CLN39_en_tessar 蔡司 天塞镜头简介

ZeissJena镜头指南

ZeissJena镜头指南⾸先,补充点历史。

⼆战后,位于耶那的蔡司公司被划⼊俄国控制的地区,(德国战后被四个胜利国拆分,俄国部分划为东德,美英法三国部分划为西德)蔡司公司许多科学家在美国的帮助下逃到西德,他们在Oberkochen建⽴起⼀座新的⼯⼚,在那⾥⽣产的在诸多产品⾥就包括顶级相机镜头。

原蔡司公司的剩余⼈员和⽣产设备及设计样本被拉到乌克兰,在那⾥建⽴起了新的相机⼚,⽣产出⼀系列沿⽤蔡司设计的苏联镜头。

在共产主义世界⾥,Zeiss Jena光学品牌被称作 "Carl Zeiss Jena"并沿⽤传统的镜头设计,包括Sonner,Biometar,Flektoon。

在西⽅不同国家Zeiss Jena光学品牌称呼不同,在美国不允许称做"Zeiss",销往美国的望远镜产品被冠以jenoptik商标,⽽镜头产品则被冠以aus jena 。

Zeiss Oberkochen也被允许使⽤镜头系列产品名称,所以sonner简称"s" ,Biometar则简称"Bm" ,Flektogon则简称"f"(Flektogon是不是这样标记不太清了)。

英国和部分欧洲国家允许使⽤ carl zeiss jena商标,但仍⽤缩写的产品系列名。

在其他⼀些地⽅,和共产主义世界使⽤⼀样的商标(共产主义世界⾥,Oberkochen不允使⽤"Zeiss"商标,所以他们⼀开始⽤opton商标,这就是为什么40年代后期的Rolleiflexes装配的是opton品牌的镜头)。

所以,"carl zeiss jena sonner"也可以叫做"Carl Zeiss Jena s" 或者 "aus Jena s",是⼀模⼀样的镜头,并没有品质差别,购买的时候⼤可不必在意。

蔡司望远镜

鹰眼——二战德国蔡司军用望远镜- SonicBBS 音速论坛论坛首页默认模式第一模式安全模式模式| 游戏大厅| 会员列表| 资料搜索| 社区条例| 社区FAQSonicBBS分流镜像:SonicChat SonicModel您还没有登陆| 登陆| 注册| 忘记密码| 注册音速邮箱论坛首页> 军事贴图> 精华区> 帖子内容发表投票| 发表新帖| 回复主题[<<] [<] [>] [>>]发表人内容jeffhunter少将【18】主题:鹰眼——二战德国蔡司军用望远镜发表时间:2007-9-22 20:32:50 编辑引用回复加入收藏第1 楼在世界的军用望远镜中,德国蔡司以其卓越的品质,多年来在世界望远镜领域独领风骚。

蔡司公司的创始人卡尔弗雷德里希蔡司原先是一位出色的技工,1846年,蔡司在德国历史名城耶拿创立了卡尔,蔡司公司。

这家公司起初主要是生产显微镜和其它一些光学仪器。

1866年,蔡司聘用了当时年仅26岁的耶拿大学教授阿贝为公司的研究员这个了不起的决定使得蔡司公司由一间规模很小的工场逐渐成为驰名全球的世界性大型企业。

1910年前后,蔡司研制出6×30规格的和7×50规格的望远镜,它们都是极为成功的望远镜,在二次世界大战中德军均大量装备过这些望远镜。

二战期间,蔡司公司亦生产了很多军用望远镜,其中为德国潜艇部队生产德8×60望远镜非常出名,它具有极为优异的光学性能,至今仍是资深望远镜收藏家追求的极品之一,二手交易价格甚至超过6000美元。

每一架都是精品,蔡司望远镜在鉴别率方面要高出一筹,清晰度高,无论从颜色,还是形象上看,不容易失真;在零件装配组合,以及外观设计上,蔡司都做得"非常德国",即考究、细致。

一丝不苟。

可以这么说,每一架出厂得蔡司都是精品。

在1902年左右,蔡司制造了第一个6X30望远镜,6X30开始被认为是理想的狩猎用望远镜,最先制造的是中心调焦的型号,有着很重要的革新,采用铸铝的镜体和宽大的棱镜室。

神头亮骚35mm蔡司CP2电影镜头效果评析

【IT168 评测】卡尔蔡司镜头可以说是很多相机用户的挚爱。

韵味十足的画质表现配合细致出众的做工,让蔡司的镜头不仅仅只是工具,更多的是一件艺术品。

不过今天我们介绍的这支蔡司镜头可并非什么常见之物。

虽然已经是熟悉的35mm镜头,虽然是熟悉的红色T*,但单单是外形就足以吓人一大跳。

夸张的外形设计与传统的镜头有很大的出入,密密麻麻的参数布满镜身,只不过依旧是蔡司引以为傲的蓝圈,还有那冷冰冰的金属材质。

▲Compact Prime CP2 35 今天的主角是卡尔蔡司推出的一支专用于可拍视频单反相机的电影镜头,也就是只闻其声不见其物的CP.2电影镜头:CP.235mm/T2.1(佳能卡口)。

为了展现这支神器的过人之处,我们将其搭载于拍摄视频能力非常出众的佳能5D Mark Ⅱ上。

拍摄剪辑两段视频,给大家看看效果,为啥这支镜头要买好几万。

▲佳能5D Mark Ⅱ可以说是目前最好的可拍视频单反相机无与伦比的外观设计 仅从外形上来看,这支CP2 35mm镜头与普通镜头截然不同。

而如此设计也都是为了满足“电影”拍摄的需求,在光学结构和操控上都进行了全新的改良。

可以说,卡尔蔡司在原先Distagon 35/f2.1的基础上,将操控做到了极致。

接下来我们先通过图片来了解这支镜头。

▲对焦环的设计只能用夸张二字来形容,谁叫是拍电影的呢▲全金属镜身拿在手里不是一般的沉▲原产德国,出身高贵▲如此夸张的镜头口径,估计如果丢了遮光罩,就只能拿帽子罩住了▲光是这个遮光照就不是一般镜头拥有的佳能5D Mark Ⅱ搭载蔡司CP2镜头拍电影 接下来我们就用佳能5D Mark Ⅱ搭载蔡司CP2镜头拍电影,由于镜头并没有设计数据环(只需要换转接环就能使用在佳能、尼康的机身上),所以全程对焦依靠手眼配合,并没有电子对焦提示。

后期影片只是进行剪辑制作,由此来看看这支镜头的实力。

非常感谢视频中心的范老先生不辞辛苦,在严寒中拍摄短片,感谢出镜演员,感谢IT168,感谢......▲造型奇特,但效果值得期待视频一:足球哥视频二:超频哥 看到神器,应当顶礼膜拜 可以说卡尔蔡司CP2镜头绝对是目前可拍视频单反相机的终极装备。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机是一款传统的35毫米胶片相机,由中国照相机制造公司(CHINA CAMERA CO., LTD)制造。

该相机采用了德国卡尔·蔡司(Carl Zeiss)制造的天塞镜头,能够捕捉高质量的影像和细节。

与其他同类相机相比,海鸥4A型具有出色的光学性能、坚固性能以及易用性能。

以下是这款相机的详细介绍。

外观设计:海鸥4A型相机的外观设计十分简洁,机身选用了铝合金材质,表面喷涂了深灰色漆面,使得整个相机看起来很沉稳有力。

同时,其尺寸也很适中,易于携带。

在相机上方,有一个向上开口的折叠取景器,取景器中还配备了一个小型视窗,以帮助用户准确定位焦点。

操作方式:相机背部有一个简单的手动曝光表,可供用户选择正确的快门速度和光圈大小。

该相机还配备了一个自拍装置,采用了2秒延迟的快门释放模式。

相机的背部还装有一个快门锁定开关以及一个多功能电源开关。

光学性能:海鸥4A型相机采用了高品质的天塞镜头,其中自动对焦系统能够捕捉详细和清晰的图像,让影像色彩还原的非常真实。

而且,该相机能够适应各种光线条件,并且在各种情况下捕捉到的图像都非常清晰。

此外,天塞镜头的光圈有五个级别,从F2.8到F16不等,适用于各种场景和拍摄需求。

易用性能:海鸥4A型相机非常容易使用。

只需要将35毫米相机拍摄标准胶片装入,旋转快门速度和光圈大小,调整手动曝光数值并准确对焦,就可以开始拍摄了。

由于该相机没有自动模式,因此在使用时需要根据场景自行设置拍摄参数。

这也是该相机的一个优点,能够帮助无论是初学者还是有经验的摄影师们提高基本摄影技能。

总结:无论您是一位摄影爱好者还是专业摄影师,海鸥4A型相机都是一个优秀的选择。

该相机很易于使用,性能稳定可靠,拍摄效果极好。

天塞镜头的优质光学效果使得该相机非常受欢迎,特别是对于那些喜欢摄影的人。

海鸥4A型相机堪称一款非常经典的相机,无论是从技术还是美学方面,都具有很高的水准。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机是一款专业的相机设备,旨在为摄影爱好者和专业摄影师提供优秀的拍摄效果和使用体验。

以下是对其主要特点和功能的介绍。

海鸥4A型相机采用了天塞镜头,这是一种高品质的镜头,能够提供清晰、细腻的图像效果。

其采用的特殊光学设计,能够有效减少镜头畸变和色差,让拍摄的照片更加真实自然。

天塞镜头还具有出色的对比度和色彩表现力,让人拍摄出更加丰富生动的画面。

海鸥4A型相机配备了一块高像素的传感器,能够捕捉更多的细节和色彩信息。

相机的有效像素达到了2400万,这意味着拍摄出的照片可以进行大尺寸的打印和细节放大,并且不会出现明显的图像失真。

相机还支持ISO感光度的调节,可以在不同的光线条件下拍摄出清晰明亮的照片。

海鸥4A型相机具备丰富的拍摄模式和功能,能够满足不同拍摄需求。

相机支持全自动拍摄模式,适合初学者使用。

相机还提供了光圈优先、快门优先、手动曝光等多种拍摄模式,方便摄影爱好者根据实际情况进行拍摄参数的调整。

相机还具备多种拍摄特效和滤镜,可以为照片添加不同的风格和效果。

海鸥4A型相机的机身设计精美,采用铝合金材质制造,手感舒适,且具有良好的防抖性能,能够减少手持拍摄时的抖动影响,拍摄出更加清晰的照片。

相机还配备了高清液晶显示屏和取景器,方便用户实时观察拍摄效果和构图。

相机还支持存储卡扩展和无线传输功能,方便用户进行照片的存储和分享。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机是一款功能强大、操作简便的相机设备,适合广大摄影爱好者和专业摄影师使用。

无论是日常拍摄还是专业摄影作品,海鸥4A型相机都能够帮助用户拍摄出高质量、出色的照片。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机

天塞镜头是一家全球知名的相机制造商,其产品广泛应用于商业、工业、科学、娱乐

等领域。

其中4A型相机是天塞镜头旗下的一款高端相机,有着出色的性能和功能。

4A型相机采用了天塞镜头最新的光学技术和传感器技术,具有36.3万像素的全画幅CMOS传感器,能够以7200赫兹的频率进行高速连拍,从而确保在高速运动场景下拍摄出

清晰的图片。

同时,该相机还配备了天塞镜头的专利超级防抖技术,能够有效稳定镜头,

消除拍摄抖动,从而拍摄出更加细腻、清晰的图片。

4A型相机具有强大的适应性,能够适应各种场景的拍摄需求。

由于其高速传感器和防抖技术,它可以应对高速运动场景、低光照场景和远距离拍摄等多种复杂情况。

此外,该

相机还支持多种曝光模式,如手动曝光、光圈优先曝光、快门优先曝光等,满足用户不同

的拍摄需求。

4A型相机还具有便捷实用的功能。

该相机支持多种存储介质,包括SD卡、CF卡和XQD 卡等,用户可以根据自己的需求选择适合自己的存储介质。

此外,4A型相机还采用了触摸屏技术,用户可以通过触摸屏快速调整相机设置和操作拍摄。

该相机还配备了WIFI功能,用户可以通过WIFI将拍摄到的照片上传到电脑或者移动设备上进行处理和分享。

总的来说,天塞镜头的4A型相机具有出色的性能和功能,能够满足用户多种拍摄需求,是一款值得信赖的高端相机。

蔡司镜头名称、涵义

蔡司镜头名称、涵义.txt16生活,就是面对现实微笑,就是越过障碍注视未来;生活,就是用心灵之剪,在人生之路上裁出叶绿的枝头;生活,就是面对困惑或黑暗时,灵魂深处燃起豆大却明亮且微笑的灯展。

17过去与未来,都离自己很遥远,关键是抓住现在,抓住当前。

蔡司镜头名称、涵义Planar (普兰纳镜头)代表像场平坦,:1896年由保罗·儒道夫博士(P. RudolphPlaner)于1896年所设计。

采用双高斯结构的镜头,出色纠正各种镜头像差。

此后,世界各地生产的各种品牌的标准镜头的设计无不受惠于普兰纳。

*Sonnar (松纳镜头)字义为阳光,于1932年由路德维希·雅可布·贝尔特勒(Dr. Ludwig Bertele)设计出来,具有深厚的细节保真和色彩平衡功力。

和普兰纳镜头成像润泽柔和不同,索纳的成像表现更加细致峭刻。

常用于照片和电影的拍摄。

*Distagon(迪斯塔根镜头)反望远结构(也称为“逆焦”结构)设计的单反廣角鏡,镜头视野极为开阔,广角和长焦表现都非常好,主用是18mm至35mm..也是常用于照片和电影拍摄,著名镜头为Distagon 21mm F2.8。

*Tessar(天塞镜头)在希腊语Tessares是4的意思,最早出现于1902年由Dr. Paul Rudolph设计,,由3组4枚构成的小巧镜头,由于空气面少最终成像不仅中心部分鲜明透亮,边角区域的细节也很清楚,因其成像锐利,反差高,素有“鹰眼”之称。

Tele-Tessar:衍生自Tessar的超望远镜头,一般为250mm以上。

特色是无球面像差、变型极低、失光极轻微且镜片组成极少,最低镜头数是300mm F/2.8,只用了7片镜片。

适合照片拍摄。

,*Biogon(比奥刚镜头)由梅塔博士于1953年发明,最初主要为旁轴相机设计。

采用双对称结构,该镜头最大的特点在于它的广角端几乎不会产生镜头畸变,著名镜头为Biogon 35mm F2。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机外观设计方面,海鸥4A型相机采用了全金属机身设计,金属材质带来了更加坚固耐用的品质感,同时也更加舒适稳固的握持手感。

相机表面采用了磨砂工艺,手感细腻,不易沾染指纹,整体线条流畅、简约大气,展现出了高端大气的外观气质。

在按键布局上,海鸥4A型相机十分人性化,各种按键和旋钮的分布合理,操作起来非常方便。

在机身正面和顶部还设计了多个功能按键,用户可以通过这些按键快捷地调整相机的各种参数,高效快捷。

海鸥4A型相机的外观设计简约大气,功能布局合理,给人一种高端大气的感觉。

在性能参数方面,海鸥4A型相机也表现出了非常强大的实力。

这款相机配备了一枚由天塞镜头研发的全新镜头,该镜头采用了最新的光学技术,并且通过数次的精密打磨和校正,保证了镜头的成像质量非常高。

这枚镜头的光圈范围广泛,可以满足不同场景下的拍摄需求,而且最小对焦距离也非常短,可以拍摄更加细致的画面。

在传感器方面,海鸥4A 型相机采用了全新的CMOS传感器,传感器的像素和画质表现都得到了很大的提升,能够拍摄更加细腻、清晰的图像。

再加上相机内置的高性能芯片,能够更快速地进行图像处理,相机的整体性能更加强大。

海鸥4A型相机在性能参数方面表现出了非常出色的实力。

在用户体验方面,海鸥4A型相机也进行了大幅度的提升。

在拍摄模式方面,相机内置了多种拍摄模式,包括自动模式、手动模式、景深优先模式、快门优先模式等,用户可以根据不同的拍摄需求选择合适的模式,并且可以进行快速切换。

在对焦速度和稳定性方面,海鸥4A型相机也得到了很大的提升,相机的对焦速度非常快,而且在低光环境下也可以快速准确对焦。

相机内置了多种滤镜和特效,用户可以通过这些滤镜和特效为自己的作品增加更多的创意元素。

海鸥4A型相机在用户体验方面表现出了非常出色的实力。

天塞镜头的海鸥4A型相机是一款非常出色的产品。

通过全新的外观设计、强大的性能参数和优秀的用户体验,这款相机能够满足用户对于高品质影像的需求,无论是日常拍摄还是专业摄影,都能够轻松应对。

蔡司七剑--七个蔡司系统中各自最令人心动的一支

蔡司七剑--七个蔡司系统中各自最令人心动的一支玩器材,大致可以分为两种人:一种以玩机为主,一种以玩镜为主,而我绝对属于后者玩镜,日系相对简单,变焦/定焦——大口径/小口径——搞定!莱卡就要复杂一些,除了口径以外还牵扯了“代”的问题,进而引出“味道”这种永远扯不清的话题然而,这点问题和玩蔡司的复杂程度相比,实在是不值一提,为什么这么说?因为蔡司的系统实在是太复杂!抛开一些非常见系统上的蔡司不提(如阿尔帕、路来双反/旁轴、诺基亚等)随随便便就能数出上十个使用蔡司镜头的系统——Y/C、G、N、T、645、ZM、ZF、ZA、哈苏、路来,这么多系统,这么多蔡头,怎么玩透?怎么玩精?这里提供一个思路——一个系统选一支,组成蔡司七剑!一、康泰时Y/C系——Planar85F1.2就是入选新七种武器--仅为此头入彼门的那支“拳头”,一想到这支头就想起一句俗话——老虎不发威你以为是病猫啊?85/1.4那头其实蛮厚道的,价定得比其他家都低,成像也不错,可就是老有人诟病它大光圈软,于是蔡司一生气,“拳头”就诞生了,这回成像是挑不出毛病了,就剩下一个问题——价格,我们来算笔账,85/1.4是5K,“拳头”光圈大了半档,加5K这是本儿,MTF显著提升,再加5K花得不冤,增加了floating element提高近摄质量,加大了装配调试难度,又得5K,因此,我觉得蔡司的定价(20K)不能算贵,还白送了一个纪念版呢至于成像方面,坛子里那几个毒贩已经放得够多了,就不提啦二、康泰时G系——Hologon16F8市面上能买到的镜头,99.9%都是由工程师设计的只有不到0.1%的镜头才是由科学家发明的,而Hologon就是其中之一(“工程师”和“科学家”之间还有“设计”和“发明”之间的区别就不解释了)Hologon的发明类似于蔡司在1896年发明Planar,在1902年发明Tessar不同的是,后两者已经被几乎所有的镜头设计厂家拷贝过而Hologon至今还没有第二个厂家能够复制所以说“Hologon是蔡司的一面旗帜”绝不为过它是蔡司作为一个镜头“发明”大厂区别于其他镜头“设计”厂家的标志性产品!Hologon的神奇之处在于——理论上只使用了三片镜片就解决了超广角镜头最难解决的畸变问题,而且是完美的解决是天才的光学/数学家的奇思妙想!除了零畸变以外,Hologon16F8的色彩和层次(特别是层次)也是蔡司头中顶级的(和传奇的莱卡口Hologon15比起来,Hologon16把其中的前两片分别分解为两片胶合的结构降低了生产成本,提高了解析力,最重要的是——价格合理得多)by bullcai三、康泰时N系——Tele-APOTessar400F4蔡司在长焦上标注APO是极其吝啬的即使已经达到甚至超过了日系厂家的APO标准也可能不标(比如Y/C那支100-300)而一旦标注了APO就一定具有超凡脱俗的光学素质Y/C的两支APO长焦200/2和300/2.8都是怪兽级的前者被一些香港器材店称作“镇店之宝”,售价5万左右而后者更是高达10万RMB和它们比起来,N系的APO-TeleTessar400F4简直太合算了!MTF与前两者在伯仲之间,而价格才2万多甚至,还带超声波自动对焦!(超长焦多用于生态/运动题材,自动对焦还是很有用的)四、康泰时645系——APO-MakroPlanar120F4康泰时645在产的时候,评价一直不高,在哈苏面前总是低人一头当时我觉得很奇怪,哈苏蔡头是蔡司嫁出去的姑娘,而康泰时蔡头是跟自己姓的儿子蔡司实在没有道理厚彼薄此至于价格上的差异,我更愿意相信是产地人工成本、镜间快门和直销/哈苏转销这几方面带来的随着康泰时的停产,645的价值也在越来越多地被人们认识到但直至今日仍然达不到哈苏的高度不过,康泰时645系中有一支头绝对可以让哈苏的“铁丝”哑口,这就是APO-MakroPlanar120F4这支微距,是蔡司所有微距头中迄今为止唯一的一支APO 其结果是惊人的!颠覆了中幅镜头分辨率比不过135头的传统观念作为Y/C系中MTF王者的MP100,和APO-MakroPlanar120F4比起来都要汗颜考虑到后者的成像面积几乎是前者的四倍,怎能不让人吃惊!吃惊!再吃惊!曾经有康泰时N系的朋友发信给德国蔡司咨询N系MS100那支微距没想到蔡司回信说你用转接环接645那支吧,实在搞笑的很!五、哈苏系——Distagon40F4IF哈苏系选了这支没选Biogon38,可能一些老派“哈丝”要跟我玩命,呵呵确实,在广角段,Biogon结构相对Distagon有先天的优势但最终结果还取决于厂家花费心血的多少(可以参考一下我的一篇旧文——纸上谈兵之——挑战旁轴相机广角镜头先天优势说)这就像龟兔赛跑,底子再好不努力也不成Biogon38这个头可能一开始就太优秀了,没有多少改进的余地,几十年来一成不变而Distagon40F4是蔡头里很少的不断通过改款提高性能的一支这一点对于以固执著称的蔡司来说绝对难得!(可能风光是哈苏的命根子,而40是风光的黄金焦段,蔡司是被哈苏逼的吧)这种不断的改进,到了IF这一代终于由量变达到了质变,乌龟超过了睡觉的兔子从MTF来看,40已经把38甩下了半个马位,虽然后者已经足够惊人暗角无疑是Distagon的长处,而畸变依然是Biogon的绝活不过对于风光来说,畸变应该不是特别重要而单反带来的精确构图和观察滤镜效果这两大优势却是风光拍摄所看重的目前阶段,真的看不出有选38而不选40IF的道理——除了拍摄建筑六、莱卡口ZM系——Biogon25F2.8对于莱卡口的ZM镜,莱卡铁杆多少有些不以为然,“不就是我们的廉价低质替代品吗?”说“廉价”,确实是ZM镜的定位但要说“低质”,机械上也许马马虎虎说得,光学上就一定要小心了特别是碰到Biogon25F2.8和Biogon35F2的时候从这两支中选出一支作为ZM的代表,让我死了不少脑细胞最终敲定25,只是因为这个焦段的Biogon更为正宗一些25是一个蔡司偏爱的焦段,这可能是他在这支头上发力的一个原因不过我觉得更大的可能性是旁轴的取景器使然内置取景器最广用到28,再广就要改用外置式了仅仅广了3毫米,凭什么让别人选择你而承受外置取景的麻烦?在25上面不发力不行啊!(蔡司的市场部在这种问题上一直是非常精明的,Y/C系的镜头群布局可见一斑)从各种机构或个人的评测结果来看,Biogon25不仅是ZM Biogon镜头群中的佼佼者而且打败了莱卡24by Vieri七、尼康口ZF系——APO-Sonnar200(或180)F2.8这支头是我杜撰出来的,请参考拙作——预测一下蔡司ZF(ZS)的下一批镜头(YY贴)其实ZF已经推出的镜头有几支我还是相当动心的像25,还有那两支微距不过我还在期待更加令人激动的新镜,包括这支长焦Y/C口的180俗称“奥林匹克松那”,是富有悠久历史的传奇镜头虽然它拥有迷人的散景和独特的柔和味道但严格地从光学上讲,绝不是一支牛镜期待ZF能够在不失去原有味道的基础上将它APO化这个要求会不会太过分?结束语这选自蔡司七个系统的七支镜头,基本上代表了蔡司在该系统上的殚精之作从焦段上说,基本涵盖了从超广角到超长焦的广阔焦段(从焦段出发,ZM系换成35mm就更理想了)而从镜头结构上说,涵盖了蔡司最主要的六种光学结构——Planar、Sonnar、Tessar、Distagon、Biogon和Hologon(玩蔡司不能不谈结构,请参考拙作——同焦段不同结构蔡司镜头猜图兼对比)全部玩过这蔡司七剑的人,起码可以宣称:蔡司——某某到此一游莱卡口ZM系没有写35那支头,依然觉得耿耿于怀!决定再出一个“蔡司七剑——第六剑version 2.0”个人更喜欢这个版本!六、莱卡口ZM系——Biogon35F2 说莱卡口的35mmF2,必然要从莱卡说起这个焦段/规格,是莱卡的根基,是他几十年来倾注了无数心血的地方!从莱卡前后四代的光学发展历程来看,这个看似简单的规格要想做到完美却也是相当的不易八妹,光学思想来自于双高斯,但使它走上神坛的是那两片萤石如果放在今天,八妹加上最新的镀膜技术,绝对能把ASPH 打翻在地,只是成本无法想象当年,也是成本的问题,八妹变成了六妹这是个可怜的孩子,分明是想告诉人们,离开萤石的双高斯在35mm是多么的无助!于是轮到了七妹哎!说什么呢?看看七妹的光学结构吧,硬生生在双高斯上打了一个补丁,打得如此难看!其结果,边角提升了,中心又恶化了,MTF变得古古怪怪最后,ASPH来了,莱卡终于放弃了双高斯,可是竟然选择了单反上迫不得已才使用的反摄远!这就像19世纪要从英格兰去美国西海岸,开始觉得理所当然应该横渡大西洋可后来发现从陆地上横跨美洲实在太难,于是转而好望角——印度——洛杉矶,绕了3/4个地球不知道费尽了千辛万苦的莱卡现在看到蔡司的Biogon35F2心里会是怎样的感受?Biogon35F2并没有使用非球面或是什么特殊材料的玻璃这也是蔡司的一贯风格,就像武林宗师通常只使用一些最简单的兵器或根本不用兵器一切从结构出发,这是蔡司的座右铭把最拿手的Biogon进行了一番大改后诞生的35F2,MTF明显超越了莱卡ASPH,而畸变更是近乎于零Biogon35F2——蔡司的巴拿马运河!by yunyan下面有位同学不经意说了句——鹰眼就是低档头的代表这话深深的刺痛了我这个蔡司粉丝怀旧的心因此,决定写几篇“蔡司怀旧老剑”蔡司怀旧老剑之一——康泰时Y/C系Tessar45F2.8对事物的评判,如果不能站在特定历史的角度,往往会有失偏颇评判天塞,就必须回到上个世纪初那个还没有发明镀膜的黑暗年代现今流行的标准镜头结构——双高斯,其实早在1896年就在蔡司科学家的图纸上演算出来了然而它对像差的完美消除仅仅只能停留在理论上因为过多的玻璃/空气接触面引起的反射严重破坏了影像到了1902年,天塞诞生了,四片三组的相对简单结构降低了反射带来的影响而成像质量,达到了这个级别所能达到的极限它出色的成像很快得到了“鹰眼”的美誉,进而引发了一轮仿造的热潮据有关机构统计,天塞是迄今为止被仿造次数最多的一种光学结构而且,这个纪录恐怕很难有人能够打破了到了二十世纪中叶,随着抗反射镀膜技术的发明和不断改进,双高斯结构的理论优势终于得以发挥天塞带着曾经的光环渐渐离人们远去,再后来康泰时也将其停产不过,最执著的蔡司迷都是怀旧的,复产天塞的呼声一直没有停息蔡司终于顺应民意,再次推出了康泰时Y/C系Tessar45F2.8 这是一支颇具特色的镜头虽然它四角结像不佳、虽然它收缩光圈焦点漂移、虽然它影调层次不够丰富、虽然它色彩不够浓郁但它拥有极强的线条刻画能力和极佳的空气通透感,拍出的照片给人印象深刻!由于原本空气接触面就少,再加上多层镀膜技术,T45号称不会漏过最最细微的一丝光线到了2002年,天塞百年诞辰的时候,蔡司再次推出T45的百年纪念版选用钛金属材料,配以更为严格的玻璃选材和最新的镀膜技术,而价格几乎与普通版相当!看起来蔡司是把它当作送给执著的蔡司迷的礼物不过,康泰时自己恐怕不会想到,留给它做这种厚道事的时日已经不多了(黯然神伤……)近些年,比较出名的采用天塞结构的镜头还有Nikon45、路来AFM35和莱卡50/2.8而其中在产的只有莱卡50/2.8了蔡司恐怕没有想到,替它延续这段传奇的竟是它几十年恩恩怨怨的老对手……(关于莱卡50/2.8还有一个小故事,多少又有点调侃莱卡反正该得罪的在第六剑version 2.0已经得罪了,就不管那些了!我在第一次看到莱卡50/2.8上一代产品的光学结构图时颇有些吃惊因为它的光学镜片结构与天塞一模一样,而光圈位置却从天塞的二/三组之间改到了一/二组之间难道说蔡司的设计不是最佳,莱卡又进行了优化?可是看了看莱卡那支的MTF,不如蔡司啊???带着这个疑惑四处搜索答案,最后得到的竟然是——莱卡为了避免向蔡司付专利费!!!这个情形一直延续到了大约上个世纪八十年代由于已经很少有人仿制天塞,蔡司停止了对它的专利保护之后,莱卡推出了50/2.8的现今版,光圈位置回到了天塞应有的二/三组之间表现大幅度提升,达到了天塞应有的水准)蔡司怀旧老剑之二——莱卡口ZM系Sonnar50F1.5近几十年来,随着计算机辅助设计的应用和镀膜/玻璃材料技术的发展各个镜头设计厂家的产品都取得了可喜的进步但是,消除像差,有时同时意味着“味道”的丢失事实上,各个厂家的产品正在往越来越趋同的方向发展(因此,一些玩家更乐于在一些老镜中去寻找那与众不同的特色)而这种“趋同”在大口径标准镜头系列里现得尤为明显因为大家无一例外地选用了基于双高斯原理的光学结构这一点,最近终于被蔡司发布的莱卡口ZM系Sonnar50F1.5所打破谈到这支镜头,必然要从七十年前那支传奇的Sonnar50F1.5说起让我们再次回到那个没有镀膜的黑暗年代天塞虽然结构简单,成像出色(当年),但有一个致命的弱点——无法制造出大光圈的镜头几经努力,依然无法突破F2.8的极限这对于喜欢人像和弱光摄影的人来说是远远不够的此时,所有的厂家都在绞尽脑汁,力图开发出更大口径的标头以莱卡为代表的多数派选择了双高斯之路,但依然受镜片/空气接触面反射的影响,效果不甚理想而蔡司另辟蹊径,开发出了轰动一时的Sonnar50F1.5这支镜头由七片三组构成,其中除了最前面一片独立镜片以外,后面两组都由三片镜片胶合而成这样做的目的主要就是为了将镜片/空气接触面减少到天塞的水平(六)以第二组为例,胶合的三片镜片中居中的一片由折射率很低的玻璃材料组成它替代了原本可以由空气组成的折射光路,从而消灭了两个镜片/空气接触面不过,这样带来的问题是设计的复杂程度大大增加了,在那个全凭笔纸运算的年代确实是一个挑战最终,努力没有白费Sonnar50F1.5马上成为市场上同级别镜头中的佼佼者,并获得“松纳油润”的美誉可惜的是,这种风光没能持续很久,镀膜技术的发展和单反的大行其道促进了双高斯的抢班夺权(它的后截距较短,不足以让出反光镜的空间)Sonnar50逐渐被人们遗忘……时隔半个世纪,蔡司重新打造莱卡口的Sonnar50F1.5,其用意何在?论分辨率和像场平整度比不过双高斯,还患有和天塞一样的收缩光圈焦点漂移的慢性病难道仅仅是为了缅怀历史?从蔡司发布的样照能够找到答案——Sonnar50继承了老松纳油润的色彩和双高斯无法企及的迷人散景非常适合于大光圈拍摄人像,喜欢标头视角人像效果的朋友不应该错过遗憾的是,这支新镜并没有完全复制老镜的镜组结构六片四组,把前面提到的那片低折射率镜片替换成了空气。

蔡司镜头总览

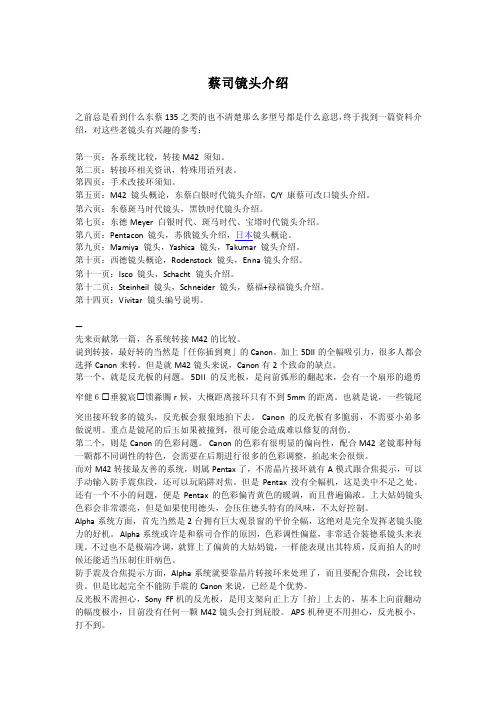

蔡司(Zeiss)镜头一览表Loxia 2/35Loxia 2/50Touit 2.8/12Touit 1.8/32Touit 2.8/50Distagon T* 2.8/15Distagon T* 3.5/18Distagon T* 2.8/21Distagon T* 2/25Distagon T* 2/28Distagon T* 1.4/35Distagon T* 2/35Planar T*1.4/50Planar T*1.4/85Apo Sonnar T*2/135Makro-Planar T*2/50Makro-Planar T*2/100Otus1.4/55Otus 1.4/85Lens Type 镜头类型微单全画幅微单全画幅APS-C画幅APS-C画幅APS-C画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅APS-C画幅APS-C画幅单反全画幅微距镜头微距镜头单反中画幅单反中画幅Focal Length mm焦距mm3550123250151821252835353585135501005585Support Mount 支持卡口SONY E SONY E SONY E SONY E SONY E Canon EF Canon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EFCanon EF Canon EFCanon EFCanon EF Canon EF Field of view (Horz)视角(水平)54.06°39.38°89°40°26°100°90°81°71°65°54°53°38°24°15.6°38°21°36.7°23.71°Flanc Distance mm 法兰距离 mm 18181818184444444444444444444444444444Filter thread 滤镜规格M52 x 0.75M52 x 0.75M67 x 0,75M52 x 0,75M52 x 0,75M 95 x 1.0M 82 x 0.75M82X0.75M67X0.75M 58 x 0.75M 72 x 0.75M 58 x 0.75M 58 x 0.75M 72 x 0.75M 77 x 0.75M 67 x 0.75M 67 x 0.75M77 x 0.75M86 x 1.00Max. Aperture 最大光圈F2.0F2.0F2.8F1.8F2.8F2.8F3.5F2.8F2.0F2.0F1.4F2.0F1.4F1.4F2.0F2.0F2.0F1.4F1.4Min. Aperture 最小光圈F22F22F22F22F22F22F22F22F22F22F16F22F16F16F22F22F22F16F16# of Diaphragm Blades光圈叶片数9999999999999999999Elements 镜片961181415131611101197611891212Group 组64851112111310897658681010Min. Focus Distance最小对焦距离0.3m 0.45m 0.18m 0.3m 0.15m 0.25m 0.3m 0.22m 0.22m 0.24m 0.3m 0.3m 0.45m 1m 0.8m 0.24m 0.44m 0.5m 0.5m Focusing method对焦方式手动手动自动自动自动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动Weight 重量340g 320g 320g 200g 290g 820g 510g 720g 600g 580g 850g 570g 380g 670g 930g 570g 680g 1030g 1200g Diameter直径Φ62mm Φ62mm Φ88mm Φ75mm Φ75mm Φ103mm Φ87mm Φ87mm Φ73mm Φ72mm Φ78mm Φ99mm Φ71mm Φ88mm Φ84mm Φ75mm Φ76mm Φ92.4mm Φ101mm Length 长度59mm 59mm 68mm 58mm 91mm 135mm 85mm 112mm 98mm 96mm 122mm 73mm 71mm 78mm 116mm 91mm 115mm 127mm 124mm Materials 材质Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal 800046008568560052002350011300127009700839013000810056009300135009150140002550026300Distagon T* 2.8/15Distagon T* 3.5/18Distagon T* 2.8/21Distagon T* 2/25Distagon T* 2.8/25Distagon T* 2/28Distagon T* 1.4/35DistagonT*2/35Planar T*1.4/50Planar T*1.4/85Apo Sonnar T*2/135Makro-Planar T*2/50Makro-Planar T*2/100Otus1.4/55Otus 1.4/85Lens Type 镜头类型单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅单反全画幅APS-C画幅APS-C画幅单反全画幅微距镜头微距镜头单反中画幅单反中画幅Focal Length mm焦距mm15182125252835355085135501005585Support Mount 支持卡口Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Nikon F Field of view (Horz)视角(水平)100°90°81°71°70°65°54°62°38°24°15.6°38°21°36.7°23.71°Flanc Distance mm 法兰距离 mm 46.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.546.5Filter thread 滤镜规格M 95 x 1.0M 82 x 0.75M82X0.75M67X0.75M 58 x 0.75M 58 x 0.75M 72 x 0.75M 58 x 0.75M 58 x 0.75M 72 x 0.75M 77 x 0.75M 67 x 0.75M 67 x 0.75M77 x 0.75M86 x 1.00Max. Aperture最大光圈F2.8F3.5F2.8F2.0F2.8F2.0F1.4F2.0F1.4F1.4F2.0F2.0F2.0F1.4F1.4Min. Aperture 最小光圈F22F22F22F22F22F22F16F22F16F16F22F22F22F16F16# of Diaphragm Blades光圈叶片数999999999999999Elements 镜片1513161110101197611891212Group组121113108897658681010Min. Focus Distance最小对焦距离0.25m 0.3m 0.22m 0.22m 0.17m 0.24m 0.3m 0.3m 0.45m 1m 0.8m 0.24m 0.44m 0.5m 0.5m Focusing method对焦方式手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动手动Weight 重量730g 470g 600g 570g 460g 500g 830g 530g 330g 570g 920g 500g 660g 970g 1140g Diameter 直径Φ103mm Φ87mm Φ87mm Φ71mm Φ71mm Φ64mm Φ78mm Φ97mm Φ69mm Φ85mm Φ84mm Φ72mm Φ76mm Φ92.4mm Φ101mm Length 长度132mm 84mm 110mm 95mm 95mm 93mm 120mm 64mm 66mm 77mm 113mm 88mm 113mm 125mm 122mm Materials 材质Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal Metal 23500113001270097007700839013000810056009300150009150140002050026300Physical 结构ZEISS Lens Model Name 蔡司镜头型号(索尼口、佳能口)市场参考价格Optics 光学Focus 对焦Aperture 光圈Primary 主要指标Physical 结构市场参考价格ZEISS Lens Model Name 蔡司镜头型号(尼康口)Primary 主要指标Aperture 光圈Optics 光学Focus 对焦。

照相机里的“金童”与“玉女”——IKONTA和BESSA II

初玩超级依康塔时,我并不了解这台机器是战前蔡司家族的宠儿,不了解它有这么显赫的出身,只是被它酷酷的外表所吸引。

而我又钟爱6×9的画幅——和经典的6×6或6×7画幅比,6×9画幅显然看上去不那么局促,画面内信息量大,延伸感强,无论是风光还是人物,多出的3cm使得画面显得大气磅礴。

当时这台机器在德国,居然还带着一块原厂的保存完好的黄绿镜,售价仅5000多人民币,皮套一看就久经沧桑,磨得发亮,毕竟是七十多岁的老爷爷了。

但里面的机器却被保存得很好,看得出它以前的主人用得非常仔细。

我拿到手后把它送到上海的老师傅那里,认认真真进行了保养,并亲自清洁了取景器,整台机器黄斑清晰明亮精准,快门清脆准确,用它试拍了一卷依尔福(Ilford)的Delta 100胶卷,蔡司天塞(Tessar)红T头的锐利风格立现,影像锐利、立体,完全不失七十年前的风范。

不过老机器毕竟是老机器,超级依康塔也有它的时代局限性。

首先对焦和取景是两个系统,对焦框在一侧,很小,看起来费劲,而且对焦时必须竖起位于镜头附近的对焦杆;而取景框平时折叠在机身中央,取景时弹开,不过弹簧片很软,取景时眼睛贴在取景框上,很容易把取景框推斜,影响观察水平线;调焦是个一分钱硬币大小的圆钮,位于镜头一侧,调焦时需要左手持机(如果不支脚架的话),眼睛贴在黄豆粒大小的黄斑对焦视窗上,右手转到调焦钮,这对新手来说需要很长的适应过程。

尽管如此,超级依康塔仍不失是一台精密的仪器:机顶两个按钮,一个是快门,一个是开机的开关。

按下开机开关,机身徐徐打开,伸出镜头,机顶取景器同时啪地一声弹起;拍摄时需要根据测光表确定参数,手动设置光圈与快门速度,然后上弦,构图,按下快门。

依康塔很先进的一点是有防重拍装置,如果拍完不过卷,或者不上弦,快门是按不动的。

拍完了一推镜头两侧的支架,镜头缩回,相机合上,一台精密的相机便变成了一个棱角分明的小盒子。

2015年6月,在收了依康塔两三个月后,我到新疆时把它带上了,做为备机拍了几卷,效果很不错。

大画幅镜头

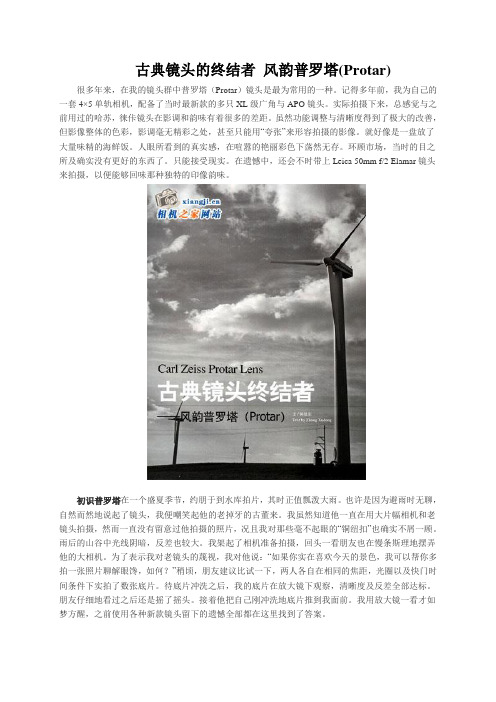

古典镜头的终结者风韵普罗塔(Protar) 很多年来,在我的镜头群中普罗塔(Protar)镜头是最为常用的一种。

记得多年前,我为自己的一套4×5单轨相机,配备了当时最新款的多只XL级广角与APO镜头。

实际拍摄下来,总感觉与之前用过的哈苏,徕佧镜头在影调和韵味有着很多的差距。

虽然功能调整与清晰度得到了极大的改善,但影像整体的色彩,影调毫无精彩之处,甚至只能用―夸张‖来形容拍摄的影像。

就好像是一盘放了大量味精的海鲜饭。

人眼所看到的真实感,在喧嚣的艳丽彩色下荡然无存。

环顾市场,当时的目之所及确实没有更好的东西了。

只能接受现实。

在遗憾中,还会不时带上Leica 50mm f/2 Elamar镜头来拍摄,以便能够回味那种独特的印像韵味。

初识普罗塔在一个盛夏季节,约朋于到水库拍片,其时正值瓢泼大雨。

也许是因为避雨时无聊,自然而然地说起了镜头,我便嘲笑起他的老掉牙的古董来。

我虽然知道他一直在用大片幅相机和老镜头拍摄,然而一直没有留意过他拍摄的照片,况且我对那些毫不起眼的―铜纽扣‖也确实不屑一顾。

雨后的山谷中光线阴暗,反差也较大。

我架起了相机准备拍摄,回头一看朋友也在慢条斯理地摆弄他的大相机。

为了表示我对老镜头的蔑视,我对他说:―如果你实在喜欢今天的景色,我可以帮你多拍一张照片聊解眼馋,如何?‖稍顷,朋友建议比试一下,两人各自在相同的焦距,光圈以及快门时间条件下实拍了数张底片。

待底片冲洗之后,我的底片在放大镜下观察,清晰度及反差全部达标。

朋友仔细地看过之后还是摇了摇头。

接着他把自己刚冲洗地底片推到我面前。

我用放大镜一看才如梦方醒,之前使用各种新款镜头留下的遗憾全部都在这里找到了答案。

当时使用的时柯达GPX彩色负片,在底片上山谷丛林中的落叶清晰可鉴。

水库泄洪口水柱上的高光也同样留有丰富的纹理。

随即请暗房师赶紧分别将两人拍摄的底片各印制一张照片。

及至此时才开始打量这支不起眼的―铜纽扣‖。

这是一支焦距为85mm的普罗塔Protar V系列镜头。

蔡司镜头介绍

百年鹰眼:蔡司 Tessar 结构,一般指 50mm F2.8 这颗。 神眼:Schneider Kreuznach C-Curtagon 35mm F2.8,又称 Baby-C。 众神的珠戒:Voigtlaender Skoparex 35mm F3.4,传世经典之一。 霹雳马:Meyer Primoplan 结构。 太阳神:苏俄 Helios 40 85mm F1.5。 八羽怪:苏俄 Helios 44 58mm F2。 辐射镜头:泛指大姑妈 50mm F1.4 这类含有稀土放射元素「钍」的镜头,辐射量并不大, 不会让摄影者变白痴。 斑马:泛指对焦环或光圈环为黑白相间样式的镜头。 镧系玻璃:高级老镜都会使用的高透光镜片,会随着时间黄化。 蔡司红:蔡司镜头对正红色的渲染,一般形容暗部的红色,关键词为「华丽」。 海尔蓝:Steinheil 镜头对正蓝色的渲染,不是暗部的蓝,关键词为「优雅」。 大姑妈黄:大姑妈镜头对正黄色的渲染,非指拍人会有肝病色,关键词为「温馨」。 妈咪呀绿:Mamiya 镜头对正绿色的渲染,不过似乎大部分人不在乎绿色,关键词为「恬静」。 施耐德紫:Schneider 镜头对紫色的渲染,在数位机上也有很好的表现,关键词为「高贵」。 磨镜:了解镜头特性的磨合过程。 蔡味:蓝色暗部配合纯色渲染的色彩表现,以蔡司为代表,不过大部分高级德头都能表现出 来。 大姑妈味:偏黄暖调配合极度细腻但不是太锐的高层次成像风格,通常出现在大姑妈镜头上, 现代 Pentax 三公主也有。 路过的熊:SDF 深藏不露的的老镜拍妹高手,性温和,不喜劝败;但身怀大量昂贵稀有老镜, 周身是毒,生人勿近。 暂时只想到这些,有想到其他再补充吧… — 在与某魔人的闲聊中讲到,改镜头也属于转接的一种,并且我觉得在这边出没的人们应该也 是对蔡头比较有兴趣,因此我就来补充一些改镜头的资讯了。 其实 …. 本来不想这么早写这段的…. 因为很怕到时候一堆人跟我抢镜头…. 请注意,改镜都有其必然的风险存在。可能拆开了装不回去、可能拆开的时候因为镜片黏在 镜身上而导致裂开、几乎一定会在改镜过程中入尘、可能弄了半天弄好了装上机身结果反光 镜打镜身 or 最后一片镜片、可能装上去因为镜组保留调整位置不够而无限远无法对焦、可 能该镜头组里面有特殊机关(尤其是浮动镜组)而导致改完之后成像异常…. 等不一而足。 所以,要走上改镜这条路,建议您有以下的想法再来改:改镜应该是觉得该镜头真的值得改, 这个镜头目前放在那就不能用,而您想让它浴火重生,让它再次成为可以陪您上山下海、与 您共度摄影生涯的朋友。如果您只是想看看这个镜头在您相机上的表现、只想改来玩玩、之 后就转手卖掉,那么建议您不要改镜。 恩,还要记住浴火之后不一定是重生,就此成灰的可能性也不低。 看了以上描述之后,如果您还是决定要改、执意要改,那么希望以 下讲的个人经验,能让一 些初次接触老镜改接的人们少一些走错路的机率。 接下来的内容,以转到 alpha 接环上的考虑为主,改镜后能手动对焦、手动调整光圈、转接 上后能连续拍照为预设立场。能转接的就不列入考虑了。 首先;建议对改镜头到 alpha mount 上有兴趣的人,先到网路上找有关于该接环镜后距。其 中镜后距离以底片时代来说,是镜头定位点到底片的距离。由于 alpha 接环这个距离是 44.5mm,所以;只要您想动刀的镜头的镜后距=> 44.5mm,那恭喜您,该镜头有很高的机率

天塞镜头

起源

天塞镜头天塞镜头(Tessar)是非对称式正光镜头的一种重要品种。最早为蔡司公司的保罗·鲁道夫於1902 年根据他自己设计的四片四组式乌那镜头(Unar)改制而成,(不是改自库克三片式镜头)。天塞镜头的基本结 构为四片三组式,前组为重钡冕石单凸透镜,中组为燧石单凹透镜,后组为一燧石凹透镜和一钡冕石凸透镜贴合 在一起而成的胶合双镜组。光圈安放在后透镜组之前。

发展历史

2002年是有“相机的鹰眼”之称的卡尔·蔡司—天塞(Tessar)镜头获得专利100周年。在“天塞”镜头100 年的发展历程中,它以成像质量高、结构简单而风行世界,除了卡尔·蔡司公司本身生产了为数众多的“天塞” 型及其衍生型设计的镜头,还授权其它一些照相机生产企业根据其专利许可证生产了无法计数的“天塞”型镜头, 至于未经其授权就直接研制和生产“天塞”型镜头的厂家和产品就更加难以计算了。为此,德国蔡司公司为“天 塞”镜头举办了一系列百年诞辰纪念活动。

天塞镜头对球面相差、色差、像散有良好的校正,是最常见的中档次镜头。常见的一种说法,认为天塞镜头 是根据1893年英国库克父子公司丹尼斯·泰洛设计的库克三片式镜头,将其后镜片变为胶合双镜组而成,并非事 实。1890年,保罗·鲁道夫设计四片二组蔡司正光镜(ZeissAnastigmat),其中前后二组都是胶合双镜组。 1899年儒道夫发现有时候将胶合双镜组分开效果更好,于是将四片二组蔡司正光镜拆成四片四组蔡司乌那镜头 (Unar)。1902年鲁道夫发现将乌那镜头的后面二镜片变回胶合双镜组,效果比乌那镜头更好,取名Tessar,来 自希腊文τ?σσερα的“四”字。保罗·鲁道夫设计的天塞镜头,最初只有f/6.3。1930年蔡司公司光学设计 家恩斯特·万德斯莱布和威利·墨尔特利用含稀土元素镧的光学玻璃制出f/3.5和f/2.8的天塞镜头。

carlzeisst镀膜与rolleihft镀膜[指导]

![carlzeisst镀膜与rolleihft镀膜[指导]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/d1d7106600f69e3143323968011ca300a6c3f6b9.png)

carl zeiss T* 鍍膜与 rollei HFT鍍膜蔡司是镜头镀膜的老祖宗,他的后期顶级T*镀膜跟它的镜头本身同样有名。

T*镀膜与禄来HFT镀膜、福伦达AR镀膜、徕卡镀膜、施耐德MRC镀膜、罗敦斯德镀膜(特别是大幅头的)等共筑了一道绝美的色彩风景线。

这些镀膜风格各异,各有自己独到的技术特色,为这些世界名镜增辉添彩。

T*镀膜与禄来HFT镀膜有着极深的渊源。

镜片以镀膜方式減少反射光、增加透光率早在上世纪70年代以前已存在,蔡司于1970年生研究成功的T膜,此镀膜不单只增加透光度,还可巳把镜片玻璃的基色进行修正,从而得到最正确颜色,使色彩透过鏡头后接近100%还原。

T*则为更后的多层膜。

"HFT"为High Fedility Transfer第一个字母简写,中文意思“高保真透光”,是1972年由禄来、蔡司和福伦达三大光学巨人联手打造的。

早期禄来镀膜据说是福伦达厂內真空炉加工,后来因真空炉损坏了,才由其它工厂代工,直到禄来在新加波建厂后才又重新加工生产。

HFT镀膜也使用在蔡司和施耐德接受OEM为禄来定制的镜头上,由禄来指定技术制作。

HFT镀膜与蔡司T*镀膜的效果很相似,只是在阴天时,HFT镀膜的镜头比T*镀膜镜头的色彩还原更加艳丽一点,特别是红色。

使用后感觉:1、正如有资料说,“HFT特有效果是色彩凝重与画面空间感,此方面略胜于原有蔡司公司的传统T*超级多层镀膜工艺”,这是HFT很牛的地方,镜头的空间感加上立体感,营造了电影般的梦幻效果;2、禄来HFT的色彩非常正,鲜艳而真实,但在大红大绿混杂时略有偏色,很轻微,不像蔡司T*有偏青明显的现象;3、禄来HFT非常通透,犹胜蔡司T*;4、禄来HFT镀膜比较软,即相对蔡司T*而言要娇气一些,使用时注意尽量别擦伤;5、在抗眩光上,禄来HFT略逊,蔡司T*抗眩光更好。

T* 鍍膜的色彩再現性與HFT鍍膜比較ZEISS 盛名的T* coating 的T是透明的意思(Transparency),當初由於軍事目的用於夜間航空攝影,而* 是指進化的意思, T* 廣義的是指此為最高級的鏡片,雖然鏡片與空氣接觸上面鍍上一層塗膜可改進影像的特質,但是多加不同層即可進一步提高效果。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

From the Series of Articles on LensNames:TessarbyH. H. NasseTessar – Creation and Development of One of the Most Successful Camera Lenses of all TimesLike many other brand-named products, camera lenses also have their own names. The simplest method is for the respective manufacturer to use a protected designation for all of its lenses. Additional product families are often distinguished through a special name or suffix. Suffixes in the form of long listings of abbreviations have become fashionable to refer to the use of prestigious technologies such as aspheric lens elements or special types of glass.In the European optical industry and at Carl Zeiss, in particular, this has always been understated. On the other hand, lenses with different design principles were given special names: Tessar, Planar, Sonnar, Biogon and Distagon are examples of famous ZEISS lens names. In a new series of articles, we will identify the origins of these names and introduce the special properties of these lenses.Almost all of these lens names come from a time when optical calculations were done without the help of computers. While we can now calculate several thousand surfaces each second with ray tracing, back then it took two minutes to calculate the path of a single ray of light through a single lens surface. During this time, the search for usable solutions with which the aberrations of the lens elements could be sufficiently reduced was accordingly difficult. Intuition, experience and extensive knowledge of the general lens interactions were in demand even more than today to design and optimize good lenses. This makes it much more under-standable that the successful result to what was often years of work required a name.The word Tessar is an acronym derived from the Greek word tessares meaning four. It expresses that this lens is comprised of four lens elements. Correspondingly, the patent from 1902 stresses the following properties:“A spherical, chromatic and astigmatic corrected lens comprised of four lens elements divided into two groups by the diaphragm. One of these groups consists of two elements separated by air, the other of two cemented elements. The refractive power of the surfaces separated by air is negative, that of the cemented surface positive."Cross section of the lens elements from the Anastigmat 1:9 and from the first ZEISS Tessar 1:6.3 based on the Unar design.Protar and Unar: father and mother of the TessarYou can often find articles explaining that this optical design is the improvement of the Cooke Triplets from Dennis Taylor – a three-element lens with a negative element in the middle – in which one of the exterior positive elements has been replaced by a cemented group to create the Tessar. There is, of course, some relationship between the two designs – this is due simply to the fact that usable solutions to lens correction problems are similar. Nonetheless, the inventor of the Tessar, Paul Rudolph, took an entirely different approach. He had calculated two predecessors, the Protar and the Unar, which were completely different from the Triplet. The Tessar contained parts of these two lenses, just like a child has genes from its mother and father.Another predecessor of the Tessar is the ZEISS Unar shown here, from which the two-element front element was used.The predecessors to the Tessar were based on the key glass innovations of the 1880s. At the age of 26, physics professor Ernst Abbe joined the microscope workshop of Carl Zeiss in 1866 with the goal of establishing a scientific basis for the construction of microscopes. A key corollary of his fundamental work was that new types of glass were required to make microscope lenses even more powerful. He found a partner in chemist Otto Schott who found a solution to this task in the short period from 1880 to 1886. It quickly became obvious that these new Schott glasses were not only useful in microscopy, but also ideal for improving camera lenses. This potential, and economic considerations such as how Carl Zeiss could become more crisis-proof through diversification, led Carl Zeiss to manufacture camera lenses beginning in 1890.All camera lenses built before 1890 exhibited considerable deficiencies in image quality, particularly when they were not extremely slow. Although spherical aberrations, chromatic aberrations and distortion were corrected relatively well on the new symmetrical lenses available from the 1860s (Aplanat from Steinheil and the Rapid Rectilinear from Dallmeyer in England), field curvature and astigmatism were so large that a lens focused to infinity in the center of the image frame delivered crisp images at the edge of an image of objects less than one meter away This had to be taken into consideration while composing the image to ensure that the photos would not be entirely unusable. For example, interior scenes always hadto be photographed from a corner of the room.In the beginning it was the AnastigmatThe first camera lenses from Carl Zeiss were called Anastigmat and described how the company was able to considerably reduce the above-described problem. It was derived from the Greek word stigma, meaning point. Astigmatism is the aberration that does not generate point-shaped focus. The word anastigmat is therefore a double negative, a “non-non-point” lens. The first and simplest anastigmats were comprised of four lens elements, arranged in two cemented groups.O ne of the predecessors of the Tessar, a ZEISS anastigmat from the 1890s.The front element is an old achromat, i.e. an achromat - a color-corrected pair of lens elements - made of the old types of glass. The old types of glass were crown glass with a low refractive index and relatively minor dispersion (color dispersion) and flint glass with a higher refractive index and higher dispersion. Flint glass, by the way, got its name from the use of flint as a supplier of the base material for glass: silicon dioxide. Furthermore, it also contained lead oxide which improved its viscosity when melted, making it easier for glassblowers to work with. At the same time, its refractive index increased, giving glass dishes more shine.As a result of the combination of refractive index and dispersion, manufacturers hadto apply to the cemented surface of the achromats the curvature seen in the sectional drawing to achieve the desired chromatic correction. With this surface curvature, it was possible to master spherical aberrations, but not astigmatism. This was different with the new achromats made from the new types of glass melted by Otto Schott. These new types of glass were known as dense crown glass because they combined a relatively high refractive index with lower color dispersion. The combinations of refractive index and dispersion now available enabled a cemented surface in achromats with a collective effect, which could be used to correct astigmatism. However, with the new achromats, very little could be done to influence the spherical aberrations. Therefore, it was a logical idea to combine both types of achromats with complementing properties to create a lens in which an old achromat was used for the front element and a new achromat for the rear element.Later, front and rear groups consisted of up to four cemented lens elements. The name Anastigmat finally became a generic term for all lenses corrected with the new methods and was no longer exclusively the domain of Carl Zeiss. These lenses therefore went by the name Protar from 1900 on. They represented considerable progress for the time, but compared to the lenses from the 1960s used for similar recording formats, they still exhibited significant aberrations. In 1899, Paul Rudolph found that the effect of the cemented surface in the anastigmats could also be achieved using suitable spacing between stand-alone lens elements. This led to the Unar consisting of four single, non-cemented lens elements. The further analysis of these two systems led Paul Rudolph to conclude that a mixture of the two would demonstrate the best behavior. This resulted in the birth of the Tessar, which was comprised of the front element of the Unar and the rear element of a simple Protar, and featured lens speed of 1:6.3 (f/6.3). At a time when apertures of 1:8 and 1:20 were common, this was a downright “high-speed” lens.Furthermore, his correction was quite good for the times despite rather moderate glass material efforts. This was important back then because anti-reflective coatings had not yet been invented, meaning that all systems featuring multiple lens elements and glass-to-air surfaces were automatically doomed to failure due to lack of contrast resulting from stray light. The maximum aperture of the Tessar soon increased to 1:4.5 and 1:3.5 as a result of the new calculations from Ernst Wandersleb.Tessar design principle model for many manufacturers around the globeThe ingeniously simple design and the good performance in every aspect of lenses with moderate maximum aperture and with medium image angles made the Tessar one of the most successful camera lenses ever. During the term of the patent, Carl Zeiss issued many licenses to other manufacturers, and when patent protection ended in 1920, the design principle was used by a wide range of manufacturers around the world. It was the standard lens on many cameras well into the 1970s. During this period, it was also continuously improved without changing the general design. Simply the advances in glass technology, similar to the time of its birth, enabled performance increases which also demonstrate the potential of the basic idea.From the outside, a Tessar from 1920 looks exactly the same as one from 1965, but the image quality of the newer lens is considerably better.Nothing expresses the famous reputation of the Tessar better than the comparison with an eagle eye.The Tessar brand name was and still is modified with prefixes:Apo-Tessars were made of special typesof glass to achieve better chromatic correction, which is required, for example, for the reproduction of line masters. Pro-Tessars were not intended for professional photography as could be suspected based on today’s popular wording. They were complex attachment systems and customers were able to replace the front lens element of the Tessar on such cameras with the attachment system to change the focal length and transform the normal lens intoa wide-angle or tele lens. From today’s perspective, these convertible lenses were a technical dead end because the focal length variations were modest, yet still required rather large and heavy attachments with a low maximum aperture. The reason for this rather unfavorable solution was that the mass-produced central shutter was preferred for too long. Most cameras today with interchangeable optics have a high-performance focal plane shutter.The Tele-Tessar is a true tele lens comprised of a positive front group and a negative rear element, i.e. a system whose length is clearly shorter than the focal length, which makes long focal lengths more convenient. There is no similarity to the general design of the Tessar and is simply intended to utilize the popularity of the name. The Tele-Apotessar incorporated special types of glass for outstandingly good correction of chromatic aberrations.The Vario-Tessar also has little in common with the general design of its namesake. Its name expresses that this Vario (zoom) lens delivers good performance at a moderate price – like the famous Tessar.With the Tele-Tessar T* 4/85 ZM it is even more difficult. It is in no way a tele lens with a reduced mechanical length like the earlier Tele-Tessars, but a nearly symmetrical lens and therefore practically distortion-free. If you are looking for famous ancestors with the same lens cross section, you will find the Heliar from Voigtländer – but Carl Zeiss does not have any property rights to this name. And because the latter is also similar to the Tessar, the name is still somehow justified. This example demonstrates that the rules of lens names have their limits and exceptions because there are always mixtures and overlapping between the traditional designs.Modern example of the Tessar design, the Tele Tessar 4/85 ZM for the 35 mm format.The name Tessar lives on in our state-of-the-art miniature lenses for camera modules in the mobile phones of our partner Nokia. The similarity to the classic Tessar is that four lens elements are usually used. The small size is also a related feature and an absolute must for the small volume of a pocket-sized device. However, the functionality of this tiny lens no longer has anything to do with the original Tessar patent. It is usually designed with four lens elements with aspheric surfaces. The resolution of these small and economical optics is far superior to the best 35 mm lenses – but this is due to the short focal length and the small image field.Cross section of a four-element lens for the camera module in a mobile phone. The head of a match is provided to demonstrate how small it is on a 24x36 mm image sensor. You can clearly see the strong aspheric surfaces of the lens elements.Some performance data shows the improvement of optic:Performance data (modulation transmission) of a historical Zeiss anastigmat from 1897. At first glance, the curves look like those of modern lenses – but the measurement was made at much lower spatial frequencies of 4, 8 and 16 line pairs per mm. If you remember that this lens was intended for the 13x18 plate format, it is understandable why so many pictures from the time were so razor sharp. A lens for the 35 mm format then had to have the same curves for 20, 40 and 80 Lp/mm. In optics, as with a car – size plays a role.Performance data (modulation transmission for 10, 20 und 40 Lp/mm) of a Tessar3.5/75 for 6x6 roll film cameras from 1922.Performance data (modulation transmission for 10, 20 und 40 Lp/mm) of a Tessar2.8/50 for 35 mm SLR cameras from 1962.Performance data (modulation transmission for 10, 20 und 40 Lp/mm) of a modernTessar design, Tele Tessar 4/85 ZM for 35 mm rangefinder cameras. If features evencrispness into the image edges that are virtually independent of the aperture and ispractically distortion-free.Performance data of a Tessar lens for a mobile phone camera measures with 20, 40and 80 Lp/mm. It is better than the best 35 mm lenses – but only for a very smallimage.Anastigmat (left front), Unar (back middle) and Tessar lenses for different camera formats.。