NSN&Sharenet

NSN切换参数配置步骤

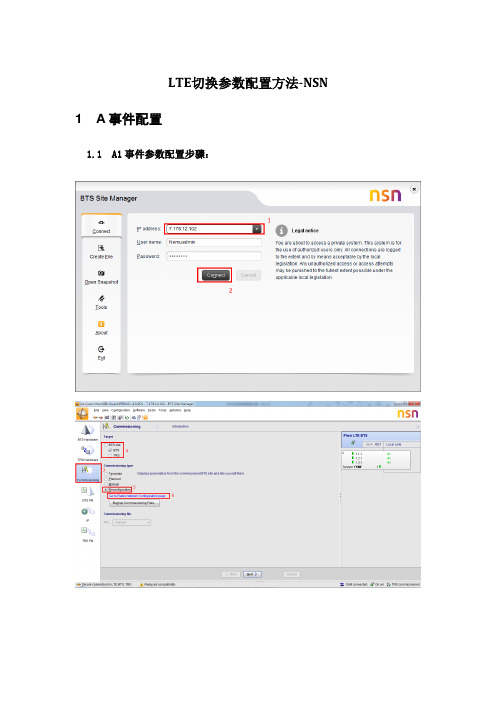

LTE切换参数配置方法-NSN 1A事件配置1.1 A1事件参数配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(6)选择需要修改的某站点,通过SiteManager登录进入参数配置修改页面步骤:(7)-(8)选择MRBTS - LNBTS,打开异频切换开关(NSN同频切换无A1及A2门限设置)步骤:(9)-(12)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL,对A1门限、迟滞及A1触发时延进行设置1.2 A2事件参数配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(8)同A1事件配置步骤(同一个站的异频切换开关只需打开一次)步骤:(9)-(11)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL,对A2门限、迟滞及A2触发时延进行设置(50即-140+50=-90dB)1.3 A3事件参数配置步骤:(1)同频A3事件配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(6)同A1事件配置步骤步骤:(7)-(9)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL,配置同频A3偏置、A3报告时长、A3触发时(2)异频A3事件配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(8)同A1事件配置步骤步骤:(9)-(13)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL - LNHOIF,配置异频A3偏置、A3报告时长、1.4 A4事件参数配置步骤:NSN无A4事件参数配置,可通过配置A5事件参数来模拟A4事件1.5 A5事件参数配置步骤:(1)同频A5事件配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(6)同A1事件配置步骤步骤:(7)-(10)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL,配置同频A5偏置、A5报告时长、A5触发时延、A5迟滞等参数(2)异频A5事件配置步骤:步骤:(1)-(8)同A1事件配置步骤步骤:(9)-(12)选择MRBTS - LNBTS - LNCEL - LNHOIF,配置异频A5偏置、A5报告时长、。

诺西NSN基站硬件基础知识介绍

合路器介绍--AFE 合路器介绍--AFE -四块载频时AFE的信号流向问题 单极化天线) (单极化天线) 因为是收发双工,所以主发射天 线即承担了发射功能又承担了主 接收功能,而分集接收天线仅仅 实现分集接收功能,以达到分集 增益的功效。

中国移动通信集团河南有限公司网优专家小组

合路器介绍--AFE 合路器介绍--AFE -使用AFE合路器的四载频扇区(单极化天线),如果出现问题将会怎么样? (单极化天线),如果出现问题将会怎么样? ),如果出现问题将会怎么样 1、从前面的图片可以看出, AFE合路器的四载频扇区(单极化天线)进行信号的 (单极化天线) 发射,所以其中一根天馈出现问题时,将会引起所带的两块载频同时出现问题。 例如:一根天线驻波比过高时,连接它的两块载频可能同时出现退服现象。 2、由于两根天线同时发射信号,所以对天线的方向、下倾角一致性要求更高。假 如天线不一致会出现什么情况呢?肯定造成覆盖区域不完全相同,可能会引起掉 话等情况,下面将进行分析。

网络、BTS、MS之间信号传送原理 网络、BTS、MS之间信号传送原理

基 带 部 分

TX

工 器

双

RX

基 带 部 分

D-BUS

TX

工 器

双

Abis from network

RX

基 带 部 分

BSC

传 输 Abis to network 板

TX RX

工 器

双

MS

MS

中国移动通信集团河南有限公司网优专家小组

载频板上红色部分显 示现使用频点 电源板,对各层 板件进行供电

诺基亚基站介绍

UltraSite特性: 不支持扩展柜 全向站最大支持12块载频,定向站最大 支持12+12+12或则4+4+4(单机柜) 基带部分和射频部分分离 最大发射功率28W左右 体积较大,比较占用空间 射频和基带部分分离 不同的合路器支持不同的跳频方式 ……..

nsn干扰排查工作手册

前言随着4G LTE基站的逐步建设,涉及电信/联通TDD/FDD站点的建设,目前已形成了2/3/4G基站共存的局面,系统间干扰的概率也大幅提高,在目前已建设的移动LTE基站中,已发现大量的TD-LTE基站受到上行干扰。

这些干扰重要涉及2/3G社区对TD-LTE社区的阻塞、互调和杂散干扰,此外尚有其他无线电设备,如PHS基站带来的外部同频干扰,具体如下表:1.干扰产生的因素和分类:1.1按照干扰产生的起因可以将干扰分为系统内干扰和系统间干扰。

系统内干扰的产生:系统内干扰通常为同频干扰。

由于数字技术相对于模拟技术的抗干扰能力较强,可以实现同频组网。

比如,TD-SCDMA 系统中,同一个社区内的不同用户使用的是相同的频率资源,它们之间是通过正交码字来进行区分的。

TD-LTE 系统中,虽然同一个社区内的不同用户不能使用相同频率资源(多用户MIMO 除外),但相邻社区可以使用相同的频率资源。

这些在同一系统内使用相同频率资源的设备间将会产生干扰,也称为系统内干扰。

系统间干扰的产生:系统间干扰通常为异频干扰。

世上没有完美的无线电发射机和接受机。

科学理论表白抱负滤波器是不可实现的,也就是说无法将信号严格束缚在指定的工作频率内。

因此,发射机在指定信道发射的同时将泄漏部分功率到其他频率,接受机在指定信道接受时也会收到其他频率上的功率,也就产生了系统间干扰。

1.2干扰产生的因素:一般来说干扰重要受使用频率、设备能力及工程实行三个因素制约。

1.2.1使用频率因素:干扰大小与干扰源系统和受害系统使用的频率有关。

●当干扰源系统的发射频率与受害系统的接受频率距离较近时,也许产生带外杂散和阻塞干扰;●当干扰源系统的发射频率(f1)与受害系统的接受频率(f2)是有倍数关系时,也许产生谐波干扰,如f2=2*f1 将也许产生二次谐波干扰;●当干扰源系统在多个频率上发射(如f1 和f2),且其多个发射频率的线性组合(如f1+f2、f1-f2、2*f1-f2、2*f2-f1 等)正好落入受害系统的接受频率范围之内,也许产生互调干扰。

NSN常用参数解释、常用操作及常见告警

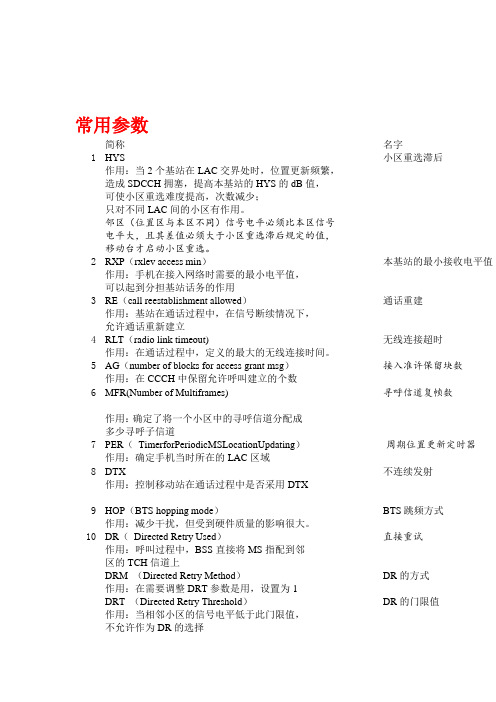

常用参数简称名字1 HYS 小区重选滞后作用:当2个基站在LAC交界处时,位置更新频繁,造成SDCCH拥塞,提高本基站的HYS的dB值,可使小区重选难度提高,次数减少;只对不同LAC间的小区有作用。

邻区(位置区与本区不同)信号电平必须比本区信号电平大,且其差值必须大于小区重选滞后规定的值,移动台才启动小区重选。

2 RXP(rxlev access min)本基站的最小接收电平值作用:手机在接入网络时需要的最小电平值,可以起到分担基站话务的作用3 RE(call reestablishment allowed)通话重建作用:基站在通话过程中,在信号断续情况下,允许通话重新建立4 RLT(radio link timeout) 无线连接超时作用:在通话过程中,定义的最大的无线连接时间。

接入准许保留块数5 AG(number of blocks for access grant msg)作用:在CCCH中保留允许呼叫建立的个数寻呼信道复帧数6 MFR(Number of Multiframes)作用:确定了将一个小区中的寻呼信道分配成多少寻呼子信道周期位置更新定时器7 PER(TimerforPeriodicMSLocationUpdating)作用:确定手机当时所在的LAC区域8 DTX 不连续发射作用:控制移动站在通话过程中是否采用DTX9 HOP(BTS hopping mode)BTS跳频方式作用:减少干扰,但受到硬件质量的影响很大。

直接重试10 DR(Directed Retry Used)作用:呼叫过程中,BSS直接将MS指配到邻区的TCH信道上DRM (Directed Retry Method)DR的方式作用:在需要调整DRT参数是用,设置为1DRT (Directed Retry Threshold)DR的门限值作用:当相邻小区的信号电平低于此门限值,不允许作为DR的选择11 PMRG(HOMarginPBGR)功率预算的切换边界作用:为了防止来回切换,源小区此值增大,可使较难切出,尽可能的保留话务在原小区;或源小区减小,容易切出到目标小区12 C2(cell reselect)小区重选作用:在微蜂窝和DCS情况下,可以激活C2的算法REO(cell reselect offset)小区重选偏置作用:提高REO值,使手机小区重选时尽可能保留原小区(如DCS1800站)13 RDIV(RX diversity) 分集接收作用:选择W定义在BTS中打开分集接收功能,但只在Ultrasite打开W14 CBA(Cell Bar Access)小区接入禁止作用:当微蜂窝载频数很少,容易引起拥塞,可考虑CBA设置为1,不能起呼,但容易切换进来15 LMRG 信号电平的切换门限16 LUR(threshold level uplink Rx level)上行接收电平门限(切换算法)作用:当基站接收的上行电平低于一定门限时,网络应启动切换算法,以使移动台能维持一定的通信质量LUR(pc lower threshold lev ul)上行接收电平功率控制下限作用:当基站接收的上行电平低于该门限值时,基站将启动功率控制过程,提高移动台的发信功率。

NSN高级规划优化试题(含答案)

一、单项选择题1.下面哪个指标对TCH DCR有直接的影响:a)BERb)TCH FERc)SACCH FERd)BLER2.下面哪条消息是在SDCCH信道上进行传送的:a)CHANNEL_REQUESTb)ALERTINGc)CM_SERVICE_REQUESTd)PAGING_REQUEST3.在通话过程中,使用DTX和不使用DTX,分别有多少个TDMA帧相关值被平均采样做为测量报告结果?a)51和204b)26和104c)12和104d)26和264.下列不需要占用SDCCH的活动为:a)SMSb)被叫c)加密d)切换5.小区选择C1算法跟以下那个因素有关?a)Rxlev_minb)MS_Txpwr_Maxc)Rxlev_Access_Mind)BS_Txpwr_Max6.在执行Direct Rrtry 功能时, Layer 3 message 出现哪一条信令?a)Immediate assignmentb)Assignment commandc)Handover commandd)Connect7.为避免因过多跨越LAC的小区重选而造成的SDCCH的阻塞,我们将与该小区有切换关系且与之LAC不同的相邻小区的哪个参数提高?a)T3212b) b. Cell_Reselect_Hysteresisc) c. Cell_Reselect_offsetd) d. Rxlev_Access_Min8.“CHANNEL REQUEST”这个消息是在 _____ 信道上发送的a) a.RACHb) b.AGCHc) c.PCHd) d.SDCCH9.话务量的计算采用以下那个测量的数据?a)resource access measurementb)resource availability measurementc)traffic measurementd)availability measurement10.手机的最大发射功率是2W,即33dBm,当手机功率从2W下降到0.1W时,我们说手机功率下降了______dBa) 3b)13c)23d)3311.Flexi BSC信令处理单元为()a)OMUb)MCMUc)BCSUd)CLS12.单个BCSU处理的载波最大容量为()a)100b)200c)500d)66013.Flexi BSC提供的通道化155M光口经SDH设备打散后最多支持()E1接口a)16b)32c)63d)6414.在Flexi BSC的BCSU单元中,每块PCU2-E提供的数据业务处理能力为()个channels@16KBpsa)256b)512c)1024d)204815.Flexi BSC提供处理的话务量最大为()Erla)10000b)12000c)15000d)1800016.MS在通话过程中能否接受SMS,下列说法正确的是()a)不能同时接收SMS,短信中心发出的SMS将丢失b)不能同时接收SMS,但通话结束后仍然可以收到c)能同时接收SMS,只能用SACCH来接收d)能同时接收SMS,也可以用FACCH来接收,但可能影响话音质量17.IMSI的分配是在()完成的a)MSCb)VLRc)HLRd)OMC18.小区有4个TRX,下面哪一个timeslot分配是最合理()a)1BCCH,2SDCCH,29TCHb)1BCCH/SDCCH,3TCHc)1BCCH,3SDCCH,36TCH19.Flexi BSC的Gb采用IP化时,当创建NSVL链路后,不能被系统正,需要分别在BSC和SGSN上检查下面哪个数据是否一致()a)IP地址b)Local Portc)NSEI值d)上述数据都检查20.1个RLC BLOCK时长约为多少()a)12 Sb)14 Sc)17 Sd)20 S21.在Flexi BSC中,处于备份下的BSCU状态为()a)WO-EXb)SP-EXc)TE-EXd)SE-NH22.处于MSC旁的码型变换器(Transcoder)主要是从BSC的()转换为MSC端()kbpsa)16/64b)64/128c)32/64d)64/3223.请将话音信号在无线接口路径的处理过程按顺序排列()a)话音、话音编码、信道编码、加密、交织、调制b)话音、信道编码、话音编码、加密、交织、调制c)话音、话音编码、信道编码、交织、加密、调制d)话音、信道编码、话音编码、交织、加密、调制二、多项选择题1.小区的覆盖半径与以下哪些因素有关:a)天线类型b)天线位置c)周围环境d)使用的频带(450, 900, 1800 MHz)2.跳频对网络的好处在于:a)增加网络容量b)抗多径效应c)频率分集d)干扰分集e)抗快衰落f)抗慢衰落3.在采用基带跳频的网络中,需要规划以下哪些跳频相关参数:a)HSN1b)HSN2c)MALd)MAIOe)HOP4.Paging group的数量与下面哪些参数有关:a)MFRb)AGc)BCCH typed)SLOe)RET5.以下哪些是BSC的功能a)功率控制b)切换控制c)信道编码和交织d)无线信道资源分配6.以下哪些是BTS的功能a)GMSK调制b)加密c)切换的判决d)与MS同步e)传送测量数据至BSCf)信道编码7.以下哪些号码是用于识别手机的?a)MSISDNb)IMSIc)MSRNd)CGIe)BSICf)TMSIg)IMEI8.以下哪些参数会影响手机的小区重选过程:a)RXPb)HYSc)TEOd)PETe)QUAf)BAR9.以下哪些方法可降低小区的话务信道拥塞:a)扩容b)改频c)下压天线俯仰角d)降低拥塞小区切出门限e)调整拥塞小区与邻区参数PMRG、LMRG值f)启用DR10.以下哪些原因的切换是靠周期性检查而不是通过切换门限的比较来触发的:a)Qualityb)Levelc)Distanced)Umbrellae)Power budgetf)Interferenceg)traffic三、填空题1.自动频率规划中,建立干扰矩阵是基于 DAC和 CF 测量2.MS,BTS,BSC,TC,MSC之间的接口分别是Um ,ABis,Ater, A3.一个TDMA帧的周期是4.615,每个TCH帧的周期是120,每个SACCH帧的周期是4804.用于查看GSM相关测量状态的MML命令是ZTPI:MEAS,查看GPRS/EDGE相关测量状态的MML是ZTPI:GPRS,查看timer设置状态的MML是ZEGO,查看feature开启状态的MML是ZWOI5.给下列各种功控类型按从高到低的优化级排序CBDAa.PC due to Upper level thresholds (UL and DL)b.PC due to Lower level thresholds (UL and DL)c.PC due to Lower quality thresholds (UL and DL)d.PC due to Upper quality thresholds (UL and DL)6.请给出网管系统三种主要的功能 RNW ,测量管理,规划数据的导入与输出7.请列出三种发现网络中硬件问题的途径告警,TRX 质量,TCH/SDCCH 可用性8.在NOKIA BTS中,BCF 是BTS的控制单元,TRX是话音的调制解调单元9.为提高数据传输速率,GPRS衍生出一种调制方式采用相移键控的GMSK技术,新增加的调制方式是8-PSK10.MCPA基站的硬件中,最大支持18载波的系统模块为 ESMB,最大支持36载波的系统模块为 ESMC11.信源编码的目的是提高通信的有效性信道编码的目的是提高数据传输的可靠性12.GPRS信道编码方式分四种CS1-CS4,纠错能力最强的编码方式CS113.移动台可执行的最大时间提前量是 63四、判断题1.不连续发射可以用来防止乒乓切换(N)2.手机使用DTX的好处是增加接收信号强度(N)3.在手机通话过程中,用来传递切换命令消息的逻辑信道是FACCH(Y)4.在GSM无线网络中由FCCH逻辑信道携带用于校正手机频率的消息(Y)5.采用天线分集接收方式的目的是为了减少多径衰落对信号接收电平的影响(Y)6.在GSM系统中采用4*3复用方式,10M带宽可允许最大站型为5/5/4(Y)五、计算题1.某地区网络中有一新建开发区,面积40KM2,预计人口80000人,手机用户渗透率约80%,根据无线链路预算的结果该地区平均小区覆盖面积0.5KM2,话务模型预测每用户忙时通话时长90S,可用频谱带宽为15.6MHz,请按GOS=2%,频率复用采用MRP方式(BCCH 3*6,TCH 3*5)的模式进行该区域的网元数量测算。

NSN常用无线参数讲解

常用参数调整CELL BARRED..............................(BAR).... N(小区禁止接入参数。

该参数允许或禁止手机接入,设为N则禁止手机正常接入,仅允许切换接入,用于多层网)CALL REESTABLISHMENT ALLOWED.............(RE)..... Y(DEFAULT: N)(呼叫重建允许。

由于突发干扰或高楼引起的“盲点”形成无线链路故障造成的断话,手机可以启动呼叫重建过程恢复通话,设为YES可以减小掉话率,但浪费无线资源,我们系统中,该参数标准设为Y。

)EMERGENCY CALL RESTRICTED................(EC)..... N(紧急呼叫限制。

对于接入等级为0~9的手机,或无SIM卡的手机,EC设为YES表示不允许紧急呼叫;反之,则允许紧急呼叫。

对于接入等级为11~15的手机,只有当其相应的接入控制比特设置为0,且EC设置为YES才不允许紧急呼叫。

我们系统中,该参数标准设为N,允许如112等紧急呼叫。

)PLMN PERMITTED...........................(PLMN)... 04,05,06,07(DEFAULT: 04) (参数允许的网络色码。

PLMN列出了手机需测量的小区的NCC码的集合,在该集合中,手机按测量出的电平大小将可以切换的目标小区报告给基站。

)NOT ALLOWED ACCESS CLASSES...............(ACC).... –(不允许接入的手机等级,该参数我们网中不使用。

)ADJACENCY ON OTHER BAND..................(DBC).... Y(小区重选或小区话务建立时是否考虑其它频段,为可切换的邻区。

)DIRECTED RETRY USED......................(DR)..... N(在呼叫建立的指配过程中,由于拥塞的原因可能导致指配失败,GSM系统使用定向重试DR功能,可以通过BSS直接将手机指配到邻区的TCH信道上。

NSN_GPS全球定位仪基本知识

GPS全球定位仪基本知识诺基亚西门子通信有限公司1、卫星轨迹:这里有24颗GPS卫星沿六条轨道绕地球运行(每四颗一组),一般不会有超过12个卫星在地球的同一边,大多数GPS接收器可以追踪8~12颗卫星。

计算LAT/LONG(2维)坐标至少需要3颗卫星。

再加一颗就可以计算3维坐标。

对于一个给定的位置,GPS接收器知道在此时哪些卫星在附近,因为它不停地接收从卫星发来的更新信号。

2、并行通道:一些消费类GPS设备有2~5条并行通道接收卫星信号。

因为最多可能有12颗卫星是可见的(平均值是8),这意味着GPS接收器必须按顺序访问每一颗卫星来获取每颗卫星的信息。

市面上的GPS接收器大多数是20并行通道型的,这允许它们连续追踪每一颗卫星的信息,12通道接收器的优点包括快速冷启动和初始化卫星的信息,而且在森林地区可以有更好的接收效果。

一般20通道接收器不需要外置天线,除非你是在封闭的空间中,如船舱、车厢中。

3、定位时间:这是指你重启动你的GPS接收器时,它确定现在位置所需的时间。

对于20通道接收器,如果你在最后一次定位位置的附近,冷启动时的定位时间一般为3~5分钟,热启动时为15~30秒。

4、定位精度:大多数GPS接收器的水平位置定位精度在2.93m~29.3m左右。

5、DGPS功能:为了将SA和大气层折射带来的影响降为最低,有一种叫做DGPS发送机的设备。

它是一个固定的GPS接收器(在一个勘探现场100km~200km的半径内设置)接收卫星的信号,它确切地知道理论上卫星信号传送到的精确时间是多少,然后将它与实际传送时间相比较,然后计算出“差”,这十分接近于SA和大气层折射的影响,它将这个差值发送出去,其他GPS接收器就可以利用它得到一个更精确的位置读数(5m~10m或者更少的误差)。

许多GPS设备提供商在一些地区设置了DGPS发送机,供它的客户免费使用,只要客户所购买的GPS接收器有DGPS 功能。

6、信号干扰:要给予你一个很好的定位,GPS接收器需要至少3~5颗卫星是可见的。

NSN自己总结常用命令

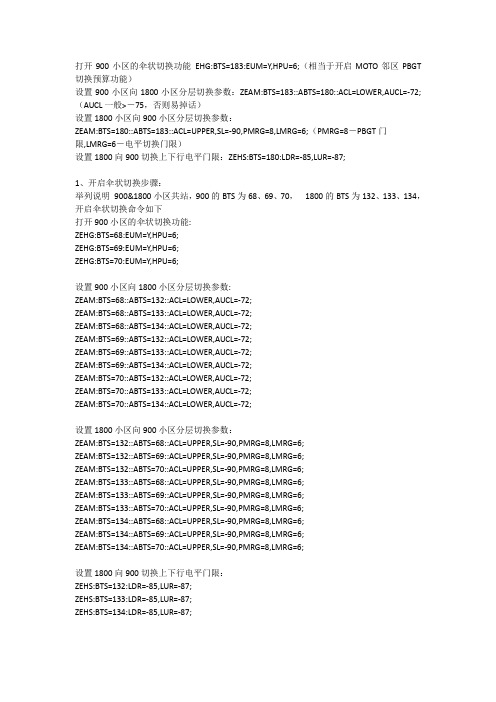

打开900小区的伞状切换功能EHG:BTS=183:EUM=Y,HPU=6;(相当于开启MOTO邻区PBGT 切换预算功能)设置900小区向1800小区分层切换参数:ZEAM:BTS=183::ABTS=180::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;(AUCL一般>-75,否则易掉话)设置1800小区向900小区分层切换参数:ZEAM:BTS=180::ABTS=183::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;(PMRG=8-PBGT门限,LMRG=6-电平切换门限)设置1800向900切换上下行电平门限:ZEHS:BTS=180:LDR=-85,LUR=-87;1、开启伞状切换步骤:举列说明900&1800小区共站,900的BTS为68、69、70,1800的BTS为132、133、134,开启伞状切换命令如下打开900小区的伞状切换功能:ZEHG:BTS=68:EUM=Y,HPU=6;ZEHG:BTS=69:EUM=Y,HPU=6;ZEHG:BTS=70:EUM=Y,HPU=6;设置900小区向1800小区分层切换参数:ZEAM:BTS=68::ABTS=132::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=68::ABTS=133::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=68::ABTS=134::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=69::ABTS=132::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=69::ABTS=133::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=69::ABTS=134::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=70::ABTS=132::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=70::ABTS=133::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;ZEAM:BTS=70::ABTS=134::ACL=LOWER,AUCL=-72;设置1800小区向900小区分层切换参数:ZEAM:BTS=132::ABTS=68::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=132::ABTS=69::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=132::ABTS=70::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=133::ABTS=68::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=133::ABTS=69::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=133::ABTS=70::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=134::ABTS=68::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=134::ABTS=69::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;ZEAM:BTS=134::ABTS=70::ACL=UPPER,SL=-90,PMRG=8,LMRG=6;设置1800向900切换上下行电平门限:ZEHS:BTS=132:LDR=-85,LUR=-87;ZEHS:BTS=133:LDR=-85,LUR=-87;ZEHS:BTS=134:LDR=-85,LUR=-87;设置1800的REOZEQM:BTS=132:::REO=6;ZEQM:BTS=133:::REO=6;ZEQM:BTS=134:::REO=6;2、修改TCH频点ZEEI:BTS=1;ZERS:BTS=1,TRX=1:L:FHO,10;ZERM:BTS=1,TRX=1:FREQ=33;(基础参数载频级参数TSC、GTRX、DAP、CH0~CH7)ZERS:BTS=1,TRX=1:U;3、修改邻区参数ZEAO:BTS=1;ZEAM:SEG=12::LAC=14231,CI=6012:NEWLAC=14233,NEWCI=6016:SYNC=N,POPT=;(至邻区的NCC、BCC、FREQ 、PMRG、LMRG、QMRG、ACL、AUCL)4、增加邻区ZEAO:BTS=**;ZEAC:SEG=12::LAC=14087,CI=9431:NCC=3,BCC=2,FREQ=54:PMRG=5,DRT=-80,SL=-955、删除邻区ZEAD:SEG=12::LAC=14087,CI=9561;6、闭TRX和启TRX的命令ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:L:FHO,TIME;ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:U;7、开半速率(需要先闭载频)ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:L:FHO,TIME;ZERM:BTS=**,TRX=*:CH0=SDCCH,CH1=TCHD,CH2=TCHD,CH3=TCHD,CH4=TCHD,CH5=TCHD,CH6=T CHD,CH7=TCHD;ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:U;8、关半速率(需要先闭载频)ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:L:FHO,TIME;ZERM:BTS=**,TRX=*:CH0=SDCCH,CH1=TCHF,CH2=TCHF,CH3=TCHF,CH4=TCHF,CH5=TCHF,CH6=TCH F,CH7=TCHF;(其中可修改CH0时隙类型)ZERS:BTS=**,TRX=**:U;9、查看功率等级和功控参数ZEUO:SEG=**;10、调整功率ZEUG:SEG=**:PMAX1=**;ZEUG:SEG=25:INC=4,RED=2,INT=1;11、功控开关:ZEUG:PENA=Y;ZEUG:PENA=N;12、电平功控ZEUS:SEG=34:UDR=-75,UDP=2,UDN=3,LDR=-85,LDP=1,LDN=1,UUR=-85,UUP=2,UUN=3,LUR=-96,L UP=1,LUN=1;UDR ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV DL RX LEVELUDP ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV DL PXUDN ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV DL NXUUR ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV UL RX LEVELUUP ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV UL PXUUN ... PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV UL NXLDR ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV DL RX LEVELLDP ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV DL PXLDN ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV DL NXLUR ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV UL RX LEVELLUP ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV UL PXLUN ... PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV UL NX13、质量功控ZEUQ:SEG=34:LDR=4,LDP=1,LDN=2,UDR=1,UDP=1,UDN=2,LUR=4,LUP=1,LUN=2,UUR=1,UUP=1,U UN=2;UDR .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL RX QUALUDP .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL PXUDN .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL NXUUR .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL RX QUALUUP .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL PXUUN .. PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL NXLDR .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL RX QUALLDP .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL PXLDN .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL NXLUR .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL RX QUALLUP .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL PXLUN .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL NXLQR .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL144 RX QUALLQP .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL144 PXLQN .. PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL144 NX修改BTS参数(关键四个个命令ZEQE、ZEQG、ZEQM、ZEQV)ZEQE :MODIFY BTS IDENTIFICATION PARAMETERS (BTS级参数包括CI、NCC、BCC、MCC、MNC、LAC、HOP)ZEQG:MODIFY RADIO LINK CONTROL DL PARAMETERSZEQM:MODIFY MISCELLANEOUS PARAMETERSZEQV :MODIFY GPRS PARAMETERS14、改跳频,要先用ZEQS闭站后才可执行ZEQS:BTS=**:L:FHO=30;(闭站)ZEQE:BTS=**:HOP=N;(关跳频)ZEQE:BTS=**:HOP=Y;(开跳频)ZEQS:BTS=**:U;(启站)15、修改NCC,BCC,LAC,CI等(在OMC下修改,因为要下发消息)ZEQS:BTS=**:L:FHO=30;(闭站)ZEQE:SEG=12:CI=4087,NCC=3,BCC=4,LAC=14087,MCC=460,MNC=00;ZEQS:BTS=**:U;(启站)16、修改RLT,RXP,HYS,DIRE,RRH等ZEQG:SEG=610:HYS=14,RXP=-98,RLT=64,DIRE=1;17、修改FRL,FRU门限值(20,40,剩余的TCH资源小于20%开始占用半速率,剩余TCH 资源大于40%时占用全速率,改为100时优先占用半速率)ZEQM:SEG=185:FRL=100,FRU=100; ZEQM:SEG=185:FRL=20,FRU=40;18、修改GPRS ENABLED, EGPRS ENABLED, ROUTING AREA CODE(RAC), DEDICATED GPRS CAPACITY(CDEF),ZEQV:SEG=**,GENA=N;ZEQV:BTS=133:CDEF=50;重新打开GENA时要注意非EDGE小区加上NSEI,否则NSEI将被系统自动分配ZEQV:SEG=**,GENA=Y;19、开载频的GPRS功能(需要先闭载频)。

NSN语音业务相关操作

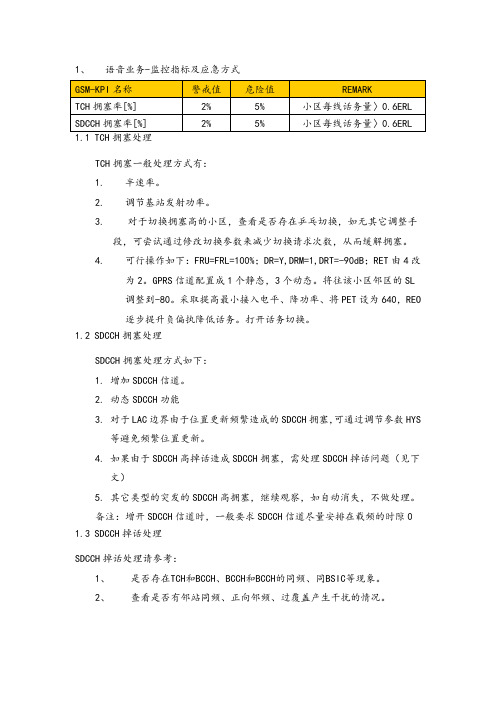

1、语音业务-监控指标及应急方式TCH拥塞一般处理方式有:1.半速率。

2.调节基站发射功率。

3.对于切换拥塞高的小区,查看是否存在乒乓切换,如无其它调整手段,可尝试通过修改切换参数来减少切换请求次数,从而缓解拥塞。

4.可行操作如下:FRU=FRL=100%;DR=Y,DRM=1,DRT=-90dB;RET由4改为2。

GPRS信道配置成1个静态,3个动态。

将往该小区邻区的SL调整到-80。

采取提高最小接入电平、降功率、将PET设为640,REO逐步提升负偏执降低话务。

打开话务切换。

1.2SDCCH拥塞处理SDCCH拥塞处理方式如下:1.增加SDCCH信道。

2.动态SDCCH功能3.对于LAC边界由于位置更新频繁造成的SDCCH拥塞,可通过调节参数HYS等避免频繁位置更新。

4.如果由于SDCCH高掉话造成SDCCH拥塞,需处理SDCCH掉话问题(见下文)5.其它类型的突发的SDCCH高拥塞,继续观察,如自动消失,不做处理。

备注:增开SDCCH信道时,一般要求SDCCH信道尽量安排在载频的时隙0 1.3SDCCH掉话处理SDCCH掉话处理请参考:1、是否存在TCH和BCCH、BCCH和BCCH的同频、同BSIC等现象。

2、查看是否有邻站同频、正向邻频、过覆盖产生干扰的情况。

3、对于前诺BSC可查看是否存在SDCCH的7745告警,如存在,复位相应的载频后观察。

4、确定是否由于LAC边界参数设置不当导致频繁位置更新占用5、异常高SDCCH掉话可尝试倒换载频。

1、查看BCF、SEG、BTS、载频状态ZEEI:BCF=XX;查看BCF状态ZEEI:SEG=XX; 查看小区状态ZEEI:BTS=XX; 查看BTS状态ZERO:SEG=XX;查看小区个载频状态1、查看小区参数设置ZEQO:SEG=XX:ALL; 查看小区所有参数设置ZEQO:SEG=XX:GPRS; 查看小区数据业务参数设置ZEQO:BTS=XX:ALL; 查看小区BTS级参数3、查看、修改小区功率设置ZEUO:SEG=8;查看小区功率POWER CTRL ENABLED为功控开关BS TX PWR MAX ....PEAK PWR(PMAX1)对应900降功率BS TX PWR MAX1X00 PEAK PWR(PMAX2)对应1800降功率ZEUG:SEG=XX:PMAX1=XX; 降900功率步长2,比如2,4,6,8降2,4,6,8db功率ZEUG:SEG=XX:PMAX2=XX;降1800功率步长2,比如2,4,6,8降2,4,6,8db功率FlexiBSC SIMBSC001 2015-02-16 09:53:31POWER CONTROL PARAMETERS OFSEG-0008 SMGONGXIAOSHE2POWER CTRL ENABLED ......... Y (功控开关)POWER CONTROL INTERVAL ..... 01 sBS TX PWR MIN ....PEAK PWR - 16 dB BS TX PWR MAX ....PEAK PWR - 00 dB (PMAX1对应900降功率,为0表示满功率为正数N表示降了Ndb功率,步长为2)BS TX PWR MAX1X00 PEAK PWR - 00 dB(PMAX2对应1800降功率,为0表示满功率为正数N 表示降了Ndb功率,步长为2)POWER INCR STEP SIZE ....... 6 dB POWER RED STEP SIZE ........2 dBPOWER DECR LIMIT BAND 0 .... 20 dB POWER DECR LIMIT BAND 1 ....20 dBPOWER DECR LIMIT BAND 2 .... 20 dB POWER DECR QUAL FACTOR .. (1)ALA ENABLED ................ N MIN INT BETWEEN ALA ........10 sPOWER LIMIT ALA ............ 6 dB BCCH TRX TX PWR REDUCTION ..0 dBMAX DL POWER REDUCTION ..... 06 dB DERIVED HO PWR SECUR MARGIN. 05 dBMAX UL POWER REDUCTION ..... 06 dB ESTIMATED DL INTERFERENCE .- 80 dBm MAXIMUM POWER COMPENSATION.. 00 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 1........ 0 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 2........ 0 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 3........ 0 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 4........ 0 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 5........ 0 dBMAXIMUM TX POWER OF COMPOSITE CELL NODE 6........ 0 dBPC AVERAGING LEV DL WINDOW SIZE ............ 04 WEIGHTING . (1)PC AVERAGING LEV UL WINDOW SIZE ............ 04 WEIGHTING . (2)PC AVERAGING QUAL DL WINDOW SIZE ............ 01 WEIGHTING . (1)PC AVERAGING QUAL UL WINDOW SIZE ............ 01 WEIGHTING . (2)PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL RX QUAL .. < 0.2% PX .. 04 NX .. 05PC UPPER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL RX QUAL .. < 0.2% PX .. 04 NX .. 05PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL DL RX QUAL .. 0.4% - 0.8% PX .. 01 NX .. 01PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL UL RX QUAL .. 0.4% - 0.8% PX .. 01 NX .. 01PC LOWER THRESHOLDS QUAL144 RX QUAL .. 0.4% - 0.8% PX .. 02 NX .. 03PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV DL RX LEVEL .. - 65 dBmPX ..02 NX .. 03PC UPPER THRESHOLDS LEV UL RX LEVEL .. - 70 dBmPX ..02 NX .. 03PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV DL RX LEVEL .. - 78 dBmPX ..01 NX .. 01PC LOWER THRESHOLDS LEV UL RX LEVEL .. - 85 dBmPX ..01 NX .. 01IDLE MODE SIGNAL STRENGHT FILTER PERIOD (20)TRANSFER MODE SIGNAL STRENGHT FILTER PERIOD (5)BINARY REPRESENTATION ALPHA (7)BINARY REPRESENTATION TAU ....................... 34 dBmBIT ERROR PROBABILITY FILTER AVERAGING PERIOD (10)DL PC WINDOW SIZE ............................... 8 dBmDL PC DEFAULT POWER REDUCTION ................... 4 dBm4、锁闭、解锁BCF、BTS、TRXZEFS:BCF ID:L; 锁闭BCF,比如:ZEFS:1:L;锁闭BCF:1,操作流程是先锁闭BTS,然后在锁闭BCF,解锁是先解锁BTS在解锁BCF,因为直接锁BCF会直接造成掉话。

NSN信道分配分析(上传版)

NSN信道分配分析NSN信道分配分析目录1.NSN信道划分 (1)2.NSN信道占用机制 (3)2.1NSN信道占用机制 (3)2.2NSN信道占用机制与MOTO及HW的区别 (3)3.关于半速率的分配与动态信道的占用 (4)3.1参数 (4)3.2实例分析 (6)3.3小结 (8)1. NSN信道划分NSN信道分配分析NSN设备信道分为公共信道,语音业务信道以及数据业务信道,其中:公共信道包括BCCH以及SDCCH信道;语音信道指除公共信道以及数据信道以外的可用信道;数据信道指用于开展数据业务所需要的信道,其范围可用以下的三个参数进行定义:●Dedicated territory (CDED):指专用于数据业务的信道,即通常我们所说的数据静态信道,其特点在于在任何情况下语音业务都不能占用,只分配给数据业务占用;●Default Territory (CDEF):指缺省情况下用于数据业务的信道,即通常的数据动态信道,其特点在于当语音业务繁忙且语音信道占用达到一定比例时,其可转换为语音信道使用;●Max Territory (CMAX):指当数据业务繁忙且数据信道不足需要升级时,其最大可使用的信道数量,并且受限于GTRX数量。

备注:时隙如果设置为HR(半速率),则不能作为CDEF(包括CDED),如果设置为DR(双速率),则可以;NSN设备信道通常都设置为DR,通过参数FRL/FRU来控制FR或HR的分配;(CDEF-CDED)这部分动态信道可以设置为DR;只有当话音时隙域全部占满,才会使用动态信道(CDEF-CDED);当话音时隙域已满时,新的话音信道请求将分配到动态时隙,此时如果动态时隙已满,则要求数据时隙域降级;数据信道一定是连续的,域升级时也是需要连续的,不能跨过正在使用语音信道;当话音信道分配到动态时隙后,一般情况下不会切换回语音时隙域;如果数据业务有申请(可能是数据时隙域升级申请,或者数据时隙域内数据业务请求),则发起小区内切换试图将该话音信道切换到语音时隙域,如果此时语音时隙域没有空闲时隙或者其他原因切换不能成功,则该时隙不能为数据业务使用,结果数据业务申请失败;CDED、CDEF以及CMAX的定义均使用可用全部时隙的百分比进行定义,具体确定时隙数量往下取整(最小为1,如4.7则为4)(与规划不同,规划时是向上取整;同时规划时CDEF一般最小设置为4TS,因为手机的多时隙能力为4),且CMAX >= CDEF >= CDED,例如:NSN信道分配分析●某小区共2块载频,其中公共信道占用1个信道,剩余15个可用信道;●CDED、CDEF以及CMAX参数分别定义为10%,40%以及100%;●CDED、CDEF以及CMAX对应的信道数分别为:2(15*10%)、6(15*40%)以及15(15*100%);2. NSN信道占用机制2.1 NSN信道占用机制NSN设备信道占用机制可用以下三种情况进行分析:CS及PS业务量都较小:PS由后向前分配占用(如下图第1小图的黄色领域);CS由前往后占用(如下图第一小图的红色领域),保证了“领域”不交叉,各自使用各自的资源;CS业务量大,PS业务量较小:系统中设计,话音业务有最高的优先级,数据业务是在话音业务的剩余时隙中使用。

NSN9000系列特色功能及产品应用培训

NSN9000S-MCU板

CPU升级为 9KSI FV1.0版本

需烧录对应程序

注:该功能版本无中文显示功能。

NSN9000S/M-SIG板

更换ISD1750为ISD17180

扩展CPU升级为 XHI FV1.0版本

说明:NSN9000S/M-SIG板具备2路IVR 功能话务员语音。(如左图)

NSN9000S/M-OGM板

4、IVR自动语音导航系统

5、专业级分机转外线功能

6、智能经济路由

根据用户需求系统可提供多种中继接口,通过路由设置,用户拨 打电话时可自动选择最经济的中继线出局,从而为企业节省话费.

7、小型呼叫中心系统

呼叫中心扩展功能

• IVR导航系统 MCU、SIG板升级+OGM板

• 电话录音系统 MCU板升级+录音系统软件+PC

WS824数字程控用户交换机

NSN9000系列产品

VER:1.0

WS824数字程控用户交换机

• 一、WS824产品特色功能 • 二、NSN9000S/M • 三、NSN9000L

1、WS824无线交换机系统

2、WS824电话录音系统

3、专业级电话会议功能

系统最大可支持32方会议,可根据客户需求最大分为3个会议厅,会 议召开者可对任何会议方(外线\分机)进行实时监控,并进行强拆\静 音(无发言权)等操作,会议召开方式可分为主动或被动加入,也可设 置会议厅密码.

欢迎辞

1技术服务

2业务咨询

3传真

①②③ 产产产 品品品 咨使故 询用障

和维 设修 置

①②③ 市产产 场品品 合报购 作价买

分分 分

分分分

分

机机 机

NSN无线网新功能介绍

MSC/HLR

BSC/PCU BSC/PCU

BTS

SGSN/GGSN

Core IP Backbone

CS voice call PS data stream

8 © Nokia Siemens Networks Presentation / Author / Date

Application server

– 联合寻呼功能可以通过PACCH(Packet Associated Control Channel)对处于分组传输状态

的用户下发CS域的寻呼消息,进行CS域的寻呼

– 避免手机在分组传输状态时由于无法接收PCH信道的寻呼消息而无法接收CS业务 – 相对Gs接口的方案,无需核心网网元的参加,实施部署简单方便

11

© Nokia Siemens Networks

Presentation / Author / Date

STIRC现网使用情况-北京移动、福建移动 北京移动: 对网络上行干扰有明显的消除作用,且改善网络KPI指标:

– – – – –

掉话率,改善幅度3%~6% 上行质量0级,改善幅度1%~4% 上行质量1~5级,改善幅度0 %~1% 切换成功率,改善幅度0 %~0.3% 其它网络KPI保持稳定,没有明显变化

SD拥塞次数 110 0 61 432 264 0 145.00 0 0 32 251 8 8 50.00

TCH拥塞次数 0 1 16 11 2 0 5.00 0 0 14 19 0 0 6.00

掉话率(2071) 0.20% 0.23% 0.25% 0.25% 0.25% 0.27% 0.24% 0.16% 0.20% 0.21% 0.22% 0.19% 0.21% 0.20%

nsn膜 标准

nsn膜标准

NSN膜的标准可能指的是NSN码,这是一种用于标识和追踪物品的全球标准。

NSN码由美国国防部制定,并在全球范围内使用。

NSN码由数字组成,通常由7位或14位数字组成,用于标识物品的制造商、供应商和特定产品。

这些信息被用于物品的采购、运输、维护和管理。

NSN码是一种全球性的

标准,用于提高物品的可追溯性和管理效率,同时也有助于提高安全性和可靠性。

在建筑领域,NSN膜可能指的是一种具有NSN码的建筑膜,这种膜可能具有防爆、隔热、防晒等功能,用于保护建筑物的窗户和玻璃。

ntc营养运输概念

ntc营养运输概念:宝宝发育的关键宝宝的营养摄取一直是家长们非常关心的问题,每个妈妈都希望自己的孩子能够健康成长。

然而,在宝宝的营养摄取中,另一个同样重要的问题就是如何将这些营养物质有效地运输到宝宝的身体内,为宝宝健康发育提供坚实的保障。

因此,的出现,成为了解决这个问题的一种重要方式。

什么是呢?是指由法国巴黎骨科研究所(Fondation Hopale)营养师、肠系膜淋巴节点和肠道微生态专家提出的新概念。

这一概念的核心是把肠胃中的各种营养物质有效地运输到身体各处,促进宝宝全身细胞组织发育,提高宝宝的免疫力和耐受力。

的主要原理是依托于肠系膜淋巴节点和肠道微生态系统,将肠胃中的营养物质通过肠道内淋巴系统的转运,送达身体各组织、器官,从而实现全身性的营养补给,提高宝宝的吸收率。

同时,还强调了“量与质”的平衡,即每种营养物质的补充要考虑到它的含量和品质,合理地搭配使用,进一步提升营养物质的吸收效果。

的诞生,离不开现代膳食调理学以及生物学、免疫学、内分泌学、神经学等学科的集成。

而在这个基础上,目前市面上已经出现了不同的NTC营养补充品和配方。

这些产品的核心配方都是把化学合成营养物质转化为合成营养物质(CSN)和天然营养物质(NSN)的混合物,重点关注肠道的健康和营养运输。

同时,这些产品还结合了适量的微生物悬液,帮助宝宝建立起健康的肠道微生态环境。

总的来说,给我们带来的启示是,宝宝的健康成长除了需要饮食的健康、营养均衡之外,还需要更为全面和有效的营养运输方式的支持。

在宝宝的日常生活中,我们应该针对性地寻找各种合适的营养补充方式,并注意搭配使用,从而实现宝宝全身营养均衡和健康成长的保障。

功率控制-NSN教程

上行DPCCH内环功率控制(续)

处理TPC指令的算法2(PCA2): 1)UE不处于软切换(PCA2) UE以5个时隙为单位进行功控。前4个slot,功率保持不变,

在第5个slot,硬判决这5个slot的TPC_est:

T PC_cmd(5t h slot) 5 1 , TPC _ est i /5 0 i 1 5 1 , TPC _ est i /5 1 i 1 0, otherwise

下行DPCCH的初始功率设置方式:

P=(Ec/Io)Req - CPICH_Ec/Io + PCPICH

注:(Ec/Io)req是UE正确接收该专用信道所需的Ec/Io,CPICH_Ec/Io是UE 测量到的公共导频信道的Ec/Io,通过RACH报告给UTRAN,PCPICH是公共导频信道的 发射功率。

22

上行DPCCH内环功率控制(续)

2)当UE处于软切换时(PCA1) a.)合并同一RLS的TPC命令字;(对不同小区的RL先进行最大比合并,

而后生成一个TPC,在不同小区分别发送该TPC命令字)

b.)合并不同RLS的TPC命令字,合并规则如下:

N Wi 1, i 1 1 N TPC_cmd g (W1 , W 2 , W N ) N Wi 1,0 i 1 1 N 1, TPC e s t,# s lot "1" Wi 0, TPC e s t,# s lot "0"

2018/11/4

15

下行DPCCH信道的开环功率控制

• 下行DPDCH初始发射功率:

PInitial R ( Eb / N 0) DL W PCPICH PTotal ( Ec / N 0) CPICH

NSN基站远程登录操作规范及要点

谢谢 谢谢

NSN基站远程登录第四步

上图是ULTRA、MINI和METRO站型的调测软件使用方法

NSN基站远程登录第五步

பைடு நூலகம்

上图是GCS连接的主要接口,Name:需要输入查找的基站 BSC串号和BCF号,输入后点击Connect连接,可登录基站。

NSN基站远程登录第六步

上图是ULTRA(四代站)登录后的界面,可在此界面检查 和修改,硬件数据库、时隙、时钟、告警、实时用户数量等

nsn基站远程登录第六步上图是ultra四代站登录后的界面可在此界面检查和修改硬件数据库时隙时钟告警实时用户数量等nsn基站远程登录第七步上图是flexiedge五代站的登录界面和连接方式nsn基站远程登录第八步五代站gcs远程登录连接通过gcs连接远程端口

NSN基站远程登录操作流程及规范

NSN基站远程登录第一步

NSN基站远程登录第七步

上图是FLEXI EDGE(五代站)的登录界面和连接方式

NSN基站远程登录第八步

五代站GCS远程登录连接,通过GCS连接远程端口。

NSN基站远程登录第九步

上图是FLEXI MULTI(六代站)登录界面和连接方式

NSN基站远程登录第十步

上图是GCS连接的主要接口,上述站型通用。

在运行里输入MSTSC 远程桌面连接指令,可直接弹

出上图界面,输入远程IP地址即可登录。

NSN基站远程登录第二步

输入IP地址后出现的登录界面,单击右边登录口,输入 账号、密码登录桌面。

NSN基站远程登录第三步

上图是已经连接的远程桌面,且标注不同站型的开通 软件,请分公司针对性使用,不然会导致连接失败。

nj树相似系数

nj树相似系数

(最新版)

目录

1.NJ 树相似系数的概念

2.NJ 树的结构

3.NJ 树相似系数的计算方法

4.NJ 树相似系数的应用

正文

1.NJ 树相似系数的概念

J 树相似系数(Nucleotide Substitution Number, NSN)是一种衡量两个核酸序列相似度的指标,其基于 NJ 树(Neighbor-Joining Tree)的构建方法。

NJ 树是一种分子进化树,用于展示不同物种或不同个体间基因序列的相似性和进化关系。

在 NJ 树中,节点表示序列的相似性,分支表示序列间的差异。

NJ 树相似系数用于衡量两个序列在 NJ 树中的相似程度。

2.NJ 树的结构

J 树是一种树形结构,其根节点表示参考序列,叶子节点表示待比较的序列。

树的每一层代表一个比对阶段,从根节点到叶子节点表示序列的逐步比对过程。

在每一层,序列被分为两组,使得两组间的差异最小。

这种分组方式沿树进行,直到所有序列都被分为叶子节点。

3.NJ 树相似系数的计算方法

J 树相似系数的计算方法基于 NJ 树的构建过程。

首先,将两个序列进行比对,得到它们的比对矩阵。

然后,通过动态规划算法构建 NJ 树。

在构建过程中,计算每个节点的相似性,并选择相似性较高的节点作为子节点。

最终,从叶子节点到根节点的路径上的相似性值之和即为 NJ 树相

似系数。

4.NJ 树相似系数的应用

J 树相似系数广泛应用于分子生物学、基因组学和生物信息学等领域。

它可以用来比较不同物种或不同个体间的基因序列相似性,从而研究它们的进化关系。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Rethinking strategy and implementation of knowledge managementfrom innovation perspective:A lesson learned from a multinational subsidiary in IndonesiaMirta Amalia a and Yanuar Nugroho b,*a Institute of Development Policy and Management (IDPM), University of Manchesterb Manchester Institute of Innovation Research (MIOIR), University of Manchester* Corresponding author. yanuar.nugroho@.This paper builds on the first author’s masters research.AbstractFacing unprecedented challenges and opportunities ahead in the knowledgeeconomy, managing knowledge has been a priority for many organisations.Knowledge Management (KM) emerges and has quickly gained weight inresearch both from information systems perspective and management sciences.An amply documented dilemma is the absence of specific implementation guidedue to different organisation’s characteristics and strategies. At times,endeavours to integrate KM into the organisation’s strategy and to customise itto meet organisation’s characteristics instead create undesired problemsbecause of its prioritisation. We explore the implementation of KM in atelecommunication multinational subsidiary in Indonesia and investigate factorsthat affect the performance as well as the impacts. Benefiting from innovationperspective we identify the way KM strategies are devised and put into action.Using in‐depth interviews and direct observation, we map some problemsassociated with the strategy and implementation of KM. We learn in our casethat the lack of organisation‐wide integrated systems, which is typical acrossdifferent organisations, does contribute to this problem. However the mainpredicament lies on the fact that KM enabling scheme is never explicitlyprioritised in the organisation’s information systems strategy.Keywords:Knowledge management, information systems, strategy, knowledge transferAcknowledgement:We thank Stan Metcalfe and Davide Consoli for the constructive comments onthe earlier draft of this paper. We are also grateful for the information providedby our informants in the interviews.“It is the historical linkage between the knowledge –information base of the economy,its global reach, its network‐based organisational form, and the information technologyrevolution that has given birth to a new, distinctive economic system …(Castells, 2000:77) 1 IntroductionOrganisations nowadays have been faced with the challenges of managing increasingly more complex activities in the knowledge‐based economy. As Castells (2000) suggests, knowledge economy is characterised as being informational, global and networked. Not only that economic activities depend upon organisation’s capacity to generate, process, and apply efficiently knowledge‐based information that it is informational, its core activities of production, consumption, distribution, and components are organised globally in interactive business networks (p.77). In his view, information and knowledge plays an important role in modern economy, giving new perspective to the works of some earlier economists who had already hinted this issue, such as Marshall (1965), Hayek (1945) and Schumpeter (1951; Schumpeter, 1952). The consequence of this is clear: organisations working in knowledge economy cannot but conceive themselves as learning agents capable of creating and managing knowledge to achieve their purpose (Antonelli, 2008).It is in this context that knowledge management (KM, hereafter) becomes significantly critical. Broadly defined, KM is ”the process of critically managing knowledge to meet existing needs, to identify and exploit existing and acquired knowledge assets and to develop new opportunities” (Quintas et al., 1997:387). As KM is seen to be a business practice (Radding, 1998), every organisation needs to critically formulates strategies in order to be able to acquire the potential value of KM (Davenport and Prusak, 2000). While KM strategy inherently depends highly on the organisation's characteristics and conditions, and the type of knowledge it manages (Greiner et al., 2007), the implementation hinges on various factors that can either facilitate or inhibit it. Then, as KM implementation impacts and affects the organisation, another challenge is to enhance the strategy and to improve the implementation processes so as to gain a better value of KM.The notion of ‘better value of KM’ is critical here as human knowledge is unevenly distributed (Antonelli, 2008) not only because of human’s inherent bounded rationality (as first coined by Simon, 1973) but also of our inability to escape from the information asymmetry. Therefore, in Antonelli’s (2008) view, KM can only be justified in so far it helps appropriate knowledge that is central to firms’ growth. In his words, “internalisation of knowledge exploitation and creation is necessary when knowledge appropriability is low” (p. 173). As communicating knowledge often implies resource sacrifice, then the implementation of KM as a technological platform must also be judged whether its benefit outweighs its cost and if it helps strategising knowledge exploitation to ensure the organisation can handle the implications arising from such implementation (Antonelli, 2008).We take up this argument and use it to present the case of a multinational company subsidiary, Nokia Siemens Network (NSN) in Indonesia. The Indonesian context might help substantiate an instance of an emerging economy and latecomer development, which might impact the operation and working of multinational subsidiary. In this case we examine how KM strategies are devised, formulated and implemented. Adoption of innovations perspective (Rogers, 2003) is used to help understand these processes as we perceive KM as a technological innovation. This case has led us to analysing several associated issues framed within these two points. First, confirming Nonaka (1994) we anchor our observation on howdifferent knowledge is managed in the organisation. KM processes as defined by Heisig (2001) is found not to be a straightforward use, but rather a trajectory from devising strategies to implementation, which must take into account the role technology (such as ICT) (Radding, 1998), and human resource practices (such as learning and reward systems) (Bartol and Srivastava, 2002). Second, in reflection, borrowing Rogers’ implementation framework of innovations (2003) what matters more is not the result of the use of KM as innovation but rather understanding the complexity of the implementation itself. Or, in other words, it is more about building a routine of continuous use of KM rather than a mere implementation. By featuring the case we modestly expect that it would enrich the literature on KM and innovation studies and widen the discussion on the role of KM as innovation in organisational performance.The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We start by reviewing literatures relevant to KM, adoption of innovations in organisations and introduce the context in which this study is based. Next, benefiting from innovation perspective we discuss how KM in this case is understood, put into strategy and implemented. Then, we highlight some problems that we found and discuss them. The last part concludes.2 Issues in managing knowledge in organisation and innovationThe question of how an organisation manages its knowledge has no single answer which encompasses all sorts of issues for all kinds of organisations. As Kluge et al. (2001) put,“The real question is how can a company systematically exploit all dimensions of knowledge and fully utilise them to improve revenues, profit and growth... Because of the very nature of knowledge, it is difficult for managers to predict what measures can really improve performance, and how to encourage and guide knowledge flows within an organisation.”(p.191)This highlights some of the predominant issues in managing knowledge in organisation. That the term ’knowledge’ in itself is not easy to define has been agreed by many (e.g. Hislop, 2005; Mertins et al., 2001; Nonaka, 1994). Part of the difficulty perhaps lies on the distinctions is between data, information, and knowledge (Hislop, 2005; Radding, 1998). At the practical level, data consists of raw numbers, words, images and facts derived from observation or measurement while information means processed data in a meaningful way and pattern (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Dretske, 1981; Hislop, 2005; Machlup, 1980) and knowledge is understood as authenticated information that has been assimilated into a coherent framework of understanding (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Vance, 1997). While this categorisation, or the one similar to this, has apparently been widely used in information systems domain, at the conceptual level we can borrow Castells’ framework (2000) to distinguish the difference between information, knowledge and understanding. He makes clear that“Knowledge and information are critical elements in all modes of development, since theprocess of production is always based on some level of knowledge and in the processingof information. However, what is specific to the informational mode of development isthe action of knowledge upon knowledge itself as the main source of productivity” (p.17) Clearly, in Castell’s view, understanding can only be achieved when knowledge has been accumulated and acted upon. It is important therefore to manage knowledge for it is critical both for managerial and workforce alike. This resonates to Hayek’s (1945) and Schumpeter’s(1951; Schumpeter, 1952) idea that knowledge, and therefore understanding, is subjective and cannot be treated as fixed. The dynamics of economic change depends on the dynamics of unique knowledge held by economic subjects rather than on the shared knowledge.From the organisational management perspective, too, knowledge is deemed important. Barnard (1938), for instance, attempts to synthesise management theories at the organisational level. Though knowledge is not his central issues, he clearly emphasises on the importance of ’behavioural knowledge’, i.e. non‐logical and non‐linguistic content, in the management process. He further posits that knowledge is essential securing a rational cooperative system in order to be able to organise problems in business management. On the contrary to Barnard’s work, Simon (1973) develops a view of organisation as ’information‐processing machine’ which emphasises the logical aspect of human reasoning. He explores the nature of human decision making and problem solving which influence the executive managers in the organisation. As such, he designs a computer model of the human thought process and argues that we as human have only a limited cognitive capacity. This brings into conclusion that, because of the limited capacity, organisation should design itself in such a way that reduces the information load on them. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) try to encapsulate both Barnard’s synthesis (which focuses on the importance of ’behavioural knowledge’) and Simon’s ’information‐processing paradigm’ (that emphasises on the logical knowledge). In their work, they posit that both ’behavioural knowledge’ –further known as tacit knowledge– and logical –or explicit– knowledge are critical to organisations.With this in mind, how do we classify knowledge? Some scholars have suggested ways to classify and characterise knowledge (Chua, 2002; Kogut and Zander, 1992; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1966). Yet, the widely used classification is perhaps the one proposed by Nonaka (1994). Building on Polanyi’s work (1966), Nonaka (1994) explains two dimensions of knowledge: explicit and tacit. Explicit –or ‘codified’– knowledge refers to knowledge that is articulated into words and numbers and transmittable in systemic language (p.16). This type of knowledge is objective, separate from individual and social value systems (Hislop, 2005). On the contrary, tacit knowledge is the knowledge that people possess which has a personal quality and is difficult to codify (Hislop, 2005) as it is “deeply rooted in action, commitment and involvement in a specific context” (Nonaka, 1994:16). In hindsight, this encapsulates Polanyi’s argument (1975) that tacit knowledge forms the background to interpret explicit knowledge, and Hayek’s reference (1945) to tacit knowledge as implicit, context‐specific knowledge. Table 1 summarises the difference between tacit and explicit knowledge.Tacit knowledge Explicit knowledgeInexpressible in a codified form CodifiableSubjective ObjectivePersonal ImpersonalContext specific Context independentDifficult to share Easy to shareTable 1 Characteristics of Tacit and Explicit KnowledgeSource: Hislop (2005:19)Nonaka (1994), then with Takeuchi (1995), suggests four modes of the conversion of tacit and explicit knowledge conversion. The first mode is socialisation. It converts tacit knowledge between individuals. In the firm context, the examples include On‐the‐Job Training (OJT) and apprentice work with mentors where individuals learn through observation, imitation and practice. To this point, knowledge is created through sharedexperiences. The second mode is called combination. It involves the use of social processes to combine explicit knowledge possessed by individuals. Existing explicit knowledge can be reconfigured through sorting, adding, and re‐categorising that lead to new (explicit) knowledge. The final two modes are concerned with conversion involving both tacit and explicit knowledge. Externalisation is the articulation of tacit into explicit knowledge through the use of metaphor (i.e. understanding and experiencing something). On the contrary, internalisation converts explicit into tacit knowledge which represents the traditional notion of ‘learning’ (as later corroborated by Becerra‐Fernandez et al., 2004). See Figure 1.Figure 1 Four Modes of Knowledge ConversionSource: Nonaka (1994:19)Knowledge conversion is essentially “a continuous process of dynamic interactions between tacit and explicit knowledge” (Nonaka, 1994:11) and in the context of firms this plays an important part of the firm’s survival in today’s economy. The conversion of knowledge and how this can benefit the firms is dealt within the discourse of KM, which has come to the top of the management agenda in the mid‐1990s (Quintas, 2002). Particularly this is because changes in markets and industries, globalisation, and new forms of competition have increased rapidly. Such changes demand continual development of organisational knowledge – a key feature of KM.There are two aspects central to KM in organisation: strategy and process. Firstly, in order to utilise the organisation's knowledge resources and capabilities, the formation of KM strategies is important (Beckman, 1999; Hansen et al., 1999; Zack, 1999). There are two categories reflecting focus of KM strategy (Choi and Lee, 2002): system strategy which emphasises the capability to create, store, distribute and apply the organisation's explicit knowledge, and human strategy that stresses knowledge sharing via interpersonal interaction utilising dialogue through social networks such as teamwork (Swan et al., 2000).The second aspect is the processes of KM (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Becerra‐Fernandez et al., 2004; Heisig, 2001; Holzner and Marx, 1979; Radding, 1998). Although many scholars propose KM process in different ways, there are basically four important processes: (1) knowledge creation, (2) storage, (3) distribution and (4) application. We adopt Heisig’s model (2001) as it is relevant in our case. The model reflects continual knowledge building which resonates to Quintas (2002) argument that organisation seeks to innovate focusing on the need to build their knowledge bases cumulatively. See Figure 2.Figure 2 KM processSource: Modified from Heisig (2001:28)1We explore Heisig’s framework. Knowledge creation is first KM process which refers to how organisations develop new content or replace the existing content (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Pentland, 1995). Then, in an effort to prevent losing track of the acquired knowledge, storage and retrieval of organisational knowledge (or ‘organisational memory’ Stein and Zwass, 1995; Walsh and Ungson, 1991) embody the second KM process (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). This process focuses on the ways knowledge in organisation is stored in people, artefacts as well as organisational entities. Next is knowledge distribution that aims to provide the right knowledge to the right person at the right time (Mertins et al., 2001). While Alavi and Leidner (2001) identify it as ‘knowledge transfer’, Becerra‐Fernandez et al. (2004) term it ‘knowledge sharing’. This process mainly concerns the effective transfer between individuals so they can understand the knowledge well enough to act on it (Jensen and Meckling, 1996). Lastly, as knowledge contributes to organisational performance when it is being applied for decision‐making and performing tasks, the application of knowledge is the most essential process of KM (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Mertins et al., 2001).Clearly, it is the issue of knowledge transfer that matters most in KM. While we can now understand why KM strategy and processes are central, it is are not always easy to implement it in firms. This possibly relates to how KM is adopted. Perceiving KM as a system (Alavi and Leidner, 2001:114), we can see it as an innovation, i.e. “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption” (Rogers, 2003:36). This system is usually ICT‐based systems which support the processes of knowledge creation, storage, distribution and application, also known as KM systems (KMS). The instances, among others, are electronic mail (e‐mail) and document management system (Becerra‐Fernandez et al., 2004; Radding, 1998), and collaboration tools like Wiki technology that enables its users to easily edit pages online in a browser (Ebersbach et al., 2006)2. Seamless KM‐related systems integration can also potentially foster KM implementation in organisations (Alavi and Leidner, 1999). To achieve this, a reliable ICT infrastructure is critical to KMS deployment. How we do understand the process in which and by which KMS are adopted and used in organisation?The diffusion theory informs us that implementation of an innovation, like KMS, in organisations generally begins when a decision‐making unit puts an innovation to use, i.e. that implementation follows the decision stage rather directly (Rogers, 2003:179). In the organisational context, however, the process is slightly different and implies an important 1 Heisig's original model uses the term Generate Knowledge. Here, the term Knowledge Creation is used assuggested by many predominant scholars in KM (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Choi and Lee, 2002; Nonaka, 1994;Quintas, 2002).2 Knowledge contained inside the Wiki is accessible to individuals in the organisation, allowing them to easilylearn new knowledge. Thus, Wiki supports the processes of knowledge creation, storage and distribution.distinction between initiation stage and implementation stage (Damanpour, 1991; Rogers, 2003). The initiation phase starts with ‘agenda‐setting’ (pp.422‐423), characterised by problem definition, prioritisation of needs and active search for innovation to contribute to problem solving. It is then followed by ‘matching’ (pp.423‐424) in the sense that organisation puts innovation into a problem, fine‐tunes and exploits it within its specific context. This stage happens when firms fine‐tune themselves with the innovation characteristics and exploit the technological feature of it and put it within the context of their needs. The implementation phase comprises three stages. It starts when the use of innovation is widely spread across organisation, and is known as the ‘clarifying’ stage (pp.427‐428). The next stage is called ‘redefining/restructuring’ (pp.424‐427) when the organisation familiarises with the innovation in two ways: reconfiguring the innovation to match the organisation’s needs and restructuring the organisation in order to implement the innovation. This implies a great deal of familiarisation through trial and practice in organisation level, which refers back to ‘clarifying’. The last stage, ‘routinising’, happens when the innovation is incorporated into organisation’s regular activities to advance the achievement of organisations’ objectives (pp.428‐430). This is depicted below.Figure 3 Innovation processes in organisationSource: Rogers (2003:421)Often, organisational innovation (Damanpour, 1991; 1992) is involved when an organisation adopts innovations, be it the implementation of a new technology, method, practices, or external relations. Organisational innovations also include the implementation of new methods for distributing responsibilities and decision making among staff for the division of work within and between firm activities and organisational units. It also covers new concepts for the structuring of activities, such as implementation of an organisational model that gives employees greater autonomy in decision making and encourages them to contribute their ideas. It is not difficult to imagine that social learning is important in organisational innovation. The idea is that one individual learns from another by means of observational modelling (Bandura, 1977; 1986; cited in Rogers, 2003:341). In many cases, social learning eases the process when an organisation adopts and familiarises itself with an innovation and needs to adjust its organisational features.In a particular instance of innovation diffusion in organisations, like KMS in a firm, it is important to look at how organisations use and innovate in and around new technology to achieve their missions and goals, improve their organisational management and develop new strategies. As discussed above, managing knowledge in fact goes beyond applying and implementing certain technological innovations. We can therefore expect that both technological innovation and organisational innovation become the core of the discussion in our case. We now turn into our case study.3 NSN Indonesia: The caseWe chose case study at Nokia Siemens Networks (“NSN” thereafter) Indonesia subsidiary as a method3 to argue for an instance of KM initiatives in one department of a multinational company subsidiary in Indonesia. The material for the case study is gathered through in‐depth interviews4 and observation in addition to publicly available secondary data. Choosing a case study as a methodology allows this study to 'tell‐it‐like‐it‐is' from the respondents' point of view (Stark and Torrance, 2005). We however realise the limitation of this method and would like the flag some of them. Firstly, due to the limited time available for the research, the method of examining a single case study is chosen as a viable option to inquire in‐depth information. Second, inherently, because of this the findings cannot be generalised. However, studying a single case study has allowed this research to examine the themes and issues in greater detail.3.1. About Nokia‐Siemens NetworkNSN is a multinational company established on April 1, 2007 as a result of a 50‐50 joint venture agreement between Nokia Networks, one of Nokia's business groups, and Siemens COMM, Siemens's carrier‐related operations for fixed and mobile networks (Nokia, 2007). Although NSN is jointly owned by Nokia and Siemens, its financial report is still consolidated by Nokia.NSN employs an estimated 60,000 people in more than 150 countries (NSN, 2009a). In the mobile network market share, Reuters (2007) reports that NSN is positioned in second place, behind the market leader Ericsson. To achieve its mission ‘to connect the world’ (NSN, 2009c), the company designs an operational model that is organised towards being close to its customers (NSN, 2009d). Its Global Head Quarter (HQ) consists of Operational HQ located in Espoo, Finland (NSN, 2009a) and a Research & Development (R&D) centre located in Munich, Germany. Hereafter, HQ refers to NSN's Global HQ.This study is conducted in the NSN's Product Customisation department (“the Department” thereafter) ‐ also known as Solution Centre ‐ located in Jakarta, Indonesia. When the study was conducted, the Department was part of the Business Support System (BSS) business unit. It aims to intensify NSN's support to Indonesian network operators in the areas of communications and information technology (Wijaya, interview, 17/6/09). Its purpose is also to become a communication technology hub for the Asia Pacific region. By establishing the Department in Jakarta, the ‘time‐to‐market’ of new products or features will be shortened because the customisation is developed in Jakarta rather than in R&D centre as it was previously done. The Department has five subdivisions, i.e. Development (DEV), System Test (ST), System Integrator (SI), Customer Product Support (CPS), and Test‐Lab Management. Its scope of work ranges from product customisation development, system test and integration of NSN's solutions, as well as consultancy services of customers’ architecture and business process. Its headcount at the time of this study was 71 employees.3 Some scholars refer to 'case study' as a method (Crotty, 1998) or an 'approach' (Stark and Torrance, 2005)while others consider it a methodology (Denzin and Lincoln, 2000; Yin, 1994)4 Please consult Appendix for the list of informants.Figure 4 Subdivision Hierarchy of the DepartmentSource: AuthorsIn Indonesia, Telkomsel5 has been one of NSN's success stories highly influenced by the Department's performance (NSN, 2009e). The Department had taken part in the customisation development and deployment of one of NSN's product called Convergent Charging solution in Telkomsel (NSN, 2009b; Schwartz, 2008). To be able to fully support its customers' needs, the Department must have sufficient related knowledge and manage them well with a comprehensive KM strategy. We now illustrate how the Department devises its strategies to manage knowledge.3.2. KM in Nokia‐Siemens NetworkThrough the interviews, all respondents acknowledge that the department has applied KM in their activities. In fact, both companies of origin –Nokia and Siemens– have applied KM (Chase, 1997; Civi, 2000; Davenport and Probst, 2002; Gamble and Blackwell, 2001; Voelpel et al., 2005). According to Gamble & Blackwell (2001),Siemens has about 100 knowledge management projects in motion ... With [its] globalknowledge‐sharing network, ShareNet, [Siemens] has chosen to focus on one of [its]key business processes, i.e. sales value creation, which is very close to our customers(pp.7‐8)The ShareNet, as cited above, is then adapted by NSN and renamed to IMS. Similarly, Nokia values KM demonstrated by establishing the Knowledge Management Department that is responsible for organising KM concepts and strategies (Chase, 1997).Learning from past experience, as well as realising the fierce competition in the mobile telecommunications market, NSN understands the importance of managing knowledge. The Head of Department describes two key points of KM strategy in the Department:“[the first point is] that knowledge management in the Department is always alignedwith the Department's product portfolio, which product will be customised by theDepartment. [Having known that], we can determine the knowledge needed to becaptured by our [human] resources, in order for us to be able to sell the product [to ourcustomer], as well as for us to execute a project. At this point, [afterwards] we can planour knowledge management program. The second point is the importance to relate[our knowledge management program] with [each employee’s] personnel5 Telkomsel has been the largest cellular telecommunications operator in Indonesia by market share (Telkomsel,2008)。