Participatory Design Process with Older Users

并行工程

并行工程已从理论向实用化方向发展,越来越多的涉及航空、航天、汽车、电子、机械等领域的国际知名企业,通过实施并行工程取得了显著效益。 如美国洛克希德 (Lockheed) 导弹与空间公司 (LMSC) 于 1992 年 10 月接受了美国国防部 (DOD) 用于“战区高空领域防御” (Thaad) 的新型号导弹开发,该公司的导弹开发一般需要 5 年时间,而采用并行工程的方法,最终将产品开发周期缩短 60% 。具体的实行如下: ·改进产品开发流程。在项目工作的前期, LMSC 花费了大量的精力对 Thaad 开发中的各个过程进行分析,并优化这些过程和开发过程支持系统。采用集成化的并行设计方法。 ·实现信息集成与共享。在设计和实验阶段,一些设计、工程变更、试验和实验等数据,所有相关的数据都要进入数据库。并各应用系统之间必须达到有效的信息集成与共享。 ·利用产品数据管理系统辅助并行设计。 LMSC 采用了一个成熟的工程数据管理系统辅助并行化产品开发。通过支持设计和工程信息及其使用的 7 个基本过程 ( 数据获取、存储、查询、分配、检查和标记、工作流管理及产品配置管理 ) ,来有效地管理它的工程数据。 CE 带来的效益:导弹开发周期由过去的 5 年缩短到 24 个月,产品开发周期缩短 60% 。大大缩短了设计评审与检查的时间 ( 一般情况下仅需 3h) ,并且提高了检查和设计的质量。 另外,像 Siemens 重型雷达设备也采用并行工程来改进产品质量及缩短开发周期。其实施有 6 个方面的要求: ·建立“一次开发成功”团队和技术中心 ; ·开发一种新的设计过程控制工具来跟踪循环中的时间延迟,消除无效的等待时间 ; ·引入 IDEF 建模系统,使工程师在建模过程中质疑并改进 ; ·过程控制工具。其软件包含获得每个通过设计中心的设计文件的历史资料以及记录 DCI 的根本原因 ; ·采用 1 个在线系统要求对取消 DCI 负责的工程管理员写出详细原因 ; ·将产品设计小组和产品测试小组合并为数字小组,并在以后负责开发测试,测试考虑则将成为设计过程的一部分。 ABB( 瑞士 ) 火车运输系统建立了支持 CE 的计算机系统、可互操作的网络系统和一致的产品数据模型,组织了设计和制造过程的团队,并应用仿真技术。应用并行工程后大大缩短了产品开发的周期。过去从合同签订到交货需 3~4 年,现在仅用 3~18 个月,对于东南亚的顾客,可在 12 个月内交货。整个产品开发周期缩短 25%~33% ,其中从用户需求到测试平台需 6 个月,缩短了 50% 。 另外,像雷诺 (Renauld) 、通用电力 (GE) 等著名企业通过实施并行工程并取得了显著效益。

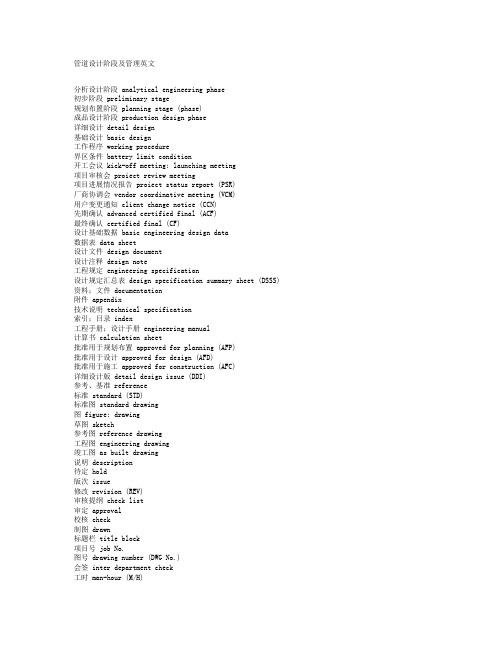

管道设计阶段及管理英文

管道设计阶段及管理英文分析设计阶段 analytical engineering phase初步阶段 preliminary stage规划布置阶段 planning stage (phase)成品设计阶段 production design phase详细设计 detail design基础设计 basic design工作程序 working procedure界区条件 battery limit condition开工会议 kick-off meeting; launching meeting项目审核会 proiect review meeting项目进展情况报告 proiect status report (PSR)厂商协调会 vendor coordinative meeting (VCM)用户变更通知 client change notice (CCN)先期确认 advanced certified final (ACF)最终确认 certified final (CF)设计基础数据 basic engineering design data数据表 data sheet设计文件 design document设计注释 design note工程规定 engineering specification设计规定汇总表 design specification summary sheet (DSSS) 资料;文件 documentation附件 appendix技术说明 technical specification索引;目录 index工程手册;设计手册 engineering manual计算书 calculation sheet批准用于规划布置 approved for planning (AFP)批准用于设计 approved for design (AFD)批准用于施工 approved for construction (AFC)详细设计版 detail design issue (DDI)参考、基准 reference标准 standard (STD)标准图 standard drawing图 figure; drawing草图 sketch参考图 reference drawing工程图 engineering drawing竣工图 as built drawing说明 description待定 hold版次 issue修改 revision (REV)审核提纲 check list审定 approval校核 check制图 drawn标题栏 title block项目号 job No.图号 drawing number (DWG No.)会签 inter department check工时 man-hour (M/H)工日 man-day (M/D)人月 man-month (M/M)项目 project项目经理 project manager设计经理 design manager状态报告 status report安装 erection; installation建设 construction试车 commissioning; running-in 开车 start-up运行中 on stream停车 shut-down大修 over haul模型 model部门 department专业;学科 discipline。

op-ampdesign

ContentsiiiContents1The Op Amp’s Place In The World 1-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Review of Circuit Theory 2-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.1Introduction 2-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.2Laws of Physics 2-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.3Voltage Divider Rule 2-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.4Current Divider Rule 2-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.5Thevenin ’s Theorem 2-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.6Superposition 2-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.7Calculation of a Saturated Transistor Circuit 2-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.8Transistor Amplifier 2-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Development of the Ideal Op Amp Equations 3-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.1Ideal Op Amp Assumptions 3-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.2The Noninverting Op Amp 3-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.3The Inverting Op Amp 3-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.4The Adder 3-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.5The Differential Amplifier 3-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.6Complex Feedback Networks 3-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.7Video Amplifiers 3-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.8Capacitors 3-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.9Summary 3-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Single Supply Op Amp Design Techniques 4-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.1Single Supply versus Dual Supply 4-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2Circuit Analysis 4-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3Simultaneous Equations 4-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.1Case 1: VOUT = +mVIN+b 4-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.2Case 2: VOUT = +mVIN – b 4-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.3Case 3: VOUT = –mVIN + b 4-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.4Case 4: VOUT = –mVIN – b 4-19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.4Summary 4-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Feedback and Stability Theory 5-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.1Why Study Feedback Theory?5-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.2Block Diagram Math and Manipulations 5-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.3Feedback Equation and Stability 5-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Contentsiv 5.4Bode Analysis of Feedback Circuits5-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.5Loop Gain Plots are the Key to Understanding Stability5-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.6The Second Order Equation and Ringing/Overshoot Predictions5-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.7References5-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6Development of the Non Ideal Op Amp Equations6-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.1Introduction6-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.2Review of the Canonical Equations6-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.3Noninverting Op Amps6-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.4Inverting Op Amps6-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.5Differential Op Amps6-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7Voltage-Feedback Op Amp Compensation7-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.1Introduction7-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.2Internal Compensation7-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.3External Compensation, Stability, and Performance7-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.4Dominant-Pole Compensation7-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.5Gain Compensation7-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.6Lead Compensation7-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.7Compensated Attenuator Applied to Op Amp7-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.8Lead-Lag Compensation7-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.9Comparison of Compensation Schemes7-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7.10Conclusions7-21. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8Current-Feedback Op Amp Analysis8-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.1Introduction8-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.2CFA Model8-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.3Development of the Stability Equation8-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.4The Noninverting CFA8-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.5The Inverting CFA8-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.6Stability Analysis8-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.7Selection of the Feedback Resistor8-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.8Stability and Input Capacitance8-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.9Stability and Feedback Capacitance8-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.10Compensation of CF and CG8-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8.11Summary8-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9Voltage- and Current-Feedback Op Amp Comparison9-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.1Introduction9-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.2Precision9-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.3Bandwidth9-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.4Stability9-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.5Impedance9-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9.6Equation Comparison9-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ContentsvContents 10Op Amp Noise Theory and Applications 10-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.1Introduction 10-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2Characterization 10-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2.1rms versus P-P Noise 10-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2.2Noise Floor 10-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2.3Signal-to-Noise Ratio 10-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2.4Multiple Noise Sources 10-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.2.5Noise Units 10-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3Types of Noise 10-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3.1Shot Noise 10-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3.2Thermal Noise 10-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3.3Flicker Noise 10-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3.4Burst Noise 10-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.3.5Avalanche Noise 10-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.4Noise Colors 10-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.4.1White Noise 10-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.4.2Pink Noise 10-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.4.3Red/Brown Noise 10-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5Op Amp Noise 10-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.1The Noise Corner Frequency and Total Noise 10-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.2The Corner Frequency 10-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.3Op Amp Circuit Noise Model 10-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.4Inverting Op Amp Circuit Noise 10-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.5Noninverting Op Amp Circuit Noise 10-17. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.6Differential Op Amp Circuit Noise 10-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.5.7Summary 10-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.6Putting It All Together 10-19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10.7References 10-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Understanding Op Amp Parameters 11-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.1Introduction 11-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.2Operational Amplifier Parameter Glossary 11-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3Additional Parameter Information 11-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.1Input Offset Voltage 11-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.2Input Current 11-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.3Input Common Mode Voltage Range 11-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.4Differential Input Voltage Range 11-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.5Maximum Output Voltage Swing 11-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.6Large Signal Differential Voltage Amplification 11-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.7Input Parasitic Elements 11-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.8Output Impedance 11-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.9Common-Mode Rejection Ratio 11-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.10Supply Voltage Rejection Ratio 11-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11.3.11Supply Current 11-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Contentsvi 11.3.12Slew Rate at Unity Gain11-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11.3.13Equivalent Input Noise11-17. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11.3.14Total Harmonic Distortion Plus Noise11-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11.3.15Unity Gain Bandwidth and Phase Margin11-19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11.3.16Settling Time11-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12Instrumentation: Sensors to A/D Converters12-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.1Introduction12-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.2Transducer Types12-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.3Design Procedure12-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.4Review of the System Specifications12-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.5Reference Voltage Characterization12-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.6Transducer Characterization12-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.7ADC Characterization12-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.8Op Amp Selection12-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.9Amplifier Circuit Design12-16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.10Test12-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.11Summary12-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12.12References12-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13Wireless Communication: Signal Conditioning for IF Sampling13-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.1Introduction13-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.2Wireless Systems13-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.3Selection of ADCs/DACs13-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.4Factors Influencing the Choice of Op Amps13-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.5Anti-Aliasing Filters13-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.6Communication D/A Converter Reconstruction Filter13-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.7External Vref Circuits for ADCs/DACs13-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.8High-Speed Analog Input Drive Circuits13-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13.9References13-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14Interfacing D/A Converters to Loads14-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.1Introduction14-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.2Load Characteristics14-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.2.1DC Loads14-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.2.2AC Loads14-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3Understanding the D/A Converter and its Specifications14-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3.1Types of D/A Converters — Understanding the Tradeoffs14-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3.2The Resistor Ladder D/A Converter14-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3.3The Weighted Resistor D/A Converter14-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3.4The R/2R D/A Converter14-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.3.5The Sigma Delta D/A Converter14-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.4D/A Converter Error Budget14-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.4.1Accuracy versus Resolution14-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14.4.2DC Application Error Budget14-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ContentsviiContents 14.4.3AC Application Error Budget 14-8. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.4.4RF Application Error Budget 14-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.5D/A Converter Errors and Parameters 14-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.5.1DC Errors and Parameters 14-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.5.2AC Application Errors and Parameters 14-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.6Compensating For DAC Capacitance 14-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.7Increasing Op Amp Buffer Amplifier Current and Voltage 14-19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.7.1Current Boosters 14-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.7.2Voltage Boosters 14-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.7.3Power Boosters 14-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14.7.4Single-Supply Operation and DC Offsets 14-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Sine Wave Oscillators 15-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.1What is a Sine Wave Oscillator?15-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.2Requirements for Oscillation 15-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.3Phase Shift in the Oscillator 15-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.4Gain in the Oscillator 15-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.5Active Element (Op Amp) Impact on the Oscillator 15-5. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.6Analysis of the Oscillator Operation (Circuit)15-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7Sine Wave Oscillator Circuits 15-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.1Wien Bridge Oscillator 15-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.2Phase Shift Oscillator, Single Amplifier 15-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.3Phase Shift Oscillator, Buffered 15-15. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.4Bubba Oscillator 15-17. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.5Quadrature Oscillator 15-18. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.7.6Conclusion 15-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15.8References 15-21. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Active Filter Design Techniques 16-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.1Introduction 16-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2Fundamentals of Low-Pass Filters 16-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2.1Butterworth Low-Pass FIlters 16-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2.2Tschebyscheff Low-Pass Filters 16-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2.3Bessel Low-Pass Filters 16-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2.4Quality Factor Q 16-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.2.5Summary 16-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.3Low-Pass Filter Design 16-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.3.1First-Order Low-Pass Filter 16-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.3.2Second-Order Low-Pass Filter 16-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.3.3Higher-Order Low-Pass Filters 16-19. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.4High-Pass Filter Design 16-21. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.4.1First-Order High-Pass Filter 16-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.4.2Second-Order High-Pass Filter 16-24. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16.4.3Higher-Order High-Pass Filter 16-26. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Contentsviii 16.5Band-Pass Filter Design16-27. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.5.1Second-Order Band-Pass Filter16-29. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.5.2Fourth-Order Band-Pass Filter (Staggered Tuning)16-32. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.6Band-Rejection Filter Design16-36. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.6.1Active Twin-T Filter16-37. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.6.2Active Wien-Robinson Filter16-39. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.7All-Pass Filter Design16-41. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.7.1First-Order All-Pass Filter16-44. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.7.2Second-Order All-Pass Filter16-44. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.7.3Higher-Order All-Pass Filter16-45. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.8Practical Design Hints16-47. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.8.1Filter Circuit Biasing16-47. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.8.2Capacitor Selection16-50. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.8.3Component Values16-52. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.8.4Op Amp Selection16-53. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.9Filter Coefficient Tables16-55. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16.10References16-63. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17Circuit Board Layout Techniques17-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.1General Considerations17-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.1.1The PCB is a Component of the Op Amp Design17-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.1.2Prototype, Prototype, PROTOTYPE!17-1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.1.3Noise Sources17-2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.2PCB Mechanical Construction17-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.2.1Materials — Choosing the Right One for the Application17-3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.2.2How Many Layers are Best?17-4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.2.3Board Stack-Up — The Order of Layers17-6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.3Grounding17-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.3.1The Most Important Rule: Keep Grounds Separate17-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.3.2Other Ground Rules17-7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.3.3 A Good Example17-9. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.3.4 A Notable Exception17-10. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.4The Frequency Characteristics of Passive Components17-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.4.1Resistors17-11. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.4.2Capacitors17-12. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.4.3Inductors17-13. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.4.4Unexpected PCB Passive Components17-14. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.5Decoupling17-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.5.1Digital Circuitry — A Major Problem for Analog Circuitry17-20. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.5.2Choosing the Right Capacitor17-21. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.5.3Decoupling at the IC Level17-22. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.5.4Decoupling at the Board Level17-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.6Input and Output Isolation17-23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17.7Packages17-24. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .。

Process Design

A process design is a network of interconnected vessels joined by pipes. Obviously it is important to calculate the flows through every vessel and pipe so that they can be correctly sized. This must be done not only for the conditions, which exist during normal production but also for those conditions, which appertain during the start-up period and for those conditions which could occur in the event of an emergency shut-down. Certain pipes and vessels are specified solely for the latter purpose. Although it is hoped that it will not be necessary to use the emergency systems, periodic testing of it (particularly the associated controls) is essential.Knowledge of the mass and volumetric flow rates for each part of the plant results from solution of the material balance. Energy balances are also important since questions such as “what is the thermal duty?”need to be answered.For a process plant consisting of a mixer, reactor and separator, the balances can be performed unit by unit. The product stream from the mixer is one of the feed streams to the reactor, while the product stream from the reactor is the feed to the separator.However, sequential calculations are impossible if a flow stream from a downstream unit is returned to a unit upstream.Recycle problems arise whenever there is a need to recycle unconverted reactant. Even near equilibrium conversion in the Haber process for ammonia would achieve only 25 percent conversion and so the nitrogen and hydrogen are recycled. The overall conversion of reactants into products can be made to be nearly 100 percent. The synthesis of methanol from carbon monoxide and hydrogen is similar in that a recycle is essential because the conversion is again about 25 percent. The production of vinyl chloride from ethylene also involves recycle streams, and many more examples of this sort could be given. More complex processes often involve several recycle loops, and at the process design stage consideration has to be given to the effect they will have not only on steady-state operation but also on the start-up process.Although the type of work outlined above will have been unfamiliar to most readers, it should be clear that the flow rates and compositions of theprocess streams are not only important but also relatively simple to obtain.。

工程全寿命设计名词解释

工程全寿命设计名词解释英文回答:Whole Life Design.Whole Life Design (WLD) is a comprehensive approach to building design that considers the entire lifecycle of a building, from planning and construction to operation, maintenance, and eventual reuse or demolition. It seeks to optimize the building's environmental, economic, and social performance over its entire lifespan.Key principles of WLD include:Long-term thinking: Considering the building beyondits initial design and construction, including future renovations, expansions, and repurposing.Systems thinking: Understanding the interrelationships between the building, its occupants, and the environment.Integrated design: Collaborating with stakeholders from various disciplines to optimize the building's performance during all phases of its lifecycle.Adaptive design: Designing buildings that can beeasily modified and reconfigured to meet changing needs and conditions.Life cycle assessment: Evaluating the environmental and economic impacts of the building throughout its lifespan.End-of-life planning: Considering the future demolition or reuse of the building, including materials recycling and waste reduction.中文回答:全寿命设计。

造船cbpd阶段划分

造船cbpd阶段划分造船CBPD阶段划分是指在船舶建造过程中的CBPD(Conceptual Design, Basic Design, Production Design)三个阶段的划分。

下面我将从多个角度全面完整地回答这个问题。

1. 概念设计阶段(Conceptual Design):概念设计阶段是船舶设计的起点,主要目标是确定船舶的基本特征和性能要求。

在这个阶段,设计师会与船东或船舶运营者进行沟通,了解他们的需求和期望。

然后,设计师会进行初步设计,包括船舶的外形、尺寸、排水量、载重能力等。

此外,概念设计阶段还会考虑到船舶的航行特性、稳性、推进系统等方面的因素。

2. 基本设计阶段(Basic Design):基本设计阶段是在概念设计阶段确定了船舶的基本特征后进行的进一步设计。

在这个阶段,设计师会对船舶的结构、系统、设备等进行详细设计。

基本设计阶段的目标是确保船舶的结构强度、稳性、舒适性、安全性等满足相关的规范和标准。

此外,基本设计阶段还会涉及到船舶的布置设计、系统集成、材料选择等方面的内容。

3. 生产设计阶段(Production Design):生产设计阶段是在基本设计阶段完成后进行的最后一阶段设计。

在这个阶段,设计师会为船舶的建造提供详细的施工图纸和技术文件。

生产设计阶段的目标是确保船舶的建造过程能够顺利进行,并且满足相关的质量标准和要求。

在这个阶段,设计师会与船厂的工程师密切合作,解决施工中可能出现的问题,并对设计进行必要的调整和优化。

总结起来,造船CBPD阶段划分包括概念设计阶段、基本设计阶段和生产设计阶段。

这三个阶段分别从船舶的基本特征确定、详细设计到施工图纸提供,确保船舶的设计和建造过程能够满足相关的要求和标准。

这个阶段划分对于船舶建造的顺利进行具有重要的指导意义。

[VIP专享]7外文翻译译文

![[VIP专享]7外文翻译译文](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/29c7ee5dba1aa8114431d961.png)

本科毕业设计外文翻译Assessment of European seismic design proceduresfor steel framed structures欧洲对钢框架结构抗震设计的评估作者姓名尹金程指导教师秦植海所在院系成人教育学院专业班级10土木完成日期 _____2012.6欧洲对钢框架结构抗震设计的评估1介绍虽然抗震设计实质性进展受益匪浅,近年来,需要提供实用和相对简单的设计方法,不可避免地导致各种各样的简化和理想化。

这些假设,某些情况下,有广告影响预期的抗震性能,因此在合理性和可靠性设计的方法下。

有必要的设计概念和应用不断评估和修改规则是根据最近的研究和对地震的行为改进的理解。

为此,本文在评估潜在的方法和主要流程采用钢结构工程的抗震设计中,用强调欧洲设计规定,制定本规定。

按照现行的抗震设计实践,这在欧洲被表示Eurocode 8(EC8)(2004),结构也可以设计出系统根据或耗散行为。

这位前,藉此结构尺寸进行回应主要集中在弹性范围内,通常是有限的地区地震活动或结构的低特殊用途与重要性。

否则,编码的目的是要实现节约型设计被耗散行为在相当大的弹性变形能得到满足在重大的地震事件。

在案件的不规则或复杂的结构,详细的非-线性动态的分析可能是必要的。

然而,常规结构设计的系统具有耗散通过指定一个经常表演结构行为因素(例如力量还原或修改因素),用它来减少所造成的指定代码,正如有弹性响应谱。

这是进行结合的能力设计概念,需要采用一种适宜的容量的确定基于一个预先定义的结构塑料机械(通常称为失效模式),伴随着提供充分的在塑性区和足够的延性等因素为其它地区。

虽然基本设计原则的能力设计可能不是故意在各种不同实际的程序代码,可以在常随因为不同的行为假设理想化和理想化设计。

摘要本文检视主要设计方法和行为方面的抗力矩典型配置和中心支撑帧。

虽然这项研究主要在欧洲的指导下,我们的讨论也涉及到规定(以1999年,2002年,2003 2005a,b作比较)。

再生混凝土-钢组合结构PBL连接件抗剪力学性能研究

再生混凝土-钢组合结构PBL连接件抗剪力学性能研究发布时间:2022-12-09T08:14:00.841Z 来源:《中国建设信息化》2022年27卷8月15期作者:曾婧1[导读] 再生混凝土-钢组合结构凭借优越的性能在现代建筑中有广泛的应用。

曾婧1(湖南交通职业技术学院长沙 410000)摘要:再生混凝土-钢组合结构凭借优越的性能在现代建筑中有广泛的应用。

其中组合结构连接件最重要的两个力学性能指标是极限抗剪承载力和抗剪刚度。

本文应用ABAQUS有限元分析软件对PBL连接件进行精细三维实体有限元分析,混凝土的本构关系选用弹塑性本构模型和损伤力学模型,混凝土的破坏准则采用Willam Warnke5参数准则,采用实体推出试验来对PBL连接件的抗剪力学性能进行研究,建立了有限元数值模型。

对PBL连接件抗剪力学性能研究,并给出了研究结果。

关键词:抗剪力学性能;推出试验;有限元分析;中图分类号:TU398.9Abstract: The composite structure of recycled concrete and steel is widely used in modern buildings due to its superior performance. The two most important mechanical performance indexes of composite structure connectors are ultimate shear capacity and shear stiffness. In this paper, ABAQUS finite element analysis software is used to conduct a fine three-dimensional solid finite element analysis of the stud shear connector. The elasto-plastic constitutive model and damage mechanics model are used for the constitutive relationship of concrete. WillamWarnke 5 parameter criterion is used for the failure criterion of concrete. The physical pushout test is used to study the shear mechanical properties of PBL connectors, and a finite element numerical model is established. The shear mechanical properties of PBL connectors are studied, and the research results are given.Key words: shear mechanical property; Push out test; Finite element analysis;正文:背景概述近年来,随着我国经济、工业实力不断的增强,建筑领域也取得了新的突破。

英语翻译

ABSTRACTAlthough the concept of Prevention through Design (PtD) is not new, many injuries still occur at construction sites because it is poorly implemented by engineers and architects,虽然通过设计预防的概念(PTD)是不是新的,许多伤害仍然发生在建筑工地的因为它是由工程师和建筑师执行不力,or it is not implemented at all. The aim of this paper is to quantify how Prevention through Design is taught in university design or construction courses offered as part of Engineering and Architecture under/degrees in Spain that focus on the construction of concrete structures. Objective and subjective methodologies were used to compare courses from the under/degrees taught in the previous system (Old) and those under the Bologna process.或者它根本没有实施。

本文的目的是量化如何预防通过设计在大学的设计或施工课程提供的工程和建筑的一部分,在西班牙/度,专注于混凝土结构的建设。

客观和主观的方法被用来比较从下/度教前系统课程(旧)和博洛尼亚进程。

A survey of 454 Engineering and Architecture students was conducted, course lecturers were interviewed,调查的454个工程和建筑的学生进行了调查,课程讲师进行了采访,and an objective analysis of the contents of the syllabi in the under/degrees was carried out. Occupational Health and Safety had a greater presence and importance in the courses under the Old degrees than those created to comply with the Bologna process.在下/程度的教学大纲的内容进行客观的分析。

老旧小区改造图纸设计工作流程

老旧小区改造图纸设计工作流程英文回答:The workflow for designing renovation blueprints for old residential communities typically involves several steps. I have been involved in such projects before, so I can provide a detailed account of the process.1. Initial Assessment: The first step is to conduct a thorough assessment of the existing conditions in the old residential community. This includes evaluating the overall infrastructure, identifying any structural issues, and understanding the needs and preferences of the residents. This assessment helps in determining the scope and scale of the renovation project.For example, when I worked on a renovation project for an old community, we started by conducting surveys and interviews with the residents to understand their requirements. We also inspected the buildings andinfrastructure to identify any areas that needed immediate attention.2. Concept Development: Once the initial assessment is complete, the next step is to develop design concepts for the renovation. This involves brainstorming ideas, creating sketches, and considering various architectural andaesthetic elements.In one project, we organized design workshops with the residents to gather their input and ideas. We thentranslated those ideas into conceptual designs that incorporated modern amenities while preserving the community's historical charm.3. Detailed Design: After finalizing the design concept, the next step is to create detailed blueprints and construction drawings. This includes specifying materials, dimensions, and technical details.During this phase, we collaborated with architects, engineers, and interior designers to ensure that therenovation plans met all safety and functional requirements. We also worked closely with contractors to ensurefeasibility and cost-effectiveness.4. Review and Approval: Once the detailed design is complete, it is essential to review and obtain approvalfrom relevant authorities and stakeholders. This mayinclude local government agencies, community associations, and residents.In my experience, we had to present our designproposals to a community board for review and approval. We incorporated their feedback and made necessary revisions to ensure that the final blueprints met everyone's expectations.5. Implementation: After obtaining approval, the final step is to implement the renovation plans. This involves coordinating with construction teams, overseeing the progress, and ensuring that the design specifications are followed.During the implementation phase, it is crucial to maintain effective communication with the residents and address any concerns or issues that may arise. Regular site visits and progress meetings help in keeping everyone informed and engaged throughout the construction process.中文回答:老旧小区改造图纸设计的工作流程通常包括以下几个步骤。

实验楼设计的注意事项

实验楼设计的注意事项英文版:Experiment Building Design Considerations1. Clear Experiment GoalsAt the initial stage of experiment building design, the goals and types of experiments should be clearly defined to provide appropriate space and facilities for different types of experiments.2. Spatial Layout ConsiderationReasonable spatial layout can ensure the smooth progress of experiments. During the design process, factors such as laboratory size, height, and width of aisles should be considered to ensure optimal space utilization and efficiency.3. Safety PrecautionsThe design of the experiment building must place a high emphasis on safety precautions, such as setting up emergency exits, equipping with fire extinguishers, and installing alarm systems, to ensure the safety of the laboratory.4. Equipment Selection & ConfigurationThe selection and configuration of experimental equipment should be based on the needs and budget of the experiments, ensuring that the selected equipment meets the experimental requirements and has a high cost-effectiveness ratio.5. Ventilation & Lighting DesignGood ventilation and lighting conditions are crucial for the smooth conduct of experiments. During the design phase, sufficient consideration should be given to the ventilation and lighting needs of the laboratory to ensure good indoor air quality and sufficient lighting.6. Environmental Protection & Energy EfficiencyThe design of the experiment building should meet environmental protection and energy efficiency requirements, adopting environmentally friendly materials and technologies to reduce energy consumption and minimize the impact on the environment.7. Optimization of Operating ProceduresThe design of the experiment building should facilitate the optimization of operational procedures, reducing unnecessary steps and time, and enhancing experimental efficiency.8. Compliance with RegulationsThe design of the experiment building must comply with relevant national and local regulations and standards, ensuring the legality and compliance of the laboratory.中文版:1. 明确实验目标在实验楼设计之初,应明确实验的目标和类型,以便为不同类型的实验提供合适的空间和设施。

过程设备设计的流程

过程设备设计的流程Process equipment design is a complex and critical process that requires careful consideration of various factors. It involves the creation of equipment and systems that are essential for carrying out specific industrial processes. From the initial concept development to the final implementation, every stage of the design process must be meticulously planned and executed to ensure the efficiency, safety, and reliability of the equipment.过程设备设计是一个复杂而关键的过程,需要仔细考虑各种因素。

它涉及到为执行特定工业过程所必需的设备和系统的创建。

从最初的概念开发到最终实施,设计过程的每个阶段都必须被精心设计和执行,以确保设备的效率、安全性和可靠性。

One of the key aspects of process equipment design is understanding the specific requirements of the process being carried out. This involves conducting a detailed analysis of the process parameters, such as temperature, pressure, flow rate, and chemical compatibility, to determine the design specifications of the equipment. By carefully considering these factors, designers canensure that the equipment is well-suited to the needs of the process and can perform optimally under the given conditions.过程设备设计的关键方面之一是了解正在进行的过程的具体要求。

工艺设备的结构介绍 英语作文

工艺设备的结构介绍英语作文Title: Introduction to Process Equipment Structure**Introduction:**Process equipment plays a crucial role in various industries, facilitating the production, processing, and handling of raw materials and products. Understanding the structure of process equipment is essential for ensuring efficient operation, maintenance, and safety. In this essay, we will explore the structure of process equipment and its components.**Structure of Process Equipment:**1. **Framework or Housing:**- The framework or housing of process equipment provides structural support and enclosure for internal components.- It is typically made of sturdy materials such as steel, stainless steel, or reinforced concrete to withstand operating conditions and loads.2. **Internal Components:**- Process equipment contains various internal components depending on its specific function and application.- Common internal components include vessels, tanks, reactors, heat exchangers, pumps, compressors, valves, pipes, and instrumentation.3. **Vessels and Tanks:**- Vessels and tanks are containers used for storing, mixing, reacting, or separating liquids, gases, or solids.- They are typically cylindrical or rectangular in shape and constructed from materials such as steel, stainless steel, or fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP).- Vessels and tanks may feature internal baffles, agitators, heating or cooling jackets, and access openings for maintenance and inspection.4. **Reactors:**- Reactors are vessels designed for chemical reactions, such as synthesis, polymerization, or decomposition.- They may have specialized internal features, such as mixing blades, baffles, catalyst beds, and temperature control systems.- Reactors are constructed from corrosion-resistant materials and may be insulated or jacketed for heat transfer.5. **Heat Exchangers:**- Heat exchangers facilitate the transfer of heat between two fluids at different temperatures.- They consist of a series of tubes or plates through which the hot and cold fluids flow, exchanging heat without mixing. - Heat exchangers may be shell-and-tube, plate-and-frame, or finned-tube designs, depending on the application and space constraints.6. **Pumps and Compressors:**- Pumps and compressors are used to transport liquids or gases within process equipment or between different process units.- They consist of a motor or engine-driven impeller or rotor that creates fluid flow or compression.- Pumps are classified based on their operating principle, such as centrifugal, positive displacement, or rotary pumps, while compressors are categorized as centrifugal, reciprocating, or rotary compressors.7. **Valves and Instrumentation:**- Valves control the flow, pressure, and direction of fluids within process equipment.- They include gate valves, globe valves, ball valves, and control valves, operated manually, pneumatically, or electrically.- Instrumentation devices, such as pressure gauges, temperature sensors, flow meters, and level indicators, monitor and control process parameters to ensure safe and efficient operation.**Conclusion:**The structure of process equipment encompasses a diverse range of components and systems tailored to specific industrial processes and applications. By understanding the function and design of these components, engineers and operators can optimize the performance, reliability, and safety of process equipment in various industries.。

Participatory design

The Role and Task of the System Architect-design,brainstorm,explainthink,analyselisten, talk,walk aroundwrite,consolidate,browsepresent,meet, teach,discussread,reviewtest,integrateassist project leaderwith work breakdown,schedule, riskstravel tocustomer,supplier,conferenceGerrit MullerPhilips Research IST-SWA-IAProf Holstlaan4(WL01)5656AA Eindhoven The Netherlandsgerrit.muller@AbstractThe role of the system architect is described from three viewpoints:deliverables, responsibilities and activities.This description shows the inherent tension in this role:a small set of hard deliverables,covering a fuzzy set of responsibilities,hiding an enormous amount of barely visible day-to-day work.DistributionThis article or presentation is written as part of the Gaudíproject.The Gaudíproject philosophy is to improve by obtaining frequent feedback.Frequent feedback is pursued by an open creation process.This document is published as intermediate or nearly mature version to get feedback.Further distribution is allowed as long as the document remains complete and unchanged.All Gaudídocuments are available at:/natlab/sysarch/version:0.1status:preliminary draft24th September20011Deliverables of the System ArchitectThe deliverables of a System Architect are stacks of paper,or the electronic equiv-alent,symbolized by the stack infigurefig:RoleSAdeliverables.Figure1:Deliverables of a system architect consists of a stack of paperTable1shows the main deliverables of a System Architect.Quite often the System Architect does not even produce all deliverables mentioned here,but does he take the responsibility for these deliverables by coordinating and integrating contributions of others.Requirements(what is needed)Specification(what will be realized)Design(how the system will be realized)Verification Specification(how the system will be verified)Verification Report(the result of the verification)Feasibility Report(the results of a feasibility study)RoadmapTable1:Classification of the main deliverables of a System Architect2System Architect ResponsibilitiesThe System Architect has a limited set of primary responsibilities,as visualized in figure2.The system architect has many secondary responsibilities,which are more specific.These secondary responsibilities have an owner,as shown in table2.In[2]the purpose of the system architecture process is described in the same terms as used here.In short the primary responsibility of the System Architect is to ensure the good functioning of the System Architecture Process.In practice this responsibility is often shared by a team of System Architects,with one chief architect taking the overall responsibility.BalanceConsistencysystemsubsystemmodule Overview Requirement Spec DesignRealizationDecomposition IntegrationKISSElegance SimpleIntegrityFigure 2:The primary responsibilities of the system architect are not "SMART"responsibility business plan,profitproject leadermarket,salabilitytechnology managerprocess,peopleengineersTable 2:(Incomplete)list of secondary responsibilities of the system architect and the related primary owner3What does the System Architect do?Figure 3shows the variety of activities of the day to day work of a system architect.A large amount of time is spent in gathering,filtering,processing and discussing detailed data in an informal setting.These activities are complemented by more formal activities like meetings,visits,reviews etcetera.The system architect is rapidly switching between specific detailed views and abstract higher level views.The concurrent development of these views is a key characteristic of the way a system architect works.Abstractions only exist for concrete factsSystem Architects which stay too long at "high"abstraction levels drift away from reality,by creating their own virtual reality.Figure 4shows the bottom up elicitation of higher level views.A system architect sees a tremendous amount of details,most of these details are skipped,a smaller amount is analyzed or discussed.A small subset of these discussed details is shared as an issue with a broader team of designers and architects.Finally thedesign, brainstorm, explain think, analyselisten, talk, walk aroundwrite, consolidate, browsepresent,meet, teach, discussread, reviewtest, integrateassist project leader with work breakdown, schedule, risks travel to customer, supplier, conferenceFigure 3:The System Architect performs a large amount of activities,where most of the activities are barely visible for the environment,but which are crucial for his functioningsystem architect consolidates the outcome in a limited set of views.The order of magnitude numbers cover the activities in one year.The opposite flow in 4is the implementation of many of the responsibilities of the system architect.By providing overview,insight and fact-based direction a simple,elegant,balanced and consistent design will crystalize,where the integrity of designs goals and solutions are maintained during the project.4Task versus RoleThe task of the system architect is to generate the agreed deliverables,see section 1This measurable output is requested and tracked by the related managers:the project leader and the line manager.Many managers appreciate their architects only for this visible subset of their work.The deliverables are only one of the means to fulfil the System Architect Respon-sibilities,as described in section 2.The system architect is doing a lot of nearly invisible work to achieve the system level goals,his primary responsibility.This work is described in section 3.Figure 5shows this as a pyramid or iceberg:the top is clearly visible,the majority of the work is hidden in the bottom.driving viewsseen detailsreal world facts10 10 2 10 4 10 7 ..10 10 infiniteQuantity (order of magnitude) architect time per item100 hrs 1 hr 0.5..10 min meetingsin deliverables informal contactssampling scanning0.1 .. 1 sec10 5 ..10 6 per yearFigure 4:Bottom up elicitation of high level viewsReferences[1]Gerrit Muller.The system architecture homepage.//natlab/sysarch/index.html,1999.[2]Gerrit Muller.The system architectureprocess.//natlab/sysarch/index.html,2000.HistoryVersion:0.1,date:September 13,2000changed by:Gerrit Muller,Pierre AmericaSmall editorial changes onlyVersion:0,date:October 10,2000changed by:Gerrit MullerCreated,no changelog yetFrom Manager perspectiveFigure5:The visible outputs versus the(nearly)invisible work at the bottom。

SmartPlant Instrumentation

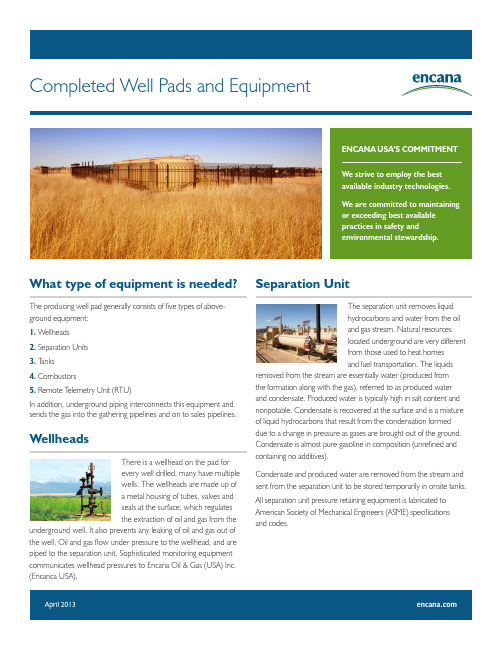

CompletedWellPadsandEquipmentFactSheetU.S.

Completed Well Pads and EquipmentWhat type of equipment is needed?The producing well pad generally consists of five types of above-ground equipment:1. Wellheads 2. Separation Units 3. T anks 4. Combustors5. Remote T elemetry Unit (RTU)In addition, underground piping interconnects this equipment and sends the gas into the gathering pipelines and on to sales pipelines.WellheadsThere is a wellhead on the pad for every well drilled, many have multiple wells. The wellheads are made up of a metal housing of tubes, valves and seals at the surface, which regulates the extraction of oil and gas from theunderground well. It also prevents any leaking of oil and gas out of the well. Oil and gas flow under pressure to the wellhead, and are piped to the separation unit. Sophisticated monitoring equipment communicates wellhead pressures to Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. (Encanca USA).Separation UnitThe separation unit removes liquid hydrocarbons and water from the oil and gas stream. Natural resources located underground are very different from those used to heat homes and fuel transportation. The liquidsremoved from the stream are essentially water (produced from the formation along with the gas), referred to as produced water and condensate. Produced water is typically high in salt content and nonpotable. Condensate is recovered at the surface and is a mixture of liquid hydrocarbons that result from the condensation formed due to a change in pressure as gases are brought out of the ground. Condensate is almost pure gasoline in composition (unrefined and containing no additives).Condensate and produced water are removed from the stream and sent from the separation unit to be stored temporarily in onsite tanks.All separation unit pressure retaining equipment is fabricated to American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) specifications and codes.FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT : Community Relations at 866.896.6371T witter | Facebook | You T ube | LinkedInT anksThe number and size of tanks on a particular pad varies depending on the amount of liquids produced. The tanks provide temporary storage of produced liquids (water and condensate) and allow for natural separation of hydrocarbons from water. The lighter hydrocarbons float to the top of the tank and the water remains at the bottom. The liquids are removed from the tank via truck or pipeline. The remaining water is disposed of per Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) regulations.Each tank or group of tanks on a well pad is enclosed by an earthen berm and a corrugated metal ring large enough to contain 150 percent of the capacity of the largest tank in the berm. Although not required by regulation, Encana USA places a plastic liner below each containment ring. COGCC regulations require that tanks be placed a minimum of 75 feet from any ignition source,50 feet from a production unit/separator, and 75 feet from awellhead. In addition, tanks must be a minimum of 200 feet from any residence. Encana USA places signs on the outside of each tank, identifying the contents.CombustorsThe combustor is a tall, cylindrical piece of equipment ranging from 10 to 30 feet in height and 2 feet or less in diameter that burns volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that may accumulate in the tanks. A specified volume of VOCs are allowed to accumulate in the tank, then are automatically released to the combustor, through piping. The VOCs are ignited and burned through the length of the combustor. Encana USA follows all state requirements for placement of combustors on well pads, based on air permitting procedures. In addition, we voluntarily place combustors in sensitive areas based on wind direction, topography, and proximity to homes. Combustors are monitored on a daily basis to ensure continuous operation.Remote T elemetry UnitIn addition to the wellheads, separation unit, tanks, pressurizers and combustors, additional equipment to remotely monitor oil and gas production are installed on each location.• a utomation enhances production, allows for minimal well-site visits and increases safety• p roduction equipment is connected to a Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system via Remote T elemetry Units (RTU)• t he SCADA system gathers and analyzes real-time well dataincluding electronic flow measurements, tank levels, and pressure which is transmitted to Encana USA’s officesAdressing landowner / neighbor concernsEncana USA works with individual landowners to minimize the visual impacts of the production equipment and public access to a landowner’s property. At the entrance to each well pad, signs identify Encana USA as the operator of the well, the well name, and display emergency phone numbers, as well as a list of safety precautions.Well pads are monitored to ensure safe and efficient operations and for maintenance purposes. Continuous monitoring is done via the RTU, and Encana USA personnel make routine site visits.Encana USA uses industry best practices for stormwater control, including placing berms around locations, proper grading to prevent runoff, and ensuring effective reclamation of natural plants and grasses.。

景观专业英文

景观中英文对照表(方案阶段)目录:Cover封面Content目录Design Explanation设计说明Master Plan总平面Space Sequence Analysis景观空间分析Function Analysis功能分析Landscape Theme Analysis景观景点主题分析图Traffic Analysis交通分析Vertical Plan竖向平面布置图Lighting Furniture Layout灯光平面布置示意图Marker/Background Music/Garbage Bin标识牌/背景音乐/垃圾桶布置图Plan平面图Hand Drawing手绘效果图Section剖面图Detail详图Central Axis中心公共主轴Reference Picture参考图片Planting Reference Picture植物选样材料类:aluminum铝asphalt沥青alpine rock轻质岗石boasted ashlars粗凿ceramic陶瓷、陶瓷制品cobble小圆石、小鹅卵石clay粘土crushed gravel碎砾石crushed stone concrete碎石混凝土crushed stone碎石cement石灰enamel陶瓷、瓷釉frosted glass磨砂玻璃grit stone/sand stone砂岩glazed colored glass/colored glazed glass彩釉玻璃granite花岗石、花岗岩gravel卵石galleting碎石片ground pavement material墙面地砖材料light-gauge steel section/hollow steel section薄壁型钢light slates轻质板岩lime earth灰土masonry砝石结构membrane张拉膜、膜结构membrane waterproofing薄膜防水mosaic马赛克quarry stone masonry/quarrystone bond粗石体plaster灰浆polished plate glass/polished plate磨光平板玻璃panel面板、嵌板rusticated ashlars粗琢方石rough rubble粗毛石reinforcement钢筋设施设备类:accessory channel辅助通道atrium门廊aisle走道、过道avenue道路access通道、入口art wall艺术墙academy科学院art gallery画廊arch拱顶archway拱门arcade拱廊、有拱廊的街道axes轴线air condition空调aqueduct沟渠、导水管alleyway小巷billiard table台球台bed地基bedding cushion垫层balustrade/railing栏杆byland/peninsula半岛bench座椅balcony阳台bar-stool酒吧高脚凳beam梁plate beam板梁bearing wall承重墙retaining wall挡土墙basement parking地下车库berm小平台block楼房broken-marble patterned flooring碎拼大理石地面broken stone hardcore碎石垫层curtain wall幕墙cascade小瀑布、叠水corridor走廊couryard内院、院子canopy张拉膜、天篷、遮篷coast海岸children playground儿童活动区court法院calculator计算器clipboard纤维板cantilever悬臂梁ceiling天花板carpark停车场carpet地毯cafeteria自助餐厅clearage开垦地、荒地cavern大洞穴dry fountain旱喷泉driveway车道vehicular road机动车道depot仓库、车场dry fountain for children儿童溪水广场dome圆顶drain排水沟drainage下水道drainage system排水系统discharge lamp放电管entrance plaza入口广场elevator/lift电梯escalator自动扶梯flat roof/roof garden平台fence wall围墙、围栏fountain喷泉fountain and irrigation system喷泉系统footbridge人行天桥fire truck消防车furniture家具、设备firepot/chafing dish火锅gutter明沟ditch暗沟gully峡谷、冲沟valley山谷garage车库foyer门厅、休息室hall门厅lobby门厅、休息室industry zone工业区island岛inn小旅馆jet喷头kindergarten幼儿园kiosk小亭子(报刊、小卖部)lamps and lanterns灯具lighting furniture照明设置mezzanine包厢main stadium主体育场outdoor terrace室外平台oil painting油画outdoor steps/exterior steps室外台阶pillar/pole/column柱、栋梁pebble/plinth柱基pond/pool池、池塘pavilion亭、阁pipe/tube管子plumbing管道port港口pillow枕头pavement硬地铺装path of gravel卵石路public plaza公共休闲广场communal plaza公共广场pedestrian street步行街printer打印机resting plaza休闲广场区rooftop/housetop屋顶pile桩piling打桩pump泵ramp斜坡道、残疾人坡道riverway河道sunbraking element遮阳构件sanitation卫生设施skylight天窗skyline地平线scanner扫描仪shore岸、海滨sash窗框slab楼板、地下室顶板stairhall楼梯厅staircase楼梯间secondary structure/minor structure次要结构secondary building/accessory building次要建筑street furniture小品(椅凳标志)solarium日光浴室terrace平台chip/fragment/sliver/splinter碎片safety belt/safety strap/life belt安全带safety passageway安全通道shelf/stand架子sunshade天棚small mountain stream山塘小溪subway地铁safety glass安全玻璃streetscape街景画sinking down plaza下沉广场sidewalk人行道footpath步行道设计阶段:existing condition analysis现状分析analyses of existings城市现状分析construction site service施工现场服务conceptual design概念设计circulation analysis交通体系分析construction drawing施工图complete level完成面标高details细部设计、细部大样示意图diagram示意图、表elevation上升、高地、海拔、正面图development design扩初设计fa鏰de/elevation正面、立面general development analysis城市总体发展分析general situation survey概况general layout plan/master plan总平面general nature environment总体自然分析grid and landmark analysis城市网格系统及地标性建筑物分析general urban and landscape concept总体城市及景观设计概念general level design总平面竖向设计general section总体剖面图layout plan布置图legend图例lighting plan灯光布置图plan drawing平面图plot plan基地图presentation drawing示意图perspective/render效果图pavement plan铺装示意图reference pictures/imaged picture参考图片reference level参考标高图片site overall arrangement场地布局space sequence relation空间序列specification指定、指明、详细说明书scheme design方案设计sketch手绘草图sectorization功能分区section剖面site planning场地设计reference picture of planting植物配置意向图reference picture of street furniture街道家具布置意向图设计描述:a thick green area密集绿化administration/administrative行政administration zone行政区位function analysis功能分析arc/camber弧形askew歪的、斜的aesthetics美学height高度abstract art抽象派artist艺术家、大师art nouveau新艺术主义acre英亩architect建筑师be integrated with与……结合起来bisect切成两份、对开bend弯曲boundary/border边界operfloor架空层budget预算estimate评估beach海滩building code建筑规范景观中英文对照表(初步设计施工图阶段)Landscape Design Development Package 景观扩初设计图册Drawing Schedule 图纸目录Sheet No 纸页号码Description 图画说明Sheet Size 纸页尺寸Revision Reference 修正参考Additional Drawing 图纸附加Deleted Drawing 图纸册除Remarks 备注Drawing 图画名词Internal Drawing Date 内部绘图日期Internal Revision Date 内部修正日期Cover Sheet 封面纸页Materials Schedule 物科目录General Legend 一般图例Standard Symbols & Abbreviations 标准象微及简写Landscape Plans (LP-) (Bound Separately) 景观设计平面图(分开缚装)Reference Plan 指引图Part 01 第一部分Client 业主Project 项目Scale 比例Designed By 设计者Drawn By 绘图者Checked By 检查者Approved By 批核者Setting-Out Plan 定位图Levels/Drainage/Irrigation Plan 标高和给排水图Materials Plan 物科图Lighting Plan 照明配置图Landscape Sections 景观设计部面图Typical Planter Details 标准种植槽详图Typical Overflow/Planter Drain Detail 标准溢流/种植槽排水详图Typical Waterpoint Detail 标准灌溉供水口详图Typical Planter Wall Detail 标准种植槽墙详图Typical Driveway/Planter Curb Detail 标准车道/种植槽道牙详图Floating Tree Collar Detail 01 (Typical) 悬浮树环详图Typical Flushed Planter Detail 标准及地面时种植槽详图Typical Trench Drain Detail 标准排水沟详图Typical Step & Wall Details 标准台阶和墙壁详图Steps Detail 台阶详图Step Lawn Detail 台阶草坪详图Typical Wheel Guard Detail 标准保安轮详图Typical Gate Detail 标准闸门详图Seatwall Detail 座墙详图Railing Detail 栋杆详图Typical Fence Detail 标准围墙详图Endpost detail 端柱详图Paving Details (LD-3) 铺地详图Paving 01 铺地Typical Void Deck Detail 标准架空层详图Typical Footpath Detail 标准行人步道详图Typical Timber Deck Detail 标准木平台详图Typical Crazy cut pattern detail 标准不规则切割平图案详图Stepping stone detail 01 (Typical) 踏步石详图 01 (标准)Typical Grass Ring Paver Detail 标准植草圈铺图案详图Pool Paving Detail 泳池铺地详图Linear Stepping Stone & Linear Stone Layers 线性踏步石及线性石层Typical Safety Matt Detail 标准安全垫详图Basketball Court & Paving Accessories Detail 篮球场及铺地附件详图Landscape Features 特色景观Water Feature 01 特色水景Feature Pot Detail 特色盆详图Pavilion 01 (Typical) 凉亭 01 (标准)View Pavilion 视图凉亭Sunken Pool Bar 沉下式泳池酒吧Typical Guardhouse Detail 标准保安亭详图Filtration Pump Room 过滤泵室Water Falls Detail 瀑布详图Ramp Trellis 斜坡花架Trellis 花架Bridge 架桥Signage Wall 标志板墙Vent Detail 通风详图Swimming Pool & Jacuzzi Details 游泳池和温泉详图Pool Reference Plan 泳池指引图Pool Setting Out 泳池定位图Pool Edge 01 泳池边缘 01Pool Steps Details 泳池台阶详图Sunken Pool Lounge 沉下式泳池休憩 Kid’s Pool 儿童泳池 Jacuzzi Detail按摩池详图 Landscape Lighting Details景观照明详图Pole Top Luminaire (Single Lamp Head) (With Banner) 柱顶灯具 (单头) Bollard Light矮柱灯Wall / Column Mounted Luminaire 挂墙 / 柱式灯具 Garden Floodlight with Earth Spike 花园插地式泛光灯 Garden Floodlight with mounting clamp 花园挂树式泛光灯 Recess-Mounted Wall Luminaire 嵌藏墙灯具Recess-Mounted Stair Steps Luminaire 嵌藏楼梯台阶灯具 (A 型) Drive-Over In-Ground Uplights埋地车道泛光灯Drive-Over Location Luminaire – Type M (5 or more sides light beam)车道位置灯具 M 型 (五或更多边灯光线)Under Water Floodlight (Recess-Mount) 水底泛光灯 (嵌藏) Under Water Floodlight (Surface-Mount) 水底泛光灯 (嵌表面) Swimming Pool Luminaire (Recess-Mount) 泳池灯具(嵌藏) Connecting Pillar连接柱Sports/Area (Post-Type) Floodlight (Single Lamp Head)运动 / 区单头柱泛光灯 Feature Column Light特色柱灯 Site Furniture Details (LD-7) 家具设置详图 Fitness Equipment 健身工具 Play Equipment 01 游乐工具 01 Parasol阳伞Pool Lounger 01 泳池躺椅 Outdoor Furniture 露天家具 Rockwork Details石景详图 Pond Edge Reference Plan 池塘边缘指引图 Continue续集Pond Edge Setting-Out Plan 池塘边缘定位图 Pond Edge (Type A) 池塘边缘 (A 型) Water Cascade Detail 01 水瀑布详图 General Notes概话说明This Landscape Design Development Detail Drawing Package is to be read in conjunction with the following notes: 阅览此景观扩初设计图册时,需结合以下设计要修重点说明并使用。

老旧小区公共空间集约化改造设计研究——以北京市西城区大栅栏厂甸11号院为例

建筑设计·理论 2021年11月第18卷总第409期Urbanism and Architecture85老旧小区公共空间集约化改造设计研究——以北京市西城区大栅栏厂甸11号院为例王梦琪,李美艳,马 腾(北京建筑大学建筑与城市规划学院,北京 100044)摘要:在存量土地优化发展的时代背景下,老旧小区公共空间成为城市更新的重点。

由于土地资源紧张,集约化改造将是老旧小区公共空间改造的主要方向。

文章通过分析老旧小区公共空间现存的问题,从规划布局、功能布置、空间设计三个方面进行集约化改造方法的探索,并以北京市西城区大栅栏厂甸11号院的改造设计为例加以验证。

关键词:老旧小区;公共空间;集约化设计;立体化;多样性[中图分类号]TU241.7 [文献标志码]A DOI :10.19892/ki.csjz.2021.32.24Research on the Intensive Reconstruction Design of Public Space in Old Residential Areas—— A Case of Changdian Yard 11 of Dashilan in Xicheng District of BeijingWang Mengqi, Li Meiyan, Ma Teng(School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing 100044, China)Abstract: Under the background of optimizing the development of stock land, the public space of old residential areas has become the focus of urban renewal. Due to the shortage of land resources, intensive reconstruction will be the main direction. By analyzing the existing problems of public space in old residential areas, this paper explores the intensive reconstruction method from three aspects of planning layout, functional layout and space design, and takes the reconstruction design of Changdian yard 11 of Dashilan in Xicheng District of Beijing for verification.Key words: old residential areas; public space; intensive design; stereoscopic; diversity1引言老旧小区在建设初期以解决人们基本居住问题为建设目标,对公共空间建设的关注度不高。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。