Science-1998-Caruso-Nanoengineering of Inorganic and Hybrid Hollow Spheres by Colloidal Templating

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1998

discoveries concerning nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the cardiovascular system

前言

當 氮 氣 (nitrogen) 燃 燒 時 , 便 會 產 生 氧 化 氮 (nitric acid) 1998 年 諾 貝 爾 醫 學 獎 , 是 由 美 國 三位病理學家奪得,他們成功發 現氧化氮是一種可以傳遞信息的 氣體 NO創新世紀

神經傳遞

越來越多證據顯示, 一氧化氮扮演抑制性non-adrencrgic non-cholinergic(NANC)神經之傳導物質。動物實驗發現, 當鈣離子進入這些神經,釋放一氧化氮造成氣管擴張,給 與一氧化氮合成脢拮抗劑,可 完全抑制NANC神經於氣管 平滑肌之作用。人類之中心與週圍呼吸道,一氧化氮也扮 演同樣角色。抑制性NANC神經為人類唯一的神經性之氣 管擴張路徑,呼吸道病變其神經反應明顯降低,可能源於 呼吸道發炎釋放過氧化基,加速一氧化氮失去活性,或者 是因神經細胞內之一氧化氮合成脢或guanylyl cyclasc功能 喪失。一氧化氮合成脢拮抗劑最常應用的是 L-NG momomethyl arginine (L-NMMA) 與 L-Ngargininc methylester ( L-NAME ) 〃 作 用 機轉為和arginine競爭一 氧化氮合成脢,導致一氧化氮合成減少,這些作用可經由 加入大量arginine而改善 。

Ignarro在 1997 年 2 月擔任新創立的一氧 化氮期刊的總編輯

Robert F. Furchgott

1998年诺贝尔医学或生理学奖

NO简介

一氧化氮

化学式NO,分子量30, 氮的化合价为+2。无色气体, 难溶于水。NO分子中有一 未配对电子,可形成自由基, 和其它分子如氧分子、超氧 自由基,或过渡金属反应。 在体内极不稳定,是一短寿 分子,半衰期仅为3~5 s。 NO具有脂溶性,可以快速透 过生物膜扩散,在体内迅速 被血红蛋白、氧自由基或氢 醌等灭活。

由NO的发现研发的药品及保健品

伊格纳罗博士研发的心血 管新产Niteworks(夜宁新) 已在美国康宝莱成功上市。它 能保持维护心脏的冠状动脉的 畅通。防止过多的凝血块阻塞 造成心脏病和中风。松弛动脉 (维持正常血压需)。促进脑 部血液流通以增进长期记忆力。

夜宁新(Niteworks)是 一项心血管革命性的营养食品 独特的配方包括:L-精氨酸专 利配方,能促进一氧化氮的产 生。 维持维他命C和维持维他 命E能帮助提升一氧化氮的含 量。 叶酸 & 蜜里萨香草能够 发挥舒缓放松的效果。

弗奇戈特(Robert F.Furchgott)的发现

纽约州立大学的弗奇戈特教授在研究乙酰胆碱等物质对 血管的影响时发现,在相近的实验条件下,同一种物质有时使血 管扩张,有时对血管没有明显的作用,有时甚至使血管收缩。弗 奇戈特及合作者对这一现象作了深入的研究,他们在1980 年 发现乙酰胆碱对血管的作用与血管内皮细胞是否完整有关:乙 酰胆碱仅能引起内皮细胞完整的血管扩张。由此弗奇戈特推 测内皮细胞在乙酰胆碱的作用下产生了一种新的信使分子,这 种信使分子作用于平滑肌细胞,使血管平滑肌细胞舒张,从而扩 张血管。弗奇戈特将这种未知的信使分子命名为内皮细胞松 弛因子(EDRF)。这篇论文在学术界引起了广泛关注,吸引了包 括加州大学洛杉矶分校的伊格纳罗(Louis J.knarro)教授在内 的许多科学工作者从事有关EDRF的研究。

中美科学家发现有助于治疗脱发的“狼人”基因

疾病 , 即威廉姆 斯综 合 征。 当基 因发生 突变 , 且复 制的基 因

多于正 常 情 况 时 , 可 能 会 出现 孤 独 症 。但 当 一 个 名 为 就 7 l .3的基 因组 区域 的某 些部 分出现缺 失 , 可能患威廉 q 2 1 就

专家认 为 , 国科学 家 的研 究成 果 了不起 , 美 他们成 功 地

据 21 年 6 7日 参 考消息》 01 月 《 援引英 国《 日邮报》 每 网

站 2 1 年 6月 6 日报 道 , 国加 利福尼亚 南部 大学和 中的两个患有狼人综合 征的病人 家族进 行 了研究 并 发现 了“ 狼人 ” 因, 一基 因 基 这

或是那些在城市 长大的人来说 , 他们大 脑的某些 区域 对压力

的反应更大 , 这或许有助 于解释 为什 么城市生活会增 加患精 神分裂和其他心理疾病 的风险。此前 有研究发 现 , 大城市 在 中长 大会增加患精神 分裂 的概 率。此外 有证据表 明 , 城市居

民情绪紊乱 和焦虑 的概率 更大。

的两项研究共对 1 0多个 家庭 的基 因组作 了分析 , 0 0 几乎 每 个家庭 都有一名孩子患有孤独症 , 但其兄弟姐妹 和父母均 不

存 在这 种问题。

中美科 学家 发现有助于治疗脱发的“ 狼人” 因 基

表于新一期《 自然 》 刊上 的研 究报 告显 示 , 于 城市 居 民 周 对

孤独症 的表 现存 在广泛的差异 , 从轻微社交 障限到完全

无法正常交流 , 以及重复 性动作 、 对某 些光 和声音 敏感 和行

极针 以相 同的方式刺 激神经 。结 果发 现大 鼠在 执行 任务 时

的表现 会变得更好 , 而且它们 犯错 较少 , 能在 更长 一段 时 并

1998年诺贝尔生理医学奖汇总

NO在心血管中信息傳導作用的發現

組員名單:B9602051 陳右霖 B9602056 陳建廷 B9602069 黃雲珮 B9602078 廖晉億 B9602095 鍾少煒

報告大綱

一. 得獎人實驗 二. NO在血管內皮作用機制 三. NO的應用 四. 總結

得獎者研究實驗

Ferid Murad

誘發式 (inducible)---iNOS 不需要鈣離子和調鈣蛋白, 細胞素可直接誘發 iNOS 產 生催化作用。

機制概述

1.

2.

3.

NOS= Nitric Oxide Synthase cGMP= cyclic GMP GC= Guanylyl Cyclase

NO活化GC (Guanylyl Cyclase) - 1

結果:

結論:心血管內皮產生一種信息分子使與其接觸的平滑 肌舒張。將此成分不明的分子命名為EDRF (Endothelium-derived Relaxing Factor,內皮衍 生舒張因子)

Louise J. Ignarro- EDRF真實身分的確認

研究背景: 1. 產生NO的藥物在血管平滑

肌的作用機制及效果 2. EDRF的作用機制研究

製造出NO的 一氧化氮合

地方

成酶的種類

功能

血管內皮

eNOS (原發式)

1使血管平滑肌細胞放鬆

照片來源:

發現: NO的訊息傳遞機制與EDRF相同,效果也一樣 認為兩者其實是相同的化學物質

證明假說的實驗─吸收光譜偏移

已知實驗: NO結合血紅素(hemoglobin)的吸收光譜分析

→光譜偏移

衍伸實驗:

將EDRF與進行相同吸收光譜實驗

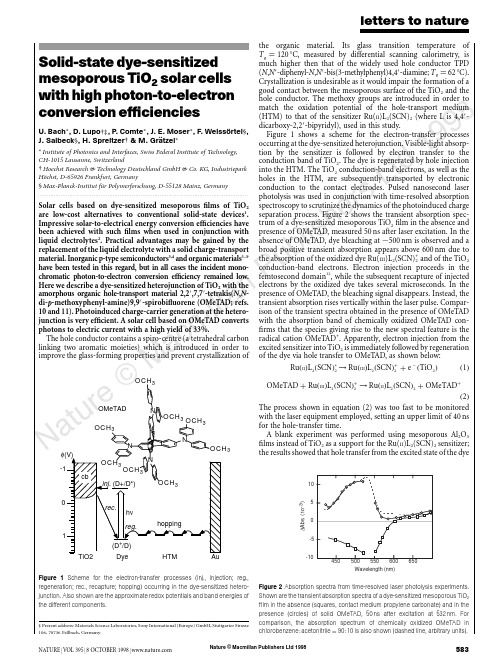

格兰特发表在Nature上1998DSSC

Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 19988Solid-state dye-sensitized mesoporous TiO 2solar cells with high photon-to-electron conversion efficienciesU.Bach *,D.Lupo †‡,P .Comte *,J.E.Moser *,F .Weissortel §,J.Salbeck §,H.Spreitzer †&M.Gratzel **Institute of Photonics and Interfaces,Swiss Federal Institute of Technology,CH-1015Lausanne,Switzerland†Hoechst Research &Technology Deutschland GmbH &Co.KG,Industriepark Ho¨chst,D-65926Frankfurt,Germany §Max-Planck-Institut fu¨r Polymerforschung,D-55128Mainz,Germany .........................................................................................................................Solar cells based on dye-sensitized mesoporous films of TiO 2are low-cost alternatives to conventional solid-state devices 1.Impressive solar-to-electrical energy conversion efficiencies have been achieved with such films when used in conjunction with liquid electrolytes 2.Practical advantages may be gained by the replacement of the liquid electrolyte with a solid charge-transport material.Inorganic p-type semiconductors 3,4and organic materials 5–9have been tested in this regard,but in all cases the incident mono-chromatic photon-to-electron conversion efficiency remained low.Here we describe a dye-sensitized heterojunction of TiO 2with the amorphous organic hole-transport material 2,2Ј,7,7Ј-tetrakis(N ,N -di-p -methoxyphenyl-amine)9,9Ј-spirobifluorene (OMeTAD;refs.10and 11).Photoinduced charge-carrier generation at the hetero-junction is very efficient.A solar cell based on OMeTAD converts photons to electric current with a high yield of 33%.The hole conductor contains a spiro-centre (a tetrahedral carbon linking two aromatic moieties)which is introduced in order to improve the glass-forming properties and prevent crystallization ofthe organic material.Its glass transition temperature of T g ¼120ЊC,measured by differential scanning calorimetry,is much higher then that of the widely used hole conductor TPD (N ,N Ј-diphenyl-N ,N Ј-bis(3-methylphenyl)4,4Ј-diamine;T g ¼62ЊC).Crystallization is undesirable as it would impair the formation of a good contact between the mesoporous surface of the TiO 2and the hole conductor.The methoxy groups are introduced in order to match the oxidation potential of the hole-transport medium (HTM)to that of the sensitizer Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2(where L is 4,4Ј-dicarboxy-2,2Ј-bipyridyl),used in this study.Figure 1shows a scheme for the electron-transfer processes occurring at the dye-sensitized heterojunction.Visible-light absorp-tion by the sensitizer is followed by electron transfer to the conduction band of TiO 2.The dye is regenerated by hole injection into the HTM.The TiO 2conduction-band electrons,as well as the holes in the HTM,are subsequently transported by electronic conduction to the contact electrodes.Pulsed nanosecond laser photolysis was used in conjunction with time-resolved absorption spectroscopy to scrutinize the dynamics of the photoinduced charge separation process.Figure 2shows the transient absorption spec-trum of a dye-sensitized mesoporous TiO 2film in the absence and presence of OMeTAD,measured 50ns after laser excitation.In the absence of OMeTAD,dye bleaching at ϳ500nm is observed and a broad positive transient absorption appears above 600nm due to the absorption of the oxidized dye Ru(III )L 2(SCN)+2and of the TiO 2conduction-band electrons.Electron injection proceeds in the femtosecond domain 12,while the subsequent recapture of injected electrons by the oxidized dye takes several microseconds.In the presence of OMeTAD,the bleaching signal disappears.Instead,the transient absorption rises vertically within the laser par-ison of the transient spectra obtained in the presence of OMeTAD with the absorption band of chemically oxidized OMeTAD con-firms that the species giving rise to the new spectral feature is the radical cation OMeTAD +.Apparently,electron injection from the excited sensitizer into TiO 2is immediately followed by regeneration of the dye via hole transfer to OMeTAD,as shown below:Ru ðII ÞL 2ðSCN Þء2→Ru ðIII ÞL 2ðSCN Þþ2þe ϪðTiO 2Þð1ÞOMeTAD þRu ðIII ÞL 2ðSCN Þþ2→Ru ðII ÞL 2ðSCN Þ2þOMeTADþð2ÞThe process shown in equation (2)was too fast to be monitored with the laser equipment employed,setting an upper limit of 40ns for the hole-transfer time.A blank experiment was performed using mesoporous Al 2O 3films instead of TiO 2as a support for the Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2sensitizer;the results showed that hole transfer from the excited state of the dyeletters to natureNATURE |VOL 395|8OCTOBER 1998|5833OCH 3φ(V)0OMeTAD Figure 1Scheme for the electron-transfer processes (inj.,injection;reg.,regeneration;rec.,recapture;hopping)occurring in the dye-sensitized hetero-junction.Also shown are the approximate redox potentials and band energies of the different components.‡Present address:Materials Science Laboratories,Sony International (Europe)GmbH,Stuttgarter Strasse 106,70736Fellbach,Germany.Wavelength (nm)1050-5-10∆A b s . (10-3)Figure 2Absorption spectra from time-resolved laser photolysis experiments.Shown are the transient absorption spectra of a dye-sensitized mesoporous TiO 2film in the absence (squares,contact medium propylene carbonate)and in the presence (circles)of solid OMeTAD,50ns after excitation at 532nm.Forcomparison,the absorption spectrum of chemically oxidized OMeTAD in chlorobenzene :acetonitrile ¼90:10is also shown (dashed line,arbitrary units).Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 19988to the OMeTAD does not contribute significantly to the photo-induced charge-separation phenomena observed.The photovoltaic performance of the dye-sensitized heterojunc-tion was studied by means of sandwich-type cells,shown schema-tically in Fig.3a.The working electrode consisted of conducting glass (F-doped SnO 2,sheet resistance 10Q per square)onto which a compact TiO 2layer was deposited by spray pyrolysis 13.This avoids direct contact between the HTM layer and the SnO 2which would short-circuit the cell.A 4.2-m-thick mesoporous film of TiO 2was deposited by screen printing onto the compact layer 14,and deriva-tized with Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2by adsorption from acetonitrile.The HTM was introduced into the mesopores by spin-coating a solution of OMeTAD in chlorobenzene onto the TiO 2film,and subsequent evaporation of the solvent.A semi-transparent gold back contact was evaporated on top of the hole conductor under vacuum.Figure 3b shows the photocurrent action spectrum of a typical cell under short-circuit conditions.The given values are not corrected for reflection and absorption losses of the conducting glass,which are estimated to be at least 15%in the visible region of the spectrum.The spectrum closely matches the absorption spectrum of the dye,confirming that the observed photocurrent arises from electron injection by the sensitizer.The maximum value of the incident photo-to-electron conversion efficiency (IPCE)is 33%,which is more than two orders of magnitude larger than the previously reported value for a similar dye-sensitized solid heterojunction 9and only a factor of ϳ2lower than with liquid electrolytes 2.The coating solution used for the device in Fig.3b contained 0.33mM N(PhBr)3SbCl 6and 15mM Li[(CF 3SO 2)2N]in addition to 0.17M OMeTAD.In the absence of these additives,the maximum IPCE was only 5%.N(PhBr)3SbCl 6acts as a dopant,introducing free charge carriers in the HTM by oxidation,as confirmed by spectro-electrochemical measurements.Partial oxidation of OMeTAD by N(PhBr)3SbCl 6is a convenient way to control the dopant level 15.On adding N(PhBr)3SbCl 6to a solution of OMeTAD in chlorobenzene,the radical cation OMeTAD +is instantly formed.The spectral features of OMeTAD +remained unchanged during solvent eva-poration and glass formation,except for a small hypochromic shift.No subsequent absorption changes were detectable over several weeks,confirming the temporal stability of OMeTAD +in the HTM.The second additive,Li[(CF 3SO 2)2N],is a source of Li +ions,which are known to be potential-determining for TiO 2(ref.16).Along with the protons from the carboxylic acid groups of Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2,they confer a positive charge on the surface of the oxide.As the sensitizer is negatively charged a local electrostatic field is produced,assisting electron injection into the TiO 2while retard-ing recapture of the electron by the oxidized dye.The lithium salt may also compensate for space-charge effects.Under light illumina-tion of the heterojunction,a net positive space charge is expected to be formed in the HTM,inducing a local field that impairs current flow.The lithium salt could screen this field,thereby eliminating the space-charge control of the photocurrent.Improvement of the photovoltaic performance of dye-sensitized heterojunctions by immersion in LiClO 4solutions was also reported by Murakoshi et al.5.Figure 4shows current-density/voltage curves employing the device structure shown in Fig.3a.Curves I and II were obtained with hole conductor containing both the N(PhBr)3SbCl 6dopant and the Li[(CF 3SO 3)2N]salt,whereas these additives were absent for curve III.Curve I was measured in the dark,whereas II and III were obtained under light illumination.The device that contains the hole conductor without additives performs poorly,the conversion yield being only 0.04%at a white-light illumination of 9.4mW cm −2.Addition of the dopant and Li +salt increases the overall conversion efficiency to 0.74%.Under full sunlight (100mW cm −2,air mass 1.5),the short-circuit photocurrent density reached 3.18mA cm −2,a value which is unprecedented for solar cells based on organic solids.Further improvement of the photovoltaic performance is expected,as many parameters of the cell assembly have not yet been opti-mized.Preliminary stability tests performed over 80h using the visible output of a 400W Xe lamp showed that the photocurrent was stable within Ϯ20%,while the open-circuit voltage and the fill factor (see Methods)increased.The total charge passed through the cell during illumination was 300C cm −2;corresponding to turnover numbers of about 8,400and 60,000for the OMeTAD and the dye,respectively.This shows that the hole conductor can sustain photo-voltaic operation without significance degradation.From the present findings,the concept of dye-sensitized hetero-junctions emerges as a very interesting and viable option for futureletters to nature584NATURE |VOL 395|8OCTOBER 1998|Wavelength (nm)abI P C E (%)Figure 3Structure and spectral response of the photovoltaic devices.a ,Structure 1,conducting F-doped SnO 2-coated glass;2,compact TiO 2layer;3,dye-sensitized heterojunction;4,gold electrode.b ,Photocurrent action spectrum for a dye-sensitized heterojunction,the structure of which is shown above.The IPCE value corresponds to the number of electrons generated by monochromatic light in the external circuit,divided by the number of incident photons.The 4.2-m-thick mesoporous TiO 2film was sensitized with Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2,spin-coated with a solution of 0.17M OMeTAD,0.33mM N(PhBr)3SbCl 6and 15mM Li[(CF 3SO 2)2N in chlorobenzene with 5%acetonitrile added.0Voltage (V)C u r r e n t d e n s i t y (m A c m –2)Figure 4Current-density/voltage characteristics.Shown are characteristics of the same device as in Fig.3,obtained in the dark (I)and under white-light illumination at 9.4mW cm −2(II).The spectral distribution corresponded to global air mass 1.5corrected for spectral mismatch.The short-circuit current density was 0.32mA cm −2,the open-circuit voltage 342mV and the fill factor 62%corresponding to an overall conversion efficiency of 0.74%.For comparison,the photocurrent-density/voltage characteristic of a cell containing no N(PhBr)3SbCl 6or Li[(CF 3SO 2)2N is also shown (III).Nature © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 19988low-cost solid-state solar cells.Photodiodes based on interpenetrat-ing polymer networks of poly(phenylenevinylene)derivatives 17,18present a related approach.The main difference to our system is that at least one component of the polymer network needs to function simultaneously as an efficient light absorber and a good charge-transport material.The dye-sensitized heterojunction cell offers a greater flexibility,as the light absorber and charge-transport material can be selected independently to obtain optimum solar-energy harvesting and high photovoltaic output.Ⅺ.........................................................................................................................MethodsCompounds.OMeTAD was pure according to 1H-NMR and HPLC analysis.The synthesis will be reported elsewhere.Ru(II )L 2(SCN)2was prepared as previously described 2.Transient absorption spectroscopy.This was carried out with a Nd-YAG laser as excitation light source,producing a 6-ns pulse at 532nm of typically 1mJ cm −2,with a repetition frequency of 30Hz.The probe light was provided by a Xe lamp,which was spectrally narrowed by cut-off and interference filters before passing the device.A monochromator combined with a photomultiplier was used as detection system.A T ektronix 524TDS oscilloscope was used to record and store the data.For the laser experiments,dye-sensitized mesoporous semiconductor films were deposited on ordinary glass.Photocurrent-voltage characteristics.These were measured with a Keithley 2400Source Meter and a 400W Xe lamp.A Schott KG3filter was used in order to approach the spectral distribution of the lamp to air mass 1.5G.The light intensity was regulated to the desired energy output by using a silicon solar cell,calibrated at the ISE-Fraunhofer Institut in Freiburg Germany.Efficiencies were corrected for the spectral mismatch.The fill factor (FF)is defined as FF ¼V opt I opt =I sc V oc ,where V opt and I opt are respectively current and voltage for maximum power output,and I sc and U oc are the short-circuit current and open-circuit voltage,respectively.Received 8May;accepted 13July 1998.1.O’Regan,B.&Gra¨tzel,M.A low-cost,high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO 2films.Nature 353,737–739(1991).2.Nazeeruddin,M.K.et al .Conversion of light to electricity by cis-X 2bis(2,2Ј-bipyridyl-4,4Ј-dicarbox-ylate)ruthenium(II)charge-transfer sensitizers (X ¼Cl −,Br −,I −,CN −and SCN −)on nanocrystalline TiO 2electrodes.J.Am.Chem.Soc.115,6382–6390(1993).3.O’Regan,B.&Schwarz,rge enhancement in photocurrent efficiency caused by UVillumination of the dye-sensitized heterojunction TiO 2/RuLL ЈNCS/CuSCN:initiation and potential mechanism.Chem.Mater.10,1501–1509(1998).4.T ennakone,K.,Kumara,G.R.R.A.,Kumarasinghe,A.R.,Wijayantha,K.G.U.&Sirimanne,P .M.Dye-sensitized nano-porous solid-state photovoltaic cell.Semicond.Sci.Technol.10,1689–1693(1995).5.Murakoshi,K.,Kogure,R.&Yanagida,S.Solid state dye-sensitized TiO 2solar cell with polypyrrole ashole transport layer.Chem.Lett.5,471–472(1997).6.Bach,U.et al .Ultrafast hole injection from dye molecules into an organic hole conductor for dyesensitized solid state solar cells.Abstract Book,Bayreuth Polymer &Materials Research Symposium ,P28(Bayreuth,1997).7.Weisso¨rtel, F.Amorphous niedermolekulare Ladungstransportmaterialien fu ¨r nanokristalline Solarzellen.Thesis,Univ.Regensburg (1996).8.Gra¨tzel,M.in Future Generation Photovoltaic Technologies Vol.404(ed.McConnell,R.)119–126(Am.Inst.Phys.,Denver,1997).9.Hagen,J.et al .Novel hybrid solar cells consisting of inorganic nanoparticles and an organic holetransport material.Synth.Met.89,215–220(1997).10.Salbeck,J.,Weisso¨rtel,F.&Bauer,J.Spiro linked compounds for use as active materials in organic light emitting diodes.Macromol.Symp.125,121–132(1997).11.Salbeck,J.,Yu,N.,Bauer,J.,Weisso¨rtel,F.&Bestgen,H.Low molecular organic glasses for blue electroluminescence.Synth.Met.91,209–215(1997).12.Tachibana,Y.,Moser,J.E.,Gra¨tzel,M.,Klug,D.R.&Durrant,J.R.Subpicosecond interfacial charge separation in dye-sensitized nanocrystalline titanium dioxide films.J.Phys.Chem.100,20056–20062(1996).13.Kavan,L.&Gra¨tzel,M.Highly efficient semiconducting TiO 2photoelectrodes prepared by aerosol pyrolysis.Electrochim.Acta 40,643–652(1995).14.Barbe´,C.J.et al .Nanocrystalline titanium oxide electrodes for photovoltaic applications.J.Am.Ceram.Soc.80,3157–3171(1997).15.Abkowitz,M.&Pai,parison of the drift mobility measured under transient and steady-state conditions in a prototypical hopping system.Phil.Mag.B 53,192–216(1986).16.Enright,B.,Redmond,G.&Fitzmaurice,D.Spectroscopic determination of flat-band potentials forpolycrystalline TiO 2electrodes in mixed-solvent systems.J.Phys.Chem.97,1426–1430(1994).17.Halls,J.J.M.et al .Efficient photodiodes from interpenetrating polymer networks.Nature 376,498–500(1995).18.Yu,G.,Gao,J.,Hummelen,J.C.,Wudl,F.&Heeger,A.J.Polymer photovoltaic cells:enhancedefficiencies via a network of internal donor acceptor heterojunctions.Science 270,1789–1791(1995).Acknowledgement.This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the European Joule III programme (OFES).Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.G.(e-mail:michael.graetzel@epfl.ch).letters to natureNATURE |VOL 395|8OCTOBER 1998|585Accumulation of persistent organochlorine compounds in mountains of western CanadaJules M.Blais *†,David W.Schindler *,Derek C.G.Muir †‡,Lynda E.Kimpe §,David B.Donald k &Bruno Rosenberg ¶*Department of Biological Sciences,University of Alberta,Edmonton,Alberta,Canada T6G 2E9‡Department of Fisheries and Oceans,Freshwater Institute,501University Crescent,Winnipeg,Manitoba,Canada R3T 2N6§Public Health Sciences,University of Alberta,Edmonton,Alberta,Canada T6G 2G3k Environment Canada,Room 300Park Plaza,2365Albert Street,Regina,Saskatchewan,Canada S4P 4K1¶Freshwater Institute,Winnipeg,Manitoba,Canada R3T 2N6.........................................................................................................................Persistent,semi-volatile organochlorine compounds,including toxic industrial pollutants and agricultural pesticides,are found everywhere on Earth,including in pristine polar and near-polar locations 1–4.Higher than expected occurrences of these com-pounds in remote regions are the result of long-range transport in the atmosphere,precipitation and ‘cold condensation’—the progressive volatilization in relatively warm locations and sub-sequent condensation in cooler environments 3,4which leads to enhanced concentrations at high latitudes.The upper reaches of high mountains are similar to high-latitude regions in that they too are characterized by relatively low average temperatures,but the accumulation of organochlorine compounds as a function of altitude has not yet been documented.Here we report organo-chlorine deposition in snow from mountain ranges in western Canada that show a 10-to 100-fold increase between 770and 3,100m altitude.In the case of less-volatile compounds,the observed increase by a factor of 10is simply due to a 10-fold increase in snowfall over the altitude range of the sampling sites.In the case of the more-volatile organochlorines,cold-condensa-tion effects further enhance the concentration of these com-pounds with increasing altitude.These findings demonstrate that temperate-zone mountain regions,which tend to receiveT able 1Correlation between organochlorine concentrations in snow and site elevationsCompound Correlation coefficientVapour pressure(Pa).............................................................................................................................................................................␣-HCH0.85*0.1Heptachlorepoxide 0.75*0.1␥-HCH 0.73*0.03Dieldrin0.42*0.016Endosulphan-I 0.76*0.008c-Chlordane 0.42*0.003t-Chlordane 0.340.003p p ЈDDT 0.000.0001.............................................................................................................................................................................PCBs.............................................................................................................................................................................S Dichloro-0.54*0.2(0.008–0.60)S Trichloro-0.53*0.04(0.003–0.022)S Tetrachloro-0.000.006(0.003–0.10)S Pentachloro-0.000.001(0.0003–0.009)S Hexachloro-0.110.0002(7ϫ10Ϫ4Ϫ0:012)S Heptachloro-0.173ϫ10Ϫ4(2:7ϫ10Ϫ5Ϫ0:0015).............................................................................................................................................................................Correlation coefficients (r )are shown for organochlorine concentrations (ng l −1)in snow and site elevation (m.a.s.l.)for the equation conc :¼a e b Elev :,where a and b are fitted constants.Asterisks show significance at P р0:05,for 19degrees of freedom.Sub-cooled liquid vapour pressures are included for pesticides at 20ЊC (ref.21)and PCBs at 25ЊC (ref.22).Published vapour pressures vary considerably,so these values represent mean reported values for all PCBs in that class.Ranges of published vapour pressures for each PCB category are shown in brackets.Only compounds with mean sample concentrations that were ten times higher than blanks were considered.†Present addresses:Department of Biology,University of Ottawa,30Marie Curie Street,PO Box 450Stn.A,Ottawa,Ontario,Canada K1N 6N5(J.M.B.);Environment Canada,867Lakeshore Road,Burlington,Ontario,Canada L7R 4A6(D.C.G.M).。

science[1].人造生命

![science[1].人造生命](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/7e0aaf325a8102d276a22f68.png)

We report the design, synthesis and assembly of the 1.08-Mbp Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome starting from digitized genome sequence information and its transplantation into a Mycoplasma capricolum recipient cell to create new Mycoplasma mycoides cells that are controlled only by the synthetic chromosome. The only DNA in the cells is the designed synthetic DNA sequence, including “watermark” sequences and other designed gene deletions and polymorphisms, and mutations acquired during the building process. The new cells have expected phenotypic properties and are capable of continuous self-replication. In 1977, Sanger and colleagues determined the complete genetic code of phage φX174 (1), the first DNA genome to be completely sequenced. Eighteen years later, in 1995, our team was able to read the first complete genetic code of a self-replicating bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae (2). Reading the genetic code of a wide range of species has increased exponentially from these early studies. Our ability to rapidly digitize genomic information has increased by more than eight orders of magnitude over the past 25 years (3). Efforts to understand all this new genomic information have spawned numerous new computational and experimental paradigms, yet our genomic knowledge remains very limited. No single cellular system has all of its genes understood in terms of their biological roles. Even in simple bacterial cells, do the chromosomes contain the entire genetic repertoire? If so, can a complete genetic system be reproduced by chemical synthesis starting with only the digitized DNA sequence contained in a computer? Our interest in synthesis of large DNA molecules and chromosomes grew out of our efforts over the past 15 years to build a minimal cell that contains only essential genes. This work was inaugurated in 1995 when we sequenced the genome from Mycoplasma genitalium , a bacterium with thesmallest complement of genes of any known organismcapable of independent growth in the laboratory. More than100 of the 485 protein-coding genes of M. genitalium aredispensable when disrupted one-at-a-time (4–6).We developed a strategy for assembling viral sized piecesto produce large DNA molecules that enabled us to assemblea synthetic M. genitalium genome in four stages fromchemically synthesized DNA cassettes averaging about 6 kbin size. This was accomplished through a combination of invitro enzymatic methods and in vivo recombination inSaccharomyces cerevisiae . The whole synthetic genome(582,970 bp) was stably grown as a yeast centromericplasmid (YCp) (7).Several hurdles were overcome in transplanting andexpressing a chemically synthesized chromosome in arecipient cell. We needed to improve methods for extractingintact chromosomes from yeast. We also needed to learn howto transplant these genomes into a recipient bacterial cell toestablish a cell controlled only by a synthetic genome. Due tothe fact that M. genitalium has an extremely slow growth rate,we turned to two faster growing mycoplasma species, M.mycoides subspecies capri (GM12) as donor, and M.capricolum subspecies capricolum (CK) as recipient.To establish conditions and procedures for transplantingthe synthetic genome out of yeast, we developed methods forcloning entire bacterial chromosomes as centromericplasmids in yeast, including a native M. mycoides genome (8,9). However, initial attempts to extract the M. mycoidesgenome from yeast and transplant it into M. capricolumfailed. We discovered that the donor and recipientmycoplasmas share a common restriction system. The donorgenome was methylated in the native M. mycoides cells andwas therefore protected against restriction during thetransplantation from a native donor cell (10). However, thebacterial genomes grown in yeast are unmethylated and so arenot protected from the single restriction system of therecipient cell. We were able to overcome this restriction Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a Chemically Synthesized GenomeDaniel G. Gibson ,1 John I. Glass ,1 Carole Lartigue ,1 Vladimir N. Noskov ,1 Ray-Yuan Chuang ,1 Mikkel A. Algire ,1 Gwynedd A. Benders ,2 Michael G. Montague ,1 Li Ma ,1 Monzia M. Moodie ,1 Chuck Merryman ,1 Sanjay Vashee ,1 Radha Krishnakumar ,1 Nacyra Assad-Garcia ,1 Cynthia Andrews-Pfannkoch ,1 Evgeniya A. Denisova ,1 Lei Young ,1 Zhi-Qing Qi ,1 Thomas H. Segall-Shapiro ,1 Christopher H. Calvey ,1 Prashanth P. Parmar ,1 Clyde A. Hutchison III ,2 Hamilton O. Smith ,2 J. Craig Venter 1,2*1The J. Craig Venter Institute, 9704 Medical Center Drive, Rockville, MD 20850, USA. 2The J. Craig Venter Institute, 10355 Science Center Drive, San Diego, CA 92121, USA.*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: jcventer@barrier by methylating the donor DNA with purified methylases or crude M. mycoides or M. capricolum extracts, or by simply disrupting the recipient cell’s restriction system (8).We now have combined all of our previously established procedures and report the synthesis, assembly, cloning, and successful transplantation of the 1.08-Mbp M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome, to create a new cell controlled by this synthetic genome.ResultsSynthetic genome designDesign of the M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome was based on the highly accurate finished genome sequences of two laboratory strains of M. mycoides subspecies capri GM12 (8, 9) (11). One was the genome donor used by Lartigue et al. [GenBank accession CP001621] (10). The other was a strain created by transplantation of a genome that had been cloned and engineered in yeast, YCpMmyc1.1-ΔtypeIIIres, [GenBank accession CP001668] (8). This project was critically dependent on the accuracy of these sequences. Although we believe that both finished M. mycoides genome sequences are reliable, there are 95 sites at which they differ. We began to design the synthetic genome before both sequences were finished. Consequently, most of the cassettes were designed and synthesized based upon the CP001621 sequence (11). When it was finished, we chose to use the sequence of the genome successfully transplanted from yeast (CP001668) as our design reference (except that we kept the intact typeIIIres gene). All differences that appeared biologically significant between CP001668 and previously synthesized cassettes were corrected to match it exactly (11). Sequence differences between our synthetic cassettes and CP001668 that occurred at 19 sites appeared harmless, and so were not corrected. These provide 19 polymorphic differences between our synthetic genome (JCVI-syn1.0) and the natural (non-synthetic) genome (YCpMmyc1.1) that we have cloned in yeast and use as a standard for genome transplantation from yeast (8). To further differentiate between the synthetic genome and the natural one, four watermark sequences (fig. S1) were designed to replace one or more cassettes in regions experimentally demonstrated (watermarks 1 [1246 bp] and 2 [1081 bp]) or predicted (watermarks 3 [1109 bp] and 4 [1222 bp]) to not interfere with cell viability. These watermark sequences encode unique identifiers while limiting their translation into peptides. Table S1 lists the differences between the synthetic genome and this natural standard. Figure S2 shows a map of the M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome. Cassette and assembly intermediate boundaries, watermarks, deletions, insertions, and genes of the M. mycoides JCVI syn1.0 are shown in fig. S2, and the sequence of the transplanted mycoplasma clone sMmYCp235-1 has been submitted to GenBank (accession # CP002027).pSynthetic genome assembly strategyThe designed cassettes were generally 1,080 bp with 80-bp overlaps to adjacent cassettes (11). They were all produced by assembly of chemically synthesized oligonucleotides by Blue Heron; Bothell, Washington. Each cassette was individually synthesized and sequence-verified by the manufacturer. To aid in the building process, DNA cassettes and assembly intermediates were designed to contain Not I restriction sites at their termini, and recombined in the presence of vector elements to allow for growth and selection in yeast (7) (11).pA hierarchical strategy was designed to assemble the genome in 3 stages by transformation and homologous recombination in yeast from 1,078 one-kb cassettes (Fig. 1) (12, 13).Assembly of 10-kb synthetic intermediates. In the first stage, cassettes and a vector were recombined in yeast and transferred to E. coli (11). Plasmid DNA was then isolated from individual E. coli clones and digested to screen for cells containing a vector with an assembled 10-kb insert. One successful 10-kb assembly is represented (Fig. 2a). In general, at least one 10-kb assembled fragment could be obtained by screening 10 yeast clones. However, the rate of success varied from 10-100%. All of the first-stage intermediates were sequenced. Nineteen out of 111 assemblies contained errors. Alternate clones were selected, sequence-verified, and moved on to the next assembly stage (11).Assembly of 100-kb synthetic intermediates. The pooled 10-kb assemblies and their respective cloning vectors were transformed into yeast as above to produce 100-kb assembly intermediates (11). Our results indicated that these products cannot be stably maintained in E. coli so recombined DNA had to be extracted from yeast. Multiplex PCR was performed on selected yeast clones (fig. S3 and table S2). Because every 10-kb assembly intermediate was represented by a primer pair in this analysis, the presence of all amplicons would suggest an assembled 100-kb intermediate. In general, 25% or more of the clones screened contained all of the amplicons expected for a complete assembly. One of these clones was selected for further screening. Circular plasmid DNA was extracted and sized on an agarose gel alongside a supercoiled marker. Successful second-stage assemblies with the vector sequence are approximately 105 kb in length (Fig. 2b). When all amplicons were produced following multiplex PCR, a second-stage assembly intermediate of the correct size was usually produced. In some cases, however, small deletions occurred. In other instances, multiple 10-kb fragments were assembled, which produced a larger second-stage assembly intermediate. Fortunately, these differences could easily bedetected on an agarose gel prior to complete genome assembly.Complete genome assembly. In preparation for the final stage of assembly, it was necessary to isolate microgram quantities of each of the 11 second-stage assemblies (11). As reported (14), circular plasmids the size of our second-stage assemblies could be isolated from yeast spheroplasts after an alkaline-lysis procedure. To further purify the 11 assembly intermediates, they were exonuclease-treated and passed through an anion-exchange column. A small fraction of the total plasmid DNA (1/100th) was digested with Not I and analyzed by field-inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE) (Fig. 2c). This method produced ~1 μg of each assembly per 400 ml yeast culture (~1011 cells).The method above does not completely remove all of the linear yeast chromosomal DNA, which we found could significantly decrease the yeast transformation and assembly efficiency. To further enrich for the eleven circular assembly intermediates, ~200 ng samples of each assembly were pooled and mixed with molten agarose. As the agarose solidifies, the fibers thread through and topologically “trap” circular DNA (15). Untrapped linear DNA can then be electrophoresed out of the agarose plug, thus enriching for the trapped circular molecules. The eleven circular assembly intermediates were digested with Not I so that the inserts could be released. Subsequently, the fragments were extracted from the agarose plug, analyzed by FIGE (Fig. 2d), and transformed into yeast spheroplasts (11). In this third and final stage of assembly, an additional vector sequence was not required since the yeast cloning elements were already present in assembly 811-900.To screen for a complete genome, multiplex PCR was carried out with 11 primer pairs, designed to span each of the eleven 100-kb assembly junctions (table S3). Of 48 colonies screened, DNA extracted from one clone (sMmYCp235) produced all 11 amplicons. PCR of the wild type (WT) positive control (YCpMmyc1.1) produced an indistinguishable set of 11 amplicons (Fig. 3a). To further demonstrate the complete assembly of a synthetic M. mycoides genome, intact DNA was isolated from yeast in agarose plugs and subjected to two restriction analyses; Asc I and BssH II (11). Because these restriction sites are present in three of the four watermark sequences, this choice of digestion produces restriction patterns that are distinct from the natural M. mycoides genome (Figs. 1 and 3b). The sMmYCp235 clone produced the restriction pattern expected for a completely assembled synthetic genome (Fig. 3c). pSynthetic genome transplantationAdditional agarose plugs used in the gel analysis above (Fig. 3c) were also used in genome transplantation experiments (11). Intact synthetic M. mycoides genomes from the sMmYCp235 yeast clone were transplanted into restriction-minus M. capricolum recipient cells, as described (8). Results were scored by selecting for growth of blue colonies on SP4 medium containing tetracycline and X-gal at 37 °C. Genomes isolated from this yeast clone produced 5-15 tetracycline-resistant blue colonies per agarose plug. This was comparable to the YCpMmyc1.1 control. Recovery of colonies in all transplantation experiments was dependent on the presence of both M. capricolum recipient cells and an M. mycoides genome.Semi-synthetic genome assembly and transplantationTo aid in testing the functionality of each 100-kb synthetic segment,semi-synthetic genomes were constructed and transplanted. By mixing natural pieces with synthetic ones, the successful construction of each synthetic 100-kb assembly could be verified without having to sequence these intermediates. We cloned 11 overlapping natural 100-kb assemblies in yeast by using a previously described method (16). In 11 parallel reactions, yeast cells were co-transformed with fragmented M. mycoides genomic DNA (YCpMmyc 1.1) that averaged ~100 kb in length and a PCR-amplified vector designed to overlap the ends of the 100-kb inserts. To maintain the appropriate overlaps so that natural and synthetic fragments could be recombined, the PCR-amplified vectors were produced via primers with the same 40-bp overlaps used to clone the 100-kb synthetic assemblies. The semi-synthetic genomes that were constructed contained between two and ten of the eleven 100-kb synthetic subassemblies (Table 1). The production of viable colonies produced after transplantation, ionfirmed that the synthetic fraction of each genome contained no lethal mutations. Only one of the 100-kb subassemblies, 811-900, was not viable.Initially, an error-containing 811-820 clone was used to produce a synthetic genome that did not transplant. This was expected since the error was a single base pair deletion that creates a frameshift in dnaA, an essential gene for chromosomal replication. We were previously unaware of this mutation. By using a semi-synthetic genome construction strategy, we were able to pinpoint 811-900 as the source for failed synthetic transplantation experiments. Thus, we began to reassemble an error-free 811-900 assembly, which was used to produce the sMmYCp235 yeast strain. The dnaA-mutated genome only differs by one nucleotide from the synthetic genome in sMmYCp235. This genome served as a negative control in our transplantation experiments. The dnaA mutation was also repaired at the 811-900 level by genome engineering in yeast (17) . A repaired 811-900 assembly was used in a final stage assembly to produce a yeast clone with a repaired genome. This yeast clone is named sMmYCP142 and could be transplanted. A complete list of genomes thathave been assembled from 11 pieces and successfully transplanted is provided in Table 1.Characterization of the synthetic transplantsTo rapidly distinguish the synthetic transplants from M. capricolum or natural M. mycoides, two analyses were performed. First, four primer pairs that are specific to each of the four watermarks were designed such that they produce four amplicons in a single multiplex PCR reaction (table S4). All four amplicons were produced by transplants generated from sMmYCp235, but not YCpMmyc1.1 (Fig. 4a). Second, the gel analysis with Asc I and BssH II, described above (Fig. 3d), was performed. The restriction pattern obtained was consistent with a transplant produced from a synthetic M. mycoides genome (Fig. 4b).A single transplant originating from the sMmYCp235 synthetic genome was sequenced. We refer to this strain as M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0. The sequence matched the intended design with the exception of the known polymorphisms, 8 new single nucleotide polymorphisms, an E. coli transposon insertion, and an 85-bp duplication (table S1). The transposon insertion exactly matches the size and sequence of IS1, a transposon in E. coli. It is likely that IS1 infected the 10-kb sub-assembly following its transfer to E. coli. The IS1 insert is flanked by direct repeats of M. mycoides sequence suggesting that it was inserted by a transposition mechanism. The 85-bp duplication is a result of a non-homologous end joining event, which was not detected in our sequence analysis at the 10-kb stage. These two insertions disrupt two genes that are evidently non-essential. We did not find any sequences in the synthetic genome that could be identified as belonging to M. capricolum. This indicates that there was a complete replacement of the M. capricolum genome by our synthetic genome during the transplant process.The cells with only the synthetic genome are self replicating and capable of logarithmic growth. Scanning and transmission electron micrographs (EM) of M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 cells show small, ovoid cells surrounded by cytoplasmic membranes (Fig. 5c-5f). Proteomic analysis of M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 and the WT control (YCpMmyc1.1) by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis revealed almost identical patterns of protein spots (fig. S4) and these were clearly different from those previously reported for M. capricolum (10). Fourteen genes are deleted or disrupted in the M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome, however the rate of appearance of colonies on agar plates and the colony morphology are similar (compare Fig. 5a and b). We did observe slight differences in the growth rates in a color changing unit assay, with the JCVI-syn1.0 transplants growing slightly faster than the MmcyYCp1.1 control strain (fig. S6). DiscussionIn 1995, the quality standard for sequencing was considered to be one error in 10,000 bp and the sequencing of a microbial genome required months. Today, the accuracy is substantially higher. Genome coverage of 30-50X is not unusual, and sequencing only requires a few days. However, obtaining an error-free genome that could be transplanted into a recipient cell to create a new cell controlled only by the synthetic genome was complicated and required many quality control steps. Our success was thwarted for many weeks by a single base pair deletion in the essential gene dnaA. One wrong base out of over one million in an essential gene rendered the genome inactive, while major genome insertions and deletions in non-essential parts of the genome had no observable impact on viability. The demonstration that our synthetic genome gives rise to transplants with the characteristics of M. mycoides cells implies that the DNA sequence upon which it is based is accurate enough to specify a living cell with the appropriate properties.Our synthetic genomic approach stands in sharp contrast to a variety of other approaches to genome engineering that modify natural genomes by introducing multiple insertions, substitutions, or deletions (18–22). This work provides a proof of principle for producing cells based upon genome sequences designed in the computer. DNA sequencing of a cellular genome allows storage of the genetic instructions for life as a digital file. The synthetic genome described in this paper has only limited modifications from the naturally occurring M. mycoides genome. However, the approach we have developed should be applicable to the synthesis and transplantation of more novel genomes as genome design progresses (23).We refer to such a cell controlled by a genome assembled from chemically synthesized pieces of DNA as a “synthetic cell”, even though the cytoplasm of the recipient cell is not synthetic. Phenotypic effects of the recipient cytoplasm are diluted with protein turnover and as cells carrying only the transplanted genome replicate. Following transplantation and replication on a plate to form a colony (>30 divisions or >109 fold dilution), progeny will not contain any protein molecules that were present in the original recipient cell (10, 24). This was previously demonstrated when we first described genome transplantation (10). The properties of the cells controlled by the assembled genome are expected to be the same as if the whole cell had been produced synthetically (the DNA software builds its own hardware).The ability tp produce synthetic cells renders it it essential for researchers making synthetic DNA constructs and cells to clearly watermark their work to distinguish it from naturally occurring DNA and cells. We have watermarked the synthetic chromosome in this and our previous study (7).If the methods described here can be generalized, design, synthesis, assembly, and transplantation of synthetic chromosomes will no longer be a barrier to the progress of synthetic biology. We expect that the cost of DNA synthesis will follow what has happened with DNA sequencing and continue to exponentially decrease. Lower synthesis costs combined with automation will enable broad applications for synthetic genomics.We have been driving the ethical discussion concerning synthetic life from the earliest stages of this work (25, 26). As synthetic genomic applications expand, we anticipate that this work will continue to raise philosophical issues that have broad societal and ethical implications. We encourage the continued discourse.References and Notes1. F. Sanger et al., Nature265, 687 (Feb 24, 1977).2. R. D. Fleischmann et al., Science269, 496 (Jul 28, 1995).3. J. C. Venter, Nature464, 676 (Apr 1).4. C. A. Hutchison et al., Science286, 2165 (Dec 10, 1999).5. J. I. Glass et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A103, 425 (Jan10, 2006).6. H. O. Smith, J. I. Glass, C. A. Hutchison III, J. C. Venter,in Accessing Uncultivated Microorganisms: From theEnvironment to Organisms and Genomes and Back K.Zengler, Ed. (ASM Press, Washington, 2008), pp. 320.7. D. G. Gibson et al., Science319, 1215 (Feb 29, 2008).8. C. Lartigue et al., Science325, 1693 (Sep 25, 2009).9. G. A. Benders et al., Nucleic Acids Res, (Mar 7, 2010).10. C. Lartigue et al., Science317, 632 (Aug 3, 2007).11. Supplementary information is available on ScienceOnline.12. D. G. Gibson, Nucleic Acids Res37, 6984 (Nov, 2009).13. D. G. Gibson et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A105, 20404(Dec 23, 2008).14. R. J. Devenish, C. S. Newlon, Gene18, 277 (Jun, 1982).15. W. W. Dean, B. M. Dancis, C. A. Thomas, Jr., AnalBiochem56, 417 (Dec, 1973).16. S. H. Leem et al., Nucleic Acids Res31, e29 (Mar 15,2003).17. V. N. Noskov, T. H. Segall-Shapiro, R. Y. Chuang,Nucleic Acids Res38, 2570 (May 1).18. M. Itaya, K. Tsuge, M. Koizumi, K. Fujita, Proc NatlAcad Sci U S A102, 15971 (Nov 1, 2005).19. M. Itaya, FEBS Lett362, 257 (Apr 10, 1995).20. H. Mizoguchi, H. Mori, T. Fujio, Biotechnol ApplBiochem46, 157 (Mar, 2007).21. J. Y. Chun et al., Nucleic Acids Res35, e40 (2007).22. H. H. Wang et al., Nature460, 894 (Aug 13, 2009).23. A. S. Khalil, J. J. Collins, Nat Rev Genet11, 367 (May).24. A mycoplasma cell, with a cell mass of about 10-13 g,contains fewer than 106 molecules of protein. (If itcontains 20% protein this is 2 x 10-14 g protein per cell. Ata molecular weight of 120 Daltons per amino acid residueeach cell contains (2 x 10-14)/120 = 1.7 x 10-16 moles ofpeptide residues. This is 1.7 x 10-16 x 6 x 1023 = 1 x 108residues per cell. If the average size of a protein is 300residues then a cell contains about 3 x 105 proteinmolecules.) After 20 cell divisions the number of progeny exceeds the total number of protein molecules present in the recipient cell. So, following transplantation andreplication to form a colony on a plate, most cells willcontain no protein molecules that were present in theoriginal recipient cell.25. M. K. Cho, D. Magnus, A. L. Caplan, D. McGee, Science286, 2087 (Dec 10, 1999).26. M. S. Garfinkel, D. Endy, G. E. Epstein, R. M. Friedman.(2007).27. D. G. Gibson et al., Nat Methods6, 343 (May, 2009).28. We thank Synthetic Genomics, Inc. for generous fundingof this work. We thank J. B. Hostetler, D. Radune, N. B.Fedorova, M. D. Kim, B. J. Szczypinski, I. K. Singh, J. R.Miller, S. Kaushal, R. M. Friedman, and J. Mulligan for their contributions to this work. Electron micrographswere generously provided by T. Deerinck and M. Ellisman of the National Center for Microscopy and ImagingResearch at the University of California at San Diego.J.C.V. is Chief Executive Officer and Co-Chief Scientific Officer of SGI. H.O.S. is Co-Chief Scientific Officer and on the Board of Directors of SGI. C.A.H. is Chairman of the SGI Scientific Advisory Board. All three of theseauthors and JCVI hold SGI stock. JCVI has filed patentapplications on some of the techniques described in this paper.Supporting Online Material/cgi/content/full/science.1190719/DC1 Materials and MethodsFigs. S1 to S6Tables S1 to S7References9 April 2010; accepted 13 May 2010Published online 20 May 2010; 10.1126/science.1190719 Include this information when citing this paper.Fig. 1. The assembly of a synthetic M. mycoides genome in yeast.A synthetic M. mycoides genome was assembled from 1,078 overlapping DNA cassettes in three steps. In the first step, 1,080-bp cassettes (orange arrows), produced from overlapping synthetic oligonucleotides, were recombined in sets of 10 to produce one hundred nine ~10-kb assemblies (blue arrows). These were then recombined in sets of 10 to produce eleven ~100-kb assemblies (green arrows). In the final stage of assembly, these eleven fragments were recombined into the complete genome (red circle). With theexception of 2 constructs that were enzymatically pieced together in vitro (27) (white arrows), assemblies were carried out by in vivo homologous recombination in yeast. Major variations from the natural genome are shown as yellow circles. These include 4 watermarked regions (WM1-WM4), a 4-kb region that was intentionally deleted (94D), and elements for growth in yeast and genome transplantation. In addition, there are 20 locations with nucleotide polymorphisms (asterisks). Coordinates of the genome are relative to the first nucleotide of the natural M. mycoides sequence. The designed sequence is 1,077,947 bp. The locations of the Asc I and BssH II restriction sites are shown. Cassettes 1 and 800-810 were unnecessary and removed from the assembly strategy (11). Cassette 2 overlaps cassette 1104 and cassette 799 overlaps cassette 811.Fig. 2. Analysis of the assembly intermediates.(a)Not I and Sbf I double restriction digestion analysis of assembly 341-350 purified from E. coli. These restriction enzymes release the vector fragments (5.5 kb and 3.4 kb) from the 10-kb insert. Insert DNA was separated from the vector DNA on a 0.8% E-gel (Invitrogen). M indicates the 1-kb DNA ladder (New England Biolabs; NEB). (b) Analysis of assembly 501-600 purified from yeast. The 105-kb circles (100-kb insert plus 5-kb vector) were separated from the linear yeast chromosomal DNA on a 1% agarose gel by applying 4.5V/cm for 3 hours. S indicates the BAC-Tracker supercoiled DNA ladder (Epicentre). (c) Not I restriction digestion analysis of the eleven ~100-kb assemblies purified from yeast. These DNA fragments were analyzed by FIGE on a 1% agarose gel. The expected insert size for each assembly is indicated. λ indicates the lambda ladder (NEB). (d)Analysis of the 11 pooled assemblies shown in (c) following topological trapping of the circular DNA and Not I digestion. One fortieth of the DNA used to transform yeast is represented.Fig. 3. Characterization of the synthetic genome isolated from yeast.(a)Yeast clones containing a completely assembled synthetic genome were screened by multiplex PCR with a primer set that produces 11 amplicons; one at each of the 11 assembly junctions. Yeast clone sMmYCp235 (235) produced the 11 PCR products expected for a complete genome assembly. For comparison, the natural genome extracted from yeast (WT) was also analyzed. PCR products were separated on a 2% E-gel (Invitrogen). L indicates the 100-bp ladder (NEB). (b)The sizes of the expected Asc I and BssH II restriction fragments for natural (WT) and synthetic (Syn235) M. mycoides genomes. (c) Natural (WT) and synthetic (235) M. mycoides genomes were isolated from yeast in agarose plugs. In addition, DNA was purified from the host strain alone (H). Agarose plugs were digested with Asc I or BssH II and fragments were separated by clamped homogeneous electrical field (CHEF) gel electrophoresis. Restriction fragments corresponding to the correct sizes are indicated by the fragment numbers shown in (b).Fig. 4. Characterization of the transplants.(a)Transplants containing a synthetic genome were screened by multiplex PCR with a primer set that produces 4 amplicons; one internal to each of the four watermarks. One transplant (syn1.0) originating from yeast clone sMmYCp235 was analyzed alongside a natural, non-synthetic genome (WT) transplanted out of yeast. The transplant containing the synthetic genome produced the 4 PCR products whereas the WT genome did not produce any. PCR products were separated on a 2% E-gel (Invitrogen). (b)Natural (WT) and synthetic (syn1.0) M. mycoides genomes were isolated from M. mycoides transplants in agarose plugs. Agarose plugs were digested with Asc I or BssH II and fragments were separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis. Restriction fragments corresponding to the correct sizes are indicated by the fragment numbers shown in Fig. 3b.Fig. 5. Images of M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 and WT M. mycoides.To compare the phenotype of the JCVI-syn1.0 and non-YCp WT strains, we examined colony morphology by plating cells on SP4 agar plates containing X-gal. Three days after plating, the JCVI-syn1.0 colonies are blue because the cells contain the lacZ gene and express beta-galactosidase, which converts the X-gal to a blue compound (a). The WT cells do not contain lacZ and remain white (b). Both cell types have the fried egg colony morphology characteristic of most mycoplasmas. EMs were made of the JCVI-syn1.0 isolate using two methods. (c) For scanning EM, samples were post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated and critical point dried with CO2,and visualized using a Hitachi SU6600 SEM at 2.0 keV. (d) Negatively stained transmission EMs of dividing cells using 1% uranyl acetate on pure carbon substrate visualized using JEOL 1200EX CTEM at 80 keV. To examine cell morphology, we compared uranyl acetate stained EMs of M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 cells (e) with EMs of WT cells made in 2006 that were stained with ammonium molybdate (f). Both cell types show the same ovoid morphology and general appearance. EMs were provided by Tom Deerinck and Mark Ellisman of the National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research at the University of California at San Diego.。

2013诺贝尔医学奖

詹姆斯-E.罗斯曼的工作

詹姆斯-E.罗斯曼则发现了让这些囊泡得以与 其目标相融合的蛋白质机制,从而可以实现对所 运“货物”的传递。 詹姆斯〃E〃罗斯曼(James E. Rothman), 耶鲁大学细胞生物学系系主任、Fergus F. Wallace 名誉生物医学教授。他曾获得多种荣誉,包括哥 伦比亚大学的露依莎〃格罗斯〃霍维茨奖、拉斯 克奖基础医学奖(2002年)、费萨尔国王奖。他 在耶鲁大学取得硕士学位,在哈佛获博士学位。 2013年获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

工作的意义

• 在这项发现过程中,三位科学家

:罗斯曼, 谢克曼和苏德霍夫揭 示了细胞内输运体系的精细结构 和控制机制。这一系统的失稳将 导致有害结果,如神经系统疾病 ,糖尿病或免疫系统紊乱。

囊泡运输之一

囊泡运输之二

W.谢克曼的工作

• 兰迪-W.谢克曼发现

了一系列与细胞囊 泡输运机制有关的 基因。

托马斯-C.苏德霍夫工作

托马斯-C.苏德霍夫 则揭示了信号是如何 实现对囊泡的控制, 使其得以精确分配其 所载“货物”。

细胞内囊泡交通的运行与调节机制

• 生物体内每一个细胞都是一个生产和运输

分子的工厂。比如,胰岛素在这里被制造 出来并释放进入血液当中,以及神经传递 素从一个神经细胞传导至另一个细胞。这 些分子在细胞内都是以“小包”的形式传 递的,即细胞囊泡。这三位获奖科学家发 现了这些“小包”是如何被在正确的时间 输运至正确地点的分子机制。

2013诺贝尔医学奖得主

细胞内囊泡交通的运行与调节机制

詹姆斯-E.罗斯曼James E. Rothman

1947年出生(66岁),耶 鲁大学细胞生物学系 系主任、纪念Fergus F. Wallace生物医学教授 。曾获多种荣誉,包 括哥伦比亚大学的露 依莎-格罗斯-霍维茨奖 、拉斯克奖基础医学 奖(2002年)、费萨尔国 王奖。。

微米级PS-PEDOT核壳型导电微球的合成与拉曼表征

微米级PS-PEDOT核壳型导电微球的合成与拉曼表征王普;李郭成;邓兆静;高康莉;韩国志【摘要】以分散聚合法制备的微米级聚苯乙烯(PS)微球为模板、3,4-乙烯二氧噻吩(EDOT)为单体、过硫酸铵(APS)为引发剂,通过氧化聚合制备了PS-PEDOT核壳型复合导电微球.采用扫描电镜、透射电镜等对导电微球的形貌和结构进行了表征,重点采用拉曼光谱研究了其核壳结构特征.并研究了超声分散、溶液pH以及单体配比对导电微球形貌的影响.实验结果表明:超声的引入可提高导电微球的单分散性,改善微球的形貌.随着pH的降低或单体配比的增加,导电聚合物在PS微球表面的负载量随之增加,当m(EDOT)/m(PS)由0.60增加到1.25时,导电微球的平均粒径由1.76 μm增加到1.91 μm.【期刊名称】《功能高分子学报》【年(卷),期】2014(027)003【总页数】6页(P272-277)【关键词】微米级;聚苯乙烯;EDOT;导电微球;拉曼表征【作者】王普;李郭成;邓兆静;高康莉;韩国志【作者单位】南京工业大学理学院,南京210009;南京工业大学理学院,南京210009;南京工业大学理学院,南京210009;南京工业大学理学院,南京210009;南京工业大学理学院,南京210009;东南大学生物电子学国家重点实验室,南京210096【正文语种】中文【中图分类】O63自20世纪70年代发现聚乙炔的导电现象以来,在世界范围内引发了导电聚合物的研究热潮。

但导电聚合物溶解性差和难以加工的特性限制了它的应用[1-2],解决这一问题的常规手段是将之与其他可加工材料复合,改善其应用性能[3-4]。

目前导电高分子的一个研究热点是将其与单分散微球复合,制备具有核壳结构的导电微球,这种导电微球在光子晶体、压敏电子器件和药物传输等领域有着潜在的应用前景[5-6]。

导电微球的性能与微球表面导电高分子的性质息息相关,与其他有机导电高分子(聚吡咯、聚苯胺)相比,聚34-乙烯二氧噻吩(PEDOT)因其较高的导电率与环境稳定性,以及较好的光学透明性,在抗静电涂层、有机发光材料和有机太阳能电池等领域被广泛使用[7-8]。

让细胞膨胀8000倍!耶鲁团队革命性发明,肉眼也能看清细胞

让细胞膨胀8000倍!耶鲁团队革命性发明,肉眼也能看清细胞2023-02-01 08:56·邱志远大夫原创学术经纬我们通过眼睛窥见世间万物,但人眼的分辨率终究是有限的。

我们可以看清窗户上的一只蚂蚁,但却看不到组成这只蚂蚁的一个个细胞。

好在,显微镜的出现让我们开始接触细胞层面的微观世界;而探索更细微的核糖体、微管等超微结构,则需要更先进的高分辨率荧光显微镜与电子显微镜。

在这样的背景下,接下来的这段设想简直是不切实际:一枚直径40微米的普通细胞,我们用肉眼就能看清基本结构;同时,普通的光学显微镜也能“平替”那些昂贵的仪器,研究其中的超微结构特征。

但科技的发展,就是实现一个个“不可能”的过程。

现在,耶鲁大学细胞生物学教授Joerg Bewersdorf带领团队,为我们表演了一场放大细胞的“魔术”。

通过对细胞的“膨胀-染色”两步改造,细胞体积被放大至少8000倍,变得肉眼可见,并且普通显微镜能够看清细胞的超微结构。

这项新技术带来的不仅是视觉奇观,还有望将前沿的生物学研究带到更广泛的地区。

▲通过最新研究的不透明显微成像技术,我们可以用肉眼看见细胞结构(图片来源:Ons M’Saad)这项突破的起点,要从2015年的一项研究说起。

当时,作为开创了光遗传学领域的先驱之一,麻省理工学院的Edward Boyden教授在《科学》杂志上发表了另一项开创性的新发明:膨胀显微成像技术(Expansion Microscopy)。

这项技术首先在聚阴离子水凝胶的帮助下,将荧光标记的生物样本放大;接下来利用荧光显微技术观察放大后的样本。

这样一来,最终的放大倍数就是物理放大与显微镜光学放大倍数的乘积。

▲利用膨胀显微成像技术看见的小鼠脑组织(图片来源:参考资料[3])在这项技术的基础上,Bewersdorf教授开始设想新的可能性。

以普通的海拉细胞为例,如果能够将细胞直径放大20倍,也就是细胞体积膨胀8000倍,那么理论上来说,肉眼就足以看见细胞的结构。

1998年诺贝尔医学奖 百年诺贝尔生理和医学奖汇总(1901-2015年)

1998年诺贝尔医学奖百年诺贝尔生理和医学奖汇总(1901-2015年)1998年诺贝尔医学奖百年诺贝尔生理和医学奖汇总(1901-2015年)百年诺贝尔生理和医学奖汇总(1901-2015年)2014年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖在瑞典揭晓,来自日本的Satoshi ōmura以及爱尔兰的William C. Campbell,以及中国的女科学家屠呦呦共同分享2015年诺贝尔奖生理学或医学奖。

屠呦呦1930年生,药学家,中国中医研究院(China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine)终身研究员兼首席研2014年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖在瑞典揭晓,来自日本的Satoshi ōmura以及爱尔兰的William C. Campbell,以及中国的女科学家屠呦呦共同分享2015年诺贝尔奖生理学或医学奖。

屠呦呦1930年生,药学家,中国中医研究院(China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine)终身研究员兼首席研究员,青蒿素研究开发中心主任。

诺贝尔委员会称,屠呦呦,威廉-坎贝尔以及Satoshi Omura 三位获奖者发展了一些疗法,这对一些最具毁灭性的寄生虫疾病的治疗具有革命性的作用。

115年诺奖--生理或医学奖总结如下(MedSci独家整理),在整个115年中,有9年因各种原因(如战争)未颁奖,实际上颁出106年。

其中,与疟疾有关的共获得两次奖,一次是1902年,英国人R.罗斯,第二次是今年!下面是全部的奖项及获奖人:时间获奖人及国籍获奖原因1901年 E.A.V.贝林(德国人)从事有关白喉血清疗法的研究1902年R.罗斯(英国人)从事有关疟疾的研究1903年N.R.芬森(丹麦人)发现利用光辐射治疗狼疮1904年I.P.巴甫洛夫(俄国人)从事有关消化系统生理学方面的研究1905年R.柯赫(德国人)从事有关结核的研究1906年 C.戈尔季(意大利人)S.拉蒙-卡哈尔(西班牙人)从事有关神经系统精细结构的研究1907年C.L.A.拉韦朗(法国人)发现并阐明了原生动物在引起疾病中的作用1908年P.埃利希(德国人)、E.梅奇尼科夫(俄国人)从事有关免疫力方面的研究1909年 E.T.科歇尔(瑞士人)从事有关甲状腺的生理学、病理学以及外科学上的研究1910年 A.科塞尔(德国人)从事有关蛋白质、核酸方面的研究1911年 A.古尔斯特兰德(瑞典人)从事有关眼睛屈光学方面的研究1912年 A.卡雷尔(法国人)从事有关血管缝合以及脏器移植方面的研究1913年C.R.里谢(法国人)从事有关抗原过敏的研究1914年R.巴拉尼(奥地利人)从事有关内耳前庭装置生理学与病理学方面的研究1915年--1918年未颁奖1919年J.博尔德特(比利时人)作出了有关免疫方面的一系列发现1920年S.A.S.克劳(丹麦人)发现了有关体液和神经因素对毛细血管运动机理的调节1921年未颁奖1922年 A.V.希尔(英国人)迈尔霍夫(德国人)从事有关肌肉能量代谢和物质代谢问题的研究1923年F.G.班廷(加拿大)J.J.R.麦克劳德(加拿大人)发现胰岛素1924年W.爱因托文(荷兰人)发现心电图机理1925年未颁奖1926年J.A.G.菲比格(丹麦人)发现菲比格氏鼠癌(鼠实验性胃癌)1927年J.瓦格纳-姚雷格(奥地利人)发现治疗麻痹的发热疗法1928年 C.J.H.尼科尔(法国人)从事有关斑疹伤寒的研究1929年 C.艾克曼(荷兰人)F.G.霍普金斯(英国人)发现可以抗神经炎的维生素发现维生素B1缺乏病并从事关于抗神经炎药物的化学研究1930年K.兰德斯坦纳(美籍奥地利人)发现血型1931年O.H.瓦尔堡(德国人)发现呼吸酶的性质和作用方式1932年C.S.谢林顿E.D.艾德里安(英国人)发现神经细胞活动的机制1933年T.H.摩尔根(美国人)发现染色体的遗传机制,创立染色体遗传理论1934年G.R.迈诺特W.P.墨菲G.H.惠普尔(美国人)发现贫血病的肝脏疗法1935年H.施佩曼(德国人)发现胚胎发育中背唇的诱导作用1936年H.H.戴尔(英国人)O.勒韦(美籍德国人)发现神经冲动的化学传递1937年A.森特-焦尔季(匈牙利人)发现肌肉收缩原理1938年 C.海曼斯(比利时人)发现呼吸调节中颈动脉窦和主动脉的机理1939年G.多马克(德国人)研究和发现磺胺药1940年--1942年未颁奖1943年 C.P.H.达姆(丹麦人)E.A.多伊西(美国人)发现维生素K发现维生素K的化学性质1944年J.厄兰格H.S.加塞(美国人)从事有关神经纤维机制的研究1945年A.弗莱明E.B.钱恩H.W.弗洛里(英国人)发现青霉素以及青霉素对传染病的治疗效果1946年H.J.马勒(美国人)发现用X射线可以使基因人工诱变1947年 C.F.科里G.T.科里(美国人)B.A.何赛(阿根廷人)发现糖代谢中的酶促反应发现脑下垂体前叶激素对糖代谢的作用1948年P.H.米勒(瑞士人)发现并合成了高效有机杀虫剂DDT 1949年W.R.赫斯(瑞士人)发现动物间脑的下丘脑对内脏的调节功能1950年 E.C.肯德尔P.S.亨奇(美国人)T.赖希施泰因(瑞士人)发现肾上腺皮质激素及其结构和生物效应1951年M.蒂勒(南非人)发现黄热病疫苗1952年S.A.瓦克斯曼(美国人)发现链霉素1953年 F.A.李普曼(英国人)H.A.克雷布斯(英国人)发现高能磷酸结合在代谢中的重要性,发现辅酶A发现克雷布斯循环(三羧酸循环)1954年J.F.恩德斯T.H.韦勒F.C.罗宾斯(美国人)研究脊髓灰质炎病毒的组织培养与组织技术的应用1955年 A.H.西奥雷尔(瑞典人)从事过氧化酶的研究1956年 A.F.库南德D.W.理查兹(美国人)W.福斯曼(德国人)开发了心脏导管术1957年D.博维特(意籍瑞士人)从事合成类箭毒化合物的研究1958年G.W.比德乐E.L.塔特姆(美国人)J.莱德伯格(美国人)发现一切生物体内的生化反应都是由基因逐步控制的从事基因重组以及细菌遗传物质方面的研究1959年S.奥乔亚A.科恩伯格(美国人)从事合成RNA和DNA的研究1960年 F.M.伯内特(澳大利亚人)P.B.梅达沃(英国人)证实了获得性免疫耐受性1961年G.V.贝凯西(美国人)确立“行波学说”,发现耳蜗感音的物理机制1962年J.D.沃森(美国人)F.H.C.克里克M.H.F.威尔金斯(英国人)发现核酸的分子结构及其对住处传递的重要性1963年J.C.艾克尔斯(澳大利亚人)A.L.霍金奇A.F.赫克斯利(英国人)发现与神经的兴奋和抑制有关的离子机构1964年K.E.布洛赫(美国人)F.吕南(德国人)从事有关胆固醇和脂肪酸生物合成方面的研究1965年 F.雅各布J.L.莫诺A.M.雷沃夫(法国人)研究有关酶和细菌合成中的遗传调节机构1966年 F.P.劳斯(美国人)C.B.哈金斯(美国人)发现肿瘤诱导病毒发现内分泌对于癌的干扰作用1967年R.A.格拉尼特(瑞典人)H.K.哈特兰G.沃尔德(美国人)发现眼睛的化学及重量视觉过程1968年R.W.霍利H.G.霍拉纳M.W.尼伦伯格(美国人)研究遗传信息的破译及其在蛋白质合成中的作用1969年M.德尔布吕克A.D.赫尔S.E.卢里亚(美国人)发现病毒的复制机制和遗传结构1970年B.卡茨(英国人)U.S.V.奥伊勒(瑞典人)J.阿克塞尔罗行(美国人)发现神经末梢部位的传递物质以及该物质的贮藏、释放、受抑制机理1971年 E.W.萨瑟兰(美国人)发现激素的作用机理1972年G.M.埃德尔曼(美国人)R.R.波特(英国人)从事抗体的化学结构和机能的研究1973年K.V.弗里施K.洛伦滋(奥地利人)N.廷伯根(英国人)发现个体及社会性行为模式(比较行为动物学)1974年 A.克劳德C.R.德·迪夫(比利时人)G.E.帕拉德(美国人)从事细胞结构和机能的研究1975年 D.巴尔摩H.M.特明(美国人)R.杜尔贝科(美国人)从事肿瘤病毒的研究1976年B.S.丰卢姆伯格(美国人)D.C.盖达塞克(美国人)发现澳大利亚抗原从事慢性病毒感染症的研究1977年R.C.L.吉尔曼A.V.沙里(美国人)R.S.雅洛(美国人)发现下丘脑激素开发放射免疫分析法1978年W.阿尔伯(瑞士人)H.O.史密斯D.内森斯(美国人)发现限制性内切酶以及在分子遗传学方面的应用1979年 A.M.科马克(美国人)G.N.蒙斯菲尔德(英国人)开始了用电子计算机操纵的X 射线断层扫描仪(简称扫描仪)1980年 B.贝纳塞拉夫G.D.斯内尔(美国人)J.多塞(法国人)从事细胞表面调节免疫反应的遗传结构的研究1981年R.W.斯佩里(美国人)D.H.休伯尔(美国人)T.N.威塞尔(瑞典人)从事大脑半球职能分工的研究从事视觉系统的信息加工研究1982年S.K.贝里斯德伦B.I.萨米埃尔松(瑞典人)J.R.范恩(英国人)发现前列腺素,并从事这方面的研究1983年B.麦克林托克(美国人)发现移动的基因1984年N.K.杰尼(丹麦人)G.J.F.克勒(德国人)C.米尔斯坦(英国人)确立有免疫抑制机理的理论,研制出了单克隆抗体1985年M.S.布朗J.L.戈德斯坦(美国人)从事胆固醇代谢及与此有关的疾病的研究1986年R.L.蒙塔尔西尼(意大利人)S.科恩(美国人)发现神经生长因子以及上皮细胞生长因子1987年利根川进(日本人)阐明与抗体生成有关的遗传性原理1988年J.W.布莱克(英国人)G.H.希钦斯(美国人)对药物研究原理作出重要贡献1989年J.M.毕晓普H.E.瓦慕斯(美国人)发现了动物肿瘤病毒的致癌基因源出于细胞基因,即所谓原癌基因1990年J.E.默里E.D.托马斯(美国人)从事对人类器官移植、细胞移植技术和研究1991年 E.内尔B.萨克曼(德国人)发明了膜片钳技术1992年E.H.费希尔E.G.克雷布斯(美国人)发现蛋白质可逆磷酸化作用1993年P.A.夏普R.J.罗伯茨(美国人)发现断裂基因1994年A.G.吉尔曼M.罗德贝尔(美国人)发现G蛋白及其在细胞中转导信息的作用1995年 E.B.刘易斯E.F.维绍斯(美国人)C.N.福尔哈德(德国人)发现了控制早期胚胎发育的重要遗传机理,利用果蝇作为实验系统,发现了同样适用于高等增有机体(包括人)的遗传机理1996年P.C.多尔蒂(澳大利亚人)R.M.青克纳格尔(瑞士人)发现细胞的中介免疫保护特征1997年S.B.普鲁西纳(美国人)发现全新的蛋白致病因子——朊蛋白(PRION)1998年芬奇戈特伊格纳罗教授(美国人)穆拉博士(美国人)发现氧化氮可以传递信息1999年君特-布洛伯尔(美国人)发现蛋白质有内部信号决定蛋白质在细胞内的转移和定位2000年阿尔维德·卡尔松保罗·格林加德埃里克·坎德尔脑细胞间信号的相互传递2001年利兰·哈特韦尔(美国)、保罗·纳斯(英国)蒂莫西·亨特(英国)导致细胞分裂的关键性调节机制,这一发现为研究治疗癌症的新方法开辟了途径2002年悉尼·布雷内(英国)约翰·苏尔斯顿(英国)罗伯特·霍维茨研究器官发育和程序性细胞死亡过程中的基因调节作用做出了重大贡献2003年保罗·劳特布尔彼得·曼斯菲尔德(英国) 核磁共振成像技术上获得关键性发现,这些发现最终导致核磁共振成像仪的出现2004年理查德·阿克塞尔琳达·巴克气味受体和嗅觉系统组织方式研究中做出贡献,揭示了人类嗅觉系统的奥秘2005年巴里·马歇尔(澳大利亚)罗宾·沃伦(澳大利亚)导致人类罹患胃炎、胃溃疡和十二指肠溃疡的罪魁——幽门螺杆菌,革命性地改变了世人对这些疾病的认识2006年安德鲁·法尔克雷格·梅洛发现了核糖核酸(RNA)干扰机制2007年马里奥·卡佩基奥利弗·史密斯马丁·埃文斯(英国) 采用胚胎干细胞在小鼠特定的基因修饰技术中的重大发现,即“基因打靶”技术,使深入研究单个基因在动物体内的功能并提供相关药物试验的动物模型成为可能2008年哈拉尔德-楚尔-豪森(Harald zur Hausen)(德国)朗索瓦丝-巴尔-西诺西(Francoise Barre-Sinoussi )吕克-蒙塔尼(Luc Montagnier)宫颈癌致病因和艾滋病病毒研究上有突出成就2009年伊丽莎白·布莱克本(Elizabeth Blackburn)卡罗尔-格雷德(Carol Greider)杰克·绍斯塔克(Jack Szostak)发现了端粒和端粒酶保护染色体的机理2010年罗伯特·爱德华兹在试管受精技术方面的发展2011年布鲁斯·巴特勒(Bruce A. Beutler)朱尔斯·霍夫曼(Jules A. Hoffmann)拉尔夫·斯坦曼(Ralph M. Steinman)先天免疫方面的发现对获得性免疫中树突细胞及其功能的发现2012年约翰·伯特兰·格登(John B. Gurdon)山中伸弥(日本)细胞核移植与克隆方面首次证实了已分化细胞(成熟的人皮肤成纤维细胞)的基因组的可通核移植技术将其重新逆转化为具有多能性干细胞(iPS)2013年詹姆斯·E·罗斯曼兰迪·谢克曼托马斯·聚德霍夫细胞如何组织其转运系统——“囊泡转运”的奥秘2014年John O’KeefeMay-Britt MoserEdvard I. Mosel 发现组成大脑定位系统(GPS)的特殊细胞2015年Satoshi ōmura(日本)William C. Campbell屠呦呦对一些最具毁灭性的寄生虫疾病的治疗具有革命性的作用,尤其是线虫和疟疾。

记1998年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖

一氧化氮是什么?

现ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ的认识:

NO是机体内一种作用广泛而性质独特的信号分子, 在神经细胞间的信息交流与传递、血压恒定的维持、免 疫系统的宿主防御反应中等方面,都起着十分重要的作 用,并参与机体多种疾病的发生和发展过程。

Blood Circulation

1628年,William Harvey(站立者) 正在给查理一世国王显示羊的心脏,提出 “心脏的概念”。

NO的启示:Just Say NO

• Idea是科学研究的首要因素。 • 尊重实验结果,让实验说话。 • 活跃、竞争的学术思想是独创精神 不可缺少的土壤

勇于向权威Say NO.

Thanks!

Just Say NO

一氧化氮是如何作为一种信号分子而发挥作用的

——记2019年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖 陆茜

1896年12月,就在阿尔夫雷德·诺贝尔去世前 不到两个月的一天,他给他的一位同事留言: “医生给我开的药竟是硝酸甘油,难道这不是

对我一生巨大的讽刺吗?他们为了不使化学

家和公众感到恐惧,因此把这种药称为三硝酸 甘油。”

1980年R.F.Furchgott 发现EDRF

技术员David Davidson

1986年,Ignarro和Furchgott 分别独立提出:

可能 EDRF=NO

1986年,Moncada以巧妙的试验设计提出令人

信服的证据证明:EDRF=NO

Moncada以证明

EDRF=NO

获得诺贝尔奖提 名,但未能获奖。

主动脉 输 送 血 管

给硝酸 甘油后

阻力 血管

非缺血区 缺血区

RF Furchgott

EDRF(NO) Nobel Prize in 2019

1998年诺贝尔医学或生理学奖

17

由NO的发现研发的药品及保健品

伊格纳罗博士研发的心血管新产品夜 宁新(Niteworks)已在美国康宝莱成 功上市。它是一项心血管革命性的营养 食品,独特的配方包括:L-精氨酸专利 配方,能促进一氧化氮的产生。能保持 维护心脏的冠状动脉的畅通。防止过多 的凝血块阻塞造成心脏病和中风。松弛 动脉(维持正常血压需)。促进脑部血 液流通以增进长期记忆力。

1998年诺贝尔医学或生理学奖

NO是体内重要的信号分子

2021/10/10

1

1998 Nobel M&P 获奖人简介

弗奇哥特

Robert F.Furchgott 美国布鲁克林南方

卫生科学中心

伊格纳罗

Louis J. Ignarro 美国加利福尼亚大

学洛杉矶分校医学 院

慕拉德

Ferid Murad 美国得克萨斯大 学卫生科学中心

7

Furchgott悖论

1953年,弗奇戈特使用离体血管条( helical strip )实验研究了肾上腺素、去甲肾上腺素、亚硝 酸钠和乙酰胆碱等对动脉条的生理作用。

但在当时的实验中存在一个令人困惑不解的现 象:给整体动物静注 ACh 引起血管舒张效应,而 ACh 对离体血管条标本产生收缩作用而不是舒张作 用? 当时被称之为“Furcthgot悖论 ” 。

2021/10/10

2

得奖者相关研究

一. Ferid Murad 硝基及亚硝基药物可以产生 NO完成心血管扩张 二. Robert F. Furchgott 內皮产生化学信息分子 EDRF (Endothelium-derived Relaxing Factor) 舒张血管 三. Louis J. Ignarro 內皮衍生舒张因子 (EDRF) 就是一氧化氮(NO)

历年与生物有关的诺贝尔奖

历年与生物有关的诺贝尔奖1901年(第一届诺贝尔奖颁发),德国科学家贝林(Emil von Behring)因血清疗法防治白喉、破伤风获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1902年,德国科学家费雪(Emil Fischer)因合成嘌呤及其衍生物多肽获诺贝尔化学奖。

美国科学家罗斯(Ronald Ross)因发现疟原虫通过疟蚊传入人体的途径获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1903年,丹麦科学家芬森(Niels Ryberg Finsen)因光辐射疗法治疗皮肤病获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1904年,俄国科学家巴浦洛夫(Ivan Pavlov)因消化生理学研究的巨大贡献获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1905年,德国科学家科赫(Robert Koch)因对细菌学的发展获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1906年,意大利科学家戈尔吉(Camillo Golgi)和西班牙科学家拉蒙·卡哈尔(Santiago Ramóny Cajal)因对神经系统结构的研究而共同获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1907年,德国科学家毕希纳(L.Buchner)因发现无细胞发酵获诺贝尔化学奖。

法国科学家阿方·拉瓦拉(Alphonse Laveran)因发现疟原虫在致病中的作用获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1908年,德国科学家埃尔利希(Paul Ehrlich)因发明“606”、俄国科学家梅奇尼科夫(Hya Mechaikov)因对免疫性的研究而共同获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1909年,瑞士科学家柯赫尔(Theodor Kocher)因对甲状腺生理、病理及外科手术的研究获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1910年,俄国科学家科塞尔(Albrecht Kossel)因研究细胞化学蛋白质及核质获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1911年,瑞典科学家古尔斯特兰(Allvar gullstrand)因研究眼的屈光学获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

1912年,法国医生卡雷尔(Alexis Carrel)因血管缝合和器官移植获诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。

钱永健

人类基因组计划 (HGP) :是一项规模宏大, 跨国跨学科的科学探索工程。其宗旨在于 测定组成人类染色体 ( 指单倍体 ) 中所包含 的 30 亿个碱基对组成的核苷酸序列,从而 绘制人类基因组图谱,并且辨识其载有的 基因及其序列,达到破译人类遗传信息的 最终目的。

—— 发 明 者 美 国斯坦福大学 的乔治· 斯塔 克 ( George Stark )

恩斯特· 鲁斯卡 (Ernst Ruska) 1906年12月25日-1988年 5月27日 德国物理学家 “电子光学的基础工作和设计了第一台 电子显微镜”

恩斯特· 鲁斯卡

电子显微镜技术的开拓者

之一, 1931 年他和马克斯 · 克诺尔成功用磁性 镜头制成第一台二级电子显微镜,实现了电子 显微镜的技术原理,基于磁场会因电子带电而 偏移的现象,使得通过镜头的电子射线能够像 光线一样被聚焦。1986年诺贝尔物理学奖一半 授予的恩斯特 · 鲁斯卡 , 以表彰他在电光学领域 作了基础性工作,并设计了第一台电子显微镜。

2012年,CRISPR/Cas9(成簇规律间隔短 回文重复技术)技术的诞生完全颠覆了传统 的生物编辑。CRISPR/Cas系统的开发为构建 更高效的基因定点修饰技术提供了全新的平 台。

人类基因组计划(human genome project, HGP) (1984-2003)

人类基因组计划与曼哈顿原子弹计划和阿 波罗计划并称为三大科学计划。

钱永健 (Roger Y. Tsien) 1952年2月1日- 美国华裔化学家

Hale Waihona Puke “发现和改造了,绿色荧光蛋白(GFP)”

钱永健

祖籍浙江,毕业于美国哈佛大学,

加州大学圣迭戈分校药理学和生物化学教授, 美国国家科学院院士,美国国家医学院院士, 美国艺术与科学院院士。 因为在发现绿色荧 光蛋白方面作出突出成就,钱永健与日裔美国 科学家下村修 、美国科学家马丁·查尔菲一 起共享2008年诺贝尔化学奖。

中空介孔二氧化硅纳米材料(HMSNs)的合成及其生物相容性

中空介孔二氧化硅纳米材料(HMSNs)的合成及其生物相容性郑昆;杨红;温刚;张元新;葛雅琨;隋新【摘要】以CaCO3为模板合成中空介孔二氧化硅纳米材料(HMSNs),并通过透射电镜(TEM)和小角X射线粉末衍射(SAXRD)对样品进行表征,通过流式细胞仪检测HMSNs样品对A549的细胞内吞能力及生物相容性.结果表明:CaCO3-HMSNs是以CaCO3为核,介孔二氧化硅为壳的纳米粒子;当材料的质量浓度为62.5μg/mL时,细胞的存活率为100%;有92.80%的细胞吸收了样品HMSNs,即HMSNs具有较高的细胞内吞能力及生物相容性.【期刊名称】《吉林大学学报(理学版)》【年(卷),期】2016(054)001【总页数】4页(P148-151)【关键词】中空介孔二氧化硅纳米材料;生物相容性;细胞内吞作用【作者】郑昆;杨红;温刚;张元新;葛雅琨;隋新【作者单位】吉林化工学院生物与食品工程学院,吉林吉林132022;吉林工贸学校,吉林吉林132021;吉林化工学院生物与食品工程学院,吉林吉林132022;吉林化工学院生物与食品工程学院,吉林吉林132022;吉林化工学院生物与食品工程学院,吉林吉林132022;吉林化工学院生物与食品工程学院,吉林吉林132022【正文语种】中文【中图分类】O613.72中空介孔二氧化硅纳米材料(HMSNs)是一种以介孔二氧化硅为壳的中空纳米材料, 由于该类材料具有较高的比表面积, 较大的孔体积, 较低的密度, 优良的化学稳定性和表面可渗透性以及较高的生物相容性等, 因此HMSNs的合成及应用具有广阔的发展前景[1]. 目前常用合成二氧化硅空心球的方法主要有:喷雾高温分解法、超声法、溶胶-凝胶法和模板法等. 其中模板法又分为硬模板法和软模板法: 硬模板法的模板使用刚性结构物质, 如以聚苯乙烯球、碳酸钙[2]、金、硅和碳材料等固体材料作为模板剂; 软模板法使用的模版剂为具有柔性结构的分子或聚集体, 如乳液[3]、表面活性剂胶束和囊泡[4]等. 目前, HMSNs主要应用于药物载体和药物的可控释放[5-10], 而与细胞作用的研究报道较少. 基于此, 本文先合成以CaCO3为模板的HMSNs, 再用透射电镜(TEM)、小角X射线粉末衍射(SAXRD)和荧光光谱对样品进行表征. 通过MTT法测试HMSNs对A549细胞的毒性, 研究其生物相容性, 并通过荧光显微镜和流式细胞仪检验HMSNs的细胞内吞能力.1.1 纳米CaCO3球的合成将1.84 g十六烷基三甲基溴化铵(CTAB), 50 mL十二烷, 5 mL正己醇和1 mL NaHCO3(0.5 mol/L)溶液依次加入100 mL两颈圆底烧瓶中, N2保护下搅拌并加热至60 ℃; 再加入0.5 mol/L的Ca(NO3)22.64 mL, 搅拌10 min, 继续加热至200 ℃, 回流60 min. 在上述体系中加入0.5 mol/L的K2HPO41 mL, 反应40 min;再加入20 mL二甘醇(DEG)搅拌10 min后停止反应. 冷却至室温, 分液. 下层液体用无水C2H5OH洗涤数次, 并分散在无水C2H5OH中[11].1.2 配制APTES-FITC溶液先配制4 mL浓度为0.025 mol/L的异硫氰酸荧光素(FITC)醇溶液, 再加入10 μL 3-氨丙基三乙氧基硅烷(APTES), 避光搅拌24 h, 即得到APTES-FITC醇溶液[12-13].1.3 CaCO3-MSNs与HMSNs的合成将25 mL无水C2H5OH, 0.3 g CTAB, 125 mL水和1.5 mL NH3·H2O混合, 超声10 min. 加入纳米CaCO3球并超声10 min后, 加入0.1 mL正硅酸乙酯(TEOS)继续超声2 h;再加入50 μL APTES-FITC醇溶液, 得到含FITC的CaCO3-HMSNs粒子. 将上述反应混合物转移至透析袋中, 依次用酸醇、醇和去离子水透析, 除去CTAB和CaCO3, 得到HMSNs.1.4 HMSNs细胞活性实验(MTT法) 1) A549细胞的培养液为DMEM, 其中加有质量分数为1%的盘尼西林和链霉素以及体积分数为10%的小牛血清. 铺96孔板, 每孔100 μL DMEM, 细胞数约为8 000个, 边缘孔用无菌磷酸盐缓冲溶液(PBS)填充.φ(CO2)=5%, 37 ℃孵育24 h. 2) 弃去上清液, 加入一定质量浓度梯度(15.625,31.25,62.5,125,250,500 μg/mL)HMSNs样品的DMEM溶液, 每孔200 μL, 6个复孔, 对照溶液为空白的DMEM.φ(CO2)=5%, 37 ℃孵育24 h. 3) 每孔加入20 μL噻唑兰(MTT)溶液, 孵育4 h. 4) 吸去孔内培养液, 加入150 μL二甲基亚砜(DMSO), 测定各孔吸光值.1.5 荧光检测及流式细胞仪检测1) 用胰酶溶液消化A549细胞后, 将DMEM溶液稀释并接种于6孔培养板(密度为每孔每毫升1.0×105个细胞),φ(CO2)=5%,37 ℃培养24 h. 2) 弃去上清液, 加入2 mL含100 μg/mL HMSNs的DMEM溶液, 孵育24 h. 3) 弃去上清液, 用PBS洗涤3次后, 再溶于2 mL PBS中, 在荧光显微镜下观察样品被A549细胞吸收的情况. 4) 每孔先用胰酶溶液消化, 再用PBS重悬细胞. 取500 μL置于1.5 mL离心管中. 用流式细胞仪测定HMSNs(带FITC标签)的细胞内吞效率.2.1 CaCO3-MSNs和HMSNs的表征图1为样品的SAXRD和广角X射线衍射(WAXRD)谱. 由图1(A)可见, 两种样品均为有序的介孔孔道结构, 2θ=2.4°, 峰位基本未发生变化, 即除去CaCO3和CTAB后, 样品HMSNs保持了原有介孔孔道的连续性和有序性. 由图1(B)可见, CaCO3-MSNs具有SiO2和 CaCO3的特征衍射峰, HMSNs具有SiO2的特征衍射峰, 即已完全除去了CaCO3核.图2为CaCO3-MSNs和HMSNs的TEM照片. 由图2(A)可见, 中间黑色部分即为CaCO3球, 四周为介孔二氧化硅. 由图2(B)可见, 除去CTAB和CaCO3即可显现出HMSNs的中空球. 综上可知, CaCO3-MSNs是以CaCO3为核, 介孔二氧化硅为壳的纳米粒子; HMSNs为中空的、壳为介孔二氧化硅的球形纳米粒子,其中的空笼可通过外壳的介孔孔道装载其他分子(如药物分子等).图3为HMSNs的荧光光谱. 由图3可见: FITC的激发波长为490~495 nm, 最大发射光波长为525~530 nm; HMSNs在490 nm波长激发下, 其荧光发射峰位于λ=540 nm附近, 即FITC已连在HMSNs上.2.2 HMSNs的生物相容性图4为MTT法测试不同质量浓度的HMSNs样品对A549细胞存活率影响的柱状分布图. 由图4可见: 当HMSNs的质量浓度为62.5 μg/mL时, A549的细胞存活率为100%;当样品的质量浓度达到125μg/mL时, 细胞存活率略降低, 表明HNSNs具有较好的生物相容性[12].2.3 HMSNs的胞吞性能图5为A549细胞内噬HMSNs的荧光显微镜照片. 若连有荧光剂FITC的HMSNs被A549内噬, 则该细胞在显微镜下发出绿色荧光. 由图5可见, 绝大多数细胞发出绿色荧光, 即HMSNs已被大部分细胞内吞. 在此基础上, 用流式细胞仪定量测定A549细胞内吞HMSNs的百分数, 结果如图6所示, 其中绿色峰面积表示吞噬HMSNs的细胞数占总细胞数的百分数. 由图6可见, 有92.80%的细胞吸收了HMSNs, 即HMSNs具有较高的细胞内吞能力.[1] Caruso F, Caruso R A, Möhwald H. Nanoengineering of Inorganic and Hybrid Hollow Spheres by Colloidal Templating [J]. Science, 1998, 282: 1111-1114.[2] ZHAO Hua, LI Yanju, LIU Runjing, et al. Synthesis Method for Silicaneedle-Shaped Nano-hollow Structure [J]. Mater Lett, 2008, 62(19): 3401-3403.[3] TENG Zhaogang, HAN Yandong, LI Jun, et al. Preparation of HollowMesoporous Silica Spheres by a Sol-Gel/Emulsion Approach [J]. Microporous Mesoporous Mater, 2010, 127(1/2): 67-72.[4] Hubert D H W, Jung M, Frederik P M, et al. Vesicle-Directed Growth of Silica [J]. Adv Mater, 2000, 12(7): 1286-1290.[5] Botterhuis N E, SUN Qianyao, Magusin P, et al. Hollow Silica Spheres with an Ordered Pore Structure and Their Application in Controlled Release Studies [J]. Chem Eur J, 2006, 12(5): 1448-1456.[6] Yang Y J, Tao X, Hou Q, et al. Fluorescent Mesoporous Silica Nanotubes Incorporating CdS Qutantum Dots for Controlled Release of Ibuprofen [J]. Acta Biomaterialia, 2009, 5(9): 3488-3496.[7] ZHU Yufang, Ikoma T, Hanagata N, et al. Rattle-TypeFe3O4@SiO2Hollow Mesoporous Spheres as Carriers for Drug Delivery [J]. Small, 2010, 6(3): 471-478.[8] CHEN Yu, CHEN Hangrong, ZENG Deping, et al. Core/Shell Structured Hollow Mesoporous Nanocapsules: A Potential Platform for Simultaneous Cell Imaging and Anticancer Drug Delivery [J]. Acs Nano, 2010, 4(10): 6001-6013.[9] YANG Yunjie, TAO Xia, HOU Qian, et al. Mesoporous Silica Nanotubes Coated with Multilayered Polyelectrolytes for pH-Controlled Drug Release [J]. Acta Biomaterialia, 2010, 6(8): 3092-3100.[10] WANG Tingting, ZHANG Lingyu, SU Zhongmin, et al. Multifunctional Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanocages for Cancer Cell Detection and the Combined Chemotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy [J]. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2011, 3(7): 2479-2486.[11] Buchold H M D, Feldmann C. Microemulsion Approach to Non-aggllomerated and Crystalline Nanomaterials [J]. Adv Funct Mater, 2008, 18(7): 1002-1011.[12] LIN Yushen, Haynes C L. Synthesis and Characterization of Biocompatible and Size-Tunable Multifunctional Porous Silica Nanoparticles [J]. Chem Mater, 2009, 21(17): 3979-3986.[13] LIN Yushen, Tsai C P, HUANG Hsingyi, et al. Well-Ordered Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as Cell Markers [J]. Chem Mater, 2005, 17(18): 4570-4573.。

Science揭秘癌症惊人起源,单细胞罪大恶极的“逆行”!

Science揭秘癌症惊人起源,单细胞罪大恶极的“逆行”!Science揭秘癌症惊人起源,单细胞罪大恶极的“逆行”!2016-02-02生物探索为什么一些细胞拥有癌症相关的突变却并没有真正癌变一直是一个谜。

1月29日,发表在《科学》杂志上的一项研究中,波士顿儿童医院的研究人员首次在活体动物中看到癌症从单个细胞发展的过程,且发现了从癌症倾向细胞变成恶性肿瘤细胞的关键步骤。

论文的第一作者Charles Kaufman说:“我们的研究发现,在一个致癌基因激活或者肿瘤抑制基因失活后,癌症开始发生;这其中涉及到的一个关键变化是,一个单细胞回到了干细胞状态。

”这一研究成果为癌症治疗提供了一组新的靶点,甚至能够帮助复兴上世纪50年代提出的“field cancerization”理论。

线索基因——crestin在这一研究中,Kaufman和同事们利用通讯作者Leonard I. Zon 实验室中的斑马鱼作为模型追踪黑色素瘤随着时间推移的发展。

所有这些鱼都携带人类癌症突变BRAFV600E,同时也缺失了肿瘤抑制基因p53。

然而,它们大部分却没有罹患癌症。

为什么呢?基于先前的研究,该研究小组对斑马鱼进行了改造,使其在当一个叫crestin的特定基因开启时,单个细胞会发出绿色荧光。

Crestin 的作用就像“灯塔”一样,指示着干细胞遗传程序特征性的激活。

这一程序通常在胚胎发育后就关闭了。

但是有时,不知为何,这一程序中的crestin和其它基因会在某些细胞中再开启。

奇妙的观察过程事实上,找到这些癌症起源细胞是一项冗长乏味的工作。

戴上护目镜,使用带荧光过滤的显微镜,Kaufman观察这些游动的斑马鱼,并用他的iPhone拍摄视频。

观察50条鱼可能需要2-3小时。

在其中30条鱼中,Kaufman看到了一小群发绿光的细胞,大小跟Sharpie记号笔的头差不多。

最终确认的是,这30条发绿光的鱼都发展成了黑色素瘤。

幸运的是,在其中的2条鱼中,Kaufman看到了单个发绿光的细胞,并观察了它分裂以及最终变成一个肿瘤团块的过程。

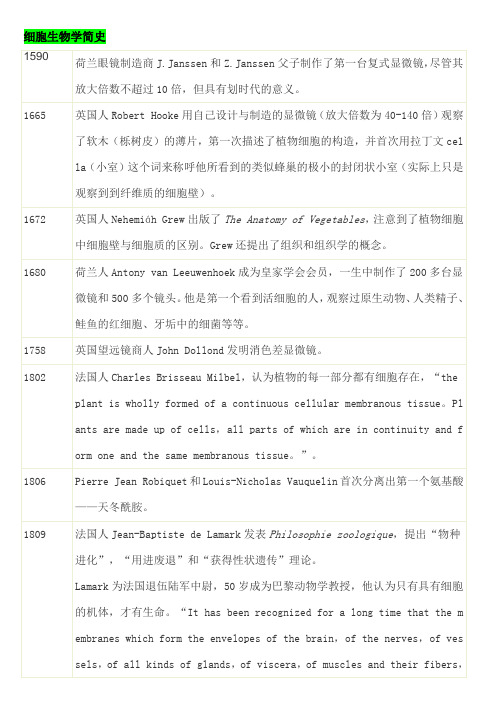

细胞生物学简史

德国人H. von Molh仔细观察了植物的细胞分裂,认为是植物的根和芽尖极易观察到的现象。

1837

捷克人Jan Evangelista Purkyne(Purkinje)把机体描述为是由几部分所组成的,即汁液(包括血液、浆液和淋巴),松散联接的纤维(腱)以及“颗粒”,也即动物细胞。

1838

1884

-85

Oskar Hertwig、Edouard Strasburger、Rudolf Kolliker和August Weismann分别独立提出染色体是遗传的基础物质。

1885

德国人August Weismann提出种质论。

1886

德国人Ernst Abbe发明复消差显微镜,并改进了油浸物镜。

1901

荷兰人Hugo de Vries提出“突变”这一概念。

1902

Walter Sutton和Theodor Boveri提出遗传的染色体学说,认为孟德尔遗传单位存在于染色体上。

1904

英国人William Bateson描述了基因连锁现象,认为一个特殊的性状可能是由不止一个基因引起的。

1905

1806

Pierre Jean Robiquet和Louis-Nicholas Vauquelin首次分离出第一个氨基酸——天冬酰胺。

1809

法国人Jean-Baptiste de Lamark发表Philosophie zoologique,提出“物种进化”,“用进废退”和“获得性状遗传”理论。

Lamark为法国退伍陆军中尉,50岁成为巴黎动物学教授,他认为只有具有细胞的机体,才有生命。“It has been recognized for a long time that the membranes which form the envelopes of the brain,of the nerves,of vessels,of all kinds of glands,of viscera,of muscles and their fibers,and even the skin of the body are in general the productions of cellular tissue。But no one,so far as I know,has yet perceived that cellular tissue is the general matrix of all organization and that without this tissue no living body would be able to exist,nor could it have been formed。”

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。