2015《英语世界》翻译比赛原文

第七届翻译大赛英文原文

OpticsManini NayarWhen I was seven, my friend Sol was hit by lightning and died. He was on a rooftop quietly playing marbles when this happened. Burnt to cinders, we were told by the neighbourhood gossips. He'd caught fire, we were assured, but never felt a thing. I only remember a frenzy of ambulances and long clean sirens cleaving the silence of that damp October night. Later, my father came to sit with me. This happens to one in several millions, he said, as if a knowledge of the bare statistics mitigated the horror. He was trying to help, I think. Or perhaps he believed I thought it would happen to me. Until now, Sol and I had shared everything; secrets, chocolates, friends, even a birthdate. We would marry at eighteen, we promised each other, and have six children, two cows and a heart-shaped tattoo with 'Eternally Yours' sketched on our behinds. But now Sol was somewhere else, and I was seven years old and under the covers in my bed counting spots before my eyes in the darkness.After that I cleared out my play-cupboard. Out went my collection of teddy bears and picture books. In its place was an emptiness, the oak panels reflecting their own woodshine. The space I made seemed almost holy, though mother thought my efforts a waste. An empty cupboard is no better than an empty cup, she said in an apocryphal aside. Mother always filled things up - cups, water jugs, vases, boxes, arms - as if colour and weight equalled a superior quality of life. Mother never understood that this was my dreamtime place. Here I could hide, slide the doors shut behind me, scrunch my eyes tight and breathe in another world. When I opened my eyes, the glow from the lone cupboard-bulb seemed to set the polished walls shimmering, and I could feel what Sol must have felt, dazzle and darkness. I was sharing this with him, as always. He would know, wherever he was, that I knew what he knew, saw what he had seen. But to mother I only said that I was tired of teddy bears and picture books. What she thought I couldn't tell, but she stirred the soup-pot vigorously.One in several millions, I said to myself many times, as if the key, the answer to it all, lay there. The phrase was heavy on my lips, stubbornly resistant to knowledge. Sometimes I said the words out of con- text to see if by deflection, some quirk of physics, the meaning would suddenly come to me. Thanks for the beans, mother, I said to her at lunch, you're one in millions. Mother looked at me oddly, pursed her lips and offered me more rice. At this club, when father served a clean ace to win the Retired-Wallahs Rotating Cup, I pointed out that he was one in a million. Oh, the serve was one in a million, father protested modestly. But he seemed pleased. Still, this wasn't what I was looking for, and in time the phrase slipped away from me, lost its magic urgency, became as bland as 'Pass the salt' or 'Is the bath water hot?' If Sol was one in a million, I was one among far less; a dozen, say. He was chosen. I was ordinary. He had been touched and transformed by forces I didn't understand. I was left cleaning out the cupboard. There was one way to bridge the chasm, to bring Solback to life, but I would wait to try it until the most magical of moments. I would wait until the moment was so right and shimmering that Sol would have to come back. This was my weapon that nobody knew of, not even mother, even though she had pursed her lips up at the beans. This was between Sol and me.The winter had almost guttered into spring when father was ill. One February morning, he sat in his chair, ashen as the cinders in the grate. Then, his fingers splayed out in front of him, his mouth working, he heaved and fell. It all happened suddenly, so cleanly, as if rehearsed and perfected for weeks. Again the sirens, the screech of wheels, the white coats in perpetual motion. Heart seizures weren't one in a million. But they deprived you just the same, darkness but no dazzle, and a long waiting.Now I knew there was no turning back. This was the moment. I had to do it without delay; there was no time to waste. While they carried father out, I rushed into the cupboard, scrunched my eyes tight, opened them in the shimmer and called out'Sol! Sol! Sol!' I wanted to keep my mind blank, like death must be, but father and Sol gusted in and out in confusing pictures. Leaves in a storm and I the calm axis. Here was father playing marbles on a roof. Here was Sol serving ace after ace. Here was father with two cows. Here was Sol hunched over the breakfast table. The pictures eddied and rushed. The more frantic they grew, the clearer my voice became, tolling like a bell: 'Sol! Sol! Sol!' The cupboard rang with voices, some mine, some echoes, some from what seemed another place - where Sol was, maybe. The cup- board seemed to groan and reverberate, as if shaken by lightning and thunder. Any minute now it would burst open and I would find myself in a green valley fed by limpid brooks and red with hibiscus. I would run through tall grass and wading into the waters, see Sol picking flowers. I would open my eyes and he'd be there,hibiscus-laden, laughing. Where have you been, he'd say, as if it were I who had burned, falling in ashes. I was filled to bursting with a certainty so strong it seemed a celebration almost. Sobbing, I opened my eyes. The bulb winked at the walls.I fell asleep, I think, because I awoke to a deeper darkness. It was late, much past my bedtime. Slowly I crawled out of the cupboard, my tongue furred, my feet heavy. My mind felt like lead. Then I heard my name. Mother was in her chair by the window, her body defined by a thin ray of moonlight. Your father Will be well, she said quietly, and he will be home soon. The shaft of light in which she sat so motionless was like the light that would have touched Sol if he'd been lucky; if he had been like one of us, one in a dozen, or less. This light fell in a benediction, caressing mother, slipping gently over my father in his hospital bed six streets away. I reached out and stroked my mother's arm. It was warm like bath water, her skin the texture of hibiscus.We stayed together for some time, my mother and I, invaded by small night sounds and the raspy whirr of crickets. Then I stood up and turned to return to my room.Mother looked at me quizzically. Are you all right, she asked. I told her I was fine, that I had some c!eaning up to do. Then I went to my cupboard and stacked it up again with teddy bears and picture books.Some years later we moved to Rourkela, a small mining town in the north east, near Jamshedpur. The summer I turned sixteen, I got lost in the thick woods there. They weren't that deep - about three miles at the most. All I had to do was cycle forall I was worth, and in minutes I'd be on the dirt road leading into town. But a stir in the leaves gave me pause.I dismounted and stood listening. Branches arched like claws overhead. The sky crawled on a white belly of clouds. Shadows fell in tessellated patterns of grey and black. There was a faint thrumming all around, as if the air were being strung and practised for an overture. And yet there was nothing, just a silence of moving shadows, a bulb winking at the walls. I remembered Sol, of whom I hadn't thought in years. And foolishly again I waited, not for answers but simply for an end to the terror the woods were building in me, chord by chord, like dissonant music. When the cacophony grew too much to bear, I remounted and pedalled furiously, banshees screaming past my ears, my feet assuming a clockwork of their own. The pathless ground threw up leaves and stones, swirls of dust rose and settled. The air was cool and steady as I hurled myself into the falling light.光学玛尼尼·纳雅尔谈瀛洲译在我七岁那年,我的朋友索尔被闪电击中死去了。

第八届华东师范大学-《英语世界》杯

第八届“华东师范大学-《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛原文英译汉原文:On HomeBy John Berger“Philosophy is really homesickness, it is the urge to be at home everywhere.”—Novalis【1】The transition from a nomadic life to a settled one is said to mark the beginning of what was later called civilization. Soon all those who survived outside the city began to be considered uncivilized. But that is another story—to be told in the hills near the wolves.【2】Perhaps during the last century and a half an equally important transformation has taken place. Never before our time have so many people been uprooted. Emigration, forced or chosen, across national frontiers or from village to metropolis, is the quintessential experience of our time. That industrialization and capitalism would require such a transport of men on an unprecedented scale and with a new kind of violence was already prophesied by the opening of the slave trade in the sixteenth century. The Western Front in the First World War with its conscripted massed armies was a later confirmation of the same practice of tearing up, assembling, transporting, and concentrating in a “no-man’s land.” Later, concentration camps, across the world, followed the logic of the same continuous practice.【3】All the modern historians from Marx to Spengler have identified the contemporary phenomenon of emigration. Why add more words? To whisper for that which has been lost. Not out of nostalgia, but because it is on the site of loss that hopes are born.【4】The term home (Old Norse Heimer, High German heim, Greek kōmi, meaning “village”) has, since a long time, been taken over by two kinds of moralists, both dear to those who wield power. The notion of home became the keystone for a code of domestic morality, safeguarding the property (which included the women) of the family. Simultaneously the notion of homeland supplied a first article of faith for patriotism, persuading men to die in wars which often served no other interest except that of a minority of their ruling class. Both usages have hidden the original meaning. 【5】Originally home meant the center of the world—not in a geographical, but in an ontological sense. Mircea Eliade has demonstrated how home was the place from which the world could be founded. A home was established, as he says, “at the heart of the real.” In traditional societies, everything that made sense of the world was real; the surrounding chaos existed and was threatening, but it was threatening because it was unreal. Without a home at the center of the real, one was not only shelterless, but also lost in nonbeing, in unreality. Without a home everything was fragmentation. 【6】Home was the center of the world because it was the place where a vertical line crossed with a horizontal one. The vertical line was a path leading upwards to the sky and downwards to the underworld. The horizontal line represented the traffic of the world, all the possible roads leading across the earth to other places. Thus, athome, one was nearest to the gods in the sky and to the dead in the underworld. This nearness promised access to both. And at the same time, one was at the starting point and, hopefully, the returning point of all terrestrial journeys.【7】The crossing of the two lines, the reassurance their intersection promises, was probably already there, in embryo, in the thinking and beliefs of nomadic people, but they carried the vertical line with them, as they might carry a tent pole. Perhaps at the end of this century of unprecedented transportation, vestiges of the reassurance still remain in the unarticulated feelings of many millions of displaced people.【8】Emigration does not only involve leaving behind, crossing water, living amongst strangers, but also, undoing the very meaning of the world and—at its most extreme—abandoning oneself to the unreal which is the absurd.【9】Emigration, when it is not enforced at gunpoint, may of course be prompted by hope as well as desperation. For example, to the peasant son the father’s traditional authority may seem more oppressively absurd than any chaos. The poverty of the village may appear more absurd than the crimes of the metropolis. To live and die amongst foreigners may seem less absurd then to live persecuted or tortured by one’s fellow countrymen. All this can be true. But to emigrate is always to dismantle the center of the world, and so to move into a lost, disoriented one of fragments.汉译英原文:家(节选)文/周国平【1】家庭是人类一切社会组织中最自然的社会组织,是把人与大地、与生命的源头联结起来的主要纽带。

英语世界参赛译文

LimboBy Rhonda LucasMy parents’ divorce was final. The house had been sold and the day had come to move. Thirty years of the family’s life was now crammed into the garage. The two-by-fours that ran the length of the walls were the only uniformity among the clutter of boxes, furniture, and memories. All was frozen in limbo between the life just passed and the one to come.The sunlight pushing its way through the window splattered against a barricade of boxes. Like a fluorescent river, it streamed down the sides and flooded the cracks of the cold, cement floor. I stood in the doorway between the house and garage and wondered if the sunlight would ever again penetrate the memories packed inside those boxes. For an instant, the cardboard boxes appeared as tombstones, monuments to those memories.The furnace in the corner, with its huge tubular fingers reaching out and disappearing into the wall, was unaware of the futility of trying to warm the empty house. The rhythmical whir of its effort hummed the elegy for the memories boxed in front of me. I closed the door, sat down on the step, and listened reverently. The feeling of loss transformed the bad memories into not-so-bad, the not-so-bad memories into good, and committed the good ones to my mind. Still, I felt as vacant as the house inside.A workbench to my right stood disgustingly empty. Not so much as a nail had been left behind. I noticed, for the first time, what a dull, lifeless green it was. Lacking the disarray of tools that used to cover it, now it seemed as out of place as a bathtub in the kitchen. In fact, as I scanned the room, the only things that did seem to belong were the cobwebs in the corners.A group of boxes had been set aside from the others and stacked in front of the workbench. Scrawled like graffiti on the walls of dilapidated buildings were the words “Salvation Army.” Those words caught my eyes as effectively as a flashing neon sign. They reeked of irony. “Salvation - was a bit too late for this fami ly,” I mumbled sarcastically to myself.The houseful of furniture that had once been so carefully chosen to complement and blend with the color schemes of the various rooms was indiscriminately crammed together against a single wall. The uncoordinated colors combined in turmoil and lashed out in the greyness of the room.I suddenly became aware of the coldness of the garage, but I didn’t want to goback inside the house, so I made my way through the boxes to the couch. I cleared a space to lie down and curled up, covering myself with my jacket. I hoped my father would return soon with the truck so we could empty the garage and leave the cryptic silence of parting lives behind.(选自Patterns: A Short Prose Reader, by Mary Lou Conlin, published by Houghton Mifflin, 1983.)地狱父母的离婚已经无法挽回,原先的房子已经被卖掉,马上我就要搬走了。

第十四届“四川外国语大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛汉译英组一等奖译文

刻下今天,抗拒遗忘【1】我们知道自己是容易忘记的。

有心人能坚持写下日记,日日记录,到时回头还能翻回去,某一年某一天,字字句句都在纸上,能唤起记忆。

也有人记忆超群,过了多少年,还能细数某时某地某事,让人惊叹。

但大部分的我们呢?我曾记过一阵日记,从开始的日日记,到后来的隔日记,再到后来的不知隔多少日记,终于有一天把日记本尘封在写字台的某个抽屉角落里了。

我也曾与好友仔细回想,在何时何地哪一个场合第一次遇见,却相顾茫然。

【2】这样的无从查考,这样的相顾茫然,并不算得上如何特殊。

【3】生活的大部分形态,总是碎片化的。

一时在东,一时在西,纷繁复杂,并不是那么容易记住的。

我们记住了海潮翻腾,侧耳又听见大江大河奔涌怒吼;记住了大江大河的浪高声宏,耳边又传来远处的人声鼎沸……热点似乎一个接着一个,连时尚流行都以百倍的速度在此起彼伏,每个似乎都在沸点上翻滚。

可新的记忆总是一页页压过旧的,遗忘总在这样不知不觉的侧耳、挪移间发生。

【4】而更多时候,生活的形态,又是屡屡重复的。

连古人都说,“年年岁岁花相似”,相似的花,相似的叶,总是最不容易区分的。

我们记忆里,只留下似曾相识的影子。

提过的话题要再提,理过的逻辑要再理,连听过的故事,也总在天南海北再听到相似的讲述。

“仙桂年年折又生”,如果枝头还是避着风头的朝向,连挂着的果子上的疤痕都一般,谁又能分清是哪一年、哪一月种下的树呢?【5】若说世上事尽是重复,无疑太消极。

而太阳每天都是新的,又高估了普通人心里的饱满度。

我们在光与影里穿行,日久年深。

有这样一个日子,我们停下来,做一个特别的标记,把它从漫长的旅途里区别出来,想想过去,看看前程,也是对自己的一种关怀。

在意义被怀疑、被消解的时候,有这样的庄重的一刻,反观静照,在一片喧腾或琐碎里执着地找到那份属于自己的历史感,也是一种觉醒。

1Record Today, Resist Forgetting【1】Forgetfulness is prone to plague us. There are those who, with unwavering diligence, chronicle their daily affairs in diaries, every word and sentence an evocative trigger for memories of a certain day in a certain year as they flip through the pages in days to come. Others are blessed with prodigious memories, able to recount events from years ago with astonishing clarity. But what about the vast majority of us? I, for one, attempted to keep a diary, only to see my entries dwindle from daily to every other day, and then to sporadic, until I finally sealed it away in a secluded corner of my writing desk drawer. I also endeavored to recall with a friend the precise moment, location, and occasion of our first encounter, but we were both lost in a fog.【2】Such a state of forgetfulness and the ensuing fog-bound befuddlement are par for the course.【3】Life, for the most part, takes on fragmented forms. We may find ourselves here today and there tomorrow, amidst a flurry of complexity that isn’t always easy to commit to memory. Just as we begin to recall the tumultuous ocean tides, the roaring rivers rush to our ears. Once the mighty rivers’ thunderous roar seeps into our memory, the distant din of chatter resounds in our ears. The current of hot topics seems to flow incessantly, with even fashion and trends surging and receding at breakneck speed, each one clamoring for our attention. Nevertheless, new memories unfailingly turn the page on the old, while forgetting sneaks up on us unnoticed amid our shifting attention and meandering movements.【4】More often than not, life feels like a cycle of repetition, as even the anci ents recognized, remarking that “flowers are similar year in and year out.” It is those very similar flowers and leaves that prove most difficult to distinguish, leaving us with faintly familiar shadows in our memory. Topics once discussed resurface, past logical reasoning requires reevaluation, and even the tales we’ve heard before catch echoes of their likeness recounted from the far reaches of the earth. As an ancient Chinese poem states, “the immortal laurel’s branches break and renew each year.”If the branches still shy away from the wind, and their fruit bears the same scars, who then can discern the year or month that saw the planting of the tree?【5】To claim that everything in the world is mere repetition is too bleak a notion. And yet, to assert that the sun rises anew each day is to overestimate the average person's sense of fulfillment. We traverse through light and shadow for years on end. But there comes a moment when we pause and create a special mark to set apart a day from the long procession of time, a moment for us to reflect on the past and gaze toward the future as an act of self-care. In times when meaning is doubted or diminished, such a moment of solemnity allows us to turn inward and unearth our own sense of history amidst the tumult and trivialities of life, which might be deemed a form of awakening.2Embossing the Present, Resisting OblivionBy Yu JinxingTrans. by Cai Qingmei(蔡清美)【1】We recognize our tendency to forget. Those mindful among us persist in maintaining a journal, capturing moments on paper, day byday. As we revisit these pages, every word and phrase can rekindle a forgotten memory. Some among us are blessed with prodigious memory, recounting intricate details of experiences from years past with astonishing precision. But what about the majority? There was a time I maintained a diary, gradually transitioning from daily entries to every other day, until eventually, gaps of weeks appeared between entries. Eventually, the diary found a quiet corner in a drawer at my writing desk. I’ve tried to recall with friends the moment of our first encounter, only to be greeted with mutual bewilderment.【2】Such perplexity, this mutual bewilderment, is not particularly unusual.【3】The larger part of life tends to be fragmented. Moments fleet from one to another, creating a tapestry too intricate to remember easily. Our attention dances from the tumultuous tides to the echoing roar of grand rivers, from the towering waves and thundering rivers to the distant hum of human voices. One trend follows another, each seemingly at its zenith. Yet, the fresh memories continue to eclipse the old ones, and oblivion manifests subtly amidst these shifting focuses.【4】Frequently, life manifests itself in cycles of repetition. Even the ancients noted, “Every year the flowers resemble the previous ones.” Similar flowers, similar leaves, they are always the hardest to differentiate. We retain in our memories only an echo of familiarity. Topics once discussed are revisited, logic previously deduced is reconsidered, and familiar stories are heard again, told with different flavors in different locales. As the sweet osmanthus blooms each year, if the orientation of the branch remains unchanged, even the scars on the hanging fruits resemble each other. Who could then discern in which year and month the tree was planted?【5】To say that everything in the world is repetitive might be too pessimistic. Yet, to claim that each day brings a new sun might overstate our ability to appreciate the nuances of the mundane. We traverse through a world of light and shadows over time. There are days when we pause, mark a special moment, carving it out from the continuum of our journey. It’s a time to reminisce about the past and gaze into the future—a form of self-care. In times when our sense of purpose is questioned or seems to dissipate, such solemn moments of introspection allow us to seek our sense of history amidst the din and trivialities. It’s a form of awakening.。

第七届 “北京外国语大学-《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉一等奖译文

翻译大赛 1 第七届 “北京外国语大学-《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉一等奖译文开阔的领地文/[美)奥尔多利奥波德译/蒋怡颖按县书记员的话来说,眼前一百二十英亩的农场是我的领地。

不过,这家伙可贪睡了,不到日上三竿,是断然不会翻看他那些记录薄的。

那么拂晓时分,农场是怎样的一番景象,是个值得讨论的问题。

管他有没有记录在册呢,反正破晓时漫步走过的每一英亩土地都由我一人主宰,这一点我的爱犬也心领神会。

地域上的重重界限消失了,那种被秷楛的压抑感也随之抛诸脑后。

契据和地图上没法标明的无边光景[1],其美妙展现在每天的黎明时分。

而那份独处的悠然,我本以为在这沙郡中已觅而不得,却不想在每一颗露珠上寻到了它的踪影。

和其他大农场主一样,我也有不少佃户。

他们不在乎租金这事,划起领地来却毫不含糊。

从四月到七月,每天拂晓时刻,他们都会向彼此宣告领地界限,同时以此表明他们对我的臣服。

这样的仪式天天有,都在极庄严的礼节中拉开帷幕,这恐怕和你所设想的大相径庭。

究竟是何方神圣立下这些规矩礼仪,我不得而知。

凌晨三点半,我从这七月的拂晓中汲取了威严,昂扬地走出小屋,一手端着咖啡壶,一手拿着笔记本,这两样象征了我对农场的主权。

望着那颗闪烁着白色光辉的启明星,我在一张长椅上坐下,咖啡壶先搁在一旁,又从衬衣前襟的口袋里取出一只杯子,但愿没人注意到,这么携带杯子确实有点随意。

我掏出手表,给自己倒了杯咖啡,接着把笔记本放在膝盖上。

一切就绪,这意味着仪式即将开始。

三点三十五分到了,离我最近的一只原野春雀用清澈的男高音吟唱起来,宣告北到河岸、南至古老马车道的这片短叶松树林,统统都归他所有。

附近的原野春雀也应声唱起歌来,一只接一只地声明着自己的领地。

歌声里没有争执,至少此时此刻没有。

我就这么聆听着,打心眼里希望在这幸福和谐中,他们的雌雀伴侣也能默许原先的领地划分。

原野春雀的吟唱声还在林中回荡,而这边大榆树上的知更鸟已开始鸣l转,歌声哦亮,他在宣告,这被冰暴[2]折断了枝丫的树权是他的地盘,当然附带着周围的一些也归他所有(对这只知更鸟而言,其实就是指树下草地里的所有蚚划,那里并不算宽敞)。

第五届 英语世界杯 翻译比赛 译文

Limbo等待By Rhonda Lucas朗达‧卢卡斯My parents’ divorce was final. The house had been sold and the day had come to move. Thirty years of the family’s life was now crammed into the garage. The two-by-fours that ran the length of the walls were the only uniformity among the clutter of boxes, furniture, and memories. All was frozen in limbo between the life just passed and the one to come. 父母最终还是离了婚,房子卖了出去,搬家的日子到了。

一个家30年生活的种种现在被塞进了车库。

车库里堆满了各色盒子、家具和回忆,杂乱不堪,从一端延伸到另一端的2英寸厚4英寸宽的木板是唯一整齐有序的。

一切的一切似乎都在焦急地等待着告别过去,迎接未来。

The sunlight pushing its way through the window splattered against a barricade of boxes. Like a fluorescent river, it streamed down the sides and flooded the cracks of the cold, cement floor. I stood in the doorway between the house and garage and wondered if the sunlight would ever again penetrate the memories packed inside those boxes. For an instant, the cardboard boxes appeared as tombstones, monuments to those memories.阳光奋力透过窗户,洒在堆成墙的硬纸板盒子上,像一条荧光河,顺着墙边流,流进冰冷水泥地上的裂缝里。

第二届《英语世界》杯”翻译比赛获奖名单

第二届“《英语世界》杯”翻译比赛获奖名单第二届“《英语世界》杯”翻译比赛评审委员会名单主任刘士聪天津南开大学外国语学院教授评委魏令查《英语世界》编审曹明伦四川大学教授、博士生导师王宏印天津南开大学外国语学院教授、博士生导师李运兴天津师范大学外国语学院教授张文北京第二外国语学院教授钱多秀北京航空航天大学外国语学院教授王丽丽中共中央编译局中央文献翻译部英文处副译审方华文苏州大学外国语学院教授第二届“《英语世界》杯”翻译比赛获奖名单一等奖(共1名)谢培瑶广东外语外贸大学高级翻译学院二等奖(共2名)陈丽解放军外国语学院陆泉枝华东师范大学三等奖(共5名)刘万琪南京大学季成山东万杰医学院郭贤路南京大学外国语学院赵志敏解放军外国语学院朱嘉明对外经济贸易大学优秀奖(共30名)王立冕厦门大学外文学院景杰同济大学外国语学院应雨桦北京外国语大学李敏南京大学张晓生江苏省泗阳县新阳中学外语组王小婧上海外国语大学研究生部林雅红厦门大学嘉庚学院蓝岚广西医科大学外国语学院翁人炬Harvestplan BV.崔秀忠甘肃省景泰县第一中学侯典峰南开大学外国语学院王文赞北京外国语大学胡溶冰上海外国语大学葛娇娇安徽大学黄春利四川大学外国语学院程雯雯四川大学外国语学院关宁黑龙江大学研究生学院王一凯中国人民大学外国语学院于彩晶中国人民大学付康妮四川大学外国语学院马楚楚苏州大学外国语学院荆康宁上海外国语大学唐玲美皇管理咨讯(重庆)有限公司金静西南民族大学外国语学院吴晓芳中国人民大学外国语学院丰云华东师范大学董亮兰州商学院马文迪华东理工大学化工学院吴瑞荣英语周报张方方苏州科技学院。

第四届语言桥杯翻译大赛参考译文

第四届语言桥杯翻译大赛参考译文第一篇:第四届语言桥杯翻译大赛参考译文第四届“语言桥”杯翻译大赛原文、参考译文、译文点评及特等奖译文一、第四届“语言桥”杯翻译大赛原文:When the Sun Stood StillRemember how time used to stretch forever? We are well into summer now here in the city.An early morning alarm gets my daughter, Morgan, up for summer school.My son, Patrick, has gone off with his uncle, and my husband and I have to go to our jobs and try to find a way to cram a vacation in somewhere.Summer wasn’t always like this.When I was growing up in a small California town called Lagunitas, a perfect stillness awaited us when we stepped out of school in June.We had no summer classes, no camps, no relatives to visit.The calendar was a blank.Every day the hills of Lagunitas pressed in and the light pressed down.It was as if the planet had come lazily to a stop so we could all hear the buzzing of the dragonflies above the creek—and the beating of our own hearts.June was far away, September a distant blur.Without school to tell us who we were—fifth-graders or sixth-graders, good students or good-offs—we were free just to be ourselves, to build forts, to moon around the neighborhood with a head full of fantastical schemes.There was time for everything.Minutes were as big as plums, hours the size of watermelons.You could spend a quarter of an hour watching the dust motes in the shaft of sunlight from the doorway and wondering if anybody else could see them.I d on’t really miss those long, slow days.What I miss is summertime, the illusion that the sun is standing still and the future is keeping its distance.Onsummer afternoons, nobody got any older.Kids didn’t have to worry about becoming adults, and adults didn’t have to worry about running out of adulthood.You could lie on your back watching clouds scud across the sky, and maybe later walk down to the store for a Popsicle.You could lose your watch and not miss it for days.These busy kids I’m raising today don’t know what summertime is.They are on city time.“My life is going too fast,” Patrick once grumbled as he got into bed.“This whole day went by just like that.I didn’t have enough fun.”He’s a city child, a child whose fun is packed into short, hurried weekends.Even in summer his hours grow shorter and begin to run together, faster and faster.It won’t be long before an hour—once an eternity—is for him, too, a walk to the grocery store, three phone calls, half a movie.Maybe that’s why we still need long school vacations—to anchor kids to the earth, keep them from rocketing too fast out of childhood.If they have enough time on their hands, they might be among the lucky ones who carry their summertime with them into adulthood.二、参考译文:夏日好时光可还记得以往时间像是永无止境地拉长了的?ADAIR LARA撰思果译夏天真正来到了我们居住的城市。

翻译竞赛英译汉参赛原文 (1)

翻译竞赛英译汉参赛原文Africa on the Silk RoadThe Dark Continent, the Birthplace of Humanity . . . Africa. All of the lands south and west of the Kingdom of Egypt have for far too long been lumped into one cultural unit by westerners, when in reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Africa is not one mysterious, impenetrable land as the legacy of the nineteenth Century European explorers suggests, it is rather an immensely varied patchwork of peoples that can be changed not only by region and country but b y nature’s way of separating people – by rivers and lakes and by mountain ranges and deserts. A river or other natural barrier may separate two groups of people who interact, but who rarely intermarry, because they perceive the people on the other side to be “different” from them.Africa played an important part in Silk Road trade from antiquity through modern times when much of the Silk Road trade was supplanted by European corporate conglomerates like the Dutch and British East India Companies who created trade monopolies to move goods around the Old World instead. But in the heyday of the Silk Road, merchants travelled to Africa to trade for rare timbers, gold, ivory, exotic animals and spices. From ports along the Mediterranean and Red Seas to those as far south asMogadishu and Kenya in the Indian Ocean, goods from all across the continent were gathered for the purposes of trade.One of Africa’s contributions to world cuisine that is still widely used today is sesame seeds. Imagine East Asian food cooked in something other than its rich sesame oil, how about the quintessential American-loved Chinese dish, General Tso’s Chicken? How ‘bout the rich, thick tahini paste enjoyed from the Levant and Middle East through South and Central Asia and the Himalayas as a flavoring for foods (hummus, halva) and stir-fries, and all of the breads topped with sesame or poppy seeds? Then think about the use of black sesame seeds from South Asian through East Asian foods and desserts. None of these cuisines would have used sesame in these ways, if it hadn’t been for the trade of sesame seeds from Africa in antiquity.Given the propensity of sesame plants to easily reseed themselves, the early African and Arab traders probably acquired seeds from native peoples who gathered wild seeds. The seeds reached Egypt, the Middle East and China by 4,000 –5,000 years ago as evidenced from archaeological investigations, tomb paintings and scrolls. Given the eager adoption of the seeds by other cultures and the small supply, the cost per pound was probably quite high and merchants likely made fortunes offthe trade.Tamarind PodsThe earliest cultivation of sesame comes from India in the Harappan period of the Indus Valley by about 3500 years ago and from then on, India began to supplant Africa as a source of the seeds in global trade. By the time of the Romans, who used the seeds along with cumin to flavor bread, the Indian and Persian Empires were the main sources of the seeds.Another ingredient still used widely today that originates in Africa is tamarind. Growing as seed pods on huge lace-leaf trees, the seeds are soaked and turned into tamarind pulp or water and used to flavor curries and chutneys in Southern and South Eastern Asia, as well as the more familiar Worcestershire and barbeque sauces in the West. Eastern Africans use Tamarind in their curries and sauces and also make a soup out of the fruits that is popular in Zimbabwe. Tamarind has been widely adopted in the New World as well as is usually blended with sugar for a sweet and sour treat wrapped in corn husk as a pulpy treat or also used as syrup to flavor sodas, sparkling waters and even ice cream.Some spices of African origin that were traded along the Silk Road have become extinct. One such example can be found in wild silphion whichwas gathered in Northern Africa and traded along the Silk Road to create one of the foundations of the wealth of Carthage and Kyrene. Cooks valued the plant because of the resin they gathered from its roots and stalk that when dried became a powder that blended the flavors of onion and garlic. It was impossible for these ancient people to cultivate, however, and a combination of overharvesting, wars and habitat loss cause the plant to become extinct by the end of the first or second centuries of the Common Era. As supplies of the resin grew harder and harder to get, it was supplanted by asafetida from Central Asia.Other spices traded along the Silk Road are used almost exclusively in African cuisines today – although their use was common until the middle of the first millennium in Europe and Asia. African pepper, Moor pepper or negro pepper is one such spice. Called kieng in the cuisines of Western Africa where it is still widely used, it has a sharp flavor that is bitter and flavorful at the same time –sort of like a combination of black pepper and nutmeg. It also adds a bit of heat to dishes for a pungent taste. Its use extends across central Africa and it is also found in Ethiopian cuisines. When smoked, as it often is in West Africa before use, this flavor deepens and becomes smoky and develops a black cardamom-like flavor. By the middle of the 16th Century, the use and trade of negro pepper in Europe, Western and Southern Asia had waned in favor of black pepper importsfrom India and chili peppers from the New World.Traditional Chinese ShipGrains of paradise, Melegueta pepper, or alligator pepper is another Silk Road Spice that has vanished from modern Asian and European food but is still used in Western and Northern Africa and is an important cash crop in some areas of Ethiopia. Native to Africa’s West Coast its use seems to have originated in or around modern Ghana and was shipped to Silk Road trade in Eastern Africa or to Mediterranean ports. Fashionable in the cuisines of early Renaissance Europe its use slowly waned until the 18th Century when it all but vanished from European markets and was supplanted by cardamom and other spices flowing out of Asia to the rest of the world.The trade of spices from Africa to the rest of the world was generally accomplished by a complex network of merchants working the ports and cities of the Silk Road. Each man had a defined, relatively bounded territory that he traded in to allow for lots of traders to make a good living moving goods and ideas around the world along local or regional. But occasionally, great explorers accomplished the movement of goods across several continents and cultures.Although not African, the Chinese Muslim explorer Zheng He deserves special mention as one of these great cultural diplomats and entrepreneurs. In the early 15th Century he led seven major sea-faring expeditions from China across Indonesia and several Indian Ocean ports to Africa. Surely, Chinese ships made regular visits to Silk Road ports from about the 12th Century on, but when Zheng came, he came leading huge armadas of ships that the world had never seen before and wouldn’t see again for several centuries. Zheng came in force, intending to display China’s greatness to the world and bring the best goods from the rest of the world back to China. Zheng came eventually to Africa where he left laden with spices for cooking and medicine, wood and ivory and hordes of animals. It may be hard for us who are now accustomed to the world coming on command to their desktops to imagine what a miracle it must have been for the citizens of Nanjing to see the parade of animals from Zheng’s cultural Ark. But try we must to imagine the wonder brought by the parade of giraffes, zebra and ostriches marching down Chinese streets so long ago –because then we can begin to imagine the importance of the Silk Road in shaping the world.。

英语世界翻译大赛原文

英语世界翻译大赛原文第一篇:英语世界翻译大赛原文第九届“郑州大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉原文The Whoomper FactorBy Nathan Cobb【1】As this is being written, snow is falling in the streets of Boston in what weather forecasters like to call “record amounts.”I would guess by looking out the window that we are only a few hours from that magic moment of paralysis, as in Storm Paralyzes Hub.Perhaps we are even due for an Entire Region Engulfed or a Northeast Blanketed, but I will happily settle for mere local disablement.And the more the merrier.【1】写这个的时候,波士顿的街道正下着雪,天气预报员将称其为“创纪录的量”。

从窗外望去,我猜想,过不了几个小时,神奇的瘫痪时刻就要来临,就像《风暴瘫痪中心》里的一样。

也许我们甚至能够见识到《吞没整个区域》或者《茫茫东北》里的场景,然而仅仅部分地区的瘫痪也能使我满足。

当然越多越使人开心。

【2】Some people call them blizzards, others nor’easters.My own term is whoompers, and I freely admit looking forward to them as does a baseball fan to ually I am disappointed, however;because tonight’s storm warnings too often turn into tomorrow’s light flurries.【2】有些人称它们为暴风雪,其他人称其为东北风暴。

【英语世界翻译赛往届赛题】-第一届原文及参考翻译

原文:Plutoria AvenueBy Stephen LeacockThe Mausoleum Club stands on the quietest corner of the best residential street in the city.It is a Grecian building of white stone.Above it are great elm-trees with birds–the most expensive kind of birds–singing in the branches.The street in the softer hours of the morning has an almost reverential quiet.Great motors move drowsily along it,with solitary chauffeurs returning at10.30after conveying the earlier of the millionaires to their down-town offices.The sunlight flickers through the elm-trees,illuminating expensive nursemaids wheeling valuable children in little perambulators.Some of the children are worth millions and millions.In Europe,no doubt,you may see in the Unter den Linden Avenue or the Champs Elysées a little prince or princess go past with a chattering military guard to do honour.But that is nothing.It is not half so impressive,in the real sense,as what you may observe every morning on Plutoria Avenue beside the Mausoleum Club in the quietest part of the city.Here you may see a little toddling princess in a rabbit suit who owns fifty distilleries in her own right.There,in a lacquered perambulator,sails past a little hooded head that controls from its cradle an entire New Jersey corporation.The United States attorney-general is suing her as she sits,ina vain attempt to make her dissolve herself into constituent companies. Nearby is a child of four,in a khaki suit,who represents the merger of two trunk line railways.You may meet in the flickered sunlight any number of little princes and princesses far more real than the poor survivals of Europe.Incalculable infants wave their fifty-dollar ivory rattles in an inarticulate greeting to one another.A million dollars of preferred stock laughs merrily in recognition of a majority control going past in a go-cart drawn by an imported nurse.And through it all the sunlight falls through the elm-trees,and the birds sing and the motors hum,so that the whole world as seen from the boulevard of Plutoria Avenue is the very pleasantest place imaginable.Just below Plutoria Avenue,and parallel with it,the trees die out and the brick and stone of the city begins in earnest.Even from the avenue you see the tops of the sky-scraping buildings in the big commercial streets and can hear or almost hear the roar of the elevated railway, earning dividends.And beyond that again the city sinks lower,and is choked and crowded with the tangled streets and little houses of the slums.In fact,if you were to mount to the roof of the Mausoleum Club itself on Plutoria Avenue you could almost see the slums from there.But why should you?And on the other hand,if you never went up on the roof, but only dined inside among the palm-trees,you would never know thatthe slums existed–which is much better.Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich,1914(From John Gross(ed.),The New Oxford Book of English Prose. Oxford:Oxford University Press,1998.pp.670~671)参考翻译:普路托利大道文/〔加拿大〕李科克译/曹明伦莫索利俱乐部坐落在这座城市最适宜居住的街道最安静的一隅。

许渊冲:翻译中国诗,是中国人还是外国人翻得好?

许渊冲:翻译中国诗,是中国人还是外国人翻得好?【导读】理解中国诗词歌剧之难,外国人远远不如中国人,而理解后,中国人用英文表达的能力却不一定在英美译者之下。

所以徐志摩说:中国诗只有中国人译得好。

中国人能否把诗词译成英文,这事有关中国文化能否走向世界,中国梦能否实现的大问题,所以就有了这篇小评论。

2010年12月2日,中国翻译协会举行“翻译文化终身成就奖暨资深翻译家表彰大会”,李肇星(右)和周明伟(左)给本文作者许渊冲颁奖《文汇报》在世界读书日发表了一篇关于《汤显祖戏剧全集》中译英的特别报道,报道中比较了外国人白之(Birch)和中国人汪榕培的译文,结论说:“两个译本各有特色,但明显可以看出译者对于中国传统文化在理解和感受上的深浅之别。

”这就是说:中国译者对汤显祖的戏剧《牡丹亭》理解和感受比外国译者更深,换句话说,就是中国人的翻译比外国人好。

但是外国人有不同的意见。

《英语世界》2015年第3期第105页上说:“在谈及由中国政府资助并由中国译者翻译出版的英文版大中华文库系列丛书时,美国著名汉学家、《中国文学选集》的编译者宇文所安(Stephen Owen)也表达了他的观点。

他说:‘中国正在花钱把中文典籍翻译成英语。

但这项工作绝不可能奏效。

没有人会读这些英文译本。

中国可以更明智地使用其资源。

不管我的中文有多棒,我都绝不可能把英文作品翻译成满意的中文。

译者始终都应该把外语翻译成自己的母语,绝不该把母语翻译成外语。

’”宇文所安宇文所安认为中国不该花钱让中国译者把中文典籍翻译成英文,而应该让英美译者来翻译;中国政府不该资助中国译者翻译出版大中华文库系列丛书。

这是一个中国译者能不能使中国文化走向世界,中国人能不能实现中国梦的大是大非问题,甚至是一个世界文化的大问题,非认真讨论不可。

大中华文库选用了《汤显祖全集》译者汪榕培英译的《诗经》。

《诗经·小雅·采薇》中有四个千古丽句:“昔我往矣,杨柳依依。

【英语世界翻译赛往届赛题】-第三届原文及参考翻译

原文:At Turtle BayBy E.B.WhiteMosquitoes have arrived with the warm nights,and our bedchamber is their theater under the stars.I have been up and down all night, swinging at them with a face towel dampened at one end to give it authority.This morning I suffer from the lightheadedness that comes from no sleep–a sort of drunkenness,very good for writing because all sense of responsibility for what the words say is gone.Yesterday evening my wife showed up with a few yards of netting,and together we knelt and covered the fireplace with an illusion veil.It looks like a bride.(One of our many theories is that mosquitoes come down chimneys.)I bought a couple of adjustable screens at the hardware store on Third Avenue and they are in place in the windows;but the window sashes in this building are so old and irregular that any mosquito except one suffering from elephantiasis has no difficulty walking into the room through the space between sash and screen.(And then there is the even larger opening between upper sash and lower sash when the lower sash is raised to receive the screen–a space that hardly ever occurs to an apartment dweller but must occur to all mosquitoes.)I also bought a very old air-conditioning machine for twenty-five dollars,a great bargain,and I like this machine.It has almost no effect on the atmosphere of the room,merely chipping the edge off the heat,and it makes a loud grinding noise reminiscent of the subway,so that I can snap off the lights,close my eyes, holding the damp towel at the ready,and imagine,with the first stab,that I am riding in the underground and being pricked by pins wielded by angry girls.Another theory of mine about the Turtle Bay mosquito is that he is swept into one’s bedroom through the air conditioner,riding the cool indraft as an eagle rides a warm updraft.It is a feeble theory,but a man has to entertain theories if he is to while away the hours of sleeplessness.I wanted to buy some old-fashioned bug spray,and went to the store for that purpose,but when I asked the clerk for a Flit gun and some Flit,he gave me a queer look,as though wondering where I had been keeping myself all these years.“We got something a lot stronger than that,”he said,producing a can of stuff that contained chlordane and several other unmentionable chemicals.I told him I couldn't use it because I was hypersensitive to chlordane.“Gets me right in the liver,”I said,throwing a wild glance at him.The mornings are the pleasantest times in the apartment,exhaustion having set in,the sated mosquitoes at rest on ceiling and walls,sleeping it off,the room a swirl of tortured bedclothes and abandoned garments,the vines in their full leafiness filtering the hard light of day,the air conditioner silent at last,like the mosquitoes.From Third Avenue comesthe sound of the mad builders–American cicadas,out in the noonday sun. In the garden the sparrow chants–a desultory second courtship,a subdued passion,in keeping with the great heat,love in summertime, relaxed and languorous.I shall miss this apartment when it is gone;we are quitting it come fall,to turn ourselves out to pasture.Every so often I make an attempt to simplify my life,burning my books behind me, selling the occasional chair,discarding the accumulated miscellany.I have noticed,though,that these purifications of mine–to which my wife submits with cautious grace–have usually led to even greater complexity in the long pull,and I have no doubt this one will,too,for I don’t trust myself in a situation of this sort and suspect that my first act as an old horse will be to set to work improving the pasture.I may even join a pasture-improvement society.The last time I tried to purify myself by fire, I managed to acquire a zoo in the process and am still supporting it and carrying heavy pails of water to the animals,a task that is sometimes beyond my strength.(选自An E.B.White Reader,pp.198-200,New York Harper& Row,1966)参考译文:居在龟湾文/〔美〕E.B.怀特译/曹明伦蚊虫随夜暖而至,我们的卧室成了它们的星空剧场。

第十一届“英语世界杯”翻译大赛英译汉原文

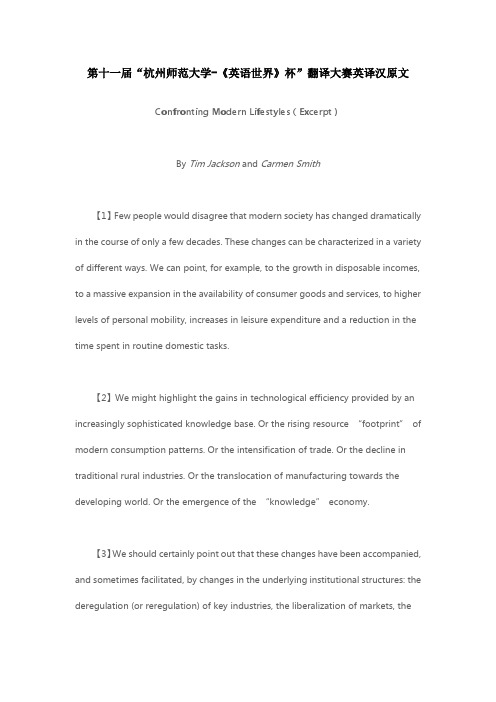

第十一届“杭州师范大学-《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛英译汉原文Confronting Modern Lifestyles(Excerpt)By Tim Jackson and Carmen Smith【1】Few people would disagree that modern society has changed dramatically in the course of only a few decades. These changes can be characterized in a variety of different ways. We can point, for example, to the growth in disposable incomes, to a massive expansion in the availability of consumer goods and services, to higher levels of personal mobility, increases in leisure expenditure and a reduction in the time spent in routine domestic tasks.【2】We might highlight the gains in technological efficiency provided by an increasingly sophisticated knowledge base. Or the rising resource “footprint”of modern consumption patterns. Or the intensification of trade. Or the decline in traditional rural industries. Or the translocation of manufacturing towards the developing world. Or the emergence of the “knowledge”economy.【3】We should certainly point out that these changes have been accompanied, and sometimes facilitated, by changes in the underlying institutional structures: the deregulation (or reregulation) of key industries, the liberalization of markets, theeasing of international trade restrictions, the rise in consumer debt and the commoditization of previously noncommercial areas of our lives.【4】We could also identify some of the social effects that accompanied these changes: a faster pace of life; rising social expectations; increasing divorce rates; rising levels of violent crime; smaller household sizes; the emergence of a “cult of celebrity”; the escalating “message density”of modern living; increasing disparities (in income and time) between the rich and the poor, the emergence of “postmaterialist”values; a loss of trust in the conventional institutions of church, family, and state; and a more secular society.【5】It is clear, even from this cursory overview, that no simple overriding “good”or “bad”trend emerges from this complexity. Rather, modernity is characterized by a variety of trends that often seem to be set (in part at least) in opposition to each other. The identification of a set of “postmaterialist”values in modern society appears at odds with the increased proliferation of consumer goods. People appear to express less concern for material things, and yet have more of them in their lives.【6】The abundance offered by the liberalization of trade is offset by the environmental damage from transporting these goods across distances to reach our supermarket shelves. The liberalization of the electricity market has increasedthe efficiency of generation, reduced the cost of electricity to consumers and at the same time made it more difficult to identify and exploit the opportunities forend-use energy efficiency.【7】To take another example, the emergence of the knowledge economy has increased the availability and the value of information. Simultaneously, it has intensified the complexity of ordinary decision-making in people’s lives. As Nobel laureate Hebert Simon has pointed out, information itself consumes scarce resources. “What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it”. This consuming effect of information makes the concept of “informed choice”at once more important and at the same time more difficult to achieve in modern society.【8】These examples all serve to illustrate that modern lifestyles are both complex and haunted by paradox. This is certainly one of the reasons why policy makers have tended to shy away from the whole question of consumer behavior and lifestyle change. It is clear nonetheless that coming to grips with consumption patterns, understanding the dynamics of lifestyle and influencing people’s attitudes and behaviors are all essential if the kinds of deep environmental targets demanded by sustainable development are to be achieved.。

第十一届“杭州师范大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖名单

第十一届“杭州师范大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖名单作者:来源:《英语世界》2020年第10期英译汉一等奖(1名)刘正飞嘉兴职业技术学院二等奖(2名)张建惠鲁东大学林天晴广东财经大学三等奖(3名)彭楚晗自由翻译安子尧自由译者赖桃广西民族大学优秀奖(43名)钱蒙生南京师范大学张含雪三峡大学郭晓阳自由职业张宇漾江苏师范大学张睿洺国际关系学院张思懿四川外国语大学孙琦西北大学王泽泽山东大学夏杨南京信息工程大学王晓慧中国人民大学王超凡中山大学附属第三医院苟巧巧成都文理学院左欣鑫四川外国语大学王亚委东北财经大学虞洋东北师范大学庞杨洋华中师范大学周圳南京林业大学董敬超自由职业李飞安徽大学姜兆淇杭州师范大学钱江学院熊霞中国民用航空飞行学院赵雁南浙江财经大学陈先宇中国巨石股份有限公司赵宇霞首都经济贸易大学李勇杰广东财经大学张鹏骞厦门大学嘉庚学院刘芸四川大学黄婉仪华南农业大学丁婷北京外国语大学李子纯中央民族大学刘常民台州学院史慧琳浙江大学孙丝雨中南林业科技大学涉外学院凌芊卉文华学院赵阳郑州大学外国语与国际关系学院董媛媛奈曼旗实验中学严雨琪南京林业大学李安晴中国人民大学袁冰心东华大学方倩云暨南大学胡淑媛暨南大学珠海校区翻译学院龚嘉诚苏州大学文正学院姚锡静中南财经政法大学汉译英一等奖(1名)刘向阳思爱普(中国)有限公司二等奖(2名)傅颖浙江商业技师学院何梓健广东外语外贸大学南国商学院三等奖(4名)周建军常州工学院毕明悦中国海洋大学江明霞成都理工大学彭楚晗自由翻译优秀奖(21名)陳颖盈宁波大学李杰杭州师范大学廖雪莹北京外国语大学马勖上海外国语大学张婷婷苏州大学麦嘉澄中山大学黄孟瑶华中师范大学张轩甄广东外语外贸大学胡文明腾讯公司熊婷北京航空航天大学朱莹北京化工大学费及竟上海工程技术大学外国语学院杨千禧北京化工大学熊霞中国民用航空飞行学院林静中国海洋大学赵宇彤延边大学邹建四川乐山施倩倩西南大学苗沈超上海师范大学天华学院施慧静上海工程技术大学白申昊 UCL(伦敦大学学院)组织奖(10名)杭州师范大学北京化工大学四川外国语大学内江师范学院广东财经大学四川大学宁波大学首都经济贸易大学中南林业科技大学广东外语外贸大学。

第十届“中国海洋大学—《英语世界》杯

第十届“中国海洋大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛XX及原文“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛肇始于2021 年,由商务印书馆《英语世界》XX 社主办。

短短数载,大赛参赛人数屡创新高,目前已经成为国内最有影响的翻译赛事之一。

为推动翻译学科进一步,促进中外文化交流,我们秉承“给力英语学习,探寻翻译之星”的理念,于2021年继续举办第十届“《英语世界》杯"翻译大赛,诚邀广大翻译爱好者积极参与,比秀佳译。

第十届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛得到中国海洋大学的大力支持,并由该校冠名本届比赛.2021年的翻译大赛包含“英译汉”和“汉译英”两个组别.大赛初评交给合办院校的老师,以确保大赛评审的权威性和公信力。

复评和终评我们将延续历届传统,从全国XX地邀请知名翻译专家进行评审。

合办院校中国海洋大学外国语学院赞助单位UXXXXre EducationXX韬略教育科技有限XX旗下品牌,秉承“您身边的留学专家”的理念,开展包括XX、XX、加拿大、、新西兰、XX等主流留学XX的留学申请及游学服务.UXXXXre核心成员毕业于世界名校,拥有申请牛津、剑桥、哈佛、斯坦福等大学的丰富经验,深谙欧美名校录取之道,迄今已助力上万名学生实现世界名校梦.协办单位中国翻译协会XX科学翻译XX中国外文局翻译专业资格考评中心中国英汉语比较研究会英汉翻译研究学科XXXX省翻译协会XX省翻译协会XX省翻译理论与教学研究会XX省翻译协会XX省翻译协会XX通译翻译有限XX《外语与翻译》编辑部英文巴士网赛程及评审1. 2021年5月发布大赛XX及原文,10月公布获奖结果,见诸以下XX:《英语世界》2021年第5期(XX及原文)和第10期(获奖结果等)、《英语世界》XX(www。

yingyushijie。

XX)、《英语世界》XX公众平台(XX号:theworldofenglish)、《英语世界》XX方微博(weibo。

XX/theworl dofenglish)、中国海洋大学外国语学院XX(flc。

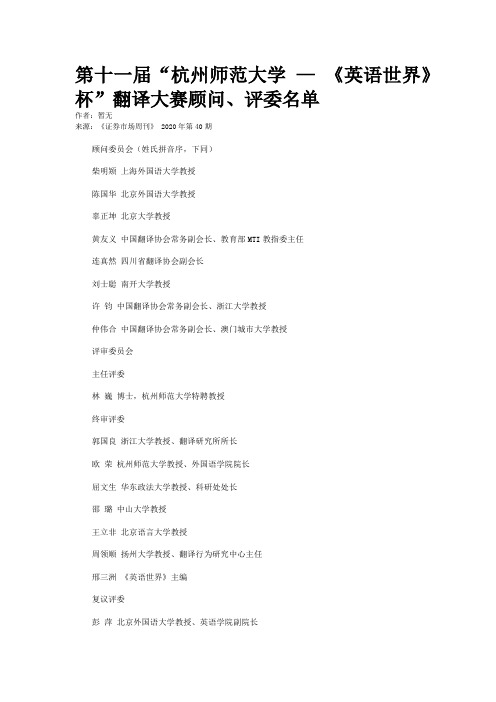

第十一届“杭州师范大学 — 《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛顾问、评委名单

第十一届“杭州师范大学—《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛顾问、评委名单

作者:暂无

来源:《证券市场周刊》 2020年第40期

顾问委员会(姓氏拼音序,下同)

柴明颎上海外国语大学教授

陈国华北京外国语大学教授

辜正坤北京大学教授

黄友义中国翻译协会常务副会长、教育部MTI教指委主任

连真然四川省翻译协会副会长

刘士聪南开大学教授

许钧中国翻译协会常务副会长、浙江大学教授

仲伟合中国翻译协会常务副会长、澳门城市大学教授

评审委员会

主任评委

林巍博士,杭州师范大学特聘教授

终审评委

郭国良浙江大学教授、翻译研究所所长

欧荣杭州师范大学教授、外国语学院院长

屈文生华东政法大学教授、科研处处长

邵璐中山大学教授

王立非北京语言大学教授

周领顺扬州大学教授、翻译行为研究中心主任

邢三洲《英语世界》主编

复议评委

彭萍北京外国语大学教授、英语学院副院长

史宝辉北京林业大学教授、外语学院院长

辛红娟宁波大学教授、外国语学院副院长

初评评委

杭州师范大学:陈军、高乾、黄四宏、吉灵娟、李佩仑、林巍、骆玉峰、钱晔、裘禾敏、沈莉娟、朱越峰 /《英语世界》杂志社:高昕昕、李园林、张迪、赵岭。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

第六届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛原文A Garden That Welcomes StrangersBy Allen LacyI do not know what became of her, and I never learned her name. But I feel that I knew her from the garden she had so lovingly made over many decades.The house she lived in lies two miles from mine – a simple, two-story structure with the boxy plan, steeply-pitched roof and unadorned lines that are typical of houses built in the middle of the nineteenth century near the New Jersey shore.Her garden was equally simple. She was not a conventional gardener who did everything by the book, following the common advice to vary her plantings so there would be something in bloom from the first crocus in the spring to the last chrysanthemum in the fall. She had no respect for the rule that says that tall-growing plants belong at the rear of a perennial border, low ones in the front and middle-sized ones in the middle, with occasional exceptions for dramatic accent.In her garden, everything was accent, everything was tall, and the evidence was plain that she loved three kinds of plant and three only: roses, clematis and lilies, intermingled promiscuously to pleasant effect but no apparent design.She grew a dozen sorts of clematis, perhaps 50 plants in all, trained and tied so that they clambered up metal rods, each rod crowned intermittently throughout the summer by a rounded profusion of large blossoms of dark purple, rich crimson, pale lavender, light blue and gleaming white.Her taste in roses was old-fashioned. There wasn’t a single modern hybrid tea rose or floribunda in sight. Instead, she favored the roses of other ages – the York and Lancaster rose, the cabbage rose, the damask and the rugosa rose in several varieties. She propagated her roses herself from cuttings stuck directly in the ground and protected by upended gallon jugs.Lilies, I believe were her greatest love. Except for some Madonna lilies it is impossible to name them, since the wooden flats stood casually here and there in the flower bed, all thickly planted with dark green lily seedlings. The occasional paper tag fluttering from a seed pod with the date and record of a cross showed that she was an amateur hybridizer with some special fondness for lilies of a warm muskmelon shade or a pale lemon yellow.She believed in sharing her garden. By her curb there was a sign: “This is my garden, and you are welcome here. Take whatever you wish with your eyes, but nothing with your hand.”Until five years ago, her garden was always immaculately tended, the lawn kept fertilized and mowed, the flower bed free of weeds, the tall lilies carefully staked. But then something happened. I don’t know what it was, but the lawn was mowed less frequently, then not at all. Tall grass invaded the roses, the clematis, the lilies. The elm tree in her front yard sickened and died, and when a coastal gale struck, the branches that fell were never removed.With every year, the neglect has grown worse. Wild honeysuckle and bittersweet runrampant in the garden. Sumac, ailanthus, poison ivy and other uninvited things不速之客threaten the few lilies and clematis and roses that still struggle for survival.Last year the house itself went dead. The front door was padlocked and the windows covered with sheets of plywood. For many months there has been a for sale sign out front, replacing the sign inviting strangers to share her garden.I drive by that house almost daily and have been tempted to load a shovel in my car trunk, stop at her curb and rescue a few lilies from the smothering thicket of weeds. The laws of trespass and the fact that her house sits across the street from a police station have given me the cowardice to resist temptation. But her garden has reminded me of mortality; gardeners and the gardens they make are fragile things, creatures of time, hostages to chance and to decay.Last week, the for sale sign out front came down and the windows were unboarded. A crew of painters arrived and someone cut down the dead elm tree. This morning there was a moving van in the driveway unloading a swing set, a barbecue grill, a grand piano and a houseful of sensible furniture. A young family is moving into that house.I hope that among their number is a gardener whose special fondness for old roses and clematis and lilies will see to it that all else is put aside until that flower bed is restored to something of its former self.(选自Patterns: A Short Prose Reader, by Mary Lou Conlin, published by Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983.)。