荷兰高速铁路南线(HSL South)投入运营

2024年全球高铁网路初步形成

促进可持续发展: 高铁有助于减少交 通拥堵和空气污染, 促进城市可持续发 展

保护自然景观:高 铁建设通常不会破 坏自然景观,有助 于保护生态环境

促进旅游业发展: 高铁有助于缩短旅 行时间,促进旅游 业的发展,从而带 动当地经济发展

PART 5

未来全球高铁网路的发展趋势

高铁网路的发展潜力

提高运输效率:高铁速度快,可以大幅缩短出行时间 促进经济发展:高铁可以带动沿线地区的经济发展,促进区域间的交流与合作 提高生活质量:高铁可以提供更加舒适、便捷的出行方式,提高人们的生活质量 推动科技创新:高铁的发展需要不断推动科技创新,促进相关产业的发展

PART 4

2024年全球高铁网路的影响

对国际交通的影响

提高国际运输效率 促进国际贸易和合作 加强各国之间的联系和交流 推动全球经济一体化发展

对旅游业的影响

高铁网络的形成将极大地促进旅游业的发展,缩短旅行时间,提高出行效率。

高铁网络的覆盖范围将扩大,使得更多的旅游景点和目的地变得容易到达。

高铁网络的便捷性将吸引更多的游客选择高铁出行,从而带动旅游业的繁荣。

共享经济模式:鼓励企业和个人共享高铁资源,提高资源利用率

绿色出行模式:推广环保、节能的高铁出行方式,降低碳排放

国际化运营:加强国际合作,推动全球高铁网路的互联互通,实现全球高铁资源的共享和 优化配置

高铁网路与其他交通方式的融合发展

高铁与其他交通方式的连接:如机场、地铁、公交等,实现无缝换乘 高铁与其他交通方式的互补:如长途运输与短途运输的结合,提高运输效率 高铁与其他交通方式的竞争:如与航空、公路等交通方式的竞争,推动技术进步和降低成本 高铁与其他交通方式的融合:如高铁与城市规划、环境保护等方面的融合,实现可持续发展

《上海铁道》报社联系方式

4

16

18 19

南京-上Hale Waihona Puke 上海-无锡-南京12 10

20

上海-苏州-南京-合肥

28

媒力· 中国 |

《上海铁道》杂志

上海铁路局运行线路

序号

21 22 23 24 25

起止站 上海(虹桥)-南京 -合肥

上海(虹桥)-南京 南京南- 虹桥 南京(南)-合肥 南京南-北京南

2012年,将有3500 公里高铁通车,全国高铁通车里程将突破1万公里(2012 年4 月16 日《新闻联播》) “十二五”末,我国将基本建成以“四纵四横”高速铁路为骨架的快速铁路网, 营业里程达1.8 万公里以上,基本 覆盖50万以上人口的城市(人民日报《中国迈入高铁时代》2012 年09月05日)

《上海铁道》杂志

动车组列车旅客群体——学历分布

动车组列车旅客群体学历分布 %

媒力· 中国 |

《上海铁道》杂志

动车组列车旅客群体——职业比例

动车组列车旅客群体职业分布 % 媒力· 中国 |

《上海铁道》杂志

动车组列车旅客群体——出行目的

G212\G213\G214\G215 D364\D316\D351\D352\D319\D361

趟数

01

虹桥——北京南

44

02 03 04

虹桥——青岛 虹桥-天津西 虹桥-济南西

15 4 6

05

虹桥-南京

G7074\G7124\G7011\G7014\G7019\G7072\G7141\G7031\G7040\G7215\G7125\G 7130\G7055\G7054\G7071\G7063\G7094\G7093\G7076\G7038\G7053\G7012\G7 017\G7216\G7122\G7121\G7126\G7131\G7136\G7139\G7140\G7135\G7138\G71 27\G7132 D3068\D3069\D3070\D3067\D3060\D3061\D3062\D3059\D3018\D3019\D3056\D3 057\D3058\D3055\D3020\D3017\D3022\D3023\D3024\D3021\D3064\D3065\D306 6\D3063

国际市场高铁发展史

国际市场高铁发展史早在20世纪初前期,当时火车“最高速率”超过时速200公里者寥寥无几。

直到1964年日本的新干线系统开通,是史上第一个实现“营运速率”高于时速200公里的高速铁路系统。

世界上首条出现的高速铁路是日本的新干线,于1964年正式营运。

日系新干线列车由川崎重工建造,行驶在东京-名古屋-京都-大阪的东海道新干线,营运速度每小时271公里,营运最高时速300公里。

第一次浪潮(1964年~1990年)1959年4月5日,世界上第一条真正意义上的高速铁路东海道新干线在日本破土动工,经过5年建设,于1964年3月全线完成铺轨,同年7月竣工,1964年10月1日正式通车。

东海道新干线从东京起始,途经名古屋,京都等地终至(新)大阪,全长515.4公里,运营速度高达210公里/小时,它的建成通车标志着世界高速铁路新纪元的到来。

随后法国、意大利、德国纷纷修建高速铁路。

1972年继东海道新干线之后,日本又修建了山阳、东北和上越新干线;法国修建了东南TGV线、大西洋TGV线;意大利修建了罗马至佛罗伦萨。

以日本为首的第一代高速铁路的建成,大力推动了沿线地区经济的均衡发展,促进了房地产、工业机械、钢铁等相关产业的发展,降低了交通运输对环境的影响程度,铁路市场份额大幅度回升,企业经济效益明显好转。

第二次浪潮(1990年至90年代中期)法国、德国、意大利、西班牙、比利时、荷兰、瑞典、英国等欧洲大部分发达国家,大规模修建该国或跨国界高速铁路,逐步形成了欧洲高速铁路网络。

这次高速铁路的建设高潮,不仅仅是铁路提高内部企业效益的需要,更多的是国家能源、环境、交通政策的需要。

第三次浪潮(从90年代中期至今)在亚洲(韩国、中国台湾、中国)、北美洲(美国)、澳洲(澳大利亚)世界范围内掀起了建设高速铁路的热潮。

主要体现在:一是修建高速铁路得到了各国政府的大力支持,一般都有了全国性的整体修建规划,并按照规划逐步实施;二是修建高速铁路的企业经济效益和社会效益,得到了更广层面的共识,特别是修建高速铁路能够节约能源、减少土地使用面积、减少环境污染、交通安全等方面的社会效益显著,以及能够促进沿线地区经济发展、加快产业结构的调整等等。

高速铁路概述

高速铁路发展概述课程名称:高速铁路运营管理指导老师:姓名:学号:班级:时间:2016年6月1日高速铁路发展概述杨凯然交通运输1304 28摘要:自1964年日本建成世界上第一条高速铁路,世界高速铁路发展经历了三次高潮,最有代表性的国家是日本、法国、德国、意大利等。

我国高速铁路起步晚,但起点高、发展快,通过引进国外核心技术、消化吸收再创新,初步具备了建设高速铁路的能力,迎来了我国高速铁路建设新时代。

高速铁路是高新技术的系统集成,其建设和运营反映了一个国家的科技实力。

我国高速铁路建设始终得到党和政府的高度重视,实现了科学的、又快又好的发展,取得了举世瞩目的成就。

关键词:国外高速铁路发展国内高速铁路发展高速铁路发展规划1.国外高速铁路发展综述世界高铁发展三次浪潮截至目前,全球投入运营的高速铁路近万公里,分布在中国、日本、法国、德国、意大利、西班牙、比利时、荷兰、瑞典、英国、韩国、中国台湾等17个国家和地区。

高速铁路作为一种安全可靠、快捷舒适、运载量大、低碳环保的运输方式,已经成为世界交通业发展的重要趋势。

世界高速铁路的发展历程可以划分为三个阶段,形成了三次建设高潮。

第一次是在上世纪60年代至80年代末,是世界高速铁路发展的初始阶段,主要由发达国家日本、法国、意大利和德国推动了这一次建设高潮。

在这期间建设并投入运营的高速铁路有:日本的东海道、山阳、东北和上越新干线;法国的东南TGV 线、大西洋TGV线;意大利的罗马至佛罗伦萨线以及德国的汉诺威至维尔茨堡高速新线,高速铁路总里程达3198公里。

这期间,日本建成了遍布全国的新干线网的主体结构,在技术、商业、财政以及政治上都取得了巨大的成功。

第二次是在上世纪80年代末至90年代中期。

由于日本等国高速铁路建设取得了巨大成就,世界各国对高速铁路投入了极大的关注并付诸实践。

欧洲的法国、德国、意大利、西班牙、比利时、荷兰、瑞典和英国等最为突出,1991年瑞典开通了X2000摆式列车;1992年西班牙引进法、德两国的技术建成了471公里长的马德里至塞维利亚高速铁路:1994年英吉利海峡隧道把法国与英国连接在一起,开创了第一条高速铁路国际连接线;1997年,从巴黎开出的“欧洲之星”列车又将法国、比利时、荷兰和国连接在一起。

高速铁路旅游英语 第十章 陆桥通道

Tourist Attractions 旅游景点

Song Yang Academy 嵩阳书院(Fig. 10-4) Song Yang Academy, located in the north of Dengfeng city, formerly named Song Yang Temple, founded in northern Wei (AD 484), for Buddhism, and for Taoism in the period of Emperor Sui Yangdi. It is renamed as the Song Yang Academy in AD 1035. It nestled below main spindle peak of Songshan, in the face of the double river basin, around by mountains.

Zhengzhou 郑州Geography & Climate 地理与气候Zhengzhou located north of the province’s center and south of the Yellow River, with a latitude ranging from 34°16¢ to 34°58¢ N and longitude ranging from 112°42¢ to 114°14¢ E. Zhengzhou borders Luoyang to the west, Jiaozuo to the northwest, Xinxiang to the northeast, Kaifeng to the east, Xuchang to the southeast, and Pingdingshan to the southwest. Zhengzhou experiences a monsoon-influenced, four-season humid subtropical climate, with cool, dry winters and hot, humid summers. Spring and autumn are dry and somewhat abbreviated transition periods.

Development and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train A Review

Transport Reviews, Vol. 26, No. 5, 593–611, September 20060144-1647 print/1464-5327 online/06/050593-19 © 2006 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/01441640600589319Development and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train: A ReviewMOSHE GIVONIThe Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London, UK(Received 8 August 2005; revised 14 November 2005; accepted 23 January 2006)A BSTRACT The inauguration of the Shinkansen high-speed train service between Tokyo and Osaka, Japan, at 210 kph maximum operating speed some 40 years ago marked the comeback of the train as an important passenger mode of transport. Since then high-speed train (HST) services have been introduced in many countries and are planned in many more, and the train has once more become the dominant mode of transport on many routes. This review summarizes the different elements of HST operation with the aim of characterizing HST operation and putting in context its impact in terms of what it is best designed for and what it can deliver. The review concludes that the HST is best designed to substitute conventional railway services on routes where much higher capac-ity is required and to reduce travel time, further improving the railway service, also against other modes, therefore leading to mode substitution. However, the high invest-ment in HST infrastructure could not be justified based on its economic development benefits since these are not certain. Finally, the following definition for HST services is suggested: high capacity and frequency railway services achieving an average speed of over 200 kph.IntroductionTransport technologies seldom make a comeback, save in nostalgia trips for well-heeled tourists. … But there is a spectacular exception: railways,written off thirty years ago as a Victorian anachronism destined to atro-phy before the steady growth of motorway traffic, have suddenly become one of the basic technologies of the twenty-first century.The reason of course is the high-speed train (Banister and Hall, 1993,p. 157)On 1 October 1964, the first high-speed train (HST) passenger service was launched on the Tokaido line between Tokyo and Osaka with trains running at Correspondence Address: Moshe Givoni, Department of Spatial Economics, Free University, De Boele-laan 1105, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Email: mgivoni@feweb.vu.nl594M. Givonispeeds of 210 kph. This date marks the beginning of the modern HST era. Since then, the HST network has expanded, first in Japan, and later in other countries, and speeds have increased. Today, about 40 years later, the HST is in many respects a distinct mode of transport.There is no single definition for high speed in the context of railway services, although the reference is always to passenger services and not to freight. High speed can relate to the infrastructure capability to support high speed (this might explain the term ‘high-speed rail’ (HSR), in addition to the fact that train and rail (or railway) are often used synonymously), the rolling stock capability to achieve high speed and/or the actual operation speed achieved. The European Union (EU) definition, given in Directive 96/48 (European Commission, 1996a), is 250 kph for dedicated new lines and 200 kph for upgraded lines in respect of the infrastructure capabilities. The same applies to the rolling stock (on specially built and upgraded lines, respectively). With some HSTs operating at speeds of 350 kph, 200 kph might not seem high speed anymore. However, HST operation is not all about (maximum) speed. Other elements are as or even more important in the overall consideration of HST as a mode of transport and in the developments of HST lines. This review examines the different elements of HST operation and puts HST operation in context in terms of what the HST can deliver and what can be expected from the introduction of HST services. It is a synthesis of the existing literature and current state of the art. It begins by describing the main technologi-cal developments in railway technology required to operate HST services (the second section) followed by definition of four models of HST (third section). Next, the development of the HST network across the world is described (fourth section). The focus then shifts to analysing the impacts of HST services, first the transport impact (e.g. effect on travel time and modal share; the fifth section) is considered, followed by the spatial and socio-economic impacts (sixth section) and the environmental impact (seventh section). The cost of HST lines is exam-ined (eighth section) before conclusions are drawn (ninth section). Technological Evolution of the Present HSTTraditionally, a speed of 200 kph was considered as the threshold for ‘high speed’(Ellwanger and Wilckens, 1994), which was achieved in Germany in tests as early as 1903. In 1955, the French set a new speed record of 331 kph and they also hold the current speed record for a ‘steel wheel on steel rail’ train of 515 kph achieved in 1990 by a F rench TGV HST (Whitelegg and Holzapfel, 1993). However, the commercial speed that can be achieved is of greater importance. The maximum operating speed on the Tokaido line now stands at 270 kph (Central Japan Railway Company, 2003), while on the TGV Atlantique line trains operate at a maximum speed of 300 kph. The standard for new lines is even higher, at 350 kph, which is the official maximum operating speed of new HST lines such as the Madrid–Barcelona line (International Union of Railways, 2003). Higher oper-ating speeds seem commercially unfeasible at present due to noise problems, high operating costs and other technical problems.The modern HST uses the same basic technology of a steel wheel on a steel rail as the first trains did at the beginning of the 19th century. Yet, many incremental engineering and technological developments were required in all aspects of train operation to allow trains to run commercially at speeds higher than 200 kph. Although much higher speeds were reached in tests by simply using more powerDevelopment and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train595 to propel conventional trains, these speeds were ‘deemed infeasible for commer-cial application because the fast-moving vehicles damaged the tracks severely’(Raoul, 1997, p. 100). In addition, the increase in the centrifugal forces as speed increases when trains run through curved sections led to discomfort to passen-gers and, furthermore, it is not enough that the train is capable of running at high speed, but the track must supports trains running at high speeds.The main technical challenges in the development of commercial HSTs were to develop a train and track that could maintain stability and the comfort of passen-gers (while the train is running at high speed), maintain the ability to stop safely, avoid a sharp increase in (train) operating costs and (track) maintenance costs, and avoid an increase in noise and vibration to areas adjacent to the line. The solution included, in most cases, building tracks that avoid tight curves; increas-ing the distance between axles in the bogies to help maintain stability and placing the bogies between carriages (and not at the ends of each carriage) to reduce weight by halving the number of bogies required to carry the carriages; improv-ing stability by preventing the cars from pivoting away from one another on curves; designing aerodynamic trains to reduce drag and shaping the train in a way that reduces the noise and vibration it induces; and using lighter and stron-ger materials (Raoul, 1997). In addition, the high speed required improvements to the signalling systems, the introduction of automatic braking/decelerating systems to improve safety, and changes in the operation of trains, e.g. the need to replace roadside signals with signals inside the driver’s cab since at high speeds the trains passed the roadside signals too fast for the driver to see them.Main Models of HSTThe different needs and special characteristics of the different countries pursuing the development of HST operation led to the evolution of different models of HSTs. The Japanese Shinkansen, which was the first modern HST in operation, can be considered as the base model for HST. Subsequently, three other models have evolved.The ShinkansenThe main features of the Shinkansen (‘new trunk line’, and the name given to the Japanese HSTs) evolved from Japan’s unique characteristics which include large metropolitan centres located a few hundred kilometres apart from each other with a high demand for travel between them. F or example, the Tokaido line connects Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya, Japan’s biggest cities (approximately 30, 16 and 8.5 million inhabitants, respectively), which are a few hundred kilometres apart from each other (Tokyo–Osaka 560 km with Nagoya located on the route 342 km from Tokyo) and generate high demand for travel between them (132 million passengers on the Tokaido Shinkansen in 2002; Central Japan Railway Company, 2003). A unique feature of the Shinkansen is the new dedicated line which in the case of Japan was required since the conventional railway network is narrow gauge and could not support HSTs. This isolates the Shinkansen services from the rest of the railway system in Japan. The geographic features of Japan together with the requirement to avoid tight curves and steep gradients (to allow for high speeds) resulted in many tunnels and bridges along the route, which is typical of the Shinkansen lines. A total of 30% of the Japanese Shinkansen lines596M. Givonirun through tunnels (Okada, 1994) leading to very high construction costs. Furthermore, construction of new lines into the city centres further exacerbates construction costs due to engineering complexity and the high land values in city centres.The TGVThe French TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse), which began operation in 1981, resem-bles the Shinkansen in purpose but differs in design philosophy. The differences are attributable to some extent to overcoming the disadvantages of the Shinkansen and to the different physical characteristics of France and Japan (Sone, 1994). The most significant difference between the TGV and the Shinkansen is probably the ability of the former to operate on conventional tracks as well, which allows the TGV to use the conventional lines as it enters and leaves the city centre, leading to significant cost savings. It also means that the HST can serve regions with no HST infrastructure and specifically serve parts of the network where at present the demand is not high enough to justify the construction of a dedicated line (Bouley, 1986).The Spanish HST, the AVE (Alta Velocidad Espanola, or Spanish High Speed), is a mix of the TGV and Shinkansen models. It uses a TGV-type rolling stocks, but like the Shinkansen it runs on a dedicated line throughout, because the Spanish conventional network is wider then the standard International Union of Railways (UIC) gauge used across most of Europe. This was favoured to allow the AVE to connect with the emerging European, and mainly French, HST network (Gómez-Mendoza, 1993).Germany’s HST, the ICE (Inter-City Express), follows the TGV model of HST, mainly in the compatibility feature. It deviates from the TGV and the Shinkansen models by adopting a mixed-use line, meaning the line is used for both passenger and freight transport (Bouley, 1986). This feature turned out to be a disadvantage since it led to high construction costs (to support the higher load of freight trains) and low utilization of the lines (since freight trains operate at much lower speeds).The Tilting HSTThe Japanese, French, Spanish and German HST trains all use a newly built track on the sections where high speed is achieved, which translates into high construc-tion costs. Yet, on many routes demand is not high enough to justify the cost of constructing new tracks that allow high-speed operation. This problem was solved by the tilting train model of HST, but at the price of lower speeds. To allow higher speeds on conventional lines with tight curves, the train tilts as it passes through curves. By simply tilting the train in tight radius curves (although by a sophisticated computerized mechanism), the discomfort passengers feel from the centrifugal force as the train goes at high speed through curves is solved. ‘The bogies remain firmly attached to the rails while the body of the carriage tilts, and so compensates for centrifugal force’ (Giuntini, 1993, p. 61). This principle is adopted by many countries as a cheaper alternative to the TGV and Shinkansen models of HST. The Swedish X-2000 and the Italian Pendolino (ETR-450) are examples of HSTs running on conventional rail using the tilting mechanism, thus avoiding the price of expensive new tracks, but reaching maximum speed of onlyDevelopment and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train597 210 kph (X-200) or 250 kph (ETR-450). Today, a tilting mechanism is also used on TGV trains, like the TGV Pendulaire, which can reach a maximum speed of 300 kph (International Union of Railways, 2003) and all the new Shinkansen models will adopt a tilting mechanism (Japan Railway and Transport Review, 2005).The MAGLEV HSTIf the tilting train model of HST is considered a downgrade from the Shinkansen and TGV models, mainly in terms of speed, the MAGLEV model of HST is an upgrade. Magnetic levitation (MAGLEV) technology was first tested in the 1970s, but it has never been in commercial operation on long-distance routes. The tech-nology relies on electromagnetic forces to cause the vehicle to hover above the track and move forward at theoretically unlimited speeds. In practice, the aim is for an operation speed of 500 kph (Taniguchi, 1993). In 2003, a MAGLEV test train achieved a world record speed of 581 kph (Takagi, 2005). The special infrastruc-ture required for MAGLEV trains means high construction costs and no compati-bility with the railway network. The MAGLEV is mostly associated with countries like Japan and Germany where MAGLEV test lines are in operation. In Japan, the test line will eventually be part of the Chuo Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka connecting the cities in about 1 hour compared with the present 2.5 hours. In China, a short MAGLEV line was opened in December 2003 connecting Shanghai Airport and the city’s Pudong financial district with trains running at maximum speed of 430 kph (International Railway Journal, 2004). However, plans to adopt MAGLEV technology for the planned Beijing–Shanghai route were abandoned in favour of a conventional steel wheel-on-steel rail HST (People’s Daily, 2004). The future of the MAGLEV, it seems, depends on its success in Japan, in the same way the development of the HST depended largely on the success of the first Shinkansen line.The main differences between the four models of HST described above in terms of maximum operating speed, compatibility with the conventional network and construction costs are summarized in F igure 1. In general, the reference in the present paper is to the Shinkansen and TGV models of HST.Development of the HST NetworkDespite the success of the Tokaido line in Japan, the spread of the HST around the world was relatively slow. It took 17 years after the opening of the Tokaido line for the first HST to be introduced outside Japan (in France) and another 7 years for the second European HST (and the world’s third) to begin service in Italy. At present, the HST covers much of Japan and Europe and is being introduced in the Far East. The USA in this respect is lagging behind (see below).In Japan, the success of the Tokaido line prompted the development of a Japanese HST network that was developed over time (Matsuda, 1993). This network (F igure 2) consists today of 2175 km of HST line in operation, with a further 215 km under construction and 349 km at the planning stage (International Union of Railways, 2003). The HST line between Paris and Lyon, which opened in 1981, was France’s first HST. This line also proved to be a success story, and in turn the driving force for developing the French HST (Polino, 1993). At present, the French HST network consists of 1541 km of HST lines in operation, 320 km under construction and another 937 km at the planning stage (International Union598M. GivoniFigure 1.Operating speed, construction cost and compatibility (with the conventional network)characteristics of the four high-speed train modelsof Railways, 2003). Despite the successful introduction of the HST in France, its spread across Europe was relatively slow. In 1988, the Italians introduced the Pendolino tilting train (ETR-450 model) on the Rome–Milan route; and in 2000 Sweden introduced its first HST, the X-2000, also a tilting-train model of HST. Next, in 1991, it was Germany’s turn to introduce the ICE between Hannover and Würzburg; and a year later Spain introduced its first HST service between Seville and Madrid. The UK joined the list of countries with HST lines in 2003 when the first phase of the link from London to the Channel Tunnel (the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, or CTRL) was opened. This line is scheduled for completion in 2007.Figure 2.Japan’s high-speed train networkDevelopment and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train599 When the above European countries were independently pursuing their HST plans, and France was pursuing the expansion of its HST network to neighbour-ing countries, the EU emerged and with it the idea of the Trans-European Networks (European Commission, 2001). The international dimension of the European HST network (F igure 3) increases the scope for HST services since many countries, e.g. Belgium and the Netherlands, do not have domestic routes that can justify HST services.Besides Japan and Europe, HST development takes place mainly in the F ar East. South Korea became the eighth country with trains operating at 300 kph in April 2004 when its HST, the KTX (Korea Train eXpress), which is a TGV model of HST, began operation. In 2005, Taiwan completed its 345-km HST line between Taipei and Kaohsiung, the first country to adopt Shinkansen technology outside Japan. China, as noted above, is also underway to join the countries operating HSTs with a planned line between Beijing and Shanghai (Takagi, 2005).In the USA only one HST line is in operation: the Acela Express tilting train running on the North East Corridor line between Boston and Washington, DC. At present, ten corridors across the USA have been designated for HST operation, but the start of construction still seems far way. The Californian HST, connecting the San F rancisco Bay area with Los Angeles and San Diego, is at the most advanced planning stages (F ederal Railroad Administration, 2005). Current debate in the USA on the future of Amtrak, the US passenger rail company, and the level of subsidies it should receive casts more doubts on the prospects for HST. With no funding for inter-city rail services, there are unlikely to be funding for HST projects, thus the fate of the proposed HST projects depends on state funding and governors’ will rather than federal funding. For an account of HST in the USA, or the lack of it, see Klein (1993) and Thompson (1994).In Australia, following a scoping study on an east coast HST network (2000 km long), connecting Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney and Brisbane (Department of Transport and Regional Services, 2001), the government decided in 2002 toFigure 3.Planned European high-speed train network. Source: International Union of Railways (2003)600M. Givoniconclude its investigation after the study showed such a network would be too expensive and that 80% of the funding would have to be public money (Anderson, 2002).With respect to MAGLEV lines, the Chuo Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka is at an advanced planning stage, and it still awaits the government’s green light (Takagi, 2005). There are currently no concrete plans for a MAGLEV line anywhere else.HST as a Mode of TransportThe main reason for the construction of the first Shinkansen and TGV lines was increasing route capacity, and this was also the case for many other lines. In Italy, capacity continues to be the main reason to construct high-speed lines, while the gain in speed will be relatively small, e.g. on the Rome to Naples line. In the UK, spare capacity on the rail network in the 1970s and 1980s was one of the main reasons for not considering HST development when other European countries started developing their HSTs (Commission for Integrated Transport, 2004).HST lines increase the capacity on the route since they usually supplement existing ones and they free capacity on the conventional network for use by freight and regional passenger services. The direct increase in capacity offered by the HST line is due to the higher frequency, which is feasible due to the higher speed and the most up-to-date signalling systems that allow relatively short headway between trains without compromising safety, and due to the use of long trains with high seat capacities. For example, the first Shinkansen, model 0, had a capacity of 1340 seats and Eurostar trains have 770 seats (International Union of Railways, 2003). The combination of a dedicated high-speed line, high-capacity trains, advanced signalling systems and high-speed enabled JR Central to carry on the Tokaido line 362 000 passengers per day on 287 daily services or a total of 132 million passengers in 2002 (Central Japan Railway Company, 2003). Higher frequency due to a higher speed and improved signalling also means that the introduction of tilting trains on existing tracks will lead to increased capacity on the route.Reducing travel time is also an important reason for introducing HST services, although not the main reason in most cases. Before the inauguration of the HST in Japan, it took 7 hours to travel between Tokyo and Osaka on the conventional line; it was then reduced to 4 hours following the inauguration of the Shinkansen and it is 2 hours 30 minutes since 1992 (Matsuda, 1993). If the green light will be given to the MAGLEV Chou Shinkansen, travel time between the cities will be further reduced to only 1 hour. The opening of the Spanish HST between Madrid and Seville reduced travel time from 6 hours 30 minutes to 2 hours 32 minutes (European Commission, 1996b) and there are many other similar examples. These time savings have an economic value which the Japanese estimate at approxi-mately €3.7 billion per year (Okada, 1994).The ability of the HST to cut travel time is determined by the average speed it achieves, which is affected mainly by the number of stops and the different speed restrictions along the route. Therefore, HSTs that have a very high maximum operating speed might still achieve a relatively low average speed and limited travel time savings due to the above. Japan and France provide the fastest services in the world at average speeds of around 260 kph (Takagi, 2005). The NozomiDevelopment and Impact of the Modern High-speed Train601 service on the Tokaido line, which stops only at the main stations along the route, achieves an average speed between Tokyo and Osaka of 206 kph. This is signifi-cantly lower than the maximum speed achieved by these HSTs.HST services can only be attractive on high-demand routes, which is why most HST services will be between city centres. Hence, cities with dense and dominant city centres (in terms of population and/or employment) are more attractive for HST services, unlike large cities which are more dispersed in nature. Since long access journey to the HST station might cancel the time savings the HST service offers (Hall, 1999) there is an incentive to provide more than one station per city. Yet, more stations/stops means a lower average speed and thus a trade-off must be made. Large metropolitan cities that are polycentric in nature can justify more than one HST station, e.g. Tokyo has three stations on the Tokaido line (Tokyo, Shinagawa and Shin-Yokohama). In contrast, the four stations planned on the CTRL (St Pancras and Stratford both in London, and Ebbsfleet and Ashford both in Kent) might not generate enough demand to justify the reduction in average speed and the longer travel time.Shorter travel times and an increased level of service (a higher frequency and also improved travelling conditions) following the introduction of HST lead to changes in the modal share on the route and to the generation of new demand. The modal share the HST captures depends mainly on the travel time it offers compared with other modes, but also on the cost of travel and travel conditions. Most of the demand shifted to the train mode following the introduction of HST services is from the aircraft and, to a lesser extent, from the car, which was the case on the Paris–Lyon and Madrid–Seville routes (Table 1). However, most of the demand for new HST services is demand shifted from the conventional railway, which has negative consequences for the conventional rail network (Vickerman, 1997). For example, on the Sanyo Shinkansen, 55% of the traffic was diverted to the new line from other rail lines (23% from the aircraft, 16% from the car and bus, and 6% new (induced) demand) (Sands, 1993b). In some cases, the traffic genera-tion effect of new HST services is substantial, such as on the Paris–Lyon and the Madrid–Seville lines (Table 1).González-Savignat (2004) observes that on relatively short routes the car has the highest modal share on the route, before the introduction of HST services, e.g. 71 and 82% on the Madrid–Zaragoza and Zaragoza–Barcelona routes, respectively, Table 1.Modal share (%) before and after the introduction of high-speed trainservicesTGV, Paris–Lyon line AVE, Madrid–Seville line Before (1981)After (1984)Change Before (1991)After (1994)Change Aircraft317−244013−27 Train407232165135 Car and bus2921−84436−8 Total10010037a10010035b a Total traffic increased by 37%. A total of 10% is related to the estimated trend of growth and 27% is considered as induced traffic.b Total traffic increased by 35%.Source: European Commission (1996).602M. Givoniboth 300 km apart. In this case, a similar percentage shift of passengers from car and aircraft to the HST means a greater shift from the car in absolute numbers. Furthermore, González-Savignat notes that in the Spanish experience, the social benefits from the diversion of passengers from the car to the HST are larger than diversion of passengers from the aircraft to the HST.In summary, by definition all HST lines fulfil the purposes of increasing the route capacity and reducing travel time. Higher capacity and travel speed lead to changes in the modal share, increasing the share of the train at the expense of the aircraft and the private car and diverting passengers from the conventional train to the HST. In addition, the introduction of HST services also leads to the generation of new demand on the route. All these sum the ‘transport’ effects of the HST. F or more evidence on the transport effect of the HST in Europe, see Vickerman (1997).HST as a Substitute to the AircraftMuch attention is given to the HST as a substitute to the aircraft and as a possible solution to the congestion and environmental problems faced by the air transport industry, although substituting the aircraft is not the main reason for introducing HSTs (for a literature review of the subject, see Givoni, 2005).Due to its speed and the location of most HST stations at the city centre, the HST can offer comparable or shorter travel times than the aircraft on some routes and can therefore substitute it. The travel time advantage depends on the average speed of the HST service and the distance each mode has to cover, since trains do not necessarily follow the direct route. F or example, on a journey between London and Paris, the HST passes almost 500 km while the aircraft only 380 km. In general, on routes of around 300 km, evidence shows that the introduction of HST services almost leads to a withdrawal of aircraft services (e.g. between Tokyo and Nagoya and between Brussels and Paris), while on routes of around 1000 km and above, the HST ceases to be a good substitute for the aircraft (e.g. between Tokyo and F ukuoka, 1070 km, the HST share of the traffic is only 10%). In between these distances, there is usually direct competition between the modes. In most cases, competition is also between the operators, the airlines and the railways. This competition means that HST services are added to the aircraft services and not really substituting them. On the London–Paris route the HST captures about 70% of the market (Eurostar, 2005), but the airlines still offer about 60 flights a day just between London Heathrow and Paris Charles de Gaulle (CDG) (Innovata, 2004), two of the most congested airports and one of the most congested routes in Europe (Central Office for Delay Analysis, 2005). However, the situation is different when HST services are introduced at large hub airports (together with the means for a fast and seamless transfer between the aircraft and the HST). In this case, many airlines choose to replace the aircraft with the HST on some routes, leading to a real mode substitution. Lufthansa adopts such mode substitution on the routes from Frankfurt airport to Stuttgart and Cologne, where the aircraft is substituted by the German ICE HST and operated by Deutsche Bahn. Air F rance uses the HST to replace the aircraft on routes from CDG to Brussels, and on other routes it uses it to complement the aircraft. Furthermore, Airlines such as Emirates, American Airlines and United Airlines use HST services from CDG to complement their flights into Paris (International Air Transport Association, 2003).。

2024年高速铁路的全球扩张

全球高速铁路市场的竞争格局和特点

竞争格局:全球高速铁路市场主要由中国、日本、德国、法国等国家主导,这些国家在 高速铁路建设、运营和管理方面具有丰富的经验和技术优势。

特点:全球高速铁路市场具有投资规模大、建设周期长、技术要求高、运营管理复杂等 特点,需要强大的资金、技术和管理能力支持。

发展趋势:随着全球城市化进程的加快,高速铁路市场需求将持续增长,未来市场将更 加注重技术创新、节能环保和智能化发展。

环保影响:噪音、振动、电磁辐射等

应对措施:采用节能技术,提高能源 利用效率,减少碳排放

应对措施:采用低噪音、低振动技术, 优化线路设计,减少对环境的影响

环保影响:土地占用和生态破坏

环保影响:能源消耗和碳排放

应对措施:优化线路设计,减少土地 占用,采取生态修复措施,保护生态 环境

高速铁路对城市发展的影响和作用

中国:计划建设多条高速 铁路,包括京沪高铁、京 广高铁等,总里程将达到3 万公里。

美国:计划建设高速铁路网 络,连接东西海岸,总里程 将达到5万公里。

欧洲:计划建设高速铁路网 络,连接欧洲各国,总里程 将达到10万公里。

日本:计划建设高速铁路网 络,连接全国各大城市,总 里程将达到2万公里。

印度:计划建设高速铁路网 络,连接全国各大城市,总 里程将达到1万公里。

俄罗斯:计划建设高速铁路 网络,连接欧洲和亚洲,总 里程将达到3万公里。

全球扩张的挑战和应对策略

技术挑战:高速铁路技术的研发和创新

应对策略:加强国际合作,共享技术 和经验

资金挑战:高速铁路建设的巨额投资

应对策略:创新融资模式,降低投资 风险

环境挑战:高速铁路对环境的影响和保 护

应对策略:加强环境保护,实现可持 续发展

铁道部今年投7000亿元使高铁初步成网

河 北分两步加速推进全省住 宅产 业化

日 , 前 河北省住 房和城 乡建设厅 印发了《 于推进 全省住宅 关

1. 57 万公里 , 区高速公路 由10 公里 发展  ̄2 6 公里 , 全 01 J t3 5 一级公 路 由2 3 公里发 展 ̄ 3 8 公里 , 19 J r3 7 高等级公 路由1 5 . 万公里 发展到 ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้1 18 . 万公里。 一个 以高速公路 、 一级公路为骨架 、 农村牧 区公路为

道与能源生 产供给能力相互 配套 , 内蒙古不断加大交 通建 设力 度 。内蒙古交 通 运输厅提 供 的数 据显示 ,“ 十一五 ” 间, 期 内蒙 古完成公 路建设 投资17 亿元 , 40 是此前5 年总和的15倍 , 年 8 .l 5 新增公 路里程33 . 万公里 。 O O  ̄2 l 年底 , 内蒙古公路总里程 达到

洪泽站工程是南水北调东线江苏段 运西线上 的重要调水泵 站 , 运河线上 的淮 阴三 站共 同构成 东线 第三提 水梯 级 , 与 工程 座落洪泽湖畔, 总投 资5 亿元 。 据介绍 , 0 2 1年南水北 调江苏段工 程进入 全面加快建设 的 1 高峰期和关键 期。 年 , 今 江苏段调水工程全 部开工建 设 , 全面完 成 规 划确定 的治污项 目, 基本建 成运河线 上调水 工程 ; 0 2 2 1 年 底 基本 建成运西 线上 的调 水工程 , 实现调水全 线水 质达标 ; 到

石方开挖 9 3 万立方米 、 62 土石方填筑 17Z" 97 i 立方米 、 混凝 土浇筑

19 立方米 , 6. 亍 完成建安工程投资4 .7 22 亿元 。

南水 北调工 程旨在缓 解 中国北方地 区水资源短缺 问题 , 也 是世界上迄 今为止规 模最 大 的水 利工 程 , 分东线 、 共 中线 和西 线三条调 水线路 。 南水 北调中线 工程流经河 南 、 河北 、 京、 北 天 津 4 省市, 个 连通长江、 淮河 、 黄河 、 海河4 大流域 。

北京2024年计划建设全球最大的高速铁路网络

通过高速铁路网络的辐射效应, 引导资本、技术、人才等生产要 素向沿线地区集聚,推动区域经 济的均衡发展。

增强国家综合交通竞争力

01

建设全球最大的高速铁路网络 将提升中国在全球交通领域的 地位和影响力。

02

高速铁路网络的建设将推动中 国铁路技术的创新和发展,增 强国家自主创新能力。

03

通过高速铁路网络的运营和管 理,积累丰富的经验和技术, 为中国参与国际铁路合作和交 流提供有力支撑。

采用环保材料和工艺,降低施 工过程中的环境污染和能源消 耗。

推广使用可再生能源和清洁能 源,减少高速铁路运营过程中

的碳排放和环境污染。

加强环保监测和管理,确保高 速铁路建设与环境保护协调发 展,实现经济效益、社会效益

和环境效益的共赢。

XX

PART 03

建设进度与安排

REPORTING

前期准备工作进展

3

通过与城市轨道交通、公交等交通方式的衔接, 构建综合交通体系,为市民提供更加便捷、多样 化的出行选择。

促进区域经济发展和产业布局优化

01

02

03

高速铁路网络的建设将加强北京 与周边城市的经济联系,促进区 域经济一体化发展。

高速铁路的开通将带动沿线城市 的旅游业、物流业等产业的发展 ,优化产业布局。

优势分析

公私合营模式有助于减轻政府财政压 力,提高项目运营效率,同时降低投 资风险。

票价制定原则和市场竞争力评估

票价制定原则

综合考虑运营成本、市场需求、乘客承受能力等因素,制定合理且具有竞争力的票价。

市场竞争力评估

与其他交通方式进行对比分析,评估高速铁路在票价、时间、舒适度等方面的竞争优势 。

维护保养计划和技术支持体系建立

江门市城市总体规划

第四章 第一节 第二节 第三节

城市空间布局................................................................................................7 城市空间发展策略 ..........................................................................................7 城市空间发展规划 ..........................................................................................7 城镇职能分工及规模等级 .............................................................................8

第三章 第一节 第二节

城市性质与规模 ...........................................................................................6 城市性质...........................................................................................................6 城市规模................................................................................6

第二章 第一节 第二节 第三节 第四节

市域城镇体系规划 .......................................................................................4 城镇化水平预测 ..............................................................................................4 城镇化发展策略 ..............................................................................................5 城镇职能分工及规模等级 .............................................................................5 市域城镇空间布局 ..........................................................................................5

高考地理一轮复习课件:交通运输布局与区域发展2

要想富先修路

6.资金与交通运输布局

(1)资金对交通运输布局的直接影响。

(2)资金对交通运输布局的间接影响。 足够的资金→推动相关技术水平的提高→使交通运输布局受自然条件限制减弱。

雅安

雅 西 高 速

西昌

雅西高速由四川盆地边缘向横断山区爬升,每 向前延伸一公里的平均海拔高程上升7.5米。雅 西高速跨越了青衣江、大渡河、安宁河等水系 和12条地震断裂带,整条线展布在崇山峻岭之 间,山峦重叠,被国内外专家学者公认为国内 乃至全世界自然环境最恶劣、工程难度最大、 科技含量最高的高速公路之一。

三、交通运输的区位因素

4.交通运输布局的一般原则

Q2:京沪高速铁路沿线的高铁站布局 有什么特点?为什么?

连接沿线主要城市,数量多,分布较均匀。城 市是区域经济发展中心,也是区域客货集散地, 运输需求量大,因此区域主要交通线应尽可能 连接沿线主要城市。

Q3:如果高铁站布局过密或过疏,会 产生哪些问题?

1.交通运输布局

概念

指各种运输方式 的线路和站点组 成的交通运输网 与客货流的地理 分布。

任务

一个区域的交通 线网、场站如何 组织、客流、货 流如何分配、引 导

目的

实现区域运输的 合理化,以获得 最大的经济效益 和社会效益

影响因素

交通运输布局既要 适应社会经济需要, 也要立足现有技术 装备,还受自然条 件影响。

要城市。 ➢ 相邻重要城市之间,常需要布局多条平行的交通线,以满足城市间庞

大的交通运输需求 (3)需求差异 (4)需求变化

读“非洲铁路分布示意图” ,简 述其分布特点并分析原因。

多分布在沿海地区,内陆地区较 少;多从沿海港口向内陆延伸, 未形成完善的铁路网。

荷兰高速铁路南线(HSL South)投入运营

4

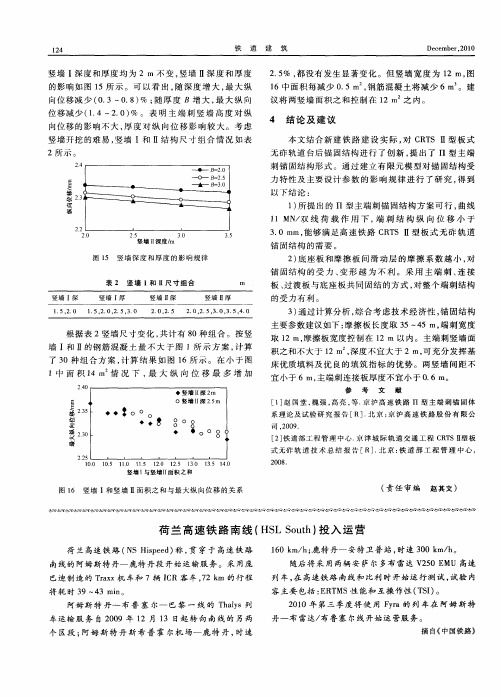

结 论 及 建 议

本文 结合 新建 铁 路 建 设 实 际 , C T I 板式 对 R S I型

竖墙 开挖 的难易 , 墙 I和 Ⅱ结 构尺 寸 组合 情 况 如 表 竖

2所 示 。

无 砟轨 道台后 锚 固结 构进行 了创新 , 出 了 Ⅱ 型主端 提 刺 锚 固结 构形 式 。通 过建立 有 限元模 型对锚 固结构受 力 特性 及主要 设计 参数 的影 响规 律 进行 了研 究 , 到 得

以下结 论 :

1 所提 出的 n 型主端束 锚 固结构 方案 可行 , ) 0 曲线

1 MN 双 线 荷 载 作 用 下 , 刺 结 构 纵 向 位 移 小 于 1 / 端

3 0mm, . 能够满 足高 速铁 路 C T I R S I型板 式无 砟 轨 道

竖墙 I 度/ I 深 m

随后 将 采 用 两 辆 安 萨 尔 多 布 雷 达 V 5 MU 高 速 2 0E

列车 , 高速铁 路 南线和 比利 时开 始运 行 测试 , 在 试验 内

容 主 要 包括 : R MS性 能 和 互 操 作 性 ( S ) E T TI 。

阿 姆 斯 特 丹~ 布 鲁 塞 尔一 巴 黎 一 线 的 T a s列 hl y 车运 输 服 务 自 2 0 0 9年 1 月 1 日起 转 向 结 报 告 [ . 京 : 道 部 工 程 管 理 中 心 , R] 北 铁

2 0 0 R

( 责任 审编

赵其文)

荷 兰 高速 铁 路 南线 ( LSuh 投入 运 营 HS ot )

荷 兰高速 铁路 ( sH sed 称 , 穿 于 高速 铁路 N i e) 贯 p

14 2

铁

道

建

2024年全球高速铁路网络不断扩张

高速铁路市场的竞争格局和发展趋势

单击添加标题

竞争格局:全球高速铁路 市场主要由中国、日本、 德国等国家主导,这些国 家在高速铁路建设、运营 和管理方面具有丰富的经

验和技术优势。

单击添加标题

发展趋势:随着全球对环 保、节能和便捷出行方式 的需求不断增加,高速铁 路市场将保持快速增长。 同时,随着新技术的不断 发展,高速铁路的运营效 率、安全性和舒适性也将

全球高速铁路网络的政策支持与市 场前景

05

各国政府对高速铁路发展的政策支持

中国:政府大力支持高速铁路建设,投资规模巨大,制定了详细的发展规划。

欧洲:欧盟对高速铁路发展给予大力支持,制定了“欧洲高速铁路走廊”计划,鼓励各国 共同建设高速铁路。

日本:政府对高速铁路发展给予大力支持,制定了详细的发展规划,鼓励企业投资高速铁 路建设。

高速铁路网络连接的关键区域

亚洲:中 国、日本、 韩国等国 家

欧洲:德 国、法国、 意大利等 国家

北美洲: 美国、加 拿大等国 家

南美洲: 巴西、阿 根廷等国 家

非洲:南 非、埃及 等国家

大洋洲: 澳大利亚、 新西兰等 国家

高速铁路网络对跨国交通的影响

提高跨国交通效率:高速铁路网 络将大大缩短跨国旅行的时间, 提高交通效率。

2024年全球高速铁路网络覆盖情况

亚洲:中国、日本、韩国 等国家高速铁路网络发达, 覆盖范围广

欧洲:法国、德国、意大 利等国家高速铁路网络成 熟,连接多个国家

北美:美国、加拿大等国 家高速铁路网络正在建设 中,覆盖范围有限

南美:巴西、阿根廷等国 家高速铁路网络正在规划 中,尚未形成规模

2024年高速铁路网络的全球扩张

2024年高速铁路网络 的全球扩张

汇报人:XX

目录

01 添 加 目 录 项 标 题

02

全球高速铁路的发展现 状

03

2024年高速铁路网络扩 张的计划

04

高速铁路网络全球扩张 的影响

05

高速铁路网络全球扩张 的挑战与机遇

06 未 来 展 望

01

添加章节标题

02

全球高速铁路的发展现状

亚洲:中国、日本、韩国等国家正在积极推进高速铁路建设,并计划实现互联 互通

北美:美国、加拿大等国家也在规划高速铁路网络,以实现跨区域互联互通

非洲:一些国家如南非、尼日利亚等正在考虑建设高速铁路,以促进经济发展 和区域一体化

高速铁路对全球交通格局的改变

高速铁路将改变 全球交通网络的 格局,提高交通 效率和便捷性

技术进步:高速铁路技术不断创新,提高速度、安全性和舒适性 网络扩张:全球高速铁路网络不断扩张,连接更多国家和地区 环保出行:高速铁路作为环保出行方式,将得到更多关注和推广 经济带动:高速铁路促进沿线经济发展,带动相关产业发展

各国高速铁路网络的互联互通前景

欧洲:计划建设泛欧高速铁路网,连接欧洲各国首都

提升生产力:高速铁路 网络可以提高生产效率 和劳动力流动性,从而 提升整个国家的生产力。

创造就业机会:高速铁 路网络的建设和运营需 要大量的劳动力,可以 创造大量的就业机会。

促进旅游业发展:高速 铁路网络可以方便游客 出行,促进旅游业的发 展,带动相关产业链的 发展。

对环境的影响

减少碳排放:高速铁路比汽车和飞机更环保,有助于减少温室气体排放 保护自然景观:高速铁路的建设和运营可以减少对自然景观的破坏 促进可持续发展:高速铁路的发展可以促进城市和地区的可持续发展 提高能源效率:高速铁路比汽车和飞机更节能,有助于提高能源效率

高铁时代2024年的高速新征程

2008年,中国开通第一条 高速铁路,成为世界上高 铁发展最快的国家之一

2024年,全球高铁网络将 进一步完善,实现更高速度、 更安全、更环保的出行方式

Part Two

建设目标: 实现全国 高铁网络 全覆盖

投资规模: 预计投资 额将达到 万亿元

建设重点: 加强中西 部地区高 铁建设, 推动区域 经济发展

印度高铁:起步较晚,技术 相对落后,但政府支持力度 加大,市场份额有望扩大

速度更快:未来高铁的速度 将进一步提升,缩短旅行时 间

智能化:未来高铁将更加智 能化,实现自动驾驶、智能 调度等功能

环保节能:未来高铁将更加 注重环保和节能,降低能耗 和排放

舒适便捷:未来高铁将更加 注重乘客的舒适度和便捷性, 提供更好的旅行体验

绿色环保技术:降 低能耗,减少排放, 实现可持续发展

超高速技术:提高 列车速度,缩短旅 行时间

智能化技术:实现 高铁的智能化运营 和管理,提高服务 质量和效率

高铁的智能化、自动化和信 息化将提高交通效率和安全 性

高铁作为智能交通系统的重 要组成部分,将发挥关键作 用

高铁将与其他交通方式实现 互联互通,提高整体交通效

1999年,中国开始建设 高速铁路

2003年,中国第一条高 速铁路线——京津城际

铁路开通运营

2008年,中国第一条设 计时速350公里的高速 铁路线——武广高铁开

通运营

2011年,中国高速铁路 运营里程突破1万公里, 成为世界上高速铁路运

营里程最长的国家

2012年,中国高速铁路 运营里程突破2万公里

游客。

促进旅游业升 级:高铁的开 通促进了旅游 业的升级,推 动了高端旅游 市场的发展。

带动相关产业 发展:高铁的 开通带动了酒 店、餐饮、购 物等相关产业 的发展,促进 了地方经济的

土耳其安伊高铁项目设计管理实践

设计咨询作为工程建设产业链的前端,对工程建设具有决定性的作用。

土耳其安伊高铁项目按照欧洲技术标准体系实施,合同约定采用欧洲标准(EN)和土耳其标准(TS),对中国企业而言,不失为一项重大挑战。

项目概况安卡拉(Ankara)至伊斯坦布尔(Istanbul)高速铁路是土耳其筹建的首条高铁,线路长约533公里,按客货共线运行规划。

设计最高时速250公里,运行时间3小时,较既有铁路缩短3.5小时。

本通道Ⅱ期工程位于通道中段,从依诺努(Inonu)至科斯科亚(Kosekoy),新建线路长158km。

经国际招标,2005年10月由中土集团代表中国铁建牵头组建的总包集团承建,2008年9月开工,实际工期70个月。

安伊高铁Ⅱ期工程线路全长158km,有桥梁10.6公里、隧道52.0公里,桥隧占线路全长的39.6%。

本段是该通道各期工程中,工程地质条件最复杂,桥梁、隧道工程最多,工程难度最大的区段。

项目设计管理情况一、管理机构及设计审批流程1.管理机构此项目业主单位为土耳其铁路总局(TCDD);监理单位为INCEO-UBM公司(西班牙公司和土耳其公司联合体);总承包商为中国铁建和土耳其公司联合组建的总包集团(CCCI)。

总包方联合项目部(PMO)之下设立设计咨询部,对整个项目设计工作进行控制,负责中外设计分包商、供货商之间的沟通与协调。

设计单位由国内外多家设计院共同完成。

综合而言,安伊高铁项目组织机构较复杂,设计管理界面较多。

2.设计审批及图纸签署流程项目设计审批采用两级审批制:首级审批由监理单位负责,二级审批由业主单位负责。

项目图纸签署流程较复杂、冗长,参加签审人员众多。

其中设计方面7级签审制:专业工程师设计→专业负责人复核→专业项目部经理初审→中土土铁项目部经理复审→PMO设计咨询部初批→PMO副经理复批→PMO经理终批。

监理方面3级签审制:专业工程师(1-2人)初审→专业主管工程师复审→监理项目经理终审。

业主方面3级签审制:专业工程师(3-4人)初批→专业部门主管复批→工程部门主管终批。

高速铁路2024年高速铁路网络覆盖全球主要城市

高速铁路的开通将缩短旅游目的地之间的时间距离,提高旅游便利 性和吸引力,促进旅游业的发展。

加强安全保障措施

高速铁路建设和运营过程中需要加强安全保障措施,确保列车运行 安全、旅客出行安全以及沿线地区的社会治安稳定。

提升国际竞争力,促进全球化进程

提升国际贸易便利化水平

高速铁路网络将缩短国际贸易的运输时间,降低物流成本 ,提高国际贸易的便利化水平。

04

高速铁路网络覆盖全球主 要城市实施计划

基础设施建设规划及时间表

01

建设高速铁路网络

根据全球主要城市的分布和交通需求,规划建设连接各大洲和主要国家

的高速铁路网络,包括高速铁路线路、车站、车辆段等基础设施。

02 03

制定详细建设计划

针对每个高速铁路项目,制定详细的建设计划,包括工程可行性研究、 初步设计、施工图设计、招投标、施工、验收等各个阶段的时间表和任 务分工。

实现城市间快速通达

高速铁路网络的建设将大大缩短城市 间的旅行时间,提高城市间的连通性 ,使得人们能够更加便捷地在不同城 市间流动。

促进区域一体化发展

高速铁路不仅连接了各大城市,也连 接了不同区域的经济中心,有助于打 破区域壁垒,推动区域一体化进程, 实现资源优化配置和经济协同发展。

推动绿色出行与可持续发展

提升服务质量

加强员工培训,提高服务意识和技能水平,为旅 客提供安全、便捷、舒适的高速铁路出行体验。

与其他交通方式衔接优化方案

实现多式联运

加强与航空、公路、水运等交通方式的衔接,优化换乘流程和时间安排,提高旅客出行效 率。

推进智能交通发展

运用大数据、人工智能等先进技术,提升高速铁路与其他交通方式的协同调度和智能化水 平。

乌得勒支中央火车站,乌得勒支,荷兰

乌得勒支中央火车站,乌得勒支,荷兰尚晋【期刊名称】《世界建筑》【年(卷),期】2018(000)004【总页数】8页(P64-71)【作者】尚晋【作者单位】【正文语种】中文荷兰最大、最繁忙的火车站正式启用了。

乌得勒支中央火车站原先是为每年约3500万乘客建造的。

目前火车站每年有8800万人。

这个数字还在不断增长,预计到2030年乘客数将达到一亿。

2003年以来,本特姆-克劳韦尔建筑师事务所一直在参与这座火车站的发展建设。

13年后,这座将火车、公共汽车和有轨电车站台集于一个起伏屋顶之下的新公共交通枢纽终于启用了。

一体化车站综合体20年后,乌得勒支中央火车站的乘客数将增长到每年约一亿人。

由于之前的建筑无法满足不断增长的乘客数,乌得勒支中央火车站的重建势在必行。

它的面积将扩大到原来的三倍,成为新的一体化车站综合体,统筹调度火车、有轨电车和公共汽车的运行。

这座车站已经成为一座自治的建筑,并且在面向会议中心和面向市区的两个入口处分别设有新的城市广场。

在2017年,面向市区的广场将建成世界上最大的自行车库,可以容纳12,500辆自行车。

起伏的屋顶在设计阶段,扬·本特姆和梅尔斯·克劳韦尔提出了设计思路,将乌得勒支中央火车站原来的平屋顶改为一道波浪,既展现富有韵律的动感,又是天然的指路标。

这道波浪沿着大厅的纵向横跨铁轨,并指明了出入口。

这道波浪有三股“起伏”:火车站上方最高,有轨电车和公交车站的两侧较低。

这些起伏也体现着车站功能的逻辑分布。

为了给车站提供更多的自然光而设计了玻璃天窗,同时也是排烟口。

天花板上连续的LED灯突出了起伏的动感。

由于钢屋顶有着生动的波浪造型,虽然建筑高度较低(18m),车站在周围的建筑和办公楼中也可以很醒目。

活力四射的车站车站一侧设有一条横跨轨道的公共步行街,过路的人无需使用“乘车芯片卡”就可以从西走到东。

餐厅、商店和将来可能出现的市场使步行街宛如城市中的街道。

巨大的玻璃幕墙悬挂在车站235m长、85m宽的屋顶下,人们可以借此一览火车、铁轨和开阔的城市景观。

印尼高铁方案

(3)线路采用全封闭、全立交设计,确保列车高速运行的安全性。

2.技术标准

(1)设计速度:350公里/小时。

(2)轨道类型:无砟轨道。

(3)供电方式:接触网供电。

(4)信号系统:采用我国自主研发的高速铁路信号系统。

3.工程建设

(1)土建工程:包括路基、桥梁、隧道、涵洞等。

(2)四电工程:包括供电、信号、通信、机电等。

(3)车站及配套设施:包括车站建筑、站前广场、停车场等。

4.生态环境保护

(1)优化线路走向,尽量减少对生态环境的影响。

(2)采用绿色施工技术,降低施工过程中的污染排放。

(3)加强生态保护,对沿线生态敏感区进行保护与修复。

5.项目投资与融资

(1)项目总投资约160亿美元。

-建立生态补偿机制,推动环境保护与经济发展相结合。

5.投资与融资策略

-预计项目总投资约160亿美元,确保资金来源的多元化和合理性。

-探索政府与社会资本合作(PPP)模式,鼓励私营企业参与。

-通过国内外金融机构贷款、债券发行等手段,降低融资成本。

四、项目实施与监管

1.组建项目公司:由我国企业与印尼企业共同成立,负责项目的规划、建设和运营。

印尼高铁方案

第1篇

印尼高铁方案

一、项目背景

随着全球经济一体化的发展,我国与印度尼西亚(以下简称“印尼”)之间的交流与合作日益紧密。为满足两国人民日益增长的出行需求,提高交通效率,促进区域经济发展,我国政府与印尼政府达成共识,决定共同推进印尼高铁项目的建设。本项目旨在建立一条连接印尼首都雅加达与第二大城市泗水的高铁线路,全长约800公里。

3.工程建设与管理

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

拜 独轨铁路建 存人] 岛j ,2 0 年动 l : - 05 r,于2 0 年4 0 9 月投入运 用先进 的信息技术 和实 现运 输物流一体 化等。 营。线路 全长54 m,最大纵 向坡度4 % ,最 小竖 曲 .5k 0 线 长度2 0I,最小 曲线半径 10n,设 有4 0 l l 0 l 个停车站 最 困难的 丁程是 1 m的跨海线路 ,总造 价约3 k 亿欧元 。

伊 朗铁 路 发展 前景

近年来 ,伊朗铁路 ( A )实施政 府制定 的新 运输政 策 ,使铁路 R 1

列车长4 .0I,高52 7n:载客 时总重约4 ,3 31 l l .3 l 0t 节编 建设进 入 了快速 发展 时期 。 国家计划 增加 基 本建设 投资 和创 造必要

组 。 目前 保 有 量 为 4 列 车 ,今 后 将 增 加 至 9 。 每 列 条 件 , 将 以 最 短 的 时 间 在 现 有 路 网基 础 上 建 成 连 接 所 有 大 城 市的 铁 列 列 车 设 7 个 座 席 ,2 2 立 席 初 期 运 量 为 单 方 向24 0 路 网 ,运 营 线 路 总 长 度 比 既 有 的83 0k 加 一 倍 ,且 主要 运 输 方 向 0 3个 0 0 m增

最 高运 行速 度 7 m/ ,并计 划将 延 士2k 0k h ∈ m,以便 与 平将显 著提高 。相关规 划和已经采取 的措施 有 :存部 分运输 方向线 路

线 ),大规模 进行既有线 电气化和信号 系统 的现代化改造 ,加快伊 朗 2 0 年 , 鹿 特 丹 ( 兰 )一 米 兰 (意 大 与巴 基 斯 坦 、土 库 曼 斯 坦 阿富汗 、阿塞拜疆 和伊批克等周边 国家 的 07 荷

些.跨越各罔边境开展运输 ,由于这些闰家铁路牵

荷兰高速铁路 ( SH ed 称,贯穿于高速铁路南线的阿姆斯 N i e )

引供 电制 式干 信号 系统 不 同以及 运输 组织 方法 特丹一 鹿特丹段开 始运输服 务 ,这标志着错综 复杂的高速线路 网正式 ¨ 各 异 ,需要建立 和采用E pi i 巾央管理系统 开始投入 商业运 营。庞 巴迪制 造的T a 1 tal r s rx 机车 和7 C 客车将 运行存 辆1 R 11 与有关 同家 铁路 基础 设施 公 司的 信息 系统 、基 线路上 "x 4 础设 施 管理 和技 术维 修 系统 、用户 系统 ( 如铁

人/ ,今后将提 高至60 0 h h 0 人/ 。列 车运行问隔7ri, n a 2 1年投入 运营的有轨 电车 实现换 乘 。 0 1

的运 输 和通过 能 力以及 基础 设施 、技 术装 备 和机车 l 的现代 化水 乍辆 段铺设 双线 ( 最主要是从 巴夫克到波斯湾 沿岸阿 巴斯港 的6 5k 1 m复

、

利 )问欧 I 运输走廊 开始采 E mfj 周 日际运输走廊 建设 ,更新改造 和购置新 的运 营机 车V N 与此 同时 I 。 , 南北 u )r la -

,

际联 运最 佳 化系统 。这条运 输 走廊 从荷 兰经 德 将针对铁路运 营管理体制进 行私有化改革 ,提 高铁路运输 _作组织 的 厂

坚 同、 国 瑞J 奥 利 意 利, 泛 同 效 干 益 0 法 、 : 地 至 大 是 欧 率“ 。 、 效

要方上行闰联旅和物萎 向升的际运客货列一 车

,

均 需

荷 高 铁 南 HLoh投 运 兰 速 路 线(SS t 入 营 u) 1

。J I I 二 司 u 阢 口 JJ 千戡 、 , 】 /\ x 苗

迪拜独 轨铁 路 的规 划

欧洲最 著名 的独轨铁 路是 l欧洲 铁路 货物 运输 的 未来发展

近 年来 ,为进一 步开 放 欧洲 铁路 网 ,充分 开拓 和利 朋货

珀塔 尔 ( p et1 独轨 铁路 。独轨铁路 主要用 于客运 ,填 物运输 的潜 力 ,并 提高铁路 在货物运输 市场 的竞争力 ,许多同 Wu p r ) a 补 地下铁 道和有 轨 电 道之 间 的运 输空 白 : 目前 ,独轨铁 路 家铁路行业 与其他 日家通过 合作 ,研究和采取增 加运量 、降低 的运量单 方 向限制在 2 万人/ ,新 的列车 编组单 方 向限制 在3 成 本 及 提 高 运 输 服 务 质 量 的组 织 和 技 术 措 施 , 推进 欧 洲 铁 路 货 h 万人, ?一 般独轨铁路 的高架 行车道 宽度为6 h 0~8 0㈨ ,南混 物运输 的发展 。其 中包 括 :组织 开行 大运 输能 力 的货 物列 车 凝土 或钢材 制成 。列车 在行 车道上 或跨坐 在行 车道上 又或悬 ( 重量 、长度 、容积增 加 的列车 )和 速度 提高 的快速 货物 列 挂在 行车道 下运 行。 由于独轨 铁路 采用高 架形式 ,因此 可 与 车 ;使用节能 和环 保型机车牵 引货物列_ 午,研究片 内燃 机乍也 J

其他 交通 1 具实现 主 体交 叉 ,从而 避免与 汽车 或有轨 电车 等 采用配备辅助 的蓄电池能源 、综 合型牵引传动 系统 、经 济型和 -

相 撞 的 交 通 事 故 。 独 轨 铁 路 的 曲 线 半 径 可 以 小 至 5 1 0i,纵 向 环保型柴油机 的电力机车 ;使川 阿尔斯通 、庞 巴迪 、两 门子 、 3

坡度 可以 大到6 %,最高 速度 为8 m/ ,但其 道岔 结构 比较 V sln Ok h o s 、Vo h、E 等一些 由主 要机车 车辆 制造 厂商设计制 o i t MD

复 杂 ,造 价 较 昂 贵 。 目前 世 界 上 约 有 3 条 独 轨 铁 路 ,分 布 在 造 ,上‘ 用于未来货物运输 发展需求 的新 型货运机车 ;改进货 O f 适 新 加 坡 、马 来 西 亚 、 日本 、 巾 闰 和 美 圈 以 及 德 罔 。 阿 联 酋 迪 运 车辆 结构 ,提高 车辆 的强度和载重量 ;货物运输组织管理采