Canonical measures and Kahler-Ricci flow

Info-Note-5-Doc9803alltext航线安全审计.en

Approved by the Secretary General and published under his authorityLine OperationsSafety Audit (LOSA)First Edition — 2002Doc 9803AN/761AMENDMENTSThe issue of amendments is announced regularly in the ICAO Journal and in the monthly Supplement to the Catalogue of ICAO Publications and Audio-visual Training Aids, which holders of this publication should consult. The space below is provided to keep a record of such amendments.RECORD OF AMENDMENTS AND CORRIGENDA AMENDMENTS CORRIGENDANo.DateapplicableDateenteredEnteredby No.Dateof issueDateenteredEnteredbyTABLE OF CONTENTSPage PageForeword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(v) Acronyms and Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(vi) Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .(vii) Chapter 1.Basic error management concepts. .1-11.1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-11.2Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-2Reactive strategies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-2Combined reactive/proactive strategies. .1-2Proactive strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-41.3 A contemporary approach to operationalhuman performance and error. . . . . . . . . . .1-51.4The role of the organizational culture . . . .1-71.5Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1-7 Chapter2.Implementing LOSA . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-12.1History of LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-12.2The Threat and Error Management Model.2-1Threats and errors defined. . . . . . . . . . . .2-1Definitions of crew error response . . . . .2-4Definitions of error outcomes. . . . . . . . .2-4Undesired Aircraft States . . . . . . . . . . . .2-42.3LOSA operating characteristics . . . . . . . . .2-5Observer assignment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-7Flight crew participation. . . . . . . . . . . . .2-72.4How to determine the scope of a LOSA . .2-72.5Once the data is collected. . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-82.6Writing the report . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-82.7Success factors for LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-8Chapter3.LOSA and the safety changeprocess (SCP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.2 A constantly changing scene. . . . . . . . . . . .3-13.3One operator’s example of an SCP . . . . . .3-2 Chapter4.How to set up a LOSA —US Airways experience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.1Gathering information. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.2Interdepartmental support . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-14.3LOSA steering committee. . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-1Safety department . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-1Flight operations and trainingdepartments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Pilots union . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-24.4The key steps of a LOSA. . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-2Action plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-24.5The keys to an effective LOSA . . . . . . . . .4-4Confidentiality and no-jeopardy. . . . . . .4-4The role of the observer . . . . . . . . . . . . .4-54.6Promoting LOSA for flight crews . . . . . . .4-5 Appendix A — Examples of the various forms utilized by LOSA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .A-1 Appendix B — Example of an introductory letterby an airline to its flight crews. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .B-1 Appendix C — List of recommended readingand reference material. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .C-1FOREWORDThe safety of civil aviation is the major objective of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Consider-able progress has been made in increasing safety, but additional improvements are needed and can be achieved. It has long been known that the majority of aviation accidents and incidents result from less than optimum human per-formance, indicating that any advance in this field can be expected to have a significant impact on the improvement of aviation safety.This was recognized by the ICAO Assembly, which in 1986 adopted Resolution A26-9 on Flight Safety and Human Factors. As a follow-up to the Assembly Resolution, the Air Navigation Commission formulated the following objective for the task:“To improve safety in aviation by making States more aware and responsive to the importance of Human Factors in civil aviation operations through the provision of practical Human Factors materials and measures, developed on the basis of experience in States, and by developing and recommending appropriate amendments to existing material in Annexes and other documents with regard to the role of Human Factors in the present and future operational environments. Special emphasis will be directed to the Human Factors issues that may influence the design, transition and in-service use of the future ICAO CNS/A TM systems.”One of the methods chosen to implement Assembly Resolution A26-9 is the publication of guidance materials, including manuals and a series of digests, that address various aspects of Human Factors and its impact on aviation safety. These documents are intended primarily for use by States to increase the awareness of their personnel of the influence of human performance on safety.The target audience of Human Factors manuals and digests are the managers of both civil aviation administrations and the airline industry, including airline safety, training and operational managers. The target audience also includes regulatory bodies, safety and investigation agencies and training establishments, as well as senior and middle non-operational airline management.This manual is an introduction to the latest information available to the international civil aviation community on the control of human error and the development of counter-measures to error in operational environments. Its target audience includes senior safety, training and operational personnel in industry and regulatory bodies.This manual is intended as a living document and will be kept up to date by periodic amendments. Subsequent editions will be published as new research results in increased knowledge on Human Factors strategies and more experience is gained regarding the control and management of human error in operational environments.ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADS Automatic Dependent SurveillanceA TC Air Traffic ControlCFIT Controlled Flight Into TerrainCNS/A TM Communications, Navigation and Surveillance/Air Traffic Management CPDLC Controller-Pilot Data Link CommunicationsCRM Crew Resource ManagementDFDR Digital Flight Data RecorderETOPS Extended Range Operations by Twin-engined AeroplanesFAA Federal Aviation AdministrationFDA Flight Data AnalysisFMS Flight Management SystemFOQA Flight Operations Quality AssuranceICAO International Civil Aviation OrganizationLOSA Line Operations Safety AuditMCP Mode Control PanelQAR Quick Access RecorderRTO Rejected Take-OffSCP Safety Change ProcessSOPs Standard Operating ProceduresTEM Threat and Error ManagementUTTEM University of Texas Threat and Error ManagementINTRODUCTION1.This manual describes a programme for the management of human error in aviation operations known as Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA). LOSA is proposed as a critical organizational strategy aimed at developing countermeasures to operational errors. It is an organizational tool used to identify threats to aviation safety, minimize the risks such threats may generate and implement measures to manage human error in operational contexts. LOSA enables operators to assess their level of resilience to systemic threats, operational risks and front-line personnel errors, thus providing a principled, data-driven approach to prioritize and implement actions to enhance safety.2.LOSA uses expert and highly trained observers to collect data about flight crew behaviour and situational factors on “normal” flights. The audits are conducted under strict no-jeopardy conditions; therefore, flight crews are not held accountable for their actions and errors that are observed. During flights that are being audited, observers record and code potential threats to safety; how the threats are addressed; the errors such threats generate; how flight crews manage these errors; and specific behaviours that have been known to be associated with accidents and incidents.3.LOSA is closely linked with Crew Resource Management (CRM) training. Since CRM is essentially error management training for operational personnel, data from LOSA form the basis for contemporary CRM training refocus and/or design known as Threat and Error Man-agement (TEM) training. Data from LOSA also provide a real-time picture of system operations that can guide organizational strategies in regard to safety, training and operations. A particular strength of LOSA is that it identifies examples of superior performance that can be reinforced and used as models for training. In this way, training inter-ventions can be reshaped and reinforced based on successful performance, that is to say, positive feedback. This is indeed a first in aviation, since the industry has traditionally collected information on failed human performance, such as in accidents and incidents. Data collected through LOSA are proactive and can be immediately used to prevent adverse events.4.LOSA is a mature concept, yet a young one. LOSA was first operationally deployed following the First LOSA Week, which was hosted by Cathay Pacific Airways in Cathay City, Hong Kong, from 12 to 14 March 2001. Although initially developed for the flight deck sector, there is no reason why the methodology could not be applied to other aviation operational sectors, including air traffic control, maintenance, cabin crew and dispatch.5.The initial research and project definition was a joint endeavour between The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project and Continental Airlines, with funding provided by the Federal Aviation Admin-istration (FAA). In 1999, ICAO endorsed LOSA as the primary tool to develop countermeasures to human error in aviation operations, developed an operational partnership with The University of Texas at Austin and Continental Airlines, and made LOSA the central focus of its Flight Safety and Human Factors Programme for the period 2000 to 2004.6.As of February 2002, the LOSA archives contained observations from over 2 000 flights. These observations were conducted within the United States and internationally and involved four United States and four non-United States operators. The number of operators joining LOSA has constantly increased since March 2001 and includes major international operators from different parts of the world and diverse cultures.7.ICAO acts as an enabling partner in the LOSA programme. ICAO’s role includes promoting the importance of LOSA to the international civil aviation community; facilitating research in order to collect necessary data; acting as a cultural mediator in the unavoidably sensitive aspects of data collection; and contributing multicultural obser-vations to the LOSA archives. In line with these objectives, the publication of this manual is a first step at providing information and, therefore, at increasing awareness within the international civil aviation community about LOSA.8.This manual is an introduction to the concept, methodology and tools of LOSA and to the potential remedial actions to be undertaken based on the data collected under LOSA. A very important caveat must be introduced at this point: this manual is not intended to convert readers into instant expert observers and/or LOSA auditors. In fact, it is strongly recommended that LOSA not be attempted without a formal introduction to it for the(viii)Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)following reasons. First, the forms presented in Appendix A are for illustration purposes exclusively, since they are periodically amended on the basis of experience gained and feedback obtained from continuing audits. Second, formal training in the methodology, in the use of LOSA tools and, most important, in the handling of the highly sensitive data collected by the audits is absolutely essential. Third, the proper structuring of the data obtained from the audits is of paramount importance.9.Therefore, until extensive airline experience is accumulated, it is highly desirable that LOSA training be coordinated through ICAO or the founding partners of the LOSA project. As the methodology evolves and reaches full maturity and broader industry partnerships are developed, LOSA will be available without restrictions to the international civil aviation community.10.This manual is designed as follows:•Chapter 1 includes an overview on safety, and human error and its management in aviationoperations. It provides the necessary backgroundinformation to understand the rationale for LOSA.•Chapter 2 discusses the LOSA methodology and provides a guide to the implementation of LOSAwithin an airline. It also introduces a model of crewerror management and proposes the error classi-fication utilized by LOSA, which is essentiallyoperational and practical.•Chapter 3 discusses the safety change process that should take place following the implementation ofLOSA.•Chapter 4 introduces the example of one operator’s experience in starting a LOSA.•Appendix A provides examples of the various forms utilized by LOSA.•Appendix B provides an example of an introductory letter by an airline to its flight crews.•Appendix C provides a list of recommended reading and reference material.11.This manual is a companion document to the Human Factors Training Manual (Doc 9683). The cooperation of the following organizations in the production of this manual is acknowledged: The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project, Continental Airlines, US Airways and ALPA, International. Special recognition is given to Professor Robert L. Helmreich, James Klinect and John Wilhelm of The University of Texas at Austin Human Factors Research Project; Captains Bruce Tesmer and Donald Gunther of Continental Airlines; Captains Ron Thomas and Corkey Romeo of US Airways; and Captain Robert L. Sumwalt III of US Airways and of ALPA, International.Chapter 1BASIC ERROR MANAGEMENT CONCEPTS1.1INTRODUCTION1.1.1Historically, the way the aviation industry has investigated the impact of human performance on aviation safety has been through the retrospective analyses of those actions by operational personnel which led to rare and drastic failures. The conventional investigative approach is for investigators to trace back an event under consideration to a point where they discover particular actions or decisions by operational personnel that did not produce the intended results and, at such point, conclude human error as the cause. The weakness in this approach is that the conclusion is generally formulated with a focus on the outcome, with limited consideration of the processes that led up to it. When analysing accidents and incidents, investigators already know that the actions or decisions by operational personnel were “bad” or “inappropriate”, because the “bad” outcomes are a matter of record. In other words, investigators examining human performance in safety occurrences enjoy the benefit of hindsight. This is, however, a benefit that operational personnel involved in accidents and incidents did not have when they selected what they thought of as “good” or “appropriate” actions or decisions that would lead to “good” outcomes.1.1.2It is inherent to traditional approaches to safety to consider that, in aviation, safety comes first. In line with this, decision making in aviation operations is considered to be 100 per cent safety-oriented. While highly desirable, this is hardly realistic. Human decision making in operational contexts is a compromise between production and safety goals (see Figure 1-1). The optimum decisions to achieve the actual production demands of the operational task at hand may not always be fully compatible with the optimumFigure 1-1.Operational Behaviours — Accomplishing the system’s goals1-2Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)decisions to achieve theoretical safety demands. All production systems — and aviation is no exception —generate a migration of behaviours: due to the need for economy and efficiency, people are forced to operate at the limits of the system’s safety space. Human decision making in operational contexts lies at the intersection of production and safety and is therefore a compromise. In fact, it might be argued that the trademark of experts is not years of experience and exposure to aviation operations, but rather how effectively they have mastered the necessary skills to manage the compromise between production and safety. Operational errors are not inherent in a person, although this is what conventional safety knowledge would have the aviation industry believe. Operational errors occur as a result of mismanaging or incorrectly assessing task and/or situ-ational factors in a specific context and thus cause a failed compromise between production and safety goals.1.1.3The compromise between production and safety is a complex and delicate balance. Humans are generally very effective in applying the right mechanisms to successfully achieve this balance, hence the extraordinary safety record of aviation. Humans do, however, occasionally mismanage or incorrectly assess task and/or situational factors and fail in balancing the compromise, thus contributing to safety breakdowns. Successful compromises far outnumber failed ones; therefore, in order to understand human performance in context, the industry needs to systematically capture the mechanisms underlying suc-cessful compromises when operating at the limits of the system, rather than those that failed. It is suggested that understanding the human contribution to successes and failures in aviation can be better achieved by monitoring normal operations, rather than accidents and incidents. The Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA) is the vehicle endorsed by ICAO to monitor normal operations.1.2BACKGROUNDReactive strategiesAccident investigation1.2.1The tool most often used in aviation to document and understand human performance and define remedial strategies is the investigation of accidents. However, in terms of human performance, accidents yield data that are mostly about actions and decisions that failed to achieve the successful compromise between production and safety discussed earlier in this chapter.1.2.2There are limitations to the lessons learned from accidents that might be applied to remedial strategies vis-à-vis human performance. For example, it might be possible to identify generic accident-inducing scenarios such as Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT), Rejected Take-Off (RTO), runway incursions and approach-and-landing acci-dents. Also, it might be possible to identify the type and frequency of external manifestations of errors in these generic accident-inducing scenarios or discover specific training deficiencies that are particularly related to identified errors. This, however, provides only a tip-of-the-iceberg perspective. Accident investigation, by definition, concen-trates on failures, and in following the rationale advocated by LOSA, it is necessary to better understand the success stories to see if they can be incorporated as part of remedial strategies.1.2.3This is not to say that there is no clear role for accident investigation within the safety process. Accident investigation remains the vehicle to uncover unanticipated failures in technology or bizarre events, rare as they may be. Accident investigation also provides a framework: if only normal operations were monitored, defining unsafe behaviours would be a task without a frame of reference. Therefore, properly focused accident investigation can reveal how specific behaviours can combine with specific circumstances to generate unstable and likely catastrophic scenarios. This requires a contemporary approach to the investigation: should accident investigation be restricted to the retrospective analyses discussed earlier, its contribution in terms of human error would be to increase existing industry databases, but its usefulness in regard to safety would be dubious. In addition, the information could possibly provide the foundations for legal action and the allocation of blame and punishment.Combined reactive/proactive strategies Incident investigation1.2.4 A tool that the aviation industry has increasingly used to obtain information on operational human perform-ance is incident reporting. Incidents tell a more complete story about system safety than accidents do because they signal weaknesses within the overall system before the system breaks down. In addition, it is accepted that incidents are precursors of accidents and that N-number of incidents of one kind take place before an accident of the same kind eventually occurs. The basis for this can be traced back almost 30 years to research on accidents from different industries, and there is ample practical evidence that supports this research. There are, nevertheless, limitationsChapter 1.Basic error management concepts1-3on the value of the information on operational human performance obtained from incident reporting.1.2.5First, reports of incidents are submitted in the jargon of aviation and, therefore, capture only the external manifestations of errors (for example, “misunderstood a frequency”, “busted an altitude”, and “misinterpreted a clearance”). Furthermore, incidents are reported by the individuals involved, and because of biases, the reported processes or mechanisms underlying errors may or may not reflect reality. This means that incident-reporting systems take human error at face value, and, therefore, analysts are left with two tasks. First, they must examine the reported processes or mechanisms leading up to the errors and establish whether such processes or mechanisms did indeed underlie the manifested errors. Then, based on this relatively weak basis, they must evaluate whether the error manage-ment techniques reportedly used by operational personnel did indeed prevent the escalation of errors into a system breakdown.1.2.6Second, and most important, incident reporting is vulnerable to what has been called “normalization of deviance”. Over time, operational personnel develop infor-mal and spontaneous group practices and shortcuts to circumvent deficiencies in equipment design, clumsy pro-cedures or policies that are incompatible with the realities of daily operations, all of which complicate operational tasks. These informal practices are the product of the collective know-how and hands-on expertise of a group, and they eventually become normal practices. This does not, however, negate the fact that they are deviations from procedures that are established and sanctioned by the organization, hence the term “normalization of deviance”. In most cases normalized deviance is effective, at least temporarily. However, it runs counter to the practices upon which system operation is predicated. In this sense, like any shortcut to standard procedures, normalized deviance carries the potential for unanticipated “downsides” that might unexpectedly trigger unsafe situations. However, since they are “normal”, it stands to reason that neither these practices nor their downsides will be recorded in incident reports.1.2.7Normalized deviance is further compounded by the fact that even the most willing reporters may not be able to fully appreciate what are indeed reportable events. If operational personnel are continuously exposed to sub-standard managerial practices, poor working conditions and/or flawed equipment, how could they recognize such factors as reportable problems?1.2.8Thus, incident reporting cannot completely reveal the human contribution to successes or failures in aviation and how remedial strategies can be improved to enhance human performance. Incident reporting systems are certainly better than accident investigations in understanding system performance, but the real challenge lies in taking the next step — understanding the processes underlying human error rather than taking errors at face value. It is essential to move beyond the visible manifestations of error when designing remedial strategies. If the aviation industry is to be successful in modifying system and individual per-formance, errors must be considered as symptoms that suggest where to look further. In order to understand the mechanisms underlying errors in operational environments, flaws in system performance captured through incident reporting should be considered as symptoms of mismatches at deeper layers of the system. These mismatches might be deficiencies in training systems, flawed person/technology interfaces, poorly designed procedures, corporate pressures, poor safety culture, etc. The value of the data generated by incident reporting systems lies in the early warning about areas of concern, but such data do not capture the concerns themselves.Training1.2.9The observation of training behaviours (during flight crew simulator training, for example) is another tool that is highly valued by the aviation industry to understand operational human performance. However, the “production”component of operational decision making does not exist under training conditions. While operational behaviours during line operations are a compromise between production and safety objectives, training behaviours are absolutely biased towards safety. In simpler terms, the compromise between production and safety is not a factor in decision making during training (see Figure 1-2). Training behaviours are “by the book”.1.2.10Therefore, behaviours under monitored conditions, such as during training or line checks, may provide an approximation to the way operational personnel behave when unmonitored. These observations may contribute to flesh out major operational questions such as significant procedural problems. However, it would be incorrect and perhaps risky to assume that observing personnel during training would provide the key to understanding human error and decision making in unmonitored operational contexts.Surveys1.2.11Surveys completed by operational personnel can also provide important diagnostic information about daily operations and, therefore, human error. Surveys1-4Line Operations Safety Audit (LOSA)provide an inexpensive mechanism to obtain significant information regarding many aspects of the organization, including the perceptions and opinions of operational personnel; the relevance of training to line operations; the level of teamwork and cooperation among various employee groups; problem areas or bottlenecks in daily operations; and eventual areas of dissatisfaction. Surveys can also probe the safety culture; for example, do personnel know the proper channels for reporting safety concerns and are they confident that the organization will act on expressed concerns? Finally, surveys can identify areas of dissent or confusion, for example, diversity in beliefs among particular groups from the same organization regarding the appropriate use of procedures or tools. On the minus side, surveys largely reflect perceptions. Surveys can be likened to incident reporting and are therefore subject to the shortcomings inherent to reporting systems in terms of understanding operational human performance and error. Flight data recording1.2.12Digital Flight Data Recorder (DFDR) and Quick Access Recorder (QAR) information from normal flights is also a valuable diagnostic tool. There are, however, some limitations about the data acquired through these systems. DFDR/QAR readouts provide information on the frequency of exceedences and the locations where they occur, but the readouts do not provide information on the human behaviours that were precursors of the events. While DFDR/QAR data track potential systemic problems, pilot reports are still necessary to provide the context within which the problems can be fully diagnosed.1.2.13Nevertheless, DFDR/QAR data hold high cost/efficiency ratio potential. Although probably under-utilized because of cost considerations as well as cultural and legal reasons, DFDR/QAR data can assist in identifying operational contexts within which migration of behaviours towards the limits of the system takes place.Proactive strategiesNormal line operations monitoring1.2.14The approach proposed in this manual to identify the successful human performance mechanisms that contribute to aviation safety and, therefore, to the design of countermeasures against human error focuses on the monitoring of normal line operations.Figure 1-2.Training Behaviours — Accomplishing training goals。

沃森和克里克发表的文章的翻译

核酸的分子结构——脱氧核糖核酸的结构我们希望证明脱氧核糖核酸盐(DNA)的结构,这种结构具有相当的生物感兴趣的新的特点。

Plauling和Corey已经提出了一种核酸结构。

他们非常友好的在其出版之前将手稿提供给我们。

他们的模型包括三个缠绕的链,与附近的糖磷酸骨架和外面的碱基。

我们认为,这种结构不理想,原因有二(1)我们相信,该材料赋予的透视图是盐,。

没有酸性氢原子,目前还不清楚是什么力量将持有的结构在一起,尤其是会互相排斥。

(2)有些距离显得有些过于小。

另三链结构也已由弗雷泽提出(在印刷中)。

在他的模型磷酸盐是在外面和内部的基础上通过氢键连接在一起。

这种结构的描述是相当不明确的,基于这个原因,我们不会对此发表评论。

我们希望提出根本不同的结构的脱氧核苷酸盐,这种结构有双螺旋且每个圈都有相同的轴线(看图)。

我们已经做出一般的化学假设,即核苷酸之间通过3'到5'磷酸二酯键连接到β- d-脱氧核糖核酸残基上。

这两条链都是右手螺旋。

但是由于这两个沿链相反的方向运行,这两条链是非常相似的。

每个链松耦合类似于Furberg的1号模型,这就是,碱基位于双螺旋的内部而磷酸盐位于外部。

糖及附近的原子结构接近Furberg 的标准配置,糖是大致垂直于与之接触的碱基。

在Z方向每一个链每隔3.4A就有一个碱基。

我们假设在同一链中相邻的核苷酸夹角为36 °,所以每条链的结构每十个核苷酸即每34A就重复一次。

一个磷原子到纵轴的间距为10A,由于磷在外面的,阳离子容易接触到他们。

其结构是一个开放的,它的水分含量是相当高的,在较低的水含量,我们希望碱基能够倾斜,这样的结构可能变得更加紧凑。

该结构新颖特点是这两条链的嘌呤和嘧啶碱基连接在一起的方式。

碱基的平面垂直于纵轴。

碱基配对,一条链的碱基和另一条链的碱基以氢键连接,因此两个碱基能够完全一致吻合,为了氢键的生成一对碱基中必须是一个是嘌呤另一个是嘧啶,碱基是如下生成的:嘌呤的1位置和嘧啶的1位置,嘌呤的6位置和嘧啶的6位置。

Canonical-Correlation-Analysis

的相关关系,可以用最原始的方法,分别计算两组 变量之间的全部相关系数,一共有pq个简单相关系 数,这样又烦琐又不能抓住问题的本质。 • 如何处理?

• 采用类似于主成分的思想,分别找出两组变量 的各自的某个线性组合,讨论线性组合之间的 相关关系,则更简捷。

典型相关是研究两组变量之间

相关性的一种统计分析方法。也是 一种降维技术。

• 典型负荷为变量与典型变量的相关系数,可由相关 系数的平方了解此典型变量解释了此变量多少比例 的变异数。

利用SPSS进行典型相关分析

• 例:研究人口出生与 受教育程度、生活水 平等的相关,如表所 示:X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 分别代表多孩率、综 合节育率、初中及以 上受教育程度的人口 比例、人均国民收入 和城镇人口比例。

• 类似于主成分分析,选择通过显著性水平检验,切 特征值累积总贡献占主要部分的那些典型变量即可。

冗余分析

• 冗余分析是通过原始变量与典型变量间的相关性, 分析引起原始变量变异的原因。以原始变量为因变 量,以典型变量为自变量,建立线性回归模型,则 相应的确定系数等于因变量与典型变量间的相关系 数的平方,它描述了由于因变量与典型变量的线性 关系引起的因变量变异在因变量的总变异中的比例。

典型相关

• 由上述方法得到的一系列典型变量u1 u2……,v1 v2……。这些典型相关系数所包含的有关原变量组 之间相关程度的信息一个比一个少。如果少数几对 典型变量就能够解释原数据的主要信息,特别是如 果一对典型变量就能够反映出原数据的主要信息, 那么,对两个变量组之间相关程度的分析就可以转 化为对少数几对或者是一对典型变量的简单相关分 析。这就是典型相关分析的主要目的。

Estimating Production Functions

2

model favors this set of proxies because the firm jointly cultivates physical capital and intangible organizational knowledge, given market conditions. Whenever its market prospects are favorable, the firm has an incentive to expand physical capital and to improve its intangible organizational capital simultaneously. Similar to prior approaches, the estimation model permits resolution of transmission bias (controlling for the simultaneous determination of unobserved firm-level productivity and factor choices), survival bias (using exit-rule estimation on an unbalanced firm panel), and omitted-price bias (removing time-invariant demand components from otherwise confounded productivity estimates). The estimation model achieves the resolution of bias on the basis of a lean set of identifying assumptions with plausible implications for productivity evolution. Its assumptions and implications set the present estimation model apart from prior approaches. First, identification of the production function does not have to rely on timing assumptions. Productivity shocks need not be fully known to the firm prior to physical investment choice (Olley and Pakes 1996) or variable input choice (Levinsohn and Petrin 2003). Instead, the asset model implies that variables related to a firm’s market conditions, and interacted with its physical investment, provide a natural source of identification for the productivity control function as long as an exit rule is estimated alongside. Estimation of an exit rule, as in Olley and Pakes (1996), is crucial if there are fixed costs of investment in organizational change, because the productivity control function for survivors changes strictly monotonically in its arguments only through the exit rule. So, an extended Olley-Pakes procedure is the estimation method of choice under an asset model of the firm. Beyond sector-level covariates, proxies to market conditions include the firmspecific mean characteristics of each firm’s competitors. When applied to a sample of medium-sized to large Brazilian manufacturing companies between 1986 and 1998, the extended Olley-Pakes procedure detects, and removes, frequently suspected biases. Bootstraps show that alternative estimators yield more volatile and less precise estimates than does extended Olley-Pakes estimation. Second, observations with non-positive investment are permissible for estimation under the asset model of the firm. Non-positive net investments occur frequently in micro data. Common theory of the firm predicts that firms with higher marginal products of capital, and lower marginal products of other factors, invest more so that a restriction to a positive-investments-only sample expectedly results in capital coefficients that exceed those in the full sample. As a consequence, the positive-investments-only subsample does not reflect the average production technology, but an initially less capital-intensive technology. Estimates from the asset model of the firm confirm this prediction in the sample of Brazilian manufacturers. 3

公共政策终结理论研究综述

公共政策终结理论研究综述摘要:政策终结是政策过程的一个环节,是政策更新、政策发展、政策进步的新起点。

政策终结是20世纪70年代末西方公共政策研究领域的热点问题。

公共政策终结是公共政策过程的一个重要阶段,对政策终结的研究不仅有利于促进政策资源的合理配置,更有利于提高政府的政策绩效。

本文简要回顾了公共政策终结研究的缘起、内涵、类型、方式、影响因素、促成策略以及发展方向等内容,希望能够对公共政策终结理论有一个比较全面深入的了解。

关键词:公共政策,政策终结,理论研究行政有着古老的历史,但是,在一个相当长的历史时期中,行政所赖以治理社会的工具主要是行政行为。

即使是公共行政出现之后,在一个较长的时期内也还主要是借助于行政行为去开展社会治理,公共行政与传统行政的区别在于,找到了行政行为一致性的制度模式,确立了行政行为的(官僚制)组织基础。

到了公共行政的成熟阶段,公共政策作为社会治理的一个重要途径引起了人们的重视。

与传统社会中主要通过行政行为进行社会治理相比,公共政策在解决社会问题、降低社会成本、调节社会运行等方面都显示出了巨大的优势。

但是,如果一项政策已经失去了存在的价值而又继续被保留下来了,就可能会发挥极其消极的作用。

因此,及时、有效地终结一项或一系列错误的或没有价值的公共政策,有利于促进公共政策的更新与发展、推进公共政策的周期性循环、缓解和解决公共政策的矛盾和冲突,从而实现优化和调整公共政策系统的目标。

这就引发了学界对政策终结理论的思考和探索。

自政策科学在美国诞生以来,公共政策过程理论都是学术界所关注的热点。

1956年,拉斯韦尔在《决策过程》一书中提出了决策过程的七个阶段,即情报、建议、规定、行使、运用、评价和终止。

此种观点奠定了政策过程阶段论在公共政策研究中的主导地位。

一时间,对于政策过程各个阶段的研究成为政策学界的主要课题。

然而,相对于其他几个阶段的研究来说,政策终结的研究一直显得非常滞后。

这种情况直到20世纪70年代末80年代初,才有了明显的改善。

高温胁迫对羽衣甘蓝生理特性的影响

根据驻马店市历年8月平均最高气温及极端最高气温有关的气象数据,驻马店市8月最高气温可达41 ℃,最高地温高于41 ℃,平均昼夜温差11 ℃左右。设定胁迫处理为38 ℃27 ℃昼12 h夜12 h,以26 ℃22 ℃昼12 h夜12 h作为对照。经测试,在正常生长条件下,0~4 d内本试验中相关生理数据变化没有显著差异,因此所有对照数据均以0 d数据作为比较。选取高度、长势、叶数一致的幼苗,放置于人工气候箱在260.5 ℃220.5 ℃8 0020 0020 008 00预处理5 d。5 d 后温度设为380.5℃270.5昼12 h夜12 h。处理期间保持气候箱内空气相对湿度80%,光照度3 000 lx。高温胁迫4 d。共8个试验组,每组设3次重复,每重复25株。为减轻高温引起的水分胁迫的伤害,每天高温处理前和高温处理后进行补水保湿。试验期间各试验组其他环境条件及管理措施保持一致。

SOD是重要的活性氧清除酶,当外来胁迫导致大量活性氧产生时,它能及时有效地清除自由基,保护细胞免受活性氧胁迫的伤害。从图3可以看出,随着高温胁迫时间的延长,4个羽衣甘蓝品种SOD活性先升高后降低。但在第0天处理时,各品种间SOD活性没有显著差异。在高温处理1 d时,穆斯博SOD活性低于叶牡丹、京引和白罗裙 在处理第4天时,各品种SOD活性与第0天相比有显著差异P0.05。从SOD活性增加的速度看,随高温胁迫的加强,京引和白罗裙SOD活性增加速度快,最高峰时分别增加75.0%和64.1% 而穆斯博和叶牡丹的SOD活性增加比较缓慢,最高峰时分别增加35.8%和49.1%。说明在高温胁迫下,各羽衣甘蓝品种均可应激提高体内SOD活性,以清除活性氧自由基对细胞造成的危害,且京引的SOD活性与穆斯博和叶牡丹相比差异显著,京引的SOD活性与白罗裙差异不显著。但当高温胁迫时间延长时,SOD活性并没有升高反而降低,京引和白罗裙的SOD活性比穆斯博和叶牡丹降低的少。这些结果都表明在高温胁迫下,京引和白罗裙叶片组织具有较强的抵御活性氧的伤害作用,而穆斯博和叶牡丹的抵御能力较弱。

Absolute and convective instabilities of a viscous film flowing down a vertical fiber2007

244502-1

© 2007 The American Physical Society

PRL 98, 244502 (2007)

PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS

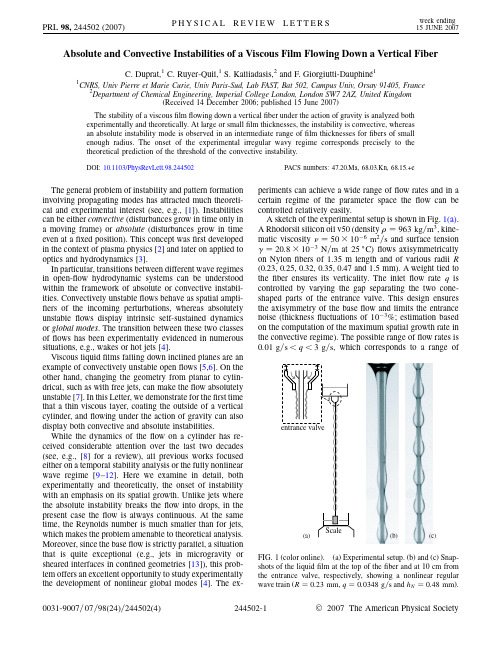

week endform film thicknesses 0:6R < hN < 3R (corresponding values of dimensionless parameters will be given later). The flow rate is measured with computer-controlled scales placed below the collecting tank. During an experiment, the liquid height variation in the tank (hence the flow rate variation) is less than 1%. A linear camera and a fast digital camera are mounted on micrometric assemblies allowing for a precise alignment of the field of view with the film for the linear camera and a precise displacement along the fiber for the fast one. Spatiotemporal diagrams obtained with the linear camera (using a vertical pixel line) allow for a sensitive detection of the film-thickness variations. Fluctuations of the film thickness with time at a given position are also recorded by orienting horizontally the pixel line. A snapshot of the flow at the inlet is depicted in Fig. 1(b) for a small flow rate on a thin fiber. A self-sustained dynamics is observed. Immediately after the inlet, the axisymmetric film of uniform thickness emerging from the capillary meniscus breaks up spontaneously into a droplike wave train. Depending on the flow rate and the fiber radius, two different regimes can be identified from the spatiotemporal evolution of the film thickness (see Fig. 2). At low flow rates and relatively small fiber radii, a regular primary wave train is observed at a constant distance from the inlet. Sufficiently close to the inlet, a power spectrum of the time variations of the film thickness reveals a well-defined frequency. Further downstream, a secondary instability disorganizes the flow. However, for even smaller fiber radii and over a rather narrow interval of (small) flow rates (the thinner the fiber the wider the range of flow rates), the waves propagate at constant speed, shape, and frequency all along the fiber [see Fig. 1(c)]. This global mode regime was observed initially by Kliakhandler et al. [9]. At larger flow rates and any radius, the primary wave train is irregular, its frequency spectrum is much broader and its onset location fluctuates in time. For thick fibers (R 0:47 mm) the regular wave regime was never observed. A quantity of particular interest is ‘‘the healing length’’ defined as the distance from the inlet to the location at

脯氨酸与植物的抗逆性

脯氨酸与植物的抗逆性王宝增(河北省廊坊师范学院生命科学学院065000)摘要本文主要介绍了脯氨酸在植物体中的合成与分解以及脯氨酸与植物抗逆性的关系。

关键词脯氨酸逆境胁迫相容性溶质抗逆性植物一生中会受到多种不利环境的影响,在诸多逆境因素中,由干旱、盐渍等因素引起的渗透胁迫(os-motic stress)是限制植物生长发育和作物产量的主要原因。

许多植物在逆境胁迫中都会积累一些相容性溶质(compatible solute),如脯氨酸、甜菜碱、糖醇等,这些物质溶解度高,没有毒性,在细胞中积累不会干扰细胞内正常的生化反应,并且可以抵抗渗透胁迫[1]。

在已知的相容性溶质中,脯氨酸在植物中的分布最为广泛[2]。

1脯氨酸在植物体中的积累脯氨酸作为蛋白质氨基酸中的一员,在植物初生代谢中的作用尤为重要。

人们在萎蔫的黑麦中首先发现了脯氨酸积累这一现象[3]。

之后,在逆境胁迫下的其他植物中也发现了脯氨酸的积累。

植物在遭受干旱、盐渍、强光与重金属污染和其他生物胁迫过程中都会有脯氨酸的大量积累,少则十几倍,多则几十倍甚至上百倍。

许多研究表明,脯氨酸主要分布在细胞质中,调节胞质和液泡之间渗透势的平衡[4]。

在水分胁迫中,它优先在细胞质中积累。

例如马铃薯细胞在正常水分条件下,细胞内的脯氨酸有34%积累在液泡中;但当其处于水分亏缺条件下时,液泡中脯氨酸含量下降,细胞质中脯氨酸含量上升[5]。

2脯氨酸的合成与分解在植物中,脯氨酸的合成主要来自谷氨酸,合成反应主要在叶绿体中完成。

谷氨酸在吡咯啉-5-羧酸合成酶(P5CS)催化下还原成谷氨酸半缩醛,后者自发转变成吡咯啉-5-羧酸(P5C),吡咯啉-5-羧酸还原酶(P5CR)进一步将吡咯啉-5-羧酸还原成脯氨酸。

在大多数植物中,吡咯啉-5-羧酸合成酶由2个基因编码,吡咯啉-5-羧酸还原酶由1个基因编码。

脯氨酸的分解代谢在线粒体中完成,分别由脯氨酸脱氢酶(PDH)和吡咯啉-5-羧酸脱氢酶(P5CDH)催化完成,脯氨酸脱氢酶催化脯氨酸转变成吡咯啉-5-羧酸,吡咯啉-5-羧酸脱氢酶催化吡咯啉-5-羧酸氧化成谷氨酸。

开放经济下的结构转型_一个三部门一般均衡模型

根据 (2)至 (4)式 ,我们可以将制造业产品衡量的总产出表示为 :

3

∑ Yt =

α

Pi, t Yi, t = A2, t kt L = w tL t + it Kt

(5)

i =1

为了将模型封闭起来 ,我们需要设定需求方 。

典型代理人最大化一生的效用 :

∑∞ βt

t =0

C1t -γ 1-

-1 γ

i =1

这里 , C1, t表示农产品的消费量 , C2, t表示制造业产品的消费量 , 其中即包括对本国制造业产品的消

费 ,也包括对国外制造业产品的消费 , C3, t表示服务的消费量 , C4, t表示国内消费的国外农产品的消费量 。

4

4

ε > 0为各产品的替代弹性

,

∑<

i=1

i

=

1

。当

γ= 1时

其中 C43, t表示国外消费的本国农产品 。

均衡消费要求消费者在等式 (8)的约束下最大化等式 (7) ,求解消费者的问题 ,得到各商品的需求函

数: 我们将物价指数定义为 :

Ci, t

∑< < =

P ε -ε

i i, t

P 4 ε -ε

j = 1 j j, t

(w tL + it Kt -

( 15 )

L3, t L

∑ =

< 3 < < i =1

ε 3

(A3, A2,

t t

)ε-

1

ε i

( A i, A2,

t t

)ε-

1

+

ε 4

(

A13, A23,

Costa Rica’s Payment for Environmental Services

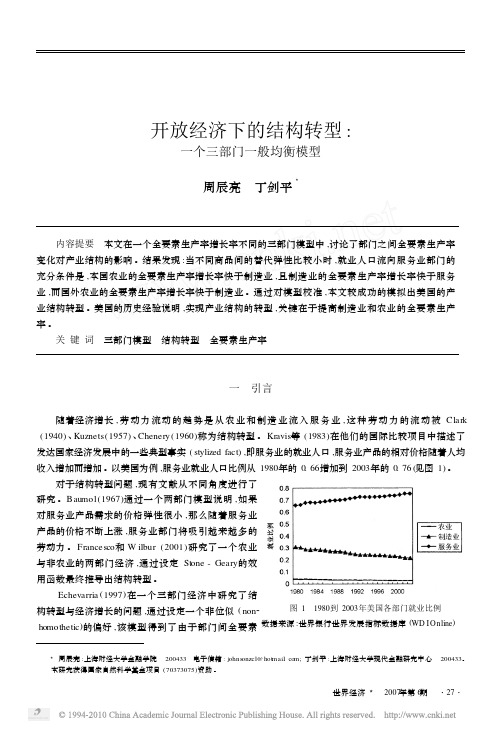

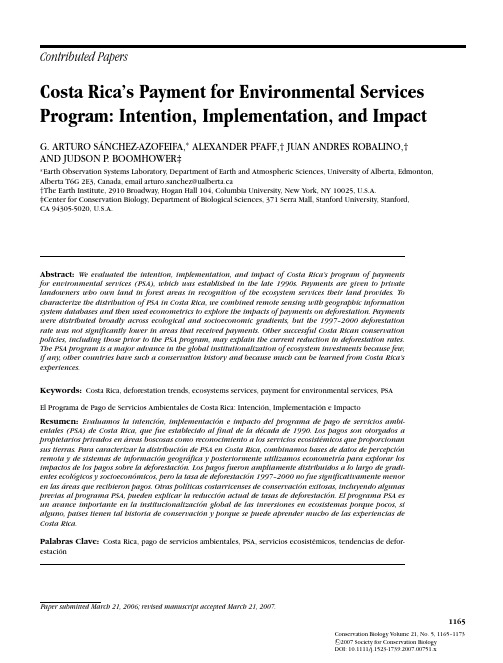

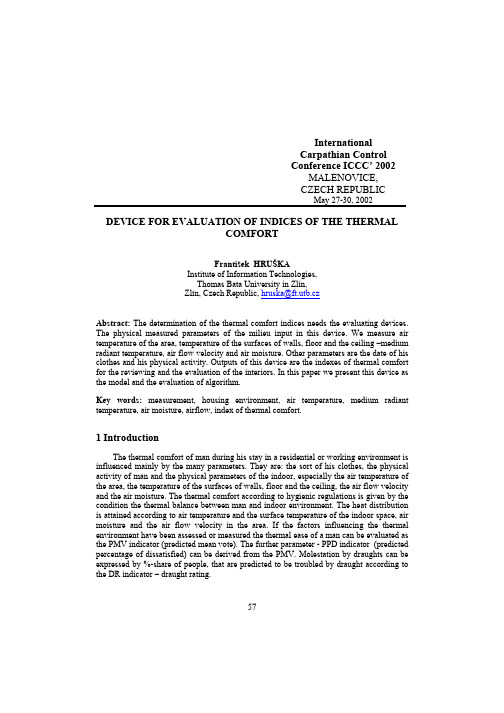

Contributed PapersCosta Rica’s Payment for Environmental Services Program:Intention,Implementation,and ImpactG.ARTURO S´A NCHEZ-AZOFEIFA,∗ALEXANDER PFAFF,†JUAN ANDRES ROBALINO,†AND JUDSON P.BOOMHOWER‡∗Earth Observation Systems Laboratory,Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences,University of Alberta,Edmonton,Alberta T6G2E3,Canada,email arturo.sanchez@ualberta.ca†The Earth Institute,2910Broadway,Hogan Hall104,Columbia University,New York,NY10025,U.S.A.‡Center for Conservation Biology,Department of Biological Sciences,371Serra Mall,Stanford University,Stanford,CA94305-5020,U.S.A.Abstract:We evaluated the intention,implementation,and impact of Costa Rica’s program of paymentsfor environmental services(PSA),which was established in the late1990s.Payments are given to privatelandowners who own land in forest areas in recognition of the ecosystem services their land provides.Tocharacterize the distribution of PSA in Costa Rica,we combined remote sensing with geographic informationsystem databases and then used econometrics to explore the impacts of payments on deforestation.Paymentswere distributed broadly across ecological and socioeconomic gradients,but the1997–2000deforestationrate was not significantly lower in areas that received payments.Other successful Costa Rican conservationpolicies,including those prior to the PSA program,may explain the current reduction in deforestation rates.The PSA program is a major advance in the global institutionalization of ecosystem investments because few,if any,other countries have such a conservation history and because much can be learned from Costa Rica’sexperiences.Keywords:Costa Rica,deforestation trends,ecosystems services,payment for environmental services,PSAEl Programa de Pago de Servicios Ambientales de Costa Rica:Intenci´o n,Implementaci´o n e ImpactoResumen:Evaluamos la intenci´o n,implementaci´o n e impacto del programa de pago de servicios ambi-entales(PSA)de Costa Rica,que fue establecido al final de la d´e cada de1990.Los pagos son otorgados apropietarios privados en´a reas boscosas como reconocimiento a los servicios ecosist´e micos que proporcionansus tierras.Para caracterizar la distribuci´o n de PSA en Costa Rica,combinamos bases de datos de percepci´o nremota y de sistemas de informaci´o n geogr´a fica y posteriormente utilizamos econometr´ıa para explorar losimpactos de los pagos sobre la deforestaci´o n.Los pagos fueron ampliamente distribuidos a lo largo de gradi-entes ecol´o gicos y socioecon´o micos,pero la tasa de deforestaci´o n1997–2000no fue significativamente menoren las´a reas que recibieron pagos.Otras pol´ıticas costarricenses de conservaci´o n exitosas,incluyendo algunasprevias al programa PSA,pueden explicar la reducci´o n actual de tasas de deforestaci´o n.El programa PSA esun avance importante en la institucionalizaci´o n global de las inversiones en ecosistemas porque pocos,sialguno,pa´ıses tienen tal historia de conservaci´o n y porque se puede aprender mucho de las experiencias deCosta Rica.Palabras Clave:Costa Rica,pago de servicios ambientales,PSA,servicios ecosist´e micos,tendencias de defor-estaci´o nPaper submitted March21,2006;revised manuscript accepted March21,2007.1165Conservation Biology Volume21,No.5,1165–1173C 2007Society for Conservation BiologyDOI:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00751.x1166Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments S´anchez-Azofeifa et al.IntroductionA new generation of conservation approaches is rapidly emerging(Ferraro&Kiss2002;Pagiola et al.2002).They differ from traditional approaches in three critical and in-terrelated ways:they emphasize human-dominated land-scapes,focus on ecosystem services,and utilize innova-tive finance mechanisms.To date,however,their imple-mentation has been on a small spatial scale.To apply the most promising initiatives worldwide,it is critical to un-derstand their intentions,designs,scopes,and limitations (Ferraro2001).Ecosystems provide services that include the pollination of crops,renewal of soil fertility,purifi-cation of water,and stabilization of climate.For global services,such as the sequestration of carbon to aid in climate stability,the origin of the service does not mat-ter.Nevertheless,many services are supplied across lo-cal and regional scales;thus,their delivery hinges on the capacity of species and ecosystems to provide benefits precisely where humans are located.Therefore,success in conservation and many other aspects of human well-being is linked intimately to the management of highly fragmented landscapes(Janzen1998;McNeely&Scherr 2002).Incentives for maintaining the provision of ecosystem services(Pagiola et al.2002;Pagiola et al.2004;Newburn et al.2005)include many components.Among them are regulatory systems of payments for ecosystem services, such as those currently operating in countries such as Australia,Costa Rica,and Mexico;market-based appro-aches to paying for ecosystem services,such as the emerg-ing international carbon market;and mitigation banking approaches,such as those operating in the United States in the context of the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.Conservation programs under the European Common Agricultural Policy and the U.S.Farm Bill,in ad-dition to various financial-incentive schemes of The World Bank,are also important initiatives.We explored the inception and initial impact of the first generation(1997–2000)of an innovative conserva-tion program established in Costa Rica:payments for en-vironmental services,or PSA(pagos por servicios am-bientales).The PSA program in Costa Rica occurred in two phases.The first phase(1997–2000)coincided with a significant drop in the national rate of deforestation (1997–2000),relative to the1986–1997time period and the high rates of forest clearing that occurred from the 1960s to the early1980s(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2001). Recently,there has been a net increase in forest cover, mostly due to land abandonment,although this process is not sufficient to reverse the existing fragmentation of the landscape or the increasing isolation of the country’s national parks and biological reserves(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2003).The second phase of the PSA program re-lates to the implementation of the Ecomarkets project (2001–today)and involves a comprehensive microtarget-ing scheme and the provision of new ecosystem services (e.g.,drinking water)that were not part of the first phase. It is tempting to assign credit for the decrease in defor-estation rates to the implementation of the PSA program. However,assigning causality to a farm-level program of this type requires a detailed analysis of deforestation over space and time and controls for other drivers of change (e.g.,international price of meat).Only by controlling for the effects of other factors(e.g.,strong forestry leg-islation),can one conclude that the implementation of the PSA program and low rates of forest clearing are not merely coincidental.Furthermore,how the PSA payments were allocated needs to be taken into account.We examined the effect of the first phase(1997–2000) of Costa Rica’s PSA program on ecological life zones,hy-drological basins,buffer zones around protected areas, planned biological corridors,and deforestation fronts.To test the hypothesis that the first generation of the PSA program has had an impact on the current low defor-estation rates,we examined payment allocation relative to the future threat of clearing and land-use changes in deforestation over space and time.Intent of Costa Rica’s PSA ProgramThree laws form the framework within which Costa Rica established the PSA program.The1995Environment Law 7554mandates a“balanced and ecologically driven envi-ronment”for all.The1996Forestry Law7575mandates “rational use”of all natural resources and prohibits land-cover change in forests.Finally,the1998Biodiversity Law promotes the conservation and“rational use”of biodiver-sity resources.Payments in the first phase were designed to address relevant forest conservation failures from a legal and insti-tutional standpoint.The PSA program compensated forest landowners for value created by either planted or natu-ral forest on their land and recognized four services:(1) greenhouse gas mitigation;(2)hydrological services;(3) scenic value;and(4)biodiversity.The program did not attempt to measure all four services on a given parcel at once.An identically valued bundle of these services was assumed to be provided by each hectare of enrolled par-cel.In the first phase enrollment was not based on parcel size,and the policy was“first come,first served.”Fac-tors such as farm size,human capital,and household eco-nomic level influenced participation in the program,and large landowners were disproportionately represented among participants at the national and regional levels(Mi-randa et al.2003;Zbinden&Lee2005).The PSA program has to compete with other land-use returns.Average returns from PSA varied from US$22toConservation Biology Volume21,No.5,2007S´anchez-Azofeifa et al.Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments1167US$42/ha/year before fencing,tree planting,and certifi-cation costs.The main competing land use is cattle ranch-ing,which shows returns from US$8to US$125,depend-ing on location,land type,and ranching practices(Arroyo-Mora et al.2005).One measure of cattle-ranching returns is the cost of renting1ha of pasture.In Cordillera Cen-tral,in the heart of Costa Rica,pasture rental ranges from US$20to US$30/ha/year(Castro et al.1998). Implementation of the PSAThree types of contracts were part of the first phase of the PSA program:forest conservation,reforestation, and sustainable forest management.Forest conservation contracts required land owners to protect existing(pri-mary or secondary)forest for5years,with no land-cover change allowed.Reforestation contracts bound owners to plant trees on agricultural or other abandoned land and to maintain that plantation for15years.Sustainable forest management contracts(eliminated briefly in2000)com-pensated landowners who prepared a“sustainable log-ging plan”to conduct low-intensity logging while keeping forest services intact.Just as in the reforestation contracts, obligations for sustainable forest management contracts were for15years,although payments arrived during the first5years.Compensation varied across these types of contracts. For conservation contracts,payment was US$210(60,000 colones)/ha in equal installments over5years.Reforesta-tion contracts paid US$537(154,000colones)/ha,with 50%paid the first year,20%the second year,and10% over the following3years.The forest management con-tracts paid US$327(94,000colones)/ha,with the same temporal structure as reforestation.Our conversion to U.S.dollars was based on the1999average exchange(287 colones/U.S.dollar)rate provided by the Costa Rican Min-istry of Planning(MIDEPLAN).(Hereafter monetary units are in U.S.dollars unless otherwise indicated.)Any PSA contract creates a legal easement that remains with the property if it is sold.Owners transfer rights to the greenhouse-gas-mitigation potential of the parcel to the national government.Costa Rica can then sell these abate-ment units on any international market.Under the PSA program rules,no individual can register<2ha or>300 ha/year,although indigenous groups may register up to 600ha/year.There is no area limit for coalitions that act through local nongovernmental organizations.Such orga-nizations can function as intermediaries between small-holders and authorities to increase participation by those who might not enroll.The Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal(FON-AFIFO),a public forestry-financing agency created under Forestry Law7575in1996,administers the PSA program. The inspection responsibilities within the program’s im-plementation,however,rest with the Sistema Nacional de Areas de Conservacion(SINAC)and with the Ministerio del Ambiente y Energ´ıa(MINAE).The primary funding source for the original PSA pro-gram was a15%consumer tax on fossil fuels estab-lished under the1996Forestry Law.Its Article69stated that FONAFIFO was to receive one-third of the revenue. The Ministry of Finance,however,rarely delivered that amount,and in2001the legislature repealed Article69 and adopted the Ley de Simplificaci´o n y Eficiencia Trib-utaria,which assigns3.5%of the tax revenue directly to the PSA program(Camacho&Reyes2002).This provided less money in theory,but increased actual transfers from the Ministry of Finance(Camacho&Reyes2002).As of 2003,such tax revenues provided an average of$6.4mil-lion/year to the PSA program(Pagiola et al.2002). Funding to the PSA program also comes from volun-tary contracts with private hydroelectric producers,who reimburse FONAFIFO for payments given to individuals such as upstream landowners in watersheds.These pri-vate agreements have generated only about$100,000to finance about2,400ha of PSA contracts.When fully im-plemented,however,these agreements are expected to provide about$600,000annually and to cover close to 18,000ha(Pagiola et al.2002).Carbon-abatement trading was expected to provide sig-nificant funding through sales of certified tradable offsets. However,no significant market for carbon abatement has emerged.The only sale has been to Norway,which con-sisted of$2million in1997for200million tons of carbon sequestration(Pagiola et al.2002).Funding was also provided by a World Bank loan and a Global Environmental Facility(GEF)grant through a pro-gram called Ecomercados(a term used to define the sec-ond phase of the PSA program after the year2000).The World Bank/GEF loan for$32.6million was designed to support current PSA contracts.Of the total$8million,$5 million was used for conservation contracts along the pro-posed sites that will eventually form part of the Mesoamer-ican Biological Corridor.The other$3million was in-tended to increase human,administrative,and monitor-ing capacity in the various institutions associated with the program,including FONAFIFO,SINAC,and MINAE(Ortiz &Kellenberg2002).MethodsData on Payments,Forest Cover,and Dimensions of Conservation InterestThe data on the payment amounts for environmental ser-vices to landowners were provided by FONAFIFO.The information on contracts we analyzed is available in vec-tor format,including the spatial location of the farms that participate in the different types of PSA contracts.WeConservation BiologyVolume21,No.5,20071168Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments S´anchez-Azofeifa et al.quantified forest cover and change based on a comprehen-sive Landsat Thematic Mapper data set produced for FON-AFIFO by the University of Alberta’s Earth Observation Systems Laboratory(EOSL)and the School of Forestry at the Costa Rica Technology Institute.The forest-cover maps were produced for1986,1997,and2000.The fol-lowing five land-cover categories were mapped:(1)forest (canopy closure>80%),(2)1986–1997and1997–2000 deforestation and reforestation,(3)mangroves,(4)non-forest,and(5)cloud/water cover.The maps had a mini-mum mapping unit of3.0ha and were generated with the same techniques implemented by the NASA Pathfinder Project(Skole&Tucker1993;S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al. 2001).Over800independent control sites were used for the validation of the1997and2000maps(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2001,2003).Overall accuracy of the forest-cover map was90%(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2003).We generated a digital elevation model(DEM)from166 digitized topographic maps(1:50,000).Elevations every 20m and supplementary elevations every10m were used to create a grid DEM,with a spatial scale of28.5m.We used the DEM to produce drainage-basin boundaries and slope and aspect maps.A series of thematic GIS maps delineating different hy-drological,biological,and conservation land uses were cross-referenced against the extent of national parks and biological reserves.Those GIS maps were of(1)drainage basins important for hydropower production,drinking-water supply,and flood control(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al. 2002a);(2)areas with potential for biological corridors that may become part of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor efforts(known as GRUAS);(3)Holdridge life zones(Holdridge1967);and(4)political boundaries of the13conservation areas in Costa Rica.National park and biological reserve areas falling in each one of the former GIS maps were eliminated because PSA payments are not allowed for public lands.From the point of view of water resource management, we placed all drainage basins into one of four categories: (1)basins in which the management of water quality is considered especially important(4drainage basins),(2) basins not important for water quality,(3)basins with existing or planned dams for hydropower(8drainage basins),and basins not planned for hydropower dams (S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2002a).Finally,we explored the spatial distribution of PSA in1-and5-km buffer areas around national parks,biological reserves,and1997–2000deforestation fronts(S´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2003; Van Laake&S´a nchez-Azofeifa2004).Data AnalysisTo reveal the spatial distribution of PSA contracts,we overlaid them with the GIS layers described above.For these and other analyses,when a PSA polygon crossed a border between two defined categories(e.g.,two differ-ent life zones),its area was divided across those units as a function of the total area falling within each category. To explore the effects of PSA contracts on changes in for-est cover due to clearing,we used5×5km grid cells, with each cell representing a nested approach with a full resolution of28.5m and no resampling of the data.We used forest and nonforest data(1986,1997,and 2000)from2000grid cells(total country area of50,100 km2)to calculate the1986–1997and1997–2000defor-estation ing a GIS approach,we also overlaid PSA locations in the context of(1)proximity to national parks and biological reserves,(2)slope,(3)aspect,(3)distances to three major market locations(San Jose[capital city], Limon[Caribbean coast],and Puntarenas[Pacific coast], and(4)life zones.Life zones were classified into three categories as a func-tion of their potential agricultural productivity:(1)“good”life zones,which included all humid areas(medium pre-cipitation)with moderate temperature,(2)“medium”life zone,which included very humid areas(high precipita-tion)in moderate to mountain elevations with moderate temperatures;and(3)“poor”life zones,which included all very humid areas with high temperatures,very dry,hot areas,and rainy life zones(Pfaff&S´a nchez-Azofeifa2004). We performed ordinary least square(OSL)regressions to explain the differences in deforestation rates across space and time based on PSA density(number of parcels per hectare)and life zones,slopes,aspect,and distances to major market locations.Finally,we explored the hypothesis that implementa-tion of the PSA program was based,in part,on expec-tations that payments for ecological services were made in areas under greatest threat of forest conversion as sug-gested by Pfaff and S´a nchez-Azofeifa(2004).We examined this hypothesis by studying the proximity of the payments to recent deforestation as an indicator of expected threat (i.e.,payments within1km of recent1986–2000defor-estation).ResultsTotal Distribution of PSA ContractsAround300,000ha of primary,secondary,or planted for-est received funding in the first phase of the PSA program through2000.The mean project size was approximately 102ha.The largest project was4025ha.The stated size limits were not fully enforced;202projects were over the 300-ha maximum and60contained less than the2-ha min-imum.From1997to2000,the number of participants en-tering the program decreased(Fig.1),probably because funds were not delivered as expected(Camacho&Reyes 2002).Payments for conservation alone were larger than the sum of the payments made for reforestation and forestConservation Biology Volume21,No.5,2007S ´anchez-Azofeifa et al.Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments 1169199719981999200020012002A r e a (h a ) u n d e r P S A20x1060x1080x10100x10Y ear:Total Investment:26,207,59916,351,37016,277,2426,966,9687,806,2907,031,799(1531)(1021)(925)(501)(406)(329)Total Participants:Figure 1.Distribution of PSA (payments for ecosystemservices)in Costa Rica by type of payment (C,conservation;R,reforestation;and M,management)between 1997and 2002.The number of people involved in the program and the total investment (in U.S.dollars)are presented for each year .management (Fig.1),but conservation contracts had the lowest payments per unit area.Reforestation and man-agement contracts generally held steady over the years,whereas conservation payments fell (e.g.,>$20million in 1997;almost $12million in 1999;and <$4million in 2001).Table 1.Distributions of PAS (payment for ecosystem services)on Costa Rican lands outside of protected areas between 1997and 2000.aArea or type of distributionnonpublic b nonpublic conservation reforestation management parks (%)area (ha)area (%)bpayment (%)payment (%)payment (%)Holdridge life zonesHumid Lower Montane 0.023,9250.80.10.70.0Humid Premontane 13.0553,550 4.4 3.60.80.0Humid Tropical1.11,068,4997.2 4.1 2.80.4Very Humid Montane7.81,728 4.0 4.00.00.0Very Humid Lower Montane 2.5113,790 4.1 3.60.50.0Very Humid Premontane 1.91,198,697 4.9 2.1 2.00.9Very Humid Tropical 12.61,151,77710.9 5.4 2.9 2.6Pluvial Montane54.6127,785 3.7 3.00.70.0Pluvial Lower Montane 45.5348,4647.87.00.50.2Pluvial Premontane 24.5373,038 6.9 6.70.20.0Dry Tropical 3.3141,544 6.3 4.9 1.40.0Conservation areas Amistad Atlantico 31.9616,6028.2 6.20.7 1.3Amistad Pacifico 13.6622,622 2.8 1.80.90.1Arenal5.1917,38010.4 2.8 4.8 2.7Cordillera Central 10.3569,2778.0 5.2 1.8 1.0Guanacaste 23.1354,1746.9 5.2 1.10.6Osa13.3424,084 4.6 3.70.50.4Pacific Central 1.2545,339 5.1 2.8 2.30.0Tempisque 3.4760,5347.4 6.1 1.30.0Tortuguero7.3303,316 5.9 3.5 1.4 1.1All of Costa Rica11.34,534,3507.04.12.00.9a Distribution is presented across Holdridge life zones and conservation areas.b Areasoutside national parks and biological reserves.Spatial Allocation of PSA ContractsThe PSA contracts were distributed broadly across ecolog-ical life zones (Table 1).Most life zones had areas under PSA ranging from 4%to 8%of their total area.The max-imum allocation was achieved for Very Humid TropicalConservation Biology Volume 21,No.5,20071170Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments S´anchez-Azofeifa et al. Table2.Distribution of PSA(payments for ecosystem services)in Costa Rica from1997to2000for areas outside national parks and biological reserves linked to conservation activities.Area or type of distributionnonpublic a nonpublic a conservation reforestation management Conservation activity parks(%)area(ha)area(%)payment(%)payment(%)payment(%) Urban water qualitySan Jose’s&three others b 6.71,102,459 3.6 2.3 1.10.2all other basins13.03,388,8828.1 4.7 2.3 1.1 Hydropower interestsactual&planned dams c13.41,597,442 5.1 2.6 1.80.7all other basins10.52,893,8998.1 4.9 2.1 1.0 Near current protected areasnear(<5km)0.0793,6307.0 5.2 1.20.6far(>5km)0.03,620,916 6.5 3.4 2.10.9In planned protected areaswithin GRUAS corridors0.0631,9349.9 6.1 2.2 1.7 outside GRUAS corridors0.03,787,737 6.3 1.90.8 3.6a Nonpublic:areas outside national parks and biological reserves.b Reventazon,Frio,Tarcoles,Terraba basins.c Reventazon,Frio,Tarcoles,Terraba,Sixaola,Pacuare,San Carlos,Savegre basins.Forest(10.9%)and the lowest allocation was observed for the Humid Lower Montane(0.8%).Of the three types of incentives that were part of the first phase of the PSA program,the conservation incentives dominated.Fewer incentives for conservation were present in the Humid Lower Montane life zone(0.1%)and more incentives were in the Pluvial Lower Montane life zone(7%).There was a broad distribution of PSA contracts across the country’s nine conservation areas.These units mostly had4–8%of their total area under PSAs contracts,al-though Arenal(10.4%)and Amistad Pacifico(2.8%)dif-fered from the other conservation areas.For these con-servation units,the spatial allocation across the types of PSA contracts also varied.Priorities for the allocation of PSA contracts as a func-tion of hydrologic basins indicated two main trends(Ta-ble2).First,from an urban quality point of view,PSA contracts were allocated more often in basins with little or no importance for drinking water(13%for all other basins vs.6.7%for San Jose’s and three other impor-tant water-supply drainage basins).Second,actual and planned basins with dams received more investment than all other basins(13.4%vs.10.0%,respectively).Our results(Table2)also indicate that there was rel-atively little difference in the intensity of PSA contracts (number of parcels per unit area)relative to their prox-imity to conservation areas,and differed little among lo-cations(7.0%near[<5km]conservation areas vs.6.5% farther from[>5km]conservation areas).Nevertheless, the differences in intensity for areas within and outside planned biological corridors were larger(9.9%in the GRUAS plans and6.3%outside of the GRUAS plans).For all cases(hydrologic basins,conservation locations,planned protected areas)conservation incentives dominated over the reforestation and management incentives.Impact of the PSA Program on DeforestationCosta Rica experienced very low deforestation rates dur-ing the study period.Deforestation rates were estimated to be0.06%/year and0.03%/year for the1986–1997and 1997–2000time periods,respectively.Of the total distri-bution of PSA payments in the country,only7.7%were located within1.0km of all deforestation fronts.Conser-vation payments were higher(3.6%)than reforestation (2.6%)and forest management(1.5%)payments in areas close to deforestation fronts.A PSA payment was only slightly more likely to be near deforestation fronts(1km) than to be farther away from them.Our results also indi-cate that there was no negative significant coefficient for the density of PSA payments(Table3).The first genera-tion of the PSA program did not reduce deforestation rates or total deforestation in Costa Rica(Table3,Fig.2). DiscussionCosta Rica’s PSA program has been a leader in the institu-tionalization of ecosystem investments through the now popular idea of payments for ecosystem services.We doc-umented the spatial distribution of the first phrase of the PSA program(1997–2000)through GIS overlays with var-ious indicators associated with conservation goals.The first phase of PSA contracts were distributed broadly along these dimensions and lacked sharp asymmetries that could indicate focused targeting.The sharpest asym-metry was for planned biological corridors.Furthermore, our econometric results suggest little,if any,impact of the level of PSA contracts on a given area’s rate of deforesta-tion.This has also been suggested by Hartshorn et al. (2005).Conservation Biology Volume21,No.5,2007S ´anchez-Azofeifa et al.Impacts of Ecosystem Services Payments 1171Table 3.Results of regression analysis for Costa Rica ’s 1997–2000deforestation,PSA (payments for ecosystem services)(conservation,reforestation,and management incentives [all]vs.conservation incentives alone),and selected control variables.aIIIIIIconservationconservationconservationallalone all alone all alone Payments −0.0004−0.0040.001−0.0005−0.0003−0.002(0.92)(0.48)(0.83)(0.92)(0.95)(0.68)Constant 0.0040.0040.0160.0160.0110.011(0.00)(0.00)(0.00)(0.00)(0.01)(0.01)Slope−0.0003−0.0003−0.0002−0.0002(0.00)(0.00)(0.00)(0.00)Good life zone b −0.0002−0.00020.00010.0001(0.93)(0.94)(0.95)(0.94)Poor life zone b −0.004−0.004−0.002−0.002(0.02)(0.02)(0.36)(0.37)Distance to San Jose −4e 08−4e 084e 094e 09(0.41)(0.40)(0.93)(0.93)Distance to Limon −3e 08−3e 08−6e 08−6e 08(0.17)(0.17)(0.03)(0.03)Distance to Puntarenas 3e 083e 088e 098e 09(0.38)(0.38)(0.81)(0.81)%cleared c 0.0080.008(0.00)(0.00)Adjusted R 20.000.000.040.040.040.04n202120211892189218871887a Allregressions were ordinary least squares for deforestation probabilities.Coefficient is reported;p value in parentheses.The dependent variable was the deforestation rate during 1997–2000,measured at the level of the 5×5km grid units of observation.The explanatoryvariable of interest was the area receiving PSA payments,again measured by grid.We tried each of the two versions of the payments variable in each of the three sets of columns.Columns II and III added more control variables (i.e.,explanatory variables other than PSA).b See Methods for definition of good and poor life zones.c The fraction of the forest in a grid cell that was cleared before 1997.From 1997through 2000little deforestation took place in Costa Rica (Figs.2&3).Yet some explanatory effects in the regressions were significant nonetheless (Table 3).Slope in particular was consistently and negatively associated with deforestation,whereas prior deforesta-Total Deforestation (ha)50100150200250T o t a l l a n d o n P S A (h a )0200400600800100012001400Figure 2.Relationship between the total area of farms in the PSA (payments for ecosystem services)program and the deforestation rate.The correlation coefficient between these two variables is 0.16.tion was consistently,positively,and significantly asso-ciated with deforestation.Distance to Limon was also significantly associated with deforestation.These results confirm many prior results in the literature (Velkamp et al.1992;S ´a nchez-Azofeifa et al.2002b ;Van LaakeDeforestation Period1960-791979-861986-971997-002000-05D e f o r e s t a t i o n R a t e (%/y r )0.00.20.40.60.81.01.21.4Figure 3.Changes in deforestation rates between 1960and 2005.Arrow is implementation of the first PSA (payment for ecosystem services)program.Conservation Biology Volume 21,No.5,2007。

the new issues puzzle