Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers

关于财务管理的英文单词

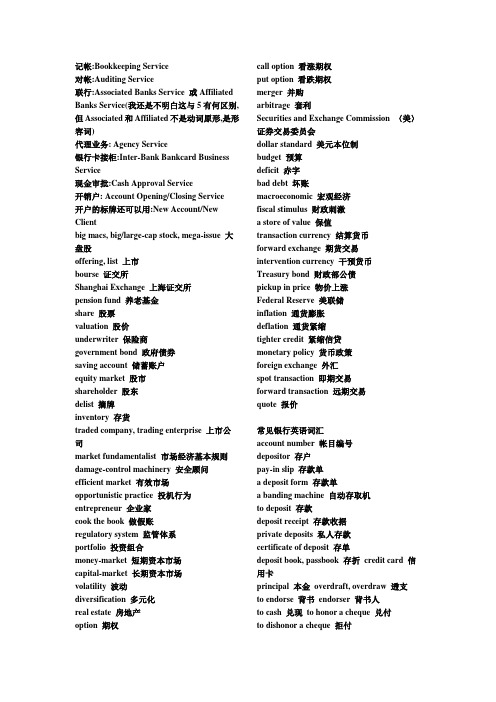

记帐:Bookkeeping Service对帐:Auditing Service联行:Associated Banks Service 或Affiliated Banks Service(我还是不明白这与5有何区别,但Associated和Affiliated不是动词原形,是形容词)代理业务: Agency Service银行卡接柜:Inter-Bank Bankcard Business Service现金审批:Cash Approval Service开销户: Account Opening/Closing Service开户的标牌还可以用:New Account/New Clientbig macs, big/large-cap stock, mega-issue 大盘股offering, list 上市bourse 证交所Shanghai Exchange 上海证交所pension fund 养老基金share 股票valuation 股价underwriter 保险商government bond 政府债券saving account 储蓄账户equity market 股市shareholder 股东delist 摘牌inventory 存货traded company, trading enterprise 上市公司market fundamentalist 市场经济基本规则damage-control machinery 安全顾问efficient market 有效市场opportunistic practice 投机行为entrepreneur 企业家cook the book 做假账regulatory system 监管体系portfolio 投资组合money-market 短期资本市场capital-market 长期资本市场volatility 波动diversification 多元化real estate 房地产option 期权call option 看涨期权put option 看跌期权merger 并购arbitrage 套利Securities and Exchange Commission 〈美〉证券交易委员会dollar standard 美元本位制budget 预算deficit 赤字bad debt 坏账macroeconomic 宏观经济fiscal stimulus 财政刺激a store of value 保值transaction currency 结算货币forward exchange 期货交易intervention currency 干预货币Treasury bond 财政部公债pickup in price 物价上涨Federal Reserve 美联储inflation 通货膨胀deflation 通货紧缩tighter credit 紧缩信贷monetary policy 货币政策foreign exchange 外汇spot transaction 即期交易forward transaction 远期交易quote 报价常见银行英语词汇account number 帐目编号depositor 存户pay-in slip 存款单a deposit form 存款单a banding machine 自动存取机to deposit 存款deposit receipt 存款收据private deposits 私人存款certificate of deposit 存单deposit book, passbook 存折credit card 信用卡principal 本金overdraft, overdraw 透支to endorse 背书endorser 背书人to cash 兑现to honor a cheque 兑付to dishonor a cheque 拒付to suspend payment 止付cheque,check 支票cheque book 支票本crossed cheque 横线支票blank cheque 空白支票rubber cheque 空头支票cheque stub, counterfoil 票根cash cheque 现金支票traveler's cheque 旅行支票cheque for transfer 转帐支票outstanding cheque 未付支票canceled cheque 已付支票forged cheque 伪支票Bandar's note 庄票,银票banker 银行家president 行长savings bank 储蓄银行Chase Bank 大通银行National City Bank of New York 花旗银行Hongkong Shanghai Banking Corporation 汇丰银行Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China 麦加利银行Banque de I'IndoChine 东方汇理银行central bank, national bank, banker's bank 中央银行bank of issue, bank of circulation 发行币银行commercial bank 商业银行,储蓄信贷银行member bank, credit bank 储蓄信贷银行discount bank 贴现银行exchange bank 汇兑银行requesting bank 委托开证银行issuing bank, opening bank 开证银行advising bank, notifying bank 通知银行negotiation bank 议付银行confirming bank 保兑银行paying bank 付款银行associate banker of collection 代收银行consigned banker of collection 委托银行clearing bank 清算银行local bank 本地银行domestic bank 国内银行overseas bank 国外银行unincorporated bank 钱庄branch bank 银行分行trustee savings bank 信托储蓄银行trust company 信托公司financial trust 金融信托公司unit trust 信托投资公司trust institution 银行的信托部credit department 银行的信用部commercial credit company(discount company) 商业信贷公司(贴现公司)neighborhood savings bank, bank of deposit 街道储蓄所credit union 合作银行credit bureau 商业兴信所self-service bank 无人银行land bank 土地银行construction bank 建设银行industrial and commercial bank 工商银行bank of communications 交通银行mutual savings bank 互助储蓄银行post office savings bank 邮局储蓄银行mortgage bank, building society 抵押银行industrial bank 实业银行home loan bank 家宅贷款银行reserve bank 准备银行chartered bank 特许银行corresponding bank 往来银行merchant bank, accepting bank 承兑银行investment bank 投资银行import and export bank (EXIMBANK) 进出口银行joint venture bank 合资银行money shop, native bank 钱庄credit cooperatives 信用社clearing house 票据交换所public accounting 公共会计business accounting 商业会计cost accounting 成本会计depreciation accounting 折旧会计computerized accounting 电脑化会计general ledger 总帐subsidiary ledger 分户帐cash book 现金出纳帐cash account 现金帐journal, day-book 日记帐,流水帐bad debts 坏帐investment 投资surplus 结余idle capital 游资economic cycle 经济周期economic boom 经济繁荣economic recession 经济衰退economic depression 经济萧条economic crisis 经济危机economic recovery 经济复苏inflation 通货膨胀deflation 通货收缩devaluation 货币贬值revaluation 货币增值international balance of payment 国际收支favourable balance 顺差adverse balance 逆差hard currency 硬通货soft currency 软通货international monetary system 国际货币制度the purchasing power of money 货币购买力money in circulation 货币流通量note issue 纸币发行量national budget 国家预算national gross product 国民生产总值public bond 公债stock, share 股票debenture 债券treasury bill 国库券debt chain 债务链direct exchange 直接(对角)套汇indirect exchange 间接(三角)套汇cross rate, arbitrage rate 套汇汇率foreign currency (exchange) reserve 外汇储备foreign exchange fluctuation 外汇波动foreign exchange crisis 外汇危机discount 贴现discount rate, bank rate 贴现率gold reserve 黄金储备money (financial) market 金融市场stock exchange 股票交易所broker 经纪人commission 佣金bookkeeping 簿记bookkeeper 簿记员an application form 申请单bank statement 对帐单letter of credit 信用证strong room, vault 保险库equitable tax system 等价税则specimen signature 签字式样banking hours, business hours 营业时间(Consumer Price Index) 消费者物价指数business 企业商业业务financial risk 财务风险sole proprietorship 私人业主制企业partnership 合伙制企业limited partner 有限责任合伙人general partner 一般合伙人separation of ownership and control 所有权与经营权分离claim 要求主张要求权management buyout 管理层收购tender offer 要约收购financial standards 财务准则initial public offering 首次公开发行股票private corporation 私募公司未上市公司closely held corporation 控股公司board of directors 董事会executove director 执行董事non- executove director 非执行董事chairperson 主席controller 主计长treasurer 司库revenue 收入profit 利润earnings per share 每股盈余return 回报market share 市场份额social good 社会福利financial distress 财务困境stakeholder theory 利益相关者理论value (wealth) maximization 价值(财富)最大化common stockholder 普通股股东preferred stockholder 优先股股东debt holder 债权人well-being 福利diversity 多样化going concern 持续的agency problem 代理问题free-riding problem 搭便车问题information asymmetry 信息不对称retail investor 散户投资者institutional investor 机构投资者agency relationship 代理关系net present value 净现值creative accounting 创造性会计stock option 股票期权agency cost 代理成本bonding cost 契约成本monitoring costs 监督成本takeover 接管corporate annual reports 公司年报balance sheet 资产负债表income statement 利润表statement of cash flows 现金流量表statement of retained earnings 留存收益表fair market value 公允市场价值marketable securities 油价证券check 支票money order 拨款但、汇款单withdrawal 提款accounts receivable 应收账款credit sale 赊销inventory 存货property,plant,and equipment 土地、厂房与设备depreciation 折旧accumulated depreciation 累计折旧liability 负债current liability 流动负债long-term liability 长期负债accounts payout 应付账款note payout 应付票据accrued espense 应计费用deferred tax 递延税款preferred stock 优先股common stock 普通股book value 账面价值capital surplus 资本盈余accumulated retained earnings 累计留存收益hybrid 混合金融工具treasury stock 库藏股historic cost 历史成本current market value 现行市场价值real estate 房地产outstanding 发行在外的a profit and loss statement 损益表net income 净利润operating income 经营收益earnings per share 每股收益simple capital structure 简单资本结构dilutive 冲减每股收益的basic earnings per share 基本每股收益complex capital structures 复杂的每股收益diluted earnings per share 稀释的每股收益convertible securities 可转换证券warrant 认股权证accrual accounting 应计制会计amortization 摊销accelerated methods 加速折旧法straight-line depreciation 直线折旧法statement of changes in shareholders’equity 股东权益变动表source of cash 现金来源use of cash 现金运用operating cash flows 经营现金流cash flow from operations 经营活动现金流direct method 直接法indirect method 间接法bottom-up approach 倒推法investing cash flows 投资现金流cash flow from investing 投资活动现金流joint venture 合资企业affiliate 分支机构financing cash flows 筹资现金流cash flows from financing 筹资活动现金流time value of money 货币时间价值simple interest 单利debt instrument 债务工具annuity 年金future value 终至present value 现值compound interest 复利compounding 复利计算pricipal 本金mortgage 抵押credit card 信用卡terminal value 终值discounting 折现计算discount rate 折现率opportunity cost 机会成本required rate of return 要求的报酬率cost of capital 资本成本ordinary annuity普通年金annuity due 先付年金financial ratio 财务比率deferred annuity 递延年金restrictive covenants 限制性条款perpetuity 永续年金bond indenture 债券契约face value 面值financial analyst 财务分析师coupon rate 息票利率liquidity ratio 流动性比率nominal interest rate 名义利率current ratio 流动比率effective interest rate 有效利率window dressing 账面粉饰going-concern value 持续经营价值marketable securities 短期证券liquidation value 清算价值quick ratio 速动比率book value 账面价值cash ratio 现金比率marker value 市场价值debt management ratios 债务管理比率intrinsic value 内在价值debt ratio 债务比率mispricing 给……错定价格debt-to-equity ratio 债务与权益比率valuation approach 估价方法equity multiplier 权益乘discounted cash flow valuation 折现现金流量模型long-term ratio 长期比率undervaluation 低估debt-to-total-capital 债务与全部资本比率overvaluation 高估leverage ratios 杠杆比率option-pricing model 期权定价模型interest coverage ratio 利息保障比率contingent claim valuation 或有要求权估价earnings before interest and taxes 息税前利润promissory note 本票cash flow coverage ratio 现金流量保障比率contractual provision 契约条款asset management ratios 资产管理比率par value 票面价值accounts receivable turnover ratio 应收账款周转率maturity value 到期价值inventory turnover ratio 存货周转率coupon 息票利息inventory processing period 存货周转期coupon payment 息票利息支付accounts payable turnover ratio 应付账款周转率coupon interest rate 息票利率cash conversion cycle 现金周转期maturity 到期日asset turnover ratio 资产周转率term to maturity 到期时间profitability ratio 盈利比率call provision赎回条款gross profit margin 毛利润call price 赎回价格operating profit margin 经营利润sinking fund provision 偿债基金条款net profit margin 净利润conversion right 转换权return on asset 资产收益率put provision 卖出条款return on total equity ratio 全部权益报酬率indenture 债务契约return on common equity 普通权益报酬率covenant 条款market-to-book value ratio 市场价值与账面价值比率trustee 托管人market value ratios 市场价值比率protective covenant 保护性条款dividend yield 股利收益率negative covenant 消极条款dividend payout 股利支付率positive covenant 积极条款financial statement财务报表secured deht担保借款profitability 盈利能力unsecured deht信用借款viability 生存能力creditworthiness 信誉solvency 偿付能力collateral 抵押品collateral trust bonds 抵押信托契约debenture 信用债券bond rating 债券评级current yield 现行收益yield to maturity 到期收益率default risk 违约风险interest rate risk 利息率风险authorized shares 授权股outstanding shares 发行股treasury share 库藏股repurchase 回购right to proxy 代理权right to vote 投票权independent auditor 独立审计师straight or majority voting 多数投票制cumulative voting 积累投票制liquidation 清算right to transfer ownership 所有权转移权preemptive right 优先认股权dividend discount model 股利折现模型capital asset pricing model 资本资产定价模型constant growth model 固定增长率模型growth perpetuity 增长年金mortgage bonds 抵押债券。

Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate

e.g.

• Enterprise existing capital of 1,000,000yuan,

A project needs capital of 500,000yuan (NPV>0), B project needs capital of 300,000yuan (NPV>0), C project needs capital of 100,000yuan (NPV<0), • Free cash flow: 200,000yuan

Evidence from the Oil Industry From 1973 to the late 1970’s, crude oil prices increased tenfold which generated large cash flows in the industry. 1.The exploration and development expenditures were so high that average returns were below the cost of capital. 2.The failure of diversification

Managers

1.To increase the resources under their control. 2.To avoid external financing and monitoring of the capital market

Main Ideas

The Role of Debt in Motivating Organizational Efficiency

Important Concept

1.Free Cash Flow

财务管理专业英语词汇表

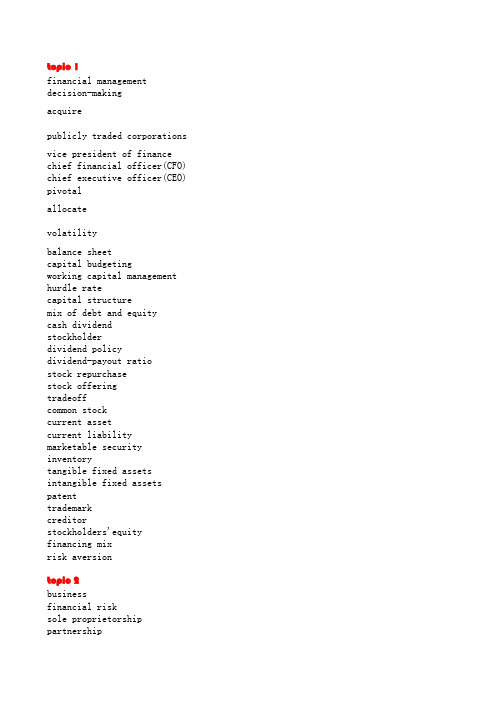

topic 1financial management decision-makingacquirepublicly traded corporationsvice president of finance chief financial officer(CFO) chief executive officer(CEO) pivotalallocatevolatilitybalance sheetcapital budgetingworking capital management hurdle ratecapital structuremix of debt and equitycash dividendstockholderdividend policydividend-payout ratiostock repurchasestock offeringtradeoffcommon stockcurrent assetcurrent liability marketable security inventorytangible fixed assets intangible fixed assets patenttrademarkcreditorstockholders'equity financing mixrisk aversiontopic 2businessfinancial risksole proprietorship partnershiplimited partnershippartnerlimited partnergeneral partnerseparation of ownership and control claimmanagenment buyouttender offerNew York Stork Exchangefinancial standardsinitial public offering(IPO)private corporationclosely held corporationshareholderhoard of directorsexecutive directornon-executive directorchairpersoncontrollertreasurerMaster of Financial ManagementMaster of AccountingMaster of Business Administration(MBA) revenueprofitearnings per sharereturnmarket sharesocial goodfinancial distressstakeholder theoryvalue(wealth)maximizationcommon stockholder or shareholderdebt holderpreferred stockholder or shareholder well-beingdiversifylearning curvegoing concernagency problemfree-riding probleminformation asymmetryretail incestorinstitutional investoragency relationshipprincipal-agent or agency relationship net present value(NPV)creative accountingstock optionagency costbonding costmonitoring coststakeovertopic 3a profit and loss statementaccelerated methodsaccounts payableaccounts receivableaccrrual accountingaccrued expenseaccumulated depreciationaccumulated retained earningsaffiliateamortizationbalance sheetbasic earnings per sharebook valuebottom-up approachcapital surpluscash flow from financingcash flow from investingcash flow from operationscheckcommon stockcomplex capital structureconvertible securitiescorporate annual reportscredit salecurrent liabilitycurrent market valuedeferred taxdepreciationdiluted earnings per sharedilutivedirect methodearnings per shareFinancial Accounting Standards Board(FA financial statementfinancing cash flowsGenerally Accepted Accounting Principlehistorical costhybridincome statementindirect methodInternal Revenue Service(IRS)inventoryinvesting cash flowsjoint ventureliabilitylong-term liabilitymarketable securitiesmoney ordernet incomenote payableoperating cash flowsoperating income(loss)outstandingpreferred stockprofitabilityproperty,plant,and equipment(PPE)real estateSecurities and Exchange Commission(SEC) simple capital structuresolvencysource of cashstatement of cash flowstatement of change in shareholders' eq statement of retained earningsstraight-line depreciationtreasury stockuse of cashviabilitywarrantwithdrawaltopic 4financial ratiorestrictive covenanatsbond indenturefinancial analystliquidity ratiocurrent ratiolast-in ,first-out (LIFO)first-in ,first out (FIFO)window dressingmarketable securitiesquick ratiocash ratiodebt management ratiosdebt ratiodebt-to-equity ratioequity multiplierlong-term debt to total capital ratios leverage ratiosinterest coverage ratioearnings before interest and taxes (EBI cash Flow Coverage Ratioasset management ratiosaccounts receivable turnover ratios inventory turnover ratioinventory processing periodaccounts payable turnover ratiocash conversion cycleasset turnover ratiototal asset turnover ratioprofitability ratiogross profit marginoperating profit marginnet profit marginreturn on asset (ROA)return on total equity ratio (ROE) return on total equity (ROTE)return on common equity (ROCE)DuPont Analysis of ROEoperating profit marginP/E ratiomarket-to-book value ratiodividend yielddividend payoutlong-term ratiodebt-to-total-capitaltopic 5time value of moneysimple interstdebt instrumentannuityfuture value(FV)present value(PV)compound interestcompoundingprincipalmortgagecredit cardteminal valuediscountingdiscount rateopportunity costrequired rate of returncost of capitalordinary annuityannuity duedeferred annuityperpetuityface valueStandard & Poor's Corporation(S&P) Moody's Investors Service,Inc.(Moody's) Fitch Investor Servicescurrent yieldyield to maturity (YTM)default riskinterest rate riskauthorized sharesoutstanding sharestreasury sharerepurchaseright to voteindependent auditorright to proxystraight or majority votingcumulative votingliquidationright to transfer ownershippreemptive rightdividend discount modelcapital asset pricing model(CAPM) constant growth modelgrowth perpetuitytopic 6protfoliodiversifiable riskmarket riskexpected returnvolatilitystand-alone riskrandom variableprobabilityprobability distributionprobability distribution function normality assumptioncoefficientstandard deviationvariancesensitivity analysisscenario analysismean-variance worldnormal distributionefficient market hypothesis(EMH) price takerinvestor rationlityrational behaviorinstitutional investorretail investorallocationally efficient markets operationally efficient markets informationally efficient markets weak formsemi-strong formstrong formanomalyunderpricinginitial public offeringsMonday effectJanuary effectvalue effectpost-earnings announcement drift behavioral financeexpected utility theoryprospect theoryportfolio theorymutual fundmean-variance frontiercovariancecorrelation coefficientNew York Stock Exchange(NYSE) capital asset pricing model(CAPM) beta coefficientcompany-specific factorarbitrage pricing theory(APT)Topic 7 Capital Budgeting capital expenditurecapital budgetfinancial distressbankruptcyexpansion projectreplacement projectindependent projectmutually exclusive projectincremental cash flowssunk costopportunity costoverheadresidual valueside effectnet present value(NPV)profitability index(PI)internal rate of return(IRR)payback period(PP)discounted payback perioddiscounted cash flow(DCF)Fortune 500sensitivity analysisbreak-even analysiasimulationcapital rationingpost-auditTopic 8 Capital Market and Raising Fu financial marketmoney marketcapital markettreasury notesprimary marketsecondary marketoption contractfuture contractrepurchaseinvestment bankMerrill LynchSalomon Smith BarneyMorgan Stanley Dean WitterGoldman Sachscollateralunderwritingunderwritersyndicate of underwritermanipulateprivately held corporationpublicly held companystock offeringgo publicinitial public offering(IPO)seasoned issuespin-offspros and consincentive stock optiondilution of controlautonomyfloatationfloatation costunderpricingunseasoned issuepublic offerprivate placementpro ratarights offerprivileged subscriptionpreemptive rightcash offernegotiate offercost of capitalhurdle raterate of returnfinancing mixconvertible debtvariable-rate debtterm loanleaseweighted average cost of capital(WACC)Topic 9 Capital Structurehybird securityventure capitalistpublicly traded firmowner’s equityventure capitalnewly listed companyinvestment bankeroffering pricevoting rightwarrantunderlying common stockoption-like securitycontingent value rightsput optionoption exchangeput priceresidual claimline of creditbank debtleaseoperating leasecapital leaselessorlesseeconvertible debtconvertible bondconversion ratiomarket conversion valueconversion premiumpreferred stockfinancing mixconvertible preferred stockoptimal capital structuredesired or target capital structure earnings before interest and taxes(EBIT operating incomebusiness riskfinancial riskfinancial leveragefinancial economistModigliani and Miller(M&M)theorem transaction costmarket imperfectionreal assetsperfect capital marketlevered firmunlevered firmtax shieldtradeoff theoryinterest deductionpecking order theoryinternal financingexternal financinggeneral-purpose assetsspecial-purpose assetsoperating leverageMoody’s and Standard & Poor’sfinancial flexibilityreserve borrowing capacityTopic 10share repurchasedividend payout ratiochronologicaldeclaration dateex-dividend daterecord datepayment dateregular dividendliquidating dividendcash dividendsstock dividendsstock split"do-it-yourself"dividendproperty dividenddividend irrelevane theoryintrinsic valuefree cash flow hypothesishomemade dividendsbrokerage feedilution of ownershipresidual dividend policytarget capital structurestable dollar dividend policyconstant dividend payout ratiolow regular plus specially designated d stock price appreciationstock buybacktender offer(=takeover bid)open marketemployee stock option program(ESOP)Topic 11working captical managementmarketable securitynet working capticaljeopardizerelaxed or conservative approach restricted or aggressive approach moderate approachspeculative motiveprecautionary motivetransaction motivecompensating balanceBaumol cash management modelMiller-orr cash management model MarketabilityUS Treasury Billmaturitydufault risktax exempt instrumentcommercial paperrepurchase agreementnegotiable certificates of deposit(CDs) bankers'acceptancedisbursementfloatmail floatprocessing floatclearing time floatlock box systemconcentration bankingslowing disbursementcentralize payableszero balance account(ZBA)accounts receivabletrade creditconsumer creditcredit and collectiong policycredit termcredit perioddiscount perioddiscount rateaging scheduleaverage age of accounts receivablebad debt loss ratiosaturation pointprocrastinationperpetual inventory systemeconomic order quantity(EOQ)just-in-time(JIT)systemmaterial requirement planning (MRP)syst财务管理决策,决策的获得,取得(在财务中有时指购买;名词形式是acquisition,意为收购)公开上市公司,公众公司,上市公司(其他的表达法如,listed corporation,public corporation,etc)财务副总裁首席财务官首席执行官关键的,枢纽的(资源,权利等)配置(名词形式是allocation,如capital allocation,意为资本配置)易变的,不稳定性的(形容词形式是volatility,意为可变的,不稳定的)资产负债表资本预算营运资本管理门坎利率,最低报酬率资本结构负债与股票的组合现金股利股东(也可以用shareholder)股利政策股利支付比率股票回购(也可以用stock buyback)股票发行权衡,折中普通股流动资产流动负债流动性证券,有价证券存货有形固定资产无形固定资产专利商标债权人股东权益融资组合(指负债与所有者权益的比例关系)风险规避企业,商务,业务财务风险(有时也指金融风险)私人业主制企业合伙制企业有限合伙制企业合伙人有限责任合伙人一般合伙人所有权与经营权分离(根据权力提出)要求,要求权,主张,要求而得到的东西管理层收购(美)要约收购(美国称tender offer;英国称takeover bid)纽约股票交易所财务准则首次公开发行股票私募公司,未上市公司控股公司股东(也可以是stockholder)董事会执行董事非执行董事主席(chairmanor chairwoman)会计长司库财务管理专业硕士会计学硕士工商管理硕士收入利润每股盈余回报市场份额社会福利财务困境利益相关者理论价值(财富)最大化普通股股东(也可以是ordinary stockholder or shareholder债权人(也可以是debtor,creditor)优先股股东(英国人用preference stockholder or shareholder)福利多样化学习曲线持续的代理问题搭便车问题信息不对称散户投资者(为自己买卖证券而不是为任何公司或机构进行投资的个人投资者)机构投资者委托-代理关系(代理关系)净现值创造性会计,寻机性会计股票期权代理成本契约成本监督成本接管损益表加速折旧法应付账款应收账款应计制会计应计费用累计折旧累计留存收益分支机构摊销资产负债表基本每股收益账面价值倒推法资本盈余筹资活动现金流投资活动现金流经营活动现金流支票普通股复杂资本结构可转换证券公司年报赊销流动负债现行市场价值递延税款折旧稀释的每股收益(公司股票)冲减每股收益的直接法每股收益(盈余)(美国)会计准则委员会财务报表筹资现金流公认会计原则混合金融工具利润表间接法美国国内税务署存货投资现金流合资企业负债长期负债有价证券拨款单,汇款单,汇票净利润应付票据经营现金流经营收益(损失)(证券等)发行在外的优先股盈利能力土地、厂房与设备房地产(有时也用real property,或者就用property表示)(美国)证券交易委员会简单资本结构偿债能力现金来源现金流量表股东权益变动表留存收益表直线折旧法库存股现金运用生存能力认股权证提款财务比率限制性条款债券契约财务分析师流动性比率流动比率后进先出先进先出账面粉饰(是基金管理人的一种做法,即在季度末售出亏损股票,使其投资组合整个季度的回报率不至于被这些不良资产所拖累)速动比率现金比率债务管理比率债务比率债务与权益比率权益乘数长期债务与全部资本比率杠杠比率利率保障比率息税前盈余现金流量保障比率资产管理比率应收账款周转率存货周转率存活周转期应付账款周转率现金周转期资产周转比率全部资产周转率盈利比率毛利经营利润净利润资产收益率权益报酬率全部权益报酬率普通权益报酬率权益报酬率的杜邦分析体系市场价值比率市盈率市场价值与账面价值的比率股利收益率股利支付率长期比率债务与全部资本比率货币时间价值单利债务工具年金未来值,终值现值复利复利计算本金抵押信用卡终值折现计算折现率机会成本要求的报酬率资本成本普通年金先付年金递延年金永续年金面值标准普尔公司穆迪公司惠誉国际公司现行收益到期收益率违约风险利息率风险授权股发行股库藏股回购投票权独立审计师代理权多数投票制累积投票制清算所有权转移权优先认购权股利折现模型资本资产定价模型固定增长率模型增长年金组合可分散风险市场风险期望收益波动性个别风险随机变量概率概率分布概率分布函数正态假设系数标准离差率方差灵敏度分析情况分析均值-方差世界正态分布有效市场假设价格接受者投资者的理性理性行为机构投资者个人投资者.散户投资者配置有效市场运营有效市场信息有效市场弱势半强式强式异常(人或事物)价格低估首发股票星期一效应一月效应价值效应期后盈余披露行为财务期望效用理论期望理论组合理论共同基金均值-方差有效边界协方差相关系数纽约证券交易市场资本资产定价模型贝塔系数公司特有风险套利定价理论资本支出资本预算财务困境破产扩充项目更新项目独立项目互不相容项目增量现金流量沉没成本机会成本制造费用残余价值附加效应净现值现值指数内部收益率,内含报酬率回收期折现回收期折现现金流财富500指数敏感性分析盈亏平衡点分析模拟资本限额期后审计ng Funds金融市场货币市场资本市场国库券一级市场二级市场期权合约期货合约回购投资银行美林公司所罗门美邦投资公司摩根士丹利-添惠公司高盛公司抵押(股份等的)签名承受;承销,报销承销商承销辛迪加操纵私人控股公司公众控股公司股票发行公开上市适时发行、增发(seasoned是指新股稳定发行。

Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow,Corporate Finance,Takeovers

Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and TakeoversMichael C. JensenAmerican Economic Review, May 1986, V ol. 76, No. 2, pp. 323-329.Corporate managers are the agents of shareholders, a relationship fraught with conflict ing interests. Agency theory, the analysis of such conflicts, is now a major part of th e economics literature. The payout of cash to shareholders creates major conflicts tha t have received little attention. Payouts to shareholders reduce the resources under ma nagers’control, thereby reducing managers’power, and making it more likely they w ill incur the monitoring of the capital markets which occurs when the firm must obtai n new capital (see Easterbrook, 1984, and Rozeff, 1982). Financing projects internall y avoids this monitoring and the possibility the funds will be unavailable or availabl e only at high explicit prices.Managers have incentives to cause their firms to grow beyond the optimal size. Growt h increases managers’power by increasing the resources under their control. It is als o associated with increases in managers’compensation, because changes in compens ation are positively related to the growth in sales (see Murphy, 1985). The tendency o f firms to reward middle managers through promotion rather than year-to-year bonuse s also creates a strong organizational bias toward growth to supply the new positions t hat such promotion-based reward systems require (see Baker, 1986).Competition in the product and factor markets tends to drive prices towards minimu m average cost in an activity. Managers must therefore motivate their organizations t o increase efficiency to enhance the problem of survival. However, product and facto r market disciplinary forces are often weaker in new activities and activities that invol ve substantial economic rents or quasi rents. In these cases, monitoring by the firm’s i nternal control system and the market for corporate control are more important. Activi ties generating substantial economic rents or quasi rents are the types of activities tha t generate substantial amounts of free cash flow.Free cash flow is cash flow in excess of that required to fund all projects that have pos itive net present values when discounted at the relevant cost of capital. Conflicts of int erest between shareholders and managers over payout policies are especially severe w hen the organization generates substantial free cash flow. The problem is how to moti vate managers to disgorge the cash rather than investing it at below the cost of capita l or wasting it on organization inefficiencies.The theory developed here explains 1) the benefits of debt in reducing agency costs o f free cash flows, 2) how debt can substitute for dividends, 3) why “diversification” p rograms are more likely to generate losses than takeovers or expansion in the same line of business or liquidation-motivated takeovers, 4) why the factors generating takeov er activity in such diverse activities as broadcasting and tobacco are similar to thosei n oil, and 5) why bidders and some targets tend to perform abnormally well prior to ta keover.I. The Role of Debt in Motivating Organizational EfficiencyThe agency costs of debt have been widely discussed, but the benefits of debt in motiv ating managers and their organizations to be efficient have been ignored. I call these e ffects the ”control hypothesis”for debt creation.Managers with substantial free cash flow can increase dividends or repurchase stock a nd thereby pay out current cash that would otherwise be invested in low-return project s or wasted. This leaves managers with control over the use of future free cash flow s, but they can promise to pay out future cash flows by announcing a ”permanent” in crease in the dividend. Such promises are weak because dividends can be reduced in t he future. The fact that capital markets punish dividend cuts with large stock price red uctions is consistent with the agency costs of free cash flow.Debt creation, without retention of the proceeds of the issue, enables managers to effe ctively bond their promise to pay out future cash flows. Thus, debt can be an effectiv e substitute for dividends, something not generally recognized in the corporate financ e literature. By issuing debt in exchange for stock, managers are bonding their promis e to pay out future cash flows in a way that cannot be accomplished by simple dividen d increases. In doing so, they give shareholder recipients of the debt the right to take t he firm into bankruptcy court if they do not maintain their promise to make the interes t and principal payments. Thus debt reduces the agency costs of free cash flow by red ucing the cash flow available for spending at the discretion of managers. These contro l effects of debt are a potential determinant of capital structure.Issuing large amounts of debt to buy back stock also sets up the required organization al incentives to motivate managers and to help them overcome normal organizationa l resistance to retrenchment which the payout of free cash flow often requires. The thr eat caused by failure to make debt service payments serves as an effective motivating force to make such organizations more efficient. Stock repurchases for debt or cash also has tax advantages. (Interest payments are tax deductible to the corporation, an d that part of the repurchase proceeds equal to the seller’s tax basis in the stock is no t taxed at all.)Increased leverage also has costs. As leverage increases, the usual agency costs of deb t rise, including bankruptcy costs. The optimal debt-equity ratio is the point at which f irm value is maximized, the point where the marginal costs of debt just offset the mar ginal benefits.The control hypothesis does not imply that debt issues will always have positive contr ol effects. For example, these effects will not be as important for rapidly growing orga nizations with large and highly profitable investment projects but no free cash flow. S uch organizations will have to go regularly to the financial markets to obtain capita l. At these times the markets have an opportunity to evaluate the company, its manage ment, and its proposed projects. Investment bankers and analysts play an important rol e in this monitoring, and the market’s assessment is made evident by the price investo rs pay for the financial claims.The control function of debt is more important in organizations that generate large cas h flows but have low growth prospects, and even more important in organizations tha t must shrink. In these organizations the pressures to waste cash flows by investing th em in uneconomic projects is most serious.II. Evidence from Financial RestructuringThe free cash flow theory of capital structures helps explain previously puzzling result s on the effects of financial restructuring. My paper with Clifford Smith (1985, Tabl e 2) and Smith (1986, Tables 1 and 3) summarize more than a dozen studies of stock p rice changes at announcements of transactions which change capital structure. Most le verage-increasing transactions, including stock repurchases and exchange of debt or p referred for common, debt for preferred, and income bonds for preferred, result in sig nificant positive increases in common stock prices. The 2-day gains range from 21.9 p ercent (debt for common) to 2.2 percent (debt or income bonds for preferred). Most le verage-reducing transactions, including the sale of common, and exchange of commo n for debt or preferred, or preferred for debt, and the call of convertible bonds or conv ertible preferred forcing conversion into common, result in significant decreases in sto ck prices. The 2-day losses range from -9.9 percent (common for debt) to -0.4 percen t (for call of convertible preferred forcing conversion to common). Consistent with thi s, free cash flow theory predicts that, except for firms with profitable unfunded invest ment projects, prices will rise with unexpected increases in payouts to shareholders (o r promises to do so), and prices will fall with reductions in payments or new requests f or funds (or reductions in promises to make future payments).The exceptions to the simple leverage change rule are targeted repurchases and the sal e of debt (of all kinds) and preferred stock. These are associated with abnormal pric e declines (some of which are insignificant). The targeted repurchase price decline see ms to be due to the reduced probability of takeover. The price decline on the sale of de bt and preferred stock is consistent with the free cash flow theory because these sale s bring new cash under the control of managers. Moreover, the magnitudes of the valu e changes are positively related to the change in the tightness of the commitment bonding the payment of future cash flows; for example, the effects of debt for preferred ex changes are smaller than the effects of debt for common exchanges. Tax effects can ex plain some of these results, but not all, for example, the price increases on exchange o f preferred for common, which has no tax effects.III. Evidence from Leveraged Buyout and Going Private Transactions Many of the be nefits in going private and leveraged buyout (LBO) transactions seem to be due to th e control function of debt. These transactions are creating a new organizational form t hat competes successfully with the open corporate form because of advantages in con trolling the agency costs of free cash flow. In 1984, going private transactions totale d $10.8 billion and represented 27 percent of all public acquisitions (by number, see G rimm, 1984, 1985, 1986, Figs. 36 and 37). The evidence indicates premiums paid aver age over 50 percent.Desirable leveraged buyout candidates are frequently firms or divisions of larger firm s that have stable business histories and substantial free cash flow (i.e., low growth pr ospects and high potential for generating cash flows)—situations where agency cost s of free cash flow are likely to be high. The LBO transactions are frequently financed with high debt; 10 to 1 ratios of debt to equity are not uncommon. Moreover, the use of strip financing and the allocation of equity in the deals reveal a sensitivity to ince ntives, conflicts of interest, and bankruptcy costs.Strip financing, the practice in which risky nonequity securities are held in approxima tely equal proportions, limits the conflict of interest among such securities’ holders a nd therefore limits bankruptcy costs. A somewhat oversimplified example illustrates t he point. Consider two firms identical in every respect except financing. Firm A is enti rely financed with equity, and firm B is highly leveraged with senior subordinated deb t, convertible debt and preferred as well as equity. Suppose firm B securities are sold only in strips, that is, a buyer purchasing X percent of any security must purchase X percent of all securities, and the securities are ”stapled”together so they cannot b e separated later. Security holders of both firms have identical unleveraged claims on t he cash flow distribution, but organizationally the two firms are very different. If fir m B managers withhold dividends to invest in value-reducing projects or if they are in competent, strip holders have recourse to remedial powers not available to the equit y holders of firm A. Each firm B security specifies the rights its holder has in the even t of default on its dividend or coupon payment, for example, the right to take the fir m into bankruptcy or to have board representation. As each security above the equit y goes into default, the strip holder receives new rights to intercede in the organizatio n. As a result, it is easier and quicker to replace managers in firm B.Moreover, because every security holder in the highly leveraged firm B has the sam e claim on the firm, there are no conflicts among senior and junior claimants over reorganization of the claims in the event of default; to the strip holder it is a matter of mov ing funds from one pocket to another. Thus firm B need never go into bankruptcy, th e reorganization can be accomplished voluntarily, quickly, and with less expense an d disruption than through bankruptcy proceedings.Strictly proportional holdings of all securities is not desirable, for example, because o f IRS restrictions that deny tax deductibility of debt interest in such situations and limi ts on bank holdings of equity. However, riskless senior debt needn’t be in the strip, an d it is advantageous to have top-level managers and venture capitalists who promote t he transactions hold a larger share of the equity. Securities commonly subject to stri p practice are often called ”mezzanine” financing and include securities with priority s uperior to common stock yet subordinate to senior debt.Top-level managers frequently receive 15-20 percent of the equity. Venture capitalist s and the funds they represent retain the major share of the equity. They control the bo ard of directors and monitor managers. Managers and venture capitalists have a stron g interest in making the venture successful because their equity interests are subordina te to other claims. Success requires (among other things) implementation of changes t o avoid investment in low return projects to generate the cash for debt service and to i ncrease the value of equity. Less than a handful of these ventures have ended in bankr uptcy, although more have gone through private reorganizations. A thorough test of thi s organizational form requires the passage of time and another recession.IV. Evidence from the Oil IndustryRadical changes in the energy market since 1973 simultaneously generated large incre ases in free cash flow in the petroleum industry and required a major shrinking of the i ndustry. In this environment the agency costs of free cash flow were large, and the tak eover market has played a critical role in reducing them. From 1973 to the late 1970’s, crude oil prices increased tenfold. They were initially accompanied by increases i n expected future oil prices and an expansion of the industry. As consumption of oil fe ll, expectations of future increases in oil prices fell. Real interest rates and exploratio n and development costs also increased. As a result the optimal level of refining and d istribution capacity and crude reserves fell in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, leavin g the industry with excess capacity. At the same time profits were high. This occurre d because the average productivity of resources in the industry increased while the ma rginal productivity decreased. Thus, contrary to popular beliefs, the industry had to sh rink. In particular, crude oil reserves (the industry’s major asset) were too high, and cu tbacks in exploration and development (E&D) expenditures were required (see Jense n, 1986).Price increases generated large cash flows in the industry. For example, 1984 cash flows of the ten largest oil companies were $48.5 billion, 28 percent of the total cash flo ws of the top 200 firms in Dun’s Business Month survey. Consistent with the agency c osts of free cash flow, management did not pay out the excess resources to shareholde rs. Instead, the industry continued to spend heavily on E&D activity even though aver age returns were below the cost of capital.Oil industry managers also launched diversification programs to invest funds outside t he industry. The programs involved purchases of companies in retailing (Marcor by M obil), manufacturing (Reliance Electric by Exxon), office equipment (Vydec by Exxo n) and mining (Kennecott by Sohio, Anaconda Minerals by Arco, Cyprus Mines by A moco). These acquisitions turned out to be among the least successful of the last deca de, partly because of bad luck (for example, the collapse of the minerals industry) an d partly because of a lack of management expertise outside the oil industry. Althoug h acquiring firm shareholders lost on these acquisitions, the purchases generated socia l benefits to the extent that they diverted cash to shareholders (albeit target shareholde rs) that otherwise would have been wasted on unprofitable real investment projects. Two studies indicate that oil industry exploration and development expenditures hav e been too high since the late 1970’s. McConnell and Muscarella (1986) find that ann ouncements of increases in E&D expenditures in the period 1975-81 were associated with systematic decreases in the announcing firm’s stock price, and vice versa. These results are striking in comparison with their evidence that the opposite market reacti on occurs to changes in investment expenditures by industrial firms, and similar SE C evidence on increases in R&D expenditures. (See Office of the Chief Economist, S EC 1985.) Picchi’s study of returns on E&D expenditures for 30 large oil firms indicat es on average the industry did not earn ” . . even a 10% return on its pretax outlays” (1 985, p. 5) in the period 1982-84. Estimates of the average ratio of the present value o f future net cash flows of discoveries, extensions, and enhanced recovery to E&D exp enditures for the industry ranged from less than 60 to 90 cents on every dollar investe d in these activities.V. Takeovers in the Oil IndustryRetrenchment requires cancellation or delay of many ongoing and planned projects. T his threatens the careers of the people involved, and the resulting resistance means suc h changes frequently do not get made in the absence of a crisis. Takeover attempts ca n generate crises that bring about action where none would otherwise occur.Partly as a result of Mesa Petroleum’s efforts to extend the use of royalty trusts whic h reduce taxes and pass cash flows directly through to shareholders, firms in the oil in dustry were led to merge, and in the merging process they incurred large increases i n debt, paid out large amounts of capital to shareholders, reduced excess expenditures in E&D and reduced excess capacity in refining and distribution. The result has bee n large gains in efficiency and in value. Total gains to shareholders in the Gulf/Chevro n, Getty/Texaco, and Dupont/Conoco mergers, for example, were over $17 billion. M ore is possible. Allen Jacobs (1986) estimates total potential gains of about $200 billio n from eliminating inefficiencies in 98 firms with significant oil reserves as of Decem ber 1984.Actual takeover is not necessary to induce the required retrenchment and return of res ources to shareholders. The restructuring of Phillips and Unocal (brought about by thr eat of takeover) and the voluntary Arco restructuring resulted in stockholder gains ran ging from 20 to 35 percent of market value (totalling $6.6 billion). The restructuring i nvolved repurchase of from 25 to 53 percent of equity (for over $4 billion in each cas e), substantially increased cash dividends, sales of assets, and major cutbacks in capita l spending (including E&D expenditures). Diamond-Shamrock’s reorganization is furt her support for the theory because its market value fell 2 percent on the announcemen t day. Its restructuring involved, among other things, reducing cash dividends by 43 pe rcent, repurchasing 6 percent of its shares for $200 million, selling 12 percent of a ne wly created master limited partnership to the public, and increasing expenditures on oi l and gas exploration by $100 million/year.VI. Free Cash Flow Theory of TakeoversFree cash flow is only one of approximately a dozen theories to explain takeovers, al l of which I believe are of some relevance (Jensen, 1986). Here I sketch out some emp irical predictions of the free cash flow theory, and what I believe are the facts that len d it credence.The positive market response to debt creation in oil industry takeovers (as well as else where, see Bruner, 1985) is consistent with the notion that additional debt increases ef ficiency by forcing organizations with large cash flows but few high-return investmen t projects to disgorge cash to investors. The debt helps prevent such firms from wastin g resources on low-return projects.Free cash flow theory predicts which mergers and takeovers are more likely to destro y, rather than to create, value; it shows how takeovers are both evidence of the conflic ts of interest between shareholders and managers, and a solution to the problem. Acqu isitions are one way managers spend cash instead of paying it out to shareholders. The refore, the theory implies managers of firms with unused borrowing power and large f ree cash flows are more likely to undertake low-benefit or even value-destroying merg ers. Diversification programs generally fit this category, and the theory predicts the y will generate lower total gains. The major benefit of such transactions may be that t hey involve less waste of resources than if the funds had been internally invested in unprofitable projects. Acquisitions not made with stock involve payout of resources t o (target) shareholders and this can create net benefits even if the merger generates op erating inefficiencies. Such low-return mergers are more likely in industries with larg e cash flows whose economics dictate that exit occur. In declining industries, merger s within the industry create value, and mergers outside the industry are more likely t o be low- or even negative-return projects. Oil fits this description and so does tobacc o. Tobacco firms face declining demand due to changing smoking habits but generat e large free cash flow and have been involved in major acquisitions recently. Forest pr oducts is another industry with excess capacity. Food industry mergers also appear t o reflect the expenditure of free cash flow. The industry apparently generates large cas h flows with few growth opportunities. It is therefore a good candidate for leveraged b uyouts and they are now occurring. The $6.3 billion Beatrice LBO is the largest eve r. The broadcasting industry generates rents in the form of large cash flows on its licen ses and also fits the theory. Regulation limits the supply of licenses and the number o wned by a single entity. Thus, profitable internal investments are limited and the indus try’s free cash flow has been spent on organizational inefficiencies and diversificatio n programs—making these firms takeover targets. CBS’s debt for stock restructuring f its the theory.The theory predicts value-increasing takeovers occur in response to breakdowns of int ernal control processes in firms with substantial free cash flow and organizational poli cies (including diversification programs) that are wasting resources. It predicts hostil e takeovers, large increases in leverage, dismantlement of empires with few economie s of scale or scope to give them economic purpose (for example, conglomerates), an d much controversy as current managers object to loss of their jobs or the changes in o rganizational policies forced on them by threat of takeover.The debt created in a hostile takeover (or takeover defense) of a firm suffering sever e agency costs of free cash flow is often not permanent. In these situations, levering th e firm so highly that it cannot continue to exist in its old form generates benefits. It cr eates the crisis to motivate cuts in expansion programs and the sale of those division s which are more valuable outside the firm. The proceeds are used to reduce debt t o a more normal or permanent level. This process results in a complete rethinking of t he organization’s strategy and its structure. When successful a much leaner and compe titive organization results.Consistent with the data, free cash flow theory predicts that many acquirers will tend t o have exceptionally good performance prior to acquisition. (Again, the oil industry fi ts well.) That exceptional performance generates the free cash flow for the acquisitio n. Targets will be of two kinds: firms with poor management that have done poorly pri or to the merger, and firms that have done exceptionally well and have large free cash flow which they refuse to pay out to shareholders. Both kinds of targets seem to exis t, but more careful analysis is desirable (see Mueller, 1980).The theory predicts that takeovers financed with cash and debt will generate larger be nefits than those accomplished through exchange of stock. Stock acquisitions tend t o be different from debt or cash acquisitions and more likely to be associated with gr owth opportunities and a shortage of free cash flow; but that is a topic for future consi deration.The agency cost of free cash flow is consistent with a wide range of data for which th ere has been no consistent explanation. I have found no data which is inconsistent wit h the theory, but it is rich in predictions which are yet to be tested.ReferencesBaker, George (1986). ”Compensation and Hierarchies.” Harvard Business School . Bruner, Robert F. (1985). ”The Use of Excess Cash and Debt Capacity as Motive for Merger.” Colgate Darden Graduate School of Business (December).DeAngelo, Harry, Linda DeAngelo and Edward M. Rice (1984). ”Going Private: Minority Freezeouts and Shareholder Wealth.” Journal of Law and Economics 27 (Oc tober).Donaldson, Gordon (1984). Managing Corporate Wealth. New York, Praeger. Dun’s Business Month (1985). Cash Flow: The Top 200: 44-50.Easterbrook, Frank H. (1984). ”Two Agency-Cost Explanations of Dividends.” Ameri can Economic Review 74 : 650-59.Grimm, W. T. (1984, 1985, 1986). ”Mergerstat Review, Annual Editions.” . Jacobs, E. Allen (1986). ”The Agency Cost of Corporate Control: The Petroleum Industry.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology (March).Jensen, Michael C. (1985). ”When Unocal Won Over Pickins, Shareholders and Socie ty Lost.” Financier 9 (November): 50-52.Jensen, Michael C. (1986). ”The Takeover Controversy: Analysis and Evidence.”Midland Corporate Finance Journal 4, no. 2 (Summer): 6-32.Jensen, M. C. and Jr. Clifford Smith (1985). ”Stockholder, Manager and Creditor Interests: Applications of Agency Theory”. Recent Advances in Corporate Financ e. E. I. Altman and M. G. Subrahmanyam. Homewood, Illinois, Irwin: 93-131. Lowenstein, L. (1985). ”Management Buyouts.” Columbia Law Review 85 (May): 73 0-784.McConnell, John J. and Chris J. Muscarella (1986). ”Corporate Capital Expenditure Decisions and the Market Value of the Firm.” Journal of Financial Economics . Mueller, D. (1980). The Determinants and Effects of Mergers. Cambridge, Oelgeschlager.Murphy, Kevin J. (1985). ”Corporate Performance and Managerial Remuneration: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 7 (April): 11-42. Picchi, B. (1985). Structure of the U.S. Oil Industry: Past and Future, Salomon Brothe rs.Rozeff, Michael (1982). ”Growth, Beta and Agency Costs as Determinants of Dividen d Payout Ratios.” Journal of Financial Research 5 : 249-259.SEC Office of the Chief Economist (1985). Institutional Ownership, Tender Offers an d Long-Term Investments.Smith, Clifford W. (1986). ”Investment Banking and the Capital Acquisition Process.”Journal of Financial Economics 15 (Nos. 1-2).。

薪酬管理外文文献翻译

薪酬管理外文文献翻译The existence of an agency problem in a corporation due to the separation of ownership and control has been widely studied in literatures. This paper examines the effects of management compensation schemes on corporate investment decisions. This paper is significant because it helps to understand the relationship between them. This understandings allow the design of an optimal management compensation scheme to induce the manager to act towards the goals and best interests of the company. Grossman and Hart (1983) investigate the principal agency problem. Since the actions of the agent are unobservable and the first best course of actions can not be achieved, Grossman and Hart show that optimal management compensation scheme should be adopted to induce the manager to choose the second best course of actions. Besides management compensation schemes, other means to alleviate the agency problems are also explored. Fama and Jensen (1983) suggest two ways for reducing the agency problem: competitive market mechanisms and direct contractual provisions. Manne (1965) argues that a market mechanism such as the threat of a takeover provided by the market can be used for corporate control. "Ex-post settling up" by the managerial labour market can also discipline managers and induce them to pursue the interests of shareholders. Fama (1980) shows that if managerial labour markets function properly, and if the deviation of the firm's actual performancefrom stockholders' optimum is settled up in managers' compensation, then the agency cost will be fully borne by the agent (manager).The theoretical arguments of Jensen and Meckling (1976) and Haugen and Senbet (1981), and empirical evidence of Amihud andLev (1981), Walking and Long (1984), Agrawal and Mandelker (1985), andBenston (1985), among others, suggest that managers' holding of common stock and stock options have an important effect on managerial incentives. For example, Benston finds that changes in the value of managers' stock holdings are larger than their annual employment income. Agrawal and Mandelker find that executive security holdings have a role in reducing agency problems. This implies that the share holdings and stock options of the managers are likely to affect the corporate investment decisions. A typical management scheme consists of flat salary, bonus payment and stock options. However, the studies, so far, only provide links between the stock options and corporate investment decisions. There are few evidences that the compensation schemes may have impacts on thecorporate investment decisions. This paper aims to provide a theoretical framework to study the effects of management compensation schemes on the corporate investment decisions. Assuming that the compensation schemes consist of flat salary, bonus payment, and stock options, I first examine the effects of alternative compensation schemes on corporate investment decisions under all-equity financing. Secondly, I examine the issue in a setting where a firm relies on debt financing. Briefly speaking, the findings are consistent with Amihud and Lev's results.Managers who have high shareholdings and rewarded by intensive profit sharing ratio tend to underinvest.However, the underinvestment problem can be mitigated by increasing the financial leverage. The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section II presents the model. Section HI discusses the managerial incentives under all-equity financing. Section IV examines the managerial incentives under debt financing. Section V discusses the empirical implications and presents the conclusions of the study.I consider a three-date two-period model. At time t0, a firm is established and goes public. There are now two kinds of owners in the firm, namely, the controlling shareholder and the atomistic shareholders. The proceeds from initial public offering are invested in some risky assets which generate an intermediate earnings, I, at t,. At the beginning, the firm also decides its financial structure. A manager is also hired to operate the firm at this time. The manager is entitled to hold a fraction of the firm's common stocks and stock options, a (where0<a<l), at the beginning of the first period. At time t,, the firm receives intermediate earnings, denoted by I, from the initial asset. At the same time, a new project investment is available to the firm. For simplicity, the model assumes that the firm needs all the intermediate earnings, I, to invest in the new project. If the project is accepted at t,, it produces a stochastic earnings Y in t2, such that Y={I+X, I-X}, with Prob[Y=I+X] = p and Prob[Y=I-X] = 1-p, respectively. The probability, p, is a uniform density function with an interval rangedfrom 0 to 1. Initially, the model also assumes that the net earnings, X, is less than initial investment, I. This assumption is reasonable since most of the investment can not earn a more than 100% rate of return. Later, this assumption is relaxed to investigate the effect of the extraordinarily profitable investment on the results. For simplicity, It is also assumed that there is no time value for the money and no dividend will be paid before t2. If the project is rejected at t,, the intermediate earnings, I, will be kept in the firm and its value at t2 will be equal to I. Effects of Management Compensation Schemes on Corporate Investment Decision Overinvestment versus UnderinvestmentA risk neutral investor should invest in a new project if it generates a positiexpected payoff. If the payoff is normally or symmetrically distributed, tinvestor should invest whenever the probability of making a positive earninggreater than 0.5. The minimum level of probability for making an investment the neutral investor is known as the cut-off probability. The project will generzero expected payoff at a cut-off probability. If the investor invests only in tprojects with the cut-off probability greater than 0.5, then the investor tendsinvest in the less risky projects and this is known as the underinvestment. Ifinvestor invests the projects with a cut-off probability less than 0.5, then tinvestor tends to invest in more risky projects and this is known as thoverinvestment. In the paper, it is assumed that the atomistic shareholders risk neutral, the manager and controlling shareholder are risk averse.It has been argued that risk-reduction activities are considered as managerial perquisites in the context of the agency cost model. Managers tend to engage in these risk-reduction activities to decrease their largely undiversifiable "employment risk" (Amihud and Lev 1981). The finding in this paper is consistent with Amihud and Lev's empirical result. Managers tend to underinvest when they have higher shareholdings and larger profit sharing percentage. This result is independent of the level of debt financing. Although the paper can not predict themanager's action when he has a large profit sharing percentage and the profit cashflow has high variance (X > I), it shows that the manager with high shareholding will underinvest in the project. This is inconsistent with the best interests of the atomistic shareholders. However, the underinvestment problem can be mitigated by increasing the financial leverage.The results and findings in this paper provides several testable hypotheses forfuture research. If the managers underinvest in the projects, the company willunderperform in long run. Thus the earnings can be used as a proxy forunderinvestment, and a negative relationship between earningsandmanagement shareholdings, stock options or profit sharing ratiois expected.As theunderinvestment problem can be alleviated by increasing the financialleverage, a positiverelationship between earnings and financial leverage isexpected.在一个公司由于所有权和控制权的分离的代理问题存在的文献中得到了广泛的研究。

外文翻译--交错董事会,管理防御和股利政策1

本科毕业论文(设计)外文翻译原文:Staggered Boards, Managerial Entrenchment, and Dividend Policy 2 Background, literature review, and hypothesis development2.1 The role of staggered boards in entrenching incumbentsIn the U.S., boards of directors can be either unitary or staggered. In firms with a unitary board, all directors stand for election each year. In firms with a staggered or classified board, directors are divided into three classes, with one class of directors standing for election at each annual meeting of shareholders. Ordinarily, a classified board has three classes of directors, which in most states of incorporation is the maximum number of classes allowed by state corporate law (Bebchuk and Cohen 2005).Boards can be removed in one of the following two ways. First, a replacement can occur due to a stand-alone proxy fight brought about by a rival team that attempts to replace the incumbents but continues to run the firm as a stand-alone entity. Second, a board may be replaced as a consequence of a hostile takeover. Either way, the difficulty with which directors can be removed critically depends on whether the firm has a staggered board.In a stand-alone proxy contest, staggered boards make it considerably more difficult to win control by requiring a rival team to prevail in two elections. In a hostile takeover, staggered boards protect incumbents from removal due to the interaction between incumbents and a board’s power to adopt and maintain a poison pill 3. Before the adoption of the poison pill defense, staggered boards were deemed only a mild defense mechanism, as they did not impede the acquisition of a control block. The acceptance of the poison pill, however, has immensely strengthened the anti-takeover power of staggered boards.Two powerful recent studies by Bebchuk and Cohen (2005) and Faleye (2007) demonstrate that firms with staggered board’s exhibit significantly lower value than those with unitary boards. Thus, the evidence is in accordance with the notion that staggered boards promote managerial entrenchment, exacerbate agency conflicts, and ultimately hurt firm value.2.2 Prior literatureExisting literature provides evidence consistent with the agency role of dividends in Alleviating Jensen’s (1986) free cash flow problem (Easterbrook 1984; Lang and Litzenberger 1989; Smith and Watts 1992; Gaver and Gaver 1993). Agency theory represents a general framework for the role of dividends as a way of reducing the costs of manager-shareholder agency conflict (Easterbrook 1984). Dividends reduce the amount of sub-optimal investment, impose additional monitoring by forcing the manager to address the external financing market, and increase managerial risk-taking (by replacing leverage, dividends lower the expected loss of human capital due to bankruptcy).Many recent studies document a negative relation between dividend payouts and Gompers et al.’s (2003) Governance Index (Jiraporn and Ning 2006; Pan 2007; John and Knyazeva 2006; and Officer 2006). The Governance Index has a serious weakness in that it assigns equal weights to all the governance provisions included in the construction of the index. Although other governance provisions may also exacerbate managerial entrenchment, there is strong empirical evidence that staggered boards have a far more potent effect than any other governance provision.4Two crucial studies by Bebchuk and Cohen (2005) and Bebchuk and Cohen (2005) show that, even after accounting for the effects of other governance provisions, staggered boards still exhibit a strong negative impact on firm value. In fact, the regression results reveal that the impact of staggered boards on firm value is seven times stronger than the effects of other governance provisions. Bebchuk and Cohen(2005) conclude that “staggered boards play a relativ ely large role compared to the average role of other provisions included in the GIM Index.”5 The effect of staggered boards on firm value is not only statistically significant but alsoeconomically significant. Having a staggered board is associated with T obin’s q that is lower by 17 percentage points (Bebchuk and Cohen 2005).Additional evidence on the effect of staggered boards is reported in several recent studies. For example, Faleye (2007) reports that staggered boards reduce the probability of forced CEO turnover, are associated with a lower sensitivity of CEO turnover to firm performance and are correlated with a lower sensitivity of CEO compensation to changes in shareholder wealth .Masulis et al. (2007) demonstrate that announcement period returns are 0.57% to 0.91% lower for bidding firms with staggered boards. They attribute this finding to the self-serving behavior of acquiring firm managers, who themselves are insulated from the market for corporate control.Jiraporn and Liu (2008) examine how capital structure decisions are influenced by the presence of a staggered board. The evidence reveals that even after controlling for the effects of other governance provisions, firms with staggered boards are significantly less leveraged than those with unitary boards. They argue that staggered boards promote managerial entrenchment, thereby allowing opportunistic managers to eschew the disciplinary mechanisms associated with debt financing. The regression results show that the impact of staggered boards on leverage is six to nine times stronger than the effects of other governance provisions included in Gompers et al.’s (2003) Index.Furthermore, staggered boards have become a subject of intense investor scrutiny. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) recommends in its 2006 proxy voting guidelines that its membership vote against proposals to stagger a board or vote for proposals to repeal staggered board provisions. Additionally, ISS recommends withholding votes for directors who ignore shareholder resolutions to de-stagger a board. ISS also lowers its governance score for firms with staggered boards6. Similarly, CalPER, the largest public pension fund in the U.S., has targeted firms for shareholder votes to remove staggered boards from their corporate charters. Various mutual fund companies including TIAA-CREF and Fidelity Investments also call for voting against the adoption of and for the removal of staggered board provisions. No other governance provisions have attracted nearly as much controversy from investorsas staggered boards, underscoring staggered boards’ dominant role relative to other governance provisions.Given the above discussion, it is obvious that staggered boards have a serious impact on several critical corporate outcomes, including overall firm value, capital structure, CEO compensation, CEO turnover and takeover gains. It also appears that the effect of staggered boards is large relative to the average effect of other corporate governance provisions. The significance of staggered boards cannot be overemphasized. Consequently, in this study, we narrowly concentrate on the role of staggered boards and investigate their impact on dividend payouts.2.3 Hypothesis developmentGrounded in agency theory, our general hypothesis is that there is a link between staggered boards and dividend payouts, as both are related to agency costs. However, it is unclear what the exact relation should be between staggered boards and dividend policy. On the basis of previous literature in this area, we advance four possible hypotheses.2.4 The irrelevance hypothesisThis view posits that there is no significant difference in dividend policy between firms with staggered boards and those with unitary boards. Dividends are “sticky.” Once dividends are initiated, managers are extremely unwilling to cut back or terminate dividends (Lintner 1956; Allen and Michaely 2003; Brav et al. 2005), possibly making irrelevant any managerial entrenchment engendered by staggered boards.2.5 The managerial opportunism hypothesisThis argument is based on the free cash flow hypothesis (Jensen 1986). This view argues that dividend policy is determined by managers who would rather retain cash within the firm for perquisite consumption, for empire building or for investing in projects that enhance their personal prestige but do not necessarily benefit shareholders. As staggered boards can entrench inefficient managers, opportunistic managers may choose to keep more cash within the firm and pay less out as dividends. The empirical prediction of this hypothesis is that firms with staggered boards shouldpay less dividends than those with unitary boards.2.6 The agency cost alleviation hypothesisPayout policy is one mechanism for alleviating the manager-shareholder conflict. However, the efficacy of payout policy in reducing agency costs hinges largely on the degree of restriction on managerial actions. Without pre-commitment, poorly-monitored managers can ex post deviate from the payout policy and use free cash flow to finance inefficient investment. Given the negative market reaction to dividend cuts and infrequent deviations from dividend policy, dividends help constrain the manager through the high cost of deviation and constitute an effective pre-commitment mechanism in the presence of a severe agency conflict (John and Knyazeva 2006).As shareholders observe that firms with staggered boards may be more prone to managerial entrenchment and rationally anticipate the larger extent of the free cash flow problem, the necessity for dividends should be stronger for firms with staggered boards than for firms with unitary boards.Dividend payment imposes a tax cost on the payer firm. Moreover, dividend paying firms also incur the cost of forgone positive-NPV projects or the additional cost of raising external financing to fund them when internal cash flow is inadequate. Since dividends are costly, firms that are less vulnerable to managerial entrenchment (i.e., firms without staggered boards) should be less inclined to pay dividends and should pay lower dividends on average.2.7 The signaling hypothesisThis hypothesis is based on an argument made by La Porta et al. (2000). This view relies critically on the assumption that firms need to raise money in the external capital markets, at least occasionally. To be able to raise external funds on attractive terms, a firm must establish a reputation for moderation in expropriating from shareholders. One way to establish such a reputation is by paying out dividends, which reduces what is left for expropriation.7A reputation for good treatment of shareholders is worth more in firms where opportunistic managers are more likely to be entrenched, i.e., in firms with staggered boards. As a result, the need to establish areputation is greater for such firms. By contrast, for firms with unitary boards, the need for a reputation mechanism is less necessary, and thus, so is the need to pay dividends. This view, therefore, posits that dividend payouts should be higher in firms with staggered boards.Because firms with plenty of growth opportunities need more financing and are thus more likely to raise capital in the external markets, the need for signaling should be stronger for these firms. As a result, one crucial implication of this hypothesis is that firms with staggered boards that exhibit stronger growth opportunities should pay more dividends than those that show weaker growth (Pan 2007).3 Sample formation and data description3.1 Sample selectionThe original sample is compiled from the Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC). The IRRC Reports Data on corporate governance provisions for about 1,500 firms. The sample firms, mainly drawn from the S&P 500 and other large corporations, represent over 90% of total market capitalization on NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ. The IRRC collects data on 24 corporate governance provisions, one of which is staggered boards .8 The sample is narrowed down further by dropping firms whose financial data do not exist in COMPUSTA T. Financial firms are excluded due to their unique accounting and financial characteristics.The final sample consists of 9,918 firm-year observations from 1990 to 2004. This sample is the largest and most recent among most studies in this area. The year distribution of the sample is displayed in Table 1. It appears that about 60% of firms in the sample have staggered boards. This proportion is remarkably constant over time, in a narrow range from 59.07% to 63.25%.Because the IRRC data include only large firms, it could be argued that our studies are biased towards firms of large size. The IRRC data covered, in 1990, over 93% of the market capitalization of the combined NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ markets (Gompers et al. 2003). Like Pan (2007), we propose that this possible large-firm bias should not constitute a serious concern for our study. Given the purpose of this study, we need a sample of firms that are potential candidates to paydividends and attempt to understand whether their dividend payouts are related to their level of managerial entrenchment. As dividends are paid mainly by large and mature firms, the IRRC sample firms are those that should be most suitable for this study. Additionally, firms can only pay dividends when they are able to generate stable earnings, i.e., when they become mature firms. On the contrary, most fast growing young firms cannot or choose not to pay dividends. Consequently, a study like ours that examines dividend policy and managerial entrenchment probably ought to include large firms in the sample, which is precisely what we do here.Source: Pornsit Jiraporn·Pandej Chintrakarn, 2009 “Staggered Boards, Managerial Entrenchment, and Dividend Policy” .J Financ Serv Res, pp.3-7.译文:交错董事会,管理防御和股利政策2背景,文献回顾,与假设发展2.1在固守任职中交错板的作用在美国,董事会成员可以是单一或交错的。

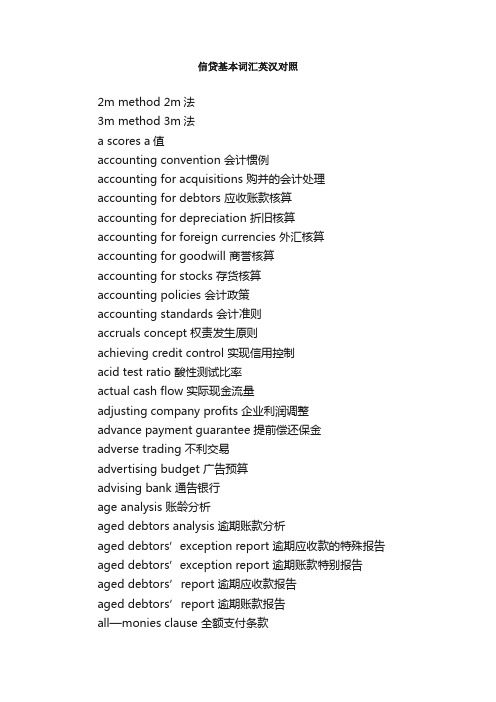

信贷基本词汇英汉对照_财务英语词汇