Biomineralization

牙本质特异性蛋白与生物矿化

蛋白含量分析

0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0

吸光值

1

8

15

22

29

34

36

41

48

55

62

组份

图1. DPP洗脱曲线图

69

磷含量分析

25 20

磷含量

15 10 5 0

17

25

33

36

40

48

56

64

组份

图2. DPP磷含量曲线

72

1

9

把蛋白质吸光曲线和磷含量曲线绘于同一坐标 内, 可以得到如下曲线图

•牙本质磷蛋白(DPP) •牙本质涎蛋白(DSP) •牙本质涎磷蛋白(DSPP)

牙 本 质 非 胶 原 蛋 白 NCPs

矿化组织特异性蛋白

•牙本质基质蛋白 (DMP1) •骨钙素(OC) •骨涎蛋白(BSP) •骨桥素(OPN) •纤维粘连蛋白(FN) •糖蛋白(FG)

多组织非特异性蛋白

血清来源蛋白

0.054

0.280

-0.045

0.224

图1 蛋白洗脱曲线与磷含量曲线分析图 1 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0.4 0.2 0

吸光值(230nm)

0.8 0.6

1

6

11

16

21

26

31

36

41

46

51

56

61

66

组份

证明:1M NaCL提取可溶性DPP

71

磷含量(mM/L)

•IgG、白蛋白

牙本质磷蛋白 Dentin Phosphoprotein, DPP Dentin Phosphophoryn, DPP

微生物矿化

1.生物矿化作用原理

生物矿化作用是生物形成矿物的作用,是在生 物的特定部位,在一定的物理化学条件下,在 生物的有机物质的控制和影响下,将溶液中的 离子转变为固相矿物的作用。

1.1生物矿化作用类型

根据受生命物质的制约程度,生物矿化作用可 分为生物诱导矿化作用和生物控制矿化作用两 种,其间存在着一系列的过度形式。生物对矿 化作用的控制程度取决于他的演化程度、矿化 机体和矿化能力。两种生物矿化作用可发生于 同一生物体,甚至同一组织中。

铁、锰、钒的微生物催化转化:生物与矿物质之间的 相互作用在分子水平上可被阐明,从本质上解释了生 物指示矿床存在、生物形成矿物,生物溶浸矿物具有 密切关系。生物与矿物,生物大分子与金属离子或氧 化物、氢氧化物之间的相互作用是支配这些生物过程 的基础。金属及其氧化物与微生物呼吸相耦合,涉及 到水 - 矿物 - 微生物界面电子传递过程,利用微生物 电池进行研究胞外电子传递,不但可以揭示生命起源 的重大理论问题,也可用于指导环境修复等应用的突 破。比如粘土型钒矿,从形成到利用,以至在生物医 学的应用。

人们通过各种有机物,包括多糖、蛋白质、多 肽、氨基酸、其它小分子有机物、人工合成高 聚物、DNA等等,对碳酸盐、磷酸盐、硫酸盐、 硫化物、氧化物、氢氧化物等很多材料进行了 模拟矿化,得到了很多有用的结果。但是,从 仿生的程度上来说,结构上仍然离自然矿物差 得很远,过程上还没有很好地达到有效的无机 -有机有序组装,功能上自然无法与生物矿物 想媲美。

化学家和材料学家开始对生物矿物进行形貌观察, XRD分析,提取其中的有机物,在实验室里诱导无机 物沉积,后来用人工合成的高分子、多肽以及其它动 物体中提取的蛋白质等,对无机物做晶型和形貌调控, 取得了非常大的成绩——发了很多好文章,非常漂亮 的SEM和TEM图片。但是,很少有工作深入到无机有机界面作用的,或者进入了,但不够深入。目前, 大家解释一种新的晶型和形貌的出现的时候,仍然套 用Mann S在二十多年前提出的晶格几何匹配、立体化 学匹配等非常模糊的概念。在一种体系中所得到的结 论,很难应用到其它体系的解释。

口腔专业英语名词解释 S

S.上牙合架shang he jiamounting cast on articulator颌架(articulator)是固定上、下牙列咬合模型和模拟咬合运动的机械装置,它具备与人体咀嚼器官相似的部件和关节。

上颌架就是将带有咬合记录的上、下颌模型转移固定在颌架上,通过颌架保持上、下模型间的高度、颌位和咬合接触关系,模拟下颌的功能运动,制作义齿,作模型外科及教学等。

烧结全瓷材料shao jie quan ci cai liaosintered all-ceranmic materials烧结全瓷修复是指在口腔修复治疗中,直接采用各种粉状瓷料与蒸馏水调拌成粉浆,涂塑在特殊耐火代型上,经过烧结制作陶瓷修复体的一种工艺过程,称为烧结全瓷材料。

烧结全瓷材料和工艺,一般是用于制作冠、嵌体、贴面等修复体。

渗透陶瓷shen tou tao ciinfiltrated ceramic熔融的玻璃基质通过毛细管作用逐渐渗入到多空的氧化铝或MgAl2O4核的网状孔隙中,从而形成一个氧化铝和玻璃相连续交织互渗的复合材料(CIPC),称为渗透陶瓷,也属全瓷修复陶瓷的一种。

玻璃基质封闭了氧化铝或MgAl2O4核的所有空隙,能有效限制裂纹的扩展,极大地提高了其挠曲程度,为其他普通口腔陶瓷材料的2~4倍,达到320~600MPa。

渗透陶瓷的强度主要是由体积比占75%的氧化铝基体的性能所决定的。

氧化铝在复合体中起到增强、增韧相的作用,并保持材料的尺寸稳定性。

渗透陶瓷全冠shen tou tao ci quan guaninfiltrated ceramic crown参见“渗透陶瓷”。

生石膏sheng shi gaogypsum未脱水的二水硫酸钙,即含2分子结晶水的硫酸钙。

生物安全性sheng wu an quan xingbiological safety生物安全性是指材料进入临床应用前具有安全使用的性质。

口腔材料是应用于人体的,与人体组织相接触,因此材料对应无毒性,无刺激性,无致癌性和致畸变等作用。

微生物矿化

1

精选ppt

生物矿化 biomineralization

生物矿化——生物给予的又一个启示

在生物体内形成无机矿物的过程。与一般矿化不

同之处是此过程中有生物体代谢、细胞、有机基质的

参与。

生物矿化有两种形式。一种是生物体代谢产物直

接与细胞内、外阳离子形成矿物质,如某些藻类的细

胞间文石。另一种是代谢产物在细胞干预下,在胞外

3

精选ppt

生物矿化这个事实发生于生物产生的初期,近代以来海洋生物学 家和地质学家对生物矿化进行了初步的研究。但真正的大规模研 究——从化学和材料学的角度——还是始于英国Bristol大学的 Mann S等人,随之出现了一大批这方面的专家,包括Weiner S, Lowenstam HA, Addadi L等人。目前生物矿化研究工作做得很 好的单位,国外的有Bristol Univ的Mann S组,Israel的 Weizmann Inst Sci,德国MPI的Colfen H等组;国内的有清华大 学的崔褔斋组(他们一直致力于生物材料和组织工程的研究,部 分研究成果已应用于临床),中科大俞书宏组,浙大唐睿康组以 及中科院的一些研究单位。现在越来越多的化学家和材料学家开 始关注这个方面。虽然已经发展了20多年,但实际上,真正的研 究还是处于初级阶段。为什么这么说呢?

9

精选ppt

人们通过各种有机物,包括多糖、蛋白质、多 肽、氨基酸、其它小分子有机物、人工合成高 聚物、DNA等等,对碳酸盐、磷酸盐、硫酸盐、 硫化物、氧化物、氢氧化物等很多材料进行了 模拟矿化,得到了很多有用的结果。但是,从 仿生的程度上来说,结构上仍然离自然矿物差 得很远,过程上还没有很好地达到有效的无机 -有机有序组装,功能上自然无法与生物矿物 想媲美。

高等高化概念全

以下红色部分为未能在文献和书籍中找到确定定义的词条,如果有更好的解释希望及时共享。

1.自动加速效应(Trommsdorf-Norrish/auto-acceleration):自由基聚合中体系黏度随转化率提高后,链段重排受到阻碍,活性端基甚至可能被包埋,双基终止困难,自由基寿命延长,但这一转化率下,体系黏度还不足以妨碍单体扩散,链增长速率常数变动不大,从而使加速显著.分子量也同时迅速增加。

2.溶剂化作用(solvent effect):对于高分子的溶解过程,溶剂化作用是溶剂和溶质相接触时,分子间产生相互作用力,此作用力大于溶质分子间的内聚力,从而使溶质分子分离,并溶于溶剂中。

对于离子聚合与电解质,溶剂化作用是溶剂分子通过它们与离子的相互作用,而累积在离子周围的过程。

该过程形成离子与溶剂分子的络合物,并放出大量的热。

溶剂化作用改变了溶剂和离子的结构。

3.阳离子聚合(cationic polymerization):由阳离子引发而产生聚合的反应的总称。

阳离子活性很高,极易发生各种副反应,很难获得高分子量的聚合物。

碳阳离子易发生和碱性物质的结合、转移、异构化等副反应。

阳离子聚合引发剂属于亲电试剂,包括质子酸、路易斯酸和高能辐射三种。

4.阴离子聚合(anionic polymerization):由阴离子引发而产生的聚合反应的总称。

凡电子给予体如碱、碱金属及其氢化物、氨基化物、金属有机化合物及其衍生物等都属亲核催化剂。

阴离子聚合反应常常是在没有链终止反应的情况下进行的。

当重新加入单体时,反应可继续进行,分子量也相应增加。

因此也称为活性聚合。

5.异构化(isomerization):改变化合物的结构而不改变其组成和分子量的过程。

一般指有机化合物分子中原子或基团的位置的改变。

6.链转移(chain transferring):链转移指活性链自由基与聚合物反应体系中的其他物质分子之间发生的独电子转移并生成大分子和新自由基的过程。

口腔生物学 名词解释

口腔生物学名词解释Oral normal/indigenous/resident flora 口腔正常/固有/常在菌群:口腔细菌与宿主在共同的进化过程中形成的细菌群体,即口腔内正常存在的微生物。

生境(habitat) :正常(固有、常居)微生物群在机体特定部位生存环境。

Oral ecosystem 口腔生态系:由牙齿、粘膜、龈沟、唾液四个生境和在这些生境中栖息的微生物所构成。

氧化还原电位(redox potential, oxidation- reduction potential, Eh)电子移动、得失,产生电位。

如果此电位和化学过程的氧化还原相关,称氧化还原电位(Eh)。

Eh值反映环境氧化还原趋势。

Eh值越高, 氧含量越高。

牙菌斑(Dental plaque, Plaque,Biofilm)是细菌粘附于牙面、修复体或其他口腔结构上的以细菌为主体的生态环境,细菌在其中进行生长、繁殖和代谢,是口腔常见的感染性疾病——龋病和牙周病的主要病因。

(其他定义:堆积在牙齿或其他硬的口腔结构表面,不能被中度水喷冲去的细菌团块。

-- Black 微生物在口腔生态系里的一种存在形式。

能容纳多种微生物生存的Biofilm (microbial film) 。

获得膜(pellicle)获得膜是被覆在牙表的不足1µm的膜,由混合唾液和细菌产物组成。

细胞外膜泡:细菌外膜向外膨出呈芽状,在形成独立成份后游离进入周围微环境的一种泡状膜结构。

生物矿化(Biomineralization) 是指生物体内的钙、磷等无机离子在生物调控下通过化学反应形成难溶性盐类,并与有机基质结合,形成机体矿化组织的过程。

晶核nucleus :溶液中离子相互结合最先析出,经集聚成有序的簇状结构后,并达到某个临界大小而得以继续成长的晶相颗粒。

牙齿脱矿(Demineralization):在酸的作用下,牙齿矿物发生溶解,钙和磷酸根等无机离子从牙齿中脱出、释放的过程。

仿生建筑著名书籍

仿生建筑著名书籍标题:仿生建筑:探索自然与建筑设计的交融【仿生建筑著名书籍】在建筑设计领域,仿生建筑作为一种创新的设计理念,正在逐渐崭露头角。

通过模仿生物的形态、结构、功能和生态行为,设计师们创造出既能满足人类需求,又能与环境和谐共生的建筑。

以下几本著名的仿生建筑书籍,深入探讨了这一主题,为我们提供了丰富的理论依据和实践案例。

1. "Biomimetic Architecture: Nature-Inspired Design and Engineering" by Michael Pawlyn这本书是仿生建筑领域的经典之作,作者Michael Pawlyn是一位资深的建筑师和生态设计专家。

他详细阐述了仿生学原理在建筑设计中的应用,通过大量实例展示了如何从自然界中汲取灵感,创造出高效、可持续且美观的建筑。

首先,Pawlyn介绍了仿生学的基本概念和方法,包括形态仿生、结构仿生、功能仿生和生态仿生等。

然后,他深入剖析了一些具有代表性的仿生建筑项目,如西班牙的“戈雅塔”(Guggenheim MuseumBilbao)、德国的“柏林动物园大象馆”(Berlin Zoo Elephant House)和英国的“伊甸园计划”(Eden Project)等。

这些案例揭示了仿生建筑的魅力和潜力:它们不仅在视觉上引人入胜,而且在功能上实现了能源效率、环保和人性化等方面的突破。

例如,“伊甸园计划”的生物气候穹顶模仿了热带雨林的生态系统,通过自然通风、太阳能采集和雨水利用等技术,实现了零碳排放的目标。

2. "Bioarchitecture: International Developments in Biologically-Inspired Design and Construction" edited by Janine Benyus and Michael Pawlyn这本书是一本集合了多位国际知名建筑师和科学家的研究成果的合集,由仿生学先驱Janine Benyus和Michael Pawlyn共同主编。

口腔生物学个人整理

名解生态连续:生物体(或细菌)栖息在一个变化的环境中的过程。

极期群落:生态延续在一个小生境中延续演化,就可以组成多种多样复杂的生物群,环境条件也趋于稳定,具体表现为菌属数和组成的无明显改变,这一稳定现象将持续到环境中另一个干扰因素出现为止,处于这种状态下的群体称极期群落。

口腔生态系(oral ecosystem):口腔菌丛之间以及它们与宿主之间相互依存共同构成了口腔生态系,许多正常菌丛和其宿主之间呈动态平衡,这种平衡对于保持宿主的健康很重要。

牙菌斑(plaque):堆积在牙表面或其他硬的口腔结构上,不能被中度水喷冲去的细菌团块。

生物膜(biofilm):指微生物群落与胞外基质相互连接而在介质表面形成的生态环境。

血链球菌:最初定植在牙菌斑中先锋菌,能利用蔗糖合成胞外多糖,对细菌生态连续起重要作用。

具有拮抗某些牙周炎可疑致病菌的能力,对牙周健康有益。

生物矿化(Biomineralization):指生物体内的钙磷等无机离子在多种生物因子的调控下通过化学反应产生难溶性盐,与有机基质结合,形成机体矿化组织。

有生理学和病理性之分。

再矿化(remineralization):牙萌出后,在没有细胞参与调控的情况下,通过钙、磷、氟等无机离子沉积达到修复或者替代牙体硬组织的一种自然过程。

内含子(intron) :即插入序列,它是位于基因的内部,能够被转录的一段DNA。

但在转录之后,与之相应的那部分转录产物在拼接中被去掉了。

外显子(exon) :就是基因中与成熟的mRNA相对应的DNA片段,它不仅包括为蛋白质编码的部分,而且包括5’和3’末端不翻译的前导序列和尾随序列。

质粒(plasmid):是一种细菌细胞内独立于染色体外的环状DNA,它具有自我复制能力。

在细胞分裂时可伴随染色体分配至子细胞中去。

噬菌体:是感染细菌细胞的病毒,能将外源基因导入细菌细胞内并得到表达,是分子生物研究中重要的载体。

噬菌体感染:指噬菌体DNA进入宿主细胞,并在其中繁殖的过程。

introduction-生物矿化

Introduction:Biomineralization Biomineralization is the study of biologically producedmaterials,such as shells,bone,and teeth,and the processesthat lead to the formation of these hierarchically structuredorganic-inorganic composites.The mechanical,optical,andmagnetic properties of these materials are exploited by theorganisms for a variety of purposes.These properties areoften optimized for a given function as compared to theproperties of a biological materials of similar composition.Materials chemists are intrigued by the exceptional controlorganisms exert over the composition,crystallography,morphology,and materials properties of biominerals and themild conditions(physiological temperature,pressure,and pH)required to form them.In recent years,therefore,thefieldof biomineralization has expanded to include the applicationof strategies adapted from biology to the production ofsynthetic materials.Biomineralization is by definition amultidisciplinaryfield that draws on researchers from biol-ogy,chemistry,geology,materials science,and beyond.Inthis issue,we focus on the role that chemistry,broadlydefined,has played and will continue to play in thedevelopment of this growingfield.The impact of chemistry in thefield of biomineralizationcan roughly be divided into three different areas:(1)thecharacterization of the crystallography,composition,andbiochemistry of the biological materials;(2)the design ofin vitro model systems to answer questions from biologysuch as testing hypotheses regarding the interactions betweenthe organic matrix and the crystals and the role of biomac-romolecules in controlling nucleation and growth of crystals;and(3)the development of new synthetic methods,whichare based upon the biological systems,for controlling crystal morphology,polymorph,and materials properties,leading to new classes of organic-inorganic composites.All three of these approaches are highlighted in the22articles assembled for this issue.The articles are arranged loosely by mineral class(e.g., carbonates,phosphates).Within each section,the articles are further organized beginning with reviews that cover funda-mental aspects of biomineralization and moving to reviews that address bioinspired materials applications.Thefirst review by Meldrum and Co¨lfen serves as an excellent introduction to many of these topics.Specifically,they provide an overview of recent developments in understanding crystal nucleation and growth mechanisms in both biological and synthetic systems and how these processes can be modified to form crystals with unusual morphologies, structures,and properties.The next six articles focus on the carbonate biominerals, primarily calcium carbonates(both crystalline polymorphs and amorphous phases),which are the most abundantly produced and widespread minerals found in biology.The contribution by Cusack and Freer highlights the diversity of calcium carbonate producing organisms and reviews the chemico-structural relationships within these biominerals. The processes of biomineralization are often under strict biological control and involve the interactions of a large number of biological macromolecules.In recent years,much progress has been made toward determining the sequences and solution-state structures of these biomacromolecules as well as establishing structure-function relationships for them.Evans reviews the current state of knowledge on the proteins associated with mineralization in mollusks.In Killian and Wilt’s contribution,they present a molecular view of biomineralization in another class of organisms,the Lara A.Estroff received her B.A.with honors from Swarthmore College (1997),with a major in Chemistry and a minor in Anthropology.Before beginning her graduate studies,she spent a year at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot,Israel,as a visiting researcher in the laboratories of Profs.Lia Addadi and Steve Weiner.During this time,she was introduced to thefield of biomineralization and studied chemical ap-proaches to archeological problems.In2003,she received her Ph.D.in Chemistry from Yale University for work done in Prof.Andrew D.Hamilton’s laboratory on the design and synthesis of bioinspired organic superstruc-tures to control the growth of inorganic crystals.After completing graduate school,she was an NIH-funded postdoctoral fellow in Prof.George M. Whiteside’s laboratory at Harvard University(2003-2005).Since2005, Dr.Estroff has been an assistant professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Cornell University.Her group focuses on bioinspired materials synthesis,in particular,the study of crystal growth mechanisms in gels and their relationships to biomineralization.In2006,she was awarded a J.D.Watson Young Investigator’s award fromNYSTAR.Volume108,Number1110.1021/cr8004789CCC:$71.00 2008American Chemical SocietyPublished on Web11/12/2008echinoderms,which include sea urchins and brittle stars.In addition to proteins,polysaccharides and proteoglycans are emerging as important components in the organic matrices associated with biominerals.Arias and Ferna´ndez review what is known about this class of molecules in controlling the growth of calcium carbonate crystals in biological and synthetic systems.In addition to the control exerted by the organisms over carbonate crystallization,the environment in which these organisms grow can also substantially influence the produc-tion of these minerals.Stanley reviews this hotly debated, and timely,topic in an article that addresses the effects of seawater chemistry(e.g.,calcium-to-magnesium ratio and pH)and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels on mineralization in coccolithophores,calcareous algae,corals,and other carbonate-producing organisms.The last two articles in the carbonate section cover the work of polymer and organic chemists toward the design of synthetic additives to control the crystallographic orientation,morphology,and polymorph of carbonate-based minerals.Sommerdijk and de With provide a thorough review of the rapidly growingfield of bioinspired “designer”small molecules and interfaces(e.g.,self-assembled monolayers and Langmuir monolayers)to control the nucleation,polymorphism,structure,and composition of crystals and organic-inorganic composites. In her article,Gower discusses the role of amorphous calcium carbonate precursors,which are stabilized by polyelectrolytes,in the formation of crystalline structures in both synthetic and biological systems.After the carbonate minerals,the phosphates are the second most prevalent family of biominerals.Since our bones and teeth are both composed of carbonated apatite(an ortho-phosphate)crystals embedded within an organic framework, there is an emphasis in the biomedical community on such systems.We begin this section with a review by Wang and Nancollas describing the physical chemistry of the ortho-phosphates.A fundamental understanding of crystal growth and dissolution for this class of materials in vitro is essential for analyzing and modeling the biological systems.A family of highly phosphorylated proteins is closely associated with the production of phosphate minerals in vivo. George and Veis review both in vitro and in vivo experiments that elucidate the role these proteins play in controlling the biomineralization of orthophosphates,such as carbonated apatite.In Omelon and Grynpas’s contribution,they discuss polyphosphates,an interesting class of biomacromolecules whose role in biomineralization is just recently becoming appreciated.Boskey and Roy review the specialized cell-culture techniques,that have been developed to study biomineral-ization of bone and teeth in vitro.Of key importance in these studies is the identification and characterization of the mineral phase and the“biological relevance”of the mineral phase that is formed.This review addresses both of these issues and provides guidelines for designing future cell-based studies of mineralization.The characterization,in situ,of the macro-and microscopic 3-D structures of biomineralized tissues is essential for understanding the spatial distribution of minerals during tissue development.Neues and Epple review the emerging field of synchrotron radiation microcomputer tomography (µCT)for imaging mineralized structures,at high resolution, in a nondestructive manner.Immense attention has been paid to the development of osteoconductive and osteoinductive materials,materials that can stimulate the production of new bone in vivo,for use in biomedical implants for the repair of damaged hard tissues. LeGeros reviews different calcium phosphate based materials for this purpose.In the contribution from Stupp and co-workers,they present recent developments in the design of structurally complex organic templates to promote hy-droxyapatite mineralization and bone repair,in vivo.Unlike traditional biomaterials,these newer synthetic constructs often incorporate multiple components,each with a specific biological function(e.g.,chemical signals to promote both cell adhesion and mineralization).In addition to the carbonates and the phosphates,there is a wide range of other inorganic minerals and organic crystals formed by biological organisms.We conclude this issue with a series of articles that cover some of these other systems and the techniques used to study them. Atomic force microscopy(AFM)can provide insight into the dynamics of crystallization,including the mechanisms by which small molecules and proteins can inhibit and/or modify crystal growth.Qiu and Orme review applications of AFM to study,among other systems,the crystallization of calcium oxalate,one of the main components of kidney stones.In recent years,molecular dynamics and other computational techniques have been applied to modeling crystal nucleation and growth.Harding and co-workers review how these computational techniques are applied to a range of biological and synthetic systems to provide insight into the role of the organic-inorganic interface in controlling crystallization.The next articles cover three specific examples of different types of biominerals and the biological organisms that produce them.Hildebrand reviews the formation of amor-phous silica by diatoms,with a focus on how genomics can contribute to our understanding of biomineralization pro-cesses.Faivre and Schu¨ler examine the formation of magnetic minerals by magnetotactic bacteria and the macromolecules that are involved.The only review in this issue to address organic crystal growth in biology is by Weissbuch and Leiserowitz,who discuss the formation of hemozoin crystals by the parasite that causes malaria.In particular,they highlight the role that molecular recognition and crystal design can play in developing novel treatments for malaria by inhibiting the growth of hemozoin crystals and,thus, poisoning the parasites.Finally,two reviews highlight bioinspired materials synthesis based upon a wide range of mineralizing systems.Brutchey and Morse focus on a protein,silicatein, which is isolated from the silica spicules of a marine sponge,to design new polymers and interfaces to control the growth of inorganic materials,including some that are important for energy production and storage.Dickerson, Sandhage,and Naik address the rapidly emergingfield of protein-and peptide-directed synthesis of inorganic ma-terials,including ceramic oxides,semiconductors,and metallic nanoparticles.It is my hope that this issue of Chemical Re V iews will introduce the broader chemistry community to the many facets of biomineralization.I also encourage the use of this4330Chemical Reviews,2008,Vol.108,No.11EditorialThematic Issue as a“reader”for advanced undergraduate and/or graduate level courses in Biomineralization.I thank all of the authors for their thought-provoking and timely contributions and the editorial staff at Chemical Re V iews for all of their help in preparing this issue.Lara A.Estroff Cornell University Ithaca,New YorkCR8004789Editorial Chemical Reviews,2008,Vol.108,No.114331。

生物无机化学

2011年 加拿大

2013年 法国 2015年 中国

ICBIC LOGO

ICBIC LOGO

/

Session Topics for ICBIC 14

Bioenergetics Small Molecules Activation Traffic and Storage of Metal Ions Metalloproteins Biogenesis of Metalloproteins Molecular Design of Metalloproteins Metal-DNA/RNA Interaction Metal Ions in Drug Design, Neuroscience, and Disease Bioorganometallic Chemistry Bionanomaterials New Trends in Bioinorganic Chemistry

What is Bioinorganic Chemistry?

Bioinorganic chemistry constitutes the discipline at the interface of the more classical areas of inorganic chemistry and biology. Bioinorganic chemistry has two major components: the study of naturally occurring inorganic elements in biology and the introduction of metals into biological systems as probes and drugs.

1977年, G.N.Schrazer发起成立了国际生物无机化学

口腔生物学练习题

(名解)生态系(ecosystem):生物之间、生物与其环境之间的相互关系。

生态学(ecology):研究生物与其环境的相互依赖和相互制约的科学。

微生态学(microecology):细胞水平或分子水平的生态学。

生态连续(ecological succession):生物体栖息在一个变化的环境中的过程。

极期群落(climax community):生物体(或细菌)栖息在一个变化的环境中的过程称生态延续,在一个小生境中延续演化组成多种多样复杂的生物群(菌群),环境条件趋于稳定,菌属数和组成的无明显改变,这种群体称极期群落. 口腔生态系(oral ecosystem):口腔正常菌丛之间以及它们与宿主之间的相互作用,许多正常菌丛和其宿主之间呈动力的平衡状,这种平衡状态对于保持宿主的健康是重要的。

绝对厌氧菌(obligate anaerobes):在无氧环境中发酵生长,氧可抑制或杀灭的细菌。

兼性厌氧菌(facultative anaerobes):在合适的碳或其他能源存在时可在有氧或无氧中生长的细菌。

微嗜氧菌:这类细菌的生长需氧,但所需氧的浓度比正常低,对需氧菌生长合适的浓度,对这类细菌抑制.牙菌斑(plaque):堆积在牙表面或其他硬的口腔结构上,不能被中度水喷冲去的细菌团块。

生物膜(biofilm):是指微生物群落与胞外基质相互连接而在介质表面形成的生态环境附着性龈下菌斑(attached subgingival plaque):附着于牙根面或牙结石表面,可能系龈上菌斑在龈沟或牙周袋内的延续。

非附着性龈下菌斑(unattached subgingival plaque):不附着于牙面或牙根面,却与结合上皮和龈沟上皮直接接触的菌斑.固有菌丛(indigengous flora):包含常以高数量(大于1%)存在于某个特殊部位上的菌属,如在龈上菌斑或舌表面。

增补菌丛(supplemental flora):包含常居的,但是以低数量(小于1%)存在的菌属,当环境改变时可以成为固有菌。

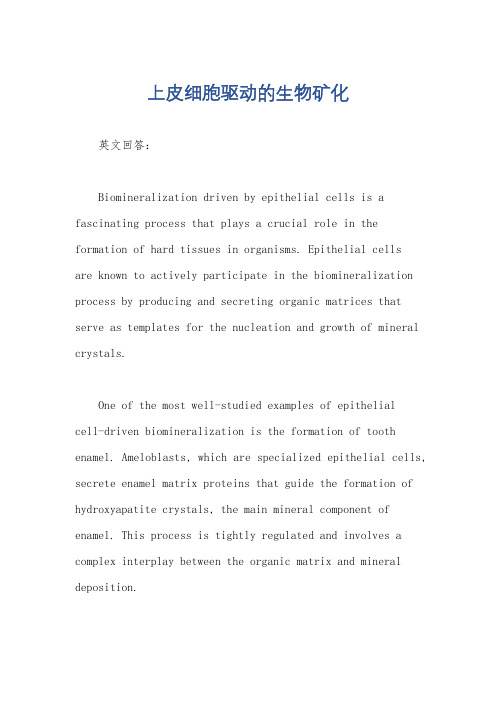

上皮细胞驱动的生物矿化

上皮细胞驱动的生物矿化英文回答:Biomineralization driven by epithelial cells is a fascinating process that plays a crucial role in the formation of hard tissues in organisms. Epithelial cellsare known to actively participate in the biomineralization process by producing and secreting organic matrices that serve as templates for the nucleation and growth of mineral crystals.One of the most well-studied examples of epithelialcell-driven biomineralization is the formation of tooth enamel. Ameloblasts, which are specialized epithelial cells, secrete enamel matrix proteins that guide the formation of hydroxyapatite crystals, the main mineral component of enamel. This process is tightly regulated and involves a complex interplay between the organic matrix and mineral deposition.In addition to tooth enamel, epithelial cells are also involved in the biomineralization of other hard tissues such as bone and mollusk shells. In bone formation, osteoblasts, which are derived from epithelial cells, secrete osteoid, an organic matrix that mineralizes to form bone tissue. Similarly, in mollusks, epithelial cells in the mantle tissue secrete proteins that initiate and regulate the formation of calcium carbonate crystals, the main component of shells.The ability of epithelial cells to drive biomineralization is not only limited to hard tissues. In the case of kidney stones, renal epithelial cells have been found to play a role in the formation of mineral depositsin the urinary tract. Understanding the mechanisms by which epithelial cells control biomineralization in different tissues is not only of fundamental importance but also has potential implications for the development of therapeutic strategies for mineralization-related disorders.In summary, epithelial cells play a crucial role in driving biomineralization in various tissues and organs,and their ability to produce and regulate organic matricesis essential for the formation of hard tissues in organisms.中文回答:上皮细胞驱动的生物矿化是一个迷人的过程,在生物体内形成硬组织中起着至关重要的作用。

(优选)微生物矿化详解.

牙釉质中有机物不同,所以无机物形貌有所区别,但主要是含氟 的羟基磷灰石。

贝壳珍珠层SEM 颗石藻(coccolith)SEM 小鼠门牙SEM

对有机物的研究发现了一些共同的特征。首先是有序 组装的大分子体系,有序组装的一个好处就是能够提 供一个相对稳定的有限的空间环境,提供无机物成核 与生长。其次,有机物带有大量的酸性官能团,包括 羧基、磷酸基、磺酸基等等,这些官能团有些起诱导 无机物成核的作用,有些起抑制过度生长的作用。还 有一点,生物矿物区别于人工复合材料的一个重要特 征,就是其中的有机物质含量很少,很多低于5%;但 就是这么少得有机物,对材料的形成过程和整体强度 的提高起了巨大的作用。这些过程都是在常温常压下 完成的,无疑是对材料学家的一种巨大的挑战。

化学家和材料学家开始对生物矿物进行形貌观察, XRD分析,提取其中的有机物,在实验室里诱导无机

物沉积,后来用人工合成的高分子、多肽以及其它动

物体中提取的蛋白质等,对无机物做晶型和形貌调控, 取得了非常大的成绩——发了很多好文章,非常漂亮 的SEM和TEM图片。但是,很少有工作深入到无机有机界面作用的,或者进入了,但不够深入。目前,

微生物矿化

生物矿化 biomineralization

生物矿化——生物给予的又一个启示

在生物体内形成胞、有机基质的

参与。

生物矿化有两种形式。一种是生物体代谢产物直

接与细胞内、外阳离子形成矿物质,如某些藻类的细

胞间文石。另一种是代谢产物在细胞干预下,在胞外

聚物超分子组装、微相组装直至体系组装,控制无机物在高分子 膜表面的诱导结晶,构筑目标性能的高分子 - 无机物复合材料。 微生物利用胞内外活性基团进行金属富集随即进行成矿过程演化 已经进入实用阶段。

壳质蛋白和钙离子在海洋生物中的生理作用研究

壳质蛋白和钙离子在海洋生物中的生理作用研究海洋生物中的壳质蛋白和钙离子壳质蛋白是一种分布广泛的天然高分子有机化合物,由多种氨基酸组成。

在海洋生物中,壳质蛋白主要存在于贝类、珊瑚、海藻等生物的骨骼中。

而钙离子是维持这些骨骼形成和硬度的关键元素。

海洋中的生物骨骼中的壳质蛋白和钙离子之间互相作用,形成了一些有趣的生理学和生态学现象。

壳质蛋白的结构和形成壳质蛋白的结构非常复杂。

最常见的壳质蛋白是固态蛋白,由多种不同尺寸和类型的亚基(subunit)组成。

每个亚基都有一个核心区域(core region),它们以一定规律排列在一起,形成多层复杂的结构。

这些结构往往非常坚硬,建立了海洋生物的壳子或骨骼。

壳质蛋白的形成通常需要必须在特定的环境中进行。

它们往往会在物理或生物过程中形成,如一些珊瑚的分泌,或贝类通过生物钙化(biomineralization)从环境中吸收钙离子的水晶形成过程中形成。

这些过程中,壳质蛋白会通过亲水性作用和电荷效应塑造结构,并整合钙离子进入它们的骨骼或壳中。

这些复杂的过程带来了严格的末端控制,涉及多种基因和代谢通路的调控。

钙离子的作用与代谢钙离子的作用以及代谢也非常重要。

在海洋中,钙离子作为一种元素广泛存在。

它可以从水环境中被吸收到海洋生物的体内,用于骨骼的形成和硬度维持。

这也使得钙离子在地球的生物地球化学循环中具有重要地位。

很多海洋生物摄取钙离子进行骨骼和壳的构建过程中使用酸碱调节机制,该机制在增加了钙离子的沉淀和固定方面具有重要作用。

除此之外,在海洋生物的代谢过程中,钙离子也扮演着关键的角色。

例如,通过维持神经的传递,调节肌肉收缩以及代谢过程中ATP的合成等过程。

壳质蛋白和钙离子的生态学意义壳质蛋白和钙离子在海洋生物骨骼中的作用被证明对海洋生态学和全球生态系统非常重要。

例如,由于骨骼在贝类、珊瑚和海藻的区域达到了极高的密度,这些海洋生物群落可以维持整个海洋食物链的营养基础。

因此,对于壳质蛋白和钙离子的能力进行研究和了解可能有助于推动我们对海洋生态系统的保护和管理。

化石的功能主治是什么

化石的功能主治是什么简介化石是指古生物或古植物在经过数百万年的埋藏和压力作用后形成的固态遗骸或碎片。

化石是研究地质历史和古生物学的重要证据,具有一系列的功能和主治。

功能化石具有以下几个主要功能和用途:1.记录地球历史:通过研究化石,科学家们能够了解地球上古生物演化和地质历史的重要线索。

化石中蕴含的信息可以帮助我们了解地球上不同时期的地理环境、生态系统以及生物之间的关系。

2.研究生物演化:化石记录了生物进化的过程和路径,通过研究化石,我们可以了解生物群落和种类的变化,以及物种的起源和灭绝。

化石对研究生物演化和进化论发展起到了重要的推动作用。

3.指导资源勘探:某些化石可以作为矿产资源的有力证据,例如古代海洋生物遗骸可以提示石油和天然气的潜在埋藏区。

通过研究化石中的生物化学物质,也可以指引人们寻找有用的矿物和地下水资源。

4.研究古环境:根据化石中的植物和动物遗骸,可以重建古环境的类型和特征。

化石中的花粉、气孔和树木年轮等结构可以提供关于古代气候、植被和地质环境的重要信息。

5.重要的教育价值:化石是古生物学、地质学等学科研究和教学的重要工具。

通过展示化石,可以激发人们对地球历史和生命起源的兴趣,启发学生对科学的好奇心,促进科学知识的传播和普及。

主治化石在人类社会中还有一些特殊的用途和主治:1.文化和艺术:化石常常被用作装饰品、手工艺品和艺术品的材料。

例如,由恐龙化石制成的骨饰、化石木材制成的家具,以及石化植物研磨成的珠宝等都具有较高的艺术欣赏和收藏价值。

2.医疗用途:根据化石中的化学成分和药用植物化石,可以对古代人类使用的草药和天然药物进行研究和开发。

化石中的有机物质可以提供药用植物的成分和特性,为现代医学提供新的启示和研究方向。

3.地球科学教育:化石是地质学、古生物学等学科的重要教学资源。

通过观察和解读化石,可以帮助学生理解地球历史、生物演化和地质过程等概念,培养他们对科学知识的兴趣和理解能力。

4.古生物学研究:化石是古生物学研究的核心对象,通过研究化石,可以了解古生物的形态、生态和行为特征。

从生物矿化作用衍生出的有机矿化作用:地球生物学框架下重要的研究主题

从生物矿化作用衍生出的有机矿化作用:地球生物学框架下重要的研究主题梅冥相【期刊名称】《地质论评》【年(卷),期】2012(058)005【摘要】Traditionally, the concept of biomineralization has been defined as the mineral formation by organism and further has been grouped into two types, L e. the biologically controlled and the biologically induced biomineralizations. This broad term of biomineralization has been emended as the process by which living forms influence the precipitation of mineral materials; correspondingly, the term of biomineral has been redefined as the product of the selective uptake of elements from the local environment, and it can incorporate into functional structures under strict biological control. Correspondingly, the concept of "organomineralization" that is derived from the broad biomineralization is used to describe a mineral formation linked to non-living organic substances, and the product resulted from the organomineralization is defined as the " organomineral" , i, e. refers to minerals that are affected by organics, mostly life-related, but not directly produced by living cells. Thus, the chief difference between the biomineral and the organomineral is that the later can not incorporate into functional structures under strict biological control. When the biomineralization attract the attention by biologists andchemists, it becomes the research object for the further understanding of " the sophisticate chemical process within life system" ; further, the biomineralization gradually becomes an attracting research field of many subjects beyond the geological field. At the same time, studies on the biomineralization result in the advances of the organomineralization. Because the organomineralization and its product, i. e. 9 the organomineral, is volumetrically important constituent of the sedimentary rock record, is synonymous with paleontology and is potentially exciting tracer for life beyond Earth, studies on the organomineralization and its product become an important researching theme within the framework of geobiology.%早期“生物矿化作用”的概念,被定义为生物形成矿物的作用,并进一步分为生物控制和生物诱导两大类型.这个宽泛的概念,被修订为生物以生命活型( living form)影响矿物物质的沉淀作用;相应地,“生物矿物”是在严格的生物控制下、从局部环境中选择性地吸收元素并融合成具有生物功能构造的矿物.“有机矿化作用”,则被定义为“与那些无生命活力的有机物质相关联的矿物形成作用”.与生物矿化作用相对应,有机矿化作用的产物被定义为“有机矿物”,用来指那些通过有机聚合物、生物的和(或)非生物的有机化合物所导致的矿物沉淀作用,但是,有机矿物并非活着的细胞所直接形成.有机矿物与生物矿物的重要区别是,有机矿物没有被融合成受到生物严格控制的功能性构造.生物学家和化学家将生物矿化作用作为关注“生命体系中复杂的化学过程”的研究主题,超越了地质学范畴并使生物矿化作用的研究成为多学科关注的迷人领域,也大大促进了有机矿化作用的研究;考虑到有机矿物是沉积岩的重要组成,而且与生物的出现同步,还是潜在性的地外生命的遗迹,因此,从生物矿化作用衍生出的有机矿化作用的研究,自然就成为与生物矿化作用存在紧密关联的、地球生物学框架下又一个重要的研究主题.【总页数】15页(P937-951)【作者】梅冥相【作者单位】中国地质大学地球科学与资源学院,北京,100083【正文语种】中文【相关文献】1.大河影响下的陆架边缘海沉积有机碳的再矿化作用 [J], 姚鹏;郭志刚;于志刚2.海水中天然细菌对不同生源要素有机物的矿化作用 [J], 谭丽菊;肖慧;CraigA.Carlson;王江涛3.颗石藻矿化作用的矿物学特征与地球环境指示意义 [J], 孙仕勇;郭鹏云;邹翔;林森;;;;;;;;4.水中有机质矿化作用的生物地球化学室内模拟研究 [J], 赵彦龙;李心清;丁文慈;闫慧;蒋倩;黄代宽;刘文景5.生物成矿作用与生物矿化作用 [J], 戴永定;刘铁兵;沈继英因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

生物矿化

硅石 (SiO2.nH2O)

大于100科,包括裸子植 芦竹、竹类、玉米、龟草、 物、被子植物和蕨类植物 金丝雀草、垂穗草、(禾

本科)等。

biomineralization 植物体内的草酸钙

草酸钙晶体是植物生长发育过程中形成的最常见的矿物, 几乎在所有高等植 物体内都有分布, 并存在于不同的组织及器官中.

在中等尺度上,组织的分级组装是由 多种细胞活动控制的,而这些细胞活 动也是通过基因表达控制的。

biomineralization

六、植物体内的生物矿化

矿化物

植物体内的生物矿物

常规分布

出现的物种

草酸钙 (CaC2O4.nH2O)

215个科,包括裸子植物 和被子植物

白檀,仙人掌科; 黄毛掌,仙人掌科; 菜豆、豆科; 皂树,蔷薇科; 葡萄,葡萄科;

基质对矿化的指导作用 细胞、代谢的参与

biomineralization

二、生物矿化的种类

化学式

CaCO3 CaCO3 CaMg(CO3)2 Ca5(PO4)3(OH) SiO2(H2O)n Fe3O4 Fe3S4 CaBR CaC2O4 NH4MgPO4

俗名

方解石 文石 白云石 羟基磷灰石 无定形水合硅 磁铁矿

biomineralization 1、植硅体的基本特征

1、植硅体产量 大,分布范围广。

从高山到平 原,从湖泊到海 洋,从森林到草 原,凡有植被的 地方,即有植硅 体的存在

2、植硅体理化 性质稳定,具有 耐腐蚀性。

当植物死亡 或凋谢之后,植 硅体不会分解, 而完整地长期保 存于土层中。

3、植硅体具有 极佳的耐高温特 性。 这种抗高温性能 可使植硅体理想 地应用于经高温 处理的依存分析 之中。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Mimi Fang November 16, 2006

Lecture Outline

Definition Examples Functions General mechanism Bone formation Bone calcification

matrix vesicles collagen

Formation of long bones

examples: humerus, radius, ulna, femur, tibia, fibula

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Mesenchymal cells migrate to site of bone formation Mesenchymal cells give rise to chondrocytes and form the shape of bone Chondrocytes secrete ECM Chondrocytes continue to grow until they become encapsulated in the ECM Primary ossification

/content/vol298/issue5592/images/data/375/DC1/1078093S1_large.jpg

Many Functions

Biomineralization function varies between organisms Functions

Mature chondrocytes hypertrophy Cartilage matrix becomes calcified, which may be mediated by matrix vesicles

6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11.

Calcified matrix is partly degraded by osteoclasts, allowing blood vessels and osteoprogenitor cells to invade Osteoprogenitor cells become osteoblasts, which lay down new bone after using the calcified matrix as a template Osteoblasts secrete osteo; vertebrate skeletons

calcium carbonates, calcium phosphates

(Weiner et al, 2005)

Examples

The field used to be called “calcification” However, many of the minerals don’t contain calcium, thus the change to “biomineralization”

Osteoporosis Rickets Bone breaks Improve bone quality

Correct dental defects and cosmetics

Tooth damage Abnormal formation Periodontal disease

Why do we care about calcification?

Carniverous marine worm Glycera teeth

atacamite (copper chloride mineral)

http://www.biophysics.u .au/STAWA/sca ns/40578a.jpg

(Weiner et al, 2002)

/weekly pics/skeleton.gif

can bind to the crystals to inhibit or shape crystal formation can transport or sequester ions

Why do we care about calcification?

Correct bone defects

Cartilage outside the primary ossification center increases in size by interstitial and appositional growth

Secondary ossification

occurs at the ends of each epiphysis similar process as primary ossification growth continues until cartilage between the ossification centers is replaced completely by bone (growth plate)

Endochondral ossification Intramembranous ossification

Endochondral Ossification

/~jgjohnso/skeletonorg.html

Endochondral Ossification

structural stability locomotion protection sound reception toxic waste disposal temporary ion storage magnetic orientation

General Biomineralization Mechanism

Bone

Derived from mesenchymal stem cells:

Osteoblasts form bone Some osteoblasts mature into osteocytes; mechanically sensitive cells that maintain bone

12.

Bone remodeling occurs

osteoclasts resorb bone areas of bone not completely filled in are called cancellous bone areas filled in are called compact bone Medullary cavity for bone marrow formed

Osteoid is the organic part of bone without the inorganic constituent

Osteoid becomes calcified and osteoblasts that remain become encapsulated into the calcified matrix and are now called osteocytes Process of bone formation continues toward both epiphyses

Bone Calcification

Main players involved:

Calcium Phosphate Matrix vesicles Collagen Alkaline phosphatase Proteoglycan aggregates

Formation of flat bones

Examples: scapula, sternum, ribs, patella, skull

1.

Mesenchymal cells give rise to osteoprogenitor cells, which develop into osteoblasts

Bone and teeth comparison Summary

What is Biomineralization?

Definition

“Biomineralization is the process by which mineral crystals are deposited in an organized fashion in the matrix (either cellular or extracellular) of living organisms” (Boskey, 1998).

Intramembranous Ossification

/histology/labmanual2002/labsection1/boneform&synovialjoints03.htm

Intramembranous Ossification

/ortho/oj/1998/oj11sp98p59.html

Skeleton of a man with Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. (A) Plates and ribbons of ectopic bone contour the skin over the back and arms can be visualized directly on the skeleton. (B) After death from pneumonia at age 40 years.

1.) Nucleation

Specific (anionic) protein nucleators that provide a template or sequester the ions and direct the ions in an ordered orientation to form the initial crystal structure

Examples

Magnetotactic bacteria

iron oxides

/v ertebra/453/photos/teeth_photo s/human-teeth.jpg