Adjustments and Refusals

Inflation measurement and adjustment

测量通货膨胀率(Rate of Inflation)

CPI this year −CPI last year Rate of inflation(通货膨胀率)= ﹡100 CPI last year

=

140 −100 100

* 100

=40%

我们在 2009 年的通货膨胀率是 40%。.

2.3 GDP deflator and CPI (GDP 平减指数和消费价格指数)

由于许多原因,通货膨胀是一个问题,但是最主要的就是一旦它开始,它的速度是不可 预计的。 然而不可预计的通货膨胀必然给整个国家的经济以及个人带来很多严重的问题。 1)重新分配收入和财富(Redistributes income and wealth): 通货膨胀可以在消费者、企业以及整个国家之间重新分配收入和财富。这种重新分配可 以通过很多种形式。例如说,任何一个以依靠固定收入为主要生活收入的居民都会因此 而受到伤害。 如果因为通货膨胀的原因而导致真实利息下降,那么一般来说储户(savers)和贷款方 (lenders)会受到伤害。如果说真实利息是 10%,通货膨胀是 20%,那么一个储户将会 丢失他们所放在银行里的那部分钱的收益率的 10%。 对于借款方来说(borrowers) , 将会少还 10%的利息,而对于贷款方来说(lenders) 就要少收入 10%。所以通货膨胀对 于贷款方(lenders)来说不是一个好消息, 而对于借款方 (borrowers)来说却是一个好消息。 税收(Tax)和政府花销(Government spending) 可能不会随着通货膨胀而发生变化。例 如说,如果财政大臣没有随着通货膨胀而去增加在酒水和香烟的税,那么政府的真实收 入(real income)将会降低,而抽烟的人和饮酒的人将会因此而获益如果我们设想他们收 入的是和通货膨胀的速度是一致的。 同样来说如果财政大臣没有随着通货膨胀而去增加 个人收入所得税免税额(income tax allowance 工人所挣得的那部分钱是不用纳税的) , 那么这部分税的重担就落在了政府的身上。 2)菜单成本(Menu costs) 如果出现了通货膨胀,饭店就会更新他们的菜单去展现新的价格。同样,所有的商店百 货业会去更改价格标签,企业需要重新计算价格,发布新的价格清单(price list)。这些 都是通货膨胀带来的成本。 3)鞋底成本(Shoe leather costs) 如果说物价是稳定的,消费者和企业就会对产品的价格有比较清晰的了解。当物价水平 增加的时候,消费者和企业就对产品的合理价格没有那么清晰的认识了。这会导致更多 的“四处购物” (穿上你的鞋子到处走 wearing out your shoes)这无疑增加了成本。当 通货膨胀速度非常快的时候, 钱就会以非常快的速度失去它的价值, 失去它储蓄的价值, 人们会尽量避免手里握着钱。人们一旦有了收入会很快的把它花掉,企业有了销售收入 也会很快就支付工资和红利(dividends) 上个世纪 90 年代的时候,当巴西的通货膨胀是 80%的时候,人们会提前结束出租车的 旅行,在距离他们最近的取款机(ATM) 下车,取上现金,付给出租车司机,然后徒步 结束整个行程。出租车司机在寻找下一个顾客之前会先把钱先存在银行。

Chapter 8 Adjustments

8-21

Entries

Dr. Unearned Photocopy Fees Cr. Photocopy Fees Earned $500 $500

2

Depreciation of plant assets

On March 7, the George Ross Photocopy Company purchased photocopy equipment and office equipment for $2,000 and $5,300 respectively.

postponement of Adjustments expenses and revenues paid or received before

Defferals

Accruals

Not mentioned

8-4

Deferrals

D E F E R R A L s

Apportioning recorded expenses

Apportioning recorded revenues

8-5

Prepaid Expenses

At the end of each month Part of prepaid expenses expire an expense of the month

or

assets exaggerated expenses understated

8-20

Illustration

On March 14, George’s agency received $1,300 as an advance fee for copying works to be done for an advertisement agency. Suppose that $500 of the copying works was finished

ConvexityAdjustments

Convexity AdjustmentsRaquel M.Gaspar,Advance Research Center, ISEG,Technical University Lisbon, Rua Miguel Lupi20,room101,1249Lisbon,PORTUGAL*****************.ptAgatha Murgoci,Department of Finance, Stockholm School of Economics,P.O.Box6501,SE-11383Stockholm,SWEDEN*********************December7,2008Executive SummaryThis article aims to clarify the notion of convexity infixed income markets.The main challenge is to provide a unified framework for all the different“convexity adjustments”that exist out there.We explain the basic and appealing idea behind the use of convexity adjustments and focus on the situations we believe are of particular importance to practitioners:yield convex-ity adjustments,forward versus futures convexity adjustments,timing and quanto convexity adjustments.We claim that the appropriate way to look into any of these adjustments is as a side effect of a measure change,as proposed by Plesser(2003).When using the appropriate setup,there may be no immediate urge to do Taylor approximations or fall into too unrealistic assumptions.By using one unified framework,we hope to clarify some issues and help the reader realize that some of the assumptions that are sometimes imposed may be unnecessary.Forfixed income markets,convexity has emerged as an intriguing and challenging notion.Tak-ing this effect into account correctly could providefinancial institutions with a competitive advantage.The idea underlying the notion of a convexity adjustment is quite intuitive and can be easily explained in the following terms.Manyfixed income products are non-standard with respect to aspects such as the timing,the currency or the rate of payment.This leads to complex pricing formulas,many of which are hard to obtain in closed-form.Examples of such products include in-arreas or in-advance products,quanto products,CMS products,or equity swaps,among others.Despite their non-standard features,these products are quite similar to plain vanilla ones whose price can either be directly obtained from the market or at least1computed in closed-form.Their complexity can be understood as introducing some sort of bias into the pricing of plain vanilla instruments.That is,we may decide to use the price of plain products and adjust it somehow to account for the complexity of non-standard products.This adjustment is what is known as convexity adjustment.We start by classifying convexity adjustments into four classes:•Yield Convexity Adjustments;•Forward versus futures price adjustments;•Modified schedule or timing adjustments;and•Mismatch between currencies or quanto adjustments.The yield convexity adjustment is somewhat unrelated to the remaining adjustments,but it is probably the“original one”in the sense that it is related to the non-linear(and convex) relationship between bond prices and their yield-to-maturity.The three remaining adjustments have traditionally been separated,both by practitioners and academics,as they concern different classes of products.Various ad hoc rules have been proposed in the literature to calculate a variety of convexity adjustments for different products.Many of them are,however,mutually inconsistent.We start by critically analyzing the market practice for each of these types of adjustments. Then,we focus on timming adjustments and,in particular,on what we define to be LIBOR adjustments and SWAP adjustments.We show that LIBOR adjustments can be obtained in closed-form,up to the solution of a system of ODEs,in any affine term structure setting. Similar results can also be derived for SWAP adjustments provided we are willing to accept a (reasonable)assumption of the swap rate dynamics.Previously existent results,such as the well-known results for lognormal LIBOR rates as in Pugachevsky(2001)or the Linear Swap Model(LSM)introduced by Hunt and Kennedy(2000) and further exploited by Hagan(2003)can be understood as particular cases of our,more general,results.Key words:Convexity adjustment,LIBOR rate,Swap rates,in-arrears products,CMS,For-ward price,futures price,forward martingale measure,swap martingale measure,affine term structures.ReferencesHagan,P.S.(2003).Convexity conundrums:Pricing cms swaps,caps,andfloors.Wilmott magazine,38–44.Hunt,P.and J.Kennedy(2000).Financial Derivatives in Theory and Practice.John Wiley &Sons,Chichester.Plesser,A.(2003).Mathematical foundation of convexity correction.Quantitative Finance3, 59–65.Pugachevsky,D.(2001).Forward cms rate adjustment.Risk,125–128.2。

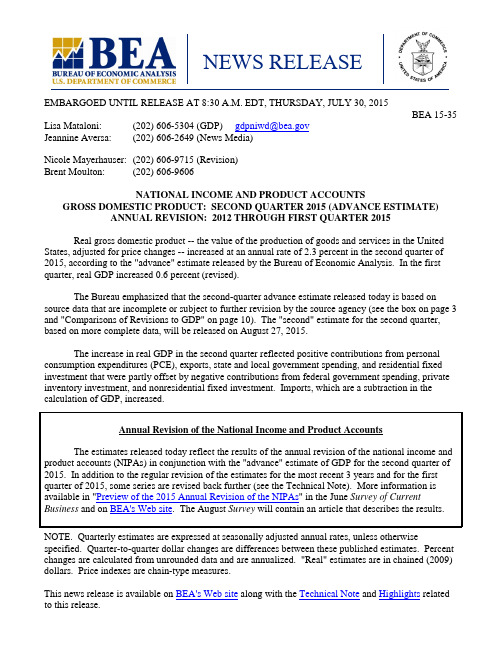

美国商务部二季度国民收入财报

NEWS RELEASEEMBARGOED UNTIL RELEASE AT 8:30 A.M. EDT, THURSDAY, JULY 30, 2015BEA 15-35 Lisa Mataloni: (202) 606-5304 (GDP) gdpniwd@Jeannine Aversa: (202) 606-2649 (News Media)Nicole Mayerhauser: (202) 606-9715 (Revision)Brent Moulton: (202) 606-9606NATIONAL INCOME AND PRODUCT ACCOUNTSGROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT: SECOND QUARTER 2015 (ADVANCE ESTIMATE) ANNUAL REVISION: 2012 THROUGH FIRST QUARTER 2015Real gross domestic product -- the value of the production of goods and services in the United States, adjusted for price changes -- increased at an annual rate of 2.3 percent in the second quarter of 2015, according to the "advance" estimate released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the first quarter, real GDP increased 0.6 percent (revised).The Bureau emphasized that the second-quarter advance estimate released today is based on source data that are incomplete or subject to further revision by the source agency (see the box on page 3 and "Comparisons of Revisions to GDP" on page 10). The "second" estimate for the second quarter, based on more complete data, will be released on August 27, 2015.The increase in real GDP in the second quarter reflected positive contributions from personal consumption expenditures (PCE), exports, state and local government spending, and residential fixed investment that were partly offset by negative contributions from federal government spending, private inventory investment, and nonresidential fixed investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.NOTE. Quarterly estimates are expressed at seasonally adjusted annual rates, unless otherwise specified. Quarter-to-quarter dollar changes are differences between these published estimates. Percent changes are calculated from unrounded data and are annualized. "Real" estimates are in chained (2009) dollars. Price indexes are chain-type measures.This news release is available on BEA's Web site along with the Technical Note and Highlights related to this release.The acceleration in real GDP growth in the second quarter reflected an upturn in exports, an acceleration in PCE, a deceleration in imports, and an upturn in state and local government spending that were partly offset by downturns in private inventory investment, in nonresidential fixed investment, and in federal government spending and a deceleration in residential fixed investment.The price index for gross domestic purchases, which measures prices paid by U.S. residents, increased 1.4 percent in the second quarter, in contrast to a decrease of 1.6 percent in the first. Excluding food and energy prices, the price index for gross domestic purchases increased 1.1 percent, compared with an increase of 0.2 percent.Real personal consumption expenditures increased 2.9 percent in the second quarter, compared with an increase of 1.8 percent in the first. Durable goods increased 7.3 percent, compared with an increase of 2.0 percent. Nondurable goods increased 3.6 percent, compared with an increase of 0.7 percent. Services increased 2.1 percent, the same increase as in the first quarter.Real nonresidential fixed investment decreased 0.6 percent in the second quarter, in contrast to an increase of 1.6 percent in the first. Investment in nonresidential structures decreased 1.6 percent, compared with a decrease of 7.4 percent. Investment in equipment decreased 4.1 percent, in contrast to an increase of 2.3 percent. Investment in intellectual property products increased 5.5 percent, compared with an increase of 7.4 percent. Real residential fixed investment increased 6.6 percent, compared with an increase of 10.1 percent.Real exports of goods and services increased 5.3 percent in the second quarter, in contrast to a decrease of 6.0 percent in the first. Real imports of goods and services increased 3.5 percent, compared with an increase of 7.1 percent.Real federal government consumption expenditures and gross investment decreased 1.1 percent in the second quarter, in contrast to an increase of 1.1 percent in the first. National defense decreased 1.5 percent, in contrast to an increase of 1.0 percent. Nondefense decreased 0.5 percent, in contrast to an increase of 1.2 percent. Real state and local government consumption expenditures and gross investment increased 2.0 percent, in contrast to a decrease of 0.8 percent.The change in real private inventories subtracted 0.08 percentage point from the second-quarter change in real GDP after adding 0.87 percentage point to the first-quarter change. Private businesses increased inventories $110.0 billion in the second quarter, following increases of $112.8 billion in the first quarter and $78.2 billion in the fourth.Real final sales of domestic product -- GDP less change in private inventories -- increased 2.4 percent in the second quarter, in contrast to a decrease of 0.2 percent in the first.Gross domestic purchasesReal gross domestic purchases -- purchases by U.S. residents of goods and services wherever produced -- increased 2.1 percent in the second quarter, compared with an increase of 2.5 percent in the first.Disposition of personal incomeCurrent-dollar personal income increased $145.0 billion in the second quarter, compared with an increase of $118.9 billion in the first. The acceleration in personal income primarily reflected upturns in personal interest income and in farm proprietors’ income that were partly offset by decelerations in government social benefits and in personal dividend income.Personal current taxes increased $26.3 billion in the second quarter, compared with an increase of $60.2 billion in the first.Disposable personal income increased $118.6 billion, or 3.7 percent, in the second quarter, compared with an increase of $58.7 billion, or 1.8 percent, in the first. Real disposable personal income increased 1.5 percent, compared with an increase of 3.8 percent.Personal outlays increased $161.9 billion in the second quarter, in contrast to a decrease of $10.3 billion in the first.Personal saving -- disposable personal income less personal outlays -- was $640.1 billion in the second quarter, compared with $683.3 billion in the first.The personal saving rate -- personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income -- was 4.8 percent in the second quarter, compared with 5.2 percent in the first. For a comparison of personal saving in BEA's national income and product accounts with personal saving in the Federal Reserve Board's financial accounts of the United States and data on changes in net worth, go to/national/nipaweb/Nipa-Frb.asp.Current-dollar GDPCurrent-dollar GDP -- the market value of the production of goods and services in the United States -- increased 4.4 percent, or $191.2 billion, in the second quarter to a level of $17,840.5 billion. In the first quarter, current-dollar GDP increased 0.8 percent, or $33.3 billion.Information on the assumptions used for unavailable source data is provided in a technical note that is posted with the news release on BEA's Web site. Within a few days after the release, a detailed "Key Source Data and Assumptions" file is posted on the Web site. In the middle of each month, an analysis of the current quarterly estimate of GDP and related series is made available on the Web site; click on Survey of Current Business, "GDP and the Economy." For information on revisions, see "Revisions to GDP, GDI, and Their Major Components."Revisions for the first quarter of 2015For the first quarter of 2015, real GDP is now estimated to have increased 0.6 percent; in the previously published estimates, first-quarter GDP was estimated to have decreased 0.2 percent. The 0.8- percentage point upward revision to the percent change in first-quarter real GDP primarily reflected upward revisions to nonresidential fixed investment, to private inventory investment, to residential fixed investment, and to federal government spending that were partly offset by a downward revision to PCE.Previous Estimate RevisedReal GDP………………………….….. -0.2 0.6Current-dollar GDP…………………… -0.2 0.8Real GDI…………………………….... 1.9 0.3Gross domestic purchases price index… -1.6 -1.6A new aggregate, the average of GDP and GDI, is a supplemental measure of U.S. economic activity. In real, or inflation-adjusted, terms this measure increased 0.5 percent in the first quarter of 2015; estimates for the second quarter will be available next month along with the estimate of second-quarter GDI.Annual Revision of the National Income and Product AccountsThe revised estimates reflect the results of the annual revision of the national income and product accounts (NIPAs). These revisions, usually made each July, incorporate newly available and more comprehensive source data, as well as improved estimation methodologies. For this annual revision, the notable revisions primarily reflect the incorporation of newly available and revised source data.The timespan of the revisions is the first quarter of 2012 through the first quarter of 2015 with two exceptions. First, a new treatment of federal refundable tax credits revised some series, including personal income, personal current taxes, government current receipts, and government current expenditures, back to 1976. Second, an updated presentation of the transfer and tax flows between the United States and the rest of the world resulted in revisions to the foreign transactions estimates back to 1999. The reference year remains 2009. None of the changes affected the current reference year for price and quantity measures; revisions to GDP and its components are limited to 2012 and later.Because of the additional data shown, tables 3, 11, and 12 of this release are each divided into two separate tables -- 3A and 3B, 11A and 11B, and 12A and 12B. There are also a number of special tables that compare the revised and previously published statistics for select periods:•Table 1A shows the percent change in real GDP and related measures and table 1B shows revisions to current-dollar GDP, to national income, and to personal income.•Table 2A shows contributions to the percent change in real GDP.•Table 4A shows the percent change in the chain-type price indexes for GDP and related measures.•Table 12C shows revisions to corporate profits by industry.With the release of the annual revision, statistics for select NIPA tables will be available on BEA's Web site (). Shortly after the GDP release, BEA will post a table on its Web site showing the major current-dollar revisions and their sources for each component of GDP, national income, and personal income. Additionally, the August 2015 Survey of Current Business will contain an article describing these revisions.Revisions to real GDPThe revisions largely reflect the incorporation of newly available and revised source data (see the box below) and improvements to estimating methodologies.•From 2011 to 2014, real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.0 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDP had increased at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent.From the fourth quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2015, real GDP increased at an averageannual rate of 2.0 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDP had increased at anaverage annual rate of 2.2 percent during this period.•The percent change in real GDP was revised down 0.1 percentage point for 2012, was revised down 0.7 percentage point for 2013, and was unrevised for 2014.o For 2012, downward revisions to personal consumption expenditures (PCE) and to state and local government spending were partly offset by an upward revision to nonresidentialfixed investment.o For 2013, the largest contributors to the downward revision were downward revisions to PCE, to state and local government spending, and to residential fixed investment.o For 2014, an upward revision to PCE was offset by downward revisions to state and local government spending, to federal government spending, and to inventory investment.•The revisions to the annual estimates typically reflect partly offsetting revisions to the quarters within the year.o For 2012, the annual rate of change in GDP was revised down 2.0 percentage points for the third quarter, while the rate of change for the first and second quarters were revisedup 0.4 percentage point and 0.3 percentage point, respectively; the growth rate for thefourth quarter was unrevised.o For 2013, downward revisions of 0.8 percentage point for the first quarter, 0.7 percentage point for the second quarter, and 1.5 percentage points for the third quarter were partlyoffset by an upward revision of 0.3 percentage point for the fourth quarter.o For 2014, an upward revision of 1.2 percentage points for the first quarter was offset by downward revisions of 0.7 percentage point for the third quarter and 0.1 percentage pointfor the fourth quarter; the second quarter was unrevised.•For the first quarter of 2012 through the first quarter of 2015, the average revision (without regard to sign) to the percent change in real GDP was 0.7 percentage point. The revisionschanged the direction of growth in real GDP for only one of the quarters: the first quarter of 2015.•For the expansion from the second quarter of 2009 to the first quarter of 2015, real GDP increased at an average annual rate of 2.1 percent, 0.1 percentage point less than in thepreviously published estimates.•Current-dollar GDP was revised down for all 3 years: $7.9 billion, or less than 0.1 percent, for 2012; $104.9 billion, or 0.6 percent, for 2013; and $70.9 billion, or 0.4 percent, for 2014.Gross domestic income (GDI) and the statistical discrepancy•From 2011 to 2014, real GDI increased at an average annual rate of 2.4 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDI had increased at an average annual rate of 2.6 percent. From the fourth quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2015, real GDI increased at an average annual rate of2.3 percent; in the previously published estimates, real GDI had increased at an average annualrate of 2.7 percent.•The statistical discrepancy is current-dollar GDP less current-dollar GDI. GDP measures final expenditures -- the sum of consumer spending, private investment, net exports, and government spending. GDI measures the incomes earned in the production of GDP. In concept, GDP is equal to GDI. In practice, they differ because they are estimated using different source data and different methods.•As a result of the annual revision, the statistical discrepancy as a percentage of GDP was unrevised (-1.3 percent) for 2012, was revised up from -1.3 percent to -1.1 percent for 2013, and was revised down from -1.0 percent to -1.2 percent for 2014.•The average of GDP and GDI is a supplemental measure of U.S. economic activity. In real, or inflation-adjusted, terms this measure increased at an average annual rate of 2.2 percent from2011 to 2014.Revisions to price measures•Gross domestic purchases -- From the fourth quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2015, the average annual rate of increase in the price index for gross domestic purchases was revised up from 1.1 percent to 1.2 percent.•Personal consumption expenditures -- From the fourth quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2015, the average annual rate of increase in the price index for PCE was 1.1 percent, 0.1percentage point higher than in the previously published estimates; the increase in the "core"PCE price index (which excludes food and energy) was also revised up 0.1 percentage point,from 1.4 percent to 1.5 percent.Revisions to income and saving measures•National income was revised down $7.6 billion, or 0.1 percent, for 2012, was revised down $118.7 billion, or 0.8 percent, for 2013, and was unrevised for 2014.o For 2012, downward revisions to corporate profits and to proprietors' income were partly offset by an upward revision to net interest.o For 2013, downward revisions to corporate profits, to proprietors' income, and to rental income of persons were partly offset by upward revisions to taxes on production andimports, to net interest, and to current surplus of government enterprises.o For 2014, offsetting revisions of note include downward revisions to proprietors' income, to rental income of persons, and to corporate profits and upward revisions to net interest,to wages and salaries, and to current surplus of government enterprises.•Corporate profits was revised down $24.6 billion, or 1.2 percent, for 2012, was revised down $69.5 billion, or 3.3 percent, for 2013, and was revised down $16.9 billion, or 0.8 percent, for2014.•Personal income was revised up $27.4 billion, or 0.2 percent, for 2012, was revised down $98.5 billion, or 0.7 percent, for 2013, and was revised down $39.7 billion, or 0.3 percent, for 2014.•From 2011 to 2014, the average annual rate of growth of real disposable personal income was revised down 0.3 percentage point from 1.8 percent to 1.5 percent.•The personal saving rate (personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income) was revised up from 7.2 percent to 7.6 percent for 2012, was revised down from 4.9 percent to 4.8percent for 2013, and was revised down from 4.9 percent to 4.8 percent for 2014.New and revised source dataThis annual revision incorporated data from the following major federal statistical sources:Agency Data Years Covered and VintageCensus Bureau Annual survey of wholesale trade 2012 (revised) and 2013 (new) Annual survey of retail trade 2012 (revised) and 2013 (new) Annual survey of manufactures 2013 (new)Economic census 2012 (new)Monthly surveys of manufactures, merchant wholesaletrade, and retail trade2012–2014 (revised)Service annual survey2012 and 2013 (revised),2014 (new)Annual surveys of state and local government financesFiscal years 2012 (revised) and2013 (new)Monthly survey of construction spending (value put inplace)2013 and 2014 (revised) Quarterly services survey 2012–2014 (revised)Current population survey/housing vacancy survey2012 and 2013 (revised)2014 (new)Office of Management andBudgetFederal Budget Fiscal years 2014 and 2015Internal Revenue Service Tabulations of tax returns for corporations2012 (revised) and2013 (new) Tabulations of tax returns for sole proprietorships andpartnershipsBLS Quarterly census of employment and wages 2012–2014 ( revised) Department of Agriculture Farm statistics 2012–2014 (revised) BEA International transactions accounts 2012–2014 (revised)Changes in methodology and presentationThe annual revision also incorporated improvements to estimating methodologies and to the presentation of the NIPA estimates, including the following:•Two new statistics that facilitate the analysis of macroeconomic trends in the U.S. economy are now presented in BEA’s current quarterly GDP news release and data tables. “The average ofGDP and GDI” provides a supplemental measure of U.S. production that reflects timing andmeasurement variations between GDP and GDI. “Final sales to private domestic purchasers”provides a measure of private demand in the U.S. economy. It reflects consumer spending and investment spending by private businesses and excludes spending by governments, net exports, and private inventory investment.•BEA introduced new seasonal adjustments and refinements to existing seasonal adjustment methods for a number of GDP and GDI components, including federal defense spending,consumer spending on services, net interest, and corporate profits.•BEA used Bureau of Labor Statistics producer price indexes for portfolio management services, for investment advice services, and for commercial bank trust services to deflate consumerspending on these financial services. These new price indexes replaced the use of input costindexes and better reflect the prices charged by providers of these financial services.•BEA reclassified federal government refundable tax credits as government social benefits and no longer records the portion of these tax credits that reduce a person’s tax liability as reductions in the income taxes paid by persons. This new treatment allows users to see the full costs andbenefits of these tax policies to the government and to recipients. This reclassification hadoffsetting impacts to personal income and to personal current taxes beginning with 1976; thepersonal saving rate was not impacted by this change.•For more information about these changes, see "Preview of the 2015 Annual Revision of the NIPAs" in the June Survey of Current Business.* * *BEA's national, international, regional, and industry estimates; the Survey of Current Business; and BEA news releases are available without charge on BEA's Web site at . By visiting the site, you can also subscribe to receive free e-mail summaries of BEA releases and announcements.* * *Next release -- August 27, 2015 at 8:30 A.M. EDT for:Gross Domestic Product: Second Quarter 2015 (Second Estimate)Corporate Profits: Second Quarter 2015 (Preliminary Estimate)Comparisons of Revisions to GDPQuarterly estimates of GDP are released on the following schedule: "Advance" estimates, based on source data that are incomplete or subject to further revision by the source agency, are released near the end of the first month following the end of the quarter; as more detailed and more comprehensive data become available, "second" and "third" estimates are released near the end of the second and third months, respectively. The "latest" estimates reflect the results of the 2014 annual revision; the results of the 2015 annual revision will be incorporated at a later date.Annual revisions generally cover at least the 3 most recent calendar years (and the associated quarters) and incorporate newly available major annual source data. Comprehensive (or benchmark) revisions are carried out at about 5-year intervals and incorporate major periodic source data, as well as improvements in concepts and methods that update the accounts to portray more accurately the evolving U.S. economy.The table below presents the average revisions to the quarterly percent changes in real and current-dollar GDP for the different estimate vintages. From the advance estimate to the second estimate (1 month later), the average revision to real GDP growth without regard to sign is 0.5 percentage point, while from the advance estimate to the third estimate (2 months later), it is 0.6 percentage point. From the advance estimate to the latest estimate, the average revision without regard to sign is 1.2 percentage points. Larger average revisions for the latest estimates reflect the fact that comprehensive revisions include major improvements to the accounts, such as the incorporation of BEA's latest benchmark input-output accounts. The quarterly estimates correctly indicate the direction of change in real GDP 96 percent of the time, correctly indicate whether GDP is accelerating or decelerating about 75 percent of the time, and correctly indicate whether real GDP growth is above, near, or below trend growth about 83 percent of the time.Revisions to Quarterly Percent Changes of GDP: Vintage Comparisons[Annual rates]Vintages compared Average Average withoutregard to signStandard deviation ofrevisions without regardto signReal GDPAdvance to second..... 0.1 0.5 0.4 Advance to third......... 0.1 0.6 0.4 Second to third............ 0.0 0.2 0.2 Advance to latest........ -0.1 1.2 1.0Current-dollar GDPAdvance to second.... 0.2 0.5 0.4 Advance to third........ 0.2 0.6 0.4 Second to third........... 0.1 0.3 0.2 Advance to latest....... 0.1 1.3 1.0 NOTE. These comparisons are based on the period from 1993 through 2013.Table 1. Real Gross Domestic Product and Related Measures: Percent Change From Preceding PeriodLine2011201220132014Seasonally adjusted at annual ratesLine 20112012201320142015IV I II III IV I II III IV I II III IV I II1Gross domestic product (GDP).................... 1.6 2.2 1.5 2.4 4.6 2.7 1.90.50.1 1.9 1.1 3.0 3.8–0.9 4.6 4.3 2.10.6 2.31 2Personal consumption expenditures...................... 2.3 1.5 1.7 2.7 1.4 2.40.7 1.1 1.1 2.5 1.4 1.7 3.5 1.3 3.8 3.5 4.3 1.8 2.92 3Goods...................................................................... 3.1 2.7 3.1 3.3 3.9 4.9 1.1 2.7 2.3 6.1 1.2 2.6 3.1 1.1 6.7 4.1 4.1 1.1 4.83 4Durable goods..................................................... 6.17.4 5.8 5.912.011.4 2.8 6.88.18.8 2.2 3.2 4.1 2.613.97.5 6.1 2.07.34 5Nondurable goods............................................... 1.80.6 1.9 2.10.5 2.00.40.9–0.3 4.80.7 2.3 2.60.4 3.4 2.4 3.20.7 3.65 6Services.................................................................. 1.80.8 1.0 2.40.1 1.20.50.20.50.7 1.5 1.2 3.7 1.4 2.4 3.1 4.3 2.1 2.16 7Gross private domestic investment........................ 5.210.6 4.5 5.432.19.710.2–1.1–3.27.1 5.213.7 4.2–2.512.67.4 2.18.60.37 8Fixed investment..................................................... 6.39.8 4.2 5.39.914.7 6.90.1 6.9 4.9 2.6 3.8 5.1 6.0 5.67.9 2.5 3.30.88 9Nonresidential.....................................................7.79.0 3.0 6.29.512.27.5–2.1 3.7 4.0 1.0 3.58.78.3 4.49.00.7 1.6–0.69 10Structures........................................................ 2.312.9 1.68.113.819.910.3–4.0–7.3–6.011.717.9 4.019.1–0.2–1.9 4.3–7.4–1.610 11Equipment.......................................................13.610.8 3.2 5.89.416.08.8–3.37.3 6.3–0.8–3.814.7 3.5 6.516.4–4.9 2.3–4.111 12Intellectual property products.......................... 3.6 3.9 3.8 5.2 6.8 1.9 3.8 1.4 6.87.8–3.2 5.2 3.57.8 4.8 6.6 6.97.4 5.512 13Residential...........................................................0.513.59.5 1.811.727.5 3.710.722.39.19.1 4.9–8.1–2.810.4 3.410.010.1 6.613 14Change in private inventories. (14)15Net exports of goods and services (15)16Exports.................................................................... 6.9 3.4 2.8 3.4 4.1 2.7 4.6 2.0–0.5 1.0 4.9 4.210.9–6.79.8 1.8 5.4–6.0 5.316 17Goods.................................................................. 6.5 3.6 2.8 4.48.1 1.8 4.7 2.2–3.80.47.5 5.014.9–9.412.2 6.0 3.9–11.7 6.817 18Services..............................................................7.6 3.0 2.7 1.2–4.7 4.8 4.2 1.57.5 2.2–0.6 2.4 2.6–0.3 4.7–7.18.97.3 2.518 19Imports.................................................................... 5.5 2.2 1.1 3.8 4.5 2.4 2.00.6–3.80.8 5.5 2.4 1.0 2.89.6–0.810.37.1 3.519 20Goods.................................................................. 5.8 2.1 1.0 4.3 5.5 2.5 1.70.6–4.3 1.1 5.3 2.60.7 4.79.9–0.89.97.2 3.720 21Services.............................................................. 4.0 3.0 1.5 1.60.0 1.6 3.50.7–0.9–0.6 6.0 1.5 2.7–6.08.2–0.611.9 6.7 2.521 22Government consumption expenditures andgross investment...................................................–3.0–1.9–2.9–0.6–1.6–1.9–1.9–1.2–3.8–4.5–2.0–2.2–2.70.0 1.2 1.8–1.4–0.10.822 23Federal....................................................................–2.7–1.9–5.7–2.4–2.6–0.4–2.90.5–5.5–9.3–5.6–5.8–6.60.3–1.2 3.7–5.7 1.1–1.123 24National defense.................................................–2.3–3.4–6.7–3.8–9.5–3.7–4.40.8–8.1–10.3–5.8–7.6–5.8–4.6–0.5 4.5–10.3 1.0–1.524 25Nondefense.........................................................–3.40.9–4.0–0.111.4 5.6–0.4–0.1–1.1–7.6–5.4–2.6–7.98.9–2.2 2.5 2.1 1.2–0.525 26State and local........................................................–3.3–1.9–1.00.6–0.8–3.0–1.2–2.3–2.6–1.10.40.2–0.1–0.2 2.60.6 1.3–0.8 2.026 Addenda:27Gross domestic income (GDI)1............................... 2.2 3.3 1.3 2.6 3.37.70.6–0.1 3.5–0.5 2.90.4 2.70.6 4.8 5.1 2.90.3.. (27)28Average of GDP and GDI........................................ 1.9 2.7 1.4 2.5 3.9 5.2 1.20.2 1.80.7 2.0 1.7 3.2–0.2 4.7 4.7 2.50.5.. (28)29Final sales of domestic product............................... 1.7 2.1 1.4 2.4 1.8 3.3 1.40.7 1.6 1.60.7 1.5 4.00.4 3.5 4.3 2.1–0.2 2.429 30Gross domestic purchases...................................... 1.6 2.1 1.2 2.5 4.6 2.6 1.50.3–0.5 1.8 1.3 2.7 2.50.5 4.7 3.8 2.9 2.5 2.130 31Final sales to domestic purchasers......................... 1.7 1.9 1.2 2.5 1.9 3.2 1.10.5 1.0 1.50.9 1.3 2.6 1.8 3.6 3.8 3.0 1.7 2.231 32Final sales to private domestic purchasers............. 2.9 2.9 2.2 3.2 2.8 4.5 1.80.9 2.2 3.0 1.6 2.1 3.8 2.2 4.2 4.3 3.9 2.0 2.532 33Gross national product (GNP)................................. 1.8 2.1 1.5 2.5 4.9 2.1 1.30.6–0.1 1.6 1.7 3.3 3.9–1.2 4.4 4.5 1.9–0.2.. (33)34Disposable personal income................................... 2.5 3.2–1.4 2.70.2 6.7 3.1–0.210.9–15.9 2.7 2.20.6 4.0 3.0 2.7 4.7 3.8 1.534 Current-dollar measures:35GDP..................................................................... 3.7 4.1 3.1 4.1 5.2 4.9 3.8 2.7 1.7 3.6 2.1 4.9 5.60.6 6.9 6.0 2.20.8 4.435 36GDI...................................................................... 4.3 5.2 2.9 4.3 3.910.0 2.4 2.0 5.2 1.1 3.9 2.3 4.4 2.27.1 6.8 3.00.4.. (36)37Average of GDP and GDI.................................... 4.0 4.6 3.0 4.2 4.57.4 3.1 2.3 3.4 2.3 3.0 3.6 5.0 1.47.0 6.4 2.60.6.. (37)38Final sales of domestic product........................... 3.8 4.0 3.1 4.1 2.3 5.6 3.2 3.1 3.1 3.1 1.8 3.5 5.9 1.9 5.8 6.0 2.2–0.1 4.538 39Gross domestic purchases.................................. 4.0 3.9 2.7 4.1 5.7 5.1 2.8 1.5 1.6 3.4 2.0 4.4 4.3 2.1 6.7 5.4 2.80.9 3.639 40Final sales to domestic purchasers..................... 4.2 3.8 2.6 4.1 2.9 5.8 2.2 1.8 2.9 2.9 1.7 3.1 4.5 3.4 5.6 5.4 2.80.0 3.740 41Final sales to private domestic purchasers......... 5.3 4.8 3.6 4.7 4.1 6.9 3.1 2.3 4.1 4.4 2.4 3.8 5.4 4.0 6.2 5.8 3.80.4 4.141 42GNP..................................................................... 3.9 4.0 3.2 4.1 5.5 4.2 3.2 2.8 1.5 3.3 2.7 5.3 5.70.4 6.8 6.2 2.0–0.1.. (42)43Disposable personal income............................... 5.0 5.1–0.1 4.2 1.69.2 4.4 1.113.3–14.7 3.1 3.9 2.0 5.6 5.2 3.9 4.2 1.8 3.7431. Gross domestic income deflated by the implicit price deflator for gross domestic product.See “Explanatory Note” at the end of the tables.。

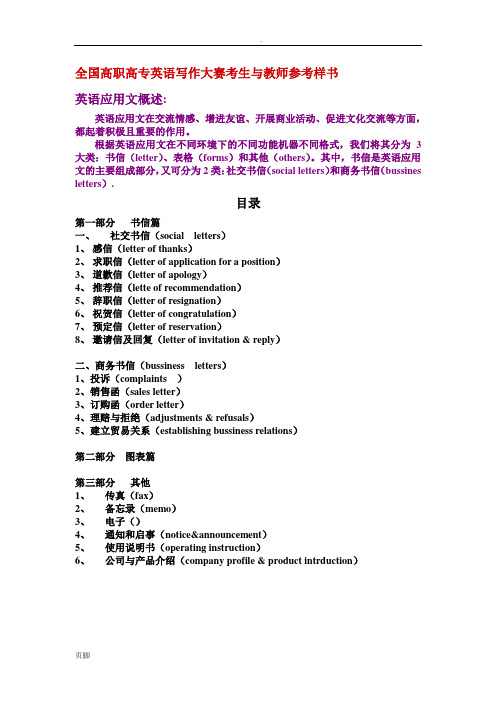

(排版好的)高职高专实用英语写作大赛复习资料

全国高职高专英语写作大赛考生与教师参考样书英语应用文概述:英语应用文在交流情感、增进友谊、开展商业活动、促进文化交流等方面,都起着积极且重要的作用。

根据英语应用文在不同环境下的不同功能机器不同格式,我们将其分为3大类:书信(letter)、表格(forms)和其他(others)。

其中,书信是英语应用文的主要组成部分,又可分为2类:社交书信(social letters)和商务书信(bussines letters).目录第一部分书信篇一、社交书信(social letters)1、感信(letter of thanks)2、求职信(letter of application for a position)3、道歉信(letter of apology)4、推荐信(lette of recommendation)5、辞职信(letter of resignation)6、祝贺信(letter of congratulation)7、预定信(letter of reservation)8、邀请信及回复(letter of invitation & reply)二、商务书信(bussiness letters)1、投诉(complaints )2、销售函(sales letter)3、订购函(order letter)4、理赔与拒绝(adjustments & refusals)5、建立贸易关系(establishing bussiness relations)第二部分图表篇第三部分其他1、传真(fax)2、备忘录(memo)3、电子()4、通知和启事(notice&announcement)5、使用说明书(operating instruction)6、公司与产品介绍(company profile & product intrduction)一、社交书信1、感信(letter of thanks)感信是受到对方某种恩惠,如受到邀请、接待、慰问,收到礼品及得到帮助之后,而表达感之情的信函……感信:感信是受到对方某种恩惠,如受到邀请、接待、慰问,收到礼品及得到帮助之后,而表达感之情的信函。

Adjustments, Financial Statements, and the Quality of Earnings

Debit

Credit

Cash Accounts receivable Inventory Equipment Accumulated depreciation - equip.

$

3,900

4,985

3,300

4,800

$

1,440

Furniture and fixtures

6,600

Accumulated depreciation - furn. & fix.

6,600

27,500 6,300

Totals

$

57,385 $

Credit

1,440 2,200 2,985 4,000 10,000 1,760 35,000

57,385

4-7

Matrix, Inc. Unadjusted Trial Balance

At December 31, 2009

Description

Credit

1,440 2,200 2,985 4,000 10,000 1,760 35,000

57,385

4-9

Unearned Revenues

End of accounting period.

Cash received.

Revenues earned.

Example includes rent received in advance (an unearned revenue).

4-16

Prepaid Expenses

After we post the entry to the T-accounts, the account balances look like this:

会计差错调整 英语

会计差错调整英语Accounting Error Adjustment.Introduction.Accounting, being the language of business, demands precision and accuracy in recording, classifying, and reporting financial transactions. Despite best efforts, errors in accounting are inevitable. When such errors are discovered, it's crucial to promptly identify, correct, and adjust them to ensure the integrity and reliability of financial statements. This article delves into the topic of accounting error adjustment, discussing its importance, types, and methods of adjustment.Importance of Accounting Error Adjustment.Accurate financial statements are essential forinternal decision-making and external stakeholders such as investors, creditors, and regulators. They provide asnapshot of the financial health and performance of a business. Accounting errors, if not corrected, can lead to misleading financial information, affecting decision-making and potentially leading to legal and financial implications. Therefore, it's imperative to adjust accounting errors promptly to ensure the reliability and transparency of financial statements.Types of Accounting Errors.There are two main types of accounting errors: errorsof principle and errors of computation.1. Errors of Principle: These are fundamental errorsthat occur due to a misunderstanding or misapplication of accounting principles or concepts. For example, recording a revenue transaction in the wrong accounting period or classifying an asset incorrectly.2. Errors of Computation: These are mathematical errors that occur during the recording of transactions, such as miscalculating the amount of a transaction, misplacing adecimal point, or entering incorrect data into the accounting system.Methods of Accounting Error Adjustment.There are two primary methods for adjusting accounting errors: the direct adjustment method and the indirect adjustment method.1. Direct Adjustment Method:This method involves making the necessary adjustments to the error directly in the current accounting period.It's typically used for errors of computation that affect only the current period's financial statements. Here's an example:Let's say a company incorrectly recorded a $10,000 sales transaction as $1,000 in the current period. To correct this error using the direct adjustment method, the company would:Debit the sales account by $9,000 (the difference between the correct amount and the incorrect amount)。

CFA考试评分中的ethics adjustment指的是什么?

全球最大的CFA(特许金融分析师)培训中心总部地址:上海市虹口区花园路171号A3幢高顿教育电话:400-600-8011网址: 微信公众号:gaoduncfa 1 CFA 考试评分中的ethics adjustment 指的是什么?What is the "ethics adjustment"?(CFA 考试评分中的"ethics adjustment"指的是什么?)The Board of Governors instituted a policy to place particular emphasis on ethics. Starting with the 1996 exams, the performance on the ethics section became a factor in the pass/fail decision for candidates whose total scores bordered the minimum passing score. The ethics adjustment can have a positive or negative impact on these candidates' final results. (CFA 理事会制定了一项对道德标准格外重视的政策。

自1996年的CFA 考试开始,对那些总分徘徊在最低通过分数(MPS )附近的考生来说,道德模块的得分成为了决定考生通过与否的重要因素。

道德模块的调整得分对这些考生的最终成绩可能产生正面影响,也可能产生负面影响。

)CFA Institute has a policy of not releasing either the minimum passing score or individual candidate scores. Consequently, CFA Institute does not release specific information about the ethics adjustment or the candidates who were affected. The adjustment has had a net positive effect on candidate scores (and thus pass rates) in most exam sessions. The published pass rates always take into account the ethics adjustment for borderline candidates.(CFA 协会既不会公布MPS ,也不会公布每个考生的得分。

CFA 三级笔记整理Los 7 Heuristic

CFA 三级笔记整理Los 7 Heuristic-Driven Biases直觉驱使的偏误

Heuristic-Driven Biases:人们用实验、试误法或个人经验来发展决策而不是研究财务报表或相关数据(看报纸新闻来做股票)

四步骤产生偏误

1.人们发展一般法则当他们发现了一些事情

2.依赖经验法则(rule of thumb)去推断信息

3.易受特定偏误影响

4.人们在特定情况时犯错

Representative:投资者的以过去经验来做预测

EX:有环保意识的就是好公司、过去的好表现代表未来也会有好表现、if-than的直观误判

Overconfidence:人们对自己的预测太有自信,导致Surprise(使报酬在信赖区间之外)

EX:低估风险(易重压在小型股及新公司)、低估可能的报酬范围使报酬在信赖区间之外

Anchoring-and-Adjustment:无法对新事物做出反应,固执于过去做出的预测(Conservatism)

EX:一样会造成surprise,对负面新闻会该跌25%却只预测跌15%,反之好心该涨25%却只涨15%

Aversion to Ambiguity:对未知的恐惧使人们迟疑

EX:在市场上涨时人们觉得市场上涨的机率大于50%,下跌时在下跌的机率大于50%,但当趋势不明显时人们可能会离开试场或寻求专家。

国际经济学英文版chapter17

e Determination in

Small Open Economy.

Foreign Repercussions

■In a two-nation world, an autonomous increase in exports in Nation 1 is equal to an autonomous increase in imports in Nation 2.

must be panied by an equal excess of saving over domestic investment at the equilibrium level of national e.

e Determination in a Small OpenEconomy

■ In an small open economy, the equilibrium condition relating injections and leakages in the e stream is:

■ e will increase by smaller and smaller amounts until total increase is 400.

■ When e has increased by 400, induced savings will have increased by 100, and equilibrium national (S=I) will again be achieved.

level of national e and production (Y) is

determined by planned flow of consumption (C)

plus planned investment (I):

Claims and Adjustments

你方肯定发错了货,由于我们急需这批所订的衬衫, 这次差错给我方带来了极大的不便和困扰。

5. Claims for delayed shipment • We have to inform you that the goods we ordered from you on 15th September have not arrived here, nor have we heard anything from you concerning the shipment.

我们必须提出索赔,共计987英镑外加检验费。

4. Claims for the wrong delivery • We regret to have to return these goods, and shall be glad if you will substitute the right goods for them as early as possible.

我方让保险检查员检查了箱外以及箱内货物,如你方将要见到 的随函附寄的报告单所示,他认为货物的损坏可能是由包装不 当引起的,而不是粗鲁搬运所致。

3. Claims for the shortage

• We have to lodge a claim against you for a short delivery of 400kg.

Claim 后的介词搭配

表示索赔的原因,接 for: claim for damage

表示索赔的金额,接 for: claim for US$1000 表示对某批货物索赔,接 on: claim on the goods 表示向某人索赔,接against: claim against the underwriter

Unit 13 Adjustments

• Refuse positively.

• End with gooe considered when dealing with a complaint

1. Reply promptly. If you are unable to reply fully, explain that it is being investigated and a full reply will be sent later.

For more useful expressions, refer to p257-p258

Blog It Out & Listen to Doctor English

• Please read these two parts and see whether Ms. Liu’s adjustment letter follows the three suggestions by Doctor English?

Adjustment Letters

What is an adjustment letter?

• Adjustment: A modification, fluctuation, or correction: • 修正,变动,改正;

• An adjustment letter: a letter to correct. 理赔信

and promise to put matters right.

4. Thank the customer for informing you about the

matter.

Useful Expressions for the Openings

1. We are concerned to learn from your letter that the goods sent under your order No. 152 did not reach you

商务英语写作Adjustmentsandrefusals

Writing a letter

•Situation:

•The office bought a photocopier last week. But it didn’t work. Ms. Zhang returned it to the store but failed to get the money back. So she wrote a complaint letter to Mr. Black, manager of the store.

2). The body

• The body should focus on your actions and decisions about the complaint.

• I have checked with the transporters, and they inform me that…

Exercises: Rearrange the sentences

a. Please accept our apologies for the delay. b. The mistake has been corrected and will never occur

again. c. Our internal research has uncovered a bottleneck in our

• 如发现确是我方地毯质量低劣,我们愿意承担一 • 切责任。 • If it is found that the quality of our carpet is

inferior to the samples, we are willing to take all responsibility.

• 对于这一严重错误,我方深表歉意。 • We wish to express our deepest regret over • the serious mistake.

所得税汇算调整后差异的账务处理流程

英文回答:The proper accounting treatment for discrepancies in ie tax following the final settlement is a matter of utmost importance forpanies, as it directly impacts the accuracy of their financial reporting. Initially, thepany is required to meticulously scrutinize the tax returns and financial statements in order to discern any disparities in the reported ie tax. Such disparities may stem from variations in the timing of revenue recognition, expenses, or other tax-deductible items. Following the identification of these differences, thepany must proceed to calculate their implications on the ie tax liability and the deferred tax assets or liabilities. This meticulous calculation is indispensable for ascertaining the precise amount of tax provision to be recognized in the financial statements.最终结算后对i税差异的适当会计处理,对于各阶层来说是极为重要的,因为它直接影响到其财务报告的准确性。

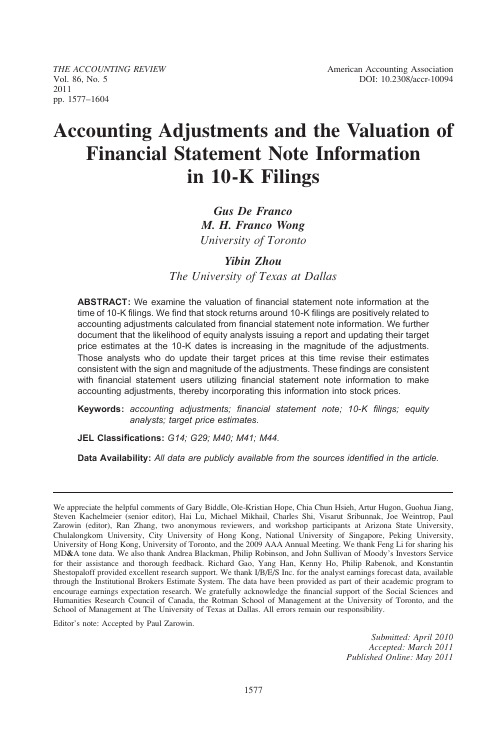

Accounting Adjustments and the Valuation of

THE ACCOUNTING REVIEW American Accounting Association Vol.86,No.5DOI:10.2308/accr-10094 2011pp.1577–1604Accounting Adjustments and the Valuation of Financial Statement Note Informationin10-K FilingsGus De FrancoM.H.Franco WongUniversity of TorontoYibin ZhouThe University of Texas at DallasABSTRACT:We examine the valuation of financial statement note information at thetime of10-K filings.We find that stock returns around10-K filings are positively related toaccounting adjustments calculated from financial statement note information.We furtherdocument that the likelihood of equity analysts issuing a report and updating their targetprice estimates at the10-K dates is increasing in the magnitude of the adjustments.Those analysts who do update their target prices at this time revise their estimatesconsistent with the sign and magnitude of the adjustments.These findings are consistentwith financial statement users utilizing financial statement note information to makeaccounting adjustments,thereby incorporating this information into stock prices.Keywords:accounting adjustments;financial statement note;10-Kfilings;equityanalysts;target price estimates.JEL Classifications:G14;G29;M40;M41;M44.Data Availability:All data are publicly available from the sources identified in the article. We appreciate the helpful comments of Gary Biddle,Ole-Kristian Hope,Chia Chun Hsieh,Artur Hugon,Guohua Jiang, Steven Kachelmeier(senior editor),Hai Lu,Michael Mikhail,Charles Shi,Visarut Sribunnak,Joe Weintrop,Paul Zarowin(editor),Ran Zhang,two anonymous reviewers,and workshop participants at Arizona State University, Chulalongkorn University,City University of Hong Kong,National University of Singapore,Peking University, University of Hong Kong,University of Toronto,and the2009AAA Annual Meeting.We thank Feng Li for sharing his MD&A tone data.We also thank Andrea Blackman,Philip Robinson,and John Sullivan of Moody’s Investors Service for their assistance and thorough feedback.Richard Gao,Yang Han,Kenny Ho,Philip Rabenok,and Konstantin Shestopaloff provided excellent research support.We thank I/B/E/S Inc.for the analyst earnings forecast data,available through the Institutional Brokers Estimate System.The data have been provided as part of their academic program to encourage earnings expectation research.We gratefully acknowledge thefinancial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada,the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto,and the School of Management at The University of Texas at Dallas.All errors remain our responsibility.Editor’s note:Accepted by Paul Zarowin.Submitted:April2010Accepted:March2011Published Online:May20111577I.INTRODUCTIONThis study examines the equity market’s and equity analysts’responses to financial statement note information at the time of 10-K filings.Financial statement note information is an integral part of the financial statements.The note information first becomes available to thepublic when companies file their 10-K reports.Prior studies examining the information content of 10-K filings document mixed evidence (e.g.,Foster and Vickrey 1978;Stice 1991;Easton and Zmijewski 1993;Qi et al.2000;Griffin 2003;Asthana et al.2004;Li and Ramesh 2009).However,these studies focus on the market response to the filings of the 10-K reports per se and,hence,they are silent regarding to what information the market is reacting.Qi et al.(2000)and You and Zhang (2009)use future profitability to proxy for the content of the 10-K reports,rather than a specific piece or set of information contained in the reports.In contrast,numerous studies have documented the value relevance of individual accounting items disclosed in the notes to the financial statements using a long-window research design (e.g.,Bowman 1980;Landsman 1986;Barth et al.1992;Ely 1995;Aboody et al.2004;Landsman et al.2008).In this study,we draw on these two strands of literature to investigate the market reaction to financial statement note information around its release in the 10-K filings and shed light on the mechanism by which note information is incorporated into equity prices.We conjecture that detailed note information is impounded into stock prices around 10-K filings because it is used by financial statement users to compute accounting adjustments.The idea that financial statement users exploit note information in financial analysis in general and in computing accounting adjustments in particular is not new and some empirical evidence exists that is consistent with this notion (e.g.,Foster 1979;Fairfield and Whisenant 2001).1A key product of financial statement analysis is accounting adjustments,which are calculated using information disclosed in financial statement notes.For example,note information can be used to capitalize the assets and liabilities associated with operating leases.These adjustments correct missing or misclassified expense and revenue items,and thus make the adjusted income statement numbers more informative as to the economic performance of a company.For this reason,we expect accounting adjustments to be informative and,hence,valued by investors.We test this prediction by examining the valuation of accounting adjustments at the time of 10-K filings,when the note information needed to compute them first becomes publicly available.To further support our conjecture that note information is incorporated into stock prices because financial statement users employ it to compute accounting adjustments,we also examine the role played by equity analysts in this process.Equity analysts are sophisticated financial statement users,who,we expect,routinely study the financial statements and associated notes of the companies they cover.Under our conjecture,equity analysts use note information to assess and calculate the accounting adjustments needed.When the amount of the adjustments required is different from the analysts’prior expectations,it will affect their assessments of the company’s future performance and valuation.Given the new information,analysts revise their target price estimates,thereby impounding financial statement note information into stock prices.We test this conjecture using a panel of nonfinancial firms,from 2002to 2007,with adjusted income statement data from Moody’s Corporate Financial Metrics (MFM),10-K filing dates from the Securities and Exchange Commission,and analysts’reports with target price estimates from Investext.We use MFM adjustments to proxy for the amount of accounting adjustments that an average financial statement user would make.MFM employs financial statement note information1Accounting analysis and adjustments are also discussed ubiquitously in financial reporting and financial statement analysis books.See,e.g.,White et al.(2002),Palepu et al.(2004),Koller et al.(2005),Penman (2006),Stickney et al.(2006),Wild et al.(2006),and Revsine et al.(2008).As a specific example,in their discussion of accounting analysis,Palepu et al.(2004,3–1)state that an ‘‘important skill is adjusting a firm’s accounting numbers ...to ‘undo’any accounting distortions.’’1578De Franco,Wong,andZhouThe Accounting ReviewSeptember 2011and additional assumptions to calculate standard adjustments to eight accounting items,as well as nonstandard adjustments to highly judgmental accounts(Jonas2006).This is one of thefirst studies to use MFM data in an equity market setting.Recently,Ge et al.(2008)use MFM data to investigate investors’assessment of equity risk attributed to operating leases andfind that it is not reflected in stock price for companies not covered by MFM.The results of our empirical analysis support our conjecture.First,stock returns around10-K filings are positively related to the annual changes in accounting adjustments.This result is consistent with equity market participantsfinding the accounting adjustments and,hence,the note information used to compute them,useful in determiningfirm value.Second,analysts are more likely to issue reports and revise their target price estimates shortly after the10-K date for companies that require a large change in accounting adjustments(in either direction).Third,those analysts who do issue reports and update their target prices around the10-K date revise their target price estimates consistent with the sign and magnitude of the change in accounting adjustments. The last two pieces of evidence lend support for our hypothesized mechanism by which detailed financial statement note information is impounded into security prices.The interpretation of our results relies on the ability of the MFM adjustments to proxy for the amount of accounting adjustments that a typicalfinancial statement user would make,given note information.There are pros and cons associated with using MFM adjustment data for this purpose. First,MFM makes systematic adjustments to a selected set of accounting issues,allowing them to be applied consistently to a large number of companies.However,the set of MFM adjustments might not be relevant for all companies.Since the methodology used by MFM is conceptually similar to the treatments found in manyfinancial reporting andfinancial statement analysis books, we believe that MFM adjustments reflect,albeit with error,the actual adjustments made by an averagefinancial statement user.Second,MFM data are available mainly forfirms with Moody’s rated debt.As a result,our sample is biased toward big companies,making the sample less representative of the population.Nonetheless,the fact that the MFM data are geared toward debt-market participants might be an advantage for us in the sense that our results are less likely attributed to a mechanical relation between our variables of interest(stock returns and equity analysts’actions)and the MFM adjustments.2Third,given Moody’s debt-market focus,the set of adjustments made by MFM might not be applicable in the equity setting.For example,MFM does not capitalize research and development costs.While we cannot correct for this omission,we focus on MFM’s income statement adjustments,because equity market participants are more oriented toward income statement information.3The above discussion suggests that the MFM adjustments measure the actual accounting adjustments with error.The key concern is that the noise in the proxy is somehow systematically correlated with omitted variables in the regressions.If this is the case,then the omitted variables must be related to value-relevant information(in the sense that they affect equity prices)in order for the adjustment proxy to exhibit the documented association with stock returns,analysts’propensity to issue reports and revise their target price estimates,and the direction of analysts’target price revisions. This potential correlated omitted variable problem is mitigated by the use of a short event window, from one day before tofive days after the10-Kfiling date,in our research design.The short window narrows the possible sources of value-relevant omitted variables.In particular,the adjustment proxy exhibits the expected association with stock return,even after controlling for news in earnings 2Given that Moody’s is one of the major bond-rating companies,its research is likely to have a direct impact on bond prices and ratings,as shown in Kraft(2010)and Batta et al.(2010).These studies use the MFM data in a debt-market setting.3Our discussion with Moody’s staff also indicates that the clients of MFM include equity institutional investors, suggesting that the MFM adjustments appeal to more than debt investors and analysts.Accounting Adjustments and the Valuation of Financial Statement Note Information in10-K Filings1579The Accounting Review September2011announcements,the tone of the forward-looking statements in the Management Discussion and Analysis section of 10-K filings,analysts’earnings forecast revisions,and analysts’target price revisions that are issued within the 10-K filing window.Hence,our findings are unlikely to be a result of omitted variables that are correlated with value-relevant information from these four sources.Our study contributes to four strands of literature.First,our results contribute to the 10-K literature.While early studies such as Foster and Vickrey (1978),Stice (1991),and Easton and Zmijewski (1993)find little evidence of a 10-K market reaction,later studies such as Qi et al.(2000),Griffin (2003),and Asthana et al.(2004)document a significant market response to 10-K reports during the EDGAR era.In a larger,more systematic study,Li and Ramesh (2009)find that 10-K reports are informative,but part of the 10-K reaction is attributed to the concurrent releases of earnings in the 10-K filing window.They also show that most of the 10-K reaction is explained by a subset of 10-K filings that coincide with the calendar quarter-end dates,such as March 31and June 30,in which (1)mutual funds are often trading to window dress their portfolios and (2)other firms are also filing their 10-Ks consistent with an intra-industry information transfer effect.In a related study,Li et al.(2011)show that the market does not react so much to 10-K reports per se ,but it does react to the subset of such information that is picked up by newswire services.Li and Ramesh (2009)also find no evidence of significant analyst forecast revisions surrounding 10-K filings.With the exception of Li et al.(2011),these studies are silent about the specific information in the 10-K reports that investors are reacting to.Our study is also related to four other 10-K/10-Q studies.Both Qi et al.(2000)and You and Zhang (2009)document that the 10-K (signed)market reaction is positively related to future profitability,consistent with 10-K reports containing useful information about future performance.Balsam et al.(2002)and Callen et al.(2006)find that the market responds accordingly around the SEC filing dates,because the releases of the full set of financial statements allow investors to estimate discretionary accruals and obtain the accruals-cash flow breakdown,respectively.Our study is similar to the latter two articles in that we identify a specific set of information in the 10-K report,namely notes to the financial statements,and use it to predict ex ante how the market would react.Hence,we contribute to this literature by showing that both the stock market and equity analysts react to the accounting adjustments computed based on financial statement note information at the time of 10-K filings.4Second,we add to the value-relevance literature,which shows that financial statement note disclosures are reflected in equity prices (e.g.,Bowman 1980;Landsman 1986;Barth et al.1992;Ely 1995;Aboody et al.2004;Landsman et al.2008).In particular,we find evidence consistent with equity analysts using detailed note information to make accounting adjustments,which induce them to revise their target price estimates that,in turn,impact stock prices.By tying the price implication of the note information to a subset of the sophisticated financial statement users,we help rule out the possibility that the results reported in prior studies are partly attributable to spurious correlation.Further,we use a short-window event-study design,thereby mitigating the correlated omitted variables problem,which is a concern for prior studies using a long-window research design (Barth et al.2001;Holthausen and Watts 2001).54Recently,Kothari et al.(2009),Li (2010),Brown and Tucker (2011),Feldman et al.(2010),and Miller (2010)have examined the information content in the10-K’s MD&A section using textual analysis.5Event studies are more powerful than association tests.Hence,any reactions from analysts and the market that we document are far more likely to come from the 10-K reports,rather than other information correlated with the financial statement adjustment information in the 10-K but issued at times other than the 10-K event window.In addition,as discussed in length earlier,we are also better in identifying and controlling for potential confounding events during the short window to mitigate the potential of correlated omitted variables.1580De Franco,Wong,andZhouThe Accounting ReviewSeptember 2011Third,our results provide additional support for the role of analysts as information intermediaries as opposed to information gatherers(Lang and Lundholm1996).Specifically,our findings are consistent with analysts processing the note information in10-K reports and transmitting it to the stock market in the form of target price revisions.This is one of the few studies using an event study to examine analysts’use offinancial statement note information in their estimates.Fairfield and Whisenant(2001)also show that the Center for Financial Research and Analysis(CFRA)successfully identifies companies with aggressive accounting and poor future performance.CFRA,however,applies its custom analysis on a small set offirms,which tend to have highly unusual activities or very aggressive accounting for a specific accounting item.In contrast,our study uses MFM data,which cover a larger sample offirms,thereby helping to generalize the notion that the analysis offinancial statements is informative.Specifically,the CFRA sample has373firms and observations.Ourfinal MFM sample includes958firms and4,944firm-year observations.Fourth,we supplement prior studies examining other types of adjusted earnings,such as pro forma earnings(e.g.,Bradshaw and Sloan2002;Bhattacharya et al.2003;Lundholm et al.2003) and economic value added(e.g.,Biddle et al.1997).Pro forma earnings are GAAP earnings excluding certain costs that the company deems to be transitory in nature,such as one-time losses, asset write-downs,and restructuring charges.MFM adjustments include not only these types of adjustments,but also adjustments to other items and,hence,they are broader than pro forma earnings.While the MFM adjustments are systematically applied,pro forma earnings are less comparable across companies,because the latter are prepared by the companies themselves.6 Economic Value Added(EVA t)is residual income computed using accounting numbers adjusted by Stern Stewart&Co.Biddle et al.(1997)find that the accounting adjustment component of EVA has an insignificant association with market-adjusted returns,suggesting that EVA accounting adjustments are of little value.While there is some overlap in the adjustments made by Stern Stewart&Co.and Moody’s MFM,such as how operating leases are handled,Stern Stewart’s adjustments are not identical to MFM and it does not apply the same set of adjustments systematically to all companies.Our study also differs from this literature in that we conduct our tests using a short-window event-study design.We also investigate the actions of equity analysts in the incorporation offinancial statement note information into stock price.The next section describes our data and provides summary statistics on Moody’s adjustments. Section III investigates the market response to accounting adjustments around the release of financial statements at10-Kfiling dates.Section IV examines the role of equity analysts in the incorporation of the accounting adjustments and,hence,financial statement note information into stock prices.Section V concludes.II.DATASample SelectionThe initial sample includes all companies in Moody’s Corporate Financial Metrics(MFM) database,which is our source of the adjustedfinancial statement data.We download all annual financial statement data,including GAAP reported and MFM adjusted balance sheets and income statements,for the time period from2002until2007for U.S.nonfinancial companies.This process results in8,327firm-year observations for1,564U.S.firms.We match the MFM data with the CRSP-6The SECfinds pro forma earnings potentially misleading if not properly disclosed.In January2003,the SEC enacted Regulation G that became effective March28,2003and regulates companies’presentation of pro forma earnings,including the requirement that companies reconcile pro forma numbers to GAAP earnings. Accounting Adjustments and the Valuation of Financial Statement Note Information in10-K Filings1581The Accounting Review September2011Compustat merged database (CCM)at the firm level by equity ticker symbol and firm name.We hand-collect target price estimates from analysts’reports downloaded from Investext,matching our sample firms to Investext by name and ticker symbol.Our requirement of stock returns limits the analysis to firms with publicly traded equity.By using some financial statement data from CCM,we avoid losing one year of sample observations.For example,in certain tests we use lagged assets as a deflator.After this step,our sample contains 4,944firm-year observations for 958U.S.firms.Our empirical tests focus on a short window from one day before to five days after the 10-K filing date.We obtain the filing dates from the Securities and Exchange Commission.While it is possible that Moody’s analysts have obtained 10-K information privately before the 10-K is publicly filed,MFM does not publicly issue their adjusted data for at least seven to ten business days following the 10-K filing date.Hence,for our tests that focus on the 10-K event window,equity analysts and other market participants have access to 10-K information but do not have access to MFM adjusted numbers,thereby ruling out the possibility that market participants and equity analysts are responding to the release of MFM data.Accounting Adjustment DataOur source of accounting adjustment data is Moody’s Corporate Financial Metrics (MFM)database.7MFM systematically adjusts the financial statements of nonfinancial corporations to improve consistency in its rating practice among analysts.The adjustments are reviewed and approved by MFM’s team of analysts and accounting specialists.Appendix A,as well as Jonas (2006),provides a detailed description of these adjustments and the underlying methodology.MFM systematically makes standard adjustments,if applicable,to underfunded defined benefit pensions,operating leases,capitalized interest,employee stock compensation,hybrid securities,securitizations,unusual and non-recurring items,and inventory on a LIFO cost basis.Underfunded defined benefit pensions,operating leases,hybrid securities,and securitizations lead to understated liabilities.MFM adds these debt-like liabilities to the balance sheet and corrects the classification of related expenses on the income statement.Adjustments for capitalized interest and employee stock compensation add missing interest expense and compensation expense,respectively,back to the income statement.Adjustments for unusual and non-recurring items include moving transitory components to below net income before unusual items.MFM also makes nonstandard adjustments to other accounts to make the financial statements more reflective of the company’s underlying economics.These involve judgmental items such as asset valuation allowances,impairments of assets,and contingent liabilities.Table 1summarizes each of these adjustments and their effects on the income statement.We expect that these adjustments correct missing or misclassified expense and revenue items on the income statement,making the adjusted earnings subtotal numbers more useful.In particular,adjusted earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)better reflects the operating performance of the company,while the adjusted items between EBIT and net income before unusual items better reflect the financing and tax strategies of the company.Finally,the adjusted items below net income before unusual items should better reflect the transitory component of earnings.87Other studies using the MFM database include Ge et al.(2008),Kraft (2010),and Batta et al.(2010).While there are some other data providers of accounting adjustments,such as Capital IQ and Bloomberg,their adjustment data suffer a number of limitations.For example,Capital IQ,which has more adjustment information than Bloomberg,does not have any adjustment information on pensions,capitalized interests,hybrids,and makes no nonstandard adjustments like Moody’s does.In addition,when Capital IQ provides some adjustment information,for example on operating leases,Capital IQ fails to fully articulate how this adjustment information affects the complete set of financial statements,like Moody’s does.8Financial statement analysis and adjustments also have the potential to improve accounting comparability across companies.In this study,we do not examine the effects of adjustments on comparability,using for example measures as in De Franco et al.(2011).1582De Franco,Wong,andZhouThe Accounting ReviewSeptember 2011T A B L E 1T h e E f f e c t o f S i x M o o d y ’s S t a n d a r d A d j u s t m e n t s o n I n c o m e S t a t e m e n t L i n e I t e m sP a n e l A :U n d e r f u n d e d D e fin e d B e n e fit P e n s i o n s ,O p e r a t i n g L e a s e s ,a n d H y b r i d S e c u r i t i e sU n d e r f u n d e d D e fin e d B e n e fit P e n s i o n s O p e r a t i n g L e a s e sH y b r i d S e c u r i t i e sC o s t o f G o o d s S o l d /S G &A E x p e n s e s /O p e r a t i n g E x p e n s e s I n c r e a s e s p r o p o r t i o n a l l y b y s e r v i c e c o s t m i n u s G A A P p e n s i o n c o s t s .D e c r e a s e s p r o p o r t i o n a l l y b y i n t e r e s t c o m p o n e n t o f r e n t e x p e n s e .N o e f f e c tD e p r e c i a t i o n N o e f f e c tI n c r e a s e s b y d e p r e c i a t i o n c o m p o n e n t o f r e n t e x p e n s e .N o e f f e c tO t h e r I n c o m e /(O t h e r E x p e n s e )N o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tA d j u s t e d EB I T I n c r e a s e s o r D e c r e a s e s I n c r e a s e s N o e f f e c t I n t e r e s t E x p e n s eI n c r e a s e s b y i n t e r e s t c o s t o n t h e P B O .I n c r e a s e s b y i n t e r e s t c o m p o n e n t o f r e n t e x p e n s e .I n c r e a s e s b y i n t e r e s t e x p e n s e f o r d e b t p o r t i o n o f h y b r i d s e c u r i t i e s c l a s s i fie d a s p u r e e q u i t y o r m i n o r i t y i n t e r e s t .D e c r e a s e s b y p r e f e r r e d d i v i d e n d s f o r e q u i t y p o r t i o n o f h y b r i d s e c u r i t i e s c l a s s i fie d a s p u r e d e b t .O t h e r L o s s o r E x p e n s e (G a i n o r I n c o m e )I n c r e a s e s b y a c t u a l l o s s e s o n p e n s i o n a s s e t s .N o e f f e c tD e c r e a s e s b y i n t e r e s t e x p e n s e f o r d e b t p o r t i o n o f h y b r i d s e c u r i t i e s c l a s s i fie d a s p u r e e q u i t y .D e c r e a s e s b y a c t u a l g a i n s o n p e n s i o n a s s e t s u p t o a m o u n t o f i n t e r e s t c o s t .I n c r e a s e s b y p r e f e r r e d d i v i d e n d s f o r e q u i t y p o r t i o n o f h y b r i d s e c u r i t i e s c l a s s i fie d a s p u r e d e b t o r m i n o r i t y i n t e r e s t .T a x e s E x p e n s eD e c r e a s e s b y t a x e f f e c t o f a d d i t i o n a l p e n s i o n c o s t s .N o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tA d j u s t e d N e t I n c o m e A f t e r -T a xB e f o r e U n u s u a l I t e m s I n c r e a s e s o r D e c r e a s e sN o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tM o o d y ’s U n u s u a l &N o n -R e c u r r i n g I t e m s —A d j u s t m e n t s A f t e r -T a xD e c r e a s e s b y a f t e r -t a x e f f e c t o f a d d i t i o n a l p e n s i o n c o s t s .N o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tG A A P N e t I n c o m e N o e f f e c tN o e f f e c tN o e f f e c t(c o n t i n u e d o n n e x t p a g e )Accounting Adjustments and the Valuation of Financial Statement Note Information in 10-K Filings 1583The Accounting Review September2011。

简述调整分录英语小作文

简述调整分录英语小作文Title: Adjusting Journal Entries。

Adjusting journal entries are crucial for accurately reflecting a company's financial position and ensuring that financial statements adhere to accounting principles. These entries are made at the end of an accounting period to update account balances and correct any discrepancies.Let's delve into the significance of adjusting journal entries and the process involved.Importance of Adjusting Journal Entries:1. Accurate Financial Reporting: Adjusting entries help ensure that financial statements present a true and fair view of the company's financial performance and position. Without these adjustments, the financial statements may be misleading.2. Matching Principle: The matching principle requiresthat expenses be recognized in the same period as the revenues they help generate. Adjusting entries facilitate the proper matching of revenues and expenses, thereby improving the accuracy of income statements.3. Compliance with Accounting Standards: Adhering to accounting standards such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) necessitates the use of adjusting entries to comply with reporting requirements.Types of Adjusting Journal Entries:1. Accruals: Accruals involve recognizing revenues or expenses before cash is received or paid. For example, accrued revenues represent revenues earned but not yet received, while accrued expenses represent expenses incurred but not yet paid.2. Deferrals: Deferrals involve recognizing revenues or expenses after cash has been received or paid. Prepaid expenses, such as insurance premiums or rent, are expensespaid in advance but recorded over multiple periods through adjusting entries. Unearned revenues, like advance payments for services, are recognized as revenue when the service is provided.3. Depreciation: Adjusting entries are also used to record depreciation expense, which allocates the cost of tangible assets over their useful lives. This ensures that the asset's cost is matched with the revenue it helps generate.Process of Making Adjusting Entries:1. Identify Adjustments: The first step is to identify the adjustments needed by reviewing account balances and considering any transactions or events that have occurred but not yet been recorded.2. Record Accruals and Deferrals: Accruals anddeferrals are recorded by adjusting the appropriate accounts. For example, to record accrued revenues, a debit is made to an asset account and a credit to a revenueaccount.3. Calculate Depreciation: Depreciation expense is calculated using an appropriate method (e.g., straight-line, declining balance) and recorded by debiting depreciation expense and crediting accumulated depreciation.4. Review and Post Entries: Once adjustments are calculated and recorded, the entries are reviewed for accuracy and posted to the general ledger.5. Prepare Adjusted Trial Balance: After alladjustments have been made and posted, an adjusted trial balance is prepared to ensure that debits equal credits and to facilitate the preparation of financial statements.Conclusion:In conclusion, adjusting journal entries play acritical role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of financial statements. By making necessary adjustments for accruals, deferrals, and depreciation, companies canprovide stakeholders with a clear and transparent view of their financial performance. Adhering to accounting standards and principles, adjusting entries are essential for maintaining integrity in financial reporting.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The following general pattern will help you better handle the tasks:

1.

2. 3. 4.

Begin with words that indicate response to the request and are neutral as to the answer. Present your justification or explanation, using positive language and you-viewpoint. Refuse positively. End with adapted, goodwill comment.

Sample Analysis

1. Adjustment for the wrong materials

Dear Mr. Presley: The correct consignment of the clothing material will reach you within 20 days.

We hope the software will bring much convenience and profit to you. Frankly yours,

4. Refusal to request for compensating for the damaged material

Dear Ms. Wilson: Every customer has a right to expect the best product and service from Caring Plastic Material. Every caring material is the result of years of experimentation.