Atom-wave diffraction between the Raman-Nath and the Bragg regime Effective Rabi frequency,

表面和界面-Surfaces and Interfaces

8. Surfaces and Interfaces8.1 IntroductionThere exist differences in the important parameters describing interfaces and surfaces:Surfaces Interfacesroughness composition conformation chain ends width (roughness) profile conformation fluctuationssnapshot of a coarse-grained moleculardynamics simulation of a block co-polymer double bilayer in waterGoundla Srinivas, IBM Almaden Research Centerthermodynamic: To allow contact between two different phases, an interface with a free energy between them is needed. Across this interface the intensive properties of the systems are changing from one phase to the other.Free energy of the interface ΔG = ΔW = 2σAA change of the interface requires a free energy ΔG, meaning a work ΔW, proportional to the area A and interfacial tension σ, is needed.work of cohesion W c = 2σwork of adhesion W c= σ1+σ2-σ12The process is assumed to be fully reversible.8.2 Polymer Surfaceair / vacuumpolymer surfacepolymer volume (bulk)Simple microscopic view: attractive forces between the atoms (spring-bead model) with force equilibrium in the volume, but missing partners at the surface→ attraction oriented towards the bulk→ surface tension / surface energy→ change of the structure at surfacea) Chain conformation in the vicinity of the surfaceComputer simulation: Structural properties of a dense polymer melt confined between two hard walls are investigated over a wide range of temperatures by dynamic Monte Carlo simulation using the bondfluctuation lattice model.The effect is present in a region close to the polymer surface. Deviation of the chain conformation is found in a region with an extension of ≈2R g .Baschnagel, Binder, Macromolecules 28, 6808 (1995)As the wall is further approached, the ability of the chains to reorient is progressively hindered, leading to an increase of R g|| and to a decrease of R g ⊥. Therefore the main effect of the wall is to reduce the orientational entropy of the polymers and to align them preferentially parallel to it.Experiments (GISANS): The samples consist of blend films of protonated and deuterated polystyrene (PS) spin coated onto glass substrates. A variation of the thickness of the blend films in a range of about 41 down to 0.66 times the radius of gyration R g of the chains in the bulk enables the determination of film thickness and confinement effects with the advanced scattering technique grazing incidence small angle neutron scattering (GISANS).The effect of the breaking of the translation symmetry by the presence of a surface is found in a more extended region of ≈8R g .Kraus et al., Europhys. Lett. 49, 210 (2000)The polymer molecule is altered in its conformation from an isotropic Gaussian chain (sphere) into an ellipsoidal shapechain segments are oriented in parallel to surfaceb) Chain end distribution Theory:Density of chain ends at the surface (de Gennes, 1992):φφρee N 2=with N length of chainφe number of ends at surfaceφ number of monomers per volume→ chain ends from a region 2R g are enriched in a layer of thickness d (typically 1-2 nm):N dae 2=ρ with segmental length aenrichment of chain ends at the surface due to entropic effects Experiments (NR): Mono-terminated polystyrenes (PS) are synthesized anionically to include a short perdeuteriostyrene sequence adjacent to the end groups for the purpose of selective contrast labeling of the end groups for neutron reflectivity (NR).The location of deuterium serves as a marker to indicate the location of the adjacent end group. Damped oscillatory end group concentration depth profiles at both the air and substrate interfaces are found. The periods of these oscillations correspond approximately to the polymer chain dimensions.contrast density depth profileKoberstein et al; Macromolecules 27,5341 (1994)c) Segment distribution in the vicinity of surfaceComputer simulation: Strong orientation of segments due to the breaking of the translational symmetry of the system by the presence of a surface. The effect is present in region close to surface only, with extension of ≈2R g.Experiments (Force balance): Strong modulation in the density in the vicinity of the surface (effect much more pronounced in case of a solid wall).transition region with significantly decreased densityd) Influence on the kineticsComputer simulation:At the polymer surface a very mobileand quasi-liquid layer is existing wellbelow a melting temperature T m. In thislayer the chain mobility is increased.at surface mobility in movement in parallel to the surface is increased in a thinlayer of thickness d (typically 2 nm)This behavior is similar to many crystal samples. The origin is the reduced number of entanglements at the surface.Experiments (FCS): Comparison of polymer diffusion, polyethyleneglycol (PEG), when adsorbed to a solid surface and in free solution(a) Flexible polymer chains that adsorb are nearly flat at dilute surface coverage (i.e., de Gennes pancake). The sticking energy for each segment is small, so no single segment is bound tightly, but the molecular sticking energy is large. (b) Diffusion coefficients (D) in dilute solution (blue circles) and at dilute coverage on a solid surface (red squares) plotted against the degree of polymerization (N) at 22°C.on surface: changed power law due to excluded volume statisticsDepending on the interaction between polymer and wall the mobility can by unchanged to bulk (neutral wall) or slowed down (attractive wall).How do polymer surfaces look in experiments?Examples:polystyrene machined titanium dual-acid-etched (DAE)titaniumSEMAFMNakamura et al, JDR 84, 515 (2005)Typically polymer surfaces are significantly smoother as compared to metal and metal oxide surfaces (independent of the surface treatment).PMDEGA after swelling in water vapor after 6 days storage in airZhong, PMB et al, Colloid. Polym. Sci. 289, 569 (2011)Homopolymer surfaces are only smooth with low surface roughness and good homogeneity if the homopolymer film is stable. If it is unstable the surface can roughen.If the polymer crystallizes a completely different polymer surface is observed. Due to the crystals present at the polymer surface, the surface roughness is significantly increased.8.3 Interface between polymerscase I: identical polymers A/A or compatible polymers A/B• interdiffusion of segments • adhesion • model of segment movementexample: PS/PS, PMMA/PMMA, PMMA/PVCcase II: incompatible polymers A/B• width of the interface in equilibrium • polymer-polymer interaction parameter (Flory-Huggins parameter) χexample: PS/PBrS, PS/PMMA, PS/PpMS, PS/PnBMAMathematical description of the interface:Rough interface j with mean z-coordinate set to zero and fluctuations in height z j (x)The rough interface can be replaced by an ensemble of smooth interfaces weighted by a probability density P j (φ)with a mean value ∫=dz z zP j j )(μand root-mean-square (rms) roughness ()∫−=dz z P z j j j )(22μσDifferent probability density function are possible and result in different interfaces: Normalized error-function (solid line) and hyperbolic-tangent (dashed line) have very similar refractive index profiles n j (z).Error function profile⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛−−−+=++j j j j j j j z z erf n n n n z n σ222)(11 results from Gaussian probability density (μi =0) ⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛−=222exp 21)(j jj z z P σσπand hyperbolic-tangent profile ⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛−−−+=++j j j j j j j z z n n n n z n σπ32tanh 22)(11results from probability density (μi =0) ⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛=−j jj z z P σπσπ32cosh 34)(2Both examples are based on symmetric probability functions, however, for real samples this symmetry is not ensured and thus asymmetric profiles can occur (e.g. polymer brush with exponential decay).a) Interface width of polymer interfacesComputer simulation (Monte-Carlo simulation by Binder, 1994):A symmetric binary mixture (polymer1, polymer2) below its critical temperature T c of unmixing is considered in a thin-film geometry confined between two parallel walls, where it is assumed that one wall prefers polymer1 and the other wall prefers polymer2. Then an interface between the coexisting unmixed phases is stabilized.with interface width χ6a L = yields rms-roughness πσ2L rms =only valid for smooth interfaces (σrmssmall) with qR g >1 and N →∞with segment length a scattering vector ()dq πλπ2sin 4=Θ=Not taking into account: - concentration dependence of χDifferent approximations in the framework of Mean Field theories:• Binder: expansion of free energy for φ=0.5 and N 1=N 2=N (with qR g >1 and χN>>1)()NaL 26−=χ• Brosetta: Integration of the quadratic gradient term in the vicinity of φ=0.5⎟⎠⎞⎜⎝⎛⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡+−=21112ln 26N N aL χ• Stamm: minimization of the free energy using a "trial"-function⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡+−=2121166N N aL πχ ⇒ It is possible to determine the polymer-polymer interaction parameter χ froma measurement of the interface width L, in case the degree of polymerization Nand the segment length a are known!• Frisch: modification of the profile on different length scales: deviation from the simple tanh-shapeb) entanglement density at the interface between two immiscible polymers The variation of entanglement density with interface width at an interface between two polymers is calculated using the relationships between chain packing and entanglement. The chain packing is obtained by the use of self-consistent mean-field techniques to calculate the average chain conformations within the interface region.calculated number of segmentsbetween entanglements as a functionof χassuming a bulk value of N e,typical for polystyrene, of 130Oslanec and Brown, Macromolecules 36, 5839 (2003)b) time dependent evolution of the interface widthHowever, all these models describe a time average and the final equilibrium interface. With experimental techniques it is possible to prepare interface between polymers far from equilibrium and to follow changes with time resolution.covering a large range of time and length scales the crossover between 4different regimes is observedt < τe: Rouse regimeτe < t < τf: Reptation regimeτf < t < τd: Blob movementτd < t: Fick diffusioncharacteristic power laws: tαRouse regime: α = 0.5Reptation regime: α = 0.25Fick Diffusion: α= 1.08.4 Rouse Model(P.E.Rouse 1953, extension B. Zimm 1956)The Rouse model describes the conformational dynamics of ideal chains. The main assumptions are: 1. no excluded volume interaction2. no hydrodynamic interactionTherefore one expects this model to work at Θ-condition or polymer melt condition.Polymers are interconnected objects with a large conformational entropy. As a consequence, the universal entropy-driven Rouse dynamics prevails at intermediate scales, where local potentials have ceased to be important and entanglements are not yet active. Key signature of the Rouse motion is the sublinear evolution of the segmental mean-square displacement2)(t2/1tr≈neutron spin echo (NSE) results on the single-chain dynamic structure factor: dynamics of poly(vinyl ethylene) on length scales covering Rouse dynamicsMean-square displacementof the protons, the solid linerepresents Rouse dynamicsRicher et al., Europhys. Lett., 66, 239(2004)Both molecular-dynamics (MD) simulations and MCT calculations on coarse-grained polymer models (bead and spring models)Bead-spring modelIn this model of a polymer molecule it consists of beads and springs forming a chain. The beads are hydrodynamics resistance sites that are dragged on by the suspending fluid. They also experience random Brownian forces caused by the thermal fluctuations in the fluid which are significant on the molecular scale. The spring is an entropic force pulling the adjacent beads together. In fact, the spring represents many monomer units that can coil and uncoil in response to the forces. This model is a reasonable representation of the polymer chain dynamics that actual polymer molecules undergo.8.5 Reptation Model(de Gennes, Doi, Edwards, 1971 + 1978)Reptation is the snake-like thermal motion of very long linear, entangled macromolecules in polymer melts or concentrated polymer solutions. It comprises:• entanglements with other chains hinder diffusion• each polymer chain is envisioned as occupying a tube of length L • movement of polymer chain is only possible within this fictive tube• special type of movement: diffusion only via movement of chain ends,keeping chain conformation unchangedtube diameter ddifferent types of movement:t < τe : no hindering in movement by tube (Rouse type movement)t = τe : density fluctuations within the chain are extended up to the length scale of the tube diameterτe < t < τf : polymer chain moves along the tubeτf < t < τd : chain starts to escape the tubet = τd : chain left the original tubet > τd : completely free movement of the chain with no remembering of the tubeExample:PE M w = 190k d = 49Å or PE M w = 17k d = 54ÅPS d ≈ 50ÅN R e , density ρ und temperature TInfluence on the interface profile:shown for different relative diffusion times t/t f 0.1 s mall →0.9 largeThe jump in the concentration profile is caused by the movement of the chain ends across the interface in the framework of the Reptation model.Attention: the profile needs to be convoluted with the tube diameter d8.6 Fick diffusionTranslation of the complete polymer chain is described as diffusion of the centerof masswith diffusion coefficient D Attention: different diffusion coefficients are existing D S self-diffusion coefficient (A moves in a matrix of A) D I inter-diffusions coefficient (A und B move with respect to each other) D T tracer-diffusion coefficient (marker T moves in matrix A)a) self-diffusion:Movement of chains in the identical environment → very difficult to detect experimentally, because no contrast between chain and environmentPossibility of marking individual chains (by deuteration or with fluorescent end-groups), but strictly this is a tracer experiment already Example: PS volume D S ≈4*10-14 cm 2/s thin film (300Å) D S ≈1.5*10-15 cm 2/s surface D S ≈9.3*10-16 cm 2/s⇒ slowing down of the diffusion due to the spatial confinementb) inter-diffusion:An interface between two polymers, which was prepared out of equilibrium (e.g. with the floating technique) is annealed above the glass transition temperature of both polymers→ broadening of the interface following the above arguments → late stages are caused by diffusion (t > τd )Experiment: X-ray- or neutron reflectivity measurementshydrogenated and deuterated polystyrene has been measured at 115 °C in-situ and in real time using NRdiffusion coefficientD = (1.7±0.2) × 10-17 cm 2/sBucknall et al., Macromolecules 32, 5453 (1999)• "fast-mode" theory B T B A A T A B I D N D N D ,,φφ+= • "slow-mode" theoryB T B A A T A B I D N D N D ,,111φφ+=Examples:Low molecular weight liquids D ≈10-6 cm 2/s polymers D ≈10-12-10-17 cm 2/s depending on temperaturec) tracer-diffusionusing small markers, e.g gold atoms in a well defined layered approachAnnealing the sample above the glass transition temperature of the polymer and probing the distances which the gold atoms had moved after defined times tReiter et al. Macromolecules 24, 1179 (1991)Dependence on molecular weight:Stamm et al., Macromolecules, 26, 2134 (1993)tracer-diffusions constant2−∝W T M D8.7 additional contributions to the interface widthIn addition to the width of the interface between two polymers which results from interdiffusion, contribution from other sources have to be taken into account. They arise from preparation: thickness variation of the filmwrinkles, dust particles, holes, impuritiesintrinsic: capillary wavesA capillary wave is a wave traveling along the phase boundary of a fluid, whose dynamics are dominated by the effects of surface tension. These waves are of thermal origin .Assuming a semi-infinite liquid with surface tension γLV a complex movement of the atoms makes a surface wavehaving a dispersion relation()g q q q LV rr r +=ργω32with ρ liquid density g Earth's accelerationSo thermal fluctuations cause a deviation from the ideal flat surface with an excess free energy density()()()()()Ζ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡ΖΔ+⎟⎠⎞⎜⎝⎛−Ζ∇+=Ζ∫∫22111d l P h A h fA L LV L exr r r γ ()()()()()Ζ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡Ζ+Ζ∇≈Ζ∫∫221d h P h A h f A L L LV L ex r r r γ yielding the height-height-autocorrelation function and power spectral density()Ζ=Ζr r c LV B q K Tk C 02)(πγ and 22214)(c LV LV B q q T k q L γγπ+=rwith K 0 modified Bessel function of zero ordercapillary waves can only be excited in an interval between λmin and λc for T>>0KA gravitation cut-off of the larges possible wavelength being excited isc c q πλ2=with LVc g q γρ=2 with the capillary length gLVργξ=being the lateral correlation length characteristic for the liquid (on the order of mm)and a short-range cut-off on the scale of the molecule diameter a is needed to avoid divergence of C(Ζ)a q 22maxmin ==πλ with a q π=maxExample: ethanol-vapor interface, σ=6.9 Åx-ray reflectivity and longitudinal diffuse scattering x-ray transverse diffuse scatteringSanyal et al.; Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 628 (1991)Attention: in case of interfaces instead of surfaces the surface tension γLV is replaced by the interface tension γLL which is orders of magnitude smaller than the surface tension→ contribution of capillary waves to rms-roughness of interface increasedExample: Direct visual observation of thermal capillary waves at the free liquid-gas interface in a phase-separated colloid-polymer mixture imaged with laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) at four different state points approaching the critical point(2004) each image is 17.5 μm by 85 μmAarts et al. Science 304,847Simple liquid → polymer:For highly viscous liquids and polymer melts the capillary waves are overdamped, their amplitude reduced.While, in general, both damped and propagating modes exist, for highly viscous polymers all modes are overdamped, which can be characterized solely by relaxation times τ.physical meaning of the over-damped relaxation timeconstantSinha, University of CaliforniaRoughness measurements are time averaged and cannot reveal the dynamic behavior of the waves.→ Need to probe the dynamics!Experiments: XPCSExample: capillary wave dynamics on glycerol surfaces investigated with XPCS performed at grazing anglesnormalized time correlation function22)()()()(ttt I t I t I g ττ+=described by exponential behavior1exp )(002+⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛−=τττg g→ relaxation times τSeydel et al., Phys. Rev. B 63, 073409 (2001)The capillary wave is identified by its wave vector q and complex frequencyΓ+=i f p ωwhere the real part reflects the propagation frequency and the imaginary part the damping.At the transition from propagating to overdamped behavior f becomes purely imaginary; i.e., ωp =0.The transition from propagating (inelastic) to overdamped (quasielastic) behavior takes place at critical wave vector254ηργLV c q =with surface tension γLV , the dynamic viscosity η, and the density ρ of the polymerExample: Mixture of water and glycerol with 65% weight concentration of glycerolMadsen et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 096104 (2004)propagation frequency ωp (circles) and the dampingconstant Γ (squares) for the water -glycerol mixture at (a)30 °C and (b) 12 °C.8.8 Thin Film Preparation Techniques a) Solution-castingpreparation of thick polymer films (thickness from 100 nm to several μm)• polymer solution deposited on top of a horizontally oriented substrate• cover full substrate to have chance for uniform film if liquid is not spreading • solvent evaporates under controlled condition (T, p, atmosphere) → a solid film remains on the substrate→ allows for slow drying: films close to equilibrium can be preparedOn the scale of the capillary length the film at the substrate edges differs from the average film.Problems occur in case of pinning effects. If the contact line gets pinned during drying, no homogenous film is formed.Example: ternary blend PS, P αMS and PI cast from toluenePanagiotou, PhD Thesis TU Munich (2004)For complex fluids (highly viscous polymer solutions), the morphology is not determined by the evaporation process, the "coffee stain" effect but essentially by the capillary instabilities.Using the appropriate couple of polymer/solvent, a outward, inward or a lack of Marangoni flow in the droplets, leading to the formation of a rim, a drop or a uniform film, respectively, occurs.b) Spin-coatingpreparation of thin polymer films with thicknesses from 1 to 1000 nm• prepare polymer solution with desired concentration c • cover substrate entirely with polymer solution• select acceleration profile and spinning parameters (time, rotational speed) • start spin-coater after defined wait time → a solid film remains on the substrate→ due to non-equilibrium the film can have enrichment or lateral structuresDepending on rotational speed ω, concentration c, molecular weight Mw and apersonal parameter (wait time, person, machine)Attention: change in slope at entanglement concentration of solutionRuderer, PMB, Chem.Phys.Chem. 10, 664 (2009)Spin-coating is a complicated non-equilibrium processTheoretical description in the framework of a 3-step model (Lawrence, 1988) 1. step – start phasedeposition of solution with C 0 → strong height variationsacceleration of the substrate → most of the solution is flung-off the substrate → film thickness ≈100 μmEnd: Homogeneous film with thickness h 0 with concentration C 0 2. step – mass reduction by conventionevaporation can be neglected in comparison with the flow of solution towards to substrate edges → change of film thickness by convection2/102020341)(−⎟⎟⎠⎞⎜⎜⎝⎛+=t h h t h ηρω 3. step – evaporation of solvent through film surfaceevaporation rate of solvent larger than change in thickness by convection at a film thickness h w → mass reduction only by solvent evaporation, no polymer can leave the substrate anymore → dry, solid film remains()0,1s w f h h φ−=With the initial amount of solvent φs,0Polymer surface depends on the used solvent and on the spin-coating parameters:I: problems with solvents which have very high evaporation rate: → formation of skin on solution surface→ elastic film surface has a changed flow field of the confined polymer solution → hydrodynamic instabilities→ resulting lateral structures which have a star-shape with the center in the center of rotationII: problems with solvents which are hygroscopic and attract water from the surrounding, but are non miscible with water:→ demixing of both components (solvent and water) gives rise to lateral structuresMüller-Buschbaum et al.; Macromolecules 31, 3686 (1998)c) Floating-techniquepreparation of single and multiple polymer films (on non-wetable substrates)Schindler, Diploma Thesis TU Munich (2010)• scratch film with scalpel at 2 mm from substrate edge • put substrate into float box (tilt angle optimal at 10-15°) • add 2-3 drops of deionized water per second • remove substrate after film had decoupled• put second substrate with larger tilt angle into the water • fix polymer film on upper edge of this second substrate • remove water with 2-3 drops/sec • dry films (e.g. 4 h at 50°C)→ typically the needed time is 3-6 hours depending on the M w and film thickness→ not possible for all film thickness (thinner films are more difficult, integer number of R g can work), not possible for heat treated filmsProblems occur in case of wrinkle formation, incorporation of dust particles or trapping of water.Example: freely floating polymer film, tens of nanometers in thickness, wrinkles under the capillary force exerted by a drop of water placed on its surfaceThe wrinkling pattern is characterized by the number and length of the wrinkles.The PS film thickness h was varied from 31 to 233 nm. As the film is made thicker, the number of wrinkles N decreases (there are 111, 68, 49, and 31 wrinkles in these images).Huang et al.; Science 317, 650 (2007)d) Adsorption from solutiondeposition of single molecules, thin layers or thick films from solution with a controlled concentrationSketch:Adsorption is usually described through isotherms, that is, the amount of adsorbate on the adsorbent as a function of its pressure (if gas) or concentration (if liquid) at constant temperature.Isotherms are described bydifferent models:Langmuir isotherm (red) andBET isotherm (green)Computer simulation:Adsorption and self-assembly of linear polymers on smooth surfaces are studied using coarse-grained, bead-spring molecular models and Langevin dynamics computer simulations. The aim is to gain insight on atomic-force microscopy images of polymer films on mica surfaces, adsorbed from dilute solution following a good-solvent to bad-solvent quenching procedure.Chremos et al., Soft Matter5, 637 (2009)Molecular Weight Competition: Upon initial mixing of a formulation, all chains attempt to adsorb on a surface. For adsorbing homopolymers, thermodynamics dictates a preference for adsorption of long chains, and so short chains, originally adsorbed, are displaced form the surface at longer times.Santore+ Fu, Macromolecules 30, 8516 (1997)Fu + Santore, Macromolecules 31, 7014 (1998) Large scale industrial applications involving substantial quantities of complex fluids such as paints, inks, and coatings employ water soluble polymers with a broad distribution of molecular weights: The likelihood that some fraction of the added chains impart the desired interfacial properties means that changes in molecular weight distribution from batch to batch can dramatically impact the properties of a formulation.Experiments: Adsorption of polymers is very common in case of polyeletrolytes and used to build up multi-layers.Layer-by-Layer (LBL) assembly: fabrication of multilayers by consecutive adsorption of polyanions and polycationsDecher et al.; Science 277, 1232 (1997)Fine-tuning the film thickness by ionic strength (addition of salt yields thicker layers; polyanion from salt, polycation from pure water)Decher + Schmitt, Progr. Colloid Polym. Sci. 89, 160 (1992) A small list of polyions already used for multilayer fabrication:e) Spray coatingdeposition of thick films from solution with a controlled concentration, depending on deposition conditions (wet droplets = spraying, dry polymer = airbrush)control parameters: number of depositions, deposition time, solvent, polymer concentration, distance nozzle-surface。

掺镧锆钛酸铅陶瓷电致畴变过程中的相变

掺镧锆钛酸铅陶瓷电致畴变过程中的相变杨凤娟;程璇;张颖【摘要】Variations of the peak intensities of (002) and (200) diffraction peaks (I (002) , I (200) ) with the applied electric fields were studied by in-situ X-ray diffraction method during the applications of different electric fields on the unpoled lanthanum-doped lead zirconate titanate (PLZT) ceramics. Considering the distribution of domain orientation, the quantitative analyses of peak intensities of I(002) and I(200) were performed. Based on the multi-peak curve fitting to the in-situ XRD spectra, the effects of the applied electric fields on the electric-field-induced domain switching and phase transition were preliminarily discussed. The results show that the electric-field-induced 90° domain switching occurs in PLZT specimens under the applied electric fields, at the same time, the electric-field-induced phase transition from tetragonal to monoclinic could also happen. The electric-field-induced domain switching and phase transition occur competitively in different electric fields. The major process is domain switching, while the minor process is phase transition.%利用原位XRD技术研究未极化掺镧锆钛酸铅(PLZT)铁电陶瓷在不同直流电场加载过程中(002)和(200)衍射峰峰强与电场强度的关系,基于铁电畴取向分布的考虑,对(002)和(200)衍射峰峰强进行定量分析。

物理学专业英语

华中师范大学物理学院物理学专业英语仅供内部学习参考!2014一、课程的任务和教学目的通过学习《物理学专业英语》,学生将掌握物理学领域使用频率较高的专业词汇和表达方法,进而具备基本的阅读理解物理学专业文献的能力。

通过分析《物理学专业英语》课程教材中的范文,学生还将从英语角度理解物理学中个学科的研究内容和主要思想,提高学生的专业英语能力和了解物理学研究前沿的能力。

培养专业英语阅读能力,了解科技英语的特点,提高专业外语的阅读质量和阅读速度;掌握一定量的本专业英文词汇,基本达到能够独立完成一般性本专业外文资料的阅读;达到一定的笔译水平。

要求译文通顺、准确和专业化。

要求译文通顺、准确和专业化。

二、课程内容课程内容包括以下章节:物理学、经典力学、热力学、电磁学、光学、原子物理、统计力学、量子力学和狭义相对论三、基本要求1.充分利用课内时间保证充足的阅读量(约1200~1500词/学时),要求正确理解原文。

2.泛读适量课外相关英文读物,要求基本理解原文主要内容。

3.掌握基本专业词汇(不少于200词)。

4.应具有流利阅读、翻译及赏析专业英语文献,并能简单地进行写作的能力。

四、参考书目录1 Physics 物理学 (1)Introduction to physics (1)Classical and modern physics (2)Research fields (4)V ocabulary (7)2 Classical mechanics 经典力学 (10)Introduction (10)Description of classical mechanics (10)Momentum and collisions (14)Angular momentum (15)V ocabulary (16)3 Thermodynamics 热力学 (18)Introduction (18)Laws of thermodynamics (21)System models (22)Thermodynamic processes (27)Scope of thermodynamics (29)V ocabulary (30)4 Electromagnetism 电磁学 (33)Introduction (33)Electrostatics (33)Magnetostatics (35)Electromagnetic induction (40)V ocabulary (43)5 Optics 光学 (45)Introduction (45)Geometrical optics (45)Physical optics (47)Polarization (50)V ocabulary (51)6 Atomic physics 原子物理 (52)Introduction (52)Electronic configuration (52)Excitation and ionization (56)V ocabulary (59)7 Statistical mechanics 统计力学 (60)Overview (60)Fundamentals (60)Statistical ensembles (63)V ocabulary (65)8 Quantum mechanics 量子力学 (67)Introduction (67)Mathematical formulations (68)Quantization (71)Wave-particle duality (72)Quantum entanglement (75)V ocabulary (77)9 Special relativity 狭义相对论 (79)Introduction (79)Relativity of simultaneity (80)Lorentz transformations (80)Time dilation and length contraction (81)Mass-energy equivalence (82)Relativistic energy-momentum relation (86)V ocabulary (89)正文标记说明:蓝色Arial字体(例如energy):已知的专业词汇蓝色Arial字体加下划线(例如electromagnetism):新学的专业词汇黑色Times New Roman字体加下划线(例如postulate):新学的普通词汇1 Physics 物理学1 Physics 物理学Introduction to physicsPhysics is a part of natural philosophy and a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through space and time, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines, perhaps the oldest through its inclusion of astronomy. Over the last two millennia, physics was a part of natural philosophy along with chemistry, certain branches of mathematics, and biology, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 17th century, the natural sciences emerged as unique research programs in their own right. Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics and quantum chemistry,and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms of other sciences, while opening new avenues of research in areas such as mathematics and philosophy.Physics also makes significant contributions through advances in new technologies that arise from theoretical breakthroughs. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism or nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products which have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons; advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.Core theoriesThough physics deals with a wide variety of systems, certain theories are used by all physicists. Each of these theories were experimentally tested numerous times and found correct as an approximation of nature (within a certain domain of validity).For instance, the theory of classical mechanics accurately describes the motion of objects, provided they are much larger than atoms and moving at much less than the speed of light. These theories continue to be areas of active research, and a remarkable aspect of classical mechanics known as chaos was discovered in the 20th century, three centuries after the original formulation of classical mechanics by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) 【艾萨克·牛顿】.University PhysicsThese central theories are important tools for research into more specialized topics, and any physicist, regardless of his or her specialization, is expected to be literate in them. These include classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, electromagnetism, and special relativity.Classical and modern physicsClassical mechanicsClassical physics includes the traditional branches and topics that were recognized and well-developed before the beginning of the 20th century—classical mechanics, acoustics, optics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism.Classical mechanics is concerned with bodies acted on by forces and bodies in motion and may be divided into statics (study of the forces on a body or bodies at rest), kinematics (study of motion without regard to its causes), and dynamics (study of motion and the forces that affect it); mechanics may also be divided into solid mechanics and fluid mechanics (known together as continuum mechanics), the latter including such branches as hydrostatics, hydrodynamics, aerodynamics, and pneumatics.Acoustics is the study of how sound is produced, controlled, transmitted and received. Important modern branches of acoustics include ultrasonics, the study of sound waves of very high frequency beyond the range of human hearing; bioacoustics the physics of animal calls and hearing, and electroacoustics, the manipulation of audible sound waves using electronics.Optics, the study of light, is concerned not only with visible light but also with infrared and ultraviolet radiation, which exhibit all of the phenomena of visible light except visibility, e.g., reflection, refraction, interference, diffraction, dispersion, and polarization of light.Heat is a form of energy, the internal energy possessed by the particles of which a substance is composed; thermodynamics deals with the relationships between heat and other forms of energy.Electricity and magnetism have been studied as a single branch of physics since the intimate connection between them was discovered in the early 19th century; an electric current gives rise to a magnetic field and a changing magnetic field induces an electric current. Electrostatics deals with electric charges at rest, electrodynamics with moving charges, and magnetostatics with magnetic poles at rest.Modern PhysicsClassical physics is generally concerned with matter and energy on the normal scale of1 Physics 物理学observation, while much of modern physics is concerned with the behavior of matter and energy under extreme conditions or on the very large or very small scale.For example, atomic and nuclear physics studies matter on the smallest scale at which chemical elements can be identified.The physics of elementary particles is on an even smaller scale, as it is concerned with the most basic units of matter; this branch of physics is also known as high-energy physics because of the extremely high energies necessary to produce many types of particles in large particle accelerators. On this scale, ordinary, commonsense notions of space, time, matter, and energy are no longer valid.The two chief theories of modern physics present a different picture of the concepts of space, time, and matter from that presented by classical physics.Quantum theory is concerned with the discrete, rather than continuous, nature of many phenomena at the atomic and subatomic level, and with the complementary aspects of particles and waves in the description of such phenomena.The theory of relativity is concerned with the description of phenomena that take place in a frame of reference that is in motion with respect to an observer; the special theory of relativity is concerned with relative uniform motion in a straight line and the general theory of relativity with accelerated motion and its connection with gravitation.Both quantum theory and the theory of relativity find applications in all areas of modern physics.Difference between classical and modern physicsWhile physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability. Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match their predictions.Albert Einstein【阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦】contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with space-time and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light.Max Planck【普朗克】, Erwin Schrödinger【薛定谔】, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales.Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity.General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved space-time, with which highly massiveUniversity Physicssystems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.Research fieldsContemporary research in physics can be broadly divided into condensed matter physics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; particle physics; astrophysics; geophysics and biophysics. Some physics departments also support research in Physics education.Since the 20th century, the individual fields of physics have become increasingly specialized, and today most physicists work in a single field for their entire careers. "Universalists" such as Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and Lev Landau (1908–1968)【列夫·朗道】, who worked in multiple fields of physics, are now very rare.Condensed matter physicsCondensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic physical properties of matter. In particular, it is concerned with the "condensed" phases that appear whenever the number of particles in a system is extremely large and the interactions between them are strong.The most familiar examples of condensed phases are solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms. More exotic condensed phases include the super-fluid and the Bose–Einstein condensate found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials,and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spins on atomic lattices.Condensed matter physics is by far the largest field of contemporary physics.Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields. The term condensed matter physics was apparently coined by Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group—previously solid-state theory—in 1967. In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics of the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics.Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.Atomic, molecular and optical physicsAtomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter–matter and light–matter interactions on the scale of single atoms and molecules.1 Physics 物理学The three areas are grouped together because of their interrelationships, the similarity of methods used, and the commonality of the energy scales that are relevant. All three areas include both classical, semi-classical and quantum treatments; they can treat their subject from a microscopic view (in contrast to a macroscopic view).Atomic physics studies the electron shells of atoms. Current research focuses on activities in quantum control, cooling and trapping of atoms and ions, low-temperature collision dynamics and the effects of electron correlation on structure and dynamics. Atomic physics is influenced by the nucleus (see, e.g., hyperfine splitting), but intra-nuclear phenomena such as fission and fusion are considered part of high-energy physics.Molecular physics focuses on multi-atomic structures and their internal and external interactions with matter and light.Optical physics is distinct from optics in that it tends to focus not on the control of classical light fields by macroscopic objects, but on the fundamental properties of optical fields and their interactions with matter in the microscopic realm.High-energy physics (particle physics) and nuclear physicsParticle physics is the study of the elementary constituents of matter and energy, and the interactions between them.In addition, particle physicists design and develop the high energy accelerators,detectors, and computer programs necessary for this research. The field is also called "high-energy physics" because many elementary particles do not occur naturally, but are created only during high-energy collisions of other particles.Currently, the interactions of elementary particles and fields are described by the Standard Model.●The model accounts for the 12 known particles of matter (quarks and leptons) thatinteract via the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental forces.●Dynamics are described in terms of matter particles exchanging gauge bosons (gluons,W and Z bosons, and photons, respectively).●The Standard Model also predicts a particle known as the Higgs boson. In July 2012CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, announced the detection of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson.Nuclear Physics is the field of physics that studies the constituents and interactions of atomic nuclei. The most commonly known applications of nuclear physics are nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons technology, but the research has provided application in many fields, including those in nuclear medicine and magnetic resonance imaging, ion implantation in materials engineering, and radiocarbon dating in geology and archaeology.University PhysicsAstrophysics and Physical CosmologyAstrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the solar system, and related problems of cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth's atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared, ultraviolet, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Hubble's discovery that the universe was expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady state universe and the Big Bang.The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleo-synthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle (On a sufficiently large scale, the properties of the Universe are the same for all observers). Cosmologists have recently established the ΛCDM model (the standard model of Big Bang cosmology) of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy and dark matter.Current research frontiersIn condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity. Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. Particle accelerators have begun probing energy scales in the TeV range, in which experimentalists are hoping to find evidence for the super-symmetric particles, after discovery of the Higgs boson.Theoretical attempts to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity into a single theory1 Physics 物理学of quantum gravity, a program ongoing for over half a century, have not yet been decisively resolved. The current leading candidates are M-theory, superstring theory and loop quantum gravity.Many astronomical and cosmological phenomena have yet to be satisfactorily explained, including the existence of ultra-high energy cosmic rays, the baryon asymmetry, the acceleration of the universe and the anomalous rotation rates of galaxies.Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complexity, chaos, or turbulence are still poorly understood. Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sand-piles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.These complex phenomena have received growing attention since the 1970s for several reasons, including the availability of modern mathematical methods and computers, which enabled complex systems to be modeled in new ways. Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems.Vocabulary★natural science 自然科学academic disciplines 学科astronomy 天文学in their own right 凭他们本身的实力intersects相交,交叉interdisciplinary交叉学科的,跨学科的★quantum 量子的theoretical breakthroughs 理论突破★electromagnetism 电磁学dramatically显著地★thermodynamics热力学★calculus微积分validity★classical mechanics 经典力学chaos 混沌literate 学者★quantum mechanics量子力学★thermodynamics and statistical mechanics热力学与统计物理★special relativity狭义相对论is concerned with 关注,讨论,考虑acoustics 声学★optics 光学statics静力学at rest 静息kinematics运动学★dynamics动力学ultrasonics超声学manipulation 操作,处理,使用University Physicsinfrared红外ultraviolet紫外radiation辐射reflection 反射refraction 折射★interference 干涉★diffraction 衍射dispersion散射★polarization 极化,偏振internal energy 内能Electricity电性Magnetism 磁性intimate 亲密的induces 诱导,感应scale尺度★elementary particles基本粒子★high-energy physics 高能物理particle accelerators 粒子加速器valid 有效的,正当的★discrete离散的continuous 连续的complementary 互补的★frame of reference 参照系★the special theory of relativity 狭义相对论★general theory of relativity 广义相对论gravitation 重力,万有引力explicit 详细的,清楚的★quantum field theory 量子场论★condensed matter physics凝聚态物理astrophysics天体物理geophysics地球物理Universalist博学多才者★Macroscopic宏观Exotic奇异的★Superconducting 超导Ferromagnetic铁磁质Antiferromagnetic 反铁磁质★Spin自旋Lattice 晶格,点阵,网格★Society社会,学会★microscopic微观的hyperfine splitting超精细分裂fission分裂,裂变fusion熔合,聚变constituents成分,组分accelerators加速器detectors 检测器★quarks夸克lepton 轻子gauge bosons规范玻色子gluons胶子★Higgs boson希格斯玻色子CERN欧洲核子研究中心★Magnetic Resonance Imaging磁共振成像,核磁共振ion implantation 离子注入radiocarbon dating放射性碳年代测定法geology地质学archaeology考古学stellar 恒星cosmology宇宙论celestial bodies 天体Hubble diagram 哈勃图Rival竞争的★Big Bang大爆炸nucleo-synthesis核聚合,核合成pillar支柱cosmological principle宇宙学原理ΛCDM modelΛ-冷暗物质模型cosmic inflation宇宙膨胀1 Physics 物理学fabricate制造,建造spintronics自旋电子元件,自旋电子学★neutrinos 中微子superstring 超弦baryon重子turbulence湍流,扰动,骚动catastrophes突变,灾变,灾难heterogeneous collections异质性集合pattern formation模式形成University Physics2 Classical mechanics 经典力学IntroductionIn physics, classical mechanics is one of the two major sub-fields of mechanics, which is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces. The study of the motion of bodies is an ancient one, making classical mechanics one of the oldest and largest subjects in science, engineering and technology.Classical mechanics describes the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, as well as astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. Besides this, many specializations within the subject deal with gases, liquids, solids, and other specific sub-topics.Classical mechanics provides extremely accurate results as long as the domain of study is restricted to large objects and the speeds involved do not approach the speed of light. When the objects being dealt with become sufficiently small, it becomes necessary to introduce the other major sub-field of mechanics, quantum mechanics, which reconciles the macroscopic laws of physics with the atomic nature of matter and handles the wave–particle duality of atoms and molecules. In the case of high velocity objects approaching the speed of light, classical mechanics is enhanced by special relativity. General relativity unifies special relativity with Newton's law of universal gravitation, allowing physicists to handle gravitation at a deeper level.The initial stage in the development of classical mechanics is often referred to as Newtonian mechanics, and is associated with the physical concepts employed by and the mathematical methods invented by Newton himself, in parallel with Leibniz【莱布尼兹】, and others.Later, more abstract and general methods were developed, leading to reformulations of classical mechanics known as Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. These advances were largely made in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they extend substantially beyond Newton's work, particularly through their use of analytical mechanics. Ultimately, the mathematics developed for these were central to the creation of quantum mechanics.Description of classical mechanicsThe following introduces the basic concepts of classical mechanics. For simplicity, it often2 Classical mechanics 经典力学models real-world objects as point particles, objects with negligible size. The motion of a point particle is characterized by a small number of parameters: its position, mass, and the forces applied to it.In reality, the kind of objects that classical mechanics can describe always have a non-zero size. (The physics of very small particles, such as the electron, is more accurately described by quantum mechanics). Objects with non-zero size have more complicated behavior than hypothetical point particles, because of the additional degrees of freedom—for example, a baseball can spin while it is moving. However, the results for point particles can be used to study such objects by treating them as composite objects, made up of a large number of interacting point particles. The center of mass of a composite object behaves like a point particle.Classical mechanics uses common-sense notions of how matter and forces exist and interact. It assumes that matter and energy have definite, knowable attributes such as where an object is in space and its speed. It also assumes that objects may be directly influenced only by their immediate surroundings, known as the principle of locality.In quantum mechanics objects may have unknowable position or velocity, or instantaneously interact with other objects at a distance.Position and its derivativesThe position of a point particle is defined with respect to an arbitrary fixed reference point, O, in space, usually accompanied by a coordinate system, with the reference point located at the origin of the coordinate system. It is defined as the vector r from O to the particle.In general, the point particle need not be stationary relative to O, so r is a function of t, the time elapsed since an arbitrary initial time.In pre-Einstein relativity (known as Galilean relativity), time is considered an absolute, i.e., the time interval between any given pair of events is the same for all observers. In addition to relying on absolute time, classical mechanics assumes Euclidean geometry for the structure of space.Velocity and speedThe velocity, or the rate of change of position with time, is defined as the derivative of the position with respect to time. In classical mechanics, velocities are directly additive and subtractive as vector quantities; they must be dealt with using vector analysis.When both objects are moving in the same direction, the difference can be given in terms of speed only by ignoring direction.University PhysicsAccelerationThe acceleration , or rate of change of velocity, is the derivative of the velocity with respect to time (the second derivative of the position with respect to time).Acceleration can arise from a change with time of the magnitude of the velocity or of the direction of the velocity or both . If only the magnitude v of the velocity decreases, this is sometimes referred to as deceleration , but generally any change in the velocity with time, including deceleration, is simply referred to as acceleration.Inertial frames of referenceWhile the position and velocity and acceleration of a particle can be referred to any observer in any state of motion, classical mechanics assumes the existence of a special family of reference frames in terms of which the mechanical laws of nature take a comparatively simple form. These special reference frames are called inertial frames .An inertial frame is such that when an object without any force interactions (an idealized situation) is viewed from it, it appears either to be at rest or in a state of uniform motion in a straight line. This is the fundamental definition of an inertial frame. They are characterized by the requirement that all forces entering the observer's physical laws originate in identifiable sources (charges, gravitational bodies, and so forth).A non-inertial reference frame is one accelerating with respect to an inertial one, and in such a non-inertial frame a particle is subject to acceleration by fictitious forces that enter the equations of motion solely as a result of its accelerated motion, and do not originate in identifiable sources. These fictitious forces are in addition to the real forces recognized in an inertial frame.A key concept of inertial frames is the method for identifying them. For practical purposes, reference frames that are un-accelerated with respect to the distant stars are regarded as good approximations to inertial frames.Forces; Newton's second lawNewton was the first to mathematically express the relationship between force and momentum . Some physicists interpret Newton's second law of motion as a definition of force and mass, while others consider it a fundamental postulate, a law of nature. Either interpretation has the same mathematical consequences, historically known as "Newton's Second Law":a m t v m t p F ===d )(d d dThe quantity m v is called the (canonical ) momentum . The net force on a particle is thus equal to rate of change of momentum of the particle with time.So long as the force acting on a particle is known, Newton's second law is sufficient to。

新能源材料性质的全量子模拟

Prof. C. Pickard

Prof. R. Needs

陈基同学

…… 各位大家!

问题一: 金属与水的界面

Structural properties of the overlayer at 160 K

问题二: 核量子效应对氢键强弱的影响

Impact of quantum nuclear effects on H-bond strength?

Density function of a quantum system

第二部分: 金属与水的界面

Water-metal interface is an important issue at the core of several fields Corrosion Electrochemistry Catalysis Excess proton in liquid water +

In 1950s, Ubbelohde effect (replace H with D) in H-bonded crystals.

Liquids: water structure is weakened, and liquid HF is strengthened Clusters: (HF)n when n > 4, strengthened, otherwise, weakened; (H2O)n always weakened Biggest question: is there a unified picture?

Rule of Thumb

问题二: 核量子效应对氢键强弱的影响

Flexible monomer with anharmonic potential must be used if one want to use force-field method in PIMD simulations

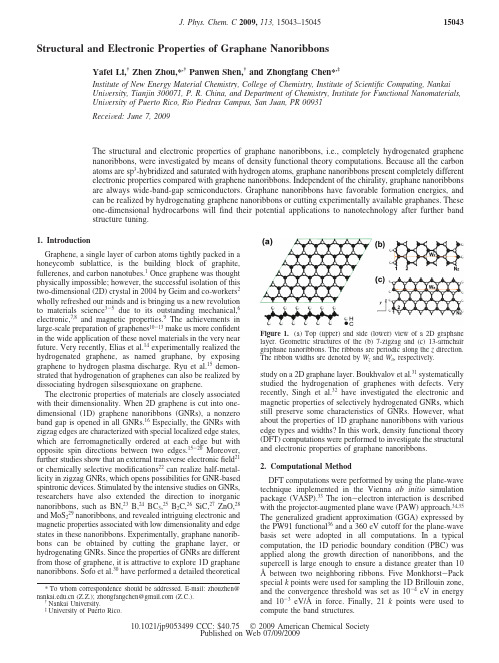

Structural and Electronic Properties of Graphane Nanoribbons

Structural and Electronic Properties of Graphane NanoribbonsYafei Li,†Zhen Zhou,*,†Panwen Shen,†and Zhongfang Chen*,‡Institute of New Energy Material Chemistry,College of Chemistry,Institute of Scientific Computing,NankaiUni V ersity,Tianjin300071,P.R.China,and Department of Chemistry,Institute for Functional Nanomaterials,Uni V ersity of Puerto Rico,Rio Piedras Campus,San Juan,PR00931Recei V ed:June7,2009The structural and electronic properties of graphane nanoribbons,i.e.,completely hydrogenated graphenenanoribbons,were investigated by means of density functional theory computations.Because all the carbonatoms are sp3-hybridized and saturated with hydrogen atoms,graphane nanoribbons present completely differentelectronic properties compared with graphene nanoribbons.Independent of the chirality,graphane nanoribbonsare always wide-band-gap semiconductors.Graphane nanoribbons have favorable formation energies,andcan be realized by hydrogenating graphene nanoribbons or cutting experimentally available graphanes.Theseone-dimensional hydrocarbons willfind their potential applications to nanotechnology after further bandstructure tuning.1.IntroductionGraphene,a single layer of carbon atoms tightly packed in ahoneycomb sublattice,is the building block of graphite,fullerenes,and carbon nanotubes.1Once graphene was thoughtphysically impossible;however,the successful isolation of thistwo-dimensional(2D)crystal in2004by Geim and co-workers2wholly refreshed our minds and is bringing us a new revolutionto materials science3-5due to its outstanding mechanical,6electronic,7,8and magnetic properties.9The achievements inlarge-scale preparation of graphenes10-13make us more confidentin the wide application of these novel materials in the very nearfuture.Very recently,Elias et al.14experimentally realized thehydrogenated graphene,as named graphane,by exposinggraphene to hydrogen plasma discharge.Ryu et al.15demon-strated that hydrogenation of graphenes can also be realized by dissociating hydrogen silsesquioxane on graphene.The electronic properties of materials are closely associated with their dimensionality.When2D graphene is cut into one-dimensional(1D)graphene nanoribbons(GNRs),a nonzero band gap is opened in all GNRs.16Especially,the GNRs with zigzag edges are characterized with special localized edge states, which are ferromagnetically ordered at each edge but with opposite spin directions between two edges.15-20Moreover, further studies show that an external transverse electronicfield21 or chemically selective modifications22can realize half-metal-licity in zigzag GNRs,which opens possibilities for GNR-based spintronic devices.Stimulated by the intensive studies on GNRs, researchers have also extended the direction to inorganic nanoribbons,such as BN,23B,24BC3,25B2C,26SiC,27ZnO,28 and MoS229nanoribbons,and revealed intriguing electronic and magnetic properties associated with low dimensionality and edge states in these nanoribbons.Experimentally,graphane nanorib-bons can be obtained by cutting the graphane layer,or hydrogenating GNRs.Since the properties of GNRs are different from those of graphene,it is attractive to explore1D graphane nanoribbons.Sofo et al.30have performed a detailed theoretical study on a2D graphane layer.Boukhvalov et al.31systematically studied the hydrogenation of graphenes with defects.Very recently,Singh et al.32have investigated the electronic and magnetic properties of selectively hydrogenated GNRs,which still preserve some characteristics of GNRs.However,what about the properties of1D graphane nanoribbons with various edge types and widths?In this work,density functional theory (DFT)computations were performed to investigate the structural and electronic properties of graphane nanoribbons.putational MethodDFT computations were performed by using the plane-wave technique implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package(VASP).33The ion-electron interaction is described with the projector-augmented plane wave(PAW)approach.34,35 The generalized gradient approximation(GGA)expressed by the PW91functional36and a360eV cutoff for the plane-wave basis set were adopted in all computations.In a typical computation,the1D periodic boundary condition(PBC)was applied along the growth direction of nanoribbons,and the supercell is large enough to ensure a distance greater than10Åbetween two neighboring ribbons.Five Monkhorst-Pack special k points were used for sampling the1D Brillouin zone, and the convergence threshold was set as10-4eV in energy and10-3eV/Åin force.Finally,21k points were used to compute the band structures.*To whom correspondence should be addressed.E-mail:zhouzhen@ (Z.Z.);zhongfangchen@(Z.C.).†Nankai University.‡University of PuertoRico.Figure1.(a)Top(upper)and side(lower)view of a2D graphanelayer.Geometric structures of the(b)7-zigzag and(c)13-armchairgraphane nanoribbons.The ribbons are periodic along the z direction.The ribbon widths are denoted by W z and W a,respectively.J.Phys.Chem.C2009,113,15043–150451504310.1021/jp9053499CCC:$40.75 2009American Chemical SocietyPublished on Web07/09/20093.Results and Discussion3.1.2D Infinite Graphane Single Layer.We began our study with the 2D infinite graphane single layer.The most stable form of the graphane layer favors a chairlike conformation with hydrogen atoms alternating on both sides of the plane.30Thus,only the chairlike graphane layer and nanoribbons were considered in this work.Figure 1a presents the optimized structure of the graphane layer in a 6×6supercell,which includes 72carbon atoms and 72hydrogen atoms.The C -C bond length is 1.52Å,rather close to those in the sp 3-hybridized diamond (1.53Å),but longer than those in graphene with sp 2hybridization (1.42Å),in agreement with the expectation that all of the carbon atoms in graphane employ sp 3hybridization.The C -H bond length is uniformly 1.11Å.According to our DFT computations,the 2D graphane layer is a semiconductor with a direct band gap of 3.43eV at the Γpoint,which achieves good agreement with the previous finding of Sofo et al.,30but is much lower than the GW calculation value (5.4eV)reportedby Lebegue et al.,37since DFT usually underestimates band gaps;however,the basic physics should not be changed.3.2.Geometric Structures of Graphane Nanoribbons.Two types of graphane nanoribons can be obtained by cutting the optimized graphane layer with a zigzag or armchair edge.Figure 1shows two examples,7-zigzag (b)and 13-armchair (c)graphane nanoribbons,with respective widths of 20.34and 22.40Å.Following the convention of GNRs,15-19we define the ribbon parameter N as the number of zigzag chains for a zigzag ribbon and the number of dimer lines along the ribbon direction for an armchair ribbon.The edge carbon atoms are all saturated with H atoms to avoid the effects of dangling bonds;therefore,each C atom in the edges is bonded to two H atoms.After full relaxation,the sp 3-bonding networks are well kept at the edge regions of both 7-zigzag and 13-armchair graphane nanoribbons.The lengths of edge C -C (1.52Å)and C -H (1.11Å)bonds are equal to those inner C -C and C -H bonds.Note that both spin-unpolarized and spin-polarized computations were performed to determine the ground state of graphane nanorib-bons,and no energy difference was found.Thus,different from zigzag GNRs with a magnetic ground state,16-19graphane nanoribbons have a nonmagnetic ground state.Since the magnetism of GNRs is derived form the localized unpaired πstate,the disappearance of magnetism in graphane nanoribbons is attributed to the absence of an unpaired πstate as a result of sp 3hybridization of all of the carbon atoms.3.3.Electronic Properties of Graphane Nanoribbons.Figure 2presents the computed electronic band structures of 7-zigzag and 13-armchair graphane nanoribbons.These two nanoribbons are both semiconducting with a direct band gap of 3.82and 3.84eV,respectively.The valence and conduction band edge are both located at the Γpoint.The flat bands at the Fermi level associated with the edge states in zigzag GNRs are absent in 7-zigzag graphane nanoribbons.To get further insight,we computed the partial charge densities associated with the valence band maximum (VBM)and the conduction band minimum (CBM)of these two nanoribbons (Figure 2).For both 7-zigzag and 13-armchair graphane nanoribbons,the VBM mainly comes from the 2s2p-hybridized oribitals localized at the inner carbon atoms,while the CBM consists mainly of 1s electron states of the inner hydrogen atoms.Therefore,the electronic properties of graphane nanoribbons are predominantly determined by the inner carbon and hydrogen atoms.Edge atoms have no contribution to either VBM or CBM,which is quite different from GNRs and other inorganic nanoribbons.15-19,23-29All of the edge carbon atoms in graphane nanoribbons are completely saturated with H atoms;thus,the edge states are absent in graphanenanoribbons.Figure 2.Band structures (left)and charge densities of VBM (right lower)and CBM (right upper)for (a)7-zigzag and (b)13-armchair graphanenanoribbons.Figure 3.Variation of the band gap (a)and the formation energy (b)of zigzag (6e N z e 16)and armchair (10e N z e 27)graphane nanoribbons as a function of ribbon width.15044J.Phys.Chem.C,Vol.113,No.33,2009Li et al.Figure3a presents the variation of band gap as a function of ribbon width for a series of zigzag and armchair graphane nanoribbons.All of the graphane nanoribbons considered are semiconducting,and the band gap decreases monotonically with increasing ribbon width.Regardless of the chirality(zigzag or armchair),the graphane nanoribbons with similar widths have very close band gaps(Figure3a),which is vigorous evidence for the quantum confinement effect.3.4.Formation Energies of Graphane Nanoribbons.It is important to discuss the experimental preparation of graphane nanoribbons.Here,we evaluated the formation energy(E f), which is defined as E f)E C-x CµC-x HµH,where E C is the cohensive energy per atom of graphane nanoribbons and x i (i)C or H)is the molar fraction of the atom in the nanoribbons.µC is taken as the cohesive energy per atom of the graphene single layer,andµH is equal to the half binding energy of H2. This approach has been used to estimate the relative stability of GNRs with different chemical compositions.22,38The formation energy of both zigzag and armchair graphane nanoribbons increases monotonically with increasing ribbon width(Figure3b),which implies that narrow ribbons are more likely to form than those wider ones.The negative formation energies of all graphane nanoribbons considered here indicate that graphane nanoribbons are more stable than the experimen-tally available graphenes.However,favorable formation energies do not mean that we can get graphane nanoribbons by directly exposing GNRs to H2,since it is difficult to dissociate H2on GNRs.However,we can use hydrogen plasma or other H atom sources to transform GNRs to graphane nanoribbons,similar to the process of the formation of graphane,14or cut the experimentally available graphane layers in the same way of obtaining graphene ribbons.4.ConclusionIn summary,we have studied the structural and electronic properties of graphane nanoribbons with zigzag or armchair edges by DFT computations.Both zigzag and armchair nano-ribbons are semiconductors with wide direct band gaps.Since the band gap of graphane nanoribbons is determined by inner atoms instead of edge atoms,the band gap decreases monotoni-cally with increasing ribbon width due to the quantum confine-ment effect.Graphane nanoribbons have more favorable for-mation energies than experimentally available graphenes,and the formation energy increases with increasing ribbon width. Overall,graphane nanoribbons have quite promising applications in optics and opto-electronics due to the wide band gap.It is expected that chemical modifications may tune graphane nano-ribbons into p-or n-type semiconductors,which would widen the applications of this novel1D hydrocarbon. Acknowledgment.Support in China by NSFC(20873067) and NCET and in USA by NSF Grant CHE-0716718,the Institute for Functional Nanomaterials(NSF Grant0701525), and the US Environmental Protection Agency(EPA Grant No. RD-83385601)is gratefully acknowledged.References and Notes(1)Saito,R.;Dresselhaus,G.;Dresselhaus,M.S.Physical Properties of Carbon Nanotubes;Imperial College:London,1999.(2)Novoselov,K.S.;Geim,A.K.;Morozov,S.V.;Jiang,D.;Zhang, Y.;Dubonos,S.V.;Grigoreva,I.V.;Firsov,A.A.Science2004,306, 666.(3)Geim,A.K.;Novoselov,K.S.Nat.Mater.2007,6,183.(4)Rogers,J.A.Nat.Nanotechnol.2008,3,254.(5)Brumfiel,G.Nature2009,458,390.(6)Lee,C.G.;Wei,X.D.;Kysar,J.W.;Hone,J.Science2008,321, 385.(7)Zhang,Y.;Tan,Y.-W.;Stormer,H.L.;Kim,P.Nature2005,438, 201.(8)Ponomarenko,L.A.;Schdin,F.;Katsnelson,M.I.;Yang,R.;Hill,E.W.;Novoselov,K.S.;Geim,A.K.Science2008,320,324.(9)Kan,E.J.;Li,Z.Y.;Yang,J.L.Nano2009,3,433.(10)Kim,K.S.;Zhao,Y.;Jang,H.;Lee,S.Y.;Kim,J.M.;Kim,K.S.; Ahn,J.H.;Kim,P.;Choi,J.Y.;Hong,B.H.Nature2009,457,706.(11)Pan,Y.;Zhang,H.;Shi,D.;Sun,J.;Du,S.;Liu,F.;Gao,H.Ad V. Mater.2008,20,1.(12)Tung,V.C.;Allen,M.J.;Yang,Y.;Kaner,R.B.Nat.Nanotechnol. 2009,4,25.(13)Subrahmanyam,K.S.;Panchakarla,L.S.;Govindaraj,A.;Rao,C.N.R.J.Phys.Chem.C2009,113,4257.(14)Elias,D.C.;Nair,R.R.;Mohiuddin,T.M.G.;Morozov,S.V.; Blake,P.;Halsall,M.P.;Ferrari,A.C.;Boukhvalov,D.W.;Katsnelson, M.I.;Geim,A.K.;Novoselov,K.S.Science2009,323,610.(15)Ryu,S.M.;Han,M.Y.;Maultzsch,J.;Heinz,T.F.;Kim,P.; Steigerwald,M.L.;Brus,L.E.Nano Lett.2008,8,4597.(16)Son,Y.-W.;Cohen,M.L.;Louie,S.G.Phys.Re V.Lett.2006,97, 216803.(17)Fujita,M.;Wakabayashi,K.;Nakada,K.;Kusakabe,K.J.Phys. Soc.Jpn.1996,65,1920.(18)Nakada,K.;Fujita,M.;Dresselhaus,G.;Dresselhaus,M.S.Phys. Re V.B1996,54,17954.(19)Jiang,D.E.;Sumpter,B.G.;Dai,S.J.Chem.Phys.2007,127, 124703.(20)Castro Neto,H.;Guinea,F.;Peres,N.M.R.;Novoselov,K.S.; Geim,A.K.Re V.Mod.Phys.2009,81,109.(21)Son,Y.-W.;Cohen,M.L.;Louie,S.G.Nature(London)2006, 444,347.(22)Kan,E.J.;Li,Z.Y.;Yang,J.L.;Hou,J.G.J.Am.Chem.Soc. 2008,130,4224.(23)Park,C.-H.;Louie,S.G.Nano Lett.2008,8,2200.(24)Ding,Y.;Yang,X.;Ni,J.Appl.Phys.Lett.2008,93,043107.(25)Ding,Y.;Wang,Y.L.;Ni,J.Appl.Phys.Lett.2009,94,073111.(26)Wu,X.;Pei,Y.;Zeng,X.C.Nano Lett.2009,9,1577.(27)Sun,L.;Li,Y.F.;Li,Z.F.;Li,Q.X.;Zhou,Z.;Chen,Z.F.;Yang, J.L.;Hou,J.G.J.Chem.Phys.2008,129,174114.(28)Botello-Me´ndez,A.R.;Lo´pez-Urı´as,F.;Terrones,M.;Terrones,H.Nano Lett.2008,8,1562.(29)Li,Y.F.;Zhou,Z.;Zhang,S.B.;Chen,Z.F.J.Am.Chem.Soc. 2008,130,16739.(30)Sofo,J.O.;Chaudhari,A.S.;Barber,G.D.Phys.Re V.B2007, 75,153401.(31)(a)Boukhvalov,D.W.;Katsnelson,M.I.;Lichtenstein,A.I.Phys. Re V.B2007,77,035427.(b)Boukhvalov,D.W.;Katsnelson,M.I.Nano Lett.2008,8,4373.(32)Singh,A.K.;Yakobson,B.I.Nano Lett.2009,9,1540.(33)Kresse,G.;Hafner,J.Phys.Re V.B1994,49,14251.(34)Blo¨chl,P.E.Phys.Re V.B1994,50,17953.(35)Kresse,G.;Joubert,D.Phys.Re V.B1999,59,1758.(36)Perdew,J.P.;Wang,Y.Phys.Re V.B1992,45,13244.(37)Lebe`gue,S.;Klintenberg,M.;Eriksson,O.;Katsnelson,M.I.arXiv: 0903.0310.(38)Barone,V.;Hod,O.;Scuseria,G.E.Nano Lett.2006,6,2748. JP9053499Properties of Graphane Nanoribbons J.Phys.Chem.C,Vol.113,No.33,200915045。

不对称外磁场下两量子比特系统的几何相

不对称外磁场下两量子比特系统的几何相苏耀恒;陈爱民;王军;李跃文【摘要】研究了不对称旋转外磁场下具有 XXZ型海森堡相互作用的两量子比特系统的几何相。

考虑体系的绝热条件,利用数值模拟的方法得到量子比特系统的4个本征态的Berry相,研究了外加旋转磁场的极角以及量子比特之间相互作用的各向异性参数对4个本征态的Berry相的影响。

研究结果表明:当极角保持不变,各向异性参数由0增加至无穷大的过程中,系统的哈密顿量由一种极限下的含外场的 XX 模型经过中间的海森堡模型,逐渐演化为另外一种极限下的 Ising模型。

4个本征态的 Berry 相都有各自独特的变化规律,且极角越小几何相趋于稳定越快。

通过对系统 Berry相的研究,可以得到系统在不同参数区间对应的模型的转化,并对本征态的几何性质有更进一步的认识。

【期刊名称】《河南科技大学学报(自然科学版)》【年(卷),期】2017(038)002【总页数】5页(P79-83)【关键词】量子信息;两量子比特系统;几何相;海森堡相互作用【作者】苏耀恒;陈爱民;王军;李跃文【作者单位】西安工程大学理学院,陕西西安 710048;西安工程大学理学院,陕西西安 710048; 西安交通大学理学院,陕西西安 710049;西安工程大学理学院,陕西西安 710048;中航光电科技股份有限公司光电设备事业部,河南洛阳471000【正文语种】中文【中图分类】O469量子信息[1]是指在物理系统的量子态中所保存的物理信息。

量子信息最基本的单元是量子比特[2],这是一个二能级态的量子系统。

例如,光子的两个偏振方向、原子中电子的两个能级或者环路中电流的不同方向等,在测量时都可以很容易被区分开来。

量子系统的哈密顿量不仅决定了量子态的能级,更决定了这个物理系统的态随时间的演化情况。

在许多应用中,哈密顿量的物理参数都是由含时的外部或环境因素决定的,因而研究含时的哈密顿量在实际的物理领域中是很重要的。

兰姆波表征形状记忆合金相变试验

兰姆波表征形状记忆合金相变试验王开圣;赵志敏【摘要】通过求解薄板的兰姆波频散方程,绘制了NiTi形状记忆合金薄板的频散曲线,并根据频散曲线选择了对合金相变敏感的兰姆波模式。

利用PZT超声探头在合金薄板中激励并接收S1及S3模式的兰姆波,测量了温度变化时兰姆波的群速度。

研究结果表明,随着NiTi合金相变过程中微观组织结构的变化,兰姆波群速度明显改变,可以根据兰姆波群速度变化测量合金薄板的相变温度。

%By solving the lamb wave dispersion equation for NiTi sheet, the dispersion curves were drawn. Lamb modes more sensitive in detecting phase transformation of NiTi alloy were selected on the basis of the dispersion curves. PZT transducers were used to excite and receive S1 and Sa Lamb waves on NiTi sheet. The wave group speed was measured whente.mperature of NiTi sheet changed. The results showed that some marked changes were observed in the dependence of the group speed versus temperature during phase transformation and phase transformation temperature of NiTi sheet might be examined by the change of the group speed.【期刊名称】《无损检测》【年(卷),期】2012(034)001【总页数】4页(P7-9,26)【关键词】兰姆波检测;模式;群速度;形状记忆合金;相变【作者】王开圣;赵志敏【作者单位】南京航空航天大学理学院应用物理系,南京210016;南京航空航天大学理学院应用物理系,南京210016【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TG115.28NiTi形状记忆合金是工程和生物医学领域应用日益广泛的新材料,也作为敏感元件和驱动器应用在智能结构中,其独特的形状记忆效应和超弹性与其热弹性马氏体相变紧密相关,工程和科研上常用示差扫描量热仪(DSC)、电阻法及变温X射线衍射(XRD)等方法测量NiTi合金相变,然而这些方法仅能检测较小的样品,很难对板、管、棒等大工件进行无损检测。

用vasp计算硅的能带结构

用vasp计算硅的能带结构在最此次仿真之前,因为从未用过vasp软件,所以必须得学习此软件及一些能带的知识。

vasp是使用赝势和平面波基组,进行从头量子力学分子动力学计算的软件包。

用vasp计算硅的能带结构首先要了解晶体硅的结构,它是两个嵌套在一起的FCC布拉菲晶格,相对的位置为(a/4,a/4,a/4), 其中a=5.4A是大的正方晶格的晶格常数。

在计算中,我们采用FCC的原胞,每个原胞里有两个硅原子。

VASP计算需要以下的四个文件:INCAR(控制参数), KPOINTS(倒空间撒点), POSCAR(原子坐标), POTCAR(赝势文件)为了计算能带结构,我们首先要进行一次自洽计算,得到体系正确的基态电子密度。

然后固定此电荷分布,对于选定的特殊的K点进一步进行非自洽的能带计算。

有了需要的K点的能量本征值,也就得到了我们所需要的能带。

步骤一.—自洽计算产生正确的基态电子密度:以下是用到的各个文件样本:INCAR 文件:SYSTEM = SiStartparameter for this run:NWRITE = 2; LPETIM=F write-flag & timerPREC = medium medium, high lowISTART = 0 job : 0-new 1-cont 2-samecutICHARG = 2 charge: 1-file 2-atom 10-constISPIN = 1 spin polarized calculation?Electronic Relaxation 1NELM = 90; NELMIN= 8; NELMDL= 10 # of ELM stepsEDIFF = 0.1E-03 stopping-criterion for ELMLREAL = .FALSE. real-space projectionIonic relaxationEDIFFG = 0.1E-02 stopping-criterion for IOMNSW = 0 number of steps for IOMIBRION = 2 ionic relax: 0-MD 1-quasi-New 2-CGISIF = 2 stress and relaxationPOTIM = 0.10 time-step for ionic-motionTEIN = 0.0 initial temperatureTEBEG = 0.0; TEEND = 0.0 temperature during runDOS related values:ISMEAR = 0 ; SIGMA = 0.10 broadening in eV -4-tet -1-fermi 0-gausElectronic relaxation 2 (details)Write flagsLWAVE = T write WAVECARLCHARG = T write CHGCARVASP给INCAR文件中的很多参数都设置了默认值,所以如果你对参数不熟悉,可以直接用默认的参数值。

质子和原子核部分子分布函数的全局分析

摘要原子核是目前高能物理实验的一个重要研究对象。

在高能核物理实验中,原子核部分子分布函数是模拟计算各种高能反应的重要输入信息,在检验标准模型和探寻新物理的过程中起到关键作用。

本论文的目的就是通过对世界上各合作组的带电轻子-原子核(包括质子)的深度非弹性散射实验数据的QCD理论分析,来获取质子和原子核的部分子分布函数。

我们发布了质子的部分子分布函数数据库IMParton16,以及原子核的部分子分布函数数据库nIMParton16(nuclear IMParton)。

本研究包含三个主要内容。

(1)研究了核子内部部分子分布的起源问题。

我们成功地建立了夸克模型和高Q2下测量到的部分子分布之间的直接联系。

(2)研究了各种核介质效应对核子内部部分子分布的影响,以及各种核介质效应的核依赖关系。

(3)我们应用部分子重组效应修正的DGLAP方程对不同实验组的数据进行了全局χ2分析,并得到了质子和原子核的部分子分布函数。

关于部分子分布的起源问题,我们发展了动力学部分子模型,并把部分∼0.1GeV2。

在该初始标度下,我们实现子分布演化的初始标度降低到了Q2了最自然最简单的仅包含价夸克分布的非微扰输入,并且参数化非微扰输入用到的自由参数个数最少,仅有三个。

我们还发现核子内部还应存在一些超越夸克模型的少量的非微扰海夸克成分。

在核介质效应研究方面,我们计算了核子费米运动引起的原子核中核子结构函数的弥散效应,束缚核子变胖效果给出的EMC效应,以及原子核中部分子重组过程增强导致的核遮蔽效应。

我们首次发现了EMC效应的强弱与核子之间剩余强相互作用能量之间的显著的线性关联。

我们在部分子层次上系统地描述了核遮蔽效应、反遮蔽效应和EMC效应。

鉴于考虑了较为全面的核物理效应,我们全局拟合确定的原子核部分子分布函数更加准确,并且参数化核效应修正因子的核依赖关系和x依赖关系时使用的自由参数最少,仅有两个。

(与其他合作组的全局拟合相比,自由参数的个数几乎小一个数量级)。

原子错位堆栈增强双层MoS_(2)高次谐波产率

关键词:高次谐波, 双层 MoS2, 堆栈方式, 波长定标 PACS:42.65.Ky, 42.65.–k, 68.65.–k

DOI: 10.7498/aps.70.20210731

1 引 言

近十年来, 强激光与固体材料相互作用产生的 高次谐波辐射逐渐成为国际强场激光物理研究领 域重点研究的课题 [1−4]. 高次谐波研究的主要动 力来源于其极有潜力的应用前景. 利用高次谐波 辐射可以获得相干的、脉冲持续时间短的极紫外 (XUV) 光源和 X 射线源. 由于固体材料的介质密 度远大于气体靶, 同等激光条件下固体产生的高次 谐波转换效率高于气体. 在气体介质中, 高次谐波 主要由电子电离、回碰产生, 而对于固体材料, 其 高次谐波主要由带内电流和带间极化贡献. 最近, 实验上已经证明 [5−11], 强激光与固体材料相互作用 能够提供一种全新的手段产生高效率的高次谐波, 将有希望实现一种新型阿秒光源.

本文针对固体高次谐波的转换效率问题, 以双 层 MoS2 为例, 研究其在不同堆栈方式下的高次谐 波辐射特性, 理论模拟发现, 层间原子错位堆栈能 够有效打破晶体对称性, 使得原有的部分带间禁戒 跃迁被允许, 带间跃迁激发通道增加, 从而提升了 载流子跃迁概率及高次谐波转换效率洛赫方程 组的方法 (SBEs) 开展强激光与双层 MoS2 材料相 互作用的理论研究 [33]. 模拟过程中, 晶体倒格矢坐 标可在直角坐标系中表示为 x||G – M, y||G – K, 和 z||G – A (光轴), 线偏振激光的传播方向沿着光 轴方向. 在单电子近似下, 多能带半导体布洛赫方 程组可以写为

高次谐波转换效率要比 G–M 方向低很多 [34], 因此 在本工作中只关注双层 MoS2 材料在 G–M 方向的 高次谐波辐射. 此外, 图 1(d) 和 1(e) 分别为 AA 型堆栈和 T 型堆栈双层 MoS2 材料在 G–M 方向的 能带结构, 图中所示共 12 条价带和 8 条导带. 对 比双层 MoS2 在两种不同堆栈方式下的能带结构, 发现不管是带隙还是能带的色散分布都几乎保持 一致, 也就是说堆栈方式对其能带结构影响很小.

光电英语词汇(T1)