John Keats

John keats

Bright star

• Of snow upon the mountains and the moors--No---yet still stedfast, still unchangeable, Pillowed upon my fair love's ripening breast, To feel for ever its soft fall and swell, Awake for ever in a sweet unrest, Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath, And so live ever---or else swoon to death. • 灿烂、轻盈,覆盖着洼地和 高山—— 呵,不,——我只愿坚 定不移地 以头枕在爱人酥软的胸 脯上, 永远感到它舒缓地降落、 升起; 而醒来,心里充满甜蜜 的激荡, 不断,不断听着她细腻 的呼吸, 就这样活着,——或昏 迷地死去。 查良铮 译

Major Literary Works

• In John Keats’ short writing career of six or seven years, he produced a variety of kinds of works, including epic, lyric and narrative poems. • Except his first poem, Lines in Imitation of Spenser (1814) and his first book, Poems, published in 1817, his major works can be divided into the five long poems and the short ones.

John Keats英文简介

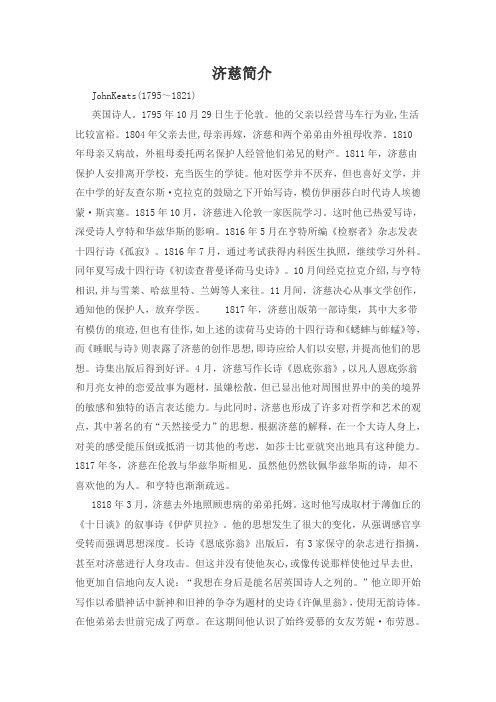

John KeatsJohn Keats (1795-1821), major English poet, despite his early death from tuberculosis at the age of 25. Keats’s poetry describes the beauty of the natural world and art as the vehicle for his poetic imagination. His skill with poetic imagery and sound reproduces this sensuous experience for his reader. Keats’s poetry evolves over his brief career from this love of nature and art into a deep compassion for humanity. He gave voice to the spirit of Romanticism in literature when he wrote, “I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections, and the truth of imagination.” Twentieth-century poet T. S. Eliot judged Keats's letters to be 'the most notable and the most important ever written by any English Poet,” for their acute reflection s on poetry, poets, and the imagination.II Early LifeKeats was born in north London, England. He was the eldest son of Thomas Keats, who worked at a livery stable, and Frances (Jennings) Keats. The couple had three other sons, one of whom died in infancy, and a daughter. Thomas Keats died in 1804, as a result of a riding accident. Frances Keats died in 1810 of tuberculosis, the disease that also took the lives of her three sons.From 1803 to 1811 Keats attended school. Toward the end of his schooling, he began to read widely and even undertook a prose translation of the Aeneid from the Latin. After he left school at the age of 16, Keats was apprenticed to a surgeon for four years. During this time his interest in poetry grew. He wrote his first poems in 1814 and passed his medical and druggist examinations in 1816.III Life as a PoetIn May 1816 Keats published his first poem, the sonnet 'O Solitude,' marking the beginning of his poetic career. In writing a sonnet, a 14-line poem with a strict rhyme scheme, Keats sought to take his place in the tradition established by great classical, European, and British epic poets. The speaker of this poem first expresses hope that, if he is to be alone, it will be in “Nature’s Observatory”; he then imagines the “highest bliss” to be writing poetry in nature rather than simply observing nature. In another sonnet published the same year, 'On First Looking into Chapman's Homer,' Keats compares reading translations of poetry to awe-inspiring experiences such as an astronomer discovering a new planet or explorers first seeing the Pacific Ocean. In “Sleep and Poetry,” a longer poem from 1816, Keats articulates the purpose of poetry as he sees it: “To soothe the cares, and lift the thoughts of man.” Within a year o f his first publications Keats had abandoned medicine, turned exclusively to writing poetry, and entered the mainstream of contemporary English poets. By the end of 1816 he had met poet and journalist Leigh Hunt, editor of the literary magazine that published his poems. He had also met the leading romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley.“Endymion,” written between April and November 1817 and published the following year, is thought to be Keats's richest although most unpolished poem. In the poem, the mortal hero Endymion's quest for the goddess Cynthia serves as a metaphor for imaginative longing—the poet’s quest for a muse, or divine inspiration.Following “Endymion,” Keats struggled with his assumptions about the power of poetry and philosophy to affect the suffering he saw in life. In June of 1818, Keats went on a physically demanding walking tour of England’s Lake District and Scotland, perhaps in search of inspiration for an epic poem. His journey was cut short by the illness of his brother Tom. Keats returned home and nursed his brother through the final stages of tuberculosis. He threw himself into writing the epic “Hyperion,” he wrote to a friend, to ease himself of Tom’s “countenance, his voice and feebleness.'An epic is a long narrative poem about a worthy hero, written in elevated language; this was the principal form used by great poets before Keats. The subject of “Hyperion” is the fall of the primeval Greek gods, who are dethroned by the Olympians, a newer order of gods led by Apollo. Keats used this myth to represent history as the story of how grief and misery teach humanity compassion. The poem ends with the transformation of Apollo into the god of poetry, but Keats left the poem unfinished. His abandonment of the poem suggests that Keats was ready to return to a more personal theme: the growth of a poet's mind. Keats later described the poem as showing 'false beauty proceeding from art' rather than 'the true voice of feeling.' Tom’s death in December 1818 may have freed Keats from the need t o finish “Hyperion.”Two other notable developments took place in Keats’s life in the latter part of 1818. First, “Endymion,” published in April, received negative reviews by the leading literary magazines. Second, Keats fell in love with spirited, 18-year-old Fanny Brawne. Keats's passion for Fanny Brawne is perhaps evoked in 'The Eve of St. Agnes,' written in 1819 and published in 1820. In this narrative poem, a young man follows an elaborate plan to woo his love and wins her heart.Keats’s great crea tive outpouring came in April and May of 1819, when he composed a group of five odes. The loose formal requirements of the ode—a regular metrical pattern and a shift in perspective from stanza to stanza—allowed Keats to follow his mind’s associations. Lite rary critics rank these works among the greatest short poems in the English language. Each ode begins with the speaker focusing on something—a nightingale, an urn, the goddess Psyche, the mood of melancholy, the season of autumn—and arrives at his greater insight into what he values.In “Ode to a Nightingale,” the nightingale’s song symbolizes the beauty of nature and art. Keats was fascinated by the difference between life and art: Human beings die, but the art they make lives on. The speaker in the poem tries repeatedly to use his imagination to go with the bird’s song, but each time he fails to completely forget himself. In the sixth stanza he suddenly remembers what death means, and the thought of it frightens him back to earth and his own humanity.In 'Ode on a Grecian Urn,' the bride and bridegroom painted on the Grecian urn do not die. Theirlove can never fade, but neither can they kiss and embrace. At the end of the poem, the speaker sees the world of art as cold rather than inviting.The last two odes, 'Ode on Melancholy' and 'To Autumn,” show a turn in Keats’s ideas about life and art. He celebrates “breathing human passion” as more beautiful than either art or nature.Keats never lived to write the poetry of 'the agonies, the strife of human hearts' to which he aspired. Some scholars suggest that his revision of “Hyperion,” close to the end of his life, measures what he learned about poetry. In the revision, 'The Fall of Hyperion: A Dream,' Keats boldly makes the earlier poem into the story of his own quest as poet. In a dream, the poem’s speaker must pass through death to enter a temple that receives only those who cannot forget the miseries of the world. Presiding over the shrine is Moneta, a prophetess whose face embodies many of the oppos ites that had long haunted Keats’s imagination—death and immortality, stasis and change, humankind’s goodness and darkness. The knowledge Moneta gives him defines Keats’s new mission and burden as a poet.After September 1819, Keats produced little poetry. His money troubles, always pressing, became severe. Keats and Fanny Brawne became engaged, but with little prospect of marriage. In February 1820, Keats had a severe hemorrhage and coughed up blood, beginning a year that he called his “posthumous existence.” He did manage to prepare a third volume of poems for the press, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems.In September 1820, Keats sailed to Italy, accompanied by a close friend. The last months of his life there were haunted by the prospect of death and the memory of Fanny Brawne.。

John Keats

His first surviving poem— An Imitation of Spenser —comes in 1814, when Keats was nineteen. In 1815, Keats registered as a medical student at Guy„s Hospital (now part of King‟s College London). Strongly drawn by an ambition inspired by fellow poets such as Leigh Hunt and Byron, but beleaguered(围困) by family financial crises that continued to the end of his life, he suffered periods of deep depression.

The Protestant Cemetery新教徒公墓,罗马 新教徒公墓 正式地叫 Cimitero acattolico (“非 宽容公墓”)和经常指 Cimitero degli Inglesi (“英国公墓”)是公墓 在 罗马位于近 Porta圣 Paolo沿着 Cestius金字塔小规模埃及样式 金字塔 修造 30BC作为坟茔并且以后合并到部分里Aurelian 墙壁 那毗邻公墓。地中海柏树和其他叶子在公墓 造成它反映在更加豪华的地区看见的公墓更加自然 的样式北欧. 因为公墓的名字表明,它是最后的休 息处非天主教徒 (不仅 基督教教会成员 或 英国人 民). [最早的已知的埋葬是那 牛津学生名为 Langton1738. 最著名的坟墓是那些英国诗人 约翰 Keats (1795-1821)和 Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)。 Keats在罗马死了 结核病. 他的 墓 志铭名义上不提及他,是由他的朋友约瑟夫Severn 和查尔斯・布朗: “这个坟墓包含是临死的所有, 一个年轻英国诗人在他的临终,在他的心脏冤苦, 在他的敌人的恶意力量,渴望是这些词在他的坟茔 石头engraven : 这里说谎名字是命令在水中的一。 “Shelley淹没了 意大利里维埃拉 他的灰是埋葬在 新教徒公墓。

ctf-约翰·格斯瓦斯的诗歌

《CTF-约翰·格斯瓦斯的诗歌》一、引言在计算机安全领域,CTF(Capture The Flag)是一种常见的竞赛形式,旨在考察参与者的网络安全技能和解决问题的能力。

然而,在今天的文章中,我们并非要讨论这种类型的竞赛,而是要深入探讨一位诗人的作品-约翰·格斯瓦斯的诗歌。

作为一位充满活力和创造力的诗人,格斯瓦斯的诗歌作品以其深刻的思想和精湛的艺术表现,深受世人喜爱。

二、浅谈约翰·格斯瓦斯约翰·格斯瓦斯(John Keats,1795年-1821年)是英国浪漫主义诗人中的一员,他的诗歌作品以其华丽、飘逸的文学风格,以及对自然、美、逝去等主题的深刻探讨而著称。

在其短暂的生命中,格斯瓦斯创作了许多令人赞叹的作品,其中包括《卓别林赞》、《夜莺颂》、《阳光颂》等。

三、深入解读1. 《卓别林赞》在格斯瓦斯的诗歌作品中,《卓别林赞》被视为其代表作之一。

这首诗歌以对卓别林的颂扬和赞美为主题,表达了对于美和艺术的追求。

作者通过描绘卓别林的形象和作品,展现了对人类创造力和想象力的无限崇敬和赞美。

2. 《夜莺颂》《夜莺颂》是格斯瓦斯的另一首经典作品,这首诗歌以夜莺为主题,通过夜莺的歌声,表达了对自然美和自由的向往。

诗中充满了对生命的热情和对美的追求,展现了浪漫主义诗人对于内心世界的探索和追求。

3. 《阳光颂》在《阳光颂》中,格斯瓦斯以阳光为象征,赞美了阳光对于人类生活的意义和作用。

作者通过对阳光的描绘,表达了对光明、希望和生命的追求,展现了对于正能量和积极生活态度的向往。

四、总结与回顾通过对约翰·格斯瓦斯诗歌作品的深入解读,我们可以感受到他对于美和艺术的热爱,以及对自然、生命和美好的向往。

他的诗歌作品充满了对人类创造力和生命力的赞美,以及对美好事物的追求和追寻。

正如他所言:“美是真理的至高表现形式”,格斯瓦斯的诗歌作品也正是在不断追求美和真理的道路上不断前行。

五、个人观点对于我个人来说,格斯瓦斯的诗歌作品深深地触动了我的内心世界,让我对生命、美和艺术有了全新的理解和感悟。

济慈生平简介(英文版)及部分诗作

John Keats (1795-1821), renowned poet of the English Romantic Movement, wrote some of the greatest English language poems including "La Belle Dame Sans Merci", "Ode To A Nightingale", and "Ode On a Grecian Urn";O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with bredeOf marble men and maidens overwrought,With forest branches and the trodden weed;Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thoughtAs doth eternity: Cold pastoral!When old age shall this generation waste,Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woeThan ours, a friend to man, to whom thou sayst,"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,--that is allYe know on earth, and all ye need to know."、John Keats was born on 31 October 1795 in Moorgate, London, England, the first child born to Frances Jennings (b.1775-d.1810) and Thomas Keats (d.1804), an employee of a livery stable. He had three siblings: George (1797-1841), Thomas (1799-1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803-1889). After leaving school in Enfield, Keats went on to apprentice with Dr. Hammond, a surgeon in Edmonton. After his father died in a riding accident, and his mother died of tuberculosis, John and his brothers moved to Hampstead. It was here that Keats met Charles Armitage Brown (1787-1842) who would become a great friend. Remembering his first meeting with him, Brown writes "His full fine eyes were lustrously intellectual, and beaming (at that time!)". Much grieved by his death, Brown worked for many years on his memoir and biography, Life of John Keats (1841). In it Brown claims that it was not until Keats read Edmund Spencer's Faery Queen that he realised his own gift for the poetic. Keats was an avid student in the fields of medicine and natural history, but he then turned his attentions to the literary works of such authors as William Shakespeare and Geoffrey Chaucer.Keats had his poems published in the magazines of the day at the encouragement of many including James Henry Leigh Hunt Esq. (1784-1859), editor of the Examiner and to whom Keats dedicated his first collection Poems (1817). It includes "To My Brother George", "O Solitude! If I Must With Thee Dwell", and "Happy is England! I Could Be Content". Upon its appearance a series of personal attacks directed at Keats ensued in the pages of Blackwood's Magazine. Despite the controversy surrounding his life, Keats's literary merit prevailed. That sameto stay with him and his family in Italy, he declined. When Shelley's body was washed ashore after drowning, a volume of Keats's poetry was found in his pocket.Having worked on it for many months, Keats finished his epic poem comprising four books, Endymion: A Poetic Romance--"A thing of beauty is a joy for ever"--in 1818. That summer he travelled to the Lake District of England and on to Ireland and Scotland on a walking tour with Brown. They visited the grave of Robert Burns and reminisced upon John Milton's poetry. While he was not aware of the seriousness of it, Keats was suffering from the initial stages of the deadly infectious disease tuberculosis. He cut his trip short and upon return to Hampstead immediately tended to his brother Tom who was then in the last stages of the disease. After Tom's death in December of 1818, Keats lived with Brown.Life of John Keats.Around this time Keats met, fell in love with, and became engaged to eighteen year old Frances "Fanny" Brawne (1800-1865). He wrote one of his more famous sonnets to her titled "Bright Star, would I were steadfast as thou art". While their relationship inspired much spiritual development for Keats, it also proved to be tempestuous, filled with the highs and lows from jealousy and infatuation of first love. Brown was not impressed and tried to provide some emotional stability to Keats. Many for a time were convinced that Fanny was the cause of his illness, or, used that as an excuse to try to keep her away from him. For a while even Keats entertained the possibility that he was merely suffering physical manifestations of emotional anxieties--but after suffering a hemorrhage he gave Fanny permission to break their engagement. She would hear nothing of it and by her word provided much comfort to Keats in his last days that she was ultimately loyal to him.Although 1819 proved to be his most prolific year of writing, Keats was also in dire financial straits. His brother George had borrowed money he could ill-afford to part with. His earning Fanny's mother's approval to marrydepended on his earning as a writer and he started plans with his publisher John Taylor (1781-1864) for his next volume of poems. At the beginning of 1820 Keats started to show more pronounced signs of the deadly tuberculosis that had killed his mother and brother. After a lung hemorrhage, Keats calmly accepted his fate, and he enjoyed several weeks of respite under Brown's watchful eye. As was common belief at the time that bleeding a patient was beneficial to healing, Keats was bled and given opium to relieve his anxiety and pain. He was at times put on a starvation diet, then at other times prescribed to eat meat and drink red wine to gain strength. Despite these ill-advised good-intentions, and suffering increasing weakness and fever, Keats was able to emerge from his fugue and organise the publication of his next volume of poetry.Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems (1820) includes some of his best-known and oft-quoted works: "Hyperion", "To Autumn", and "Ode To A Nightingale". "Nightingale" evokes all the pain and suffering that Keats experienced during his short life-time: the death of his mother; the physical anguish he saw as a young apprentice tending to the sick and dying at St. Guy's Hospital; the death of his brother; and ultimately his own physical and spiritual suffering in love and illness. Keats lived to see positive reviews of Lamia, even in Blackwood's magazine. But the positivity was not to last long; Brown left for Scotland and the ailing Keats lived with Hunt for a time. But it was unbearable to him and only exacerbated his condition--he was unable to see Fanny, so, when he showed up at the Brawne's residence in much emotional agitation, sick, and feverish, they could not refuse him. He enjoyed a month with them, blissfully under the constant care of his beloved Fanny. Possibly bolstered by his finally having unrestricted time with her, and able to imagine a happy future with her, Keats considered his last hope of recovery of a rest cure in the warm climes of Italy. As a parting gift Fanny gave him a piece of marble which she had often clasped to cool her hand. In September of 1820 Keats sailed to Rome with friend and painter Joseph Severn (1793-1879, who was unaware of his circumstances with Fanny and the gravity of his health.Keats put on a bold front but it soon became apparent to Severn that he was terminally ill. They stayed in rooms on the Piazza Navona near the Spanish Steps, and enjoyed the lively sights and sounds of the people and culture, but Keats soon fell into a deep depression. When his attending doctor James Clark (1788-1870) finally voiced aloud the grim prognosis, Keats's medical background came to the fore and he longed to end his life and avoid the humiliating physical and mental torments of tuberculosis. By early 1821 he was confined to bed, Severn a devoted nurse. Keats had resolved not to write to Fanny and would not read a letter from her for fear of the pain it would cause him, although he constantly clasped her marble. During bouts of coughing, fever, nightmares, Keats also tried to cheer his friend, who held him till the end.John Keats died on 23 February 1821 in Rome, Italy, and now rests in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, by the pyramid of Caius Cestius, near his friend Shelley. His epitaph reads "Here lies one whose name was writ in water", inspired by the line "all your better deeds, Shall be in water writ" from Francis Beaumont (1584-1616) and John Fletcher's (1579-1625) five act play Philaster or: Love Lies A-bleeding. Just a year later, Shelley was buried in the same cemetery, not long after he had written "Adonais" (1821) in tribute to his friend;I weep for Adonais--he is dead!O, weep for Adonais! though our tearsThaw not the frost which binds so dear a head!And thou, sad Hour, selected from all yearsTo mourn our loss, rouse thy obscure compeers,And teach them thine own sorrow, say: "With meDied Adonais; till the Future daresForget the Past, his fate and fame shall beAn echo and a light unto eternity!"Fanny Brawne married in 1833 and died at the age of sixty-five. English poet and friend of Brown's, Richard Monckton Milnes (1809-1885) wrote Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats (1848). During his lifetime and since, John Keats inspired numerous other authors, poets, and artists, and remains one of the most widely read and studied 19th century poets.Biography written by C. D. Merriman for Jalic Inc. Copyright Jalic Inc. 2007. All Rights Reserved.Works:长篇叙事诗Endymion《恩底弥翁》;The Eve of St.Agnes《圣艾格尼丝节前夜》;Lamia《拉米亚》;(颂诗)Ode to Psyche《普赛克颂》;《希腊古瓮颂》Sleep and Poetry《睡与诗》"As I lay in my bed slepe full unmete Was unto me, but why that I ne might Rest I ne wist, for there n'as erthly wight[As I suppose] had more of hertis ese Than I, for I n'ad sicknesse nor disese."CHAUCER.What is more gentle than a wind in summer? What is more soothing than the pretty hummer That stays one moment in an open flower,And buzzes cheerily from bower to bower?What is more tranquil than a musk-rose blowing In a green island, far from all men's knowing? More healthful than the leafiness of dales?More secret than a nest of nightingales?More serene than Cordelia's countenance?More full of visions than a high romance? What, but thee Sleep? Soft closer of our eyes! Low murmurer of tender lullabies!Light hoverer around our happy pillows! Wreather of poppy buds, and weeping willows! Silent entangler of a beauty's tresses!Most happy listener! when the morning blesses Thee for enlivening all the cheerful eyesThat glance so brightly at the new sun-rise. But what is higher beyond thought than thee? Fresher than berries of a mountain tree?More strange, more beautiful, more smooth, more regal,Than wings of swans, than doves, than dim-seen eagle?What is it? And to what shall I compare it?It has a glory, and nought else can share it:The thought thereof is awful, sweet, and holy, Chacing away all worldliness and folly;Coming sometimes like fearful claps of thunder,Or the low rumblings earth's regions under;And sometimes like a gentle whisperingOf all the secrets of some wond'rous thingThat breathes about us in the vacant air;So that we look around with prying stare,Perhaps to see shapes of light, aerial lymning,And catch soft floatings from a faint-heard hymning; To see the laurel wreath, on high suspended,That is to crown our name when life is ended. Sometimes it gives a glory to the voice,And from the heart up-springs, rejoice! rejoice! Sounds which will reach the Framer of all things, And die away in ardent mutterings.No one who once the glorious sun has seen,And all the clouds, and felt his bosom cleanFor his great Maker's presence, but must know What 'tis I mean, and feel his being glow:Therefore no insult will I give his spirit,By telling what he sees from native merit.O Poesy! for thee I hold my penThat am not yet a glorious denizenOf thy wide heaven--Should I rather kneelUpon some mountain-top until I feelA glowing splendour round about me hung,And echo back the voice of thine own tongue?O Poesy! for thee I grasp my penThat am not yet a glorious denizenOf thy wide heaven; yet, to my ardent prayer, Yield from thy sanctuary some clear air, Smoothed for intoxication by the breathOf flowering bays, that I may die a deathOf luxury, and my young spirit followThe morning sun-beams to the great ApolloLike a fresh sacrifice; or, if I can bearThe o'erwhelming sweets, 'twill bring to me the fair Visions of all places: a bowery nookWill be elysium--an eternal bookWhence I may copy many a lovely sayingAbout the leaves, and flowers--about the playing Of nymphs in woods, and fountains; and the shade Keeping a silence round a sleeping maid;And many a verse from so strange influenceThat we must ever wonder how, and whenceIt came. Also imaginings will hoverRound my fire-side, and haply there discover Vistas of solemn beauty, where I'd wanderIn happy silence, like the clear meanderThrough its lone vales; and where I found a spot Of awfuller shade, or an enchanted grot,Or a green hill o'erspread with chequered dressOf flowers, and fearful from its loveliness,Write on my tablets all that was permitted,All that was for our human senses fitted.Then the events of this wide world I'd seizeLike a strong giant, and my spirit teazeTill at its shoulders it should proudly seeWings to find out an immortality. Stop and consider! life is but a day;A fragile dew-drop on its perilous wayFrom a tree's summit; a poor Indian's sleep While his boat hastens to the monstrous steepOf Montmorenci. Why so sad a moan?Life is the rose's hope while yet unblown;The reading of an ever-changing tale;The light uplifting of a maiden's veil;A pigeon tumbling in clear summer air;A laughing school-boy, without grief or care, Riding the springy branches of an elm.O for ten years, that I may overwhelmMyself in poesy; so I may do the deedThat my own soul has to itself decreed.Then will I pass the countries that I seeIn long perspective, and continuallyTaste their pure fountains. First the realm I'll pass Of Flora, and old Pan: sleep in the grass,Feed upon apples red, and strawberries,And choose each pleasure that my fancy sees; Catch the white-handed nymphs in shady places, To woo sweet kisses from averted faces,--Play with their fingers, touch their shoulders white Into a pretty shrinking with a biteAs hard as lips can make it: till agreed,A lovely tale of human life we'll read.And one will teach a tame dove how it bestMay fan the cool air gently o'er my rest; Another, bending o'er her nimble tread,Will set a green robe floating round her head, And still will dance with ever varied case,Smiling upon the flowers and the trees:Another will entice me on, and onThrough almond blossoms and rich cinnamon;Till in the bosom of a leafy worldWe rest in silence, like two gems upcurl'dIn the recesses of a pearly shell.And can I ever bid these joys farewell?Yes, I must pass them for a nobler life,Where I may find the agonies, the strifeOf human hearts: for lo! I see afar,O'er sailing the blue cragginess, a carAnd steeds with streamy manes--the charioteer Looks out upon the winds with glorious fear:And now the numerous tramplings quiver lightly Along a huge cloud's ridge; and now with sprightly Wheel downward come they into fresher skies,Tipt round with silver from the sun's bright eyes. Still downward with capacious whirl they glide, And now I see them on a green-hill's sideIn breezy rest among the nodding stalks.The charioteer with wond'rous gesture talksTo the trees and mountains; and there soon appear Shapes of delight, of mystery, and fear,Passing along before a dusky spaceMade by some mighty oaks: as they would chase Some ever-fleeting music on they sweep.Lo! how they murmur, laugh, and smile, and weep: Some with upholden hand and mouth severe; Some with their faces muffled to the earBetween their arms; some, clear in youthful bloom, Go glad and smilingly, athwart the gloom;Some looking back, and some with upward gaze; Yes, thousands in a thousand different waysFlit onward--now a lovely wreath of girlsDancing their sleek hair into tangled curls;And now broad wings. Most awfully intentThe driver, of those steeds is forward bent,And seems to listen: O that I might knowAll that he writes with such a hurrying glow.The visions all are fled--the car is fledInto the light of heaven, and in their steadA sense of real things comes doubly strong,And, like a muddy stream, would bear alongMy soul to nothingness: but I will striveAgainst all doublings, and will keep aliveThe thought of that same chariot, and the strange Journey it went.Is there so small a rangeIn the present strength of manhood, that the high Imagination cannot freely flyAs she was wont of old? prepare her steeds, Paw up against the light, and do strange deeds Upon the clouds? Has she not shewn us all? From the clear space of ether, to the small Breath of new buds unfolding? From the meaning Of Jove's large eye-brow, to the tender greening Of April meadows? Here her altar shone,E'en in this isle; and who could paragonThe fervid choir that lifted up a noiseOf harmony, to where it aye will poiseIts mighty self of convoluting sound,Huge as a planet, and like that roll round, Eternally around a dizzy void?Ay, in those days the Muses were nigh cloy'd With honors; nor had any other careThan to sing out and sooth their wavy hair.Could all this be forgotten? Yes, a schism Nurtured by foppery and barbarism,Made great Apollo blush for this his land.Men were thought wise who could not understand His glories: with a puling infant's forceThey sway'd about upon a rocking horse,And thought it Pegasus. Ah dismal soul'd!The winds of heaven blew, the ocean roll'dIts gathering waves--ye felt it not. The blue Bared its eternal bosom, and the dewOf summer nights collected still to makeThe morning precious: beauty was awake!Why were ye not awake? But ye were deadTo things ye knew not of,--were closely wedTo musty laws lined out with wretched ruleAnd compass vile: so that ye taught a schoolOf dolts to smooth, inlay, and clip, and fit,Till, like the certain wands of Jacob's wit,Their verses tallied. Easy was the task:A thousand handicraftsmen wore the maskOf Poesy. Ill-fated, impious race!That blasphemed the bright Lyrist to his face, And did not know it,--no, they went about, Holding a poor, decrepid standard outMark'd with most flimsy mottos, and in largeThe name of one Boileau!O ye whose chargeIt is to hover round our pleasant hills!Whose congregated majesty so fillsMy boundly reverence, that I cannot traceYour hallowed names, in this unholy place,So near those common folk; did not their shames Affright you? Did our old lamenting Thames Delight you? Did ye never cluster roundDelicious Avon, with a mournful sound,And weep? Or did ye wholly bid adieuTo regions where no more the laurel grew?Or did ye stay to give a welcomingTo some lone spirits who could proudly singTheir youth away, and die? 'Twas even so:But let me think away those times of woe:Now 'tis a fairer season; ye have breathedRich benedictions o'er us; ye have wreathedFresh garlands: for sweet music has been heardIn many places;--some has been upstirr'dFrom out its crystal dwelling in a lake,By a swan's ebon bill; from a thick brake,Nested and quiet in a valley mild,Bubbles a pipe; fine sounds are floating wildAbout the earth: happy are ye and glad.These things are doubtless: yet in truth we've had Strange thunders from the potency of song; Mingled indeed with what is sweet and strong, From majesty: but in clear truth the themesAre ugly clubs, the Poets PolyphemesDisturbing the grand sea. A drainless showerOf light is poesy; 'tis the supreme of power;'Tis might half slumb'ring on its own right arm. The very archings of her eye-lids charmA thousand willing agents to obey,And still she governs with the mildest sway:But strength alone though of the Muses bornIs like a fallen angel: trees uptorn,Darkness, and worms, and shrouds, and sepulchres Delight it; for it feeds upon the burrs,And thorns of life; forgetting the great endOf poesy, that it should be a friendTo sooth the cares, and lift the thoughts of man. Yet I rejoice: a myrtle fairer thanE'er grew in Paphos, from the bitter weedsLifts its sweet head into the air, and feedsA silent space with ever sprouting green.All tenderest birds there find a pleasant screen, Creep through the shade with jaunty fluttering, Nibble the little cupped flowers and sing.Then let us clear away the choaking thornsFrom round its gentle stem; let the young fawns, Yeaned in after times, when we are flown,Find a fresh sward beneath it, overgrownWith simple flowers: let there nothing beMore boisterous than a lover's bended knee; Nought more ungentle than the placid lookOf one who leans upon a closed book;Nought more untranquil than the grassy slopes Between two hills. All hail delightful hopes!As she was wont, th' imaginationInto most lovely labyrinths will be gone,And they shall be accounted poet kingsWho simply tell the most heart-easing things.O may these joys be ripe before I die.Will not some say that I presumptuouslyHave spoken? that from hastening disgrace'Twere better far to hide my foolish face?That whining boyhood should with reverence bow Ere the dread thunderbolt could reach? How!If I do hide myself, it sure shall beIn the very fane, the light of Poesy:If I do fall, at least I will be laidBeneath the silence of a poplar shade;And over me the grass shall be smooth shaven; And there shall be a kind memorial graven.But oft' Despondence! miserable bane!They should not know thee, who athirst to gain A noble end, are thirsty every hour.What though I am not wealthy in the dowerOf spanning wisdom; though I do not knowThe shiftings of the mighty winds, that blow Hither and thither all the changing thoughtsOf man: though no great minist'ring reason sorts Out the dark mysteries of human soulsTo clear conceiving: yet there ever rollsA vast idea before me, and I gleanTherefrom my liberty; thence too I've seenThe end and aim of Poesy. 'Tis clearAs any thing most true; as that the yearIs made of the four seasons--manifestAs a large cross, some old cathedral's crest, Lifted to the white clouds. Therefore should IBe but the essence of deformity,A coward, did my very eye-lids winkAt speaking out what I have dared to think.Ah! rather let me like a madman runOver some precipice; let the hot sunMelt my Dedalian wings, and drive me down Convuls'd and headlong! Stay! an inward frown Of conscience bids me be more calm awhile.An ocean dim, sprinkled with many an isle, Spreads awfully before me. How much toil!How many days! what desperate turmoil!Ere I can have explored its widenesses.Ah, what a task! upon my bended knees,I could unsay those--no, impossible! Impossible!For sweet relief I'll dwellOn humbler thoughts, and let this strange assay Begun in gentleness die so away.E'en now all tumult from my bosom fades:I turn full hearted to the friendly aidsThat smooth the path of honour; brotherhood, And friendliness the nurse of mutual good.The hearty grasp that sends a pleasant sonnet Into the brain ere one can think upon it;The silence when some rhymes are coming out; And when they're come, the very pleasant rout: The message certain to be done to-morrow.'Tis perhaps as well that it should be to borrow Some precious book from out its snug retreat, To cluster round it when we next shall meet. Scarce can I scribble on; for lovely airsAre fluttering round the room like doves in pairs; Many delights of that glad day recalling,When first my senses caught their tender falling. And with these airs come forms of elegance Stooping their shoulders o'er a horse's prance, Careless, and grand--fingers soft and round Parting luxuriant curls;--and the swift bound Of Bacchus from his chariot, when his eye Made Ariadne's cheek look blushingly.Thus I remember all the pleasant flowOf words at opening a portfolio.Things such as these are ever harbingersTo trains of peaceful images: the stirsOf a swan's neck unseen among the rushes:A linnet starting all about the bushes:A butterfly, with golden wings broad parted, Nestling a rose, convuls'd as though it smarted With over pleasure--many, many more,Might I indulge at large in all my storeOf luxuries: yet I must not forgetSleep, quiet with his poppy coronet:For what there may be worthy in these rhymes I partly owe to him: and thus, the chimesOf friendly voices had just given placeTo as sweet a silence, when I 'gan retraceThe pleasant day, upon a couch at ease.It was a poet's house who keeps the keysOf pleasure's temple. Round about were hung The glorious features of the bards who sungIn other ages--cold and sacred bustsSmiled at each other. Happy he who trustsTo clear Futurity his darling fame!Then there were fauns and satyrs taking aim At swelling apples with a frisky leapAnd reaching fingers, 'mid a luscious heapOf vine leaves. Then there rose to view a fane Of liny marble, and thereto a trainOf nymphs approaching fairly o'er the sward: One, loveliest, holding her white band toward The dazzling sun-rise: two sisters sweet Bending their graceful figures till they meet Over the trippings of a little child:And some are hearing, eagerly, the wild Thrilling liquidity of dewy piping.See, in another picture, nymphs are wipingCherishingly Diana's timorous limbs;--A fold of lawny mantle dabbling swimsAt the bath's edge, and keeps a gentle motionWith the subsiding crystal: as when oceanHeaves calmly its broad swelling smoothiness o'er Its rocky marge, and balances once moreThe patient weeds; that now unshent by foamFeel all about their undulating home.Sappho's meek head was there half smiling downAt nothing; just as though the earnest frownOf over thinking had that moment goneFrom off her brow, and left her all alone.Great Alfred's too, with anxious, pitying eyes,As if he always listened to the sighsOf the goaded world; and Kosciusko's wornBy horrid suffrance--mightily forlorn.Petrarch, outstepping from the shady green,Starts at the sight of Laura; nor can weanHis eyes from her sweet face. Most happy they!For over them was seen a free displayOf out-spread wings, and from between them shone The face of Poesy: from off her throneShe overlook'd things that I scarce could tell.The very sense of where I was might wellKeep Sleep aloof: but more than that there came Thought after thought to nourish up the flame Within my breast; so that the morning light Surprised me even from a sleepless night;And up I rose refresh'd, and glad, and gay, Resolving to begin that very dayThese lines; and howsoever they be done,I leave them as a father does his son. Ode to a Nightingale《夜莺颂》My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness painsMy sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,Or emptied some dull opiate to the drainsOne minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,But being too happy in thy happiness, -That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,In some melodious plotOf beechen green, and shadows numberless, Singest of summer in full-throated ease.O for a draught of vintage! that hath beenCooled a long age in the deep-delved earth,Tasting of Flora and the country-green,Dance, and Provencal song, and sunburnt mirth.O for a beaker full of the warm South,Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,With beaded bubbles winking at the brimAnd purple-stained mouth;That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,And with thee fade away into the forest dim.Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forgetWhat thou among the leaves hast never known,The weariness, the fever, and the fretHere, where men sit and hear each other groan; Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last grey hairs, Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies; Where but to think is to be full of sorrowAnd leaden-eyed despairs;Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,Or new Love pine at them beyond tomorrow.Away! away! for I will fly to thee,Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,But on the viewless wings of Poesy,Though the dull brain perplexes and retards: Already with thee! tender is the night,And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne, Clustered around by all her starry Fays;But here there is no lightSave what from heaven is with the breezes blown Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs, But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet Wherewith the seasonable month endowsThe grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;Fast-fading violets covered up in leaves;And mid-May's eldest childThe coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves. Darkling I listen; and for many a timeI have been half in love with easeful Death,Called him soft names in many a mused rhyme,To take into the air my quiet breath;Now more than ever seems it rich to die,To cease upon the midnight with no pain,While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroadIn such an ecstasy!Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain -To thy high requiem become a sod.Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!。

keats描写时光的诗歌

约翰·济慈(John Keats)是英国19世纪著名的浪漫主义诗人之一,他的诗歌作品主题广泛,其中一些作品涉及了对时光的描写。

以下是一首济慈描写时光的诗歌:

《秋颂》

(一)

露水晶莹的八月早晨,

饱经风霜的岁月已尽,

熠熠闪耀的金色秋分,

丰收的季节已来临。

(二)

夕阳洒下柔和的光辉,

在田野上挥别夏日,

沉甸甸的果实垂头丧气,

沐浴着金黄的秋意浓。

(三)

采摘吧,欢庆吧,你们人类,

品尝那甜美的葡萄佳酿,

畅饮那芳香醇厚的醇酒,

在丰收的季节里欢唱。

(四)

夜幕即将降临的时刻,

晚霞映照着天边残云,

收获的人们归去的路上,

留下的是明月的清辉光。

(五)

时光荏苒不停歇,

季节更迭亦如斯,

让我们珍惜每一个时刻,把握美好的金秋时光。

John Keats 约翰 济慈

1. 《夜莺颂》的主题表达了夜莺不朽与美妙的歌 声。全诗笼罩在一片幽暗之中,我们可以听到它 的歌声却见不到它的身影,这就更突出了夜莺的 精神特性。 2. 《夜莺颂》的主题表达了审美体验的短暂性与 欺骗性。诗人对莺歌德反映是麻木 (drowsynumbness),眩晕(intoxication),幻觉 和对死亡的渴求。——当然,这是诗后面所提到 的 3. 《夜莺颂》的主题表达了审美体验中两种相悖 的因素和情感。对夜莺的歌声,诗人既感到喜悦 (esctatic)又感到悲哀(plaintive)。我们看到的一 方面是夜莺的不朽与欢快,一方面则是人生的短 暂与痛苦。

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird! 永生的鸟,你不会死去 No hungry generations tread thee down; 饿的世代无法将你蹂躏 The voice I hear this passing night eas heard 今夜,我偶然听到的歌曲 In ancient days by emperor and clown: 当使古代的帝王和村夫喜悦 Perhaps the self-same song that found a path 或许这同样的歌也曾激荡 Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, 露丝忧郁的心,使她不禁落泪 She stood in tears amid the alien corn; 站在异邦的谷田里想著家 The same that oft-times hath 就是这声音常常 Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam 在失掉了的仙域里引动窗扉 Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn. 一个美女望著大海险恶的浪花 Forlorn! the very word is like a bell 失掉了,这句话好比一声钟 To toll me back from thee to my sole self! 使我猛省到我站脚的地方 Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well 别了!幻想,这骗人的妖童 As she is famed to do, deceiving elf. 不能老耍弄它盛传的伎俩 Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades 别了!别了!你怨诉的歌声 Past the near meadows, over the still stream, 流过草坪,越过幽静的溪水 Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep 溜上山坡,而此时它正深深 In the next valley-glades: 埋在附近的溪谷中 Was is a vision, or a waking dream? 这是个幻觉,还是梦寐 Fled is that music -- Do I wake or sleep? 那歌声去了-我是睡?是醒?

约翰·济慈(JohnKeats)

约翰·济慈(JohnKeats)《夜莺颂》是英国诗人约翰·济慈的诗作。

全诗共八节。

开始写诗人自己听莺歌而置身瑰丽的幻想境界。

继而写纵饮美酒,诗兴大发,凭诗意遐想,随夜莺飘然而去,深夜醉卧花丛,缕缕芳香袭面而来,诗人陶然自乐,心旷神怡,愿就此离别人世。

人都有一死,而夜莺的歌却永世不灭。

想到此,梦幻结束,重返现实。

在济慈看来,他生活于其中的社会是庸俗、虚伪和污浊肮脏的,而永恒的大自然则绮丽秀美、清新可爱。

因而对丑的鞭挞和对美的追求构成了他抒情诗的基调。

评论家认为诗人以夜莺的歌声象征大自然中永恒的欢乐,并与现实世界中人生短暂、好景不长相对照。

诗人把主观感情渗透在具体的画面中,以情写景,以景传情,意境独特新奇,不落俗套。

通篇由奇妙的想象引领,写来自然、流畅。

另外此诗也是浪漫主义抒情诗歌中的力作。

第一节My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness painsMy sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, Or emptied some dull opiate to the drainsOne minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,But being too happy in thine happiness --That thou, light winged Dryad of the trees,In some melodious plotOf beechen green, and shadows numberless, Singest of summer in full-throated ease.第二节O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth, Tasting of Flora and the country green, Dance, and Provencal song, and sunburnt mirth! O for a beaker full of the warm SouthFull of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,And purple-stained mouth,That I might drink, and leave the world unseen, And with thee fade away into the forest dim.第三节Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forgetWhat thou amongst the leaves hast never known, The weariness, the fever, and the fretHere, where men sit and hear each other groan; Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last grey hairs. Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin,and dies; Where nut to think is to be full of sorrowAnd leaden-eyed despairs;Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,Or new Love pine at thembeyond to-morrow.第四节Away! away! for I will fly to thee,Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,But on the viewless wings of Poesy,Though the dull brain perplexes and retards. Already with thee! tender is the night,And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne, Clustered around by all her starry Fays;But here there is no light,Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.第五节I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,Nor what soft incensehangs upon the boughs,But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet Wherewith the seasonable month endows The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild--White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine; Fast fading violets covered up in leaves;And mid-May's eldest child,The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.第六节Darkling I listen; and for many a timeI have been half in love with easeful Death, Called him soft names in many a mused rhyme, To take into the air my quiet breath;Now more than ever seems it rich to die,To cease upon the midnight with no pain,While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroadIn such an ecstasy!Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain --To thy high requiem become a sod.第七节Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!No hungry generations treadthee down;The voice I hear this passing night eas heardIn ancient days by emperor and clown:Perhaps the self-same song that found a path Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, She stood in tears amid the alien corn;The same that oft-times hathCharm'd magic casement, opening on the foamOf perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.第八节Forlorn! the very word is like a bellTo toll me back from thee to my sole self!Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so wellAs she is famed to do, deceiving elf.Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fadesPast the near meadows, over the still stream,Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deepIn the next valley-glades:Was is a vision, or a waking dream?Fled is that music -- Do I wake or sleep?注释1、hemlock:毒胡萝卜精,一种毒药,人服后,将全身麻木而死亡。

约翰济慈

John 第一部分 Keats' works

My class one, our home

Electrical and Mechanical

调研方法

Prose:

Drama:

John 第一部分 Keats' works

My class one, our home

Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats (1848) The Letters of John Keats (1958) Letters of John Keats: A New Selection (1970)

Comห้องสมุดไป่ตู้ent

comment

08机电1班 Beauty is truth, truth 班风展示 beauty. Electrical and Mechanical My class one 美就是真,真就是 美。

THANKS

第二部分

Electrical and Mechanical

My class one, our home

Comment

建议总结

Proposals

Comment

Comment on John Keats' poetry:

In his short writing career of six or seven years , he produced vorious kinds of works, including epic,lyric and narrative poems. His poetry , characterized by exact and closely-knit construction , emotional descriptions ,and by force of imagination, gives transcendental values to the physical beauty of the world. His artistic aim is to create a beautiful world of imagination as opposed to the sordid(miserable) reality of his day. His leading principle is "Beauty is truth, truth beauty."

JohnKeats约翰

John Keats约翰·济兹简介1795-1821 Endymion恩底弥翁;Isabella伊莎贝拉;The Eve of Sanit Agnes圣爱尼节前夜;Ode on a Grecian Urn希腊古瓮颂;Ode to a Nightingale夜莺颂;To Autumn秋颂;Hyperion赫披里昂(未完成)Introductionborn October 31, 1795, London, Englanddied February 23, 1821, Rome, Papal States [Italy]John Keats, miniature oil on ivory by Joseph Severn, 1819.English Romantic lyric poet who devoted his short life to the perfection of a poetry marked by vivid imagery, great sensuous appeal, and an attempt to express a philosophy through classical legend.YouthThe son of a livery-stable manager, John Keats received relatively little formal education. His father died in 1804, and his mother remarried almost immediately. Throughout his life Keats had close emotional ties to his sister, Fanny, and his two brothers, George and Tom. After the breakupof their mother's second marriage, the Keats children lived with their widowed grandmother at Edmonton, Middlesex. John attended a school at Enfield, two miles away, that was run by John Clarke, whose son Charles Cowden Clarke did much to encourage Keats's literary aspirations. At school Keats was noted as a pugnacious lad and was decidedly “not literary,” but in 1809 he began to read voraciously. After the death of the Keats children's mother in 1810, their grandmother put the children's affairs into the hands of a guardian, Richard Abbey. At Abbey's instigation John Keats was apprenticed to a surgeon at Edmonton in 1811. He broke off his apprenticeship in 1814 and went to live in London, where he worked as a dresser, or junior house surgeon, at Guy's and St. Thomas' hospitals. His literary interests had crystallized by this time, and after 1817 he devoted himself entirely to poetry. From then until his early death, the story of his life is largely the story of the poetry he wrote.Early worksCharles Cowden Clarke had introduced the young Keats to the poetry of Edmund Spenser and the Elizabethans, and these were his earliest models. His first mature poem is the sonnet "On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer" (1816), which was inspired by his excited reading of George Chapman's classic 17th-century translation of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Clarke also introduced Keats to the journalist and contemporary poet Leigh Hunt, and Keats made friends in Hunt's circle with the young poet John Hamilton Reynolds and with the painter Benjamin Haydon. Keats's first book, Poems, was published in March 1817 and was written largely under “Huntian” influence. This is evident in the relaxed and rambling sentiments evinced and in Keats's use of a loose form of the heroic couplet and light rhymes. The most interesting poem in this volume is "Sleep and Poetry," the middle section of which contains a prophetic view of Keats's own poetical progress. He sees himself as, at present, plunged in the delighted contemplation of sensuous natural beauty but realizes that he must leave this for an understanding of “the agony and strife of human hearts.” Otherwise the volume is remarkable only for some delicate natural observation and some obvious Spenserian influences.In 1817 Keats left London briefly for a trip to the Isle of Wight and Canterbury and began work on Endymion, his first long poem. On his return to London he moved into lodgings in Hampstead with his brothers. Endymion appeared in 1818. This work is divided into four 1,000-line sections, and its verse is composed in loose rhymed couplets. The poem narrates a version of the Greek legend of the moon goddess Diana's (or Cynthia's) love forEndymion, a mortal shepherd, but Keats puts the emphasis on Endymion's love for Diana rather than on hers for him. Keats transformed the tale to express the widespread Romantic theme of the attempt to find in actuality an ideal love that has been glimpsed heretofore only in imaginative longings. This theme is realized through fantastic and discursive adventures and through sensuous and luxuriant description. In his wanderings in quest of Diana, Endymion is guilty of an apparent infidelity to his visionary moon goddess and falls in love with an earthly maiden to whom he is attracted by human sympathy. But in the end Diana and the earthly maiden turn out to be one and the same. The poem equates Endymion's original romantic ardour with a more universal quest for a self-destroying transcendence in which he might achieve a blissful personal unity with all creation. Keats, however, was dissatisfied with the poem as soon as it was finished.Personal crisisIn the summer of 1818 Keats went on a walking tour in the Lake District (of northern England) and Scotland with his friend Charles Brown, and his exposure and overexertions on that trip brought on the first symptoms of the tuberculosis of which he was to die. On his return to London a brutal criticism of his early poems appeared in Blackwood's Magazine, followed by a similar attack on Endymion in the Quarterly Review. Contrary to later assertions, Keats met these reviews with a calm assertion of his own talents, and he went on steadily writing poetry. But there were family troubles. Keats's brother Tom had been suffering from tuberculosis for some time, and in the autumn of 1818 the poet nursed him through his last illness. About the same time, he met Fanny Brawne, a near neighbour in Hampstead, with whom he soon fell hopelessly and tragically in love. The relation with Fanny had a decisive effect on Keats's development. She seems to have been an unexceptional young woman, of firm and generous character, and kindly disposed toward Keats. But he expected more, perhaps more than anyone could give, as is evident from his overwrought letters. Both his uncertain material situation and his failing health in any case made it impossible for their relationship to run a normal course. After Tom's death (George had already gone to America), Keats moved into Wentworth Place with Brown; and in April 1819 Brawne and her mother became his next-door neighbours. About October 1819 Keats became engaged to Fanny.The year 1819Keats had written "Isabella," an adaptation of the story of the "Pot of Basil" in Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, in 1817–18, soon after the completion of Endymion, and again he was dissatisfied with his work. It was during the year 1819 that all his greatest poetry was written—"Lamia," "The Eve of St. Agnes," the great odes ( "On Indolence," "On a Grecian Urn," "To Psyche," "To a Nightingale," "On Melancholy," and "To Autumn" ), and the two versions of Hyperion. This poetry was composed under the strain of illness and his growing love for Brawne; and it is an astonishing body of work, marked by careful and considered development, technical, emotional, and intellectual. "Isabella," which Keats himself called “a weak-sided poem,” contains some of the emotional weaknesses of Endymion; but "The Eve of St. Agnes" may be considered the perfect culmination of Keats's earlier poetic style. Written in the first flush of his meeting with Brawne, it conveys an atmosphere of passion and excitement in its description of the elopement of a pair of youthful lovers. Written in Spenserian stanzas, the poem presents its theme with unrivaled delicacy but displays no marked intellectual advance over Keats's earlier efforts. "Lamia" is another narrative poem and is a deliberate attempt to reform some of the technical weaknesses of Endymion. Keats makes use in this poem of a far tighter and more disciplined couplet, a firmer tone, and more controlled description.The odes are Keats's most distinctive poetic achievement. They are essentially lyrical meditations on some object or quality that prompts the poet to confront the conflicting impulses of his inner being and to reflect upon his own longings and their relations to the wider world around him. All the odes were composed between March and June 1819 except "To Autumn," which is from September. The internal debates in the odes centre on the dichotomy of eternal, transcendent ideals and the transience and change of the physical world. This subject was forced upon Keats by the painful death of his brother and his own failing health, and the odes highlight his struggle for self-awareness and certainty through the liberating powers of his imagination. In the "Ode to a Nightingale" a visionary happiness in communing with the nightingale and its song is contrasted with the dead weight of human grief and sickness, and the transience of youth and beauty—strongly brought home to Keats in recent months by his brother's death. The song of the nightingale is seen as a symbol of art that outlasts the individual's mortal life. This theme is taken up more distinctly in the "Ode on a Grecian Urn." The figures of the lovers depicted on the Greek urn become for him the symbol of an enduring but unconsummated passion that subtly belies the poem'scelebrated conclusion, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all ye know on earth, and all ye nee d to know.” The "Ode on Melancholy" recognizes that sadness is the inevitable concomitant of human passion and happiness; the transience of joy and desire is an inevitable aspect of the natural process. But the rich, slow movement of this and the other odes suggests an enjoyment of such intensity and depth that it makes the moment eternal. The "Ode to Autumn" is essentially the record of such an experience. Autumn is seen not as a time of decay but as a season of complete ripeness and fulfillment, a pause in time when everything has reached fruition, and the question of transience is hardly raised. These poems, with their rich and exquisitely sensuous detail and their meditative depth, are among the greatest achievements of Romantic poetry. With them should be mentioned the ballad "La Belle Dame sans merci," of about the same time, which reveals the obverse and destructive side of the idyllic love seen in "The Eve of St. Agnes."Keats, detail of an oil painting by Joseph Severn, 1821; in the National Portrait Gallery, LondonKeats's fragmentary poetic epic, Hyperion, exists in two versions, the second being a revision of the first with the addition of a long prologue in a new style, which makes it into a different poem. Hyperion was begun in the autumn of 1818, and all that there is of the first version was finished by April 1819. In September Keats wrote to Reynolds that he had given up Hyperion, but he appears to have continued working on the revised edition, The Fall of Hyperion, during the autumn of 1819. The two versions of Hyperion cover the period of Keats's most intense experience, both poetical and personal. The poem is his last attempt, in the face of increasing illness and frustrated love, to come to terms with the conflict between absolute value and mortal decay that appears in other forms in his earlier poetry. The epic's subject is the supersession of the earlier Greek gods, the Titans, by the later Olympian gods. Keats's desire to write something unlike the luxuriant wandering of Endymion is clear, and he thus consciously attempts to emulate the epic loftiness of John Milton's Paradise Lost. The poem opens with the Titans already fallen, like Milton's fallen angels, and Hyperion, the sun god, is their one hope of further resistance, like Milton's Satan. There are numerous Miltonisms of style, but these are subdued in the revised version, as Keats felt unhappy with them; and the basis of the writing is revealed after all as a more austere and disciplined version of Keats's own manner. There is not enough of the narrative to make its ultimate direction clear; but it seems that the poem's hero was to be the young Apollo, the god of poetry. So, as Endymion was an allegory of the fate of the lover of beauty in theworld, Hyperion was perhaps to be an allegory of the poet as creator. Certainly this theme is taken up explicitly in the new prologue to the second version.The second version of Hyperion is one of the most remarkable pieces of writing in Keats's work; the blank verse has a new energy and rapidity, and the vision is presented with a spare grandeur, rising to its height in the epiphany of the goddess Moneta, who reveals to the dreamer the function of the poet in the world. It is his duty to separate himself from the mere dreamer and to share in the sufferings of humankind. The theme is not new to Keats—it appears in his earliest poetry—but it is here realized far more intensely. Yet with the threat of approaching death upon him, Keats could not advance any further in the direction that he foresaw as the right one, and the poem remains a fragment.Last yearsThere is no more to record of Keats's poetic career. The poems "Isabella," "Lamia," "The Eve of St. Agnes," and Hyperion and the odes were all published in the famous 1820 volume, the one that gives the true measure of his powers. It appeared in July, by which time Keats was evidently doomed. He had been increasingly ill throughout 1819, and by the beginning of 1820 the evidence of tuberculosis was clear. He realized that it was his death warrant, and from that time sustained work became impossible. His friends Brown, the Hunts, and Brawne and her mother nursed him assiduously through the year. Percy Bysshe Shelley, hearing of his condition, wrote offering him hospitality in Pisa; but Keats did not accept. When Keats was ordered south for the winter, Joseph Severn undertook to accompany him to Rome. They sailed in September 1820, and from Naples they went to Rome, where in early December Keats had a relapse. Faithfully tended by Severn to the last, he died in Rome.LettersThe prime authority both for Keats's life and for his poetical development is to be found in his letters. This correspondence with his brothers and sister, with his close friends, and with Fanny Brawne gives the most intimate picture of the admirable integrity of Keats's personal characterand enables the reader to follow closely the development of his thought about poetry—his own and that of others.His letters evince a profound thoughtfulness combined with a quick, sensitive, undidactic critical response. Spontaneous, informal, deeply thought, and deeply felt, these are among the best letters written by any English poet. Apart from their interest as a commentary on his work, they have the right to independent literary status.ReputationIt is impossible to say how much has been lost by Keats's early death. His reputation grew steadily throughout the 19th century, though as late as the 1840s the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman could refer to him as “this little-known poet.” His influence is found everywhere in the decorative Romantic verse of the Victorian Age, from the early work of Alfred Tennyson onward. His general emotional temper and the minute delicacy of his natural observation were greatly admired by thePre-Raphaelites, who both echoed his poetry in their own and illustrated it in their paintings. Keats's 19th-century followers on the whole valued the more superficial aspects of his work; and it has been largely left for the 20th century to realize the full range of his technical and intellectual achievement.Graham Goulder Hough Ed.Additional ReadingThree major critical biographies are Walter Jackson Bate, John Keats (1963, reprinted 1978); Robert Gittings, John Keats (1968, reissued 1985); and Aileen Ward, John Keats: The Making of a Poet, rev. ed. (1986). Special studies are Claude Lee Finney, The Evolution of Keats's Poetry, 2 vol. (1936, reprinted 1963), a detailed account of the origins of the poems; M.R. Ridley, Keats' Craftsmanship (1933, reissued 1963); John Spencer Hill (ed.), Keats: The Narrative Poems(1983), a collection of 19th- and 20th-century criticism; and Wolf Z. Hirst, John Keats(1981), a study of his life and work. Helen Vendler, The Odes of John Keats(1983); and John Barnard, John Keats (1987), are both critical assessments.。

约翰济慈

夜 莺 颂

他年仅25岁,可是他遗下的诗篇一直誉满人 间,被认为完美地体现了西方浪漫主义诗歌的 特色,并被推崇为欧洲浪漫主义运动的杰出代 表。

他主张“美即是真,真即是美”,擅长描绘 自然景色和事物外貌,表现景物的色彩感和立 体感,重视写作技巧,语言追求华美,对后世 抒情诗的创作影响极大。

济慈诗才横溢,与雪莱、拜伦齐名。

John Keats's life

约翰· 济慈(JohnKeats 1795—1821),出生于18世 纪末年的伦敦,他是杰出的英 诗作家之一,也是浪漫派的主 要成员。 1810年,济慈被送去当药剂 师的学徒。五年后济慈考入伦 敦的一所医学院,但没有一年, 济慈便放弃了从医的志愿,而 专心于写作诗歌。

ppt制作: 彭玉琴

Page 12

John

K e a ts

Page 1

contents

John Keats's life John Keats's privacy

John Keats's valentine

John Keats's poems His style Magnum opus

Page 2

His influence

Page 3

Keats's hometown

芬 妮 布 朗

Page 4

Movie

Bright stars

Page 5

济 慈

his valentine

Page 6

假如没有你的话,我真的会活不下去, 但仅仅有你还不够,我要的是贞洁而 贤惠的你 。

我每时每刻都在忍受折磨,我之所以 要这么说,正是因为我实在不堪忍受 这些痛苦了。

John_Keats

Keats's first book, Poems, was published in 1817. It was about this time Keats started to use his letters as the vehicle of his thoughts of poetry. "Endymion", Keats's first long poem appeared, when he was 21. Keats's greatest works were written in the late 1810s, among them "Lamia", "The Eve of St. Agnes", the great odes including "Ode to a Nightingale", Ode To Autumn" and "Ode on a Grecian Urn". He worked briefly as a theatrical critic for The Champion.

Next year he became a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. Before devoting himself entirely to poetry, Keats worked as a dresser and junior house surgeon. In London he had met the editor of The Examiner, Leigh Hunt, who introduced him to other young Romantics, including Shelley. His poem, "O Solitude", also appeared in The Examiner.

John Keats

epitaph carved on his tomb: Here lies one whose name was writ in water 此地长眠者,声名水上书

he once said: I think, I shall be among the English poets after my death 我想我死后定能跻身英国诗人之列

II. life

born in London, son of a livery-stable keeper + 8, father died + 14, mother died + 15, his guardian, a merchant, took him from school and apprenticed him to learn surgery, he served the apprenticeship for 5 years, and then surgeon’s helper for 2 years + but he early contracted a love of poetry under the influence of his young teacher Charles Cowden Clarke + made friends with Leigh Hunt, Hazlitt and Shelley 1817, passed the exam and got the licence as a surgeon 1818, gave up medicine for poetry

我像个天文学家那样 发现一颗新的星体,无比惊奇, 或者像科尔特斯凝视着太平洋 睁大着眼睛,与鹰隼无异—— 他的同伴们彼此看着,相互猜想—— 站在达利安峰顶上,默默地。

关于悲秋的英语美文欣赏 英美名家

悲秋是英国文学中一个常见的主题,它表达了人们对于秋季的深切情感和对生命的思考。

下面将介绍一些英美名家关于悲秋的美文,带领读者领略秋天的忧郁和美丽。

1. John Keats的《To Autumn》John Keats是英国浪漫主义诗人,他创作了许多以大自然为主题的美丽诗篇。

其中,他的《To Autumn》便是一首关于秋天的诗歌,其中充满了对秋季的赞美和悲怆之情。

诗中描述了丰收的季节、蜜蜂采蜜、果实成熟的场景,通过细腻的描绘,展现了秋天的丰富和悲鸣的情感。

2. William Wordsworth的《Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood》威廉·华兹华斯是英国浪漫主义诗人中的另一位巨匠,他的《Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood》中也包含了对秋天的回忆和悲秋的情感。

诗中他通过对自然变化的观察,表达了对逝去时光的惆怅和对生命意义的思索,使得秋天的悲美得以充分展现。

3. Emily Dickinson的《The morns are meeker than they were》艾米莉·狄金森是美国文学史上的杰出女诗人,她的《The morns are meeker than they were》,则是一首关于秋天的美丽诗篇,通过抒发对悲秋的情感,反映了她对于生活和世界的领悟。

诗中的深沉和悲怆,让人仿佛能够感受到秋天的凄凉和美丽。

4. Robert Frost的《Nothing Gold Can Stay》罗伯特·弗罗斯特是20世纪美国诗坛的杰出代表,他的《Nothing Gold Can Stay》同样表达了对悲秋的情感。

诗中他通过对一切美好的事物都会逝去的观察,描绘了秋天的深邃和悲哀,使得读者能够领略到秋天那份短暂而珍贵的美好。

济慈简介

济慈简介JohnKeats(1795~1821)英国诗人。

1795年10月29日生于伦敦。

他的父亲以经营马车行为业,生活比较富裕。

1804年父亲去世,母亲再嫁,济慈和两个弟弟由外祖母收养。

1810年母亲又病故,外祖母委托两名保护人经管他们弟兄的财产。

1811年,济慈由保护人安排离开学校,充当医生的学徒。

他对医学并不厌弃,但也喜好文学,并在中学的好友查尔斯·克拉克的鼓励之下开始写诗,模仿伊丽莎白时代诗人埃德蒙·斯宾塞。

1815年10月,济慈进入伦敦一家医院学习。

这时他已热爱写诗,深受诗人亨特和华兹华斯的影响。

1816年5月在亨特所编《检察者》杂志发表十四行诗《孤寂》。

1816年7月,通过考试获得内科医生执照,继续学习外科。

同年夏写成十四行诗《初读查普曼译荷马史诗》。

10月间经克拉克介绍,与亨特相识,并与雪莱、哈兹里特、兰姆等人来往。

11月间,济慈决心从事文学创作,通知他的保护人,放弃学医。

1817年,济慈出版第一部诗集,其中大多带有模仿的痕迹,但也有佳作,如上述的读荷马史诗的十四行诗和《蟋蟀与蚱蜢》等,而《睡眠与诗》则表露了济慈的创作思想,即诗应给人们以安慰,并提高他们的思想。

诗集出版后得到好评。

4月,济慈写作长诗《恩底弥翁》,以凡人恩底弥翁和月亮女神的恋爱故事为题材,虽嫌松散,但已显出他对周围世界中的美的境界的敏感和独特的语言表达能力。

与此同时,济慈也形成了许多对哲学和艺术的观点,其中著名的有“天然接受力”的思想。

根据济慈的解释,在一个大诗人身上,对美的感受能压倒或抵消一切其他的考虑,如莎士比亚就突出地具有这种能力。

1817年冬,济慈在伦敦与华兹华斯相见。

虽然他仍然钦佩华兹华斯的诗,却不喜欢他的为人。

和亨特也渐渐疏远。

1818年3月,济慈去外地照顾患病的弟弟托姆。

这时他写成取材于薄伽丘的《十日谈》的叙事诗《伊萨贝拉》。

他的思想发生了很大的变化,从强调感官享受转而强调思想深度。

john keats(济慈)

1、每当我害怕 2、哦,孤独 3、明亮的星 4、夜莺颂 5、希腊古瓮颂 6、人生的四季 7、给拜伦 8、咏阿丽莎巉岩 9、初读贾浦曼译荷马有感 10、无情的妖女 11、忧郁颂 12、秋颂 13、蝈蝈和蛐蛐

His Position in English Literature

Life Story

He was born in London on October 31, 1795; His father died when he was nine and his mother died when he was fifteen. In the family atmosphere at Clarke's, Keats developed an interest in classics and history which would stay with him throughout his short life. The headmaster's son, Charles Cowden Clarke, would become an important influence, mentor and friend, introducing Keats to Renaissance literature including Tasso, Spenser and Chapman's translations. Published his first book, Poems, in 1817; Died in Rome on February 23, 1821.

Major Literary Works

Produced a variety of work, including epic, lyric (抒情诗)and narrative poems. Odes(颂诗,赋)are regarded as Keats‟s most important and mature works. Lines in Imitation of Spenser《仿斯宾塞》 (1814): his first poem On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer (1816): his first important poem Sleep and Poetry (1817): expression of his own poetic aspirations

john keats名词解释

John Keats 名词解释1. 引言约翰·济慈(John Keats)是英国浪漫主义时期最著名的诗人之一。

他以其感性、富有想象力和美丽的诗歌而闻名于世。

本文将对John Keats进行全面详细、完整且深入的解释,探讨他的生平、作品和影响。

2. 生平约翰·济慈于1795年10月31日出生在伦敦一个工人阶级家庭中。

他从小就展现出对艺术和文学的兴趣,并在早年受到了古典希腊文化和罗马神话的影响。

然而,他的父亲去世后,家庭陷入贫困,这使得他不得不放弃学业并找工作来支持家庭。

尽管如此,济慈坚持追求自己的文学梦想,并在1818年发表了他的第一本诗集《奥德与其他诗篇》。

这本诗集虽然没有取得商业上的成功,但为济慈赢得了一些批评家和同行诗人的赞誉。

然而,在1820年代初期,济慈的生活受到了许多不幸的打击。

他失去了他深爱的兄弟汤姆,同时自己也被诊断出患有结核病。

面对这些困难,济慈决定放弃医学事业,全身心地投入到写作中。

然而,他的健康状况不断恶化,最终在1821年2月23日去世,享年仅25岁。

尽管他的生命非常短暂,但他留下了一系列优秀的诗歌作品,成为了英国文学史上不可忽视的重要人物。

3. 作品约翰·济慈一生中创作了许多优秀的诗歌作品。

以下是他最著名和具有代表性的几首诗歌:3.1《致太阳》(“To Solitude”)这首诗探讨了孤独和自我反思对于个体成长和内心平静的重要性。

济慈通过描绘大自然和内心世界之间微妙而美丽的联系来表达这种思想。

3.2《秋天时节》(“To Autumn”)这首诗是济慈最后完成的作品之一,也是他最著名的作品之一。

它描述了秋天的美景和大自然变迁的景象,以及对时光流逝和生命短暂的思考。

3.3《希腊古物》(“Ode on a Grecian Urn”)这首诗是济慈最受欢迎和广为人知的作品之一。

它探讨了艺术与现实生活之间的关系,并通过描绘一个古希腊花瓶上的画面,表达了对美、时间和永恒存在的思考。

英国诗人约翰·济慈的经典名言(13条)

英国诗⼈约翰·济慈的经典名⾔(13条)约翰·济慈的名⾔

1、听到的声⾳很美,那听不到的声⾳更美。

2、此地长眠者,声名⽔上书。

3、青春的梦想,是未来真实的投影。

4、诗⼈是把名字写在⽔上的⼈。

5、别让夜枭作伴,把隐秘的悲哀讲给它听,因为阴影不宜于找阴影结合。

6、只有在得到⽣活的验证之后,谚语对你来说才成其为谚语。

7、当波状的云把将逝的⼀天映照,以胭红抹上残梗散碎的⽥野。

8、美与真是⼀回事,这就是说美本⾝。

9、⼈们应该彼此容忍:每个⼈都有弱点,在他最薄弱的⽅⾯,每个⼈都能被切割捣碎。

10、旋律是很美妙的,但听不见的会更美。

11、许多富有创见的⼈并没有想到这⼀点他们被习惯引⼊歧途。

12、⼀个⼈,看着⼀朵花慢慢地开放,是最幸福的事。

13、⼈们应该彼此容忍:每⼀个⼈都有弱点,在他最薄弱的⽅⾯,每⼀个⼈都能被切割捣碎。

共13条

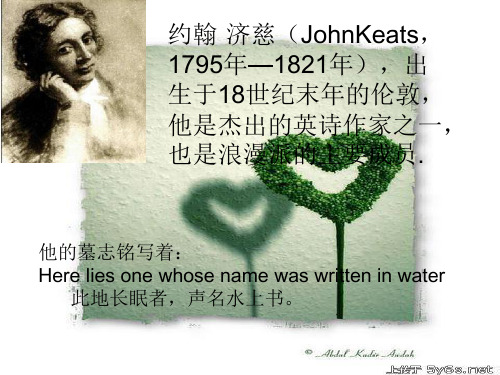

约翰·济慈

约翰·济慈(John·Keats,1795年10⽉31⽇—1821年2⽉23⽇),出⽣于18世纪末年的伦敦,杰出的英国诗⼈作家之⼀,浪漫派的主要成员。

济慈才华横溢,与雪莱、拜伦齐名。

他善于运⽤描写⼿法创作诗歌,将多种情感与⾃然完美结合,从⽣活中寻找创作的影⼦。

他的诗篇能带给⼈们⾝临其境的感受。

他去世时年仅25岁,可他遗下的诗篇誉满⼈间,他的诗被认为完美体现了西⽅浪漫主义诗歌特⾊,济慈被⼈们推崇为欧洲浪漫主义运动的杰出代表。