Isospin breaking in scalar and pseudoscalar channels of radiative $Jpsi$-decays

Quantum Mechanics

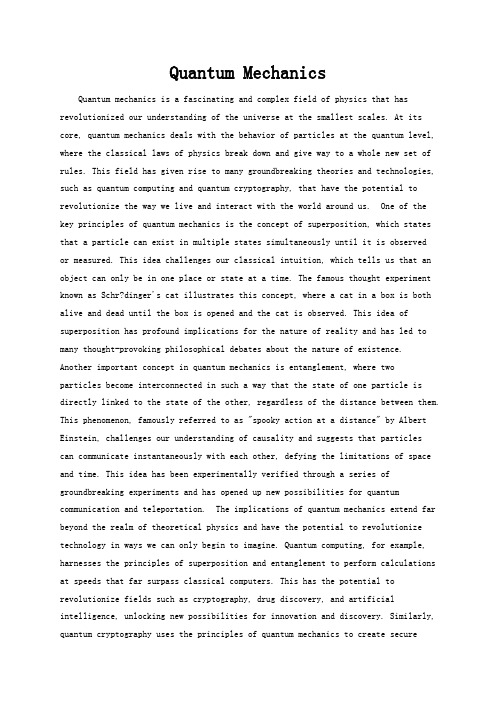

Quantum MechanicsQuantum mechanics is a fascinating and complex field of physics that has revolutionized our understanding of the universe at the smallest scales. At its core, quantum mechanics deals with the behavior of particles at the quantum level, where the classical laws of physics break down and give way to a whole new set of rules. This field has given rise to many groundbreaking theories and technologies, such as quantum computing and quantum cryptography, that have the potential to revolutionize the way we live and interact with the world around us. One of the key principles of quantum mechanics is the concept of superposition, which states that a particle can exist in multiple states simultaneously until it is observedor measured. This idea challenges our classical intuition, which tells us that an object can only be in one place or state at a time. The famous thought experiment known as Schr?dinger's cat illustrates this concept, where a cat in a box is both alive and dead until the box is opened and the cat is observed. This idea of superposition has profound implications for the nature of reality and has led to many thought-provoking philosophical debates about the nature of existence. Another important concept in quantum mechanics is entanglement, where twoparticles become interconnected in such a way that the state of one particle is directly linked to the state of the other, regardless of the distance between them. This phenomenon, famously referred to as "spooky action at a distance" by Albert Einstein, challenges our understanding of causality and suggests that particlescan communicate instantaneously with each other, defying the limitations of space and time. This idea has been experimentally verified through a series of groundbreaking experiments and has opened up new possibilities for quantum communication and teleportation. The implications of quantum mechanics extend far beyond the realm of theoretical physics and have the potential to revolutionize technology in ways we can only begin to imagine. Quantum computing, for example, harnesses the principles of superposition and entanglement to perform calculations at speeds that far surpass classical computers. This has the potential to revolutionize fields such as cryptography, drug discovery, and artificial intelligence, unlocking new possibilities for innovation and discovery. Similarly, quantum cryptography uses the principles of quantum mechanics to create securecommunication channels that are theoretically impossible to hack, offering a new level of security and privacy in an increasingly digital world. Despite the incredible potential of quantum mechanics, there are still many challenges and mysteries that remain to be solved. The field is notoriously complex and counterintuitive, with many of its fundamental principles defying our classical understanding of the world. This has led to many debates and disagreements among physicists about the true nature of quantum mechanics and how best to interpretits implications. The famous Copenhagen interpretation, for example, posits that particles exist in a state of superposition until they are observed, while the many-worlds interpretation suggests that every possible outcome of a quantum event actually occurs in a separate parallel universe. These differing interpretations highlight the deep philosophical questions that quantum mechanics raises about the nature of reality and our place in the universe. In conclusion, quantum mechanics is a field that continues to push the boundaries of our understanding of the universe and challenge our most deeply held beliefs about the nature of reality. Its principles of superposition, entanglement, and uncertainty have revolutionized our understanding of the quantum world and opened up new possibilities for technology and innovation. While there are still many mysteries and debates surrounding quantum mechanics, its potential to revolutionize fields such as computing, communication, and cryptography is undeniable. As we continue to explore the implications of quantum mechanics, we are sure to uncover even more profound insights into the nature of the universe and our place within it.。

Copy of Echinoderm word

5

Feeding behaviors

• Some echinoderms are ____________, others are detritus foragers (sea cucumbers) or plank tonic feeders (basket stars). • Sea stars are carnivorous and prey on worms or on mollusks such as clams. Most sea urchins are herbivores and gaze on algae. Brittle stars, sea lilies and sea cucumbers feeds on dead and decaying matter that drifts down to the ocean floor.

7

reproduction

• _______ reproduction • A Echinoderm is a male or female. The males and females discharge their eggs and sperm into the water where they are fertilized. • ______ reproduction • Many echinoderms have remarkable powers of regeneration. If a piece of certain echinoderms is chopped off, a new piece or even a new echinoderm can regrow.

3

Echinoderm

• _______________larvae at larval stages • Adult _____________enables animals to sense potential food, predators and other aspects of their environment from direction.

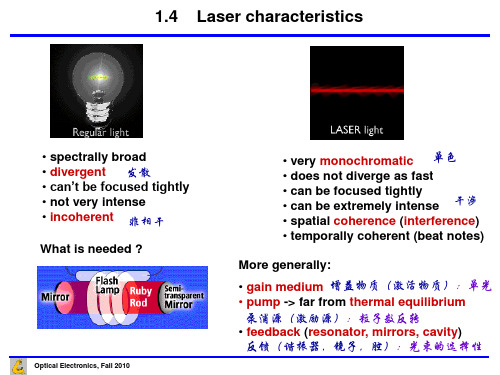

Laser Principle

kink in output power 扭结、弯曲

Laser history

Javan invents He-Ne laser Maiman builds first Townes invents and Schawlow and Townes (ruby) LASER builds first MASER propose LASER Spectra introduces first fiber optic communication IBM builds first system Hall buildsAlferov builds first laser printer (Chicago) player Einstein predicts CD Ti:Sapphire laser heterostructure laser semiconductor stimulated emission laser Nakamura builds builds quantum built Faist nanowire laser at UCB blue laser diode cascade laser

Optical Electronics, Fall 2010

Optical Electronics, Fall 2010

Optical Electronics, Fall 2010

Optical Electronics, Fall 2010

Optical Electronics, Fall 2010

laser as amplifier

Input Monitor tap

隔离器

Isolator

隔离器

Isolator Monitor tap Output

翻译

Thermal entanglement in a two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ spin chainunder an inhomogeneous magnetic field 在不均匀磁场作用下的两个量子比特海森堡海森伯 XXZ 自旋链中的热纠缠State Key Laboratory for Superlattices and Microstructures, Institute of Semiconductors, Chinese Academy of Sciences,超晶格、微结构,半导体研究所中国科学院,国家重点实验室P. O. Box 912,Beijing 100083, People’s Republic of China China Center of Advanced Science and Technology (CCAST) (World Laboratory), P. O. Box 8730, Beijing 100080,People’s Republic of China中国中心的先进的科学与技术 (CCAST) (世界实验室)、邮政信箱8730,北京 100080,中国人民共和国Received 15 March 2005; published 2 September 2005The thermal entanglement in a two-qubit Heisenberg XXZ spin chain is investigated under an inhomogeneous magnetic field b. We show that the ground-state entanglement is independent of the interaction of z-component Jz. The thermal entanglement at the fixed temperature can be enhanced when Jz increases. We strictly show that for any temperature T and Jz, the entanglement is symmetric with respect to zero inhomogeneous magnetic field, and the critical inhomogeneousmagnetic field bc is independent of Jz. The critical magnetic field Bc increases with the increasing b but the maximum entanglement value that the system can arrive at becomes smaller.两个量子比特海森堡海森伯 XXZ 自旋链中的热纠缠是根据不均匀磁场 b 进行调查。

Kaons and antikaons in asymmetric nuclear matter

Amruta Mishra∗ Department of Physics,Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, New Delhi - 110 016, India Stefan Schramm† and W. Greiner

and its width, which in turn strongly influence the antikaon-nucleus optical potential, are very sensitive to the many-body treatment of the medium effects. Previous works have ¯ self energy has a strong impact on the shown that a self-consistent treatment of the K scattering amplitudes [14, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25] and thus on the in-medium properties of the antikaons. Due to the complexity of this many-body problem the actual kaon and antikaon self energies (or potentials) are still a matter of debate. The topic of isospin effects in asymmetric nuclear matter has gained interest in the recent past [26]. The isospin effects are important in isospin asymmetric heavy-ion collision experiments. Within the UrQMD model the density dependence of the symmetry potential has been studied by investigating observables like the π − /π + ratio, the n/p ratio [27], the ∆− /∆++ ratio as well as the effects on the production of K 0 and K + [28] and on pion flow [29] for neutron rich heavy ion collisions. Recently, the isospin dependence of the in-medium NN cross section [30] has also been studied. In the present investigation we will use a chiral SU(3) model for the description of hadrons in the medium [31]. The nucleons – as modified in the hot hyperonic matter – have previously been studied within this model [32]. Furthermore, the properties of vector mesons [32, 33] – modified by their interactions with nucleons in the medium – have also been examined and have been found to have sizeable modifications due to Dirac sea polarization effects. The chiral SU(3)f lavor model was generalized to SU(4)f lavor to study the mass modification of D-mesons arising from their interactions with the light hadrons in hot hadronic matter in [34]. The energies of kaons (antikaons), as modified in the medium due to their interaction with nucleons, consistent with the low energy KN scattering data [35, 36], were also studied within this framework [37, 38]. In the present work, we investigate the effect of isospin asymmetry on the kaon and antikaon optical potentials in the asymmetric nuclear matter, consistent with the low energy kaon nucleon scattering lengths for channels I=0 and I=1. The pion nucleon scattering lengths are also calculated. The outline of the paper is as follows: In section II we shall briefly review the SU(3) model used in the present investigation. Section III describes the medium modification of ¯ ) mesons in this effective model. In section IV, we discuss the results obtained the K(K for the optical potentials of the kaons and antikaons and the isospin-dependent effects on these optical potentials in asymmetric nuclear matter. Section V summarizes our results and discusses possible extensions of the calculations. 3

Inflation in Realistic D-Brane Models

Contents

1. Introduction 2. Fluxes, Warping and Moduli Fixing 2.1 GKP Compactifications 2.2 Anti-Branes and Supersymmetry Breaking 2.3 Seeking Slow Rolls 2.4 Sticking the Standard Model in the Throat 3. The Effective Theory 3.1 Supersymmetric Terms 3.2 Supersymmetry-Breaking Terms 4. Inflationary Dynamics 4.1 Domain of Validity of Approximations 4.2 Inflationary Dynamics 4.2.1 4.2.2 4.2.3 Qualitative Description Numerical Results Scaling Arguments 1 3 3 6 7 8 10 11 13 14 15 16 16 20 24 25 30 30 32 34

The possibility of having cosmological inflation arise due to the relative motion of D-branes and their anti-branes is very attractive [1, 2, 3].1 It provides an explicit and

1

See also [4] for an early brane-antibrane proposal which does not rely on the relative inter-brane

98 德国 缺陷 正电子湮没

Appl.Phys.A66,599–614(1998)Applied Physics AMaterialsScience&Processing©Springer-Verlag1998 Invited paperReview of defect investigations by means of positron annihilationin II−VI compound semiconductorsR.Krause-Rehberg,H.S.Leipner,T.Abgarjan,A.PolityFachbereich Physik,Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg,06099Halle,Germany(Fax:+49-345/5527160,E-mail:krause@physik.uni-halle.de)Received:19November1997/Accepted:20November1997Abstract.An overview is given on positron annihilation stud-ies of vacancy-type defects in Cd-and Zn-related II−VI com-pound semiconductors.The most noticeable results among the positron investigations have been obtained by the study of the indium-or chlorine-related A centers in as-grown cad-mium telluride and by the study of the defect chemistry of the mercury vacancy in Hg1−x Cd x Te after post-growth an-nealing.The experiments on defect generation and annihila-tion after low-temperature electron irradiation of II−VI com-pounds are also reviewed.The characteristic positron life-times are given for cation and anion vacancies.PACS:61.70;78.70BII−VI compound semiconductors are considered for appli-cations in fast-particle detectors and can cover the whole wavelength range from the far infrared to the near ultraviolet in optoelectronic devices.The width of the band gap can be adjusted in pseudo-ternary compounds such as Hg1−x Cd x Te by varying the composition x.The II−VI semiconductors appeared promising for emitter or detector devices because of their excellent optical features together with the pre-dicted favorable transport properties.However,no techno-logical breakthrough has been achieved.This is mainly be-cause no II−VI compound,except CdTe,can be amphoteri-cally doped.Bulk crystals of ZnSe,CdSe,ZnS,and CdS are always n-type,independent of impurities[1].ZnTe appears only as p-type[2].A number of theoretical approaches for this behavior exists but nofinal experimental proofs for these theories have been given.The reason for the compensation could be the existence of extrinsic defects introduced during crystal growth.However,intrinsic defects or complexes of in-trinsic defects with dopants have also been discussed.The research on II−VI compounds was greatly stimulated by the growth of nitrogen-doped,p-type ZnSe layers by mo-lecular beam epitaxy(MBE)[3,4].p–n junctions were made, andfirst ZnSe-based blue lasers could be fabricated[5,6]. Nevertheless,the doping behavior of nitrogen-doped ZnSe layers is also not fully understood.It is not clear why only the nitrogen doping during MBE works for p-type conductiv-ity and why other epitaxial growth techniques provide hole densities of one order of magnitude lower[7].Obviously,the understanding of point defects in II−VI semiconductors is far from being complete.Vacancy-type defects,for example monovacancies and complexes contain-ing a vacancy,play an important role.A prominent defect in doped CdTe is the A center,identified by electron para-magnetic resonance measurements as a cadmium vacancy paired off with a dopant atom at the nearest neighbor site[8]. The dominant defect in Hg1−x Cd x Te is the mercury mono-vacancy,acting as an acceptor.A high concentration of V Hg may be the reason for the p-conductivity.These examples show the importance of experimental tools for the detection of vacancy-type defects.Such a method is positron annihila-tion,which was successfully applied for the investigation of the structure and the concentration of such defects in elemen-tal and compound semiconductors[9–11].Significant contri-butions have been made by positron annihilation to revealing the structure of such important defects in III−V compounds as the EL2defect and the DX center[12–14].The aim in this paper is to review available experimen-tal data on defect studies in II−VI compounds by positron annihilation.The paper is organized as follows.The relevant methods of positron annihilation spectroscopy and theoretical calculations of the positron lifetime in II−VI compounds are introduced in Sect.1.The experimental results on cadmium mercury telluride,cadmium telluride,and zinc-related II−VI compounds are reviewed in Sect.2.Section3summarizes positron data on irradiation-induced defects.1Basics of positron annihilation in semiconductors1.1Positron lifetime and Doppler-broadening spectroscopy The detection of defects by means of positron annihilation is based on the capture of prehensive treatments of positron annihilation in solids can be found elsewhere[15–18].Attractive potentials for positrons exist for open-volume defects,e.g.vacancies,and for negatively charged non-open600volume defects,e.g.acceptor-type impurities.The potential is based in the latter case only on the Coulomb attraction be-tween the positron and the negative defect[19].The main reason for the binding of positrons to an open-volume defect is the lack of the repulsive force of the nucleus.Additional Coulombic contributions,which enhance or inhibit the trap-ping owing to a negative or a positive charge,respectively, occur for charged vacancies[18].The positrons in a typical conventional positron experi-ment are generated in an isotope source.They penetrate the sample,thermalize and diffuse.They can be trapped in de-fects during diffusion over a mean distance of about100nm. This may result in characteristic changes of annihilation pa-rameters.The positron lifetime for open-volume defects is increased in relation to the undisturbed bulk.This is due to the reduced electron densities in these defects.The clustering of vacancies in larger agglomerates can be observed as an in-crease in the defect-related positron lifetime.The lifetime of a positron is monitored in positron lifetime spectroscopy(PO-LIS)as the time difference between the birth of the particle in the radioactive source,indicated by the almost simultan-eous emission of a1.27-MeVγquantum,and the annihilation in the sample,resulting inγrays with an annihilation energy of0.511MeV.The lifetime spectrum is formed by the col-lection of several million annihilation events.In general,the spectrum consists of several exponential decay components, which can be numerically separated(see Sect.1.3).Doppler-broadening spectroscopy(DOBS),as another positron technique,utilizes the conservation of momentum during annihilation.The total momentum of the positron and the electron is practically equal to the momentum of the annihilating electron.This momentum is transferred to the annihilationγquanta.The momentum component in the propagation direction,p z,results in a Doppler shift of the an-nihilation energy of∆E=p z c/2(where c is the speed of light).The accumulation of several million events for a whole Doppler spectrum in an energy-dispersive system leads to the registration of a Doppler-broadened line,which is caused by the contributions of electron momentums in all space di-rections.The distribution of electron momentums may be different close to defects,and this is reflected in characteris-tic changes of the shape of the annihilation line.Annihilations with core electrons having higher momentums are reduced, for example,for a vacancy,and thus the annihilation line be-comes narrower.The annihilation line is usually specified by shape parameters,such as the S parameter,which is defined as the area of afixed central region of the Doppler peak normal-ized to the whole area under the peak,i.e.to the total number of annihilation events.Another parameter is the W parameter, defined in the wing parts of the annihilation line.This param-eter is determined mainly by the annihilations of the positrons with core electrons.The W parameter is thus more sensitive to the chemical nature of the surrounding of the annihilation site.A plot of the W parameter versus the S parameter may be used for the identification of defect types[20,21].The slope of the line corresponds to the R parameter,which is charac-teristic for a certain defect type,independent of the defect concentration.If the pairs of(S,W)values plotted for differ-ent sample conditions lie on a straight line running through the bulk values(S b,W b),one has to conclude that one sin-gle defect type having different concentrations dominates the positron trapping.Positrons from an isotope source have a broad energy dis-tribution of up to several hundred keV.This leads to a mean penetration depth of some10µm,and thin epitaxial layers cannot be studied.Therefore,the slow positron beam tech-nique[22]was developed.It is based on the moderation of positrons,i.e.the generation of monoenergetic positrons with energies in the eV range.The energy of the positron beam can be adjusted in an accelerator stage.This allows the registra-tion of annihilation parameters as a function of the penetra-tion depth.Hence,depth profiling is possible with a variable information depth of up to a fewµm.The basics of the defect profiling by slow positrons in comparison with other methods was presented by Dupasquier and Ottaviani[23].A main result of the positron experiments is the positron trapping rateκ,which is proportional to the defect concentra-tion C,κ=µC.(1) The proportionality constantµis the trapping coefficient (specific trapping rate),which must be determined in correla-tion to an independent reference method.The determination of the trapping coefficient for semiconductors has been re-viewed by Krause-Rehberg and Leipner[24].Equation(1) holds strictly only in the case of a rate-limited transition of the positron from the delocalized bulk state into the deep bound state of the defect[18].This case describes well the positron trapping in vacancies.The trapping coefficient for small vacancy clusters(n≤5)increases with the number of incorporated vacancies n,µn=nµv,(2) whereµv is the trapping coefficient of monovacancies[25].1.2Temperature dependence of positron trapping in chargeddefectsThe trapping coefficientµin(1)is always a specific con-stant for a given temperature.The attractive potential is su-perimposed by a long-range Coulomb potential in the case of a charged defect.A positive charge causes a strong repul-sion of the positron,and trapping is practically impossible.In contrast,a negative charge promotes positron trapping com-pared to a neutral defect by the formation of a series of attractive shallow Rydberg states[26].The positron bind-ing energy to the shallow Rydberg states is of the order of some10meV and,therefore,the enhancement of positron trapping is especially effective at low temperatures,where the positron may not escape by thermal activation.Thus,a dis-tinct temperature-dependent trapping rate was obtained for negatively charged vacancies in Si[27]and in GaAs[28].A detailed description of the temperature dependence of positron trapping in negatively charged vacancies was given by Le Berre et al.[28].Non-open volume defects,such as acceptor-type impuri-ties or negatively charged antisite defects,may also act as positron traps provided that they carry a negative charge.The extended shallow Rydberg states are exclusively responsible for positron trapping.The binding energy of the positron is small and therefore these defects are called shallow positron traps.The positron–position probability density at the defect601 nucleus is vanishingly small because of the repulsion fromthe positive nucleus.Therefore,the positron is located andannihilates in the bulk surrounding the defect.The electrondensity felt by the positron equals the density in the bulkand hence the positron lifetime of the shallow trap is closeto the bulk lifetime.Positron trapping to these shallow trapsis important at low temperatures in practically all compoundsemiconductors.Manninen and Nieminen[29]calculated thetemperature dependence of the positron detrapping rateδ:δ=κCmk B T2πh23/2exp−E bk B T.(3)Here,κand C are the trapping rate and the concentration of the shallow positron traps.m is the effective positron mass,k B the Boltzmann constant,and E b the positron binding energy.The description of the trapping in charged defects shows that in the presence of several charged defect types in the ma-terial the temperature dependence of positron trapping may be rather complex and a quantitative evaluation of the annihi-lation parameters as a function of the temperature T is often not possible.1.3Trapping modelA phenomenological description of positron trapping was given by Berlotaccini and Dupasquier[30]and was later gen-eralized[31,32].The model is referred to as the“trapping model”.The aim is the quantitative analysis of lifetime spec-tra in order to calculate the trapping rates and the correspond-ing defect concentrations.Only one extended model that is sufficient for the interpretation of the experimental results is discussed in this paper.This model(Fig.1)includes two dif-ferent types of non-interacting open-volume defects and one shallow positron trap exhibiting thermal detrapping with the detrapping rateδ.The corresponding differential equations ared n b(t) d t =−(λb+κd1+κd2+κd3)n b(t)+δn d1(t),d n d1(t) d t =−(λd1+δ)n d1(t)+κd1n b(t),d n d2(t) d t =−λd2n d2(t)+κd2n b(t),d n d3(t)d t=−λd3n d3(t)+κd3n b(t).(4)Defect d1is the shallow positron trap,and d2and d3are open-volume defects,such as vacancies and vacancy agglom-erates.b denotes the bulk state.The n i are the normalized numbers of positrons in the state i(i=b,d1,d2,d3)at the time t,andλi are the corresponding annihilation rates(inverse positron lifetimes).The starting conditions are n b(0)=1and n d1(0)=n d2(0)=n d3(0)=0.The solution of(4)is a sum of four exponential decay terms,the prefactors of which are the intensities I1to I4.The lifetimesτ1toτ4are found in the exponents.The lifetimes and intensities are obtained asτ1=2Λ+Ξ,τ2=2Λ−Ξ,τ3=1λd2,τ4=1λd3,andFig.1.Scheme of a trapping model including two types of open-volumedefects,d2and d3,and one shallow positron trap,d1.The latter exhibitsthermally induced detrapping with the temperature-dependent detrappingrateδ.The individual trapping ratesκd1,κd2,andκd3and the correspond-ing annihilation ratesλd1,λd2,andλd3are drawn as arrows.λb is the bulkannihilation rateI1=1−(I2+I3+I4),I2=δ+λd1−12(Λ−Ξ)Ξ×1+κd1δ+λd1−12(Λ−Ξ)+κd2λd2−12(Λ−Ξ)+κd3λd3−12(Λ−Ξ),I3=κd2(δ+λd1−λd2)λd2−12(Λ+Ξ)λd2−12(Λ−Ξ),I4=κd3(δ+λd1−λd3)λd3−12(Λ+Ξ)λd3−12(Λ−Ξ).(5)The abbreviations in(5)areΛ=λb+κd1+κd2+κd3+λd1+δ,Ξ=(λb+κd1+κd2+κd3−λd1−δ)2+4δκd1.(6)The two long-lived lifetimes are equal to the defect-related lifetimes:τ3=τd2andτ4=τd3,and they are inde-pendent of the defect concentrations.The average positronlifetimeτfor this model is given byτ=4j=1I jτj.(7)The result(5)represents the components of the lifetime spec-trum.The experimental spectrum may be decomposed in suchcomponents,and the lifetimes and their intensities can beused to determine the corresponding trapping and detrappingrates.Equation(1)then provides the defect concentrations.Cases where the number of independent defects is smallerthan three can easily be obtained from(5)by setting the cor-responding trapping rates to zero.6021.4Theoretical calculation of positron lifetimesThe positron lifetimes in the bulk and in lattice defects of II −VI compounds were first theoretically calculated by Puska [33]who used the linear muffin-tin orbital band-structure method within the atomic sphere approximation.Monovacancies were treated in different charge states by the corresponding Green’s function method.More recent calcu-lations from the same group [34,35]used the superimposed-atom model [36].A supercell approach with periodic bound-ary conditions for the positron wave function retaining the three-dimensional character of the crystal was employed.The electron–positron correlation potential was treated with the local-density approximation (LDA)[37].The results of pure LDA calculations provided lifetimes,which were too low compared to experimental values.The calculation method was hence modified in such a way that the d-electron en-hancement factors for Zn ,Cd ,and Hg were scaled to provide the correct lifetimes for the pure metals [34,35].Another ap-proach used the enhancement factors for d electrons in Ag and Au [38].Calculations of positron lifetimes of vacan-cies were carried out with unscaled LDA [34,35],providing values that are obviously too small compared to the bulk life-times of the scaled LDA calculations.In order to compare the theoretical defect-related lifetimes to the experimental ones and to the bulk lifetimes (Table 1),the vacancy lifetimes given by Plazaola et al.[34,35]were multiplied by the ratio of the bulk lifetimes calculated for the pure and scaled LDA,respec-tively.No relaxation effects and Jahn-Teller distortions were taken into account in these computations.Although the positron lifetimes for almost all II −VI com-pound semiconductors have been calculated,only materials for which experimental data exist are included in Table 1.The calculated bulk lifetimes agree reasonably well with the ex-perimental values.However,the lifetimes calculated for the vacancies are always distinctly smaller than the measured ones.Table 1.Calculated and experimental positron lifetimes for II −VI semiconductors.The bulk lifetimes were calculated using a modified semi-empirical local density approximation (LDA)[34,35].The LDA lifetimes for the vacancies given by Plazaola et al.[34,35]are scaled by a factor to allow a more realistic comparison to the experiments (see text).The experimental values of the cation vacancies (vacancies of group II atoms)are related to the A centers in In -or Cl -doped CdTe ,to the mercury vacancies in Hg 1−x Cd x Te ,and to the Zn vacancies as part of complexes in Zn -related compounds,respectively.The only experimental value for anion vacancies (vacancies of group VI atoms)is that of the tellurium vacancy in Hg 1−x Cd x Te MaterialBulk lifetime /psCation-vacancy lifetime /ps Anion-vacancy lifetime /ps Calculated Experimental Calculated Experimental Calculated Experimental CdTe286291[104]298320±5[45,46]312–281[68]330±15[44,52,68]283±1[44]285±1[45,46]280±1[52]HgTe274274[68]285–300–Hg 0.8Cd 0.2Te –274[68]–309[69]–325±5[93]286[69]305[54,70]275[54]319[97]278[70]282[97]ZnO –169±2[88]–255±16[86,87]––183±4[86,87]211±6[102]ZnS 225230[78,80]240290[80]237–ZnSe 240240[79]253–260–ZnTe260266[78]266–297–2Characterization of defects in as-grown II –IV compounds 2.1Cadmium tellurideCadmium telluride can be amphoterically doped.However,the doping and compensation behavior are still not com-pletely understood.Important defects for the understanding of the compensation are the impurity-vacancy complexes called “A centers”[39].These centers consist of a group-II vacancy paired off with either a group-VII donor (F ,Cl ,Br ,I )on the Te site,or with a group-III donor (e.g.Ga ,In )the Cd site [40].The ionization level of the Cl -related A center,(V Cd Cl Te )−/0,was determined by photolumines-cence measurements to be located at 150meV above the va-lence band [41].The levels for the isolated monovacancies were also investigated experimentally.The 2−/−level of the Cd vacancy was found with electron paramagnetic resonance at E d −E v <470meV [42]and the 0/+level of the Te va-cancy (F center)at E d −E v <200meV (E d defect ionization level,E v position of the top of the valence band)[43].2.1.1The A center.Weakly In -doped cadmium telluride was studied by positron lifetime spectroscopy as a func-tion of the temperature [44–46].Distinct positron trapping in a monovacancy-type defect was found.The defect-related lifetime was given first as 330±5ps [44],but was corrected later to 320±5ps [45,46].The lifetime was interpreted to be either due to isolated Cd monovacancies in a double negative charge state or due to (V Cd In Cd )−complexes.The average positron lifetime exhibited a distinct decrease with decreasing temperature,which was attributed to the presence of shal-low positron traps,i.e.negatively charged non-open volume defects.The compensation mechanism in iodine-doped CdTe lay-ers grown by MBE was investigated by photoluminescence (PL),conductivity measurements,and Doppler-broadening603spectroscopy [47].The DOBS S parameter increased dis-tinctly with increasing iodine concentration,i.e.with the free-electron concentration.The iodine doping obviously induced vacancy-type defects.This result is in agreement with the proposed microscopic structure of the iodine-related A center [40].Kauppinen and Baroux [48]investigated CdTe crystals doped with In or Cl with positron lifetime and Doppler-broadening spectroscopy.The Doppler measurements were carried out in a background-reducing coincidence setup [49,50].Vacancy-type defects were found in all samples.Defect-related lifetimes of 323and 370ps were separated in CdTe :In and in CdTe :Cl ,respectively.The indium-or chlorine-related A centers were assumed to be the positron traps responsible.This interpretation was supported by the Doppler measure-ments in the high-momentum range of the spectrum,where the annihilation with core electrons dominates.It was con-cluded that the annihilation takes place in the cadmium va-cancy that is part of the A center.The distinct difference in the positron lifetime for In -and Cl -related A centers was ascribed to different open volumes.A stronger outward lat-tice relaxation was assumed for V Cd Cl Te .However,the ob-served longer lifetime may also be interpreted by the occur-rence of an additional defect with larger open volume (see discussion of Fig.3).In contrast to In doping,chlorine impurities lead to high-resistance CdTe material.A series of CdTe samples contain-ing chlorine in a concentration range from 100to 3000ppm was studied by positron lifetime measurements [51,52].The average positron lifetime measured as a function of the sam-ple temperature is shown in Fig.2.The reference sample exhibited a single-component spectrum with a temperature-independent lifetime of 280±1ps that was attributed to the bulk lifetime.The average lifetime increased strongly with in-100200280300320340360380300Sample temperature [K]A v e r a g e l i f e t i m e [p s ]Fig.2.Average positron lifetime as a function of the sample temperature measured in cadmium telluride with a chlorine content in a range from 100to 3000ppm [52].A nominally undoped sample is included for reference.The full lines are fits according to the trapping model of Fig.1and (5)L i f e t i m e [p s ]Cl content [ppm]10101T r a p p i n g r a t e [s ]-1Cl content [ppm]Fig.3a,b.Decomposition of the positron lifetime spectra measured in chlorine-doped cadmium telluride at room temperature as a function of the chlorine content [52].a Positron lifetime components.The two long-lived lifetimes (and ◦)represent the lifetimes τd2and τd3related to two de-fects with different open volumes.The shortest lifetime ()is the reduced positron bulk lifetime τ1,which corresponds reasonably to the lifetime (full line)calculated from a trapping model with two open-volume defects (ob-tained from (5)by setting κd1=0).b Trapping rates of the defects d2(A center)and d3calculated from the decomposition of the spectra.The dashed lines in a and b are drawn to guide the eyecreasing Cl content,showing that open-volume defects,prob-ably in a complex with chlorine,were present.It should be noted that the observed change of 100ps in τat T ≥250K is exceptionally large,indicating that the defect-related positron lifetime must be high.The open volume of the defects should thus be distinctly larger than that of a monovacancy.The lifetime spectra were decomposed at first into two components yielding a defect-related positron lifetime of 350to 395ps ,which increased with increasing Cl content [51].These results correspond well to the characteristic lifetime of 370ps found in CdTe :Cl by Kauppinen and Baroux [48].However,the variance of the fit in the experiments by Polity et al.[51]was rather poor,indicating the presence of an-other unresolved lifetime component.Indeed,repeated meas-urements with a higher figure of 2×107annihilation events allowed the decomposition of three components at tempera-tures above 250K for the same samples [52].Two lifetimes with τd2=(330±10)ps and τd3=(450±15)ps were sepa-rated (Fig.3a).Hence,the previously obtained defect-related lifetime of 370ps must be regarded as an unresolved mixture of τd2and τd3.The defect d2represents a monovacancy-related defect and is attributed to the chlorine A center,V Cd Cl Te .Defect d3obviously exhibits an open volume dis-tinctly larger than that of a monovacancy.The ratio τd3/τb =1.6indicates that d3comprises at least the open volume of a divacancy.For comparison,this ratio equals 1.34for the nearest-neighbor divacancy in CdTe according to the calcula-tions of Puska [38].In contrast to the earlier results [51],the reduced bulk lifetimes τ1calculated according to a trapping model with two open-volume defects (solid line in Fig.3a)agreed reasonably well with the measured values.This trap-ping model is obtained from (5)by setting κd1=0,i.e.neg-lecting the shallow traps in this temperature range.The trapping rates κd2and κd3calculated from the de-composition of the lifetime spectra are shown in Fig.3b.The trapping rates of both open-volume defects increase with the Cl content,leading us to the conclusion that not only d2,but604also d3,represents a complex containing Cl.The concentra-tions C d2and C d3can be estimated according to(1).When the Cl content is increased from100to3000ppm,the d2(A cen-ter)density increases from3×1016to4×1017cm−3and the d3density from1×1016to1×1017cm−3.Hence,the total chlorine content in the defects d2and d3amounts to less than2%of the Cl added during crystal growth.Trapping coeffi-cients ofµ=9×1014s−1and1.8×1015s−1were used for these estimations[52].Samples from the same set were stud-ied in correlated photoluminescence measurements.The con-centration of the A centers was determined from the shift of the zero-phonon line of the1.4-eV band,which is character-istic for the A center.The concentrations obtained in this way were within the error limits of the positron measurements.The temperature dependence of the average lifetimeshown in Fig.2exhibits a decrease towards lower T,indi-cating the presence of shallow positron traps.The trapping model analysis(solid line in Fig.2)including the tempera-ture dependence(3)of the detrapping rateδrevealed that the concentration of the shallow traps did not depend on the chlorine content.The shallow traps were attributed to neg-atively charged acceptor-type impurities in agreement with photoluminescence results[52].2.1.2Silver diffusion experiments.The diffusion of silver in p-type cadmium telluride results in an increase in the degree of compensation as detected by photoluminescence and Halleffect measurements[53].This is illustrated in the upper part of Fig.4,where the hole concentration is plotted against the time after silver was injected by dipping the crystal into anAgNO3solution.When the silver diffusion was carried out in p-type CdTe crystals,the concentration of Ag Cd impurities increased.This was indicated by the enhancement of the corresponding (A0,X)bound exciton line in the PL spectra.It was supposed that the interstitially diffusing silver interacts with vacanciesaccording to the defect reactionV Cd+Ag i→Ag Cd.(8)In order to confirm this assumption,positron lifetime meas-urements were carried out.As the native concentration of vacancies was too low to be detected by positron annihilation, post-growth annealing at820◦C under equilibrium condi-tions in a Te atmosphere was performed in a two-zone fur-nace over a period of6weeks.The annealing conditions were chosen in such a way as to increase the concentration of Cd vacancies to a level of several1016cm−3.An average positron lifetime of294.5ps was found after this procedure[54].The increase of about10ps in the positron lifetime compared to the bulk value was attributed to these cadmium vacan-cies.A silver diffusion experiment was carried out thereafter under conditions comparable to those used by Zimmermann et al.[53].The result is shown in the lower part of Fig.4. The average positron lifetime decreased markedly during the diffusion experiment carried out at room temperature.This decrease was taken as a proof of the dominance of the defect reaction(8),resulting in a decrease in the V Cd concentration.A similar experiment was performed by Grillot et al.[55]in CdS,where cadmium vacancies were alsofilled by diffusing silver.However,the time constants of the diffusion process mon-itored by the change in the hole concentration and by the change inτare distinctly different(Fig.4).Although the electrical measurement shows the activation of the silver in-terstitials acting as donors in the bulk CdTe,the decrease in the average positron lifetime reflects reaction(8).Since the silver diffusion should be much faster than the kinetics of(8), it was concluded that an additional barrier has to be overcome for the Ag i in order for cadmium vacancy sites to become occupied[54].2.2Mercury cadmium tellurideThe intermixing of the semiconductor CdTe with the semi-metal HgTe allows the adjustment of the width of the band gap by variation of the composition x in Hg1−x Cd x Te. The material with a composition of about x=0.2becomes a narrow-gap semiconductor and is of interest for infrared de-tector applications in the atmospheric transmission window around10µm.The Hg vacancy is the most important point defect because of its electrical activity as an acceptor and the high diffusivity of mercury[56,57].Furthermore,the Hg partial pressure is already rather high at low temperatures. The stoichiometry,i.e.the content of mercury vacancies,can be influenced by post-growth annealing under defined vapor pressure conditions[58].The Hg vacancy is negatively charged and is thus an in-teresting subject for the application of positron annihilation techniques.Thefirst positron experiments on Hg1−x Cd x Te were reported by V oitsekhovskii et al.[59],Dekhtyar et al.[60],and Andersen et al.[61].The positron annihilation results of post-growth annealing and diffusion experiments Averageholedensity[cm]-3Averagelifetime[ps]Time[h]210´110´Fig.4.Hole density determined by Hall effect measurements and average positron lifetime as a function of the time after silver injection into a p-type cadmium telluride sample.The upper part of the plot was taken from Zim-mermann et al.[53],the lower part from Krause-Rehberg et al.[54].The decrease in the hole concentration corresponds to a diffusion constant D Ag of interstitial silver of1×10−8cm2/s[53]。

Mapping of spin lifetimes to electronic states in n-type GaAs near the metal-insulator tran

a r X i v :0706.1884v 1 [c o n d -m a t .m t r l -s c i ] 13 J u n 2007APS/123-QEDMapping of spin lifetimes to electronic states in n -type GaAs near the metal-insulatortransitionL.Schreiber,M.Heidkamp,T.Rohleder,B.Beschoten,∗and G.G¨u ntherodtII.Physikalisches Institut,and Virtual Institute for Spin Electronics (ViSel),RWTH Aachen University,Templergraben 55,52056Aachen,Germany(Dated:February 1,2008)The longest spin lifetimes in bulk n -GaAs exceed 100ns for doping concentrations near the metal-insulator transition (J.M.Kikkawa,D.D.Awschalom,Phys.Rev.Lett.80,4313(1998)).The respective electronic states have yet not been identified.We therefore investigate the energy dependence of spin lifetimes in n -GaAs by time-resolved Kerr rotation.Spin lifetimes vary by three orders of magnitude as a function of energy when occupying donor and conduction band states.The longest spin lifetimes (>100ns)are assigned to delocalized donor band states,while conduction band states exhibit shorter spin lifetimes.The occupation of localized donor band states is identified by short spin lifetimes (∼300ps)and a distinct Overhauser shift due to dynamic nuclear polarization.PACS numbers:78.47.+p,78.55.Cr,85.75.-dWithin the framework of the emerging field of spin-tronics,the spin degree of freedom is exploited for infor-mation storage as well as processing and could serve as a qubit for quantum computation [1].Spin coherence and long spin lifetimes are a prerequisite for novel spintronic devices.Electron spins in Si-doped bulk n -GaAs drew at-tention,when long spin lifetimes T ∗2>100ns and coher-ence lengths larger than 100µm were determined using time-resolved Faraday rotation [2,3].Since then n -GaAs was used as a model system to investigate spin injectionand spin transport phenomena [4,5,6].The long T ∗2of bulk n -GaAs,however,is restricted to a doping concen-tration in the vicinity of the metal-insulator transition (MIT)and shortens dramatically towards both sides of the transition [2,7].Similar results in n -type GaN [8],and n -type Si [9]point to a universal phenomenon.How-ever,the respective electronic states yielding these long T ∗2near the MIT have not been identified so far.Various spin relaxation mechanisms have been consid-ered to explain the dependence of T ∗2on carrier concen-tration,temperature,and magnetic field B .The relevant relaxation mechanisms differ substantially for delocalized spins with,e.g.,the D’yakonov-Perel’(DP)dephasing mechanism [10,11,12,13],and for spins localized at im-purity sites with,e.g.,relaxation by hyperfine interaction [13,14,15].Concerning the electronic states of n -type semiconductors,the MIT was shown to occur within the donor band (DB)[16],which is separated from the con-duction band (CB).Near the Fermi level (E F ),the elec-tronic structure is governed by both doping induced dis-order and local Coulomb correlation.The former yields Anderson-localized states in the upper and lower donor band-tails,which are separated from extended states in the center by mobility edges [17].The latter may lead to a Coulomb gap U at E F [18].Both interactions yield a complex electronic structure with coexisting localized and delocalized DB states as well as CB states.Spin dephasing in n -GaAs has mostly been investigated forstates at E F [2,3].There is,however,no energy-resolvedstudy of T ∗2,which would allow to assign spin lifetimes to the respective electronic states of both the donor and the conduction band.We expect that this assignment helps to identify the dominant spin relaxation mechanisms in the vicinity of the MIT.In this Letter,we study the spin lifetime T ∗2of co-herent electron spin states in n -GaAs,which are opti-cally excited in both the donor and conduction band and probed by time-resolved Kerr rotation (TRKR)at 6K.Due to the coexistence of distinct electronic states,thesample is not characterized by a single T ∗2:T ∗2varies by three orders of magnitude as a function of photon en-ergy.The longest T ∗2values which may exceed 100ns are found for delocalized donor band states,while free con-duction band states exhibit shorter spin lifetimes.Our time-resolved Kerr signal shows up to three exponential decay regimes with different precession frequencies.The latter can change due to an additional nuclear magnetic field arising from dynamically polarized nuclei,when res-onantly pumping spins into localized DB states.Two (001)-oriented,500µm thick GaAs wafers with different Si-doping concentrations have been investi-gated:Sample A with a carrier concentration of (2.4±0.2)×1016cm −3is doped close to the MIT (critical car-rier concentration in Si:GaAs n c ∼=1.5×1016cm −3)[16].Reference sample B has a carrier concentration of (1.5±0.4)×1018cm −3and is therefore degenerated [18].We used two tuneable,mode-locked Ti:Al 2O 3lasers pro-viding ∼150fs optical pulses corresponding to a spectral width of ≈6nm at a repetition frequency of 80MHz.Electronic phase-locking of both lasers enables us to em-ploy one laser for spin pumping at an energy E pu and the other one for probing the spin orientation at an en-ergy E pr after a variable delay time ∆t =0...16ns.The normal-incident pump pulses,which were circularly po-larized by a photo-elastic modulator (PEM),excite spin-polarized electrons and holes oriented along the beam2∆t (ps)θ∆t (ps)∆t (ps)sample Bsample A2.00-0.8θK (arb. units)7.60-5.3θK (arb. units)FIG.1:(Color)Time-resolved Kerr rotation for photon en-ergies E =E pu =E pr at 6K with (a)θK (∆t )for sample A at B =1T;the red line shows the shift of the beating node;(b)θK (∆t,E )for sample A at B =1T;(c)θK (∆t,E )for the degenerate sample B at B =6T.Arrows mark the respective energies,above which the transmission drops below 5%.direction in the strain-free mounted samples with an av-erage power P =50W/cm 2.The projection of the pump induced spin magnetization onto the surface nor-mal of the sample is determined with linearly polarized laser pulses by Faraday rotation θF in transmission and by Kerr rotation θK in reflection.Transverse magnetic fields B are applied in the plane of the sample.In Figure 1(a),we plot θK (∆t )of sample A measured for various photon energies E =E pu =E pr at B =1T and at T =6K.Obviously,the spins precess at all energies E ,but the damping of the oscillations andthus T ∗2is E -dependent:for E below the CB edge T ∗2is long,whereas for the highest E ,at which CB states arepumped,T ∗2is much reduced.Strikingly,a node in the oscillation envelope (red line in Fig.1(a))near the band edge indicates that the spins precess with at least two Larmor frequencies ω(i ).Therefore,θK (∆t )is described by n decay componentsθK (∆t )=n iA (i )exp−∆t3 constant and exhibits|g∗|=|g0|=0.43.Near the CBedge(green),B-independent values of T∗2∼100...300psare determined,which distinguish themselves by a rapiddecrease ofω(E).At the beginning of the third region(blue),T∗2sets-in at∼6ns and decreases with increasingE.The correspondingωdecreases slightly and saturatesat high E.The overlap in energy of the second and thirdregion,which occurs due to the spectral width of thelaser pulses,generates the node in the oscillation enve-lope shown in Figure1[19].For the degenerate sample B,T∗(i) 2(E)can befitted by one component i.As expected[2,7],T∗2is over-all shorter compared to sample A and T∗2increases with the increase of B,which is typical for the DP dephasing mechanism[10].In the following,we assign the T∗(i)2of the spins ob-served in the three energy ranges to carriers occupying different electronic states.Since hole spins relax quickly 10ps in GaAs and excitons are broken up at high magneticfields B 1T[20],we consider single elec-tron states.Since the carrier concentration of sample A is slightly above n c,E F lies within the delocalized DB states as sketched in Figure3.Thus delocalized DB states are pumped at lowest E,which exhibit the longest T∗2(red component in Fig.2).However,to our knowl-edge there is no relaxation mechanism of spins,which accounts for their distinct B-dependence.We assign the second energy range(green),which is missing for the degenerate sample B,to Anderson localized electronic states at the DB tail.Their distinct E-dependence of ωand T∗2can be linked to the decrease of localization length upon approaching the DB tail.The localization of electrons yields spin relaxation due to hyperfine inter-action with the nuclei[14,15].This gives rise to dynamic nuclear polarization and a nuclearfield,which altersω(Overhauser shift)[21].However,from Ref.[14]long T∗2∼300ns are expected for localized electron spins, although we could not reproduce this result with insu-lating n-GaAs samples using TRKR.In Ref.[15],an additional short T∗2∼100ps component is predicted, when both localized and delocalized spins are pumped. This is assigned to their cross-relaxation rate.Whereas this might explain our short T∗2,it does not account for the distinctω(E)dependence.In the third energy regime (blue),electrons are pumped in the CB.The decrease of ωobserved for both samples is due to g∗:The absorption of the pump pulse lifts the local chemical potential,thus reducing the absolute value of the energetically averaged g∗factor according to its dispersion in the CB[20].The apparent decrease of T∗2(E)might be explained by car-rier cooling and interband relaxation.Due to both,the carriers relax below the probed energy.This notion can be confirmed by sweeping E pu with E pr heldfixed at the bottom of the CB.The corre-spondingfits of T∗(i)2(E pu)andω(i)(E pu)of sample Aat B=1T are shown in Figure3(a)and(b).Indeed,pr23452345E (eV)E (eV)T(i)2*(ps)T(i)2*(ps)ω(i)/ω0FIG.3:(Color)Upper left:sketch of density of DB and CBstates.Fitted spin lifetimes T∗(i)2and Larmor frequenciesω(i) as a function of pump laser energy E pu at magneticfields B for MIT sample A(full symbols)for different probe energies E pr is marked with vertical grey lines.For comparison data from Fig.2with E pu=E pr are also plotted(open symbols).this method allows to correct T∗2for energy relaxation, since T∗2(E pu)(blue full symbols)decreases only slightly compared to Figure2.However,there is an additionalshort T∗(i)2(E pu)(green full symbols),which results from probing localized spins at the DB tail because of the spec-tral width of the probe pulses.To clarify this point, E pr isfixed at an energy even lower than the band gap(Fig.3(c)-(e)).For this E pr,the longest T∗(i)2(E pu)(red) attributed to delocalized DB states is observed,which turned out to be nearly constant at B=0T.Note that the average pump power is held constant,but the excited carrier density changes by orders of magnitude in the ab-sorbing regime.This has a negligible effect on the longest T∗2.More strikingly,additional components i become ob-servable,when E pu passes the localized and CB states. Thus,different electronic states become occupied either due to direct optical excitation or carrier relaxation as sketched in Figure3(upper left).From the onset of the θF signal(not shown),we deduce that the delocalized DB states are occupied within∆t<10ps for all E pu. At B=1T(Fig.3(d))and E pu beyond the band edge,the two long T∗(i)2components(blue and red)generate nodes in the oscillation envelope(Fig.1(a))and can be separated by theirω(i)(Fig.3(e)).Forfitting,however, the longest T∗2(red)of delocalized DB had to befixed with minor influence on the blue component.The lat-4∆t (ns)FIG.4:(Color)Faraday rotationθF(∆t)of sample A for left(σ−)and right(σ+)circularly polarized pump pulses(red ar-rows)at B=1T,E pu=1.514eV and E pr=1.494eV.Inset:fitted normalized Larmor frequenciesω(i)and correspondinglateral nuclear magneticfields BN for both polarizations as afunction of the average pump power.ter can be clearly assigned to CB states by comparing it to T∗2(E pu)and g∗(E pu)of Figure3(a)and(b).The existence of three components i and their onset whensweeping E pu confirms our assignment of T∗(i)2(E)to thethree types of electronic states.Since an optically pumped spin imbalance of localized electrons leads to pronounced dynamic nuclear polariza-tion(DNP)[21],wefinally check our assignment of elec-tronic states to T∗2by identifying DNP.When resonantly exciting localized spins at,e.g.,E pu=1.514eV,then DNP is optically observed by the Overhauser shift.This shift results in a change ofωdue to the presence of a lateral nuclear magneticfield B N adding up to B.Since spins exhibiting long T∗2are most sensitive to this shift, we chose the same E pr as in Figure3(c)-(e).In order to generate a well-defined longitudinally pumped spin com-ponent and thus to control the direction of B N with re-spect to B,we replaced the PEM by a quarter-waveplate and rotated sample A as sketched in Figure4[22].In this geometry,θF(∆t)exhibits nodes in the oscillation envelope at long∆t,proving the presence of two longT∗(i) 2components with differentω(i).The dependence ofωon the type of circularly polarizationσ±of the pump pulses,is clarified by thefittedω(i)in the inset of Fig-ure4.The sign and magnitude of B N is determined by σ±and the pump power,respectively.B N saturates for σ+at-90mT,when|g∗|=0.43is assumed to be con-stant.However,the blue component,which is likely due to spins in the CB(cp.to Fig.3(e)),is more sensitive to B N than the spins attributed to delocalized DB states (red).However,this point needs further investigation. Since DNP is not observable when E pu is reduced below 1.5eV,our assignment of localized states is confirmed. The pronouncedω(loc)(E)dependence of the localized spins(green)(see Fig.2left)compared to theωvari-ation(blue)in the inset of Figure4suggests that the ω(loc)(E)is indeed influenced by increasing localization and thus responsible for a rise of B N at the DB tail[23]. In summary,we have studied the energy dependence of spin lifetimes in n-type GaAs for electron doping near the metal-insulator transition.Distinct spin lifetimes have been assigned to both donor and conduction band states. Spin states at the Fermi level are delocalized donor band states with the longest spin lifetime,which may exceed 100ns.The strong decrease of spin lifetimes in the con-duction band is related to energy relaxation of hot elec-trons.Localized donor band states exhibit the shortest spin lifetimes of∼300ps.Resonant optical pumping of these localized states yields strong dynamic nuclear po-larization.This work was supported by BMBF and by HGF.∗Electronic address:beschoten@physik.rwth-aachen.de [1]D.D.Awschalom and M.E.Flatte,Nature Phys.3,153(2007).[2]J.M.Kikkawa and D.D.Awschalom,Phys.Rev.Lett.80,4313(1998).[3]J.M.Kikkawa and D.D.Awschalom,Nature397,139(1999).[4]Y.Kato et al.,Science306,1910(2004).[5]S.A.Crooker et al.,Science309,2191(2005).[6]X.Lou et al.,Nature Phys.3,197(2007).[7]R.I.Dzhioev et al.,Phys.Rev.B66,245204(2002).[8]B.Beschoten et al.,Phys.Rev.B63,121202R(2001).[9]V.Zarifis and T.G.Castner,Phys.Rev.B36,6198(1987).[10]J.Fabian and S.D.Sarma,J.Vac.Sci.Technol.B17,1708(1999).[11]P.H.Song and K.W.Kim,Phys.Rev.B66,035207(2002).[12]Z.G.Yu et al.,Phys.Rev.B71,245312(2005).[13]B.I.Shklovskii,Phys.Rev.B73,193201(2006).[14]R.I.Dzhioev et al.,JETP Lett.74,200(2001).[15]W.O.Putikka and R.Joynt,Phys.Rev.B70,113201(2004).[16]D.Romero et al.,Phys.Rev.B42,3179(1990).[17]P.Anderson,Phys.Rev.189,1492(1958).[18]A.Efros and M.Pollak,eds.,Electron-Electron Interac-tion in Disordered Systems(North-Holland,Amsterdam, 1984).[19]The third region sets in at even lower energy E≈1.514eV,where T∗2cannot be determined exactly dueto the beating.[20]M.Oestreich et al.,Phys.Rev.B53,7911(1996).[21]D.Paget et al.,Phys.Rev.B15,5780(1977).[22]G.Salis et al.,Phys.Rev.B64,195304(2001).[23]Even with the PEM,ωchanges whithin∼1min afterswitching on the pump.We attribute this to an Over-hauser shift.。

Ising spin glass under continuous-distribution random magnetic fields Tricritical points an