Small arm transfers and state complicity in international law: Challenging the limitations

机械手毕业设计外文翻译--最小化传感级别不确定性联合策略的机械手控制

毕业设计(论文)有关外文翻译院系:机械电子工程学院专业:自动化姓名:学号:指导教师:完成时间:2009-4-25说明1、将与课题有关的专业外文翻译成中文是毕业设计(论文)中的一个不可缺少的环节。

此环节是培养学生阅读专业外文和检验学生专业外文阅读能力的一个重要环节。

通过此环节进一步提高学生阅读专业外文的能力以及使用外文资料为毕业设计服务,并为今后科研工作打下扎实的基础。

2、要求学生查阅与课题相关的外文文献3篇以上作为课题参考文献,并将其中1篇(不少于3000字)的外文翻译成中文。

中文的排版按后面格式进行填写。

外文内容是否与课题有关由指导教师把关,外文原文附在后面。

3、指导教师应将此外文翻译格式文件电子版拷给所指导的学生,统一按照此排版格式进行填写,完成后打印出来。

4、请将封面、译文与外文原文装订成册。

5、此环节在开题后毕业设计完成前完成。

6、指导教师应从查阅的外文文献与课题紧密相关性、翻译的准确性、是否通顺以及格式是否规范等方面去进行评价。

最小化传感级别不确定性联合策略的机械手控制摘要:人形机器人的应用应该要求机器人的行为和举止表现得象人。

下面的决定和控制自己在很大程度上的不确定性并存在于获取信息感觉器官的非结构化动态环境中的软件计算方法人一样能想得到。

在机器人领域,关键问题之一是在感官数据中提取有用的知识,然后对信息以及感觉的不确定性划分为各个层次。

本文提出了一种基于广义融合杂交分类(人工神经网络的力量,论坛渔业局)已制定和申请验证的生成合成数据观测模型,以及从实际硬件机器人。

选择这个融合,主要的目标是根据内部(联合传感器)和外部( Vision 摄像头)感觉信息最大限度地减少不确定性机器人操纵的任务。

目前已被广泛有效的一种方法论就是研究专门配置5个自由度的实验室机器人和模型模拟视觉控制的机械手。

在最近调查的主要不确定性的处理方法包括加权参数选择(几何融合),并指出经过训练在标准操纵机器人控制器的设计的神经网络是无法使用的。

Optimizedstairca...

Optimized staircase profiles for diffractive optical devices made from absorbing materialsBernd Nöhammer,Christian David,and Jens GobrechtLaboratory for Micro-and Nanotechnology,Paul Scherrer Institut,CH-5232Villigen,SwitzerlandHans Peter HerzigInstitute of Microtechnology,University of Neuchâtel,CH-2000Neuchâtel,Switzerland We report on the optimization of staircase grating profiles for the case of absorbing grating inga simple numerical algorithm,we determined the grating parameters,maximizing the first-order diffractionefficiency for different numbers of staircase steps.The results show that there is a significant differencebetween the staircase profiles for nonnegligible and negligible absorption.The obtained solutions are ofimportance for diffractive optics in the soft-x-ray and extreme-ultraviolet ranges.Because of the progress in lithography and replicationtechniques that permit low-cost mass fabrication, diffractive optical elements(DOEs)have becomeimportant optical devices.1The most important andalso simplest form of DOE is gratings.There are also many other types of DOE that are generalized formsof gratings with a varying grating constant,such asFresnel zone plates or computer-generated holograms. Consequently the task of finding the optimum surfacerelief of a DOE can often be simplified to the problemof finding the optimum shape of a grating.In conventional optics the absorption of the gratingmaterial is usually negligible;therefore only the phase-shifting properties of the material(described by the real part of the refractive index)have to be taken intoaccount for this shape-optimization process.However,for wavelengths l in the extreme-ultraviolet(EUV)and x-ray ranges,where the refractive index n is conve-niently written as n͑l͒12d͑l͒1i b͑l͒,d and b areoften of the same order of magnitude;therefore absorp-tion(described by b)also has to be taken into accountfor the calculation of optimized grating profiles.A requirement for many applications is to diffract as much light as possible in a single(e.g.,the first)diffraction order.In the case in which absorption isnegligible,this is achieved by use of a blazed grating structure that has a sawtoothlike shape and a heighth c calculated from h cl͞j d j[Fig.1(A),dashed lines]. However,when absorption of the diffracting structures plays a role,the shape of the grating that gives maxi-mum first-order diffraction efficiency is quite different.Tatchyn et al.2have shown that in this general case the optimum profile is still sawtooth shaped and has the same slope as in the case of zero absorption[Fig.1(A), solid lines],but the structures are narrower,resulting in an open part b1.The size of the open fraction b1͞b depends on the ratio d͞b as indicated in Fig.1(B)and has to be calculated numerically.In practice,fabrication of a continuous sawtooth pro-file with the required accuracy is difficult.There-fore the ideal profile is often approximated by a stair-case profile(Fig.2).Such staircase profiles can be fabricated by use of several aligned lithography stepsand subsequent etching or deposition of the gratingmaterial.3For the case of staircase profiles optimized for neg-ligible absorption,the N distinct steps of the staircasehave equal width(w iw j;i,j1,...,N)and the heights,h i,of the steps follow the ideal profile for zeroabsorption,leading to h i͓͑i21͒͞N͔l͞j d j.Such pro-files give good results for optics in the visible spectral range,where absorption is normally negligible.Also, in the case of the first x-ray optics with staircase pro-files,which have been recently reported,4–6b was suf-ficiently small for the relevant photon energies in the hard-x-ray range.However,when considering optics in the EUV and soft-x-ray region,in most cases ab-sorption will play a role.In the current work we show how to optimize the design of a staircase profile to ob-tain maximum first-order diffraction efficiency for this case of nonnegligible absorption.In the EUV and soft-x-ray spectral ranges,thewavelength of the light is typically smallcomparedFig.1.(A)Design of a transmission grating maximizing the first-order diffraction efficiency in the case of absorbing grating material(solid lines)and in the case of negligible absorption(dashed lines).(B)Correlation between free de-sign parameter b1and the optical properties of the grating material(quantif ied by d͞b).Published in Optics Letters 28, issue 13, 1087-1089, 2003which should be used for any reference to this work1Fig.2.General form of a staircase profile enabling the optimization of the first-order diffraction efficiency.with the period b and the height of the gratings used;therefore in most cases a grating can be treated as a thin structure,and the thin-element approximation can be used (for a discussion of the validity of the thin-element approximation see,for example,Ref.1).In addition,d and b are typically very small;conse-quently ref lections at surfaces between different materials are negligible.With these approximations the diffraction efficiency h can be calculated with the aid of a Fourier analysis of the transmission function.For a discrete profile we get 1h ÉNX i 1f i É2,(1)wheref i exp ͑22p h i b ͞d ͒exp ͓2p i ͑h i 2x i ͔͒sin ͑p w i ͒͞p ,(2)and the normalized heights (h i ),widths (w i )andmiddle positions (x i )of the steps are denotedh i h i j d j ͞l ,w i w i ͞b ,x i x i ͞b .(3)Equation (1)is a sum of contributions from each step of the staircase profile shown in Fig.2.The first term in Eq.(2)describes the absorption within one step.The second term gives the phase of each contribution,originating from the material phase shift (h i )and the position of the step within the grating (x i ).The third term is obtained from the Fourier transform of a rect-angular function with width w i .The analytical treat-ment of the problem would be rather complex since the efficiency is a complicated sum over functions of all staircase parameters.Therefore we used a numerical approach,applying a local search algorithm 7to find the optimum values for the parameters in Eq.(3)with respect to diffraction efficiency.The principle of the algorithm is to make small,ran-dom,trial changes in the actual profile,where the change is allowed to take place only if the new profile (the new set of parameters h i ,w i ,and x i )has a higher diffraction efficiency than the previous one.By re-peating this step until a large number (n trial .100)of subsequent trial changes fails to improve the diffrac-tion efficiency,an optimum set of values of h i ,w i ,and x i will ultimately be reached.This kind of algorithm could fail because of the presence of local maxima and as a consequence would never yield reasonable results for the design parame-ters of the grating.However,the numerical resultsshow that the total number of maxima is rather small;therefore it is sufficient to repeat the whole algorithm a few (typically 20)times with different,randomly chosen starting parameters for the grating in order to obtain a parameter set that represents the global optimum with respect to diffraction efficiency.Figure 3shows the numerical results of using this algorithm in the case of a staircase profile with four levels.For low values of absorption (high values of d ͞b )we obtain the expected staircase profile,which has steps with equal width and normalized heights of 0,1͞4,1͞2,and 3͞4.When we go to higher values of absorption,the widths (as well as the heights)of the second and the third steps decrease and finally approach zero.The widths of the first and the fourth steps both increase,and for values of d ͞b near zero they both approach a value equal to half of the grating period b .Therefore in the limit of infinite absorption a conventional binary amplitude grating is obtained.These results for high values of absorption can be qualitatively understood because the staircase profile always has to provide an optimum approximation of the ideal profile in terms of diffraction efficiency.For the ideal grating in the case of strong absorption the main contributions to the diffraction efficiency come from regions of the grating with smallheight.Fig.3.Optimum normalized widths w i (A)and heights h i (B)of a four-step staircase profile as a function of d ͞b of the grating material.Fig.4.First-order diffraction efficiency of a four-step pro-file (solid curve)featuring optimal values for the heights and widths of the steps.In addition,the diffraction ef-ficiency of the ideal continuous profile (see Fig.1)and a four-step profile optimized for negligible absorption aredepicted.Fig.5.First-order diffraction efficiency for different opti-mized grating designs.Therefore it is important to get a good approximation of the region with zero height (provided by the first step with w 1ഠb 1)and a short region with small height at the beginning of the sawtooth (provided by the second and third steps,which therefore tend to have rather small widths and heights in the case of high absorption).In Fig.4the diffraction efficiency of a four-step pro-file with optimal values for h i ,w i ,and x i is depicted.In addition,the diffraction efficiency of the ideal con-tinuous profile and a four-step profile with the con-ventional design rule optimized for zero absorption are plotted for comparison.For high values of d ͞b thetwo different staircase profiles nearly have the same diffraction efficiency,whereas for values of d ͞b below 10a significant difference can be observed.There-fore the optimal design of the staircase profile has to be used in this case to guarantee maximum diffrac-tion efficiency (e.g.,for d 2the optimum four-step profile gives 22%diffraction efficiency in comparison with only 16%for a four-step profile optimized for zero absorption).When different step numbers N of the staircase profile are used,similar results are found.For high values of d ͞b (typically d ͞b .10)the anticipated profile optimized for zero absorption [w i w j and h i ͑i 21͒͞N ]is obtained.For the case of high absorption the staircase profile gives a good approxi-mation of the ideal continuous profile in regions with small or zero structure height and an inferior approximation in regions of large structure heights,as expected.Figure 5shows the first-order diffraction efficiencies of optimized profiles with different step numbers N .For small values of absorption a larger number N of steps leads to a strongly improved diffraction efficiency,whereas for strong absorption very little difference is found among all profiles.This is because,for all profiles,the normalized width of the region with zero height approaches 1͞2,going to small values of d ͞b .Consequently in the limit of infinite absorption all the staircase profiles will have the same optical properties as a binary amplitude grating.In summary,we have shown that material absorp-tion has to be taken into account for the optimization of gratings in the EUV and x-ray ranges.By use of a numerical local search algorithm we were able to calculate the optimum parameters for maximum first-order diffraction efficiency of gratings with staircase profiles.This work was funded by the Swiss National Sci-ence Foundation. B.N öhammer ’s e-mail address is **********************.References1.H.P.Herzig,ed.,Micro-optics (Taylor &Francis,Lon-don,1998).2.R.Tatchyn,P.L.Csonka,and I.Lindau,J.Opt.Soc.Am.72,1630–1639(1982).3.M.B.Stern,in Micro-optics ,H.P.Herzig,ed.(Taylor &Francis,London,1998),pp.53–86.4.E.Di Fabrizio,F.Romanato,M.Gentili,S.Cabrini,B.Kaulich,J.Susini,and R.Barrett,Nature 401,895–898(1999).5.W.Yun,i,A.A.Krasnoperova,E.Di Fabrizio,Z.Cai,F.Cerrina,Z.Chen,M.Gentili,and E.Gluskin,Rev.Sci.Instrum.70,3537–3541(1999).6.B.N öhammer,J.Hoszowska,H.P.Herzig,and C.David,presented at the X-Ray Microscopy Conference 2002,Grenoble,France,July 29–August 2,2002.7.E.Aarts and J.K.Lenstra,Local Search in Combinato-rial Optimization (Wiley,Chichester,U.K.,1997).。

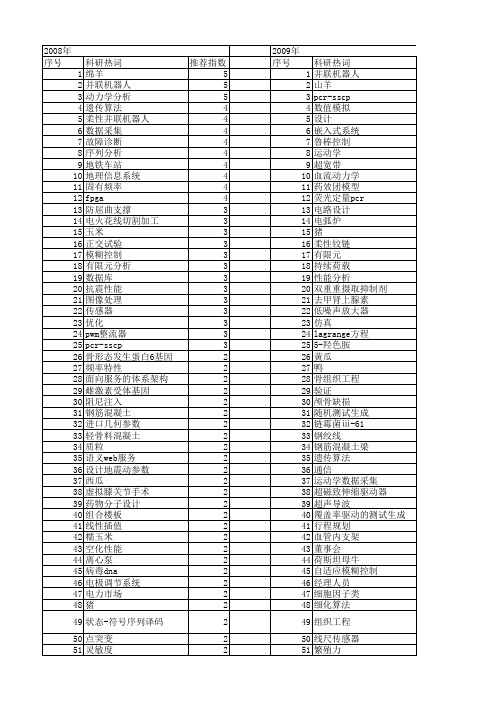

【北京市自然科学基金】_设计_基金支持热词逐年推荐_【万方软件创新助手】_20140729

53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106

107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160

黄芩苷 黄芩 鲁棒性'输出跟踪 鲁棒性 高速 高级加密标准 高繁殖力 高科技厂房 高斯模型 高层钢结构 骨缺损 骨架 骨形态发生蛋白受体ib基因 骨密度 马赫-曾德尔干涉仪 马蔺 首尔 饲料配方系统 风力发电机 频率响应 颈动脉 颅内动脉瘤 面向服务的体系结构 非脆弱 非线性系统 非线性度 非线性动态系统辨识 非定常计算 需求侧管理 集成框架 集成服务平台 集成式石英谐振器 集成学习 集团企业 集中柔度 隶属度函数 隧道工程 隔舌 隐私性 隐私保护 隐式授权 随机故障 随机性检测 降噪 阻遏蛋白质类 阻尼比 闪耀光纤光栅 锻模优化设计 锥束ct重建 错配碱基 错误拒绝率 锅炉 链球菌,变异 铁电存储器

模态分析 桥梁 柔顺机构 机械设计 机器人 有限元 无源性 数据流图 敏度分析 拓扑优化 抗震设计 承载力 戴尔福特菌 性能分析 并联柔性机器人 嵌入式系统 嵌入式数据库 小干扰rna 天然气 大范围形变 多网格编码调制 均匀设计 地下结构 合成 叶轮进口流动 可视化 发酵罐 反馈线性化 压型钢板 压力脉动 博弈 单片机 动应力 动力学 功率控制 分类标准 分子对接 减震技术 克隆 催化燃烧 信息融合 二值化 xbrl实例生成器 web服务 rna干扰 rice信道 lagrange方程 ked方法 dsp canopen ansys 龙芯2号微处理器 龙芯2号处理器 齿兰环斑病毒

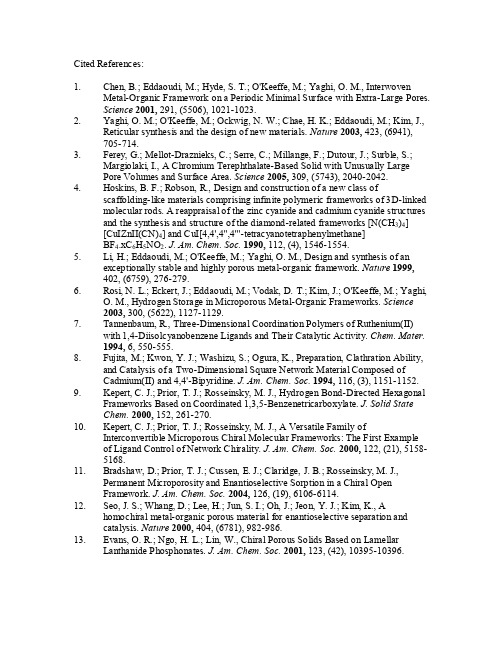

CitedReferences:引用的参考文献

Cited References:1. Chen, B.; Eddaoudi, M.; Hyde, S. T.; O'Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M., InterwovenMetal-Organic Framework on a Periodic Minimal Surface with Extra-Large Pores.Science 2001, 291, (5506), 1021-1023.2. Yaghi, O. M.; O'Keeffe, M.; Ockwig, N. W.; Chae, H. K.; Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J.,Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 2003, 423, (6941),705-714.3. Ferey, G.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Serre, C.; Millange, F.; Dutour, J.; Surble, S.;Margiolaki, I., A Chromium Terephthalate-Based Solid with Unusually LargePore Volumes and Surface Area. Science 2005, 309, (5743), 2040-2042.4. Hoskins, B. F.; Robson, R., Design and construction of a new class ofscaffolding-like materials comprising infinite polymeric frameworks of 3D-linked molecular rods. A reappraisal of the zinc cyanide and cadmium cyanide structures and the synthesis and structure of the diamond-related frameworks [N(CH3)4][CuIZnII(CN)4] and CuI[4,4',4'',4'''-tetracyanotetraphenylmethane]BF4.xC6H5NO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, (4), 1546-1554.5. Li, H.; Eddaoudi, M.; O'Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O. M., Design and synthesis of anexceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 1999,402, (6759), 276-279.6. Rosi, N. L.; Eckert, J.; Eddaoudi, M.; Vodak, D. T.; Kim, J.; O'Keeffe, M.; Yaghi,O. M., Hydrogen Storage in Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science2003, 300, (5622), 1127-1129.7. Tannenbaum, R., Three-Dimensional Coordination Polymers of Ruthenium(II)with 1,4-Diisolcyanobenzene Ligands and Their Catalytic Activity. Chem. Mater.1994, 6, 550-555.8. Fujita, M.; Kwon, Y. J.; Washizu, S.; Ogura, K., Preparation, Clathration Ability,and Catalysis of a Two-Dimensional Square Network Material Composed ofCadmium(II) and 4,4'-Bipyridine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, (3), 1151-1152. 9. Kepert, C. J.; Prior, T. J.; Rosseinsky, M. J., Hydrogen Bond-Directed HexagonalFrameworks Based on Coordinated 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylate. J. Solid StateChem. 2000, 152, 261-270.10. Kepert, C. J.; Prior, T. J.; Rosseinsky, M. J., A Versatile Family ofInterconvertible Microporous Chiral Molecular Frameworks: The First Exampleof Ligand Control of Network Chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, (21), 5158-5168.11. Bradshaw, D.; Prior, T. J.; Cussen, E. J.; Claridge, J. B.; Rosseinsky, M. J.,Permanent Microporosity and Enantioselective Sorption in a Chiral OpenFramework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, (19), 6106-6114.12. Seo, J. S.; Whang, D.; Lee, H.; Jun, S. I.; Oh, J.; Jeon, Y. J.; Kim, K., Ahomochiral metal-organic porous material for enantioselective separation andcatalysis. Nature 2000, 404, (6781), 982-986.13. Evans, O. R.; Ngo, H. L.; Lin, W., Chiral Porous Solids Based on LamellarLanthanide Phosphonates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, (42), 10395-10396.14. Hu, A.; Ngo, H. L.; Lin, W., Chiral Porous Hybrid Solids for PracticalHeterogeneous Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Aromatic Ketones. J. Am. Chem.Soc. 2003, 125, (38), 11490-11491.15. Doucet, H.; Ohkuma, T.; Murata, K.; Yokozawa, T.; Kozawa, M.; Katayama, E.;England, A. F.; Ikariya, T.; Ryoji, N., trans-[RuCl2(phosphane)2(1,2-diamine)]and Chiral trans-[RuCl2(diphosphane)(1,2-diamine)]: Shelf-Stable Precatalystsfor the Rapid, Productive, and Stereoselective Hydrogenation of Ketones. Angew.Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1998, 37, (12), 1703-1707.16. Hu, A.; Ngo, H. L.; Lin, W., Chiral, Porous, Hybrid Solids for HighlyEnantioselective Heterogeneous Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α,β-Keto Esters.Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, (48), 6000-6003.17. van den Berg, M.; Minnaard, A. J.; Schudde, E. P.; van Esch, J.; de Vries, A. H.M.; de Vries, J. G.; Feringa, B. L., Highly Enantioselective Rhodium-CatalyzedHydrogenation with Monodentate Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, (46),11539-11540.18. Miyashita, A.; Yasuda, A.; Takaya, H.; Toriumi, K.; Ito, T.; Souchi, T.; Noyori,R., Synthesis of 2,2'-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1'-binaphthyl (BINAP), anatropisomeric chiral bis(triaryl)phosphine, and its use in the rhodium(I)-catalyzedasymmetric hydrogenation of .alpha.-(acylamino)acrylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc.1980, 102, (27), 7932-7934.19. Jia, X.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Yao, X.; Chan, A. S. C., Highly enantioselectivehydrogenation of enamides catalyzed by rhodium-monodentate phosphoramiditecomplex. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, (32), 5541-5544.20. Wang, X.; Ding, K., Self-Supported Heterogeneous Catalysts for EnantioselectiveHydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, (34), 10524-10525.21. Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, K., Quasi Solvent-Free Enantioselective Carbonyl-Ene Reaction with Extremely Low Catalyst Loading. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl.2003, 42, (44), 5478-5480.22. Takizawa, S.; Somei, H.; Jayaprakash, D.; Sasai, H., Metal-Bridged Polymers asInsoluble Multicomponent Asymmetric Catalysts with High Enantiocontrol: AnApproach for the Immobilization of Catalysts without Using any Support. Angew.Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, (46), 5711-5714.23. Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Li, M.; Ding, K., Heterogenization of Shibasaki's Binol/LaCatalyst for Enantioselective Epoxidation of α,β-Unsaturated Ketones withMultitopic Binol Ligands: The Impact of Bridging Spacers. Angew. Chem., Int.Ed. Engl. 2005, 44, (39), 6362-6366.24. Cho, S.-H.; Ma, B.; Nguyen, S. T.; Hupp, J. T.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T. E., A metal-organic framework material that functions as an enantioselective catalyst forolefin epoxidation. Chem. Comm. 2006, (24), 2563-2565.25. Wu, C. D.; Hu, A.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W., A Homochiral Porous Metal-OrganicFramework for Highly Enantioselective Heterogeneous Asymmetric Catalysis. J.Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, (25), 8940-8941.26. Dybtsev, D. N.; Nuzhdin, A. L.; Chun, H.; Bryliakov, K. P.; Talsi, E. P.; Fedin, V.P.; Kim, K., A Homochiral Metal-Organic Material with Permanent Porosity,Enantioselective Sorption Properties, and Catalytic Activity. Angew. Chem., Int.Ed. Engl. 2006, 45, (6), 916-920.27. Hasegawa, S.; Horike, S.; Matsuda, R.; Furukawa, S.; Mochizuki, K.; Kinoshita,Y.; Kitagawa, S., Three-Dimensional Porous Coordination PolymerFunctionalized with Amide Groups Based on Tridentate Ligand: SelectiveSorption and Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, (9), 2607-2614.Reviews and Books:28. Eddaoudi, M.; Moler, D. B.; Li, H.; Chen, B.; Reineke, T. M.; O'Keeffe, M.;Yaghi, O. M., Modular Chemistry: Secondary Building Units as a Basis for theDesign of Highly Porous and Robust Metal-Organic Carboxylate Frameworks.Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, (4), 319-330.29. McMorn, P.; Hutchings, G. J., Heterogeneous enantioselective catalysts:strategies for the immobilisation of homogeneous catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, (2), 108-122.30. Song, C.; Garces, J. M.; Sugi, Y., Shape-Selective Catalysis: Chemical Synthesisand Hydrocarbon Processing. American Chemical Society: Washington DC,1999; Vol. 738, p 410.31. Kitagawa, S.; Kitaura, R.; Noro, S.-i., Functional Porous Coordination Polymers.Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, (18), 2334-2375.32. Ding, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X., Self-Supported ChiralCatalysts for Heterogeneous Enantioselective Reactions. Chemistry a EuropeanJournal 2006, 12, (20), 5188-5197.33. Bradshaw, D.; Claridge, J. B.; Cussen, E. J.; Prior, T. J.; Rosseinsky, M. J.,Design, Chirality, and Flexibility in Nanoporous Molecule-Based Materials. Acc.Chem. Res. 2005, 38, (4), 273-282.34. Mueller, U.; Schubert, M.; Teich, F.; Puetter, H.; Schierle-Arndt, K.; Pastre, J.,Metal-organic frameworks-prospective industrial applications. J. Mater. Chem.2006, 16, (7), 626-636.35. Maspoch, D.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Veciana, J., Old materials with new tricks:multifunctional open-framework materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, (5), 770-818.。

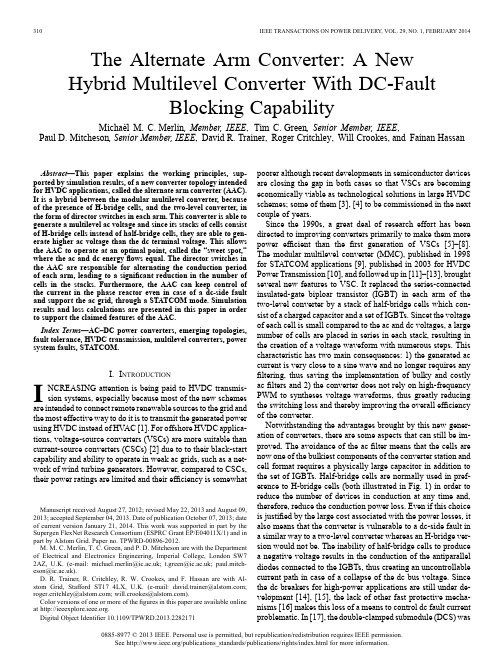

The Alternate Arm Converter A New Hybrid Multilevel Converter With DC-Fault Blocking Capability

The Alternate Arm Converter:A NewHybrid Multilevel Converter With DC-FaultBlocking CapabilityMichaël M.C.Merlin,Member,IEEE,Tim C.Green,Senior Member,IEEE,Paul D.Mitcheson,Senior Member,IEEE,David R.Trainer,Roger Critchley,Will Crookes,and Fainan HassanAbstract—This paper explains the working principles,sup-ported by simulation results,of a new converter topology intended for HVDC applications,called the alternate arm converter(AAC). It is a hybrid between the modular multilevel converter,because of the presence of H-bridge cells,and the two-level converter,in the form of director switches in each arm.This converter is able to generate a multilevel ac voltage and since its stacks of cells consist of H-bridge cells instead of half-bridge cells,they are able to gen-erate higher ac voltage than the dc terminal voltage.This allows the AAC to operate at an optimal point,called the“sweet spot,”where the ac and dc energyflows equal.The director switches in the AAC are responsible for alternating the conduction period of each arm,leading to a significant reduction in the number of cells in the stacks.Furthermore,the AAC can keep control of the current in the phase reactor even in case of a dc-side fault and support the ac grid,through a STATCOM mode.Simulation results and loss calculations are presented in this paper in order to support the claimed features of the AAC.Index Terms—AC–DC power converters,emerging topologies, fault tolerance,HVDC transmission,multilevel converters,power system faults,STATCOM.I.I NTRODUCTIONI NCREASING attention is being paid to HVDC transmis-sion systems,especially because most of the new schemes are intended to connect remote renewable sources to the grid and the most effective way to do it is to transmit the generated power using HVDC instead of HV AC[1].For offshore HVDC applica-tions,voltage-source converters(VSCs)are more suitable than current-source converters(CSCs)[2]due to to their black-start capability and ability to operate in weak ac grids,such as a net-work of wind turbine generators.However,compared to CSCs, their power ratings are limited and their efficiency is somewhatManuscript received August27,2012;revised May22,2013and August09, 2013;accepted September04,2013.Date of publication October07,2013;date of current version January21,2014.This work was supported in part by the Supergen FlexNet Research Consortium(ESPRC Grant EP/E04011X/1)and in part by Alstom Grid.Paper no.TPWRD-00896-2012.M.M.C.Merlin,T.C.Green,and P.D.Mitcheson are with the Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering,Imperial College,London SW7 2AZ,U.K.(e-mail:michael.merlin@;t.green@;paul.mitch-eson@).D.R.Trainer,R.Critchley,R.W.Crookes,and F.Hassan are with Al-stom Grid,Stafford ST174LX,U.K.(e-mail:david.trainer@; roger.critchley@;will.crookes@).Color versions of one or more of thefigures in this paper are available online at .Digital Object Identifier10.1109/TPWRD.2013.2282171poorer although recent developments in semiconductor devices are closing the gap in both cases so that VSCs are becoming economically viable as technological solutions in large HVDC schemes;some of them[3],[4]to be commissioned in the next couple of years.Since the1990s,a great deal of research effort has been directed to improving converters primarily to make them more power efficient than thefirst generation of VSCs[5]–[8]. The modular multilevel converter(MMC),published in1998 for STATCOM applications[9],published in2003for HVDC Power Transmission[10],and followed up in[11]–[13],brought several new features to VSC.It replaced the series-connected insulated-gate biploar transistor(IGBT)in each arm of the two-level converter by a stack of half-bridge cells which con-sist of a charged capacitor and a set of IGBTs.Sincet the voltage of each cell is small compared to the ac and dc voltages,a large number of cells are placed in series in each stack,resulting in the creation of a voltage waveform with numerous steps.This characteristic has two main consequences:1)the generated ac current is very close to a sine wave and no longer requires any filtering,thus saving the implementation of bulky and costly acfilters and2)the converter does not rely on high-frequency PWM to syntheses voltage waveforms,thus greatly reducing the switching loss and thereby improving the overall efficiency of the converter.Notwithstanding the advantages brought by this new gener-ation of converters,there are some aspects that can still be im-proved.The avoidance of the acfilter means that the cells are now one of the bulkiest components of the converter station and cell format requires a physically large capacitor in addition to the set of IGBTs.Half-bridge cells are normally used in pref-erence to H-bridge cells(both illustrated in Fig.1)in order to reduce the number of devices in conduction at any time and, therefore,reduce the conduction power loss.Even if this choice is justified by the large cost associated with the power losses,it also means that the converter is vulnerable to a dc-side fault in a similar way to a two-level converter whereas an H-bridge ver-sion would not be.The inability of half-bridge cells to produce a negative voltage results in the conduction of the antiparallel diodes connected to the IGBTs,thus creating an uncontrollable current path in case of a collapse of the dc bus voltage.Since the dc breakers for high-power applications are still under de-velopment[14],[15],the lack of other fast protective mecha-nisms[16]makes this loss of a means to control dc fault current problematic.In[17],the double-clamped submodule(DCS)was0885-8977©2013IEEE.Personal use is permitted,but republication/redistribution requires IEEE permission.See /publications_standards/publications/rights/index.html for more information.Fig.1.Electrical schematic of half-bridge cells(left)and H-bridge cells(right). suggested as a new type of cell to deal with this issue.The DCS connects two half-bridge cells together into one cell through one additional IGBT and two diodes.This configuration offers the possibility of switching in a reverse voltage,similar to the H-bridge cell,in order to respond to the need for negative stack voltage in case of a dc-side fault.However the DCS does not fully solve the dc fault issue because:1)only half the available positive voltage can be translated into negative voltage,leavinga voltage deficit from that needed to fully control the current and2)the power losses are increased by50%compared to using two half-bridge cells during normal operation because of the addi-tional IGBT in the conduction path.This paper presents the analysis of a new converter topology, which is part of a new generation of VSCs[18],[19],based on the multilevel approach but also takes some characteristics from the two-level VSC.As explained through this paper,one of the features of this topology lies in its ability to retain control of the phase current during the loss of the dc-bus voltage,thanks to the presence of H-bridge cells in the arms.The key advantage of this new topology lies in its reduced number of cells;thus, it does not compromise the efficiency of the converter,nor on the number of devices and even saves volume because of the reduced number of cells per arm.A component level simulation of a20-MW converter is used to confirm the claimed character-istics of this new topology.II.D ESCRIPTION OF THE T OPOLOGYA.Basic OperationBriefly presented in[20],the alternate arm converter(AAC) is a hybrid topology which combines features of the two-level and multilevel converter topologies.As illustrated in Fig.2, each phase of the converter consists of two arms,each with a stack of H-bridge cells,a director switch,and a small arm in-ductor.The stack of cells is responsible for the multistep voltage generation,as in a multilevel converter.Since H-bridge cells are used,the voltage produced by the stack can be either positive or negative;thus,the converter is able to push its ac voltage higher than the dc terminal voltage if required.The director switch is composed of IGBTs connected in series in order to withstand the maximum voltage which could be applied across the director switch when it is in the open state.The main role of thisdirector Fig.2.Schematic of the alternate arm converter,with the optional middle-point connection shown in a dashedline.Fig.3.Idealized voltage and current waveforms over one cycle in a phase con-verter of the AAC,showing the working period of each arm.switch is to determine which arm is used to conduct the ac cur-rent.Indeed,the key feature of this topology is to use essentially one arm per half cycle to produce the ac voltage.By using the upper arm to construct the positive half-cycle of the ac sine wave and the lower arm for the negative part,the maximum voltage that each stack of cells has to produce is equal to half of the dc bus voltage,which is approximately half the rating of the arm of the MMC.The resulting voltage and current waveforms of the cells and reactor switches are illustrated in Fig.3.The aim of the AAC is to reduce the number of cells,hence the volume and losses of the converter station.The short period of time when one armfinishes its working period and hands over conduction of the phase current to the op-posite arm is called the overlap period.Since each arm has an ac-tive stack of cells,it can fully control the arm current to zero be-fore opening the director switch,hence achieving soft-switchingFig.4.STATCOM modes of the AAC during a dc-side fault:alternate arms (mode A),single working arm(mode B),and dual working arms(mode C). of the director switch,further lowering the power losses.Al-though normally short,the overlap period can provide additional control features,such as controlling the amount of energy stored in the stacks,as explained in Section II-C.B.DC Fault ManagementOne of the important characteristics of this converter is the ability of its arms to produce negative voltage.In fact,the AAC already uses this ability to produce a converter voltage higher than the dc terminal voltage without requiring the opposite arm to also produce a higher than normal positive voltage from its stack of cells,provided that the director switch is suitably rated. This ability is put to use in normal operation when the converter produces a voltage which is higher than the dc bus voltage.It can be extended to the case when the dc bus voltage collapses to a low level,for example,a fault on the dc side.Since enough cells are present in the stacks to oppose the ac grid voltage,the converter is thus able to keep all of its internal currents under control,in contrast to the two-level converter or half-bridge ver-sion of the MMC.Furthermore,even if the absence of a dc bus voltage means that it is no longer possible to export ac-tive power to the dc side,it does not prevent reactive power exchange with the ac side.Since the arms of the AAC are still operational,the entire converter can now act as a STATCOM, similar to that in[9].There are some choices over how the di-rector switches are used in this mode,as illustrated in Fig.4, which lead to different modes that can be achieved by the AAC during a dc-side fault:one arm conducts per half cycle simi-larly to normal operation,one arm works continuously or the two arms working together,potentially increasing the reactive power capability to2.0p.u.This STATCOM mode of managing the converter during dc fault can help to support the ac grid during a dc outage,in contrast to the worsening effect that can be brought about by other topologies because of their inability to control dc-side fault current.C.Energy BalanceThe ability of the converter to generate relativelyfine voltage steps comes from its cells and,more specifically,from the charged capacitors inside.However,since the resulting ac current isflowing through them,the charge of these capacitors willfluctuate over time,depending on the direction of the current and the switching states of the cells.Due to the large number of cells,it is easier to look at the amount of energy which is stored by the stacks of cells as a whole.Assuming that this charge is evenly distributed among the various cells, thanks to some rotation mechanisms,the only requirement left to ensure satisfactory operation of the converter is to keep the energy of the stacks close to their nominal value.To achieve this,the converter has to be operated in such way that the net energy exchange for the stacks over each half cycle is strictly zero.Based on the time functions(1)of and(1) The energy exchange corresponds to the difference between the amount of energy coming from the ac side(2)and going to the dc side(3)(2)(3) By equating these two energies,an ideal operating point is identified as described in(4).This operating point is called the “sweet spot”and is defined by a ratio of the ac voltage magni-tude to dc voltage magnitude(4) It is important to remark that this sweet spot specifies an ac peak voltage higher than the dc terminal voltage,that is,half the dc bus voltage.The converter is thus required to generate its ac voltage in overmodulation mode,at a level of approximately 27%higher than the dc terminal voltage. The presence of H-bridge cells is thus fully justified since these cells are required to provide a negative voltage,thus pushing the voltage higher than the dc terminal voltage.By choosing the turns ratio of the transformer between the converter and the ac grid in order to obtain the ac voltage of the sweet spot,the con-verted energy willflow through the converter without a deficit or surplus being exchanged with the stacks.In practice,discrepancies between the converter and its the-oretical model[used to derived(2)and(3)leading to(4)]will lead to a small fraction of the converted energy being exchanged with the stack.To remedy this,the overlap period(i.e.,the small period of time when one arm hands over conduction of the phase current to the other arm)can be used to run a small dc current through both arms to the dc side.This will result in an exchange of energy between the stacks and the dc capacitor,which can be used to balance the energy in the stacks.D.Number of DevicesThe device count in the AAC can be obtained by following a series of steps,given the particular operating mechanism described before.The calculation presented below only gives the minimal requirement under normal operation.An additional margin has to be added to comply with the different operating conditions applied to each project.It is,however,important to note that the stacks of the AAC can generate as much negative voltage as positive voltage;thus,the AAC is able to provide an ac voltage up to200%of the dc terminal voltage without requiring extra cells.First,the number of cells is obtained by calculating the max-imum voltage that a stack has to produce.Since the two arms of a single-phase converter have to support at least the total dc bus voltage,and assuming a symmetrical construction,this maximum voltage has to be at least half the dc bus voltage.Fur-thermore,given that this topology is intended to have dc-fault blocking capability,the arms should be able to produce at least the ac peak voltage in order to maintain control over the current in the phase reactor with the dc voltage reduced to zero.There-fore,the stacks should be rated to deliver the ac peak voltage. Since the sweet spot defines the ac peak voltage as27%higher than half the dc bus voltage,the minimum requirement can then be increased up to the ac peak voltage.However,if dc-fault blocking is not a requirement,this voltage can remain at half the dc bus voltage.Furthermore,the maximum voltage of the stacks also defines how long an arm can stay active beyond the zero-crossing point of the converter voltage in order to provide an overlap period.The longer the overlap period,the higher the voltage that the stack has to produce,hence the more cells are required.Once the maximum voltage of the stack is set,the number of cells is directly obtained by dividing this voltage by the nominal voltage of a cell.Second,the required number of series IGBTs,which form the director switch,is determined based on the maximum voltage applied across the director switch,as illustrated in Fig.3.This voltage is the difference between the converter voltage and the voltage at the other end of the director switch,which is con-nected to the(nonconducting)stack of cells.The nonconducting stack can be set to maximize its voltage in order to lower the voltage across the director switch,taking care not to reverse the voltage across the director switch.Equation(5)summarizes all of these arguments and presents the maximum voltage across the director switch.By implementing the sweet spot definition (4)into(5),it yields(6),a function of the dc bus voltage and the peak stack voltage(5)(6) Table I summarizes the voltage ratings required of the stack of cells and the director switch given three choices made over the need to block dc fault current and the extent of overlap.In defining these voltages,these choices will also determine the number of semiconductor devices in the AAC.TABLE IV OLTAGE R ATINGS OF THE S TACKS AND D IRECTOR SWITCHESThe resulting number of cells per stack is given by(7),where is the nominal voltage of a cell(7) Equation(8)presents the total number of semiconductor de-vices()in a three-phase AAC,with being the number series-IGBTs in the director switch obtained by dividing the maximum voltage of a director switch()by the voltage applied to an IGBT,here assumed to be the same to the voltage of a cell().(8)Using the dc-fault blocking case(given in Table I)and the definition of the sweet spot(4),the total number of semicon-ductor devices becomes the value of the following equation:(9)III.S IMULATION R ESULTSA.Model CharacteristicsIn order to confirm the operation of this new topology,a sim-ulation model has been realised in Matlab/Simulink using the SimPowerSystems toolbox.The characteristics of this model have been chosen in order to reflect a realistic power system, albeit at medium voltage(MV),and key parameters are sum-marized in Table II.The transformer interfacing the ac grid and the converter has its turns ratio defined such that the con-verter operates close to the sweet-spot ac voltage,as defined in Section II-C.The number of cells chosen for each stack follows the second case from Table II so that dc-side fault blocking is available.A small additional allowance was made so that the converter can still operate and block faults with an ac voltage of1.05p.u.The choice is therefore for nine cells charged at1.5 kV each per stack.The minimum number of cells for operation without overlap(sweet spot operation only)and without fault blocking would be seven cells.The choice of nine cells per stack allows the AAC to operate with1-ms overlap period which is sufficient to internally manage the energy storage within the cur-rent rating of the IGBTs(1.2kA).Finally,a dcfilter has been fitted to the AAC model,as illustrated in Fig.2,and tuned to have critical damping and a cutoff frequency at50Hz;well below thefirst frequency component expected on the dc side which is a six-pulse ripple(i.e.,300Hz in this model).C HARACTERISTICS OF THE 20-MW AAC MODELB.Performance Under Normal ConditionsBased on this model,the behavior of the AAC was simulated under normal conditions in order to test its performance.In this section,the converter is running in recti fier mode,converting 20MW and providing 5-MV Ar capacitive reactive power.Fig.5shows the waveforms generated by the AAC in this simulation.First,the converter is very responsive.Second,the waveform of the phase current in the ac grid connection is high quality with only very low amplitude harmonics,as shown by the Fourier analysis in Fig.6.Third,the dc current exhibits the character-istic six-pulse ripple inherent in the recti fication method of this converter,but attenuated by an inductor placed between the con-verter and the dc grid.Fourth,this recti fication action of the cur-rent is particularly observable in the fourth graph which shows the arm currents in phase A,indicating when an arm is con-ducting.Finally,the fifth graph presents the average voltage of the cells in both stacks of phase A,with their offstate voltage being controlled to stay at the reference value of 1.5kV.The voltage and current waveforms have been postprocessed together with the switching commands sent to the converter from the controller,in order to determine the generated power losses.For this example,all of the semiconductor devices were based on the same IGBT device [21]from which the losses curves have been extracted to compute the energy lost through conduction and switching at every simulation time step (2s).A simulation of 1.5s was used in which the first 0.5s was ignored in order to focus only on the steady-state portion.The obtained results are summarized in Table III.As can be observed in Table III,the switching loss relative to the total power losses is low,as could be expected from a mul-tilevel converter,meaning that the conduction loss isdominant.Fig.5.Simulation results of a 20-MW AAC model running in recti fier mode under normalconditions.Fig.6.Fourier transform of the grid-side ac current generated by the AAC.However,the conduction loss is kept small despite the use of H-bridge cells by the fact that the stacks do not have to be rated for the full dc bus voltage because of the presence of the di-rector switches;the conduction loss of a director switch device is less than that of an H-bridge cell.The director switches do not incur any switching loss thanks to the soft-switching capability of the arms (through controlling the arm current to zero before opening of the director switch).Finally,a large amount of the power losses comes from the dc inductor but this is not repre-sentative of a large converter.In this scale model of 20MW,the current at 1kA is typical of a much later converter and it is the voltage that has been scalded down by reducing the number of cells and levels (while keeping the cell voltage at a value typicalB REAKDOWN OF THE P OWER L OSSES AT 20MWof a larger converter 1.5kV).Since the Q factor of the inductor and the current have not been scaled,the loss in the in-ductor is proportionately large.C.Robustness Against AC FaultsSince the AAC is a type of VSC,it does not rely on a strong ac voltage to operate.As a consequence,the AAC is able to cope with ac-side faults.Fig.7shows the results of the simulation where the ac voltage drops to 0.3-p.u.retained voltage between 0.20and 0.35s,similar to a major fault on the ac grid.The con-verter switches into voltage-control mode and supplies 1.0-p.u.capacitive reactive power current.When the ac voltage returns to its nominal value,the converter switches back to normal op-eration and full power is reapplied with a ramp function of more than 50ms.Several observations can be made.First,the converter is able to react quickly to the fault and reduces the power as a conse-quence.Second,the quality of the ac current waveform deteri-orates during the fault,mainly because fewer levels are needed to construct the reduced converter voltage waveform.Third,the cell capacitors display greater voltage fluctuation during the fault because the converter is running far away from the sweet spot,but this does not prevent the AAC from generating reac-tive power during the outage.D.DC Fault Blocking CapabilityThe intended ability to block current during dc faults was tested by simulating the temporary reduction of the dc bus voltage to zero,equivalent to a dc-side fault.The graph in Fig.8shows the waveforms generated during this simulation,where the dc bus voltage is lost between 0.20and 0.35s followed by a ramp up back to normal operations.When observing the sequence of events during this simula-tion,it can be seen that when the dc voltage collapses to zero,it leads to a rapid discharge of the dc bus capacitor which is out-side the control of the converter in opposition to the cell capac-itors.At the moment of fault,the dc filter behaves similar to an RLC circuit with a precharged capacitor (20kV)and inductorFig.7.Simulation results of a 20-MW AAC model running in recti fier mode when an ac-side fault occurs between 0.20and 0.35s.(1kA),resulting in a theoretical peak current of 5.1kA which is close to the current spike observed in the third graph.However,the fourth graph shows that the converter is able to keep control of the ac reactor current and its arm currents so that no fault cur-rent flows from the ac side to the dc side,demonstrating the dc fault blocking capability of the converter itself.Since the converter is no longer able to exchange active power with its dc bus voltage at zero,the active currents are controlled back to zero.Then,from 0.25s,the AAC starts injecting 1.0-p.u.reactive current,thus acting as a STATCOM supporting the ac grid during the outage of the dc link.The stack in conduction at the instance of the fault sees its stored energy rise because it temporarily stores the still incoming en-ergy (while the active current is being reduced),but converges back to its reference value over the period when the fault is present.Finally,when the dc voltage has returned,the converter is able to resume operation quickly.This simulation shows the ability of the AAC to cope with the dc-side fault and even run as a STATCOM to support the ac grid,in the absence of dc bus voltage.Furthermore,in the current simulation,the AAC keeps the same alternating mechanisms of its arms (mode A in Fig.4)but,by activating both arms continuously (mode C in Fig.4),the maximum reactive power could reach up to 2.0-p.u.current.Fig.8.Simulation results of a20-MW AAC model running in rectifier mode when a dc-side fault occurs between0.20and0.35s.IV.C ONCLUSIONThe AAC is a hybrid topology between the two-level con-verter and the modular multilevel converter.By combining stacks of H-bridge cells with director switches,it is able to generate almost harmonic-free ac current,as does the modular multilevel approach.And by activating only one arm per half cycle,like the two-level converter,it can be built with fewer cells than the MMC.Since this topology includes cells with capacitors which are switched into the current path,special attention needs to be paid to keeping their stored energy(equivalently,the cell capacitor voltage)from drifting away from their nominal value.By ex-amining the equations,which govern the exchange of energy between the ac and dc sides,an ideal operating condition has been identified,called the“sweet spot.”When the converter is running at this condition,the energy levels of the stacks return to their initial values at the end of each cycle without any addi-tional action.In cases where this equilibrium is not attained,an overlap period can be used to run a small dc current in order to balance the stacks by sending the excess energy back to the dc capacitors.A discussion of the total number of devices required by this topology has also been presented.Providing dc fault blocking and overlap both require more than the bare minimum number of cells,and adding cells does lead to increased conduction power loss which gives rise to a design tradeoff. Simulations of a small-scale model show that this converter is able to deliver performance under normal conditions,in terms of efficiency and current waveform quality,and provide rapid responses in the case of ac-or dc-side faults.Its ability to keep control of the current even during dc faults is a significant ad-vantage,especially in multiterminal HVDC applications,and can be extended into STATCOM operation in order to support the ac grid during the outage,by providing potentially up to 2.0-p.u.reactive current.R EFERENCES[1]T.Hammons,V.Lescale,K.Uecker,M.Haeusler,D.Retzmann,K.Staschus,and S.Lepy,“State of the art in ultrahigh-voltage transmis-sion,”Proc.IEEE,vol.100,no.2,pp.360–390,Feb.2012.[2]D.Jovcic,D.van Hertem,K.Linden,J.-P.Taisne,and W.Grieshaber,“Feasibility of dc transmission networks,”in Proc.2nd IEEE PowerEnergy Soc.Int.Conf.Exhibit.Innovative Smart Grid Technol.,Dec.2011,pp.1–8.[3]SIEMENS,Borwin2press release,2010.[4]Energinet.dk Svenska Kraftnät Vattenfall Europe Transmission,AnAnalysis of Offshore Grid Connection at Kriegers Flak in the BalticSea,Joint Pre-feasibility study Energinet.dk.,2009[Online].Avail-able:http://www.svk.se/global/02_press_info/090507_kriegers-flak-pre-feasibility-report-final-version.pdf,Tech.Rep.[5]B.Andersen,L.Xu,P.Horton,and P.Cartwright,“Topologies for vsctransmission,”Power Eng.J.,vol.16,no.3,pp.142–150,2002.[6]R.Jose,L.Jih-Sheng,and P.Fangzheng,“Multilevel inverters:Asurvey of topologies,controls,applications,”IEEE Trans.Ind.Elec-tron.,vol.49,no.4,pp.724–738,Aug.2002.[7]M.Bahrman and B.Johnson,“The abcs of hvdc transmission technolo-gies,”IEEE Power Energy Mag.,vol.5,no.2,pp.32–44,Mar.2007.[8]High-V oltage Direct Current(HVDC)Power Transmission UsingV oltage Sourced Converter(VSC)BSi,2011,pD IEC/TR62543:2011.[9]J.Ainsworth,M.Davies,P.Fitz,K.Owen,and D.Trainer,“Staticvar compensator(statcom)based on single-phase chain circuit con-verters,”Proc.Inst.Elect.Eng.,Gen.,Transm.Distrib.,vol.145,no.4,pp.381–386,Jul.1998.[10]A.Lesnicar and R.Marquardt,“An innovative modular multilevel con-verter topology suitable for a wide power range,”presented at the IEEEBologna Power Tech Conf.,Bologna,Italy,Jun.2003.[11]S.Allebrod,R.Hamerski,and R.Marquardt,“New transformerless,scalable modular multilevel converters for hvdc-transmission,”inProc.IEEE Power Electron.Specialists Conf.,Jun.2008,pp.174–179.[12]J.Dorn,H.Huang,and D.Retzmann,“Novel voltage sourced con-verters for hvdc and facts applications,”in Proc.CIGRE,Osaka,Japan,2007.[13]R.Marquardt,“Modular multilevel converter:An universal concept forhvdc-networks and extended dc-bus-applications,”in Proc.Int.PowerElectron.Conf.,Jun.2010,pp.502–507.[14]C.Franck,“Hvdc circuit breakers:A review identifying future researchneeds,”IEEE Trans.Power Del.,vol.26,no.2,pp.998–1007,Apr.2011.[15]J.Hafner and B.Jacobson,“Proactive hybrid hvdc breakers—A keyinnovation for reliable hvdc grids,”in Proc.CIGRE,Bologna,Italy,2011.[16]J.Yang,J.Fletcher,and J.O’Reilly,“Multi-terminal dc wind farm col-lection and transmission system internal fault analysis,”in Proc.IEEEInt.Symp.Ind.Electron.,Jul.2010,pp.2437–2442.[17]R.Marquardt,“Modular multilevel converter topologies with dc-shortcircuit current limitation,”in Proc.IEEE8th Int.Conf.Power Electron.ECCE Asia,,Jun.2011,pp.1425–1431.[18]D.Trainer,C.Davidson,C.Oates,N.Macleod,D.Critchley,and R.Crookes,“A new hybrid voltage-sourced converter for HVDC powertransmission,”in CIGRE Session,2010.[19]C.Davidson and D.Trainer,“Innovative concepts for hybrid multi-level converters for hvdc power transmission,”in Proc.9th IET Int.Conf.AC DC Power Transm.,Oct.2010,pp.1–5.[20]M.Merlin,T.Green,P.Mitcheson,D.Trainer,D.Critchley,and R.Crookes,“A new hybrid multi-level voltage-source converter with dcfault blocking capability,”presented at the9th IET Int.Conf.AC DCPower Transm,London,U.K.,Oct.2010.。

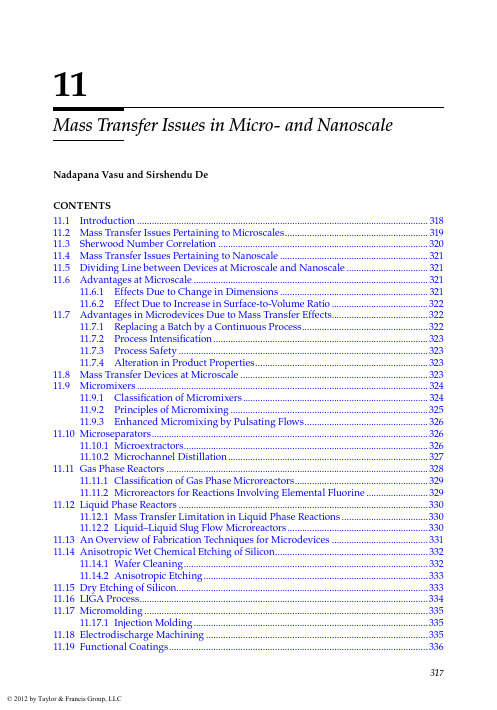

Mass Transfer Issues in Micro- and Nanoscale

Nadapana Vasu and Sirshendu De Contents 11.1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 318 11.2 Mass Transfer Issues Pertaining to Microscales........................................................... 319 11.3 Sherwood Number Correlation...................................................................................... 320 11.4 Mass Transfer Issues Pertaining to Nanoscale............................................................. 321 11.5 Dividing Line between Devices at Microscale and Nanoscale.................................. 321 11.6 Advantages at Microscale................................................................................................ 321 11.6.1 Effe

2006年天津大学校级领导班子述职会-天津大学研究生e-Learning平台

13

天津大学 Tianjin University

14

天津大学 Tianjin University

8

三,研究目标和内容

分析水下环境制约因素

在Matlab/simulink中搭建水下声学传感器 通信模型

构建协作MIMO通信系统

利用Stackelberg博弈模型进行协作节点选 择和功率分配

天津大学 Tianjin University

9

四,技术问题和方法

天津大学 Tianjin University

12

五,工作条件和计划

2013.9——2013.12 熟悉协作MIMO和博弈论理论 知识,掌握相关仿真软件的使用方法; 2014.1——2014.2 考虑水下声学通信环境的多 样性,搭建水下声通信系统模型; 2014.3——2014.5 提出适合于水下节点通信的 协作MIMO通信模型并进行验证; 2014.6——2014.8 设计基于Stackelberg博弈的 协作MIMO通信模型,并对模型、算法的可行性和有 效性进行仿真和验证; 2014.9——2014.11 撰写毕业论文,准备答辩。

10

四,技术问题和方法

针对问题3: ——构建基于Stackelberg博弈的买家-卖家模型,按照节点位置 和信道优劣状况设定协作节点的功率价格,计算源节点和协作节 点的效益函数

U Sn =CSn Rm PRmSn

m 1 M

U Rm =( Rm c) PRm Sn

n 1

N

——限制协作节点个数,可以设定一常数作为单位功率获得的效 益阈值,某节点被选择后,若源节点单位功率获得的效益大于此 阈值,则选择该节点,否则不选

单分子综述-NATURE NANOTECHNOLOGY-Single-molecule junctions beyond electronic transport-2013