Chabrol_2009_Personality-and-Individual-Differences

2011Tell Me a Good Story and I may lend you money,the role of narratives in peer-to-peer decisions

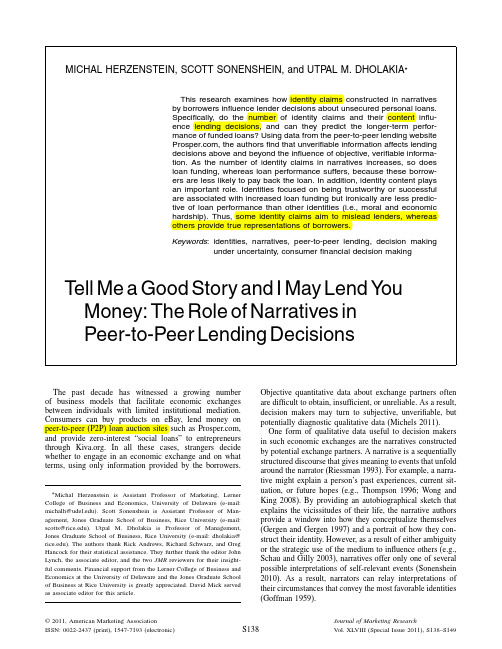

MICHAL HERZENSTEIN,SCOTT SONENSHEIN,and UTPAL M.DHOLAKIAThis research examines how identity claims constructed in narrativesby borrowers influence lender decisions about unsecured personal loans.Specifically,do the number of identity claims and their content influ-ence lending decisions,and can they predict the longer-term perfor-mance of funded loans?Using data from the peer-to-peer lending website,the authorsfind that unverifiable information affects lendingdecisions above and beyond the influence of objective,verifiable informa-tion.As the number of identity claims in narratives increases,so doesloan funding,whereas loan performance suffers,because these borrow-ers are less likely to pay back the loan.In addition,identity content playsan important role.Identities focused on being trustworthy or successfulare associated with increased loan funding but ironically are less predic-tive of loan performance than other identities(i.e.,moral and economichardship).Thus,some identity claims aim to mislead lenders,whereasothers provide true representations of borrowers.Keywords:identities,narratives,peer-to-peer lending,decision makingunder uncertainty,consumerfinancial decision making Tell Me a Good Story and I May Lend Y ou Money:The Role of Narratives inPeer-to-Peer Lending DecisionsThe past decade has witnessed a growing number of business models that facilitate economic exchanges between individuals with limited institutional mediation. Consumers can buy products on eBay,lend money on peer-to-peer(P2P)loan auction sites such as , and provide zero-interest“social loans”to entrepreneurs through .In all these cases,strangers decide whether to engage in an economic exchange and on what terms,using only information provided by the borrowers. *Michal Herzenstein is Assistant Professor of Marketing,Lerner College of Business and Economics,University of Delaware(e-mail: michalh@).Scott Sonenshein is Assistant Professor of Man-agement,Jones Graduate School of Business,Rice University(e-mail: scotts@).Utpal M.Dholakia is Professor of Management, Jones Graduate School of Business,Rice University(e-mail:dholakia@ ).The authors thank Rick Andrews,Richard Schwarz,and Greg Hancock for their statistical assistance.They further thank the editor John Lynch,the associate editor,and the two JMR reviewers for their insight-ful comments.Financial support from the Lerner College of Business and Economics at the University of Delaware and the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University is greatly appreciated.David Mick served as associate editor for this article.Objective quantitative data about exchange partners often are difficult to obtain,insufficient,or unreliable.As a result, decision makers may turn to subjective,unverifiable,but potentially diagnostic qualitative data(Michels2011). One form of qualitative data useful to decision makers in such economic exchanges are the narratives constructed by potential exchange partners.A narrative is a sequentially structured discourse that gives meaning to events that unfold around the narrator(Riessman1993).For example,a narra-tive might explain a person’s past experiences,current sit-uation,or future hopes(e.g.,Thompson1996;Wong and King2008).By providing an autobiographical sketch that explains the vicissitudes of their life,the narrative authors provide a window into how they conceptualize themselves (Gergen and Gergen1997)and a portrait of how they con-struct their identity.However,as a result of either ambiguity or the strategic use of the medium to influence others(e.g., Schau and Gilly2003),narratives offer only one of several possible interpretations of self-relevant events(Sonenshein 2010).As a result,narrators can relay interpretations of their circumstances that convey the most favorable identities (Goffman1959).©2011,American Marketing AssociationISSN:0022-2437(print),1547-7193(electronic)S138Journal of Marketing ResearchV ol.XLVIII(Special Issue2011),S138–S149Role of Narratives in Peer-to-Peer Lending Decisions S139RESEARCH MOTIVATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS The idea that narratives may involve the construction of a favorable identity poses two key questions for research. First,whereas narratives can provide diagnostic informa-tion to a decision maker who is considering an economic exchange,the veracity of the narrator’s story is difficult to determine.Because a narrative offers the possibility of describing either an authentic,full,true self or a partial, inauthentic,misleading self,potential exchange partners are left to intuit the truth of the presentation.Accordingly a key question to consider is,given their potential for diagnostic and misleading information,to what extent do narratives influence economic exchange transactions?Previous con-sumer research has largely focused on narratives of con-sumption experiences(Thompson1996)or consumption stories(Levy1981),but scholars have not examined the role of narratives in economic exchanges.We believe that narratives may be a particularly powerful lens,in that they allow the consumer to attempt to gain better control over the exchange and thus can provide a means to help con-summate the exchange.Second,to what extent do narratives affect the perfor-mance and outcomes of an economic exchange?Narrative scholars claim that the construction and presentation of a narrative can shape its creator’s future behavior(Bruner 1990)but rarely examine the nature of this influence empir-ically.Such an examination would be critical to understand-ing how a mixture of quantitative and qualitative factors shapes outcome quality(e.g.,Hoffman and Yates2005). We examine these two questions using data from the online P2P loan auctions website,,by studying borrower-constructed narratives(particularly the identities embedded in them),the subsequent decisions of lenders, and transaction performance two years later.We define identity claims as the ways that borrowers describe them-selves to others(Pratt,Rockmann,and Kaufmann2006). Borrowers can construct an identity based on a range of ele-ments,such as religion or success.The elements become an identity claim when they enter public discourse as opposed to private cognition.With this framework,we make several contributions.First,by developing and testing theory around how nar-ratives supplement more objective sources of information that decision makers use when considering afinancial trans-action,we draw attention to how narrators can intentionally exploit uncertainty and favorably shape circumstantial facts to obtain resources,such as access to money in unmediated environments.The narrative,as a supplementary,yet some-times deal-making or deal-breaking,information source for decision makers is predicated on compelling stories versus objective facts.It thus offers a means for people to recon-struct their pasts and describe their futures in positive ways. Second,by linking narratives to objective performance measures,we show how narratives may predict the longer-term performance of lending decisions.Because the deci-sion stakes are high in this unmediated and unsecured financial arena,lenders engage in highly cognitive pro-cessing(Petty and Wegener1998).The strong disincen-tive of potentialfinancial loss leads to cognitive process-ing,which tends to produce accurate attributions about a person and the probabilities of future events(Osborne and Gilbert1992).Because of this motivation for accuracy,we suspect lenders use narratives to help them make invest-ment decisions.Third,from a practice perspective,the recentfinancial crisis has exposedflaws in the criteria used to make lend-ing decisions.Quantitativefinancial metrics,such as credit scores,have proven unreliable for predicting the ability or likelihood of consumers to repay unsecured loans(Feldman 2009).A narrative perspective on the consummation and performance offinancial transactions offers the promise of improving systems for assessing borrowers.RESEARCH SETTINGWe conducted our research on (hereinafter, Prosper),the largest P2P loan auction site in the United States,with more than one million members and$238mil-lion in personal loans originated since its inception in March2006(as of June2011).On Prosper,borrowers and lenders never meet in person,so we can assess the role of narratives in overcoming the uncertainty that arises during financial transactions between unacquainted actors.The process of borrowing and lending money through a loan auction on Prosper is as follows:Before posting their loan request,borrowers give Prosper permission to ver-ify relevant personal information(e.g.,household income, home ownership,bank accounts)and access their credit score from Experian,a major credit-reporting ing this and other information,such as pay stubs and income tax returns,Prosper assigns each borrower a credit grade that reflects the risk to lenders.Credit grades can range from AA, which indicates that the borrower is extremely low risk(i.e., high probability of paying back the loan),through A,B,C, D,and E to HR,which signifies the highest risk of default. Borrowers then post loan requests for auction.When post-ing their loan auctions,borrowers choose the amount(up to $25,000)and the highest interest rate they will pay.They also may use a voluntary open-text area,with unlimited space,to write anything they want—that is,the borrower’s narrative(see Michels2011).After the listing becomes active,lenders decide whether to bid,how much money to offer,and the interest rate. A$1,000loan might befinanced by one lender who lends $1,000or by40lenders,each lending$25for example. Most lenders bid the minimum amount($25)on individual loans to diversify their portfolios(Herzenstein,Dholakia, and Andrews2011).After the auction closes,listings with bids that cover the requested amount are funded.If a list-ing receives bids covering more than its requested amount, the bids with the lowest interest rates win.If the auc-tion does not receive enough bids,the request remains unfunded.Prosper administers the loan,collects payments, and receives fees of.5%to3.0%from borrowers,as well as a1%annual fee from lenders.We employed three dependent variables in our study. First,loan funding is the percentage of the loan request to receive a funding commitment from lenders.For exam-ple,if a loan request for$1,000receives bids worth$500, loan funding is50%.If it receives bids worth$2,000,loan funding equals200%.A higher loan funding value signi-fies greater lender interest.Second,percentage reduction infinal interest rate captures the decrease in the inter-est rate between the borrower’s maximum specified rate and thefinal rate.For example,if a borrower’s maximumS140JOURNAL OF MARKETING RESEARCH,SPECIAL ISSUE 2011T able 1DEFINITIONS OF IDENTITIES AND EXAMPLES FOR DATA CODINGIdentityDefinitionExamplesTrustworthy (Duarte,Siegel,and Young 2009)Lenders can trust the borrower to pay back the money on time.“I am responsible at paying my bills and lending me funds would be a good investment.”(Listing #17118)Successful (Shafir,Simonson,and Tversky 1993)The borrower is someone with a successful business or job/career.“I have [had]a very solid and successful career with an Aviation company for the last 13years.”(Listing #18608)Hardworking (Woolcock 1999)The borrower will work very hard to pay the loan back.“I work two jobs.I work too much really.I work 26days a month with both jobs.”(Listing #18943)Economic hardship (Woolcock 1999)The borrower is someone in need because of hardship,as a result of difficult circumstances,bad luck,or other misfortunes that were,or were not,under the borrower’s control.“Unfortunately,a messy divorce and an irresponsible ex have left me with awful credit.”(Listing #20525)Moral (Aquino et al.2009)The borrower is an honest or moral person.“On paper I appear to be an extremely poor financial risk.In reality,I am an honest,decent person.”(Listing #17237)Religious (Weaver and Agle 2002)The borrower is a religious person.“One night,the Lord awaken me and myspouse our business has been an enormous success with G-d on our side.”(Listing #21308)interest rate is 18%and the final rate is 17%,the per-centage reduction in interest rate is 18−17 /18=5 56%.rate decreases only if the loan request receives full greater lender interest results in greater reduc-of the interest rate.Third,loan performance is the payment status of the loan two years after its origination.We further classify the types of identity claims made by prospective borrowers.Borrowers in our sample employed six identity claims in their narratives:trustworthy,economic hardship,hardworking,successful,moral,and religious.In Table 1,we provide definitions and illustrative examples of each identity claim.Borrowers provided an average of 1.53 SD =1 14 identity claims in their narratives.RESEARCH HYPOTHESESWho Is Likely to Provide More Identity Claims in Their Narratives?Narratives,when viewed as vehicles for identity work,provide opportunities for people to manage the impres-sions that others hold of them.Impression management the-ory posits that people want to create and maintain specific identities (Leary and Kowalski 1990).Narratives provide an avenue for impression management;through discourse,people can shape situations and construct identities that are designed specifically to obtain a desired outcome (Schlenker and Weigold 1992).Some scholars argue that people use narratives strategically to establish,maintain,or protect their desired identities (Rosenfeld,Giacalone,and Riordan 1995).However,the use of impression manage-ment need not automatically signal outright lying;people may select from a repertoire of self-images they genuinely believe to be true (Leary and Kowalski 1990).Nevertheless,strategic use of impression management means that,at a minimum,people select representations of their self-image that are most likely to garner support.In economic exchanges involving repeated transactions,each party receives feedback from exchange partners thateither validates or disputes the credibility of their self-constructions (Leary and Kowalski 1990),so they can determine if an identity claim has been granted.Prior transactions also offer useful information through feedback ratings and other mechanisms that convey and archive rep-utations (Weiss,Lurie,and MacInnis 2008).However,in one-time economic exchanges,such feedback is not avail-able.Instead,narrators have a single opportunity to present a convincing public view of the self,and receivers of the information have only one presentation to deem the presen-ter as credible or not.We hypothesize that in these conditions,borrowers are strategic in their identity claims.Borrowers with satisfac-tory objective characteristics are less likely to construct identity claims to receive funding;they feel their case stands firmly on its objective merits alone.In contrast,borrowers with unsatisfactory objective characteristics may view narratives as an opportunity to influence the attribu-tions that lenders make,because in narratives,they can counter past mistakes and difficult circumstances.In this scenario,borrowers make identity claims that offset the attributions made by lenders about the borrower being fundamentally not a creditworthy person.These disposi-tional attributions are often based on visible characteristics (Gilbert and Malone 1995).The most relevant objective characteristic of borrowers is the credit grade assigned by Prosper,derived from the borrower’s personal credit history (Herzenstein,Dholakia,and Andrews 2011).With more than one identity claim,borrowers can present a more com-plex,positive self to counteract negative objective informa-tion,such as a low credit grade.Thus:H 1:The lower the borrower’s credit grade,the greater isthe number of identities claimed by the borrower in the narrative.Role of Narratives in Peer-to-Peer Lending Decisions S141Impact of the Number of Identity Claims onLenders’DecisionAlthough economists often predict that unverifiable information does not matter(e.g.,Farrell and Rabin1996), we suggest that the number of identity claims in a bor-rower’s narrative play a role in lenders’decision making, for at least two reasons.First,borrower narratives with too few identities may fail to resolve questions about the borrower’s disposition.If a borrower fails to provide suf-ficient diagnostic information for lenders to make attri-butions about the borrower(Cramton2001),lenders may suspect that the borrower lacks sufficient positive or dis-tinctive information or is withholding or hiding germane information.Second,the limited diagnostic information provided by fewer identity claims limits a decision maker’s ability to resolve outcome uncertainties.Research on perceived risk supports this reasoning;decision makers gather informa-tion as a risk-reduction strategy and tend to be risk averse in the absence of sufficient information about the decision (e.g.,Cox and Rich1964).In the P2P lending arena,the loan request and evaluation process unfold online with-out any physical interaction between the parties.Further-more,on Prosper,borrowers are anonymous(real names and addresses are never revealed).This lack of seemingly relevant information is especially salient,because many decision makers view unmediated online environments as ripe for deception(Caspi and Gorsky2006).To the extent that the identity claims presented in a narrative reduce uncertainty about a borrower,lenders should be more likely to view the listing favorably,increase loan funding,and decrease thefinal interest rate.Therefore,the number of identity claims in a borrower’s narrative may serve as a heuristic for assessing the borrower’s loan application and lead to greater interest in the listing.Although we suggest that the number of identities bor-rowers claim result in favorable lending decisions,we also argue that these identity claims may persuade lenders erroneously,such that lenders fund loans with a lower likelihood of repayment.Borrowers can use elaborate multiple-identity narratives to craft“not-quite-true”stories and make promises they mightfind difficult to keep.More generally,a greater number of identity claims suggests that borrowers are being more strategic and positioning them-selves in a manner they believe is likely to resonate with lenders,as opposed to presenting a true self.Therefore,we posit that,consciously or not,borrowers who construct sev-eral identities may have more difficulty fulfilling their obli-gations and be more likely to fall behind on or stop loan repayments altogether.Thus,despite the high stakes of the decision,lenders swayed by multiple identities are more likely to fall prey to borrowers that underperform or fail (Goffman1959).H2:Controlling for objective,verifiable information,the more identities borrowers claim in their loan requests,the morelikely lenders are to(a)fund the loan and(b)reduce itsinterest rate,but then(c)the lower is the likelihood of itsrepayment.Role of the Content of Identity Claims onLender Decision Making and Loan PerformanceWe also examine the extent to which select identities affect lenders’decision making and the longer-term per-formance of loans.With a limited theoretical basis for determining the types of identities most likely to influ-ence lenders’decision making,this part of our study is exploratory.Research on trust offers a promising starting point(Mayer,Davis,and Schoorman1995),because it sug-gests that identities may reduce dispositional uncertainty and favorably influence lenders.Trust is a crucial element for the consummation of an economic exchange(Arrow 1974).Scholars theorize that trust involves three compo-nents:integrity(borrowers adhere to principles that lenders accept),ability(borrowers possess the skills necessary to meet obligations),and benevolence(borrowers have some attachment to lenders and are inclined to do good)(Mayer, Davis,and Schoorman1995).We theorize that trustworthy,religious,and moral iden-tities increase perceptions of integrity because they lead lenders to believe that borrowers ascribe to the lender-endorsed principle of fulfilling obligations,either directly (trustworthy)or indirectly by adhering to a philosophy (religious or moral).Specifically,a moral identity tells potential lenders that the person has“a self-conception organized around a set of moral traits”(Aquino et al.2009, p.1424),which should increase perceptions of integrity.A religious identity signals a set of role expectations to which a person is likely to adhere,and though religions vary in the content of these expectations(Weaver and Agle 2002),many of them include principles oriented against lying or stealing and toward honoring contractual agree-ments.A hardworking identity should increase perceptions of integrity,because hardworking people are determined and dependable,which often makes them problem solvers (Witt et al.2002),meaning that they will do their best to meet their obligations,a disposition likely to resonate with lenders.We also reason that the religious and moral identities invoke in lenders a sense of benevolence,which is a foun-dational principle of many religions and moral philoso-phies.Similarly,the economic hardship identity may invoke benevolence,because the borrower exhibits forthrightness about his or her past mistakes and thus suggests to lenders that the borrower is trying to create a meaningful relation-ship based on transparency.We theorize that an identity claim of success can increase perceptions of ability and the belief that the narrator is capable of fulfilling promises(Butler1991).Lenders are more likely to lend money to a borrower if they perceive that the person is capable of on-time repayment(Newall and Swan2000).A successful identity likely describes the past or present,but it also can serve as an indication of a probable future(i.e.,the borrower will continue to be successful),which helps“fill in the blanks”about the bor-rower in a positive way.In contrast,economic hardship likely constructs the borrower as someone who has had a setback,which ultimately undermines perceptions of ability and thus negatively affects lenders’decisions.We have offered some preliminary theory in support of these specific relationships between identity content and loan funding/interest rate reductions,but this examinationS142JOURNAL OF MARKETING RESEARCH,SPECIAL ISSUE2011remains exploratory,so we pose these relationships as exploratory research questions(ERQ):ERQ1:Which types of identity claims influence lending deci-sions,as indicated by(a)an increase in loan fundingand(b)a decrease in thefinal interest rate?We also explore the impact of the content of identity claims on loan performance.We envision two potential sce-narios.In thefirst,identities are diagnostic of the borrower or serve as self-fulfilling prophecies.Examining the ability aspect of trustworthiness,we anticipate a negative relation between an economic hardship identity and loan perfor-mance(borrowers validate their claim of setbacks)but a positive relation between a successful identity and loan per-formance(borrowers prove their claim of past success). Moreover,we expect the four integrity-related identities—trustworthy,hardworking,moral,and religious—to indicate better loan performance.After a self-presentation as having integrity,the borrower probably has a strong psychological desire for consistency between the narrative and his or her actions(Cialdini and Trost1998).That is,in their narra-tives,borrowers may make an active,voluntary,and public commitment that psychologically binds them to a partic-ular set of beliefs and subsequent behaviors(Berger and Heath2007).Because these four identities speak to funda-mental self-beliefs versus predicted outcomes(e.g.,success or hardship),they can strongly motivate borrowers to live up to their claims.Thus these identities,regardless of their accuracy,can become true and predict the performance of the lending decision.In the other scenario,however,identities improve the lender’s impression of the borrower,thereby allowing bor-rowers to exert control over the provided impressions (Goffman1959).Borrowers(or narrators,more generally) construct positive impressions and may misrepresent them-selves and send signals that may not be objectively war-ranted.Despite the belief that self-constructing identities are helpful for a lending decision,they actually may have no impact or even be harmful to lenders.These mixed pos-sibilities lead to another exploratory research question: ERQ2:How are the content of identity claims and loan perfor-mance related?STUDYDataOur data set consists of1,493loan listings posted by borrowers on Prosper in June2006and June2007.We extracted this data set using a stratified random sampling ing a web crawler,we extracted all loan listings posted in June2006and June2007(approximately5,400 and12,500listings,respectively).A significant percentage of borrowers on Prosper have very poor credit histories, and most loan requests do not receive funding.To avoid overweighting high-risk borrowers and unfunded loans,we sampled an equal number of loan requests from each credit grade.To do so,wefirst separated funded loan requests from unfunded ones,then divided each group by the seven credit grades assigned by Prosper.We also eliminated all loan requests without any narrative text,for three reasons. First,including loan requests without narratives could con-found the borrower’s choice to write something other than narratives in the open text box with the choice to write nothing at all.Second,the vast majority of listings lack-ing a narrative do not receive funding.Third,loan requests without text represent only9%of all loans posted in June 2006and4%of those posted in June2007.We nevertheless used the“no text”loans in our robustness check.We randomly sampled posts from the14subgroups (2funding status×7credit grades).In2006,we sampled 40listings from each subgroup(until data were exhausted) to obtain513listings;in2007,we sampled70listings from each subgroup to obtain980listings,for a total of 1,493listings.Each listing includes the borrower’s credit grade,requested loan amount,maximum interest rate,loan funding,final interest rate of funded loans,payback sta-tus of funded loans after two years,and open-ended text data.Before combining the data from2006and2007,we tested for a year effect but found none,which supports their combination.Dependent VariablesThefirst dependent variable,loan funding,ranges from 0%to905%in our data set,but requiring an equal inclu-sion of all credit ratings skews these statistics.The mean percentage funded(including all listings)is105.74%(SD= 129 2)and that for funded listings is205.45%(SD=119 6). Because it was skewed,we log-transformed loan fund-ing as follows:Ln(percent funded+1).The second depen-dent variable,percentage reduction in thefinal interest rate, ranges from0%to56%in our data set.The mean per-centage reduction in interest rate for all listings is6.4% (SD=10 7)and for funded listings is11.88%(SD=12 75). Because the distribution is skewed,we log-transformed it (we provide the distributionfigures in the Web Appendix, /jmrnov11).The third dependent variable is loan performance,mea-sured two years after loan funding.For each funded loan in our data set,we obtained data about whether the loan was paid ahead of schedule and in full(31.1%of funded list-ings),was current and paid as scheduled(40.5%),involved payments between one and four months late(7.1%),or had defaulted(21.3%).This dependent variable may appear ordered,but the likelihood ratio tests reveal that a multino-mial logit model fares better than an ordered logit model for analyzing these data(for both the number and content of identities).Thus,in the following analysis,we employ a multinomial logit model.Independent VariablesWe read approximately one-third of all narratives and developed our inductively derived list of six identity claims (Miles and Huberman1994):trustworthy,economic hard-ship,hardworking,successful,moral,and religious,as we define in Table1.Two research assistants examined the same data and determined these six identities were exhaustive.Next,five additional pairs of research assistants (10total)coded the entire data set.We coded each iden-tity as a dichotomous variable that receives the value of1 if the identity claim was present in a borrower’s narrative and0if otherwise.A pair of research assistants read each listing in the data set,independently atfirst,then discussed them to determine the unified code for each listing.Accord-ing to20randomly sampled listings from our data set,used。

国际神经精神访谈MINI 6.0(调查问卷)

e-mail: dsheehan@

tel: +33 (0) 1 53 80 49 41; fax : +33 (0) 1 45 65 88 54

e-mail: even-sainteanne@orange.fr

M.I.N.I. 6.0.0 (October 10, 2010) (10/10/10)

过去的 2 周 既往发作情况

a 您的食欲几乎每天是减少还是增加呢? 您的体重是否会在不刻意努力的情况下减 否

是

否

是

少或增加(例如,在一个月里,对一个体重为 160 磅/ 70 公斤的人而言,体重增减

大约 5%或 8 磅,或 3.5 公斤)呢?

如果对任何一个问题的回答为“是 ”,则标记为“ 是”。

b 您是否几乎每晚都有睡眠问题(难以入睡、半夜醒来、早上醒得过早或睡眠过 多)?

F50.0 F41.1

F60.2

M.I.N.I. 6.0.0 (October 10, 2010) (10/10/10)

2

M.I.N.I - China/Mandarin - Version of 16 Jan 12 - Mapi Institute.

ID6273 / MINI6.0_AU11.0_cmn-CN.doc

评分指导:

必须对所有的问题评分。 通过圈选每个问题右边的“是”或“否”来进行评分。 访谈员的临床判断应当被用来标记患者 的回答。 访谈员在提出问题和对答案进行评分时,需要特别注意文化信仰的多样化。 访谈员应当在必要时要求获 得一些例子,以确保对回答做准确的标记。 应当鼓励患者对任何不完全清楚的问题提出澄清的要求。 临床医生必须确保患者会考虑到问题的各个方面(例如,时间范围、频率、严重程度和/或其它选择)。 在 M.I.N.I.中,最有可能由于器质性原因或者因酒精或药物的使用而引发的症状不应当被标记为肯定的回答。

爱德华个人偏好量表

爱德华个人偏好量表“爱德华个人偏好量表”(EDWARDS' PERSONAL PREFRENCE SCHEDVLE)是爱德华以莫瑞(H.A.Murry)的十五种人类需要理论为基础编制的,简称EPPS。

这十五种人类需要是:成就(ach)、顺从(def)、秩序(ord)、表现(exh)、自主(aut)、亲和(aff)、省察(int)、求助(suc)、支配(dom)、谦卑(aba)、慈善(nur)、变异(chg)、持久(end)、异性恋(het)、攻击(agg)。

“爱德华个人偏好测验”自编制起至今大约已有30多年的历史,它被广泛地应用于研究和咨询工作。

根据该测验的结果能较快地了解到人的一般性格特点与需要特点,能对从事不同职业的人加以区分,还可以对特定工作中的人员做出可能成功与失败的估价。

“爱德华个人偏好测验”适用年龄范围较广,可用于中学生、大学生和正常成人,既可进行团体测验也可进行个人测验。

量表结果测评“爱德华个人偏好量表”是由这十五种需要量表和一个稳定性量表所组成的。

整个测验共有225对叙述组成的题目,其中有15个题目重复两次。

答题时,被试必须对每道题都做出选择。

完成整个量表评定约需40-50分钟。

在十五个量表中,每个量表有九种叙述,这九种叙述轮流与其他需要叙述配对,每种叙述重复两、三次,令被试每题的叙述做强迫选择。

之所以采用强迫选择的形式,是因为爱德华发现赞同陈述的机率是依赖于陈述的社会需求的价值尺度。

通过使用强迫选择形式,被试必须在项目内容的基础上(即需要和动机),而不是在陈述的社会需求的基础上作出反应。

强迫选择形式的使用也导致了可比性分数——这些分数显示出个体之间各种需要的相对强度。

“爱德华个人偏好测验”的十五种需要得分最高为28分,最低为 0分,因国内目前还没有较为成熟的常模,所以解释时主要考虑被试各种需要的排列顺序及其组合结构。

稳定性分数最高为15分,最低为 0分,稳定性分数越高,被试回答问题的稳定性越低,当稳定性分数大于 7分时,答卷的真实性值得怀疑。

很全面的九型人格课件全

A型

线性性思维方式

胆汁质

B型

发散性思维方式

抑郁质

O型

推理性思维方式

多血质

AB型

聚合平衡性思维方式

粘液质

星座分析

3月21日---4月19日

白羊座

火星

4月20日---5月20日

金牛座

金星

5月21日---6月20日

双子座

水星

6月21日---7月22日

巨蟹座

月亮

7月23日---8月22日

狮子座

1号

完美

1号 识人之术:

面部表情:变化少,严肃,笑容不多;眼神:讲话方式/语调:缺乏幽默感,直接;毫不留情,不懂得婉转;重复讯息多次;速度偏慢,声线较尖。常用词汇: 应该、不应该,对、错;不、不是的;照规矩。

身体语言:挺、硬,可以长久保持同一姿势;着装特征: 1、非常干净整洁的印象 2、对颜色、饰物的搭配很认真

1号 识人之术:

1号代表人物

1号的性格倾向

完美型

身心受压,自我防卫时倾向4#

身心舒泰,无忧无虑时倾向7#

顺境时·放松时: 认为环境与他的要求接近时,会处于轻松状态。 1号→ 7号:尝试新鲜刺激的事物,旅游,娱乐,追求快乐逆境时·受压时: 环境不断变化,他的努力无法达到他要求的改善,他所处的环境倾向混乱,却无能为力时 1号→ 4号:非常情绪化,向火山爆发。

Type One 1号

The Perfection 完美型

性格形成

心理创伤:当他表达自己的看法时,总是感觉受到了严厉 的斥责或惩罚防御机制:听话、小心行事习惯性行为:严格自控,遵守纪律,小心谨慎主要人格特征:正直,公平,追求质量,关注细节

1号基本特性

新核心综合学术英语教程第二册_Unit_2

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy was a Greco-Egyptian writer of Alexandria, known as a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. Ptolemy was the author of several scientific treatises, three of which were of continuing importance to later Islamic and European science. The first is the astronomical treatise now known as the Almagest. The second is the Geography, which is a thorough discussion of the geographic knowledge of the Greco-Roman world. The third is the astrological treatise known in Greek as the Tetrabiblos (―Four books‖), in which he attempted to adapt horoscopic astrology to the Aristotelian natural philosophy of his day.

In this unit, you will

• learn about the concept ―scientific method‖ and its application in science; • research ―verification of theories‖ and falsification of theories‖ on the Internet and find reliable information; • learn words, expressions, and sentence patterns related to the theme and use them in writing and speech; • learn strategies such as listening for introduction (listening), skimming (reading), agreeing and disagreeing (discussing), writing thesis statements (writing), etc; • learn the deductive and inductive method of reasoning; • give an oral presentation on an assigned topic to the class.

科技文献检索作业及答案

科技文献检索1.使用《中文科技期刊数据库(维普)》同名作者功能,检索西安理工大学第一作者为张明所发表的论文,请写出检索式,检中文献条数,并任选择其中的两篇以标准格式标注。

(5分) 2.利用《中国学术期刊全文数据库(CNKI)》,检索一个你感兴趣的主题,在检索结果中以被引频次排序,在引用频次最高的前五名文献中任选其一,以标准格式标注出该篇文献及其二级参考文献,参考文献,共引文献,同被引文献,引证文献,二级引证文献,相似文献各一篇。

(10分)3.任选一个中文学位论文数据库,查找2007年至今,北京交通大学博士论文收录情况,写出检索数据库名称,检索式,检中文献条数,并任选两篇以标准格式标注。

(5分)4.使用BALIS馆际互借系统,借阅一本图书。

要求:写出该书所属图书馆及其索书号,并以标准格式标注出该书,BALIS馆际互借系统生成的订单号,并以无格式文本形式复制出“申请单撤销”界面所显示文字。

(5分)5.请写出检索中外文专利的主要资源,任选其中之一检索本学科专利。

写出检索的资源名称,检中文献条数,并以标准格式标注。

(5分)6.列出北京交通大学图书馆外文全文期刊数据库名称,并将本专业全文数据库列出。

(5分)7.利用本专业外文全文数据库检索本专业期刊论文,写出数据库名称、检索式,检中条数,并任选两条以标准格式标注。

(5分)8.利用PQDT数据库检索本专业学位论文,写出检索式,检中条数,并任选两条以标准格式标注。

(5分)9.利用Science direct(Elsevier)数据库,检索“ComputerScience(计算机科学)”领域 2011年全年25篇最热门的论文,将前两条以标准格式标注。

(5分)10.使用Engineering Village 查找2007年至今有关轨道交通(rail transit)方面,北京交通大学的作者(beijing jiaotong university或100044)以英文(English)发表的期刊论文(Journal article)。

九型人格中的李小龙自我欣赏,动画借鉴他人的 ppt课件(1)

第三型:事业型

• 【欲望特质】:追求成果 〖基本困思〗:我若 没有成就,就没有人会爱我。 〖主要特征〗: 强烈好胜心,喜欢认威,常与别人比较,以成就 衡量自己的价值高低,着重形象,工作狂,惧怕 表达内心感受 ;希望能够得到大家的肯定。是 个野心家,不断地追求有效,希望与众不同,受 到别人的注目、羡慕,成为众人的焦点。 〖主 要特质〗:自信、活力充沛 、风趣幽默 、满有 把握 、处世圆滑 、积极进取 、美丽形象 〖生活 风格〗:爱数说自己成就,逃避失败,按着长远 目标过活。 孙悟空

Bruce Lee

一、功夫荣誉 1957年,获香港校际拳击赛冠军

1967年,在美国创立跨越门派限制的、世界性的 现代中国功夫——“科学的街头格斗技”——截拳道 (Jeet Kune Do),时年二十七岁

1972年,以截拳道宗师身份,入选国际权威武术 杂志《黑带》名人堂。这标志着李小龙新创截拳道获 得国外武术界的权威公认

第四型:自我型

• 【欲望特质】:追求独特 〖基本困思〗:我若不是独特 的,就没有人会爱我。 〖主要特征〗:情绪化,追求浪 漫,惧怕被人拒绝,觉得别人不明白自己, 占有欲强, 我行我素生活风格:爱讲不开心的事,易忧郁、妒忌,生 活追寻感觉好;很珍惜自己的爱和情感,所以想好好地滋 养它们,并用最美、最特殊的方式来表达。他们想创造出 独一无二、与众不同的形象和作品,所以不停地自我察觉 、自我反省,以及自我探索。 〖主要特质〗:易受情绪 影响、倾向追求不寻常、艺术性而富有意义的事物 、多 幻想,认为死亡、苦难、悲剧才是极具价值和真实的生命 、对美感的敏锐可见于独特的衣着,及对布置环境的品味 显出他的独特性、极具创造力、过分情绪化、容易沮丧或 消沉 、常觉生命是一个悲剧 、对人若即若离,怕亲密的 关系令人发现自己不完美就会 九型人格 离他而去。 〖生 活风格〗:爱讲不开心的事,易忧郁、妒忌,生活追寻感 觉好。

海伦凯勒励志英语作文

Helen Kellers life is a testament to the power of the human spirit and serves as a source of inspiration for many.Born in1880,she was left deaf and blind by an illness at the age of19months.Despite these immense challenges,she managed to overcome her disabilities and lead a life of remarkable achievements.Early Life and Struggles:Helens early years were filled with frustration and isolation.Unable to communicate with the world around her,she was often misunderstood and considered a difficult child.It was not until the age of seven that her life took a significant turn when her family hired Anne Sullivan,a young teacher who herself had overcome significant visual impairment.The Impact of Anne Sullivan:Anne Sullivan played a pivotal role in Helens life.Through patience and innovative teaching methods,she managed to break through Helens isolation.The famous story of Helens realization that the water flowing over her hand was the same as the sign for water in Annes fingers is a powerful illustration of the breakthrough they achieved together.Education and Advocacy:With Sullivans help,Helen learned to communicate using sign language and later,the manual alphabet.She went on to attend the Perkins School for the Blind and then Radcliffe College,becoming the first deafblind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. Helens education was not just for personal growth but also to advocate for the rights of people with disabilities.Writing and Public Speaking:Helen Keller became a prolific author and public speaker.Her autobiography,The Story of My Life,is a classic in the genre of inspirational literature.She wrote numerous books and articles on her experiences and the importance of education and accessibility for the disabled.Philanthropy and Social Activism:Beyond her writing,Helen Keller was deeply involved in philanthropy and social activism.She worked with the American Foundation for the Blind,advocating for better conditions and opportunities for the visually impaired.Additionally,she was a supporter of the womens suffrage movement and a pacifist during World War I.Legacy:Helen Kellers legacy is one of resilience,determination,and the pursuit of knowledge despite overwhelming odds.Her life story continues to inspire people around the world to overcome their own challenges and to fight for the rights of others.In conclusion,Helen Kellers journey from a seemingly hopeless beginning to a life of profound impact is a narrative of the triumph of the human will.Her story encourages us to look beyond our limitations and to strive for a world where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential.。

爱德华个性偏好量表

维度名称得分说明对竞争成功的需要achievement 7做事喜欢尽力而为,事业上锐意进取,渴望成功;目标取向,脚踏实地,竞争意思强;喜欢完成一些需要运用技巧和付出努力的工作;努力达到和超越自己设立的高标准,提高工作效率和质量;期望成为公认的权威;更愿意从事一些具有重大意义的事情;希望能完成一些困难的任务,喜欢解决复杂问题;在竞争中渴望获胜;对接受领导的需要deference 4喜欢从他人那里获得建议;期望知道他人对自己感兴趣问题的看法;乐于按照他人的指示和期望行事;容易符合他人、赞扬他人;愿意接受他人领导,喜欢让他人来做决定;遵从习俗,避免做有背习俗的事情;听从指示,遵守政策和制度;热切学习和效仿榜样和权威人物;喜欢与同事合作,特别是年长或有经验的;计划执行前,征求专家的意见;对计划规则的需要order 6喜欢做出准确和整洁的东西;日常事物中遵守固定的时间表,在解决复杂问题前制订详细计划;期望工作是井然有序的;在旅行前做事先的计划;喜欢制订长期计划,并为自己拟定具体的工作目标和步骤,定期检查工作进度;将工作上用到的东西编排得有次序,便于查找,并一直保持这种次序;定时定量进餐,生活有规律;对自我表现的需要8 喜欢在众人面前讲话,透过言语或非言语地行为表现自己的自信和重要性;喜欢谈一些表现自己机智幽默的话题,喜欢讲笑话和故事,喜欢谈论自己所经历得一些奇特和冒险的事情;希望他人能注意到自己的存白其意义的字眼,或提出明知没有人能回答出来的问题; 对独立自主的需要autonomy 9喜欢能随自己意志来去自如,按照自己的意思做事;希望不受他人影响,能独立决定自己的事;喜欢作别人认为不合常规的事,喜欢采用与周围人不同的做法;经常回避要按照例行方法办事的场合;有勇气向上司置疑或与权威争辩;避开责任和任务;喜欢独立做事或解决难题,不喜欢别人的督导和指引;喜欢那些乐于授权的上司;喜欢独立完成不需要合作的工作;对人际交往的需要affiliation 7喜欢对朋友忠实,参加各成员之间彼此温暖与友善的团体,喜欢帮助朋友做事;喜欢结交新朋友和广交朋友;喜欢与朋友共享一切,喜欢与朋友共事而不喜欢独自工作;喜欢与朋友有深厚的交情;经常给朋友打电话或写信;喜欢与同事和客户建立和维持一种情感关系;希望在工作中有关系密切的朋友;喜欢团队合作;团结的气氛;喜欢与他人共享信息;在工作中擅长交际;愿意参加小组或更多人的聚会;对人际省察的需要interaception 9喜欢分析别人的感情与动机,观察别人在某种情况下的感觉;喜欢了解同事和客户在不同问题上的看法和体会他们的情感;喜欢设身处地去替别人考虑问题,体察别人的行为和反映;对行为的动机比行为本身更有兴趣,以动机而不是最后结果来评价他人;喜欢研究分析和预测他人的行为;对获得帮助的需要succorance 7当遇到困难时,期望获得朋友的帮助;希望获得他人的鼓励;希望他人友好的对待自己;当有问题时,希望朋友能表示同情与理解,重视他人的意见;希望别人能时常关心自己,喜欢接近那些善于关心别人的人;当自己生病时,喜欢朋友们为此感伤;喜欢让别人替自己做事情;对支配管理的需要dominance 7喜欢表明自己的观点和立场;期望成为一个团体的领导,发布命令,指挥他人;希望别人把自己看成是个领导,在一群人中喜欢首先发言;希望被提拔或指派担任一定的职务、承担一定的责任;喜欢替团体做决策;喜欢被拉去解决冲突和矛盾;期望影响他人来按照自己的想法办事,喜欢指导他人的工作,希望经常被请教;对温顺谦卑的需要abasement 5当作错事时容易感到内疚;认为没有做好事就应该受到指责;把错误和困难归因于自己的能力不足;认为个人应该忍受痛苦,而不是伤害他人;遇事不与人争执常常屈从,避免与人有公开的矛盾;在不适应的情形下表现出沮丧;在上司和有能力的同事面前表现得缺乏自信;在很多方面假定别人比自己强;很难坚持己见,在公众场合表现出从众行为;对表达关心的需要nurturance 6当朋友遇到麻烦时愿意伸出援手;易宽容和原谅别人;友好的对待他人;对不幸的人提供感情支持;喜欢替别人做点小事;聆听他人的困难,根据“利他”原则来决定行动的方案;喜欢协助同事和下属;对新奇变化的需要change 7追求新的和不同的事物;对新经验和事物采取欢迎得态度;喜欢旅行和认识不同的人;不喜欢做重复性的工作,希望在每天的工作中体验到新奇和变化;乐于尝试各种新的不同的工作,敢于承担风险,尝试新方法,思维具有创新性;随时都会摒弃那些不合用的做法和程序;能忍受上司和工作环境得频繁变化;追求新的时尚,好赶时髦;对持久忍耐的需要endurance 5办事喜欢从头到尾,从不半途而废;在困难面前坚持不懈;对于指定的工作能全力以赴;尽管失败,仍追求目标;执着地去解决问题,乐于付出额外的努力,直到完成全部任务后才罢休;即使进展缓慢,也会坚持解决难题;在任务完成之前,不愿改变方向开始另一个任务;重耐力和恒心;能长时间不分心地工作,不受周围干扰;对进取攻击的需要Aggression 4对与自己相反的意见好主动出击;喜欢公开批评他人,告诉别人自己的看法;好开别人玩笑;当对某人不满时会直接说出来;在受辱后会进行报复;易发怒,当别人不按照自己的意愿做事会职责别人;说话时喜欢压住对方的势头,甚至是咄咄逼人;喜欢阅读报纸杂志上有关暴力的文章;。

主观幸福感测量研究

主观幸福感的测量研究摘要:本文主要介绍了目前主流的两种主观幸福感测量的研究思路及其相应的测量方法。

一种是基于被试自我报告的“评价幸福”,主要采用自陈量表测量主观幸福感,另一种是基于被试实时情绪体验的“体验幸福”,主要采用结构化问卷及访谈相结合的形式测量。

本文对比分析了两种不同测量思路,指出应将多种测量方法结合以进一步探讨主观幸福感的总体情况。

最后本文对主观幸福感测量未来的发展方向做出了展望。

关键词:主观幸福感;总体满意感量表;体验取样法;日重现法;U指数主观幸福感的研究目前主要有两种取向,每种研究取向提供一种主观幸福感的概念,而且各自又依赖于不同的测量方法。

第一种研究取向将主观幸福感看做是个体对生活以及它的各方面的总体评价,而对主观幸福感的测量需要被试报告他们在工作、社会关系等生活领域的总体幸福与满意度,即评价幸福(evaluated well-being)。

例如欧洲调查指标(eurobarometer question)。

第二种研究则将主观幸福感看做跨时间多重情绪反应的整合,强调即时的情绪体验,这一研究取向从效用概念的区分出发,重新诠释体验效用,并针对体验效用提出客观幸福(objective happiness)的概念,也即体验幸福(experienced well-being),并发展出适合体验幸福的测量方法。

1. 评价幸福早期典型对幸福感的测量方法多是单题测验,这类问题通常要求受测者用一个整体印象回答。

如世界价值调查(World Values Survey),来自81个国家的被试被问到一个问题,“考虑一下你所有的情况,近来你对自己的生活总体情况满意吗?”。

美国综合社会调查(The General Social Survey,GSS)中,人们被问到,“你认为近期发生的所有事怎么样,你觉得自己非常幸福、十分幸福还是不太幸福?”。

历经几十年的发展,幸福感评估技术取得了长足的进步,测量技术逐步系统化,经历了从简单笼统到具体,从单一到系统的发展历程。

大五人格模型和大三人格模型的比较

LOOKING BEYOND THE FIVE-FACTOR MODEL: COLLEGE SELF-EFFICACY AS A MODERATOR OF THE RELATIONSHIPBETWEEN TELLEGEN’S BIG THREE MODEL OF PERSONALITY AND HOLLAND’S MODEL OF VOCATIONAL INTEREST TYPESBy Elizabeth A BarrettThe Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality and Tellegen’s Big Three Model of personality were compared to determine their ability to predict Holland’s RIASEC interest types. College self-efficacy was examined as a moderator of the relationship between Tellegen’s Big Three model and the RIASEC interest types. A sample of 194 college freshmen (i.e., less than 30 credits completed) was drawn from the psychology participant pool of a mid-sized Midwestern university. Instruments included the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) to measure the FFM; the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire Brief Form (MPQ-BF) to measure Tellegen’s Big Three model of personality; the College Self-Efficacy Inventory (CSEI) to measure college self-efficacy; and the Self Directed Search (SDS) to measure Holland’s RIASEC model of vocational interests. Findings from correlational analyses supported previous research regarding relationships among the FFM and the RIASEC interest types, and relationships among Tellegen’s Big Three and the RIASEC interest types. As hypothesized and tested via regressions for each of the six interest types, Tellegen’s Big Three model predicted all six vocational interests types (p < .001 for all), while the FFM only predicted two types at p < .05. College self-efficacy did not moderate the relationship between Tellegen’s Big Three and the RIASEC interest types. Implications and future research are discussed.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSSeveral people have assisted me with the completion of this thesis, and I wish to thank the following people for their help and guidance:In acknowledgement of excellent guidance of this project, Dr. McFadden chairperson, whose knowledge and encouragement pushed the progress of this thesis and my development as a writer and researcher.Dr. Adams and Dr. Miron, committee members, who graciously gave their time and shared their expertise in the completion of this project, specifically, Dr. Adams who aided with the data analysis of this project and worked through multiple analysis problems with me.iiTABLE OF CONTENTSPage INTRODUCTION (1)THEORY AND LITERATURE REVIEW (4)Personality Traits and Vocational Interests Defined (4)The Five-Factor Model (FFM) of Personality (4)Holland’s Theory of Vocational Interest Types (5)Overlap between the FFM and RIASEC (7)Criticisms and Limitations of the FFM (9)Looking Beyond the FFM: Tellegen’s Big Three Model of Personality (11)Comparing Tellegen’s Big Three and the FFM (14)College Self-Efficacy: Moderating Role (16)Conclusion (20)METHOD (22)Participants (22)Procedure (23)Measures (23)Methods of Data Analysis and Missing Data (27)RESULTS (29)Descriptive Statistics (29)Relationship between the FFM and the RIASEC Interest Types:Hypothesis 1a-1e (29)Relationship between Tellegen’s Big Three and the RIASEC InterestTypes: Hypothesis 2a-2c (30)Comparing the FFM and Tellegen’s Big Three: Hypothesis 3 (31)College Self-Efficacy as Moderator: Hypothesis 4 (32)iiiTABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) DISCUSSION (34)The Relationship between the FFM and the RIASEC Interest Types (34)The Relationship between Tellegen’s Big Three and the RIASECInterest Types (35)Comparing Tellegen’s Big Three and the FFM (36)College Self-Efficacy as a Moderator (37)Limitations (38)Implications and Future Research (39)Conclusions (41)APPENDIXES (42)Appendix A: Tables (42)Table A-1. Holland’s Vocational Personality Types Described: RIASEC.. 43 Table A-2. Overlap Between the FFM and RIASEC (44)Table A-3. The Big Three of Tellegen measured by the MPQ: HigherOrder and Primary Trait Scales (45)Table A-4. Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations (47)Table A-5. Regression Analysis: Realistic Interest Type as DependentVariable (48)Table A-6. Regression Analysis: Investigative Interest Type as DependentVariable (48)Table A-7. Regression Analysis: Artistic Interest Type as DependentVariable (49)Table A-8. Regression Analysis: Social Interest Type as DependentVariable (49)Table A-9. Regression Analysis: Enterprising Interest Type as DependentVariable (50)Table A-10. Regression Analysis: Conventional Interest Type asDependent Variable (50)Table A-11. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis:Realistic Interest Type as Dependent Variable (51)Table A-12. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis:Investigative Interest Type as Dependent Variable (51)Table A-13. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis:Artistic Interest Type as Dependent Variable (52)Table A-14. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis: SocialInterest Type as Dependent Variable (52)Table A-15. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis:Enterprising Interest Type as Dependent Variable (53)ivTABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)Table A-16. Hierarchical Multiple Moderated Regression Analysis:Conventional Interest Type as Dependent Variable (53)Appendix B: Figure (54)Figure B-1. Holland’s Hexagonal Model (55)Appendix C: Information Sheet and Surveys (56)REFERENCES (73)vINTRODUCTIONPersonality traits and vocational interests are two major individual difference domains that influence numerous outcomes associated with work and life success. For example, research has shown that congruence between personality traits and one’s vocation is related to greater job performance and job satisfaction (Barrick, Mount, & Judge, 2001; Hogan & Blake, 1999; Zak, Meir, & Kraemer, 1979). Additionally, specific personality traits are hypothesized to play a role in determining job success within related career domains (Sullivan & Hansen, 2004). Personality is a relatively enduring characteristic of an individual, and therefore could serve as a stable predictor of why people choose particular jobs and careers.Personality traits and vocational interests are linked by affecting behavior through motivational processes (Holland, 1973, 1985). Personality traits and vocational interests influence choices individuals make about which tasks and activities to engage in, how much effort to exert on those tasks, and how long to persist with those tasks (Holland, 1973, 1985; Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005). Research has shown that when individuals are in environments congruent with their interests, they are more likely to be happy because their beliefs, values, interests, and attitudes are supported and reinforced by people who are similar to them (Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005). Furthermore, research has demonstrated that personality and interests may shape career decision making and behavior; personality and interests guide the development ofknowledge and skills by providing the motivation to engage in particular types of activities (Sullivan & Hansen, 2004).As relatively stable dispositions, personality traits influence an individual’s behavior in a variety of life settings, including work (Dilchert, 2007). Individuals often prefer jobs requiring them to display behaviors that match their stable tendencies. Thus individuals will indicate a liking for occupations for which job duties and job environments correspond to their personality traits. Such a match between personal tendencies and job requirements can support adjustment and eventually occupational success, making the choice of a given job personally rewarding on multiple levels (Dilchert, 2007).People applying for jobs need to try to understand themselves more fully in order to determine if they will be satisfied with their career choices based on their personality traits. This process can be aided by vocational counselors who conduct vocational assessments. The purpose of vocational assessment is to enhance client self-understanding, promote self-exploration, and assist in realistic decision making (Carless, 1999). According to a model proposed by Carless (1999), career assessment is based on the assumption that comprehensive information about the self (e.g., knowledge of one’s personality) in relation to the world of work is a necessary prerequisite for wise career decision making.Self-efficacy beliefs--personal expectations about the ability to succeed at tasks (Bandura, 1986)--are often assessed by vocational counselors. This study examines college self-efficacy--belief in one’s ability to perform tasks necessary for success incollege (Wang & Castaneda-Sound, 2008). Self-efficacy determines the degree to which individuals initiate and persist with tasks (Bandura, 1986), and research has found that personality may influence exploration of vocational interests, through high levels of self-efficacy (Nauta, 2007).There is an abundance of literature supporting that the Five-Factor Model (FFM) (discussed in depth in following sections) of personality predicts Holland’s theory of vocational interest types; however, there is little literature that extends beyond use of the Five-Factor Model. This is due to the adoption of the FFM as an overriding model of personality over the past fifteen years. However, as will be demonstrated later, several criticisms of the model have surfaced. In light of these criticisms the purpose of this study is to extend the existing literature that has established links between the FFM and Holland’s vocational interest types, while examining the relationship between an alternate personality model, Tellegen’s Big Three (as measured by the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ)) and Holland’s types. Furthermore, this study will examine the moderating role that college self-efficacy plays on the relationship between Tellegen’s Big Three and Holland’s interest types.THEORY AND LITERATURE REVIEWPersonality Traits and Vocational Interests DefinedPersonality traits refer to characteristics that are stable over time and are psychological in nature; they reflect who we are and in aggregate determine our affective, behavioral, and cognitive styles (Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005). Vocational interests reflect long-term dispositional traits that influence vocational behavior primarily through one’s preferences for certain environments, activities, and types of people (Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005).The Five-Factor Model (FFM) of PersonalityThe FFM, often referred to as the Big Five personality dimensions, is a major model that claims personality consists of five dimensions: Openness to Experience (i.e., imaginative, intellectual, and artistically sensitive), Conscientiousness (i.e., dependable, organized, and persistent), Extraversion (i.e., sociable, active, and energetic), Agreeableness (i.e., cooperative, considerate, and trusting), and Neuroticism, sometimes referred to positively as emotional stability (i.e., calm, secure, and unemotional) (Harris, Vernon, Johnson, & Jang, 2006; McCrae & Costa, 1986; McCrae & Costa, 1987; Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005; Nauta, 2004; Sullivan & Hansen, 2004). The FFM provides the foundation for several personality measures (e.g., NEO-PI, NEO-PI-R, NEO-FFI) that have proved to be valid and reliable and are widely utilized in research today (Costa & McCrae, 1992). There appears to be a large degree of consensusregarding the FFM of personality and the instruments used to measure the model. For instance, the FFM has been shown to have a large degree of universality (McCrae, 2001), specifically in terms of stability across adulthood (McCrae & Costa, 2003) and cultures (DeFruyt & Mervielde, 1997; Hofstede & McCrae, 2004, McCrae, 2001).Holland’s Theory of Vocational Interest TypesHolland’s theory of vocational interests has played a key role in efforts to understand vocational interests, choice, and satisfaction.Holland was very clear that he believed personality and vocational interests are related:If vocational interests are construed as an expression of personality, then theyrepresent the expression of personality in work, school subjects, hobbies,recreational activities, and preferences. In short, what we have called ‘vocational interests’ are simply another aspect of personality…If vocational interests are anexpression of personality, then it follows that interest inventories are personalityinventories. (Holland, 1973, p.7)Vocational interest types, as classified by Holland, are six broad categories (discussed later in the section) that can be used to group occupations or the people who work in them. Holland’s theory of vocational interest types and work environments states that employees’ satisfaction with a job as well as propensity to leave that job depends on the degree to which their personalities match their occupational environments (Holland, 1973, 1985). Furthermore, people are assumed to be most satisfied, successful, and stable in a work environment that is congruent with their vocational interest type. Two ofHolland’s basic assumptions are: (a) individuals in a particular vocation have similar personalities, and (b) individuals tend to choose occupational environments consistent with their personality (Holland, 1997).A fundamental proposition of Holland’s theory is that, when differentiated by their vocational interests, people can be categorized according to a taxonomy of six types, hereinafter collectively referred to as RIASEC (Holland, 1973, 1985). Holland’s theory states that six vocational interest types--Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional (RIASEC)--influence people to seek environments which are congruent with their characteristics (Harris, Vernon, Johnson, & Jang, 2006; Holland, 1973, 1985; Nauta, 2004; Roberti, Fox, & Tunick, 2003; Sullivan & Hansen, 2004; Zak, Meir, & Kraemer, 1979). Holland used adjective descriptors to capture the distinctive characteristics of each interest type (Hogan & Blake, 1999). These are summarized in Table A-1. Holland’s approach to the assessment of vocational interest types was based on the assumption that members of an occupational group have similar work-related preferences and respond to problems and situations in similar ways (Carless, 1999).Realistic types like the systematic manipulation of machinery, tools, or animals. Investigative types have interests that involve analytical, curious, methodical, and precise activities. The interests of Artistic types are expressive, nonconforming, original, and introspective. Social types want to work with and help others. Enterprising types seek to influence others to attain organizational goals or economic gain. Finally, Conventional types are interested in systematic manipulation of data, filing records, or reproducing materials (Tokar, Vaux, & Swanson, 1995).According to Holland’s theory, these interest types differ in their relative similarity to one another, in ways that can be represented by a hexagonal figure with the types positioned at the six points (see Figure B-1). Adjacent types (e.g., Realistic and Investigative) are most similar; opposite types (e.g., Realistic and Social) are least similar, and alternating types (e.g., Realistic and Artistic) are assumed to have an intermediate level of relationship (Holland, 1973, 1985; Tokar, Vaux, & Swanson, 1995).Overlap between the FFM and RIASECMany studies provide evidence of the links between the FFM of personality and the RIASEC interest types. An extensive review of the research investigating the links between the FFM and the RIASEC types identified ten studies that found Extraversion predicts interest in jobs that focus on Social and Enterprising interests. Ten studies showed Openness to Experience predicts interest in jobs that focus on Investigative and Artistic interests. Six studies found Agreeableness predicts interest in jobs that focus on Social interest; six studies showed Conscientiousness predicts interests in jobs that focus on Conventional interests; and one study found Neuroticism predicts interests in jobs that focus on Investigative interests (see Table A-2 for the citations). One discrepancy in this research has been Costa and McCrae’s claims that the FFM applies uniformly to all adult ages, but Mroczek, Ozer, Spiro, and Kaiser (1998) found substantial differences between the structures emerging from older individuals as compared to undergraduate students, in that the five factor structure failed to emerge in the student sample (i.e., agreeableness failed to emerge) as it did with the older sample.All of the links discussed between the FFM of personality and the RIASEC interest types provide the foundation for hypotheses 1a – 1e. Hypotheses 1a – 1e will add to the literature, previously discussed, by assessing current college students early in their college careers. These are the people who have the potential to be most influenced by vocational and career counselors. Given that research has found a discrepancy in FFM profiles of younger and older individuals, it is important to test its efficacy in predicting vocational interests.Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Extraversion will significantly positively correlate withSocial and Enterprising types, but not Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, andConventional types.Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Openness to Experience will significantly positivelycorrelate with Investigative and Artistic types, but not Realistic, Conventional,Social, and Enterprising types.Hypothesis 1c (H1c): Agreeableness will significantly positively correlate withSocial types, but not Realistic, Conventional, Enterprising, Investigative, andArtistic types.Hypothesis 1d (H1d): Conscientiousness will significantly positively correlatewith Conventional types, but not Realistic, Enterprising, Investigative, Social, and Artistic types.Hypothesis 1e (H1e): Neuroticism will significantly negatively correlate withInvestigative types, but not Realistic, Enterprising, Conventional, Social, andArtistic types.Criticisms and Limitations of the FFMThe whole enterprise of science depends on challenging accepted views, and the FFM has become one of the most accepted models in personality research. Many critiques of the FFM ask “Why are there five and only five factors? Five factor protagonists say: it is an empirical fact…via the mathematical method of factor analysis, the basic dimensions of personality have been discovered.” (McCrae & Costa, 1989, p. 120). Has psychology as a science achieved a final and absolute way of looking at personality or is there a way to further our conceptualization of personality? In the article by Costa and McCrae (1997) explaining the anticipated changes to the NEO in the new millennium, they anticipate only minor wording modifications and simplifications. Thus it appears as if the FFM is viewed as a final or almost final achievement (Block, 2001). One claimed benefit of the FFM is evidence of heritability is strong for all 5 factors, but evidence is strong for all personality factors studied; it does not single out the Costa and McCrae factors (Eysenck, 1992). In other words, all the criteria suggested by Costa and McCrae are necessary but not sufficient to mark out one model from many which also conform to this criteria.The debate that has been most prominent over the past 15 years, and which has probably attracted the most attention, concerns the number and description of the basic, fundamental, highest-order factors of personality. Evidence from meta-analyses of factorial studies provide evidence that three, not five personality factors, emerge at the highest level of analysis (Royce & Powell, 1983; Tellegen & Waller, 1991; Zuckerman, Kuhlman, & Camac, 1988; Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Thornquist, & Kiers, 1991).Altogether, Eysenck (1992) has surveyed many different models, questionnaires and inventories, reporting in most cases a break-down into 2 or 3 major factors; but never 5. Additionally, Jackson, Furnham, Forde, and Cotter (2000) and Tellegen (1985) have contradicted Costa and McCrae’s (1995) assertions that a five-factor model seems most appropriate, with results showing that a three-factor solution is both more clear and parsimonious.Another critique of the FFM lies in its development. The initial factor-analytic derivations of the Big Five were not guided by explicit psychological theory, and therefore some have asked the question, “Why these five?” (e.g., Revelle, 1987; Waller & Ben-Porath, 1987). As Briggs (1989) points out, the original studies leading to the FFM “prompted no a priori predictions as to what factors should emerge, and a coherent and falsifiable explanation for the five factors has yet to be put forward” (p. 249).A further developmental critique of the FFM is the lack of lower order factors. Theoretically, factors exist at different hierarchical levels, and the FFM only measures five higher order factors (Block, 2001). The FFM operates at a broadband level to measure the main (i.e., higher order) categories of traits (McAdams, 1992). Within each of the five categories, therefore, may be many different and more specific traits, as traits are nested hierarchically within traits (McAdams, 1992).Another limitation of the FFM lies in researchers’ inability to consistently link the personality traits to the Holland interest types. Research has found that although there is a significant overlap between the FFM and RIASEC interest types, the RIASEC types do not appear to be entirely encompassed by the Big-Five personality dimensions (Carless,1999; Church, 1994; DeFruyt & Mervielde, 1999; Tokar, Vaux, & Swanson, 1995). Three personality dimensions in the FFM predict the RIASEC types, but there is less evidence to support that the other two predict the RIASEC types. Specifically, there appears to be significant overlap with Conscientiousness, Openness, and Extraversion in predicting the RIASEC interest types, but less research has been able to find links between Agreeableness and Neuroticism with the RIASEC interest types. This is a limitation of the FFM in relating to vocational interests (Costa, McCrae, & Holland, 1984; Gottfredson, Jones, & Holland, 1993; Tokar, Vaux, & Swanson, 1995).Looking Beyond the FFM: Tellegen’s Big Three Model of PersonalityIn light of these criticisms of the FFM, it seems attention could be paid to alternate models of personality to investigate the dimensions underlying Holland’s interest types. The literature base is sparse here, and alternative personality models warrant further study, particularly with regard to vocational interests (Blake & Sackett, 1999; Church, 1994; Larson & Borgen, 2002; Staggs, Larson, & Borgen, 2003). One such model is Tellegen’s Big Three which addresses many of the criticisms of the FFM.Many vocational psychology researchers use the Big Five model of personality, often measured by the NEO-PI or NEO-PI-R, but less often the Big Three model of personality measured by the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) is used (Tellegen, 1985; Tellegen & Waller, 1991). This model of personality resulted from ten years of research on focal dimensions in the personality literature (Tellegen, 1985; Tellegen & Waller, 1991). Tellegen’s (1985; Tellegen & Waller, 1991) Big Three modeldefines three higher order factors. These represent the clusters of items from a factor analysis that composed the three higher order traits. The lower order factors consist of items clustered in each of the higher order factors. The higher order factors are: Positive Emotionality (PEM), Negative Emotionality (NEM), and Constraint (CT) (Tellegen, 1985; Tellegen & Waller, 1991). These higher order traits correlate minimally with one another and encompass 11 lower order traits. Refer to Table A-3 for a description of the three higher order traits and the 11 lower order traits.There are only three published studies that have examined the Big Three model as relating to vocational interests. Blake and Sackett (1999) reported that the Artistic type moderately related with the MPQ Absorption lower order trait (Larson & Borgen, 2002). The Social type negatively related to the MPQ Aggression lower order trait; the Enterprising type related moderately to the MPQ Social Potency lower order trait; and the Conventional type related moderately to the MPQ Control lower order trait.Staggs, Larson, and Borgen (2003) also analyzed the lower order traits, specifically, as opposed to the higher order factors of PEM, NEM, and CT. They identified seven personality dimensions that have a substantial relationship with vocational interests: Absorption predicted interest in Artistic occupations; Social Potency predicted interest in Enterprising occupations; Harm Avoidance predicted interest in science and mechanical activity occupations; Achievement predicted interest in science and mathematic occupations; Social Closeness predicted interest in mechanical activity occupations; Traditionalism predicted interest in religious activities; and Stress Reaction predicted interest in athletic careers. Staggs, Larson, and Borgen (2003) used a collegestudent sample, but were not studying the RIASEC types; they were using a different conceptualization of vocational interests as measured by the Strong Interest Inventory which measures General Occupational Themes.Larson and Borgen (2002) found that the PEM factor was more strongly correlated with Social interests than with Enterprising interests; however, PEM did strongly correlate with all six RIASEC types (p < .001). This finding shows strong evidence that the PEM higher order trait relates to the RIASEC types. Larson and Borgen (2002) also found that the CT factor was negatively related to Realistic and Artistic interest types, and that the NEM factor was negatively related to Artistic interest types. Larson and Borgen (2002) utilized a sample of “gifted” adolescent students, which is a very limited and non-generalizable sample. In contrast, the current study tests a freshman college student sample, which is more generalizable to the population of students who are seeking vocational guidance.The links between the MPQ and the RIASEC interest types are under-researched. Although some vocational research has utilized the MPQ, more needs to be done to determine the relationships between Tellegen’s Big Three and Holland’s RIASEC interest types. However, the research provides support for the idea that there are alternative personality dimensions (i.e., Tellegen’s Big Three), outside of the FFM, that can significantly predict vocational interests, in particular the RIASEC types. Hypotheses 2a – 2c will test relationships between the Tellegen’s Big Three (as measured by the MPQ-BF) and the RIASEC interest types.Hypothesis 2a (H2a): The PEM factor will significantly positively correlate with all six RIASEC types.Hypothesis 2b (H2b): The CT factor will significantly negatively correlate withRealistic and Artistic types, but not with Investigative, Social, Enterprising, andConventional types.Hypothesis 2c (H2c): The NEM factor will significantly negatively correlate with Artistic types, but not with Investigative, Social, Enterprising, Realistic, andConventional types.Comparing Tellegen’s Big Three and the FFMAn earlier discussion proposed criticisms of the FFM. In light of these criticisms an alternate personality model was considered: Tellegens’ Big Three, measured by the MPQ. This model of personality resolves all the previous criticisms of the FFM: five versus 3 factors, lack of lower order factors, and model development issues.Tellegen’s (1985) understanding of personality differs from the conception of the FFM. Tellegen believes personality can be summed by three overriding traits or factors versus the 5 factors of the FFM. This is an inherent difference in the two models of personality, which guided the development of instruments used to measure these models, in terms of a three versus a five factor structure. Furthermore, Tellegen (1985) utilized a bottom-up approach to development of the MPQ, in which constructs were based on iterative cycles of data collection and item analyses designed to better differentiate the primary scales. In contrast, Tupes and Chrtistal (1961) emphasized deductive, top-down。

APA格式参考文献清单制作简明规则

APA格式参考文献清单制作简明规则一、总的说明1. 各个条目均不用给出文献标记类型(因为不是给国内期刊投稿),也不用。

2. 各个条目的后续行缩四个字符,即两个汉字的空间。

3. 英文的参考文献在上,中文的参考文献在下。

4. 中英文的条目均用字母升序排列,不用多余地以方括号括住的阿拉伯数字排列(因为不是给国内期刊投稿)。

5. 结合本规则里的第一至第三部分,一一读懂本规则里的第四部分的实例,将大有裨益。

6. 第四部分里的实例不能涵盖全部的情况,所以碰到本规则外的未尽情况时,要多查阅权威参考书。

二、条目的制作1. 姓名1.1 姓在前,名在后,中间加逗号。

1.2 名字一律缩略,以缩略点结束。

缩略点也就是结束点。

1.3 两个作者之间用&或and连接(前后保持一致),第一个作者的缩略名之后用逗号。

第二个作者也是姓名颠倒,中间用逗号。

1.4 三个作者时,头两个作者的缩略名后面均用逗号,第三个作者前用&或and。

第二个和第三个作者的姓名也颠倒,中间用逗号。

1.5 四个或四个以上的作者时,第一个作者的处理方法如第1条,其余作者只用斜体的et al.代替。

1.6 没有作者姓名但有机构名称时,用该机构名代替作者姓名。

1.7 既没有作者名又没有机构名时,则顺延将文章名或书名代替(即条目的第一部分是文章名或书名)1.8 对书籍的篇章的条目而言,书籍本身的编者的姓名不颠倒。

2. 出版年份2.1 放在作者名的后面,用圆括号。

以句点结束。

2.2 杂志、报纸等出版物的文章除了提供年份之外,需要提供月份或月份加日子。

3. 出版物名称3.1 书、期刊、报纸、长诗、长篇小说等用斜体。

3.2 书、长诗、长篇小说等用句子格式,但是名称内的专有名词和形容词仍需大写。

期刊、杂志、报纸等的文章用句子格式,但期刊、杂志和报纸等的名称用标题格式。

3.3 上述名称内如有副标题,则副标题后的首字母需要大写(即冒号后的首字母要大写)。

3.4 文章不斜体,也不加引号。

大学思辨英语教程 精读4教学课件Unit_7

Erich Seligmann Fromm (1900-1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. His research topics range from sociology, anthropology, and ethics to religion, politics, and mythology.

In Text A, Erich Fromm conducts an in-depth investigation of the problems of American education and society that make individuality impossible and modern man unhappy.

Background Knowledge

(3) Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud were the most decisive influences on Fromm’s thinking. Search for information about Fromm’s comments on Marx and Freud.

Personality and Individual Differences