Monthly Review on Price Indices

金融词汇缩写

CPI Consumer Price IndexPPI Producer Price IndexJVC joint venture company 合资公司K. D. knocked down 拆散K. D. knocked down price 成交价格L. B. letter book 书信备查簿LB licensed bank 许可银行L.& D. loans and discounts 放款及贴现Li. liability 负债LI letter of interest (intent) 意向书lifo (LIFO) last in, first out 后进先出法L. I. P. (LIP) life insurance policy 人寿保险单LIRCs low interest rate currencies 低利率货币L/M list of materials 材料清单LMT local mean time 当地标准时间LRP limited recourse project 有限追索工程LRPF limited recourse project financing 有限追索工程融资i. s. lump sum 一次付款总额i. s. t. local standard time 当地标准时间LT long term 长期Ltd. limited 有限〔公司〕m million 百万M matured bond 到期的债券M&A merger & acquisition 兼并收购MA my account 本人帐户Mat. maturity 到期日Max., max maximum 最大量M. B. memorandum book 备忘录MBB mortgage-backed bonds 抵押支持的债券MBO management by objectives 目标管理M/C marginal credit 信贷限额m/c metallic currency 金属货币MCA mutual currency account 共同货币帐户MCP mixed credit program 混合信贷方案M/d months after deposit 出票后......月M. D. maturity date 到期日M. D. (M/D) memorandum of deposit 存款(放〕单M. D. malicious damage 恶意损坏mdse. merchandise 商品MEI marginal efficiency of investment 投资的边际效率mem. memorandum 备忘录MERM multilateral exchange rate model 多边汇率模型M. F. mutual funds 共同基金MF mezzanine financing 过渡融资mfg. manufacturing 制造的MFN most favoured nations 最惠国mfrs. manufacturers 制造商mg milligram 毫克M/I marine insurance 海险micro one millionth part 百万分之一min minimum 最低值、最小量MIP monthly investment plan 月度投资方案mks. marks 商标mkt. market 市场MLR minimum lending rate 最低贷款利率MLTG medium-and-long-term guarantee 中长期担保M. M. money market 货币市场MMDA money market deposit account 货币市场存款帐户MMI major market index 主要市场指数MNC multinational corporation 跨〔多〕国公司MNE multinational enterprise 跨国公司MO (M. O.) money order 汇票MOS management operating system 经营管理制度Mos. months 月MP market price 市价M/P months after payment 付款后......月MPC marginal propensity to consume 边际消费倾向Mrge.(mtg. ) mortgage 抵押MRJ materials requisition journal 领料日记帐MRO maintenance, repair and operation 维护、修理及操作MRP manufacturer's recommended price 厂商推荐价格MRP material requirement planning 原料需求方案MRP monthly report of progress 进度月报MT medium term 中期M/T mail transfer 信汇mthly monthly 每月MTI medium-term insurance 中期保险MTN medium-term note 中期票据MTU metric unit 米制单位n. net 净值N. A. net assets 净资产n. a not available 暂缺NC no charge 免费N/C net capital 净资本n. d. no date 无日期N. D. net debt 净债务n. d. non-delivery 未能到达ND next day delivery 第二天交割NDA net domestic asset 国内资产净值N.E. net earnings 净收益n. e. no effects 无效n. e. not enough 缺乏negb. negotiable 可转让的、可流通的Neg. Inst., N. I. negotiable instruments 流通票据nego. negotiate 谈判N. E. S. not elsewhere specified 未另作说明net. p. net proceeds 净收入N/F no fund 无存款NFD no fixed date 无固定日期NFS not for sale 非卖品N. G. net gain 纯收益NH not held 不追索委托N. I. net income 净收益N. I. net interest 净利息NIAT net income after tax 税后净收益NIFO next in, first out 次进先出法nil nothing 无NIM net interest margin 净息差NIT negative income tax 负所得税N. L. net loss 净损失NL no load 无佣金n. m. nautical mile 海里NM no marks 无标记N. N. no name 无签名NNP net national product 国民生产净值NO. (no.) number 编号、号数no a/c no account 无此帐户NOP net open position 净开头寸NOW a/c negotiable order of withdrawal 可转让存单帐户N/P net profit 净利NP no protest 免作拒付证书N. P. notes payable 应付票据NPC nominal protection coefficient 名义保护系数NPL non-performing loan 不良贷款NPV method net present value method 净现值法N. Q. A. net quick assets 速动资产净额NQB no qualified bidders 无合格投标人NR no rated 〔信用〕未分等级N/R no responsibility 无责任N. R. notes receivable 应收票据N. S. F. (NSF) no sufficient fund 存款缺乏NSF check no sufficient fund check 存款缺乏支票nt. wt. net weight 净重NTA net tangible assets 有形资产净值NTBs non-tariffs barriers 非关税壁垒ntl no time lost 立即NTS not to scale 不按比例NU name unknown 无名N. W. net worth 净值NWC net working capital 净流动资本NX not exceeding 不超过N. Y. net yield 净收益NZ$ New Zealand dollar 新西兰元o order 订单o. (O.) offer 发盘、报价OA open account 赊帐、往来帐o/a on account of 记入......帐户o. a. overall 全面的、综合的OAAS operational accounting and analysis system 经营会计分析制OB other budgetary 其他预算O. B. ordinary business 普通业务O. B. (O/B) order book 订货簿OB/OS index overbought/oversold index 超买超卖指数OBV on-balance volume 持平数量法o. c. over charge 收费过多OC open cover 预约保险o/d, o. d.,(O. D.) overdrawn 透支OD overdraft 透支O/d on demand 见票即付O. E. (o. e. ) omission excepted 遗漏除外O. F. ocean freight 海运费OFC open for cover 预约保险O. G. ordinary goods 中等品O. G. L. Open General License 不限额进口许可证OI original issue 原始发行OII overseas investment insurance 海外投资保险ok. all correct 全部正确o. m. s. output per manshift 每人每班产量O. P. old price 原价格O. P. open policy 不定额保险单opp opposite 对方opt. optional 可选择的ord. ordinary 普通的OS out of stock 无现货O/s outstanding 未清偿、未收回的O. T. overtime 加班OTC over-the -counter market 市场外交易市场OV A overhead variance analysis 间接费用差异分析OW offer wanted 寻购启示OWE optimum working efficiency 最正确工作效率oz ounce(s) 盎司ozws. otherwise 否那么p penny; pence; per 便士;便士;每P paid this year 该年〔红利〕已付p. pint 品托〔1/8加仑〕P.A. particular average; power of attorney 单独海损;委托书P.A. personal account; private account 个人账户、私人账户p.a., per ann. per annum 每年P&A professional and administrative 职业的和管理的P&I clause protection and indemnity clause 保障与赔偿条款P&L profit and loss 盈亏,损益P/A payment of arrival 货到付款P/C price catalog; price current 价格目录;现行价格P/E price/earning 市盈率P/H pier-to-house 从码头到仓库P/N promissory note 期票,本票P/P posted price (股票等)的牌价PAC put and call 卖出和买入期权pat. patent 专利PAYE pay as you earn 所得税预扣法PAYE pay as you enter 进入时支付PBT profit before taxation 税前利润per pro. per procurationem 〔拉丁〕由...代理PF project finance 工程融资PFD preferred stock 优先股pk peck 配克〔1/4蒲式耳〕PMO postal money order 邮政汇票P.O.C. port of call 寄航港,停靠地P.O.D. place of delivery 交货地点P.O.D. port of destination; port of discharge 目的港;卸货港P.O.R. payable on receipt 货到付款P.P. payback period 〔投资的〕回收期P.P.I. policy proof of interest 凭保证单证明的保险利益POE port of entry 报关港口POP advertising point-of-purchase advertising 购物点广告POR pay on return 收益PR payment received 付款收讫PS postscript 又及PV par value; present value 面值;现值q. quarto 四开,四开本Q. quantity 数量QB qualified buyers 合格的购置者QC quality control 质量控制QI quarterly index 季度指数qr. quarter 四分之一,一刻钟QT questioned trade 有问题交易QTIB Qualified Terminal Interest Property Trust 附带可终止权益的财产信托quad. quadruplicate 一式四份中的一份quotn. quotation 报价q.v. quod vide (which see) 参阅q.y. query 查核R option not traded 没有进行交易的期权R. response; registered; return 答复;已注册;收益r. rate; rupee; ruble 比率;卢比;卢布RAD research and development 研究和开发RAM diverse annuity mortgage 逆向年金抵押RAN revenue anticipation note 收入预期债券R&A rail and air 铁路及航空运输R&D research and development 研究与开发R&T rail and truck 铁路及卡车运输R&W rail and water 铁路及水路运输R/A refer to acceptor 洽询〔汇票〕承兑人R/D refer to drawer 〔银行〕洽询出票人RB regular budget 经常预算RCA relative comparative advantage 相比照拟优势RCMM registered competitive market maker 注册的竞争市场自营商rcvd. received 已收到r.d. running days=consecutive days 连续日RDTC registered deposit taking company 注册接受存款公司Re. subject 主题re. with reference to 关于RECEIVED B/L received for shipment bill of lading 待装云提单REER real effective exchange rate 实效汇率ref. referee; reference; refer(red) 仲裁者;裁判;参考;呈递REO real estate owned 拥有的不动产REP import replacement 进口替代REP Office representative office 代办处,代表处REPO, repu, RP Repurchase Agreement 再回购协议req. requisition 要货单,请求REVOLVER revolving letter of credit 循环信用证REWR read and write 读和写RIEs recognized investment exchanges 认可的投资交易〔所〕Rl roll 卷RLB restricted license bank 有限制牌照银行RM remittance 汇款rm room 房间RMB RENMINBI 人民币,中国货币RMS Royal Mail Steamer 皇家邮轮RMSD Royal Mail Special Delivery 皇家邮政专递RMT Rail and Maritime Transport Union 铁路海运联盟ROA return on asset 资产回报率ROC return on capital 资本收益率ROE return on equity 股本回报率ROI return on investment 投资收益ROP registered option principal 记名期权本金ro-ro roll-on/roll-off vessel 滚装船ROS return on sales 销售收益率RPB Recognized Professional Body 认可职业〔投资〕机构RPI retail price index 零售物价指数RPM resale price maintenance 零售价格维持措施〔方案〕rpt. repeat 重复RRP Reverse Repurchase Agreement 逆回购协议RSL rate sensitive liability 利率敏感性债务RSVP please reply 请回复RT Royalty Trust 特权信托RTM registered trade mark 注册商标Rto ratio 比率RTO round trip operation 往返作业RTS rate of technical substitution 技术替代率RTW right to work 工作权利RUF revolving underwriting facility 循环式包销安排RYL referring to your letter 参照你方来信RYT referring to your telex 参照你方电传S no option offered 无期权出售S split or stock divided 拆股或股息S signed 已签字s second; shilling 秒;第二;先令SA semi-annual payment 半年支付SA South Africa 南非SAA special arbitrage account 特别套作账户SAB special assessment bond 特别估价债券sae stamped addressed envelope 已贴邮票、写好地址的信封SAFE State Administration of Foreign Exchange 国家外汇管理局SAIC State Administration for Industry and Commerce 〔中国〕国家工商行政管理局SAP Statement of Auditing Procedure 【审计程序汇编】SAR Special Administrative Region 特别行政区SAS Statement of Auditing Standard 【审计准那么汇编】SASE self-addressed stamped envelope 邮资已付有回邮地址的信封SAT (China) State Administration of Taxation 〔中国〕国家税务局SATCOM satellite communication 卫星通讯SB short bill 短期国库券;短期汇票SB sales book; saving bond; savings bank 售货簿;储蓄债券;储蓄银行SBC Swiss Bank Corp. 瑞士银行公司SBIC Small Business Investment Corporation 小企业投资公司SBIP small business insurance policy 小型企业保险单SBLI Savings Bank Life Insurance 储蓄银行人寿保险SBN Standard Book Number 标准图书号SC sales contract 销售合同sc scilicet namely 即SC supplier credit 卖方信贷SCF supplier credit finance 卖方信贷融资Sch schilling 〔奥地利〕先令SCIRR special CIRR 特别商业参考利率SCL security characteristic line 证券特征线SCORE special claim on residual equity 对剩余财产净值的特别要求权SD standard deduction 标准扣除额SDB special district bond 特区债券SDBL sight draft, bill of lading attached 即期汇票,附带提货单SDH synchronous digital hierarchy 同步数字系统SDR straight discount rate 直线贴现率SDRs special drawing rights 特别提款权SE shareholders' equity 股东产权SE Stock Exchange 股票交易所SEA Single European Act 【单一欧洲法案】SEAF Stock Exchange Automatic Exchange Facility 股票交易所自动交易措施SEATO Southeast Asia Treaty Organization 东南亚公约组织sec second(ary); secretary 第二,次级;秘书sect. section 局部Sen senator 参议院Sept. September 九月SET selective employment tax 单一税率工资税sextuplicate 〔文件〕一式六份中的一份SEC special economic zone 经济特区SF sinking fund 偿债基金Sfr Swiss Frank 瑞士法郎SFS Summary Financial Statements 财务报表概要sgd. signed 已签署SHEX Sundays and holidays excepted 星期日和假日除外SHINC Sundays and holidays included 星期日和假日包括在内shpd. shipped 已装运shpg. shipping 正装运shpt. shipment 装运,船货SI Statutory Instrument; System of Units 有效立法;国际量制SIC Standard Industrial Classification 标准产业分类SIP structured insurance products 结构保险产品SITC Standard International Trade Classification 国际贸易标准分类sk sack 袋,包SKD separate knock-known 局部散件SLC standby LC 备用信用证SMA special miscellaneous account 特别杂项账户SMEs small and medium-sized enterprises 中小型企业SMI Swiss Market Index 瑞士市场指数SML security market line 证券市场线SMTP supplemental medium term policy 辅助中期保险SN stock number 股票编号Snafu Situation Normal, All Fouled Up 情况还是一样,只是都乱了SOE state-owned enterprises 国有企业SOF State Ownership Fund 国家所有权基金sola sola bill, sola draft, sola of exchange 〔拉丁〕单张汇票sov. sovereign 金镑=20先令SOYD sum of the year's digits method 年数加总折旧法spec. specification 规格;尺寸SPF spare parts financing 零部件融资SPQR small profits, quick returns 薄利多销SPS special purpose securities 特设证券Sq. square 平方;结清SRM standard repair manual 标准维修手册SRP Salary Reduction Plan 薪水折扣方案SRT Spousal Remainder Trust 配偶幸存者信托ss semis, one half 一半SS social security 社会福利ST short term 短期ST special treatment (listed stock) 特别措施〔对有问题的上市股票〕St. Dft. sight draft 即期汇票STB special tax bond 特别税债务STIP short-term insurance policy 短期保险单sub subscription; substitute 订阅,签署,捐助;代替Sun Sunday 星期日sund. sundries 杂货,杂费sup. supply 供给,供货t time; temperature 时间;温度T. ton; tare 吨;包装重量,皮重TA telegraphic address=cable address 电报挂号TA total asset 全部资产,资产TA trade acceptance 商业承兑票据TA transfer agent 过户转账代理人TAB tax anticipation bill 〔美国〕预期抵税国库券TACPF tied aid capital projects fund 援助联系的资本工程基金TAF tied aid financing 援助性融资TAL traffic and accident loss 〔保险〕交通和意外事故损失TB treasury bond, treasury bill 国库券,国库债券T.B. trial balance 试算表t.b.a. to be advised; to be agreed; to be announced; to be arranged 待通知;待同意;待宣布;待安排t.b.d. to be determined 待〔决定〕TBD policy to be declared policy 预保单,待报保险单TBV trust borrower vehicle 信托借。

99FED财政报告

For use at11:00a.m.,E.D.T.ThursdayJuly22,1999Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve SystemMonetary Policy Report to the CongressPursuant to theFull Employment and Balanced Growth Act of1978 July22,1999Letter of TransmittalBOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THEFEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEMWashington,D.C.,July22,1999THE PRESIDENT OF THE SENATETHE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVESThe Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report to the Congress,pursuant to the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of1978.Sincerely,Alan Greenspan,ChairmanTable of ContentsPage Monetary Policy and the Economic Outlook1 Economic and Financial Developments in19994Monetary Policy Report to the CongressReport submitted to the Congress on July22,1999, pursuant to the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of1978M ONETARY P OLICY AND THE E CONOMICO UTLOOKThe U.S.economy has continued to perform well in 1999.The ongoing economic expansion has moved into a near-record ninth year,with real output expand-ing vigorously,the unemployment rate hovering around lows last seen in1970,and underlying trends in inflation remaining subdued.Responding to the availability of new technologies at increasingly attractive prices,firms have been investing heavily in new capital equipment;this investment has boosted productivity and living standards while holding down the rise in costs and prices.Two of the major threats faced by the economy in late1998—economic downturns in many foreign nations and turmoil infinancial markets around the world—receded over thefirst half of this year.Eco-nomic conditions overseas improved on a broad front. In Asia,activity picked up in the emerging-market economies that had been battered by thefinancial crises of1997.The Brazilian economy—Latin America’s largest—exhibited a great deal of resil-ience with support from the international community, in the wake of the devaluation and subsequentfloat-ing of the real in January.These developments,along with the considerable easing of monetary policy in late1998and early1999in a number of regions, including Europe,Japan,and the United States,fos-tered a markedly better tone in the world’sfinancial markets.On balance,U.S.equity prices rose substan-tially,and in credit markets,risk spreads receded toward more typical levels.Issuance of private debt securities ballooned in late1998and early1999,in part making up for borrowing that was postponed when markets were disrupted.As these potentially contractionary forces dissi-pated,the risk of higher inflation in the United States resurfaced as the greatest concern for monetary pol-icy.Although underlying inflation trends generally remained quiescent,oil prices rose sharply,other commodity prices trended up,and prices of non-oil imports fell less rapidly,raising overall inflation rates. Despite improvements in technology and business processes that have yielded striking gains in effi-ciency,the robust growth of aggregate demand, fueled by rising equity wealth and readily available credit,produced even tighter labor markets in thefirst half of1999than in the second half of1998.If this trend were to continue,labor compensation would begin climbing increasingly faster than warranted by productivity growth and put upward pressure on prices.Moreover,the Federal Open Market Commit-tee(FOMC)was concerned that as economic activity abroad strengthened,thefirming of commodity and other prices might also foster a less favorable infla-tion environment.To gain some greater assurance that the good inflation performance of the economy would continue,the Committee decided at its June meeting to reverse a portion of the easing undertaken last fall when globalfinancial markets were dis-rupted;the Committee’s target for the overnight fed-eral funds rate,a key indicator of money market conditions,was raised from43⁄4percent to5percent. Monetary Policy,Financial Markets,and the Economy over the First Half of1999The FOMC met in February and March against the backdrop of continued rapid expansion of the U.S. economy.Demand was strong,employment growth was brisk,and labor markets were tight.Nonetheless, price inflation was still low,held in check by a sub-stantial gain in productivity,ample manufacturing capacity,and low inflation expectations.Activity was supported by a further settling down offinancial markets in thefirst quarter after a period of considerable turmoil in the late summer and fall of 1998.In that earlier period,which followed Russia’s moratorium on a substantial portion of its debt pay-ments in mid-August,the normal functioning of U.S.financial markets had been impaired as investors cut back sharply their credit risk exposures and market liquidity dried up.The Federal Reserve responded to these developments by trimming its target for the overnight federal funds rate by75basis points in three steps.In early1999,the devaluation and subse-quentfloating of the Brazilian real in mid-Januaryheightened concerns for a while,but market condi-tions overall improved considerably.At its February and March meetings,the FOMC left the stance of monetary policy unchanged.The Committee expected that the growth of output might well slow sufficiently to bring production into close enough alignment with the economy’s enhanced potential to forestall the emergence of a trend of ris-ing inflation.Although domestic demand was still increasing rapidly,it was anticipated to moderate over time in response to the buildup of large stocks of business equipment,housing units,and durable goods and more restrained expansion in wealth in the absence of appreciable further increases in equity prices.Furthermore,the FOMC,after taking account of the near-term effects of the rise in crude oil prices,saw few signs that cost and price inflation was in the process of picking up.The unusual combination of very high labor resource utilization and sustained low inflation suggested considerable uncertainty about the relationship between output and prices.In this envi-ronment,the Committee concluded that it could wait for additional information about the balance of risks to the economic expansion.By the time of the May FOMC meeting,demand was still showing considerable forward momentum,and growth in economic activity still appeared to be running in excess of the rate of increase of the economy’s long-run capacity to expand output.Bor-rowers’heavy demands for credit were being met on relatively favorable terms,and wealth was further boosted by rapidly rising equity prices.Also,the economic and financial outlook for many emerging-market countries was brighter.Trends in inflation were still subdued,although consumer prices—even apart from a big jump in energy prices—were reported to have registered a sizable rise in April.At its May meeting,the FOMC believed that these developments tilted the risks toward further robust growth that would exert additional pressure on already taut labor markets and ultimately show through to inflation.Moreover,a turnaround in oil and other commodity markets meant that prices of these goods would no longer be holding down infla-tion,as they had over the past year.Yet,the economy to date had shown a remarkable ability to accommo-date increases in demand without generating greater underlying inflation trends,as the continued growth of labor productivity had helped to contain cost pres-sures.The uncertainty about the prospects for prices,demand pressures,and productivity was large,and the Committee decided to defer any policy action.However,in light of its increased concern about the outlook for inflation,the Committee adopted an asymmetric directive tilted toward a possible firm-ing of policy.The Committee also wanted to inform the public of this significant revision in its view,and it announced a change in the directive immediately after the meeting.The announcement was the first under the Committee’s policy of announcing changes in the tilt of the domestic directive when it wants to communicate a major shift in its view about the balance of risks to the economy or the likely direction of its future actions.In the time leading up to the FOMC’s June meet-ing,economic activity in the United States continued to move forward at a brisk pace,and prospects in a number of foreign economies showed additional bor markets tightened slightly fur-ther.The federal funds rate,however,remained atSelected interest rates45672/53/255/207/28/199/3011/1212/162/43/315/197/18/189/2910/1511/1712/222/33/305/186/30199719981999Note.The data are daily.Vertical lines indicate the days on which the Federal Reserve announced a monetary policy action.The dates on the horizon-tal axis are those on which either the FOMC held a scheduled meeting or a policy action was st observations are for July 19,1999.2Monetary Policy Report to the Congress July 1999the lower level established in November1998,when the Committee took its last of three steps to counter severefinancial market strains.With those strains largely gone,the Committee believed that the time had come to reverse some of that accommodation, and it raised the targeted overnight federal funds rate 25basis points,to5percent.Looking ahead,the Committee expected demand to remain strong,but it also noted the possibility that a further pickup in productivity could allow the economy to accommo-date this demand for some time without added infla-tionary pressure.In light of these conflicting forces in the economy,the FOMC returned to a symmetric directive.Nonetheless,with labor markets already tight,the Committee recognized that it needed to stay especially alert to signs that inflationary forces were emerging that could prove inimical to the economic expansion.Economic Projections for1999and2000The members of the Board of Governors and the Federal Reserve Bank presidents see good prospects for sustained,solid economic expansion through next year.For this year,the central tendency of their forecasts of growth of real gross domestic product is 31⁄2percent to33⁄4percent,measured as the change between the fourth quarters of1998and1999.For 2000,the forecasts of real GDP are mainly in the21⁄2percent to3percent range.With this pace of expansion,the civilian unemployment rate is expected to remain close to the recent41⁄4percent level over the next six quarters.The increases in income and wealth that have bolstered consumer demand over thefirst half of this year and the desire to invest in new high-technology equipment that has boosted business demand during the same period should continue to stimulate spend-ing over the quarters ahead.However,several factors are expected to exert some restraint on the economy’s momentum by next year.With purchases of durable goods by both consumers and businesses having risen still further and running at high levels,the stocks of such goods probably are rising more rapidly than is likely to be desired in the longer run,and the growth of spending should moderate.The increase in market interest rates should help to damp spending as well.And unless the extraordinary gains in equity prices of the past few years are extended, the impetus to spending from increases in wealth will diminish.Federal Reserve policymakers believe that this year’s rise in the consumer price index(CPI)will be larger than that in1998,largely because of the rebound in retail energy prices that has already occurred.Crude oil prices have moved up sharply, reversing the decline posted in1998and leading to a jump in the CPI this spring.For next year,the FOMC participants expect the increase in the CPI to remain around this year’s pace,with a central tendency of 2percent to21⁄2percent.Futures market quotes sug-gest that the prevailing expectation is that the rebound in oil prices has run its course now,and ample industrial capacity and productivity gains may help limit inflationary pressures in coming months as well. With labor utilization very high,though,and demand still strong,significant risks remain even after the recent policyfirming that economic andfinancial conditions may turn out to be inconsistent with keep-ing costs and prices from escalating.Although interest rates currently are a bit higher than anticipated in the economic assumptions under-lying the budget projections in the Administration’s Mid-Session Review,there is no apparent tension between the Administration’s plans and the Fed-eral Reserve policymakers’views.In fact,Federal Reserve officials project somewhat faster growth in real GDP and slightly lower unemployment rates into 2000than the Administration does,while the Admin-istration’s projections for inflation are within the Federal Reserve’s central tendencies.1.Economic projections for1999and2000PercentIndicatorFederal Reserve governorsand Reserve Bank presidentsAdministration1Range Centraltendency1999Change,fourth quarterto fourth quarter2Nominal GDP...........43⁄4–51⁄25–51⁄2 4.8Real GDP...............31⁄4–431⁄2–33⁄4 3.2Consumer price index3..13⁄4–21⁄221⁄4–21⁄2 2.4Average level,fourth quarterCivilian unemploymentrate................4–41⁄24–41⁄4 4.32000Change,fourth quarterto fourth quarter2Nominal GDP...........4–51⁄44–5 4.2Real GDP...............2–31⁄221⁄2–3 2.1Consumer price index3..11⁄2–23⁄42–21⁄2 2.4Average level,fourth quarterCivilian unemploymentrate................4–41⁄241⁄4–41⁄2 4.71.From the Mid-Session Review of the budget.2.Change from average for fourth quarter of previous year to average forfourth quarter of year indicated.3.All urban consumers.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System3Money and Debt Ranges for1999and2000At its meeting in late June,the FOMC reaffirmed the ranges for1999growth of money and debt that it had established in February:1percent to5percent for M2,2percent to6percent for M3,and3percent to 7percent for debt of the domestic nonfinancial sec-tors.The FOMC set the same ranges for2000on a provisional basis.As has been the case since the mid-1990s,the FOMC views the ranges for money growth as bench-marks for growth under conditions of price stability and the historically typical relationship between money and nominal income.The disruption of the historically typical pattern of the velocities of M2 and M3(the ratio of nominal GDP to the aggregates) during the1990s implies that the Committee cannot establish,with any confidence,specific target ranges for expected money growth for a given year that will be consistent with the economic performance that it desires.However,persistently fast or slow money growth can accompany,or even precede,deviations from desirable economic outcomes.Thus,the behav-ior of the monetary aggregates,evaluated in the con-text of otherfinancial and nonfinancial indicators, will continue to be of interest to Committee members in their policy deliberations.The velocities of M2and M3declined again in the first half of this year,albeit more slowly than in1998. The Committee’s easing of monetary policy in the fall of1998contributed to the decline,but only to a modest extent.It is not clear what other factors led to the drop,although the considerable increase in wealth relative to income resulting from the substantial gains in equity prices over the past few years may have played a role.Investors could be rebalancing their portfolios,which have become skewed toward equi-ties,by reallocating some wealth to other assets, including those in M2.Even if the velocities of M2and M3were to return to their historically typical patterns over the balance of1999and in2000,M2and M3likely would be at the upper bounds of,or above,their longer-term price-stability ranges in both years,given the Com-mittee’s projections of nominal GDP growth.This relatively rapid expansion in nominal income reflects faster expected growth in productivity than when the price-stability ranges were established in the mid-1990s and inflation that is still in excess of price stability.The more rapid increase in productivity,if it persists for a while and is sufficiently large,might in the future suggest an upward adjustment to the money ranges consistent with price stability.However,con-siderable uncertainty attends the trend in productiv-ity,and the Committee chose not to adjust the ranges at its most recent meeting.Debt of the nonfinancial sectors has expanded at roughly the same pace as nominal income this year—its typical pattern.Given the stability of this relation-ship,the Committee selected a growth range for the debt aggregate that encompasses its expectations for debt growth in both years.The Committee expects growth in nominal income to slow in2000,and with it,debt growth.Nonetheless,growth of this aggregate is projected to remain within the range of3percent to 7percent.E CONOMIC ANDF INANCIAL D EVELOPMENTSIN1999The economy has continued to grow rapidly so far this year.Real gross domestic product rose more than 4percent at an annual rate in thefirst quarter of1999, and available data point to another significant gain in the second quarter.1The rise in activity has been 1.Allfigures from the national income and product accounts cited here are subject to change in the quinquennial benchmark revisions slated for this fall.2.Ranges for growth of monetary and debt aggregatesPercentAggregate19981999Provisional for2000M2............1–51–51–5M3............2–62–62–6 Debt...........3–73–73–7Note.Change from average for fourth quarter of preceding year to averagefor fourth quarter of year indicated.Change in realGDP 1994199519961997199819990–+ 2 4Note.In this chart and in subsequent charts that show the components ofreal GDP,changes are measured from thefinal quarter of the previous period tothefinal quarter of the period indicated.4Monetary Policy Report to the Congress July1999brisk enough to produce further substantial growth of employment and a reduction in the unemployment rate to 41⁄4percent.Growth in output has been driven by strong domestic demand,which in turn has been supported by further increases in equity prices,by the continuing salutary effects of government saving and inflows of foreign investment on the cost of capital,and by more smoothly functioning financial markets as the turbulence that marked the latter part of 1998subsided.Against the background of the easing of monetary policy last fall and continuing robust economic activity,investors became more willing to advance funds to businesses;risk spreads have receded and corporate debt issuance has been brisk.Inflation developments were mixed over the first half of the year.The consumer price index increased more rapidly owing to a sharp rebound in energy prices.Nevertheless,price inflation outside of the energy area generally remained subdued despite the slight further tightening of labor markets,as sizable gains in labor productivity and ample industrial capacity held down price increases.The Household SectorConsumer SpendingReal personal consumption expenditures surged 63⁄4percent at an annual rate in the first quarter,and more recent data point to a sizable further advance in the second quarter.The underlying fundamentals for the household sector have remained extremely favor-able.Real incomes have continued to rise briskly with strong growth of employment and real wages,and consumers have benefited from substantial gains in wealth.Not surprisingly,consumer confidence—as measured,for example,by the University of Michigan Survey Research Center (SRC)and Con-ference Board surveys—has remained quite upbeat in this environment.Growth of consumer spending in the first quarter was strong in all expenditure categories.Outlays for durable goods rose sharply,reflecting sizable increases in spending on electronic equipment (espe-cially computers)and on a wide range of other goods,including household furnishings.Purchases of cars and light trucks remained at a high level,supported by declining relative prices as well as by the funda-mentals that have buoyed consumer spending more generally.Outlays for nondurable goods were also robust,reflecting in part a sharp increase in expendi-tures for apparel.Finally,spending on services climbed steeply as well early this year,paced by sizable increases in spending on recreation and bro-kerage services.In the second quarter,consumers apparently boosted their purchases of motor vehicles further.In all,real personal consumption expendi-tures rose at more than a 4percent annual rate in April and May,an increase that is below the first-quarter pace but is still quite rapid by historical standards.Real disposable income increased at an annual rate of 31⁄2percent in the first quarter,with the strong labor market generating marked increases in wages and salaries.Even so,income grew less rapidly than expenditures,and the personal saving rate declined further;indeed,by May the saving rate had moved below negative 1percent.Much of the decline in the saving rate in recent years can be explained by the sharp rise in household net worth relative to dispos-able income that is associated with the appreciationChange in real income and consumption1994199519961997199819990–+2468Percent, annual rateWealth and saving4561978198219861990199419980–+24681012Note.The wealth-to-income ratio is the ratio of net worth of households to disposable personal income.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 5of households’stock market assets since 1995.This rise in wealth has given households the wherewithal to spend at levels beyond what current incomes would otherwise allow.As share values moved up further in the first half of this year,the wealth-to-income ratio continued to edge higher despite the absence of saving out of disposable income.Residential InvestmentHousing activity remained robust in the first half of this year.In the single-family sector,positive funda-mentals and unseasonably good weather helped boost starts to a pace of 1.39million units in the first quarter—the highest level of activity in twenty years.This extremely strong level of building activity strained the availability of labor and some materials;as a result,builders had trouble achieving the usual seasonal increase in the second quarter,and starts edged off to a still-high pace of 1.31million units.Home sales moderated in the spring:Sales of both new and existing homes were off some in May from their earlier peaks,and consumers’perceptions of homebuying conditions as measured by the Michigan SRC survey have declined from the very high marks recorded in late 1998and early this year.Nonethe-less,demand has remained quite robust,even in the face of a backup in mortgage interest rates:Builders’evaluations of new home sales remained very high at mid-year,and mortgage applications for home pur-chases showed strength into July.With strong demand pushing up against limited capacity,home prices have risen substantially,although evidence is mixed as to whether the rate of increase is picking up.The quality-adjusted price of new homes rose 5percent over the four quartersended in 1999:Q1,up from 31⁄4percent over the preceding four-quarter period.The repeat sales index of existing home prices also rose about 5percent between 1998:Q1and 1999:Q1,but this series posted even larger increases in the year-earlier period.On the cost side,tight supplies have led to rising prices for some building materials;prices of plywood,lum-ber,gypsum wallboard,and insulation have all moved up sharply over the past twelve months.In addition,hourly compensation costs have been rising relatively rapidly in the construction sector.Starts of multifamily units surged to 384,000at an annual rate in the first quarter and ran at a pace a bit under 300,000units in the second quarter.As in the single-family sector,demand has been supported by strong fundamentals,builders have been faced with tight supplies of some materials,and prices have been rising briskly:Indeed,apartment property values have been increasing at around a 10percent annual rate for three years now.Household FinanceIn addition to rising wealth and rapid income growth,the strong expenditures of households on housing and consumer goods over the first half of 1999were encouraged by the decline in interest rates in the latter part of 1998.Households borrowed heavily to finance spending.Their debt expanded at a 91⁄2per-cent annual rate in the first quarter,up from the 83⁄4percent pace over 1998,and preliminary data for the second quarter indicate continued robust growth.Mortgage borrowing,fueled by the vigorous housing market and favorable mortgage interest rates,was particularly brisk in the first quarter,with mortgage debt rising at an annual rate of 10percent.In the second quarter,mortgage rates moved up consider-ably,but preliminary data indicate that borrowing was still substantial.Consumer credit growth accelerated in the first half of 1999.It expanded at about an 8percent annual rate compared with 51⁄2percent for all of 1998.The growth of nonrevolving credit picked up,reflecting brisk sales and attractive financing rates for automo-biles and other consumer durable goods.The expan-sion of revolving credit,which includes credit card loans,slowed a bit from its pace in 1998.Households apparently have not encountered added difficulties meeting the payments associated with their greater indebtedness,as measures of household financial stress improved a bit on balance in the first quarter.Personal bankruptcies dropped off consid-erably,although part of the decline may reflectPrivate housing starts198819901992199419961998.4.81.2Millions of units, annual rateSingle-familyMultifamilyQ2Q26Monetary Policy Report to the Congress July 1999the aftermath of a surge in filings in late 1998that occurred in response to pending legislation that would limit the ability of certain debtors to obtain forgiveness of their obligations.Delinquency rates on several types of household loans edged lower.Delin-quency and charge-off rates on credit card debt moved down from their 1997peaks but remained at historically high rates.A number of banks continued to tighten credit card lending standards this year,as indicated by banks’responses to Federal Reserve surveys.The Business SectorFixed InvestmentReal business fixed investment appears to have posted another huge increase over the first half of1999.Investment spending continued to be driven by buoyant expectations of sales prospects as well as by rapidly declining prices of computers and other high-tech equipment.In recent quarters,spend-ing also may have been boosted by the desire to upgrade computer equipment in advance of the roll-over to the year 2000.Real investment has been rising rapidly for several years now;indeed,the average increase of 10percent annually over the past five years represents the most rapid sustained expan-sion of investment in more than thirty years.Although a growing portion of this investment has gone to cover depreciation on purchases of short-lived equipment,the investment boom has led to a notable upgrading and expansion of the capital stock and in many cases has embodied new technologies.These factors likely have been important in the na-tion’s improved productivity performance over the past few years.Real outlays for producers’durable equipment increased at an annual rate of 91⁄2percent in the first quarter of the year,after having surged nearly 17per-cent last year,and may well have re-accelerated in the second quarter.Outlays on communications equipment were especially robust in the first quarter,driven by the ongoing effort by telecommunications companies to upgrade their networks to provide a full range of voice and data transmission services.Purchases of computers and other information pro-cessing equipment were also up notably in the first quarter,albeit below last year’s phenomenal spending pace,and shipments of computers surged again in April and May.Shipments of aircraft to domestic carriers apparently soared in the second quarter,and business spending on motor vehicles,including medium and heavy trucks as well as light vehicles,has remained extremely strong as well.Real business spending for nonresidential struc-tures has been much less robust than for equipment,and spending trends have varied greatly across sec-tors of the market.Real spending on office buildings and lodging facilities has been increasing impres-sively,while spending on institutional and industrial structures has been declining—the last reflecting ample capacity in the manufacturing sector.In the first quarter of this year,overall spending on struc-tures was reported in the national income and product accounts to have moved up at a solid 53⁄4percent annual rate,reflecting a further sharp increase in spending on office buildings and lodging facilities.However,revised source data indicate a somewhat smaller first-quarter increase in nonresidential con-struction and also point to a slowing in activity in April and May from the first-quarter pace.Delinquency rates on household loans1988199019921994199619982345PercentCredit card accounts at banksAuto loans at domestic auto finance companiesMortgagesQ1Q1Q1Note.The data are quarterly.Source.Data on credit card delinquencies are from bank Call Reports;data on auto loan delinquencies are from the Big Three automakers;data on mort-gage delinquencies are from the Mortgage Bankers Association.Change in real business fixedinvestment0–+1020Percent, annual rateBoard of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 7。

外贸函电-价格与反还盘

We wish to inform you that our price has been

accepted by other buyers in your city, at which

substantial business has been done, and that

III. Specimen Letters (2)

希望贵方重新考虑这一优惠价格,早日来电订货,以 便我们确认。

We hope you will consider it and cable us your order for our confirmation at your earliest convenience.

level.

我们的价格订得合理 。

IV. Useful Expressions

(4) We are unable to accept your offer as other suppliers have offered us more favorable terms. 我们不能接受你们的报价,因为其他供应商向我 们提出更优惠的价格。

IV. Useful Expressions

(2)

Your

counter-offer

is

not

in

keeping with the current market.

你方的还盘与现行市价不符 。

IV. Useful Expressions

(3) Our price is fixed at a reasonable

III. Specimen Letters (1)

报价实盘英语作文模板

报价实盘英语作文模板英文回答:Quotation Strategy Paper。

Executive Summary。

This quotation strategy paper outlines our comprehensive approach to quoting and competitively pricing our products and services. The paper covers market research, competitor analysis, and our internal processes for developing and issuing quotations. By adhering to these strategies, we aim to maximize revenue, retain customers, and maintain a competitive edge in the marketplace.Market Research and Competitor Analysis。

In-depth market research is crucial to understandingthe competitive landscape and customer needs. We conduct thorough research to identify our target customers, analyzetheir purchasing patterns, and determine the prevailing market prices.Similarly, comprehensive competitor analysis helps us benchmark our pricing and quotation strategies against industry leaders. We monitor their pricing, terms and conditions, and value propositions to stay informed and make informed decisions.Internal Quotation Process。

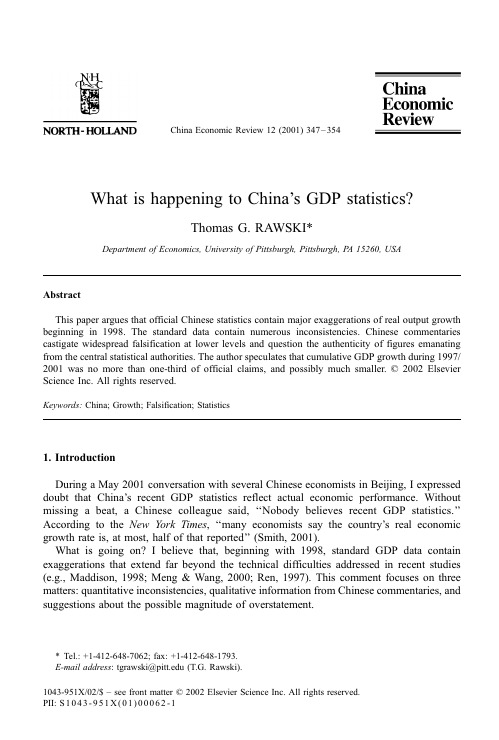

What’s happening to China’s GDP statistics,China Economic Review

What is happening to China’s GDP statistics?Thomas G.RAWSKI*Department of Economics,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,P A 15260,USAAbstractThis paper argues that official Chinese statistics contain major exaggerations of real output growth beginning in 1998.The standard data contain numerous inconsistencies.Chinese commentaries castigate widespread falsification at lower levels and question the authenticity of figures emanating from the central statistical authorities.The author speculates that cumulative GDP growth during 1997/2001was no more than one-third of official claims,and possibly much smaller.D 2002Elsevier Science Inc.All rights reserved.Keywords:China;Growth;Falsification;Statistics1.IntroductionDuring a May 2001conversation with several Chinese economists in Beijing,I expressed doubt that China’s recent GDP statistics reflect actual economic performance.Without missing a beat,a Chinese colleague said,‘‘Nobody believes recent GDP statistics.’’According to the New York Times ,‘‘many economists say the country’s real economic growth rate is,at most,half of that reported’’(Smith,2001).What is going on?I believe that,beginning with 1998,standard GDP data contain exaggerations that extend far beyond the technical difficulties addressed in recent studies (e.g.,Maddison,1998;Meng &Wang,2000;Ren,1997).This comment focuses on three matters:quantitative inconsistencies,qualitative information from Chinese commentaries,and suggestions about the possible magnitude of overstatement.1043-951X/02/$–see front matter D 2002Elsevier Science Inc.All rights reserved.PII:S 1043-951X (01)00062-1*Tel.:+1-412-648-7062;fax:+1-412-648-1793.E-mail address :tgrawski@ (T.G.Rawski).China Economic Review 12(2001)347–3542.Quantitative inconsistenciesOfficial figures for recent GDP growth appear in the top row of Table 1.The yearbook figures imply that real GDP grew by 24.7%between 1997and 2000.During the same 3years,energy consumption dropped by 12.8%.The implied reduction of 30%in unit energy consumption over 3years seems implausible,despite the rapid growth of computer manufac-ture and other activities with low unit energy consumption.Rapid growth of energy efficiency is not a hallmark of China’s economy:in 1997/1998,for example,the efficiency of energy conversion in producing thermal electricity,coke,and refined oil products all declined,and the ‘‘total efficiency of energy conversion’’was no better than the average for 1983/1984(China Statistical Yearbook ,2000,pp.55and 246;China Statistical Abstract ,2001pp.7and 130).International comparisons highlight the implausibility of recent Chinese growth claims.Table 2presents capsule summaries of several Asian economies during comparably short time periods going back to the 1950s.China’s recent official growth story is an obvious misfit:in every other instance,including China’s own experience 10years earlier,substantial GDP growth coincided with increased energy use,higher employment,and rising consumer prices.Returning to recent Chinese data,the clash between output and energy trends is only one of many unlikely elements.The figures for 1997/1998bristle with inconsistencies.Could farm output increase in all but one province despite floods that rank among China’s top 10natural disasters of the 20th century?1Could industrial production rise 10.75%even though only 14of 94major products achieved double-digit growth and 53suffered declining physical output?2Could investment spending jump 13.9%even though steel consumption and cement output rose by less than 5%?3Skeptical Chinese analysts point to many such puzzles (e.g.,Meng,1999).4Subsequent figures seem equally dubious.Data on consumption,which Chinese accounts identify as ‘‘a major driving force in the rapid development of the economy,’’are especially problematic (GDP Growth,2000,p.1).Table 3compares national data on retail sales growth with survey figures showing changes in per capita outlays by urban and rural households.With one exception,5national figures for retail sales grow 1Agricultural output data are from China Statistical Yearbook (1999,p.382).For the classification of the 1998floods among the top 10natural disasters of the 20th century,see Zhongguo tongji (China Statistics ,no.8,1999,p.38).2Industrial output value and physical commodity output for 1997/1998are from China Statistical Yearbook (1999,pp.424and 445–446).3Investment spending and cement output from China Statistical Yearbook (1999,pp.183and 446);increased steel consumption of ‘‘about 4%’’from Zhongguo wujia (China Price,no.3,1999,p.8).4For further examples,see Meng (1999).5The exception is the figure showing that that rural per capita cash expenditure on consumption rose by 12.2%during 1999/2000.This result is inconsistent with reports that rural per capita net income rose by only1.9%during 1999/2000(China Statistical Abstract ,2001,p.96).There is also an internal inconsistency in the source,which shows a drop in per capita cash outlay of RMB 197.7or 8.4%during 1999/2000together with increases of RMB 80and RMB 140.1in expenditure on production and on consumption respectively (China Monthly Indicators ,2001,pp.88–89).T.G.Rawski /China Economic Review 12(2001)347–354348more rapidly than per capita expenditure figures shown in household budgets.The difference is far too large to attribute to population growth,which is approximately 1%per year.A further difficulty is that,particularly in rural areas,retail sales rise more rapidly than household income,implying an increase in the average propensity to consume —i.e.,the share of consumption spending in household income.However,recent studies find a declining trend in the average propensity to consume among both urban and rural households through 1998(Tao,2000;Zhang,2000);subsequent reports indicating that ‘‘moderate income growth has intensified people’s tendency to save money’’(Bing,2001)point to a continuing Table 2Episodes of growth in Asian economies,1957–2001(cumulative percentage change)Cumulative change inJapan,1957/1961Taiwan,1967/1971Korea,1977/1981China,1987/1991China,1997/2001Real GDPOfficial52.849.721.631.834.5Alternate0.4/11.4Energy consumption40.185.233.619.8À5.5Employment4.617.09.423.20.8Consumer prices 10.620.6111.746.6À2.3Sources:Japan:Ohkawa and Shinohara (1979,pp.282,389,393)and .jp/english/1431.htm (Table 9-20);Taiwan:Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of China for 1982(1983,p.103,employment,and p.209,power consumption)and .tw;Korea:www.nso.go.kr/eng;Chinese data for 1987/1991are from China Statistical Yearbook (2000,pp.55,118,239,and 289);data for 1997/2001are from Table 1.Table 1Chinese GDP and related data,official and alternate figures,1998–2001(percentage change)1998199920002001Cumulative growth (1998–2001)Real GDPOfficial7.87.18.07.934.5AlternateÀ2.0/+2.0À2.5/+2.0 2.0/3.0 3.0/4.00.4/11.4a Energy useÀ6.4À7.8 1.1 1.1À5.5Urban formal employment2.3 1.6 1.2 1.20.8Consumer price index À0.8À1.40.4À0.5À2.3Figures for 2001cover only the first two quarters.The cumulative growth calculations assume no change for the second half of 2001.Alternate figures are author’s guesses —see text.Sources:Data for 1997–2000are from China Statistical Yearbook (2000,p.21,official real GDP,and p.118,urban employment)and from China Statistical Abstract (2001,p.130,energy,and p.84,prices).Figures for 2000/2001are from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,pp.14,15,32,and 70).The energy data for 2000/2001refer to production rather than consumption.a Endpoints of cumulative growth range based on low and high annual growth figures.T.G.Rawski /China Economic Review 12(2001)347–354349decline in the ratio of consumption spending to income —the exact opposite of what the retail sales data imply.rmation from Chinese commentariesBeginning in 1998,Chinese analysts complain that the statistics system has become enmeshed in a ‘‘wind of falsification and embellishment’’[jiabao fukuafeng ].ExtensiveTable 3Growth of retail sales and per capita income and expenditure,1997–2001(percentage change,nominal amounts)1998199920002001Cumulative growth (1997–2001a )Aggregate retail sales6.8 6.89.710.338.0Urban dataRetail sales7.17.110.611.641.6Per capita aIncome5.27.97.36.730.0Living expense3.4 6.58.24.624.6Rural dataRetail salesCounty5.2 5.78.39.331.6Below county7.0 6.68.37.432.7Per capita aNet income3.4 2.2 1.9À7.5À0.4Cash outlaySeries A0.8À0.9À8.5À6.8À14.8Series BÀ1.5À1.5À0.7À6.8À10.2Cash outlay for consumptionSeries A0.2 1.412.2 6.621.5Series B À1.7À0.8 5.9 6.610.1Figures for 2001cover only the first one or two quarters.Calculated values for cumulative growth assume no change for the remainder of 2001.Sources:Data for retail sales are from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,p.34).Urban income data for 1997/2000are from China Statistical Abstract (2001,p.94)and measure total income.The figures for 2000/2001are from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,p.88)and cover two quarters of 2001and refer to disposable income.Rural income data for 1997/2000are from China Statistical Abstract (2001,p.100)and measure net income.The figures for 2000/2001are from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,p.88)and measure cash income and cover only the first quarter of 2001.Urban outlays for living expenses from China Statistical Abstract (2001,p.93)and (for the first half of 2001)from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,p.81).Rural cash outlay and cash outlay for consumption:Series A is from China Monthly Indicators,vol.16(2001,July,pp.88–89).Series B is from China Statistical Abstract (2001,p.98,for 1997/2000);the figure for 2000/2001is taken from Series A.a Indicates data from household surveys.T.G.Rawski /China Economic Review 12(2001)347–354350T.G.Rawski/China Economic Review12(2001)347–354351 commentary in Chinese sources,including many specific and detailed accounts,6leaves no room to doubt that intentional falsification of economic performance indicators is common-place throughout the business community and at every level of government.The result is ‘‘universal falsification of statistics,as a‘statistical bubble’works its way up through the system,and provides mistaken reportage to the decision-making levels’’(Meng,1999,p.78). Premier Zhu Rongji complained in March2000that‘‘falsification and exaggeration are rampant’’(Nation Moves Boldly Forward,2000,p.5).Starting in1998,the National Bureau of Statistics(NBS)has rejected provincial data on economic growth,which it dismisses as‘‘cooked local figures’’(Xu,1999).Despite recent efforts to create statistical networks that bypass local,and provincial governments,the Bureau lacks the capacity to collect data outside normal information channels,particularly since survey research remains subject to interference from lower-level officials(e.g.,Hu,Chen,& Zhou,2000,p.24).Chinese policy discussions often ignore the official growth scenario.A July2001 account cites Wu Jinglian’s view that‘‘China has reversed its downward momentum in economic growth,which started in1997’’(Factors Favour Economy in Latter6Months, 2001).An August2001summary of views on fiscal policy notes that deficit spending ‘‘was introduced in1998to overcome insufficient domestic demand and dwindling exports,’’and then observes that because‘‘the economy has been revived,some economists say that the positive policy should be weakened’’(Jia,2001,p.1).But official projections show that growth in the‘‘revived’’economy of1999/2001is slower than in1997and no greater than in the endangered economy of1998.These(and other) texts suggest that prominent Chinese economists base their analysis on private maps of recent trends that differ substantially from the official picture sketched in Table1.In addition,many Chinese accounts directly contradict official figures.For example:‘‘Per capita income in urban and rural areas continued to fall in the first quarter of this year’’(Wang,1999).‘‘In October(1999),66per cent of[apparently urban]consumers said their household incomes had either remained unchanged or had decreased during the previous12 months’’(Bu,1999).‘‘In recent years,rural incomes have gone down year by year[zhunian xiajiang]’’(Wang,2000).4.Toward an alternate view of recent GDP growthSince abandoning provincial growth reports,the NBS has offered no public explanation of how its central office derives the figures that serve as official estimates of China’s national growth.Pressure to affirm official growth targets overwhelms local and provincial statistical bureaus,Chinese economic analysts,and even international bankers and market researchers whose firms pursue business ties with Chinese government agencies.Can we believe that the central offices of the NBS remain untouched by these circumstances?6For further examples and discussion,see Rawski(2001a,2001b).For readers who share this author’s discomfort with the official data,analysis of recent economic trends must begin by exploring alternatives to the official figures in Table 1.The size and diversity of China’s economy pose formidable obstacles to any such effort.7Nonetheless,China’s civil aviation industry offers a starting point for reassessing recent GDP growth.Airline travel appeals to a high-income clientele.Since rising inequality is a prominent feature of China’s economy in the 1990s (e.g.,Xu &Zou,2000),income growth among the airlines’prosperous clientele surely exceeded the norm,probably by a large margin.A fierce price war slashed ticket prices during 1998.8Airlines routinely offered discounts of 30–40%to travelers on domestic routes.With customers’incomes rising and ticket prices plunging,passenger traffic should have grown well ahead of disposable income and aggregate consumption,the largest components of aggregate income and expenditure.Yet the data for 1997/1998show that passenger miles rose by only 2.2%on domestic routes and 3.4%overall.9In the absence of major shifts in the structure of GDP,the elementary economics of demand and consumption points to 2.2%as a generous upper bound for overall real growth during 1997/1998.Declining energy use,output reductions in many branches of industry,mass layoffs,widespread excess capacity,inventory accumulations,and the impact of major floods make this a far more plausible measure of 1997/1998GDP growth than the official figure of 7.8%.And 2.2%is an upper bound.The actual result could have been far lower,perhaps even negative.The (entirely plausible)qualitative picture presented in Chinese reports indicates that GDP growth declined slightly in 1998/1999and improved thereafter.The continuation of excess supply,downward price pressure,near-zero employment creation,widespread excess capacity,inventory build-up,and large-scale accumulation of idle bank deposits indicate that real growth remains well below the 7%level needed to absorb new urban labor force entrants (Ge,1999).These considerations underline the proposed alternate figures for GDP growth shown in Table 1.These figures represent little more than guesses about China’s recent GDP performance.They are not firmly grounded in empirical data.But unlike the official figures,the alternate series does seem consistent with Chinese policy discussions and with official data on changes in employment,prices,and energy consumption.Official performance measures for recent years imply that China’s economy has entered an unprecedented interlude that combines high-speed growth with declining energy use,9Note that both the number of overseas travelers arriving in China and China’s income from international tourism increased during 1997/1998,although more slowly than in prior years (Zhongguo tongji [China Statistics ],no.11,2000,p.48).8In February 1999,‘‘the CAAC [Civil Aviation Administration of China]and the State Development Planning Commission issued an urgent circular that put a halt to selling domestic air tickets at unreasonable discount prices’’(Zhao,1999).7Commenting on an earlier paper (Rawski,2001a),an NBS official said something like:‘‘If you believe that we at NBS cannot measure China’s GDP,what makes you think you can do better?’’T.G.Rawski /China Economic Review 12(2001)347–354352T.G.Rawski/China Economic Review12(2001)347–354353 falling prices,minimal employment growth,widespread excess supply,rampant over-capacity,low expectations,and large-scale pump-priming.Even though recent growth claims defy economic logic and clash with a broad array of credible information from Chinese sources,economists both within and outside China have continued the long-standing practice of routinely adopting official figures.This‘‘business as usual’’approach is a recipe for bad policy and flawed research.The alternative is to hypothesize that the NBS has run afoul of the same political pressures that have caused local authorities to become‘‘obsessed with...GDP growth rates—the leading criteria for evaluating cadre performance’’(Gilley,2001,p.18),to conclude that official data showing7–8%real GDP growth for recent years reflect official objectives rather than economic outcomes,and to continue the search for alternate figures that can provide a realistic appraisal of China’s recent economic performance. ReferencesBing,L.(2001,February13).Deposits up as income growth slows.China Daily,1.Bu,R.(1999,December6).Increased renting expected.China Daily Business Weekly,6.China monthly economic indicators,vol.16.(2001,July).Beijing:National Bureau of Statistics.Factors favour economy in latter6months.(2001,July30).China Daily,4.GDP growth expected to reach8per cent.(2000,November24).China Daily,1.Ge,Y.(1999).Fangfan he huajie shehui fengxian—1999—nian Zhongguo jiuye zhengce xuanzi(Prevent and resolve social risk—China’s employment policy choices for1999).Beijing:Development Research Center. Gilley,B.(2001,July12).Breaking barriers.Far Eastern Economic Review,14–19.Hu,S.,Chen,X.,&Zhou,H.(2000).On rural statistics.Zhongguo tongji(China Statistics)(6),24–26.Jia,H.(2001,August7–13).Rethink on fiscal policy.China Daily Business Weekly,1and24.Maddison,A.(1998).Chinese economic performance in the long run.Paris:OECD.Meng,L.(1999).Analysis of economic conditions and policies during the past several years.Gaige(Reform)(3), 73–82.Meng,L.,&Wang,X.(2000).An estimate of the reliability of statistical data on China’s economic growth.Jingji yanjiu(Economic Research)(10),3–13.Nation moves boldly forward.China Daily(2000,March6),5.Ohkawa,K.,&Shinohara,M.(Eds.)(1979).Patterns of Japanese economic development:a quantitative appraisal.New Haven,CT:Yale University Press.Rawski,T.G.(2001a,January–February).China by the numbers:how reform has affected China’s economic statistics.China Perspectives(also available from /~tgrawski/papers2000)(33),25–34. Rawski,T.G.(2001b).China’s GDP statistics:a case of caveat lector?Available at:/~tgrawski/ papers2001.Abbreviated version published as The credibility gap:China’s recent GDP statistics.China Economic Quarterly,5.1,18–22.Ren,R.(1997).China’s economic performance in international perspective.Paris:OECD.Smith,C.S.(2001,July18).China reports7.8%growth in economy.New York Times,W1.Taiwan,Yearbook.(1983).Zhonghua minguo71—nian tongji tiyao(Statistical yearbook of the Republic of China for1982).Taipei:Xingzheng yuan zhuji chu.Tao,C.(2000).Influence of widening income disparities on the operation of China’s economy.Jiage lilun yu shijian(Price Theory and Practice)(10),13–14.Wang,C.(1999,April29).State to bolster demand.China Daily,1.Wang,X.(2000).Analysis of the current economic situation.Caimao jingji(Finance and Trade Economics)(4), 5–10.Xu,B.(1999,February 15).Statisticians seek reliability.China Daily Business Weekly ,1.Xu,L.C.,&Zou,H.(2000).Explaining the changes of income distribution in China.China Economic Review ,11(2),149–170.Zhang,P.(2000).Income differentials,interest rate,and consumption.Caimao jingji (Finance and Trade Economics)(8),16–22.Zhao,H.(1999,August 18).Aviation sector to make profit.China Daily ,2.Zhongguo tongji nianjian 1999(China statistical yearbook 1999).Beijing:Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.Zhongguo tongji nianjian 2000(China statistical yearbook 2000).Beijing:Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.Zhongguo tongji zhaiyao 2001(China statistical abstract 2001.)Beijing:Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.T.G.Rawski /China Economic Review 12(2001)347–354354。

商务英语谈判unit 6 Price Bargaining[精]

![商务英语谈判unit 6 Price Bargaining[精]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/d182e7670740be1e650e9aec.png)

9.按这个价格,我们不能说服用户购买你们的产品。 We are not in a position to purchase our end-users to

Unit 6 Price Bargaining

9. We hope we could conclude business with you at something near our level. 我们希望以接近我们的价格水平与你方达成此笔交易。

10. I’m afraid we will have to call the whole deal off if you still insist on your original quotation. 如果你们仍然坚持你们原先的报价,恐怕我们只好取消整笔交 易了。

Unit 6 Price Bargaining

IV. Keys to Exercises

1. Translate the following sentences into Chinese

1. It would be very difficult for us to push any sales if we buy it at this price. 如果我们以这个价格购买,我们促销产品将会非常困难。

2. Your price is much higher than we expected.

3. The price of your goods is about 15% higher than that of other manufactures.

ch07SECURITY-MARKET INDICATOR SERIES(投资学,赖利)

Factors in Constructing Market Indexes

The sample of firms to include

What is the intended population that the sample is to represent? How large a sample is needed for the index to be representative? Should the weighting system be based on price, total firm value, or equally weighted? How should the values of the index be reported and tracked (arithmetic or geometric mean)?

Sample used is limited

30 non-randomly selected blue-chip stocks are not representative of the 1800 NYSE listed stocks Similar to assuming an investment of one share per stock Places more weight on higher-priced stocks rather than those with higher market values Introduces a downward bias in DJIA by reducing weight of growing companies whose stock splits

Chapter 7 Questions

企业降成本规则

Workstream Members and their Roles/Responsibilities (1/3)

Not a hyerarchical report

Local Local Leaders Leaders

Workstream Workstream Leader Leader Sponsor Sponsor 支持者 General Manager (Site) Team Team Members Members Local Local Coordinators Coordinators

PMO

Source: PMO

Recommend. PMP

• PP impact of workstream globally • ICS Impact • Net impact • Plan for 2009

Local coordinators

Team members (Global and local)

• Contact/involve additional resources (within his/her specific areas) to • PP impact of schedule/progress in a project implementation workstream • Prepare and present analyses assigned to him/her individually and with its globally sub-team help • ICS Impact • Identify additional opportunities to generate EOP/FCF impact • Net impact • Participate in the jour-fix plant meetings and in the related problem-solving • Plan for 2009 sessions

论文写作与研究第4章 文秋芳著

PROCEDURES FOR REVIEWING THE LITERATURE

Beginning researchers often feel overwhelmed once they enter the library because of the vast amount of materials surrounding them. This section recommend to you a set of procedures which can help you reviewing the literature effectively.

Constructing a working bibliography

What is working bibliography? A tentative list of references for the preparation of reviewing literature. It serves two purpose. Firstly, it can be used as a blueprint to guide your review of the literature. Secondly,It can be taken as a resource bank from which you construct the section of references for your thesis in the end.

There are 4 main kinds of sources for locating reference.① Indices ②unpublished papers ③Journals ④Books

4.1.1Indices

高二英语经济指数单选题50题

高二英语经济指数单选题50题1. The _____ measures the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period.A. GDPB. CPIC. PPID. PMI答案:A。

解析:GDP(国内生产总值)是衡量一个国家在一定时期内生产的所有最终商品和服务的市场价值的指标,这是GDP的基本定义。

选项B,CPI 消费者物价指数)主要衡量消费者购买一篮子商品和服务的价格变化。

选项C,PPI( 生产者物价指数)反映生产环节价格水平。

选项D,PMI(采购经理人指数)反映制造业或服务业的商业活动情况。

2. Which economic index is mainly used to reflect the inflation rate at the consumer level?A. GDPB. CPIC. PPID. PMI答案:B。

解析:CPI是主要用于反映消费者层面通货膨胀率的经济指数。

通货膨胀意味着物价的普遍上涨,CPI通过追踪一篮子消费者商品和服务的价格变化来衡量这种上涨程度。

选项A的GDP是关于生产的价值衡量。

选项C的PPI侧重于生产环节价格。

选项D 的PMI是关于商业活动的指数。

3. China's GDP growth rate has been stable in recent years. GDP stands for _____.A. Gross Domestic ProductB. General Domestic ProductC. Grand Domestic ProductD. Global Domestic Product答案:A。

解析:GDP的全称是Gross Domestic Product(国内生产总值)。

这是固定的经济术语表达。

上调产品价格英语作文

上调产品价格英语作文标题,The Impact of Price Adjustments on Products。

In today's global market, the adjustment of product prices plays a crucial role in shaping consumer behavior, market competition, and overall economic dynamics. Understanding the implications of such adjustments is essential for businesses, consumers, and policymakers alike. This essay explores the various aspects of priceadjustments on products, analyzing their effects ondifferent stakeholders and the broader economy.Firstly, price adjustments influence consumerpurchasing decisions. When prices decrease, consumers may perceive products as more affordable, leading to increased demand and higher sales volumes. Conversely, priceincreases may deter consumers, causing a decline in demand and sales. For example, during promotional periods or sales events, discounted prices often attract more customers, stimulating purchasing activity. On the other hand, suddenprice hikes may lead consumers to seek alternative products or delay their purchases, affecting businesses' revenue streams.Moreover, price adjustments impact market competition. In highly competitive industries, pricing strategies are crucial for companies to gain a competitive edge. Lowering prices can help businesses attract more customers and gain market share, while raising prices may signal product differentiation or quality improvements. However, excessive price competition can lead to price wars, where companies continuously lower prices to undercut rivals, ultimately eroding profitability for all players involved. Therefore, strategic price adjustments are essential for companies to maintain their competitive positions while ensuring sustainable profits.Furthermore, price adjustments have broader economic implications. Inflationary pressures, changes in production costs, and shifts in consumer preferences can all influence price dynamics. Central banks closely monitor inflation rates and consumer price indices to gauge economic healthand adjust monetary policies accordingly. When prices rise persistently, central banks may raise interest rates tocurb inflation, which can impact borrowing costs for businesses and consumers. Conversely, deflationarypressures may prompt central banks to implement expansionary monetary policies to stimulate spending and investment.Additionally, price adjustments can affect income distribution and societal welfare. Lower prices may benefit consumers, particularly those with limited purchasing power, by making essential goods more affordable. However, price reductions may also lead to lower revenues for producers, potentially impacting wages and employment in affected industries. Conversely, price increases may boostprofitability for businesses but can burden consumers, especially if wages do not keep pace with rising costs. Policymakers often face the challenge of balancing the interests of consumers and producers while promotingoverall economic stability and social equity.In conclusion, price adjustments on products havemultifaceted effects on consumers, businesses, and the economy as a whole. Understanding the dynamics of pricing mechanisms is crucial for stakeholders to make informed decisions and navigate market uncertainties effectively. By analyzing the impact of price adjustments from various perspectives, policymakers can develop strategies to promote sustainable economic growth, enhance market competition, and improve societal welfare.This essay draws on various examples and analyses to illustrate the complex interplay between price adjustments and their consequences, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of modern markets. As businesses continue to adapt to evolving consumer demands and competitive pressures, strategic pricing strategies will remain essential for driving growth and maintaining profitability in an increasingly dynamic global economy.。

Commodity Prices, Monetary Policy, and Inflationw