大气科学专业导论报

大气科学导论试题库汇总

大气科学导论试题库第一章1、什么是大气科学?参考答案答:大气科学是研究大气的各种现象及其演变规律,以及如何利用这些规律为人类服务的一门学科。

2、大气科学的研究对象是什么?参考答案答:大气科学的研究对象主要是覆盖整个地球的大气圈,也研究大气与其周围的水圈、冰雪圈、岩石圈和生物圈相互作用的物理和化学过程,此外还研究太阳系其他行星的大气。

3、大气的组成如何?参考答案答:地球大气的组分以氮、氧、氩为主,它们占大气总体积的99.96%。

其它气体含量甚微,有二氧化碳、氪、氖、氨、甲烷、氢、一氧化碳、氙、臭氧、氡、水汽等。

大气中还悬浮着水滴、冰晶、尘埃、孢子、花粉等液态、固态微粒。

第二章1、基本的气象要素有哪些?参考答案答:描述大气基本状态的参数有:温度、压力、湿度和风。

这4个物理量是表征大气基本状态的参数,又称气象要素,此外,还有降水量、云量、云状等。

2、常见气压场的形式有哪些?常用温标有哪几个?参考答案答:常见气压场形式:高压、低压、槽、脊、鞍形场。

气温的单位—般有用摄氏温标,华氏温标和绝对温标。

3、参考系有哪几个分类?地球参照系属于什么参照系?参考答案答:参考系有惯性系和非惯性系之分。

在大气科学的研究中,一般是以旋转的地球作为参考系,这是一个非惯性系。

4、为什么流体质点既要小又要大?参考答案答:连续介质假设中的流体质点既要充分小,以使它在流动中可当作一个点,同时又要足够大,能保持大量分子具有确定的平均效应值——各种宏观物理量值。

这种既大又小的流体质点,有时也称作流体微团或流体体素,一般则简称为流点。

在我们气象研究上,经常会用到这个概念——流体块,一个小的空气块。

5、站在转动的地球上观测单位质量空气所受到力有哪些?各作用力定义特点如何?参考答案答:站在旋转地球上观测单位质量空气所受到的力可以分为两类,一类是真正作用于大气的力,称做基本力,或牛顿力,包括气压梯度力、地心引力、摩擦力。

另一类是站在随地球一起旋转的非惯性系中观察大气运动时所表现的力,称做惯性力,包括惯性离心力和地转偏向力。

大气科学导论第三章大气运动1

视示力:科氏力和惯性离心力

f 2sin ~ 2 7.292105 sin 450 ~ 104 f1 2 cos ~ 2 7.292105 sin 450 ~ 104

大气运动方程的分量形式

du

1 p

dt Fx x fv f1w

dv dt

Fy

1

p y

标架方向固定

2、 重力只出现在 z方向 重力一般在水平面上也有分量

在中高纬度地区,当所考虑范围不是很大时, 切平面与球面差别不是很大,两坐标系的区别也 不大。但在高纬或极地附近二者的区别明显。

局地直角坐标系:

在一个不大的范围内,又可以将(x, y, z)的方 向看成不变; 考虑全球范围或极地地区的大气运动问题时必须 采用球坐标系,其余情况采用局地直角坐标系。

2、若等压线为圆形,且中心气压高,向外降低, 称为“高压”。在 无摩擦情况下:

地转偏向力

气压梯度力

P1 P0

惯性离心力

V

地转偏向力 + 惯性离心力 + 气压梯度力 = 0

此平衡称为“梯度风平衡”,此时的风称为“梯度风”。

北半球,高压中,风呈顺时针旋转,称为“反气旋”

3、若等压线为圆形,且中心气压低,向外升高,

D V Vg 称为 “地转偏差”

地转偏差,指向摩擦力的右侧,且与之垂直, 指向低压一侧

Байду номын сангаас

地转偏差的作用:

低压

高压

辐合 上升运动 恶劣天气

辐散 下沉运动

好天气

思考题

1. 旋转参考系中运动方程的矢量形式? 2. 地球旋转(自转)会产生哪些力? 3. 为什么地球不可能是一个绝对球体? 4. 在赤道上,水平运动有没有科氏力? 5. 惯性离心力是怎么产生的?如果空气微

2023年大气科学专业就业前景调查报告

2023年大气科学专业就业前景调查报告随着社会经济的发展,气象学和大气科学逐渐成为重要的热门学科,特别是随着环保意识不断提高,大气科学专业的发展前景也变得越来越广阔。

本文将从大气科学专业的学科划分、教学内容和就业方向三方面分析该专业的就业前景。

一、大气科学专业的学科划分大气科学专业是一门涉及气象、气候、大气环境、飞行技术、水文学等领域的交叉学科,主要分为大气物理学、大气化学、大气动力学三个学科方向。

大气物理学主要研究大气中的温度、湿度等物理性质;大气化学则研究大气中的气体、颗粒物、化学反应等化学性质;大气动力学则研究大气运动规律、风力、气压等动力学性质。

二、大气科学专业的教学内容大气科学专业课程设置涵盖气象学、环境科学、地球物理学、空间科学等多个领域。

主要包括以下几个方面:1.大气物理学的基础知识2.大气化学的基础知识3.大气动力学的基础知识4.气象科学与技术方向的训练课程5.大气环境科学课程6.计算机和信息处理的应用7.实践和科研实验三、大气科学专业的就业方向目前,大气科学专业的就业方向相对较为广泛,主要有以下几种:1.气象局、气象科研机构、环境监测机构等相关机构大气科学专业是气象局、气象科研机构、环境监测机构等单位的主要招聘对象。

在这些单位中,大气科学专业的毕业生可以从事气象预报、气象监测、大气环境保护、气象科研等工作。

2.民用航空局、空中交通管理局等相关单位大气科学专业的毕业生可以在民用航空局、空中交通管理局等相关单位从事天气预报与监测、飞行导航和飞行技术等领域的工作。

3.机构和企事业单位等相关领域大气科学专业的毕业生也可以选择进入机构和企事业单位等相关领域,如电力、煤炭、钢铁、化工等领域,从事大气环境管理、大气环境监测、环保评估等工作。

4.高校科研机构等大气科学专业毕业生还可以选择在高校科研机构从事大气科学研究方面的工作,如大气环境模拟与预测、气候变化与问题分析等研究工作。

总结:在就业方面,大气科学专业的专业性强,相关工作包括气象预报、气象监测、大气环境保护和气象科研等领域,且就业前景良好。

大气科学专业的概述

大气科学专业的概述大气科学是一门研究地球大气层及其相互作用的学科,它涵盖了气象学、气候学、大气物理学、大气化学和大气动力学等多个领域。

这门学科的研究对象是地球大气层中的气候、天气、空气质量以及与人类和自然环境的相互作用。

大气科学的研究范围广泛,涉及到大气层的结构、成分、动力学过程以及其对地球系统的影响等方面。

气象学是大气科学的核心领域之一,它研究的是地球大气层中的天气现象,包括气象观测、天气预报、气候变化等。

气象学的研究内容主要包括气象观测技术、天气系统的形成和演变、天气预报模型等。

气候学是大气科学的另一个重要领域,它研究的是地球大气层的长期变化和气候系统的运行规律。

气候学的研究内容包括气候变化的原因和机制、全球气候模式、气候预测等。

气候学的研究对于了解和应对全球气候变化具有重要意义。

大气物理学是研究大气层中的物理过程和现象的学科,它主要关注大气层中的辐射、传热、湍流等物理过程。

大气物理学的研究内容包括大气辐射、大气传热、大气湍流等。

大气物理学的研究对于了解大气层中能量和质量的传递过程具有重要意义。

大气化学是研究大气层中的化学反应和物质转化的学科,它主要关注大气层中的大气组分、气溶胶、大气化学反应等。

大气化学的研究内容包括大气层中的气体成分分析、大气污染物的来源和转化、大气化学反应动力学等。

大气化学的研究对于了解大气层中的化学过程和空气质量的影响具有重要意义。

大气动力学是研究大气层中的运动和力学过程的学科,它主要关注大气层中的风、气压、气旋等现象。

大气动力学的研究内容包括大气层中的风场结构、大气层中的气旋演变、大气层中的辐合辐散等。

大气动力学的研究对于了解大气层中的运动规律和天气系统的形成具有重要意义。

总的来说,大气科学是一门综合性的学科,它研究的是地球大气层中的各种现象和过程。

大气科学的研究对于了解和应对气候变化、天气灾害、空气污染等具有重要意义。

随着科技的不断发展,大气科学在气象预报、气候变化预测、环境保护等方面的应用也越来越广泛。

大气科学导论小结

大气科学导论小结现代大气科学不仅是研究大气状态及其变化规律、成因的一门科学,而且是研究大气与周围海洋、陆地、冰雪和生物圈层相互作用的动力、热力和化学过程的一门综合性科学。

近几十年来,由于大气遥感技术的不断发展以及计算机技术的普遍应用,使得大气科学获得了突飞猛进的发展。

现在已成为一门拥有大气探测、天气学与大气环流、大气动力学、气候学、大气物理、大气化学和全球变化等众多学科的综合性学科,而且大气科学也从简单的定性描述演变为一种可以精确进行数值计算、数值模拟的科学,并且可以较准确的预报预测未来几天甚至十几天以上的天气气候变化。

大气科学与人类生存、社会发展变得越来越关系密切。

因此,面向大气科学类各专业学生开设全面介绍现代大气科学的研究对象、研究特点、学科分支、与其它学科的关系以及未来发展趋势的课程——《现代大气科学导论》是非常重要和有意义的。

大气科学是一门研究大气的各种现象及其演变规律的一门学问,也可称作气象学.它是地球科学的一个组成部分。

它的分支学科主要有大气测探,气候学,大气物理学,大气化学,人工影响天气,应用气象学等。

作为具有介绍性、引导性及提高学生专业兴趣等性质的专业课程,该课程的教学目的、教学重点与采用的教学方式与措施手段,具有与其他专业课程明显不同的特点。

在课程设置之前,我们已经认识到设置这门课程的必要性。

了解大气科学专业学习的特点,了解专业研究和应用领域,开阔专业视野,增加学好专业基础性课程的认识,激发专业学习兴趣,为后续的学习打下良好的基础。

结合"导论"的教学内容,我们首先介绍大气科学专业是理科专业,本专业的学习方式前后关联程度大,需要踏踏实实地打好基础,才能为将来的专业课程学习提供坚实的基础。

对于大气科学的社会需求来说,一个明显的需求是要为社会提供较为准确的天气预报服务和气候变化预测服务。

大气科学的研究对象──地球大气,无论它的组分,它的结构,还是它的运动,都存在着确定性和不确定性两个方面。

F12大气科学导论

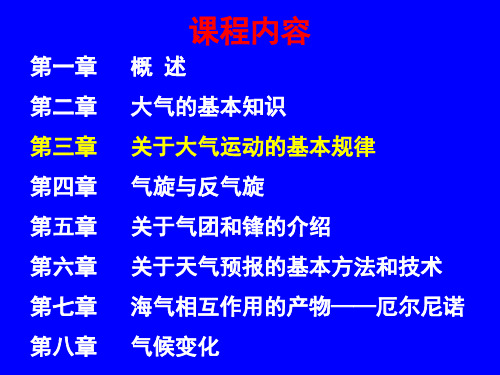

南京信息工程大学2010年硕士研究生入学考试《大气科学导论》考试大纲科目代码:F12科目名称:大气科学导论第一部分课程目标与基本要求一、课程目标:大气科学导论课程主要介绍大气科学的研究对象、研究内容和研究方法以及大气科学领域的基本知识,并重点解析一些基本的大气现象和大气运动的基本规律以及相关的科学问题,并介绍一些基本的天气预报思路和方法。

使学生们初步建立起大气科学的理念,以培养他们学习的兴趣,为今后专业课的学习打下基础。

二、基本要求:要求学生掌握有关内容的基本概念、基本理论和基本方法,以便提高综合分析及解决问题的能力。

第二部分课程内容与考核目标第一章概述(引言)1、掌握大气科学的研究对象和内容2、理解大气科学的学科体系3、了解大气科学的发展历史及现状4、了解大气科学在生产建设中的应用第二章关于大气的基本知识1、掌握大气的主要成分及其在天气、气候变化中的作用(干洁大气成分、水汽、杂质)2、掌握表征大气的基本要素(气温、气压、空气湿度、风)3、掌握大气的垂直分层(对流层、平流层、中间层、热层、外层)4、掌握温度的全球分布特征5、掌握大气中湿度的分布特征第三章关于大气运动的基本规律1、掌握研究大气运动的主要坐标系2、掌握决定大气运动的主要因子和作用力3、掌握大气运动的若干基本规律(大气静力方程、大气运动方程、大气连续方程、热力学能力方程)4、掌握风场和气压场的关系(地转风、梯度风、热成风地转偏差)第四章气旋和反气旋1、掌握气旋和反气旋的基本概念2、掌握气旋和反气旋的天气学特征及其分类3、掌握涡度的基本概念、物理本质4、了解台风的基本概念(定义、结构和天气、生命史和台风灾害)第五章关于气团、锋和锋生的概念1、掌握气团的定义(气团的概念、源地、形成的物理过程及气团的分类)2、掌握锋和锋生的定义(锋的概念、锋的分类、锋生和锋消的概念)3、掌握锋与天气的联系(暖锋天气、冷锋天气、准静止锋天气、锢囚锋天气)第六章关于天气预报的基本方法和技术1、了解天气预报技术的历史发展、大气科学理论研究的深入和发展2、了解天气预报的基本思路和方法(天气图预报法、长期天气预报)3、了解天气预报的新技术(数值天气预报、综合集成方法、中小尺度气象学的研究和临近预报、天气预报业务自动化)第七章海气相互作用的产物——厄尔尼诺1、掌握ENSO的定义2、了解厄尔尼诺的生命期及其特征3、了解厄尔尼诺对世界及中国气候的影响4、了解有关厄尔尼诺的理论和推测第八章大气遥感探测1、了解人类探测大气的历史、常规探测的局限性2、掌握大气遥感探测基础知识,电磁波谱和大气信号、遥感的分类和特点3、了解气象雷达探测系统、常用气象雷达、雷达气象学的发展4、了解气象卫星遥感技术、气象卫星云图及其分析和应用、气象卫星的发展现状和展望第三部分有关说明与实施要求1.考试目标的能力层次的表述本课程对各考核点的能力要求一般分为三个层次用相关词语描述: 较低要求——了解一般要求——理解、熟悉、会较高要求——掌握、应用一般来说,对概念、原理、理论知识等,可用“了解”、“理解”、“掌握”等词表述;对应用方面,可用“会”、“应用”、“掌握”等词。

大气科学概论PPT概要

第二节

大气的铅直结构

第二节

对流层: 特点:

大气的铅直结构

主要天气现象均发生在此层。 温度随高度升高而降低。(平均高度每升高100m, 气温下降0.65℃。) 空气具有强烈的垂直运动和不规则的乱流运动。

大气成分与结构

大气的组成

大气的铅直结构 大气的物理性质

第一节

大气的组成

地球大气由三个部分组成: 干洁大气(即干空气) 水汽 悬浮在大气中的固液态杂质

表2-1 干洁大气的成分(高度25km以下) 气体成分 氮 氧 氩 二氧化碳 臭氧 干洁大气 所占体积(%) 78.08 20.95 0.93 0.032 0.00006 100 临界温度(℃) -147.2 -118.9 -122.0 31.0 -5.0 -140.7 临界压强(大气压) 33.5 40.7 48.0 73.0 92.3 37.2

大气成分

二、水汽

作用:

在天气气候变化中扮演了重要角色。

能强烈吸收地面放射的长波辐射并向地面和周围大气放 出长波辐射,对大气起着“温室效应”。

三、大气中的杂质

大气中悬浮着的各种固体和液体微粒(包括气溶胶粒子和

大气污染物质两大部分)。

气溶胶粒子: 作用:

吸收太阳辐射,使空气温度增高,但也削弱了到达地

二、太阳高度角、太阳方位角和昼长

太阳高度角 (h) 定义 太阳光线与地表水平面之间的夹角。(0°≤h≤90°)

赤道地区一年中春分和 秋分时太阳高度角最大, 冬至和夏至时,太阳高 度角最小。

水平面上得到的太阳辐射能随着h的增加而增加。 h的计算公式

大气科学导论

InvitrogenInstitution: CSTNet and CERNET | Sign In as Individual | FAQ Summary of this ArticledEbates: Submit a response to this article Related articles in Science Similar articles found in: SCIENCE Online Alert me when: new articles cite this article Download to Citation ManagerCollections under which this article appears:Atmospheric ScienceThe Ascent of AtmosphericSciencesPaul J. Crutzen and Veerabhadran Ramanathan *Atmospheric science matters to everyone every day. It has beeninfiltrating public awareness lately for compelling reasons: theAntarctic ozone hole, global warming, and El Niño, a combinedatmosphere-ocean phenomenon that causes severe weather. Thefirst two are side effects of the industrial revolution, and El Niño is nature's warning against taking good weather for granted.Atmospheric science has become a multidisciplinary, high-techactivity rife with new and sophisticated instrumentation, computers,information technology, and measurement platforms, includingsatellites and aircraft. Air chemistry (1-4), including the prediction and subsequent verification that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) destroy ozone, has recently moved to the field's forefront. Revelations about the susceptibility of people and ecosystems to both natural and humanly forced atmospheric changes also have been central. On a more purely scientific level, efforts to understand and predict the complex phenomenon of weather led to the discovery of chaos theory by meteorologist Edward Lorenz. Now, chaos theory helps physicists, chemists, biologists, economists, and many others striving to understand complex phenomena.A comprehensive story about the ascent of atmospheric sciences over the past few centuries would fill library shelves. In these few pages, we first chronicle only a few developments in chemistry and meteorology up to the early 1970s, before the possibility of human influence beyond the local scalebecame actualized. To illustrate how humanity's hand has grown to have global effects, we then zero in on two contemporary issues: atmospheric ozone and global warming.Secret AirEven by the mid-17th century, the properties of air had received remarkably little thought. Robert Boyle knew as much at the time as anybody when he opined that the atmosphere consists not of the "subtlematter," or ether, that his contemporaries presumed to fill the universe, but primarily of "exhalations of the terraqueous globe," that is, emanations from volcanoes, decaying vegetation, and animals. By the end of the 19th century, however, research into the nature of air already had proven invaluable. About a century ago, William Ramsay assessed the situation this way: "To tell the story of the development of men's ideas regarding the nature of atmospheric air is in great part to write a history of chemistry and physics." Isolation of air's actual constituents began in the 18th century. Joseph Black identified carbon dioxide in the 1750s; Daniel Rutherford isolated nitrogen in 1772. A few years later, Carl Scheele and Joseph Priestley independently discovered oxygen. In 1781, Henry Cavendish established the composition of air to be 79.16% nitrogen and 20.84% oxygen regardless of location and meteorological conditions. By 1894 Lord Rayleigh and Ramsay had discovered argon in air. Thousands of chemical compounds have now been detected in the air, many at concentrations even less than 10-12 in molar mixing ratios (less than 1 part per trillion).In 1839 (3), Christian Schönbein literally smelled a previously unidentified air component that would prove central to the scientific and public interest. During electrolysis experiments with water, he noticed a sharp odor. He ascribed it to a compound, which he called "ozone," after a Greek word meaning "ill smelling." In 1864 Jacques L. Soret recognized that ozone was the "dioxide of the O atom." In 1878, Alfred Cornu noticed the absence in sunlight of wavelengths shorter than 310 nanometers and postulated the presence of an absorbing gas in the atmosphere. Two years later, Walter N. Hartley measured the spectral properties of ozone and concluded that it was Cornu's absorber. The absorption of this ultraviolet (UV) radiation is essential for the survival of many of the planet's life-forms.In 1902, L¨¦on-Philippe Teisserenc de Bort discerned another important clue about ozone. Making measurements aboard a balloon, he found that at altitudes above 8 to 10 kilometers temperature did not further decline with altitude as it did at lower altitudes. He called this regime of more constant temperature, which is maintained by ozone's absorption of solar UV radiation, the stratosphere; the region below he dubbed the troposphere.In the 1920s, Gordon M. B. Dobson measured the total amount of ozone in vertical columns of atmosphere. He found maximum amounts at higher latitudes and during early spring. These findings showed that stratospheric circulation plays a major role, implying upward transport from the troposphere to the stratosphere in the tropics with the return flow at middle and higher latitudes, the so-called Brewer-Dobson (after Alan Brewer) circulation. The theoretical framework for this circulation was developed over the next 50 years. A unified picture of the dynamical processes responsible for stratosphere-troposphere exchange of ozone and other gases was presented in 1995 by James Holton, Peter Haynes, Michael McIntyre, and their colleagues. The upward transport through the cold region of the tropical troposphere causes the stratosphere in general to be dry and cloud-free.In 1930, the field of atmospheric photochemistry (3-5) began when Sydney Chapman proposed that ozone is produced photochemically from oxygen. Solar UV radiation with wavelengths shorter than 240 nanometers breaks O2 molecules into two oxygen atoms, each of which then combines with another O2 to yield ozone, O3. The reverse process occurs when oxygen atoms from the photolysis of ozone react withO3 molecules, resulting in O2. David Bates and Marcel Nicolet extended this scheme in 1950 by showing that hydroxyl-based radicals derived from the photolysis of water molecules can catalytically convert ozone and atomic oxygen into O2.Air chemistry is just one--in fact one of the youngest--of the atmospheric sciences. The invention of the thermometer by Galileo Galilei and by others in the 1590s, and the 1643 invention of the barometer by Galileo's disciple Evangelista Torricelli, marked the start of experimental meteorology (6, 7). By the end of the 17th century, Edmond Halley had recognized the role of solar heating in the trade winds. His solar heat budget estimates revealed that the tropics receive much more solar radiation than the high latitudes. By the mid-18th century, George Hadley adopted Halley's idea and concluded that equatorial air must respond to the more intense solar heating first by rising and then by drifting poleward before returning to lower levels at the equator. Hadley also developed the correct explanation for the trade winds by deducing that Earth's rotation deflects the equator-directed surface flow toward the west relative to Earth.During the 19th century, observational technology took another leap, this time in the form of instrumented balloons. Significant advances in observation tools took place during World War II, including weather radar and "radiosondes," or instrumented balloons bearing radio transmitters. The new observations revealed large, longitudinally asymmetric motions in the atmosphere, such as extratropical cyclones, and the midlatitude jet stream. Armed with the new data, Jacob Bjerknes, Carl-Gustaf Rossby, and Jule Charney transformed the science of atmospheric motion into its modern form between 1920 and 1970 (8, 9).Basically, the equator-to-pole gradient of radiative heating that Halley discerned leads to gradients in temperature, potential energy, and zonal air flows, such as the upper troposphere jet stream. The jet is unstable to small perturbations, and the resulting wavelike eddy motions grow and concentrate temperature gradients to form narrow warm and cold fronts, which generate much of local weather. The poleward transfer of heat in the extratropics is accomplished by these eddies, without which the polar regions would be more than 50¡ãC colder and the tropics would be much hotter.With a theoretical foundation for atmospheric circulation coming into place, another question arose: How is surface temperature regulated (10)? Jean-Baptiste Fourier suggested in 1824 that the atmosphere behaves like the glass cover of a box exposed to the sun by allowing sunlight to penetrate to Earth's surface and then retaining much of the "obscure radiation" (wavelengths greater than about 4 µm that emanate from Earth's surface). By the mid-19th century, John Tyndall had demonstrated that the key process retaining this long-wave radiation is its selective infrared (IR) absorption by atmospheric H2O and CO2.Constructing such greenhouse models of the atmosphere required accurate measurements of solar and IR transmission. That's where Samuel Langley's observations of lunar and solar spectra from 1885 to 1890 came in. Those data, and the identification of numerous H2O and CO2 absorption bands in spectroscopic measurements, set the stage for the famous study in 1896 by the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius. He developed a detailed model for the surface-atmosphere radiation budget and used it to reveal the largesensitivity of surface temperature to increases in atmospheric CO2. Arrhenius included the positive feedback due to water vapor (the dominant greenhouse gas), whose atmospheric loading increases with temperature because of the increase in saturation vapor pressure with temperature. As a result, a water-vapor-based greenhouse effect increases with a warming.In 1967, Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald reformulated the greenhouse theory. They demonstrated that surface temperature is not determined solely by the energy balance at the surface (as assumed by Arrhenius and others), but also by the energy balance of the surface-troposphere-stratosphere system. The underlying concept is that the surface and the troposphere are so strongly coupled by convective heat and moisture transport that the relevant forcing governing surface warming is the net radiative perturbation at the top of the troposphere. This concept of a radiative-convective equilibrium, which is used extensively in astrophysics, was originally proposed in 1862 by Lord Kelvin to explain the temperature decrease in the troposphere.Another big part of the atmospheric and climate equations is clouds (10). For decades, models have predicted that clouds have a net cooling effect. Data from the NASA Earth Radiation Budget Satellite Experiment confirmed those predictions in 1989. The data reveal that solar radiation reflected by clouds exceeds their greenhouse effect by a significant 15 to 20 W.m-2--a cooling effect about five times larger than the warming effect from a doubling of CO2. Small changes in cloudiness, therefore, can have large but uncertain feedback effects on climate. A comprehensive study by Robert Cess and colleagues in 1990 revealed that cloud feedback simulations using so-called general circulation models (GCMs) yield varying results. Until there is a theory or a model of the hydrological cycle that can accommodate the scales of all cloud systems--from tens of meters (cumulus) to more than 1000 kilometers (tropical cirrus)--rigorous climate prediction will remain out of reach.There are other obstacles that have been keeping a detailed quantitative understanding of climate and the general circulation at bay. After all, these phenomena depend on numerous complex physical processes, among them radiative transfer; land surface processes; and the formation of clouds, ice, and snow cover. Computers began coming to the rescue in the mid-1950s, and thanks to their ever-increasing power, today's GCMs are starting to account for many of these processes, albeit not reliably yet. In the 1950s, weather prediction drove the development of GCMs (by Jule Charney, John von Neumann, and Norman Phillips), but once such models were available they were put to wider use for such tasks as simulating general atmospheric circulation, climate, and global warming.Growing Impacts of Human Activities: Ozone and CFCs (4, 5)Air pollution is as ancient as the harnessing of fire for cooking, heating, smelting metal, and clearing land. Diminishing wood resources in some European locations within the past millennium spurred coal use and with it a rise in sulfur-based air pollution, which has led to one of the most publicly recognized forms of pollution--acid rain.Coal use increased 500-fold during the industrial period. The dearth of control and regulation enabled urban air pollution to worsen into a major problem, culminating in the killer smog of 5 to 9 December 1952 in London: An estimated 4000 people died because of it. Since then, legislation has been passed toprevent a repeat. Still, with the continuing growth of coal and oil use in North America and Europe, and the construction of high chimneys to alleviate local pollution, the problem of acid rain has grown to international dimensions.Based on data from a network of sites in Europe, which was established in the 1950s by the International Meteorological Institute in Stockholm, Svante Od¨¦n showed that highly acidic precipitation had spread to much of northern and Western Europe by 1968. Ecological consequences, such as forest decline and fish deaths, were most pronounced in the Scandinavian countries. The problem gained international attention in 1972 with the presentation of a Swedish study at the first U.N. Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. This study made a strong case for reducing sulfur emissions. Since then, Europe and North America have made considerable progress, but the use of sulfur-rich coals in parts of Asia is leading to a repeat of regrettable history.In the 1940s and 1950s, the Los Angeles Basin began suffering from a new kind of air pollution, especially during sunny summer days. It caused poor visibility, eye irritation, and crop damage. Arie Haagen-Smit showed that this type of pollution could be simulated by irradiating mixtures of air and car exhaust with sunlight. "Photochemical smog" has now become commonplace around the world.By 1970, the chemistry of ozone production near the surface (often called "bad" ozone, compared to the "good" ozone in the stratosphere that absorbs harmful solar UV radiation) had been identified. It begins with the attack by hydroxyl radicals (HO) on hydrocarbons or carbon monoxide, producing peroxy-radicals. These radicals donate O atoms to O2 to form ozone, whereas NO and NO2 are catalysts for ozone formation. The hydroxyl radicals themselves are produced when solar UV radiation infiltrates mixtures of ozone and water vapor in air.Hiram Levy pointed out in 1972 that these radicals play a major role in atmospheric chemistry. Despite their rarity (the average molar mixing ratio of HO in air is 4 x 10-14), they are known as the "detergent of the atmosphere." The lifetimes of most gases--whether derived from natural processes or human activities--are determined by their reactivity with HO and can vary from hours to years. Some gases, such as CFCs and nitrous oxide, do not react with HO. That's how they end up being so influential in stratospheric ozone chemistry.Tropospheric ozone (about 10% of total atmospheric ozone) is central to atmospheric cleaning because of its role in creating HO. Contrary to the widespread belief that tropospheric ozone originates in the stratosphere, one of us, Paul J. Crutzen, proposed in 1972 that the global troposphere itself is an important source of its own ozone and that human activity plays a major role.The argument was based on tropospheric NO x (NO + NO2), much of which is produced by the burning of fossil fuel and tropical biomass. Depending on NO x concentrations, large amounts of ozone can be produced or destroyed during the oxidation of ever-present carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4), levels of which have been rising. Together, these conditions have led to a substantial increase in tropospheric ozone, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. The tropics and the Southern Hemisphere also are influenced by human activity through extensive burning of biomass.Human activity influences stratospheric ozone as well. In 1970, Crutzen and Harold Johnston called attention to the catalytic role of NO x in controlling levels of stratospheric ozone and to the possibility of ozone destruction by NO-emitting supersonic aircraft. The rate-limiting reaction is O + NO2NO + O2. The oxygen atoms come from the photolysis of O3, and the NO2 comes from the reaction NO + O3NO2 + O2. The net result is 2 O3 3 O2, or, in other words, ozone destruction.Clearly, the role of NOx species as catalysts in ozone chemistry is complex. We now know that above about 25 kilometers, NO x catalyzes ozone destruction, but that the opposite holds at lower altitudes. The biosphere also is involved in the natural control of stratospheric ozone. That's because stratospheric NO forms by the oxidation of N2O, which is produced largely by microbes in soils and waters. This is just one of many ways in which the biosphere is involved in atmospheric chemistry and climate, a complex dynamic most fully developed by James Lovelock in his much-debated Gaia hypothesis, which invokes self-regulating relations between atmospheric chemical composition, the biosphere, and climate.As it turned out, large supersonic fleets were never built, but the research that emerged because of that possibility greatly improved knowledge about the stratosphere's chemistry and dynamics. This was important because in the meantime an enormous time bomb already had been ticking for several decades. After their introduction in the 1930s as better and safer refrigerants, emissions of the CFCs CFCl3 andCF2Cl2 began increasing. In 1972, Lovelock made the first worldwide CFC measurements on a research ship between England and Antarctica using his powerful electron capture technique, allowing measurements of gases with molar mixing ratios in the 10-12 range and below. He concluded from his data that CFCl3 was accumulating in the atmosphere, but without consequences for the environment. Two years later, however, Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland pointed out that when CFC gases break down in the stratosphere, they produce Cl and ClO. These radicals then attack ozone catalytically much as do NO and NO2, but even more effectively.With unabated CFC emissions, calculations suggested that ozone depletion would peak at altitudes near 40 kilometers, causing local losses up to some 30% to 40% after several decades. By the late 1970s, several nations, including the United States, Canada, Norway, and Sweden, had responded to this alarming finding by forbidding the use of CFC gases as propellants in spray cans. Their use for other purposes continued, however.One reason for this modest response was that the Molina-Rowland mechanism was thought to result in ozone depletion largely above 30 kilometers. Most ozone is located at lower altitudes, however. And there, formation of the rather unreactive molecules, ClONO2 and HCl, protects ozone from otherwise much greater destruction.This sense of complacency rapidly evaporated in 1985 when Joe Farman of the British Antarctic Survey and colleagues published a most surprising set of measurements. Their data revealed 40% depletion of total ozone during austral spring compared to levels measured since 1956 at the Halley Bay Station inAntarctica. These depletions were much greater than predicted, and they occurred in a geographic region where such depletions were unexpected.Subsequent measurement campaigns in the Antarctic--headed by David Hofmann, Susan Solomon, and James Anderson--revealed that the greatest ozone depletions occur at altitudes between 12 and 22 kilometers, exactly the range of naturally maximum ozone concentrations. Also, ClO and OClO radicals were found to be far more prevalent than predicted, suggesting that new chemistry was afoot. Solomon, Rowland, and their colleagues proposed that under the cold conditions prevailing in the ozone hole region, HCl and ClONO2 molecules react on ice particles to yield Cl2, which in sunlight dissociates rapidly into two ozone-destroying Cl atoms.Through laboratory simulations Luisa and Mario Molina discovered yet new ozone-depleting catalysis, this one involving the reaction of ClO with another ClO as the rate-limiting step. This chemistry is especially important at altitudes below about 25 kilometers. Because annual increases in stratospheric chlorine were exceeding 5%, ozone depletion was increasing by twice that much. The Molinas' study and many others show the great importance of laboratory simulations of chemical reactions of atmospheric interest (11, 12).Further research showed that the chlorine activation reactions could occur on solid or supercooled liquid particles containing mixtures of water and sulfuric and nitric acids. Such particles can form at temperatures about 10¡ãC higher than the freezing point of water ice from sulfuric acid-containing aerosol. They also can be players in the Arctic. Depending on temperatures, ozone losses of up to 30% have occurred there in some years during the past decade in late winter to early spring. Total ozone loss over the Antarctic has been reaching the yet more dramatic levels of 50% to 70% each year during spring. After the discovery of the ozone hole, international regulations to limit CFC production picked up speed, resulting in a total phase out of production in the industrial world since 1996.It is hard to tell if stratospheric ozone destruction or global warming is more sinister in the public mind. The realization that a doubling of CO2 would warm the globe significantly inspired Arrhenius to resurrect Tyndall's suggestion that history's glacial epochs may be due to large reductions in atmospheric CO2. Another impetus for investigating the connection between CO2 and surface warming was Guy S. Callendar's conclusion in the late 1930s that fossil fuel combustion had been increasing atmospheric CO2. In 1958, Charles D. Keeling began continuous measurements of CO2 at the Mauna Loa Observatory and demonstrated beyond any doubt that CO2 is increasing at a rate of about 1.5 parts per million (ppm) per year due to anthropogenic activities.Then came Manabe's and Wetherald's 1975 GCM study, which showed that doubling CO2 can warm the globe by up to 3 K. Nearly simultaneously, the global warming problem took off in another attention-getting direction. One reason was the identification by one of us, Veerabhadran Ramanathan, that CFCs have a direct greenhouse effect and that a molecule of CFCl3 or CF2Cl2 was about 10,000 times or more effective than a molecule of CO2 at enhancing the greenhouse effect.In 1976, CH4 and N2O joined the list of greenhouse gases. A few years later, tropospheric ozone also joined the list, which has grown to include several tens of greenhouse gases. These developments culminated in an international study in 1986 (13) sponsored by the World Meteorological Organization. The study concluded that the non-CO2 gases significantly added to the warming by CO2. The global warming problem suddenly had become more urgent.The urgency was further accentuated by the fact that the surface warming trend, which began in the 1970s and continued unabated into the 1990s, had reached the point where the global mean surface temperature was higher than ever recorded during the 20th century. James Hansen undertook GCM simulations that included observed trends in CO2 and other trace gases. The simulated temperature trends supported scenarios in which the human input of such gases indeed was the cause of surface warming, a finding that placed global warming higher on the political agenda. The problem's global nature demanded international reviews. So in the late 1980s, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established to make a comprehensive assessment (14). It concluded that "the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate."That point coincides with the finding that global warming is also influenced by stratospheric ozone depletion. As shown by Venkatachalam Ramaswamy, for example, the observed lower stratospheric cooling during the 1980s and 1990s is explained by the radiative response to ozone destruction, a process carrying implications for tropospheric climate as well.An Uncertain Future and the Need for SynthesisWe start the new century with formidable environmental challenges that affect the welfare of all humans. On the potentially positive side, stratospheric ozone could recover and the ozone hole could disappear by midcentury, although we cannot rule out the possibility of it becoming worse before it gets better due to cooling of the stratosphere by increasing CO2. On the negative side, by the early 22nd century, atmospheric CO2 is expected to double from its concentration of 280 ppm (14) prior to inputs from human industry.Unfortunately, the negative possibility seems a good bet. After all, nearly 75% of the world's population by then, which is projected to approach 10 billion people, will be striving to match Western standards of living. Those efforts will likely entail enormous additions of atmospheric pollutants, land surface alteration, and other environmental stresses. The net radiant heat added to the planet (since 1850) by greenhouse gases is likely to amount to at least 4 W.m-2. According to our best understanding of the system, that could warm the planet by about 1.5 to 3 K, depending on competing effects from aerosols. The atmosphere and the planet, it would seem, are headed toward uncharted territory.One of the major surprises could very well be the response of El Niño (15) to such a warming. Warren Washington and Gerald Meehl have proposed that global warming can lead to an increase in the frequency of El Niños through feedback mechanisms involving clouds and ocean circulation in the Pacific. It may well be argued that the environmental expansion of human activity has jolted Earth into a new geological era, the "Anthropocene."Temptations to engineer the atmosphere to mitigate the negative effects of human activities could become enormous. Might it be possible to combat global warming by burying CO2 in the deep ocean, or by supplying iron to parts of the ocean to increase photosynthetic and oceanic CO2 uptake, or by adding light-scattering particles to the atmosphere to scatter sunlight back into space? How about adding propane to counter stratospheric ozone loss? The practicality, cost, and side effects of such efforts pose major problems. We focus here instead on the scientific issues that may help us anticipate our future challenges.The air, whose composition is a product of biological and industrial processes and of atmospheric chemistry, is a primary factor for Earth's climate and our health and quality of life. This system can only be effectively studied within the broader context of the biogeochemical cycles of carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen, all of which have been perturbed by human activity.We've already noted how variations of atmospheric CO2 are linked with such life-defining phenomena as glacial-interglacial cycles and surface temperature. Although the variation in solar insolation caused by orbital changes is the basic forcing mechanism for the glacial-interglacial cycles (as originally suggested by James Croll in 1864 and showed quantitatively by Milutin Milankovitch in 1920 with the aid of a climate model), numerous amplifying mechanisms are required to account for the magnitude of the changes. The CO2 concentration during the last major glaciation was about 200 ppm and increased to about 280 ppm prior to human CO2 contributions. Its concentration in 1999 was about 367 ppm, and it continues to rise by about 1.5 ppm annually. Much is now understood about the carbon cycle, but knowledge gaps remain. One of them is the role of terrestrial biota, which has been acting as a sink for CO2, but may not necessarily play that role indefinitely.The sulfur cycle also has been perturbed by human activities. Cloud droplets and ice crystals form by nucleation around submicrometer aerosols consisting of sulfates and organics. That is why aerosols and clouds are strongly linked with climate. Human activities have led to a large increase in these aerosol species. The anthropogenic emission of SO2, which converts into sulfate particles in the atmosphere, exceeds that from natural sources, including volcanic emissions and biological "exhalations," by more than a factor of two.Sulfate particles cool climate directly by scattering sunlight back into space. Sulfates also cool indirectly by nucleating more cloud drops and increasing the brightness (albedo) of clouds. In 1990, Robert Charlson, Joachim Langer, and Henning Rodhe used a global model of the sulfur budget and estimated that the direct cooling effect of sulfates for the past century may have counteracted as much as 20% to 30% of the greenhouse warming. Meanwhile, estimates of cooling from the indirect effect of sulfate range from negligible to offsetting the entire greenhouse forcing (14) .Carbonaceous aerosols from fossil fuel combustion and biomass burning have become another major source of particles. The combination of strong absorption of light by black carbon and scattering by organics and sulfates significantly reduces the amount of solar energy reaching the surface. That raises the specter of regional effects on the hydrological cycle and photosynthesis. One of the main challenges now is to unravel the linkages between aerosols, cloud formation, and climate change. These include the。

大气科学专业导论报

大气科学专业导论报望着书桌上的草稿纸和笔,我的确想不出一个很棒的框架将自己专业的导论报告写的很动美,因为大气科学专业,对于我这个来自西藏的孩子来说,是一个很陌生的生词,对它几乎毫无了解。

在平时的生活中也不怎么关注,我更没想到我选的专业竟然连我自己都不怎么了解。

在刚开学,那段时间,我曾害怕过,我曾也迷茫过,因为我对此专业毫无了解,万一这个专业所要学习的专业课程内容不符合我的特长,不符合我的兴趣爱好呢?如果事情真成这样,我应该怎么办呢?转专业对于我来说是一件不可能的事情,因为我是一名定向生,定向生是不容许转专业的,我问过我认识的学姐,还到图书管去看了相应的书,才知道了此专业的主要要学习的内容,之后不久开展了大气科学专业导论课,让我对自己将要学习的专业有了进一步的了解。

我了解到大气科学专业的基本概念,目前的发展领域,与它所相连的主要的其他专业。

我在老师讲课中知道了,传统的‘气象学’分支学科主要为气象和气候学,1960年以来,随着‘气象学’研究内容的迅速扩展,人们广泛采用‘大气科学’这个术语,其分支学科主要有:大学探测,动力气象学,气候学,大气物理学,大气化学,人工影响天气,应用气象等,知道了大气科学专业并不是一门独立的专业,而是与其他多种专业相互交融。

由于气候变化是大气圈,水圈,生物圈,冰雪圈和岩石圈这五大圈层相互作用的结果,气候研究不可避免地涉及到这五大圈层,现代气候研究已将大气圈与地球系统中的其他圈层相互联系在一起,并且提出了全球气候系统和地球系统的概念,大学科学开始从大气圈,水圈生物圈,冰雪圈和岩石圈的相互作用来理解全球气候变化,理解发生在大气中的各种运动和过程(包括物理的,化学的,生物的),因此,现代大气科学已经与地球科学的其他有关分支相互交融,成为了一门交叉性很强的自然科学学科。

此外还发现大气科学是一门实验科学,其发展在很大程度上依赖于观测,新观测事实的揭示不断推动着大气科学的发展。

大气科学观测一直是学科本身发展的第一关键要素,从20世纪半叶开始,观测平台已经从单一陆地平台,向地基,天基和空基,仪器实地观测和主动,被动遥感综合探测多平台发展,到20 世纪末,大气科学观测与圈层观测开始走向一体化,即综合的和跨学科观测开始成为主流。

大气科学导论大气的基本知识PPT共87页

大气科学导论大气的基本知 识

26、机遇对于有准备的头脑有特别的 亲和力 。 27、自信是人格的核心。

28、目标的坚定是性格中最必要的力 量泉源 之一, 也是成 功的利 器之一 。没有 它,天 才也会 在矛盾 无定的 迷径中 ,徒劳 无功。- -查士 德斐尔 爵士。 29、困难就是机遇。--温斯顿.丘吉 尔。 30、我奋斗,所以我快乐。--格林斯 潘。

大气科学导论-第二章(大气的基本知识1)

低层大气的主要成分

一 干洁大气

干洁大气的定义:

除去水汽及其他悬浮在大气中的固、液 体质粒以外的整个混合气体。

干洁大气的成分变化:

0~90 km : 主要成分和含量比例基本保持不变。 90km以上: 氮稍有减少,氧稍有增多,氩和二氧

化碳明显减少,其中氧分子和氮分子开始离解 。

各种成分介绍:

氮气(N2):

气溶胶粒子:Aerosol

定义:大气中沉降速率极小、尺度在10-4μm到100μm 分类:液体质粒、固体质粒

之间的固态和液态微粒。

固体质粒的来源:有机质数量较少,大多为植物花粉、 无机质数量较多,主要来源于:尘粒、烟粒、海洋中

微生物和细菌等;

浪花飞溅的盐粒,流星飞逝后留下的灰烬,火山尘埃等。

1、定义:表示大气冷热程度的物理量,反映一定条

件下空气分子平均动能大小。

通常指距地面1.5m高处百叶箱中的空气温度。

2、单位:摄氏度(℃)温标;绝对温标,以K表示;

华氏温标:℉,水的沸点为212℉

o

3、单位换算:

5 o C ( F 32) 9

K oC 273.15

o

F

9o C 32 5

2、标准大气压:在纬度为45的海平面上,温度为

0℃时,所测得的水银柱高高为760mm的大气压强,

为一个标准大气压(1atm=1013.25Pa)。 3、单位:1Pa=1N/m2,mb—毫巴,Pa—帕斯卡 1mb=100Pa=1hPa(百帕); 水银气压计 1atm=101325Pa=1013.25mb=760mmHg

时间变化:最大值出现在春季,最小值出现在夏季。 空间变化:

大气中的可变化成分——O3

大气科学专业调查报告

大气科学专业调查报告1. 引言大气科学专业是一门研究地球大气系统的学科,主要关注气候变化、天气预报、空气污染等方面的问题。

为了深入了解该专业的状况,本调查报告将针对大气科学专业进行调查并分析结果。

2. 调查方法本次调查采用了问卷调查的方式,共向20名大气科学专业的学生和教师发送了问卷,并邀请他们填写。

问卷中包含关于大气科学专业的基本信息、课程设置、实践教学及就业情况等方面的问题。

3. 调查结果3.1 专业背景根据问卷结果显示,被调查者中有60%的人是大气科学专业的本科生,占比最多;30%为研究生,占比次之;剩下的是教师和研究人员。

3.2 课程设置大气科学专业的课程设置主要包括气象学、气候学、大气物理学、大气化学等方面的基础课程。

此外,还有专业选修课程,如气象灾害防治、大气遥感等。

3.3 实践教学大气科学专业注重实践教学,根据调查结果显示,实验课程在整个专业课程中占比较大。

学生们通过实验课程能够更好地理解和掌握专业知识。

3.4 就业情况大气科学专业具有广阔的就业前景。

根据本次调查显示,35%的被调查者选择从事气象预报员的工作,其次是从事研究员及教师的工作。

另外,还有一部分学生选择从事环境保护、气象仪器研发等相关行业。

4. 分析与总结大气科学专业在课程设置上注重基础知识的学习,并结合实践教学,以培养学生的实际操作能力。

就业方面,大气科学专业具有较好的就业前景,尤其是在气象预报员、研究员及教师等方面。

然而,也需注意该专业的发展与实际需求的匹配,进一步优化课程设置,提升学生的竞争力。

5. 结论本调查报告通过对大气科学专业的调查分析,揭示出该专业的课程设置、实践教学及就业情况等方面的情况。

希望通过此报告,能够更好地了解该专业,并为未来的学生和教育改革提供参考。

以上为大气科学专业调查报告的摘要,详细内容请参见附录。

热带天气系统大气科学导论

热带天气系统大气科学导论第八章热带天气系统热带和中纬度天气系统的背景差异1.气压场: 热带等压(高)线均匀, 呈纬向分布; 而中纬度等压线密集, 大槽大脊, 南北梯度大2.温度场: 类似于气压场.热带等温线均匀, 呈纬向分布; 而中纬度等温线密集, 南北梯度大第一节热带气旋(台风)热带气旋的分类1.热带低压: 中心附近最大平均风力6至7级,即风速为10.8一17.1米/秒;2.热带风暴: 中心附近最大平均风力8至9级,即风速为17.2-24.4米/秒;3.强热带风暴: 中心附近最大平均风力10至11级,即风速为24.5-32.6米/秒;4.台风(typhoon, 飓风hurricane): 中心附近最大平均风力12级-13级,即风速在32.7-41.4米/秒;5.强台风: 中心附近最大平均风力14级-15级,即风速在41.5-50.9米/秒。

6.超强台风: 中心附近最大平均风力16级以上,即风速大于51.0米/秒。

热带气旋定义:是发生在热带或副热带海洋上的气旋性涡旋,在北半球做逆时针方向旋转,在南半球做顺时针方向旋转。

它主要是依靠水汽凝结释放出的潜热而发展的。

在北半球的西太平洋, 人们常把强热带气旋叫“台风”。

在北半球的大西洋和东太平洋, 人们称强热带气旋为“飓风”。

南半球人们通常称之为热带气旋。

热带气旋----命名为什么要命名?Tropical cyclones are named to provide ease of communication between forecasters andthe general public regarding forecasts, watches, and warnings. Since the storms canoften last a week or longer and that more than one can be occurring in the same basin atthe same time, names can reduce the confusion about what storm is being described.热带气旋如何命名?1998年12月,在菲律宾马尼拉举行的台风委员会第31届委员会决定,从2000年1月1日起,西北太平洋和南海热带气旋将采用新的命名方法。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

大气科学专业导论报

望着书桌上的草稿纸和笔,我的确想不出一个很棒的框架将自己专业的导论报告写的很动美,因为大气科学专业,对于我这个来自西藏的孩子来说,是一个很陌生的生词,对它几乎毫无了解。

在平时的生活中也不怎么关注,我更没想到我选的专业竟然连我自己都不怎么了解。

在刚开学,那段时间,我曾害怕过,我曾也迷茫过,因为我对此专业毫无了解,万一这个专业所要学习的专业课程内容不符合我的特长,不符合我的兴趣爱好呢?如果事情真成这样,我应该怎么办呢?转专业对于我来说是一件不可能的事情,因为我是一名定向生,定向生是不容许转专业的,我问过我认识的学姐,还到图书管去看了相应的书,才知道了此专业的主要要学习的内容,之后不久开展了大气科学专业导论课,让我对自己将要学习的专业有了进一步的了解。

我了解到大气科学专业的基本概念,目前的发展领域,与它所相连的主要的其他专业。

我在老师讲课中知道了,传统的‘气象学’分支学科主要为气象和气候学,1960年以来,随着‘气象学’研究内容的迅速扩展,人们广泛采用‘大气科学’这个术语,其分支学科主要有:大学探测,动力气象学,气候学,大气物理学,大气化学,人工影响天气,应用气象等,知道了大气科学专业并不是一门独立的专业,而是与其他多种专业相互交融。

由于气候变化是大气圈,水圈,生物圈,冰雪圈和岩石圈这五大圈层相互作用的结果,气候研究不可避免地涉及到这五大圈层,现代气候研究已将大气圈与地球系统中的其他圈层相互联系在一起,并且提出了全球气候系统和地球系统的概念,大学科学开始从大气圈,水圈生物圈,冰雪圈和岩石圈的相互作用来理解全球气候变化,理解发生在大气中的各种运动和过程(包括物理的,化学的,生物的),因此,现代大气科学已经与地球科学的其他有关分支相互交融,成为了一门交叉性很强的自然科学学科。

此外还发现大气科学是一门实验科学,其发展在很大程度上依赖于观测,新观测事实的揭示不断推动着大气科学的发展。

大气科学观测一直是学科本身发展的第一关键要素,从20世纪半叶开始,观测平台已经从单一陆地平台,向地基,天基和空基,仪器实地观测和主动,被动遥感综合探测多平台发展,到20 世纪末,大气科学观测与圈层观测开始走向一体化,即综合的和跨学科观测开始成为主流。

随着气候系统概念的提出,大气科学观测的范围从大气圈向气候系统其他圈层扩展。

还有数值天气预报是气象预报预测的基础,数值天气预报的成功,是二世纪大气科学最重大的科技和社会进步之一。

卫星资料同化对提高数值预报准确率和延长预报时效具有至关重要的作用。

提高数值天气预报水平迫切需要气象卫星提高分辨率和高精确度温,湿,风等全球大气垂直探测资料。

现代数值天气和模拟的理论突破,以20世纪初皮叶克泥厮的工作为标志,而以电子计算机为运算工具的现代数值天气预报和模拟研究实验,则起源于1946年美国普林斯顿大学高级研究院研制第一台电子计算机ENIAC项目中的气象项目。

数值天气预报业务化应用,则最早在1954年9月由瑞典斯德哥尔摩大学气象研究所的气象家完成。

从20世纪50年代后期开始,数值天气预报无论是在理论上还是在实践中,都获得飞速的发展,数值天气预报与社会生活密切相关。

在20世纪后半叶经历了以人工预报为主,数值天气预报逐渐有参考的价值到二者效果和作用相当。

一直到大约从80年代开始,由于短期数值天气预报技巧的持续稳定提高而在业务预报逐渐占剧主导过程,今天数值天气预报的成

就,是一系类技术进步的和科学发展相互融合的反映,很多学者提出了今后数值天气改进的主要领域。

海洋历来是大气科学最为关心的领域,海洋覆盖了地球表面的70%,海洋热容是大气热容的100倍,海洋的含水量是大气的900倍,全球有78%的大气降水落入海洋。

大气与海洋的种种不仅局限于上述数字,海洋上有规律的信风,最早孕育和提醒了气象学家,大气运动有可能存在某种规律。

天气和气候模式,不仅是当前天气气候的主要手段,也是大气科学研究的重要工具。

天气和气候的变化造成的社会和环境问题不仅关系到人类生存的环境,,而且对经济发展和社会积极能够部具有潜在的重大影响,是社会和经济发展可持续发展最关键的问题之一。

由于天气,气候变化直接涉及人类社会的发展,对公众,资源,安全,环境等诸多方面都有重要影响,因此,大气科学研究的领域越来越宽,社会需求越来越大。

大气科学目前是地球科学领域中最活跃的学科,科学和技术的发展使大气科学在20世纪最后的几十年里获得了快速发展,与此同时人类对生存环境的极大关注,使大气科学的科学使命更加广阔和神圣,在这世纪交替之时,世界上各主要发达国家和国际组织以及以大气科学专业为支撑基础的气象服务机构纷纷出台中长期的大气科学研究和业务发展规划选择有效和关键的举措,力争在21世纪前将大气科学推向一个新的高度。

在这些长期的发展规划中,一个显著的特征就是发达国家的机构和组织都旗帜鲜明地提出了大气科学应该摆脱传统气候的概念,天气,气候的变化,不单是大气内部动力过程导致,地球大气系统也绝对不是环立地存在,其变化和演化规律与其他圈层的各种过程乃至人类活动是相互联系和制约的,是多方面和多途径的复杂过程。

另一方面,环境与社会经济和人民生活各方面的密切联系,使得现代农业,沿海经济,资源利用和环境保护多种产业发展乃至各种应急管理和灾害预案的确定和实施等社会各个领域,多行业都对以大气科学为基础的各种环境信息的评估和预测提出了更高的需求,这些都是使得大气科学工作者必须站在更高的科学高度,审视学科的发展

据资料所知,在《大气科学进入21世纪》这本书中,美国科学家研究委员会的专家对美国气象局2025年的现代化业务服务进行了解和展望,今天有效的大尺度天气预报为7~10天,即目前数值天气预报技术位于预报极限的一半。

伴随着社会发展,大气科学所包含的职业越来越多,所能够提供服务也就越来越多,生活中很多人都意识到关注每日生活中预告的未来几天的天气变化。

各个大中小城市都注目着每日的生活。