How to Read a Clinical trial paper

临床实验注册的英文版

临床实验注册的英文版Registration of Clinical Trials: English VersionIntroduction:Clinical trials play a crucial role in advancing medical knowledge and improving patient care. However, it is essential to ensure transparency and accountability in the conduct of these trials. The registration of clinical trials is a pivotal step, providing important information to researchers, healthcare professionals, and the public. In this article, we will discuss the significance of clinical trial registration and guidelines for registering trials in English.Importance of Clinical Trial Registration:1. Enhancing Transparency:Clinical trial registration serves as a means to enhance transparency in medical research. Registered trials provide detailed information about the study design, methods, interventions, and outcomes, enabling researchers to evaluate the robustness of the trial and replicate the findings if necessary.2. Prevention of Publication Bias:Registration of clinical trials helps to prevent publication bias, where only positive or statistically significant results are published, while negative or inconclusive results remain unpublished. By registering all trials, regardless of their outcomes, researchers and healthcare professionals gain access to a comprehensive database of trial information, enabling a more accurate assessment of the effectiveness and safety of interventions.3. Avoiding Duplication:Registered trials allow researchers to determine whether a specific research question has been previously addressed, avoiding unnecessary duplication of efforts. This ensures that resources are effectively utilized, maximizing the impact of clinical research.4. Protecting Research Participants:Clinical trial registration helps to protect research participants by providing an overview of ongoing trials. Potential participants can review the registered trials to assess whether they may be eligible to participate, further emphasizing the principles of informed consent and patient autonomy.Guidelines for Registering Clinical Trials in English:1. Choose a Recognized Registry:Select a reputable clinical trial registry that is compliant with international standards. The World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) is a widely recognized example. Ensure that the selected registry allows registration of your trial in the English language.2. Provide Detailed Trial Information:When registering your clinical trial in English, it is essential to provide comprehensive information to facilitate clear understanding. The following details should be included:a. Trial Identification: Register a unique trial identification number to distinguish your trial from others.b. Title and Acronym: Provide a concise and informative title for your trial, along with any relevant acronyms.c. Study Design: Describe the study design, including the type of trial (e.g., randomized controlled trial, observational study), allocation, blinding, and any special considerations (e.g., crossover design).d. Interventions: Clearly specify the interventions being evaluated, including the dosage, duration, and administration details.e. Participants: Describe the target population and eligibility criteria for enrollment, including age range, gender, and any specific medical conditions or previous treatments required or excluded.f. Outcomes: List the primary and secondary outcomes that will be measured in the trial, along with the relevant assessment methods.g. Ethics and Informed Consent: Detail the ethical considerations involved in the trial, including ethical review board approval and informed consent procedures.h. Funding and Sponsorship: Disclose any financial support or sponsorship received for the trial.i. Contact Information: Provide contact details for the principal investigator or study coordinator for inquiries or collaborations.3. Regularly Update Trial Information:As the trial progresses, ensure to update the registered information promptly. Any modifications or amendments to the trial protocol should beduly recorded. Regular updates will provide accurate and up-to-date information to interested parties.Conclusion:Clinical trial registration in the English language is essential to promote transparency, prevent publication bias, avoid duplication of efforts, and protect research participants. Following guidelines for registering trials in English, such as choosing a recognized registry and providing detailed trial information, ensures a comprehensive and useful database for researchers, healthcare professionals, and the public. By adhering to the principles of clinical trial registration, we facilitate the advancement of medical knowledge and contribute to improved patient care.。

临床实验报告英文

Title: Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of a New Antihypertensive Drug in Patients with Essential HypertensionIntroduction:Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a common chronic condition affecting millions of people worldwide. It is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. The aim of this clinical trial was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a new antihypertensive drug, Drug X, in patients with essential hypertension.Materials and Methods:Study Design:This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial. The study duration was 12 weeks.Participants:A total of 200 patients with essential hypertension were enrolled in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows:1. Age between 18 and 70 years2. Diagnosed with essential hypertension according to the American Heart Association guidelines3. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 m mHg at baseline4. Willingness to comply with the study protocolExclusion Criteria:1. Patients with secondary hypertension or other cardiovascular diseases2. Patients with a history of allergic reactions to the study drug orits active ingredients3. Patients on concurrent antihypertensive medications4. Patients with severe liver or kidney dysfunction5. Pregnant or lactating womenRandomization and Blinding:Participants were randomly assigned to two groups: the Drug X group and the placebo group. The randomization process was performed using a computer-generated randomization list. Both the participants and the investigators were blinded to the treatment allocation.Interventions:The participants in the Drug X group received Drug X at a dose of 10 mg once daily, while the participants in the placebo group received a matching placebo. All participants continued their baseline antihypertensive therapy throughout the study.Outcome Measures:The primary outcome measure was the change in SBP and DBP from baseline to the end of the study. Secondary outcome measures included the proportion of participants achieving blood pressure control (SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg), the incidence of adverse events, and the changes in laboratory parameters.Data Analysis:The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. The primary and secondary outcome measures were compared between the two groups using the independent t-test or chi-square test, as appropriate. The safety analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, and adverse events were categorized based on the World Health Organization's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).Results:Of the 200 enrolled participants, 191 completed the study. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. At the end of the study, the mean change in SBP from baseline was -15.2 mmHg in the Drug Xgroup and -8.5 mmHg in the placebo group (p < 0.001). The mean change in DBP from baseline was -9.8 mmHg in the Drug X group and -5.2 mmHg in the placebo group (p < 0.001). The proportion of participants achieving blood pressure control was 78% in the Drug X group and 38% in the placebo group (p < 0.001).The incidence of adverse events was similar between the two groups, with the most common being dizziness, headache, and nausea. All adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and resolved without any intervention.Conclusion:The results of this clinical trial demonstrate that Drug X is an effective and safe antihypertensive agent in patients with essential hypertension. The drug significantly reduced SBP and DBP, leading to a higher proportion of participants achieving blood pressure control. The adverse event profile was favorable, with no significant differences between the Drug X group and the placebo group.Recommendations:Based on the findings of this study, Drug X can be considered as a potential treatment option for patients with essential hypertension. Further research is needed to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of the drug in a larger population.Authors' Contributions:- Author 1: Conceived and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.- Author 2: Contributed to the study design, analyzed the data, and reviewed the manuscript.- Author 3: Provided statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript.Conflict of Interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.Funding:This study was funded by [Funding Source Name].Ethical Approval:The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board [IRB Name] and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.Acknowledgments:We thank the participants for their contribution to this study.References:- [List of references]。

学习临床试验常见英文

学习临床试验常见英文展开全文临床试验常见英文缩写ADR(Adverse drug reaction)不良反应AE(Adverse event)不良事件SAE(Serious Adverse Event)严重不良事件CRF(Case report form/case record form)病例报告表CRO(Contract research organization)合同研究组织EC(Ethics Committee)伦理委员会GCP(Good clinical practice)药品临床试验管理规范EDC(Electronic data capture)电子数据采集IB(Investigator's Brochure)研究者手册ND (Not Done) 未做NA (Not Applicable) 不适用UK (Unknown) 未知PI(Principal investigator )主要研究者Sub-I(Sub-investigator) 助理研究者QA(Quality assurance) 质量保证QC(Quality control) 质量控制SDV(Source data verification)原始资料核对SD(Source data)原始数据SD(Source document ) 原始文件SFDA 国家食品药品监督管理局SOP(Standard operating procedure) 标准操作规程IRB 机构审查委员会ICF(Informed Consent Form) 知情同意书TMF(trial master file)研究管理文件夹临床试验常见英文单词A· Active control ,AC 阳性对照,活性对照阳性对照,活性对照· Adverse drug reaction ,ADR 药物不良反应药物不良反应· Adverse event ,AE 不良事件· Approval 批准· Assistant investigator 助理研究者· Audit 稽查· Audit report 稽查报告· Auditor 稽查员B· Bias 偏性,偏倚· Blank control 空白对照· Blinding/masking 盲法,设盲· Block 层C· Case history 病历· Case report form/case record form ,CRF 病例报告表,病例记录表· Clinical study 临床研究· Clinical trial 临床试验· Clinical trial application ,CTA 临床试验申请· Clinical trial exemption ,CTX 临床试验免责· Clinical trial protocol ,CTP 临床试验方案· Clinical trial/study report 临床试验报告· COA(药品检测报告)· Co-investigator 合作研究者· Comparison 对照· Compliance 依从性· Computer-assisted trial design ,CATD 计算机辅助试验设计· Contract research organization ,CRO 合同研究组织· Co ntract/agreement 协议/合同· Coordinating committee 协调委员会· Coordinating investigator 协调研究者· Cross-over study 交叉研究· Cure 痊愈· CTRB 临床试验文件夹D· Documentation 记录/文件· Dose-reaction relation 剂量—反应关系· Double blinding 双盲· Double dummy technique 双盲双模拟技术E· Elec tronic data capture ,EDC 电子数据采集系统· Electronic data processing ,EDP 电子数据处理系统· Endpoint criteria/measurement 终点指标· Essential documentation 必需文件· Excellent 显效· Exclusion criteria 排除标准F· Failure 无效,失败· Final report 总结报告· Final point 终点· Forced titration 强制滴定G&H· Global 全球· Generic drug 通用名药· Good clinical practice ,GCP 药物临床试验质量管理规定· Good manufacture practice ,GMP 药品生产质量管理规范· Good non-clinical laboratory practice ,GLP 药物非临床研究质量管理规范· Health economic evaluation ,HEV 健康经济学评价· Hypothesis test ing 假设检验I· Improvement 好转· Inclusion criteria 入选标准· Independent ethics committee ,IEE 独立伦理委员会· Information gathering 信息收集· Informed consent form ,ICF 知情同意书· Informed consent ,IC 知情同意· Initial meeting 启动会议· Inspection 视察/检查· Institution inspection机构检查· Institutional review board ,IBR 机构审查委员会· Intention to treat 意向治疗· Interactive voice response system ,IVRS 互动式语音应答系统· International Conference on Harmonization ,ICH 国际协调会议· Investigational new drug ,IND 新药临床研究· Investigational product 试验药物· In vestigator 研究者· Investigator’s brochure ,IB 研究者手册L· Local 局部M&N· Marketing approval/authorization 上市许可证· Matched pair 匹配配对· Monitor 监查员· Monitoring 监查· Monitoring report 监查报告· Multi-center trial 多中心试验· New chemical entity ,NCE 新化学实体· New drug a pplication ,NDA 新药申请· Non-clinical study 非临床研究O· Obedience 依从性· Optional titration 随意滴定· Original medical record 原始医疗记录· Outcome 结果· Outcome assessment 结果指标评价· Outcome measurement 结果指标P· Patient file 病人指标· Patient history 病历· Placebo 安慰剂· Placebo control 安慰剂对照· Preclinical study 临床前研究· Principle investigator ,PI 主要研究者· Product license ,PL 产品许可证· Protocol 试验方案· Protocol amendment 方案补正Q&R· Quality assurance ,QA 质量保证· Quality assurance unit ,QAU 质量保证部门· Quality control ,QC 质量控制· Rand omization 随机· Regulatory authorities ,RA 监督管理部门· Replication 可重复· Run in 准备期S· Sample size 样本量,样本大小· Serious adverse event ,SAE 严重不良事件· Serious adverse reaction ,SAR 严重不良反应· Seriousness 严重性· Severity 严重程度· Simple randomization 简单随机· Single blind ing 单盲· Site audit 试验机构稽查· Source data ,SD 原始数据· Source data verification ,SDV 原始数据核准· Source document ,SD 原始文件· Sponsor 申办者· Sponsor-investigator 申办研究者· Standard operating procedure ,SOP 标准操作规程· Statistical analysis plan ,SAP 统计分析计划· Study audit 研究稽查· Subgroup 亚组· Sub-investigator 助理研究者· Subject 受试者· Subject diary 受试者日记· Subject enrollment 受试者入选· Subject enrollment log 受试者入选表· Subject identification code ,SIC 受试者识别代码· Subject recruitment 受试者招募· Subject screening log 受试者筛选表· System audit 系统稽查T&U· Trial error 试验误差· Trial master file 试验总档案· Trial objective 试验目的· Trial site 试验场所· Triple blinding 三盲· Unblinding 破盲· Unexpected adverse event ,UAE 预料外不良事件V&W· Variability 变异· Visual analogy scale 直观类比打分法· Vulnerable subject 弱势受试者· Wash-out 清洗期· Well-being 福利,健康EDC 系统常见英文缩写· 1.SCR (screening) 筛选· 2.DOV (date of visit) 访视第一天· 3.ELIG ( ELIGIBILITY ) 入排合格· 4.DEM ( DEMOGRAPHY )人口统计学· 5.MEDSX (medical history) 既往史· MHX1 : CANCER RELATED CURRENT MEDICAL CONDITIONS 该肿瘤手术史及肿瘤相关症状· MHX2 : NON-CANCER RELATED MEDICAL CONDITIONS· 与该肿瘤无关的病史· 6.VS /VITALS ( VITAL SIGNS ) 生命体征· 7.ECOG/PS 体能评分 note:后面具体讲解· 8. ECG : 12-LEAD ECG 心电图· 9. ECHO ( ECHOCARDIOGRAM ) 超声心动图· 10. HAEMA ( LOCAL LABORATORY – HAEMATOLOGY )血常规· 11. CHEM ( LOCAL L ABORATORY – CLINICAL CHEMISTRY )血生化· 12. URIN ( urine ) 尿常规· 13. C1 ( Cycle1 ) 第一周期· 14. WD : End of Therapy/DISCONTINUATION 结束治疗(停止用药)· 15. FU ( Follow-up ) 随访· 16.CMED( CONCOMITANT MEDICATIONS ) 伴随药物· 17. AE ( NON-SERIOUS ADVERSE EVENTS ) 不良事件· 18. SAE ( SERIOUS ADVERSE EVENTS ) 严重不良事件· 19. EOS( End of Study ) 结束研究:肿瘤以病人死亡事件为准· 20. UNS ( Unscheduled Visit ) 不预期访问· 21.ND (Not Done) 未做· 22. NA (Not Applicable) 不适用· (Unknown) 未知临床试验常见语句描述一. 临床试验过程描述1)一般描述:1. Subject was diagnosed with XX in September, 2010, and had XX surgery in December, 2010.患者于 2010 年 9 月确诊 XX 疾病,于 2010 年 12 月行 XX 术。

临床试验英文方案模板

临床试验英文方案模板Title: Clinical Trial English Protocol TemplateIntroduction:Clinical trials play a crucial role in the development and evaluation of new medical interventions, ranging from drugs to medical devices. An effective clinical trial protocol serves as a blueprint for the entire study, outlining the objectives, design, methodology, and analysis plan. This article aims to provide a comprehensive template for an English clinical trial protocol, ensuring clarity, consistency, and adherence to international standards.1. Title and Abstract:1.1 Title: Provide a concise and informative title that reflects the study's purpose.1.2 Abstract: Summarize the study's background, objectives, methods, and expected outcomes.2. Introduction:2.1 Background and Rationale: Describe the scientific and clinical basis for the study, highlighting the need for the intervention being investigated.2.2 Study Objectives: Clearly state the primary and secondary objectives of the study, including any exploratory or safety endpoints.3. Study Design:3.1 Study Type: Identify the study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial, observational study, etc.).3.2 Study Setting: Specify the study location(s) and the characteristics of the study population.3.3 Sample Size Calculation: Explain the rationale and methodology used to determine the sample size required to achieve study objectives.3.4 Randomization and Blinding: Describe the randomization process and any blinding procedures implemented.3.5 Data Collection and Management: Detail the data collection methods, data management procedures, and quality control measures.4. Participants:4.1 Inclusion Criteria: Clearly define the characteristics that potential participants must possess to be eligible for the study.4.2 Exclusion Criteria: Identify the characteristics that would exclude potential participants from the study.4.3 Recruitment and Informed Consent: Describe the recruitment strategies and the process for obtaining informed consent from participants.5. Intervention:5.1 Study Treatment: Provide a detailed description of the investigational intervention, including dosage, administration route, and frequency.5.2 Comparator: If applicable, describe the control group or the standard treatment against which the intervention will be compared.5.3 Concomitant Medications: Specify any allowed or prohibited concomitant medications during the study period.6. Study Outcomes:6.1 Primary Outcome(s): Clearly define the primary outcome(s) and the methodology for assessing them.6.2 Secondary Outcome(s): List and describe any secondary outcomes, including their assessment methods.6.3 Safety Measures: Explain the procedures for monitoring and reporting adverse events or safety concerns.7. Statistical Analysis:7.1 Data Analysis Plan: Provide a detailed description of the statistical methods that will be used to analyze the data.7.2 Interim Analysis: Specify any planned interim analyses, including stopping rules for efficacy or safety.7.3 Handling of Missing Data: Describe the approach to handling missing data in the analysis.8. Ethical Considerations:8.1 Institutional Review Board (IRB): State that the study will be conducted in compliance with the local IRB and ethical guidelines.8.2 Informed Consent: Explain how the informed consent process will be carried out, ensuring participant autonomy and privacy.8.3 Data Protection: Outline the measures taken to protect the confidentiality and integrity of participant data.9. Study Timeline:9.1 Study Duration: Estimate the overall duration of the study, including participant recruitment, intervention, and follow-up.9.2 Study Milestones: Provide a timeline for key study milestones, such as the start and completion of data collection and analysis.10. Dissemination of Results:10.1 Publication Policy: Describe the plan for disseminating study results, including the intended target audience and the timeline for publication.10.2 Authorship: Define the criteria for authorship and the process for assigning authorship on study publications.Conclusion:A well-designed clinical trial protocol is essential for conducting rigorous and ethical research. By following this template, researchers can ensure consistency and transparency in their clinical trial protocols, facilitating the evaluation and replication of study findings. It is crucial to adapt the template to the specific requirements and guidelines of thestudy's regulatory authority and ethical committee.。

临床试验英文术语

临床试验英文术语English: A clinical trial is a research study conducted to evaluate a potential new treatment or intervention for a particular medical condition. The purpose of a clinical trial is to gather data on the safety and effectiveness of the treatment in a controlled and regulated environment. Clinical trials are typically divided into four phases, with each phase serving a different purpose in the evaluation process. Phase I trials focus on determining the safety and dosage of the treatment, while Phase II trials examine the preliminary effectiveness of the treatment. Phase III trials compare the new treatment to existing standard treatments, and Phase IV trials are conducted after the treatment has been approved for use to gather additional information on long-term effects and optimal use.Translated content: 临床试验是一项研究,旨在评估对特定医疗条件的潜在新治疗或干预措施。

药物临床试验紧急破盲的流程

药物临床试验紧急破盲的流程英文回答:Emergency Unblinding of a Clinical Trial.Emergency unblinding of a clinical trial is the process of revealing the treatment assignment of a participant before the end of the trial. This is typically done when there is a serious adverse event (SAE) or other safety concern that requires immediate medical intervention.The decision to unblind a clinical trial is made by the study sponsor in consultation with the study investigators and the regulatory authorities. The sponsor must submit a request to the regulatory authorities explaining the reason for the unblinding and the steps that will be taken to protect the integrity of the trial.Once the regulatory authorities have approved the request, the study investigators will unblind theparticipant's treatment assignment and provide the necessary medical care. The participant will also be informed of their treatment assignment and the reason for the unblinding.Emergency unblinding can have a significant impact on the integrity of a clinical trial. It can lead to bias in the results and make it difficult to interpret the data. Therefore, it is important to only unblind a clinical trial when there is a clear and compelling safety concern.中文回答:药物临床试验紧急破盲流程。

专业英语Section II

This approach to drug discovery is sometimes referred to as structure-based drug design. The first unequivocal(明确的) example of the application of structure-based drug design leading to an approved drug is the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor ( 碳 酸 酐 酶 抑 制 剂 ) dorzolamide(多佐胺)which was approved in 1995.

Drug Design

Drug design is the approach of finding drugs by design, based on their biological targets. Typically a drug target is a key molecule involved in a particular metabolic(代谢)or signalling pathway (信号通路) that is specific to a disease condition or pathology ( 病 理 ) , or to the infectivity or survival of a microbial pathogen(病原体).

The activity of a drug at its binding site is one part of the design. Another to take into account is the molecule’s druglikeness (类药性), which summarizes the necessary physical properties for effective absorption. One way of estimating druglikeness is Lipinski's Rule of Five (类药5规则).

医学文献深度阅读的方法

文文献阅读举例例

临床研究的类型 ! 随机对照临床试验(Randomized Clinical Trial, RCT) ! 病例例对照研究(Case-control Study) ! 队列列研究(Cohort Study) ! Meta分析(Meta-analysis)

病例例对照研究 (Case-control Studies)

用用减少样本数的

SI:正常对照组明

Bergman最小小模型技术 显高高于NGT、IGT、

结合多样本静脉葡萄糖 T2DM;AIR:NGT

耐量量(FSIGT)试验分别测 显著高高于正常对照

定各类受试组患者的胰 组,但在IGT和

岛素敏敏感性指数(SI),

T2DM下降;DI:

OGTT中糖负荷后30min 胰岛素增值与血血糖增值

# 亚组分析显示,已经患有CVD 及 eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 亚组 有更更大大获益

! 失访比比例例低,高高质量量研究,结果真实可靠: " 96.8% 完成随访 " 99.7%患者生生存状态随访完整

! 有外部专家委员会对终点事件及安全性数据进行行行裁决:可靠

27

LEADER 研究

# 讨论中列列举已知的知识、与研究发现的关联,如何解释获得的结果,并

引导至至结论;

# 仔细研读牛牛人人写的讨论部分,不不同的人人对同样的数据可能有不不同的看法 和分析方方式,图表的趋势解析,论据的组合,都是非非常看功力力力的部分, 逻辑的缜密性

" 方方法:研究方方法的细节,看研究如何完成,评价方方法能否得出可靠 地结果

! 零次文文献:指未经发表或进入入社会交流、未经系统加工工整理理的最原始 文文献,也叫灰色色文文献,未发表的研究报告,google搜索包含一一部分

keytruda单词

keytruda单词Keytruda(帕博利珠单抗)一、单词释义Keytruda是一种药物的商品名,其通用名为pembrolizumab,是一种人源化单克隆抗体,属于免疫检查点抑制剂类药物,主要通过阻断程序性死亡受体1(PD - 1)及其配体(PD - L1)之间的相互作用,来激活人体自身的免疫系统对抗肿瘤细胞。

二、单词用法1. 在医学领域,尤其是肿瘤学方面,“Keytruda”作为一种特定药物的名称使用。

例如,医生可能会说“我们考虑给患者使用Keytruda进行治疗”。

2. 在药物研究报告和临床试验的表述中,“Keytruda”常被提及。

像“Keytruda在黑色素瘤的治疗试验中显示出了良好的效果”。

三、近义词1. Opdivo(纳武利尤单抗),这也是一种免疫检查点抑制剂,和Keytruda作用机制相似,都在肿瘤免疫治疗中发挥重要作用。

2. Tecentriq(阿替利珠单抗),同样属于免疫治疗药物的范畴,与Keytruda有类似的治疗理念,都是通过调节免疫系统来对抗癌症。

四、短语搭配1. Keytruda treatment(Keytruda治疗)2. Keytruda injection(Keytruda注射)3. Keytruda clinical trial(Keytruda临床试验)五、双语例句(一)英语例句1. My friend's doctor rmended Keytruda for his lung cancer. It's like a ray of hope in the dark tunnel of his illness. He was so excited, thinking this might be the magic bullet to fight the cancer cells.2. Keytruda has revolutionized cancer treatment. It's not just a drug; it's a game - changer. Imagine it as a super - hero that unlocks the power of the body's immune system to battle the evil cancer.3. I heard that Keytruda is really expensive. But for those with no other options, it's like a precious lifeline. Isn't it amazing how modern medicine can offer such possibilities?4. The research on Keytruda is ongoing. Scientists are constantly trying to find out how to make it even more effective. It's like a never - ending quest for the best weapon against cancer.5. Keytruda doesn't work for everyone. Just like not all keys fit all locks. But when it does work, it can be truly miraculous.6. In the oncology ward, patients often talk about Keytruda. Some are full of hope, believing it will save them. Others are a bit skeptical, like "Is Keytruda really that good?" But they all know it's one of the big hopes in cancer treatment.7. Keytruda is given through injection. It's a bit scary for some patients at first. But they soon realize it could be their best chance. "Just take it as a little prick for a big gain," a nurse said to a patient once.8. The pharmaceuticalpany behind Keytruda is constantly promoting its benefits. They see it as a star product. And indeed, in the world of cancer drugs, it shines brightly.9. Keytruda's side effects need to be carefully monitored. It's like walking on a tightrope. You want the benefits of the drug, but you also have to deal with the possible downsides.10. When my neighbor was diagnosed with advanced cancer, the doctor mentioned Keytruda. We were all like "Wow, that's a high - tech solution." But then we also worried about the cost and the uncertainty of its effectiveness.(二)汉语例句1. 我听说Keytruda对某些癌症效果特别好。

如何评阅临床研究论文

如何评阅临床研究论文How to Review a Clinical Research Paper如何评阅临床研究论文Michael D. Hill迈克尔·D·希尔Peer review is an essential component ofthe scientific process. It is imperfect, to be sure, but there is widespreadagreement that it is the best way to ensure that reliable scientificinformation is published. Being a reviewer is only 1 component of the processof publication. If you are an author or want to be an author, you have a dutyto take part in reviewing your colleagues’ papers, just as your colleagues havereviewed your papers. Reviewing papers is a helpful part of learning thetechnical art of medical writing because you see and learn by example, bothgood and bad. Although it is a volunteer duty, there is a skill in providing auseful review and mentorship and experience matter in how you provide yourreview. Herein, I provide some steps on how to review papers for Stroke,specifically focussing on clinical papers.同行评阅是科学过程的重要组成部分。

医学生文献查询方法

医学生文献查询方法As a medical student, searching for literature in the medical field is crucial for staying updated with the latest developments and research. 作为一名医学生,在医疗领域检索文献对于了解最新的发展和研究至关重要。

First and foremost, utilizing reliable databases is key to efficient and effective literature searching. The use of databases such as PubMed, Medline, and Cochrane Library can provide access to a wide range of medical literature, including journal articles, clinical trials, and systematic reviews. 首先,利用可靠的数据库是高效有效检索文献的关键。

使用像PubMed、Medline和Cochrane Library这样的数据库可以获取广泛的医学文献,包括期刊文章、临床试验和系统评价。

Additionally, refining search terms and using filters can help narrow down the results to the most relevant and recent literature. This can be achieved by using specific medical subject headings (MeSH terms) and applying filters for publication date, study type, and language. 此外,优化检索词并使用过滤器可以帮助缩小结果范围,使其更相关和新近。

临床试验iwrs操作流程

临床试验iwrs操作流程Clinical trial IWRS (Interactive Web Response System) operations involve a complex process that requires a deep understanding of the system and its functions.临床试验IWRS(交互式网上反馈系统)的操作涉及一个复杂的流程,需要深入了解系统及其功能。

First and foremost, it is essential to understand the basic functions of IWRS. This includes the ability to randomize patients into different treatment arms, manage drug supplies, capture and report adverse events, and track overall trial progress.首先,并且非常重要的是,我们要了解IWRS的基本功能。

这包括将患者随机分配到不同的治疗组,管理药物供应,捕获和报告不良事件,并跟踪整个试验的进展情况。

In addition, a thorough knowledge of the specific protocols and requirements of the clinical trial is necessary in order to accuratelyinput data and execute the appropriate actions within the IWRS system.此外,对临床试验的具体协议和要求进行全面的了解是必要的,以便准确输入数据并在IWRS系统中执行适当的操作。

Furthermore, the operational flow of IWRS also involves coordinating with various stakeholders such as clinical research coordinators, pharmacists, and site investigators to ensure that the system is being utilized effectively and efficiently.此外,IWRS的操作流程还涉及与临床研究协调员、药剂师和试验中心研究者协调合作,以确保该系统得到有效和高效地使用。

一期药物临床试验流程

一期药物临床试验流程英文回答:Phase I Clinical Trial Process.Phase I clinical trials are the first stage of testing a new drug in humans. They are typically small, involving a few dozen to a few hundred people, and are designed to evaluate the safety and tolerability of the drug.The phase I trial process typically includes the following steps:Pre-screening: Potential participants are screened to ensure they meet the eligibility criteria for the trial. This includes a medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests.Informed consent: Participants are given detailed information about the trial and its risks and benefits.They must provide written informed consent before participating.Baseline assessment: Participants undergo a series of tests to establish their baseline health status. This includes a physical examination, blood tests, and other tests as needed.Drug administration: Participants are given the drug in increasing doses. The doses are typically given over a period of several days or weeks.Safety monitoring: Participants are closely monitored for any adverse events that may be caused by the drug. This includes physical examinations, blood tests, and othertests as needed.Pharmacokinetic studies: Pharmacokinetic studies are conducted to determine how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted in the body. This information is used to design future clinical trials and to develop dosing regimens.Data analysis: The data from the phase I trial is analyzed to assess the safety and tolerability of the drug. The results of the trial are then used to design future clinical trials.中文回答:一期药物临床试验流程。

临床试验患者招募流程

临床试验患者招募流程English Answer:Clinical Trial Patient Recruitment Process.Clinical trials are research studies that evaluate the safety and effectiveness of new or existing treatments. Recruiting participants for clinical trials is an essential part of the research process. A well-designed recruitment strategy can help to ensure that the trial is conducted efficiently and that the results are generalizable to the target population.There are several steps involved in the patient recruitment process:1. Identifying and screening potential participants. Potential participants are identified through a variety of methods, such as advertising, referrals from healthcare providers, and community outreach. Once potentialparticipants are identified, they are screened to determine if they meet the eligibility criteria for the trial.2. Obtaining informed consent. Before participating ina clinical trial, potential participants must provide informed consent. This involves understanding the risks and benefits of the trial and agreeing to participate voluntarily.3. Enrolling participants. Once potential participants have provided informed consent, they are enrolled in the trial. This typically involves completing a baseline assessment and receiving the study intervention.4. Following participants through the trial. Participants are followed through the trial to collect data on their safety and efficacy. This data is used to evaluate the effectiveness of the study intervention and to ensure that the participants are not experiencing any adverse events.5. Closing the trial. Once the trial has completed, thedata is analyzed and the results are published.Participants are typically notified of the results and are provided with information about how to access the study intervention, if applicable.The patient recruitment process is an important part of the clinical trial process. By following a well-designed recruitment strategy, researchers can help to ensure that the trial is conducted efficiently and that the results are generalizable to the target population.Chinese Answer:临床试验患者招募流程。

临床实验方案的英文

临床实验方案的英文Clinical Trial ProtocolIntroductionClinical trials play a crucial role in the development and evaluation of new medical interventions. These trials involve carefully designed and executed research plans called clinical trial protocols. A clinical trial protocol outlines the objectives, methodology, and ethical considerations involved in a clinical trial. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how clinical trial protocols are formulated in English.1. Study BackgroundIn this section, the background information of the study is presented. It includes an overview of the disease or condition under investigation, the current standard of care, and the rationale behind conducting the clinical trial. Additionally, it may also highlight any relevant previous research that justifies the need for the study.2. Study ObjectivesThe study objectives define the primary and secondary endpoints of the clinical trial. They clearly state the research questions and what the study aims to achieve. Objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). They serve as the foundation for determining the study design, patient population, and data analysis plan.3. Study DesignThis section describes the overall design of the clinical trial, including the study type, randomization procedures, blinding techniques, and allocation ratio. It outlines the treatment arms and the rationale for their selection, as well as the duration of the study and any follow-up periods. The design should be robust enough to generate reliable and statistically significant results.4. Study PopulationThe study population includes the criteria for participant selection, such as age range, gender, inclusion, and exclusion criteria. These criteria ensure that the participants represent the target population and minimize confounding factors. They may also specify the recruitment strategies and the number of participants required.5. Interventions and AssessmentsThis section provides detailed information about the investigational treatments or interventions being studied. It outlines the dosage, frequency, route of administration, and duration of treatment. Additionally, it describes the assessments and outcome measures used to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the intervention. These measures may include laboratory tests, physical examinations, patient-reported outcomes, and imaging techniques.6. Safety and Ethical ConsiderationsThe safety and ethical considerations are of paramount importance in clinical trials. The protocol should include a comprehensive plan for adverse event monitoring, reporting, and management. It should also address the protection of participants' rights, confidentiality, and informed consent.Ethical approval from relevant institutional review boards or ethics committees should be obtained prior to the initiation of the study.7. Statistical AnalysisThis section outlines the statistical methods to be used for data analysis and sample size calculation. It should include details on the primary and secondary endpoints, statistical tests, and methods for handling missing data and controlling for confounding variables. The analysis plan should be robust and statistically sound, ensuring the reliability and validity of the study findings.8. Data Collection and ManagementData collection procedures, case report form designs, and data management strategies should be clearly described in the protocol. This includes methods for ensuring data accuracy, completeness, and confidentiality. Furthermore, it should explain how data will be stored, shared, and monitored throughout the duration of the study.ConclusionThe formulation of a comprehensive and well-designed clinical trial protocol is essential for conducting ethical and scientifically rigorous clinical trials. It provides a roadmap for researchers, regulatory authorities, and healthcare professionals involved in the trial. Adhering to standardized guidelines and ensuring clarity in writing protocols are crucial for the successful execution of clinical trials.Word Count: 627.。

医学英文文献阅读技巧

医学英文文献阅读技巧Baisonfield医学文献阅读心得医学论文段落摘抄分析下面文字来源于《生殖与不孕》杂志2008年一篇关于子宫内膜的文献,是方法部分的2段。

During surgery, the presence, localization, and extent of typical powder-burn and subtle lesions, adhesions, and deep infiltrating implants were recorded. Disease was classified according to the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) score (18). After adhesiolysis, all lesions were treated as follows: complete removal of ovarian endometriomas by stripping, excision of deep endometriosis, and coagulation of peritoneal implants with bipolar forceps. Specimens underwent thorough histologic analysis. Clinical and ultrasound examinations, pain, and occurrence of pregnancy were assessed at 3-month intervals for 3 years and, in the absence of new symptoms, once yearly thereafter. Follow- up was closed in June 2007.Pain recurrence was defined on the basis of a postoperative VAS pain score of R5 in women with preoperative pain symptoms. The recurrence of ovarian endometrioma was defined as the presence of a cyst with a typical aspect, as detected by transvaginal ultrasonography, characterized by a round, homogeneous, hypoechoic, low-level echo cyst or with thininternal heterogeneous trabeculation, with or without internal septa, no or poor vascularization of capsule, and septa (19). When the cyst was indistinguishable from a transient corpus luteum cyst or hemorrhagic cyst, the diagnosis of recurrence was made only when the cyst persisted after successive menstrual cycles.下面是点评:1 During surgery, the presence, localization, and extent of typical powder-burn and subtle lesions, adhesions, and deep infiltrating implants were recorded.这个句子中注意3个单词:Presence表示存在,但是我们喜欢用existence,这是从汉语对应过来的,其实英语中基本不用这个,而用presence。

Clinical Trial Agreement

Clinical Trial AgreementA clinical trial agreement is a legal document that outlines the terms and conditions of a clinical trial. It is an essential document that governs the relationship between the sponsor, the investigator, and the institution conducting the study. The purpose of the clinical trial agreement is to ensure that all parties involved in the trial understand their roles and responsibilities, and that the trial is conducted in compliance with applicable laws and regulations.One of the key requirements of a clinical trial agreement is that it must be written in clear and concise language. This is important because the agreement is a legal document that will be used to resolve disputes between the parties involved in the trial. The agreement should clearly state the purpose of the trial, the procedures that will be followed, and the responsibilities of each party.Another important requirement of a clinical trial agreement is that it must be in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. This includes regulations set forth by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory bodies. The agreement should outline the requirements for obtaining informed consent from study participants, the procedures for collecting and analyzing data, and the reporting requirements for adverse events.In addition to legal compliance, a clinical trial agreement must also address financial considerations. This includes the compensation that will be provided to the investigator and the institution conducting the study, as well as any expenses that will be incurred during the trial. The agreement should also outline the payment schedule and the procedures for resolving any disputes related to payment.Another important aspect of a clinical trial agreement is the protection of intellectual property. The agreement should outline the ownership of any intellectual property that is generated during the trial, as well as the procedures for protecting that property. This includes procedures for filing patents, trademarks, and copyrights, as well as procedures for protecting trade secrets.Finally, a clinical trial agreement must address the issue of liability. This includes the procedures for indemnification, which is the process of protecting one party from legal liability in the event that the other party is sued. The agreement should also outline the procedures for resolving disputes related to liability, including the procedures for arbitration or mediation.In conclusion, a clinical trial agreement is a critical document that outlines the terms and conditions of a clinical trial. It is essential that the agreement be written in clear and concise language, in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations, and that it address financial considerations, intellectual property, and liability. By addressing these key requirements, a clinical trial agreement can help ensure the success of a clinical trial and protect the interests of all parties involved.。

医学文献检索的使用

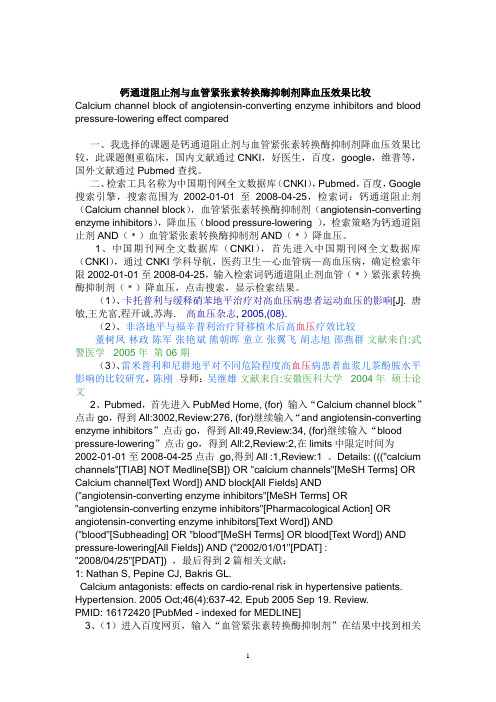

钙通道阻止剂与血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂降血压效果比较Calcium channel block of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and blood pressure-lowering effect compared一、我选择的课题是钙通道阻止剂与血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂降血压效果比较,此课题侧重临床,国内文献通过CNKI,好医生,百度,google,维普等,国外文献通过Pubmed查找。

二、检索工具名称为中国期刊网全文数据库(CNKI),Pubmed,百度,Google 搜索引擎,搜索范围为2002-01-01至2008-04-25,检索词:钙通道阻止剂(Calcium channel block),血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors),降血压(blood pressure-lowering ),检索策略为钙通道阻止剂AND(﹡)血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂AND(﹡)降血压。

1、中国期刊网全文数据库(CNKI),首先进入中国期刊网全文数据库(CNKI),通过CNKI学科导航,医药卫生—心血管病—高血压病,确定检索年限2002-01-01至2008-04-25,输入检索词钙通道阻止剂血管(﹡)紧张素转换酶抑制剂(﹡)降血压,点击搜索,显示检索结果。

(1)、卡托普利与缓释硝苯地平治疗对高血压病患者运动血压的影响[J]. 唐敏,王光富,程开诚,苏海. 高血压杂志, 2005,(08).(2)、非洛地平与福辛普利治疗肾移植术后高血压疗效比较董树凤林政陈军张艳斌熊朝晖童立张翼飞胡志旭邵燕群文献来自:武警医学 2005年第06期(3)、雷米普利和尼群地平对不同危险程度高血压病患者血浆儿茶酚胺水平影响的比较研究,陈刚导师:吴继雄文献来自:安徽医科大学 2004年硕士论文2、Pubmed,首先进入PubMed Home, (for) 输入“Calcium channel block”点击go,得到All:3002,Review:276, (for)继续输入“and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors”点击go,得到All:49,Review:34, (for)继续输入“blood pressure-lowering”点击go,得到All:2,Review:2,在limits中限定时间为2002-01-01至2008-04-25点击go,得到All :1,Review:1 。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

How to Read a Clinical Trial Paper: A Lesson in Basic Trial StatisticsShail M. Govani, MD, MSc, and Peter D. R. Higgins, MD, PhD, MScDr. Govani is a Fellow and Dr. Higgins is an Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, both in the Division of Gastroenterology of the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Address correspondence to:Dr. Peter D. R. Higgins1150 W. Medical Center DriveSPC 5682Ann Arbor, MI 48109;Tel: 734-647-2964;Fax: 734-763-2535;E-mail: phiggins@ KeywordsStatistics, clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, outcomes, clinical research Abstract: While the number of clinical trials performed yearly is increasing, the application of these results to individual patients is quite difficult. This article reviews key portions of the process of applying research results to clinical practice. The first step involves defining the study population and determining whether these patients are similar to the patients seen in clinical practice in terms of demographics, disease type, and disease severity. The dropout rate should be compared between the different study arms. Design aspects, including randomization and blinding, should be checked for signs of bias. When comparing studies, clinicians should be aware that the outcomes being studied may vary greatly from one study to another, and some outcomes are much more reliable and valuable than others. The definition of clinical response should also be scrutinized, as it may be too lenient. Surrogate outcomes should be viewed cautiously, and their use should be well justified. Clinicians should also note that statistical significance, as defined by a P-value cutoff, may be the result of a large sample size rather than a clinically significant difference. The treatment effect can be estimated by calculating the number needed to treat, which will demonstrate whether changes in clinical practice are worthwhile. Finally, this article discusses some common issues that can arise with figures.I n the last decade, the number of publications dedicated toresearch in gastroenterology has expanded dramatically.1In parallel, the number of clinical trials has been increasing, with more than 18,000 ongoing clinical trials in the United States alone.2 With this rapid growth in research, clinicians find themselves trying to keep up with wave after wave of studies and trying to determine how these studies apply to their patients. As researchers learn more about disease processes, clinical trial design is also changing and becoming more complex. Medical school and subsequent clinical training provide limited education on how to evaluate these stud-G o V A n I A n d H I G G I n sies and incorporate their results into practice. Thus, this article will review some important concepts in the evalua-tion of therapeutic trials.Are These Subjects Like My Patients?The first step in the process of reviewing a trial should involve determining whether the subjects in the study are representative of the patients a clinician sees in his or her practice. Were the study subjects sicker, or did they have more complicated disease? Did they fail more prior medications, or did they have longer disease durations? Patients who enroll in clinical trials are usually different from the average patient with a particular disease. This trend has been well studied in oncology studies and is also a factor in gastroenterology clinical trials.3 Compared to the average patient, study subjects often have a longer duration of disease, more complications, more active dis-ease, and more previous medication failures.Recruitment methods also influence the make-up of the study population and can lead to different response rates. This effect was demonstrated in a mock irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) study in which 3 patient samples were recruited and then examined.4One sample was recruited from a primary care practice in the United Kingdom, another was recruited from gastroenter-ologists’ offices in the United States, and the third was recruited by newspaper advertisement in the United States. These 3 samples had significant clinical and demographic differences (Table 1).In publications of clinical trials, the first table in the paper usually summarizes the characteristics of the study sample, and readers should examine this table to deter-mine not only the age, race, and gender of the population but also the typical disease severity, disease duration, and medication history. Clinicians can only apply the results of a study to patient care if all of these factors appear to be similar to those of the patients seen in clinical practice. What Happened to the Subjects?Did They Drop Out? Why?After comparing real-world patients and the study sam-ple, the next step is a review of the Consolidated Stan-dards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. This flow diagram is usually the first figure in the paper, and it shows the flow of subjects from recruitment through the end of the study (or early exit from the study). Special attention should be paid to the number of patients in each arm who dropped out of the study. Subjects drop out of studies for many reasons, but 2 of the most impor-tant reasons are lack of benefit (they were too sick to stay in the study) and side effects (which made them want to leave the study). Clinicians can compare the percentage of subjects in each arm of the study who drop out due to lack of benefit. If the subjects consider the treatment to be more effective than placebo, then the dropout rate due to lack of benefit should be lower in the treatment arm than in the (less effective) placebo arm. If this is the case, this finding not only validates the statistical signifi-Table 1.Differences in Sample Characteristics Depend on Recruitment Method *Difference between UK primary care practice and US newspaper advertisement.**Difference between UK primary care practice and US gastroenterology clinics.†Difference between US newspaper advertisement and US gastroenterology clinics.NS=not significant.Adapted from Longstreth GF, et al.4H o w t o R e A d A C l I n I C A l t R I A l P A P e Rcance of the study results but also indicates that patients consider this difference to be clinically significant. In some studies, the reasons for leaving the study are not specified, and readers have to make do with comparing the exit rate for each arm. While the exit rate is a cruder measure, the more effective treatment arm should have a lower exit rate (if the treatment is well tolerated).Is the Study Design Biased?While readers may be tempted to skip the methods sec-tion of a paper, the study design should be reviewed care-fully, with a particular focus on the comparator group, allocation of subjects to treatment arms, and blinding. In disease states with established therapies such as inflam-matory bowel disease (IBD), the comparator should be the standard-of-care therapy. Functional disease states should incorporate a placebo group and/or a comparator that has proven to be effective (if available) to ensure that the placebo effect is measured. For example, in studies of rifaximin (Xifaxan, Salix Pharmaceuticals) versus placebo for treatment of IBS, 32% of the placebo-treated patients reported relief of symptoms, while 41% of subjects in the treatment arm reported improvement.5 Without the pla-cebo comparator, the effect of rifaximin on IBS symptoms would appear quite large, but readers need to discount results by the size of the placebo effect.The allocation of subjects to each treatment arm should be well defined. The CONSORT diagram should be easy to follow and similarly detailed for each arm. To avoid bias, subject allocation must be concealed so that investigators cannot anticipate which arm the next sub-ject will enter. If the investigators knew a very sick patient would be likely to receive placebo, they could avoid enrolling that patient, which could result in biased enroll-ment. Randomization may be at the population level or clustered at the site level; in the latter case, all the subjects at 1 site are in a single arm.The blinding process is defined as single-blind if the subject is unaware of the allocation, while double-blind refers to a study in which the investigators are also unaware of the individual patient’s allocation. Blinding of both participants and evaluators is equally important, as patients who are aware of their intervention may have lower compliance, and investigators who are aware of the intervention may overestimate a treatment effect. Not sur-prisingly, studies comparing outcomes with and without blinding have shown a significant overestimation of the treatment effect in studies conducted without blinding.6,7 Unfortunately, study investigators rarely report whether the blinding process was successful. In a 2007 analysis of 1,599 studies, only 2% reported the success of the blinding process; of those, almost half determined that blinding was unsuccessful (ie, patients could determine or guess whether they were receiving active drug or placebo).8The blinding process can be difficult in many studies, especially trials involving a procedure. Subjects often go to remarkable lengths to determine whether their study medication is active drug or placebo; especially given the information available on the Internet, extreme care must be taken to preserve the blind. If patients in a placebo-controlled trial can deduce that they are in the placebo arm, they could be less likely to report improvement, leading to underesti-mation of the placebo effect and overestimation of the relative treatment effect.Does the Study Include an Intention-to-Treat Analysis?All subjects who have been randomized should be counted in the analysis. Some subjects may not receive the inter-vention or may drop out of the study after a short period of time, but for the purposes of analysis, they should still be considered as having been assigned to their treatment arm. An analysis that includes all randomized subjects is called an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. As soon as subjects are randomized, the intention to treat them with their assigned intervention is established, even if they never receive this intervention.Occasionally, clinical trials will be greatly damaged by a high rate of early drop out, and investigators will be tempted to present a per-protocol analysis, in which only subjects who received their assigned intervention are considered. This analysis can be presented, but it should be presented only as a secondary endpoint, after the pre-sentation of the ITT results. Despite the importance of performing an ITT analysis, fewer than 50% of papers in some well-regarded journals identify their analysis as an ITT analysis; even among these papers, verifying that the analysis was performed correctly is difficult.9Is This a Test of Superiority? Equivalence? Noninferiority?While most trials in the literature compare 2 therapies with the intent of proving that one is superior to the other, trials of equivalence and noninferiority are occa-sionally performed. In cases where a new therapy is more convenient or cheaper, an equivalence or noninferiority study can be appropriate. For example, a recent trial examined whether individualized duration of treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was noninferior to standard treatment duration.10Studies of noninferiority and equivalence can be particularly difficult to interpret due to the definitions ofG o V A n I A n d H I G G I n snoninferiority and equivalence. The acceptable amount of difference between the standard therapy and the alterna-tive therapy must be defined in advance of the study, and the authors must provide a strong rationale for this defini-tion. For example, in the HCV study mentioned above, the study authors assumed a sustained virologic response (SVR) rate of 48% in patients receiving standard therapy, and they allowed an acceptable margin (∆) of 5% with individualized therapy. In other words, the authors were willing to declare individualized treatment noninferior to standard therapy if the SVR rate with individualized therapy was within 5% of the SVR rate achieved with standard therapy. Readers then have to decide whether they would accept using a treatment that is up-to-5% less effective than the standard-of-care therapy.From the standpoint of study design, the sample size needed to determine noninferiority or equivalence is always much higher than the size needed to determine superiority. The methods section should define every aspect of the sample size calculation so that the reader can replicate this calculation if necessary. Typically, the design of an equivalence study requires that the 95% confidence interval of the difference between the treatments be less than the previously defined acceptable difference. This requirement often results in a required sample size about 4 times larger than the sample size needed for a superiority study. If a study is initially designed to test for superiority but this outcome is not found, switching to an equivalence study would be inappropriate for 2 reasons: (1) the acceptable difference would not have been defined in advance, and (2) the sample size would be too small.Does the Measurement Matter?Is It Reproducible? Accurate?One of the overlooked issues that can make a clinical trial difficult to generalize to the patients clinicians see in everyday practice is the study’s measurement of success. Clinical trials require detailed definitions of success—for example, criteria for remission or clinical response in IBD trials—and these definitions usually involve several mea-surements, sometimes a clinical severity index, and some form of a scale. Several issues related to these measure-ments are discussed below.First, is there good evidence that the measurement itself is reproducible and precise? Many measures are not very reproducible, including histologic assessment of dysplasia and endoscopy in patients with ulcerative coli-tis.11,12 Endoscopic grading instruments are quite complex and suffer from a high level of disagreement in the middle of the scale, much like histologic grading of dysplasia. This disagreement creates noise in the data.A second issue is whether the amount of change seen in the clinical index or score is clinically meaningful to patients. Does a change of 3 points on the index presented in a published paper translate to a meaningful improve-ment for real-world patients? This question is important to consider, as results can be statistically significant with-out being clinically meaningful.A third issue is whether the measurement has been validated. Validity can have a number of meanings, but it generally includes whether the index is measuring all of the important aspects of a disease, whether it measures them accurately, whether the measurement is reproduc-ible in subjects whose condition has not changed, and whether the instrument is responsive to small but clini-cally important changes. For example, the commonly used Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) can be influenced by postinflammatory IBS, which can lead to symptoms that will not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy. In the future, instruments measuring Crohn’s disease activity will likely have separate subjective symp-tom scales and objective measures of inflammation to better define disease activity.Surrogate OutcomesIdeally, the outcome being studied should be the one in which clinicians are most interested. Primary out-comes—such as remission, cure, and nonrecurrence—are stronger and more meaningful than surrogate outcomes such as biomarker levels. While measuring surrogate biomarkers may appear to be an easy, inexpen-sive, and less invasive method of determining a clinical outcome, the validity of the surrogate markers should be scrutinized closely. A glaring example of the misuse of surrogate markers was the use of class 1c antiarrhythmic medications to prevent sudden cardiac death based on the evidence that these medications suppress the num-ber of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Previ-ous research had shown a correlation between PVCs and poor clinical outcomes. However, a prospective random-ized trial comparing these drugs to placebo showed an increased risk of cardiac death in the treatment arms despite successful suppression of PVCs.13Such faulty reasoning likely led to many deaths and is a lesson of the importance of surrogate outcome choice.Bucher and colleagues suggested a 3-step approach to assessing the validity of a surrogate outcome.14 First, a strong independent association should exist between the surrogate and the desired outcome. Second, evi-dence from randomized controlled trials in other drug classes should show that improvement in the surrogate leads to an improvement in the clinical outcome. Lastly, randomized controlled trials within the same drug class should demonstrate similar improvements in the sur-H o w t o R e A d A C l I n I C A l t R I A l P A P e Rrogate, which lead to improvements in the desired clini-cal outcome. For example, mucosal healing (typically defined as endoscopic healing) is often used as a surro-gate marker for clinical improvement in IBD. In apply-ing these rules, readers will notice that steroids have not led to improvements in mucosal healing despite leading to clinical improvement.15However, other immuno-modulators, including azathioprine, methotrexate, and infliximab (Remicade, Janssen Biotech), have shown improvement in mucosal healing and clinical improve-ment.16,17 Any surrogate marker that has an inconsistent correlation with important clinical outcomes has to be viewed skeptically and should not be considered an ideal primary endpoint for clinical trials.Dichotomous Outcomes, Continuous Outcomes, Correlations, and Time-to-Event EndpointsSome studies focus on a dichotomous outcome endpoint like clinical remission or response. The definitions of these endpoints are critical and should be scrutinized carefully to ensure that they are not too lenient. For example, early studies of Crohn’s disease therapies defined clinical response as a reduction in CDAI score of 70 points or more, and remission was defined as an overall CDAI score less than 150 points. More recently, the US Food and Drug Administration has encouraged changing the definition of clinical response to a decrease of 100 points or more. In addition, Sandborn and col-leagues have suggested that decreases in CDAI scores of 70 or 100 points (∆70, ∆100) should only be used as secondary outcome measures and should be coupled with a CDAI score less than 150 points.18Other studies may present a continuous outcome measure, which provides more power to detect a differ-ence between groups. For example, if a study evaluating 2 immunomodulator drugs for the treatment of Crohn’s disease compared the differences in CDAI scores before and after drug use, the study could conclude that there is a difference between the 2 drugs even if that difference is only 5 points. On the other hand, when the outcome is dichotomized (hopefully into a clinically meaningful dif-ference) and a statistically significant difference is found, these findings are more meaningful for clinical care.Other outcomes, including correlations and time-to-event endpoints (ie, time to remission), should also be treated carefully. In testing for correlations, the null hypothesis is that there is no correlation. The P-value in such tests is very sensitive to weak correlations, as even small correlations will be considered significant. In general, it is probably best to ignore the P-value for correlations and instead look at the correlation itself (and its 95% confidence interval). A correlation of 90% with a confidence interval of 85–95% is impressive, while a correlation of 23% with a confidence interval of 1–57% is not very impressive, although the latter would have a significant P-value (P<.05). A study that reports a cor-relation and gives a P-value but not a 95% confidence interval should be viewed with caution.Time-to-event data are also weaker endpoints than outcomes measured at a particular time point, such as remission. Remission rates at a particular time point (ie, 12 weeks) provide 1 data point for each subject, and the rates between study arms can be compared, usually with a t-test. The t-test for a dichotomous outcome (ie, remission vs nonremission) sets a high bar for suc-cess. In contrast, statistical tests for time-to-event data compare the survival rate, which is essentially an esti-mate of the slope across the entire follow-up period. This approach effectively counts each subject multiple times by looking at each subject at multiple time points, thus adding to the statistical power of the test.The problem with a time-to-event analysis is that it can produce a significant P-value, but this value may not reflect a clinically meaningful difference. Examples of these types of studies include the placebo-controlled studies of budesonide as maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease.19,20 These studies revealed that budesonide was associated with a longer time to relapse; however, the outcomes in the placebo and budesonide arms were the same at 18 months. In addition, the time-to-relapse curves were not presented with confidence intervals, making it difficult to interpret whether meaningful dif-ferences were achieved. While time-to-event analysis is considered an acceptable approach, especially in oncol-ogy, a statistically significant result with this design does not carry as much clinical weight as a statistically sig-nificant result from a t-test of a dichotomous, clinically meaningful endpoint evaluated at a single time point, given that the time-to-event analysis sets a much lower bar for success.Multicenter TrialsMulticenter trials offer a chance to expand the sample size in studies of rare diseases and to ensure some population diversity. However, a potential weakness of a multicenter trial is the lack of standardization of both the intervention and the outcome. The protocol for the intervention has to be especially rigid and detailed in a multicenter trial. Similarly, the chosen outcome should be validated and reproducible across multiple centers. For endoscopic endpoints, reproducibility has proven problematic, leading many studies to move to grading of endoscopic appearance by central reviewers in order to improve consistency. Analyses of multicenter trials should always consider site as a covariate, as a few out-lier sites can skew the outcome.G o V A n I A n d H I G G I n sShifting Target OutcomesSince the first gastrointestinal clinical trial, T ruelove and Witt’s 1954 study of cortisone for the treatment of ulcer-ative colitis, target outcomes have changed and become more stringent.21 While clinicians keep raising the bar as their body of knowledge grows, the incremental gain in patient outcomes does not appear to be as great. Over time, clinicians will need to determine whether there is an improved, long-term, benefit-to-risk ratio that results from achieving biologic or endoscopic remission in patients with IBD. In an example from another field of medicine, very tight control of blood pressure showed no survival benefit over usual control; to avoid similar missteps, clinicians need prospective evidence that tight control in IBD will improve outcomes.22How Are Missing Data Addressed?One of the challenges of all trials is how to deal with missing data. Subjects often drop out of a study before the primary endpoint date is reached, fail to show up for appointments, or change their mind and refuse to undergo the scheduled endoscopy at the final evaluation. There are 2 common methods for handling missing data. The most rigorous method is to consider any subject who has missing data as one who would have failed to meet the endpoint. This method is often called nonresponder imputation. It lowers success rates (and placebo rates), thus making results look less impressive.Another approach is to use the last observation at which the subject was measured in place of the missing data; this approach is especially common in maintenance studies with repeated measurements. Called the last-observation-carried-forward approach, this method is reasonable, but it may inflate the success rates of both the primary intervention and the control arm, as a common reason patients do not return for visits is that they feel the treatment does not provide a clinical benefit.Finally, a third approach for addressing missing data is called imputation, in which other data are used to estimate what the missing data would have been. This approach is generally considered appealing but questionable, as it is impossible to check the accuracy of these estimates.Do the Design and Methods Conform to the Prestudy Guidelines?A number of clinical journals and funding sources expect clinical trials to be registered on the ClinicalT web-site. This website contains a large amount of information about the trial, including endpoints, date of first enroll-ment, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a description of the intervention. An interested reader can view the registration page for the trial to ensure that the endpoints did not change during the study and that the trial was truly prospective. A review of the endpoints listed on this website may reveal that the trial’s secondary endpoints were exploratory (ie, not defined prior to initiation of the trial). Readers may also discover that some of the outcomes mentioned on the initial registration page are not reported in the published paper. In these instances, the reader could presume that the outcome results were disappointing. How Good Are the Results?Many readers rely on P-values to determine if a clinically important effect is present. The P-value is based on the assumption that the null hypothesis is true (that the treat-ment arms are equally effective), and the P-value gives the probability that the difference observed between the 2 treatment arms is due to chance alone. For example, if testing the difference in blood pressures between 2 popu-lations that truly had the same blood pressure resulted in a P-value of .04 (from a student’s t-test), then there would only be a 4/100 chance of seeing a difference of that magnitude by chance alone.Statistically, a P-value serves as a combination of 2 measurements: effect size (the difference between the 2 groups) and precision (the variation of that difference represented by the confidence interval). These 2 values should be displayed in a paper and should be examined separately. A very large study will have more precision, which will generally lead to a smaller P-value without a meaningful change in effect size. A very small study will inherently have less precision, in which case a clinically meaningful effect size may be missed due to a higher P-value. Thus, a small effect size—for example, a 5% response rate in 1 arm and 10% response rate in the other arm—will be statistically significant in a very large study (>500 patients per arm), but it will be unlikely to produce a significant P-value if the study has only 50 patients per arm.To illustrate how a large sample size can make a small effect significant, consider the 2 examples in Figure 1.A large sample size, as shown in Figure 1A, can make a blood pressure difference of 2.5 mmHg between sample populations statistically significant. When the difference between the 2 groups is larger (12 mmHg), a sample size of 50 patients per group is only barely sufficient to yield a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (Figure 1B). While these 2 hypothetical studies have similar P-values, the larger, more expensive study has, in effect, “bought” a better P-value with larger sample sizes. The smaller study may have a larger and more clinically relevant effect, but this effect is difficult to detect with a small sample size. If the smaller study had failed to reach。