第二十六届“第二十六届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛”竞赛原文

韩素音青翻译奖赛中文原文及参考译文和解析

老来乐Delights in Growing Old六十整岁望七十岁如攀高山。

不料七十岁居然过了。

又想八十岁是难于上青天,可望不可即了。

岂知八十岁又过了。

老汉今年八十二矣。

这是照传统算法,务虚不务实。

现在不是提倡尊重传统吗?At the age of sixty I longed for a life span of seventy, a goal as difficult as a summit to be reached. Who would expect that I had reached it? Then I dreamed of living to be eighty, a target in sight but as inaccessible as Heaven. Out of my anticipation, I had hit it. As a matter of fact, I am now an old man of eighty-two. Such longevity is a grant bestowed by Nature; though nominal and not real, yet it conforms to our tradition. Is it not advocated to pay respect to nowadays?老年多半能悟道。

孔子说“天下有道”。

老子说“道可道”。

《圣经》说“太初有道”。

佛教说“邪魔外道”。

我老了,不免胡思乱想,胡说八道,自觉悟出一条真理: 老年是广阔天地,是可以大有作为的。

An old man is said to understand the Way most probably: the Way of good administration as put forth by Confucius, the Way that can be explained as suggested by Laotzu, the Word (Way) in the very beginning as written in the Bible and the Way of pagans as denounced by theBuddhists. As I am growing old, I can't help being given to flights of fancy and having my own Way of creating stories. However I have come to realize the truth: my old age serves as a vast world in which I can still have my talents employed fully and developed completely.七十岁开始可以诸事不做而拿退休金,不愁没有一碗饭吃,自由自在,自得其乐。

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (3)Hidden within Technology‘s Empire, a Republic of Letters (3)隐藏于技术帝国的文学界 (3)"Why Measure Life in Heartbeats?" (8)何必以心跳定生死? (9)美(节选) (11)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (16)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (16)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (18)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (18)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (21)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (21)On Going Home by Joan Didion (25)回家琼.狄迪恩 (25)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (28)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (28)Beyond Life (34)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (34)Envy by Samuel Johnson (39)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (39)《中国翻译》第一届“青年有奖翻译比赛”(1986)竞赛原文及参考译文(英译汉) (41)Sunday (41)星期天 (42)四川外语学院“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)第七届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)The Woods: A Meditation (Excerpt) (46)林间心语(节选) (47)第六届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (50)第五届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文及获奖译文选登 (52)第四届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文、参考译文及获奖译文选登 (54) When the Sun Stood Still (54)永恒夏日 (55)CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)第三届竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)Here Is New York (excerpt) (56)这儿是纽约 (58)第四届翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (61)Reservoir Frogs (Or Places Called Mama's) (61)水库青蛙(又题:妈妈餐馆) (62)中译英部分 (66)蜗居在巷陌的寻常幸福 (66)Simple Happiness of Dwelling in the Back Streets (66)在义与利之外 (69)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (69)读书苦乐杨绛 (72)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (72)想起清华种种王佐良 (74)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (74)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (76)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (76)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (79)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (79)可爱的南京 (82)Nanjing the Beloved City (82)霞冰心 (84)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (84)黎明前的北平 (85)Predawn Peiping (85)老来乐金克木 (86)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (86)可贵的“他人意识” (89)Calling for an Awareness of Others (89)教孩子相信 (92)To Implant In Our Children‘s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (92)心中有爱 (94)Love in Heart (94)英译汉部分Hidden within Technology’s Empire, a Republic of Le tters 隐藏于技术帝国的文学界索尔·贝娄(1)When I was a boy ―discovering literature‖, I used to think how wonderful it would be if every other person on the street were familiar with Proust and Joyce or T. E. Lawrence or Pasternak and Kafka. Later I learned how refractory to high culture the democratic masses were. Lincoln as a young frontiersman read Plutarch, Shakespeare and the Bible. But then he was Lincoln.我还是个“探索文学”的少年时,就经常在想:要是大街上人人都熟悉普鲁斯特和乔伊斯,熟悉T.E.劳伦斯,熟悉帕斯捷尔纳克和卡夫卡,该有多好啊!后来才知道,平民百姓对高雅文化有多排斥。

韩素音青年翻译奖

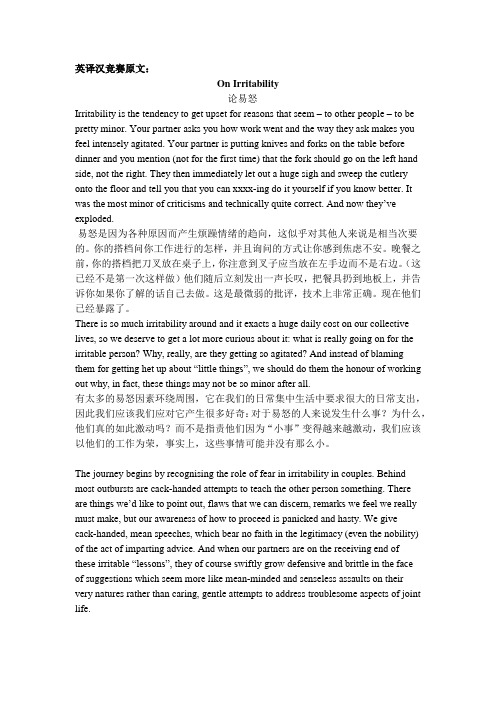

On IrritabilityIrritability is the tendency to get upset for reasons that seem – to other people – to be pretty minor. Your partner asks you how work went and the way they ask makes you feel intensely agitated. Your partner is putting knives and forks on the table before dinner and you mention (not for the first time) that the fork should go on the left hand side, not the right. They then immediately let out a huge sigh and sweep the cutlery onto the floor and tell you that you can xxxx-ing do it yourself if you know better. It was the most minor of criticisms and technically quite correct. And now they’ve exploded.There is so much irritability around and it exacts a huge daily cost on our collective lives, so we deserve to get a lot more curious about it: what is really going on for the irritable person? Why, really, are they getting so agitated? And instead of blaming them for getting het up about “little things”, we should do them the honour of working out why, in fact, these things may not be so minor after all.The journey begins by recognising the role of fear in irritability in couples. Behind most outbursts are cack-handed attempts to teach the other person something. There are things we’d like to point out, flaws that we can discern, remarks w e feel we really must make, but our awareness of how to proceed is panicked and hasty. We give cack-handed, mean speeches, which bear no faith in the legitimacy (even the nobility) of the act of imparting advice. And when our partners are on the receiving end of these irritable “lessons”, they of course swiftly grow defensive and brittle in the face of suggestions which seem more like mean-minded and senseless assaults on their very natures rather than caring, gentle attempts to address troublesome aspects of joint life.The prerequisite of calm in a teacher is a degree of indifference as to the success or failure of the lesson. One naturally wants for things to go well, but if an obdurate pupil flunks trigonometry, it is – at base – their problem. Tempers can stay even because individual students do not have very much power over teachers’ lives. Fortunately, as not caring too much turns out to be a critical aspect of successful pedagogy.Yet this isn’t an option open to the fearful, irritable lover. They feel ineluctably led to deliver their “lessons” in a cataclysmic, frenzied manner (the door slams very loudly indeed) not because they are insane or vile (though one could easily draw theseconclusions) so much as because they are terrified; terrified of spoiling what remains of their years on the planet in the company of someone who it appears cannot in any way understand a pivotal point about conversation, or cutlery, or the right time to order a taxi.One knows intuitively, when teaching a child, that only the utmost care and patience will ever work: one must never shout, one has to use extraordinary tact, one has to make ten compliments for every one negative remark and one must leave oneself plenty of time…All this wisdom we reliably forget in lov e’s classroom, sadly because increasing the level of threat seldom hastens development. We do not grow more reasonable, more accepting of responsibility and more accurate about our weaknesses when our pride has been wounded, our integrity is threatened and our self-esteem has been violated.The complaint against the irritable person is that they are getting worked up over “nothing”. But symbols offer a way of seeing how a detail can stand for something much bigger and more serious. The groceries placed on the wrong table are not upsetting at all in themselves. But symbolically they mean your partner doesn’t care about domestic order; they muddle things up; they are messy. Or the question about one’s day is experienced as a symbol of interrogation, a lack o f privacy and a humiliation (because one’s days rarely go well enough).The solution is, ideally, to concentrate on what the bigger issue is. Entire philosophies of life stir and collide beneath the surface of apparently petty squabbles. Irritations are the outward indications of stifled debates between competing conceptions of existence. It’s to the bigger themes we need to try to get.In the course of discussions, one might even come face-to-face with that perennially surprising truth about relationships: that the other person is not an extension of oneself that has, mysteriously, gone off message. They are that most surprising of things, a different person, with a psyche all of their own, filled with a perplexing number of subtle, eccentric and unforeseen reasons for thinking as they do.The decoding may take time, perhaps half an hour or more of concentrated exploration for something that had until then seemed as if it would more rightfully deserve an instant.We pay a heavy price for this neglect; every conflict that ends in sour stalemate is a blocked capillary within the heart of love. Emotions will find other ways to flow for now, but with the accumulation of unresolved disputes, pathways will fur and possibilities for trust and generosity narrow.A last point. It may just be sleep or food: when a baby is irritable, we rarely feel the need to preach about self-control and a proper sense of proportion. It’s not simply that we fear the infant’s intellect might not quite be up to it, but because we have a much better explanation of what is going on. We know that they’re acting this way –and getting bothered by any little thing – because they are tired, hungry, too hot or having some challenging digestive episode.The fact is, though, that the same physiological causes get to us all our lives. When we are tired, we get upset more easily; when we feel very hungry, it takes less to bother us. But it is immensely difficult to transfer the lesson in generosity (and accuracy) that we gain around to children and apply it to someone with a degree in business administration or a pilot’s license, or to whom we have been married for three-and-a-half years.We should try to see irritability for what it actually is: a confused, inarticulate, often shameful attempt to get us to understand how much someone is suffering and how urgently they need our help. We should – when we can manage it – attempt to help them out.。

韩素英翻译大赛参赛题

英译汉原文Hidden Within Technology’s Empire, a Republic of LettersWhen I was a boy “discovering literature”, I used to think how wonderful it would be if every other person on the street were familiar with Proust and Joyce or T.E. Lawrence or Pasternak and Kafka. Later I learned how refractory to high culture the democratic masses were. Lincoln as a young frontiersman read Plutarch, Shakespeare and the Bible. But then he was Lincoln.Later when I was traveling in the Midwest by car, bus and train, I regularly visited small-town libraries and found that readers in Keokuk, Iowa, or Benton Harbor, Mich., were checking out Proust and Joyce and even Svevo and Andrei Biely. D. H. Lawrence was also a favorite. And sometimes I remembered that God was willing to spare Sodom for the sake of 10 of the righteous. Not that Keokuk was anything like wicked Sodom, or that Proust’s Charlus would have been tempted to settle in Benton Harbor, Mich.I seem to have had a persistent democratic desire to find evidences of high culture in the most unlikely places.For many decades now I have been a fiction writer, and from the first I was aware that mine was a questionable occupation. In the 1930’s an elderly neighbor in Chicago told me that he wrote fiction for the pulps. “The people on the block wonder whyI don’t go to a job, and I’m seen puttering around, trimming the bushes or paintinga fence instead of working in a factory. But I’m a writer. I sell to Argosy and Doc Savage,” he said with a certain gloom. “They wouldn’t call that a trade.”Probably he noticed that I was a bookish boy, likely to sympathize with him, and perhaps he was trying to warn me to avoid being unlike others. But it was too late for that.From the first, too, I had been warned that the novel was at the point of death, that like the walled city or the crossbow, it was a thing of the past. And no one likes to be at odds with history. Oswald Spengler, one of the most widely read authors of the early 30’s, taught that our tired old civilization was very nearly finished. His advice to the young was to avoid literature and the arts and to embrace mechanization and become engineers.In refusing to be obsolete, you challenged and defied the evolutionist historians.I had great respect for Spengler in my youth, but even then I couldn’t accept his conclusions, and (with respect and admiration) I mentally told him to get lost.Sixty years later, in a recent issue of The Wall Street Journal, I come upon the old Spenglerian argument in a contemporary form. Terry Teachout, unlike Spengler, does not dump paralyzing mountains of historical theory upon us, but there are signs that he has weighed, sifted and pondered the evidence.He speaks of our “atomized culture,” and his is a responsible, up-to-date and carefully considered opinion. He speaks of “art forms as technologies.” He tells us that movies will soon be “downloadable”—that is, transferable from one computer to the memory of another device—and predicts that films will soon be marketed like books. He predicts that the near-magical powers of technology are bringing us to the threshold of a new age and concludes, “Once this happens, my guess is that the independent movie will replace the novel as the principal vehicle for serious storytelling in the 21st century.”In support of this argument, Mr. Teachout cites the ominous drop in the volume of book sales and the great increase in movie attendance: “For Americans under the age of 30, film has replaced the novel as the dominant mode of artistic expression.”To this Mr. Teachout adds that popular novelists like Tom Clancy and Stephen King “top out at around a million copies per book,” and notes, “The final episode of NBC’s ‘Cheers,’ by contrast, was seen by 42 million people.”On majoritarian grounds, the movies win. “The power of novels to shape the national conversation has declined,” says Mr. Teachout. But I am not at all certain that in their day “Moby-Dick” or “The Scarlet Letter” had any considerable influence on “the national conversation.” In the mid-19th century it was “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”that impressed the great public. “Moby-Dick” was a small-public novel.The literary masterpieces of the 20th century were for the most part the work of novelists who had no large public in mind. The novels of Proust and Joyce were written in a cultural twilight and were not intended to be read under the blaze and dazzle of popularity.Mr. Teachout’s article in The Journal follows the path generally taken by observers whose aim is to discover a trend. “According to one recent study 55 percent of Americans spend less than 30 minutes reading anything at all. . . . It may even be that movies have superseded novels not because Americans have grown dumber but because the novel is an obsolete artistic technology.”“We are not accustomed to thinking of art forms as technologies,” he says, “but that is what they are, which means they have been rendered moribund by new technical developments.”Together with this emphasis on technics that attracts the scientific-minded young, there are other preferences discernible: It is better to do as a majority of your contemporaries are doing, better to be one of millions viewing a film than one of mere thousands reading a book. Moreover, the reader reads in solitude, whereas the viewer belongs to a great majority; he has powers of numerosity as well as the powers of mechanization. Add to this the importance of avoiding technological obsolescence and the attraction of feeling that technics will decide questions for us more dependably than the thinking of an individual, no matter how distinctive he may be.John Cheever told me long ago that it was his readers who kept him going, people from every part of the country who had written to him. When he was at work, he was aware of these readers and correspondents in the woods beyond the lawn. “If I couldn’t picture them, I’d be sunk,” he said. And the novelist Wright Morris, urging me to get an electric typewriter, said that he seldom turned his machine off. “When I’m not writing, I listen to the electricity,” he said. “It keeps me company. We have conversations.”I wonder how Mr. Teachout might square such idiosyncrasies with his “art forms as technologies.” Perhaps he would argue that these two writers had somehow isolated themselves from “broad-based cultural influence.” Mr. Teachout has at least one laudable purpose: He thinks that he sees a way to bring together the Great Public of the movies with the Small Public of the highbrows. He is, however, interested in millions: millions of dollars, millions of readers, millions of viewers.The one thing “everybody” does is go to the movies, Mr. Teachout says. How right he is.Back in the 20’s children between the ages of 8 and 12 lined up on Saturdays to buy their nickel tickets to see the crisis of last Saturday resolved. The heroine was untied in a matter of seconds just before the locomotive would have crushed her. Then came a new episode; and after that the newsreel and “Our Gang.” Finally there was a western with Tom Mix, or a Janet Gaynor picture about a young bride and her husband blissful in the attic, or Gloria Swanson and Theda Bara or Wallace Beery or Adolphe Menjou or Marie Dressler. And of course there was Charlie Chaplin in “TheGold Rush,” and from “The Gold Rush” it was only one step to the stories of Jack London.There was no rivalry then between the viewer and the reader. Nobody supervised our reading. We were on our own. We civilized ourselves. We found or made a mental and imaginative life. Because we could read, we learned also to write. It did not confuse me to see “Treasure Island” in the movies and then read the book. There was no competition for our attention.One of the more attractive oddities of the United States is that our minorities are so numerous, so huge. A minority of millions is not at all unusual. But there are in fact millions of literate Americans in a state of separation from others of their kind. They are, if you like, the readers of Cheever, a crowd of them too large to be hidden in the woods. Departments of literature across the country have not succeeded in alienating them from books, works old and new. My friend Keith Botsford and I felt strongly that if the woods were filled with readers gone astray, among those readers there were probably writers as well.To learn in detail of their existence you have only to publish a magazine like The Republic of Letters. Given encouragement, unknown writers, formerly without hope, materialize. One early reader wrote that our paper, “with its contents so fresh, person-to-person,” was “real, non-synthetic, undistracting.” Noting that there were no ads, she asked, “Is it possible, can it last?” and called it “an antidote to the shrinking of the human being in every one of us.” And toward the end of her letter our correspondent added, “It behooves the elder generation to come up with reminders of who we used to be and need to be.”This is what Keith Botsford and I had hoped that our “tabloid for literates” would be. And for two years it has been just that. We are a pair of utopian codgers who feel we have a duty to literature. I hope we are not like those humane do-gooders who, when the horse was vanishing, still donated troughs in City Hall Square for thirsty nags.We have no way of guessing how many independent, self-initiated connoisseurs and lovers of literature have survived in remote corners of the country. The little evidence we have suggests that they are glad to find us, they are grateful. They want more than they are getting. Ingenious technology has failed to give them what they so badly need.索尔·贝娄索尔·贝娄(Saul Bellow,1915-2005)美国作家。

韩素音英语竞赛24-27届原文

―CATTI杯‖第二十七届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛英译汉竞赛原文:The Posteverything GenerationI never expected to gain any new insight into the nature of my generation, or the changing landscape of American colleges, in Lit Theory. Lit Theory is supposed to be the class where you sit at the back of the room with every other jaded sophomore wearing skinny jeans, thick-framed glasses, an ironic tee-shirt and over-sized retro headphones, just waiting for lecture to be over so you can light up a Turkish Gold and walk to lunch while listening to Wilco. That‘s pretty much the way I spent the course, too: through structuralism, formalism, gender theory, and post-colonialism, I was far too busy shuffling through my Ipod to see what the patriarchal world order of capitalist oppression had to do with Ethan Frome. But when we began to study postmodernism, something struck a chord with me and made me sit up and look anew at the seemingly blasé college-aged literati of which I was so self-consciously one.According to my textbook, the problem with defining postmodernism is that it‘s impossible. The difficulty is that it is so...post. It defines itself so negatively against what came before it – naturalism, romanticism and the wild revolution of modernism –that it‘s sometimes hard to see what itactually is. It denies that anything can be explained neatly or even at all. It is parodic, detached, strange, and sometimes menacing to traditionalists who do not understand it. Although it arose in the post-war west (the term was coined in 1949), the generation that has witnessed its ascendance has yet to come up with an explanation of what postmodern attitudes mean for the future of culture or society. The subject intrigued me because, in a class otherwise consumed by dead-letter theories, postmodernism remained an open book, tempting to the young and curious. But it also intrigued me because the question of what postmodernism –what a movement so post-everything, so reticent to define itself – is spoke to a larger question about the political and popular culture of today, of the other jaded sophomores sitting around me who had grown up in a postmodern world.In many ways, as a college-aged generation, we are also extremely post: post-Cold War, post-industrial, post-baby boom, post-9/11...at one point in his fa mous essay, ―Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,‖ literary critic Frederic Jameson even calls us ―post-literate.‖ We are a generation that is riding on the tail-end of a century of war and revolution that toppled civilizations, overturned repressive social orders, and left us with more privilege and opportunity than any other society in history. Ours could be an era to accomplish anything.And yet do we take to the streets and the airwaves and say ―here we are, and this is what we dema nd‖? Do we plant our flag of youthful rebellion on the mall in Washington and say ―we are not leaving until we see change! Our eyes have been opened by our education and our conception of what is possible has been expanded by our privilege and we demand a better world because it is our right‖? It would seem we do the opposite. We go to war without so much as questioning the rationale, we sign away our civil liberties, we say nothing when the Supreme Court uses Brown v. Board of Education to outlaw segregation, and we sit back to watch the carnage on the evening news.On campus, we sign petitions, join organizations, put our names on mailing lists, make small-money contributions, volunteer a spare hour to tutor, and sport an entire wardrobe‘s worth of Live S trong bracelets advertising our moderately priced opposition to everything from breast cancer to global warming. But what do we really stand for? Like a true postmodern generation we refuse to weave together an overarching narrative to our own political consciousness, to present a cast of inspirational or revolutionary characters on our public stage, or to define a specific philosophy. We are a story seemingly without direction or theme, structure or meaning –a generation defined negatively againstwhat ca me before us. When Al Gore once said ―It‘s the combination of narcissism and nihilism that really defines postmodernism,‖ he might as well have been echoing his entire generation‘s critique of our own. We are a generation for whom even revolution seems trite, and therefore as fair a target for blind imitation as anything else. We are the generation of the Che Geuvera tee-shirt.Jameson calls it ―Pastiche‖ –―the wearing of a linguistic mask, speech in a dead language.‖ In literature, this means an author s peaking in a style that is not his own – borrowing a voice and continuing to use it until the words lose all meaning and the chaos that is real life sets in. It is an imitation of an imitation, something that has been re-envisioned so many times the original model is no longer relevant or recognizable. It is mass-produced individualism, anticipated revolution. It is why postmodernism lacks cohesion, why it seems to lack purpose or direction. For us, the post-everything generation, pastiche is the use and reuse of the old clichés of social change and moral outrage – a perfunctory rebelliousness that has culminated in the age of rapidly multiplying non-profits and relief funds. We live our lives in masks and speak our minds in a dead language – the language of a society that expects us to agitate because that‘s what young people do. But how do we rebel against a generation that is expecting, anticipating, nostalgic for revolution?How do we rebel against parents that sometimes seem to want revolution more than we do? We don‘t. We rebel by not rebelling. We wear the defunct masks of protest and moral outrage, but the real energy in campus activism is on the internet, with websites like . It is in the rapidly developing ability to communicate ideas and frustration in chatrooms instead of on the streets, and channel them into nationwide projects striving earnestly for moderate and peaceful change: we are the generation of Students Taking Action Now Darfur; we are the Rock the V ote generation; the generation of letter-writing campaigns and public interest lobbies; the alternative energy generation.College as America once knew it –as an incubator of radical social change –is coming to an end. To our generation the word ―radicalism‖ evokes images of al Qa eda, not the Weathermen. ―Campus takeover‖ sounds more like Virginia Tech in 2007 than Columbia University in 1968. Such phrases are a dead language to us. They are vocabulary from another era that does not reflect the realities of today. However, the technological revolution, the revolution, the revolution of the organization kid, is just as real and just as profound as the revolution of the 1960‘s – it is just not as visible. It is a work in progress, but it is there. Perhaps when our parents finally stop pointing out the things that we arenot, the stories that we do not write, they will see the threads of our narrative begin to come together; they will see that behind our pastiche, the post generation speaks in a language that does make sense. We are writing a revolution. We are just putting it in our own words.汉译英竞赛原文:保护古村落就是保护―根性文化‖传统村落是指拥有物质形态和非物质形态文化遗产,具有较高的历史、文化、科学、艺术、社会、经济价值的村落。

第二十六届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文

第二十六届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文来源:中国译协网英译汉竞赛原文:How the News Got Less MeanThe most read article of all time on BuzzFeed (?)contains no photographs of celebrity nip slips(?)and no inflammatory (煽动性的;激动的)ranting(吼、闹). 译:最具阅读性的文章It’s a series of photos called “21 pictures that will restore your faith in humanity,”只有一系列被称作“21张将让你重拾对人类的信仰的照片”, which has pulled in nearly 14 million visits so far. 到目前为止,这些照片引来了将近一千四百万的观众参观。

At Upworthy too, hope is the major draw.(?)同样在病毒式媒体网站,希望也是“This kid just died. What he left behind is wondtacular,(?)”这个少年刚刚过世,他留给世人的是an Upworthy post about a terminally (处于末期症状上;致命地)ill teen singer, 病毒式媒体网站上关于患有晚期癌症青年歌手的邮件赢得一千五百万人的关注和筹集到三十多万美元来用于癌症研究。

earned 15 million views this summer and has raised more than $300,000 for cancer research.The recipe for attracting visitors to stories online is changing.网上吸引观众关注故事的秘诀正发生改变。

二十六届韩素音参赛译文(汉译英)

Lost in CitiesTr.Woo FenbyAlong the Aihui-Tengchong Line,a demarcation line discovered and named by Mr.Hu Huanyong in1935for Chinese population,nature and historical geography,we can see that the penetration and decentralization of interest and power have fundamentally changed the state of cities since the emergence of long-distance trade—while cities are swelling,people are alienating.Even to the present day,Alain de Lille’s words still remain startlingly revealing that all-powerful is money instead of Julius Caesar.In ancient Rome,columns were divided according to the proportion of human body;by the time of the Renaissance,human beings had been regarded as the finest scale on earth.Within the cities of China nowadays, waterways are straightened,transportation networks are extended into all directions,and huge urban squares and building facades are expanded to accommodate more business activities.All of these are telling people that the aesthetic standard has turned out to be nothing but the power and capital behind the constructions.Not until one day when we look back at our own children standing on a dust-covered road swarming with vehicles, will we find out that the colossus of a city harbors no opportunity for them to show a smiling face.The evil of planning and designing lies not in seeking profit itself,butthe obsession in doing so to the neglect of all other human needs.The number of cities is increasing,their size expanding,and the urban-rural structure disintegrating;but the designated function and purpose of cities have been forgotten:the wisest no longer understand the forms of social life,yet the most ignorant are intending to build them.As cities grow bigger,people are dwarfed.People and their cities are closely bound up to yet utterly incompatible with each other.Having failed to obtain such means of life with more substantial and satisfactory content as are contrary to those in the business world,people are reduced to bystanders,readers,listeners and passive observers.Hence,year in and year out,we are not living in the real sense of the word,but in an indirect manner,far away from our intrinsic natures.These natures,sweeping past those silent and confused faces in the photos attached,can occasionally be seen in a kite floating across the sky,or in a smile of children at the sight of a pigeon.The isolation between humans and cities makes the former feel at sea; but to our comfort,we have never forgotten about living.As the homeland for deities from the very beginning,cities represented eternal value,consolation and divine power.The segregation and discrimination among people in the past will not persist,because what the city expresses in the end will not be the intention of a deified ruler any more,but that of each individual and the general public within the city.It will no longer bethe conflict per se,but a container instead providing a dynamic stage for daily contradiction and conflict as well as challenge and embrace.One day,art and thought will make their sudden appearance in a city corner and become interwoven with our life.Perhaps,we can only announce with confidence on this day:Better City,Better Life!(542words)。

全国新概念英语作文大赛第26届获奖

全国新概念英语作文大赛第26届获奖全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1A Journey of Growth: Embracing Challenges and Seizing OpportunitiesAs I stand before you today, my heart swells with a profound sense of gratitude and accomplishment. To be recognized at the 26th National New Concept English Writing Competition is an honor that fills me with immense pride and humility. This platform has not only celebrated my passion for the English language but has also served as a catalyst for personal growth and self-discovery.Looking back, I can vividly recall the trepidation that gripped me when I first embarked on this journey. The mere thought of articulating my thoughts in a language that was not my mother tongue seemed like an insurmountable obstacle. However, it was this very challenge that ignited a fire within me – a determination to conquer my fears and push beyond my perceived limitations.The English language has always held a certain allure for me, a door to a vast world of knowledge, culture, and diverseperspectives. As I delved deeper into the intricacies of grammar, syntax, and vocabulary, I found myself captivated by the sheer beauty and precision of this remarkable medium of communication. Each word, carefully chosen and masterfully woven, had the power to paint vivid pictures, evoke emotions, and shape narratives that could transcend boundaries.Yet, my growth extended far beyond the confines of linguistic proficiency. Through the process of crafting my submission, I discovered the invaluable art of self-expression. Writing became a canvas upon which I could pour my innermost thoughts, weaving together personal experiences, dreams, and reflections into a tapestry of authenticity. With every word committed to the page, I felt a liberating sense of vulnerability, allowing my true self to shine through the ink.Moreover, the English language opened doors to a wealth of literature, exposing me to diverse cultures, philosophies, and perspectives that broadened my horizons. I found myself transported to distant lands, immersed in the lives of characters whose struggles and triumphs resonated with my own. Through their stories, I gained a deeper understanding of the human condition, cultivating empathy, and appreciating the richness of our global tapestry.The path to this achievement was not without its challenges. There were moments when the weight of self-doubt threatened to undermine my efforts, when the words seemed to elude me, and the temptation to surrender loomed large. Yet, it was in these trying times that I discovered the true essence of perseverance. Each obstacle became an opportunity to sharpen my resolve, to seek guidance from mentors and peers, and to embrace the iterative process of refinement.Looking ahead, I am filled with a renewed sense of purpose and determination. This achievement has not only validated my linguistic capabilities but has also instilled in me a profound appreciation for the transformative power of language. I now stand ready to embark on new adventures, to explore uncharted territories of knowledge, and to contribute my voice to the rich tapestry of global discourse.To my fellow writers and language enthusiasts, I extend a heartfelt invitation to embrace the challenges that lie ahead. For it is in the midst of adversity that we discover the true depths of our resilience and the boundless potential of our creativity. Let us celebrate the diversity of our voices, for it is through this harmonious symphony that we can weave a narrative of understanding, empathy, and progress.To the esteemed organizers of this competition, I express my sincere gratitude for providing a platform that nurtures young minds and fosters a love for the English language. Your unwavering commitment to excellence has inspired countless individuals like myself to push the boundaries of our capabilities and to embrace the transformative power of words.As I stand on the precipice of new horizons, I carry with me the lessons learned, the memories forged, and the unwavering belief that language has the power to unite, to inspire, and to shape the course of our collective destiny. This achievement is not merely a personal triumph but a testament to the enduring spirit of human expression and the boundless potential that lies within each of us when we dare to dream, to persevere, and to embrace the challenges that life presents.Thank you, and may the journey of growth continue to unfold, one word at a time.篇2A Leap of FaithAs I stood at the edge of the diving board, my heart pounded against my chest like a captive bird desperate for escape. The crystal-clear waters of the Olympic-sized poolshimmered invitingly before me, but my mind conjured up a thousand reasons why I should retreat to safer ground. After all, I was just an ordinary thirteen-year-old girl – what business did I have attempting such a daring feat?It had all started a few months earlier when my English teacher, Mrs. Roberts, announced the 26th National New Concept English Writing Contest. She had that familiar glint in her eye, the one that meant she was challenging us to step out of our comfort zones and embrace something extraordinary. "This year's theme is 'Taking the Plunge,'" she had declared, her voice ringing with enthusiasm. "I want you all to write about a time when you overcame your fears and took a risk that changed your life forever."At first, the words had seemed like a foreign language, incomprehensible and daunting. What did I, a shy bookworm who spent more time lost in the pages of novels than living life itself, know about taking risks? But then, as I pondered the prompt, memories began to surface – memories of a summer long ago, when I had faced my greatest fear head-on.It had been the summer before sixth grade, and my family had decided to spend a week at a resort in the mountains. While my parents had envisioned a relaxing getaway filled with hikingand stargazing, my younger brother, Tommy, had other plans. From the moment we arrived, he had been enchanted by the resort's massive swimming pool, complete with a towering diving board that seemed to touch the clouds."Can we go swimming, pleeease?" Tommy had begged, his eyes wide with anticipation.My mother had laughed, ruffling his hair affectionately. "Of course, sweetheart. But promise me you'll stay away from that diving board. It's much too high for little ones like you."Tommy had readily agreed, but I knew better. His promises were as flimsy as a spider's web, easily broken at the slightest temptation.Sure enough, the next day found us lounging by the pool, and Tommy was already eyeing the diving board with a gleam of mischief in his eyes. Before I could stop him, he had scampered off, scaling the ladder with the agility of a mountain goat."Tommy, get down from there!" I had shouted, my voice trembling with fear.But it was too late. With a whoop of delight, he had launched himself into the air, his small body arcing gracefully before plunging into the water with a mighty splash.In that moment, time seemed to stand still. Seconds ticked by like hours as I waited with bated breath for my brother to resurface. When he finally broke through the surface, sputtering and grinning from ear to ear, relief washed over me like a tidal wave."Did you see that, Sis?" he had crowed, treading water triumphantly. "I did it! I conquered the diving board!"As I watched him celebrate his victory, something shifted within me. Suddenly, I found myself envying his fearlessness, his ability to take risks without hesitation. In that moment, I made a decision – a decision that would change the course of my life forever."Wait for me, Tommy!" I had called out, surprising even myself with my boldness. "I'm coming too!"And so, with trembling legs and a pounding heart, I had climbed the seemingly infinite steps to the diving board's precipice. From that dizzying height, the pool below had appeared as a mere puddle, and doubt had threatened to consume me. But then I had glanced at Tommy, still beaming with pride, and something deep within me had stirred – a fierce determination to conquer my fears, just as he had conquered his.With a deep breath, I had taken the plunge.Those few seconds of freefall had been both terrifying and exhilarating, a chaotic blend of adrenaline and apprehension. And then, in a flash, I had broken through the water's surface, emerging victorious and utterly transformed.From that day on, I had become a different person – more daring, more willing to embrace the unknown. I had discovered a newfound confidence that had propelled me through countless challenges, from academic pursuits to extracurricular endeavors. And now, as I stood poised on the precipice of adulthood, I knew that it was this very spirit of fearlessness that had brought me to this moment – a moment where I had the opportunity to share my story with the world.With a deep breath, I plunged into the task of crafting my essay, letting the words flow like water from a mountain stream. I poured my heart and soul onto the page, reliving that fateful day at the pool and the profound impact it had had on my life. I wrote of the exhilaration of facing one's fears, the rush of adrenaline that comes with taking a leap of faith, and the immense personal growth that can blossom from such courageous acts.When I finally set down my pen, I knew that I had created something special – a piece that encapsulated the very essence of "Taking the Plunge." And so, with a mixture of pride and trepidation, I had submitted my essay to the contest, never daring to dream that it would be chosen as a winner.But fate, it seemed, had other plans.Months later, as I sat in Mrs. Roberts' English class, she had called me to the front of the room, a radiant smile playing upon her lips."Congratulations, Emily," she had announced, her voice brimming with pride. "Your essay has been selected as a winner in the 26th National New Concept English Writing Contest."In that moment, a wave of emotions had washed over me –disbelief, elation, and a profound sense of gratitude. For it was in that instant that I realized the true power of taking risks, of embracing the unknown with open arms.As I had accepted the award, clutching the framed certificate to my chest, I had made a silent vow to myself: to never stop taking the plunge, to never allow fear to govern my actions or limit my potential. For it was in those moments of courage, those leaps of faith, that we truly soared.And so, as I stand here today, a young woman poised on the precipice of adulthood, I carry that lesson with me like a torch, illuminating my path forward. The world may present innumerable challenges and uncertainties, but I will face them all with the same fearlessness that propelled me from that diving board all those years ago.For at the end of the day, life is a series of plunges – some small, some monumental, but all equally important in shaping who we are and who we aspire to become. And it is those who have the courage to take that leap, to embrace the unknown with open arms, who will truly soar.篇3A Journey of Growth: My Experience in the National New Concept English Writing CompetitionAs I stand here, clutching the award that bears witness to my triumph in the 26th National New Concept English Writing Competition, a wave of emotions washes over me. This achievement is not merely a recognition of my linguistic prowess but a testament to the transformative journey that has shaped me into the person I am today.It was a crisp autumn morning when my English teacher, Mrs. Liu, announced the competition in class. Her eyes sparkled with enthusiasm as she extolled the virtues of this prestigious event, igniting a spark of curiosity within me. Little did I know then that this spark would kindle a flame that would guide me through uncharted territories of self-discovery and personal growth.The initial stages were daunting, to say the least. Staring at the blank page, my mind seemed to rebel against the flow of words, forming an impenetrable barrier between my thoughts and their expression on paper. Doubt crept in, whispering insidiously, questioning my abilities and undermining my confidence. It was then that I realized the true essence of this competition – it was not merely a test of linguistic proficiency but a challenge to conquer the demons of self-doubt and insecurity that so often hold us back.With unwavering determination, I embarked on a journey of self-exploration, delving deep into the recesses of my mind and soul to unearth the stories that lay buried within. Each word I penned became a brushstroke, painting a vivid tapestry of my innermost thoughts and experiences. The process was arduous, yet profoundly cathartic, as I poured my heart onto the pages,allowing my words to flow freely, unencumbered by the shackles of fear or self-imposed limitations.As the deadline loomed closer, the pressure mounted, but so did my resolve. Late nights were spent meticulously crafting sentences, polishing phrases, and sculpting paragraphs into a cohesive whole. It was a labor of love, fueled by a burning desire to express myself in a language that had once seemed foreign and intimidating.When the fateful day arrived, and my essay was submitted, a sense of accomplishment washed over me. Regardless of the outcome, I had already emerged a victor, having conquered the demons that had once held me back. The journey had transformed me, instilling in me a newfound confidence and a deeper appreciation for the power of language to bridge cultural divides and forge connections across borders.Months passed, and the anticipation grew, until finally, the announcement was made – my essay had been chosen as one of the winners in this prestigious competition. In that moment, I felt a surge of pride and validation, not just for my linguistic abilities but for the courage and perseverance that had carried me through this transformative experience.As I stand before you today, basking in the warmth of this accomplishment, I am reminded of the profound impact this journey has had on my life. It has taught me the value of resilience, the importance of self-belief, and the power of language to transcend boundaries and touch the hearts of others.To my fellow competitors, I extend my heartfelt congratulations. Your dedication and passion have been an inspiration, reminding me that true excellence is not a solitary pursuit but a collective endeavor, where we challenge and motivate one another to reach ever greater heights.To the organizers and judges of this esteemed competition, I offer my deepest gratitude. Your tireless efforts and unwavering commitment to fostering linguistic excellence have provided a platform for aspiring writers like myself to showcase our talents and hone our craft.And to my teachers, mentors, and loved ones, words cannot fully express the depth of my appreciation. Your guidance, support, and unwavering belief in me have been the driving force behind my success, propelling me forward even when the path seemed shrouded in uncertainty.As I look ahead, I am filled with a renewed sense of purpose and determination. This experience has ignited within me a passion for language and storytelling, and I am eager to continue exploring the boundless realms of self-expression through the written word.To my fellow students and aspiring writers, I implore you to embrace the challenges that lie ahead, for it is through these trials that we truly grow and discover the depths of our potential. Let this competition be a catalyst for your own journey ofself-discovery, a testament to the transformative power of language and the indomitable spirit of the human mind.In the words of the great Maya Angelou, "There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you." Today, I stand before you, my story told, my voice heard, and my spirit soaring. This is not the end but merely the beginning of a lifelong odyssey, where words will be my compass, guiding me through uncharted territories of self-expression and personal growth.Thank you, and may the power of language continue to inspire, uplift, and unite us all.。

韩素英翻译大赛原文

Outing A.I.: Beyond the Turing TestThe idea of measuring A.I. by its ability to “pass” as a human – dramatized in countless sci- fi films – is actually as old as modern A.I. research itself. It is traceable at least to 1950 when the British mathematician Alan Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a paper in which he described what we now call the “Turing Test,” and which he referred to as the “imitation game.” There are different versions of the test, all of which are revealing as to why our approach to the culture and ethics of A.I. is what it is, for good and bad. For the most familiar version, a human interrogator asks questions of two hidden contestants, one a human and the other a computer. Turing suggests that if the interrogator usually cannot tell which is which, and if the computer can successfully pass as human, then can we not conclude, for practical purposes, that the computer is “intelligent”?More people “know” Turing’s foundational text than have actually read it. This is unfortunate because the text is marvelous, strange and surprising. Turing introduces his test as a variation on a popular parlor game in which two hidden contestants, a woman (player A) and a man (player B) try to convince a third that he or she is a woman by their written responses to leading questions. To win, one of the players must convincingly be who they really are, whereas the other must try to pass as another gender. Turing describes his own variation as one where “a computer takes the place of player A,” and so a literal reading would suggest that in his version the computer is not just pretending to be a human, but pretending to be a woman. It must pass as a she.Passing as a person comes down to what others see and interpret. Because everyone else is already willing to read others according to conventional cues (of race, sex, gender, species, etc.) the complicity between whoever (or whatever) is passing and those among which he or she or it performs is what allows passing to succeed. Whether or not an A.I. is trying to pass as a human or is merely in drag as a human is another matter. Is the ruse all just a game or, as for some people who are compelled to pass in their daily lives, an essential camouflage? Either way, “passing” may say more about the audience than about the performers.That we would wish to define the very existence of A.I. in relation to its ability to mimic how humans think that humans think will be looked back upon as a weird sort of speciesism. The legacy of that conceit helped to steer some older A.I. research down disappointingly fruitless paths, hoping to recreate human minds from available parts. It just doesn’t work that way. Contemporary A.I. research suggests instead that the threshold by which any particular arrangement of matter can be said to be “intelligent” doesn’t have much to do with how it reflects humanness back at us. As Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (now director of research at Google) suggest in their essential A.I. textbook, biomorphic imitation is not how we design complex technology. Airplanes don’t fly like birds fly, and we certainly don’t try to trick birds into thinking that airplanes are birds in order to test whether those planes “really” are flying machines. Why do it for A.I. then? Today’s serious A.I. research does not focus on the Turing Test as an objective criterion of success, and yet in our popular culture of A.I., the test’s anthropocentrism holds such durable conceptual importance. Like the animals who talk like teenagers in a Disney movie, other minds are conceivable mostly by way of puerile ventriloquism.Where is the real injury in this? If we want everyday A.I. to be congenial in a humane sort of way, so what? The answer is that we have much to gain from a more sincere and disenchanted relationship to synthetic intelligences, and much to lose by keeping illusions on life support. Some philosophers write about the possible ethical “rights” of A.I. as sentient entities, but that’s not my point here. Rather, the truer perspective is also the better one for us as thinking technical creatures.Musk, Gates and Hawking made headlines by speaking to the dangers that A.I. may pose. Their points are important, but I fear were largely misunderstood by many readers. Relying on efforts to program A.I. not to “harm humans” (inspired by Isaac Asimov’s “three laws” of robotics from 1942) makes sense only when an A.I. knows what humans are and what harming them might mean. There are many ways that an A.I. might harm us that have nothing to do with its malevolence toward us, and chief among these is exactly following our well-meaning instructions to an idiotic and catastrophic extreme. Instead of mechanical failure or a transgression of moral code, the A.I. maypose an existential risk because it is both powerfully intelligent and disinterested in humans. To the extent that we recognize A.I. by its anthropomorphic qualities, or presume its preoccupation with us, we are vulnerable to those eventualities.Whether or not “hard A.I.” ever appears, the harm is also in the loss of all that we prevent ourselves from discovering and understanding when we insist on protecting beliefs we know to be false. In the 1950 essay, Turing offers several rebuttals to his speculative A.I., including a striking comparison with earlier objections to Copernican astronomy. Copernican traumas that abolish the false centrality and absolute specialness of human thought and species-being are priceless accomplishments. They allow for human culture based on how the world actually is more than on how it appears to us from our limited vantage point. Turing referred to these as “theological objections,” but one could argue that the anthropomorphic precondition for A.I. is a “pre-Copernican” attitude as well, however secular it may appear. The advent of robust inhuman A.I. may let us achieve another disenchantment, one that should enable a more reality-based understanding of ourselves, our situation, and a fuller and more complex understanding of what “intelligence” is and is not. From there we can hopefully make our world with a greater confidence that our models are good approximations of what’s out there.人工智能:超越图灵实验以人工智能“冒充”人的能力的来衡量人工智能的这个概念---已经被数不清的科幻电影搬上了荧幕---实际上已经和现代人工智能研究一样久远了。

韩素音青年翻译奖赛16

第十六届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛英译汉原文Necessary FictionsThe most pathetic in Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s play The Visit is the Schoolmaster. The play tells the story of a town bribed by an enormously wealthy lady (the “visitor” of the title) to murder her former lover. That, at least, is the surface plot. The real plot is the reenactment by the townspeople of the archetypal ritual sacrifice that is the subject of Sir James Frazer’s study of primitive religion, The Golden Bough, and that classical scholars such as Gilbert Murray and F. M. Cornford have found at the root of Greek tragedy. The play thus moves on two levels. On one, it is the story of a judicial murder for money, an indictment of materialism. On the other, it has nothing to do with motives in the conventional sense. It is a play about religious impulses that are independent of the ways people explain them.Dürrenmatt’s Schoolmaster is a key figure because he represents the liberal and rational heritage of Western culture. He is “Headmaster of Guellen College, and lover of the noblest Muse.” He sponsors the town’s Youth Club and describes himself as “a humanist, a lover of the ancient Greeks, an admirer of Plato.” He is a true believer in all those liberal and rational values that Western culture has inherited from antiquity.In keeping with these values, Dürrenmatt’s schoolmaster is horrified by the plans of his fellow townspeople, whom he has tried to inspire with visions of nobility, to commit murder. As the climax approaches, however, he crumbles. Not only does he know of the murder plan, he knows he will become a part of it:I know something else. I shall take part in it. I can feel myself slowly becoming a murderer. My faith in humanity is powerless to stop it.The Schoolmaster has discovered that the apparently absolute values of “the ancient Greeks…and Plato” have limits. Other values, hidden and irrational, are at least as powerful. Are the latter true and the formernothing more than lovely and venerable fictions?The Visit brilliantly explores one of the most ancient paradoxes in Western experience, a paradox that appears in the Old Testament in the contrast between the Gentiles who worship graven idols and the Hebrews who worship invisible truth: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth underneath, or that is in the waters under the earth.” The same paradox recurs in the conflict between pagan learning and Christian revelation in the early centuries of the Christian era, and again, in the high Middle Ages, in the debate between Thomistic rationalism, which sees the world as an intelligible and orderly expression of divine reason, and the mysticism of St. Bonaventure’s The Mind’s Road to God, which sees the world as a delusion and turns from it to suprarational experience. In the seventeenth century the paradox is embodied in the conflict between science and revelation, a conflict that was renewed in the nineteenth century by the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species.It is still with us. No one could be more devoted to humane values – or more knowledgeable in the field of biology – than Jacques Monod, co-recipient of the 1965 Nobel Prize for medicine and physiology. In a much-admired essay,“On Values in the Age of Science” (1969), Monod proclaimed the end of the Age of Faith:Modern nations…still teach and preach some more or less modernized versions of traditional systems of values, blatantly incompatible with what scientific culture they have. The western, liberal-capitalist countries still pay lip service to a nauseating mixture of Judeo-Christian religiosity, “Natural”Human rights, pedestrian utilitarianism and XIX Century progressivism…They all lie and they know it. No intelligent and cultivated person, in any of these societies can really believe in the validity of these dogma…While a great many “intelligent and cultivated persons” undoubtedly agree with Monod, many others do not. Dürrenmatt is a case in point. What he shows through his Schoolmaster is that a rational and secular value system of the kind proposed by Monod is delusion that may crumble as soon as it issubjected to stress. Dürrenmatt had good reason to believe his message. The Visit was written in 1956 when memories of the Holocaust were still vivid. Since then, confidence in rational and secular values has continued to decline. In 1979, in what was almost a national paroxism of disgust, the people of Iran rejected Western rationalism and opted for a form of government that looks very much like theocracy. The diatribes of Iran’s Mullahs are hardly less passionate than tirades of America’s Moral Majority and the sermons of its radio and television evangelists. It is interesting and significant that the American Mullahs consistently identify “secular humanism” as the chief corruption of modern society. In fact, in 1979 the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, a normally moderate body, felt the pressure sufficiently to include a denunciation of “humanistic secularization” in its proceedings.While the Schoolmasters of Western society dream of nobility, the Faithful quote the Sermon on the Mount:No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and Mammon.And:Take therefore no thought of the morrow, for the morrow shall take no thought for the things of itself.And:Everyone that heareth these things, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon sand.The conflict between the graven idols of secular humanism and the invisible realities known only to the saving remnant of the devout is very much alive today. If Dürrenmatt is correct, there is little to be said for humanism. It is an illusion, a fiction, a thin coating of rationalizations covering something awesome and terrifying. The Mullahs have won.Before abandoning humanism and all its works, however, let us consider it from another angle. For the sake of speculation, let us imagine a humanism that is a way of seeing. The things it sees are human creations or things that have special human significance. This sort of humanism will be interested in the values these things express but not in any particular set of those values.A humanism that is a way of seeing will be committed describing what it sees. It will seek to fix the condition of the human spirit at a particular place in a particular moment of time in relation to a particular experience, and it will choose its places and times and experiences because they express the condition of the human spirit with particular clarity. They are the evidence concerning the nature of the human spirit that has accumulated throughout history. In other words, they are to humanism what the raw materials of physics, biology, and chemistry are to science.。

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (3)Beauty (excerpt) (3)美(节选) (3)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (8)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (8)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (11)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (11)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (14)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (14)On Going Home by Joan Didion (18)回家琼.狄迪恩 (18)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (22)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (22)Beyond Life (28)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (28)Envy by Samuel Johnson (33)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (33)中译英部分 (37)在义与利之外 (37)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (37)读书苦乐杨绛 (40)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (40)想起清华种种王佐良 (43)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (43)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (45)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (45)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (48)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (48)可爱的南京 (51)Nanjing the Beloved City (51)霞冰心 (53)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (53)黎明前的北平 (54)Predawn Peiping (54)老来乐金克木 (55)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (55)可贵的“他人意识” (58)Calling for an Awareness of Others (58)教孩子相信 (61)To Implant In Our Children’s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (61)英译汉部分Beauty (excerpt)美(节选)Judging from the scientists I know, including Eva and Ruth, and those whom I've read about, you can't pursue the laws of nature very long without bumping撞倒; 冲撞into beauty. “I don't know if it's the same beauty you see in the sunset,”a friend tells me, “but it feels the same.”This friend is a physicist, who has spent a long career deciphering破译(密码), 辨认(潦草字迹) what must be happening in the interior of stars. He recalls for me this thrill on grasping for the first time Dirac's⑴equations describing quantum mechanics, or those of Einstein describing relativity. “They're so beautiful,” he says, “you can see immediately they have to be true. Or at least on the way toward truth.” I ask him what makes a theory beautiful, and he replies, “Si mplicity, symmetry .对称(性); 匀称, 整齐, elegance, and power.”我结识一些科学家(包括伊娃和露丝),也拜读过不少科学家的著作,从中我作出推断:人们在探求自然规律的旅途中,须臾便会与美不期而遇。

英汉翻译

第二十一届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛英译汉Beyond LifeI want my life, the only life of which I am assured, to have symmetry or, in default of that, at least to acquire some clarity. Surely it is not asking very much to wish that my personal conduct be intelligible to me! Yet it is forbidden to know for what purpose this universe was intended, to what end it was set a-going, or why I am here, or even what I had preferably do while here. It vaguely seems to me that I am expected to perform an allotted task, but as to what it is I have no notion. And indeed, what have I done hitherto, in the years behind me? There are some books to show as increment, as something which was not anywhere before I made it, and which even in bulk will replace my buried body, so that my life will be to mankind no loss materially. But the course of my life, when I look back, is as orderless as a trickle of water that is diverted and guided by every pebble and crevice and grass-root it encounters. I seem to have done nothing with pre-meditation, but rather, to have had things done to me. And for all the rest of my life, as I know now, I shall have to shave every morning in order to be ready for no more than this!I have attempted to make the best of my material circumstances always; nor do I see to-day how any widely varying course could have been wiser or even feasible: but material things have nothing to do with that life which moves in me. Why, then, should they direct and heighten and provoke and curb every action of life? It is against the tyranny of matter I would rebel—against life’s absolute need of food, and books, and fire, and clothing, and flesh, to touch and to inhabit, lest life perish. No, all that which I do here or refrain from doing lacks clarity, nor can I detect any symmetry anywhere, such as living would assuredly display, I think, if my progress were directed by any particular motive. It is all a muddling through, somehow, without any recognizable goal in view, and there is no explanation of the scuffle tendered or anywhere procurable. It merely seems that to go on living has become with me a habit.And I want beauty in my life. I have seen beauty in a sunset and in the spring woods and in the eyes of divers women, but now these happy accidents of light and color no longer thrill me. And I want beauty in my life itself, rather than in such chances as befall it. It seems to me that many actions of my life were beautiful, very long ago, when I was young in an evanished world of friendly girls, who were all more lovely than any girl is nowadays. For women now are merely more or lessgood-looking, and as I know, their looks when at their best have been painstakingly enhanced and edited. But I would like this life which moves and yearns in me, to be able itself to attain to comeliness, though but in transitory performance. The life of a butterfly, for example, is just a graceful gesture: and yet, in that its loveliness is complete andperfectly rounded in itself, I envy this bright flicker through existence. And the nearest I can come to my ideal is punctiliously to pay my bills, be polite to my wife, and contribute to deserving charities: and the program does not seem, somehow, quite adequate. There are my books, I know; and there is beauty “embalmed and treasured up” in many pages of my books, and in the books of other persons, too, which I may read at will: but this desire inborn in me is not to be satiated by making marks upon paper, nor by deciphering them. In short, I am enamored of that flawless beauty of which all poets have perturbedly divined the existence somewhere, and which life as men know it simply does not afford nor anywhere foresee.And tenderness, too—but does that appear a mawkish thing to desiderate in life? Well, to my finding human beings do not like one another. Indeed, why should they, being rational creatures? All babies have a temporary lien on tenderness, of course: and therefrom children too receive a dwindling income, although on looking back, you will recollect that your childhood was upon the whole a lonesome and much put-upon period. But all grown persons ineffably distrust one another. In courtship, I grant you, there is a passing aberration which often mimics tenderness, sometimes as the result of honest delusion, but more frequently as an ambuscade in the endless struggle between man and woman. Married people are not ever tender with each other, you will notice: if they are mutually civil it is much: and physical contacts apart, their relation is that of a very moderate intimacy. My own wife, at all events, I find an unfailing mystery, a Sphinx whose secrets I assume to be not worth knowing: and, as I am mildly thankful to narrate, she knows very little about me, and evinces as to my affairs no morbid interest. That is not to assert that if I were ill she would not nurse me through any imaginable contagion, nor that if she were drowning I would not plunge in after her, whatever my delinquencies at swimming: what I mean is that, pending such high crises, we tolerate each other amicably, and never think of doing more. And from our blood-kin we grow apart inevitably. Their lives and their interests are no longer the same as ours, and when we meet it is with conscious reservations and much manufactured talk. Besides, they know things about us which we resent. And with the rest of my fellows, I find that convention orders all our dealings, even with children, and we do and say what seems more or less expected. And I know that we distrust one another all the while, and instinctively conceal or misrepresent our actual thoughts and emotions when there is no very apparent need. Personally, I do not like human beings because I am not aware, upon the whole, of any generally distributed qualities which entitle them as a race to admiration and affection. But toward people in books—such as Mrs. Millamant, and Helen of Troy, and Bella Wilfer, and Mélusine, and Beatrix Esmond—I may intelligently overflow with tenderness and caressing words,in part because they deserve it, and in part because I know they will not suspect me of being “queer” or of having ulterior motives.And I very often wish that I could know the truth about just any one circumstance connected with my life. Is the phantasmagoria of sound and noise and color really passing or is it all an illusion here in my brain? How do you know that you are not dreaming me, for instance? In your conceded dreams, I am sure, you must invent and see and listen to persons who for the while seem quite as real to you as I do now. As I do, you observe, I say! and what thing is it to which I so glibly refer as I? If you will try to form a notion of yourself, of the sort of a something that you suspect to inhabit and partially to control your flesh and blood body, you will encounter a walking bundle of superfluities: and when you mentally have put aside the extraneous things—your garments and your members and your body, and your acquired habits and your appetites and your inherited traits and your prejudices, and all other appurtenances which considered separately you recognize to be no integral part of you,—there seems to remain in those pearl-colored brain-cells, wherein is your ultimate lair, very little save a faculty for receiving sensations, of which you know the larger portion to be illusory. And surely, to be just a very gullible consciousness provisionally existing among inexplicable mysteries, is not an enviable plight. And yet this life—to which I cling tenaciously—comes to no more. Meanwhile I hear men talk about “the truth”; and they even wager handsome sums upon their knowledge of it: but I align myself with “jesting Pilate,” and echo the forlorn query that recorded time has left unanswered.Then, last of all, I desiderate urbanity. I believe this is the rarest quality in the world. Indeed, it probably does not exist anywhere. A really urbane person—a mortal open-minded and affable to conviction of his own shortcomings and errors, and unguided in anything by irrational blind prejudices—could not but in a world of men and women be regarded as a monster. We are all of us, as if by instinct, intolerant of that which is unfamiliar: we resent its impudence: and very much the same principle which prompts small boys to jeer at a straw-hat out of season induces their elders to send missionaries to the heathen…汉译英可贵的“他人意识”上世纪中叶的中国式“集体主义”,自从在世纪末之前,逐渐分解以及还原为对个人和个体的尊重,初步建立起个人的权益保障系统之后,“我们”——这个在计划经济时代使用频率极高的词,已被更为普遍的"我"所代替。

韩素音 汉译英

汉译英竞赛原文:屠呦呦秉持的,不是好事者争论的随着诺贝尔奖颁奖典礼的临近,持续2个月的“屠呦呦热”正在渐入高潮。

当地时间7日下午,屠呦呦在瑞典卡罗林斯卡学院发表题为“青蒿素——中医药给世界的一份礼物”的演讲,详细回顾了青蒿素的发现过程,并援引毛泽东的话称,中医药学“是一个伟大的宝库”。

对中医药而言,无论是自然科学“圣殿”中的这次演讲,还是即将颁发到屠呦呦手中的诺奖,自然都提供了极好的“正名”。

置于世界科学前沿的平台上,中医药学不仅真正被世界“看见”,更能因这种“看见”获得同世界对话的机会。

拨开层层迷雾之后,对话是促成发展的动力。

将迷雾拨开、使对话变成可能,是屠呦呦及其团队的莫大功劳。

但如果像部分舆论那样,将屠呦呦的告白简单视作其对中医的“背书”,乃至将其成就视作中医向西医下的“战书”,这样的心愿固然可嘉,却可能完全背离科学家的本意。

听过屠呦呦的报告,或是对其研究略作了解就知道,青蒿素的发现既来自于中医药“宝库”提供的积淀和灵感,也来自于西医严格的实验方法。

缺了其中任意一项,历史很可能转向截然不同的方向。

换言之,在“诺奖级”平台上促成中西医对话之前,屠呦呦及其团队的成果,正是长期“对话”的成果。

而此前绵延不绝的“中西医”之争,多多少少都游离了对话的本意,而陷于一种单向化的“争短长”。

持中医论者,不屑于西医的“按部就班”;持西医论者,不屑于中医的“随心所欲”。

双方都没有看到,“按部就班”背后本是实证依据,“随心所欲”背后则有文化内涵,两者完全可以兼容互补,何必非得二元对立?屠呦呦在演讲中坦言,“通过抗疟药青蒿素的研究历程,我深深地感到中西医药各有所长,两者有机结合,优势互补,当具有更大的开发潜力和良好的发展前景”。

这既是站在中医药立场上对西方科学界的一次告白,反过来也可理解为西医立场上对中医拥趸们的提醒。

毋宁说,这是一个科学家对科学研究实质的某种揭示。

科学研究之艰深莫测,科学家多有体认,作为旁观者的我们也屡屡耳闻。

第十二届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)

第十二届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)霞冰心四十年代初期,我在重庆郊外歌乐山闲居的时候,曾看到英文《读者文摘》上,有个很使我惊心的句子,是:May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.我在一篇短文里曾把它译成:“愿你的生命中有够多的云翳,来造成一个美丽的黄昏。

”其实,这个sunset 应当译成“落照”或“落霞”。

霞,是我的老朋友了!我童年在海边、在山上,她都是我的最熟悉最美丽的小伙伴。

她每早每晚都在光明中和我说“早上好”或“明天见”。

但我直到几十年以后,才体会到云彩更多,霞光才愈美丽。

从云翳中外露的霞光,才是璀璨多彩的。

生命中不是只有快乐,也不是只有痛苦,快乐和痛苦是相生相成,互相衬托的。

快乐是一抹微云,痛苦是压城的乌云,这不同的云彩,在你生命的天边重叠着,在“夕阳无限好”的时候,就给你造成一个美丽的黄昏。

一个生命会到了“只是近黄昏”的时节,落霞也许会使人留恋、惆怅。

但人类的生命是永不止息的。

地球不停地绕着太阳自转。

东方不亮西方亮,我床前的晚霞,正向美国东岸的慰冰湖上走去……The Rosy CloudBingxinDuring the early 1940s I was living a retired life in the Gele Mountains in the suburbs of Chongqing (Chungking). One day, while reading the English language magazine Reader's Digest I found a sentence that touched me greatly. It read: "May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset."In a short article of mine, I quoted this sentence and translated it as "Yuan ni de shengming zhong you guo duo de yunyi, lai zaocheng yige meili de huanghun. " (literally: May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.) *As I see it now, the word "sunset" in the English sentence should have been translated as luozhao (the glow at sunset) or luoxia (the rosy cloud at sunset), instead of dusk.She has been my dear old friend, the Rosy Cloud! She was my closest and most beautiful little companion when, in my childhood, I played on the beach or in the hills. Bathed in the brilliant sunshine, she would say to me "Good morning!" at dawn and "See you tomorrow!" at dusk. But not until several decades later did I come to realize that the more clouds there are the more beautiful the rays of sunlight will be, and the glow of the sun breaking through the clouds becomes most resplendent and colorful.Life contains neither unalloyed happiness nor mere misery. Happiness and misery beget, complement and set off each other.Happiness is a wisp of fleecy cloud; misery a mass of threatening dark cloud. These different clouds overlap on the horizon of your life to create a beautiful dusk for you when "the setting sun is most lovely indeed."**An individual's life must inevitably reach the point when "dusk is so near,"*** and the rosy sunset cloud may make one nostalgic and melancholy. But human life goes on and on. The Earth ceaselessly rotates on its axis around the sun. When it is dark in the east, it is light in the west. The rosy sunset cloud is now sailing past my window towards Lake Waban on the east coast of America ...*This sentence appears in Chinese and English in the article "For Young Readers Again, Newsletter No.4", written by Bing Xin in the Gele Mountains, on December 1, 1944.** and *** These two poetic lines are taken from a poem "On the Plain of Tombs" by Li Shangyin (813-858), a well-known poet of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The two lines read like this: "The setting sun appears sublime, / But O! 'Tis near its dying time." (Tr. Xu Yuanchong) They imply that the setting sun has infinite beauty, but it is a pity that it is near the dusk, and the beautiful scene cannot last long. The two lines are often used to deplore the ephemeral nature of things, and to express the feelings at the loss of past glory and at the advent of old age.。

第23届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛英译汉原文

英译汉竞赛原文:Are We There Yet?America’s recovery will be much slower than that from most recessions; but the government can help a bit.美国的经济复苏将会比经历衰退后更加缓慢;但政府会有所帮助“WHITHER goest thou, America?” That question, posed by Jack Kerouac on behalf of the Beat generation half a century ago, is the biggest uncertainty hanging over the world economy. And it reflects the foremost worry for American voters, who go to the polls for the congressional mid-term elections国会中期选举投票on November 2nd with the country’s unempl oyment rate stubbornly stuck at nearly one in ten. They should prepare themselves for a long, hard ride.“美国今后的去向如何?”这是半个世纪前由杰克·凯鲁亚克代表“美国垮了的一代”提出的问题,它是笼罩着世界经济的最大的不确定因素。