Method of Cone Calorimeter Used for Estimation of the Visibility

dematal方法的英文表达

dematal方法的英文表达Dematal Method: A Comprehensive Overview.The Dematal method, often referred to as Deming's 14 Points or Deming's philosophy, is a set of principles and guidelines for improving the quality of products and services. Developed by the renowned management expert Edward Deming, this methodology has been widely adopted by organizations across various industries, aiming to enhance operational efficiency, reduce waste, and improve customer satisfaction.Deming's 14 Points outline a comprehensive approach to quality management, focusing on the systematic elimination of defects and errors rather than mere inspection or testing. These points emphasize the importance of leadership, employee training, process improvement, and customer focus, among other critical areas.The first point emphasizes the need for organizationsto adopt a long-term perspective in their pursuit of quality. This means that companies should focus on sustainable improvements rather than short-term fixes, ensuring that their quality efforts are sustainable and scalable.The second point highlights the importance of improving product quality by constantly seeking to understand and address the root causes of problems. Deming believed that focusing on symptoms alone was insufficient; instead, organizations needed to dig deep to understand the underlying issues that were causing defects and errors.The third point emphasizes the role of management in setting clear goals and expectations for quality. Management should communicate these goals to employees and provide them with the tools and resources necessary to achieve them.The fourth point emphasizes the importance of adopting a proactive approach to quality management, seeking to prevent problems before they occur rather than waiting tofix them after they have arisen. This requires a culture of continuous improvement and a focus on process control.The fifth point emphasizes the need for management to recognize and reward employees for their contributions to quality. This fosters a culture of engagement and ownership, where employees feel valued and motivated to contribute to quality efforts.The sixth point highlights the importance of employee training and education in achieving quality. Demingbelieved that employees were the backbone of anyorganization and that investing in their development was crucial to achieving long-term success.The seventh point emphasizes the need for management to remove barriers that prevent employees from contributing to quality efforts. This includes providing them with the freedom to suggest improvements, implement changes, andtake ownership of their work.The eighth point highlights the importance ofdeveloping strong relationships with suppliers and partners to ensure the quality of incoming materials and components. This requires a focus on supply chain management and the development of long-term relationships based on trust and mutual respect.The ninth point emphasizes the need for organizations to continuously improve their processes and procedures. This involves regularly reviewing and revising processes to eliminate waste, increase efficiency, and reduce the potential for errors.The tenth point highlights the importance of using statistical methods to understand and manage variation in processes. Deming believed that by understanding and controlling variation, organizations could achieve consistent and predictable results.The eleventh point emphasizes the need for organizations to implement rigorous quality control systems to ensure that products and services meet customer requirements. This requires a focus on prevention ratherthan inspection, with quality being built into products and services from the outset.The twelfth point highlights the importance of management's role in setting an example of quality leadership. Management should demonstrate a commitment to quality by their actions and decisions, creating a culture where quality is valued and expected.The thirteenth point emphasizes the need for organizations to focus on improving their products and services from the customer's perspective. This requires a deep understanding of customer needs and expectations, as well as a focus on delivering value and satisfaction.The fourteenth point serves as a reminder that improving quality is a never-ending journey. Organizations should always strive to improve their processes, products, and services, seeking to eliminate defects and errors wherever they may occur.In conclusion, the Dematal method provides acomprehensive framework for organizations seeking to improve the quality of their products and services. By adopting these principles and guidelines, companies can create a culture of continuous improvement, engage their employees, and deliver value to their customers. While implementing the Dematal method may require significant time and effort, the resulting improvements in quality, efficiency, and customer satisfaction are well worth the investment.。

四川大学化工考研884复试面试英语题库翻译原文

1.When a fluid flows through a duct or over a surface, the velocity over a place at right angles tothe stream is not normally uniform. The variation of velocity can be shown by the use ofstreamlines which are lines so drawn that the velocity vector is always tangential to them. The flow rate between any two streamlines is always the same. Constant velocity over a cross-section is shown by equidistant streamlines and increase in velocity by closer spacing ofstreamlines.2.It is found the heat transfer rate per unit area q is dependent on those physical propertieswhich affect flow pattern. The thermal properties of the fluid and the velocity of flow the fluid over the surface, the temperature difference t and a factor deternming the natural circulation effect cause by expansion of the fluid on heating.3.The oil distilled in a very large steel tower, the technical names of which is the fractionatingtower. The tower is thirty to fifty meters tall and its diameter is one to three meters. It isdivided into chambers, each of which contains a layer of trays. There are holes in the trays. The chanbers are at different heights, and temperature at each height is different.4. A group of operation for separating the components of mixture is based on the transfer ofmaterial from one homogeneous phase to anther. Unlike purely mechanical separation, these methods utilize differences in vapor pressure or solubility, not density or particle size. The driving force for transfer is a conoantration differce to or a concentration gradient, much as a temperature difference or a temperature gradient provides the driving force heat transfer.5.The three most important characteristics of an individual particle are its composition, its sizeand its shape. Composition determine such properties as density and conductivity, provided that the particle is completely uniform. A particle shape may be regular such as spherical or cubic, or it may be irregular as, for example, with a piece of broken glass.6.homogeneous catalysis is the industrical oxo process for manufacturing normal iosobuty(异丁醛)。

锥形量热仪的工作原理及应用

到火焰熄灭为止所释放热量的总和 ,即

t

THR = ∫HRR ,单位为 MJ / m2 。

t =0

end

将 HRR 与 THR 结合起来 , 可以更好地评价材料 的燃烧性和阻燃性 , 对火灾研究具有更为客观 、 全面 的指导作用 。 313 质量损失速率 ( Ma ss Lo ss Rate ,简称 MLR)

HRR 是指在预置的入射热流强度下 ,材料被点燃

后 ,单位面积的热量释放速率 ,即

・

q 1 ΔHC q″ = = × 1 . 10 ×c A A r0

・

ΔP

Te

x02 - xO2

0

1 . 105 - 1 . 502

( 6)

HRR 是表征火灾强度的最重要性能参数 ,单位为 kW/ m2 ; HRR 的 最 大 值 为 热 释 放 速 率 峰 值 ( Peak of HHR ,简称 pkHRR) ,pkHRR 的大小表征了材料燃烧时

王庆国 张军 张峰

( 青岛科技大学高分子科学与工程学院 青岛 266042)

E2mail :qgwang @263. sina. com

摘 要 锥形量热仪是当前能够表征材料燃烧性能的最为理想的试验仪器 ,它的试验环境同火灾材料的真实燃 烧环境接近 ,所得试验数据能够评价材料在火灾中的燃烧行为 。本文介绍了锥形量热仪的结构 、 工作原理和应用 ,并 就燃烧性能在材料评价 、 材料设计和火灾预防等方面的重要意义作了阐述 。 关键词 锥形量热仪 ; 氧耗原理 ; 燃烧性能 中图分类号 TH89

作者简介 : 王庆国 ,男 ,1971 年生 ,讲师 ,山东莒南人 ,现主要从事高聚物材料阻燃和火灾中高聚物材料燃烧行为研究 。

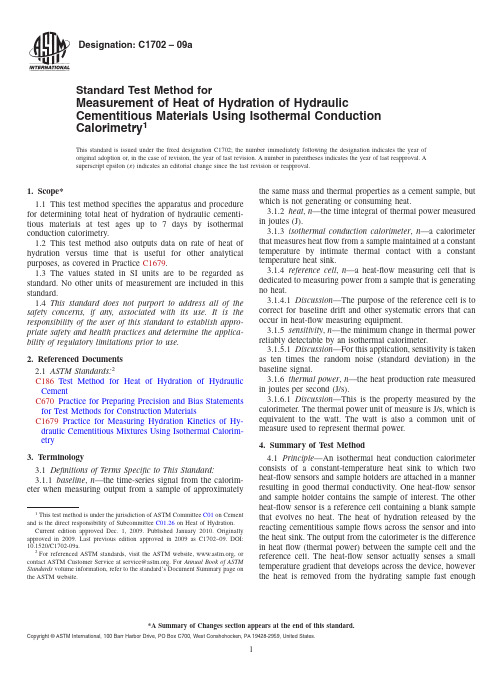

C1702

Designation:C1702–09aStandard Test Method forMeasurement of Heat of Hydration of Hydraulic Cementitious Materials Using Isothermal Conduction Calorimetry1This standard is issued under thefixed designation C1702;the number immediately following the designation indicates the year of original adoption or,in the case of revision,the year of last revision.A number in parentheses indicates the year of last reapproval.A superscript epsilon(´)indicates an editorial change since the last revision or reapproval.1.Scope*1.1This test method specifies the apparatus and procedure for determining total heat of hydration of hydraulic cementi-tious materials at test ages up to7days by isothermal conduction calorimetry.1.2This test method also outputs data on rate of heat of hydration versus time that is useful for other analytical purposes,as covered in Practice C1679.1.3The values stated in SI units are to be regarded as standard.No other units of measurement are included in this standard.1.4This standard does not purport to address all of the safety concerns,if any,associated with its use.It is the responsibility of the user of this standard to establish appro-priate safety and health practices and determine the applica-bility of regulatory limitations prior to use.2.Referenced Documents2.1ASTM Standards:2C186Test Method for Heat of Hydration of Hydraulic CementC670Practice for Preparing Precision and Bias Statements for Test Methods for Construction MaterialsC1679Practice for Measuring Hydration Kinetics of Hy-draulic Cementitious Mixtures Using Isothermal Calorim-etry3.Terminology3.1Definitions of Terms Specific to This Standard:3.1.1baseline,n—the time-series signal from the calorim-eter when measuring output from a sample of approximately the same mass and thermal properties as a cement sample,but which is not generating or consuming heat.3.1.2heat,n—the time integral of thermal power measured in joules(J).3.1.3isothermal conduction calorimeter,n—a calorimeter that measures heatflow from a sample maintained at a constant temperature by intimate thermal contact with a constant temperature heat sink.3.1.4reference cell,n—a heat-flow measuring cell that is dedicated to measuring power from a sample that is generating no heat.3.1.4.1Discussion—The purpose of the reference cell is to correct for baseline drift and other systematic errors that can occur in heat-flow measuring equipment.3.1.5sensitivity,n—the minimum change in thermal power reliably detectable by an isothermal calorimeter.3.1.5.1Discussion—For this application,sensitivity is taken as ten times the random noise(standard deviation)in the baseline signal.3.1.6thermal power,n—the heat production rate measured in joules per second(J/s).3.1.6.1Discussion—This is the property measured by the calorimeter.The thermal power unit of measure is J/s,which is equivalent to the watt.The watt is also a common unit of measure used to represent thermal power.4.Summary of Test Method4.1Principle—An isothermal heat conduction calorimeter consists of a constant-temperature heat sink to which two heat-flow sensors and sample holders are attached in a manner resulting in good thermal conductivity.One heat-flow sensor and sample holder contains the sample of interest.The other heat-flow sensor is a reference cell containing a blank sample that evolves no heat.The heat of hydration released by the reacting cementitious sampleflows across the sensor and into the heat sink.The output from the calorimeter is the difference in heatflow(thermal power)between the sample cell and the reference cell.The heat-flow sensor actually senses a small temperature gradient that develops across the device,however the heat is removed from the hydrating sample fast enough1This test method is under the jurisdiction of ASTM Committee C01on Cementand is the direct responsibility of Subcommittee C01.26on Heat of Hydration.Current edition approved Dec.1,2009.Published January2010.Originallyapproved st previous edition approved in2009as C1702–09.DOI:10.1520/C1702-09a.2For referenced ASTM standards,visit the ASTM website,,orcontact ASTM Customer Service at service@.For Annual Book of ASTMStandards volume information,refer to the standard’s Document Summary page onthe ASTM website.*A Summary of Changes section appears at the end of this standard. Copyright©ASTM International,100Barr Harbor Drive,PO Box C700,West Conshohocken,PA19428-2959,United States.that,for practical purposes,the sample remains at a constant temperature(isothermal).4.2The output from the heat-flow sensor is an electrical voltage signal that is proportional to the thermal power from the sample.This output must be calibrated to a known thermal power.In this method this is accomplished by measurements on a heat source that emits a constant and known power level. The integral of the thermal power over the time of the test is the heat of hydration.4.3Two methods are described.In Method A the sample and water are both temperature equilibrated and mixed inside the calorimeter.This method is the most direct way to determine heat of hydration.In Method B the sample is mixed outside of the calorimeter then put into the calorimeter.This method offers certain practicality,but depending on the materials being analyzed and procedures used for mixing and handling,this method may suffer from small errors due to periods of hydration being missed or spurious heat being introduced or taken away from the calorimeter during setup or combinations thereof.Methods of correction are offered for these potential errors.5.Significance and Use5.1This method is suitable for determining the total heat of hydration of hydraulic cement at constant temperature at ages up to7days to confirm specification compliance.It gives test results equivalent to Test Method C186up to7days of age (Poole(2007)(4)).5.2This method compliments Practice C1679by providing details of calorimeter equipment,calibration,and operation. Practice C1679emphasizes interpretation significant events in cement hydration by analysis of time dependent patterns of heatflow,but does not provide the level of detail necessary to give precision test results at specific test ages required for specification compliance.6.Apparatus6.1Miscellaneous Equipment:6.1.1Balance—Accurate to0.01g.6.1.2Volumetric Dispenser—A device for measuring vol-ume or mass of water,accurate to0.1mL.This could be a syringe,pipette,or weighing device.6.1.3Sample Holder—A device that holds the cement paste and provides intimate contact with the calorimeter heat sensing device and prevents evaporation of mixing water.If using commercially manufactured equipment,consult the recom-mendations of the manufacturer in choosing sample holders.6.1.4Resistance Heater—An electrical device fabricated from material with similar heat capacity and shape as the test sample,but containing a resistor connected to a constant-voltage power supply such that a stable output of0.0106 0.0002J/s can be generated(see Note1).N OTE1—A simple procedure for fabricating heaters and blanks having the same approximate shape and heat capacity as a sample is to make specimen similar to one used in a determination out of plaster of Paris embedded with a small resistor.Plaster of Paris has only a transient heat of hydration and is not aggressive to electronic components.A resistance of100-300ohms is a convenient value when using voltages of0.1-10 volts to drive heat production.6.1.5Reference Specimen—A sample fabricated from an inert material with similar heat capacity and shape as the test sample.This is used in the reference cell.6.1.6Multimeter—An instrument for measuring DC voltage and resistance values for the resistance heater described in 6.1.4to an accuracy of1%.This instrument is only required if the calorimeter does not contain built-in calibration capability.6.1.7Power Supply—A constant voltage DC power supply with a power output range sufficient to simulate the maximum output of a hydrating cement sample(see Note2).This equipment is only required if an instrument does not contain built-in calibration capability.N OTE2—A power output of at least0.33J/s is needed for most applications.6.1.8Insulated Container—Used in the Method B de-scribed in8.3.5.1.This device can be fabricated using a500 mL(approximate volume)container insulated with at least30 mm of polystyrene on the sides and top.6.1.9Temperature Measuring Device—Used in Method B described in8.3.5.1.The device shall be capable of measuring temperature changes to the nearest0.1°C and of a physical configuration that allows it to operate in the confines of the insulated container described in6.1.8.6.2Calorimeter—The schematic design of a calorimeter is given in Fig.1.It shall consist of a sample holder for the test and reference specimens,each thermally connected to heat flow sensors,which are thermally connected to a constant-temperature heat sink.The actual design of anindividual FIG.1Schematic Drawing of a Heat ConductionCalorimeterinstrument,whether commercial or homemade,may vary,but it should follow the criteria given below.Any other suitable arrangement that satisfies sections 6.2.1,6.2.2,and 6.2.3is acceptable.6.2.1Instrument Stability —The baseline shall exhibit a low random noise level and be stable against drift.This property shall be verified on a new instrument and whenever there are questions about performance.The rate of change of the baseline measured during a time period of 3days shall be #20µJ/s per gram sample per hour of the test and a baseline random noise level of #10µJ/s per gram sample (see Note 3).In practice the baseline is measured for 3days and a straight line is fitted to the power (J/g/s)versus time (h)data using a linear regression procedure.The long term drift is then the slope in the line J/g/s/h and the baseline noise level is the standard deviation (J/g/s)around this regression line.N OTE 3—The rationale for these limits is found in Poole (2007)(4).6.2.2Instrument Sensitivity —The minimum sensitivity for measuring power output shall be 100µJ/s.6.2.3Isothermal Conditions —The instrument shall main-tain the temperature of the sample to within 1K of the thermostated temperature.6.3Data Acquisition Equipment —Data acquisition equip-ment may be built into the calorimeter instrument package,or it may be an off-the-shelf,stand-alone,item.The data acqui-sition equipment shall be capable of performing continuous logging of the calorimeter output measurement at a minimum time interval of 10s.It is useful,for purposes of reducing amount of data,to have the flexibility to adjust the readinginterval to longer times when power output from the sample is low.Some data acquisition equipment is designed to automati-cally adjust reading intervals in response to power output.The equipment shall have at least 4.5-digit-measuring capability,with an accuracy of 1%,or comparable capabilities to condi-tion the power output into the same quality as integrated signal amplifiers.7.Instrument Calibration7.1Instrument Calibration —Commercially manufactured instruments designed for measuring heat of hydration of cementitious materials may have instrument specific calibra-tion procedures.Conform to these procedures if they exist.In addition,the instrument shall be capable of providing data described in 7.1.1.1,7.1.2.1,and 7.1.2.2,and calculations in 7.1.4.If there are no instrument calibration procedures,cali-brate the instrument according to the following procedure.Calibration shall be at least a two-point process.This is illustrated schematically in Fig.2.7.1.1Mount the resistance heater and the blank specimen in their respective measuring cells and start data collection.This step measures the baseline calorimeter output (in units of V or mV)when no heat is being generated.7.1.1.1Measure this baseline when it reaches a constant value (drift #20µJ/s per gram sample per hour).7.1.1.2Record this output as V 0for P 0=0(see Note 4).N OTE 4—V 0may not be zero voltage,but may be a positive or negative number.The practice of using a test cell and a reference cell usually results in the V 0being a relatively small number but,depending on the variability in properties of some hardware,it may not bezero.FIG.2(A)Schematic Steady-State Calibration Using A 2-Point Calibration Process And (B)Multi-Point CalibrationProcess7.1.2Power in the heater circuit is related to voltage and resistance by the following equation:P5I2R(1) where:P=power,J/s,I=applied current,amperes,andR=resistance,ohms.Apply sufficient voltage to the heater circuit to generate a heat output of approximately0.1J/s,measured to an accuracy of 5%.7.1.2.1Allow the output to stabilize signal at a drift of #0.1%over60min or#0.05%over30min.7.1.2.2Record this output as V1for a power P1(see Note5). This is the minimum requirement for a calibration sequence.At the users discretion any number of voltage levels may be used to characterize the operating range of the calorimeter.N OTE5—The early C3A reaction of a typical portland cement evolvesa maximum power of about0.02J/s/g.The alite phase typically evolves heat at a maximum power of about0.002J/s/g during thefirst24h of hydration.A5g sample then generates power peaks in the range of0.10 J/s/g in thefirst few minutes after adding water,and in the range of0.010 J/s/g in thefirst24h.7.1.3Calibration Coeffıcients—Calculate calibration coeffi-cients byfitting the power versus voltage output data to a to a mathematical relationship using standard curvefitting tech-niques.Power(P),in units of J/s(or watts),is the dependent variable(y)in the calibration equation,and output voltage(V), in units of mV,is the independent variable(x).This equation is then used to translate mV output to power units meaningful for calculating heatflow(see Note6).N OTE6—A linear calibration equation is found to be suitable in many instruments over the operating range necessary to analyze portland cements,as in the following equation:P=A+BV.In this case,thefitted coefficients A(y-axis intercept)and B(slope)are in units of J/s and J/s/mV,respectively.7.1.4In a multi-channel instrument containing several calo-rimeters,all channels shall be calibrated individually.How-ever,it is possible to calibrate all calorimeters simultaneously using multiple resistance heaters and having the same current passing through the heaters in all calorimeter cells.7.1.5Calibration shall be executed at regular intervals to determine the calibration coefficient.The length of the time intervals between calibrations is dependent on the instrument and the personnel,and must be determined empirically.If the calibration coefficient differs more than2%from one calibra-tion to the next,then calibrations intervals must be reduced until this stability limit is reached.8.Procedure8.1Turn on the calorimeter equipment and data acquisition unit.Determine that the calorimeter is at temperature equilib-rium by verifying that the baseline is stable over a period of a few minutes.The temperature of the heat sink during the test shall be23.06 1.0°C,unless a different temperature is required by the analysis.8.2Method A—This method is used when an instrument is configured so that cementitious materials and water can be temperature equilibrated and mixed while in place in the calorimeter cell.8.2.1Weigh at least3g of cementitious material(see Note 7),the mass recorded to the nearest0.01g,and place in the calorimeter cell.Weigh or determine volumetrically sufficient water to give a paste water-cementitious materials ratio of at least0.40,but in any case sufficient water to completely wet the sample,and place the water holder in the cell.Higher water-cementitious materials ratios may be required to get thorough mixing of cement and water(see Note8).Allow any change in the calorimeter output caused by this process to return to the baseline level.N OTE7—Amount of sample required varies among calorimeter de-signs.Since the exothermic reaction tends to slow down after thefirst24 h,a sample that is too small will generate a signal late in the test period that is too weak to detect reliably.If inconsistent results are obtained,then a larger sample size may be required.Sample sizes between about3and 15g have been reported to be useful for maintaining a strong signal late in the test for portland-cement based cements.Normally a signal of at least 10µJ/s/g at the end of the test is sufficient to give good results.Tests designed to run for1-3days can use a sample mass at the smaller end of this range,while longer tests,such as7days,require a sample mass at the larger end of this range.N OTE8—The w/c required for good mixing will probably have to be determined empirically by examining specimens after completion of testing for evidence of poor mixing.8.2.2Start data collection,then mix the water with the cementitious materials to form a uniform paste.Some com-mercial calorimeters and data acquisition equipment are pro-grammable to collect data at prescribed interval lengths or at intervals that vary with the rate of change of power levels.Data are collected more rapidly when power output is high than when it is low.If thisflexibility is not a feature of the data acquisition component of the calorimeter,then collect readings every30s throughout the length of the test(see Note9).N OTE9—It is only necessary to collect data every10s through the period of an early and short-lived heat evolution peaks.In portland cements this is over within approximately30min.Data collection every 10min is adequate after this point.Adopting this practice will reduce the size of datafiles.8.3Method B—This method is used when cement paste is mixed outside of the calorimeter and then loaded into the calorimeter cell.In this procedure,a small amount of the early heat-of hydration data may be lost.For non-portland-based cements,the error could be more significant.Also,the baseline may also be disturbed during the early period of the test due to spurious heat gains to the sample or losses from the sample while outside of the calorimeter, e.g.during mixing and handling.Procedures for correcting these errors are included in paragraphs8.3.5.1and8.3.5.2,respectively.8.3.1Conditioning Materials—All materials shall be at a temperature of2362°C before mixing unless a different temperature condition is required for the analysis.8.3.2Mixing and Charging of Cement Paste—The mixing of the cement paste shall be made in such a way that the time between the addition of water and the time when the sample is put into the calorimeter is less than5min.Mixsufficientcement paste at a water-cementitious materials ratio of0.40or higher to give a sample containing a mass of dry cement in the range described in Method A.Determine the mass of the paste sample to the nearest0.01g,put it into the calorimeter sample holder,and cover to prevent evaporation of mixing water. 8.3.3Care should be taken that the incidental warming or cooling of the sample and the sample holder due to handling are minimal.Although the method provides a correction for such temperature effects,it is not designed to handle large temperature differences between the sample and the calorim-eter(see Note10).N OTE10—Use of insulating cotton gloves may be helpful in minimiz-ing heating of the sample from handling.8.3.4Load the sample and sample container into the calo-rimeter.Start data collection10min after adding water to cement during mixing,and collect data as described in8.2.2.8.3.5Error Corrections for Method B—Two corrections may be needed for Method B.One is a correction for early hydration data lost during thefirst10min,while mixing, handling,and equilibrating the sample in the calorimeter (8.3.5.1).The other is a correction for heat gained or lost from or to the environment during mixing and handling before the sample is put into the calorimeter(8.3.5.2).8.3.5.1Correction for Early Hydration—Equilibrate a500g sample of cement,250mL of water,and the polystyrene insulated container described in6.1.8to2361°C.Record the starting temperature.Place the cement and water in a plastic bag and mix quickly by kneading the bag.Place the bag in the polystyrene insulated container as soon as mixing is complete along with a thermocouple.Cover and measure temperature at 10min after adding water to the cement.Record the tempera-ture rise to the nearest0.1°C.The calculation of the heat-of-hydration during this10min period is described in9.2.1. 8.3.5.2Correct for Temperature Change Due to Mixing and Handling—A determination of the heat increase or decrease in the sample during mixing and handling of the sample is determined by mixing an inert sample with water,using the same mass of materials and the same procedure as in a heat of hydration determination,then introducing equivalent mass of paste used in a determination into a calorimeter cell that has been running at baseline.Collect data at10s intervals,as in a normal determination,until the signal has returned to the baseline.The calculation of the heat is described in paragraph 9.2.2.9.Calculation9.1Method A—For Method A,the total heat of hydration, Q t,is the integrated value of the power versus time data, collected as described in8.2without further correction.9.1.1Remove Leading Edge Data—For both Methods A and B,there may be data collected during instrument setup and thermal equilibration that is not pertinent to thefinal determi-nation.These data shall be removed.9.1.2Many data acquisition units and commercial calorim-eters incorporate the calibration equation into the software and present the raw output data in units of J/g of cement.If this is not the case,then the output data will be in units of mV,and must be transformed into thermal power using the calibration coefficients determined from Eq2.P n5A1BV n(2) where:P n=power input level used in the instrument calibration, andV n=voltage output level used in the instrument calibra-tion.9.1.3Calculation of Q t—The total heat of hydration of the sample,Q t,is calculated by integrating the power/g versus time data over the time interval of the test(t0to t e,in units of seconds)as in Eq3:Q t5*t5t0t e Pdt(3)where:t0=the time the cement and water are mixed,taken as zero (in Method A),andt e=the end of the test.t0will be different for Method A and Method B.9.1.4Operationally,the integration is executed by averaging the power output from two consecutive readings and multiply-ing by the time interval of the reading,giving an output for each time increment in units of J/g.The heat so calculated in each time increment is then summed over the duration of the test,as in Eq4.Q t5(t5t0t e S P~t i!–P~t i11!2D3~t i11–t i!(4)where:P(t i)=the power output at time t i,andP(t i+1)=the power output at the next time interval(t i+1). In Method A,t0is taken as zero when water is added to the cement.9.2Method B—The total heat evolved during the calorim-eter run,Q t is calculated as in Eq3and4,but t0is the600s(10 min).Q t must be corrected for heat evolved prior to introduc-tion of the sample into the calorimeter,denoted as Q2,and for any heat gained or lost during sample mixing and handling, denoted as Q3.The total heat,Q t’is then calculated from Eq5.Q t’5Q t1Q21Q3(5) 9.2.1Determine Q2—From the temperature rise and sample composition data in8.3.5.1,calculate the heat evolved during thefirst10min of hydration using Eq6.Q25D T~F c3C c1~1–F c!3C w!F c(6)where:D T=the temperature rise during the test described in8.3.4, F c=the mass fraction of the cement in the paste,C c=the heat capacity of dry cement(nominally0.75kJ/kg/K),andC w=the heat capacity of water(nominally4.18kJ/kg/K).9.2.2Determine Q 3—Q 3is calculated from the data col-lected according to paragraph 8.3.5.2,and using Eq 2and 3.The initial time (t 0)will be taken as zero when the sample is first put into the calorimeter,and t e will be the time when the signal returns to the baseline.10.Report10.1Test Report —Report the following information:10.1.1Cement sample identification.10.1.2Date and time when the test was performed.10.1.3Instrument used.10.1.4The mass of dry cement in sample.10.1.5The name of the data file.10.1.6Date of the calibration used.10.1.7A figure showing the resulting thermal power curve.10.1.8Calculated heat of hydration and the method (A or B)used.11.Precision and Bias11.1Precision —A complete interlaboratory study has not been completed for this test method.Therefore the precision of the method has not been determined (Note 11).N OTE 11—Two sources of published data give indications of the potential precision of the method.Data from Wadso and Arndt (1,2,3)were derived using methods that appeared to most closely resemble Method B in this test method.The program included 18laboratories,each of which analyzed 2cements.No within-laboratory repeatability data were reported.From these data,a between-laboratory standard deviation of 10.5kJ/kg at 3days was calculated.Two laboratories should be expected to differ by no more than 29kJ/kg in 95%of such paired laboratory comparisons.This is the d2s value as described in Practice C670.The VDZ (2006)(5)round robin included 20laboratories each conducting analysis on 5cements.Tests are believed to be 7-day results.Analogs to Methods A and B of this test method were represented,but the precision data were not separated according to this classification.A within-laboratory standard deviation of 4.6kJ/kg was reported (d2s =12.9kJ/kg).A between-laboratory standard deviation of 13.6was reported (d2s =35.3kJ/kg).11.2Bias —Bias cannot be determined because there is no standard material having an accepted reference value (Note 12).N OTE 12—Bias relative to solution calorimetry,as in Test Method C186is of interest.Poole (2007)(4)compared heat of hydration determinations by solution calorimetry and conduction calorimetry among laboratories and found no consistent bias between the two methods.12.Keywords12.1heat of hydration;hydraulic cement;isothermal con-duction calorimetry;portland cementREFERENCES(1)Wadso L,Goldberg RN,Standards in Isothermal Microcalorimetry (IUPAC Technical Report),Pure Appl Chem 73,pp.1625-39,2001.(2)Wadso L,Temperature Changes within Samples in Heat Conduction Calorimeters,Thermochim.Acta 366,pp.121-7,2000(3)Wadso L.and Markus Arndt,“An International Round Robin Test of Isothermal Conduction Calorimetry for Measurement of 3Days Hydration.”This is an internet posting:http://epena.u-bourgogne.fr/nanocem-calorimetry-group/literature-on-isothermal-cement calorimetry/recent-round-robin-studies.(4)Poole,Toy S,Revision of Test Methods and Specifications for Controlling Heat of Hydration in Hydraulic-Cement,PCA R&D Serial No.3007,Portland Cement Association,Skokie,IL,2007.(5)VDZ,“Round Robin Heat of Hydration 2006,”Research Institute of the German Cement Industry,Cement Chemistry Department,Dussel-dorf,Germany,2006.SUMMARY OF CHANGESCommittee C09has identified the location of selected changes to this test method since the last issue,C1702–09,that may impact the use of this test method.(Approved December 1,2009)(1)Revised Section 11.ASTM International takes no position respecting the validity of any patent rights asserted in connection with any item mentioned in this ers of this standard are expressly advised that determination of the validity of any such patent rights,and the risk of infringement of such rights,are entirely their own responsibility.This standard is subject to revision at any time by the responsible technical committee and must be reviewed everyfive years and if not revised,either reapproved or withdrawn.Your comments are invited either for revision of this standard or for additional standards and should be addressed to ASTM International Headquarters.Your comments will receive careful consideration at a meeting of the responsible technical committee,which you may attend.If you feel that your comments have not received a fair hearing you should make your views known to the ASTM Committee on Standards,at the address shown below.This standard is copyrighted by ASTM International,100Barr Harbor Drive,PO Box C700,West Conshohocken,PA19428-2959, United States.Individual reprints(single or multiple copies)of this standard may be obtained by contacting ASTM at the above address or at610-832-9585(phone),610-832-9555(fax),or service@(e-mail);or through the ASTM website ().Permission rights to photocopy the standard may also be secured from the ASTM website(/ COPYRIGHT/).。

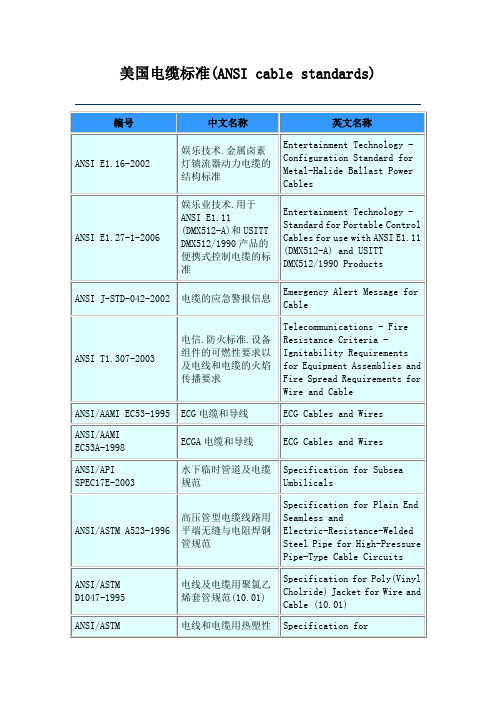

美国电缆标准(ANSI cable standards)

电线和电缆用热塑性绝缘体和护套测试方法

Methods of Testing Thermoplastic Insulations and Jackets for Wire and Cable

ANSI/ASTM D2655-2000

额定电压达到2000伏的电线和电缆交联聚乙烯绝缘材料规范(10.02)

ANSI/ASTM D4732-2002

电信电线和电缆用冷充填化合物规范

Specification for Cool-Application Filling Compounds for Telecommunications Wire and Cable

ANSI J-STD-042-2002

电缆的应急警报ge for Cable

ANSI T1.307-2003

电信.防火标准.设备组件的可燃性要求以及电线和电缆的火焰传播要求

Telecommunications - Fire Resistance Criteria - Ignitability Requirements for Equipment Assemblies and Fire Spread Requirements for Wire and Cable

ANSI/ASTM D1523-2000

工作温度90℃的电线和电缆用合成橡胶绝缘规范(10.01)

Specification for Synthetic Rubber Insulation for Wire and Cable, 90°C Operations (10.01)

ANSI/ASTM D2219-2002

ANSI/ASTM D4244-1995

重负载和超重负载丙烯腈丁二烯聚氯乙烯(NBR PVC)电线和电缆护套通用规范

Unit 6 Methods of Elevation

Unit 6 Methods of Elevation Determination——高程测量方法An elevation is a vertical distance above or below a reference datum.高程是高于或低于一个参考基准的垂直距离。

Although vertical distance can be referenced to any datum, in surveying, the reference datum that is universally employed is that of mean sea level (MSL).尽管这个垂直距离可以参考任何一个基准,在测量中,普遍使用的参考基准是平均海水面(MSL)。

MSL is assigned a vertical value (elevation) of 0.000 ft or 0.000 m.MSL被指定为高程值为0ft或0m。

All other points on the earth can be described by the elevations above or below zero. 地球上的所有其他点都可以用高于或低于0的高程来描述。

Permanent points whose elevations have been precisely determined (benchmarks) are available in most areas for survey use.在大多数区域内都有高程已被精确测定的永久点(水准点)可被用于测量。

In China, 7 years of observations at tidal stations in Qingdao from 1950 to l956 were reduced and adjusted to provide the Huanghai vertical datum of 1956.在中国,青岛验潮站从1950年到1956年7年的观测,被归纳并整理后提供了1956年黄海高程基准。

ExovaWarringtonfire威灵顿消防集团

Exova Warringtonfire威灵顿消防集团Exova威灵顿消防集团为国际市场提供消防安全设计策略、消防产品检测及认证的全方位服务。

我们由专业工程师和科学家组成的专家团队一向以严谨和友好的服务闻名业界。

该防火测试实验室在英国,德国,意大利,加拿大,澳大利亚拥有多个防火测试实验室,在中东和亚太地区亦设立了多家办事处。

消防咨询服务涵盖消防安全工程设计、常规设计审核、火场勘查、风险评估以及消防安全管理的所有方面。

消防产品检测服务包括按多个国家(BS, EN, DIN, NF, ASTM, IMO, AS, NFPA, UL, IEC)及国际标准(ISO)进行的消防测试和评估。

Exova在英国皇家认可委员会的认可编号为UKAS0249,目前轨道车辆上需要机车防火材料需要BS6853:1999标准要求的,由Exova实验室进行测试并出具测试报告和证书,在整个轨道车辆的业界人员都得到非常高的认可,确保工厂和贸易商的产品进行测试的数据的真实性和权威性。

请资质认可的测试标准和项目请参考如下:-BS 476:PART 3: 2004 - External Fire exposure roof test-BS 476:PART 4:1970 - Non-combustibility test for materials-BS 476:PART 5: 1979 - Method of test of ignitability-BS 476:PART 6: 1989 - Method of test for propagation for products-BS 476:PART 7: 1997 - Surface spread of flame test for materials-BS 476:PART 11: 1982 - Method for assessing the heat emission from building materials -BS 476:Part 12:1991 - Ignitability of Products by Direct Flame Impingement-BS 476:Part 15:1992 - Method for measuring heat release of products - Cone Calorimeter-BS 6401 - Smoke density test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex B.1 - Toxicity test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex B.2 - Determination Of Weighted Summation Of Toxic Fume, R. Area Based Test Method.-BS 6853: 1999: Annex D.8.3 - Small Scale Smoke Test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex D.8.4 - Panel Smoke Test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex D.8.5 - Seating Smoke Test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex D.8.6 - Flooring Smoke Test-BS 6853: 1999: Annex D.8.7 - Cable Smoke Test-BS EN 13823 (SBI) - Single Burning Item Test-BS EN 1869 - Fire blanket test-BS EN 50268 (Superseded by IEC 61034)-BS EN 60695-11 Glow Wire test-BS EN 60695-12 Glow Wire test-BS EN 60695-13 Glow Wire test-BS EN ISO 1182 - Non-combustibility test.-BS EN ISO 11925-2 - Ignitability when subjected to Direct Flame Impingement-BS EN ISO 1716 - Bomb Calorimeter-BS EN ISO 4589: Part 2 - Oxygen Index Test-BS EN ISO 4589: Part 3 - Elevated Oxygen Index Test-BS EN ISO 4589: Part 3 – Appendix A Temperature Index Test-BS EN ISO 9239-1 – Radiant Panel Floor Test-BS 5803 (loft Insulation)-NFP 92-501 - Epiradiateur-NFP 92-503 - Electric Burner Test-NFP 92-504 - Rate of Spread of Flame test-NFP 92-505 - Dripping Test-NFX 10-702 - Smoke Density Test-NFX 70-100 - Mass Based Toxicity Test-F-Rating summary report in accordance with NFF 16-101-DIN 4102: Part 7 – Roof test-ISO 5659-2: 2006 - Determination of Specific Optical Density-ISO 5660-1 - Cone Calorimeter-ISO 9705:1993 - Full-scale room test for surface products.-ISO 5658 - Surface Spread of Flame Test.-EN 1869 - Fire blanket test-European Directive 95/28/EC: Annex IV-European Directive 95/28/EC: Annex V-IMO A.653 (16) As Amended By IMO Resolution MSC 61(67): Annex 1, Part 5-IMO Resolution A.652 (16) - Recommendation on Fire Test Procedures for upholstered furniture-IMO Resolution A 471 (Xll) as amended by A.563 (14) - Recommendation on test method for determining the resistance to flame of vertically supported textiles and films-IMO Resolution A.688 (17) - Fire Test Procedures for ignitability of bedding components.-IMO Resolution MSC 40(64) - Full-scale room test for surface products.-IMO Resolution MSC 61(67): Annex 1, Part 1 - Non-combustibility test.-IMO Resolution MSC 61(67): Annex 1, Part 2 - Smoke and Toxicity testMSC / Circ 1006-ASTM E648-03 – Radiant Panel Floor Test-ASTM E662-03 – Smoke Density Test-NES 711 – Smoke Density Test-NES 713 – Toxic Gas Emissions-NFX 10-702 - Smoke Density Test-NFX 70-100 - Mass Based Toxicity Test-BS EN 60684-2 fluorine content-ABD 0031 Smoke and toxicity-IEC 50267-2: Parts 1, 2 & 3 – Gas emission test-IEC 60754: Part 1 – Gas emission test-IEC 60754: Part 2 – Gas emission test-CERTIFIRE DTS 63 – Temporary Protective Coverings TestPackage includes all tests specified in DTS 63Mining Grating Test(In-house Test Procedure)PAS 017 Amended 14 September 1999Clause 10.1 - Flammable Liquid TestMudguard Testing -(In-house Test Procedure)WFR TP 002: January 1999BS 476:PART 3: 2004External Fire exposure roof testDD ENV 1187: Test 1DD ENV 1187: Test 2DD ENV 1187: Test 4ENV 1187 Test 4 / BS 476: Part 3: 2004 combination testDIN 4102: Part 7NORD TEST NT 006UIC 564-2 Appendix 5UIC 564-2 Appendix 11UIC 564-2 Appendix 12UIC 564-2 Appendix 13CEN TS 45545-2 Annex A CEN TS 45545-2 Annex BAnnex A with Annex B packageCEN TS 45545-2 Annex C (Smoke and Toxicity Chamber Test)ISO 5659-2 in one mode only (as required in prCEN TS 45545-2 where no toxicity measurement is required)IEC 332-1 - Small Scale Cable Propagation TestIEC 50267-2: Parts 1, 2 & 3 – Gas emission testIEC 60754: Part 1 – Gas emission testIEC 60754: Part 2 – Gas emission test以上Exova威灵顿实验室相关资料,由南京睿督*************)公司提供。

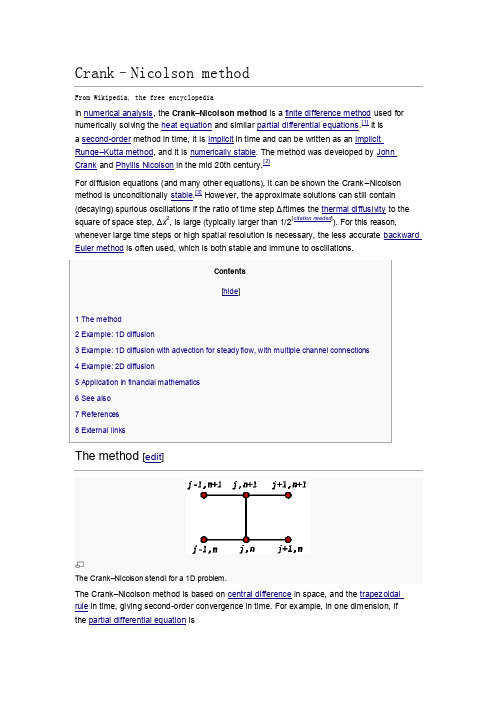

Crank–Nicolsonmethod

Crank–Nicolson method From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediathen, letting , the equation for Crank–Nicolson method is a combination of the forward Euler method at and the backward Euler method at n + 1 (note, however, that the method itself is not simply the average of those two methods, as the equation has an implicit dependence on the solution):The function F must be discretized spatially with a central difference.Note that this is an implicit method: to get the "next" value of u in time, asystem of algebraic equations must be solved. If the partial differentialequation is nonlinear, the discretization will also be nonlinear so thatadvancing in time will involve the solution of a system of nonlinear algebraicequations, though linearizations are possible. In many problems, especiallylinear diffusion, the algebraic problem is tridiagonal and may be efficientlysolved with the tridiagonal matrix algorithm, which gives a fast directsolution as opposed to the usual for a full matrix.The Crank–Nicolson method is often applied to diffusion problems. As anexample, for linear diffusion,whose Crank–Nicolson discretization is then:or, letting :which is a tridiagonal problem, so that may be efficientlysolved by using the tridiagonal matrix algorithm in favor of amuch more costly matrix inversion.A quasilinear equation, such as (this is a minimalistic exampleand not general)would lead to a nonlinear system of algebraic equationswhich could not be easily solved as above; however, it ispossible in some cases to linearize the problem by usingthe old value for , that is instead of .Other times, it may be possible toestimate using an explicit method and maintainstability.The Crank–Nicolson method is often applied to diffusion problems. As an example, for linear diffusion,whose Crank–Nicolson discretization is then:or, letting :which is a tridiagonal problem, so that may be efficiently solved by using the tridiagonal matrix algorithm in favor of a much more costly matrix inversion.A quasilinear equation, such as (this is a minimalistic example and not general)would lead to a nonlinear system of algebraic equations which could not beeasily solved as above; however, it is possible in some cases to linearize theproblem by using the old value for , that is instead of .Other times, it may be possible to estimate using an explicitmethod and maintain stability.。

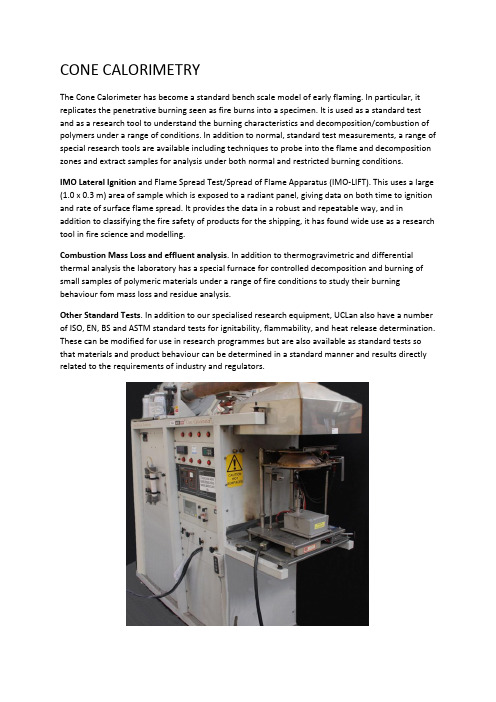

CONECALORIMETRY-...

CONE CALORIMETRYThe Cone Calorimeter has become a standard bench scale model of early flaming. In particular, it replicates the penetrative burning seen as fire burns into a specimen. It is used as a standard test and as a research tool to understand the burning characteristics and decomposition/combustion of polymers under a range of conditions. In addition to normal, standard test measurements, a range of special research tools are available including techniques to probe into the flame and decomposition zones and extract samples for analysis under both normal and restricted burning conditions.IMO Lateral Ignition and Flame Spread Test/Spread of Flame Apparatus (IMO-LIFT). This uses a large (1.0 x 0.3 m) area of sample which is exposed to a radiant panel, giving data on both time to ignition and rate of surface flame spread. It provides the data in a robust and repeatable way, and in addition to classifying the fire safety of products for the shipping, it has found wide use as a research tool in fire science and modelling.Combustion Mass Loss and effluent analysis. In addition to thermogravimetric and differential thermal analysis the laboratory has a special furnace for controlled decomposition and burning of small samples of polymeric materials under a range of fire conditions to study their burning behaviour fom mass loss and residue analysis.Other Standard Tests. In addition to our specialised research equipment, UCLan also have a number of ISO, EN, BS and ASTM standard tests for ignitability, flammability, and heat release determination. These can be modified for use in research programmes but are also available as standard tests so that materials and product behaviour can be determined in a standard manner and results directly related to the requirements of industry and regulators.Cone calorimetry (ISO 5660)A very well-established tool, providing data on surface ignition and penetrative burning.This has become the established small-scale standard for measuring the rate of heat release and the effective heat of combustion from a burning polymer under a controlled radiant heat source (ISO 5660 part 1). Heat release rate is the major cause of fire spread and growth, and the timing and magnitude of the peak rate of heat release (PRHR) and the short term (e.g. 3 minute) average rates of heat release are the single most important factor in predicting fire growth rate. The cone is established as the principal technique for the measurement of a number of fire and flammability hazard parameters for early or well-ventilated fires. The cone calorimeter can also be used to determine smoke generation (ISO 5660 part 2).The apparatus consists essentially of a conical electric heater (preset to 10 - 100 kW m-2) delivering uniform radiance to the sample (100 mm x 100 mm x up to 50 mm thick). The sample is mounted on a load cell recording its mass during the experiment. A spark is used to ignite flammable vapours. Air passes through the apparatus and tests are typically carried out under very well ventilated conditions (a modified cone calorimeter is available for studies in oxygen depleted environments, see below). The fire effluent gases travel upward into an instrumented hood system from where gas samples are collected.The cone calorimeter measures heat release on the basis of oxygen consumption calorimetry. This is based on the fact that the heat output from many combustible materials including most natural and synthetic plastics, rubbers and textiles is almost always a constant 13.6 kJ per gram of oxygen consumed. Other gas measurements, such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide concentrations are made, together with measurement of smoke density. The cone calorimeter experimental conditions are usually characterised by the following parameters:Output data are recorded for mass loss, for oxygen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide concentrations, for smoke density and fire effluent flow as a function of time. The raw data is manipulated and heat release rates and effective heats of combustion are calculated together with averaged data calculated by oxygen consumption calorimetry. Fire gas and smoke yields per gram of sample burnt are also calculated. Typical output summaries may include:。

电力变压器短路承受能力试验相电流精确测量方法

电力变压器短路承受能力试验相电流精确测量方法%何东升1,许呈盛2,刘光祺",罗海凹1,丁晓军1(1.国家智能电网输配电设备质量监督检验中心,广东东莞523325;2.广东工业大学,广东广州 510006;3.云南电网有限责任公司电力科学研究院,云南昆明650217)摘要:介绍了变压器短路试验的基本情况和标准对短路试验相电流测量的规定 要求。

针对目前三角形联结绕组的变压器相电流无法直接测量的问题,提出了一种等效 线路测量方法。

通过公式推导和理论计算,搭建电路图,实现动态系统建模、仿真和分 析,并对此测量方法进行了应用验证。

所提测量方法符合标准要求,且提高了检验效率 和测量精度,保证了检测的公正性和故障定位的有效性,具有一定的推广和借鉴意义。

关键词#变压器,■短路试验,■相电流测量,■测量方法中图分类号:TM 406文献标志码:B文章编号#2095-8188(2018)14-0042-04 DOI #10.16628/j. cnki. 2095-8188. 2018. 14. 008何东升( 1978—),男,高级工程师,主 要从事高、中、低压 电力电器产品的试 验、认证与设备研 发。

Phase Current Accurate Measurement Metliod of Power TransformerShort Circuit Withstand Capability TestHE Dongsheng1,XU Chengsheng2,LIUGuangqi3,LUOHaiao1,DINGXiaojun1(1. China National Q uality Supervision and Testing Center for Smart G rid Transmissionand D istribution E quipm ent,Dongguan523325,C h in a;2.Guangdong University of Technology,Guangzhou510006,C h in a;3.E lectric Power Research In s titu te,Yunnan Power Grid Co.,L td.,Yunnan650217,C hina)Abstract :This paper introduced the basic conditions of transformer short-circuit test standard for phase current m easurement of short-circuit test. In view of the problem that the transformer phasecurrent in triangle junction winding ccn not be measured directly without external lead terminal,ameasurementmethod of equivalent circuit was proposed,which,through formula derivation and theoretical calculation,constructsthe circuit diagram,realizes the dynamic system modeling,the simulation and the analysis,and carries on theapplication verification to this m easuring method. This measurement method meets the standard requirements,andimproves the test efficiency and measurement accuracy,and ensures the fairness and effectiveness of the detection ofthe fault location,it has certain promotional and reference significance.Key words:transform er $short-circuit test $phase current measurement ;measurement method0引言电力变压器突发短路试验是衡量变压器抗短 路能力的一项重要测试项目,短路过程中流经绕组的电流比额定电流要大十几倍甚至几十倍,试验过 程中在漏磁场的作用下产生巨大的短路电动力,其 力会驱使绕组变形、撑条垫块移位,或者直接导致 机械部件和绝缘部件断裂甚至爆炸,这对变压器的许呈盛(1994 一),男,硕士研究生,研究方向为非晶合金配电变压器的抗短路能力提升方法 刘光祺(1986—),男,工程师,主要从事高电压研究工作。

Supercriticalflu