国际经济学全套课件194p(英文版)

国际经济学 (19)

C H A P T E R 19Macroeconomic Policy and Coordination under FloatingExchange Rates浮动汇率下的宏观经济政策和协调A s the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates began to show signs of strain in the late 1960s, many economists recommended that countries allow currency values to be determined freely in the foreign exchange market. When the governments of the industrialized countries adopted floating exchange rates early in 1973, they viewed their step as a temporary emergency measure and were not consciously following the advice of the economists then advocating a permanent floating-rate system. So far, however, it has proved impossible to put the fixed-rate system back together again: The dollar exchange rates of the industrialized countries have continued to float since 1973.The advocates of floating saw ft as a way out of the conflicts between internal and external balance that often arose under the rigid Bretton Woods exchange rates. By the mid-1980s, however, economists and policymakers had become more skeptical about the benefits of an international monetary system based on floating rates. Some critics describe the post-1973 currency arrangements as an international monetary "nonsystem,"a freefor- all in which national macroeconomic policies are frequently at odds. Many observers now think that the current exchange rate system is badly in need of reform. Why has the performance of floating rates been so disappointing, and what direction should reform of the current system take? In this chapter our models of fixed and floating exchange rates are applied to examine the recent performance of floating rates and to compare the macroeconomic policy problems of different exchange rate regimes.Case for Floating Exchange RatesAs international currency crises of increasing scope and frequency erupted in the late 1960s, most economists began advocating greater flexibility of exchange rates. Many argued that a system of floating exchange rates (one in which central banks did not intervene in the foreign exchange market to fix rates) would not only automatically ensure exchange rate flexibility but would also produce several other benefits for the world economy. The case for floating exchange rates rested on three major claims:1. Monetary policy autonomy. If central banks were no longer obliged to intervene in currency markets to fix exchange rates, governments would be able to use monetary policy to reach internal and external balance. Furthermore, no country would be forced to import inflation (or deflation) from abroad.2. Symmetry. Under a system of floating rates the inherent asymmetries of Bretton Woods would disappear and the United States would no longer be able to set world monetary conditions all by itself. At the same time, the United States would have the same opportunity as other countries to influence its exchange rate against foreign currencies.3. Exchange rates as automatic stabilizers. Even in the absence of an active monetary policy, the swift adjustment of market-determined exchange rates would help countriesmaintain internal and external balance in the face of changes in aggregate demand. The long and agonizing periods of speculation preceding exchange rate realignments under the Bretton Woods rules would not occur under floating.Monetary Policy AutonomyUnder the Bretton Woods fixed-rate system, countries other than the United States had little scope to use monetary policy to attain internal and external balance. Monetary policy was weakened by the mechanism of offsetting capital flows (discussed in Chapter 17). A central bank purchase of domestic assets, for example, would put temporary downward pressure on the domestic interest rate and cause the domestic currency to weaken in the foreign exchange market. The exchange rate then had to be propped up through central bank sales of official foreign reserves. Pressure on the interest and exchange rates disappeared, however, only when official reserve losses had driven the domestic money supply back down to its original level. Thus, in the closing years of fixed exchange rates, central banks imposed increasingly stringent restrictions on international payments to keep control over their money supplies. These restrictions were only partially successful in strengthening monetary policy, and they had the damaging side effect of distorting international trade.Advocates of floating rates pointed out that removal of the obligation to peg currency values would restore monetary control to central banks. If, for example, the central bank faced unemployment and wished to expand its money supply in response, there would no longer be any legal barrier to the currency depreciation this would cause. As in the analysis of Chapter 16, the currency depreciation would reduce unemployment by lowering the relative price of domestic products and increasing world demand for them. Similarly, the central bank of an overheated economy could cool down activity by contracting the money supply without worrying that undesired reserve inflows would undermine its stabilization effort. Enhanced control over monetary policy would allow countries to dismantle their distorting barriers to international payments.Advocates of floating also argued that floating rates would allow each country to choose its own desired long-run inflation rate rather than passively importing the inflation rate established abroad. We saw in the last chapter that a country faced with a rise in the foreign price level will be thrown out of balance and ultimately will import the foreign inflation if it holds its exchange rate fixed: By the end of the 1960s many countries felt that they were importing inflation from the United States. By revaluing its currency—that is, by lowering the domestic currency price of foreign currency—a country can insulate itself completely from an inflationary increase in foreign prices, and so remain in internal and external balance. One of the most telling arguments in favor of floating rates was their ability, in theory, to bring about automatically exchange rate changes that insulate economies from ongoing foreign inflation.The mechanism behind this insulation is purchasing power parity (Chapter 15). Recall that when all changes in the world economy are monetary, PPP holds true in the long run: Exchange rates eventually move to offset exactly national differences in inflation. If U.S. monetary growth leads to a long-run doubling of the U.S. price level, while Germany's price level remains constant, PPP predicts that the long-run DM price of the dollar will be halved. This nominal exchange rate change leaves the real exchange rate between thedollar and DM unchanged and thus maintains Germany's internal and external balance. In other words, the long-run exchange rate change predicted by PPP is exactly the change that insulates Germany from U.S. inflation.A money-induced increase in U.S. prices also causes an immediate appreciation of foreign currencies against the dollar when the exchange rate floats. In the short run, the size of this appreciation can differ from what PPP predicts, but the foreign exchange speculators who might have mounted an attack on fixed dollar exchange rates speed the adjustment of floating rates. Since they know foreign currencies will appreciate according to PPP in the long run, they act on their expectations and push exchange rates in the direction of their long-run levels.Countries operating under the Bretton Woods rules were forced to choose between matching U.S. inflation to hold their dollar exchange rates fixed or deliberately revaluing their currencies in proportion to the rise in U.S. prices. Under floating, however, the foreign exchange market automatically brings about the exchange rate changes that shield countries from U.S. inflation. Since this outcome does not require any government policy decisions, the revaluation crises that occurred under fixed exchange rates are avoided.1SymmetryThe second argument put forward by the advocates of floating was that abandonment of the Bretton Woods system would remove the asymmetries that caused so much international disagreement in the 1960s and early 1970s. There were two main asymmetries, both the result of the dollar's central role in the international monetary system. First, because central banks pegged their currencies to the dollar and accumulated dollars as international reserves, the U.S. Federal Reserve played the leading role in determining the world money supply and central banks abroad had little scope to determine their own domestic money supplies. Second, any foreign country could devalue its currency against the dollar in conditions of "fundamental disequilibrium," but the system's rules did not give the United States the option of devaluing against foreign currencies. Thus, when the dollar was at last devalued in December 1971, it was only after a long and economically disruptive period of multilateral negotiation.A system of floating exchange rates, its proponents argued, would do away with these asymmetries. Since countries would no longer peg dollar exchange rates or need to hold dollar reserves for this purpose, each would be in a position to guide monetary conditions at home. For the same reason, the United States would not face any special obstacle to altering its exchange rate through monetary or fiscal policies. All countries' exchange rates would be determined symmetrically by the foreign exchange market, not by government decisions.2Exchange Rates as Automatic Stabilizers1Countries can also avoid importing undesired deflation by floating, since the analysis above goes through, in reverse, for a fall in the foreign price level.2The symmetry argument is not an argument against fixed-rate systems in general, but an argument against the specific type of fixed-exchange rate system that broke down in the early 1970s. As we saw in Chapter 17, a fixed-rate system based on a gold standard can be completely symmetric. The creation of an artificial reserve asset, the SDR, in the late 1960s was an attempt to attain the symmetry of a gold standard without the other drawbacks of that system.The third argument in favor of floating rates concerned their ability, theoretically, to promote swift and relatively painless adjustment to certain types of economic changes. One such change, previously discussed, is foreign inflation. Figure 19-1, which uses the DD-AA model presented in Chapter 16, examines another type of change by comparing the economy's response under a fixed and a floating exchange rate to a temporary fall in foreign demand for its exports.A fall in demand for the home country's exports reduces aggregate demand for every level of the exchange rate, E, and so shifts the DD schedule leftward from DD] to DD2. (Recall that the DD schedule shows exchange rate and output pairs for which aggregate demand equals aggregate output.) Figure 19-la shows how this shift affects the economy's equilibrium when the exchange rate floats. Because the demand shift is assumed to be temporary, it does not change the long-run expected exchange rate and so does not move the asset market equilibrium schedule A A1. (Recall that the/\/\ schedule shows exchange rate and output pairs at which the foreign exchange market and the domestic money market are in equilibrium.) The economy's short-run equilibrium is therefore at point 2; compared with the initial equilibrium at point 1, the currency depreciates (E rises) and output falls. Why does the exchange rate rise from El to E21 As demand and output fall, reducing the transactions demand for money, the home interest rate must also decline to keep the money market in equilibrium. This fall in the home interest rate causes the domestic currency to depreciate in the foreign exchange market, and the exchange rate therefore rises from El to E2.The effect of the same export demand disturbance under a fixed exchange rate is shown in Figure 19-1 b. Since the central bank must prevent the currency depreciation that occurs under a floating rate, it buys domestic money with foreign currency, an action that contracts the money supply and shifts AAl left to AA2. The new short-run equilibrium of the economy under a fixed exchange rate is at point 3, where output equals Y3. Figure 19-1 shows that output actually falls more under a fixed rate than under a floating rate, dropping all the way to K3 rather than Y2. In other words, the movement of the floating exchange rate stabilizes the economy by reducing the shock's effect on employment relative to its effect under a fixed rate. Currency depreciation in the floating rate case makes domestic goods and services cheaper when the demand for them falls, partially offsetting the initial reduction in demand. In addition to reducing the departure from internal balance caused by the fall in export demand, the depreciation reduces the current account deficit that occurs under fixed rates by making domestic products more competitive in international markets.We have considered the case of a transitory fall in export demand, but even stronger conclusions can be drawn when there is a permanent fall in export demand. In this case, the expected exchange rate Ee also rises and AA shifts upward as a result. A permanent shock causes a greater depreciation than a temporary one, and the movement of the exchange rate therefore cushions domestic output more when the shock is permanent. Under the Bretton Woods system, a fall in export demand such as the one shown in Figure 19-lb would, if permanent, have led to a situation of "fundamental disequilibrium" calling for a devaluation of the currency or a long period of domestic unemployment as export prices fell. Uncertainty about the government's intentions would have encouraged speculative capital outflows, further worsening the situation by depleting central bankreserves and contracting the domestic money supply at a time of unemployment. Advocates of floating rates pointed out that the foreign exchange market wouldautomatically bring about the required real currency depreciation through a movement in the nominal exchange rate. This exchange rate change would reduce or eliminate the need to push the price level down through unemployment, and because it would occurimmediately there would be no risk of speculative disruption, as there would be under a fixed rate.The Case Against Floating Exchange RatesThe experience with floating exchange rates between the world wars had left many doubts about how they would function in practice if the Bretton Woods rules were scrapped. Some economists were skeptical of the claims advanced by the advocates of floating and predicted instead that floating rates would have adverse consequences for the world economy. The case against floating rates rested on five main arguments:1. Discipline. Central banks freed from the obligation to fix their exchange rates might embark on inflationary policies. In other words, the "discipline" imposed on individual countries by a fixed rate would be lost.2. Destabilizing speculation and money market disturbances. Speculation on changes in exchange rates could lead to instability in foreign exchange markets, and this instability, in turn, might have negative effects on countries' internal and external balances. Further,disturbances to the home money market could be more disruptive under floating thanunder a fixed rate.3. Injury to international trade and investment. Floating rates would make relative international prices more unpredictable and thus injure international trade and investment.4. Uncoordinated economic policies. If the Bretton Woods rules on exchange rate adjustment were abandoned, the door would be opened to competitive currency practices harmful to the world economy. As happened during the interwar years, countries might adopt policies without considering their possible beggar-thy-neighbor aspects. All countries would suffer as a result.5. The illusion of greater autonomy. Floating exchange rates would not really give countries more policy autonomy. Changes in exchange rates would have such pervasive macroeconomic effects that central banks would feel compelled to intervene heavily in foreign exchange markets even without a formal commitment to peg. Thus, floating would increase the uncertainty in the economy without really giving macroeconomic policy greater freedom.DisciplineProponents of floating rates argue they give governments more freedom in the use of monetary policy. Some critics of floating rates believed that floating rates would lead to license rather than liberty: Freed of the need to worry about losses of foreign reserves, governments might embark on overexpansionary fiscal or monetary policies, falling into the inflation bias trap discussed in Chapter 16 (p. XXX). Factors ranging from political objectives (such as stimulating the economy in time to win an election) to simple incompetence might set off an inflationary spiral. In the minds of those who made the discipline argument, the German hyperinflation of the 1920s epitomized the kind of monetary instability that floating rates might allow.The pro-floaters' response to the discipline criticism was that a floating exchange rate would bottle up inflationary disturbances within the country whose government was misbehaving; it would then be up to its voters, if they wished, to elect a government with better policies. The Bretton Woods arrangements ended up imposing relatively little discipline on the United States, which certainly contributed to the acceleration of worldwide inflation in the late 1960s. Unless a sacrosanct link between currencies and a commodity such as gold were at the center of a system of fixed rates, the system would remain susceptible to human tampering. As discussed in Chapter 17, however, commodity-based monetary standards suffer from difficulties that make them undesirable in practice.Destabilizing Speculation and Money Market DisturbancesAn additional concern arising out of the experience of the interwar period was the possibility that speculation in currency markets might fuel wide gyrations in exchange rates. If foreign exchange traders saw that a currency was depreciating, it was argued, they might sell the currency in the expectation of future depreciation regardless of the currency's longer-term prospects; and as more traders jumped on the bandwagon by selling the currency the expectations of depreciation would be realized. Suchdestabilizing speculation would tend to accentuate the fluctuations around the exchange rate's long-run value that would occur normally as a result of unexpected economic disturbances. Aside from interfering with international trade, destabilizing sales of a weak currency might encourage expectations of future inflation and set off a domestic wage-price spiral that would encourage further depreciation. Countries could be caught in a "vicious circle" of depreciation and inflation that might be difficult to escape. Advocates of floating rates questioned whether destabilizing speculators could stay in business. Anyone who persisted in selling a currency after it had depreciated below its longrun value or in buying a currency after it had appreciated above its long-run value was bound to lose money over the long term. Destabilizing speculators would thus be driven from the market, the pro-floaters argued, and the field would be left to speculators who had avoided long-term losses by speeding the adjustment of exchange rates toward their longrun values.Proponents of floating also pointed out that capital flows could behave in a destabilizing manner under fixed rates. An unexpected central bank reserve loss might set up expectations of a devaluation and spark a reserve hemorrhage as speculators dumped domestic currency assets. Such capital flight might actually force an unnecessary devaluation if government measures to restore confidence proved insufficient.A more telling argument against floating rates is that they make the economy more vulnerable to shocks coming from the domestic money market. Figure 19-2 uses theDD-AA model to illustrate this point. The figure shows the effect on the economy of a rise in real domestic money demand (that is, a rise in the real balances people desire to hold at each level of the interest rate and income) under a floating exchange rate. Because a lower level of income is now needed (given E) for people to be content to hold the available real money supply, A A1 shifts leftward to AA2: Income falls from Y] to Y2 as thecurrency appreciates from E1 to E2. The rise in money demand works exactly like a fall in the money supply, and if it is permanent it will lead eventually to a fall in the home price level.Under a fixed exchange rate, however, the change in money demand does not affect the economy at all. To prevent the home currency from appreciating, the central bank buys foreign reserves with domestic money until the real money supply rises by an amount equal to the rise in real money demand. This intervention has the effect of keeping AA[ in its original position, preventing any change in output or the price level.A fixed exchange rate therefore automatically prevents instability in the domestic money market from affecting the economy. This is a powerful argument in favor of fixed rates if most of the shocks that buffet the economy come from the home money market (that is, if they result from shifts in AA). But as we saw in the previous section, fixing the exchange rate will worsen macroeconomic performance on average if output market shocks (that is, shocks involving shifts in DD) predominate.Injury to International Trade and InvestmentCritics of floating also charged that the inherent variability of floating exchange rates would injure international trade and investment. Fluctuating currencies make importers more uncertain about the prices they will have to pay for goods in the future and make exporters more uncertain about the prices they will receive. This uncertainty, it was claimed, would make it costlier to engage in international trade, and as a result trade volumes—and with them the gains countries realize through trade—would shrink. Similarly, greater uncertainty about the payoffs on investments might interfere with productive international capital flows.Supporters of floating countered that international traders could avoid exchange rate risk through transactions in the forward exchange market (see Chapter 13), which would grow in scope and efficiency in a floating-rate world. The skeptics replied that forward exchange markets would be expensive to use and that it was doubtful that forward transactions could be used to cover all exchange-rate risks.At a more general level, opponents of floating rates feared that the usefulness of each country's money as a guide to rational planning and calculation would be reduced. A currency becomes less useful as a unit of account if its purchasing power over imports becomes less predictable. Uncoordinated Economic PoliciesSome defenders of the Bretton Woods system thought that its rules had helped promote orderly international trade by outlawing the competitive currency depreciations that occurred during the Great Depression. With countries once again free to alter their exchange rates at will, they argued, history might repeat itself. Countries might again follow self-serving macroeconomic policies that hurt all countries and, in the end, helped none. In rebuttal, the pro-floaters replied that the Bretton Woods rules for exchange rate adjustment were cumbersome.In addition, the rules were inequitable because, in practice, it was deficit countries that came under pressure to adopt restrictive macroeconomic policies or devalue. Thefixed-rate system had "solved" the problem of international cooperation on monetary policy only by giving the United States a dominant position that it ultimately abused.The Illusion of Greater AutonomyA final line of criticism held that the policy autonomy promised by the advocates of floating rates was, in part, illusory. True, a floating rate could in theory shut out foreign inflation over the long haul and allow central banks to set their money supplies as they pleased. But, it was argued, the exchange rate is such an important macroeconomic variable that policymakers would find themselves unable to take domestic monetary policy measures without considering their effects on the exchange rate.Particularly important to this view was the role of the exchange rate in the domestic inflation process. A currency depreciation that raised import prices might induce workers to demand higher wages to maintain their customary standard of living. Higher wage settlements would then feed into final goods prices, fueling price level inflation and further wage hikes. In addition, currency depreciation would immediately raise the prices of imported goods used in the production of domestic output. Therefore, floating rates could be expected to quicken the pace at which the price level responded to increases in the money supply. While floating rates implied greater central bank control over the nominal money supply, M s, they did not necessarily imply correspondingly greater control over the policy instrument that affects employment and other real economic variables, the real money supply, M S IP. The response of domestic prices to exchange rate changes would be particularly rapid in economies where imports make up a large share of the domestic consumption basket: In such countries, currency changes have significant effects on the purchasing power of workers' wages.The skeptics also maintained that the insulating properties of a floating rate are very limited. They conceded that the exchange rate would adjust eventually to offset foreign price inflation due to excessive monetary growth. In a world of sticky prices, however, countries are nonetheless buffeted by foreign monetary developments, which affect real interest rates and real exchange rates in the short run. Further, there is no reason, even in theory, why one country's fiscal policies cannot have repercussions abroad.Critics of floating thus argued that its potential benefits had been oversold relative toits costs. Macroeconomic policymakers would continue to labor under the constraint of avoiding excessive exchange rate fluctuations. But by abandoning fixed rates, they would have forgone the benefits for world trade and investment of predictable currency values. CASE STUDYExchange Rate Experience Between the Oil Shocks, 1973-1980 Which group was right, the advocates of floating rates or the critics? In this Case Study and the next we survey the experience with floating exchange rates since 1973 in an attempt to answer this question. To avoid future disappointment, however, it is best to state up front that, as is often the case in economics, the data do not lead to a clear verdict. Although a number of predictions made by the critics of floating were borne out by subsequent events, it is also unclear whether a regime of fixed exchange rates would have survived the series of economic storms that has shaken the world economy since 1973. The First Oil Shock and Its Effects, I973-I975As the industrialized countries' exchange rates were allowed to float in March 1973, an official group representing all IMF members was preparing plans to restore world monetary order. Formed in the fall of 1972, this group, called the Committee of Twenty, had been assigned the job of designing a new system of fixed exchange rates free of the asymmetries of Bretton Woods. By the time the committee issued its final "Outline of Reform" in July 1974, however, an upheaval in the world petroleum market had made an early return to fixed exchange rates unthinkable.Energy Prices and the 1974-1975 Recession.In October 1973 war broke out between Israel and the Arab countries. To protest support of Israel by the United States and the Netherlands, Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), an international cartel including most large oil producers, imposed an embargo on oil shipments to those two countries. Fearing more general disruptions in oil shipments, buyers bid up market oil prices as they tried to build precautionary inventories. Encouraged by these developments in the oil market, OPEC countries began raising the price they charged to their main customers, the large oil companies. By March 1974 the oil price had quadrupled from its prewar price of $3 per barrel to $ 12 per barrel.The massive increase in the price of oil raised the energy prices paid by consumers and the operating costs of energy-using firms and also fed into the prices of nonenergy petroleum products, such as plastics. To understand the impact of these price increases, think of them as a large tax on oil importers imposed by the oil producers of OPEC. The oil shock had the same macroeconomic effect as a simultaneous increase in consumer and business taxes: Consumption and investment slowed down everywhere, and the world economy was thrown into recession. The current account balances of oil-importing countries worsened.The Acceleration of Inflation. The model we developed in Chapters 13 through 17 predicts that inflation tends to rise in booms and fall in recessions. As the world went into deep recession in 1974, however, inflation accelerated in most countries. Table 19-1 shows how inflation in the seven largest industrial countries spurted upward in that year. In a number of these countries inflation rates came close to doubling even though unemployment was rising.What happened? An important contributing factor was the oil shock itself: By directly raising the prices of petroleum products and the costs of energy-using industries, the increase in the oil price caused price levels to jump upward. Further, the worldwide inflationary pressures that had built up since the end of the 1960s had become entrenched in the wage-setting process and were continuing to contribute to inflation in spite of the deteriorating employment picture. The same inflationary expectations that were driving new wage contracts were also putting additional upward pressure on commodity prices as speculators built up stocks of commodities whose prices they expected to rise.Finally, the oil crisis, as luck would have it, was not the only supply shock troubling the world economy at the time. From 1972 on, a coincidence of adverse supply disturbances pushed farm prices upward and thus contributed to the general inflation.。

国际经济学英文课件(萨尔瓦多第十版)ch

International investment and multinational corporations

International investment environment

Political environment: stability, policies, and regulations that affect foreign investment.

New trade theory departs from the assumption of perfect competition and focuses on the role of increasing returns to scale and monopolistic competition.

Classical trade theory posits that specialization in production based on comparative advantage results in increased production and consumption in all countries.

关税是一种税收,由政府对进口商品征收,以增加进口成本并保护国内产业。

关税定义

关税种类

关税作用

包括基本关税、附加关税、反倾销关税和报复性关税等。

通过提高进口商品价格,降低国内市场的竞争压力,保护国内产业和就业。

03

02

01

出口补贴是指政府给予出口企业的财政补贴,以降低出口成本,增加出口量。

出口补贴定义

Balance of trade

The balance of trade is a crucial component of the international balance of payments. It measures the value of a country's exports minus the value of its imports. A positive balance of trade indicates that a country is exporting more goods and services than it is importing, while a negative balance of trade indicates the opposite.

国际经济学之贸易政策工具(英文版)(ppt 45页)

Introduction

▪ This chapter is focused on the following questions:

• What are the effects of various trade policy

instruments?

–Who will benefit and who will lose from these trade policy instruments?

Introduction

Classification of Commercial Policy Instruments

Commercial Policy Instruments

Trade Contraction

Price

Tariff Export tax

Quantity

Import quota Voluntary Export Restraint (VER)

–Thus, the volume of wheat traded declines due to the imposition of the tariff.

Basic Tariff Analysis

• The increase in the domestic Home price is less than

trade (Qw), two curves are defined:

• Home import demand curve

–Shows the maximum quantity of imports the Home country would like to consume at each price of the imported good.

国际经济学之贸易 政策工具(英文 版)(ppt 45页)

国际经济学英文原版PPT_c04

aLC /aTC > aLF/aTF Or aLC /aLF > aTC /aTF Or, we consider the total resources used in each industry

Unit factor requirements can vary at every quantity of cloth and food that could be produced.

Fig. 4-2: The Production Possibility Frontier with Factor Substitution

and say that cloth production is labor intensive and food production is land intensive if LC /TC > LF /TF.

• This assumption influences the slope of the production possibility frontier:

• The Heckscher-Ohlin theory:

Emphasizes resource differences as the only source of trade Shows that comparative advantage is influenced by:

• Relative factor abundance (refers to countries)相对要素充裕度 • Relative factor intensity (refers to goods)相对要素密集度 Is also referred to as the factor-proportions theory(要素比例理论)

国际经济学课件

International trade theory policies are the microeconomics aspects of international economics because they deals with individual nations treated as single units and with the (relative)price of individual commodities. On the other hand,since the balance of payments deals with total receipts and payments while adjustment policies affect the level of national income and the general price index,they represent the macroeconomics aspects of international economics.These are often referred to as open-economy macroeconomics or international finance.

2、在国内外经济学教学中,国际经济也已被越来 越多的大学列为经济类学生的必修课程之一,成为 一门十分重要的课程。

3、经济类学科硕士和博士研究生考试内容之一。 4、理论对实践的指导作用。

5、学会分析问题的方法。

第五页,共598页。

课时安排:54课时

第六页,共598页。

学习的总体要求:

作业要按时按质按量完成;

第十四页,共598页。

二、国际经济学的特征

1、 国际经济学研究以国家或独立的行政区域为单位的跨国界的资源分 配; 2、国际经济学不同于区域经济学;

国际经济学英文课件(萨尔瓦多第十版)

International Economic Theories and Policies ■ International Trade Theory 国际贸易理论

■ Analyzes the basis of and the gains from international trade.

FIGURE 1-3 Imports and Exports as a Percentage of U.S. GDP, 1965-2001.

Salvatore: International Economics, 10th Edition © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

■ 1980 to present

■ Most pervasive and dramatic period of globalization 全球化最广泛和剧烈的阶段

■ Fueled by improvements in telecommunications and transportation 受益于电信和运输极大改善

imports and exports of goods and services to GDP 用一国商品和服务进出口总值比上GDP的比值来 粗略衡量

Salvatore: International Economics, 10th Edition © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Salvatore: International Economics, 10th Edition © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

International Trade and the Nation’s Standard of Living

国际经济学英文PPT

Elasticity Approach

Marshall-Lerner Condition o depreciation will improve trade balance if nation’s demand elasticity for imports plus foreign demand elasticity for that nation’s expห้องสมุดไป่ตู้rts is greater than 1

o

Exchange Rate Pass Through

o o complete pass through – import prices change by full proportion of change in exchange rates partial pass through – percentage change in import prices is less than percentage change in exchange rate

Exchange Rate Effect on Costs and Prices o assume: some costs denominated in francs o assume: appreciation of dollar

o costs increase but not as much as if all costs were denominated in dollars

Exchange-rate adjustment and the BOP

Automatic mechanisms may restore balance-of-payments equilibrium, but at the cost of recession or inflation As an alternative, governments allow exchange rates to change

国际经济学讲义英文版

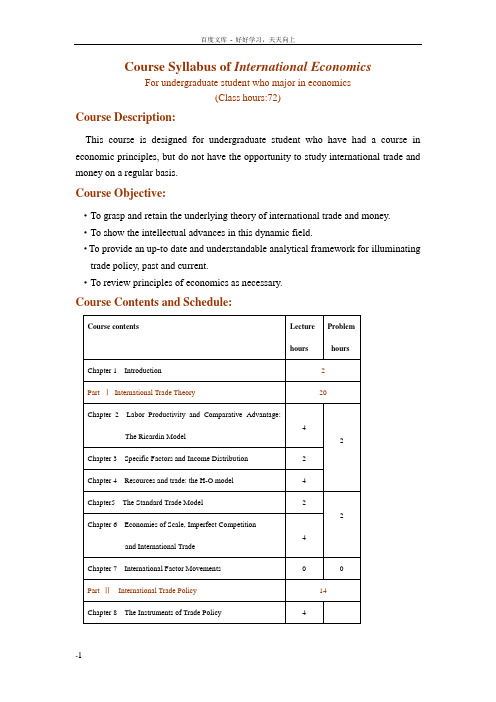

Course Syllabus of International EconomicsFor undergraduate student who major in economics(Class hours:72)Course Description:This course is designed for undergraduate student who have had a course in economic principles, but do not have the opportunity to study international trade and money on a regular basis.Course Objective:·To grasp and retain the underlying theory of international trade and money.·To show the intellectual advances in this dynamic field.·To provide an up-to date and understandable analytical framework for illuminating trade policy, past and current.·To review principles of economics as necessary.Course Contents and Schedule:Textbook and Reference Books:Textbook·Paul , Maurice Obstfeld. International Economics , 6e, 清华大学出版社,2004. Reference Books·[美]保罗•克鲁格曼,茅瑞斯•奥伯斯法尔德,《国际经济学》,第五版,中译本,中国人民大学出版社,2003.·李坤望主编,《国际经济学》,第二版,高等教育出版社,2005.·姜波克、杨长江编著,《国际金融学》,第二版,高等教育出版社,2004. ·Dominick Salvatore. International Economics, Prentic Hall International , 8e, 清华大学出版社,2006.PREFACE§ place of this book in the economics curriculum§ Distinctive Features of International Economics: Theory and PolicyThis book emphasized several of the newer topics that previous authors failed to treat in a systematic way :·Asset market approach to exchange rate determination.·Increasing returns and market structure.·Politics and theory of trade policy.·International macroeconomic policy coordination·The world capital market and developing countries.·International factor movements.§3. Learning Features·Case studies·Special boxes·Captioned diagrams·Summary and key terms·Problems·Further readingCHAPTER 1 Introduction§1. What Is International Economics About?Seven themes recur throughout the study of international economics :·The gains from trade(national welfare and income distribution)·The pattern of trade·Protectionism·The balance of payments·Exchange rate determination·International policy coordination·International capital market§2. International Economics: Trade and Money·Part I (chapters 2 through 7) :International trade theory·Part II (chapters 8 through 11) : International trade policy·Part III (chapters 12 through 17) : International monetary theory·Part IV (chapters 18 through 22) : International monetary policyCHAPTER 2Labor Productivity and Comparative Advantage:The Ricardin Model*Countries engage in international trade for two basic reasons :·Comparative advantage : countries are different in technology (chapter 2) or resource (chapter 4).·Economics of scale (chapter 6).*All motives are at work in the real world but only one motive is present in each trade model.§1. The Concept of Comparative Advantage1.Opportunity cost: The opportunity cost of roses in terms of computers is the number of computers that could have been produced with the resources used to produce a given number of roses.Table 2-1 Hypothetical Changes in ProductionMillion Roses Thousand ComputersUnited States -10 +100South America +10 -30Total 0 +70advantage: A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good in terms of other goods is lower in that country than it is in other countries.·Denoted by opportunity cost.·A relative concept : relative labor productivity or relative abundance.3. Comparative advantage and trade : Trade between two countries can benefit both countries if each country exports the goods in which it has a comparative advantage. §2. A One-Factor Economypossibilities : a LC Q C + a LW Q LW≤LFigure 2-1Home’s Production Possibility Frontierprice and supply·Labor will move to the sector which pays higher wage.·If P C/P W>a L C/a LW (P C/a L C>P W/a LW, wages in the cheese sector will be higher ), the economy will specialize in the production of cheese.·In a closed economy, P C/P W =a L C/a LW.§3. Trade in a One-Factor World·Model : 2×1×2·Assume: a L C/a LW< a L C*/a LW*Home has a comparative advantage in cheese.Home’s relative productivity in cheese is higher.Home’s pretrade relative price of cheese is lower than foreign.·The condition under which home has this comparative advantage involves all fourunit labor requirement, not just two.(If each country has absolute advantage in one good respectively, will there exist comparative advantage?)the relative price after trade·Relative price is more important than absolute price, when people make decisions on production and consumption.·General equilibrium analysis: RS equals RD. (world general equilibrium)·RS: a “step” with flat sections linked by a vertical section.(L/a L C)/(L*/a LW*)Figure 2-3World Relative Supply and Demand·RD: subsititution effects·Relative price after trade: between the two countries’ pretrade price.(How will the size of the trading countries affect the relative price after trade? Which country’s living condition improve more? Is it possible that a country produce both goods?)gains from tradeThe mutual gain can be demonstrated in two alternative ways.·To think of trade as an indirect method of production :(1/a L C)( P C/P W)>1/a LW or P C/P W>a L C/a LW·To examine how trade affects each country’s possibilities of consumption.Figure 2-4Trade Expands ConsumptionPossibilities(How will the terms of trade change in the long-term? Are there incomedistribution effects within countries? )numerical example :·Two crucial points :(1)When two countries specialize in producing the goods in which they have a comparative advantage, both countries gain from trade.(2)Comparative advantage must not be confused with absolute advantage; it is comparative, not absolute, advantage that determines who will and should produce a good.Table 2-2 Unit Labor RequirementsCheese WineHome a LC=1 hour per pound a LW=2 hours per gallonForeign a*L C=6 hours per pound a*L W=3 hours per gallon Analysis: absolute advantage; relative price; specialization;the gains from trade.wages·It is precisely because the relative wage is between the relative productivities that each country ends up with a cost advantage in one good.·Relative wages depend on relative productivity and relative demand on goods. Special box : Do wages reflect productivity ?Table 2-3 Changes in Wages and Unit Labor CostsCompensation Compensation Annual Rate of Increaseper Hour, 1975Per Hour,2000in Unit Labor Costs,(US=100) (US=100) 1979-2000United States 100 100South Korea 5 41Taiwan 6 30Hong Kong 12 28 NASingapore 13 37 NASource: Bureau of Labor Statistics(foreign labor statistics home page, )·Debates about relative wages and relative labor productivity.·Long-run convergence in productivity produces long-run convergence in wages.§4. Misconceptions About Comparative AdvantageThe proposition that trade is beneficial is unqualified. That is, there is no requirement that a country be “competitive” or that the trade be “fair”.and competitivenessmyth1:Free trade is beneficial only if your country is strong enough to stand up to foreign competition.·The gains from trade depend on comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage.·The competitive advantage of an industry depend on relative labor productivity and relative wage.·Absolute advantage: neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for comparative advantage (or for the gains from trade).pauper labor argumentmyth2: Foreign competition is unfair and hurts other countries when it is based on low wages.·Whether the lower cost of foreign export goods is due to high productivity or low wages does not matter. All that matter to home is that it is more efficient to “produce” those goods indirectly than to produce directly.myth3:Trade exploits a country and make it worse off if its workers receive much lower wage than workers in other nations.·Whether they and their country are worse off?·What is the alternative ?(if it refuse to trade, real wages would be even lower ).§5. Comparative Advantage With Many Goods·Model: 2×1×n·For any good we can calculate a Li /a Li*, label the goods so that the lower the number, the lower this ratio.a L1/a L1*<a L2/a L2*<…<a LN/a LN *(or a L1*/a L1>a L2*/a L2>…>a LN*/a LN)wages and specialization·Any good for which a Li*/a Li>w/w* will be produced in home. (Relative productivity is higher than it’s relative wage, wa Li<w*a Li*, goods will always be produced where it is cheapest to make them.)·All the goods to the left of the cut end up being produced in home.Table 2-4 Home and Foreign Unit Labor RequirementsRelative HomeHome Unit Labor Foreign Unit Labor ProductivetyRequirement(a Li)Requirement(a*Li)Advantage(a*Li/a Li)Apples 1 10 10Bananas 5 40 8Caviar 3 12 4Dates 6 12 2Enchiladas 12 9If w/w*=3, A、B、C will be produced in Home and D、E in Foreign.·Is such a pattern of specialization beneficial to both countries?(Hint: Comparing the labor cost of producing an import good directly and indirectly).the relative wage in the multigood model·w/w*: RD of labor equals RS of labor.·The relative derived demand for home labor (L/L*) will fall when the ratio of hometo foreign wages (w/w*) rises, because:(1)The goods produced in home became relative more expensive.(2)Fewer foods will be produced in home and more in foreign.Figure 2-5 Determination of relative of wages.RD: derived form relative demand for home and foreign goods.RS: determined by relative size of home and foreign labor force (Labor can’t move between countries).§6. Adding Transport Costs and Nontraded Goods·There are three main reasons why specialization in the real international economy is not so extreme:(1)The existence of more than one factor of production(2)Protectionism(3)The existence of transport cost.Eg: Suppose transport cost is a uniform fraction of production cost , say 100 percents.For goods C and D in table 2-4:D: Home 6hours < 12hours×1/3×2 foreignC: Home 3hours×2 >12hours×1/3 foreignThus, C and D became nontraded goods.·In practice there is a wide range of transportation costs.In some cases transportation is virtually impossible: services such as haircut and auto repair ; goods with high weight-to-value ratio, like cement.·Nontraded goods : Because of absence of strong national cost advantage or because of high transportation cost.·Nations spend a large share of their income on nontraded goods.§7. Empirical Evidence on the Ricardian Model·Misleading predictions :(1)An extreme degree of specialization.(2)Neglect the effects on income distribution.(3)Neglect differences in resources among countries as a cause of trade.(4)Neglect economics of scale as a cause of trade.·The basic prediction of the Ricardian model has been strongly confirmed by a number of studies over years.(1)Countries tend to export those goods in which their productivity is relative high.(2)Trade depend on comparative not absolute advantage.Figure 2-6Productivity and exportsAnswers to Problems of Chapter 21. a. b. a LA/ a LB=3/2=c. P A/ P B= a LA/ a LB=2. a.b.If the relative price of apples after trade is between and 5 Home and Foreign will specialize in the production of apples and bananas respectively. The world relative supply of apples is 3. a .RD include the pointsb. the equilibrium relative price of apples is P A /P B =2c. Home produces only apples and trades them for bananasForeign produces only bananas and trade them for applesd. Home :(1/ a LA )(P A /P B )=(1/3)×2= Foreign :(1/*LB a )(P A /P B )=(1/1)× =4.211/8003/1200//**==LB LA a L a L 21/132=>LB a 51/121*=>LA a 21)212()11()2,21()5,51(,、,、、The equilibrium relative price of apples is , it equals pretread relative price of apples in Home, So Home produces both apples and bananas, neither gains nor loss form trade; Foreign produces only bananas and trades it for apples, Foreign gains from trade.answer is identical to that in problem3 since the amount of “effective labor”has not changed.6.·Pauper labor argument.·Relative wage reflects relative productivity, international trade can’t change it ·Trading with a less productive and low-wage country will rise, no lower its standard of living.7.·to determine comparative advantage need for all four unit labor requirements (forboth the manufacture and the service sectors)·is an absolute advantage in services, this is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for determining comparative advantage.·The competitive advantage depends on both relative productivity and relative wages.8. ·*ωω=·Since . is considerably more productive in services, Service prices are relative low.·Most services are nontraded goods·P= , . purchasing power is higher than that of Japan.9.·The gains from trade decline as the share of the nontraded goods increases, notrade, no gains.10.·Label the countries so that(a LC /a LW )1<(a LC /a LW )2…<( a LC /a LW )N·Any country to the left of RD produces cheese and trades it for countries to right of RD produces wine and trades it for cheese.·If the intersection occurs in a horizontal portion, the Country with that a LC /a LW produces both goods.*LSLSaa<*31PCHAPTER 3Specific Factors and Income Distribution* The failures of the Ricardian model·A n extreme degree of specialization.·W ithout effects on the income distribution.( because it supposes labor is the only factor )* There are two main reasons why international trade has strong effects on the distribution of income.·S hort-term: specific factor, chapter3.·L ong-term: relative abundance and relative intensity, chapter4. (resource endowment theory or factor proportions theory ).* What is a specific factor?Specific factor: --- can be used only in the particular sector.Mobile factor: --- can move between sectors.·Think of factor specificity as a matter of time.·Labor is less specific than most kinds of capital.§1. The Specific Factors Modelof the model : 2×3×2.·America and Japan;·Labor (L)、Capital (K)、Terrain (T) ;mobile factor specific factorQ M=Q M(K,L M)、Q F=Q F(T,L F)、L=L M+L F·Manufacture and Food.possibilities·Production of manufactures and food is determined by the allocation of labor.Figure 3-3·Because of diminishing returns, PP is a bowed-out curve instead of a straight line. ·The slope of PP, which measures the opportunity cost of manufacture in terms of food is =MPL F/MPL M.dQ F/dQ M=(dQ F/dL)/(dQ M/dL)=-MPL F /MPL M=-1/MPL M* MPL F; (MPL F↑/MPL M↓)↑, wages, and labor allocation·The demand for labor: MPL M*P M=W M , MPL F*P F=W F·The allocation of labor: W M=W F , L=L M+L FFigure3—4P M、P F L M、L F Q M、Q F·The production of specific factor modelMPL M*P M=MPL F*P F=W MPL F/MPL M=P M/P F(opportunity cost=relative price)Figure 3-5distribution of income within the manufacturing sectorFigure 3-2MPL M*dL Mtotal income: Q M=∫Lwages: (W/P M)*L MMPL M*dL M (W/P M)*L Mincome of capitalists: ∫L·What happens to the allocation of labor and the distribution of income when P M andP F change? ( Figure3-6. 3-7. 3-8 )① Notice that any price change can be broken into two parts : an equal proportional change in P M and P F , and a change in only one price.Eg: P M↑P M↑10% + P M↑7%P F↑F↑10%② A equal proportional change in price have no real effects on the real wage, real income of capital owner and land owner.Figure 3-6③ A change in relative priceFigure 3-7·Wage rate rise less than the increase in P M.·Labor shifts from the food sector to the manufacturing sector andQ M rises while Q F falls.Figure 3-8 P M/P F↑5. Relative prices and the distribution of income①A rise in P M benefits the owners of capital , hurts the owner of land.Figure 3A-3W/ P M↓, income of capitalists in term of P M rises (the shadow), income of capitalists in term of P M、P F rises.Figure 3A-4②Because W/P M drops and W/P F rises, the real wage of the workers is uncertain. Itdepends on their consumptions structure.§2. International Trade in the Specific Factors Model·For trade to take place, the two countries must differ in P M/ P F. If RD is the same, RS is the source of trade ; if technologies is also the same , differences in resources can affect RS.Figure 3-9and relative supplyAn increase in the capital stock (capital per worker) raises the marginal product of K↑M↑Q M↑Q F↓,RS shift to the right.Figure 3-10Correspondingly, T MPL F↑M↓Q F↑, RS shift to the left. Suppose L J=L A , K J>K A, T J<T Aor(K/L)J>(K/L)A,(T/L)J<(T/L)A).Then the situation will look like that in Figure 3-11.Figure 3-11pattern of trade·The amount of the economy can afford to import is limited by the amount it exports. ·Budget constraint: D F-Q F =( P M/ P F)×(Q M-D M)import exportFigure3-12two fectures:①slope = -P M/P F②tangent PF at the production point after trade. ·The budget constraint and the trading equilibrium.Figure 3-13Japan: ( P M/P F)↑Q M↑Q F↓, D M↓D F↑,Figure 3-13 continuedAmerican: ( P M/ P F)↑Q M↓Q F↑, D M↑D F↓,§3. Income Distribution and the Gains from Tradedistribution: who gains and who loses from international trade?·Trade benefits the factor that is specific to the export sector of each country but hurts the factor to the import-competing sectors, with ambiguous effects on mobile factors.gains from trade.Does trade make each country better off?Is trade potentially a source of gain to everyone?Figure 3-14① The pretrade production and consumption point is shown as point 2.② Part of the budget constraint (AB) represents situations in which the economyconsumes more of both manufacture and food than it could in the absence of trade (point2).③ It is possible in principle for a country’s government to use taxes and subsidiesto redistribute income to give each individual more of both goods.·The fundamental reason why trade potentially benefits a country is that it expands the economy’s choices. This expansion of choice means that it is always possible to redistribute income in such a way that everyone gains from trade.§4. The Political Economy of Trade: A Preliminary ViewThere are two ways to look at trade policy:(1) (Normative analysis) Given its objectives, what should the government do?What is the optimal trade policy?(2) (Positive analysis) What are the governments likely to do in practice?trade policy·Economists: to maximize the national welfare, free international trade is the optimal policy.·Three main reasons why economists do not regard the income distribution effects of trade as a good reason to limit trade (P57).distribution and trade politics·An example : an import quota : . sugar (P200).·Problems of collective action (P 231).·Typically, those who lose from trade in any particular product are a much more concentrated, informed, and organized group than those who gain.·The formulation of trade policy: A kind of political process.Special box: Specific factors and the beginning of trade theory.CHAPTER 4Resources and Trade:The Heckscher-Ohlin Model(Factor Endowment Theory)*Comparative advantage is influence by the interaction between relative abundance and relative intensity.*Relative abundance: the proportions of different factors of production are available in different countries.If(T/L)H<(T/L)F, Home is labor-abundant and Foreign is land-abundant“per captia”,“relative” , no country is abundant in everything.*Relative intensity: the proportions of different factors of production are used in producting different goods.At any given factor prices, if (T C/L C)<(T F/L F), production of Cloth is labor-intensive and production of Food is land-intensive. A good can’t be both labor-intensive and land-intensive.(Factor-proportions theory)§1. A Model of Two-Factor Economy1. Assumption of the modelThe same two factors are used in both sectors: T、L ; Cloth、Food.(1)Alternative input combinations: In each sector, the ratio of land to labor used in production depends on the cost of labor relative to the cost of land, w/r.Figure 4A-2w/r↑T↑L↓T/L↑(T C/L C↑and T F/L F↑)(2) Relative intensityAt any given wage-rental ratio, food production use a higher land-labor ratio, foodproduction is land-intensive and cloth production is labor-intensive.Figure 4-2price and goods prices(1)One-to-one relationshipBecause cloth production is labor-intensive while food production is land-intensive. The one dollar worth isoquant line of cloth and food are shown as 4-3-1 two isoquants CC and FF are tangent to the same unit isocost line.Figure 4-3-1When P C rises, the slope of the unit isocost line w/r rises, that is, there is one-to-one relationship between factor price ratio w/r and the relative price of cloth P C/P F (Figure4-3-2). The relationship is illustrated by the curve SS.(Suppose the economy produce both cloth and food).Figure 4-3-2Figure 4-3-3(2)Stolper-Sammelson effectIf the relative price of a good rises, the real income of the factor which intensivly used in that good will rise, while the real income of the other factor will fall.↑↑T C/L C↑,T F/L F↑MPL C↑, MPL F↑W/P C↑, W/P F↑Figure 4-4and output(1)Relative price、resources and productionGiven the prices of cloth and food and the supply of land and labor, it is possible to determine how much of each resource the economy devoted to the production of each good; and thus also to determine the econom y’s output of each good.Figure4-5.The slope of OcC is Tc/Lc, the slope of O F F is T F/L F(2)Rybczynski effectIf goods prices remain unchanged, an increase in the supply of land will rise the output of food more than proportion to this increase, while the output of cloth will fall.Figure4-6T↑T F↑L F↑;T C↓L C↓Q F↑Q C↓Rybczynski effect: At unchanged relative goods price, if the supply of a factor of production increases, the output of the good that are intensive in that factor will rise, while the output of the other good will fall.Figure 4-7·The economy could produce more of both cloth and food than before.·A biased expansion of production possibilities.·An economy will tend to be relatively effective at producing goods that are intensive in that factors with which the country is relative well-endowed.§of International Trade Between Two-Factor Economies1. Resources、relative prices and the pattern of tradeAs always, Home and Foreign are similar along many dimentions, such as relative demand and technology. The only difference between the countries is their resources: Home has a lower ratio of land to labor than Foreign does.·relative abundance relative supply relative prices trade(T/L)H<(T/L)F (T C/L C)<(T F/L F)RS lies to the right of RS*,(P C/P F)H<( P C/P F)F Home trade Cloth for Food,Foreign trade Food for Cloth.·H-O proposition: Countries tend to export goods whose production is intensive in factors with which they are abundantly endowed.Figure 4-82. Trade and the distribution of income·According to Stolper-Samuelson effect, a rise in the price of cloth raises the purchasing power of labour in terms of both goods, while lowering the purchasing power of land in terms of both goods. Thus,in Home,laborers are made better off while landowners are made worse off.·Owners of a country’s abundant factors gain from trade,but owners of a country’s scare factors lose.·The distinction between income distribution effects due to immobility and those due to differences in factor intensity.The specific factor model: Sectors; temporary and transitional problemThe H-O model: Factors; permanent problem·Resources and trade (factor endowment theory)Short-run analysis: The specific factor modelLong-run analysis: H-O model3. Factor price equalization·Factor price equalization proposition: International trade produces a convergence of relative goods prices. This convergence, in turns, causes the convergence of the relative factor prices. Trade leads to complete equalization of factor prices. (Figure4-8,4-4 or Figure 4A-3)Figure 4A-3·One-dollar-worth isoquant lines.·G oods’ price and technologies are the same, so CC、FF are the same inboth countries.·w/r are the same in both countries.·In an indirect way the two countries are in effect trading factors of production. (Home exports labor: more labor is embodied in Home’s exports than its imports;Foreign exports land: more land is embodied in F oreign’s exports than its imports.)·In the real world factor prices are not equalized (Table4-1). Why?Table 4-1 Comparative lnternational Wage Rates(United States=100)Hourly compensationCountry of production workers,2000United States 100Germany 121Japan 111Spain 55South Korea 41Portugal 24Mexico 12Sri Lanka* 2*1969. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Foreign Labor Staistics Home Page.Three assumptions crucial to the prediction of factor price equalization are in reality certainly untrue.(1)Both countries produce both goods.(Trading countries are sufficiently similar intheir relative factor endowments)(2)Technologies are the same.(Trade actually equalizes the prices of goods in twocountries).(3)There are barriers to trade: natural barriers (such as transportation costs) andartificial barriers (such as tariffs, import quotas, and other restrictions).Case study: North-south trade and income inequality·Why has wage inequality in . increased between the late 1970s and the early 1990s?(1)Many observers attribute the change to the growth of world trade and inparticular to the growing exports of manufactured goods from NIEs.Table 4-2 Composition of Developing-Country Exports(Percent of Total)Agricultural Mining ManufacturedProducts Products Goods1973 30 221995 14Source: World Trade Organization(2)Most empirical workers believed that trade has been at most a contributingfactor to the growing inequality and that the main villain is technology.§3. Empirical Evidence on the H-O Model1.Tests on dataTable 4-3 Factor Content of and lmports for 1962Imports ExportsCapital per million dollars $2,132,000 $1,876,000 Labor(person-years) per million dollars 119 131 Capital-labor ratio (dollars per worker) $17,916 $14,321 Average years of education per workerProportion of engineers and scientists in work forceSource:Rodert Baldwin,“Determinants of the Commodity Structure of Ecomomic Review61(March1971), ·Leontief paradox: . exports were less capital-intensive than . imports. (Capital-labor ratio)·. exports were more skilled labor-intensive and technology-intensive than its imports. (Average years of education; scientists and engineers per unit of sales)·A plausible explanation: . may be exporting goods that heavily use skilled labor and innovative entrepreneurship(such as aircraft and computer chips), while importing heavy manufactures that use large amounts of capital (such as automobiles).on global dataTable 4-4 Testing the Heckscher-Ohlin ModelFactor of Production Predictive Success*CapitalLaborProfessional workersManagerial workersClerical workersSales workersService workersAgricultural workersProduction workersArable landPasture landForest*Fraction of countries for which net exports of factor runs in predicted direction.Source: Harry , Edward , and Leo Sveikauskas,“Multicountry, Multifactor Tests of the Factor Abundance Theory,”American Economic Review 77(December 1987), .·If the factor-proportion theory was right, a country would always export factors for。

国际经济学英文课件 (3)

TABLE 10.4 U.S. balance of payments, 1980–2008 (billions of dollars)

Note that the U.S. has been competitive in services such as Transportation,

engineering, brokers’ commissions, certain health care services

Trade and Balance of Payments

Goals of chapter

• Relationship between trade and macroeconomics

• Expenditure-switching versus expenditurereducing policies

– However, it could eventually become a problem

• If interest rates rise because the economy is booming and the high government debt could crowd out private investment

Which came first, the chicken or egg?

• The “saving glut” version: Savings in China,

Japan and Germany are too high compared to

their domestic investment opportunities

Describe what you see in this slide

What about this one?

国际经济学双语第1章

1.3 Trade Based on Comparative Advantage: David Ricardo

Gains from Specialization and Trade with Comparative Advantage

The Change in the World Output Resulting from Specialization

1.3 Trade Based on Comparative Advantage: David Ricardo

An Example of Compaarative Advantage

Country

iPads

Output per labor hour

Cost differences govern the international movement of goods. The concept of cost is founded upon the labor theory of value.

1.2 Trade Based on Absolute Advantage: Adam Smith

The gain from production and trade is the increase in the world output that results from each country specializing in its production according to its

comparative advantage.

The more efficient country should specialize in and export that good in which it is relatively more efficient (where its absolute advantage is bigger).

(克鲁格曼)英文课件国际经济学CH06

– Marginal Cost (MC) is the amount it costs the firm to produce one extra unit.

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

Slide 6-12

5.The Theory of Imperfect Competition

▪ Monopoly: A Brief Review

• Marginal revenue

– The extra revenue the firm gains from selling an additional unit

– Its curve, MR, always lies below the demand curve, D.

• Increasing the amount of all inputs used in the

production of any commodity will increase output of that commodity in the same proportion.

▪ In practice, many industries are characterized by

Table 6-1: Relationship of Input to Output for a Hypothetical Industry

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

Slide 6-6

3.Economies of Scale and Market Structure

Slide 6-3

2.Economies of Scale and

国际济学课件-精品文档

绪论

研究对象和内容

二、国际经济学的研究对象和内容 研究对象:国际经济学是以国际经济关系

和国际经济活动为研究对象的经济学科。该学 科研究对象的特殊性主要体现在两方面:一方 面,国际交易不同于国内交易;另一方面,国 际经济关系是发生在国与国之间的。

进出口总额

绪论

经济全球化中的中国经济

主要方面的表现: (一)中国的对外贸易(如上图)

对外贸易的持续增长给中国经济发展带来的利益: (1)为中国产业开辟了庞大的境外市场; (2)有利于解决我国改革和发展动力不足的问题; (3)增加财政收入和创造就业机会; (4)为中国发挥后发优势、实施赶超战略、缩小与 发达国家的差距提供了途径; (5)为中国的经济结构调整、技术进步和产业升级 提供了新的契机,使中国成为一个重要的世界制造业中 心。

绪论

经济全球化中的中国经济

三、经济全球化中的中国经济

始于1978年的改革开放,使中国幸运地搭上 了经济全球化的快车。从1979年到2019年的25年 间,我国GDP年均增长9.4%,GDP由1400亿美元 增至16500亿美元,位居世界第六, 人均GDP从 181美元增至1269美元; 对外贸易额由293.3亿美 元猛增到11547.4亿美元, 跃居世界第三。 中国 已成为推动全球经济增长的一支重要力量。

内容:(1)国际贸易 (2)国际金融 (3)国际生产 (4)其它

绪论

0.3 经济全球化中的中国经济

一、经济全球化(Economic Globalization) (一)经济全球化的涵义

经济全球化:是指随着科学技术和国际社会 分工的发展以及社会化程度的提高,世界各国、 各地区的经济活动越来越超出一国和地区的范围 而相互联系和密切结合的趋势。经济全球化是生 产社会化和经济关系国际化发展的客观趋势。

国际经济学课件 ppt

03

新兴市场和发展中 国家崛起

金砖国家等新兴市场和发展中国 家成为全球经济增长的重要引擎 。

国际经济合作与竞争的格局变化

发达国家与发展中国家合作与竞争并存

01

发达国家在国际经济合作中发挥主导作用,发展中国

家则通过区域一体化等方式寻求合政策信息和经验,提高货币政策决 策的科学性和有效性。

货币政策工具的合作与创新

共同研究和开发新的货币政策工具,应对全球经济挑战和 危机。

财政政策协调与合作

宏观经济稳定

通过国际财政政策协调与合作, 各国可以共同应对全球经济波动 和危机,维护宏观经济的稳定和

增长。

财政纪律与监督

国际股票市场与债券市场的区别

股票市场主要涉及企业所有权,而债券市场主要涉及债务和借贷关系。

国际投资的风险与回报

国际投资的风险

包括政治风险、汇率风险、经济风险等 。政治风险指因东道国政治环境不稳定 导致的投资风险;汇率风险指因汇率波 动导致的投资价值变化;经济风险指因 东道国经济环境不稳定导致的投资风险 。

世界银行

世界银行是一个国际金融机构,旨在通过提供长期贷款和技术援助,减少全球贫 困和支持发展中国家的经济发展。世界银行的主要目标是减少全球贫困和支持发 展中国家的教育、卫生和基础设施建设等方面的工作。

固定汇率与浮动汇率制度

固定汇率制度

固定汇率制度是指一国政府通过政策手段维持本国货币与另一国货币之间的固定汇率。在固定汇率制 度下,中央银行需要承担维持汇率稳定的责任,通过干预外汇市场来稳定汇率。

区域经济一体化组织在推动贸易自由化、投资便利化等方面发挥越 来越重要的作用。

全球金融监管加强

《国际经济学》PPT课件

美国

欧共体

日本

所有国家

产品/时间

1965 1986

1965 1986 1965 1986 1965 1986

食品

32 74

61 100 73 99 56 92

农业原材料 14

45

4

28

0 59

4 41

能源

92

0

11 37

33 28 27 27

矿产品与金属 0

16

0

40

2

31 1 29

制成品

39

71

10 56 48 50 19 58

二 H-O定理

1。 基本假设与基本内容

前提要素不能跨国流动——如果,未来若干年,只要是可移 动的商品,

将形成美国人设计、港台商人投资、大陆生产、出口到美国市场销售。可移

动的服务也会转移到印度和中国。也许美国能够留住的只是那些不可移 动的

服务20,21/8比/18如餐馆、理发店、洗衣店和超市。”

10

2X2X2模型 X为劳动密集产品,Y为资本密 集产品 A为劳动丰富的国家 技术相同 规模报 酬不变 需求偏好一样 要素国内自由流动诡计间 不能流动 产品要素市场是完全竞争的 自由贸易 无摩擦成本 贸易平衡 资源充分利用

X商品的劳动生产 Y商品的劳动生产

率

率

A国

6

4

B国

1

5

优势分析——分工情况——贸易情况——结果

假定国际交换比例1:1,A用6个X交换B上午6个Y,则获利2 个Y;6个Y在B国需1.2小时,这可生产1.2个X则获利4.8个X。

2021/8/18

3

第三节 比较优势理论

一假定与内容13 两利相权取其重,两害相权取其轻。

国际经济学双语第1章-PPT精品

In like manner, the U.K has an absolute advantage in cloth production.

Chapter 1 Classical Theories of International Trade

1.1 Mercantilism 1.2 Trade Based on Absolute Advantage: Adam Smith 1.3 Trade Based on Comparative Advantage: David

Ricardo 1.4 Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost 1.5 Comparative Advantage with More Than Two

Commodities and Countries 1.6 Theory of Reciprocal Demand 1.7 Offer Curve and Terms of Trade

Two assumptions, within each country:

Labor is the only factor of production and is homogeneous (i.e. of one quality).

The cost or price of a good depends exclusively upon the amount of labor required to produce it.

《国际经济学》(全套课件218P).ppt

2020/7/24

20

2、按征收关税的依据

正税; 进口附加税;

反补贴税 反倾销税

差价税(也称做滑动关税)

按照国内市场与国际市场的差价征收,如欧共体的 农业关税。

2020/7/24

21

3、按征税的优惠程度

普通税

最惠国税

中美最惠国待遇问题(1999年克林顿改为正 常贸易关系)

普遍优惠制(GSP) 特惠税

2020/7/24

23

“毕业”条款:

美国从1981年4月1日起率先采用的一种保护措施。即 对一些受惠国家(或地区),或对他们的某些产品,当其 在国际市场上显示出较强的竞争能力时,取消其享受优惠 的资格,称其为“毕业”(GRADUATION)。

1988年1月29日,美国政府宣布:从1989年1月1

日起,取消新加坡、韩国、台湾和香港出口至美国的 产品享受普惠制待遇的资格,这是美国援用“毕业”

碳关税——美国为保护其国内企业针对发展中

国家采取的措施将会是又一个主要的趋势。

第六章 贸易保护政策:关税

关税是历史上最重要的一类贸易保护政策, 通过本章的学习,你可以了解:

关税的概念、种类和征收方式 小国关税效应、大国关税效应 最优关税率、有效保护率 关税的总体均衡分析

2020/7/24

双重联合机制:

欧洲联盟从1995年1月1日起实施的一种新的保护措施,

它由二部分组成:一是对优惠幅度的调整;二是与之相配

套的紧急保护,即“毕业机制”。<<<

2020/7/24

24

特惠税:

针对某个国家或者地区进口的商品,给予优惠的低关 税或者免税,如洛美协定(Lome Convention )

1975年2月28日,非洲、加勒比海和太平洋地区46 个发展中国家(简称非加太地区国家)和欧洲经济共 同体9国在多哥首都洛美开会,签订贸易和经济协定, 全称为《欧洲经济共同体-非洲、加勒比和太平洋地 区(国家)洛美协定》,简称“洛美协定”或“洛美 公约”。

国际经济学英文版(internationaleconomics)PPT课件

▪ Growth of emerging markets ▪ international capital movements regain importance

6

Economic interdependence

Exports of goods and services as percent of Gross Domestic Product, 2001

Ch 16 Exchange-Rate Systems

Ch 17 Macroeconomic Policy in an Open Economy

Ch18 International Banking: Reserves, Debt and Risk

International Economics

By Robert J. Carbaugh 9th Edition

8

Economic interdependence

Interdependence: Impact

Overall standard of living is higher

▪ Access to raw materials & energy not availo goods & components made less expensively elsewhere

International Economics

By Robert J. Carbaugh 9th Edition

Ch 1 The International Economy Ch 2 Foundations of Modern

Trade Theory

Ch 3 International Equilibrium

国际经济学英文课件萨尔瓦多第十版ppt

Technical Progress

All technical progress reduces the amount of both labor and capital required to produce any given level of output.

Three different types of Hicksian technical progress:

Growth of Factors of Production

The Rybczynski Theorem

At constant commodity prices, an increase in the ende by a greater proportion the output of the commodity intensive in that factor and will reduce the output of the other commodity.

Salvatore: International Economics, 10th Edition © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Technical Progress

All technical progress reduces the amount of both labor and capital required to produce any given level of output.

The production frontier will shift out evenly in all directions at the same rate at which technical progress takes place.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

International Economics: Theory and Policy,8/e Paul R. Krugman, professor at MIT- Princeton University,

Nobel Laureate for Economics in 2008 Maurice Obstfeld, professor at UCLA, MA(Cambridge)Ph.D(MIT)

Enhance the understanding of various economies of the world and their interdependence.

Provide a framework to explore the knowledge of macroeconomic issues in open economy with reagrads to its theoretical and practical implications of the international competition.

Oct.15,2009~Dec.10,2009

International Economics

Syllabus

Objectives Nine weeks allocation Evaluation policy Textbook and further reading suggestion

2019/11/28

Anyone who appeared in events will be marked in the final score. The exam breakdown will be placed as: class participation and final exam weights respectively

International Economics, 7th edition.(see Review P3) Steven Husted, professor of economics at Arizona State University,co-

editor of Journal of Int’l Money and Finance,Ph.D.(UCLA). Research interests:international finance Michael Melvin, professor of economics at University of Pittsburg, Ph.D (Michigan State University). Research interests:international trade policy and finance

2019/11/28

5

Textbook

. International Economics, 10th Edition by Robert J. Carbaugh

(Hardcover - 2005) Washington Central University

: 1 Used & new from $90.00 Buy This edition on Amazon

Chapter Reading would be strictly needed before and after class events.

Weekly Essay is also suggested to address the major points and comments on each topic.

2019/11/28

3

Nine weeks allocation

Week 6------week14

2019/11/28

4

Evaluation policy

Class participation 20% Final Examination 80%

English as worki1/28

6

Robert Carbaugh:11/e

/InternationalEconomics $129.81

2019/11/28

7

Steven Husted and Michael Melvin

7/e $124.34

2019/11/28

8

Paul Krugman :8/e /krugman/

2019/11/28

9

Customer Review

By A Customer:

Very good learning medium with a sufficient indepth coverage, March 24, 1999

2

Objectives

This course is specially prepared for economics students who are supposed to be Internationally thinking of the business world

The objective of the course is to