上海翻译报价收费标准英文翻译

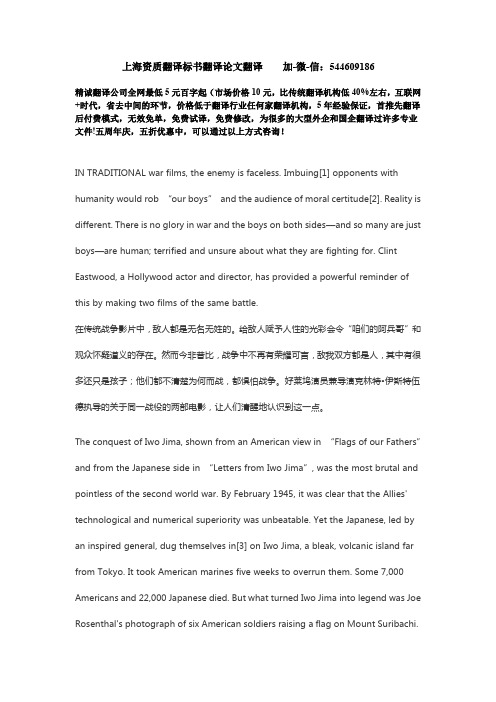

上海网站翻译标书人工翻译

上海网站翻译标书人工翻译加-微-信:544609186精诚翻译公司全网最低5元百字起(市场价格10元,比传统翻译机构低40%左右,互联网+时代,省去中间的环节,价格低于翻译行业任何家翻译机构,5年经验保证,首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改,为很多的大型外企和国企翻译过许多专业文件!五周年庆,五折优惠中,可以通过以上方式咨询!FEW peoples are as proud of their uniqueness as are the Chinese.Many feel the same way about one of their national emblems:the South China tiger.So two Americans who have questioned its pedigree have created quite a stir.很少有民族像中国人那样为自己独有的血统倍感自豪。

对于他们的民族象征之一——华南虎,许多中国人也是抱此态度。

因此,两位美国人对华南虎血统的质疑自然就引起了轩然大波。

In2004Stephen O'Brien,head of genetics at the National Cancer Institute in Maryland,published the results of a20-year study into the species.His findings concluded that of the five beasts he sampled,labelled in the Chinese zoos where they were kept as South China tigers,only two were of“unique lineage”.Three were no different genetically from the Indochinese tiger,a separate sub-species endemic to Vietnam,Myanmar,Cambodia,Thailand and Laos.2004年,马里兰州国家癌症研究所遗传中心主任史蒂芬•奥布莱恩(Stephen O’Brien)发表了一项历时20年的物种研究成果。

上海法律英文翻译中英文翻译价格

上海法律英文翻译中英文翻译价格qq:544609186精诚翻译公司全网最低5元百字起(市场价格10元,比传统翻译机构低40%左右,互联网+时代,省去中间的环节,价格低于翻译行业任何家翻译机构,5年经验保证,首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改,为很多的大型外企和国企翻译过许多专业文件!五周年庆,五折优惠中,可以通过以上方式咨询!Vitamin D plays an important part in the human immune response and deficiency can leave individuals less able to fight infections like HIV-1. Now an international team of researchers has found that high-dose vitamin D supplementation can reverse the deficiency and also improve immune response."Vitamin D may be a simple,cost-effective intervention,particularly in resource-poor settings,to reduce HIV-1risk and disease progression,"the researchers report in today's(June15) online issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.The researchers looked at two ethnic groups in Cape Town,South Africa, to see how seasonal differences in exposure to ultraviolet B radiation, dietary vitamin D,genetics,and pigmentation affected vitamin D levels, and whether high-dose supplementation improved deficiencies and the cell's ability to repel HIV-1."Cape Town,South Africa,has a seasonal ultraviolet B regime and one of the world's highest rates of HIV-1infection,peaking in young adults, making it an appropriate location for a longitudinal study like this one,"said Nina Jablonski,Evan Pugh Professor of Anthropology,Penn State, who led the research.One hundred healthy young individuals divided between those of Xhosa ancestry--whose ancestors migrated from closer to the equator into the Cape area--and those self-identified as having Cape Mixed ancestry--a complex admixture of Xhosa,Khoisan,European,South Asian and Indonesian populations--were recruited for this study.The groups were matched for age and smoking.The Xhosa,whose ancestors came from a place with more ultraviolet B radiation,have the darkest skin pigmentation,while the Khoisan--the original inhabitants of the Cape--have adapted to the seasonally changing ultraviolet radiation in the area and are lighter skinned.The Cape Mixed population falls between the Xhosa and Khoisan in skin pigmentation levels.。

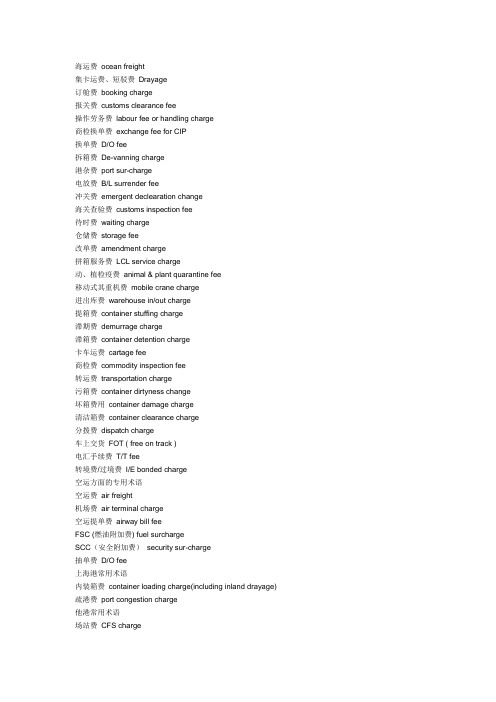

国际物流各种费用中英文表达法

国际物流各种费用中英文表达法海运费ocean freight 集卡运费、短驳费Drayage 订舱费booking charge 报关费customs clearance fee 操作劳务费labour fee or handling charge 商检换单费exchange fee for CIP 换单费D/O fee 拆箱费De-vanning charge 港杂费port sur-charge 电放费B/L surrender fee 冲关费emergent declaration charge 海关查验费customs inspection fee 待时费waiting charge 仓储费storage fee 改单费amendment charge 拼箱服务费LCL service charge 动、植检疫费animal & plant quarantine fee 移动式起重机费mobile crane charge 进出库费warehouse in/out charge 提箱费container stuffing charge滞期费demurrage charge 滞箱费container detention charge 卡车运费cartagefee 商检费commodity inspection fee 转运费transportation charge 污箱费container dirtyness charge 坏箱费用container damage charge 清洁箱费container clearance charge 分拨费dispatch charge 车上交货FOT ( free ontrack ) 电汇手续费T/T fee 转境费/过境费I/E bonded charge 空运方面的专用术语空运费air freight 机场费air terminal charge 空运提单费airway bill fee FSC燃( 油附加费) fuel surcharge SCC (安全附加费)security sur-charge 抽单费D/Ofee 上海港常用术语内装箱费container loading charge(including inland drayage)疏港费port congestion charge他港常用术语场站费CFS charge文件费document charge物流费用分析常见的物流费用包括以下几种:海洋运费:Ocean Freight从装运港到卸货港的海洋运输费用,按照货物运输方式及性质计价方式回不一样,如集装箱运输,按照每个集装箱收费,集装箱分为普通干箱(GeneralPurpose, Dry和特种集装箱,按照集装箱大小分为20' , 40 ' , 20高箱H4h, ' H(H高箱),45等;特种集装箱分为挂衣箱、平板箱、框架箱、冷冻箱、开顶箱、半封闭箱等。

最新翻译服务收费标准——2023

最新翻译服务收费标准——2023

以下是我们的最新翻译服务收费标准,适用于2023年。

1. 文件类型

- 文字稿件翻译:¥X/千字

- 口译服务:¥Y/小时

请注意,以上价格仅适用于常见的文件类型,如商务信函、合同、报告等。

对于特殊领域、技术性较高或极其复杂的文件,价格可能有所浮动。

2. 翻译语言

我们提供以下常见语言对之间的翻译服务:

- 中文英文

- 中文西班牙文

- 中文法文

- 中文德文

- 中文俄文

如果您需要其他语言对之间的翻译服务,请与我们联系以获取报价和可行性评估。

3. 机关认证文件翻译

对于需要机关认证的文件翻译,价格可能会有所不同。

请与我们的团队联系以获得准确的报价。

4. 付款方式

我们接受以下付款方式:

- 银行转账

- 支付宝

- 微信支付

请在确认订单后的48小时内完成付款。

如需延期,请提前与我们联系。

5. 附加费用

以下是可能会导致额外费用的情况:

- 紧急翻译服务(小于24小时):额外收取总费用的20%

- 翻译文件格式不标准:根据实际情况另行报价

- 陪同口译服务:每小时额外收取¥Z

请注意,以上附加费用仅在适用情况下收取。

以上为最新的翻译服务收费标准,如有任何问题或特殊需求,请随时与我们联系。

谢谢!。

翻译公司收费标准

100起

130

150

200

300

录取通知书

150起

180

200

250

350

护照

100起

130

150

200

300

出生证明

150起

180

200

250

350

死亡证明

150起

180

200

250

350

未获刑证明

150

130

150

200

300

婚姻证明

100起

130

150

200

300

职业证明

100起

130

二.口译收费标准

形式

收费

语种

陪同翻译(旅游、

解说、展会等)

单位:天

交互传译(会谈、谈判、技术交流等)

单位:天

同声传译(论坛、讲座、国际会议等,需配两人)

单位:天

英语

1500-2000

2800-3500

8000-10000

日语

2000-2500

3500-5000

8500-1200

韩语

2000-2500

文章来源:上海翻译公司

2500-3000

4000-5500

9000-12500

土耳其语

3500-4000

5000-6500

10000-13500

印地语

3500-4000

5000-6500

10000-13500

荷兰语

6000-7000

12000-15000源自17000-22000希伯来语

6000-7000

12000-15000

翻译服务收费标准

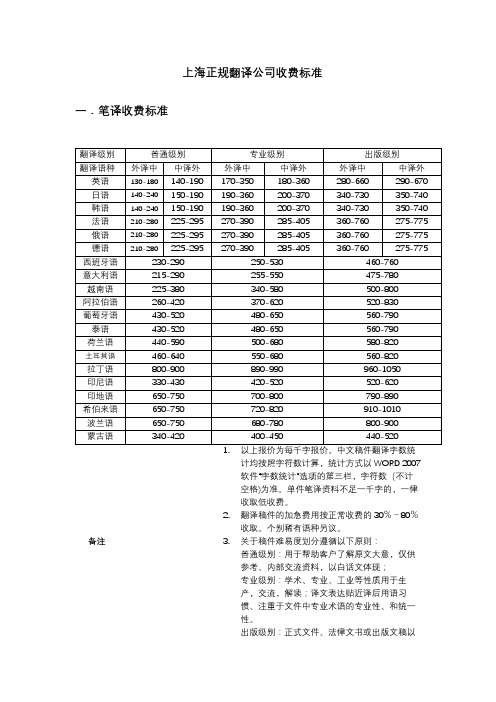

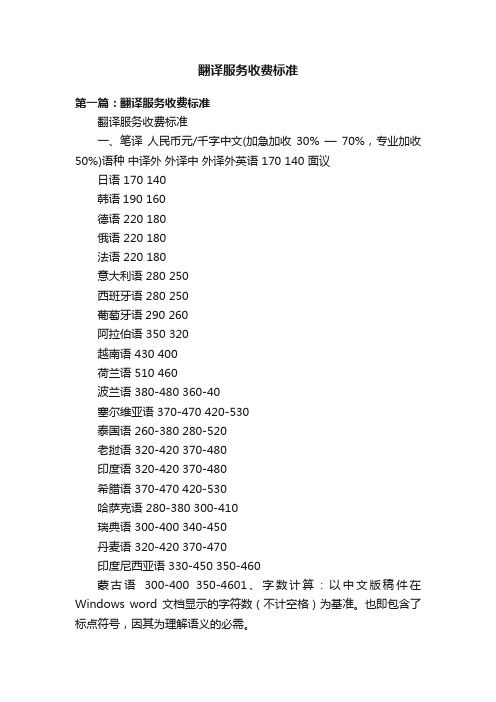

翻译服务收费标准第一篇:翻译服务收费标准翻译服务收费标准一、笔译人民币元/千字中文(加急加收30% —70%,专业加收50%)语种中译外外译中外译外英语 170 140 面议日语 170 140韩语190 160德语 220 180俄语 220 180法语 220 180意大利语 280 250西班牙语 280 250葡萄牙语290 260阿拉伯语 350 320越南语 430 400荷兰语 510 460波兰语 380-480 360-40塞尔维亚语 370-470 420-530泰国语 260-380 280-520老挝语 320-420 370-480印度语 320-420 370-480希腊语 370-470 420-530哈萨克语 280-380 300-410瑞典语 300-400 340-450丹麦语 320-420 370-470印度尼西亚语 330-450 350-460蒙古语300-400 350-4601、字数计算:以中文版稿件在Windows word文档显示的字符数(不计空格)为基准。

也即包含了标点符号,因其为理解语义的必需。

2、图表计算:图表按每个A4页面,按页酌情计收排版费用。

3、外文互译:按照中文换算,即每个拉丁单词乘以二等于相应的中文字数。

4、日翻译量:正常翻译量3000-5000字/日/人,超过正常翻译量按专业难易受20%加急费.5、付款方式:按预算总价的20%收取定金,按译后准确字数计总价并交稿付款。

6、注意事项:出差在原价格上增加20%,客户负责翻译的交通、食宿和安全费用。

二、口译价格:(1)交传报价(元/人/天,加小时按100-150元/小时加收费用)类型英语德、日、法、俄、韩小语种一般活动 700 800 1500商务活动 500-1200 500-1500 800-3000中小型会议 1200-3000 1500-3000 2500-3000大型会议 1200-4000 2500-6000 4000-9000(2)同传报价(元/人/天)类别中-英互译日、韩、德、俄、法、韩-中互译小语种-中互译商务会议 5000-8000 6000-10000 8000-10000中小型会议 5500-8000 7000-12000 8000-12000大型国际会议 6000-9000 8000-12000 12000-16000第二篇:联想服务收费标准LENOVO CHINA SERVICES现场交付中心Field Services Delivery文件编号FILE NO。

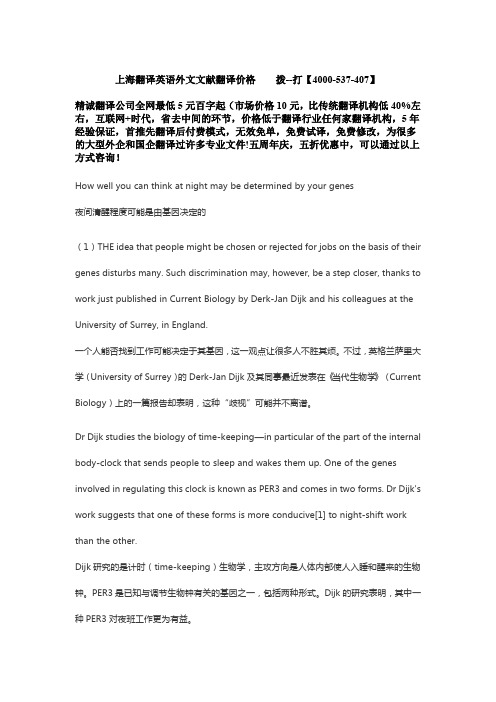

上海翻译英语外文文献翻译价格

上海翻译英语外文文献翻译价格拨--打【4000-537-407】精诚翻译公司全网最低5元百字起(市场价格10元,比传统翻译机构低40%左右,互联网+时代,省去中间的环节,价格低于翻译行业任何家翻译机构,5年经验保证,首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改,为很多的大型外企和国企翻译过许多专业文件!五周年庆,五折优惠中,可以通过以上方式咨询!How well you can think at night may be determined by your genes夜间清醒程度可能是由基因决定的(1)THE idea that people might be chosen or rejected for jobs on the basis of their genes disturbs many.Such discrimination may,however,be a step closer,thanks to work just published in Current Biology by Derk-Jan Dijk and his colleagues at the University of Surrey,in England.一个人能否找到工作可能决定于其基因,这一观点让很多人不胜其烦。

不过,英格兰萨里大学(University of Surrey)的Derk-Jan Dijk及其同事最近发表在《当代生物学》(Current Biology)上的一篇报告却表明,这种“歧视”可能并不离谱。

Dr Dijk studies the biology of time-keeping—in particular of the part of the internal body-clock that sends people to sleep and wakes them up.One of the genes involved in regulating this clock is known as PER3and comes in two forms.Dr Dijk's work suggests that one of these forms is more conducive[1]to night-shift work than the other.Dijk研究的是计时(time-keeping)生物学,主攻方向是人体内部使人入睡和醒来的生物钟。

翻译收费标准

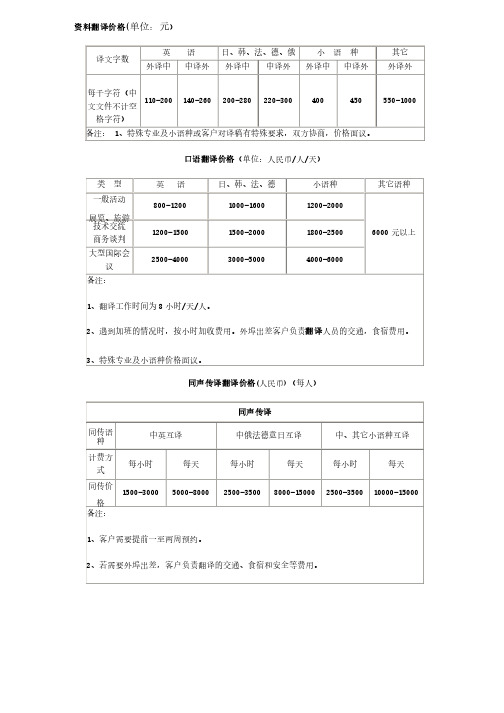

资料翻译价格(单位:元)译文字数英语日、韩、法、德、俄小语种其它外译中中译外外译中中译外外译中中译外外译外每千字符(中文文件不计空格字符)110-200 140-260 200-280 220-300 400 450 550-1000备注:备注: 1 1 1、特殊专业及小语种或客户对译稿有特殊要求,双方协商,价格面议。

、特殊专业及小语种或客户对译稿有特殊要求,双方协商,价格面议。

口语翻译价格(单位:人民币(单位:人民币//人/天)类型英语日、韩、法、德小语种其它语种一般活动展览、旅游800-1200 1000-1600 1200-2000 6000元以上技术交流商务谈判1200-1500 1500-2000 1800-2500 大型国际会议2500-40003000-50004000-6000备注:1、翻译工作时间为8小时小时//天/人。

2、遇到加班的情况时,按小时加收费用。

外埠出差客户负责翻译人员的交通,食宿费用。

3、特殊专业及小语种价格面议。

同声传译翻译价格(人民币人民币))(每人)同声传译同传语种中英互译中俄法德意日互译中、其它小语种互译计费方式每小时每天每小时每天每小时每天同传价格1500-30005000-80002500-35008000-15000 2500-3500 10000-15000备注:1、客户需要提前一至两周预约。

2、若需要外埠出差,客户负责翻译的交通、食宿和安全等费用。

3、提供国外进口红外同传设备租赁并负责技术支持。

、提供国外进口红外同传设备租赁并负责技术支持。

4、一般安排两名同声传译译员,每20分钟轮换一次。

分钟轮换一次。

录译价格 单位:元单位:元//分录象带时录象带时长 (分钟)(分钟) 中←→英中←→英 中←→日法德俄中←→日法德俄 中←→小语种中←→小语种 外←→外外←→外 中→英中→英英→中英→中中→外中→外外→中外→中中→外中→外外→中外→中外←→外外←→外 100以内以内 100-300 300以上以上180-240 160-230 140-220 150-200 130-180 120-160240-300 220-290 180-240 160-240 300-400 290-440 200-290 200-290320-580 300-540双方协商价格优惠双方协商价格优惠中外文录入排版价格日 文文 韩 文文 俄 文文 阿 拉拉 伯 40元/版 (A4A4))40元/版 (A4A4))50元/版 (A4A4))60元/版 (A4A4))备注:免费送软盘一张,激光打印稿一份。

正规翻译公司收费标准

正规翻译公司收费标准

我国的翻译行业正在飞速发展,翻译公司也随之增多。

为了提高翻译行业的服务质量,各家翻译公司在收费上都有一定的标准。

一般来说,收费标准一般通过工作量、翻译难度、技术要求以及客户的要求来确定。

较简单的翻译收费标准是按字数来计算,一般每1000字的汉译外文正规收费在200-350元之间,每1000字的外译汉文正规收费也在200-350元之间;外译汉文口译收费标准主要按照工作量来计算,一般为500-1000元/项;英译汉和汉译英的口译一般收费为100-150元/小时,会议口译则可以收取较高的报酬。

而正规翻译公司还会根据客户的具体需求而定制收费标准,如:客户所提供的文件类型、技术难度、要求翻译进度、服务内容、内容复杂度、行业类型、译文格式等等。

一般来说,译稿的收费范围也会比字数收费更高一点,有的甚至会按照客户的文件字数的三分之二收取报酬,以此激励客户提供尽可能精练的文字,以节省翻译公司的工作量和翻译成本。

同时,正规翻译公司还会根据客户的质量要求给予相应的报酬加成,比如:正规公司会额外奖励翻译专家因质量标准高等原因额外花费的心血,客户对质量有着很高的要求,把质量和时间放在首位的情况下,正规翻译公司会根据客户的要求,进行不同程度的费用调整,以符合客户的质量要求。

总之,正规翻译公司有着完善的收费标准体系,收费标准的金额主要由客户的文件字数、翻译难度以及质量要求来决定,根据客户的实际需求来动态调整收费标准,以确保翻译质量。

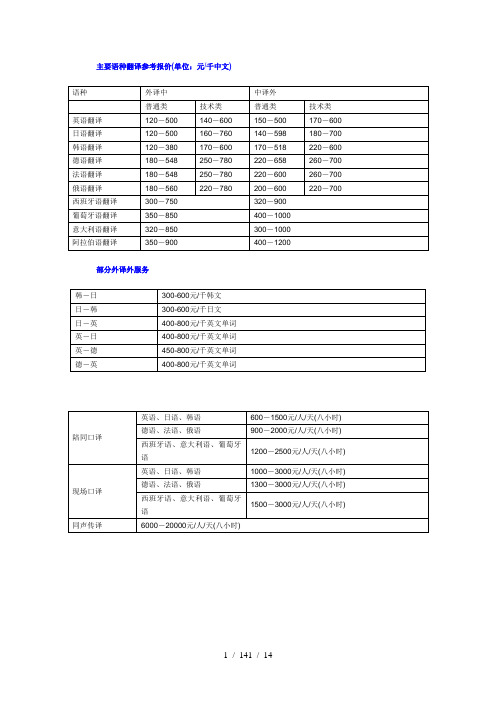

主要语种翻译价格

400-1200

部分外译外服务

韩-日

300-600元/千韩文

日-韩

300-600元/千日文

日-英

400-800元/千英文单词

英-日

400-800元/千英文单词

英-德

450-800元/千英文单词

德-英

400-800元/千英文单词

陪同口译

英语、日语、韩语

600-1500元/人/天(八小时)

德语、法语、俄语

900-2000元/人/天(八小时)

西班牙语、意大利语、葡萄牙语

1200-2500元/人/天(八小时)

现场口译

英语、日语、韩语

1000-3000元/人/天(八小时)

德语、法语、俄语

1300-3000元/人/天(八小时)

西班牙语、意大利语、葡萄牙语

1500-3000元/人/天(八小时)

同声传译

6000-20000元/人/天(八小时)

220-658

260-700

法语翻译

180-548

250-780

220-600

260-700

俄语翻译

180-560

220-780

200-600

220-700

西班语翻译

300-750

320-900

葡萄牙语翻译

350-850

400-1000

意大利语翻译

320-850

300-1000

阿拉伯语翻译

350-900

主要语种翻译参考报价(单位:元/千中文)

语种

外译中

中译外

普通类

技术类

普通类

技术类

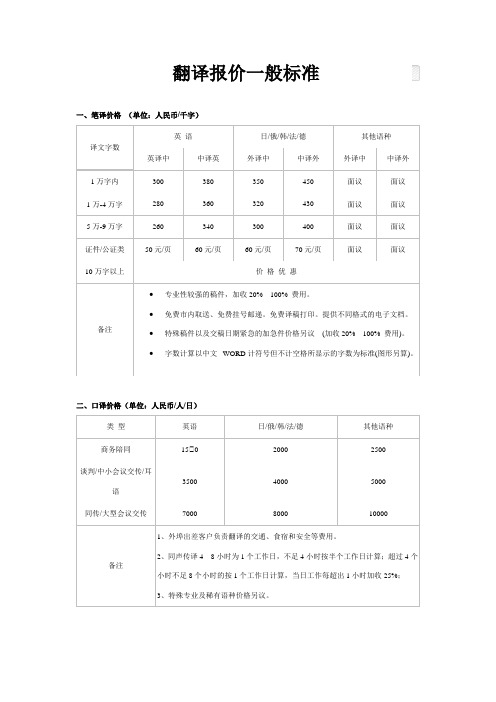

翻译报价一般标准

四、电影、电视剧本,录音带、VCD 等音频、视频翻译价格 语 种 英译中 中译英 其他语种 备注 价 格 100-200 元/分钟 150-300 元/分钟 200-300 元/分钟 提供非编、配音及各种后期处理。

翻译报价一般标准

一、笔译价格 (单位:人民币/千字) 英 语 译文字数 英译中 1 万字内 1 万-4 万字 5 万-9 万字 证件/公证类 10 万字以上 300 280 260 50 元/页 中译英 380 360 340 60 元/页 外译中 350 320 300 60 元/页 中译外 450 430 400 70 元/页 外译中 面议 面议 面议 面议 中译外 面议 面议 面议 面议 日/俄/韩/法/德 食宿和安全等费用。 2、同声传译 4—8 小时为 1 个工作日,不足 4 小时按半个工作日计算;超过 4 个 备注 小时不足 8 个小时的按 1 个工作日计算,当日工作每超出 1 小时加收 25%; 3、特殊专业及稀有语种价格另议。

三、网站翻译价格(由三部分组成,即页面翻译制作费用和文本、图形翻译费用) 翻译制作费用 文本部分 图形部分 以网页页面计,即一个 HTML、ASP、PHP 等类似文档,平均 300 元人民币/页面 文本部分与常规翻译收费相同,详细请查看翻译报价。 如客户无特殊要求则不收费,如有其它要求费用另议。

价 格 优 惠

• •

备注

专业性较强的稿件,加收 20%—100% 费用。 免费市内取送、免费挂号邮递。免费译稿打印。提供不同格式的电子文档。 特殊稿件以及交稿日期紧急的加急件价格另议 (加收 20%—100% 费用)。

• •

字数计算以中文 WORD 计符号但不计空格所显示的字数为标准(图形另算)。

二、口译价格(单位:人民币/人/日) 类 型 商务陪同 谈判/中小会议交传/耳 3500 语 同传/大型会议交传 7000 8000 10000 4000 5000 英语 15 0 日/俄/韩/法/德 2000 其他语种 2500

翻译代理服务费收费标准-语言翻译代理费

翻译代理服务费收费标准-语言翻译代理

费

背景

本翻译代理服务费收费标准-语言翻译代理费(以下简称“本标准”)制定的目的是规范翻译代理服务的收费标准,保证客户与代理商的权益,促进翻译代理行业的发展。

收费标准

本标准的语言翻译代理费收费标准如下:

翻译语言 | 收费标准(人民币/千字)

---|---

英语 | 80-120

法语 | 100-150

德语 | 100-150

俄语 | 120-160

日语 | 100-150

韩语 | 100-150

西班牙语 | 120-160

备注:

1. 以上收费标准均为每(1)千字计算。

2. 如需要涉及技术方面内容翻译,请与代理商协商,另行商议。

服务内容及流程

代理商提供的翻译代理服务包括人工翻译及机器翻译(若有可

行性)。

服务流程如下:

1. 客户与代理商联系,告知所需翻译语言,文本类型,字数等。

2. 代理商给出报价。

3. 双方确定翻译服务内容及费用。

4. 客户提供待翻译文本。

5. 代理商核对后,安排相应资源进行翻译。

6. 翻译完成后,代理商进行初步质量审核。

7. 客户审核翻译后如有意见可与代理商协商修改,代理商进行

修改后确认。

8. 客户支付费用后,代理商交付翻译成果。

结论

本标准的制定,不仅为广大客户提供了更为规范化的翻译代理服务,也推动了翻译代理行业的不断发展。

希望各代理商严格按照本标准执行,提高翻译代理服务的质量和信誉。

同时,客户也应选择合适的代理商,并遵守双方签订的翻译服务协议,共同打造翻译代理服务的良好生态。

英语翻译收费标准

英语翻译收费标准Translation Fee RatesTranslation services are charged based on various factors such as the complexity, subject matter, urgency, and word count of the document. Our translation agency follows a standard fee rate that ensures fair pricing for both clients and translators.The fee rate for translation services is as follows:1. Standard Rate: The standard rate for translation services is $0.10 per word. This rate applies to general documents that are not highly specialized or technical in nature. It includes documents such as personal correspondence, basic marketing materials, and general business documents.2. Specialized Rate: For documents that require specialized knowledge or expertise, such as legal, medical, or technical materials, the rate is $0.15 per word. These types of materials require additional research and understanding of specific terminology to provide accurate translations.3. Urgent Rate: If you need a document to be translated urgently, within 24 hours or less, an additional fee of 20% will be applied to the standard or specialized rate, depending on the nature of the document. This ensures that your urgent translation needs can be met promptly.4. Minimum Charge: We also have a minimum charge of $30 for any translation project. This ensures that even small documents orshort passages can be accommodated.5. Editing and Proofreading: If you have already translated the document yourself or used machine translation, and require editing and proofreading services, the rate is $0.05 per word.6. Additional Services: We also provide additional services such as formatting, transcreation, and localization. These services are charged separately based on the specific requirements of the project.Payment Terms:Payment for translation services can be made either by bank transfer or using online platforms such as PayPal. For larger projects, we require a 50% upfront payment before starting the translation process. The remaining balance is to be paid upon completion of the project. For smaller projects, full payment is required upfront.Please note that these rates are subject to change based on the specific requirements of each project. For a more accurate quote, please provide us with the details of your project, including the word count, subject matter, and any specific instructions or requirements.We strive to deliver high-quality translations at competitive rates, ensuring client satisfaction.。

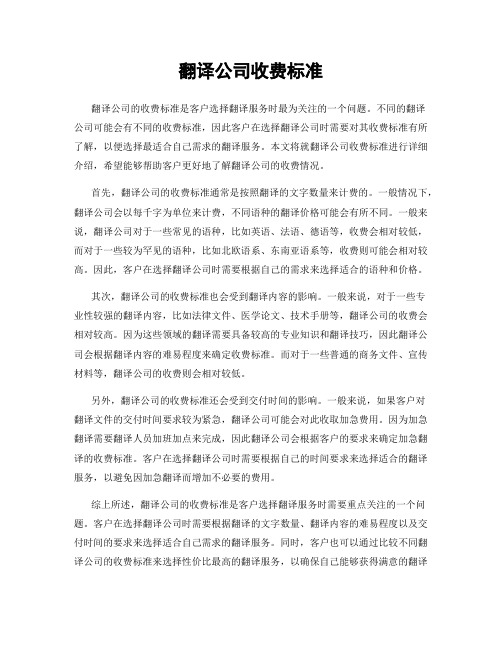

翻译公司收费标准

翻译公司收费标准翻译公司的收费标准是客户选择翻译服务时最为关注的一个问题。

不同的翻译公司可能会有不同的收费标准,因此客户在选择翻译公司时需要对其收费标准有所了解,以便选择最适合自己需求的翻译服务。

本文将就翻译公司收费标准进行详细介绍,希望能够帮助客户更好地了解翻译公司的收费情况。

首先,翻译公司的收费标准通常是按照翻译的文字数量来计费的。

一般情况下,翻译公司会以每千字为单位来计费,不同语种的翻译价格可能会有所不同。

一般来说,翻译公司对于一些常见的语种,比如英语、法语、德语等,收费会相对较低,而对于一些较为罕见的语种,比如北欧语系、东南亚语系等,收费则可能会相对较高。

因此,客户在选择翻译公司时需要根据自己的需求来选择适合的语种和价格。

其次,翻译公司的收费标准也会受到翻译内容的影响。

一般来说,对于一些专业性较强的翻译内容,比如法律文件、医学论文、技术手册等,翻译公司的收费会相对较高。

因为这些领域的翻译需要具备较高的专业知识和翻译技巧,因此翻译公司会根据翻译内容的难易程度来确定收费标准。

而对于一些普通的商务文件、宣传材料等,翻译公司的收费则会相对较低。

另外,翻译公司的收费标准还会受到交付时间的影响。

一般来说,如果客户对翻译文件的交付时间要求较为紧急,翻译公司可能会对此收取加急费用。

因为加急翻译需要翻译人员加班加点来完成,因此翻译公司会根据客户的要求来确定加急翻译的收费标准。

客户在选择翻译公司时需要根据自己的时间要求来选择适合的翻译服务,以避免因加急翻译而增加不必要的费用。

综上所述,翻译公司的收费标准是客户选择翻译服务时需要重点关注的一个问题。

客户在选择翻译公司时需要根据翻译的文字数量、翻译内容的难易程度以及交付时间的要求来选择适合自己需求的翻译服务。

同时,客户也可以通过比较不同翻译公司的收费标准来选择性价比最高的翻译服务,以确保自己能够获得满意的翻译结果。

希望本文能够帮助客户更好地了解翻译公司的收费情况,从而更好地选择适合自己的翻译服务。

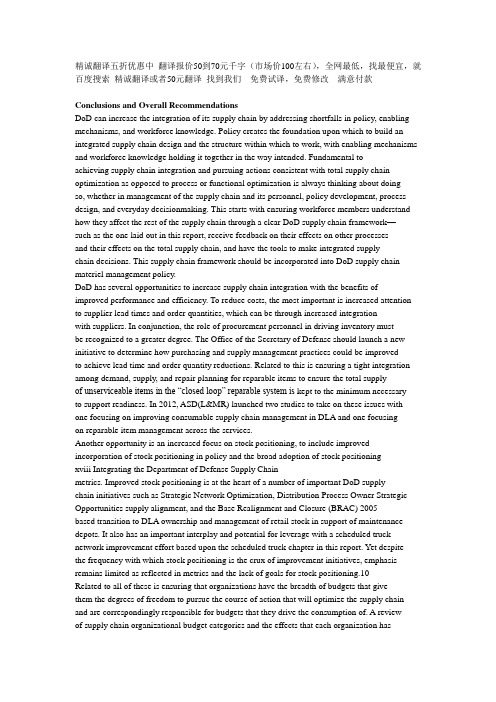

上海翻译公司报价精诚翻译

精诚翻译五折优惠中翻译报价50到70元千字(市场价100左右),全网最低,找最便宜,就百度搜索精诚翻译或者50元翻译找到我们免费试译,免费修改满意付款Conclusions and Overall RecommendationsDoD can increase the integration of its supply chain by addressing shortfalls in policy, enabling mechanisms, and workforce knowledge. Policy creates the foundation upon which to build an integrated supply chain design and the structure within which to work, with enabling mechanisms and workforce knowledge holding it together in the way intended. Fundamental toachieving supply chain integration and pursuing actions consistent with total supply chain optimization as opposed to process or functional optimization is always thinking about doing so, whether in management of the supply chain and its personnel, policy development, process design, and everyday decisionmaking. This starts with ensuring workforce members understand how they affect the rest of the supply chain through a clear DoD supply chain framework—such as the one laid out in this report, receive feedback on their effects on other processesand their effects on the total supply chain, and have the tools to make integrated supplychain decisions. This supply chain framework should be incorporated into DoD supply chain materiel management policy.DoD has several opportunities to increase supply chain integration with the benefits of improved performance and efficiency. To reduce costs, the most important is increased attention to supplier lead times and order quantities, which can be through increased integrationwith suppliers. In conjunction, the role of procurement personnel in driving inventory mustbe recognized to a greater degree. The Office of the Secretary of Defense should launch a new initiative to determine how purchasing and supply management practices could be improvedto achieve lead time and order quantity reductions. Related to this is ensuring a tight integration among demand, supply, and repair planning for reparable items to ensure the total supplyof unserviceable items in the ―closed loop‖ reparable system is kept to the minimum necessaryto support readiness. In 2012, ASD(L&MR) launched two studies to take on these issues with one focusing on improving consumable supply chain management in DLA and one focusingon reparable item management across the services.Another opportunity is an increased focus on stock positioning, to include improved incorporation of stock positioning in policy and the broad adoption of stock positioningxviii Integrating the Department of Defense Supply Chainmetrics. Improved stock positioning is at the heart of a number of important DoD supplychain initiatives such as Strategic Network Optimization, Distribution Process Owner Strategic Opportunities supply alignment, and the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) 2005-based transition to DLA ownership and management of retail stock in support of maintenance depots. It also has an important interplay and potential for leverage with a scheduled truck network improvement effort based upon the scheduled truck chapter in this report. Yet despite the frequency with which stock positioning is the crux of improvement initiatives, emphasis remains limited as reflected in metrics and the lack of goals for stock positioning.10Related to all of these is ensuring that organizations have the breadth of budgets that givethem the degrees of freedom to pursue the course of action that will optimize the supply chain and are correspondingly responsible for budgets that they drive the consumption of. A reviewof supply chain organizational budget categories and the effects that each organization hason costs should be conducted to determine where there is misalignment, with changes made accordingly. Aligning budget authority and organizational effects should also be part of the design process when standing up new organizations or changing organizational designs. Finally, progress toward supply chain integration could accelerate with improved end-toend information sharing, to include outside of DoD to the supply base. This includes ensuringeach organization knows what information it produces—and more importantly, could produce that it is not—that would be valuable to its upstream and downstream partners. It alsoincludes ensuring that organizations develop capabilities to utilize this information to the full potential.Overall Contract SpendingTop Line DoD Contract Spending, 1990–2011Figure 2-1 presents total DoD spending from 1990 to 2011 as well as total dollars spent on defense contracts. Contract spending is tracked in FY 2011 dollar amounts by the lower portions of the bars,corresponding with the left-hand y-axis, and as a percentage of total DoD outlays by the line at the top ofthe graph, corresponding with the right-hand y-axis. The upper portions of the bars represent noncontractDoD spending in FY 2011 dollar amounts, including funding for personnel, organic construction, andmaintenance, etc.Between 2001 and 2011, dollars obligated to contract awards by DoD more than doubled, and contract spending outpaced growth in other DoD outlays.1 This growth was predominantly in productsand services, which experienced a 21-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.4 percent and 9.4percent, respectively, compared to the R&D category’s 5.4 percent annual growth. Contract spendingrelative to DoD outlays reversed sharply beginning in 2008, but largely as a result of other DoD outlaysincreasing rapidly rather than of the comparatively small but sustained decline in contract spending. Interms of average annual growth, the increase in DoD contract spending since 1990 far outpaced that ofother DoD outlays. Between 1990 and 2011, other outlays grew by only 0.2 percent per year, whilecontract spending grew by 4.0 percent. This difference was also striking during the post-9/11 period. Overthe last 11 years, contract spending grew by 7.4 percent annually, while other outlays increased at 4.4percent per year.In the years 2008 to 2011 there was a profound shift in DoD contract spending. While absoluteobligations for defense services contracts declined by $25 billion and dropped from 64 percent of totalDoD acquisition outlays to 55 percent, noncontract defense spending increased by $71 billion and increased from 36 percent of DoD acquisition outlays to 45 percent. Therefore, as DoD contracts spending decreased at an annual average of 2.1 percent in total value, its noncontract acquisitions increased by an 11.1 percent CAGR for the same period.Given that there was no significant change in overall DoD contract spending between 2010 and 2011, it is possible that an equilibrium in the ratio between DoD contracts spending and other spendinghas been reached. This kind of steady relationship for DoD spending, split between contracts and otheraccounts, has not been seen since the years 1995 to 2001, although the current level of spending andpercentage of contract spending was much higher in 2010 to 2011 than in those years. However, anticipated reductions in defense spending beginning in 2012 will likely affect all DoD outlays in thecoming years.DoD Contract Obligations by Category in Percentage Terms, 1990–2011Assembled from the previous three figures, the lines in Figure 2-5 track the changes in the composition ofDoD contract obligations among products, services, and R&D contract dollars. Each line tracks thepercentage of total DoD contract dollars awarded in each category in the period 1990 to 2011. Comparing the relative levels of defense obligations in each of the three categories, clear shifts in priorities are evident following the end of the Cold War and following U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq.These shifts are most pronounced in contract obligations for products and services. Reductions in bothmilitary and civilian personnel after the Cold War led to an increase in outsourcing to continue providingmany services, while obligations for products decreased with the smaller force structure. The relativeshares of product and services obligations converged in 1998 and 1999, with the former decreasing andthe latter increasing. After this point, products edged up over services, and the gap widened with theinitiation of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. The relative shares of services and products appeared tobegin converging again after 2008, as absolute levels of obligations declined sharply for products whileobligations for services remained relatively stable. However, FY 2011, the most recent fiscal year, saw asharp increase in product obligations (mostly by the Navy) and a small decrease in services obligationsthat widened this gap.The data for recent years show the degree to which operations in Afghanistan and Iraq independently influenced DoD obligations. While contract dollars for products decreased significantlyduring U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq in 2009 and 2010, the sudden increase in 2011 may be a one-timeadjustment or may mark the end of the resulting ―peace dividend.‖ Obligations for services, however,declined more slowly than that on products after 2009 and continued to decrease in 2011. A similar trendwas seen post–Cold War/post–Gulf War, as products obligations decreased at an average of 1.3 percentannually while services obligations increased by 3.3 percent from 1990 to 2000. One explanation mightbe that in the wake of major operations, obligations for products decreases more abruptly while obligations for services declines more slowly. This is due, perhaps, to the longer-term nature of demandfor services contracts, as opposed to contracts for products (e.g., fuel, munitions), which are more easilyterminated (or not renewed) at the end of a conflict, when demand also ends or is reduced.DoD Contract Obligations by Component, 1990–2011In Figure 3-1, the total DoD contract obligations for each year, presented in the aggregate in Figure 2-1,are broken down by each military department’s share of the total. The Army, Navy, and Air Force areindividually presented, and the remaining DoD components are combined into the category of Other DoDand their obligations are aggregated.In the past decade, trends in contract obligations by the key DoD components are visibly tied to operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Until 2002, each of these components’ contract obligations wasrelatively flat. This changed rapidly after 9/11, with the greatest increases occurring in the Army: 139percent total growth from 2002 to 2010 at an annual rate of 7 percent. Growth in the Other DoD category(111 percent total increase from 2002 to 2010) was driven primarily by the Defense Logistics Agency(DLA) and, to a lesser extent, by the Tricare Management Agency (TMA). Obligations by the Navy grewsomewhat more slowly, rising 54 percent from 2002 to 2010, followed by the Air Force at 14percentgrowth during this period.From 2008 to 2011, due to the drawdown in Iraq and increased fiscal austerity measures, the relative component shares of DoD contract obligations underwent a major shift. This affected the Armymost of all, and its overall contract obligations decreased at an average of 7.7 percent per year between2008 and 2011. Air Force obligations decreased only slightly at 0.5 percent per year on average, whileNavy contract obligations increased by 1.5 percent annually. The category of Other DoD grew in value bya yearly average of 2.5 percent during the past three years, largely driven by obligations by the U.S.Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), TMA, and the Defense Information System Agency (DISA).Share of DoD Total Contract Obligations by Component, 1990–2011To show the relative shares of total DoD contract obligations by the individual DoD departments from1990 to 2010, the percentage lines from the previous four figures are grouped together in Figure 3-9. Allvalues represented in the graph are expressed in percentage of total DoD contract obligations for eachyear.Driven by operations in Iraq and Afgh anistan, the Army’s contract obligations grew rapidly post- 2001 to claim the largest share of defense contract dollars (40 percent at its peak in 2008 compared to 27percent in 2001). However, with U.S. troops withdrawn from Iraq, the Army’s share plunged from 38percent in 2010 to 34 percent in 2011. The Navy’s share of defense contract dollars held mostly steadyafter 2004 at 25 percent, following a long decline from 1990 levels. In the last two years observed, Navycontract obligations surged from 24 percent to 28 percent due to both decreasing Army obligations and asurge in Navy contract obligations. In an unprecedented occurrence, the Air Force dropped to the lowestshare of defense contract obligations in 2008 at nearly 17 percent and, after a rise to 18 percent in 2009and 2010, returned to 17 percent in 2011. However, this share does not reflect the Air Force’s contractobligations for classified projects. Furthermore, the decline in Air Force and Navy shares of DoD contractdollars obligated was absolute gains observed in both of these accounts over the past decade. Meanwhile,the collective share of the category of all Other DoD entities rose to its highest point at 21 percent of DoDcontract obligations in 2011, surpassing its previous peak in 2006.Defense Contract Obligations by Competition, 1990–2011To determine levels of competitiveness in contract awards, this report uses FPDS data on the number ofoffers received from distinct entities before a contract is awarded. Contracts awarded after receivingmultiple offers are deemed the most competitive, followed by those awarded after a single offer andcontracts awarded under no competition. Note that in Figure 4-1 below, unlabeled contracts are those thatare either unlabeled in FPDS or those that were determined by CSIS analysis to be erroneously labeled(for example, if the contract is designated as competed and there are zero bidders, or if it is designated asnoncompeted and there are several bidders). In keeping with previous CSIS reports, classification doesnot include the Fair Opportunity / Limited Sources column. Due to contradictions between that columnand the Extent Completed column, IDV contracts may be classified differently in this report than ingovernment publications.In Figure 4-1, total DoD contract obligations (presented earlier in Figure 2-1) are broken into four broad categories: competition with multiple offers, competition with a single offer, no competition, andunlabeled contracts.Competition in DoD contracting was stable between 1990 and 1996, with between 42 and 47 percent of obligations going to contracts that were competed and received multiple offers, and between 34and 38 percent going to contracts that were not competed. From 1997 through 2001, the shares for bothcompetition with multiple offers and no competition increased by approximately 5 percent; this wasprimarily a result of a decrease in unlabeled contracts. As a result, this change may merely reflect betterreporting rather than a change in contracting practice. Also notable is the period from 1997 to 2000, whencontracts labeled ―No Competition‖ (Unlabeled Exception) represented the vast majority of No Competition contract value; this data deficiency was corrected starting in 2001.From 2000 through 2011, DoD contract dollars awarded with no competition and withcompetition with multiple offers have both increased at a 7 percent annual growth rate. The share ofcontracts that had no competition declined from a high of 41.5 percent in 2001 to 36.9 percent in 2010,but increased again to 39.6 percent in 2011. Meanwhile, competition with multiple offers, which accounted for 50 percent of contract value in 2010, fell to 48.6 percent in 2011.Competitively awarded contracts receiving only a single offer increased from $9 billion in 2000to $44 billion in 2011. This is down from $48 billion in 2010, but overall, competitions receiving only asingle offer have increased at a 15.1 percent annual growth rate since 2000. Looking at the 2008 to 2011downturn period, however, competition with a single offer declined at nearly two and a half times the rateof competition with multiple offers (-4.4 percent versus -1.8 percent annual growth, respectively). Nonetheless, competition with a single offer accounted for 11.7 percent of contract dollars in 2011, whichshould be of concern to those in and out of government advocating for greater use of competition. Factorscontributing to this trend might include:s, or such that one company has a significant and obvious advantage;-heritage defense contractors;scares away potential competitors.Defense Contract Obligations by Funding Mechanism, 1990–2011Figure 4-2 presents trends in the choice of funding mechanism for DoD contract dollars. Funding mechanisms, or the conditions under which the government pays its obligations, are divided here into thefollowing categories: cost reimbursement, fixed price, time and materials (a form of cost based contractdistinguishable from cost reimbursement by the responsibilities assumed by the customer and the contractor), and ―combination‖ (a mix of cost and fixed price).The 1990s saw a significant increase in the use of cost reimbursement contracts, at the expense of fixed price contracts. Cost reimbursement contracts, which accounted for only 18.4 percent of DoDcontract dollars in 1990, rose to a high of 34.7 percent in 1998, while fixed price contracts, which accounted for 74.3 percent of DoD contract dollars in 1990, dropped to 58.7 percent in 1998. This trendbegan to reverse itself in 1999, but the shares of fixed price and cost reimbursement contracts have notreturned to their 1990 levels.The data for 2000 to 2011 reveal additional interesting trends. Fixed price contracts grew at an8.2 percent annual growth rate for 2000 to 2011, compared to 7 percent for cost reimbursement. For theyears 2008 to 2011, the change is even more pronounced: the total value of fixed price contracts decreased slightly (-0.5 percent annual growth rate), compared to a 4.9 percent annual growth rate for costreimbursement contracts. This change is driven by a $2 billion decrease in fixed price contract valuebetween 2010 and 2011, in parallel to a $3 billion increase in cost reimbursement contract value. Within the fixed price category, there was an $11 billion decline in basic Fixed price, along with increases of $6 billion and $2 billion in Fixed price Incentive and Fixed price with Economic Price Adjustment. In the cost reimbursement category, Cost Plus Award Fee contracting declined by $7 billionbetween 2000 and 2011, countered by increases of $6 billion and $3 billion in Cost Plus Fixed Fee andCost Plus Incentive, respectively. The increased use of incentive fees is consistent with recent government-wide contracting policy, but the relative shift from fixed price to cost plus is not. While contracts labeled Combination, which include elements of both cost-based and fixed price contracts, declined significantly in 2009 and 2010, their value nearly doubled between 2010 and 2011,from $6.3 billion to $11.4 billion. This is of concern because with combination contracts, it is impossibleto determine how many dollars are awarded on a fixed price or cost basis. For example, in the $11.4billion awarded in 2011, it is possible that $9 billion was awarded on a cost basis and $2.4 billion wasawarded on a fixed price basis, which would significantly affect the trend lines for the two categories.This category bears watching in FY 2012 to see if this rise was a one-year anomaly or the start of a trend.Defense Contract Obligations by Vehicle, 1990–2011In Figure 4-3, total DoD contract obligations are broken out by contract vehicles. The Indefinite DeliveryVehicles (IDV) category is further broken out into Federal Supply Schedule (FSS), Multiple AwardIndependent Delivery Contracts (IDCs), and Single Award IDCs. Purchase Orders and Definitive Contracts form separate categories.The key trend for DoD contract vehicles in the 1990s was the rapid decline in the use of purchase orders. Claiming a 36 to 40 percent share of total DoD contract value from 1990 to 1994, purchase ordersfell to below 23 percent in 1995 and 1996 and to below 1.5 percent in 1997. Since then, purchase ordershave not exceeded 3 percent of total DoD contract value. In 1997, definitive contracts accountedtwo-thirds of overall DoD contract value, with IDVs (primarily Single Award IDCs) taking up most of theremainder. The share going to definitive contracts declined for the rest of the 1990s, but remained over 61percent in 1999.From 2000 onward, IDVs gradually overtook definitive contracts as the majority of DoD contract value. Definitive contracts and IDVs held 59.3 and 38.9 percent shares, respectively, of overall DoDcontract value in 2000, compared to 42.1 percent for definitive contracts and 55.1 percent for IDVs in2010. This trend reversed somewhat in 2011, as the share of overall DoD contract value going to IDVsdropped to 52.4 percent, while the share going to definitive contracts rose to 44.8 percent. This changewas driven by an increase of $9 billion in definitive contracts in 2011, along with a $10 billion drop inIDVs. Specifically, a $14 billion drop in Single Award IDC was paralleled by a $4 billion rise in FSScontracts.In the years 2000 to 2011, definitive contracts had a 4.7 percent annual growth rate, compared to 10.4 percent for IDVs. Within IDVs, Multiple Award IDCs grew the fastest (14.4 percent annual growthrate), followed by Single Award IDCs (9.5 percent annual growth rate) and FSS contracts (7.8 percentannual growth rate). For 2008 to 2011, overall IDVs (-3.0 percent annual growth rate) declined at almosttwice the rate of definitive contracts (-1.7 percent annual growth rate). This change was driven by a largedecrease in Single Award IDC value (-7.4 percent annual growth), along with a significant slowing of thegrowth in Multiple Award IDCs (7.0 percent annual growth rate).Top 20 DoD Contractors, 2001 and 2011DoD relies heavily on the private sector for the equipment and services needed to meet national securityrequirements. Firms supporting DoD vary significantly, ranging from large publicly traded firms to smallprivately held companies; from firms that generate a significant share of their revenue from DoD contractwork to companies whose share of revenue from defense contracts is but a fraction of overall operations.As the security environment changes over time, so does the composition of firms contracting withThis chapter surveys the industrial base supporting DoD over the past 10 years. The focus is on the top 20DoD contractors (i.e., those taking the largest shares of total DoD contract dollars) and on the breakdownof the industrial base into small, medium, and large companies.In 2001 DoD contract obligations reached some $181 billion awarded to some 46,000 contractors. In 2011, DoD contract awards totaled $375 billion and included slightly over 110,000 contractors. Table5-1 shows the top 20 DoD contractors for 2001 and 2011. The top 5 contractors are identified in a separate cadre. Values are expressed in millions of FY 2011 dollars.Total contract awards for the top 20 DoD contractors increased from $77 billion in 2001 to $163 billion in 2011. While contract revenue for the top 20 companies more than doubled, their share of thetotal DoD contract awards remained constant at 43 percent in 2001 and 2011. The share of the next top 15contractors increased from 13 percent of total DoD awards in 2001 to 17 percent of the total in 2011.The composition and ranking of the top 5 DoD contractors remained nearly intact. The only noticeable change between 2001 and 2011 is the result of an acquisition: in late 2001 Northrop Grumman(seventh) acquired Newport News Shipbuilding (third). The combined company, Northrop GrummanCorporation, became the third-largest defense contractor, a rank it held until early 2010. In 2011 NorthropGrumman spun off its shipbuilding business, the combined Newport News and Gulf Cost Shipbuilding,into a new company, Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII). Following the spinoff, Northrop Grummandropped to fifth place on the top 20 list.A more substantial shift in the composition and market share over the past 10 years occurred among companies ranked 6 to 20. The number and market share of health care contractors, which increased from two in 2001 to three in 2011, and their market share rose from 1 percent to over 3 percentof total DoD contract awards. In absolute terms, contract values for health care firms more than tripled, inreal terms, between 2001 and 2011. If the top three health care firms in 2011 were combined, their dollarawards would total over $9 billion, and they would be ranked sixth on the list. This highlights the sharpgrowth in DoD health care expenses from an industrial base perspective. It also illustrates a key challengefor defense policymakers grappling with a defense budget drawdown: spiraling health care costs. The data seem to refute that the same defense firms are gaining an ever-larger share of themarket. In the past decade, the top 5 defense contractors actually lost market share, and of the firms inplaces 6 to 20, defense contract dollars went to different contractors over time.Defense Contract Obligations by Contractor Size, 2000–2011Figure 5-1 illustrates the changes in distribution of all DoD contract dollars across contractors classifiedby their relative sizes: small, medium, and large. In this report, any organization designated as small bythe FPDS database—according to the criteria established by the federal government—was categorized assuch. The threshold for a compan y to be considered ―large‖ is $3 billion in total annual revenue. Toprovide greater granularity in this analysis, the large category is further broken out into the ―Big 6‖contractors (Lockheed, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and BAE Systems)and the rest of the large (greater than $3 billion in total annual revenue) contractors. Companies notdesignated as either small or large are considered ―medium.‖ Contracts awarded to subsidiaries are rolledinto their parent contractors’ data; thus, those contractors are not distinguished separately. This breakdown is not meant to reflect the federal standard for small business set asides and varies from thoserules in two critical ways. First, if FPDS reports that a small business has been acquired by a large business, CSIS classifies dollars obligated to that company as going to a larger contractor. Second, thisreport includes all contracts and does not exclude waived contracts (e.g., overseas contracts).A continuing area of concern for policymakers is the market share captured by small, medium, and large companies. In DoD contracting, a combination of growth in the market share of large contractors and small-business set-aside programs put pressure on mid-tier contractors, who have lostsignificant market share from a high of 35.6 percent in 2001 to a low of 25.4 percent in 2011. During the2008 to 2011 period, the contract value awarded to mid-tier firms has declined (-4.5 percent annualgrowth rate) faster than the value awarded to all other contractor size categories. The Big 6 have alsoshown the most significant fluctuation in market share during the current downturn; from 29 percent in2008, the share of contract value going to the Big 6 declined to 26.7 percent in 2010, with the gains splitbetween other large contractors and small contractors. This trend was reversed somewhat in 2011,。

上海资质翻译标书翻译论文翻译

上海资质翻译标书翻译论文翻译加-微-信:544609186精诚翻译公司全网最低5元百字起(市场价格10元,比传统翻译机构低40%左右,互联网+时代,省去中间的环节,价格低于翻译行业任何家翻译机构,5年经验保证,首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改,为很多的大型外企和国企翻译过许多专业文件!五周年庆,五折优惠中,可以通过以上方式咨询!IN TRADITIONAL war films,the enemy is faceless.Imbuing[1]opponents with humanity would rob“our boys”and the audience of moral certitude[2].Reality is different.There is no glory in war and the boys on both sides—and so many are just boys—are human;terrified and unsure about what they are fighting for.Clint Eastwood,a Hollywood actor and director,has provided a powerful reminder of this by making two films of the same battle.在传统战争影片中,敌人都是无名无姓的。

给敌人赋予人性的光彩会令“咱们的阿兵哥”和观众怀疑道义的存在。

然而今非昔比,战争中不再有荣耀可言,敌我双方都是人,其中有很多还只是孩子;他们都不清楚为何而战,都惧怕战争。

好莱坞演员兼导演克林特•伊斯特伍德执导的关于同一战役的两部电影,让人们清醒地认识到这一点。

The conquest of Iwo Jima,shown from an American view in“Flags of our Fathers”and from the Japanese side in“Letters from Iwo Jima”,was the most brutal and pointless of the second world war.By February1945,it was clear that the Allies' technological and numerical superiority was unbeatable.Yet the Japanese,led by an inspired general,dug themselves in[3]on Iwo Jima,a bleak,volcanic island far from Tokyo.It took American marines five weeks to overrun them.Some7,000 Americans and22,000Japanese died.But what turned Iwo Jima into legend was Joe Rosenthal's photograph of six American soldiers raising a flag on Mount Suribachi.分别站在美国人和日本人角度拍摄的两部电影《父辈的旗帜》(Flags of our Fathers)和《硫黄岛来信》(Letters from Iwo Jima),均取材于攻占硫黄岛一役,它是二战中最惨烈也是最无谓的一场战役。

上海英文资料翻译公司翻译报价

上海英文资料翻译公司翻译报价加-微-信:544609186精诚翻译公司全网最低5元百字起(市场价格10元,比传统翻译机构低40%左右,互联网+时代,省去中间的环节,价格低于翻译行业任何家翻译机构,5年经验保证,首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改,为很多的大型外企和国企翻译过许多专业文件!五周年庆,五折优惠中,可以通过以上方式咨询!CANCER cells manage their energy production in a most peculiar way.Most cancer cells,however,use a less efficient mechanism called glycolysis to power themselves.They thus cut their mitochondria out of the loop.肿瘤细胞产生能量的方式极为特别。

正常细胞依靠线粒体(是由大约20亿年前寄居在单细胞动植物祖先体内的细菌演化而来)氧化糖分子从而释放有用的能量,而大多数肿瘤细胞则通过糖酵解作用来为自身供能。

这种作用机制效率较低,但不需要线粒体参与。

That cancer cells often rely on glycolysis was discovered by Otto Warburg in 1930.Now,it looks a lot more interesting,for Evangelos Michelakis and his colleagues at the University of Alberta,in Canada,are testing a drug called dichloroacetate that suppresses the Warburg effect and reactivates the mitochondria.The result shows why mitochondrial suppression is so important to tumours:when they are unsuppressed,the tumour they are in stops growing.肿瘤细胞通常依靠糖酵解供能是Otto Warburg于1930年发现的,但这一被后人称为“Warburg效应”的现象一直以来只是让人感到好奇而已,而且还颇有争议。

收费标准 英文怎么说

收费标准英文怎么说As a Baidu Wenku document creator, I would like to discuss the topic of "收费标准" in this document. 。

When it comes to discussing the topic of "收费标准" (Fee Standards), it is important to consider various factors that may influence the pricing of goods or services. In this document, we will explore the concept of fee standards and how they are determined in different industries.The concept of fee standards refers to the established criteria or guidelines used to determine the cost of goods or services. These standards can vary greatly depending on the industry, the nature of the goods or services, and the overall market conditions. It is essential for businesses and service providers to establish clear and transparent fee standards to ensure fairness and consistency in pricing.In many industries, fee standards are influenced by factors such as production costs, market demand, competition, and regulatory requirements. For example, in the healthcare industry, fee standards for medical procedures and services are often determined based on the cost of equipment, staff salaries, and overhead expenses. Similarly, in the legal profession, fee standards for legal services are influenced by factors such as the complexity of the case, the experience of the attorney, and the prevailing market rates.It is important for businesses and service providers to carefully consider all relevant factors when establishing fee standards. By taking into account the various costs and market conditions, they can ensure that their pricing is competitive and sustainable. Additionally, transparent fee standards can help build trust and credibility with customers, leading to long-term success and customer satisfaction.In conclusion, the concept of fee standards is a crucial aspect of pricing goods and services in various industries. By carefully considering factors such as production costs, market demand, and regulatory requirements, businesses and service providers can establish fair and transparent fee standards that benefit both themselves and theircustomers. It is essential for businesses to regularly review and update their fee standards to ensure that they remain competitive and sustainable in the ever-changing market environment. Thank you for reading this document on "收费标准" (Fee Standards).。

各种费用明细英文翻译

海运费ocean freight集卡运费、短驳费Drayage订舱费booking charge报关费customs clearance fee操作劳务费labour fee or handling charge商检换单费exchange fee for CIP换单费D/O fee拆箱费De-vanning charge港杂费port sur-charge电放费B/L surrender fee冲关费emergent declearation change海关查验费customs inspection fee待时费waiting charge仓储费storage fee改单费amendment charge拼箱服务费LCL service charge动、植检疫费animal & plant quarantine fee移动式其重机费mobile crane charge进出库费warehouse in/out charge提箱费container stuffing charge滞期费demurrage charge滞箱费container detention charge卡车运费cartage fee商检费commodity inspection fee转运费transportation charge污箱费container dirtyness change坏箱费用container damage charge清洁箱费container clearance charge分拨费dispatch charge车上交货FOT ( free on track )电汇手续费T/T fee转境费/过境费I/E bonded charge空运方面的专用术语空运费air freight机场费air terminal charge空运提单费airway bill feeFSC (燃油附加费) fuel surchargeSCC(安全附加费)security sur-charge抽单费D/O fee上海港常用术语内装箱费container loading charge(including inland drayage) 疏港费port congestion charge他港常用术语场站费CFS charge文件费document chargeBAF BUNKER AJUSTMENT FACTOR 燃油附加费系数BAF 燃油附加费,大多数航线都有,但标准不一。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

标题

英文说明书翻译

拨--打【4000-—537-407】

内容简介精诚翻译提前您,找翻译服务时,请勿在收到翻译稿件之前进行银行转账,根据我们的经验,要求未做事之前银行卡付款的,很多是骗子,请你切记切记!精诚翻译五折优惠中六年经验!首推先翻译后付费模式,无效免单,免费试译,免费修改。

Putting fresh groceries in the fridge is the quickest and easiest option after a shop, but whether or not those items belong in there is another story.

把新鲜食品放冰箱里是从商店回来后最先做、也是最容易做的事,但那些食物是否该放冰箱里却是另一回事。

Surprisingly, most fruits and vegetables are better off out of the fridge at first, with many of them only needing refrigeration once fully ripe.

出人意料的是,大多数水果蔬菜最好先不要放冰箱里,其中有很多只在完全成熟之后才需要冷藏。

Daily Mail Australia spoke to leading senior nutritionist from NAQ Nutrition, Aloysa Hourigan, to find out what should be in the fridge and what should remain at room temperature.

《每日邮报》驻澳大利亚记者向NAQ Nutrition首席高级营养师阿罗伊莎霍瑞根咨询了什么该放冰箱里、什么该常温保存。

BREAD

面包

Putting bread in the fridge will dry it out so if you are not going to eat it fast, then the better option is to freeze it and get slices out as you need them. 面包放冰箱里会变干,所以如果你吃得慢的话,最好冷冻,吃的时候切片。

For those who do choose to keep it in the fridge, multi grain bread is the best choice as it doesn't dry out as easily as white or wholemeal bread does. 对那些选择冷藏的人来说,最好选杂粮面包,因为它不像白面包或全麦面包那么容易变干。

TOMATOES

西红柿

Tomatoes are commonly refrigerated after purchase, but there is a reason they are kept at room temperature at the supermarket.

西红柿买回来通常会冷藏,但在超市里常温放置是有原因的。

'In terms of becoming ripe enough to eat, tomatoes do better when they are out of the fridge,' Ms Hourigan said.

霍瑞根女士说:“想让西红柿变熟能吃,不放冰箱里确实更好。

”

'Once they reach their ripeness they can go in the fridge otherwise they start to spoil...but tomatoes won't ripen in the fridge by themselves.'

“一旦熟了就要冷藏,否则会开始腐烂……但西红柿放冰箱里是不会自己变熟的。

”ORANGES

橙子

If you leave them out of the fridge for too long they will gradually lose their

Vitamin C content over time and the fridge will keep those levels higher for longer.

如果橙子在冰箱外放置时间过长就会逐渐失去维C,冷藏可使维C较长时间保持更高水平。

POTATOES

土豆

'Potatoes should never be stored in the fridge, the best way to store them, as well as onions, is in a cool dark place like the bottom of the pantry,' Ms Hourigan said.

霍瑞根女士说:“土豆永远不要存放在冰箱里,贮存土豆和洋葱最好的方法就是放在像食品柜底部这样阴暗凉爽的地方。

”

'If they are in the light they go green on the skin and spoil and if they are in the fridge they become moist which is not ideal.'

“如果有光照,土豆皮会变绿,土豆会腐烂;冷藏的话又过于潮湿,也不是理想状态。

”BERRIES

浆果

'Berries - especially strawberries - ripen up much better out of the fridge, however they will spoil fairly quickly so you need to pick the perfect time,' Ms Hourigan said.

霍瑞根女士说:“浆果,尤其是草莓,不放冰箱里会熟得更透,但烂得也快,所以你要把握好最佳时间。

”

HONEY

蜂蜜

'Honey is better in the cupboard than in the fridge as it crystallises...it doesn't go off in the cupboard,' Ms Hourigan said.

霍瑞根女士说:“蜂蜜放橱柜里要比放冰箱里更好,因为它会结晶……放橱柜里也不会变质。

”

GARLIC

大蒜

'If they are whole bulbs they can just sit in a dish or container near where food is prepared,' Ms Hourigan said.

霍瑞根女士说:“如果是整头大蒜,放在盘子或容器里就行,放在做饭时方便拿的地方。

”

'Once you've peeled it however, it is better off in the fridge as it won't retain it's flavour otherwise.'

“但一旦剥皮了,最好冷藏,因为不放冰箱里就不能保持它的味道。

”

B2。