电化学的发展史

电化学原理PPT课件

(saturated calomel electrode,SCE) 6.导线;7. Hg;8.纤维

以标准氢电极的电极电势为标准,

可以测得SCE的电势为0.2415V。

.

21

对电极(辅助电极)

对电极一般使用惰性贵金属材料如铂丝等, 以免在此表面发生化学反应,用于与工作 电极形成回路。

.

22

电化学工作站

.

17

电化学三电极系统

• 工作电极(Working electrode) • 参比电极(Reference electrode) • 对电极(Auxiliary electrode)

.

18

工作电极

滴汞电极(极谱法) 铂电极 金电极 碳电极 热解石墨(PG)

玻碳(GC) 碳糊 碳纤维

.

19

参比电极

.

9

电分析成为独立的方法学

• 三大定量关系的建立 1833年法拉第定律Q=nFM 1889年能斯特W.Nernst提出能斯特方程

1934年尤考维奇D.Ilkovic提出扩散电流方程 Id = kC

.

10

近代电分析方法

(1) 电极的发展:化学修饰电极、超微电极 (2) 多学科参与:生物电化学传感器 (3)与其他方法联用:光谱-电化学、HPLC-EC、

1753年,俄国著名电学家利赫曼为了验证

富兰克林的实验,不幸被雷电击死,这是

做电实验的第一个牺. 牲者。

4

电化学的发展史

1791年, 意大利伽伐尼的青蛙实验 (电化学的起1799年, 伏特堆 (伏特电池/原电池的雏形)

.

6

电化学的发展史

1807年, 戴维电解木灰(potash)和苏打(soda), 分别得到钾(potassium)和钠(sodium)元素

电化学的起源与发展

电化学的起源与发展起源阶段:1.伽伐尼效应(1791年):意大利科学家路易吉·伽伐尼发现,将两种不同的金属与青蛙肌肉组织接触时会引起肌肉收缩,这一现象被解释为“动物电”,但后来证明这是由于化学反应产生的电流导致的,这一发现启发了后续对电化学现象的研究。

2.伏打电池(1799年):亚历山德罗·伏打受伽伐尼实验启发,发明了第一款连续供电的装置——伏打堆(Voltaicpile),这是一种早期的化学电池,它首次实现了稳定持续的电能转换,标志着电化学学科的诞生。

发展阶段:1.电解定律(1833年):英国科学家迈克尔·法拉第通过对电解过程的定量研究,提出了电解定律,其中包括著名的法拉第电解定律,阐明了电能与化学物质之间转化的数量关系。

2.原电池与电解:随着伏打电池的出现,科学家们开始对各种化学反应与电流之间的联系进行深入研究,开展了大量电解水和其他物质的实验。

3.电化学基本原理确立:19世纪,伴随着对电解质溶液理论、原电池热力学、电极过程动力学和界面电化学等领域的探索,电化学的基本理论框架逐渐完善。

4.应用领域扩展:随着时间的推移,电化学的应用领域不断拓宽,涵盖了化学电源(如燃料电池、二次电池)、电镀、金属提炼(电解冶金)、防腐蚀、电化学分析、电化学合成以及新型电化学能源存储系统(如锂离子电池)等领域。

近现代发展:20世纪以来,电化学在材料科学、生物医学、环境科学、能源科学等诸多领域中发挥了重要作用。

例如,电化学传感器、电化学储能技术、电化学表面改性技术、光电化学以及生物电化学信号传输等方面的研究均取得了显著进展。

电化学的历史发展是一个逐步揭示电能与化学反应之间相互作用规律的过程,从最初的自然现象观察到现代复杂体系的理论构建和实际应用,经历了几个世纪的积累和创新。

电化学发展史

电化学发展史电化学是物理化学的一个重要组成部分,它不仅与无机化学、有机化学、分析化学和化学工程等学科相关,还渗透到环境科学、能源科学、生物学和金属工业等领域。

电化学作为化学的分支之一,是研究两类导体(电子导体,如金属或半导体,以及离子导体,如电解质溶液)形成的接界面上所发生的带电及电子转移变化的科学。

传统观念认为电化学主要研究电能和化学能之间的相互转换,如电解和原电池。

但电化学并不局限于电能出现的化学反应,也包含其它物理化学过程,如金属的电化学腐蚀,以及电解质溶液中的金属置换反应。

一、16-17世纪:早期的相关研究公元16世纪标志着对于电认知的开始。

在16世纪50年代,英国科学家William Gilbert (威廉·吉尔伯特,1540-1605)花了17年时间进行磁学方面的试验,也或多或少地进行了一些电学方面的研究。

吉尔伯特由于在磁学方面的开创性研究而被称为“磁学之父”,他的磁学研究为电磁学的产生和发展创造了条件。

吉尔伯特按照马里古特的办法,制成球状磁石,取名为“小地球”,在球面上用罗盘针和粉笔划出了磁子午线。

他证明诺曼所发现的下倾现象也在这种球状磁石上表现出来,在球面上罗盘磁针也会下倾。

他还证明表面不规则的磁石球,其磁子午线也是不规则的,由此认为罗盘针在地球上和正北方的偏离是由陆地所致。

他发现两极装上铁帽的磁石,磁力大大增加,他还研究了某一给定的铁块同磁石的大小和它的吸引力的关系,发现这是一种正比关系。

吉尔伯特根据他所发现的这些磁力现象,建立了一个理论体系。

他设想整个地球是一块巨大的磁石,上面为一层水、岩石和泥土覆盖着。

他认为磁石的磁力会产生运动和变化。

他认为地球的磁力一直伸到天上并使宇宙合为一体。

在吉尔伯特看来,引力无非就是磁力。

吉尔伯特关于磁学的研究为电磁学的产生和发展创造了条件。

在电磁学中,磁通势单位的吉伯(gilbert)就是以他的名字命名,以纪念他的贡献。

1663年,德国物理学家Otto vonGuericke(奥托·冯·格里克1602-1686)发明了第一台静电起电机。

电化学历史简介

电化学历史简介电化学的历史可以追溯到18世纪末和19世纪初,当时科学家们开始研究化学反应与电流之间的联系。

以下是电化学发展的一些重要里程碑:1.1791年,意大利科学家Luigi Galvani发表了金属能使蛙腿肌肉抽缩的“动物电”现象,这一般被认为是电化学的起源。

2.1799年,Alexandro G. A. A. Volta在Galvani的工作基础上发明了用不同的金属片夹湿纸组成的“电堆”,即现今所谓的“伏打堆”,这是化学电源的雏型。

在直流电机发明以前,各种化学电源是唯一能提供恒稳电流的电源。

3.1834年,英国科学家迈克尔·法拉第发现了法拉第电解定律,该定律描述了电解质溶液中化学反应和电势之间的关系,为电化学奠定了定量基础。

这一理论被广泛应用于电池和电解池等设备的设计和研究中。

4.19世纪下半叶,经过赫尔姆霍兹和吉布斯的工作,赋予电池的“起电力”(今称“电动势”)以明确的热力学含义。

1889年,能斯特用热力学导出了参与电极反应的物质浓度与电极电势的关系,即著名的能斯特公式。

5.1923年,德拜和休克尔提出了人们普遍接受的强电解质稀溶液静电理论,大大促进了电化学在理论探讨和实验方法方面的发展。

6.20世纪40年代以后,电化学暂态技术的应用和发展、电化学方法与光学和表面技术的联用,使人们可以研究快速和复杂的电极反应,可提供电极界面上分子的信息。

随着时间的推移,电化学逐渐发展成为物理化学的一个重要分支,其应用领域也不断扩展,包括电解工业、机械工业、环境保护、化学电源、金属的防腐、生命现象的研究以及电化学分析法等。

以上信息供参考,建议查阅专业书籍或咨询电化学领域专家了解更多详细信息。

电化学发展的历程与前景

电化学发展的历程与前景电化学是研究电荷在电化学介质中移动、在电极表面发生反应并形成电流的科学。

这一领域的研究对于现代科技的发展有着重要的贡献,如电池、太阳能电池、燃料电池等都是基于电化学原理的创造。

本文将介绍电化学发展的历程和未来的前景。

一、电化学发展的历程1. 电化学的起源电化学最早的研究可以追溯到18世纪,当时欧洲的科学家们开始研究电荷的性质和电流在物体中的流动。

最早关于电荷的性质的研究可以追溯到英国研究者史密斯于1767年发现一个新物质,经加工处理后可以吸引琉璃棒上的绸子,被称为“电”。

由此,科学家们开始对电荷的性质进行了解和研究。

2. 电化学理论的建立1781年,英国化学家普里斯特利(Priesstley)发现了“新空气”,即氧气。

这是对当时既有化学学说的冲击,因为既有的学说认为空气是不变的、不能分解的物质。

随着研究的深入,化学家们发现,在化学反应中,电子的转移和物质的变化有着密切的联系。

因此,他们开始研究电子在物质中的转移和化学反应的关系,并逐渐形成了电化学理论。

3. 电池的出现1800年,意大利物理学家伏打发明了第一种电池——伏打电池。

这种电池由锌、铜两种金属和盐水构成的。

伏打电池的出现推动了电化学的发展,并有助于科学家们在实验中研究电荷和电流的性质。

4. 电分解定律的发现1803年,英国化学家法拉第在研究电解的过程中发现了电分解定律,即电解池中的材料质量与通过电解池中的电流的量成正比例。

法拉第的研究成果导致电化学的研究得以深入,并得到了认可。

5. “转化理论”的提出据以往的研究所述,当时的学者们普遍认为所有的物质都是由少量元素组成的,并且认为元素之间的转化是不可能的。

但是随着电化学的研究,科学家们开始发现当物质被放在电场中时,它会与电荷相互作用,从而发生化学反应。

基于这一发现,瑞典化学家贝里尔(Berzelius)提出了“转化理论”,即元素并不是永久不变的,而是可以转化为别的元素。

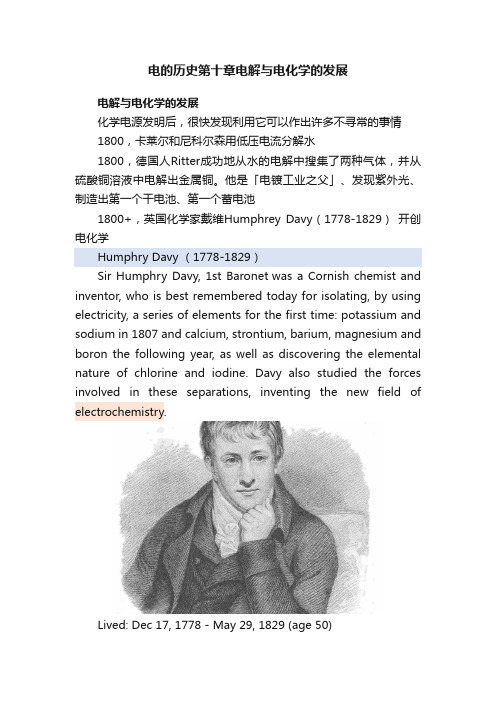

电的历史第十章电解与电化学的发展

电的历史第十章电解与电化学的发展电解与电化学的发展化学电源发明后,很快发现利用它可以作出许多不寻常的事情1800,卡莱尔和尼科尔森用低压电流分解水1800,德国人Ritter成功地从水的电解中搜集了两种气体,并从硫酸铜溶液中电解出金属铜。

他是「电镀工业之父」、发现紫外光、制造出第一个干电池、第一个蓄电池1800+,英国化学家戴维Humphrey Davy(1778-1829)开创电化学Humphry Davy (1778-1829)Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet was a Cornish chemist and inventor, who is best remembered today for isolating, by using electricity, a series of elements for the first time: potassium and sodium in 1807 and calcium, strontium, barium, magnesium and boron the following year, as well as discovering the elemental nature of chlorine and iodine. Davy also studied the forces involved in these separations, inventing the new field of electrochemistry.Lived: Dec 17, 1778 - May 29, 1829 (age 50)Discovered: Calcium · Barium · Potassium · Sodium · Boron Inventions: Davy lamp · Arc LampWritten works: Consolations in Travel; Or, the Last Days of a Philosopher (1830) · Elements of chemical philosophy (1812) Awards: Copley Medal (1) · Rumford Medal (1) · Royal Medal (1)Buried: Cimetière des RoisTimeline1778,Davy was born in Penzance, Cornwall, in the Kingdom of Great Britain on 17 December 1778, the eldest of the five children of Robert Davy, a woodcarver, and his wife Grace Millett.1794,After Davy's father died in 1794, Tonkin apprenticed him to John Bingham Borlase, a surgeon with a practice in Penzance.1806,By 1806 he was able to demonstrate a much more powerful form of electric lighting to the Royal Society in London.1810,In 1810, chlorine was given its current name by Humphry Davy, who insisted that chlorine was in fact an element.1822,The Navy Board approached Davy in 1822, asking for help.1827,In January 1827 he set off to Italy for reasons of his health.Sir Humphry Davy, in full Sir Humphry Davy, Baronet, (born December 17, 1778, Penzance, Cornwall, England—died May 29, 1829, Geneva, Switzerland), English chemist who discovered several chemical elements (including sodium and potassium) and compounds, invented the miner’s safety lamp, and became one of the greatest exponents of the scientific method.Early LifeDavy was the elder son of middle-class parents who ownedan estate in Ludgvan, Cornwall, England. He was educated at the grammar school in nearby Penzance and, in 1793, at Truro. In 1795, a year after the death of his father, Robert, he was apprenticed to a surgeon and apothecary, and he hoped eventually to qualify in medicine. An exuberant, affectionate, and popular lad, of quick wit and lively imagination, he was fond of composing verses, sketching, making fireworks, fishing, shooting, and collecting minerals. He loved to wander, one pocket filled with fishing tackle and the other with rock specimens; he never lost his intense love of nature and, particularly, of mountain and water scenery.While still a youth, ingenuous and somewhat impetuous, Davy had plans for a volume of poems, but he began the serious study of science in 1797, and these visions “fled before the voice of truth.”He was befriended by Davies Giddy (later Gilbert; president of the Royal Society, 1827–30), who offered him the use of his library in Tradea and took him to a chemistry laboratory that was well equipped for that day. There he formed strongly independent views on topics of the moment, such as the nature of heat, light, and electricity and the chemical and physical doctrines of Antoine Lavoisier. On Gilbert’s recommendation, he was appointed (1798) chemical superintendent of the Pneumatic Institution, founded at Clifton to inquire into the possible therapeutic uses of various gases. Davy attacked the problem with characteristic enthusiasm, evincing an outstanding talent for experimental inquiry. In his small private laboratory, he prepared and inhaled nitrous oxide (laughing gas) in order to test a claim that it was the “principle of contagion,” that is, caused diseases. He investigated the composition of the oxides and acids of nitrogen, as well as ammonia, and persuaded his scientific andliterary friends, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, and Peter Mark Roget, to report the effects of inhaling nitrous oxide. He nearly lost his own life inhaling water gas, a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide sometimes used as fuel.The account of his work, published as Researches, Chemical and Philosophical, Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and Its Respiration (1800), immediately established Davy’s reputation, and he was invited to lecture at the newly founded Royal Institution of Great Britain in London, where he moved in 1801, with the promise of help from the British-American scientist Sir Benjamin Thompson (Count von Rumford), the British naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, and the English chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish in furthering his researches—e.g., on voltaic cells, early forms of electric batteries. His carefully prepared and rehearsed lectures rapidly became important social functions and added greatly to the prestige of science and the institution. In 1802 he became professor of chemistry. His duties included a special study of tanning: he found catechu, the extract of a tropical plant, as effective as and cheaper than the usual oak extracts, and his published account was long used as a tanner’s guide. In 1803 he was admitted a fellow of the Royal Society and an honorary member of the Dublin Society and delivered the first of an annual series of lectures before the board of agriculture. This led to his Elements of Agricultural Chemistry (1813), the only systematic work available for many years. For his researches on voltaic cells, tanning, and mineral analysis, he received the Copley Medal in 1805. He was elected secretary of the Royal Society in 1807.Davy's application of electrochemistry leads to the discovery of new elementsMajor DiscoveriesDavy early concluded that the production of electricity in simple electrolytic cells resulted from chemical action and that chemical combination occurred between substances of opposite charge. He therefore reasoned that electrolysis, the interactions of electric currents with chemical compounds, offered the most likely means of decomposing all substances to their elements. These views were explained in 1806 in his lecture “On Some Chemical Agencies of Electricity,” for which, despite the fact that England and France were at war, he received the Napoleon Prize from the Institut de France (1807). This work led directly to the isolation of sodium and potassium from their compounds (1807) and of the alkaline-earth metals magnesium, calcium, strontium, and barium from their compounds (1808). He also discovered boron (by heating borax with potassium), hydrogen telluride, and hydrogen phosphide (phosphine). He showed the correct relation of chlorine to hydrochloric acid and the untenability ofthe earlier name (oxymuriatic acid) for chlorine; this negated Lavoisier’s theory that all acids contained oxygen. He also showed that chlorine is a chemical element, and experiments designed to reveal oxygen in chlorine failed. He explained the bleaching action of chlorine (through its liberation of oxygen from water) and discovered two of its oxides (1811 and 1815), but his views on the nature of chlorine were disputed.In 1810 and 1811 he lectured to large audiences at Dublin (on agricultural chemistry, the elements of chemical philosophy, geology) and received £1,275 in fees, as well as the honorary degree of LL.D., from Trinity College. In 1812 he was knighted by the Prince Regent (April 8), delivered a farewell lecture to members of the Royal Institution (April 9), and married Jane Apreece, a wealthy widow well known in social and literary circles in England and Scotland (April 11). He also published the first part of the Elements of Chemical Philosophy, which contained much of his own work. His plan was too ambitious, however, and nothing further appeared. Its completion, according to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, would have “advanced the science of chemistry a full century.”His last important act at the Royal Institution, of which he remained honorary professor, was to interview the young Michael Faraday, later to become one of England’s great scientists, who became laboratory assistant there in 1813 and accompanied the Davys on a European tour (1813–15). By permission of Napoleon, he travelled through France, meeting many prominent scientists, and was presented to the empress Marie Louise. With the aid of a small portable laboratory and of various institutions in France and Italy, he investigated the substance “X”(later called iodine), whose properties andsimilarity to chlorine he quickly discovered; further work on various compounds of iodine and chlorine was done before he reached Rome. He also analyzed many specimens of classical pigments and proved that diamond is a form of carbon.Sir Humphry Davy lectures the Royal InstitutionLater YearsShortly after his return, he studied, for the Society for Preventing Accidents in Coal Mines, the conditions under which mixtures of firedamp and air explode. This led to the invention of the miner’s safety lamp and to subsequent researches on flame, for which he received the Rumford medals (gold and silver) from the Royal Society and, from the northern mine owners, a service of plate (eventually sold to found the Davy Medal). After being created a baronet in 1818, he again went to Italy, inquiring into volcanic action and trying unsuccessfully to find a way of unrolling the papyri found at Herculaneum. In 1820 he became president of the Royal Society, a position he held until 1827. In 1823–25 he was associated with the politician and writer JohnWilson Croker in founding the Athenaeum Club, of which he was an original trustee, and with the colonial governor Sir Stamford Raffles in founding the Zoological Society and in furthering the scheme for zoological gardens in Regent’s Park, London (opened in 1828). During this period, he examined magnetic phenomena caused by electricity and electrochemical methods for preventing saltwater corrosion of copper sheathing on ships by means of iron and zinc plates. Though the protective principles were made clear, considerable fouling occurred, and the method’s failure greatly vexed him. But he was, as he said, “burned out.” His Bakerian lecture for 1826, “On the Relation of Electrical and Chemical Changes,” contained his last known thoughts on electrochemistry and earned him the Royal Society’s Royal Medal.Davy’s health was by then failing rapidly; in 1827 he departed for Europe and, in the summer, was forced to resign the presidency of the Royal Society, being succeeded by Davies Gilbert. Having to forgo business and field sports, Davy wrote Salmonia: or Days of Fly Fishing (1828), a book on fishing (after the manner of Izaak Walton) that contained engravings from his own drawings. After a last, short visit to England, he returned to Italy, settling at Rome in February 1829—“a ruin amongst ruins.”Though partly paralyzed through stroke, he spent his last months writing a series of dialogues, published posthumously as Consolations in Travel, or the Last Days of a Philosopher (1830).Sir Humphrey Davy (1778-1829) lecturing at the Surrey Institute, engravingby Thomas Rowlandson。

第一章电化学概述

1-2 电化学在国民经济中的应用

一. 电化学工业 1. 2. 3. 4.

电解工业(氯碱工业) 电冶金 电有机合成 电化学加工

二. 化学电源

1. 2.

传统化学电源(一次电池,二次电池)(便携性) 燃料电池

三. 金属腐蚀与防护

1. 2.

金属腐蚀理论机理、类型 电化学保护技术

四.电化学测量技术

1. 2. 3.

7 R.N.Adams, Electrochemistry at solid electrodes, 1969 8 *J.O'M.Bockris and A.N.Reddy, Modern Electrochemistry, Plenum, New York, 1970 9 *Analytical Electrochemistry, Joe Wang, 2000 电化学动力学,吴浩青,李永舫, 1998, 10 *电化学动力学,吴浩青,李永舫, 1998,高等教育出版社 生命科学中的电分析化学, 彭图治, 编著, 11 生命科学中的电分析化学, 彭图治,杨丽菊 编著, 1999 电极过程动力学导论, 查全性, 12 *电极过程动力学导论, 查全性, 1976(1987 2nd Edition) 13 电化学研究方法, 田昭武, 1984 电化学研究方法, 田昭武, 14 *电化学测定方法, 腾岛 昭 等著, 陈震等译, 1995 电化学测定方法, 等著, 陈震等译, 15 电分析化学, 蒲国刚,袁倬斌,吴守国编著, 1993 电分析化学, 蒲国刚,袁倬斌,吴守国编著,

3.1934年巴特勒-伏尔默(Butler-Volmer) 提出了电化学动力学方程式(电子得 失)。 4.1940年代弗鲁姆金(Frumkin)迟缓放电 理论的提出,奠定了电化学动力学基础。

电化学原理讲解

电分析成为独立的方法学

• 三大定量关系的建立 1833年法拉第定律Q=nFM 1889年能斯特W.Nernst提出能斯特方程

1934年尤考维奇D.Ilkovic提出扩散电流方程 Id = kC

近代电分析方法

(1) 电极的发展:化学修饰电极、超微电极 (2) 多学科参与:生物电化学传感器 (3)与其他方法联用:光谱-电化学、HPLC-EC、

更灵敏的检测方法

循环伏安法

检测限10-5 mol/L

改变加载 电位的波形

示差脉冲伏安法(DPV) 方波伏安法(SWV)

检测限10-8 mol/L 扫描速率快

示差脉冲伏安法DPV Differential-Pulse Voltammetry

示差脉冲伏安法的激发信号(施加的电压)

示差脉冲伏安图

Differential-pulse voltammograms for a 1.3 × 10−5 M chloramphenicol solution.

方波伏安法SWV Square-wave Voltammograms

方波伏安法的激发信号(施加的电压)

方波伏安图

Square-wave voltammograms for TNT solutions of increasing concentration from 1 to 10 ppm (curves b–k), along with the background voltammogram (curve a) and resulting calibration plot (inset).

无/有液体接界电池

化学电池的阴极和阳极

发生氧化反应的电极称为阳极,发生还 原反应的电极叫做阴极。

一般把作为阳极的电极和有关的溶液体系写在左边,把

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

电化学的发展史

201013020427 杨艳艳

摘要: 电化学是研究电与化学反应相互关系的学科, 主要通过化学反应来产生电能以及研究电流导致化学变化方面的研究。

主要介绍电化学200多年的发展史以及探讨未来电化学的研究动向。

关键词:电化学发展史未来

电化学的发展从伏特的第一个化学电池开始已经经历过两个多世纪的

发展。

现在的电化学已经成为国民经济与工业中不可缺少的一部分,应用于

各个不同的领域,例如; 电解、电镀、光电化学、电催化、金属腐蚀等。

同

时电化学在生物、汽车工业、分析等这些新兴科学范畴也占有着举足轻重的

作用。

1电化学

电化学是研究电和化学反应之间的相互作用,化学能和电能之间的相互转化及相关规律的科学。

电化学是物理化学的重要分支,主要研究电子导体一离子导体、离子导体一离子导体的界面现象、结构化学过程以及与此相关现象。

研究内容包括2个方面:(1)电解质研究(电解质的导电性质、离子的传输特性、参与反应的离子的平衡性质等);(2)电极研究(电化学界面的平衡性质和非平衡性质)。

现代电化学是十分注重研究电化学界面结构、界面上的电化学行为及其动力学。

电化学现象普遍存在于自然界,如金属的腐蚀、人或动物的肌肉运动、大脑信息的传递、生物电流以及细胞膜的功能机制等等,无不涉及电化学过程的作用。

电化学技术成果与人类的生活和生产实际密切相关,如化学电源、腐蚀保护、表面精蚀、金属精炼、各种化学药品的电解合成、治理环境、人造器官、生物电池、心脑电图、信息传递等。

涉及电化学研究领域十分广泛,其理论方法和技术应用越来越多地与其他自然科学或技术学科相互交叉、相互渗透[1]。

电化学是一门古老而又年轻的学科,一般公认电化学起源于1791年意大利解剖学家伽伐尼(Gal一vani)发现解剖刀或金属能使蛙腿肌肉抽缩的“动物电”现象;1800年伏特(Volta)制成了第一个实用电池,开始了电化学研究的新时代。

在经历了一个多世纪以后,电化学科学的发展和成就举世瞩目,无论是基础研究还是技术应用,从理论到方法,都有许多重大突破。

电化学科学的发展,推动了世界科学的进步,促进了社会经济的发展,对解决人类社会面临的能源、交通、材料、环保、信息、生命等问题,已经作出并正在作出巨大的贡献。

2早期电化学发展的四

大事件

(1)1780年伽伐尼在青蛙解剖实验中发现当青蛙的四条腿猛烈痉挛时, 会引起起电机的发出火花, 由这个意外的发现伽伐尼在1791年发表了生物学与电化学之间存在联系的现象。

(2)1833年天才实验家法拉第在经过大量实验之后提出了“电解定律”:m=QM/nF。

“电解定律”作为电化学的基础为电化学的发展指明了方向。

(3)1839年格罗夫发明燃料电池,利用铂黑作为电极的氢氧燃料电池点燃了演讲厅的照明灯, 从此燃料电池进入了历史的舞台。

燃料电池发展到现在已经有了实质性的飞跃。

(4)1905年塔菲尔通过实验获得了塔菲尔经验公式:

η=a+blgi;i=Aexp(Bη/RT)

其中a,b称为塔菲尔常数,由电解槽性质决定[2]。

3 发展趋势

3.1 20 世纪后五十年电化学的回顾

20 世纪后50年,在电化学的发展史上出现了两个里程碑:Heyrovsky 因创立极谱技术而获得1959 年的诺贝尔化学奖,Marcus 因电子传递理论(包括匀相和异相体系的电子传递) 而获得1992 年的诺贝尔化学奖. Marcus 工作的开拓性部分是在50 年代后期创立的. 这一时期,电化学在理论、实验和应用领域均有长足的、关键的发展,并且主要集中在界面电化学(包括界面结构、界面电子传递和表面电化学)[3]。

20世纪后50 年是电化学新体系研究和实验信息的丰产期. 实验上发现了一些有重要意义的表面光谱效应,包括金属、半导体电极的电反射效应,金属电极表面红外光谱选律,表面分子振动光谱的电化学Stark 效应,表面增强拉曼散射效应,表面增强红外吸收效应. 这一时期电化学应用技术也有不小的突破. 发明了对信息技术至关重要的锂离子二次电池,镍氢化物电池和导电聚合物电池。

被誉为21 世纪“绿色”发电站和解决电动汽车动力最佳选择的燃料电池,从实验室研究进入商品化的前夕,已筛选出最有商品化希望的四种燃料电池:磷酸燃料电池(PAFC),熔融碳酸盐燃料电池(MCFC) ,固体氧化物燃料电池(SOFC) 和聚合物电解质燃料电池(PEFC) ,此外甲醇直接燃料电池的实验室研究也倍受重视。

电催化氧化物电极,例如二氧化钌电极在电解工业的应用,引来了氯碱工业的一场革命. 表面功能电沉积给古老的电镀工业带来了新生. 钝化、表面处理、涂层、缓蚀剂、阴极和阳极保护

等技术在金属防腐蚀中的广泛应用,保证金属成为现代社会的支柱材料成为可能[4]。

3.2 21 世纪的若干发展趋势

21 世纪的前期,界面电化学的分子、原子水平研究仍然是电化学理论研究的重点,主要有:界面结构微观模型的进一步完善,尤其是离子特性吸附结构模型和半导体-溶液界面微观模型的建立,界面结构微观模型在界面传荷动力学和表面电化学中的应用;Marcus 固-液界面电子传递理论的进一步完善,建立内球过程的电子传递理论,电子传递理论的进一步实验验证,以及在电化学新体系中的应用;化学键合吸附(包括电催化过程的吸附) 的量子化学模型及计算、表面化学键的性质;纳微米体系的界面结构、界面动电现象、界面电子传递、光电过程、发光过程等实验和理论[5]。

21 世纪,由于材料、能源、信息、生命、环境对电化学技术的要求,电化学新体系和新材料的研究将有较大的发展. 目前可预见的有:1) 纳米材料的电化学合成;2) 纳米电子学中元器件、集成电路板、纳米电池、纳米光源的电化学制备;3) 微系统、芯片实验室的电化学加工以及界面动电现象在驱动微液流中的应用;4) 电动汽车的化学电源和信息产业的配套电源;5) 氢能源的电解制备;6) 太阳能利用实用化中的固态光电化学电池和光催化合成;7) 消除环境污染的光催化技术和电化学技术;8) 玻璃、陶瓷、织物等的自洁、杀菌技术中的光催化和光诱导表面能技术;9) 生物大分子、活性小分子、药物分子的电化学研究;10) 微型电化学传感器的研制。

21 世纪前期,电化学实验技术估计不会有大的突破,我国电化学队伍中的量子电化学力量相对薄弱,而21 世纪前期电化学的机会将较多地赋予电化学新体系. 因此,我国电化学研究应当向电化学新体系研究倾斜,包括研制电化学体系新材料,新体系的结构和性能,新体系的应用基础等的研究。

参考文献:

[1]王淑敏,王作辉,电化学的应用和发展.2010年38卷第8期。

[2]汪丰云.有机电化学的发展史.化学教育.2001年第7~8合期

[2]岑远.电化学的发展及应用.科技创新导报.2012 NO4

[3]分析实验室: 电化学分析的发展和应用. 2003年11月第22卷第6期.

[4]林仲华.21 世纪电化学的若干发展趋势.电化学.2002年2月第8卷第2期.。