英美文学笔记

英国文学与美国文学学习笔记摘抄

英国文学与美国文学学习笔记摘抄I.Literature文学i)English Literature英国文学I .Old and Medieval English literature(450-1066)&(1066-15世纪后期)上古及中世纪英国文学Background:英伦三岛自古以来遭遇过3次外族入侵,分别为古罗马人、盎格鲁-萨克逊人&诺曼底人。

其中后两次在英国文学史上留下了深远影响。

中世纪时期(约1066-15世纪后期)即从诺曼底征服起到文艺复兴前夕,为英国封建社会时期的文学,盛行文学形式为民间抒情诗(the folk ballad)和骑士抒情诗(the romance)。

I)The Anglo-Saxon Period(450-1066)盎格鲁撒克逊文明兴盛时期(上古时期)文学表现形式主要为诗歌散文。

i代表人物和主要作品:第一部民族史诗(the national epic)《贝奥武甫》Beowulf,体现盎格鲁撒克逊人对英雄君主的拥戴和赞美,歌颂了人类战胜以妖怪为代表的神秘自然力量的伟大功绩。

"Down off the moorlands' misting fells cameGrendel stalking;God's brand was on him.大踏步地走下沼泽地,上帝在每个人身上都打下了烙印。

"II)The Norman Period(1066-1350)诺曼时期In the early 11th century all England was conquered by the Danes for 23 years. Then the Danes were expelled, but in 1066 the Normans came from Normandy in northern France to attack England under the leadship of the Duck of Normandy who claimed the English throne. For the last Saxon king, Harold ,had promised that he would give his kingdom to William, Duck of Normandy, as an expression of his gratitude for protecting his kingdom during the invasion by the Danes. This is known as the Norman Conquest.诺曼征服Middle English中世纪英语III)The Age of chaucer(1350-1400)乔叟时期The Hundred Years' War英法百年战争Geoffrey Chaucer杰弗里.乔叟-中世纪最伟大诗人、英国民族文学奠基者。

英美文学中英结合笔记

13. Marlowe’s greatest achievement lies in that he perfected the blank verse and made it the principal medium of English drama.马洛的艺术成就在于他完善了无韵体诗,并使之成为英国戏剧中最重要的文体形式。

9. Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the first important English essayist.费兰西斯.培根是英国历史上最重要的散文家。

(I)Edmund Spenser埃德蒙.斯宾塞

10. the theme of Redcrosse is not “Arms and the man,” but something more romantic-“Fierce wars and faithful loves.”《仙后》的主题并非“男人与武器”,而是更富浪漫色彩的“残酷战争与忠贞爱情”。

英美文学选读(英国)浪漫主义时期笔记

Chapter 3 The Romantic Period1. The Romantic Period: The Romantic period is the period generally said to have begun in 1798 with the publication of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads and to have ended in 1832 with Sir Walter Scott’s death and the passage of the first Reform Bill in the Parliament. It is emphasized the special qualities of each individual’s mind.2.Social background:a. during this period, England itself had experienced profound economic and social changes. The primarily agricultural society had been replaced by a modern industrialized one.b. With the British Industrial Revolution coming into its full swing, the capitalist class came to dominate not only the means of production, but also trade and world market.3.The Romantic Movement:it expressed a more or less negative attitude toward the existing social and political conditions that came with industrialization and the growing importance of the bourgeoise. The romantics demontrated a a strong reaction against the dominant modes of thinking of the 18th-century writers and philosophers. They saw man as an individual in the solitary state. Thus, the Romanticism actually constitutes a change of direction from the outer world of social civilization to the inner world of the human spirit.The Romantic period is an age of poetry. Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats are the major Romantic poets. They started a rebellion against the neoclassical literature, which was later regarded as the poetic revolution. Wordsworth and Coleridge were the major representatives of this movement. Wordsworth defines the poet as a “man speaking to men”, and poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” Imagination, defined by Coleridge, is the vital faculty that creates new wholes out of disparate elements. The Romantics not only extol the faculty of imamgination, but also elevate the concepts of spontaneity and inspiration, regarding them as something crucial for true poetry. The natural world comes to the forefront of the poetic imagination. Nature is not only the major source of the poetic imagery, but also provides the dominant subject mattre. It is in solitude, in communion with the natural universe, that man can exercise this most valuable of faculties.Romantics also tend to be nationalistic, defending the great poets and dramatists of their own national heritage against the advocates of classical rules.Poetry: to the Romantics, poetry should be free from all rules.they would turn to the humble people and the common everyday life for subjects.Prose: It’s also a great age of prose. With education greatly developed for the middle-class people, there was a rapid growth in the reading public and an increasing demand for reading materials.Romantics made literary comments on the writers with high standards, which paved the way for the development of a new and valuable type of critical writings. Colerige, Hazlitt, Lamb, and De Quincey were the leading figures in this new development.Novel: the 2 major novelists of the period are Jane Austen and Walter Scott.Gothic novel: a tyoe of romantic fiction that predominated in the late 18th century, was one of the Romantic movement. Its principal elements are violence, horror, and the supernatural, which strongly appeal to the reader’s emotion. With is description of the dark, irritional side of human nature, the Gothic form exerted a great influence over the writers of the Romantic period.3. Ballads: the most important form of popular literature; flourished during the 15th century; Most written down in 18th century; mostly written in quatrains; Most important is the Robin Hood ballads.4. Romanticism: it is romanticism is a literary trend. It prevailed in England during the period of 1798-1832. Romanticists were discontent with and opposed to the development of capitalism. They split into two groups.Some Romantic writers reflected the thinking of those classes which had been ruined by the bourgeoisie called Passive Romantic poets represented by Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey.Others expressed the aspiration of the labouring classes called Active or Revolutionary Romantic poets represented by Byron and Shelley and Keats.5. Lake Poets:Wordsworth, Coleridge and Robert Southey have often been mentioned as the “Lake Poets” because they lived in the Lake District in the northwestern part of England6. Byronic Hero a proud, mysterious rebelling figure of noble origin rights all the wrongs in a corrupt society, and is against any kind of tyrannical rules; It appeared first in Childe H arold’s Pilgrimage and then further developed in later works as the Oriental Tales, Manfred and Don Juan; the figure is somewhat modeled on the life and personality of Byron himself, and makes Byron famous both at home and abroad.7. Main Writers:A. William Blake(1757-1827):1. Literarily, Blake was the first important Romantic poet, showing a comtempt for the rule of reason, opposing the calssical tradition of the 18th century,and treasuring the individual’s imagination.2. His first printed work, Poetic Skelches, is a collection of youthful verse. Joy, laughter, love and harmony are the prevailing notes.3. The Songs of Innocence is a lovely volume of of poems, presenting a happy and innocent world, though not without its evils and sufferings. The wretched child described in “The Chimney Sweeper,”orphaned, exploited, yet touched by visionary rapture, evokes unbearable poignancy when he finally puts his trust in the order of the universe as he knows it. Blake experimented in meter and rhyme and introduced bold metrical innovations which could not be found in the poetry of his contemporaries.4. The Songs of Experience paints a different world, a world of misery, poverty, disease, war and repression with a malancholy tone. The little chinmney sweeper sings “notes of woe”while his parents go to the church and praise “God & his Priest & King”—the very intrument of their repression. A number of poems in the Songs of Experience also find a counterpart in the Songs of Experience. The 2 books hold the similar subject-matter, but the tone, emphasis and conclusion differ.5. Childhood is central to Blake’s concern in the Songs of Innocence and the Songs of Experience, and this concern gives the 2 books a strong social and historical reference. The two “Chimney Sweeper”poems are good examples to reveal the relation between an economic ciecumstance, i.e. the exploitation of child labor, and an ideological circumstance, i.e. the role played by religion in making people compliant to exploitation. The poem from the Songs of Innocence indicates the conditions which make religion a consolation, a prospect “illusionary happiness;”the poem from the Songs of Experience reveals the nature of religion which helps bring misery to the poor children.6. Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell marks his entry into maturity. The poem plays the double role both as a satire and a revolutionary prophecy. Blake explores the relationship of the contrries. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence. The “Marriage”means the reconciliation of the contraries, not the subordination of the one to the other.Main works: Poetical SketchesSongs of Innocence is a lovely volume of poemsHoly Thursday reminds us terribly of a world of loss and institutional cruelty.Songs of Experience paints a different world, a world of misery, poverty, disease, war and repression with a melancholy tone.Marriage of Heaven and HellThe book of UrizenThe Book of LosThe Four ZoasMilton7. Language Character: he writes his poems in plain and direct language. His poems often carry the lyric beauty with immense compression of meaning. He distrusts the abstractness and tends to embody his views with visual images. Symbolism in wide range is also a distinctive feature of his poetry.B. William Wordsworth(1770-1850) In 1842 he received a government pension, and in the following year he succeeded Southey as Poet Laureate.Lyrical Ballads:But the Lyrical Ballads differs in marked ways from his early poetry, notably the uncompromising simplicity of much of the language, the strong sympathy not merely with the poor in general but with particular, dramatized examples of them, and the fusion of natural description with expressions of inward states of mind.Short poems:According to the subjects, Wordsworth’s short poems can be calssified into two groups: poems about nature and poems about human life.Wordsworth is regarde as a “worshipper of nature.”He can penetrate to the heart of things and give the reader the very life of nature. “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”is perhaps the most anthologized poem in english literature, and one that takes us to the core of Wordsworth’s poetic beliefs. It’s nature that gives him “strength and knowledge full of peace.”Wordswoth thinks that common life is the only subject of literary interest. The joys and sorrows of the common people are his themes. “The Solitary Reaper” and “To a Highland Girl” use rural figures to suggest the timeless mystery of sorrowful humanity and its radiant beauty. In its daring use of subject matter and sense of the authenticity of the experience of the poorest, “Resolution and Independence ”is the triumphant conclusion of ideas first developed in the Lyrical Ballads.Wordsworth is a poet in memory of the past. To him, life is a cyclical journey. Its beginning finally turns out to be its end. His philosophy of life is presented in his masterpiece The Prelude.Wordsworth deliberate simplicity and refusal to decorate the truth of experience produced a kind of pure and profoud poetry which no othr poet has ever equaled. He maintained that the scenes and events of everyday life and the speech of ordinary people were the raw material of which poetry could and should be made.Main Works:Descriptive Sketches, and Evening WalkLyrical Ballads.The PreludePoems in Two VolumesOde: Intimations of ImmortalityResolution and Independence.The ExcursionPoets: The Sparrow’s Nest, To a Skylark, To the Cuckoo, To a Butterfly, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud( is perhaps the most anthologized poem in English literature.), An Evening Walk, My Heart Leaps up, Tintern AbbeyThe ThornThe sailor’s motherMichael,The Affliction of MargaretThe Old Cumberland BeggarLucy PoemsThe Idiot BoyMan, the heart of man, and human life.The Solitary ReaperTo a Highland GirlThe Ruined CottageThe PreludeLanguage character: he can penetrate to the heart of things and give the reader the very life of nature. And he thinks that common life is the only subject of literary interest. The joys and sorrows of the common people are his themes. His sympathy always goes to the suffering poor.He is the leading figure of the English romantic poetry, the focal poetic voice of the period. His is a voice of searchingly comprehensive humanity and one that inspires his audience to see the world freshly, sympathetically and naturally. The most important contribution he has made is that he has not only started the modern poetry, the poetry of the growing inner self, but also changed the course of English poetry by using ordinary speech of the language and by advocating a return to natureC. Percy Bysshe Shelley(1792-1822)he grew up with violent revolutionary ideas, so he held a lifelong aversion to crulty, injusticce, authority, institutional religion and the formal shams of respectable society, condemming war, tyranny and exploitation. He realized that the evil was also in man’s mind. Even after a revolution, that is after the restoration of human morality and creativity, the evil deep in man’s heart might again be loosed. So he predicated that only through gradual and suitable reforms of the existing institutions couls benevolence be universally established and none of the evils would survive in this “genuin society,”where people could live together happily, freely and peacefully.Shelley expressed his love of freedom and his hatredtoward tyranny in several of his lyrics. One of the greatest political lyrics is “Men of England.” It is not only a war cry calling upon all working people to risse up against their political oppressors, but an address to them pointing out the intolerable injustice of economic exploitation. The poem was later to become a rallying song of the British Comuunist Party.Best of all the well-known lyric pieces is Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”here Shelley’s rhapsodic and declamatory tendencies find a subject perfectly suited to them. The autumn wind, burying the dead year, preparing for a new spring, becoms an image of Shelley himself, as he would want to be, in its freedom, its destructive-constructive potential, its universality. The whole poem had a logic of feeling,a not easily analyzable progression that leads to the triumphant, hopeful and convincing conclusion: if winter comes, can spring be far behind?Shelley’s greatest achievement is his four-act poetic drama, Prometheus Unbound. The play is an exultant work in praise of humankind’s potential, and Shelley himself recognized it as “the most perfect of my products.”Main works:The Necessity of Atheism, Queen Mab: a Philosophical Poem, Alastor, or The Spirit of SolitudePoem: Hymn to Intellectual Beauty, Mont BlancJulian and Maddalo, The Revolt of Islam, the Cenci, Prometheus Unbound, Adonais, Hellas,Prose: Defence of PoetryLyrics:genuine society,“Ode to Liberty”,“Old to Naples”“Sonnet: England in 1819”, The Cloud, To a Shylark, Ode to the West WindPolitical lyrics: Men of EnglandElegy: Adonais is a elegy for John Keats’s early deathTerza rimaPersonal Characters: he grew up with violent revolutionary ideas under the influence of the free thinkers like Hume and Godwin, so he held a life long aversion to cruelty, injustice, authority, institutional religion andthe formal shams of respectable society, condemning war, tyranny and exploitation. He expressed his lo ve for freedom and his hatred toward tyranny in several of his lyrics such as “Ode to Liberty”,“Old to Naples”“Sonnet: England in 1819”Shelley is one of the leading Romantic poets, and intense and original lyrical poet in the English language. Like Blake, he has a reputation as a difficult poet: erudite, imagistically complex, full of classical and mythological allusions. His style abounds in personification and metaphor and other figures of speech which describe vividly what we see and feel. Or express what passionately moves us.D: Jane Austen(1755-1817): born in a country clergyman’s family:Main Works:Novel: Sense and SensibilityPride and Prejudice(the most popular)Northanger AbbeyMansfield ParkEmmaPersuasionThe WatsonsFragment of a NovelPlan of a NovelPersonal Characters: she holds the ideals of the landlord class in politics, religion and moral principles; and her works show clearly her firm belief in the predominance of reason over passion, the sense of responsibility, good manners and clear—sighted judgment over the Romantic tendencies of emotion and individuality.Her Works’ Characters: his works’s concern is about human beings in their personal relationships. Because of this, her novels have a universal significance. It is her c onviction that a man’s relationship to his wife and children is at least as important a part of his life as his concerns about his belief and career. Her thought is that if one wants to know about a man’s talents, one should see him at work, but if one wan ts to know about his nature and temper, one should see him at home. Austen shows a human being not at moments of crisis, but in the most trivial incidents of everyday life. She write within a very narrow sphere. The subject matter, the character range, the social setting, and plots are all restricted to the provincial life of the late 18th century England. Concerning three or four landed gentry families with their daily routine life.Her novels’ structure is exquisitely deft, the characterization in the hig hest degree memorable, while the irony has a radiant shrewdness unmatched elsewhere. Her works’ at one delightful and profound, are among the supreme achievements of English literature. With trenchant observation and in meticulous details, she presents the quiet, day-to-day country life of the upper-middle-class English.G: Questions and answers:1. what are the characteristics of the Romantic literature? Please discuss the above question in relation to one or two examples.a. in poetry writing, the romanticists employed new theories and innovated new techniques, for example, the preface to the second edition of the Lyrical Ballads acts as a manifesto for the new school.b. the romanticists not only extol the faculty of imagination, but also elevate the concepts of spontaneity and inspiration.c. they regarded nature as the major source of poetic imagery and the dominant subject.d. romantics also tend to be nationalistic.2.Make a contrast between the two generations of Romantic poets during the Romantic AgeThe poetic ideals announced by Wordsworth and Coleridge provided a major inspiration for the brilliant young writers who made up the second generation of English Romantic poets. Wordsworth and Coleridge both became more conservative politically after the democratic idealism. The second generation of Romantic poets are revolutionary in thinking. They set themselves against the bourgeois society and the ruling class.3.what are Austen’s writing features?Jane Austen is one of the realistic novelists. Aust en’s work has a very narrow literary field. Her novels showa wealth of humor, wit and delicate satire.4. what is the historical and cultural background of English Romanticism?a. Historically, it was provoked by the French Revolution and the English Industrial Revolution.b. Culturally, the publication of French philosopher Rousseau’s two books provided necessary guiding principles for the French Revolution which aroused great sympathy and enthusiasm in England;c. England experienced profound economic and social changes: the enclosure movement and the agricultural mechanization; the capitalist class grasped the political power and came to dominate the English society.H. topic discussion:1. Discuss the artistic features of Shelley’s poems.A. Percy Bysshe Shelly is an intense and original lyrical poet in the English language.B. His poems are full of classical and mythological allusions.C. His style abounds in personification and metaphor and other figures of speechD. He describes vividly what we see and feel, or expresses what passionately moves us.2. What does Wordsworth mean when he said “All good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings recollected in tranquility”?This sentence is considered as the principle of Wordsworth’s poetry c reation which was set forth in the preface to the Lyrical Ballads. Wordsworth appealed directly on individual sensations, as the foundation in the creation and appreciation of poetry.3. How do you describe the writing style of Jane Austen? What is the significance of her works?Jane Austen is a writer of the 18th century through she lived mainly in the 19th century. She holds the ideals of the landlord class in politics, religion, and moral principles. Austen’s main literary concern is about human beings in their personal relationships. Austen defined her stories within a very narrow sphere.。

英美文学史复习笔记5篇

英美文学史复习笔记5篇第一篇:英美文学史复习笔记英美文学复习时期划分——Early & Medieval literature 包括The Anglo-Saxon Period 和The Anglo-Norman Period ——Renaissance 文艺复兴——Revolution & Restoration 资产阶级革命与王权复辟——Enlightenment 启蒙运动——Romantic Period 浪漫主义时期——Critical Realism 批判现实主义——20th Modernism 现代主义传统诗歌主题:nature, life, death, belief, time, youth, beauty, love, feelings of different kinds, reason(wisdom), moral lesson, morality.修辞名称:meter格律, rhyme韵, sound assonance谐音, consonance和音, alliteration头韵, form of poetry诗歌形式, allusion典故, foot音步, iamb抑扬格, trochee扬抑格, anapest抑抑扬格, dactyl扬抑抑格, pentameter五音步文学体裁:诗歌poem,小说novel,戏剧novel起源:Christianity 基督教Bible圣经myth神话The Romance of king Arthur and his knights亚瑟王和他的骑士(笔记)一、1、The Anglo-Saxon period(496-1066)这个时期的文学作品分类:(pagan异教徒)(Christian基督徒)2、代表作:The song of Beowulf《贝奥武甫》(national epic)(民族史诗)采用了隐喻手法3、Alliteration押头韵(写作手法)例子:of man was the mildest and most beloved.To his kin the kindest, keenest for praise.二、The Anglo-Norman period(1066-1350)Canto 诗章受到法国影响English literature is also a combination of French and Saxon elements.1、romance传奇文学 Arthurian romances亚瑟王传奇2、代表作:Sir Gawain and the Green Knight(高文爵士和绿衣骑士)是一首押头韵的长诗 knighthood 骑士精神三、Geoffrey Chaucer(1340-1400)杰弗里。

英美文学学习笔记-Period-EL

Chapter 2 The Neoclassical PeriodA basic introduction to the neoclassical period.1) What we now call the neoclassical period is the one in English literature between the return of the Stuarts to the English throne in 1660 and the full assertion of Romanticism which came with the publication of Lyrical Ballads by Wordsworth and Coleridge in 17982) The English society of the neoclassical period was a turbulent one.3) Towards the middle of the eighteenth century, England had become the first powerful capitalist country in the world. It had become the work-shop of the world, her manufactured goods flooding foreign markets far and near.Briefly discuss "Enlightenment Movement" ---4) The eighteenth-century England is also known as the Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason. The Enlightenment Movement was a progressive intellectual movement which flourished in France and swept through the whole Western Europe at the time. The movement was a furtherance of the Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centures. Its purpose was to enlighten the whole world with the light of modern philosophical and artistic ideas. The enlighteners celebrated reason or rationality, equality and science. They held that rationality or reason should be the only, the final cause of any human thought and activities. They believed that when reason served as the yardstick for the measurement of all human activities and relations, every superstition, injustice and oppression was to yield place to "eternal truth," "eternal justice' and natural equality."5) They called for a reference to order, reason and rules: the enlighteeners advocated universal education; They believed that human beings were limited, dualistic, imperfect, and yet capable of rationality and perfection through education. If the masses were well educated, they thought, there would be great chance for a democratic and equal human society. As a matter of fact, literature at the time, heavily didactic and moralizing, became a very popular means of public education. Famous among the great enlighteners in England were those great writers like John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele, the two pioneers of familiar essays, Jonathan Swift, Daniel Defoe, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Henry Fielding and Samuel Johnson.1) What is "neoclassicism"? ---1) In the field of literature, the Enlightenment Movement brought about (导致)a revival of interest in the old classical works. The tendenchy is known as neoclassicism. According to the neoclassicists, all forms of literature were to be modeled after the classical works of the ancient Greek and Roman writers and those of contemporarhy French ones. They believed that the artistic ideals should be order, logic, restrained emotion and accuracy, and that literature should be judged in terms of its service to humanity. This belief led them to seek proportion, unity, harmony and grace in literary experssions, in an effort to delight, instruct and correct human beings, primarily as social animals. Thus a polite, urbane, witty, and intellectual art developed.1) The mid-century was, however, predominated by a newly rising literary form--- the modern English novel, which, contray to the traditional romance of aristocrats, gives a realistic presentation of life of the common English people. This --- the most significant phenomenon in the history of the development of English literature in the eighteenth century---is a natural product of the Industrial Revolution and a symbol of the growing importance and strength of the English middle class. Among the pinoeers were Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, Tobias, George Smollett, and Oliver Goldsmith.2) Gothic novels: mostly stories of mystery and horror which take place in some haunted or dilapidated Middle Age castles.3) Robert Burns and William Blake also joined in, paving the way for the flourish of Romanticism earlyu the next century.4) In the theatrical world, Richard Brinsley Sheridan was the leading figure among a host of playwrights. And of the witty and satiric prose, those written by Jonathan Swift are especially worth studying, his A Modest Proposal being generally regarded as the best model of satire, not only of the period but also in the whole English literary history.Daniel Defoe1) It's a real wonder that such a busy man as Defoe would have found time for literary creation. The fact is that, at the age of nearly 60, he started his first novel Robinson Crusoe, Which was an immediate success. In the following years, he wrote four other novels: Captain Singleton, Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack and Roxana, apart from the second and thethird part of Robinson Crusoe and a pseudo-factual account of the Great Plague in 1664-1665, A Journal of the Plague Year (1722)2) Robinson Crusoe, an adventure story very much in the spirit of the time, is universally considered his masterpiece.RobinsonCrusoe 1) Here Pope advises the critics not to stress too much the artificial use of Conceit orthe external beauty of language but to pay soecial attention to True Wit which is best setin a plain style.2) The poem, as a comprehensive study of the theories of literary criticism, exertedgreat influence upon Pope's contemporary writers in advocating the classical rules andpopularizing the meoclassicist tradition in England.3)(节选) Some to conceit alone their taste confine, And glittering thoughts struck out atevery line; Pleased with a work whre nothing's just or fit, One glaring chaos and wildheap of wit. Poets, like painters, thus unskilled to trace, The naked nature and the livinggrace, With gold and jewels cover every part, And hide with ornaments their want ofart, true wit is Nature ot advantage dressed, What oft was thought, but ne'er so wellexpressed.An Essay on CriticismJohn Bunyan1) In prison he wrote The Pilgrim's Progress, which was published in 1678 after his release.2) Bunyan's other works include Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, The Life and Death of Mr.Badman, The Holy War and The Pilgrim's Progress, Part II.3) The Pilgrim's Progress is the most successful religious allegory in the English language. Its purpose is to urge people to abide by Christian doctrines and seek salvation through constant struggles with their own weaknesses and all kinds of social evils. Besides, a rich imagination and a natural talent for storytelling also contribute to the success of the work which is at once entertaining and morally in structive.4) Vanity Fair seels all kinds of merchandise such as hourses, lands, honors, titles, lusts, pleasures. It symbolizes the society where everything becomes goods and can be bought by money.Alexander Pope1) As a representative of the Englishtenment, Pope was one of the first to introduce rationalism to England.2) Pope made his name as a great poet with the publication of An Essay on Criticism in 1711. The next year, he published The Rape of the Lock, a finest mock epic.The Dunciad , generally considered Pope's best satiric work took him over ten years for final completion.1) Robinson Crusoe is supposed based on the real adventure of an Alexander Selkirk who once stayed alone on the uninhabited island for five years. Actually, the story is an imagination.2) In Robinson Crusoe, Defoe traces the growth of Robinson from a naive nad artless youth into a shrewd and handened man, tempered by numerous trials in his eventful life.3) In the novel, Robinson is a real hero and he is an embodiment of the rising middle-class virtues in the mid-eighteenth century England.4) Robinson Crusoe is an adventure story very much in the spirit of the time. so it verysuccessfulTo the RightHonorable theEarl ofChesterfield.1) The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, and The History of Amelia. The foremer is a masterpiece on the subject of human nature and the latter the story of the unfortunate life of an idealized woman, a maudlin picture of the social life at the time.2) Fielding has been regarded by some as "Father of the English Nove." fo his contribution to theestablishement of the form of the modern novel. Of all the 18 century novelists he was the first to set out,both in theory and practice, to write specifically a comic epic in prose." the first to give the modern novel its structure and style.1) Tom Jones, the full title being The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, is generallyconsidered Fielding's masterpiece.2) For a time, tom became a national hero. People were fond of this young fellow withmanly virtues and yet not without fault-honest, kind-hearted, high-spirited, loyal, and brave, but impulsive, wanting prudence and full of animal spirits. In a way, the young man stands for a wayfaring everyman, who is expelled from the paradise and has to gothrough hard experience to gain a knowledge of himself and finally to approach perfectness.3) Tom Jones brings its author the name of the "Prose Homer." By this, Fielding hasindeed achieved his goal of writing a "comic epic in prose."Tom Jones, the full title being The History of Tom Jones Samuel Johnson1) As a lexicographer, Johnson distinguished himself as the author of the firstg English dictionary by an Englishman---A Dictionary of the English Language, a gigantic task which Johnson undertook single-handedly and finished in over seven years.2) Samuel Johnson was the last great neoclassicist enlightener in the later eighteenth century.Jonathan Swift1) Jonathan Swift, in 1726, he wrote and published his greatest satiric work, Gulliver's Travels.2) Swift is a master satirist. His A Modest Proposal" is generally taken as a perfect model. By suggesting that poor Irish parents sell their one-year-old babies to the rich English lords and ladies as food, Swift is making hte most devastating protest aginast the inhuman exploitation and oppression of the Irish people by the English ruling class.3) Swift is one of the greatest masters of English prose. "Proper words in proper places."4) SWIFT'S CHIEF WORKS ARE: A taleof a Tub, The Battle of the Books, The Drapier's Letters,Gulliver's Travels and A Modest Proposal1) Gulliver's Travels, Jonathan's best fictional work, was published in 1726, under thetitle of Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, by Samuel Gulliver. Thebook contains four parts, each dealing with one particular voyage during which Gullivermeets with extraordinary adventures on some remote island after he has met withshipwreck or piracy or some other misfortune.2) As a whole, the book is one of the most effective and devastating criticisms andsatires of all aspects in the then English and European life---socially, politically,religiously, philosophically, scientifically, and morally. its social significance is greatand its exploration into human nature profound." My gentleness and good behaviour had gained so far on the Emperor and his count,and indeed upon the army and people in general, that I began to conceive hopes ofgetting my liberty in a short time, I took all possible methods to cultivate this favorabledisposition."Gulliver's TravelsHenry Fielding1) In this poem, Gray reflects on death, the sorrows of life, and the mysteries of humanlife with a touch of his personal melancholy. The poet compares the common folk withthe great ones, wondering what the commons could have achieved if they had had the chance.2) Here he reveals his sympathy for the poor and the unknown, but mocks the great ones who despise the poor and bring havoc on them.Elegyh Written in a Country Churchyard Richard Brinsley Sheridan1) The year 1777 saw the appearance of his masterpiece The School for Scandal, which brought him quite a fortune.2) Sheridan was the only important English dramatist of the eighteenth century. His plays, especially The Rival and the School for Scandal, are generally regarded as important links between the masterpieces of Shakespeare and those of Bernard Shaw, and as true classics in English comedy.3) Besides The Rivals and The School for Scandal, Sheridan's other works included: St. Patrick's Day, or the Scheming Lieutenant, a two-act farce; the Duenna, a comic opera; The Critic, a burlesque and a satire on sentimental drama; and Pizarro, a tragedy adapted from a German play.The School for Scandal.1) The School for Scandal is one of the great classics in English drama. It is a sharpsatire on the moral degeneracy of the aristocratic-bourgeois society in the eighteenth-century England, on the vicious scandal-mongering among the idle rich, on the reckless life of extravagance and love intrigues in the high society and, above all, on the immorality and hypocrisy behind the mask of honorable living and high-soundingmoral principles. And in terms of theatrical art, it shows the playwright at his best. Nowonder, the play has been regarded as the best comedy since Shakespeare.Thomas Gray1) Horace Walpole, author of the famous Gothic novel The Old Castle of Otranto2) Thomas Gray declined the Poet laureateship in 1757.3) His masterpiece, "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" was published in 1751. The poem once and for all established his fame as the leader of the sentimental poetry of the day, especially " the Graveyard School." hHis poems, as a whole, are mostlhy devoted to a sentimental lamentation or meditation on life,past and present.4) His other poems include "Ode on the Spring, Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College, Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat, Hymnb to Adversity, and two translations from old Norse: the Descent of Odin,and The Fatal Sisters.。

英美文学教程笔记.

English LiteratureChapter OneEnglish Literature in the Middle Age (5th -15th )Main points:I. Background information of the Anglo-Saxon period.II. Literary characteristics of the Anglo-Saxon period.III. Background information of the Anglo-Norman period.IV. Literary characteristics of the Anglo-Norman period.V. Important literary works and men of letters of the Anglo-Norman period.VI. Geoffrey ChaucerI . Background information of the Anglo-Saxon periodThe period can be roughly divided into two stages: the Anglo-Saxon period and the Anglo-Norman period.1.The making of the nation.1.1 The inhabitants of the nationThe native Celts凯尔特人(they inhabit in what is now Ireland, Wales and Scotland )------- the Roman Conquest ( this conquest was led by Julius Caesar in 55B.C., which lasted 4 centuries, but it made little influence on the nation’s literature )------- the Anglo-Saxon Conquest in about 449 by three Teutonic tribes 条顿部落--- the Anglos, the Saxons, the Jutes.The Anglo-Saxons were Christianized in the 7th century, which influenced the literature in two aspects: one is the great number of Christian poetry which forms an important part of English literature of this period; the other is Christian color in pagan works, for the monks recorded the oral literature with their Christian ideas. (The ideas usually do not go with the content of the whole being.)1.2 The languageIn the 7th, the three tribes mixed into a whole people called English and the language spoken by them is generally called Anglo-Saxon, that is the Old English.II. Literary characteristics of the Anglo-Saxon period.The main literary form of the period is poetry and there are two groups: pagan poetry and religious poetry, and often Christian one.The most important works left is Beowulf《贝奥武甫》or《贝尔武夫》The introduction to BeowulfIt is the earliest complete epic in English literature and it is regarded as the national epic of the English people.----- Definition of epic or national epic 史诗: it is a poetic account of the deeds of one or moregreat heroes, or of a nation’s past history.----- 3182 lines, two parts with an interpolation between the two.----- The theme of the poem: Beowulf is one of the nation’s heroes of the English people. With the descriptions of his heroic deeds, the song reflects events taking place on the Scandinavian peninsula at the beginning of the 7th century.----- The significance of the poem: The story represents 1) the fight of the ancient people against beasts and natural forces ( e.g. flood, volcano ); 2) it reflects the features of tribal society of ancient time; 3)Beowulf’s deeds presents the ideal virtues of ancient Anglo-Saxons.( courage,prowess, devotion to his people )----- Characteristics of the poem: an alliterative verse头韵体诗歌; pagan in spirit and matter, yetwith visible Christian marks.III. Background information of the Anglo-Norman period.3.1 The Norman ConquestThe beginning of the Anglo-Norman period is marked by the Norman Conquest in 1066. The influences of the conquest on the English society are: 1) the nation turned from the tribal society to the feudal society; 2) the conquest brought for the nation French civilization and the French language.3.2 The languageAt first, French was the language of the upper class or the oppressor and Old English was the language of the oppressed. Then Old English was combined with French to form a new language ---- Middle EnglishIV. Literary characteristics of the Anglo-Norman periodThe main literary forms of the period are poetry and prose.( romance in the form of prose ) Literary characteristics------ 中古英诗呈现法国诗风与英格兰本土传统交融的情景。

【英美文学选读】名词解释笔记总结

01. Humanism(人文主义)Humanism is the essence of the Renaissance.It emphasizes the dignity of human beings and the importance of the present life. Humanists voiced their beliefs that man was the center of the universe and man did not only have the right to enjoy the beauty of the present life,but had the ability to perfect himself and to perform wonders.02. Renaissance(文艺复兴)The word “Renaissance”means “rebirth”,it meant the reintroduction into western Europe of the full cultural heritage of Greece and Rome.2>the essence of the Renaissance is Humanism. Attitudes and feelings which had been characteristic of the 14th and 15th centuries persisted well down into the era of Humanism and reformation.3> the real mainstream of the English Renaissance is the Elizabethan drama with William Shakespeare being the leading dramatist.03. Metaphysical poetry(玄学派诗歌)Metaphysical poetry is commonly used to name the work of the 17th century writers who wrote under the influence of John Donne.2>with a rebellious spirit,the Metaphysical poets tried to break away from the conventional fashion of the Elizabethan love poetry.3>the diction is simple as compared with that of the Elizabethan or the Neoclassical periods,and echoes the words and cadences of common speech.4>the imagery is drawn from actual life.04. Classicism(古典主义)Classicism refers to a movement or tendency in art,literature,or music that reflects the principles manifested in the art of ancient Greece and Rome. Classicism emphasizes the traditional and the universal,and places value on reason,clarity,balance,and order. Classicism,with its concern for reason and universal themes,is traditionally opposed to Romanticism,which is concerned with emotions and personal themes.05. Enlightenment(启蒙运动)Enlightenment movement was a progressive philosophical and artistic movement which flourished in France and swept through western Europe in the 18th century.2> the movement was a furtherance of the Renaissance from 14th century to the mid-17th century.3>its purpose was to enlighten the whole world with the light of modern philosophical and artistic ideas.4>it celebrated reason or rationality,equality and science. It advocated universal education.5>famous among the great enlighteners in England were those great writers like Alexander pope, Jonathan Swift, etc.06.Neoclassicism(新古典主义)In the field of literature,the enlightenment movement brought about a revival of interest in the old classical works.2>this tendency is known as neoclassicism. The Neoclassicists held that forms of literature were to be modeled after the classical works of the ancient Greek and Roman writers such as Homer and Virgil and those of the contemporary French ones.3> they believed that the artistic ideals should be order,logic,restrained emotion and accuracy,and that literature should be judged in terms of its service to humanity.07. The Graveyard School(墓地派诗歌)The Graveyard School refers to a school of poets of the 18th century whose poems are mostly devoted to a sentimental lamentation or meditation on life. Past and present,with death and graveyard as themes.2>Thomas Gray is considered to be the leading figure of this school and his Elegy written in a country churchyard is its most representative work.08. Romanticism(浪漫主义)1>In the mid-18th century, a new literary movement called romanticism came to Europe and then to England.2>It was characterized by a strong protest against the bondage of neoclassicism,which emphasized reason,order and elegant wit. Instead,romanticism gave primary concern to passion,emotion,and natural beauty.3>In the history of literature. Romanticism is generally regarded as the thought that designates a literary and philosophical theory which tends to see the individual as the very center of all life and experience. 4> The English romantic period is an age of poetry which prevailed in England from 1798 to 1837. The major romantic poets include Wordsworth,Byron and Shelley.09. Byronic Hero(拜伦式英雄)Byronic hero refers to a proud,mysterious rebel figure of noble origin.2> with immense superiority in his passions and powers,this Byronic Hero would carry on his shoulders the burden of righting all the wrongs in a corruptsociety. And would rise single-handedly against any kind of tyrannical rules either in government,in religion,or in moral principles with unconquerable wills and inexhaustible energies.3> Byron‘s chief contribution to English literature is his creation of the “Byronic Hero”10. Critical Realism(批判现实主义)Critical Realism is a term applied to the realistic fiction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.2> It means the tendency of writers and intellectuals in the period between 1875 and 1920 to apply the methods of realistic fiction to the criticism of society and the examination of social issues.3> Realist writers were all concerned about the fate of the common people and described what was faithful to reality.4> Charles Dickens is the most important critical realist.11. Aestheticism(美学主义)The basic theory of the Aesthetic movement——“art for art‘s sake” was set forth by a French poet,Theophile Gautier,the first Englishman who wrote about the theory of aestheticism was Walter Pater.2> aestheticism places art above life,and holds that life should imitate art,not art imitate life.3> According to the aesthetes,all artistic creation is absolutely subjective as opposed to objective. Art should be free from any influence of egoism. Only when art is for art‘s sake,can it be immortal. They believed that art should be unconcerned with controversial issues,such as politics and morality,and that it should be restricted to contributing beauty in a highly polished style.4> This is one of the reactions against the materialism and commercialism of the Victorian industrial era,as well as a reaction against the Victorian convention of art for morality‘s sake,or art for money’s sake.美学运动的基本原则“为艺术而艺术”最初由法国诗人西奥费尔。

《英美文学选读》笔记

P3Middle English literature strongly reflects the principles (原则) of the medieval Christina doctrine (中世纪基督教学说) , which were primarily (主要) concerned with the issue of personal salvation (拯救)P4Geoffrey Chaucer is the greatest writer of this period.Chaucer characteristically( 表示特性地) regard life in term of aristocratic ideals (贵族理想) ,but he never lost the ability of regarding life as a purely(纯粹地) practical matter , the art of being at once involved in and detached from a given situation is peculiarly (特有地) Chaucer’sChaucer bore (带有)marks of humanism and anticipated ( 预期的)a new era (时代) to comeIn short, Chaucer develops his characterization (描述) to a higher artistic (艺术的,有美感的) level by presenting characters (引出人物) with both typical and individual dispositions (部署)Chaucer’s reputation (名誉) has been securely established as one of the best English poets for his wisdom, humor and humanityChapter 1Renaissances: The Renaissances which means rebirth or revival, is actually a movement stimulated ( 刺激) by a series of historical events, In essence( 本质上) , is a historical period in which the European humanist thinkers (人道主义思想家) and scholars (学者) made attempt( 努力/尝试) to get rid of ( 摆脱) those old feudalist ideas ( 封建主义) in medieval Europe , to introduce new ideas that expressed the interests of the rising bourgeoisie (新兴的资产阶级) and to recover the purity (纯度) of the earlychurch from the corruption( 腐败,堕落) of the Roman Catholic Church/P7 P8Humanism is the essence ( 本质) of the RenaissanceThomas More , Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare and the best representatives of the English humanistWhen Henry VIII declared himself through the approval of the Parliament( 国会) as the supreme (极大的,最高的) Head of the Church of England in 1534 , the Reformation in England was in its full swing ( 高潮)P10The religious reformation was actually as reflection of the class strugglewaged ( 工资 )by the new rising bourgeoisie against the feudal class and its ideology ( 意识形态)The first period of the English Renaissance was one of imitation andassimilation ( 模仿与同化)In the early stage of the Renaissance, poetry and poetic drama were the most outstanding literary forms and they were carried on especially by Shakespeare and Ben JonsonThe Elizabethan drama , in its totally, is the real mainstream( 主流) of the English RenaissanceThe most famous dramatists in the Renaissance England are Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare and Ben JonsonP12Edmund Spenserhe was born in London and received good education & left Cambridge in 1576.in 1580, he was made secretary of Lord Grey of wilton. Spenser’s masterpiece(代表作)is the “ Faerie Queene ” is great poem of its age。

《英美文学选读》笔记,全面归纳

《英美文学选读》笔记,全面归纳9年elf担任造反发言人。

主要的有:《儒林外史》(1794)、《洛书》(1795)。

四祖(1796-1807)无论他想象什么,他也看到了。

作为一个富有想象力的诗人,他用视觉形象而不是抽象的术语来表达自己的观点。

布雷克在平原上写他的诗《怀伊河谷》本身,用一个细节描述了归来的流浪者思想的宁静中心,传达了一种自然秩序的感觉,立刻生动地表现了船停下来的情景;炎热的热带阳光照耀了一整天。

其他水手一个接一个地渴死了,只有水手还活着,一直被口渴折磨着(1595),这首诗表达了诗人第二次婚姻所引起的深刻的个人感情;阿莫里蒂(1595),一系列十四行诗。

理解他的影响spesser诗歌的主要品质(完美的旋律②罕见的美感③精彩的想象力④崇高的道德纯洁它也揭示了人类在敌对的道德秩序中实现崇高愿望的挫折。

最后一个场景,浮士德面临他的厄运,出色地呈现了一些移民到殖民地的恐惧;有些人堕落到农场工人的水平,他是一个无辜的叛逆者,时间的三个统一,建筑的空间规律应该坚持时间的三个统一,建筑的空间规律应该坚持,这本书很快变成了一个开放的道路的伟大小说,一个\史诗般的散文\其主题是\真正荒谬的\人性,暴露在各种各样的约瑟夫悲剧:艾琳(1749);几百篇论文出现在他编辑的两个期刊——《漫步者》,他必须取悦,但他也必须指导;他不能冒犯宗教或宣扬不道德;杜纳(1775),喜剧歌剧;《批评家》(1779),一部滑稽剧《水手的灵魂》中每一个相应的变化都被记录下来。

整个经历是一场极度疲劳的考验。

(2)\可汗\是柯勒律治吸食鸦片后在梦中创作的。

诗人在阅读忽必烈汗的作品时睡着了。

河流、宏伟宫殿的形象\人类想象力的产物是调和对立的装置(诗歌);第12行到第30行是抑扬格五音步,其多样性是多节奏的;第31行到第34行是抑扬顿挫的四步抑扬顿挫,第35行是抑扬顿挫的五步抑扬顿挫。

他悲叹堕落的希腊,表达了他热切的希望被压迫的希腊人民应该赢得他们的自由;他赞美法国大革命,而在大陆上,他被誉为自由的捍卫者,人民的诗人。

英美文学史复习笔记

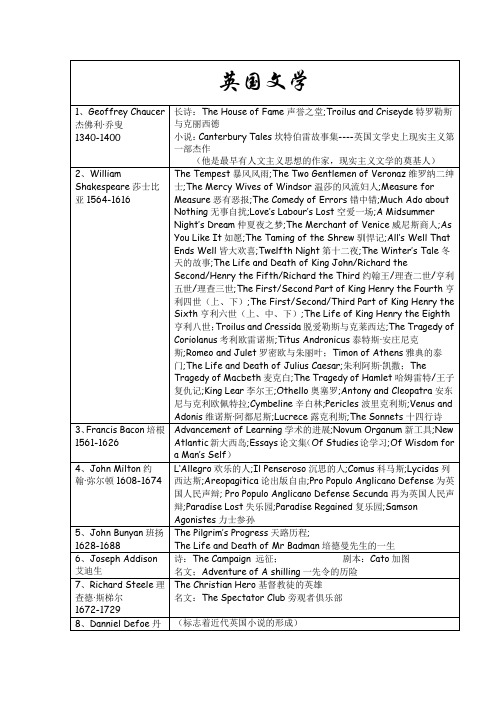

Chapter 1 Old and Medieval EnglishLiterature(450—1066-1340)1.Beowulf: a typical example of Old English poetry is regarded as the national epic of the Anglo-Saxons. It is an example of the mingling of nature myths and heroic legends.2.Romance:①It uses narrative verse or prose to sing knightly adventures or other heroic deeds is a popular literary form in the medieval period.②It has developed the characteristic medieval motifs of the quest, the test, the meeting with the evil giant and the encounter with the beautiful beloved.③The hero is usually the knight, who sets out on a journey to accomplish some missions. There are often mysteries and fantasies in romance.④Romantic love is an important part of the plot in romance.Characterization is standardized, While the structure is loose and episodic, the language is simple and straightforward.⑤The importance of the romance itself can be seen as a means of showing medieval aristocratic men and women in relation to their idealized view of the world.2. Heroic couplet:Heroic couplet is a rhymed couplet of iambic pentameter. It is Chaucer who used it for the first time in English in his work The Legend of Good Woman.3. The theme of Beowulf:The poem presents a vivid picture of how the primitive people wage heroic struggles against the hostile forces of the natural world under a wise and mighty leader. The poem is an example of the mingling of the nature myths and heroic legends.5. Chaucer’s achievement:①He presented a comprehensive realistic picture of his age and created a whole gallery of vivid characters in his works, especially in The Canterbury Tales.②He anticipated a new ear, the Renaissance, to come under the influence of the Italian writers.③He developed his characterization to a higher level by presenting characters with both typical qualities and individual dispositions.④He greatly contributed to the maturing of English poetry. Today, Chaucer’s reputation has been securely established as one of the best English poets for his wisdom, humor and humanity.6. “The F ather of English poetry”:Originally, Old English poems are mainly alliterative verses with few variations.①Chaucer introduced from France the rhymed stanzas of various types to English poetry to replace it.②In The Romaunt of the Rose (玫瑰传奇), he first introduced to the English the octosyllabic couplet (八音节对偶句).③In The Legend of Good Women, he used for the first time in English heroic couplet.④And in his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales, he employed heroic couplet with true ease and charm for the first time in the history of English literature.⑤His art made him one of the greatest poets in English; John Dryden called him “the father of English poetry”.【例题】The work that presented, for the first time in English literature, a comprehensive realistic picture of the medieval English society and created a whole gallery of vivid characters from all walks of life is most likely ______________. (0704)A. William Langland’s Piers PlowmanB. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury TalesC. John Gower’s Confession AmantisD. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight【答案】BChapter 2: The Renaissance Period(14th—mid-17th Century)1.The Renaissance:The Renaissance marks a transition from the medieval to the modern world. Generally, it refers to the period between the 14th & 17th centuries. It first started in Italy, with the flowering of painting, sculpture & literature. From Italy the movement went to embrace the rest of Europe. 2. Humanism:Humanism is the essence of the Renaissance. It sprang from the endeavor to restore a medieval reverence for the ancient authors and is frequently taken as the beginning of the Renaissance on its conscious, intellectual side. Through the new learning, humanists not only saw the arts of splendor and enlightenment, but the human values represented in the works. Thomas More, Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare are the best representatives of the English humanists.Ⅰ. William Shakespeare1. The bibliographyWilliam Shakespeare is one of the most remarkable playwrights and poets the world has ever known.3. The major contributions38 plays (historical plays, tragedies and comedies)2 narrative poems: Venus, The Rape of Lucrece154 sonnets4. His play-creationfive historical plays: Henry IV, part I, II, and III; Richard III; and Titus Andronicus(泰特斯, 提图斯).four Comedies, including: The Comedy of Errors; The Two Gentlemen of Verona(维罗纳); The Taming of the Shrew(泼妇的驯服), and Love’s Labor’s LostFive historical: Richard II, King John, Henry IV, part I, II, Henry V Six comedies: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, As You like(皆大欢喜), Twelfth Night, and the Merry Wives of Windsor(温莎公爵的快乐情妇)Two tragedies: Romeo and Juliet, Julius CaesarSeven tragedies: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra(克利奥帕特拉), Troilus and Cressida(特洛伊罗斯和克雷西达), Coriolanus(科里奥兰纳斯)Two comedies: All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measureromantic tragicomedies: Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, and The TempestTwo final plays: Henry III, and The Two Noble Kinsmen7. Shakespeare’s writing characteristicsThe progressive significance of the theme--humanismThe successful character portrayal—women’s charactersThe masterhand in constructing the plotThe ingenuity of his poetryThe mastery of his languageⅡ. John MiltonLycidashis 3 major poetical works:Paradise Lost (1667), Paradise Regained (1671), & Samson Agonistes (1671).①Epics: Paradise Lost失乐园Paradisen Regained复乐园②Dramatic poem: <Samson Agonistes力士参孙③The Defence of the English People为英国人民声辩④On His Blindness我的失明Chapter 3: The Neoclassical Period(17th—18th Century, 1660~1798) 1. Duration:Neoclassical period is the one in English literature between the return of Stuarts to the English throne in 1660 and the full assertion of Romanticism which came with the publication of Lyrical Ballads by Wordsworth and Coleridge in 1978.It’s in fact a turbulent period.8. Gothic novels:Gothic novels are mostly stories of mystery and horror which take place in some haunted or dilapidated Middle Class castles. They appeared from the middle part of the 18th century. Richard Brinsley Sheridan was the leading figure among a host of playwrights. And of the witty and satiric prose, those written by Jonathan Swift are worth studying.【例题】The British bourgeois or middle class believed in the following notions EXCEPT ______. (0904)A. self - esteemB. self - relianceC. self - restraintD. hard work【答案】AⅠ. Daniel Defoe1. Daniel Defoe’s major works:The Shortest Way with the Dissenters.The True-born EnglishmanThe ReviewRobinson Crusoe (most famous of his work, his masterpiece)Captain Singleton《辛格尔顿船长》Moll Flanders《摩根.佛兰德斯》Colonel Jack《杰克上校》Roxana《罗克珊娜》A Journal of the Plague Year. 《大疫年日记》Ⅱ. Jonathan Swift2. MasterpiecesA Tale of a Tub (satirist) 《木桶的故事》The Battle of the Books 《书籍之战》The Examiner 《主考》Gulliver’s Travels (his greatest satiric work) 《格列佛游记》A Modest Proposal (more powerful) 《一个温和的建议》The Drapier’s Letters《专培儿之信》Ⅲ. Henry Fielding2. Contributions:①Father of the English Novel—because of his contribution and establishment of the form of the modern novel②Of all the eighteenth-century novelists he was the first to set out, both in theory and practice:First: give the modern novel both its structure and its styleSecond: adopted the “third-person narration” in which the author became the all-knowing God3. Main works:The earlier essays:The True Patriot and the Liberty of Our Own TimesThe Jacobite’s JournalThe Convent-garden JournalPlays:The Coffee-House PoliticianThe Tragedy of TragediesPasquinThe Historical Register for the YearNovels:The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his friend Mr. Abraham AdamsThe History of Jonathan Wild the GreatThe History of Tom Jones, a Foundling –masterpiece on subject of human natureThe history of Amelia- a story of the unfortunate life of an idealized woman, a maudlin picture of the social lifeChapter 4: The Romantic Period1798—1832, the early 30 years in19th Century )1. Historical background:Internationally,①The French Revolutions:②RousseauThese paved the way for the development of Romanticism in theliterature internationallyNationally,①Industrial revolution (Industrialization, Further capitalization andUrbanization)②The survival of fittest (the sharper contradiction between capitalistsand the labors)These are the national basis of the production of Romanticism3. The definition, duration and characteristics of the Romanticism:①The definition:The Romantic Movement, which associated with vitality, powerful emotion and dreamlike ideas, is simply the expression of life as seen by the imagination rather than by prosaic common sense.【例题】Which of the following poems is a landmark in English poetry? (0704)A. Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor ColeridgeB. “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”by William WordsworthC. “Remorse”by Samuel Taylor ColeridgeD. Leaves of Grass Walt Whitman【答案】A6. Main representatives:①Main representatives—poets:Pre-Romanticism: (Blake and Burns)The first generation: (Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey)The younger generation: (Byron, Shelley and Keats)②Main representatives—novelistsJane Austen --- love and marriageWalter Scott --- main works (book) human nature③Gothic novelistsAnn Radcliffe and Mary ShelleyGothic novel:It is a type of romantic fiction that predominated in the late 18th century & was one phase of the Romantic MovementWorks like The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Ann Radcliffe & Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley are typical Gothic romanceⅠ.William Blake1.Introduction:English poet, artist, & philosopher, made distinguished contributions to both Literature & art. He ranks with great poets in the English language & may be considered the earliest of the major English Romantic poets.4. Main works:Early works: Poetical Sketches《诗学札记》Songs of Innocence《天真之歌》Songs of Experience《经验之歌》The Marriage of Heaven and Hell《天堂与地狱的婚姻》The similarities and differences between two volumes: Generally:Hold the similar subject-matterThe childhood is the central to his concernThe tone, emphasis and conclusion differSpecifically:Infant Joy against Infant SorrowLamb against TygerChimney SweeperⅠagainst Chimney SweeperⅡThe Book of UrizenThe Book of LosThe Four ZoasMilton【例题】William Blake’s central concern in the Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experiences_______, which gives the two books a strong social and historical reference. (0804)A. youth hoodB. childhoodC. happinessD. SorrowⅡ. William Wordsworth1. Introduction:William Wordsworth, known as “the Lake Poets” together with Coleridge and Southey,is the leading figure of the English Romantic poetry, the focal poetic voice of the period2. Types of his poem according to his poetic outlook:According to t he subjects, Wordsworth’s short poems can be classified into two groups: poems about nature and poems about human life.①Poems about nature:I Wandered Lonely as a CloudAn Evening WalkMy Heart Leaps upThe Sailor’s MotherThe Affliction of MargaretThe Old Cumberland BeggarThe Idiot BoyThe Solitary ReaperTo a Highland GirlⅢ. Percy Bysshe Shelley1. Introduction:Shelley is one of the leading Romantic poets, an intense & original lyrical poet in the English language.3. His major works:Early works:Queen Mab:Alastor or The Spirit of SolitudeHymn to Intellectual BeautyMont BlancJulian and MaddaloThe Revolt of IslamThe CenciHellasThe CloudTo a Skylark:: AdonaisOde to the west Wind (Best of all the well-known lyric pieces )Ode to LibertyOde to NaplesSonnet: England in 1819Men of EnglandMajor prose essay: Defense of PoetryⅣ.Jane Austen1. Introduction:It was Jane Austen who brought the English novels, as an art of form, to its maturity and she had been regarded as one of the greatest of all novelists.Austen is universally regarded as the founder of the novel which deal with unimportant middle-class people.2.Major works:In her lifelong career, Jane Austen wrote altogether six complete novels, which can be divided into two distinct periods.Sense and Sensibility理智与情感Her first novelPride and Prejudice傲慢与偏见The most popular of her novels dealing with the five Bennet sisters & their search for suitable husbands Northanger Abbey 诺桑觉寺satirizes those popular Gothic romances of the late 18th centuryMansfield Park曼斯菲尔德庄园presents the antithesis of worldliness & unworldlinessEmma 爱玛gives the thought over self-deceptive vanityPersuasion 劝导contrasts the true love with the prudential calculations【例题】“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” The quoted part is taken from ______. (0804)A. Jane EyreB. Wuthering HeightsC. Pride and PrejudiceD. Sense and Sensibility【答案】CChapter 5: The Victorian PeriodⅠ. Charles Dickens2. His Major Works:Period of youthful optimistSketches by Boz (1836); The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-1837); Oliver Twist (1837-1838);Nicholas Nickleby (1838-1839); The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841); Barnaby Rudge(1841)American Notes (1842); Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-1845); A Christmas Carol (1843); Dombey & Son (1846-1848); David Copperfield (1849-1850)Bleak House (1852-1853); Hard Times (1854); Little Dorrit (1855-1857);A Tale of Two Cities (1859); Great Expectations (1860-1861); Our Mutual Friend (1864-1865); Edwin Drood (unfinished)(1870)【例题】Among the works by Charles Dickens _______ presents his criticism of the Utilitarian principle that rules over the English education system and destroys young hearts and minds. (0804)A. Bleak HouseB. Pickwick PaperC. Great ExpectationsD. Hard Times【答案】DⅡ. Charlotte Bronte1. Charlotte's Literary Creation and her Writing Characteristics:Charlotte Bronte's works are all about the struggle of an individual towards self-realization,about some lonely & neglected young women with a fierce longing for love, & understanding & a full, happy life. Besides, she is a writer of realism combined with romanticism. Her works are famous for the depiction of the life of the middle-class workingwomen, particularly governesses.Jane Eyre:Ⅲ. Thomas Hardy2. His Major Works:Poetry: The DynastsHardy himself divided his novels into three groups:A Pair of Blue Eyes (1873); The Trumpet Major (1880)Desperate Remedies-;The Hand of EthelbertaUnder the Greenwood TreeThe Return of the NativeThe Mayor of CasterbridgeTess of the D'UrbervillesJude the Obscure【例题】Thomas Hardy's pessimistic view of life predominated most of his later works and earns him a reputation as a ______ writer. (0904)A. realisticB. naturalisticC. romanticD. stylistic【答案】BChapter 7: The Modern Period1. Modern period: from the second half of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century.6. The development Dramas in the 20th century:①Modernism:Oscar Wilde —the pioneer of modern dramaGeorge Bernard Shaw –best known since ShakespeareW.B. Yeats, Lady Georgory, J.M. Synge and Sean O’CaseyⅠ. George Bernard Shaw3. His major works:Five novels -- best one Cashel Byron's Profession (1886)Criticism -- Our Theaters in the Nineties (1931).Man and Superman (1904) and Back to Methuselah(1921).Caesar and Cleopatra (1898) and St. Joan (1923). Too True to Be Good (1932)Ⅱ. T. S. EliotHe won various awards, including the Nobel Prize and the Order of Merit in 1948.3. T. S. Eliot's major achievement in drama writing:He was one of the important verse dramatists in the first half of the 20th century. Besides some fragmentary pieces, Eliot had written in his lifetime five full-length plays:Murder in the Cathedral (1935)大教堂谋杀案The Family Reunion (1939)团员The Cocktail Party (1950)鸡尾酒会The Confidential Clerk (1954)机要秘书The Elder Statesman (1959) 资深政客Part Two: American LiteratureChapter 1: The Romantic Period。

(精品)英美文学考研复习笔记