.6 S ATA power 1.25mm cable pin headerSupport SATADOM power current is 1A max at V_5P power railSupport external 5V SATA power with 1A max current. Support external 12V SATA power with 1A max current. Support external VCC3 SATA power with 1A max current.Table 15: SATA power 1.25mm cable pin header signalsClear CMOS(1-2)JUMPER (1-3)NormalClear CMOSCMOS clear Normal: 1-3Clear CMOS: 1-2AT/ATX(8-6)JUMPER (Default)ATX AT Mode(4-6)mSATA/PCIE(5-7) IN JUMPER (Default)PCIEmSATA3G Module (5-7) NAConnector:TF-CON;SBU,B/B,3P ,1.25MM,MA,ST,GOLD,1A,SMT ACES ELECTRONIC CO.,LTD 85205-03701TF-CON;SBU,B/B,4P ,1.25MM,MA,ST,GOLD,1A,SMT ACES ELECTRONIC CO.,LTD 85205-047011.3.7 A TX power 4P/DC power 4.2mm pin headerV_5PJ_SATA_PWR13P*1_WAFER_1.25mm_RA_White/HTPPOP1132G N D 1G N D 2+12VJ_SATA_PWR24P_B/B_1.25MM_MA_ST_Gold INVCC31A1A 1A VCC J_PW4P_12P*2_ATX_4.2mm_FM_Black_W/PressFit IN11223344DC_INConnector part 2Px2, 4.2mm, STLOTES CHIA TSE TERMINAL INDUST ABA-POW-003-K781.4Thermal Management and Fan Control∙Nuvoton NCT6104D SuperIO: backup alternate solution as it leverages existing hardware in the designs, but software infrastructure must be put in place to support this solution.Regardless of solution chosen, BIOS/driver/tools support and subsystem validation is required, even if solution is not needed by pilot.Board must use SuperIO solution for hardware monitoring and thermal management. SuperIO implementation must be supported by BIOS, tools and drivers necessary for custom thermal profile management no later than by fab B samples.BIOS/tools/driver support and subsystem validation is required.The thermal management capability must support temperature sensors near CPU VR FETs as well as near or on the memory components; shall only one temperature sensor be feasible it must be located near the CPU VR FETs.The following thermal management features must be supported:∙Temperature monitoring at the following locations:o remote diode near CPU VR FETso remote diode near or on the memory components∙Voltage monitoring (in priority order): +12V, V_SM, CPU VCC_VCGI, CPU VNN_SVID1.4.1C PU FansBoard must implement a 4-pin fan header for the processor/heatsink 4-wire fan. Processor/heatsink fan must be tachometer/PWM controlled and header color must be white, as shown in Figure 3.Figure 11: Processor fan header.1.4.2F an Header RequirementsThe below requirements must be met for the 4-pin processor/heatsink fan (CPU FAN) header: ∙Closed loop fan speed control via the FANPWM0 signal routed to pin-4∙Route fan tachometer signal to FANTACH0 input∙Support 2A continuous draw∙Clearly label as “CPU FAN”∙Locate closest to the CPU as required by the CDPG boxed CPUMITAC Desktop Board PD10AI BIOS Specifiction1.MAIN PAGE2.ADVANCED PAGE2.1 INTEL(R) I210 GIGABIT NETWORK CONNECTION – 00:22:4D:4D:00:012.3.1 NIC CONFIGURATION2.2INTEL(R) I210 GIGABIT NETWORK CONNECTION – 00:22:4D:4D:00:022.1.1NIC CONFIGURATION2.3 DRIVER HEALTH2.3.1INTEL(R) PRO/1000 7.3.20 PCI-E2.4TRUSTED COMPUTING2.5 SMART SETTINGS。

Common Mode Filter Design Guide

Common M ode F ilter D esign G uideIntroductionThe selection of component values for common mode filters need not be a difficult and confusing process. The use of standard filter alignments can be utilized to achieve a relatively simple and straightforward design process, though such alignments may readily be modified to utilize pre-defined component values.GeneralLine filters prevent excessive noise from being conducted between electronic equipment and the AC line; generally, the emphasis is on protecting the AC line. Figure 1 shows the use of a common mode filter between the AC line (via impedance matching circuitry) and a (noisy) power con-verter. The direction of common mode noise (noise on both lines occurring simultaneously referred to earth ground) is from the load and into the filter, where the noise common to both lines becomes sufficiently attenuated. The result-ing common mode output of the filter onto the AC line (via impedance matching circuitry) is then negligible.Figure 1.Generalized line filteringThe design of a common mode filter is essentially the design of two identical differential filters, one for each of the two polarity lines with the inductors of each side coupled by a single core:L2Figure 2.The common mode inductorFor a differential input current ( (A) to (B) through L1 and (B) to (A) through L2), the net magnetic flux which is coupled between the two inductors is zero.Any inductance encountered by the differential signal is then the result of imperfect coupling of the two chokes; they perform as independent components with their leak-age inductances responding to the differential signal: the leakage inductances attenuate the differential signal. When the inductors, L1 and L2, encounter an identical signal of the same polarity referred to ground (common mode signal), they each contribute a net, non-zero flux in the shared core; the inductors thus perform as indepen-dent components with their mutual inductance respond-ing to the common signal: the mutual inductance then attenuates this common signal.The First Order FilterThe simplest and least expensive filter to design is a first order filter; this type of filter uses a single reactive component to store certain bands of a spectral energy without passing this energy to the load. In the case of a low pass common mode filter, a common mode choke is the reactive element employed.The value of inductance required of the choke is simply the load in Ohms divided by the radian frequency at and above which the signal is to be attenuated. For example, attenu-ation at and above 4000 Hz into a 50⏲ load would require a 1.99 mH (50/(2π x 4000)) inductor. The resulting common mode filter configuration would be as follows:50Ω1.99 mHFigure 3.A first order (single pole) common mode filter The attenuation at 4000 Hz would be 3 dB, increasing at 6 dB per octave. Because of the predominant inductor dependence of a first order filter, the variations of actual choke inductance must be considered. For example, a ±20% variation of rated inductance means that the nominal 3 dB frequency of 4000 Hz could actually be anywhere in the range from 3332 Hz to 4999 Hz. It is typical for the inductance value of a common mode choketo be specified as a minimum requirement, thus insuring that the crossover frequency not be shifted too high.However, some care should be observed in choosing a choke for a first order low pass filter because a much higher than typical or minimum value of inductance may limit the choke’s useful band of attenuation.Second Order FiltersA second order filter uses two reactive components and has two advantages over the first order filter: 1) ideally, a second order filter provides 12 dB per octave attenuation (four times that of a first order filter) after the cutoff point,and 2) it provides greater attenuation at frequencies above inductor self-resonance (See Figure 4).One of the critical factors involved in the operation of higher order filters is the attenuating character at the corner frequency. Assuming tight coupling of the filter components and reasonable coupling of the choke itself (conditions we would expect to achieve), the gain near the cutoff point may be very large (several dB); moreover, the time response would be slow and oscillatory. On the other hand, the gain at the crossover point may also be less than the presumed -3 dB (3 dB attenuation), providing a good transient response, but frequency response near and below the corner frequency could be less than optimally flat.In the design of a second order filter, the damping factor (usually signified by the Greek letter zeta (ζ )) describes both the gain at the corner frequency and the time response of the filter. Figure (5) shows normalized plots of the gain versus frequency for various values of zeta.Figure 4.Analysis of a second order (two pole) common modelow pass filterThe design of a second order filter requires more care and analysis than a first order filter to obtain a suitable response near the cutoff point, but there is less concern needed at higher frequencies as previously mentioned.A ≡ ζ = 0.1;B ≡ ζ = 0.5;C ≡ ζ = 0.707;D ≡ ζ = 1.0;E ≡ ζ = 4.0Figure 5.Second order frequency response for variousdamping f actors (ζ)As the damping factor becomes smaller, the gain at the corner frequency becomes larger; the ideal limit for zero damping would be infinite gain. The inherent parasitics of real components reduce the gain expected from ideal components, but tailoring the frequency response within the few octaves of critical cutoff point is still effectively a function of ideal filter parameters (i.e., frequency, capaci-tance, inductance, resistance).L0.1W n1W n 10W nRadian Frequency,WG a i n (d B )V s V s LR s LCs LC j L R j LC LR LCCMout CMin L L n n n L ()()=++=−+⎛⎝⎜⎞⎠⎟=+−⎛⎝⎜⎞⎠⎟≡≡≡≡111111212222ωωζωωωωωωζradian frequencyR the noise load resistance LFor some types of filters, the design and damping char-acteristics may need to be maintained to meet specific performance requirements. For many actual line filters,however, a damping factor of approximately 1 or greater and a cutoff frequency within about an octave of the calculated ideal should provide suitable filtering.The following is an example of a second order low pass filter design:1)Identify the required cutoff frequency:For this example, suppose we have a switching power supply (for use in equipment covered by UL478) that is actually 24 dB noisier at 60 KH z than permissible for the intended application. For a second order filter (12dB/octave roll off) the desired corner frequency would be 15 KHz.2)Identify the load resistance at the cutoff frequency:Assume R L = 50 Ω3)Choose the desired damping factor:Choose a minimum of 0.707 which will provide 3 dB attenuation at the corner frequency while providing favorable control over filter ringing.4)Calculate required component values:Note:Damping factors much greater than 1 may causeunacceptably high attenuation of lower frequen-cies whereas a damping factor much less than 0.707 may cause undesired ringing and the filter may itself produce noise.Third Order FiltersA third order filter ideally yields an attenuation of 18 dB per octave above the cutoff point (or cutoff points if the three corner frequencies are not simultaneous); this is the prominently positive aspect of this higher order filter. The primary disadvantage is cost since three reactive compo-nents are now required. H igher than third order filters are generally cost-prohibitive.Figure 6.Analysis of a third order (three pole) low pass filter where ω1, ω2 and ω4 occur at the same -3dB frequency of ω05)Choose available components:C = 0.05 µF (Largest standard capacitor value that will meet leakage current requirements for UL478/CSA C22.2 No. 1: a 300% decrease from design)L = 2.1 mH (Approx. 300% larger than design to compensate for reduction or capacitance: Coilcraft standard part #E3493-A)6)Calculate actual frequency, damping factor, and at-tenuation for components chosen:ζ = 2.05 (a damping factor of about 1 or more is acceptible)Attenuation = (12 dB/octave) x 2 octaves = 24 dB 7)The resulting filter is that of figure (4) with:L = 2.1 mH; C = 0.05 µF; R L = 50 ΩL 1L 2VCMout s VCMin s R R L s R L s sC R L s sC R L s L L s L s sC L L R s L Cs L L C R s L L L L L L L()()()()=+⎛⎝⎜⎞⎠⎟+++++⎛⎝⎜⎜⎜⎜⎞⎠⎟⎟⎟⎟=++++222121*********11Butterworth →+++112212233s s s n n n ωωω()()L L R R L L L n n L 12111222+==+ωω;()L L C n 1n2C =2;ωω2211414=.L L L L n n n 12L n3n2L2n2L2C R =1;R R ωωωωωω33224422===ωπωζωμn n n Lf C L L R L =====294248070727502rad /sec =1Hn .1215532πLC=Hz (very nearly 15KHz)The design of a generic filter is readily accomplished by using standard alignments such as the Butterworth (“maxi-mally flat”) alignments. Figure (6) shows the general analysis and component relationships to the Butterworth alignments for a third order low pass filter. Butterworth alignments provide an inherent ζ of 0.707 and a -3 dB point at the crossover frequency. The Butterworth alignments for the first three orders of low pass filters are shown in Figure (7).The design of a line filter need not obey the Butterworth alignments precisely (although such alignments do pro-vide a good basis for design); moreover, because of leakage current limits placed upon electronic equipment (thus limiting the amount of filter capacitance to ground),adjustments to the alignments are usually required, but they can be executed very simply as follows:1)First design a second order low pass with ζ ≥ 0.52)Add a third pole (which has the desired corner fre-quency) by cascading a second inductor between the second order filter and the noise load:L = R/ (2 π f c )Where f c is the desired corner frequency.Design ProcedureThe following example determines the required compo-nent values for a third order filter (for the same require-ments as the previous second order design example).1)List the desired crossover frequency, load resistance:Choose f c = 15000 Hz Choose R L = 50 Ω2)Design a second order filter with ζ = 0.5 (see second order example above):3)Design the third pole:R L /(2πf c ) = L 250/(2π15000) = 0.531 mH4)Choose available components and check the resulting cutoff frequency and attenuation:L2 = 0.508 mH (Coilcraft #E3506-A)f n= R/(2πL 1 )= 15665 HzAttenuation at 60 KHZ: 24 dB (second order filter) +2.9 octave × 6 = 41.4 dB5)The resulting filter configuration is that of figure (6)with:L 1 = 2.1 mH L 2 = 0.508 mH R L = 50 ΩConclusionsSpecific filter alignments may be calculated by manipu-lating the transfer function coefficients (component val-ues) of a filter to achieve a specific damping factor.A step-by-step design procedure may utilize standard filter alignments, eliminating the need to calculate the damping factor directly for critical filtering. Line filters,with their unique requirements, yet non-critical character-istics, are easily designed using a minimum allowable damping factor.Standard filter alignments assume ideal filter compo-nents; this does not necessarily hold true, especially at higher frequencies. For a discussion of the non-ideal character of common mode filter inductors refer to the application note “Common Mode Filter Inductor Analysis,”available from Coilcraft.Figure 7.The first three order low pass filters and their Butterworth alignmentse i +–e O +–R LL 2Ce i +–e O +–R LL 1Ce i +–e O +–R LL 1L 2Filter SchematicFilter Transfer FunctionButterworthAlignmentFirst OrderSecond OrderThird Ordere e Ls R o iL =+11e e LCs Ls R oi L=++112e e L L R s L Cs L L s R o iLL =++++111231212()e e s o in=+11ωe e LCs Ls R oiL =++112e e s s so i n n n =+++122133221ωωω。

符合EMIEMC标准的SerDes—基本测试策略和指南