a review of land use regression models to aesses spatial variation of outdoor air pollution

penalized regression model

penalized regression modelPenalized regression models are a class of regression models that use penalties to regularize the coefficients of the model. The penalties are imposed to control the complexity of the model and to prevent overfitting. There are several types of penalized regression models, including:1. Lasso regression (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator): In lasso regression, the penalty is the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients. This penalty encourages sparsity, meaning that many of the coefficients will be zero, which can be useful for feature selection.2. Ridge regression: In ridge regression, the penalty is the sum of the squares of the coefficients. This penalty encourages smaller coefficients, which can be useful for reducing variance and improving the interpretability of the model.3. Elastic net regression: The elastic net regression is a combination of lasso and ridge regression. The penalty is a combination of the lasso and ridge penalties, with a mixing parameter that controls the relative contributions of the two penalties.4. Adaptive Lasso: Adaptive lasso regression is an extension of lasso regression that adapts the penalty to the data. The penalty is based on the empirical covariance matrix of the data, which can be useful for handling high-dimensional data.5. Group Lasso: Group lasso regression is an extension of lasso regression that allows for grouped penalties. The penalties can be imposed on groups of coefficients, which can be useful for capturing correlations between variables within a group.In summary, penalized regression models are a useful tool for regression analysis, particularly in high-dimensional data settings. The choice of penalty and the tuning parameters can have a significant impact on the performance of the model, and it is important to carefully consider these choices in the context of the data and the problem at hand.。

An evaluation framework for land readjustment practices

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https:///publication/271965616 An evaluation framework for land readjustment practicesARTICLE in LAND USE POLICY · FEBRUARY 2015Impact Factor: 3.13 · DOI: 10.1016/ndusepol.2014.12.004CITATION 1READS 993 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:Ahmet YilmazYildiz Technical University 2 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONSSEE PROFILE Volkan CagdasYildiz Technical University6 PUBLICATIONS 25 CITATIONSSEE PROFILEAvailable from: Ahmet YilmazRetrieved on: 22 March 2016Land Use Policy 44(2015)153–168Contents lists available at ScienceDirectLand UsePolicyj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /l a n d u s e p olAn evaluation framework for land readjustment practicesAhmet Yilmaz ∗,Volkan C ¸a˘g das ¸,Hülya DemirYildiz Technical University,Department of Surveying Engineering,34220Istanbul,Turkeya r t i c l ei n f oArticle history:Received 1April 2014Received in revised form 15November 2014Accepted 14December 2014Keywords:Land readjustment Evaluation frameworkMonitoring and evaluation Performance indicatorsa b s t r a c tLand readjustment (LR)is an important technique used in a variety of countries to realize the development plans by converting rural land into urban land and providing city infrastructure.Although the main aim and the processes are similar around the world,each country has a different degree of success in the application of LR,which reveals the need for a comprehensive evaluation.However,the research to date has generally tended to focus on describing the main concepts such as the usage,principles,advantages,and disadvantages of the existing implementations rather than evaluating LR.A systematic approach,which provides an objective basis and removes subjectivity by identifying good practices and their indicators,is needed to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the LR process.In this article,we analyzed a wide range of ISI journal articles on LR to establish a framework and a methodology that will help evaluate and compare the national LR processes.The main contribution of this article is to build an awareness for the establishment of an internationally agreed methodology to evaluate the performance of a country’s LR in a systematical way,which is currently not available in the literature.©2014Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.IntroductionThe purpose of this study was to develop a methodology to mea-sure and compare the performance of the existing LR strategies in order to learn from the successful implementations.It is also aimed to present a set of good practices and their indicators under various aspects to provide an objective basis and to provide a systematic evaluation and monitoring of LR.Therefore,this article introduces the notion of ‘evaluation framework’developed in organizational sciences and a methodology for LR.Considering the good practices derived from 18ISI journal articles on LR,the proposed evalua-tion framework identifies performance indicators that have been constituted to measure the extent to which they meet at different evaluation levels and for different aspects of LR.Currently,almost 50%of the world population live in urban areas;however,it is expected to increase to 70%by the middle of this century.Developing countries currently account for more than 95%of the global urban population growth,and in the period between 2000and 2030,the urban population is expected to dou-ble and the built-up area of these countries are expected to triple in size (UN-Habitat,2012).The pressures of urbanization in most∗Corresponding author.Tel.:+902123835314;fax:+902123835274.E-mail addresses:ayilmaz@.tr (A.Yilmaz),volkan@.tr (V.C ¸a˘g das ¸),hudemir@.tr (H.Demir).countries around the world create the need for methods to assem-ble the development land by focusing on increasing the efficiencyof the transformation from a rural to an urban economy,in terms of balancing agglomeration benefits and congestion costs from concentration (Home,2007).Therefore,land management strate-gies need to deal with three main objectives,land assembly for (re)development,cost recovery for the costs of the public infra-structure works and capturing the value that occurs as a result of the change of the land use or the density (Van Der Krabben and Jacobs,2013).It is also possible to extend these objectives to support country-related land policy objectives such as ensur-ing efficiency in land markets,enabling sustainable development,and achieving social goals such as the provision of social housing.From these objectives,land assembly can be broadly defined as the key stage in development processes involving land acquisition from landowners,land preparation,planning of streets,open spaces and main services,planning the built form,division of land into building plots,and delivery of the planned form (Golland,2003;cited in Louw,2008,p.70).The key feature of land assembly is that it may involve changes in land ownership through the acquisition of the necessary parcels of land for property and infra-structure development where possible (Louw,2008).However,the process of using the common land assembly methods entails a huge upfront cost,which becomes a burden on the budget of public institutions.Moreover,such financial difficulties combined with the landowners withholding land from and disagreements over/10.1016/ndusepol.2014.12.0040264-8377/©2014Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.154 A.Yilmaz et al./Land Use Policy44(2015)153–168the distribution of the land value increment,usually translates into long time scales and complexity,which may hinder the entire process of land assembly.Realizing the development of land and providing infrastructure usually generates prospective land values,which should be col-lected by the public.Otherwise,it will remain to the landowners as an“unearned increment”.Therefore,to overcome the free-rider problems in land assembly,land management strategies usually involve a tool or mechanism to recover the costs of public works by using the increase in the property values.It is clear thatfinancing the projects would be easier if the government body responsible could skim development gains,capture value increases,and recover its costs(Van Der Krabben and Needham,2008).For the implementation of these strategies,various develop-ment models are used,including public sector and private sector initiatives as well as public–private partnerships.These develop-ment models vary according to the main purpose of the strategy and its relation to other strategies regarding planning,land assembly, and cost recovery and value capturing(see:Van Der Krabben and Jacobs,2013).Each model has pros and cons;however,compared with other common methods,LR has several more advantages, particularly when public funds for compulsory purchase and infra-structure provision are limited(Home,2007).The term land readjustment or land pooling refers to a technique for managing andfinancing urban land development,whereby a group of neighboring landowners on an urban fringe area are combined in a partnership or a government agency consolidates a selected group of land parcels for the unified planning,servicing and subdivision of land with the project costs being recovered by the sale of some of the plots for cost recovery and the distribution of the remaining plots back to the landowners to develop or to sell for development(Archer,1992,1994).In terms of land assembly,although there are difficulties in project areas due to landowners withholding their land from sale (including farmers,developers,land speculators and investors), many landowners can be encouraged to participate in LR projects when there is a possibility of their land gaining a significant increase in the market value(Archer,1992).In terms of cost recovery,LR can increase the efficiency of urbanization at a reduced cost since the project site and infrastructure rights of way do not have to be bought or compulsorily acquired.The cost of the infrastructure works and subdivisions can befinanced with a short-term loan and then quickly recovered by the sale of some of the new building plots. Using LR in land assembly,infrastructure and development costs can be substantially recovered from within the project(UN-Habitat, 2013).Differently from the common land assembling methods,LR has the potential to overcome the hold-out and free-rider problems of land management strategies.Moreover,using LR it is possible not only to recover the cost of installing a complete infrastruc-ture,but also to capture the additional socially created value that can be used to subsidize low-cost housing,or,indeed,for any pub-lic purpose(Doebele,2002).In terms of value capturing,pre-and post-land values can be determined,and the difference can fully or partially be captured by the implementing body in LR.Moreover, as stated by Viitanen(2002)the LR procedure is justified not only based on the involved costs and the efficiency of the method but also based on its fair treatment of landowners,improvements in plan quality,savings to the community,and environmental bene-fits.Furthermore,it facilitates the participation of property owners in the process,ensures a fair distribution of development costs and profits created by spatial plans(Sonnenberg,1996),and preserves the original ownership structure and social networks.Concerning the main land management objectives,LR can, in theory,be considered the best land management strategy. However,countries have varying degrees of success and accep-tance in the implementation of LR due to different institutional arrangements(Li and Li,2007;UN-Habitat,2013).For instance, in Germany,LR was intensively employed in the postwar recon-struction of the damaged cities and the accommodation of the recent wave of urbanization(Doebele,1982).Similarly,LR is the key part of the urban planning system in Japan.Since1954when Land Readjustment Act was put into effect in Japan,LR has been used for the development of new cities,prevention of disorderly growth,and urban renewal and reconstruction(Hayashi,2000; Montandon and De Souza,2007;Nishiyama,1987).During the 1954–2003period,approximately30%of the urban area was developed through LR projects in Japan(Archer,1997;Sorensen, 2000a,b).In Spain,although the practical experience of LR was unsatisfactory until the mid-1990s,after the legal reforms with the Valencia Regional Planning Law of1994,LR(and if necessary, compulsory LR)became the standard procedure.Since then,LR has been implemented all around the Valencia Region as well as other Spanish Regions in hundreds of cases,involving thousands of hectares.In addition,almost all the major real estate developments in Spain are performed using LR(Blanc,2008;Munoz Gielen and Korthals Altes,2007).Contrasting the mentioned best practices in Germany,Japan and Spain,LR is perceived as a rather unwieldy and time-consuming process in France(Sonnenberg,1996;Viitanen,2000).LR in France is,in quantitative terms,not more important than other develop-ment procedures,and permanently under5%of new developments (Renard,2003).Similarly,in Finland,the new Real Property Forma-tion Act came into force in1997,which redefined the former urban LR procedure that had been in force for36years,but had hardly ever been put into practice(Viitanen,2000).Finally,in Turkey,while legal arrangements regarding LR have been included in numerous laws and regulations since the second half of the19th century(C¸ete, 2010),compared with the other land assembling methods,LR has not been used widely in the implementation of development plans since only about one-third of all urban parcels is produced through LR projects(Turk,2005).Although LR theoretically provides a better land management, in reality,only a few countries achieve positive outcomes.In the remaining countries,the procedure is still not introduced or the usage and success levels are far behind expectations.Therefore,the LR models/systems that are not successful or not accepted as the main land management and land assembly tool by the countries should be evaluated to clarify the problems that need to be solved and define the performance gaps that need to be addressed.To this end,countries should test their existing LR system and compare the results with the best or expected results of an ideal system to iden-tify the problems in their strategies and the performance gaps in their models/systems that need improvements.By understanding how LR can be efficiently implemented and maintained,it is pos-sible to define the good practices and the success factors in terms of different aspects that should be addressed when the method is being introduced to a country for thefirst time or when existing LR policies are improved.Overall,the difference between the countries regarding their level of acceptance and success in using LR highlights the need for a comprehensive evaluation.However,the existing literature is mostly centered on describing the main concepts such as the usage, principles,advantages and disadvantages of the existing LR imple-mentations.In these studies,some comparisons have also been made(see section“A general overview of evaluations”),however; the researchers have not addressed the necessity of a systematic approach that will provide a global evaluation mechanism of an efficient LR.Thus,a systematic approach is required to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the existing LR practices of countries and their institutional and technical environments to develop the content of future reform initiatives.Systematic comparisons and evaluations are good sources to learn from the success andA.Yilmaz et al./Land Use Policy44(2015)153–168155experience to improve the performance of others,and as explained in section“A general overview of evaluations”,the notion of‘eval-uation framework’developed in organizational sciences may serve this purpose.The literature presents several evaluation frameworks that focus on the different aspects of land management and land administration(LA),yet LR seems to be a missing component.This article responds to these requirements by providing;(1)a system-atic approach for the evaluation and comparison of LR to improve the existing LR practices of countries and their institutional and technical environment,(2)an objective basis that removes the sub-jectivity from evaluations using the good practices and their indica-tors,(3)a contribution to the literature regarding land management in terms of the use of evaluation frameworks.The remaining part of this article is organized as follows:the next section gives an out-line of the LR process,section“A general overview of evaluations”explains the notion of an evaluation framework,and examples for the domains of land administration and land management.Section “An evaluation framework for land readjustment studies”develops an evaluation framework for LR based on articles published in ISI journals and Section“Conclusion”concludes the present article. Land readjustmentLR is a land-management tool used to reorganize land for urban development by forming its location,shape and size according to the spatial plans,and provide land needed for public purposes such as roads and green areas(Seele,1982).Briefly,the LR projects start with a formal decision which can either be a private initiative as is the case in Japan,France,Sweden,and South Korea,or a public initiative as implemented in Germany,Japan,Turkey,Finland, Australia,South Korea and Indonesia.Then,the LR project area is defined by mathematically adding or pooling the parcels,which are located within the project boundaries.In some countries including Japan,Germany,Finland,Australia,South Korea and Turkey where publicly initiated LR projects are implemented,decisions on LR projects may be made directly by local governments without ask-ing the consent of landowners.In such cases,the process is handled as an administrative issue.However,in some cases the support of landowners can still be obtained to a limited extent at the beginning of the publicly initiated LR projects.On the other hand, in privately initiated LR projects,the main condition is to ensure a consensus between the landowners as applied in France,Sweden and Taiwan.Otherwise,the project cannot be initiated.However,in some countries such as Germany and Japan,the privately initiated projects do not need the approval of all landowners.If two-thirds of the landowners owning two-thirds of the total land area agree to participate in the project,then it becomes compulsory for the others.Following the participation process,the area allocated for public purposes according to the spatial plans are extracted from the project area.In Japan,Germany,France,Sweden,Finland, Australia,South Korea and Taiwan,landowners make more con-tributions in terms of reducing their land to recover the cost of the project.This land portion is called reserve or cost equivalent land and is sold at the end of the project to pay for costs such as planning,administration and construction.Then,the remaining area is subdivided into urban parcels according to the master plan,and allocated to the landowners based on their shares in the project.The calculations in the allocation process could be area or value-based.While some countries have only one allocating base (only land-based in Turkey and Indonesia,and only value-based in Sweden,France and Australia),in some other countries such as Japan,Germany,South Korea and Taiwan,the calculations regarding the allocation can be based on either an area or a value. In Germany,Japan,France,Sweden,Finland,Australia,South Korea,India,and Taiwan,after the allocation of the land,the value difference between the initial and allocated plots is calculated for each landowner and compensated through money payments.There is a considerable number of studies in the literature regarding LR.Most of the research has focused on the general concepts or key characteristics of the LR process in countries such as;Germany(Davy,2007;Doebele,1982;Dransfeld,2001; Müller-Jökel,2001,2002,2004;Seele,1982;Supriatna,2011); Japan(Doebele,1982;Carlsson,1991;Hayashi,2000;Montandon and De Souza,2007;Nishiyama,1987;Sorensen,2000a,b,2007; Supriatna,2011);France(Gaudet,2007);Holland(Van Der Krabben and Needham,2008;Needham,2002);Sweden(Carlsson,1991; Kalbro,2002);Australia(Doebele,1982);Taiwan(Doebele,1982; Chou and Shen,1982;Lee,1982;Lin,2005);Turkey(C¸ete,2010; Turk,2005,2007;Turk and Korthals Altes,2010a,b);India(Mathur, 2012,2013);Finland(Viitanen,2002);Indonesia(Supriatna,2011), Israel(Alterman,2007);China(Li and Li,2007);Korea(Doebele, 1982;Lee,2002)and Nepal(Karki,2004).These studies provide an adequate background for the general usage,main principles,advan-tages and disadvantages,experiences,problems,and future recom-mendations regarding LR.Therefore,this study focuses on describ-ing the good practices and their indicators to develop an evaluation framework that can be used for the systematic evaluation of LR without duplicating the literature.Before employing these theories to examine LR,it is necessary to provide an overview of the evalu-ations and the use of the good practices and indicators in different word-wide organizations and in the land management domain.A general overview of evaluationsEvaluation is the systematic collection and analysis of data in order to assess the strengths and weaknesses of programs,poli-cies,and organizations to improve their effectiveness(Baird,1998). When evaluation involves good practices and their indicators,it eliminates the subjectivity and provides an objective basis for learning from the success and experience in improving the per-formance of others.Good practices can be the main goals or the results expected from an ideal,efficient or well-functioning sys-tem and indicators are the ways to measure the state or level of the good practices.As stated by the UN-Habitat(2003)good prac-tices and indicators are reference points for evaluations and they constitute a critical component of an evaluation framework.In recent years,there has been an increasing interest in the use of evaluation and performance indicators by the word-wide organizations to assess the outcomes of their projects and pro-grams.For instance,the regulations governing the evaluation of the United Nations activities were promulgated in2000,and simi-lar regulations and policies have been issued in several UN system organizations.The United Nations Evaluation Group(UNEG),a group of professional practitioners,undertook to define the norms aiming to contribute to the professionalization of the evaluation function,and provide guidance for evaluation offices in prepar-ing their evaluation policies or other aspects of their operations (UNEG,2005).Similarly,the International Evaluation Group(IEG) carries out independent and objective evaluation of the strategies, policies,programs,projects,and corporate activities of the World Bank Group.Due to the diversity of projects and programs,IEG uses a variety of evaluation approaches,which include assessing outcomes against stated objectives,benchmarks,standards,and expectations,or assessing what might have happened without the project,program,or policy.Moreover,IEG is working with the Regional Centers for Learning on Evaluation and Results Initiative, and the International Program for Development Evaluation Train-ing to help countries develop their own monitoring and evaluation capacity(IEG,2014).In terms of the recent land management studies,researchers have shown an increased interest for the development of the156 A.Yilmaz et al./Land Use Policy44(2015)153–168evaluation frameworks,particularly for assessing the land admin-istration systems.For instance,in order to assess the success and effectiveness of a LA system,International Federation of Survey-ors(FIG,1995)suggested a set of criteria in1995.In2004,Daniel Steudler developed an evaluation framework based onfive evalu-ation levels,i.e.policy level,management level,operational level, external factors and review process.These levels are adapted and developed from the organizational pyramids and divided into eval-uation aspects.For each aspect,good practices and their indicators are developed and the evaluation framework is tested with case studies in Switzerland,Sweden,Latvia and Lithuania(Steudler, 2004).Rajabifard et al.(2006)developed the cadastral template, which is mainly a standard form to be completed by cadastral orga-nizations presenting their national cadastral system.The cadastral template()now represents the results of34country templates based on six statistical and two descrip-tive indicators.Chimhamhiwa et al.(2009)presented a conceptual model for measuring end-to-end performance of land adminis-tration systems based on cross-organizational business processes. Bandeira et al.(2010)developed a comparative methodology for the evaluation of national land administration systems and applied it to the cases of Honduras and Peru in order to evaluate their systems.The mentioned studies put in a global effort to estab-lish an evaluation methodology that is systematically accepted, and a research corporation on land administration.However,even though land administration attracts great attention,there is still no internationally agreed methodology for evaluating and comparing LR practices.The literature provides an adequate background about the main concepts such as the usage,principles,advantages and disadvan-tages of the existing LR implementations.In the related studies, evaluations and comparisons are also made;however they only cover the main process or the key characteristics defined by the authors.For instance,Larsson(1997)describes the methods and uses of LR in Germany,France,Japan and Western Australia and then discusses the advantages,problems and possibilities for future methodological developments.Agrawal(1999)reviews and com-pares LR policies and procedures of Japan,Korea,Thailand and Malaysia based on twenty criteria categorized under four main groups.Hong and Needham(2007)published the book‘Analyz-ing Land Readjustment Economics,Law,and Collective Action’,in which they advanced the research on LR.The book starts with describing LR as an alternative to the common land assembly tools and uses case studies to discuss the how the land assembly schemes intervenes in the property rights.In one case study,Davy(2007) analyzed the legal issues related to the public intervention using the German LR system as an example and described the balance that the courts and government officials need to maintain in protec-ting both public and private property rights.The legal,geopolitical, and land administrative contexts of LR in Israel was described by Alterman(2007),who revealed that even though LR may be accepted as a land management tool,its functions are often con-strained by legal and political institutions.In addition,Sorensen (2007)examined the wide application of LR in Japan and with a culture-centric view,he concluded that special norms,such as group harmony and consensus formation are so important to LR that only countries with these cultural norms can make use of the technique.Moreover,based on the experience of the Netherlands, Needham(2007)affirmed the idea that cooperative attitudes and trust in the government can be learned and created by prop-erty owners and developers through repeated interactions in LR projects.Li and Li(2007)showed how providingfinancial rewards to both developers and property owners can increase the number of property exchanges in two experimental LR like schemes in Hong Kong,China.Sagalyn(2007)hypothetically assessed the possibil-ity of transferring some LR ideas to the redevelopment of Times Square in New York City,and argued that LR does not seem capa-ble of lowering the risk for the government and developers when it comes to dealing with complex urban redevelopment projects.The last part of the book provides conclusions on institutional require-ments and how to meet these requirements to organize instigated property exchanges,and focuses on how laws,social norms,and the market interact to form an incentive system that will encour-age the owners to exchange their property right in a way that is profitable for all concerned parties.Home(2007)summaried the LR method,explored issues relating to trans-national transfer and different social and legal cultures,and evaluated the factors influ-encing its adoption and success,and its potential application for different land assembly situations.Turk(2008)defined the basic conditions required for the efficient application of a LR model,and examined the LR systems of ten countries based on twelve key crite-ria.Tan et al.(2009)described different governance structures for the conversion of farmland in the Netherlands,Germany,and China, and comparedfive identified differences in these countries in the realms of land property,land-use planning,the role of the market, and the role and performance of governance structures.In summary,unlike the mentioned studies regarding land administration,the LR literature failed to establish an internation-ally accepted methodology,and a research corporation for a global evaluation mechanism of LR practices.Therefore,the lack of an agreed methodology resulted in academicians using various criteria or success factors to evaluate and compare LR practices and con-centrate on different aspects of LR,without establishing a common concept.Furthermore,previous studies on LR did not address the indicators that provide an objective basis for making queries on the existence or the success levels of the LR practices,and mon-itoring the results.Consequently,the current literature seems to be insufficient to establish an ongoing monitoring and evaluation system for different countries.Therefore,to eliminate the short-comings of the author-chosen evaluation criteria we defined the good practices with respect to the broad international consensus on what constitutes the ideal LR and its strategies on different aspects.In addition,the good practices discussed in this article are provided with quantitative and qualitative indicators that can con-stitute an optimum benchmark for most of these ing the good practices together with the indicators,it is possible for countries to determine whether their strategies can provide a suc-cessful implementation of the LR system and identify the areas that can be improved.Moreover,to our knowledge none of the previous comparison studies clearly addressed the data that needs to be col-lected and analyzed to evaluate how well a LR system is functioning in a country and to compare the outcomes of the related strategies with the expected outcomes of an ideal LR.This article contributes to the LR literature by building an awareness on the importance of establishing an internationally accepted methodology to evaluate the existing LR practices and draw attention to the issues that need to be addressed when a country is introducing these policies.We also aim to provide an objective basis for evaluation that is free from subjectivity from evaluations by using the good practices and their indicators and contribute to the literature in the land management domain in terms of the use of evaluation frameworks.One difficulty in adopting a common comparison framework for systems within the land management domain is that they are generally in a constant reform process and,more importantly,they have strong social and cultural links,and implications.Moreover, these systems reflect the particular and distinctive perceptions that societies have of their land.However,as indicated by the earlier studies on land administration,in spite of the different social,polit-ical,and administrative background of each country,it is possible to develop a methodology and framework to evaluate and compare these systems with each other,by taking economic,cultural,and environmental issues into consideration(Steudler,2004).。

施加生物炭对黑土区坡耕地改土培肥效应的持续影响

2 0 2 1年3月农业机械学报第52卷第3期doi:10.6041/j. issn. 1000-1298.2021.03.034施加生物炭对黑土区坡耕地改土培肥效应的持续影响魏永霞1>2肖敬萍1王鹤1石蕴1刘慧2,3(1.东北农业大学水利与土木工程学院,哈尔滨150030;2.东北农业大学农业农村部农业水资源高效利用重点实验室,哈尔滨150030;3.东北农业大学文理学院,哈尔滨150030)摘要:为探明施加生物炭对黑土坡耕地的持续影响,以东北黑土区1.5。

、3。

、5。

的坡耕地田间径流小区为研究对象,对土壤结构及其养分进行为期4年的观测。

于2016年试验开始前,按75 t/hm2—次性施加玉米秸秆生物炭,各坡 度均设置不施加生物炭的对照组,共计6个小区,后续年份不再施加生物炭。

结果表明,单次施加生物炭能够提高 土壤气相、液相比例,提高通气性和持水能力,改善土壤三相比例,较对照组土壤孔隙度提高2. 83% ~5. 56%,土壤 容重降低1.89% ~3. 62%。

施炭后土壤中有机质、铵态氮、速效钾含量显著提高,分别提高9.54%~ 18.21%、21.35% ~28.02%、11. 99% ~22. 71%。

各项指标均随着时间的推移有所降低。

采用随机森林回归模型评估得出综合肥力等级指数,并拟合回归方程预测2020—2022年等级指数,比较肥力变化情况得出单次施用生物炭对培肥 土壤作用的有效年限为6 ~7年。

_关键词:生物炭;黑土坡耕地;改土培肥效应;随机森林模型中图分类号:S152.5; S158.2 文献标识码:A文章编号:1000-1298(2021)03-0305-10 OSID:Continual Influences of Applying Biochar on Soil Improvementsin Sloping Farmland of Black Soil Region in Northeast ChinaW E I Yongxia1,2X I A O Jingping1W A N G H e1S H I Y u n1L I U H u i2,3(1. School o f W ater C onservancy a n d C ivil E n g in e erin g,N ortheast A gricultu ral U niversity,H arbin150030,C hina2.K ey Laboratory o f H igh E fficiency U tilization o f A gricultu ral W ater R esources,M inistry o f A griculture a n d R u ra l A ffa irs,N ortheast A gricultu ral U niversity,H arbin150030,C hina3.School o f S cien ce,N ortheast A gricultu ral U niversity,H arbin150030,C h in a)Abstract :In order to ascertain the sustained influence of the application of biochar on sloping farmland in black soil region of Northeast C h i n a,field runoff plots with 1. 5。

land use pattern的概念

land use pattern的概念Land use pattern refers to the arrangement and distribution of different types of land uses within a given area. It is essential in understanding how land is utilized and allocated for various purposes, such as residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, recreational, and conservation.Land use pattern analysis involves examining the spatial distribution and characteristics of land uses, including their size, shape, density, and proximity to other land uses. It provides valuable insights into the dynamics and interactions between different land uses, as well as their impacts on the environment, economy, and society.To better understand the concept of land use patterns, let us delve into the key factors and processes that shape them:1. Natural Factors: Land use patterns are heavily influenced by natural factors such as topography, soil fertility, water resources, and climate. For example, flat and fertile land is more suitable for agriculture, while mountainous areas may be used for forestry or conservation purposes.2. Economic Factors: Economic activities, such as agriculture, industry,and commerce, play a significant role in shaping land use patterns. The availability of resources, transportation networks, market demand, and labor force all influence the spatial distribution of different land uses. For instance, industrial activities tend to concentrate near transportation hubs and natural resources, whereas residential areas are often located close to amenities and services.3. Planning and Policy: Land use planning and policies implemented by governments and local authorities also play a crucial role in shaping land use patterns. Zoning regulations, urban growth boundaries, land preservation policies, and infrastructure development plans all influence the allocation and organization of land uses within a region. These measures aim to achieve sustainable development, protect natural resources, and create livable communities.4. Social and Cultural Factors: Social and cultural factors, including population growth, demographic changes, lifestyle preferences, and cultural traditions, shape land use patterns. For example, the demand for housing, recreational spaces, and amenities differs based onsocio-economic status, age groups, and cultural practices. These factors influence the distribution and design of residential areas, parks, and public infrastructure.5. Environmental Considerations: Understanding and mitigating the environmental impacts of land use patterns is essential for sustainable development. Preservation of ecologically sensitive areas, forest conservation, protection of water bodies, and control of pollution are vital considerations in land use planning. A balanced land use pattern considers the carrying capacity of the environment and reduces the negative impacts of human activities.6. Interactions and Feedback: Land use patterns are not static but constantly evolving in response to changes in the above factors. Interactions and feedback between different land uses can result in land use changes over time. For instance, commercial development near residential areas may result in increased traffic congestion, leading to the need for transportation improvements or changes in land use regulations to address the issue.By analyzing land use patterns, we can gain insights into the spatial organization of human activities, identify trends, assess the efficiency of land use, and make informed decisions for sustainable development. It allows us to create functional and well-designed communities that meetthe needs of residents, balance economic growth with environmental conservation, and promote social well-being.。

Modeling the Spatial Dynamics of Regional Land Use_The CLUE-S Model

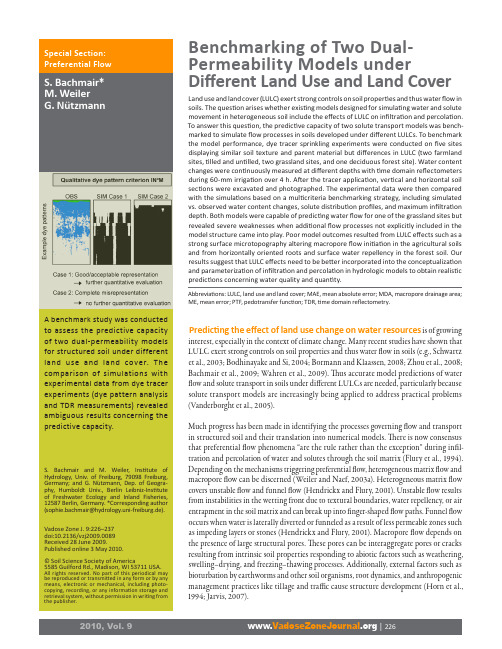

Modeling the Spatial Dynamics of Regional Land Use:The CLUE-S ModelPETER H.VERBURG*Department of Environmental Sciences Wageningen UniversityP.O.Box376700AA Wageningen,The NetherlandsandFaculty of Geographical SciencesUtrecht UniversityP.O.Box801153508TC Utrecht,The NetherlandsWELMOED SOEPBOERA.VELDKAMPDepartment of Environmental Sciences Wageningen UniversityP.O.Box376700AA Wageningen,The NetherlandsRAMIL LIMPIADAVICTORIA ESPALDONSchool of Environmental Science and Management University of the Philippines Los Ban˜osCollege,Laguna4031,Philippines SHARIFAH S.A.MASTURADepartment of GeographyUniversiti Kebangsaan Malaysia43600BangiSelangor,MalaysiaABSTRACT/Land-use change models are important tools for integrated environmental management.Through scenario analysis they can help to identify near-future critical locations in the face of environmental change.A dynamic,spatially ex-plicit,land-use change model is presented for the regional scale:CLUE-S.The model is specifically developed for the analysis of land use in small regions(e.g.,a watershed or province)at afine spatial resolution.The model structure is based on systems theory to allow the integrated analysis of land-use change in relation to socio-economic and biophysi-cal driving factors.The model explicitly addresses the hierar-chical organization of land use systems,spatial connectivity between locations and stability.Stability is incorporated by a set of variables that define the relative elasticity of the actual land-use type to conversion.The user can specify these set-tings based on expert knowledge or survey data.Two appli-cations of the model in the Philippines and Malaysia are used to illustrate the functioning of the model and its validation.Land-use change is central to environmental man-agement through its influence on biodiversity,water and radiation budgets,trace gas emissions,carbon cy-cling,and livelihoods(Lambin and others2000a, Turner1994).Land-use planning attempts to influence the land-use change dynamics so that land-use config-urations are achieved that balance environmental and stakeholder needs.Environmental management and land-use planning therefore need information about the dynamics of land use.Models can help to understand these dynamics and project near future land-use trajectories in order to target management decisions(Schoonenboom1995).Environmental management,and land-use planning specifically,take place at different spatial and organisa-tional levels,often corresponding with either eco-re-gional or administrative units,such as the national or provincial level.The information needed and the man-agement decisions made are different for the different levels of analysis.At the national level it is often suffi-cient to identify regions that qualify as“hot-spots”of land-use change,i.e.,areas that are likely to be faced with rapid land use conversions.Once these hot-spots are identified a more detailed land use change analysis is often needed at the regional level.At the regional level,the effects of land-use change on natural resources can be determined by a combina-tion of land use change analysis and specific models to assess the impact on natural resources.Examples of this type of model are water balance models(Schulze 2000),nutrient balance models(Priess and Koning 2001,Smaling and Fresco1993)and erosion/sedimen-tation models(Schoorl and Veldkamp2000).Most of-KEY WORDS:Land-use change;Modeling;Systems approach;Sce-nario analysis;Natural resources management*Author to whom correspondence should be addressed;email:pverburg@gissrv.iend.wau.nlDOI:10.1007/s00267-002-2630-x Environmental Management Vol.30,No.3,pp.391–405©2002Springer-Verlag New York Inc.ten these models need high-resolution data for land use to appropriately simulate the processes involved.Land-Use Change ModelsThe rising awareness of the need for spatially-ex-plicit land-use models within the Land-Use and Land-Cover Change research community(LUCC;Lambin and others2000a,Turner and others1995)has led to the development of a wide range of land-use change models.Whereas most models were originally devel-oped for deforestation(reviews by Kaimowitz and An-gelsen1998,Lambin1997)more recent efforts also address other land use conversions such as urbaniza-tion and agricultural intensification(Brown and others 2000,Engelen and others1995,Hilferink and Rietveld 1999,Lambin and others2000b).Spatially explicit ap-proaches are often based on cellular automata that simulate land use change as a function of land use in the neighborhood and a set of user-specified relations with driving factors(Balzter and others1998,Candau 2000,Engelen and others1995,Wu1998).The speci-fication of the neighborhood functions and transition rules is done either based on the user’s expert knowl-edge,which can be a problematic process due to a lack of quantitative understanding,or on empirical rela-tions between land use and driving factors(e.g.,Pi-janowski and others2000,Pontius and others2000).A probability surface,based on either logistic regression or neural network analysis of historic conversions,is made for future conversions.Projections of change are based on applying a cut-off value to this probability sur-face.Although appropriate for short-term projections,if the trend in land-use change continues,this methodology is incapable of projecting changes when the demands for different land-use types change,leading to a discontinua-tion of the trends.Moreover,these models are usually capable of simulating the conversion of one land-use type only(e.g.deforestation)because they do not address competition between land-use types explicitly.The CLUE Modeling FrameworkThe Conversion of Land Use and its Effects(CLUE) modeling framework(Veldkamp and Fresco1996,Ver-burg and others1999a)was developed to simulate land-use change using empirically quantified relations be-tween land use and its driving factors in combination with dynamic modeling.In contrast to most empirical models,it is possible to simulate multiple land-use types simultaneously through the dynamic simulation of competition between land-use types.This model was developed for the national and con-tinental level,applications are available for Central America(Kok and Winograd2001),Ecuador(de Kon-ing and others1999),China(Verburg and others 2000),and Java,Indonesia(Verburg and others 1999b).For study areas with such a large extent the spatial resolution of analysis was coarse(pixel size vary-ing between7ϫ7and32ϫ32km).This is a conse-quence of the impossibility to acquire data for land use and all driving factors atfiner spatial resolutions.A coarse spatial resolution requires a different data rep-resentation than the common representation for data with afine spatial resolution.Infine resolution grid-based approaches land use is defined by the most dom-inant land-use type within the pixel.However,such a data representation would lead to large biases in the land-use distribution as some class proportions will di-minish and other will increase with scale depending on the spatial and probability distributions of the cover types(Moody and Woodcock1994).In the applications of the CLUE model at the national or continental level we have,therefore,represented land use by designating the relative cover of each land-use type in each pixel, e.g.a pixel can contain30%cultivated land,40%grass-land,and30%forest.This data representation is di-rectly related to the information contained in the cen-sus data that underlie the applications.For each administrative unit,census data denote the number of hectares devoted to different land-use types.When studying areas with a relatively small spatial ex-tent,we often base our land-use data on land-use maps or remote sensing images that denote land-use types respec-tively by homogeneous polygons or classified pixels. When converted to a raster format this results in only one, dominant,land-use type occupying one unit of analysis. The validity of this data representation depends on the patchiness of the landscape and the pixel size chosen. Most sub-national land use studies use this representation of land use with pixel sizes varying between a few meters up to about1ϫ1km.The two different data represen-tations are shown in Figure1.Because of the differences in data representation and other features that are typical for regional appli-cations,the CLUE model can not directly be applied at the regional scale.This paper describes the mod-ified modeling approach for regional applications of the model,now called CLUE-S(the Conversion of Land Use and its Effects at Small regional extent). The next section describes the theories underlying the development of the model after which it is de-scribed how these concepts are incorporated in the simulation model.The functioning of the model is illustrated for two case-studies and is followed by a general discussion.392P.H.Verburg and othersCharacteristics of Land-Use SystemsThis section lists the main concepts and theories that are prevalent for describing the dynamics of land-use change being relevant for the development of land-use change models.Land-use systems are complex and operate at the interface of multiple social and ecological systems.The similarities between land use,social,and ecological systems allow us to use concepts that have proven to be useful for studying and simulating ecological systems in our analysis of land-use change (Loucks 1977,Adger 1999,Holling and Sanderson 1996).Among those con-cepts,connectivity is important.The concept of con-nectivity acknowledges that locations that are at a cer-tain distance are related to each other (Green 1994).Connectivity can be a direct result of biophysical pro-cesses,e.g.,sedimentation in the lowlands is a direct result of erosion in the uplands,but more often it is due to the movement of species or humans through the nd degradation at a certain location will trigger farmers to clear land at a new location.Thus,changes in land use at this new location are related to the land-use conditions in the other location.In other instances more complex relations exist that are rooted in the social and economic organization of the system.The hierarchical structure of social organization causes some lower level processes to be constrained by higher level dynamics,e.g.,the establishments of a new fruit-tree plantation in an area near to the market might in fluence prices in such a way that it is no longer pro fitable for farmers to produce fruits in more distant areas.For studying this situation an-other concept from ecology,hierarchy theory,is use-ful (Allen and Starr 1982,O ’Neill and others 1986).This theory states that higher level processes con-strain lower level processes whereas the higher level processes might emerge from lower level dynamics.This makes the analysis of the land-use system at different levels of analysis necessary.Connectivity implies that we cannot understand land use at a certain location by solely studying the site characteristics of that location.The situation atneigh-Figure 1.Data representation and land-use model used for respectively case-studies with a national/continental extent and local/regional extent.Modeling Regional Land-Use Change393boring or even more distant locations can be as impor-tant as the conditions at the location itself.Land-use and land-cover change are the result of many interacting processes.Each of these processes operates over a range of scales in space and time.These processes are driven by one or more of these variables that influence the actions of the agents of land-use and cover change involved.These variables are often re-ferred to as underlying driving forces which underpin the proximate causes of land-use change,such as wood extraction or agricultural expansion(Geist and Lambin 2001).These driving factors include demographic fac-tors(e.g.,population pressure),economic factors(e.g., economic growth),technological factors,policy and institutional factors,cultural factors,and biophysical factors(Turner and others1995,Kaimowitz and An-gelsen1998).These factors influence land-use change in different ways.Some of these factors directly influ-ence the rate and quantity of land-use change,e.g.the amount of forest cleared by new incoming migrants. Other factors determine the location of land-use change,e.g.the suitability of the soils for agricultural land use.Especially the biophysical factors do pose constraints to land-use change at certain locations, leading to spatially differentiated pathways of change.It is not possible to classify all factors in groups that either influence the rate or location of land-use change.In some cases the same driving factor has both an influ-ence on the quantity of land-use change as well as on the location of land-use change.Population pressure is often an important driving factor of land-use conver-sions(Rudel and Roper1997).At the same time it is the relative population pressure that determines which land-use changes are taking place at a certain location. Intensively cultivated arable lands are commonly situ-ated at a limited distance from the villages while more extensively managed grasslands are often found at a larger distance from population concentrations,a rela-tion that can be explained by labor intensity,transport costs,and the quality of the products(Von Thu¨nen 1966).The determination of the driving factors of land use changes is often problematic and an issue of dis-cussion(Lambin and others2001).There is no unify-ing theory that includes all processes relevant to land-use change.Reviews of case studies show that it is not possible to simply relate land-use change to population growth,poverty,and infrastructure.Rather,the inter-play of several proximate as well as underlying factors drive land-use change in a synergetic way with large variations caused by location specific conditions (Lambin and others2001,Geist and Lambin2001).In regional modeling we often need to rely on poor data describing this complexity.Instead of using the under-lying driving factors it is needed to use proximate vari-ables that can represent the underlying driving factors. Especially for factors that are important in determining the location of change it is essential that the factor can be mapped quantitatively,representing its spatial vari-ation.The causality between the underlying driving factors and the(proximate)factors used in modeling (in this paper,also referred to as“driving factors”) should be certified.Other system properties that are relevant for land-use systems are stability and resilience,concepts often used to describe ecological systems and,to some extent, social systems(Adger2000,Holling1973,Levin and others1998).Resilience refers to the buffer capacity or the ability of the ecosystem or society to absorb pertur-bations,or the magnitude of disturbance that can be absorbed before a system changes its structure by changing the variables and processes that control be-havior(Holling1992).Stability and resilience are con-cepts that can also be used to describe the dynamics of land-use systems,that inherit these characteristics from both ecological and social systems.Due to stability and resilience of the system disturbances and external in-fluences will,mostly,not directly change the landscape structure(Conway1985).After a natural disaster lands might be abandoned and the population might tempo-rally migrate.However,people will in most cases return after some time and continue land-use management practices as before,recovering the land-use structure (Kok and others2002).Stability in the land-use struc-ture is also a result of the social,economic,and insti-tutional structure.Instead of a direct change in the land-use structure upon a fall in prices of a certain product,farmers will wait a few years,depending on the investments made,before they change their cropping system.These characteristics of land-use systems provide a number requirements for the modelling of land-use change that have been used in the development of the CLUE-S model,including:●Models should not analyze land use at a single scale,but rather include multiple,interconnected spatial scales because of the hierarchical organization of land-use systems.●Special attention should be given to the drivingfactors of land-use change,distinguishing drivers that determine the quantity of change from drivers of the location of change.●Sudden changes in driving factors should not di-rectly change the structure of the land-use system asa consequence of the resilience and stability of theland-use system.394P.H.Verburg and others●The model structure should allow spatial interac-tions between locations and feedbacks from higher levels of organization.Model DescriptionModel StructureThe model is sub-divided into two distinct modules,namely a non-spatial demand module and a spatially explicit allocation procedure (Figure 2).The non-spa-tial module calculates the area change for all land-use types at the aggregate level.Within the second part of the model these demands are translated into land-use changes at different locations within the study region using a raster-based system.For the land-use demand module,different alterna-tive model speci fications are possible,ranging from simple trend extrapolations to complex economic mod-els.The choice for a speci fic model is very much de-pendent on the nature of the most important land-use conversions taking place within the study area and the scenarios that need to be considered.Therefore,the demand calculations will differ between applications and scenarios and need to be decided by the user for the speci fic situation.The results from the demandmodule need to specify,on a yearly basis,the area covered by the different land-use types,which is a direct input for the allocation module.The rest of this paper focuses on the procedure to allocate these demands to land-use conversions at speci fic locations within the study area.The allocation is based upon a combination of em-pirical,spatial analysis,and dynamic modelling.Figure 3gives an overview of the procedure.The empirical analysis unravels the relations between the spatial dis-tribution of land use and a series of factors that are drivers and constraints of land use.The results of this empirical analysis are used within the model when sim-ulating the competition between land-use types for a speci fic location.In addition,a set of decision rules is speci fied by the user to restrict the conversions that can take place based on the actual land-use pattern.The different components of the procedure are now dis-cussed in more detail.Spatial AnalysisThe pattern of land use,as it can be observed from an airplane window or through remotely sensed im-ages,reveals the spatial organization of land use in relation to the underlying biophysical andsocio-eco-Figure 2.Overview of the modelingprocedure.Figure 3.Schematic represen-tation of the procedure to allo-cate changes in land use to a raster based map.Modeling Regional Land-Use Change395nomic conditions.These observations can be formal-ized by overlaying this land-use pattern with maps de-picting the variability in biophysical and socio-economic conditions.Geographical Information Systems(GIS)are used to process all spatial data and convert these into a regular grid.Apart from land use, data are gathered that represent the assumed driving forces of land use in the study area.The list of assumed driving forces is based on prevalent theories on driving factors of land-use change(Lambin and others2001, Kaimowitz and Angelsen1998,Turner and others 1993)and knowledge of the conditions in the study area.Data can originate from remote sensing(e.g., land use),secondary statistics(e.g.,population distri-bution),maps(e.g.,soil),and other sources.To allow a straightforward analysis,the data are converted into a grid based system with a cell size that depends on the resolution of the available data.This often involves the aggregation of one or more layers of thematic data,e.g. it does not make sense to use a30-m resolution if that is available for land-use data only,while the digital elevation model has a resolution of500m.Therefore, all data are aggregated to the same resolution that best represents the quality and resolution of the data.The relations between land use and its driving fac-tors are thereafter evaluated using stepwise logistic re-gression.Logistic regression is an often used method-ology in land-use change research(Geoghegan and others2001,Serneels and Lambin2001).In this study we use logistic regression to indicate the probability of a certain grid cell to be devoted to a land-use type given a set of driving factors following:LogͩP i1ϪP i ͪϭ0ϩ1X1,iϩ2X2,i......ϩn X n,iwhere P i is the probability of a grid cell for the occur-rence of the considered land-use type and the X’s are the driving factors.The stepwise procedure is used to help us select the relevant driving factors from a larger set of factors that are assumed to influence the land-use pattern.Variables that have no significant contribution to the explanation of the land-use pattern are excluded from thefinal regression equation.Where in ordinal least squares regression the R2 gives a measure of modelfit,there is no equivalent for logistic regression.Instead,the goodness offit can be evaluated with the ROC method(Pontius and Schnei-der2000,Swets1986)which evaluates the predicted probabilities by comparing them with the observed val-ues over the whole domain of predicted probabilities instead of only evaluating the percentage of correctly classified observations at afixed cut-off value.This is an appropriate methodology for our application,because we will use a wide range of probabilities within the model calculations.The influence of spatial autocorrelation on the re-gression results can be minimized by only performing the regression on a random sample of pixels at a certain minimum distance from one another.Such a selection method is adopted in order to maximize the distance between the selected pixels to attenuate the problem associated with spatial autocorrelation.For case-studies where autocorrelation has an important influence on the land-use structure it is possible to further exploit it by incorporating an autoregressive term in the regres-sion equation(Overmars and others2002).Based upon the regression results a probability map can be calculated for each land-use type.A new probabil-ity map is calculated every year with updated values for the driving factors that are projected to change in time,such as the population distribution or accessibility.Decision RulesLand-use type or location specific decision rules can be specified by the user.Location specific decision rules include the delineation of protected areas such as nature reserves.If a protected area is specified,no changes are allowed within this area.For each land-use type decision rules determine the conditions under which the land-use type is allowed to change in the next time step.These decision rules are implemented to give certain land-use types a certain resistance to change in order to generate the stability in the land-use structure that is typical for many landscapes.Three different situations can be distinguished and for each land-use type the user should specify which situation is most relevant for that land-use type:1.For some land-use types it is very unlikely that theyare converted into another land-use type after their first conversion;as soon as an agricultural area is urbanized it is not expected to return to agriculture or to be converted into forest cover.Unless a de-crease in area demand for this land-use type occurs the locations covered by this land use are no longer evaluated for potential land-use changes.If this situation is selected it also holds that if the demand for this land-use type decreases,there is no possi-bility for expansion in other areas.In other words, when this setting is applied to forest cover and deforestation needs to be allocated,it is impossible to reforest other areas at the same time.2.Other land-use types are converted more easily.Aswidden agriculture system is most likely to be con-verted into another land-use type soon after its396P.H.Verburg and othersinitial conversion.When this situation is selected for a land-use type no restrictions to change are considered in the allocation module.3.There is also a number of land-use types that oper-ate in between these two extremes.Permanent ag-riculture and plantations require an investment for their establishment.It is therefore not very likely that they will be converted very soon after into another land-use type.However,in the end,when another land-use type becomes more pro fitable,a conversion is possible.This situation is dealt with by de fining the relative elasticity for change (ELAS u )for the land-use type into any other land use type.The relative elasticity ranges between 0(similar to Situation 2)and 1(similar to Situation 1).The higher the de fined elasticity,the more dif ficult it gets to convert this land-use type.The elasticity should be de fined based on the user ’s knowledge of the situation,but can also be tuned during the calibration of the petition and Actual Allocation of Change Allocation of land-use change is made in an iterative procedure given the probability maps,the decision rules in combination with the actual land-use map,and the demand for the different land-use types (Figure 4).The following steps are followed in the calculation:1.The first step includes the determination of all grid cells that are allowed to change.Grid cells that are either part of a protected area or under a land-use type that is not allowed to change (Situation 1,above)are excluded from further calculation.2.For each grid cell i the total probability (TPROP i,u )is calculated for each of the land-use types u accord-ing to:TPROP i,u ϭP i,u ϩELAS u ϩITER u ,where ITER u is an iteration variable that is speci fic to the land use.ELAS u is the relative elasticity for change speci fied in the decision rules (Situation 3de-scribed above)and is only given a value if grid-cell i is already under land use type u in the year considered.ELAS u equals zero if all changes are allowed (Situation 2).3.A preliminary allocation is made with an equalvalue of the iteration variable (ITER u )for all land-use types by allocating the land-use type with the highest total probability for the considered grid cell.This will cause a number of grid cells to change land use.4.The total allocated area of each land use is nowcompared to the demand.For land-use types where the allocated area is smaller than the demanded area the value of the iteration variable is increased.For land-use types for which too much is allocated the value is decreased.5.Steps 2to 4are repeated as long as the demandsare not correctly allocated.When allocation equals demand the final map is saved and the calculations can continue for the next yearly timestep.Figure 5shows the development of the iteration parameter ITER u for different land-use types during asimulation.Figure 4.Representation of the iterative procedure for land-use changeallocation.Figure 5.Change in the iteration parameter (ITER u )during the simulation within one time-step.The different lines rep-resent the iteration parameter for different land-use types.The parameter is changed for all land-use types synchronously until the allocated land use equals the demand.Modeling Regional Land-Use Change397Multi-Scale CharacteristicsOne of the requirements for land-use change mod-els are multi-scale characteristics.The above described model structure incorporates different types of scale interactions.Within the iterative procedure there is a continuous interaction between macro-scale demands and local land-use suitability as determined by the re-gression equations.When the demand changes,the iterative procedure will cause the land-use types for which demand increased to have a higher competitive capacity (higher value for ITER u )to ensure enough allocation of this land-use type.Instead of only being determined by the local conditions,captured by the logistic regressions,it is also the regional demand that affects the actually allocated changes.This allows the model to “overrule ”the local suitability,it is not always the land-use type with the highest probability according to the logistic regression equation (P i,u )that the grid cell is allocated to.Apart from these two distinct levels of analysis there are also driving forces that operate over a certain dis-tance instead of being locally important.Applying a neighborhood function that is able to represent the regional in fluence of the data incorporates this type of variable.Population pressure is an example of such a variable:often the in fluence of population acts over a certain distance.Therefore,it is not the exact location of peoples houses that determines the land-use pattern.The average population density over a larger area is often a more appropriate variable.Such a population density surface can be created by a neighborhood func-tion using detailed spatial data.The data generated this way can be included in the spatial analysis as anotherindependent factor.In the application of the model in the Philippines,described hereafter,we applied a 5ϫ5focal filter to the population map to generate a map representing the general population pressure.Instead of using these variables,generated by neighborhood analysis,it is also possible to use the more advanced technique of multi-level statistics (Goldstein 1995),which enable a model to include higher-level variables in a straightforward manner within the regression equa-tion (Polsky and Easterling 2001).Application of the ModelIn this paper,two examples of applications of the model are provided to illustrate its function.TheseTable nd-use classes and driving factors evaluated for Sibuyan IslandLand-use classes Driving factors (location)Forest Altitude (m)GrasslandSlope Coconut plantation AspectRice fieldsDistance to town Others (incl.mangrove and settlements)Distance to stream Distance to road Distance to coast Distance to port Erosion vulnerability GeologyPopulation density(neighborhood 5ϫ5)Figure 6.Location of the case-study areas.398P.H.Verburg and others。

Land+use+planning+in+the+Netherlands;+fi...