评第十三届韩素音翻译奖英译汉参考译文

韩素音青翻译奖赛中文原文及参考译文和解析

老来乐Delights in Growing Old六十整岁望七十岁如攀高山。

不料七十岁居然过了。

又想八十岁是难于上青天,可望不可即了。

岂知八十岁又过了。

老汉今年八十二矣。

这是照传统算法,务虚不务实。

现在不是提倡尊重传统吗?At the age of sixty I longed for a life span of seventy, a goal as difficult as a summit to be reached. Who would expect that I had reached it? Then I dreamed of living to be eighty, a target in sight but as inaccessible as Heaven. Out of my anticipation, I had hit it. As a matter of fact, I am now an old man of eighty-two. Such longevity is a grant bestowed by Nature; though nominal and not real, yet it conforms to our tradition. Is it not advocated to pay respect to nowadays?老年多半能悟道。

孔子说“天下有道”。

老子说“道可道”。

《圣经》说“太初有道”。

佛教说“邪魔外道”。

我老了,不免胡思乱想,胡说八道,自觉悟出一条真理: 老年是广阔天地,是可以大有作为的。

An old man is said to understand the Way most probably: the Way of good administration as put forth by Confucius, the Way that can be explained as suggested by Laotzu, the Word (Way) in the very beginning as written in the Bible and the Way of pagans as denounced by theBuddhists. As I am growing old, I can't help being given to flights of fancy and having my own Way of creating stories. However I have come to realize the truth: my old age serves as a vast world in which I can still have my talents employed fully and developed completely.七十岁开始可以诸事不做而拿退休金,不愁没有一碗饭吃,自由自在,自得其乐。

韩素音青年翻译奖

On IrritabilityIrritability is the tendency to get upset for reasons that seem – to other people – to be pretty minor. Your partner asks you how work went and the way they ask makes you feel intensely agitated. Your partner is putting knives and forks on the table before dinner and you mention (not for the first time) that the fork should go on the left hand side, not the right. They then immediately let out a huge sigh and sweep the cutlery onto the floor and tell you that you can xxxx-ing do it yourself if you know better. It was the most minor of criticisms and technically quite correct. And now they’ve exploded.There is so much irritability around and it exacts a huge daily cost on our collective lives, so we deserve to get a lot more curious about it: what is really going on for the irritable person? Why, really, are they getting so agitated? And instead of blaming them for getting het up about “little things”, we should do them the honour of working out why, in fact, these things may not be so minor after all.The journey begins by recognising the role of fear in irritability in couples. Behind most outbursts are cack-handed attempts to teach the other person something. There are things we’d like to point out, flaws that we can discern, remarks w e feel we really must make, but our awareness of how to proceed is panicked and hasty. We give cack-handed, mean speeches, which bear no faith in the legitimacy (even the nobility) of the act of imparting advice. And when our partners are on the receiving end of these irritable “lessons”, they of course swiftly grow defensive and brittle in the face of suggestions which seem more like mean-minded and senseless assaults on their very natures rather than caring, gentle attempts to address troublesome aspects of joint life.The prerequisite of calm in a teacher is a degree of indifference as to the success or failure of the lesson. One naturally wants for things to go well, but if an obdurate pupil flunks trigonometry, it is – at base – their problem. Tempers can stay even because individual students do not have very much power over teachers’ lives. Fortunately, as not caring too much turns out to be a critical aspect of successful pedagogy.Yet this isn’t an option open to the fearful, irritable lover. They feel ineluctably led to deliver their “lessons” in a cataclysmic, frenzied manner (the door slams very loudly indeed) not because they are insane or vile (though one could easily draw theseconclusions) so much as because they are terrified; terrified of spoiling what remains of their years on the planet in the company of someone who it appears cannot in any way understand a pivotal point about conversation, or cutlery, or the right time to order a taxi.One knows intuitively, when teaching a child, that only the utmost care and patience will ever work: one must never shout, one has to use extraordinary tact, one has to make ten compliments for every one negative remark and one must leave oneself plenty of time…All this wisdom we reliably forget in lov e’s classroom, sadly because increasing the level of threat seldom hastens development. We do not grow more reasonable, more accepting of responsibility and more accurate about our weaknesses when our pride has been wounded, our integrity is threatened and our self-esteem has been violated.The complaint against the irritable person is that they are getting worked up over “nothing”. But symbols offer a way of seeing how a detail can stand for something much bigger and more serious. The groceries placed on the wrong table are not upsetting at all in themselves. But symbolically they mean your partner doesn’t care about domestic order; they muddle things up; they are messy. Or the question about one’s day is experienced as a symbol of interrogation, a lack o f privacy and a humiliation (because one’s days rarely go well enough).The solution is, ideally, to concentrate on what the bigger issue is. Entire philosophies of life stir and collide beneath the surface of apparently petty squabbles. Irritations are the outward indications of stifled debates between competing conceptions of existence. It’s to the bigger themes we need to try to get.In the course of discussions, one might even come face-to-face with that perennially surprising truth about relationships: that the other person is not an extension of oneself that has, mysteriously, gone off message. They are that most surprising of things, a different person, with a psyche all of their own, filled with a perplexing number of subtle, eccentric and unforeseen reasons for thinking as they do.The decoding may take time, perhaps half an hour or more of concentrated exploration for something that had until then seemed as if it would more rightfully deserve an instant.We pay a heavy price for this neglect; every conflict that ends in sour stalemate is a blocked capillary within the heart of love. Emotions will find other ways to flow for now, but with the accumulation of unresolved disputes, pathways will fur and possibilities for trust and generosity narrow.A last point. It may just be sleep or food: when a baby is irritable, we rarely feel the need to preach about self-control and a proper sense of proportion. It’s not simply that we fear the infant’s intellect might not quite be up to it, but because we have a much better explanation of what is going on. We know that they’re acting this way –and getting bothered by any little thing – because they are tired, hungry, too hot or having some challenging digestive episode.The fact is, though, that the same physiological causes get to us all our lives. When we are tired, we get upset more easily; when we feel very hungry, it takes less to bother us. But it is immensely difficult to transfer the lesson in generosity (and accuracy) that we gain around to children and apply it to someone with a degree in business administration or a pilot’s license, or to whom we have been married for three-and-a-half years.We should try to see irritability for what it actually is: a confused, inarticulate, often shameful attempt to get us to understand how much someone is suffering and how urgently they need our help. We should – when we can manage it – attempt to help them out.。

韩素音英译汉原文

Outing A.I.: Beyond the Turing TestThe idea of measuring A.I. by its ability to “pass” as a human – dramatized in countless scifi films – is actually as old as modern A.I. research itself. It is traceable at least to 1950 when the British mathematician Alan Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a paper in which he described what we now call the “Turing Test,” and which he referred to as the “imitation game.” There are different versions of the test, all of which are revealing as to why our approach to the culture and ethics of A.I. is what it is, for good and bad. For the most familiar version, a human interrogator asks questions of two hidden contestants, one a human and the other a computer. Turing suggests that if the interrogator usually cannot tell which is which, and if the computer can successfully pass as human, then can we not conclude, for practical purposes, that the computer is “intelligent”?More people “know” Turing’s foundational text than have actually read it. This is unfortunate because the text is marvelous, strange and surprising. Turing introduces his test as a variation on a popular parlor game in which two hidden contestants, a woman (player A) and a man (player B) try to convince a third that he or she is a woman by their written responses to leading questions. To win, one of the players must convincingly be who they really are, whereas the other must try to pass as another gender. Turing describes his own variation as one where “a computer takes the place of player A,” and so a literal reading would suggest that in his version the computer is not just pretending to be a human, but pretending to be a woman. It must pass as a she.Passing as a person comes down to what others see and interpret. Because everyone else is already willing to read others according to conventional cues (of race, sex, gender, species, etc.) the complicity between whoever (or whatever) is passing and those among which he or she or it performs is what allows passing to succeed. Whether or not an A.I. is trying to pass as a human or is merely in drag as a human is another matter. Is the ruse all just a game or, as for some people who are compelled to pass in their daily lives, an essential camouflage? Either way, “passing” may say more about the audience than about the performers.That we would wish to define the very existence of A.I. in relation to its ability to mimic how humans think that humans think will be looked back upon as a weird sort of speciesism. The legacy of that conceit helped to steer some older A.I. research down disappointingly fruitless paths, hoping to recreate human minds from available parts. It just doesn’t work that way. ContemporaryA.I. research suggests instead that the threshold by which any particular arrangement of matter can be said to be “intelligent” doesn’t have much to do with how it reflects humanness back at us. As Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (now director of research at Google) suggest in their essential A.I. textbook, biomorphic imitation is not how we design complex technology. Airplanes don’t fly like birds fly, and we certainly don’t try to trick birds into thinking that airplanes are birds in order to test whether those planes “really” are flying machines. Why do it for A.I. then? Today’s serious A.I. research does not focus on the Turing Test as an objective criterion of success, and yet in our popular culture of A.I., the test’s anthropocentrism holds such durable conceptual importance. Like the animals who talk like teenagers in a Disney movie, other minds are conceivable mostly by way of puerile ventriloquism.Where is the real injury in this? If we want everyday A.I. to be congenial in a humane sort of way, so what? The answer is that we have much to gain from a more sincere and disenchanted relationship to synthetic intelligences, and much to lose by keeping illusions on life support. Some philosophers write about the possible ethical “rights” of A.I. as sentient entities, but that’s not my point here. Rather, the truer perspective is also the better one for us as thinking technical creatures.Musk, Gates and Hawking made headlines by speaking to the dangers that A.I. may pose. Their points are important, but I fear were largely misunderstood by many readers. Relying on efforts to program A.I. not to “harm humans” (inspired by Isaac Asimov’s “three laws” of robotics from 1942) makes sense only when an A.I. knows what humans are and what harming them might mean. There are many ways that an A.I. might harm us that have nothing to do with its malevolence toward us, and chief among these is exactly following our well-meaning instructions to an idiotic and catastrophic extreme. Instead of mechanical failure or a transgression of moral code, the A.I. may pose an existential risk because it is both powerfully intelligent and disinterested in humans. To the extent that we recognize A.I. by its anthropomorphic qualities, or presume its preoccupation with us, we are vulnerable to those eventualities.Whether or not “hard A.I.” ever appears, the harm is also in the loss of all that we prevent ourselves from discovering and understanding when we insist on protecting beliefs we know to be false. In the 1950 essay, Turing offers several rebuttals to his speculative A.I., including a striking comparison with earlier objections to Copernican astronomy. Copernican traumas that abolish the false centrality and absolute specialness of human thought and species-being are pricelessaccomplishments. They allow for human culture based on how the world actually is more than on how it appears to us from our limited vantage point. Turing referred to these as “theological objections,” but one could argue that the anthropomorphic precondition for A.I. is a“pre-Copernican” attitude as well, however secular it may appear. The advent of robust inhuman A.I. may let us achieve another disenchantment, one that should enable a more reality-based understanding of ourselves, our situation, and a fuller and more complex understanding of what “intelligence” is and is not. From there we can hopefully make our world with a greater confidence that our models are good approximations of what’s out there.。

“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛汉译英之体感

【 关键 词 】 “ 韩素音青年翻译 奖”竞赛 ;汉译英

自改革 开放以来 , 我 国和世界其他地 区间接触 日益频繁 , 作为沟通 、交 流桥梁的翻译工作者在其 中扮演 的角色越来越 重要 。为培养更 多 “ 高层次 、应用型 、专业性 口笔译 人才” 。 我 国也定期举办 各类 型的翻译大赛 ,鼓励更 多优 秀的人才投 身到翻译领域 中来 ,为社会主义现代化建设 服务 。“ 韩素音 ” 青年翻译奖竞赛 即为其 中的焦点赛 事之 一。笔者作为 M T I 专 业 的一名研究 生 ,参加了今年第二十五届 “ 韩 素音”翻译大 赛 。本文 回忆 了笔者 在参 加该项赛事 中 ,翻译 的全过程 ,并 由此得 出的一些 体会 ,旨在能够加深 自己对 翻译 的理解 ,升 华 、提高 自身 的翻泽能力 。 “ 韩素 音青年翻译奖”竞赛 由来 “ 韩 素音青年 翻译奖 ”竞赛前 身为 《 中国翻译 》编辑 部 1 9 8 6年 开始每年定期举办 的 “ 青 年有奖翻译 比赛 ” 。1 9 8 9年 3月 , 英籍华裔 , 韩 素音 女士前来 我国访 问期间 , 与 当时 《 中 国翻译 》杂 志主编叶君健会面 时 ,得 知了国 内正在举办这一 青年翻译赛事 。 作为一名非常支持 中国翻译事业 的爱 国人士 , 韩素影女 士当即表示 愿意 出资一笔赞助 基金来 使这项充满意 义 的活动更好 的开展 下去 。后 经商议 , 《中国翻译 》杂 志决 定用这笔基金设立 “ 韩素音青年翻译奖” , 此后每年举办的 “ 韩 素音青年翻译奖 ”竞赛 ,由此诞生 。

一

、

二 、 翻 译 过 程 回 顾

第二十五届 “ 韩素音青年 翻译 奖”竞赛 的汉译英原文名 为《 传 统百货 会否成 为 “ 消 失的行业 ” 》 ,全 文字数 9 1 9 字, 文章讲述 了传统 百货面临 的挑 战及未来 发展 的对策 ,是一个 典型 的应用 型文本。笔者在翻译过程 中 ,依 次经过了译前准 备一翻译—译 后检查 ,三个 阶段 。译前 准备 阶段 ,笔者在通 读全文 的基础上 , 首先找 出文 中专业词汇 , 如“ 传统百货 ” 、 “ 电 商营销 ” 、 “ 同业竞争 ” 、 “ 线上线下一体化 ” 、 “ 差异化竞争 ” 、 “ 商 业模式 ” 、“ 实体 店”等 ; 其次 ,把握整篇 文章的脉络 ,理清 句与句之 间 ,段 与段之间的 内在逻辑关 系 ; 再次 ,读完全文 后 ,通过 网络查 找相关的平行文本 ,熟悉其行 文 、用词等习 惯 ,参考相关 已有 的专业术语 翻译 ,并作好 记录。进 入到动 手翻译 阶段 , 有 了前 期的准备工作 , 为这一 阶段 的翻译做 了 很好的铺垫 。最后一个 阶段是译后检查 , 笔者在译完初稿后 , 首先抛开原 文 ,通读译文 ,修改不通顺 的地方 ,以求行文流 畅; 其次 ,对个人觉 得欠妥的用词 ,语句 ,与同学 、导师协 商之后进行 了修改 。 三、翻译体感 翻译— —仁者见仁 ,智者见智 。 笔 者最大的感触是对于翻译而言 , 仁者见仁 , 智者见智 。 译完文章后 ,笔者将译文发给湖南大学 、湖南师 范大学 、广 东外语外贸大学在读 翻译研究生批改 , 他们提 出的宝贵 意见 , 非常值得参考 。 但 同时也发现 了每个人 的修改 意见都不 一样 , 笔者试着将 每个 修改人的意见用不 同颜 色的笔标 出 ,惊奇 的 发现整片译 文接 近百分之六十左右都是修 改过的 ,其 中有着 短语搭配 的不 同意见 , 句子不 同次序 , 修饰性词语 , 如形容词 、 副词 的不 同用词 ,动名词 、过去分词 的用法 ,时态等 ,就连 同一处地方都 出现了好几种修改意见 。虽然 一篇 文章被修改

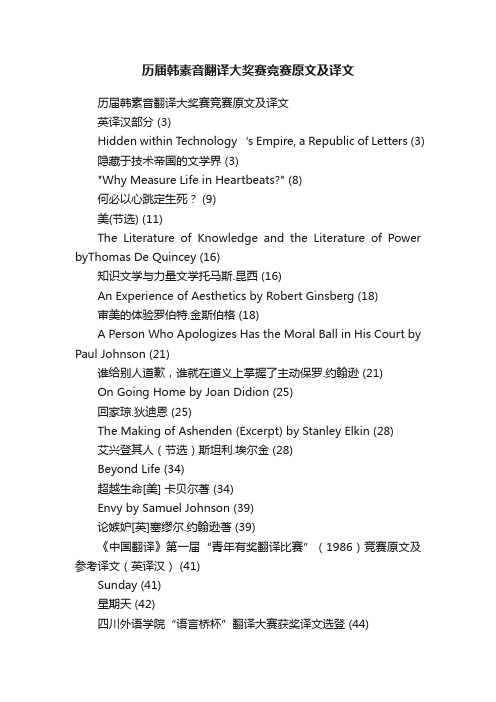

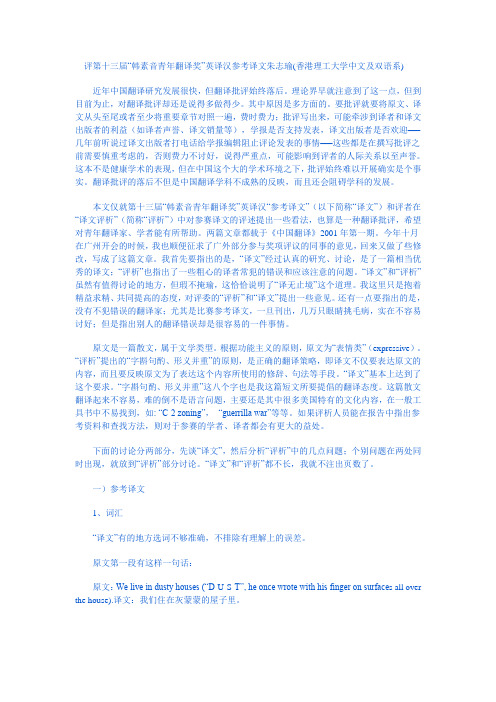

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (3)Hidden within Technology‘s Empire, a Republic of Letters (3)隐藏于技术帝国的文学界 (3)"Why Measure Life in Heartbeats?" (8)何必以心跳定生死? (9)美(节选) (11)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (16)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (16)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (18)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (18)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (21)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (21)On Going Home by Joan Didion (25)回家琼.狄迪恩 (25)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (28)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (28)Beyond Life (34)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (34)Envy by Samuel Johnson (39)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (39)《中国翻译》第一届“青年有奖翻译比赛”(1986)竞赛原文及参考译文(英译汉) (41)Sunday (41)星期天 (42)四川外语学院“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)第七届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (44)The Woods: A Meditation (Excerpt) (46)林间心语(节选) (47)第六届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛获奖译文选登 (50)第五届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文及获奖译文选登 (52)第四届“语言桥杯”翻译大赛原文、参考译文及获奖译文选登 (54) When the Sun Stood Still (54)永恒夏日 (55)CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)第三届竞赛原文及参考译文 (56)Here Is New York (excerpt) (56)这儿是纽约 (58)第四届翻译竞赛原文及参考译文 (61)Reservoir Frogs (Or Places Called Mama's) (61)水库青蛙(又题:妈妈餐馆) (62)中译英部分 (66)蜗居在巷陌的寻常幸福 (66)Simple Happiness of Dwelling in the Back Streets (66)在义与利之外 (69)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (69)读书苦乐杨绛 (72)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (72)想起清华种种王佐良 (74)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (74)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (76)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (76)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (79)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (79)可爱的南京 (82)Nanjing the Beloved City (82)霞冰心 (84)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (84)黎明前的北平 (85)Predawn Peiping (85)老来乐金克木 (86)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (86)可贵的“他人意识” (89)Calling for an Awareness of Others (89)教孩子相信 (92)To Implant In Our Children‘s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (92)心中有爱 (94)Love in Heart (94)英译汉部分Hidden within Technology’s Empire, a Republic of Le tters 隐藏于技术帝国的文学界索尔·贝娄(1)When I was a boy ―discovering literature‖, I used to think how wonderful it would be if every other person on the street were familiar with Proust and Joyce or T. E. Lawrence or Pasternak and Kafka. Later I learned how refractory to high culture the democratic masses were. Lincoln as a young frontiersman read Plutarch, Shakespeare and the Bible. But then he was Lincoln.我还是个“探索文学”的少年时,就经常在想:要是大街上人人都熟悉普鲁斯特和乔伊斯,熟悉T.E.劳伦斯,熟悉帕斯捷尔纳克和卡夫卡,该有多好啊!后来才知道,平民百姓对高雅文化有多排斥。

2022韩素音国际翻译大赛(英译汉)二等奖译文

行禅人生中的“疫”与益1965年,加里·斯奈德、艾伦·金斯伯格和菲利普·韦伦暂别凡尘杂念,行走在塔玛佩斯山上,冥思苦想。

在此番或曰作环山行禅的旅途中,他们既是诗人,又是佛学生。

他们依循佛教传统以顺时针方向经行,哪儿的自然风光让他们眼前一亮,他们就在哪儿择定仪式并逐一施行:以佛教、印度教的咏唱、诵咒、念经、祈愿等形式。

在1992年的一次采访中,斯奈德鼓励后来的经行者们能像他们表现出来的那样富有创新力。

采访最后他还想说点什么,但欲言又止,或许他原本还想说道说道他们仨选停的地点吧。

经行,是指出于特定目的,围绕神物进行庄严的旋回往返的活动。

这一古老的仪式植根于世界上诸多文化。

那么在现代的语境下,它的意思是什么呢?斯奈德解释道:“要诀是你得用心,得行动,一边走、一边停,一心一意。

它不过是人类驻足欣赏风光——同时也是审视自身——的一种方式。

”二十世纪九十年代末,我在加利福尼亚大学戴维斯分校研究生院师从斯奈德学习诗歌。

他教会我,人类察觉并能阐明自己在哪、周围是什么,有多么的重要。

这也是生物地域主义所倡导的观点。

二十世纪九十年代,英文教授、摄影师大卫·罗伯特森效仿斯奈德,推行环山绕行。

他会带着学生前往塔山作短途旅行,以纪念斯奈德、金斯伯格与韦伦。

1998年3月里寒冷的一天,我彼时的男友、现时的丈夫和我一同参与他组织的长达14英里的上山、下山旋回往返徒步,途中我们会停下来诵念相同的佛教、印度教咒语、经文,在1965年三人朝圣的十个地点祈愿。

罗伯特森此举意在让戴维斯分校里学习荒野文学课程的学生离开教室而深入风土。

该门课程以斯奈德的诗歌为一大特色,因此让学生去一趟塔山看上去是一个不错的选择。

雾气里弥漫着加州湾月桂的浓烈气味。

整整一天的时间里,我们在雾气中翻越一座又一座青翠的山坡、穿越一片又一片的加州栎、花旗松、北美红杉。

终于,我随大部队穿过了最后一片丛林。

这也太难熬了,即便我身体强壮、酷爱徒步。

On Going Home

On Going Home【概述】本文是 2001年第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉部分的参赛原文。

原文作者Joan Didion 是位散文文体大家,她的文章极有文采和个性,要贴切地表达成汉语确实要下一番功夫。

而这篇文章艰深的背景知识更是给准确翻译设置了很大障碍。

不了解该文的作者及其生活道路、创作思想,不了解文章的写作背景及反映的时代特征,好些地方会觉得把握不准,甚至一筹莫展。

【翻译要点评析】1 . the Canton dessert plates: 查英文词典我们可能会取“ the former name of Guangzhou ”这一释义,然后把这一部分译成“产自广州的甜点盘子”。

但 The Dolphin Reader (Hunt, 1990) 收录的 On Going Home 中对“ canton ”的注释为“ Fine Chinese porcelain ”。

据此注释,“ canton ”在这里应是指这些盘子的质地,而不是产地。

另外,《英汉辞海》(王同亿, 1987)里有“ Canton china ”词条,译文第一条为“广东瓷;广东瓷器,尤指青花瓷”;韦伯斯特电子词典( 2000 Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Version 2.5. )有“ Canton ware ”词条,释义照录于下:“ ceramic ware exported from China especially during the 18 th and 19 th centuries by way of Canton and including blue-and-white and enameled porcelain and various ornamented stonewares ”(从中国出口的陶瓷器,特别是 18、19世纪期间经由广州出口的,包括青花上釉瓷器和各种有装饰的粗陶器)。

英汉翻译

第二十一届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛英译汉Beyond LifeI want my life, the only life of which I am assured, to have symmetry or, in default of that, at least to acquire some clarity. Surely it is not asking very much to wish that my personal conduct be intelligible to me! Yet it is forbidden to know for what purpose this universe was intended, to what end it was set a-going, or why I am here, or even what I had preferably do while here. It vaguely seems to me that I am expected to perform an allotted task, but as to what it is I have no notion. And indeed, what have I done hitherto, in the years behind me? There are some books to show as increment, as something which was not anywhere before I made it, and which even in bulk will replace my buried body, so that my life will be to mankind no loss materially. But the course of my life, when I look back, is as orderless as a trickle of water that is diverted and guided by every pebble and crevice and grass-root it encounters. I seem to have done nothing with pre-meditation, but rather, to have had things done to me. And for all the rest of my life, as I know now, I shall have to shave every morning in order to be ready for no more than this!I have attempted to make the best of my material circumstances always; nor do I see to-day how any widely varying course could have been wiser or even feasible: but material things have nothing to do with that life which moves in me. Why, then, should they direct and heighten and provoke and curb every action of life? It is against the tyranny of matter I would rebel—against life’s absolute need of food, and books, and fire, and clothing, and flesh, to touch and to inhabit, lest life perish. No, all that which I do here or refrain from doing lacks clarity, nor can I detect any symmetry anywhere, such as living would assuredly display, I think, if my progress were directed by any particular motive. It is all a muddling through, somehow, without any recognizable goal in view, and there is no explanation of the scuffle tendered or anywhere procurable. It merely seems that to go on living has become with me a habit.And I want beauty in my life. I have seen beauty in a sunset and in the spring woods and in the eyes of divers women, but now these happy accidents of light and color no longer thrill me. And I want beauty in my life itself, rather than in such chances as befall it. It seems to me that many actions of my life were beautiful, very long ago, when I was young in an evanished world of friendly girls, who were all more lovely than any girl is nowadays. For women now are merely more or lessgood-looking, and as I know, their looks when at their best have been painstakingly enhanced and edited. But I would like this life which moves and yearns in me, to be able itself to attain to comeliness, though but in transitory performance. The life of a butterfly, for example, is just a graceful gesture: and yet, in that its loveliness is complete andperfectly rounded in itself, I envy this bright flicker through existence. And the nearest I can come to my ideal is punctiliously to pay my bills, be polite to my wife, and contribute to deserving charities: and the program does not seem, somehow, quite adequate. There are my books, I know; and there is beauty “embalmed and treasured up” in many pages of my books, and in the books of other persons, too, which I may read at will: but this desire inborn in me is not to be satiated by making marks upon paper, nor by deciphering them. In short, I am enamored of that flawless beauty of which all poets have perturbedly divined the existence somewhere, and which life as men know it simply does not afford nor anywhere foresee.And tenderness, too—but does that appear a mawkish thing to desiderate in life? Well, to my finding human beings do not like one another. Indeed, why should they, being rational creatures? All babies have a temporary lien on tenderness, of course: and therefrom children too receive a dwindling income, although on looking back, you will recollect that your childhood was upon the whole a lonesome and much put-upon period. But all grown persons ineffably distrust one another. In courtship, I grant you, there is a passing aberration which often mimics tenderness, sometimes as the result of honest delusion, but more frequently as an ambuscade in the endless struggle between man and woman. Married people are not ever tender with each other, you will notice: if they are mutually civil it is much: and physical contacts apart, their relation is that of a very moderate intimacy. My own wife, at all events, I find an unfailing mystery, a Sphinx whose secrets I assume to be not worth knowing: and, as I am mildly thankful to narrate, she knows very little about me, and evinces as to my affairs no morbid interest. That is not to assert that if I were ill she would not nurse me through any imaginable contagion, nor that if she were drowning I would not plunge in after her, whatever my delinquencies at swimming: what I mean is that, pending such high crises, we tolerate each other amicably, and never think of doing more. And from our blood-kin we grow apart inevitably. Their lives and their interests are no longer the same as ours, and when we meet it is with conscious reservations and much manufactured talk. Besides, they know things about us which we resent. And with the rest of my fellows, I find that convention orders all our dealings, even with children, and we do and say what seems more or less expected. And I know that we distrust one another all the while, and instinctively conceal or misrepresent our actual thoughts and emotions when there is no very apparent need. Personally, I do not like human beings because I am not aware, upon the whole, of any generally distributed qualities which entitle them as a race to admiration and affection. But toward people in books—such as Mrs. Millamant, and Helen of Troy, and Bella Wilfer, and Mélusine, and Beatrix Esmond—I may intelligently overflow with tenderness and caressing words,in part because they deserve it, and in part because I know they will not suspect me of being “queer” or of having ulterior motives.And I very often wish that I could know the truth about just any one circumstance connected with my life. Is the phantasmagoria of sound and noise and color really passing or is it all an illusion here in my brain? How do you know that you are not dreaming me, for instance? In your conceded dreams, I am sure, you must invent and see and listen to persons who for the while seem quite as real to you as I do now. As I do, you observe, I say! and what thing is it to which I so glibly refer as I? If you will try to form a notion of yourself, of the sort of a something that you suspect to inhabit and partially to control your flesh and blood body, you will encounter a walking bundle of superfluities: and when you mentally have put aside the extraneous things—your garments and your members and your body, and your acquired habits and your appetites and your inherited traits and your prejudices, and all other appurtenances which considered separately you recognize to be no integral part of you,—there seems to remain in those pearl-colored brain-cells, wherein is your ultimate lair, very little save a faculty for receiving sensations, of which you know the larger portion to be illusory. And surely, to be just a very gullible consciousness provisionally existing among inexplicable mysteries, is not an enviable plight. And yet this life—to which I cling tenaciously—comes to no more. Meanwhile I hear men talk about “the truth”; and they even wager handsome sums upon their knowledge of it: but I align myself with “jesting Pilate,” and echo the forlorn query that recorded time has left unanswered.Then, last of all, I desiderate urbanity. I believe this is the rarest quality in the world. Indeed, it probably does not exist anywhere. A really urbane person—a mortal open-minded and affable to conviction of his own shortcomings and errors, and unguided in anything by irrational blind prejudices—could not but in a world of men and women be regarded as a monster. We are all of us, as if by instinct, intolerant of that which is unfamiliar: we resent its impudence: and very much the same principle which prompts small boys to jeer at a straw-hat out of season induces their elders to send missionaries to the heathen…汉译英可贵的“他人意识”上世纪中叶的中国式“集体主义”,自从在世纪末之前,逐渐分解以及还原为对个人和个体的尊重,初步建立起个人的权益保障系统之后,“我们”——这个在计划经济时代使用频率极高的词,已被更为普遍的"我"所代替。

韩素音英文翻译

It’s Time to Rethink ‘Temporary’We tend to view architecture as permanent, as aspiring to the sta tus of monuments. And that kind of architecture has its place. But so does architecture of a different sort. For most of the first decade of the 2000s, architecture was about the statement building. Whether it was a controversial memorial or an impossibly luxurious condo towe r, architecture’s raison d’être was to make a lasting impression. A rchitecture has always been synonymous with permanence, but should it be?In the last few years, the opposite may be true. Architectural bi llings are at an all-time low. Major commissions are few and far betw een. The architecture that’s been making news is fast and fleeting: pop-up shops, food carts, marketplaces, performance spaces. And while many manifestations of the genre have jumped the shark (i.e., a Toys R Us pop-up shop), there is undeniable opportunity in the temporary: it is an apt response to a civilization in flux. And l ike many prevailing trends — collaborat ive consumption (a.k.a., “sh aring”), community gardens, barter and trade —“temporary” is so retro that it’s become radical.In November, I had the pleasure of moderating Motopia, a panel at University of Southern California’s School of Architecture, with Ro bert Kronenburg, an architect, professor at University of Liverpool a nd portable/temporary/mobile guru. Author of a shelf full of books onthe topic, including “Flexible: Architecture that Responds to Chang e,” “Portable Architecture: Design and Technology” and “Houses in Motion: The Genesis,” Kronenburg is a man obsessed.Mobility has an innate potency, Kronenburg believes. Movable envi ronments are more dynamic than static ones, so why should architectur e be so static? The idea that perhaps all buildings shouldn’t aspire to permanence represents a huge shift for architecture. Without that burden, architects, designers, builders and developers can take advan tage of and implement current technologies faster. Architecture could be reusable, recyclable and sustainable. Recast in this way, it coul d better solve seemingly unsolvable problems. And still succeed in cr eating a sense of place.In his presentation, Kronenburg offered examples of how portable, temporary architecture has been used in every aspect of human activi ty, including health care (from Florence Nightingale’s redesigned ho spitals to the Airstream trailers used as mobile medical clinics duri ng the Kennedy Administration), housing (from yurts to tents to archi tect Shigeru Ban’s post-earthquake paper houses), culture and commer ce (stage sets and Great Exhibition buildings, centuries-old Bouqinis tes along the Seine, mobile food, art and music venues offering every thing from the recording of stories to tasty crème brulees.) Kronenburg made a compelling argument that the experimentation in herent in such structures challenges preconceived notions about whatbuildings can and should be. The strategy of temporality, he explaine d, “adapts to unpredictable demands, provides more for less, and enc ourages innovat ion.” And he stressed that it’s time for end-users, designers, architects, manufacturers and construction firms to rethin k their attitude toward temporary, portable and mobile architecture.This is as true for development and city planning as it is for ar chitecture.City-making may have happened all at once at the desks of master planners like Daniel Burnham or Robert Moses, but that’s really not the way things happen today. No single master plan can anticipate the evolving and varied needs of an increasinglydiverse population or achieve the resiliency, responsiveness and flexibility that shorter-term, experimental endeavors can. Which is n ot to say long-term planning doesn’t have its place. The two work we ll hand in hand. Mike Lydon, foundingprincipal of The Street Plans Collaborative, argues for injecting spontaneity into urban development, and sees these temporary interve ntions (what he calls “tactical urbanism”) as short-term actions to effect long-term change.Though there’s been tremendous media atten tion given to quick an d cheapprojects like San Francisco’s Pavement to Parks and New York’s “gutter cafes,” Lydon sees something bigger than fodder for the sty le section. “A lot of these things were not just fun and cool,” he says. “It was not just a bott om-up effort. It’s not D.I.Y. urbanism. It’s a continuum of ideas, techniques and tactics being employed at all different scales.”“We’re seeing a lot of these things emerge for three reasons,”Lydon continues. “One, the economy. People have to be more cre ative about getting things done. Two, the Internet. Even four or five years ago we couldn’t share tactics and techniques via YouTube or Faceboo k. Something can happen randomly in Dallas and now we can hear about it right away. This is feeding into this idea of growth, of bi-coasta lcompetition between New York and San Francisco, say, about who do es the cooler, better things. And three, demographic shifts. Urban ne ighborhoods are gentrifying, changing. They’re bringing in people lo oking to improve neighborhoods themselves. People are smart and engag ed and working a 40-hour week. But they have enough spare time to get involved and this seems like a natural step.”Lydon isn’t advocating an end to planning but encourages more sh ort-term doing, experimenting, testing (which can be a far more satis fying alternative to waiting for projects to pass). While this may no t directly change existing codes or zoningregulations, that’s O.K. because, as Lydon explains, the practic es employed “shine a direct light on old ways of thinking, old polic ies that are in place.”The Dallas group Build a Better Block — which quickly leapt from a tinygrass-roots collective to an active partner in city endeavors —has demonstrated that when you expose weaknesses, change happens. If their temporary interventionsviolate existing codes, Build a Better Block just paints a sign i nforming passers-by of that fact. They have altered regulations in th is fashion. Sometimes — not always — bureaucracy gets out of the wa y and allows for real change to happen.Testing things out can also help developers chart the right cours e for their projects. Says Lydon, “A developer can really learn what’s working in the neighborhood from a marketplace perspective — it co uld really inform or change their plans. Hopefully they can ingratiat e themselves with the neighborhood and build community. There is real potential if the developers are really looking to do that.”And they are. Brooklyn’s De Kalb Market, for example, was suppos ed to be in place for just three years, but became a neighborhood cen ter where there hadn’t been much of one before. “People gravitated towards it,” says Lydon. “People like going there. You run the riskof people lamenting the loss of that. The developer would be smart to integrate things like the community garden — [giving residents an] opportunity to keep growing food on the site. The radio station c ould get a permanent space. The beer garden could be kept.”San Francisco’s PROXY project is similar. Retail, restaurants an d cultural spaces housed within an artful configuration of shipping c ontainers, designed by Envelope Architecture and Design, were given a five-year temporary home ongovernment-owned vacant lots in the city’s Hayes Valley neighbor hood whiledevelopers opted to sit tight during the recession. Affordable ho using is promised forthe site; the developers will now be able to create it in a neigh borhood that has become increasingly vibrant and pedestrian-friendly.On an even larger scale, the major developer Forest City has been testing these ideas of trial and error in the 5M Project in downtown San Francisco. While waiting out the downturn, the folks behind 5M h ave been beta-testing tenants and uses at their 5th & Mission locatio n, which was (and still is) home to the San Francisco Chronicle and n ow also to organizations like TechShop, the co-working space HubSoma, the art gallery Intersection for the Arts, the tech company Square and a smattering of food carts to feed those hungry, hardworking tenan ts. A few years earlier, Forest Citywould have been more likely to throw up an office tower with some luxury condos on top and call it a day: according to a company vice president, Alexa Arena, therecession allowed Forest City to spend time “re-imagining places for our emerging economy and what kind of environment helps facilitate that.”In “The Interventionist’s Toolkit,” the critic Mimi Zeiger wrote that the real success for D.I.Y. urbanist interventions won’t be based on any one project but will “happen when w e can evaluate the m ovement based on outreach, economic impact, community empowerment, en trepreneurship, sustainability and design. We’re not quite there yet.”She’s right. And one doesn’t have to search for examples of tem porary projects that not only failed but did so catastrophically (see: Hurricane Katrina trailers, for example). A huge reason for tactical urbanism’s appeal relates to politics. As onepractitioner put it, “We’re doing these things to combat the sl owness of government.”But all of this is more than a response to bureaucracy; at its best it’s a boldexpression of unfettered thinking and creativity … and there’s certainly not enough of that going around these days. An embrace of t he temporary and tactical may not be perfect, but it could be one of the strongest tools in the arsenal of city-building we’ve got.汉译英:语言与社会身份一个人的语言与其在社会中的身份其实密不可分。

2021韩素音英译汉译文

最深刻的人生我们头顶就是天空,布满了亮晶晶的星星。

我们经常躺在木筏上,看着天上的星星,并且讨论它们是造出来的还是偶然冒出来的。

吉姆说星星是造出来的,但我认为星星是偶然冒出来的。

我想如果要造那么多的星星,得花费相当长的时间。

吉姆说月亮可以把它们生出来,而这个说法似乎很有道理,所以我就没有反驳他了,因为我曾见过青蛙一次下的籽儿,也差不多有那么多,所以月亮当然也能下出那么多的星星来。

我们还常常看那些掉下来的星星,看着它们划出一道亮光。

吉姆认为是因为它们变坏了,所以才被赶出了自己的窝。

越来越多的人注意到天空被来自城市的光污染遮蔽。

有些人很多年来一次也没有见过月亮和星星。

对于我们整个人类的现况而言,这是一个恰当的暗喻。

十五世纪印度一位神秘主义诗人,迦比尔,类似于神秘的鹅妈妈,他有句令人难忘的名言,他说:“他们把自己的生命浪费在了各种主义中。

”尽管他只考虑他那个时代的少数几个主要宗教传统,但这个观点更深刻地适用于我们了解的各种宗教、政治派别、精神信仰、商人虚构的身份,甚至是构建哲学的理论。

这些信念的光辉,在最积极的方面可以对我们的人生作出指导。

但它们通常相当于一种光污染。

拥有知识的感觉是真理最大的敌人。

信仰和理论,以及与之相关的身份认同,和政治一样不可缺少,也一样具有吸引力,但是,从真正的哲学的角度来看,最坏而言,它们是阻碍,最好而言,它们是一次长长旅程的起点和终点,在这段旅程中,偶尔会身处黑暗,不过正好可以看一看我们头顶上照耀着的东西。

借用威廉·詹姆斯“最深刻的人生无处不在”这句话,我要讲的故事是最深刻的人生是如何无处不在的。

一个意义非凡的人生所具有的和谐就好比繁星,让我们这儿的任何一个人看见并思考。

伟大哲学家的问题、故事和命令不是在天体上闲逛的天使所说的话。

甚至最令人钦佩的思想家对我们而言也是和我们一样的普通人,他们也会做普通的事情,偶尔会感到疼痛或快乐,并且有时候会作出改变。

与普通人相比,他们并没有额外的非凡之处。

韩素音英译汉原文

韩素音英译汉原文Outing A.I.: Beyond the Turing TestThe idea of measuring A.I. by its ability to “pass” as a human – dramatized in countless scifi films – is actually as old as modern A.I. research itself. It is traceable at least to 1950 when the British mathematician Alan Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a paper in which he described what we now call the “Turing Test,” and which he referred to as the “imitation game.” There are different versions of the test, all of which are revealing as to why our approachto the culture and ethics of A.I. is what it is, for good and bad. For the most familiar version, a human interrogator asks questions of two hidden contestants, one a human and the other a computer. Turing suggests that if the interrogator usually cannot tell which is which, and if the computer can successfully pass as human, then can we not conclude, for practical purposes, that the computer is “intelligent”?Mor e people “know” Turing’s foundational text than have actually read it. This is un fortunate because the text is marvelous, strange and surprising. Turing introduces his test as a variation on a popular parlor game in which two hidden contestants, a woman (player A) and a man (player B) try to convince a third that he or she is a woman by their written responses to leading questions. To win, one of the players must convincingly be who they really are, whereas the other must try to pass as another gender. Tur ing describes his own variation as one where “a computer takes the place of player A,” and so a literal reading would suggest that in his version the computer is not just pretending to be a human, but pretending to be a woman. Itmust pass as a she.Passing as a person comes down to what others see and interpret. Because everyone else is already willing to read others according to conventional cues (of race, sex, gender, species, etc.) the complicity between whoever (or whatever) is passing and those among which he or she or it performs is what allows passing to succeed. Whether or not an A.I. is trying to pass as a human or is merely in drag as a human is another matter. Is the ruse all just a game or, as for some people who are compelled to pass in their daily lives, an essential camouflage? Either way, “passing” may say more about the audience than about the performers.That we would wish to define the very existence of A.I. in relation to its ability to mimic how humans think that humans think will be looked back upon as a weird sort of speciesism. The legacy of that conceit helped to steer some older A.I. research down disappointingly fruitless paths, hoping to recreate human minds from available parts. It just doesn’t work that way. ContemporaryA.I. research suggests instead that the threshold by which any particular arrangement of matter can be said to be “intelligent” doesn’t have much to do with how it reflects humanness back at us. As Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (now director of research at Google) suggest in their essential A.I. textbook, biomorphic imitation is not how we design complex technology. Airplanes don’t fly like birds fly, and we certainly don’t try to trick birds into thinking that airplanes are birds in order to test whether those p lanes “really” are flying machines. Why do it for A.I. then? Today’s serious A.I. research does not focus on the Turing Test as an objective criterion of success, andyet in our popular culture of A.I., the test’s anthropocentrism holds such durable conceptual importance. Like the animals who talk like teenagers in a Disney movie, other minds are conceivable mostly by way of puerile ventriloquism.Where is the real injury in this? If we want everyday A.I. to be congenial in a humane sort of way, so what? The answer is that we have much to gain from a more sincere and disenchanted relationship to synthetic intelligences, and much to lose by keeping illusions on life support. Some philosophers write about the possible ethical “rights” of A.I. as sentient entit ies, but that’s not my point here. Rather, the truer perspective is also the better one for us as thinking technical creatures.Musk, Gates and Hawking made headlines by speaking to the dangers that A.I. may pose. Their points are important, but I fear were largely misunderstood by many readers. Relying on efforts to program A.I. not to “harm humans” (inspired by Isaac Asimov’s “three laws” of robotics from 1942) makes sense only when an A.I. knows what humans are and what harming them might mean. There are many ways that an A.I. might harm us that have nothing to do with its malevolence toward us, and chief among these is exactly following our well-meaning instructions to an idiotic and catastrophic extreme. Instead of mechanical failure or a transgression of moral code, the A.I. may pose an existential risk because it is both powerfully intelligent and disinterested in humans. T o the extent that we recognize A.I. by its anthropomorphic qualities, or presume its preoccupation with us, we are vulnerable to those eventualities.Whether or not “hard A.I.” ever appears, the harm is al so in the loss of all that we prevent ourselves from discovering and understanding when we insist on protecting beliefs we know tobe false. In the 1950 essay, Turing offers several rebuttals to his speculative A.I., including a striking comparison with earlier objections to Copernican astronomy. Copernican traumas that abolish the false centrality and absolute specialness of human thought and species-being are pricelessaccomplishments. They allow for human culture based on how the world actually is more than on how it appears to us from our limited vantage point. Turing referred to these as “theological objections,” but one could argue that the anthropomorphic precondition for A.I. is a“pre-Copernican” attitude as well, however secular it may appear. The advent of robust inhuman A.I. may let us achieve another disenchantment, one that should enable a more reality-based understanding of ourselves, our situation, and a fuller and more complex understanding of what “intelligence” is and is not. From there we can hopefully make our world with a greater confidence that our models are good approximations of what’s out there.。

韩素音翻译原文(1)

英译汉竞赛原文:How the News Got Less MeanThe most read article of all time on BuzzFeed contains no photographs of celebrity nip slips and no inflammatory ranting. It’s a series of photos called “21 pictures that will restore your faith in humanity,” which has pulled in nearly 14 million visits so far. At Upworthy too, hope is the major draw. “This kid just died. What he left behind is wondtacular,” an Upworthy post about a terminally ill teen singer, earned 15 million views this summer and has raised more than $300,000 for cancer research.The recipe for attracting visitors to stories online is changing. Bloggers have traditionally turned to sarcasm and snark to draw attention. But the success of sites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy, whose philosophies embrace the viral nature of upbeat stories, hints that the Web craves positivity.The reason: social media. Researchers are discovering that people want to create positive images of themselves online by sharing upbeat stories. And with more people turning to Facebook and Twitter to find out what’s happening in the world, news stories may need to cheer up in order to court an audience. If social is the future of media, then optimistic stories might be media’s future.“When we started, the prevailing wisdom was that snark ruled the Internet,”says Eli Pariser, a co-founder of Upworthy. “And we just had a really different sense of what works.”“You don’t want to be that guy at the party who’s crazy and angry and ranting in the corner — it’s the same for Twitter or Facebook,” he says. “Part of what we’re trying to do with Upworthy is give people the tools to express a conscientious, thoughtful and positive identity in social media.”And the science appears to support Pariser’s philosophy. In a recent study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, researchers found that “up votes,”showing that a visitor liked a comment or story, begat more up votes on comments on the site, but “down votes” did not do the same. In fact, a single up vote increased the likelihood that someone else would like a comment by 32%, whereas a down vote had no effect. People don’t want to support the cranky commenter, the critic or the troll. Nor do they want to be that negative personality online.In another study published in 2012, Jonah Berger, author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On and professor of marketing at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, monitored the most e-mailed stories produced by the New York Times for six months and found that positive stories were more likely to make the list than negative ones.“What we share [or like] is almost like the car we drive or the clothes we wear,”he says. “It says something about us to other people. So people would much rather be seen as a Positive Polly than a Debbie Downer.”It’s not always that simple: Berger says that though positive pieces drew more traffic than negative ones, within the categories of positive and negative stories, those articles that elicited more emotion always led to more shares.“Take two negative emotions, for example: anger and sadness,” Berger says. “Both of those emotions would make the reader feel bad. But anger, a high arousal emotion, leads to more sharing, whereas sadness, a low arousal emotion, doesn’t. The same is true of the positive side: excitement and humor increase sharing, whereas contentment decreases sharing.”And while some popular BuzzFeed posts — like the recent “Is this the most embarrassing interview Fox News has ever done?”— might do their best to elicit shares through anger, both BuzzFeed and Upworthy recognize that their main success lies in creating positive viral material.“It’s not that people don’t share negative stories,” says Jack Shepherd, editorial director at BuzzFeed. “It just means that there’s a higher potential for positive stories to do well.”Upworthy’s mission is to highlight serious issues but in a hopeful way, encouraging readers to donate money, join organizations and take action. The strategy seems to be working: barely two years after its launch date (in March 2012), the site now boasts 30 million unique visitors per month, according to Upworthy. The site’s average monthly unique visitors grew to 14 million people over its first six quarters — to put that in perspective, the Huffington Post had only about 2 million visitors in its first six quarters online.But Upworthy measures the success of a story not just by hits. The creators of the site only consider a post a success if it’s also shared frequently on social media. “We are interested in content that people want to share partly for pragmaticreasons,” Pariser says. “If you don’t have a good theory about how to appear in Facebook and Twitter, then you may disappear.”Nobody has mastered the ability to make a story go viral like BuzzFeed. The site, which began in 2006 as a lab to figure out what people share online, has used what it’s learned to draw 60 million monthly unique visitors, according to BuzzFeed. (Most of that traffic comes from social-networking sites, driving readers toward BuzzFeed’s mix of cute animal photos and hard news.) By comparison the New York Times website, one of the most popular newspaper sites on the Web, courts only 29 million unique visitors each month, according to the Times.BuzzFeed editors have found that people do still read negative or critical stories, they just aren’t the posts they share with their friends. And those shareable posts are the ones that newsrooms increasingly prize.“Anecdotally, I can tell you people are just as likely to click on negative stories as they are to click on positive ones,” says Shepherd. “But they’re more likely to share positive stories. What you’re interested in is different from what you want your friends to see what you’re interested in.”So as newsrooms re-evaluate how they can draw readers and elicit more shares on Twitter and Facebook, they may look to BuzzFeed’s and Upworthy’s happiness model for direction.“I think that the Web is only becoming more social,” Shepherd says. “We’re at a point where readers are your publishers. If news sites aren’t thinking about what it would mean for someone to share a story on social media, that could be detrimental.”汉译英竞赛原文:城市的迷失沿着瑗珲—腾冲线,这条1935年由胡焕庸先生发现并命名的中国人口、自然和历史地理的分界线,我们看到,从远距离贸易发展开始的那天起,利益和权力的渗透与分散,已经从根本结构上改变了城市的状态:城市在膨胀,人在疏离。

回家,第13届韩素音翻译大赛参考译文∣文学翻译

回家,第13届韩素音翻译大赛参考译文∣文学翻译今天“高斋翻硕”给大家分享第13届韩素音国际翻译比赛英译汉原文和官方参考译文节选。

原文I am home for my daughter’s first birthday. By “home” I do not mean the house in Los Angeles where my husband and I and the baby live, but the place where my family is, in the Central Valley of California. It is a vital although troublesome distinction. My husband likes my family but is uneasy in their house, because once there I fall into their ways, which are difficult, oblique, deliberately inarticulate, not my husband’s ways. We live in dusty houses (“D-U-S-T,” he once wrote with his finger on surfaces all over the house, but no one noticed it) filled with mementos quite without value to him (what could the Canton dessert plates. mean to him?官方参考译文我回家给女儿过周岁生日。

我所说的“家”,并非指丈夫,我和小宝宝在洛杉矶的家,而是指位于加州中央谷地的娘家。

这样区分,尽管麻烦,却很重要。

丈夫不是不喜欢我娘家的人,但是在我娘家却颇不自在。

第十二届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)

第十二届“韩素音青年翻译奖”竞赛原文及参考译文(汉译英)霞冰心四十年代初期,我在重庆郊外歌乐山闲居的时候,曾看到英文《读者文摘》上,有个很使我惊心的句子,是:May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.我在一篇短文里曾把它译成:“愿你的生命中有够多的云翳,来造成一个美丽的黄昏。

”其实,这个sunset 应当译成“落照”或“落霞”。

霞,是我的老朋友了!我童年在海边、在山上,她都是我的最熟悉最美丽的小伙伴。

她每早每晚都在光明中和我说“早上好”或“明天见”。

但我直到几十年以后,才体会到云彩更多,霞光才愈美丽。

从云翳中外露的霞光,才是璀璨多彩的。

生命中不是只有快乐,也不是只有痛苦,快乐和痛苦是相生相成,互相衬托的。

快乐是一抹微云,痛苦是压城的乌云,这不同的云彩,在你生命的天边重叠着,在“夕阳无限好”的时候,就给你造成一个美丽的黄昏。

一个生命会到了“只是近黄昏”的时节,落霞也许会使人留恋、惆怅。

但人类的生命是永不止息的。

地球不停地绕着太阳自转。

东方不亮西方亮,我床前的晚霞,正向美国东岸的慰冰湖上走去……The Rosy CloudBingxinDuring the early 1940s I was living a retired life in the Gele Mountains in the suburbs of Chongqing (Chungking). One day, while reading the English language magazine Reader's Digest I found a sentence that touched me greatly. It read: "May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset."In a short article of mine, I quoted this sentence and translated it as "Yuan ni de shengming zhong you guo duo de yunyi, lai zaocheng yige meili de huanghun. " (literally: May there be enough clouds in your life to make a beautiful sunset.) *As I see it now, the word "sunset" in the English sentence should have been translated as luozhao (the glow at sunset) or luoxia (the rosy cloud at sunset), instead of dusk.She has been my dear old friend, the Rosy Cloud! She was my closest and most beautiful little companion when, in my childhood, I played on the beach or in the hills. Bathed in the brilliant sunshine, she would say to me "Good morning!" at dawn and "See you tomorrow!" at dusk. But not until several decades later did I come to realize that the more clouds there are the more beautiful the rays of sunlight will be, and the glow of the sun breaking through the clouds becomes most resplendent and colorful.Life contains neither unalloyed happiness nor mere misery. Happiness and misery beget, complement and set off each other.Happiness is a wisp of fleecy cloud; misery a mass of threatening dark cloud. These different clouds overlap on the horizon of your life to create a beautiful dusk for you when "the setting sun is most lovely indeed."**An individual's life must inevitably reach the point when "dusk is so near,"*** and the rosy sunset cloud may make one nostalgic and melancholy. But human life goes on and on. The Earth ceaselessly rotates on its axis around the sun. When it is dark in the east, it is light in the west. The rosy sunset cloud is now sailing past my window towards Lake Waban on the east coast of America ...*This sentence appears in Chinese and English in the article "For Young Readers Again, Newsletter No.4", written by Bing Xin in the Gele Mountains, on December 1, 1944.** and *** These two poetic lines are taken from a poem "On the Plain of Tombs" by Li Shangyin (813-858), a well-known poet of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The two lines read like this: "The setting sun appears sublime, / But O! 'Tis near its dying time." (Tr. Xu Yuanchong) They imply that the setting sun has infinite beauty, but it is a pity that it is near the dusk, and the beautiful scene cannot last long. The two lines are often used to deplore the ephemeral nature of things, and to express the feelings at the loss of past glory and at the advent of old age.。

评第十三届韩素音翻译奖英译汉参考译文

评第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉参考译文朱志瑜(香港理工大学中文及双语系)近年中国翻译研究发展很快,但翻译批评始终落后。

理论界早就注意到了这一点,但到目前为止,对翻译批评却还是说得多做得少。

其中原因是多方面的。

要批评就要将原文、译文从头至尾或者至少将重要章节对照一遍,费时费力;批评写出来,可能牵涉到译者和译文出版者的利益(如译者声誉、译文销量等),学报是否支持发表,译文出版者是否欢迎──几年前听说过译文出版者打电话给学报编辑阻止评论发表的事情──这些都是在撰写批评之前需要慎重考虑的,否则费力不讨好,说得严重点,可能影响到评者的人际关系以至声誉。

这本不是健康学术的表现,但在中国这个大的学术环境之下,批评始终难以开展确实是个事实。

翻译批评的落后不但是中国翻译学科不成熟的反映,而且还会阻碍学科的发展。

本文仅就第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉“参考译文”(以下简称“译文”)和评者在“译文评析”(简称“评析”)中对参赛译文的评述提出一些看法,也算是一种翻译批评,希望对青年翻译家、学者能有所帮助。

两篇文章都载于《中国翻译》2001年第一期。

今年十月在广州开会的时候,我也顺便征求了广外部分参与奖项评议的同事的意见,回来又做了些修改,写成了这篇文章。

我首先要指出的是,“译文”经过认真的研究、讨论,是了一篇相当优秀的译文;“评析”也指出了一些粗心的译者常犯的错误和应该注意的问题。

“译文”和“评析”虽然有值得讨论的地方,但瑕不掩瑜,这恰恰说明了“译无止境”这个道理。

我这里只是抱着精益求精、共同提高的态度,对评委的“评析”和“译文”提出一些意见。

还有一点要指出的是,没有不犯错误的翻译家;尤其是比赛参考译文,一旦刊出,几万只眼睛挑毛病,实在不容易讨好;但是指出别人的翻译错误却是很容易的一件事情。

原文是一篇散文,属于文学类型。

根据功能主义的原则,原文为“表情类”(expressive)。

“评析”提出的“字斟句酌、形义并重”的原则,是正确的翻译策略,即译文不仅要表达原文的内容,而且要反映原文为了表达这个内容所使用的修辞、句法等手段。

第23届韩素音青年翻译奖竞赛参考译文

英译汉原文:Are We There Yet?America’s recovery will be much slower than that from most recessions; but the government can help a bit.“WHITHER goest thou, America?” That question, posed by Jack Kerouac on behalf of the Beat generation half a century ago, is the biggest uncertainty hanging over the world economy. And it reflects the foremost worry for American voters, who go to the polls for the congressional mid-term elections on November 2nd with the country’s unemployment rate stubbornly stuck at nearly one in ten. They should prepare themselves for a long, hard ride.The most wrenching recession since the 1930s ended a year ago. But the recovery—none too powerful to begin with—slowed sharply earlier this year. GDP grew by a feeble 1.6% at an annual pace in the second quarter, and seems to have been stuck somewhere similar since. The housing market slumped after temporary tax incentives to buy a home expired. So few private jobs were being created that unemployment looked more likely to rise than fall. Fears grew over the summer that if this deceleration continued, America’s economy would slip back into recession.Fortunately, those worries now seem exaggerated. Part of the weakness of second-quarter GDP was probably because of a temporary surge in imports from China. The latest statistics, from reasonably good retail sales in August to falling claims for unemployment benefits, point to an economy that, though still weak, is not slumping further. And history suggests that although nascent recoveries often wobble for a quarter or two, they rarely relapse into recession. For now, it is most likely that America’s economy will crawl along with growth at perhaps 2.5%: above stall speed, but far too slow to make much difference to the jobless rate.Why, given that America usually rebounds from recession, are the prospects so bleak? That’s because most past recessions have been caused by tight monetary policy. When policy is loosened, demand rebounds. This recession was the result of a financial crisis. Recoveries after financial crises are normally weak and slow as banking systems are repaired and balance-sheets rebuilt. Typically, this period of debt reduction lasts around seven years, which means America would emerge from it in 2014. By some measures, households are reducing their debt burdens unusually fast, but even optimistic seers do not think the process is much more than half over.Battling on the busAmerica’s biggest problem is that its poli ticians have yet to acknowledge that the economy is in for such a long, slow haul, let alone prepare for the consequences.A few brave officials are beginning to sound warnings that the jobless rate is likely to “stay high”. But the political debate is mor e about assigning blame for the recession than about suggesting imaginative ways to give more oomph to the recovery. Republicans argue that Barack Obama’s shift towards “big government” explainsthe economy’s weakness, and that high unemployment is proof t hat fiscal stimulus was a bad idea. In fact, most of the growth in government to date has been temporary and unavoidable; the longer-run growth in government is more modest, and reflects the policies of both Mr Obama and his predecessor. And the notion that high joblessness “proves” that stimulus failed is simply wrong. The mechanics of a financial bust suggest that without a fiscal boost the recession would have been much worse.Democrats have their own class-warfare version of the blame game, in which Wall Street’s excesses caused the problem and higher taxes on high-earners are part of the solution. That is why Mr. Obama’s legislative priority before the mid-terms is to ensure that the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of this year for households earning more than $250,000 but are extended for everyone else.This takes an unnecessary risk with the short-term recovery. America’s experience in 1937 and Japan’s in 1997 are powerful evidence that ill-timed tax rises can tip weak economies back into recession. Higher taxes at the top, along with the waning of fiscal stimulus and belt-tightening by the states, will make a weak growth rate weaker still. Less noticed is that Mr. Obama’s fiscal plan will also worsen the medium-term budget mess, by making tax cuts for the middle class permanent.Ways to overhaul the engineIn an ideal world America would commit itself now to the medium-term tax reforms and spending cuts needed to get a grip on the budget, while leaving room to keep fiscal policy loose for the moment. But in febrile, partisan Washington that is a pipe-dream. Today’s goals can only be more modest: to nurture the weak economy, minimize uncertainty and prepare the ground for tomorrow’s fiscal debate. To that end, Congress ought to extend all the Bush tax cuts until 2013. Then they should all expire—prompting a serious fiscal overhaul, at a time when the economy is stronger.A broader set of policies could help to work off the hangover faster. One priority is to encourage more write-downs of mortgage debt. Almost a quarter of all Americans with mortgages owe more than their houses are worth. Until that changes the vicious cycle of rising foreclosures and falling prices will continue. There are plenty of ideas on offer, from changing the bankruptcy law so that judges can restructure mortgage debt to empowering special trustees to write down loans. They all have drawbacks, but a fetid pool of underwater mortgages will, much like Japan’s loans to zombie firms, corrode the financial system and harm the recovery.C leaning up the housing market would help cut America’s unemployment rate, by making it easier for people to move to where jobs are. But more must be done to stop high joblessness becoming entrenched. Payroll-tax cuts and credits to reduce the cost of hiring would help. (The health-care reform, alas, does the opposite, at least for small businesses.) Politicians will also have to think harder about training schemes, because some workers lack the skills that new jobs require.Americans are used to great distances. The sooner they, and their politicians, acceptthat the road to recovery will be a long one, the faster they will get there.译文:我们到达目的地了吗?与大多数衰退之后的复苏相比,这次美国经济的复苏会慢得多。

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文详解

历届韩素音翻译大奖赛竞赛原文及译文英译汉部分 (2)Beauty (excerpt) (2)美(节选) (2)The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power byThomas De Quincey (5)知识文学与力量文学托马斯.昆西 (5)An Experience of Aesthetics by Robert Ginsberg (6)审美的体验罗伯特.金斯伯格 (6)A Person Who Apologizes Has the Moral Ball in His Court by Paul Johnson (8)谁给别人道歉,谁就在道义上掌握了主动保罗.约翰逊 (8)On Going Home by Joan Didion (11)回家琼.狄迪恩 (11)The Making of Ashenden (Excerpt) by Stanley Elkin (13)艾兴登其人(节选)斯坦利.埃尔金 (13)Beyond Life (17)超越生命[美] 卡贝尔著 (17)Envy by Samuel Johnson (20)论嫉妒[英]塞缪尔.约翰逊著 (20)中译英部分 (23)在义与利之外 (23)Beyond Righteousness and Interests (23)读书苦乐杨绛 (25)The Bitter-Sweetness of Reading Yang Jiang (25)想起清华种种王佐良 (26)Reminiscences of Tsinghua Wang Zuoliang (26)歌德之人生启示宗白华 (28)What Goethe's Life Reveals by Zong Baihua (28)怀想那片青草地赵红波 (30)Yearning for That Piece of Green Meadow by Zhao Hongbo (30)可爱的南京 (32)Nanjing the Beloved City (32)霞冰心 (33)The Rosy Cloud byBingxin (33)黎明前的北平 (33)Predawn Peiping (33)老来乐金克木 (34)Delights in Growing Old by Jin Kemu (34)可贵的“他人意识” (36)Calling for an Awareness of Others (36)教孩子相信 (38)To Implant In Our Children’s Young Hearts An Undying Faith In Humanity (38)英译汉部分Beauty (excerpt)美(节选)Judging from the scientists I know, including Eva and Ruth, and those whom I've read about, you can't pursue the laws of nature very long without bumping撞倒; 冲撞into beauty. “I don't know if it's the same beauty you see in the sunset,”a friend tells me, “but it feels the same.”This friend is a physicist, who has spent a long career deciphering破译(密码), 辨认(潦草字迹) what must be happening in the interior of stars. He recalls for me this thrill on grasping for the first time Dirac's⑴equations describing quantum mechanics, or those o f Einstein describing relativity. “They're so beautiful,” he says, “you can see immediately they have to be true. Or at least on the way toward truth.” I ask him what makes a theory beautiful, and he replies, “Simplicity, symmetry .对称(性); 匀称, 整齐, elegance, and power.”我结识一些科学家(包括伊娃和露丝),也拜读过不少科学家的著作,从中我作出推断:人们在探求自然规律的旅途中,须臾便会与美不期而遇。

韩素音英译汉原文教学文稿

韩素音英译汉原文Outing A.I.: Beyond the Turing TestThe idea of measuring A.I. by its ability to “pass” as a human – dramatized in countless scifi films – is actually as old as modern A.I. research itself. It is traceable at least to 1950 when the British ma thematician Alan Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a paper in which he described what we now call the “Turing Test,” and which he referred to as the “imitation game.” There are different versions of the test, all of which are revealing as to why our approach to the culture and ethics of A.I. is what it is, for good and bad. For the most familiar version, a human interrogator asks questions of two hidden contestants, one a human and the other a computer. Turing suggests that if the interrogator usually cannot tell which is which, and if the computer can successfully pass as human, then can we not conclude, for practical purposes, that the computer is “intelligent”?More people “know” Turing’s foundational text than have actually read it. This is unfortunate because the text is marvelous, strange and surprising. Turing introduces his test as a variation on a popular parlor game in which two hidden contestants, a woman (player A) and a man (player B) try to convince a third that he or she is a woman by their written responses to leading questions. To win, one of the players must convincingly be who they really are, whereas the other must try to pass as another gender. Turing describes his own variation as one where “a computer takes the pla ce of player A,” and so a literal reading would suggest that in his version the computer is not just pretending to be a human, but pretending to be a woman. It must pass as a she.Passing as a person comes down to what others see and interpret. Because everyone else is already willing to read others according to conventional cues (of race, sex, gender, species, etc.) the complicity between whoever (or whatever) is passing and those among which he or she or it performs is what allows passing to succeed. Whether or not an A.I. is trying to pass as a human or is merely in drag as a human is another matter. Is the ruse all just a game or, as for some people who are compelled to pass in their daily lives, an essential camouflage? Either way, “passing” may say mo re about the audience than about the performers.That we would wish to define the very existence of A.I. in relation to its ability to mimic how humans think that humans think will be looked back upon as a weird sort of speciesism. The legacy of that conceit helped to steer some older A.I. research down disappointingly fruitless paths, hoping to recreate human minds from available parts. It just doesn’t work that way. Contemporary A.I. research suggests instead that the threshold by which any particular arrangement of matter can be said to be “intelligent” doesn’t have much to do with how it reflects humanness back at us. As Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (now director of research at Google) suggest in their essential A.I. textbook, biomorphic imitation is not how we design complex technology. Airplanes don’t fly like birds fly, and we certainly don’t try to trick birds into thinking that airplanes are birds in order to test whether those planes “really” are flying machines. Why do it for A.I. then? Today’s serious A.I. research does not focus on the Turing Test as an objective criterion of success, and yet in our popular culture of A.I., the test’s anthropocentrism holds such durable conceptual importance. Like the animals who talk like teenagers in a Disney movie, other minds are conceivable mostly by way of puerile ventriloquism.Where is the real injury in this? If we want everyday A.I. to be congenial in a humane sort of way, so what? The answer is that we have much to gain from a more sincere and disenchanted relationship to synthetic intelligences, and much to lose by keeping illusions on life support. Some philosophers write about the possible ethical “rights” of A.I. as sentient entities, but that’s not my point here. Rather, the truer perspective is also the better one for us as thinking technical creatures.Musk, Gates and Hawking made headlines by speaking to the dangers that A.I. may pose. Their points are important, but I fear were largely misunderstood by many readers. Relying on efforts to program A.I. not to “harm humans” (inspired by Isaac Asimov’s “three laws” of robotics from 1942) makes sense only when an A.I. knows what humans are and what harming them might mean. There are many ways that an A.I. might harm us that have nothing to do with its malevolence toward us, and chief among these is exactly following our well-meaning instructions to an idiotic and catastrophic extreme. Instead of mechanical failure or a transgression of moral code,the A.I. may pose an existential risk because it is both powerfully intelligent and disinterested in humans. To the extent that we recognize A.I. by its anthropomorphic qualities, or presume its preoccupation with us, we are vulnerable to those eventualities.Whether or not “hard A.I.” ever appears, th e harm is also in the loss of all that we prevent ourselves from discovering and understanding when we insist on protecting beliefs we know to be false. In the 1950 essay, Turing offers several rebuttals to his speculative A.I., including a striking comparison with earlier objections to Copernican astronomy. Copernican traumas that abolish the false centrality and absolute specialness of human thought and species-being are priceless accomplishments. They allow for human culture based on how the world actually is more than on how it appears to us from our limited vantage point. Turing referred to these as “theological objections,” but one could argue that the anthropomorphic precondition for A.I. is a “pre-Copernican” attitude as well, however secular it may appear. The advent of robust inhuman A.I. may let us achieve another disenchantment, one that should enable a more reality-based understanding of ourselves, our situation, and a fuller and more complex understanding of what “intelligence” is and is not. From there we can hopefully make our world with a greater confidence that our models are good approximations of what’s out there.。

韩素音翻译大赛英译汉原文解读与译赏(2020年7月整理).pdf

Globalization全球化颜林海【标题解读】写作分析:何谓全球化?回答这个问题的过程就是就是人类对客观事物的认识过程,即“定义”的过程,换句话说,“定义”就是界定一种事物的本质(即意义)的说明。

“定义”有许多方式,最常见的有:列举法(illustration),分类法(classification),过程分析法(process analysis),因果法(cause and effect),比对法(comparison and contrast);除了以上方法外,还有特征枚举法(enumerating characteristics),词源法(etymology),类比法(analogy),排除法(exclusion)(M.S. Spangler & R.Werner,1990:131—135)。

从写作或其他媒介的角度,作为一篇文章的标题,作者必然要围绕标题来展开,而要展开这个话题,就必须对该字词加以界定,即定义。

篇体分析:从上下文看,这是一篇由一档电视谈话节目转写而成的书面文档;电视访谈类节目虽然重在访谈,但并非人与人之间的私下闲聊,因此,节目主持人也往往会提前大致拟定一个围绕某一话题而展开的提纲,这就与文章写作大同而小异了。

理解与翻译时,注意访谈中人物对话的转换,还要注意书写文本在断句上与访谈情景有时并不一致,如(25)句。

翻译分析:在翻译之前,译者也应对标题中涉及到的概念加以认识和理解。

译者在分析某一核心字词时必须注意该字词的音形义的分析。

此篇文章中globalization与音没有多大关系,主要分析该字词的“形”和“义”。

而字“形”的分析涉及到该词的词源和构词方式。

词源分析:Globalization一词逆推词源关系如下:globalization。

构词分析:globalization不过是globalize的名词拼写形式,核心意义在globalize;而此词的构形属于英语中“形容词+动词后缀ize”构词法,其表达的意义为“使...‘形容词’化”或“使...变成‘形容词’”。

韩素音青年翻译

英译汉竞赛原文:The Posteverything GenerationI never expected to gain any new insight into the nature我从未想过要对我们这一代人的本质,of my generation, or the changing landscape of American 或者说在美国大学变化中的风景,colleges, in Lit Theory. Lit Theory is supposed to be the class 在理论上获得任何新的见解。

文学理论应该是where you sit at the back of the room with every other jaded 你和其他穿着sophomore wearing skinny jeans, thick-framed glasses, an 紧身牛仔裤和一件夸张的T恤,带着厚框眼镜和ironic tee-shirt and over-sized retro headphones, just waiting 超大号的复古耳机的疲惫不堪的学生们坐在教室的后排,等待for lecture to be over so you can light up a Turkish Gold and着讲座结束,然后你可以点亮一根土耳其黄金,walk to lunch while listening to Wilco. That’s pretty much 听着Wilco去吃中饭。

这也是the way I spent the course, too: through structuralism,我度过课程最好的方式:通过结构主义,formalism, gender theory, and post-colonialism, I was far too 形式主义,性别理论,后殖民主义,我相当busy shuffling through my Ipod to see what the patriarchal world 忙碌的通过我的iPod看资本主义order of capitalist oppression had to do with Ethan Frome. But 压迫的男权世界秩序跟伊坦。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

评第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉参考译文朱志瑜(香港理工大学中文及双语系)近年中国翻译研究发展很快,但翻译批评始终落后。

理论界早就注意到了这一点,但到目前为止,对翻译批评却还是说得多做得少。

其中原因是多方面的。

要批评就要将原文、译文从头至尾或者至少将重要章节对照一遍,费时费力;批评写出来,可能牵涉到译者和译文出版者的利益(如译者声誉、译文销量等),学报是否支持发表,译文出版者是否欢迎──几年前听说过译文出版者打电话给学报编辑阻止评论发表的事情──这些都是在撰写批评之前需要慎重考虑的,否则费力不讨好,说得严重点,可能影响到评者的人际关系以至声誉。

这本不是健康学术的表现,但在中国这个大的学术环境之下,批评始终难以开展确实是个事实。

翻译批评的落后不但是中国翻译学科不成熟的反映,而且还会阻碍学科的发展。

本文仅就第十三届“韩素音青年翻译奖”英译汉“参考译文”(以下简称“译文”)和评者在“译文评析”(简称“评析”)中对参赛译文的评述提出一些看法,也算是一种翻译批评,希望对青年翻译家、学者能有所帮助。

两篇文章都载于《中国翻译》2001年第一期。

今年十月在广州开会的时候,我也顺便征求了广外部分参与奖项评议的同事的意见,回来又做了些修改,写成了这篇文章。

我首先要指出的是,“译文”经过认真的研究、讨论,是了一篇相当优秀的译文;“评析”也指出了一些粗心的译者常犯的错误和应该注意的问题。

“译文”和“评析”虽然有值得讨论的地方,但瑕不掩瑜,这恰恰说明了“译无止境”这个道理。

我这里只是抱着精益求精、共同提高的态度,对评委的“评析”和“译文”提出一些意见。

还有一点要指出的是,没有不犯错误的翻译家;尤其是比赛参考译文,一旦刊出,几万只眼睛挑毛病,实在不容易讨好;但是指出别人的翻译错误却是很容易的一件事情。

原文是一篇散文,属于文学类型。

根据功能主义的原则,原文为“表情类”(expressive)。

“评析”提出的“字斟句酌、形义并重”的原则,是正确的翻译策略,即译文不仅要表达原文的内容,而且要反映原文为了表达这个内容所使用的修辞、句法等手段。

“译文”基本上达到了这个要求。

“字斟句酌、形义并重”这八个字也是我这篇短文所要提倡的翻译态度。

这篇散文翻译起来不容易,难的倒不是语言问题,主要还是其中很多美国特有的文化内容,在一般工具书中不易找到,如: “C-2 zoning”,“guerrilla war”等等。

如果评析人员能在报告中指出参考资料和查找方法,则对于参赛的学者、译者都会有更大的益处。

下面的讨论分两部分,先谈“译文”,然后分析“评析”中的几点问题;个别问题在两处同时出现,就放到“评析”部分讨论。

“译文”和“评析”都不长,我就不注出页数了。

一)参考译文1、词汇“译文”有的地方选词不够准确,不排除有理解上的误差。

原文第一段有这样一句话:原文:We live in dusty houses (“D-U-S-T”, he once wrote with his finger on surface s all over the house).译文:我们住在灰蒙蒙的屋子里。

“灰蒙蒙”在汉语中多用来形容空气的质量,与原文意思有偏离,甚至会引起不必要的联想;似可译为“满是灰尘”或“到处都是灰尘”,因为可以用手指在上面写字。

第二段:原文:〔We〕were … to find in family life the source of all tension and drama.译文:……经受家庭生活中种种紧张和冲突…这里drama译成“冲突”;由于前面已经有了“紧张”,再用一个类似的词有点重复。

Drama 有excitement的意思,是中性,和前面tension连起来用甚至可以指好的一面,而“紧张”与“冲突”在这里都带有贬意。

这句话中的tension译为“冲突”比较好,drama可译为“刺激”之类的中性词。

同一段里的anxiety一词译成“忧虑”,而实际上它没有“忧”的意思;不如照辞典译成“焦虑”。

这段里还有一句:原文:We did not fight. Nothing was wrong.译文:我们没吵过架,也没出过岔子。

Nothing was wrong.其实表示的是“没有什么问题”,或“没有什么不妥”,甚至“一切正常(normal)”的意思,与它对应的并非就是“出岔子”、“出错”。

另外此句标点也值得讨论,后面再谈。

同段作者提到五十年代离开家时的复杂心情是现在的年轻人没有经历过的,原文是这样说的:原文:I suspect that it is irrelevant to the children born of the fragmentation after World War II.译文:这个问题大概与二战后破碎家庭里出生的孩子无关。

将irrelevancy 译成“无关”有点费解,而且语气不够,根据上下文应该是“想都想不到”的意思。

“fragmentation”译成“破碎家庭”,范围限制得太窄了。

英文的抽象名词最难译,因为汉语经常是用具象来表达,所以评者加上了“家庭”二字。

原文的意思应该是泛指二次大战给社会、政治、价值观、以至家庭等等造成的“破裂”与“断层”。

译成“废墟”也过于具体,不如稍微引申一点,说“二战后的动荡时期”,甚至“破裂时期”都可以。

还有一些小的选词问题,如My husband likes my family but is uneasy in their house,其前半部分被译成“丈夫不是不喜欢我娘家人”,在此不知是否有必要一定将likes前面加上双重否定?再如将I see no one中的see一词译成“访晤”,似嫌太大、太正式,不如简单译成“我谁都没去见”。

将uneasily译成了“拘束”,不如照原文的否定式译为“不安”来得贴切。

另外将horehound drop译成“带苦味的薄荷糖”本来也没有什么错误,只是太长,而且读来不像是一种名称。

原文是一个名词,译文不宜改成解释性的短语。

不如译成“苦味薄荷糖”(中文有“怪味鸡”)或“苦薄荷”,甚至“薄荷糖”,让读者知道是块糖就够了,因为它在原文中的“功能”就是拿来哄小孩的一块糖而已,它的味道怎样并不重要,加上“带苦味的”反而容易引起读者不必要的联想。

2、句法、语意原文第一段:原文:Nor does he understand that when we talk about sale-leasebacks and right-of-way condemnations we are talking in code about the things we like best, the yellow fields and the cottonwoods and the rivers rising and falling and the mountain roads closing when the heavy snow comes in.译文:其实丈夫不明白,我们谈售后回租和依法征用公地时侯,是在用娘家人特有的语言谈论最来劲儿的东西,像金黄色的田野、棉白杨、时涨时落的河水,以及下大雪时封闭的山路。

首先原文中Nor一词表示和上文的衔接关系,在“译文”没有体现出来;加上一个“也”字就解决了。

可能译者认为如果使用“也”的话,前面不宜用句号,所以用了“其实”来衔接,可是这样意思就有出入了。

其次,原文中连用了三个and,有一定的修辞效果,这点也未能传译出来。

这里中文连用三个“和”字可能效果未必如原文那样,但是可以使用其它补救手段,如加上“甚么…啊,〔甚么〕…啊”之类的短语,或译成“我们谈…,谈…,谈…”也能达到一些连词重复的效果。

另外right-of-way condemnations的意思是指政府在修路架桥时可能会占用一些私人土地,这就否定了私人对土地的“优先使用权”(right-of-way);译成“依法征用公地”,从逻辑上讲也有问题,因为既然是公地就不需“征用”了;应是“私地”。

第二段:原文:There was no particular sense of moment about this, none of the effect of romantic degradation, of “dark journey,” for which my generation strived so assiduously.译文:这没有什么特别的意思,与浪漫沉沦沾不上边儿,与我们这一代人所驱趋之若骛的“黑暗之旅”也沾不上边。

这句话理解有些错误,which 的先行词应该是effect,而“译文”把它理解成journey了。

原文中第二个of(“dark journey”)前实际上省略了一个none,而which分句应该是修饰前面两者,即“浪漫沉沦”的效果(effect)和“黑暗之旅”的效果,如果像“译文”中那样,则只修辞邻近的一句。

所以,“与我们这一代人所驱趋之若骛的”应该放在“浪漫沉沦”前面。

这句话的分析可以从语意入手,就是靠对全文的理解和语感;还有一种方法就是看句法。

如果which 修饰journey的话,为了清楚起见,作者就不会在journey后面使用一个逗号。

差别虽然细微,译者只要细心留意还是能够看出区别的。

另外文中的sense of moment(意思是sense of importance)译成“没有什么特别的意思”不好懂,应是“毫无意义”。

第三段最后一句:原文:We get along very well, veterans of a guerrilla war we never understood.译文:我们现在相处得很好,就像打过游击战的老兵一样,真不明白过去为何时有龃龉。

这是最难译的一句,“译文”处理得不是很好。

如果光看译文,读者很难理解为甚么在这里突然出现“游击战”这个词;而且译文中三个短句的关系也不清楚。

是因为“我们相处得好”才“像游击战的老兵”,还是因为“像老兵”所以“不明白”?仔细对照原文我们可以看出,“译文”的理解不能算错,因为在译者心中,“游击战”和“龃龉”可能是一回事,就是:“就像游击战的老兵一样,但是我们不明白过去为甚么打游击战”(暗喻改为明喻也不好)。

其实原文的两个分句之间的关系也不清楚,可能有不同的理解:1)We get along very well, (in spite of the fact that we are)veterans of a guerrilla war we never understood. 2) We get along very well, (because we are) veterans of a guerrilla war we never understood.模糊性、多义性是文学作品的特点,作者刻意要这样写,译者非不得已应尽量保留。